Research papers

Recycling carbon taxes for reindustrialisation

Addressing structural rigidity and financialisation in natural resource exporting countries

Les Papiers de Recherche de l’AFD ont pour but de diffuser rapidement les résultats de travaux en cours. Ils s’adressent principalement aux chercheurs, aux étudiants et au monde académique. Ils couvrent l’ensemble des sujets de travail de l’AFD : analyse économique, théorie économique, analyse des politiques publiques, sciences de l’ingénieur, sociologie, géographie et anthropologie. Une publication dans les Papiers de Recherche de l’AFD n’en exclut aucune autre.

Les opinions exprimées dans ce papier sont celles de son (ses) auteur(s) et ne reflètent pas nécessairement celles de l’AFD. Ce document est publié sous l’entière responsabilité de son (ses) auteur(s).

AFD Research Papers are intended to rapidly disseminate findings of ongoing work and mainly target researchers, students and the wider academic community. They cover the full range of AFD work, including: economic analysis, economic theory, policy analysis, engineering sciences, sociology, geography and anthropology. AFD Research Papers and other publications are not mutually exclusive.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of AFD. It is therefore published under the sole responsibility of its author(s).

Recycling carbon taxes for reindustrialisation

Addressing structural rigidity and financialisation in natural resource exporting countries

AUTHORS

Guilherme Magacho

Antoine Godin

Sakir Devrim Yilmaz

Agence Française de Développement

Danilo Spinola

Birmingham City University COORDINATION

Guilherme Magacho (AFD)

Abstract

Inclusion of developing and emerging countries in the low carbon transition agenda is imperative to meet climate goals, and policies should be tailored to their unique characteristics. Despite their significance, the structural specifics of these countries are frequently overlooked in lowcarbon transition models. In an effort to establish an appropriate framework for such analyses, this article formulates a Structural StockFlow Consistent (Structural SFC) model designed for open developing economies. This model categorizes production into three sectors: resource based exports, non-tradable goods and services, and other tradable sectors. While SFC models play a crucial role in emphasizing financial constraints, they frequently lack a multi-sectoral viewpoint and disregard structural specificities. Our model makes a dual contribution: (1) it offers a flexible framework capable of accommodating diverse country characteristics while balancing short-term demand with long term structural strategies, and (2) it underscores the inadequacy of relying solely on carbon pricing for economies deeply rooted in carbon-intensive sectors. By incorporating structurally distinct sectors within a genuinely monetary framework, the model enables us to comprehend the decisive role played by financial constraints arising from structural rigidities in shaping the dynamics of the low-carbon transition. Our findings show that the efficacy of carbon pricing is contingent on a country’s commercial, financial, and production structure.

Furthermore, the results emphasize the significance of carbon tax recycling in preventing recessions and promoting sustainable decarbonization. This is accomplished by bolstering innovation and competitiveness in lowemission industries.

Keywords

Low-carbon transition, Stock-Flow Consistent Model, Developing and emerging countries, Structural changes, Industrialization

JEL Classification

E37, F18, Q56

Original version

English

Accepted Mars, 2024

Résumé

L’inclusion des pays en développement et émergents dans l’agenda de transition bas carbone est nécessaire pour atteindre les objectifs climatiques, et les politiques doivent être conçues en fonction de leurs idiosyncrasies. Malgré l’importance de ces pays dans la décarbonation de l’économie mondiale, leurs spécificités structurelles sont souvent négligées dans les modèles de transition bas carbone. Dans le but de construire un cadre approprié pour ces pays, cet article développe un modèle structurel stock-flux cohérent (SFC structurel) pour les économies en développement ouvertes, catégorisant la production en trois secteurs: les exportations basées sur les ressources naturelles, les biens et services non échangeables et les autres secteurs échangeables. Bien que les modèles SFC soient importants pour mettre en évidence les contraintes financières, ils ne tiennent pas compte des spécificités structurelles. Les contributions de cet article sont doubles: (1) il fournit un cadre polyvalent qui capture les différentes caractéristiques des pays et contraste les dynamiques de demande de court terme avec des stratégies structurelles de long terme, et (2) il démontre que le seul recours à la tarification du carbone est insuffisant pour les économies ancrées dans des secteurs à forte intensité carbone.

En prenant en compte des secteurs structurellement différents dans un cadre véritablement monétaire, le modèle permet de comprendre comment les contraintes financières dérivées des rigidités structurelles jouent un rôle décisif dans la détermination de la dynamique de la transition bas carbone.

Le modèle démontre que l’efficacité de la tarification du carbone dépend de la structure commerciale, financière et productive des pays. Il montre également que le recyclage de la taxe carbone est essentiel pour éviter les récessions et promouvoir une décarbonation durable en renforçant l’innovation et la compétitivité dans les industries à faibles émissions.

Transition bas carbone, Stock-Flow Consistent Model, Pays en développement et émergents, Changements structurels, Industrialisation

TheParisAgreementestablishedaglobalobjectivetolimitclimatechangetowellbelow 2˚C(andstrivefor1.5˚C),callingfortargetedpoliciestoachievenet-zerocarbonemissions (UNFCCC,2015).Despitedevelopingandemergingcountriescontributingto63%ofglobal emissions,itisimperativetoincorporatethemintoalow-carbontransitionstrategytailored totheirdistinctivecharacteristics.However,manyeconomicmodelsoverlooktheunique featuresoftheseeconomies,disregardingtheintricateinterplaybetweenfinanceandinherentstructuralconstraints.Aslow-carbontransitionpoliciesaffectindustriesindiverseways (SavonaandCiarli,2019),distinctdynamicsemergebasedontheproductive,commercial, andfinancialframeworksofcountries(IMF,2020;Peszkoetal.,2020;Magachoetal.,2023).

Thisoversightcanimpedeacomprehensiveunderstandingofthechallengesthesenations faceinadoptinggreentechnologiesandtransitioningtolow-emissionsectors.

ThisstudyintroducesaStructuralStock-FlowConsistent(StructuralSFC)modeltoinvestigatethedynamicsofalow-carbonshiftinsmallopendevelopingeconomies.Themodel dissectstheproductionprocessintodistinctindustries,acknowledgingtheheterogeneity oftheproductivestructureinherentindevelopingandemergingcountries.Inthisinitial versionofthemodel,weincorporatethreestructurallydifferentsectors:resource-based commoditiesexportindustries,non-tradablegoodsandservices,andothertradablegoods andservices,whichcompeteinternationallybasedonbothpriceandquality.

SFCmodelsstandoutinelucidatingfinancialconstraintsduetotheirinherentlymonetary nature(GodleyandLavoie,2007)bydistinguishingresourceconstraints(i.e.currentaccount)fromfinancialconstraints(i.e.financialaccount)(BorioandDisyatat,2015).However, multi-industryrepresentationinthesemodelsisuncommon,withafewnotableexceptions (Bergetal.,2015;JacksonandJackson,2021;Dunzaetal.,2021;Yilmazetal.,2023).By includingsectorswithstructuraldifferenceswithinagenuinelymonetarymodel,wecangain insightsintohowfinancialconstraintsarisingfromstructuralrigiditiescriticallyinfluencethe trajectoryofthelow-carbontransition.

Thecontributionofthepaperistwofold.Firstly,themodelprovidesaversatileframeworkthat canbetailoredtomatchspecificcountrycharacteristics,supportingpolicyanalysisacross diversesettings.Becauseitisatrulymonetarymodel,withdynamicequilibrium,some hysteresismayemerge,andthemovingpathwilldependonthestructuralcharacteristicsof theeconomy.Inaliteraturedominatedbystaticequilibriummodels,thisapproachprovides insightfulcomprehensionoftheimportanceofcomplementaryofshort-term(demand) andlong-term(structural)policies.Secondly,calibratingthemodelforeconomiesthat relyexcessivelyoncarbon-intensiveindustries,itshowsthatcarbonpricesmaynotbean effectivemeasure.Thisisarecessivemeasureasitdrainsresourcesfromtheeconomy thatwillnotnecessarilyreinvestedingreenindustries.Recyclingcarbontax,forexample, provednecessarytoavoidrecessionandledtorecovery.Usingthisresourcestostimulate innovationandthecompetitivenessoflow-emittingindustriescanpromoteasustainable long-termdecarbonisationpath.

Thepaperisdividedintofoursectionsfollowingthisintroduction.Thenextsectiondiscusses thethesignificanceofincorporatingfinanceinastructuralmacroeconomicmodeltounder-

standtheimpactsoflow-carbontransitionpoliciesindevelopingandemergingcountries. Section3describestheproductiveandfinancialstructureofthemodel.Section4presents thesimulationresultsdesignedtodemonstratetheapplicabilityofthemodel.Finally,the concludingremarksdiscusstheadvancesandcontributionsofthisapproach.

Thegreentransitionhasemergedasacentraltopicinglobaldiscussions,markedbynumerousdevelopingnationscommittingtoreducetheirgreenhousegas(GHG)emissionsin alignmentwiththeParisAgreement(UNFCCC,2015).Thisrenewedcommitmentpresents anadditionalchallengeforeconomiesalreadygrapplingwithvariousaspectsofeconomic andsocialsustainability.Tomeettheirdevelopmentobjectives,emergingeconomiesmust notonlypursueeconomicgrowthbutalsofosteraninclusivesystemthataddressespoverty andinequalitysimultaneously(Porcileetal.,2023).

Macroeconomicmodelshavebeenextensivelyemployedtoofferguidancetopolicymakers atbothnationalandinternationallevelsregardingtheconsequencesofclimatepolicies. Thesemodelsaimtoascertainhowsuchpoliciesaffecteconomicgrowth,publicdebt, employment,andotherpertinentmacroeconomicvariables(Stern,2007).Inconventional multisectoralmacroeconomicmodels,liketheComputableGeneralEquilibrium(CGE),the significanceoffinanceanditsinteractionwithreal-worldfactorsisoftendownplayed.Onlya fewCGEmodelsaddressingclimateconcernsincorporatefinance(Liuetal.,2017;Paroussos etal.,2020).finance’simpactonlong-termdynamicsislimited,primarilytreatedasa technologicalorsectoralfrictioninaccessingfundingsources(Liuetal.,2017;Paroussosetal., 2020).Duetoassumptionssuchasmarket-clearinginterestrates,whereallsavingsare inevitablyinvested,anyfinancialconstraintsinonesectorcanleadtoexcessiveinvestments inothers,resultinginaprevalentcrowding-ineffect.However,thisscenariodoesnotalways mirrorreal-worldsituations,particularlyinthecontextofclimatechange.Forexample, duringperiodsofheightenedsystemicriskswheredefaultrisksescalate,bankstypically scalebacklendingacrosssectors.Conversely,duringperiodsofeconomicupswingwhen anticipatedprofitsincreaseanddefaultrisksdiminish,banksaremorelenientwiththeir lending(Mercureetal.,2019).

Equilibriummodelsaregroundedinrationalchoicetheory,whereindividualagentsare guidedbyincentivesinmakingrationaldecisionstomaximizetheirobjectivesandparticipateinmarketdynamics.Withinthisframework,theinteractionsofindividualagentsform asystemcharacterizedbychecksandbalances,ultimatelyleadingtoastableequilibrium thatactsasaself-regulatingmechanismgoverningeconomicbehavior.Theinterplay betweenvariousinterdependentmarketsresultsinageneralequilibrium.

TheNewKeynesianschool(Mankiw,1995;Stiglitz,1989)introducesfrictionsthatcandisrupt thisequilibrium.Inthepresenceofmarketfailures,suchasexternalities,systemstability maynotbeachieved.Governmentinterventionbecomesjustifiedtoaddressthesefailures andreachasecond-bestsituation.Externalities,likegreenhousegas(GHG)emissions, necessitatecreatingincentivesthatpenalizeindustriesresponsiblefortheirgeneration,

particularlycarbon-intensiveactivities.Bypenalizinghigh-emissionactivities,thesystem canrebalanceitself,generatingnewincentivestoinvestincarbon-savingactivities.In thissystem,financialinstitutionsneithercreatenordestroymoney,asthereisnoactive creditcreation.Savingsareconsistentlyavailabletobetransformedintonewinvestments inthemostprofitableactivities(Mercureetal.,2019).Thesystemreliesonanautomatic mechanismthatreadjuststheeconomyandintroducesincentives,suchascarbonpricing, tofacilitatethegreentransition.

Thisapproachmaynotbeappropriateforanalysingtransitiondynamicswheredemanddeficienciesmayconstraininvestmentandleadtotrajectoriesthatdivergefromadetermined ex-ante equilibrium.Thisisthecase,especiallyinthecontextofdevelopingeconomies, wherestructuralrigiditiesreducetheirabilitytomigratefromdecliningtoemergingindustries.Thisisevenmorerelevantforhighlyfinancialisedeconomies,wherefinancial imbalancescanconstrainthereallocationoffundsfromlessprofitableinvestmentstomore profitableones.Tounderstandthetransitiondynamicsoffinancialiseddevelopingcountries, weneedtoaddressthesethreefundamentalelementsthatinteractwitheachotherand canmakethisprocessespeciallychallengingforemergingeconomies:structuralrigidity, demanddeficiencyandfinancialisation.

TheStructuralisttheory(Chenery,1975;Haraguchietal.,2017;Chang,1994)providesvaluable insightsintotheissueofstructuralrigidity.Developingeconomiesrequireenhancedcapabilitiesandabsorptivecapacitytoadaptanddiffusecutting-edgetechnologieswithintheir productivestructures(LeeandLim,2001;SilverbergandVerspagen,1995).Theestablishment ofaninnovativeeconomycapableoftraversingsectorsandswiftlyreadaptingandupgradingdemandsasubstantialeconomicandsocialeffortincreatingthenecessarysupply conditions.Thisisachievedthroughthedevelopmentofarobustanddynamicnational innovationsystem(Lundvall,2007).Inthiscontext,catchingupisfarfromautomaticand necessitatessignificantinvestmentsinphysicalandhumancapital,aswellasresearch anddevelopment(R&D)(GrossmanandHelpman,1991).Toeffectivelyassimilateand spreadnewtechnologies,developingnationsmustprioritiseinvestmentsineducationand skill-building,therebybolsteringtheirhumancapital.R&Dinvestmentisalsoessentialfor developingindigenoustechnologieswell-suitedtothelocalcontextandadaptingforeign technologiestolocalconditions.Yet,limitedaccesstofundingandhighborrowingcosts posesignificantobstaclesinmobilizingresourcesfortheseendeavors,especiallyforsmall andmedium-sizedenterprises(SMEs)(Leeetal.,2015).

Overcomingtheseobstaclesnecessitatesdevelopingnationstoenactpoliciesthatsupport structuralchange.Examplesincludeindustrialstrategiesthatpromotetechnologicaleducationandadvancement,aswellastradepoliciesfacilitatingtheintegrationofsmalland medium-sizedenterprises(SMEs)intoglobalvaluechains(GVCs)(Sikharulidze,2011).Such policiescanhelpaddressthelackofabsorptivecapacityandthelimitedaccesstofinance thathinderdevelopingcountriesfromeffectivelycatchingupwithdevelopedeconomies. Furthermore,internationalcooperationandpartnershipscanplayavitalroleinproviding financialandtechnicalassistancetodevelopingcountriesintheirpursuitofsustainableand inclusiveeconomicgrowth(PietrobelliandRabellotti,2011).

Thesecondsignificantobstacletosustainableandinclusiveeconomicgrowthindeveloping

nationsisdemanddeficiency,particularlyconcerningbalanceofpaymentschallenges.Ina monetaryeconomy,investmentdecisionsareinfluencedbyexpectations.Duringperiodsof highuncertainty,agentstendtoshifttheirassetstowardsliquidassets,reducingspending andresultinginalackofdemand.Supplyrespondsbyreducingproductioncapacity, impedinggrowth,andcausingunemployment(Pasinetti,2001).

Foropendevelopingeconomies,constrainedbylimitedforeigncurrencyaccess,theneed tosecureforeignexchangeforessentialimportsforconsumptionandinvestmentbecomes critical.Thischallengeisheightenedforcountriesthatlagintechnologicalinnovation, relyingonimportingadvancedtechnologyandhistoricallyfacingexternalrestrictionsand crises(Thirlwall,1979;CimoliandPorcile,2014).Balance-of-paymentsconstraintsexert significantpressureontheeconomytoadjusttotheavailabilityofforeigncurrencywhen importsarecrucialforthestructuralchangeprocess.Currencydevaluationscannotpersist indefinitelytocompensateforthislackofforeignexchange.Theeconomicadjustment occursvia quantity ratherthanprices.Thisadjustmentimpliesthatgrowthisconstrained bydemandthroughthebalance-of-paymentschannel,forcingexportsandimportstobe balancedinthelongruntoavoidanexplosionofforeigndebt.

Toaddressbalanceofpaymentsconstraints,developingcountriesmustenhancetheir exportpotentialbydiversifyingproduction,advancingtechnologically,andimprovingthe qualityofproductsandservices.Additionally,policyinitiativesthatsupportlocalindustries, includinginvestmentsininfrastructure,educationalprograms,andresearchanddevelopment(R&D),canreduceimportdemandwhilestrengtheningdomesticproduction(Botta etal.,2023;Porcileetal.,2022).

Thethirdbarrierisfinancialization,whichimpedessustainableandinclusivegrowth.The currentglobaleconomicframeworkheavilyreliesonopenfinancialaccounts,pressuring nationaleconomiestoaligntheirdomesticmacroeconomicpolicieswiththerulesand demandsofinternationalcapitalmarkets.Consequently,monetarypoliciesoftenfocus oninflationcontrolandattractingforeignportfolios,withsignificantimplicationsforreal economies(Frankel,2010;BorioandDisyatat,2015).Thisemphasiscompelsdeveloping nationstoprioritizeshort-termfinancialequilibriumoverlong-termgrowth(Ghoshetal., 2016).Suchanorientationposesrisksofvolatilecapitalmovements,potentialfinancial unrest,andeconomicallydamagingcrises(Stiglitz,2002).Moreover,dependingonforeign capitalinflowsmayresultinanover-relianceonshort-termfinanceratherthanlong-term investmentinproductivecapacities,undermininggrowthprospects(ReinhartandRogoff, 2009).

Therefore,developingcountriesmustcarefullymanagetheircapitalaccountsandformulatefinancialpoliciesthatprioritizelong-termsustainablegrowthovershort-termfinancial stability.Thismayinvolveimplementingcapitalcontrols,establishingregulatoryoversight, andfosteringdomesticfinancialecosystemsthatencourageenduringproductiveinvestments(Ghoshetal.,2016).Additionally,itiscrucialfordevelopingcountriestoexertgreater influenceinshapingtherulesoftheinternationalfinancialsystem,ensuringalignmentwith theneedsandprioritiesoftherealeconomyratherthansolelycateringtothedemandsof internationalcapitalmarkets.

ThethreebarriersoutlinedabovecannotbeadequatelycapturedwithinaComputableGen-

eralEquilibrium(CGE)framework.IntheCGEapproach,market-clearingmechanismstend todownplaythesignificanceoffinancialconstraintsandstructuralrigiditiesintheeconomy. Asanalternativeframework,employingStock-FlowConsistent(SFC)modelingenablesa betterunderstandingoftheinterconnectednessbetweeneconomicstructure,demand,and financialdynamics.Thisapproachfacilitatestheconnectionofshort-runmacroeconomic dynamicswithlong-runeconomictrajectories,sheddinglightonthekeymacroeconomic challengesfacedbycountriesstrivingforagreentransition.TheSFCapproachallowsfor moneycreationandrecognizesfeedbackloopsbetweenfinanceandtherealsideofthe economy.Short-termdisequilibriumandimbalancesamongdifferenteconomicsectors canhaveasubstantialimpactonlong-termeconomicgrowthandsustainabilityinthis approach.

InaCGEframework,mechanismsthatdiscourageinvestmentsinoneindustryautomaticallyencourageinvestmentinothers.EspeciallyinCGEmodelslackingfinance(andan investmentfunctiondependentonprofitability)wherenationalsavingsautomaticallydetermineinvestmentthroughthesaving-investmentidentity,anegativeshock,suchascarbonpricing,tohighemissionindustriesreallocatesinvestmenttowardsrenewableenergy. Conversely,inanSFCframework,anegativeshockintheenergysector,suchasacarbon tax,mayhaveunintendedconsequences,suchasreducingoveralldemand,leadingtoa contractioninothersectorsandultimatelycausingarecession.UnlikeCGEmodels,which relyonasaving-investmentidentity,investmentinlow-emissionsectorsinSFCmodelsis fundamentallydrivenbyprofitabilityinthesesectors,dependentondemandandfinancing costs.Additionally,theseinvestmentsareconstrainedbytheavailabilityoffinance,implying thatthedynamicsofinvestmentingreenindustriesaredrivenbyacomplexinterplayofreal andfinancialconditions.

Similarly,crowding-outeffects,particularlyofpublicinvestmentonprivateinvestment,predominateinaCGEframeworkwhereagivenamountofnationalsavings,derivedfrom consumerandgovernmentdecisions,determinetotalinvestment.Incontrast,SFCmodels allowforbothcrowding-inandcrowding-outeffects,dependingontheimpactofpublic investmentonprivatedemand,lendingrates,andfinancialdynamics.Furthermore,inan SFCframework,theexplicitmodelingofthefinancialsectorimpliesthatfinancialchannels mayexacerbatethecontractionaryeffectsofnegativeshocks,suchasthelossofexports, leadingtoadeeperrecessionand,insomecases,acurrencycrisis(Godinetal.,2023).This perspectivesharplycontrastswiththedynamicsofCGEmodels,inwhichmovementsinthe exchangerateensurelong-termstabilizationofthecurrentaccounteitherbyareductionin imports,anincreaseinexports,oracombinationofboth.

ThelimitationsoftheCGEframeworkunderscorethenecessityformorecomprehensive andintegratedmodelscapableofcapturingtheintricatefeedbackmechanismsbetween therealandfinancialsectorsandtheinterplaybetweenenvironmentalandeconomic outcomes.Suchmodelscouldfurnishpolicymakerswithamoreaccurateunderstanding oftheimpactofpolicymeasuresoneconomicandenvironmentalsustainability.Therole ofpolicyinthisnewlyproposedframeworkisnotablydistinct.Insteadofservingsolelyasa mechanismtoaddressmarketfailures,policyplaysanactivedevelopmentalroleinfostering structuralchangewhilemaintainingmacroeconomicstability,especiallyinthesensitive contextoffinancialisation,openfinancialaccounts,andfinancialdominance(Bottaetal.,

2023).

Theproposedframeworkemphasizesthepivotalroleofpolicyinaddressingthetriadof barriersthathindersustainableandinclusiveeconomicgrowth.Policyinterventionbecomes imperativetostimulatestructuralchangeandmaintainmacroeconomicstabilitywithin therealmsoffinancialisationandopenfinancialaccounts.Insteadofmerelyrectifying marketfailures,policiesmustproactivelycontributetopromotingsustainablegrowthand development.Thisshiftinpolicyfocuscanspanvariousdomains,encompassingtheencouragementofinnovation,strengtheningeducation,improvinginfrastructure,andstrategicallydirectingindustrialdevelopmenttonurturenewsectorsandfortifyexistingones. Furthermore,macroeconomicpoliciesshouldalignwithlong-termdevelopmentgoalswhile safeguardingshort-termmacroeconomicstability,especiallywhenconsideringexternal factorssuchascapitalflows,exchangeratevolatility,andglobalfinancialcrises.However, theeffectivenessofthesepolicieshingesonthespecificcharacteristicsofeachcountry, includinginstitutionalframeworks,politicalwill,andtheavailabilityoffinancialresources. Hence,tailoringpoliciestosuitindividualcountrycontextsbecomesparamounttoensure theyeffectivelysupportsustainableandinclusivegrowth.

Thedynamicsofthestructuraltransformationprocessinresource-exportingcountriesshould consideratleastthreedistinctsectors(Skott,2021).Firstandforemost,itisessentialtocategorizetheeconomyintotradableandnon-tradablesectors,asglobaldynamicsaffectthem throughdifferentchannels.Whilebothsectorsbenefitfromeconomicupturns,characterized bylowercostsofaccessingcredit,inputs,andcapitalgoods,aswellasincreaseddomestic demand,theimpactontradedgoodsisnuanced.Theseindustries,competingwithimports forthedomesticmarketandwithothereconomiesforexports,maynotfullycapitalizeon upturnsduetoexchangeratedynamics.

Additionally,withintradablegoods,aspecificsectordeservesattention:theoneproducing goodsbasedonnaturalresources.Thissector,heavilyreliantoncommodityexports,experiencesuniqueimpactsduringeconomiccycles,especiallyinthecontextofrisingcommodity prices.Unlikeothertradablesectors,itcanbedisproportionatelypositivelyaffectedduring economicupswings.Furthermore,givenitsdirectdependenceonenvironmentalservices anditsconnectiontoenvironmentalimpacts,understandinghowthegreentransitionaffectscountriesreliantonnaturalresourceexportsiscrucial.

BasedonYilmazandGodin(2020),wedevelopacontinuous-timemulti-sectoralSFCmodel foranopendevelopingeconomy.ThemodelbyYilmazandGodin(2020)providesimportant insightsintohowanemergingopeneconomyoperates,highlightingfinancialandtrade relationshipswiththerestoftheworld.Furthermore,becauseitisbuiltonacontinuoustimebasis,thedynamicsofdisequilibriumanddifferentadjustmentsaremodelledexplicitly.1

1Foradetaileddiscussionoftheadvantagesofusingacontinuous-timemodeloveradiscrete-timemodel,see Gandolfo(2012)andYilmazandGodin(2020)

FollowingSkott(2021),wedividetheproductivesectorsintothree:resource-basedgoods (r),non-tradablegoodsandservices(n)andtradablemanufacturedgoods(m).Themain structuralcharacteristicsoftheproductivesectorsarethefollowing:

• Resource-basedgoods(r):producesahomogenousgoodforexportmarketonly;itis price-taker(producescommodity);investmentisdrivenmainlybyexpectedpricesin internationalmarket;anditoperatesatfullcapacity

• Non-tradablegoodsandservices(n):producesheterogeneousgoodsonlyforthe domesticmarket;itisaprice-maker(duetoimperfectcompetition);investmentis mainlydrivenbyexpecteddemand,despitedependingonpricesandidlecapacity utilisation;itoperatesbellowfull-capacity

• TradableManufacturedgoods(m):producesheterogeneousgoodsandservicesfor exportanddomesticmarketmarkets;itisaprice-maker(imperfectcompetition); investmentisdrivenbydomesticandforeigndemandandthecapacitytoabsorbthis demand;itoperatesbellowfull-capacity

Besidestheproductivesectors,wealsoconsiderinstitutionalsectors.Thesesectorsdo nothirelabourorproduce.Instead,theyareresponsibleforgeneratingfinaldemandand organisingthefinancialtransactions:

• Households(H):consumesgoodsandservices;incomecomesfromwages,profits,interestondepositsandsocialtransfers;paysincometaxes,socialcontributions,interest onlending;investsinfirmsandbanksandreceivesdividends

• Government(G):taxesproductionandincome,consumesonlynon-tradablegoods andservices,paysunemployedbenefitsandinterestonbonds;receivesCentralBank profits;investsinfirmsandbanksandreceivesdividends

• Banks(B):financefirmsandhouseholdsbyloansandgovernmentdebtviapurchases ofpublicbonds;borrowfromCentralBankaccordingtotheirfinancialneeds

• CentralBank(C):accommodatesbanks’moneydemandanddeterminesthepolicy rateaccordingtoaTaylorRule

• RestoftheWorld(W):besidesimportsandexports,alsofinancesfirmsandbanksby loansandFDIandgovernmentdebtthroughpurchasesofpublicbonds

Figure1highlightsthemostimportanttransitionsbetweentheproductiveandinstitutional sectors.Notalltransitionsarepresented,butwecanseefromsomekeyinter-sectoral relations.

Aswementionedabove,themodelpresentedhereisamulti-sectoralversionoftheprototypegrowthmodelin(YilmazandGodin,2020).AppendixApresentsallmodelequations. Herewedetailthefundamentalmodificationsfromtheprototypemodelandlayoutthemost importantcharacteristicsofourmodel,particularlyfocusingonthestructuraldifferences betweenthesectors.

Notalltransitionsarepresented.Solidlinesrepresentflowsofgoodsandservices(compensatedformonetary payments),anddashedlinesrepresentflowoffunds(compensatedforinterestpaymentsanddividends).A: Advances;B:Bonds;L:loans;D:Deposits;R:Reserves;G:Governmentconsumption;C:Householdconsumption;X: Exports;IM:Imports;IC:Intermediateconsumption;andI:Capitalinvestment.

Inmostdevelopingeconomies,evenwhentheunemploymentrateislow,labourshortages arenotimportantconstraintstogrowthbecausetheseeconomiesaredualwithlarge amountsofhiddenunemployment(Skott,2021).Therefore,productionisnotconstrained bylabourshortages,althoughwagesmayincreaseduetoreducedunemployment,leading tohighercostsandlowerprofitability.

Inthecaseofresource-basedgoods,weassumethatallproductionisexported,andhence therearenoinventoriesinthissector.Productionisthereforedeterminedbytheproductive capacity,whichisgivenbythestockofcapitalandthemaximumcapacityutilizationthat avoidsover-depreciationofcapital.Intheothertwosectors,capacityutilizationvaries, andhenceproductionisnotnecessarilydeterminedbyactualcapitalstock.Firmswill produce(constrainedbythestockofcapital)accordingtoexpectedsalesandinvestment ininventoriestomeetadesiredinventorytarget,whichservesasabuffertomeetdemand inexcessofexpectedsales.(Charpeetal.,2011).

Inallsectors,investmentisdeterminedbythedifferencebetweenexpectedgrossprofitabilityandtheaveragecostofthird-partycapital,whichisgivenbytheaverageinterestrateon newcontractsandtheleverageratio.Thehighertheexpectedprofitabilityinrelationtothe costofthird-partycapital,thegreatertheinvestmentinnewcapital.Expectedgrossprofits depend,ontherevenueside,onexpectedsales,expectedpricesandtaxes.Onthecostside, theydependonexpectedunitcosts(laborcostsandproductionfactorsasaproportionof production).

Producersofresource-basedgoodsknowthatallproductionnotconsumeddomestically willbeexportedattheongoingglobalprices,andthereforetheuncertainvariablesare expectedpricesandtheexpectednominalexchangerate.Producersofnon-tradableand othergoodsandservices,ontheotherhand,arepricemakers;therefore,theywillreceive thepricetheycharge.However,unlikeresourceexporters,theymaynotsellalloftheir production;therefore,expectedprofitabilitydependsonexpectedsales.

Othertradablegoodsandservicesareproducedforthedomesticmarketandexports.Asthe producersarepricemakersinthismarketaswestressedabove,pricecompetitivenessand demandmatterindeterminingthevolumeofexportsandimports.Eventhoughdeveloping countriestendtoproducelesssophisticatedgoodsthandevelopedeconomies,non-price competitivenessisanimportantdeterminantoftheircapacitytoexport(Fagerberg,1988; Basile,2001;BenkovskisandWörz,2016).Theshareofworldexportsthereforedepends onpricecompetitiveness,determinedbyrelativepricesandtheexchangerate,andnonpricecompetitiveness,whichisafunctionoftheproductivitygapinrelationtoareference economy,asin(Yilmazetal.,2023;Godinetal.,2023)

Firmsborrowtoproduceandinvest.Forsimplicity,however,wewillabstractfromlending forworkingcapitalandfocusonlyonlong-termlending.Firmswillfirsttrytofinance theirfinancialneedsbytheequitymarket(domestic,foreignandpublicdirectinvestment).

Theywillthenattempttodosothroughforeignloans,andtheremainingfinancialneeds willbemetthroughdomesticloans.Financialrestrictionsoninvestmentthereforearise fromdifficultiesinaccessingforeigncreditandtheincreaseininterestratesonnational loans.

Householdsconsumenon-tradableandothertradablegoodsbasedontheirdisposable incomeandwealth.Households’disposableincomeismainlydrivenbywagesanddividends,althoughitalsocomprisesinterestontheirdepositsandsocialtransfersfromthe government,lessofincometaxandsocialcontributionspaidtothegovernment.

Salariesarenotdeterminedinternallybyeachsector,butbytheeconomyasawhole.The lowertheemploymentrate,thelowerthesalarybargainingpower;therefore,realwagescan growatadifferentratethanproductivitygrowth.Furthermore,nominalwagesgrowinline withexpectedinflation.

Weassumethatthegovernmenthasastrictfiscalruleforitsconsumption,whichchanges accordingtoexpectedinflationandrealoutputgrowth.Thegovernmentconsumesonly non-tradablegoodsandservices,whichincludesallgovernmentactivities(publichealth, publiceducationandpublicadministration).Thegovernmentalsopaysabasicincometo theunemployed(socialtransfers),andtheamountofthesetransfersgrowswithconsumer inflationandgrowthinpercapitaproduction.

Thepublicprimarydeficitevolvesaccordingtototaltaxation,socialcontributions,public consumptionandsocialtransfers.Inadditiontotheprimarydeficit,thegovernmentmust alsofinanceinterestexpenditureonitsobligations.Tofinanceitsdeficit,thegovernment issuesbonds.Firstly,itdecidestheamountofbondsissuedinforeigncurrency,andthenthe

governmentissuesbondsindomesticcurrencyaccordingtoitsfinancialneeds.However, onlyaportionofthesebondssuppliedisabsorbedbybankdemand,creatingagapbetween thetargetandtheactualOperatingAccount.2.Iftheoperatingaccountislow,thegovernmentincreasestheinterestrateonbondstoreachtheinterestratedesiredbybanks.

Commercialbanksfinancefirms’andhouseholds’financialneeds.Interestratesaregiven bythepolicyrate(definedbytheCentralbank)andamark-up,whichisassumedtobe constant.BanksarerequiredtomaintaincompulsorydepositswiththeCentralbankin accordancewiththemandatoryreserverequirements.Iftheirdepositsandownfundsare insufficienttocovertheirloansandreserves,theyneedadvancesfromtheCentralbank.On theotherhand,ifthereisexcessliquidity,theylendtotheCentralbank,whichpaysthebase rateastheinterestrate.

TheCentralbankisresponsibleformonetarypolicy,aswellasensuringliquiditythrough advancestocommercialbanks.Thecentralbank’sprofitsaregivenbythedifference betweentherevenuefromtheseadvancesandtheinterestoncompulsorydeposits.The baseratefollowsasimplifiedTaylorrule,wherethedistancebetweenexpectedinflation andtheinflationtargetisusedasareference.TheCentralbankalsoconductsopenmarket operationswithforeignreservestoreducenominalexchangeratevolatility.IftheCentral Bankwantstokeepthenominalexchangeratefixed,itabsorbsanyexcesssupplyofforeign currency(withinafullysterilizedintervention)overdemand,increasingitsreserves.

Internationalcapitaltendstobedrawntowardsfinancingenterprisesinproductivesectors, eitherthroughportfolioinvestmentsorforeigndirectinvestment(FDI),andtowardsacquiring publicdebt.Whencapitalflowsaredirectedtofinancingpublicdebt,itdiminishesthe government’srelianceonbanks,asmentionedearlier.Conversely,whencapitalflowsare directedthroughportfolioinvestmentsandFDI,theyalleviatetheneedfordomesticloans bycompanies.

Globalfinancialflowsaredeterminedbyinternationalliquidity.Theinfluxofnewforeign capitalinvestments,whetherdirectorindirect,iscontingentontheanticipatedprofitability oftheseinvestmentsinforeigncurrency.Apartfromequityinvestments,foreigncapital streamsalsocontributetogovernmentfinancingthroughtheacquisitionofbondsdenominatedinbothdomesticandforeigncurrencies.Aspreviouslymentioned,theissuance offoreigncurrencybondsisagovernmentaldecision,representingalow-riskinvestment forforeigninvestorsbutposingariskydebtforthegovernment.Inthecaseofbonds denominatedinthenationalcurrency,thedeterminingfactorfortheflowisthedisparity betweentheinterestrateofferedbythegovernmentandtheglobalinterestrate,alongwith theexternalriskpremium,whichtakesintoaccounttheexchangerateriskforinternational investors.

2TheOperatingAccountisnecessarytoensurethatthegovernmentwillbeabletopayitsexpenses,andwillvary accordingtothedifferencebetweenthesupplyanddemandforbonds

Thenominalexchangerateisdeterminedbyamechanismforadjustingthesupplyand demandforforeigncurrency(whichcomprisecurrentaccountandcapitalflows).Expected exchangeratedepreciationandexpectedcommoditypricesfollowatypicalbackwardlookingexpectationstructure.

Oneofthemostusedinstrumentstopromotedecarbonisationiscarbonpricing.Thismechanismfallsintothreemaincategories:emissionstradingsystems(ETS),carbontaxationor mechanismsthatcombineelementsofETSandtaxation(Narassimhanetal.,2018).The assumptionunderlyingthesemechanismsisthatrelativepricechangewillleadhouseholdsandcompaniestoredirecttheirconsumptionorinvestmenttowardsindustriesor technologiesthatemitlesscarbon.High-emittingindustries(orindustriesproducingwith high-emittingtechnologies)willeitherchargeahigherpricefortheiroutputorreducetheir margins,leadingtolessdemandandlessinvestment.Ontheotherhand,low-emission industrieswillseetheirdemandincreaseandinvestmentwillflowintotheseindustries, leadingtodecarbonisation.

However,theeffectivenessofthistypeofmeasuredependsonsomestructuralcharacteristics.First,forrelativepricechangetoplayaroleinconsumptiondecisions,itmustbe priceelastic.Ifthepriceelasticityofdemandsubstitutionislow,thechangeinrelative priceswillhavealimitedimpact.Second,fromaproductionpointofview,thereisaneed fortheeconomytobeabletoproduceeitherwithlow-emissiontechnologiesorinlowemissionindustries.Ifcarbonpricingmechanismsareimplemented,andtherearenoviable technologicalalternatives,investmentwillnotflowtotheseindustries.Third-andhere financeplaysadecisiverole-demandandinvestmentmustflowfromahigh-emittingtoa low-emittingindustryortechnologyratherthanjustreducingintheformer.

Totesttheeffectivenessofcarbonpricinginresource-exportingcountries,weanalysed theimpactofthegovernmentimplementingacarbontax.3 Inthesimulations,weassume thatresource-basedindustry(r)emitsmoreGHGthanothertradablegoods(m),andnontradables(n)donotemitdirectly(butindirectlyonlyduetotheuseofotherindustries inputs).

Whilethecarbontaxmaydisproportionatelyaffectresource-basedindustriesinterms ofproduction,itconcurrentlygeneratesincreasedtaxrevenues,whichmayserveasa significantmechanismtoinstigatestructuralchangesacrossvarioussectors.Weexaminedthreedistinctapplicationsofthesefeatures.Firstly,weevaluatedtheimpactofthe governmentretainingtheserevenues,leadingtoanaugmentationofthepublicsurplusand consequentlyexertingapositiveinfluenceonpublicdebtandinterestrates.Secondly,we simulatedscenarioswherethegovernmentredistributedthecarbonfundtohouseholds throughSocialTransfers,resultinginnodirectimpactonthefiscalbalance.It’simportantto notethatinthiscase,thegovernmentisnotdepletingfundsfromtheeconomy;rather,itis

3Aswedevelopedacountrymodel,notaworldmodel,modellinganETSisnotpossible,asitisnecessaryto modelnotonlythedomesticcarbonmarketbutalsothedemandandsupplyfunctionsofimportingandexporting carbon.

redirectingresourcesfromhigh-emittingindustriestowardsconsumptionbyothersectors.

Lastly,weexploredthepotentialoutcomesifthegovernmentchosetoinvestdirectlyinsocial infrastructureinsteadoftransferringfundstohouseholds.Thisapproachaimstocreate capacitiesforlow-emissionindustries,fosteringtheircompetitivenessinbothdomesticand internationalmarkets.Theunderlyingconceptofthispolicyisnotonlytoboostdemandfor low-emissionindustriesintheshorttermbutalsotoincentivizetheindustrybyestablishing thenecessaryconditionsforstructuralchange.

Foranalyticalpurposes,thebaselinescenario(absentacarbontax)isestablishedona trajectoryofbalancedgrowth,asdetailedinAppendixA.Consequently,thecarbontaxcan beinterpretedasashockthatinitiatesanewdynamic,potentiallydeviatingfromastateof equilibrium.Dependingonthemagnitudeanddirectionofthisshock,ithasthepotentialto inducestructuraltransformationsintheeconomy,resultingineitheracatching-upeffect oraneconomicsetbackwithcorrespondingrepercussions.Table2outlinescertainkey macroeconomicvariablesthatremainstableinthebaselinescenariobutmayundergo impactsduetothecarbontaxshock.

Fixedinvestment,n %ofGDP11.5%Productivitygrowth%peryear2.0%

Fixedinvestment,m %ofGDP10.1%Populationgrowth%peryear1.0%

Exports,r %ofGDP20.0%Interestrate,FX %peryear4.0%

Exports,m %ofGDP5.0%Interestrate,policy%peryear6.0%

Importpropensity,m

ForeignEquity,r

ForeignEquity,n

ForeignEquity,m

Y D m 27.2%Interestrate,bonds%peryear10.0%

EQn 10.0%Bonds,excl.FX %ofGDP54.0%

%ofGDP1.0%

ForeignEquity,B %of EQB 20.0%ReserveswithCB%ofGDP20.0%

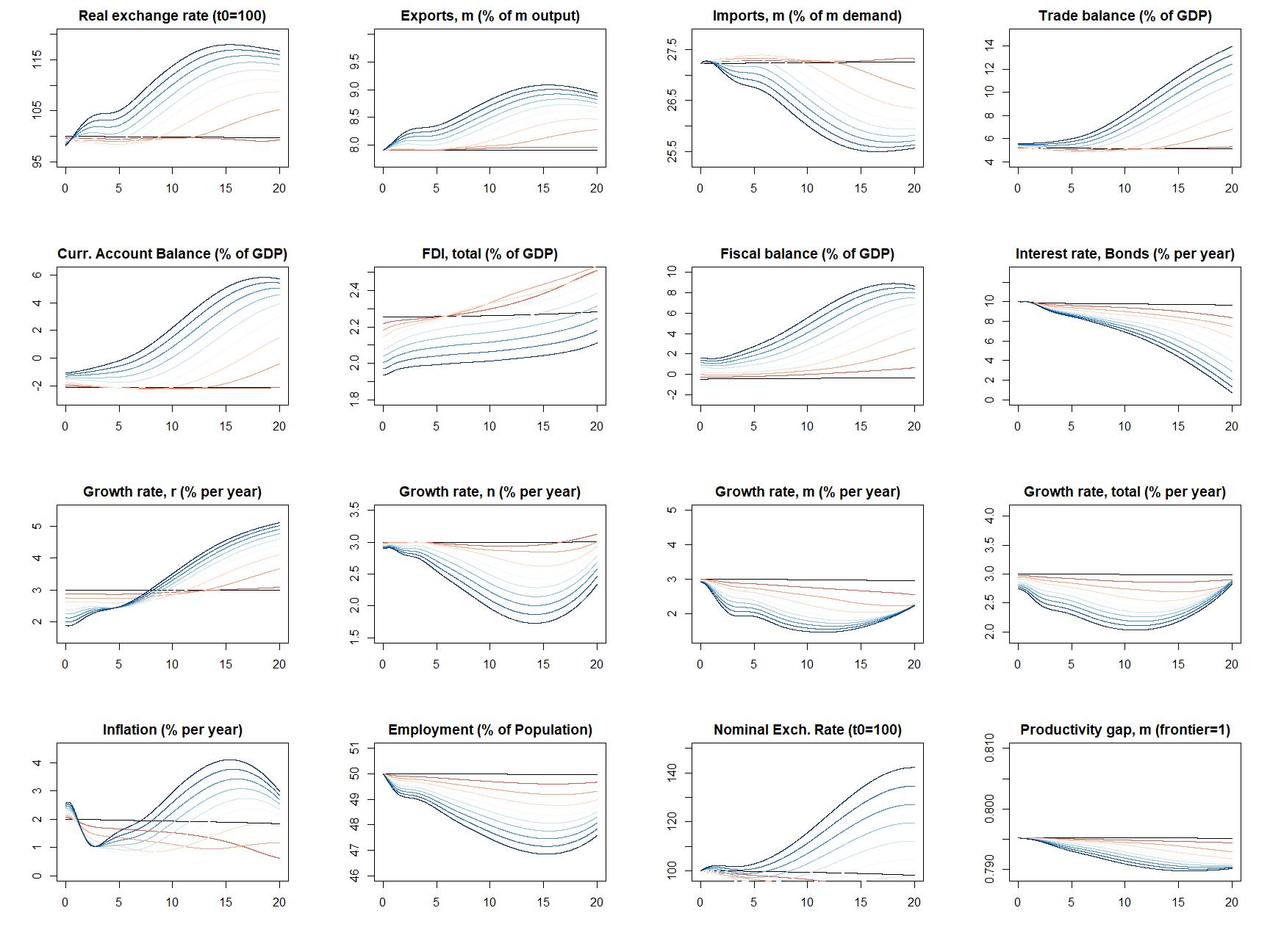

Figure2displaysthedynamicsofseveralmacroeconomicvariablesfollowingtheimplementationofacarbontaxwithoutrecycling.Theimmediateconsequencesofthecarbontax includeajumpininflationandadeclineintheprofitabilityofresource-basedindustries, resultinginreducedinvestmentswithinthissector.Giventhattheindustryoperatesatfull capacity,thedeclineininvestmentleadstoadecreaseintheoverallgrowthrate,causing economicgrowthtodropfrom3.0%tolessthan2.0%peryear.

Theeconomicramificationsofcarbontaxationextendbeyondtheeffectsonaspecific industry.Giventheinterconnectednessofindustriesthroughinputandcapitaldemand, whereincomegeneratedinonesectorbecomesthedemandforothers,thecarbontaxis inherentlyacontractionarymeasure.Theriseinfiscalsurplus(accompaniedbyadecline ininterestrates)provesinsufficienttocounterbalancetheseadverseeffects.Thedecline

Carbontaxfromzero(inred)to10%(inblue)ofbaseyear’ssalesvalue.

ininvestmentswithinnaturalresourceindustriestranslatestoreduceddemandforsectors involvedintheproductionofcapitalgoods.(inthecaseofthemodel,m).Consequently,the overallgrowthrateoftheeconomyexperiencesacontinuousdeceleration,accompanied byadeclineintheemploymentrate.

Whiletheinitialeffectontherealexchangerateisnegative,markedbyanappreciationof thecurrencyduetoadomesticpriceincrease,theoveralllowdemandforgoodsresults inrealdepreciationintheshortterm.Thereduceddemandleadstoincreasedinventories, causingadeclineinthemark-up.Consequently,enhancedpricecompetitivenessstimulatestheexportofmanufacturedgoods.Importsarelikewiseaffectedbythesegainsin pricecompetitiveness,fallingasaproportionofoveralldemand.Thedeclineinimports isexpeditedbyreduceddemandforcapitalgoodsandotherinputs.Thesetrade-related impactscollectivelyresultinasurplusinthecurrentaccount.

Theaccumulationofcurrentaccountsurplusesservestoforestallasustainedrealexchange ratedepreciation.Severalperiodsfollowingtheimplementationofthecarbontax,the economyexhibitspositiveoutcomesfromboththefinancialandfiscalperspectives,despite experiencingadownturnintermsofproduction.Inthemediumterm,employmentcontinues todecline,alongwithanoverallgrowthratereaching2.0%,primarilyattributedtoadecrease intradablesotherthannaturalresources.Despitefiscalandcurrentaccountsurplusesand

fallinginterestrates,thiscyclepersists,anditisonlyafternearly15yearsthatemployment beginstorecover.Theresurgenceispropelledbytherecoveryinnaturalresources,which, inturn,stimulatesnon-tradablesthroughdemandandincomeeffects.

However,thelong-termrepercussionscouldbesevere.Thedecreaseininvestmentin resource-basedindustries(r)failstospuranincreaseininvestment/productioninother tradablegoodsandservices(m),therebythwartingtheanticipatedstructuralshifttowards low-emissionindustries.Insufficientdemand,financialization,andstructuralrigidityplay pivotalrolesinimpedingthistransformation.Thedeclineindemandresultsinreduced imports,improvingthecurrentaccountpositiondespiteadecreaseinexportsfromresourcebasedindustries.Coupledwithafiscalsurplus,thissituationfostersapositivefinancial environment,attractingforeigndirectinvestment(FDI)thatsustainsthiscycle.Theadverse conditionsontheproductiveside,despiteadecreaseininterestrates,proveinsufficient toreversethefavorablefinancialcycle,leadingtheeconomyintoanextendedperiodof financialbonanzacharacterizedbyadeclineinmanufacturingandtradableservices.This processmirrorsaFinancialDutchDisease,where,despitethelossofcompetitivenessin manufacturing,self-reinforcingfinancialmechanismspreventcurrentaccountdeficitsfrom triggeringareversalofexchangerateappreciation.(Botta,2015).

Inthiscontext,itisevidentthatthecarbontaxwithoutrecyclingmechanismshascontractionaryeffectsbothintheshortandmedium/long-term.Despitethefavorableoutcomeson thefiscalandfinancialfronts,thispolicyexertssubstantialadverseimpactsonproduction andemployment.Essentially,asthegovernmentwithdrawsresourcesfromtheeconomy, demanddiminishes,andthedeclineininterestratesfailstocounterbalancethesenegative shocks.Thediminishingincentivesforinvestmentcreateafeedbackloop,furthersuppressingdemandandcausingthenationtolagbehindintermsofincomeandthetransitionto low-carbonindustries.

Inthepreviousscenario,thetaxrevenuesgeneratedfromthecarbontaxweredirected towardsaugmentingthefiscalsurplus.Thisincreaseinthefiscalsurplusoccurredinthe shortterm,facilitatingadeclineintheinterestrateongovernmentbonds.Despitethe lowerinterestratesandtheupswinginpublicsavings,awidespreaddecreaseininvestment ensuedduetoinsufficientdemand.

Alternatively,wenowexploretwocaseswherethesetaxrevenuesareemployedtoinvigorate theeconomy.Inthefirstcase,weexaminetheimplicationsofrecyclingtaxrevenuesas socialtransfers,andinthesecondcase,allocatingthemtoinfrastructureinvestments.

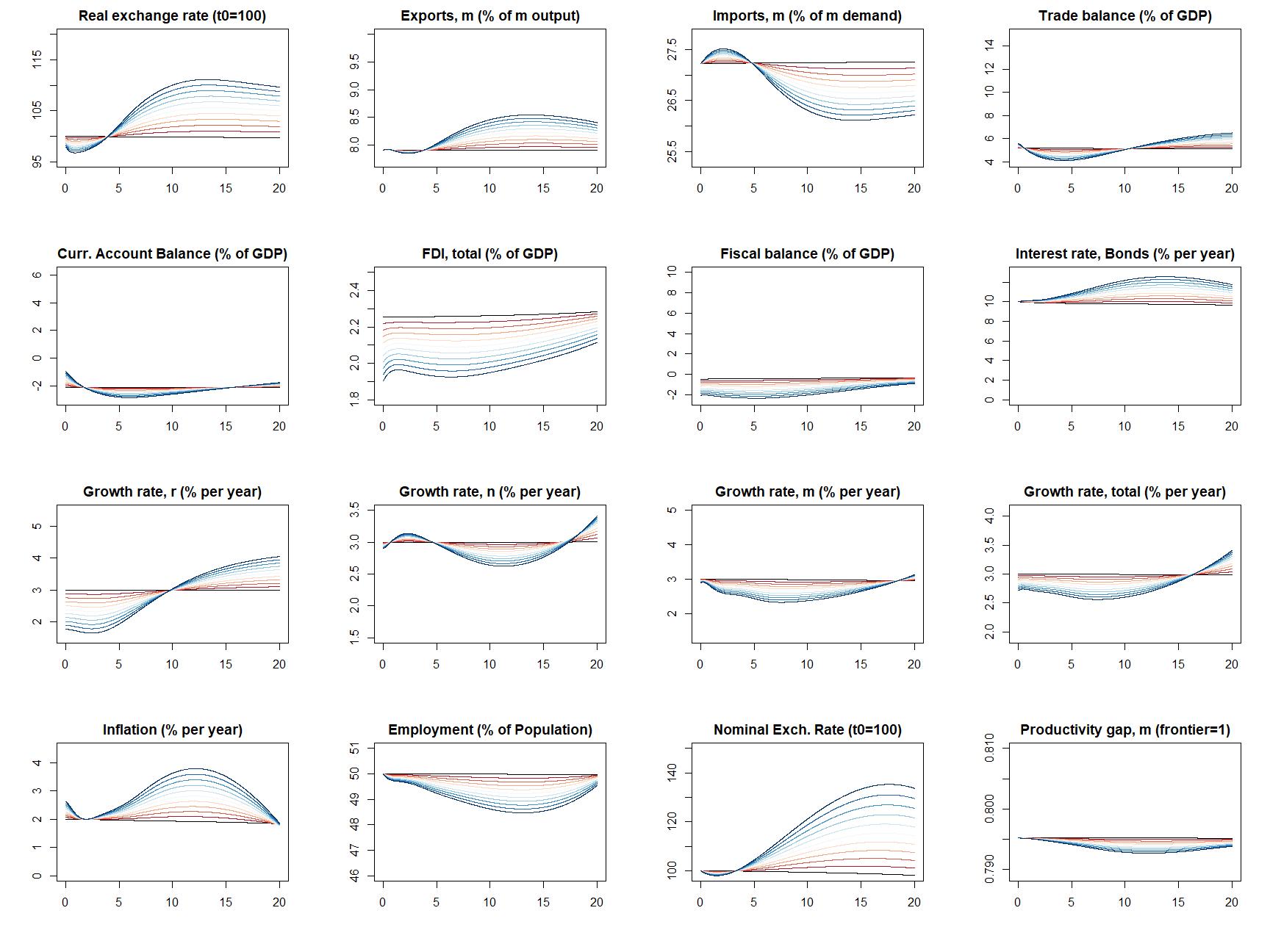

Figure3illustratesthescenarioinwhichfiscalrevenuesfromthecarbontaxarechanneledto households,augmentingtheirdisposableincomethroughsocialtransfers.Theimmediate consequencesmirrorthoseobservedpreviously:higherinflation,adeclineinprofitability andinvestmentwithinnaturalresourcessector,resultinginanoverallreductioninthe economicgrowthrate.Thedistinctionliesinthefactthat,inthiscase,insteadofafiscal surplus,thefiscaldeficitisexacerbated.

Intheshortrun,weobservethatduetothegovernment’sshiftawayfromdrainingresources, thereisasustainedhighdemandfornon-tradables,preventingacontinuousdeclineinthe overallgrowthrate,whichstabilizesat2.7%.Althoughtheemploymentratecontinuesto decreaseduetoproductivitygrowingat2.0%peryearandpopulationat1.0%,thecurrent accountdeteriorates,alongwiththefiscaldeficit.Consequently,despitedisinflation,interest ratesincrease.

Carbontaxfromzero(inred)to10%(inblue)ofbaseyear’ssalesvalue.

However,thisdynamicisswiftlyreversed.Fiscalandcurrentaccountdeficitscontinueto escalate,transformingthescenariointoaninflationaryenvironmentinthemediumrun. Theincreaseininterestratesaimstopreventinertialinflationbyreducingdemandand attractingforeigncapitaltofinancethecurrentaccountdeficit,butitprovestoberecessive. Non-tradablesandtradablesotherthannaturalresourceswitnessadeclineintheirgrowth ratesinthemedium-run.

Therecoveryofemploymentisdrivenmainlybynaturalresources,whichbecomesmore profitableduetoexchangeratedepreciation.However,thisisaveryslowprocess-materializingonlyafterperiod10inthesimulationwhenthegrowthrateofthissectorsurpasses3%. Thenegativeimpactofthepolicyonemploymentisnotaspronouncedasintheprevious casewherethereisnorecycling,buttherecoverystartsatthesameperiodandisdrivenby thesamefactor:exportsofnaturalresourcebasedproducts.

Figure3:SimulationofCarbontax(recycledassocialtransfers)Hence,recyclingthecarbontaxbytransferringtheseresourcesdirectlytohouseholds, therebyaugmentingtheirdisposableincomeandconsumption,canserveasanintriguing instrumenttomitigatetheissuesassociatedwithinsufficientdemandandtheconflicts betweenfinancialandproductivecyclesobservedintheearliersimulation.Furthermore, despitebeingacontractionarymeasureintheshortterm,thesocialcostsofthecarbon taxintermsofemploymentareoffsetbyariseinsocialspending.However,owingto structuralrigidities,thesectorsthatreapthebenefitsofthetransitionarenotthetradable ones(m),butthenon-tradables(n).Asrealdepreciationoccursatagradualpacedue torisinginflationandpricecompetitivenessalonefailstoinstigateasubstantialsurgein exportsfortradablesectors,thegrowthinthesesectorsdoesnotadequatelyoffsetthe declineinnaturalresources,whicharehigh-emissionindustries.Rather,inthelongrun, asshowninfigures,thenaturalresourcessector(r)experiencesarecoverypropelledby macroeconomicconditionsunfavorabletoothersectors.Thisleadstheeconomytorevert toapatternofspecializationinnaturalresources,consequentlyrelyingonhigh-emission industries.

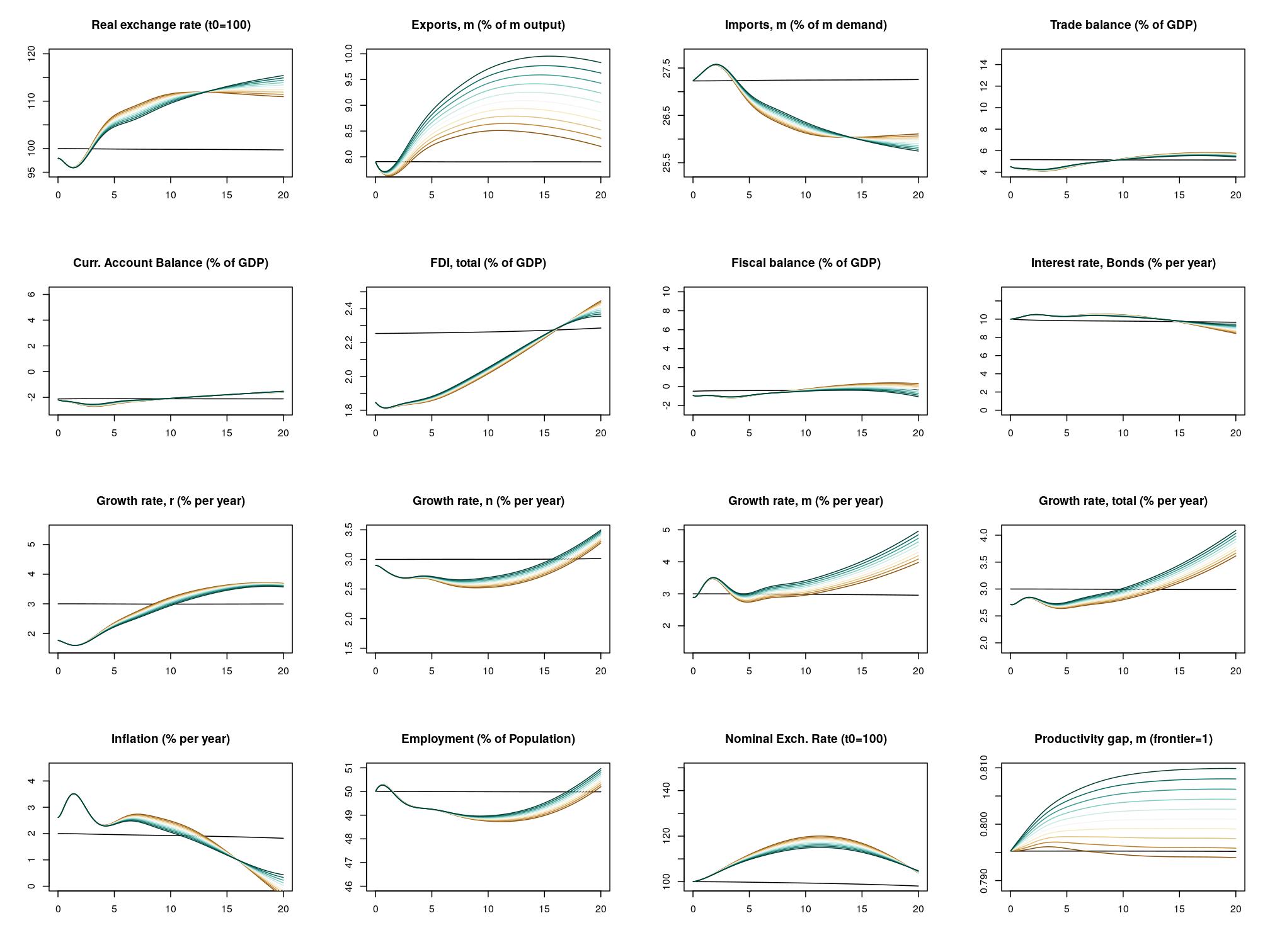

Finally,Figure4depictsthethirdsetofsimulationsinwhich,ratherthanrecyclingcarbon taxationthroughsocialtransfers,thegovernmentoptstoinvestininfrastructure,withthe objectivetofosterthedevelopmentofessentialtechnologicalandproductivecapacities andtherebyeffectivelyenhancingtheinternationalcompetitivenessoflow-emissionindustries(Dosietal.,2015).Inthiscase,wehavebothdemandimpacts,aswehadintheprevious simulation(sincetheseinvestmentsdemandcapitalgoods),andsupply-sideimpacts.In thesimulation,weincludeaterminproductivitygrowthfunctionoftradablesectors(m)that dependsonpublicinvestmentininfrastructure.4 Becauseproductivityincreasesnon-price competitiveness,investmentininfrastructureincreaseslow-emissionindustries’competitivenessindirectly.Consolietal.(2023)showed,however,thattheseimpactsmaybedirect, asbetterenvironmentalperformanceleadstohigherexportcapacity.

Theeconomicdynamicsunderthisscenarioexhibitsignificantdivergencefromtheprevious ones.Intheshortterm,asurgeininflation,drivenbyheighteneddemandforcapitalgoods, resultsinanappreciationoftherealexchangerate.This,inturn,leadstoareduction inexportsandanincreaseinimports,consequentlycausinganexpansionofthecurrent accountdeficit.Theupswinginimportsisfurtherfueledbythehigherdomesticdemand forimportedmanufacturedgoods.Aswemoveintothemediumterm,thecurrentaccount deficitleadstoadepreciationoftherealexchangerate.This,coupledwiththeimpactson pricenon-pricecompetitiveness,fostersgrowthinexportsandadeclineinimports.

Themostsignificantcontrastbetweenrecyclingcarbontaxrevenuesthroughinfrastructure investmentsandsocialtransfersliesintheirmediumtolong-termimpacts.Aslow-emission 4Thenewproductivitygrowthequationbecomes:

Carbontaxfromzero(inred)to10%(inblue)ofbaseyear’ssalesvalue.

industriesgaincompetitivenessinbothdomesticandinternationalmarketsduetoproductivitygrowth,exportsexperienceaquickerrecovery,andimportscommenceadeclineat anearlierstage.Thisresultsinamorerapidrecuperationoftheseindustries,evidentafter thesimulationperiod4wherethegrowthrateofmstartstoincrease.Consequently,there isaswiftertransitionfromhightolow-emissionindustries.Unliketheotherscenarios,the recoveryofemploymentandgrowthrateisnotreliantonnaturalresources.Instead,itis thelow-emissionindustriesthatdrivetheeconomicupturn,preventingtheeconomyfrom encounteringbothinsufficientdemand,asinthecaseofnon-recycling,andthedeteriorationoffiscalandcurrentaccounts,asobservedinthecaseofrecyclingthroughsocial transfers.

Inadditiontomitigatingconflictingpatternsbetweenfinancialandproductiondynamics andaddressingissuesofinsufficientdemand,investmentsininfrastructureovercomeone oftheprimarybottlenecksfortheeffectivenessofacarbontaxinpromotingthetransition. Developingcountriesoftengrapplewithstructuralrigiditiesthatcanimpedeorslowdown theshifttowardlow-emissionindustries.However,asdemonstratedinthislatestsimulation, acombinationofdemandandsupplypoliciesiscrucialforfosteringthistransitioninsuch economies.Ifthegovernmentcanutilizeresourcestocultivatetechnologicalandproductive capabilitiesinkeyindustriesessentialforthetransition,theseindustrieswillnotonlyexpand

attheexpenseofcarbon-intensiveonesbutalsoinstigateapositivecumulativeprocessof structuraltransformationandeconomiccatchingup.

Thepositiveresultsofinvestingininfrastructurehingesonitsabilitytostimulateproductivity growthwithinlow-emissionindustries.5 Accordingtothebaselinescenario,a1.0percentage pointincreaseinGDPdevotedtopublicinvestmentisprojectedtocorrespondtoa0.1%risein annualproductivitygrowth.Thisaccelerationwouldcontributetonarrowingtheproductivity gap.However,ifthisimpactfallsshort,therecoverycannotrelyonincreasedexportsfrom othertradablesectors.Consequently,allsectorsexceptnaturalresourcesmayexperiencea diminishedgrowthrate.Thisunderscoresacrucialconsiderationwhenreallocatingcarbon taxestodrivereindustrialization:prioritizinginvestmentinsectorswiththegreatestpotential forproductivitygainsandinternationalmarketaccess.

Theinclusionofdevelopingcountriesinthedecarbonizationagendaiscrucialforachieving net-zeroemissionsintheforthcomingdecades,sincepresently,thesenationscontribute to63%ofglobalemissionsandtheirsignificanceisontherise(AbubakarandDano,2020). However,itisimperativetotailorpoliciestotheiruniquecharacteristics.Traditionalmacroeconomicmodels,oftenrootedindynamicsofdevelopedeconomies,fallshortinaddressing keychallengesconfrontingdevelopingandemergingcountriesduringthepursuitofa sustainableandequitabletransition.Structuralrigiditiesstandoutasaprimarychallenge forthesenationsastheyendeavortoshiftfromhigh-emissiontolow-emissionindustries. Hence,thereisacompellingneedtodeveloptoolsthataccountforthesespecificities, addressingtheprimaryconstraintsthatmayariseinthistransformativeprocess.

ThispaperintroducesaStructuralStock-FlowConsistent(Structural-SFC)modelspecifically tailoredfornaturalresource-exportingcountries.Giventheheterogeneousnatureoftheir productivestructures,wheresectorssignificantlydifferinaspectslikemarketstructure, productivity,andinvestmentdynamics,relyingonaone-sectormodeloramulti-sector modelwithstructurallysimilarsectorsmayleadtomisleadinganalysesofmacroeconomic factors.Moreover,theroleoffinanceiscrucialinthistransition,asthereisnoinherent guaranteethatdeclininginvestmentinhigh-emissionindustrieswillautomaticallytranslate intoincreasedinvestmentinlow-emissionindustries.TheadoptionofSFCmodelsproves essentialinthiscontext,offeringatoolthataccommodatesmoneycreationanddestruction throughcredit,thusplacingbanksandfinancialinstitutionsatthecenterofthedynamics drivingthetransition.

Inordertounderstandtheimpactsofalow-carbontransitionintheseeconomies,especially thoseinwhichtheexportbasketisexcessivelydependentonhigh-emissionindustries,we testedtheimpositionofacarbontax,whichincreasesthesalepriceofthissector,andleads tolowerprofitability.

5AppendixCprovidesasensitivityanalysisconcerningthekeyspeedofadjustmentswithinthemodelandthe effectofpublicinfrastructureinvestmentontheproductivityoftradablegoods.Alteringthespeedsofadjustment hasminimaleffectsontheoveralldynamics.Thesamecannotbesaidfortheparameterthatgaugestheinfluence ofinvestmentonproductivity.

Thefindingsindicatethatwithoutrecyclingcarbontaxrevenues,theeffectivenessofthis measureislimited.Essentially,asindustriesareconnectedthroughinput-output,capitalabsorption,andincome-consumptionrelationships,fallinginvestmentinhigh-emittingindustriesleadstofallingdemandandinvestmentinallotherindustries.Anticipatedadjustment mechanisms,suchasrisingexportsandfallingimportsinotherindustriescompensatingfor thedeclineinhigh-emissionexports,donotmaterialize.Theabsenceofpersistentcurrent accountdeficitsandrealexchangeratedepreciationfurtherhinderstheautomaticshiftof investmentfromhigh-tolow-emissionindustries.Financialdynamicsalsoexacerbatethe situation,withpositivefinancialconditionsattractingforeigncapitaldespitechallengesin theproductivesectors.Thisprolongedfinancialbonanzacontributestoalackoftransition, intensifyingproblemsinlow-emissiontradablesectorsandimpedingthedesiredeconomic shift.

Therecyclingofcarbontaxrevenuespresentsamorefavorablescenarioforthelow-carbon transition.Whentheserevenuesaredirectedtowardsocialtransfers,theissueofinsufficient demandisaddressed,andtheprofitabilityofotherindustriesremainsintactdespitethe declineinhigh-emissionindustries’profitability.However,thetransitionisslowdueto existingstructuralrigidities.Conversely,iftheserevenuesareusedtobuildcapacityinlowemissionindustries,withenvironmentalpoliciesthatgoesbeyondcarbontax(Costantini andMazzanti,2012),thetransitionprocesswilloccurmorequicklyaslow-emissionindustries becomemoreinternationallycompetitive.This,inturn,setsoffacumulativecausalityprocess,whereexportgrowthboostsprofitabilityinlow-emissionindustries,drivingincreased investment,generatingmoredemand,andfurtheramplifyingcompetitivenessgains.

Asthemodelisbuiltonatheoreticalcalibration,notrepresentinganyspecificcountry,the simulationsareexplanatory.However,thesensitivityanalysisweconducted(presented inAppendixC)indicatesthatthefindingscanbegeneralizedtocountriessharingsimilar productionstructures.Additionally,beingaprototypeversion,themodel’srelativesimplicity doesn’tprecludeitsapplicabilitytospecificcountries.Givenitsmulti-sectoralframework,it canaccommodatetheconsiderationofenvironmentalissuesuniquetovarioussectorsin differentcountries.Thisincludesexaminingtheimpactsofclimatechangeonkeyindustries, theconsequencesofbiodiversitylossduetolandusepractices,andtheeffectsofwaterintensiveactivitiesinregionsfacingwaterstress.

Abubakar,I.R.andDano, U.L. (2020).Sustainable urbanplanningstrategies formitigatingclimate changeinsaudi arabia. Environment, Development and Sustainability,22(6):5129–5152.

Basile,R. (2001).Export behaviourofitalianmanufacturingfirmsoverthe nineties:theroleofinnovation. ResearchPolicy, 30(8):1185–1201.

Benkovskis,K.andWörz, J. (2016).Non-price competitiveness of exportsfromemerging countries. Empirical Economics,51:707–735.

Berg,M.,Hartley,B.,and Richters,O. (2015).A stock-flowconsistent input–outputmodelwith applicationstoenergy priceshocks,interest rates,andheatemissions. NewJournalofPhysics, 17:015011.

Borio,C.andDisyatat,P. (2015).Capitalflowsand thecurrentaccount:Takingfinancing(more)seriously. BISWorkingPapers 525.

Botta,A. (2015).The macroeconomicsofa financialdutchdisease. LevyEconomicsInstitute

ofBardCollegeWorking Paper,850:1–24.

Botta,A.,Porcile,G., Spinola,D.,andYajima, G.T. (2023).Financial integration,productive developmentandfiscal policyspaceindeveloping countries. Structural ChangeandEconomic Dynamics,66:175–188.

Chang,H.J. (1994).State, institutionsandstructural change. Structural ChangeandEconomic Dynamics,5(2):293–313.

Charpe,M.,Chiarella,C., Flaschel,P.,andSemmler, W.(2011). FinancialAssets, DebtandLiquidityCrises

CambridgeBooks.

Chenery,H.B. (1975).The structuralistapproach todevelopmentpolicy. TheAmericanEconomic Review,65(2):310–316.

Cimoli,M.andPorcile, G. (2014).Technology, structuralchangeand bop-constrainedgrowth: astructuralisttoolbox. CambridgeJournalof Economics,38(1):215–237.

Consoli,D.,Costantini, V.,andPaglialunga,E. (2023).We’reinthis together:Sustainable energyandeconomic competitivenessinthe eu. Researchpolicy, 52(1):104644.

Costantini,V.andMaz-

zanti,M. (2012).Onthe greenandinnovativeside oftradecompetitiveness? theimpactofenvironmentalpoliciesandinnovation oneuexports. Research policy,41(1):132–153.

Dosi,G.,Grazzi,M., andMoschella,D. (2015).Technologyand costsininternational competitiveness:From countriesandsectorsto firms. Researchpolicy, 44(10):1795–1814.

Dunza,N.,Naqvi,A.,and Monasterolo,I. (2021). Climate sentiments, transitionrisk,and financialstabilityina stock-flowconsistent model. Journalof Financial Stability, 54(100872):xxxx.

Fagerberg,J.(1988).Internationalcompetitiveness. Theeconomicjournal, 98(391):355–374.

Frankel,J. (2010). Monetarypolicyinemerging markets:Asurvey.NationalBureauofEconomic Research.

Gandolfo,G. (2012). Continuous-time econometrics:theory andapplications.Springer Science&BusinessMedia.

Ghosh,A.R.,Ostry, J.D.,andChamon,M. (2016).Twotargets,two instruments:Monetary

andexchangerate policiesinemerging market economies. JournalofInternational MoneyandFinance, 60:172–196.

Godin,A.,Yilmaz,S.-D., Andrade,J.,Barbosa,S., Guevara,D.,Hernandez, G.,andRojas,L. (2023). Cancolombiacopewith alow-carbontransition?

AFDResearchPapers, 285:1–60.

Godley,W.andLavoie,M. (2007). MonetaryEconomics:AnIntegratedApproachtoCredit,Money, Income,Productionand Wealth.Basingstoke:PalgraveMacMillan.

Grossman,G.M.andHelpman,E. (1991).Trade, knowledgespillovers,and growth. Europeaneconomicreview,35(2-3):517–526.

Haraguchi,N.,Cheng, C.F.C.,andSmeets,E. (2017).Theimportance ofmanufacturingin economicdevelopment: Hasthischanged? World Development,93:293––315.

IMF (2020). WorldEconomicOutlook:ALong andDifficultAscent.InternationalMonetaryFund.

Jackson,A.andJackson, T. (2021).Modellingenergytransitionrisk:The

impactofdecliningenergyreturnoninvestment (eroi). EcologicalEconomics,185(107023):xxxx.

Knoblach,M.,Roessler, M.,andZwerschke,P. (2020).Theelasticityof substitutionbetween capitalandlabour intheuseconomy: A meta regression analysis. OxfordBulletinof EconomicsandStatistics, 82(1):62–82.

Lee,K.andLim,C. (2001).Technological regimes, catchingupandleapfrogging: findingsfromthekorean industries. Research policy,30(3):459–483.

Lee,N.,Sameen,H.,and Cowling,M. (2015).Accesstofinanceforinnovativesmessincethefinancialcrisis. Researchpolicy, 44(2):370–380.

Liu,J.Y.,Xia,Y.,Fan, Y.,Lin,S.M.,andWu, J. (2017).Assessment ofagreencreditpolicy aimedatenergy-intensive industriesinchinabased onafinancialcgemodel. JournalofCleaner Productio,163:293–302.

Lundvall, B. A. (2007). National innovationsystems— analytical concept anddevelopmenttool. Industryandinnovation, 14(1):95–119.

Magacho,G.,Espagne, E.,Godin,A.,Mantes,A., andYilmaz,D. (2023). Macroeconomicexposure ofdevelopingeconomies tolow-carbontransition. World Development, 167:106231.

Mankiw,N.G.(1995). Real businesscycles:Anew Keynesianperspective. MacmillanEducationUK.

Mercure,J.F.,Knobloch, F.,Pollitt,H.,Paroussos,L., Scrieciu,S.S.,andLewney, R. (2019). Modelling innovationandthe macroeconomics of low-carbontransitions: theory,perspectivesand practicaluse. Climate Policy,19(8):1019–1037.

Narassimhan, E., Gallagher,K.S.,Koester, S.,andAlejo,J.R. (2018).Carbonpricing inpractice:areviewof existingemissionstrading systems. ClimatePolicy, 18(8):967––991.

Paroussos, L., Fragkiadakis,K.,and Fragkos,P.(2020).Macroeconomicanalysisof greengrowthpolicies: theroleoffinanceand technicalprogressin italiangreengrowth. Climatic Change, 160(4):591–608.

Pasinetti,L.L. (2001).The principleofeffectivedemandanditsrelevancein

thelongrun. Journalof PostKeynesianEconomics, 23(3):383–390.

Perez-Montiel, J. andManera, C. (2021). Government public infrastructure investmentandeconomic performanceinspain (1980–2016). Applied Economic Analysis, 30(90):229–247.

Peszko,G.,vander Mensbrugghe,D.,Golub, A.,Ward,J.,Zenghelis, D.,Marijs,C.,Schopp,A., Rogers,J.A.,andMidgley, A. (2020). Diversification andCooperationina

DecarbonizingWorld: ClimateStrategiesfor FossilFuel–Dependent Countries.Washington, D.C.:TheWorldBank.

Pietrobelli,C.and Rabellotti,R. (2011). Globalvaluechains meet innovation systems:arethere learningopportunities fordevelopingcountries? World development, 39(7):1261–1269.

Porcile,G.,Alatorre,J.E., Cherkasky,M.,Gramkow, C.,andRomero,J. (2023). Newdirectionsinlatin americastructuralism: Athree-gapmodelof sustainabledevelopment. EuropeanJournalof EconomicsandEconomic

Policies: Intervention, 20(1):forthcoming.

Porcile,G.,Spinola,D., andYajima,G.T. (2022). Growthtrajectoriesand politicaleconomyin astructuralistopen economymodel. Review ofKeynesianEconomics, ...:forthcoming.

Reinhart,C.M.andRogoff, K.S.(2009).Theaftermath offinancialcrises.

American Economic Review,99(2):466–472.

Savona,M.andCiarli,T. (2019).Structuralchanges andsustainability.aselectedreviewoftheempiricalevidence. Ecological Economics,105:244–260.

Sikharulidze,D.(2011).The integrationofsmalland medium-sizedenterprises intoglobalvaluechain.EuropeanScientificJournal, 20:15–22.

Silverberg,G.andVerspagen,B. (1995).Anevolutionarymodeloflong termcyclicalvariationsof catchingupandfallingbehind. JournalofEvolutionaryEconomics,5:209––227.

Skott,P. (2021).Fiscal policyandstructural transformation in developingeconomies. StructuralChangeand Economic Dynamics, 56:129–140.

Stern,N.H. (2007). The economicsofclimate change:theSternreview. CambridgeUniversity Press.

Stiglitz,J.E. (1989). Markets,marketfailures, anddevelopment. The American economic review,79(2):197–203.

Thirlwall,A.P. (1979). The balance of payments constraint asanexplanationof internationalgrowthrate differences. BNLQuarterly Review,32(128):45–53.

UNFCCC (2015). Paris AgreementtotheUnited Nations Framework ConventiononClimate Change.Paris:United Nations.

Yilmaz,S.-D.,Ben-Nasr, S.,Mantes,A.,BenKhalifa,N.,andDaghari, I. (2023).Climatechange, lossofagricultural productionandthe macroecnomy:Thecase oftunisia. AFDResearch Papers,286:1–106.

Yilmaz,S.-D.and Godin,A. (2020). Modellingsmallopen developingeconomies inafinancializedworld: Astock-flowconsistent prototypegrowthmodel. AFDResearchPapers, 125:1–64.

A.1.1. Productionandinvestment

ProductionprocessinallsectorsisdeterminedbyaLeontieffunctionwherecapitalispartially employed, Y P j = min(aj Nj ,uj Kj /bj ) 6.Productionisdeterminedbyactualcapital(K),the capital-outputratio(b)andthecapacityutilizationrate(u),andhencelabouremployed (N )isdeterminedbyproductionandlabourproductivity(a):

where j standsforallproductivesectors: j = {r,n,m

Besideslabourandcapital,intermediateinputsarealsousedforproduction.Thematrices ofdomesticandimportedintermediateconsumption(IC and ICIM )aregivenby

IC

IC

where ci j and ci,IM j arethedomesticandimportedinputsof i necessarytoproduceoneunit of j 7 Forsimplicity,however,weassumethatnatural-resourcesandnon-tradedgoodsare notimported.

Capital(K)accumulatesaccordingtoinvestments(I)andthedepreciationrate(δ).Investmentincreasescapitalwhilstitdepreciatesasaproportionofthecurrentstock,as follows:

Fornaturalresources,allproductionnotconsumeddomesticallyisexported,andhence thereareinventoriesinthissector.Inthecaseoftheothertwosectors,actualinventories evolveaccordingtoactualdemand(Y D)andproduction:

6Knoblachetal.(2020)discusstheempiricalestimatesofcapitalandlaboursubstitutionandshowstheyare verylowintheaggregatelevel.Onecanexpectthatinthesectorallevelitisevenlower.

7Alternatively,inmatricialterms: IC = c ˆ YP andIC

ICisthematrixofintermediateconsumption, c isthetechnicalcoefficientmatrix, YP isthevectorofoutput,thesuperscript M indicatedimports,andthehat indicatesadiagonalvector.

where j′ standsforallproductivesectorsbutnatural-resources: j′ = {n,m}

Sectoralinvestmentisdeterminedbytheexpectedgrossprofitability(re)andtheaverage costofthird-partycapital,whichisgivenbytheaverageoftheinterestrateofnewcontracts (iL,a)andtheleverageratio(l).Thehighertheexpectedprofitabilityconcerningthecostof third-partycapital,thehigherwillbetheinvestmentinnewcapital:

where κ0 istheautonomousinvestment, κ1 isthesensitivityoftheinvestmentratetonet expectedprofitability(expectedprofitabilitydiscountedbyinterestpayments).

Theleverageratioandtheaverageinterestrateofnewcontractsaregivenby

and

where L isthetotallendingindomesticcurrency, LFX isthetotallendinginforeigncurrency, iL and iFX arethedomesticlendinginterestrateandtheworldinterestrate(inforeign currency), µFX isthemark-upoverforeignlendingand iL,e istheexpectedinterestrate.

Expectedgrossprofitsdepend,ontherevenueside,onexpectedsales,expectedprices, advalorem taxationonsales(tY )andspecifictaxonproduction(τ ).8 Onthecostside,it dependsonexpectedunitcosts(UCe).

Producersofcommodities,however,knowthatallproductionnotconsumeddomestically willbeexported,andhencetheuncertainvariablesareexpectedprices(pW,e)andexpected nominalexchangerate(ee).Therefore,expectedgrossprofitabilityisgivenby:

where pK isthecurrentpriceofcapital.

Producersofnon-tradedandothergoodsandservicesareprice-makers.Theexpected grossprofitabilitywillaccountforfutureexpectedsalesasfollowing:

Forallproductivesectors,unitcostsdependonlabourandinputcostsasaproportionof production.Unitlabourcostsaregivenbywages(w),andinputpricesandthetechnical 8Carbontaxesmaybeinterpretedasspecifictaxesifoneassumesthatcarbonemissionsperunitofproduction remainconstant.

coefficientsgivelabourproductivityandunitinputcosts.Inmatricialterms,wehave

orconsideringonlytheinputsdifferentfromzero:

Natural-resourceexportersproduceforintermediateconsumptionandtheexternalmarket andsellalltheirproductionatagivenpriceastheyproducecommodities.Exportrevenue (X)isgivenbyproduction(Y P )discountedbythedemandforintermediateconsumption), worldprice(pW )andthenominalexchangerate(e):

wherethesubscript r referstooperationsofnatural-resourceexporters.

Non-tradablegoodsandservicesproduceonlyforthedomesticmarket,andthesegoods arenotimported.Actualsalesinthissectoraregivenbythesummationofintermediate consumptionofallthreesectorsandfinaldemand.Becausethissectordoesnotexportand doesnotproducecapitalgoods,onlygovernmentandhouseholdconsumptioncontributes tothefinaldemand:

Besidescompetingwithimports,othertradedgoodsandservicesareproducedforthe domesticmarketandexports.Theshareofworldexportsisafunctionofpriceandnon-price competitiveness,asfollow:

where ηX isthepriceelasticityofdemandforexports,whichmeasuresthepricecompetitiveness,and ε = am aW m measurestheimpactoftheproductivitygaponnon-pricecompetitiveness.

Exportsrevenueof m arethusgivenby

where Y W istheworldGDPmeasuredinconstantprices.

RealworldGDPevolvesaccordingtoworldproductivitygrowthandpopulationgrowth:

Importpropensity(σIM m )istheshareofimportsintotaldemand,excludingexports,which includesdomesticabsorptionandintermediateconsumption.Importpenetrationdepends onrelativepricesandthepriceelasticityofdemandforimports(ηIM ):

Thepriceofimportedgoodsinnationalcurrency(

)isgivenbyitsworldprice,the exchangerateandtheimporttax(tIM m ):

Totalimportsare,therefore,thesummationoftheimportshareofdomesticabsorptionand importedintermediateconsumption:

whereabsorptionincludesdemandfromhouseholdconsumption(Cm)andthesummation ofcapitalinvestmentofproductivesectors:

Domesticintermediateconsumptionisgivenbythedomestictechnicalcoefficients,which dependontheimportpenetrationandthetechnicalcoefficient:

and

where T standsfortotal.

Importpenetrationalsodeterminesthepriceofcapitalsinceitistheweightedpriceof domesticandimportedgoods:

Actualsalesofdomesticproducersinothertradedgoodsandservicessector(Y D)is,therefore,givenbyfinaldemandabsorbedbydomesticproducersanddemandfordomestic inputs:

Inthecaseofnaturalresources,totalproductionisgivenby:

Intheothertwosectors,however,capacityutilizationisnotconstant.Firmswillproduce (constrainedbythestockofcapital)accordingtoexpectedsales(Y e),currentinventories (V )anddesiredratesofinventories(

):

istheinvestmentininventories.

Expectedsalesfollowabackwards-lookingprocesswherefirmsadjusttheirexpectation accordingtoactualdemand.However,knowingthattheeconomyisgrowing,theyalso accountforahistoricalgrowthrateofsales,whichhasalong-termfactor,givenbythe historicalgrowthrateofcapital(gK )andamedium-termfactor,givenbythehistorical growthrateofcapacityutilization(gu):

Actualandhistoricalchangeincapacityutilizationratesaregivenrespectivelyby:

Expectedgrossprofitabilitydependsonpricesandexpectedsales.Firmshaveadesired pricebasedontheirmark-up(µn)overunitcosts:

9Inthecaseofinvestmentinfixedcapitalandinventories,theshort-termadjustmentisnotconsideredonce firmsinvestwithafocusonmedium-andlong-termexpecteddemand.Therefore,wehave

Mark-upsadjusttoreducethedistancebetweencurrentanddesiredinventories:10

Producerspriceadjuststowardsthedesiredpriceaccordingtoaspeedofadjustmentthat dependsontheprobabilityoffirms’toremarkprices:

where πe isexpectedinflation(π

).

Salespriceisgivenbyproducerspriceandtaxation,whichincludesadvaloremandspecif taxes:

Firmsborrowonlytoinvest(weabstractfromworkingcapitallending).TotalFinancialNeeds (TFN )offirmsisgivenbytheinvestmentmultipliedbythepriceofcapital(pK )discounted bynon-distributedprofits,whichisgivenbythedifferencebetweennetprofits(NF )and dividends.

where σD istheshareofprofitsdistributedasdividends.

Netprofitsarecalculatedastotalsalesdiscountedbyallcosts(taxation,wages,inputcosts andinterestpayments):

Dividendsaredistributedaccordingtotheshareofinvestorsintotalequity(EQ),anditis proportionaltonetprofits,asfollows:

where i standsforthedifferentinvestors(H, G and F standforhouseholds,governmentand foreign,respectively).

Firmswillfirsttrytofinancetheirfinancialneedsbytheequitymarket,andthen,theywilltryto doitbyforeignlending,andtheremainingfinancialneedsareclosedbydomesticlending. Assumingthatfirmswilluseforeignlendingtoavoidamismatchbetweenrevenuesand 10AsdiscussedbyYilmazandGodin(2020),eventhoughthereisthepossibilityofcounter-cyclicalmark-upsdue tocollusionbygoodproducers,weassumethatmark-upsworkasequilibrators,andhencetheyarepro-cyclical.

costsinforeignanddomesticcurrency,buttheyhaveazerolowerbound,wehavethat

where σIM c istheshareoftradedinputsthatfirmsbelievetobeaffectedbytheexchange ratepath-throughand

Therefore,lendinginforeignanddomesticcurrenciesevolvesasfollows:

where DDI, PDI and FDI are,respectively,householddomesticdirectinvestment,direct publicinvestmentandforeigndirectinvestment.

Householdsconsumenon-tradableandothertradablegoodsbasedontheirdisposable income,wealth,andaccesstonewloans.Households’disposableincome(YDH )includes wages,dividends(Div),interestontheirdeposits(iD)andsocialtransfersfromthegovernment(ST ).However,theyhavetopayincometaxes(tH ),socialcontributions(sc)and interestontheirloans(iL).

wheredividendsincludesthosereceivedfromproductivesectors(j)andbanks(B),and

Householdswilldecidehowmuchtheywillconsumeandthendistributebetweenthetwo sectors.Furthermore,consumptiontakestimetoadjusttoincomeandwealth,andhence targetconsumptionisgivenby

Actualconsumptionadjuststowardstargetconsumptionasfollows:

Thedifferencebetweendisposableincomeandconsumptiongiveshouseholdsavailable fundsforinvesting.Basedontheshareoffirms’investmentintotalinvestment,households willdistributethecompositionoftheirinvestmentasfollow:

Theremainingfundsaresavedasdeposits:

Householdequityevolvesduetonewinvestments,asdiscussedbefore,butalsoduetonondistributedprofits.Thereby,itisgivenby:

Thespendingonnon-tradedgoodshastwocomponents:anautonomousandonethat dependsonrelativeprices.FollowingaLinearExpenditureSystem(LES)withnoautonomous consumptionof m11,wehavethatconsumptionofinrealterms(Cn)isgivenby:

Theremainingconsumptionisthenspentonothertradablegoodsandservices(Cm):

Thelowertheemploymentrate,thelowerthewagebargainingpower;hence,realwagescan growatadifferentrateofproductivitygrowth.Moreover,nominalwagesgrowaccordingto expectedinflation.Thereby,wehavethat:

ALESfortwogoodshasthefollowingstructure:

where γN istheemploymentrateinwhichbargainingpoweriscapableofguaranteeingthat allexpectedconsumersinflationandproductivitygrowthistransferredtowages, pC isthe averageconsumerprices,and pc,e istheexpectedconsumerprices:

and

where λp isthetargetinflationdefinedbytheCentralBank.

Assumingthatgovernmenthasastrictfiscalruleforitsconsumption,whereitchanges accordingtoexpectedinflationandrealoutputgrowth(

),wehavethat:

Governmentconsumesonlynon-tradedgoodsandservices,whichincludesallgovernmentalactivities(publichealth,publiceducationandpublicadministration):

Thegovernmentalsopaysabasicrevenueforunemployedpeople(socialtransfers),and thevaluegrowswithconsumers’inflationandoutputpercapitagrowth:

Asasourceofrevenuegovernmenttaxeshouseholdincomeandfirms’salesandproduction, importsandsocialcontributions:

Governmentinvestsdirectlyinproductiveactivitiesandbanks(PDI).PublicDirectInvestmentisaproportionofgovernmentexpenses,whilstitsdistributionfollowsthecurrent distributionofgovernmentequity:

Governmentequityevolvesduetonewinvestments,asdiscussedbefore,andduetonondistributedprofits:

Besidestheprimarydeficit,thegovernmentmustalsofinanceitsbonds’interestspending. Centralbankprofitanddividendsreceivedfromfirms,ontheotherhand,reduceGovernmentFinancialNeedsasfollow:

where

isgovernmentbondswithbanks,

isgovernmentbondswithforeignersin domesticcurrencyand BFX G inforeigncurrency,

Tofinanceitsdeficit,thegovernmentissuesbonds.Firstly,thegovernmentdecideshow muchbondsareissuedinforeigncurrency(theforeignfinancialmarketswillabsorbthem), whichisexogenoustothemodel:

Thetotalsupplyofbondsindomesticcurrency(B

)willbegivenbythe GFN discountedby bondsissuedinforeigncurrencyaddedbythedifferencebetweenthetargetandtheactual OperatingAccount(OA):

where λO isthetargetoperatingaccountthatgovernmentwanttokeeptoguarantee liquidityasashareofGDP.

Bondsissuedbythegovernmentandabsorbedbybanksaregivenby:

where iB,d isthedesiredinterestratebywhichthemarketacceptstoabsorballsupplyof bonds.

Thedesiredinterestrateisgivenbythepolicyrateplusariskofdefaultpremium,which dependsonthegovernment’sgrossdebt(DG)toGDPratio.

GDPiscalculatedfromademandperspective:

Governmentoperatingaccountandthebondsinterestrateevolveasfollows:

Thegovernmentadjuststheactualinterestratetowardsthedesiredinterestrateatthe speed βiB :

Interestratesaregivenbythepolicyrate(definedbytheCentralBank)andaconstantmarkup:

Banksareobligatedtokeepcompulsorydepositswiththecentralbankaccordingtothe requiredreservesratio(σrr)andtheirtotaldeposits:

Ifdepositsandownfundsareinsufficienttocovertheirlendingandreserves,theyneed advancesfromCentralBank.Ifthereisanexcessofliquidity,theyborrowittotheCentral Bank,whichpaysthepolicyrateasinterestrate

Banksdistributeprofitsaccordingtotheshareofequity:

Forsimplification,weassumethatthedepositsinterestrateisequaltothepolicyrate,

and,hence,banksprofits(excludingcapitalgains)canbewrittenas:

and

Thesummationofdistributedprofitsisgivenby

Banks’ownfunding(OF )evolvesaccordingtonewinvestmentsandretainedprofits

Thecentralbankisresponsibleforthemonetarypolicy,besidesguaranteeingliquiditythrough advancestocommercialbanks.Centralbankprofitisgivenbythedifferencebetween revenuefromtheseadvancesandtheinterestofcompulsorydeposits:

PolicyratefollowsasimplifiedTaylorrule,wherethedistancebetweenexpectedinflation andtheinflationtargetisusedasareference:

where λp istheinflationtarget.(distancebetweenthecurrentandthecapitalutilisationrate theCBthinkisadequatecanalsobeusedtohavethecompleteTaylorrule)

Thecentralbankalsodoesopenmarketoperationswithforeignreserves(RFX CB )toreducethe volatilityofthenominalexchangerate.IfCentralBankwantstokeepthenominalexchange ratefixed,itabsorbsallexcessforeigncurrencysupply(FXS )overdemand(FXD),thereby increasingitsFXreserves.Ifitwantstoletitfloat,itonlykeepsaconstantshareofthe country’snominalGDPasreservestoguaranteeliquidity.Thereby,wehavethat:

wherethevalueof σFX 0 determinestheCentralBank’sintentiontokeep e fixedorfloating.

Firmscanbefinancedeitherbyportfolioorforeigndirectinvestments(FDI)

12.Ashareof worldfinancialflowsgivestheflowofnewforeignequityinvestments(directandindirect)

12FDIisdefinedhereasequityinvestmentsbecausethereisnoothertypeofequityinthemodel.

accordingtotheprofitabilityandtheactualshareofequityintotalequity:

Foreigncapitalflowsalsofinancethegovernmentbybuyingbonds.Inthecaseofbondsin domesticcurrency,whatdeterminestheflowisthedifferencebetweentheinterestratepaid bythegovernmentandtheworldinterestrateaddedbytheexternalriskpremium(limited bythesupplyofbonds):

Theworldfinancialdependsonworldgrowthrateinnominalterms,whichisgivenby populationandproductivitygrowth,andinternationalinflation(

):

Changeinequityis,therefore,thesummationofnewinvestmentsandretainedprofits:

Thenominalexchangerateisdeterminedbytheadjustmentofsupplyanddemandfor foreigncurrency,asfollows:

Expectedexchangeratedepreciationandexpectedcommoditiespricesfollowatypical backwards-lookingexpectationstructure:

Bankswillallocatetheremainingforeigncurrencyasreserves:

Sectoraloutputhastobeequaltototaldemandforguaranteeingabalancedgrowthpath. InaclassicalLeontiefsystem,weneedtohave

,where

isavectorofsectoral production, A isthematrixofdomestictechnicalcoefficients,and FD isavectoroffinal demand(includingchangesininventories).

However,becauseinvestmentinfixedcapitalandchangesininventoriesareinducedby demandgrowth,weneedtoconsideradynamicLeontiefsystem,wheretheinversematrix embodiesthecapital-flowmatrixandthedesiredchangesininventories.Therefore,wehave that

whereYP ,C,G,Xarevectorsofproduction,finalconsumption,governmentexpenditureand exports,respectively, σIM isadiagonalvectorofimportpropensity,and d isthedynamic Leontiefmatrix,whichisgivenby:

B,inturn,isthecapital-flowcoefficientmatrix(consideringthatonlythesector m produces capitalgoods):

and g isexogenouslygivenbythesummationofproductivitygrowthandpopulationgrowth:

g = αPop + αa