STAR POST (ART)

“Most great learning happens in groups. Collaboration1 is the stuff of growth.” — Ken Robinson (2010)

In this issue of STAR POST, we invite you to navigate the different group learning environments: to respond to artworks collectively, engage in collaborative dialogues about art processes and works of art, and partake in community art experiences that harness the richness of our diversity. As you read, we encourage you to reflect on the pedagogical approaches that will help build a learning culture of care, mutual trust and connectedness, and where every child’s ideas, dreams and aspirations can take flight.

The old African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child”, is an apt reminder of the need to actively collaborate with our fellow art teachers and our art partners such as the museums, creative industries, art practitioners, and community groups. Doing so is sometimes humbling and enabling. We hope the ideas presented here will help us envision possibilities, and support us to provide our students with the quality art education that they deserve.

Let’s journey together! Enjoy the read.

1 STAR POST Issue 1/2016 focuses on Planning for group learning and collaborative art-making, which is one of the four distinctive and effective art teaching practices that foster emerging 21st CC, as identified in the PAM Research Report: Enhancing 21st Century Competencies in Physical Education, Art and Music (2015).

Read about group learning and collaborative art-making in STAR’s new publication, Inquiry In and Through Art: A Lesson Design Toolkit (2016), p. 42–44.

I am in New York City, looking at a reproduction of Chen Chong Swee’s After Bath, a work on paper from 1952. I first saw this painting in Singapore, as I walked around the newly opened National Gallery Singapore in January 2016. I was excited to see the beautifully renovated building and the collection within it. I was also hoping to select a few artworks for the teacher workshops I was scheduled to lead the following week. As some of you may know, STAR had generously invited me to conduct a couple of teacher workshops on facilitating meaningful encounters with works of art.

After Bath was one of the many works that caught my attention during that first museum visit. Looking back, I think I was compelled by the gentleness of the painting, as well as by the narrative it suggests. Now, as I look at the image almost two months later, the scene seems even more compelling; in so many ways, it feels more real and alive. What led to this enhanced sense of the work, you may wonder? It is no exaggeration to say that I owe it to a group of Singaporean art teachers, and to their perceptive responses to Chen Chong Swee’s creation.

To explain, let me backtrack for a moment. As I finalised my planning for the workshops, I indeed decided to introduce After Bath to participating teachers. More specifically, I decided to use this image to model what a guided dialogue about a work of art might look and feel like. With this goal in mind, I projected the image onto a screen1 and invited the group of teachers to observe it closely. This act of observation soon led to insights, questions, and interpretations, which in turn triggered deeper observation and further comments. The group’s collective response evolved and built up over time as participants continued to take in the work with increasingly acute eyes and minds, while also

considering and responding to each other’s contributions.

The teachers’ comments brought me right into the world of After Bath Early on, it became clear that this scene is set on a hill, or at the top of a ravine. I imagined what I might see if I looked down from where the women are. I conjured up the fresh scents of nature, and the feeling of earth beneath bare feet. I heard evocative sounds in my mind (birds? silence?) and envisioned the humble village beyond the gate. I understood in new ways the fragility — and importance — of the wooden bathhouse behind the figures, as well as the human care suggested by the objects piled neatly against it (buckets? soap? a broom?). The potted plants reinforced this sense of care. And then, there were the three women, casual, relaxed, comfortable with each other. Participants considered, what might the nature of their talk be? Or might they simply be sharing a quiet moment? The easy fluidity of Chen Chong Swee’s brushwork, the gentleness of the lines, the softness of the colours, all became characters in themselves as the conversation progressed. So did the patterns on the women’s clothes, which helped participants place this scene somewhere in Southeast Asia.

Try as I may, I will never successfully replicate through writing the experience of evolving inquiry, discovery, and meaning-making that transpired in real time as these art teachers interacted with the painting and with each other. What I nevertheless hope to convey is that these viewers’ insights, questions, and observations activated After Bath in a poignant way, enabling me — and hopefully others in the room — to become participants in the world Chen Chong Swee created back in 1952. Or, perhaps it is more apt to say that we were co-creating the world of After Bath — albeit driven by the highly specific visual prompts embodied in the painting.

I share this experience — just one of countless delightful learning moments I had in Singapore — in the hope of illustrating a couple of ideas that, in my view, are essential to the work of those who mediate experiences between viewers and artworks. The first one is that, as thinkers including Hans-Georg Gadamer, Louise Rosenblatt and others have posited, the meaning of a work of art is inexhaustible. It always goes beyond the artists’ intention, and continues to reveal itself with each new

As we help activate art objects for learners, we also have the luxury of gaining unique access to these objects: We watch them unfold, time and again, through the eyes and minds of diverse viewers.

encounter. So, it is quite possible that Chen Chong Swee may have had some very specific thoughts about this painting. Perhaps a renowned critic or art historian, too, may have commented authoritatively on After Bath. However, the teachers’ responses, their own experience of the work, were valid and significant in their own right. Moreover, as our group’s response brought the work to life in fresh ways, it contributed to After Bath’s ever-evolving meaning (even if, at that particular point, we were the only ones aware of it).

The second idea — closely interrelated with the first one — is that the term “meaning” need not refer to a propositional explanation such as, “The meaning of After Bath is …” or “After Bath is really about …” Instead, as aestheticians including Wolfgang Iser have suggested, the meaning of a work of art can have the structure of experience. That is, the meaning of an artwork can include the shifting ideas, and emotions, and sensorial responses that emerge as a spectator engages with the work in real time. From this perspective, in the teachers’ experience with After Bath, the meaning of the work would be all that emerged as the group responded to the work through conversation: What was said, what was imagined, what was felt and sensed — both individually and collectively.

Embracing these notions of “meaning” makes our job as art educators both harder and more exciting. Harder because, if we see meaning as something that is experiential and ever-evolving, our responsibility is no longer to learn some facts about a work of art, and then pass them on to students in top-down fashion. Instead, our task becomes to create spaces where fresh responses to works of art can thrive. This challenge brings excitement to our practice. As we help activate art objects for learners, we also have the luxury of gaining unique access to these objects: We watch them unfold, time and again, through the eyes and minds of diverse viewers.

Many of us have learned to think about teaching as an altruistic, selfsacrificial practice, where our own selves must be put to the side so we can serve others. Inspired by philosopher of education Chris Higgins, I like to take a different stance. I believe that the nurturing and human flourishing of teachers is essential to both our lives and our practices. To

bring this point home: As I facilitated the encounter with After Bath, not only did I (hopefully) help participants experience the painting in rewarding ways — I, too, had a deeply fulfilling experience, one that will forever colour my sense of After Bath, and help fuel my work as an art educator.

It seems random, in a way, to focus this short article exclusively on the experience with After Bath. After all, the teachers who participated in my workshops responded to other artworks in ways that were equally poignant and inspiring. Also inspiring were so many other interactions I had during my two weeks in Singapore. The forward-looking vision of art education propelled by STAR; the ingenuity and dedication of the museum educators at the Singapore Art Museum and the National Gallery Singapore; the deep commitment and inquisitiveness of art teachers across primary and secondary schools; the formidable artwork of children, adolescents, and professional artists; the warmth and generosity of colleagues who introduced me to the local foods and ways of life. How humbling it was to have the opportunity to learn from all these offerings. After two stimulating weeks in Singapore, I return to my work not only with several new artworks alive within me, but also with renewed energy, and with a broader, deeper vision of what art and museum education can be.

1 It would have been ideal to do this work with the original painting. Unfortunately this is not always possible for logistical reasons.

View Chen Chong Swee’s After Bath (1952) at http://bit.ly/1S2OfmZ

Access summary of workshop Three Kinds of Dialogue about Works of Art, by Associate Professor Olga Hubard, conducted on 19 January 2016 at: http://bit.ly/22juWIQ

… I believe that interactive experiences with works of art, at their best, can help people become wideawake to themselves and their worlds and bring them into particularly close, vivid contact with aspects of what it means to be human. In this age of efficiency, when the focus of so much education is on outcomes that are readily measurable, meaning-full encounters with art and their humanizing potential strike me as experiences that are well worth nurturing and protecting.

… meaningfulness takes place when works of art, and the experiences they stimulate, enter viewers’ lives in ways that matter, in ways that feel alive and relevant.

Gallery dialogues are championed by those who advocate constructivist pedagogies — an approach to education where learners inquire and construct meaning for themselves, building on their past knowledge and experience. In addition, gallery dialogues embody the much-theorized notion that the meaning of a work is not a fixed entity to be unearthed, so to speak, but something fluid, multi-layered, and inexhaustible that continues to be shaped as each new spectator interacts with the work over time.

… I envision spaces where viewers are invited to observe artworks with fresh, curious eyes; spaces where participants feel safe sharing a diversity of responses — thoughts, feelings, wonderings, imaginings; spaces where trust and respect contribute to genuine collective meaning-making processes. I also picture spaces where explorations of artworks are deep and thoughtful and playful, where artworks and their various facets come to life, and where the unexpected is as welcome as the tried and cherished. In such spaces, regardless of the questions educators may or may not ask, and regardless of whether words such as “joy” and “sorrow” and “fear” are even uttered, emotions — along with the other ways of knowing that make up our human minds — are sure to enter meaningfully into people’s experiences of art.

u Mdm Chun Wee San, Programme Manager (Art), STAR

Acknowledge all students’ responses and do so in a consistent manner (Hubard, 2015), hence encouraging wideranging perspectives. Every contribution enriches the experience of interpreting an artwork and unveils the layers of meanings embedded in the work. New meanings (including unexpected and surprising ones!) emerge as the work is interpreted and re-interpreted, and teachers play a crucial role to stimulate that flow of insights. “… good gallery teaching works to discover meanings rather than to assign meanings to works of art and that educators must avoid assuming an authoritative voice, in order to allow visitors [students] to construct their own meanings” (Burnham & Kai-Kee, 2011, p. 59). Dewey once said that it is the viewer’s interpretation that keeps the work alive (Dewey, 1934), so show your appreciation for students’ input: “Thank you for bringing this work to life!”

Pose open-ended questions, use conditional language

Open-ended questions are essential in a generative conversation about artworks as they invite varied responses that emerge from multiple viewpoints. By asking open-ended questions, teachers model for students that there is more than one way of looking at artworks, that artworks are multi-dimensional and multi-faceted in nature. Do also use conditional language (“What might the people be thinking or feeling?”, “Why do you imagine the artist might have chosen this painting style?”), as such language suggests possibilities, alternatives, and an open-ness to ambiguities. Scholars have reminded us that the meaning of an artwork extends beyond what the artists intended (Eco, 1989), thus interpreting artworks is not merely an exercise of guessing the artist intent or figuring out what the teacher is thinking. Open-ended questions can help to provoke a rich variety of fresh perspectives.

Encourage students to share their observations (“What is one thing that caught your attention?”, “What else did you notice that have not come up in the conversation?”), offer their opinions (“Do you agree or disagree with what was shared? What makes you say so?”, “What do you find most interesting about the work? Why?”), or connect to personal experiences (“Does this bring to mind something that you are familiar with?”, “Which of the characters in the artwork can you connect to most?”). Burham and Kai-Kee (2011) noted that “… the encounter with artworks is as much a matter of the heart as of the mind, that learning about artworks is motivated and held together by emotion as much as by intellect”. In that respect, students are more likely to be engaged when they are emotionally connected to the artwork and the conversation about it.

As the dialogue unfolds, be attentive to students’ verbal and non-verbal responses. Give students time to think and support them in making their thinking visible by probing deeper with facilitative questions and paraphrasing what they say. Nurture attentive and respectful listeners amongst students as well, and build a community of inquiry where every voice matters and divergent ideas are celebrated. Role model for students what it means by listening with care, considering others’ viewpoints (“What’s another perspective on that?”, “How does the information on the label support or change your experience with or understanding of the work?”), and building on one another’s ideas (“Would anyone like to add to what was shared?”, “Who would like to elaborate …?”, “Anyone else would like to keep going with that idea?”). Teachers should “link answers that relate, even when there are disagreements. Show how the students’ thinking evolves, how some observations and ideas stimulate others, how opinions change and build.” (Housen & Yenawine, 2001).

Barrett, T. (2004). Improving student dialogue about art. Teaching Artist Journal, 2(2), 87-94. Burnham, R., & Kai-Kee, E. (2011). Teaching in the art museum. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. Dewey, J. (1934/1980). Art as experience. New York: Perigree. Eco, U. (1989). The open work. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Housen, A., & Yenawine, P. (2001). Basic VTS at a glance. New York: Visual Understanding in Education. Hubard, O. (2015). Art museum education: Facilitating gallery experiences. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Hubard, O. (2016). Three kinds of dialogue about works of art. Lecture, Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts.

u Mrs Vivian Tan, Head of Department (Aesthetics), St. Joseph’s Institution

Imagine walking into an art classroom filled with beautiful paintings hung neatly on the walls. The students, seated in groups, work quietly. The teacher sits in a corner of the room and calls out the students’ names one at a time. Picking up their artwork, they eagerly approach her for feedback. Upon seeing this, you might exclaim, “Wow! This teacher has fantastic classroom management skills!”

I used to perceive these characteristics as essential to the ideal art classroom, one that is ever-ready for an unannounced visit by the school administrators or visitors. I teach art to students from 13 to 16 years old. Although collaborative learning among students is encouraged, many teachers are hesitant to explore the potential of student-peer interaction in their classrooms, and prefer a teacher-centered approach because it is more manageable. In comparison, they view studentpeer interaction as time consuming and are uncertain about the depth of learning that takes place during such an interaction.

Lev Vygotsky (1978), a developmental theorist and researcher, first wrote about the importance of both teacher-student and student-peer interaction in the process of learning in the late 1970s, and it has had an important impact on the educational environment ever since. As a committed art teacher, I want to engage my

students in learning actively. This has resulted in me having to give up some of the control I have over the class, and the belief that I am the sore information provider within the art classroom. According to Jaquith and Hathaway (2012), knowledge gained through first-hand inquiry is powerful. I wish to give autonomy to my students so that they can acquire, develop knowledge and skills through personal and collaborative paths.

Research has revealed that the biggest hindrance to effective discussions is that teachers have a difficult time shifting from an information-giving role to that of a facilitator (Dillon, 1987). Teachers tend to dominate class discussions, turning them into mini-lectures with one-way communication. As a practicing art educator, I undertook a six-week qualitative case study in order to yield rich insights into how I might improve my teaching. Data were collected through journaling, audio recording, student journals and interviews. Through my research, I found that when I changed from a teacher-centered approach to encourage more collaborative dialogue among my students, they became more engaged, and there was a stronger sense of community within the class.

I propose that an investigation focused on art pedagogical practices that might enhance my own ability to facilitate meaningful collaborative dialogue among my students might include a focus on five attributes of meaningful collaborative dialogue:

The first attribute is an increase in competence level. At the start of the art lesson unit, when collaborative dialogue was newly introduced, some students appeared to be under pressure when they could not come up with ideas to contribute to the discussion. They were uncertain about how to ask constructive questions. Others thought it was a waste of time when they did not receive the feedback they wanted from their peers. During the middle and late phases of the lesson unit, the students became more confident and comfortable talking with their peers about art. In some cases, the discussion extended to the sharing of personal intentions, where art and life overlapped. This suggests that collaborative dialogue becomes more meaningful over time and with practice.

Secondly, time set aside for listening, reflecting, and talking. I have observed that thinking takes time, and learning how to respond takes more time. It is important for teachers to help their students slow down or allow time for them to talk to their peers and write about their feelings and responses to their aesthetic experiences (Heid, 2005). Conversations between peers become more meaningful when teachers allocate time for students to listen, reflect, and share.

A third important attribute is an adaptation of responsive teaching strategies. While maintaining control, teachers must be willing to step into the background to support the students’ learning needs and growing independence and be ready to step up again when the situation requires it. During the beginning phase of the art lesson unit, I had observed that my students needed time to get used to learning collaboratively. This challenged me to recalibrate my teaching practices — I needed to check regularly on the students to make sure they were talking, asking questions, and listening to each other. During the later phases of the lesson unit, I reduced my involvement when I observed that the students were more at ease with holding collaborative dialogue. Such timely intervention is necessary to meet students’ varying needs for the space to develop meaningful constructive dialogue.

A willingness to listen to diverse opinions constitutes the fourth attribute. Hagaman (1990) has suggested that individuals should be encouraged to listen carefully to the comments of others in a discussion group and be willing to reconsider their own judgments and opinions. According to Willis (2007), coming to a single “correct” judgment for the group during discussions should be viewed as counterproductive to collaborative learning. Students need to develop a willingness to be challenged by others and value this process as helpful for the reconstruction of their own ideas. A willingness to do so will build confidence and resilience.

The final attribute is the establishment of a caring community within the art classroom. Care is defined as the reciprocal relationship between two people who engage in understanding and empathy toward one another (Nodding, 1992). Heid (2007) elaborated on Nodding’s definition by stating that it is the responsibility of the teacher to cultivate an environment that supports

the reciprocation of care in the art classroom. Studies in neuroimaging have shown that when students participate in well-designed, supportive groups, their brain scans reveal significant transference of information from the intake areas into the memory storage regions of the brain (Willis, 2007). This implies that collaborative dialogue is best facilitated in a caring classroom. Reagan (1994) cited Carol Gilligan, who maintains that women tend to be more comfortable with relationships, and their sensitivity to the needs of others makes them particularly receptive to collaborative work. I found that my male students welcomed collaborative dialogue too. They shared that listening to different perspectives exposed them to new ideas and knowledge that they might otherwise not have had access to if they learned independently. However, negative comments not supported by explanation were considered hurtful and unbeneficial. To address this issue, students should be asked to provide reasons for their judgments, reflecting on the criteria employed in making these judgments (Hagaman, 1990).

Unfolding Collaborative Dialogue Practices: A Closer Look at a Teacher’s Self Reflexive Process through Instructional Design

The Gift of Change art lesson unit was designed to facilitate collaborative dialogue within my classroom. Collaborative dialogue refers to knowledge-building dialogue. It is a cognitive and social activity (Swain, 2000). The lesson unit incorporated discussions about brainstorming, creating, and critique throughout the art-making process. Two classes of 14-year-old boys participated in the lesson unit, which was based on the “big idea” (Walker, 2001) of creating change in communities. I found the work of Abigail Housen (1999) and Robin Alexander (2005) to be helpful in designing the brainstorming phase.

At the start of the art lesson unit, the students were given the following prompt:

You are in a situation that you are unhappy with and you wish to see a change. There is an opportunity to meet with the person(s) who can help to change that situation. You decide to make two clay artworks to bring

along for the meeting. The artworks are meant both as a gift and a conversation starter

I introduced artists whose works shared a similar big idea. The first image I showed was Art-Eggcident by Henk Hofstra. Typically, I would start to explain the work to the students. For this art lesson unit, I kept quiet to give the students some time to look at the image.

Anthony: Why did the artist make eggs?

Me: That’s a very good question. Before we answer that, can you tell me the different ways we can cook eggs?

Students: Scramble eggs! Hardboiled eggs!

Me: Good! Think a little harder now. When do you see eggs presented in the same state as Art-Eggcident?

Dusky: When I am hungry in the morning!

Anthony: On the frying pan!

Jerry [very softly]: The streets are frying the eggs. [Some students laugh.]

Anthony: I know! It’s about climate change!

Me: How do you know?

Anthony: Because Jerry said that the streets are frying the eggs, which means that the roads are getting hotter.

[Some students cheer and clap.]

Students: Wohooo!

Me: This is interesting. Anthony, you just mentioned that you built your answer based on Jerry’s comment?

Anthony: Yeah.

Matthew: I think there’s another possible change here. The artist wants to encourage people to harness energy from the heat!

[Some students clap excitedly.]

While facilitating the collaborative dialogue above, I asked questions based on the students’ comments and refrained from giving answers. Many students raised their hands to share their ideas, and I noticed an increase in engagement level. Suddenly they were the ones doing the talking and thinking as they built on one another’s responses to arrive at different interpretations. This finding supported Vygotsky’s (1978) belief that students are able to produce something together that they could not produce alone in an environment that has both structured teacher guidance and collaboration with peers.

My art classroom was transformed during this brainstorming phase. I witnessed how the students gained different perspectives through the incorporation of the skills of listening and responding within classroom dialogue, with a marked increase in the ability to hear diverse points of view. My role in this collaborative environment was to watch for episodes of students’ behavior that provided exemplars and highlight them when they happened, as with the case of Anthony and

Jerry. The students felt it was an interactive lesson and appreciated being able to express personal opinions. Previously, in my non-collaborative art classroom, students listened passively to my explanation about artworks. Those who did not find my explanation interesting became disengaged, resulting in pockets of private discussions that disrupted the class. Learning became engaging and enjoyable when my students were encouraged to express their ideas freely, build on answers, and consider alternative viewpoints. This supported Gibbs’s (1995) finding that showed that students gained a greater level of understanding of concepts and ideas when they talked, explained, and argued about them with their peers instead of just listening passively to a lecture or reading a text.

On one particular day, student-artists gathered excitedly around a few desks that had been pushed together to form a large circle. I had just told them that they would take turns sharing their art-making experiences and artistic intentions with their peers. Sharing as a large class during the art lesson was a new experience for them, as they had often worked independently, turning in work without the benefit of peer critique and affirmation.

Ping’s voice was shaky when he began to talk about his artwork in front of the class. He apologised with embarrassment that his art was about an unpleasant family issue. He likened that to washing his family’s dirty linen in public, “My artwork is about change, and the idea I want to communicate is my difficult relationship with my dad.”

He explained that it had been four months since he had last spoken cordially with his father. He felt that his father did not understand him and mostly talked down to him. Ping had decided to stop talking to him, as they

would always end up arguing. He did not like being in this situation. His first clay piece showed a big smiley face and a smaller one. For the second piece, Ping intended to make a frame to go with the first piece. The frame was supposed to bind the two faces together, and this was his hope: that he could be close to his father again.

There was a deep silence as the class listened to Ping’s sharing. Finally, Scott raised his hand to say that he felt Ping knew exactly what he wanted to do for his artwork and he should carry on with this very strong idea. He only had one suggestion, and that was for Ping to present this gift of change to his dad.

As a teacher observer, I was amazed by the power of Ping’s sharing. I knew the benefits of a critique session, but I had rarely conducted it with my younger middle school students, as I thought that they would be bored listening to others and I would end up dealing with discipline issues. For this lesson unit, the individual sharing was short and focused, and peer response was invited but not compulsory. My students subsequently shared that this process gave them the opportunity to be reflective. Some of them felt that they could use the suggestions given by their peers, while others felt that talking about their own work and listening to others deepened their learning.

As for Ping, the experience of sharing in front of his classmates gave him the courage to make progress. He spoke to his father about his sharing after that class. In the subsequent weeks that followed, he invited his father to go out for meals with him, just the two of them. His father also asked to see his artwork.

The final phase of my art lesson unit traditionally signaled a winding down of activity in the art classroom, when students would hand in their artwork and complete a self-reflection sheet. This was not the case for the Gift of Change art lesson unit. I planned a student-led critique session with three critique formats for the students to choose from: interview, positive critique, and gallery walk. I was eager to find out if my students’ comfort level with collaborative learning had increased over time. Group leaders were appointed for each group, and handheld devices were used to record the discussions.

By removing myself physically from the group critiques, I explored the potential of student-peer interaction and how students learned through such interactions.

Andy comfortably assumed the role of a student-leader for the interview group. He appointed the interviewer for each student-artist and read the prompt clearly to

the group: Imagine you are a young rising artist about to be interviewed by an art magazine. Your manager has prepared eight questions for you to choose from. Select five of these questions for the interviewer to ask you during the meeting. I prepared the eight interview questions before the lesson because some students had shared during the brainstorming phase that a difficulty they faced with peer feedback was thinking of meaningful questions to ask. About 15 minutes into the critique phase, Andy ran up to me excitedly to report that his group had completed all of the interviews. I could see from their faces that they were proud to be on task. The students shared that the interview session went smoothly because the prescribed questions had put everyone at ease. The interviewers need not think of probing questions on the spot and the interviewers could choose from a range of questions to talk about their works. However, some student-artists shared that they would have preferred a chance to contribute one or two of their own interview questions. Interview time should also have been allocated for each student-artist so that everyone had a fair chance to talk about their work.

The positive critique group, on the other hand, went beyond the time limit. Their prompt was as follows: If you were the artist, suggest one thing you would do to improve this artwork. The discussion was not always focused on positive suggestions, but the group members shared with conviction and without inhibition how they felt about the artworks. For example, Adam, the quietest boy in class, was challenged repeatedly by some of his peers regarding his artistic intention.

They felt that although well made, his work did not quite match his intentions. Instead of offering him suggestions, the discussion turned into a debate. Andy shared later that he did not feel that the conversation was helpful in suggesting new ways for him to improve, but he felt he became a stronger person. He knew he was quiet, but he surprised himself when he defended his artistic intentions for over 10 minutes. Ping expressed it this way: “Questions or issues which many people have problems with are worth talking about.”

The prompt for the gallery walk group was the most open-ended: Make personal responses to the artwork after the artist has given a presentation about his works. From the playback of the recording, it was obvious that the discussion went off topic after 5 minutes, with several failed attempts to bring it back on track. The sharing by the student-artists went well, but the members generally did not know how to respond to the artwork and what questions to ask. Subsequently, the members shared with me that some guidelines on what to ask and how to respond would have been useful.

The journey I took with my students to learn about the potential of facilitating collaborative dialogue has opened up new questions for further discussion and exploration. Time was a recurring issue for the students throughout the lesson unit. One student thought that debating an issue was a waste of time because it took too long. Some felt that if their peers were not as engaged, they would rather learn independently so as to not waste time. I saw a need in my future classroom practice to help students understand that learning takes time to develop and broaden.

Vygotsky (1978) argued that children are capable of performing at higher intellectual levels when asked to work in collaborative situations than when asked to work individually (p. 153). In the art classroom, I observed that the student-artists became more reflective of their artwork and art-making journey through collaborative dialogue. As critics, they also became participants and advocates for each other’s creative processes. They walked the creative journey together from the start, when ideas were first conceived. They offered diverse responses on how the work could be improved during critique sessions. These responses had the potential to become a springboard for new ideas. The creative journey in the collaborative art room was not lonely, even though the artists embarked on very personal art-making journeys.

While I valued the efficiency and manageability of the teacher-centered approach, I now perceive collaborative dialogue between student and peer as essential in an ideal art classroom, where students develop significant inquiry when given the space and time to reflect individually and in collaboration. As much as possible, I strive to give my students the autonomy to co-create a collaborative environment where they are both the artists and the critics, and are comfortable assuming both roles.

AUTHOR NOTE

The research for this article was conducted as part of the author’s Master of Arts in Art Education degree from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA). Thanks are extended to MAAE faculty who facilitated the design, implementation, and reporting of this research.

1. Pseudonyms used throughout.

2. Students quotes that appear in the article are excerpts from transcribed class observations conducted between July and August 2013.

Adapted from “The Power of Collaborative Dialogue”, first published in Art Education, 68(5). Used with permission of the National Art Education Association.

• Alexander, R. (2005). Culture, dialogue and learning: Notes on an emerging pedagogy. Keynote Address for the Tenth Annual International Conference of the International Association for Cognitive Education and Psychology. University of Durham, U.K.

• Dillon, J. T. (1987). The multidisciplinary world of questioning. In W. W. Wilen (Ed.) Questions, questioning techniques, and effective teaching (pp. 4966). Washington, DC: National Education Association.

• Gibbs, J. (1995). Tribes. Sausalito, CA: CenterSource Systems.

• Hagaman, S. (1990). The community of inquiry: An approach to collaborative learning. Studies in Art Education, 31(3), 149-157.

• Heid, K. (2005). Aesthetic development: A cognitive experience. Art Education, 58(5), 48-53.

• Heid, K. (2007). (Review of the book The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education by N. Noddings). New York: Teachers College Press, 2005. 412-415. ISBN: 0-8077-4609-6

• Housen, A. (1999). Eye of the beholder: Research, theory and practice. Paper presented at the conference of Aesthetic and Art Education: A Transdisciplinary Approach. Sponsored by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Service of Education. Lisbon, Portugal.

• Jaquith, D. B. & Hathaway, N. E. (Eds.). (2012). The learner-directed classroom: Developing creative thinking skills through art. Amsterdam Avenue, NY: Teachers College Press

• Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools New York, NY: Teacher’s College Press.

• Reagan, S. B. (1994). Writing with: New directions in collaborative teaching, learning, and research. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

• Swain, M. (2000). The output hypothesis and beyond: Mediating acquisition through collaborative dialogue. In JP Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 97-114). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

• Walker, S. (2001). Teaching meaning in art making Worcester, MA: Davis Publications.

• Willis, J. (2007). Cooperative learning is a brain turneron. Middle School Journal, 38(4), 3-14.

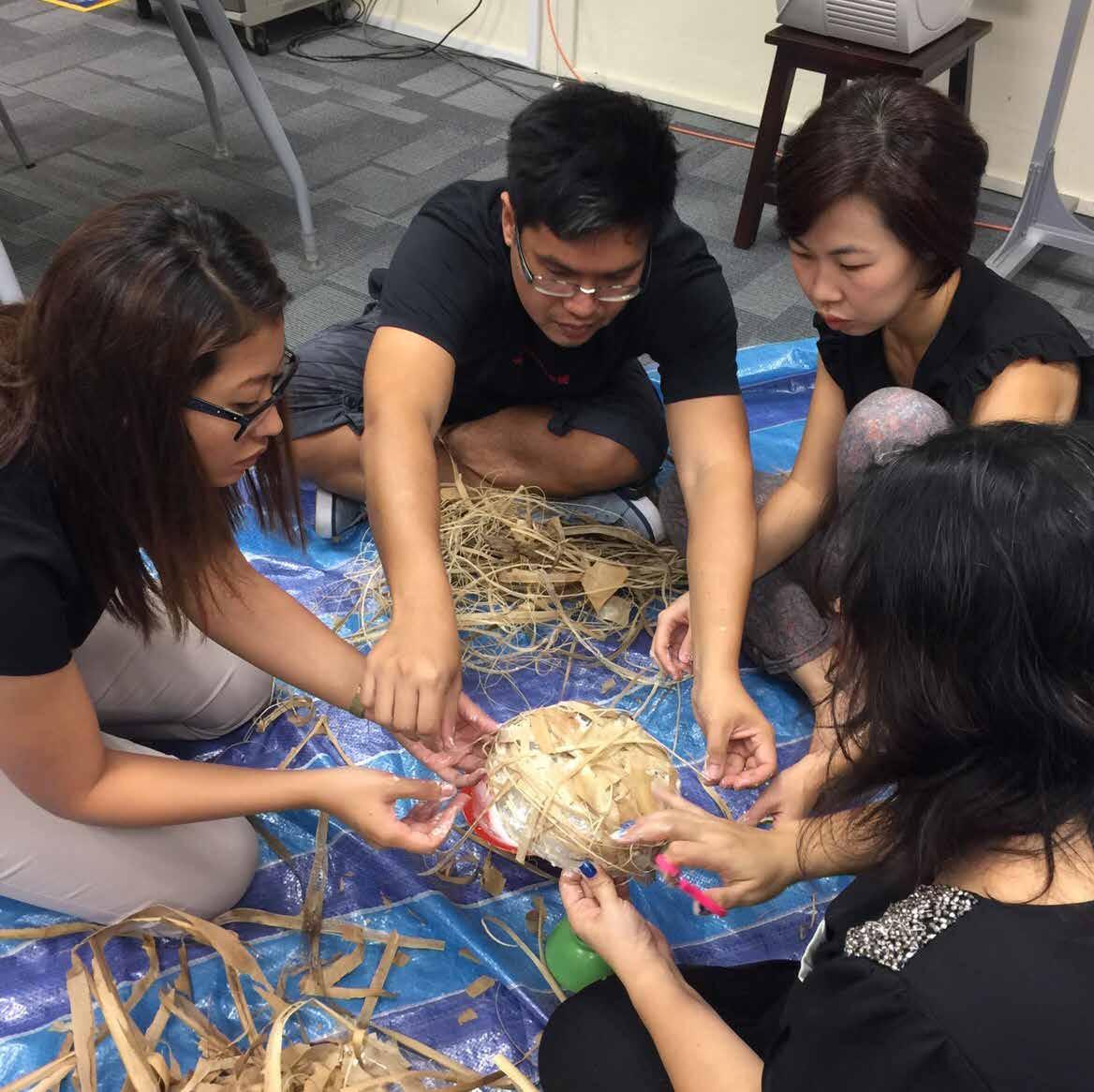

COMM.A.S workshops aim to introduce art educators to strategies for fostering collaborative art processes and building communities through joint, participatory art activities. Participants worked with local art practitioners to conceptualise ways to design and facilitate art inquiry that emphasises the value of collective learning, and draw inspiration from the rich diversity of the community within and beyond the art class. The inaugural run of COMM.A.S workshops (11−13 Nov 2015) were helmed by photographer and artist Mintio, as well as Installation and Land artist Twardzik Ching Chor Leng.

At the Vernacular Photography & Cyanotype Printing workshop, Mintio led a group of participants to revisit precious memories, uncovering the stories of kinships and friendships behind many old family photographs. Connections were made and friendships developed as participants shared about their personal photographs, giving others access to their lived experiences. These conversations helped to build the trust and respect necessary for collaboration. The activity of looking at photographs was the beginning of the journey to appreciate how joint narratives can be shaped through the process of assembling photographic images and collective meaning-making.

Participants were tasked to create a combined narrative based on the theme of ‘Relationships’, this task was specially designed to benefit from a group perspective. They developed their ideas through negotiation with others and considering different viewpoints. After the initial compositions were formed, participants then took the composited images a step

further into the realm of cyanotype printing, where they worked together to explore the endless possibilities of this versatile medium.

Another group of participants were engaged in collaborative art-making processes in Land Art, and were working with materials from the environment, such as soil, vegetation, water, stone and wood. Armed with only trash bags and plastic gloves, participants had to cultivate their resourcefulness as they collected and used materials from the immediate surroundings for their site-specific installation works. Working in small groups of 3 – 4, participants learnt with and from one another, built their collective understanding about Land Art, and also devised a range of strategies (including some really novel ones!) to realise their creative endeavours with whatever available materials.

At the end of the 3-day workshop, participants came together to reflect on their group learning experiences, and examined the perceived benefits of collaborative learning. Using the Design Thinking approach, they also created empathy and journey maps to deepen their understanding of the different types of collaborative learners, and the learning process that they will undergo in group inquiry. Finally, they consolidated a list of useful ideas and promising practices for supporting learning communities in art classrooms. This list contributes to our art teaching fraternity’s shared understanding of the opportunities and challenges in collaborative learning; we believe that over the years, new understanding will emerge as art teachers continue to extend their inquiry into this important area of student learning.

u The Jigsaw Classroom is a cooperative learning strategy developed in the early 1970s by Elliot Aronson and his students at the University of Texas and the University of California.

u Students are organised into small “home” groups. Each group member is assigned a different piece of information (could be an artwork, text, problem, task etc).

u All members assigned to the the same piece of information will then come together to form “experts” groups, to discuss and share ideas about the information.

u Thereafter, students return to their “home” groups to share their learning as “experts” of the assigned information.

u Read more at https://www.jigsaw.org/

I Like, I Wish, What If

u Peer feedback is essential in group work to move the teams further and advance the learning together.

u Typically used in the Design Thinking process, I Like, I Wish, What If is a simple strategy to facilitate the process of giving positive and constructive feedback, to help realise the full potential of the team.

u For instance, “I like how the colours express the message our group hopes to convey. I wish we could use larger fonts for better readability. What if we could reconsider the choice of images used because ...”

u I Like, I Wish, What If is one way of harnessing the power of feedback to encourage personal voice and increase open communication.

u Read more at http://stanford.io/1HT93to

u Chalk Talk Thinking Routine allows the voice of every student to be heard.

u Students are asked to think about ideas, questions, or problems, and upon reflecting on them, to pen down their thoughts about the prompt, as well as responding to their peers’ reactions to the same prompt.

u Through this silent written conversation, students learn to build on others’ responses, make connections between ideas, extend their thinking, and appreciate diverse perspectives.

u Read more at http://bit.ly/1qyxzdX

u Compass Points Thinking Routine invites group members to explore an idea or proposition together from different angles. A modified set of questions is presented below:

u E = Excited: What excites you about our ideas for the art task? What’s the upside?

u W = Worrisome: What do you find worrisome about these ideas? What challenges do you anticipate?

u N = Need to Know: What else do we need to know or find out to evaluate our options or deepen our understanding of the ideas, questions or perceived obstacles?

u S = Stance or Suggestion for Moving Forward: What is your current stance or opinion on the idea? What suggestions do you have that might help us move the ideas forward?

u Read more at http://bit.ly/1XCR281

u Ms Ang Hwee Qin, Art Teacher, Zhonghua Secondary School

Our Hawker Centres — A Heritage & Art Project, as the name suggests, strives to raise awareness and celebrate Singapore’s hawker culture and heritage with wall murals painted in the various hawker centres. Our Secondary 2 Art Elective Programme (AEP) students participated in this initiative to apply and broaden learning outside the classroom setting.

Our students went through stages of planning and researching, and their journey started at the end of Secondary 2 when one of the stimuli for their end-of-year Drawing and Painting paper was “Hawker”. As part of their learning, students went through the various processes to brainstorm and interpret the given theme. They derived possible ideas through different generative processes, like photography, sketching and research. They also learnt from artists’ works and the visual culture in their environment.

After the examinations, the students were informed that the whole AEP class would be involved in the mural painting project the following year. At first, some of the students were daunted, while others felt excited.

As a practice in Zhonghua, our students are involved in learning tasks and processes, as well as given structured time for reflections, so that learning can be distilled. Without reflection, the activity that they went through would merely be undigested actions and information. As teachers, we also have to find ways to encourage students’ participation, without them perceiving the learning opportunity as a chore. Through assurance and working as a class, the students pooled together their ideas and resources from their Drawing and Painting papers for the composition of the mural. The initial composition was accepted and that boosted the students’ confidence. In addition, the fact that they got to plan and do the mural together made the project “fun”.

The actual creation process started with five student-volunteers recceing the site at Serangoon Garden Market and Food Centre. They took measurements and went around to survey the working environment. They further refined the composition, taking into consideration some physical fixtures at the actual site. The final composition was then re-drawn as a digital drawing with Photoshop. Through discussions and negotiations, the team of students learnt the importance of communication, and made decisions by considering the issue from different perspectives.

Our Hawker Centres — A Heritage & Art Project is a joint initiative of the National Environment Agency (NEA) and National Heritage Board (NHB), and organised in partnership with the National Arts Council (NAC) and Nippon Paint Singapore. Thus far, more than 70 schools and organisations have created 133 wall murals and art installations in 44 of our hawker centres.

View the commemorative compilation of murals and art installations here: http://online.fliphtml5.com/uzgk/ugmg/#p=1

The planning team then divided the class into small working teams. Work was allocated according to the various tasks, e.g. preparing the ground, drawing the outlines, preparing the paint, etc. Throughout the three days of painting, caring passersby offered kind words and useful advice to our students. Some rendered help by providing snacks, stools and ladders to ease the painting process. This communal spirit taught our students to be appreciative, more selfless and be grateful to others. The mural was completed in three days by the students’ own efforts and they were very proud of their achievement. The painted mural might not be the most astounding piece, but what the students have learnt and gained was invaluable.

As teachers, our role was more of a facilitative one than a direct instructional one. At times, when uncomfortable situations arose, we were tempted to take over to instruct or build ideas for them to speed things up. However, we also recognised that it was more meaningful for students to learn to respect others and create meaning through working together. Art learning experiences need not always focus solely on developing students’ art skills and knowledge. We can definitely design learning experiences to make learning more meaningful and rewarding for our students. This realisation to view students’ contributions as important to the whole experience of learning is also essential to our growth as teachers.

At the end of the project, the students gave kind words to one another, and reflected on their learning experience together. Students recognised and understood the success of their teamwork, and knew that their individual success depended on everyone’s full participation. The diversified and embracing flavours of our local hawker culture has interestingly seeped into our art classroom.

Exploring Inquiry in 3D Art-Making with Mdm Norlita Marsuki (Orchid Park Sec Sch) and Mrs Serene Ang-Lin (Greendale Sec Sch)

Teacher leadership is defined as “the process by which teachers, individually or collectively, influence their colleagues, principals, and other members of the school community to improve teaching and learning practices with the aim of increased student learning and achievement” (York-Barr & Duke, 2004, p. 287).

The STAR Champions programme is one of the leadership development platforms where STAR nurtures our arts teacher-leaders. Since its inception in 2012, the programme has been committed to enhancing arts teaching competencies and fostering a teacherled and collaborative culture within the arts teaching fraternity. Facilitated by the teaching faculty from STAR, teacher-leaders trial new pedagogical approaches in their respective schools and codevelop pedagogical resources for the fraternity.

With a focus on teacher agency and empowerment, the programme provides the avenue for arts teacher-leaders to collaboratively champion high quality pedagogies through organised workshops and professional support networks. The STAR Zonal Art Workshop is one such avenue where STAR Champions share their learning and teaching practices with other art teachers through role-modelling, experiential learning and generative pedagogical discussions.

The STAR Champions (Primary Art) programme started its first run in 2012; since then, this learning community has become a dynamic melting pot of ideas, interactions and inspiration! We are delighted to launch the STAR Champions (Secondary Art) in 2015 to advance this important work of supporting and learning alongside the fraternity, and collectively transforming art education in Singapore.

Read about the Journey of our Art STAR Champions (Primary) at http://bit.ly/22Hv9po

The key area is the conscientious practice of noting how not only my teacher-speak in class promotes inquiry but also how the activities designed are aligned to the same curriculum intent. It was useful for me as I do see myself thinking harder about the value of each activity not just in terms of how it fulfils art-making objectives but also in terms of how each activity explicitly promotes an autonomous investment in the art-making process. Thus, the careful sequencing of the many activities is more nuanced given the awareness I emphasised towards inquiry. I achieve this by relying on Thinking Routines, something I used as handles to sustain my own effort towards inquiry and to make learning more persistently explicit.

u Mr Juraimy Abu Bakar, CHIJ Katong Convent

Renewed, recharged, refreshed!

Felt renewed — learnt new pedagogical approaches — Inquiry in idea generation, art-making and art discussion, relooked established practices and re-assessed their relevance and adapt.

Felt recharged — in my conviction to deliver student-centric lessons, become empowered to deliver more impactful and engaging art lessons e.g. using Artful Thinking Routines, inquiry-based approaches.

Felt refreshed through the synergistic and collective learning with fellow STAR Champions, become more sensitive to delivering effective lessons through reflective practices.

u Ms Ng Siew Kuan, Ang Mo Kio Secondary School

Being an art advocate means that I am willing to remain openminded; learn-unlearn-relearn art pedagogies, approaches, instructions, strategies etc. to better meet the needs of the art learners, in our quest to better prepare them to be 21st century global citizens. Students and teachers must be able to understand and appreciate the benefits and values of art education throughout their stay with us in schools.

Being a teacher-leader, I must keep up with the emerging research and practices of art education; select the appropriate approaches to help the students learn better and art teachers to teach better; explore differentiated instruction for students under our care; and experiment with various resources and environment. The modes of assessment that we design for our students must be sound. The list goes on, basically it means not to be passive but to come forth and share with others who are keen to explore some of my tried-and-tested teaching practices in their schools and clusters. We can start by being a nurturing classroom teacher, and be nurturing and encouraging art colleagues to the beginning, as well as experienced art teachers.

It was an enriching experience to put theory into practice. The sharing on inquiry-based approach to learning and the reading resources, including the book, Making Thinking Visible, which were provided as part of the course, have given me confidence, widened my teaching repertoire and positively contributed to my professional mastery. The Thinking Routines were numerous and I had the autonomy to choose what were suitable for my lessons and my students. All in all, I was able to implement what was recommended, and because prototyping the recommended strategies with my students yielded positive outcomes, it became exciting and rewarding to lead, share and inspire others to do the same.

u Mdm Farah Diba A Aziz, Edgefield Secondary School

To me, art advocacy means contextualising my learning to classroom practices, and being able to share my new knowledge with my colleagues. This opens up avenues to explore the teaching of art. Engaging in inquiry-based teaching has allowed me to see the shift in the focus of art teaching, from technical competency to meaning-making. For my teachers and me, inquiry-based teaching compels us to practise disciplined questioning to get the students to see the relevance of art in their surroundings, and to make sense of the world through art. Reflecting upon this experience, I gather that the type of art experience we offer to students is dependent on the mind-set of the teacher and how he/she sees the role of art education in the holistic development of the child. An advocate for art has the responsibility to help others see how art education can contribute to the total development of the child, how the child can use skills and knowledge learnt in art to manoeuvre in a globalised world.

u Mdm Michelle Yin, Deyi Secondary School

Our first batch of STAR Champions (Secondary) share their thoughts on learning and leading through the 2015 STAR Champions programme

MUS.E.S 2016 (13 – 15 January) is organised by STAR, in partnership with Asian Civilisations Museum, National Gallery Singapore, NUS Museum, Singapore Art Museum and the Singapore Tyler Print Institute; and supported by Ministry of Education and Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth Joint Working Committee for Arts Education (MOE-MCCY JWCAE).

Museums are places of wonder and discovery; they share knowledge, inspire ideas and hold immense potential to enhance students’ educational experience. Numerous research studies have found various benefits of museum visits. For instance, in their “first-ever, large-scale, random-assignment experiment” to determine the effects of a school museum visit, Greene, Kisida, and Bowen (2014) reported that students who attended an art museum visit showed “improvements in their knowledge of and ability to think critically about art, display stronger historical empathy, [and] develop higher tolerance” (p. 86). A recent multi-year study commissioned by The Whitney Museum of American Art, the Walker Art Center, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, found that intensive museum-based teen art programs had profound long-lasting impact on the participants, effects that last well into adulthood, in areas such as developing lifelong relationship with museums and culture, enhancing their engagement with the community, and shaping their personal identity. [Read about both research at http://bit.ly/1vk8Onh and http://bit.ly/1PGpwAr]

In its 2nd run this year, the Museum Education Symposium (MUS.E.S) seeks to harness the pedagogical affordances of museums to enhance and enliven students’ experiences of visual arts. Through MUS.E.S, participants had the opportunities to:

u deepen their appreciation and understanding of how the museums and galleries can be used as alternative learning spaces to extend and enrich students’ learning;

u investigate the use of artworks and artefacts as educational resources to support the teaching and learning of art; and

u strengthen their knowledge of inquiry-based approaches to teaching and learning through studio practices and discussion on art.

For this year’s Symposium, we are also privileged to have with us two renowned art educators, Professor Julia Marshall (San Francisco State University) and Associate Professor Olga Hubard (Teachers College, Columbia University), to deliver the Keynote Lectures, and reframe our perspectives towards contemporary art and museum-based learning. [Read about their Lectures on p. 23]

SMART MOVES!

Have you conducted museum-based art lessons with your students? What was the experience like, for you and your students? How did you facilitate meaningful gallery dialogues? What has worked for you, and what hasn’t? We invite you to share your museum-based learning journeys with us in STAR POST! Please write to Mdm Chun Wee San (chun_wee_san@moe.gov.sg)

Inspiring the art teaching fraternity

MUS.E.S 2016 Keynote Lectures

Opening Address by Mr Wong Siew Hoong

Learning by doing, with renowned contemporary Chinese ink painter Hong Sek Chern at the National Gallery Singapore

Finding the fine balance between giving and receiving, with artist Ezzam Rahman at the Singapore Art Museum

At Asian Civilisations Museum, slowing down, observing closely, in deep thoughts

Screen printing in action at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute

Applying the learning ... at the NUS Museum, MUS.E.S 2015 participants, Mr Ang Kok Yeow and Ms Gina Chai shared their experiences of incorporating museum-based learning into their art curriculum

What is contemporary art? How can we help students to understand it and appreciate it? Moreover, how can current art practice transform our teaching, student’s learning and personal art-making? These are questions Julia Marshall addresses in her discussion of current topics, thinking and practices in contemporary art. Beginning with ways to engage young people with current works, Marshall explores how contemporary art models creative thinking, interpretation and invention in concrete and visible ways — and how this visibility not only helps us understand art but also provides steps to creative meaning-making young people can utilise in their art practice. Along with many examples of contemporary art, student work and ideas for art projects and lessons will be presented.

This talk acknowledges that facilitating meaningful engagements with works of art is a sophisticated endeavour, rooted on sound understandings about the complexities of art interpretation and its mediation. From this perspective, Olga Hubard will elaborate on key questions that excellent facilitators consider as they engage learners with works of art. These include: Why engage with works of art? What forms can dialogues with artworks take? What are the dynamics and purposes of varying forms of dialogue? How might educators honour the merit of contemporary viewers’ interpretations when these diverge from understandings that surrounded an artwork’s origin? How do embodied ways of knowing such as emotions and bodily sensations factor into viewers’ responses to art? How might poetic activities contribute to learners’ experiences with artworks? And, what do these all mean for educators and their students?

https://vimeo.com/159911581 https://vimeo.com/161119710

Ichigo Ichie

a?edge is a project by STAR exhibition date: 4-22 March 2016 https://staraedge.wordpress.com/

a | edge, an acronym for Art Educators’ Developmental & Generative Explorations, is an annual art teachers’ exhibition. It encourages art teachers to sustain and continue to hone their art practice. Since the exhibition’s open call started in 2011, the theme changed annually based on graphical symbols and punctuations.

In 2012’s exhibition, a graphical forward slash (/) was used to provoke teachers to reflect on the balance between their own art practices and teaching practices, and question their ‘aesthetic edge’. For 2013 and 2014, the marks (:) and (-) were used respectively. In 2015, we used (...) to symbolise our teacher-artists’ past, present and future efforts to be beacons in our continuous cycle of practice, to make meaning and enrich our understanding of the philosophy and practice of art.

The fifth and final instalment of the punctuation themed series is the question mark (?). Also known as the interrogation point, query, and eroteme, the question mark indicates an interrogative clause, or phrase. In this exhibition, art teachers respond to the question mark with thoughtful, provocative works.

a?edge Exhibition Vernissage and Launch of PAM Research Report: Enhancing 21st Century Competencies in Physical Education, Art and Music were officiated by Director-General of Education, Mr Wong Siew Hoong on 4 March at SOTA Gallery.

This year’s theme, a punctuation in the form of a question mark (?), symbolises the inquiry process of art-making. It is an enduring question when we ask what are the perspectives we draw for ourselves and for whom we teach. Often the reframing of thoughts and ideas shape and create the better classrooms we design within the environments we teach. The process also becomes a discovery, a space where we nurture dispositions and habits of mind that make sense in an increasingly complex world. The disposition to connect, to make meaning thus provides a powerful goal for the inquiry process which most teacher-artists go through daily. Therein also lies duality of responsibilities we make in our artistic representations, to self and vocation.

Mrs Rebecca Chew, STAR Academy Principal

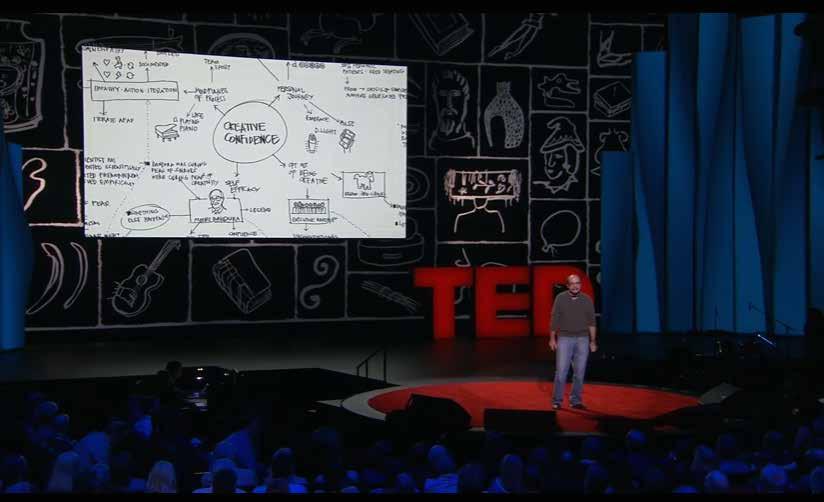

On 27 August 2015, a few members of STAR attended a lecture by Mr Tom Kelley on Leading with Creative Confidence. Mr Kelley is the partner at global design and innovation firm IDEO, and co-author of the book Creative Confidence. He started the talk by assuring the audience that every one of us is creative and we can all develop creative confidence. In fact, we have lots more creative potential than we imagined, waiting to be unearthed, to be reclaimed. Mr Kelley defined creative confidence as a natural human ability that resides in each of us. A creatively confident individual has the courage to act on new ideas, even poorly formed ones, still in their infancy. Like muscles, creative confidence can be “strengthened and nurtured through effort and experience”, so with the right approach, we can grow our creativity! Mr Kelley offered three practical suggestions to help us get started:

Embracing experimentation can help fuel the fires of innovation. — Tom and David Kelley

Mr Kelley urged the audience to learn through experiments. Citing the example of Ankit Gupta and Akshay Kothari, he shared how the two participants of Launchpad (a Stanford University design course) conducted hundreds of small experiments a day just to test their new product — a newsreader app. During the user tests, they spoke to users to understand their needs and kept asking questions to determine what users really value. They also observed how users interacted with the app, and the information gathered helped them to improve their product. The duo created thousands of iterations, using customer feedback to drive the next iteration. According to Mr Kelley, besides helping us to envision our ideas and translate plans into concrete actions, the main purpose of experimenting through prototype is to learn. It encourages us to take risks, try, fail early and learn from doing and through failures. Creative confidence is thus built through this experience of relentless experimenting.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes. — Marcel Proust

When we travel to foreign cities, we are often very alert to the new things around us. We become exceptionally sensitive to the environment and hyper-focused on details, noticing things which could be easily unnoticeable. Mr Kelley encouraged us to adopt this traveller mindset in our daily lives as well, to experience a sense of ‘Vuja De’ (the reverse of ‘déjà vu’) amidst familiarity. This entails being acutely observant and aware of our surroundings, seeing them with fresh eyes and always asking the ‘why’ questions. Mr Kelley opined that it is through such fascination with our immediate surroundings and the seemingly mundane everyday existence that we may uncover untapped opportunities, gain deeper insights, spark new ideas, and imagine the possibilities.

If you can get that diversity of thinkers and you can get them to work together and build on each other’s ideas, you’re definitely going to come up with new-tothe-world stuff. — David Kelley

Mr Kelley emphasised the importance of building on the ideas of others. Unlike copying someone’s ideas, building involves expanding existing ideas or even cross-pollinating ideas. The key is harnessing the power of diversity, and to effectively do so, it requires team members to learn with humility and an open mind. Mr Kelley pointed out that people within the same fraternity will tend to think the same, and so there is value in learning from others outside the industry. He shared an example of how one could adapt the practices of a different industry for own context. The medical team from Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children recognised the similarities between Ferrari’s Formula One pitstop handovers and the hospital’s handovers from surgery to Intensive Care, so they contacted Ferrari and worked with them to design a new set of protocol to reduce the risks involved in handover procedures. After implementing the modified protocols, the hospital observed a significant decrease in technical and informational errors; the research work with Ferrari has transformed the way the hospital staff work and also improved patient safety.

Kelley on Creative confidence: Unleashing the creative potential in all of us http://bit.ly/1VBLu0G

David Kelley on How to build your creative confidence? http://bit.ly/1OW7DTa

At its core, creative confidence is about believing in your ability to create change in the world around you. It is the conviction that you can achieve what you set out to do. We think this self-assurance, this belief in your creative capacity, lies at the heart of innovation

That combination of thought and action defines creative confidence: the ability to come up with new ideas and the courage to try them out ...

... The first step toward being creative is often simply to go beyond being a passive observer and to translate thoughts into deeds.

In our experience, one of the scariest snakes in the room is the fear of failure, which manifests itself in such ways as fear of being judged, fear of getting started, fear of the unknown. And while much has been said about fear of failure, it still is the single biggest obstacle people face to creative success.

The surprising, compelling mathematics of innovation: if you want more success, you have to be prepared to shrug off more failure ...

... It’s hard to be “best” right away, so commit to rapid and continuous improvements.

Creative confidence is an inherently optimistic way of looking at what’s possible ... New opportunities for innovation open up when you start the creative problem-solving process with empathy toward your target audience ...

Kelley, D., & Kelley, T. (2013). Creative confidence: Unleashing the creative potential within us all. Crown Business.

The constraints that teachers faced when nurturing creativity in schools are real and challenging, what should we then do as educators, especially us, the art educators? How can we play a part in actively nurturing creative thinking? I believe in applying the daffodil principle, that is, to “Think BIG and start small”. In the following sections, I will suggest a few possible ways forward.

Reclaim our creativity. Become familiar with our own beliefs about creativity. Be passionate in what we do!

Teachers’ beliefs influence the expectations they hold for their students and the way in which they design educational experiences (Longshaw, 2009; Lim & Chai, 2008). These expectations and beliefs have important implication for how teachers nurture students’ creativity. It is important for us to reflect on our past schooling experiences, be aware of the potential problematic beliefs that we may hold about creativity, and understand our own as well as others’ perceptual and emotional obstacles to creativity, so that they will not undermine our own efforts in promoting creativity. Understanding the ‘Big 5 Model of Personality’ and knowing the best ‘Combination of Personality Traits for Creativity’ will help us reclaim our creativity.

Help address misconceptions held by students, colleagues and parents, and create a supportive learning environment for creative expressions

A good way to start is to explore the definitions and beliefs about creativity already held by students, colleagues and parents. These “implicit theories” (Sternberg, 1985) are important as they influence the everyday judgements and decisions about the nature and value of creativity. We can further discuss on what it means to nurture creativity — how can we create an environment that will help nurture creative thinking and creativity in our classrooms? Dialogues among students, parents and teachers facilitated by researchers who have expertise in this area would be a very useful way to start the process of forming common understanding and contribute to creating a more conducive environment.

u Mdm Victoria Loy, Master Teacher (Art), STAR

With a supportive environment established, the nurturing of creativity in the classrooms will then be enacted by the teachers. Teachers need to be mindful of the three different aspects of teaching, namely: teaching creatively, teaching for creativity and creative learning (Fautley & Savage, 2007). I will focus on these aspects in the following sections.

Having the creative discipline to lead in designing some generic creative meta-narrative for other subject teachers is crucial. I believe questioning our current practice is a viable way to start. How can we start the journey of engaging students to understand the subject matter in a creative manner? To do this, we will need to have a certain mastery of the subject. It is only when we know our discipline well enough can one be an inspiration for his/her students. How can we make connections between the subject content covered and life? How can we make learning more authentic? How can we design activity that is rich in multi-sensory stimulations (including visual, audio and kinaesthetic) for inspiration and curiosity? Do the activities we designed encompass more than the usual sense of responsibility and ownership to unleash individual creative powers? Does the art experience help personal growth of self-belief for further development in creativity? How can the activity we designed provide quality space (e.g. task ‘open-endedness’, choice, risktaking, time for reflection, time for ‘off-task’/ break and freedom of self-expression) for individuals to develop creativity effectively? In short, the psychologising of creativity as a subject matter needs to be carried out by teachers so that students can be engaged in creative work (Smith & Girod, 2003).

We need to be mindful that creativity takes time to develop, hence allowing time for thinking and exploring of ideas is important. However, as time is a precious commodity for both teachers and students, employing established ‘tried-and-tested’ techniques, such as De Bono’s ‘Six Thinking Hats’ to facilitate creative thinking in six different perspectives, can help to reduce down time. Having real interesting and colourful hats in class could create a vibrant and fun learning environment. Often, it is where there is fun that creativity will be unleashed

the most. Creating an encouraging, positive and non-threatening learning environment is the key to nurturing creativity. Varied modes of delivery, for example co-operative learning, collaborative learning, and group work are encouraged. Other creative problem solving techniques, such as ‘Wild Ideas’, ‘S.C.A.M.P.E.R’, ‘Bug-listing’ and ‘P.M.I’ (Plus, Minus, Interesting) can also be used to stimulate creative thinking.

In order to teach creatively, we need to strike a good balance between process exploratory learning and product making. Authentic learning experiences can be designed and formative assessment should be carried out more often. Most importantly, we will have to design challenging, well-structured tasks that could immerse students in the psychological state of flow (Ng, 2009).

Engaging students’ creativity through school activities

A more creative and holistic approach to developing school programmes and learning experiences at school level would help develop a thriving creative environment that will enhance and nurture creativity further. Having the vision of building a creative learning community will help set the direction for the staff. We can ‘re-visit the old’; review the current school practices and think of how we can infuse creativity to transform learning experiences and outcomes. For example, instead of having a school sports day in which there is relatively low students’ participation, schools can explore new possibilities and re-design it into a Sports Carnival in which all teachers and students are involved. Creative ideas, for example: mascot designs, class banner designs, creative and impact slogans, cheer groups, selfdesigned class t-shirts and so on can be incorporated.

Experiential learning outside classrooms which involve real-life situations could stimulate students’ creative ideas and could produce endless opportunities to learn new creative skills. We can have an Arts Carnival or Art Bazaar (a concept similar to flea market) in which all the students are allowed to set up stalls selling items such as hand-made items, home-cooked food to the school community to raise funds for the needy students in the school. This is also a good platform for nurturing social responsibility and creativity among students. Schools could also provide other innovative platforms like the creative enterprising cafes where students are involved in experimenting with various recipes for bubble teas and sandwiches. Other creative enterprise platforms also include ‘Creative shops’ (can be both physical shop and on-line sales via platforms such as Carousell1) where students are given a head-start to experience success in selling their creative designs and artworks to the public. Students can also embark on creative projects that can help serve our community, for example, creating colourful hanging mobiles in the orphanages, and designing interesting 2D/3D wall murals or installations for hospitals or elderly homes. Such creative projects will not only nurture the creativity in our students, but will also help nurture them into socially responsible and concerned citizens.

To sum up, teaching creatively requires all professionals/educators to critically ‘think out-of-the box’ in our current practice and plan learning beyond the classroom as ‘creative waves’ in the education field.

Teach for creativity: The role of creativity in secondary school academic subjects

All academic subjects are human creation and they are dependent on the creativity of the subject matter experts to break new grounds. Infusing creativity in all secondary school subjects is desirable. The concept of infusing the teaching of creativity explicitly and incorporating it across the curriculum was accelerated mainly over the last decade. Through infusion, knowledge would incorporate thinking, relevancy and application (Dewey, 1933; Perkins & Swartz, 1992). Swartz and Parks (1992) claimed that infusion will enhance students’ thinking skills and the learning of the subject matter content.

To teach for creativity, we would need to adopt an attitude of inclusion for both teaching and learning. In this digital age, it is wise for us to maximise the affordances of new technologies in our effort to nurture creativity. Various on-line platforms such as Google docs and wordle.com can be used to facilitate brainstorming with greater visual impact. Glogster, multimedia posters with the web interactive usage could facilitate creative thinking and art-making too. It is also essential to perhaps organise intensive workshops to teach students and teachers some basic creative thinking skills for them to apply in conjunction with the use of web technology.

1 Under parental or legal guardian supervision