2024/2025 SEASON

By Siwoo Park

Noun:

A state in which opposing forces or in uence are balanced

Writers

Sanghoo Ahn

Sooho (Andy) Cho

Eunso (Gracia) Kang

Eun Taek Oh

Suhyeon (Gabriella) Shin

Dongwon (Dylan) Seo

Soyeon Ahn

Uchan Seo

Jiyong (Lysander) Chun

Yonjun (Colin) Kim

Sta

Mr. Jason Sannegadu

Mr. Robert Mclaughlin

Ms. Akanksha Guleria

Content Editors

Darby Seo Lee

Dylan Seo

Design

Siwoo Park

Equilibrium, our school’s student-led magazine on History and Global Politics, is testament to the creativity and commitment that students have for the Humanities. e writers and editors have worked hard throughout the term to create a publication that is lled with insightful articles on historical topics and current a airs.

Equilibrium highlights the essentialness of the humanities within our school. In a world where STEM subjects o en dominate educational discussions, Equilibrium serves as a reminder of the enduring importance of History, Politics, and the Social Sciences in helping us understand the complexities of human society. e magazine also encourages collaboration, as students work together across year groups, exchanging ideas and supporting one another in the writing and editing process.

e theme of this edition, “Con ict vs Cooperation,” is important because it addresses how wars and alliances have shaped history and continue to in uence global politics today. Understanding why states engage in con ict or choose to cooperate with each other helps us learn from past events and work towards resolving current international challenges more e ectively.

Equilibrium is not just a magazine; it is a platform for student voice and a celebration of the humanities at our school. I would like to thank the editors and the writers for creating such an outstanding edition, building upon the success of previous ones.

Mr. Sannegadu

History Teacher (Assistant Vice Principal, Pastoral and Head of Houses)

“To act on the belief that we possess the knowledge and the power to shape the processes of society entirely to our liking is likely to make us the destroyers of a civilization.”

- Friedrich Hayek [ e Pretence of Knowledge]

“Security is not strengthened by arms alone. It derives from relations of trust and good-neighborliness among nations and peoples.”

- Mikhail Gorbachev

“We must act not alone but together, to combat disease and su ering wherever it exists in the world.”

- John F. Kennedy

Colin Kim Y9

In Eastern Europe, aka the Balkans, a country known as Yugoslavia was created in 1918. Yugoslavia comprised Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, North Macedonia and Montenegro. ese countries that were part of Yugoslavia were never intending to unify and they ended up disbanding in 1991-1992. So how has this country lasted less than a century? If none of the countries intended to unify, then why was it even formed? is article will delve into how international organisations led to the creation and the destruction of Yugoslavia.

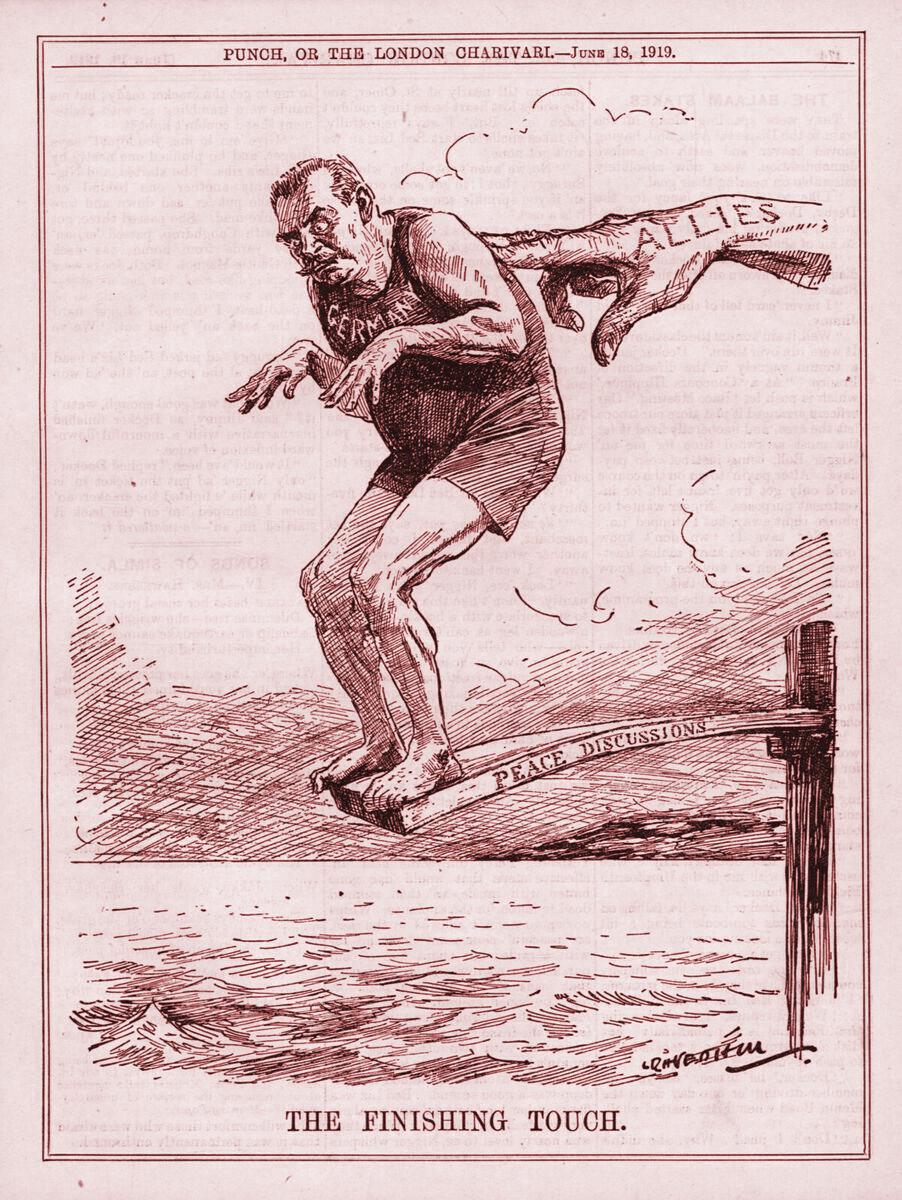

Yugoslavia is located in the Balkans where most of the countries do not have pleasant relationships. In fact, that is where the spark of World War 1 started. A er World War 1, most of the European nations were in ruins and these nations wanted to gure out a way to prevent another great war like this from happening. American President, Woodrow Wilson, had fourteen points that were put forward at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. One of them was about the creation of an international organisation. Unfortunately for him, only four of them made it to the Treaty of Versailles to be rati ed. is may have been Wilson’s idea but America refused to sign it and did not join the League of Nations. As a result, Great Britain and France were mostly in charge of leading the League of Nations. However, the $aw of this international organisation was a lack of armed forces and the larger in$uences of the stronger nations. ese stronger nations started to disarm Germany and made them pay debt to prevent another war from happening. ey also tried to solve disputes between countries like con$icts in the Balkans or ways of dealing with the distribution of territory of the former Ottoman empire. As negotiations mainly happened with the stronger and more in$uential countries, the ideas of the smaller countries were barely considered. As well as distributing the land in the Ottoman empire however Britain and France wanted. Britain and France also decided to separate Austria and Hungary, make Czechoslovakia and unify some countries in the Balkans to form Yugoslavia. is could only lead to tension between many countries as they were forced around however Britain and France wanted. Czechoslovakia ended up splitting in 1992 which was also known as the Velvet Divorce and Israel and Palestine are having con$icts to this day. e League of Nations ends up as a big failure because of these actions and the exclusion of many countries when cooperating

about how to deal with such con$icts happening across the world.

e result of this forceful uni cation could only have led to one outcome, con$ict. As stated before, Yugoslavia was made up of six nations. All these nations had di%erent ethnic groups within them. ere were Serbs, Slovenes, Croats, Macedonians, Bosniaks, Montenegrin and various other ethnicities. ere were also many minorities within these six regions. In Croatia, there was a 12.2% Serb minority. Moreover, Serbia had two separate states called Kosovo and Vojvodina which were composed of Albanians. To add to that, Bosnia and Herzegovina were made up of Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats while Muslims were a very small minority within most of these countries due to the Balkans being the Ottoman Empire’s former territory. ese ethnicities could have got along peacefully without causing too much con$ict. However, most of these ethnicities were very nationalist so they had a lot of pride and felt like the superior ethnic group of Yugoslavia. is was an unstable foundation which was prone to a lot of con$ict. On the other hand, Yugoslavia was actually not that tense for a period of time. Under the presidency of Josip Broz Tito, these six neighbouring countries were told to live in unity and Tito advocated for brotherhood in the nation. Tito also jettisoned the Yugoslavian monarchy, which was almost a dictatorship, that was in place before his presidency. Furthermore, Tito’s presidency caused Yugoslavia to become a regionally powerful country as well as having a strong economy. For the time being, it seemed that Yugoslavia would be at peace and would never face new ethical or religious con$icts again. However, it was what happened a er Tito’s death that sparked the con$ict which led to the disbandment of Yugoslavia.

A er the death of Tito, the Yugoslavian econ-

omy became unstable due to the 1973 oil crisis and trade boundary disputes. Furthermore, the growing economy was favouring certain areas over others. is led to more ethnic division between the North, Croatia and Slovenia, and the south, Serbia. However, this problem of ethnic divide was also due to the fact that the ethnic lines did not follow the borders of the six states. is meant that there were various minorities in each state which were very nationalistic. Such failure to divide borders properly was bound to lead to large amounts of con ict. is has happened in various di erent places such as the dispute between India and Pakistan’s borders a$er India declared independence from the British Empire. Another factor that led to the con ict was the creation of two new autonomous provinces, Kosovo and Vojvodina. Kosovo was made up of Albanians while Vojvodina had a Hungarian ethnicity which is what made matters worse. e spark of the con ict was when ethnic Serbs in Serbia were targeting the Albanian majority in Kosovo. Strikingly, the Serbian leader Slobodan Milo%evi& supported these movements which led to the ousting of both autonomous province governments. Milo%evi& put his allies into their places as well as caused another coup d’etat in Montenegro. Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Albanians of Kosovo were against Serbia. e con icts got worse as the six states were forced into a multi-party system. is led to the fall of communism around 1990, and thus, the increasing ethnic tension. e Yugoslav Wars broke out in 1991 with enormous amounts of con ict. Croatia and Slovenia declared independence along with Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Montenegro ended up breaking up in 2006 which led to the complete end of Yugoslavia.

e breakup of Yugoslavia was caused by ethnic tension, West Europe supremacy and inability to cooperate e ectively. Yugoslavia is only one

of the nations that have su ered such a fate. e League of Nations’s inability to be inclusive has not only led to the creation but the fall of Yugoslavia as well. Many believe that international organisations can provide solutions to many problems. However, they can also be the main root of such con icts.

Two Red Giants: How was con ict sparked because of Khrushchev’s ideology between the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union?

e People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union grew apart in the 1950s. But why would this Sino-Soviet split occur if they were both communist? In reality, communism is lled with numerous subgroups that ght over every small di$erence. For example, Stalin assassinated Trotsky because Trotsky disagreed with him. Despite having worked together in the Russian Revolution, small di$erences in the way they thought resulted in death. Khrushchev’s ascension to leader of the Soviet Union created cracks between himself and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) because of similar reasons. If not for Khrushchev’s communism clashing with Mao’s communism, the Soviets and the PRC would have been friends for longer.

So what is communism anyway? Some would say it’s abolishing private property. Some would say totalitarian dictatorships. It all started with Marx, as a reaction to capitalism. Communism is the abolition of exploitation by capitalists by seizing the means of production, via establishing a dictatorship of the proletariat through class struggle (encyclopedia of Marxism). At the same time, communism is the goal, while the process leading to communism is socialism. A%er Marx, there was Lenin, who led the Russian revolution. Marxism-Leninism is what most Communists agree on as the correct path to communism. e developments a%er Marxism-Leninism is when communists start to argue. Since Stalin became the next leader a branch of communism under his name was formed - Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism, the next step on the road to communism. Before Khrushchev, Mao and Stalin were similar enough to be allies. ere are two di$erent types of communism that uses Mao’s name: Marxism-Leninism-Maoism and Mao-Zedong thought. Mao-Zedong thought is Marxism-Leninism applied to the speci c characteristics of the Chinese revolution, and the one this article will refer to (Peking review). Maoism is an international form of Mao-Zedong thought, developed by Chairman Gonzalo. As Mao-Zedong thought is Marxist-Leninism applied to China, it is not con icting with Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism, which is a continuation of Marxism-Leninism in Russia. Going back to the previous example, when Lenin died Stalin thought that the revolution should strengthen itself in Russia rst while Trotsky believed that the world revolution should start immediately. As Stalin defeated Trotsky, Trotsky became a revisionist - someone who tried to betray the core principles of communism, in the name of reform. To be a revisionist is the worst crime to communists, as they are insidious traitors to the world revolution.

Mao saw Khrushchev as a revisionist. e rst sign of this was Khrushchev’s so-called De-Stalinisation, beginning with his ‘Secret Speech’ (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica). Khrushchev was a rm anti-Stalinist, denouncing the cult around Stalin, criticised the Great Purge, and relaxed restrictions on culture (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica). Mao did not like Khrushchev criticising the methods Stalin used to propel the Soviet Union from an agrarian, undeveloped country into a superpower capable of challenging the American capitalist world order. Relaxing censorship was seen as inviting subversive capitalist media that would undermine the people’s faith in the revolution. Stalin’s socialist realism had been simple and direct for the people, while Khrushchev wanted complicated messages to mislead the people. While Khrushchev claimed that the Great Purge targeted innocent communists, Mao thought that it was necessary to remove any possible dissent proactively, so as to maintain the communist party’s revolutionary course. e cult of personality was surely justi ed, as the people must trust a revolutionary leader over any revisionist who tries to mislead the people. e di$erence between a revisionist and Lenin, Stalin and Mao is that the latter developed communist theory while staying true to communist principles. As Khrushchev invited capitalist subversion into the Soviet Union, Mao could not have a pleasant working relationship with someone he viewed as a traitor.

Of course, small ideological di$erences can be forgiven - but Khrushchev crossed the line when he started to actively harm the international communist revolution. Communism was supposed to erode sel shness and division, yet Khrushchev started the precedent of imposing Russian interests over all else. First was the ludicrous ‘peaceful coexistence with capitalism’ (Bowen, B. E., 2010). Contrary to all the lessons

gained from the Russian Revolution, Khrushchev decided that detente with the Capitalist powers was the path forward. He ignored how the US had invaded North Korea when the people rose against the corrupt, dictatorial South Korean government of Syungman Rhee, how the empires of Britain and France had sent soldiers against the Bolshevik revolution, and how the Chinese revolution fought, not negotiated, with the anti-communist Chiang Kai-Shek. Khrushchev justi ed his revisionism by stating that the communist revolution is inevitable, as is Marxist theory. However, he failed to realise that the revolution will not come by peace, but by bloody and vigorous class con ict. Why did the revolution not manifest in Germany, as Marx predicted? Capitalism seeks to preserve itself by state terrorism against the masses: to seek peace with such a tyrannical force is a betrayal of the world revolution. Khrushchev sought to impose this revisionism because of his nationalistic sel shness - he placed Russia over the world revolution. is is clear in the Cuban Missile Crisis. When Cuba was invaded by US-trained Capitalist terrorists in the Bay of Pigs invasion, a highly illegal act of trying to overthrow a popular government, the Soviets pledged help and sent nuclear missiles to defend Cuba (U.S. Department of State). en Khrushchev showed his nationalism and cowardice by bending over to the US and removing the missiles (U.S. Department of State). He claimed that he was afraid of nuclear war. Compare this Capitalist-pleasing mentality to Chairman Mao. Mao said “ e Chinese people are not to be cowed by US atomic blackmail” to the Finnish delegation in 1955. He said that US nuclear bombs could not kill all the Chinese people - and if there was war, just like how WW1 led to Lenin’s revolution and WW2 led to China, North Korea, and Eastern Europe becoming communist, WW3 would turn the US and the rest of the world communist (Tse-tung,

M, 1955). If Khrushchev was dedicated to the World Revolution and Marxist theory then he would wage nuclear war gladly, knowing that Communism would win in the end. Yet he prioritised his own power and country over the revolution: how could Mao help someone who only cared about himself, not communism?

e Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia is well known, but less so is Khrushchev’s invasion of Hungary in 1956. Khrushchev brutally murdered thousands of Hungarians with his tanks, permanently damaging Communism’s image in the eyes of the world (A&E Television Networks). How could Khrushchev let this happen? First, his relaxation of Stalinist policies allowed capitalist spies to in ltrate Hungary, causing a demonstration of more freedom (A&E Television Networks). If Stalinist policies had been maintained these capitalist subversives would never have been able to rouse the proletariat to protest. When these capitalists protested Khrushchev appointed Imre Nagy, a famous Anti-Stalinist, as lthe eader of Hungary. If Khrushchev had faith in Communism he would have called upon the proletariat to rise up and kill these spies, not appoint an Anti-Stalinist who immediately tried to leave the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet alliance in contrast to NATO. By bathing Hungary in blood, Khrushchev turned the ideology of the common people into an ideology maintained by the iron st of Moscow. Socialist leaders do not appoint leaders to other countries as they wish, and they certainly do not invade fellow communist nations. Khrushchev was forced to use force because he knew that his communism was revisionist, thus the people of Hungary would never have listened to him. If Khrushchev believed in international solidarity he would have negotiated with Imre and swayed him with communistic logic, not execute him a%er having appointed him personally (A&E Television Networks). Khrushchev should

have let the people of Hungary choose their leader, as is the people’s dictatorship, instead of turning it into the Moscow dictatorship. A communist that does not liberate the people is no communist at all. How could Mao collaborate with someone who invaded brother nations and suppressed the people’s dictatorship by forcing his choice upon them?

e ideological motivations behind the Sino-Soviet Split are o%en overlooked. However, it is important to realise that geopolitical, pragmatic di$erences were a result of ideological clashes in the rst place. If not for Khrushchev’s revisionism, Mao would have had nothing to fear from the Soviet Union - since before Khrushchev plunged the heart of the revolution into a dark path, all communist nations collaborated peacefully. He purposefully sided with the West against Castro and thus delayed the world revolution for decades. And it was not just under his rule that the Soviet Union was turned revisionist: the next major Soviet leader, Brezhnev, was also a revisionist; albeit less so. is is why Stalin and Mao purged unfaithful party members with great zeal. If you don’t root out revisionism, then capitalism will take over once more - it is sad to see that China today has also become revisionist. e only true communist nation currently is the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. e world revolution, so promising less than a century before, was destroyed due to Khrushchev. is is why no one calls themselves Khrushchevites, while Maoists are active in India and the Philippines.

World War I, o%en referred to as the “Great War,” marked a pivotal moment in History, reshaping European alliances and nations whilst kindling another world war. e war kindled the rise of two major coalitions: the Allies, including Britain, France, Russia, and later the United States - and the Central Powers, centred around Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. ough formed from mutual political interests and a desire for security, the two parties kindled the deadliest con icts in human history. e paradox of cooperation lies within the origins of World War 1; cooperation that nations desired ultimately pervaded chaos within Europe

A major example of how cooperation resulted in con ict during WW1 can be seen in the alliance between Austria-Hungary and Germany. With a Bosnian Serb nationalist’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the royal heir of Austria-Hungary, Austria-Hungary sought support in Germany for its vindictive assert of dominance to Serbia. In response to her appeal for support, Germany advocated for Austria-Hungary’s vengeance with a “blank cheque”. is led to the infamous Austria Hungarian ultimatum, leading to the declaration of war.

Following the Austrian ultimatum, Russia was obliged to intervene between Austria Hungary and Serbia’s con ict - especially with Germany’s steadfast support. is response was driven by a combination of pan-Slavic sentiment and strategic interests in the Balkans. Not only did Russia’s mobilisation demonstrate solidarity with Serbia, its consequences were only the pervasion of further con ict, as Germany declared war against Russia. is serial reaction of alliances re ects how the initial cooperation between Austria-Hungary and Germany inadvertently escalated the con ict. France, allied with Russia, was drawn into the war as well, viewing the Russian mobilisation as a direct threat. What began as a localised con ict transformed into a full-scale war involving multiple great powers. is shows that the very alliances, with a cooperative e$ort to foster a sense of “security”, instead expanded the scale of the war - ultimately leading to a devastating global war.

Furthermore, another example can be seen from e Paris Peace Conference that followed the Great War. e conference, held in 1919, aimed to establish a framework for international cooperation and maintainable peace. Nevertheless, the product made from this conference, the Treaty of Versailles (TOV), set the stage for World War II. e TOV had a catastrophic im-

pact on Germany’s economy. Its reparations triggered hyperin ation in Germany, devastating its economy. As her nancial circumstances annihilated, Germany’s citizens were a ected. $is led to an increase in crime rates and a spike in prostitution as individuals desperately writhed for money. Following Germany’s social unrest, a suitable environment for extremist groups to gain popularity was established with the debilitation of Germany’s government. With central governments weakend, radical ideologies were acclaimed by the public - resulting in the emergence of the Nazi Party.

In addition to economic and political chaos, anti-Semetism gained traction as individuals sought for a scapegoat for their unfortunate circumstances. Many Germans criticised the ‘unfaithful Germans’, or the Jewish community - accusing them for causing the defeat of the Central Powers and its a%ermath, such as the fall in German economy. $ese dangerous narratives had devastating consequences.

As nationalist fervour intensi ed with the governments’ response to their defeat, Jewish individuals faced unjust discrimination, with the erosion of their rights and an increase in violence against them. Laws stripped them of their citizenship and human rights, paramilitary forces targeted Jews with violence and persecution. $e tragic outcome of this anti-Semitism ultimately gave birth to the holocaust, showcasing the destructive potential of cooperation turned inward against certain communities.

Finally, the events that followed WWI pose serious questions regarding the nature of cooperation in international relations and whether it always leads to peace. While the meeting was intended to promote stability and peace, the punitive measures imposed on Germany contributed to greater con ict. $is interaction of

cooperation and con ict demonstrates that, while nations may band together for a similar goal, the consequences can be deeply harmful if not well examined. Cooperation and con ict, rather than opposing forces, frequently coexist within the same framework, emphasising the need for a more nuanced understanding of their roles in making history.

Gabriella Shin Y11

How do global health systems function in a world of pandemics, and what insights does COVID-19 provide?

$e COVID-19 pandemic exposed signi cant gaps in global health systems, revealing significant weaknesses in the ability of countries to coordinate responses. Speci cally, the pandemic exposed how poorly prepared health systems were. Developing nations struggled to protect their populations, while a&uent countries pursued strategies that excluded vulnerable states from accessing essential equipment and vaccines. Pandemic readiness is the ‘weakest link’ to public good, due to the absence of readiness in a country that can rapidly spread pandemic viruses beyond borders. $us, coordinated action to shore up the weakest link is crucial. While the immediate crisis has passed, COVID-19 continues to impact vulnerable regions, highlighting the need for sustained preparedness in three ways: vaccine nationalism, unequal healthcare infrastructure, and the coordination of human capital in healthcare.

Perhaps most striking was nationalism in the procurement of vaccines, the ticket out of pandemic-era restrictions. About a year a%er the outbreak of the disease, the COVID-19 Vaccine Global Access (COVAX) Facility was launched to ensure equitable availability of COVID-19 vaccines around the world. $e scheme’s logic was simple: since many states did not have resources to directly buy pandemic vaccines, the scheme would be run on contributions from developed states. Developed states would, on the other hand, be guaranteed priority in vaccine procurement of up to 20% of their population level by contributing to the scheme. Since virtually all developed countries would contribute, it was hoped that the scheme would be the largest buyer of COVID-19 vaccines and, thus, the buyer with the strongest bargaining power. $is virtuous cycle would attract further funding from developed countries. However, not only were wealthy countries reluctant to contribute signi cant sums to COVAX, they pursued vaccine procurement through bilateral agreements with pharmaceutical companies. In the end, the tens of billions of dollars in funding that went into bilateral purchases outshadowed the resources of COVAX, e ectively pricing out COVAX from procuring adequate quantities of vaccines.

Vaccine procurement was, however, only the most visible. Global miscoordination in pandemic readiness also showed in widespread infrastructure inequalities. Such inequalities are o%en rooted in developing states’ narrow tax bases and unstable tax collection mechanisms. $is limited capacity hinders the investment in critical infrastructure projects. Particularly for poor nations with long-standing debt problems, reliably providing even basic services such as sanitation is di cult. In addition, this scal instability increases the need to borrow money from external creditors like the IMF. However,

countries that seek nancial assistance are forced into economic reforms that exacerbate infrastructure de ciencies. For instance, conditionalities from the IMF and other foreign creditors o%en include austerity measures that downsize public spending in areas such as health care. Such conditions strained already fragile health systems, making it even more difcult for these countries to respond to the pandemic. For instance, the existing vulnerabilities in the Tunisian healthcare system meant that Tunisia came to a standstill when COVID-19 cases surged. A%er the 2011 Tunisian revolution, Tunisia embarked on economic reforms supported by loans from the IMF and other international organisations. To secure these loans, Tunisia was required to implement austerity measures. In exchange for macroeconomic stability, the health system, in particular, was downsized and underfunded. By the start of the pandemic, Tunisia faced a shortage of medical equipment, and outdated healthcare facilities were unable to meet the needs of the population. Likewise, Jamaica’s limited health infrastructure made the COVID-19 pandemic a particularly painful experience. Starting in 2010, Jamaica entered into a series of debt-stabilisation agreements with the IMF, which required the country to maintain an annual scal surplus of 7.5%, which led to 10-20% across all areas of public spending. $ese measures also forced severe cuts in healthcare services. Only around 500 ICU beds were distributed throughout the country with the majority concentrated in the coastal areas. Doctors and nurses o%en worked long hours, sometimes up to 30 hours without breaks. Compounded with the lack of access to vaccines, developing countries like Tunisia and Jamaica experience more brutal lockdowns designed to limit overburdening of health infrastructure.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the

e ects of the miscoordination of medical human capital. Developing states have experienced severe medical brain drain over decades, and the adverse e ects of this brain drain weighed heavily on health systems’ ability to respond to the pandemic. Emigration of highly skilled individuals from developing countries is generally signi cant, with some nations losing between 10% and 30% of their tertiary-educated population to developed countries. $is e ect is especially pronounced in the healthcare sector, for which developed countries have particularly liberal immigration policies. For instance, 51 per cent of all doctors from Kenya migrate to countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States in search of better working conditions and higher salaries. $is migration of health workers le% a severe shortage of healthcare workers, whose e ects were pronounced during the pandemic. $e WHO estimates that at least 2.3 healthcare workers per 1,000 people are needed for e ective healthcare interventions, and yet, countries with the worst record of pandemic response fall far short of this number due to medical brain drain. For instance, India, the largest exporter of doctors to developed economies, has around 0.9 doctors per 1,000 people and had one of the highest death tolls during this pandemic.

Despite these gargantuan miscoordinations, global institutions survived the COVID-19 pandemic relatively unscathed. But it is clear that, though global consensus is more necessary than ever, national interest o%en con icts with global needs. $e pursuit of vaccine nationalism and the miscoordination of healthcare resources are worrying, as the world enters an age of pandemics.

Embracing the bestowment of globalisation as an economic leverage, the renowned superpowers– e United States and China–have engaged in bilateral and transnational trade for decades (Bown, C. P). Indeed, with the ever-increasing prevalence of interdependence within our world today, economic cooperation is considered imperative in wielding mutual bene ts for even the most disparate states. Nevertheless, such assertion tends to be rather challenged than reinforced given the anarchic nature of the world order; the primary objective of sovereign states is to maximise the realisation of self-interests, a critical misalignment to the purported pursuit of cooperation. For instance, China’s annual GDP growth averaging 9.6 per cent between 1978 and 2017 resulted in the inexorable burgeoning of China’s political in uence, military forces, and technological power (Zhang, Y). In response, the US has attended the matter with vigilance and circumspection as it undoubtedly confronted its preeminent status on the global stage. Eventually, addressing such circumstances prompted the decoupling of interstate relations in addition to an unconventional approach to con ict: a trade war. Initiated by the Trump administration in January 2018, the trade war was a success in terms of revealing the vastly integrated notion of interdependence in the status quo, to the extent of substantially impacting the South Korean supply chains. Pri-

or to the commencement of such con ict, the extensive economic ties interjoining the three supply chains acted as a benefactor to South Korean industries and their respective supply chains. However, with the onset of the US-China Trade War and the subsequent instability in economic cooperation, the global competitiveness of South Korean supply chains has severely weakened in recent years as seen with semiconductors. Inculpating the economic curtailment to the overreliance on external states, a strategic realignment in the South Korean supply chain is a necessary procedure–diverting its dependency through the establishment and diversi cation of new trade alliances (Song, Y).

Prior to the unprecedented outbreak of the trade war, the extensiveness of the US and China’s multinational economic cooperation had immensely bene ted South Korean industries and their respective supply chains. Having acted as a pivotal supplier of intermediate goods such as semiconductors, machinery, and various industry components which are assembled through Chinese factories and exported to the US, South Korea’s strategic role in the global supply chains culminated in 2018. is dependency on the two economic powerhouses can be accentuated through the case of semiconductors. South Korea has played a signi cant role in the global semiconductor industry, being its largest export product that accounts for 18.9% of the country’s total exports. Consequently, South Korean rms such as Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix robustly held their dominance over memory chip fabrications, producing roughly 73% of the global DRAM market and 51% of the NAND ash market (2023, May 9). Due to its profoundly integrated presence in the global supply chain involving such production of intermediate goods, South Korea essentially exerted a bilateral dependency on both the US and China. For instance, China has been a key

market for South Korean semiconductors, responsible for 33% of semiconductor exports. Meanwhile, the South Korean semiconductor market is deemed lucrative for US suppliers of equipment, materials, and services utilised in the fabrication process. Indeed, total US exports to South Korean markets amounted to $22 billion in 2022–which would have been higher prior to the trade war–representing a staggering 20% of the global market (Jeong, H). Hence, the involvement in a multilateral value chain substantially increased the internationalisation of South Korea’s production processes which contributed to the growth in the nation’s value-added exports. However, this re ection of the value created within the exporting country is severely undermined by the proportionate increase in its dependence on foreign imports, deleterious when those speci c supply chains are obstructed (Chung, S).

Extending on the depiction of the US-China trade relationship as a benefactor to the growth of e South Korean supply chain, the assertion remains a normative statement unless an o$cial pledge is promulgated. Nevertheless, the proliferation of South Korea’s economy as a global powerhouse facilitated the establishment of auspicious trade agreements, invigorating the interdependence stemming from a substantially multilateral practice. Accentuating this, South Korea strategically bene ted from the Korea-US Free Trade Agreement, in addition to the formation of bilateral supply chains with China in pivotal industries. First and foremost, the KORUS FTA enabled the in ux of Korean exports into the US market, penetrating prevalent sectors utilising high-value goods such as automobiles and electronics –contributing to South Korea’s $29 billion trade surplus with the US in 2023 alone (Jeong, H). Since its implementation in 2012, the agreement undoubtedly delivered positive impacts on the South Korean

economy, not only accelerating export growth but also a substantial increase in direct foreign investments in key industries. Encouraging technological advancements, such US investments have played a crucial role in further boosting the Korean economy, resulting in an accumulated trade volume of $169 billion up until 2023. Complementing the economic advantages that the KORUS FTA endows upon South Korea, its cooperative intertwinement with Chinese supply chains has propelled further growth. For instance, high-tech industries such as semiconductors have accounted for a staggering 50% of all exports, commensurate to $46.9 billion in trade revenue. is has been mainly due to the Chinese intermediary position in the global supply chain, enabling South Korean rms to access materials for high-tech manufacturing at a relatively low cost. us, South Korea bene ted immensely from the extensive network that China o ered, actively bridging and expediting the entry of rms into new relevant markets, especially in Southeast Asia (Cho, E. K., & Shim, W). Proving its necessity again amid the US-China trade war, the KORUS FTA and the inveterate establishment of bilateral supply chains with China, have unequivocally stimulated the forefront of the Korean economy.

Despite the seemingly evident economic advantages deriving from the rise of interdependence in modern global a airs, the con$icting interests of innately anarchic states are bound to reciprocate with their corresponding repercussions. As seen through the deterioration of US-China trade relations, the strictly multilateral cooperation has prompted the erosion of the overall competitiveness in South Korea’s global supply chains. Unsurprisingly, Korea’s reliance on the two economies is resolutely conveyed through its export statistics, with China accounting for 26.8% of all exports while the

US contributed to a relatively modest 12% at the exposition of the trade war in 2018 (Chung, C). Due to the monumental increase in tari s and the imposition of import restrictions between the two involved economies, the primary industries such as automobiles and semiconductors were inevitably forced to tolerate an adverse loss in demand. For instance, exports from the semiconductor industry alone dropped severely by 20% in 2023 compared to the years leading up to the initial stages of the trade war (Jeong, H). Moreover, the increase in costs of essential raw materials and components has had an onerous impact on South Korean companies, burdening them with a he%y cost of production. In fact, as of 2022, 34% of Korea’s semiconductor components were imported from China, underscoring the price increases the industry experienced amid the continuing uncertainties revolving around the dimensions of the trade war (Cho, E. K., & Shim, W). Consequently, the continuing price increases have constructively reinstated and surfaced the potential over-reliance on Chinese imports, exposing the implicit vulnerabilities of bilateral supply chains. is has also precipitated managerial considerations for South Korean companies, vitalising the necessity to search for alternative supply chains with lower risk pro les to vicissitudes in external circumstances (Jeong, S).

e relatively complex and convoluted position of South Korea within the US-China trade relations has obligated inevitable decision-making, rede ning the Korean stance beyond the limits of economic interests, and evolving into the realm of diplomatic relations. US restrictions and sanctions on advanced Chinese technological goods have le% South Korea in the midst of a cumbersome situation, having to decide whether to continue its tech exports to China. Having already been coerced to navigate through such a precarious position of adhering to US policies and the lucrative technology market in China, the Biden administration further imposed sanctions on Chinese semiconductor access in the US market. Successively, South Korea’s semiconductor industry was confronted with drastic repercussions due to the extensive integration with China, jeopardising 50% of its semiconductor exports (Jeong, H). However, such sanctions not only a ected the production capabilities of South Korean semiconductor companies but also instigated critical discourse in their compliance with the newly placed restrictions. South Korean companies either risked losing access to American technology, which is essential for their own competitive production of goods, or the majority of their exports to China if they did not comply with US trade sanctions. For South Korea, the consequences associated with aligning with US export controls were o%en understated and overlooked, despite the palpable strain in the $1.05 billion–or about 34%– of its semiconductor materials imports in 2022 (Cho, E. K., & Shim, W). Hence, in the case that South Korea complied with such restrictions, vital revenue streams would have deteriorated inde nitely, limiting access to one of their largest and most prominent markets in terms of automobiles and semiconductors. Furthermore, halting exports to China would have le% vacillating uncertainties regarding the possibility of retaliation. is

speci cally includes cost increases due to disruption in supply chains, reduced market access for key industries, risks of losing foreign direct investments in China, as well as augmented diplomatic and trade tensions. Conversely, neglecting such US export restrictions would have severely curtailed South Korea’s share of the US high-tech market (Kim, J. J., & Chungku, K). Ultimately, the intricate relationships of the three nations and their respective economies have exacerbated the overall well-being of Ko rea’s supply chains, manifesting the vulnerabilities of extensive interconnectedness.

A%er experiencing the largely problematic aspects of its established supply chains, South Korean companies are now opting for a realignment of their production routes. With the potential for further escalations in the US-China trade relations, constructing alternative supply chains is an imperative and pragmatic measure in mitigating risks associated with reliance on single-market dependencies. is comes with the diversi cation of production bases, shi%ing the majority of their manufacturing plants to Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, ailand, and Cambodia. e “China +1” strategy as it is commonly referred to, allows South Korean companies to still maintain a part of their operations in China while diversifying adversities by expanding into countries with highly cost-e ective labour and fewer trade barriers compared to China. e recent growth in China’s GDP per capita and the commensurate amelioration in standards of living have driven up labour costs substantially, promoting even more companies to adopt such measures regardless of the trade war itself. In tandem, the development of the “Korea +1” strategy, which aids South Korean companies in developing manufacturing plants in domestic regions, signi cantly reinforced the stability of major supply chains amid further tari hikes

and the resulting economic disruptions (Chung, C). Notwithstanding the necessity of South Korean companies to develop supplementary supply chains, the ongoing US-China trade war has emphasised the requisite of South Korea to foster regional trade partnerships and multilateral agreements. For instance, South Korea’s proactive role in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) which includes ASEAN, nations, China, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, aims to foster an expansive trade integration throughout Asia. Utilising the RCEP, South Korea could potentially diversify its supply chains, reinvigorating and rigidifying economic relations within the region. In summary, this prospective agreement demonstrates South Korea’s sophisticated approach to assembling alliances beyond the scope of the two global economic powerhouses, bolstering its capabilities to waver contingent trade uncertainties (Jeong, S).

e prevalence of economic prosperity in the modern world is o%en proven to be an overstatement as evidently portrayed through the US-China trade war on Korean supply chains. Economic cooperation still remains a cornerstone of global interdependence and interconnectedness, highlighting the liberalist approach in which states are naturally inclined to cooperate on the global stage. However, as much as economic cooperation espouses the relevancy of such assertion, the otherwise can be stated simultaneously. While states tend to be cooperative in terms of establishing trade relationships, it is ultimately a means to an end in order to culminate self-interests. ereby, the US-China Trade War predominantly demonstrated the anarchic nature of the international system where domestic interests trump and prevail over collaborative gains. Explored through the case of South Korea, it is certain and unequivocal that the common proverb “ e Miracle of

the Han River” is a direct product of South Korea’s unyielding economic power founded upon interdependence. Similar to the majority of economically active nations, the dependencies of American and Chinese supply chains have been the underlying propellant in driving South Korea to its position in the status quo. Nonetheless, the unavoidable consequences of the US-China trade war aggravated Korean supply chains, to an extent that equalises the degree of bilateral interdependence between the two gargantuan. Hence, in order to thrive in the modern economy of interconnectedness, securing an array of monolithic alliances has become the quintessential agenda for many, re$ecting South Korea’s eventual integration into the broader global economic spectrum. Whatever the future holds for this promising peninsula, the US-China trade war has de nitely acted as a wake-up call, providing guidance through the increasingly volatile global trade landscape with resilience and adaptability.

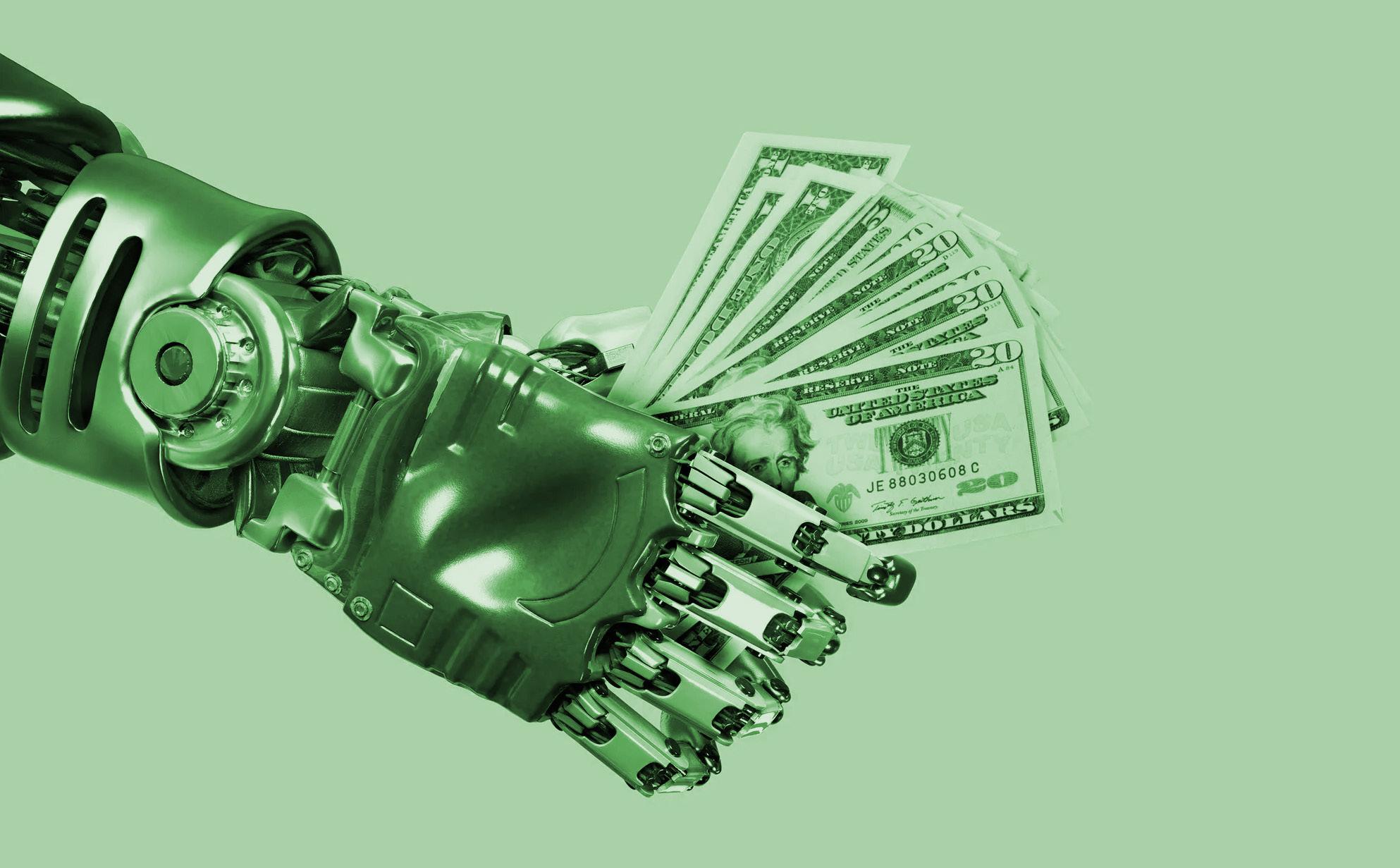

To what extent should AI technology be shared globally to foster cooperation and innovation?

Arti cial Intelligence, estimated to reach $15.7 trillion by 2030, will companionably reshape industries, labour markets, and seemingly every other aspect of life. Only recently, breakthroughs have begun to come with such vigour—see the latest OpenAI version, GPT-4— that promises huge changes in the way people work, live, and communicate. Meanwhile, a very important debate is forming: whether AI should remain proprietary—a eld controlled by a few big corporations and countries—or it should be a shared resource accessible to all. is debate touches not only on economic considerations but also on ethical, political, and social issues. I believe that AI should be treated as a globally shared resource. Opening AI to the world will provide an impetus to balanced development, inspire global cooperation, and permit overcoming collectively some of the biggest challenges humanity is facing, which include: global warming, disease control, and poverty. In many ways, this question speaks to the greater choice between competition and cooperation that carries behind it a potential to transform and, depending on how the stakes have been set, will be one that will further entrench corporate power and deepen global inequalities or create hitherto-unknown levels of collaboration and shared progress.

en there is the other extreme of people who believe that AI has to be proprietary; private control will ensure rapid changes in technology. It will protect intellectual property and be used responsibly, they add. One of the major arguments favouring proprietary AI is that it will spur investment in innovation. at is, developing advanced AI models into which high nances and intellect are required would elicit companies only when exclusivity and pro t will be enough motivation to take such a heavy amount of risks. Technology rms like Google, Microso%, and OpenAI have invested billions of dollars cumulatively into the development of breakthrough technologies such as GPT-4, autonomous driving systems, and personalised medicines. What this means is that entry into capital-intensive and high-risk AI research would not be possible, because without the ability to pro t from them, the willingness to nance such investments might reduce. e GPT series developed by OpenAI shows the progress substantial investment can achieve in AI development. Keeping AI proprietary can let the economies of these investments pay back for the company and continued innovation is caused by it that lets AI’s technology evolve at a breathtakingly fast pace.

In addition, competition in the private sector is usually referred to as one of the major driving factors for technological development. roughout history, competition between companies has caused great leaps in all elds, whereby every company tries to be better than its opponents. is dynamic has been re$ected in the arena of AI, in which giants like Google, Microso%, and Amazon are in aggressive competition to prove themselves as forerunners in inventing high-value and e&cient applications. For example, the competition for improving autonomous driving technology accelerated tremendous innovation whereby businesses like Tesla and

Waymo have made breakthroughs possible that without the urge to outcompete others would not be achievable. Advocates would argue that competition grants better quality products, faster cycles of innovation, and economic gain that eventually trickles down to the consumer and society at large.

Another major consideration in proprietary AI includes the protection of intellectual property and also the control usage of technology. Patents, along with other forms of protection of intellectual property, will be vital to ensuring that companies can protect their innovations and prevent competitors from copying or otherwise misusing such innovations. For example, these protections, in the case of AI, would embolden companies to invest in high-stakes research with the security of not having it replicated immediately. Intellectual property rights also give companies a certain level of control over how and where their AI technologies are deployed, reducing the risk of misuse. For example, strong proprietary control can forestall the irresponsible use of sensitive technologies like facial recognition or autonomous weapons. In that respect, proprietary AI gives companies the right to control and police the usage of their inventions and makes the technological world a safer place.

e advocates continuously propose that the sharing of AI technology globally can act as the staple behind cooperation, reduction in inequalities, and accumulation of progress towards solving very complex challenges. ere are better reasons for making AI a shared resource, considering impending global issues that one could master with:. AI has enormous potential to contribute signi cantly in the elds of climate science, medical research, and disaster prediction, whereby advanced technologies can empower humanity to take huge steps toward

solutions for universal problems. For instance, AI diagnostic tools could powerfully enhance healthcare in low-income countries where medical expertise and resources are limited. Just think about the big possibilities: if AI technology became public, researchers, governments, and organisations throughout the world could collaborate and work together in the interest of common causes. ese could mean breakthroughs that may otherwise not have occurred.

Other reasons that favour sharing AI technology revolve around equity and access. In its currently available form, the bene ts of AI have fallen disproportionately to a lot of rich nations and corporations, while large, under-resourced regions of the world have no access or ways to develop advanced technologies. Keeping AI proprietary, however, keeps the technological edge skewed toward the wealthier regions of the world, further entrenching existing global disparities. Opening up the technology could democratise technology, reducing disparities and making ways for all nations and communities to bene t from the potential of AI. For example, AI tools intended to improve agriculture, education, and public health may be game-changers for people in low-income countries who otherwise might not have access to such resources. One result of providing access to AI at a nancial capacity level is the lost opportunity for AI to be harnessed for the common good.

Most importantly, shared AI allows for one key advantage: collaborative innovation. As opensource platforms have done in both the so%ware and biotechnology arenas, large groups working together create more rapid, complete developments.

As an example, the open-source AI framework TensorFlow allows researchers from anywhere

around the world to build on top of other models and share applications that help further advance the technology in a variety of other industries. If AI technologies were shared in the same way, then researchers, scientists, and developers from around the world could take special insights and know-how in order to solve problems of the world. In that respect, international collaboration may provide solutions for complex issues which are not possible under fragmented corporate competition. Perhaps, then, considering either point of view, the balanced approach o ers the most e ective going forward—one that allows AI to help humanity without undermining the motivations for private investments. Other than fully open or closed access, shared framework access with regulation could set a balance between encouraging innovation and promoting public good. at could allow companies to retain the profitability of their developments while making those technologies or tools that the public can use for research and social applications freely available. e pharmaceutical industry may be a possible model insofar as companies retain patents to protect pro ts but allow exceptions in public health for cases of need. e sharing of research and data by companies and countries during the COVID-19 pandemic expedited vaccine development because millions bene ted without sacri cing proprietary interests. Similarly, AI can be made equally manageable whereby government and international organisations like the United Nations would encourage sharing practices in AI with due regard to social bene t.

Another way of ensuring responsible use and nondiscrimination with AI technologies could be through active government intervention and public-private partnerships. By underwriting AI research with a public purpose, or by encouraging corporations to share applications

bene ting society, governments can ll in the gap between private innovation and the common good. e collaboration that exists between governments and corporations has spawned remarkable progress on space exploration, medicine, and clean energy. Encouraging similar endeavours in AI would help bring corporate innovation into concert with public interest and make the future of AI more inclusive. Ultimately, the debate as to whether AI should be globally shared or proprietary re$ects a larger tension between competition and cooperation in the modern age. While proprietary AI incentivizes investment and rapid progress, sharing AI as a global resource may enable collaborative e orts to be waged on behalf of solving humanity’s biggest challenges. What is needed is a balanced approach that can protect the investment of the companies while ensuring that the bene ts of AI reach out to all. In a world where everything changes for good by AI, the policymakers, corporations, and researchers have the onus to ensure that AI will be for all humankind, not for a few privileged only. Yet the most stringent question has always been: will such a consensus over AI in the future be characterised by cooperation and mutual advancement or marked by con$ict on who is in control?

By Siwoo Park

“Without continual growth and progress, such words as improvement, achievement, and success have no meaning.” - Benjamin Franklin

“Those who make peaceful revolution impossible will make violent revolution inevitable.” - John F. Kennedy

“The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.” - Sir Winston Churchill

“You are needed now more than ever before. Take up the mantle of change. For this is your time.” - Sir Winston Churchill

Shanghai – a modern metropolis home to both glistening skyscrapers and a plethora of historic sites – is more than just “significant” when looking into China’s history. “The Pearl of the Orient”, “Paris of the East”, and “The Gateway to China” - the city’s countless nicknames showcase the pivotal cultural and historical roles Shanghai has had and continues to have. From a rural fishing village to one of the most iconic skylines in the world, a revolutionary development took place, proportional to the nation’s steep economic growth curve. Like the Chinese saying, “Jade must be carved to become a gem”, the hardships and challenges the city faced during its transformation are crucial in understanding the country’s history.

Until the 18th century, Shanghai existed as a rather meagre town, perched on the Chang Jiang River (or the Yangtze River) delta region, with most of its population working in the fishing industry. It was the 1842 Nanjing Treaty that altered the village’s fate when British, French, and American concessions were established on the west bank of the Huangpu River. (The river that meanders through nowadays Shanghai) Foreign capital and diplomats rushed into the small riverside foundation of Puxi where multi-storeyed buildings flaunted their glamourous façades and western culture first stepped into Chinese territory. The westernisation boom of Shanghai only deepened when locals started to wear European-style clothing, and speak in English and French, therefore absorbing Western customs. Shanghainese people became the first ones to have a taste of what it is like to be a “civilised person” (WenMingRen) referring to themselves as “Modern Miss” or “Modern Mister”.

However, after reaching the pinnacle of luxury and modernisation – The Shanghainese Renaissance - in the Republican era, waited for a gloomy future following the Communist victory in 1949. The Cosmopolis’ position as a melting pot where the East meets the West was no longer appreciated. The city’s trade-heavy economy drastically shifted to an industrial one, businesses and buildings were nationalised, and former elites including the bourgeois class were sent to re-education camps. Shanghai was also the centre point of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) – a political campaign that left centuries of tradition erased in a decade. Churches were burnt with their priests imprisoned, university professors denounced or beaten to death, and wealthy people’s houses were looted. As massive state-owned factories for textiles and steel dominated newly developed neighbourhoods, the city received a new persona: a smoke-veiled city of iron and labour. Modernism was redefined, embracing its new meaning of being productive and utilitarian, not being the most opulent and alluring.

“The Pearl of the Orient” endured several more decades before seeing hope of a second renaissance – the Deng Xiaoping era. The new leader of China demanded reforms and globalisation of the nation, establishing Special Economic Zones (or SEZs) in the cities of Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Shanghai. Signalling the comeback of Shanghai to the global stage was Pudong’s urbanisation – conquering both sides of the Huang-

pu – where glinting, cloud-kissing skyscrapers started soaring as if taking turns. Icons such as the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Jinmao Tower embodied the reorientation of the nation’s economic standing, from being conservative and isolated to removing barriers to international engagement. This period also marked the re-emergence of foreign investment, thanks to the government encouraging private entrepreneurship and tax incentives. By the end of the 1990s, (when the Pudong development was at its peak) China had emerged as a crucial driver of the world economy, transforming as a hub of manufacturing, trade, and investment.

The momentum of Shanghai’s resurgence did not dither with the arrival of the 21st century – in fact, it accelerated. The 2000s and 2010s witnessed the city ascend to new heights, both literally and economically, mirroring China’s growing influence on the global stage. Pudong, once farmland, now dazzled with structures such as the Shanghai World Financial Centre and the Shanghai Tower, rising skyward one by one like declarations of ambition. Hosting the 2010 World Expo solidified the city’s status as an international metropolis – a space where tradition danced with modernity. Foreign enterprises flooded in, innovation parks multiplied, and the service economy flourished. Shanghai was no longer just participating in China’s growth - it was leading it. Elevated highways, a sprawling underground network, and glittering business districts painted the portrait of a metropolis redefined. As wealth poured in and the skyline shimmered brighter each year, Shanghai became the face of China’s 21st-century economic dream – confident, connected, and unstoppable.

As seen above, Shanghai has risen from a once-neglected fishing village to every modern city’s aspiration. The secret behind this transformation lies in the courage and pioneering spirit the city has embodied – always choosing to lead. In truth, Shanghai had no choice but to be first: the first to confront Western powers, the first to reopen to the world, first to shine as a beacon of China’s revival. Time and again, circumstances compelled Shanghai to set an example for the rest of the nation –and “The Pearl” answered that call. To say that Shanghai reflects the rise of China would be an understatement. China awakened from centuries of slumber. She rose with purpose, and the world watched her transformation, thanks to the significant role Shanghai has played.

But how could just a single war be the cause for rapid advancement in modern technology? To start off with, war has always instigated technological advancements, tactical changes ,and enlightening ideas. Most nations would develop the overall quality of their military to outsmart their opponents which led to the urgency of innovative ideas during wartime. We can see this today in modern warfare where Ukraine and Russia are trying to construct the cheapest and most undetectable drones on the battlefield. World War 1 was perfect in setting this environment. The Great War was one of the largest wars at the time with multiple nations fighting each other for 4 years. In fact, World War 1 accelerated innovations in warfare and civilian life that may have otherwise emerged more gradually. World War 1 had increased the urgency for these advancements as both sides needed innovative ideas during wartime to win. With this new urgency for reducing fatalities and increasing defenses, medication, communication, and weaponry were all developed at a much more rapid pace. Military Historian David Silbey also stated that various countries would use “all of their resources of science and intelligence and said how do we do this better?” Such thoughts during a time of panic and despair would push countries to try and increase productivity, reduce fatalities, and improve weaponry.

World War 1 is known as a tragic and sorrowful event on this planet. However, amidst all this conflict, it was a time of great technological advancements. Despite its brutality, World War 1 catalyzed major advancements in medical, transportation, and sanitation technologies that still benefit us today. A few examples of advancements that have helped us in the modern world are paper tissue, blood banks, and mobile X-ray machines. How could such astonishing revolutions in technology happen in such a time of suffering and economic strain? This excerpt will delve into how the Great War developed global technology that affects all of us in everyday life.

The urgency of the advancements can be seen in the following technologies. Though it was made in 1884, the Maxim gun was used in World War 1 for almost the first time. Especially in trench warfare, armies would use machine guns and stop many enemy troops from advancing. Here, the urgency for a gun with a high fire rate to stop enemy troops was needed. This led to a great change in tactics in warfare as simply charging forward became less effective in war. Another advancement was the mobile X-ray. This was created by Marie Curie solely for the war effort at the time. With the mobile X-ray, soldiers could have access to improved healthcare on the battlefield. The mobile X-ray was also made because of the urgency of healthcare to treat wounded or ailing men. Adding on, tissue was a product invented for the war efforts. Due to the cotton shortage caused by uniform production during the war, nations needed an alternative for cotton that was cheaper and affordable. Kimberly-Clarke, later the founder of Kleenex and Kotex, used something called cellucotton which was made of wood pulp. These were used for gas mask filters and bandages as they were great at absorbing liquids. This case also shows a high demand for a tool in the war.

brought change and development to humankind. This all applies to other advancements such as hydrophones, which were used by submarines to detect icebergs; tracer bullets which were used to fend off Zeppelins and so on.

World War 1 also led to post-war developments as inventions were later released to the public and modified for household purposes. The cellucotton used in the gas masks and bandages were soon released to civilians as tissues and sanitary pads. This was developed by nurses as cellucotton was great at absorbing liquids. The companies that sold these products during the 20s were Kleenex and Kotex. Radio communication in aviation was also developed further after the war. During the war, a pilot who had a set of headphones and a microphone flew up to the sky. Like that, radio communication was invented but it was not favoured by most pilots. However, without World war 1 this invention would not have been thoroughly investigated. World war 1 made this technology vital as it was a time of urgency and there was no space for miscommunication. This technology has developed into the modern headphone set that pilots use in all planes, allowing all of us to fly safely. Finally, zippers were also a post-war development of the war. Zippers were invented during World War 1 and were put on some soldiers’ uniforms. Zippers were apparently better at protecting heat and useful for pilots to use as pockets. These post-war inventions were developed for the purpose of changing military tools into household items. The military equipment was most likely mass-produced and the end of the war would make many companies feel hesitant about their remaining factories. The products would be released to ordinary people in a modified way.

World War 1 was a tragic event that many people consider a tragedy that humanity should be ashamed of. Some people would consider it a foolish war that led to the destruction of both sides. However, World War 1 is a lesson that humanity has learned from. An event that led humanity into a brighter future so that we could live in a peaceful world in the present. It played a pivotal role in improving our quality of living: from how political leaders approach international conflict resolution; business and industry; and simple household chores and clothing that support us without us knowing it. World War 1 also brought out a change in policies and international organizations instead of individual alliances, a factor that led to the start of the War. World War 1 was not just a time of tragedy, it was an event that

Over the past years, global politics have played out under the nationalist, anti-elitist, and even radical influence of right-wing populist movements all over the world. Since the Great Recession, the popularity of European right-wing populist movements has experienced exponential growth ignited by rising Euroscepticism, anti-immigration especially from the Middle East and Africa, and most importantly frustration over the economic policies of the European Union. However, populist radical right parties have been visible in Western European politics since the 1980s (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019). Meanwhile, right-wing populist parties in America were established in the legislatures of various democracies beginning in 2009, and have remained the dominant political force in the Republican party since the 2010s. While the contemporary left is entangled in the crisis of socialism that came along with the rise of right-wing populist parties, it has faced great difficulties engaging in combat with the rise of this phenomenon. In some cases, including the Boston Tea Party Movement beginning in 2009, much of the left discounted right-wing populist initiatives as simply publicity campaigns or Public Relations (PR) activities by neoliberal capital. For instance, the Boston Tea Party Movement, criticises the Obama administration as its name referring to tax without representation during the Boston Tea Party. The letters TEA, being “Tax Enough Already”, criticises how government levies are wrongly used yet heavily priced tax money and further reinforces the stance for future Trumpism along with Trump’s proposal of eliminating income taxes and his America First policy. However, it fails to reconcile itself to rightwing populism, the left is presented with a situation that it is unable to fully comprehend, nor can it develop an appropriate counter strategy against it. Therefore, this has allowed right-wing populists’ false framing of professionalism in mainstream media and central politics, resulting in fragmentation and political gridlocks within institutions.

This global surge of right-wing populism has significantly reshaped political discourse and policymaking in democratic nations, primarily America. All those fringe ideologies have now become mainstream along with previously considered unconventional topics such as immigration, national identity, and mainly cultural homogeneity placed as the center of parliamentary debates and national referenda. As more and more political discourses focus on heavily provocative views in order to gain more attention, the increase in political skepticism such as Subversion 2.0 is conspicuous, even with how articles such as The New York Times suggest “Trump’s Return to power elevates ever fringier conspiracy theories”. Not only this, but Donald Trump himself has numerously yet infamously and notoriously claimed bizarre statements. For instance, during the presidential debate against Kamala Harris, he baselessly said “In Springfield, they’re eating the dogs, the people that came in, they’re eating the cats…They’re eating the pets of the people that live there.” In countries like Hungary, right-wing populist leaders have gained enough influence to challenge liberal democratic norms, weaken judicial independence, and consolidate media control under government-friendly ownership. These developments have not only redefined the political scope within these countries but also have strained international institutions including but not limited to the European Union, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the United Nations (UN).

The rise of right-wing populism has accelerated political polarization on a global scale, thereby resulting in political stalemate (deadlock) and loss of public trust in democracy. In the United States, Donald Trump’s presidency concentrated on nationalism and an “America First” foreign policy, leaving lasting effects on international diplomacy. Moreover, leaders like Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have intertwined right-wing populist rhetoric with strongman governance. This consequently weakens the balance between the majority rule and minority rights. With these on trend, we face civil unrest and the emergence of counter-movements, yet many liberal parties remain reactive rather than directional, failing to develop a proper counter-alternative.

The digital age has further accelerated the rise and influence of right-wing populism by providing new platforms for communication and mobilization. Social media, in particular, has allowed populist leaders to bypass traditional media channels and speak directly to their

audiences, often using emotionally charged rhetoric and simplified messaging to build loyalty and spread their narratives. Algorithms on platforms like Facebook and Twitter tend to amplify polarizing content, which helps these movements gain visibility and attract supporters who feel alienated by mainstream political discourse. Such misinformation and conspiracy theories have flourished in these spaces, deepening divisions and undermining trust in established institutions such as the press, academia, and even electoral systems. The public opinions incorporated with rapid shifts and growing hostility between opposing ideological groups have shaped the current political landscape more unpredictably.

This increasingly fragmented landscape has had profound implications for governance. The ability of institutions to function effectively has been impeded not only by polarization but also by the delegitimization of professionalism, which populist rhetoric frequently frames as elitist or out of touch with “the people.” In many cases, policy decisions have been subordinated to political theatrics, where symbolism and identity politics overshadow evidence-based governance. Thereby, this has not only compromised the quality of democratic deliberation but has also normalized reactionary policies that would have been politically untenable in previous decades.

The global rise of right-wing populism represents overall a transformative challenge to all liberal forms and institutional stability. Fueled and fooled by disillusionment with a high economic gap and a national identity that is said to be lost and eroded, these movements have now reshaped today’s political discourse. While their rise has been met with resistance and civil mobilization for civil unrest, the ultimate failure of left-wing parties to develop a counter has therefore left a vacuum in today’s status quo and further political imagination. Thereby, the question remains not simply how to resist right-wing populist parties but also how to reconstitute and reconstruct democracy in this world defined by disinformation and withdrawal of legitimization as professionals.

Dylan Seo Y12

How should South Korea respond to rising geopolitical tension in Crossstrait relations in the case of war?

Eighty years after the Second World War in 1945, the world in 2025 is still engulfed in the smoke and clouds of war, finding it difficult to settle down from geopolitical conflicts between nations. The wave of war started with the Russia-Ukraine War in 2022 and continued with the Israel-Hamas War in 2024, covering the world in the heat of two full-scale wars in addition to ongoing civil conflicts. Furthermore, on May 7th, a limited three-day conflict even erupted between India and Pakistan, and Russia is reorganising military bases near the Finnish border and redeploying some military forces, among other actions, signifying that countries worldwide have entered the highest state of tension in the 21st century.

In the international situation that has become extremely unstable over the past five years, governments around the world are once again regressing to the situation just before the outbreak of World War II, moving away from the movement for large-scale disarmament and cooperative relations for multilateral peace that had continued for the past 70 years under the leadership of the UN and the United States through the Cold War. European countries, which had been carrying out large-scale disarmament and reducing defence spending, are once again exploring the intention of rearmament. Among them, Poland has actually moved towards rearmament by signing a defence contract worth about 40 trillion Korean Won with Korea and introducing K-2 Black Panther tanks and K-9 self-propelled howitzers. Furthermore, the growth trend of the global Korean defense export market, extending beyond Norway, which has explored the intention to acquire additional weapons, to include Morocco, Peru, UAE, the Philippines, India, etc., across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, clearly shows the worldwide intention to strengthen military power. Thus, the arrow of war that began in Ukraine, one of the powder kegs of Europe, has led to the revival of power politics and political realism throughout the world, becoming the whistling arrow of a new Cold War era.

The political and military tension that began in Ukraine on the other side of the globe has engulfed Taiwan, another powder keg of the world located in East Asia. Especially, the geopolitical characteristics of Taiwan, which is geographically very close to the Korean Peninsula and surrounded by China, the world’s 3rd largest military power, South Korea, the 5th, and Japan, the 8th, have led to concerns from various experts that China’s invasion of Taiwan scenario would not just end as an invasion war seen in the Russia-Ukraine War, but has a high possibility of escalating into a proxy war between the U.S.-led West and China, as well as a third World War. Concerns about China’s invasion of Taiwan have been raised continuously over the past decade, but the unstable international situation over the past three years and the second U.S.-China trade conflict, which began simultaneously with the launch of the second Trump administration, have fallen into the cycle of mutual tariff imposition, leading to the emergence of arguments for an invasion of Taiwan within the year in China, thus continuously raising the military and political tension in the East Asian region surrounding Taiwan. This period is much earlier than most predictions of the year 2027 as the year of the invasion, which is the 100th anniversary of the People’s Liberation Army’s establishment year and the final year of President Xi Jinping’s third term on the way to President Xi’s fourth term. Although there is no possibility or sign that China will invade Taiwan within the year 2025, given that the current era is one where the conflict between the rising power China and the existing hegemonic power the United States, predicted by Thucydides’ Trap, may manifest as an invasion of Taiwan in the near future like 2027, this response will describe what direction South Korea can take to manage and resolve diplomatic and military pressure in the event of a contingency regarding the global issue of China’s invasion of Taiwan.

First of all, the reason behind the point that the South Korean military gets brought up in discussions about a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan is simple. South Korea is not only one of the United States’ allies but also a significant power in East Asia with the world’s fifth-largest military. Furthermore, it is geologically close to Taiwan, and in contrast to Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, whose development has been limited by their Peace Constitution, the South Korean military has been steadily developing its capabilities over the past seventy-plus years. This positions South Korea as a critically important asset for the United States. That being said,

regardless of U.S. expectations, any decision Korea makes about intervening in Taiwan absolutely has to put Korea’s national interests first. This is genuinely a national task that calls for intricate political calculation and firm resolve.