A Reflective Lens: Music Pedagogical Research to Transform Practice

A publication by the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts

Copyright ©2016 by Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR), Ministry of Education, Singapore

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. No part of it may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR).

Published by Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) 2 Malan Road

Singapore 109433 http://www.star.moe.edu.sg

ISBN: 978-981-09-8446-5

Co-operative Learning Structure in Group Music

Composition

Adela Josephine Juying Primary School

Use of Reflective Practice in Developing Students’ Listening and Ensemble Performing Skills in Guitar Ensemble Co-Curricular Activity

Chen Li Yan, Huang Yewei Martin

St Patrick’s School

Becoming a Reflective Practitioner: A Music Teacher’s Exploration of Singing Games

Allen Losey, Mohamed Salleh Mohamed Yasin Tampines Primary School

Benefits of Informal Learning Pedagogy and Popular Music with Normal Technical Students: SelfDirected Learning through the Use of Technology

Pauline Fong Liew Yueh

Jurongville Secondary School

Acknowledgements

The Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts would like to express our appreciation to our following partners in the co-construction of arts pedagogical knowledge:

Arts and Heritage Division, Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY)

National Arts Council (NAC)

Research Consultant Associate Professor Lum Chee Hoo, National Institute of Education, Singapore

Principals, staff and students of

• Jurongville Secondary School

• Juying Primary School

• St. Patrick’s School

• Tampines Primary School

APRF is supported by Arts & Culture Strategic Review (ACSR).

Foreword

This edition of music research by teachers bring to light different refracted lenses of inquiry into music education practices in our classrooms. We often teach in ways we feel most comfortable, habitually and iteratively. We want to challenge our own thinking and find new wonderful ways of re-shaping and re-designing our classroom practice. We can only move into these adaptive ways of learning when we re-discover our own practice again.

These teacher-writers encourage us to actively engage in a continuous process of exploration and reflection to better inform and enhance our music teaching-learning cycles. They share here their collective experience and transformation of practice for purposeful teaching and learning with the arts fraternity. The dialogic spaces support reflective inquiry that strengthens not only the professional music teaching practice, but also deepens shared knowledge in the co-construction of knowledge on arts education pedagogy in Singapore classrooms. Exciting times.

Rebecca Chew Academy Principal Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts

Arts Pedagogical Research Fund

This publication is made possible by the Arts Pedagogical Research Fund (APRF), supported by the collaboration between the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). APRF serves to support arts teachers in developing pedagogical understanding via research, and teacher-researchers undergo a year-long professional development programme organised by the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR).

The APRF Professional Development programme aims to deepen teacher-researchers’ understanding of pedagogical research through workshops and research consultation sessions with research consultants. With sessions spread out through the year, teacher-researchers are supported as they embark on each stage of research.

Through the stages of research, teachers develop a deeper understanding of music pedagogy and engage in reflective dialogues with a community comprising STAR officers, research consultants and fellow teacher-researchers. Most importantly, they also develop a spirit of inquiry and a critical stance towards their teaching practice which will continue to support their classroom practice beyond the pedagogical research.

To find out more about APRF, please visit the STAR website: www.star.moe.edu.sg

“I used to think group music composition is not feasible for Primary 4 students as it is complicated and requires students to have a certain level of music background. I also believed the process might be too much trouble to manage as it could get disruptive when students discuss their composition.

Now I think that group music composition, if facilitated properly, is a meaningful learning process which helps to build students’ music understanding as they learn from one another. Through the research process of analysing students’ conversations and interview transcripts, I also found that students find the composition process rich and meaningful. My research findings further inform that composition helps to develop students’ social-emotional competencies and 21st Century Competencies.

Co-operative learning structure is so useful in facilitating students’ composition process. When students are given a certain role to play, they can be more focused and contribute to achieving the group goal. Moreover, there is individual accountability and everyone is engaged in the learning process.”

Co-operative Learning Structure in Group Music Composition

Adela Josephine

Juying Primary School

Abstract

This research examines the use of co-operative learning structure in group music composition activities for Primary 4 students. Students collaborated in small groups of five to six members over five lessons of one-hour duration each, working on two compositions. Ten students from two groups were the target group of the study. Their group discussions were transcribed and analysed. Besides lesson transcriptions and fieldnotes, other data collection methods included interview transcriptions and reflective journaling which students completed at the end of the study. The findings of the study indicated that co-operative learning structure helps students in working on their compositions as students’ musical understanding were enhanced and students’ interactions within the group allowed them to develop social and emotional competencies as well as 21st Century Competencies (21CC). Moreover, co-operative learning provides opportunities to develop students’ leadership capacity as the group-elected leaders were required to help the group achieve their group goals; in this case, creation and performance of a group composition.

Introduction

As a music teacher teaching in a neighbourhood primary school, I had my own initial reservations about teaching music composition, although creating music is one of the learning outcomes of the General Music Programme. I perceived that music composition required a certain level of musical knowledge and understanding, and was therefore not within everyone’s ability, much less primary school children with little or no musical background. However, since the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) launched a new initiative in 2012 on studentcentric principles in arts learning, I started reflecting on my classroom teaching. One of the principles that struck me the most was facilitating creativity in music making. I began thinking of ways in which I could provide opportunities for my students to create or improvise music. How do I start? How much parameter should I set for beginners?

With the belief that “the one who does the work does the learning”, student-centric teaching is about providing opportunities for students to be actively engaged in the learning process (Doyle, 2011). This made me review my role as a teacher; from being the only one giving information to being a facilitator in helping students discover or explore the information on their own. Putting this in the context of teaching composition, I saw merits in allowing students to be in-charge of their own learning by allowing them to create music. I consciously started providing my students opportunities to create or improvise, but limited them mostly to creating or improvising movements or adding on simple instrumentation or body percussion. Although there were times I allowed my students to improvise some melodies on their recorders or Orff instruments, these activities were mostly done on a one-off basis.

Literature Review

Children’s composition has increasingly become the interest of researchers over the years. One of the main reasons is that music composition activities are crucial in reinforcing musical concepts (Wiggins, 1989) as they engage students in experiences that require them to think musically and expand their musical understanding (Blair, 2009). Composition helps students develop problem-solving skills in making musical decisions (Dunbar-Hall, 2002) and also creates in students ownership and pride for their own creation (Wiggins, 1989).

With these benefits in mind, I was even more motivated to research on this topic. However, I was geared towards researching on group music composition rather than individual music composition, as social interaction is seen as an essential ingredient in the learning process (Vygotsky, 1978). Previous research has shown that group music composition facilitates communication of music among group members, which will lead to musical development (Ginocchio, 2003). As students work together towards a common goal, they can fill in the gaps in one another’s understanding, enabling the overall competence of the group to move forward (Wiggins, 2005).

In my process of reflection, I wondered if there was a structure that could be applied on group music composition activities to facilitate the composition process, helping students to develop both their musicality and social skills. Since co-operative learning structures have been widely researched on and proven to have many benefits, I wanted to apply co-operative learning into group music composition activities. I hoped to see the workings of these benefits, such as promoting higher achievement rather than competitive or individualistic learning, resulting in higher-level reasoning, more frequent generation of new ideas and solutions, and greater transfer of learning from one situation to another (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 1991). As most research on the application of co-operative

1. How does cooperative learning structure facilitate group composition?

learning structure was done in the context of core academic subjects and in Western classrooms, this research was to ascertain if the benefits highlighted in the rich literature of co-operative learning structure could also be seen in the Singapore upper-primary music classroom.

Research Purpose and Questions

The purpose of this study is to examine the use of cooperative learning structure in group music composition for upper primary students. The following questions were raised for the study:

2. To what extent does co-operative learning structure help to develop students’ musicality and social skills?

3. What are students’ views on cooperative learning structure in doing group composition? Does it help them in carrying out the task?

4. What are the skills students need to have in order for co-operative learning structure to be successfully implemented in group composition?

Methodology

Implementation of Co-operative Learning Structure

Co-operative learning structure is a way of organising instruction that involves students working together to help one another learn. This means structuring learning tasks so that students must serve as one another’s resource in order to be successful (Sapon-Shevin, 1994) in solving a problem, completing a task or achieving a goal (Li & Lam, 2005).

Students should work in small groups of between four to six members (Slavin, 1984) and each member has a role to play such as group leader, time-keeper, scribe, and so on. These roles have to be decided amongst the students, rather than be prescribed by the teacher. Since the class for this research consisted of thirty-five students, they were divided into seven groups of five, chosen randomly to ensure there was a good mix in each group. Each group was heterogeneous with mixed-ability students of gender and ethnicity mix; this was to ensure that everyone had equal opportunity for success (Slavin, 1986). Students remained in this group for the duration of the study. Each group was given a task to complete (in this case, music composition) within a stipulated time (Slavin, 1991). They were also given time to plan their composition and practise together (Wiggins, 1994).

The group goal was to complete a composition, with notation, and to perform the composition as a group. Each group member was required to contribute ideas, to work together with others, and to motivate one another (Slavin, 1991). However, an important element of cooperative learning structure is individual accountability to ensure there is no free-rider problem (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 1991). This individual accountability means, when evaluating the group music composition, that there should be a form of evaluation to determine if every student has contributed and played his / her part in their group music composition. This was done through the implementation of peer evaluation at the end of the study.

To ensure a rigorous data collection process, ten students were focused on from two different groups (i.e. Group 1 and Group 2). They were observed during the lessons and interviewed after the lessons. For the benefit of understanding the findings and discussion section, the participants’ roles are illustrated in Table 1.

Group 1

Student A (leader)

Student B (assistant leader)

Student C (noise controller)

Student D (time keeper)

Student E (scribe)

Group 2

Student F (leader)

Student G (assistant leader)

Student H (noise controller)

Student I (time keeper)

Student J (scribe)

Designing the Group Music Composition Activities

Before the study commenced, my Primary 4 students had been given exposure to basic musical elements such as beat, rhythm, melody, tempo, dynamics, structure, and form (Wiggins, 1989). They revised these musical elements in the first two weeks of the study. They were also introduced to the concept of ‘melodic and rhythmic ostinato’ where they were provided with opportunities for random exploration (Wiggins, 1994) and they were engaged in sufficient performing and listening experiences prior to the composition (Wiggins, 2005). These elements were crucial in their ensuing group composition. Due to this consideration, the study was conducted in Term 3 instead of Term 2 as initially planned.

The study lasted for five weeks and consisted of onehour lessons with two major composition activities. The first composition activity was to create a piece of work by combining musical elements introduced in the first three lessons of the study. It served as a scaffolding for students’ second composition, which would be a new composition composed from scratch. I was particularly interested in the second composition activity as its success depended on each group being able to understand the first few lessons and then transferring their learning into creating something new. Furthermore, the second composition task had fewer parameters set for them.

The main instruments used for the composition were Orff instruments (xylophones and metallophones) and handheld percussion instruments. There were eight musical concepts focused in this study to facilitate music composition activities: beat, rhythm, melody, rhythmic ostinato, melodic ostinato, bordun accompaniment, pentatonic scale and form in music (in this case, ABA form).

Lesson Concepts Task

1.

• Beat vs. rhythm

• Melody

• Pentatonic scale

• Bordun accompaniment

2.

• Rhythmic ostinato

• Melodic ostinato

3.

• Composition Activity 1

• Change the lyrics of the song

• Change the melody of the song using pentatonic scale

• Choose bordun accompaniment style

• Create a rhythm ostinato

• Create a melodic ostinato using pentatonic scale

• Perform the piece as a group with

- 1 person singing the new lyrics

- 1 person playing the melody

- 1 person playing the bordun accompaniment

- 1 person playing the rhythmic ostinato

- 1 person playing the melodic ostinato

4.

• Form in Music

• Composition Activity 2

5.

• Performance

Table 2: Task Overview

• Compose a song in ABA form with melodic and rhythmic ostinato

• Perform the newly-composed piece as a group with

- 1 person singing the new lyrics

- 1 person playing the melody

- 1 person playing the bordun accompaniment

- 1 person playing the rhythmic ostinato

- 1 person playing the melodic ostinato

I designed the tasks such that they were given in bitesizes with proper scaffolding so that students were able to internalise the concept one at a time. Students were provided with clear instructions written on the whiteboard (Wiggins, 1994) and they were given prompts on which musical elements to focus on (i.e. melody, melodic ostinato, rhythmic ostinato, and so on) (Peterson & Madsen, 2010). Students were allowed to use graphic notation or alphabets (letter names) instead of staff notation, whichever they were more comfortable with, so that they could channel their creativity naturally (Auh & Walker, 1999). The first composition task had more prescriptive parameters (i.e. the rhythm pattern for the melody) set for the students to work on, whereas the second composition activity allowed students free reign with the rhythm patterns for their melody.

In Lesson One:

Students were only asked to change the lyrics and the melody of the song. Here, the rhythm patterns were prescribed for them. For beginners, I deemed it advisable to prescribe every aspect of the composition except for the melody. Before the composition exercise, I determined the rhythm and meter signature commensurate with the students’ level of understanding (Brophy, 1996); in this case, the meter signature chosen was 4/4. Students were also asked to change the melody of the song using a five-tone scale set – pentatonic scale, which is good and manageable for beginners (Ginnochio, 2003).

In Lesson Two:

Students were tasked to create various 1-bar rhythm patterns using stick notation before deciding on a rhythmic ostinato to accompany the song. Afterwards, they were to add pitches to the rhythm pattern to turn it into a melodic ostinato. Students were provided with opportunities for random exploration while figuring out the task (Wiggins, 1994).

In Lesson Three:

Students were tasked to piece everything together as they needed to come up with a performance with the set parameters. The task was given in such a way that everyone needed to be involved and serve as one another’s resource to complete the task.

In Lesson Four:

Students were introduced to a more complex concept of form in music – namely, the Ternary (ABA) form. They were then presented with the second composition activity that required them to start their composition from scratch, and applying the musical elements they had learned previously. They performed at the end of this lesson, and they were given suggestions on which areas to improve upon by Lesson Five, at which they had their final performance.

Data Collection

Lesson Recordings, Transcriptions and Fieldnotes

Since two groups were observed, there were two separate video cameras capturing the group discussions and students’ interactions at every lesson. In addition, each of the ten students under observation had an individual audio voice recorder to pre-empt any video camera malfunctioning and resulting loss of data. This was especially helpful during Lesson Four when the video cameras ran out of battery, and the second half of the lesson was not video-recorded. The recordings of each group from each lesson were then transcribed word for word by the research assistant using the video file, checked against the audio file from each individual voice recorder, to ensure accuracy in transcribing the discussion. It was interesting to discover that although both groups were in the same lesson completing the same tasks, the lesson recordings and transcriptions captured very different discussions and responses from each group.

I felt that the most significant data source for this qualitative study came from the edited version of lesson transcriptions when I added the field notes; particularly noting down students’ behaviour and body language. Since the nature of the research questions required me to study and

analyse the process of completing the task (rather than just focusing on the end product which was the composition piece performed), I felt that the minute details of students’ reactions to a particular situation were very useful.

Student Interviews

I conducted four interview sessions; each done after every lesson, with the exception of Lesson Five. The duration for each interview was between 20 and 25 minutes, with interviews being conducted at 7a.m. before the school’s daily flag rising ceremony at 7.25a.m. Due to timetable constraints, the interviews were conducted two days after each lesson and there was a need to recap what students had done in the lesson, as some of them could not remember the exact details of their conversations and discussions.

The main purpose of the interviews was to discuss the lesson they had undergone. Students explained their musical decisions and their group decisions in other areas; such as their strategy or approach in completing the task, the members’ roles, and the choice of instruments. They also talked about the dynamics of the group.

The research assistant then transcribed the interviews so that the data could be processed. However, since the interview was recorded on an audio recorder (without video), the research assistant had some difficulty at times in identifying the conversation source, since there were at least five students at one interview. Although she used voice recognition software to extract samples of the students’ audio voice from the video recordings and matched them with the audio recordings from the interview sessions, accuracy might have been compromised.

Reflection Journal

At the end of the study, students completed a two-page journal with some guiding questions to gather how they felt about the activities.

Q1. Do you enjoy working in a group? Why?

Q2. Does working in a group help you complete the tasks assigned to you? How?

Q3. What are the benefits of working in groups for you personally?

Q4a. What are some of the problems you encountered when working in groups?

Q4b. How did your group go about solving the problems?

Q5. If you were given a choice to do a similar composition, would you choose to do it in groups or on your own? Why?

Q6. How do you feel about your group’s composition? Are you satisfied with the outcome? Why?

Q7. Do you now feel more confident about composing music? Why?

Q8. If you are given another chance to learn more or do another music composition, would you do it? Why?

Table 3: Guiding Questions in Students’ Reflection Journal

Data Analysis

Preliminary Coding

Since I was handling multiple data sources requiring complex analysis, I decided on a two-step coding process. The first process was to scribble some notes on the right hand column of the transcription scripts, jotting down phrases that captured the essence of the data. I also copied the phrases (i.e. the preliminary codes) onto another piece of paper. The purpose of this was to collate all the phrases before categorising them.

Before categorising the codes, I also jotted down some phrases containing key ideas from the literature review pertaining to the topics of ‘co-operative learning’ and ‘music composition’. This helped me re-word the codes when categorising them. While re-wording the codes or categorising them, I was working out response to the research questions in my head. Therefore, when I interpreted a particular behaviour or discussion displayed by students, I would relate it to the vocabulary within my literature review. This flowed into the second process, which was to re-word the codes before categorising them further. The lesson transcripts were coded first, before I moved on to the interview transcript, and finally, the reflection journal.

Categorising and Labelling Codes

The re-worded specific codes I gathered from the first coding process were categorised into a more general codes category such as ‘Leader’s role’, ‘Interactions between peers’ and ‘Group decision making’. After that, I further grouped these general codes categories into a theme such as ‘Working in groups’, ‘Music composition activities’ and ‘Teaching and instructional methods’.

The specific codes were then labelled according to the categories. This helped in analysing the data, especially when I wanted to quote from students’ script on a particular idea.

C Working in groups

Table 4 below shows a sample of the specific codes organised into the categories that fall under the theme ‘Working in groups’.

C1 Interaction between peers

C1.1. Peer coaching (pointing at notes, clapping the rhythm, singing the notes, counting the beat)

C1.2. Peer correction

C1.3. Peer demonstration

C1.4. Asking peer for clarification of concept/task

C1.5. Explaining concept / task to peer

C1.6. Consulting peers for opinion

C1.7. Guiding peer to practise his part

C1.8. Peer support (holding the paper, removing the F & B on instrument)

C1.9. Peer checking

C1.10. Peer reminder (to stay on task, to complete the melody part)

C1.11. Giving peers instruction

C1.12. Disagreement

C3 Group decision making

C4 Leader’s roles

Table 4: Sample of Code Category

C3.1. Dominant personalities dominate the discussion

C3.2. Members suggesting ideas

C3.3. Questioning the credibility of input

C3.4. Discussing the unsure parts repeatedly

C3.5. Members stating weaknesses & preferences of roles / instruments to play

C3.6. Conforming / yielding to one idea

C3.7. Voting on who to play the instrument (Group 2) / lyrics

C4.1. Leader asking members’ preferences

C4.2. Leader reminding pupils to stay on task

C4.3. Leader mediating disagreement

C4.5. Leader cueing when to play the parts (performance)

C4.6. Leader assigning roles to members

C4.7. Leader scolding non-participative members

Discussion

From the field notes gathered throughout the five lesson observations and students’ responses in the small group interviews and the reflection journal, I found that cooperative learning structure helped in facilitating group composition activities. Although the end product, i.e. the performance quality, varied from group to group in a class of mixed musical abilities, what was more important was the notable snippets of conversations and behaviours captured, transpiring from students’ collaboration in a group.

The findings can be categorised into these three themes:

1. Social-emotional learning and development of 21st Century Competencies

2. Enhancement of students’ musical understanding

3. Development of students’ leadership capacity

Social-Emotional Learning and Development of 21st Century Competencies

The nature of the tasks allowed students opportunity for responsible decision-making; from choosing the roles of the group members to the actual composition activities. Students were given opportunities to plan how they would want to solve their composition task. It was rather interesting how the two groups, Group 1 and Group 2, adopted different approaches to solve their composition tasks. Although they adopted different strategies to complete their compositions, they ultimately displayed quality control, wanting the best outcome for their group.

Group 1 started off by appointing the members to play a certain instrument and the respective part (e.g. Student B will play melody and Student D will play bordun), then working out the composition together. From the very beginning, the group leader, Student A, asked for members’ preference, assessed the members’ playing skills and then assigned them their respective roles. When Student D could not play the bordun accompaniment, Student C was asked to replace him. For the next four lessons, the members struck to their original roles and strived to improve their own individual parts. They completed the activities quite quickly since they figured out the parts together. Mostly Student A and Student B dominated in decisionmaking. They had plenty of time to practise their composition pieces over and over again so they were ready to perform. Moreover, Student A and Student B were very supportive of their group members, encouraging them and teaching them if they were unable to play the part. Group 1 worked really well and rarely had any arguments in the process.

Group 2 approached their tasks differently – mostly using ‘first-comefirst-serve’ basis in choosing their individual part or instrument or using ‘scissors-paper-stone’ to resolve conflicts. For the first three lessons, they separated the parts.Each part was done by a different person. For example, Student A did the lyrics, Student B the melody etc. However, by the fourth lesson they realised that their strategy was not working well, especially when they kept changing instruments at each lesson. Since they argued a lot, they normally did not have enough time to practise, resulting in them always being unready to perform. For the second composition activity, they changed their strategy by working out the parts together. They even had one round of everyone trying out the instrument (part) to determine the most suitable person to anchor that part. They managed to practise and put up a decent performanceat the end. They also went further by notating their composition using staff notation.

Throughout the five lessons, I observed that students were generally able to think critically, and assess options and possibilities before making sound decisions in completing their composition. During the post-performance conferencing, when asked about their decisions, for example in choosing a certain rhythm pattern or a certain tone set, students were able to give sound reasoning that showed that these decisions were satisfactorily thought through. Some of them also made mistakes but overcame the challenges. They displayed the Emerging 21st Century Competency ‘critical

thinking’. They were also able to communicate effectively, express their ideas, manage the information given to them from the first few lessons, and apply the knowledge into their composition activities. In doing so, they displayed ‘information and communication skills’; which is one of the Emerging 21st Century Competencies as well (MOE, 2010). These two Emerging 21CC were developed through the nature of the tasks, which required them to collaborate and co-operate in order to solve a complex problem (i.e. a problem that consists of multiple parts to solve).

It was also evident that in the process, students gained self-awareness of their strengths and weaknesses, and also exercised self-control to minimise conflicts within the group. There were also some instances in which the group analysed the members’ weaknesses and strengths before making a decision.

No, I am not good at singing. Can I play the percussion instrument please?

[Student I, Personal Communication during Lesson]

So we chose Student B to play the melody because she is very clear and she can play the complicated notes really fast.

[Student A, Personal Communication during Lesson]

Besides self-awareness, it was evident that students learnt how to be socially aware that everyone had different ideas and they had to appreciate and respect the differences. From the transcripts of the group discussions, it was evident that as the lesson progressed, they argued less and were less critical of the ideas suggested. Feedback was given in a constructive manner. Their relationship management skills also developed.

Sometimes when I made a mistake, my group mates did not scold me. They tried to understand and encourage me because… everyone makes mistakes.

[Student J, Interview]

We learn that not everybody can play everything. We need to put in our best… doing the most suitable role to help the group.

[Student B, Interview]

Enhancement of Students’ Musical Understanding

The beauty of group work, that allows students to work towards a common goal, is the opportunity to learn from one another.

Peer Coaching

There was notable evidence that students who were musically-inclined added value to their group mates’ learning. For example, in Group 1, Student B, the most musical person in the group, always helped her group mates to keep the beat by tapping or gesturing the beat. She even coached Student C in playing the bordun accompaniment correctly as he had the tendency to lose time. When he played the 4/4 rhythmic ostinato and came to the last beat which was a rest, he had a tendency to speed up during the rest and not keep to the rhythm. Student B had to gesture the rest to him. Similarly, in Group 2, there were many instances when Student G, the most musical person in the group, corrected her peers during the process. Every time Student I played the rhythm wrongly

on his percussion instrument, she would stop the practice and guide him. She was also the one who directed the whole practice by conducting the group and specifically instructing them when to come in.

From the lesson videos, peer coaching happened mostly through peer demonstration in either singing or playing an instrument, especially during the first two lessons when students had just been exposed to the concepts. This was before students had put everything together for their composition. For example, when Student C asked Student A in Lesson One how to play the different types of bordun accompaniment, Student A took over the xylophone and demonstrated the three different types of bordun. She then suggested he play another pattern as it sounded more complicated compared to the other two patterns.

Peer Correction

From the transcripts, it was found that students used precise music terminologies (specifically the eight concepts focused in the study) in their discussion. Another piece of notable students’ behaviour was peer correction when someone misinterpreted something. For example, Student A corrected her group members who were confused between melody and melodic ostinato: “No, that one is melodic ostinato, the melody is this one, following the lyrics of the song.” Student J from Group 2 also corrected her peers by explaining the difference between rhythmic ostinato and melodic ostinato: “Rhythmic ostinato is only the rhythm, only clapping like using ‘ta, ta’. Melodic ostinato adds the melody played on the xylophone.” Musical concepts were reinforced during peer correction.

My group mates corrected me from the mistakes I made so that is how I succeeded in playing my bordun accompaniment.

[Student C, Reflective Journal]

Peer correction also happened in instances like correcting the way an instrument should be played. For example, Student A showed Student C that he should hit in the middle of the xylophone keys, and Student G told Student H that he was not supposed to use the stick to hit the bongo.

Peer correction further took place during the practice for the performance, where the musically-inclined members did some quality control of the performance. For example, Student A corrected Student D saying, “Student D, you sing it too fast. Try to do it slower.” Of course, it was followed by peer coaching and in this case, Student A and Student E taught Student D how to sing the melody at accurate tempo.

Consulting Peers

It was heartening to observe how the coaching and correcting part did not turn out to be one-sided as there were many instances in which members who were not so musically-inclined asked the more musical members for help. For example, in choosing a percussion instrument to play the rhythmic ostinato, Student J asked Student G whether it was better to use the egg shaker or tambourine. Student H asked Student G to teach him how to sing the melody, “How to sing again?” On a separate occasion, Student D asked Student A what he should play for rhythmic ostinato before she replied, “tika tika ti ti rest” while demonstrating how to play the rhythm on the percussion instrument. Student C also clarified with Student B which notes to remove for the pentatonic scale, “Which are the notes we have to take out, B and what ah?” as he removed the bars from the metallophone.

Besides asking for help, there were also instances where students consulted each other for decisions. For example, Student B consulted Student A in deciding whether she should play the higher octave or lower octave for the melody played on the xylophone.

Justifying Musical Decisions

In Lesson Three when students performed their first composition activity, I questioned my students’ musical decisions from “why this percussion instrument” to “why this rhythm pattern”, then posing some reflection questions so that they were able to learn by reflecting and therefore, improve their performance.

Group 1’s performance was neatly conducted by Student B, but I realised that it was quite short with everyone starting and ending in unison after just a few bars of music. So I posed the group a question, “What do you think you can do for the introduction?” To my surprise, Student A replied, “Bordun play first.” However, I did not want to stop there but probed further by asking, “Why do you think the bordun should start first?” She then replied, “So that it can control the beat first.” From her response, I gathered that she understood the rationale behind the decision made. I also asked the group, “What should come in after the bordun?” and Student B replied, “percussion instrument playing rhythmic ostinato.” They also explained that they would improve their performance by coming in one at a time, but Student B would still conduct by giving the signal for each part to come in.

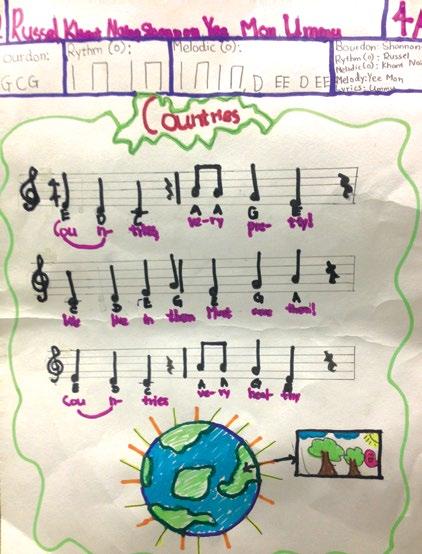

Notation of Group Composition

I asked my students to come up with a score of their composition and some of them surprised me by writing down the notation. They were only given a drawing block to draw their score on and were required to submit it by the end of the day. Some groups wrote simple stick notations and some went further to write in staff notation. This showed their musical understanding throughout the five lessons.

Development of Students’ Leadership Capacity

When each group was asked to decide on their individual roles (group leader, assistant group leader, scribe, time keeper and noise controller), both groups almost unanimously chose those with the most dominant personality. Both group leaders who were elected, Student A and Student F, displayed qualities of assertiveness and outspokenness, which helped them to lead their group. The next most outspoken member in the group became the assistant leader. The decision was somehow unanimous and these students naturally assumed the leadership roles.

From the observations and field notes jotted down, there were a lot of noteworthy leadership behaviours displayed by the four of them: reminding peers to stay on task, mediating disagreement among peers, making final decisions (in the event of disagreements in the group; as seen in Group 2), reprimanding non-participative members, reiterating teacher’s instructions to peers, checking if a member was on task (especially when tasks were divided and done by different individuals), confirming group decisions, and maintaining discipline during discussions by maintaining the noise level. As I coded the transcripts, I realised that the five lessons had given the leaders good opportunities to develop their leadership skills.

To me, it was interesting to observe Student A as I found her to be a very responsible and caring leader. She was the only one who asked for members’ preferences throughout the activities such as asking which instrument they wanted to play or what lyrics they wanted to write down. She facilitated the group discussions well and managed to evaluate members’ strengths before deciding who should be playing a certain instrument. Initially, Student D wanted to play the bordun but when she realised that he could not keep the beat all the time, she asked Student C to try playing the bordun instead. Although Student C was not

that good initially, she felt that it was the most suitable role for him and even made effort to coach him. She showed the greatest initiative compared to other group leaders as she was decisive in how they were to proceed to complete the task. For example, she told her group members that they should change the melody first before changing the lyrics of the song as she felt the melody was more difficult to work on compared to the lyrics.

Another interesting observation from both groups was that both group leaders were more assertive than the assistant group leaders. Yet, the assistant group leaders, Student B and Student G, were the most musical in their respective group. Even at the last lesson, Student E commented, “We worked well together but without Student G, we won’t be able to work together. She was guiding us.” Similarly, in Group 1, Student B was the group “conductor” as she always guided the group in practising the piece.

Although the group leaders seemed to be quite assertive, I found that they were also encouraging. Student E spurred her group on at the last practice before the performance, “Two more minutes to practise. Look at the clock. When we start, only one minute left. Just do, just do it.” Student G also repeatedly told Student H and Student I, who were sometimes detached and easily distracted, “Just try lah!”

Limitations and Recommendations

One limitation of the study was the short time frame in conducting the activities. The short duration was further compounded by the lack of continuity in the music lessons due to disruption in between weeks by public holidays and school events. Thus, the time lapse between lessons meant that some students might have forgotten what they had done in the previous lesson.

Since only ten students were studied in-depth, it is not viable to generalise the findings across the Primary 4 cohort in Singapore. My recommendation is to replicate the study with another group of Primary 5 or 6 students who are better able to verbalise their thoughts and perform higherorder reasoning and thinking skills.

This study can also be extended to analyse the depth of students’ thinking by using some visible thinking tools as they work co-operatively and solve complex problems in groups.

Implications and Conclusion

This study has many implications concerning students gaining from co-operative learning, and music teachers can be greatly encouraged to give students opportunities to create in groups as the learning acquired is priceless. It is also advisable that given tasks be spread across a few lessons so that students have opportunities to work with one another over a longer period of time. This will allow them to solve more complex problems. To set the stage for success, teachers can present the tasks in bite-sizes and give proper scaffolding during the process. This will create a conducive environment to learn where students are assured that the tasks are doable and they are given support to succeed. When students are more ready to solve a more complex problem on their own, teachers can then empower the students to make more decisions in solving the problem. This approach will encourage students to take ownership of their own learning.

As reflective practitioners, educators should exercise our professional judgement whether we can stretch our students further by challenging them with more complex problems. With a student-centric approach in music learning, our role as teachers shifts from simply imparting knowledge to that of helping our students discover knowledge. As such, there is a need for mindset changes and for us to develop facilitation skills or questioning techniques to provoke

critical thinking. This will also equip teachers to be better lesson facilitators. If we are able to conduct student-centric lessons in our classroom, our music lessons will not only enhance students’ musical understanding but also allow them to internalise their learning and develop their socialemotional competencies (SEC) and 21CC. For example, if we continuously get our students to reflect on their own actions and decisions over a course of time, not only will our students have a deeper understanding of the content but they will also likely be more reflective and critical in their thinking.

Finally, I strongly encourage music teachers in the fraternity to try out similar activities of co-operative learning simply as the students themselves gain the most out of enjoying the learning process. At the end of this study, I realised that there is so much learning taking place during these group composition activities and truly, this has countered my initial reservations about teaching music composition. I now believe that through music lessons, we can impart students with 21st Century Competencies to prepare them for the future.

We get together to work on the task and we can hear different, funny and better ideas from each other.

[Student G, Reflection Journal]

We all had fun and enjoyed ourselves very much while composing the song.

[Student B, Reflection Journal]

I learnt something; you will never know you can if you never try. We succeeded in solving the problems by telling each other’s mistake and asking them to improve.

[Student C, Reflection Journal]

References

Auh, M. & Walker, R. (1999). Compositional strategies and musical creativity when composing with staff notations versus graphic notations among Korean students. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 141, 2-9.

Blair, D. (2009). Stepping aside: Teaching in a student-centred music classroom. Music Educators Journal, 95(42), 42-45.

Brophy, T. (1996). Building literacy with guided composition. Music Educators Journal, 83(3), 15-18.

Doyle, T. (2011). Learner-centred teaching: Putting the research on learning into practice. Virginia: Stylus Publishing.

Dunbar-Hall, P. (2002). Creative music making as music learning: Composition in music education from an Australian historical perspective. Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, 23(2), 94-105.

Ginocchio, J. (2003). Making composition work in your music program. Music Educators Journal, 90(1), 51-55.

Johnson D. W., Johnson R. T. & Holubec, E. J. (1991). Cooperation in the classroom. Edina: Interaction Book Company.

Li, M. P. & Lam, B. H. (2005). Cooperative learning. Retrieved from http://www.ied.edu.hk/aclass/

Ministry of Education, Singapore. (2010). Competencies for the 21st Century. Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/ press/files/2010/03/21st-century-competencies-annex-a-to-c.pdf

Peterson, C. W. & Madsen, C. K. (2010).Encouraging cognitive connections and creativity in the music classroom. Music Educators Journal, 97(2), 25-29.

Sapon-Shevin, M. (1994). Cooperative learning and middle schools: What would it take to really do it right? Theory into Practice, 33(3), 183-190.

Slavin, R. E. (1984). Students motivating students to excel: Cooperative incentives, cooperative tasks and student achievement. The Elementary School Journal, 85(1), 53-63.

Slavin, R. E. (1986). Using student team learning. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Center for Research on Elementary and Middle Schools, Johns Hopkins University.

Slavin, R. E. (1991). Cooperative learning and group contingencies. Journal of Behavioural Education, 1(1), 105115.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In Mind and Society (pp. 79-91). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wiggins, J. (1989). Composition as a teaching tool. Music Educators Journal, 75(8), 35-38.

Wiggins, J. (1994). Children’s strategies for solving compositional problems with peers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 42(3), 232-252.

Wiggins, J. (2005). Fostering revision and extension in student composition. Music Educators Journal, 91(3), 35-42.

“Through pedagogical research, we learnt that we have to go beyond considering the instructional methodologies of teaching and learning music, to consider how we as teachers can give our students a deeper learning experience to build their understanding in the music making process. Thought must be given to what is the most appropriate approach even as we provide a range of music learning experiences to meet the varied learning needs of our students.

Pedagogical research has given us the opportunity to develop a better understanding of how students look at music, how teachers look at music teaching, and how we can make it meaningful for both parties.

Assessing our current practice builds our understanding of how students are learning, affirms our existing good practices and gives us a way forward in developing approaches which are more likely to be successful in sustaining students’ interest and passion for music learning.”

Use of Reflective Practice in Developing Students’ Listening and Ensemble Performing Skills in Guitar Ensemble Co-Curricular Activity

Chen Li Yan, Huang Yewei Martin

St. Patrick’s School

Abstract

This research study examines the use of reflective practice as a tool to capture students’ music learning in listening and ensemble performing skills. Students’ perception and views on the role and effectiveness of reflective practice in facilitating their music learning are also explored in this study. Data were collected from these reflection journals, video recordings, and reflective dialogues. The qualitative results revealed that reflective practice creates a platform for students to become more aware, and hence, take greater ownership of their own musical learning. This acquisition and practice of soft skills in reflective practice in music learning are aligned with the development of the 21st Century Competencies and social and emotional competencies for which Singapore schools are equipping our students. Results of the findings carry implications for teachers to explore the approach in infusing and promoting a reflective culture for our students that supports the teaching and learning of these competencies and skills.

1. To what extent is the use of reflective practice effective in examining the musical learning experiences in students?

Introduction

The Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) has been steadily making the transition towards student-centric values-driven education through the teaching and learning of thinking skills and 21st Century Competencies (21CC) (MOE, 2014). The 21CC framework (MOE, 2010) focuses on the importance of equipping our students with the values, competencies and outcomes they must have to thrive in today’s rapidly changing society. With the growing nation-wide emphasis on development of skills for lifelong learning, we realise the increasing need to develop students as reflective learners. Using reflective practice to help students identify their own strengths and weaknesses as well as make responsible decisions, we sought to raise self-awareness in our students and inculcate in them a greater ownership of their learning, which are part of the social and emotional competencies specified in the 21CC framework.

According to the MOE 2015 Primary / Secondary General Music Programme Syllabus, music learning plays a role in developing 21CC in our students. The processes of creating and performing ensemble music provide a natural platform and opportunity to engage our students in decision-making. This is in line with the greater emphasis on Co-Curricular Activities (CCAs) in schools as another important platform to develop these competencies. In our school, structured reflective practice, such as use of reflection journals and reflective dialogue, had been used widely in our students’ leadership training camps. However, it had not been widely extended to the CCA groups, in particular, the music CCA groups in our school. In our study, we sought to experiment and examine the use of reflective practice as a tool to capture students’ musical learning experiences on an instrument. The research questions that we addressed are:

2. How can reflective practice facilitate the development of ensemble performing skills in a new ensemble setting?

3. What are the students’ perceptions concerning the value of using reflective practice in their musical learning experiences?

Literature Review

The ability to step back from events to evaluate the effectiveness of actions, make judgements, exercise responsible decision-making, and explore possible alternatives, are important skills for students to develop. The results of the findings provided some evidence for the development and acquisition of soft skills, in line with 21CC.

While reflection engages students in a metacognitive thinking process (Burwell, 2005), it also enables them to reconstruct their experiences and deepen their reflection. It is a vehicle whereby students can articulate their thinking skills that go beyond being mere knowledgebased and practice-based. This critical thinking skill makes practice more efficient because when musicians possess a certain amount of metacognition about their practice, they can think about what they need to do in order to improve (Parncutt, 2007). According to Bolton (2005), this level of self-evaluation is also recognised as part of the development of an independent learner.

One approach for facilitating reflective process is through the use of the learner journal, which is an accumulation of material based on the writer’s process of reflection (Moon, 1999). Burnard and Hennessy (2009) also noted that journaling is an approach to providing a platform that stimulates reflection as it not only allows the capturing of thinking, but it also helps the writer to connect knowledge and ideas. Journaling is also a vehicle used for logical extension of the types of thinking in class (Knowlton, 2013).

Learning seems to be enhanced during journaling when students develop a greater awareness of their own thinking and monitor their learning progress. This has the potential to allow students to set realistic learning targets for their own development. It is generally recognised that the journal provides a focusing point in encouraging the writer to make sense of information about the subject matter (Burnard & Hennessy, 2009). In the study by Latukefu (2009), the student participants highlighted that writing assisted them in thinking

and problem solving. The journals provided an opportunity for students to solve a problem by thinking about the solution, carrying out the solution and then refining the solution, if needed. The benefits of journaling is further supported by Dart et al. (1998) as their findings revealed that journal writing aided reflective and metacognitive thinking, as well as provided a means for reconstruction of experiences.

Next, the use of reflective dialogue in the reflective thinking process, highlighted by Lamb (2011), is also a powerful tool to develop reflective thinking skills. Hatton and Smith (1995) shared similar findings that the most common type of reflection was descriptive, leading on to dialogue reflection where further issues and alternative explanations were discussed. Hence, it is important to provide opportunities for verbal interaction to engage in dialogue in order to facilitate reflective action.

Taking an active role in musical dialogues, students can be given exposure to think in a broader context, to identify problems, and to offer effective solutions. This is crucial in providing a richer profile of students’ musical understanding. Results of many studies provide evidence of the use of reflective thinking in the process of music composition (Martin, 2000), but relatively few studies have examined the effectiveness of reflective thinking on students’ learning progress of musical skills; particularly in the areas of listening and ensemble performing skills.

Methodology

Change of Ensemble Setting

For our study, the current Guitar CCA ensemble setting of only regular prime guitars was changed with the introduction of new guitar instruments. The idea for this change began when the guitar ensemble members attended a concert performed with varied guitar instrumentation. Much curiosity was generated among the members when they

saw the new instruments and were enthralled by the different tonality and pitch range that each of these new instruments produced. That spurred us to explore what kind of new experiences these instruments with distinct build and exclusive tones could bring to the ensemble. Hence, we introduced a Soprano Guitar, a Guitarron and a Bass Guitar in the ensemble setting of our study.

Selection of Participants

The study was carried out in a guitar ensemble CCA group in an all boys’ secondary school in Singapore. Eleven 15year old Secondary Three students who had received at most 2 years of guitar training were selected to participate in this research project. However, for a qualitative approach for an in-depth study, we focused only on four members. They are presented in this report using fictitious names: John, William, Matthew and Lucas. These four members were the ones selected to play on the newly introduced instruments (Soprano Guitar, Guitarron and Bass Guitar). The selection of members to the new instruments was done primarily with the matching of the physical size of the instruments with the physical build of the member.

Design of Reflection Journals

Our reflection journal was designed with guiding questions to prompt reflective writing and to encourage more focused and in-depth reflection. We crafted questions that were exploratory and scaffolded, so as to get members to focus on their thinking and to participate in the reflection.

Adapted from the tools for ‘Making Thinking Visible’ (Ritchhart & Perkins, 2008), the use of thinking routines as learning tools was explored to help direct students’ thinking and improve their learning.

Two routines were selected to guide our design of questions in the reflection journal to help structure the students’ thinking and deepen their learning.

A. The ‘See-Think-Wonder’ routine was applied in our designing of Reflection Journal 1 (Appendix 1) to set a platform for students to make and inquire on their observations.

B. The ‘Connect-Extend-Challenge’ routine, adopted in our Reflection Journal 2 (Appendix 2), allowed students to make connections to prior knowledge, extend their ideas and discuss their challenges.

From Reflection Journal 3 to 5 (Appendices 3 – 5), students were given greater space and flexibility to reflect on any relevant subject areas. However, there were still some guiding questions provided to help direct their thinking.

The Reflective Practice Lesson

A briefing was first conducted for all the members during the last week of the June holidays on the objective of the research study and their role in this study. Details such as completing a journal at the end of CCA practice sessions and videoed reflective dialogues between selected members and teacher-researchers were also highlighted during the briefing.

The study was implemented between July and September 2014 of Term 3, from Week 2 to Week 11. Every guitar practice session lasted about 2 hours and all the 11 members wrote an entry in their weekly reflection journals after practice.

Journal 1 in Term 3 Week 2 Journal 2 in Term 3

Journal 5 in Term 3 Week 11 (September Holiday)

Handwritten journals were done for the first two journals and subsequently for Journal 3 to Journal 5, the mode of journaling was switched from handwritten to email. Members were allowed to complete their reflection at home and submit via email by the following day.

There was an inclusion of instructor’s feedback in Journal 3. All the emailed submissions of the members’ Journal 3 reflections were forwarded to the instructor for him to read and provide comments. These comments were then given back to the members to read in the following week.

A short interview with the instructor was also conducted on the following week to get his perspective on the reflection journals. The instructor’s responses in this report are presented using the fictitious name Mr Tan.

Data Collection and Instrumentation

Data was collected in the form of reflection journals, audio recordings of instructor interviews, as well as video recordings of practice sessions and small group reflective dialogues with the four selected members. Some of the questions asked in the reflective dialogues with the four selected members were extensions of the journal questions, prompting them to share a deeper reflection in greater detail and eliciting more responses.

Data Analysis

The video recordings of practice sessions and small group reflective dialogues were transcribed for data analysis. Results of the transcripts and members’ responses to the reflection journals were then coded and categorised into various themes that were inherently connected to the research questions of this study to present the findings.

Findings

The following accounts for the six most prominent themes identified from our data analysis. The themes are: (a) Learning Experiences; (b) Listening Experiences; (c) Technical Challenges; (d) Emotional Challenges; (e) Impact of Instructor’s Feedback; and (f) Perceptions on Reflective Practice.

Learning Experiences

We felt that the majority of the data analysed fell into the category of addressing the members’ learning experiences. For example, the following was what John wrote:

I learnt that the flat, natural and sharp signs are located on the left of the note. I also learnt that a sharp is one semi-tone higher than a note while a flat is one semi-tone lower… I learnt that a crotchet is one beat and that a dotted note is multiplying 1.5 beats to it.

[Journal 04, 1 Aug 2014]

From this entry, we can picture how John might have struggled with recognising flats and sharps on his guitar at the beginning. However, by his fourth journal, he could describe the differences between the flats, sharps and dotted notes in his music rather confidently.

Another common thread found within the students’ responses was about the development of instrumental skills and how it affected the musical sounds produced. This was what William commented on his first attempt to play his new instrument, the Guitarron:

...put hand at an angle and when you play, you play in a circular motion and at the largest angle of hand of the circle. Your hand is closed to about hundred and seventy degrees when you play…

[Reflective Dialogue 01, 11 July 2014]

It is worth noting that the introduction of reflective practice has given us an opportunity to keep track of the development of William’s individual instrumental skills, as seen in his third reflection journal:

I used more hand strength to get the note out and sound nice. This will come with practice as it trains my strength over time.

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

Similarly, John also discussed his own instrumental skills, in particular, new playing techniques such as pizzicato and tambour.

(pizzicato) ...placing the side of your palm on the saddle and using your thumb to play the strings. This will produce a muted sound.

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

(tambour) …tapping the bridge with your thumb while holding a chord. One thing that helped me was that I already knew the chords. Another thing that helped me was that I was already used to tapping the bridge because I had a part earlier in the piece that required me to do it.

[Journal 02, 18 July 2014]

We believe that with the introduction of reflective practice, it provided the members a focus point where they could make sense of and develop their understanding towards their individual musical learning as seen in the above journal entries.

Clear statements of their learning experiences existed within most of their reflection journals. As the members reflected upon their ideas, they not only understood the content, but also gained experience and developed deeper understanding of themselves. Thus, we agreed there was potential for developing greater awareness in their learning processes through the use of reflective practice.

Listening Experiences

We observed that with the change of an ensemble setting through the introduction of new guitar instrumentation, it resulted in members examining and articulating the different tonality and pitch produced by these new instruments:

Crisp and soothing sopranos, complimented by the booming and mellow Guitarron meant a bigger diversity in terms of sound. It gives more energy to the music we play due to the different ranges... these new parts make the piece sound very nice and appealing to the audience because of the range of the sound…

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

On another level, we also managed to make use of the members’ reflective dialogues to further validate the above comments. The following entry allowed us to consider that the members were now more aware of how these different sounds complement each other in the ensemble:

…it’s like re-energised, this whole ensemble was reborn with new sound. Because it was just all the same instruments but now we have deeper bass and much richer substance. So now it’s more, it’s different, it’s fun, it’s energising to hear more sound, more lively music instead of the same old guitar.

[Reflective Dialogue 03, 25 July 2014]

Similarly when we introduced a higher-grade prime guitar (from 2C to 4P prime guitar and Z series prime guitar) to the ensemble, the members who had the change revealed the following in their last reflection:

…especially with the new instruments, the two new 4Ps and the Z Series… I can say that the instrument sounds truly amazing. It seems much easier to play as well. I was able to play a certain part of a song which I could not play on my old guitar. That made me really happy. Sound wise, the 4P sounds much clearer and louder, and it seems to sound brighter and I like that...

[Journal 05, 8 Sept 2014]

The above entries showed us that reflective practice provides potential as a tool for the development and acquisition of a musician’s listening skills. It is reasonable to understand the members’ anxiety and excitement towards their new listening experiences since this was the first time they were introduced to the playing of these new instruments. Nonetheless, we felt it might be worth exploring the continual effects of this novel experience.

Technical Challenges

From the data collected, we gathered entries that described some of the various challenges, in terms of instrumental skills, that the selected members were facing. For example, the following was what Lucas had to overcome when playing his new instrument, the Soprano Guitar:

…the fret board is very small… When pressing the string it’s very painful on my finger…

[Reflective Dialogue 01, 11 July 2014]

…tension of string on soprano is very high… very hard to press… learnt to play the soprano with skin and nails.

[Journal 02, 18 July 2014]

Likewise, we found a similar entry from William, with regard to the physical challenge he faced when playing his new instrument:

Because after playing for a while the shoulder gets tired and then my hand tends to shrink back a little bit. And then it goes out of position instead of playing the right string. I end up playing one string higher or lower.

[Reflective Dialogue 01, 11 July 2014]

And again:

The notes are also difficult to find as there are no frets on the Guitarron so I have to use my hearing to get the right pitch. This adds more multitasking as I not only have to read the notes and count... but also have to ensure that I get the right pitch.

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

We feel that the challenges mentioned above could also be due to the members’ lack of experience and prior knowledge on how to best handle their instruments. Nonetheless, we believe that the implementation of reflective practice allowed them to pen down these concerns and made them aware of these challenges while in the process of wanting to improve on their handling of their new instruments.

Another form of technical challenge that we also identified from the data collected was the grasping of certain elements of music, like rhythm. For example, Matthew wrote the following:

Confusing part is the rhythm when playing without the other sections… hard to catch up…

[Journal 01, 11 July 2014]

We found a similar entry from William’s reflection journal:

…unorthodox 6 beat timing (rhythm) is different from the songs we were used to…

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

Similarly, John mentioned the following:

I learnt that a crotchet is one beat and that a dotted note is multiplying 1.5 beats to it. This was very useful and something new I learnt today. Today, I also learnt a new rhythm exercise that was different variations to the C major scale. This helped me improve my rhythm.

[Journal 04, 1 August 2014 ]

We believe that rhythmic playing will remain a constant challenge for most of the members throughout the research study and even beyond. This is inevitable as they progress to more challenging pieces of music where rhythmic playing can become more complex. However, as we observed from John’s final entry, it showed us that aided by reflective practice, there were some signs of improvement in grasping the rhythm and a sense of understanding on how to improve their rhythmic playing.

Emotional Challenges

We made observation of this particular category as we were interested to find out if the technical challenges, mentioned previously, had any impact on the members’ emotional wellbeing. We were duly rewarded with some interesting entries and recorded dialogues that allowed us to examine the members’ affective development. Matthew, in particular, was very expressive about the challenges that he was facing:

It’s one of the biggest things I am shameful about, because rhythm is something so important about music, yet here I am, not being able to do it correctly or understand fully what it is.

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

And again:

…not familiar with the song and percussion part yet. We often come in late and I feel worried when we play because I would be stressed out that I’m playing the wrong part.

[Journal 03, 25 July 2014]

However, not all entries that we were able to identify were negative. For example, the following was what John wrote about the ensemble group’s progress:

…More people can play their part. Correct tempo… Good, we’re making good progress.

[Reflective dialogue 02, 18 July 2014]

Similarly, Lucas wrote the following positive and glowing comment:

…feel happy about the improvement that I have achieved… Over the past few weeks, I have grown my nails to play the soprano with a better sound and also trained my fingers to press the high tension strings.

[Journal 04, 1 August 2014]

From the statements above, it is significant to know that through reflective practice, these members were again more aware of the progress they were making and how they felt about it.

Impact of Instructor’s Feedback

With the introduction of the instructor’s feedback, we were interested to find out what kind of impact or effect it had on the members’ musical learning. The following was from one of the entries made by John:

…I also wrote that I didn’t know how to play louder… Mr Tan took that into consideration and he told me to use more force and… that’s why I can play much louder (today)…

[Reflective dialogue 02, 18 July 2014]

We managed to find a similar entry from Matthew:

…the feedback is very helpful to the way we learn… we’re telling him (Mr Tan) about our problems and he writes back on how we can help ourselves instead of relying on him…

[Reflective Dialogue 04, 1 August 2014]

Another entry, by William, was also akin to what Matthew and John wrote:

…it (the feedback) was encouraging and we felt assured that we are not alone in our troubles…

[Reflection Journal 04, 1 August 2014]

In general, most entries that we collected highlighted a positive response towards the introduction of feedback as part of their reflective practice. We realised members observed that their instructor took their concerns into consideration and thus, helped make their subsequent practice sessions more fruitful.

It is also worth noting that through providing feedback, it also helped members reflect on what was taught in the previous practice and, moving ahead, how to better apply the skills taught into the next few practice sessions. We feel that the following entry made by John aptly describes this:

…Mr Tan’s comments were really useful today… now I can read the notes because I know the semi-tone difference between sharps and flats… And the angle of attack on the strings… as I could play much louder today…

[Reflective Dialogue 04, 1 August 2014]

Perceptions of Reflective Practice

Reflective practice seems to provide opportunity to reconstruct the ensemble members’ experiences and deepen their thoughts. This was found to be the case for the majority of members in this study, with the journal acting as a means of documenting their rehearsal processes, recording their development as a performer, and helping them to recall what they had learnt on a specific day. From the entries submitted, we were able to evaluate the effectiveness of their learning as they progressed. For example, Matthew commented the following:

I feel the reflection journal for me is a great tool… when I look back at those things, oh this could be improved on or I wish I could have done this or maybe I could have done this better. When I look back I want to see… what I read, what I wrote before, I want it to be better than who I am currently… I feel like it gives me a sort of a goal.

[Reflective Dialogue 03, 25 July 2014]

From Matthew’s comment, we concur with his belief that reflective practice can be used as a possible platform for members to reflect on their own performance and identify their own areas of weakness. Matthew further reinforced his belief through one of his journal entries:

…figure out and really think of my flaws in the instrument I play... allowed for me to recognise the problem in my music playing and allowed for quicker fixing than just sweeping the problems under the rug.

[Journal 04, 1 Aug 2014]

This supports previous research findings which emphasised that such a level of self-evaluation is recognised across all areas of discipline as being important in the development of the independent learner (Bolton, 2005). It can further be used to motivate members in the achievement of a variety of specific performance skills.

Other than feedback from the members, we were also able to gain some insights from the instructor with regard to the use of reflective practice:

…it’s

a good avenue for me to tell the student what I feel and it’s a very intimate way. They don’t have to see my face or feel that I’m scolding them… it’s a good way to dialogue and to record... the dialogue can continue...

[Interview with instructor, 1 Aug 2014]

We were able to see that reflective practice provided both the instructor and the ensemble members with the opportunity to develop a productive interactive relationship through a constant exchange of views. Members sought advice from instructor on music related performance problems. On the other side, viewing students’ reflections about how they played, the types of challenges they faced, and how they attempted to overcome these challenges, the instructor was able to better adjust the level of guidance and insight to offer to the members. The journal entries from the members further provided the instructor a profile of their growing music understanding.

However, we also recognise that students need the time and space after an event to record their questions and actions, and to critically reflect on these events and processes through writing, conversation and interaction with peers (Smith, 2001). This was typified by the entries from two members who highlighted the negative factors in the processes of reflective practice:

…generic answers… a model answer kind of thing. Not something that they actually think about, just to get it over with...

[Reflective Dialogue 03, 25 July 2014]

...honestly I feel that it (reflection journal) only helps temporarily as:1: It depends on our moods how sincere our reflections are

2: Not everyone agrees with having to write a reflection journal

3: Most of us lose interest after a while

[Journal 04, 1 Aug 2014]

As seen from the above responses, we observe that to garner a rich and fruitful experience from reflective practice, it is worth exploring how best to implement this, as external factors like time and spatial constraints can have an effect on the way the members approach their reflection.

Discussion