6 minute read

Reckoning with Personal History Ginny Craven

Reckoning with Personal History

By: Ginny Craven

Advertisement

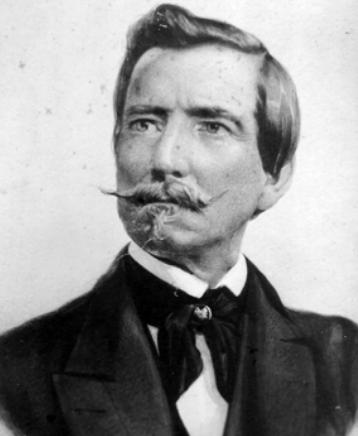

Admiral Raphael Semmes It’s Juneteenth . . . Sadly, I didn’t even know what Juneteenth was until two or three years ago. And, even sadder, I don’t think I’m alone in that ignorance. It seems that, like much of the country, I have awakened to history. And, I have begun to re-examine the narrative that I have absorbed apparently by osmosis – without any particular thought or discernment.

I was raised in Virginia in the 60s. Mine was a genteel existence – romanticized and soft at the edges. The version of history that I got in school was straight out of Gone with the Wind, a hushed reverence for the “heroes” of the Civil War. In high school, I dated a guy that could recite Robert E. Lee’s farewell address to the Army of Northern Virginia. I can still hear that seductive Tidewater drawl. The devoted admiration was embedded in the culture; there was no real malice, no insight, and, amazingly, no perceived racism – just blindness, just deep sleep . . .

These sentiments were echoed in my own family’s narrative. I am just three generations removed from Admiral Raphael Semmes. He was the pillar of the Confederate Navy – still reputed to be the most successful raider in maritime history. He hunted and sank U.S. supply ships all over the world. I have the music and lyrics to a South African folk song, circa 1862, Dar Come Da Alabama, describing the local excitement when his infamous sloop-of-war, Alabama, arrived in Cape Town harbor. Raphael Semmes got around.

I was always caught up in the stories –the dashing admiral with the piercing blue eyes and handlebar moustache. He made history. There is even a certain family resemblance; that jawline is an enduring trait. I was always so proud of this lineage… until I woke up.

I live near Charlottesville, Virginia – a blissfully blue oasis in a red sea. It is an area still steeped in Civil War history, but with a measure of equanimity, an expanded lens on this blight on American history. Then, in 2017, as the statue of Robert E. Lee that loomed in a downtown park was brought into question, this very liberal town was suddenly transformed into the poster child for racial inequity. It made me sad, shook me to the core.

In the summer of 2020, when the U.S. was torn by racial conflict, when it seemed that the old wounds were laid bare, I had a bit of a personal existential crisis. Not to be melodramatic, but it was alarming to wake up with such a start. I am a liberal; I consider myself to be intellectually curious. Yet, most disturbing, I had accepted my family narrative without a question. In fact, my illustrious great-great-grandfather was a traitor

to our country, a slave owner, a protector of the Southern way of life – deifying white men, devaluing everyone else. He fiercely defended the “Lost Cause,” the ideology that claimed the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery.

Reconcilingvs the editorialized

I have reconciled my own story. To be sure, I feel no guilt for his deeds per se, but I am deeply ashamed of my own shallow response. Until fairly recently, I never really considered “true” history – never delved in to explore. To be clear, I believe that history belongs in the past; it is contextual and cannot be judged by modern mores, but the implications are nonetheless grave. It took me most of my life to realize that the stories that I had so readily incorporated into my own heritage were, at best, highly editorialized – white lies, if you’ll pardon the pun. I am interested in my infamous great, great grandfather, whose conquests resulted in an international lawsuit. After the Civil War, the U.S. sued Britain for damages –demanding compensation for the 65 ships sunk by the Alabama, which was built in Liverpool. Still, no matter what perverse selfimportance I had gleaned from his triumphs, I nonetheless took down a painting of him from my guestroom, removed the volumes by and about him, and relegated them to an out-of-the-way bookshelf in my basement. I just don’t feel good about celebrating him.

Then, there is my maternal history – also auspicious, also unseemly. The Scripps family helped to shape media in the U.S. –the Detroit News, UPI, WWJ Radio -- part of an early 20th century Detroit brain trust. They also supported and participated in various inventions. The Scripps-Booth Rocket was an early car with a V-2 cylinder engine, built in 1913. The International DN Class is a type of iceboat. The name comes from the Detroit News, the Scripps family newspaper. The first iceboat of this type designed and built in the Detroit News hobby shop in 1936-37. In 1939, they built a marine engine: Scripps Model 302 Marine V12. I have some photos in my living room – one a gathering on the front porch of Moulton –the “Scripps Mansion,” my great grandparents’ weekend estate. The shot includes Henry Ford, Edsel Ford, Orville Wright, and my great grandfather, William Edmund Scripps, among other aviation cronies. Moulton had an airstrip since WE Scripps was an avid aviator. Perhaps that explains another of my family photos – my grandmother with Amelia Earhart, posed wearing those adorable little 1920s hats. Apparently, Amelia flew a glider on that airstrip in 1929.

These were smart people – innovative people. They had plenty of money and plenty of power. How cool! How much have I swelled with pride at the accomplishments of my famous family, as though their achievements somehow distinguished me. But, then, I looked further. I examined more closely – remembered the stories of vulgar excess. They were entitled, rich robber barons – likely forming the foundation of white supremacy. My grandmother relayed a story of a Christmas party at Moulton – her parents’ home. Her mother-in-law, my great grandmother was known for being a mean drinker, and this night was no exception. Apparently, after several martinis, she took offense at something my grandmother said, and hit her squarely over the head with her diamond encrusted evening bag. Whoa! Bad form to be sure! The next day, my grandmother received a delivery – a fulllength ermine cape as an apology present. Repulsive conspicuous consumption at its finest!

So, who were these people? Were they brilliant? Yes. Were they talented? Yes. Did they contribute? Most definitely. Were they good people? Hell, no!

It is interesting that the cultural crisis in the U.S. has dove-tailed with my own renaissance or reconciliation. Our nation is struggling to separate the great deeds from the character, the contributions from the huge human shortcomings and despicable personal philosophies. So, it is with me. I have felt some level of responsibility – not for their actions, but for perpetuating the myth. It is coming full circle though. What an eerie coincidence that the Alabama was sunk on June 19, 1864 – what would later be Juneteenth. And, on June 5, 2020 in the height of the protests over George Floyd’s shooting and just days before his funeral, the towering statue of Admiral Raphael Semmes was removed from its pride of place in Mobile, Alabama. That seems right to me. The statue now resides in the Mobile Historical Museum – a far less celebrated position – just like the painting that now languishes in my basement. Left to right: Fred Hoover, Edsel Ford(barely visible in the back), Orville Wright, George Hallett, Fred Black, Jimmy Piersol, Henry Ford and William Scripps. The original photo is in the Ford Museum and Village in Dearborn Michigan.

Amelia Earhart(left)with the author’s grandmother, Virginiua Scripps.