Accuracy of a New Noninvasive Automatic Ocular Surface Analyzer for the Diagnosis of Dry Eye Disease-Two-Gate Design Using Healthy Controls

Janosch Rinert , Giacomo Branger , Lucas M Bachmann , Oliver Pfaeffli , Katja Iselin , Claude Kaufmann , Michael A Thiel , Philipp B Baenninger

Affiliations

PMID: 35543570 DOI: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003052

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the diagnostic performance of measurements from a new noninvasive, automated ocular surface analyzer (IDRA) in the diagnosis of dry eye disease (DED).

Methods: We prospectively identified patients with and without DED using best practice methods. Subsequently, all participants underwent IDRA analysis, consisting of 5 components: noninvasive tear film break-up time, tear meniscus height, lipid layer interferometry, eye blink quality, and infrared meibography. The manufacturer provides cutoff values for a pathologic result for each of these components. Using a stepwise augmentation multivariate logistic regression model, we identified the components with the strongest association for the presence of DED. For the 3 components with the strongest association (interferometry, tear meniscus, and infrared meibography), we calculated the probability of DED.

Results: We enrolled 40 patients (80 eyes) with DED (mean age 60.5 years; women 78.3%) and 35 healthy subjects (70 eyes, mean age 31.1 years; women 21.7%). The IDRA had an area under the curve of 0.868 (95% confidence interval: 0.809-0.927) to detect DED. A normal (≥80) interferometry combined with a normal (>0.22) tear meniscus and a normal (≤40) infrared meibography was associated with an estimated probability of 18% for the presence of DED, whereas the estimated probability of DED was as high as 96% when all 3 findings were pathologic.

Conclusions: The results of IDRA showed a positive concordance with routine clinical diagnostic tests. The new analyzer is an easyto-access diagnostic tool to rule out the presence of DED in the extramural setting and to guide a timely DED treatment.

Copyright © 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

References

Clegg JP, Guest JF, Lehman A, et al. The annual cost of dry eye syndrome in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom among patients managed by ophthalmologists. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006;13:263–274.

Verjee MA, Brissette AR, Starr CE. Dry eye disease: early recognition with guidance on management and treatment for primary care family physicians. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9:877–888.

Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30:379–387.

Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:334–365. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:276–283.

Ozulken K, Aksoy Aydemir G, Tekin K, et al. Correlation of non-invasive tear break-up time with tear osmolarity and other invasive tear function tests. Semin Ophthalmol. 2020;35:78–85.

Gumus K, Crockett CH, Rao K, et al. Noninvasive assessment of tear stability with the tear stability analysis system in tear dysfunction patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:456–461.

Eom Y, Lee JS, Kang SY, et al. Correlation between quantitative measurements of tear film lipid layer thickness and meibomian gland loss in patients with obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction and normal controls. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:1104–1110.e2.

Jung JW, Park SY, Kim JS, et al. Analysis of factors associated with the tear film lipid layer thickness in normal eyes and patients with dry eye syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:4076–4083.

Review

PromisingHigh-TechDevicesinDryEyeDiseaseDiagnosis

AndreaDeLuca,AlessandroFerraro,ChiaraDeGregorio,MariateresaLaborante,MarcoCoassin , RobertoSgrullettaandAntonioDiZazzo*

OphthalmologyComplexOperativeUnit,UniversityCampusBio-Medico,00128Rome,Italy

* Correspondence:a.dizazzo@policlinicocampus.it

Abstract: Background:Dryeyedisease(DED)isacommonanddebilitatingconditionthataffects millionsofpeopleworldwide.Despiteitsprevalence,thediagnosisandmanagementofDED canbechallenging,astheconditionismultifactorialandsymptomscanbenonspecific.Inrecent years,therehavebeensignificantadvancementsindiagnostictechnologyforDED,includingthe developmentofseveralnewdevices.Methods:Aliteraturereviewofarticlesonthedryeye syndromeandinnovativediagnosticdeviceswascarriedouttoprovideanoverviewofsomeofthe currenthigh-techdiagnostictoolsforDED,specificallyfocusingontheTearLabOsmolaritySystem, DEviceHygrometer,IDRA,Tearcheck,Keratograph5M,CorneaDomeLensImagingSystem,I-PEN OsmolaritySystem,LipiViewIIinterferometer,LacryDiagOcularSurfaceAnalyzer,Tearscope-Plus, andCobraHDCamera.Conclusions:Despitethefactthatconsistentuseofthesetoolsinclinical settingscouldfacilitatediagnosis,nodiagnosticdevicecanreplacetheTFOSalgorithm.

Keywords: dryeyedisease;diagnosticdevice;ocularsurface

1.Introduction

Citation: DeLuca,A.;Ferraro,A.;De Gregorio,C.;Laborante,M.;Coassin, M.;Sgrulletta,R.;DiZazzo,A. PromisingHigh-TechDevicesinDry EyeDiseaseDiagnosis. Life 2023, 13, 1425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ life13071425

AcademicEditors:José-María Sánchez-González,Carlos Rocha-de-Lossadaand AlejandroCerviño

Received:8May2023

Revised:15June2023

Accepted:19June2023

Published:21June2023

Copyright: ©2023bytheauthors. LicenseeMDPI,Basel,Switzerland. Thisarticleisanopenaccessarticle distributedunderthetermsand conditionsoftheCreativeCommons Attribution(CCBY)license(https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ 4.0/).

TheTFOSDEWSII(TearFilmandOcularSurfaceSocietyInternationalDryEye WorkshopII,2017)definesdryeyedisease(DED)as“amultifactorialdiseaseoftheocular surfacecharacterizedbyalossofhomeostasisofthetearfilmandaccompaniedbyocular symptoms,inwhichtearfilminstabilityandhyperosmolarity,ocularsurfaceinflammation anddamage,andneurosensoryabnormalitiesplayetiologicalroles”[1].Theprevalenceof DEDexhibitsapositivecorrelationwithadvancingageandvariesbetweenfivepercentand fiftypercentacrosstheoverallpopulation[2].DEDischaracterizedbyarangeofsymptoms suchasocularpain,burning,stinging,discomfort,aforeignbodysensation,poorvisual acuity,photophobia,andirritation[1,2].Thesymptomsofdryeyediseasecanrangefrom minordiscomforttosubstantialgrievancesthatinterferewithdailyfunctioning,decrease qualityoflife,andcarrynotableconsequencesforthesocioeconomicstructure[1,2].

Thefirstphaseintheprocessofdiagnosingdryeyediseaseinvolvestheutilizationof triagequestions,whichcouldestablishtheneedforadditionalDEDevaluationandexclude disorderssuchasconjunctivitis,blepharitis,Sjögrensyndrome,infection,andlid-related disease.

BasedontheTFOSDEWSII,adryeyediagnosisrequiresthepatienttoscorepositivelyononeoftwospecificsymptomquestionnaires(DEQ-5,DryEyeQuestionnaire-5 score ≥ 6orOSDI,OcularSurfaceDiseaseIndexscore ≥ 13).Thismustbefollowedbythe presenceofaminimumofonepositiveclinicalsign,suchasdecreasedtearfilmstability (NIBUT,non-invasivetearbreak-uptime,<10s),elevatedtearosmolarity(>308mOsm/L), significantinter-eyedisparityinosmolarity(>8mOsm/L),orocularsurfacedamageindicatedbyfluoresceinandlissaminegreen(>5cornealspots,>9conjunctivalspots,orlid margin ≥ 2mmlengthand ≥ 25%width).

OSDIreferstoaverifiedquestionnairethatiscommonlyemployedinclinicaltrials duetoitsabilitytoprovidearapidassessmentofdryeyedisease(DED)anditsimpacton thequalityoflife(QoL)ofpatients[3].TheOSDIconsistsof12itemsthataimtoevaluate

thesymptomsexperiencedbypatientsduringtheprecedingweek.Itisorganizedinto threesections:theoccurrenceofsymptoms,theimpactonvision-relatedqualityoflife,and theidentificationofanyenvironmentaltriggers[3].Eachitemisevaluatedusingascale rangingfromzerotofour.Thescaleusedtomeasurefrequencyisasfollows:noneofthe time(0),someofthetime(1),halfofthetime(2),themajorityofthetime(3),andtheentire time(4).Theoverallnumericalvalueiscalculatedutilizingarangethatextendsfromzero toonehundred,wherebyelevatedscoresdenoteheightenedlevelsofimpairment.Ascore of0to12isregardedasnormal;ascoreof13to22suggestsmilddisease;ascoreof23to 32denotesmoderateDED;andascoreof33to100indicatessevereDED[3].Furthermore, OSDIdoesnotdiscriminatebetweenevaporativeandaqueousdeficiencies[4].

ItispossiblethattheTFOSDEWSIIdiagnosticalgorithmisnotthemosteffective methodwhenusedinaclinicalenvironment,despitethefactthatitprovidesbotha comprehensiveandfullapproachtodetectingdryeyedisease.Althoughitoffersacomplete evaluation,thediagnosticproceduretypicallyconsistsofanumberofstepsthatcanbe challengingtocarryoutinfast-pacedclinicalsettingswithlimitedtime.

Therefore,inthispaper,weexaminenewhigh-techimagingsystemsforocularsurface evaluation.Thesesystemsclaimtohaveseveralbenefitsovertraditionalmethodsofdiagnosis,suchasbeingnon-invasive,providingstandardizedandobjectiveresults,enabling themonitoringofdiseaseprogressionandtreatmenteffectiveness,beinguser-friendly,and enablingrapidtaskexecution.However,regardlessofthestudiesreviewed,thereliability ofthesedevicesislow.

2.MaterialsandMethods

Aliteraturereviewofarticlesondryeyesyndromeandinnovativediagnosticdevicespublishedinthelast15yearsandavailableontheNationalLibraryofMedicine wascarriedoutwithoutanyrestrictionoflanguage,especiallyfocusingontheTearLab OsmolaritySystem,IDRA,Tearcheck,Keratograph5M,I-PenOsmolaritySystem,Lipiview IIInterferometer,LacryDiagOcularSurfaceAnalyzer,CorneaDomeLensImagingSystem, DEviceHygrometer,Tearscope-Plus,andCobraHDCamera.Allpublishedpeer-reviewed randomizedclinicaltrials,meta-analyses,systematicreviews,andobservationalstudies aboutthesetopicswereevaluated.Table 1 showsallthedevicesanalyzedandtheexams theyperform.

TearLabOsmolaritySystem® (TearLabCorporation,SanDiego,CA,USA)isanoninvasivediagnosticdevicethatanalyzestheosmolarityofapatient’stears.Osmolarity referstothetotalconcentrationofdissolvedsubstancespresentinasolutionwithout regardtotheirdensity,size,molecularweight,orelectricalcharges.Theprocessoftears evaporating,adecreaseintheproductionoftears,andthedysfunctionofthemeibomian glandareallfactorsthatcontributetoanelevationintearosmolarity.Theevaluationof tearosmolarityisconsideredahighlyeffectivediagnostictoolforeverytypeofdryeye syndrome[5].Thetearfilmoftheexposedocularsurfaceareaexhibitsalowerosmolarity. Variousenvironmentalfactorssuchaswind,cigarettesmoke,indoorairconditioning,and heat,aswellasprolongedcomputeruseleadingtoreducedblinkingfrequency,havebeen identifiedaspotentialimpedimentstoevaporation,therebyaffectingtearosmolarity[6]. Tearosmolaritywasalsofoundtocorrelatewithincreasedconcentrationsofinflammatory cytokinesandmatrixmetalloproteinases(MMPs),aswellasHLA-DR(HumanLeukocyte Antigen-DR)overexpression,suggestingthattearosmolaritycouldpotentiallyserveasa predictivemeasureforocularsurfacediseasesthatarelinkedtohighlevelsofinflammatory mediators[6].

TearLabOsmolaritySystem®

Tearcheck®

Keratograph5M®

I-PENOsmolaritySystem®

LipiView® IIinterferometer

LacryDiagOcularSurfaceAnalyzerx

CorneaDomeLensImagingSystem® x

Tearscope-PlusTM x

CobraHDCamera

NIBUT,non-invasivetearbreak-uptime;LLT,lipidlayerthickness;TMH,tearmeniscusheight;RH,relativehumidity.

TheTearLabOsmolaritySystemiscomposedofasetofinstruments,includinga readerdevice,pens,andtestcards.Thereaderisasmallcountertopdevicethatcalculates andshowstheosmolaritytestresultsonaliquidcrystaldisplay.TheTearLabosmolarity deviceisequippedwithapairofpensthatareusedtoholdthetestcardandtransmitthe datatothereader.Thetestcardisattachedtothepensandtakesasampleof50nLin milliosmolesperliter(mOsm/L)units.Thecontactbetweenthetearfilmandtheeyelid occursatthetemporalmargin.Afterhearingthebeepconfirmingsuccessfultearcollection, thepenisdockedintothereader[7].

Thisosmometerhasseveraladvantages,includingbeingasmall,portabledevicethat canbeusedinadoctor’sofficeandrequiringlessthan100nLoftearfluid[5].Furthermore, itusesatemperature-correctedtearfluidimpedancemeasurement,enablinganindirect evaluationoftearosmolarityandprovidingpreciseresultswithinabrieftimeframe[5,8].It mayalsobeusedincombinationwithotherdiagnostictools,suchastheLipiViewsystem, toprovideamoredetailedimageofapatient’sdryeyecondition.AccordingtoSzczesnaIskander,itisnecessarytotakeaminimumofthreeconsecutivemeasurementstoobtain clinicallytrustworthytearosmolarityvaluesusingtheTearLabOsmolaritySystem.TheutilizationofthehighestosmolarityvaluetoidentifyDEDrequirescarefulconsiderationdue tothefrequentoccurrenceofanomalousreadingsoftearosmolarity[9].Nevertheless,Szalai etal.foundsignificantoverlapintearosmolarityvaluesmeasuredwiththeTearLabsystem inthecontrol(22healthyindividuals)anddryeyegroups(21patientswithnon-Sjögren syndromedryeye(NSSDE)and20patientswithSjögrensyndromedryeye(SSDE)),implyingthatmeasurementoftearosmolarityutilizingtheTearLabosmometerishighlyvariable anddoesnotdistinguishindividualsdiagnosedwithdryeyediseasefromhealthycontrols (meantearosmolaritywas 296.77 ± 16.48mOsm/L inNSSDE, 303.36 ± 17.22mOsm/L in SSDE,and303.52 ± 12.92mOsm/Linthecontrolgroup; p =0.018)[10].

Asaresult,TearLabisaquicktoolinclinicalpractice,butitsusefulnessislimitedby theliterature-reportedlowreliabilityinrecognizingDEDanditsprimaryuseinevaporative dryeye.

IDRA® OcularSurfaceAnalyzer(SBMSISTEMI,Inc.,Torino,Italy)isadiagnostictool thatusesinfraredandultravioletlighttoevaluatethehealthoftheocularsurface.Changes inthetearfilmandmeibomianglands,whichcanbeindicativeofDED,canbedetected bytheinstrument.TheinstrumentisabletoidentifyMGaswellasallthreelayersofthe tearfilm(lipid,aqueous,andmucin).Thisallowsphysicianstodeterminewhichpartsof thetearfilmrequiretreatmentbasedonthetypeofinsufficiency.IDRAmustbeplaced betweenaslitlampandabiomicroscope.Itspinshavebeendesignedtofitperfectlyinto theholeleftbyremovingtheplateusedforthetonometer,anditconductsa5-minute non-invasivetest[11].Theinstrumentproducesabeamofwhitelightontothecorneal surface,andtheresultantreflectionoflightfromthetearfilmpresentsawhite,fan-shaped regionthatcoverstheinferiorthirdofthecornea[12].ThefiveparametersincludeNIBUT, TMH,lipidlayerinterferometry,ocularblinkquality,andinfraredmeibography.The non-invasivebreak-uptime(NIBUT)isdeterminedthroughtheutilizationofPlacido’s disctoprojectringpatternsonthecornea,followedbythemeasurementoftheduration insecondsbetweenthecompleteblinkandthefirstdisturbanceofthereflectedimage onthecornea[11].Theutilizationofinfraredilluminationinnon-invasivemeibography hasthecapabilitytoidentifymorphologicalalterationsinthemeibomiangland.Onthe otherhand,tearinterferometrycanbeemployedtoassessthelipidlayerofthetearfilm. Theevaluationofmeibomianglandmorphologyoffersvaluableclinicalevidenceforthe diagnosisofevaporativeDED,whileassessmentsofthelipidlayerofthetearfilmfacilitate themonitoringofmeibomianglandfunction[10].Thephotographshowstheidentification oftheupperandlowertearmeniscusaswellastheevaluationoftearmeniscusheight alongthelowerlidmargin[11].Aprospectivestudywith75patients(40withDEDand 35healthysubjects)foundgoodconcordancebetweentheIDRAocularsurfaceanalyzer andstandarddiagnosticproceduresindifferentiatingbetweenindividualswithnormal

ocularfunctionandthosewithdryeyedisease.Ithadanareaunderthecurveof0.868 (95%confidenceinterval:0.809–0.927)todetectDED[13].

Thelipidlayerisimportantforregulatingtheevaporationofthetearfilm.Atestfor lipidlayerpattern(LLP)evaluationisbasedoninterferencephenomena,butitisinfluenced bysubjectiveinterpretationofthepatterns[14].Thelipidlayerthicknessesaredetermined throughtheutilizationofDr.Guillon’sinternationalgradingsystem,whichenablesthe calculationoftheaverage,maximum,andminimumthicknessesofthelipidlayerpattern grades[15].Thegradesareconvertedtonanometerunitsandclassifiedintoarangeof 15to100nmaccordingtotheobservedpatterns.ThemaximumcutoffwavelengthofIDRA is100nm[16].

DespitethefactthatIDRAhasthebenefitofassessingmultipleocularsurfaceparameterswithasingledevice,thefindingsarecontradictory.Inaretrospectivecross-sectional studywith47non-Sjögrendryeyepatients,Jeonetal.demonstratedasignificantcorrelationbetweendryeyesymptomsandthepartialblinkrateaswellasmeibomiangland dropoutratesmeasuredusingIDRA.Ontheotherhand,Leeetal.demonstratedthat IDRAexhibitedaconsiderablylowerpercentageofmeibomianglanddropoutandagreater partialblinkratethananotherdevice,LipiView® II,inacross-sectional,single-visitobservationalstudywith47participants[11,12].Thesefindingssuggestthatthesedevices shouldnotbeusedinterchangeablywhenassessingmeibomianglanddropoutsandpartial blinkrates[11].Rinertetal.demonstratedafavorablecorrelationbetweeneveryday clinicaldiagnosticexaminations.Theresearchersfoundthattheutilizationofpathologic meibography,interferometry,andtearmeniscusmeasurementswiththeanalyzerproduced a96%estimatedprobabilityofdryeyedisease.Simultaneously,thepercentageofeyesexhibitingpathologicalobservationsinthethreesetsofexaminationswasrelativelyminimal, suggestingthatdryeyedisease(DED)maymanifestindiverseclinicalpresentationsand necessitateacomprehensiveassessment[13].

Thus,IDRAappearstobeaninterestingdevicefordiagnosingDEDbecauseitevaluatesallthreecomponentsofthetearfilm;however,theliteraturepresentsconflictingand limitedfindings.

Tearcheck® (E-Swin,Houdan,France)isastand-alonedevicewithanintegrated screenthatallowstheusertoviewallacquisitionsandexamsinrealtime.Thedevice facilitatesquickevaluationsthatincludenineexaminations:non-invasivebreaktime,tear filmstability,ocularsurfaceinflammatoryassessment,meibographyIR,Demodex,eye redness,abortiveblinking,tearmeniscusheight,andtheOSDIquestionnaire.Thisresults inasimpledryeyeanalysis.

UsingtheDemodexexam,anenlargedimageofthebaseoftheeyelashescanbe obtained,allowingforthetracingandvisualizationofsignsindicatingthepresenceof Demodexmites.Asaresult,thedevicetakeshigh-resolutionimagesoftheocularsurface, enablingthedetectionofchangesinthecornea,conjunctiva,andtearfilm,suchasthe existenceofinflammationorocularsurfacedamage(dryspotsorerosion).

Althoughthedeviceisnon-invasiveandsimpletouse,thereisnoevidenceinthe literaturetosupportitsuseinthediagnosisandmanagementofDED.

Keratograph5M® (Oculus,Wetzlar,Germany)isadiagnosticdevicethatusesnoninvasiveimagingtechnologytoevaluatethehealthofthecornea.Thedevicecanidentify changesinthesurfaceandshapeofthecornea,whichcanbeindicativeofDED.Itisa cornealtopographerthatisequippedwitharealkeratometerandacolorcamera.Its purposeistocaptureexternalimagesbyprojectingaringpatternfromaplacidodisconthe tearfilmsurfaceusinganinfraredlightsource.Itmayevaluatenon-invasivebreak-uptime (NIBUT),meibography,bulbarredness,tearmeniscusheight,lipidlayer(interferometry), andtearfilmdynamics(monitoringoftearfilmparticleflow,fromwhichinferencesabout tearfilmviscositycanbeinferred).

Thefindingsofthistoolintheliteraturearealsocontradictory.Ontheonehand, thekeratographhassignificantexaminerbias[17],butontheotherhand,ithasbeen reportedtohavestronginter-examinerreproducibility(meandifferencebetweenexaminers

of0.08 ± 0.55and0.13 ± 0.50gradeunitsintwoseparatesessions,respectively)with lowwithin-subjectvariability(95%limitsofagreementfortwodifferentexaminersof 1.02to+1.10and 1.27to+1.09gradeunits,respectively)[18].Inaprospectivestudy with42patientswithDEDand42healthysubjects,Tianetal.foundthatutilizingthe non-invasiveKeratographtearbreak-uptime(NIKBUT)andtearmeniscusheight(TMH) measurementsthroughtheK5Mdevicecouldserveasastraightforwardandnon-invasive methodforscreeningdryeyewhilealsoexhibitingsatisfactorylevelsofrepeatabilityand reproducibility(coefficientofvariation(CV%) ≤ 26.1%andintraclasscorrelationcoefficient (ICC) ≥ 0.75forallmeasurements).Nevertheless,itwasobservedthatNIKBUTsexhibited greaterreliabilityinindividualswithdryeyedisease(DED)ascomparedtoTMH[19].

Sutphinetal.concludedthatkeratographicmeasurescannotbeconsideredinterchangeablealternativesforcommonlyusedclinicalmeasures.Furthermore,theyfound thatthereisnospecifictestthatcanprovideobjectivesupportforthediagnosis[20].Indeed, accordingtoPérez-Bartolomé etal.,theKeratograph5Mwasobservedtooverestimate ocularrednessscoresincomparisontosubjectivegradingscaleswhenutilizedforthe purposeofassessingthedegreeofocularredness[21].Furthermore,inanobservational cross-sectionalstudyof47subjectswithDEDand41normalcontrolsubjects,Chenetal. showedalimitedassociationbetweenthekeratographtearmeniscusheight(TMH)and Schirmerscoresamongindividualswithdryeyedisease(DED).Theyalsodemonstrated thatinthecomparisonofFourier-domainopticalcoherencetomography(FD-OCT)andthe Keratograph5M,bothinstrumentsexhibitednotablediagnosticprecisionindistinguishingbetweennormalpatientsandthosewithdryeyedisease.However,itwasobserved thattheFD-OCTmeasurementsoftearmeniscusheight(TMH)weremoredependable thanthekeratographdataintheDEDgroup[22].Specifically,whilethekeratographand FD-OCTmeasurementsofTMHwerecloselycorrelated,theformertendedtoyieldlower measurementsthanthelatter[23].

DespitethefactthattheKeratograph5Misanon-invasivediagnostictopographerfor DED,itisnotyetasubstituteformultipleclinicaltestssuchastheSchirmertestandFBUT becauseitsreliabilityisveryweak.

I-PENOsmolaritySystem® (I-MEDPharmaInc.,Dollard-des-Ormeaux,QC,Canada) isaportableelectricaltoolthatassessestheosmolarityoftearsbymeasuringtheelectrical impedanceoftheeyetissuesonthepalpebralconjunctivalmembrane.Theoccurrenceofan inflammatorycascadeattheocularsurfaceisinitiatedbytearfilmhyperosmolarity,which ultimatelyleadstothelossofgobletcells,epithelialinjury,andtheproductionofcytokines. Thisconditionisresponsibleforcausingoculardistressandvisionimpairmentinpatients withDED.TheI-PEN’susefulnesshasbeenquestionedintheliterature,thoughnumerous studieshaveconsideredtheI-Penappropriateandreliableforclinicaluse[24–26].Parketal. concludedthattheI-Penosmometerdemonstratesfavorableperformanceindiagnosing DEDinclinicalsettings;however,itshouldnotbesolelyrelieduponforevaluatingDED. Nonetheless,theI-Penosmometercanserveasavaluabletoolforscreeningandidentifying dryeyedisease[24].Incontrast,someresearchersfailedtoestablishanycorrelations betweentearfilmosmolarityvaluesacquiredthroughtheI-PENsystemandvarious subjectiveorobjectiveparametersofdryeyedisease(DED).Furthermore,theyshowed thattheI-PENsystemwaslesseffectivethantheTearLabOsmolaritySystemindelineating subjectswithandwithoutdryeyedisease[7,27,28].Shimazakietal.foundnostatistically significantdifferenceinmeantearfilmosmolaritybetweentheDED(871eyes)andnonDED(51eyes)groupsusingtheI-PENsystem(294.76 ± 16.39vs.297.76 ± 16.72mOsms/L, respectively, p =0.32).Furthermore,motionmayaffectosmolarityreadingsacquired throughtheI-Pensystem;however,theinfluenceofthisfactorcanbeminimizedifthe measurementsarecarriedoutbyahighlytrainedclinician[29].Alanazietal.evaluatedthe relationshipbetweenosmolarityresultsacquiredbytheTearLabTMandI-Pen® systemsin individualswithahighbodymassindex(BMI).TheI-Pen® results(294–336mOsm/Linthe studygroupof30malesubjectswithahighBMIand278–317mOsm/Linthecontrolgroup of30healthymales)weresignificantlyhigherthantheTearLabTM scores(278–309mOsm/L

inthestudygroupand263–304mOsm/Linthecontrolgroup).Furthermore,theoutcomes obtainedfromtheI-Pen® measurementsexhibitedsignificantvariationsinosmolarity valuesanddemonstratedaconsiderablelackofaccuracyindistinguishingnormaleyesas comparedtotheTearLabTM system[29].

Asaresult,theI-PENisaportable,easy-to-use,autocalibrateddevicethatisnot affectedbyvariationsintearfilmvolumeandrequiresonlyasimpletouchofthepalpebral conjunctiva.Nevertheless,itcanonlydetecttearosmolarity,andfurtherinvestigationsare requiredtodetermineitsutility.

LipiView® IIinterferometer(TearScienceInc.,Morrisville,NC,USA)isadevicefor ocularimagingthatexaminestheinterferometricpatternofthetearfilm.Itachievesthisby measuringthelipidlayerthickness(LLT)ofthetearfilmwithnanometeraccuracy;however, ithasanuppercut-offtoassessLLTvaluesof100nm[11].Inadditiontothat,itrecords thedynamicsofblinkingandimagesthestructureofthemeibomiangland.Comparedto IDRA,inacross-sectionalsingle-visitobservationalstudywith47participants,MinLee etal.foundnosignificantdifferenceinLLT.However,IDRAhadaconsiderablylowerrate ofMGdropoutandahigherPBR(IDRAMGdropout 45.36 ± 21.87 andPBR 0.23 ± 0.27; LipiView® IIinterferometerMGdropout36.51 ± 17.53andPBR0.51 ± 0.37)[11].In comparisontoKeratograph5M(K5M),Wongetal.showedthatLVIIexhibitedastatistically significantreductioninmeiboscoresandalowerpercentageofMGdropoutin20subjects (1.43 ± 0.78vs.1.90 ± 0.81, p =0.001)[30].Theseresultssuggestthatthereispoor interchangeabilitybetweenthemethodsusedtoevaluateDEDfeatures,particularlyMG dropoutsandPBR.

Inconclusion,thedataobtainedfromtheLVIILLTshouldbecomparedtoother instruments.However,additionalstudieswithlargersamplesizesarenecessary.

LacryDiagOcularSurfaceAnalyzer(QuantelMedical,Cournon-d’Auvergne,France) isanophthalmicdeviceusedtodiagnoseandmonitorthetearfilmandmeibomianglands. Ittakesnon-invasivephotographswithwhiteorinfraredlighttoassesstheheightof thelowertearmeniscus,thedistancebetweentheupperandlowereyelids,tearfilm interferometry,andnon-invasivetearfilmbreak-uptime.Tothetal.demonstratedthatit isanon-invasive,simple-to-usedeviceabletoanalyzethetearfilmandsavephotosfor lateruse[31].Despitethisresult,thereisagreatdealofvariabilitybetweenmeasurements performedbythisinstrumentandthoseperformedbyanotherinnovativedevice,such astheOCULUSKeratograph5M,possiblyreflectingdifferencesinimageprocessingor theneedforsubjectiveevaluationbytheobserverforaconsiderablenumberofthese measurements[32,33].Wardetal.,forinstance,evaluatedtherepeatabilityoftheLacryDiag OcularSurfaceAnalyzerforbothintra-andinter-observermeasurementsandcompared ittotheOCULUSKeratograph5Min30healthysubjects.Theirfindingsrevealedagood relationshipbetweenthedevices(nodifferencesinmeanvaluesfortearmeniscusheight, NIBUT,ortearfilminterferometry,exceptforlipidlayerinterferometry),butlowagreement foranyindividualobserver(intra-observervariabilityforNIBUTwassignificantlyhigher fortheKeratograph, p =0.0003forobserverAand p <0.0001forobserverB).Accordingto theauthors,theobservedinconsistencycouldbeattributedtotheutilizationofrepeated testingandtheinclusionofsubjectswithoutdryeyeconditions.Therefore,theauthors concludedthatintheidentificationandfollow-upofpatientswithdryeyedisease(DED), itisessentialtoconsiderthereproducibilityofthetestinginstrumentandtheutilizationof differentoutcomemeasures[33].

Insummary,LacryDiagisapromisinginstrumentforassessingtheocularsurface,but thereisalackofresearchaboutitinthemedicalliterature.

CorneaDomeLensImagingSystem® (Occyo,Innsbruck,Austria)isanimagingsystem thatattemptstoprovideuniformocularsurfacecolorphotographsrespectingposition, illumination,focus,andoperatorindependence.Thisisachievedbyovercomingthe limitationsofobjectivemethodsthatarebasedondigitalocularsurfaceimages.Thedevice iscomposedofanovelimaginglensthatconformsaccuratelytothecurvatureoftheeye, enablinghigh-resolutionimagingofthevisibleocularsurface.Inaddition,thedevice

incorporatesafixationtargetthatguaranteesacentralizedviewintothelens,thereby minimizingeyemovements.Furthermore,thesetiscomposedofsoftwaredesignedfor eyetrackingaswellasanilluminationunit.Tomaintainthestabilityofthepatient’shead, achinrestandaforeheadbandareutilized.Theaimofthesystemistoobtainphotographs inastandardizedmannerwithouttheneedforhumanintervention.Therefore,according toLins,thistoolpossessestheabilitytoevaluatetheextentofbulbareyerednessinan objectiveandreplicablemanner,utilizingtheimagesithascaptured[34].

Thistechnologyhasthepotentialtoprovideanobjectivetechniquebasedonthedigital ocularsurfaceforassessingbulbareyeredness,overcomingthelimitationsofsubjective photographicscalesthatsufferfrominter-ratervariability.However,itsroleintheDED diagnosticprocessshouldbeinvestigatedinfuturestudies.

DEviceHygrometer© (AI,Rome,Italy)isacomplete,low-costdiagnostic-therapeutic toolforocularsurfacemanagementthathasthecapabilitytoquicklyidentifytheentities ofproduction,clearance,andstability,alongwiththeseverityoftearfilmevaporation, anddrivesthesubsequenttherapythroughtheutilizationofsimplealgorithms.The deviceoperatesbydetectingchangesintherelativehumidity(RH)levelswithinaconfined environmentsurroundingtheocularsurface(Figure 1).

Thediagnosticcomponentofthedeviceworksbymeasuringtheevaporationofthe tearfilmfromtheocularsurfaceatavariablespeedthatmaybemodifiedbytheuser. Atacertaintemperature,thedevicemeasuresthebaselineandpost-stimulusrelative humidityvalues.Thesensorisplacedinacupontheorbitaledgesbytheoperator.The measurementsarecarriedoutinaclosedenvironmentmadeupofthecupandtheocular surfacesystem.Usingtheacquireddata,itispossibletoconstructprogressioncurvesfor relativehumidity(RH)thathavebeencorrectedfortemperature.Thecollecteddataare “basal”valuesthatarecombinedwithmeasurementstakeninreactiontodiversekinds ofstimuli,suchasairblows,alterationsintemperaturewithinthemicroenvironment surroundingtheocularsurface,lightstimuli,andsoon.Additionally,anon-contact samplemechanismbuiltintothedeviceallowsforthecollectionofacertainamountof tearevaporation.Despitethefactthatincompleteblinkingandtearclearancemayhavean impactontheaccuracyofmeasurementsobtainedfromtheDEvice© ,itrepresentsalowcost,efficient,accurate,rapid,andsafer(asitisnon-contact)instrumentformeasurementof tearfilms.Indeed,apreliminaryobservationalpilotstudywith8patients(2withDEDand 6healthysubjects)hasshownthatindividualswithdryeyedisease(DED)showedhigher relativehumidityvaluescomparedtohealthyindividuals.However,additionalstudies involvingalargersamplesizearenecessarytoconfirmthesefindings.Thediagnostic deviceexhibitspotentialforlocaldrugnebulization,therebypresentinganoptionfor alternativetherapeuticapplicationsinthefuture[35].

Thus,eventhoughitisapromisingdiagnostictool,itsuseinclinicalpracticeisnow limitedtoevaporativedryeye.

Tearscope-PlusTM (Keeler,Windsor,UK)isarelativelynewportabledevicethatmay beconnectedtoaslitlampforconductingnon-invasiveassessmentsofthetearfilm.It allowstheexaminationoftheinterferencepatternsofthelipidlayeracrossthewhole corneawithouttheneedforfluorescein,therebyenablingtheevaluationofnon-invasive break-uptime(NIBUT),tearmeniscalheight(TMH),andlipidlayerthicknessofthetear film(LLT).Guillon’sclassificationisemployedforthepurposeofdeterminingthethickness ofthelipidlayer(LLP,lipidlayerpattern).Thesystemincludesfivedifferenttypesof lipidlayerpatterns:openmeshwork(OM),closedmeshwork(CM),wave(W),amorphous (AM),andcolorfringe(CO).InadditiontonormalLLPsandevents,atypicaloneswere described.Thismethodiseffectiveforinvestigatingthequalityandstructureofthetear film;nevertheless,itisdependentontheobserver’sjudgment,whichcanbeaffectedby thesortofpatternthatisviewed[36].Visualizingthickerlipidlayerscanbechallenging duetothelackofdistinguishingmorphologicaltraitsandcolorfringes.Additionally, thesubjectiveperceptionoftheobservercaninfluencethefindings.García-Resúaetal. showedthat,althoughtherewasasignificantcorrelationbetweenclassificationsmadeby

experiencedobserversbasedonGuillon’sschema,misinterpretationsofthepatternsmight stilloccur,evenwithinthesameobserver[14].

findings. The diagnostic device exhibits potential for local drug nebulization, thereby presenting an option for alternative therapeutic applications in the future [35].

The figure shows a side and rear

schematic representation of a monosensor diagnostic prototype with: an eyepiece cup (10); the sensor (20) placed inside it; a processing board (30) equipped with processor (31), memory (34), and wireless connection device (32); the optional connection cable (33); a digital screen (40) with buons (41); and a rechargeable power supply baery (50) placed in the handle [35].

Figure1. Aschematicdesignofthediagnostictoolsystem.Thefigureshowsasideandrearviewof theschematicrepresentationofamonosensordiagnosticprototypewith:aneyepiececup(10);the sensor(20)placedinsideit;aprocessingboard(30)equippedwithprocessor(31),memory(34),and wirelessconnectiondevice(32);theoptionalconnectioncable(33);adigitalscreen(40)withbuttons (41);andarechargeablepowersupplybattery(50)placedinthehandle[35].

Thus, even though it is a promising diagnostic tool, its use in clinical practice is now limited to evaporative dry eye.

DespitethefactthatFodoretal.demonstratedthatlowertearmeniscusheightmeasurementsweremorerepeatablewithTearscopethanslit-lampbiomicroscopywithout stainingin31healthyindividuals,thesubjectivityinherentinitsuselimitsbothitsrepeatabilityanditsutilityincomparisontootherinstrumentsthataremoreobjective(Oculus® Keratograph5MandLipiView® )[37,38].

Finally,Tearscopepresentsareliableandconsistentmethodofincreasingclinical observationandidentificationofocularphysiologicalalterations;yet,thisautomated procedureissusceptibletohumanerror.

Tearscope-PlusTM (Keeler, Windsor, UK) is a relatively new portable device that may be connected to a slit lamp for conducting non-invasive assessments of the tear film. It allows the examination of the interference paerns of the lipid layer across the whole cornea without the need for fluorescein, thereby enabling the evaluation of non-invasive break-up time (NIBUT), tear meniscal height (TMH), and lipid layer thickness of the tear film (LLT). Guillon’s classification is employed for the purpose of determining the thickness of the lipid layer (LLP, lipid layer paern). The system includes five different

CobraHDCamera(CSO,Florence,Italy)isanon-mydriaticdigitalfundusdevice withmodulesdesignedforretinalscreeninganalysis.Additionally,itincludesadedicated moduleformeibography[17].

References

InastudyconductedbyPult,theassociationbetweenage,sex,anddryeyesymptoms, aswellasthequantificationofmeibomiangland(MG)loss,wasinvestigatedusingaCobra funduscamera.Thestudyinvolved112participantsandrevealedsubstantialstandard deviationsinthemeanMGlossbetweenparticipantswithandwithoutdryeyesymptoms (30 ± 17%and45 ± 18%,respectively)[39].

IphraandGantzinvestigatedtheinter-sessionrepeatability(ISR),inter-examiner reproducibility(IER),andwithin-subjectvariability(WSV)oftheCobraHDfunduscamerameibographer.ThisstudyutilizedPhoenixsoftware.Participantswereclassifiedas eithersymptomaticorasymptomaticfordryeyebasedontheirOcularSurfaceDisease Index(OSDI)questionnairescores.TodeterminetheIER,seventy-fourparticipantswere evaluatedonthesamedaybytwoexaminers,referredtoasExaminer1andExaminer 2.Subsequently,sixty-sixoftheseparticipantswerere-examinedbyExaminer1ona differentdatetocalculatetheISR.TheresultsshowedthattheCobraHDfunduscamera meibographerhadgoodrepeatabilityandreproducibility,andclinicallysimilarfindings shouldbeobtainedwhenusedbydifferentexaminersondifferentoccasions[40].

Inconclusion,althoughtheCobraHDcameracanonlydetectmeibomianglandloss, itisusefulforthemeibographicassessmentandfollow-upofDEDprogression.

3.Discussion

Easyandrapiddryeyediseasediagnosisisstillachallengingunmetneedinopthalmology.Thealgorithmsproposedbyvariousinternationalsocietiesandcommitteesare frequentlytime-consumingandcostly,andtheiruseinthecontextofabusymedicalsetting islimited.Although20%ofourpatientssufferfromDEDandoculardiscomfortimpact almost40%ofsurgeonspractice,aproperDEDdiagnosticmethodisstillmissed[41–43]. Therefore,severalnewdiagnostictoolsaimtofillthisgap,makingthediagnosiswitha single“click”,althoughatahighercost.

Theconsistentuseoftheseinstrumentsinclinicalsettingsmayfacilitatethediagnosis, tracking,andpreventionofocularsurfacediseasessuchasdryeyesyndrome.However, theresultsintheliteraturearefewandinconsistent.Mostlikely,thereisnoclearway forpractitionerstousetheseautomatedtoolstodiagnosedryeyesinastandardizedway. Furthermore,thelackofintra-andinterobserverrepeatabilityincertainmeasurement instrumentslimitsneutralityandincreasesbias,influencingtheiruseanddistribution. Apotentialdrawbackoftheseimagingsystemsistheirhighcost,whichcanlimittheir accessibilityinmanyhealthcarecenters.

4.Conclusions

NodiagnosticinstrumentcanreplacethecomplexTFOSalgorithm,andthereis nosingletoolforaspecificdiagnosis,butresearchinthisfieldisveryactive,andsuch primordialdevicesmaybeapromisingrealityintheverynearfuture.

Funding: Thisresearchreceivednoexternalfunding.

InstitutionalReviewBoardStatement: Notapplicable.

InformedConsentStatement: Notapplicable.

DataAvailabilityStatement: Datasharingnotapplicable.

ConflictsofInterest: Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictofinterest.

1. Craig,J.P.;Nichols,K.K.;Akpek,E.K.;Caffery,B.;Dua,H.S.;Joo,C.-K.;Liu,Z.;Nelson,J.D.;Nichols,J.J.;Tsubota,K.;etal.TFOS DEWSIIDefinitionandClassificationReport. Ocul.Surf. 2017, 15,276–283.[CrossRef][PubMed]

2. Stapleton,F.;Alves,M.;Bunya,V.Y.;Jalbert,I.;Lekhanont,K.;Malet,F.;Na,K.-S.;Schaumberg,D.;Uchino,M.;Vehof,J.;etal. TFOSDEWSIIEpidemiologyReport. Ocul.Surf. 2017, 15,334–365.[CrossRef][PubMed]

3. Hashmani,N.;Munaf,U.;Saleem,A.;Javed,S.O.;Hashmani,S.ComparingSPEEDandOSDIQuestionnairesinaNon-Clinical Sample. Clin.Ophthalmol. 2021, 15,4169–4173.[CrossRef][PubMed]

4. Machali´nska,A.;Zakrzewska,A.;Safranow,K.;Wiszniewska,B.;Machali´nski,B.RiskFactorsandSymptomsofMeibomian GlandLossinaHealthyPopulation. J.Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016,7526120.[CrossRef]

5. Srinivasan,S.;Nichols,K.K.Editorial:Collectingtearosmolaritymeasurementsinthediagnosisofdryeye. ExpertRev.Ophthalmol. 2009, 4,451–453.[CrossRef]

6. Versura,P.;Campos,E.C.TearLab® OsmolaritySystemfordiagnosingdryeye. ExpertRev.Mol.Diagn. 2013, 13,119–129. [CrossRef]

7. Tavakoli,A.;Markoulli,M.;Flanagan,J.;Papas,E.Thevalidityofpointofcaretearfilmosmometersinthediagnosisofdryeye. OphthalmicPhysiol.Opt. 2022, 42,140–148.[CrossRef]

8. Benelli,U.;Nardi,M.;Posarelli,C.;Albert,T.G.TearosmolaritymeasurementusingtheTearLabOsmolaritySysteminthe assessmentofdryeyetreatmenteffectiveness. ContactLensAnteriorEye 2010, 33,61–67.[CrossRef]

9. Szczesna-Iskander,D.H.MeasurementvariabilityoftheTearLabOsmolaritySystem. ContactLensAnteriorEye 2016, 39,353–358. [CrossRef]

10. Szalai,E.;Berta,A.;Szekanecz,Z.;Szûcs,G.;Módis,L.Evaluationoftearosmolarityinnon-SjögrenandSjögrensyndromedry eyepatientswiththeTearLabsystem. Cornea 2012, 31,867–871.[CrossRef]

11. Lee,J.M.;Jeon,Y.J.;Kim,K.Y.;Hwang,K.-Y.;Kwon,Y.-A.;Koh,K.Ocularsurfaceanalysis:AcomparisonbetweentheLipiView® IIandIDRA® Eur.J.Ophthalmol. 2021, 31,2300–2306.[CrossRef]

12. Jeon,Y.J.;Song,M.Y.;Kim,K.Y.;Hwang,K.-Y.;Kwon,Y.-A.;Koh,K.Relationshipbetweenthepartialblinkrateandocularsurface parameters. Int.Ophthalmol. 2021, 41,2601–2608.[CrossRef]

13. Rinert,J.M.;Branger,G.;Bachmann,L.M.M.;Pfaeffli,O.;Iselin,K.;Kaufmann,C.;Thiel,M.A.M.;Baenninger,P.B.Accuracyofa NewNoninvasiveAutomaticOcularSurfaceAnalyzerfortheDiagnosisofDryEyeDisease-Two-GateDesignUsingHealthy Controls. Cornea 2023, 42,416–422.[CrossRef]

14. García-Resúa,C.;Pena-Verdeal,H.;Miñones,M.;Giráldez,M.J.;Yebra-Pimentel,E.Interobserverandintraobserverrepeatability oflipidlayerpatternevaluationbytwoexperiencedobservers. ContactLensAnteriorEye 2014, 37,431–437.[CrossRef]

15. Guillon,J.P.Non-invasivetearscopeplusroutineforcontactlensfitting. ContactLensAnteriorEye 1998, 21 (Suppl.S1),S31–S40. [CrossRef]

16. Zhao,Y.;Tan,C.L.S.;Tong,L.Intra-observerandinter-observerrepeatabilityofocularsurfaceinterferometerinmeasuringlipid layerthickness. BMCOphthalmol. 2015, 15,53.[CrossRef]

17. Garduño,F.;Salinas,A.;Contreras,K.;Rios,Y.;García,N.;Quintanilla,P.;Mendoza,C.;Leon,M.G.Comparativestudyoftwo infraredmeibographersinevaporativedryeyeversusnondryeyepatients. EyeContactLens 2021, 47,335–340.[CrossRef]

18. Ngo,W.;Srinivasan,S.;Schulze,M.;Jones,L.Repeatabilityofgradingmeibomianglanddropoutusingtwoinfraredsystems. Optom.Vis.Sci. 2014, 91,658–667.[CrossRef]

19. Tian,L.;Qu,J.-H.;Zhang,X.-Y.;Sun,X.-G.RepeatabilityandReproducibilityofNoninvasiveKeratograph5MMeasurementsin PatientswithDryEyeDisease. J.Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016,8013621.[CrossRef]

20. Sutphin,J.E.;Ying,G.-S.;Bunya,V.Y.;Yu,Y.;Lin,M.C.;McWilliams,K.;Schmucker,E.;Kuklinski,E.J.;Asbell,P.A.;Maguire, M.G.;etal.CorrelationofMeasuresfromtheOCULUSKeratographandClinicalAssessmentsofDryEyeDiseaseintheDryEye AssessmentandManagementStudy. Cornea 2022, 41,845–851.[CrossRef]

21. Pérez-Bartolomé,F.;Sanz-Pozo,C.;Martinez-De-La-Casa,J.M.;Arriola-Villalobos,P.;Fernández-Pérez,C.;García-Feijoó,J. Assessmentofocularrednessmeasurementsobtainedwithkeratograph5Mandcorrelationwithsubjectivegradingscales. J.Fr. Ophtalmol. 2018, 41,836–846.[CrossRef][PubMed]

22. Chen,M.;Wei,A.;Xu,J.;Zhou,X.;Hong,J.ApplicationofKeratographandFourier-DomainOpticalCoherenceTomographyin MeasurementsofTearMeniscusHeight. J.Clin.Med. 2022, 11,1343.[CrossRef]

23. Baek,J.;Doh,S.H.;Chung,S.K.ComparisonofTearMeniscusHeightMeasurementsObtainedwiththeKeratographandFourier DomainOpticalCoherenceTomographyinDryEye. Cornea 2015, 34,1209–1213.[CrossRef][PubMed]

24. Park,J.;Choi,Y.;Han,G.;Shin,E.;Han,J.;Chung,T.-Y.;Lim,D.H.EvaluationoftearosmolaritymeasuredbyI-Penosmolarity systeminpatientswithdryeye. Sci.Rep. 2021, 11,7726.[CrossRef][PubMed]

25. Fagehi,R.;Al-Bishry,A.;Alanazi,M.;Abusharha,A.;El-Hiti,G.;Masmali,A.Investigationoftherepeatabilityoftearosmolarity usinganI-PENosmolaritydevice. TaiwanJ.Ophthalmol. 2020, 11,168–174.[CrossRef][PubMed]

26. Chan,C.C.;Borovik,A.;Hofmann,I.;Gulliver,E.;Rocha,G.ValidityandReliabilityofaNovelHandheldOsmolaritySystemfor MeasurementofaNationalInstituteofStandardsTraceableSolution. Cornea 2018, 37,1169–1174.[CrossRef]

27. Shimazaki,J.;Sakata,M.;Den,S.;Iwasaki,M.;Toda,I.TearFilmOsmolarityMeasurementinJapaneseDryEyePatientsUsinga HandheldOsmolaritySystem. Diagnostics 2020, 10,789.[CrossRef]

28. Nolfi,J.;Caffery,B.Randomizedcomparisonof invivo performanceoftwopoint-of-caretearfilmosmometers. Clin.Ophthalmol. 2017, 11,945–950.[CrossRef]

29. Alanazi,M.;El-Hiti,G.;Alhafy,N.;Almutleb,E.;Fagehi,R.;Alanazi,S.;Masmali,A.CorrelationbetweenosmolaritymeasurementsusingtheTearLabTM andI-Pen® systemsinsubjectswithahighbodymassindex. Adv.Clin.Exp.Med. 2022, 31,1413–1418. [CrossRef]

30. Wong,S.;Srinivasan,S.;Murphy,P.J.;Jones,L.Comparisonofmeibomianglanddropoutusingtwoinfraredimagingdevices. ContactLensAnteriorEye 2019, 42,311–317.[CrossRef]

31. Tóth,N.;Szalai,E.;Rák,T.;Lillik,V.;Nagy,A.;Csutak,A.Reliabilityandclinicalapplicabilityofanoveltearfilmimagingtool. GraefesArch.Clin.Exp.Ophthalmol. 2021, 259,1935–1943.[CrossRef]

32. Garcia-Terraza,A.L.;Jimenez-Collado,D.;Sanchez-Sanoja,F.;Arteaga-Rivera,J.Y.;Flores,N.M.;Pérez-Solórzano,S.;Garfias,Y.; Graue-Hernández,E.O.;Navas,A.Reliability,repeatability,andaccordancebetweenthreedifferentcornealdiagnosticimaging devicesforevaluatingtheocularsurface. Front.Med. 2022, 9,893688.[CrossRef]

33. Ward,C.D.;Murchison,C.E.;Petroll,W.M.;Robertson,D.M.EvaluationoftheRepeatabilityoftheLacryDiagOcularSurface AnalyzerforAssessmentoftheMeibomianGlandsandTearFilm. Transl.Vis.Sci.Technol. 2021, 10,1.[CrossRef]

34. Lins,A.Image-basedEyeRednessUsingStandardizedOcularSurfacePhotography.InProceedingsofthe2ndMCIMedical TechnologiesMaster’sConference,Innsbruck,Austria,27–29September2021.

35. Gaudenzi,D.;Mori,T.;Crugliano,S.;Grasso,A.;Frontini,C.;Carducci,A.;Yadav,S.;Sgrulletta,R.;Schena,E.;Coassin,M.;etal. AS-OCTandOcularHygrometerasInnovativeToolsinDryEyeDiseaseDiagnosis. Appl.Sci. 2022, 12,1647.[CrossRef]

36. Guillon,J.P.Abnormallipidlayers.Observation,differentialdiagnosis,andclassification. Adv.Exp.Med.Biol. 1998, 438,309–313.

37. Fodor,E.;Hagyó,K.;Resch,M.;Somodi,D.;Németh,J.ComparisonofTearscope-plusversusslitlampmeasurementsofinferior tearmeniscusheightinnormalindividuals. Eur.J.Ophthalmol. 2010, 20,819–824.[CrossRef]

38. Markoulli,M.;Duong,T.B.;Lin,M.;Papas,E.ImagingtheTearFilm:AComparisonBetweentheSubjectiveKeelerTearscopePlusTM andtheObjectiveOculus® Keratograph5MandLipiView® Interferometer. Curr.EyeRes. 2018, 43,155–162.[CrossRef]

39. Pult,H.Relationshipsbetweenmeibomianglandlossandage,sex,anddryeye. EyeContactLens 2018, 44,S318–S324.[CrossRef]

40. Ifrah,R.;Quevedo,L.;Gantz,L.RepeatabilityandreproducibilityofCobraHDfunduscamerameibographyinyoungadults withandwithoutsymptomsofdryeye. OphthalmicPhysiol.Opt. 2023, 43,183–194.[CrossRef]

41. Coassin,M.;Mori,T.;DiZazzo,A.;Poddi,M.;Sgrulletta,R.;Napolitano,P.;Bonini,S.;Orfeo,V.;Kohnen,T.Effectof minimonovisioninbilateralimplantationofanovelnon-diffractiveextendeddepth-of-focusintraocularlens:Defocuscurves, visualoutcomes,andqualityoflife. Eur.J.Ophthalmol. 2022, 32,2942–2948.[CrossRef]

42. Bandello,F.;Coassin,M.;DiZazzo,A.;Rizzo,S.;Biagini,I.;Pozdeyeva,N.;Sinitsyn,M.;Verzin,A.;DeRosa,P.;Calabrò,F.;etal. Oneweekoflevofloxacinplusdexamethasoneeyedropsforcataractsurgery:Aninnovativeandrationaltherapeuticstrategy. Eye 2020, 34,2112–2122.[CrossRef][PubMed]

43. Antonini,M.;Gaudenzi,D.;Spelta,S.;Sborgia,G.;Poddi,M.;Micera,A.;Sgrulletta,R.;Coassin,M.;DiZazzo,A.OcularSurface FailureinUrbanSyndrome. J.Clin.Med. 2021, 10,3048.[CrossRef][PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’sNote: Thestatements,opinionsanddatacontainedinallpublicationsaresolelythoseoftheindividual author(s)andcontributor(s)andnotofMDPIand/ortheeditor(s).MDPIand/ortheeditor(s)disclaimresponsibilityforanyinjuryto peopleorpropertyresultingfromanyideas,methods,instructionsorproductsreferredtointhecontent.

OPENACCESS

EDITEDBY

AlejandroNavas, InstitutodeOftalmologíaFundación deAsistenciaPrivadaConde deValenciana,I.A.P,Mexico

REVIEWEDBY

MelisPalamar, EgeUniversity,Turkey PabloDeGracia, MidwesternUniversity,UnitedStates QihuaLe, Eye,Ear,Nose,andThroatHospital ofFudanUniversity,China

*CORRESPONDENCE

José-MaríaSánchez-González jsanchez80@us.es

SPECIALTYSECTION

Thisarticlewassubmittedto Ophthalmology, asectionofthejournal FrontiersinMedicine

RECEIVED 07May2022

ACCEPTED 21July2022

PUBLISHED 10August2022

CITATION

Sánchez-GonzálezMC, Capote-PuenteR, García-RomeraM-C, De-Hita-CantalejoC, Bautista-LlamasM-J,Silva-VigueraC andSánchez-GonzálezJ-M(2022)Dry eyediseaseandtearfilmassessment throughanovelnon-invasiveocular surfaceanalyzer:TheOSAprotocol. Front.Med. 9:938484.

doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.938484

COPYRIGHT

©2022Sánchez-González, Capote-Puente,García-Romera, De-Hita-Cantalejo,Bautista-Llamas, Silva-VigueraandSánchez-González. Thisisanopen-accessarticle distributedunderthetermsofthe CreativeCommonsAttributionLicense (CCBY).Theuse,distributionor reproductioninotherforumsis permitted,providedtheoriginal author(s)andthecopyrightowner(s) arecreditedandthattheoriginal publicationinthisjournaliscited,in accordancewithacceptedacademic practice.Nouse,distributionor reproductionispermittedwhichdoes notcomplywiththeseterms.

TYPE Methods

PUBLISHED 10August2022

DOI 10.3389/fmed.2022.938484

Dryeyediseaseandtearfilm assessmentthroughanovel non-invasiveocularsurface analyzer:TheOSAprotocol

MaríaCarmenSánchez-González,RaúlCapote-Puente, Marta-CGarcía-Romera,ConcepciónDe-Hita-Cantalejo, María-JoséBautista-Llamas,CarmenSilva-Vigueraand José-MaríaSánchez-González*

VisionScienceResearchGroup,VisionSciencesoftheUniversityofSeville(CIVIUS),Department ofPhysicsofCondensedMatter,OpticsArea,UniversityofSeville,Seville,Spain

WedescribetheroleofOSAasanewinstrumentinthestudyofdry eye,andwerecommendaprotocolforconductingthetestsaswellas describetheadvantagesanddisadvantagescomparedwithotherinstruments. Acomparisonwithotherocularsurfacedevices(TearscopePlus,Keratograph 5M,anterior-segmentocularcoherencetomography,EasyTearView-Plus, LipiView,IDRA,andLacryDiag)werepresentedduetomanualorautomatic procedureandobjectiveorsubjectivemeasurements.Thepurposeofthis studywastodescribetheOSAasnewnon-invasivedryeyediseasediagnostic device.TheOSAisadevicethatcanprovideaccurate,non-invasiveand easy-to-useparameterstospecificallyinterpretdistinctfunctionsofthetear film.ThisOSAprotocolproposedalessertohighernon-invasiveocular surfacedryeyediseasetearfilmdiagnosticmethodology.Acompleteand exhaustiveOSAandOSAPlusexaminationprotocolwaspresentedwithin thesubjectivequestionnaire(DryEyeQuestionnaire5,DEQ5),limbaland bulbarrednessclassification(withintheEfrongradeScale,interferometry lipidlayerthickness(LLT)(accordingtoGuillonpattern),tearmeniscusheight (manuallyorautomatic),firstandmeannon-invasivebreakuptime(objective andautomatic)andmeibomiangland(MG)dysfunctiongradeandpercentage (objectiveandautomatic).TheOSAandOSAPlusdevicesarenoveland relevantdryeyediseasediagnostictools;however,theautomatizationand objectivityofthemeasurementscanbeincreasedinfuturesoftwareordevice updates.Thenewnon-invasivedevicessupposedrepresentarenewalinthe dryeyediseasediagnosisandintroduceatendencytoreplacetheclassic invasivetechniquesthatsupposedlessreliabilityandreproducibility.

KEYWORDS

ocularsurfaceanalyzer,dryeyedisease(DED),dryeyesyndromediagnostic,tearfilm, non-invasiveoculardevices

Introduction

Ocularsurfacepathologyisageneraltermthatincludes dryeye,withinvolvementofthecornea,conjunctiva,eyelids, andmeibomianglands(MGs).Dryeyeisagroupofdisorders characterizedbylossoftearfilmhomeostasis,duetoeither lipidlayeralterationowingtotheMGs(evaporativedryeye) orinsufficientaqueoustearproduction(hyposecretorydryeye) leadingtotissuedamageandinflammation(1).

Therearevarioustechniquesformeasuringanddiagnosing dryeye.Themostcommontestsforthisdiagnosisare invasiveandcanyieldresultsthatdifferfromthenatural propertiesofthetear,sonon-invasivemethodswould bemoreappropriate(2).Ocularsurfacediagnostictests fordryeyediseaseshouldcombinehighprecision,good sensitivityandreproducibility.Amongthemostcommonly useddiagnosticdevices,Placidomethodringshavebeen usedindifferentstudiesasanalternativetobreak-uptime (BUT)toavoidtheuseoffluorescein,althoughtheyhave aweakcorrelationwithotherdryeyediseasediagnostic measurements(3).

Ithasbeenrecommendedthatocularsurfacemeasurements beperformedfromlessinvasivetomoreinvasive(4).Such measurementsincludetheuseofaquestionnairetocollect symptoms(5),evaluationoflimbalandbulbarconjunctival hyperemia(6),assessmentoftearmeniscus(7),studyoflipid layerthickness(LLT)andpattern(8),non-invasivetearbreakuptime(NIBUT)(9)andinfraredmeibography(10).However, someofthemeasuresusedtoevaluatedryeyecanbeinfluenced bythesubjectivityoftheexaminer.

Amongthenon-invasivedevicesfordryeyemeasurement areTearscopePlus R (Keeler,Windsor,UnitedKingdom), Polaris(bonOptic,Lübeck,Germany),EasyTearViewplus R (EasyTear,Rovereto,Italy),OculusKeratograph5M R (Oculus,Arlington,WA,UnitedStates)(K5M),LipiView R interferometer(TearScienceInc.,Morrisville,NC, UnitedStates),IDRA R OcularSurfaceAnalyzerfromSBM System R (Orbassano,Torino,Italy),LacryDiag R Ocular SurfaceAnalyzer(QuantelMedical,Cournon-d’Auvergne, France)andOcularSurfaceAnalyzer(OSA)fromSBM System R (Orbassano,Torino,Italy)(11–13).Asummaryof thefunctionalitiesoftheocularsurfacedevicesispresented in Table1.RegardingTearscopePlus,thedeviceisattached totheslitlamp,andthemeasurementisachievedthrough imageanalysissoftware(14).PolarisusesLEDlighttoimprove thevisibilityofboththelipidlayerofthetearfilmandthe tearmeniscus(15).Ontheotherhand,OculusKeratograph introducestearanalysissoftwarewithanintegratedcaliper thatallowscapturingimagesforabettermeasurementofthe heightofthetearmeniscus(16).Anteriorsegmentoptical coherencetomography(AS-OCT)alsoallowsthemeasurement oftheheightofthetearmeniscusthroughintegratedsoftware, producingaveryhigh-qualityresolutioninmicrometers.

AS-OCTandKeratographaretwocomparablemethods(17). EasyTearViewplus R isalsoattachedtotheslitlamp,and throughwhiteLEDlights,itachievesanalysisofthelipidlayer, NIBUTandtearmeniscus;withinfraredLEDs,itperforms meibography,andthesoftwarequantifiestheimagestructures (18).LipiView R allowsautomatedmeasurementsofthelipid layerwithnanometerprecision.Thelimitationisthatonly valuesgreaterthan100nmaredisplayed(19).IDRA R is attachedtotheslitlamptoperformthemeasurementquickly andinafullyautomatedmanner(20).LacryDiag R useswhite lightinitssystemtocaptureimagesandinfraredlightfor theanalysisoftheMGs(13).Finally,OSA R isdesignedto performdryeyeassessmentbasedonthefollowingdiagnostic measurements:DryEyeQuestionnaire(DEQ-5),limbaland bulbarconjunctivalrednessclassification,tearmeniscus height,LLTinterferometry,NIBUT,andmeibographygland dysfunctionlosspercentage.

Inthepresentstudy,wedescribetheroleofOSA asanewinstrumentinthestudyofdryeye,andwe recommendaprotocolforconductingthetestsaswellas describetheadvantagesanddisadvantagescomparedwith otherinstruments.

Materialsandequipment Questionnaire

Manyquestionnairestoanalyzeandclassifysymptoms areenteredintothesoftwareoftheinstrumentsfordry eyeassessment:OcularSurfaceDiseaseIndex(OSDI) inKeratograph5M(21),StandardPatientEvaluation ofEyeDrynessQuestionnaire(SPEED)inIDRA(20) andDryEyeQuestionnaire(DEQ-5)inOSA(5).Onthe contrary,LD(3, 22),LipiView(19, 20),EasyTearViewplus, PolarisandTearscopePlus(23, 24)havenoquestionnaires intheirsoftware.

Thesensibilityandspecificityareinfluencednotonlyby thenumberofitemsineachquestionnaire,orthetimestudied butalsobythecapacitytoclassifysymptoms.TheOSDI isa12-itemquestionnairefocusingondryeyesymptoms andtheireffectsinthepreviousweek.Insubjectswith andwithoutdryeyedisease,theOSDIhasshowngood specificity(0.83)andmoderatesensitivity(0.60)(25).The SPEEDhaseightitemstoevaluatethefrequencyandseverity ofsymptomsinthelast3months.Sensibilityandspecificity valuesare0.90and0.80,respectively(26, 27).IntheDEQ5,thesymptomsinthepastweekareanalyzedthroughfive questions.Thissurveyhasbeenvalidatedincomparisonto theOSDI(Spearmancorrelationcoefficients, r =0.76)(28) and(r =0.65, p < 0.0001).Thesensitivityis0.71,andthe specificityis0.83(29).Thus,anyofthesethreequestionnaires couldbeagoodoptiontoanalyzedryeyesymptoms,although

theDEQ-5mightbequickertouse,giventhenumberof items.TheadvantagethatOSApresentswithrespecttoother dryeyeanalyzersisthatthequestionnairehasfewitems andiscompletedquickly.However,asdisadvantages,wefind thatquestionnaireswithagreaternumberofitemshave greaterrepeatability.

Limbalandbulbarredness classification

Regardingthelimbalandbulbarrednessclassifications (LBRC),Keratograph5Mhassoftware(RScan)tosaveimages andobjectivelyclassifythemintofourdegreesrangingfrom0 to3(30).IDRA,LacryDiagandOSAusesubjectiveprocedures, giventhatthesoftwareonlyshowstheimagetakenandthe analysismustbecarriedoutbyanobserverusingascale(31).

Efronissoftwarewidelyusedtosubjectivelyclassify rednessineyes(enteredinOSA,IDRAandLacryDiag). TheEfronscalehasachievedexcellentreproducibility(32, 33)andisoneofthemoreaccuratescalesbasedonfractal dimension(34).Comparingobjectiveandsubjectiveredness classifications,thehighestreproducibilityisobservedwhen hyperemiaisassessedandscoredautomatically(6, 30).

Amongtherestoftheocularsurfacedevices,TearscopePlus, Polaris,EasyTearViewplusandLipiViewinterferometerdo notofferarednessanalyzer.Therefore,theidealdevicehas toimplementandautomatic,objective,non-invasiveLBRC assessmentintegratedintoaplatformandsoftwarewithin therestoftheocularsurfaceparameters.Theadvantage thatOSApresentswithrespecttootherdryeyeanalyzersis thattheLBRCiscarriedoutaccordingtotheinternational scaleestablishedbyEfron.However,asdisadvantages,we findthattheanalysisofrednessissubjectivewhilethe Keratograph5Mpresentsasoftwarethatperformsitobjectively andautomatically.

Lipidlayerthickness

Therearedifferentdevicestomeasurethethicknessofthe lipidlayer,mostofwhicharebasedonopticalinterferometry, suchasOSA.ThesedevicesareTearscopePlus,EasyTear Viewplus,Polaris,Keratograph5M,andLipiView.Thebasic technologyinthemisthesame;themeasurementisperformed non-invasivelybyobservingthephenomenonofinterference fringes,whichallowsthethicknessofthelipidlayersecretedby theMGstobeanalyzed.

WithTearscopePlus,EasyTearViewplusandPolaris,the resultobtainedhasasubjectiveandqualitativecomponent, astheobservercomparestheimageheseeswiththesame classificationthatexistsforthethicknessofthelipidlayer infivedifferentcategoriesasdescribedbyGuillon(35) (amorphousstructure,marbledappearance,wavyappearance, yellow,brown,blueorreddishinterferencefringes).This sameclassificationallowsaquantitativeequivalent(from thinnertothicker: < 15nm–notpresent, ∼15nm–open meshwork, ∼30nm–closedmeshwork, ∼30/80nm–wave, ∼80nm–amorphous, ∼80/120nm–colorfringes, ∼120/160nm–abnormalcolor)usedbyOSAandIDRA. Keratograph5Musesfourinterferometricpatternsinsteadof five1=openmesh(13–15nm);2=closedmesh(30–50nm); 3=wave(50–80nm);and4=colorfringe(90–140nm).Inboth devices,thesubjectivityoftheobserverisinfluentialduring classification;thistypeofmeasurementisconsideredtobe morereliableandrepeatable,withlessdeviationintheresults (36–38).

OnlyLipiViewiscapableofmeasuringwithnanometer precision(39).Itisanon-invasiveinstrumentthattakeslive digitalimagesofthetearfilm,measuresitslipidcomponent,and assessesLLTusinganinterferencecolorunit(ICU)score(usual average ≥ 75scorepoints).Illuminationisprojectedoverthe lowerthirdofthecorneafromacolorinterferencepatternasa resultofthespecularreflectionatthelipidaqueousborder.The

detectedcolorisrelatedtothedeviceandisshownasanICU, whichisequivalenttonanometers.

DifferentpublicationssupportthereliabilityoftheLLT measurementwithLipiView,bothinitsvalueasadiagnostic elementcomparedtootherdevicesinwhichtheobserver intervenesandinitsintra-andinterobserverrepeatability(19, 20, 40, 41).TheadvantagethatOSApresentswithrespect totherestofdryeyeanalyzersisthattheclassificationof thelipidpatternofthetearfilmiscarriedoutinaccordance withtheinternationalscaleestablishedbyGuillon.However,as disadvantages,wefindthattheanalysisofthelipidthicknessis ofaqualitativenature,whileLipiViewpresentsasoftwarethat measuresthethicknessofthelipidlayerquantitatively.

Tearmeniscusheight

Severalocularsurfacedevices(EasyTearViewplus,ASOCT,Keratograph5M,LipiView,OSAandIDRA)present thepossibilityofmeasuringtearmeniscusheight,andthe

acquisitionofmultipleimagesisperformednon-invasively,as thewatercontentcanbeaccuratelyevaluatedwithanintegrated caliperalongtheedgeofthelowerorsuperioreyelid.OSA PlusandIDRAareuniquedevicesthatautomaticallyand objectivelymeasurethetearmeniscusheightofthelowerlid. Scientificevidenceisneededtoestablishtherepeatabilityand reproducibilityofthesedevices.

Theworkspresentedontearmeniscusheightarescarce,but theysupportitsrepeatability,inboththeonecarriedoutina slitlamp(42)andtheonecompletedwithKeratograph5M, whichhasasignificantcorrelationwithtraditionaldiagnostic testsfordryeyedisease(43, 44).Futurelinesofresearchshould measurethetearmeniscusvolumeinsteadoftheheightto estimatetheaqueouslayerofthetear.TheadvantagethatOSA presentswithrespecttootherdryeyeanalyzersisthattheheight ofthetearmeniscusismeasuredmanually(withOSA)and automatically(withOSAPlus),makingitanobjectivetest.In thissense,therestofthedryeyeanalyzerdevicesperforma manualmeasurementoftheheightofthetearmeniscus.

Non-invasivebreak-uptime

NIBUTisobjectivelymeasuredbyKeratograph5M,OSA, IDRAandLacryDiag.Thesedevicesrecordthefirstalterationof thetearfilm(FNIBUT)aswellastheaverageBUTforallpoints ofmeasurement(MNIBUT).Keratograph5M(45–48)performs themeasurementautomaticallyfor24s,butusingOSA(49), IDRA(12, 50, 51)andLacryDiag(13, 52),theclinicianmanually activatesandstopsvideorecording.Keratograph5Mhas showngoodrepeatabilityandreproducibilityinpatientswith dryeyeandhealthycontrols(43).Itisthemostcommonly utilizedinstrumentinocularsurfacestudiesandisusedfor thevalidationoftheotherdevices(11, 13, 36, 53).OSAand LacryDiagmeasurementsofNIBUTareobtainedthroughthe detectionofdistortionsincircularringsthatarereflectedinthe tearfilmusingthePlacidoringsaccessory(13).EmployingOSA PlusandIDRA,gridscanbeinsertedintotheinternalcylinder ofthedevicetoprojectstructuredimagesontothesurfaceof thetearfilm,andtheexaminercanchoosebetweenmanualor automaticanalysis.Inavalidationstudy,IDRAshowedgood sensitivityandspecificityvaluesforNIBUT(12).

NIBUTcanbesubjectivelymeasuredbyTearscopePlus, PolarisandEasyTearViewplus.Theseinstrumentsprojectagrid ofequidistantcirclesoflightontothesurfaceoftheeyethat areblurredbythetearfilmrupture.TheNIBUTistakenasthe timeelapseduntiltheblurofthelinescanbeobserved.Polaris (54),EasyTearViewplus(55),TS(56–58)andKeratograph 5MproducedsimilaraverageresultsrelatingtoNIBUTinthe studycarriedoutbyBandlitzetal.(11).BecauseKeratograph 5MistheonlydevicethatperformstheNIBUTmeasurement fullyautomatically,itistherecommendedinstrumentfor themeasurementofthisparameter.TheadvantagethatOSA

presentswithrespecttotherestofdryeyeanalyzersisthat themeasurementoftheFNIBUTandMNIBUTiscarriedout automaticallyandobjectively.Therefore,itisonaparwith otherdryeyeanalyzerdevicessuchastheKeratograph5M andtheLacryDiag.

Meibomianglanddysfunction

Non-contactinfraredmeibographyisatechniqueused tostudyMGdysfunctionbyevaluatingMGdropout.The qualificationofthedegreeofMGdropoutcanbedetermined subjectivelybymeansofascaleorobjectivelythroughsoftware thatautomaticallycalculatestherelationshipbetweentheareaof lossofMGandthetotalareaoftheeyelid(valuerangingfrom 0to100%)(59).Automaticobjectivemeasuresmaybemore usefulfordetectingearlyglandloss(60).

Thenon-invasiveinstrumentsthatcanperformthestudy ofMGdysfunctionareKeratograph5M,OSA,IDRA,EasyTear Viewplus,LacryDiagandLipiView.Theanalysisofmeibography withEasyTearViewplusandLipiView(20, 61, 62)iscarried

outsubjectivelybycomparingitwithascale.InLacryDiag, theanalysisissemiautomatic.Theexaminermanuallydelimits theexamarea,andthesoftwareprovidesthepercentageof MGloss(13).OSA(49)andIDRA(12, 20, 50, 51)have automatic,semiautomaticormanualproceduresforanalyzing thepresentandabsentglandareaandshowMGlossina classificationoffourdegrees:0–25,26–50,51–75,and76–100%.Inthemanualprocedure,theexaminerselectsthearea inwhichtheMGsarelocated.Inaddition,OSAPlusand IDRAperformautomatic3Dmeibography.UsingKeratograph 5M,theanalysiscanbesubjectivebycomparingtheimage obtainedwithareferencescalewithfourdegrees(ranging from0to3)(13, 45, 46)orsemiautomaticthroughthe ImageJsoftwarethatprovidesthetotalareaanalyzedandthe areacoveredbyMGs(47, 60, 63, 64).Theadvantagethat OSApresentswithrespecttotherestofdryeyeanalyzers isthatthemeasurementoftheMGDpercentageiscarried outautomaticallyandobjectively.Therefore,itrepresentsan improvementoverotherdryeyeanalyzerdevicessuchasthe Keratograph5MandtheLacryDiagthatperformmanualor semi-automaticmeasurementusingsoftware.

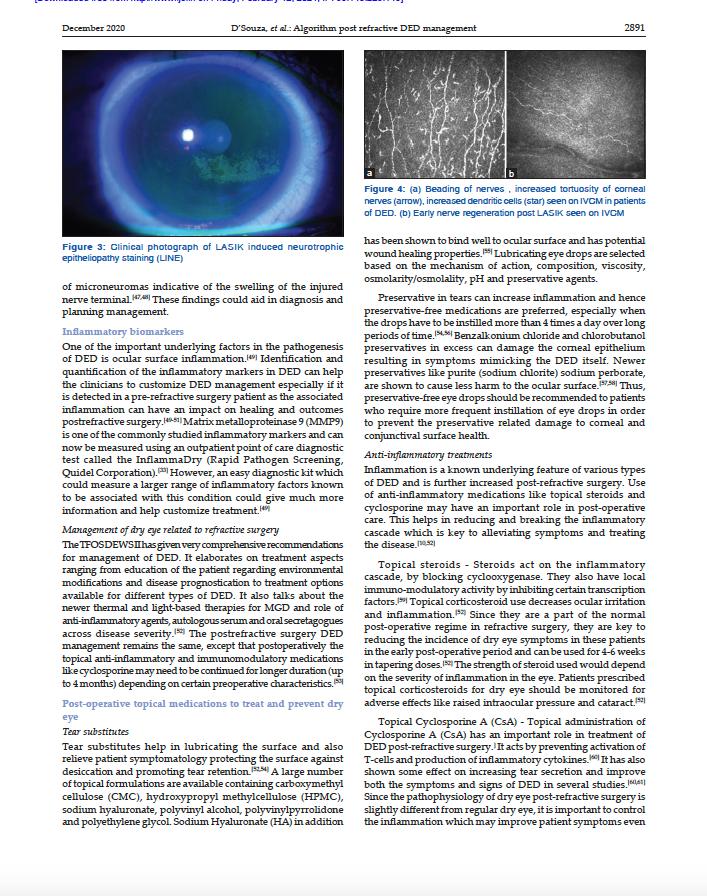

FIGURE3

Lipidlayerthicknessassessmentwithintheopticinterferometer. (A) Nolipidpresent(<15nmoflipidthickness). (B) Openmeshworkpattern (∼15nmoflipidthickness). (C) Closemeshworkpattern(∼30nmoflipidthickness). (D) Wavepattern(∼30/80nmoflipidthickness). (E) Amorphouspattern(∼80nmoflipidthickness). (F) Colorfringespattern(∼80/120nmoflipidthickness)andnopatientachievedabnormal color( 120/160nmoflipidthickness).

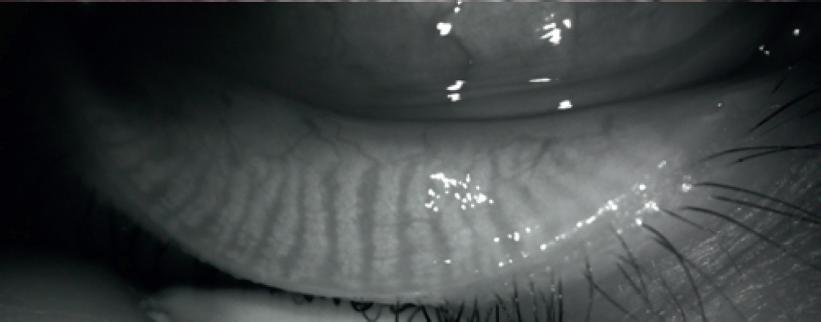

FIGURE4

Tearmeniscusheight(TMH)measuredwiththecaliper.Thecentralgreencirclerepresentsastandardmeasureofreferencetocalculatethe TMH. (A,B) Imagesrepresenttherightandlefteye,respectively.Aresult ≤0.20mmimpliesanabnormalTMHand >0.20mmsupposeawithin thenormTMH.

Theocularsurfaceanalyzer protocol:Methodsandanticipated

results

Non-invasivetearfilmanalysisisperformedwiththe IntegratedClinicalPlatform(ICP)withintheOSA.TheOSA includesafullassessmentoftheocularsurfacethrougha combinationofdryeyediseasediagnostictests.Thetestallows thequickassessmentofthedetailsofthetearfilmcomposition, includingthelipid,aqueousandmucinlayers,inadditionto conjunctivalrednessclassificationandMGassessment.The instrumentisfitintheslitlamptonometerhall.Regarding thetechnicaldata,theimageresolutionissixmegapixels,the acquisitionmodeismultishotandmovieacquisition,thefocus canbemanualorautomatic,andPlacidodiscandNIBUTgrids areavailable.Furthermore,thecolorandsensitivitytoinfrared camerasareaccessible,andthelightsourceisaninfraredorblue light-emittingdiode(LED).AnOSAdeviceimagewaspresented in Figure1

TheOSAprotocolexaminationincludesallavailablenoninvasivedryeyediseasetestsinthedevice.Temperature andhumidityroomexaminationconditionsmustbestable duringallmeasurements.Illuminationoftheroomshould beperformedundermesopicconditions.Thepatientmust notwearsoftorrigidcontactlensesatleast48hprior totheexamination.Inaddition,nolubricants,eyedropsor make-upshouldbeusedbeforethemeasurements.Ocular surfacetestsaretakeninalternatingfashionbetweenbotheyes. Furthermore,betweenOSAmeasurementsteps,thesubjects blinknormallywithin1min.Priortothenextmeasurement, thesubjectblinksdeliberatelythreefulltimes.Theorderofthe measurementsisfromminortomajortearfilmfluctuationsin thefollowingorder.

Subjectivequestionnaire

ThequestionnaireincludedintheOSAplatformisthe DEQ-5(5, 65–67).Ithasfivequestionsdividedintothreeblocks: (I)Questionsabouteyediscomfort:(a)Duringatypicalday inthepastmonth,howoftendidyoufeeldiscomfort(from nevertoconstantly)and(b)Whenyoureyesfeeldiscomfort, howintensewasthefeelingofdiscomfortattheendofthe day,within2hofgoingtobed?(fromneverhaveittovery intense).(II)Questionsabouteyedryness:(a)Duringatypical dayinthepastmonth,howoftendidyoureyesfeeldry?(from nevertoconstantly)and(b)Whenyoufeltdry,howintense wasthefeelingofdrynessattheendoftheday,within2hof goingtobed?(fromneverhaveittoveryintense).(III)Question aboutwateryeyes:(a)Duringatypicaldayinthepastmonth, howoftendidyoureyeslookorfeelexcessivelywatery?(from nevertoconstantly).

Attheendofthequestionnaire,theOSAplatform summarizestheresults,withscoresrangingfrom0to4for questionsI-a,II-aandIIIandscoresrangingfrom0to5 forquestionsI-bandII-b.Thetotalpossiblescoreinthis questionnaireis22points.Chalmersetal.(5)describedmean healthypopulationresultsof2.7 ± 3.2pointswithinaclinical differencetodetectsixpoints(68)(basedonthevariation betweenseverityclassification)(5).

Limbalandbulbarredness classification

TheLBRCwasdetectedwithinthebloodvesselfluidityof theconjunctivatoevaluatetherednessdegreewiththeEfron (69)Scale(0=normal,1=trace,2=mild,3=moderate and4=severe).Forthismeasurement,noconewasplaced onthedevice.Acentralpicturemustbetakentoassesslimbal conjunctivalredness(Figure2).Therefore,anasalandtemporal picturemustbetakentoassessbulbarconjunctivalredness (Figure1).Efron(69)andWuetal.(30)didnotreportmean healthypopulationvalues,althoughtheyestablishedclinically normalasgrade0–1.Theclinicaldifferencetodetectis0.5 grading(68).

Lipidlayerthickness

Atthispoint,thequalityofthetearfilmlipidwasassessed. TheLLTevaluationwasperformedwithopticinterferometry. Furthermore,theevaluationofthequantityofthelipidlayer wasclassifiedintosevendifferentpatterncategoriesdefined byGuillon(35).Forthismeasurement,aplainconeis placedonthedevice.Thepatientmustblinknormallyduring anapproximately10-svideorecording.Later,thevideois comparedwiththesevenvideostomatchtheexactlipidlayer pattern(Figure3).

Tearmeniscusheight

TheTMHtestevaluatestheaqueouslayerquantitywithin amillimetercaliper(≤ 0.20mm–abnormaland > 0.20mm–normal).Forthismeasurement,theplainconeisplacedon thedevice.Thepictureconsistsofacentralcaptureofthe tearmeniscusfocalizedinthecenterofthegreensquare (Figure4).Later,themillimetercaliperisplacedatthestart andendofthetearmeniscus,andtheheightisobtained. Multiplemeasurementscanbeperformedaswellasnasal ortemporalTMH.Meanhealthypopulationresultswere presentedbyseveralauthors.Nicholsetal.(42)reported 0.29 ± 0.13mm(measuredwithaslitlamp),Weietal.(44) reported0.29 ± 0.04mm(measuredwithKeratograph4),

(A) Placiddiskringsreflectedontearfilmjustafterinitialdoubledeliberateblinks. (B) FirstPlacidorings deformation(difficulttoseevisuallybyahuman)thismomentautomatedestablishesthefirstnon-invasivebreak-uptime(FNIBUT). (C) Mean andgeneralPlacidoringsdeformation(difficulttoseevisuallybyahuman)thismomentautomatedestablishesthemeannon-invasivebreak-up time(MNIBUT).

ormanualestablishesglandspresence. (A) Righteyeuppereyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern. (B) Lefteyeuppereyelidrealmeibomiangland pattern. (C) Righteyeloweyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern. (D) Lefteyeloweyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern.

Analyzer(OSA)fromSBMSystem R (Orbassano,Torino,Italy). (A) Simulated3Drighteyeuppereyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern. (B) Simulated3Dlefteyeuppereyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern. (C) Simulated3Drighteyeloweyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern. (D) Simulated3Dlefteyeloweyelidrealmeibomianglandpattern.

Tianetal.(43)reported0.27 ± 0.12mm(measuredwith Keratograph5M),Lietal.(70)reported0.19 ± 0.02mm (measuredwithocularcoherencetomography,OCT)and Wangetal.(71)reported0.34 ± 0.15mm(measuredwith OCT).Theminimalclinicaldifferencetodetectwassetat 0.1mm(68).

Non-invasivebreak-uptime

Regardingthismeasurement,thetearfilmmucinlayer quantityisassessed.TheFNIBUTandMNIBUTareevaluated withaspecialgridcone,whichevaluatesthetearfilmbreakin seconds.ThePlacidoconeissetforthistest.Thepatientmust deliberatelyblinktwotimes;afterthis,thevideorecordingstarts andstopsatthefirstinvoluntaryblink.Thedeviceautoanalyzes themeasurementandreportsthefirstpointoftheblurgridas theFNIBUTandthegeneralizedtearfilmBUTastheMNIBUT (Figure5).Meanhealthypopulationresultswereestablishedby Nicholsetal.(58)11.2 ± 6.8s(measuredwithTearscopePlus) andTianetal.(43)10.4 ± 4.2s(measuredwithKeratograph 5M).Theminimalclinicaldifferencetodetectwassetat5s(68).

Meibomianglandsdysfunction

TheMGdysfunctionpercentageusmeasuredwithan infrarednon-contactcamerathatevaluatestheupperandlower lidafterevertingitwithaswab.Forthismeasurement,no coneisplacedonthedevice.MGpicturesoftheupperand lowereyelidsmustbecapturedinsidethegreensquare.After thecatch,MGassessmentcanbeperformedautomatically ormanually(Figure6).Inaddition,acombinationofboth methodscanbeperformedwiththesemiautomatedmethodthat allowstheadditionorremovalofnon-detectedMGsmanually. TheMGdysfunctionpercentagecanbeclassifiedintofour degrees: ∼0%–Grade0, < 25%–Grade1,26–50%–Grade2, 51–75%–Grade3and > 75%–Grade4(72, 73).Thedevice permittoperformasimulatedorreal(withOSAPlus)3DMG pattern(Figure7).

Futureresearchlinesand limitations

Newemerginglinesofresearcharefocusedonthesearchfor identifiersthatallowustorecognizebiomarkersoftheeffectsof theocularsurfaceinamoreobjective,automatedandminimally invasiveway.Toenhancethefield,thedevelopmentofnew algorithmiccalculationsandtheincorporationofsoftware fordataanalysis,suchbigdataandmachinelearning,will allowustorecognize,detectandclassifymoreaccuratelythe differentvalues,includingtheinterrelationsbetweenthem,inan

automatedwaywithdifferentparameters(74).Independentand dissociatedobservationofthetearfilm,inclusionofpalpebral parametersandanalysisofproinflammatoryfactorswithoutthe needforinvasive,expensive,rapidorinvitedtestsarepotential futuredirectionsthatshouldbeanalyzed(75, 76).

Futureresearchersshouldconsiderthattheintensity ofilluminationproducedbytheseinstrumentsintheir measurementscancauseanincreaseintheblinkrateand reflextearing(77).Therefore,themainlimitationsfound arethelackofobjectivityandautomationinthemeasures conducted,absenceofcorrelationsbetweenexistingtestsand lackofextrapolationtoothersimilarsystems.However,the lackofintra-andinterobserverrepeatabilityinsomeofthe measurementtoolsduetotheinteractionofanobserver limitsneutralityandincreasesbiases,whichimpactthevalidity oftheresults.Withinthelimitationsofthisstudy,an accuracyandrepeatabilityresearchisneededtovalidatethis ocularsurfacedevice.

Conclusion

TheOSAisadevicethatcanprovideaccurate,noninvasiveandeasy-to-useparameterstospecificallyinterpret distinctfunctionsofthetearfilm.Theuseofvariablesand subsequentanalysisofresultscangeneraterelevantinformation forthemanagementofclinicaldiagnoses.TheOSAand OSAPlusdevicesarenovelandrelevantdryeyedisease diagnostictools;however,theautomatizationandobjectivity ofthemeasurementscanbeincreasedinfuturesoftware ordeviceupdates.

Dataavailabilitystatement

Theoriginalcontributionspresentedinthisstudyare includedinthearticle/supplementarymaterial,furtherinquiries canbedirectedtothecorrespondingauthor.

Authorcontributions

MS-G,RC-P,M-CG-R,CD-H-C,M-JB-L,CS-V,and J-MS-G:conceptualization,methodology,writing—original draftpreparation,writing—reviewandeditingandsupervision. Allauthorsreadandagreedtothepublishedversion ofthemanuscript.

Funding

ThisstudyreceivedfundingfromESTEVEPharmaceuticals S.A(EnglishEditingServicesandArticleProcessingCharges).

Thefunderwasnotinvolvedinthestudydesign,collection, analysis,interpretationofdata,thewritingofthisarticleorthe decisiontosubmititforpublication.

Acknowledgments

Weappreciatethesupportofferedbythemembersof theDepartmentofPhysicsofCondensedMatter,Faculty ofPhysics,UniversityofSeville,withspecialthanks toJavierRomero-LandaandClaraConde-Amiano.In addition,wealsoappreciatethetechnicalsupportoffered bythemembersandfacilitiesoftheFacultyofPharmacy, UniversityofSeville,withspecialthankstoMaríaÁlvarez-deSotomayor.

References

1.JonesL,DownieLE,KorbD,Benitez-del-CastilloJM,DanaR,DengSX,etal. TFOSDEWSIIManagementandTherapyReport. OculSurf. (2017)15:575–628. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.006

2.KottaiyanR,YoonG,WangQ,YadavR,ZavislanJM,AquavellaJV.Integrated multimodalmetrologyforobjectiveandnoninvasivetearevaluation. OculSurf. (2012)10:43–50.doi:10.1016/J.JTOS.2011.12.001

3.RemonginPE,RousseauA,BestAL,BenHadjSalahW,LegrandM,Benichou J,etal.[MultimodalevaluationoftheocularsurfaceusingathenewLacrydiag device]. JFrOphtalmol. (2021)44:313–20.doi:10.1016/J.JFO.2020.06.045

4.FoulksGN.Challengesandpitfallsinclinicaltrialsoftreatmentsfordryeye. OculSurf. (2003)1:20–30.doi:10.1016/S1542-0124(12)70004-6

5.ChalmersRL,BegleyCG,CafferyB.Validationofthe5-ItemDryEye Questionnaire(DEQ-5):discriminationacrossself-assessedseverityandaqueous teardeficientdryeyediagnoses. ContactLensAnteriorEye. (2010)33:55–60.doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.12.010

6.PetersonRC,WolffsohnJS.Sensitivityandreliabilityofobjectiveimage analysiscomparedtosubjectivegradingofbulbarhyperaemia. BrJOphthalmol. (2007)91:1464–6.doi:10.1136/BJO.2006.112680

7.NiedernolteB,TrunkL,WolffsohnJS,PultH,BandlitzS.Evaluationof tearmeniscusheightusingdifferentclinicalmethods. ClinExpOptom. (2021) 104:583–8.doi:10.1080/08164622.2021.1878854

8.AritaR,FukuokaS,MorishigeN.Functionalmorphologyofthelipidlayerof thetearfilm. Cornea. (2017)36:S60–6.doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000001367

9.LanW,LinL,YangX,YuM.Automaticnoninvasivetearbreakuptime (TBUT)andconventionalfluorescentTBUT. OptomVisSci. (2014)91:1412–8. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000418

10.AritaR,SuehiroJ,HaraguchiT,ShirakawaR,TokoroH,AmanoS.Objective imageanalysisofthemeibomianglandarea. BrJOphthalmol. (2014)98:746–55. doi:10.1136/BJOPHTHALMOL-2012-303014

11.BandlitzS,PeterB,PflugiT,JaegerK,AnwarA,BikhuP,etal.Agreementand repeatabilityoffourdifferentdevicestomeasurenon-invasivetearbreakuptime (NIBUT). ContLensAnteriorEye. (2020)43:507–11.doi:10.1016/J.CLAE.2020.02. 018

12.VigoL,PellegriniM,BernabeiF,CaronesF,ScorciaV,GiannaccareG. Diagnosticperformanceofanovelnoninvasiveworkupinthesettingofdryeye disease. JOphthalmol. (2020)2020:5804123.doi:10.1155/2020/5804123

13.WardCD,MurchisonCE,PetrollWM,RobertsonDM.Evaluationof therepeatabilityofthelacrydiagocularsurfaceanalyzerforassessmentofthe meibomianglandsandtearfilm. TranslVisSciTechnol. (2021)10:1.doi:10.1167/ TVST.10.9.1

14.UchidaA,UchinoM,GotoE,HosakaE,KasuyaY,FukagawaK,etal. NoninvasiveinterferencetearmeniscometryindryeyepatientswithSjögren syndrome. AmJOphthalmol. (2007)144:6.doi:10.1016/J.AJO.2007.04.006

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheresearchwasconductedinthe absenceofanycommercialorfinancialrelationshipsthatcould beconstruedasapotentialconflictofinterest.

Publisher’snote

Allclaimsexpressedinthisarticlearesolelythoseofthe authorsanddonotnecessarilyrepresentthoseoftheiraffiliated organizations,orthoseofthepublisher,theeditorsandthe reviewers.Anyproductthatmaybeevaluatedinthisarticle,or claimthatmaybemadebyitsmanufacturer,isnotguaranteed orendorsedbythepublisher.

15.AbdelfattahNS,DastiridouA,SaddaSVR,LeeOL.Noninvasiveimagingof tearfilmdynamicsineyeswithocularsurfacedisease. Cornea. (2015)34:S48–52. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000570

16.BaekJ,DohSH,ChungSK.Comparisonoftearmeniscusheight measurementsobtainedwiththekeratographandfourierdomainoptical coherencetomographyindryeye. Cornea. (2015)34:1209–13.doi:10.1097/ICO. 0000000000000575

17.Arriola-VillalobosP,Fernández-VigoJI,Díaz-ValleD,Peraza-NievesJE, Fernández-PérezC,Benítez-Del-CastilloJM.Assessmentoflowertearmeniscus measurementsobtainedwithKeratographandagreementwithFourier-domain optical-coherencetomography. BrJOphthalmol. (2015)99:1120–5.doi:10.1136/ BJOPHTHALMOL-2014-306453

18.ZhouN,EdwardsK,ColoradoLH,SchmidKL.Developmentoffeasible methodstoimagetheeyelidmarginusinginvivoconfocalmicroscopy. Cornea. (2020)39:1325–33.doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000002347

19.LeeY,HyonJY,JeonHS.Characteristicsofdryeyepatientswith thicktearfilmlipidlayersevaluatedbyaLipiViewIIinterferometer. Graefes ArchClinExpOphthalmol. (2021)259:1235–41.doi:10.1007/S00417-020-05 044-5

20.LeeJM,JeonYJ,KimKY,HwangK-Y,KwonY-A,KohK.Ocularsurface analysis:acomparisonbetweentheLipiView R IIandIDRA R EurJOphthalmol. (2021)31:2300–6.doi:10.1177/1120672120969035

21.GuarnieriA,CarneroE,BleauAM,Alfonso-BartolozziB,Moreno-Montañés J.RelationshipbetweenOSDIquestionnaireandocularsurfacechangesin glaucomatouspatients. IntOphthalmol. (2020)40:741–51.doi:10.1007/s10792019-01236-z

22.VerrecchiaS,ChiambarettaF,KodjikianL,NakouriY,ElChehabH,Mathis T,etal.Aprospectivemulticentrestudyofintravitrealinjectionsandocularsurface in219patients:IVISstudy. ActaOphthalmol. (2021)99:877–84.doi:10.1111/aos. 14797

23.LawrensonJG,BirhahR,MurphyPJ.Tear-filmlipidlayermorphologyand cornealsensationinthedevelopmentofblinkinginneonatesandinfants. JAnat. (2005)206:265–70.doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00386.x

24.PrabhasawatP,TesavibulN,KasetsuwanN.Performanceprofileofsodium hyaluronateinpatientswithlipidteardeficiency:randomised,double-blind, controlled,exploratorystudy. BrJOphthalmol. (2007)91:47–50.doi:10.1136/bjo. 2006.097691

25.SchiffmanRM,ChristiansonMD,JacobsenG,HirschJD,ReisBL.Reliability andvalidityoftheocularsurfacediseaseindex. ArchOphthalmol. (2000)118:615–21.doi:10.1001/archopht.118.5.615

26.NgoW,SituP,KeirN,KorbD,BlackieC,SimpsonT.Psychometric propertiesandvalidationofthestandardpatientevaluationofeyedryness questionnaire. Cornea. (2013)32:1204–10.doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318294 b0c0

27.HashmaniN,MunafU,SaleemA,JavedSO,HashmaniS.Comparingspeed andosdiquestionnairesinanon-clinicalsample. ClinOphthalmol. (2021)15:4169–73.doi:10.2147/OPTH.S332565

28.SimpsonTL,SituP,JonesLW,FonnD.Dryeyesymptomsassessedby fourquestionnaires. OptomVisSci. (2008)85:b013e318181ae36.doi:10.1097/OPX. 0b013e318181ae36

29.AkowuahPK,Adjei-AnangJ,NkansahEK,FummeyJ,Osei-PokuK,Boadi P,etal.Comparisonoftheperformanceofthedryeyequestionnaire(DEQ-5)to theocularsurfacediseaseindexinanon-clinicalpopulation. ContactLensAnterior Eye. (2021)2021:101441.doi:10.1016/j.clae.2021.101441

30.WuS,HongJ,TianL,CuiX,SunX,XuJ.Assessmentofbulbarrednesswith anewlydevelopedkeratograph. OptomVisSci. (2015)92:892–9.doi:10.1097/OPX. 0000000000000643

31.BaudouinC,BartonK,CucheratM,TraversoC.Themeasurementofbulbar hyperemia:challengesandpitfalls. EurJOphthalmol. (2015)25:273–9.doi:10.5301/ ejo.5000626