Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

Luding County, situated in Ganzi Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China, is well known for the “Luding Bridge” and its rich heritage resources. On September 5, 2022, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake struck Luding County. A total of 93 people lost their lives in the earthquake, which also inflicted immeasurable damage on notable heritage sites, including Moxi Town. In fact, this was not the first major earthquake to occur in the region. From the 2008 Wenchuan(汶川)earthquake to the 2013

Ya’an (雅安) earthquake and now the Luding earthquake, western Sichuan has consistently been a earthquake-prone area, with numerous historical heritage sites, such as Tibetan villages, Qiang (羌) villages, and revolutionary monuments, suffering continuous damage. The protection of these historical sites, particularly the unique ethnic heritage of Luding, amid earthquake-prone activity, has become an issue of growing academic interest.

On the international level, the 17th UNESCO session in 1972 adopted Article 10, Section 4 of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which stipulated that world heritage sites affected by earthquakes, landslides, and similar disasters should be included in the List of World Heritage in Danger, representing the first official acknowledgment of the risks that natural disasters pose to heritage. In 2006, the 30th World Heritage Committee officially

adopted the term “Disaster Risk” to broadly refer to hazards such as earthquakes that impact heritage, formally defining the concept and standardizing related terminology for the first time. Over time, international organizations, represented by UNESCO, have issued a series of documents to guide heritage conservation efforts in the context of earthquake disasters. At the local level, with growing public attention to heritage, regulations such as the Regulations on the Protection and

Utilization of Traditional Villages in Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture mandate that governments conduct geological disaster risk assessments, monitoring, early warning, and prevention near heritage sites. At present, a well-developed heritage management system has been established from top to bottom in response to frequent earthquakes.

However, from international conventions to national heritage management measures and down to local regulations, there is a systemic disconnect between Earthquake Disaster Risk (EDR) Management and its actual effectiveness. These measures appear to be ineffective in providing adequate prevention or reduction, as each earthquake still results in extensive damage to heritage sites. During the Wenchuan earthquake, the hydraulic heritage site of Dujiangyan(都江堰)suffered severe damage;1 in the Ya’an earthquake, numerous iconic Hanque(汉阙)stone carvings collapsed.2 These cases not only leave heritage managers with deep regret

1. World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region, “Earthquake Damage to Dujiangyan, Sichuan” (in Chinese), July 21, 2008, https://www.whitrap.org/index.php?classid=1518&newsid=1774&t=show.

2 Xinhua News Agency, “National Cultural Heritage Administration: A Three-Year Plan to Restore Cultural Relics Damaged in the Lushan Earthquake” (in Chinese), Sina News, May 20, 2013, https://collection.sina.com.cn/yjjj/20130520/1007114135.shtml

but also provoke critical reflection: Why do heritage sites continue to suffer significant damage despite the existence of a comprehensive EDR Management framework? How can the synergy between top-level policy directives and practical response measures be strengthened to improve heritage protection? This is an urgent issue that demands our attention.

1.2 Aims of dissertation

The objective of this study is to provide a concise overview of the distinct approaches to heritage management under EDR in Luding County, and to provide reflection for subsequent responses to related situations. It examines how global frameworks such as the ICOMOS Guidelines and national legislations are interpreted, or neglected, within the local context of Luding County. Besides, by identifying key issues in the local management system, such as institutional fragmentation and ambiguous responsibility distribution, the study proposes localized management recommendations tailored to this region.

Additionally, it is expected that the Moxi Town, Luding case study can be used as an opportunity to recognise the vulnerability of the heritage, the riskiness of heritage conservation and the uniqueness of the heritage management approach in the Luding area. It will enable the academic community to identify the difference between the EDR heritage management system in earthquake-prone areas such as western Sichuan and other areas such as Japan and Taiwan, and the need to adapt the conservation approach to the local context.

1.3 Scope of the study

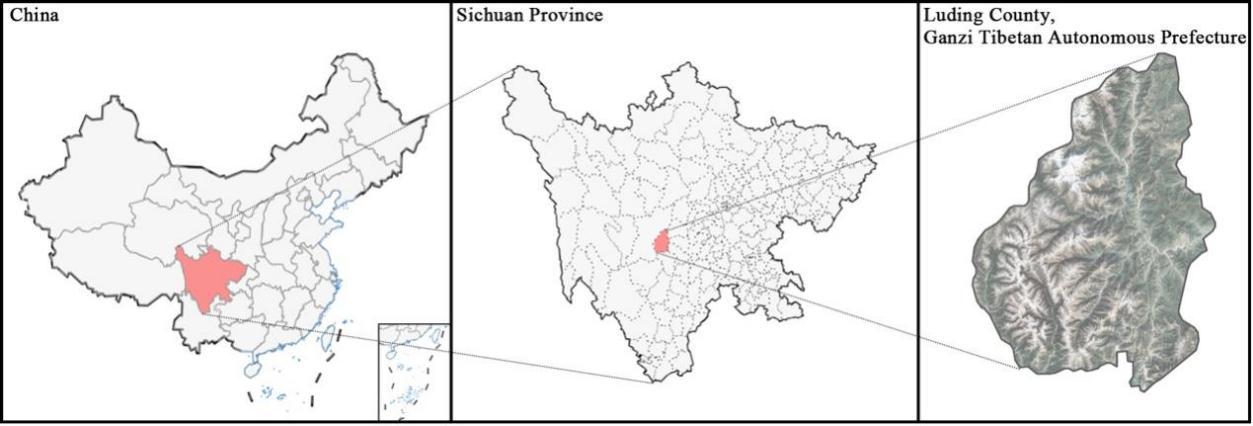

Figure 1. Location of Luding County (Source: drawn by author)

This research takes Luding County as the research area, the 2022 Luding earthquake as its study background, Moxi Town, a renowned traditional village in Luding County, Sichuan Province, as the case study (see Figure 1). It analyzes the various earthquake disaster reduction plans and heritage conservation regulations that providing guidance in Luding, to evaluates their effectiveness in disaster prevention and post-earthquake recovery measures. Based on these findings, it assesses heritage management measures under the EDR context and proposes recommendations.

This study designates Luding County as the research area for several reasons. Firstly, it is a significant cultural heritage hub in western Sichuan, consisting of 90 natural villages including Moxi Town that exhibit rich cultural diversity (see Table

1). 3 The county has well-preserved Tibetan and Yi (彝) settlements and is 3. Luding County People’s Government, “Overview of Luding” (in Chinese), December 12, 2023, http://www.luding.gov.cn/ldgk/article/556361

historically significant due to major events like the “Seizing of Luding Bridge ”

Secondly, from a physical geography perspective, this region features a rare topographic gradient, ranging from deep gorges at around 1,000 meters in elevation to Gongga Mountain at 7,556 meters, resulting in a vertical relief of over 6,000 meters. Situated along the Longmenshan Fault Zone, it experiences earthquakeprone activity, with 12 earthquakes above magnitude 4.5 recorded between 2005 and 2025, making it highly susceptible to secondary disasters such as landslides, rockfalls, and debris flows.4

The high coupling of natural, cultural and policy factors, along with the overlapping risks in this region, makes it an ideal case study for this research.

Table 1. Major Heritage Sites in Luding County

Heritage Protection Level

National-Level

Heritage Name

Tea and Horse Ancient Road Luding Bridge

Site of the Pre-Battle Meeting for the Red Army’s Luding Bridge Assault

Dadu River Suspension Bridge

Provincial-Level Moxi Catholic Church

Former General Headquarters in Hualinping Former Residence of Comrade Zhu De

Former Site of the Lanan Soviet Government

Tang Dynasty Tombs in Ganlu Temple

Prefecture-Level

Burial Site in Baozi Village Luobodikan Neolithic Site Tibetan Watchtower in Maoziping Dadu River Bridge

Cliff Inscriptions at Lengqi

Site of the Battle of Chengzipo Burial Site in Xiatianba

4. USGS, “Earthquake Data for Luding County, Sichuan Province,” https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/search/

1.4 Challenges and limitations

Earthquakes are characterized by sudden onset and unpredictability, posing challenges for immediate response measures. Moreover, the issuance timelines of different management policies also vary. As of the time of writing, two years have passed since the Luding earthquake. Due to time constraints, data collection for this study is subject to a time lag, and the gathered management policy documents exhibit temporal inconsistencies. As a result, this study was unable to conduct realtime field investigations and had to rely on post-earthquake sources such as official releases, media reports, and oral accounts from affected residents.

Despite these limitations, this study will systematically analyze the collected policy information, transforming qualitative data into a structured description to mitigate the effects of temporal inconsistencies.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Evolution of international EDR management

Disaster Risk Management within the realm of heritage conservation has undergone continuous development since the mid-20th century. In 1972, UNESCO’s 17th General Conference adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, which stated, “The Committee shall publish a List of World Heritage in Danger for properties requiring major conservation operations and assistance under this Convention.” It emphasized threats such as fires, earthquakes, landslides, and floods. 5 This is the first time that natural disasters such as earthquakes have been brought to the attention of an international conference in an official form. In 1983, UNESCO’s 22nd General Assembly presented and discussed a report strongly recommending international measures to counter the destruction and impacts of natural disasters, which marks the formalization of UNESCO's inclusion of disaster risk in the field of heritage conservation. However, during this period, UNESCO focused primarily on mitigating the direct risks of earthquakes while neglecting secondary hazards and their long-term effects.

After the 1990s, the United Nations launched the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction program, and ICOMOS began taking responsibility for disaster risk reduction efforts for immovable heritage at international and local

5 UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, Paris, November 16, 1972, art. 11, sec. 4.

Japan,9 Switzerland, and Greece.10 Today, an international disaster risk reduction management framework for heritage, led by ICOMOS-ICORP, has been established. These frameworks provide guidance for large-scale disaster prevention and rescue operations. Nevertheless, the diversity of disaster types, national contexts, and policies globally underscores the need for localized policy documents to refine and adapt heritage disaster risk management systems (see Table 2)

Table 2. International Documents on Heritage Management in the Context of EDR

Year Name and general content

1972 UNESCO’s 17th General Conference publication a List of World Heritage in Danger.

1983 UNESCO’s 22nd General Conference recommending international measures to counter the destruction and impacts of natural disasters.

1990s the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction ICOMOS began taking responsibility for disaster risk reduction efforts for immovable heritage

1994 Establishment of IATF

the International Inter-Agency Task Force on Risk Preparedness and Cultural Heritage

1997 Establishment of ICOMOS-ICORP

the international committee on risk preparedness 2006 the 30th World Heritage Committee adopted the term “Disaster Risk” to broadly refer to hazards such as earthquakes that impact heritage

2.2 Brief description of regional EDR management

On the national level, In the Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China issued by ICOMOS in 2015, it was recognized that “the Wenchuan postearthquake relics rescue project reflects the level of emergency response and professional capacity of Chinese cultural heritage workers in dealing with the

9. Kyoto Declaration 2005: Adopted at an International Symposium on Protecting Cultural Properties and Historic Areas from Disasters (2005).

10. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, “International Workshop on Disaster Risk Management at World Heritage Properties,” https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/526

2.3 Current research on heritage management in the context of EDR

Although research on heritage management within EDR context has developed a relatively comprehensive theoretical framework and practical system at both international and local levels, variations in regional administrative structures and responsibility allocation mechanisms hinder the establishment of universally applicable standards. Research on specific regions still requires a contextualized analysis to uncover their unique characteristics in depth. Ahmadreza Shirvani Dastgerdi examined post-earthquake debris management following the 2016–2017 central Italy earthquakes, emphasizing the importance of international documents such as the Sendai Framework in disaster risk management. 14 He proposed adopting this international framework to enhance the safety and resilience of Italy’s historic villages and towns under the EDR context, addressing the country’s deficiency in national-level management agreements(Shirvani Dastgerdi, 2020) L.

Binda highlighted the significance of interdisciplinary collaboration in postearthquake heritage management by analyzing the establishment of “Function 15: Protection of Cultural Heritage” following the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake in Italy. An effective interdisciplinary collaboration body should consist of cultural heritage representatives, structural engineering scholars, fire department officials, and art specialists from the department of culture. By incorporating representatives from government agencies, heritage academia, emergency management, and cultural 14.United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai, Japan, March 18, 2015.

communities, such collaboration ensures a holistic understanding of heritage attributes and conditions, facilitating the development of more effective conservation strategies and addressing complex challenges(Binda, 2010). Stelios Lekakis conducted a comparative analysis of the effectiveness of Western heritage management approaches and traditional management methods in the cultural heritage restoration practices following the Kathmandu earthquake in Nepal. The research highlights the necessity of recognizing the limitations of conventional Western models in localized contexts and advocates for integrating indigenous management and restoration approaches, utilizing community participation mechanisms embedded in local culture and religious traditions to mitigate natural disaster challenges. Such an approach not only enhances the long-term conservation of cultural heritage but also reinforces community identity and heritage continuity, ensuring the transmission of both tangible and intangible cultural assets to future generations(Lekakis, 2018).

The mountainous region of Western Sichuan, characterized by both a high concentration of heritage sites and earthquake-prone activity, has garnered academic interest regarding heritage management under the EDR framework.

Based on an analysis of post-earthquake reconstruction in the Jiuzhaigou

UNESCO World Heritage Site, Bin Shi argued that the key to achieving the goal of “building back better” lies in linking the restoration process with heritage values.

However, in practice, the recovery and reconstruction planning for Jiuzhaigou failed

to adequately consider these heritage values. Therefore, a shift is needed in the government-driven “top-down” reconstruction model, emphasizing the crucial role of management teams in recognizing heritage values and making informed restoration choices(Shi, 2023). Li Cheng’s research on the Jiuzhaigou earthquake emphasized that post-disaster heritage management and recovery are shaped by various factors. In Tibetan minority communities, religious beliefs serve as a source of spiritual resilience and social cohesion, assisting residents in overcoming adversity and reconstructing their settlements(Cheng, 2025). Similar to Jiuzhaigou, Luding County possesses abundant heritage resources yet experiences earthquakeprone activity. Given its status as a settlement for Tibetan and other ethnic minority groups, these studies offer critical insights for the present research.

In conclusion, scholarly research on heritage management in the context of EDR can be broadly divided into two key areas, the first concerns the study of governance models and legal frameworks. Scholars emphasize the significance of international documents, arguing that in practical applications, international guidelines should be fully respected and effectively implemented. Simultaneously, regional and ethnic specificities should be thoroughly incorporated into earthquake risk responses, utilizing local cultural knowledge and resources to develop a dynamic “global-local” adaptation framework. The second focus is on examining the value of heritage conservation under the EDR context. In standard heritage management practices, factors such as authenticity and cultural diversity are typically prioritized. However,

within the EDR framework, especially in earthquake-prone regions, safety considerations must be equally paramount. When safety consideration conflicts with other heritage management values, whose interests should take precedence?

How can the understanding of heritage values be improved among non-heritage professionals involved in heritage management? These are key questions of concern for scholars.

Consequently, heritage management research under the EDR framework presents a multifaceted challenge. It demands a critical reassessment of the topdown organizational structure to uncover weaknesses in decision-making while also requiring localized approaches that integrate regional characteristics to enhance heritage safety without compromising its values. This bidirectional research aims to establish a new balance between heritage conservation and EDR reduction.

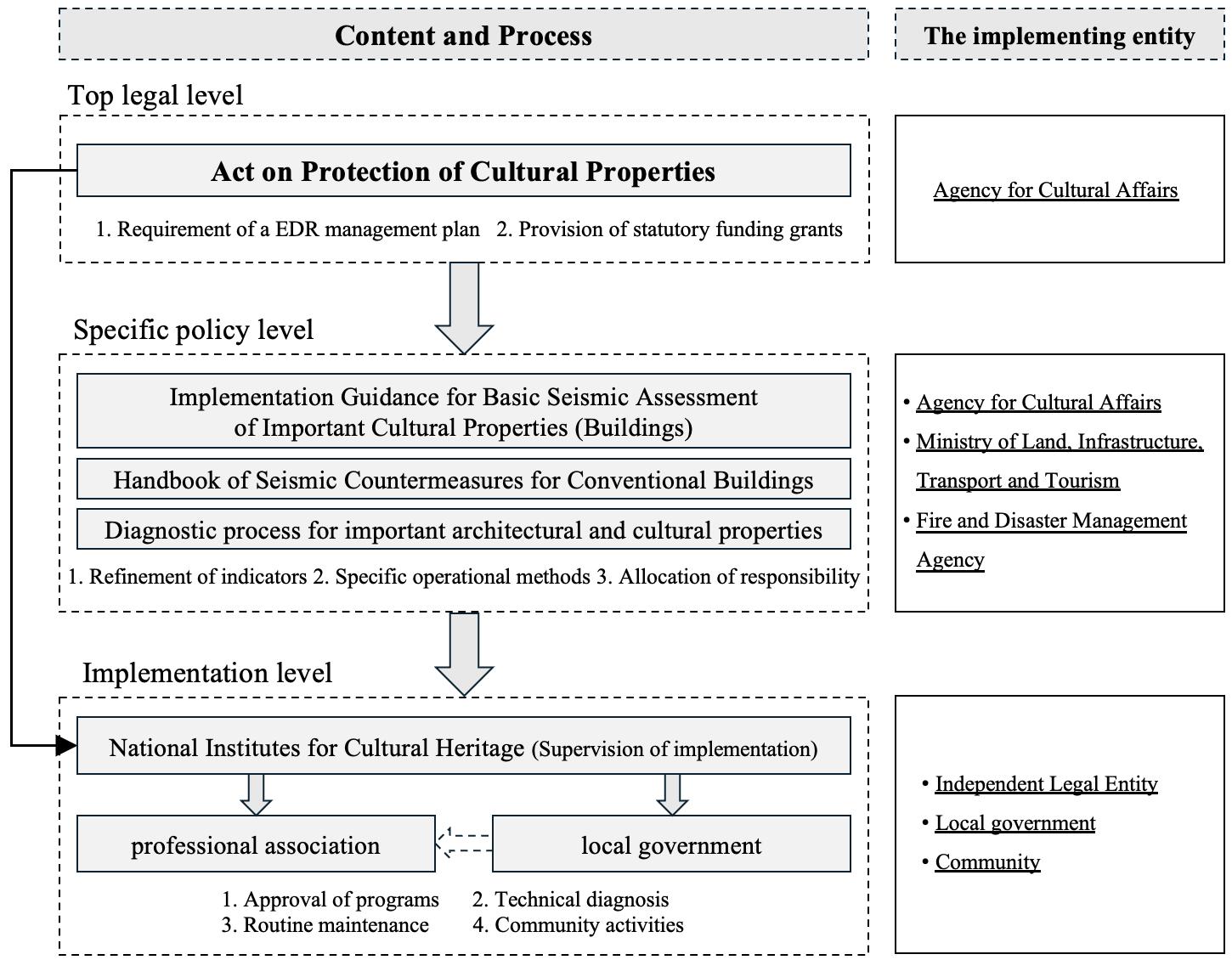

of its management, of its restoration, or of the integrity of its surroundings. The Act on Protection of Cultural Properties grants the government substantial intervention authority in cultural property management and restoration to minimize damage in emergency situations.15

In recent years, Japan has continuously refined its management policies, developing a comprehensive framework that extends from the Act on Protection of Cultural Properties as the overarching legal foundation to encompass technical standards, regional planning, funding mechanisms, and community participation.

This forms a complete chain of “law - operational guidelines -implementation.” The integration of them ensures effective execution of measures. This framework, combining legal enforcement with technical flexibility, constitutes the core of Japan’s heritage management system under EDR.

15 Japan, Act on Protection of Cultural Properties (Act No. 214 of May 30, 1950, as amended to Act No. 7 of March 30, 2007), unofficial English translation from the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo, http://www.tobunken.go.jp/

Figure 2 Heritage Management System in the Context of EDR in Japan (Source: drawn by author)

A notable example is Himeji Castle, a national treasure and UNESCO World Heritage Site, which has preserved significant historical and cultural value since its inception. The “Heisei Restoration” conducted in 2009 was not merely an external refurbishment but a comprehensive EDR reinforcement project. This reinforcement project played a crucial role in Himeji Castle’s resilience during the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (magnitude 7.3). More specifically, these reinforcement measures are directly linked to Japan’s overarching EDR heritage management framework. From the foundational Act on Protection of Cultural Properties to specialized reinforcement guidelines, every layer of Japan’s management framework has been integral to Himeji Castle’s EDR resilience. The synergy between these management

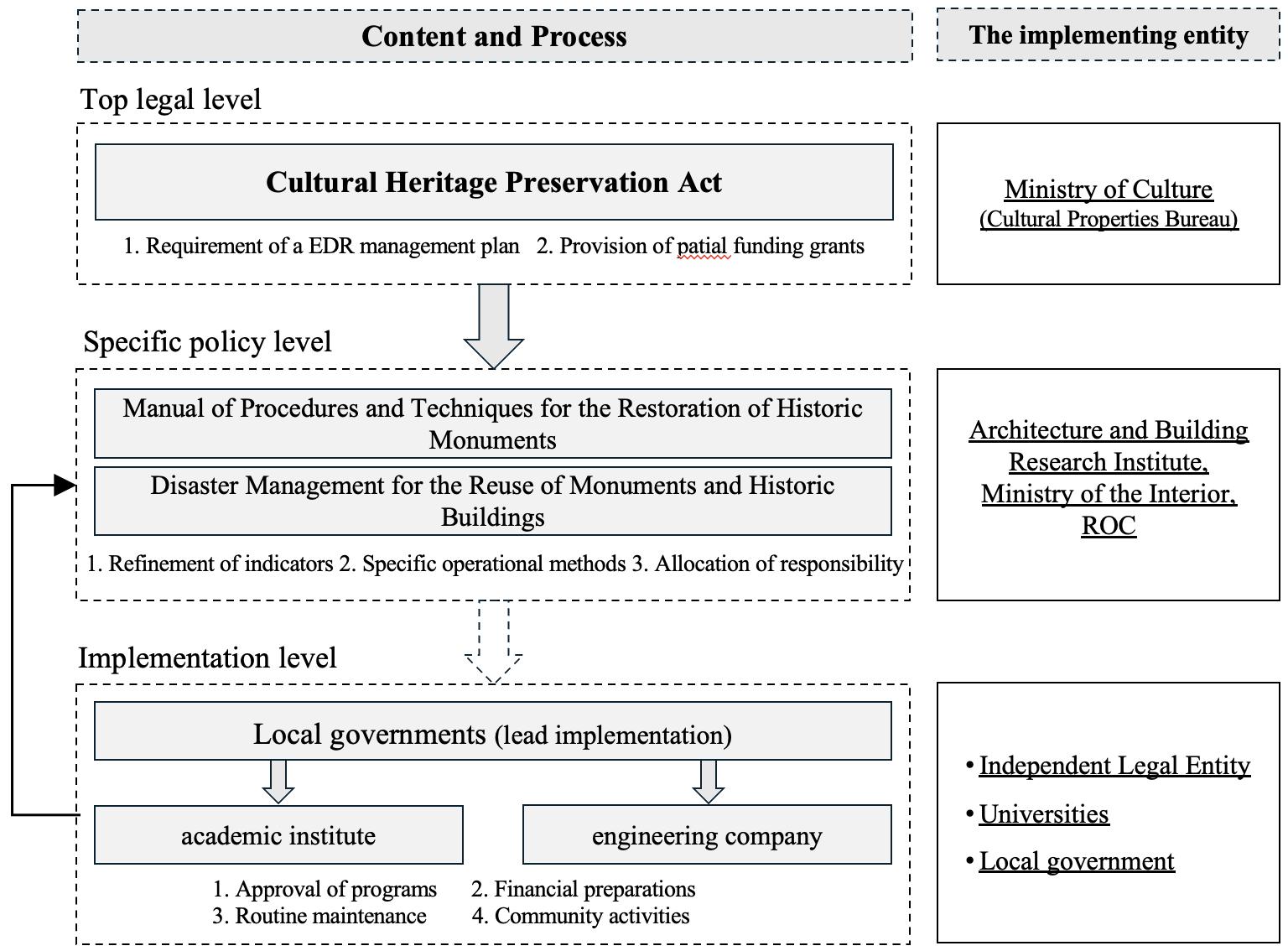

In recent years, Taiwan has developed a multi-tiered EDR heritage management framework, with the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act at its core, enforcing seismic measures, offering detailed guidelines through technical manuals, and enabling local governments to formulate “adaptive reuse plans” tailored to their heritage assets.

Figure 3. Heritage Management System in the Context of EDR in Taiwan (Source: drawn by author)

On the other hand, in contrast to Japan, where centralized laws guarantee national standardization, legal security, and systematic coherence, Taiwan places greater emphasis on local government flexibility and collaboration with universities and communities.

Research, and Restoration & Reuse Plan.” Following the restoration, extensive efforts in heritage EDR prevention were undertaken through local and community collaboration, including designating the area surrounding Longshan Temple as a “disaster prevention priority zone” and mandating emergency response training for nearby residents and businesses.

Up to the present, despite enduring multiple earthquakes, such as the 2013 Nantou earthquake, the 2016 Kaohsiung earthquake, and the 2022 Taitung earthquake, the main structure of Longshan Temple has remained virtually undamaged. Each time an earthquake occurs, community members promptly execute pre-established contingency plans to cordon off dangerous zones, effectively mitigating secondary risk. The case of Lukang Longshan Temple demonstrates how local governments and communities act as the final executors of measures, offering valuable insights for heritage protection under EDR

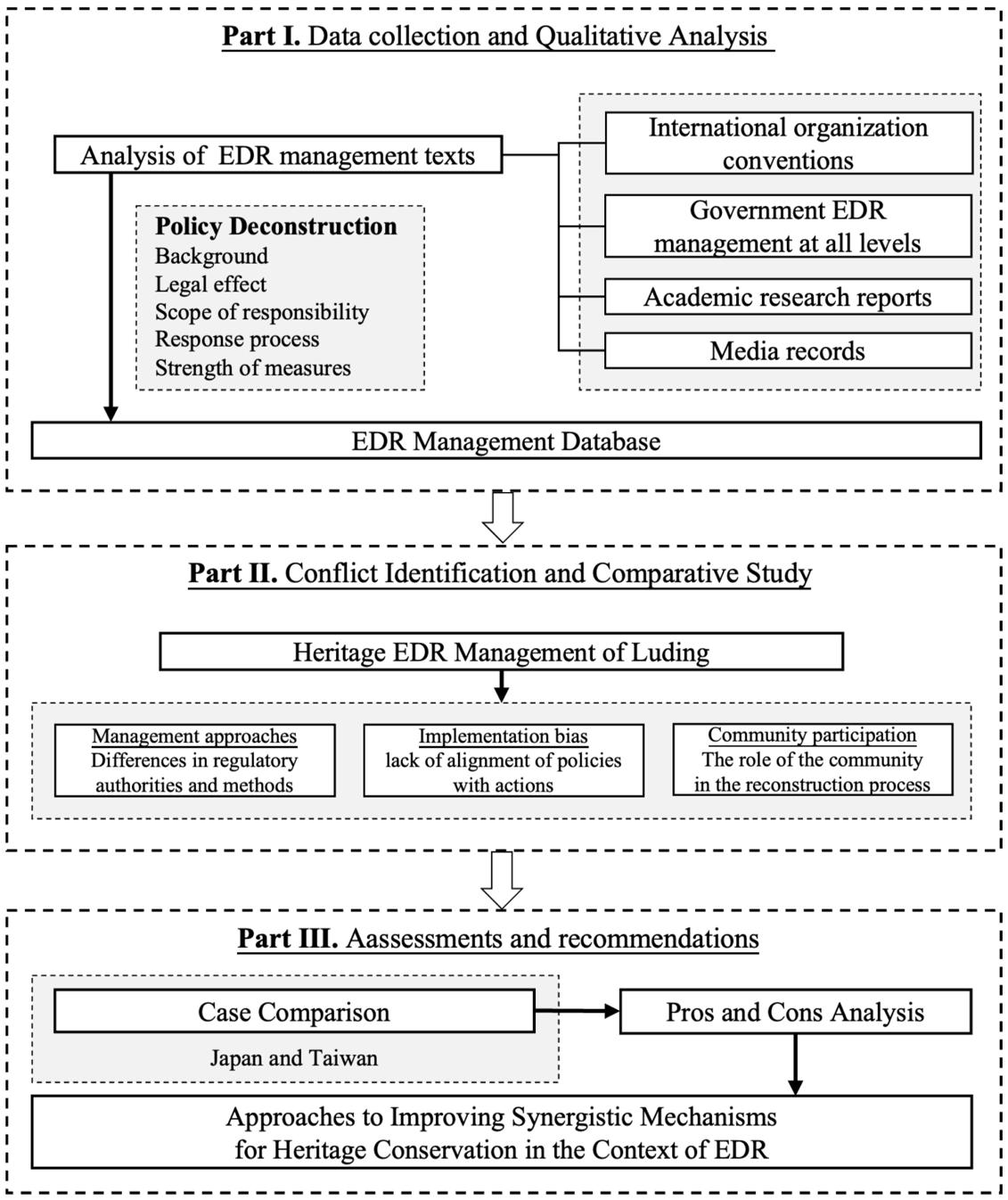

Conducting comparative studies with successful international cases is crucial for scholars and policymakers striving to enhance management frameworks. Japan and Taiwan, which both face frequent earthquakes and possess rich cultural heritage, offer valuable examples for comparative learning regarding heritage management in Luding County’s EDR scenario.

Finally, the study conducts a comparative analysis to highlight the characteristics of Luding’s heritage management under EDR by referencing relevant practices in Japan and Taiwan. The study identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the Luding case in areas such as legal support, community participation, and postdisaster response, offering context-specific recommendations for improving heritage resilience in disaster-prone regions.

Figure 4 Technological Route (Source: drawn by author)

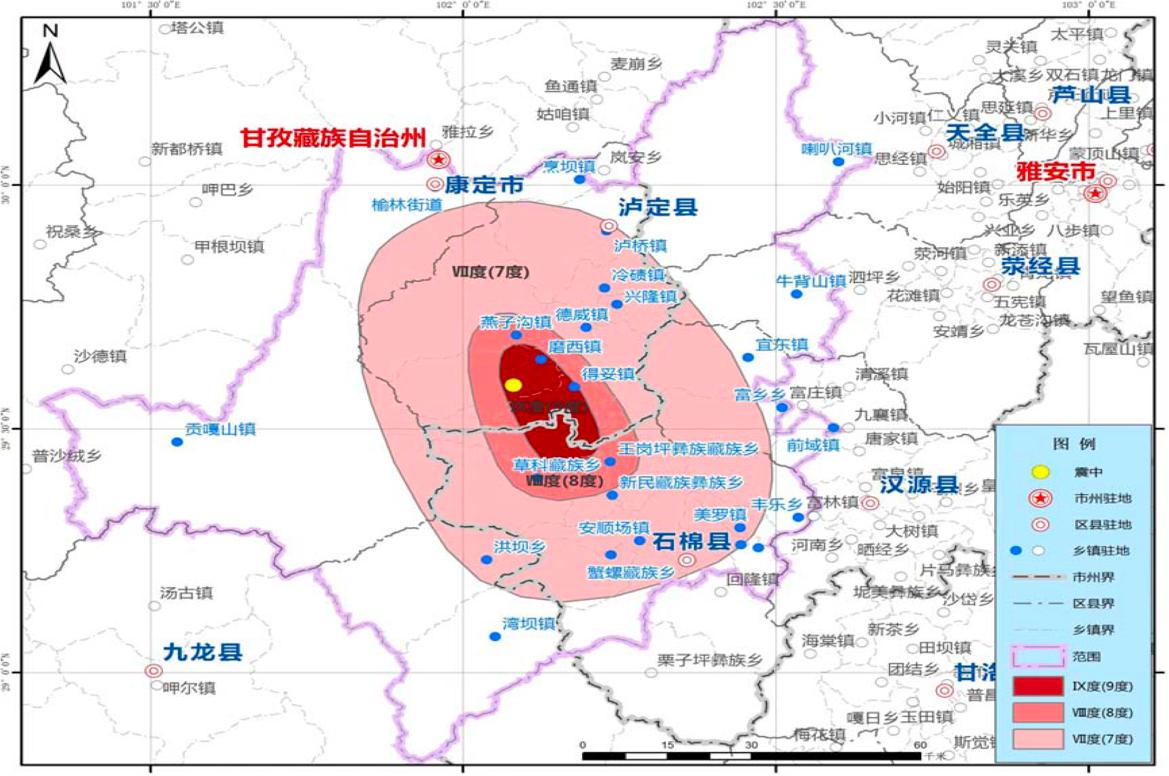

occurrences of cracked brick walls, fallen roof tiles and bricks, building leaning, severe structural deterioration, and total collapses, especially affecting older residential dwellings and traditional wooden structures. Furthermore, landslides, road subsidence, and collapses triggered by the earthquake frequently occurred, severely disrupting key transportation arteries, including National Highway 318 and Provincial Highway 211, thereby impeding the timely arrival of rescue teams and emergency supplies. According to post-earthquake assessments, the towns of Moxi, Detuo, Yanzigou, and Dewei in Luding County experienced the highest seismic intensity level of IX, representing the most severely affected areas (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Seismic Intensity Map (The Moxi Town is in the darkest red area of the map and has the highest seismic intensity. Source: General Plan for Post-disaster Reconstruction of the 9·5 Luding Earthquake, Sichuan Government)

caused extensive damage to Moxi Town’s heritage structures, positioning it as a crucial case study for examining heritage management in the context of EDR in Luding County (see Table 2).

Specific to individual buildings, the Moxi Catholic Church, built in 1918, has long suffered from weathering and earthquake damage, leading to severe issues such as wall cracks, roof leaks, and wooden component decay. The building’s structural integrity was further compromised, especially after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, the 2013 Ya’an Lushan earthquake, and the 2014 Kangding earthquake. In an effort to enhance its preservation, extensive restoration was undertaken between 2019 and 2020, involving repairs to the roof, structural beams, flooring, and interior carvings, along with foundation reinforcement, leading to partial structural stabilization. During the Luding earthquake in September 2022, the church’s bell tower and main walls developed cracks, while parts of the load-bearing walls and columns sustained deformations. Additionally, the priest’s residence suffered exterior wall cracks and structural distortions. Moreover, fissures in the church’s primary structure exceeded one foot in width, with fallen bricks, debris, and wooden boards littering the ground, signifying extensive destruction (see Figure 7).

Table 3. Type of Building Damages in Moxi Town19

Type and Description Level of

1. Cracking of brick walls:

Visible fissures appear across the brick surface, localized structural stress yet not necessarily full integrity loss. Low

2.Falling tiles and bricks:

Roof or wall elements detach and scatter, creating debris that signals minor but potentially worsening structural damage.

3.Building leaning:

The building’s visible tilt suggests significant foundational shifts or framing deformation.

4.Damage to the main structure of the building:

Severe disruptions to loadbearing components compromise the building’s core integrity and heighten collapse risk.

5.Collapse of building:

A substantial portion of the structure has given way, leaving rubble and immediate hazards for occupants and rescue efforts.

Medium

19. Materials 1 and 2 are sourced from China News Service, YouTube video, accessed April 20, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L35D8aknTBE Materials 3 and 4 are from the Lifeline program by CCTV, broadcast December 26, 2022, https://tv.cctv.com/2022/12/26/VIDE4vs71Lyq7H6h3fCCo9Db221226.shtml Material 5 is from Caixin Science, accessed April 20, 2025, https://science.caixin.com/2022-0907/101936844.html

Figure 7. Moxi Catholic Church after the Earthquake (Source: provided by local government)

Figure 8 Moxi Catholic Church before the Earthquake (Source: wikipedia.org)

5.3 National level: Interdisciplinary research on EDR response and heritage management

At the national level, heritage management under the EDR context is currently executed primarily through two administrative lines: cultural heritage authorities and emergency management authorities. Regarding cultural heritage authorities, the highest legislative document at the national level is the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics (revised in November 2024).

The core principles of this law are “protection as primary, rescue as priority, rational utilization, and strengthened management.” Specifically, regarding architectural heritage, it emphasizes restoration principles such as “no alteration of original conditions” and “minimal intervention,” assigning responsibilities to governments at all levels for ensuring heritage safety. Nevertheless, this legal document does not explicitly mention terms such as “earthquake” or “natural disasters,” nor does it include specific guidelines or provisions addressing the protection of cultural heritage, particularly architectural structures, under circumstances involving natural disasters like earthquakes. In other words, this law does not provide explicit guidance or requirements regarding heritage rescue, reinforcement, restoration, or responsive measures specifically in the context of earthquakes and other natural disasters.20

20. People’s Republic of China, Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics (in Chinese), first passed November 19, 1982; latest amendment November 8, 2024.

Regarding emergency management departments, the highest-level legislation currently available is the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protecting Against and Mitigating Earthquake Disasters (revised December 2008). In Article 39, which addresses the seismic resilience of existing structures, it explicitly mandates that buildings of “significant historical, artistic, or commemorative importance” must be evaluated for seismic performance and reinforced when necessary, emphasizing the legislative intent of proactive disaster risk management for heritage sites. According to Article 69, “Local governments are required to coordinate relevant departments and experts to specify protective boundaries and measures for representative cultural heritage sites and structures of historical or ethnic significance, based on earthquake damage evaluation results.” This article sets higher expectations for heritage management after earthquakes, seeking a harmonious balance between emergency response and cultural continuity, thereby aligning disaster management with heritage conservation. Although not specifically a cultural heritage conservation law, it integrates buildings of cultural significance or considerable historical importance into statutory protection within the broader earthquake preparedness framework, thus establishing a legislative foundation that emphasizes both pre-disaster mitigation and post-disaster conservation. This approach is crucial for preserving the authenticity, integrity, and cultural continuity of historic structures.21

21. People’s Republic of China, Law on Earthquake Prevention and Disaster Reduction (in Chinese), revised 2008, adopted May 1, 2009, arts. 39 and 69.

5.4 Provincial level: limitations in vertical policy coordination

Following the Luding earthquake, the State Council’s Earthquake Relief Command Office and the Ministry of Emergency Management elevated the national earthquake emergency response to Level II. The Sichuan provincial government initiated a Level I earthquake emergency response, with military forces, fire rescue teams, and emergency response units rushing to the disaster area to conduct rescue operations.

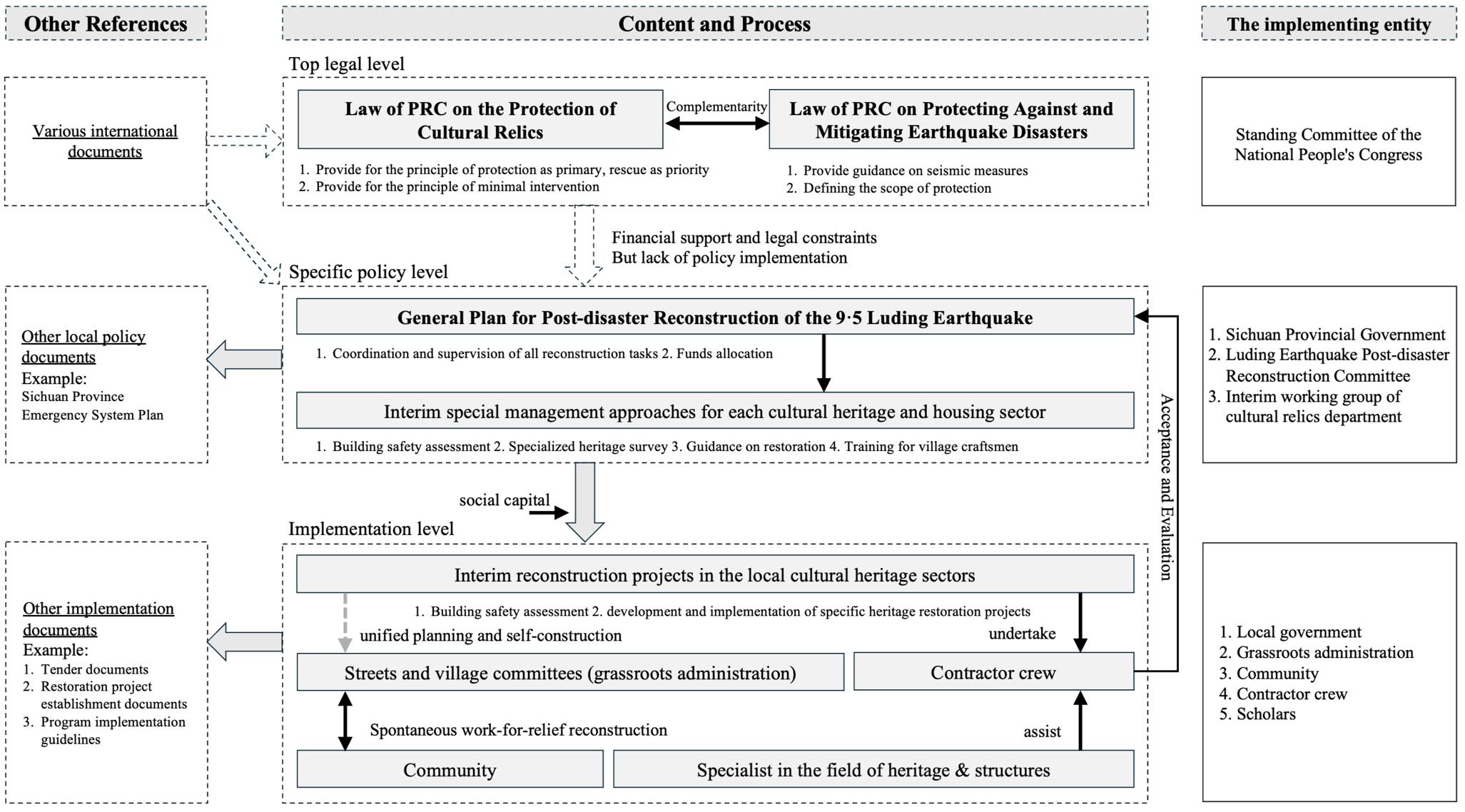

Based on the existing management structure, Sichuan Province swiftly formed the “9·5 Luding Earthquake Post-disaster Reconstruction Committee” and fully implemented reconstruction measures under the guidance of the “General Plan for Post-disaster Reconstruction of the 9·5 Luding Earthquake.” The Plan clearly established an organizational framework with the provincial government at its core, responsible for integrating, coordinating, and supervising all reconstruction activities. Local governments within disaster areas, including Luding County, assume primary responsibility for specific recovery and reconstruction tasks, including drafting and implementing plans, as well as performing maintenance and restoration of cultural heritage sites, thereby ensuring orderly progress of reconstruction. For example, after the earthquake, the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Heritage Administration, collaborating with the Ganzi Prefecture Cultural Heritage Department, rapidly implemented emergency preservation measures for heritage

sites in the affected region. 22 The Luding County Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology conducted structural safety assessments and emergency reinforcement projects for national-level heritage sites such as Luding Bridge, showing the rapid response capabilities of local heritage conservation institutions during emergencies.23

However, from the perspective of heritage management, although the General Plan demonstrates significant attention to post-disaster reconstruction under the direct leadership of the provincial government and provides support for resource integration and mobilization, several limitations are evident upon close analysis of its policy design: First, the plan does not consider the role of international heritage management frameworks or national heritage disaster prevention strategies in this reconstruction effort, thus restricting effective integration of international expertise and national-level resources. Second, the plan notably underemphasizes grassroots governance, insufficiently recognizing the critical contributions made by local neighborhoods, community groups, and ethnic minorities in the reconstruction process. Local organizations have unique strengths in engaging residents, accurately capturing community needs, and swiftly adapting to evolving circumstances. Failure to adequately include these entities could compromise the authenticity of tangible heritage and the effective preservation of intangible cultural

22. Xiaoling Wu, “The Epicenter Damage to Moxi Catholic Church and Mao Zedong’s Former Residence: PostDisaster Protection and Restoration to Be Carried Out in an Orderly Manner” (in Chinese), Sichuan Online, September 7, 2022, https://sichuan.scol.com.cn/ggxw/202209/58602259.html.

23 Jieying Ma, “Moxi Conference Site Damaged by Earthquake: Cracks Over One Foot Long Appear Less Than Two Years After Last Renovation” (in Chinese), Xinde Net, September 9, 2022, https://xinde.org/show/53017

public welfare initiatives, semi-commercial projects, and purely market-oriented ventures.

Concerning funding support, the provincial government exercises centralized control over both the acquisition of central financial resources and their distribution to local administrations. From a macro perspective, the direction of fund allocation not only reflects governmental developmental priorities, but also provides essential support to sectors that are less accessible to free-market mechanisms. For example, this has significantly promoted development in ethnic minority border regions.

Nevertheless, while this model is beneficial for resource integration, it also reveals certain risks related to the efficient use and supervision of allocated funds. For

example, the Sichuan Provincial Discipline Inspection Commission reported corruption involving officials in Sijing Town, Tianquan County, who embezzled postdisaster reconstruction subsidies, highlighting associated risks in fund management processes.26 Therefore, government departments at various administrative levels must urgently enhance their supervision and governance of fund utilization, ensuring that each allocation genuinely contributes to effective post-disaster reconstruction, and facilitating the continuous optimization of funding processes toward greater transparency and efficiency.

26 Sichuan Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection, “Crackdown on Corruption Around the People” (in Chinese), September 2022, https://www.scjc.gov.cn/scjc/dsjm/2024/7/12/26be53f578794530bba622bfcb9576f7.shtml

For buildings classified as Level B and selected Level C, local authorities provided technical guidelines and specialized training during reconstruction implementation, enabling local artisans to conduct reinforcement works, under supervision by technical professionals. This approach, to a certain extent, facilitated the conservation and continuity of historical and cultural characteristics within the villages.27 In contrast, restoration work for heritage buildings must be conducted by teams officially qualified for heritage restoration, strictly following the procedures outlined by the Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics, adhering to the fundamental principles of “minimal intervention” and authenticity preservation. The plan specifically advocated for retaining traditional architectural features, such as earth-wood and stone elements, to preserve the original character at a microscale, while at a macro-scale, it emphasized maintaining the existing spatial structure and street network, discouraging extensive demolition and redevelopment. For damaged components or foundations, the use of concealed reinforcement methods was allowed only after a comprehensive assessment of their potential impacts on heritage values, followed by formal approval by heritage authorities, to confirm compliance with technical standards and guarantee structural safety and integrity.

In the case of Moxi Catholic Church, which possesses significant cultural value, administrative authorities facilitated expert involvement, forming a

27 Sichuan Provincial People’s Government, Special Implementation Plan for the Reconstruction of Urban and Rural Housing and Municipal Infrastructure after the Luding Earthquake (in Chinese), sec. 2, 3, December 2022.

multidisciplinary technical team from architectural heritage conservation, structural engineering, and cultural relic restoration to conduct site inspections. Their conservation plan adhered strictly to the principle of minimal intervention, balancing safety with cultural functionality. As Zheng Kui, Director of the local Investment Promotion Bureau, indicated, the construction team carefully numbered each displaced brick to facilitate precise repositioning, aiming to preserve the authenticity of original construction materials and restoration techniques.28

However, information from the local government indicates that the project management team responsible for restoring Moxi Catholic Church includes Jingyan Engineering Consulting Co., Ltd. and Zhongcheng Hongye Engineering Technology Group Co., Ltd. These teams primarily specialize in infrastructure projects, and although they possess qualifications in “professional contracting of ancient architecture,” they lack substantial prior experience in heritage building restoration.

As of now, the government has yet to release further details regarding the progress of restoration works for Moxi Catholic Church. At the practical level, it remains uncertain whether the current composition of professional teams in heritage conservation projects poses risks related to inadequate expertise, a concern deserving further consideration.

Overall, the heritage management measures under EDR in Luding have demonstrated a relatively systematic approach, with notable strengths in strong

28. Sichuan Daily, “‘Renewal’ of an Ancient Street in Hailuogou Scenic Area” (in Chinese), Sichuan Daily, September 5, 2023, http://sc.news.cn/20230905/0ff3fcc89bc743bba8c7be0ef759de7a/c.html

issues such as vague directives, delayed actions, insufficient coverage, and decisionmaking conflicts, resulting in grassroots governance often playing a greater role at the very beginning.

Village committees, as local administrative bodies in rural China, assumed essential leadership roles during reconstruction following the earthquake.

According to Wang Deqing, village secretary of Wajiao Village(挖角村)in Luding County, before external rescue teams arrived, the village committee quickly mobilized residents to carry out casualty assessments, mutual assistance and selfrescue efforts, emergency resource distribution, and disaster data collection and reporting, demonstrating the rapid response capability of grassroots organizations in emergency situations (see Figure 10) 29 Once professional rescue teams assumed their duties, the village committee gradually transferred responsibilities to them, underscoring their critical intermediary role during the initial disaster relief phase. Ms. Ling, a resident of Gonghe Village (共和村) , recalled that following rescue operations, the villagers’ assembly initiated a “work-for-relief reconstruction(以工 代赈)” project, motivating villagers to actively clear debris and collapsed houses, thereby collectively rebuilding their community. 30 Such autonomous community actions underscore the significant contribution of grassroots organizations to recovery efforts under EDR.

29. Xinhua News Agency, “A Village Party Secretary’s 48 Hours After the Earthquake” (in Chinese), Xinhua News, September 9, 2022, http://www.news.cn/2022-09/09/c_1128988324.htm

30. China Rural Development Foundation, “Our Home, We Build It Ourselves” (in Chinese), December 5, 2022, https://www.cfpa.org.cn/news/news_detail.aspx?articleid=3343

Regarding village housing reconstruction, the model of unified planning combined with self-construction was actively promoted during the recovery and achieved positive practical outcomes. This model refers to government-established planning standards and technical assistance combined with independent construction efforts by local residents. At the Xingfu New Village

resettlement site in Luding County, this approach facilitated the creation of new villages that incorporated traditional Western Sichuan architecture blended with local Tibetan and Yi cultural elements. According to local villager Ouyang Min, she planned to establish a guesthouse and therefore planned to adopt a shophouse style, integrating commercial and residential functions in her new building.31 This model of unified planning combined with self-construction enables substantial resident involvement in housing development and architectural design, ensuring authentic, sustainable preservation of regional cultural heritage, thus offering a practical pathway for the living transmission of local traditions. However, in practice, the varying technical abilities among villagers resulted in inconsistent building quality, adversely affecting housing safety. Therefore, during implementation, essential challenges remain, such as harmonizing overall planning requirements with individual needs, maintaining high-quality construction standards, and ensuring fair distribution of funds.32

31. “‘9·5’ Luding Earthquake First Anniversary: Some Residents Move to New Homes, Confident in Future Life” (in Chinese), China News Service, September 5, 2023, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/sh/shipin/cns/2023/09-05/news969361.shtml.

32 Xinhua News Agency, “‘9·5’ Luding Earthquake: One-Year Anniversary Follow-Up Visit” (in Chinese), Xinhua News, September 5, 2023, http://www.news.cn/2023-09/05/c_1129847306.htm

Figure 10. Wang Deqing participates in disaster relief at the scene (Source: provided by local government)

Figure 11. Xingfu New Village disaster relief site (Source: provided by local government)

Consequently, this study develops a heritage management system in the context of EDR with significant characteristics of Luding County through the analysis of top-down strategies, together with bottom-up disaster prevention practices (see Figure 12 ).

Figure 12. Heritage Management System in the Context of EDR in Luding County

(Source: drawn by author)

However, it is important to recognize that excessively large organizational structures are less conducive to detailed operations and may lead to oversights, especially in heritage conservation tasks that emphasize regional characteristics, uniqueness, and authenticity. Japan’s central-led approach explicitly incorporates detailed procedures and standard guidelines for heritage reinforcement; in contrast,

Luding’s “Committee” lacks adequate management mechanisms in these areas.

Japan’s approach is grounded in extensive legal developments and accumulated expertise, with deep-rooted practices in the EDR field fostering a comprehensive understanding of both international standards and local circumstances. Conversely, in Luding’s model, the temporarily established “Committee” evidently neglects guidance from relevant international documents and national-level legislation, potentially leading to operational oversights and insufficient regulatory supervision due to excessive centralization.

Regarding construction and community participation, Japan, Taiwan, and Luding uniformly apply principles of minimal intervention and authenticity preservation, while also emphasizing the importance of local craftsmen’s participation in the reconstruction process. Japan and Taiwan emphasize the integration of traditional techniques with modern technology, and Luding also promotes maintaining traditional architectural characteristics, demonstrating a shared conservation approach. Additionally, each region supports community involvement to different extents: Luding employs the unified planning and self-

Chapter 6: Discussion and Conclusion

As an important county-level administrative unit in western Sichuan Province, the Luding case possesses significant and unique characteristics. Located at the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau, Luding features ethnic diversity and earthquake-prone activity. Such distinctive geographical and cultural features imply that heritage management strategies here cannot directly replicate experiences from other countries; instead, they must originate from local contexts, exploring locally appropriate management approaches. In this case, heritage restoration illustrates a governance pattern characteristic of China, involving rapid mobilization of multiple resources to ensure efficient emergency responses and post-disaster recovery. Additionally, approaches such as “unified planning and self-construction” and “work-for-relief reconstruction” demonstrate local residents’ strong willingness to engage in village landscape restoration and architectural heritage management, indicating further potential for grassroots organizations in reconstruction activities. However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations of this approach, including relatively low inter-departmental collaboration efficiency and unclear integration of relevant laws and regulations. These issues should not be viewed simply as deficiencies, but rather as inherent challenges in the governance structure of a large nation, particularly in scenarios demanding rapid disaster response, where precise policy formulation and implementation inevitably face potential gaps.

As mentioned above, both the Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics and the Law on Protecting Against and Mitigating Earthquake Disasters provide constraints on heritage management under EDR conditions to some extent, yet they operate independently without effective integration, sometimes even in opposition. Such fragmentation in the legal system poses significant obstacles to establishing a fully integrated and coordinated heritage management mechanism in earthquake-prone areas. Heritage management in earthquake-prone areas is inherently complex, particularly in regions like Luding, as it encompasses structural safety, disaster mitigation technology, and social dimensions such as ethnic cultural identity. Approaches limited to technical or cultural perspectives alone fall short of fulfilling the multiple objectives and sustained benefits required in heritage management. Consequently, for heritage-rich and earthquake-prone areas such as Luding, it is advisable to facilitate active collaboration among government agencies, technical experts, local communities, and academic researchers. This cooperative approach would help minimize informational silos, integrate local cultural features with scientific methodologies, and ultimately create more resilient, comprehensive heritage management frameworks tailored to the EDR context. In Luding and most other parts of China, heritage restoration efforts are generally led by government agencies and external professional teams, with communities primarily participating in auxiliary labor roles or supporting tasks. This model tends to disconnect local cultural knowledge from restoration techniques, leading to unsustainable heritage maintenance and management practices once external teams withdraw. The study

finds that the underlying cause is not a lack of willingness for community participation, but rather the excessive concentration of authority at the provincial level during the restoration process and the overly broad scope of governmental control. Insufficient empowerment of local communities, coupled with a shortage of indigenous craftsmen and technical expertise, has led to a reliance on external construction teams. Moving forward, it is first recommended that local craftsmen be encouraged to acquire professional credentials, progressively building localized, specialized heritage conservation teams. Furthermore, at the regulatory level, it is important to clearly empower community organizations with decision-making roles throughout the heritage restoration process, promoting efficient allocation of public resources and social capital, and transitioning from a model of “government-led, community-executed” to “government-guided, community-actively involved” heritage management.

Situated in a earthquake-prone region, Luding faces a challenge where traditional wooden structures are vulnerable under earthquake conditions, making it difficult to maintain a balance between authenticity and safety, often resulting in prioritizing safety over authenticity, which conflicts with mainstream international heritage management principles. Instead, prioritizing authenticity alone, such as employing traditional restoration techniques, may compromise the seismic resilience of the structures. For instance, despite undergoing major restoration prior to the Luding earthquake, the Moxi Catholic Church still sustained significant

damage. Therefore, achieving an appropriate balance between these two elements represents the central challenge. This study recommends proactively adopting Japan’s restoration approaches emphasizing minimal intervention and concealed reinforcement, as well as deeply exploring local traditional crafts and materials. The conflict between modernity and tradition is not irreconcilable; rather, in the local context, this issue has yet to attract adequate attention from researchers and policymakers. The introduction of extensive professional expertise and focused research will facilitate effective resolution.

Analyzing and evaluating heritage management frameworks should avoid simplistic or premature conclusions based on short-term studies; instead, such evaluations must thoroughly consider broader national institutional contexts, societal backgrounds, and local cultural practices. Due to China’s extensive geographical area and diverse geological and cultural heritage conditions, highly specific policy designs are impractical for universal application; hence, nationallevel guidance necessarily adopts a broader, more macro-oriented approach. In situations where local authorities lack sufficient experience, intermediate governments should mobilize appropriate resources, striving to make contextsensitive decisions and implementing more flexible policies tailored to local conditions. This approach reflects governance experience accumulated by governments at all levels over long-term heritage management practices, as well as compromise solutions resulting from resource constraints and competing

stakeholder interests. It is expected that under the EDR context, heritage management will better achieve coordination between national-level policy guidelines and local practical experiences, balancing technical safety requirements with socio-cultural values, thus serving as a key direction for continuous exploration in the heritage conservation field.

Bibliography

1. Japan. Act on Protection of Cultural Properties (Act No. 214 of May 30, 1950, as amended to Act No. 7 of March 30, 2007). Enacted May 30, 1950; effective August 29, 1950. English translation. http://www.tobunken.go.jp/.

2. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Guidelines for Assessing Seismic Resistance of Important Cultural Properties (Buildings). Approved April 8, 1999; revised June 21, 2012.

3. Binda, L., C. Modena, F. Casarin, F. Lorenzoni, L. Cantini, and S. Munda. “Emergency Actions and Investigations on Cultural Heritage after the L’Aquila Earthquake: The Case of the Spanish Fortress.” Springer Science Business Media B.V., 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-010-9217-3

4. CCTV News. “Ministry of Finance Allocates Budget of 15 Million Yuan for Emergency Road Clearance in Luding Earthquake-Affected Areas.” CCTV News, September 7, 2022. (in Chinese) https://contentstatic.cctvnews.cctv.com/snowbook/index.html?item_id=9534777765344141002&toc_style_id=feeds_def ault.

5. Changhua County Cultural Affairs Bureau and Zhenfu Wang. “Investigation, Research, Restoration, and Reuse Plan for the Lugang Longshan Temple, a National Monument of Changhua County.” May 2022. (in Chinese).

6. China News Service. “‘9·5’ Luding Earthquake First Anniversary: Some Residents Move to New Homes, Confident in Future Life.” China News Service, September 5, 2023. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/sh/shipin/cns/2023/0905/news969361.shtml

7. China Rural Development Foundation. “Our Home, We Build It Ourselves.” December 5, 2022. (in Chinese). https://www.cfpa.org.cn/news/news_detail.aspx?articleid=3343.

8. Cheng, Li Cheng; Jun Li; Huan Ling; Xiurong Wei; Lunchao Mou; Shuang Wu; Geoffrey Wall. “Sustainable Livelihoods Following an Extreme Event: Post-Earthquake Practices of the Tibetan Community in Jiuzhaigou World Heritage Site, China.” Sustainable Development (2025): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3217.

9. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted November 16, 1972. Article 11, Section 4.

10. Cultural Heritage Preservation Act (in Chinese). Ministry of Culture. Amended November 29, 2023.

11. Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture People’s Congress Standing Committee. Regulations on the Protection and Utilization of Traditional Villages in Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Passed June 27, 2022. Article 25. (in Chinese).

12. ICORP, ICOMOS –. “International Scientific Committee on Risk Preparedness.” Accessed January 25, 2025. https://icorp.icomos.org/index.php/about-icorp/.

13. ICOMOS China. Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China (Revised 2015). Articles 17–18. (in Chinese).

14. International Workshop on Disaster Risk Management at World Heritage Properties. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed January 25, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/526

15. Kyoto Declaration 2005: adopted at an international symposium on protecting cultural properties and historic areas from disasters.

16. Lekakis, Stelios; Shobhit Shakya; Vasilis Kostakis. “Bringing the Community Back: A Case Study of the Post-Earthquake Heritage Restoration in Kathmandu Valley.” Sustainability 10, no. 8 (2018): 2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082798.

17. Luding County People’s Government. “Overview of Luding.” Published December 12, 2023. Accessed February 9, 2025. http://www.luding.gov.cn/ldgk/article/556361. (in Chinese)

18. Ma, Jieying. “Moxi Conference Site Damaged by Earthquake: Cracks Over One Foot Long Appear Less Than Two Years After Last Renovation.” Xinde Net, September 9, 2022. (in Chinese) https://xinde.org/show/53017.

19. Ministry of Culture Cultural Heritage Bureau. “National Historic Monument Lukang Longshan Temple Overall Restoration Project and Mural Restoration Explanation Meeting.” Press release October 7, 2022. Accessed February 15, 2025. https://www.boch.gov.tw/home/zh-tw/news/96669.

20. People’s Republic of China. Law on Earthquake Prevention and Disaster Reduction (in Chinese). Revised 2008; adopted May 1, 2009. Articles 39, 69.

21. People’s Republic of China. Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics of the People’s Republic of China (in Chinese). Passed November 19, 1982; amended November 8, 2024.

22. Shi, Bin; Lu Huang. “Research on Optimization of Post-Earthquake Restoration Planning Strategy of Jiuzhaigou World Heritage Site Based on Value Correlation: From the Perspective of Heritage Site Administrators.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 22, no. 5 (2023): 3028–3045. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2171734

23. Shirvani Dastgerdi, Ahmadreza; Flavio Stimilli; Carlo Pisano; Massimo Sargolini; Giuseppe De Luca. “Heritage Waste Management: A Possible Paradigm Shift in the Post-Earthquake Reconstruction in Central Italy.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 10, no. 1 (2020): 76–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-072019-0087

24. Sichuan Daily. “‘Renewal’ of an Ancient Street in Hailuogou Scenic Area.” Sichuan Daily, September 5, 2023. Accessed April 3, 2025. http://sc.news.cn/20230905/0ff3fcc89bc743bba8c7be0ef759de7a/c.html. (in Chinese)

25. Sichuan Earthquake Administration; Sichuan Provincial Development and Reform Commission. 14th Five-Year Plan for Earthquake Prevention and Disaster Reduction in Sichuan Province (in Chinese). December 30, 2021.

26. Sichuan Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection. “Crackdown on Corruption Around the People.” September 2022. https://www.scjc.gov.cn/scjc/dsjm/2024/7/12/26be53f578794530bba62 2bfcb9576f7.shtml. (in Chinese)

27. Sichuan Provincial People’s Government. Special Implementation Plan for the Reconstruction of Urban and Rural Housing and Municipal Infrastructure after the Luding Earthquake (Section 2, p. 3; in Chinese). December 2022.

28. Stovel, Herb. Risk Preparedness: A Management Manual for World Cultural Heritage. ICCROM, UNESCO, ICOMOS, World Heritage Centre.

29. UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Adopted November 16, 1972. Article 11, Section 4.

30. UNESCO. Issues Related to the State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties: Strategy for Reducing Risks from Disasters at World Heritage Properties. WHC-06/30.COM/7.2. Paris: UNESCO, 2006.

31. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “International Workshop on Disaster Risk Management at World Heritage Properties.” Accessed January 25, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/526.

32. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Workshop for Cultural Heritage Managers on Disaster Planning for Central and Eastern Europe and New Independent States.” Accessed January 22, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/events/273.

33. UNESCO World Heritage Committee. World Heritage 28 COM, Distribution Limited WHC-04/28.COM/26. Paris: UNESCO, October 29, 2004.

34. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction, Sendai, Japan, March 18, 2015.

35. USGS. “Earthquake Data for Luding County, Sichuan Province.” USGS. Accessed February 7, 2025. https://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/search/

36. World Heritage Institute of Training and Research for the Asia and the Pacific Region under the Auspices of UNESCO. “Earthquake Damage to Dujiangyan, Sichuan.” Published July 21, 2008. Accessed February 9, 2025. https://www.whitrap.org/index.php?classid=1518&newsid=1774&t=show.