PUBLISHED STUDIES

For over 30 years, M&S Technologies has set the standard in computerized vision testing with cutting edge software and hardware technologies. Since our inception, we’ve invested millions of dollars in research and development. This has resulted in comprehensive testing features with unsurpassed accuracy and ease of use in all the products we provide to the field of vision care.

Over twenty years ago, M&S developed computerized clinical trial testing for a leading pharmaceutical company. Why? Because use of lighted chart boxes and paper forms in clinical trials resulted in too many errors and delays.

Today, the Clinical Trial Suite (CTS) provides researchers and sponsors a multitude of testing algorithms customized to meet the requirements of simple to complex clinical trials.

The FDA recognizes CTS Test Results for use in all phases of clinical trial and is backed by validated, peer-reviewed, and published studies by prominent industry professionals. CTS has been used in over 170 clinical trials by over 50 sponsors in 43 countries.

A product alone cannot ensure complete customer satisfaction, which is why M&S maintains an in-house team of Product Engineering and Technical Support personnel. This team, along with our 24-hour replacement warranty, web-based assistance, and strong network of distributors and industry partners fulfill our promise to provide complete customer satisfaction.

TECHNOLOGY TRAINING, INSTALLATION AND SITE CERTIFICATION

We offer training and certification services for clinical sites worldwide. The comprehensive program follows specific criteria for initial training, certification and follow-up re-certification based upon the duration of the clinical trial and specific needs of the sponsor.

Training includes, but is not limited to, review and understanding of test protocol, verification of device operation, data entry, calibration, luminance settings and test distance. Certification criteria are rigid, and investigators must demonstrate a complete understanding of testing objectives and successfully complete schedules.

STELLAR SUPPORT, WARRANTY AND EXTENDED SERVICE

• Each trial is assigned a dedicated CTS Technical and Administrative Specialist as a point of contact to assist with study protocols, implementation and most importantly ultimate service.

• CTS comes with a software warranty and technical support that lasts the duration of the trial.

• Hardware and software support is available 24 hours/day, 7 days a week to accommodate international customers and our software allows us to diagnose, remotely update, or add modules.

• Should any hardware issue arise, our “Spare-in-the-Air” Replacement Warranty Program assures that you will be up and running with a replacement unit within 24 hours. (International delivery times will vary based on location, customs, schedules.)

INTRODUCTION

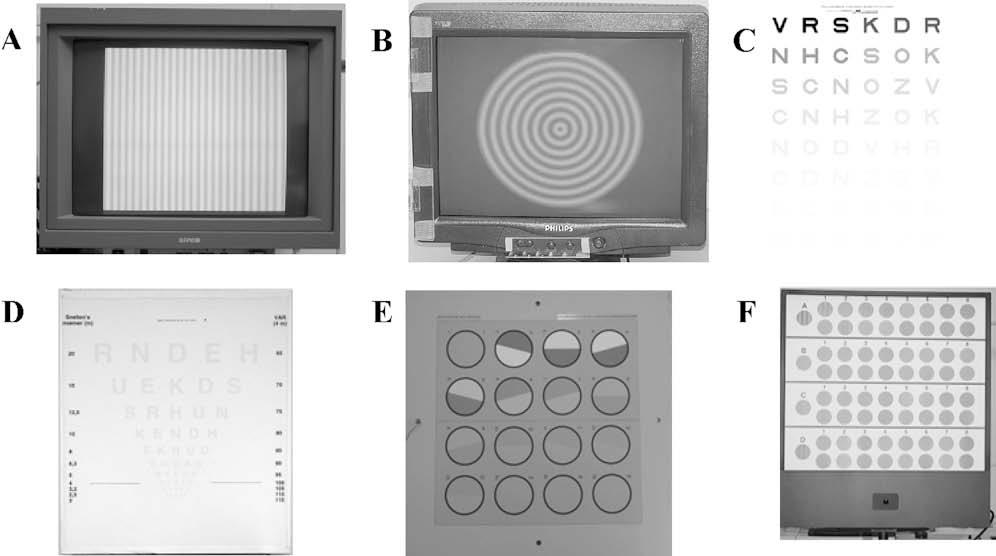

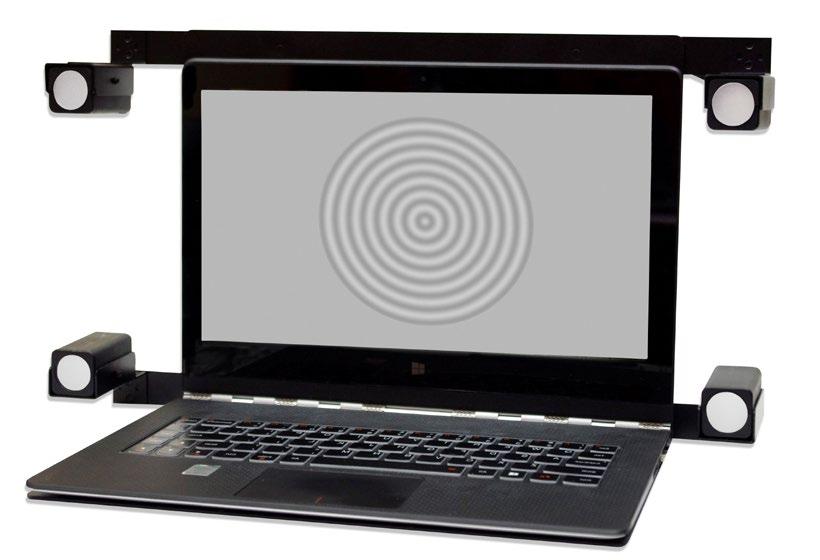

Ophthalmic clinical trials typically require multiple visual acuity and contrast sensitivity measurements. Contrast sensitivity curve testing used in multi-center FDA clinical trials involve more than 100 subjects to reliably detect clinically significant losses in contrast sensitivity. Computer-based vision testing could help improve workflow and precise detection of clinically significant losses with fewer subjects. Contrast vision tests such as 10% contrast acuity, 25% contrast acuity, and contrast threshold tests for fixed optotype sizes, need careful evaluation before inclusion in clinical trials.

The purpose of this clinical study was to evaluate visual acuity and different contrast test methods using a computer-based test system to characterize the clinical effects of refractive error and to identify a robust contrast testing method for future product evaluation.

METHODS

Study Design: Prospective, monocular (right eye) measurement study in subjects who have had previous bilateral implantation of a monofocal intraocular lens conducted at two clinical sites (USA). Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity measurements were made with a computer-based system (M&S Technologies, Inc.) and a chart based system (Vector Vision).

Endpoints: Repeatability at best refractive correction and the rate of change with induced refractive error (+0.25 D, +0.50 D, and +0.75 D) were evaluated for the following:

Mesopic 100% contrast visual acuity, mesopic 25% low contrast acuity and mesopic 10% low contrast acuity (Computer-based system)

Mesopic contrast threshold at 0.30 logMAR (Computerbased system)

Mesopic contrast sensitivity curve without glare and with glare (repeatability only, no defocus testing for the glare condition) for spatial frequencies 1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 18 cpd with the computer-based and chart-based systems. Photopic uncorrected and best corrected visual acuity at 100% contrast were compared between the computer- and chart-based systems.

Ophthalmic

Evaluation of an Electronic Visual acuity for Use in

RESU lTS

Mesopic contrast sensitivity with the computer-based system was better than the chart system at 1.5 by 0.35 logunits (p<0.05 in each case, Figure 1A) and with glare 3.0 cpd by 0.16 logunits (p<0.05, spatial frequencies and glare conditions, the mean differences were within 0.13 logunits and not statistically (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). The highest contrast sensitivity (i.e. lowest contrast) available in the for 1.5 cpd and 2.08 logunits for 3 cpd, whereas the computer-based system can present up to 2.40 frequencies. This test method difference of 0.40 logunits may explain the measured difference between

FIGURE 1a

Computer vs. Chart: Mesopic, No Glare

FIGURE

Computer vs. Chart:

Contrast sensitivity test-retest showed no statistically significant differences. The mean paired differences 0.13 logunits for the computer based system (Figure 2A & 2B) and 0.11 log units for the chart system the no-glare and with-glare conditions. Test-retest standard deviation was up to 0.38 logunits for both frequencies and glare conditions. Interestingly, the computer-based system showed a constant standard chart system showed increasing standard deviation with spatial frequency.

FIGURE 2a

Repeatability: Computer-Based, Mesopic without Glare

FIGURE

Repeatability: Computer-Based,

FIGURE 3a

Repeatability: Chart-Based, Mesopic without Glare

Repeatability: Chart-Based,

© 2017 Abbott Medical Optics Inc. SC2017OTH0012 ARVO 2017

Age (years) Mean ± SD 71.3 ± 5.9 Age Group, n (%) 60 – 69 13 (41.9%) 70 – 79 15 (48.4%) > = 80 3 (9.7%) Sex, n (%) Male 12 (38.7%) Female 19 (61.3%) Race, n (%) African American 5 (16.1%) White 26 (83.9%)

VaRIablE N Mean SD. Median Min. Max. Sphere (D) 31 -0.42 0.56 -0.50 -2.25 0.75 Astigmatism (D) 31 +0.19 0.29 0.00 0.00 0.75 MRSE (D) 31 -0.32 0.55 -0.25 -2.25 0.75

TablE 1. Demographics for study subjects (N = 31 subjects)

TablE 2. Refractive Outcomes

FIGURE

Sanjeev Kasthurirangan,1 Carrie Garufis,1 Jay Rudd,2 Jonathan Solomon3 — 1Johnson & Johnson Vision,

cuity and Contrast Sensitivity Test System

Ophthalmic Clinical Trials

Vision, Santa Ana, CA, US; 2Clarus Eye Center, Lacey, WA, US; 3Solomon Eye Associates, Bowie, MD, US

RESU lTS

1.5 and 3.0 cpd without glare (p<0.05, Figure 1B). For all other statistically significantly different chart system is 1.97 logunits 2.40 logunits at all spatial between the two systems.

FIGURE 1b

Chart: Mesopic, with Glare

Mean photopic visual acuity with the computer-based system was slightly better than the chart system: 0.04 logunits for uncorrected distance visual acuity (UCDVA) and 0.03 logunits for best corrected visual acuity (BCDVA) (Table 3). The mesopic contrast acuity tests with the computer-based system showed a mean difference within 0.01 logMAR and repeatability standard deviation within 0.10 logMAR (Table 4). The contrast threshold test with the computer-based system had a mean difference of -0.01 logunits and a repeatability standard deviation of 0.08 logunits (Table 4). All four letter-based contrast tests plotted on the same graph show a roughly linear trend of increasing visual acuity with decreasing contrast (Figure 4).

TablE 3. Photopic uncorrected and best corrected visual acuity for the computer- and chart-based systems.

differences were within system (Figure 3A & 3B) across both systems across spatial standard deviation, whereas the

Computer-Based, Mesopic with Glare

4. Test-retest repeatability of the mesopic acuity and contrast threshold testing with computer-based testing.

Contrast sensitivity curves did not show a noticeable decrease with defocus (Figure 5) and only 0.0 D vs. 0.75 D was statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) at 6 cpd and 12 cpd (approximately 0.20 logunits). All four letter-based tests showed a statistically significant decrease in performance at 0.50 D and 0.75 D induced defocus, compared to 0.0 D (Table 5).

Chart-Based, Mesopic with Glare

CONClUSIONS

TablE 5. Effect of defocus on the letter-based contrast acuity and contrast threshold tests with the computer-based system

Contrast sensitivity testing with the two systems was largely equivalent with similar repeatability (0.38 logunits).

The computer-based system measured slightly better contrast sensitivity at low spatial frequencies, likely due to the limited range of contrast available in the chart-based system.

Visual acuity testing was slightly better (2 letters) with the computer-based system compared to the chart-based system.

Mesopic visual acuity (100% contrast, 25% contrast and 10% contrast) and contrast threshold for a fixed letter size measured with the computer-based system showed very good repeatability of approximately 1 letter for the letter-based tests and 0.01 logunit for the contrast threshold test.

The letter-based tests showed a clear reduction in performance with induced optical defocus compared to the spatial contrast sensitivity test.

FIGURE 2b

FIGURE 3b

VaRIablE N Paired Difference Mean SD Median 95% CI UCDVA 31 -0.04 0.11 -0.02 -0.09 -0.00 BCDVA 31 -0.03 0.06 -0.04 -0.05 -0.01

letter Test N Paired difference Mean SD Median 95% CI 100% (logMAR) 31 -0.01 0.06 0.00 -0.12 0.11 25% (logMAR) 31 -0.01 0.04 0.00 -0.09 0.07 10% (logMAR) 31 0.00 0.10 0.02 -0.20 0.21 Sensitivity for 20/40 letter (logunits) 31 -0.01 0.08 0.00 -0.16 0.15

FIGURE 4 0 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

TablE

FIGURE 5 letter Test 0.0 D vs. 0.25 D 0.0 D vs. 0.50 D 0.0 D vs. 0.75 D Paired Mean (95% CI) Paired Mean (95% CI) Paired Mean (95% CI) 100% (logMAR) -0.05 (-0.08, -0.02) -0.10 (-0.14, -0.06) -0.17 (-0.22, -0.12) 25% (logMAR) -0.03 (-0.05, -0.00) -0.06 (-0.09, -0.03) -0.13 (-0.17, -0.09) 10% (logMAR) -0.01 (-0.04, +0.01) -0.04 (-0.07, -0.02) -0.10 (-0.14, -0.06) Sensitivity for 20/40 letter (logunits) -0.04 (-0.07, +0.00) -0.10 (-0.15, -0.04) -0.17 (-0.24, -0.10)

Financial Disclosure: Sanjeev Kasthurirangan, Carrie Garufis, Abbott Medical Optics, E, Employment; Jay Rudd, Jonathan Solomon, Abbott Medical Optics, F, Financial Support

4229

Article Comparison of Backlit and Novel Automated ETDRS

Visual Acuity Charts

Paul A. Harris, OD, Southern College of Optometry, Memphis, Tennessee

Laurel E. Roberts, Southern College of Optometry, Memphis, Tennessee

Rachel Grant, OD, Southern College of Optometry, Memphis, Tennessee

ABSTRACT

Background: This study was conducted to compare two different methods and presentation systems of testing visual acuity to determine whether they are equivalent.

Methods: We compared the results of taking visual acuity (VA) measures with the standard backlit Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (backlit ETDRS) and Automated ETDRS (A-ETDRS) VA charts (M&S Technologies, Inc., Niles, IL) on 111 healthy subjects with corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better. Testing was done under four conditions— with spectacles, uncorrected, with +1.50 blur over spectacles, and with +3.00 blur over spectacles—to assess correlation of primary outcomes between charts across a wide range of acuity measures. Visual acuity measures were recorded in letter count, logMAR, and standard Snellen measures.

Results: Correlations between the backlit ETDRS and the A-ETDRS chart types were 0.93 (uncorrected), 0.60 (with spectacles), 0.76 (+1.50 blur over spectacles), and 0.50 (+3.00 blur over spectacles), with all correlations statistically significant at p< 0.001.

Conclusion: This study shows that traditional backlit ETDRS and A-ETDRS charts are functionally equivalent to each other under a variety of testing conditions, mimicking both clinical and research applications. Additional benefits of the automated system over the backlit charts include: the ability to calibrate the system precisely, faster testing and scoring times combined, and less chance for error to enter into the conversion of the raw data into logMAR, letter, or Snellen scores. For all of these reasons, Automated-ETDRS testing is preferred.

Keywords: automated testing, backlit screen, digital screen display, Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study, electronic vision chart, ETDRS, logMAR, optotype, Snellen, Visual acuity

Background

Visual acuity is one of the most important tools in determining visual function and has been established as the “gold standard” in prospective clinical trials, especially regarding eye disease and treatment. 1,2 The assessment of visual acuity with optotype charts is the most standardized test of visual function. These high-contrast printed charts include black optotypes, letters, or symbols on a white background and are externally illuminated.

The charts allow a diverse patient population to be tested. Theoretically, visual acuity testing should give a precise, reproducible, and reliable result that represents the state of macular function. The testing further implies that any acuity changes are related to disease or treatment. However, visual acuity can be influenced and altered by external factors, including but not limited to exam room lighting, contrast, design of the chart, subject motivation, and scoring technique. 3,4

Optometry & Visual Performance 87 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

The Snellen eye chart is the most widely used method of visual acuity measurement in clinical practice, in part due to its ease of use and availability. Snellen’s original chart had a single large letter at the top, and with each successive row, the letters became more numerous and progressively smaller.5 The letters are not equal in their legibility; there is also unequal letter and line spacing.

4,6,7 In addition, since its original conception, many variations in size, sequence, chart layout, and design of the optotypes were made; subsequently, there is no broadly accepted “standard” Snellen chart.5 Most commonly, visual acuity measurements are determined under high-contrast conditions, as previously mentioned. Over time, the required contrast level for the chart can be impacted by stains and fading, which may alter reflectivity. Room position and room illumination may also introduce variability.3

ETDRS Standards

The Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart is based on the previously designed Bailey-Lovie logMAR chart to establish a standardized measurement of visual acuity. The inclusion of administration and scoring protocols serves to improve the precision of visual acuity measurement in the range of poorer visual acuities.5 The ETDRS chart

has been recognized to be highly reliable for vision testing1 and has been considered one of the standard tools for measuring acuity in prospective clinical research for more than 30 years.

1,8,9 Each Sloan letter on the ETDRS chart (ten in total) has approximately equal legibility or difficulty, and each line has the same overall difficulty.10 Each row contains five letters, with the spacing between each letter being equal to the width of one letter and the space between lines being equal in height to the letters of the next lower line.10 The letter size from row to row changes in equal logarithmic intervals.4,6 The chart itself is non-reflective, white, highimpact polystyrene with the black letters creating a contrast level of approximately 90%. The accompanying light box produces a standardized illumination of 120 cd/m2, which conforms to the ANSI specifications.3,11,12 All other light sources in the room should be turned off to reduce any potential glare sources.

Although considered the standard for clinical research, ETDRS and other logMAR charts are not widely used in clinical practice.16 As evidence of this, at Southern College of Optometry, the 90+ clinical testing lanes and the 50+ student practice lanes are equipped with computerbased chart systems, while there are only two ETDRS charts in place for compliance with specific FDA clinical protocols. This ratio is similar in most North American optometry schools. It is thought that the test format, including the length of test administration, unfamiliar scoring,

Optometry & Visual Performance 88 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

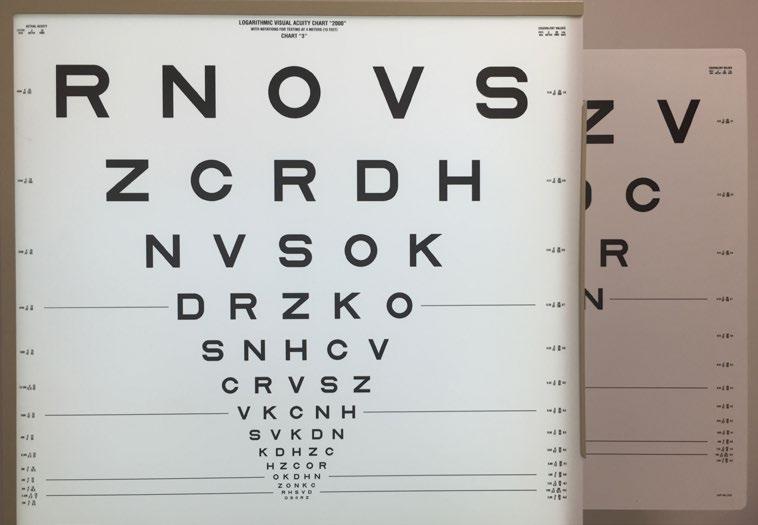

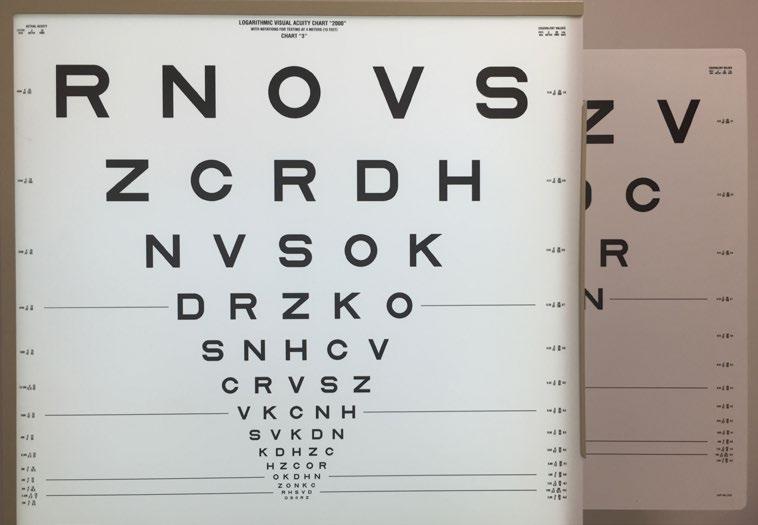

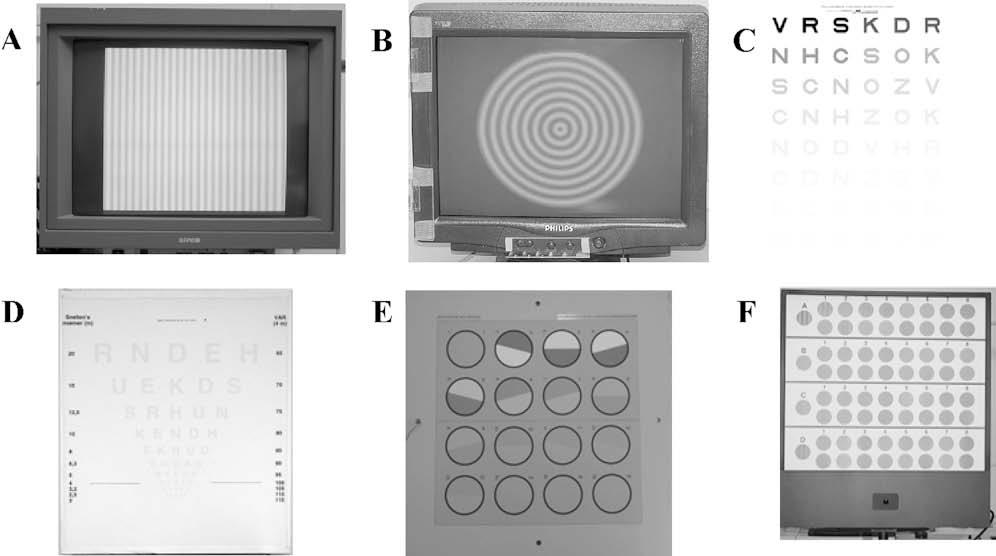

Figure 1. The backlit ETDRS chart with the A-ETDRS computer screen behind. The backlit chart starts at 20/200, while the A-ETDRS chart starts at 20/100. The sizes of the letters and spacing from 20/100 to 20/10 are exactly the same.

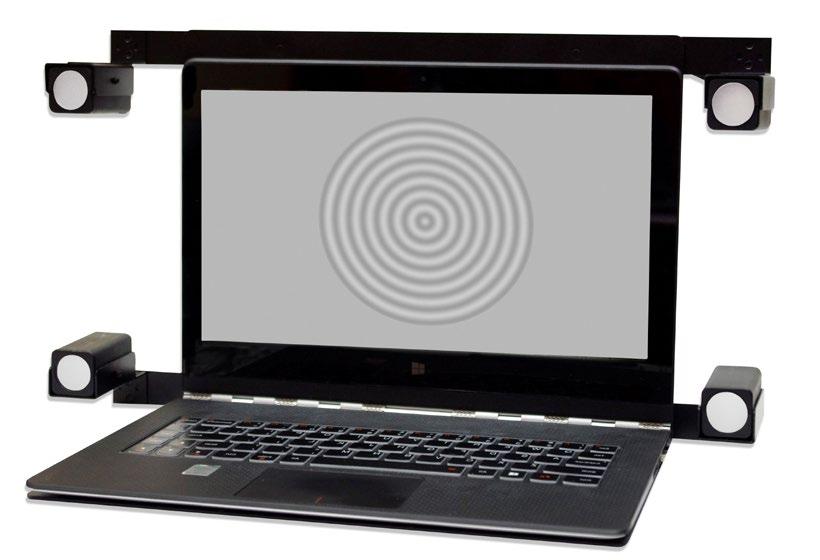

Figure 2. The A-ETDRS opening screen.

and patients memorizing letter sequences, as well as the inherent difficulty in discussing logMAR acuity with patients, contribute to the practical limitations.9,14,15

The standard ETDRS chart is a large, floor-mounted, backlit device that takes up a significant amount of space and requires manual changes amongst the three provided plastic sheets (Figure 1).

The Automated ETDRS chart (A-ETDRS; M&S Technologies, Inc., Niles, IL),5 which is part of the Clinical Trial Suite offered by M&S, has the potential to make the test more portable, more difficult to memorize, easier to score, and it may speed up testing time (Figure 2).

Computerized Testing

Technological advancements have improved the incorporation of technology, such as computer-based displays, in all facets of health care, including electronic vision testing. Various forms of electronic and automated displays exist on the market and continue to gain popularity with patients and practitioners alike. The inevitable trend towards using more computer-based displays for the measurement of visual acuity has specific research advantages that come from computer control of visual displays for measuring visual acuity.5 Computer displays can provide selectable options, such as optotypes, spacing and crowding arrangements, contrast, and color. Research has shown that another advantage of a computerized acuity system is the ability to increase the test-retest repeatability through repetition and averaging of measurements.8,16 Furthermore, a computerbased acuity chart allows random order presentation and automated processing.8

Purpose

This study was conducted to compare two different methods and presentation systems of testing visual acuity to determine whether they are equivalent. Should that aim be met, then additional benefits would accrue to the

user of A-ETDRS. In many clinical studies, subjects spend a great deal of time, under many different conditions, reading the backlit ETDRS charts from top to bottom, over and over. Since there are only three different charts, which must be manually changed, there is a chance that subjects could begin to know some of the letter sequences in those charts. This could lead to an overestimation of their visual acuity, which is not related to the specific testing or experimental condition. Randomization of each “chart” in the A-ETDRS configuration would eliminate memorization from prior exposures, thus increasing the validity of the measure.

An additional benefit that would result from the aim being met is increased reliability in the calculation of the letter count, from which the logMAR and/or visual acuity measure is derived. The standard backlit ETDRS charts must be manually scored. This process is highly repetitive and adds time to the process of getting the letter count. The A-ETDRS system immediately provides the user with all of the scores needed, without the need for a separate recording system or the counting or calculation of any of the scores. This should save time and guarantee that the measures reported are indeed the measures obtained.

This study also addresses some of the issues raised in discussion of some early attempts to computerize the ETDRS testing process.17 Issues that have been raised include pixelation of the letters on the computer screen, where individual pixels are visible to the naked eye, and anti-aliasing.a These specifically affect the ability cleanly to present letters smaller than 20/20 on older computer monitors. Smaller screens limit the size of the largest letter that can be shown to a subject. Larger computer monitors with smaller pixels, packed much more closely together on the screen in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions (dot pitch), combine to allow for much larger letters than before, while being able to present letters down

Optometry & Visual Performance 89 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

to 20/8 Snellen visual acuity levels. Aliasingb occurs in computer graphics when a screen cannot render as smooth a curve as intended and it appears on the screen as jagged. When viewed extremely closely, what is seen are small steps rather than smooth curves. Anti-aliasing software has been used to attempt to minimize these effects. The typical panel displays used now in these systems do not need anti-aliasing software because of the smaller dots, which are packed much more closely together. The M&S Technologies Smart System II used in this study has a 22-inch digital flat panel screen with a resolution of 1680 x 1050.

Lastly, the new control systems, which use a separate tablet with built-in scoring, should allow for faster data collection times.

Methods

One hundred and eleven (N=111) secondand third-year students from Southern College of Optometry (SCO), with corrected visual acuity of 20/20 or better binocularly, had their visual acuity taken eight separate times, with each of the conditions being randomized. Visual acuity was measured four different times on each of the two different types of charts. The four conditions for each chart included: with spectacles, without spectacles, with +1.50 spheres over spectacles, and with +3.00 spheres over spectacles. For each subject, randomization was across all 8 conditions, and all testing was done on the same day at a single sitting. The randomization table was generated by research randomizer.c All testing was done at 4 meters. The standard ETDRS protocol has the subject wearing a +0.25 DS lens to compensate for this distance. The +0.25 lens was not used in any of our 8 test conditions. We created the two pairs of spectacles for testing, one pair of +1.50 spheres and the other of +3.00 spheres, in frames large enough to allow them to be worn over the subjects’ own spectacles without difficulty. Those subjects who wore contact lenses were asked not to wear their contact lenses on the day of testing, but instead

to wear their spectacle correction. This made the randomization of the uncorrected conditions on both the backlit and the A-ETDRS charts less time-consuming than if we had our subjects remove their contact lenses and then readapt to them for the next condition.

All testing was done binocularly in a room where the only illumination came from the two charts. Both displays were on all the time. Whenever a backlit chart was to be used for testing, one of the three charts was selected based on a randomization table. It should be noted that for each subject, four different measures were made on the backlit chart, but there are only three different charts. Each chart had an equal chance of being used at any time. Although it was time-consuming to change the charts manually, it was done to minimize any chance of a subject memorizing the charts, as well as to simulate formal research protocols. In the cases where the randomization table indicated that the same backlit chart was to be used again, the researcher went through the chart changing routine and simply put the prior chart back in position. This was to encourage the thought in the subjects that the charts were different each time.

When the backlit ETDRS charts were used, printed score sheets were available for each of the three charts. The appropriate score sheet was selected, and the subject was asked to read each letter distinctly from the top of the chart. Every letter was marked on the recording form as either correct or incorrect. The total number of letters correct was recorded, and a conversion chart was used to derive the logMAR and Snellen score for that condition.

The protocol used to measure visual acuity with these charts followed standard ETDRS research protocol, where for every measurement, letters were read at a speed of one per second, beginning at the top left of the chart and proceeding line by line, left to right, with an opportunity to correct an error only before the next letter was attempted. The

Optometry & Visual Performance 90 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

procedures for encouraging letter recognition and the stopping rule are standardized. Training materials for Ophthalmic Clinical Trial Training and Certification are available from the Emmes Corporation.d The researchers did not anticipate any of the subjects triggering the standard protocol for the conditions when visual acuity was worse than 20/200. When this was encountered, the A-ETDRS program returned a standard value of 20/250 and a letter count of 34, and similar results were recorded with the backlit ETDRS chart. The portion of the standardized testing protocol used to change the working distance to one meter was not done.

The A-ETDRS uses an Android tablet with the M&S Technologies, Inc. custom control program, which synchronizes with the main Smart System through a Bluetooth connection. Each time the protocol is run, the chart provides a random sample of the 10 ETDRS letters, making memorization of the chart impossible. There are two phases of determining the endpoint

of visual acuity measures, range-finding and thresholding. During the range-finding phase, the subject finds the smallest line of letters that they believe they can read completely correctly and proceeds to read them aloud. The operator presses the button on the control software that corresponds to that line of letters. Figure 3 shows the screen from the tablet. The letters shown to the subject on the display screen are also displayed to the operator on the tablet.

Figure 4 shows the screen that the subject would see after the operator presses the number 20 on the tablet’s screen, indicating that the subject got all the letters correct on the 20/20 line but made a mistake on the 20/16 line. At this point, the program switches to the thresholding phase. Now the tablet asks the operator to specify how many letters the subject correctly reports on each subsequently smaller line and finally stops either when the subject is unable to get any letters correct on the next smaller line or no more smaller lines exist to be shown.

After the A-ETDRS testing is complete, the system saves the results and reports the test results to the main screen, which can be printed. A sample set of data includes the eye (Right, Left, or Both), test distance (4 meters in this protocol), spectacles (on or off), light level (photopic vs. mesopic), and the visual acuity results in three forms (letter score, visual acuity, and logMAR). The letter score is the total number of letters that the subject said correctly, which results in a standard Snellen equivalent and a logMAR score. For example, a letter score of 87 converts to a Snellen VA of 20/20 and a logMAR score of -0.04.

Test times were measured for all trials using a stopwatch function on the investigator’s smart phone. Timing started as soon as the A-ETDRS chart was presented and terminated when the program displayed the scores to the computer screen for recording. For the backlit chart, timing was started when the subject said the first letter and finished when they were no

Optometry & Visual Performance 91 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

Figure 3. Android tablet with control program showing the lines from 20/50 to 20/16 in the red background area. Pressing the “Up” or the “Down” buttons on the screen changes the display to different parts of the chart.

Figure 4. The A-ETDRS opening screen.

Table 1 .logMAR scores by condition and chart type. Note: Significance test based on paired t-tests for Automated vs. Backlit on the common sample within each condition.

Note: Significance test based on paired t-tests for Automated vs. Backlit on the common sample within each condition.

longer able to get any letters correct. Time to change the plastic test cards in the backlit box was not included in the timing, nor was the time to count and score the subject’s results.

Weber Contrast was calculated for each of the targets using measurements collected with the Konica-Minolta LS-110 luminance meter, which measures the amount of reflected or emitted light from an area of 0.33 of a degree. On the backlit box, the white area was 181 cd/m2, while the black was 1.35 cd/m2. This produced a Weber Contrast of 99.25%. On the M&S Technologies A-ETDRS screen, the white was 120 cd/m2, and the black was 0.72 cd/m2, which produced a Weber Contrast of 99.4%. The backlit box was not adjustable in luminance. The M&S system was at its calibrated light value of 120 cd/m2. Both are compliant with ANSI Z80.21-2010 (R2015) and ISO 8597:1994(E) standards.11,12

All subjects gave informed consent after a verbal and written explanation of the experiment, which was approved by the Southern College of Optometry Institutional Review Board in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical Analysis

Measurement of visual acuity with the ETDRS charts yields two different scores. The first is a Letter Score, which is a count of the total number of letters correct from the largest letter until the subject stops getting letters correct.

There is also a calculated logMAR visual acuity level assigned to this value.

LogMAR scores for both Backlit ETDRS and A-ETDRS chart types were compared under each of four testing conditions (uncorrected, with spectacles, +1.50 blur over spectacles, and +3.00 blur over spectacles) using paired t-tests. Findings were also confirmed using nonparametric alternatives (Wilcoxon sign-rank tests), as well as a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), which yielded the same conclusions. Thus, for ease of presentation, the mean comparisons of each chart type at each testing condition are shown here. BlandAltman plots were used to illustrate agreement between A-ETDRS and Backlit ETDRS chart types. Correlations between A-ETDRS and Backlit ETDRS chart types were examined using Pearson’s r.

Results

Analyses were conducted using Stata/SE software, version 13.e Table 1 shows means, standard deviations (SDs), standard errors (SEs), and 95% confidence intervals comparing logMAR scores on A-ETDRS and Backlit ETDRS charts for each condition. There were no significant differences between the chart types at any condition. Figure 5 shows mean logMAR values for Automated and Backlit charts graphically, with error bars. The widest standard deviations exist for the uncorrected measures,

Optometry & Visual Performance 92 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

mean SD SE 95% Confidence Interval (CI) Difference Sig With spectacles (n= 110) Automated -.16 .12 .01 -.18, -.14 -.001 p = .89 Backlit -.16 .10 .01 -.18, -.14 Uncorrected (n= 87) Automated .20 .47 .05 .10, .30 -.028 p = .13 Backlit .23 .46 .05 .13, .32 +1.5 Blur over spectacles (n= 111) Automated .29 .22 .02 .24, .33 -.005 p = .70 Backlit .29 .20 .02 .25, .33 +3.0 Blur over spectacles (n= 102) Automated .71 .21 .02 .67, .75 -.010 p = .62 Backlit .72 .19 .02 .69, .76

and here the visual acuities measured trended to be worse with the backlit ETDRS. However, the differences were neither statistically nor clinically significant. Figures 6 to 9 show Bland-Altman plots for each study condition, which plot the difference of the paired chart vs. their average. There were only very few cases where individual values fell outside the range of agreement.

Correlations between Automated and Backlit chart types were 0.93 (uncorrected), 0.60 (with spectacles), 0.76 (+1.50 blur over spectacles), and 0.50 (+3.00 blur over spectacles), with all correlations statistically significant at p< 0.001.

It was decided to eliminate any data points in the Bland-Altman plots when one or both logMAR values was greater than 1.0, because we had not anticipated that we would have significant numbers of these measures. Indeed, only 9 subjects in the +3.00 blur and 24 subjects

Optometry & Visual Performance 93 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

Figure 5. Mean logMAR values for Automated and Backlit EDTRS charts

Figure 6. Bland-Altman plot for the “with spectacles” condition.

Figure 7. Bland-Altman plot for the “uncorrected” condition.

Figure 8. Bland-Altman plot for the “+1.50 blur over spectacles” condition.

Figure 9. Bland-Altman plot for the “+3.00 blur over spectacles” condition.

in the uncorrected conditions had one or more logMAR measures greater than 1.0. This accounted for the different number of subjects in each direct comparison. Figure 6 shows the Bland-Altman plot for the “with spectacles” condition. Three of the 110 subjects (2.73%) fell outside the 95% limits of agreement.

Figure 7 shows the Bland-Altman plot for the “uncorrected” condition. Three of the 87 subjects (3.45%) fell outside the 95% limits of agreement. The number of subjectsfor this condition was the smallest, because 24 of the subjects had either the A-ETDRS or the backlit ETDRS visual acuity worse that 1.0 logMAR and therefore were not included in the analysis.

Figure 8 shows the Bland-Altman plot for the “+1.50 blur over spectacles” condition. Four of the 111 subjects (3.6%) fell outside the 95% limits of agreement.

Figure 9 shows the Bland-Altman plot for the “+3.00 blur over spectacles” condition. Six of the 102 subjects (5.88%) fell outside the 95% limits of agreement. The N for this condition was reduced to 102 as nine subjects had either the A-ETDRS or the backlit ETDRS visual acuity worse than 1.0 logMAR.

The authors independently took the raw scores from the A-ETDRS testing and verified that the computer algorithm indeed yielded the correct Letter and logMAR Scores for each measurement for the first 20 subjects.

Timing data for all 444 trials on the A-ETDRS chart across all conditions averaged 21.24 seconds (SD 18.6 seconds), with a range from 3 to 180 seconds. The average time varied across the conditions, with the corrected measures averaging the fastest (24.88 seconds SD 9.9 seconds) The “+3.00 blur over spectacles” condition averaged 39.1 seconds (SD 25.7).

Timing data for all 444 trials on the backlit ETDRS averaged 18.7 seconds (SD 11.9 seconds), with a range from 2 to 117 seconds. This was only the time to perform the test and did not include the time to score the results or to change the chart prior to starting each trial (Table 2).

Discussion

The four different testing conditions for each chart were chosen to represent both real-world conditions (uncorrected and with spectacles) as well as some research-based conditions (simulated 1.50 D and 3.00 D of uncorrected myopia). We did not anticipate any of our subjects triggering the standard protocol for the conditions when visual acuity was worse than 20/200. When this was encountered, the A-ETDRS program returned a standard value of 20/250 and a letter count of 34. As we reviewed the results, nine subjects in the “+3.00 blur over spectacles” and 24 subjects in the “uncorrected” group had visual acuities worse than 20/200, or logMAR greater than 1.0. In future studies, we will repeat measures in those conditions following the standard protocol, which is to reduce the working distance to one meter and repeat the testing. In that setup, the 20/200-sized letters at four meters are equivalent to 20/800 at one meter. This was not done. Measures where the visual acuity was greater than logMAR 1.0 were removed for analysis. This did not affect any measures in either the “spectacles” or the “+1.50 blur over spectacles” groups.

Calibration

In formal research settings, having testing instruments able to be calibrated is a must. Many individual systems are used for periods of years. Though the backlit ETDRS systems have been the gold standard for many years, there is no easy way to calibrate them, short of changing bulbs until the measured luminance levels are within standards. Luminance of the bulbs in the units varies, and the plastic sheets

Optometry & Visual Performance 94 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

All With Spectacles Uncorrected +1.50 Blur over Spectacles +3.00 Blur over Spectacles Number N=444 N=111 N=111 N=111 N=111 Average 31.2 24.8 26.8 39.1 16.6 SD 18.6 9.9 15.9 15.7 9.0 Low 3 10 3 12 10 High 180 77 95 118 180

Table 2. Timing data for each condition

are prone to yellowing over time, which reduces contrast. The A-ETDRS systems ship with a luminance measuring system, the use of which is integrated into the system. Periodically, as prompted by the software, the measuring system is suspended directly in front of the screen, and the system varies the illumination to reach the exact specified amount of 120 cd/m2. Both the bright and dark luminance measures are taken and adjusted to ensure proper calibration, within very tight tolerances. This is a major advantage of the A-ETDRS system over the backlit ETDRS targets.

Randomized letters

Two major advantages accrue to those using A-ETDRS over standard backlit charts. The scoring step is eliminated, from the hard copy made during the testing to however the results are being recorded. The first benefit is that errors are eliminated in the calculation of the score. Others have reported that in their experience, manual recording systems are prone to error.18 A second benefit is that about 30 seconds are saved, which is the typical time it takes to do the actual scoring.19

Time Saving from Automation

The new A-ETDRS is faster to use than standard ETDRS testing when scoring time on the standard ETDRS charts was added to the time needed to perform the test. The A-ETDRS system automatically scores the trial and shows all measures (letter score, Snellen visual acuity, and logMAR) immediately after the testing. All 444 A-ETDRS tests averaged 21.2 seconds (SD 18.6 seconds). Laidlaw et al. found an average time for standard EDTRS measures of 56 seconds with adult populations, and on average their computerized system was 7-10 seconds slower.18 Timing for each of the backlit ETDRS trials was recorded in our study, but these did not include the time spent scoring each of the results. We only recorded the raw data for each trial on the matching score sheet for that trial, but we did

not take the time to perform the letter count and corresponding conversion to logMAR while the subject was present. We neglected to record the time it took for scoring the data as we did it during downtime between subject sittings, and we did not add in the time to change the backlit ETDRS charts, which would affect this comparison even more. In a future study, the timing of the scoring and conversion to logMAR values as well as changing the charts should be done for each data point to be comparing like entities.

Conclusions

The findings of this study show that the traditional and automated ETDRS charts are functionally equivalent to each other under a variety of testing conditions, mimicking both clinical and research applications. Use of the A-ETDRS system by M&S Technologies is faster and less prone to recording errors or calculation errors, can be calibrated regularly, and is very easy. These findings set the stage for the adoption of the A-ETDRS chart by M&S Technologies in any clinical research study or clinical trial setting that calls for ETDRS testing.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to: Jan Gryczynski, PhD, Founding Partner COG Analytics, Potomac, MD, for his assistance with the statistics in this paper.

References

1. Beck R, Moke P, Turpin A, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: Adaptation of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;135:194-205. http://bit.ly/2qH31bW

2. Ferris FL, Bailey I. Standardizing the measurement of visual acuity for clinical research studies: Guidelines from the Eye Care Technology Forum. Ophthalmology 1996;103:181-2. http://bit.ly/2HavdyP

3. Ehrmann K, Fedtke C, Radić A. Assessment of computer generated vision charts. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2009;32:13340. http://bit.ly/2qJJt6C

4. Williams MA, Moutray TN, Jackson AJ. Uniformity of visual acuity measures in published studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:4321-7. http://bit.ly/2qJCdb7

Optometry & Visual Performance 95 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

5. Bailey IL, Lovie-Kitchin JE. Visual acuity testing. From the laboratory to the clinic. Vision Res 2013;90:2-9. http://bit. ly/2HdOhMA

6. Rosser D, Laidlaw D, Murdoch IE. The development of a “reduced logMAR” visual acuity chart for use in routine clinical practice. Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:432-6. http://bit. ly/2qHCqLO

7. Ferris FL 3rd, Sperduto RD. Standardized illumination for visual acuity testing in clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:97-8. https://go.nature.com/2qJD37J

8. Rosser D, Murdoch IE, Fitzke FW, Laidlaw DAH. Improving on ETDRS acuities: Design and results for a computerised thresholding device. Eye 2003;17:701-6. http://bit.ly/2H9qrSu

9. Ferris FL, Bailey I. Standardizing the measurement of visual acuity for clinical research studies: Guidelines from the Eye Care Technology Forum. Ophthalmology 1996;103(1):181-2. http://bit.ly/2qISQDM

10. Ferris FL 3rd, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, et al. New visual acuity charts for clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94:91-6. http://bit.ly/2H9RQn3

11. American National Standards Institute, Inc. American National Standards for Ophthalmics – Instruments – General-Purpose Clinical Visual Acuity Charts, ANSA Z80.21-2010 (R2015), The Vision Council, Alexandria, VA. http://bit.ly/2qEMfds

12. Technical Committee ISO/TC 172, Optics and optical instruments – Visual acuity testing – method of correlating optotypes, International Standard ISO 8597, International Organization of Standardization 1984, Genève, Switzerland. http://bit.ly/2qIwfXO

13. Kaiser PK. Prospective evaluation of visual acuity assessment: A comparison of Snellen versus ETDRS charts in clinical practice (An AOS Thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2009;107:311-24. http://bit.ly/2qMtYLw

14. Lovie-Kitchin JE. Validity and reliability of visual acuity measurements. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 1998;8:363-70. http://bit.ly/2HbPFjb

15. Kuo HK, Kuo MT, Tiong IS, et al. Visual acuity as measured with Landolt C chart and Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) chart. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:601-5. http://bit.ly/2qKEjY7

16. Shah N, Laidlaw DAH, Shah SP, et al. Computerized repeating and averaging improve the test-retest variability of ETDRS visual acuity measurements: Implications for sensitivity and specificity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:9397-402. http://bit.ly/2HehuHC

17. McClenaghan N, Kimura A, Stark LR. An evaluation of the M&S Technologies Smart System II for visual acuity measurement in Young Visually-Normal Adults. OVS 2007;84:3:218-23. http:// bit.ly/2HehuHC

18. Laidlaw DAH, Tailor V, Shah N, Atamian S, Harcourt C. Validation of a computerised logMAR visual acuity measurement system (COMPlog): comparison with ETDRS and the electronic ETDRS testing algorithm in adults and amblyopic children. J Ophthalmol 2008;92:241-4. http://bit.ly/2qHDVJW

19. Bokinni Y, Shah N, Maquire O, Laidlaw DAH. Performance of a computerised visual acuity measurement device in subjects with age-related macular degeneration: Comparison with gold standard ETDRS chart measurements. Eye 2015;29:1085-91. http://bit.ly/2qIJic1

a. https://goo.gl/U3zCun

b. https://goo.gl/tbzBN5

c. https://www.randomizer.org

d. https://goo.gl/qaYrTu

e. https://www.stata.com

Correspondence regarding this article should be emailed to Paul A. Harris, OD, MS, at pharris@sco.edu. All statements are the author’s personal opinions and may not reflect the opinions of the representative organizations, ACBO or OEPF, Optometry & Visual Performance, or any institution or organization with which the author may be affiliated. Permission to use reprints of this article must be obtained from the editor. Copyright 2018 Optometric Extension Program Foundation. Online access is available at www.acbo.org.au, www.oepf.org, and www.ovpjournal.org.

Harris PA, Roberts LE, Grant R. Comparison of backlit and novel automated etdrs visual acuity charts. Optom Vis Perf 2018;6(2):87-96.

Optometry & Visual Performance 96 Volume 6 | Issue 2 | 2018, April

AComputerizedMethodofVisualAcuity Testing:AdaptationoftheEarlyTreatmentof DiabeticRetinopathyStudyTestingProtocol

ROYW.BECK,MD,PHD,PAMELAS.MOKE,MSPH,ANDREWH.TURPIN,PHD, FREDERICKL.FERRISIII,MD,JOHNPAULSANGIOVANNI,SCD, CHRISA.JOHNSON,PHD,EILEENE.BIRCH,PHD,DANIELLEL.CHANDLER,MSPH, TERRYA.COX,MD,PHD,R.CLIFFORDBLAIR,PHD,ANDRAYMONDT.KRAKER,MSPH

● PURPOSE: Todevelopacomputerizedmethodofvisual acuitytestingforclinicalresearchasanalternativetothe standardEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathy Study(ETDRS)testingprotocol,andtoevaluateits test-retestreliabilityandconcordancewithstandard ETDRStesting.

● DESIGN: Test-retestreliabilitystudy.

● METHODS: Multicentersettingofastudypopulationof 265patientsatthreeclinicalsites.Visualacuitywas measuredwithboththeelectronicvisualacuitytesting algorithm(E-ETDRS)andstandardETDRSprotocol (S-ETDRS)twiceononeeyeofeachpatient.E-ETDRS testingwasconductedusingtheelectronicvisualacuity tester(EVA),whichutilizesaprogrammedPalm(Palm, Inc,SantaClara,California,USA)hand-helddevice communicatingwithapersonalcomputerand17-inch monitoratatestdistanceof3meters.

● RESULTS: FortheE-ETDRSprotocol,test-retestreliabilitywashigh(r 0.99;with89%and98%ofretests within0.1logMARand0.2logMARofinitialtests, respectively)andcomparablewiththatofS-ETDRS testing(r 0.99;with87%and98%ofretestswithin 0.1logMARand0.2logMARofinitialtest,respectively).TheE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSscoreswerehighly correlated(r 0.96forinitialtestsandr 0.97for repeattests).Basedonestimatesof95%confidence

AcceptedforpublicationAug21,2002.

InternetAdvancepublicationatajo.comNov14,2002.

FromtheJaebCenterforHealthResearch(R.W.B.,P.S.M.,R.C.B., R.T.K.),Tampa,Florida;CurtinUniversity(A.H.T.),Bentley,Western Australia;theNationalEyeInstitute,DivisionofEpidemiologyand ClinicalResearch,theNationalInstitutesofHealth(F.L.F.,J.P.S.G., T.A.C.),Bethesda,Maryland;DiscoveriesinSightResearchLabs,Devers EyeInstitute(C.A.J.),Portland,Oregon;andtheRetinaFoundationof theSouthwest(E.E.B.),Dallas,Texas.

ThisstudywassupportedbytheNationalEyeInstitutegrant#EY13095.

InquiriestoRoyW.Beck,MD,PhD,JaebCenterforHealthResearch, 3010E.138thAve.,Suite9,Tampa,FL33613;fax:(813)975-8761; e-mail:rbeck@jaeb.org

intervals,achangeinvisualacuityof0.2logMAR(10 letters)fromabaselinelevelisunlikelytoberelatedto measurementvariabilityusingeithertheE-ETDRSor theS-ETDRSvisualacuitytestingprotocol.

● CONCLUSIONS: TheE-ETDRSprotocolhashightestretestreliabilityandgoodconcordancewithS-ETDRS testing.Thecomputerizedmethodhasadvantagesover theS-ETDRStestinginelectronicallycapturingthedata foreachtestedletter,requiringonlyasingledistancefor testingfrom20/12to20/800,potentiallyreducingtestingtime,andpotentiallydecreasingtechnician-related bias.(AmJOphthalmol2003;135:194–205.©2003 byElsevierScienceInc.Allrightsreserved.)

VISUALACUITYISACOMMONPRIMARYOUTCOME measureinclinicalresearchofeyediseases.In multicenterclinicaltrials,considerableeffortis placedonthestandardizationofacuitytestingacross sites.1–3 Tomoreeasilystandardizemeasurementofvisual acuityinclinicaltrialsandtoprovideamethodtodirectly captureacuitydataelectronically,wehavedevelopeda computerizedvisiontestercalledtheelectronicvisual acuitytester(EVA).

PreviouslywereportedontheadaptationoftheAmblyopiaTreatmentStudy(ATS)visualacuitytestingprotocol fortheEVA.4 Thistestingprotocolwasdevelopedto facilitatethestandardizationofvisualacuitytestingin clinicaltrialsofpediatriceyediseaseinvolvingchildren from3to6yearsold.5

Wenowreportonthedevelopmentandevaluationofa secondtestingprotocolfortheEVA,oneforthetestingof olderchildrenandadults.Thisprotocolisbasedinparton thetestingprotocoldevelopedforEarlyTreatmentfor DiabeticRetinopathyStudy(ETDRS),1,6 aprotocolwhich hasbeenthestandardforvisualacuitytestinginmost clinicalresearchformorethan15years.Weconducteda studytoassesstest-retestreliabilityforboththeelectronic

194 0002-9394/03/$30.00 PIIS0002-9394(02)01825-1

© 2003BY ELSEVIER SCIENCE INC.ALLRIGHTSRESERVED.

(E-ETDRS)andstandardETDRS(S-ETDRS)protocols andtocomparevisualacuityscoresobtainedwiththetwo protocols.

METHODS

● DESCRIPTIONOFTHEEVA: TheEVAutilizesaprogrammedPalmhand-helddevice(Palm,Inc.,SantaClara, California,USA)thatcommunicateswithapersonal computerrunningaLinuxoperatingsystem(IBMCorp., Armonk,NewYork,USA)(Figure1).Stimuliarehigh contrast,black-and-whiteletterswithluminanceof85to 105candelas/meter2 andcontrastof98%.BothSloanand HOTVlettersetsareavailable.Singlelettersarepresented framedwithcrowdingbarsthatarespacedaletterwidth aroundtheletter.Withahigh-resolution(1600 1200) 17-inchmonitor,letterscanbedisplayedfrom20/800(1.6 logarithmoftheminimumangleofresolution[logMAR]) to20/12( 0.2logMAR)atatestdistanceof3meters. Lettersarerenderedandpresentedonthemonitorby manipulatingtheindividualpointsinagraphicalimage, knownaspixels(pictureelements).Lettersizesaredeterminedbytranslatingoctavesteps(3logMARlines)tothe numberofpixelsforagivenstrokewidth,beginningwith 3pixelsfora20/12letter.Lettersizeisaclose,butnot exact,approximationofthelogMARprogressionofthe ETDRScharts(withinabout2%ofthelettersizeateach logMARlevel).ThePalmhand-helddevice,whichis connectedtothepersonalcomputerthroughaserialcable, providesinstructionsforthetechnician,displaystheletter thatisbeingillustratedonthemonitor,recordstheresponses, andsendsinstructionstothepersonalcomputerwithregard tothesequenceofletterpresentations.Thesizeofeachletter presentationcanbeeithercontrolledbythetechnicianor determinedfromacomputerprogrambasedonthesubject’s responses.BoththelettergraphicsandthePalmapplications arewrittenintheCprogramminglanguage.

● ELECTRONICETDRSVISUALACUITYTESTINGPROTOCOL: TheE-ETDRStestingprotocolisdescribedin Figure2.Testingbeginswithascreeningphasetodetermineanapproximatevisualacuitythreshold,usingthe lettersV,R,K,andD(whichhavebeenreportedtobeof intermediateandcomparableidentificationdifficulty6). Thisphaseisfollowedbythresholdtestingtodeterminean upperlogMARlevelatwhich5of5lettersarecorrectly identifiedandalowerlogMARlevelatwhich0of5letters arecorrectlyidentified.Thespecificletterstestedateach logMARlevelarethesamelettersasthoseonthe original-seriesETDRSchartsfortherightandlefteyes.6 A letterscoretoapproximatetheS-ETDRSscoreiscomputedasthenumberofletterscorrectlyidentifiedduring thresholdtesting,plus5lettersforeachlogMARline abovetheupperboundarythrough20/800.

California,USA)hand-helddevice(bottom)thatcommunicates withapersonalcomputerrunningaLinuxoperatingsystem(IBM, Armonk,NewYork,USA).Withahigh-resolution(1600 1200)17-inchmonitor(top),singleletterscanbedisplayedfrom 20/800to20/12atatestdistanceof3meters.

ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL. 135,NO. 2 195

FIGURE1. Electronicvisualacuitytester.Theelectronicvisual acuitytesterutilizesaprogrammedPalm(Palm,Inc.,SantaClara,

FIGURE2. ElectronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy(E-ETDRS)visualacuitytestingstrategy.Testingbeginswith ascreeningphasetodetermineanapproximatevisualacuitythreshold.Thisphaseisfollowedbythresholdtestingtodetermineanupper logMARlevelatwhich5of5lettersarecorrectlyidentifiedandalowerlogMARlevelatwhich0of5arecorrectlyidentified.

● STUDYPROTOCOL: Thetest-retestreliabilityofboth E-ETDRSandS-ETDRStestingwereevaluatedatthree sites.Thestudypopulationconsistedofindividualsage7

yearsoldandolderwhowerebeingseenaspatientsatthe threesitesandwhoagreedtoundergothetesting.The studywasapprovedbytherespectiveInstitutionalReview

AMERICAN JOURNALOF OPHTHALMOLOGY 196 FEBRUARY2003

Boards,andwasinaccordancewiththeDeclarationof Helsinki;informedconsentwasobtainedfrompatients.

VisualacuitywasmeasuredwithboththeE-ETDRSand S-ETDRSprotocolstwiceononeeyeofeachpatient.The E-ETDRStestingprotocol,whichusessingle-letterpresentationsata3-metertestdistance,isdescribedabove.The S-ETDRStestingprotocolusesa5-letterperlinechartat a4-metertestdistance.Thepatientisaskedtoreadeach letterstartingatthetopofthechart(20/200).Iffewer than20lettersarecorrectlyidentifiedat4meters,testing isalsodoneat1meter.Testingendswhennolettersare correctlyidentifiedonaline.

Forthe first151patients,therighteyewasthestudyeye; thereafter,theeyewiththeworseacuitywastestedsoasto increasethenumberofeyeswithreducedacuityinthe studysample.Attwosites(atwhich128and60patients participated)thetestingorderwasS-ETDRS,E-ETDRS, repeatE-ETDRS,andrepeatS-ETDRS.Thistestingorder permittedcompletionoftheinitialS-ETDRStesting beforeanyothertestingtoavoidinterferingwithother studiesforwhichtheS-ETDRSdatawerebeingused.At onesiteatwhich77patientsparticipated,patientswere notparticipatinginanyotherstudiesusingtheacuitydata; thereforethetestingorderoftheS-ETDRSandE-ETDRS protocolswasrandomlydeterminedfortheinitialtests, followedbyrepeattestinginthesameorder.Thetesting wasconductedinsequencewithoutabreakunlessthe patientwastired,inwhichcaseashortbreakwasgiven.In

TABLE2. BaselineCharacteristicsofSubjects

mostcases,apatient’srepeattestingwasconductedbythe sametechnicianastheonewhoconductedtheinitial testing.TheS-ETDRStestingwasconductedwithcharts placedinaretroilluminatedlightboxatatestdistanceof 4meters(aspertheprotocol,thetestdistancewasreduced to1meterwhentheletterscoreat4meterswaslessthan 20).6 TheE-ETDRStestingwasconductedatatest distanceof3meters.TheS-ETDRSletterscorewas calculatedasthenumberofletterscorrectlyidentifiedat

LetterScore LogMARValue SnellenEquivalent 5 1.6 20/800 10 1.5 20/640 15 1.4 20/500 20 1.3 20/400 25 1.2 20/320 30 1.1 20/250 35 1.0 20/200 40 0.9 20/160 45 0.8 20/125 50 0.7 20/100 55 0.6 20/80 60 0.5 20/63 65 0.4 20/50 70 0.3 20/40 75 0.2 20/32 80 0.1 20/25 85 0.0 20/20 90 0.1 20/15 95 0.2 20/12 LogMAR logarithmoftheminimalangleofresolution.

TABLE1. ConversionsBetweenLetter,LogMAR,and SnellenVisualAcuityScores

BaselineCharacteristics* TotalNumber 265 Agen(%) 7–17years 24(9) 18–50years 108(41) 50years 130(50) mean( SD),years 50 22 Femalesex,number(%) 155(59) Ethnicity,number(%) Caucasian 201(77) AfricanAmerican 40(15) Hispanic 11(4) Asian 9(3) Other 1(.4) Education,number(%) Lessthanhighschool 30(15) Highschool 56(28) College 80(40) Post-graduate 35(17) Clinicaldiagnosis,number(%) Normal 53(20) Uncorrectedrefractiveerror 21(8) Age-relatedmacular degeneration 25(10) Diabeticretinopathy 15(6) Otherretinaldisease 58(22) Cataract 11(4) Opticnerve 3(1) Cornea 5(2) Uveitis 30(11) Glaucoma 29(11) Amblyopia 2(1) Other 11(4) VisualacuityoninitialS-ETDRS test,number(%) 20/20(logMAR 0.00) 55(21) 20/20to 20/40(logMAR 0.02to0.28) 77(29) 20/40to20/100(logMAR 0.30to0.70) 80(30) 20/100(logMAR 0.70) 53(20) S-ETDRS standardEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy.

anddiagnosis(2). ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL. 135,NO. 2 197

*Missingdata:age(3),gender(3),ethnicity(3),education(64),

4metersplus30whenthe4-meterscorewas 20andplus thenumberofletterscorrectlyidentifiedat1meterwhen the4-meterscorewas 20.Alltestingwasconducted eitherwiththepatient’scurrentspectaclesorwithout correction.Arefractionwasnotperformedforpurposesof thestudy;thereforethemeasuredacuitiesdidnotnecessarilyrepresentbest-correctedvisualacuity.Studyenrollmentcontinueduntiltherewereatleast50subjectswith studyeyeswithacuityworsethan20/100.

Theprimarydiagnosis/causeofvisuallossofeacheye wasrecordedasoneofthefollowing:normal,uncorrected refractiveerror,maculardisease(age-relatedmaculardegeneration,diabeticretinopathy,orotherretinaldiseases ordystrophies),cataract,opticnervedisease,uveitis, glaucoma,amblyopia,orother.

● DATAANALYSIS: Onlypatientswhohadscoresfor allfourtestswereincludedintheanalysis(datafrom14 patientswithincompletetestingwerenotincluded).For boththeE-ETDRSandS-ETDRStests,theletterscores wereconvertedtologMARequivalentsusingtheformula logMAR 1.7 (.02)(letterscore).ConversionsbetweenletterscoresandSnellenscoresaregiveninTable1. Withthisconversion,a5-letterdifferenceinvisualacuity isequivalenttoadifferenceof0.1logMARandtoone Snellenline.

Toassesstest-retestreliability,frequencydistributionsof thedifferencesinvisualacuityscoresbetweentheinitial andrepeattestscorewereevaluatedandintraclasscorrelationcoefficientswerecomputed.Ninety-fivepercent confidenceintervals(95%CI)foranacuityscorewere determinedbasedonthestandarderrorofmeasurement,7 andforachangeinanacuityscorefromabaselinelevel weredeterminedbasedonthestandarderrorofthe differences.Analyseswerereplicatedinsubgroupsbased onvisualacuityandage.McNemartestwasusedto compareproportionsinpaireddata;Fisherexacttestwas usedtocompareproportionsbetweensubgroups.Separate assessmentsweremadeusingidenticalmethodsforthe S-ETDRSandE-ETDRStests.

TocompareE-ETDRSscoreswiththeS-ETDRS scores,frequencydistributionsofthedifferencesbetween E-ETDRSandS-ETDRSvisualacuityscoresforeach subjectwereconstructedandintraclasscorrelationcoefficientswerecomputed.Analyseswerereplicatedinsubgroupsbasedonvisualacuityandage.Similarmethods wereusedtocompareE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSscoresina subsetthatincludedonlyeyeswithhightest-retestreliability(bothE-ETDRSandS-ETDRStest-retestscores within fiveletters).

Bland-Altmanplots8 wereconstructedtofurtherassess test-retestreliabilityandtheconcordanceofS-ETDRS andE-ETDRSaccordingtolevelofvisualacuity.All analyseswereconductedusingSASsoftwareversion8 (Cary,NorthCarolina,USA).9

E-ETDRS electronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy;S-ETDRS standardETDRS.

*0.1logMAR 5letters;0.2logMAR 10letters;0.3 logMAR 15letters.

†Duetorounding,percentagesmaynotsumto100and/or theirrespectivecumulativepercentages.

RESULTS

● DESCRIPTIONOFSUBJECTS: Themeanageof265 patientswas50 22yearsold;155werefemale(59%), and201wereCaucasian(77%).Fifty-three(20%)study eyeswereconsiderednormal(includingcorrectedrefractiveerror),21hadanuncorrectedrefractiveerror(8%), and189hadeyedisease(72%).Visualacuitywasbetter than20/40in132eyes(50%),20/40to20/100in80eyes (30%),andworsethan20/100in53eyes(20%)(Table2).

● TEST-RETESTRELIABILITYASSESSMENTS: Thedistributionsofthetest-retestdifferencesforboththeE-ETDRS andS-ETDRStestingappearedsimilar(Table3).Forboth methods,thecorrelationbetweentheinitialandtheretest visualacuityscoreswas0.99.FortheE-ETDRStesting, 89%oftheretestscoreswerewithin0.1logMARofthe initialtestscoreand98%werewithin0.2logMAR; whereasfortheS-ETDRStesting,87%oftheretestscores werewithin0.1logMARoftheinitialtestscoreand98% werewithin0.2logMAR(Table4andFigure3).

Test-retestreliabilitywashighacrosstherangeofvisual acuity.Withbothtestingmethods,morethan90%of

AbsoluteValueof DifferenceinLetters* E-ETDRS (Number 265) S-ETDRS (Number 265) n(%)† Cumulative Percent† n(%)† Cumulative Percent† 034(13)13%44(17)17% 163(24)37%71(27)43% 253(20)57%40(15)58% 340(15)72%27(10)69% 426(10)82%28(11)79% 519(7)89%21(8)87% 612(5)93%12(5)92% 7 5(2)95%12(5)96% 8 5(2)97%2(1)97% 9 3(1)98%2(1)98% 10 1(.4)98%1(.4)98% 11 1(.4)99%2(1)99% 12 1(.4)99%2(1)100% 13 0(0)99%1(.4)100% 14 1(.4)100%0(0)100% 15 0(0)100%0(0)100% 16 0(0)100%0(0)100% 17 0(0)100%0(0)100% 18 1(.4)100%0(0)100%

TABLE3. Test-RetestDifferencesWiththeElectronic ETDRSandStandardETDRSProtocols

AMERICAN JOURNALOF OPHTHALMOLOGY 198 FEBRUARY2003

TABLE4. Test-RetestDifferencesWiththeElectronicETDRSandStandardETDRSProtocolsAccordingtoVisualAcuity*

0.30to0.70;and 20/100 logMAR 0.70.

5letters;0.2logMAR 10letters;0.3logMAR 15letters;0.4logMAR 20letters. ‡Positivevaluemeansrepeatscorewashigher(better).

retestswerewithin0.2logMARoftheinitialtesteven whenacuitywasworsethan20/100.Whenacuitywas betterthan20/40,theproportionofretestswithin0.1 logMARoftheinitialtestwashigherwiththeE-ETDRS methodthanwiththeS-ETDRSmethod(P .02;Table 4andFigure4).Table4alsoprovidesthe95%CIforboth methodsforanindividualacuityscoreaswellasfora changeinacuity.

Test-retestreliabilitywashighirrespectiveofage(Table 5).Withbothtestingmethods,morethan95%ofretests werewithin0.2logMARoftheinitialtesteveninpatients 65yearsoldorolder.

● COMPARISONOFE-ETDRSANDS-ETDRSSCORES: Comparingeachpatient’sE-ETDRSscoreandS-ETDRS score,therewasnotendencyforscoresononetesttobe higherthanontheother(Table6).Thecorrelation

betweentheE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSacuityscoreswas 0.96fortheinitialtestsand0.97fortheretests.The E-ETDRSandS-ETDRSscoresdifferedby 0.1logMAR on74%oftheinitialtestsand79%oftherepeattestsand differedby 0.2logMARon94%and96%oftests, respectively(Table6andFigure5).

AgreementbetweentheE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSscores waslowerinpatientswithacuityworsethan20/100 comparedwithpatientswithacuityof20/100orbetter(for agreementwithin0.2logMAR, P .05forinitialtests and P .01forrepeattests;Table6andFigure6),but agreementwassimilarwhencomparingpatients65years oldorolderwithpatientsyoungerthan65yearsold (Table7).

Withtheanalysislimitedtothe207patientswithhigh test-retestreliability(test-retestscoreswithin0.1logMAR withboththeE-ETDRSandS-ETDRStests),the

AllPatients(Number 265) VisualAcuity 20/40 (Number 132) VisualAcuity20/40to20/100 (Number 80) VisualAcuity 20/100 (Number 53) E-ETDRSS-ETDRSE-ETDRSS-ETDRSE-ETDRSS-ETDRSE-ETDRSS-ETDRS Absolutevalueof difference† number(%) 0.1logMAR235(89)231(87)126(95)115(87)68(85)72(90)41(77)44(83) 0.2logMAR261(98)260(98)132(100)131(99)79(99)78(98)50(94)51(96) 0.3logMAR264(100)265(100)132(100)132(100)80(100)80(100)52(98)53(100) 0.4logMAR265(100)265(100)132(100)132(100)80(100)80(100)53(100)53(100) Differencebetween repeatandinitial scoresinletters‡ mean SD0.77 3.641.10 3.500.29 2.800.77 3.381.15 3.651.50 3.331.42 5.091.34 4.00 (95%CI)(0.33to1.21)(0.68to1.53)( 0.19to0.77)(0.18to1.35)(0.34to1.96)(0.76to2.24)(0.01to2.82)(0.24to2.44) Intraclass correlation coefficient .99 .99 .94 .86 .91 .87 .93 .95 95%CI(two-sided) foracuityscore, logMAR: halfwidth .10 .10 .08 .09 .09 .08 .14 .11 95%CIforchange betweentwo acuityscores, logMAR Half-widthof two-sidedCI .14 .14 .11 .13 .13 .11 .20 .15 WidthofonesidedCI .12 .12 .09 .11 .11 .10 .17 .13 CI

logarithmoftheminimalangle

*VisualacuitybasedonletterscorefrominitialstandardETDRStest.Visualacuity 20/40 logMAR 0.28;20/40–20/100 logMAR

ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL. 135,NO. 2 199

confidenceinterval;E-ETDRS electronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy;logMAR

ofresolution;S-ETDRS standardETDRS;SD standarddeviation.

†0.1logMAR

E-ETDRSandS-ETDRSscoresdifferedby 0.1logMAR on81%oftheinitialtestsand84%oftherepeattests,and differedby 0.2logMARon95%and99%oftests, respectively.

● DIFFERENCESAMONGCENTERS: Althoughtherewere somedifferencesinthecharacteristicsofthepatientswhen comparingthethreeclinicalsites(aswasexpected,dueto thedifferenttypesofpatientseachhadaccesstofor inclusioninthestudy),therewerenomeaningfuldifferencesintheresultscomparingthecenters(datanot shown).

AttheonesiteatwhichthetestingorderofS-ETDRS andE-ETDRSwasdeterminedatrandom,thetest-retest reliabilityresultsandtheresultsofthecomparisonofthe

Thedottedlinesseparatethetest-retestscoresthatwerewithin 10lettersofeachotherfromthoseinwhichthedifferencewas greaterthan10letters.

scoresonthetwotestsweresimilartotheoverallresults (datanotshown).

DISCUSSION

WEFOUNDTHATOURCOMPUTERIZEDVISUALACUITY testingprotocolhastest-retestreliabilitycomparabletothe standardETDRScharttestingprotocolonwhichitwas based.Withbothtestingmethods,closeto90%ofpatients testedwithin0.1logMAR(5letters)oftheinitialscoreon theretest,andmorethan95%testedwithin0.2logMAR (10letters)ontheretest.Test-retestreliabilitydidnot varywithage,but,notunexpectedly,variabilitywas slightlygreaterinpatientswithpooracuity.Still,about

FIGURE3.Distributionoftest-retestdifferencesinacuity scores(number 265).Apositivedifferenceindicatesthe repeatscorewasbetterthantheinitialscore.

AMERICAN JOURNALOF OPHTHALMOLOGY 200 FEBRUARY2003

FIGURE4.BlandAltman8 plotoftest-retestdifferenceversus averagevisualacuityscore(number 265).Apositivedifferenceindicatestherepeatscorewasbetterthantheinitialscore.

E-ETDRS electronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy;logMAR logarithmoftheminimalangleofresolution;S-ETDRS standardETDRS.

*Threepatientsaremissingdataonage.

†0.1logMAR 5letters;0.2logMAR

CI confidenceinterval;E-ETDRS electronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy;logMAR logarithmoftheminimumangle ofresolution;SD standarddeviation;S-ETDRS standardETDRS;SD standarddeviation.

*VisualacuitybasedonletterscorefrominitialstandardETDRStest: 20/40 logMAR 0.28;20/40 –20/100 logMAR0.30to0.70; and 20/100 logMAR 0.70.

†0.1logMAR 5letters;0.2logMAR 10letters;0.3logMAR 15letters;0.4logMAR 20letters. ‡NegativevaluemeansS-ETDRSletterscorewashigher(better).

80%ofpatientswithpooracuity(worsethan20/100)had retestscoreswithin0.1logMAR(5letters)oftheinitial testscores,andabout95%retestedwithin0.2logMARof theinitialscore.Basedonourestimatesof95%CI,we foundthatachangeinacuityof0.2logMAR(10letters)

fromabaselinelevelisunlikelytoberelatedtomeasurementvariabilityusingeithertheE-ETDRSorthe S-ETDRSvisualacuitytestingprotocol.

WefoundagreementbetweentheE-ETDRSand S-ETDRSscorestobehigh,suggestingstrongconcurrent

AbsoluteValueof Difference† Age 40YearsOld(Number 86) Age40– 65YearsOld (Number 94) Age 65YearsOld(Number 82) E-ETDRS n(%) S-ETDRS n(%) E-ETDRS n(%) S-ETDRS n(%) E-ETDRS n(%) S-ETDRS n(%) 0.1logMAR 80(93) 72(84) 79(84) 84(89) 74(90) 72(88) 0.2logMAR 84(98) 83(97) 93(99) 93(99) 81(99) 81(99) 0.3logMAR 86(100) 86(100) 94(100) 94(100) 81(99) 82(100) 0.4logMAR 86(100) 86(100) 94(100) 94(100) 82(100) 82(100)

TABLE5. Test-RetestDifferencesWiththeE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSProtocolsAccordingtoAge*

10letters;0.3logMAR 15letters;0.4logMAR 20letters.

AllPatients (Number 265) VisualAcuity 20/40 (Number 132) VisualAcuity20/40to20/100 (Number 80) VisualAcuity 20/100 (Number 53) Initialtest Absolutevalueofdifference† number(%) 0.1logMAR 196(74) 108(82) 58(73) 30(57) 0.2logMAR 248(94) 127(96) 75(94) 46(87) 0.3logMAR 261(98) 131(99) 80(100) 50(94) 0.4logMAR 262(99) 131(99) 80(100) 51(96) DifferencebetweenE-ETDRSand S-ETDRSscores,letters mean SD 0.14 5.94 0.48 5.09 0.45 5.25 0.19 8.44 (95%CI)‡ ( 0.86to0.58)( 1.35to0.40)( 0.72to1.62) ( 2.52to2.14) Intraclasscorrelationcoefficient .96 .77 .76 .81 Repeattest Absolutevalueofdifference† number(%) 0.1logMAR 210(79) 117(89) 64(80) 29(55) 0.2logMAR 255(96) 130(98) 78(98) 47(89) 0.3logMAR 260(98) 131(99) 79(99) 50(94) 0.4logMAR 263(99) 131(99) 80(100) 52(98) DifferencebetweenE-ETDRSand S-ETDRSscores,letters mean SD 0.47 5.14 0.95 4.28 0.10 4.64 0.11 7.36 (95%CI)‡ ( 1.09to0.15)( 1.69to 0.22)( 0.93to1.13) ( 2.14to1.91) Intraclasscorrelationcoefficient .97 .82 .85 .86

TABLE6. DifferencesBetweenE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSAccordingtoVisualAcuity*

ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL. 135,NO. 2 201

FIGURE5.DistributionofdifferencesbetweenacuityscoresonelectronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy (ETDRS)andstandardETDRStesting(number 265).ApositivedifferenceindicatestheelectronicETDRSscorewasbetter thanthestandardETDRSscore.

validity.Thedifferencesinvisualacuityscores,however, weregreaterincomparingthetwotestingmethodsthanin therepeatingofeachtest.Thisistobeexpectedbecause thetwotestingstrategiesandtheirmethodsofcomputing thevisualacuityscorediffer,thusaddingasecondsource

ofvariationinadditiontothetest-retestvariability.Thisis particularlytrueforthetestingofpatientswithlowvision, forwhomtheS-ETDRSscorecombinestheresultsof testingat4metersand1meter,whereastheE-ETDRS testingisatasingledistance.TheE-ETDRSscorewas

AMERICAN JOURNALOF OPHTHALMOLOGY 202 FEBRUARY2003

FIGURE6.BlandAltman8 plotofdifferencebetweenacuityscoresonelectronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy (ETDRS)andstandardETDRSvsaveragevisualacuityscore(number 265).Apositivedifferenceindicatestheelectronic ETDRSscorewasbetterthanthestandardETDRSscore.ThedottedlinesseparatetheE-ETDRS:S-ETDRSscoresthatwere within10lettersofeachotherfromthoseinwhichthedifferencewasgreaterthan10letters.

developedtobesimilartotheS-ETDRSletterscoreandto maintaintheadvantagesofletterscoringoverlinescoring.6,10 –13 However,somevariationundoubtedlyisdueto differencesinthescoringmethodsandtotheeffectof usingsingle-letterpresentationswiththeE-ETDRS procedureandlinepresentationswiththeS-ETDRS

procedure. 14 – 16

TherewasnotendencyfortheEETDRSandS-ETDRSscorestobehigherorlowerthan theother.

Forbothprocedures,retestscoresonaveragewereabout oneletter(orless)higherthantheinitialtestscores, indicativeofaninconsequentiallearningeffect.Mostprior

ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL. 135,NO. 2 203

TABLE7. DifferencesBetweenE-ETDRSandS-ETDRSAccordingtoAge

E-ETDRS electronicEarlyTreatmentforDiabeticRetinopathyStudy;logMAR logarithmoftheminimalangleofresolution;S-ETDRS standardETDRS.

*0.1logMAR 5letters;0.2logMAR 10letters;0.3logMAR 15letters;0.4logMAR 20letters.

studies2,3,6,11 havealsoreportedthatthelearningeffectis minimalusingS-ETDRSorsimilartesting.

Campariniandcolleagues17 reportedtheresultsofan adaptivestrategyforvisualacuitycharttestingcalled ETDRS-fast.Theprocedureinvolvesadeterminationof approximatethresholdfollowedbythetestingofall5 lettersonaline.Theapproximatethresholdisdetermined byshowingoneletterperlineonthechartstartingat 20/200untilaletterismissedandthenshowingmultiple lettersperlineuntilthelowestlinewith4or5correctis identified.Smallerlinesarethentestedasperthestandard ETDRStestingprotocoluntil0or1letteriscorrectona line.Aletterscoreisdetermined,similartoourscoring method,byassumingthatallletterslargerthanthelargest testedlinewouldhavebeencorrectlyidentifiedandnone oftheletterssmallerthanthesmallesttestedlinewould havebeencorrectlyidentified.Bothtest-retestreliability (r 0.96;97%ofretestswithin0.1logMARofinitialtest) andthecorrelationoftheETDRS-fastscorewiththe standardETDRSscore(r 0.95)werefoundtobehighin astudyof57patientswithacuitiesintherangeof20/100 to20/10,mostofwhomhadacuityof20/40orbetter.

WiththeE-ETDRStestingmethod,thenumberof letterpresentationsinourstudyaveragedabout25letters (forthescreeningphaseandthresholdtestingcombined) whenvisualacuitywasbetterthan20/40andabout30 letterswhenacuitywas20/40orworse.Comparedwith S-ETDRStesting,thenumberofletterpresentationswith theE-ETDRSmethodusuallywillbefewerforacuities betterthan20/63.Thebettertheacuity,thelargerthe differenceinnumberofletterstestedwillbe.Forinstance, withacuityof20/20,about55letterswillbetestedwith S-ETDRStestingcomparedwithabout25letterswith E-ETDRStesting.Forverypooracuity,however,the E-ETDRSproceduremaytestmorelettersthanwillthe S-ETDRSprocedure,dependingonwhetherS-ETDRS testingisalsodoneat1meter.

Severalotherstudieshavedemonstratedthatthe ETDRStestingandsimilaroptotypetestingwithletter scoringhavehightest-retestreliability.2,6,11,13 Mostofthe studieshavepredominatelyincludedeyeswithnormalor

near-normalvision.OnlythestudyofBlackhurstand associates2 includedasubstantialnumberofeyeswith visualimpairment.Inthatstudy,visualacuitywastested twiceusingtheETDRSchartsin89eyeswithacuityof 20/100orbetterandin75eyeswithacuityworsethan 20/100.Test-retestreliabilitywashigherintheeyesinthe bettervisiongroup.Thepercentagesofeyeswithretest scoreswithin0.1logMARand0.2logMARoftheinitial scoreswere92%and98%,respectively,inthebettervision groupand80%and89%,respectively,intheworsevision group.Theintraclasscorrelationcoefficientwas0.95in eachgroup.

Insummary,theE-ETDRSprotocolhashightest-retest reliabilityandgoodconcordancewithS-ETDRStesting. Althoughweexpectthatthistestingmethodwillbeuseful forpediatricpatientsasyoungas6or7yearsofage,wehad toofewchildreninthestudytobeabletodeterminethis and,therefore,willbeconductingaseparatetest-retest reliabilitystudyinapediatricpopulation.Foraclinical trial,thepotentialadvantagesofusingacomputerized methodoftestingovermanualtestingincludebetter standardizationofthetestingprocedureacrossmultiple sites,lesstrainingrequiredforthetechniciansadministeringthetest,reductionofpotentialbiasbylimitingtherole ofthetechnicianinthetestingprocedure,theabilityto testvisualacuityfrom20/800to20/12atasingletest distance,theabilitytodirectlycapturethetestingdata electronicallywithouttheneedtomanuallyrecordevery responseonascoresheetandtocalculatethescore automatically,andtheneedforfeweroptotypepresentationswhenvisualacuityisgood.Disadvantagesincludethe costofpurchasingandmaintainingtheequipment,the inabilitytomeasure20/10visualacuityatthe3-metertest distance(althoughthiswouldbepossibleifthetest distancewereincreasedto4meters),andthefactthat lettersizeisacloseapproximation,butnotanexact logMARprogression,duetothemethodbywhichthe lettersarerenderedonthepersonalcomputer.Despitethe potentialadvantagesoftheE-ETDRSprotocol,incorporatingthisnewprocedureintoongoingclinicalstudiesthat areusingtheS-ETDRSprotocoltoassesschangeinvisual

AbsoluteValueof Difference* Age 40YearsOld(Number 86) Age40– 65YearsOld(Number 94) Age 65YearsOld(Number 82) InitialTestn(%)RepeatTestn(%)InitialTestn(%)RepeatTestn(%)InitialTestn(%)RepeatTestn(%) 0.1logMAR61(71) 73(85) 73(78) 74(79) 60(73) 62(76) 0.2logMAR82(95) 84(98) 87(93) 91(97) 77(94) 77(94) 0.3logMAR86(100) 86(100) 93(99) 92(98) 79(96) 79(96) 0.4logMAR86(100) 86(100) 93(99) 93(99) 80(98) 81(99)

AMERICAN JOURNALOF OPHTHALMOLOGY 204 FEBRUARY2003

acuityseemsinappropriate.However,fornewclinical studies,theE-ETDRSmethodisaviablealternativethat shouldbeconsidered.TheE-ETDRSprotocolcanbe adaptedforuseoncommercially-availablecomputerized visualacuitytestersusingdifferentoperatingsystems. However,forusewithstandardofficepersonalcomputers, considerablemodificationswouldbeneededtoprovidethe necessarypixelresolution.Informationontherequired technicalspecificationscanbeobtainedbycontactingthe authors.Futureworkisindicatedtodeterminewhetherthe E-ETDRStestingalgorithmcanbemodifiedtofurther reducethenumberofletterpresentationsbyalteringthe stoppingrulesand/orreducingthenumberofpresentations ateachlogMARlevel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thefollowingresearchstaffparticipatedinthestudyatthe clinicalsites:R.Mercer,L.Goodman,D.Koutsandras,T. LaReau,R.Nashwinter,J.P.Rowan,G.Foster,W.R. O’Donnell(NationalEyeInstitute,DivisionofEpidemiologyandClinicalResearch,NationalInstitutesofHealth, Bethesda,MD);K.G.Locke,C.E.Wilson(Retina FoundationoftheSouthwest,Dallas,TX);andJ.Thompson,T.Smith,C.Blachly,K.Novitsky(Discoveriesin SightResearchLabs,DeversEyeInstitute,Portland,OR).

REFERENCES

1.EarlyTreatmentDiabeticRetinopathyStudyResearch Group.Earlytreatmentdiabeticretinopathystudydesignand baselinepatientcharacteristics.ETDRSreportnumber7. Ophthalmology1991;98:741–756.

2.BlackhurstDW,MaguireMG,MacularPhotocoagulation StudyGroup.Reproducibilityofrefractionandvisualacuity measurementunderastandardprotocol.Retina1989;9:163–169.

3.ElliottDB,SheridanM.Theuseofaccuratevisualacuity

measurementsinclinicalanti-cataractformulationtrials. OphthalmicPhysiolOpt1988;8:397–401.

4.MokePS,TurpinAH,BeckRW,etal.Computerized methodofvisualacuitytesting:adaptationoftheamblyopia treatmentstudyvisualacuitytestingprotocol.AmJOphthamol2001;132:903–909.

5.HolmesJM,BeckRW,RepkaMX,etal.Theamblyopia treatmentstudyvisualacuitytestingprotocol.ArchOphthalmol2001;119:1345–1353.

6.FerrisFL,KassoffA,BresnickGH,BaileyI.Newvisual acuitychartsforclinicalresearch.AmJOpthalmol1982;94: 91–96.

7.CrockerL,AlginaJ.Introductiontoclassicalandmodern testtheory.NewYork:Holt,RinehartandWinston,1986: 150 –151.

8.BlandJM,AltmanDG.Statisticalmethodsforassessing agreementbetweentwomethodsofclinicalmeasurement. Lancet1986;1:307–310.

9.SAS.SAS/STATuser’sguide,version8.Cary,NC:SAS Institute,Inc,1999.

10.VandenBoschME,WallM.Visualacuityscoredbythe letter-by-letterorprobitmethodshaslowerretestvariability thanthelineassignmentmethod.Eye1997;11:411–417.

11.Lovie-KitchinJE.Validityandreliabilityofvisualacuity measurements.OphthalmicPhysiolOpt1988;8:363–370.

12.BaileyIL,BullimoreMA,RaaschTW,TaylorHR.Clinical gradingandtheeffectsofscaling.InvestOphthalmolVisSci 1991;32:422–432.

13.ArditiA,CagenelloR.Onthestatisticalreliabilityof letter-chartvisualacuitymeasurements.InvestOphthalmol VisSci1993;34:120 –129.

14.StagerDR,EverettME,BirchEE.Comparisonofcrowding barandlinearoptotypeacuityinamblyopia.AmOrthoptJ 1990;40:51–56.

15.FlomMC,WeymouthFW,KahnemanD.Visualresolution andcontourinteraction.JOptSocAm1963;53:1026 –1032.

16.StuartJA,BurianHM.Astudyofseparationdifficulty:its relationshiptovisualacuityinnormalandamblyopiceyes. AmJOphthalmol1962;53:471–477.

17.CampariniM,CassinariP,FerrignoL,MacalusoC.ETDRSfast:implementingpsychophysicaladaptivemethodstostandardizedvisualacuitymeasurementwithETDRScharts. InvestOphthalmolVisSci2001;42:1226 –1231.

ACOMPUTERIZED METHODOF VISUAL ACUITY TESTING VOL 135,NO 2 205

Validationofanautomated-ETDRSnearandintermediatevisual acuitymeasurement

DOI:10.1111/cxo.13018

YiPang ODPhD

LaurenSparschu BS

ElyseNylin BS

DepartmentofDean’sEducation,IllinoisCollegeof Optometry,Chicago,Illinois,USA

E-mail:ypang@ico.edu

Background: Theaimofthisstudywastodeterminetherepeatabilityofanautomated-ETDRS (EarlyTreatmentDiabeticRetinopathyStudy)nearandintermediatevisualacuitymeasurement insubjectswithnormalvisualacuityandsubjectswithreducedvisualacuity.Theagreementof automated-ETDRSwithgoldstandardchart-basedvisualacuitymeasurementwasalsostudied.