One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of looking at things.”

Henry

Miller© 2022 Natural Traveler LLC 5 Brewster Street Unit 2, No. 204 Glen Cove, New York 11542

One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of looking at things.”

© 2022 Natural Traveler LLC 5 Brewster Street Unit 2, No. 204 Glen Cove, New York 11542

Tony Tedeschi

Senior Editor

Bill Scheller

Staff Writers

Ginny Craven Aglaia Davis

Andrea England David E. Hubler Jay Jacobs Skip Kaltenheuser Samantha Manuzza Buddy Mays John H. Ostdick Pedro Pereira Frank I. Sillay Kasia Staniaszek Kendric W. Taylor

Photography

Katie Cappeller Karen Dinan

Skip Kaltenheuser Buddy Mays Janet Safris Kasia Staniaszek Chris Taylor Art

Sharafina binti Teh Sharifuddin

Editor’s Letter Page 3

Contributors Page 4

Fogg’s Horn: Tea at the Princess Page 5

Autumn in the Cascades Buddy Mays Page 8

A Man of Uncommon Influence Candy Tedeschi Page 14

Chasing the Northern Lights Candy & Tony Tedeschi Page 18

A Short History Jay Jacobs Page 23

Reckoning with Personal History Ginny Craven Page 24

An Italian American Family at Table Alice Marchitti Scheller Page 27

Hem and Ho: A Conversation Kendric W. Taylor Page 31

Carnival: The People Strike Back Skip Kaltenheuser Page 37

Madelineville John H. Ostdick Page 42

John’s Village Madeline Ostdick Page 46

Waaaaht ? Wanna Buy a Blender? Malcolm P. Ganz Page 62

Mind of a Peanut Sharafina binti Teh Sharifuddin Page 65

Cover Photo by Candy Tedeschi

We have become so focused upon whatever our particular choice in media, we sometimes overlook the impactful presence of those who’ve actually helped us fashion who we become . . . until they are not with us anymore. Once we are cajoled to “say a few words” about them, the view comes into focus again. That’s not to say we’ve forgotten their positive influences, it’s just that as we grow older, we slip away from those connections, which played such prominent roles in our lives.

“Burt never stopped encouraging me to learn more, do more, be active in medical organizations,” Candy Tedeschi reminisces about her mentor, Dr. Burton A. Krumholz. “I’m eternally grateful he pushed me to become the nurse practitioner I am today, with his influence demonstrated for the many patients I treat each year, as part of that army of healthcare providers who are better caregivers because of him.”

Bill Scheller’s connection with his family and roots in Paterson, New Jersey, are a major element in how he looks at life. For Italian Americans, the locus of points that shaped their lives was around the dinner table, where the meaningful exchanges of each day occurred. And it was the care of the homemade meal that graced the center of the table and themed the dialog. “I suppose pasta was the villain responsible for padding us so well,” Bill recalls about his mother. Perhaps so, but it was the price you paid gladly to

participate in the dialog of the evening meal or the midday Sunday weekend feast.

For others, these connections become a matter of coming to terms with an ancestral past. Few as dramatic as Ginny Craven.

“I am just three generations removed from Admiral Raphael Semmes,” Ginny Craven writes. “He was the pillar of the Confederate Navy still reputed to be the most successful raider in maritime history. He hunted and sank U.S. supply ships all over the world.”

The towering statue of Admiral Raphael Semmes was removed from its pride of place in Mobile, Alabama, she writes. “That seems right to me. The statue now resides in the Mobile Historical Museum a far less celebrated position.”

Maybe the way to deal with the pluses and minuses of all this to satirize it to music during the pre Lenten days before Easter, each year.

“Carnival remains irrepressible despite authority’s many stompings over the centuries,” writes Skip Kaltenheuser, the ultimate Carnival chronicler. “When Carnival collided with the Church, it softened with themes of redemption and renewal. The carnival spirit, burned in effigy, departs taking the woes of the year, leaving all with a clean slate. Has there ever been a city more in need of a spiritual cleanse than Washington? --

TonyTedeschi

Vivid photos by Buddy Mays are the answer to any thoughts that you’ve had your fill of fall colors, with his portfolio, “Autumn in the Cascades” (Page 7).

Candy Tedeschi memorializes her mentor, Dr. Burton A. Krumholz in “A Man of Uncommon Influence” (Page 14)

“Chasing the Northern Lights” finally produces its night show north of the Arctic Circle in Norway for Candy and Tony Tedeschi (Page 18).

It’s hard to imagine a more well connected family than the Confederate admiral and the media moguls who make up the ancestry of Ginny Craven in her memoir, “Reckoning with Personal History” (Page 24).

One can never overstate the veneration for the cuisine, which arises from special recipes, described in his mother’s variation on the theme by Alice Marchitti Scheller in “An Italian American Family at Table” Page 27).

Poetic contributions gracing this issue are Jay Jacobs’, “A Short History,” (Page 23) and Samantha Marie’s, “” (Page 30).

Some of the last century’s most prominent personae are part of “Hem and Ho, A Conversation Or An Afternoon in Paris: A Fable,” By Kendric W. Taylor (Page 31).

Reporting on the menage ranging from joyous music and dance to biting satire during pre Lenten celebrations far and wide has been a specialty of Skip Kaltenheuser, here on display in his “Carnival, The People Strike Back” (Page 37).

The yuletide creation and expansion of “Madelineville,” is John H. Ostdick’s reminiscence, followed by his daughter, Madeline’s story about how the town came to life in her imagination as “John’s Village” (Page 46).

The beginnings of off price merchandising, kinda, is detailed in Malcolm P. Ganz’s, Waaaaht? contribution, “Wanna Buy a Blender” (Page 62).

Karen Dinan’s latest back cover has solidified her ownership of that space, which should cause everyone to flip over our issues before you do anything else.

You get to the point where you’ve had quite enough of traveling to places where they want to feed you bugs or set you up with the chief’s daughter. Even an intrepid sort like myself longs for a little civilization now and then, so I asked myself: where is the most civilized place on the planet? Civilized, that is, without bus exhaust and dollar stores.

So I headed to Bermuda. Bermuda, I figured, would be like a cross between Martha’s Vineyard and the Cotswolds.

Boy, was I surprised. After a lifetime of “what I figured” and “what it was” winding up poles apart, and expecting no better, I discovered that Bermuda was a cross between Martha’s Vineyard and the Cotswolds.

On the Vineyard account was the gentle rolling countryside, with the sea not far away, as on a New England saltwater farm. Every square inch was manicured, lovingly tended, matted and framed like a painting of a place too good to be true. The Cotswolds element was provided by a little jewel of a Gothic church, and by narrow byways with names like Pigeon Berry Lane. As it turned out, I wasn’t the first to get this feeling about the place. I saw later that two of the streets were

named Nantucket Lane (close enough) and Cotswold Lane.

OK, that’s a lot of lanes. A bit twee, you say. Go soak your head. Sometimes twee is balm for the soul. Especially if the soul has been fed too many bugs, and the chief’s daughter was a fright.

There’s another kind of balm Bermuda offers, one that’s becoming rarer as the world starts to act like its phone just died in the middle of an IMPORTANT TWEET, and to look more and more like an unmade bed. I’m talking about formality, and the oddly surprising calm that it can produce. Formality means predictability, and a certain lulling sensation. And Bermuda is a formal place.

Bermuda’s formality comes across most visibly in dress. A sixth generation local told me that this derives from the long British military presence in the islands, back in the imperial heyday when Bermuda was called “the Gibraltar of the West.” What did British officers wear in warm climates back then? Why, the same thing Alec Guinness wore in “The Bridge on the River Kwai” shorts! And what was that gent wearing, briefcase in hand, walking along Front Street in downtown Hamilton? A blue blazer,

starched white shirt, repp silk tie and Bermuda shorts.

“The shorts are a throwback to the military,” my gen six local told me. “They got their start as a local trademark when tailors here began refining officers’ baggy khaki shorts for civilian wear.” They’re now ubiquitous as Bermudian business attire, creased, hemmed just at the right spot on the knee, and totally at home with jacket and tie.

But there had to be more to it than shorts. I thought about where I might find the quintessence of Bermudian formality and local tradition, and concluded that the place to look was afternoon tea at the venerable Hamilton Princess, a big pink cake of a hotel.

I was staying elsewhere, and thought it might be appropriate to call the Princess first, to see if non guests were welcome. “Are you serving tea at four?” I asked the English accented woman who answered the telephone.

“Yes,” she answered.

“Is it all right to come to tea if one isn’t registered at the hotel?”

“Are you registered at the hotel?”

“No. That’s why I’m asking.”

“I’ll switch you to dining services.”

“Hello?” (Another Englishwoman’s voice.)

“Hello, I’m wondering if I can come to tea if I’m not registered at the hotel.”

“What is your name, sir?” I gave her my name and spelling. At this point, I was tempted to add “Viscount.”

“I don’t have you listed as a guest.”

“I know that. I’m calling to ask if it’s all right to come to tea if I’m not a guest.”

“No, sir.”

Now we were deep in Monty Python territory, and I had the John Cleese part. Clearly, there was nothing to do but get dressed in the best clothes I’d packed (alas, no Bermuda shorts, and I wouldn’t have felt comfortable showing up in the cargo variety with 46 pockets), head into Hamilton on my rented motor scooter, and crash tea at the Princess. But when I sauntered into the hotel with my best ersatz viscount air, all I found was a small room off the lobby where a dozen people in tennis outfits stood around a samovar and a tray of marble pound cake slices. I poured a cup, drank it, and was gone in five minutes. Crashing tea at the Princess had been about as difficult, and as exciting, as stopping at a diner for lunch.

It took a bit of the polish off my formal, civilized vision. I’d have felt better, truth to tell, if they had thrown me out. -- 30 --

Oregonisnotwhatmostpeoplewoulddescribeasa“leafpeeper”state, certainlynotlikeVermontorPennsylvania,NorthCarolinaorColorado, whoseannualautumncolordisplaysattractvisitorsfromallovertheworld. ButOregon’sspectacularCascadeRange,a100milewide,295 milelong chainofdormantvolcanicpeaks,andcraggy,heavilytimberedmountains runningnorthtosouthfrombordertoborder,doeshaveitsautumnal moments.

FromearlySeptemberwhentheuncountablestandsofvinemapleand swordfernsbegintheirannualtransformation,untilmidNovemberwhenthe lastleavesofaspen,willow,andbigtoothmaplefinallydecidethatwinterhas arrived,theCascadesarecheckerboardedwithbandsofbrilliantcolor.

Bend,OregonbasedphotographerBuddyMays,whohasbeen photographingtheCascadecolorchangeformorethan20years,saysfallis themostbeautifultimeoftheyeartobeinthemountains.

“Thetouristshaveallgonehome,”hesays,“themosquitoesareinbug heaven,thedustonthehikingtrailshassettled,andmostofthewildlandfires arefinallyout.Whenthemapleandaspentreesbegintochangecolorand thefernsturngoldandthefallcropofmushroomsstarts tofruit,walkingina Cascade forest is akin to “strollingthroughafairylandglade.”

What followsaresomeofBuddy’sfavoritefallphotographs.Nodoubt,he iswanderinginsomeelfinOregonforestatthisverymoment,foragingfor mushrooms,admiringthescenery,andtakingmorepictures.

Thecanopyofabigtoothmaple,clingingto a rockybankalong the Willamette River near Oakridge,Oregon,turnsbrightyellowinmidOctober.ThebigleafisnativetoOregon andthePacificNorthwestandgrowsabundantlythroughouttheCascadeRange.Itis America’stallestmapletree,reachingheightsof100feet,anditswoodwasusedbyearly northwestIndiantribesforcanoepaddles.

EarlyonawarmSeptembermorning,mistrisesfromClearLakeattheheadofOregon’s famousMcKenzieRiver.Especiallyinautumnwhenlakeshorevinemapleandwillow scrubbegintheirannualcolorchange,thelakeisapopular withkayakersandcanoeists.

OntheUpperDeschutesRiver,apleinairpaintercapturesthegoldencolorof aspensandwillowsgrowinginprofusionalongtheriver’sbanks.Thisstretchof river near Dillon Falls known as the Deschutes PaddleTrail,isoneofthe main leafpeepingareas in the state from midOctobertoearlyNovember.

Continuallyscrapingthevelvetfromhismassiveantlersontreebarkorbrush, thisadultbullelkreadiesforautumnruttingseasoninthenorthernOregon Cascades near Mount Hood. He could haveupto40femalesinhisbreeding harembymid November.

Moreashrubthanatree,vinemaplebushescansometimesreach20feetin height. It is earliestoftheOregonautumncolorchangers,oftenbeginningto turn either red, goldorsometimesboth,inearlySeptember.Thisoneis growingalongMarionCreeknearDetroit,OregoninthewesternCascades.

Akayakerpaddlesthroughthereflectionofariversideaspenforestasshe navigatesthequietwateraboveDillonFallsontheupperDeschutesRiver. Hundredsofkayakersandcanoeistsfloatthisareaeachdayduringtheautumn colorchange.

AcrownoffallenmapleleavesswathesthismossyboulderattheedgeofLake CreekinthecentralOregonCascadesnearthetownofSisters.Vinemapleis soabundantherethatbytheendofthefallseason,thestreamwillbe completelyblanketedwithleaves.

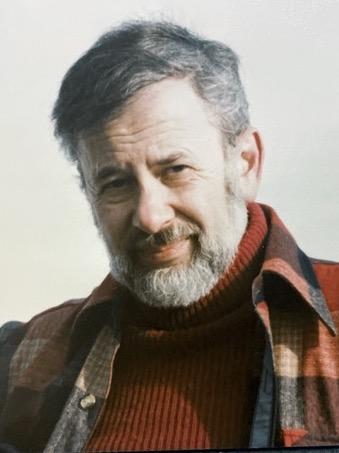

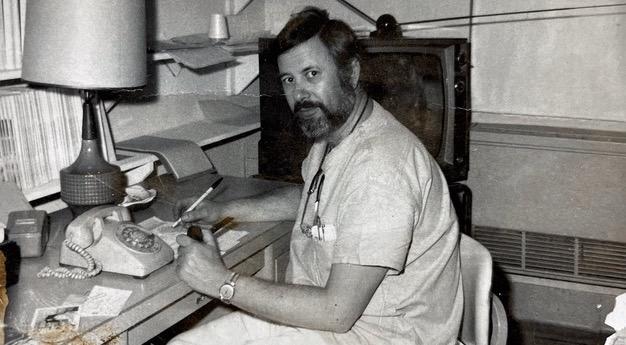

Editor’s Note: There is almost aninevitabilitytothemultipliereffectgeneratedby goodpeople. Dr.BurtonA.Krumholzwastheembodimentofthatphenomenon. AnOB/GYNMD,Dr.Krumholznotonlypracticedmedicineatthehighestlevel ofprofessionalism,hetaughtnewdoctorsskills,whichtheywouldutilizethrough lifetimesinmedicine.Hisprofessionalachievementsaremany,butinthefinal analysis,aperson’scontributionsgofarbeyondlinesonaCV. Thisparticular aspectofDr.Krumholz’slifestoryisabouthowhemultipliedhisbeneficial influenceoncountlessthousandsofpatientsthroughtheprofessionalshe influenced,includingmywife,Candy,inhercaseoverthemanyyearsshehas tendedtopatientsasagynecologicalnursepractitioner.Dr.KrumholzdiedonJuly 20th attheageof93.FollowingareCandy’sthoughtsonhermorethanfourdecades asacolleagueandfriend ofaveryspecialman.

In 1979, after spending five years working as a nurse in a neonatal intensive care unit caring for premature babies, I was looking for something different. I interviewed with Dr. Burton A. Krumholz, who was the associate chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Long Island Jewish Medical Center. He offered me a position as a staff nurse on a New York State grant educating and caring for women who had been exposed to diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy. DES is a drug women took ostensibly to prevent miscarriages, but caused numerous problems in their daughters. DES exposure and the problems associated with it were new to me and I was constantly asking Dr. Krumholz many questions. He patiently answered them and gave me articles to read. Finally he had had it with all the questions. He told me I was a pain in the ass and I should go back to school to become a nurse practitioner and work with him in that capacity. So I did.

When I’d finished my class work, I did a preceptorship with him and at the hospital GYN clinic. When the residents found out I worked for Dr. Krumholz, they could not believe I could work with him. They called him a “grizzly bear.” I answered back that he was a “teddy bear.” OK, maybe in reality, he was a grizzly bear with the residents, but Burt had a strong view of how residents should learn and he made sure they learned well. He wanted those he taught to go out into the community when they graduated and be able to practice the best of the latest in medicine.

Dr. Juliana Opatich, one of his past residents, said they dreaded when he gave grand rounds for them. “He would present a patient case,” she says, “then start asking questions. He’d begin with the medical students and work his way up to the senior

residents. If no one got the correct answer, they got a lecture on that topic. Burt was always ahead of everyone else in the community in his specialty of diagnosing and caring for women with diseases of the lower genital tract, abnormal Pap tests, along with the treatment and care for those conditions.”

For doctors like Helen Greco, today chief of the division for benign obstetrics and gynecology at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, a professional relationship with Dr. Krumholz played a significant role, lasting decades.

“My memories of him span over 30 years,” she says. “I was a new resident and he was department vice chair. Immediately I came to know him as a revered educator and a renowned expert in the field of colposcopy and DES. He was tough on his residents with the expectation that your clinical skills, once mastered, would be equal to, or better than, those who had had the privilege of teaching you. This challenge he posed to each of us was at times bumpy, but the benefit of the experience far outweighed those bumpy moments.”

As hard as he was on residents, when they graduated and were out on their own, past residents would tell me that they were actually grateful, and loved and respected him for it. His influence was so universal, one of his past residents said that she would write in the patient’s chart when she was referring someone to him for treatment “refer to BAK.” When staff would ask her what’s a “BAK,” she’d answer, “Burton A. Krumholz of course.”

“Our relationship grew from student teacher to that of colleagues and ultimately friends,” Dr. Greco explains. “He took on his role as mentor and leader in his field very

early in his career and continued to advance the medicine every day that he practiced. From my changing perspective, I learned from him that we are all lifetime learners, ever evolving to adopt to the current course, and willing to develop the practice needed to better the outcomes for our patients.”

If he were sometimes a hard person to deal with, he directed that hardness at specific targets. Case in point: he and I always tried to get the medical records before a new patient came in for her first office visit. Sadly, most women had very little knowledge of exactly why they were there. This particular patient had extensive records, which I reviewed before her visit and shared with Burt. He asked that I sit in on his interview with her.

As he asked her questions and she responded, I could tell by the tone of his voice that Burt was becoming more and more angry. It was making the woman more and more upset, until she started crying. I asked why she was crying and she said he is angry with me. He looked at her and told her he was not angry with her; he was angry at all the prior doctors who had mistreated her. That was typical of Burt. He hated when women were not get properly diagnosed and treated accordingly. He had the highest level of respect for women and how they were cared for.

On the professional side Burt was very active in local and national organizations like the American College of OB/GYN and positions in Nassau and Queens County, New York OB/GYN medical associations, including president. He had gotten interested in colposcopy while working at Nassau County Medical Center as chairman of OB/GYN when he opened a closet and found a machine called a colposcope, basically a fancy mobile microscope on a stand. He knew that it was a new part of evaluating women for abnormal Pap tests. It was a part of women’s health that was

growing and much research was being done. He decided he wanted to be part of that research and education, so he joined the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) in the late 1960s as one of the early members of that organization. He was elected to the board of directors and held every position on the board until he became the president in 1992. He lectured all over the world and wrote numerous articles, which helped set the standards we have in place to this day.

Beyond his professional resume, Burt was a warm and loving man, dedicated to his family. When his children were camp age, he took off every summer to be camp doctor so he could be close to them. He like to speak of the accomplishments of his three daughters, two sons and three grandchildren. He loved to travel with his wife, Shelley, and talk about his golf and tennis games.

There are also many stories about the “grizzly bear’s” lighter side. Once, after giving a lecture in Southeast Asia, he was honored with an award but told in order to receive it he had to sing a song that it was a tradition. “I don’t sing,” he protested. Eventually, reluctantly, he sang “Happy Birthday.” A moment his wife, Shelley, wouldn’t let him forget.

Burt never stopped encouraging me to learn more, do more, be active in ASCCP. I’m eternally grateful he pushed me to become the nurse practitioner I am today, with his influence demonstrated for the many patients I treat each year, as part of that army of healthcare providers who are better caregivers because of him.

In the words of Dr. Greco, “the lifetime of dedication, devotion to his family and circle of friends and colleagues, as well as his warm smile and turned up lab coat collar, will be forever etched in my fond memories of what I see when I picture my friend, colleague and teacher.”

Rest in peace, my friend.

Most of the “normal people” among our friends view vacations during the colder months as escapes to warmer climes. Not my wife, Candy. It isn’t that she doesn’t have good things to say about such vacations. But over the past few years, she’s had a near obsession to see the northern lights. So, we took a trip to Iceland in 2018, where rainy nights obscured any chance of a viewing. Next, we booked a cruise to Norway, in 2020, through the North Sea above the Arctic Circle. It was postponed twice due to the pandemic.

There was also a trip to Antarctica, having something to do with glaciers and lots of penguins, about as far south as you can get from the northern lights, so I was beginning to sense the pull of ice in some ancestral DNA. She is, after all, descendent of the Vikings who invaded Scotland, according to ancestry.com, which based that conclusion upon the origin of her family name.

The thing is, when chasing the northern lights, you only have a few hours of maximal viewing even on a good night. So, one needs to consider how to fill all those other hours. The ice caves in Iceland looked like an interesting choice. Surrounded by the gleaming light that filled the cave overcame dead numb legs from crossing two icy streams to get there and almost made me forget the gloomy nights on that trip. Almost.

The onboard perks of cruising with Cunard to just about anywhere are so wonderful it almost made up for the faint onboard sighting, during our journey through the North Sea. Almost.

The helicopter ride above Norway’s northernmost mountains, or the cruise through the country’s fjords, were two other side trips we were glad we opted for. You get a sense that tour companies overhype the gaudy reds and greens they feed you in their northern lights promos.

In reality, gaudy, they are not. Wispy, they are. Hard to capture on camera in any way but at their wispiest. See Candy’s photo on the cover or the one on the next page. The more I look at those photos, the more mystical it feels. Maybe the real beauty is in nuance. Anyway, re side trips to the far north. It’s stark beauty is almost the antidote to those sun drenched beaches and crystal clear, waters of the warmer climes. Almost.

When I was eight years old, we collected bugs and placed them in a jar. We poked holes in the cap so they could breathe, and gave them grass so they could climb and eat.

It was the age of innocence.

In 1963, I was eleven years of age.

In November of that year on the twenty second day, President Kennedy was shot and killed.

It was the end of innocence.

When the ‘70s came around and I was a young man of twenty, we marched, and protested, and loved freely and ingested mind altering substances. It was the age of awareness.

The eighties came and clinging to it were a few pages written during the previous decades. But the print had faded and the once hard edges of truth and reason that characterized those eras had softened and were ill defined.

It was an age of diminishing returns. While in my forties, the ‘90’s were the future come at last. But there were no flying cars, robot servants or tours of the moon. The bedrock precepts of institutional stability and the accuracy of historical events, once taken for granted, were questioned and challenged, and the Ten Commandments were removed from public buildings.

It was the time of false gods.

The second millennium brought my fifth and sixth decades along with a technological noise that blotted out clear thinking, long held traditions, and human interaction. It brought new ways of looking at things that flew in the face of reason. It brought wonders along with evil to pocket size handheld screens. It brought lies and gossip parading as news.

It brought thieves, perverts and mass murderers on an unprecedented scale. It brought daily news of horrific depravities.

It brought new terms like ‘mis spoke’ and ‘political correctness’ and ‘new normal’.

It brought maniacs to the highest offices. It was, and remains, the age of insanity.

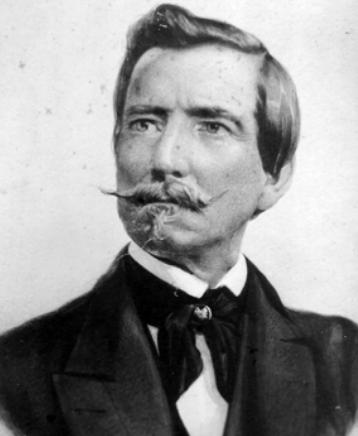

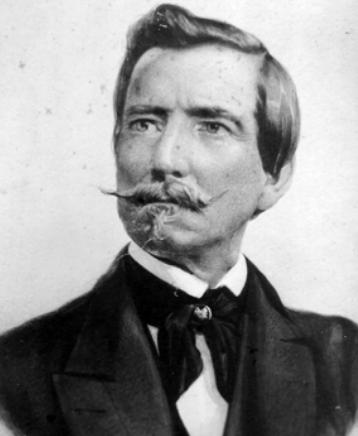

These sentiments were echoed in my own family’s narrative. I am just three generations removed from Admiral Raphael Semmes. He was the pillar of the Confederate Navy still reputed to be the most successful raider in maritime history. He hunted and sank U.S. supply ships all over the world. I have the music and lyrics to a South African folk song, circa 1862, Dar ComeDaAlabama , describing the local excitement when his infamous sloop of war, Alabama, arrived in Cape Town harbor. Raphael Semmes got around.

It’s Juneteenth . . . Sadly, I didn’t even know what Juneteenth was until two or three years ago. And, even sadder, I don’t think I’m alone in that ignorance. It seems that, like much of the country, I have awakened to history. And, I have begun to re examine the narrative that I have absorbed apparently by osmosis without any particular thought or discernment.

I was raised in Virginia in the 60s. Mine was a genteel existence romanticized and soft at the edges. The version of history that I got in school was straight out of Gone with the Wind, a hushed reverence for the “heroes” of the Civil War. In high school, I dated a guy that could recite Robert E. Lee’s farewell address to the Army of Northern Virginia. I can still hear that seductive Tidewater drawl. The devoted admiration was embedded in the culture; there was no real malice, no insight, and, amazingly, no perceived racism just blindness, just deep sleep . . .

I was always caught up in the stories the dashing admiral with the piercing blue eyes and handlebar moustache. He made history. There is even a certain family resemblance; that jawline is an enduring trait. I was always so proud of this lineage… until I woke up.

I live near Charlottesville, Virginia a blissfully blue oasis in a red sea. It is an area still steeped in Civil War history, but with a measure of equanimity, an expanded lens on this blight on American history. Then, in 2017, as the statue of Robert E. Lee that loomed in a downtown park was brought into question, this very liberal town was suddenly transformed into the poster child for racial inequity. It made me sad, shook me to the core.

In the summer of 2020, when the U.S. was torn by racial conflict, when it seemed that the old wounds were laid bare, I had a bit of a personal existential crisis. Not to be melodramatic, but it was alarming to wake up with such a start. I am a liberal; I consider myself to be intellectually curious. Yet, most disturbing, I had accepted my family narrative without a question. In fact, my illustrious great great grandfather was a traitor

to our country, a slave owner, a protector of the Southern way of life deifying white men, devaluing everyone else. He fiercely defended the “Lost Cause,” the ideology that claimed the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery.

I have reconciled my own story. To be sure, I feel no guilt for his deeds per se, but I am deeply ashamed of my own shallow response. Until fairly recently, I never really considered “true” history never delved in to explore. To be clear, I believe that history belongs in the past; it is contextual and cannot be judged by modern mores, but the implications are nonetheless grave. It took me most of my life to realize that the stories that I had so readily incorporated into my own heritage were, at best, highly editorialized white lies, if you’ll pardon the pun. I am interested in my infamous great, great grandfather, whose conquests resulted in an international lawsuit. After the Civil War, the U.S. sued Britain for damages demanding compensation for the 65 ships sunk by the Alabama, which was built in Liverpool. Still, no matter what perverse self importance I had gleaned from his triumphs, I nonetheless took down a painting of him from my guestroom, removed the volumes by and about him, and relegated them to an out of the way bookshelf in my basement. I just don’t feel good about celebrating him. Then, there is my maternal history also auspicious, also unseemly. The Scripps family helped to shape media in the U.S. the Detroit News, UPI, WWJ Radio part of an early 20th century Detroit brain trust. They also supported and participated in various inventions. The Scripps Booth Rocket was an early car with a V 2 cylinder engine, built in 1913. The International DN Class is a type of iceboat. The name comes from the Detroit News, the Scripps family newspaper. The first iceboat of this type

designed and built in the Detroit News hobby shop in 1936 37. In 1939, they built a marine engine: Scripps Model 302 Marine V12. I have some photos in my living room one a gathering on the front porch of Moulton the “Scripps Mansion,” my great grandparents’ weekend estate. The shot includes Henry Ford, Edsel Ford, Orville Wright, and my great grandfather, William Edmund Scripps, among other aviation cronies. Moulton had an airstrip since WE Scripps was an avid aviator. Perhaps that explains another of my family photos my grandmother with Amelia Earhart, posed wearing those adorable little 1920s hats. Apparently, Amelia flew a glider on that airstrip in 1929. These were smart people innovative people. They had plenty of money and plenty of power. How cool! How much have I swelled with pride at the accomplishments of my famous family, as though their achievements somehow distinguished me. But, then, I looked further. I examined more closely remembered the stories of vulgar excess. They were entitled, rich robber barons – likely forming the foundation of white supremacy. My grandmother relayed a story of a Christmas party at Moulton her parents’ home. Her mother in law, my great grandmother was known for being a mean drinker, and this night was no exception. Apparently, after several martinis, she took offense at something my grandmother said, and hit her squarely over the head with her diamond encrusted evening bag. Whoa! Bad form to be sure! The next day, my grandmother received a delivery a full length ermine cape as an apology present. Repulsive conspicuous consumption at its finest!

So, who were these people? Were they brilliant? Yes. Were they talented? Yes. Did they contribute? Most definitely. Were they good people? Hell, no!

It is interesting that the cultural crisis in the U.S. has dove tailed with my own renaissance or reconciliation. Our nation is struggling to separate the great deeds from the character, the contributions from the huge human shortcomings and despicable personal philosophies. So, it is with me. I have felt some level of responsibility not for their actions, but for perpetuating the myth. It is coming full circle though. What an eerie coincidence that the Alabama was sunk on June 19, 1864 what would later be Juneteenth. And, on June 5, 2020 in the height of the protests over George Floyd’s shooting and just days before his funeral, the towering statue of Admiral Raphael Semmes was removed from its pride of place in Mobile, Alabama. That seems right to me. The statue now resides in the Mobile Historical Museum a far less celebrated position just like the painting that now languishes in my basement.

Lefttoright:FredHoover,EdselFord(barely visibleintheback),OrvilleWright,George Hallett,FredBlack,JimmyPiersol,HenryFord andWilliamScripps.Theoriginalphotoisin theFordMuseumandVillageinDearborn Michigan.

By Alice Marchitti Scheller

By Alice Marchitti Scheller

Fifteenyearsaftershedied,I’mstillgoingthroughboxesofmymother’sthings. I recentlyfoundafewpagesshewrotelateinlife,describing,forherfood oriented Internetchatgroup,themealssheandherfamilyatewhenshewasagirlintheThirties. Iretypeditwhilelisteningtooneofhertapes,ofthegreattenorBeniaminoGiglisinging Neapolitansongs.

Growing up during the Depression in the bosom of an Italian family we always ate well, though on a shoestring. The food was freshly prepared each day, always with fresh, seasonal ingredients. Leftovers were unheard of.

Meat. while not being too costly by present comparison, was considered something of an extravagance and we usually ate it two or three times a week. Protein was dried legumes, cheese, and eggs. We did not eat eggs for breakfast except on unusual occasions. I recall eggs being the main ingredient for Saturday night dinners, as hapless Catholics spent eternity in Hell for eating meat on Friday, back in the pre Pope John XXIII days. (I wonder if the meat-eaters got reprieved when the rules changed?) You can whip up a simple little tomato sauce, then just before you are ready to eat and the sauce is bubbling gently, poach as many eggs as you need in the sauce. Serve eggs and sauce in a soup bowl, with a crusty loaf of bread, and enjoy Eggs in Purgatory. (Is Purgatory still there? I haven’t heard it mentioned in a long time.)

We didn’t eat omelets, we ate frittatas. These could be any ingredients at all, set in beaten eggs and cooked in a frying pan lightly touched with olive oil. Being southern Italians, we rarely ate butter. We didn’t need a spread for our bread because it was always used to mop up the delicious juices in the bottom of the bowl of whatever it was

we were eating, and to cook with anything but olive oil, or sometimes fatback, was heresy. Some of my favorite frittatas were made with cubes of boiled potatoes, chopped onions lightly browned, and beaten eggs (with an eggshell of water added) poured over all and lightly cooked until the eggs were set, then flipped over to the other side. When the vegetable garden was ready, we had asparagus, broccoli, zucchini or peppers in our frittata.

When I was older and our family had successfully weathered the Depression, I made a frittata on Sunday mornings which was a mixture of mozzarella, salami or prosciutto, and eggs, which kept everyone satisfied until the big event of the week Sunday dinner.

I must make mention of another Friday night specialty. We called it macaroni pie, although it was made with fine egg noodles rather than macaroni. Simply cook a package of egg noodles and drain well. Meanwhile beat six eggs with a tablespoon of fresh parsley, salt, pepper, and grated Romano or Parmesan cheese in a large bowl. Add the drained noodles, mix all together, and pour into a lightly oiled, heated frying pan. Allow to brown slightly, then place a dinner plate over the “pie” and turn onto the dish. Slide it back into the pan and continue cooking. This requires a little dexterity, but just take your time and don’t get nervous.

Summer was the best time of all. Everyone had gardens and everyone’s garden had, primarily, tomatoes – beautiful Jersey tomatoes with a flavor that I have not found in any others in this country. We had both plum tomatoes and the big round beauties, bursting with juice. How good they were picked form the vine, warm from the sun and eaten out of hand (if Grandma wasn’t looking). Then the dark green bell peppers, and the long, skinny hot peppers that turned a bright red and looked like so many Christmas ornaments hanging from their green vines. These were hung up to dry on back porches and in kitchens and attics. Zucchini, asparagus, green beans, broccoli, eggplant, lettuce, and most necessary of all, beds of parsley and basil and peppermint. Grandma would pick some of the zucchini flowers and do wondrous things with them; she mixed a little flour, salt, pepper, baking powder and the washed flowers into a batter that made lovely little pancakes pizzella , they were called, as were any little fritter like goodies similarly prepared. Sometimes Grandma stuffed the zucchini blossoms, which I remember eating although I cannot duplicate the stuffing. I know there were bread crumbs and garlic but there must have been other things, and they were sautéed.

Luckily, I remember how to make the stuffing for the bell peppers. Take the crumbs of a loaf of day old Italian bread and crumble it into a large bowl. Remove the stem end from fresh ripe tomatoes after they have been peeled and squish them into the bread until it is nice and moist, add some slivered garlic, chopped basil and parsley, a tablespoon or two of olive oil, salt and pepper, and mix. Use your hands so you can lick your fingers. Stuff your peppers, cover them with a little bit of the crust you have left from the bread, and sauté them gently in olive oil, turning as they brown on each side. They can be eaten warm or cold they are great either way.

The string beans would be boiled and marinated with vinegar, oil, garlic, and basil to be eaten cold or tossed into a salad with the fresh, crisp lettuce, and tomatoes. For zucchini, the recipes are too numerous to mention. A few that come to mind: zucchini frittata, cubed zucchini and celery simmered in a tomato sauce and, at the last minute, a couple of beaten eggs poured into the bubbling sauce; or as one of the ingredients for a beautiful summer minestrone.

Of course, there were foods to be had for the picking without the labor of planting and cultivating these were to be found growing wild in the fields and countryside surrounding our city. There were tender dandelion greens that had to be picked early before they became too tough for salad, and wild mushrooms. However, I remember every year hearing of some family who suffered a tragedy because they had eaten the wrong mushrooms. I knew personally of one paterfamilias who had his wife eat the mushrooms several hours before he did!

Fish, unlike today, was abundant and inexpensive, but most of the time we went out to eat fish. There were many little Italian restaurants that specialized in things like clams, mussels, or calamari with a fiery hot tomato sauce, or scungilli (conch) either in salad or in the hottest of tomato sauces served over biscotti – hard, toasted slices of Italian bread. My father taught me to eat raw clams on the half shell, with a drop or two of lemon juice or hot sauce, when I was very young.

My father’s tastes and mine were similar, and he enjoyed giving me new surprises in foods. But there was one I did not appreciate. It was during the Easter season, and he took me to our local pastry shop where we had a dish of delicious pudding with candied fruit and pignole nuts mixed into it. I thought it was chocolate pudding, but he later informed me it was made of pig’s blood.

We did eat meat – mostly chicken, veal, or sausage; beef was used primarily to make meatballs or brasciola . The chicken was served in many ways, but it had to be a fresh killed chicken. My mother and I spent part of Saturday afternoons at the chicken store, where she poked at the squawking fowl crammed into their cages. When she made her choice, the poor bird was unceremoniously hung by its feet on the scale. Sometimes at least four or five chickens had to be poked and weighed until one was deemed satisfactory. Then the bird was taken into the rear of the shop and would reappear shortly thereafter, plucked and cleaned. I really hated the chicken store, but that did not affect my enjoyment of chicken. It underwent such a transformation in our kitchen into soup, or as a beautiful roast stuffed chicken, or broiled with a marinade of lemon, oil, oregano, and garlic.

Veal was another versatile meat for us. While the cutlets were favored, a breast of veal was also very popular. In was called panzetta. The butcher would cut a deep pocket in the meat, which was a long, flat piece of veal. This was stuffed with a bread, parsley, egg, and cheese mixture, then roasted and sliced.

I suppose pasta was the villain responsible for padding us so well. Most Italians must have their pasta at least once a week, preferably twice. A few of the old-timers insisted on it every day. There was such a variety of sauces that we never tired of it. I still love to make noodles it is so easy. A few cups of flour, eggs, salt, a few drops of oil, a little water, and a lot of kneading until the dough is elastic and smooth then rolling it out so thin, nearly like strudel dough, folding it, and cutting it to the desired shapes.

Asshegotolder,mymotherturnedthejobofrollingthedoughovertomyfather,and eventuallyIboughtherapastamachinewithanelectricmotor. It’stheoneIusetoday. Thegardensherecalledwashergrandmother’s,takingupnearlyeveryinchofspace behindalittlehousethatwasthelastresidenceinPaterson,NewJerseywithout electricity. Irememberitasmostlyweeds,withafewtomatoplantshangingon. My greatgrandmothermuststillhavebeenmakingsauce.

Parisismostlyacityofmemories, leftoverliketheabandonedsteamertrunks inthecellarsofthegreathotels -theRitz,GeorgeCinq,theCrillon...

By Kendric W. TaylorThe old man at the corner table had been watching for some time. I had noticed him earlier because of the likeness to photographs I recall seeing of Lloyd George, the British prime minister during the Great War. It was as if George had stepped out of a quiescent rotogravure from the 1920’s into this Parisian bistro. The place itself was a relic, aged, dark, smoky with the reek of too many Gauloises, an old fashioned zinc topped bar in the rear. A white mustache and van dyke beard adorned the old man’s face; a halo of white frizzy hair touched the dark fur collar of

his overcoat. He wore an old fashioned, wide brimmed, black hat, almost like that of one of the many artists who had once frequented this arrondissement. He sat quietly sipping his cognac, leaning forward occasionally, his hands gripping the cane between his knees, almost as if he were gently exercising. Finally he spoke in English across the tables:

“Colonel Lawrence?”

“No, I’m sorry.”

“Of course. You resemble him but slightly. The late Leslie Howard did more so.”

“The movie actor from the 1930s?”

“Yes,” the old man replied. He paused, then asked: “May I join you?” motioning to my table.

I could hardly refuse. I had nowhere to go in particular, and for once felt less like being alone.

“Thank you,” the old man answered. “Do you mind?” He rose slowly and moved his glass to where I was sitting, gracefully shrugging his overcoat from his shoulders and placing it carefully over the wire back of the wood bottomed chair next to me.

Our voices echoed softly past the vacant clutter of the afternoon; the doors of the establishment tightly shut against the chill on the avenue outside. We were alone, except for the propriétaire , sitting in shirtsleeves on a stool at the bar, working over an account ledger.

“I am grateful for the company,” the old man continued, “and you speak English. Usually at this time of day, it is quite empty here.”

I nodded back with a slight smile: late afternoon had always been a favorite time to drink. It generally led to headache and an early evening, but I liked the feeling the alcohol provided, and how good the music sounded playing on the jukebox.

“Were you speaking of T.E. Lawrence?” I asked. “Yes.”

“Lawrence of Arabia? You knew him?”

The old man leaned back, his glass empty, a subtle hint that a refill would be welcome. I caught the eye of the owner for two refills and waited for my new companion to continue. “Yes, I knew him at Versailles in 1919 at the peace conference. I was a junior diplomat. He was here with Prince Faisal. Lawrence wore his army uniform and an Arab headdress. He looked exemplary, although the British delegation were restrained in their enthusiasm.”

I sat looking at him. He sipped slowly, wiping his billowy white mustache afterward with great care. His hands were long and tapered as they fluttered over the long silver handle of his cane; his nails were clean. An exquisite looking signet ring adorned the little finger of one hand. A pair of yellowed kid gloves was folded exactly on the corner of the table next to him. He wore an old fashioned high collar with a narrow black tie, which only added to his aura of an ancien boulevardier . I wondered if spats completed the ensemble, but it would have been impolite to look under the table.

The owner brought the new drinks, adding two small dishes to the few he brought from the other’s table, completing to what now seemed to have become my

accounting. “Ah monsieur, you cannot imagine the excitement here in Paris at the end of that terrible war the crowds in the streets, the rejoicing even well into 1919. Some say, it lasted even into 1929. At the same time, of course, the wounded, the blind and maimed, they were with us, and yes, and even those who would never return.

“I read once,” I said, “ that, later, in England, in the 1930s, after Lawrence had renounced fame, he would sometimes turn up under his new name at fashionable cocktail parties. Of course, everyone knew who he was, and he knew they did.”

“And they knew he knew it, “the old man replied. “I’m sure he quite enjoyed it. Brilliant mind, though bizarre. I had forgotten he had passed on. He did bear a resemblance to Leslie Howard. Or possibly I mentioned that.”

I looked across the table thoughtfully, my mind adding and subtracting dates. Was he fooling with me, I wondered: “Have you been reading Hemingway by chance? There is a story where an elderly man discusses Lawrence with an American, at a railway café. Do you know Hemingway?”

“No. Proust.”

“I mean did you know of Hemingway,” I attempted to explain: “wait excuse me you knew Marcel Proust?”

“Oh yes. He would dine often at the Ritz. Book a chambre and have his meal served there. He was quite eccentric you know. He would send his man over from his apartment for a bottle of Ritz beer, which he liked.”

“Well, Paris is a literary Mecca,” I conceded. “So I guess it’s possible; but so long ago. How could you . . .”

“Yes,” the old man continued without stopping: “I introduced them.”

Now what, I wondered: “Who? You introduced whom?”

“Lawrence. Proust. We sat in this same bistro late one afternoon for an apéritif . It was a fashionable location at the time. It was very crowded. Lawrence caused quite a stir. Proust was nervous and did not look at all well. Our waiter was a slim Tonkinese, who obviously knew who Lawrence was. He kept trying to catch his eye, but Proust was immersed in complaints about his health, dominating the conversation. This was no easy task, as Lawrence always demanded his share of attention.”

I was getting the hang of it now, and settled back in my chair: “Don’t tell me about the waiter: Ho Chi Minh.”

The old man’s countenance brightened: “I am impressed. I forget what name the waiter went by, but exactly so. Ho lived in Paris in the ‘20s. Two pure revolutionaries from opposite sides of the globe and cultural spectrum as well. I often wonder if they had been able to converse Lawrence of Hanoi, perhaps.”

“Who left the tip?”

“A jejune point,” the old man smiled, “but I did. Certainly not those two.”

“Your English is excellent,” I said, overwhelmed by all of this.

“As is yours, “he replied, nodding slightly.

“Hah, well, I have the advantage: it’s the only language I know.”

“Just so. Of course, my mother was English,” the old man explained, “although I have not lived there for many years.”

“Do you remember much of England as it was?”

“My great grandmother once told my mama that her great grandmother’s most luminous memory during a long life was as a young girl seeing Charles the Second walking with his spaniels through the streets of Oxford. The child would curtsy, and the dogs would swirl around her for a moment, before chasing off to follow their master in his progression down the thoroughfare.”

“My God,” I said, having trouble with this one, “that was the late 17th century.”

“Exactly so. Your knowledge of history is excellent -- for an American,” he offered kindly. “It is said you are a people with no history, and, as I have heard as well, no appreciation of history.”

“Well, I’m English by heritage,” I explained. “Anyway, it looks like you’re a living link to Charles the Second -- so to speak.

“Actually,” I continued, “I had a relative, who had a relative, and so forth, who was widely known as the last living person to have shaken hands with George Washington.’

“Formidable! Another living statue, I see,” the old man nodded toward me with a small smile.

“Yes, our link to the past.” I was all in on this now: “Beg pardon, but back to your encounter with Lawrence and Ho: could it be possible in the kitchen that day, George Orwell was there arm deep in dirty pots and pans,” referring to Orwell’s description in his book, Down and Out in Paris and London.”

The old man’s eyebrows rose quizzically above the white moustache: “Hardly. He would have been still a schoolboy at that time, wetting his bed at night. But in the same book, he describes living rough here in Paris in the Latin Quarter, although he probably makes it sound worse than it was. He relates seeing Joyce sitting outside at LesDuexMagot one day, but was too shy to approach him. “

This was perfect: my imagination couldn’t let this one go by either: “Wow, imagine Joyce, Proust, Orwell, perhaps Hemingway, even Ezra Pound, all at one table, your own good self there as well a literary frieze.” I was tickled pink conjuring this: “And there’s our friend Ho, waiting on them, trying to coax a tip out of the bunch,” I added excitedly.

It was the old man’s turn to peer sharply at me: “Do you often get carried away thus: you have a vivid imagination; even for an American.” He shifted slightly to gaze thoughtfully through the open white curtains of the large, plate glass window, the late afternoon sun burnishing the brass rods into gold.

He slowly turned his attention back to me: “But it is true, soon after the war, in the ‘20s, artists and writers and composers of all stripes from all over the world began coming to Paris, attracted by the cultural and sexual freedom, and not incidentally, the low cost of living. In those vibrant days, it was possible to attend a ballet or opera, with music by, say, Stravinsky or Ravel, librettos by Colette, and sets and costumes by Matisse or Picasso.

“Of course, that was long ago,” he continued. “At my age now, Paris is mostly a city of memories, left over like the abandoned steamer trunks in the cellars of the great hotels -- the Ritz, George Cinq, the Crillon. One unlocks them both with care, each one releasing a remembrance of youth, of love, adventure, disappointment . . .”

He had me again: “Steamer trunks?”

“In the grand hotels of Paris, these items were once labeled consigne how do you say ‘left luggage,’ because of the wars. Now they stand guarded by chicken wire and covered with dust, deep in the hotels’ catacombs, like lost magnums in forgotten wine cellars: ungainly artifacts from another age, ghostly sepulchers of mémoire.”

Now it was my turn: “Your gift for ripe metaphor, matches my imagination,” I said, not unkindly.

“Ah, you’re a writer,” the old man offered.

“I have a small literary magazine, yes,” I demurred. “ But please, how did they get there,” I urged, “the trunks?”

He leaned back in his chair, the polished handle of his cane resting against his waistcoat: “There were many reasons. In August 1914 the Germans were only 20 miles from Paris. The government and the tourists had fled in panic, the latter abandoning their bagage , likely forever. Our salvation came in the form of the Paris taxis, when the Poilus were rushed out of the city in taxicabs to halt the invader: “The Miracle of the Marne,” it was called.

“Then, in June of 1940, the same thing occurred, only this time the Germans did arrive (one admires them for their deadly persistence), and again the tourists fled.”

I took a moment to visualize the trunks, keys lost, and locks rusted, stacked neatly and forgotten, some sitting undisturbed for decades, their peeling stickers the last hurrah of the grand hotels, the fashionable spas, the luxury ocean liners that no longer existed.

“But wouldn’t the owners have sent for them later?”

“Improbable . These were not people who worried about old clothes. They would merely purchase new wardrobes. Assuredly they took their valuables with them.”

“But the hotels -- why didn’t the hotels dispose of them?”

“A good hotelier discomfits no one; certainly such elevated guests. And, perhaps the patrons might indeed one day return.

The old man paused suddenly: “There is one that will never be reclaimed. One that belonged to my one true love. Inside, along with her wardrobe, were my letters, and a modest pearl necklace,” he continued, “but expensive, of good quality,” he added.

I was almost afraid to ask.

“Whose trunk was it,” I inquired in a small voice.

He looked at me silently for a long while, his brow furrowing, his breath halting. A small eternity passed: then the name came whispering across the table, each word seeming to carry immense pain; divulged sadly, as if the old man had not spoken them aloud for decades: “Mata Hari.”

He paused. I sat there speechless for a moment: “The spy? From the Great War?”

“She betrayed many people. Still, foolishly, one hoped . . .”

My nose itched terribly. My mouth opened, then closed, unable to form an intelligent question in the face of such a drama true or not. I could hear every sound outside on the boulevard, while all was still within the café. I looked down at my drink, sipped from it, then replaced the glass on the damp tabletop. Finally, I

started to speak, but the old man raised his hand, not impolitely. I knew there would be no further explanations.

“But what of you,” he asked. You have been to Paris before, if I may observe. But you do not seem to be enjoying it.”

“Yes. No. Paris once was magic for me, but I made the mistake of sharing it with someone whose interest had moved on, without bothering to mention it to me. ”

“Ah, une affaire de coeur,” he nodded sagely, “Yes, it was a messy ending it took its toll. So I thought perhaps a change of scenery, as they say, might help . . . The first glimpse I ever had of Paris was arriving at the Gare du Nord. It was March, and stepping outside, the trees were already green. I didn’t expect that. It was beautiful, the streetlamps shining through the leaves down the avenue.”

“Yes, quite so.”

“It’s funny,” I said, “a private investigator told me once that every hour somewhere in the world, there is always someone screwing someone else over.”

The old man smiled in reply, sipping at his cognac.

“So you are alone now?”

“Yes.”

“But there will be someone else, no doubt?”

“Oh yes, I would hope. Maybe I will be smarter next time. Or if not, I’ll come back for the trees.”

“There are worse reasons.”

. . . asuperbbarometerofhowpeopleview theforcesbumpingtheirlivesaround

Since ancient times, new beginnings that’s carnival. It’s our craving to shuck memories of the slings and arrows that paralyze us. New Year’s resolutions disappear in the first head wind, but carnival has been serious about new beginnings since the Greeks partied to praise Dionysus, and the Romans thanked Bacchus for wine and flora, fertility heavy on their minds.

Murdered by Titans, Dionysus/Bacchus was reborn. His worship generated irrational exuberance, frenzied revels by women, and much early theater and standup comedy. When condemned by Rome as a sinister source of vice and revolutionary unrest, the frolic was periodically rejuvenated by slaves and poor free men.

These traditions celebrating man as a free being without hierarchy blended easily with the various pagan rites of spring practiced by Germanic and other tribes. The Church tried to suppress carnival but ultimately decided if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em, layering on compatible beliefs as they co-opted the locals. Carnival, or carne vale, comes from Latin, and means “flesh, farewell,” as Carnival heralds in the Lenten fast that leads to Easter. The mix with local and aboriginal beliefs creates an amazing array of traditions, extending to the New World and locales as far flung as India.

Most Americans know Carnival through New Orleans Mardi Gras, or through Rio or Trinidad, but the roots are firmly in Europe.

Napoleon and Hitler banned Carnival, but its anti authoritarian roots quickly grew back. For years I’ve shouldered the task of chronicling carnivals across different cultures a sense of duty. With anti authoritarian and satirical roots planted by the ancients, Carnival is a superb barometer of how people view the forces bumping their lives around, as well as of the U.S. image abroad. Carnival jabs are thrown throughout the world. My first carnival was in Cologne, Germany. Barely a month after the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke in 1998; I nearly kicked my camera off my balcony, lunging for it as a masterpiece of German engineering rounded Koln Cathedral. A grinning Bill Clinton, big as a Mack truck, groped a peeved Statue of Liberty, followed by a padlocked White House atop which stood Uncle Sam throwing blood sausages to a crowd roaring approval. They could take a joke even if a finger wagging Joe Lieberman and members of the pious press couldn’t. Germans couldn’t understand America’s mania over this fiasco as more pressing worldly concerns tumbled into the fire. One sojourn included sleepy towns in Portugal. In Torres Verdes, the centerpiece not a float, the centerpiece was called “Bushlandia.” Artfully rendered, five or so stories high, the sculpture offered up the President George W. Bush as a primitive king in furs, wielding a jeweled club and a scepter with a golden skull. He wore a crucifix on which was a soldier. Bush sat within the jaws of giant skull beneath the crown of the Stature of Liberty, about which crawled wormy critters in turbans. Other heads of the coalition of the willing — old Europe, new Europe, always confusing were in his court. Prime Minister Tony Blair fanned Bush with feathers and scratched his backside. On the sculpture’s flip side, a bearded fellow hauled a wheelbarrow of explosives. Beneath him a government minister struggled to feed the world’s poor

children. Nuclear missiles flanked Bush. Penguins blew time out whistles as toxic waste washed over nature. To the beat of Brazilian bands amid the samba gyrations of hotties, all revelers passed before Bush. A small town in Portugal made a colossal comment on U.S. leadership. Until Trump paraded in, no one brought out the foreign carnival knives like Bush following his invasion of Iraq.

Perhaps the fastest punches are thrown in Basel, Switzerland. This unique Protestant take begins in a blacked out city at 4 a.m. the Monday after Ash Wednesday. Thousands of costumed pipers and drummers accompany huge gaslit lanterns, painted with satirical images of political figures and issues of the day. A carnival favorite, Silvio Berlusconi — likened to a hybrid of the Godfather and Benito Mussolini, running his media empire like an Orwellian villain will no doubt once again be prominent. The Swiss miss Bush, another favorite — and boy did they work him over but while Bush now keeps a low profile, Berlusconi still continues to offer up new material.

Unless the pandemic(s) rise up so much that revelers beat a retreat into another pandemic coma, imagine the worldwide pent up Carnival energy waiting to explode. The gatling gun of topics occupying Carnival’s collective mind are reloaded in perpetuity. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir the Underwear poisoner will at least deflect some of the ire that would normally be awaiting the US. Recently Trump was mercilessly pilloried through Europe. The Covid variants will likely perform, one way or another. Imagine Saudi Arabia’s MBS as a coroner with a chain saw, or China’s Xi going after Taiwan, the little island country portrayed as a maiden whose refusals to a boorish Xi fall on deaf ears, as a Hong Kong maiden looks on in terror.

If the small towns in Portugal can use Carnival to speak truth to power, why can’t

Washington? The threat of ridicule at Carnival might rein in excesses, perhaps an invasion, a war without end.

A modest proposal: bring Carnival to Washington. The city may not have the religious roots of many carnival strongholds, but no place can fake religion like Washington. Imagine Carnival’s potential in the nation’s capital. True, it’s a challenging venue where fewer people can take a joke and images are often decided by consultants, bipartisan grifters with multiple masters. On the other hand, we’ve no shortage of folks willing to play the fool. Everything old is new again. Washington’s potential never runs dry.

Some things challenge humor’s sensibilities. It’s a fine line between humor and pathos. Satire can only sustain so much

tragedy before it turns sour. There’s not much to be done with an apartheid state practicing brutal ethnic cleansing, for example, that isn’t pulled down by reality. But consider carnival’s pagan roots, the rites of spring chasing the winter demons, to hopeful fertility, to planting anew. Carnival remains irrepressible despite authority’s many stompings over the centuries. When Carnival collided with the Church, it softened with themes of redemption and renewal. The carnival spirit, burned in effigy, departs taking the woes of the year, leaving all with a clean slate. Has there ever been a city more in need of a spiritual cleanse than Washington?

The villagelayout,whichchangedfromyeartoyearbasedonwhim, wouldalwayscatertoasenseofflowandnarrative.

Story & Photos by John H. OstdickThe Village of Madelineville had a modest start as an early family Christmas gift of two incongruous ceramic homes, one in the Southern Plantation Style, the other a Connecticut Dutch Colonial.

These two structures, lit by bright white bulbs inside, found a place high on the living room mantel of a small cottage in Dallas, Texas. That Christmas season, the village’s municipal jurisdiction stretched merely four feet long and eight inches deep.

In the years that followed, Madelineville (for its first years it was simply “The Village”) became more than an annual smattering of

ceramic pieces. It became a tradition, a springboard of imagination and joy — and of enthusiastic expansion. Each passing year, additional characters and new structures entered the scene, often with a certain whimsy that featured an eye for fun rather than architectural or time period symmetry. One local retailer supplied many of these; my wife, Michelle, and I found others at roadside distractions during scattered travels across the country, and/or during what we referred to as “time traveling” in the state’s collectible parlors. The seasonal town relocated from the mantel to a grouping of tables, and its

spread gained a couple of feet in each direction.

As the rich aroma of Thanksgiving turkey started to dissipate each year, like clockwork a series of muffled grunts and salty language escaped from the tiny utility room off the kitchen as I balanced awkwardly on a step ladder and stretched out to retrieve the town materials strategically packaged and crammed on shelves above the washer and dryer. Repeatedly I stepped down, ferried a couple of boxes to a small room between the kitchen and the living room, and returned for more until the floor was littered with them.

I embraced this ritual, following a couple of caveats I enforced. I was very ill for my first several Christmases, hounded by seasonal croup that relegated me to bed or dispatched me away from the festivities to a spot on a distant couch. After the doctor explained that the fresh cut Christmas trees were the annual culprits, my allergies cursed the family with a fake silver tree each year. Nonetheless, freed from my affliction, Christmas became even more important to me — especially after becoming a parent.

My early pledge held that The Village, while ambitious, would never envelop our little “Mouse House,” as we called it. The Village layout, which changed from year to year based on whim, would always cater to a sense of flow and narrative. As a writer and editor, the idea that The Village could both retell and remake holiday stories each year (and additionally inspire the creation of a

different tale to anyone who might approach it) charmed me.

Although my son, Hunter, never took any interest in the process, from her earliest years my daughter, Madeline, would drag a dinner table chair from two rooms away and perch in front of the village, studying every detail. She moved some of the characters to match a flow she perceived proper. Before long, she began naming the characters and creating backstories for them. When I realized what she was doing, it affirmed my narrative ambition for the town. I didn’t ask her to share the world she had created, at least not until years later, because I wanted it to be her personal treasure.

Although I didn’t realize it, The Village magic touched others who visited frequently during the holidays as well. One of Madeline’s best friends on the block, Bolton, would enter The Village in her own way. She identified a single skater on the ridiculously small skating rink (a circle of reflective plastic) as “Madeline,” and grudgingly identified a girl figure who was part of a skating duo as herself. “I would always want to be on my own, but that silly boy was always following me,” she would tell me years later, laughing.

The amusing detail about the two girl skaters is that they were identical twins in appearance (I considered this a laziness by the manufacturer of the skating set). And blond. Madeline had dark hair. If I had known Bolton’s narrative, I would have purchased another single female skater and painted dark hair on her. Luckily, imagination has no limits. When, as a young adult, Bolton shared this skater quandary with me, I immediately added another single female skater to the mix, ending that silly boy’s long pursuit. The need to paint one of them dark-haired was long past as well, as no one involved even noticed their blondness any longer.

The third Village player, fast friend to both Madeline and Bolton, was Meg, also bright and full of life. Meg never told a long story in her life not that her tales were not intricate and detailed, but rather as a youth she delivered every word in her life as if it had just crested the world’s tallest rollercoaster and was headed pell mell downhill. She danced from notion to notion like a bee, pollinating everyone’s thoughts in the room. Maybe she intuitively realized all the ground she had to cover in her life; fittingly, she eventually would be a historian.

I never figured out where Meg fit into The Village populace, although I imagined the three girls settling into a row at The Village theater, a recreation of New York’s Radio City Music Hall, feeding their voracious appetites for movies.

Whenever Meg entered the cottage, she would stop, take a deep breath, and smile serenely. “Mrs. O, your house always smells delicious,” she would often say. Indeed, the air was usually filled with intoxicating aromas. Everyone thought it fitting the year Shelly’s Café and a neighboring small bakery joined The Village menagerie (Michelle was a trained Pastry Chef by this time). I could imagine Meg sitting at a counter stool, legs swinging gently while enjoying the diner’s redolence.

One year brought the addition of an homage to children’s book author Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline character, a house favorite. (She was the inspiration for naming our baby girl Madeline.)

An adult woman, a la the story’s chaperone Miss Clavel, led a group of similarly dressed little girls:

In an old house in Paris that was covered withvines, livedtwelvelittlegirlsintwostraightlines Theyleftthehouse,athalfpastnine... The smallest one was Madeline.

In our Village’s case, there were only four sets of two girls, all the same size. But one held a balloon floating above her. This time, it was my turn to develop a backstory, if somewhat obvious. The balloon girl was Madeline. As in the book, all the unnamed classmates wore flat sailor hats and identical coats, but Madeline stands out, not because of the way she looks, but because unlike the other girls, she is utterly fearless.

Whether that was the case or not, I thought of Madeline as fearless as well. Sometimes, I would even find myself talking to the balloon Madeline as I passed The Village, especially as my daughter grew older and was away from the house more often. It was during this time that I morphed The Village into Madelineville.

Once Madeline eventually slipped away to college, we sold our little cottage and moved to a ranch-style abode that offered room for Madelineville to spread “putting a little more air in the landscape,” as I described it at the time. I constructed a simple plywood base with two-by-fours for legs and draped it with white cloth. The two level town enjoyed a renaissance of sorts.

Since that point, we have settled into a comfortable pattern. Each year, I painstakingly conjure a slightly different vintage. Most often, the off beat collections of homes occupy upper Madelineville, and the theater, churches, stores, and skating rink the lower expanse. A ski slope, with two moving

skiers, forms the left border of town. The theater and firehouse most often hold down the right side. A gondola car hovers on an overhead cable. Pragmatic whimsy fills in all the rest.

After I finish, I text images to Madeline, who stayed in New York after graduating from NYU. She replies with praises, and occasional suggestions for changes. She zeroes in immediately if I try to eliminate one of my lesser favorite items, such as the four figures representing the three fictional Christmas Spirits who visit Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1843 novella A Christmas Carol , and demand that they return. (The characters just never seem to fit, even on this whimsical canvas, I futilely say.) When Madeline shared my Village snapshots with Bolton one year, she asked if I would start sending her a preview image each year.

Madeline’s annual return home for Christmas is a joyous event. Madelineville’s shimmering lights burn for most of the time she is there. Although she never calls it Madelineville, The Village is part of a holiday pact with me, a connection that spread to others but remains our own. Then she returns to her evolving life.

After New Year’s Day each year, I methodically deconstruct the town. The structures are tucked into their fitted boxes, the figures first wrapped in cloth for protection and then carefully stowed away as well.

The last building to be packed away is always the theater, where I imagine that the three girls sit watching old black and white holiday classics until the curtain falls. The three young women, living in three different states, remain fast friends.

The last characters retired each year are the skaters and Miss Clavel and girls in two lines, and finally Madeline, the little girl with the balloon.

With each passing year, I realized the time would come when Madeline would stop coming home to The Village. Each year, I hoped that year would never come. It took a society crippling pandemic in 2020 to stop her. Madeline was determined that she would not bring a virus home to her parents, so she experienced the Christmas 2020 Madelineville, and the rest of the year’s holiday events, by Facetime or Zoom.

Everyone adapted. I erected a reduced version of Madelineville, because somehow the need for the full Village seemed less robust without Madeline. Fortunately, her brother, Hunter, who lives in town, came by and three fourths of the family had a lovely Christmas Day. Among the many virtual events Madeline creatively shared, she and I watched a streaming movie together (in honor of the annual Christmas Day theater movie that was also part of our tradition).

During the past few years, Madeline had mentioned that while she was growing up she had created various stories for The Village residents, and I urged her to write about them. This made her uncomfortable, however What I didn’t fathom was that the stories I imagined her developing as a youth no longer suited the adult Madeline and her life experiences. In 2020, without telling me, she labored over an adult adaptation that flowed from her many years of Village life. She presented the resulting short story, titled simply “John’s Village,” to me as her Christmas present. Frankly, her creativity overwhelmed me.

After New Year’s Day that year, retiring The Village was a little less structured. I felt the tradition had turned a corner as I put the Madeline character to rest for another year. My Madeline may not be home for every Christmas, but she will always be in Madelineville.

shewasnowsure, AmodernAmericanfairytale . . .

Nestled high up in the heart of the Sawatch mountains of Colorado sits a small town, which at one time sat, largely untouched by time, until 1956, when it was pulled, quite against its will, into the modern era. It was pulled because it was “discovered,” as much as a town can be discovered when it has existed for decades to the people who already reside there (an inherently American story). Like most of the great American monuments, it established itself as a day trip on a much larger journey, a footnote in a guidebook. For many who knew of the town or passed through its unpaved streets, that’s all it ever really amounted to just a blurb in a hardcover motorist’s book. But to the people who built it, it represented the manifestation of a collective spirit that blanketed the town as easily as its regular snowfall, touching every crevice, blessing every brick.

Initially erected in the late 19th century to provide the most threadbare of accommodations to miners who plundered the nearby mountains for gold and silver – the settlement all but disappeared, as poor-quality ore drove the industry from the area in the first decades of the twentieth century, despite its placement on the Denver, South Park, and Pacific Railroad lines. The makeshift structures fell apart in the harsh winter elements and the town’s numbers dwindled. The country sank into The Great Depression and any construction, mining, and logging jobs that could be found in the area evaporated. In 1935, as part of his Second New Deal, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the Works Progress Administration, an agency dedicated to the creation of public works projects largely related to public infrastructure that would require the employment of millions of out-of-work laborers. At its peak, it employed three million men and women, ultimately leading to the creation of 40,000 new and 85,000 improved buildings nationwide. Its long reach would extend up the mountainside of Colorado where the former mining town sat, all but smudged out of existence.

Against all odds, the perverse little tribute to that most American ideal – Plunder –received a second life, deviating drastically from its origins. Under the WPA, the town received funding to build a humble mountain lodge, dubbed the Underwood Lodge, after its architect, who also designed several lodges within the national park system. The idea was to create a recreational facility that could be used by the community –infrastructure developments undertaken under the umbrella of the agency included such things (like tennis courts, parks, community centers, auditoriums, zoos, and botanical gardens) that a harsher society might deem inessential and let fall to waste. The humble mountain lodge would provide an opportunity for winter sports like tobogganing and skiing and drive tourism to the starved region (at least in theory), and construction on it promptly began in 1936. Laborers flocked to the area with the promise of steady, paid work, bringing craftsmen and artisans and experts in a wide range of additional fields – to build and furnish these spaces. Writers further employed under the Federal Writers’ Project, a subsect of the WPA, carefully documented the construction of the building, and by extension, the area’s transformation from Ghost Town to nascent ski village. Many of these workers, displaced from urban centers and disillusioned with city dwelling, did not leave when work was complete, captivated by what they created.

In evocation of the American Arts and Craft style of the late 19th and early 20th century, which lauded the aesthetic and technical potential of the applied arts, the Lodge was designed with a keen understanding of the importance of individual craftsmanship, which many with left leaning philosophical values felt had been warped by industrialization, with mechanization creating a dehumanizing distance between designer and manufacturer. Many of these craftsmen were young women, who were taught the decorative arts in urban center training programs and schools. Laborers –skilled and unskilled took up residence in a nearby tented city and rotated shifts to provide work. At one time, a hundred construction workers were onsite, including many Italian immigrants, who worked on similar projects in the area.