ROCKY MOUNTAINS

Photography by Blake Jorgenson

Stable and comfortable across any terrain, Talon/Tempest is designed to adapt to every move. Available in a range of volumes, this iconic series is your trusted partner for every adventure.

TABLE of CONTENTS

UPFRONT

P.11 Publisher’s Message: Hold the Gaze

FEATURES

P.16 A Radical Beauty

P.36 Dodging Cow Pies

P.46 Cloudline

DEPARTMENTS

P.12 Back Yard: Black Mountain Rides Again

P.31 Mountain Lifer: Cassie Ayoungman

P.51 Trail Mix

P.52 Book Reviews

P.55 Gallery

P.61 Gear Shed

P.64 Back Page

ON THIS PAGE Leah Poirier wading into Waterworld, a 90-metre quartzite crag jutting out of Revelstoke Lake. LAURA SZANTO

In the spirit of respect and truth, we honour and acknowledge that Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published in the traditional Treaty 7 Territory, which includes the ancestral lands of the Stoney Nakoda First Nations of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Wesley; the Tsuut’ina First Nation; the Blackfoot Confederacy First Nations of Siksika, Kainai, and Piikani; and the Métis Nation of Alberta, Region 3. We acknowledge the past, present and future generations of these Nations who continue to lead us in stewarding this land, as well as honour their knowledge and cultural ties to this place.

PUBLISHERS

Bob Covey bob@mountainlifemedia.ca

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Erin Moroz erin@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

PHOTO EDITOR

Brooke Riopel brooke@mountainlifemedia.ca

COPY EDITOR

Kristin Schnelten kristin@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL Noémie-Capucine Quessy noemie@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Bob Covey, Ryan Creary, Lindsay Davies, Sylvia Dekker, Melissa DuBois, Gary Finley, Karl Lee, Maxime Légaré-Vézina, Jane Marshall, Margaret McKeon, Erin Moroz, Laura Ollerenshaw, Rocking A Photography, Steve Shannon, Laura Szanto, Emma Stewart, Daniel Stewart, Cy Whitling, Evan Wong.

SALES & MARKETING

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2025. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703. Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email bob@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Rocky Mountains is published every October and May and circulated throughout the Rockies from Revelstoke to Calgary and Jasper to Fernie. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life, visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please email Bob at bob@mountainlifemedia.ca.

OUR COMMITMENT TO THE ENVIRONMENT

Mountain Life is printed on paper that is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is an international, membership-based, non-profit organization that supports environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests. Mountain Life is PrintReleaf certified. It measures paper consumption over time automatically reforested at planting sites in Canada.

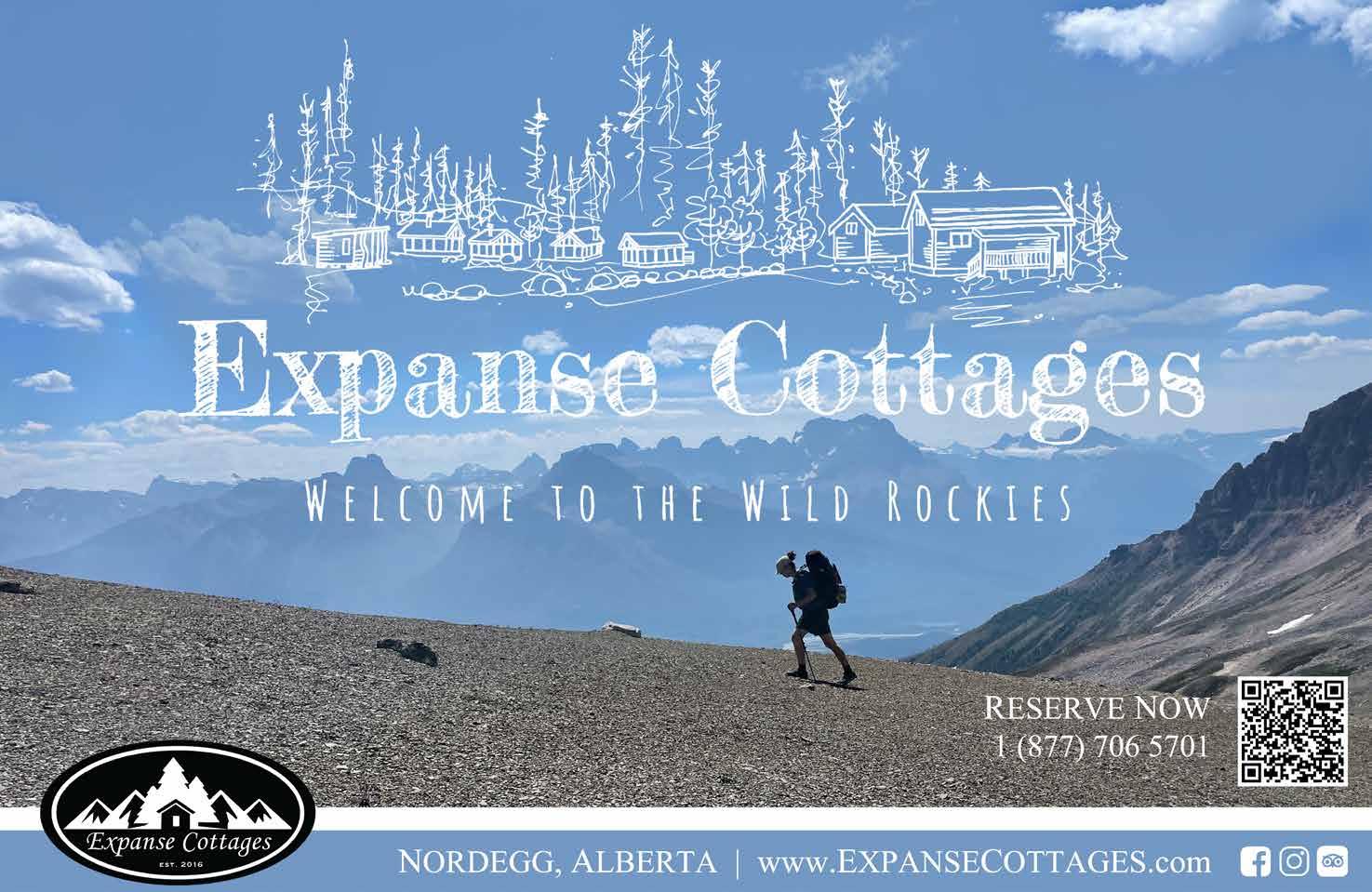

MINER’S CAFE

Homemade in Nordegg Pie, food & espresso!

619 Miners Crescent , Nordegg, Alberta l @nordeggminerscafe l #PeoplePiePlace

Hold the gaze

It was the story of the summer.

Last year, in late July, Rocky Mountain communities and people across the world watched in disbelief as a massive wildfire razed parts of Jasper to the ground.

Residents of forested towns have always known that, when it comes to our biggest threat of natural disaster, wildfire is at the top of the list. Other communities have burned. For the last handful of years, Alberta and BC have been a mess of evacuations and wildfire emergencies. And smoky skies in summer have become ubiquitous.

Yet, until you experience it, the terrifying circumstances of a wildfire event, and the painful, drawn-out, disruptive conditions afterward, are pushed to the back of our collective minds.

We don’t want to go there.

But if we don’t learn from Jasper, not only will that community’s suffering be for naught, other Rockies towns run the risk of repeating the pattern. So, in this edition of Mountain Life Rocky Mountains, we go there.

We go other places, too: to gnarly Nordegg, where Laura Ollerenshaw digs into MTB trails unearthed from the ashes; to complicated K-Country, where agriculture and adventure overlap on the Eastern Slopes; and all the way to the Andes, where editor Erin Moroz cold-plunges into Peru.

But by holding the gaze of displaced Jasperites—perhaps the first climate change refugees some of us know personally—we seek to understand what resilience looks like. In the context of communities learning to be more resistant to fire, it’s simple but critical stuff: Build with fire-proof materials. Install a sprinkler. Check your insurance policy. Prep your evacuation kit. Clean your yard.

And then seize the friggin’ day. Because, just as we can no longer be cavalier about wildfire in a warming, drying climate, neither can we live under a blanket of fear. Wildfires are going to happen. But communities don’t have to burn.

So get on the lake, hit the trails, study the stars and load up the camper. (And venture up to Jasper! The town needs your support.)

Go forth this summer and take absolutely nothing for granted. – BC

MAXIME LÉGARÉ-VÉZINA

Black Mountain Rides Again

words :: Laura Ollerenshaw

After decades of overgrowth and obscurity— followed by a forest fire—a dedicated group of volunteers with a bold vision have brought Black Mountain’s mountain bike trails in Nordegg, AB, back to life.

For thirty years, the mountain bike trails at Black Mountain slept. Forgotten, overgrown and partially logged, the trails were impassable and nearly impossible to distinguish amongst the deadfall, matted undergrowth and sections of clear cut. But Hannah and Dennis Landon knew they were there, somewhere—and were on a quest to find them.

The couple had heard about the trails while running an outdoor leadership program at Frontier Lodge near Nordegg. Built in the 1990s by Steven Johnson, who ran a mountain bike program at that same lodge, the network of trails was initially the location for the Black Mountain Challenge races held on the mountain—until 1995, when the festival was moved to its current location and later renamed the Fat Tire Festival. After the move, the trails at Black Mountain were all but forgotten.

“We looked around to see if we could find any of the old trails, and there’s a gated road. Hannah sent an email to the land manager Don Livingston and asked, ‘Can we have access to that gate? Would we be allowed to open any old trail if we can find it?’” recalls Dennis. “So that’s all we were looking to do, is bring a little back online. And then he said, ‘Give me a call. I have a better idea.’”

Livingston, now retired, was the director of recreation, ecosystem and land management for Alberta Environment and Parks and had worked in the Rocky Mountain House area for about 35 years. He’s also a biker, and had been involved in the ‘90s Black Mountain Challenge, where he volunteered with first aid.

Livingston knows the area and the people working there, and he knows the mountain. His better idea was to apply to the FRIAA (Forestry Resource Improvement Association of Alberta) fund to finance the building of a trail system. Created in 1997, FRIAA collects and administers forest industry funds in part from stumpage fees. The fund is mandated to facilitate forest resources for the benefit of all Albertans, and recreation is deemed an acceptable use.

And it seems they have.

NORCA had started preliminary work on the trail system when, on July 19, 2022, a fire broke out on Black Mountain, burning 507 hectares or roughly five square kilometres of forest.

Hannah and Dennis created a volunteer group they called Nordegg Off-Road Cycling Association (NORCA), wrote a plan, received $1.82 million in funding and then coordinated the trail network with West Fraser, the logging and lumber producer that manages the Black Mountain forestry area. The initiative progressed quickly because all groups involved have been enthusiastically on board— government, industry and community.

“We’ve been very fortunate to work with really great people. We wanted to build this with collaboration, friendship and goodwill and minimize any potential areas of conflict,” says Hannah.

“Our application for the grant money had been approved, and then the lightning struck. We stood up at our property, watched the flames crest the mountain and I cried. I thought, ‘Oh, man, this might wreck our whole project,’” Hannah says.

But instead of derailing the plan, the fire moved the timeline forward. West Fraser was able to salvage log the trees still usable—to do that, they constructed a service road to access the top of the mountain, a project that wasn’t planned for at least ten years. Instead of being a disaster, the fire opened not only the views, but more options.

“It reset their entire harvest plan. Before, when we were planning our

Trail building through harvested forest on Black Mountain JADEN PIERSON

“We’ve been very fortunate to work with really great people. We wanted to build this with collaboration, friendship and goodwill and minimize any potential areas of conflict.”

– Hannah Landon

lower network trails, we were thinking we had to pace this with their…harvest plans, but now the whole mountain is harvested. And we’ve heard secondhand that they probably won’t be back for 100 years because so much on the top of the mountain has been harvested,” Hannah says.

NORCA had started working with trail designer Brady Starr about a year before the fire and he had done some conceptual planning. After the fire, they had to reevaluate.

“When I initially saw the upper portion of the hill, it was an old spruce tree forest with some slightly mature cut blocks and it was quite dense, but once the fire came through, it changed everything. You had these spectacular views, and you could see the ridges and where the trails could naturally go,” says Starr. “Building through a cut block or a burned forest had its challenges as well, especially after they salvage logged it, but I think it’s enhanced the area. It almost feels like you’re in the alpine when you’re at the top now.”

Planning trails is a science and an art. Starr first references Google Earth as well as contour and topographic maps, then plans generally where the trails will go before walking the site.

“You walk around the forest for a while, looking where you want your trails to go. Then you connect the dots and look where you need to grade, being mindful of any potential environmental concerns,” Starr says. “From there, you lay it out a couple of times. Sometimes you get lucky and it goes well the

first time, but typically it’s a multi-stage process.”

The Black Mountain trail network officially opened in July 2024, with car and trailer parking, bathrooms, bike racks and picnic tables. The shuttle road is ready and awaiting legislative sign off before it can open to the public. Currently they’ve completed about 26 km of trails, ranging from advanced single track to entry-level, accessible flow trails, with Châska—a blue, six-km dual-climbing trail—acting as the main access from the base of the mountain to the top. The lower flow trails are built with accessibility in mind, and all trails and features are clearly signed. There are still about 20 to 24 km of trails planned from their current grant funds, but Hannah and Dennis have many ideas for future development.

Black Mountain is not the only place to bike in Nordegg. In and around the hamlet, the Nordegg Trail Society is also working hard to enhance the trail system. Last summer, the volunteer organization finished new bike trails on Coliseum Mountain. This summer, proposed work includes additional trails on Coliseum and a trail to connect Baldy (Shunda) Mountain.

“I always hoped that we’d be able to do more in the Nordegg area,” Johnson says. “And I thought the terrain and scenery was worthy of being somewhere people would come to. I’m so pleased they’ve gotten the vision and they’re taking it on. They’re making what I hoped would someday happen, happen.”

Steve Shannon on Magic Forest in the newly created Black Mountain trail network. LINDSAY DAVIES

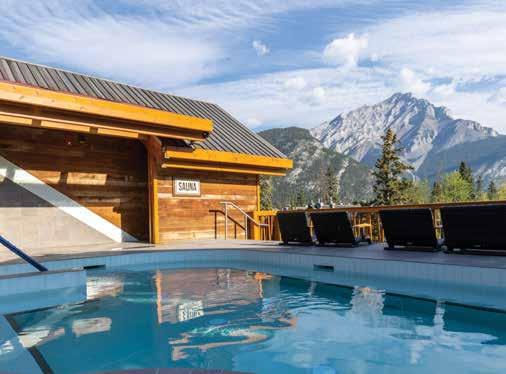

Visiting the serene and less crowded spots near Ban National Park o ers a refreshing escape from the bustling tourist hubs. Take Roam's Route 6 to explore the secluded trails by Lake Minnewanka. In Canmore, Roam’s Route 12 can conveniently take you to the beautiful Grassi Lakes Trailhead, perfect for a scenic adventure. Or find inspiration and wonder with a visit to the Cave & Basin National Historic Site within the Town of Ban on Route 4. Explore where Roam Transit can take you.

Location: Grassi Lakes Trailhead

A RADICAL BEAUTY

words :: Bob Covey

photos :: Steve Shannon

Loni Klettl’s boots crunch over a blackened pinecone on a popular hiking trail near the Athabasca River. The seed capsule crumbles beneath her sole, its woody scales disintegrating.

Through the blackened trees, an exposed moonscape is carpeted with electric-green grass. Far in the distance, Roche Bonhomme—Old Man Mountain to locals—has the same snowy headdress but a new, charred cape.

Until last summer’s wildfire erased the canopy in this lodgepole forest, Old Man was never visible from this vantage point.

“He’s seen all this before,” Klettl says, taking in the fascinating burn scar, beyond which lie vast patches of pure, even-aged pine forest—evidence of large, intense fires in previous centuries.

Klettl, now 65 years old, was born in Jasper. Her earliest travels on the national park’s extensive trail system were by bassinet. She and her siblings grew up, for parts of their youth, in the backcountry where their warden father was posted; her first steps were in a twobedroom cabin along the park’s North Boundary trail.

Klettl knows Parks Canada trail crew members by name, can describe in detail how most routes evolved, and has some kind of relationship with most every valley bottom approach, subalpine connector and summit scramble in the park—official, unofficial or otherwise.

And as for this particular path— which winds behind Old Fort Point, one of the park’s iconic landmarks and the site of one of the area’s first trading posts—the tread of Klettl’s tires and the soles of her boots have traversed it thousands of times.

But, until recently, it never looked like this.

Massive black root balls, stumps and snappedoff trees tangle together. Leopard-patterned trunks, bark bubbled from radiant

heat, form a kaleidoscopic middle ground that stretches into the matte-grey horizon. Aspen stands retain a metres-high singe on the trees’ white bark. And spiral patterns of charcoaled logs give clues to the intensity of the winds that blew through here.

In the middle of the burn zone, some see the blackened forest as hideous—a terrible toll exacted by the July 2024 Jasper Wildfire Complex. Others, like Klettl, see the raw, ravaged and arresting aftermath of the fire as having a spellbinding, surreal beauty. “I can’t stay out of the burn,” she says. “I just find it so fascinating.”

On July 22, 2024, foreshadowed by record drought conditions, lit by lightning and driven by extreme winds, the Jasper Wildfire Complex raced down the Athabasca River Valley towards the town of Jasper, 30 kilometres away.

In less than two days, the flames burned thousands of meadows, shrublands and forests of all ages and types, culminating in a building, billowing column of heat that collapsed on itself above the slopes of Whistlers Mountain on July 24.

The resulting ember shower hurtled untold numbers of white-hot firebrands— pinecones, sticks and other flaming debris—onto a vulnerable townsite. The wind-driven burning fragments found purchase on cedar shakes, woodpiles and other flammable objects—or entered buildings through gaps— to ignite dozens of structure fires almost simultaneously. This onslaught would have immediately outmatched any conceivable brigade of fire responders, replicating the same tragic pattern repeated in Los Angeles, Lahaina, Lytton and elsewhere.

The devastation—358 structures lost, including the homes of more than 1,800 Jasperites—has been tallied at $1.2 billion in insured losses.

But the numbers are far from the entire story.

Everyone who had a relationship with Jasper National Park will have different journeys of reconciliation with what was lost in the fire, says Jasper Community Team Society executive director and volunteer firefighter Tristan Tomkins.

As such, Tomkins says, it’s too early to celebrate opportunities to build back better, when some residents will never be able to build back at all. It’s insensitive, he feels, to suggest that the fire, which has caused so much heartache, disruption and trauma, has silver linings that people ought to appreciate. And, as long as the community is struggling to find temporary housing for people whose homes were burned, Tomkins says it’s too soon to suggest that a phoenix will somehow rise from the ashes.

visitors are welcome. But Jasper—the park and the town—has changed forever. And it will take years for both to heal.

It so happens that for many, including Klettl—who, like hundreds of other Jasperites, lost her home and everything in it—the best place to start that healing journey is on the trails.

“Is 70 per cent of town saved a success, when you look at the other 30 per cent and all the hardship that it’s caused? It’s kind of hard to bring those things together.”

– Christine Nadon

“That might be for people to discover on their own, but it’s not for anyone else to say,” Tomkins says. “And for some, a phoenix might not ever rise.”

Make no mistake, the rebuild is on, businesses are open and

Near Old Fort Point, where a trail formerly snaked through dense lodgepole pine and Douglas fir forest, a water-washed path now meanders over an exposed valley bottom. Minerals in rock bluffs, once hidden from view, twinkle in the sun (as do broken bottles and exposed bush camps). New spines, plateaus and whaleback ridges draw the wanderer’s eye.

For Klettl—who has wandered more than most in Jasper—the trails have never been more alluring.

“I don’t see doom and gloom when I look around the burn,” she says. “I look up and see uncovered road beds, incredible geology and different ascents.”

While some have been reluctant to visit the burned areas, Klettl has plunged headlong into her work and recreation there. Instead of grieving the scorched forest, she’s celebrating the new landscape, with its myriad new sightlines, access points and alpine opportunities. “Everything is so open. I find it so interesting,” she says.

Nurse, athlete and Jasper Park Cycling Association member Laura Mahoney surveys the Athabasca River Valley from above the west end of the Jasper townsite, where hundreds of homes were destroyed by the July 2024 wildfire.

Local bike mechanic and freelance pasta maker Max Hester noodles around in the fire-scarred forest. Some riders see the raw, ravaged and arresting aftermath of the fire as having a spellbinding, surreal beauty.

In the weeks following July 22, 2024, the Jasper Wildfire Complex held the interest of the entire nation. Twelve months of fickle news cycles later, however, some Rockies tourists have no prior knowledge of the fire, the largest in Jasper National Park’s recorded history. “Not all of our guests know we even had a fire,” says Jasper Raft Tours guide Brad Stewart.

The jarring sight of the burn scar, both in the forest and the more confronting scene in the townsite, catches people off guard. The temporary housing on either end of town, the mangled skeletons of incinerated gas pumps and the burned remains of the historic Anglican church—not to mention the ongoing heavy construction amongst entire blocks of levelled lots—is a lot to take in.

“People ask, ‘What happened here?’” Stewart says.

Leaning into his oars, rowing one of the 13 replacement boats his company raised funds for after their fleet was burned, Stewart ponders exactly how he’ll respond to that question this summer. Eventually, he and other frontline staff in Jasper will have a rote answer, and he’s confident the changes to the ecology will help put a fascinating, distracting face on the disaster.

But not everyone will be able to field pointed, personal questions as coolly as relaxed raft guides, small-talk-seasoned bartenders or Jasper’s marketing professionals.

Resident Clara Adriano, who was recently recognized by Jasper municipal council for her behind-the-scenes support of Jasper newcomers and wildfire evacuees, is putting the message out to visitors to please tread lightly when discussing the 2024 wildfire.

“Ask us about the best places to eat, our favourite hike or the must-see places in Jasper. But please try not to ask us about what we lost, if our home is standing or about the losses many are still trying to recover from,” she says. “Not many of us are ready to talk about it yet.”

Back on the river, Jasper’s Christine Nadon is taking a turn at the oars.

When her house burned, she and her partner lost six boats—one canoe, four kayaks and a 16-foot raft, with which they’d often take their friends on lazy evening floats.

“It feels good to get on the water again,” she says. “And from here, the burn doesn’t look nearly as severe as I thought it would.”

Nadon, the Municipality of Jasper’s director of protective and legislative services, has been one of the community’s foremost public-facing officials since the fire. From her post as incident commander—a post she shared with various Parks Canada officers— she distilled and shared critical information about the complex, lifealtering event to media members, visitors and the general public.

But speaking to her fellow residents about the fire is hard for Nadon. Not because she doesn’t have answers, or because she can’t speak to the totality of the response. It’s because reconciling what was lost and what was saved is so damned difficult.

“Every single person who showed up to help us did so to the best of their knowledge and abilities, and I couldn’t be more proud of having been part of that team,” she says to a crowd of residents at a springtime wildfire information session.

"I don’t see doom and gloom when I look around the burn. I look up and see uncovered road beds, incredible geology and different ascents."

– Loni Klettl

Tomkins, who was among the 40 firefighters who made a desperate last stand on July 24 and ultimately saved 70 percent of the town, is more of a straight shooter.

“People ask me if I lost my home,” Tomkins says. “I tell them, ‘No. But I lost a lot of homes.’ That changes the subject pretty quickly.”

It’s not that Tomkins doesn’t want to talk about the fire. Through his work as the chair of the Jasper Volunteer Fire Brigade, the 36-year-old Brit has taken a special interest in helping his colleagues address the very real trauma they experienced. He is helping spearhead the Pathfinders program, an initiative that empowers local leaders with training and tools to assist others navigating recovery.

But reliving and relitigating the cruel, random destruction—how this home was saved but not that one—or attempting to answer impossible questions about impossible choices and situations the emergency crews found themselves in—he’s not going there. It’s still too raw.

“There hasn’t been much time for grieving. That process is still happening, and I think community-wide you can feel that,” he says.

“But is 70 per cent of town saved a success, when you look at the other 30 per cent and all the hardship that it’s caused?” Nadon asks. “It’s kind of hard to bring those things together.”

The fire has done this in Jasper: It’s pulled things apart. It’s pushed people out. It’s left permanent scars. Some residents who built their whole lives here won’t ever be back. Some will rebuild, but others will decide not to—because they have neither the resources, time nor energy to invest in the long road ahead. Many, like 69-year-old Patrick Mooney, whose rented Cabin Creek home was vaporized along with nearly the entire neighbourhood of houses around it, have been floating precariously between temporary accommodations since the community was evacuated last summer.

Following the fire, Mooney spent more than a month in a Grande Prairie reception centre with dozens of other Jasper evacuees. He then moved to a local hotel and, more recently, was given a spot amongst the rows of mobile housing procured by Parks Canada, positioned adjacent to the park’s largest campground. Even though he’s grateful to be housed at all, he says the constant uncertainty has been exhausting.

“I think for many people in Jasper, this fire robbed them of their sense of security, their sense of stability,” Mooney says. “That’s been maybe the hardest part of recovery.”

Mooney is a retired Community Outreach worker. In addictions parlance, a language he’s familiar with, recovery starts with acceptance, self-reflection and amends. Connection and community are important bridges. Finally, reintegration follows restoration and resilience.

But a year after the Jasper Wildfire Complex impinged the town, some residents still don’t accept that the fire was, for all intents and purposes, unstoppable.

Despite the size of the wildfire, its intensity, the 100 km per hour winds it was riding on and the driest conditions recorded since weather stations were installed in the park in the 1960s, there are some who have latched onto misperceptions around the health of the forest and clung to false narratives about the lack of an appropriate, urgent response.

And despite research showing the increased frequency of extreme fires engulfing forests across the planet as a direct symptom of a warming, drying climate, the anti-science pushback against a “climate change narrative,” has become a normal part of the mainstream discourse.

In Jasper, consistent community fireproofing messaging began in the early 2000s with two main champions: Greg Van Tighem, fire chief at the time, as well as Alan Westhaver, Parks Canada’s former long-time fire and vegetation specialist. By the 1990s, managers were well aware that the absence of wildland fire had increased hazards to the town and, between 2003 and 2012, Westhaver oversaw about 1,000 hectares of fuel reduction immediately around the townsite and the neighbouring Fairmont Jasper Park Lodge. From 2014 to 2018, the town and Parks Canada issued many additional contracts to remove beetle-killed trees from those areas, as well as those adjacent to critical infrastructure and evacuation routes. And, beginning in 2018, Parks Canada initiated commercial logging operations in the national park. The mechanical tree harvesting and forest-thinning was renewed in 2025.

Those efforts will never be enough for some, of course. But, shortly after the fire, Mayor Richard Ireland, who lost his home of 67 years in the disaster, rejected entirely any suggestion that there was a failure to prepare for wildfire.

“Everyone got out of town. Most of our town was spared. That could not have happened without the preparatory work done on the landscape,” Ireland says.

Westhaver, who was one of the principal developers of the FireSmart Canada program and continues to work closely with other researchers examining major wildland-urban fire disasters on several continents, is adamant that, while extreme wildfires are inevitable, wildland-urban disasters are not.

Additionally, he says that when extreme wildfires do occur, it’s the conditions within very close range of structures that make the difference between home survival and loss.

“If I had a million dollars, I’d spend 90 per cent of it within 30 metres of homes,” Westhaver says.

He adds that engaging with residents to help them understand and do the little things in their communities, where losses matter most, would make a big difference in preventing disasters such as the Jasper fire.

“We need to redefine this problem—it cannot be solved in the forest,” he says.

To say retired Jasper railroader Lee DeClercq is particular might be an understatement. This is someone who flicks the dirt off his mushrooms in the grocery store to save money.

In that same fastidious fashion, DeClercq has been one of many Jasper residents who for years has taken pains to remove flammable items around his home and make a break in the path of potential ignition. He remembers taking part in multiple neighbourhood fireproofing work bees—denuding trees, tidying up dead branches and removing resin-dense juniper bushes from the areas surrounding the yards.

“I did all kinds of little things to get rid of combustibles once the municipality started making us more aware of the potential of fire,” he says.

Still, of all the homes in Jasper’s now-flattened Cabin Creek neighbourhood, the DeClercq house was the one that many locals agreed, pre-fire, should have been among the most vulnerable.

DeClercq’s lot is the furthest west in all of Jasper. His house sits high atop a hill. And the three-storey structure has cedar cladding not only on the roof (as mandated by Jasper National Park’s tragically misguided, and since updated, Town of Jasper Land Use Policy) but also on its entire exterior—from the foundation to the fascia board.

In the urban wildfire context, DeClercq’s place looks like a matchstick ready to light. Yet his home was one of only five in the devastated Cabin Creek development still standing after the final flames were put out. The keys? Luck, of course—but also DeClercq’s decision to follow basic FireSmart principles.

Additionally, to minimize the flammability of his house, years ago he affixed a rudimentary farm sprinkler atop the roof. During fire season, he turns it on every four days. Westhaver says that DeClercq’s experience is a positive example of what FireSmart collaboration can accomplish.

“What we need is more teamwork between residents and fire responders before the fire," he says. "We already have some great examples of this in Jasper—just not enough.”

Wildfires don’t come into town as a wall of flames, Westhaver says. Instead, the common denominators of communities that burn is that they’re bombarded by burning embers and that properties are vulnerable to ember ignition.

“That’s what people are describing in Jasper,” Westhaver says. “When that huge column collapsed, embers piled up just like snowflakes and ignited combustible objects on or around people’s homes.”

And when multiple structures ignite, fires merge, quickly overwhelming any conceivable response by firefighters, no matter how wellresourced they are.

“We’ve been improving our technology and firefighting capabilities for well over 100 years and yet these events are more frequent than ever,” Westhaver laments.

Loni Klettl, who has been travelling on Jasper’s trails for six decades, is fascinated by the fire-affected landscape.

"Everyone got out of town. Most of our town was spared. That could not have happened without the preparatory work done on the landscape."

– Richard Ireland, mayor

What would change the game, Westhaver says—more than all the feller bunchers, bulldozers and massive sprinkler systems that any community could round up—is public buy-in to work within the community.

“This is the turnaround that needs to take place,” he says. “But I’m not sure who’s going to take on that leadership role if the fire fraternity doesn’t."

Within the townsite, Jasper will be in recovery mode for years. Demolitions, site clean-ups, soil sampling, remediation, permits, inspections—not to mention the actual construction—all take time. In the surrounding forest, however, the pace of progress is astounding.

David Smith, former fire specialist with Jasper National Park, is confident that, between the aspen clones he’s already spotted coming up and the wildflower super-bloom he knows will pop en masse this summer, many parts of the park will be visually stunning to behold. “In a couple of years, some of these places are going to be unbelievable,” he says.

But it’s not just the fire-affected areas that have experienced a sudden facelift. West of the townsite, on what’s known as the Pyramid Bench, expansive new views have emerged.

The Bench didn ’ t burn in the 2024 wildfire, but it was

logged—first in 2018, and again this past winter/spring. The felling is happening in the name of wildfire hazard reduction, and the resulting clearcuts have opened the forest in nearly as dramatic a fashion as that of the fire.

“The new views on the Bench are incredibly amazing,” says trail advocate Loni Klettl.

However, instead of upturned blackened stumps, wind-bent trees and newly unveiled rock gardens, the forest floor here is covered in coarse, woody debris and piles of branches waiting to be burned. Wherever possible, non-fire-prone species, such as aspen and Douglas fir, have been retained. And as for the labyrinth of trails hikers and bikers use to access these corridors of lakes and wetlands, they’re still very much alive.

“The trails all come back,” Klettl says.

Firefighter Tristan Tomkins, like most Rockies residents and visitors, helps release the pressures of his everyday life by spending time outside. He says that, despite the new facades of the community and the park, what ultimately draws people to Jasper can’t be burned: “What makes Jasper, Jasper—community, a sense of welcome and natural beauty—those things might not look exactly the same right now, but they’re all still here.”

PREVIOUS SPREAD Jasper’s Laura Mahoney banks around a scorched aspen stand. The intense scarring on fire-resistant species is evidence of the Jasper wildfire’s high severity. ABOVE Jasper-based mountain biker Josh Scott takes flight where the forest canopy has been incinerated. Many plants thrive when fire eliminates competition from other plants and increases sunlight to the forest floor. Jasper’s network of trails look different, but are very much alive, advocates suggest.

Photo by Andrew Chad; Location: Bear Creek Falls

Seek and You Will Find in Golden BC

There are places that seem to have their own gravity. At the eastern edge of British Columbia, where the Columbia and Kicking Horse Rivers meet and the Purcell and Rocky Mountains part, all trails lead to Golden.

Golden is surrounded by six incredible national parks. To the east, Yoho, home to Takakkaw Falls and Emerald Lake, holds more natural wonders than one could hope to explore in a lifetime. Quiet and vast Kootenay sits to the south, while Glacier National Park, steeped in mountaineering histor y, lies to the west. For those seeking untouched wilderness, Golden is also home to the highest concentration of backcountry lodges in the world, catering to all types of adventurers.

Golden has become a destination for mountain biking. Unlike some places where trails are scattered, Golden is a true trail nexus with over 120 kilometres of trails that are accessible directly from downtown. The CBT and Moonraker networks offer smooth, flowy intermediate terrain. For technical singletrack, Mountain Shadows delivers excellent pedal laps, and Mount 7 offers a legendary 1100m descent prized by downhill mountain bikers.

At the valley floor, Golden sits where two rivers meet, each with its own distinct character. The Kicking Horse River is famous for its whitewater rafting tours with thrilling Class IV rapids.

Kinbasket Lake Resort

The gateway to the magnificent Kinbasket Lake. Offering lakefront camping with full hookup RV sites, lakefront cabins and tent sites, fishing, swimming, boating, and more!

1-250-344-1270

www.kinbasketlakeresort.com

The Columbia River and its wetlands offer unforgettable canoe, kayak, or paddleboard journeys, with towering mountains and abundant wildlife. Recognized as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance, the wetlands are home to hundreds of thousands of birds, fish, reptiles, and mammals. To help protect the lakes, rivers, and wetlands, please follow Clean Drain Dry guidelines to completely clean and dry your watercraft before entering new waterways.

Closer to town, Kicking Horse Mountain Resort has lift-accessed alpine hiking, mountain biking, and the world’s largest enclosed grizzly bear refuge. Opening in early May, the Golden Skybridge offers a mountain coaster and Canada’s highest suspension bridges. Visitors can also join guided tours ranging from aerial sightseeing and horseback riding to hiking, wildlife walks, and climbing adventures.

For fewer crowds and stunning scenery, locals recommend visiting in the spring or fall. Spring brings rejuvenation, as wildlife stirs and rivers swell with fresh snowmelt, while fall offers cooler temperatures and amazing trail conditions.

After a day of adventure, Golden’s cozy lodges, vacation rentals, cabins, and full-service hotels will make you feel right at home.

Start planning: tourismgolden.com/life

Mistaya Lodge

Helicopter access only in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. All inclusive packages let guests enjoy guided hiking, swimming, nature watching, photography, full catering & relaxation! 1-250-344-6689

www.mistayalodge.com Get the FREE Golden APP tourismgolden.com/localapp

Cassie Ayoungman

Building connection through climbing

words :: Jane Marshall

For many in the Bow Valley, the first introduction to Cassie Ayoungman came through an Indigenous film night at artsPlace, where her nonprofit, Soul of Miistaki, was featured in the Arc’teryx Alberta film Cultural Climbing Camp. The short film captured a diverse group learning to rock climb at Bow Valley crags while listening to Blackfoot Elders share stories. The participants’ on-camera reflections revealed just how powerful the experience had been.

A member of the Siksika Nation and an avid adventurer, Ayoungman understands the healing power of the mountains. With Soul of Miistaki (miistaki is the Blackfoot word for mountain), she’s creating access to mountain sports—offering scholarships, reduced fees and community-based support—while rooting the experience in the Indigenous history of Treaty 7 lands.

ABOVE High atop Pigeon Spire in the Bugaboos. BELOW Cassie near Everest Base Camp in her ribbon skirt—a powerful symbol of identity, resilience and reclamation. SUBMITTED

Over tea, Ayoungman reflected on her journey. Right from the start, her path has been focused on strengthening her community: She launched its inaugural fitness program and then joined the Canadian military program Bold Eagle, where she took medic training. This experience inspired Ayoungman to complete paramedic studies in Calgary, then came a full-time role at Siksika Emergency Medical Services.

During her time in Calgary, she found herself drawn to the mountains, and drove there often to hike and immerse herself in the land. Ayoungman loves a challenge, and she pushed herself with tougher, longer days out. For her, the elevation and physicality felt like therapy. “Movement is medicine,” she says.

Climbing came next, despite a fear of heights. “I’d cry. It challenged my mind, and I learned a lot about myself by learning to climb,” Ayoungman says, adding the process was both confronting and empowering. Mountain activities were helping her unlock power and potential, and she took things to the next level when she moved to Canmore in 2021—while still working for Siksika EMS. As Ayoungman’s outdoor skills expanded, she discovered a critical gap: There were few Indigenous climbers, and none in her community. Ayoungman wanted to change that.

In 2021, the Canmore-based Dirtbabe Collective, a nonprofit focused on therapeutic mountain skills, helped her secure a grant, and Ayoungman ran a climbing course for ten Siksika women. The success of this camp inspired Ayoungman to found her own nonprofit, and in 2023 Soul of Miistaki was born.

The goal of Soul of Miistaki is simple: increase diversity in mountain activities and provide outdoor opportunities for those historically excluded—particularly within BIPOC communities. Soul of Miistaki now offers climbing, hiking and skiing programs specifically for BIPOC individuals, as well as events that include allies.

Cassie’s work resonates deeply with her family, who, like many Indigenous families, carry the weight of intergenerational trauma. Her great aunt, Laura Sitting Eagle, participated in two Soul of Miistaki camps and appeared in the film.

“I went to residential school when I was six,” Laura recalls. “At seven, I was sent to Edmonton with tuberculosis. I didn’t see my parents again until I was 12. I kept thinking, Where are they?”

Healing has taken time, but she says, “I tell people, ‘Don’t pity me.’ I went through a lot and worked hard to better myself and my kids. I pushed them to get an education. I’m proud when someone graduates. Cassie makes me proud.”

She remembers praying for participants during camp smudges. “In our culture, rocks are holy and alive,” she says. “It was beautiful. We talked about residential school and how hard we worked to be where we are. I told them, ‘You need to know I worked hard—and now it’s up to you to work hard, too. Go for your dreams.’”

The camps facilitate intergenerational knowledge-sharing. Elders speak freely outdoors, while people listen and build connection— through story and through stone.

Artist Kayla Bellerose, from the Sawridge First Nation and Bigstone Cree Nation, joined the 2022 Cultural Climbing Camp after completing a mural of the Three Sisters in Canmore. Growing up in rural Alberta, climbing was never on the radar for Bellerose. “None of my family members were interested in climbing,” she says. “There were no mountains!” But in Calgary, where she completed her fine arts degree, bouldering gyms opened a door.

Through Soul of Miistaki, she found belonging: “The camp was beautiful. Elders shared teachings from a Blackfoot perspective. We were women of colour from different backgrounds, and we felt safe enough to be vulnerable.”

For Bellerose, outdoor climbing had once felt intimidating. “But they had professional guides who made it enjoyable,” she says. “Being in that environment helped me feel confident and supported.”

She describes Cassie as a leader—for Indigenous communities and for the broader outdoor world. “She’s creating a safe space for diversity. I have respect and love for her and the work she’s doing,” says Bellerose.

Good teachers are key to creating that safe space. Soul of Miistaki partners with Yamnuska Mountain Adventures (YAM), whose guides bring technical skill and open minds.

“Our guides at YAM are keen to work with Cassie and curious to learn,” says Tim Ricci, Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) member and Yamnuska’s director of operations. “These synergies are what make a great relationship.”

Cassie is also an Arc’teryx Alberta ambassador with support from the company’s No Wasted Days Community Grant Program. “Cassie is an inspiring leader in the outdoor space,” says Tammy Primeau, Arc’teryx Alberta’s community marketing manager. “She’s elevating Indigenous voices and helping move the outdoor industry toward equitable access. Our hope is that everyone can see themselves outdoors and experience the power of the mountains.”

What’s next for Ayoungman? She dreams that one day there will be a climbing gym on the Siksika Nation, that one day she will witness an Indigenous person become an ACMG-certified rock climbing guide, and that Soul of Miistaki will have a ski mentorship program. Ayoungman is ready for whatever life throws at her, and the community is climbing right alongside her.

Canmore’s Cassie Ayoungman, 33, a Blackfoot-Niitsitapi athlete, founded Soul of Miistaki to create space in the mountains for underrepresented groups. SUBMITTED

Dodging Cow Pies

Where rangeland and mountain recreation overlap

words

:: Sylvia Dekker

The contradiction wasn’t lost on me. Moments ago, I had tapped my brakes and paused to admire the fluid team of horse, rider and dogs pushing a cluster of bawling bovine off the road and up a grassy slope.

Now on the trail, dodging thick, wet cow pies, I grumbled about the very tradition the cowboy was keeping alive as I squelched up the path, pitted with cloven footprints.

I was beyond the “Welcome to Kananaskis Country” sign, in a sprawling 4,000-square-kilometre puzzle of parks, ecological reserves and wildland areas bejeweled with sundry ecosystems, verdant valleys, shimmering lakes, crumbly peaks and bubbling creeks. More than four million folks flock to this area every year for the endless recreational opportunities and stunning natural beauty.

Back on the highway, other signs jut out along the side of the roads snaking into this worldclass chunk of eastern Rockies: “Kananaskis conservation pass required. Keep your pets on leash. Cattle at large next 22 kms.”

The latter sentence surprises newcomers and annoys regulars. “Why are there cows here anyway?” I overheard a fellow hiker mutter at a muck-splattered trailhead. My toddler is thrilled when moos reverberate down the trail, but for many hikers, hints of farm devalue the wild surroundings.

Kananaskis is not simply a playground for fresh-air lovers, though. In 1978, “K-Country” was born as a multi-use area and notable source of income for both government and private businesses. Timber leases, oil and gas development, recreation, tourism and grazing were expected to share one chunky, complicated zone.

For the most part, recreation and grazing parties coexist well. Hikers rattle over cattle guards, brake for panicking calves and leave gates as they were found.

But there are undercurrents of conflict and concern. Standing on the edges of trampled brooks and sounding off on online forums, recreationists question if cows truly fit in amongst the mountains. Fences, manure and moos are at odds with the vision of a pristine natural area—beef in the backcountry, say some respondents on an online survey, should be phased out. Many recreationists believe the path to ensuring a diverse, healthy environment for plants and animals cannot include grazing, and are not convinced there is benefit seen beyond the rancher’s beefy paycheck.

• • •

Rangelands in Kananaskis are managed under agricultural dispositions, aka grazing permits, or licenses issued and renewed annually by the government and managed through the Kananaskis Country Public Land Use Zone. The disposition holder pays a fee to use the land and, according to the province’s Rangeland Grazing Framework, they collaborate with the government “to ensure that agricultural land use sustains environmental, economic and social benefits for the people of Alberta.”

The economic benefits are clear. Crown rangelands like those grazed in Kananaskis support about 14 per cent of Alberta’s beef herd, an industry that contributes more than $4 billion to the province’s GDP and employs tens of thousands of Albertans.

Grazing dispositions are part of a system developed to avoid the disastrous open-range policy of the United States, which resulted in range wars and environmental degradation. As the land owner, the government is responsible for overarching decisions. The disposition holder is responsible for day-to-day management and invests in their dispositions. “They ensure that they are following legislation and delivering under the stewardship model,” says Lindsye Murfin, manager of the Alberta Grazing Leaseholders Association.

“It is important to not put the financial profit of a few above the well-being of nature, which provides humans many tangible and intangible benefits that may not be measured monetarily but are still incredibly valuable,” says hiker and camper Lucy Poley.

That’s where stewardship comes in. A term that crops up a lot in government and industry documents on the subject, stewardship is the reciprocal relationship leaseholders have with the land.

Lorne Fitch, a retired provincial fish and wildlife scientist, says, “Those that care—the good stewards—are boots on the ground,” something he believes we desperately need in an area “that is a part of Alberta’s DNA.”

Rancher-cowboy Wolter van der Kamp—whose cattle I’ve often encountered in one of my go-to areas in southern Kananaskis—keeps environmental sustainability at the heart of his every day. “Economic benefits aside,” he says, “the use of these lands by animal agriculture offers a vast amount of ecological services which are very hard to put a price on.”

This is all dependent, however, on management. According to the Rangeland Grazing Framework, if managed well, healthy rangelands can provide an array of services, including clean air and water, flood mitigation, biodiversity, wildlife habitat, renewable

resources, carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling and the aesthetics of natural landscapes.

Many recreationists question how grazing cattle could possibly contribute to things like aesthetics or clean water. Their worries are well-founded: According to a review on the ecological costs of grazing in the west, studies show the negative effects cattle can have on the ecosystem when grazing is done wrong, from disrupting ecosystem function to altering species composition.

Often, it’s the visually distressing effects that raise criticisms, but most recreationists are simply not on site enough to accurately judge management and impacts. “Some measures may not look great in year one or two but are done for the betterment of the whole system,” explains van der Kamp, adding, “This can be difficult to see unless you’re involved in the long-term planning process.”

For those recreationists—like myself and Poley—with favourite trails and places visited year-round and year after year, the apparent mismanagement of consistently trampled places is troubling and contributes to tensions between livestock and those visiting the areas they graze.

When it comes down to it, it’s not only about aesthetics or having to dodge cow pies.

“Crown and private rangelands of Alberta provide most of the remaining prime habitat for birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians and insects” says Alberta’s Stewardship for Rangeland Sustainability publication. Yet, drive up one of the multiple roads into Kananaskis, and one is more likely to see cows than the native elk, sheep, deer, bear and moose that call the area home.

Wolter and Katie van der Kamp at the top of Grass Pass. KARL LEE

In the past, vast herds of bison and elk flowed across the prairiefoothill-mountain interfaces. Grazing was intense and impact severe. Predator pressure and natural migration patterns granted the land periods of rest and recovery.

“The natural system was built by disturbance,” says Fitch, including flooding, grazing and fire, factors which also once kept woody species encroachment under control.

Without licking tongues and flames, van der Kamp says, “Rosehips lead to aspen lead to spruce takeover, and a dense spruce forest is just a green desert.” While each of these species have their place, they can quickly advance on grasslands, one of the most productive, climate-stabilizing and endangered ecosystems on earth.

Countering methane-fueled climate claims, controlling bush and tree density isn’t the only way grazing bovine can help the planet. A study on the effects of large mammalian grazers on soil carbon pool stability says grazing can increase soil carbon sequestration and soil carbon stability, a nature-based climate solution.

While Fitch explains native rangelands do have a maximum saturation point, every bit counts. “For every gram of carbon in the soil,” Murfin says, “that soil can store four grams of water.”

“Eighty to 90 per cent of our water originates in this landscape,” Fitch says. Whether the rain and snow melt can seep into the land versus flowing away depends more on soil compaction—something recreational traffic and logging contribute to—and the amount of ground-covering leaf litter left behind, which grazing can help or hinder.

The overarching consensus on the effects of cattle presence (munching on habitats and their inhabitants): It relies highly on context. The caveat it depends—on species, management, ecosystem and beyond—threads through the research and discussions on the subject.

While cattle are not ecologically synonymous with bison, they currently fill the void left by overhunting at the end of the 19th century, both van der Kamp and Murfin say. Distribution and grazing habits vary between the two species, but cattle now provide part of the disturbance these lands were built with.

Like bison, the impact of cattle on ecosystems and ecological processes come from the ground up: Grazers remove plant biomass, trample, add nutrients, disperse propagules, alter soil compaction and texture, and can modify microclimate. Whether there is a net positive or negative effect depends on grazing frequency and, pivotally, grazing intensity.

These days, grazing intensity—or stocking rate—is controlled by animal unit months (AUMs) and set by the government. An AUM allotment for a particular area is calculated by assessing the forage available against the amount of forage required by one mature cow and her suckling calf—one animal unit—for one month. Bulls may count for two animal units and yearlings less than one, depending on weight. “This allows a different allotment of animals for every spot based on size, shape, terrain and vegetation,” van der Kamp explains.

On grasslands, research shows appropriate stocking rates can support biodiversity by providing resources for species typical of both short and tall vegetation on grazed and ungrazed landscapes. Small mammals adapted to dense cover are impacted negatively by livestock grazing, but species adapted to more open plant communities see a positive impact, says a study on cattle-deer compatibility in North America.

For large mammals, van der Kamp says grazing keeps the plant in a vegetative state longer. This means instead of setting seed and becoming less digestible and nutritious by July, a green plant may freeze up in September. The resulting forage, he explains, has a higher energy and protein content and is more palatable.

Wolter van der Kamp and neighbours moving cattle up Marston Creek Valley, with a view over Eden Valley and van der Kamp's property. ROCKING A PHOTOGRAPHY

“Animals that might have similar diets to cattle, such as ungulates,” says Murfin, “are often found on grazing leases.”

The problem is studies can only speculate through the lens of current perceptions. “What we’re seeing and interpreting as native isn’t,” says Fitch. Though there is an understanding that many rangeland species may benefit from some amounts of grazing, research on ranching conducted in Kananaskis says so far in Canada, the effects of grazing on biodiversity have not been sufficiently examined to garner such sweeping statements.

What we do know, according to research on restoring grazing-induced heterogeneity in Canadian grasslands, is habitat heterogeneity supports biodiversity. When done well, grazing can provide what the Stewardship for Rangeland Sustainability publication calls a “mosaic of disturbance.”

Fitch says it’s when disturbance is perceived as excessive by passersby that folks lash out against grazing.

Cattle naturally respond to variation in topography, forage and water resources, resulting in selective grazing habits. This means favoured forages and habitats like riparian areas can become overused.

Riparian zones—the green ribbons stretching along streams and lakes—are among the most productive habitats in North America. In fact, they support more than 80 per cent of Alberta’s wildlife. What makes them good places for wildlife also means they are attractive to both livestock and recreationists. Poley worries, “These sensitive areas can pretty quickly become destroyed.”

“Properly timed access [to riparian zones] with periods of rest have proven to be beneficial,” says Murfin. “Disturbance often stimulates regeneration.”

When grazing happens too soon, too long, too much and too often, though, these essential belts of life suffer. Streams overused by cattle are wider, shallower and warmer, and have reduced cover and more fine sediment. That’s bad news for baby fish. “Every one of our native trout species is imperiled,” says Fitch. He believes this is a clear report card on our management of the Eastern Slopes overall, though livestock are only one piece of the impact puzzle.

Luckily—as a review on the ecological costs of grazing states— riparian zones are resilient. These areas can repair, revive and thrive if given respite during the growing season and if sensitive areas are avoided during vulnerable periods, Fitch explains.

The reality is both the two- and four-legged herds trailing through Kananaskis have rights to Crown land.

Van der Kamp knows disturbance during the time of young things, whether plant or animal, can create the biggest impact. The earliest ranchers can move cattle back onto their dispositions, he says, is June 15, meaning bovine are absent during the time birds are nesting and bears are emerging with their cubs.

Distributing cattle so favoured areas don’t become overused is also vital—and a challenge to get right. Disposition holders can manipulate livestock movement and deter predators with horseback range riders and by distributing salt blocks, building trails and developing watering sites such as gravity-filled tanks.

However, van der Kamp tells me water development is not common in Kananaskis dispositions due to logistics. “It’s a very large landscape,” he says. “I’d sure love to see off-site watering in forestry [dispositions], but you’d have to helicopter [supplies] in, and it’d come at an incredible cost.”

Instead, van der Kamp fences off many of his riparian zones in the spring and again in the fall. Not all disposition holders do, though, and seeing a creek with its once green banks grazed down and stinking of farm is upsetting. The way cows can thrash watering sites is not lost on him, but van der Kamp compares the cattle slurping from a creek here or a pond there with our beloved trail network.

“Trails are considered sacrificial ground,” he says. They exist for the greater good, so hiker impact—which Fitch says can be devastating on wildlife populations—is concentrated in a small area. Similarly, sometimes one natural watering site becomes a sacrificial chunk livestock can use so other places can be rested or avoided.

The reality is both the two- and four-legged herds trailing through Kananaskis have rights to Crown land. “Both have more in common than they realize,” says van der Kamp. “We are passionate about the beauty and the ecological benefits we receive from this landscape and feel as though we need to protect it for the future.”

Kevin Dekker, hiking the hills south of the Sheep River. SYLVIA DEKKER

“Let’s get outside of our own perceptions for a while to see the real issue: cumulative impacts of everything we do in the landscape,” says Fitch. It’s the only way to move forward. Unfortunately, van der Kamp and Fitch know that in both camps there are some who care and others who don’t. Proof: trails littered with colourful bags of dog poop.

Unlike those trotting the trails with their four-legged sidekicks, disposition holders are not anonymous. “The department of Forestry and Parks has a fleet of rangeland agrologists whose main job is to ensure that grazing disposition holders are meeting their legislated responsibilities in terms of proper stewardship and range health,” says Murfin.

During field audits and disposition visits, range health—the ability of the rangeland to perform key ecosystem functions—is assessed and measured via a list of set factors. This, along with a stewardship assessment, advises permit renewals or tenure recommendations.

Because it depends, there is no Kananaskis grazing recipe for disposition holders to follow. Instead, there is a pantry of agrologist input, guidebooks and ever-growing and shifting research.

The way forward is a combination of what Fitch says are the three indivisible ingredients of stewardship: awareness, ethics,

action. Cows and Fish—a group focused on healthy riparian areas— has spent decades educating people and adapting grazing practices to reflect new insights.

“If we continue to argue over… which one is more important— fish or cows, cows or water quality, water quality or agriculture—we may be missing the point,” says the society’s booklet Riparian Areas and Grazing Management.

Point being cows and wildlife and recreation and aesthetics all have value. “We need to measure these things together as opposed to pitting one land use against another,” says Fitch.

“Getting rid of cattle is not going to fix the issues in our forest reserves,” says Fitch, despite many recreationists believing otherwise. “Look beyond the cow pie.”

Given holistic management and working together, van der Kamp believes, “We can keep our eastern slopes pristine for generations to come.”

For outdoor enthusiasts, the line between annoyance at navigating sloppy trails and appreciating what Poley calls the “stirring” vision of cowboys keeping tradition alive may always be blurry. At the very least, each slippery cow-pie discovery entertains and motivates my little hikers up the trail.

LEFT Taking a break to examine wildflowers on High Noon Hills, a popular year-round trail along Sheep River Road. RIGHT A cowboy pushes cows from the road and up the slope near the Windy Point/Foran Grade Trailhead, Bluerock Wildland Provincial Park. SYLVIA DEKKER

Voices from Jasper

From the heart of Jasper, Stories of Resilience – Voices from Jasper brought together ten residents to share personal stories and creative reflections one year after the wildfire. Through art and storytelling, the program elevates the lived experiences of recovery in a changing climate, highlighting grief, strength, belonging, and the power of community.

July 25, 2025

July 25 – August 16, 2025

Opening Event at the Jasper Art Gallery

Exhibition at the Jasper Art Gallery

All that’s missing IS YOU

JASPER | BANFF | LAKE LOUISE

Cloudline

words :: Erin Moroz

TYPE I FUN: It’s fun in the moment—perhaps an all-inclusive vacation. The whole thing is goddamn enjoyable; someone cooks your meals and cleans up after you. You day drink and lie in the sun. The good times don’t stop rolling.

TYPE II FUN: It was a good time in retrospect—character building. You did the thing, and while you were doing the thing you suffered a bit and were relieved when it stopped. But when you look back on the thing from your cozy quarters with your feet up: Wow! Turns out the journey was the destination—what an adventure/marathon/slog.

TYPE III FUN: An experience that involves risk and suffering— you could die. You make in-the-moment bargains with your deity of choice to stop the pain/humiliation/trauma. You’ll never do this asinine thing again. Redemption is a lost cause.

over the kelly-green carpet of the Andes, we emerged, blearyeyed, to snorting horses and donkeys in the distance and the busyness of prepping hot breakfast and drinking water while porters dismantled camp like a pit crew.

The Salkantay route in the Peruvian Andes has become an alternative to the popular and crowded Inca Trail. Both will take you to Machu Picchu—one, the Salkantay, is seen as more of an effort. You must be reasonably fit, with the knees of an 8-yearold or at least the ability to ignore the gradual betrayal of your own body. Unlike the classic Inca Trail, the Salkantay Trek offers a more rugged, remote approach, passing by sacred lakes and unnamed peaks before descending into a lush cloud forest.

While trekking the Salkantay route to Machu Picchu last fall, our group spent a fair amount of time pondering, sometimes chuckling and often commiserating on the 74-kilometre hike. Between the scratching of Peruvian mosquito bites (more of a horsefly bite really) and bandaging of blisters, we pontificated: Why were we doing this when we could be on a beach somewhere?

Our Indigenous Quechuan guide, the indomitable, barrelchested Juan Carlos Pillco Chuhui of Cusco’s Alpaca Expeditions, wore a fluorescent green T-shirt that screamed, “The journey is the destination!” Is it, though? Isn’t the destination the destination, we questioned, gasping our way to the top of 4,650 m Salkantay Pass in driving rain.

Pillco grew up in the high-altitude village of Huama in Peru’s Sacred Valley, where Spanish is a second language and storytelling is still the primary method of passing down history. He is part of a movement to reclaim Quechuan identity in tourism—Quechua language, traditions and rituals once pushed to the fringes are now front and centre for travelers who want a deeper connection to the land they are hiking through.

“Quechua is the language of our ancestors,” Pillco told our crew one evening over too many Cusqueñas. He spoke of Pachamama, the earth mother, of sacred lakes and mountains that watch over travelers. In the dinner tent surrounded by new friends and darkness, it was easy to believe in them, too.

Mornings at altitude began with a buenos dias and a hand pushing a scalding mug of coca leaf tea through the tent flap— the herbal drink is a Quechuan cure-all for altitude, sluggish limbs and existential dread. As the mist lifted and sun stretched

On the Inca Trail, trekkers follow in the footsteps of the flash-in-the-pan Incan dynasty that ruled much of western South America from 1438 to 1533, in an area that encompasses modern day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and large parts of Colombia, Chile and Argentina. Machu Picchu was a royal estate and religious site; the Spanish arrived in South America in 1498 and began their conquest of the Incans in 1532—a campaign of displacement, execution and, let’s be honest, general cultural destruction of the region’s Indigenous inhabitants.

Yet, against the odds, Quechuan culture survived—not just in the remote villages of the Andes but in the very way travelers experience Peru today. Tourists who set foot on these trails rely on the knowledge and endurance of Quechuan porters and guides, men and women whose ancestors built these same paths centuries ago. Alpaca Expeditions is one of the few trekking companies that actively employs Indigenous Quechuans in leadership roles, ensuring they are not just the labour force but also the storytellers.

And tourism is a lifeline for those working its trails. Our tour company, Alpaca, is at the forefront: hiring female porters and breaking a long-standing gender barrier in Andean trekking, limiting pack weights to less than the country’s mandated amount and ensuring their workers are given proper gear, such as quality sleeping bags and sturdy tents.

“Our main goal as a sustainable, local tour operator has always been to treat our team—porters, chefs and guides— better. It’s special for our team to work for a company that genuinely cares for them,” says Raul Ccolque, owner of Alpaca Expeditions. “Many of our team members have been with us for eight or nine years. To us, being sustainable means actively involving local communities, ensuring Quechuan families benefit directly from the tourism industry.” And Alpaca does give back to the local villages, in the form of sponsorship dollars and funding for medical necessities like optometrist and dentist visits to remote communities.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Erin Moroz; Emma Stewart; submitted; Erin Moroz x3; submitted.

Visiting Machu Picchu feels like stumbling into the past—a sacred refuge that went quiet for centuries, swallowed by the green until someone finally asked the right question. (The locals were always aware of the site, passing down oral histories long before American professor Hiram Bingham “discovered” it in 1911.) Every day, 4,000 humans step onto its stone terraces, their movements restricted since the Covid pandemic to threehour slots in one of four parceled sections. Each visitor’s permit costs $85 CAD. Multiply that amount by the 1.5 million tourists who flock to Machu Picchu annually—purchasing baby alpaca sweaters (none of that adult alpaca shit, please), sipping pisco sours and hiring guides, porters and drivers—and the financial impact of tourism becomes undeniable. Tourism contributes $30 billion CAD yearly to Peru’s economy, with more than 2 million travelers visiting the Cusco region alone.

Before we step onto the ruins of Machu Picchu, we witness the landscape, surreal and sweeping. Alpine meadows are dotted with purple tarwi and later, on the descent, Toblerone-style emerald peaks fade, layer upon layer, beyond sight into a nearly silent jungle where the only sounds are bird calls from unseen places and the crunch of boots finding purchase on trails strewn with baby-head boulders. We sample muña (a relative of mint), eat so much passion fruit it’s obnoxious and keep a keen eye on the jungle for one of the 400 species of orchids native to the region.

Our crew of seven travellers is as varied as the landscape, at least to a Westerner: the wise, grey-haired couple from Atlanta; the dry-witted doctor from Edinburgh (via Derry, Ireland); the Milwaukee sisters; and the Canucks (who incidentally everyone quizzed about weed), myself and my compatriot from Coquitlam. All came equipped with tales of other places one must see and of the full lives lived by those fortunate enough to adventure internationally.

All but the fittest hikers in our pack felt the extreme impact of altitude. The Quechuan people, though, have adapted to the thin air over centuries; in fact, studies suggest many Indigenous Peruvians have larger lung capacity than those of us who live at sea level and a unique genetic adaptation to low oxygen levels at high altitude.

My Canadian counterpart, Jordan, hadn’t made it to Cusco

in time to acclimatize for the three-day recommended window and was nearly crippled by altitude sickness during the early days of the trek. By day three, though, he was resurrected and

You must be reasonably fit, with the knees of an eight-year-old or at least the ability to ignore the gradual betrayal of your own body.

holding court in the hot tub, “Back from the dead with his harem of 20-year-olds,” Emma the Irishwoman playfully deadpanned as he nestled amongst the bikinis of the trekking herd mirroring our path (but unnervingly fuelled by song and trivia games in the way of 20-somethings). Emma had functioned as a patient lifeline for Jordan the first days of the trek—literally coaxing him step by step when, he said, “It felt like the inside of [his] head wanted to get out.”

As the kilometres slip by, we visit family-run coffee farms, duck beneath avocado trees and cold dip in the Aobamba River along the trek through montane forest before reaching the final long, flat march along the train tracks to Aguas Calientes. And we discover the journey isn’t measured in kilometres—not accurately, anyway, we would realize while inspecting the distance listed on our souvenir T-shirts over yet another pisco sour at the end of our journey. Over the span of five days and five nights we had experienced a stretching and wrinkling of space and time culminating in the conclusion that maybe distance isn’t that useful a metric after all.

Suddenly we were back to crisp bed sheets and private toilets—and, dear god, is that air conditioning? At our journey’s end the suffering blurs to nostalgia, the memories sharpen and say, "Wait a minute, what an adventure!" Type II fun indeed.

Machu Picchu was more than I never imagined. I expected something akin to a dusty church, but it delivered prodigious disbelief—not merely from location, but also in structural integrity, the colourful tales of Spanish deception and the indomitable spirit of the Indigenous Peruvians.

Erin was a guest of Alpaca Expeditions while in Peru.

LEFT TO RIGHT Emma Stewart; Erin Moroz; Melissa DuBois

REVELSTOKE PADDLE FEST | AUGUST 15 TO 17

Revy Paddle Fest doesn’t draw crowds so much as it gathers them—along the Illecillewaet and Columbia Rivers flowing through mountainous Revelstoke, BC. From August 15 to 17, Revelstoke and Western Canada’s river community will come together for a weekend of paddling, clinics and celebration. The planned events range from beginner to advanced, supporting a variety of watercraft including kayaks, canoes, SUPs and packrafts. This event is all about inclusivity—whether you’re young or old, a spectator, novice paddler or seasoned pro, there’s something for everyone.

Evenings are packed with great music, food trucks and a beer garden at Powerhouse Road Park, located in the industrial area of Revelstoke. Organized by the nonprofit Revelstoke Paddlesport Association and embraced by paddlers from all over, Revy Paddle Fest is a celebration of community, adventure and rivers. To learn more, visit paddlerevelstoke.com.

STORIES OF RESILIENCE

“From the ashes a fire shall be woken/A light from the shadows shall spring/Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king.” – J.R.R. Tolkien

A collection of writing, visual art and photography is rising from the ashes of Jasper’s devastating wildfire.

Stories of Resilience, is a signature program of The Resilience Institute that engages citizens in thematic learning and creative expression to explore themes of healing, change, and resilience in the context of a changing climate.

The Voices from Jasper initiative is presented by Roots for Resilience, a partnership between The Resilience Institute and the Canadian Red Cross.

DO YOU EVEN SCHNERP, BRO?

Summer campsites are hard to come by; it’s the inevitable, mathematical, Rockies camping conundrum. Supply < demand. But thanks to a software-savvy backcountry buff, formerly frustrated campers are finding their happiness again.

Daniel Thareja is a Canmore-based coder. In 2022, he built schnerp.com, a website that helps people find last-minute cancellations on different camping reservation platforms. Thareja created Schnerp (his buddies’ slang for seeking out powder stashes) to book his own backcountry sites, but he soon saw it could be a decent side hustle and has been expanding the app’s reach ever since. He started out watching all of Parks Canada, BC Parks and Alberta Parks campgrounds, but Thareja’s internet trawlers now scan country-wide (except Quebec).

If you didn’t plan your summer camping six months in advance (Parks Canada opened online reservations in January)—or if you simply struck out while waiting in queue—you can still enter in your preferred sites and dates and let Schnerp’s bots do the work. A tiered membership structure allows first-timers to scan up to 10 sites for free; basic and premium plans allow for more requests and faster scans.

“What does reliance mean? For me, it’s about being able to sit with loss and still find hope,” says Jasper poet Paulette BlanchetteDubé

Blanchette-Dubé and nine other participants explore their experiences of the July 2024 wildfire, capturing their journeys through their own evolving narratives, art and photography. Those

insights are relevant not only to Jasper, but to any community navigating similar challenges due to a changing climate, says Brooklyn Rushton, strategic adaptation fellow for The Resilience Institute.

“There is such a huge space for community learning,” Rushton says.

Stories of Resilience—Voices from Jasper debuts at the Jasper Art Gallery (500 Robson St.) on July 25, one year after the Jasper wildfire reshaped both the landscape and the lives of residents. Rushton says it’s a perfect way to engage with the community while giving space for residents to heal.

“Don’t ask your server or tour guide if they lost their home in the fire. Instead, go to the gallery and experience residents’ stories.”

To explore the journeys of other Stories of Resilience communities, visitresilienceinstitute.ca

DANIEL STEWART

BOB COVEY

GARY FINLEY

Ktunaxa Nation Council

Lillian Rose and Trevor Kehoe, editors

I first heard the Ktunaxa creation story soon after moving to Windermere, BC. Afterward, each time I drove past hoodoos I remembered they are the ribs of the monster Yawuʔnik The western slopes of Rocky Mountains— which pinked with evening light through my kitchen window—formed the body of the giant chief animal, Naⱡmuqȼin. Every day, I could see and feel I was in ?amaki?is Ktunaxa, the Ktunaxa homeland.

QAPKIⱠ: KTUNAXA V: TO TELL SOMEONE

EVERYTHING

This book, qapkiⱡ: Ktunaxa v: to tell someone everything, also begins with the Ktunaxa creation story, and it really does tell everything—from land claims and the violence of residential schools to modern Ktunaxa food and fashion. Included are profiles of Elders, youth, communities, land and water guardians, artists and businesses, with the Ktunaxa language woven throughout.

MELTDOWN: THE MAKING AND BREAKING OF A FIELD SCIENTIST

University of Alberta Press

By Sarah Boon

Part science book, part memoir, Meltdown: The Making and Breaking of a Field Scientist tells the story of Sarah Boon’s path as a science student in the late 1990s through the late 2010s, studying glaciology and cold-regions hydrology. It is a story about a

Each story, poem, image and vision statement offers another view and another view until the reader looks through a multi-sided prism, always with the same focal point: the experiences of the Ktunaxa people and the Ktunaxa homeland.