MAGAZINE

gillnets threaten wildlife

waters The Net Consequence

science and

Dr. Pauly

OCEANA.ORG SPRING 2024 Founded on Fish A closer look at Oceana’s campaigns in Canada and Peru Set

in Southern California

Are

advocacy compatible? Ask

Board of Directors

Sam Waterston, Chair

María Eugenia Girón, Vice Chair

Diana Thomson, Treasurer

James Sandler, Secretary

Keith Addis, President

Gaz Alazraki

Herbert M. Bedolfe, III

Ted Danson

Nicholas Davis

Maya Gabeira

César Gaviria

Loic Gouzer

Jena King

Ben Koerner

Sara Lowell

Kristian Parker, Ph.D.

Daniel Pauly, Ph.D.

David Rockefeller, Jr.

Susan Rockefeller

Lex Sant

Simon Sidamon-Eristoff

Rashid Sumaila, Ph.D.

Valarie Van Cleave

Elizabeth Wahler

Jean Weiss

Antha Williams

Ocean Council

Susan Rockefeller, Founder

Kelly Hallman, Vice Chair

Dede McMahon, Vice Chair

Anonymous

Samantha Bass

Violaine and John Bernbach

Rick Burnes

Vin Cipolla

Barbara Cohn

Ann Colley

Edward Dolman

Kay and Frank Fernandez

Carolyn and Chris Groobey

J. Stephen and Angela Kilcullen

Ann Luskey

Peter Neumeier

Carl and Janet Nolet

Ellie Phipps Price

David Rockefeller, Jr.

Andrew Sabin

Elias Sacal

Regina K. and John Scully

Maria Jose Peréz Simón

Sutton Stracke

Mia M. Thompson

David Treadway, Ph.D.

Edgar and Sue Wachenheim, III

Valaree Wahler

David Max Williamson

Raoul Witteveen

Leslie Zemeckis

Editorial Staff

Editor

Sarah Holcomb

Designer

Alan Po

Senior Communications Manager

Gillian Spolarich

Creative Director

Patrick Mustain

Oceana Staff

Andrew Sharpless Chief Executive Officer

James F. Simon President

Jacqueline Savitz Chief Policy Officer

Kathryn Matthews, Ph.D. Chief Scientist

Matthew Littlejohn

Senior Vice President, Strategic Initiatives

Joshua Laughren

Senior Vice President, Oceana Canada

Liesbeth van der Meer, DVM

Senior Vice President, Chile

Christopher Sharkey Chief Financial Officer

Janelle Chanona Vice President, Belize

Ademilson Zamboni, Ph.D. Vice President, Brazil

Pascale Moehrle

Executive Director and Vice President, Europe

Renata Terrazas Vice President, Mexico

Daniel Olivares Vice President, Peru

Gloria Estenzo Ramos, J.D. Vice President, Philippines

Hugo Tagholm Executive Director and Vice President, United Kingdom

Beth Lowell Vice President, United States

Nancy Golden Vice President, Global Development

Dustin Cranor Vice President, Global Marketing and Communications

Susan Murray Deputy Vice President, U.S. Pacific

Vera Coelho

Deputy Vice President, Europe

Kathy A. Whelpley

Chief of Staff, President’s Office

Michael Hirshfield, Ph.D.

Senior Advisor

Oceana’s Privacy Policy: Your right to privacy is important to Oceana, and we are committed to maintaining your trust. Personal information (such as name, address, phone number, email) includes data that you may have provided to us when making a donation or taking action as a Wavemaker on behalf of the oceans. This personal information is stored in a secure location. For our full privacy policy, please visit Oceana.org/privacy-policy. Oceana Magazine is published by Oceana Inc. For questions or comments about this publication, please call our membership department at +1.202.833.3900 or write to Oceana’s Member Services at 1025 Connecticut Ave. NW, Suite 200, Washington, DC 20036 USA.

Cover Photo: © Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock Please Recycle.

FSC Logo

Features Contents To help navigate Oceana’s work, look for these six icons representing our major campaigns. Founded on Fish 10

Hiscock © Sierra Club Seal Society The Net Consequence 20 Protect Species Reduce Bycatch Increase Transparency Stop Overfishing Curb Pollution Protect Habitat CEO Note Oceana campaigns to save North Atlantic right whales on the brink of extinction 3 | 4 | For the Win Oceana celebrates new victories around the world 6 | News & Notes The powerful potential of refillable bottles, launch of the world’s largest cruise ship, and more Q&A Gloria Estenzo Ramos on big wins in the Philippines 8 | 10 | Founded on Fish Oceana campaigns to protect abundant oceans in Canada and Peru 20 | The Net Consequence Long nets weighted to the seafloor endanger ocean life off Southern California 30 | Quiz Discover more about North Atlantic right whales 29 | Supporter Spotlight Henry Engelhardt: Funding the future of the oceans 26 | Ask Dr. Pauly Are science and advocacy compatible? 28 | Oceana’s Victories Looking back at big wins over the last year Parting Shot A North Atlantic right whale swims with her newborn calf 32 | 1

© Oceana

Canada/Nicholas

Call us today at +1.202.833.3900, email us at info@oceana.org, visit Oceana.org/give, or use the envelope provided in this magazine to make a donation. Oceana is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization and contributions are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of the law. Please Give Generously Today A healthy, fully restored ocean could feed more than 1 billion people each day, forever. Your support makes an ocean of difference © Oceana/Perrin James

CEO Note

“Save the whales” is a call to action just about everyone can get behind. Turn to the last two pages of this issue of Oceana Magazine for a photo that will remind you why you care. Taken off the coast of Georgia, it shows a 21-year-old North Atlantic right whale named Porcia. Look closely, and you’ll see something even more wonderful. Among the Atlantic spotted dolphins swimming with her, you’ll see her baby. That calf, an inspiration to one’s spirit, is also a gift to the future of this species. North Atlantic right whales are threatened by extinction. Less than 360 are alive today, of which less than 70 are breeding females. This calf is part of the thinnest of lifelines to the continued presence of this amazing species in our ocean.

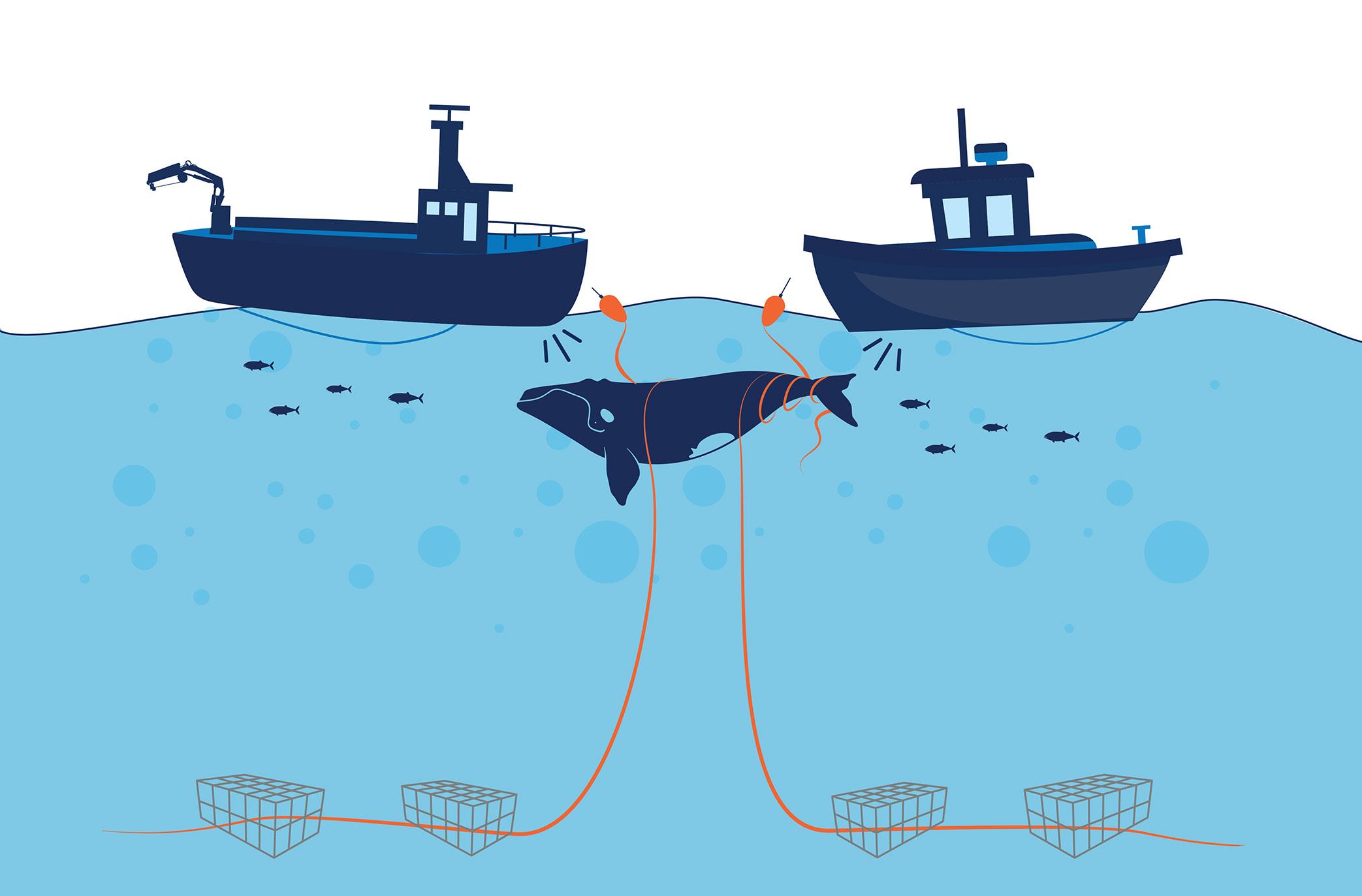

What’s killing them? Often the whales are struck by speeding vessels or entangled in fishing gear. As I write this note to you today, a dead calf was found off Georgia’s coast. The child of Juno (see photo on page 30), this calf was first sighted in November 2023 off South Carolina. Its short life ended when it was run over by a boat estimated by the U.S. National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to be 35-57 feet (approximately 10-17 meters) long. Badly injured in its head and mouth by that collision, Juno’s calf didn’t even make it to its first birthday.

These collisions could be stopped by the simplest of remedies. Mandatory, well-enforced speed limits on vessel crossing areas where the whales are present. Predictable migration patterns allow scientists to map these seasonal “go slow” zones quite precisely. But boaters, such as the operator of the smaller boat that probably killed Juno’s calf, regularly go at speeds much too fast to give the whales time to get out of the way. We don’t let automobile drivers go as fast as they want, particularly in school zones where children are more likely to be crossing. Why do we let boaters do this, even as this marvelous whale teeters on the edge of extinction?

The answer is that some powerful policymakers, prodded by vessel owners and the boating industry, both recreational and commercial, have slowed NOAA in updating its speed limits. Self-interest drives extreme statements from people in some marine businesses. Here’s one: “It’s as if NOAA wants Florida to hang up a ‘closed for business’ sign,” said Mike Rubin, president and CEO, Florida Ports Council.

These extreme statements rapidly drive some politicians to make extreme threats. U.S. Senators Joe Manchin (D-WV), Ted Budd (R-AZ), and John Boozman (R-AZ), and Rep. Buddy Carter (R-GA) introduced legislation to force NOAA to

indefinitely postpone the mandatory speed limits that are essential to saving these mother whales and their calves from being killed.

Extinction will be the consequence.

Oceana and our allies fight these battles every day. Our team continues to campaign on behalf of North Atlantic right whales. Along with advocating for the laws that make our oceans abundant, we campaign to keep them biodiverse. “Biodiversity” is an abstract word. What does it mean? It means that all the creatures that have made the ocean their home shall not perish from this Earth. It means we need to save the whales.

To our donors: Thank you for your support. Your generosity powers our campaigns. This issue will update you on our progress, and our continuing campaigns across many of our teams in the Americas, Europe, and Asia.

For the Oceans,

Andrew Sharpless CEO Oceana

Andrew Sharpless CEO Oceana

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 3

© Oceana

For the Win

Oceana and its allies achieved six new victories to help protect and restore the world’s oceans

New law in Belize gives people the power to protect offshore oil moratorium

Facing an increased risk of offshore drilling, Belize’s government passed a new law that requires any decision to open its ocean to oil and gas drilling to first be voted on by the Belizean people.

Belizeans overwhelmingly favor protecting their ocean from offshore drilling. The Mesoamerican Reef — the second longest barrier reef in the world — stretches nearly 300 kilometers (185 miles) along Belize’s coast. These waters support a rich marine ecosystem — plus Belize’s tourism, fisheries, and economy. New offshore

oil exploration and drilling poses a threat to Belizeans’ way of life.

The new law ensures that the voices of Belizeans are heard through a national referendum before oil exploration takes place in the country’s waters. This victory would not have been possible without campaigning by Oceana and its allies, who secured 22,090 signed petitions from Belizean voters to ensure that “people power” is at the center of decisions about the future of the country’s ocean. In 2017, Oceana, the people of Belize, and the Belizean government made history by unanimously passing an indefinite moratorium on offshore oil in Belize.

© Oceana/JC Cuellar

4

Oceana’s Vice President in Belize Janelle Chanona delivered 22,090 signed petitions to Belize Governor General Her Excellency Dame Froyla Tzalam. The petitions secured Belizean voters the power to decide whether to allow offshore oil and gas drilling in the country’s waters.

Five-Year Plan issues smallest number of drilling leases in US history

In the United States, President Biden’s administration finalized its Five-Year Plan for offshore oil and gas leasing, which includes the fewest number of proposed lease sales to date — three leases, instead of the 11 originally proposed.

Spain sanctions fishing vessels for disabling trackers

Responding to information provided by Oceana, the government of Spain sanctioned 25 Spanish-flagged fishing vessels for repeatedly disabling their automatic identification system.

Spain designates seven new marine protected areas

The Spanish government designated seven new marine protected areas in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, bringing the total marine area protected in Spain from 12% to 21% and protecting key ecosystems.

New Victories to Stop Overfishing

Mediterranean countries fight overfishing with new sanctions

A new sanction system, created by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean, will allow the commission to penalize states that fail to tackle overfishing or illegal fishing by their fleets.

EU sets sustainable catch limits

The European Union set more sustainable catch limits for the fisheries it manages in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. These limits, set for 2024, aim to rebuild fish populations.

© Oceana/Carlos Suarez

In one of Spain’s newly designated marine protected areas, rubberlip grunt fish swim among coral.

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 5

Adapted from: © Gettyimages/Dorling Kindersley

News & Notes

Largest ever cruise ship is released on the seas

In January 2024, Royal Caribbean launched the world’s largest cruise ship, Icon of the Seas, into the ocean. Holding up to 10,000 passengers and crew, Icon of the Seas towers with over 20 decks and boasts theme park activities. The ship stretches nearly 400 meters (a quarter mile) long. “Cruise ships are floating cities, complete with urban waste streams like sewage, air pollution, and trash, concentrated for thousands of people. They bring this waste to many of the most beautiful and delicate natural marine areas,” says Jacqueline Savitz, Oceana’s Chief Policy Officer. Two decades ago, Oceana announced one of its earliest victories when Royal Caribbean committed to installing advanced wastewater treatment technology on all of its ships. This news came

after reports that Royal Caribbean and other companies were dumping inadequately treated waste into the oceans. “Passengers generally want to know that their ships are alleviating impacts, and while new technologies are starting to be applied, the vessels continue to get

Increasing refillable beverage packaging delivers big potential to cut pollution

Reusable beverage packaging is a proven solution to growing plastic pollution, according to a new report from Oceana. Refillable glass bottles can be sold, used, returned, washed, refilled, and sold again as many as 50 times. That means one refillable bottle can eliminate up to 49 single-use plastic bottles. Refillable bottles were once standard around the world, until companies started replacing them with single-use plastic bottles in the 1970s. Although refillables have disappeared in places like the United States, they continue to be sold in large numbers in countries

larger, making it difficult to imagine the cruise industry and natural marine ecosystems coexisting sustainably,” Savitz says. A sister ship to Icon of the Seas will debut in 2025, and a third ship of the same size is expected in 2026.

including Mexico, Germany, the Philippines, and Chile. Oceana’s “Refill Again” report, released in November 2023, charts a promising outcome if companies increase the sale of refillables globally and bring them back to the U.S. and other markets. A 10-percentage point increase in reusable packaging between 2023 and 2030 could eliminate over 1 trillion single-use plastic bottles and cups during this time, preventing over 153 billion from entering oceans and waterways, Oceana’s analysis found. Refillables also offer a lower carbon footprint than any other packaging option. Oceana is campaigning for major beverage companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi to increase their sale of refillable bottles.

Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas holds up to 10,000 passengers and crew, and weighs nearly 250,000 gross tons.

© Oceana/Pilar Marín

6

© Wikimedia Commons/Chakie2

North Atlantic right whales remain at risk of extinction

Boats continue to speed through slow zones along the U.S. East Coast — putting critically endangered whales at risk, according to an Oceana analysis released in October 2023. Named for being the “right” whale to hunt because they were often found near shore, swim slowly, and tend to float when killed, only around 356 North Atlantic right whales remain. Today, boat strikes are one of the top threats to their survival. Studies have found that reducing boat speeds significantly reduces the risk of whales incurring injuries and death. Conservationists say stronger safeguards and increased enforcement are needed to save these whales. These protections are especially important during the whales’ calving season, when some right whales travel more than 1,609 kilometers (1,000 miles) between their southern calving grounds and their northern feeding grounds from November to April. Twelve

calves were born in the 2022/2023 season, and 15 in 2021/2022. So far this season, scientist have documented 19 new calves born, the first of whom died after being critically injured by a boat strike off the coast of South Carolina. Two other calves are not expected to

survive. Oceana is campaigning for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to release its updated vessel speed rule that will provide improved protections for these whales.

Chilean mining company stops dumping waste into the ocean

After mining companies extract the minerals and metals they want, what’s left behind? The refining process creates a sludge byproduct called “tailings.” And some mining companies are harming marine life by disposing this waste into the ocean a practice banned by many countries, including Brazil, Denmark, United Kingdom, Greece, Canada, the United States, Russia, and China. Following campaigning by Oceana, the Chilean mining company CAP committed to stop disposing its tailings into the ocean, which the company had been doing for more than 40 years. This win arrived following a lengthy process:

In 2017, Oceana revealed that CAP was disposing tailings into the sea; Chile’s environmental authorities brought charges against CAP in 2018; and in 2019, CAP agreed to

stop the practice within the next four and a half years. Following campaigning by Oceana and its allies, mining companies cannot dump tailings in Chile’s ocean.

The Chilean company CAP dumped its mining waste into Chile’s ocean — a practice no longer allowed thanks to campaigning by Oceana and its allies.

North Atlantic right whale “Halo” was spotted swimming with her calf near St. Catherine’s Island in the U.S. state of Georgia on Jan. 14, 2024. Halo is 19 years old and this is her third calf.

© Oceana/Lucas Zañartu

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 7

© Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, taken under NOAA permit #26919

is

Before joining Oceana, Ramos worked with Philippine Earth Justice Center to file environmental cases against projects that have harmed the country’s fisheries and marine ecosystems. Frequent visits to her father’s coastal hometown in Cebu throughout her childhood fostered Ramos’ deep appreciation for the ocean and its importance to the Philippines, which is home to some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity and largest fisheries.

Q&A with Gloria Estenzo Ramos, Oceana’s leader in the Philippines

2023 was a big year for Oceana in the Philippines. What accomplishments are you most proud of?

GER: There are three! First, we’re proud that, despite strong lobbying from the industrial fishing industry, public tracking devices are now required on all commercial fishing vessels. The President of the Philippines also mandated that vessel monitoring requirements be fully implemented, which will help reduce illegal fishing in our waters.

Our second cause for celebration is sardines. The Fisheries Bureau

instructed all regional offices across the Philippines to carry out a National Sardine Management Plan, which will help ensure this very important fishery stays healthy.

Finally, we worked with 25 local governments to establish coastal greenbelt areas, which will help protect mangrove forests. We are now campaigning for a national law to protect these vital ecosystems.

Oceana’s leadership and partnership with artisanal fishers, academics, and local authorities was critical to accomplishing all three of these victories.

Gloria (“Golly”) Estenzo Ramos

Vice President of Oceana in the Philippines.

Gloria (“Golly”) Estenzo Ramos

Vice President of Oceana in the Philippines.

8

President of the Philippines Ferdinand (“Bongbong”) Marcos (front right) with Gloria Estenzo Ramos, Vice President of Oceana in the Philippines (center), Oceana Board Member Susan Rockefeller (back right), Josie Cruz Natori, founder and CEO of The Natori Company (front left), Rhea Yray-Frossard, Campaign and Research Director at Oceana in the Philippines (back left), at the Asian Cultural Council Gala held on Nov. 8, 2023 at the Manila Hotel. © Josie Natori

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing accounts for up to 40% of the fish caught in the Philippines. How does this affect local artisanal fishing communities?

GER: Overfishing has caused an alarming decline in the seafood artisanal fishers rely on. When commercial fishing vessels illegally encroach in the coastal waters exclusively reserved for artisanal fishers, they decrease the amount of food and income available to those communities. Weak implementation of fisheries laws and regulations is a big reason why artisanal fishers face poverty in the Philippines. These fishers say that implementing tracking requirements for commercial vessels is their last hope.

How will the new victories help to hold illegal fishers accountable?

GER: A fully implemented tracking system deters illegal commercial fishing. Merely turning off the tracking devices is now a criminal act. If the government holds commercial fishers accountable for illegal fishing, especially if it results in their licenses being revoked, there is great hope for our fisheries to rebound.

Thanks to campaigning by Oceana and its allies, the Philippines government is taking steps to rebuild sardine fisheries. Why are sardines especially important?

GER: Many artisanal fishers depend on sardines for their livelihoods and sustenance. Sardines account for 15% of fish production in the Philippines. These small fish are packed with essential nutrients such as omega-3 fatty acids,

When Oceana pushes for action and transparency about the true state of our fisheries, we are rocking the boat.

vitamins, and minerals, which are important for young children and pregnant or nursing mothers, especially given the issue of malnutrition in our country.

What is the purpose of the National Sardines Management Plan?

GER: Through the National Sardines Management Plan, the Philippines government is introducing new rules to ensure the sardine population stays healthy, like closing fishing during seasons when the sardines are breeding and putting limits on catching juvenile fish. The government is also taking steps to help fishers increase their income, such as improving cold storage to keep the fish fresh longer and strengthening connections between artisanal fishers and the markets for their catch. We’re working closely with artisanal fishers and both national and local athorities in the Philippines to ensure that this plan is properly implemented across the country.

Campaigning in the Philippines is important, but often risky work. What challenges do you and your team face?

GER: When Oceana pushes for action and transparency about the true state of our fisheries, we are rocking the boat. Some are not so enthusiastic about our

efforts. The Philippines is the most dangerous country in Asia for environmental defenders, including campaigners like ourselves, as well as lawyers, prosecutors, and judges. The security challenge is real, but Oceana has taken extra precautions to ensure our team remains safe as we campaign to save our oceans.

What changes are you campaigning for in 2024 and beyond?

GER: We’re campaigning to protect Panaon Island, which is home to coral reefs that are still vibrant and thriving. These corals are far healthier than those in other parts of our waters, and we must prioritize their protection before irreparable damage is done. The bill to declare Panaon Island as a marine protected area is nearing the finish line. We’re just waiting for the Senate’s approval and the President’s signature which we hope will take place very soon.

We’re also campaigning for a bill to establish a national coastal greenbelt zone to protect mangroves, which the Senate is currently considering. And we’re collecting baseline data for a potential new campaign focused on fishers’ livelihoods and nutrition stay tuned.

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 9

Feature

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

10

A fisher catches Atlantic cod using a hook and line near Petty Harbour, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Founded on Fish

How

Oceana is campaigning

to protect abundant oceans

in Canada and Peru

By Sarah Holcomb

Search for the world’s longest, most sprawling coastline and you’ll find it in Canada. Look for the world’s largest fishery and you’ll end up surrounded by millions of anchoveta in the waters of Peru.

It’s no surprise that fishing looms large in these two countries, driving their economies and providing a cultural touchstone to rich traditions. Both countries depend on

abundant fish — especially those at the bottom of the food chain — and flourishing ocean habitat for fish to thrive.

Since it established campaign teams in Canada and Peru in 2015, Oceana has fought to ensure that healthy fisheries and healthy habitats last far into the future, just as they have thrived in centuries past.

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 11

The capelin are coming

When tens of thousands of shiny silver fish roll up onto the shores of Canada’s easternmost province, Newfoundland and Labrador, word spreads fast. Every year, the small forage fish, called capelin, come to spawn on the beaches during the summer. And they draw scores of northern cod, humpback whales, sea birds, and, of course, human observers, with them.

“The capelin leaps out of the ocean and into the above-surface realities for people,” describes Shane Mahoney, a resident of Newfoundland and Labrador and founder of Conservation Visions Inc.

People gather at coves known as capelin hotspots to scoop up the fish with nets or whatever buckets — or, in the case of some college students, pasta strainers — they have on hand. Local beaches transform into festivals, lit with

campfires, covered in beach blankets, and brimming with family picnics. For kids, the annual event known as the “Capelin Roll” might be their first encounter with Canada’s oldest industry: wild fisheries.

Capelin has been harvested alongside cod since humans have lived in Newfoundland and Labrador. People cook with capelin, or find other uses like fertilizer, bait, or dog food. “This fish is quite democratic,” says Jack Daly, Marine Scientist at Oceana Canada. “Everybody can grab it.”

Today, aside from the summertime Capelin Roll fishing bonanza, capelin are largely caught by Canada’s fishing industry and exported to Japan, China, and Europe. Capelin eggs draw demand as roe for sushi. After intense industrial fishing, capelin has now suffered a steep decline, currently at approximately 9% of its historic population.

For many, this trajectory eerily echoes the infamous northern cod collapse of 1992, when one of Canada’s most prominent fisheries disappeared after years of overfishing and poor environmental conditions. When Oceana partnered with a Canadian polling agency to conduct a survey in Newfoundland and Labrador, it found that over 80% of people in the province support closing the commercial capelin fishery so the fish can recover before it’s too late.

“I think everyone belongs as part of the decision-making process. [Even if] you are not a fish harvester, you’re still a human being who needs to live on this planet, eat somehow, and deal with the consequences of climate change,” says Jasmine Paul, a fourthgeneration commercial fisher in Newfoundland and Labrador. “I think everyone should be involved and have as much information as possible.”

Feature

12

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock Capelin has suffered a steep decline, currently at just 9% of its historic population off northeast Newfoundland and Labrador.

All about rebuilding of Fisheries and Oceans did not reduce the existing fishing quota — approximately 14,500 tonnes (16,000 tons) of capelin. Sciencebased limits are a must to rebuild fisheries, Oceana’s team argues, for capelin as well as Canada’s dozens of other depleted fish populations.

Capelin is not an isolated case. Less than one-third of Canada’s fish stocks can be considered healthy today, Oceana’s 2023 Fisheries Audit confirmed. The rest are in critical or cautious zones, or have an unknown status. Since its establishment in Canada, Oceana has focused on rebuilding Canada’s fisheries, starting with making scientific information about the status of fish populations available to the public for the first time in 2017 — and every year since.

In 2019, Oceana won a breakthrough victory. It successfully revamped Canada’s fisheries law to require depleted fish populations to be rebuilt and well-managed. “Now we’re implementing the law,” says Joshua Laughren, Oceana’s Senior Vice President in Canada.

According to Oceana’s latest analysis, a dramatic turnaround is possible. The number of healthy fish stocks in Canada could be brought from 30% to 80% within a decade. It will take urgent action and require the government to track all forms of fishing and steadily monitor boats.

Capelin are among the most important fish populations to rebuild. As forage fish, they’re food for many other species, from puffins to seals to humpback whales. That means capelin are foundational to a healthy economy in Newfoundland and Labrador, which not only depends on fishing, but increasingly on ocean-based tourism. “A lot is riding on the little fish,” says Laughren.

In the face of mounting scientific evidence that the capelin fishery is nearing the edge, industry pressure continues to sway decision-making. Government scientists confirmed that capelin populations are depleted, yet Canada’s Minister

Rebuilding fisheries also goes hand-in-hand with protecting ocean habitats. “If we don’t have healthy habitats, whatever fisheries management we do won’t be successful because there’s no healthy place for them to live,”

says Laughren. Canada’s ancient coral forests can be wiped out with a single pass of a trawl net.

When Oceana came to Canada in 2015, less than 1% of the country’s oceans were protected from industrial fishing. Today it’s at 15% and growing. In 2024, Canada’s government is expected to designate a new protected area off the West Coast that will cover nearly 140,000 square kilometers (54,000 square miles). This area includes 97% of Canada’s coralcovered seamounts.

The stunning diversity and abundance of life on [Canada’s] seamounts leave no room for hesitation about protecting them.

– Dr. Robert Rangeley

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 13

A fisher cleans his catch of Atlantic cod in the fishing village of Quidi Vidi, Newfoundland and Labrador.

A resident of Newfoundland and Labrador uses a cast net to catch capelin for personal use at Middle Cove Beach.

Feature

Oceana Canada/Nicholas

©

Hiscock

14

Oceana previously led an expedition to gather scientific evidence for the protection of these seamounts, working with the Canadian government and First Nations to bring to light their importance and put a plan in place for their management. Canada and the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, the Council of the Haida Nation, Pacheedaht First Nation, and Quatsino First Nation have since signed a memorandum of understanding to cooperatively manage the new protected area.

“The stunning diversity and abundance of life on the seamounts leave no room for hesitation about protecting them,” said Dr. Robert Rangeley, Oceana’s Science Director in Canada. “This is a critical step toward protecting this extremely important marine ecosystem.”

Protecting Peru’s ocean

Thousands of miles to the south of Canada, the sandy, rocky shores of Peru loom over an ocean abounding with marine life. Peruvians have practiced fishing for millennia — from submerging reed baskets to trap fish, to later fashioning nets made of cactus threads and hooks from shells.

In the last century, Peru’s fishing underwent a dramatic transformation. As the country rapidly exported fish to feed allied troops during World War II, its catch skyrocketed. Between 1938 and 1970, Peru’s total fish landings increased by 400 times in less than 40 years.

By weight, roughly 80% of the fish caught in Peru today are Peruvian anchoveta, silver fish in the anchovy family that, to a Canadian, might resemble a smaller version of capelin. As forage fish, they’re

a cornerstone of the ecosystem. And in Peru’s economy, the small fish boast big value in the fishmeal and fish oil industries. Now the country’s fourth-largest export, Peru’s fishmeal is shipped around the world to use for livestock, pet food, and farmed fish feed.

Little information about the full extent of industrial fishing in Peru was available to the public, however, until 2017, when Oceana successfully campaigned for the country’s authorities to make near real-time data from Peru’s vessel monitoring system accessible online.

Industrial fishing — much like intensive farming on land — takes a toll on the marine environment. A 2022 survey revealed that 85% of Peruvians are concerned that authorities are not protecting the Peruvian sea and its resources. Nearly all (98%) of those surveyed supported the creation of marine protected areas (MPAs) to conserve biodiversity in the ocean.

Peru’s first-ever offshore marine protected area was established in the Nazca Ridge National Reserve in 2021, following campaigning by Oceana and its allies. Covering more than 60,000 square kilometers (over 23,000 square miles) off Peru’s southwest coast, it protects a vast underwater mountain range home to over a thousand recorded species. Over 40% of the fish and invertebrates seen here are found nowhere else on Earth.

Initial celebration gave way to disappointment, however. Caving to industry pressure, Peru’s government granted commercial fishers the ability to fish for tuna, anchoveta, and other species inside the so-called protected area. In fact, says Carmen Heck Franco, Oceana’s Policy Director and Campaign Coordinator in Peru, commercial fishers took a greater interest in Nazca Ridge after it was “protected,” fishing more frequently in attempts to establish their presence there.

© Oceana/Patircia Majluf

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 15

An industrial vessel fishes anchoveta, a key species in Peru’s marine ecosystems.

“The Peruvian legal framework is clear on the prohibition of industrial fishing within marine protected areas. We are determined to ensure that this prohibition is enforced in the Nazca Ridge and future protected areas,” says Heck. “The fishing industry is very influential in Peruvian politics, but we know that sustainability can triumph over private interests. It has been done before.”

The fight over fishing

Led by local artisanal fishing leaders, Oceana accomplished one of its most significant victories in Peru in May 2023: A victory that gave artisanal fishers the exclusive right to fish Peru’s coastal waters.

More than 50,000 Peruvian artisanal fishers rely on Peru’s coastline to provide 80% of the fish that feeds the country’s population. Amidst an industrial fishing boom, Peru’s small-scale artisanal fisheries remain as vital as ever. “Fishing is as important to Peru’s cultural heritage as it is to its economy,” emphasizes Juan Carlos Sueiro, Oceana’s Fisheries Director in Peru.

The five nautical miles closest to Peru’s shore are particularly important, serving as a breeding ground for anchoveta and other fisheries. This area is “likely more significant for biodiversity than any other coastal zone,” according to Oceana’s Science Director in Peru, Juan Carlos Riveros. Artisanal fishers possessed the exclusive right to fish in this zone for over 30 years, using selective gear that causes minimal impact to ocean life and habitats.

In recent years, however, boats using purse seines — weighted nets that surround a school of fish, capturing the fish and sometimes other creatures that happen to be in the way — grew increasingly popular. Despite not using lowimpact, traditional artisanal fishing methods, these boats enjoyed the same close-to-coast privileges afforded to artisanal vessels.

In a big win, Oceana and its artisanal fisher allies successfully campaigned for a new law that reserved the zone closest to the coast for fishers using truly artisanal methods, not purse seines.

“The approval of this law will ensure the country’s food supply for the present and for future generations,” emphasized a group of artisanal fishers from Lima known as the collective, “Guardians of the Five Marine Miles.”

Now, Oceana’s team is addressing the next challenge: the evergrowing number of illegal fishing boats on the water. “Peru’s fleet is too big, and it continues increasing even though the building of new vessels has been prohibited for 10 years,” explains Heck. “The law isn’t being followed.”

These new vessels — the same kind that use purse seines — impact artisanal fishers in the coastal zone. “Studies have already proven that artisanal fishers have been suffering a decrease in income because the fleet is too big,” says Heck. “The fishers need to increase their fishing effort in order to catch the same amount of fish they caught before, requiring more time and more money.”

Oceana and its allies campaigned to increase the government’s ability to enforce the decade-old prohibition,

Feature

© Oceana/Eduardo Sorensen

© Oceana/Eduardo Sorensen

16

A coral reef in the tropical Pacific Sea, captured during Oceana’s 2022 expedition off Peru’s coast.

reclassifying the act of building these vessels as a crime, and penalizing those who build them.

Fishing is as important to Peru’s cultural heritage as it is to its economy

– Juan Carlos Sueiro

In January 2024, the new law was published, giving prosecutors and police better tools to fight this crime and contribute to the common goal of protecting the oceans.

Coming together

The future of fisheries and their habitats — in Peru, Canada, and beyond — remains tightly interconnected. Oceana continues to campaign for science-based catch limits and regulations to keep fishing in check, and protections to safeguard biodiversity for good.

“The ocean and fishing [are] a shared human heritage. Every country, every culture, everywhere in the world knows how to fish and has always fished, so it’s one thing that brings us all together as people,” says fourth-generation fisher Jasmine Paul. “It might be different species and different techniques but there’s just some kind of connection to going out there, catching your own food, and bringing it home.”

And with the right protections in place, both fish and fishers will thrive for generations to come.

© Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

Fishing boats lie half-finished in a shipyard. In the last eight years, Peru’s small and medium-scale fleet increased by 2,080 vessels, but only 201 of these vessels had requested the required permits, according to the General Directorate of Captaincy and Coast Guard (Dicapi).

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 17

Currently, there are an estimated 20,000 small and medium-sized fishing vessels in the Peruvian sea. An excess of boats affects marine ecosystems and the fishing economy.

©

18

Oceana/Sebastián Castañeda

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 19

The Net Consequence

Long nets weighted to the seafloor endanger ocean life off Southern California

By Sarah Holcomb

© Oceana/Alan Po Feature 20

For newborn great white sharks, the warm waters swirling the Southern California Bight provide a perfect nursery. Every year, many great whites — along with dozens of other shark species — birth their pups off the U.S. state of California’s southern coast.

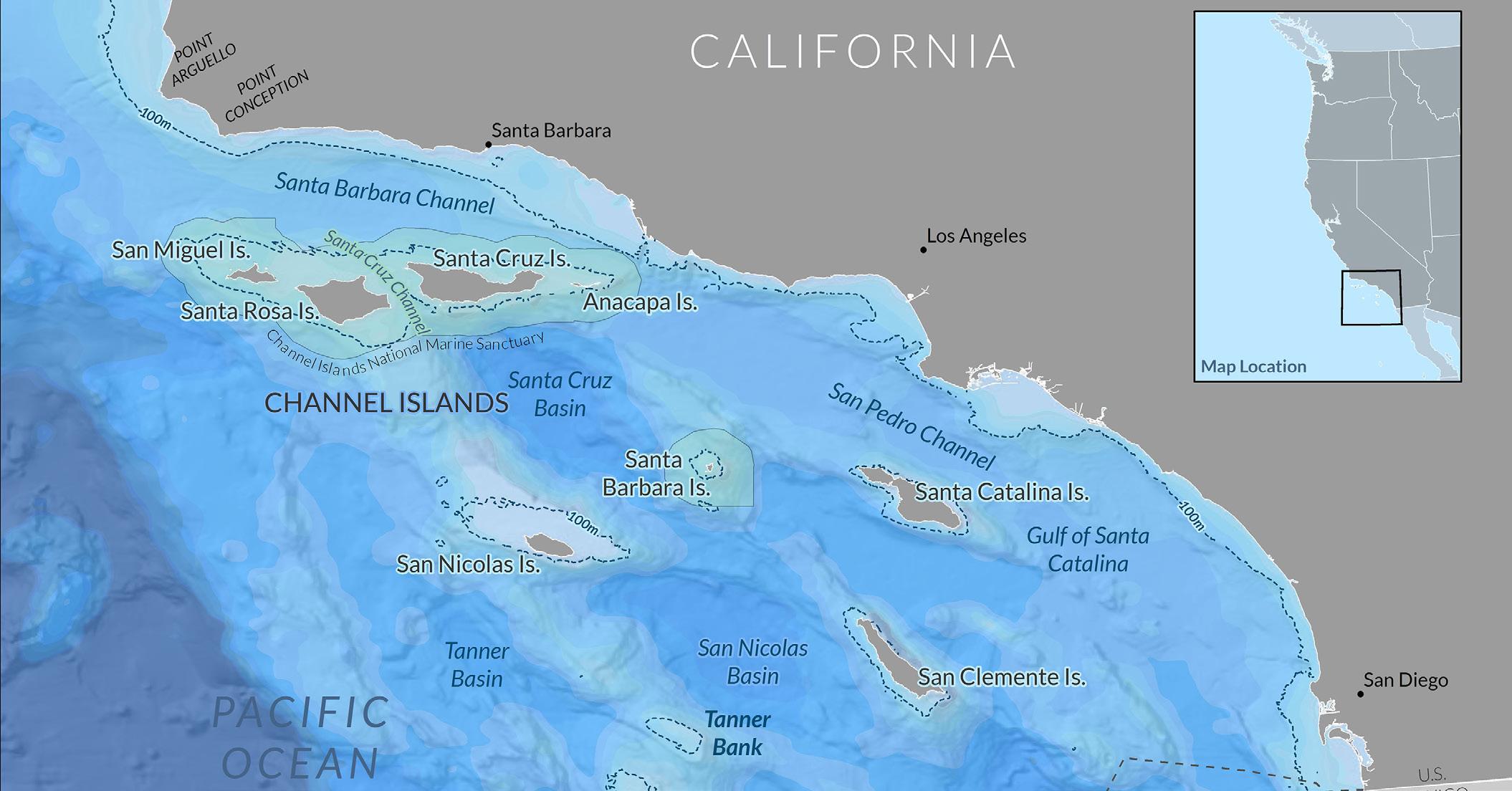

Besides offering a first-class shark nursery, these waters play host to a wide range of ocean life. Home to the Channel Islands — nicknamed the “Galapagos of North America” — here you’ll find almost every topography under the sea, from coral gardens, to underwater canyons, to elaborate kelp forests. Colliding currents from the south and north create “the perfect setting” for a biodiversity hotspot, says Dr. Geoff Shester, Oceana’s California Campaign Director. Young white sharks swim freely, enjoying plenty of food with few predators around.

area’s spectacular marine life. Near-invisible fishing nets lie in wait, anchored to the seafloor. And these nets can measure up to 1.8 kilometers (1.1 miles) — the length of 36 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

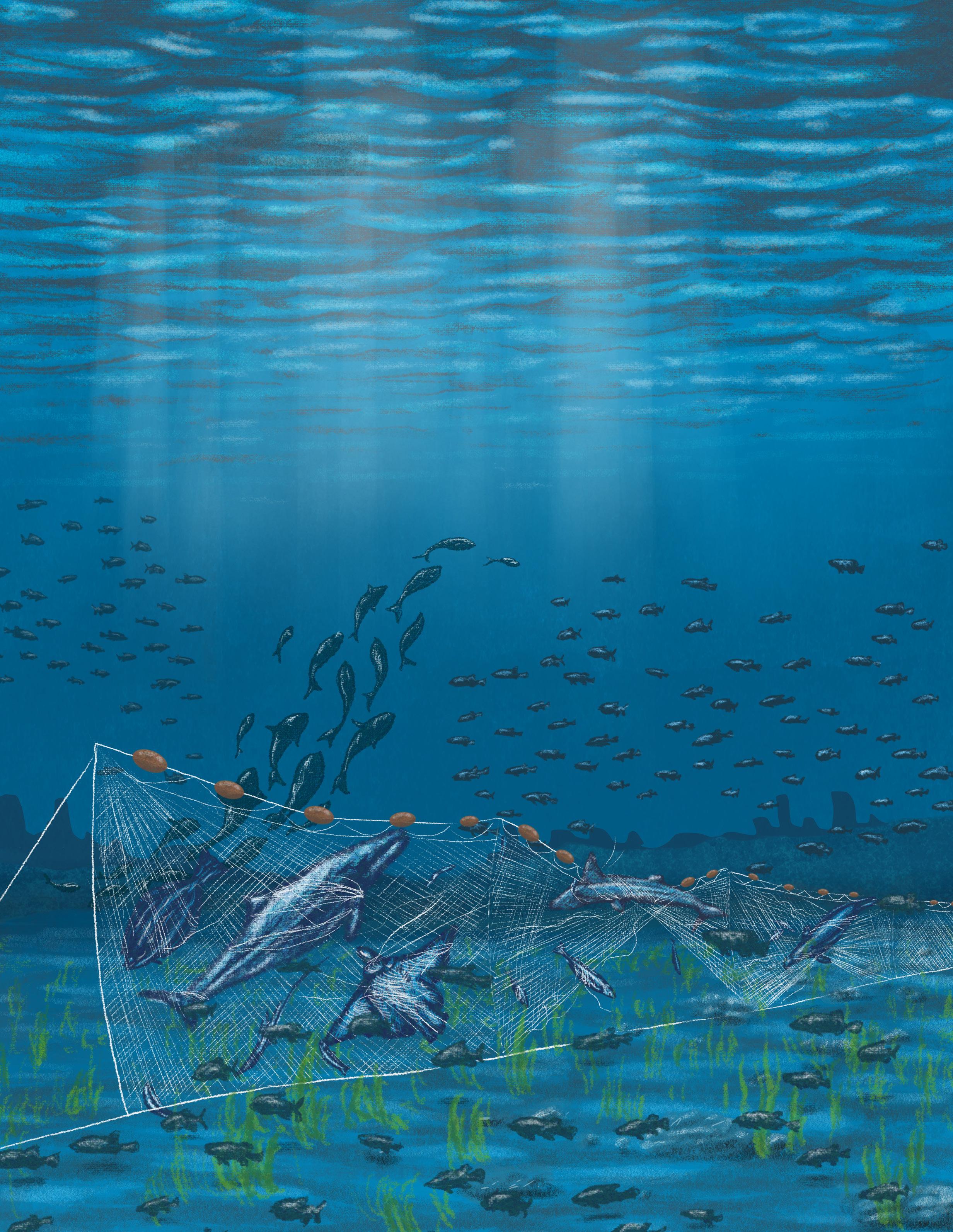

Nets don’t discriminate

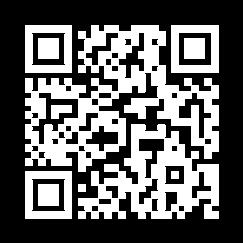

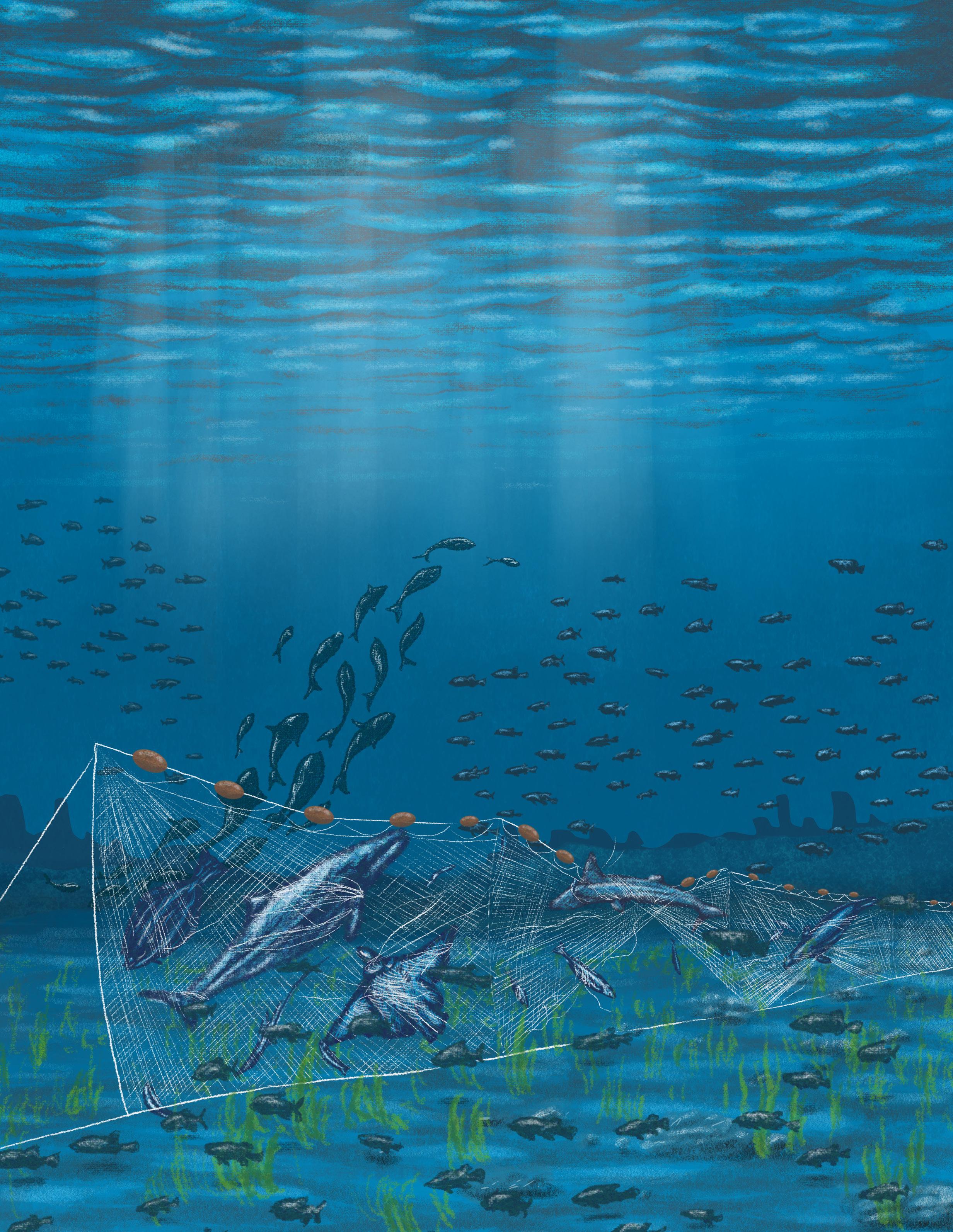

But these abundant waters also hide one of the greatest threats to juvenile white sharks and the “Set gillnets,” the technical term for these mile-long, stationary nets, do not actually target sharks. The set gillnet fishery aims to catch California halibut and white seabass swimming along the seafloor. But the nets are responsible for more juvenile great white shark deaths in these waters than any other humanrelated cause. They also catch a wide swath of other ecologically important species.

After fishers weight set gillnets to the seafloor, the nets are permitted to “soak” underwater for an unlimited period of time. The nets are often set in the water for

between 24-48 hours — plenty of time for marine animals to get tangled up in a mile of mesh. “Essentially anything within a certain size bracket that swims into [the nets] is going to be caught,” explains Oceana Pacific Marine Scientist Caitlynn Birch. The longer the nets are set, the more animals are likely to die in them.

Far from empty, the waters surrounding the Channel Islands are a high-traffic zone for marine life. Thousands of gray whales make their way through on a “migration super-highway,” says Shester. Abundant sea life has made the Islands a favorite destination of humpback whales coming to feed. And at the bottom of the sea reign the kings and queens of the kelp forest: critically endangered giant sea bass, who can grow up to around 250 kilograms (up to 550 pounds). Set gillnets ensnare all of these species and more than 120 others, including sea lions, sharks, rays, and whales.

© Oceana

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 21

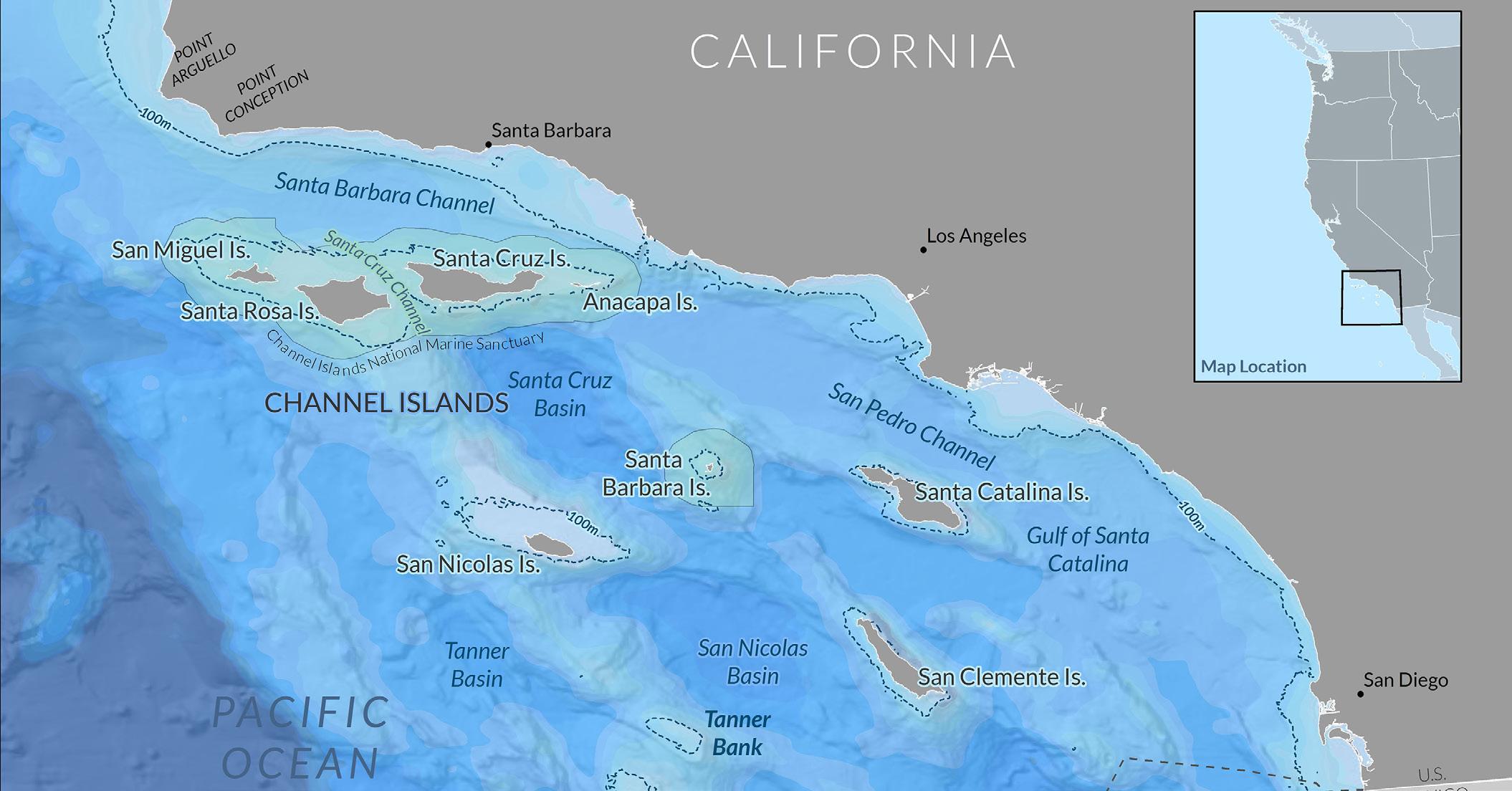

A map of the Southern California Bight — the gradually curving coastline between Point Conception in the U.S. state of California and Punta Colonet in Baja California, Mexico. Set gillnets continue to be used in Southern California federal waters between three and 200 nautical miles from shore. They’re also used in state waters beyond one nautical mile from the Channel Islands.

Many animals caught will already be dead by the time the nets are pulled out of the water. Two in three will end up thrown overboard as waste. “Many species caught are undesirable or illegal to sell,” says Birch, “or when the nets are brought up, the fish are too damaged from other predators.”

The state of California’s risk assessment found that the set gillnet fishery poses a higher ecological risk than any other statemanaged fishery.

Some might ask: Why are set gillnets allowed at all?

The only exception

Travel up the southern California coastline and you’ll be looking at areas where set gillnets are illegal to use. In fact, they have been banned for over 100 years in the waters off Northern California. Citizens and lawmakers voted to close off more parts of the California coast to the nets over time, including all waters within three nautical miles of the entire Southern California coast in 1990, plus the Central California coast in 2002.

Since then, scientists have documented the dramatic recovery of harbor porpoise, giant sea bass, and multiple shark species in these areas that were depleted prior to the set gillnet bans.

Southern California’s offshore waters are a different story. Set gillnets continue to be used in Southern California federal waters (between three and 200 nautical miles from shore). They’re also used in state waters beyond one nautical mile from the Channel Islands.

The set gillnet fishery is not only legal in many parts of Southern

California’s waters; it’s also the only fishery allowed to catch several strictly prohibited species. “This fishery has the odd exemption that allows them to take white sharks,” says Shester, “and sell them dead or alive to a museum, aquarium, researchers, or even as taco meat.”

A similar exemption applies to the rare giant sea bass. “Giant sea bass were nearly wiped out entirely due to fishing pressure in the early 1900s, and have been prohibited for decades in all other fisheries,” says Shester. “Yet set gillnets still catch them and those fishers are allowed to keep them.”

Today, Oceana and its allies are campaigning for stronger regulations to reduce the

unnecessary waste from set gillnets, while supporting more selective fishing methods, like hook-and-line fishing. From 20072022, halibut caught with hook and line sold for approximately 30% more per pound compared to halibut caught with set gillnets.

About 25 set gillnet fishers remain active today. While bycatch estimates reveal the set gillnet fisheries’ outsized impact on marine life, inconsistent tracking by state and federal managers means that the true scale of catch and the discarded bycatch remains a mystery.

For campaigners, the key to winning new regulations lies in this missing data.

Feature

Shutterstock

©

22

Great white sharks are powerful swimmers who can migrate long distances. Juvenile white sharks are frequently seen in shallow nearshore waters off Southern California.

Keeping track

If an entangled sea lion or whale can surface with parts of a net around its body off Southern California, the set gillnet fishery isn’t found at fault. Fishers aren’t required to mark their nets. Without this “fingerprint,” it’s difficult to prove where the net came from, even if other factors point to the fishery, says Shester.

In the absence of robust data, the status quo remains in place. “We see the lack of data as a big, big problem, especially given the fishery’s track record,” Birch emphasizes.

After years of inaction, change may soon be in store for the set gillnet fishery. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife is preparing

to roll out a regulatory package in 2024. “Right now we’re focused on campaigning for regulations that could be put in place in the nearterm to reduce the impact of the fishery,” explains Shester.

One such regulation would require fishers to mark their gear, allowing scientists to pinpoint the true extent of the entanglement problem.

Next, Oceana is advocating for reduced maximum soak times, which would require fishers to pull in their nets more frequently — and improve the likelihood that unwanted animals will survive.

Oceana is also advocating for observers — third-party scientists — to be present on the fishing vessels and keep track of the

animals that are caught, helping to fill in missing data. Under federal law, all fishers are required to report their interactions with marine mammals. Using data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, however, Oceana found that just 6% of the total estimated interactions are selfreported. Independent observers are necessary, Oceana’s team concluded.

Currently, California does not have the authority to require observers for any of the state’s fisheries. “Having a third-party data source is really important for accurate and sustainable fisheries management,” Birch explains. “If we can help establish a state fishery observer program, this could be one of the biggest wins for California fisheries.”

© Sierra Club Seal Society

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 23

A California sea lion suffers from monofilament net wrapped around its neck, the same type of mesh netting used in the California set gillnet fishery.

The Oceana approach is to keep fishers on the water, but using...science and technology to fish in a way that’s smarter and allows ecosystems to thrive.

– Dr. Geoff Shester

Biodiversity and beyond As Oceana campaigns to regulate this harmful fishing gear, the goal isn’t to shut down fishing, Shester says. “The Oceana approach is to keep fishers on the water, but using the benefit of science and technology to fish in a way that’s smarter and allows ecosystems to thrive.”

The giant kelp forests surrounding the Channel Islands support more than 1,000 species beneath their canopies. The campaign to regulate set gillnets is “not just a fishery issue,” Shester says. “It’s about protecting havens for biodiversity. We need to protect them during this time of unprecedented climate change and ocean acidification.” Because set gillnets are “indiscriminate,” the fishery impacts vulnerable species whose population status we don’t yet know, says Shester. “This is exactly how biodiversity is lost.”

In April 2024, Oceana will launch an expedition to the Channel Islands, documenting its biodiversity as the campaign continues to bring visibility to this important ecosystem and the threats it faces.

© Shutterstock/Joe Belanger

© Shutterstock/Joe Belanger

Feature 24

Critically endangered giant sea bass can grow up to around 250 kilograms (up to 550 pounds).

Make their future your legacy Include the ocean in your plans Join the LegaSea Circle by including a gift for Oceana in your will, trust, or beneficiary designation. You can help protect and restore marine wildlife and habitats for years to come, while enjoying financial benefits for yourself or your loved ones.

Oceana.org/legasea | plannedgiving@oceana.org | +1.202.833.3900 Email or call to request our LegaSea Circle brochure or to let us know you have added Oceana to your estate plans.

© Oceana/Andre Baertschi

Ask Dr. Pauly

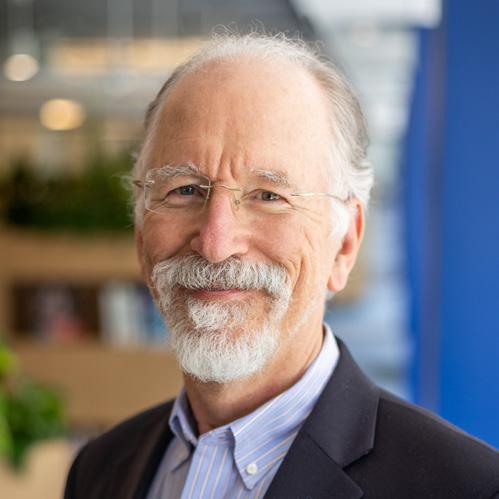

Dr. Daniel Pauly is the founder and principal investigator of the Sea Around Us project at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, as well as an Oceana Board Member and recipient of the 2023 Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement.

Are science and advocacy compatible?

Editor’s Note: World-renowned fisheries scientist and Oceana Board Member Dr. Daniel Pauly has contributed his scientific expertise to Oceana Magazine for over a decade. Across more than 30 issues, he has answered questions on wideranging subjects from illegal fishing to marine heatwaves. We have been honored to share Dr. Pauly’s insights and perspective with readers of Oceana Magazine. Please enjoy this final installment of Ask Dr. Pauly.

Dear Reader: This is my last “Ask Dr. Pauly” column for Oceana Magazine, which I began writing in 2012. In May 2024, I will be 78 years old, and it is time to reduce my workload. I cannot, however, leave without dealing with the old canard (which means “duck” in French; don’t ask) that scientists should not be involved in advocacy.

I have dealt with this question about science and advocacy for a long time, given that I am a published scientist and a member of Oceana’s Board of Directors.

In many ways, the canard creates a problem where there shouldn’t be any problems to begin with. This was eloquently stated in 1993 by Mary O’Brien, who taught publicinterest science and environmental advocacy at the University of Montana.

“[T]here are infinite questions that you could ask about the universe, but as only one scientist, you must necessarily choose to ask only certain questions,” she wrote. “Asking certain questions means not asking other questions, and this decision has implications for society, for the environment, and for the future. The decision to ask any question, therefore, is necessarily a value-laden, social, political decision as well as a scientific decision.”¹

This point becomes even more salient when considering how the range of views expressed by scientists and scholars that are deemed politically “acceptable” during a given period, also called the “Overton Window” (look it up!) can vary enormously. For example, studying or teaching history in the United States was considered harmless for a long time. But studying or teaching the history

Dr. Daniel Pauly speaks at the National Symposium on Fisheries in Manila, Philippines in 2014.

26

© Oceana

of chattel slavery has now become politically risky for academic historians and history teachers in multiple U.S. states.

Another way to deal with the canard is to consider that scientists and other scholars are citizens of the countries in which they live and work. As citizens, as well as moral beings, they can and should contribute to the well-being of their country — and by extension — to humanity as a whole, to the best of their abilities.

Indeed, there is nothing in the ethos of science that says scientists should be silent when they encounter abuse in their disciplines, be it an abuse of data, a corporation lying about its real environmental impact, or an industry performing inhumane tests.

Medical doctors are expected to help their patients recover from bacterial illnesses, not to be neutral as to the fate of bacteria and people. Why, then, should scientists studying biodiversity remain neutral regarding the decline of North Atlantic right whales, for example, whose last remaining population is threatened by ships that refuse to slow down to avoid lethal collisions? Does the science of cetology (i.e., the scientific study of whales and their relatives) suffer from cetologists preferring for the species they study not to go extinct, and thus becoming advocates for their protection?

This point is not a reductio ad absurdum, but an increasingly common problem for scientists working on environmental issues. We are in an age where more and

more populations and species are going extinct. It’s time to kill the canard.

Finally, in science, there are guardrails to prevent personal opinions from shaping scientific discourse too strongly. The main one is anonymous peer review, formally developed in the 1970s, to help reduce scientific claims to the level supported by the available data. The peer-review system is now slowly failing because fewer scientists are interested in spending hours reviewing papers anonymously for no tangible personal benefit, especially when academic publishers are profiting enormously from this labor.² Peer review, however, remains important and must be revitalized, as it prevents many unsupported claims from being published, or even put to paper in the first place.

In addition to peer review, scientists and scholars are required

¹ O’Brien, M.H. 1993. Being a Scientist Means Taking Sides. BioScience, Vol. 43(10): 706-708.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1312342

to disclose their source(s) of funding, unlike other fields such as politics, where many funding sources accessible to politicians are not publicly known, even if they heavily influence a politician’s stances.

In conclusion, scientists can, and in many cases, arguably should, be advocates. In fact, the idea that activism is not compatible with science is usually pushed by people with a political agenda that benefits from the non-involvement of scientist-citizens and is designed to hide the agenda they unavoidably have.

I conclude this column by thanking successive editors of Oceana Magazine and their colleagues for improving over 10 years’ worth of my clunky prose, and the readers of this magazine, who I hope, did appreciate the personal views of a scientist AND advocate.

² One article about this — and there are many — is Buranyi (2017). Is the staggeringly profitable business of scientific publishing bad for science?

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jun/27/profitable-business-scientific-publishing-bad-for-science .

Dr. Daniel Pauly on board the Oceana Ranger off the coast of Spain’s Balearic Islands.

27

© Oceana/Juan Cuetos

Oceana’s victories over the last year

With the help of its allies, Oceana has won 28 victories in the last 12 months

Spain designates seven new marine protected areas

President Biden’s five-year plan protects U.S. waters from expanded offshore drilling

EU sets sustainable catch limits to help recover fish populations

Spain sanctions 25 fishing vessels for disabling public tracking devices

New law in Belize gives people the power to protect offshore oil moratorium

Mediterranean countries can now penalize states who fail to tackle overfishing and illegal fishing

U.S. state of Delaware bans plastic foam food containers, limits plastic straws

Chile approves new marine protected area in iconic Humboldt Archipelago

Philippines requires rebuilding of sardine fisheries

EU requires tracking systems for all its fishing vessels

Philippines requires commercial fishing vessels to install monitoring devices

Brazil’s Supreme Court upholds ban on bottom trawling in Rio Grande do Sul

Public database in the Philippines increases transparency at sea

New law in U.S. state of Maine sets density limits for future salmon farms

Newly approved innovative fishing gear will reduce bycatch off U.S. West Coast

European Commission releases public database disclosing activities of EU vessels fishing outside of EU waters

Peru passes new law to protect its oceans and artisanal fishers

New laws in U.S. state of Oregon prohibit plastic foam and enable refill systems

New law in U.S. state of Washington reduces plastic waste

Mexico joins the Port State Measures Agreement to address illegal fishing

Brazil’s Museum of Tomorrow becomes a plasticfree zone

Panama commits to reduce plastic pollution

Deep-sea corals and seafloor habitats protected in U.S. Pacific waters

Oceana defends EU policy to rebuild fisheries from attack

Chile creates a new marine protected area, Pisagua Sea

Chile rejects Dominga mining project, protects marine life

New York City limits single-use plastic utensils

New Chile law increases transparency in salmon farming and reduces threats to marine life

28 © Oceana/Carlos Minguell

Supporter Spotlight

Henry Engelhardt: Funding the future of the oceans

In a world filled with complex problems — and people seeking to solve them — how does one decide which organizations to support? The founder and former CEO of Admiral Group, Henry Engelhardt knows that “there is no shortage of good causes,” and donates to many of them through the Moondance Foundation, a charity he founded with his wife Diane Briere de L’Isle Engelhardt that aims to relieve poverty, improve health, preserve the environment, and more.

“Start with what you’re passionate about, then talk to people inside and around charities to see which one you think will really make a difference...Find organizations you trust, then back them,” Engelhardt advises. “Sometimes we support causes that aid one person, sometimes we support causes that help entire oceans.”

Engelhardt was drawn to Oceana because he recognized the importance of seafood to humanity’s collective future. “What really made us believe in Oceana was its attitude towards fishing,” he said. “Oceana demonstrates that if managed correctly, there are, and will be, enough fish in the ocean to feed the world forever — a never-ending supply.”

A compelling vision is important, but the “how” matters just as much. As a successful businessperson, Engelhardt looks for clear-cut results. “Oceana makes progress,” he says. “They don’t just waffle on about the cause; they get out there and make things happen.” Also important: transparency. “We like that Oceana is honest about its wins and losses. It’s certainly not easy trying to influence governments to change the way we do things today for the benefit of the future, but Oceana’s track record is impressive.”

The Moondance Foundation has provided key support for Oceana’s newest campaign team in the United Kingdom. Oceana is currently campaigning to end overfishing, prevent new offshore oil and gas drilling, and ban destructive bottom trawl fishing in marine protected areas in the U.K. Half of the “top 10” U.K. fish stocks are overfished or have been reduced to

Oceana demonstrates that if managed correctly, there are, and will be, enough fish in the ocean to feed the world forever.

a critically low size, a 2023 Oceana report found. “I am keen to see the U.K. become a more responsible country when it comes to fishing,” Engelhardt says.

Oceana and its allies are campaigning to turn the tide on overfishing in countries around the globe. “Wouldn’t it be great if the people of the world could get together to ensure a never-ending supply of fish?” Engelhardt asks. With continued support, an ever-abundant ocean is more than possible.

Henry Engelhardt is the founder and former chief executive of Admiral Group, a Welsh motor insurance company, and co-founder of the Moondance Foundation.

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 29

© Diane Briere de L’Isle Engelhardt

Quiz: Meet the “Super Moms” of this North Atlantic right whale calving season

First sighted in 1986, this season marks her eighth documented calf. She is at least 38 years old.

Named for a small “speck” of a scar on the right side of her head.

Named for a unique pattern on her head resembling the tree found on the U.S. state of South Carolina’s flag.

North Atlantic right whales face mutiple, sometimes fatal, threats, including boat strikes and fishing gear entanglements.

30 Quiz

Spot the North Atlantic right whale

Match the "Super Mom" to the description

Horton

Juno

Palmetto

Palmetto. © Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, taken under NOAA Permit #26919

Horton. © Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, taken under NOAA Permit #26919 Juno. © Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, taken under NOAA Permit #26919

Imagine how hard it would be to spot them from a boat!

© Nick Hawkins

Dive into trivia!

1. What feature do observers often use to distinguish one North Atlantic right whale from another?

A) Large patches of raised tissue on their heads

B) The shape of their blow spouts

C) The white markings on their bellies

2. What do researchers use to determine a North Atlantic right whale’s age after it has died?

A) Blubber

B) Ear wax

C) The color of its back

3. Where do North Atlantic right whales usually socialize?

A) At the water’s surface

B) During deep dives

C) In cold waters only

4. What is the North Atlantic right whale’s status on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species?

A) Vulnerable

B) Endangered

C) Critically Endangered

Learn more about Oceana’s campaign:

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 31

Match the Super Mom: Palmetto - 3; Horton - 2; Juno - 1 Dive into Trivia: 1. A; 2. B; 3. A; 4. C

© Oceana

32

North Atlantic right whale “Porcia” and her calf were sighted with Atlantic spotted dolphins on Jan. 5, 2023 approximately 17 nautical miles off Cumberland Island in the U.S. state of Georgia.

SPRING 2024 | Oceana.org 33 © Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, taken under NOAA permit 20556

Global Headquarters: Washington, D.C.

Asia: Manila Central America: Belmopan Europe: Brussels | Copenhagen | Cornwall | Geneva | London | Madrid

North America: Ft. Lauderdale | Halifax | Juneau | Mexico City | Monterey | New York | Ottawa | Portland | Toronto South America: Brasilia | Lima | Santiago

Go to Oceana.org and give today. 1025

Suite

USA phone:

You can help Oceana restore our oceans with your financial contribution. Call us today at +1.877.7.OCEANA, visit us online at Oceana.org/give, or use the envelope provided in this magazine. You can also invest in the future of our oceans by remembering Oceana in your will. Please contact us to find out how. All contributions to Oceana are tax-deductible. Oceana is a 501(c)(3) organization as designated by the Internal Revenue Service.

Connecticut Ave NW,

200 Washington, DC 20036

+1.202.833.3900 toll-free: 1.877.7.OCEANA

Spear Lighthouse,

is near St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, is located at the most easterly point in North America.

Oceana’s accomplishments wouldn’t be possible without the support of its members. Cape

which

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

Andrew Sharpless CEO Oceana

Andrew Sharpless CEO Oceana

Gloria (“Golly”) Estenzo Ramos

Vice President of Oceana in the Philippines.

Gloria (“Golly”) Estenzo Ramos

Vice President of Oceana in the Philippines.

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

© Oceana Canada/Nicholas Hiscock

© Shutterstock/Joe Belanger

© Shutterstock/Joe Belanger