CDE Forging New Frontiers

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the latest edition of the NUS CDE Research Newsletter, covering a topic of profound importance to our global community: Energy. From new materials to breakthroughs in device engineering, being at the leading edge of energy innovation is among the highest priorities for our CDE community. In this issue, we are joined by guest editor, Professor Lee Poh Seng. We thank him for his stewardship of this important topic and our colleagues who are pioneering new advancements in the field!

All the best,

Dean Ho Editor-in-Chief

Designing energy systems that can think, adapt and endure

Energy systems are in the midst of a quiet but profound transformation. Grids are becoming more dynamic and bidirectional, cities are layering digital infrastructure onto ageing assets, and industry, shipping and data centres face mounting pressure to decarbonise even as demand for mobility, trade and computation grows. In a tropical, resource-constrained setting, the question is straightforward but not easily answered: how do we stay cool, connected and competitive within tight carbon, land and water limits?

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

At the College of Design and Engineering (CDE), we approach this as a systems challenge. No single device, algorithm or material will solve it. Meaningful progress comes from joining up advances across domains and scales: from nanoscale heat transfer and catalytic surfaces, to building- and campus-level cooling and power, and on to regional grids and energy markets.

“Meaningful progress comes from joining up advances across domains and scales: from nanoscale heat transfer and catalytic surfaces, to building- and campuslevel cooling and power, and on to regional grids and energy markets.”

The work featured in this issue reflects that perspective. In power systems, colleagues are developing data-driven forecasting, optimisation and control tools for decentralised, renewable-rich grids that must remain reliable, flexible and, increasingly, fair. In thermal management, we are revisiting cooling from first principles, with efforts in advanced dehumidification, high-performance heat exchangers and liquid-cooled, low-water concepts for high-density AI data centres. On storage and fuels, research spans safer and more sustainable batteries, compact and inherently safer fuel storage, and low-carbon fuels such as ammonia and hydrogen, from fundamental chemistry through to engines and industrial heat applications. Electrified mobility and ASEAN-wide system studies add another layer, examining how EVs, renewables and cross-border interconnections can be orchestrated to support an affordable, reliable net-zero pathway.

A unifying thread is the emerging role of the NUS Energy Solutions Hub (NESH) under NUS Sustainable Futures. NESH is intended to act as a systems integrator for CDE and the wider university, linking cooling and power at the data-centre and campus scale, storage and fuels at the industrial scale, and markets and policy at national and regional scales. The planned Phase 2 of the Sustainable Tropical Data Centre Testbed (STDCT 2.0) with JTC on Jurong Island is a concrete example: a living lab for liquid cooling, warm- and seawater-based heat rejection, low-carbon power architectures and grid-supportive, AI-intensive operations in one of the world’s most demanding climates.

In parallel, there is growing interest within CDE in building a coherent nuclear engineering research agenda aligned with our national context. Advanced nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors are clearly a long-term option, but they sit squarely within

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

questions we already work on: high-power-density thermal-hydraulics and heat removal, materials and structural integrity under extreme conditions, integration of firm low-carbon supply into renewable-rich coastal grids, and safety and systems engineering for complex, high-consequence infrastructure. Developing foundational research and talent in nuclear engineering is therefore a natural extension of our broader energy systems work.

Underlying all of this is a simple point: the connections matter as much as the individual innovations. Algorithms only have impact when they are embedded in devices, markets and institutions. Materials only change outcomes when they can be manufactured and deployed at scale. Regional models only matter when they inform investment, regulation and cooperation. Any future exploration of nuclear options will be no different; it will need to be evaluated and developed as part of an integrated system that includes renewables, grids, cooling, storage, shipping, data centres and industry.

My hope is that this issue of the CDE Energy Newsletter serves both as a snapshot of our current efforts and as an invitation. Many of the challenges we face cut across departments, disciplines and sectors. If you see resonance with your own work, I encourage you to reach out, start a conversation and explore collaboration with our colleagues, with NESH, and with emerging efforts in strategic areas such as nuclear engineering.

Professor Lee Poh Seng Head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering

Co-Director of NUS Sustainable Futures in charge of the NUS Energy Solutions Hub (NESH) Programme Director of the STDCT project.

A new current of change

At the NUS Energy Solutions Hub, researchers and partners are pooling expertise across disciplines to reimagine from the ground up how tropical cities can stay cool, connected and carbon-conscious.

Across the globe, energy demand is rising, data centres are mushrooming and urban skylines continue to tower. Nowhere is this convergence more intense than in the tropics, where the need to stay cool and connected is colliding with the call to slash emissions.

Rather than tackling these issues in isolation, researchers across the National University of Singapore (NUS) come together under the NUS Sustainable Futures

initiative, a community-building platform convening experts from every discipline to find actionable paths towards a resilient, low-carbon world.

Among its first missions is the NUS Energy Solutions Hub (NESH) — a cross-disciplinary initiative seed funded by the Office of the Deputy President (Research and Technology) and led by Professor Lee Poh Seng, Head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at CDE, and Co-Director of NUS Sustainable Futures in charge of NESH. For Prof Lee, the question is not just how to generate cleaner energy, but how to redesign the entire system that uses it.

“Energy sustainability is a systems problem,” he says. “We cannot solve it by improving one component alone — whether it is a battery, a building or a data centre. We need to integrate expertise across engineering, design and the social sciences to make solutions that are viable in the real world.”

Energising collaboration

NESH is built upon this principle of integration. Its five pillars of research — spanning multi-energy districts, urban redevelopment, digital infrastructure, energy policy, as well as sustainable industry and transport — weave together as a framework for collaboration. Each connects different fields to address the interconnected challenges of energy security, decarbonisation and urban resilience.

Take the issue of cooling, for instance. Singapore’s tropical climate demands enormous amounts of energy for air-conditioning — new materials, passive design and data-driven controls could dramatically cut consumption. In another area, researchers are devising ways to make the island’s growing digital infrastructure — from cloud facilities to edge devices — run on less power and more intelligence. These projects exemplify NESH’s approach to blend deep technical expertise with a sensitivity to the social and spatial realities of tropical urban life.

“NESH was created to connect the full spectrum of NUS energy research,” adds Prof Lee. “By fostering collaboration between disciplines and partners, we’re able to translate scientific innovation into practical solutions that improve lives, especially in dense, tropical cities like Singapore.”

Professor Lee Poh Seng is the Co-Director of NUS Sustainable Futures in charge of the NUS Energy Solutions Hub (NESH).

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Turning ideas into impact

These ideas are already moving into large-scale demonstration. In November 2025, NUS and JTC signed an MoU to explore Phase 2 of the Sustainable Tropical Data Centre Testbed (STDCT 2.0) and a Jurong Island microgrid, a development led by Prof Lee from the NUS side. Slated to begin in 2026, the project will test climate-adapted cooling, low-carbon power architectures and grid-supporting operations in a multi-megawatt facility embedded within Singapore’s largest low-carbon data centre park.

Building on the first-phase testbed hosted at CDE, STDCT 2.0 will investigate next-generation approaches such as liquid cooling, ultra-low-water concepts, seawater-based heat rejection and hydrogen-compatible backup systems — all crucial as AI-class data centres push energy demands to new extremes. The Jurong Island setting, with its emerging ecosystem of hydrogen-ready plants, sustainable fuels and energy-storage pilots, will allow integrated studies linking digital infrastructure with industrial decarbonisation.

“We see Jurong Island as one integrated opportunity,” says Prof Lee, who is also the Programme Director of the STDCT project. “It is a place where ongoing industrial and energy developments can serve as living laboratories, helping us re-imagine how we design, power and cool AI-ready infrastructure in a hot, humid and resource-constrained setting.”

NESH’s impact is also taking shape in clean transport. A major cross-disciplinary project led by Professor Yang Wenming recently secured an $8.3 million grant to develop a next-generation ammonia marine engine with high efficiency and near-zero greenhouse gas emissions. The initiative brings together expertise in combustion, materials, catalysis and fuel systems, and signals the maritime sector’s growing interest in green ammonia as a viable future fuel.

“We see Jurong Island as one integrated opportunity. It is a place where ongoing industrial and energy developments can serve as living laboratories, helping us re-imagine how we design, power and cool AI-ready infrastructure in a hot, humid and resourceconstrained setting.”

Multidisciplinarity at the core

“Strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration across engineering, science, policy and industry is key. The challenges ahead, whether integrating renewables, greening digital infrastructure or decarbonising transport, all cut across domains,” Prof Lee says. “NESH’s role is to bring these threads together so solutions are technically robust, economically viable and environmentally sustainable.”

This approach is vital not only for Singapore but for tropical cities worldwide. Developing models that reflect the realities of heat, humidity and land constraints enables NESH to offer insights that can be adapted across the region.

“Energy research cannot happen in silos,” says Prof Lee. “The complexity of the climate challenge demands that we work across boundaries — uniting science, policy and industry to build a cleaner, more resilient world.”

Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Ice mixed with amino acids stores methane in minutes

A reusable, biodegradable ice material captures methane rapidly, paving the way for safer and cleaner storage of natural gas and biomethane.

If you have ever cooked on a gas stove or seen a flame flicker to life with the turn of a knob, you have seen natural gas in action. Supplying that energy at scale, however, is far more complicated. Today, natural gas is mostly stored under high pressure or cooled into liquid at -162 °C — both methods that are energy-intensive and costly. An alternative approach, called solidified natural gas, locks methane inside an ice-like cage known as a hydrate. But in practice, these hydrates usually form far too slowly to be practical on a larger scale.

Researchers led by Professor Praveen Linga from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, have found a simple workaround by adding amino acids — the building blocks of proteins. In a new published in Nature Communications, the researchers showed that freezing water with a small amount of these naturally occurring compounds produces an “aminoacid-modified ice” that locks in methane gas in minutes. In tests, the material reached 90 per cent of its storage capacity in just over two minutes, compared with hours for conventional systems.

Professor Praveen Linga showed that freezing water with a small amount of amino acids produces an “amino-acid-modified ice” that locks in methane gas in minutes.

The method also brings environmental benefits. Because amino acids are biodegradable, the method averts the environmental risks posed by surfactants often used to speed up hydrate formation. It also allows methane to be released on demand with gentle heating, after which the ice can be refrozen and reused, creating a closed-loop storage cycle. This combination of performance and sustainability makes the approach attractive for large-scale natural gas storage as well as for smaller, renewable sources of biomethane. The team also sees potential for adapting the technique to store other gas, including carbon dioxide and hydrogen.

Faster hydrates with a biological twist

The concept behind the new material is highly effective yet elegantly simple: mix water with amino acids, freeze it and then expose the ice to methane gas. In the lab, this amino-acid-modified ice quickly transformed into a white, expanded solid — evidence that methane had been locked inside as hydrate. Within just over two minutes, the material stored 30 times more methane than plain ice could hold.

This is possible because amino acids change the surface properties of the ice. Hydrophobic amino acids such as tryptophan encourage the formation of tiny liquid layers on the ice surface as methane is injected. These layers act as fertile ground for hydrate crystals to grow, producing a porous, sponge-like structure that speeds up gas capture. By contrast, plain ice tends to form a dense outer film that blocks further methane from diffusing inward, slowing the process dramatically.

To probe what was happening at the molecular level, the team turned to Raman spectroscopy, a technique that tracks how light scatters from vibrating molecules. These experiments showed methane rapidly filling two types of microscopic cages inside the hydrate structure, with occupancies above 90 per cent. “This gives us direct evidence that the amino acids are not only speeding up the process but also allowing methane to pack efficiently into the hydrate cages,” said Dr Ye Zhang, the lead author of the paper, a Research Fellow from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering.

The team also tested different amino acids and found a clear pattern. Notably, hydrophobic ones like methionine and leucine worked well, while hydrophilic ones such as histidine and arginine did not. This “design rule,” Prof Linga said, could guide future efforts to tailor ice surfaces for gas storage.

From lab results to energy storage cycles

The researchers’ work is still at the proof-of-concept stage, but the performance of the modified ice is very promising. At near-freezing temperatures and moderate pressures, the amino acid ice outperformed some of the most advanced porous materials, including metal-organic frameworks and zeolites, used for storing natural gas — not only in how much methane it could hold, but also in how quickly it filled. And unlike surfactant-based systems, it did not produce foaming during gas release, which is a major hurdle for large-scale operation.

“What we are showing is a simple, biodegradable pathway that can both work quickly and be reused. It makes gas storage safer, greener and more adaptable.”

Equally important is the ability to empty and reuse the system. By gently warming the hydrate, the team could recover all the stored methane. The leftover solution could then be frozen again to form fresh amino acid modified ice, setting up a repeatable ‘charge–discharge’ cycle reminiscent of how batteries store and release energy.

Reusability and sustainability makes the method appealing for handling smaller, distributed supplies of renewable biomethane, which are often too modest in scale to justify expensive liquefaction

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

or high-pressure storage facilities. The team is also exploring how to scale up the process for larger systems, including reactor designs that maintain efficient gas–liquid–solid contact, as well as tests with natural gas mixtures containing methane, ethane and propane. Other directions include improving hydrate stability through amino acid-engineered composite systems, and eventually adapting the method for gases such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen.

“Natural gas and biomethane are important components in the energy mix today, but their storage and transport have long relied on methods that are either costly or carbon-intensive,” added Prof Linga. “What we are showing is a simple, biodegradable pathway that can both work quickly and be reused. It makes gas storage safer, greener and more adaptable.”

Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Making ammonia burn cleanly at industrial heat

A single-atom platinum catalyst lights ammonia at 200°C and keeps it burning steadily at 1,100°C with low NOx , generating high-grade, carbon-free heat for steel, cement and chemicals.

Ammonia is a tempting fuel for the world’s hottest jobs. It can be made from air, water and renewable electricity, stored as a liquid and shipped using know-how industry already has.

However, the snag is that it is stubborn to ignite, burns sluggishly and tends to spew nitrogen oxides (NOx), when pushed to high temperatures. That mix has kept

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Forging New Frontiers

heavy industry — where highgrade heat is non-negotiable — tethered to fossil fuels.

CDE researchers have now shown that design at the atomic scale can change the equation. In work published in Joule, a team led by Professor Yan Ning from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and Assistant Professor He Qian from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering designed a catalyst that gets ammonia burning just above 200°C and sustains clean combustion at 1,100°C. Importantly, it converts the fuel completely into nitrogen and water, with only trace amounts of NOx. This means that industries could one day use ammonia to generate high-grade heat without producing carbon dioxide or harmful exhaust gases.

Why ammonia heat has been hard to harness

Industrial furnaces and reactors need intense, controllable heat delivered on demand. In principle, ammonia can provide that without carbon. But in practice, it is tricky. Ammonia’s “flammability window” is narrow — it only burns cleanly in a tight range of fuel–air mixes. In addition, the “light-off” temperature — the point where it starts burning readily — is high, and flames can become unstable. When operators raise temperature to keep the flame alive, NOx usually climbs.

“Heavy industry needs high-quality heat, not just a clean exhaust,” says Asst Prof He. “We set out to kill two birds with one stone: make ammonia easier to ignite and keep NOx low when you run it hot.”

The team’s approach, known as high-temperature catalytic ammonia combustion, uses a surface catalyst to help ammonia react with oxygen more easily. The tricky part is finding a material that can not only trigger combustion early, but also withstand the punishing temperatures needed for industrial heat.

Professor Yan Ning (left) and Assistant Professor He Qian (right) led a group to design a catalyst that gets ammonia burning just above 200°C and sustains clean combustion at 1,100°C.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

A durable catalyst, built atom by atom

The researchers found their answer in a material that distributes individual platinum atoms — each one acting as a tiny reaction site — across a tough support made from alumina strengthened with zirconia. This design prevents the metal atoms from clumping together under heat and helps the catalyst maintain its structure at over 1000°C.

When tested in the lab, the catalyst ignited ammonia at around 215°C — far lower than the 500°C or more usually needed — and kept it burning steadily at 1,100°C. Every molecule of ammonia was converted, with no unburned traces left behind and almost no NO x formation. The catalyst also grew stronger with use: after its first run, its performance improved and remained stable through repeated high-temperature cycles.

At lower temperatures, the single platinum atoms help ammonia molecules break apart and recombine with oxygen to form nitrogen and water, the cleanest possible outcome of combustion. At higher temperatures, the structure of the catalyst steers the reaction away from NO x formation. Advanced imaging confirmed that even after 80 hours of operation, the platinum atoms stayed dispersed and active, showing the thermal endurance of the catalyst.

“What matters here is the design logic,” says Prof Yan. “Pairing a heatstable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

Asst Prof He adds: “Industries could retrofit their systems with minimal changes, gaining the benefits of clean heat without having to rebuild their plants from scratch.”

“What matters here is the design logic,. Pairing a heat-stable support with isolated metal atoms enables us to achieve both early ignition and resilience at extreme temperatures. The system naturally favours the formation of nitrogen over nitrogen oxides.”

The researchers’ next step is to bring this concept closer to the factory floor. Supported by the NUS Centre for Hydrogen Innovations, the team is preparing for pilot-scale trials using facilities equipped for safe ammonia handling. They aim to test the catalyst in practical setups, such as industrial burners, gas turbines or high-temperature reactors, to see how it performs under real operating conditions.

“Ammonia has always held promise as a low-carbon fuel, but making it truly usable required solving a long-standing chemistry problem,” says Du Yankun, first author of the paper. “Our catalyst shows that it is possible to unlock ammonia’s energy cleanly and reliably. That brings us one step closer to carbon-free industrial heat.” Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Balancing the charge towards clean mobility

A coordinated control approach keeps electric vehicles, solar power and the grid in perfect harmony, enabling stable, battery-free ultra-fast charging that makes the most of the sun.

ltra-fast electric-vehicle charging stations juggle between three fastmoving sources of variability: solar power that fluctuates with passing clouds, vehicles that change their charging demand abruptly as they move through different fast-charging phases, as well as grid connections that can only tolerate limited swings in power without causing disturbances.

In many stations, these fluctuations are buffered using large battery systems, but this comes with added cost and maintenance. Associate Professor Sanjib Kumar Panda from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, wanted to find out: can stability still be achieved without adding yet another energy storage device?

A smarter way to share the load

Associate Professor Sanjib Kumar Panda led a team to develop a coordinated-control algorithm that keeps electric vehicles, solar power and the grid in perfect harmony, without relying on additional energy storage devices.

Assoc Prof Panda’s team set out to develop a coordinatedcontrol algorithm that manages all these interactions in real time, without relying on additional energy storage devices. Detailed in a paper published in the IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, the algorithm monitors four key factors: how quickly the grid can safely ramp power up or down; how much energy the solar plant can supply at its most efficient operating point (a condition known as maximum power point tracking, or MPPT); each vehicle’s charging capacity; and the limits set by its battery management system.

When sunlight fluctuates or a car begins charging, the controller redistributes available power among all connected vehicles in proportion to what they can handle, while keeping total grid power within the permitted bounds. If both the grid and solar irradiance fluctuate concurrently, with solar power generation higher than the allowable limit, it temporarily reduces solar output to safeguard the system — a kind of real-time compromise that keeps everything running smoothly.

“We wanted to make the system ‘think’ as a whole, not as separate components,” says Assoc Prof Panda. “Each charger adapts to what the others are doing, and the grid stays steady even when conditions change suddenly.”

To evaluate the approach, the team built a laboratory-scale setup powered by solar emulators and a solid-state transformer (SST), with seven fast-charging ports for different vehicle types. Over hour-long trials, the system maintained solar power extraction at more than 99% efficiency and delivered nearly full charging energy to every port — all while keeping grid fluctuations within strict ramp-rate limits and staying within each vehicle’s battery constraints. The current distortions on

the grid side also stayed well below the code limits, showing that stability and efficiency could coexist.

“Intelligently designed software algorithms can in fact take up the role of hardware storage devices — there is no need to supply ever more batteries if you can control the flow of power between different available resources precisely,” adds Assoc Prof Panda.

Making storage-free fast-charging possible

The implications of the researchers’ study go beyond laboratory results. As electric vehicles proliferate, ultra-fast charging stations will become focal points of power demand. Without meticulous control, they could strain local grids or squander renewable energy resources. The team’s coordinated-control method offers a way to integrate solar power into these systems, reducing stress on the grid and cutting out the cost and complexity of grid-scale batteries.

“Our aim is to make solar-assisted charging practical and reliable enough for use in the real world, which is often messy and unpredictable.”

In their comparison study, using a battery to achieve similar performance would have increased installation costs by up to 10%. The proposed method achieves the same stability using only algorithms and sensors — a leaner and more adaptable path for large-scale deployment.

“Fast EV charging shouldn’t come at the expense of grid health or adopting clean-energy goals,” Assoc Prof Panda notes. “Our aim is to make solar-assisted charging practical and reliable enough for use in the real world, which is often messy and unpredictable.”

The next question, he adds, is how such intelligent systems might connect with broader digital frameworks — for instance, linking to secure communication protocols, blockchain-based energy management or digital-twin-based pilot projects within real utility electrical power networks.

Looking ahead, the team will focus on bringing more renewable sources into the grid without compromising stability as supply and demand will continue to

fluctuate in a dynamic environment. A particular challenge is that many modern renewables rely on power-electronics-based controllers rather than traditional inertia based on spinning synchronous machines — so they do not have the natural “buffering” effect that helps to stabilise the grid. The team aims to develop control methods that allow these inverter-based systems to play a stabilising role even as renewable energy penetration grows. Their work will feed into upcoming efforts under the Singapore Energy Market Authority’s Energy Grid 3.0 Grant Call.

Injecting intelligence into tomorrow’s electrified world

From wind farms and ports to electric buses and charging hubs, Professor Dipti Srinivasan is designing optimisation frameworks that make renewable energy systems smarter, fairer and more efficient.

As the gears of electrification throttle at full speed, electrons are no longer flowing in one direction. They pulse across a dense, interconnected web of solar panels, offshore wind farms, high-capacity batteries and electric vehicles (EVs) — each node both consumer and supplier.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Managing this relentless current has become one of the defining challenges of the clean-energy era. One that requires keeping a network of moving parts in balance while demands balloon, data inundates and carbon budgets grip.

At the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Professor Dipti Srinivasan studies this orchestration problem from a systems perspective, exploring how algorithms, economics and engineering can work in tandem to steer decentralised energy systems towards both efficiency and equity. Her body of work, spanning renewable forecasting, grid optimisation and smart mobility, sheds light on how intelligence, when woven into energy networks, can make them cleaner, more adaptive and inherently fair.

Forecasting the grid

Renewables have transformed the energy landscape, but their variability makes the grid harder to manage. Predicting when the wind blows or the sun shines can mean the difference between stability and chaos.

To meet this challenge, Prof Srinivasan and her team develop computational models that help the grid think ahead. They have built ensemble learning frameworks that blend multiple forecasting methods into a unified, self-correcting process — learning from past errors to predict power output more accurately. In other studies, they’ve tackled the heavy lifting behind large-scale optimisation, devising algorithms that can process thousands of variables in seconds rather than hours, cutting computation times without losing precision.

These advances allow renewable-rich power systems to dispatch electricity faster and more reliably, closing the gap between prediction and operation. As Prof Srinivasan puts it, “We want the grid to be anticipatory, to sense change before it happens, not react after the fact.”

Professor Dipti Srinivasan leads teams to design optimisation frameworks that make renewable energy systems smarter, fairer and more efficient.

Fairness and coordination, at scale

Indeed, forecasting is only part of the bigger puzzle. As energy systems become more distributed, coordination, and fairness, come into the picture.

In one study, Prof Srinivasan’s team designed a multi-agent framework that lets different players within a port, from terminals to the authority itself, trade energy locally without giving up private data. The system balances the port’s energy costs while keeping transactions secure against cyber attacks.

Another project took inspiration from social welfare theory to rethink how electric vehicle charging stations allocate their limited capacity. By using a lexicographic optimisation model — a kind of mathematical pecking order that weighs fairness and efficiency simultaneously — the system ensures that every driver gets a fair share of fast-charging power, even during peak hours.

These ideas, with ethics in their core as much as engineering, shed new perspectives on how cooperation can emerge in competitive energy markets. “Fairness is not a side constraint,” Prof Srinivasan explains. “It is the condition that allows distributed systems to function sustainably.”

“Fairness is not a side constraint. It is the condition that allows distributed systems to function sustainably.”

Driving electrification on the ground

The same principles now power Prof Srinivasan’s research in electrified transport — where vehicles, routes and batteries form yet another complicated energy network. Her team recently built a three-layer optimisation framework for electric bus fleets that spans from long-term charger planning to real-time charging schedules.

The framework works by modelling every bus’s usage pattern, battery health and charging opportunity, which enables it to trim lifecycle costs while extending battery lifespan. Case studies on campus shuttle systems showed up to a 90% reduction in uneven battery wear — evidence that smart planning can keep fleets running longer, cleaner and cheaper.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Looking ahead, Prof Srinivasan plans to advance her work in uncertainty modelling, EV-charging optimisation, demand-side management and renewable forecasting, while exploring new avenues that apply deep learning, multi-agent systems and optimisation techniques to strengthen power-system resilience.

“Our goal is to bridge research and real-world deployment by incorporating AI, multi-agent systems and optimisation into the fabric of tomorrow’s energy networks,” says Prof Srivinasan. “From port terminals and wind farms to virtual power plants and electric transport, these approaches help us build smarter, more sustainable grids — systems that can learn, adapt and ultimately make electrification more resilient.”

Industrial Systems Engineering and Management

Powering a shared energy future

New modelling shows that linking ASEAN’s power grids could accelerate the region’s path to net zero, cutting costs and easing the burden of a just energy transition.

Across Southeast Asia, the appetite for electricity is increasingly voracious. By 2050, consumption is expected to more than triple from 2018 levels as populations grow and economies industrialise further. However, the region still generates most of its power from fossil fuels, giving it one of the fastest-rising emissions trajectories in the world. Hydropower from the Mekong Basin remains the region’s dominant source of renewable energy, while the vast solar and wind potential across its member states is still largely untapped.

Each ASEAN country has pledged to cut emissions under the Paris Agreement, but the question remains: how can a diverse region of ten1 countries with uneven resources and infrastructure decarbonise both effectively and affordably?

That inquiry underpins a new study led by Dr Su Bin, Senior Research Fellow from the Energy Studies Institute and the Department of Industrial Systems Engineering and Management at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, conducted in collaboration with ExxonMobil. The study builds an integrated model of ASEAN’s power sector to test how different strategies, from “go it alone” national plans to fully connected regional grids, might influence the journey to net zero. The findings paint a clear picture where greater crossborder cooperation could make the energy transition faster, fairer and far less costly.

A region connected by power

Dr Su Bin’s study builds an integrated model of ASEAN’s power sector to test how different strategies, from “go it alone” national plans to fully connected regional grids, might influence the journey to net zero.

The model, which simulates power generation, transmission and storage across all ten ASEAN countries from 2018 to 2050, explores three pathways. The first assumes each country develops its power system independently. The second allows for crossborder electricity trade through the ASEAN Power Grid — a regional initiative to interconnect Southeast Asia’s national electricity systems — while maintaining moderate emission goals. The third envisions a fully connected system targeting net-zero emissions by 2050.

The team found that building transmission links between countries — at a cost of only about 0.5% of total infrastructure investment — could reduce overall system costs by an outsized 12%. Regional trade would also lower the average price of electricity by more than 10% while allowing countries with limited renewable resources to import clean energy from their neighbours. For example, Lao PDR and Indonesia could become major exporters of hydropower and solar power, while importers such as Thailand, Vietnam, Brunei and Singapore could avoid overbuilding fossil-fuel capacity or rushing prematurely into exorbitant carbon-capture systems.

In the most ambitious scenario, renewables would account for about 92% of ASEAN’s power generation by 2050, nearly half of it from solar energy. Hydropower would continue to play a major role where geography allows, and wind power would

1 At the time of the study, ASEAN consisted of ten member states. Timor-Leste joined the Association after the study was completed.

take off in the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Fossil fuels — largely natural gas equipped with carbon capture and storage — would make up the remaining 8%, offset by biomass-based technologies capable of extracting carbon from the atmosphere.

“We often think of energy transitions in national terms, but the reality is that power systems do not stop at borders,” says Dr Su. “When countries connect their grids, they share more than just something tangible like electricity. They also transmit flexibility, resilience, security and opportunity.”

“When countries connect their grids, they share more than just something tangible like electricity. They also transmit flexibility, resilience, security and opportunity.”

Bridging the investment gap

Transitioning to a cleaner, interconnected power system will require substantial and uneven investment. The study estimates that total investment in generation infrastructure alone could reach roughly 30–45% of ASEAN’s 2018 GDP by 2050. Developing economies with abundant sources of renewable energy but weaker financial systems, especially in the Greater Mekong subregion and parts of the Indonesian archipelago, face an uphill battle. This uneven burden emphasises the need for joint financing and policy frameworks that promote a just and inclusive transition.

Beyond the economics, the study highlights governance and policy gaps that must be addressed. In particular, harmonising regulations, ensuring energy security and building trust across jurisdictions will be as important as engineering and capital. Regional mechanisms for benefit sharing, coordinated grid planning and investment support could help turn modelling scenarios into reality.

“While our paper focuses on technical feasibility, it prompts further thought and exploration, for policymakers and industry alike,” says Dr Su. “For example, how can ASEAN strengthen its financing architecture to support large-scale renewable investments? What regional mechanisms could balance the costs and benefits of cross-border grids?”

“Above all, the data tells us the transition is technically and economically possible,” Dr Su adds. “The next step is to make it politically and institutionally possible too.”

Building safer batteries

Associate Professor Palani Balaya develops sodium- and lithium-ion battery technologies, raising their performance and safety for an increasingly electrified world.

As electrification spreads from motorcycles, cars and trailers to neighbourhood microgrids, the energy density of the batteries is becoming increasingly higher, and as a result, they are getting increasingly heavier and riskier. While battery capacity is a crucial differentiator, safety, cost and supply resilience are also unmistakable ingredients in formulating efficient, highperformance batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries remain the dominating workhorse, but its flammable liquids and tight supply chains leave gaps for other chemistries to fill. At the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, Associate Professor Palani Balaya and his team explore those options,

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

pushing ceramic- and polymer-based alternatives that let sodium, an earth-abundant element, carry the charge.

Turning grain boundaries into express lanes

To make sodium-based batteries a viable alternative, one major hurdle must be addressed: ensuring ions can move quickly through solid materials. In solid-state batteries, which replace flammable liquids with non-combustible solids, the junctions between microscopic crystals, called grain boundaries, often slow ion movement, favouring the growth of tiny metallic tendrils known as dendrites, which shorten battery life.

Assoc Prof Balaya’s team found a way to turn those vulnerable junctions into ionconducting pathways. Detailed in their paper published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A, they introduced small amounts of two elements into a ceramic material commonly used as solid electrolytes, which altered both its crystal structure and the chemistry along the grain boundaries. This dual adjustment created smoother channels for sodium ions to flow and prevented the formation of dendrites that can cause micro short-circuits. If not mitigated, such short circuits can trigger a dangerous chain reaction known as thermal runaway.

“We created a safer, more stable ceramic electrolyte that could sustain efficient ion transport over many cycles.”

“We created a safer, more stable ceramic electrolyte that could sustain efficient ion transport over many cycles,” says Assoc Prof Balaya. “When used in a prototype solid-state sodium battery, the material enabled decent storage capacity and stability, showing that solid ceramics can rival conventional liquid-based systems in performance, without the fire risk.”

To improve flexibility and interface contact between the solid layers, the researchers also blended the ceramic particles into a polymer to create a hybrid ceramicpolymer electrolyte. This combination retained high storage performance at 60°C while adding the pliability needed for practical manufacturing. Taken together, the researchers’ work enables durable, non-flammable sodium batteries suited for large-scale storage systems where safety and cost matter as much as capacity.

A team led by Associate Professor Palani Balaya developed ceramic- and polymer-based sodium-ion batteries, raising their performance and safety for an increasingly electrified world.

A softer path to solid power

While one line of Assoc Prof Balaya’s work focused on strengthening the solid electrolyte, another explored the more flexible components of solid-state batteries — the polymers that help bind active electrode materials together and support smooth ion movement between them.

In another study published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces , the team compared several polymer electrolytes and identified one made from a flexible fluoropolymer as the most promising candidate. It showed the right mix of softness and structure: low crystallinity for faster ion movement, minimal pores to prevent contact loss and high thermal stability for safe operation.

Using this polymer with modified ceramic electrodes, the researchers built a solidstate sodium-ion battery that worked at room temperature — an important step toward real-world use. The prototype delivered steady performance and retained about 85% of its capacity after 200 charge-discharge cycles, with highly reduced safety hazards of liquid electrolytes.

Beyond performance, the work underscored a key design philosophy: solidstate batteries are not just about discovering one “perfect” material, but about balancing structure, flexibility and stability across all components. This holistic approach allows the team to fine-tune how ions travel, how layers connect and how cells endure thousands of cycles, ultimately translating lab discoveries into reliable energy-storage solutions.

Looking ahead, the team is working to lower the operating temperature of their solid-state sodium-ion cells to around 45°C using a hybrid ceramic-polymer electrolyte. Achieving this would allow the batteries to run safely and efficiently much closer to ambient conditions, reducing the energy required for heating and making the technology more practical for real-world use. To reach this goal, they are exploring the use of two-dimensional materials and newly formulated ceramic electrolytes as both passive and active fillers to improve ion transport at lower temperatures.

With additional support from industry partners, the team also plans to develop bipolar all-solid-state sodium-ion batteries — a stacked architecture that can significantly reduce weight, simplify packaging and raise overall energy density. This may involve co-development opportunities, prototype demonstration projects or potential commercialisation pathways such as spin-offs. Issue 07 | Dec 2025

A smarter way to stay cool

A new heat exchanger design combines condensation and desiccant processes to manage humidity more efficiently, reducing energy use without sacrificing comfort.

In Singapore, about a quarter of household electricity use goes to cooling, and a significant portion of that energy is spent not on lowering temperature, but on removing the air’s moisture. It is an unseen burden in the tropics, where latent cooling — the energy needed to dehumidify the air — can make up to 50% of total cooling demand. As the region warms and humidity rises, that share is expected to grow.

Most air-conditioning systems deal with moisture by overcooling the air until water condenses on chilled coils, then reheating it to a comfortable temperature. It is also very wasteful as too much energy is lost in the cycle of cooling and reheating. Associate Professor Ernest Chua from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, wondered whether there might be a smarter balance. One that could tame the tropics’ moisture without driving temperatures so low.

His team turned to desiccant-coated heat exchangers, or DCHEs. These devices can remove moisture in two ways: by condensation, as in conventional systems, and by sorption, where a desiccant layer chemically locks in water vapour from the air. “Conventional systems depend almost entirely on condensation, which means the coils have to run much colder than necessary,” says Assoc Prof Chua. “If we can harness both condensation and sorption, we can achieve the same level of comfort at warmer coil temperatures — and that’s a big step toward greater efficiency.”

The team’s study, published in Energy, investigates how DCHEs behave under below-dew-point conditions — a regime where condensation and sorption occur together. Most prior studies examined only sorption, leaving a gap in understanding how the two processes interact and how to select desiccant materials that remain stable when condensation is present.

A new guide for below-dew-point cooling

To fill that gap, the researchers developed a three-step guide for evaluating desiccant materials and operating conditions below the dew point.

The first step tests stability, exposing a coated heat exchanger to long cycles of extreme, condensation-heavy conditions to see if the material breaks down or dissolves. The second step identifies the transition temperature — the point at which dehumidification shifts from being dominated by condensation to being driven primarily by sorption. The final step examines how factors such as inlet humidity, air contact time and switching time affect system performance.

Associate Professor Ernest Chua and his team designed a new heat exchanger that combines condensation and desiccant processes to manage humidity more efficiently.

To demonstrate the process, the team used a composite superabsorbent polymer–lithium chloride (SAP–LiCl) coating. It proved highly stable even in the presence of water, maintaining its structure and dehumidification ability after extended testing. The researchers determined that the transition between condensationand sorption-dominant behaviour occurred around 15°C, a temperature range suitable for air-conditioning systems operating just below the dew point.

“This transition temperature is critical,” explains Assoc Prof Chua. “It tells us exactly when a desiccant begins to contribute meaningfully to dehumidification. If the operating temperature sits on the right side of that boundary, the system can work more efficiently without sacrificing comfort.”

The findings showed that the DCHE could remove nearly four times more moisture from air than a conventional condensation-only coil. It could also match or surpass a conventional coil’s dehumidification performance using coolant roughly 5°C warmer. That difference, though small, translates into large energy savings, as warmer coils raise evaporator efficiency and reduce chiller load. Under optimised conditions, the researchers estimate an improvement of about 20% in energy use.

From laboratory concept to working prototype

To test the concept in a full system, the team built a desiccant-coated heat pump (DCHP) prototype. The design alternates two coated heat exchangers between evaporator and condenser roles — one coil cools and dries the air, the other releases stored moisture and prepares for the next cycle.

The prototype delivered a cooling capacity of 1.5 kW (about the output of a typical air-conditioner for a small room) and produced almost five times more cooling energy than the electricity it consumed. The team also found that a 15-minute switching cycle provided the best balance between efficiency and dehumidification. Raising the evaporator temperature from 12°C to 18°C reduced cooling output but increased energy efficiency by roughly 50%, which offers flexibility depending on operational needs.

“Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in the real conditions they face, not just in the laboratory.”

The implications are significant for humid places like Singapore, where the energy spent removing moisture from the air accounts for up to half of total cooling demand. Importantly, the combined condensation-sorption approach demonstrated by the researchers could support humidity control in settings that depend on precise moisture management, from commercial buildings and offices aiming to reduce chiller loads, to data centres protecting sensitive hardware, to hospitals and pharmaceutical facilities that rely on stable indoor conditions. Even industrial drying processes, such as food or textile production, could benefit from pre-dried intake air and more efficient heat recovery, underscoring the wider role for DCHEs in improving comfort and efficiency across a multitude of environments.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to apply the same framework to other advanced materials. Among the most promising are metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), crystalline compounds whose tuneable porous structures make them highly effective at capturing moisture. Recognised in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their versatility in catalysis and gas storage, MOFs could extend the performance of DCHE systems even further.

“Ultimately, this is about using materials thoughtfully,” says Assoc Prof Chua. “Once we understand how sorption and condensation interact, we can design cooling systems that perform well in the real conditions they face, not just in the laboratory.”

Mechanical Engineering

Riding the heat wave

A new nanoscale design channels hybrid light–vibration waves to carry heat more efficiently, allowing better thermal management in compact, energy-hungry electronics.

Your phone warms up after a 20-minute Facetime call. Your laptop hums loudly while editing a large video file. Heat is a by-product of modern electronics — from everyday gadgets to the high-resolution screens and processors that power electric vehicles.

As components get smaller and more powerful, that heat becomes increasingly difficult to tame. In the cramped spaces of modern chips, the usual carriers of thermal energy — electrons and phonons (the tiny vibrations of atoms) — keep colliding

Issue 07 | Dec 2025 Forging

with surfaces and scattering in all directions. Instead of dissipating, that heat lingers instead, straining energy efficiency and making devices fickler.

Assistant Professor Shin Sunmi pondered if heat could be made to move differently, not through the chaotic jostling of particles, but in waves. At the Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, her team turned to an unusual phenomenon called surface phonon polaritons (SPhPs): ripples that arise when infrared light couples with atomic vibrations on the surface of certain materials such as silicon dioxide. These hybrid waves behave like guided beams of thermal energy, theoretically able to travel long distances without the usual loss from boundary collisions. However, in practice, they’ve remained elusive — hard to generate, harder still to detect.

“The idea of using light-coupled waves to carry heat has been around for some time,” says Asst Prof Shin. “The challenge was how to actually measure them and confirm that this invisible form of heat flow truly exists in solids.”

Catching invisible waves

To make those waves visible to measurement, Asst Prof Shin’s group designed a grating-enhanced micro-thermometer — a suspended device with two thin beams connected by a nanoscale bridge of silicon dioxide. One beam serves as a heater, while the other acts as a sensor. The sensing beam’s surface is patterned with a fine grating, just a few micrometres wide, that lets the mid-infrared waves couple into it more effectively.

The pattern allows the surface heat waves to be absorbed instead of bouncing off, much like how the V-shaped grooves on a vinyl record captures sound waves. Computer simulations showed that this design nearly doubles the amount of infrared energy absorbed across key wavelengths, greatly improving the detectability of SPhP-mediated heat flow.

When the team tested heat channels of various lengths, they noticed something unusual. In shorter channels — just tens of micrometres long — heat seemed to flow effortlessly, barely slowing down with distance. Instead of scattering in all directions,

Assistant Professor Shin Sunmi and her team introduced a new nanoscale design that channels heat more efficiently, allowing better thermal management in compact, energy-hungry electronics.

it travelled almost as though riding a guided wave of light. The team’s measurements also confirmed it. Even in structures a thousand times thinner than a human hair, heat moved nearly as efficiently as it does through bulk silicon dioxide. Devices with the patterned grating design showed a marked improvement too, carrying about 70% more of this light-driven heat than their flat-surfaced counterparts.

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance,” Asst Prof Shin notes. “That’s a clear signature that these surface waves can act as longrange energy carriers, even in structures this small.”

“It was surprising to see heat behaving almost independently of distance.”

The team’s design, detailed in their new paper published in ACS Nano, not only confirms that SPhPs can move heat efficiently, but also provides a way to tune how well they interact with solid structures — by adjusting the geometry rather than changing materials.

New ways to control heat

As data centres mushroom across the globe, driven by the boom in artificial intelligence, the world’s ever-growing appetite for computing power is also fuelling an “electronic heat wave.” A large share of the world’s energy bill today goes simply into preventing machines from overheating. Finding new ways to direct heat could make future electronics leaner, cooler and far more energy efficient.

The researchers’ solution is elegantly simple: instead of relying on bulky heat sinks or exotic materials, it reshapes surfaces at the nanoscale to influence how heat moves across. Shaping how light and matter interact at the nanoscale enabled the team to open a new route for managing thermal energy where traditional methods lack gusto.

In principle, devices that can guide heat in this way could help reduce dependence on fans and heavy thermal components, improve the stability and performance of compact chip designs and make electronics more resilient in high-temperature or demanding environments — from electric drivetrains to wearable sensors and photonic circuits. On a larger scale, with cooling already accounting for up to 40% of total power use in some data centres, even modest improvements in how heat moves through chips may translate into meaningful energy savings.

Looking ahead, the team plans to probe the theoretical upper limit of how much heat surface phonon polaritons can carry, and to demonstrate thermal routing, using these guided waves to steer heat intentionally across micron-scale paths. By integrating such wave-based heat channels into next-generation, chiplet-based microelectronics, the team aims to show that nanoscale surface design can serve as a practical cooling strategy for densely packed, high-power chips where conventional heat-spreading methods reach their limits.

Fuelling the future of sustainable shipping

A new engine concept turns ammonia into its own source of hydrogen, charting new waters for cleaner, more efficient shipping without the need to store hydrogen onboard.

Each year, international shipping moves over 80% of global trade and emits around one billion tonnes of greenhouse gases. Heavy fuel oil remains the industry’s workhorse, prized for its reliability and energy density but notorious for its carbon footprint. As the International Maritime Organization pushes toward net-zero emissions by 2050, the search for viable carbon-free fuels is on.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Among the candidates, ammonia has been in the spotlight. It is carbon-free, easily liquefied for transport and can be produced on a large scale through wellestablished industrial routes. It also carries a high concentration of hydrogen by volume — a property that makes it an attractive hydrogen carrier. However, ammonia is difficult to ignite, burns slowly and tends to leave behind unburned fuel and nitrogen oxides that harm efficiency as well as the environment.

Hydrogen, by contrast, burns quickly and cleanly, and blending it with ammonia improves both performance and emissions. Its storage requirements, however, are its Achilles’ heel. Hydrogen must be chilled to -253°C or compressed at high pressures, requiring bulky, costly tanks — impractical for long voyages at sea.

This long-standing dilemma — how to capture the best of both fuels without their drawbacks — is what Associate Professor Yang Wenming and Senior Research Fellow Dr Zhou Xinyi from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore set out to address.

Their study, published in Joule, introduces a new concept for an ammonia–hydrogen engine with a single ammonia fuel supply. In essence, the engine makes its own hydrogen as it runs, avoiding the need to carry a separate supply altogether.

Turning fuel into its own catalyst

Most ammonia-hydrogen engine concepts today rely on external reformers: separate reactors that heat ammonia to around 550°C and use catalysts such as ruthenium to break it down into hydrogen and nitrogen. These systems consume additional energy for heating, add mechanical complexity and occupy valuable space. They also face trade-offs between cost, conversion rate and durability, all of which are critical for ship engines expected to run continuously for decades.

Associate Professor Yang Wenming (left) and Dr Zhou Xinyi (right) introduced a new concept for an ammonia–hydrogen engine with a single ammonia fuel supply.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought that we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself,” says Assoc Prof Yang.

In the team’s concept, one cylinder in a multi-cylinder engine operates on a fuelrich ammonia mixture. Under the intense temperature and pressure of combustion, part of the ammonia decomposes into hydrogen. This hydrogen-rich exhaust is then recirculated to the other cylinders, enriching their combustion and improving efficiency — all using the same fuel.

In-cylinder reforming gas recirculation (IRGR) concept coupled with active pre-chamber.

Forging New Frontiers

“Instead of processing ammonia outside the engine, we thought that we could produce hydrogen inside the engine cylinder itself.”

To keep this process stable, the researchers introduce an active prechamber ignition system. It ignites a small, easily combustible mixture in a prechamber, sending hightemperature turbulent jets into the main chamber to ignite the ammonia-rich fuel. This ensures reliable ignition without relying on pilot diesel, thereby averting carbon dioxide emissions from fossil-based ignition fuels.

“More importantly, integrating active pre-chamber technology can extend the ammonia-rich limit of the main chamber, thereby increasing the total hydrogen production,” says Dr Zhou.

Initial experiments and simulations suggest that this in-cylinder reforming approach could improve thermal efficiency, cut unburned ammonia and significantly reduce

nitrous oxide emissions, which is one of the key environmental challenges for ammonia engines as the nitrous oxides are approximately 273 times more potent than carbon dioxide in terms of warming the planet.

“The concept also simplifies the system. No bulky reformers, no expensive catalysts and fewer energy losses,” adds Assoc Prof Yang.

Charting new waters

Assoc Prof Yang and Dr Zhou’s work is a step toward making hydrogen practical at sea. His team’s analysis also reveals an important balance: more hydrogen is not always better. Once the hydrogen fraction exceeds roughly 12% of the engine’s energy input, the efficiency gains level off while combustion temperatures, and thus nitrous oxide emissions, rise. The proposed configuration, where one reforming cylinder supports three combustion cylinders, achieves an effective hydrogen mix without affecting emissions.

The researchers also outlined some pertinent challenges that need to be resolved. The physics inside the reforming cylinder are complex, governed by fast-changing flows, turbulent reactions and shifting temperatures and pressures. Understanding how hydrogen forms and behaves under such transient conditions will be key to refining the design.

They also highlighted several possible future directions. For instance, oxygen-enriched combustion could extend the limits of ammonia-rich operation, especially since ships already carry air-separation systems. High-pressure direct injection of liquid ammonia may help improve conversion efficiency near cylinder walls. Moreover, coupling the setup with a small supplementary reformer downstream — powered by the engine’s own exhaust heat — could further raise overall efficiency without increasing system size.

To advance their line of research, the team plans to build the first prototype incylinder reforming gas recirculation engine with the support of a major project from the Singapore Maritime Institute (SMI), then validate this technology route in both laboratory and onboard demonstrations, and advance its commercialisation.

“Shipping decarbonisation will require many complementary solutions,” says Assoc Prof Yang. “But if we can design engines that generate hydrogen from the very fuel they burn, we can overcome one of the largest practical barriers — hydrogen storage — and chart a course toward a zero-carbon maritime sector.” Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Mechanical Engineering

Keeping the ammonia flame alive

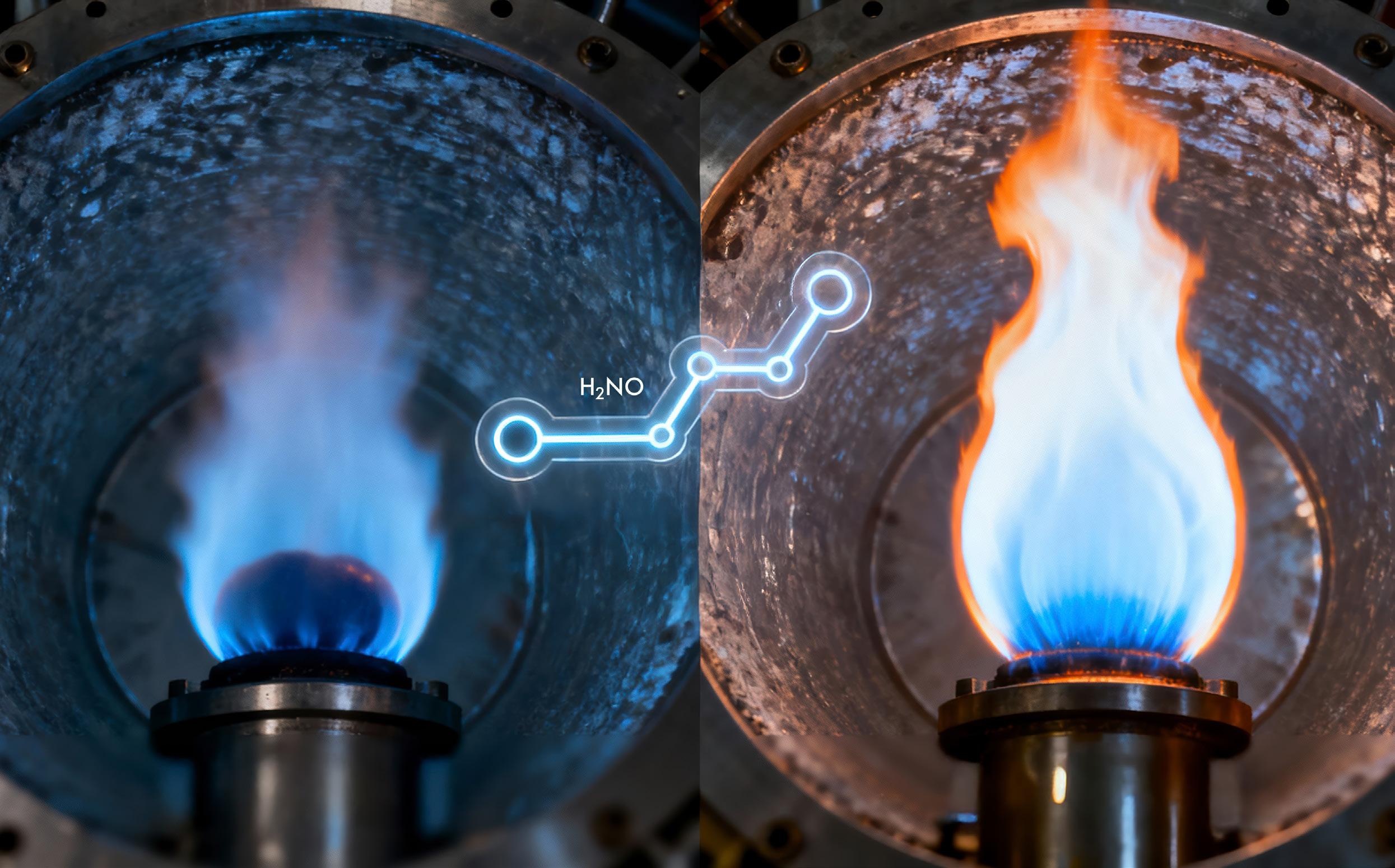

The chemistry of ammonia flames shows that even a small dose of hydrogen can turn an unstable or near-extinction flame into a steadier source of clean power.

Ammonia may be packed with hydrogen, nature’s lightest and most energydense carrier, and contain no carbon, but it is an oddly obstinate fuel. It ignites slowly, burns unstably and easily blows out — a temperamental quality that makes engineers skittish about using it in real turbines or engines. Yet its potential is too valuable to ignore. Finding out when and how ammonia keeps burning, especially under the intense pressures of real combustion systems, could help turn it into a practical low-carbon energy carrier.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

Associate Professor Zhang Huangwei from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore, wanted to uncover what lies between a stable ammonia flame and a fickle one.

His team’s study, published in Combustion and Flame, used a detailed simulation model known as a premixed counterflow flame — a controlled setup where two opposing jets of fuel and air meet head-on, imitating how flames behave inside engines. By recreating these conditions at high pressures up to 25 atmospheres, similar to those in actual gas turbines, the researchers could explore exactly where an ammonia flame stabilises, weakens or quenches under engine-relevant conditions.

The sweet spot

The team’s simulations revealed the beauty of ammonia flames, lying in its interacting flame chemistry pathways, which leads to fascinating flame bifurcation phenomenon. When too much energy radiates away from the flame, the reaction slips into a “weak flame” — a cooler, slower-burning state that exists only within a narrow range of flow conditions. It glows faintly but stays alive, surviving where most flames would fade.

Adding hydrogen, however, changes the picture. Even a small fraction of about 10% by volume injects a strong dose of resilience. It triggers a low-temperature chemical route, known as the H2NO pathway, that helps the flame recover lost heat and stay alight. In the process, hydrogen dramatically widens ammonia’s burning limits, the range of mixtures and pressures in which the flame can sustain itself. Under these conditions, the flame can endure where pure ammonia would have long been snuffed out.

By laying out these flame transitions, Assoc Prof Zhang’s team produced a comprehensive regime map that shows where different flame modes appear and vanish. Such maps are invaluable to turbine designers, who must ensure that combustion remains stable under constantly changing loads and airflow patterns. They also reveal how fragile the balance is between temperature, pressure and chemistry — and how a touch of hydrogen can stabilise the system.

Associate Professor Zhang Huangwei led a team to explore exactly where an ammonia flame stabilises, weakens or quenches under engine-relevant conditions.

Issue 07 | Dec 2025

“Ammonia carries energy cleanly, but the real challenge is keeping the flame in its sweet spot when pressure and heat loss conspire against it,” adds Assoc Prof Zhang.“A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

Forging New Frontiers

“A small dose of hydrogen goes beyond making it burn faster — it keeps it from dying out.”

The team’s next steps involve refining radiation models to capture reabsorption effects — how some emitted heat is recycled back into the flame — and incorporating sensitiser species to modulate the reactions of ammonia flame chemistry.

From fundamental flame chemistry to future energy systems

The team’s findings form part of Singapore’s Low-Carbon Energy Research (LCER) Programme, a national initiative that supports research and development of emerging low-carbon energy alternatives that have the potential to help reduce Singapore’s carbon footprint.

Assoc Prof Zhang leads a larger project that couples ammonia cracking — breaking the molecule into hydrogen and nitrogen — with gas-turbine combustion and waste-heat recovery. Supported by the LCER Programme, the project aims to design integrated systems that can generate power efficiently while keeping nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions low.

Other strands of the project span fundamental chemistry to system-level design. On one front, researchers are developing catalytic models and laboratory reactors to improve ammonia cracking efficiency — partially splitting ammonia into hydrogen and nitrogen to create a more reactive, lower-emission fuel stream. On another, teams are using laser-based diagnostics to probe excited flame radicals to understand how these cracked fuels behave in gas-turbine conditions. Parallel efforts tackle the engineering and economic facets: assessing energy efficiency, waste-heat recovery and the techno-economic feasibility of combining cracking and combustion in a single integrated system.

Together, these efforts move toward pilot-scale gas-turbine demonstrations, where the goal is to prove that ammonia, when intelligently cracked and combusted, can deliver stable power generation with minimal emissions.