STAR POST (ART)

Issue

2 / 2016

a newsletter for art teachers, by art teachers

2 / 2016

a newsletter for art teachers, by art teachers

36 Drawing on the Move

39 Making 3D Art in a Classroom – Possibilities, Challenges and Transcending the Physical

42 Announcements

“Pedagogical documentation1 is the teacher’s story of the movement of children’s understanding.” — (Wien, Guyevskey, & Berdoussis, 2010)

Effective art teaching entails documentation. Documentation guides teachers’ reflective practices, as well as shape and deepen learners’ understanding. This issue of STAR POST explores documentation as a means to understand how students think and learn, "the teacher who perceives how children learn and who can help others see that learning can contribute significantly to the child’s development” (Helm, Beneke, & Steinheimer, 2007, p. 7).

STAR POST shares how art teachers can use Video Selfies to gain insights into own teaching practice and enhance student learning. We will also look at how students can use documentation for selfreflection and peer feedback to extend own and others' learning. Documentation is not entirely new to the arts community, in fact, it is an integral part of the artistic and curatorial practice. By engaging in documentation, not only are art teachers and students learning from thinking made visible, they are also involved in fundamental art practices and processes that shape the artist’s thinking and develop artistic dispositions.

Enjoy the read.

1 STAR POST Issue 2/2016 focuses on Documenting Teaching and Learning as Part of an Artistic Cycle, which is one of the four distinctive and effective art teaching practices that foster emerging 21st CC, as identified in the PAM Research Report: Enhancing 21st Century Competencies in Physical Education, Art and Music (2015).

Read about pedagogical documentation in STAR’s publication, Inquiry In and Through Art: A Lesson Design Toolkit (2015), p. 28–31.

u Mr Lim Kok Boon, Master Teacher (Art), STAR

In order to be an effective teacher, it helps to be a reflective practitioner. Good reflective practice often starts by questioning oneself how well students have learnt, and how differently things could be done. Basic reflective questions might sound like:

u What did I do well today? What would I do differently if I could go back in time?

u Should I ask for help from another person?

Having said that, educational researchers have explicated reflective practices in other ways, to help teachers deepen their understanding of reflection in practice.

According to Donald Schön (1984, 1991), reflective practices can be distinguished as reflection-in-action, and reflection-on-action. To Schön, reflection in practice can be reflexive, and pensive. Reflection-in-action is concerned with practising criticality, continually in one’s professional work. Reflection-in-action involves seeing one’s current performance in a continuum, constantly comparing and evaluating them against past performances and desired goals, and making adjustments along each step of the way. Reflection-in-action is performed as a reflex, without much conscious thought. Reflection-on-action on the other hand, is concerned with evaluating one’s performance after the activity has taken place. Reflectionon-action is associated with the set of basic reflective questions posed above.

In comparison, Smyth (1989) regards reflective practice that leads to success and transformation as four sequential stages. These four steps are, and can also be characterised by these accompanying questions:

1. Describing: What did I do?

2. Informing: What does this mean?

3. Confronting: How did I come to be like this?

4. Reconstructing: How might I do things differently?

In Smyth’s case, reflection in the first instance means being able to describe what had happened. Next, the teacher can analyse these actions and explain the implications of one’s work. In Smyth’s third stage, the reflective practice involves interpreting and associating one’s performance and action, and being able to explain these in relation to one’s contexts and teaching beliefs. Lastly, in the fourth stage, the teacher can evaluate one’s action, and suggest ways to do differently. Smyth’s concept of reflection in practice is similar to Schön’s concept of reflection-onaction, except that it further explains what to think about. In some instances, Smyth’s model has been used to evaluate or study the quality of one’s reflective practices. In other occasions, Smyth’s model has been used to guide the design of professional development activities.

In this text, we take reflective practice1 to refer to the regular, repeated exercise of looking at what is done in the classroom, thinking about why it is done, and evaluating its effectiveness. It is a process of collecting information, through self-observation or getting help from others, and evaluation of one’s teaching practices. Reflective practice, as alluded by Schön and Smyth, can therefore, challenge set ways of doing something, and give rise to a higher order of professional practice. Reflective practice essentially is a means to make sense of and deepen one’s professional experience, one lesson at a time.

Reflective practice is best supported by evidence of students’ learning or information about what had happened in the classroom. The value proposition of a Video Selfie2, using video recordings as a documentation of a taught class, has the following advantages:

u It aids reflection-on-action, because it presents a candid viewpoint of what the teacher and students do and say. The teacher can view the video and recall what had happened rather than depend on memory. If the video recording is allowed to run throughout the lesson, then it shows an accurate depiction of how time and space are used. Such a video recording would show things happening in the classroom that a teacher might not be aware of, such as:

• Who gets called to answer questions; more, less or not at all;

• Whether wait time is provided for questions, routines or activities;

• Teacher-student interaction, including movement around the entire classroom to check on students’ learning;

• What students are doing at different points in a given lesson, if they are unchallenged, or overwhelmed by a particular task or instruction;

• Clarity of instructions; and

• Teachers’ body language and fluency of speech.

u It allows some critical distance from what had happened to look at a particular aspect of the lesson that transpired. With these evidence, a teacher can scrutinise their performance for themselves. This “reality” might differ from what the teacher remembered and felt about the lesson.

u These evidence would be permanent, as long as the video files are suitably archived, and can thus be viewed repeatedly, over a period of time. It is also reusable for professional development discussions amongst trusted colleagues.

Additionally, a Video Selfie can reduce the reservations and self-consciousness of students, associated with having another teacher or authoritative figure in the classroom, and taking notes of what is happening.

How Video Selfies are used to support reflective practice

Harvard University’s Centre for Educational Policy Research offers a six-step process for using videodocumentation for self-reflection. These are:

Step 1 Establish a goal for viewing.

Step 2 Focus on evidence, rather than irrelevant or reactive details.

Step 3 Focus on evidence that is important.

Step 4 Use context to reason about classroom interactions.

Step 5 Make connections with principles of effective teaching.

Step 6 Plan future instruction.

This six-step process is aligned to what Schön and Smyth have suggested about effective reflection in practice.

Step 1: Establish a goal for viewing

Having a clear goal and purpose helps decide what to look for in a video recording. Self-observation goals can relate to teacher-instruction, in the following areas:

• Professional development, focusing on teachermoves a teacher wants to work on;

• Appropriateness of curricula material and whether they are used effectively; or

• Assessing students’ learning, specifically the use of formative assessment strategies.

The goal for viewing encompasses looking out for successes and areas for improvement. The goal for viewing will give an idea where the camera should be placed in the classroom, and which part of the lesson needs to be recorded.

Step 2: Focus on evidence, rather than irrelevant or reactive details

A video recording contains tremendous amount of visual and auditory information. Students directly in front of the camera might be shuffling through their bags and pencil

• 1Reflective Practice is listed as one of the professional development modes in Learning Continuum concept of MOE’s Teacher Growth Model.

• 2The term “Video Selfie” is used by Centre for Education Policy Research, Harvard University.

cases, and this could be distracting to the video viewer. Irrelevant details, such as repeated unconscious gestures, body language, or unintended filler words could also be distracting to the video viewer. For example, a teacher might unconsciously push his or her hair back every time his or her back is turned to the board, or inserts word and phrases into sentences, seemingly unintentionally. For example, inserting “got it?”, or “um…uh…” frequently. Noticing these may not be relevant to the goal for viewing. For the viewing to be purposeful, focus on features of the classroom that can be used to draw conclusions about instruction. For instance, if the goal for viewing is on how students in small groups interact when group work is assigned, then noticing the messy table is an irrelevant detail if it does not hamper students’ engagement in learning.

Step 3: Focus on evidence that is important

To focus on features of the classroom that can be used to draw conclusions about instruction, the viewer has to be selective on evidence that is important. As a guide, important evidence will typically relate to the qualitative, or quantitative measure of teacher-instruction that influences students’ learning, as well as what students do that demonstrate whether they are on-task, off-task, learning or distracted from learning. For example, if a teacher’s instruction takes 20 minutes to tell, and students are visibly distracted, then the instruction duration might be too long, and there might be other ways to convey the intent of the instruction. Sometimes, simplifying the task, or breaking the tasks up into 2-3 chunks may be more effective in an hour of art lessons.

Step 4: Use context to reason about classroom interactions

Take time to pause the video and think about the root causes for teacher and student behaviours or interactions. Return to contextual information (not captured in the video) to explain and explore the evidence collected. For example, a teacher’s or students’ behaviours may have been affected by an event before the lesson captured on the video recording. Specifically, students’ behaviours may be related to something that happened in the previous lesson or something that happened earlier in the day to the whole class. These may affect students’ readiness to learn, or participate in certain activities.

Step 5: Make connections with principles of effective teaching

Take time to make connections between what is observed in the video and principles of effective teaching, relevant educational theories, and relevant evidencebased teaching practices. For example, John Hattie’s publication, Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximising Impact on Learning (2011), suggests visible learning strategies that make differences in students’ learning.

Step 6: Plan future instruction

Take time to brainstorm, and map out actionable ideas in relation to the evidence collected from the video recording. Your goals to improve instruction ought to be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Timely (S.M.A.R.T). Focus on improving students’ learning. That can be used to drive lesson planning for the subsequent lesson with the same class, or inform changes to the lesson plan with another class. Plan to video record a lesson again to evaluate if changes made a difference.

Harvard University’s Centre for Educational Policy Research also suggests the following Noticing Rubric for Independent Practice of Using Video Selfies for self-reflection in relation to the six-step process (CEPR, 2015, p.20):

Identifying What’s Important

I identified what was most important in my classroom and instruction.

Making Connections

I made connections between important parts of classroom instruction and principles of effective teaching.

I identified details related to instruction but did not highlight the most important details.

I made connections between multiple parts of classroom instruction.

I did not differentiate between important and unimportant details.

I made connections between unimportant parts of classroom instruction or made no connections at all.

Incorporating Contextual Knowledge

I readily incorporated contextual knowledge into my analysis.

I incorporated some contextual knowledge into my analysis.

I did not incorporate contextual knowledge into my analysis.

Drafting Next Steps

I generated multiple next steps in my analysis and implemented them.

I generated some next steps in my analysis and planned to implement them.

I did not incorporate next steps into my analysis.

There are limitations to using Video Selfies for reflecting on practice. As a video recording, it provides some evidence of what transpired in class, serving as a snapshot with which the learning and teaching activity can be analysed. This is only a snapshot because we can only see what the digital camera is pointing at, limited by the angle of view, or hear what the camera’s microphone can pick. When a camera is placed at the back of the classroom, the video viewer will not be able to see what happens in the front of the classroom in detail. Therefore, the placement of the video camera deserves some consideration, in relation to the purpose of video documentation. In some instances, the presence of a video camera may induce students to “act up”, rather than respond and behave in a way without a video camera.

To be able to reflect on practice and act on them does not come naturally, given the nature of our Singapore classrooms, our teaching loads, and a fine balance with commitments within and beyond the school. To be able to reflect on practice and act on them takes commitment, effort and time. A video recording that is an hour long will require at least 45 minutes of viewing if we fast-forward and skim through what are considered irrelevant details. Added time is required to pause and ponder, for making connections, incorporating knowledge, and drafting next steps. A teacher would need to have a certain level of confidence, and technical knowledge to operate the equipment and software required to capture and playback the video recordings.

Reflective practice is important because it empowers teachers to become evaluators of their teaching, and help teachers plan their self-improvement. Reflective practice is important because it allows the teacher to model critical thinking, and earn the rights to ask students to think critically too. Teachers are lifelong learners and mastering the craft of teaching is always a “work in progress”, a blend of reflection-in-action, and reflectionon-action. To be a confident reflective practitioner means being fully aware of the plethora of reflective practices and be able to use a selected mode at will, the best fit for the intent and purpose.

Center for Educational Policy Research (CEPR) (2015). Teacher Video Selfie: A self-guided module for analysing videos of your own instruction. Best Foot Forward Project, Harvard University. Accessed August 22, 2016 from cepr.harvard.edu/files/cepr/files/l1a_ teacher_video_selfie.pdf

Gaston, J. (2016). Record yourself to improve your practice. [blog post] Accessed August 22, 2016 from http://www.edutopia.org/discussion/record-yourselfimprove-your-practice

Guimaraes, C. (2015). New Harvard toolkit supports using video to refine practice. [blog post] Accessed August 22, 2016 from https://www.teachingchannel. org/blog/2015/10/15/harvard -video-observationtoolkit/

Reflective practice is important because it empowers teachers to become evaluators of their teaching, and help teachers plan their selfimprovement.

Hattie, J. (2011). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. Abington, Oxon: Routledge.

Schön, D. A. (1984). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1991) The reflective turn: Case studies in and on educational practice. New York: Teachers Press, Columbia University.

Smyth, J. (1989). Developing and sustaining critical reflection in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 40(2), 2-9.

Besides using videos to support self-observation of teaching, the following are examples of other reflective practices:

Using checklists for reflection

Using reflective conversations

Using students’ talk

Using students’ work

Using a self- or peer-assessment checklist as a basis for reflection. These checklists could be based on different models (e.g. Skillful Teacher’s Map of Pedagogical Knowledge), for a variety of situations. These serve as considerations of good practices rather than strict rules. For a start, use the ones found in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015) if they fit your needs:

• Teaching for Understanding Reflection Checklist (p.154)

• Collaborative Art Project Checklist (p.155)

• A Checklist for Assessment Planning (p.173)

Do a Think-Pair-Share about a particular aspect of classroom teaching with a colleague, sharing why something was done, and whether it was effective. The colleague asks clarifying or probing questions which support the reflective process. A critical friend might be able to question assumptions behind certain teaching practices, and offer plausible alternative interpretations of what happened in class. In some schools, teachers meet weekly to practise reflective conversations. For conversations that require more structure, consider using Praise-Question-Polish protocol, found on p. 192 in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015).

Recording what students say they understand, or learn in group settings, to uncover the actual learning that takes place. This depends on the students being open and honest about what they have learnt.

Collecting, analysing and interpreting students’ quality of learning by looking at a range of student learning artefacts. These can include individual work, works by the same student over time, or works by different students for one assignment. For art, this can include developmental preparatory studies, final work from one student, or a range of such work from many students.

Using coaching as a tool for reflection

Using Action Research, Lesson Study, or Learning Study

Using reflective journals and portfolios

Using a coach’s or peer’s formal and informal feedback as a basics for reflection, obtained from a lesson observation, walk through, or looking at students’ work. Video Selfies can support coaching because it provides a view of what happened, can be repeatedly viewed, and can be used comparatively over time. For a brief idea of how coaching works, consider reading Key Ideas of Coaching, found on p. 194 in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015).

Using different approaches of critical inquiry to shine a light on a particular aspect of classroom teaching, giving focus by using research questions to guide the inquiry.

Using written or typed journals, and a body of teaching artefacts forming a portfolio, as a basis for reflection. This could be supplemented with photographs taken by the teacher or student of what happened in the classroom.

Creating pedagogical exhibits

Referring to the documentation of teaching and learning, such as lesson goals, instructional strategies used, alongside students’ responses and one’s personal reflection. Sharing and discussing the documentation with another teacher allows an alternative interpretation and evaluation of the learning process, as well as follow-up action to take with students. For more details, refer to p. 184 in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015).

• Built on suggestions found in Hansen, A. (2012). Reflective learning and teaching in primary schools. London; California: Sage.

• In these examples of reflective practices, Video Selfies can provide a source of documentation to draw information or evidence. A generic set of reflection questions related to classroom teaching for experienced teachers can be found in p. 10.

How will you first describe your lesson?

All the students met the objectives

How do you know?

Some of the students met the objectives

Why only some?

None of the students met the objectives

What could you have done differently?

Was the work too easy?

Who did? Have you any reasons?

Did you provide scaffolding?

Were you stretching the more abled?

What could you have done to support others?

Was there enough support?

Were the objectives appropriate?

Did you need differentiated objectives?

Were the objectives appropriate?

In 2014 STAR POST Issue 4, we featured an article on how art teachers use information from pedagogical documentation to inform curricular decisions. Documentation tells stories about the learning process and experience, they also paint portraits of the learners, illuminating their thinking, feelings and worldviews. A curation of many small documentation over a period of time, provides a larger, richer picture of learning.

There are two key components of documentation: collecting it and interpreting it. Collecting documentation is akin to gathering evidence of students’ learning and making the thinking visible, this is a process that requires astute observation and recording with discernment. The documenter wears the hat of a researcher or inquirer, collecting information purposefully to make sense of what is going on for the learners, and seeing learning through learners’ eyes; for instance, how they learn and interact with peers, how they approach problems, how they explore ideas and so on. What to document is often determined by what interest the teachers — their wonderings, curiosities and questions about students’ learning. In fact, “a teacher’s question is a perfect place to begin documenting. A question creates the opportunity to frame documentation as a response to this query” (Stacey, 2015).

But for documentation to be meaningful, teachers need to move beyond simply gathering information. What is most important about documentation is what teachers do with them, how they interpret the documentation, and respond to it to move student learning forward. For a start, art teachers may consider the different ways of interpreting and sharing documentation of learning found in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015), p. 28-31.

What can documentation do for student learning?

“Teachers and students use the power of peers positively to progress learning.” (Hattie, 2012)

Purposeful documentation gives teachers access to student thinking and learning — their understandings, misconceptions, as well as how the thinking evolves; this help teachers reflect on their teaching practices and craft subsequent instructional decisions, so lessons can be truly responsive to students’ needs. Likewise, documentation also informs students about their learning. It can be shared back with learners, using it as a basis for peer critique, self-assessment and reflection, to

u Mdm Chun Wee San, Programme Manager (Art),

Documentation of student learning can take various forms:

• Audio / Video recordings

• Photos showing work in progress

• Observation logs / Checklists

• Colleagues’ observation logs

• Students’ reflection

• Teachers’ reflection

• Peer feedback

• Records of student-led conferences, discussions

• Learning artefacts (e.g. students’ work at different stages of the process, journals, preparatory studies, writings)

• Artefacts of practice (e.g. lesson plans, Scheme of Work)

shape future learning experiences. When teachers share documentation of student learning, it is also a form of validation of their work and experiences, an expression of valuing learning.

According to Stacey (2015), “documentation at its best leads to reflection and dialogue”. Documentation has the potential to support self-reflection. Students could revisit key moments and reflect upon a learning activity by examining documentation of that experience. Documentation also serves as a visual reference for students to make connections and extend understanding from previous learning.

When documentation is shared and talked about, it provides students with opportunities to learn to provide constructive peer feedback, which includes identifying positive aspects of the work to affirm peers’ efforts, and offering suggestions to help peers improve the work. Peer feedback creates a meaningful platform for students’ voices to be heard, empowering them to share their unique insights. It also encourages students to take greater ownership of their learning, and contributes to building a class culture where students help one another become better learners. Collecting documentation and using it as a basis for peer feedback can make the process more meaningful. Have a go at it!

Here are some strategies that teachers could use to elicit student feedback and facilitate discussion.

u TAG

• Tell the artist something that you like about the work.

• Ask the artist a question about the work.

• Give the artist a suggestion to improve the work.

u Two Stars

u

• What are two positive aspects (stars, pluses) of the work?

• What is an area that needs improvement (wish, suggestion)?

u Plus / Minus / Interesting

• What are the positive aspects/features about the ideas/work?

• What are the negative aspects/features about the ideas/work?

• What are the interesting aspects/features about the ideas/work?

u S-O-S (Statement-Opinion-Support)

• For instance, after looking at the different ideas generated for an art task, the teacher presents a statement about the idea generation process, "The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas." (quote by Linus Pauling)

• Students offer their opinions in response to the statement, and support with evidence or examples based on own and others' work and processes.

References

Einarsdottir, J., & Wagner, J. T. (2006). Nordic childhoods and early education: Philosophy, research, policy, and practice in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Greenwich, CT: IAP-Information Age Pub.

Krechevsky, M., Mardell, B., Rivard, M., & Wilson, D. G. (2013). Visible learners: Promoting Reggio-inspired approaches in all schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. London: Routledge.

Stacey, S. (2015). Pedagogical documentation in early childhood: Sharing children’s learning and teachers’ thinking. Redleaf Press.

Tolisano, S. R. (Dec 19, 2015). Documentation of/for/as Learning [blog post]. Retrieved from http://langwitches.org/blog/2015/12/19/documentation-offoras-learning/

Wien, C. A., Guyevskey, V., & Berdoussis, N. (2011). Learning to Document in Reggio-inspired Education. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 13(2). Retrieved August 15, 2016, from http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v13n2/wien.html

“Documentation is not about finding answers, but generating questions.” (Filippini in Turner & Wilson, 2010)

Students could discuss in pairs or small groups, referencing the documentation of learning, to clarify doubts, provoke thinking, deepen understanding, elicit different perspectives, or simply engage in meaningful conversations about learning. Some possible question starters and conversation enhancers for document-based discussion include:

• Why did you choose this idea?

• How would it be different if you use another colour scheme?

• What are the reasons for using these images? How do they contribute to your artistic intention?

• Suppose that you get to do this art task again, what would you do differently?

• Did you consider other ways of attaching parts of the assemblage together?

• What would change / happen if you try another technique?

• Which part of the art process do you find most challenging?

• What do you mean by…?

• What do you plan to do next?

• Could you use some other materials to create the textures?

• How did you know when / which / where…?

u I noticed that… I wonder… (Observing and noticing, followed by a question of interest to probe thinking, clarify doubts or invite explanation). For instance:

• I noticed that you have created some interesting textures.

• I wonder how or why you did that.

Simply put, speech bubbles are bubbles with words, placed on a photograph or a student’s work. These could be used to facilitate self-reflection, whereby students articulate their thinking and make the thoughts visible to themselves and others. These word bubbles can then serve as visual reminders of key ideas or for generating discussions.

"Documentation is the practice of observing, recording, interpreting, and sharing through a variety of media the processes and products of learning in order to deepen and extend learning.”

“Interpreting documentation is essential to the practice of documentation and what distinguishes it from display.”

(Krechevsky, Mardell, Rivard, & Wilson, 2013)

“From a pedagogical perspective, documentation is not simply to capture or make visible a memory from the past (retrospective), but rather, to enable us to analyse and deconstruct, and to be able to make choices for possible learning processes tomorrow (prospective). These documents, then, become active “agents” in planning new learning challenges and preconditions for further cooperative and investigative work and play among the children.”

(Einarsdottir & Wagner, 2006)

“When we share pedagogical documentation with children, giving them an opportunity for further response, we become co-owners of the curriculum. How the children respond — what they say, what they notice, how they will engage with the documentation — will inform our decisions about what to do next.”

(Stacey, 2015)

“Pedagogical documentation is a research story, built upon a question or inquiry “owned by” the teachers, children, or others, about the learning of children. It reflects a disposition of not presuming to know, and of asking how the learning occurs, rather than assuming — as in transmission models of learning — that learning occurred because teaching occurred.”

(Wien, Guyevskey & Berdoussis, 2011)

u Miss Khor Ting Yan, STAR Intern

In Reliqvarivm: A selection of performance art relics from Singapore, curator Daniela Beltrani approached a number of artists who collected relics from performance art pieces in the past, and chose thirteen of the relics to be shown (Reliqvarivm). She also interviewed the collectors, asking them why they collected these relics and what they could remember about the performance. Here, we observe the evidence of documentation at different levels:

1. The relics represent a form of documentation, they are the remains of the performances, some form of evidence that the performance happened. Other forms of documentation of the performances would be through photographs or videos.

2. Documentation of the curator’s research in the form of interviews with the relics collectors, revealing her artistic process.

3. No doubt these objects could stand alone, being interesting artifacts in and of themselves. I would say, however, that Beltrani’s documentation of the interviews with collectors becomes a significant extension of the show and adds a new layer of meaning to these objects. Thus, we see documented research becoming part of the work.

Based on the above example and literature on documentation, I propose to approach the role of documentation in artistic practice in three broad categories: personal, artistic, and pedagogical.

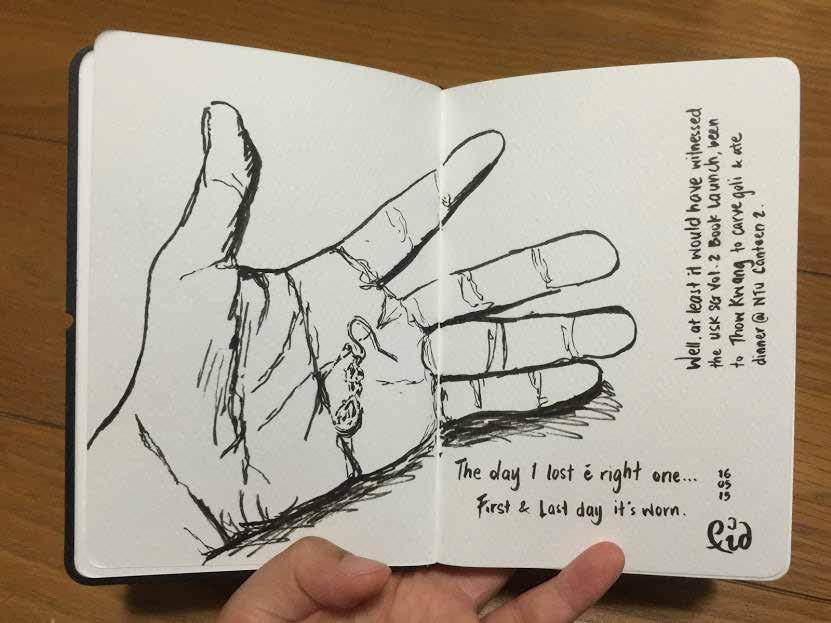

Documentation for personal purposes largely facilitates gathering materials, recording thought processes, and building an ‘interest’ bank for art-making, and developing interest and knowledge, which may or may not influence art-making. I usually have a notebook with me, to jot down thoughts or ideas that I may have throughout the day, that I think are worth writing down. These thoughts and ideas may not be coherent, nor feasible, nor make any sense, but I write them down anyway. I also have the habit of taking photographs of things that caught my eye. Similarly, I may not always know why I captured these images, as the images might also not be conventionally ‘beautiful’

or ‘instagram-worthy’, but so long as they sustain my interest, I would capture them. There are times when I do not know what works to make, feel stuck in my art practice, or simply feel uninspired, this is when these documentation come in handy! I would flip through my notes, scroll through my images, and more often than not, find something that I could work with. Looking through these notes and images over time also helps me to identify what I am naturally drawn to as a person and an artist, and this allows me to delve into deeper exploration and research in these areas.

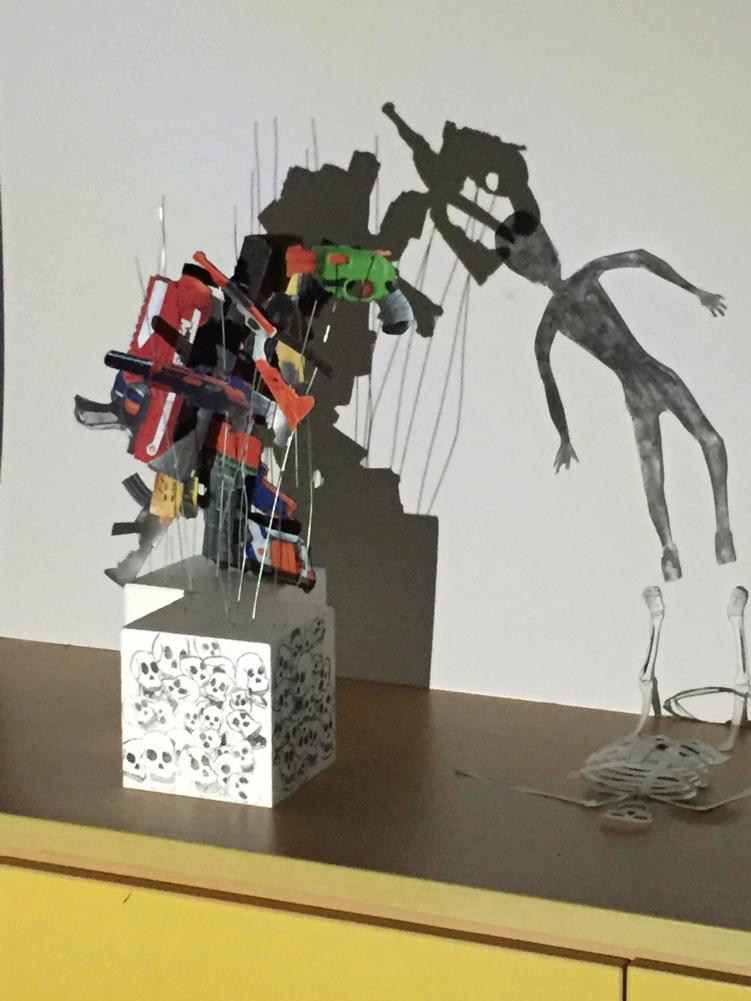

Within one’s art practice, documentation of work process would aid in tracking the development of the piece of work. This could be photographs and writings in the form of a research log, or even physical artifacts. In doing so, the artist is made more conscious of the artistic process, constantly moving back and forth between the work being made, the research being done, letting each continuously stimulate the other. Also, should there be a point in which the work stops working for the artist, there is a way to reevaluate the entire process. I remember painting in Junior College, and getting so engulfed in the process of it that I would forget to step back once in a while. My art teacher would take five or ten steps back, and beckon me to step back too. Only then, would I realise that lines that were meant to be straight were curving in weird ways, and my proportions were greatly skewed. Documenting the process of an art piece would be similar to this act of stepping back and looking from another perspective.

There is also the documentation of completed pieces for the purpose of archiving them. Documentation of performance or installation pieces preserves what is otherwise something ephemeral and transient. For installation pieces, documenting them would provide reference for subsequent set-ups.

In certain instances, the documentation itself could become part of the work, or even the work itself. An example would be artist Tehching Hsieh and his one-year performance piece of 1980-1981. In this piece he “punch[ed] a Time Clock in his studio every hour on the hour for one year” (Hsieh, 2008). He documented this punching of the Time Clock every hour by shooting one frame each time. During 1980-1981, there were days when his studio was opened to the public for viewing of this process. The piece now exists only through his time cards, the documented photographs, and an unedited film of all the stills. As such, Hsieh’s documentation of his work, in some sense, has become the work itself.

Documentaries could function as these finished pieces of works as well. Documentaries are known to be factual, telling the truth. However, the process of making the film itself can be manipulative. Alexander Kluge, a German author and film director said, “A documentary film is shot with three cameras: 1) the camera in the technical sense; 2) the filmmaker’s mind; and 3) the generic patterns of the documentary film, which are founded on the expectations of the audience that patronises it” (MinhHa, 1990). Furthermore, as the audience, one does not want to be told what is the “right” thing to do, but to be moved, disturbed, or inspired by the images on screen and resolve to take action on their own accord. In order to achieve such a response, what to document, and how to do so ought to be carefully considered: through providing new insights, bringing the unseen to light, or using different approaches to talk about prevalent issues — for example, through humour or satire. Documentary is thus not just simply a portrayal of facts, but an art form — “the creative treatment of actuality” (Grierson & Hardy, 1971).

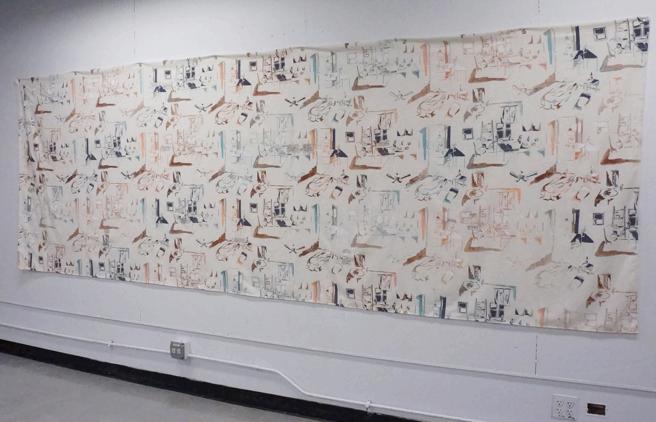

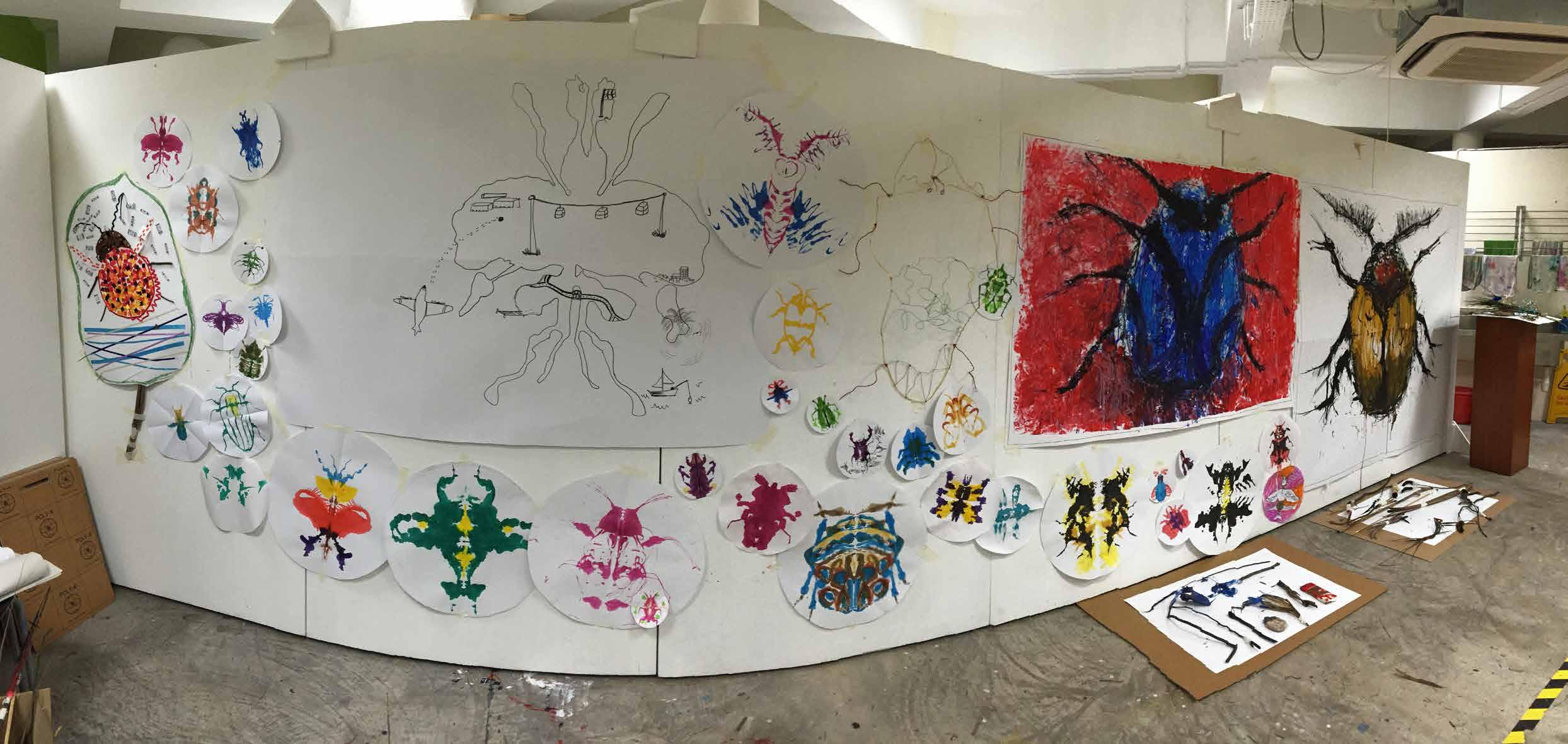

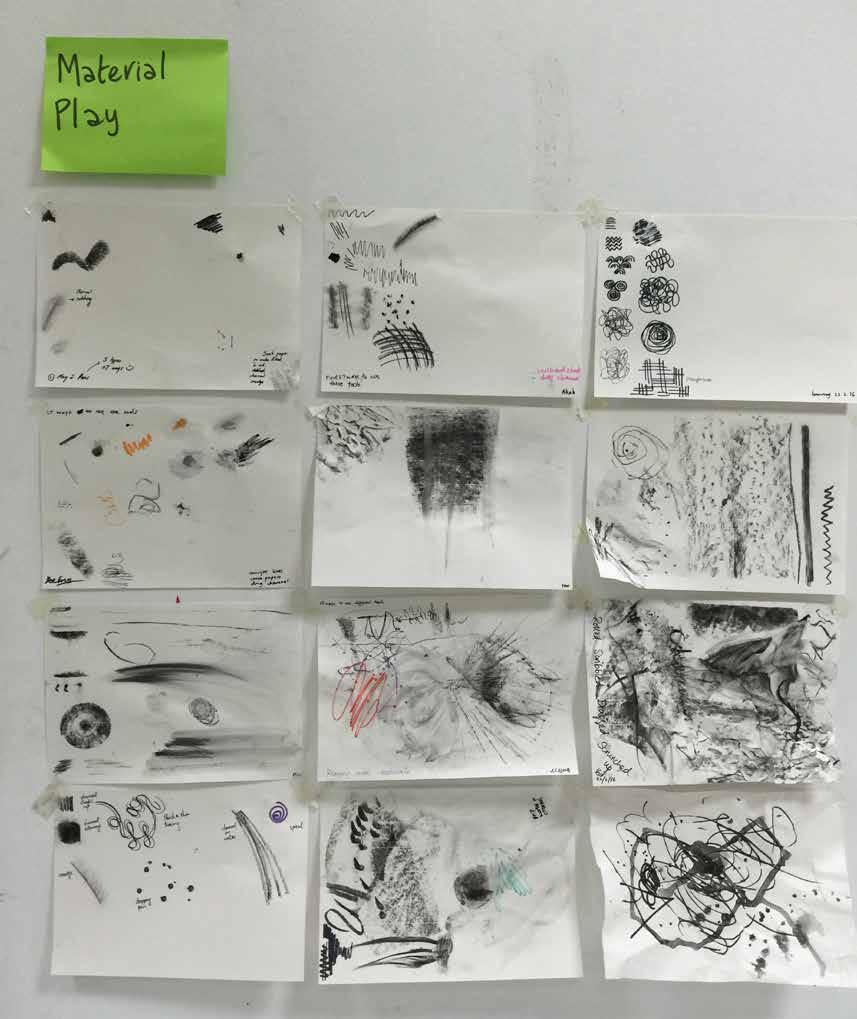

Top: Documentation of Process

Bottom: Documentation of Planning for Print

Shifting perspectives slightly from an artist to an art educator, teaching students documentation would aid us greatly in having their thought processes and ideas be made more visible and tangible. Instead of having only their final piece of work before us, their journals would provide us with information on their processes. This would also allow us to engage in dialogues with students during their art-making process — to prompt further development or extension of certain thought processes or pushing experimentation beyond what they have already done. With visual documentation, teachers would be able to show tangible examples of commendable thought or material processes, allowing students to learn from one another. Through teaching students to document their work well and consistently, and prompting students to intermittently reflect and review their processes, students would gradually understand that art-making is not merely about the final product, but also the process.

No doubt, there are limits to documentation. It is however, definitely valuable in the process of art-making, be it for the collection of source material, tracking the progress of our work, archiving artwork, or helping our students to grow as artists.

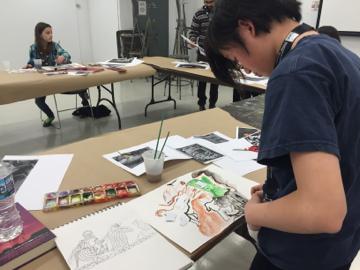

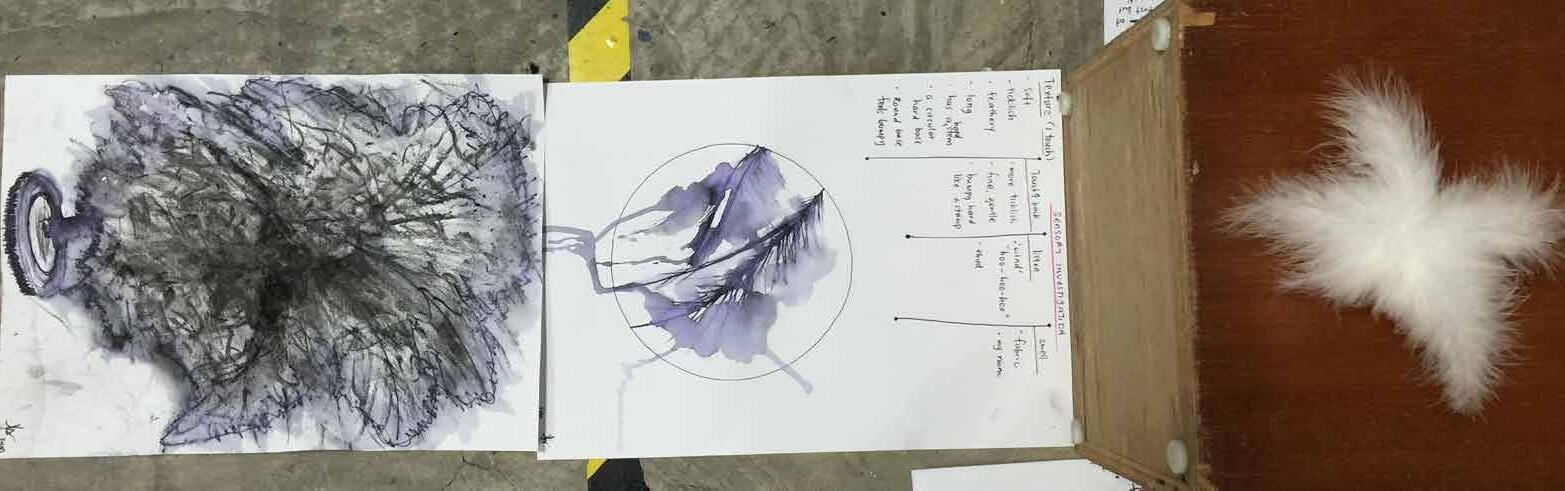

Middle School Painting Class: making ideas visible through sketching them out, and talking through with them before working on final piece

Documentation: When does it make learning visible? (n.d.). In Making Learning Visible. Retrieved July 25, 2016, from http://www.makinglearningvisibleresources.org/ documentation-when-does-it-make-learning-visible.html

Grierson, J., & Hardy, F. (1971). Grierson on Documentary. New York: Praeger.

Gürelli, K. (2004). The role of documentation in contemporary art: Issues of institutional practice (Thesis. Institute of Fine Arts, Bilkent University). Retrieved July 22, 2016, from http://www.thesis.bilkent.edu.tr/0002486. pdf

Hsieh, T. (2008). Tehching Hsieh. Retrieved July 25, 2016, from http://www.tehchinghsieh.com/

Michelle (Michy Wichy). (2012, 1 Aug). FOI 8 Opening Night: Reliqvarivm. Retrieved July 28, 2016, from https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=pHFsXK9w0EY

Minh-Ha, T. T. (1990). Documentary is/not a name. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/778886?seq=10#page_scan_ tab_contents

Moore, M. (2014). Michael Moore’s 13 rules for making documentary films. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from http:// www.indiewire.com/2014/09/michael-moores-13-rulesfor-making-documentary-films-22384/

Nancy, D. F. (2002). Towards a definition of studio documentation: Working tool and transparent record. Working Papers in Art & Design 2: Academic Journals Database. Retrieved July 25, 2016, from https://www. herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/12305/WPIAAD_ vol2_freitas.pdf

Nimkulrat, N. (2007). The role of documentation in practice-led research. Journal of Research Practice 3.1 Retrieved July 20, 2016, from http://jrp.icaap.org/index. php/jrp/article/view/58/83

Nodding, H., & Louise, E. (2011). The Contemporary Art of Documentation. Conservation Journal 59. Retrieved July 22, 2016, from http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/ journals/conservation-journal/spring-2011-issue-59/thecontemporary-art-of-documentation/

Reliqvarivm: a selection of performance art relics, chan hampe galleries. (2012). Web. Retrieved July 25, 2016, from http://www.chanhampegalleries.com/reliqvarivm -aselection-of-performance-art-relics/

Trisha, D. (n.d.). How to write a documentary script. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from http://www.unesco. org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CI/CI/pdf/ programme_doc_documentary_script.pdf

Yap, K. K. (2011). Portfolio review: A documentation process in the visual arts. SingTeach, Issue 33. Retrieved July 22, 2016, from http://singteach.nie.edu.sg/issue33teachered/

Khor Ting Yan is a Singaporean artist, currently completing her undergraduate studies in Bachelor of Fine Arts with an Emphasis in Art Education at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She was an intern at STAR from JuneAugust 2016. She will join the art teaching fraternity upon completing her studies. Ting Yan shares her internship experience with STAR POST.

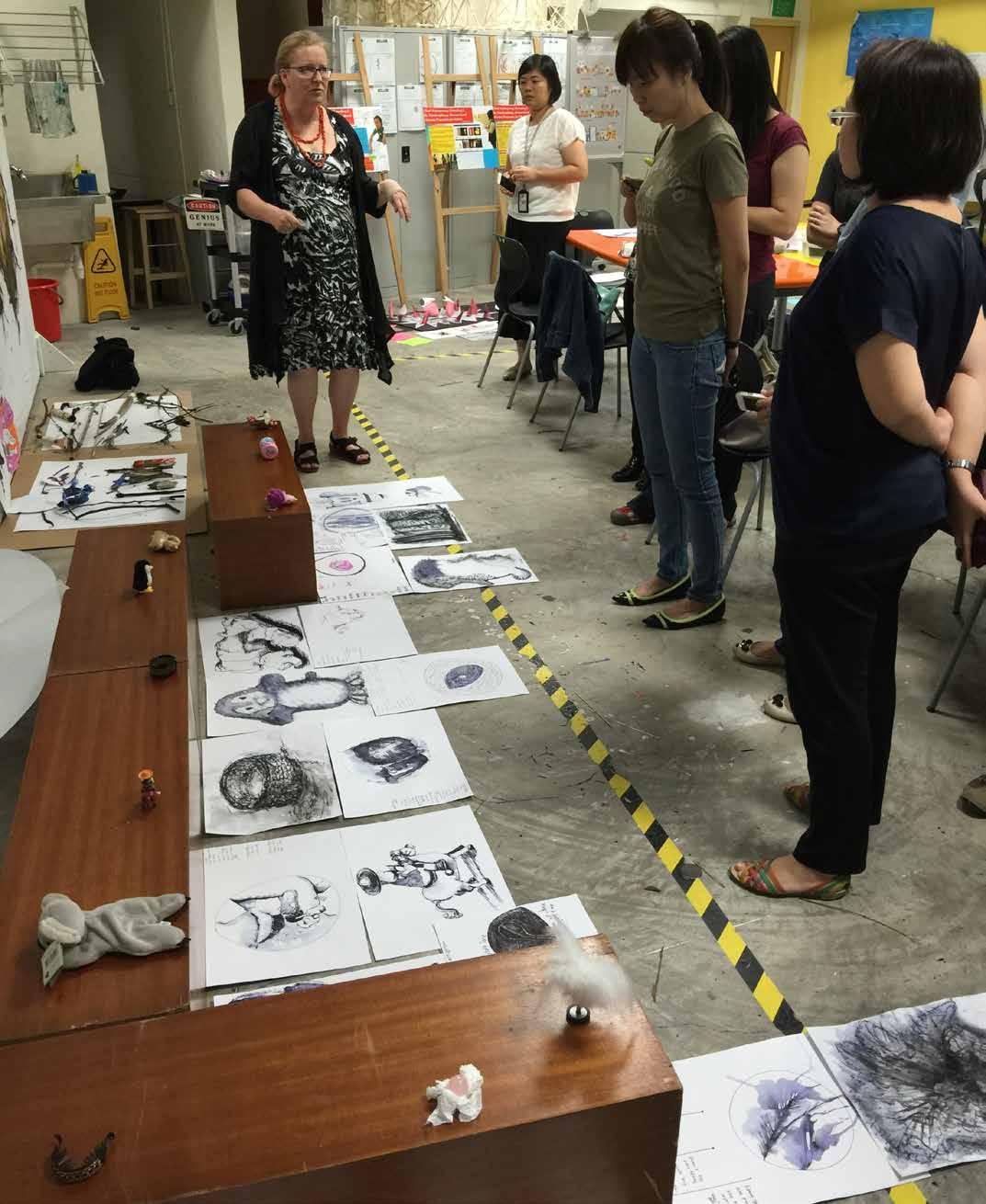

What struck me the most throughout my internship at STAR was "heart": the heart to learn, to teach, a heart for education, for students. As I sat in for the STAR Zonal Art workshop on 18th July, I got to see how STAR Champions shared their knowledge on inquiry-based learning with other art teachers. I thought to myself, are the STAR Champions not already busy enough with their own lesson plans, administrative work at school, CCAs, why would they be willing to prepare workshops for other teachers? With this question in mind, I approached two of the STAR Champions. Upon hearing that I am an intern, the two experienced teachers greeted me with much enthusiasm and excitement, warmly welcoming me into the fraternity. I asked them why they were willing to put in this extra time to plan training for other teachers when they were already so busy. Mdm Farah’s response was immediate and without hesitation: a simple “Why not?”. She grinned, and explained that if she could see a teaching approach being effective for her students, what more in sharing with a greater audience and have it cascade further and wider. Such is the selfless mindset that she embraced — for the growth of the fraternity as a whole, and the advancement of our art education.

Besides the workshops, I also had the privilege to help develop resources for art teachers, it made me realise that there was so much that went behind the teaching of a class of students. Each lesson is the effort of not only one teacher, but a whole ministry of people who desires to develop a love for learning in the generations after them. I think it is also a reminder for me, that when I eventually do start to teach, to remember that I am not alone as a teacher. There are resources available, and people willing to share knowledge, or simply give support. Observing the workshop participants ask questions genuinely, nodding in agreement, and writing down notes as each other shared, the sharing of learning was so evident. Despite the saying “too many cooks spoil the broth”, in education, I do not think there can be too many cooks — I think we just take turns to cook, passing on the ‘secrets’ of the trade from generation to generation, believing in what we do, and the people whom we serve, and trusting the next generation to do the same, or better.

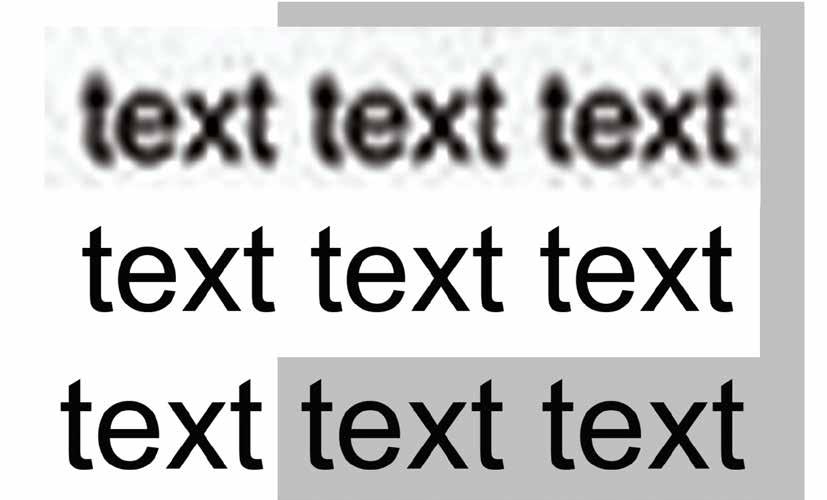

• Most common image format for web-use, Microsoft office documents, projects requiring printing

• *Lossy

• Note: Pay attention to resolution and file size, adjust accordingly for purpose — for web 72 dpi, for print at least 300 dpi

Graphics Interchange Format & Portable Network Graphics

• GIF: Great for web-use, especially for animations due to small file size, limited to 256 colours

• PNG: Created as a more powerful alternative to GIF, retains transparency, retains sharpness of text/ lines/solid shapes

• *Lossless

• Not suitable for print

• High quality file

• Large file size

• For printing and storage

• *Lossless

• Retains large amount of unprocessed data acquired from camera sensors

• Highly editable, requires photo-editing software

• To be exported as other image formats before being used on web or for printing

*Lossy and Lossless are terms used to describe the type of compression of a file. Lossy means data is lost in order to reduce the file size, reducing the quality of the image, whereas Lossless means compression occurs without a reduction in quality.

PSD Photoshop Document

• Used for editing

• Retains layers to aid the editing process

• In-process file, should be exported to other image formats before being used on web or for printing

• Used to compile documents and/or images independent of individual applications for printing

• *lossless

http://socialcompare.com/en/comparison/image-file-formats

https://makeawebsitehub.com/image-formats-mega-cheat-sheets/ http://www.insight180.com/the-ultimate-cheat-sheet-on-file-formats/

The difficult task for the teacher is to devise situations in which the young will move from the habitual and the ordinary, and consciously undertake a search.

Maxine Greene, American educational philosopher, author, social activist, and teacher (1917-2014)

u Ms Seow Ai Wee, Programme Director (Art), STAR

I wrote the above quote on a pink post-it back in 2005 when I was a graduate student at Teachers College, Columbia University. From the book Releasing the Imagination: Essays on Education, the Arts, and Social Change (1995) by American philosopher and educator Maxine Greene, the quote struck a guilty chord in me at that time: Did I create a positive culture of exploration and experimentation in my art classroom when I was a secondary school art teacher back in Singapore? Did I inspire students to create the extraordinary using ordinary materials, processes and ideas? Did I encourage students to be curious and challenge them to consider what could be otherwise through the lens of art?

I confess, there were times where the expediency of the “I say; you do; just follow” approach to art production took precedence over sustained engagement and purposeful inquiry. Devising learning situations in the art classroom that will prod students to embark on a purposeful journey of inquiry is a difficult task and requires work. Before class, the art teacher has to familiarise himself/herself with every aspect of the topic or theme to be introduced. During class, the art teacher has to skilfully navigate students’ lively group discussion and provide guidance as they work independently or collaboratively to explore, develop and create their artworks. After class, the art teacher has to reflect and revise his/her plan to extend the inquiry journey that might go on for a term, a semester or even the whole year. It is hard work but it is also rewarding work as students’ imaginative and critical senses become awaken, and they begin to enjoy the journey of inquiry.

The pink post-it with Greene’s quote has followed me to every work desk since 2005 as I taught different age groups and in various settings. It is now pasted on my work desk at the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) and will guide the work we do for art teachers and the larger art fraternity. As a team, we will continue to work hard to devise learning situations that invite you (perhaps even push you) to undertake a journey of inquiry into pedagogical approaches, artistic practices and research methods. My hope is that the multiple modes of professional learning opportunities presented by STAR will help you break away from the habitual and seek out the extraordinary as educator, artist, and researcher in the 21st century.

u Mdm Chun Wee San, Programme Manager (Art), STAR

Over the past few months, our art teachers from the STAR Champions programme (Primary and Secondary), the various STAR Zonal Art Workshops and Inquiry-based Art Lesson Design Course have been inquiring into inquiry. Some of the key questions that we investigated and continued to do so include: Why inquiry? What might inquiry look like in our classroom contexts? How does learning art through inquiry foster the 21st century competencies? How might an inquiry approach to art teaching and learning shape the way we experience art? What emerged from these exploration are the numerous tried and cherished ideas, practical tips, perceptive insights, and also thoughtful (sometimes difficult) questions that spur deeper thinking and challenge own taken-for-granted assumptions! So, what do our art teachers say about learning art through inquiry?

Teachers as facilitators...

Inquiry-based learning is a powerful approach and it impacts both teachers and students positively. It encourages art teachers to take a step back and reflect on their teaching — to facilitate learning rather than just impart knowledge and skills, and to recognise students’ individual voice. It empowers the students to make decisions and play a bigger, more active role in their learning. Art teaching and learning then become more meaningful.

— Mdm Kerina Maksin, Henry Park Primary School

The thinking that drives inquiry...

Inquiry requires one to question and seek for answers. It will require the learner to play a proactive role in his or her learning. In art inquiry, there is no definite “correct” answer to a question but many possible responses to one’s query. This way, students learn to be critical thinkers, make connections and seek personal meaning. In an inquiry-based art classroom, teachers promote curiosity by facilitating personal interpretations, get students to work collaboratively and build on one another’s knowledge. The challenge will be to look into how each lesson unit can gear towards inquiry by examining the lesson purpose, lesson structure, and assessment processes in the instructional design. The thinking behind the planning of how inquiry is to take place for the art lesson is also critical.

— Mdm Jennifer Soh, Greenwood Primary School

Using Art Inquiry Model for lesson design...

The model helps to develop my awareness of how I string together activities to structure the learning of my students. I need to be clear of what each activity sets out to achieve, and not doing it just because it seems fun. I need to consistently think about how an activity will lead onto the next one. Using the model also means setting aside more time for sharing and discussion during lessons. Sometimes it can be challenging, as I need to constantly think on the spot of what questions I can ask to probe students to think deeper about their artistic intentions, and move them away from cold and cliché treatment or portrayal of themes.

— Ms Low Sok Hui, Hwa Chong Institution

Inquiry-based learning can be daunting if it is not adequately supported or guided (Kuklthau, Maniotes, & Caspari, 2007). Research, as well as our art teachers’ experiences, inform us that a meaningful inquiry-based learning experience requires careful planning and thoughtful scaffolding.

Dr Sharon Friesen spoke about inquiry being a disposition that is cultivated during teaching and learning, rather than work that gets done by students, or simply a process that they go through. Dispositions, as we know, cannot be taught directly. They have to be developed over a sustained period of time, through different situations and learning contexts, as students immersed themselves in a culture that values curiosity, wonderment and questioning.

There are many facilitation strategies which teachers can employ to nurture students’ inquiring minds, here are a few for a start:

An inquiry classroom places the learner at the centre of the learning experience. Teachers can engage students in tasks that are worthwhile for each of them, and turn their questions and wondering into sustained exploration in art-making. Teachers can design art tasks that invite students to make meaningful and personal connections to themes and big ideas. An example of art tasks that caters for student diversity is the Elegant Art Task (Kay, 1997). Elegant Art Task are open-ended performance tasks that are worth-solving and relevant to students’ experiences. Read more about them in STAR’s Inquiry In and Through Art: A Lesson Design Toolkit (2015), p. 160.

documentation of practice

In a lesson unit on Storytelling through Photography, Ms Shirley Toh led her students on a journey to create photo-narratives of memories in schools.

Elegant Art Task:

Using a mascot (personal toy) that represents you, create a series of photographs to tell your story about a memorable time in school.

Choices/Options: 1) The mascot you choose; 2) The way you tell your story. Enabling Constraints: The photographs must show 2 places in the school.

This is the first time that I have adopted an inquiry-based approach to introduce an art form and discuss the artistic intentions. I find inquiry-based learning to be dynamic and engaging. By nature of the approach, students are placed at the centre of the whole learning experience. Through it, they gain confidence in understanding the art world and also demonstrate greater enthusiasm in expressing their intentions through their artworks.

— Ms Shirley Toh, Ang Mo Kio Primary School

In the lesson unit, teachers can also provide students with a variety of opportunities to Connect & Wonder, Investigate, Make, Express and Reflect to explore questions that are central to the art practice. As students engage in the various learning experiences, they get to develop different habits of mind, and learn to “think critically and creatively, and how to make discoveries — through inquiry, reflection, exploration, experimentation, and trial and error” (Alberta Education, 2010, p. 19), and a host of other socio-emotional competencies that prepare them for the future. Read more about the Art Inquiry Model in Inquiry In and Through Art (2015), p. 61.

In this logo design lesson, students were tasked to design a logo based on the theme My Desired Company. Ms Quek Imm Ki provided a range of learning experiences to develop students’ understanding of logo design.

• To induct Secondary 2 art students to the world of logo design, Ms Quek showed them a variety of logo designs and led the class in a discussion of design intentions, an integral part of the design process (Connect & Wonder).

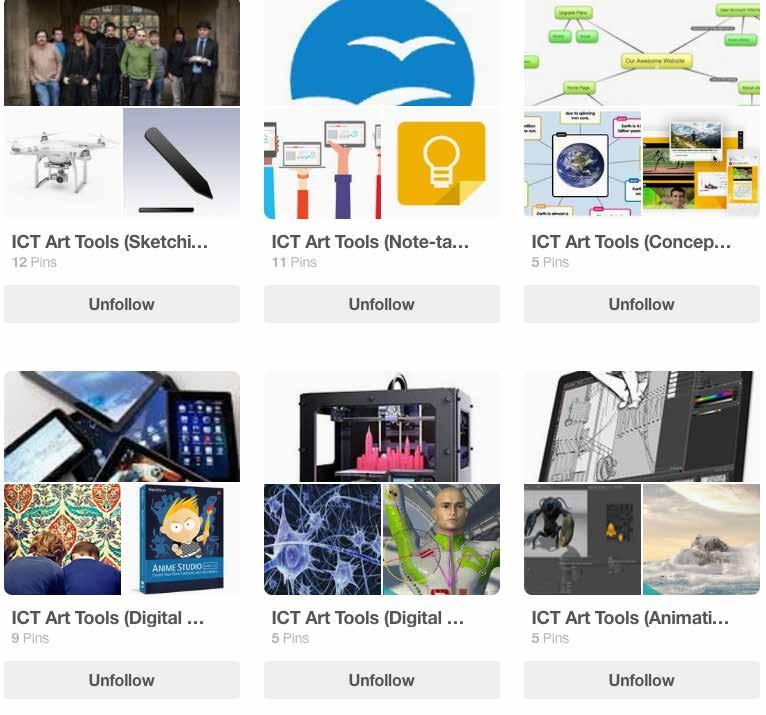

• The students then investigated the theme My Desired Company based on their interests, passion, aspirations and/or qualities they wanted to communicate through their designs. Thereafter, students generated possible design ideas by exploring fonts, text and/or images (Investigate). Adopting a flipped classroom approach, Ms Quek got the students to learn about ‘Creating logo design using Adobe Photoshop CS6’ through watching teacher-selected videos prior to the next lesson. In class, students worked in groups to clarify their understanding of the techniques and concepts shown in the video lessons.

• Students then applied their understanding through creating their digital logos using Adobe Photoshop CS6, while Ms Quek supported their exploration of ideas and techniques with teacher demonstration and timely guidance (Make).

• Upon completion of the artwork, students uploaded their designs onto the online sharing portal Padlet and presented their design intentions with a short write-up (Express). They also reflected on their design journey (Reflect) and provided feedback for their peers.

Inquiry-based learning in art is a good, useful and meaningful teaching and learning approach for both teachers and students. For me, it teaches me to be more deliberate and mindful in each inquiry process (connect and wonder, investigate, express, make and reflect); so that I can scaffold the learning experience, and guide the students while making the lesson unit more engaging, meaningful and relevant for them. It helps students take ownership of their learning, and develop them to become better thinkers who are more reflective in their art learning. It allows me to deepen my understanding of art pedagogy, knowledge creation and application. It also makes me more reflective in my teaching practices. I also learnt that the way teachers use questions can determine the outcomes of learning, whether it is gaining deeper understanding or merely learning facts. Students asking carefully considered questions in inquiry-based learning can also help to deepen understanding as they work to bring meaning to their experiences.

— Ms Quek Imm Ki, Kuo Chuan Presbyterian Secondary School

According to Darling-Hammond (2015), “successful inquiry approaches require planning and well-thought-out approaches to collaboration, classroom interaction, and assessment”, in order to acquire rich understanding, which is also the outcome of effective inquiry. A thoughtfully-scaffolded lesson unit consists of a series of interrelated lessons, weaved together coherently to build the momentum of investigation, sustain interest and progressively deepen learning. Effective teachers provide scaffolds to help students along the way, breaking complex tasks and information into bite-sized bits, and supporting with appropriate, timely assistance.

documentation of practice

Prior to creating individual 3D paper assemblages, students worked in small groups to explore different techniques for manipulating paper. Each group investigated 6-8 ways of transforming paper into 3D forms, and through doing so, develop understanding of the material and its possibilities, and how they could use paper to express artistic intentions. This exploratory activity was followed by a Gallery Walk where students had the opportunity to view their peers’ works and identify techniques of interest to them. Their teacher, Ms Laura Lim, also used question prompts to invite thoughts and guide the conversation.

Gallery Walk:

Pupils walked around to pick a technique they considered new. Pupils had to explain their choices:

1. Why do you consider the technique new?

2. How might you make use of this new technique in your paper assemblage?

3. How do you think the technique you had chosen relates to emotions?

My Primary 6 pupils were excited about art learning through inquiry and took ownership of their art-making. This inspired me! I was heartened to see that the inquiry-based lessons had created opportunities for my pupils to go through the thinking processes that allowed them to develop as inquirers. They discussed, shared and made their thoughts visible. It was a long process but it was worthwhile to see your students think critically and learn to become independent learners.

— Ms Laura Lim, Xinghua Primary School

References

Questions feature prominently in an inquiry-based classroom; instead of providing directive instructions, teachers ask questions to stimulate thinking and advance learning. Effective teachers have a repertoire of questioning strategies at their disposal to facilitate learning, understand students’ thinking and build a culture of inquiry. For instance, open-ended questions open up discussion and invite multiple responses; thinking routines Think, Puzzle, Explore helps students develop questions that they are genuinely interested to pursue; What makes you say that? makes students' thinking visible by inviting them to clarify their thoughts and elaborate on their ideas; and the use of hypothetical questions, for example, ‘what if…’, ‘if…, then…’ and ‘why’ questions foster creative thinking, promote curiosity and encourage imagination.

Different questioning strategies elicit different responses, and the choice of questions is often dependent on intent. Regardless the types of questions, what matters most is that students’ responses are listened to, considered and discussed to extend thinking, make connections and build understanding; as Dillon (1994) aptly pointed out, “it makes no difference whether the question is higher or lower cognitive, whether it is simple or complex, whether it is fact or interpretation. What makes the difference is whether the answer to the question is predetermined to be right, whether it is to be recited or discussed.” Refer to Let’s Talk about Art kit and Inquiry In and Through Art (2015), p. 96 to learn more about questioning strategies.

Teachers play a pivotal role in students’ inquiry. To be effective facilitators, teachers need to embrace the spirit of inquiry, and through modelling and coaching, teach students how to use some of the visual inquiry strategies. Teachers also need to constantly challenge themselves to think deeper, ask new questions and keep the inquiry alive, in order to cultivate the inquiry dispositions in the children we work with and support (Friesen, 2012).

Alberta Education. (2010). Inspiring education: A dialogue with Albertans. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Education.

EDtalks. (2012). Inquiry as a disposition [Video file]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/49954182

Friesen, S., & Scott, D. (2013). Inquiry-based learning literature review. Retrieved from http://galileo.org/focus-on-inquiry-lit-review.pdf

Kay, S. I. (1997). Shaping elegant problems for visual thinking. In J. Simpson, J. Delaney, K. Carroll, C. Hamilton, S. Kay, M. Kerlavage, and J. Olson, Creating meaning through art: teacher as choicemaker (p. 359-388). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lampert, N. (2013). Inquiry and Critical Thinking in an Elementary Art Program. Art Education, 66(6), 6-11.

Darling-Hammond, L., Barron, B., Pearson, P. D., Schoenfeld, A. H., Zimmerman, T. D., Cervetti, G. N., Chen, M., Tilson, J. L. (2015). Powerful Learning What We Know About Teaching for Understanding Somerset: Wiley.

Peat, A. (2010). A question of creativity. Retrieved from http://library. teachingtimes.com/articles/creativity-ttc5.htm

Ritchhart, R. (2012). The power of questions. Creative Teaching and Learning. Vol 2.4. Retrieved from http://www.ronritchhart.com/ Papers_files/The%20Power%20of%20Questions.pdf

Dr Sharon Freisen on Inquiry as a Disposition http://bit.ly/2diCV97

Provide choices and empower students to make decisions.

Nurture student voice through art discussion and art-making. Voice

Connect themes and big ideas to the interests and experiences of students.

Place ideas at the heart of learning experience — encourage students to express ideas and consider others’ ideas.

Build on students’ existing proficiencies, prior knowledge and lived experiences.

Encourage student questioning. Ask them questions and let those questions drive the learning!

Listen to students’ thoughts, use the information to promote further inquiry and guide your instructional decisions.

Model the thinking, actions and behaviours of an inquirer. Make your inquiry process visible for students to see and discuss.

Inquiry-based learning is a participatory experience. Create opportunities for students to learn with and from one another.

Meaningful inquiry takes time. Inquiring mindset takes time to grow. Allow time for students to learn to be an inquirer.

Build a class culture that respects and values inquiry.

Provide opportunities for exploration and experimentation of ideas, materials, tools and processes.

Reflection is key! “We do not learn from experience... we learn from reflecting on experience.” – John Dewey

Create a secure and supportive environment where students feel safe to take sensible risks, try new things, make mistakes and to learn from them.

Notice and celebrate the successes along the inquiry journey. Showcase the process and evidence of inquiry!

As part of STAR’s Senior and Lead (ST/LT) programme, a study trip to Melbourne was organised to provide Art/Music Senior and Lead teachers with a changed context to broaden their perspectives and reframe their assumptions and practices, whilst also providing opportunities for collegial sharing and deep reflection.

The objectives of the trip were:

1. Gain new and/or reframed insights in art and music pedagogical approaches in the classroom context; and

2. Broaden perspective on Australia’s education system and culture

Prior to the study trip, the teachers attended a module on Pedagogical Mastery for 21st Century Arts Educators, conducted by Monash University (Melbourne, Australia). The pedagogical module was designed based on the framework The Qualities of Quality by Project Zero of Harvard Graduate School of Education. The understanding of quality in arts education was informed by the Four Lenses of Quality: Student Learning, Pedagogy, Community Dynamics and Environment (LPEC). Throughout the trip, the teachers made reference to the four lenses to inform their learning and reflection. Besides attending lectures and discussions at the Monash University, the team also visited schools to observe lessons and had dialogue sessions with the arts teachers. STAR POST invites some of the Senior teachers to share their observations and learning experiences.

It was inspiring to see how the teachers provided positive learning experiences by creating a functional aesthetic space for their students to learn, and immerse themselves in art. Often, we talk about learning beyond the classroom walls, but usually these are made up of learning journeys or museum visits. Mrs Sue Storr showed us how learning can be extended beyond the classroom walls through her storytelling session at the foyer and ‘parade square’, using artworks created by the students when they were in kindergarten. The chalk drawings she did on the ground not only set the stage for inquiry, but also inspired her students to learn about the topic for the day. In the art room, she prepared several stations for her students to explore different types of painting. It was interesting to hear the students' conversations, everyone was engaged in the exploration of ideas and materials, and was having fun learning from one another.

I have also observed that in the Australian schools we visited, every student had a visual journal for them to conceptualise their ideas and document their thought processes. It was amazing to see the flow of students’ thoughts and ideas that led to the final work, all consolidated within a journal. Through this journaling, students reflected on their experiences, penned down their feelings and explored meaning in them.

— Mdm Aliah Hanim Binte Mahmud, Queenstown Primary School

Our trip to the National Gallery of Victoria and Top Arts exhibition has given me insights into how art lessons could be conducted outside the classrooms. As I toured the gallery, learning about the artwork done by the indigenous artists in Australia, I began to see how I could make the connection between artists’ works and students’ art learning. The activity conducted by the National Gallery of Victoria enabled me to learn about the possible art activities that I could do to link Singapore cultures to relevant topics/themes. I could also plan learning journeys to the Singapore Art Museum, National Gallery Singapore, and NUS Museum for my students to deepen their art knowledge, and help them make meaningful personal connection with the artworks.

— Ms Jessica Kho Siok Ching, Marymount Convent School

By teaching through inquiry and incorporating the LPEC framework, I have become more attuned to the learning needs of my students. I made sure that the lessons I designed relate to their experiences. The environment must be conducive for them to experience art and see that art is everywhere around them. The class culture should also encourage questioning, through verbal cues or posters, around the classroom for students to be aware of the possible ways of looking at artworks and investigate processes in art-making.

— Mdm Faruzah Osman, Bedok South Secondary School

During the ST/LT programme, I had the opportunity to work with a group of Art/ Music Senior/Lead teachers. Even though most of us did not know each other before we attended the programme, we were open to sharing our teaching experiences and worked together towards a common goal — to achieve professional renewal and positive transformation in our arts teaching beliefs and practices. During the few weeks that we spent together, there were a lot of opportunities for us to interact and this helped build a collaborative culture amongst us. From this experience, I have learnt the importance of teamwork — working together as pedagogical leaders to lead our peers in the arts teaching fraternity. We need to constantly keep abreast of the emergent trends in arts pedagogy and professional practice so as to keep up with the fast-changing world. Although there might be challenges along the way, I am sure we can achieve our goals if we adopt a positive mindset and have the determination. This could also be made possible if Art/Music Senior/Lead teachers work collaboratively and put our ideas into practice together. I also believe that through networking and communication, we can build a strong learning community to support one another, and build the teaching resources for all of us in the fraternity.

— Ms Jessica Kho Siok Ching, Marymount Convent School

Although the ST/LT programme has come to an end, it is not the end of the chapter; but rather, it is the beginning of the chapter for me as I embark onto the next phase of my teaching career. The programme has helped me to become a more reflective practitioner in my teaching and learning. I learnt to understand the importance of engaging myself in professional growth, and working collaboratively with other Senior and Lead teachers to build a strong teaching community. We support one another for a common goal — provide opportunities for our students to develop their creative selves, foster good values in them through art, and equip them with skills and competencies for the 21st century. As a teacher-leader, I need to constantly upgrade myself in my art pedagogical knowledge and skills so as to develop my competency as Art Senior Teacher. At the school level, I will work with the art teachers in my school to design inquiry-based lessons using the thematic approach, and build a learning circle to share art ideas and teaching resources. There is so much that we can do as art educators for our students. To conclude, I need to step out and reach out, so that my students will be able to take ownership of their learning and face the challenges ahead with a positive mindset!

— Ms Jessica Kho Siok Ching, Marymount Convent School

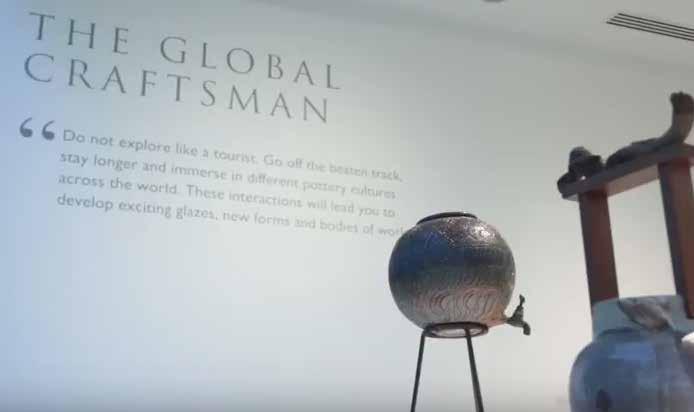

As part of the MOE-NAC Master Artist Series and in conjunction with the NIE Art Gallery exhibition, Dr Iskandar Jalil: A Master Potter’s Philosophy & Process, STAR invited Dr Iskandar, a highly-regarded local ceramist, for a conversation at A Dialogue with Dr Iskandar Jalil – Master Potter, Inspiring Teacher.

At the dialogue, participants had the joy of listening to Dr Iskandar share candidly about his personal experiences in pottery-making, particularly his lifetime inquiry into the materials and processes of pottery, and the personal values that shape his works. Participants were inspired not only by Dr Iskandar’s relentless pursuit of the mastery of pottery, but also the art of teaching. It is this passion for his craft that drives his lifelong quest to raise public awareness and foster appreciation of ceramics, and playing an instrumental role in shaping a ceramics culture in Singapore. STAR POST shares some nuggets of wisdom from the Master Potter.

It was just a dialogue, then a conversation, but now it is a sacred conversation. Nothing can interrupt this private talk, between clay and me!

My prepared and wedged clays will always dictate me what to do and vice versa. I have to listen and to have a dialogue with the clay prior to commencing. Even the different types of clay will influence the outcomes of the works.

I always tell my students: whatever you do, understand your material well. Know what it can do for you, not what you want it to do for you, follow the flow.

I have 84 journals at home. Every time I bring them along with me (on my trips), one at a time. For one town I do one writing, I photograph. And then I write. And based on this, I do my work. So it is essential, for art teachers, you must have your own journal, your own writing. Keep them and then it is very useful. It gives you a culture, it gives you an identity.

I lean towards a method of mentorship that involves immersive environments to stimulate a deeper form of learning as opposed to surface instruction or training in a classroom or studio... travel extensively but do not explore like a tourist... go off the beaten track, stay longer and immerse in different pottery cultures. These interactions will lead you to develop exciting glazes, new forms and bodies of work.

It’s about understanding what the material can do for us, then can it be successful. We should understand our students, what they can do, what they should do.

In life, I cannot expect everything to be perfect. Sometimes I need failure, experiencing and learning from it.

Source of quotes:

• Exhibition Catalogue of Dr Iskandar Jalil: A Master Potter’s Philosophy & Process http://bit.ly/2cTGXH6

• Iskandar Jalil first Singaporean artist to receive prestigious Japanese award. http://bit.ly/2dM0hm7

• Iskandar Jalil. http://bit.ly/2cUVEoo

• Iskandar Jalil’s lifework in two exhibitions. http://bit.ly/2dTKP84

• Iskandar Jalil plans his ‘last show’. http://bit.ly/2dz4P01

• Majulah!: 50 Years of Malay/Muslim Community in Singapore. http://bit.ly/2dz4fiX

• The Potter’s Touch. http://bit.ly/2dMTLA5

• Video Feature: At the wheel with Iskandar Jalil. http://bit.ly/2cUVXj2

• Why Singaporean potter Iskandar Jalil shares a close affinity with Japan. http://bit.ly/1Fy0Ncz

Dr Iskandar Jalil: A Master Potter’s Philosophy & Process

http://bit.ly/2duYymR

Dr Iskandar Jalil is a renowned Master Potter and art educator in Singapore. A recipient of the Cultural Medallion for Visual Arts in 1988, he became the first Singaporean to receive Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, in 2015. This Order was presented to Dr Iskandar in recognition of his significant contribution towards cultural exchange and mutual understanding between Japan and Singapore through pottery. He had also received two Colombo Plan Scholarships, one for the study of textile weaving and spinning in India (1966) and the other for ceramics engineering in Japan (1972). Dr Iskandar began his career as a math and science teacher before transitioning to teach pottery at the Baharuddin Vocational Institute, and later at Temasek Polytechnic’s School of Design until his retirement in 1999. He was recently conferred an honorary doctorate, Doctor of Letters (honoris causa), by the Nanyang Technological University on 25 July 2016.

About MOE-NAC Master Artist

MOE-NAC Master Artist series is jointly organised by Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (Ministry of Education) and National Arts Council. Through the format of artist talks, dialogues or workshops, veteran Singapore artists share their art practices, inspirations and philosophies. This particular session was supported by venue partner, National Institute of Education.

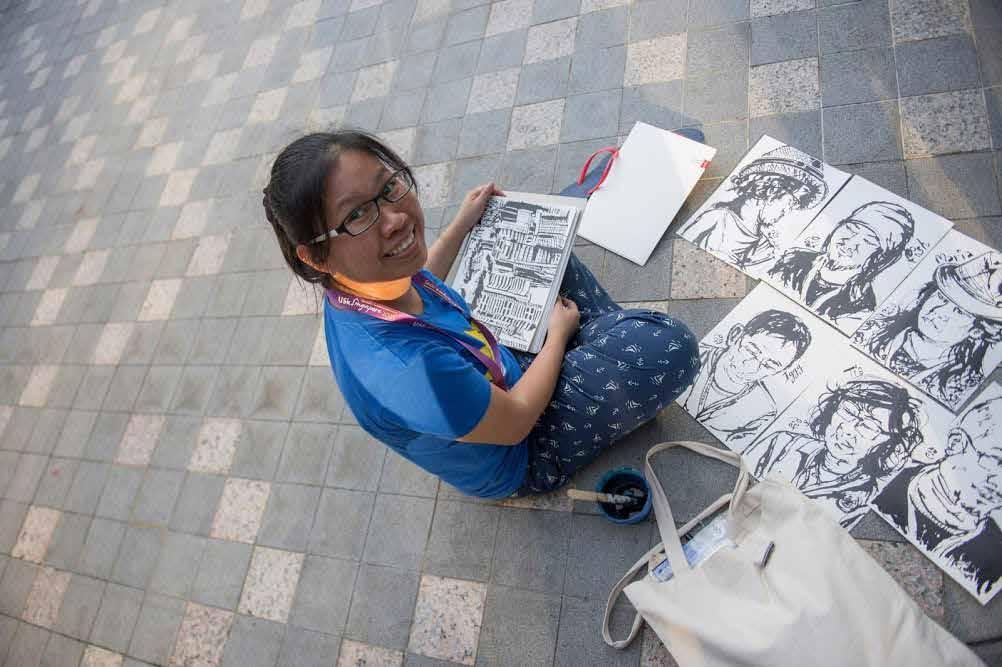

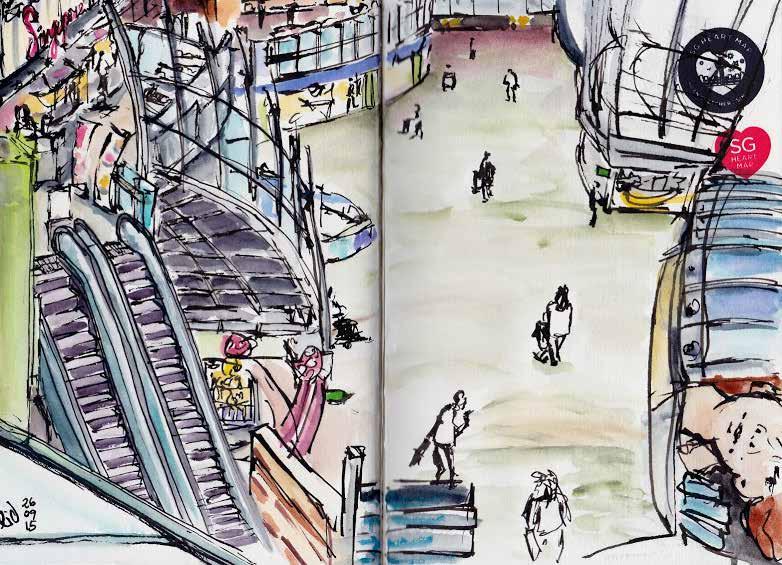

En plein air is the French expression for in the open air, and plein-air painting simply means painting in the outdoor. This painting approach dates back to the 19th century when the Impressionists revolutionised painting with their spontaneous landscape paintings, executed entirely outdoors to capture the fleeting effects of light at different seasons, weather conditions and times of the day. The Impressionists were essentially interested in recording the moment on-site. In recent years, a new art practice quite similar to plein-air painting has emerged and gained much popularity globally. Known as “Urban Sketching”, artists draw attention to the world, through their on-location drawings and sketches. The Urban Sketchers have formed communities all around the globe, including Singapore.

Amongst us, there are art teachers who have joined the bandwagon of going places armed with a sketchbook and drawing tools too! Ms Rafidah Dahri (St. Joseph's Institution Junior) has been an enthusiastic member of the Urban Sketchers Singapore (USKSG) group since 2014. “Ever since joining the USKSG group, I have had the opportunity to get to know and learn from various artists from all walks of life!” Through the monthly USKSG sketchwalks, Ms Rafidah has broadened her repertoire of drawing skills and gained deeper insights into this art form. “I have been learning a lot, especially about how to approach drawing, I also realised that sometimes, the lesser control you have over the drawing, it is all the better!” The year 2015 has been especially meaningful for Ms Rafidah as she had many opportunities to participate in collaborative projects organised by USKSG, and the learning experience was one which she found “a real treat and humbling”.

For Ms Rafidah, her art practice as an urban sketcher has definitely positively impacted and influenced her teaching, developing her to be a more observant art educator, attuned to students’ needs and interests.

Being out and about really broadens my perspective about the real-life relevance of an art form. I learnt so much just by observing, trying it out for myself, talking to people, and getting to know how people react/feel/work towards an artwork. There’s just so much out there that we can learn if we think beyond where we’re working from.

My art practice opens doors to many things that I can share with my students and fellow colleagues. It also helps me understand artists better. I honestly believe that there is an artist in all of us!

For all the urban sketchers wannabes out there, Ms Rafidah has some tips to share with you!

For starters, try drawing from pictures, still-life objects and then moving objects in the urban surroundings. You’ll transit quite nicely if you’re afraid of diving straight into sketching en plein-air.