Low fares on more than 750 routes

Restaurant NOBI offers wonderful experiences, delicious food and drinks, and atmospheric moments at a scenic spot by the Aura River.

Located by the Aura River in the heart of Turku, Restaurant OOBU offers a unique dining experience where tradition meets modern flavors.

Savor fresh seafood and locally sourced ingredients, from smoked salmon soup to lamb and fish dishes, all served in the elegant atmosphere of the historic Bassi House.

All our dishes are gluten and lactose free, crafted with care to ensure a delightful dining experience for everyone.

Whether you're looking for a relaxing lunch or an unforgettable dinner, OOBU is your gateway to the best of Finnish cuisine.

Opening Hours:

Lunch 11:00-14:30

Tuesday 11:00-22:00

Wednesday 11:00-22:00

Thursday 11:00-22:00

Friday 11:00-23:00

Saturday 12:00-23:00

Sunday & Monday closed

Book your table today and indulge in the flavors of the archipelago!

Läntinen Rantakatu 9 20100 Turku

www.oobu.fi info@oobu.fi

+358 (0)20 128 09 00

Secure your table at OOBU now—scan the QR code and reserve your spot for an unforgettable dining experience!

Turku Times

Magazine for Visitors Issue 2/2025

Autumn-Winter-Spring www.turkutimes.fi

ISSN 2342-2823 (print)

ISSN 2669-8285 (online)

Graphic design & layout

Petteri Mero

Mainostoimisto Knok Oy

The (b)oldest city in Finland! 8

A hotline in a cold world 10

A short history of sisu 12

Captain Finland: How to make it in Finland, Part 2 14 Turku timeline 16

Maps of Turku & Ruissalo Island 18

Hotels providing Turku Times 20

The oldest folks in the building 22

Scale Models at the Maritime Museum – A journey into the past 25

Best regards, Tove 30

The hotel room: a writer’s haven – Column by Arttu Tuominen 32

Editor in chief

Roope Lipasti

Sales manager

Raimo Kurki

raimo.kurki@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 45 656 7216

Sales manager

Kari Kettunen kari.kettunen@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 40 481 9445

Published by Mobile-Kustannus Oy

Betaniankatu 3 LH FI-20810 Turku, Finland

Member of Finnish Magazine Media Association (Aikakausmedia)

Publisher Teemu Jaakonkoski

Printed by Newprint Oy

Cover photos

Vartiovuori Observatory.

Photo: Jaska Poikonen / Visit Turku Archipelago Turku Art Museum.

Photo: Visit Turku Archipelago Hotel Seurahuone & Gunnar.

Photo: Visit Turku Archipelago Turku Castle.

Photo: Jarmo Piiroinen / Visit Turku Archipelago Arttu Tuominen.

Photo: Mikko Rasila / WSOY

Dear readerS,

I am pleased to welcome you to Turku – the oldest and boldest city in Finland.

historic, yet innovative city

Turku is a city with a heart that beats with history, but where the future is being built with determination and sustainability. As a city, Turku is an internationally recognised pioneer in climate matters. Our ambitious goal is to be a carbon-neutral city in 2029 when our city will celebrate its 800th anniversary, and a resource-wise and waste-free city by 2040. We also enhance biodiversity and promote the circular economy, and Europe’s first biodiversity park has been established in Turku.

Turku is the cradle of Finnish education – the country’s first university was founded here in 1640. With a total of six universities and universities of applied sciences and their about 40,000 students, our city is guaranteed to be brimming with energy, intelligence, creativity and the ability to renew. The unique status of Åbo Akademi, the only Swedish-speaking university in Finland, is a significant part of the identity of our bilingual city.

The success of Turku is also guaranteed by the long-term, regional cooperation between higher education institutions, companies and the city. This cooperation provides a strong starting point for business and innovation. We are an internationally renowned centre of expertise in fields such as bioeconomy, circular economy, pharmaceutical development and the maritime industry – for example, the world’s largest cruise ships are built at the Turku shipyard.

Turku is a city of experiences all year round. The Cultural Riverside, stretching from Turku Cathedral to the sea, is the heart of urban culture, where culture lovers can enjoy numerous concerts, theatre performances, art exhibitions, a rich selection of museums and a

wide variety of events. At the end of 2026, Fuuga – a world-class concert hall known for its acoustics and architecture – will also be completed on the banks of the Aura River.

The banks of river are a true oasis for both locals and visitors. Along the river you will find not only culture, but also beautiful scenery, atmospheric cafés and top-tier restaurants. Turku’s food culture is diverse and of high-quality, and the city is deservedly known as Finland’s culinary capital. Here, food is not just nourishment – it is culture, encounters and delicious experiences.

In Turku’s many excellent restaurants, you can enjoy anything from lunch made with ingredients from local producers to Michelin-level dinners. You can enjoy both local dishes and international cuisine aboard riverboats, in a former prison, or on rooftops with panoramic views of Turku. Our traditional market hall is also well worth a visit. Food is part of Turku’s identity – and we take pride in sharing its richness with every visitor. Whether you’re a gourmet, an adventurous foodie or a fan of local produce, Turku offers a culinary journey to remember.

Vibrating with modern urban culture, Turku is nestled in the embrace of the world’s most beautiful archipelago, surrounded by over 40,000 islands and islets. As a port city, the sea is an integral part of Turku's identity. You can sense the maritime atmosphere just a few kilometers from the city center on Ruissalo Island, where enchanting oak forests, pristine beaches, and winding nature trails await.

Turku is a unique combination of history, urban culture and maritime experiences. Most importantly, Turku is a place where smiles are shared, and everyone can feel at home. I hope the city captures your heart during your visit – and inspires you to return again and again.

A warm welcome to Turku!

Piia Elo Mayor of turku

What do archaeological discoveries reveal about the daily life of past ages? Turku’s old Convent Quarter comes to life in the renewed Aboa Vetus museum.

Arkeologian ja nykytaiteen museo

Museet för arkeologi och nutidskonst

Museum of archaeology and contemporary art

Itäinen Rantakatu 4–6, Turku | Östra Strandgatan 4–6, Åbo | www.avan.fi

Written

During the Cold War, a hotline ran through Finland. Its purpose was to prevent the accidental outbreak of nuclear war. Traces of it still linger in the landscape.

In 1962, the world trembled. We had never been so close to nuclear war. The Soviet Union intended to deploy nuclear missiles to Cuba, and the United States responded that it would mean war.

War didn’t break out, but it was a wake-up call: the world needed a direct line between the great powers, one that would operate immediately, without the delay that usually accompanied diplomatic relations, where a message from Washington to Moscow or vice versa could take hours. That was far too long when the world could be destroyed in minutes.

The communications link was quickly built and operational in just a couple of months. The hotline wasn’t exactly a red telephone, like in the movie Doctor Strangelove, but something in that direction. Actually, it wasn’t a telephone at all, but a teleprinter, or telex system. These electromechanical devices were once used to send text from one place to another, typically along a telegraph line. Physically, the machine resembled a typewriter and printed a message on paper.

In the case of the hotline, the line was of course very well encrypted. At first, there were teleprinters at each end. In the 1970s, they were replaced with fax machines. Each party used its own language in its transmissions, and the texts were translated at the receiving end.

for example, off the coast of Denmark, a Soviet ship severed it while towing a ship that had run aground on a sandbar.

So it seems that undersea cables have been vulnerable for a long time!

The risk of cable breaks was also taken seriously by the authorities: in the places where the line ran, digging with an excavator required police supervision.

Nonetheless, there were so many accidents that eventually the route of the line was marked with red metal posts, which can still be seen here and there in the landscape.

The hotline wasn’t exactly a red telephone, like in the movie Doctor Strangelove, but something in that direction.

Given the technology at the time, the system was not entirely simple, as it had to cover a long distance. The line ran from Moscow to Tallinn, then to Helsinki and onward to Turku, where it plunged into the sea, emerged in Stockholm, and continued via Copenhagen and London to Washington. There was also a backup line in Finland, which went via Lappeenranta to Helsinki and then to Hämeenlinna before reaching Turku.

The line itself was a cable with a diameter of about five centimeters. Inside a pitch-coated lead tube were four pressurized copper pipes, within which the actual copper conductors ran. If the pressure dropped, meaning that the line had been broken or someone had tried to infiltrate it, the system sounded an alarm.

Because the distances were long, the signal needed to be amplified every so often. Special repeater stations were built every few dozen kilometers, which dotted the fields of Finland for a couple of decades. The stations weren’t just some chicken coops – they were built to be bombproof. These concrete bunkers were built underground if possible, and above ground if not. They were a few square meters in size and filled with the best technology of the day.

A few of these huts still remain in Finland, one near the eastern border in Lappeenranta and another near Hämeenlinna.

DeSpite all the precautionS, the cable did suffer breaks every once in a while, usually when some farmer was out in a field digging some kind of ditch – the cable was buried only 60 centimeters deep. Of course, Finland wasn’t the only place where the cable was disrupted. Once,

The line itSelf was tested continuously. Test messages were sent once an hour to ensure it was working. It was agreed that these messages should be as apolitical as possible, to avoid misunderstandings.

The Soviets sent things like texts by their classic authors (maybe not War and Peace, though...)

For their part, the Americans sent baseball scores and excerpts from the Kama Sutra, which seems to show that there’s no limit to human childishness.

The line has also been used in real situations. The first time appears to be when Kennedy was assassinated. The Soviet Union, in turn, made contact via the line during the Six-Day War in 1967.

In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, Israel accidentally torpedoed the USS Liberty reconnaissance ship, at which point President Johnson saw fit to inform Kosygin of the Soviet Union that there was nothing more to it: it was simply a case of friendly fire and an aircraft carrier was being sent to the area, but no need to worry. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan a few years later were also discussed on the hotline.

I MySelf have written a novel about the hotline, which was published in the fall of 2025. It’s intertwined with my own childhood in the 1970s and ’80s, when the line ran through my best friend’s yard, which of course sparked our imaginations. The book follows a group of kids growing up in the shadow of the Cold War and the fear of nuclear weapons, from 1970 until the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.

Despite all the madness of humanity, the hotline was a symbol of hope for us then, as it is now in my book. The fact that it existed meant that someone was trying, at least a little. And the loss of that kind of connection would be a terrible thing. s

Sisu is as important to Finns as the right to bear arms is to Americans, afternoon tea to the English, and surströmming to Swedes.

Sisu has its own national emoji, is considered a key element of the Finland brand, and in 2017 was the overwhelming winner in a contest to find the word that best describes Finland. So, what is sisu all about?

Written by Matti MäkeLä

by Christina saarinen

According to Wikipedia, “Sisu is a Finnish word variously translated as stoic determination, tenacity of purpose, grit, bravery, resilience, and hardiness.” As you can see, there is a lot of meaning packed into one word, and Wikipedia even fails to mention that the meaning of sisu has changed over time. During the Middle Ages, and long after, sisu was generally defined as an undesirable tendency or characteristic in an individual.

It was really only after Finland’s independence that sisu was transformed into a positive phenomenon that defined Finnishness and united the nation. A strong early representation of Finnish sisu was provided by the runners who dominated the Olympics in the 1920s and ’30s (Finland won 10 of the 15 long-distance gold medals awarded in 1920–36), as well as the other athletes who raised Finland to second in the Olympic standings of the era, right after the United States. Unfortunately, Paavo Nurmi, who won nine Olympic gold medals and was proclaimed the “King of Runners,” attributed his success not to sisu, but to training harder and more systematically than his competition.

What really put Finnish sisu on the world map was the Winter War. The word was probably first defined in English by Time magazine in January 1940, when the Soviet Union’s brutal war of aggression had been going on for a little over two months: “It is a compound of bravado and bravery, of ferocity and tenacity, of the ability to keep fighting after most people would have quit, and to fight with the will to win.”

However, the resilience deriving from sisu cannot be stretched forever, and in truth, it must be admitted that Finland’s policy of acquiescing to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and ’70s, dubbed “Finlandization,” didn’t seem to demonstrate much sisu. If Finland successfully walked the tightrope of independence during the presidential term of J. K. Paasikivi (1946–56), then during the far-too-long presidency of Urho Kekkonen (1956–81), Finland seemed to be constantly falling off the rope.

haven’t forgotten their sisu, however, and it is constantly referenced when explaining the success of Finns in things like ice hockey, rally car racing, and Formula One. Nokia CEO Jorma Ollila also offered it as an explanation for the success his company enjoyed in its peak years: “You overcome all obstacles. You need quite a lot of sisu to survive in this climate.” (It was unclear whether he was referring to Finland’s often wretched weather or the challenges of the mobile phone business.)

When you add a pinch of the stoicism mentioned in Wikipedia to this recipe in Time, the result is Finnish sisu on steroids. This is how the Finnish national novel The Unknown Soldier describes the perspective of the cynical Corporal Lehto, a man struggling with personal demons: “They can’t offer anything worse than death, and he can deal with that.”

In Under the North Star, the second masterpiece by Väinö Linna, the author of The Unknown Soldier, we go even further into the dark side of sisu. In his work, Linna describes the Finnish hatred that drove the 1918 Civil War. This was sisu in its old-fashioned meaning, which, according to Linna, is “like a bog pond: deep and black.”

But – if sisu is simply the ability to fight bravely against a seemingly overwhelming barbarian attack, then global history is full of Finnish sisu. Take, for example, the Greek warriors of Thermopylae, the heroes of present-day Ukraine, and even the late-19th-century Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud , whose remark before battle was something even Cpl. Lehto would have been proud of: “Today is a good day to die.”

Sisu is actually a complex concept, and it’s been used to respond to a variety of challenges in different eras. After World War II, Finland was in a desperate situation. The Soviet Union had occupied the rest of Eastern Europe, and Finland had to try to maintain its independence, democracy and existence with a totalitarian superpower next door. In that period, the resilient side of sisu helped, which Time magazine once again described during the 1952 Helsinki Olympics as follows: “The Finns are not stupidly hiding their eyes from their future, but they are determined not to fall into another fight with a powerful and predatory next-door neighbor 66 times their size… the Finns have learned to walk the nerve-racking path of independence like tight-rope walkers.”

As important of a concept as it is, sisu has of course also been commercialized, and in Finland, the word sisu can be found on such products as candy, trucks and buses, trams, t-shirts, hoodies and mugs, and – in many people’s minds, unfortunately – in the name of the nationalist organization Suomen Sisu. The most recent sector is film: two films named Sisu have already been made. In the first, Aatami Korpi – according to a tagline, “the man who refuses to die” – slaughters Nazis in Lapland. In the second, we get to the origins of sisu, and Korpi travels to his home region, Soviet-occupied Karelia, to take revenge on Soviet soldiers (this is where Korpi begins to deserve the nickname “the Finnish Rambo”: in the second Rambo film, Rambo returns to Vietnam to win the war the Americans had already lost once).

A country’S national identity is always reflected in its relation to others. Finns believe that sisu sets them apart from the other Nordic countries. According to this view, Swedes enjoy their coffee and buns (fika), and Danes sit beside a warm fire with wool socks on (hygge), while Finns crush granite into dust with their bare hands (the national emoji for sisu is a person bursting through gray stone), and eat the fat off of meat and the pits out of olives. Okay, the last two are actually how the Spartans are depicted in the comic book Asterix at the Olympic Games, but I’ll justify them with the fact that, in Finnish literature, characters from the Kalevala and The Unknown Soldier have often been compared to the Spartans for their fearlessness and discipline. Overall, defining sisu is difficult, and it has both its good side (persistence, belief in oneself even amid difficulties) and its dark side (smugness, arrogance, stubbornness). Perhaps in trying to define it we encounter the same problem as US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart when considering whether he could define hard-core pornography: “Perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.” s

1229

The Pope orders the bishopric to be moved from Nousiainen to the new city of Turku. By the river Aura in Koroinen, there is a white memorial cross standing in the place where the Bishop’s little castle once was. It is a nice place to visit, as is the entire riverbank, where one can walk or go jogging.

1300

The Turku cathedral is inaugurated. It is the most beautiful cathedral in Finland. Not least because it is also the only proper cathedral in Finland.

1308

The first documented mention of the Turku Castle, although the construction probably began as early as the 1280s. Builders in Turku were in no hurry, as the castle wasn’t completed until 1588. The most magnificent Renaissance period in the history of Finland was seen in Turku castle during the reign of Catharina Jagiellon and Duke John (later king John III) 1562–1563.

1414

The first bridge over river Aura is built. It was called The Pennybridge.

1500

Turku is not quite a Hanseatic city, but almost. It is one of the major cities in Sweden and its international trade is significant.

1543

Mikael Agricola, the father of written Finnish, publishes his first book. It is also a milestone of Protestantism in Finland.

1634

The first map of Turku is published, and for a good reason, too: there were already 6,000 habitants, so the city was huge!

1640

The University of Turku is established. Nowadays, Turku is still a renowned city of higher education with more than 40,000 students studying at six universities.

Written by roope Lipasti

Finlands first printing house is established in Turku. It prints books, among them the thesis Aboa Vetus et Nova by Mr Daniel Juslenius (1676–1752), in which he studies the birth of Turku. His conclusion was that the people in Turku are decendants of Jaafet, the third son of Noah.

Sweden loses Finland to Russia in 1809, and in 1812 Helsinki is declared as the new capital – something that still slightly upsets people in Turku.

Turku burns down and almost the whole city must be built again, which is the reason why Turku doesn’t have a medieval centre anymore.

The first Christmas tree illuminated with electric lamps is erected in front of the Cathedral. The tradition became regular in the 1930s.

1917 Finland declares independence.

The University of Turku is established again, since the original Academy was moved to Helsinki after the great fire in 1827. Åbo Akademi University, the only university in Finland with Swedish as official language, was founded in 1918. (Åbo is the name of Turku in Swedish.)

Finland is at war with Russia. Turku suffers great damage during the bombings, among other buildings the castle is partly burned.

1956, 1976, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1993, 1995, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2010. TPS, the biggest ice-hockey club in Turku, wins the Finnish championship.

Turku suffers from the so called “Turku sickness” – meaning that many beautiful old buildings were demolished in order to be replaced with modern blockhouses.

Turku is the European Capital of Culture.

Turku is the sixth largest city in Finland with 206,000 inhabitants. It also is one of the nicest cities and most popular holiday destinations in Finland, with its historical attractions and magnificent archipelago. s

01 centro hotel

Yliopistonkatu 12, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 2 211 8100 www.centrohotel.com

02 forenoM aparthotel turku

Kristiinankatu 9, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 20 198 3420 www.forenom.com

03 forenoM preMiuM apartMentS turku kakolanMäki

Michailowinkatu 1, 20100 Turku

Tel. 020 198 3420 www.forenom.com

04 hiiSi hotel turku Seaport

Toinen poikkikatu 4, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 20 778 0777 www.hiisihomes.fi

05 holiday club caribia

Kongressikuja 1, 20540 Turku

Tel. +358 30 087 0900 www.holidayclubresorts.com

06 hoStel S/S bore

Linnankatu 72, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 40 843 6611 www.hostelbore.fi

07 hotel helMi

Tuureporinkatu 11, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 20 786 2770 www.hotellihelmi.fi

08 hotel kakola

Kakolankatu 14, 20100 Turku

Tel +358 2 515 0555 www.hotelkakola.fi

09 hotel Martinhovi

Martinkatu 6, 21200 Raisio

Tel. +358 2 438 2333 www.martinhovi.fi

10 hotel palo

Luostarinkatu 12, 21100 Naantali

Tel. +358 2 4384 017 www.palo.fi

11 original SokoS hotel kupittaa Joukahaisenkatu 6, 20520, Turku

Tel. +358 10 786 6000 www.sokoshotels.fi

12 original SokoS hotel Wiklund Eerikinkatu 11, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 10 786 5000 www.sokoshotels.fi

13 park hotel

Rauhankatu 1, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 2 273 2555 www.parkhotelturku.fi

14 radiSSon blu Marina

palace hotel

Linnankatu 32, 20100 Turku Tel. +358 20 123 4710 www.radissonblu.fi

15 Scandic haMburger börS

Kauppiaskatu 6, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 30 030 8420 www.scandichotels.fi

16 Scandic Julia

Eerikinkatu 4, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 30 030 8423 www.scandichotels.fi

17 Scandic plaza turku

Yliopistonkatu 29, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 30 030 8421 www.scandichotels.fi

18 Solo SokoS hotel

turun Seurahuone

Eerikinkatu 23, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 10 786 4000 www.sokoshotels.fi

19 tuure bed and breakfaSt

Tuureporinkatu 17, 20100 Turku

Tel. +358 2 233 0230 www.tuure.fi

World’s easiest bus ride:

The absolute best fish and seafood lunch in town.

You are warmly welcome.

Open mon-sat 11-15

Located in Turku Market hall.

Eerikinkatu 16

Single ticket (valid for 2h) € 3,15

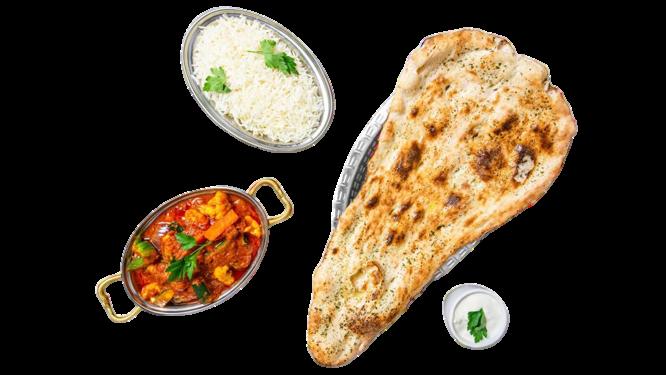

I N T I A N H E L M I B A R & G R I L L

Intian Helmi brings you the finest Indian cuisine With over 15 years of experience come and indulge in our authentic Indian dishes. Freshly prepared food using traditional techniques, a clay oven to lock in those flavours and the blends of different sauces that are famous all around the world and can be experienced right here.

Brahenkatu 14, 20100, Turku +358 41 318 6460

In many Finnish churches, the oldest remains are over 450 million years old. Fossils can be found not only in churches, but also in many other public buildings in Finland. Stone floors are a good place to look for them.

There’s one! And another! And another!

If you put on your paleontology glasses, you can spot something amazing in quite a few public buildings in Finland. For example, there are several churches where you can find fossils – and not just the vicar! In Turku, you can find them at the cathedral, and in the Tampere region, at the Finlayson and Nokia churches.

But also in Helsinki, when you go to the basement toilets at the Oodi Library, have a look down at your feet, and not only so you don’t trip on the stairs. At the Ateneum Art Museum, too, there is more to see than just the exhibitions if you keep your eyes firmly on the floor.

Finland has hardly any fossils of its own because the Ice Ages washed them away. The Åland Islands and the bottom of

the Baltic Sea are exceptions. According to archaeologist Ilari Aalto , the fossils that can be found in the flooring materials of Finnish buildings generally originate from southern Sweden or Estonia.

Aalto is working on a doctoral dissertation about brickmakers and medieval churches, so the material he usually digs up in churches is a little more recent, but he enjoys spotting fossils too. He first came across orthocones – the fossils most frequently found in Finnish floors – as a young boy visiting Häme Castle:

Orthocones existed in many sizes, ranging from tiny to several meters long.

“I’m always happy when I see them. There are a lot of them in southern Sweden, in particular, because there are large limestone deposits there. The older floor slabs in Turku Cathedral were brought from there sometime in the 18th century. Orthocones lived in the ancient Baltic Sea, which was near the equator back then – though strictly speaking, there was only one big sea at that time,” Aalto says.

Since then, the continents have wandered across the planet, and today, that ancient section of seabed is off the coast of Finland.

Orthocones are ancestors of modern octopuses and squids, and like their descendants, they were also predators. Orthocones aren’t a single species, however. Instead, they’re a so-called wastebasket taxon, into which creatures that seemed similar were collected in the 19th century. Orthocones existed in many sizes, ranging from tiny to several meters long.

They grew a horn-shaped cone – a protective shell – that was made up of chambers. The older the creature, the more chambers it had, like adding rooms onto a house. It’s the same thing that happens when people grow up: first you get a studio apartment, and then move on from there.

Orthocones had tentacles and a beak and apparently swam backwards. And how did they end up encased in stone? The answer lies in the slab material:

“It’s limestone, which is made up of calcium from dead animals. Long ago, they sank to the bottom of the sea, and over time, they turned into limestone. For example, the orthocones in the Turku Cathedral lived during the Ordovician period, about 450 million years ago, when the sea was teeming with life.”

Da Vinci knew

For Ilari Aalto, the age of fossils is precisely what’s fascinating about them:

“Fossils massively exceed the entire time period that humans have been around. It was a completely different world, and yet the same Earth, and our very own Baltic Sea! Back then, the land was desolate and empty, but the seas teemed with life. It’s also interesting to think about what people in the 18th century thought about them. At that time, they had no concept of evolution or of how rocks are formed,” Aalto reflects.

In A Description of the Northern Peoples, published in 1555, Olaus Magnus explains the shapes of fossils by saying that since nature is hierarchical, and humankind is the crown of creation, even rocks might imitate things like the shape of a human hand, and so on.

Noah’s flood was used to explain why fossils of mussels could be found in the mountains.

“Leonardo da Vinci, though, believed they were there because the mountains formed afterwards, lifting the fossils into their places. And that’s exactly the case,” Aalto says.

Although fossils are fairly common, Aalto points out that it’s quite rare to become a fossil, that is, to be petrified:

“All in all, we haven’t even found very many fossils of land animals. The seas were better places because fossilization requires, first, time and, second, pressure. As dead animals accumulated on the sea floor, they were eventually buried deeper and deeper and came under greater pressure, ultimately forming limestone as organic material was replaced by minerals.” s

It was a completely different world, and yet the same Earth, and our very own Baltic Sea!

MUUMIEN JA PEIKKOJEN TARINA HISTORIEN OM MUMINFIGURERNA OCH TROLLEN A TALE OF MOOMINS AND TROLLS

1.9.2025–6.4.2026

Opening hours: Wednesdays 12:00–18:00

Explore unique exhibitions and enjoy hands-on fun for all ages - from warships to sailing ships and scale models

Adventure awaitsfrom deck to dock!

Naantalin museo, Humppi Mannerheiminkatu 21 P. 02 435 2727 www.naantali.fi/museo

Written by otto hoLMborG

Scale models of ships have fascinating stories to tell. The best ones we come up with ourselves.

At Turku'S ForuM MarinuM, there are dozens of scale models in the main exhibition alone. The vast collections include a couple of hundred models in total. The types of vessels vary from a Hanseatic cog to a submarine from World War II, and everything in between. Imagine all those fully rigged sailing ships, paddle-wheelers, steamboats, and ocean liners that are ready to take you on a journey into the past.

Historical periods have shaped the purpose of a ship in time and space. In real life, the basic idea of all vessels has always been simple: to carry goods and people and get them across the waters. At museums, the focus is sometimes just on the ship, its voyages, the

cargo it carried, or maybe the battle it won in a war. I would like to change the perspective from the ship to its users, to the world and minds of the individual people who were once on board and experienced real life on these vessels.

Being on board a medieval merchant ship was certainly something different from being on board a warship in a naval battle in the 20th century. However, there are always some similarities when it comes to being at sea. In both cases, there are human souls in a relatively small space, aboard a moving (and floating) man-made construction that is under the influence of nature and the vast waters around the globe.

Scale models tell different stories to different people. For me, the way to look at these models is to imagine the human beings who have used these ships and lived their lives among them. In traditional maritime beliefs, the ship (usually she) had a soul of its own. In a museum, a scale model is just one way to present and tell about a real ship. When the original ship no longer exists, perhaps it is possible to see the people as the spirit of the ship?

If the people, the crew, and the passengers are left out, a scale model is just a distant, technical approach to just another man-made machine. But it is the history and connection to real life that bring these artefacts to life. It is their ability to tell a story, whether it is fact or fiction. Perhaps a ship, and even a scale model, always reflects something about the humanity that created it. Otherwise, it would be just a ghost ship.

Ships are typically seen through their size, strength, draught, and tonnage. Besides these facts, ships were always made by people and used by people. Therefore, they are loaded with experiences that an outside viewer can only imagine. Sometimes there are written stories about scale models, sometimes there is no information at all. Most of the models exhibited in the museum do not have any human figures onboard, and this makes the thought process even more fascinating. Who were they, what did they look like, and especially how did they feel about being on board? This human factor is something that creates the connection between an artefact and a visitor at the museum.

There are and have always been specialists who have wanted to build a scale model of a historical ship. This desire, combined with deep knowledge and skills, is one typical reason for the scale models that exist. Another explanation is quite simple: shipping companies have had a long-standing tradition of also creating a miniature of the ship that the dockyard built for them. Some companies had a huge fleet of ships, and many of these scale models have found their way into maritime museums around the world. Some models are considered more important than others, and in this way professional

For many people, ships symbolise thoughts of freedom, boundlessness and yearning for something better.

museums curate their collections that reflect the constantly changing historical values.

The scale models are also quite a popular way to decorate at home. When the sea is nearby, you might want to place a beautiful sailing ship by the window. In the Forum Marinum museum shop, the models are among the most popular items, even though the bigger ones are quite expensive. The state-of-the-art handicraft is something to give your loved ones as a gift, maybe on a birthday at a certain age or on a very special occasion, to commemorate a once-in-a-lifetime achievement. A well-made ship model represents dignity, and a ship expresses all those feelings that are worth celebrating.

Is it just the aesthetics of a ship, or what kind of other meanings does it hold? Maybe a model of a ship calms your mind, takes you back to the voyage you once experienced, or maybe it simply creates a dream that never happened. Whatever the case, for many people, ships symbolise thoughts of freedom, boundlessness and yearning for something better. I guess the emotional effect is quite the same whether you are in a museum exhibition or not. A ship reminds us of hope and exploring things.

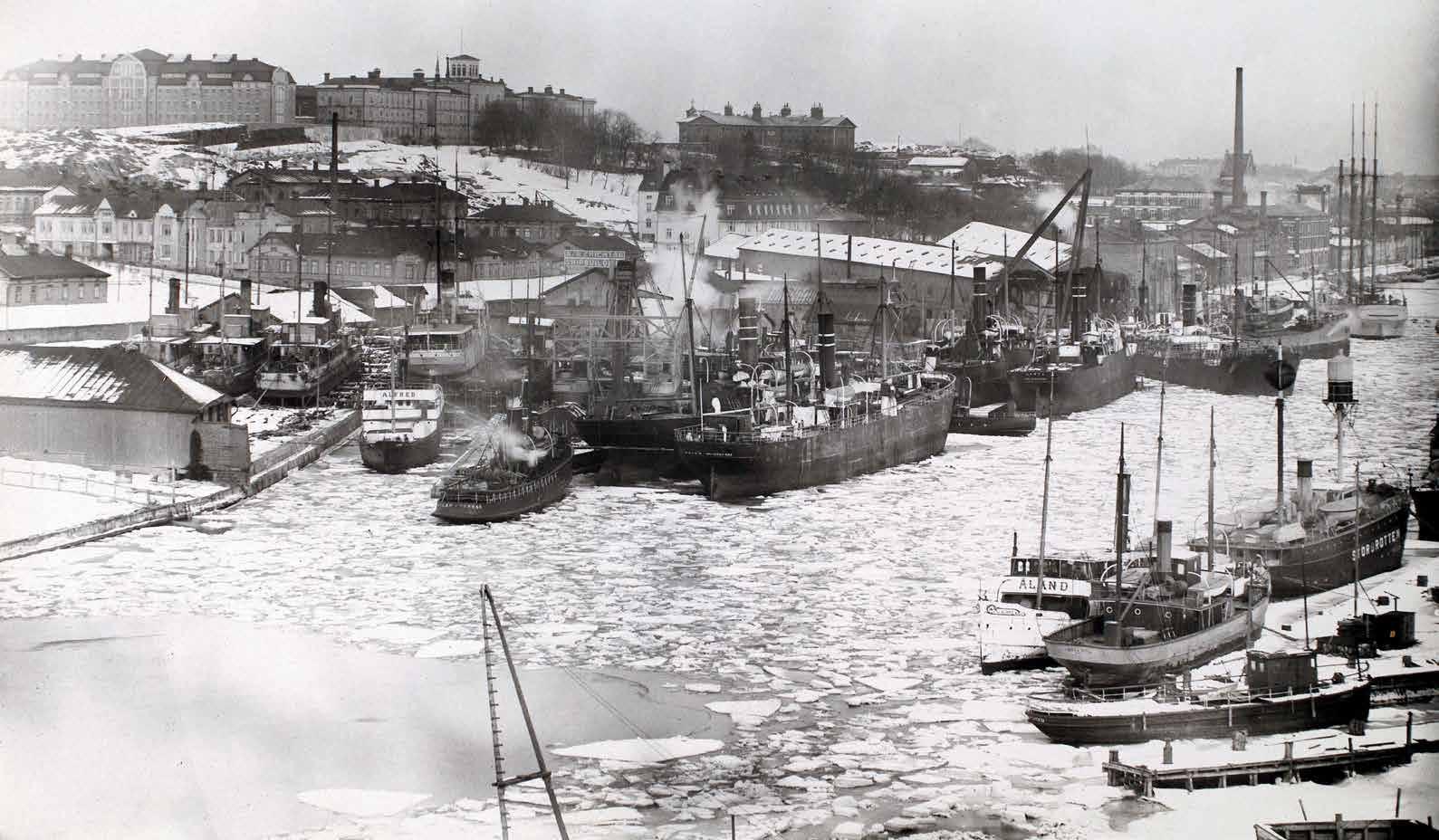

Turku is located by the River Aura, and the museum Forum Marinum was founded on the banks of the river. The area used to be the hot spot of the city’s maritime traffic for hundreds of years. Merchant vessels sailed into the heart of the city, ships were built in the dockyard, and barges supplied the needs of the industry. Ships

The area used to be the hot spot of the city’s maritime traffic for hundreds of years.

came and went. Everything happened in the middle of the city, even though there were fences and rugged areas that isolated the harbour area from the citizens.

There must have been noise, lights, smells and a special vibe around this industry. The seamen and harbour workers shaped the atmosphere and left their mark on the city, which is surrounded by an archipelago of 40,000 islands. In those days, ships were seen as part of everyday life in Turku, and they were not hidden in container areas or behind other restricted walls.

Nowadays, when the whole maritime industry is economically at its all-time high, ships are kept away from city centres. In Turku, the old industry once located along the river, which was considered the rough side of the town. Later, there was a desire to make these areas cleaner and safer. No more unpleasant dark alleys and the dirty side effects of ships and the industry around them.

This change in the city structure started in Turku in the late 1970s and continued through the early decades of the 2000s. The shipbuilding industry is currently experiencing its golden age, as the biggest and finest cruising ships in the world are built in Turku. But at the same time, have we lost something in the way we see and feel the ships? How we see them, hear them, and use them as an emotional getaway on an evening walk towards the harbour.

The variety of ships that were once right in front of our eyes and under our noses as a part of Turku’s everyday life can now be found in the maritime museum. The scale models cannot replace the authentic feel of real ships, but once again they have the power to make an impact on people’s minds. The scale models at the museum help us understand timelines; short ones that we ourselves get to live, but also longer ones, times lived by others, that still touch our own time. This is just one way to look at the models. I welcome you to visit and find your own way to experience them. The museum and its scale models offer imaginative adventures and journeys through human history like no other! s

Varmista näkyvyytesi: Puh. 045 656 7216 | Puh. 040 481 9445 www.aikalehdet.fi

Eerikinkatu 19, Turku 60°26'96"N 22°15'78"E

We create functional identities and unforgettable brands. So stop hiding and let’s level up your image!

Time flies and the city of Turku changes its shape, but one thing remains: The Original Dennis Italian Restaurant!

Address Linnankatu 17 20100 Turku

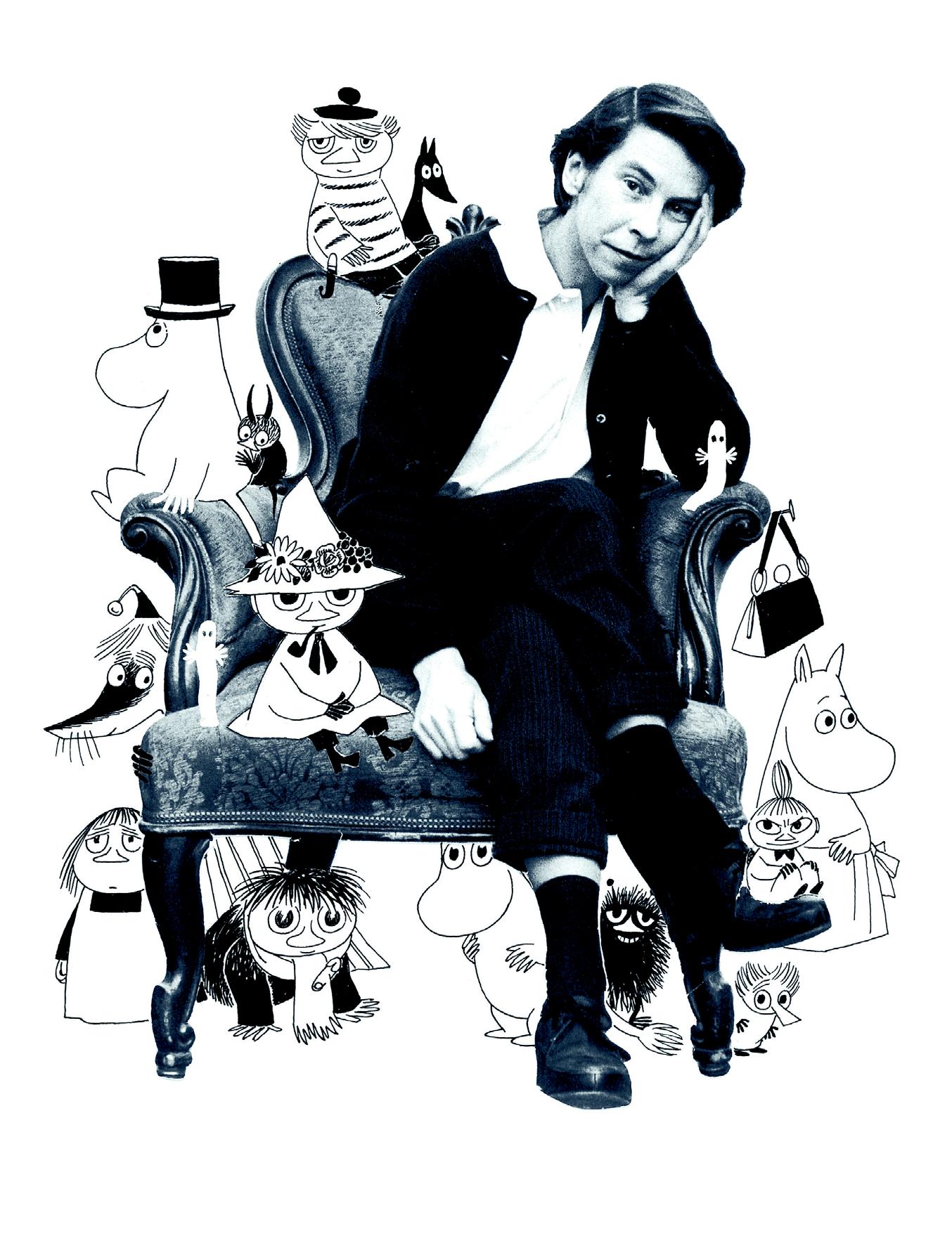

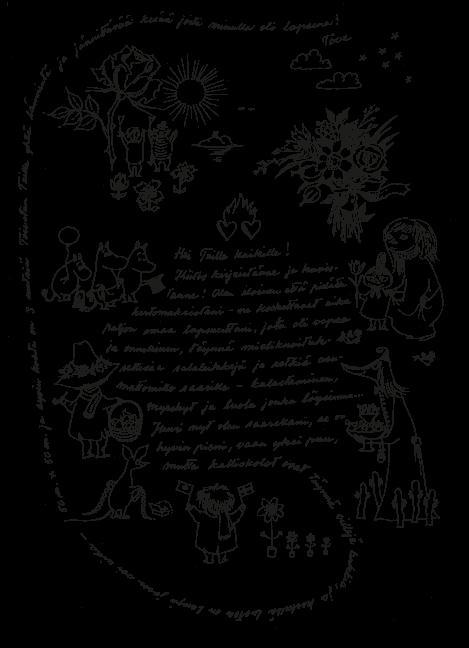

Tove Jansson diligently replied to fan mail from around the world – thousands and thousands of letters. Now a book about the letters has been published.

TThe author herself has said that all the characters in Moominvalley have something of her in them.

he “mother” of the Moomins, Tove Jansson (1914–2001), is probably one of Finland’s most famous people around the world. Her Moomin stories continue to captivate new generations, and no wonder, since life in Moominvalley is so rich, exciting and humane.

Tove was already a celebrity in her lifetime, and the postal service brought her letters by the sackful from people all over the world. She tried to answer them all. It was no small task, and eventually it even interfered with her work. But she was so kind-hearted, or felt such a sense of responsibility, that her writing of books would have come to nothing if she hadn’t answered the letters. In fact, even the press appealed to children not to write to Tove anymore. In 1974, the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter published an interview of her with the headline “Save Tove from the children.”

To the credit of the postal service, it should also be noted that even letters addressed simply to “Moominvalley, Finland,” or to a specific Moominvalley resident, arrived in Helsinki at the artist’s apartment in the Ullanlinna neighborhood, or, in the summer, at the summer cottage she shared with her partner Tuulikki Pietilä on Klovharun, a lonely islet off the shore from Porvoo.

Tuula Karjalainen, an art historian and author of Tove Jansson’s biography, became interested in this fan mail and dug up the letters and Tove’s replies to them from archives and from people around the world who received her replies. The book Tove Jansson ja maailman lapset (Tove Jansson and the Children of the World) was born.

What did fans – mostly children and young adults – want to know about their idol? A lot of normal fan stuff, of course, like what Tove’s favorite color is (blue, green), whether she’s a vegetarian (the book doesn’t say), and what her blood type is (we don’t get an answer to this either).

But a lot of big issues were also considered. For example, what Tove thought God was like, or what she thought about the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Tove took these questions seriously and delved into the topics. For example, the atomic bombs are of course a horrifying thing, but the end result could be that they saved lives, as crazy as it sounds.

The young people also talked a lot about their own problems, loneliness, shyness, and so on. Tove herself had felt lonely and even bullied during her school days, so she had plenty of sympathy and advice to offer.

On the other hand, some of the letters expressed admiration and outright love for the author. Tove usually responded to these with more restraint, reminding fans that she shouldn’t be admired. She said, as her character Snufkin would have said, that if you admire somebody too much, you can never be really free.

The fan letters could be quite long, too: the record seems to be 74 pages.

The Moomins felt so vivid and real that even adults behaved strangely sometimes: at a literary matinee in Japan, Tuula Karjalainen was asked – in all seriousness – whether there were still many Moomins in the forests of Finland.

Of all the creatures in Moominvalley, there was one in particular that fans often asked about, wondering why it existed in the first place and hoping that Tove would help it somehow. This creature was the Groke. The Groke is a girl who spreads nothing but coldness around her. Wherever the Groke sits down freezes, and nothing will grow there.

Many people thought that was terrible. To one person, Tove replied:

“The Groke really has been a problem. If you’re as cold as she is, no one wants to play with you. But I think you’ve come up with a marvelous idea – the Groke could make refrigerators. With a job like that, she could finally find a coworker like herself, the kind of person she has always been looking for.

Trust me, it will all work out. Tove”

The author herself has said that all the characters in Moominvalley have something of her in them. One of the characters whose traits she would have liked to embody more was Little My, because she

Best regards, Tove!

dares to say no, and she knows how to say it. Unfortunately, Tove wasn’t strong in those traits, so she obediently responded to the letters, which arrived at a rate of 1,500–2,000 per year. Even if she had responded to “only” a thousand letters, that would still be three letters a day. That’s a lot of stamps already.

When Tove and Tuulikki Pietilä took a long trip abroad, Tove asked her brothers to sort her letters and to send a card in response to them, promising that Tove would write when she returned from her trip.

Of course, the famous author also constantly received all kinds of requests. She made a compilation of them at the end of a collection of her short stories published in 1999:

“We await your prompt response to our inquiry regarding the printing of Moomin motifs in pastel colors on toilet paper.”

“Dear friend, I have been thinking about you for so long now that it really is high time that I dared to make a small request: could you please, when you get around to it, draw all your cute little characters in color for my granddaughter Emanuela.”

“My cat is dead! Write quick!”

“Now, don’t be alarmed, but do you have any idea what your newspaper comics can do to expectant mothers?”

“We have launched a new, discreet mini sanitary pad... We’ll appeal to a younger customer base with the line ‘All of Little My’s days are safe days’ – a witty remark that, with your permission...” s

Tuula

Awriter’s work is solitary. For the most part, the work is done alone, with one’s own thoughts. When a book is finally published, the author stumbles out of his or her cell to bask in the limelight for a moment, only to retreat as soon as possible, back into silence, to create something new. Or at least that’s how I would prefer it to go. After all, a writer’s most important job is to write.

But the more you publish, and the more frequently your books come out, the more you need to be visible, because the book business runs on promotion. For an introvert accustomed to toiling alone, getting up on a book fair stage and giving interviews requires major effort. And nowadays, the marketing no longer takes place only when a book is released, but all year long.

I’m from Pori, a smaller city on the coast, and the peaceful rhythm of life there suits me. My beloved hometown has everything a person needs. But sometimes I’m forced to leave Pori. Promoting my books has taken me all over Finland and the world. This year alone, I’ve spent over 70 days traveling and almost as many nights in hotels.

As in previous years, most of my trips this year will be abroad. My two longest book tours lasted 10 and 19 nights. That’s a long time to be away from family.

I’m happy to admit that I don’t enjoy traveling. I don’t like bumming around the airport, and I don’t love sitting on a cramped bus or train, gnawing on a sandwich. I won’t even start on the joy of dragging a suitcase through a station in the sleet.

Traveling truly teaches you to appreciate the small luxuries of everyday life, of which, for me, peace and quiet are the most important. I long for the silence of my own office. Because it’s a long way from Pori to anywhere else, the trip can often take up to fifteen hours, using multiple means of transport. When the writer reaches his or her destination, a crowd of strangers often awaits. Everyone wants a piece of you. You have to be cheerful and social, and take everyone into account. The language is foreign, as are the culture and local customs. Nonetheless, you’re supposed to network and be able to discuss your future plans in an interesting way. Up on stage, you need to be funny and intelligent. In addition to being a good

When the door to the room closes behind you, the cacophony of different voices ends, and there is space to breathe freely for a moment.

writer and storyteller, you’re also supposed to know how to be an entertainer and a salesperson.

Please don’t get the wrong idea. Being invited to appear abroad is a great honor and a privilege, but for an introverted writer, traveling is an energy-sapping ordeal. To be abroad is to be far away from one’s family, home, and familiar people. Once you arrive, the program is usually tightly scheduled, and there is very little time for oneself.

In truth, the only peace to be found is in your hotel room. On a book tour, a hotel room is often the only space where you can be completely alone with your own thoughts. When the door to the room closes behind you, the cacophony of different voices ends, and there is space to breathe freely for a moment. When I travel, my hotel room is a haven for me, a place to retreat to when the flood of external stimuli becomes too much. When you close the hotel room door behind you, you’ve finally arrived – you’re safe. And if, in addition to a bed and a shower, the room also has a desk, internet access and an electric kettle, life becomes downright luxurious. s

Arttu Tuominen (b. 1981) is an internationally awarded author and environmental engineer from Pori who derives his creative inspiration from the madness of Pori, the nature of the coast, and the waves of the Bothnian Sea. Tuominen has written eleven crime novels, of which Alec, published in 2025, marked the beginning of the new Kide trilogy.

The stately Turku Castle has guarded the mouth of the Aura River since the late 13th century. Within its tall granite walls, history has unfolded in remarkable ways. Over the centuries, the castle has been both defended and besieged, with its governors changing over time. During Duke John’s era, it became a stage for courtly life. The medieval rooms of the keep and the Renaissance floor built by the duke allow visitors to experience both the grandeur and hardships of times past.

Crown’s People

– Exhibition on the Castle’s Soldiers and Defence Who were the soldiers, and where did they come from? What was their daily life like? Who else played a crucial role in maintaining the castle’s defences? And what happened when news of an impending siege reached the castle? Discover the answers in this engaging exhibition.

Opening Hours Tue–Sun 10am–5pm

Linnankatu 80, tel. +358 2262 0300

Guided Tours turunlinna.fi/en

Luostarinmäki is the only wooden quarter that survived the Great Fire of Turku in 1827. The over 200-year-old buildings remain in their original locations, forming a unique historical environment in the heart of the city.

Christmas Time in Luostarinmäki 9–28 December Christmas arrives in Luostarinmäki homes. How did the residents of Luostarinmäki spend the biggest celebration of the year?

Opening Hours during the Christmas time 9.–28.12.

Tue–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat–Sun 10am–17pm.

Vartiovuorenkatu 2, tel. +358 2262 0350

Guided Tours luostarinmaki.fi/en

The Qwensel House, the oldest surviving wooden building in Turku by the Aura River, showcases an 18th-century bourgeois home alongside a 19th-century pharmacy. The Pharmacy Museum features Finland’s oldest preserved pharmacy interior, dating back to 1858. Visitors can also explore the workrooms of a self-sufficient pharmacy, including the materials room, two laboratories, and an herb room.

In the Qwensel House, step into the life of Joseph Pipping, the father of Finnish surgery and the home’s most famous resident. The interior is decorated in the Rococo and Gustavian styles of the late 18th century, offering a glimpse into the elegance of the era.

At Christmastime, the exhibition The Christmas Table Settings at the Qwensel House evokes the festive traditions of of a gentry family home at the turn of 18th and 19th century. The quaint Cafe Qwensel offers sweet and savoury delights as well as homemade, 18th century style beverages.

Opening Hours Tue–Sun 10am–6pm Läntinen Rantakatu 13b, tel. +358 2262 0280

Guided Tours qwensel.fi/en

Housed in a beautiful Art Nouveau building from 1907, the Biological Museum showcases Finnish flora and fauna, stretching from the Turku archipelago in the south to the fells of Lapland in the north. Take a peek at the outer archipelago in spring or marvel at the rich biodiversity of a Ruissalo grove.

Opening Hours Tue–Sun 9am–5pm Neitsytpolku 1, tel. +358 2262 0340 biologinenmuseo.fi/en