Celebrating 60 years of

Celebrating 60 years of

With an innovative, fresh approach to shape, design and construction, the all-new QST lineup delivers exceptional performance for every skier regardless of terrain or conditions.

THE ULTRA-DURABLE CAMINO® CARRYALL

Ordinary days aren’t measured in miles.

They aren’t improvised at altitude. They don’t begin at first light, lead you above the clouds, and end with dwindling sunlight as you take refuge in the shadows of summits. But then, ordinary days never make great stories.

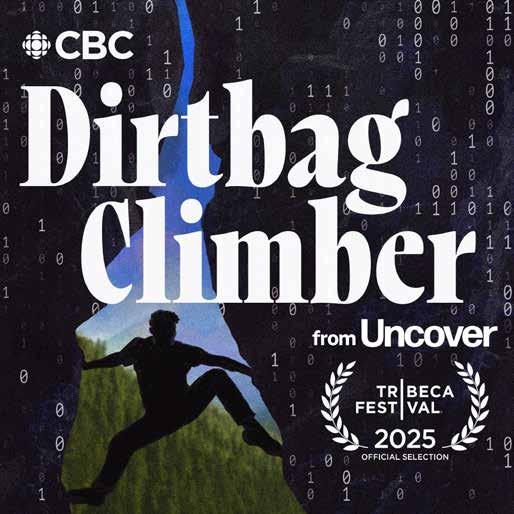

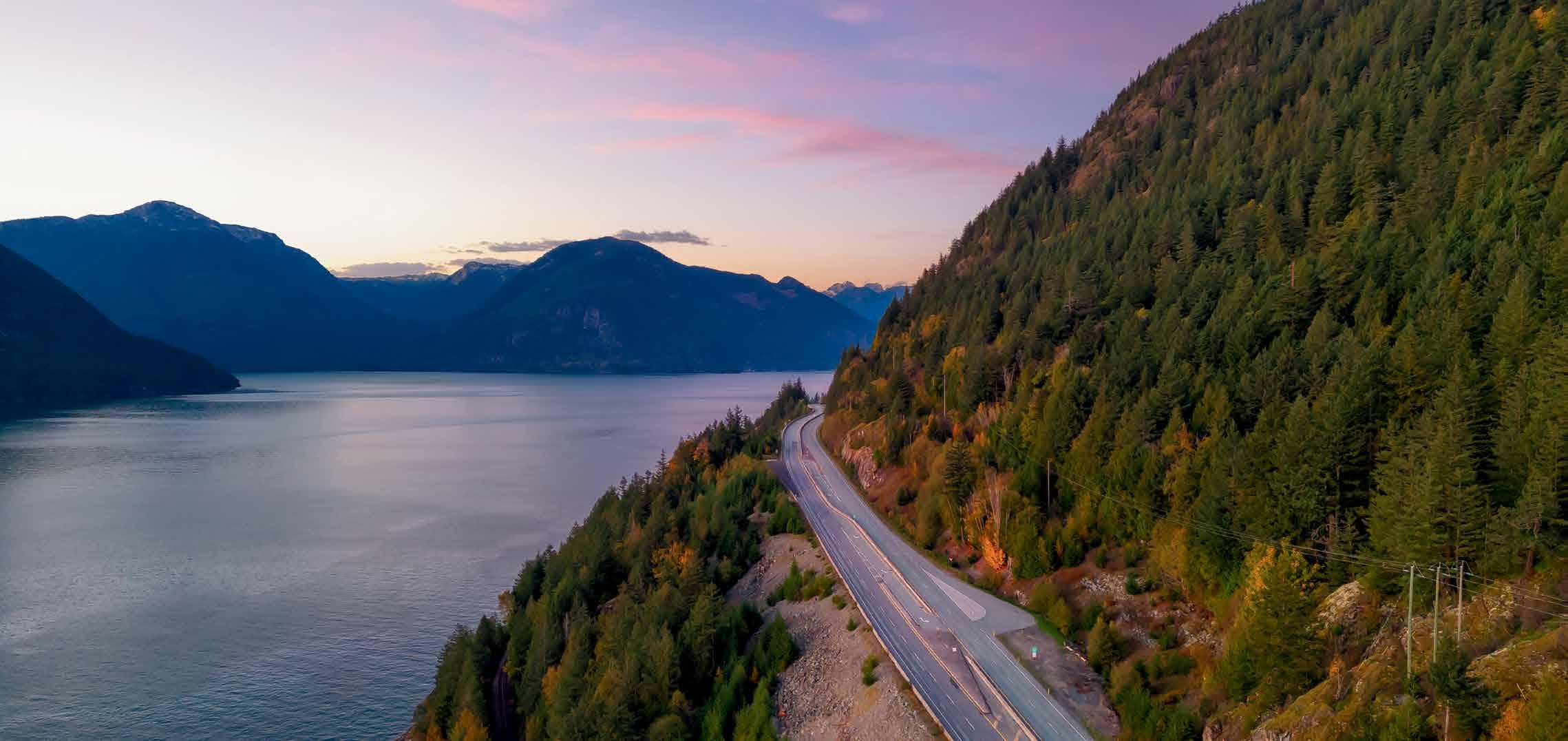

P.24 DIRTBAG CLIMBER A Squamish True-Crime Podcast?!

P.27 CINEMA IN THE SNOW GLOBE 25 Years of the Whistler Film Festival

P.42 BELL TO BELL Chamonix Ski Patrol

P.76 HIDDEN GEMS Apex is Your New Favourite Hill DEPARTMENTS

P.16 BACKYARD Home Turf

P.55 EPIC TRIP Beneath the Tide

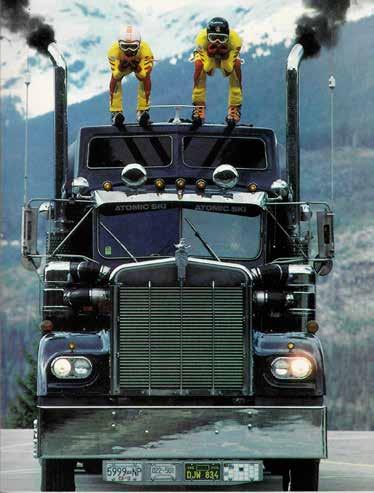

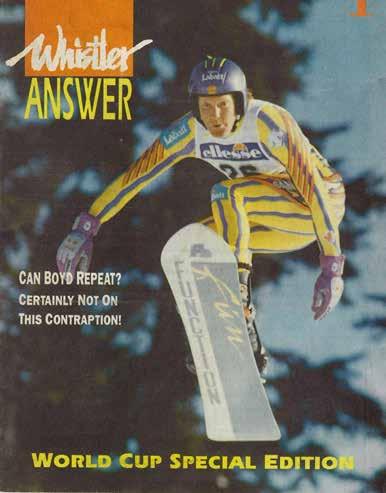

P.87 MOUNTAIN LIFERS Westside Story

P.96 GALLERY Capture Winter

Mountain Life Coast Mountains operates within and shares stories primarily set upon the unceded territories of two distinct Nations—the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and the Lilwat7úl. We honour and celebrate their history, land, culture and language.

PUBLISHERS

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Feet Banks feetbanks@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER

Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

MANAGING EDITOR

Kristin Schnelten kristin@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL

Noémie-Capucine Quessy noemie@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Colin Adair, Jorge Alvarez, Steve Andrews, Leslie Anthony, Jarrod Au, Jessy Braidwood, Chris Bowers, Olly Bowman, Mary-Jane Castor, Chris Christie, Ollie Dickerson, Oskar Enander, Ben Girardi, Robert Greso, Mark Gribbon, Grant Gunderson, Brian Hockenstein, Erin Hogue, Lani Imre, Alex Joel, Blake Jorgenson, Reuben Krabbe, Cédric Landry, Stu MacKay-Smith, Jimmy Martinello, Mason Mashon, David McColm, Oisin McHugh, Paul Morrison, Robin O’Neill, Celeste Pomerantz, Spencer Seabrooke, Steve Shannon, Andrew Strain, Anatole Tuzlak.

SALES & MARKETING

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2025. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703. Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email feet@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Coast Mountains is published every February, June and November and circulated throughout Whistler and the Sea to Sky corridor from Pemberton to Vancouver. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please call 604 815 1900.

Mountain Life is printed on paper that is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is an international, membership-based, non-profit organization that supports environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests. Mountain Life is PrintReleaf certified. It measures paper consumption over time automatically reforested at planting sites in Canada.

“It goes beyond the turn,” skier Marcus Caston tells me in this issue. “You have the turn and then you have the transition—floating between turns—that is where the real magic happens.”

That floating sensation, that’s kinda what it’s all about, isn’t it? That’s what we’re after: a brief moment of weightlessness—dancing with gravity, defying it while also completely under its pull. The physics. The dynamic relationship of centripetal force and balance, of where you are and where you want to be. The feeling of finding that edge, then pushing beyond it…and onto the next one.

The next one…Kinda like winters. Each is amazing but, particularly this time of year, it’s the one coming up that matters. The optimism of what could possibly come, an excitement for the future: “Bro, I heard it’s gonna be a huge winter…”

The immediate future, at least. Because, long term, things aren’t looking that shit-hot. But the more the gravity of our situation (personal, global, environmental, whatever) tries to pull us into a vortex of frustration, fear, anger and disconnection, the more important it is to lean the other way, sink an edge and give in to that brief time-warp moment where intent and momentum detach you from the inevitable and shift you in a new direction and a tiny, unexplored future. That turn. And the next one. That lap, and the one after that. It’s freedom.

So here’s to the winter to come, which is also the one we’re in right now. The future is upon us. Turn & Burn.

The risk, with this mag or anything else, is that we’ll become too unrelatable. Perfect pow shots, sled-accessed summits, fancy flights to the French Alps, Kyrgyzstan treks or cruises to Antarctica.

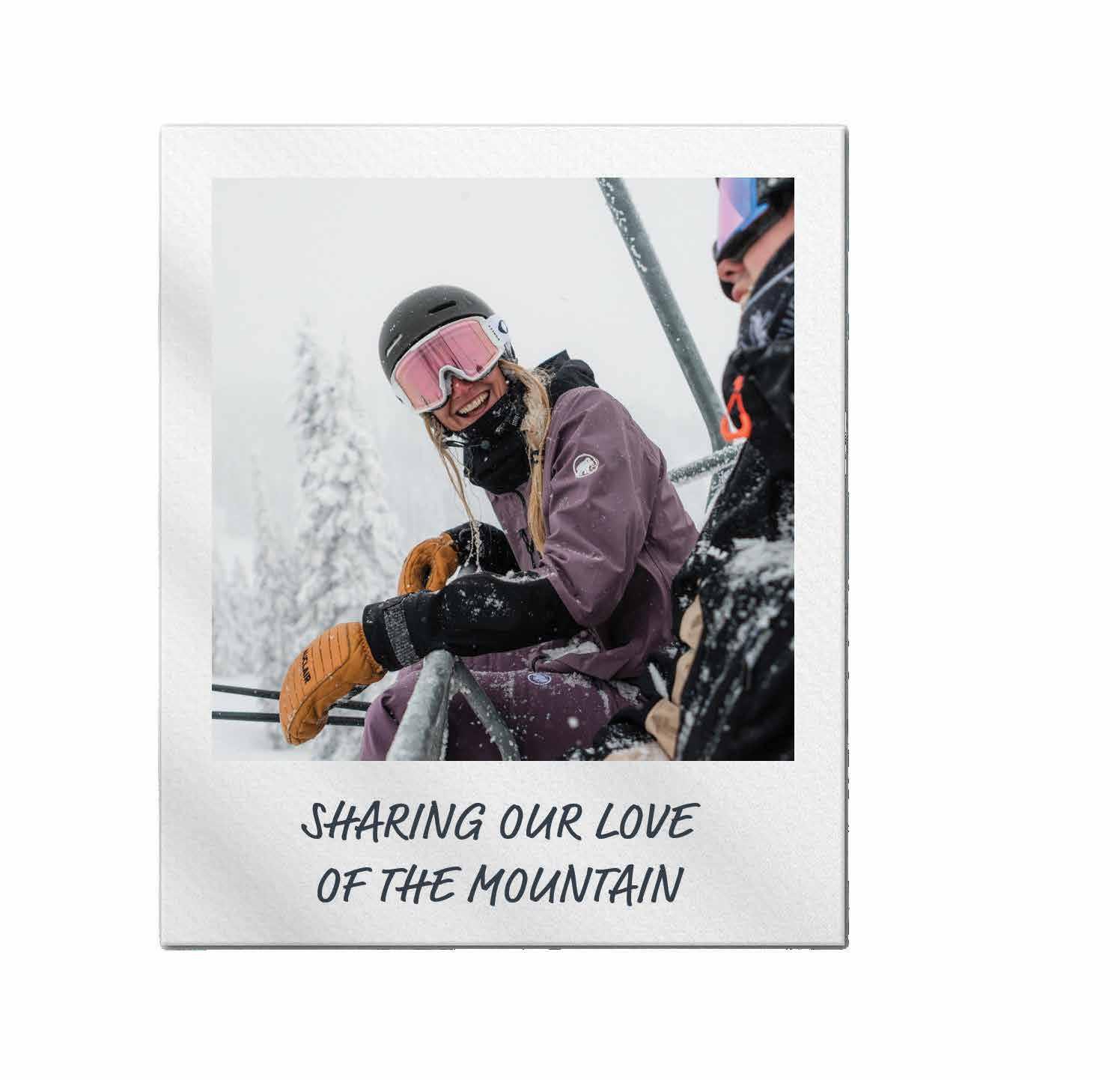

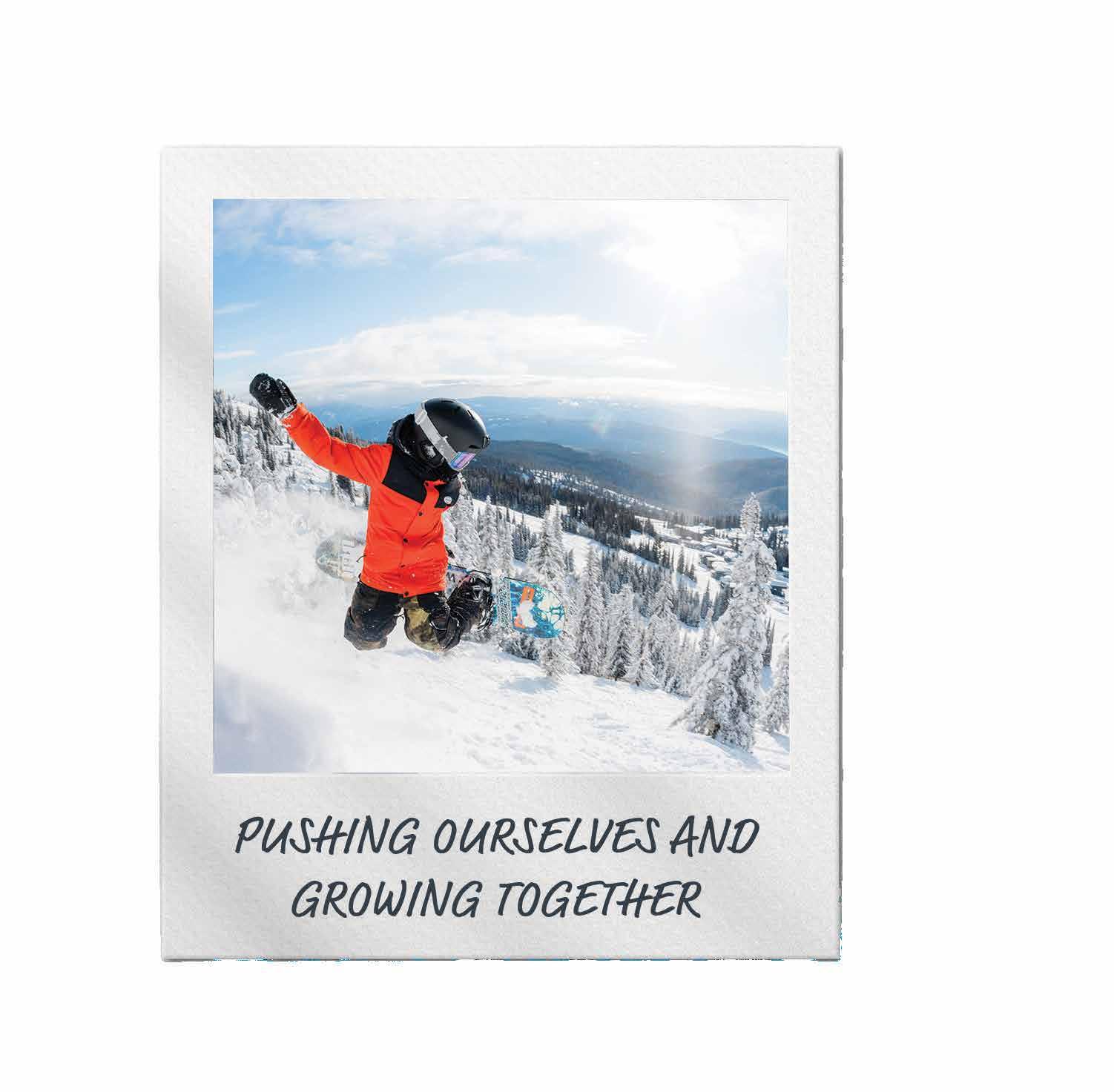

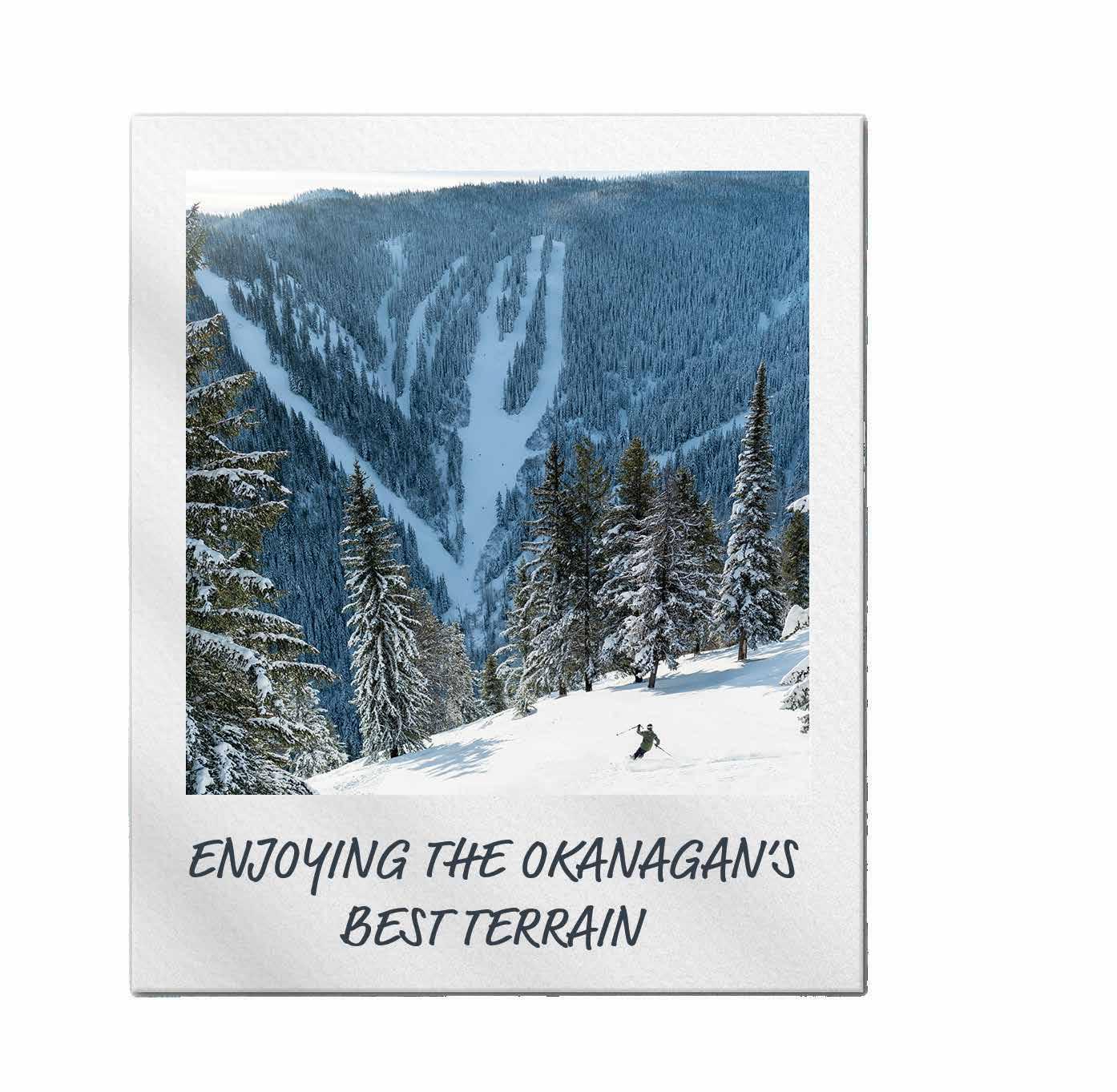

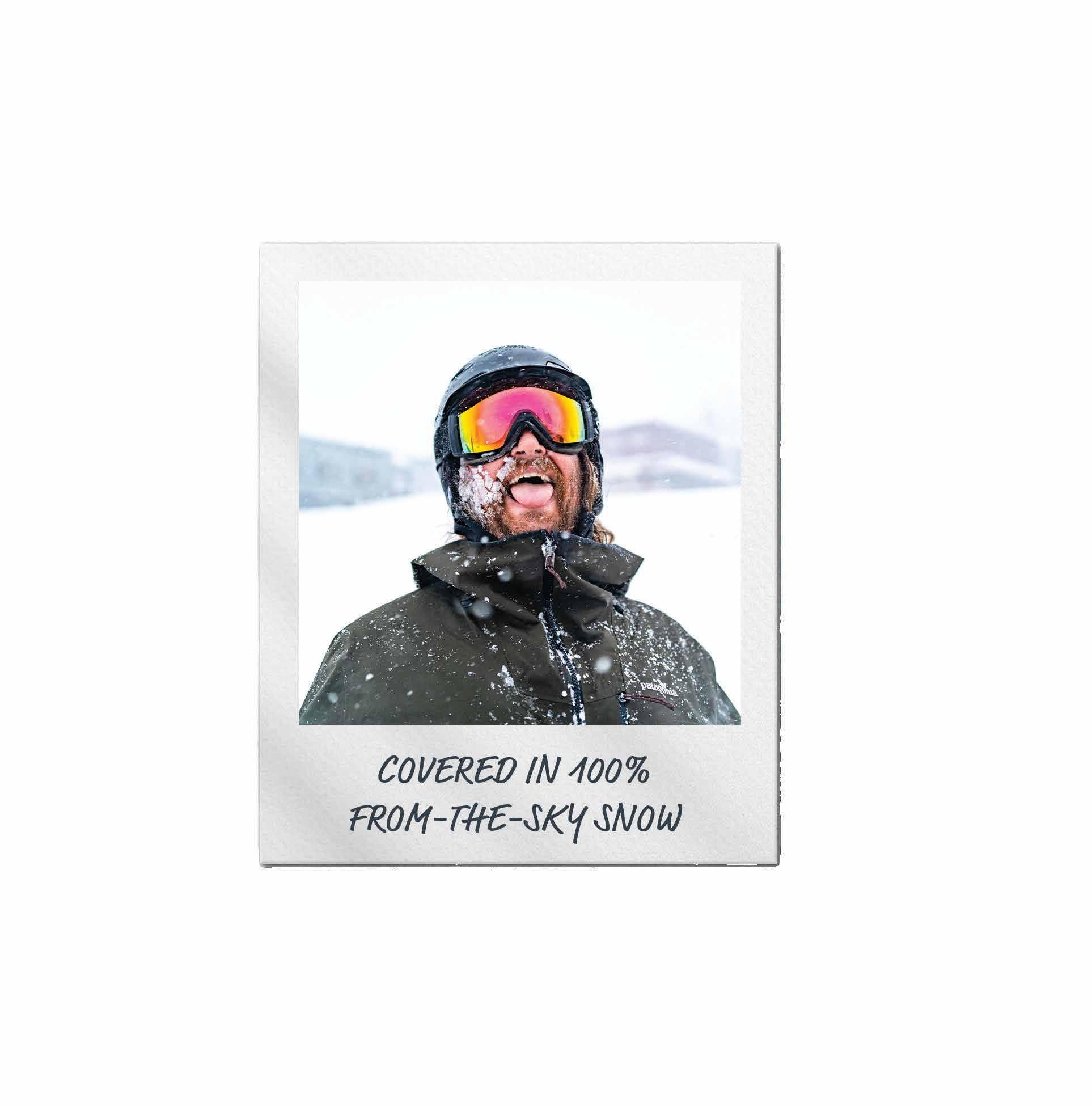

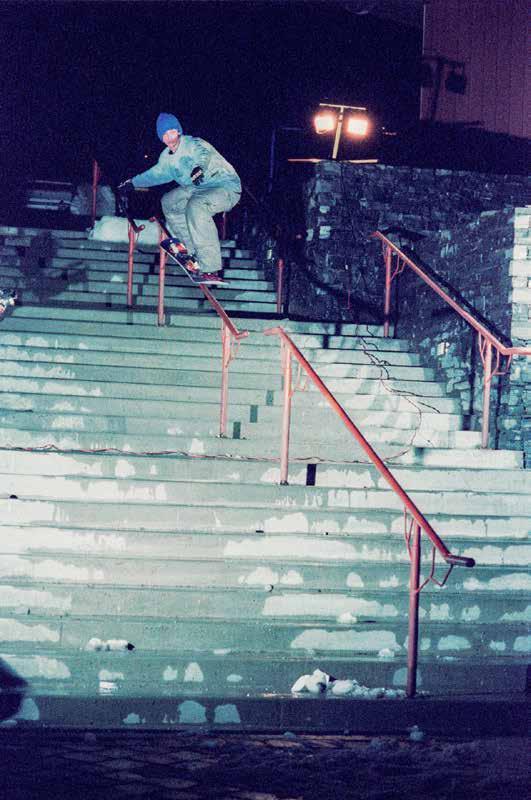

It’s rad, but for most of us it’s kinda unreachable. Shredding the ski hill though, anyone can get into that. “It’s easy,” says local photographer Ben Girardi. “Hop on the lift, meet some friends and go.”

Ben made it up Whistler Blackcomb about 50 times last winter. Even the days he’s shredding with his family, he always has some kind of camera at the ready. “If you are looking for fresh pow with no other people around it can be tricky,” he admits, “but I like how that forces you not to care, or to get creative. You can shoot a lot and hone your skills.”

Or you can just go for a rip. For much of his young life, Whistler icon Sean Pettit was one of the most celebrated skiers in the world, known for big tricks on gnarly lines, drops and booters in the backcountry. Then he pivoted to mainly snowboarding, on the ski hill, and having all-day fun. “Riding the chairlift is unmatched,” Sean says. “You can’t get that much riding done in a day without a chairlift. Fresh pow is overhyped; you’ll be a better rider if you ride tracked-out bumpy runs all day. If the snow is soft, I’ll snowboard. If it’s icy, hardpacked, or I want to hike and get on something steep, I’ll ski. That’s the best tool for those conditions. You don’t hammer a nail with a screwdriver.”

And with that mentality, you can always hammer a full day of good laps on the ski hill with your crew. So here are a couple of our favourite inbounds, on-mountain, “shred with my friends” photos to help all of us get amped for the upcoming season. Giv’r!! –Feet Banks

Construction

Construction

Construction

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com 604-366-8116

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com 604-366-8116

Construction

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com 604-366-8116

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com 604-366-8116

Hard to believe, but some climate-change news can be uplifting, hopeful—even tasty. Such is the collaboration between Squamishbased Backcountry Brewing and the estate of celebrated Whistler artist Chili Thom, a collaboration that brings together craft-brew industry sponsors and a loyal, beer-forward community to raise funds for Protect Our Winters (POW) Canada—an environmental charity advocating for policy solutions to climate change.

“Chili lived and breathed the outdoors, as is obvious in his art,” says close friend and business manager Nora Clarke. “And POW is something he would have thrown his entire weight behind, so it felt like a natural pairing.”

Ben Reeder, marketing director at Backcountry Brewing agrees: “As we continue to see wilder weather, it makes sense to raise funds in Chili’s name for a charity fighting to protect the natural environment.”

It’s a fight Chili was always up for. Back in October of 2012—when raising your voice against reckless resource exploitation was still cool—dozens of Sea to Sky folk attended a massive protest in Victoria against Enbridge’s proposed Northern Gateway pipeline to BC’s North Coast. The group’s bus rocked with creative signs, costumes and the energy of commitment. Thom,

whose personal credo—”Your experience in nature depends on how you choose to position yourself within it”—led the charge, amped by an expedition that year to the Great Bear Rainforest with some 50 other Canadian artists looking to give visual voice to BC’s fragile coast. The “Art for an OilFree Coast” experience further opened his eyes to the deep harm we were doing the planet. “Nature has given me a lifetime of inspiration,” he offered in an interview. “But there comes a point where you have to look inside and ask, What am I willing to sacrifice [for it]?”

A few hours of protest didn’t seem like much, but four more years of staunch opposition from British Columbians actually worked: On November 28, 2016, the feds killed the ill-advised pipeline and enacted a tanker ban on BC’s North Coast—a victory that buoyed Thom’s journey to the other side when, two days later, he surrendered to a battle with cancer.

On the heels of that loss, Backcountry started an annual tradition of launching a beer featuring Thom’s art on the can to raise money for cancer research. In 2023, the partnership with POW was established, “driven by a shared commitment to building POW’s momentum in the Sea to Sky region to support educational and advocacy efforts in the fight against climate change,” says Arianne Dufour, director of development and partnership for POW Canada, which boasts

more than 40,500 members. To date, the collaboration has raised more than $24,000.

“Backcountry isn’t going to stop climate change,” Ben says, “so our goal is to help an organization with potential impact like POW increase membership to have more power to lobby government.”

POW membership is free and the Backcountry collab makes signing up easy. Each year, both the formula for Protect Our Winters Pale Ale (PA) and the artwork it comes in gets a reboot. This year’s PA is a hazy version with artwork titled “Green Burst”—a bit of a graphic departure for Thom that still features his snowy and beloved “Chili trees.” A dollar from each fourpack, $.50 from each tasting-room sleeve and $50 per keg is donated to POW—along with money raised from the sale of Thom art prints and label stickers. There’s also a launch party to look forward to—beer, tunes, dancing… and more beer.

“The collaboration [with Backcountry] has always felt unique and fun, as it pulls from so many different things we feel would be important and meaningful to Chili,” Nora says. “He was always stoked on supporting a local business, and the energy Ben and his crew bring to marketing their beer is so fun, chaotic and weird, it would have been right up Chili’s alley!” – Leslie Anthony

Find out where to buy the Chili/POW beer in your area at backcountrybrewing.com

CBC drops a new true-crime podcast with Squamish roots

When Steven Chua moved from Montreal to Squamish in 2017 to take a reporting job at the local paper, he looked forward to a mellow, small-town gig in a beautiful natural environment, maybe get into rock climbing or biking or something.

What he wasn’t expecting, three months into the gig, was a murder, a mystery and an eight-year investigation that would bring him into a world of neo-Nazis, online scams and buried gold.

“The crime stories I covered when I arrived were stuff like kids skateboarding or fireworks and graffiti,” Chua says. And then, on the road to Cat Lake, a burned-out SUV containing a body. A body with a bullet hole in it. A murder.

“That jolted me,” Chua says. “Like, whoa…stuff really happens here.”

The body belonged to a somewhat mysterious local climber who went by the name of Jesse James, but almost nothing else was known. Who was Jesse James? Who killed him? And why?

The answers, some of them, took years to arrive. Others remain a mystery. In 2020, the RCMP released a statement no one expected: DNA evidence had revealed that Squamish climber/van-lifer Jesse James was actually Britt Greenbaum, an American fugitive with a long history of aliases and a dark past, including a stint as the head of an online white-supremacist organization (albeit short-lived, after his Jewish ancestry was publicized).

“This guy had a well-documented life and did all kinds of crazy things,” Chua says. “Nazis, bitcoin, buried gold, multiple fake names… one reveal after another. I couldn’t believe it was real.”

International media flocked to town but Chua, by then an avid climber with real local contacts, got the scoop and his reporting quickly caught the interest of numerous true crime podcast producers. In September 2025, the CBC released Dirtbag Climber, a

five-episode true crime podcast hosted by Steven as he dives into one of the wildest mysteries in Sea to Sky history.

“It was a process,” Chua says of turning his investigative print stories into a full-on audio feature. “Audio and video take so much longer. There are so many logistics around getting good tapes that can bring you into the moment. We had an amazing production team working really hard. With print journalism, it’s so nimble. A single reporter with a cell phone can get a story.”

On the road to Cat Lake, a burned-out SUV containing a body. A body with a bullet hole in it.

A murder. The body belonged to a somewhat mysterious local climber who went by the name of Jesse James, but almost nothing else was known.

Eight years after he covered the biggest news event of his young career, Steven Chua is still climbing rocks, returning to Squamish often from his new home in the lower mainland. With the release of Dirtbag Climber, he says he’s not sure what the future holds: “On to the next adventure, I guess. One thing I’ve realized is you can never predict how things are going to go.” –Feet Banks

Featured at the 2025 Tribeca Festival in New York, Dirtbag Climber is available anywhere you get your pods or on the CBC True Crime YouTube account.

In the mountains, not much good ever comes from peaking early. Because—in this theater of knife ridges and wind-packed cornices, where route finding, instinct, intention and awareness of self and surroundings can separate life and death—experience matters.

Which is exactly how Angela Heck feels about the Whistler Film Festival (WFF), which this winter celebrates a quarter century of bringing cinematic joy—and stars—to Whistler’s silver screens.

“I think a film festival takes a while to hit its stride,” Angela says. “But Whistler is friendly, people want to come here, and we hear again and again that this is a great festival for filmmakers. That’s something worth building on.”

With a consistent focus on Canadian film, the festival found an early champion in George Strombolopolous, one of the country’s most respected arts and culture journalists and media personalities. Strombo, as he’s known, has attended almost every year since 2005, when he set up his CBC talk show The Hour in the Garibaldi Lift Company during the festival and the vibe of it all made a real impact.

“It wasn’t slick or overproduced,” George says. “It was a real, vibrant and rugged mountain experience, and I made a lot of really

good friends. Whistler and this festival have that rare energy: a mix of creativity, chaos and mountain air that’s hard to find anywhere else.”

A top Hollywood trade publication, Variety magazine, was another early fan. A partnership established in 2011 brought industry visibility and street cred to the fest and helped usher it into a new era.

Which isn’t to say the WFF doesn’t understand where it is.

Back in 2001, when local tour-de-force founders Shauna Hardy and Kasi Lubin screened the very first WFF opening movie, they chose the now-classic locally filmed John Zaritsky documentary Ski Bums. Twenty-five years later, mountain culture and films remain an important part of the festival, with local filmmakers like Mike Douglas and Darcy Hennessey finding early success here.

“The mountain culture program speaks to the Whistler audience and who we are as a community and a festival,” says Angela Heck, WFF executive director. “We lost the Village 8 theatres this year, which limits our screening opportunities, but we’ve made sure to preserve this program as well as the short films program. All in all, this year will see the same number of films as prior years, but some won’t have second showings.”

Taking the reins from festival co-founder Shawna Hardy in 2021, Angela says this year the festival is building on previous drives to empower more Canadian and women-driven films, and this year the festival is leaning into accessibility for the disabled and deaf community—both on-screen and at the fest itself.

“Last year we had some deaf filmmakers,” she says. “We had ASL [American Sign Language] translators here. This year we are partnering with Whistler Adaptive Sports on the premier of Forward, a mountain culture film we think the Whistler audience will love (see page 30).”

New ideas, old friends and the efforts of a huge number of

festival volunteers have enabled the WFF to evolve sustainably and create its own identity in a crowded film festival industry.

“It’s unpretentious, creative and real,” Strombo says, adding that Whistler is also the perfect expression of being, “Canadian, independent and proudly unconventional.”

All this and only 25 years young. “The Toronto Film Fest just had its 50th year,” Angela says. “Cannes is 78. Whistler can be proud of where this festival is right now.” – MJ Castor

The Whistler Film Festival runs December 3 to 7, 2025. whistlerfilmfestival.com

Rob: 604-935-9172

Sherry: 604-902-7220

E: BoydTeam@evrealestate.com

W: BoydTeam.evrealestate.com

Engel & Völkers Whistler 36-4314 Main St. Whistler, BC

“It was funny,” says Clayton March. “I was in my wetsuit, all ready to go and we were rolling my chair down to the beach. This guy came up with a real concerned look.”

“Are you guys okay?” the fellow asked Clay and his brother Tanner. “The trail is a bit steep ahead.”

You should see some of the waves we’re gonna ride, Clay thought to himself. The slope of the trail is the last thing to be concerned about.

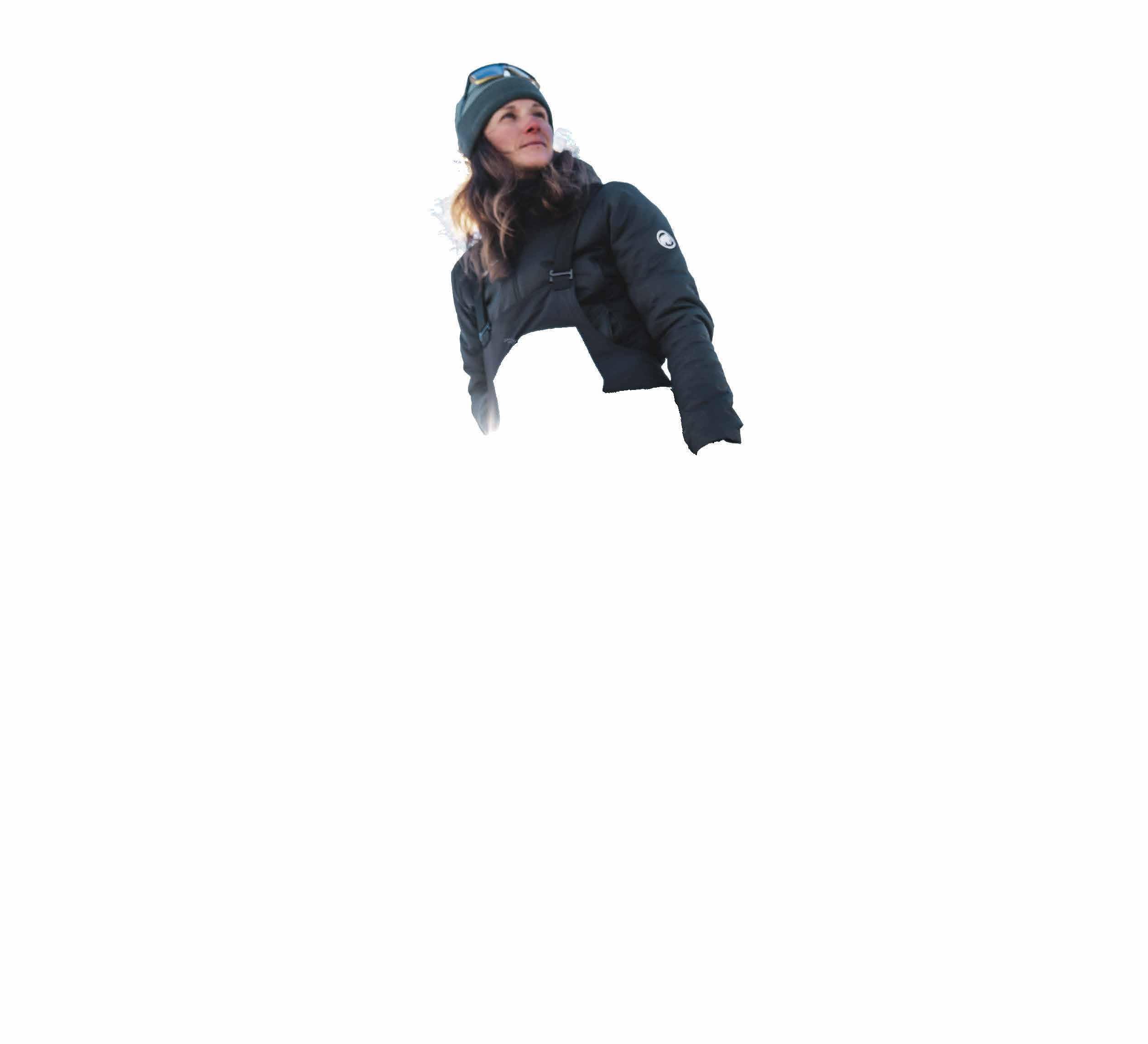

But this is the life of an adaptive surfer. Clay was born with cerebral palsy, the first to arrive of three triplets. With limited mobility, his journey to becoming a surfer and skier relied heavily on his brother Tanner. The duo recently finished filming Forward, a feature documentary exploring the limits of what’s possible and a reminder that everyone belongs in the (sometimes extreme) environments many of us take for granted.

“We started surfing together six years ago,” Tanner says. “My dad used to strap a chair to his windsurf board when we were kids and take Clay windsurfing. Every summer our family goes to Tofino so I just started bringing Clay out, starting in the whitewash and eventually we got out back. But every time we went out, a crowd would gather on the beach to talk to us when we came in: Why are we doing this? How? Some people would get pretty emotional. That gave me the idea that there might be a perception that needs to be changed.”

“My dad used to strap a chair to his windsurf board when we were kids and take Clay windsurfing.“

Tanner ran the idea past an old friend, filmmaker Nic Collar, who came to the next family Tofino trip and shot some proof of concept footage. “Nic and Clay and I talked about it,” Tanner says, “and decided why stop at surfing? Let’s get more people involved and check another dream off the list and get Clay out cat skiing.”

Clay had a bit of experience riding in a sit ski with his family on their home ski hill in the Okanagan, but he’d never skied with Tanner at the helm and had little to no experience in powder. Producer Ryan Scott came to the project with the idea to include adaptive athletes at the top of their game, so after a few training sessions (including a rip around Whistler Mountain with Whistler Adaptive Sports and local sit ski slayer Alex Cairns), Clay, Tanner and crew found themselves at Skeena Cat Skiing with Paralympic alpine skier (and badass snowmobiler/freeskier) Mac Marcoux.

“He is crazy,” Clay says of Mac, who became legally blind in 2007 and has since won five world championships and six Paralympic medals for visually impaired skiing. “Watching him ski, especially in

the film,” Clay adds, “the lines he takes…I wouldn’t ski that stuff even with full vision.”

Also featuring professional adaptive surfers Victoria Feige and Kai Colless, one of the goals of Forward was to showcase what can be achieved with resilience, inclusion and the power of community. “This is a celebration of adaptive sport,” Nic says. “So why not showcase what is possible at the beginning of that journey and at the highest end as well.”

“It was so cool to meet and learn from Victoria and Kai,” Tanner says. “Just to see the lives they have been able to live through sport.”

Although, as the film outlines, not everyone is willing to give adaptive athletes a chance. “We tried to do an avalanche course,” Clay says. “The instructor was really gung ho for it, but the insurance company was not.”

Apparently, the insurance company for the guiding company offering the avy course required all participants be capable of standing in the snow for at least four straight hours.

“That’s the hardest part,” Clay says, “overcoming peoples’ perceptions of what is possible and not possible.”

At Skeena Cat Skiing, just outside of Smithers, BC, the Forward team found a willing crew with open minds, everyone ready to help. “When Tanner pitched the idea, their response was, ‘How can we make it happen?’” Clay says. “They were so good adapting to whatever we needed. At the end of each run the cat driver would build a ramp to make it easier for us to get the chair back in the cat.”

With no shortage of powder in the Skeena terrain, Tanner says it took a few days to get Clay’s equipment dialled in and for him to learn how to navigate deep pow with a sit ski. Safety was the top priority.

“We went into it worried about Clay being submerged,” he says. “And that happened on the first run. I got dragged down and the chair was stuck above me. I was dangling by one arm, useless. Luckily we had a guide right there to dig out Clay’s face. Then we ate shit all day on day two, so we made some changes—shifted Clay’s weight way back and started to make progress.”

In a sport so hung up on powder and face shots, Clay—sitting just a few feet off the ski—enjoyed a complete whiteout for the entirety of every run. “It was fun,” he says. “I think it speaks to the trust I have for my brother and our team. Going down the slope, I couldn’t see anything. But I knew he’d have my back. I loved it.”

“I have never heard him say, ‘Stop,’” Tanner says. “He always wants to go faster.”

“I think,” Clay says, “the best is yet to come.”

Forward is competing as part of the Mountain Culture program at the 2025 Whistler Film Festival.

words :: MJ Castor

photography :: Cédric Landry

In the late 1990s, top Whistler snowboarders (and a very select few skiers) started exploring the Sea to Sky corridor on snowmobiles because, as they saw it, the ski hills were getting too busy.

The best historical document of that era is Treetop Films’ Clearcut, filmed in the all-time snow-hammered winter of 1998–99. Realizing what was possible via snowmobile access, a new culture exploded.

A quarter century later, the local sled-access shred scene is established—maybe a bit too established. Certainly, there is always good fun to be found by going further and deeper but, for the classic zones, one could even say sledland is getting too busy.

The solution? Go north.

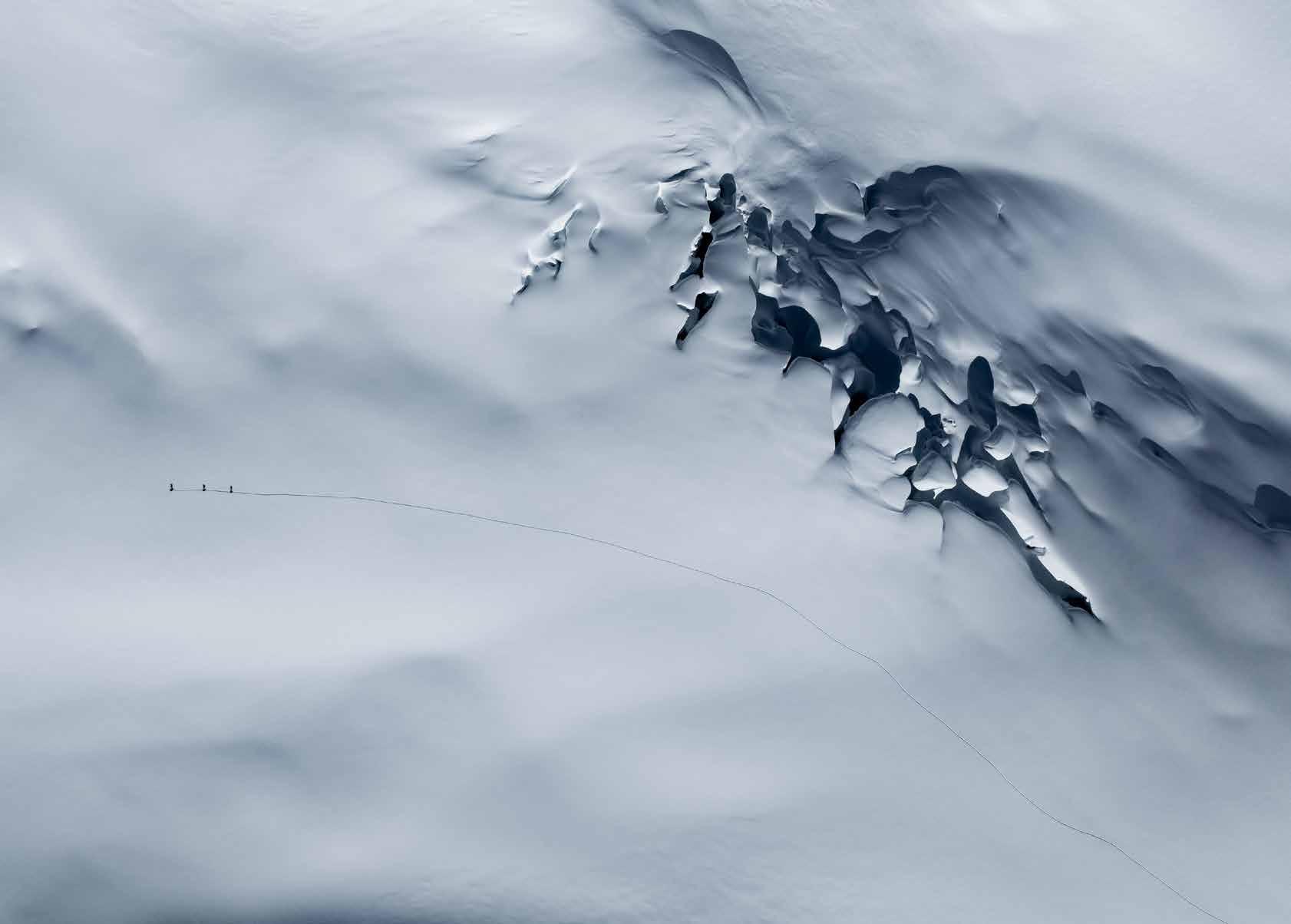

“I like seeing new things,” says Joel Loverin. “Anything new is amazing, anything different.” After more than two decades snowboarding in Whistler, Joel is accustomed to getting up early, snowmobiling in the dark and hiking for hours to access some the region’s big peaks and burly lines. “And getting away from the hungry sled skiers down here is nice, too. The ability of sledders in the Sea to Sky is pretty high—people can get into a lot of places they never used to.”

So he drove north to connect with photographers Cedric Landry and Cam Unger (an old roommate and shred buddy) who have both migrated to Terrace in recent years. “We found a zone a few years ago and did this crazy climb up a glacier,” Joel says. “That just opened up a huge new area—as far as you could see—but weather was coming and we couldn’t stay. We had to go back for another look.”

“The access is pretty gnarly. Everything is huge in there. Looks chill until you sled up to it, then it’s, Whoa…” – Joel Loverin

50 YEARS OF

“We’d get up super early and go as far as we could to get to these peaks, only to realize none of them get any sun at all that time of year. But that’s why we are there, scoping. We’ll go back and know when and where the light will be good. That always works for me—having an idea of a place, having been there and having photos of the lines I can study.”

“Camping by the highway is too loud so we found a spot not too far off. We had this arctic tent with a woodstove in it, but when the fire went out it got cold. Really cold. It’s pretty high elevation and the sun comes up way later. Getting up for early light we were so bundled—puffy pants, puffy jackets, heated socks…still frozen.”

“We did the longest runs ever. Big, long tandem punches up ridges—huge punches and some of the longest tandems we’ve ever done. And then crazy runs. One run was a minute and 51 seconds of full-tilt ripping.”

“We saw a few heli-ski tracks but not one sled track. I’m not sure sledders have ever been in there. We saw one sledder once, from the top of a peak, waaaaay in the distance. That’s why we came here—that and perfect coastal snow. We went to all the sickest places we want to ride and now we’re juiced up to come back and shred.”

Get out of the way, you tossers!”

We’re in Chamonix, the undisputed mecca of big, burly, preconceptionshattering ski mountaineering. It’s our second day in-country. Clear skies, fresh snow, perfect. Except not quite.

“Get off the run!”

English people keep yelling at me. Actually, they’re yelling at all three of us—me, snowboarder Eric Greene and Rich Stoner, our new buddy from New Jersey who runs a media empire dedicated entirely to après ski. We’re not doing anything. The ski run is easily 40 feet wide. Better call it 13.72 metres, because Europe. We are just stopped and waiting for the rest of our Helly Hansen crew.

“Move off!”

Chamonix is the beating heart of extreme ski and shred freedom, a place where the sports are pushed further than perhaps anywhere else on the planet, but that’s beyond the resort ropes. Here, on-

piste, at Balme, one of three main ski resorts in the valley, the local tradition (or maybe it’s just the English tourists’ tradition) seems to be that anyone stopping on a ski run ought to do so on the side, very much on the very edge of the side, regardless of how much room other skiers have to go around.

Instead of moving over, we just start skiing again, but local customs are a funny thing. Mountain staff in Chamonix will holler like heck and even shut down the chairlift if you don’t lower the safety bar immediately after boarding the chair, like one second after. Meanwhile, local skiers skin and bootpack up steep, stunning (and non-avalanchecontrolled) chutes just a few hundred meters away and no one bats an eyelid.

“Remember what the van driver told us,” Seb Ramsay, a UK journalist and total ripper, chuckles at my ignorance and disbelief of the local customs. “If it makes sense, it’s not French.”

But that was day two, a free day (thanks to the “ski free” voucher that came with my brand-spanking-new Helly Hansen outerwear) with no agenda other than to shred Balme, try not to get yelled at and maybe drink the odd personal-size bottle of Jägermeister with Erik Meusburger, a retired Norwegian ski racer turned Helly product manager. “They sell these in every café right by the cash till,” he points out, handing me a tiny bottle, “so they must want us to drink them.”

I also discover that, when they’re not yelling at people, the average European tourist over here seems utterly unmotivated to leave the groomed, marked on-piste runs. So, after checking the snowpack and feeling good, our crew spends the afternoon blissfully lapping sunny powdery glades. Fresh turns all day, and if we’d skied past the lift and into the valley, we’d have ended up in Switzerland.

Chamonix, what a place.

with Marcus Caston

No stranger to Europe, extended ski trips or packing the right gear to shred hard, Helly Hansen team member Marcus Caston offers these tips for anyone heading out for a rip in the old country.

BRING YOUR OWN SKIS.

Don’t roll the dice on rental boards, especially from your hotel. Chances are they’re all-mountain carvers for Euro tourists who want to stay on-piste.

HIRE A GUIDE.

They find the good snow, it’s safer and it's more fun. It’s worth the cash to have a really great experience.

ROLLER DUFFEL BAGS AND SKI BAGS. Wheels on your gear make life easier getting your stuff around train stations and busses.

ENJOY THE ENTIRE EXPERIENCE.

Stop for lunch, eat the food, try the wine, go to new places for après. There’s more to life, and Chamonix, than just skiing all day. Do it all.

In the beginning, the little village at the base of Mount Blanc was only a big deal for summer visitors, with a mountain guiding company established as early as 1821. Things changed, they say, in 1893 when a Norwegian showed up with a pair of wooden skis and inspired a few locals to hand-carve some of their own. Originally using skis as a means of winter travel to visit patients throughout the valley, Dr. Michel

coincided with the completion of the first section of the Aiguille du Midi cable car. Mont Blanc, the Haute, the Aiguille du Midi—for any contemporary skier, even one who rarely leaves the BC Coast mountains, these names are canonical and the mountains of Chamonix are spoken of with a mix of awe and reverence. Every serious ski mountaineer, pro shredder or mountain guide worth his or her salt has made the

“If it makes sense, it’s not French.”

Payot is considered the first true skier of the region. In 1903 he was part of the team of skiers that linked Chamonix, France, to Zermatt, Switzerland, on a high-alpine traverse that later became known as the Haute Route, probably the most famous alpine ski route in the world.

In 1929 the valley played host to the inaugural Winter Olympic Games, which

pilgrimage to this valley of ultimate serosity. Chamonix-Mont-Blanc is the mecca of big mountain culture and sport.

I can see why. “Imagine taking the Tantalus Range,” I texted to my friends back home, “and lining it up beside Mount Currie, Wedge, Whistler Blackcomb and Atwell. Now make everything 25 to 30 per cent higher… That’s one side of the valley.”

Come home to Pemberton! Born and raised in Pemberton Valley, I am the fourth generation of my family to call this beautiful valley home and this li le slice of paradise has my heart. I know the valley and the people, I truly enjoy sharing my love of Pemberton with others and helping them to find the perfect proper to call home. As a licensed Realtor® with over 20 years of experience, I have the skills, background and knowledge to guide you through the process with confidence.

Let’s connect!

www.realestatepemberton.com

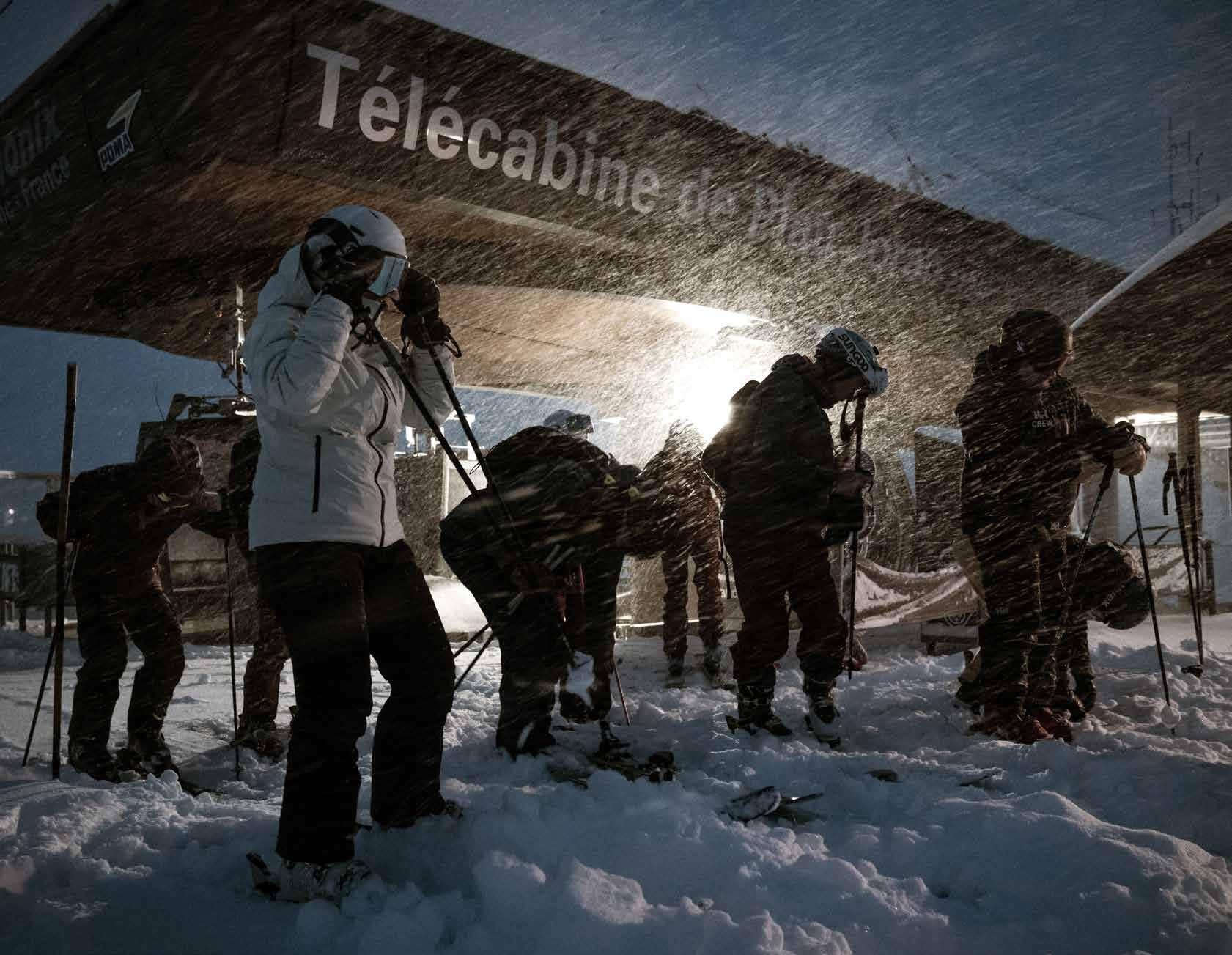

Day one started in the dark. And in the rain. 06:30 at the base of Les Grands Montets, one of the larger, steeper Cham resorts. Our job was simple: tag along with the Grands Montets ski patrol from bell to bell—open the resort, close the resort—and report on it. The subtext of the story being that if the Chamonix ski patrol—some of the best on the planet in the epicentre of ski mountaineering culture and terrain—trust and choose Helly Hansen gear day in and day out, it’s probably more than good enough for you and me.

Besides, standing in the rain in the dark in centre of the skiing universe is a pretty good way to field test your outerwear. Helly Hansen has been working on an inherently waterproof, forever-chemical-free LIFA Infinity Pro fabric for the past few years, and it seems like they figured it out to me.

“That’s one of the things I like,” explains Marcus Caston, a Helly team skier since 2012. “I pick an outfit I like and stick with it through the entire winter—sunny, rainy, hot, cold, après, whatever. I don’t want six jackets in my bag. I want versatile gear that works.”

With so much wide-open terrain, patrollers here will perform avy control in and above the most skiable areas, then set poles to indicate runs considered safe and on-piste.

Now, by definition, blatantly stating the subtext of a story may be journalistically irresponsible (but so is going on companyprovided trips). Let the record show, however: I’ve never been one to follow the rules (and only a fool says no to a trip to Chamonix).

Our ski patrol escort, Laurent Langoisseur, arrives and whisks our dozen-strong crew into the Plan Joran gondola. Halfway up the rain turns to snow, but it’s still pitch black. The early bird doesn’t get the worm in Chamonix, it gets to go up the mountain first.

With about 70 full-time professionals across all resorts in the valley, Chamonix patrol responds to about 1,000 calls a year, with Grands Montets seeing about 350 to 400 of those. “Some are sprained wrists or knees,” Laurent explains. “Some are rescues. If we can access people who go off-piste we will, but if we need skins or anything we call mountain rescue.” Aka Peloton de Gendarmerie de Montagne, a fully funded local search and rescue service operated as a branch of the French military.

For North American shredders used to resorts like Whistler Blackcomb, the European concept of on-piste/off-piste may need some explaining (and I’m not even sure I understand it fully). Famous for its offpiste offerings, Les Grands Montets covers more than 1,800 hectares, most of it above treeline, and the resort tops out at 3,275 meters/10,745 feet. With so much wideopen terrain, patrollers here will perform avy control in and above the most skiable areas, then set poles to indicate runs considered safe and on-piste. Everything a foot or so beyond those bamboo markers however— you’re on your own.

Our first run is on-piste, a wide groomer with 12 to 15 cm (4 to 5 inches) of fresh snow. Ideal, except it’s still dark. Like really dark. “Just go straight for a few hundred metres and you will see the lights of the

Lognan patrol hut,” Laurent tells us. He hangs back and off we go, skiing almost blind in totally unfamiliar terrain. It’s a rush. I’m locked into every bump and sound, eyes desperately seeking—and not really finding—any visual frame of reference. Kinda, sorta able to follow Marcus Caston’s lead as the first dim glimmer of dawn wafts through the clouds, I make it to the patrol shack to celebrate a wild first run in Europe with coffee, fresh croissants and the morning patrol briefing.

Because France is inherently more stylish than Canada, head of patrol Christophe Boloyan is called the chef de piste, as if the ski experience at Les Grands Montets is a world-class meal that must be expertly prepared and served up on a silver platter. Which isn’t that far off, actually. With

a dozen patrollers ready to go, Christophe explains that ski cutting will be patrol’s main avy control method today. When needed they can also throw hand charges, utilize bomb trams or remote-fire explosions through a network of gas-filled pipes called Gazex positioned in hard-to-reach, snow-loaded zones above regular on-piste areas.

Daylight has arrived by the time we leave the meeting, and Laurent brings us to the top of the Bochard gondola for the kind of first tracks only ski patrollers get— unhurried, leisurely and perfect.

After noting a few fences and piste markers that need attention, Laurent takes us into the Enchanted Forest, an off-piste grove of larch trees offering fairytale pow turns that no one enjoys more than Marcus Caston, a huge proponent of the art of the turn.

“It goes beyond the turn,” he says. “You have the turn and then you have the transition—floating between turns—that is where the real magic happens.”

Racing-trained and originally skiing out of Snowbird, Utah, Caston lived in Switzerland for the past two winters, skiing all over the place and working on his web series, Return of the Turn. “What I like about it over here is the mountains are bigger, so it makes you more thoughtful about conditions and terrain and safety,” he says while pointing out some of classic (and incredibly burly) ski lines on the nearby Aiguille du Chardonnet. Caston has only been to Chamonix once before. The first time he was filming with Warren Miller, so today’s lines are substantially more chill—though he shreds the heck out of them and then points

out his favourite ski-up raclette hut. We are so deprived on North American hills.

After lunch, Christophe, Laurent and whatever patrollers are not stationed atop the hill treat us to an avalanche-dog demonstration and some hands-on rescuetoboggan training. Maybe it’s because we are guests, maybe because it seems like a mellower day for skier visits and issues, maybe it’s because we’ve got fresh snow and the sun is starting to emerge, but Les Grands Montets ski patrol seem friendlier and more relaxed than some of their North American counterparts.

Or maybe it’s because we’re with Helly Hansen, who established International Ski Patrol Day in 2022 as an opportunity to celebrate patrollers around the globe. Who doesn’t like a little workplace recognition, especially when tragedy comes with the job?

“We had two deaths last week, both collisions,” says Laurent, a Chamonix local since 1987 who started patrolling in 1995 and has rescued people in every sort of terrain imaginable. “But those numbers are decreasing slowly. I think more signage is helping.”

Our day shadowing patrol is thankfully accident-free, and we finish things off shooting photos off the top of the mountain with the Aiguille du Dru behind us. With

its 3,754-metre summit, the Dru is one of Europe’s greatest rock climbs. I’ve grown up reading tales of harrowing adventure on its walls. Now, one ridge over, it’s almost close enough to touch (the only thing in the way is a steel cable and an all-time greatlooking ski chute that requires a guide and a long bushwack to get out of). The vibe, the exaltation of Chamonix, everyone in town walking around with ice axes on their packs… it all makes sense.

guy free, then we might send him through an area of off-piste that we know has been busy, but mostly—because that’s the rules— we want to clear the ski runs that we open to the public.”

Led by Marcus and crafty Danish ripper/ new buddy Claus Madsen, we turn last sweep into a semi-chaotic free-for-all, slashing turns on ridges, hunting down patches of pow and spreading out wide enough to hopefully find anyone who’s lost or needs

and lining it up beside Mount Currie, Wedge, Whistler Blackcomb and Atwell. Now make everything 25 to 30 per cent higher… That’s one side of the valley.

As the sun dips below the mountains to the west, Laurent leads us on the final sweep to ensure the mountain is clear and free of anyone needing assistance. He says, “If we have enough ski patrol and we have one

help, but not so wide that we get lost ourselves. Top to bottom on a closed ski hill is always a good time; in Chamonix it’s better. Plus, there was no one on the hill to yell at us when we stopped to collect the troops.

The secret to eating copious amounts of soul-elevating cheese and bread for every single meal is to be sure to eat the accompanying pickles and gherkins. The vinegar and fermentation help cut through the heavy oils and keep your digestive system from bunging up. See also: wine.

Still reeling from a feast of raclette (on top of the previous day’s feast of fondue), day three sees our crew convene at the Brévent side of Brévent-Flégère on a bluebird day with paragliders and chukkas (basically European mountain ravens) playfully catching updrafts. Sadly, the same winds have thwarted our goal of reaching the iconic Aiguille du Midi—the gondola is closed.

From Brévent, the views of Mont Blanc are spectacular and the lift lines are definitely more hectic that the North American crews are used to, with no real line, just a throng of people funneling in from all directions and stepping on each other’s gear. Elbows up!

The good news is Brévent-Flégère ski patrol have sectioned off an entire run for us, with race gates in place, for the first annual Helly Hansen First Tracks competition, two runs of giant slalom and two freeski runs on an adjacent knoll. With competitors—media and company employees—from all over the world and a wide mix of skill levels (and two people on snowboards), the event would be graded on a curve.

“We judged based on how someone skied to the ability level they had,” says Marcus, who co-judged with professional ski coach and guide Warren Smith. “Who can do the best with what they have?”

Ski Canada editor Lori Knowles crushes the GS course, with aggressive turns and a tight line. On the freeski pitch Claus Madsen and Øyvind Vedvik, Helly Hansen’s VP for

sailing, both choose to hit the solitary (small) rock feature on the face, sacrificing turns for airtime in hopes of impressing the judges. Eric Greene, on a hotel rental snowboard from the early 2000s, flashes the whole slope in a single slash. A dark horse with zero competitive sports experience, I opt for line fluidity and link some nice-feeling turns down a steep section with a sneaky patch of untouched beside a tree.

The comp ends, après awaits—at the infamous Chambre Neuf, with booted skiers jumping on tables to a band playing what sounds like early 2000 punk-pop covers. Or Party & Bullsh*t, a hole-in-the-wall pub with (Seb discovers) another secret hole-in-the-

wall back room within it. We pass ski legend Glen Plake’s apartment (he’s out of town) and catch more than a few influencer types attempting organized photoshoots on the bridge over the Arve River that runs right through town. For dinner, cheese and bread. What else?

Our airport shuttle leaves at 5 a.m. In total, this trip ends up working out to 40 hours of travel for about 80 hours in Chamonix. Worth every second, and fat snowflakes tumble through the night as we drive back to the Geneva airport. I get home and check my ski boot. Yes! It’s safe and sound. I don’t always win trophies for my skiing, but when I do they say “Chamonix” on them.

Every moment in Aspen is an opportunity to create your masterpiece. Pause and immerse yourself in a world of colorful curiosities that ignite conversations and bold ideas that awaken wonder in your soul. Curate your perfect getaway at AspenChamber.org.

S e a E d g e S a u n a , P a r k s v i l l e F e a t u r e d

u n a c a | s e c r e t s a u n a c o m p a n y c a

B u i l t b y S e c r e t S a u n a C o

words & photography :: Erin Hogue

“Make sure your seatbelts are fastened,” the flight attendant reminds us over the intercom as the seatbelt sign glows in my face. Vomit is streaming down my chin and not one, but two, full barf bags sit in my lap. It’s at that moment—90 minutes after boarding—that our plane finally begins to taxi toward the runway. Which means the only napkin I’ll see for the next 20 minutes is the nicest jacket I own.

“I’m sorry,” I reluctantly mutter into the phone. “I have to go.” I hang up, trying to figure out what I must have done in another lifetime to rack up this kind of karma. What the f*ck, universe?

I’m flying home from Ontario. The day had kicked off at the funeral for my two stillborn nieces. Something so heart wrenching I’m not even going to attempt to put into words. Emotionally spent, I had turned to my boyfriend for support. He’d been doing the best job at being there for me all week—that is, unfortunately, until moments before the plane took off. It seems the rocky state of our relationship had become too much, and the person I thought could be “my person” ended things over the phone while I sat trapped in my seat. This all proved to be too much, causing me to do something I almost never do: throw up. Then, to really show me where my karma stood, the first barf bag I reached for was sealed shut with someone else’s disgusting old chewing gum. Really life? Really?? This is how this all has to all go down?

Out of pure stubbornness I refuse to ruin my favorite jacket by wiping puke on it. Instead, I wait an agonizing 20 minutes for the seatbelt sign to turn off so the flight attendant can bring me a tissue. Somehow I survive the flight, deplane and make it home to Whistler. The proceeding 72 hours find me in a daze of confusion. My entire focus is set on simply putting one foot in front of the other, desperately hoping the weight of the past two weeks would disappear. It doesn’t. Instead, I soak my camera in water and eliminate my ability to shoot the story I was flying back for in the first place. Everything has fully and quite literally just been one of those “What the F, life?” situations.

The next decision comes almost too easily. What does one do when yet another attempt to put the pieces of life back together falls apart and none of it makes sense? One says, “F*ck it, I’m going surfing.”

The gloomy clouds of Whistler fade from the rearview mirror, and within days I roll a fully setup Wonder Vans campervan into the dry, sunbaked desert of Baja. The air feels like a warm embrace and the landscape is a mix of golden sand and jagged cacti stretching endlessly under deep blue skies. I’m excited to meet up with snowboarder and Pemberton/Lil’wat legend-in-the-making Sandy Ward for our first surf together. At the beach, we bask in the smell of salt and sand as the ocean glimmers a shimmering invitation, no wetsuit needed.

I paddle out, feeling the dry heat on my back, until the first giant wave rears up and smacks me right in the face. I try to duck-dive the next—but instead get tossed. I’m insistently reminded that I have zero clue what I’m doing as I’m pummeled by one wave after another and pushed back to shore.

I fight with the ocean, like I’d been fighting myself for months—trying to get somewhere but ending up in exactly the same place. I’d been secretly hoping the rolling waves of the ocean would not only lessen the crushing weight in my chest, but also stop the endless circles in my head as I struggle to make some kind of sense out of everything. I feel like I try so hard to do everything right yet somehow still get it wrong.

In the water, I glance back at Sandy—she’s in the same situation, paddling hard only to be relentlessly pushed back to shore. We catch each other’s eye and burst out laughing: “Who made surfing so bloody hard?”

We immediately abandon any hope of making it past the break and decide to become whitewash queens, sticking to the bunny hill of surfing.

Those early days of the trip feel like a never-ending, beyond-my-control, uphill battle—a hurricane hits us, I get heatstroke, Sandy gets food poisoning. Nothing goes to plan, and everything feels harder than it should. Yet through it all, a smile never seems to leave Sandy’s face—the perfect companion for less-than-ideal circumstances.

Paddling out into the glassy ocean, we can feel the stillness around us, broken only by the gentle splash of our hands cutting through the waves.

More faces from home arrive, including Pemberton-based snowboarder Darrah Reid-McLean. Our crew of snowboarders is joined by the world’s best surf coach, Matt Lindsay. Every morning starts with the smooth aroma of cappuccinos and cool, almost crisp, air wafting in as we slide open the van door to catch a hint of morning light rising over the horizon.

Paddling out into the glassy ocean, we can feel the stillness around us, broken only by the gentle splash of our hands cutting through the waves. The sky slowly shifts from deep indigo to soft shades of pink and orange as the first rays of sunlight touch the water. Each morning brings me a little further back from the edge.

But surfing is still so hard. Stop forcing it, I tell myself. Wait patiently for the right wave. Know that it’s coming. I remind myself I cannot will a wave to break or force myself into one that’s not ready—it doesn’t work that way. Instead, I must learn to sit and wait—hoping, knowing, the right wave is coming. And somehow this acceptance of patience also helps me realize I no longer need the walls I built around myself to keep me safe. Let go. Trust that the right wave will come. I can’t force the pieces of my life back together. Instead, I have to be open. I have to wait and trust that life has got my back.

And if not, Matt does. “Erin, let’s get you a wave,” he says. “This is it…PADDLE!”

So I do. I paddle, I arch my back, look up, pop up, look down the wave and this time—for the first time—it all comes together. Reality slows down and nothing else in life matters as I pump up and down the face of the wave, all the way to the beach.

A corner has been turned. Catching wave after wave, my mind begins to quiet as the sorrow and anguish slowly dissolve into the sea. Just one more, just one more. Even when it’s too dark to see. Just one more. It’s not about the biggest wave, the gnarliest trick or the first anything. It’s about the feeling—a feeling of letting go, blended with the quiet triumph of achievement. It’s the undeniable rush of overcoming challenges, and this time, for me, it’s also the feeling of piecing myself back together in a way that makes me realize certain facets I once thought were so integral to life are, in fact, completely irrelevant. I, we, everything is already whole.

Everyone gets it. “Dude, you did it,” Darrah hugs me on the beach. “You did what you came here to do!”

Who knew surfing had the power to lighten the load and illuminate the darkness? I guess lots of people know it, and maybe subconsciously even I knew it. That’s why I ended up here. Because, for me, it’s very similar at home, on a snowboard, in the mountains—waiting for the right storm, the good light, the moment everything lines up. Gliding on a board—of wood, foam or whatever—can somehow just make everything make sense again. Maybe it’s because it bends time and forces us into the present. Maybe it’s because it challenges us, or that it surrounds us with friends. Or maybe it’s that it forces us to fall, over and over and over, until the only option is to just get back up.

But really, it doesn’t matter—who cares about the “why?” It just works. Every time.

words :: Kara-Leah Grant

The backcountry can humble even the strongest among us. Take Margus Riga, the legendary photographer, rider and endurance suffer artist. He once tackled all three North Shore mountains in a single day. By the final summit, he’d eaten nearly everything he’d packed. Running on fumes, with only one option left, chomped into his last snack: a whole lemon. Don’t be Margus. Pack smart so you don’t end up sucking citrus for survival—especially as the temperature plunges and the snow sweeps in.

Kick off your hunt for the ideal energy boost with Pembertonbased Stay Wyld Mushrooms, coming in hot with their Focused Energy Gummies. Think lion’s mane and organic green tea distilled into a low-sugar gummy.

These gummies deliver steady energy and sharp focus— essential when every decision counts. “Focused Energy Gummies strengthen your most vital tool in the wilderness: your brain,” says founder Chris Brown. “Lion’s mane supports clarity, memory and decision-making for safe, enjoyable travel in complex terrain.”

The five-star reviews on their website back them up. Plenty of users even report dropping their daily coffee with regular gummy use. And what’s easier in the backcountry than eating a gummy?

Gum, that’s what. Marie Thiffault is the adventure entrepreneur behind Sunii Energy Gum, manufactured just down the road in Richmond. She lives and breathes mountain energy, living between Vancouver and Whistler so she can make the most of her city career without sacrificing fun in the mountains.

Sunii Energy Gum rivals Stay Wyld Mushrooms for a lightweight option. The mint-flavoured gum blends caffeine, taurine and B vitamins. Chewing activates buccal absorption, sending the caffeine straight through the membranes in your mouth for a fast kick that bypasses digestion and dodges the crash, jitters and stomach issues common with coffee or energy drinks.

“Sunii is a fast-acting energy gum made for the moments that matter,” says Thiffault. “It’s a nudge to tackle the to-do list, whether that’s climbing Panorama Ridge, skiing one more line or just getting out for a walk and finishing a work project.”

If you crave caffeine the classic way, Gradient Coffee keeps the stoke alive. Pemberton roasters Chris Ankeny and Matt Bruhns teamed up with Norco Race Division to create Trail Speed, a playful and sporty blend that has a hint of brightness (acidity) backed with a robust, full-bodied chocolate-nut flavour that’s perfect for that preride boost.

Backcountry coffee aficionados will be stoked to know that Gradient’s product line also features single-serve instant coffee sachets. “We wanted a great coffee we could take anywhere with us: Fast, light and easy to brew, our new Rover instant makes coffee easy,” says Matt. In winter months, the warmth makes the brew worth the effort.

But can gummies, gum or instant coffee ever be as satisfying as actual food? Amélié Legaré, Mountain Lifer to the core, swears by Love and Lemon’s Energy Balls to increase flagging energy levels on the slopes (find the recipe online). “The balls are perfect to bring skiing because they’re compact and nutritious, they taste like a cookie and they don’t crumble easily. They feel like jet fuel for the skin track.”

Even with perfect prep, someday you’ll face the mountains empty-handed. There will be no snacks, no coffee and not even any lemons. Learn pranayama, a yogic practice of breath control, at your local yoga studio and draw on it to refill your energy tanks. Pranayama can also warm up your system from the inside out, a bonus superpower in freezing conditions.

“A consistent yoga practice increases your game exponentially,” says Gin Perry, owner of Shala Yoga in Squamish. “There are so many pranayamas that can help you harness extra energy in sports. For example, kapalabhati breath energizes the body, clears stagnation and activates the mind.”

You’ll never run out of breath practices or forget to pack it. When crisis hits, stop, drop and breathe yourself back online. (Or dig into the acid in your first aid kit, but that’s supposed to be for emergencies.)

The mountains will hand you enough lemons, but that doesn’t mean sucking them is your only energy option.

words & illustration :: Carmen

Kuntz

Once entirely necessary for backcountry adventure, the skill of reading and predicting weather is now almost a lost art. Modern comforts and tech tools like GORE-TEX, 4G networks and global weather data have made it easy for us to forget how to notice and interpret weather and have altered our connection to the environment.

We default to apps, satellite maps and hourly predictions, but when those fail—due to bad signal or a dead battery—we are left with our senses. Learning to read the weather without a phone means paying attention. Not just to what’s happening around you, but also what’s happening to you. Pressure, light, sound, humidity, wind—your environment is a constant stream of real-time data. You just need to tune in. The secret lies in observation, pattern recognition and understanding how atmospheric systems behave. Here’s how to start:

Clouds form when moist air rises, cools, reaches saturation and condenses into droplets or ice crystals. Where and how that occurs can reveal what the atmosphere is doing and what the weather will do. Nephology (the study of clouds) is a complex branch of meteorology. But in the backcountry, a few basics can go a long way.

Fair-weather cumulus clouds are small, flat and puffy. They form from weak, rising air and indicate calm, stable conditions with no rain. Their big siblings—the larger, faster-growing cumulus clouds— appear tall and cauliflower-shaped, form in unstable air and can lead to rain showers. And their nasty cousins, cumulonimbus clouds, are large, towering and dark. These signal severe weather, including heavy rain, lightning or hail. Altostratus clouds, which appear as grey sheets or patches, often precede frontal systems and usually appear 12 to 24 hours before precipitation arrives. And cirrus, those highaltitude, wispy clouds composed of ice crystals, often signal moisture aloft and an approaching front.

Clouds evolve, so learn the basics and then watch the transitions, not just static shapes.

Not to be confused with the DOMS (delayed-onset muscle soreness) that occur naturally after a long day in the mountains, aching joints or even sensitive sinuses can be your bodily barometer telling you pressure is dropping. A falling barometer warns that a low-pressure system (which favours cloud formation, wind, precipitation) is on its way. If your body reacts and the sky or wind shifts, those signals reinforce one another.

Wind is the physical motion of air in response to pressure gradients. When a front or system approaches, wind often shifts direction, gains speed or changes temperature. Paying attention to the wind throughout the day helps you make more accurate predictions. A directional shift (e.g., from southerly to westerly) suggests changing air masses. Wind signals often reach you before clouds darken or rain begins, so read them carefully.

When observing wind direction and temperature, always consider immediate geography so you don’t lose info in the translation. Valleys trap cold air, and saddles can act like wind tunnels. South-facing slopes dry early. North-facing slopes don’t. Local weather takes on a new meaning in mountain environments, so the subtilties should be noted. Always interpret weather signals in the context of terrain.

Rising moisture in the air affects how sound travels; in dense, humid air, sound carries farther. If distant rivers, voices or bird calls suddenly seem louder, humidity might be rising and rain could be on the way. But if birds go quiet, pikas or marmots vanish and bugs disappear, this could mean time to hunker down. Wild animals read weather instinctively and know when to take cover.

And when it comes to thunder, the old “5 seconds = 1 mile (1.6 kilometre)” rule is a reliable approximation used by meteorologists and outdoor educators as well as search and rescue teams. It’s simple, effective and potentially lifesaving, as lightening can strike up to 15 kms away from a storm’s center.

Reading weather is about the constant calibration of observation and analysis. Use all your senses! Recognize cloud forms and transformations. Monitor pressure and trends. Observe shifts in wind. Note changes in sound, humidity and wildlife behaviour. Interpret all of that information through terrain context. Over time spent outdoors, patterns emerge. Especially if you are observing all these things again and again in the same area. Ideally, noting and being able to predict how conditions evolve becomes a sixth sense in the mountains. Connected technology is great—using your senses in combination with your phone apps will enhance your outdoor experience—but tech can (and will) fail at times. When that happens, you’ll be stuck with nothing but your brain and experience to stay dry, warm and out of trouble. Start learning!

words :: Jon Turk illustration :: Lani Imre

Most readers are familiar with the story: In December of 1914, Ernest Shackleton and his crew sailed toward Antarctica to attempt the first overland transcontinental crossing. Unfortunately, the ship was trapped in sea ice and eventually crushed. After many harrowing adventures, Shackleton and five of the men sailed an open boat to South Georgia Island to organize the rescue of the remaining crew. The open-boat sailors landed on the west side of the island and then three of them made an even more desperate overland journey across mountains and glaciers to a whaling station on the east coast.

Less well known is the fact that, as the men were crossing the forbidding mountains—exhausted, ill-equipped, and near the ends of their endurance—each of them felt the presence of a Spirit Helper. Shackleton wrote: “During that long and racking march of thirty-six hours over the unnamed mountains and glaciers of South Georgia, it seemed to me often that we were four, not three.”

Adventure involves pushing the human body to its extremes and peering into the abyss, beyond the boundaries of our human consciousness. Many who have approached these unknowns— including mountaineer Reinhold Messner, polar explorer Peter Hillary, sailor Joshua Slocum and warrior Lozen, a Chiricahua Apache woman who fought alongside Geronimo—have all felt aided by Spirit Helpers.

In almost all aboriginal societies, individuals identify with an animal spirit that helps them communicate with the powers in the Other World and stands by their side in time of need. But what do we make of Spirit Helpers in our uber-technological, AI-crazed modern

world? Don’t get excited: I’m not going to try to convince anyone to believe in anything you’re not comfortable believing in, but I will share my personal encounters with a Spirit Helper.

When I was in Siberia, injured and barely able to walk, the old shaman woman Moolynaut healed me with the help of Kutcha the Raven. And from that moment on, Raven has become my Spirit Helper.

This is the winter issue of Mountain Life—Turn and Burn.

Turning is just turning, no big deal, but the “burn” part of that phrase implies closeness to the edge. And the edge of skiing—the boundary, the zone where perhaps, if we are lucky, we can peer beyond our human consciousness—lies in climbing backcountry mountains and skiing down them.

After my dear wife, Chris, died in an avalanche on Mount Tom in the California Sierra, I carried her ashes to the top of Three Sisters Peak overlooking Fernie, BC. And when we stood on the ridge above Chris’s favorite ski run, Raven flew across the landscape and gradually coasted downward until she was an arm’s length above my head. Then she dropped lower, to waist height, and glided down the mountain, executing perfectly carved turns just above the summer talus, as if she were skiing like a human.

I don’t believe Spirit Helpers guarantee safe passage. The world doesn’t work that way. What keeps us alive out there on the edge is our own awareness. And even though Raven might not intervene directly, just knowing that she is out there, cawing at our fragility, keeps me full of wonder, keeps me looking into the sky, keeps me feeling the snow, feeling alive. Present. Aware. A tingling awareness of the greater journey that I am on as I pull off my climbing skins, take a deep breath and drop into the fall line. Turn and burn.

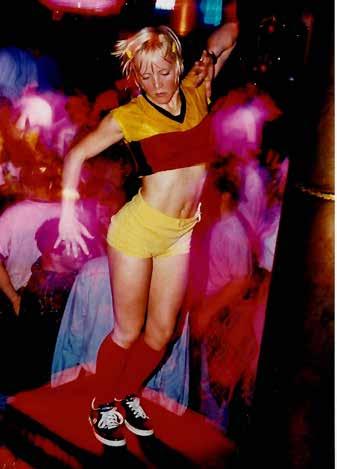

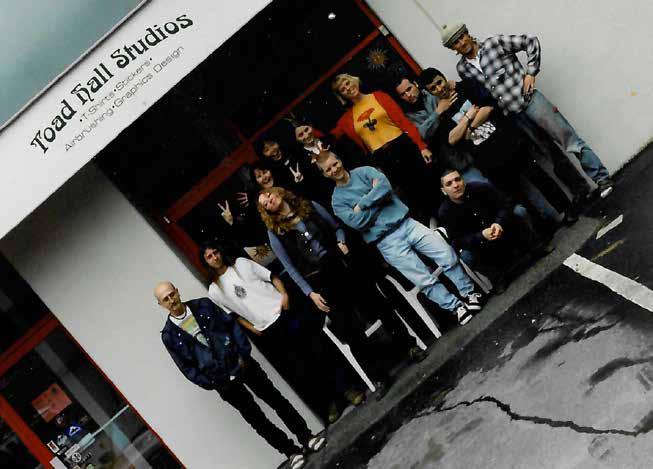

Hype is generally at odds with cool, particularly in the Whistler snowboard scene of the early 2000s. But when the Gnarcore crew needed to drum up attention for the premiere of their third nobudget shred flick Help Is On The Way, they turned to an unlikely source: David Bowie.

“Bowie was unknown in North America when he arrived in 1971,” says Dave Rouleau, co-founder of Gnarcore. “So he created a largerthan-life persona through DIY advertisements and photoshoots of himself roaming around New York city wearing eccentric clothes.”

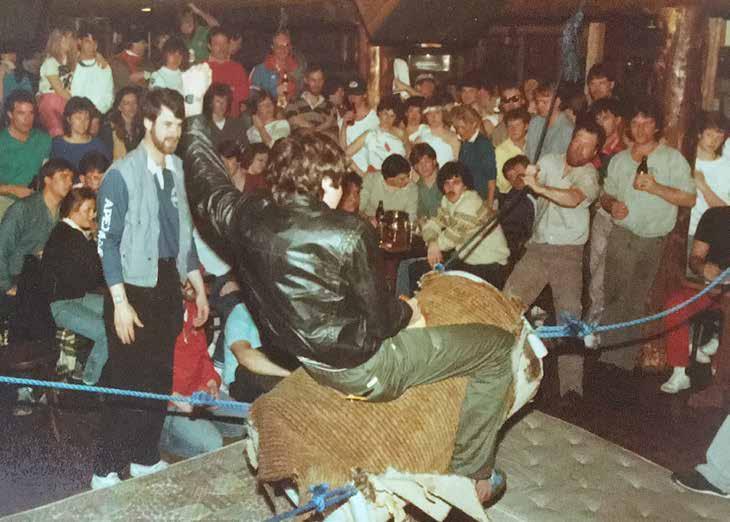

Rouleau says Gnarcore copied the strategy to shift the narrative from “Who the hell are these people?” to “I need to pay attention to them.” They draped the inside of Merlin’s Bar with white sheets splattered in blood, painted signs, built light boxes with the film’s title and even rented a limo to drive directly up to their red-carpeted entrance with photographer friends enlisted to pose as paparazzi. Tickets to the premiere cost five bucks and were preprinted with a note that said, “You lucky bastard.”

It worked. The premiere sold out and Help Is On The Way became an instant classic and a calling card for the future. The liner notes to the film laid the Gnarcore mission out clearly: “Redefine what can be done with little budget, some imagination and really good snowboarding.”

Before GoPros, social media engagement statistics and relentless branded content, a keen shredder’s only window into local snowboard culture consisted of buying magazines or once-ayear DVDs (or VHS tapes) from a handful of local production crews like Whiskey or Skids. Rouleau flipped the script with a passionate crew, a website and a creative universe that would pull inspiration from anywhere (even skiers). But it wasn’t an easy path.

Dave Rouleau moved to Whistler in 2003, another wide-eyed 19-year-old snowboarder from Alberta ready to grab the local scene by the short and curlies. The reality didn’t quite line up—he found a segregated summer glacier scene and a lot of old-guard pros with a gatekeeping attitude.

“In the private camp parks, it was all these rock-star dudes with big egos,” Rouleau says. “I went from admiring them to, F*ck these guys, we’re gonna do our own thing. But over in the public park there were dudes like Robjn Taylor and Logan Short. No egos, no competition. These guys had something.”

Sessioning the glacier every day, Rouleau took to sharing his staff meals out the back door of the restaurant where he worked, hooking up other cash-strapped up-and-comers. “I’d tell them to come by for some chicken fingers and fries, then they’d see me on the hill and be like, ‘Yo, Dave. You’re the homie now.’”

Despite a total lack of experience with filming or editing, Rouleau had vision—and an ally. Lauren Graham moved into the house he was renting (the now-legendary Art Barn) and she had film school credentials, industry experience and Shot In The Dark, a DIY all-female snowboard film under her belt. “I got to witness her making the films and doing the business side of it,” Rouleau says. “I absorbed everything she was doing.”

One helpful friend turned into many, and Rouleau began to understand the strength of a collective. “There’s power if you actually tell people your plans,” he says. “They get on board, they band together. It’s a force—the big dogs don’t understand us but we can do this. We can blow it up.”

Benny Stoddard, who was managing the terrain park at the time, saw the potential and wanted to come on board. Rouleau had already been stacking clips of his talented, lesser-known friends and Gnarcore Videoplay had officially begun. (The name was originally a joke: “It’s gotta be gnarly and it’s gotta be core!”)

“It’s like Fight Club, right? Buddy shows up with his duffel bag at the door, like, ‘I want in on this,’” says Rouleau. “People said, ‘Hey man, follow your dreams.’ I got pumped full of idealism and would have super-idealistic bouts of creativity that lasted for years.”

The Art Barn became a clubhouse for snowboarders who just wanted to shred, including future icons like Gerhard Gross, Molly Milligan, Keith Martin, Jess Kimura, Andrew Geeves and E-Man Anderson. And when Rouleau came home one day to find Whiskey filmmaker Sean Kearns and top snowboarder JP Walker visiting Graham, “She ended up showing them our first Gnarcore film right there in our house.”

Low on budget, high on creativity, Rouleau and Gnarcore released their second flick, Shoot The Ones You Love, in 2004. The success of Help Is On The Way (the hype worked) helped launch a number of careers, while other members of the Gnarcore roster moved on to start families and settle into adulthood. Not Rouleau, though. Alongside tech-savvy boarder/skater Lenny Rubenovitch, he rode the wave of stoke into a new platform: web 2.0.

“I would look at websites in New York and L.A.” Rouleau says. “Whistler was pretty small, but it had that element to it—we knew it could be a cultural institution. So we started Gnarcore.com, just posting bar photos and having fun with it and just doing what’s ridiculous. It’s culture.”

“In the private camp parks, it was all these rock-star dudes with big egos. I went from admiring them to, F*ck these guys, we’re gonna do our own thing.” – Dave rouleau

The truth lies next to your skin.

“There’s power if you actually tell people your plans. They get on board, they band together. It’s a force—the big dogs don’t understand us but we can do this. We can blow it up.” – Dave rouleau

With a weekly online blog and a series of short films and edits inspired by what was happening on skateboard platforms like The Berrics, the Gnarcore site gained popularity quickly thanks to their “Walk in the Park” series, which featured a single terrain park run from local slayers and visiting pros like Jake Kuzyk or “whoever else was sleeping on our floor that week.”

Carving their own space in the early days of the digital age gave Gnarcore global street cred and separated them from the Whistler crews that had come before. Recently, snowboard pro and Airtime podcast host Jody Wachniak said, “They created a ripple effect felt within snowboarding to this day.”

But the internet moves fast. “I was getting older, and still into older music,” Rouleau says. “I remember sitting in this home office I’d made with Dave Brocklebank. He was young and new, editing clips with his type of music and style. I saw a shift where I was like, ‘Okay, my influence might not be it anymore. I might need to pass the reins.’ A lot of my friends didn’t get it, but it’s a movement. It moves and sometimes it moves outside of us. I learned that from skating—once you get old, you pass the torch. They’re going to keep it going.”

Brocklebank went on to start D.O.P.E. Industries, his own DIY empire rooted in the Gnarcore vibe. “That aspect of snowboarding—talent meshed with personality and style…it’s definitely influential,” says Whistler snowboarder Brin Alexander, who grew up influenced by both crews, waving the flag at huge contests and events like the Natural Selection Tour with his own pro model D.O.P.E. snowboard. Whiskey and Skids set the foundations for the BC/Whistler snowboard culture archetype, but Gnarcore and D.O.P.E. put it out for the world to see. The legacy continues with Shmobb, a new generation of Whistler snowboarders riding against the grain in favour of authenticity, creativity and, most importantly, fun.

Dave Rouleau stepped away from snowboarding for a while, and even moved back to Alberta, but these days he’s back on a board, taking a hard look at returning to the Sea to Sky. And last summer he started filming skateboarding again with his wife.

“I’m in my 40s,” he says, “but I’m still able to find that stride. Once something is a part of you, it never leaves. I just want to do what I love and it’s kind of come full circle. You move around, see the world and then you come back and realize we really got something special here. I think the biggest thing is being where there are people choosing to live their life in a certain way.”

And that will always be cool.

words :: Feet Banks

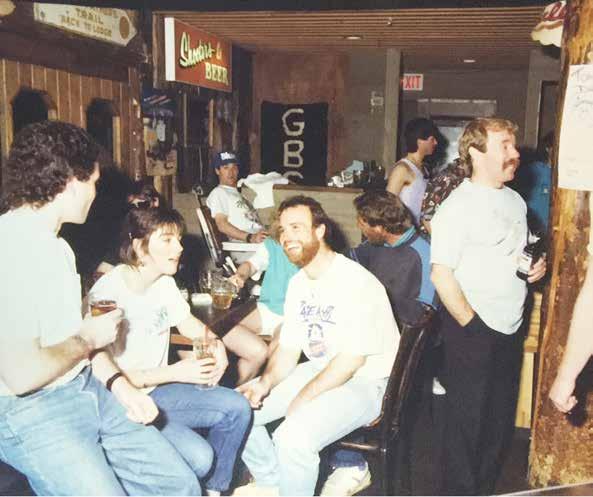

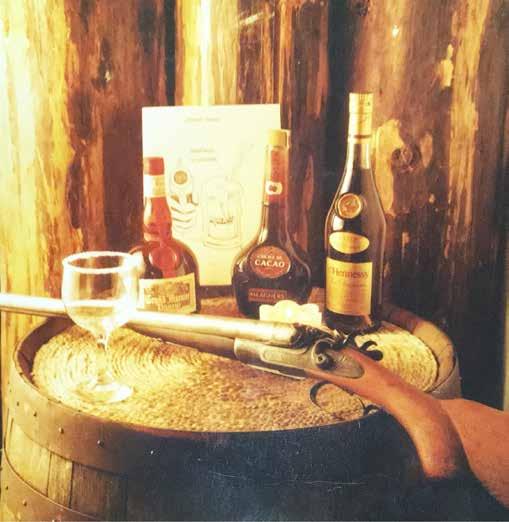

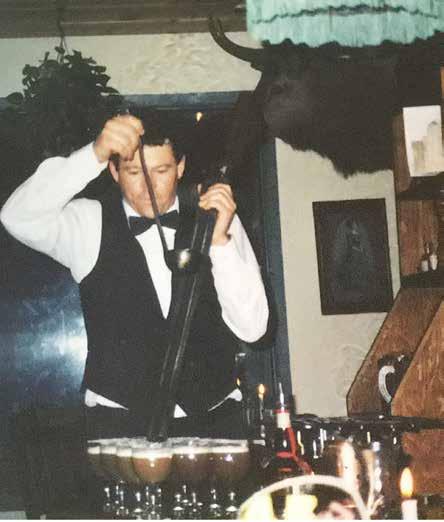

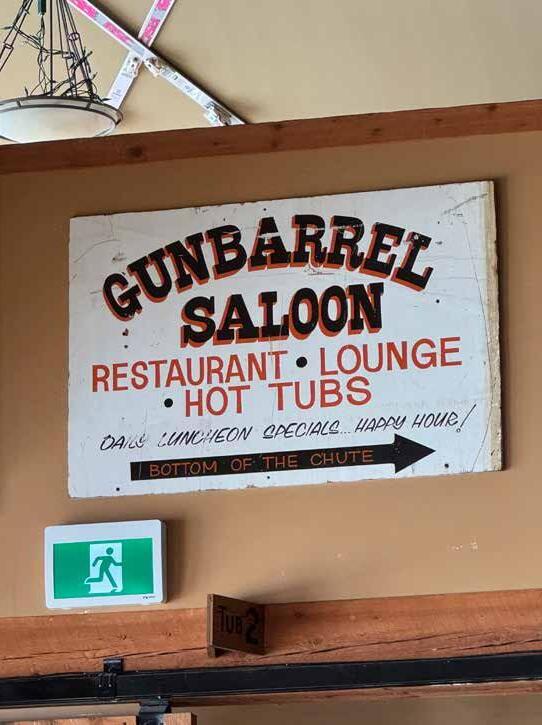

“I guess my first memory of skiing Apex is more remembering the first rule,” says Ty Spence. “Our family would go in the pub for lunch (it’s the 1980s so all the parents would go in there), and the rule was if I saw a policeman walk in, I had to hide under a table.”

The pub was the Gunbarrel Saloon, one of the most celebrated ski-hill bars in BC history. Ty’s father, Glen, was one of the original Gunbarrel founders. He opened the saloon in 1981, a full 20 years after a community fundraiser installed the first Poma lift on Beaconsfield Mountain (a 35-minute drive southwest of Penticton, BC) and Apex Alpine officially opened. With $3 day tickets ($2 for kids), a vertical rise of 370 metres (1,200 feet) and the summit sitting at 2,178 metres (7,146 feet), by 1962 Apex was touted as having “some of the finest snow conditions and alpine skiing to be found anywhere” in an article in the Spokane Spokesman review.

As interest grew, Apex put in their first T-bar in 1968 and a double chair in 1971. A better access road went in ’79 with big development plans on the horizon, including the Stock’s triple chairlift set to open in 1981.

“We had a camper, so we’d drive up from North Vancouver to ski there,” Glen Spence says. “There were a bunch of cabins there already, but in 1979 we heard about a land auction so we drove up and got a lot. Ten grand for a lot at a ski hill is a pretty good deal, even back then.”

After building a cabin over the summer, Glen, his brother Brian and another friend recognized the need for a proper après spot at their new winter home. When they heard resort management was looking for proposals to lease space and start a bar, Glen and his team went all in.

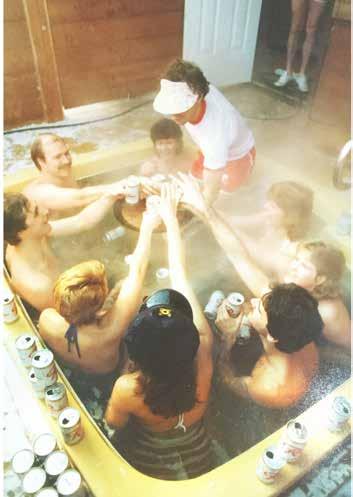

doors onto the Gunbarrel dancefloor) and a dedicated hot tub building right next door.

“I lived above the Gunbarrel,” says Canadian ski-mountaineering icon Eric Pehota. “That place was our living room.”

Fresh out of high school, Pehota moved to Apex in 1982 hoping for a job that would allow him to ski every day. “It was snowing hard on the drive up for my job interview,” he says. “I had to pull over and fill my truck up with rocks then drive up the hill in reverse. Got the job, though—a liftie.”

During the first week of work, Pehota met a young ski technician named Trevor Petersen and forged a friendship that would eventually lead the duo to Whistler and a new approach to big-mountain skiing in Canada.

“If you get one of the first chairs after a pow day, it’s your duty to automatically ski right under the chair. Just a mad dash, choking on snow and making noise the whole way down to psych up everyone else on the mountain.”

“We invited one of the owners to a house party,” he says. “Maybe that helped our proposal a bit, but between the three of us we had zero knowledge of the industry—we’d never even washed a dish—so we learned by making mistakes. Everyone up there was young and partying in those days and it’s a ski-hill bar—it became a party place right off the bat.”

Located a bit up-slope from the newly constructed main base lodge (and thus more insulated from police visits), the original Gunbarrel had swinging saloon doors (more than a few local hotdoggers carried enough momentum to blast right through the

Pehota and Petersen would ski every day on their lunch breaks. “As the season went on, our lunch hours got longer and longer,” Eric says. “Eventually we got fired but they let us keep our passes. That was amazing. I guess it was getting into spring and things were slowing down anyhow.”

These days, Apex has expanded lift capacity to include a high-speed quad chair that gives access to their 79 named runs. Slightly separated from the BC coast and the big winter storms that ravage it, Apex snowfall average charts in about six metres (20 feet). But what the mountain is best known for— what separates it from almost every small- and medium-sized ski hill in the province—is that it’s steep, with perfect straightshot fall-line runs and fast, rolling cruisers. “I learned about stretching out the groin there,” Eric says, “because one leg is gonna be up around your ear. It was steeper than anything I’d grown up with.”

Steep slopes and consistent temperatures also make for fast skiers. “I’d be with my daughter at all the interior BC races and see Apex kids on the podium,” says Michael Ziff. An Apex kids ski coach who learned to race in Quebec, Ziff spent a few years shredding Whistler before eventually ending up in Penticton in 2020. “They were the smallest team of the field, but they were skiing really well.”

Ziff points out that the Apex T-Bar is directly adjacent to the race-training course. “The kids can probably get 3 to 4 laps on the course in the time it takes a racer at a larger, busier resort to get one lap, wait in a lift line, then ski back over to the course.”

Racers aren’t the only ones taking advantage of Apex’s steep slopes, quick access and general lack of lift lines. “I first showed up there in 1999 for some mogul-skiing madness,” says Josh Dueck, “and I moved there from Whistler right away. I fell in love with it. That’s where I wanted to coach and spend my time. The small-hill vibe, the Gunbarrel. There’s just a real ski culture there and Wade Garrod kickstarted a great freestyle program.”

Skiing out of Kimberley, BC, as a kid, Josh competed in freestyle as a youth and got his first head-coaching job at Apex in 2002. After a 2004 ski accident at SilverStar in Vernon, BC, left him paralyzed below the waist, Josh hopped in a sit ski and kept on givin’ er, tenaciously giving back to the sport, advocating for accessibility and collecting hardware—two X Games medals and three from the Paralympics, including a gold and silver at Sochi in 2014. He’s also that guy you likely saw on the internet (or the Ellen DeGeneres Show) in 2012 after he became the first sit-ski athlete to land a backflip on snow.

“Gary Denton got his pass clipped two years ago for ducking ropes and poaching lines. Gary Denton is 75 years old.”

Skiing with ex-pros like Josh and Ty (who competed in freestyle, halfpipe and big air) or founders like Glen is a treat on any hill, so when Mountain Life co-publisher Jon Burak and I checked into our hotel in Penticton we had no idea what Apex held for us. Michael Ziff called to say, “I’ll meet you up there.”

“Where do you want to meet? What time?” I asked.

Ziff laughed. “It’s a Wednesday. I’ll just meet you on the hill.”

Which is exactly what happened, because with blue skies and no fresh snow, a Wednesday at Apex meant absolutely no lift lines. We didn’t quite have the hill to ourselves, but it definitely felt like it.

TO P U S H I N G

L I M I T S

Fast, empty cruisers, steep glades, a couple nice cat tracks to launch off—the kind of day, and ski hill, that blows away expectations. Après at the new version of Gunbarrel still has a vibe.

“My dad sold the Gunbarrel the year I turned eighteen,” Ty says. “Convenient for him, but I still acted like I owned it for a while at least.”