Embark on a culinary journey

Taste local flavors at the Tampere Market Hall or enjoy a meal or drinks at one of the city’s great restaurants.

Find culture experiences for every taste

Tampere is known for its vivid cultural life. The city is famous for its theatres, live music and various festivals. Additionally, Tampere is quite possibly the most interesting city of diverse museums in Finland themed museums from art to police and from spies to history of labor offer exploring for every taste.

Admire Tampere from above

Enjoy panoramic views from Moro Sky Bar or Näsinneula and Pyynikki observation towers.

Explore the architectural sights of Tampere

The Tampere Cathedral, Main Library Metso and the Tampere Main Fire station introduce you to the Finnish architectural history, alongside with the development of the city. The newer architecture can be admired around Nokia Arena and Tammela Stadium.

Dive into the history of Tampere

Visit the Labour Museum Werstas in the Finlayson area and enjoy the old times charm at the Tallipiha Stable Yards. Don’t forget to visit the Milavida Museum to hear about the factory owners’ life.

Sweat it out in the Sauna Capital

Since 2018 Tampere has been known as the Sauna Capital of the World. Try for example, Sauna Restaurant

Kuuma right in the city centre, Rauhaniemi or Kaupinoja by the lake, or the oldest public sauna still in use, Rajaportti. Discover the authentic Finnish sauna experience and compare the differences!

Enjoy the great outdoors by the lakes

Hop on the tram and head to nearby nature, whether for a walk or with skis for a cross-country adventure. Tampere also offers plenty of opportunities for ice skating, either on the frozen lakes or in rinks around the city.

Tampere has a lot of boutiques selling quality vintage and second-hand clothes and items. Explore the city’s design gems as well!

Theatres in Tampere offer experiences for the whole family, with performances ranging from classics to modern plays. There’s something for the whole family in Vapriikki Museum Centre, too! Visit Finnish Museum of Games and Hockey Hall of Fame, among other interesting exhibitions.

Discover Home of the Moomin Museum

In the world’s only Moomin Museum, located in Tampere Hall, you can experience something truly unique and see Moomin artworks exactly as Tove Jansson originally created them. An experience you cannot miss when visiting Tampere!

Tampere Times

Magazine for Visitors Issue 2/2025

Autumn-Winter-Spring www.tamperetimes.fi

ISSN 2343-3817 (print)

ISSN 2669-8293 (online)

Graphic design & layout

Petteri Mero

Mainostoimisto Knok Oy

Welcome to Tampere: Autumn adventures in Finland’s most loved city 8

A hotline in a cold world 10

A short history of sisu 12

Captain Finland: How to make it in Finland, Part 2 14

Tampere in a nutshell 18

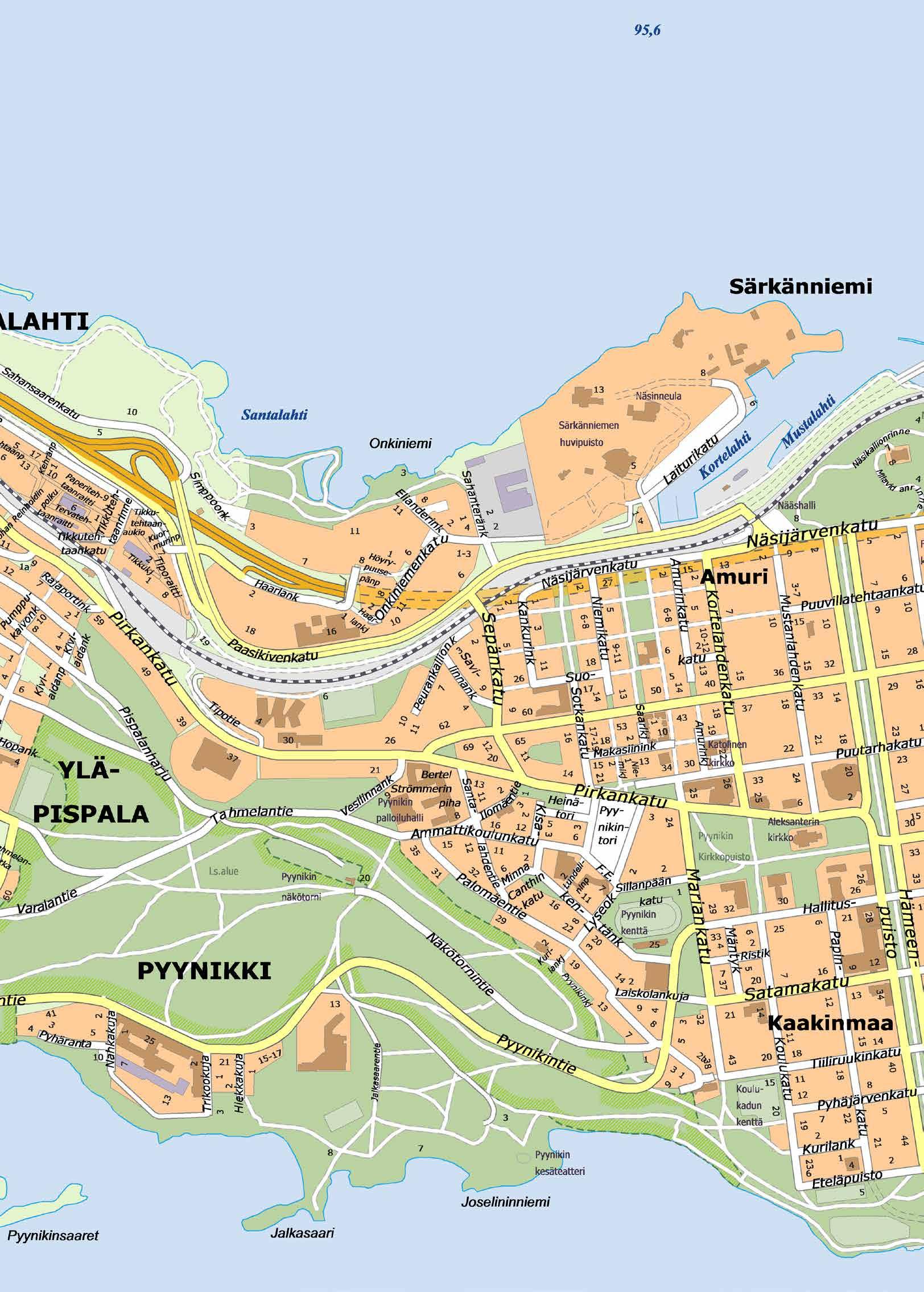

Map of Tampere 20

Hotels providing Tampere Times 22

Welcome to the Moominhouse! – The 80th anniversary exhibition of the Moomins 25

The oldest folks in the building 30 Best regards, Tove 34

The hotel room: a writer’s haven – Column by Arttu Tuominen 36

Editor in chief Roope Lipasti

Sales manager Raimo Kurki

raimo.kurki@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 45 656 7216

Sales manager

Kari Kettunen

kari.kettunen@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 40 481 9445

Published by Mobile-Kustannus Oy Betaniankatu 3 LH FI-20810 Turku, Finland

Member of Finnish Magazine Media Association (Aikakausmedia)

Publisher Teemu Jaakonkoski

Printed by Newprint Oy

Cover photos

Tampere in autumn

Photo: Laura Paronen / Visit Tampere

Cross-country skiers.

Photo: Laura Vanzo / Visit Tampere

Dining in Tampere

Photo: Laura Vanzo / Visit Tampere

Northern lights over Näsijärvi

Photo: Laura Vanzo / Visit Tampere

Arttu Tuominen.

Photo: Mikko Rasila / WSOY 12

Moomin themed nursing room and play area

Mini-Ratina

Over 100 shops and the best brands in Tampere! Food, fashion, beauty, home decor & much more!

Welcome to Tampere – a city where autumn paints the parks and lakesides in gold, and the season invites you to slow down, explore and enjoy. Whether you're here for a weekend getaway or an extended stay, Tampere offers a rich mix of nature, culture and urban charm.

Located between two scenic lakes, Näsijärvi and Pyhäjärvi, Tampere is known for its unique blend of industrial heritage and natural beauty. The city’s red-brick factory buildings now house galleries, cafés and creative spaces, while nearby forests and waterfronts offer peaceful escapes just minutes from the city centre.

Tampere buzzes with international energy. This year, we’ve hosted the European Athletics U20 Championships, the FIBA EuroBasket 2025, and the Disc Golf World Championships, welcoming athletes and fans from around the globe. These events have highlighted Tampere’s role as a city where sport and culture go hand in hand. Our wonderful Nokia Arena is a host to regular sports and cultural events.

For culture lovers, autumn is a perfect time to explore our museums, theatres and music venues. The Moomin Museum offers a magical journey into the world of Tove Jansson, while Vapriikki Museum Centre presents exhibitions ranging from history to science and design. Local theatres and concert halls come alive with performances that reflect both Finnish traditions and international influences.

Tampere buzzes with international energy.

And of course, no visit to Tampere is complete without experiencing our sauna culture. From the historic Rajaportti sauna in Pispala to the modern lakeside saunas like Kuuma, there’s a warm welcome waiting for you. After a sauna, enjoy a meal at one of our many restaurants, where local ingredients meet bold Nordic flavours.

Whether you're strolling through the autumn leaves in Pyynikki, enjoying panoramic views from Näsinneula, or simply relaxing in a cosy café, Tampere invites you to discover its rhythm – one that’s welcoming, creative and distinctly Finnish.

Enjoy your sTay in TaMpere – where every season has its own story.

Ilmari Nurminen Mayor of TaMpere

The Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra’s symphony concerts are held on Fridays, and a monthly chamber music series on Sunday afternoons at the Tampere Hall. You’re invited.

Concerts, tickets, offers and news at tamperefilharmonia.fi

Written

During the Cold War, a hotline ran through Finland. Its purpose was to prevent the accidental outbreak of nuclear war. Traces of it still linger in the landscape.

In 1962, the world trembled. We had never been so close to nuclear war. The Soviet Union intended to deploy nuclear missiles to Cuba, and the United States responded that it would mean war.

War didn’t break out, but it was a wake-up call: the world needed a direct line between the great powers, one that would operate immediately, without the delay that usually accompanied diplomatic relations, where a message from Washington to Moscow or vice versa could take hours. That was far too long when the world could be destroyed in minutes.

The communications link was quickly built and operational in just a couple of months. The hotline wasn’t exactly a red telephone, like in the movie Doctor Strangelove, but something in that direction. Actually, it wasn’t a telephone at all, but a teleprinter, or telex system. These electromechanical devices were once used to send text from one place to another, typically along a telegraph line. Physically, the machine resembled a typewriter and printed a message on paper.

In the case of the hotline, the line was of course very well encrypted. At first, there were teleprinters at each end. In the 1970s, they were replaced with fax machines. Each party used its own language in its transmissions, and the texts were translated at the receiving end.

for example, off the coast of Denmark, a Soviet ship severed it while towing a ship that had run aground on a sandbar.

So it seems that undersea cables have been vulnerable for a long time!

The risk of cable breaks was also taken seriously by the authorities: in the places where the line ran, digging with an excavator required police supervision.

Nonetheless, there were so many accidents that eventually the route of the line was marked with red metal posts, which can still be seen here and there in the landscape.

The hotline wasn’t exactly a red telephone, like in the movie Doctor Strangelove, but something in that direction.

Given The Technology at the time, the system was not entirely simple, as it had to cover a long distance. The line ran from Moscow to Tallinn, then to Helsinki and onward to Turku, where it plunged into the sea, emerged in Stockholm, and continued via Copenhagen and London to Washington. There was also a backup line in Finland, which went via Lappeenranta to Helsinki and then to Hämeenlinna before reaching Turku.

The line itself was a cable with a diameter of about five centimeters. Inside a pitch-coated lead tube were four pressurized copper pipes, within which the actual copper conductors ran. If the pressure dropped, meaning that the line had been broken or someone had tried to infiltrate it, the system sounded an alarm.

Because the distances were long, the signal needed to be amplified every so often. Special repeater stations were built every few dozen kilometers, which dotted the fields of Finland for a couple of decades. The stations weren’t just some chicken coops – they were built to be bombproof. These concrete bunkers were built underground if possible, and above ground if not. They were a few square meters in size and filled with the best technology of the day.

A few of these huts still remain in Finland, one near the eastern border in Lappeenranta and another near Hämeenlinna.

DespiTe all The precauTions, the cable did suffer breaks every once in a while, usually when some farmer was out in a field digging some kind of ditch – the cable was buried only 60 centimeters deep. Of course, Finland wasn’t the only place where the cable was disrupted. Once,

The line iTself was tested continuously. Test messages were sent once an hour to ensure it was working. It was agreed that these messages should be as apolitical as possible, to avoid misunderstandings.

The Soviets sent things like texts by their classic authors (maybe not War and Peace, though...)

For their part, the Americans sent baseball scores and excerpts from the Kama Sutra, which seems to show that there’s no limit to human childishness.

The line has also been used in real situations. The first time appears to be when Kennedy was assassinated. The Soviet Union, in turn, made contact via the line during the Six-Day War in 1967.

In 1973, during the Yom Kippur War, Israel accidentally torpedoed the USS Liberty reconnaissance ship, at which point President Johnson saw fit to inform Kosygin of the Soviet Union that there was nothing more to it: it was simply a case of friendly fire and an aircraft carrier was being sent to the area, but no need to worry. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan a few years later were also discussed on the hotline.

I Myself have written a novel about the hotline, which was published in the fall of 2025. It’s intertwined with my own childhood in the 1970s and ’80s, when the line ran through my best friend’s yard, which of course sparked our imaginations. The book follows a group of kids growing up in the shadow of the Cold War and the fear of nuclear weapons, from 1970 until the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.

Despite all the madness of humanity, the hotline was a symbol of hope for us then, as it is now in my book. The fact that it existed meant that someone was trying, at least a little. And the loss of that kind of connection would be a terrible thing. s

Sisu is as important to Finns as the right to bear arms is to Americans, afternoon tea to the English, and surströmming to Swedes.

Sisu has its own national emoji, is considered a key element of the Finland brand, and in 2017 was the overwhelming winner in a contest to find the word that best describes Finland. So, what is sisu all about?

Written by Matti MäkeLä

by Christina saarinen

According to Wikipedia, “Sisu is a Finnish word variously translated as stoic determination, tenacity of purpose, grit, bravery, resilience, and hardiness.” As you can see, there is a lot of meaning packed into one word, and Wikipedia even fails to mention that the meaning of sisu has changed over time. During the Middle Ages, and long after, sisu was generally defined as an undesirable tendency or characteristic in an individual.

It was really only after Finland’s independence that sisu was transformed into a positive phenomenon that defined Finnishness and united the nation. A strong early representation of Finnish sisu was provided by the runners who dominated the Olympics in the 1920s and ’30s (Finland won 10 of the 15 long-distance gold medals awarded in 1920–36), as well as the other athletes who raised Finland to second in the Olympic standings of the era, right after the United States. Unfortunately, Paavo Nurmi, who won nine Olympic gold medals and was proclaimed the “King of Runners,” attributed his success not to sisu, but to training harder and more systematically than his competition.

WhaT really puT Finnish sisu on the world map was the Winter War. The word was probably first defined in English by Time magazine in January 1940, when the Soviet Union’s brutal war of aggression had been going on for a little over two months: “It is a compound of bravado and bravery, of ferocity and tenacity, of the ability to keep fighting after most people would have quit, and to fight with the will to win.”

However, the resilience deriving from sisu cannot be stretched forever, and in truth, it must be admitted that Finland’s policy of acquiescing to the Soviet Union in the 1960s and ’70s, dubbed “Finlandization,” didn’t seem to demonstrate much sisu. If Finland successfully walked the tightrope of independence during the presidential term of J. K. Paasikivi (1946–56), then during the far-too-long presidency of Urho Kekkonen (1956–81), Finland seemed to be constantly falling off the rope.

Finns haven’T forgoTTen their sisu, however, and it is constantly referenced when explaining the success of Finns in things like ice hockey, rally car racing, and Formula One. Nokia CEO Jorma Ollila also offered it as an explanation for the success his company enjoyed in its peak years: “You overcome all obstacles. You need quite a lot of sisu to survive in this climate.” (It was unclear whether he was referring to Finland’s often wretched weather or the challenges of the mobile phone business.)

When you add a pinch of the stoicism mentioned in Wikipedia to this recipe in Time, the result is Finnish sisu on steroids. This is how the Finnish national novel The Unknown Soldier describes the perspective of the cynical Corporal Lehto, a man struggling with personal demons: “They can’t offer anything worse than death, and he can deal with that.”

In Under the North Star, the second masterpiece by Väinö Linna, the author of The Unknown Soldier, we go even further into the dark side of sisu. In his work, Linna describes the Finnish hatred that drove the 1918 Civil War. This was sisu in its old-fashioned meaning, which, according to Linna, is “like a bog pond: deep and black.”

But – if sisu is simply the ability to fight bravely against a seemingly overwhelming barbarian attack, then global history is full of Finnish sisu. Take, for example, the Greek warriors of Thermopylae, the heroes of present-day Ukraine, and even the late-19th-century Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud , whose remark before battle was something even Cpl. Lehto would have been proud of: “Today is a good day to die.”

Sisu is actually a complex concept, and it’s been used to respond to a variety of challenges in different eras. After World War II, Finland was in a desperate situation. The Soviet Union had occupied the rest of Eastern Europe, and Finland had to try to maintain its independence, democracy and existence with a totalitarian superpower next door. In that period, the resilient side of sisu helped, which Time magazine once again described during the 1952 Helsinki Olympics as follows: “The Finns are not stupidly hiding their eyes from their future, but they are determined not to fall into another fight with a powerful and predatory next-door neighbor 66 times their size… the Finns have learned to walk the nerve-racking path of independence like tight-rope walkers.”

As important of a concept as it is, sisu has of course also been commercialized, and in Finland, the word sisu can be found on such products as candy, trucks and buses, trams, t-shirts, hoodies and mugs, and – in many people’s minds, unfortunately – in the name of the nationalist organization Suomen Sisu. The most recent sector is film: two films named Sisu have already been made. In the first, Aatami Korpi – according to a tagline, “the man who refuses to die” – slaughters Nazis in Lapland. In the second, we get to the origins of sisu, and Korpi travels to his home region, Soviet-occupied Karelia, to take revenge on Soviet soldiers (this is where Korpi begins to deserve the nickname “the Finnish Rambo”: in the second Rambo film, Rambo returns to Vietnam to win the war the Americans had already lost once).

A counTry’s naTional identity is always reflected in its relation to others. Finns believe that sisu sets them apart from the other Nordic countries. According to this view, Swedes enjoy their coffee and buns (fika), and Danes sit beside a warm fire with wool socks on (hygge), while Finns crush granite into dust with their bare hands (the national emoji for sisu is a person bursting through gray stone), and eat the fat off of meat and the pits out of olives. Okay, the last two are actually how the Spartans are depicted in the comic book Asterix at the Olympic Games, but I’ll justify them with the fact that, in Finnish literature, characters from the Kalevala and The Unknown Soldier have often been compared to the Spartans for their fearlessness and discipline. Overall, defining sisu is difficult, and it has both its good side (persistence, belief in oneself even amid difficulties) and its dark side (smugness, arrogance, stubbornness). Perhaps in trying to define it we encounter the same problem as US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart when considering whether he could define hard-core pornography: “Perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.” s

tampere@zbase.fi +358 50 345 2810

FRI 3.10. 19:30

fri 10.10. 18:30

fri 17.10. 18:30

sat 25.10. 17:00

wed 29.10. 18:30 KÄRPÄT hifk tps jukurit k-espoo

tue 10.3. 18:30 tue 17.3. 18:30 tappara hpk saipa 2025 2026 October November December

sat 1.11. 18:30

fri 14.11. 18:30

thu 4.12. 18:30 fri 12.12. 18:30 fri 19.12. 19:30 tue 30.12. 18:30 hpk kookoo k-espoo kärpät

tue 25.11. 18:30 kalpa tappara pelicans

sat 3.1. 17:00 wed 7.1. 18:30 sat 10.1. 17:00 tps sport hifk

wed 14.1. 18:30 sat 17.1. 17:00 fri 23.1. 18:30

tue 27.1. 18:30 sat 31.1. 17:00 jyp ässät tappara sport kalpa

tue 3.2. 18:30 fri 6.2. 19:30 sat 14.2. 15:00 tue 17.2. 18:30 pelicans kookoo jukurit lukko fri 6.3. 18:30

The connection to ocean from the Tampere region was cut when the ice age was finally over. As the ice melted, the land rose up and the lakes were born – also Näsijärvi and Pyhäjärvi, and little later the Tampere Rapids. A must see attraction from the ice age is Pyynikki, a 90 hectare ridge area, which is almost in the centre of the city. From here there are marvellous views to lake Pyhäjärvi. It is also a beautiful place for other outdoor activities.

Tampere was an ideal place to build a village, because there were good waterways to both north and south. The first signs of permanent living in the area are from the 7th century.

By the 13th century Tampere region had grown, and it was an important market place. It was inhabited by the Pirkka tribe and even today the Tampere province is called Pirkanmaa, “The land of the Pirkka”.

Tampere was not yet an actual city, but in 1638 Finland’s governor Per Brahe ordered two yearly fairs to be held at the the Tampere Rapids. That’s why Turku – the then capital of Finland – and Tampere have got a special connections of fates, for when the whole city of Turku burned in 1827, the damage was so severe partly because all the men from Turku happened to be at the Tampere fair.

The King Gustav III of Sweden finally granted Tampere the full township status. And no wonder, because Tampere was huge: 3.2 square kilometres with population of no less than 200!

1824

The beautiful old church of Tampere was built. The architect was Charles Bassi.

A Scotsman called James Finlayson set up a cotton factory near the Tampere Rapids. It was the first but not last major factory in the remarkable industrial history of Tampere. Finlayson still is a brand every Finn knows. Also from that time on, the use of waterpower from Tampere Rapids became important.

From the 1840’s Tampere became the most industrialised city in Finland. Soon there were factories that made iron, paper, machinery, clothes, shoes and many other things. Even to this day Tampere is sometimes called “Manse”, which comes from the saying that Tampere is the Manchester of Finland.

Tampere is also a vibrant theatre city. The first one, Tampereen Työväen Teatteri – The Tampere Workers Theatre – was established 1901. In 2020 there are over 10 professional theatres in the area.

In 1918 Finland was torn by a civil war with two sides: the “reds” and the “whites”. As a working class city, Tampere sided with the reds (who lost). Tampere saw severe battles, thousands died in war efforts and even more in prison camps.

Finland was in war against Russia, and Tampere was an important centre of war industry. For example Tampella made mortars and cannons. Tampere was also bombed, but luckily there was little damage.

Näsinneula, the high tower that Tampere is famous for, was built. Few years later The Särkänniemi Amusement Park opened its doors.

During the 90’s the heavy industry of Tampere was in trouble. One reason was the collapse of Soviet Union, but all and all the world was changing. The chimneys were no longer active, and the factories shut down. Nowadays they are renovated for apartments, museums and such. Industry in today’s Tampere in mostly high tech.

Tampere is the third biggest city in Finland, with 260,000 inhabitants in the city. It has four universities and a very vivid cultural life. Tampere is also a city of vision and courage: the brand new tramway is a good example of that! s

01 courTyard by MarrioTT

TaMpere ciTy hoTel

Yliopistonkatu 57, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 29 357 5700 www.marriott.com

02 dreaM hosTel TaMpere

Åkerlundinkatu 2, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 45 236 0517 www.dreamhostel.fi

03 holiday inn TaMpere cenTral sTaTion

Rautatienkatu 21, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 3 2392 2000 www.ihg.com

04 hoTel hoMeland

Kullervonkatu 19, 33500 Tampere

Tel. +358 3 3126 0200 www.homeland.fi

05 hoTel kauppi

Kalevan puistotie 2, 33500 Tampere

Tel. +358 3 253 5353 www.hotelli-kauppi.fi

06 lapland hoTel TaMpere

Yliopistonkatu 44, 33100 Tampere

Tel. + 358 3 383 0000 www.laplandhotels.com

07 lillan bouTique hoTel

Kurjentaival 35, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 10 200 7305 www.lillan.fi

08 norlandia TaMpere hoTel

Biokatu 14, 33520 Tampere

Tel +358 50 3844400 www.norlandiahotel.fi

09 original sokos hoTel ilves

Hatanpään valtatie 1, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 20 123 4631 www.sokoshotels.fi

10 original sokos hoTel villa

Sumeliuksenkatu 14, 33100, Tampere

+358 20 123 4633 www.sokoshotels.fi

11 radisson blu grand

hoTel TaMMer

Satakunnankatu 13, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 20 123 4632 www.radissonblu.com

12 scandic eden nokia

Paratiisikatu 2, 37120 Nokia

Tel. +358 3 4108 1627 www.scandichotels.fi

13 scandic rosendahl

Pyynikintie 13, 33230 Tampere

Tel +358 3 244 1111

www.scandichotels.fi

14 scandic TaMpere ciTy

Hämeenkatu 1, 33100 Tampere

Tel. + 358 3 244 6111 www.scandichotels.fi

15 scandic TaMpere häMeenpuisTo

Hämeenpuisto 47, 33200 Tampere

Tel. +358 3 4108 1628

www.scandichotels.fi

16 scandic TaMpere koskipuisTo

Koskikatu 5, 33100 Tampere

Tel. +358 3 4108 1626

www.scandichotels.fi

17 scandic TaMpere sTaTion

Ratapihankatu 37, 33100 Tampere

Tel +358 3 339 8000

www.scandichotels.fi

18 solo sokos hoTel Torni TaMpere

Ratapihankatu 43, 33100, Tampere

Tel. +358 20 123 4634

www.sokoshotels.fi

19 spa hoTel holiday club

TaMpereen kylpylä

Lapinniemenranta 12, 33180 Tampere

Tel. +358 30 687 0000 www.holidayclub.fi

Kaleva Sports Park is an inviting skating venue in the middle of the town.

Kaleva Sports Park Salhojankatu 35 33540 Tampere

tampere.fi/sorsapuistonkentta

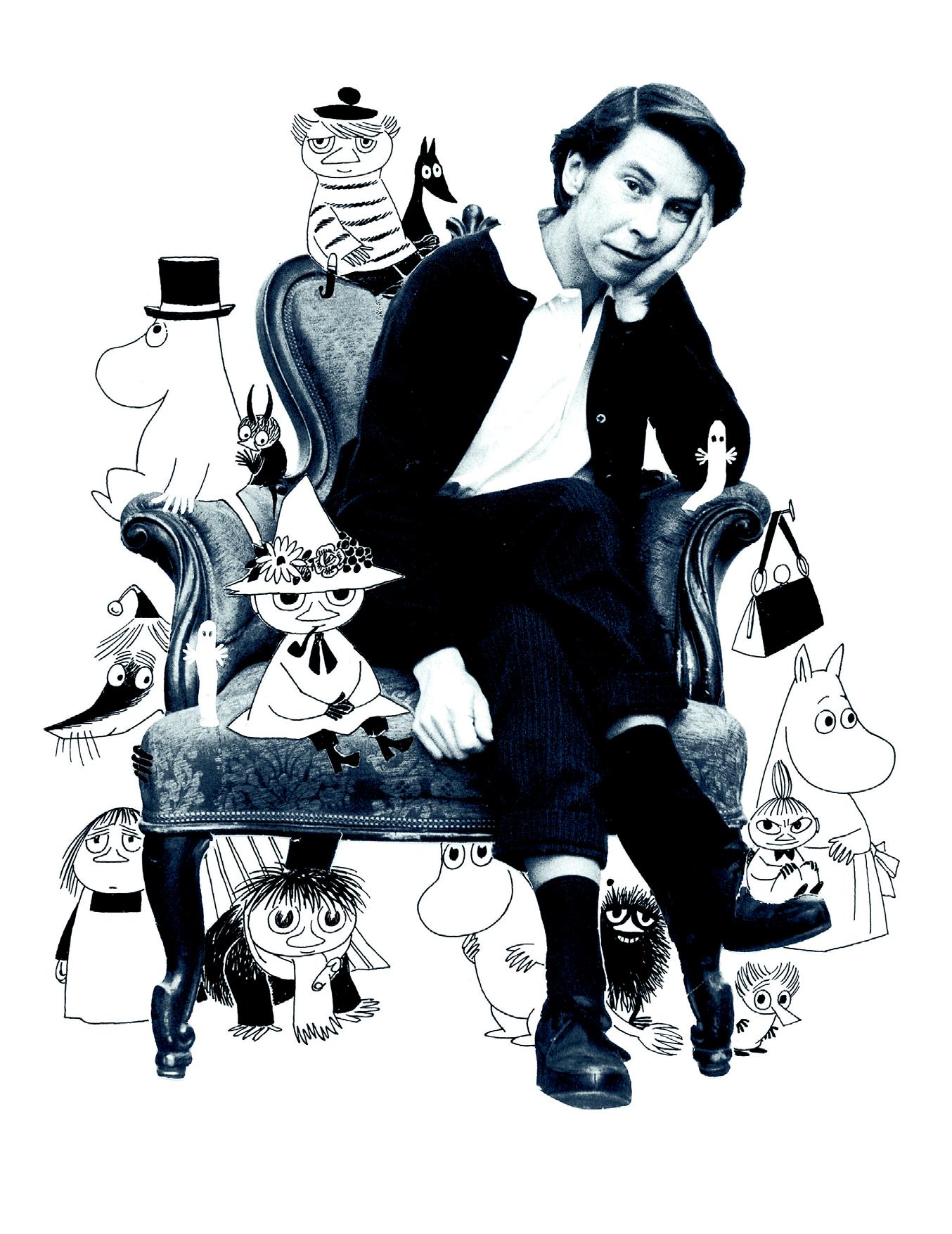

Written by Virpi nikkari

The world’s only Moomin Museum in Tampere presents a special exhibition that celebrates the 80th anniversary of Tove Jansson’s (1914–2001) Moomin stories. Her first Moomin book, The Moomins and the Great Flood, was published in 1945. Eight decades later, the exhibition Welcome to the Moominhouse! invites both longtime fans and first-time visitors to step inside the heart of the Moomin world. At its centre is the Moominhouse – not only a building, but a symbol of belonging, friendship, and safety.

The exhibition opens with a charming animation telling the story of The Moomins and the Great Flood, the very

first Moomin tale. It follows the Moomin family on an exciting adventure, culminating in their arrival at lush Moominvalley. There, they find the Moominhouse built by Moominpappa, carried to the valley by the flood. The round, blue house with its turreted roof resembles an old-fashioned porcelain stove, and the Moomins feel instantly at home. “Three rooms,” said Moominpappa. “One sky-blue, one sunshine-yellow and one spotted. And a guestroom in the attic for you, small creature [Sniff].”

Readers have long been fascinated by the house’s floor plan. In Finn Family Moomintroll, it is described in detail: guest rooms for Hemulen, Snork, Snorkmaiden, Thingumy and Bob, and the Muskrat, while Moomintroll shares his room with Snufkin. As more friends and wanderers arrive, the house expands from two storeys to three floors and a basement. Its growth reflects the Moomins’ open spirit – always welcoming those in need.

A HIGHLIGHT OF THE EXHIBITION IS THE FULL-SCALE RECREATION OF THE PARLOUR FROM THE MOOMINHOUSE TABLEAU.

A highlight of the exhibition is the full-scale recreation of the parlour from the Moominhouse tableau built by Tove Jansson, her life partner Tuulikki Pietilä, and their friend Pentti Eistola between 1976 and 1979. For the first time, visitors can step into a room that until now existed only in miniature. The rosy wallpaper, velvety curtains, and carefully selected furniture give a rare sense of the atmosphere of the house, as if you were actually inside it.

The parlour also displays Tove Jansson’s original illustrations of the Moominhouse and its inhabitants. They range from playful scenes of daily life to more poignant moments, such as in Moominvalley in November (1970), where friends gather at the empty Moominhouse, longing for the Moomin family who have gone on adventures. Here, the house becomes more than just a backdrop; it is a character in its own right, full of memories and hope.

The exhibition reveals the secrets of the famous five-storey Moominhouse tableau, the crown jewel of the Moomin Museum’s permanent exhibition. Built over three years without blueprints, the stunning creation is made of wood, glass, textiles, and countless miniature objects collected by Jansson, Pietilä, Eistola and their numerous friends. Visitors can see documentary footage, sketches, material samples, and items from the Paraphernalia collection including tools, supplies, and miniature accessories used in the creation of the tableaux. These pieces illustrate the immense craftsmanship and playful creativity behind the Moominhouse.

The tableau itself is full of surprises: staircases, hidden passageways, handmade furniture, even a sauna and a secret treasure. Like the Moomin stories, it invites visitors to look closer, to explore and to delight in the unexpected. Symbolically, the tableau reminds

us of the joy of play. Creativity and imagination are not just for children – they are essential for adults, too, something Tove Jansson deeply believed in.

The Moominhouse exhibition is a highlight of Moomin 80, a year-long celebration marking eight decades of Tove Jansson’s beloved characters. Tampere marks the anniversary with performances, workshops, and exhibitions across the city. The theme of the year is “The Door Is Always Open.” The first Moomin story began with displacement and ended with the family finding shelter and a sense of belonging. Similarly, the Moominhouse has always symbolised a place from which no one is turned away – a refuge of openness, safety, and togetherness.

This openness reflects Jansson’s own values. She imagined the Moominhouse as a space where everyone is welcome, where differences are celebrated, and where acceptance and equality thrive – values that resonate as strongly today as they did when the stories were first written.

Welcome to the Moominhouse! is more than just a display of objects. It invites reflection on what “home” truly means: not just walls and a roof, but safety, acceptance, friendship, and freedom.

The exhibition also honours Jansson’s philosophy: individuality, tolerance, and the joy of play. In the Moominhouse, doors are always open, and imagination is valued. For Jansson, play was vital for both children and adults, helping people connect and offering a respite from life’s challenges.

For anyone drawn to art, literature, storytelling, or simply the warmth of belonging, this exhibition is a rare opportunity. s

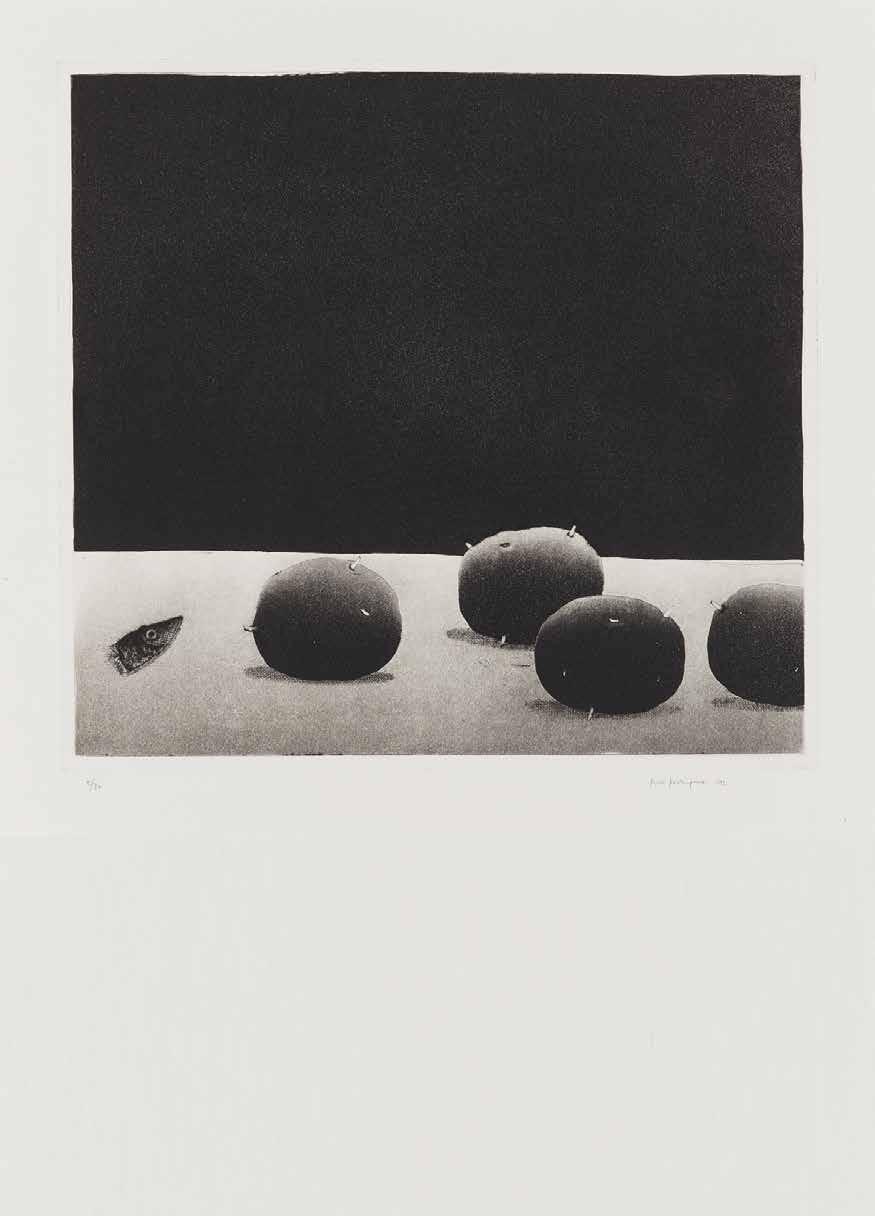

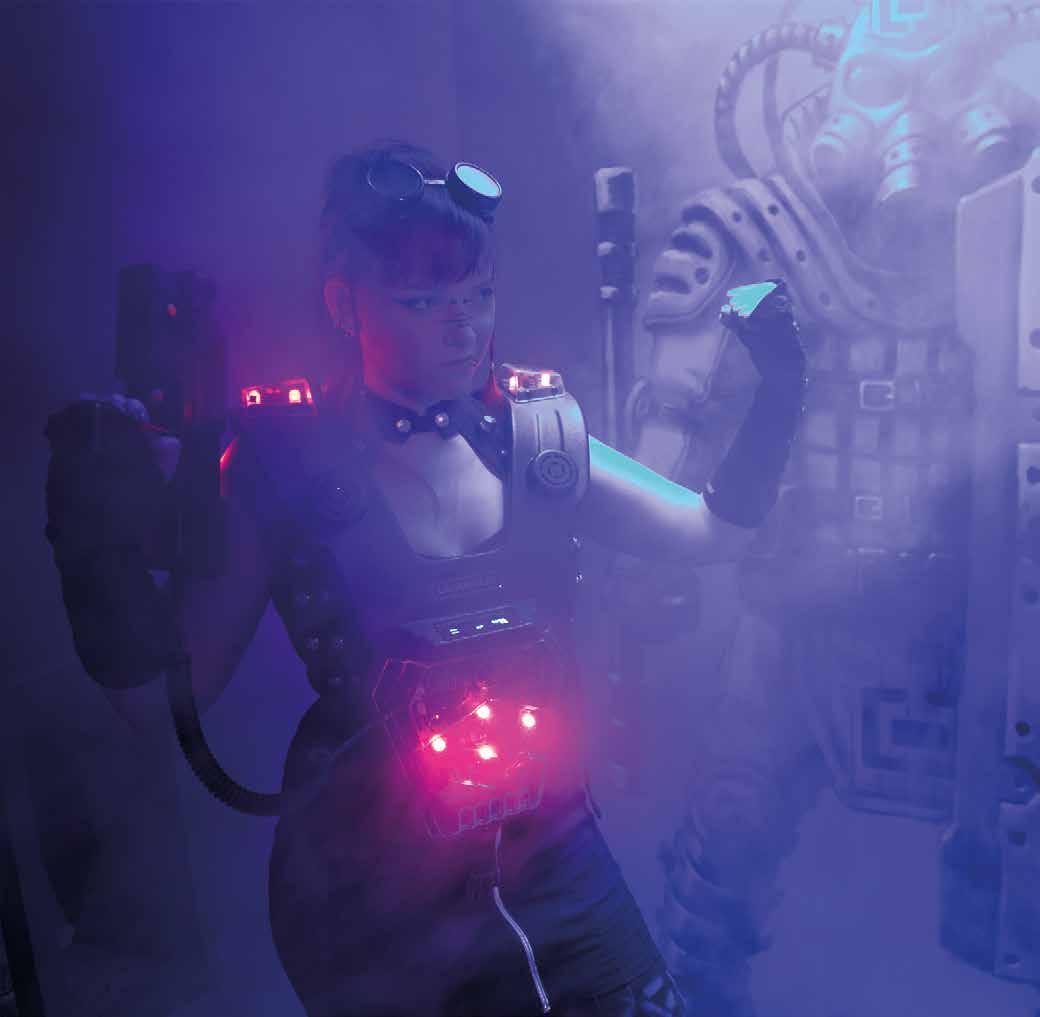

Young Artist of the Year 2025, Man Yau, has built an exhibition where a glossy surface carries a quiet violence – and suggests that beauty should be seen differently. Her sculptures are at once strikingly beautiful and profoundly political.

Based in Helsinki, Man Yau is one of the most compelling contemporary artists in Finland today. Through her art, Yau explores the feeling of being exposed and under pressure, approaching it from the perspective of a woman and a BIPOC artist (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color). Receiving the prestigious Young Artist of the Year award came as a surprise even to her, bringing both delight and dread. “I suppose every artist under 35 working in Finland would want this, because there’s simply no other way to get this kind of visibility,” Yau reflects.

Man Yau’s artistic path has emerged at the crossroads of design and fine art. Although she holds master’s degrees in both fields, the idea of turning toward sculpture first arose during her initial studies at Aalto University, then known as the University of Art and Design Helsinki. The interest in unique expression and the exploration of material meanings led her to deepen her path as a sculptor.

Man Yau’s works are visually captivating. She explains that she uses beauty deliberately as a tool of emphasis. Yet this beauty is often

Written by Jyrki MattiLa

only a surface, beneath which lies a deeper and sometimes painful story. “In reality it might actually be a very violent work,” Yau explains. Her art often draws from personal, even everyday experiences. One of the backstories of the new Peep Show series shown in Tampere Art Museum began with a situation where an assumption based on appearance was combined with a scent lingering in the air, making visible hidden racialized prejudices. This experience of quiet violence—acts concealed in everyday assumptions, language, and glances—was transformed into a bronze sculpture with fragile porcelain nails.

However, Yau does not want to dictate how her works should be experienced. Once the sculptures leave her studio, they begin to live lives of their own in the minds of viewers. “If someone just walks past a piece, I’m not going to be like, hey, you have to see it this way,” she says. s

THE YOUNG ARTIST OF THE YEAR 2025 – MAN YAU

27.9.2025–11.1.2026

The Moomin Museum

The Moomin Museum is the only museum in the world dedicated entirely to the Moomins’ art and stories. Its collections include around 2,000 original works donated by Tove Jansson, from delicate book illustrations to paintings and large-scale Moomin tableaux.

The permanent exhibition offers a journey through the entire Moomin saga, from dark forests and comets to wistful autumn moods. Guided tours are available in different languages and for all ages. Workshops in the museum’s Studio invite children and adults to create and play. The shop and café at Tampere Hall provide a chance to take a piece of Moomin magic home.

The Moomin Museum invites visitors to step inside the house, open the door to imagination, and rediscover why these stories continue to captivate hearts around the world.

MOOMIN MUSEUM

Tampere Hall, Yliopistonkatu 55, 33100 Tampere. See on the map (page 21).

Emil Aaltonen museum of industry and art. The permanent collection represents Aaltonen’s life and displays some of his art collection. The exhibited artists are masters of older Finnish painting. Temporary exhibitions.

Admission 3€ / 2€

1.6.–31.8. wed 12am–6pm, thu, sat, sun 12am–4pm 1.9.–31.5. wed 12am–4pm, sat, sun 12am–4pm www.pyynikinlinna.fi Tel. +358 3 212 4551

The world’s first spy museum in the city center introduces you to the world of real life James Bonds where a single device can change the world more than governments.

World of eavesdropping, hidden cameras and microphones, secret weapons, hacking, code breaking, picking locks...

In many Finnish churches, the oldest remains are over 450 million years old. Fossils can be found not only in churches, but also in many other public buildings in Finland. Stone floors are a good place to look for them.

There’s one! And another! And another!

If you put on your paleontology glasses, you can spot something amazing in quite a few public buildings in Finland. For example, there are several churches where you can find fossils – and not just the vicar! In Turku, you can find them at the cathedral, and in the Tampere region, at the Finlayson and Nokia churches.

But also in Helsinki, when you go to the basement toilets at the Oodi Library, have a look down at your feet, and not only so you don’t trip on the stairs. At the Ateneum Art Museum, too, there is more to see than just the exhibitions if you keep your eyes firmly on the floor.

Finland has hardly any fossils of its own because the Ice Ages washed them away. The Åland Islands and the bottom of

the Baltic Sea are exceptions. According to archaeologist Ilari Aalto , the fossils that can be found in the flooring materials of Finnish buildings generally originate from southern Sweden or Estonia.

orthocones

Aalto is working on a doctoral dissertation about brickmakers and medieval churches, so the material he usually digs up in churches is a little more recent, but he enjoys spotting fossils too. He first came across orthocones – the fossils most frequently found in Finnish floors – as a young boy visiting Häme Castle:

Orthocones existed in many sizes, ranging from tiny to several meters long.

“I’m always happy when I see them. There are a lot of them in southern Sweden, in particular, because there are large limestone deposits there. The older floor slabs in Turku Cathedral were brought from there sometime in the 18th century. Orthocones lived in the ancient Baltic Sea, which was near the equator back then – though strictly speaking, there was only one big sea at that time,” Aalto says.

Since then, the continents have wandered across the planet, and today, that ancient section of seabed is off the coast of Finland.

Orthocones are ancestors of modern octopuses and squids, and like their descendants, they were also predators. Orthocones aren’t a single species, however. Instead, they’re a so-called wastebasket taxon, into which creatures that seemed similar were collected in the 19th century. Orthocones existed in many sizes, ranging from tiny to several meters long.

They grew a horn-shaped cone – a protective shell – that was made up of chambers. The older the creature, the more chambers it had, like adding rooms onto a house. It’s the same thing that happens when people grow up: first you get a studio apartment, and then move on from there.

Orthocones had tentacles and a beak and apparently swam backwards. And how did they end up encased in stone? The answer lies in the slab material:

“It’s limestone, which is made up of calcium from dead animals. Long ago, they sank to the bottom of the sea, and over time, they turned into limestone. For example, the orthocones in the Turku Cathedral lived during the Ordovician period, about 450 million years ago, when the sea was teeming with life.”

Da Vinci knew

For Ilari Aalto, the age of fossils is precisely what’s fascinating about them:

“Fossils massively exceed the entire time period that humans have been around. It was a completely different world, and yet the same Earth, and our very own Baltic Sea! Back then, the land was desolate and empty, but the seas teemed with life. It’s also interesting to think about what people in the 18th century thought about them. At that time, they had no concept of evolution or of how rocks are formed,” Aalto reflects.

In A Description of the Northern Peoples, published in 1555, Olaus Magnus explains the shapes of fossils by saying that since nature is hierarchical, and humankind is the crown of creation, even rocks might imitate things like the shape of a human hand, and so on.

Noah’s flood was used to explain why fossils of mussels could be found in the mountains.

“Leonardo da Vinci, though, believed they were there because the mountains formed afterwards, lifting the fossils into their places. And that’s exactly the case,” Aalto says.

Although fossils are fairly common, Aalto points out that it’s quite rare to become a fossil, that is, to be petrified:

“All in all, we haven’t even found very many fossils of land animals. The seas were better places because fossilization requires, first, time and, second, pressure. As dead animals accumulated on the sea floor, they were eventually buried deeper and deeper and came under greater pressure, ultimately forming limestone as organic material was replaced by minerals.” s

It was a completely different world, and yet the same Earth, and our very own Baltic Sea!

Loved by the people of Tampere since 1929

Rauhaniemi folk spa offers its visitors the most atmospheric sauna experience and stunning views across the lake Näsijärvi. Rauhaniemi is a popular tourist spot offering traditional Finnish experiences to people from all over the world. The saunas are open every day of the year and in the winter you can go ice swimming.

For more information go to www.rauhaniemi.net

Lifestyle store in the center of Tampere. We have many traditional quality brands for men and women.

Come and visit our shop by the Laukontori harbour.

Myymme laadukkaita klassikkomerkkien vaatteita.

Tervetuloa tutustumaan myymäläämme Laukontorilla.

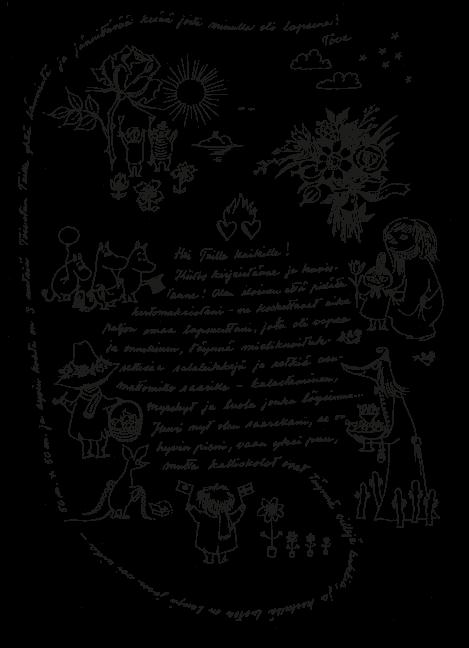

Tove Jansson diligently replied to fan mail from around the world – thousands and thousands of letters. Now a book about the letters has been published.

TThe author herself has said that all the characters in Moominvalley have something of her in them.

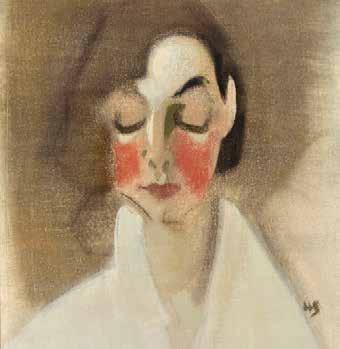

he “mother” of the Moomins, Tove Jansson (1914–2001), is probably one of Finland’s most famous people around the world. Her Moomin stories continue to captivate new generations, and no wonder, since life in Moominvalley is so rich, exciting and humane.

Tove was already a celebrity in her lifetime, and the postal service brought her letters by the sackful from people all over the world. She tried to answer them all. It was no small task, and eventually it even interfered with her work. But she was so kind-hearted, or felt such a sense of responsibility, that her writing of books would have come to nothing if she hadn’t answered the letters. In fact, even the press appealed to children not to write to Tove anymore. In 1974, the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter published an interview of her with the headline “Save Tove from the children.”

To the credit of the postal service, it should also be noted that even letters addressed simply to “Moominvalley, Finland,” or to a specific Moominvalley resident, arrived in Helsinki at the artist’s apartment in the Ullanlinna neighborhood, or, in the summer, at the summer cottage she shared with her partner Tuulikki Pietilä on Klovharun, a lonely islet off the shore from Porvoo.

Tuula Karjalainen, an art historian and author of Tove Jansson’s biography, became interested in this fan mail and dug up the letters and Tove’s replies to them from archives and from people around the world who received her replies. The book Tove Jansson ja maailman lapset (Tove Jansson and the Children of the World) was born.

What did fans – mostly children and young adults – want to know about their idol? A lot of normal fan stuff, of course, like what Tove’s favorite color is (blue, green), whether she’s a vegetarian (the book doesn’t say), and what her blood type is (we don’t get an answer to this either).

But a lot of big issues were also considered. For example, what Tove thought God was like, or what she thought about the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Tove took these questions seriously and delved into the topics. For example, the atomic bombs are of course a horrifying thing, but the end result could be that they saved lives, as crazy as it sounds.

The young people also talked a lot about their own problems, loneliness, shyness, and so on. Tove herself had felt lonely and even bullied during her school days, so she had plenty of sympathy and advice to offer.

On the other hand, some of the letters expressed admiration and outright love for the author. Tove usually responded to these with more restraint, reminding fans that she shouldn’t be admired. She said, as her character Snufkin would have said, that if you admire somebody too much, you can never be really free.

The fan letters could be quite long, too: the record seems to be 74 pages.

The Moomins felt so vivid and real that even adults behaved strangely sometimes: at a literary matinee in Japan, Tuula Karjalainen was asked – in all seriousness – whether there were still many Moomins in the forests of Finland.

Of all the creatures in Moominvalley, there was one in particular that fans often asked about, wondering why it existed in the first place and hoping that Tove would help it somehow. This creature was the Groke. The Groke is a girl who spreads nothing but coldness around her. Wherever the Groke sits down freezes, and nothing will grow there.

Many people thought that was terrible. To one person, Tove replied:

“The Groke really has been a problem. If you’re as cold as she is, no one wants to play with you. But I think you’ve come up with a marvelous idea – the Groke could make refrigerators. With a job like that, she could finally find a coworker like herself, the kind of person she has always been looking for.

Trust me, it will all work out. Tove”

The author herself has said that all the characters in Moominvalley have something of her in them. One of the characters whose traits she would have liked to embody more was Little My, because she

Best regards, Tove!

dares to say no, and she knows how to say it. Unfortunately, Tove wasn’t strong in those traits, so she obediently responded to the letters, which arrived at a rate of 1,500–2,000 per year. Even if she had responded to “only” a thousand letters, that would still be three letters a day. That’s a lot of stamps already.

When Tove and Tuulikki Pietilä took a long trip abroad, Tove asked her brothers to sort her letters and to send a card in response to them, promising that Tove would write when she returned from her trip.

Of course, the famous author also constantly received all kinds of requests. She made a compilation of them at the end of a collection of her short stories published in 1999:

“We await your prompt response to our inquiry regarding the printing of Moomin motifs in pastel colors on toilet paper.”

“Dear friend, I have been thinking about you for so long now that it really is high time that I dared to make a small request: could you please, when you get around to it, draw all your cute little characters in color for my granddaughter Emanuela.”

“My cat is dead! Write quick!”

“Now, don’t be alarmed, but do you have any idea what your newspaper comics can do to expectant mothers?”

“We have launched a new, discreet mini sanitary pad... We’ll appeal to a younger customer base with the line ‘All of Little My’s days are safe days’ – a witty remark that, with your permission...” s

Tuula

Awriter’s work is solitary. For the most part, the work is done alone, with one’s own thoughts. When a book is finally published, the author stumbles out of his or her cell to bask in the limelight for a moment, only to retreat as soon as possible, back into silence, to create something new. Or at least that’s how I would prefer it to go. After all, a writer’s most important job is to write.

But the more you publish, and the more frequently your books come out, the more you need to be visible, because the book business runs on promotion. For an introvert accustomed to toiling alone, getting up on a book fair stage and giving interviews requires major effort. And nowadays, the marketing no longer takes place only when a book is released, but all year long.

I’m from Pori, a smaller city on the coast, and the peaceful rhythm of life there suits me. My beloved hometown has everything a person needs. But sometimes I’m forced to leave Pori. Promoting my books has taken me all over Finland and the world. This year alone, I’ve spent over 70 days traveling and almost as many nights in hotels.

As in previous years, most of my trips this year will be abroad. My two longest book tours lasted 10 and 19 nights. That’s a long time to be away from family.

I’m happy to admit that I don’t enjoy traveling. I don’t like bumming around the airport, and I don’t love sitting on a cramped bus or train, gnawing on a sandwich. I won’t even start on the joy of dragging a suitcase through a station in the sleet.

Traveling truly teaches you to appreciate the small luxuries of everyday life, of which, for me, peace and quiet are the most important. I long for the silence of my own office. Because it’s a long way from Pori to anywhere else, the trip can often take up to fifteen hours, using multiple means of transport. When the writer reaches his or her destination, a crowd of strangers often awaits. Everyone wants a piece of you. You have to be cheerful and social, and take everyone into account. The language is foreign, as are the culture and local customs. Nonetheless, you’re supposed to network and be able to discuss your future plans in an interesting way. Up on stage, you need to be funny and intelligent. In addition to being a good

When the door to the room closes behind you, the cacophony of different voices ends, and there is space to breathe freely for a moment.

writer and storyteller, you’re also supposed to know how to be an entertainer and a salesperson.

Please don’t get the wrong idea. Being invited to appear abroad is a great honor and a privilege, but for an introverted writer, traveling is an energy-sapping ordeal. To be abroad is to be far away from one’s family, home, and familiar people. Once you arrive, the program is usually tightly scheduled, and there is very little time for oneself.

In truth, the only peace to be found is in your hotel room. On a book tour, a hotel room is often the only space where you can be completely alone with your own thoughts. When the door to the room closes behind you, the cacophony of different voices ends, and there is space to breathe freely for a moment. When I travel, my hotel room is a haven for me, a place to retreat to when the flood of external stimuli becomes too much. When you close the hotel room door behind you, you’ve finally arrived – you’re safe. And if, in addition to a bed and a shower, the room also has a desk, internet access and an electric kettle, life becomes downright luxurious. s

Arttu Tuominen (b. 1981) is an internationally awarded author and environmental engineer from Pori who derives his creative inspiration from the madness of Pori, the nature of the coast, and the waves of the Bothnian Sea. Tuominen has written eleven crime novels, of which Alec, published in 2025, marked the beginning of the new Kide trilogy.