CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research Background

Fromthe18thtothelate19thcentury,significantmigrationoccurredfromChina's southeasterncoastalregionstoSoutheastAsia,bringingreligioustraditionsthrough the practice of “Fen Xiang” (incense division). By the 19th century, Singapore’s Chinesecommunitywasprimarilystructuredaroundfivedialectgroups:Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hainanese, and Hakka, with temples functioning as pivotal centersforbothreligiouspracticesandsocialgovernance.1

The enactment of Singapore's 1966 Land Acquisition Act led to widespread government reclamation of temple lands for urban redevelopment.2 While some historicallysignificantandfinanciallyrobusttemplesreceivedpreservationstatus as national heritage sites, most temples were either relocated or demolished. In response, temples with stable congregations and sufficient financial resources merged, applying for new 30-year land leases and thus creating the United Temples.3

However,uncertaintiesrelatedtoleaserenewalsputthefutureofUnitedTemples

1 KeMulin(柯木林), The Functions of Chinese Temples and Clan Associations in Singapore =“新加坡华人庙宇与 会馆的功能,” Encyclopedia of Chinese Culture in Singapore,accessedMarch22,2025

2 HanghangchaDatabase(行行查行业研究数据库), Amendment History of Singapore's Land Acquisition System

3 Lin,WeiYi, National Development and Integration of Temples in Rural Areas: The Case of Tampines United Palace =“国家发展与乡区庙宇的整合: 以淡滨尼联合宫为例”(Singapore:SingaporeSocietyofAsianStudies, 2006),173–97

at risk. Initially, government objectives prioritized functional integration over the preservationofreligiousandculturalheritage,leavingmanytemplesinadequately protected.4 Additionally,mostUnitedTemplesaremanagedbynon-specialistswho relymoreonpersonalexperienceandintuitionratherthanprofessionalexpertise inspatialplanning,communityengagement,orheritageconservation.Thissituation challenges the temples' long-term viability, highlighting the necessity of policy support, enhanced management practices, and optimized spatial strategies to ensuretheirsustainability.

1.2 Basic Spatial Elements and Layout of Temples

Folkreligionlacksasystematictheoreticalframework,and consequently,temples associatedwiththesebeliefstypicallyexcludeinstitutionalreligiousspacessuchas seminaries,lecturehalls,orscripturehallscommonlypresentinorganizedreligions. Instead, folk temples frequently evolve toward entertainment and social interaction bothfordeitiesandworshippers incorporatingspacessuchasopera stages, teahouses, and folk performance areas. These are complemented by traditional cultural activities including float parades, stilt-walking performances, andNuodances.5 Overtime,astablearchitecturalcompositionandstandardspatial elementshaveemergedwithintemplearchitecture,typicallycomprisingtheprayer

4 HanghangchaDatabase(行行查行业研究数据库), Amendment History of Singapore's Land Acquisition System

5 ZhuYongchun(朱永春), An Analysis of Folk Belief Architecture and Its Elements: A Case Study of Modern Folk Belief Buildings in Fuzhou =“民间信仰建筑及其构成元素分析 以福州近代民间信仰建筑为例,” New Architecture (新建筑),no.05(2011):118–121.

hall(殿堂),worshippavilion(拜亭),forecourt(miaocheng 庙埕),operastage(戏 台),andjosspaperfurnace(化金炉).6

The prayer hall serves as the primary space for enshrining the principal deity. Its interior usually consists of three distinct zones: the entrance area (bu kou 步口), themainprayerhall(zhengting 正厅),andtherearshrine(houxuan 后轩)(Figure 1). The entrance area mainly facilitates movement but may also include incense burners, extending worship space. The main prayer hall is spacious and columnsupported, designed to accommodate worshippers’ circulation and ritual bowing comfortably. Separated by a partition, the rear shrine houses the deity statues, reinforcingitssacredandexclusivestatus.

Theworshippavilionlocatedinfrontoftheprayerhallservesasatransitionalarea

6 LiaoRan(廖然), A Study of Folk Temple Architecture in the Ancient City of Quanzhou =“泉州古城民间信仰宫 庙建筑研究”(Master’sthesis,HuaqiaoUniversity,2023).

Figure1.Spatiallayoutofprayerhallintraditionaltemples.(Source:LiRan6)

bridging the temple’s interior and exterior. Typically, incense burners are placed centrally,flankedbybenchesoneitherside.Thisarrangementnotonlyexpandsthe ritualspacebutalsocreatesacommunalareawhereresidentscanrelax,cooldown, orseekshelterfrominclementweather.

Theforecourt (miao cheng 庙埕) is theopenspace directly infrontof thetemple structure,usuallyrectangularandconnectedtosurroundingroads,residences,and environments.Itsdimensionsvaryaccordingtothetemple'sscaleandgeographical conditions,servingasacommunalvenueforfolkactivities,socialinteractions,and publicperformances(Figure2a).

The opera stage functions primarily for ritualistic performances honoring the deities.Eventssuchasdeitybirthdays,enlightenmentcelebrations,orpeaceprayers held in the tenth lunar month often involve multi-day performances as acts of gratitudetowardsthegods.Localoperatroupesareinvitedtoperformtraditional operas and musical pieces on these stages (Figure 2b). However, opera stages in Nanyang(SoutheastAsia)templesdifferfromthoseinancestraltemplesinChina.

Established primarily by immigrants, temples in Nanyang extended their roles beyondreligiousrituals,becomingvitalcommunitycenters.Theyservedashubsfor clan solidarity, provided comfort against homesickness, acted as informal employment referral points, and functioned as grassroots arbitration centers to mediate local disputes. Temples in Nanyang also played a significant educational role,uncommoninChina.Forexample,ChongWenGe,Singapore’searliestChinese

However, the worship pavilion and opera stage underwent simplification (Figure3).

(a)Independenttemples

(b) SharedPrayerhall

Figure3KeySpatialComponentsofUnitedTemples(Source:Author)

Duetoitsinfrequentuse,theoperastageisnolongerconstructedasapermanent structure;instead,itistemporarilyassembledduringspecialoccasions(Figure4a). Similarly,theworshippavilionwassimplifiedbyremovingitsoriginalroof,replaced by a temporary tent structure under which incense burners are placed. This arrangementmaintainsthepavilion’sritualandcommunalfunctions,enablingdaily worshipandprovidingasocialspacefordevotees.Nevertheless,sometempleshave maintained their original architectural designs; for example, Clementi United Temple retained the traditional style of its worship pavilion during construction (Figure4b).

1.3 Community Participation in United Temples

Thetermcommunityrefersto"agroupofpeoplewholivetogetherinadefinedarea with a sense of organization." Ioannis Poulios categorizes heritage conservation methodologies into three distinct types based on the community-professional relationship: material-based, values-based, and living heritage approaches.8 The material-based approach is expert-driven, prioritizing physical and historical preservation without significant community involvement. The values-based approach recognizes heritage's social significance, encouraging community engagement yet still prioritizing material conservation.9 Conversely, the living heritage approach emphasizes sustainable protection of tangible and intangible

8 Poulios,Ioannis,“DiscussingStrategyinHeritageConservation:LivingHeritageApproachasanExampleof StrategicInnovation,” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 4,no.1(2014): 16–34.

9 Poulios,Ioannis, Existing Approaches to Conservation,in The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach –Meteora, Greece (London:UbiquityPress,2014),19–24.

(a) Opera Stage in Ang Mo Kio United Temple (b) Worship Pavilion in Clementi United Temple

Figure 4 The Opera Stage and Worship Pavilion in United Temples (Source:Author)

heritageaspects,positioninglocalcommunitiesatthecenterofconservationefforts, withprofessionalsplayingsupportiverolestoensuresustainability10

If historical buildings are regarded as cultural heritage, then temples and shrines mustberecognizedasembodyingintangiblevaluesthatfarexceedtheconventional definition of “ intangible cultural heritage. ” 11 Chinese temples, as vessels of traditionalculture,arenotonlysitesofreligiouspracticebutalsoserveasspiritual anchors and communal gathering spaces for Chinese migrants who settled in Nanyang. Over more than a century of evolution, these temples have fulfilled multifaceted roles that extend beyond religion facilitating worship, fostering socialcohesion,andcontributingtopublicwelfareandculturaleducation.

However, with the relocation of temples and their consolidation into United Temples, many have lost their original autonomy and the core community of devotees from their previous locations. This shift introduces considerable uncertainty regarding their future development, particularly in terms of resource allocation, attracting followers in new contexts, and adapting management strategies.Thesechallengesmustbeaddressedtoensurethecontinuedvitalityand relevanceofUnitedTemples.

Atthesametime,templecultureremainsunfamiliartomanyyoungergenerations,

10 Poulios,Ioannis, A Living Heritage Approach: The Main Principles,in The Past in the Present: A Living Heritage Approach – Meteora, Greece (London:UbiquityPress,2014),129–134.

11 QiXiaojin(齐晓瑾), Place and Monumentality: Understanding a Folk Shrine in Fujian =“场所与纪念性 理 解一座福建神祠,” Architectural Heritage (建筑遗产),no.01(2019):92–98.

whorarelyparticipateinrelatedactivities.Theagingoftemplecommitteesreflects anirreversibledemographictrend,posinglong-termsustainabilityconcerns.

HueGuanThyehasemphasizedthatthefutureofUnitedTemplesdependsontheir capacity to serve broader societal needs. He asserts that sustainable temple operation relies not only on attracting new devotees but also on establishing effective management frameworks and meaningful community roles. By acting as catalysts for community development, temples can maintain their relevance and societalvalueovertime.7

Therefore,communityparticipationisessentialtothesustainabledevelopmentof United Temples. However, because spatial decisions are often made by a limited numberofcommitteemembers,theresultinglayoutsmaynotadequatelyreflectthe broadercommunity'sneeds potentiallyhinderingmeaningfulpublicengagement andlong-termviability.

1.4 Literature Review

1.4.1ChineseTemplesinSingapore

UnderstandingUnitedTemplesinSingaporenecessitatesabroaderexplorationof Chinesetemplesasawhole,whichprovidesthefoundationalcontextandresearch basis for this study. According to the Singapore Historical GIS (SHGIS), there are approximately 1,206 physical Chinese temples in Singapore. Scholars such as Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thye have conducted extensive research on these

Temple in 1974. Initially, temples affected by land acquisition expressed strong grievancesregardingrelocation.Inresponse,theauthoritiesagreedtosellaparcel oflanddesignatedforreligioususedirectlytotwoormoreoftheaffectedtemples. Thispragmaticsolutionwasintendedtoreducethefinancialburdenofrelocation, thusgivingrisetotheconceptofthe"UnitedTemple."15

1.4.2UnitedTemples

United Temples represent a distinctive organizational model within Singapore’s Chinesetemplelandscape,emerginginresponsetourbanredevelopmentinitiatives andlandpolicyreforms.Theirevolutioninbothspatialformandsocialfunctionhas garneredincreasingscholarlyattention.

Lin Wei Yi (2006) introduced the concept of United Temples, framing them as symbols of rural-urban integration during Singapore’s modernization 3 Chen Bi (2010)furtherexaminedtheirroleandsignificanceincontemporarycommunities, arguing that temples continue to play vital roles in fostering community connections.14 HueGuanThye(2012)offeredamacro-levelanalysisoftheirorigins, government involvement, and the interaction between temple congregations and stateauthorities,highlightingshiftingdynamicsintemplegovernance.15 Expanding onthis,Hue(2022)proposedaclassificationsystemforsub-templeswithinUnited

14 ChenBi(陈碧), Union and Integration: A Study on United Temples in Singapore XiamenUniversity,2010.

15 Hue,GuanThye,“TheEvolutionoftheSingaporeUnitedTemple:TheTransformationofChineseTemplesin theChineseSouthernDiaspora,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 5(2012):157–74.

Temples, distinguishing them as Ancestral Temples, Geographical Temples, and Deity-RelatedTemples.Hisresearchdemonstratedhowspatial,social,andcultural factorscollectivelyshapetempleformation.16

Whilethesestudiesofferimportantsociologicalandanthropologicalinsights,they largelyoverlookdetailedarchitecturalexaminationsofUnitedTemplespatialforms.

Building on this foundational research, more recent studies have adopted interdisciplinary perspectives, integrating approaches from Architecture and Heritage Conservation. For instance, in the architectural field, Shawn Teo (2015)

conductedatypologicalanalysisof64UnitedTemples,17 revealinguniquespatial, social, and ritual characteristics. His work emphasized the interrelation between spatiallayoutandritualpractice,usingtypologyasamethodologicaltooltodeepen understanding of United Temple design. However, his study did not address the conservation of these temples within the framework of contemporary urban development.18

OstenBangPingMah(2019)andcolleaguesexploredtheapplicationofdigitaland visualizationtechnologiesinsafeguardingtheintangibleheritageofUnitedTemples, including spatial documentation and digital mapping.19 Meanwhile, Huang Shuna

16 Hue,GuanThye,YidanWang,KennethDean,RuoLin,ChangTang,JuhnKhaiKlanChoo,YilinLiu,etal.,“A StudyofUnitedTempleinSingapore AnalysisofUnionfromthePerspectiveofSub-Temple,” Religions 13,no. 7(2022).

17 From1974to2012,atotalof64UnitedTempleswereestablished.Between2015and2019,fournew UnitedTempleswereformed,bringingthecurrenttotalto68.Source:SHGISwebsite

18 ShawnTeo, Using Types – Combined Temples in Singapore (Master’sthesis,NationalUniversityofSingapore, 2015).

19 OstenBangPingMahetal.,“GeneratingaVirtualTourforthePreservationofthe(In)tangibleCultural

(2024), employing a critical heritage research framework, assessed the heritage valueofSingapore’sfirstUnitedTemple theFivefoldJointTemple andproposed a new evaluation model. Her study highlighted the predominance of top-down heritage conservation in Singapore and advocated for greater community participation and the protection of intangible cultural dimensions.20 However, these studies did not involve in-depth analysis of architectural space and were primarily focused on government-level heritage assessment, without fully consideringtheroleoftempleparticipantsinheritageconservation.

1.4.3HeritageConservationandManagement

AsauniqueformofChinesetempleinSingapore,UnitedTemplespossesssignificant historicalandcommunalvalueTheyrepresentmorethanaphysicalconsolidation of religious institutions; they embody negotiated space, shared faith, and communityco-management.Theirsignificanceliesintheintegrationofspirituallife, urban adaptation, and grassroots collaboration.21 As such, United Temples are deservingoflong-termconservationasdynamicandlivingculturalheritagesites.

In the context of heritage conservation and management in urbanizing Southeast Asia,internationalinstitutionsemphasizesustainabilityasakeymanagementgoal,

HeritageofTampinesChineseTempleinSingapore,”2019.

20 HuangShuna(黄舒娜), Critical Heritage Studies and Heritage Conservation Practices in Singapore: A Case Study of the First United Temple, Fivefold Joint Temples =“批判性遗产研究理论与新加坡遗产保护实践 以第 一座联合庙‘伍合庙’为例”(Master’sthesis,NationalUniversityofSingapore,2024).

21 Kerr,JamesSemple,“ConservationPlan,”1982.

community heritage in varying ways, with the key being to ensure that the communitytakesaleadingroleinheritagemanagement,allowingtourismtodrive sustainableheritagedevelopmentratherthanposeathreat27

Thecommunity-centeredapproachisnotonlysignificantinheritageconservation andmanagementbutalsoplaysacrucialroleinspatialplanninganddesign.Guido Cimadomo (2014) emphasizes the importance of bottom-up, community-driven design,wherelocalinputshapesspacesthatmeetgenuineneedsandfostersocial cohesion 28 For United Temples, applying these principles can enhance both functionality and heritage conservation by incorporating community feedback. Involving temple managers and local communities in the design process not only elevates the cultural and functional value of temples but also strengthens communitybonds,ensuringthetemples'long-termsustainabilityandvitality.

In summary, the analysis of architectural space forms plays a crucial role in assessing architectural value during heritage evaluations, while community participation,asapeople-centeredheritagemanagementapproach,isequallyvital.

Exploringtherelationshipbetweenspatialdesignandcommunityinvolvementcan offertemplemanagerssustainablestrategiesfororganizingtemplespaces.

Additionally,duetothelackofheritageprotectionmeasuresforUnitedTemplesby government agencies like URA, investigating community-led approaches to their

27 TimWinter, Conserving Heritage in East Asian Cities: Planning for Continuity and Change,2012.

28 GuidoCimadomo,“ADifferentPerspectiveonArchitecturalDesign:Bottom-upParticipativeExperiences,” 2014.

totheprotectionandtransmissionofChinesetempleculturalheritage.

1.6 Research Methodology

1.6.1ResearchDesignandCaseSelection

This research adopts a comparative case study approach, focusing on two United TemplesinSingapore:AngMoKioJointTempleandChaiCheeUnitedTemple.These twositeswereselectedfortheircontrastingspatialconfigurationsandmanagement models, providing a meaningful basis to examine how temple space influences communityparticipation.AngMoKioJointTemplefeaturesindependentlymanaged sub-temples with separate prayer halls, while Chai Chee United Temple operates underacentralizedspatialandorganizationalstructure.

1.6.2FieldworkPeriodandDataCollectionMethods

ThisstudyconductedfieldworkattwoUnitedTemples AngMoKioJointTemple and Chai Chee United Temple during major festivals to observe spatial use and communityparticipation.ResearchwascarriedoutduringtheNineEmperorGods Festival(October8–11,2024)atAngMoKioJointTemple,andduringtheXuantian ShangdiBirthdayCelebrations(March28–31,2025)atChaiCheeUnitedTemple.

A total of 240 valid questionnaires were collected, with 120 responses from each temple.31 Thesurveysfocusedonworshippreferences(specificvs.alldeities),visit frequency,andagegroup.Inaddition,semi-structuredinterviewswereconducted

31 SeeAppendixB

withtemplemanagersandvolunteerstounderstandspatialorganizationandritual practices.Participantobservationduringthefestivalsprovidedfurtherinsightsinto howpeopleinteractwiththetemplespace.

Respondents ranged from under 20 to over 70 years old, including both regular worshippers and occasional visitors. This helped capture how different spatial layouts influence levels of engagement and participation across age groups and templefamiliarity.

1.6.3DataAnalysisApproach

Survey data was processed using Excel and visualized through comparative bar chart. 32 Analysis focused on the correlation between spatial layout and participationbehavior.Worshippreferenceswerecross-tabulatedwithagegroups andtempletypetounderstandhowspatialdesignaffectsritualinteraction.

The findings are used to support the broader argument that community participationintempleritualsissignificantlyinfluencedbyspatialaccessibilityand layoutlogic,especiallyduringfestiveperiods.Theseresultsarefurtherinterpreted in Chapter 4 to illustrate the strengths and challenges of different United Temple modelsinsustainingactiveengagementandheritagecontinuity.

1.7 Research Significance

ThesignificanceofthisstudyliesinthefactthatthemanagersofUnitedTemplesin Singaporeareoftennon-professionals,anddecision-makingoftenreliesonpersonal

32 SeeChapter4,Figures26and27

experience, lacking systematic spatial planning and heritage conservation awareness.Thisstudyfillstheresearchgapinthisareathroughbothquantitative and qualitative analysis, providing strategic recommendations for temple management and sustainable development, while also offering insights for improvingSingapore’stempleheritageconservationpolicies.

CHAPTER 2 THE SPATIAL FORM AND CONSERVATION STATUS

ThischapteranalyzesAngMoKioJointTempleandChaiCheeUnitedTempleascase studies, comparing them from three perspectives: the composition and transformationofthetemples,thespatialformandlayout,andthecurrentstateof temple conservation. (Figure 5) Through this comparison, it aims to explore the similaritiesanddifferencesbetweenthetwotypesoftemplesintermsofcommunity participationandtemplemanagement.

2.1 The Evolution of United Temple

Located at 791 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1, Singapore, Ang Mo Kio Joint Temple was rebuiltin2011upontherenewalofits30-yearlease Itcomprisestemples GaoLin GongTemple,KimEangTongTemple,andLengSanGiamTemple whichwerefirst merged in 1978 as a result of urban redevelopment in the 1970s. Similarly, Chai Chee United Temple, located on Chai Chee Street and completed in 1995, was formedthroughtheconsolidationofthreetemples:HockSanTeng,ZhuYunGong, andHockLengKengTemple (Figure6)

Figure5.AngMoKioJointTemple(Left)andChaiCheeUnitedTemple(Right)(Source:Googlemap)

21.1Theintroductionofsub-temples

(1)AngMoKioJointTemple

GaoLinGong(檺林宫)

As the oldest constituent temple within Ang Mo Kio Joint Temple, Gao Lin Gong traces its origins back to 1888. It was founded by four immigrants from Nan'an, Fujian,allbearingthesurnameHuang,whobroughtwiththemthedeityXingFuDa RenfromtheirancestralvillageinChina.InitiallylocatedintheareaknownasKow TiowKio,thetemplefunctionedasafamilyshrineandwasthereforealsoreferred toas"TuaLangKong"(TempleoftheLordsinHokkien).Beyonditsreligiousrole,

GaoLinGongalsoplayedavitalsocialfunctioninthecommunity,organizingmajor festivals, establishing schools, and distributing herbal medicine as part of its charitableactivities.(Figure7)

Figure6.LocationofthetwoUnitedTemplesinSingapore (Source:Googlemap)

Over time, the temple expanded to include additional deities, and its festive celebrations grew into large-scale community events. Even after relocation and reconstruction, Gao Lin Gong has continued its traditions, such as maintaining a herbal garden and holding regular spirit-medium consultations. These practices demonstratethetemple'songoingcommitmenttofaithanditssustainedconnection with the local community. Together, these historical and functional attributes highlightGaoLinGong’sculturalheritagevalueanditsenduringvitalityasaliving religiousspaceincontemporarysociety.

Kim Eang Tong, established in 1961 at Cheok Sua, is thesole temple in Singapore devoted to the Kim Eang sect. This Spiritual religious tradition, which blends Buddhist and Taoist teachings, originated from Luofu Mountain in Huizhou, Guangdong, China, and was traditionally practiced only among the Hakka community.

The temple in Singapore was founded by Hu Jin Fu, a devotee of Hokkien Anxi descent. Initially, Kim Eang Tong’s practices such as blade-slashing initiation

Figure7 TheoriginalGaoLinGongtemplebeforethemerger

KimEangTong(金英堂)

rituals and the use of the term "Tong" in its name led to suspicion from local villagersandtheauthorities,whoassociateditwithsecretsocieties.Thetemplewas once even ordered to cease operations for investigation. Nevertheless, Kim Eang TonggraduallygainedafootholdintheAngMoKioarea,servingasaspiritualrefuge thatprovidedblessingsandhealing.Thetemplegainedparticularrecognitionforits use of talismans and practices rooted in traditional Chinese medicine, with the temple master highly regarded for his expertise in herbal remedies. In 1975, the templewasmovedaspartofthearea'surbantransformation.

LengSanGiam(龙山岩)

Leng San Giam was founded in the 1950s on Cheng San Road by Chew clan immigrantsfromYongchunCounty,Fujian,China.ThetempleisdedicatedtoFaChu Gongandisrenownedamongdevoteesforitsperceivedspiritualefficacy,especially forrevealing“luckynumbers”relatedtogambling.

Accordingtoworshippers,FaChuGongonceinstructedthatthetempleshouldbe builtonaspecificsitetoavoidfuturedisruptionscausedbyurbanredevelopment. However,duetoalackofunderstandingoftheconceptof“redevelopment”atthe time and failed negotiations, the villagers were ultimately unable to construct the templeonthedesignatedsite.33

33 “ANGMOKIOHERITAGETRAIL:ACompanionGuide,” Ang Mo Kio Heritage Trail Booklet,2021, https://www.studocu.com

(Source:nlb.gov.sg)

ZhuYunGong(竹云宫)

ZhuYunGongTemplewasestablishedinthe1960s,originallylocatedatLane33in Geylang, and has a history spanning several decades. The temple enshrines a number of deities including the Monkey God (Qi tian Da sheng), the North Pole

HeavenlyEmpress,SacredLordZhang,theGreatEmperorforHeavenlyAssistance (GuanGong),andNezha,theThirdPrince.Ithaslongprovidedreligiousservicesto peoplefromallwalksoflife,earningdeeprespectandenjoyingasteadystreamof devotees.

As the number of followers grew, the temple outgrew its original space and was relocatedtoNo.1T,SiglapRoad,whereitwasrebuiltin1970.In1988,duetoland redevelopmentplans,itwasmovedagaintoNo.11,NapaiRoad.However,sincethe government did not approve the site for religious use, the temple formed a Construction Committee in 1990 to manage fundraising and rebuilding efforts. It wasofficiallyregisteredin1992.

Figure8 This1993photographshowstheHockSanTengTemple,locatedoffNewUpperChangi Road(formerlyOldChangiRoad).Thetempleisawoodenstructureraisedonstonebalusterswith azincroof.

Thatsameyear,undertheinitiativeofHockSanTengTemple,ZhuYunGongTemple joined Hock San Teng and Hock Leng Keng Temple Temples to establish the Chai

CheeUnitedTemple.ConstructionbeganinFebruary1994andwascompletedon5 May1995.Onthesameday,thedeitiesofZhuYunGongTemplewereceremoniously usheredintothenewpremisesandenthroned.

HockLengKengTemple(福灵宫)

HockLengKengTemple,dedicatedtotheHeavenlyEmperor(XuanTianShangdi), has served the local community for over a century. According to a plaque in the temple, it was founded by five respected elders Zhou Biguan, Cai Baohe, Chen Xiaosong,LinWumao,andHuangZiying.Thetemplebeganasasimpleattap-roofed hutbuiltforworship.

Duetoitslonghistoryandstrongsupportfromdevotees,amanagementcommittee wasestablished25yearsagotooverseetempleaffairs.Beyondreligiousfunctions, the temple also supports charitable efforts, providing care to the underprivileged andelderlywhenresourcesallow.

In 1985, the temple was affected by MRT construction plans. The committee launched a fundraising campaign for relocation, receiving strong community support.In1995,thenewtemplewascompleted,andthedeitiesweremovedtothe newlybuiltChaiCheeUnitedTemple.35

35 FromBooklet: Introduction to the Establishment of Chai Chee United Temple, https://www.chaicheeunitedtemple.org.sg/, accessed March 22, 2025.

CheokSuakampong,whereasGaoLinGongwasalreadylocatedatthecurrentsite anddidnotrelocate.Therefore,afterthemerger,GaoLinGong,actingasthe“host,” was placed in the central position, while Leng San Giam and Kim Eang Tong, as “guests,”occupiedthesides.

2.1.3 Naming United Temples

Regarding the naming of United Temples after the merger, Lin argues that the degreeofintegrationamongmergedtemplescanbereflectedinthenamingmethod. Hueobservedthattemplesoftenadoptnamesderivedfromgovernment-designated administrative districts when creating new titles,” while some others attempt to create new names by combining characters from the original temples. In the two case studies discussed here, both temples adopted administrative district naming conventions. Although this approach may weaken the individuality and historical associations of the original temples, it highlights the urban history of the temples andreflectsthenationalcontextofrapidurbanization.Thetwocasesarelocatedin theAngMoKioandChaiCheeareas,respectively.

2.2 Spatial Layout of the Case Study Temples

2.2.1Spatialformfollowssocialfunction.

AccordingtothemanagementofAngMoKioJointTemple,beforeitsrelocation,the operastageofGaoLinGonginthekampongnotonlyhostedreligiousperformances but also functioned as a classroom for local children. The temple had even establishedaChineseschool,apracticethatwascommonamongmanytraditional

Chinesetemples(Figure10).Withurbanization,thesocialfunctionsoftempleshave gradually shifted. While their religious role remains, their social role has evolved fromservingspecificgroups suchasprovidingcommunity-basedhealthcareand education to offering broader services such as charitable aid, student sponsorships, and community events. This functional transformation, driven by urbandevelopment,inevitablyleadstochangesinspatialconfigurations.

For example, the opera stage, which once also served educational purposes like functioning as a classroom, has been significantly diminished. Due to land constraints, opera stages are no longer permanent structures but are now temporarilyerectedforspecialoccasions.Forexample,inOctober2024,duringthe celebrationoftheNineEmperorGodsFestivalatLengSanGiamDouMuGong,Ang MoKioJointTempleerectedatemporarystageforpuppetperformances(Figure11).

TheForecourt,ontheotherhand,wasintentionallypreservedasavenuefortemple eventsandrituals.Todemarcatethespace,UnitedTemplesoftensetuptemporary metal-framedtentswithredandwhitestripedplasticcanopies,whichalsofunction as worship pavilions with incense burners placed beneath. This arrangement preservesthetraditionalspatiallayoutoftempleceremonies(Figure12).

Figure10 TheChineseschoolofGaoLinGongduringthekampongera.(Source:GaoLinGong)

Figure11.LengSanGiamDouMuGongstageforapuppetshow.2024.10.11.(Source:Author.)

Accordingtoaninterview36 withthemanagementofGaoLinGongatAngMoKio

JointTemple,thedecisiontounitethetemplesin1978involveddiscussionsbythe committeesofthethreetemples.GaoLinGong,the"maintemple,"wasplacedinthe center,whileKimEangTongandLengSanGiamwerepositionedoneithersideas "guest temples."Thisspatial arrangement consideredtheinfluenceoftheoriginal locations of the temples on devotees. For those United Temples sharing the same prayerhall,hierarchyisreflectedinthesizeofthespacewheredeitiesareenshrined.

Inthelate1980s,thelandforHockSanTengwasrequisitionedbytheHousingand DevelopmentBoard(HDB).Afterrequestinglandfromthegovernment,thetemple was granted a 2,000-square-meter plot in 1992, where both Chai Chee United Temple and Hock Leng Keng Temple were registered. Within Chai Chee United Temple,thewidthoftheshrineforHockSanTeng’smaindeity,FuDeZhengShen (Tua Pek Kong), including the Tai Sui altar, is 7.2 meters; the shrine for Zhu Yun Gong’sQiTianDaShengis6meters;andtheshrineforHockLengKeng’sXuanTian ShangDiis4.8meters.Thespatialratioofthethreeshrinesisthusapproximately 6:5:4.(Figure13)

36 InterviewwithtemplemanagerofGaoLinGongTemple,seeAppendixA,InterviewTranscript.

Figure13 ShrineAreasamongtheTemplesinChaiCheeUnitedTemple (Source:Author) Notably,thespatialhierarchyisreflectednotonlyinthesizeoftheshrinesbutalso inthearchitecturalstructureofthetemple.Thewidthofeachshrinecorresponds exactlytothecolumnspacing intheprayerhall.Beforethetemple’sconstruction, the positions of the front columns for Hock San Teng and Zhu Yun Gong were deliberatelyadjustedtoaccommodatethewidthoftheshrines,furtheremphasizing theimportanceandrankofeachdeitywithinthetemplelayout.(Figure14)

14 SpatialRelationshipbetweenShrinesandColumnsinChaiCheeUnitedTemple (Source: Author)

Oneofthekeyreasonsforthisspatialhierarchyliesinthearrangementofdeities withinasharedprayerhall,wheretheorderrespectsthehierarchicalstructureof theTaoistpantheon.37 Amongthedeities,TuaPekKong(FuDeZhengShen)holds arelativelyhighpositionintheTaoisthierarchy,whichexplainshislargernumber ofdevotees.

Another contributing factor is economic strength, although in shared-main-hall temples, the spatial hierarchy is less affected by financial power. In contrast, in templeswithindependentprayerhalls,suchasthoseinAngMoKioJointTemple, economicresourcesplayamoresignificantroleindeterminingspatialhierarchy eveniftheprincipaldeityofasub-templedoesnotholdaparticularlyhighposition intheTaoistpantheon.(Figure15)

37 ShawnTeo, Using Types – Combined Temples in Singapore (Master’sthesis,NationalUniversityofSingapore, 2015).

Figure

devoteesandhasmoreflourishingincenseofferings.

Figure16 TaoistDeitiesofAngMoKioJointTemple (Source:Author)

Therefore, whether temples share or maintain independent prayer halls, spatial hierarchy within United Temples is closely related to the number of devotees, reflectingthepopularityandcommunityengagementofeachsub-temple.

22.3FunctionalSpaceAnalysis

Currently,theUnitedTemplesareequippedwithofficespaces,meetingrooms,and other facilities to allowtemple managers tobetter handle daily tasks, particularly financial work. Storage rooms and warehouses are also provided for keeping incenseandspiritpapers.Additionally,therearekitchensandrestrooms.However, thekitchenisgenerallysmallandonlysuitablefordailyuse.Duringmonthlyrituals or deity birthdaybanquets,meals areusuallyorderedfromoutsidevendors,with onlyasmallportionoffoodpreparationdonewithinthetemplekitchen.

AtAngMoKioJointTemple,notonlyaretheprayerhallseparate,buttheauxiliary spaces suchastheofficesandkitchens arealsoindependentlyarrangedforeach

(a)NineEmperorGods (b)SanWangFuDaRenandYangFuYuanShuai (c)SanJiaoLaoZuShi -LengSanGiamTemple -GaoLinGongTemple -KimEangTongTemple

sub-temple. These service spaces are symmetrically laid out, meaning the spaces andfunctionsonbothsidesofthecentralaxisaremirrored.Incontrast,ChaiChee

United Temple has only one set of shared service spaces for the entire temple, including a single main office that serves all three sub-temples. (Figure 17) A dedicatedstaffmemberisresponsibleforhandlingthetemple’sfinancialaccounting there.

During the relocation process, due to urban development, limited space in new templebuildings,andgovernmentregulations,manytempleswereunabletofully preserve historical objects such as plaques or community activities like night marketssurroundingtheoriginalkampongtemples.Asaresult,devotees’memories oftheoriginaltemplesandtheirsurroundingcommunitiesaregraduallyfading.In addition,therelocationoftemplesfurtherawayfromtheiroriginalneighborhoods has led to a decline in the number of worshippers. Coupled with Singapore’s multiculturalsociallandscapeandthenon-utilitariannatureofTaoism,thenumber ofyoungdevoteeshasalsobeendecreasing.

Figure17.ComparisonofAuxiliarySpacesintheTwoTemples (Source:Author)

According to interviews conducted by Huang Shuna with the management committeeoftheFivefoldJointTemple,whilethenumberofyoungworshippersis currentlydecreasing,someoverseasyouthstillvisitorparticipateduringweekends ortempleceremonies.Meanwhile,manyMalaysianyouthremaindevotedtotemple worship, having followed their parents in these practices since childhood, and a significantnumbercontinuetotraveltoSingaporeforworship.20

Similarly,inthefieldresearchandinterviewsconductedforthisstudy,templesare facing challenges such as a declining number of devotees and the erosion of memories associated with kampong temples. However, temple managers emphasizedthatsuchchangesareinevitable.Whatismoreimportantnowishow tocarryonthetradition,whichremainshighlysignificantforChinesetemplesand ChineseculturalheritageinSingapore.

2.3 Conclusion

In conclusion, This chapter presents a comparative analysis of Ang Mo Kio Joint Temple and Chai Chee United Temple, focusing on three aspects: temple composition,spatiallayout,andconservationstatus,torevealhowUnitedTemples haveevolvedandadaptedunderurbanredevelopment.

Both temples were formed due to land policies, with mergers mainly based on geographical proximity rather than deity systems or dialect groups. Their names follow administrative district conventions, reflecting Singapore’s urbanization trajectory.

CHAPTER 3: TEMPLE SPACE PLANNING AND COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION

Throughtheauthor'sobservations,itwasfoundthatthespatiallayoutoftemples influences the participation of both devotees and residents from surrounding communities. Based on the analysis of spatial elements in temples, this chapter comparesandobservescommunityparticipationpatternsinthetwounitedtemples, aiming to explore the relationship between spatial configuration, community engagement,andtemplemanagement.

3.1 Importance of Community Participation in Sustainability

According to temple managers, successfully renewing the land lease is one of the most critical factors in determining whether a temple can continue to operate. However,aftertherenewal,templesalsofacetheburdenofmaintenanceandrepair costs. Whether sufficient funds can be raised for the 30-year lease renewal and ongoing upkeep depends largely on incense donations and contributions from prominentfamiliesorbenefactors.Thesefinancialresourcesarecloselytiedtothe temple’s level of activity, especially when temples actively engage the community throughceremonies,culturalevents,andcharitableinitiatives.Sucheffortsnotonly reflect the vibrancy of the temple but also help attract more community participationandsupport.Infact,sometempleshavegraduallyadoptedcommercial strategiestoenhanceengagement. Forexample,AngMoKioJointTemplesuccessfullyreneweditsleaseandunderwent renovationin2011.ChaiCheeUnitedTemple,ontheotherhand,completeditslease

renewalinFebruary2024,withthetotalcostreachingapproximatelySGD3million. Like many other United Temples, these two temples organize regular monthly religious activities. Typically, rituals are conducted independently by each subtemple rather than collectively by the United Temple. The temples coordinate to avoidschedulingconflicts,withmajorritualscommonlyheldonthe1st,15th,and 30th days of the lunar calendar. Additionally, celebrations are organized for importantfestivalsandthebirthdaysofeachtemple’smaindeity,oftenlastingthree tofourconsecutivedays.(Figure18)

Asshowninthediagram,thereisaclearcorrelationbetweenthelevelofcommunity participation, frequency of activities, and visitor flow in temples. (Figure 19)

Figure18.GaoLinGongAnnualEventsSchedule(Left)andXuanTianShangDiBirthday CelebrationPrograminHockLengKeng(Right) (Source:FacebookofTemples)

Although specific data on incense offerings is unavailable, interviews with temple managementandon-siteobservationsindicatethatbeyondregularritualactivities, ChaiCheeUnitedTemplealsoorganizeseventssuchasscholarshipawardsthrough its central committee. These initiatives significantly increase community engagement. Such activities not only raise the temple’s visibility within the neighborhoodbutalsostrengthentiesbetweenthetempleandlocalresidents.This heightened sense of participation reinforces the temple’s religious role and contributes to its long-term sustainability. Higher visitor flow often translates to greater incense offerings and donations, which are critical for the temple’s daily operations,leaserenewalfees,andfuturerepairsandmaintenance.

Figure19.RelationshipBetweenTempleActivityFrequencyandCommunityFlow (Source:Author)

greater religious activity, which in turn boosts incense donations and financial support providing a stronger foundation for lease renewal and future sustainability.

3.2 Plaza Space and Ritual Activities

Clarifying the importance of community participation in United Temples, it is equallysignificanttoanalyzehowdifferentspatialelementsinfluenceparticipatory behaviors.

Firstistheforecourtspace.Duringmajorfestivalssuchasdeitybirthdays,temples often utilize the forecourt for erecting temporary stages. For instance, during the NineEmperorGodsFestivallastyear,LengSanGiamDouMuGongofAngMoKio

JointTemplesetupatemporarypuppetshowstageintheopenspaceinfrontofthe temple.Thestagewasconnectedtotheadjacentroads,whichenhancedaccessibility for both devotees and local residents. (Figure 21) The space is also used for other activitiessuchasthe"PeaceBridgeCrossing"ritualandfestivebanquetsorganized byGaoLinGong.Indailyuse,thesetemporaryinstallationsaredismantled,leaving onlyaportionofthehard-pavedareatoserveasaplaceforsocialinteractionand restamongcommunitymembers.(Figure22)

A similar arrangement can be observed at Chai Chee United Temple. Although its original land had long been requisitioned under urban development policies, the temple has clearly defined its boundaries using a low wall that also encloses the forecourt. (Figure 23) The space here is larger, allowing it to serve as a venue for hostingbanquetguestsduringtemplefestivities,andfunctioningasaparkingarea on regular days. (Figure 24) In addition, theforecourt space is usedto place ritual elements such as the joss paper furnace or statues of the Tiger Deity. From the

Figure21 OverviewofAngMoKioJointTemple (Source:Author)

Figure22 TwoDifferentForecourtStatesofAngMoKioJointTemple (Source:Author)

perspective of both festive ceremonies and daily worship, the direct connection betweentheforecourtandtheroadsignificantlyenhancestheconvenienceofritual activitiesandencouragesgreatercommunityparticipation.

ThecoreofanytempleisitsPrayerHall,wherecommunitymembersengagemost

Figure23 OverviewofChaiCheeUnitedTemple (Source:Author)

Figure24 TwoUsageStatesoftheForecourtatChaiCheeUnitedTemple (Source:Author)

3.3 Community Participation in Prayer Halls

InterviewswithAngMoKiotemplestafffurtherrevealthatspatialorganizationis deeplyintertwinedwithreligiouslogicandbeliefdifferences.Thetempleadopteda fullyseparatedlayoutprimarilybecauseofsignificanttheologicaldifferencesamong the three sub-temples. One of them, Jin Ying Tang, is Singapore’s only temple representing the Jinying sect, also known as “Three Teachings” (San Jiao), which synthesizeselementsofBuddhism,Taoism,andImmortalTeachings.Devoteesmust undergo a formal initiation ceremony to become disciples, and the temple’s operations resemble those of a formal religious institution rather than a general worshipsite.

In contrast, Chai Chee United Temple emphasizes a unified ritual process and a shared main altar space, reinforcing the primacy of its main deity. As discussed earlier, the allocation of altar space within the temple reflects the hierarchy of deitiesbasedontheirsignificanceandthenumberofworshippers.Insuchshared spaces,thetempletypicallyarrangesastandardizedworshipsequenceaccordingto the deities’ ranks, guiding devotees through signposts and route markers. The common sequence of worship at Chai Chee United Temple begins with paying respecttotheJadeEmperoroutsidethemainentrance,followedbytheEarthGod (FudeZhengshen)inthemainhall,andfinallyXuantianShangdiandQitianDasheng atthesides.(Figure25)

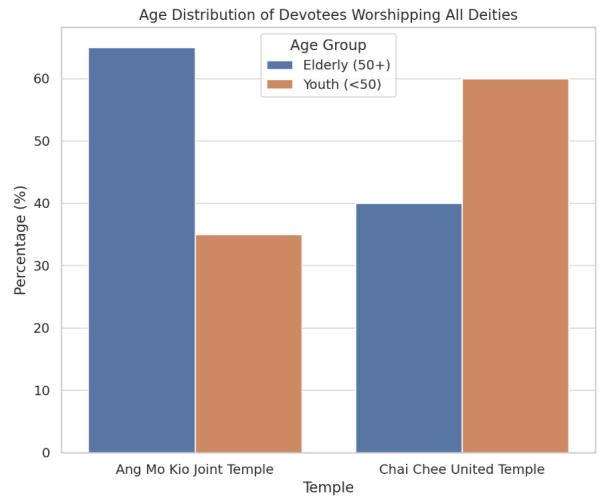

The following data was compiled by the author through questionnaire surveys, organized into tables,39 and subsequently visualized as two bar charts: Worship Preference by Temple, and Age Distribution of Devotees Worshipping All Deities.

39 SeeAppendixC

Figure25 WorshipRoutesinAngMoKioandChaiCheeUnitedTemples (Source:Author)

Figure26WorshipPreferencebyTemple (Source:Author)

Thefirstfigureillustratesthedifferencesinworshippreferencesbetweendevotees atAngMoKioJointTempleandChaiCheeUnitedTemplebasedonfieldsurveydata. Itcomparesthosewhochoosetoworshipspecificdeities(suchasapatrondeityor one enshrined at home) with those who worship all deities in the main hall. The findings show that in both temples, most local devotees familiar with the temple tendtoworshipspecificdeities,withanotablyhigherproportionatAngMoKioJoint Temple (70%). During festive periods, however, more peripheral residents who arelessinvolvedinregulartempleactivities opttoworshipalldeitiesinthemain hallinasinglevisit.ThistrendisparticularlyprominentatChaiCheeUnitedTemple (40%),indicatingthatitscentralizedspatiallayoutismoreappealingtofirst-time visitorsorthoseunfamiliarwiththetemple.(Figure26)

Thesecondfigurefurtherbreaksdowntheagedistributionofthosewhoworship

Figure27.AgeDistributionofDevoteesWorshippingAllDeities (Source:Author)

oftenbroughtfromChinabyearlyimmigrantsandwereintentionallymadecompact and portable. According to interviewees,40 these images "crossed the ocean" and represent the continuation of ancestral beliefs particularly meaningful for early settlerswhocouldnotaffordtotransportlargestatues.Theplacementofthesedeity figuresmuststrictlyfollowritualprotocols.Someofthesmallerstatuesevendate backtotheGuangxueraoftheQingDynasty,symbolizingbothhistoricalcontinuity andsacredauthority.(Figure28)

Mostdevoteesfollowaspecificworshipsequence beginningatthecentralshrine andthenproceedingtothesidealtars.Intervieweesindicatedthattheydonotpay

40 InterviewwithtemplemanagerofGaoLinGongTemple,seeAppendixA,InterviewTranscript.

Figure28 ThedeitystatuedatingbacktotheQingDynasty.(Source:Author)

closeattentiontowhichdeitybelongstowhichsub-temple;instead,theypreferthe convenienceandspiritualassuranceofworshippingmultipledeitiesinasinglevisit.

Some even likened the united temple to a "larger version of the household altar," appreciating the time efficiency and overall enhanced worship experience. This spatialconfigurationnotonlyoptimizescirculationandimprovesspatialefficiency, butalsoembodiesthecollectivespiritoftheUnitedTemplemodel.

More importantly, an analysis of the committee structure at Chai Chee United Temple reveals a significant correlation between shrine size and administrative hierarchy. In other words, the larger theshrine, the greater the temple’s financial stake and its role in the overall organization. This spatial hierarchy reflects the ownershipstructurewithintheUnitedTemple.Asshowninthediagram,thetemple with the largest shrine Hock San Teng has its representative serving as the chairmanofthejointcommittee,whiletheleadersofZhuYunGongandHockLeng

Keng serve as secretary/vice-chair and treasurer, respectively. This alignment between spatial and organizational hierarchies illustrates that, despite being a mergedinstitution,theUnitedTemplemaintains aclear governancesystem one thatspatiallyreflectstheinternalbalanceofpower.(Figure29,Figure30)

Figure29.MembersoftheAdHocCommitteeanditssubsequentformationsareasfollows (Source:Author)

3.5 Conclusion

This chapter explored how spatial layout influences community participation in United Temples, using Ang Mo Kio Joint Temple and Chai Chee United Temple as casestudies.Throughfieldobservation,surveys,andinterviews,itwasevidentthat temple space particularly prayer halls, forecourts, and shrine arrangements shapeshowdevoteesengagewithreligiouspractices.

Temples with centralized layouts, such as Chai Chee United Temple, are more accessible to casual visitors and younger worshippers, encouraging continuous worshipandstrongercommunityinteraction.Incontrast,AngMoKioJointTemple, withitsindependentlyorganizedspaces,bettersupportsestablishedlocaldevotees withclearworshipintentionsbutofferslessintegrationforbroadercommunityuse.

The study also revealed how spatial hierarchy seen in shrine size and layout

CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSION

This research has systematically explored the relationship between spatial morphology, community participation, and sustainable heritage conservation through the comparative case studies of Ang Mo Kio Joint Temple and Chai Chee

United Temple in Singapore. The study addresses a critical gap by linking spatial configurationdirectlywithcommunityengagement,underscoringthenecessityof participatory approaches in the sustainable management and conservation of UnitedTemples,especiallygiventheabsenceofspecificprotectivelegislationfrom governmentalagencies.

Significant findings indicate that temple spatial forms significantly impact management practices and community involvement. Firstly, spatial hierarchy within temples manifested through shrine size, placement, and architectural structuring reflects both historical precedence and the operational influence of eachsub-temple,subsequentlyshapingcommunityengagementpatterns.InAngMo KioJointTemple,separatespatialzonesforindividualsub-templesenhanceidentity preservation andcater todevoteesfamiliarwithspecific deities, thus maintaining strong cultural continuity. Conversely, the unified main hall design of Chai Chee

UnitedTemplefostersacollectiveworshipexperience,makingitaccessibletonew devotees and enhancing communal participation, particularly among younger demographicsandlessfrequentvisitors.

Secondly, flexible and multi-functional spaces such as temple forecourts and

adaptable ritualspaces (e.g.,temporaryoperastages andworshippavilions)have proven essential in encouraging broader community involvement beyond regular religious activities. These areas facilitate social interaction, hosting community events,culturalperformances,andritualceremonies,therebystrengtheningsocial bondsandincreasingvisitorflowandparticipation.Thisspatialadaptabilityaligns withmodernurbantemplefunctionstransitioningtowardcommunityserviceroles, responding proactively to contemporary urban challenges such as declining devoteesandrisingoperationalcosts.

Based on the comparative analysis, this research proposes a community-centric spatial optimization model for United Temples. It recommends that future spatial planningoradaptivereuseoftemplesshouldprioritizepreservingessentialritual spaces due to their cultural and religious significance, while simultaneously promoting spatial flexibility to accommodate diverse community functions. Specifically,templeforecourtsandcommunalareasshouldbedeliberatelydesigned to facilitate accessibility and visibility from surrounding neighborhoods, thereby activelyinvitingcommunityinteractionandparticipation.

Additionally, the research underscores the importance of collaborative managementstructuresinvolvingbroadercommunityrepresentation,ratherthan exclusivegovernancebytemplecommittees.Byintegratingstructuredcommunity participation mechanisms such as regular community forums, participatory designworkshops,andfeedbacksessions templescanensurethatspatiallayouts

accurately reflect community needs and preferences. Such collaborative practices not only reinforce the social relevance of temples but also cultivate shared communityownershipandlong-termsustainability.

Lastly,publiceducationandculturalengagementinitiativesarevitalcomplements to physical space optimization. Initiatives like educational workshops, cultural heritage tours, and interactive exhibitions can be strategically integrated into templespacestoattractyoungergenerations,fosteringadeeperappreciationand engagementwithtraditionaltempleculture.

While this study provides significant insights into spatial design and community participation, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research is primarilyqualitative,basedoncasestudiesoftwotemples.Thegeneralizabilityof findings to other United Temples or different cultural contexts may be limited.

Second,thetemporalscopeofthisstudyconstrainedlong-termassessmentofthe impactofspatialchangesoncommunitydynamicsandtemplesustainability.

Future research should extend this comparative framework to a broader range of temples, incorporating quantitative analysis to validate qualitative findings. Longitudinal studies could further explore how spatial adaptations influence community engagement over extended periods. Additionally, future studies could integrateadvancedtechnologiessuchasGISmappingandvirtualrealitytovisualize spatial interventions, aiding in more effective participatory planning and heritage management.

REFERENCE LIST

[1]. “ANG MO KIO HERITAGE TRAIL: A Companion Guide.” AngMoKioHeritageTrailBooklet , 2021. https://www.studocu.com

[2]. Attorney-General's Chambers (AGC). SingaporeStatutesOnline http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/ Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[3]. Australia ICOMOS. TheBurraCharter:TheAustraliaICOMOSCharterforPlacesofCultural Significance(Revised edition). Burwood, VIC: Australia ICOMOS Inc., 1999.

[4]. ChaiCheeUnitedTempleBrochure . 2001.1

[5]. Chen Bi (陈碧). UnionandIntegration:AStudyonUnitedTemplesinSingapore= “联与合: 新 加坡联合庙研究.” Xiamen University, 2010

[6]. Chen Aiwei (陈爱薇). FromSeekingBlessingstoServingtheCommunity:TheTransformationof LocalTemples= “从保平安结善缘到服务社区:本地庙宇功能转型.” LianheZaobao , November 17, 2022. https://www.zaobao.com.sg/news/singapore/story20221117-1334151

[7]. Chen Fei (陈非). Community-LedSustainableHeritageConservationandPlace-Making:ACase StudyofPokfulamVillage,HongKong= “社区主导的可持续历史保护与地方营造 以中国香港 薄扶林村为例.” ArchitecturalJournal(建筑学报), no. 06 (2022): 90–95. https://doi.org/10.19819/j.cnki.ISSN0529-1399.202206014

[8]. Cimadomo, Guido. “A Different Perspective on Architectural Design: Bottom-up Participative Experiences.” 2014.

[9]. CulturalHeritagePreservationandManagementinSoutheastAsia . Association for Asian Studies Conference, 2015.

[10]. Gu Chaolin and Liu Jiayan (顾朝林 刘佳燕). UrbanSociology= “城市社会学.” Beijing: Tsinghua University Press (清华大学出版社), 2013

[11]. Hanghangcha Database (行行查行业研究数据库). AmendmentHistoryofSingapore'sLand

AcquisitionSystem= “新加坡土地征用制度的修订历程具体情况.”

https://www.hanghangcha.com/hhcQuestion/detail/787829.html. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[12]. HeritageConservationofKyotoGionFestival . Kyoto Gion Festival: Immerse Yourself in Japan’s Grandest Festival. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[13]. HeritageConservationofMercatdeSantaCaterina,Barcelona https://mercatdesantacaterina.com/en/history/history. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[14]. Huang Shuna (黄舒娜). CriticalHeritageStudiesandHeritageConservationPracticesin Singapore:ACaseStudyoftheFirstUnitedTemple,FivefoldJointTemples= “批判性遗产研究理论 与新加坡遗产保护实践 以第一座联合庙 伍合庙 为例.” Master s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2024.

[15]. Hue, Guan Thye (许源泰). ChineseTemplesandTransnationalNetworks:Hokkien CommunitiesinSingapore= “新加坡的华族庙宇与跨国网络 - 以田调资料中的闽南主神和闽南道 坛为例.” WorkingPapers16-06. Göttingen: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, 2016, pp. 7–39.

[16]. Hue, Guan Thye (许源泰). TransformationofTraditionalChineseReligiousBeliefsinSouthEastAsianSociety:ACaseStudyofTaoismandBuddhisminSingapore= “中华传统宗教信仰在东 南亚的蜕变: 新加坡的道教和佛教研究.” PhD diss., Nanyang Technological University, 2011.

[17]. Hue, Guan Thye. “The Evolution of the Singapore United Temple: The Transformation of Chinese Temples in the Chinese Southern Diaspora.” ChineseSouthernDiasporaStudies , vol. 5. Canberra: The Australian National University, 2012, pp. 157–74.

[18]. Hue, Guan Thye, Yidan Wang, Kenneth Dean, Ruo Lin, Chang Tang, Juhn Khai Klan Choo, Yilin Liu, et al. “A Study of United Temple in Singapore Analysis of Union from the Perspective of SubTemple.” Religions13, no. 7 (2022).

[19]. ICCROM. InternationalCentrefortheStudyofthePreservationandRestorationofCultural PropertyReport . 2015.

[20]. IntroductiontotheEstablishmentofChaiCheeUnitedTemple https://www.chaicheeunitedtemple.org.sg/. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[21]. Ji Li and Sukanya Krishnamurthy. “Community Participation in Cultural Heritage Management: A Systematic Literature Review Comparing Chinese and International Practices.” 2020.

[22]. Ke Mulin (柯木林). TheFunctionsofChineseTemplesandClanAssociationsinSingapore= “新加坡华人庙宇与会馆的功能.” EncyclopediaofChineseCultureinSingapore(新加坡华族文化百 科). Accessed Mar. 22, 2025

[23]. Kerr, James Semple. “Conservation Plan.” 1982.

[24]. Kerr, James Semple. TheConservationPlan:AGuidetothePreparationofConservationPlans forPlacesofEuropeanCulturalSignificance(6th ed.). National Trust of Australia (NSW), 2004.

[25]. Lee, John Susanna. TheWeatheredWanshanFudeTemple= “饱经沧桑福德祠.” Flickr , June 27, 2011. https://www.flickr.com/photos/11435676@N04/5875363119. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[26]. Liao Ran (廖然). AStudyofFolkTempleArchitectureintheAncientCityofQuanzhou= “泉州 古城民间信仰宫庙建筑研究.” Master’s thesis, Huaqiao University (华侨大学), 2023

[27]. Li Zhixian (李志贤). FieldResearchonZhongyuanFestivalatWanShanFudeTemplein Singapore(2015–2016)= “新加坡万山福德祠中元节田野调查(2015 年–2016 年).” UniversalSocial ScienceResearchNetwork(普世社会科学研究网).

http://www.pacilution.com/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=10842. Accessed Mar. 22, 2025.

[28]. Lin, Wei Yi. NationalDevelopmentandIntegrationofTemplesinRuralAreas:TheCaseof TampinesUnitedPalace= “国家发展与乡区庙宇的整合: 以淡滨尼联合宫为例.” Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies, 2006, pp. 173–97.

[29]. Osten Bang Ping Mah, Yingwei Yana, Jonathan Song Yi Tan, Yi-Xuan Tan, Geralyn Qi Ying Tay, Da Jian Chiam, Yi-Chen Wang, Kenneth Dean, Chen-Chieh Feng. “Generating a Virtual Tour for the Preservation of the (In)tangible Cultural Heritage of Tampines Chinese Temple in Singapore.” 2019.

[30]. Poulios, Ioannis. “Discussing Strategy in Heritage Conservation: Living Heritage Approach as an Example of Strategic Innovation.” JournalofCulturalHeritageManagementandSustainable Development4, no. 1 (2014): 16–34.

[31]. Poulios, Ioannis. ExistingApproachestoConservation . In ThePastinthePresent:ALiving

Appendix A

Transcription of Interviews

采访时间:2025 3/25

采访对象:菜市联合宫总宫管理人员 (男,35 岁)

访谈人:李杰

访谈人: 你好,我想参观一下这座联合庙。您现在在忙吗? 菜市管理人员: 没有,平时这里都比较闲。

访谈人: 你是这里的工作人员吗?不知道您是否有时间接受采访?

菜市管理人员: 我是刚来这里的,从中国来新加坡才一个月,所以对庙的情况了解有限,不 过基本的情况还是清楚的。

访谈人: 我是新加坡国立大学的研究生,正在研究庙宇文化,想收集一些资料。您对这里的 历史了解多少呢?

菜市管理人员: 这里原本是三座庙宇 最初并不在这里。由于新加坡的土地价格较高 后来 就将这三座庙合并建在一起。

访谈人: 我注意到庙宇的神像大小不同,为什么中间的神像最大?

菜市管理人员: 这可能与最初建庙时的出资情况有关,可能是当时捐资较多,所以规模较 大。

菜市管理者:当然有 我们这里是由福山亭、竹云宫和福灵宫三间庙组成 每个庙的主神都 有自己的神龛 面积大小是按照原本庙宇信众的多少来分配的 比例大概是 3:2:1。这样安排 也是根据香火的盛行程度来的,毕竟信众多的神祇,自然需要更大的空间来容纳。

访谈人:所以神龛的大小和位置,也反映了各分庙在联合庙中的地位?

菜市管理者:可以这么说。福山亭的玄天上帝香火最旺,所以它的神龛最大,放在最显眼的 位置。竹云宫和福灵宫的神像则依次摆放在旁边。这样安排不仅仅是为了尊重信仰习惯,更重要 的是 它会影响到信众的祭拜顺序和整个祭祀空间的流动性。

访谈人:您是指大部分信众会选择拜完玄天上帝后,顺着一侧依次拜下去? 菜市管理者:对 很多信众一进来就先拜玄天上帝 毕竟是庙里最主要的神祇 之后就会顺 势沿着一边拜过去,把所有神像都拜一遍,这样的空间设计让大家“拜拜”更加顺畅。

访谈人: 这个庙宇的土地租约情况如何? 菜市管理人员: 这里的土地租期是 30 年 之前的租约在去年到期 刚刚续约。

访谈人: 平时来庙里拜神的人多吗?

Formatted: Font: SimSun, Not Bold

菜市管理人员: 初一、十五以及初二、十六的时候人比较多。此外,每个月也有一个大节 日 例如本月三月初一就有大型的庙会 每个神明的生日都会有特别的祭祀活动。

访谈人: 这个庙宇主要是福建人信仰的吗?

菜市管理人员: 是的 这里以福建人为主 但也有其他地方来的信众。我本人是福建人 但 这里的工作人员也有来自江苏的。

访谈人: 这三座庙合并后,哪个庙的人流量最大? 菜市管理人员: 中间的"大白宫"最受欢迎 信众最多。两侧的庙宇人流较少 不过也有固定 的信众群体。

访谈人: 这里的庙宇管理是如何运作的?

菜市管理人员: 主要是庙宇的管理人员负责日常运营,比如香火管理、财务、祭祀活动等。 此外,还有一些义工帮忙。

访谈人: 这里的收入来源是什么?

菜市管理人员: 主要是香油钱和租赁收入。这片土地的租赁价格大概是 380 万新币,租期 30 年。

访谈人: 这里的信众平时大多来自附近社区吗?

菜市管理人员: 是的,主要是周边社区的居民。不过也有一些人专程从其他地方过来祭拜。

访谈人: 这里的庙宇和国内庙宇有什么不同?

菜市管理人员:

国内的庙宇一般是独立的,但这里是联合庙,由三座庙宇合并而成。此外, 新加坡的庙宇管理比较严格 每天都有固定的运作模式。

访谈人: 这里的祭祀活动是否固定?

菜市管理人员: 是的,除了初一十五的例行祭拜,每月还有大型的神明诞辰庆典,有些信众 会专门前来参加。

访谈人: 这里的信众以老年人为主吗?

菜市管理人员: 主要是中老年人 但也有年轻人 尤其是在节庆期间 年轻人会带着家人一 起来。

访谈人: 感谢您的时间和分享!

采访时间:2025 3/25

采访对象:菜市联合宫两位信众(一男一女)

访谈人:李杰

访谈人:请问您平时来这里拜神,祭拜的顺序是怎么样的? 信众 男:我一般都是先拜玄天上帝 他是这里最大的神 香火最旺 拜完后就顺着一路拜下 去,把所有神像都拜一遍,这样才觉得心安。

访谈人:那您会特别区分这些神像属于哪个分庙吗?

信众 男:不会特别在意啦 反正都是神 能一起拜最好 多个神保佑嘛。而且这里神像的摆 放刚好顺着一条路,拜起来很顺畅,不用绕来绕去。

访谈人:相比其他庙宇,您觉得联合庙的这种形式有什么特点?

信众 男:嗯,联合庙好啊,一个地方就能拜到好几个神,省时间。像我们家里拜神,通常也 是几尊神像摆在一起 联合庙就是放大版的家里神龛 很方便。

访谈人:您是第一次来这里拜神吗?

信众 女:不是,之前家里人带我来过几次,不过我自己来得不多。

访谈人:那您觉得这里的拜神流程怎么样?

信众 女:挺好的,神像都摆在一块儿,进门就能看到玄天上帝,拜完就顺着边上继续拜下 去,不用到处走,很方便。而且这样感觉好像所有神明都在一起,比较有“庙”的感觉 访谈人:那您对联合庙这种模式有什么看法?

信众 女:我觉得挺好啊 反正庙里大家都是来拜神的 不管是哪个庙合在一起 还是分开 的,只要方便信众就好。而且这里人多,感觉香火也比较旺,气氛比较好。

Formatted: Font: SimSun, Not Bold, Not Italic, Font color: Auto

采访时间:2025 3/25

采访对象:檺林宫联合庙管理人员(男:68 岁)

访谈人:李杰

访谈人: 你好,我想来参观一下这座庙宇,同时也想和您聊一聊,可以吗? 檺林宫管理者: 当然可以!我们这座庙原本是一座小庙,最早建在甘榜(Kampong,村 落),已经有很多年的历史了。

访谈人: 那旁边的两座庙呢? 檺林宫管理者: 旁边的两座庙原本不在这里。这座庙一直都在这个位置,而那两间庙是后来 迁过来的。早些年庙宇的管理方式不同 每间庙都是独立的个体。

访谈人:我明白了。新加坡的城市规划影响了这些庙宇的发展,对吧?

檺林宫管理者: 是的。过去在乡村地区,庙宇一般都是单独存在的。但后来,随着城市化进 程的推进,政府推行了一些合并政策,促使一些小庙联合起来,共同使用一片庙地。

访谈人:这个庙很特别吗?

檺林宫管理者 特别啊 全新加坡就此一家 唯一的金英堂 这个是需要入教才行 要举行入 教仪式的。

访谈人: 那他们香火钱会不会相对要好一点

檺林宫管理者:因为要入教,和基督教什么都一样,有很多有钱人给他们啊,还有你看庙前 面的中国鹤,象征着吉祥,这个是很特别的

访谈人: 他们是佛教吗,我看中间有佛教神像

檺林宫管理者: 是道教啦,他们是三个教了,最左边是太上老祖

访谈人: 那这个庙和旁边的豪林宫为什么不通呢,我看有些联合庙是通开的 檺林宫管理者: 每个庙都要有私密空间啊。以前的庙宇建筑大多是木质结构的,空间可以调 整,所以相邻的庙宇之间可以互相连通。但随着时代变迁,建筑材料和管理方式发生了变化,而 信仰观念不同啦 现在的庙宇就一人一间喽 就变成固定结构 不再允许随意打通相连。

访谈人:请问在重建联合庙时,是怎样决定檺林宫的位置的呢? 檺林宫管理者:其实我们原本就在这块地上 没有搬过 所以后来联合建庙的时候 大家都 认同我们继续坐中间的位置。算是“地主”啦 别的两间庙是后来搬过来的。

访谈人:那这个位置安排,是不是也跟经济实力有关呢? 檺林宫管理者:我们财力一般啦 没有特别多钱。但位置上确实是因为我们本来就在这里 大家也尊重这个“主客”的关系。

访谈人: 您觉得现在的庙宇和过去相比,有什么不同吗?

74

檺林宫管理者: 当然不一样了。以前的庙宇用地相对宽裕,只要有钱,就能建造一座庙宇。 现在土地资源紧张 政府对庙宇建设也有严格的规定 比如建筑高度、使用年限等 都有明确的 限制。

访谈人:这座庙搬迁到这里以后,原有的物品都保留下来了吗?

檺林宫管理者:只能说尽量保留。有些老物件因为各种原因丢失了,但主要的文化元素还是 得以传承下来。我们也希望能够保存庙宇的历史和故事。

访谈人: 这座庙的文化价值如何体现呢?

檺林宫管理者: 这不仅仅是一座庙宇,它也是社区的一个象征,比如檺林宫地区(Ang Mo Kio)的地标之一。很多信众在这里聚集,庙宇承载着他们的信仰和情感。

访谈人:这座庙原本的空间是什么样的?

檺林宫管理者: 以前的庙比较小,空间有限,所以很多活动都是在庙外进行的。现在庙宇的 规模扩大了 但由于规划要求 空间布局上仍然需要精心设计。

访谈人:我注意到庙里的办公室和后厨都设在神龛后方,这样的布局有什么特别的 原因吗?

檺林宫管理者:是的,传统的庙宇基本上都是这样安排的。神龛在前面是供信众祭拜的,而 后面是我们日常管理的地方。办公室主要是处理财务 比如每天香火钱的统计、管理庙务支出 等。后厨则是用来准备供品,或者大节日的时候做一些斋菜给信众。

访谈人:那你们这里的宴席空间是怎么安排的? 檺林宫管理者:我们这里没有固定的宴席空间,主要是利用庙前的空地。比如大节日时,我 们会摆上桌椅,供信众吃饭、交流。有时候不是节日,但一些信众拜完神后,也会坐下来聊聊 天、休息一下 所以这个广场不仅仅是个仪式空间 也算是个社区交流的地方。

访谈人:所以相比于室内宴席空间,这种利用广场空间的方式,您觉得有什么优势吗? 檺林宫管理者:当然有啊!广场空间比较开放,空气流通好,不像室内那么闷。而且这样的 话 不仅是信众 附近的居民也可以过来坐坐 甚至有时候不是来拜拜的人也会在这里和熟人打 个招呼、聊几句。这种开放式的设计,让庙和社区的联系更紧密。

访谈人:刚刚提到庙前的空地,平时是不能使用的,那大节日时你们是怎么协调使用的呢? 檺林宫管理者:对的,我们平时不能随意使用,要提前申请,比如九皇五帝诞辰,我们去年 就申请了在前面搭建临时平台,这样信众过来拜拜会更方便。不过大部分时间这些空地是不能动 用的。

访谈人:那信众平时来拜神的时候,会不会觉得广场空间有限,或者停车不方便? 檺林宫管理者:会啊,特别是初一、十五的时候,大家都开车来,但这边没有空地可以停 车 很多人只能停在附近的住宅区或者商业区 然后走过来。

访谈人:那这些是什么神?

檺林宫管理者:三王府大人 原型你应该知道 你中国来的 你应该听说过杨家将吧

系?

檺林宫管理者:是的,我们的信仰网络不局限于新加坡。比如在马来西亚的麻坡(Muar), 也有信众会前来参与庙会活动 他们和本地信众保持着长期的联系。

访谈人:这座庙的地契情况如何?

檺林宫管理者: 这里的庙宇是合并后的,地契是共同管理的。目前的使用年限是 20 年,可 能会延长至 30 年,但具体情况还是要根据政府的规定来决定。

访谈人: 看来庙宇的发展受到政府的严格管理,对吧?

檺林宫管理者: 是的,新加坡政府在城市规划方面非常严格,尤其是庙宇用地的问题。庙宇 的运营不仅仅是宗教事务,也涉及到土地管理、建筑规范等多个方面。

访谈人: 感谢您与我分享这么多信息,让我对这座庙的历史和现状有了更深入的了解! 檺林宫管理者: 不客气,欢迎随时来参观和交流!

Appendix B

联合庙信众问卷调查表 (United Temple Visitor Questionnaire)

亲爱的受访者,

您好!本问卷旨在了解您对联合庙空间使用与参拜体验的看法。所有信息将仅用于学术研究,敬 请放心填写,感谢您的宝贵意见!

基本信息(Basic Information)

1. 您的年龄段(Your age group)

☐ 20 岁以下 (Under 20)

☐ 21–30 岁

☐ 31–40 岁

☐ 41–50 岁

☐ 51–60 岁

☐ 61 岁及以上 (61 or above)

2. 您的身份(Your status)

☐ 本地居民 (Local resident)

☐ 附近社区居民 (Nearby community resident)

☐ 游客 / 外地访客 (Visitor/tourist)

3. 您来此庙宇的频率(How often do you visit this temple?)

☐ 每月数次 (Several times a month)

☐ 仅在节日或神明生日 (Only during festivals/deity birthdays)

☐ 偶尔 (Occasionally)

☐ 第一次来 (First time)

参拜行为(Worship Preference)

4. 您通常参拜(Which deities do you usually worship when visiting?)

☐ 特定神明(如家中供奉的主神)(Specific deity)

☐ 所有殿内神明 (All deities in the prayer hall)

☐ 随缘拜拜 (No fixed preference)

5. 您是否知道您所拜的神明的来历或信仰背景?(Do you know the background of the deity you worship?)

☐ 了解 (Yes)

☐ 略有了解 (Somewhat)

☐ 不清楚 (Not really)

空间体验(Spatial Experience)

6. 您是否觉得庙宇内的空间布局清晰易懂?(Is the temple’s layout easy to understand and navigate?)

☐ 非常清晰 (Very clear)

☐ 一般 (Neutral)

☐ 感到困惑 (Confusing)

7. 以下哪些空间您曾使用?(请选择所有适用项)(Which of the following spaces have you used?)

☐ 拜殿 / 主殿 (Main Prayer Hall)

☐ 中庭或庙前广场 (Courtyard or front plaza)

☐ 香炉区 (Incense area)

☐ 戏台空间 (Opera stage area)

☐ 茶水区 / 社区交流区 (Rest area / social space)

社区参与感(Sense of Community)

8. 您是否参加过庙宇举办的以下活动?(Have you participated in any of the following?)

☐ 节庆庆典 (Festivals/celebrations)

☐ 社区聚会 / 宴席 (Community feasts/events)

☐ 义诊 / 讲座 (Free clinics / talks)

☐ 没有参加过 (None)

9. 您是否觉得庙宇是社区交流的重要空间?(Do you consider the temple an important place for community interaction?)

☐ 是的 (Yes)

☐ 一般 (Neutral)

☐ 否 (No)

10. 您对庙宇空间或活动还有哪些建议?(Any suggestions for the temple’s space or activities?)

(开放式回答栏)

如需更多说明或想参与访谈,请填写您的联系方式(可选): 姓名:___________ 电话 / 邮箱: 再次感谢您的参与与支持!