6 minute read

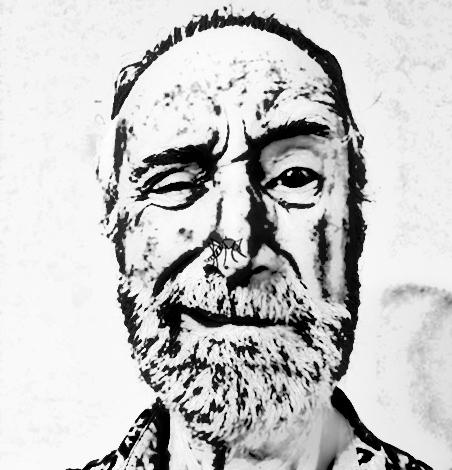

Waaaaht? Wanna Buy a Blender? Malcolm P. Ganz

There wasa kind of subcontracting crew for the shoe store manager’s “other business.” By Malcolm P. Ganz

Advertisement

During one of those writer interludes when even your go-to editors have gone, I took a job selling shoes at a store on 14th Street in Lower Manhattan. At the very least, I needed rent money for my apartment in the East Village, vital to my preservation of independence. Fourteenth Street was the northern terminus of the Lower East Side, a neighborhood that, through the years, has been the first home of various immigrant groups. During this particular period, it belonged to Hispanics, the vast majority of whom were hard-working people, making their way in their new-found home country. There were also a select number, who had been recruited as a kind of subcontracting crew for the shoe store manager’s “other business.” He was a fence. In deference to a need for anonymity, let’s call him Sonny.

“You wanna buy a sweater?” he asked, barely an hour into my employment. “Cashmere. Right off the rack. Never been worn.”

“We sell sweaters here, too?” I replied, confusedly surveying the store for the men’s clothing section.

Sonny grimaced at my reply. He gave me his boy-I-got-a-live-one-here look, then said, “let’s just say it fell off a truck.”

“Oh.”

He produced the sweater from a small back room, which looked like a haven where employees could slip away for a moment’s seclusion when the store was without customers. The sweater was a beautiful, buff-colored pullover. “Feel that,” he said holding out one of the sleeves. “I’ll let it go for forty bucks. Cost you three times that at Bloomingdales, if and when they ever get their replacement shipment.”

I was only making two hundred dollars for two days work at the time, but even at almost half my day’s pay, the sweater looked and felt so good, the price was tempting. Nonetheless, I passed.

“There’ll be others,” he said and returned the sweater to the back room.

For the most part, Sonny kept me apart from his extracurricular business dealings, particularly the front-end negotiations with his “suppliers.” But occasionally I was exposed to that end of things. One evening when Sonny left the store in my hands while he took a dinner break, a particularly sinister-looking guy came in hoisting a large cardboard box.

“Sonny in?” he inquired, playing with a toothpick in the corner of his mouth, which was the southern terminus for a scar that ran up one side of his face and down the other.

“Dinner,” I said.

“I’ll wait.”

He plopped the box down on one of the customer seats and took the one alongside.

I had to know, of course, so I asked, “what’s in the box?”

“Sweaters.”

Clearly, he was a man of few words.

“Can I look?”

He leaned sideways and unfolded the four cardboard flaps to reveal the contents, then slid back down into his seat again. Stacked inside were mohair sweaters, very popular at the time, and expensive. At Bloomies, it would cost me a day’s pay. On top was one in a soft rust color. It sang to me.

“May I?” I asked.

He nodded.

I removed the sweater and tried it on. Perfect fit.

“How much?” I asked.

He studied me a moment, as if trying to discern my net worth. “Gimme twentyfive,” he replied.

I almost swooned. A seventy-five percent discount on top-end merchandise is tempting, even if it cuts into the rent money. But watching Sonny work for a number of weeks by then, I knew he never dealt without negotiating.

“I don’t know,” I said, shaking my head. “It’s nice, but --”

“Twenty,” he said, curtly.

Way to work it, Ganz, I thought. I wandered over to one of the full-length mirrors to get a more-admiring look at myself, wherein I noticed a loose thread hanging from the seam at the lower edge of the sweater. “What’s this?” I said, fingering the thread.

The sweater salesman pushed himself to his feet and advanced on me, during which he reached into his back pocket, removing a stiletto, whose blade sprang into place as he came alongside me. With one lightning swipe, he removed the dangling thread and set it free to float harmlessly to the floor. “What’s what?” he asked. “I don’t see nada.”

I quickly removed my wallet, fished out a twenty and handed it to him. He returned to his seat to wait for Sonny.

By the time I’d started getting regular writing gigs and moved my abode to airier climes on the periphery of the city, Sonny’s “other business” had grown to the point where he needed a storage facility to hold everything from small kitchen appliances to color TVs.

Our story moves to a couple of years later when, with my steady girlfriend, we found ourselves on the Lower East Side and I asked if she’d not mind my stopping by to say hello to Sonny. She’d heard the stories about him and agreed with a smile. As we entered the store, Sonny emerged from the back room grinning from ear to ear.

I had barely finished the intro of my girlfriend, when he asked, “You guys got an apartment together? You wanna buy a bedroom suite? Complete set: headboard, dresser, armoire, two end tables? Still in the crates.”

“A bit light on cash,” I answered. “You know how it is with freelancers who have to work in shoe stores to pay the rent.”

“Make you a great price,” he replied.

“I’m sure, but no can do.”

Undeterred, he countered, “You wanna buy a blender?”

I looked at my girlfriend who was giving me hernada look, so I said no thanks. We had a bit more of a chat, then left.

“We could use a blender,” I said after we’d left the store.

“I know,” she replied and let the conversation fade away.

It was another year before I found myself in the neighborhood once again. By then, my girlfriend and I had moved into an apartment and we could use any number of things Sonny sold at cut-rate prices, so I headed for the shoe store. When I walked in, I was met by an unfamiliar character in a drab suit and a striped shirt with a badly matched tie. I asked about Sonny.

“Never heard of him,” the man replied.

“He was the store manager here.”

“I’m the store manager here.”

“Then I’d find it hard to believe you’ve never heard of Sonny.”

The store manager studied me a moment without comment.

“I used to work here,” I said.

Finally, he replied, “Then you’ll understand when I say the company would prefer not to discuss him.”

So, I thought, Sonny was finally communing with the subcontractors under some sort of state or municipal supervision. I guess it had to turn out that way. At first, the thought sent a chill up my spine, then I couldn’t help but smile. From the look on the new store manager’s face, it was clear he didn’t understand my reaction. Sonny would be OK wherever the hell he was. He was a survivor, a player, someone who’d figure an angle. He was an original, an innovator -- to my way of thinking the guy who first understood the potential for off-price-merchandise.

By the time I got back to our apartment, I couldn’t come up with an answer to my girlfriend’s admonition, “He was a crook. You just can’t justify that.”

“I just couldn’t dislike the guy. He was fun.”

“That’s it?” she replied. “He was fun?”

She turned to go back to her chores, then stopped and took a step back toward me. “What’s that?” she asked. “You mumbled something.”

“The blender,” I said.

“What about it?”

‘We should have bought it when we had the chance.”