AMARACHI OKAFOR

Ask yourself…

Ask Yourself © 2014 - 2021 Amarachi Okafor

Edited by Amarachi Okafor and Sontee IjohoPublished by ORIE STUDIO in 2021 as print documentation of the project. www.amarachiokafor.art

Book and cover design by Julia P. Ames

Cover Image: Ask Yourself, 2014

Photography by Amarachi Okafor, edited by Adolphus Opara

All images © ORIE STUDIO (Studio Amarachi Okafor), except where otherwise credited.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without the written permission of the publisher and the author.

Every attempt has been made to secure the rights to reproduce the artworks images that appear in this documentary publication. However, if any have been inadvertently overlooked, please contact the author and the publisher.

ISBN 978-978-978-174-4

WHO ARE WE? Kamri Apollo 34

PRE-PRODUCTION STUDIO PROCESSES

Painting and installation Dimensions 37

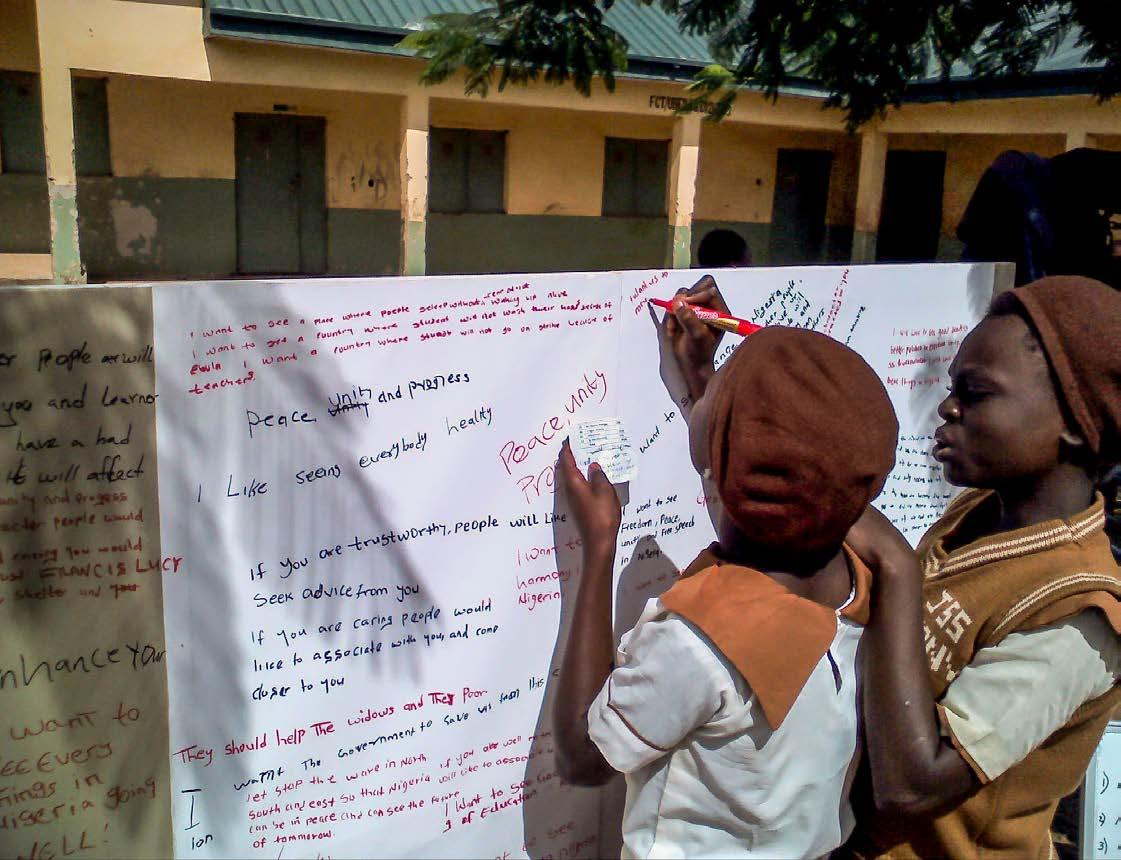

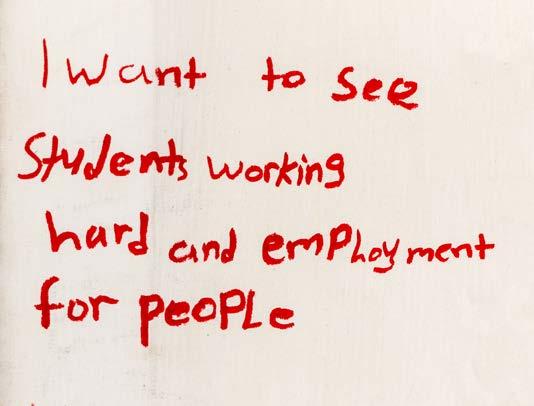

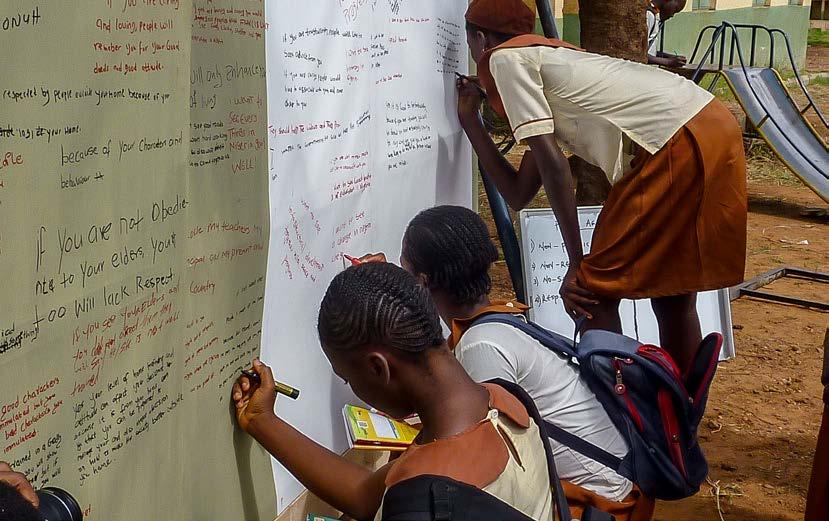

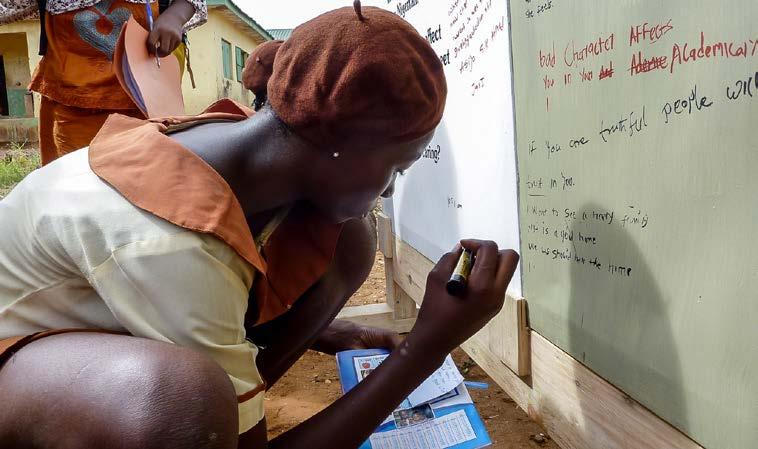

ART MEETING WITH SECONDARY SCHOOL CHILDREN

J.S.S. Nyanya 1, Abuja—Participation Dimension (Interaction) 44

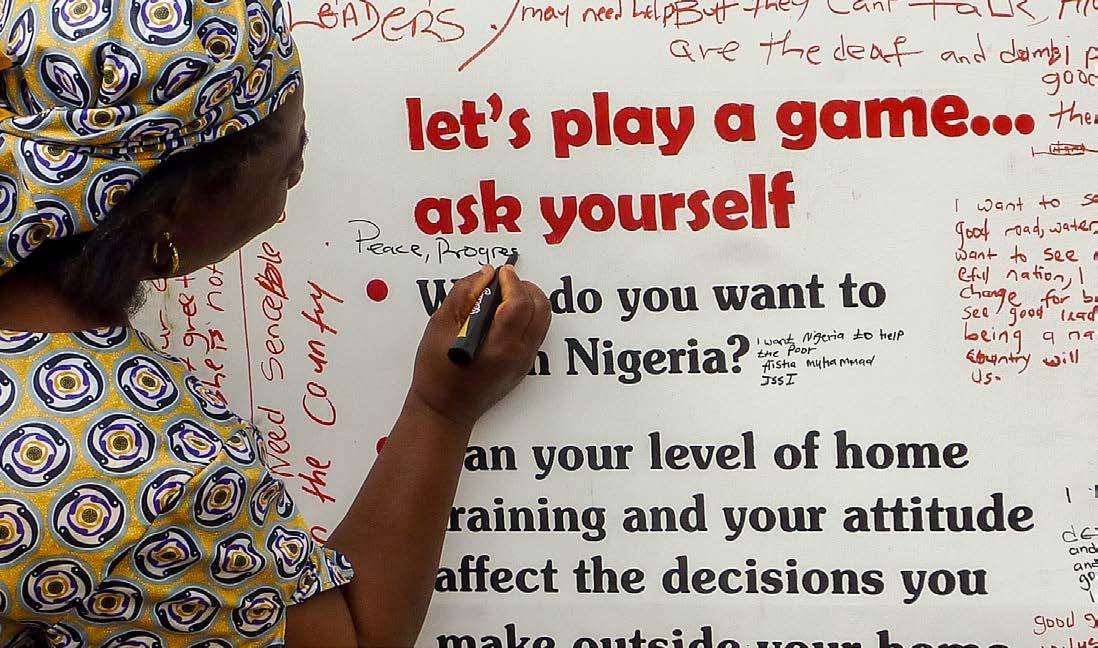

ART MEETING WITH THE MARKET PUBLIC Wuse Market, Abuja—Participation Dimension (Interaction)

68

ART IN NIGERIA AND THE PUBLIC SPACE Uche Nnadozie 92

ART MEETING WITH TERTIARY SCHOOL STUDENTS

FCT College of Education, Zuba-Abuja—Participation Dimension (Interaction)

106

ART IN CONTEMPORARY NIGERIA: NEO STYLISTIC MODELS Ayo Adewunmi 130

ART MEETING WITH PROFESSIONALS AND POLICY MAKERS

Federal Secretariat. Head of Civil Service of the Federation, Abuja —Participation Dimension (Interaction) 140

One nation, united and peaceful!

Where peace and justice must reign!

May we be guided right to serve our Fatherland, that the labour of our past heroes shall not be in vain.

Help our youth to know the truth to grow in love and honesty and attain great heights, living just and true.

To all Nigeria children including me,

To the future of Nigeria.

It is often easier to blame other people where we go wrong!

It is often in our habit to disregard the value for integrity and excellence; and excuse mediocrity.

Do we teach our youth to put down merit and dignity in work? Ask Yourself!

Today, we see poor level of work output, including unsafe healthcare.

Our education system can be in better shape. ...because we started to prefer shortcuts that return us to even longer routes.

Do we disrespect the honest man who earns a lower income; And we uphold materialism over sustaining strong connections in relationships.

The outcome will be less and less trust in ourselves. And by our standards, today, not all must take responsibility for the consequences of their actions?

What are we doing?

Ask Yourself!

I express many thanks to all who have participated in, and enabled this project, to in various ways and different capacities, come to fruition.

My thanks also go to the following organisations and individuals whose presence and support I felt during various stages of the project.

National Gallery of Art, Abuja – Headquarters. Universal Basic Education Board (U.B.E.B.)

J.S.S. (Junior Secondary School) Nyanya

Mallam Daudu Yahaya (Principal)

Olukemi Adebimpe-Ojo (Vice-Principal Administration)

Elisabeth Olajumoke Daramola (Cultural and Creative Arts, Teacher)

All the participants

A.M.M.L. (Abuja Markets Management Limited); Wuse Market

Ibrahim Sulaiman (Manager, A.M.M.L., Wuse Market), Austin Tihal (Chief Security Officer, Wuse Market)

All the Participants

F.C.T. College of Education, Zuba

A.B. Sulaiman (Dean, School of Vocational and Technical Education)

Dauda Nuhu (Head of Department, Fine and Applied Arts)

Mabel Nee Chukwu (Art Teacher, Fine and Applied Arts). All the participants

Abuja Investment Company Limited

Eagle Square Car Park, Central Business District, Abuja, led by Mr Seyi

All the security personnel

All the participants

Also, huge thanks to, Yakie Ayalon, Tee-Jay Dan, Douglas Izie-Enogieru, Nuhu Dalyop, Ngozi Akande, Eva Barta Martin, Addis Okoli, and Ikechukwu Nwosu.

Ayodeji Adegoke, Tom Sunday Godwin, Godwin Okoi, Uchendu Mbele, Christian Obadan, Cyprain Ozioko, Odu Marcilina Ele, Sontee Ijoho, Semshak Simput and all others whom I may have failed to mention here.

I am thankful for the African Artists foundation National Arts Competition – their initiative inspired me to produce this work. I am infinitely grateful to my family and close friends for their continuous support.

Primarily, I thank the Almighty Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth is named.

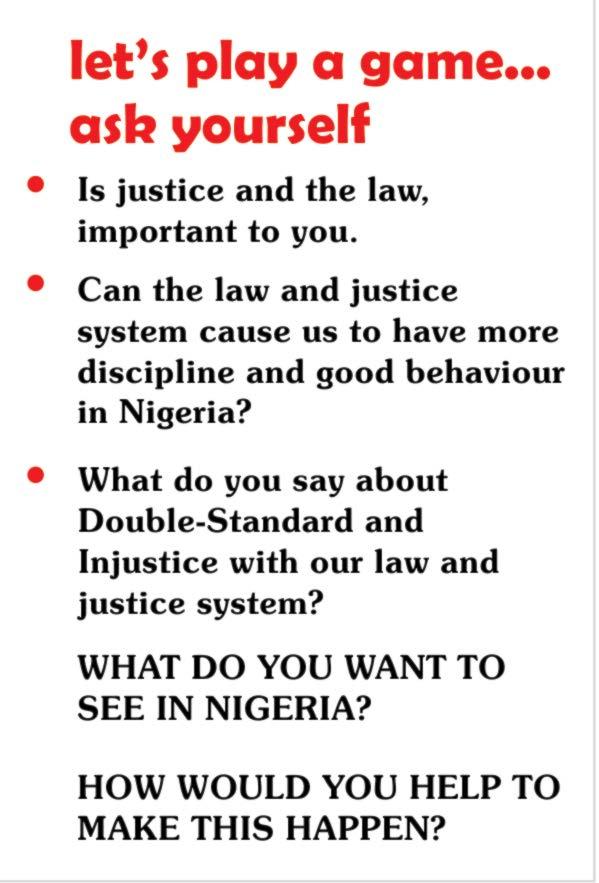

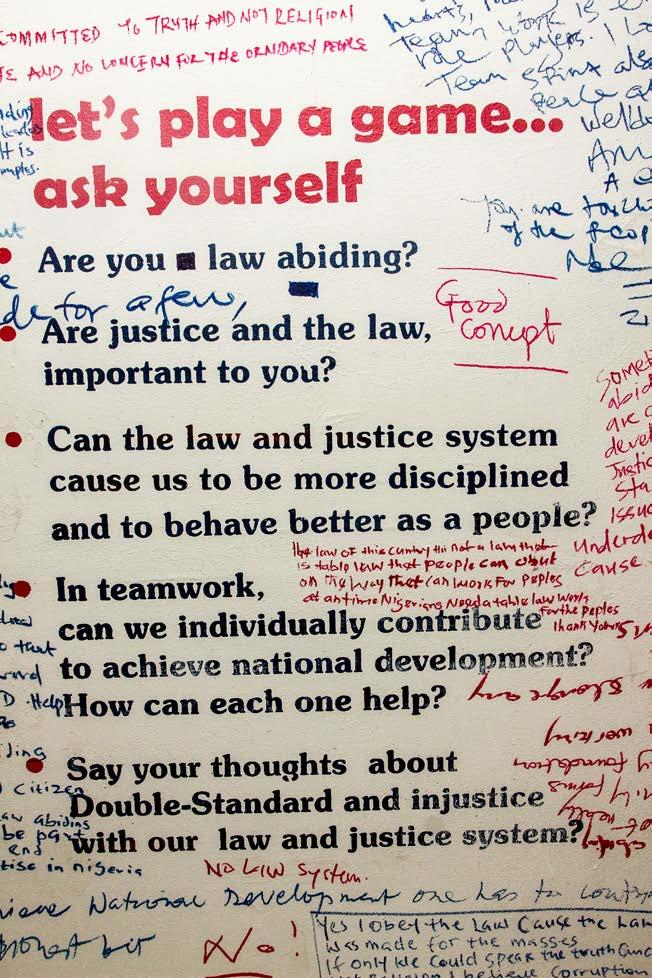

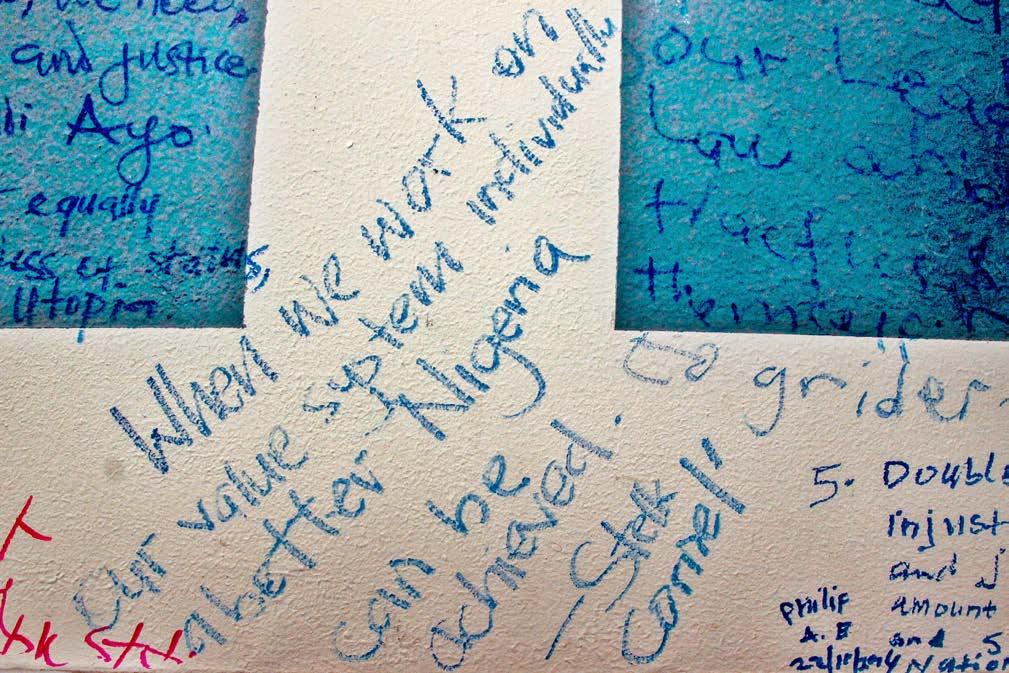

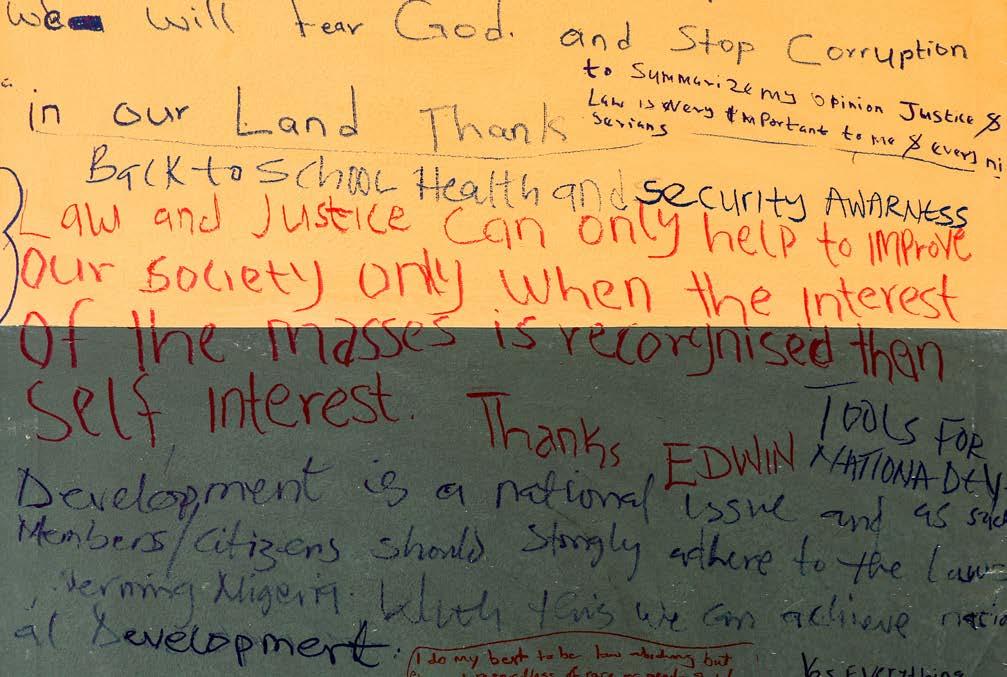

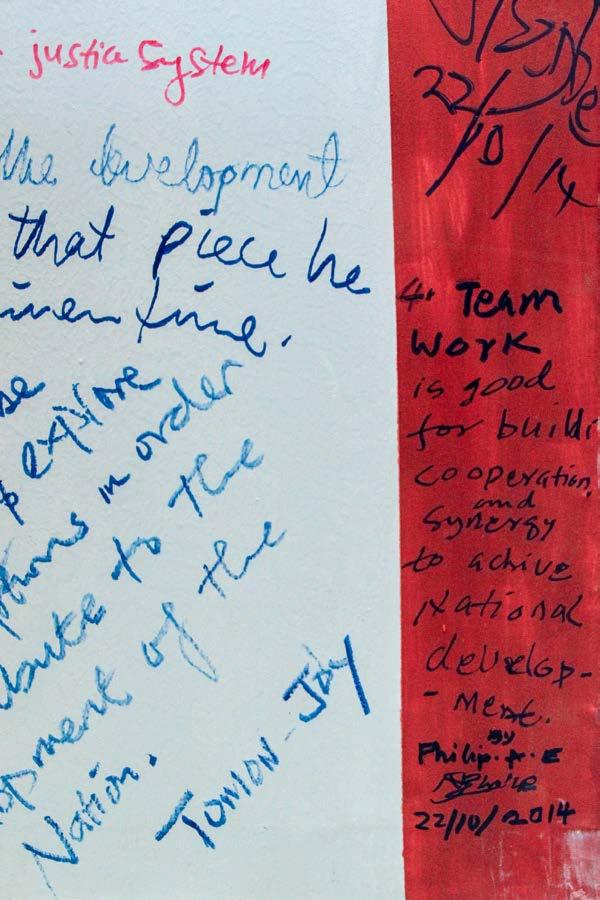

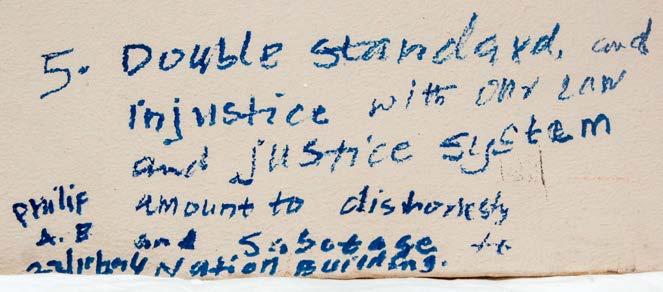

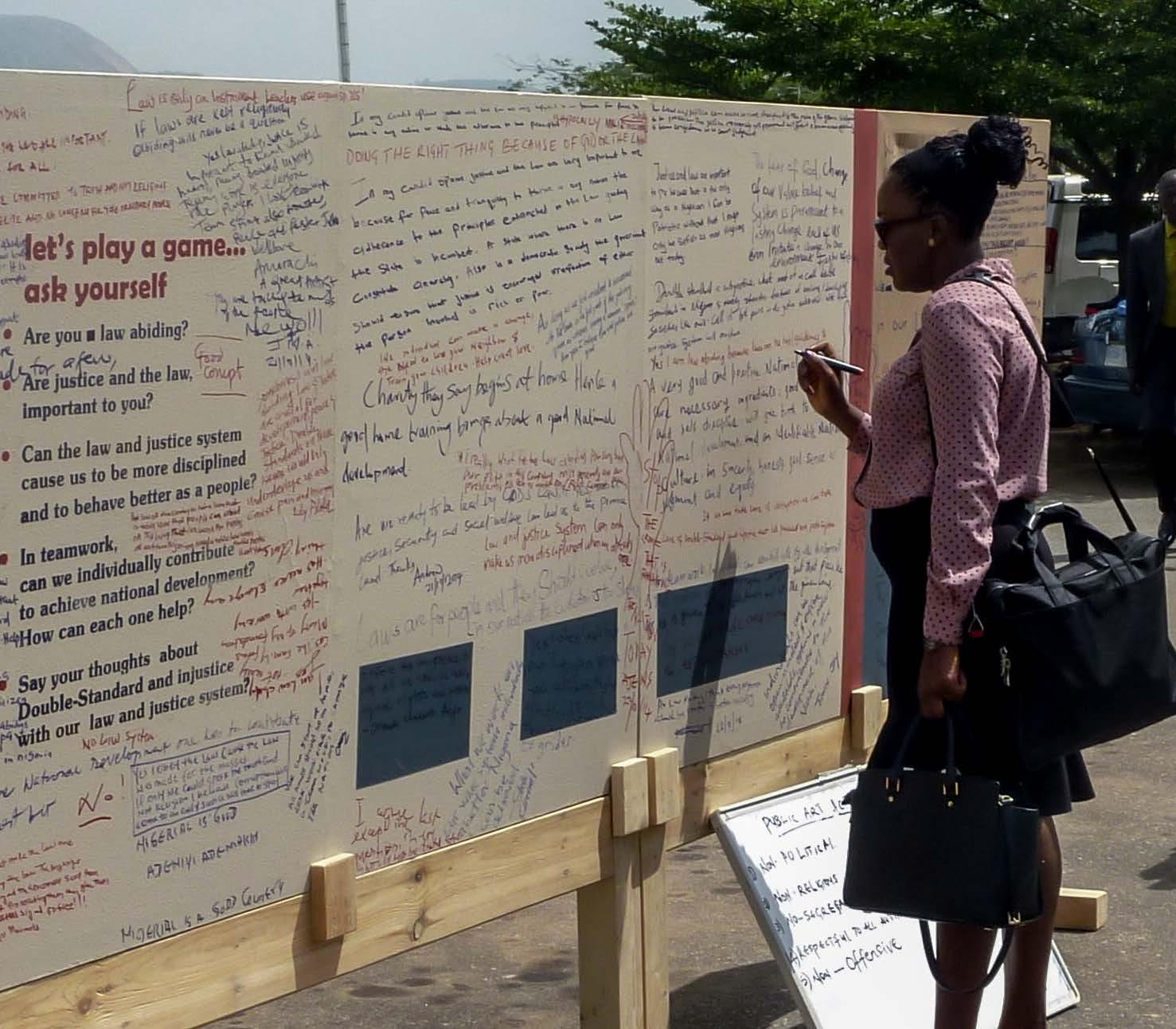

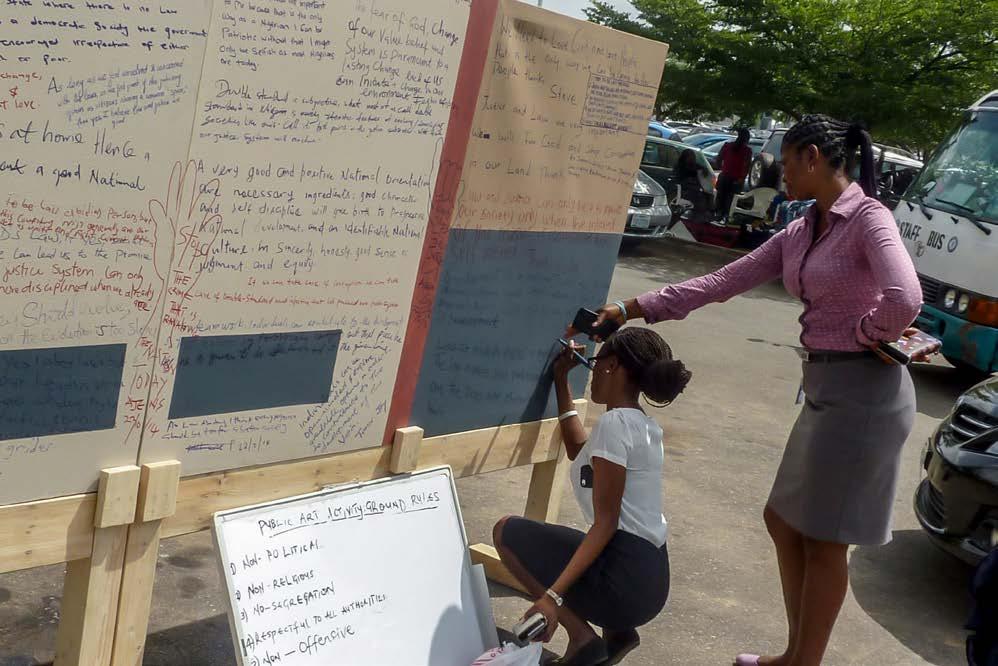

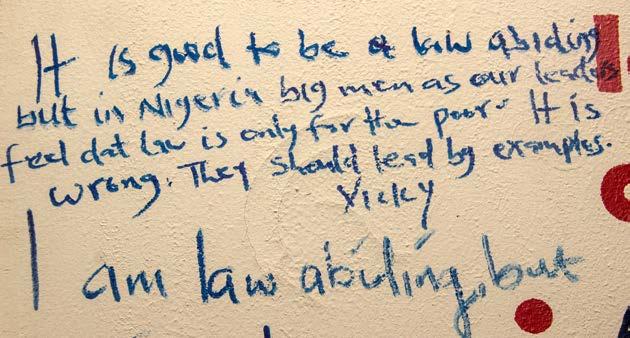

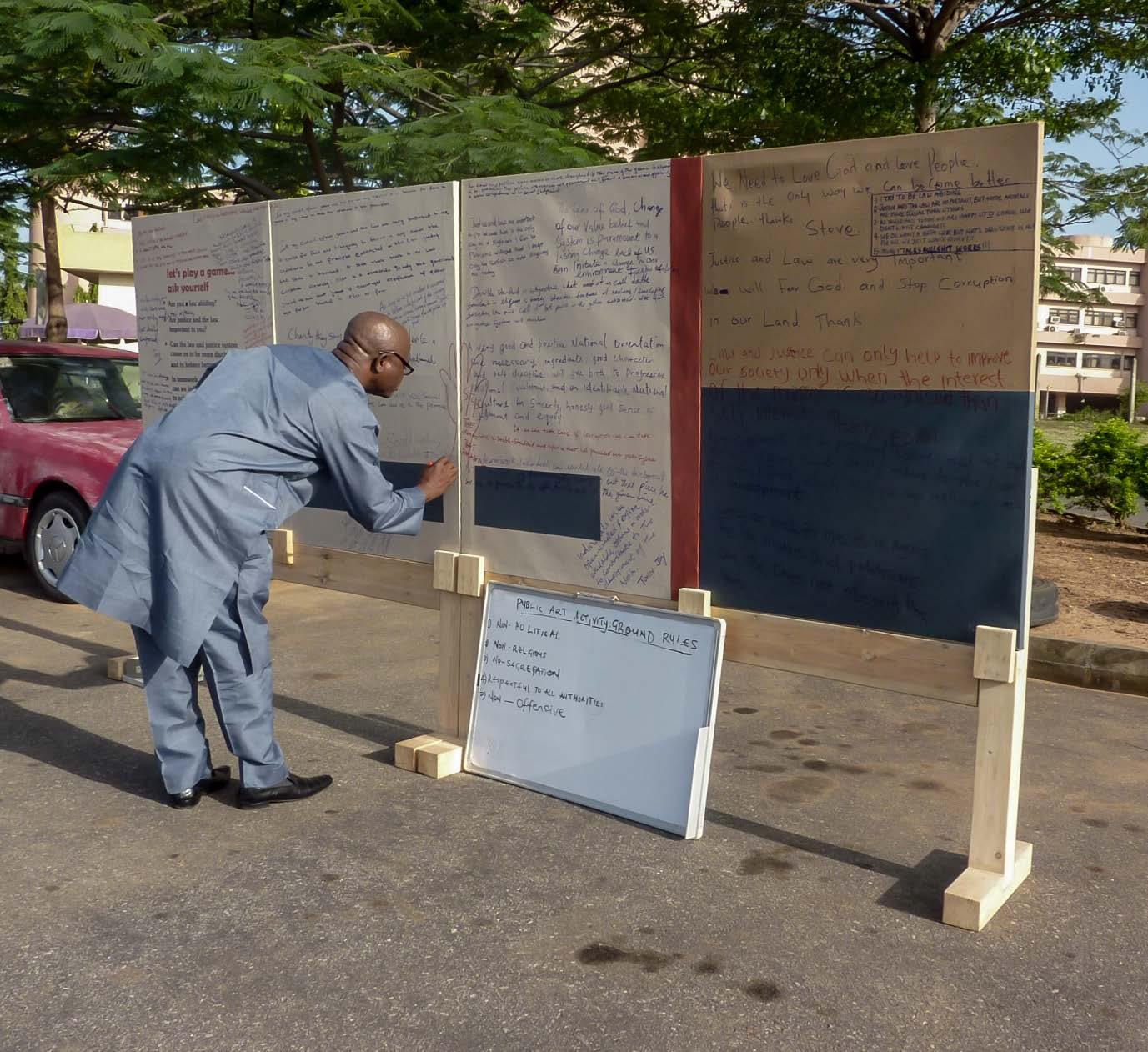

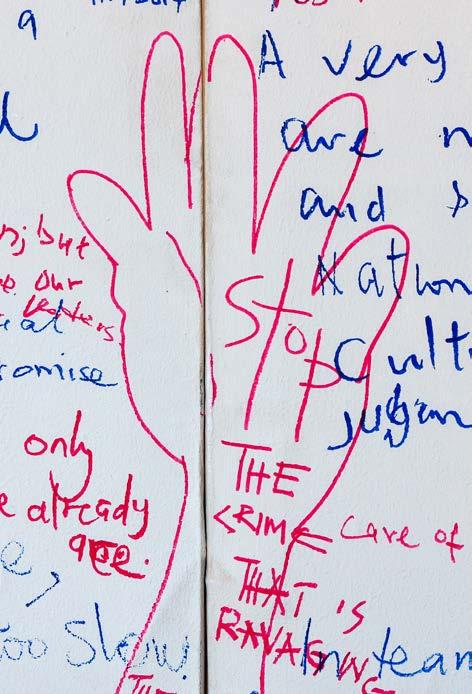

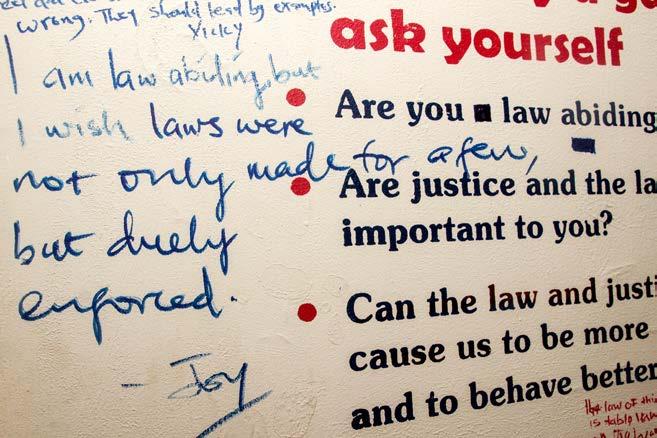

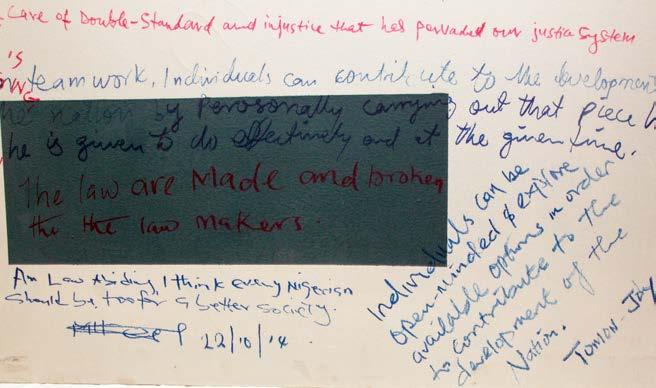

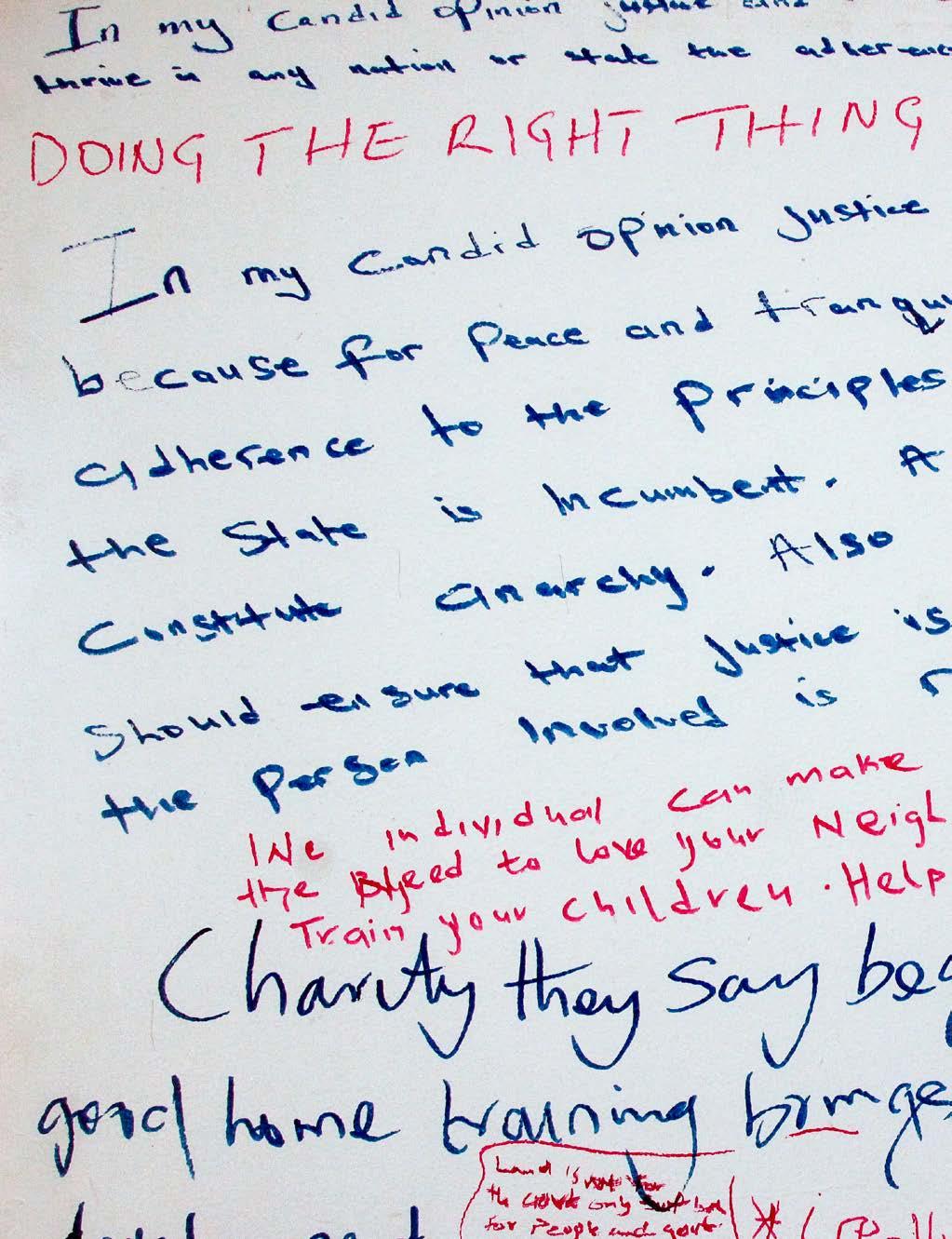

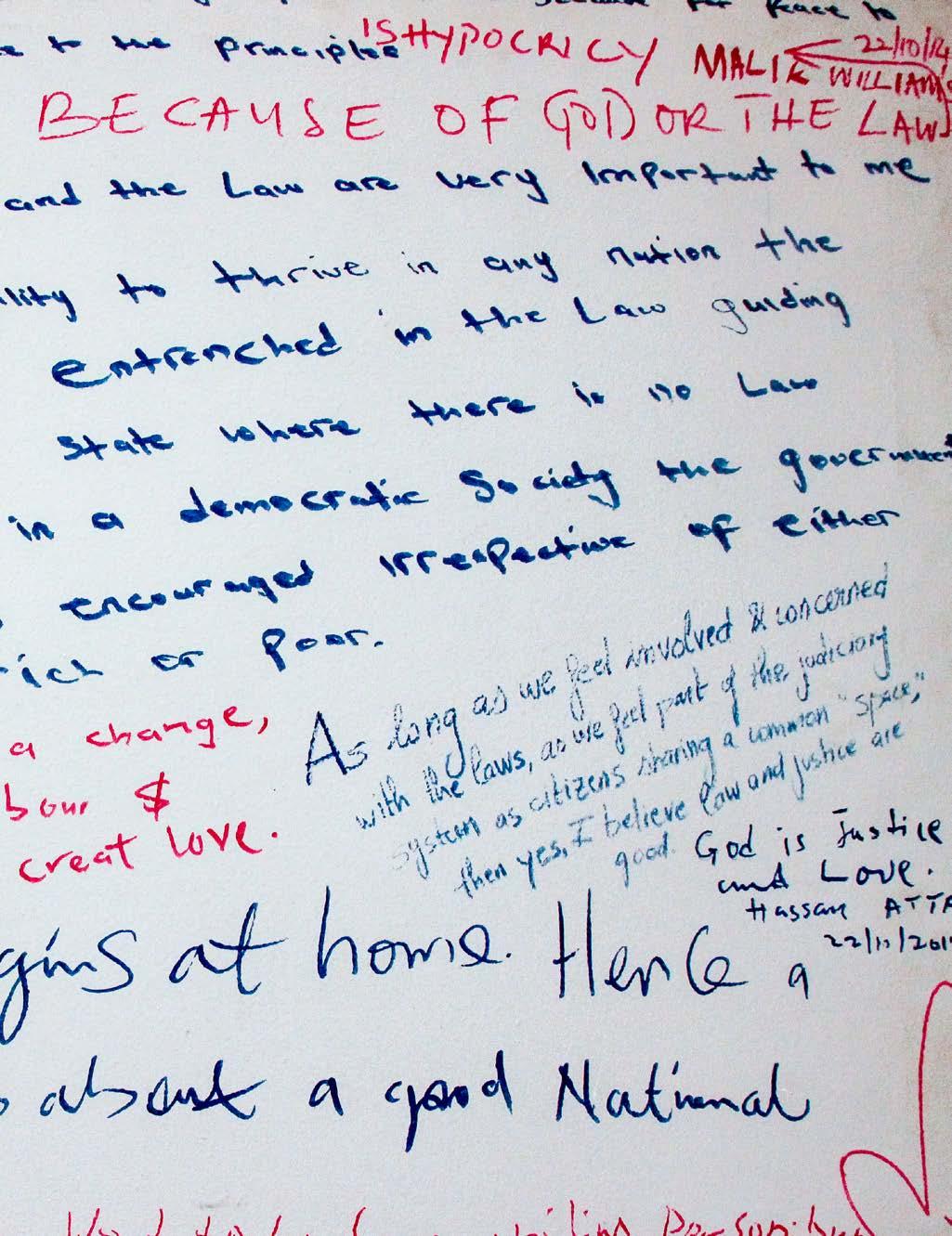

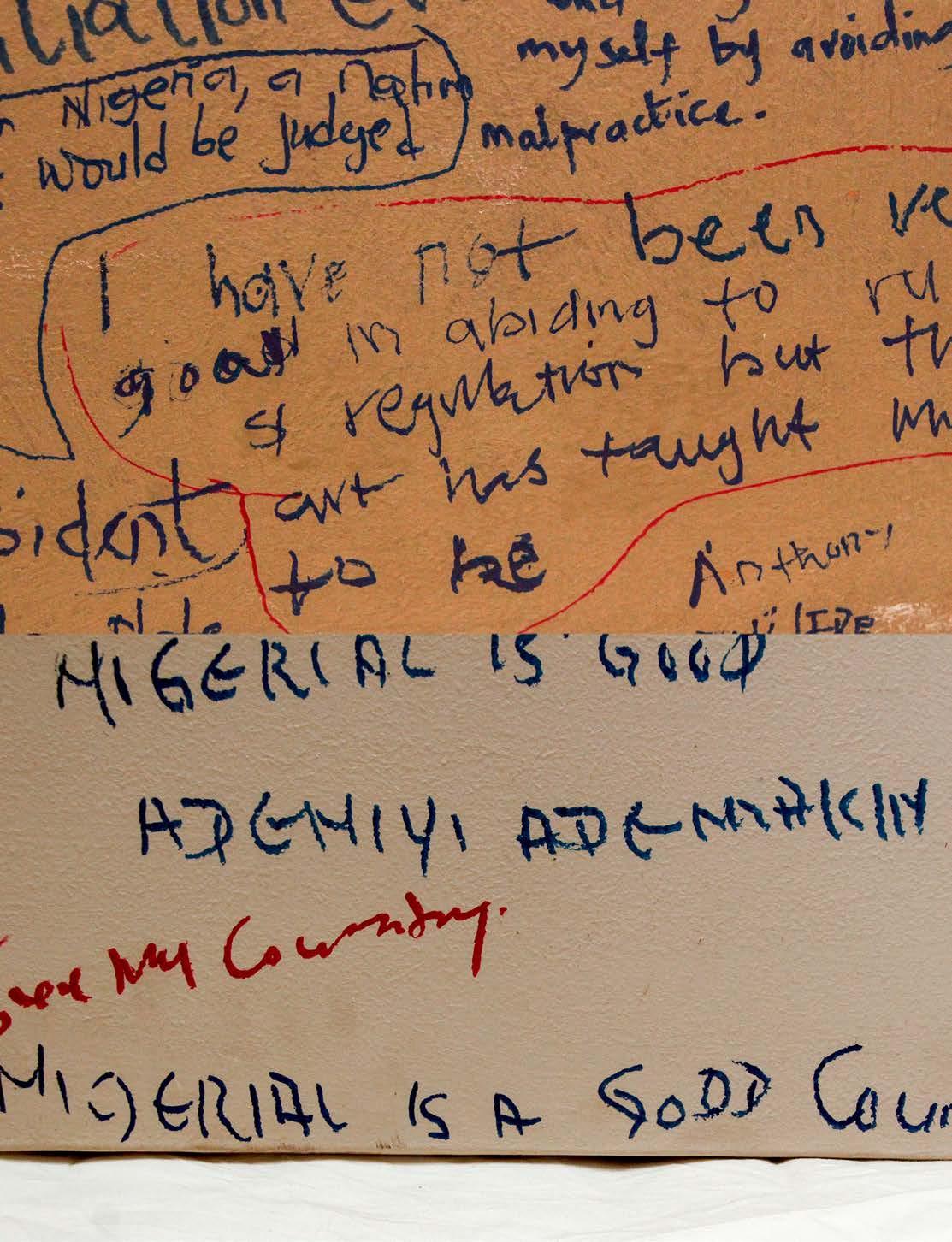

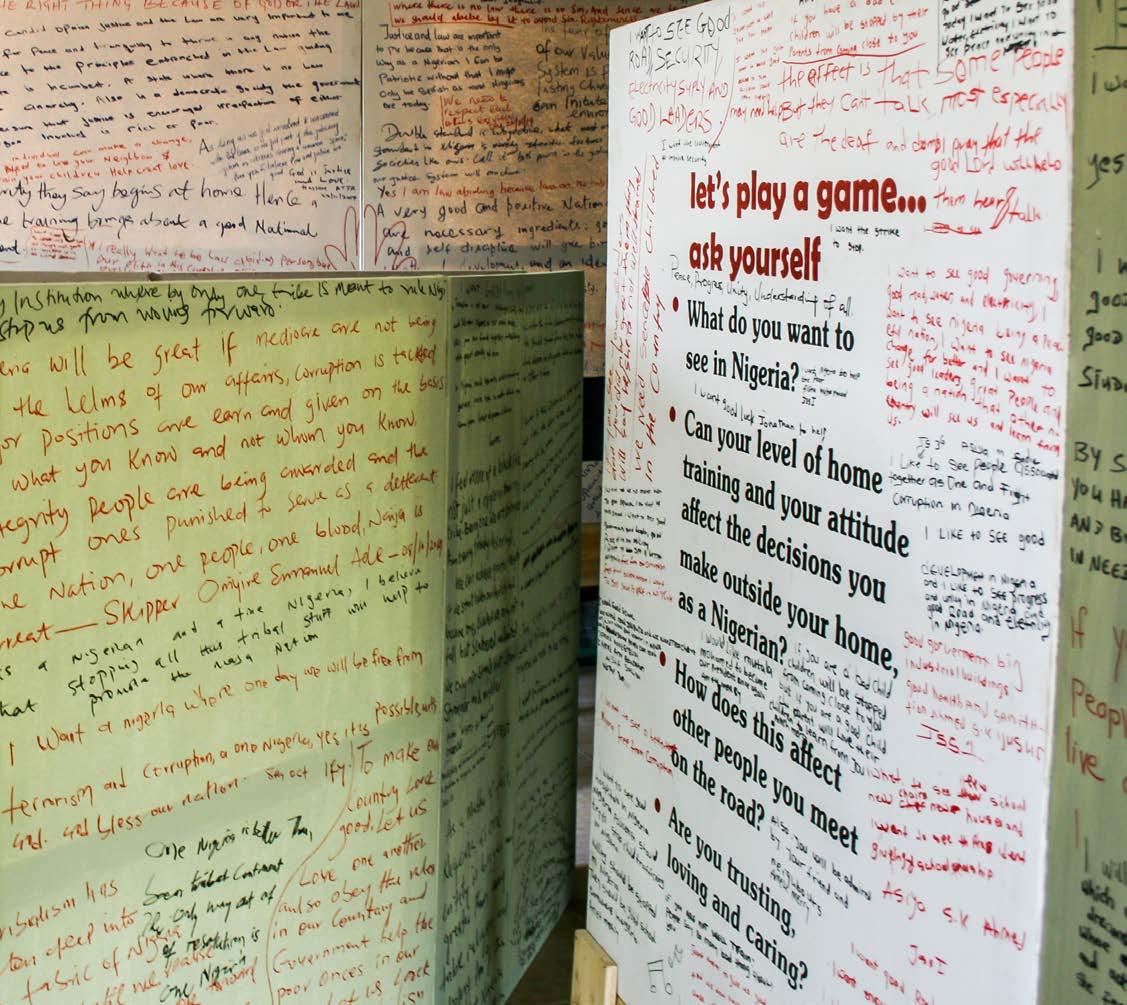

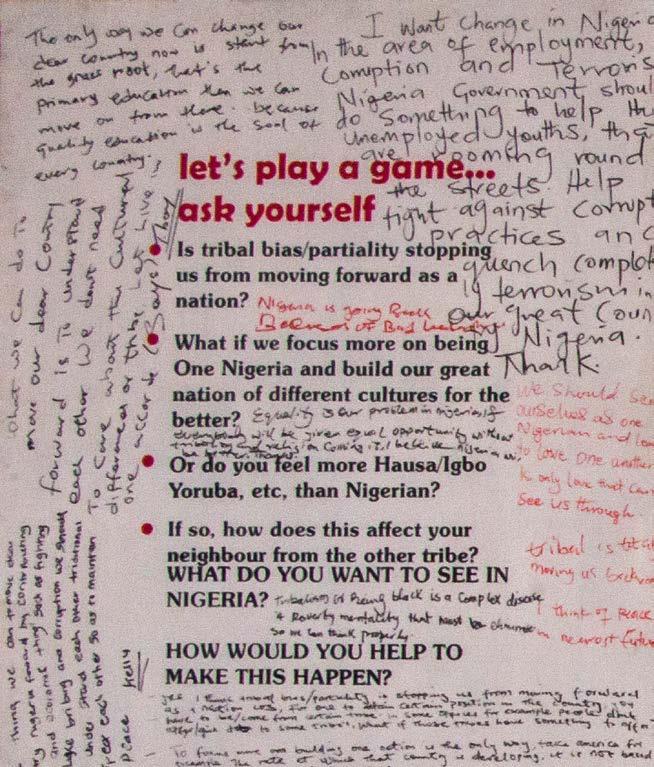

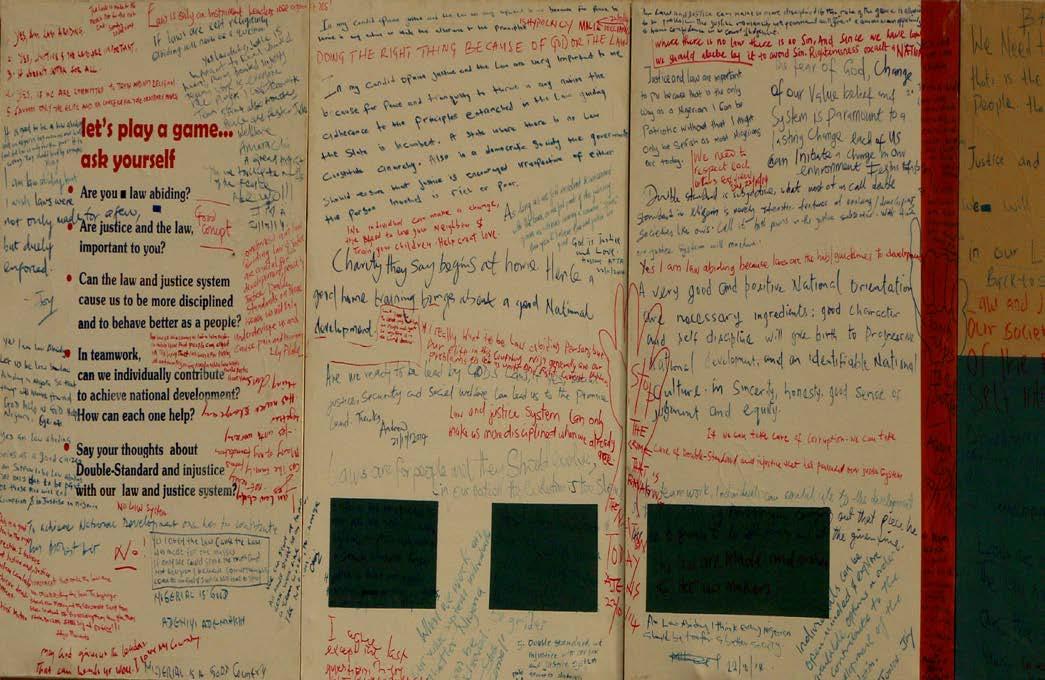

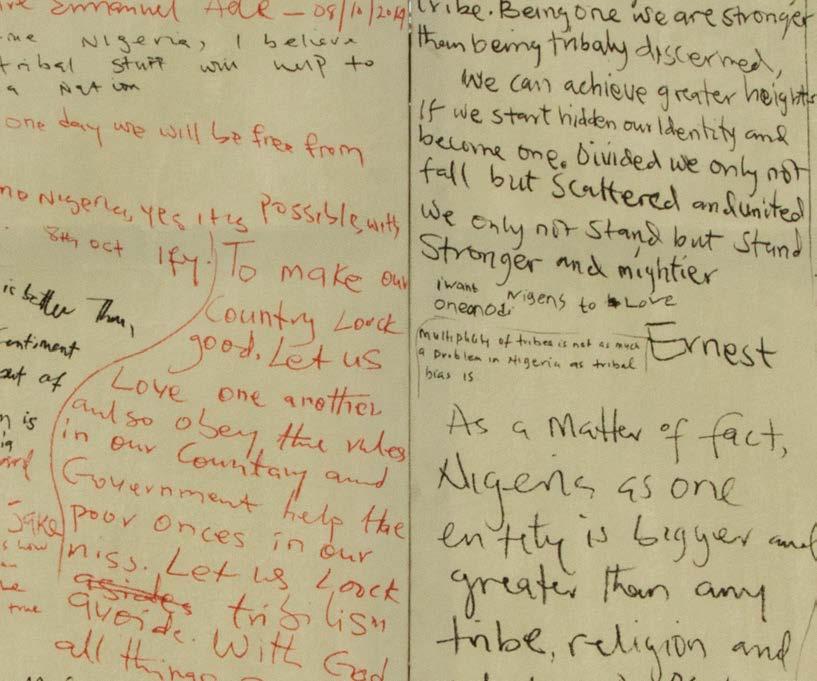

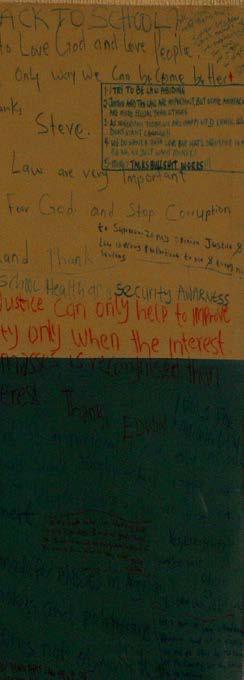

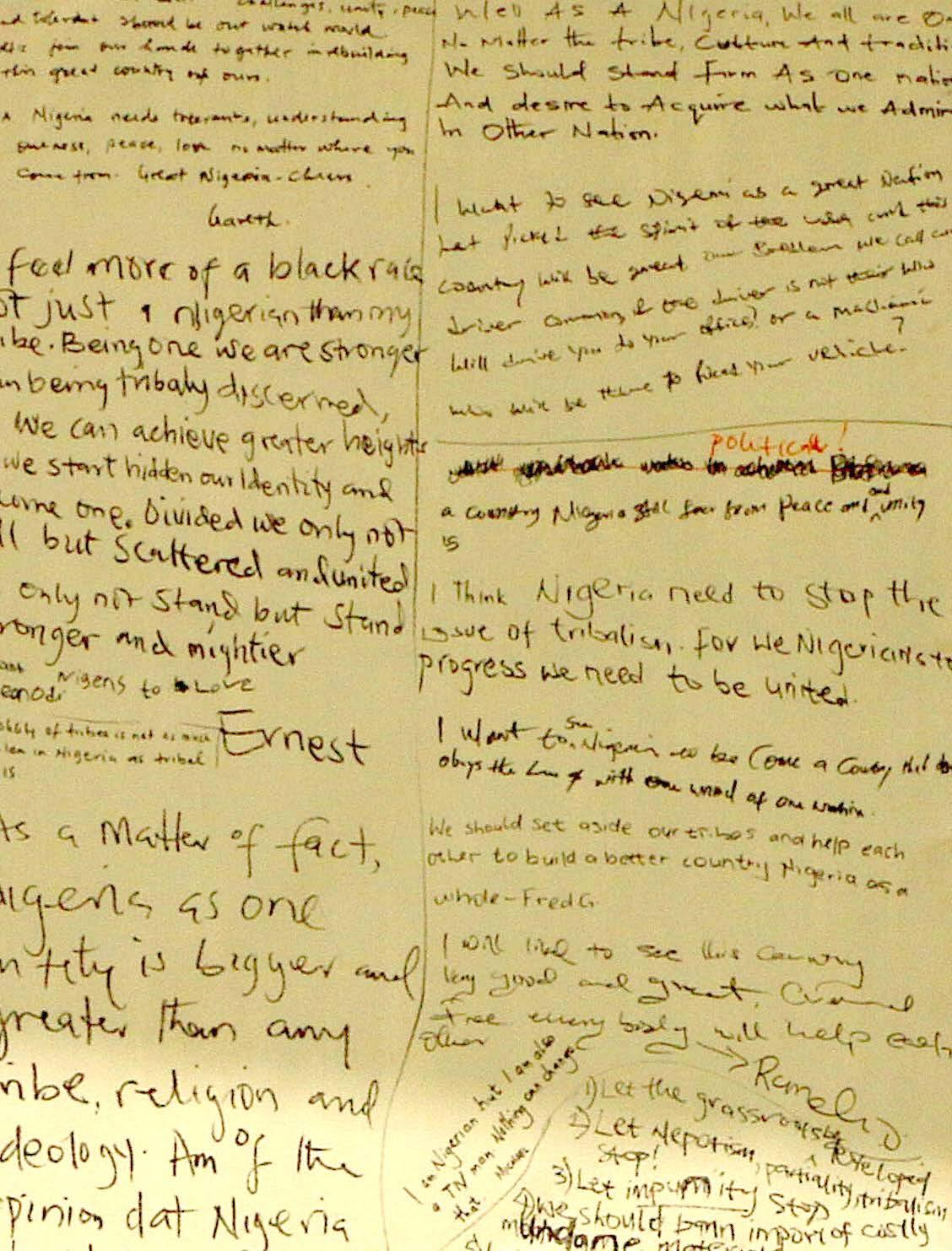

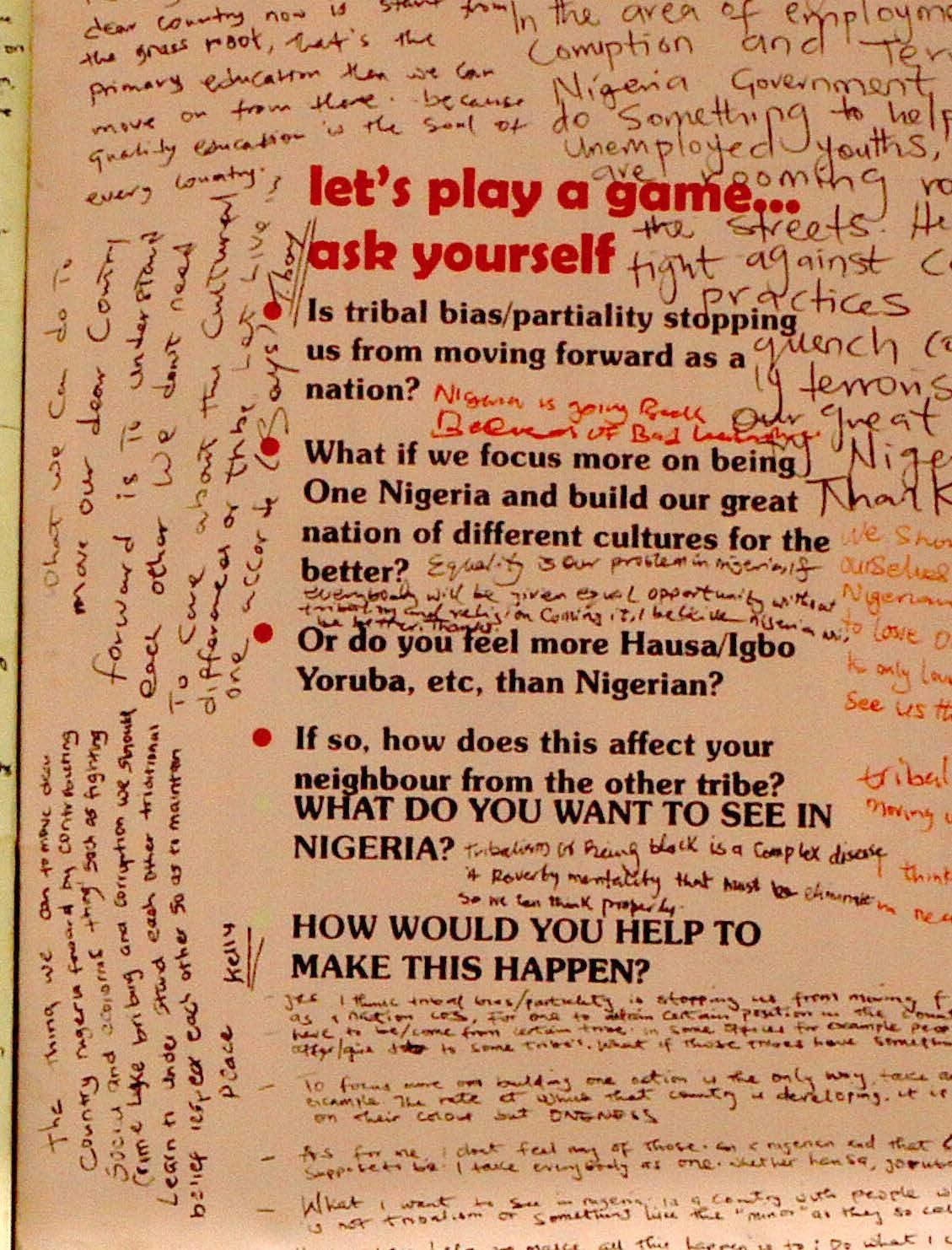

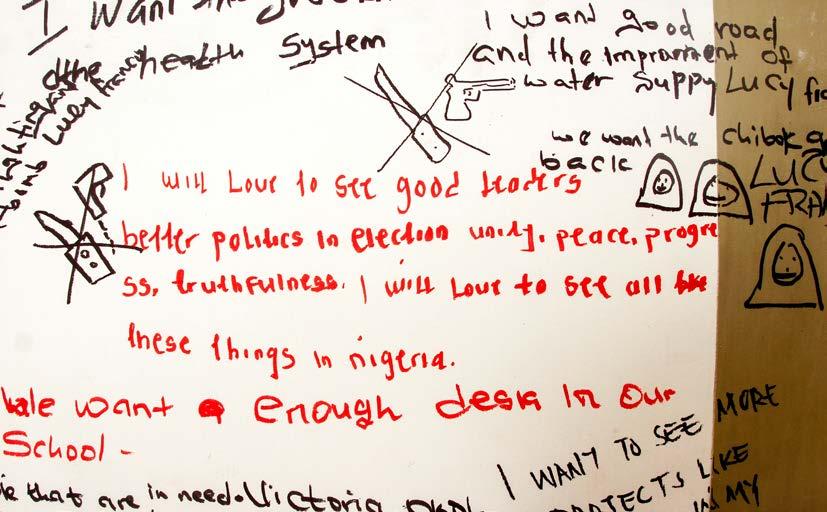

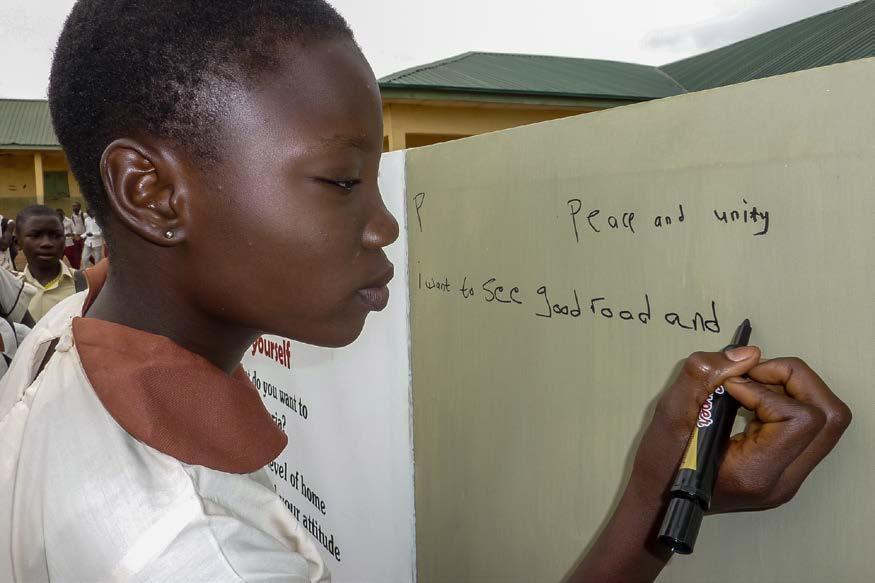

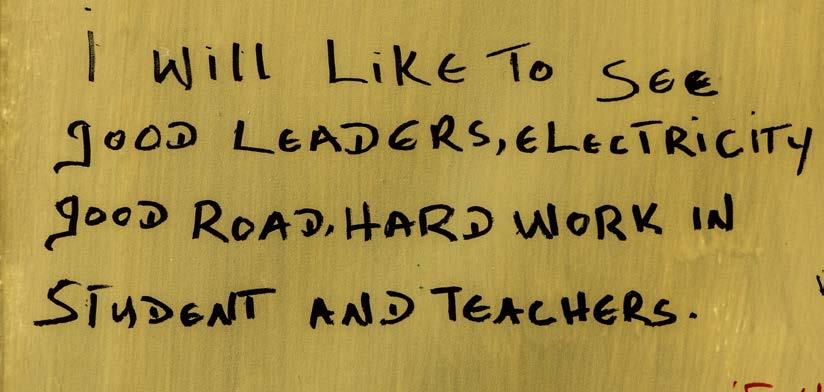

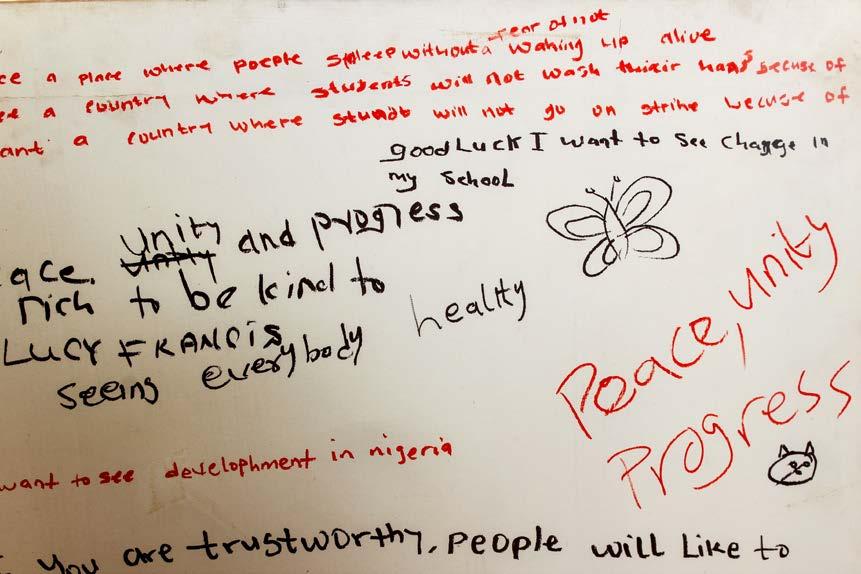

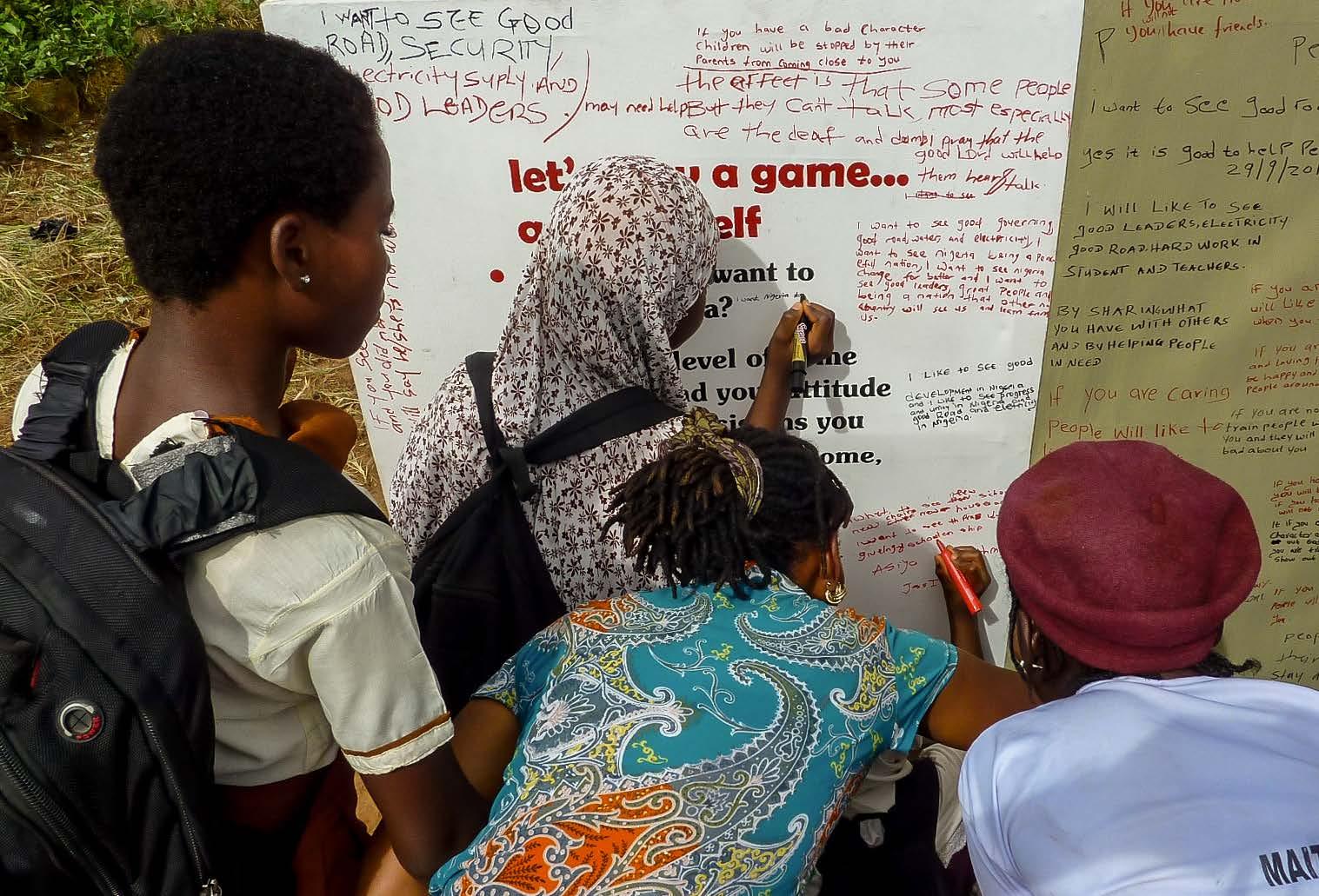

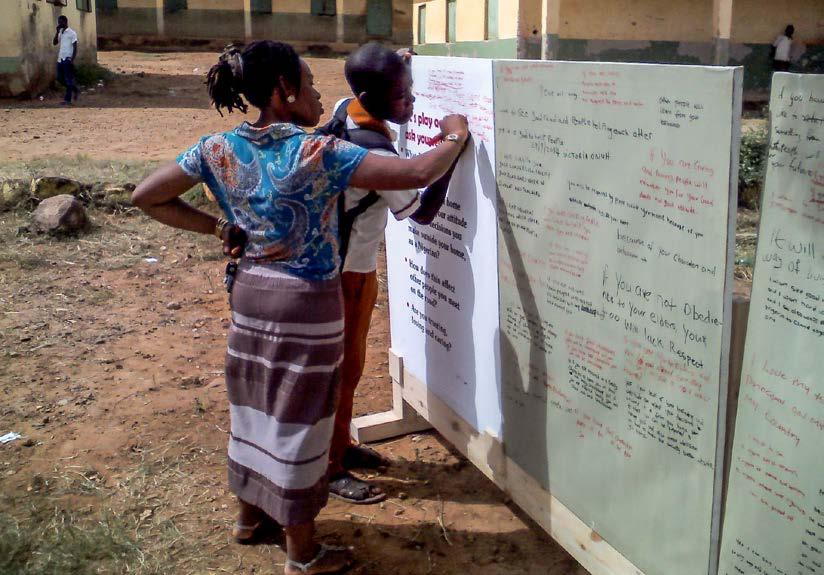

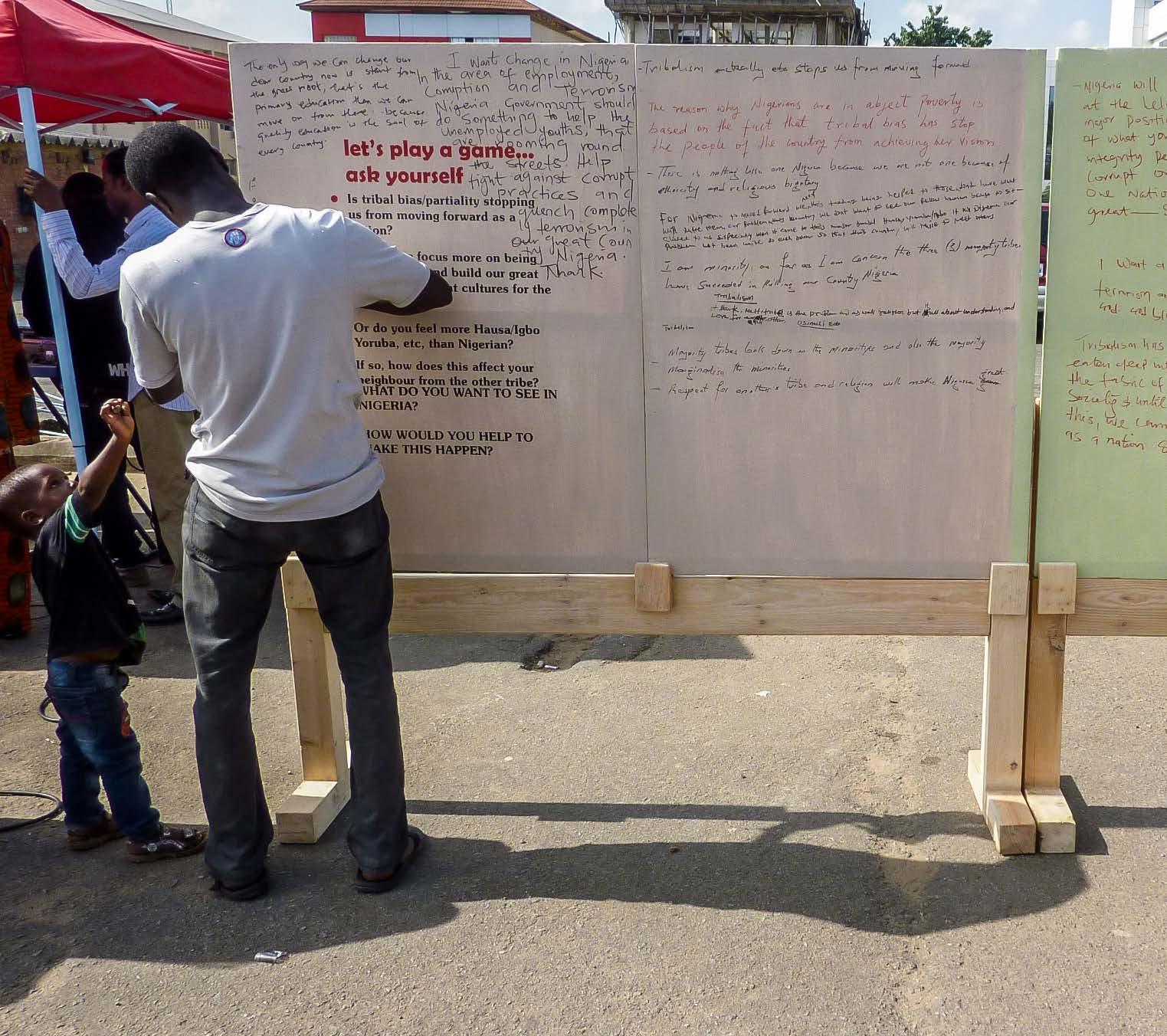

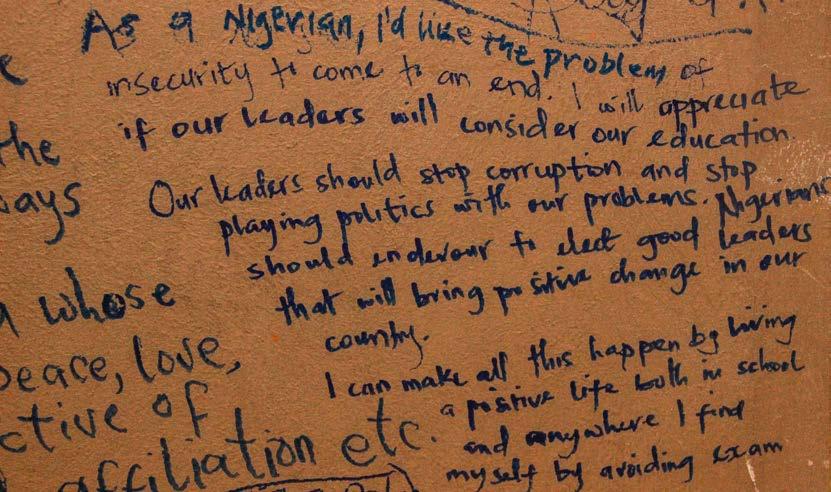

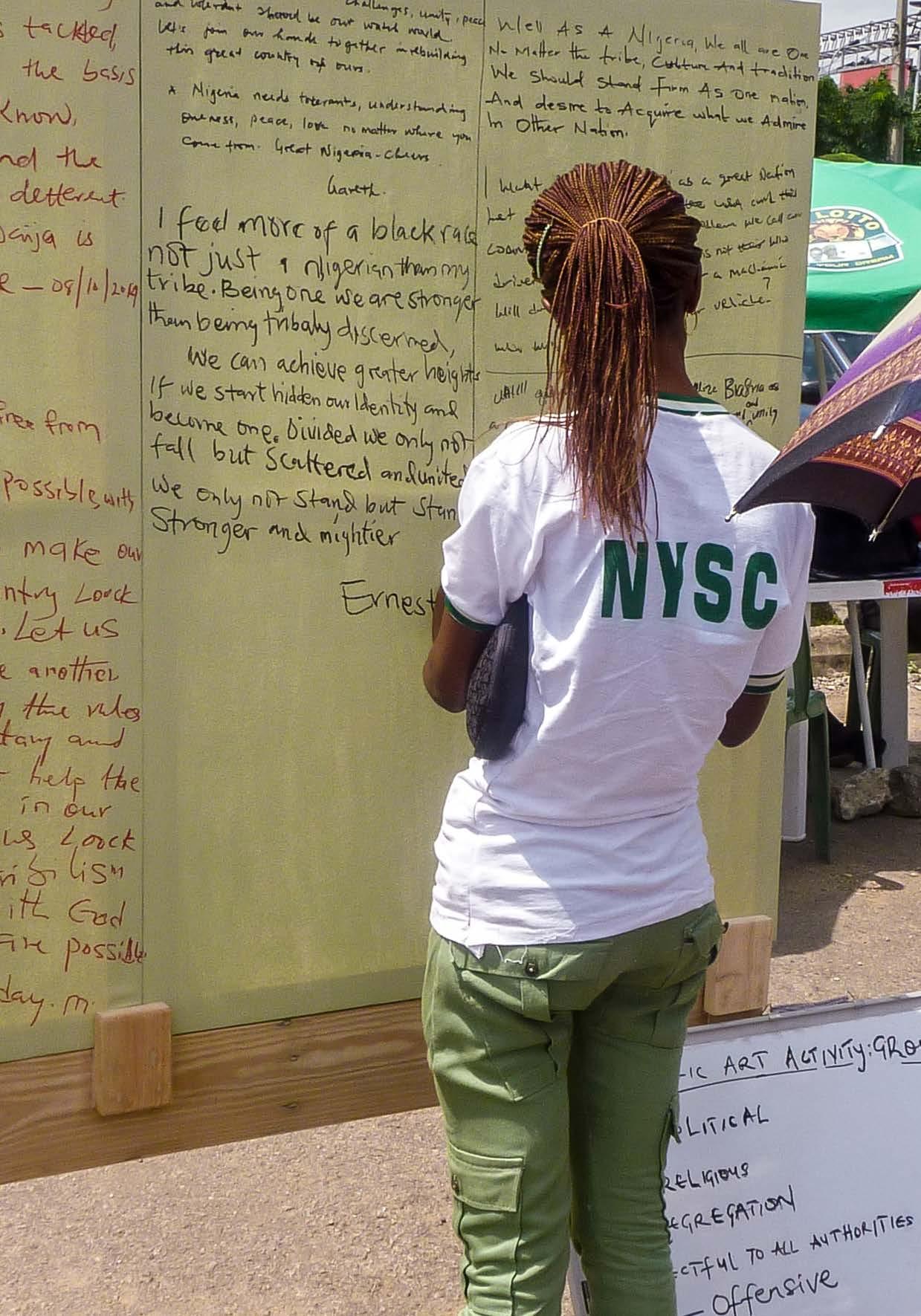

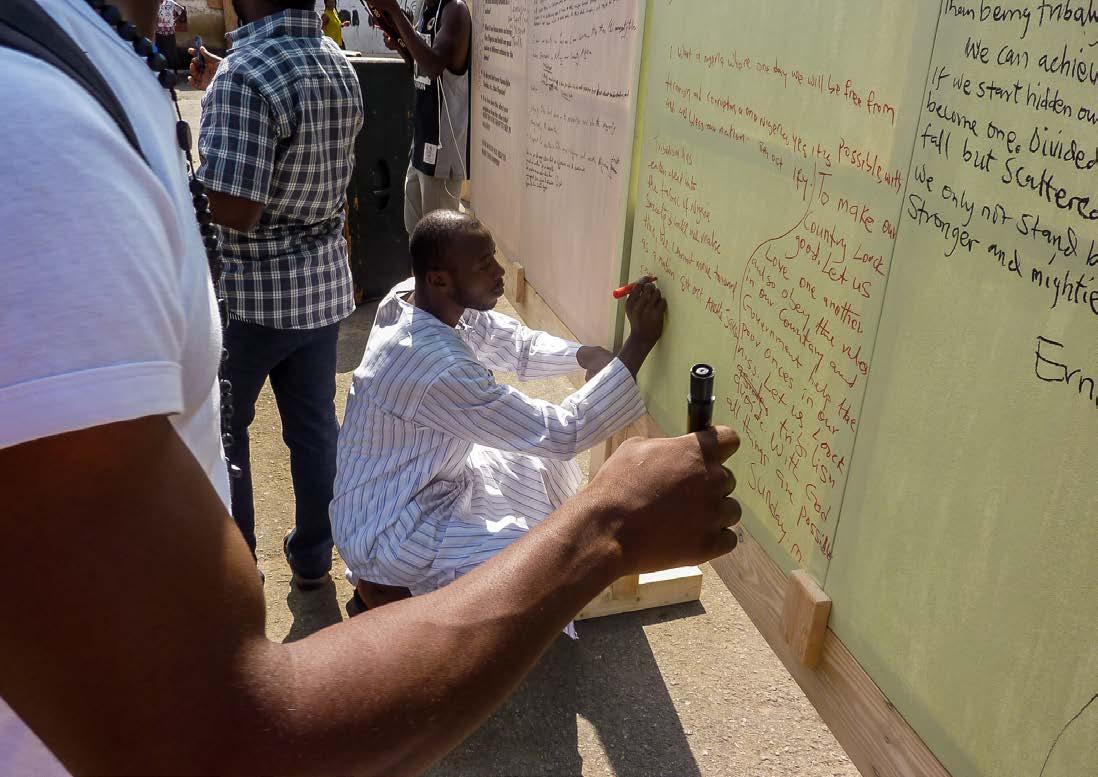

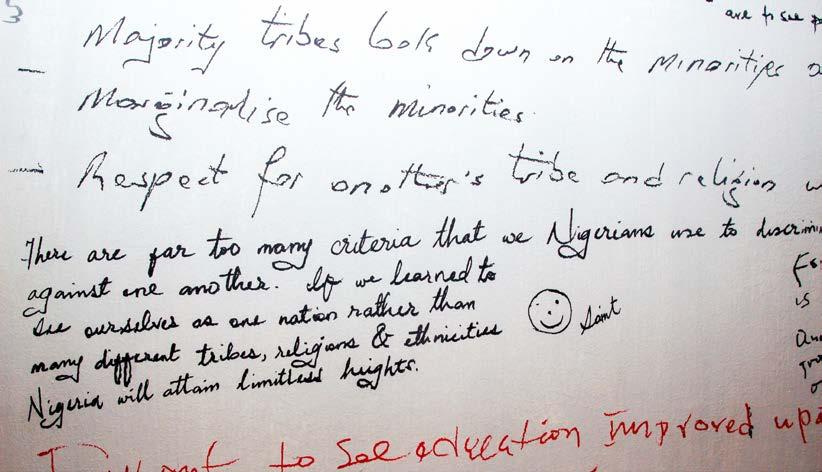

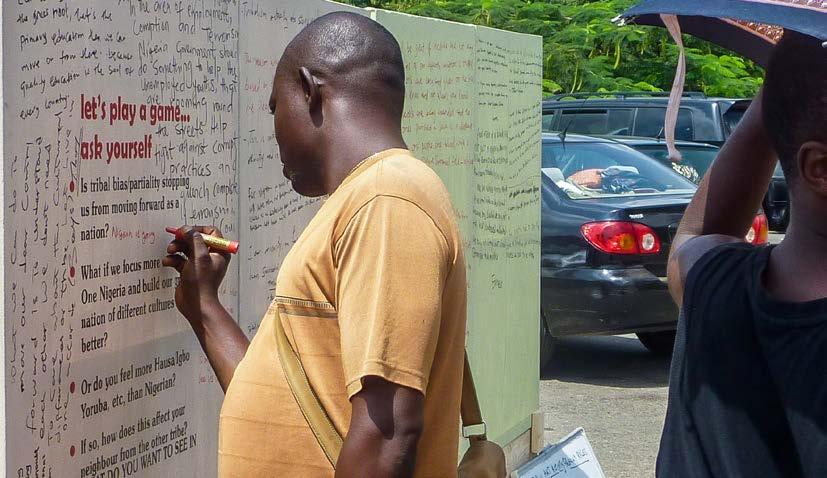

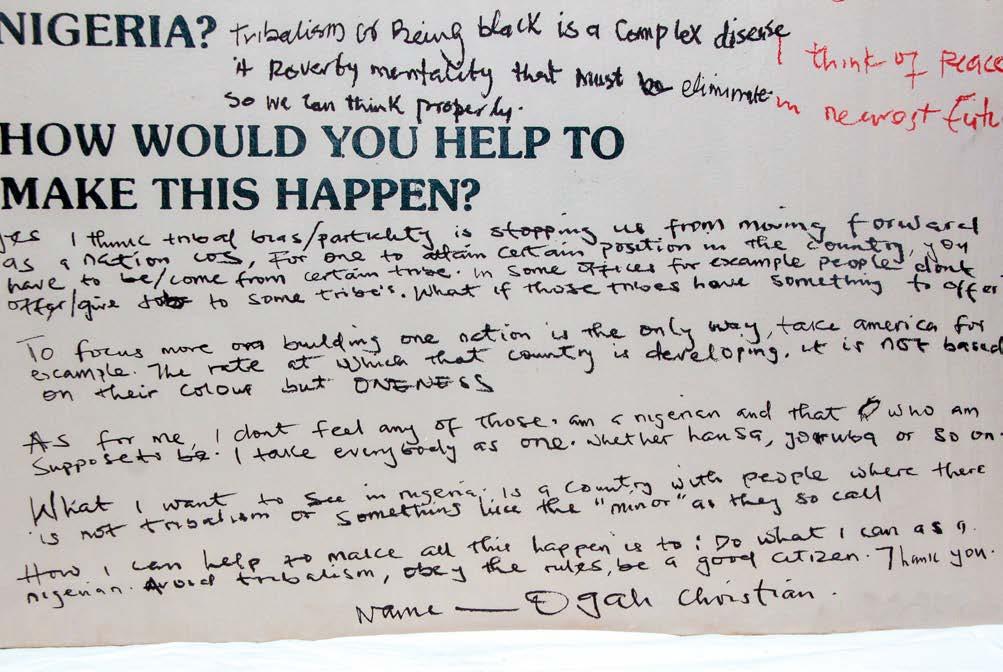

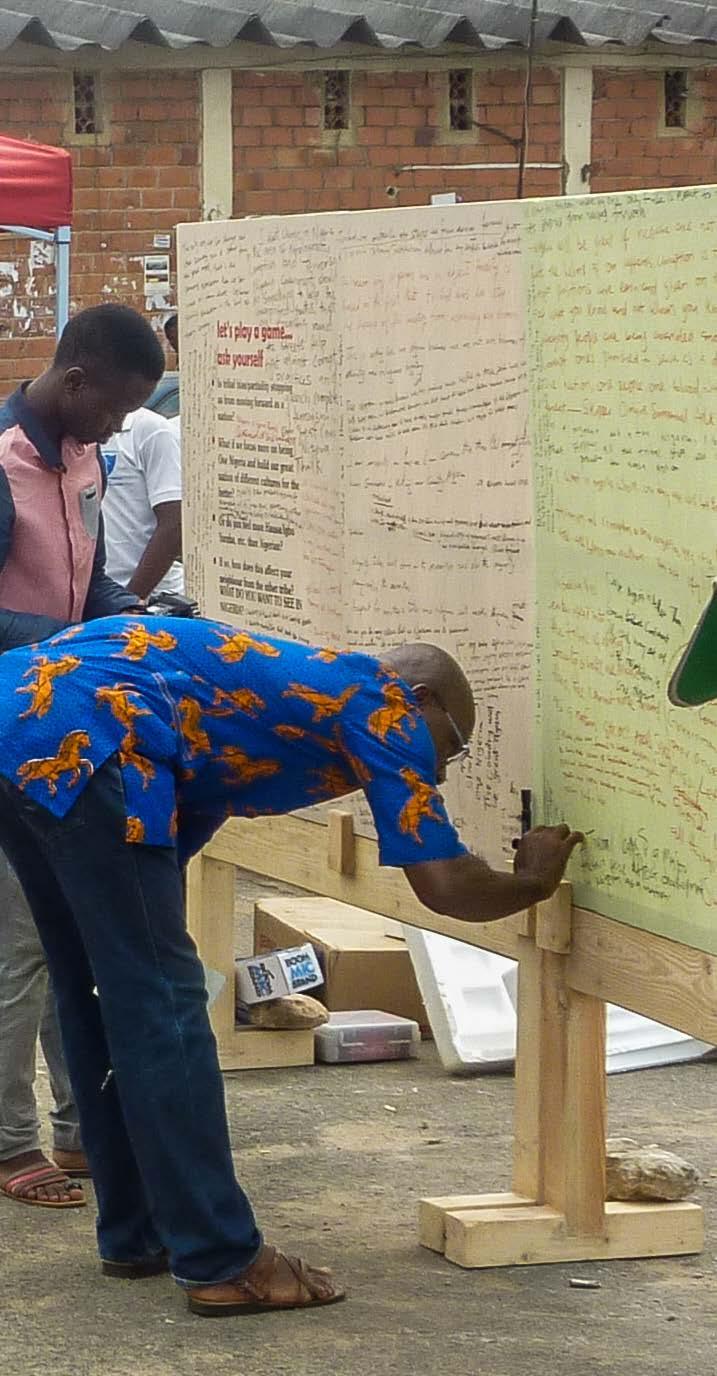

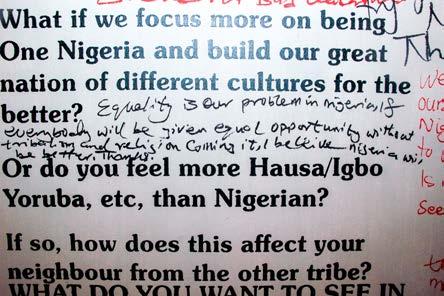

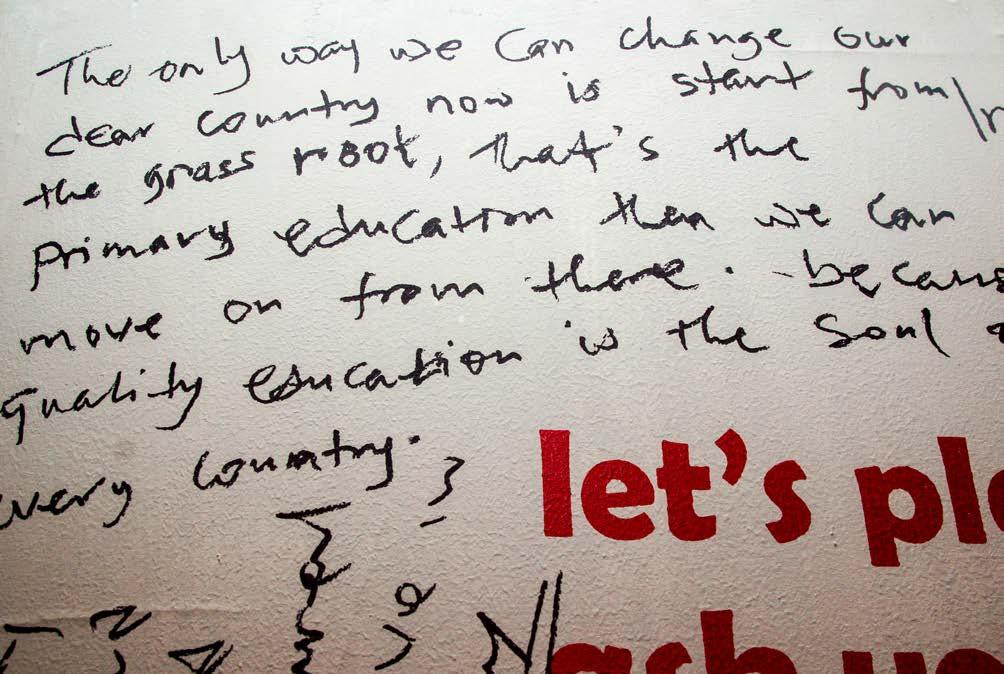

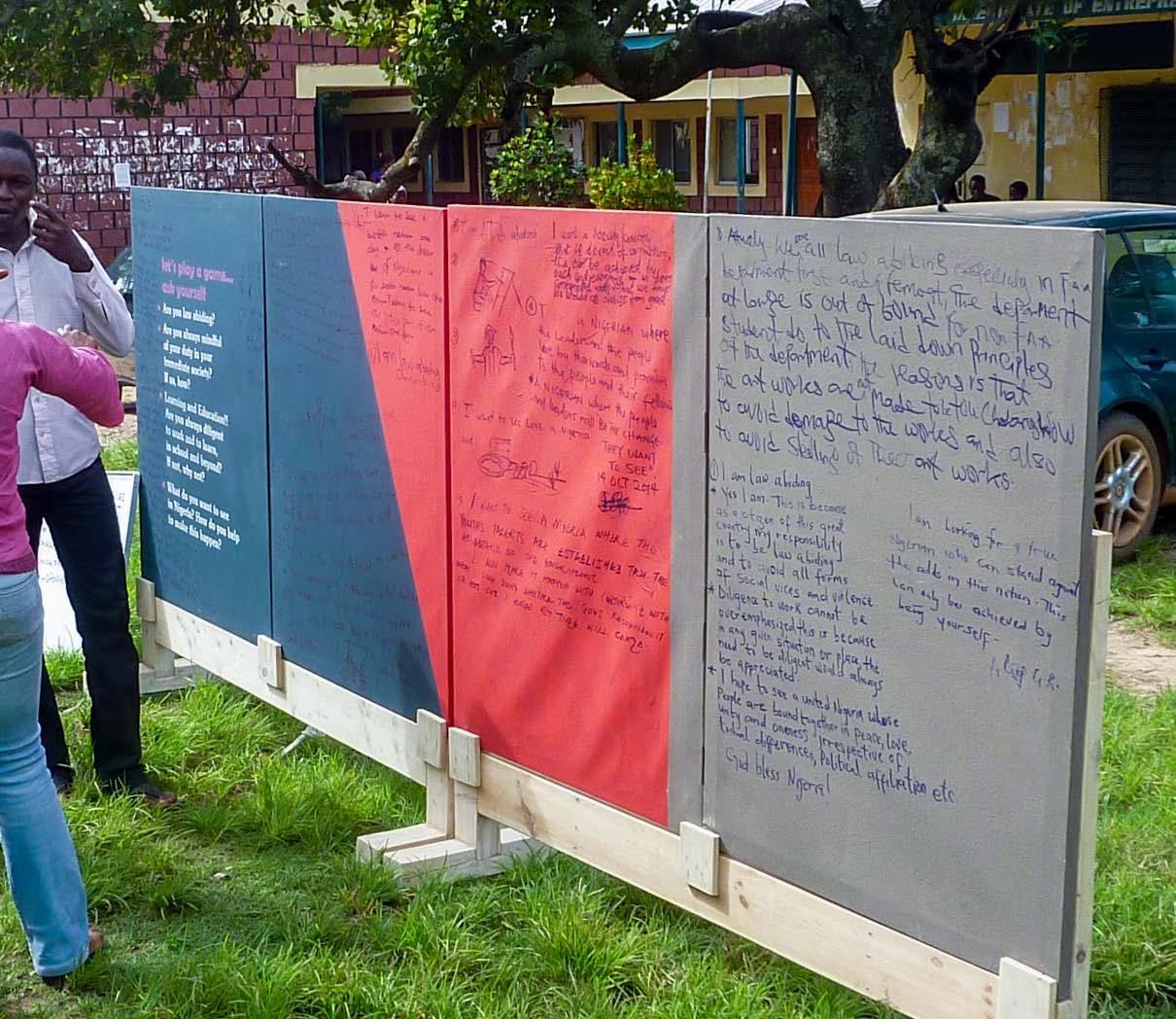

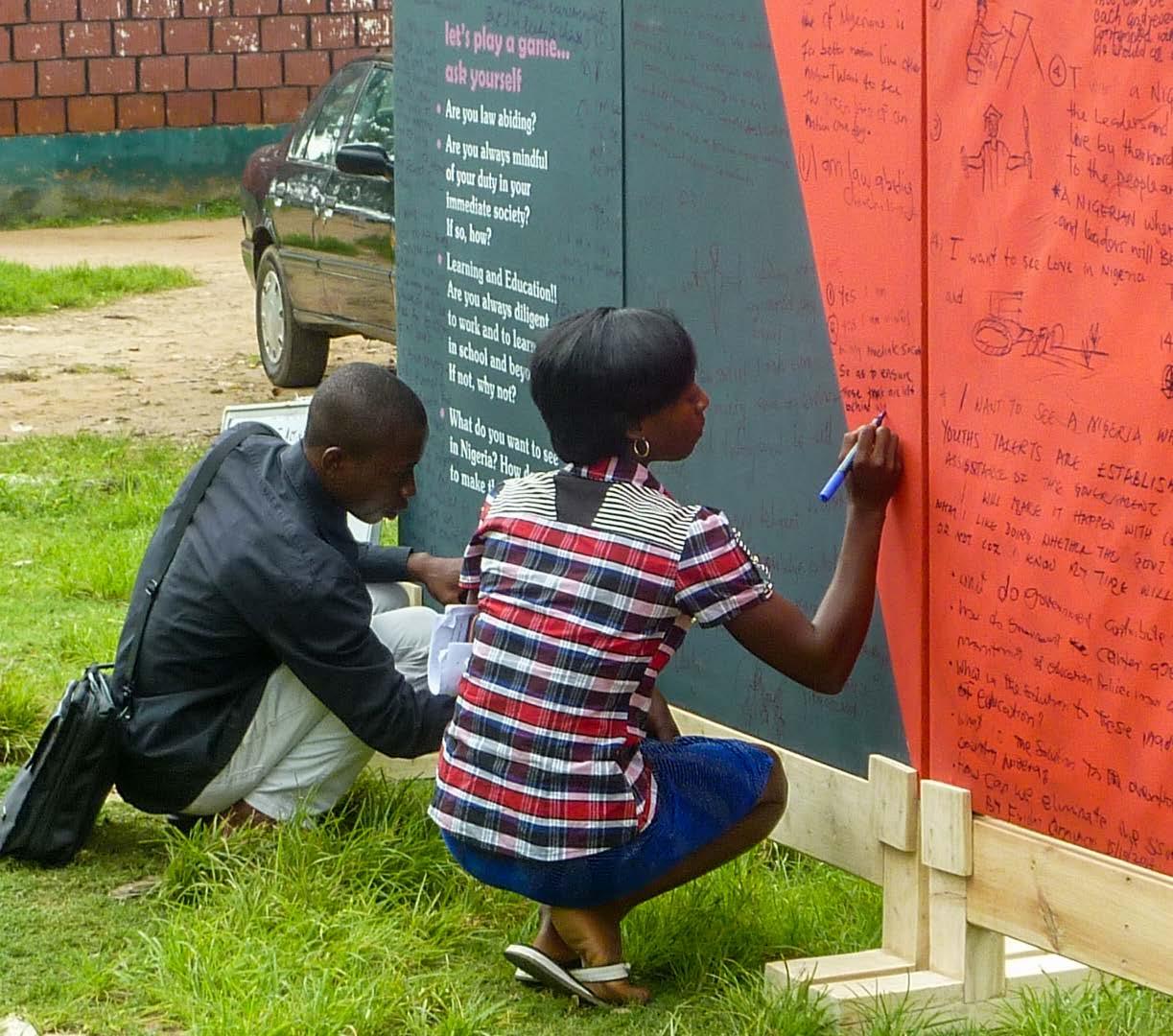

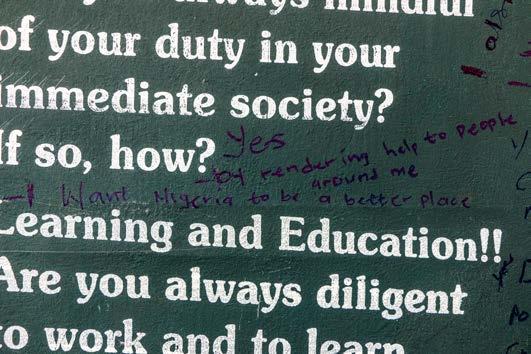

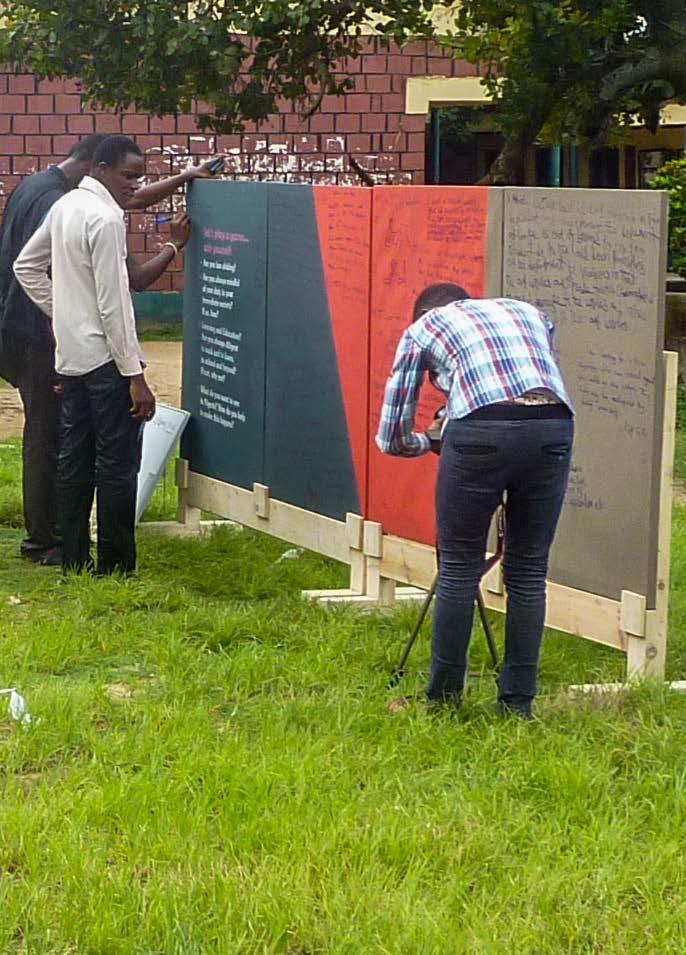

Ask Yourself is a multi-dimensional art intervention comprising of playful and experiential public art event-series of writing and reading, enacted also as a reminder, that we need to, in Nigeria today, more than before, hone and perfect these and other useful/problem-solving skills today, rather than later.

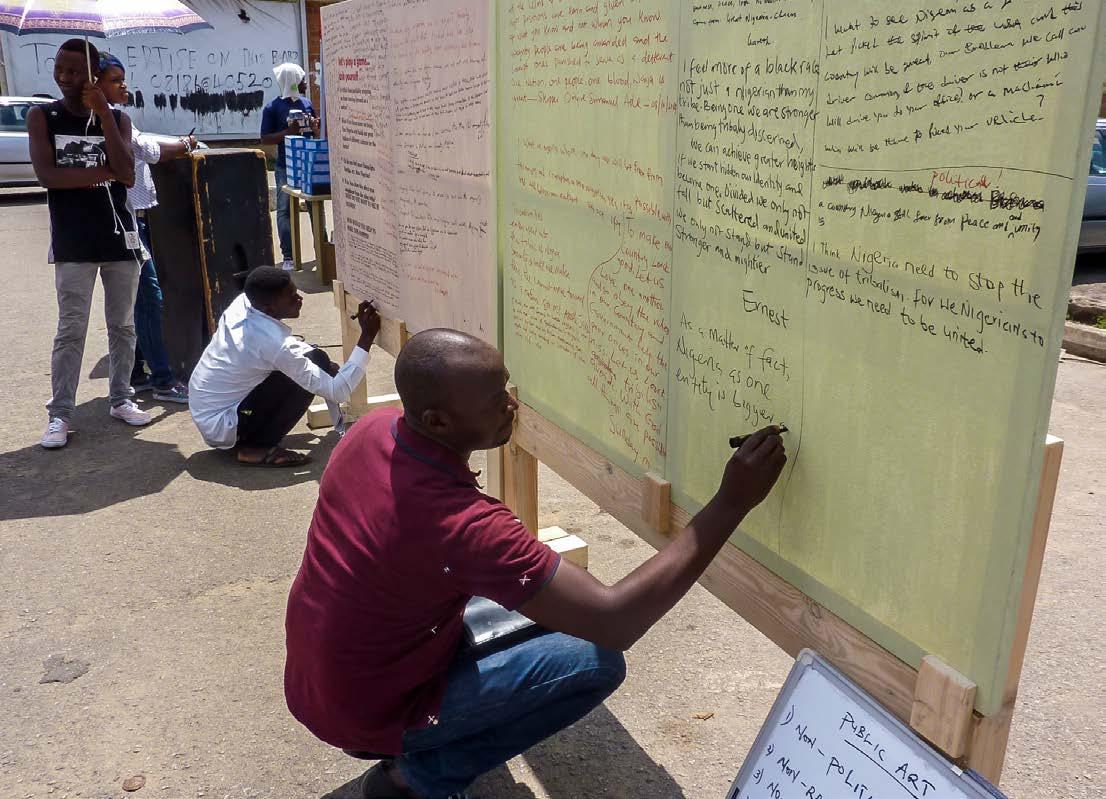

It is a participatory public-art activity that moves to its audiences for collaboration, asking many pertinent questions. It brings art and its engagement opportunity directly to the audience in the real world and embraces a collective model for making arti.

This relational events-series, at the onset, happened for 8 days in 4 locations (2 days per location), at an average of 7 hours per day.

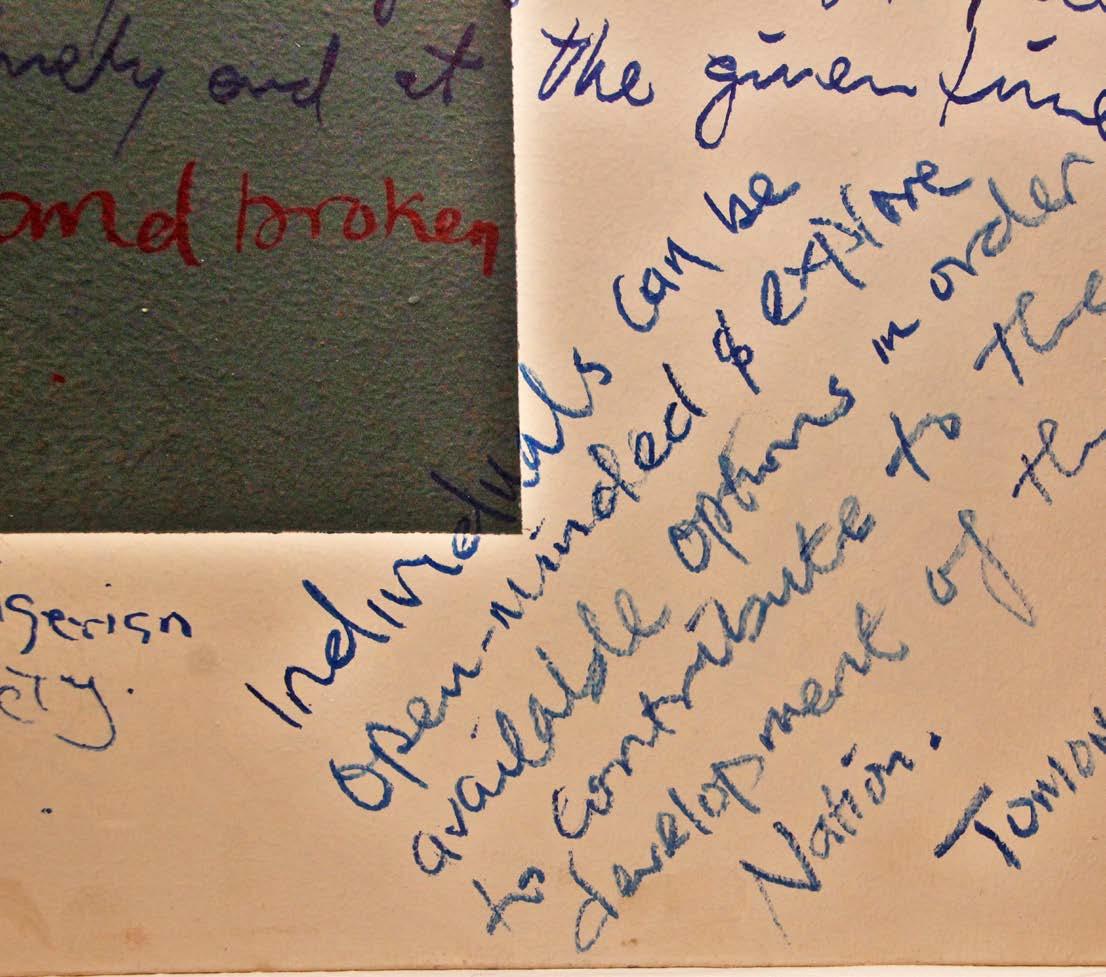

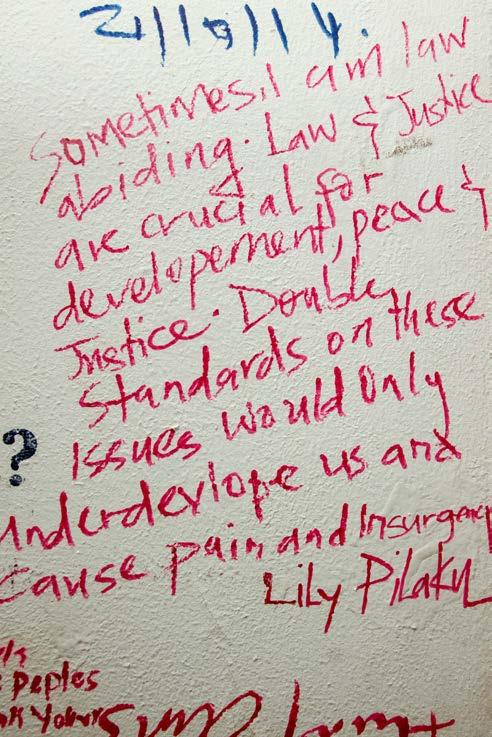

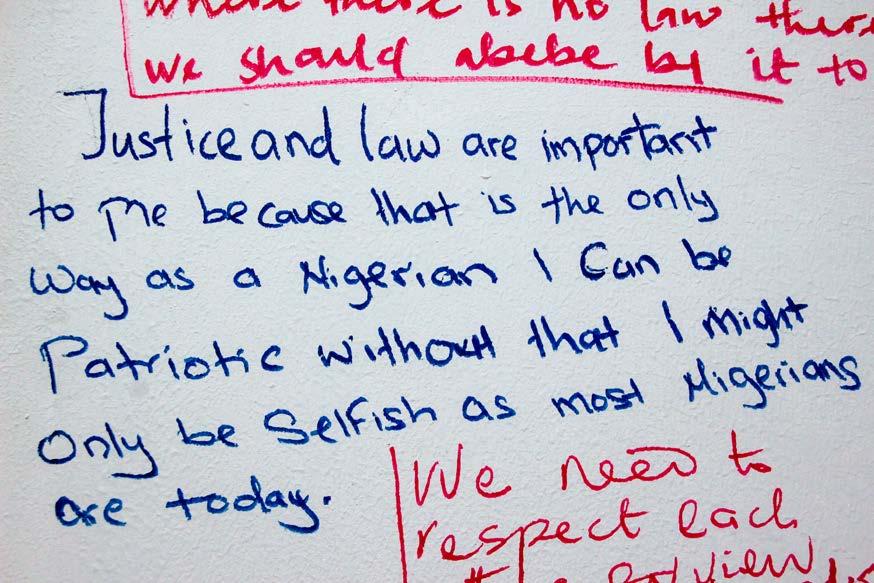

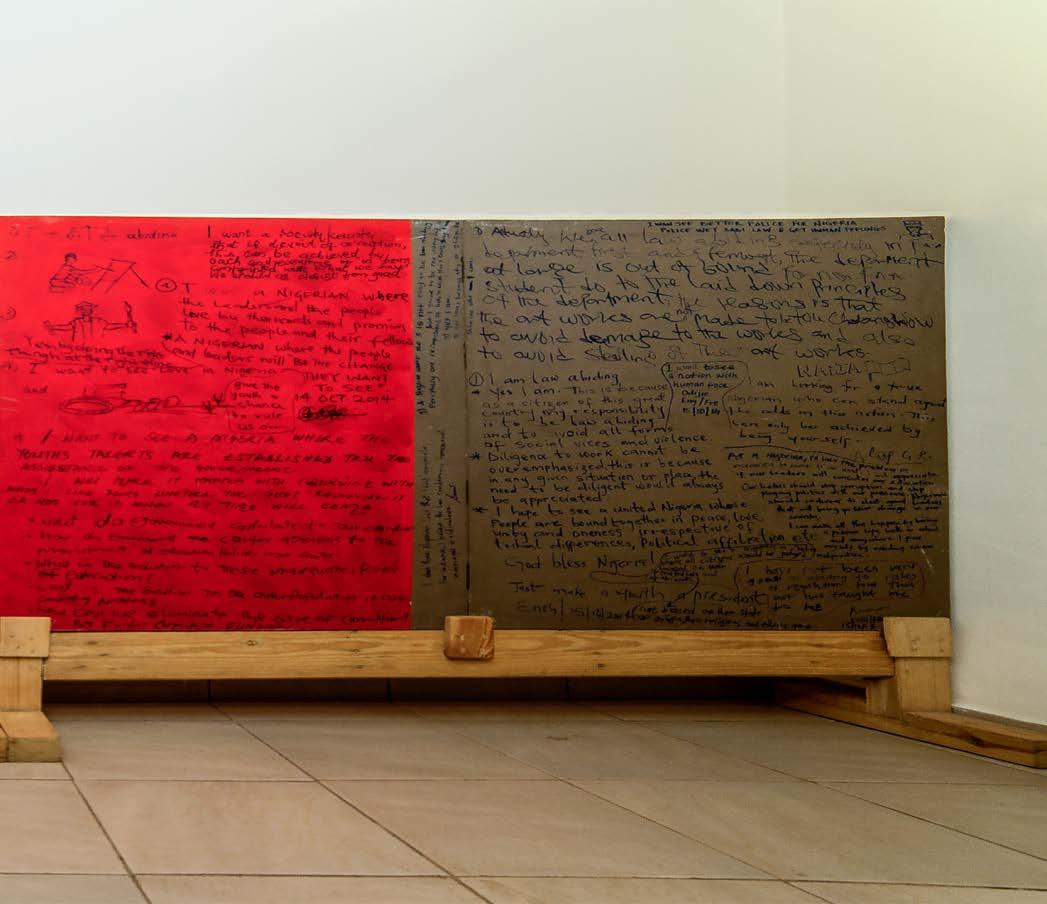

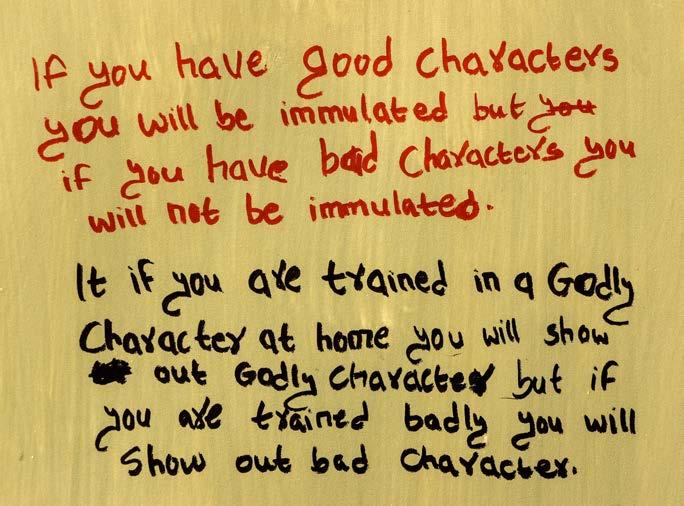

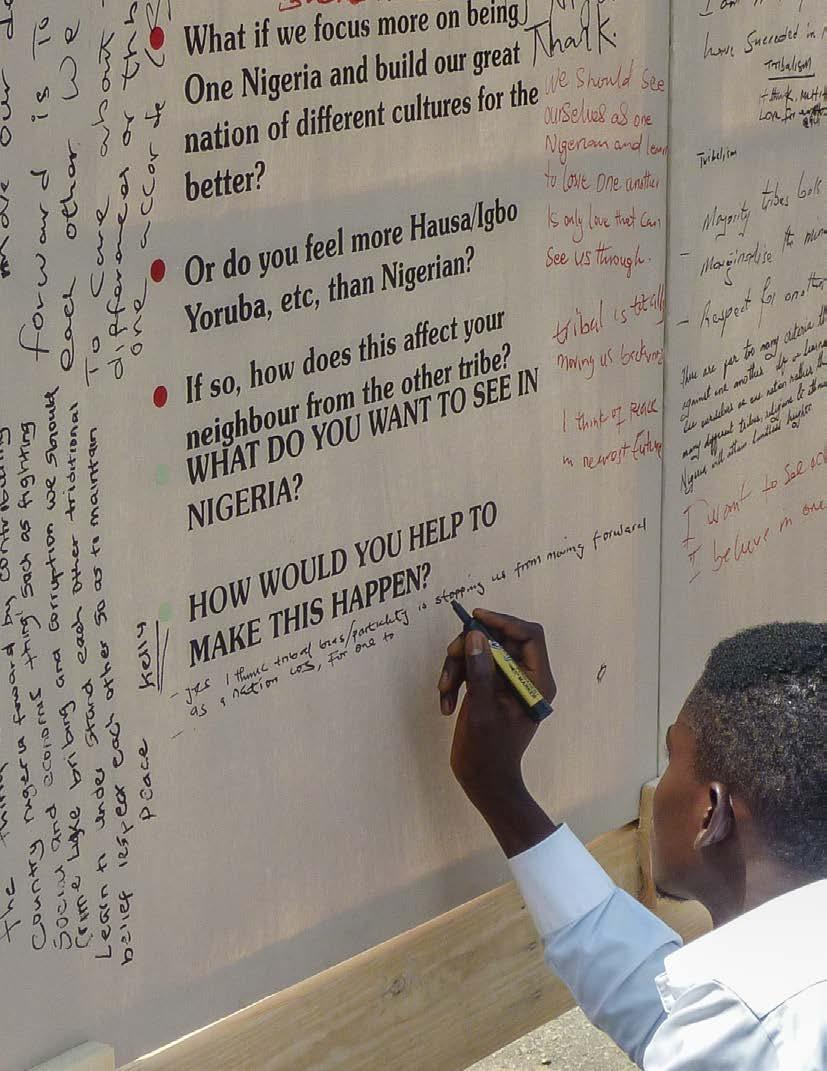

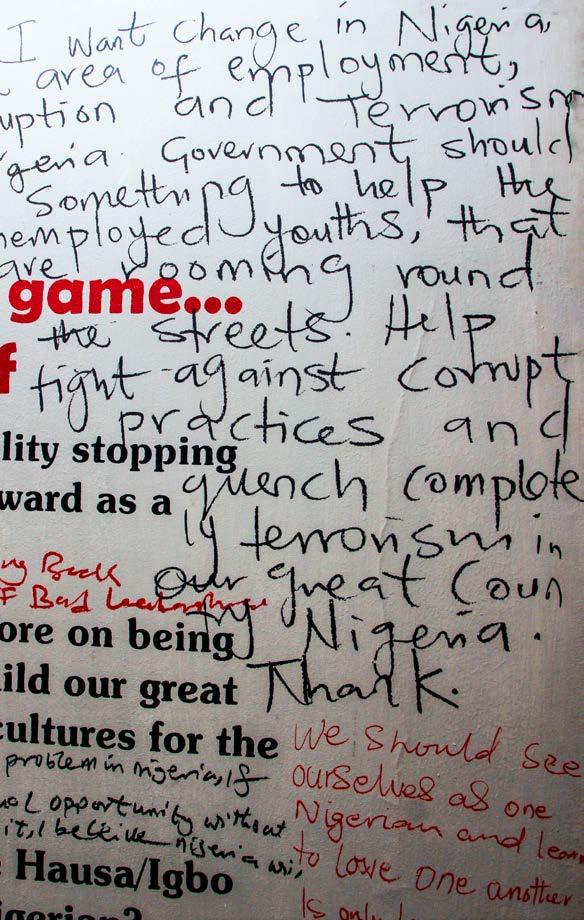

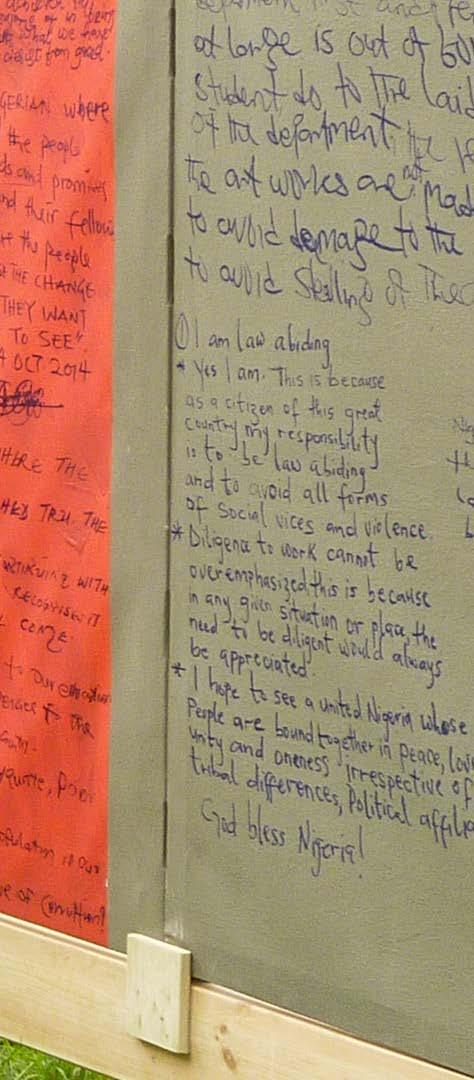

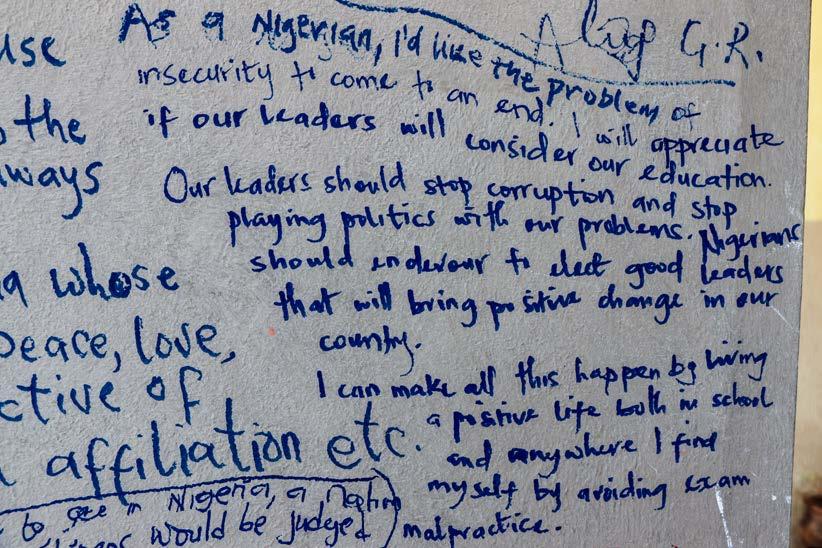

The art uses and includes text/writing, drawing, notes, an Installation (of painting), four Artist-Books, Film, this book, and many conversations and ephemeral discourses (that are (and will be) left in our memories alone) as both elements and residues of the multiple interventions.

I intend for these to continually present to us and remind us of: who we are, what we want, what we think, how we think, and what we say about our Nigerian-ness, and by extension, about our humanity.

This art is for sensitisation. It is meant as a catalyst for positive change. Although it poses as easy chit-chat times for the public, it provides everyone opportunities on many levels, to think on our individual contribution to the society where we belong.

Using the actions of painting, drawing, reading, and writing, involving Abuja residents, we present to and remind ourselves again, of who we are, what we want, what we think, how we think, and what we [can] say about our current situation in the country.

Ask Yourself worked actively (at its’ initial four locations) with up to 400 people as collaborators, assistants, volunteers and participants, whereas up to 351 people actively participated as collaborating audience (at those initial locations alone).

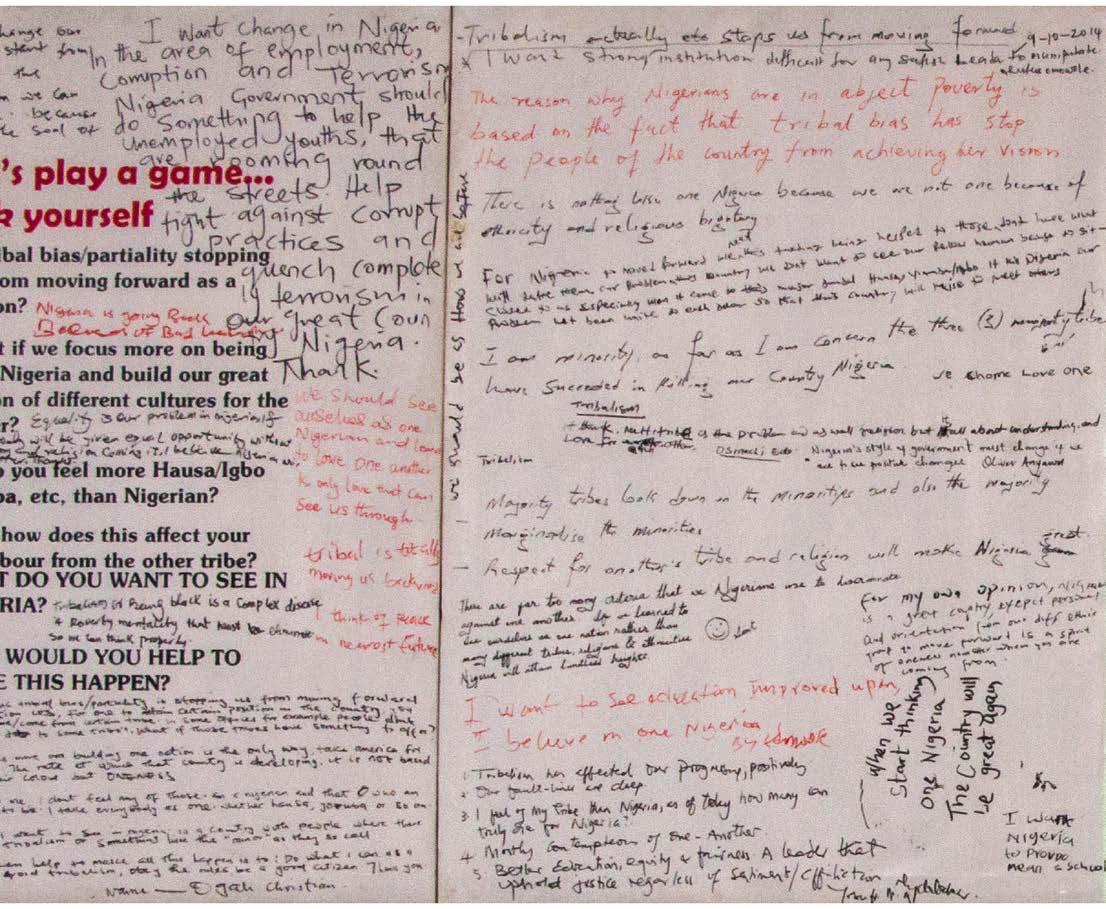

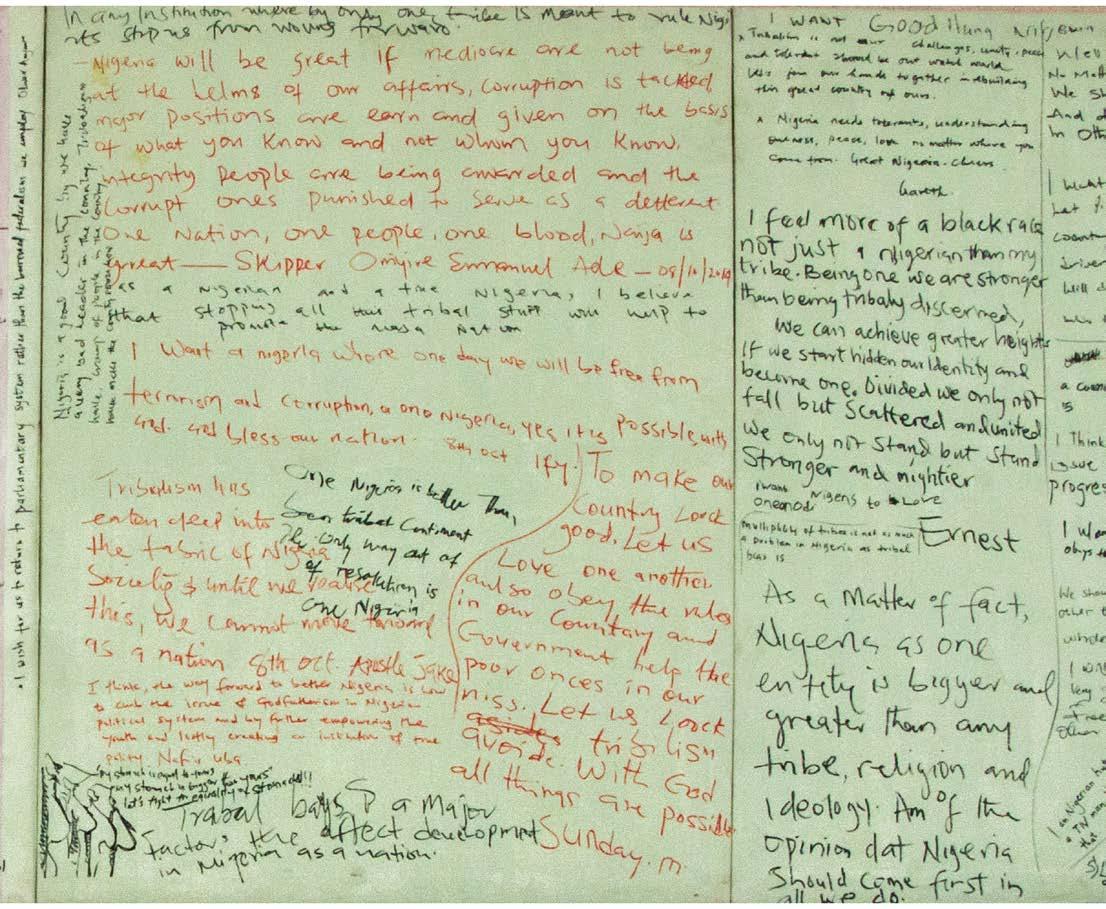

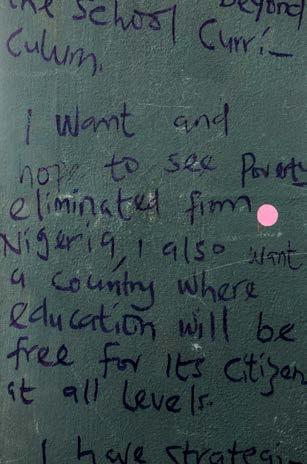

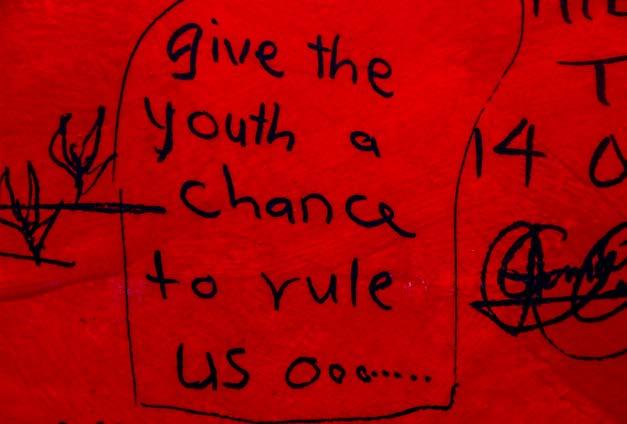

Making the work however reveals that the Nigerian people are dissatisfied about many thingsii. The content of the artwork, formed in association with its audience imbibes the differences among the participating individuals, as variant manifestations of a common spirit; and speaks the shared values and convictions of this society. These convictions are part of our evolving history and as such our memory as a people.

This book is on the one hand, purposely a communication tool made to document and display the voices of the ‘various artists’ that were part of this work, especially those of the school children as I am quite passionate about matters of children and their learning. This is central in my practice. On the other hand, it is one of the artworks that emanated from this project- just like the film, the painting, the interaction series, or the Artist- Books

The Artist-Books allow for continued sensitisation and participation with the workiii; the informative paintings are beautiful to look at, and the documentary film will continue to screen. Speaking to ourselves as we live on, let us continue to go forward rightly, asking ourselves…

And in response to our time, may we through advocacy create long term loyalty to our country and to our world!

Ask Yourself continues to question, and we might just make an impact!

What do you want to see in Nigeria…?

Are you law abiding…?

Ask Yourself!

Within my society, who am I? What sort of person do I represent?

Who do my neighbours see me as?

…and then I thought, as I wondered, that some intervention is apt in Nigeria, a case study of Abuja today, to try and cause a positive shift in the thought pattern of the average Abuja inhabitant, towards individually restoring positive standards in our system.

An artistic intervention seemed imperative, for Nigeria- in 2014?

Intervention:

• (Of things) to occur incidentally so as to modify or hinder.

• To interfere with force or a threat of force. To interfere in the affairs of another (country).

Intervene by inciting a ‘learning focused’ public discussion and sensitisation via art, using educational tools. Let us go ‘back to the drawing board’ and discuss this matter! Let us put up fresh drawing boards too, to draw up, and capture new paradigms that we can hold in our imaginations towards a better Nigeria?

The purpose is to intervene in the minds of people living in Nigeria, by activating interaction that can generate impactful output; to sensitise via art, using all important educational tools. As we go back to ourselves, and to reason again in mutual understanding. This is aimed at gradually leading us to shift our thoughts, to give us the people power, responsibility, hope and richness of soulas persons, and as a people. It is meant to give us personal experiences that can affect our mind-sets, and in turn our actions, hopefully, positively towards a collective societal progressive transformation.

When we are able to look inwards at ourselves first, then chances are that we may want to consider looking to our individual selves for solutions, rather than to other people. We may then, also consider growing or exploiting

ideas and methods for constructive change towards achieving an admirable society.

How can we lead ourselves to that place where we – the people have and hold a longing to be great?

Now, to start: What am I doing and how do I act?

And how do I affect things and other people by this way that I act and these things that I do?

Do my decisions and activities cause suffering to other people?

Do I need to change? What can I (as an individual) do, to improve (things in) Nigeria?

• Is indiscipline and a chaotic vicious circle becoming the pattern in the structure of our system today?

• Are we losing hope, and responding by our disregard for our people and for anything; but money; and we are raising another generation, thus?

• Would we like to consider the possibility of a change – of thinking, of behaviour, of results? To reinstate our richness of soul as a people and as dignified individuals?

• Would we like to be more patriotic, and attain ‘a system to emulate’?

To take shortcuts that return us to longer routes. Day by day, more of us prefer ‘passing exams’ to learning

To disregard/put down dignity of work; skills acquisition/ perfection; personal development and merited remuneration for work

To adopt standards where we are neither necessarily accountable for our actions nor want to be responsible for the consequences of these

To disregard the value for integrity and excellence, preferring money and material things

We have many that have ‘passed’ various exams, but do not have the required knowledge

In favour of the search for quick, free, easy money

(We adapt to) Lackadaisical behaviour. General lack of ability to deliver sound results on endeavours

Disrespect for the low-income earner, and the less privileged

Poor output in the labour market including unsafe healthcare

We excuse mediocrity. Blame others or/and the government for inefficiency and for our incompetence

Less and less trust in the quality of work done here, and in our local products

Extensive degree of materialism over building strong connections in relationships

i See Hilde Hein, ‘What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and Meaning’, in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 54, No. 1 (Winter, 1996), pp. 1-7, Published b: Wiley. Online: http:// www.jstor.org/stable/431675 (accessed 07.10.14)

ii The people are bothered by the high level of corruption that depresses the system, ethnic bias, lawlessness and chaos, poor standard of education, poor infrastructure, lawlessness, and double-standard with the justice system.

iii At my invitation, the public also intervened performatively, alongside myself, by bringing action at my displayed artwork–as they stopped to ponder on and engage with the questions that I present.

This will be the series of four events; and their resultant object pieces that would show writing (text) and drawing.

The art = four Events Series of Collective Mark Making four object art pieces Resulting in Intervention. Installation.

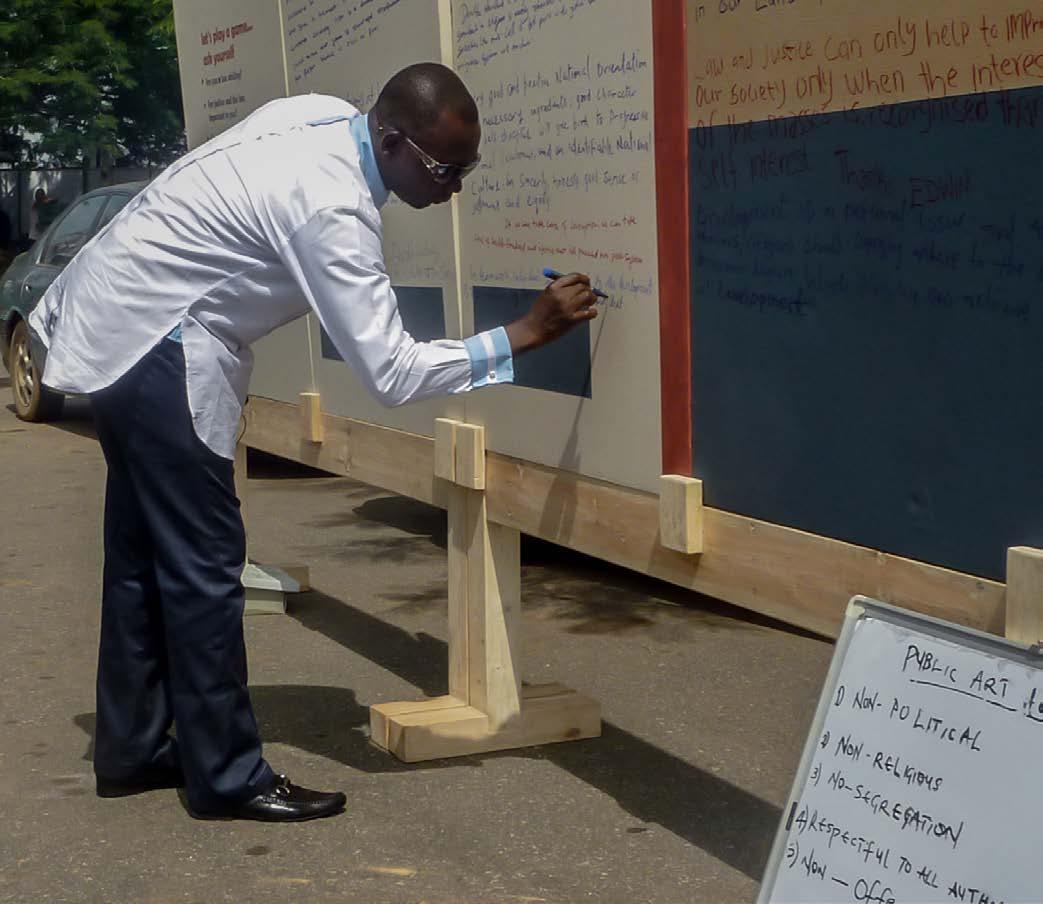

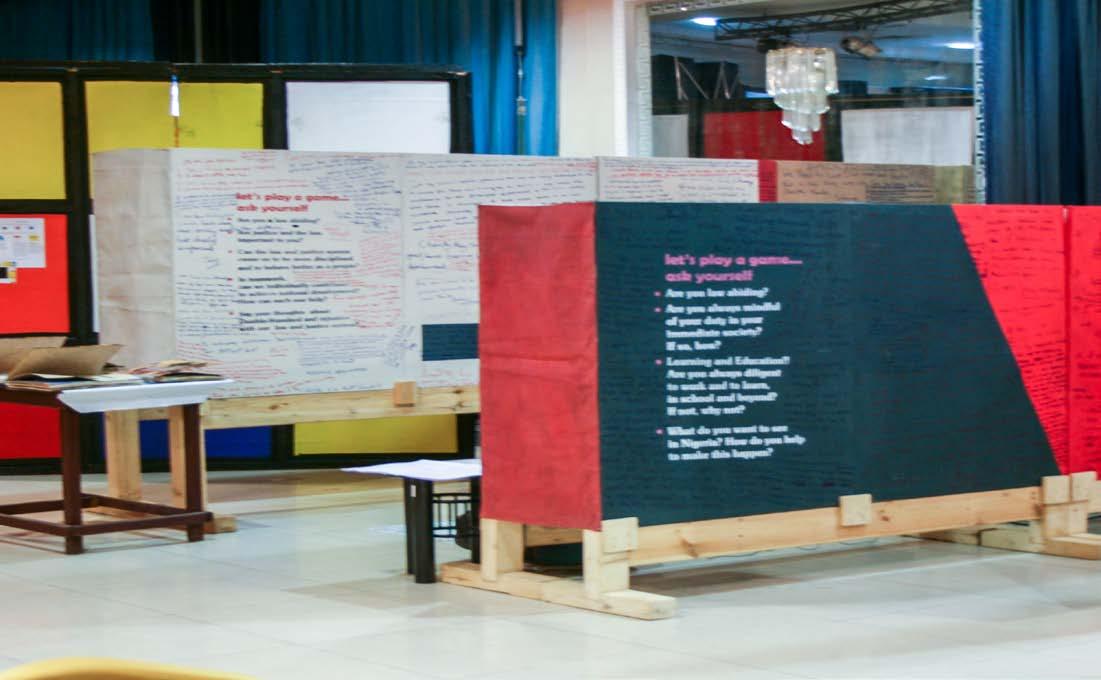

With permission from the relevant authorities, I will site four sets of discussion boards measuring 122cm by 366cm each, at the following places in the city of Abuja:

1. A learning place – Learning and education. Target: children

2. A learning place – Learning and education. Target: young adults.

3. A work place – [The Federal Secretariat and The Head of Civil Service of the Federation]. An impressive collection of working adults. Target: Adult professionals and policy makers.

4. A market place – Target: All levels of the public.

Each board in four strips of 122cm by 92cm each. At these ‘places’, the public would be invited to participate in this open collabora-

tion. The discussion boards will already have prompters and instructions on them to guide participants and the discussion; each one, leaning to a topic and asking for contributions. There will be writing and drawing inks made available. The platform will be canvas stretched on chassis, already well prepared for archival storage.

The discussion events at the four locations will happen in succession of one another rather than simultaneously. The project will employ this interchange to be dynamic. For a final decision on the participation sites, I will care about the security of the work, and about weather condition.

Let us discuss. Let’s make art...

A. Is ‘justice and consistency of the law’ important for you? Can justice return values to us? How much would you tolerate double-standard?

Let us discuss. Let’s make art...

B. Might ethnic consciousness be a hindrance to us as a nation, rather than a consciousness of a ONE NIGERIA?

Let us discuss. Let’s make art...

C. What do you say to us focusing firstly on parents and family as first law enforcers towards effective nation building?

Sontee Ijoho is a practising visual artist. He works closely with this Artist - Amarachi Okafor.

I have been privileged to be closely connected to the art of Amarachi Okafor in recent times, having seen a good portion of her process and working alongside her, learning a great deal along the way. With her impressive background in curating and fine art, Amarachi takes into great consideration every aspect of her work from how archival every bit of material is to the minutest aesthetical details. Interlaced with the apparent fluidity and quirkiness of her work one would always find a subtle yet poignant message that invokes deeper reasoning. As it is quite difficult to define or categorize Ask Yourself, the best I can do is relay to you my experience of the project from creation to exhibition. Of course, the journey isn’t over and, since you’ve come this far, I trust that I can count on you to discover what lies ahead for yourself.

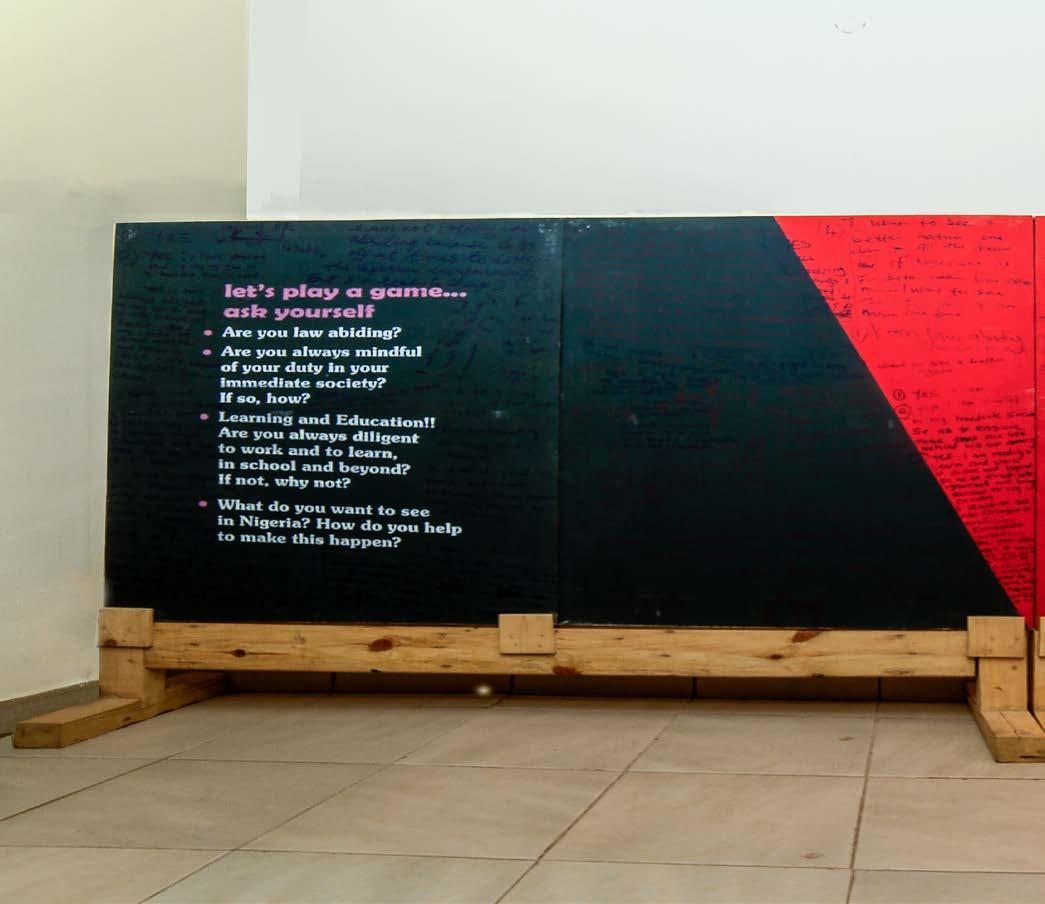

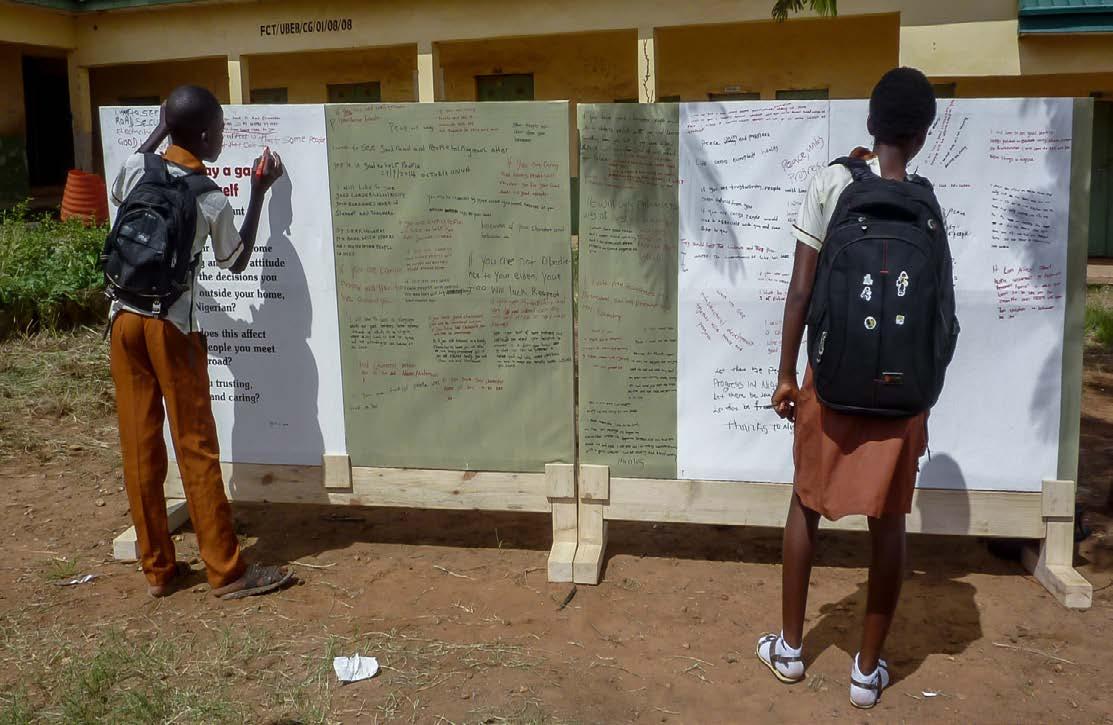

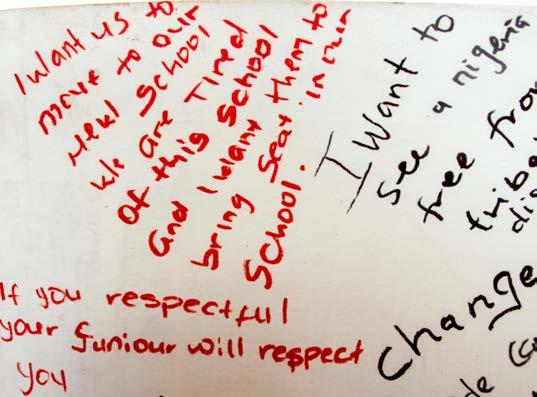

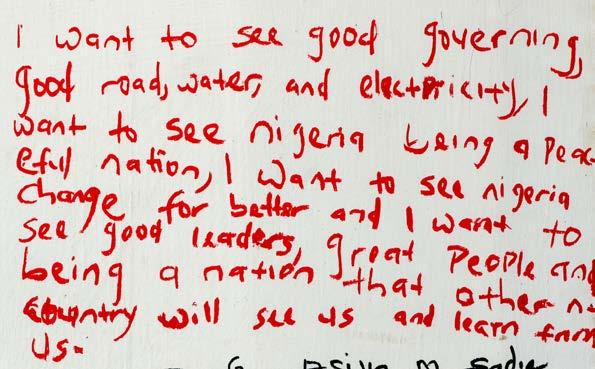

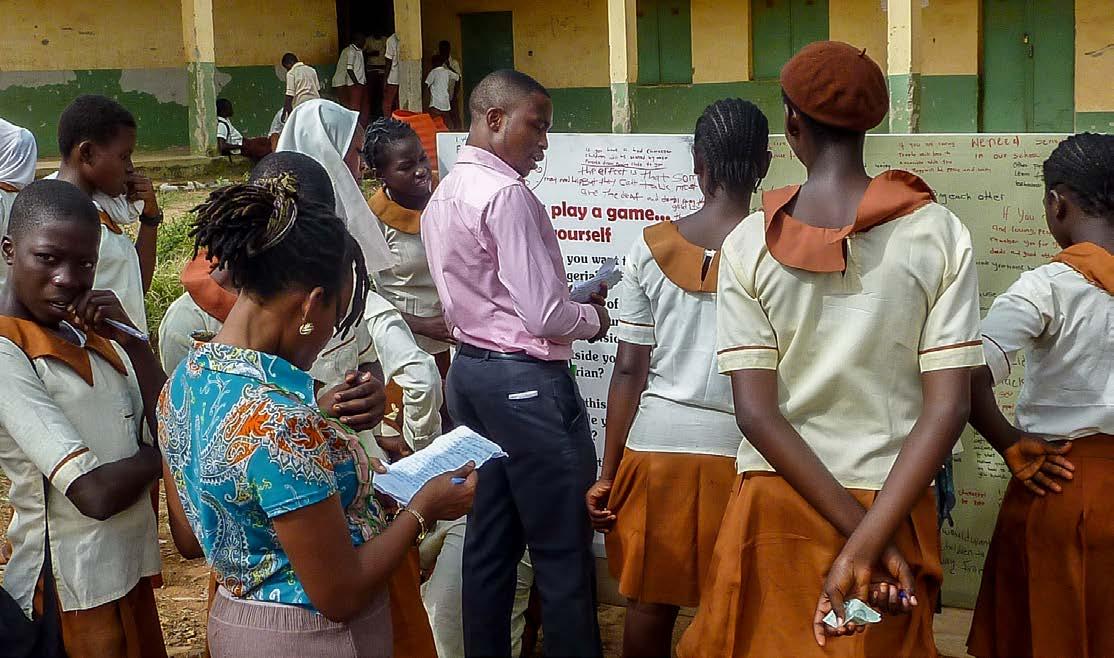

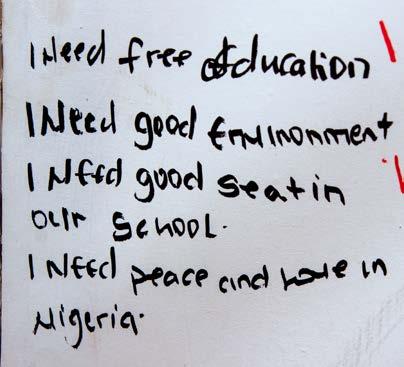

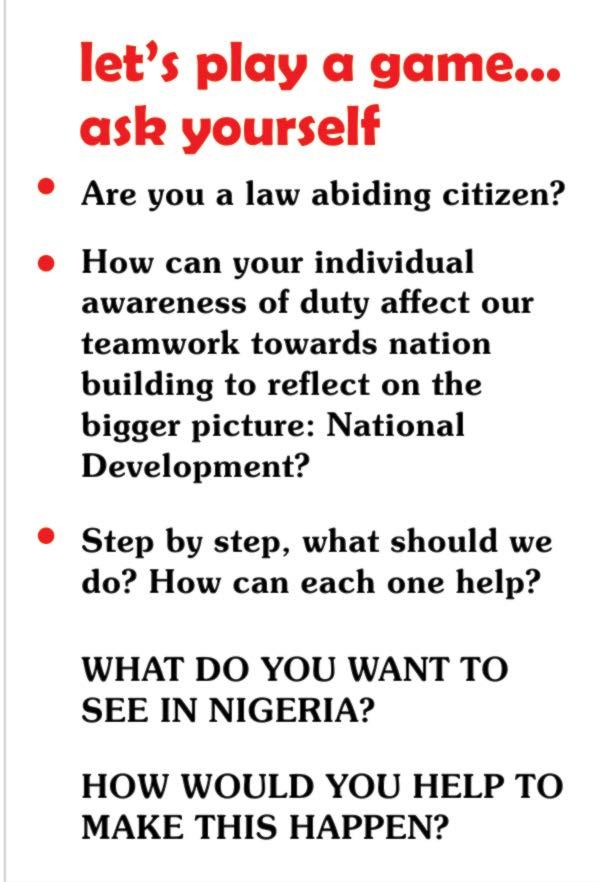

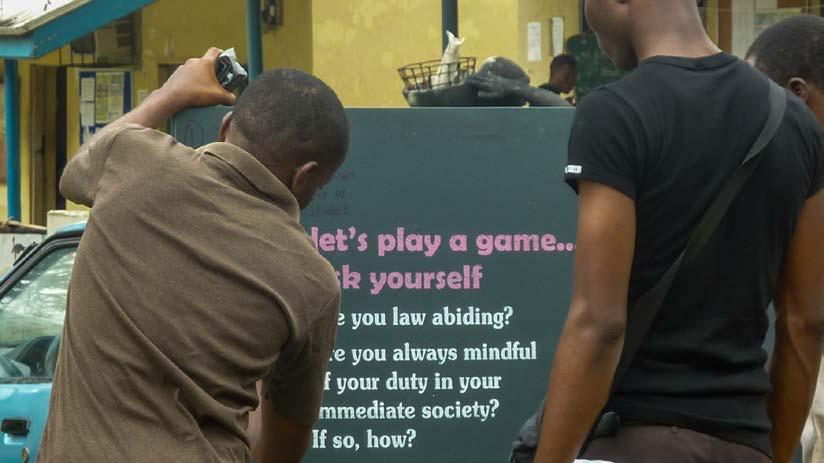

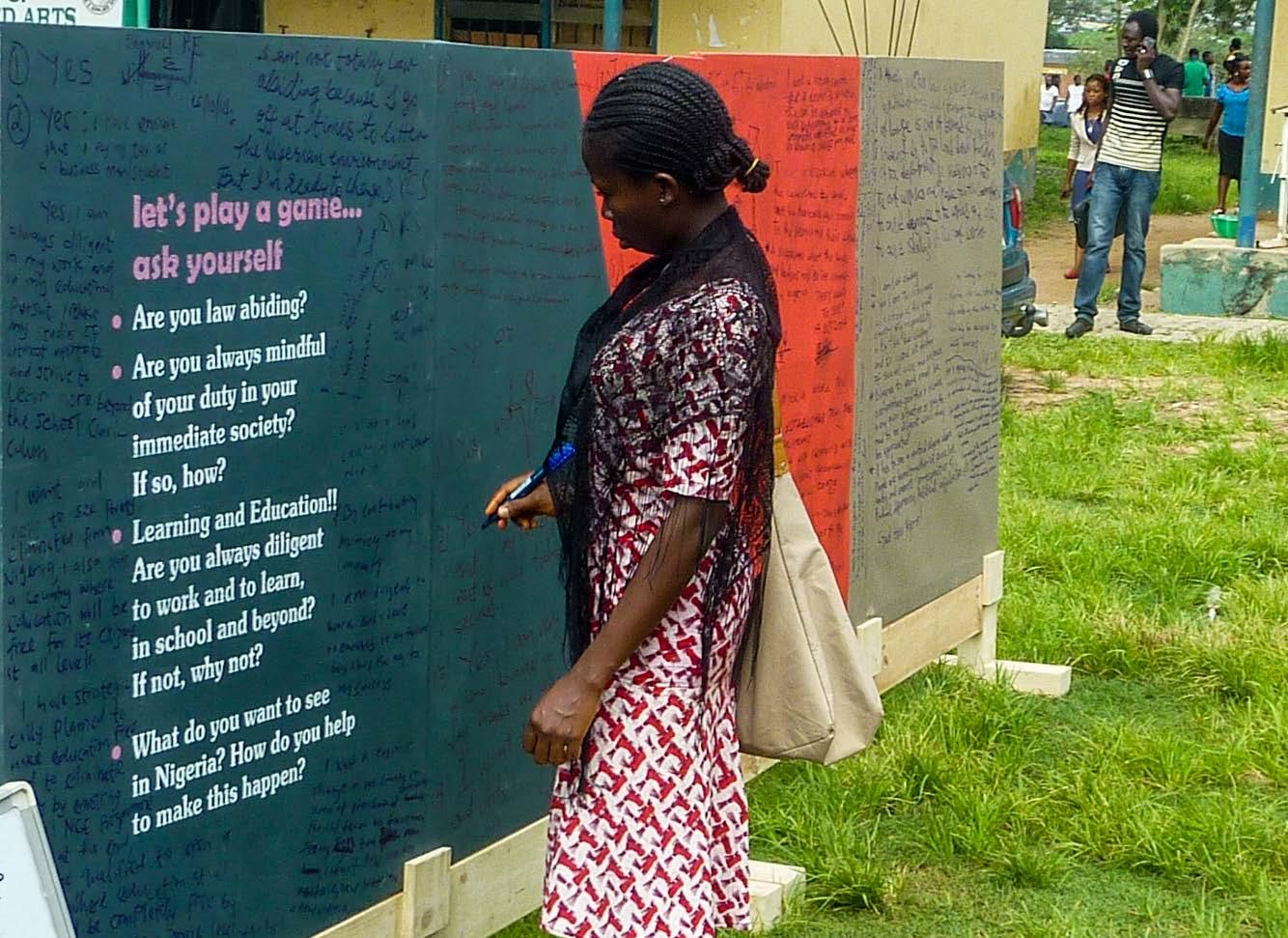

At first glance, I was convinced that Ask Yourself would turn out to be a painting or, perhaps, a series of paintings judging by the large canvasses Amarachi had put together, each hinged at the centre to allow folding for maximum portability. There were eight of these canvasses and each one was painted with Acrylic and Tempera in different colours and simple patterns. The focus of the paintings were the words inscribed on them; “Let’s play a game. Ask yourself...” Beneath these words are a series of questions, different for each painting, that I think steer one’s critical eye inwards making you think about your own impact on the world.

After creating eight paintings, colour coordinated in sets of two, Amarachi had large wooden frames built onto which each painting could be mounted individually. At this point Ask Yourself had taken the third

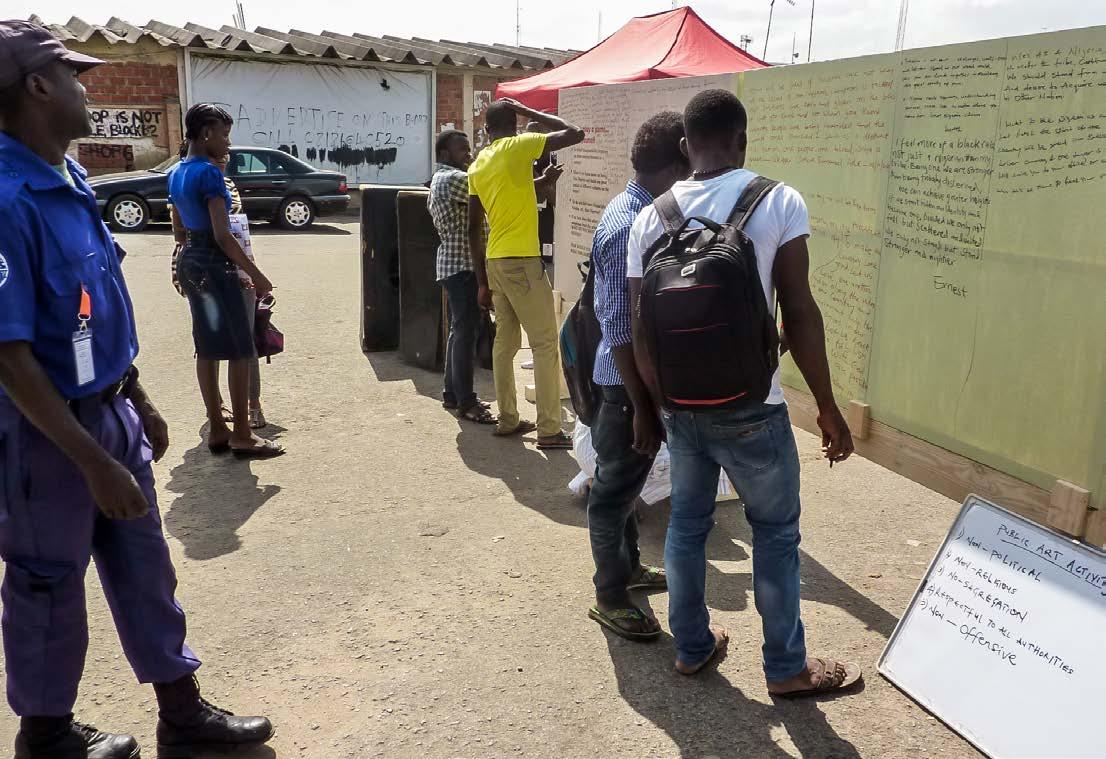

dimensional scope of free standing sculptures. The aforementioned components combined together to form the facade of the project. The sculptures were then to be displayed in public spaces to attract the attention and participation of passers-by.

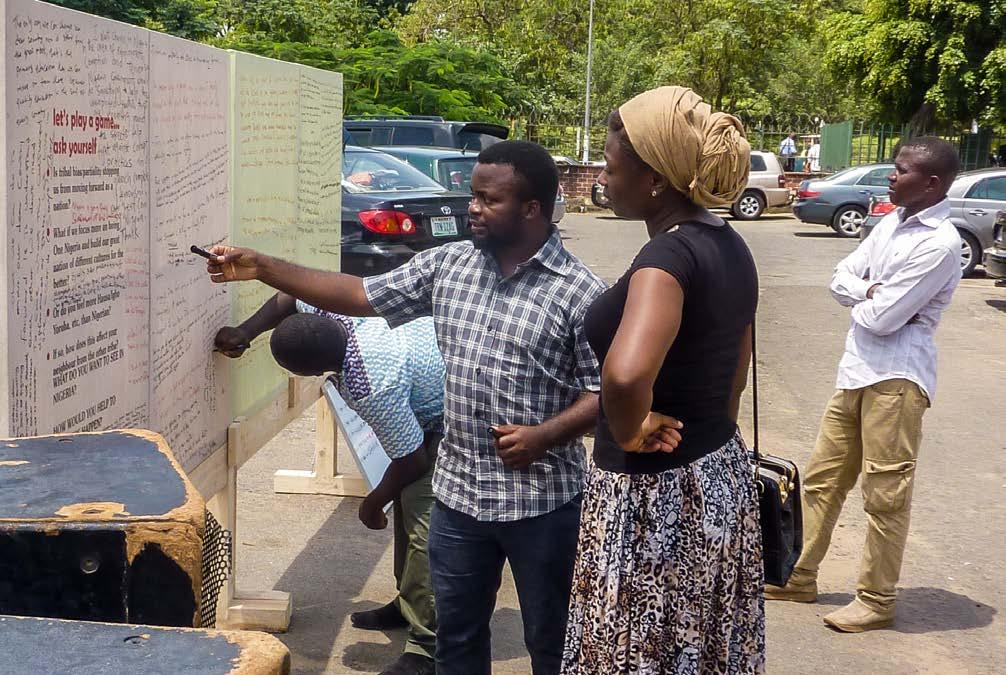

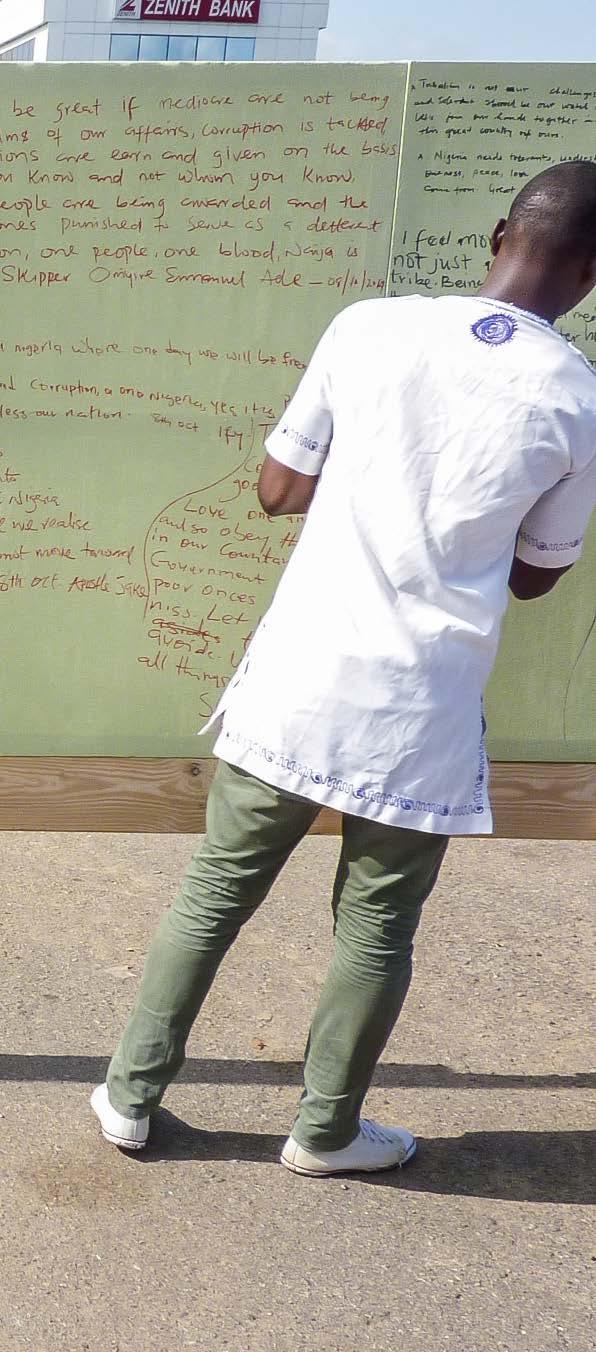

Ask Yourself took on a different dimension when the paintings left the studio and were reassembled at the selected destinations. One of the aims in the process of selection of these locations was to capture as close a representation of the Nigerian population in our audience as possible. Amarachi had chosen a Junior Secondary School in Nyanya, the Federal Secretariat in Central Area, Wuse Market and the FCT College of Education in Zuba- all locations in Abuja, Nigeria. Each of these is a public and well-populated space, varying in a virtually symmetrical pattern on the geographical map of Abuja and, frequented mostly by people with at least a basic grasp of the English language. Ask Yourself had morphed into a social intervention programme.

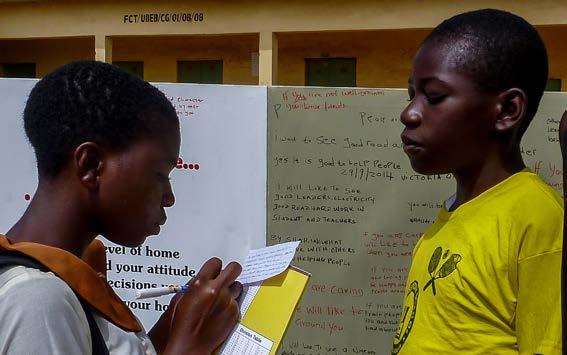

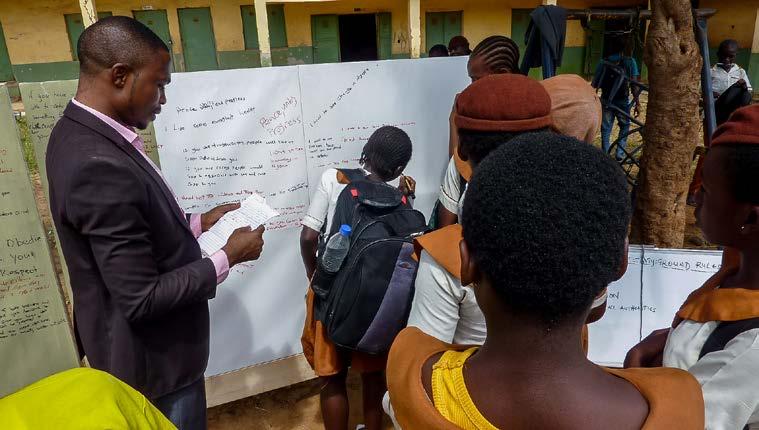

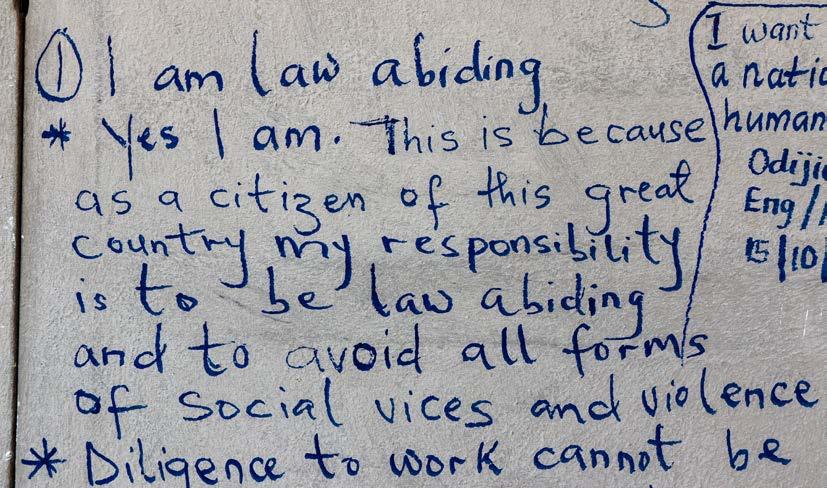

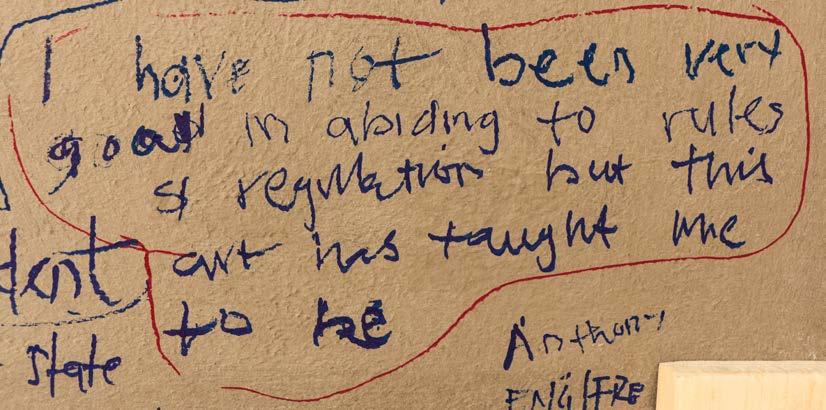

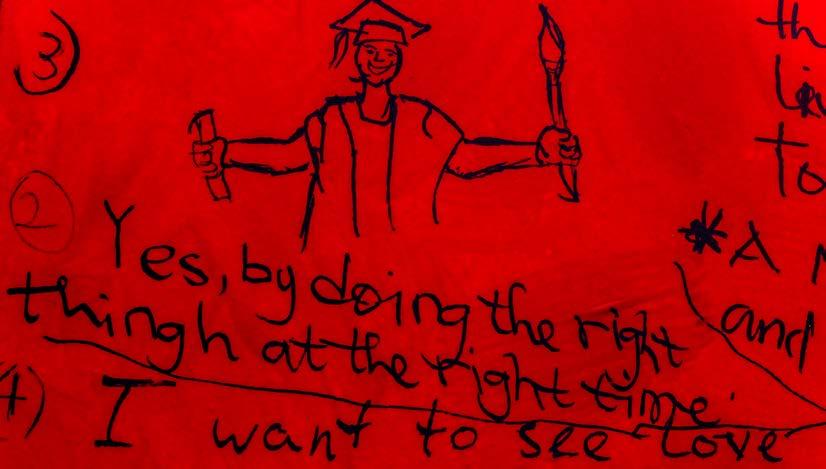

The first place we visited was the public Junior Secondary School in Nyanya. It was a unique experience for me watching the children excitedly scramble to air their opinions on the large mounted canvasses. They were set up like blackboards with a reasonable number of different coloured markers available so that we could get as many people writing on them as possible at the same time. The children asked questions and

ijohodrew pictures interacting freely with us and with one another. I got a pleasant feeling that getting to put their marks onto the artwork gave the people a sense of ownership of Ask Yourself. The Junior Secondary School was the only location where onlookers and participants consisted primarily of children. From all locations we received variedly interesting views. As is the nature of the project, we were able to get people engaged in conversation, and writing their opinions on the boards the ball kept rolling. I’d like to think that we captured opinions from all walks of the Nigerian society.

Ask Yourself is also a documentary. From the first day at JSS Nyanya there was an active camera crew capturing video and still footage for the creation of the movie. Willing participants were fitted with microphones and interviewed. Generally people were given the opportunity to express themselves in as many different mediums as possible and, express themselves they did. I recall an interesting old security guard at Wuse Market with limited formal education and a lot to say about the Nigerian structure of government and its effects on the rate of our development.

Another route by which one can access the artwork is in its book and artist-books. In the turns of Ask Yourself pages you will find a feast for the eyes and mind. With an extravaganza of detailed images of the work, the book gives you a detailed look at the words

of those men, women and children who participated in the project, a closer look than any of the previous forms of the project had been able to present. One gets the feeling that the Ask Yourself team and all the members of the Nigerian public who participated in the project have all come together to write this book. Let it not be said that Amarachi Okafor leaves any stones unturned.

Some of the most powerful aspects of the Ask Yourself project are completely ephemeral in nature. You can watch videos and look at photographs, you can listen to the sounds and read the words but, there isn’t any way to capture the entire experience of the art work. One cannot reproduce the feelings of members of the team interacting with the Nigerian public and witnessing people’s passionate reactions to the state of their nation. One cannot, in any form of media, encapsulate the catharsis a person goes through when allowed to express themselves in ways that they never have before. If only you could have witnessed some of the conversations stirred amongst participants of the project which we were unable to record. This, to me, is the most beautiful thing about Ask Yourself.

Can you look at Ask Yourself in any of its forms and not be compelled towards a sense of inflection? Does it not draw you to look inwards and reflect on your impact on your immediate environment and society as a whole? I cannot speak for Amarachi Okafor

but I believe that, besides being a captivating piece of art, these were some of the aims of the project. Thoughts were invoked and questions were asked that will perhaps leave a lasting impression on at least one person in Abuja. Children spoke with freedom about what they would like to see in the nation to which they have been tagged future leaders. Adults rambled and opined and wrote in an environment of positivity on how we can all come together and improve our Nigeria. I am deeply honoured to have been a part of Ask Yourself.

I work in the broadcasting industry. I consider this a privilege because it affords me the opportunity to grow…grow by understanding my environment from the perspective that many broadcasters enjoy, acquiring and assimilating a massive amount of eclectic knowledge!

I believe that growth and progress can be better realised through an understanding of oneself and the society at large.

As a talk radio presenter, my job includes pushing the boundaries of the status quo, highlighting as many facets of our numerous challenges, encouraging the questioning mind of a nation blessed with an abundance of intellectual diversity. Alas, therein lies the source of my bewilderment; what hinders this great nation from attaining the levels of success we can, potentially, attain?

We are all, individually, and subsequently, collectively, products of the foundations laid by those who have come before us. We are all products of our lives’ experiences. We are all products of choices we have made, which have been informed by the latter, choices made by reconciling our past with a dynamic present.

Nature has proved, and continues to be, a ready source of instruction for me. I hold the view that nature has all the answers we unwittingly trouble ourselves over. Nature is dynamic, it is constantly evolving by adapting to life as we know it. Some animals will not breed if they consider their circumstances unfavourable to do so for any number of reasons. These reasons may include a rise in the numbers of their natural predators, or a shortage of their food source. At times like these, nature’s perfect formula of nat-

ural selection is automatically activated; the welfare of the weak members of the species are sacrificed for the strong. This might seem like a harsh thing to do, but it will ensure the survival of the entire species by keeping them from extinction.

actions as soon as they are barely out of the parking lot of their places of worship. How can a people who claim to be as religious as we do, allow so much corruption and evil eat so deep into the fabric of our society?

The latter led me to question our identity;

A thing does what it does because it is genetically ‘programmed’ to do so. Its ‘programing‘ will always be the best course of action and will have a near perfect chance of success because that is what it exists for. It is natural!

In the course of my job, I find myself discussing a variety of socio-cultural issues and matters of governance. Looking back over the last five-and-a-half decades, an objective and unbiased introspection of Nigeria and how we have managed matters of development will reveal the obvious; our approach to problem-solving is unchanged and insufficient to take us to the next level of development. I reckon the reason may not be far removed from the reality that we have not yet put our ‘best foot forward‘, we have not addressed our challenges from our potential ‘natural’ abilities. We are acting outside our genetic ‘Programming.’

The result of this is made manifest from the apparent contradictions that we are. We call ourselves ‘a very hospitable people’, yet our regard for the value of human life leaves much to be desired. We call ourselves ‘very religious people’, yet it is not uncommon to see people shirk of the mantle of religion and return to their unholy utterances and

Who is the Nigerian? I have pondered this question deeply, without getting any closer to a satisfactory answer.

All through the ages, religion has featured prominently as part of the foundations of many civilisations. Ours is no different. We existed before our colonial masters ever knew of our existence. One might even argue that we may not have been ‘civilised’, but we were certainly ‘organised.’ We were a collection of orderly and structured societies with rules that governed how we interacted with one another. And then ‘civilisation’ came. Foreigners with their different customs and habits came.

This provided us, the different kingdoms and empires in our corner of Africa, with a unique opportunity. I shall attempt to expatiate this after my next point.

Colonisation brought with it some challenges which included a basis for comparison. In a situation like this, the near-perfect laws of nature would ‘kick in’ to ensure a species would evolve to the next stage of its existence. There would be a period

of uncertainty marked with flashes of hitherto unseen behaviour. The result would always be the same; the triumphant adaptation, assimilation and evolution of the species! This is the opportunity I make reference to. Has our story been true to nature? Have we triumphed in our adaptation, assimilation and subsequent ‘growth’ since the advent of colonialisation? Today, we might argue that we enjoy the benefits of technology, but essentially, our thought processes are not commensurate to the level of advancement available to us these past five-and-a-halfdecades. We have witnessed the periods of uncertainty which have been marked with the number of times our leadership and governance has changed (authoritarian and democratic). We have witnessed the flashes of hitherto unseen behaviour displayed in the Nigerians who have excelled in various fields across the globe, but still yet, we grapple with the same fundamental challenges of development.

kamri Apollois clearly apparent. Our culture of law enforcement is, at best, under par. I made reference to the former above. If we are truly a Godfearing society, then why do we permit this level of injustice and evil in our society? Perhaps we are a God-fearing people, but the question is this;

I fear the answer to this question may lie in identity crises of national proportions. I have stated the importance of religion in the development of nations and empires through time. A Middle Eastern gentleman of some repute once said there are two things which make a people conform to the generally accepted actions of societies; the fear of The Lord God Almighty, and fear of the rule of law. The effectiveness of the latter

Which God do we fear? I ask this question because we constantly bear witness to many people take oaths and make promises on the holy books of our two major religions, only to carry out their tasks/jobs with total disregard for that which they had sworn by. It is important to question ourselves at this point about our beliefs, our religious beliefs. Who do we fear more? The two major religions brought to the shores of this corner of Africa by strangers from far flung lands, or our traditional and ancestral gods? These are questions we must, individually, answer. One thing, however, is certain; we are carrying on outside our ‘programed’ behaviour, that which has been genetically encoded in us for centuries. I fear that if we do not adapt and assimilate that which comes from without, then progress and development may be our lot for a while.

(WUSE MARKET, ABUJA)

Artist, art essayist, curator with the National Gallery of Art, Nigeria

Initially, it was believed that art making was exclusively the prerogative of the artist, alone in his studio, making all the visual statements on behalf of himself and the society. But at a point in history, the society that has all this time been the artist’s patron began to influence him and succeeds in including its’ views for the artist’s work to materialise.

Now, the artist involves his audience/public as they join her/him in art production, as Amarachi Okafor has done with Ask Yourself – art that she produced with the public in public squares, for the enlightenment, entertainment and pleasure of the same public. Over 351 ‘artists’ participated to make this participatory and interactive art, where Amarachi was the lead artist. But what about? About issues “aimed at collective societal positive transformation,” according to

Okafor. And through what mode of making? Through an unusual, artistically strange and visually/aesthetically abnormal pattern of making, yet meaningful, relevant and also fitting into postmodernism. The context and even the content of her message are multi-dimensional and will be analysed in detail in the body of this discourse.

This essay attempts to look at Okafor’s artistic and creative innovation through a historical interrogation of such creative occurrences in the annals of art history. It weighs the impact of her creative methodology on her society – Nigeria. Amarachi Okafor’s creative methodology involves taking art making-processes to public spaces where she, the artist, and her audience partake in the production with one message in mind – “sensitising ourselves as individuals and as a soci-

ety in need to move forward positively in all facets of life”. Here, Okafor’s methodology and her message will also be x-rayed in context, in order to see if there is a parking space for such an artistic innovation [locomotive] within the parking lounge of Nigeria’s contemporary art, probably, this is a new artistic order – a neo-contemporary Nigerian art.

From the beginning of time, art has been part of human existence and endeavors. It is a motivating factor found in the fabric of every successful civilisation. Specifically, art and artists have always been considered imperative in any given society/civilisation right from the people of the Upper Paleolithic era (the Old Stone Age) to the 21st century of our common era – (the postmodern age on the art calendar).

Art rendered support and strength initially to religion and later to socio-political issues in particular and society in general. It can better be referred to as ‘art for the people by the people’. At a time

in history, art became a means of distinguishing between civilisations, ranging from the Neolithic era with the mysterious but dynamic monuments such as the Stonehenge, to the Egyptian pyramids and tombs which are the offshoots of numerous public artworks along the Nile, palaces and cities. Some of these were known to have been commissioned by the Pharaohs whose kingships were absolute and ‘divine’ as well as key, in Egyptian civilisation - a civilisation that largely determined the characteristic of Egyptian art.1 The Pharaohs commissioned these tombs and pyramids as public art, a reflection of their political achievements during their reign. These were the kinds of attainments that they were prepared to go with, into the next life.

The production of these works of art can be perceived as participatory since the making of the art had involved thousands of slaves (some historical accounts refute this, suggesting that these ‘artists’ were paid and therefore did not work as slaves whilst making the art).

The making of the monuments was indeed participatory and reflected the glory, divinity and longevity of the patrons – the Pharaohs. The making, and the monuments them-

selves, have socio-political implications since the tombs and pyramids revealed the political strength, affluence and wealth of the Pharaohs. It is pertinent to note that the Pharaohs were not alone in the preparation for an ‘afterlife’ for it was the essence of Egyptian cosmology, so the entire Egyptian society was involved. It was a kind of civic obligation for every Egyptian to have his own tomb. See Fig. 1 & 2.

uche nnadozie

uche nnadozie

About 1,500 years later the Greco-Roman civilisation emerged first with the Hellenistic period. The art making of the Hellenistic time was also public oriented, thus resulting in an international culture uniting the Hellenistic world.

Although the Greek art had little political artistic expression, it was court oriented because the Hellenistic princes were involved in collecting art, acquiring skills as critics and connoisseurs and then disseminating this Greek art making methodology to the locals whom they were ruling.2

On the other hand, Roman art takes its features mostly based on the imperial role that the Roman State (empire) played.

What are some of its features and what impact did Roman art have on its public? Art making in the Roman society had socio-political/cul-

tural tendencies. They were very public oriented. Most public art was meant for public awareness, as a source of information and were utilised to unify the people. For instance, the “Julio-Claudian emperors, Augustus’ successors in the first century AD continued their policy of glorifying by art [using] a vast variety of public works.”3 The ‘Ara Pacis Augustae’ [altar of the Augustan peace] monument was public art with socio-religious and political connotations that narrated the pacification of the entire empire in the Augustan years following the establishment of the new government in 27 BC.

Another way in which public art was made people oriented and involving of the public [probably] through its message even if not necessarily through its mode of production was by the memorialisation of actual events through monumental forms as expressed in numerous imperial triumphal arches in ancient Rome. The triumphal arch is one of the most popular type of commemorative monuments. It is “an ornamental version of a city gate moved to the center of the city to permit the entry of triumphal processions into the forum.”4 ‘The Arch of Titus’ celebrated his victory and by extension the Roman supremacy in the Jewish war of 66 – 70 AD.

The Column of Trajan is another kind of commemorative public art. The Column at 100 Roman feet high spoke for Trajan, on the one hand as a Leader, and, on the other hand, for the people of Rome as followers, or as a society that produced the Leader. The Column chronicled Trajan’s successful campaigns and the further expansion of the Roman civilisation. Helen Gardner vividly referred to the Column as

…a sculptural narrative [journalistic nature] of military architecture, fortifications, bridges, and so on, to show the Roman technical superiority over the barbarian foe. The emperor’s figure is seen many times throughout the narrative, appearing as a kind of major motif. It reveals what Rome thought to be her mission – bringing civilisation to the benighted. Towns are built, crops harvested, rituals performed, and imperial speeches given. The

reliefs on the Column are not only an exaltation of Trajan, but a hymn to Ramanitas.5

Africa, and Nigeria particularly are no exceptions. In the ancient societies in Nigeria, the artist was the rallying point for all socio-religious issues. He gave support and energy to religious, and in turn political institutions.

Art making at that time was participatory because where the common people needed the artist to lead in producing the Mbari houses, the ancestral groves, the masks (for community policing) and the Ikenga, the rulers needed him to lead in decorating the palaces and to document kings and nobles.6 Thus the ancient artist involved the people especially as extra hands, in his art making processes. An example is with the building of an Mbari house.

What about the Ife and Benin heads, are

the artists not also involved in assisting the monarchs to visually document them? There is some semblance in the art making culture of the Mediterranean world and that of Nigeria, where the former is well versed with creating public art and open space monuments, the latter made art pieces for segregated members of society (religious cults and kings’ courts). Another concept of public art and its far-reaching effects on its publics is body art – the ichi facial scarifications of the Igbos which initially included the cheeks but later became confined to the forehead. According to Cornelius Adepegba, the wearers of the ichi markings were quite revered and respected by the Igbos. During the trans-Atlantic slave trade, European slave buyers avoided these mark wearers due to their political potency, with the fear that they could lead other slaves to cause mutiny or to jump overboard in the course of movements across the oceans.7

Cultural production in contemporary Nigeria is not so different from what it was during the ancient times. In the beginning, in Nigeria, it started with Aina Onabolu’s naturalistic art which was later severely criticised, for it was regarded as a slavish copying of the European orthodox artistic methodology. Yet others argued, that Onabolu and his ‘Euro-traditional’ realism is essentially nationalistic and politically relevant. Nkiru Nzegwu particularly opined that Onabolu and his group proved “a political point, that colonised African artists can equally paint like their European counterparts,” in other words, using “European naturalistic style to fight the battle of racial differences.”8

The Nigerian artist’s ideological approach to visual culture took a swift and different dimension with the introduction of artistic manifestoes such as Negritude in the 1940s with emphasis on Ben Enwonwu’s paintings; Natural Synthesis championed by the

Zaria Art Society in the 1950s, and the radical approach to visual political discourses precipitated by the civil war. None of the products of this era, however, is public art. They were constituted in the studio and taken straight to the galleries and the museums. They were the characteristics of modern Nigeria’s aesthetic which lasted for over 50 years.

At the turn of the millennium, Nigeria’s contemporary art began to experience radical changes in techniques, media and processes, art making generally became within the framework of conceptual art, concept and meaning began to matter a lot, and new forms/media (electronic, performance and installation art) emerged. One factor that aided the emergence of the new trend is of course globalisation.9 Kunle Filani gave further insight:

The global space opened up for creative interaction among artists and art scholars. This

warranted a cross-fertilisation of ideas among artists from all over the world. More avant-garde experiments continued and many Nigerian artists both at home and abroad responded to globalisation in various ways that still emphasised the issue of African identity. The underlying political and economic collapse of the 1970s to 1990s became the thematic structure upon which many conceptual artists constructed their forms.10

Yet scholars and artists like Krydz Ikwuemesi, Thierry William Kondedji, Lucie Tonya and Chijioke Onuora do not agree with Filani on his opinion about some of these art forms. Onuora queried the creative relevance of such art forms with emphasis on installation.11 Ikwuemesi particularly berated the idea of this form of art, calling installation art a western idea when in the real sense it is not new anywhere, and not new in Africa. Nonetheless, it is only recently that Installation Art is being fully appropriated (in Nigeria) as an art form. He

further stressed that “to claim a new birth for it in Africa or elsewhere is like claiming new birth for a re-christened old child.”12

Thierry Kondediji and Lucie Tonya (cited by Ikwuemesi) insist that installation art is African; it is a creative rebirth which has revealed that creativity in contemporary Africa can relate to the past. They assert that whatever these art forms are now reinvented and called, they are “indeed close to the religious altars and are cultural dispositions, set… by the priests.”13 But Ikwuemesi disagrees saying that there are other cultures with sacred groves which could have inspired the contemporary Installation Art.

Whatever the case maybe, we have a new art trend in Nigeria, one whose characteristics involve asserting liberty and the rights of creativity; taking art directly to the public and, as a result, can eliminate the need for galleries or museum spaces; propagates new art forms and explores new visual possibilities with complex visual narratives.

This is perhaps neo-contemporary Nigerian art and we must come to terms with its prevailing influence on a younger generation of Nigerian artists both at home and

abroad. Like with any other artistic era/epoch, what is the origin of Neo-Contemporary Nigerian Art?

Helen Gardner, the art historian, may not have foreseen the emergence of postmodernism, let alone globalisation, but in the conclusion of her very incisive and detailed art chronology, she envisages an emerging international art world which is as a result of the west losing her tradition and the non-western parts of the world either losing or modifying theirs.14

In their analysis of what they termed the ‘paradox of postmodernism’, H.W. and Anthony Janson termed postmodernism a mechanism fashioned to reject modernism. This was the barometer used to measure (define) the late 20th century culture. Even as a usurper of an established tradition, postmodernism neither “resolutely refuses to define a new meaning” nor imposes an alternative order in its’ (modernism) place.15 It is a phenomenon that sprang from a post-industrial

society which has since moved into an information age. Although a global phenomenon, different nations can have different positions and terminologies for the artistic trends produced during this period. However, all of these may still be grouped under the rubric of postmodernism. (See Fig. 9, an example of Modern Art by Pablo Picasso).

involving the people in the art making process

In Nigeria, for instance, modern art (contemporary, for Nigeria) showed up in the early 20th century and if we agree with the theory that contemporary art in any given period lasts for only a hundred years,16 it means then that the contemporary Nigerian art (Modern Art in global circles) should completely shift by 2020.

Postmodernist trends have been noticed since 2000 in our art parlance but without much recognition or acceptance at the beginning. This was probably why in 2009 OkekeAgulu remarked that “contemporary art in Nigeria seemed more in tune with late 19th century art trends than it did with cutting edge 21st century forms.”17

At the beginning, some ‘art masters’ in Nigeria were uncomfortable with the arrival

of these new trends even though they were itching for new creative possibilities. This probably inspired Jacob Jari’s 1998 article - Natural Synthesis and the Dialogue with Mona Lisa - where he was anxious about a post- Natural Synthesis era in Nigerian Contemporary art.18 Thus like Gardner, Jari probably did not know how this change would come, but he did foresee beyond Natural Synthesis.

In 2006, Kunle Filani - who as I mentioned earlier had encouraged Nigerians to embrace this new trendwas quite critical about the same trend in a paper titled Modernity in Contemporary Nigerian Art and the Illusion of the Ripening Plantain. Filani berated the artistic tendencies, asking artists involved in performance and installation to be more creative. He regarded these inclinations as extreme and suggested that the artists should be called to order. Not to spare the curators of these trends, he accused them of seeking cheap glory by misleading the artists in the name of installation19 but today the story has changed! (See Figs. 9 – 12 Installations by renowned Nigerian Printmaker, Bruce Onobrakpeya).

Nigeria lags 20 years behind the new art

epoch. This is because we refer to ‘art since 1980’ as postmodern art. Nevertheless, a gradual progression is being accommodated. Postmodernists are far more issue-oriented than the previous art era, and their work spreads across (accommodating) a wider spectrum of concerns than ever before. According to the Janson brothers, “the principal manifestation of post modernism is ‘Appropriation’.”20 It looks back self-consciously to earlier art by imitating previous styles and by taking over specific motifs or even entire images. In this art-making period, artists borrow more systematically from tradition than was the norm.

In postmodernism there can be the freedom to adopt existing imageries but there is also the possibility to alter the meaning of these imageries radically by bringing them to new contexts. There is then more emphasis placed on content and process over aesthetics. Another unique feature of postmodernism is the option to merge art forms - there can be no distinction between painting, sculpture or photography. Having said all these, how have we localised postmodernism?

Neo-Contemporary Nigerian art, citing Harrie Bazunu and Tobenna Okwuosa, is “art making strategies that push beyond the conventional boundaries, … rebranding Nigeria and contemporary Nigerian art that is considered insipid by some national and international art critics.” 21 It is an art trend and era for the 21st century, that appears more proactive than reactive. Moyo Okediji calls it a “new modern” - an exposition that explores new media, using new methods to pursue new meaning. Tonie Okpe reasons alongside by saying that Nigeria’s art education culture deters the massive embracing of these trends which are contemporary “within a global context… with an abundance of possibilities in form, theme, subject matter…material and process [with]… visually non-traditional material occupy[ing] centre stage within this art form.”22

What are some of these materials? They include found objects –discarded materials, and various forms of waste or disused objects, electronic appliances, film/ video making and theatrical performance. The artists of neo-contemporary Nigerian art have an “understanding … [about the]

critical appropriation of disused objects in the above-mentioned techniques.”23 Some are master recycling/repurposing artists of international repute such as El Anatsui, Junkman, Sokari Douglas Camp, Moyo Okediji, Ayo Adewumi, Yinka Shonibare, Bruce Onabrakpeya, Jelili Atiku, Amarachi Okafor, Bright Eke and Nnenna Okore just to mention a few.

involving the people in the art making process

inter-related, this is why one cannot agree less with Ikwuemesi when he says that installation art has an ancient global creative and artistic ancestry; then what about Public art?

They deploy their newfound modes of expression, sensitivity, intellect and creativity to transform ubiquitous materials into elements of profound artistic statements through Film, Video art, Computer Animation, Performance, Installation and Public Art or art in the public spaces.

The neo-contemporary, postmodern artist has continued from their modernist counterparts to use their ‘weird’ media in documenting the socio-political recklessness of our political class and to re-contextualise Public Art. It is imperative to state here and now that in terms of creative innovation, invention or methodology, there is nothing new in art, but in terms of appropriation, probably, there might be something. Throughout art history, we find that artistic trends are often

Since neo-modernism knows no bounds even in Nigeria, Amarachi in creating an artistic phenomenon called Ask Yourself, has explored the essence of Public Art. Her art projects a semblance with the art of times past, that had aimed to serve the public, though in a different way. Amarachi’s public art is a great example of a Nigerian neo-contemporary postmodernist art form that can have impact on audiences and lives beyond the confines of a gallery or museum. This is not the form of public art commissioned by the State to adorn public buildings and squares. No! If we pay any attention to Twylene Mayer, then we would say that it is not that type of public art which adds aesthetic veneer to buildings and government facilities such as those of eras past, but public art that is “intended to preserve civic norms … and potentially contribute to public dialogue in a myriad of ways.”24

Public art in this context, influenced by the prevailing circumstances of the 21st century in Nigeria and the globe at large, is public art of experimentation, questioning and dissent, one that challenges the public realm as other forms of art do not “and offers the promise of imaginative, if not always literal liberation.”25

What about the public space as material?

Amarachi employed this physical or virtual methodology with the intent to create “a zone open to all and belonging to none, a place of social, intellectual, and political exchange characterised by freedom of movement and expression.”26

A sk Y ourself within the context and content of Neo-contemporary Art.

Amarachi Okafor is an innovative artist who studied, apprenticed and has worked with the renowned sculptor El Anatsui. At the University of Nigeria, she obtained a B.A Hons in Painting, an MFA in Sculpture and later an MA, Curatorial Practice from Falmouth University in the UK.

A former Curator with National Gallery of Art, Nigeria, Amarachi by virtue of her artistic processing and production is vividly a neo-contemporary artist based in Nigeria. She has spent years in her practice projecting her new art trend with tremendous results –winning awards and participating in many artist residencies. She is obsessed with unconventional artistic methodology that is laden with meaning, and innovation. One of Amarachi’s methods isworking collaboratively and creating opportunities to give other people actual (artistic) experiences. Although she trained in an environment where the Uli ideology and style reigned, Amarachi did not pick up that esthetic. She ushered in reactive modernist styles and advanced then to rather proactive neo-modernist ones, transcending from the trappings of Nigeria’s post-independent culture and the artistic expressions associated with it [Uli, for instance]27 to applying a neo-modernist/contemporary artistic force. Ask Yourself is public art created by adopting the public space as material– “which is a place of social, intellectual and political exchange characterised by freedom of movement and expression.” It would appear that

Amarachi went back in time to the Pharaonic and the Greco-Roman era to interrogate the essence of ‘art in the public space’, adopting her inspiration from their experiences (past) and bringing it to the present (today).

involving the people in the art making process

the sense that it poses as a catalyst for producing (positive) change in people, aiding us to look inwards to ourselves first and begin to think of growing or generating ideas and methods for constructive change towards achieving an admirable society.

Ask Yourself is a monumental installation, produced with the characteristics of Painting, and Sculpture Installation. It imbibes Performativity and uses Text as a visual language.28

Ask Yourself is multi-dimensional, involving many neo-contemporary art techniques including Film that recorded the ephemeral aspects (participation and interaction) of the piece which included processes such as painting, experiential conversations, reading, writing and drawing activities. Essentially, it is an artwork produced alongside the public, for the same public – in the public space.

One can classify Amarachi’s Ask Yourself as Interactive Installation, a sub-category of Installation Art which “can involve the audience acting on the work of art or the piece responding to the audience’s or user’s activities.” This installation technique is used by artists who are interested in using “audience participation to co-author the meaning of the installation”29 – collaboratively.

One cannot but agree with Amarachi –that Ask Yourself is sensitisation, sensitisation in

Ask Yourself as an art piece was produced with many collaborators. This brings us to the issue of a parking space for such artistic innovation in the parking lounge of Nigeria’s visual art. Is there a space for Amarachi’s artistic broth? Can we box it into creative specifics despite its complex dimensions? Can it be said to be relevant to our experience as a people? The answer is yes! Yes!! And yes!!! Her art is classifiable. It is post-modernist. It is conceptual. It is installation. It is Film. It is Painting. It is Public art – a participatory kind produced in the studio as well as in the public space. Finally, it is a new modernist/contemporary Nigeria art –the art of the future, an art meant for the public by the public.30

At the beginning of this discourse we tried to revisit some historical monuments of wonderful art civilisations in the Mediterranean and there is no doubt that Ask Yourself does compare indeed, the difference being Time and Place! Hence, it becomes necessary to conclude this discourse with Twylene Mayer’s suggestions on the role of Public art such as Ask Yourself. Mayer postulated that: Public art can help us see past the illusion.

It may even offer solutions and improve lives, but ultimately, accountability lies beyond its scope. Public art is not going to relieve urban blight, eliminate violence, redistribute wealth, or curb the police state by itself, but it can insert doubt.... It can inspire us all- viewers, direct participants, …to re-evaluate what we mean by quality of life, to reassess what we think we know, and to reconsider how we choose to live with ourselves and each other. In the world of art, critique, pleasure and insight can come together to re-imagine and forge new modes of public life.31

1. H.W. Janson and A.F. Janson, History of Art for Young People, 5th Edition (New York: Harry M. Abrams Inc, 1997), 38-41.

2. Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, 7th Edition (New York: Jovanorich, 1980), 144

3. ibid p.194

4. ibid p.196

5. ibid p.196

6. There were no public monuments in this part because of lack of materials and the enabling environment but at the peak of the Benin empire, there came court art pieces such as the ‘Oba heads’ rendered in bronze; and the Ife art which at the beginning were terracotta heads.

7. Cornelius Adepegba, Nigerian Art: Its Traditions and Modern Tendencies (Ibadan: JODAD Publishers, 1995), 15. See Chike Aniakor, Reflective Essays on Art and Art History (Pan-African Circle of Artists Press, 2005), 9

8. Kunle Filani, NIVATOUR: Tenor of creativity in contemporary Nigerian Art in NIVATOUR 2, KoreaNigeria: A Friendship over decades (Abuja: National Gallery of Art, The Korean Art Museum and Total Museum of Contemporary Art, 2013), 7

Also see Nkiru Nzegwu, Introduction: Contemporary Nigerian Art: Euphorizing the Art Historical Voice in Contemporary textures: Multidimensionality in Nigerian Art cited by Kunle Filani in NIVATOUR 2: Tenor of creativity in contemporary Nigerian Art.

9. “Globalization is the gradual coalescence or sudden collision of identities, resources, political power and economic interests, an intercultural ferment, creating networks of trade and commerce, expanding or shrinking spheres of influence. It can also be defined as a process of infiltration and counter-infiltration, surrender, conquest, shifting paradigms, and widening spheres of cross-communal interaction. In one sense, it broadens participation by connecting different world –yet palpable fears remain that it assists the strong to easily overrun and (re) colonize the weak… Globalization, by contrast is a more recent phenomenon, through the foundation for its final emergence had been laid long ago. With every new book written, every ship that set sail, the invention of the airplane, the liberalization of learning, the slave trade, transnational wars and conflicts, natural disasters and finally, the arrival of the Internet, -the stage had been set, a situation had been created, a chain of networks that can no longer be broken, a monster that is hard to tame, a delineation of new geographies. Globalization is born.”

Source: Uchechukwu Nwosu, Uche Okeke, Culture, Synthesis and Globalization, in Nku Di Na Mba: Uche Okeke and Modern Nigerian Art, ed. Paul Dike and Pat Oyeloa (Abuja: NGA, 2003), 281

10. See note 8

11. Onuorah made this statement as an introduction in a misplaced exhibition catalogue.

12. Krydz Ikwuemesi, Installation, African Art and the Politics of Cultures in Trends: Six Artists Single Platform (Abuja: NGA, 2013), 18

13. ibid

14. Gardner, Art through the Ages, 889.

15. See note 1

16. Filani, NIVATOUR: Tenor of creativity in Contemporary Nigerian Art, 3

17. Bisi Silva, The New Face of Painting (http://katrinschulze. blogspot.com.br/2009/09/bisi-silva-new-face-ofcontemporary.html). Cited by Harrie Bazunu and Tobenna Okwuosa, in Ridding Nigeria of Filth: A Reading of Moyo Okediji, Bright Eke and Harrie Bazunu’s Application of Discarded Materials: ajofaa: Awka Journal of Fine and Applied Arts, no.1 (2013): 49.

18. Jacob Jari, Natural Synthesis and the Dialogue with Mona Lisa, in The Zaria Art Society: A New Consciousness, ed. Paul Dike and Pat Oyelola (Abuja: NGA,1998), 45-49.

19. Kunle Filani, Modernity in contemporary Nigerian Art and the Illusion of the Ripening Plantain, A Paper presented at the 2nd National Symposium on Nigerian Art, organized by National Gallery of Art in Conjunction with the Dept of Fine and Applied Arts, Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife, 26th- 29th September, 2006.

20. Appropriation “is the deliberate inclusion of ‘borrowed’ images or forms by other artists in a new work of art, some of it electronic in contrast to copying or imitation. It raises all manner of questions concerning intellectual property rights and originality, an area of heated debate since the mid 1980s.”

Source: H.W. Janson and A.F. Janson, History of Art for Young People, 598

21. Harrie Bazunu and Tobenna Okwuosa, Ridding Nigeria of Filth: A Reading of Moyo Okediji, Bright Ugochukwu Eke and Harrie Bazunu’s Application of Discarded materials, ajofaa: awka journal of fine and applied arts, no. 1 (2013), 49.

22. Tonie Okpe, Conceptual Art: A Reception Musing, A Paper presented at an induction course organized by National Gallery of Art, for her new staff in conjunction with Rock Edge Consulting Ltd in Abuja, 2nd August, 2011.

23. See note 21.

24. Twylene Mayer, ‘Foreword’ in Artists Reclaim the Common: New works/New Territories/New Publics, ed. Glenn Harper (Washington: ISC Press, 2013), 7.

25. ibid

26. ibid

27. Bazunu and Okwuosa Ridding Nigeria of Filth: A Reading of Moyo Okediji, Bright Eke and Harrie Bazunu’s Application of Discarded materials, 50.

28. Interview with Amarachi Okafor in her studio at the outskirts of Abuja on 3rd April, 2015.

*Graffiti art –a type of ‘street art’ is a graphic and image that is sprayed-painted or stenciled on publicly view able walls, buildings, buses, trains and bridges, usually done without permission and most time considered illegal or an art of vandalism.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art. Retrieved on 6 September 2011.

29. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Installation_ art&oldid=464340109

30. This is my personal evaluation about what Amarachi’s ‘Public art’ meant

31. See note 24.

PARTICIPATION

DIMENSION

(INTERACTION)

FCT College of Education

Zuba-Abuja

Art and the society were two inseparable entities in the traditional African society. Art was life and life was art. Art was everywhere and in everything - religion, architecture, tools, utensils, performances and the like; art was of essence, duly appreciated and artists were revered. This cannot be said of the contemporary times.

The trajectory between art in traditional Nigerian society and that of the contemporary Nigerian society has been an experience of upheaval. Therefore, to discuss art in contemporary Nigeria, we must first attempt to define ‘Art’ (contextualising ‘Art’) and then define the phrase ‘Contemporary Nigeria’, recognising that it is a result of an accumulation of experiences. Consequently, we shall be able to discern the relationship between art and the contemporary Nigerian society.

We shall then discuss historic landmarks which have either aided or constrained the development of art and art appreciation in contemporary Nigeria. While considering the impact of certain individuals and projects on the reinvigoration of creative professionalism at various intervals in the history of art development, we will focus, for the purpose of illustration, on the Ask Yourself Project and use it as a prototype for societal reawakening of artistic engagements.

Defining ‘Art’ is a complex thing to do because the definition varies with historic timelines and cultural contexts. Art has been defined by several people in various ways. No singular definition of art is universally acceptable, as definitions differ from one community to another. Ekpo (2008), substantiating the complexity of the definition

of art, states, “In Africa, it is difficult to find words that can literarily translate to the Western concept of art as it is understood today. In many African cultures and languages, art is not an entity by itself, it is embedded in an object or performance that is admired as appropriate or good-looking.”1 Art may be defined as the visual expression of aesthetics; art is the product or the process of creating something beautiful. But then, the meaning of aesthetics is also a controversial phenomenon since aesthetic judgment may be based on different indices. Sometimes aesthetics is quantified based on physical attributes and at other times it is quantified based on conceptual attributes. Thus, the definition of art and aesthetics is progressively changing; it is dependent on time and media of expression. As the boundaries of the art genres keep expanding so does its definition.

Contemporary Nigeria is a tapestry of ethnicities, a cultural collage of over 250 ethnic nationalities, with hundreds of ethnic languages and dialects. Contemporary Nigeria has resulted from a few factors. One, was the decision by the colonialists to marry the diverse nationalities into a single nation, a second factor considers the experiential relationships between the diverse cultures; a third is the nation’s political history with the succession of military juntas; a fourth factor encompasses the religious and social afflictions of the different ethnicities. The combination of all these factors birthed the

contemporary Nigerian society.

Contemporary Nigeria therefore is a conglomeration of societies with seemingly incompatible socio-political, cultural and religious characters, but whose survival has been rooted on a self-styled political and economic relationship, giving rise to the common cliché, “Unity in Diversity”.

The traditional Nigeria has always had a very rich artistic tradition. The various ethnic nationalities, however, had their artistic traditions rooted in their cultures and religions. The Nok and Ife terracotta, the Igbo-Ukwu bronzes were established artistic traditions which date back to centuries before the scramble for and partitioning of Africa. As fate had it, the Nigerian geographical space brought together several ethnic nationalities, the marriage of which enabled cross fertilisation of artistic ideas that occasioned hybrid stylistic art as different cultures borrowed from one another. This premise gave rise to the modern Nigerian art in the early 20th century.

Ordering a direction for the modern art of Nigeria during the early 20th century was quite challenging and controversial. This was attested to by the various ideology driven propositions, beginning from the efforts of Aina Onobolu (regarded as the father of modern Nigerian art) who propagated naturalism in the style of the West, to Kenneth

Murray who to the contrary preferred that the traditional African art expression was not discarded. Murray “saw creativity in the interpretative expression of the African traditional art and therefore encouraged his students not to throw away traditional ideology in their artistic creations.”2

Ayo Adewunmiperiod between the 1970s and 1980s saw the rapid development of art schools across the nation, with the synthesis ideology of the Zaria Revolutionaries trickling down and shaping stylistic directions for art schools (Institutional and Ideological).

Other notable actions of activism in the early period include those of John Digby Clarke, who then in Omu Aran, Central Nigeria (present day Kwara State), advocated for the synthesis of traditional Yoruba style with the new western style, as a solution. There was also the Oye Ekiti workshop of Father Kevin Carroll which supported and promoted traditional African Art. Furthermore, there were the Mbari-Mbayo workshops, the non-formal workshops of Ulli and Georgina Beier in the 1960s. All of these had impact on the artistic landscape of Nigeria before the late 1960s. It was in the 1960s that a small revolution, which soon blossomed and produced a radical departure in art stylistic approach in Nigeria, started at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology, Zaria. The revolution, a counter reaction to Western stylistic approach became like the mustard seed which grew into a habitation for all sorts of modern artists.

The point to note here is that actions and counter reactions, usually informed by certain agitation or dissatisfaction and resulting in new artistic forms were the foundation for contemporary Nigerian art. The

The art schools took the center stage in the development of modern art in between the 1960s and 1980s. The role of the art schools in the development of art in Nigeria is very significant. The art schools became a laboratory for visual art explorations and the development of new styles that eventually defined these schools. The Nsukka School, the Zaria School, the Ife School, the Yaba School and the Enugu school were pioneers in this respect.

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a surge in professional exhibitions, in the formation of art cooperatives, the establishment of modern galleries and improvement in art criticism. All these strengthened the art profession and created an environment for competitive practice. In a swift turn from the 1990s, technological development expanded the scope of visual art, and with the internet making the world a global village, it became possible to view international art shows from the comfort of one’s bedroom. This promoted an easy fertilization of creative ideas which worked well in two ways: local artists kept abreast of international art and the international community also had the privilege to see the contemporary works

from these parts.

From the 1990s more artists began to explore concepts which defined art not just as an object but also as a process. Installation art, Performance art, Video art and Multi-media became media for creative expressions, making it even easier to take art back to the society. From the 1970s art had become elitist in patronage and in appreciation (courtesy of ‘academic art’). The new media offered improved interactive audience engagement and better understanding since society could conceptually relate with the art.

It is important to note, though, that some of the new media like Installation and Performance, imported as artistic media, had long existed in traditional African societies as part of ceremonies and functions but, were not regarded as art forms until now.

Performance art is an artistic activity in which the artist’s presence is a crucial part of the medium of expression. Kostelanetz (2009) describing performance art states that “all performance art shares two elements: first, the various parts of the[a] Performance[s] function[s] disharmoniously in the tradition of a visual-art collage, (which is) based upon assembling elements [that are] normally found apart; second, a piece of Performance art must be live, because a recorded piece, whether in film or audio tape, has no spontaneity. Performance art may also incorporate elements of shock, social criticism or protest, and audience involvement.”3

Although Kostelanetz’ use of the phrase “function disharmoniously” may be controversial, the elements that are alluded to, nevertheless, conform totally with certain essentials used in Performances that are part of rituals and ceremonies in traditional Africa. The processes and the compositions of these rites connote what modern and post-modern art have termed ‘Performance art’ and ‘Installation art’. We must, however, not fail to consider and appreciate another school of thought which believes that whereas these Performances and Installations are part of the traditional African society, aesthetics was not the primary objective in this custom. The idea being stressed here, then, is that the local African society has a relationship, indeed, with the fundamentals and principles of Performance and Installation art forms.

The chronological history of modern art in Nigeria would help us to understand how contemporary art attained its stylistic and conceptual state in Nigeria. What is now known as contemporary or modern art was not created from emptiness. It is the product of many years of artistic engagements, experiments and activism from the traditional period to the present time. These creative journeys birthed contemporary Nigerian art.

The landmarks of artistic development in Nigeria include the transition from traditional to modern art beginning with the

work of Aina Onabolu; the radical revolution of the 1960s; the growth of art criticism and documentation of the 1980s; the multiplication of art cooperatives and ideological schools of the 1990s alongside the internet/ digital technological impact of the 2000s. In the course of these landmarks, there were developmental constraints which include poor funding, lack of art education, galleries’ exploitative ‘patronage/support’ of artists, the problem of art appreciation and that of actually defining art.

Ayo AdewunmiIt is therefore not surprising that the modern academically trained artist viewed traditional art through this prism of the West, considering the role of the West in art education during the colonial era and even after.

Perhaps one of the major constraints is an issue of a definition of art by modern artists which tends to adopt the Western delineation - consigning traditional art from other cultures [besides the West] as primitive and uncivilized. Explaining ‘Western Civilisation and Art’ Ekpo (2008) observes that, Westerners saw themselves as ‘civilized’ and considered others ‘uncivilized’, or savages. Hence, the two words ‘civilized’ and ‘savage’ became a dichotomy and a prism through which one looked at the peoples of the world. One was civilized if from the West and a savage or primitive person if from the so-called non-Western world.

This skewed perspective created complexities in interpretation as modern art became elitist in character and therefore difficult to understand by the common people; and since the common people could not place ‘modern’ art, misunderstanding and further misinterpretation produced poor appreciation (of modern art) by the general society.

Such a scenario (of relegation) is contradictory to the reality regarding art and the society in Africa. Africans by nature are very artistic as exemplified in their approach to textile design, architecture, pottery, craft and performances. To categorise levels of (academic) art appreciation and use this understanding of academic (modern) art as the standard for measuring art appreciation in the African context is therefore completely unrealistic.

Between the early and mid-20th century it happened that modern art was made elitist

when a class distinction was unofficially created which gave an advantage to modern art over traditional art. This brought into play ideological and conceptual gaps that made a stronger case for ‘modern art’. Modern artists ill evaluated traditional art and traditional artists even though they drew inspiration from these.

The traditional society is well attuned and conversant with its ‘traditional art’. Its artists engage in the creative processes around textile, fashion design, traditional architecture, murals, body art, crafts and performances, all of which are no less art than the modern art. The matter of an artificial disconnect between traditional art and modern art, which advertently does position modern art beyond the reach of the contemporary society, demands a redress for the sustainable development of art in Nigeria. This was responsible for the pockets of agitations from the 1960s as stated earlier.

In a bid to resolve this gap created with the discrimination between modern art and the traditional art, which had produced a short-

fall in society’s appreciation of modern art, some artists and art organizations designed projects aimed at taking art back to the society and engaging their participation. Neo-stylistic models began in the 1980s. The renowned artist El Anatsui collected waste traditional utensils and objects from various rural villages around Nsukka, south east Nigeria, for his creative exploration, thereby re-introducing these traditional objects for modern interpretation and appreciation. In essence, Anatsui created an interface between the society and contemporary art – in that sense.

In 2005, Art Is Everywhere (AIE), a waste-to-art project, was initiated as a project that encourages collaborative creative processes involving young artists from academic and non-academic backgrounds. In a similar attempt to create synergy between the society and the artists, the Life In My City Art Festival (LIMCAF), a national visual art competition which began in 2007 with the object of positioning art for social development, tasks younger artists on themes that relate to their environment.

At the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, many other artists explored artistically, rela-

tionships between the society and contemporary art, using new media and materials. These artists include Ayo Aina, Ike Francis, Nkechi Nwosu-Igbo, and lately, artists like Amarachi Okafor, Jelili Atiku, and Lanre Tejuosho.

Amarachi Okafor, in her body of work titled Ask Yourself, brings on one of such ideological projects aimed at involving the society in the creative process, allowing for reciprocal public participation as part of the creative process, enabling interaction between the society and art. More importantly it spurs the society into voicing its mind through artistic media.

The contemporary Nigerian society is a creation of decades of distressing experiences; beginning with the intrusion of colonialists, their attendant abuse and derogatory assaults on the sensibilities of Africans, the Nationalists’ struggle at the Independence era, to the activism that engineered a massive rejection of colonial domination. These were followed by the distressing experiences of military rule which skewed civil attitudes, removed leadership responsibleness and introduced corruption.

Following in turn, we beheld the political class of the democratic era and their inhumanity. This era saw massive looting of the nation’s treasury, leadership deception and impoverishment of the citizenry. It is not uncommon to encounter pathetic stories of deprivation and extreme poverty; stories bordering on child abuse and neglect, indigent children roaming the streets in search of food for themselves and their families, where many of them are not able to afford school fees. This is the opposite of what we should expect from a supposedly ‘rich nation’ like Nigeria. This is the background that has coloured the contemporary Nigerian society with various shades of unpleasant experiences – our society now abounds in angry outbursts against its leadership and the political class; a people deprived of basic life necessities -. This and more are the bases for the perceived aggressiveness, emotional overflow, activism and such kinds of reaction arising with the ordinary people.

An outlet for these repressed emotions becomes a necessity, and art does provide a channel for letting off energies. The artist, who herself is part of society, can draw inspiration from this tumultuous multidi-

mensional dilemma of said society.

Ask Yourself fits in here as a project that not only interfaces with the society but engages it in a creative process.

Ask Yourself explores a multiple-medium creative process: painting, drawing, texts, reading and dialogue. Conventionally, these media seem incompatible and complicate issues for those who would usually like to classify artistic creation into thematic, stylistic or ideological groups.

The Ask Yourself creative process also combines dialogue, objects, video, installation, and performance. This is a combination that may not readily be decipherable when trying to place the work under an artistic genre. With the project, Amarachi Okafor has employed a multidimensional creative process using multimedia and multi-genre methodologies. Within the framework of contemporary Nigerian art, she sets a double-edged artistic model that connects art with the society.

Ask Yourself involves four carefully selected groups of society: the first group being the children who participated from within the location of their school (a secondary school in Nyanya), the second group comprises regular Nigerians who participated at the mar-

ketplace location (Wuse Market), the third were youth from a tertiary institution (College of Education, Zuba) and the fourth, policy makers who participated at the Federal Secretariat, all within the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja.