Introduction

Proposal for SustainableResidential Development of Site CL526, St Anne’s Road Lincoln LN2 5RA

and Site Context

This document presents a development proposal for registered brownfield site CL526 at St Anne’sRoadLincoln,previouslyoccupiedaspartoftheCountyHospitalcomplexandadjacent to its enduring operational base (see Fig.1 and 2).

The site occupies the colloquial ‘uphill’ area of Lincoln close to the ‘cultural’ and ‘cathedral’ quarters defined as key intervention sites in the city’s latest masterplan (COLC, 2012), containing some of the area’s most notable historic buildings and architecture. Hospital properties border the site to the east with north, west and south perimeters occupying prominent position along Greetwell, St Anne’s and Sewell Roads respectively, all providing well used passage for motor, cycle and pedestrian travel to and from the south side of the City (Fig.3.)

2DMapofsiteCL256location, StAnne’sRoad(COLC,2017)

3DMapofsiteboundary (Google,2020)

Fig.3.Viewsofthesitefromnorthwest,southwest,westandsouthborders(lefttoright) (Culliford,2021)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

As part of Lincoln’s Abbey ward, the location offers a vibrant and eclectic context for development with an immediate surrounding of mixed landscape, architecture, local community and services including five distinct and diverse ‘character areas’ identified by Heritage Connect Lincoln (2008).

Of particular note is proximity to the Arboretum park (Fig. 4) immediately opposite the southern boundary, created in 1872 and retaining UK Govt Green Flag status since 2014 (HM Government, 2016 p5). The area remains a popular local amenity, providing an important functional and aesthetic pedestrian link between the city’s uphill northern and downhill southern districts.

1. Site Design and Development Concept

1.1 A Sustainable Approach

The proposed site design is informed by emerging policy and good practice in sustainable planning and design, taking a crucial steer from Lincoln City’s latest local plan and supporting policies (Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee [CLJSPC], 2015).

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Sustainable Outcomes Guide (appendix 1.) provides a practical index of considerations to ensure the long-term social, economic and environmental sustainability of new development, guided by widely recognised United Nations (UN) objectives for global sustainability (2016). These RIBA principles alongside factors influencing successful place design according to the National Design Guide (appendix 2.) and Building Research Establishment (BRE) standards for residential construction (BRE, 2018a) (BRE, 2018b) are adopted to drive development decisions and outcomes that:

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Minimise negative environmental impacts through the entire development lifecycle.

Optimise value for stakeholders and occupants, balancing capital investment with longer- term costs and outcomes.

Support comfort and wellbeing of future occupants and provide agility to accommodate changing needs.

Respect and enhance local setting, character and aesthetic including neighbouring communities.

Consider and contribute to the local economy in procurement of components, services and skills.

With the intention of creatinga long-term,valued asset forthe localneighbourhood, anearly programme of consultation is proposed to engage the wider community and stimulate inclusiveness and pride in the development, as well as inform decisions on communal landscaping, outdoor facilities and architectural detailing.

1.2 Building Mix and Use of Space

The majority residential development will offer mixed tenure housing and shared outdoor space to address evolving local need and stimulate a diverse, inclusive neighbourhood (HM Government, 2019 p35 115-117), contributing to the urban vision presented in Lincoln’s latest masterplan (COLC, 2012 p10).

Forecast housing requirement outlined in the city’s housing strategy (COLC, 2020 pp 6-7) demands new accommodation including private and social dwellings for independent older people, two and minimum four bedroom properties, and affordable housing to support growing numbers of households challenged in meeting open market purchase and rental costs. Dwellings proposed for the site addresses this need, incorporating 40% affordable homes and exceeding The City’s minimum requirement (COLC, 2020 p11 2.9), maximising accessibility for local residents including key workers from the adjacent hospital site.

Properties comprise apartments, bungalows, terrace, semi-detached and town houses ranging from one to four bedrooms, and maximum three stories in keeping with surrounding building form and scale. Small commercial units below apartments provide incubation space for local businesses delivering products and services that support community culture and wellbeing.

Parking is primarily located off street to reduce vehicle pollution and enhance aesthetic, allocated at an average ratio of 0.8:1 (space to dwelling) with modest additional visitor provision. Pedestrianised communal space, landscaped features and outdoor seating flow around the development offering safe transition and opportunity for engagement and interaction (HM Government, 2019 p22 74,76).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Structured planting creates privacy and soft boundaries between dwelling blocks and around the development perimeter, extending the site’s south face towards the nearby Arboretum park. Figure. 5 illustratessimilar approaches to space design at the award-winning Goldsmith Street development, Norwich.

Fig.5.Examplesoftheaestheticgainfromvehiclefreefrontagesandpedestrianised space(MikhailRiches,2019)

1.3 Landscaping and Drainage

The development’s prominent and extensive position along St Anne’s Road and Sewell Road creates opportunity to improve local surface drainage as well as enhance surrounding aesthetic and bio diversity, delivering significant community and environmental benefit from natural landscaping features (UKGBC, 2020 p2). Increased atmospheric temperatures and air quality impacts from nearby roads and hospital buildings, known as urban heat island effect (UHI), are mitigated with the introduction of absorbent landscaping and vegetation.

Flood risk to the site is low, however, relative proximity to the river Witham and surrounding highrisk area(Hemsworth, 2010 p30)demandsconsideration of contribution to downstream flooding (Fig. 6.). The approach to drainage seeks to minimise surface runoff and reduce pressure on existing wastewater infrastructure through low maintenance sustainable urban drainage (SUDS) components and infiltration techniques (CIRIA, 2012 pp 26).

Fig.6.Mapshowing siteproximityto downstreamriver Witham (Google,2020)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Intermittent guarded tree pits (Healthy et al., 2018) line the development’s roadside boundary, increasing surface water drainage (Fig. 6.) and creating attractive screening from traffic acoustic and pollution for dwellings, outdoor space and public pavements (Fig. 8.) (Trees & Design Action Group [TDAG], 2012 p3).

Fig.7.Imageoftypicaltreepitsystem absorbingsurfacewaterrunoff (CIRIA,2012p363)

Fig.8.Roadsideurbantreepitinstallation atGrangetown,Cardiff(Susdrain,2020b)

Additional storm water filtration is provided via a shallow swale (Fig. 9.) and structured planting of hardy shrubs along the inner site perimeter, creating a soft boundary and increasing biodiversity. A rain garden installation surrounds the development’s single apartment block, to absorb rainwater redirected from down pipes and afford the benefits of a garden aesthetic to occupants and visitors.

Fig.9.Exampleofshallowgrass swaleandpermeablepavingat nearbyAlbionCloseLincoln, aSUDSawardwinningdevelopment (Susdrain,2020a)

Installation of water penetrable paving and permeable hard landscaping surfaces extend stormwater filtration and absorption throughout communaloutdoor space and parking bays, significantly improving natural drainage and reducing downstream runoff from existing tarmac surfacing across the pre-developed site (Fig. 9.).

Tree pits and soft planting installed around the site perimeter are echoed at reduced scale throughout the development to extend drainage, biodiversity and aesthetic benefits and

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

create soft sectioning between dwelling blocks, parking bays and communal spaces (HM Government, 2019 pp24 84,86, 31 103).

1.4 Local Vernacular

Theprominent buildingform andarchitecturalstyle surroundingthedevelopmentsitecanbe categorised into five notable types (Fig. 10.):

1. DiversemassingofLincolnCountyHospitaltotheeastwith‘’limitedinterrelationship between buildings’’ (COLC, 2009 p4-5) including modern development of largely box shaped, steel framed properties.

2. Traditionalresidentialstreets ofmixedperioddetachedandsemi-detacheddwellings to the north along and adjoining Greetwell Road.

3. Largedistinctivecharacterproperties alongSewellRoadandLindumTerracetowards Lincoln Cathedral (COLC, 2009c), with many due for imminent renovation (Franklin Ellis, 2014).

4. Steep, sloping red brick terrace streets including and adjacent to Millman road, leading to Monks Road and the south of the City.

5. The Victorian Arboretum park (COLC, 2009a) dominating the south face, with terraced landscaping leading down towards central Lincoln, traditional red brick boundary walls and higher level shrubs and trees visible from adjacent streets.

Proposed design acknowledges the importance of synergywith surrounding architecture and form (Lee, 2017 p13)aswell asthe impacton neighbouringcommunitiesand the subsequent sense of place they afford (HM Government, 2019 pp 14-16).

Guided by identity factors described in the National Design Guide (HM Government, 2019) and addressing local development policy LP29 Protecting Lincoln’s Setting and Character (CLJSPC, 2015 p73), the following principles are adopted to inform architectural approach:

Materials and detailing from surrounding architecture are incorporated to reflect and compliment the traditional local aesthetic (Fig. 11.), creating a point of unity between neighbouring uphill and downhill communities.

Existing views towards the cathedral and arboretum are protected for surrounding streets and dwellings, through consideration of building form and placement.

Prominence of site position is respected, with building and landscape design balancing the more industrial look of the adjacent hospital site and enhancing the aesthetic along surrounding roads.

Neighbouring communities are engaged in site design and detailing, including street naming, to encourage local adoption.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Fig.10.Examplesofsurroundinglandscapeandarchitecture/1.Hospitalbuildings,2.Greetwell Road,3.TypicaldwellingsalongSewellRoadandLindumTerrace,4.MillmanRoadTerraces,5. Arboretumviewfromsouthofsite,6.Parktreesandshrubsvisiblefromsite.(Culliford,2021)

Fig.11.Examplesof traditionalarchitectural detailing(lefttoright)along Arboretumboundaryand SewellRoad(Culliford,2021)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

1.5 Transport and Mobility

The development isaccessibleby road andfootpathwithproximitytopublictransport routes within and outside the city boundary, safeguarding mobility for all residents and reducing demand on cars for essential travel (RIBA, 2019 p33) (CLJSPC, 2015 p88 LP36).

VehicularaccessisproposedviaanexistingsiteentranceonSewellRoad,reducingcongestion risk having previously accommodated regular traffic flow to and from the site. Landscaping design along western and southern boundaries (see 1.3 Landscaping and Drainage) aims to slow passing traffic and increase pedestrian safety.

Amenity to live and work within short commute from the development is significant, with three large employers, County Hospital, Siemens and Anglian Water operating within a mile of the site. Additional opportunity exists via local SME and national retail businesses located nearby in the cathedral quarter, Greetwell Road, Outer Circle Road and Allenby Industrial Estate (Fig.12.).

Fig.12.Locationofprincipleeconomicsiteswithinamile ofthedevelopment(Google,2020)

Residential parking provision remains in demand, with national policy driving low carbon vehicle infrastructure (Department for Transport, 2018 pp 7,8) and ownership forecast to increase in line with affordability (ibid, 2018 pp 9,42,43). In the absence of specific local standards(CLJSPC,201p41 4.7.11)aguidingvehicleprovisionof80%(0.8spaces)perdwelling, including private and share spaces, is adopted for the site to offset the necessity of car ownership for many occupants with surrounding infrastructure and services to support alternative travel where possible.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

A local travel report confirms availability and high standard of pedestrian access surrounding the site, including a zebra crossing at Greetwell Road close to the St Anne’s Road junction (HSP Consulting, 2016 p6), with robust public transport networks across the city affording sustainable transport opportunity for residents.

The nearest bus stop is located less than 100 meters from the development (Fig.13.), with nearby citycentre coachand train stationsproviding a growing numberof routes to local and national destinations.

Fig.13.Mapshowinglocationofnearbybusstops,preparedforlocaltravel plantosupportnearbydevelopment.StAnne’ssitemarkedinred (HSPConsulting,2016)

Reduction in car use is facilitated via existing marked bicycle routes in surrounding streets, leading to off road and dedicated paths as part of the local cycle network (Access Lincoln, 2020a). A hire and charge station is accessible in adjacent hospital grounds (Hour Bike Ltd., n.d.), with extended provision proposed as part of the development’s shared facilities (see 1.8 Communal Outdoor Features).

1.6 Access to Services and Amenities

The proposed dwelling and tenure mix is expected to attract a diversity of residents including those in and approaching retirement and young families, for whom close proximity to local services and facilities is imperative (CLJSPC, 2015 p70).

Amenityofpedestrian, cycle and bus routesto and from the development (1.5 Transport and Mobility) ensures access to an extensive mix of services within a short distance, often less than a mile, supporting the UK Government’s concept of the walkable neighbourhood (2009 p45 4.4)

Smaller, independent retailers operating in nearby Bailgate provide the tradition and communityofalocalhighstreet(Fig.14.),withlargerstoresandsupermarketsavailablealong Outer Circle Road, all accessible by foot, bus or bike.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Residentsarewellservedbyaccesstoeducation,healthandrecreationwithatleastonelocal primary,secondaryschooland GPsurgerywithinamileofthedevelopment,aswellasalarge public park directly adjacent (RIBA, 2019 p42) (Fig. 4.). Dedicated communal space across the development seeks to enhance existing local provision and provide opportunity for community activity, with small commercial units ringfenced for products and services to address local neighbourhood need (Fig. 15.).

Fig.14.Viewofindependentshopson Bailgateinthenearbycathedralquarter (COLC,2009b)

1.7 Building Orientation

Fig.15.Imageshowinggroundfloormixed commercialunitsatGranthamStreet,Lincoln (MeetLincolnandLincolnshiren.d)

Placement of properties in final site design will exploit the south facing elevation, sitting 100 feet above the lower end of the Arboretum park and adjacent residential streets. Optimised internal daylight levels and solar gain offer significant contribution to occupant comfort and well-being as well as reducing demand and associated costs for internal heating and lighting systems (HM Government, 2019 p39 126) (BRE, 2018 p79). Avoiding direct east or west orientation mitigates against risk of noise and air pollution via adjacent road and hospital sites, as well as optimising outlook from primary living spaces and gardens.

All dwellings benefit from primary living and outdoor space facing from direct south (single storey bungalows and apartment blocks along the southern border) to south, south west or south, south east (housing blocks surrounding central green communal space) (Fig. 16.). The resulting outlook affords optimum rotation from true south (Ciob, 2010 p276) to afford a minimum average daylight factor (a standard measure of the proportion of external light reaching internal spaces) of between 2-4%, exceeding where possible the minimum BREAAM standard for residential dwellings (BRE, 2018 p80).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Fig.16.Mapillustratingprimaryorientationofproposed dwellings(markedbottomlefttoright)SSW,S,SSE(Google, 2020)

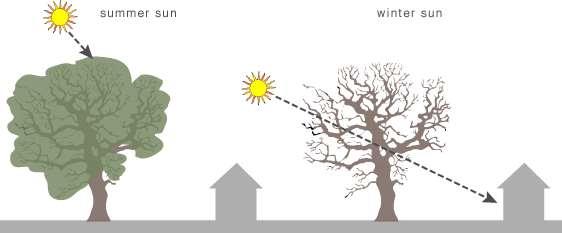

Positioning also exploits Solar gain for the majority of dwellings, increasing output from specified solar PV panelling (2.4.2 Heat and Power) and reducingdemand on heating systems throughincreasedpassivetemperaturesduringcoolerseasons.Placementofdeciduoustrees alongsouthernboundariesprovidesshadefromwinterglareandsummerheat(Fig.17.),with building features to further enhance natural light absorption and solar gain considered in the construction specification for individual dwellings (2.4.1 Indoor Comfort).

Fig.17.Illustrationofdeciduousplantingtomitigateexcess heatandglarefromsouthernorientation(Greenspec.co.uk,

1.8 Communal Outdoor Features

The local aspiration for community cohesion (COLC, 2012 p10) (CLJSPC, 2015 pp 46 4.9.1 59 5.9.1) is delivered through considered outdoor space and facilities that enrich the experience of those living, working or engaging in the development (HM Government, 2019 pp 26,28).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

In addition, wellbeing and property values are increased in the surrounding neighbourhood by enhanced local aesthetic and green space (Cowan R, 2005 p 7).

Shared features gift extended garden and biodiversity to residents and visitors (Fig. 18.) and include:

Rain gardens surrounding the development’s apartment block, contributing natural drainage whilst enhancing views and outdoor air quality (1.3 Landscaping and Drainage)

Living walls welcoming residents and visitors at the main entrance (Sewell Road), affording the development a distinctive aesthetic signature, with potential to contribute to site SUDS features through rain water irrigation.

Playareas located betweenterrace housingblocks, offering safe interaction spacefor families and social engagement between residents.

Communal green space in the centre of the development providing a destination for neighbourhoodeventsandactivities,echoing,onasmallscale,provisionandaesthetic afforded by the nearby Arboretum park.

Green pockets of planting with mixed outdoor seating placed throughout transition routes, incorporating sustainable drainage and providing opportunity for meeting, resting and socialising as well as attracting footfall for businesses occupying commercial units. (Cowan & Hill, 2005 p27) (Worpole & Knox, 2007 p5).

Fig.18.Exampleofoutdoorfeaturesandfacilitiessuccessfullyincorporatedinurbandesign (lefttoright)gableendraingardenatGrangetownCardiff(Susdrain,2020b),statement livingwallatM&SEccleshallroadSheffield(UKGBC,n.d.),landscapedcommunalspaceand playareasatGoldsmithstreetNorwich(MikhailRiches,2019)

Shared access to the suite of outdoor facilities invites pride, participation and stewardship fromresidentsinandaroundthedevelopment,evolvingandsecuringthemforlongtermuse. (Halliday, 2019 p432) (HM Government, 2019 p48).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

A communal cycle park and charge station extends existing provision for the city (Access Lincoln, 2020b) and supports local and national aspiration for reduced car use. (HM Government, 2019 pp 31,102).

2. Private Dwelling Specification

2.1 Introduction and Property Context

The following specification is prepared for construction of a new private dwelling at plot 1 within the proposed development, commissioned by proprietors of the nearby Lindum Medical Village (currently under development at Sewell Road) with the intention to offer convenient, quality accommodation for short term tenure by staff and visitors.

The plot is located along the site’s southern boundary, occupying a direct south facing position(Fig.19.),andestablishesthe designblueprint for singlestoreydwellingsintendedas part of the development’s mixed accommodation proposition. Access is via the north facing frontage, placing core living space and private garden to the rear of the property to exploit natural daylight, solar gain and uninterrupted views towards nearby parkland.

Fig.19.Locationofproposedprivatedwellingwithin thedevelopmentsite(Google,2020)

Future occupants of the dwelling gain benefit from the services and features of the wider development(see1.6 Access to Services and Amenities,1.8 Communal Outdoor Features)and are well served by local amenities accessible by road, foot and public transport (see 1.5 Transport and Mobility).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

2.2 Approach to Design and Construction

RIBA sustainability principles and BRE new construction standards adopted for proposed development design (see. 1.1 A Sustainable Approach) are extended to individual dwelling specification and construction management.

2.3 Construction Materials and Techniques

2.3.1

Specifying Sustainability

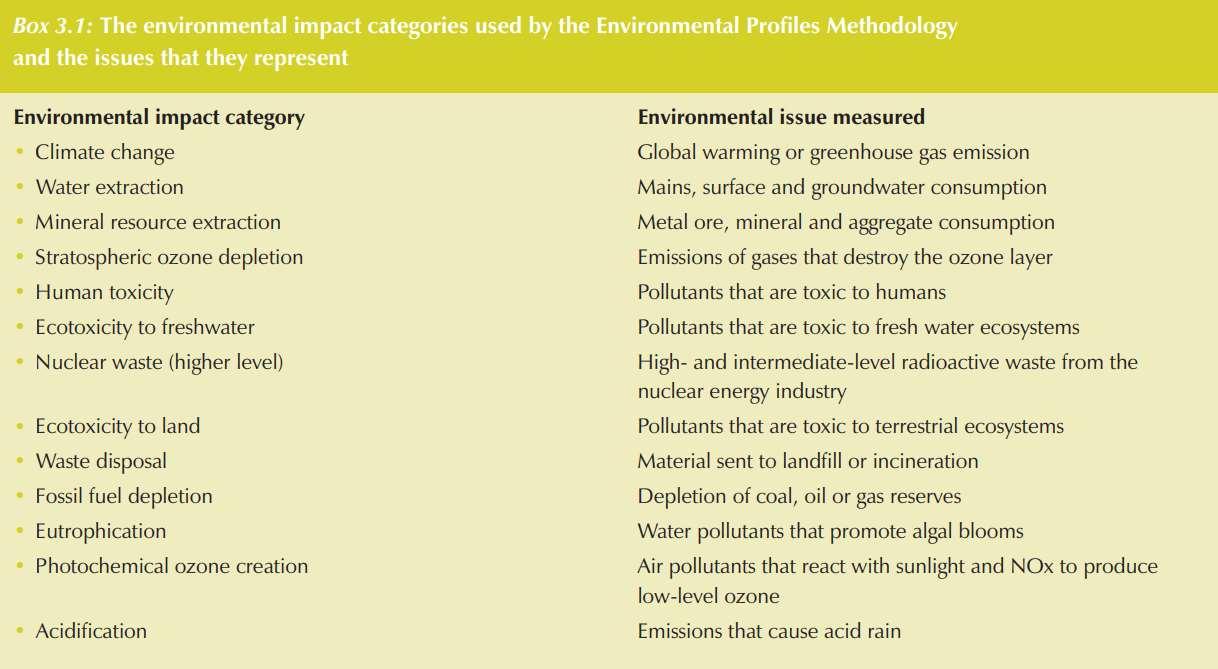

Building materials are selected based on performance against all sustainable construction principles outlined inthesitedesignand development concept (1.1 A Sustainable Approach), with specific consideration of emissions and use of natural resources associated with their production,operationaluseandeventualretirement (Anderson etal.,2008p4).Contribution to thermalperformance and moisture control are also key to minimiseheat loss and improve air quality for occupants, ensuring a healthy, efficient and resilient property.

The BRE Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) tool (Anderson et al., 2008 Ch3) and Home Quality Mark (HQM) manual (BRE, 2018b) inform final material selection, respectively providing environmental impact ratings based on performance against multiple factors (appendix 3) and technical standards that exceed regulatory requirement for sustainable home design. Building efficiency principles demanded for the renowned Passivehaus standard provide additional reference for the build, however, are not formally adopted due to the absence of holistic sustainability considerations (Edwards, 2014 pp 274, 276).

2.3.2

Exterior Elements

Traditional red brick and slate are specified for external, visible building components (wall leaf and roof covering) supported by structural timber frame, affording resilience against natural wear and erosion to minimize long term maintenance and costs. Local policy is addressed by protecting neighborhood distinctiveness and respecting architectural context of adjacent hospital and park sites (CLJSPC, 2015 p73) (Fig. 10.). Slate provides a robust and durable roof surface appropriate for solar panel installation proposed as a primary home energy source (2.4 Property Services and Facilities).

Brick and slate will be reclaimed from nearby hospital buildings due for demolition (Fig. 20.), forecast to supply the majority of the development’s single storey and terrace housing and integrated with new material provision for remaining properties (Fig. 21.). The reclamation opportunityextendsmateriallifeandreducesimmediateandlong-termwasteduetoongoing recycling potential.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Transport costs and associated emissions are also reduced compared with re purchase and reduced investment in locally sourced new materials is offset through commissioning of local trades during installation.

Fig.20.Hospitalbuildingsduefor demolition,StAnne’sRoadLincoln (Culliford,2021)

Fig.21.Successfulblendingofoldand newredbrickatDruryLane,Lincoln (Google,2020)

2.3.3 Use of Timber

Timberisadoptedastheprimarystructuralmaterial,minimizingtotalbuildcomponents(BRE, 2018a Mat 06) and affording efficiencies in procurement and installation from local suppliers and trades. Steel and concrete provide equal opportunity for offsite construction and build efficiency but are deselected dueto lower structural efficiency(the ratio of maximum load to material weight) and higher environmental impact from manufacture and disposal.

External load bearing frames use Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certified softwood (FSC, n.d.) contributing a lightweight, A+ rated, low embodied energy material versus steel or concrete alternatives (Chong, 2010). Water based preservative is applied as a sustainable alternative totraditionaloil based products,ensuring equal durabilitywithsignificantly lower volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions (Kubba, 2017 p264). Further protection from moisture is provided via the property’s external brick leaf. Comparable timber is adopted for the open plan truss roof, requiring structural (C24) grade softwood to support exterior slate tiles and solar panels.

Internal Walls incorporate open paneltimber studpartition (FSCnon-structural [C16] grade), available from UK sources and with lower embodied energy versus masonry or aluminium frame partitions (Anderson et al., 2008 p191), with floor structure adopting structural grade joists of comparable specification.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Timber is also chosen for window frames, with FSC certified hardwood offering significant durability against external exposure and reduced embodied energy to offset increased cost versus treated softwood, metal or UPVC alternatives (Anderson et al., 2008 p188). Offsite finishing with low VOH coating minimizes future maintenance and reduces construction time and cost. Double glazing is specified over triple glazed units to reduce cost and minimize potential solar loss associated with triple panes. The incorporation of low emissive (low-e) glassreducesUvalue(ameasureof materialthermaltransfer)and provideshighthermaland acoustic efficiency (Fig. 22.), a prerequisite in reducing heat loss from the property and ensuring effectiveness of internal ventilation systems according to Passivehaus principles (Edwards, 2014 p276).

Fig.22.IllustrationofSolarandthermalbenefitsfrom low-ecoatedglass(Glow,2019)

2.3.4 Internal Components, Sheathing and Insulation

Oriented Strand Board (OSB) and bio composite plasterboard alternative provide respective external and internal facings to the timber frame structure, elected over traditional plywood and plasterboard due to lower embodied carbon and cost (Anderson et al., 2008 p191) (Quintana et al., 2018). The breathability and composability of bio composite board makes positivecontributiontoairqualityandcomfortforoccupantsaswellasreducinglifetimebuild impact through recycling potential.

Timber is re specified for floor structure supporting a deck of OSB floor panels, offering significant embodied energy reduction in comparison to solid concrete aswell asefficiency in procurement and labour across the property’s multiple timber components. OSB is substituted for eco grade plywood in bathrooms and kitchen where high resistance to moisture balances reduced LCA credentials.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

The dwelling is insulated throughout with mineral wool, a significantly lower cost alternative to sheep’s wool affording the same contractor and occupier comfort and wellbeing via natural,non-toxic composition and contributingtothermalperformance and reduced energy use (BRE, 2018b p71 ) (BRE, 2018a 5.0 HEA 02 HEA 04). Mineral wool also offers highest grade fire resistance in comparison to man-made insulation materials.

Products specified for the build afford structural agility for reconfiguration of space to accommodate future need, enabling appropriate function and comfort for occupants in the long term (HM Government, 2019 p47 156). BREEAM new construction material efficiency values are addressed through re use of existing components and reduction of construction cost by minimizing the overall material portfolio (BRE, 2018a 9.0 MAT 06).

2.4 Property Services and Facilities

2.4.1 Indoor Comfort

The property benefits from access to natural daylight and solar gain from a south facing position, optimising comfort for occupants and reducing demand on light and heating systems. Mitigation against seasonal overheating and glare is provided through recessed window frames and external shades(Fig. 23.)as well as deciduous planting(Fig. 17.).Internal LED lightsourcesofferlow impactartificiallightingwhererequired,minimising energyoutput and cost.

Fig.23.Exampleofwindowshadingdesignat GoldsmithStreet,Norwich(MikhailRiches,2019)

2.4.2 Heat and Power

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Solar PV panels mounted on the south facing roof provide a significant volume of annual electricity demand to the dwelling (the CIBSE, 2006 pp. 8-9), reducing grid consumption and up to 98% of associated carbon emissions.

Return on purchase is expected in under ten years when combined with UK government funding schemes (Energy Saving Trust, 2020a) with added benefit of low cost and complexity installation and ongoing maintenance.

In recognition of government plans to retire production of non-renewable domestic boilers by 2025, an air source heat pump (ASHP) is specified as a renewable heating alternative, powering a wet internal space heating system and providing back-up hot water supply to subsidise solar PV provision (Fig. 24.). With lower space demand and installation costs versus alternative renewable sources, for example ground source heat pumps (GSHP) and biomass boilers, as well as a competitive energy input: output ratio of 1:4, ASHP offers further efficiency through volume procurement of systems and servicing where specified across the development.

Underfloor heating is discounted in favour of radiators, to reduce capital costs and increase ease of operation and maintenance for the dwelling’s transient occupancy.

Fig.24.Illustrationofairsourceheatpumpoperation (Remodellingcalclator.org,2020)

2.4.3

Ventilation

Air quality inside the property is optimised via installation of a mechanical ventilation and heatrecovery system (MVHR) (Fig. 25.),mitigatingagainst fresh air loss asa result of reduced leakage and natural ventilation levels achieved during construction.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

A whole house system operating from loft space offers a low carbon, low operating cost alternative to air conditioning including up to 91% heat retention and transfer as well as reportedindoorhealthand comfortimprovementsubjecttoappropriateoperation(see2.4.6 System Operation)

Fig.25.IllustrationofgenericMVHRunitoperation(CIBSE,2019)

2.4.4 Water

A rain water harvesting system is installed to collect and recycle runoff from the property roof, collected in a ground level tank to facilitate non-potable re use such as irrigation or car washing. Further passive water savings are achieved through specification of high efficiency (A+ rated) plumbing components including low flow toilets, taps and shower sensors.

Future occupants are engaged in water saving practices via the provision of a comprehensive home efficiency pack (see 2.4.6 System Operation).

2.4.5 Mobility

Single space private parking to the front of the dwelling supports accessibility and mobility for future occupants requiring vehicle access. Charge point ready infrastructure linked to PV panels and secondary mains back up provides agility for future installation, anticipating the forecast uptake in electric vehicle use (Department for Transport, 2018 pp 9,42,43) and likely emerging subsidies to support this.

2.4.6

System Operation

Enduring system performance and efficiency is heavily reliant on understanding of operation and controls. Less traditional schemes are at greater risk of under-performance, notably MVHR where research has highlighted the impact of inefficiency resulting from poor installation and occupant use (Zero Carbon Hub, 2013). A comprehensive home pack containing non-technical system guidance is provided to occupants to encourage best practice and appropriate operational use of domestic heat, light, power and water systems.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Smart meters are installed to monitor energyand wateruse throughout the dwelling,proven to increase domestic resource efficiency (Energy Saving Trust, 2020b).

Post occupancy surveying is scheduled for up to 24 months following completion to measure performance against expectation and provide opportunity for improvement and future learning, with specific value for wider site development (BRE, 2018a MAN 04).

2.5

Construction Management

Principles and standards applied to site and dwelling design remain central to the approach for site and project management, adopting BREEAM values specific to management of residential development (BRE, 2018a).

Continual improvement at project and site scale is facilitated via regular review and ‘lessons learnt’ procedures, ensuring best practice is documented and shared to optimize future performance (BRE, 2018a MAN 03).

2.5.1

Procurement

Guided by principles in the British Standard IS0 20400 for sustainable procurement (International Organisation for Standardization [ISO], 2017), consideration of environmental, social and economic impacts of the build are embedded in approaches to commissioning materials and services and afforded equal weight versus standard criteria of cost, qualityand lead time (Berry & Shaun, Mccarthy, 2011 p11).

Attention is paid to the sustainability credentials and culture of contractors and suppliers alongside those of the specific components being procured (see 2.3.1 Specifying Sustainability),withlocalsupplychainsengagedwhereverpossibletoretaineconomicbenefit within the city.

2.5.2 Waste

Project waste management is informed by a widely adopted approach championed by the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP), prioritising site waste reduction to avoid subsequent downstream management and disposal (Fig. 26.).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Fig. 26. The WRAP waste management hierarchy (2012)

The re use of brick and slate from surrounding buildings has a significant impact on waste accumulationduringpropertyconstruction and eventual end of life. Themajorityof specified construction components require minimal packaging for delivery to site (specifically timber, reclaimedbrickandslate,OSBoutersheathpanels)andpackagingwillremainaconsideration in the procurement of all other structural, functional and decorative materials deployed in the build.

A site waste management plan (SWMP) will inform project decision making and exploit opportunities to design out waste during all phases, specifically addressing contributing practices including over ordering and damage of materials, and ongoing changes to design and specification (BRE, 2018a 4.0 MAN 01). This is also reflected in performance standards embedded in all contractor agreements.

Where waste production is unavoidable, effort will be focused on the potential for future re use and recycling of waste materials respectively, with sustainable disposal being the final consideration only in instances where preferred options are unachievable.

2.5.3 Safety and Wellbeing

Site safety is embedded in the project management approach through explicit policy requirement as part of contractor procurement, as well as inclusion in all construction documentation and project meeting agendas, to encourage cultural adoption.

Immediate safety risks for contractors and long terms impacts for occupants are reduced through specification of materials with low or zero toxic emissions, such as low VOC paints and surfacetreatments,use of naturaltimber and sheathing, and brickand slaterequiring no additional treatment.

Localneighbourhoodsand habitatsareprotectedfromavoidablenoiseandpollution through careful consideration of site access, operational times and heavy plant use as well as construction materials and methods. For instance, offsite construction of trusses and timber frames are recommended to reduce installation time (see 2.3.3 Use of Timber).

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Disruption isfurther mitigatedthrough ongoing consultationwithlocalresidentsand hospital managers, providing regular updates on build schedule and potential disturbance.

3. Closing Summary

The St Anne’s Road site (CL526) grants the opportunity for transforming a prominent space within Lincoln’s uphill district to create a sustainable asset for the city; proposing a blueprint forlocalurbandevelopmentthatrespondstogrowinglocaldemandforaffordable,accessible accommodation and facilities.

The city’s economy can benefit from an increase in skills provision and service demand from new communities,withsocialand environmentalimprovementsgiftedtotheneighbourhood through enhancement of urban landscape and outdoor amenity.

The central location facilitates low impact living, reducing dependency on car use through close proximityof essential and recreational services, employment sitesand publictransport. Sustainability is embedded in dwelling design where considered specification achieves long term, resource efficient comfort and performance.

Adjacentbrownfieldsitestothenorthandwestofthedevelopmentofferfurther opportunity to advance the accommodation, landscape and architectural gains of the proposed scheme in surrounding space.

Bibliography

A Quintana, J Alba, R Del Ray, L. G.-G. (2018). Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of gypsum plasterboard and a new kind of bio-based epoxy composite containing different natural fibers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 185, 408–420.

Access Lincoln. (2020a). Lincoln_Cycle_Network_Map_Download.pdf https://accesslincoln.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/Lincoln_Cycle_Network_Map_Download.pdf

Access Lincoln. (2020b). Lincoln Hire Bike Stations Map. https://accesslincoln.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/Park__Bike_Map_Download-1.pdf

Anderson, J. (n.d.). Green Guide to Specification. 2008.

Berry, C., & Shaun, Mccarthy. (2011). Guide to sustainable procurement in construction. CIRIA report, CIRIA, London.

BRE. (2018a). BREEAM New Construction. http://www.breeam.org/page.jsp?id=20

BRE. (2018b). Home Quality Mark ONE: SD239 England

Central Lincolnshire Joint Strategic Planning Committee. (2015). Central Lincolnshire Local Plan.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

January, 1–198.

Chong, W. K. (2010). The Green Guide to Specification, 4th edn. In Construction Management and Economics (Vol. 28, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190903460656

Ciob. (2014). Rough Guide to Sustinability. In Brian Edwards (Vol. 1, Issue 2).

CIRIA. (2012). The SuDS Manual.

COLC. (2009a). Arboretum Character Area Statement

COLC. (2009b). Bailgate and Castle Hill Character Area Statement.

COLC. (2009c). Lindum Terrace Character Area Statement.

COLC. (2012). City of Lincoln Masterplan. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 172.

COLC. (2017). Map of Brownfield Sites 526, 754, 756 Lincoln. City of Lincoln Brownfield Site Register. https://maps.lincoln.gov.uk/WebMapLayers8/Map.aspx?x=498714&y=371766&resolution=0.5 &epsg=27700&mapname=planning&baseLayer=BackgroundMaps&datalayers=BackgroundMap s%2CBrownfield Land Register%2CselectFeaturesControl_container

COLC. (2020). City of Lincoln Draft Housing Strategy

Culliford, N. (2021). Private Image Collection.

Department for Transport. (2018). The road to zero. Next steps towards cleaner road transport and delivering our industrial strategy. UK Department of Transport, July, 90. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_dat a/file/723501/road-to-zero.PDF

Edwards, B. (2014). Rough Guide to Sustainability (Vol. 1, Issue 2).

Energy Saving Trust. (2020a). Generating Renewable Energy: Solar Panels. https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/advice/solar-panels/

Energy Saving Trust. (2020b). Smart Metering Advice Project. https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/casestudy/smart-metering-advice-project-smap/

Franklin Ellis. (2014). 2016_1140_FUL Lindum Medical Village Design & Access Statement (Issue November). https://development.lincoln.gov.uk/onlineapplications/files/B7ADA3F97381109FF8092466E56C15ED/pdf/2016_1140_FULDESIGN_AND_ACCESS_STATEMENT-427177.pdf

FSC. (n.d.). FSC Labels. N.D. Retrieved December 30, 2020, from https://www.fsc-uk.org/enuk/about-fsc/what-is-fsc/fsc-labels

Google. (2020). Google Maps. https://www.google.com/maps/@53.233903,-0.5258084,17z Government, H. (2009). Manual for Streets (Vol. 162, Issue 3).

Greenspec.co.uk. (n.d.). Passive Solar Design: Sitting and Orientation. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.greenspec.co.uk/building-design/solar-siting-orientation/ Healthy, S., Journal, C., Urban, N., Pit, T., & Factors, D. (2018). Urban Tree Pit Design Factors for Stormwater Management Performance. 6.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Hemsworth, M. (2010). Lincoln Policy Area Strategic Flood Risk Assessment The Lincoln Policy Area Partners JBA Project Manager February

Heritage Connect, L. (2008). What is a Character Area? http://heritageconnectlincoln.com/article/what-is-a-character-area

HM Government. (2016). Celebrating amazing spaces. Green Flag Award http://www.greenflagaward.org.uk/about-us/

HM Government. (2019). National Design Guide.

HSP Consulting. (2016). Lindum Medical Village Framework Travel Plan September, 1–27.

International Organisation for Standardization (ISO). (2017). ISO 20400:2017 Sustainable procurement — Guidance. https://www.iso.org/standard/63026.html

Kubba, S. (2017). Handbook of Green Building Design and Construction. Lee, S. (2017). Aesthetics of Sustainable Architecture Sang Lee [ ed .] November 2011

Ltd., H. (n.d.). Lincoln Hire Bike Scheme. https://www.hirebikelincoln.co.uk/ Mikhail Riches. (2019). The largest Passivhaus scheme in the UK http://www.mikhailriches.com/project/goldsmith-street/

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). (2019). RIBA Sustinable Outcomes Guide. Susdrain. (2020a). Albion Close, Lincoln: SUDS Awards 2020. 1–17. Susdrain. (2020b). Greener Grangetown , Cardiff susdrain SuDS Awards 2020. 1–13.

The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE). (2006). Renewable energy sources for Buildings. In Energy Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(80)90024-5

Trees & Design Action Group. (2012). Trees in the Townscape: A Guide for Decision Makers. Issue 3. http://www.tdag.org.uk/uploads/4/2/8/0/4280686/tdag_trees-in-thetownscape_november2012.pdf

UKGBC. (n.d.). Project Case Study Sustainable Learning Stores : Marks and Spencer Ecclesall Road. 1–3. https://www.ukgbc.org/sites/default/files/Ecclesall Road_0.pdf

UKGBC. (2020). Nature-based solutions to the climate emergency: The benefits to business and society

United Nations. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals

Zero Carbon Hub. (2013). Ventilation in New Homes. https://www.zerocarbonhub.org/sites/default/files/resources/reports/ZCH_Ventilation.pdf#:~: text=Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery in New Homes,are attributable to exposure to outdoor air pollution.

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Appendices

Appendix 1. Illustration of RIBA sustainability outcomes. (RIBA, 2019 p8)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

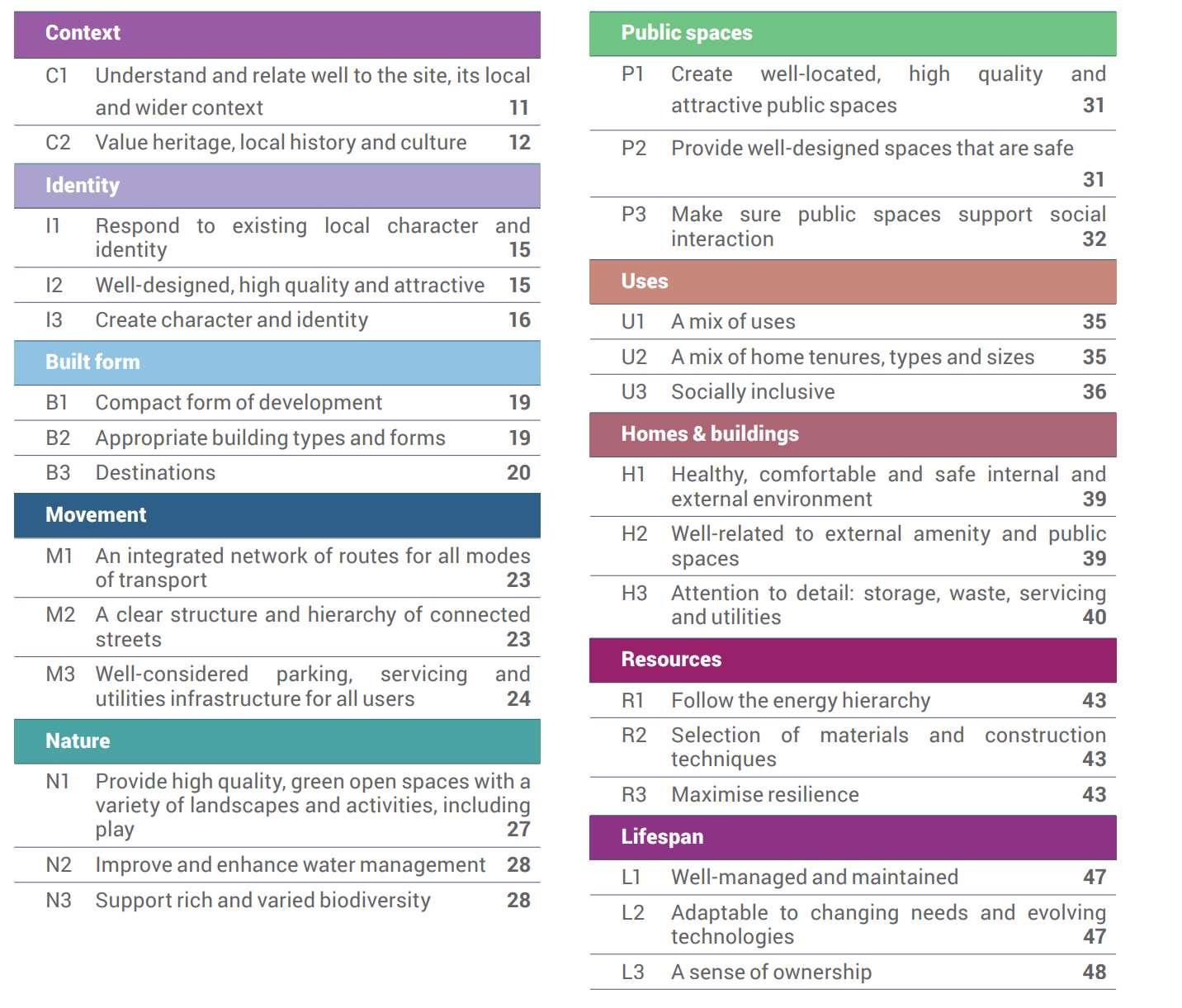

Appendix 2. Ten characteristics of well-designed places according to the UK Government National Design Guide (HM Government, 2019 p3)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21

Appendix 3. Individual measures contributing to the BRE lifecycle assessment tool for construction material specification (Anderson et al., 2008 p11)

N Culliford: Sustainable Planning, Design and Construction on a Brownfield Site_11Jan21