D U B A I

Sustainability in the Desert ?

UPP 508

Global

Professor : Dr. Sevin Yildiz

Team Members :

Tom Bos

Neha Pol

Justin Bologna

Angelo Brown

D U B A I

UPP 508

Global

Professor : Dr. Sevin Yildiz

Team Members :

Tom Bos

Neha Pol

Justin Bologna

Angelo Brown

Figure o1 : Context Map of Dubai

Figure 02 : Dubai’s rapid development of the past 30 years

Figure 03 : Dubai rises from the desert

Figure 04 : City of Dubai

Figure 05 : Dubai’s Sustainable City above

Figure 06 : Jelbel Ali, Dubai’s electricity and water plant

Figure 07 : Original plan for the 1959 dredging of Dubai Creek

Figure 08 : Original plan for the 1959 dredging of Dubai Creek

Figure 09 : Photographed for publicity, Sheikh Rashid and others watch as some of the first oil from Fatah field is pumped from a barge into a sand bund onshore.

Figure 10 : Sheikh Rashid drives the first pile into port Rashid.

Figure 11 Migrant workers in Dubai

Figure 12 : ADNOC offshore oil rig

Figure 13 : Gross Domestic Product at Constant Prices For 2022 - Emirate of Dubai

Figure 14 Tourism Growth in Dubai

Figure 15 Burj Khalifa Skyline

Figure 16 : Dubai Tourism : Mix of Cultures and Ethnicity

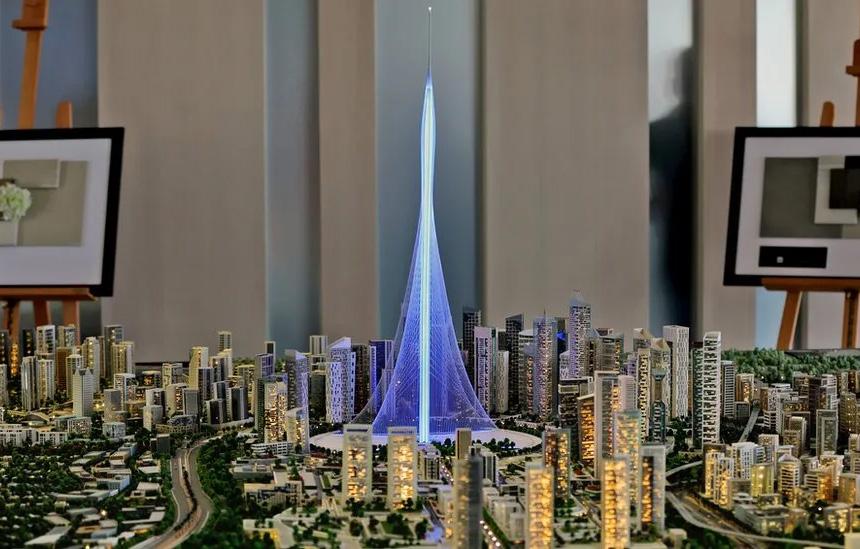

Figure 17 : New Dubai tower ‘to surpass’ world’s tallest building Burj Khalifa

Figure 18 : 2008 Financial Crisis sparked a surge in construction activity.

Figure 19 : The Sustainable City

Figure 20 : Aerial View of Sheikh Zayed Road

Figure 21 : Future vision of Dubai 2050

Figure 22 : Dubai’s World Islands in 2010, an artificial archipelago off the coast of the city .

Figure 23 : US President Biden meets with UAE president Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed.

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in a city which was built on fossil fuel extraction, in a country whose national economy still is?

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in a city which is pursuing large scale green infrastructure?

How should we judge the city’s efforts? Greenwashing ?

What are the structural factors inhibiting and aiding a sustainable Dubai?

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in a city based on intense tourism and development?

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in such an inhospitable natural environment?

Dubai is one of the most fascinating cities in the world. One of the earliest records of the city comes from an Italian trader named Gaspero Balbi in 1580 when he visited the area hunting for pearls (Government of UAE). That small town relied on fishing, pearl diving and the construction of boats. The town was also a hub for trade, providing accommodation and supplies for traders as they passed through, selling gold, spices, and textiles. Centuries later, through lines are visible. Dubai is now a hub for global trade, travel, and investment. For hundreds of years Dubai acted as a dependency. Britain formed a maritime truce with local rulers in 1820, and from this point forward they would rule the surrounding emirates. Including Dubai. Continuing its early legacy as a hub for trade, Dubai would now be a central connecting point in the global economy, especially between Europe and India.

1833 marked another crucial transition, as Maktoum bin Butti officially settled Dubai and declared it separate from Abu Dhabi. The same family still rules the emirate to this day. From that point forward, Dubai remained a crucial hub for trade, and in 1917 it was the center of the world’s pearl industry. One gram of pearl was worth 320g of gold. In 1966 dubai discovered Oil off its coast, setting the emirate up for untold expansion. Soon after, the British announced their plans to withdraw in 1971. While Bahrain and Qatar decided on independence, the remaining emirates banded together to form a new nation (Government of UAE).

In 1968 the ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Zayed declared that he wanted to keep close ties with other emirates. On February 18, 1968, Sheikh Rashid the leader of Dubai met with Sheikh Zayed and they agreed to form a union. Together they would conduct foreign affairs, build defense, security and social services. The emirates themselves would remain responsible for internal affairs. This became known as the Union Accord. Dubai and Abu Dhabi were first joined by Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Quwain and Fujairah. In 1972 Ras Al Khamah joined the federation, finalizing the UAE as it is known today. The rulers of the emirates form the Supreme Council of Rulers, which is the

decision making body for the UAE. Decisions are made by majority, but most require Abu Dhabi and Dubai to move forward, giving outsized influence to the original founding members of the UAE. This political formation would give Dubai a seat at the global table up to the modern day.

Today, the small fishing town has morphed into a metropolis of 2,919,178 (Government of UAE).

The tipping point in its modern iteration was the discovery of Oil in 1966. The infusion of oil into the economy supercharged the city,allowing massive growth and the construction of monuments like the Burj Khalifa and man made archipelagos to demonstrate this wealth. With the help of oil wealth,

Dubai has become a city of trade and tourism.

During Dubai’s transition toaneweconomycentered around trade and tourism it has positioned itself as a sustainable city. The government has created a sustainable city that produces more energy than it consumes (sustainable city). Dubai has also built one of the largest solar fields, and committed to planting over a million trees. All of these actions seem like a productive shift from a former oil economy to one that prioritizes sustainability (National Geo). But in Dubai’s current existence it continues carbon intensive construction, has the third busiest airport in the world, and spends untold energy on an indoor ski slope. Can Dubai pivot to

a successful city centered around sustainability? Or is this just a policy in name only as Dubai continues a march toward higher emissions. This briefing will discuss this question through the lens of geography, politics, tourism, and design to determine its progress as a sustainable city.

Area : 13.5 square miles

Population : 2,919,178.

The UAE is composed of 7 emirates:

Location :

Dubai is located off the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, with a coast of about 72 km, and the emirate covers a total area of 4,114 square kilometers, sharing borders with Abu Dhabi, Sharjah and Oman. It is the most densely populated of all of the emirates in the UAE (Britannica) .

Topography :

Dubai lies directly within the Arabian Desert, surrounded with sandy desert patterns. During the summer temperatures hover around 41.8 C (105 F) and most days are sunny. Winters are short and temperatures remain consistent at 23 C (73 F) (Britannica). Because of the Arabian Gulf’s shallow waters, it is very humid throughout the year.

Threat of desertification :

Dubai has a shocking environment for a city of three million people that has seen rapid

expansion over the past 50 years. Unbearably warm weather and desertification is becoming more and more rampant. Desertification is a type of land degradation whereby fertile, farmable land in arid regions becomes unproductive. This happens when water and soil are overburdened. Vegetation struggles to survive, and the land itself becomes increasingly unstable. Dubai receives food from across the UAE and other import sources. The UAE is already 80 percent desert and each square mile lost to desertification has an impact on food production. In 2002 the UAE had 75,00 hectares of arable land but by 2018 this number had shrunk to just 42,300 (BBC) . Without no domestic food production, Dubai will remain reliant on imported food which is also resource intensive. Desertification is primarily caused by a lack of water, another problem that Dubai is trying it’s best to mitigate.

Visitors might never guess that Dubai has a water problem. In fact, tourists can scuba dive in the world’s deepest pool and ski in a mall with penguins. A single fountain sprays more than 22,000 gallons of water in the air (Paul). This fresh water doesn’t come from aquifers or rivers, but from the ocean. Dubai relies upon energy-intensive desalination for its fresh water.

The desalination process produces a waste known as brine, which is combined with other chemicals, and released back into the Arabian Gulf. This has led to pollution, increased salinity, and increased water temperatures, harming plant, animal, and human communities.. According to a 2021 study, desalination in combination with climate change

will increase the coastal water temperature by at least five degrees ( Le Quesne) The other resource intensive practice that Dubai has proposed to increase tourism is the construction of artificial islands. The projects have been linked to higher water temperatures and algae blooms (Le Quesne). Algae blooms can cause the desalination plants to completely shut down (Al-Shehhi) Even with a glowing global image, filled with man-man islands, Dubai is a city in the middle of the desert. There is no natural water, and the cycle of getting water has multiple impacts on climate that make the continued existence of the city increasingly difficult. In fact the city is trying more radical tools to find alternative solutions.

Dubai’s growth over the past 50 years from Oil has lavished the city with prosperity. Massive skyscrapers, man-made islands, and foreign investment can be found in abundance. But it also contributed the worst ecological footprint per person of any nation in the world (WWF).

Dawn Chatty, a professor of anthropology writes, “To undo that is going to require serious financial effort as well as social transformation. Dubai’s all out growth model has directly affected it’s only ecology and environment with desertification. To reverse these impacts Dubai is attempting to pivot to a new industrial strategy that will continue economic growth. The Dubai Industrial Strategy outlines the city’s plan in an attempt to “promote

environmentally friendly and energy-efficient manufacturing” This has resulted in some success, like the Solar Park which is among the worlds biggest. But these positive developments don’t come close to the ecological damage that is being carried out to the greater region. In order for Dubai to survive, the city must try to avoid ecological disaster by curbing growth. If they don’t, this city could soon be consumed by the desert.

Can vast oil wealth save a city being consumed by the desert?

Any discussion of sustainability in the Persian Gulf involves a huge “elephant in the room”: The UAE and Dubai have reached their current levels of wealth, development, and global prestige due – at least in large part – to oil wealth. The UAE produced 3.06 million barrels per day in 2022: 4.2% of total global production (OPEC, 2023). However, today the vast majority of the country’s oil reserves are controlled by Abu Dhabi, and oil production now only makes up a very small share of economic activity in Dubai. While reputable and precise data on reserves and production by the emirate are not publicly available, the Government of Dubai indicated that in 2022, “Mining and quarrying” made up only 2.1% of the emirate’s GDP. By examining Dubai’s economic history, this chapter explains the historical and current roles of oil in the emirate,

and it ends with a discussion of environmental imperatives for Dubai given this history.

Up until the discovery of oil in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Persian Gulf was a fairly undeveloped region, and its small economy was based on pearl fishing, date palm farming, and some trade of general merchandise (Government of the UAE, 2023). While it is important to not fall into the “great man of history” trope, one man undeniably shaped the history of Dubai more than any other. From the very beginning of his reign as Emir, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum had grand visions of transforming the sleepy region into a highly developed trading hub. In the late 1950s, he commissioned the dredging of Dubai Creek to allow for greater trade and navigability.

In 1963 Rashid granted a concession to an American company to begin searching for oil, and in 1966, Fateh oil field was discovered approximately 60 miles off the coast (Dubai Petroleum, 2017). This was a huge boon to Dubai, but from the very beginning Rashid was aware that Dubai’s oil reserves were limited. He spearheaded long-range economic development and diversification efforts during his tenure as ruler from 1958-1990. After 1966, Rashid directed some of the first oil profits to the construction of a deepwater port to aid in exports. Named after the Emir, Port Rashid opened in 1972.

Over the course of the 1970s, three more oil fields were discovered in Dubai’s waters, and oil wealth continues to be used for economic development in other areas. Rashid led the charge on a number of other projects, including Jebel Ali port, which is now the world’s 11th busiest (Lloyd’s List, 2023); the Dubai World Trade Centre; and the Dubai dry docks. These efforts all tie into an attempt to follow the “Singapore model,” becoming a massive trade hub. Indeed, Dubai has succeeded in this aim, since Jebel Ali port is by far the biggest in the Middle East.

To compliment the emirate’s robust infrastructure, the government of Dubai encouraged investment by creating a “business-friendly” environment. Multiple authors suggest that liberal economic policies minimizing the cost of movement to capital and labor can explain the massive expansion of business activity in the past 50 years (Hvidt, 2009; Mishrif and Kapetanovic, 2018; Nyarko, 2010). For example, the Jebel Ali Free Zone opened in 1985, designed to attract foreign direct investment by offering 100% foreign ownership, corporate taxes as low as 0%, and no restrictions on capital repatriation, among other incentives (Jafza, n.d.).

Emirati citizens are small in number and quite wealthy, so to realize its massive amount of industrial activity and construction, Dubai has imported an equally massive amount of low-wage labor, mostly from Asia. Nyarko estimates that,

as of 2010, only 20% of UAE residents are Emirati citizens. Another 23% are Iranian, about 50% are Indian, Filipino, or Bangladeshi, and about 5% are high-income expatriates from other developed nations. Low-skilled migrant workers are typically hired on contract with no pathway to citizenship, and labor abuses are rampant. There have been countless allegations and documented cases of deadly working conditions, retaliation, wage theft, exorbitant recruitment fees, and confiscated passports (Human Rights Watch, 2023a and 2023b; Jacobs, 2018; Pattisson, 2022).

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in a city built on fossil fuel extraction?

Oil wealth was used to finance much of Dubai’s development, but without decades of intentional, long-range economic development policy, the city would not be the hub of global capital that it is today. This is, of course, not a moral claim or a suggestion that Dubai’s leaders should be celebrated. If crafty planning makes up one side of the story, carbon emissions and labor abuses make up the other.

Today, more than 70% of Dubai’s GDP can be attributed to trade, transportation, storage, finance, insurance, manufacturing, real estate, and construction (Government of Dubai and Dubai Statistics Center, 2022). Yet, oil still continues to actively contribute to the economic success of Dubai. While specific data are hard to come by, Abu Dhabi’s oil wealth funds a large degree of federal spending in the UAE, which mostly goes to social programs and “governmental affairs” (UAE Ministry of Finance, 2022). Under the UAE’s federal system, the emirates have a large degree of autonomy, though, and a starker example of Dubai benefitting from continued Abu Dhabi’s oil wealth came in 2008.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and real estate crash, Dubai, which had invested billions of dollars in mega-developments, was left with more than $120 billion in debt, requiring a $20 billion bailout from Abu Dhabi to meet short-term financial obligations (Ulrichsen, 2020). While this was obviously not ideal for Dubai and it weakened the emirate’s political autonomy, it also proved that Emirati oil serves as a financial safety net for Dubai, supporting continued investor confidence. Even though Dubai’s oil has dried up, the city continues

to reap the economic benefits of past extraction and the continued oil wealth of its neighbor, Abu Dhabi.

If Dubai no longer directly profits from oil extraction, is all of this moot? Perhaps the most pressing and obvious environmental imperative for a state with fossil fuel reserves is to leave them in the ground, but Dubai has none (or almost none) to leave. What, then, is the imperative for Dubai?

This is a highly-debated philosophical question with no clear, singular answer, but many have argued that the nations which have benefited most from natural resource extraction have the greatest responsibility to unilaterally invest in renewable energy technology. This is perhaps also complicated by the fact that the UAE escaped colonial rule less than 60 years ago, a fact which could be used to make the case that they have far less responsibility than Europe and North America, where some countries have benefited from centuries of violent colonialism. Be that as it may, Dubai’s government is in the position to invest in green technology, and it claims to be doing so in a paradigm-shifting way. In Chapter 5, we evaluate whether Dubai is really doing enough.

Background

Today, Dubai is a major tourism hub, but this is a relatively new development. When the oil magnet started to run low on their main source of income

in the early 90s, the city was able to transition into a tourist capital. This launched the city into the spotlight, and it has become to be seen as one of the pinnacle of tourism.

However Dubai hasn’t engaged in the most sustainable practices to put their city in the best position possible for future generations, and one of the largest contributors to their economy and rapid growth, tourism, is a large contributor to their carbon footprint. The biggest reason for this carbon footprint is arguably due to how Dubai is marketed. The city itself has served as a model for tourism and growth. Luxury and expensive real estate have become synonymous with Dubai, in order to bring outsiders with large amounts of income into their city. We can see this be done through a multitude of avenues that manage to keep both tourists and luxury paired together and hand in hand. One of the ways that Dubai is marketed as a city of luxury is through advertising to fly in one of their luxury A380s out of their Emirates airline. These are the largest passenger airliner in the world, and Dubai’s Emirates airline boasts the largest fleet of these planes. To fly in one of these planes is even seen as a part of the “Dubai Experience”. This is very enticing to those who are interested in traveling to Dubai, and has become knit into their culture. However, The Emirates line alone emitted 26,966,466 metric tonnes of CO2 in their operations from 2022-23, which was a 45.7% increase from the year prior (The Emirates Group, 2023). How can the Emirates group claim that they are implementing sustainable practices, while their carbon emissions are rapidly increasing? There have been efforts to offset the large amount of carbon emissions by the line, but those haven’t seem to have had much of an impact yet in their operations. This also begs the question, is there a sustainable way to keep intense tourism as the pillar of a city’s economy? Airlines are not the only contributor to the large carbon footprint in the tourism industry, as a study in 2012 noted that “the average Dubai hotel produces 6,500 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions a year, while the average European hotel produces 3,000 tonnes.” (Vij 2012). Perhaps this large number (almost double) can be

Source:

What does it mean to pursue sustainability in a city whose economy is based on intense tourism and development?

attributed to Dubai’s high need for air conditioning because of its climate, or other factors such as the popularity of luxury hotels. Since this study, there have been attempts to reduce carbon usage specifically for hotels, with many for hotels pivoting and becoming energy efficient. Plus, there is now mandated reporting for energy consumption levels for every hotel. How will Dubai continue to reduce the impact of the large amount of CO2 emissions that the tourism industry emits, as it continues to boom?

Dubai has also invested in both luxury real estate and architectural wonders in order to draw in wealthier people from all over the world to entice them to come and invest in Dubai infrastructure. These developments both are risky and costly, all the while increasing their carbon footprint. Architectural wonders like the Burj Khalifa cost a whopping $1.5 billion dollars to construct.

The city has also recently launched a $8.7 trillion dollar plan to propel Dubai’s growth into a global financial center (Turak, 2023). Is this the smartest way that Dubai could use its wealth? When Dubai was faced with the global financial crisis in 2008, the housing market took a substantial hit as well. The property values plummeted over 50% from their historical peak just the year before (Watson, 2020). They were only able to avoid complete collapse with the help of Abu Dhabi. Instead of looking to bring in outside sources of income, should Dubai divert some of its massive amount of funds towards its people? Many people left the emirate when the housing property values crashed, which added more weight to the huge blow financially. If the city of Dubai is looking to pursue sustainable growth and development, is being funded by outside sources the best idea going forward?

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Dubai’s primary focus was on rapid economic expansion, intensive construction, and heavy dependency on air conditioning due to its challenging climate. Urbanization surged, driven by booming industries like real estate, tourism, and finance. However, sustainability took a back seat during this period, with initiatives often inclined towards immediate infrastructure needs rather than long-term environmental concerns. Initial efforts included investments in water desalination plants, wastewater treatment, and improvement in air conditioning technology to tackle the hot climate. Yet, sustainability remained secondary as economic growth and modernization took

precedence in urban development projects.

After the 2008 global financial crisis, Dubai underwent a construction boom, notable for its ambitious mega-projects such as the Burj Khalifa, Dubai Marina and Palm Jumeirah. Following the crisis, Dubai reevaluated its development strategy, placing greater emphasis on sustainability. Key initiatives included the Dubai Strategic Plan 2015,

outlining goals for sustainable development, environmental protection, and infrastructure enhancement. In response to global trends like climate change and resource scarcity, Dubai launched the Clean Energy Strategy 2050 in 2015, aiming to achieve 75% renewable energy usage by 2050, leveraging the city’s abundant solar resources.

The Sustainable City stands out as a prime example of Dubai’s commitment to sustainability. It’s a mixed-use development designed to be fully sustainable, includes features like solar panels, green buildings and electric vehicle charging stations. With solar-powered villas and urban farming plots, it exemplifies eco-conscious living, promoting self-sufficiency and reducing carbon footprints associated with food transportation. The emphasis on community living and environmental stewardship fosters a sustainable lifestyle for residents. While these technologies can be effective in reducing resource consumption and impact on the environment, there is a risk of over-reliance on technology without sufficient consideration of simpler, low-tech solutions that may be more appropriate and accessible, especially for smaller-scale developments or less affluent communities.

Dubai is also prioritizing sustainable transportation, with efforts like expanding the Metro, investing in electric vehicles, and promoting walking, cycling, and public transit. These initiatives align with Dubai’s sustainability goals and aim to create a more efficient and eco-friendly transportation system.

The project to widen Sheikh Zayed Road is a significant infrastructure initiative aimed at enhancing transportation efficiency and accommodating the city’s growing population and traffic volume, but temporary lane closures caused delays and frustration for commuters and businesses. Social disruption, Noise, dust, and traffic diversions during the construction phase did cause inconvenience for residents and businesses along the road corridor, affecting their quality of life and economic activities. This highlighted

the challenges of large-scale construction in crowded urban areas like Dubai, stressing the need for better planning and communication. This also encourages urban sprawl by facilitating easier access to peripheral areas of the city for development. This can lead to increased land consumption, loss of natural habitats, and further strain on infrastructure and resources.

Dubai Metro and public transportation infrastructure: While the Dubai Metro is a sustainable transportation initiative that reduces traffic congestion and carbon emissions, but it has limited connectivity with other modes of transportation and lacks integration with surrounding land use and development patterns.

As a result, commuters may still rely heavily on private cars, undermining the overall sustainability of the transportation system. To address these

challenges, efforts should be made to improve connectivity between the Dubai Metro and other transportation modes, as well as to integrate the metro system more effectively into the urban fabric of Dubai. This could involve initiatives such as enhancing feeder bus services, implementing bike-sharing programs, and developing transitoriented development projects around metro stations. By addressing these issues, the Dubai Metro can further enhance its contribution to sustainable transportation in the city.

What does it mean to

Pursue sustainability in a city which is pursuing large scale green infrastructture ?

Dubai’s approach to sustainability often relies heavily on technology to achieve its goals. This reliance on technology creates a cycle where technological solutions are used to address sustainability challenges, but in turn, require further technological advancements to sustain and optimize their effectiveness. Heavy reliance on technology can create dependencies and vulnerabilities, particularly in the event of technological failures, cybersecurity threats, or disruptions to global supply chains. While technology can mitigate environmental impacts, it is essential to strike a balance with nature and consider the long-term sustainability of technological solutions. Dubai must avoid overreliance on technology at the expense of natural ecosystems and traditional knowledge systems.

The UAE declared 2023 to be the “Year of Sustainability” in a press release, remarking that sustainability is one of the country’s “deep-rooted values,” and celebrating the country’s green energy investments (UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2023). Indeed, some of the technologies implemented in Dubai have been impressive, and the city does seem to be moving in a positive direction, but does it really live up to the sustainability rhetoric of its officials? A sober account of the facts suggests not.

Dubai sits in a desert, and the globe is only getting hotter, requiring massive amounts of air conditioning. It receives very little rainfall, and the vast majority of its drinking water comes from energy-intensive and polluting desalination plants. The emirate no longer has an oil-based economy, but it was built on oil, and it continues to benefit from Abu Dhabi’s petroleum wealth. The sectors it has diversified to are also far from sustainable. Tourism and luxury real estate development generate enormous emissions, both on- and off-site. And as a center of finance and business, Dubai has embedded itself in the heart of a global economic system based upon a fantasy of infinite growth and natural resource extraction.

The government of Dubai is very deliberate about projecting an image of sustainability and modernity to the world. Given that oil wealth was necessary (although not sufficient on its own) for Dubai’s transformation into the highly developed city that it is today, this is a textbook example of “greenwashing”: using public relations tools to make misleading claims about one’s sustainability. Why bother to greenwash in the first place, though? Bringing social theorists into conversation yields interesting insights into the politics and motivations of Dubai’s (and the UAE’s) leadership.

The concept of “worlding,” as used by Ananya Roy and Aihwa Ong, helps to explain the actions of Dubai’s government (2011). For Roy and Ong, a worlding framework suggests that non-western cities take a variety of approaches to pursue recognition and status amongst other cities on the global stage. For Dubai, presenting an image of modernity, liberalism, technological advancement, and greenness is tied up in the pursuit of global status. Indeed, Dubai may be one of the most status-obsessed cities on earth, with projects like the Burj Khalifa and the World Islands. In a region of petrostates, absolute monarchies, and religious conservatism (e.g., Saudi Wahhabism,) Dubai has gone to great lengths to build a brand. Claims of sustainability are simply one part of maintaining and building that brand. Even oil drilling, itself, is greenwashed in Dubai. Dubai Petroleum, the state-owned oil company, has “sustainability” as one of its website’s five main tabs. The site’s “Environment” page is only 258 words, 89 of which are spent telling the story of how employees one time saved a turtle trapped in plastic, with photos included (Dubai Petroleum, 2018).

There is an economic logic to greenwashing, too. As a brand, Dubai seeks foreign investment. By marketing itself as sustainable, the emirate eases oil-related ethical qualms for potential investors. Perhaps even more importantly, it placates current and potential customers of international investors, who might launch a boycott. Precisely the same logic applies to the international political sphere. Greenwashing and other PR moves allow the UAE to appear sustainable and modern, ameliorating potential reservations on the part of foreign governments (especially more powerful ones), who do not want to be perceived as supporters of an autocracy built on petroleum and labor abuses.

In both the economic and political cases, plausible deniability is enough. As Walter Lippman argued, political affairs, especially foreign ones, are simply too large and complex for the public to fully understand them (1922). Thus, people rely on a simplified and biased mental conception of the world, which is subject to sway by the media. The government of the UAE does not aim to fool every astute observer into thinking that they are completely sustainable, because they do not need to. Muddying the waters is enough to ensure that there is no effective, popular, international resistance to economic and political engagement with the country.

Dubai is a city built around excess and spectacle, and it frequently seeks to be the “most,” no matter the cost. Dubai constructed the world’s tallest building; it has the world’s largest fleet of the largest passenger planes and the Middle East’s busiest port; and it has implemented some of the most advanced technologies in its infrastructure. This all comes at the cost of having one of the largest per capita carbon footprints and some of the worst labor abuses of any highly-developed country in the world (International Trade Union Confederation, 2023).

This is not to say that we should abandon Dubai, though. Justly or not, massive amounts of resources have been poured into the city, so we ought to make the most out of the resulting situation. Dubai has produced some genuinely compelling green technologies, and it is well-positioned to continue to do so, given the political will. A more sustainable Dubai would mean massive shifts in resource allocation and a fundamental political reorientation from worlding and maximalism to equity and restraint.

ADNOC. (n.d.-a). [ADNOC offshore oil rig] [Photograph]. https://www.offshore-technology.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2022/10/rig-13102022.jpg

ADNOC. (n.d.-b). [ADNOC onshore oil rig] [Photograph]. https://www.adnoc.ae/-/media/adnoc-v2/sub-brands/ adnoc-onshore/images/content/banners/onshore-hero1. ashx?h=532&w=1600&hash=4609344BE5442605F70FEB92C179C285

Allan, N. (1959). [Plan for the dredging of Dubai Creek, prepared by Allan Nevil of Sir William Halcrow and Partners] [Photograph]. Dubai as it Used to Be. https://www. dubaiasitusedtobe.net/DredgingDubaiCreek1959.shtml

Al-Shehhi, M. R., & Abdul Samad, Y. (2022). A GIS-Based Spatiotemporal Model for Predicting Future Land Use/ Land Cover Change in Dubai, UAE, Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Remote Sensing, 14(10), 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14102457

Britannica. Dubai. 3/12 https://www.britannica.com/ place/Dubai-United-Arab-Emirates

Chapman, L. (2021). Sheikh Rashid’s Unseen Oil 1966. https://www.dubaiasitusedtobe.net/SheikhRashidsOil1966.shtml

De Burca, J. (2024, February 13). United Arab Emirates top green buildings. Constructive Voices. https://constructive-voices.com/united-arab-emirates-top-green-buildings/#:~:text=Some%20examples%20of%20sustainable%20architecture,East%20Headquarters%20in%20 Abu%20Dhabi

Dubai Petroleum. (n.d.). [Falah Field offshore oil rig] [Photograph]. https://www.dubaipetroleum.ae/about-us/ oil-and-gas-assets/falah-field/

Dubai Petroleum. (2017, November 6). Our journey. https://www.dubaipetroleum.ae/about-us/our-journey/, https://www.dubaipetroleum.ae/about-us/our-journey/

Dubai Petroleum. (2018, January 4). Environment. Dubai Petroleum. https://www.dubaipetroleum.ae/sustainability/ responsible-operations/environment/, https://www.dubaipetroleum.ae/sustainability/responsible-operations/environment/

Government of Dubai, & Dubai Statistics Center. (2022). Gross Domestic Product at Constant Prices—Emirate of Dubai [dataset]. https://www.dsc.gov.ae/Report/Gross%20 Domestic%20Product%20at%20Constant%20Prices%20 2022.xls

Government of the UAE. (2023, July 20). Economy in the past and present. U.Ae. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/ economy/economy-in-the-past-and-present

Hejze, L. (1970). Sheikh Rashid Driving the first Pile [Photograph]. Dubai as it Used to Be. https://www.dubaiasitusedtobe.net/PortRashid1959-2008.shtml

Human Rights Watch. (2023a, November 21). UAE: Migrant Worker Abuses Linked to Broader Climate Harms | Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/21/uaemigrant-worker-abuses-linked-broader-climate-harms

Human Rights Watch. (2023b, December 3). Questions and Answers: Migrant Worker Abuses in the UAE and COP28. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/12/03/questions-and-answers-migrant-worker-abuses-uae-and-cop28

Hvidt, M. (2009). The Dubai Model: An Outline of Key Development-Process Elements in Dubai. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 41(3), 397–418. JSTOR.

International Trade Union Confederation. (2023). Global Rights Index 2023: Countries. ITUC GRI. https://www. globalrightsindex.org/en/2023/countries

Jacobs, H. (2018, December 15). Dubai’s glittering, futuristic metropolis came at the cost of hundreds of thousands of workers, and recommending it as a tourist destination feels wrong. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/ dubai-development-tourism-workers-problem-2018-12

Jafza. (n.d.). Why Jafza. Jebel Ali Free Zone (Jafza). Retrieved March 7, 2024, from https://www.jafza.ae/about/ why-jafza/

Kunzig, R. (2017, April 3). The Surprising Ways Dubai Is Making Itself More Sustainable. National Geographic. Retrieved March 9, 2024, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/dubai-ecological-footprint-sustainable-urban-city

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public Opinion. Project Gutenberg. http://www.public-library.uk/pdfs/8/670.pdf

Lloyd’s List. (2023). One Hundred Ports 2023. Lloyd’s List. https://lloydslist.com/one-hundred-container-ports-2023

Le Quesne, W.J.F., Al-Matrushi, I., Abdullah, I. A., Abdel-Fattah, A. M., & Hammoudeh, S. (2021). Economic diversification and energy policy in the GCC: The case of the United Arab Emirates. Marine Policy, 128. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0025326X21009747

Mishrif, A., & Kapetanovic, H. (2018). Dubai’s Model of Economic Diversification (pp. 89–111). https://doi. org/10.1007/978-981-10-5786-1_5

Nyarko, Y. (2010). The United Arab Emirates: Some Lessons in Economic Development (Working Paper 2010/11). United Nations University - World Institute for Development Economics Research. https://core.ac.uk/download/ pdf/6290591.pdf

OPEC. (2023). Oil Data: Upstream [dataset]. Annual Statistical Bulletin 2023. https://asb.opec.org/ASB_Charts.html?chapter=1525

Pattisson, P. (2022, February 2). Allegations of worker exploitation at ‘world’s greatest show’ in Dubai. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/feb/02/allegations-of-worker-exploitation-atworlds-greatest-show-expo-2020-dubai

Paul, A. (2023, November 18). Dubai Turns to Solar Power for Water Desalination. The New York Times: https://www. nytimes.com/2023/11/18/business/dubai-water-desalination.html

Phelan, J. (2022, January 26). How Dubai is pushing back its encroaching deserts. BBC Future. Retrieved March 9, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220125-howdubai-is-pushing-back-its-encroaching-deserts

Rashid, N. A. (1966). [Early oil being pumped into a Dubai sand bund with Sheikh Rashid] [Photograph]. Dubai as it Used to Be. https://www.dubaiasitusedtobe.net/images/ sheikhrashid01.jpg

Roy, A., & Ong, A. (2011). Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uic/ detail.action?docID=819328

Stead, L., & Stead, L. (2023, November 15). Dubai: a leader in sustainable building trends. MIPIM World Blog. https://blog.mipimworld.com/development/dubai-a-leader-in-sustainable-building-trends/#prettyPhoto/0/

The Emirates Group (2023). Annual Report 2022-2023. Retrieved from https://c.ekstatic.net/ecl/documents/annual-report/2022-2023.pdf

The Sustainable City. (n.d.). Retrieved March 9, 2024, from https://www.thesustainablecity.ae/ Turak, N. (2023, January 4). Dubai announces $8.7 trillion economic plan to boost trade, investment and Global Hub Status. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/04/ dubai-announces-8point7-trillion-economic-plan-toboost-trade-investment.html

UAE Government. (n.d.). The United Arab Emirates’ Government. Retrieved March 9, from https://u.ae/ en/more/history-of-the-uae

UAE Ministry of Finance. (2022, October 10). UAE approves Federal General Budget 2023-2026 with total estimated expenditures of AED 252.3 billion [Press Release]. UAE Ministry of Finance. https://mof.gov. ae/uae-approves-federal-general-budget-2023-2026with-total-estimated-expenditures-of-aed-252-3-billion-2/

UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2023, January 21). UAE President announces 2023 as ‘Year of Sustainability’ [Press Release]. https://www.mofa.gov.ae/en/ mediahub/news/2023/1/21/21-01-2023-uae

Ulrichsen, K. C. (2020). The Political Economy of Dubai. In Dubai’s Role in Facilitating Corruption and Global Illicit Financial Flows (pp. 13–22). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

U. S. Mission UAE. (2022, July 16). Joint Statement Following Meeting Between President Biden and President of the UAE Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed in Jeddah. U.S. Embassy & Consulate in the United Arab Emirates. https://ae.usembassy.gov/joint-statement-following-meeting-between-president-bidenand-president-of-the-uae-sheikh-mohammed-binzayed-in-jeddah /

Vij, M. (2012). Tourism and Carbon Foot Prints in the United Arab Emirates - Challenges and Solutions, 3(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/https://www.researchgate. net/publication/271383034_Tourism_and_carbon_ foot_prints_in_United_Arab_Emirates_-_challenges_and_solutions

Watson, K. (2010, November 25). Dubai’s debt crisis: One year on. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/ business-11837714

UPP 508 Global Urbanization Planning

March 2024

Professor : Dr. Sevin Yildiz

Team Members :

Tom Bos

Neha Pol

Justin Bologna

Angelo Brown