Advantages of Sustainable modes of Transport and Pedestrian movement

Introduction: Vienna, Austria

1. Cover Page

2. Introduction to Sustainable modes of Transport and factors affecting the Quality and Accessibility

3. Introduction to Vienna History and Site selection for Analysis.

4. Site 1: Museum Quarter (Heritage Conservation area) and its detailed analysis, Best Practice and Conclusion.

5. Site 2: Stephansplatz (Shopping and Cultural District) and its detailed analysis, Best Practice and Conclusion.

6. Site 3: Sonnwendviertel (New housing development) and its detailed analysis, Best Practice and Conclusion.

7. References

Introduction: Sustainable modes of transport and pedestrian movements

• Sustainable transportation refers to modes of transport and transportation systems that are environmentally friendly, and create economic feasibility and social inclusivity.(Litman.T.,2015,)

• Examples of sustainable modes of transport include walking cycling, buses, rain and tram networks

• Implementing public transport modes plays a pivotal role in the sustainable development of a city.(Kaszczyszyn, P & Sypion, N. (2019).

• Well-designed and maintained pedestrian infrastructure is essential for facilitating public transport use (Jens, 2015).

Written in Buehler,R., Pucher.J & Altshuler.A (2017).

NOTE: This report focuses on analysing sustainable transport modes, namely bus, tram, and train networks, and their pedestrian accessibility. Cycling, another sustainable transport mode, is not included due to its extensive nature, which exceeds the word limit of this study.

• Environmental Benefits: Utilisation of public transportation systems (bus and trams) reduces the reliance on private vehicles, leading to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution and noise pollution. It helps improve air quality, and create a healthier environment for residents, (Litman.T.,2015 & Gossling.S.,Et .al (2018)

• Vienna is the capital of Austria with a population of 1.99 million people with an annual growth of 0.77% (over 40% of the people being migrants).

• One of the most culturally and historically prominent cities, Vienna is situated on the far east of Austria with River Danube flowing through it.

• Vienna stands as a testament to the intersection of history, culture, and innovation.

• Vienna consistently secures the top position as the most Livable city (Quality of Life Index), attributing its success significantly to sustainability factors such as diminished traffic congestion and decreased air pollution(Mercer, 2023)

• The key to Vienna’s success has been a coordinated package of mutually reinforcing transport and land-use policies that have made car use slower, less convenient, and more costly while improving conditions for walking, cycling, and public transport. (Buehler,R., Pucher.J & Altshuler.A (2017)

Brief History: Vienna’s implementation of Sustainable modes of Transport

• Health benefits: encourages physical activity leading to improved health. (Chaix et. al 2014 & Noorbhai, H.,2022) It contributes to increased physical fitness, reduces cases of obesity (Rissel et al., 2012) reduces risk of chronic diseases, and has been shown to improve mental wellbeing.

• Improve accessibility and mobility of residents of all age groups and economic backgrounds: These modes of transport increase the accessibility for all residents, especially for children and elderly who are unable to drive private vehicles. Sustainable modes of transport provide affordable transportation options. (Lucas,K., 2012, & Ravensbergen, L, et.al (2022)

• Neighbourhood development: Walkable places promote balanced urban development and public services while providing people with a better place to live, which leads to improved neighbourhood satisfaction (Lee, S. M. et al., 2017)

• Increases community interactions: Walking and utilising sustainable modes of transport promotes social interaction and community engagement. People sharing public modes of transport have opportunities to connect with other individuals, fostering a sense of community and reducing social isolation (Leyden,. (2003).

Factors influencing the Quality and Accessibility of Sustainable modes of Transport and Pedestrian movements

PERMEABILITY

Bentley (l985) defines permeability as “the extent to which an environment allows people a choice of access through it from place to place”. permeable urban space should be an accessible and convenient location which provides people options of passing through it, continuity, structural character value as well as opportunities to easily walk around in a clearing. Yavuz, A. (2014)

LEGIBILITY

Way-finding through signages help people effectively reach transport hubs, and enables the usage of the Transport systems (Rüetschi, Urs-J & Timpf, S. (2004) AMENITIES AND SIGNAGE

Legibility has been one of the main desirable qualities of navigation in urban environments. Legibility is the ability to easily navigate and understand one’s surroundings. It allows people to intuitively find their way to intended destinations and points of interest.(Kevin Lynch, 1964)

Trees are some of the most prominent natural features in towns and cities from both visual and functional perspectives. (K. J. Livesley et al. 2016) GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

SOCIAL PRESENCE

Natural surveillance: Eyes on the street: Areas with high levels of pedestrian activity and people present are generally perceived as safer. An active vibrant street fosters community safety and reduces crime. Streets lined with shops, residences and active uses encourage natural surveillance by passersby and residents, (Jane Jacobs 1961)

INCLUSIVITY

Accessibility Factors Quality Factors

Creating a space which is inclusive for all age groups, creates social cohesion and belonging and facilitates wellbeing (Mouratidis,K., 2021)

A well-designed public lighting system can enhance pedestrians' sense of safety and comfort (Trop, T., Shoshany Tavory, S., & Portnov, B. A.,2023) Lighting is an effective form of surveillance. (Perkins, D.D., Wandersman, A., Rich, R.C. and Taylor, R.B., 1993) STREET LIGHTING

Healthy frontages create value by building high ‘ Walk Appeal’. A space with good frontage can enhance the pedestrian experience and vibrancy of the urban space (Mouzon.S., 2015,) BUILDING FRONTAGE

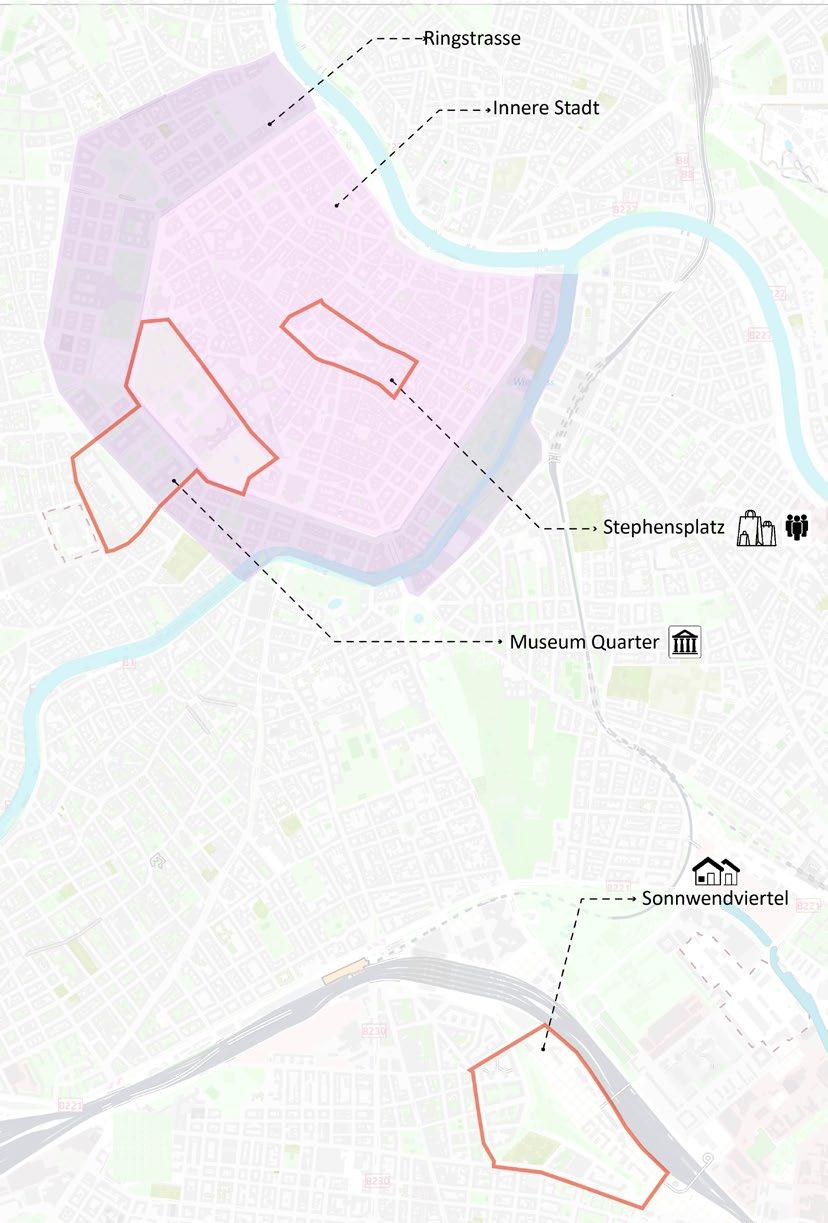

Site selection for Analysis in Vienna.

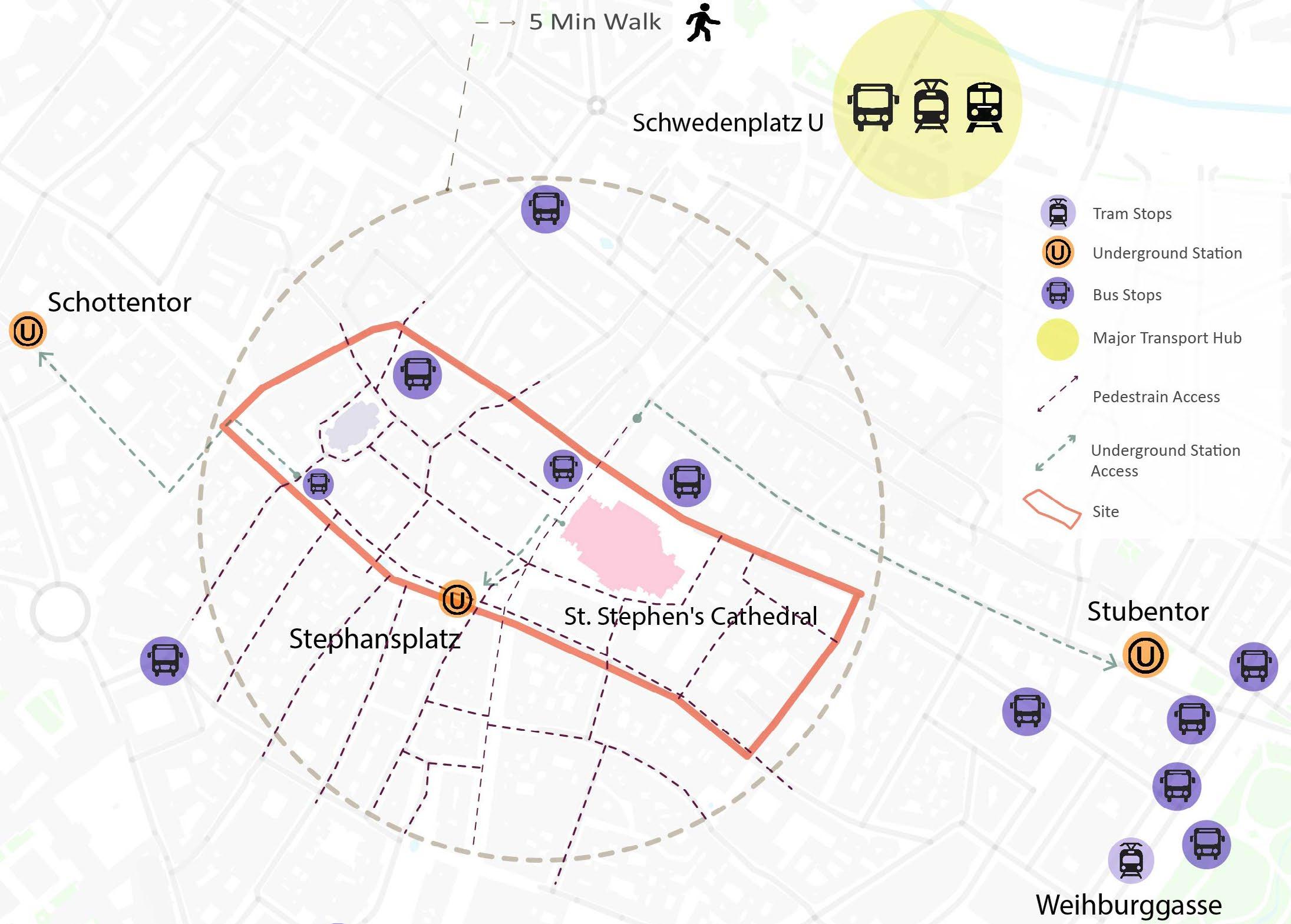

Stephansplatz (Shopping and Cultural District)

Overlooking the St. Stephan’s Cathedral, an Iconic hub blending historic charm with modern shopping, dining, and cultural experiences for visitors.

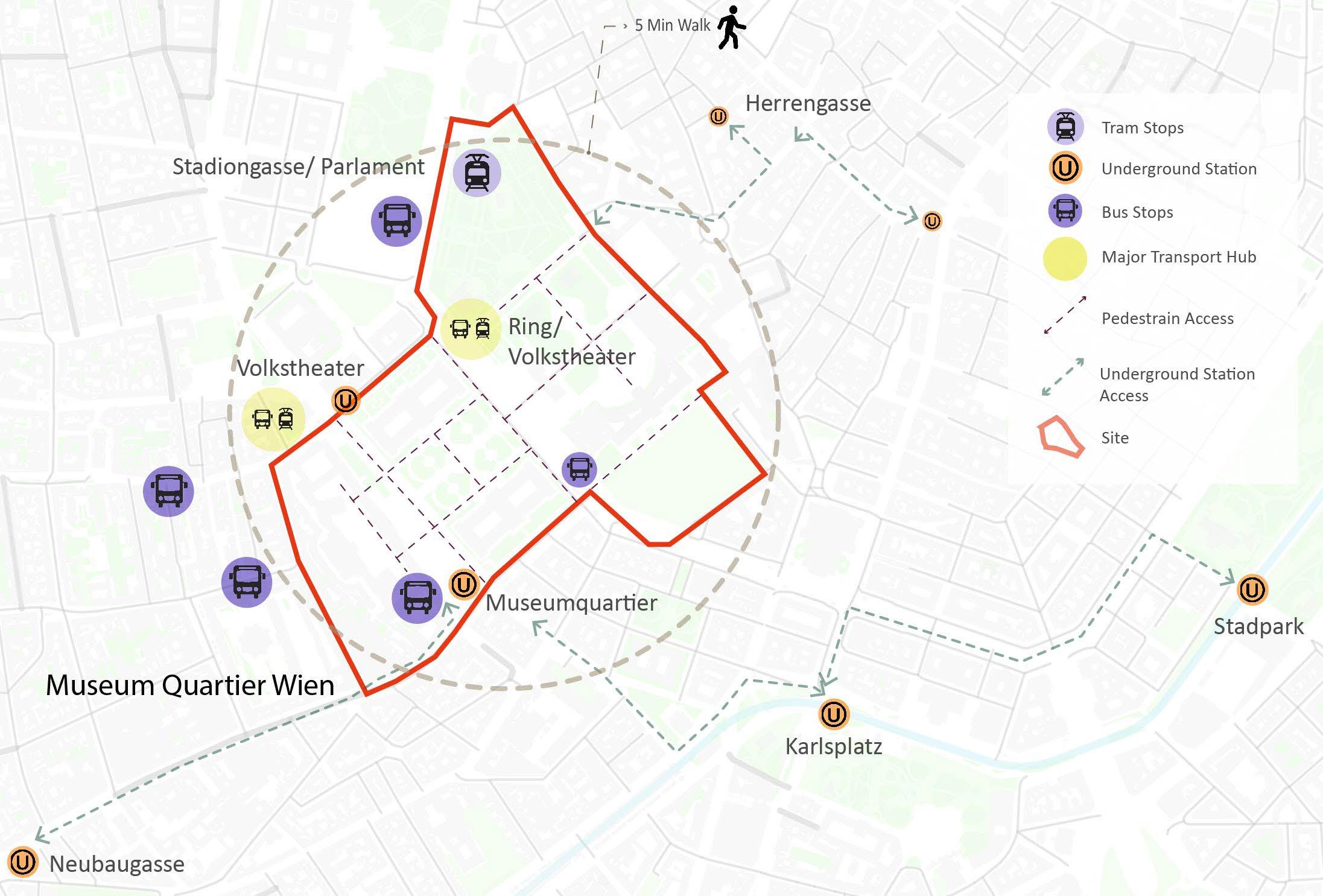

Museum Quarter (Heritage Conservation Area)

A cultural epicenter, housing worldclass museums, contemporary art venues, vibrant cafes, and outdoor spaces, fostering creativity and exploration.

Sonnwendviertel (New Housing Development)

Innovative urban housing project, emphasizing sustainability, diversity, and community engagement for a dynamic residential experience.

St. Stephensplatz is one of the main shopping streets of Vienna. It is one of the prime examples of a old cultural district, which is now a major pedestrian centric public realm with a contextual blend of modern amenities and direct transportation link to the underground train-line, makes the space a easily accessible destination.

As a cultural and retail hub is centrally located and one of the largest cultural complexes in the world. This area attracts significant number of visitors and residents. It is well served by public transport and a pedestrian-friendly environment

Sonnwendviertel is selected for the study as it is a new development which has put emphasis on designing a sustainable transport friendly neighbourhood by integrating a pedestrian friendly environment. It has a good access to sustainable modes transport.

Source: Vecteezy

Elements of User Centric Design

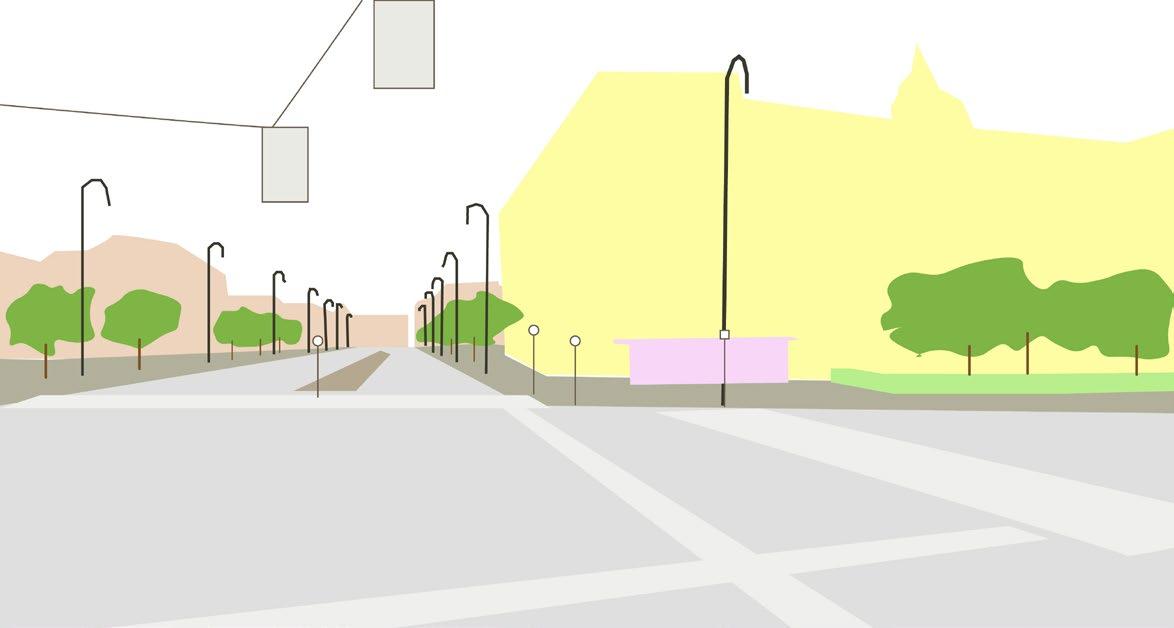

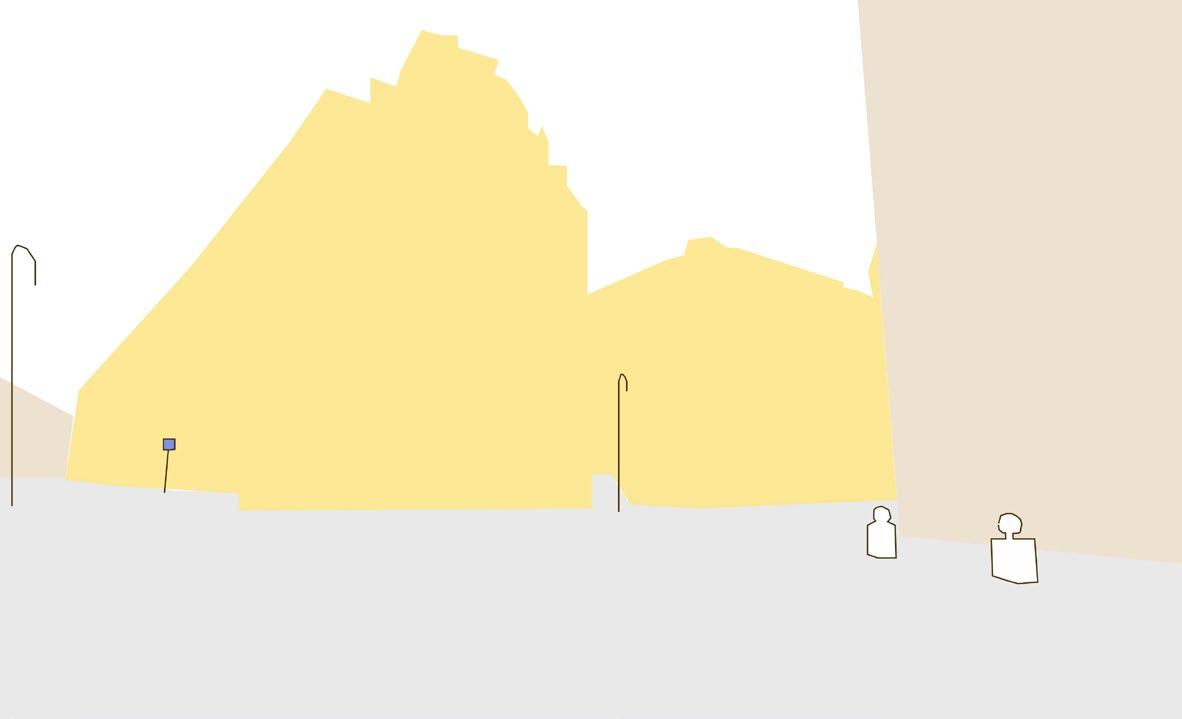

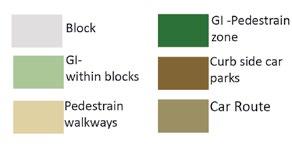

Decoding - Quality and Accessibility around Museum Quarter

Dedicated pedestrian corridors contributed by a linear stretch of trees, with rest areas seating which fosters social cohesion

Pedestrian-crossings across the multi-modal streets which is also enhanced with good quality signals and signages

Tram-line movement corridor across vehicular route, along with bus stop and cycle stand on either side of the alley

Small green infrastructure along pedestrian pathway, enhanced by seating and street lights

Intermediate crossing lane, ease of pedestrian movement with pause points created between two way car route- provided by signages and maps for user understanding

Building with good architecture value, increases legibility of the area. Buildings fronted with GI and alternate pedestrian walkways, creates a permeable movement of pedestrians

Sustainable modes of Transport

Pedestrian pathway enhanced with linear stretch of light poles, trees on the background

Pedestrian pathway along linear stretch of trees, with few signages and light poles

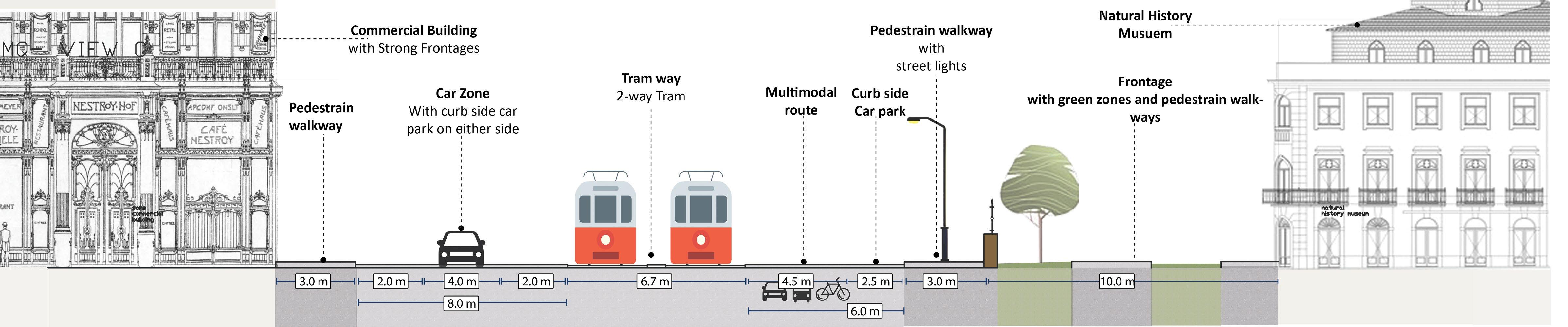

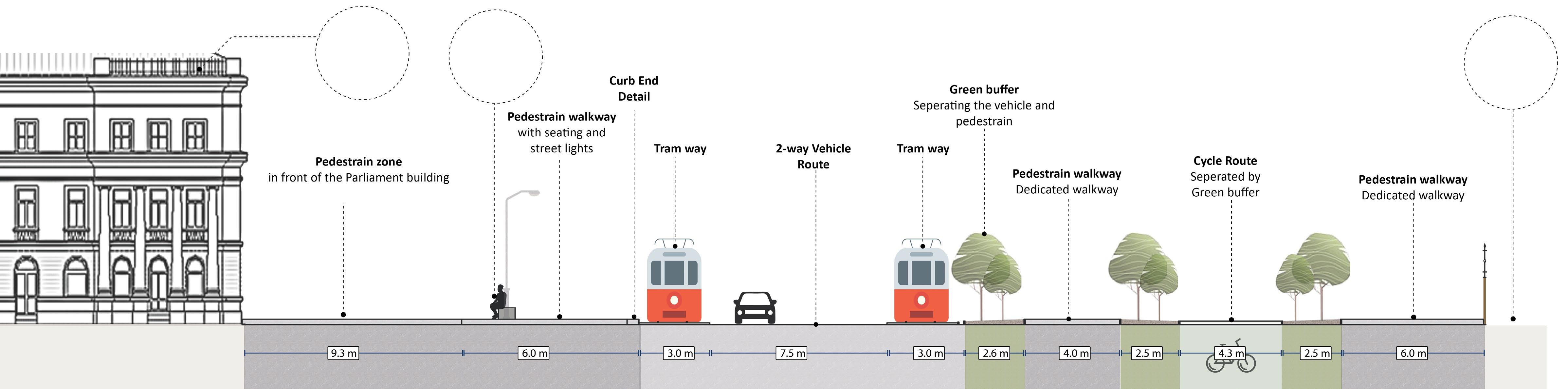

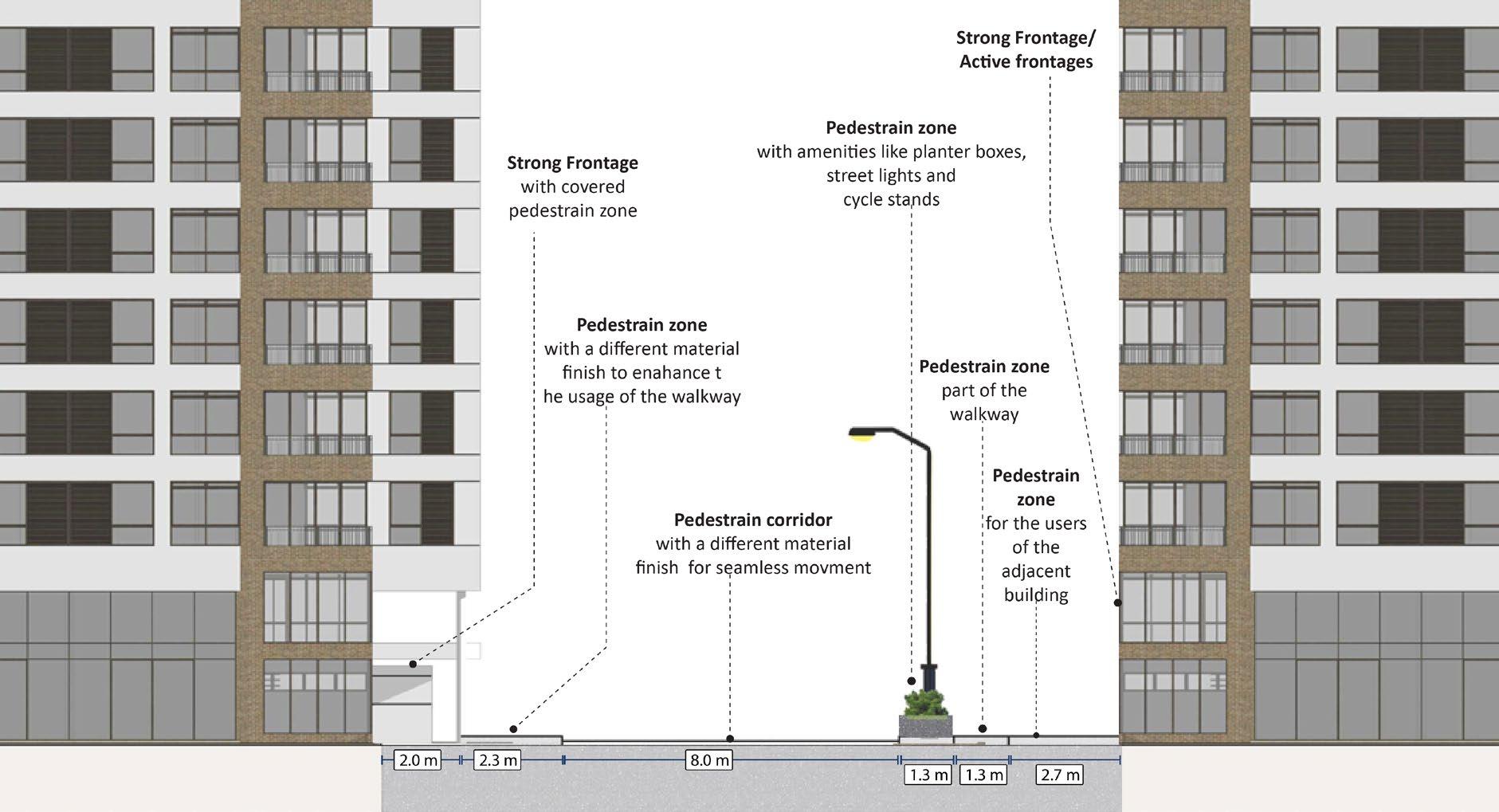

Section and Details

• The street section at point D showcases a commercial building of architectural significance, alongside the renowned Natural History Museum. A noticeable prioritization of pedestrian movement towards the museum contrasts with the greater emphasis on vehicular flow at the opposite end. However, this multi-modal street appears less pedestrian-friendly, attributed to its considerable width and insufficient pedestrian-oriented amenities

• The facade of the Natural History Museum, adorned with green infrastructure and featuring an alternative pedestrian walkway, fosters a sense of permeability. This design offers pedestrians an alternative path away from the bustling street, enhancing their experience by providing a tranquil route

• The section of the street at point D runs alongside the Parliament building and the Volksgarten, passing by the Volkstheater tram and train lines. Here, a distinct separation between various modes of transport enhances the pedestrian experience, making it pleasant to walk towards sustainable transportation options.

• Through the strategic use of distinct materials on walkways, clear demarcations are established between pedestrian zones and pathways. Abundant lighting and signage facilitate smooth pedestrian movement towards the transport hub. Additionally, a diverse range of green infrastructure serves as a visual barrier to vehicular traffic. The width of pedestrian walkways, complemented by tree-lined paths, creates a comforting enclosure that promotes a sense of safety without inducing claustrophobia.

Pedestrian pathway along the main museum building enhanced with underground train-line access, linear stretch of trees,bollards, and important Digital Signages

B C D

Landmark building fronted by tram-line running along vehicular route. The pedestrian pathway is supported with signages, shrub beds, seating, phone booths, stops along with a few active shopfronts.

A designated pedestrian pathway, along with a tram-line in front of the Austrian Parliament building is enhanced with signages, bollards, sculptures, etc. Which limits vehicular movement on the way

Best Practice

Accessibility Factors:

Quality Factors:

The neighbourhood boasts a wealth of amenities and signage to facilitate navigation toward transport hubs, enhanced by its rich heritage and excellent legibility. Its permeability is further augmented by the presence of alternate pedestrian walkways, ensuring ease of movement throughout the area.

The walkways are adorned with meticulously designed lighting fixtures and GI amenities. The expansive open spaces surrounding them nurture social cohesion due to the large pedestrian zones.

Heritage district with well-established link to transport hub, which helps in easy accessibility to/from other parts of the city

Contextual human centric development- well thought out design interventions, which include digital display, signages, seating, drainage, GI, and other amenities- which are a blend between the old character and newer concepts of urban design

movement is prioritized with different facilities and mix use of materials on the movement corridors

Proximity to multiple modes of sustainable transport, prominently the underground train-line

This area is highly legible due to strong character, developed routes and nodes which also support the social presence of users in the area.

by its efficient transport options and pedestrian-friendly layout. Trams connect the area to the city center, while bike lanes and walkable streets make it easy to explore. Its urban setup seamlessly integrates cultural attractions with practical mobility solutions, enhancing accessibility for visitors.

Museum Quarter (Museum Quarter) is characterized

Stephansplatz offers a harmonious blend of shopping and culture in Vienna, centered around St. Stephan’s Cathedral, characterized by bustling streets. The area’s urban design merges old architecture with modern amenities and sustainable public transport.

Sustainable modes of Transport

The commercial and cultural hub has well-established pedestrian access, to sustainable modes of transport

Tall buildings with strong architectural character, adding to the aesthetic value and legibility of the area.

Elements like large sculptures and installations add to the overall legibility value of the area.

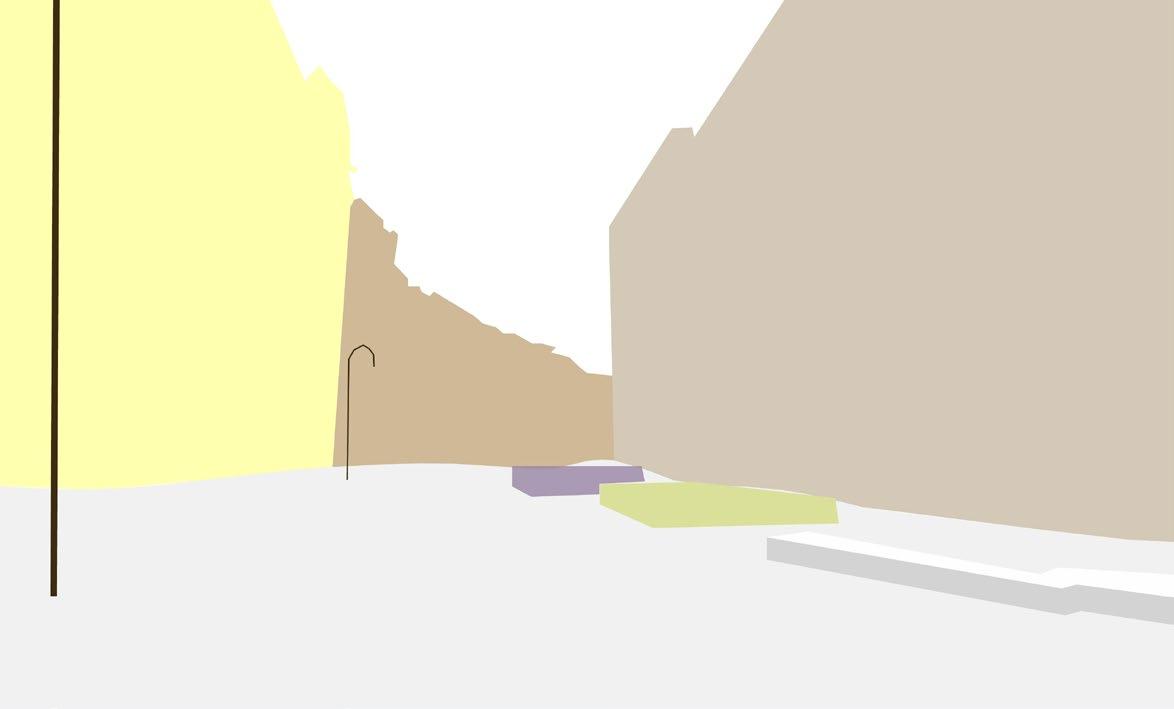

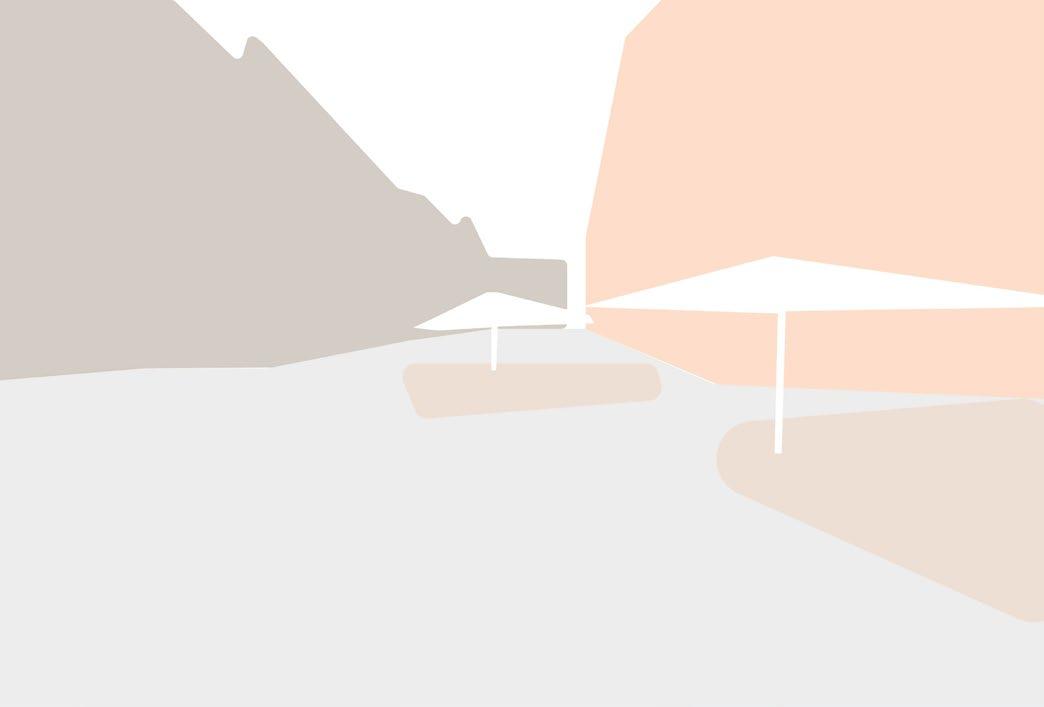

Shaded cafe seating with small shrub beds and lighting separating streetfront movement zone for pedestrians accessing storefront.

light poles, raising elemental aesthetic to the public space.

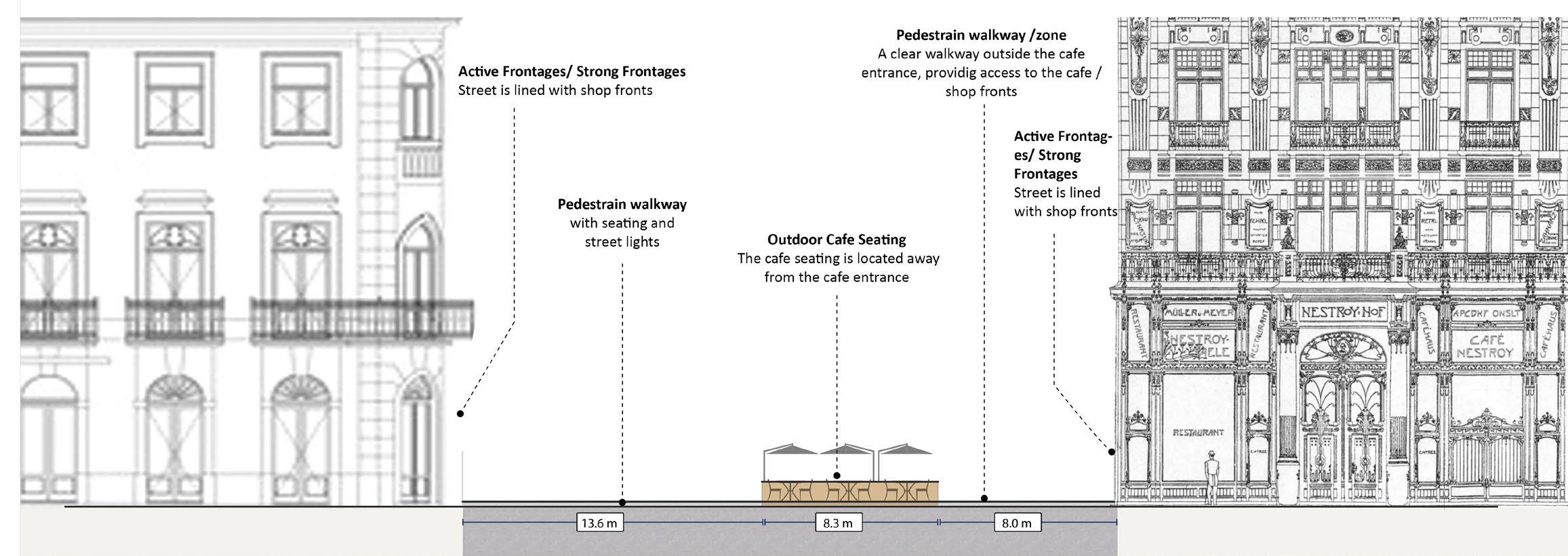

The Graben street serves as a primary thoroughfare, providing pedestrians with access to sustainable modes of transportation within the neighborhood. As a bustling high street, it caters primarily to individuals frequenting the area’s shopping and dining establishments. While it offers ample opportunities for those engaging in commerce and gastronomy, seating amenities for casual passersby are comparatively limited

Cycle stand, bollards, and light poles contribute to the small elements adding to the quality of the neighbourhood

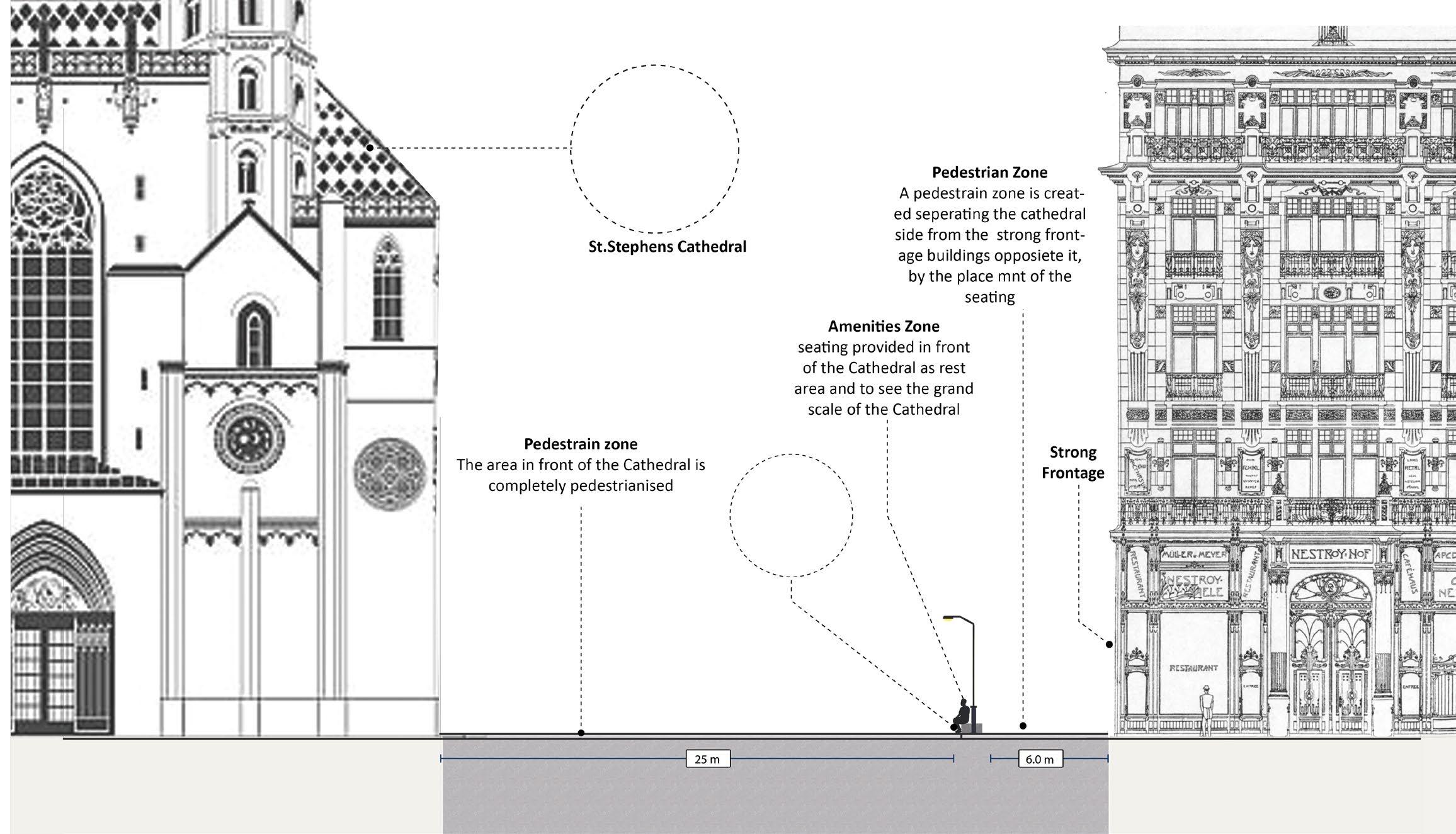

St. Stephan’s Cathedral

Minimal and efficient signage

Pedestrian pathway under along the block

Designated pedestrian pathway in the allies, connecting the main square- allowed due to well-established movement for vehicles Creates a sense of permeability.

Sections and Details

The street section at point B, situated in front of St. Stephan’s Cathedral, showcases a fully pedestrianized square, with space for pedestrian movement and social interaction. Street furniture, lighting fixtures, and signage amenities delineate the square from the pedestrian zone in front of the buildings opposite the Cathedral. The open public space in front of the cathedral forms a captivating enclosure, offering an unobstructed view of the cathedral in all its majestic splendor

Section at C

Architectural supported by elemental character prioritized through contextual design

Large pedestrian corridor, supported by chamfered cornered buildings for ease of movement for the large footfall in area

Aesthetic landmark buildings contributing to the legibility

Lighting bollardsseparating street front zones from the main movement corridor, along with lighting the space

Advantage of major of underground train-line in close proximity, easing the connectivity to the area via sustainable mode of transport in the city Small elements of seating for public amenity, retrofitted to cater to the large footfall Chamfered corners of buildings, supporting the movement across alleyssupporting the natural block permeability created in the area

Aesthetic buildings with high-quality character

The street section at point C delineates a pedestrian movement corridor along a bustling high street, characterized by vibrant and dynamic storefronts. This street is particularly conducive to those utilizing the shopping amenities, boasting robust frontages and engaging enclosures, complemented by effective lighting and signage infrastructure. However, seating amenities are somewhat limited, typically available only to paying customers

The permeability between blocks seamlessly connects to the central public realm, acting as a conduit to both the primary node and the nearby public transport stop. This area experiences substantial foot traffic, facilitated by its clear navigability and easy-to-follow layout.

The public space and pedestrian walkway at St. Stephen’s Square are paved entirely with large-format granite stone slabs. This choice of flooring facilitates smooth and effortless movement, particularly for disabled pedestrians. The use of granite not only provides durability and resilience and fosters a sense of inclusivity

Accessibility Factors:

Shaded cafe-front seating area, supporting active street fronts. This element is accommodate keeping in mind movement along immediate shop-front area, alongside considering no compromise in main movement corridor for pedestrian movement Clear sense of direction- created through the balanced enclosed space on the street with the buildings

Quality Factors:

The neighbourhood boasts abundant high-quality signage and amenities, benefiting from exceptional legibility courtesy of its towering, historically significant buildings. Additionally, its permeability is enhanced by wellconnected walkways and thoroughfares that seamlessly link to adjacent streets

The walkways are brightly illuminated, offering ample space for social gatherings and interactions. Along the high street are active/strong storefronts. User centric design elements like seating, and floor finish, cater to individuals of all ages and abilities, ensuring inclusivity and accessibility.

A highly legible retail and cultural hub, which is elevated through the presence of nodes, routes and iconic landmarks.

This area is an example to a efficient public realm developed, in a tight urban environment, which purely prioritises pedestrian movement and engagement

This neighbourhood is highly permeable through various quality links creates across the blocks Strong pedestrian movement allows a sense of safety and social cohesion, which is a key to the success of a public space

The lack of green infrastructure in the area is due to limitations in the retrofitted provisions made in the old urban set-up

The Grand Place in Brussels, Belgium, intertwines historic beauty with bustling commerce. Surrounded by ornate guildhalls, it offers an enchanting backdrop for shopping, dining, and exploring local culture. The presence of Brussels Town Hall is a pedestrian friendly public square, with ample space to admire the historic building and interact.

Materiality of the Street

Grand Place, Brussels, Belgium.

Aesthetic

playgrounds, and other communal areas. Architectural diversity adds character, blending modern aesthetics with sustainable features. Walkability is prioritized, promoting a healthy lifestyle. Sustainability initiatives, including green roofs and energy-efficient design, underscore environmental responsibility.

Permeability within blocks

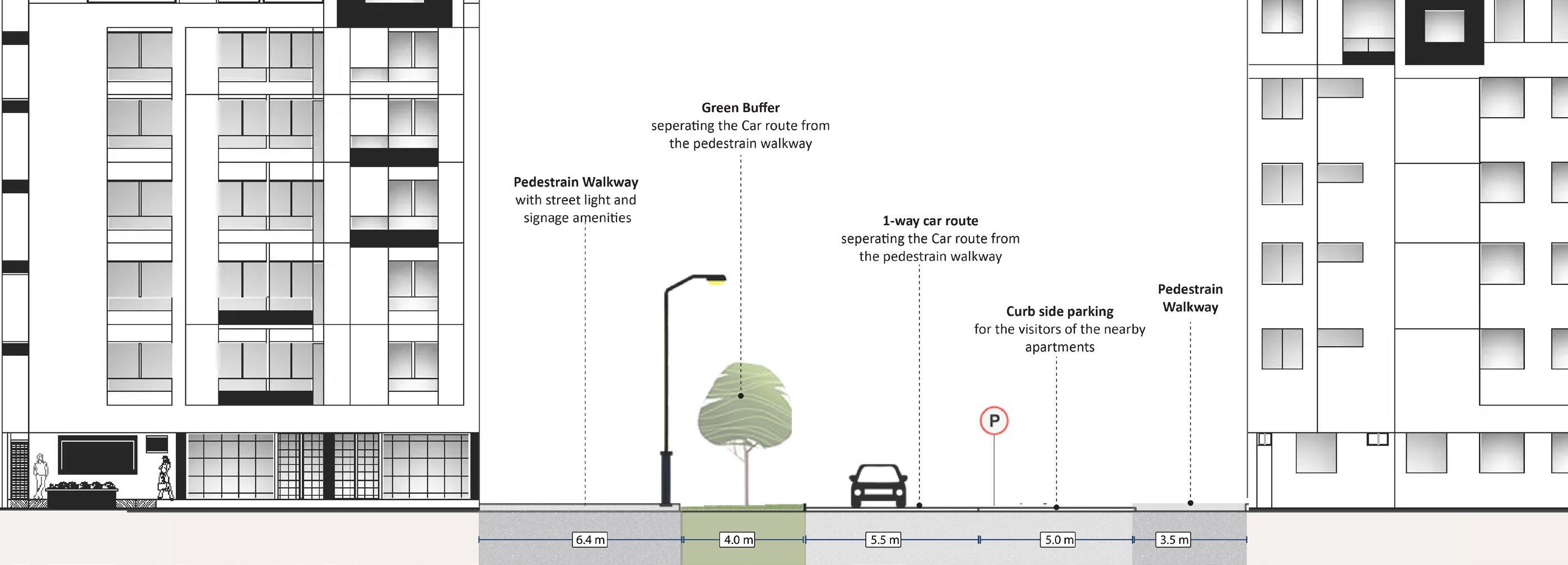

Decoding-Quality and Accessibility of Sonnwendviertel

Accessibility Factors:

Quality Factors:

The neighbourhood’s permeability is enhanced by the arrangement of urban blocks and the strategic design of the central linear park. The neighbourhood consists of high-quality amenities, including wellplaced signage, contributing to its overall functionality and appeal.

The central GI spine serves as a unifying element, seamlessly connecting the neighbourhood, while additional GI spaces within the urban blocks provide additional opportunities for social cohesion This inclusive neighbourhood caters to residents of all ages, offering amenities for children as well as rest stops for all.

quality of the area. This deliberate design fosters a safer and pleasant experience for the pedestrians.

Best Practice

One of the prominent housing developments, with a well-established access to different modes of sustainable transport. A development that encourages social interaction with the placement of blocks and large central green space Though the area is moderately legible, it is compensated by being an example of a good quality human centric housing development, with provision of good lighting, use of materials, permeability and accessibility.

Vauban district,Freiburg, Germany.

A pioneering housing project showcasing sustainable design, community involvement, and mixed-use development. Its eco-friendly features, pedestrian-friendly layout, and vibrant social atmosphere make it a model for modern urban living- with bikes, trams, car-sharing, efficient pedestrian corridors, makes it a sustainable project. Coates, G.J. (2013)

The varied material finishes along the walkway signify distinct movement and usage patterns

1. Buehler,R., Pucher.J & Altshuler.A.,(2017) Vienna’s path to Sustainable Transport, International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 11:4, pp.257-271, Available at: DOI:10.1080/15568318.2016.1251997 (Accessed on 11th April 2024)

2. Buehler.R & Pucher. J., (2016) Transforming Urban Transport – the Role of Political Leadership, at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), Available at: https://research.gsd.harvard.edu/tut/files/2020/07/ViennaCase2016.pdf (Accessed on April 16th, 2024)

3. Chaix, B., Kestens, Y., Duncan, S., Merrien, C., Thierry, B., Pannier, B., Brondeel, R., Lewin, A., Karusisi, N., Perchoux, C. and Thomas, F., (2014) Active transportation and public transportation use to achieve physical activity recommendations? A combined GPS, Accelerometer, and Mobility survey study, International Journal of behavioural nutrition and physical activity, 11, pp.1-11. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0124-x (Accessed on 11th April 2024)

4. Coates, G.J., (2013) The sustainable urban district of Vauban in Freiburg, Germany. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics, 8(4), pp.265–286. Available at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.2495/dne-v8-n4-265-286 (Accessed on April 16th, 2024)

5. Cordeiro.P.,(2015) Grand Place of Brussels-World Heritage Site-1998, Journal ‘Sustainable Development , Culture, Traditions, Vol 1a/2015, Available at: https://sdct-journal.com/images/Issues/2016_1a/4.pdf (Accessed on April 16th 2024)

6. Gössling, Stefan & Choi, Andy & Dekker, Kealy & Metzler, Daniel. (2019). The Social Cost of Automobility, Cycling and Walking in the European Union. Ecological Economics. 158. Available at: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.016 (Accessed on April 17th, 2024)

7. Halpern.C & Orlandi.C (2020), Comparative analysis of Transport Policy Processes-Vienna, Congestion reduction in Europe. Advancing Transport Efficiency, Technical Note No:10, Available at: https://create-mobility.eu/RESOURCES/ MATERIAL/TechnicalNote-10_ViennaTN.pdf (Accessed on April 16th, 2024)

8. Kaszczyszyn, P & Sypion, N., (2019). Walking Access to Public Transportation Stops for City Residents. A Comparison of Methods. Sustainability. Available at: 11. 13. 10.3390/su11143758. (Accessed on 11th April 2024)

9. Knoflacher H (2023) A Key Factor in Vienna Becoming the “Greenest City” in 2020 was the Paradigm Shift in the Transport System 50 Years Earlier. Green Energy and Environmental Technology. Intech Open. Available at: http://dx. doi.org/10.5772/geet.18. (Accessed on April 15th, 2024)

10. Kochergina, E. (2017). Urban Planning Aspects of Museum Quarters as an Architectural Medium for Creative Cities. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Available at: DOI: 245. 052031. 10.1088/1757899X/245/5/052031. (Accessed on 12th April 2024)

11. Lee, S.M., Conway, T.L., Frank, L.D., Saelens, B.E., Cain, K.L. and Sallis, J.F., (2017). The relation of perceived and objective environment attributes to neighbourhood satisfaction. Environment and Behaviour, 49(2), pp.136-160. (Accessed on 12th April 2024)

12. Leyden, (2003). Social Capital and the Built Environment: The Importance of Walkable Neighborhoods. American journal of public health. Available at: 93. 1546-51. 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1546. (Accessed on April 17th, 2024)

13. Litman.T., (2015), Evaluating Public transit Benefits and Costs, Best practices Guidebook, Victoria transport Policy Institute, Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130962286, (Accessed on April 12th, 2024)

14. Lucas, K., (2012), Transport and social exclusion: Where are we now? Transport Policy, Volume 20,2012, pp105-113, ISSN 0967-070X, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.01.013. (Accessed on: April 17th, 2024)

15. Lynch, K., (1964). The image of the city. MIT press. Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. (Accessed on: April 17th, 2024)

16. Mercer, (2023), Quality of Living city Ranking 2023, Global Mobility/ Workforce Strategy, Available at: https://www.mercer.com/insights/total-rewards/talent-mobility-insights/quality-of-living-city-ranking/ (Accessed on April 15th, 2023)

17. Mouratidis, K., (2021), Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being, Cities, Volume 115,103229, ISSN 0264-2751, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103229. (Accessed on 13th April 2024)

18. Mouzon.S., (2015), Frontages- A City’s Smallest Part, But Greatest Key to Value, Available at: https://originalgreen.org/blog/frontages---a-citys-smalles, (Accessed on April 13th, 2024)

19. Noorbhai, H., (2022). Public transport users have better physical and health profiles than drivers of motor vehicles, Journal of Transport & Health, Vol 25, 101358, ISSN 2214-1405, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jth.2022.101358. (Accessed on 11th April 2024)

20. Perkins, D.D., Wandersman, A., Rich, R.C. and Taylor, R.B., (1993). The physical environment of street crime: Defensible space, territoriality, and incivilities. Journal of environmental psychology, 13(1), pp.29-49. (Accessed on April 12th, 2024)

21. Ravensbergen, L., Liefferinge, M, Jimenez, I., Merrina, & El-Geneidy, A. (2022). Accessibility by public transport for older adults: A systematic review. Journal of Transport Geography. Available at: DOI: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2022.103408, (Accessed on April 17th, 2024)

22. Rissel, C., Curac, N., Greenaway, M. and Bauman, A., (2012). Physical activity associated with public transport use—a review and modelling of potential benefits. International journal of environmental research and public health, 9(7), pp.2454-2478. Available at: DOI: 10.3390/ijerph9072454 (Accessed on 11th April 2024)

23. Rüetschi, Urs-J & Timpf, S. (2004). Modelling Wayfinding in Public Transport: Network Space and Scene Space. Conference: Spatial Cognition IV: Reasoning, Action, Interaction, International Conference Spatial Cognition 2004, Frauenchiemsee, Germany, October 11-13, 2004, Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence (Subseries of Lecture Notes in Computer Science). 3343. 24-41. Available at: DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-32255-9_2. (Accessed on April 15th, 2024)

24. Tavassolian.G, Nazari M., (2015), Studying Legibility Perception and Pedestrian Place in Urban Identification. International Journal of Science, Technology and Society. Special Issue: Research and Practice in Architecture and Urban Studies in Developing Countries. Vol. 3, No. 2-1, 2015, pp. 112-115. Available at: DOI: 10.11648/j.ijsts.s.2015030201.32 (Accessed on April 14th, 2024)

25. Trop, T., Shoshany Tavory, S., & Portnov, B. A. (2023). Factors Affecting Pedestrians’ Perceptions of Safety, Comfort, and Pleasantness Induced by Public Space Lighting: A Systematic Literature Review. Environment and Behavior, 55(12), 3-46. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/00139165231163550 (Accessed on April 12th, 2024)

26. World Population Review, 2024, Vienna Population 2024, Available at: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/vienna-population, Accessed on April 16th 2024.

27. Yavuz, A. (2014). Permeability as an indicator of environmental quality: Physical, functional, perceptual components of the environment. Conference: World Journal of Environmental research, Available at: https://www.researchgate. net/publication/273894904_Permeability_as_an_indicator_of_environmental_quality_Physical_functional_perceptual_components_of_the_environment (Accessed on April 14th, 2024)