THE ETS OPPORTUNITY

Despite polarising views, the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is set to remain a cornerstone of New Zealand’s climate strategy for the foreseeable future.

Words SAM MANDER

all while creating new revenue streams. Carbon farming doesn’t just mean planting pine trees on productive farmland.

WHAT IS IT AND HOW DOES IT WORK?

The ETS is a government initiative regulated by the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It operates as a marketbased mechanism by assigning a monetary value to carbon dioxide emissions through NZUs. Each NZU represents one tonne of carbon dioxide either emitted or sequestered. Unlike emitters who purchase NZUs to offset their emissions, landowners who sequester carbon by growing eligible forests can earn and sell NZUs on market trading platforms. For instance, earning 1000 NZUs in 2024 allows participants to claim and sell them from January 2025, either immediately or by holding them to potentially capitalise on future market gains. At the current price of $63 per NZU, 1000 NZUs could generate $63,000 – similar to trading stocks on a financial market.

ELIGIBLE FOREST LAND

For forest areas to be eligible to enter the ETS they must meet MPI’s ‘forest land definition’:

9 Must be at least 1ha.

9 Have potential to reach an average canopy width of 30m.

9 Have potential to reach a canopy cover of at least 30%.

For farmers, the ETS is not just a potential regulatory mechanism to come – it is a lucrative opportunity, right now. It provides landowners with a pathway to unlock significant revenue streams through carbon-related investments. Some farmers are unknowingly sitting on assets worth hundreds of thousands of dollars in the form of eligible forest land generating offsets via carbon credits or New Zealand Units (NZUs). Although there’s much debate over whether the ETS is fit for purpose, the huge potential for earnings available to farmers within the existing regulatory framework can’t be ignored. It allows farmers to diversify their operations, optimise land use, and contribute to climate goals,

9 Trees that are species that can grow to at least 5m in height.

9 Forest that does not have gaps greater than 15m on canopy edges of perimeter trees or have clear gaps greater than 1ha within forest areas.

9 Met this ‘forest land’ definition after 31 December 1989.

A forest that meets ‘forest land definition’ is labelled ‘Post-1989 forest land’.

Pre-1990 forest land is a forest area that meets ‘forest land definition’ before 1 January 1990. Pre-1990 forest areas are not eligible to be registered into the ETS (figure two).

STANDARD AND PERMANENT ETS FOREST LAND

There are two models available for forest types registering into the scheme – Standard (Averaging) and Permanent.

Standard ETS forest land, formerly known as Averaging, can be applied to any forest, however, is most applicable to rotational forestry (e.g. Pinus radiata plantations that allow flexible timber harvesting). While harvesting requires surrendering NZUs for lost carbon, this can be offset by replanting.

NZUs are earned only in the first rotation, up to the species-specific average age. For Pinus radiata harvested at 28 years that is 16 years old. So NZUs are earned only up to year 16 from planting and in the first rotation only. After harvest, replanting avoids NZU surrender but no additional NZUs are earned in future rotations. This option suits those balancing timber production with carbon credit income.

Permanent ETS forest land is designed for long-term carbon sequestration (usually 50 years) and biodiversity protection. Once registered, these forests must remain standing for at least 50 years, although it does allow for selective harvesting of trees so long as 30% canopy cover is maintained. Permanent forests earn more NZUs over time due to consistent carbon storage, making them appealing for landowners prioritising long-term carbon income and no timber product (e.g. native forests or planted trees where harvesting is not suitable).

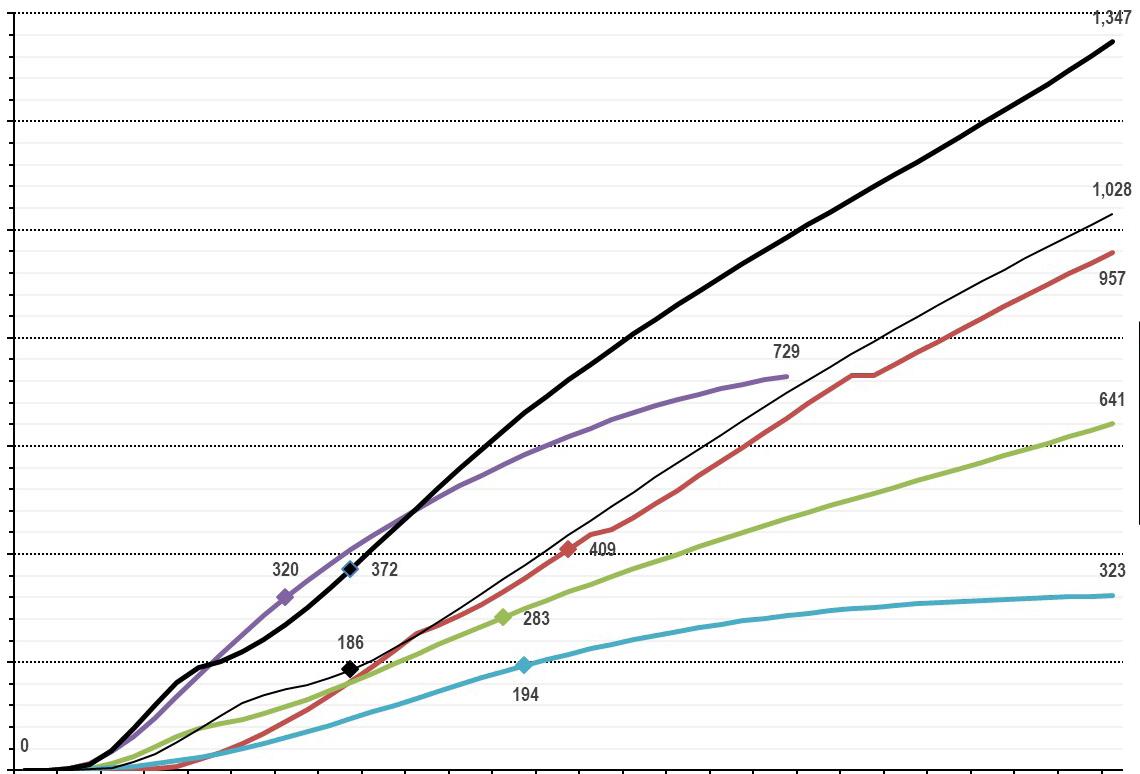

FIGURE THREE. CO2 SEQUESTRATION PROFILES BY FOREST TYPE

CALCULATING NZU EARNINGS

Registered participants earn their NZUs annually based on two methods:

9 The MPI Carbon Look-Up Tables for participants with <100ha registered.

9 Field Measurement Approach (FMA) for participants with >100ha registered.

For most dairy farmers, forest land areas are going to be less than a total of 100ha, therefore the MPI Carbon Look-Up Tables will be used to calculate carbon stocks.

When using the MPI Carbon Look-Up Tables, NZU earnings are fixed annually, on a per hectare basis, based on the age and species of the forest at the time of registration. Registered participants can ‘back claim’ NZUs to the start of a reporting period (currently 2023–2025).

Therefore, if you register in 2025, your forest will start earning NZUs based on its age, starting in 2023. If you miss this window for registration, you will start

earning in the next reporting period (2026–2030).

Pinus radiata is currently the only species that has regional variation. Like much of the ETS, the look-up tables are likely to be in a state of flux going forward as research continues. It’s likely that these tables will be updated in the near future to better accommodate the diverse nature of sequestration across multiple forest species that they do not currently capture.

One major announcement is the consultation released for the exotic hardwoods category, specifically for the changes that may come for space-planted poplar and willow. The proposal is the first of the tables to see an update, and includes creating new carbon tables for these species, with a focus on stocking rates below 220 stems per hectare. This change may or may not take place as of 2026. Changes would have large reductions in NZU

earnings (up to 60%) for low-density planted poplar/willow forests.

CARBON OPPORTUNITIES FOR NEW ZEALAND DAIRY FARMERS

Dairy farmers could potentially enter areas of native regeneration, riparian planting and agroforestry into the ETS, not just plantation forestry blocks.

Dryland corners and inefficient irrigation zones, hill country blocks and laneways could all provide opportunities to enter the scheme and create other farm management wins.

Agroforestry

Agroforestry is the integration of trees into pastures, and is gaining traction as a sustainable farming model that balances productivity and resilience. The approach offers multiple ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration, livestock shade and shelter and improved consumer

perception. Canterbury dairy farms which currently lack shade on a significant scale could benefit on all aspects.

Agroforestry focuses on complementing farming, not diminishing it. Historically, except for poplar and willow species on hill country, agroforestry research in New Zealand focused on woodlot species models, such as interplanted Pinus radiata, Macrocarpa, and Eucalyptus. These trials often showed unacceptable levels of reduced pasture production due to shading from evergreen species, and foresters lost interest as low-density plantings often produced poor-quality timber.

The emergence of NZU earnings has changed the game entirely, shifting the focus from timber production to carbon credits. Forests only require 30% canopy cover to qualify for ETS, a goal achievable with 40 stems per hectare for most species on average.

Poplar is a standout species for agroforestry and is well researched for erosion control on sheep and beef farms. There are limited reasons why it shouldn’t be thought of as of equal value for dairy agroforestry. One study showed that pasture production would only decrease, on average, by 10% at a poplar forest planted for erosion control at 40 stems to the hectare, which is also ETS eligible. Its deciduous nature provides additional sunlight during the winter months rendering more pasture growth.

There is a raft of financial benefits to consider additional to NZU earnings.

One study showed that in hot regions, trees can lower cow body temperature by 0.5–1 degree which resulted in an increase of 1.5–4 litres of milk production, per cow, per day.

Another study showed that providing shade to dairy cows can mitigate heat stress, leading to increased milk production. Specifically, it notes that cows with access to shade produced

TABLE ONE. ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

Summary of the key ETS forest models discussed as Permanent forests. These should be considered as indicative only and as a nationwide average. Capital costs are likely to vary depending on land use. We have used a carbon price sensitivity analysis to show the potential variation in return on investment.

without shade. Research has found cows start using shade when temperatures reach 20°C.

Increased pasture production (especially in hot, dry climates with high evapotranspiration), reduced soil temperatures, improved soil moisture retention, improved biodiversity, improved soil structure, reduced nutrient leaching, and adding highquality fodder from leaves, are all part of the added benefits to agroforestry.

The Exotic Hardwood category currently offers the quickest return for agroforestry. Individual trees can be

MORE READING

are replaced. Farmers may want to take trees over the years for fencing or yard building. Key exotic hardwood agroforestry species include:

• Poplar and Willow

• Eucalyptus

• Mulberry Honey Locust

The Standard or Permanent category can be used, however, most would opt for Permanent.

Native regeneration

Native regeneration presents an opportunity for farmers with eligible

forest land. While high eligibility exists on sheep and beef systems, there are examples on eligible dairy farms. Areas such as the South Island West Coast, Northland, and the Waikato have good opportunity, where there is a nearby local seed source.

One of the key advantages in native regeneration areas is the nil capital investment required, aside from consultant assessments or management costs, as the forest has naturally established itself.

Typically, these regenerating forests are registered at an average age of 15–20 years, though some may be younger or older. Once registered, the forest enters a 50-year permanent sequestration period, allowing farmers to benefit from sustainable carbon credits without significant upfront expenses.

Key species include:

• Mānuka and Kānuka

• Mixed podocarp

• Native growing within gorse Beech

In all instances, the Permanent ETS forest category will be used.

Riparian

Dairy farmers across New Zealand are actively planting riparian zones along waterways. Where eligibility criteria are met, these areas can be registered in the ETS. Forest land does not need to meet eligibility requirements individually; for instance, a 0.8ha riparian planting or a waterway with an average width of

Proposed changes to look-up tables for space-planted hardwoods including poplar and willow.

• mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/58705

Agroforestry and benefits of shade

• massey.ac.nz/~flrc//workshops/12/Manuscripts/McIvor_2012.pdf doi.org/10.1080/00288230809510439

• nzffa.org.nz/farm-forestry-model/resource-centre/tree-grower-articles/february-2009/in-summer-shade-rules-thescience-behind-why-trees-help-maintain-dairy-productivity

less than 30m can be linked to other eligible forest land on the farm to form larger, connected areas. While profits are generally low, carbon income typically offsets planting costs over time. If external funding is secured, these plantings can generate passive income once registered.

In all instances, the Permanent ETS forest category will be used.

Plantation

Less common on dairy farms due to the typically limited areas of non-productive land large enough to support a woodlot stand. However, small woodlots have been successfully established in problematic areas, such as gorse and broom blocks, or in dryland corners on productive farmland.

These areas are retired from farming entirely and can serve as excellent family succession tools. Over 30–50 years, depending on the species, these high-value timber crops generate significant cash at harvest and can be continuously rotated, providing long-term financial outcomes.

Key species examples:

• Pinus radiata

• Redwoods Eucalyptus

• Macrocarpa

• Tōtora

In most cases, the Standard ETS forest category is chosen to allow for timber production. However, many farmers are now favouring the Permanent Forest model due to its quicker, more consistent income and lower establishment and management costs, as it eliminates the need for silviculture.