A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST COLLEGE OF ART AT WILLAMETTE UNIVERSITY

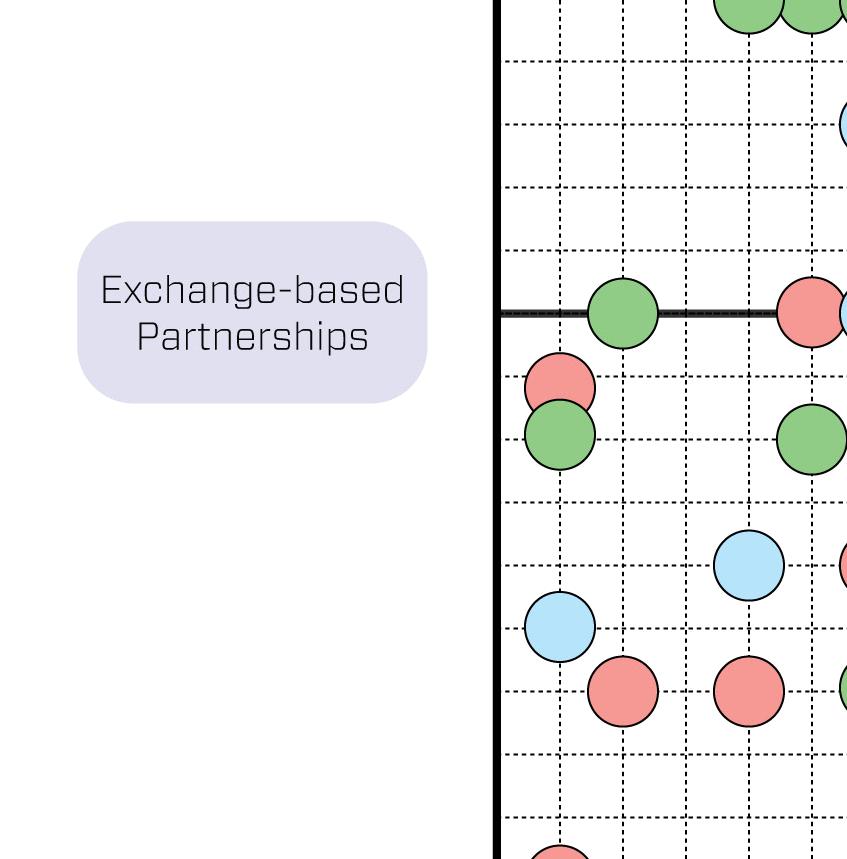

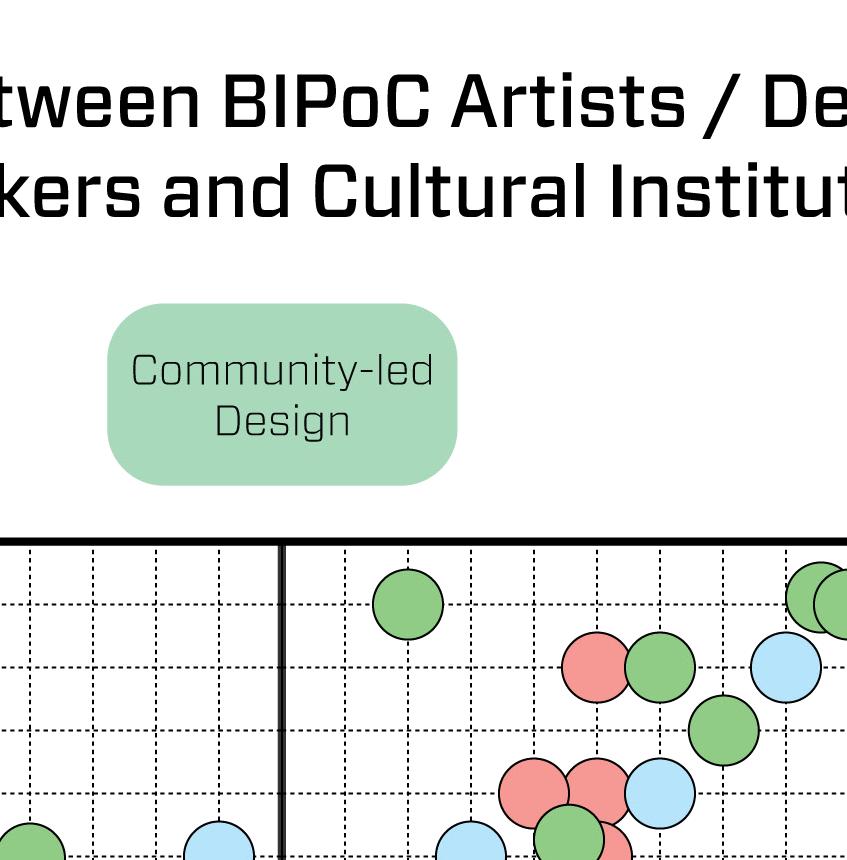

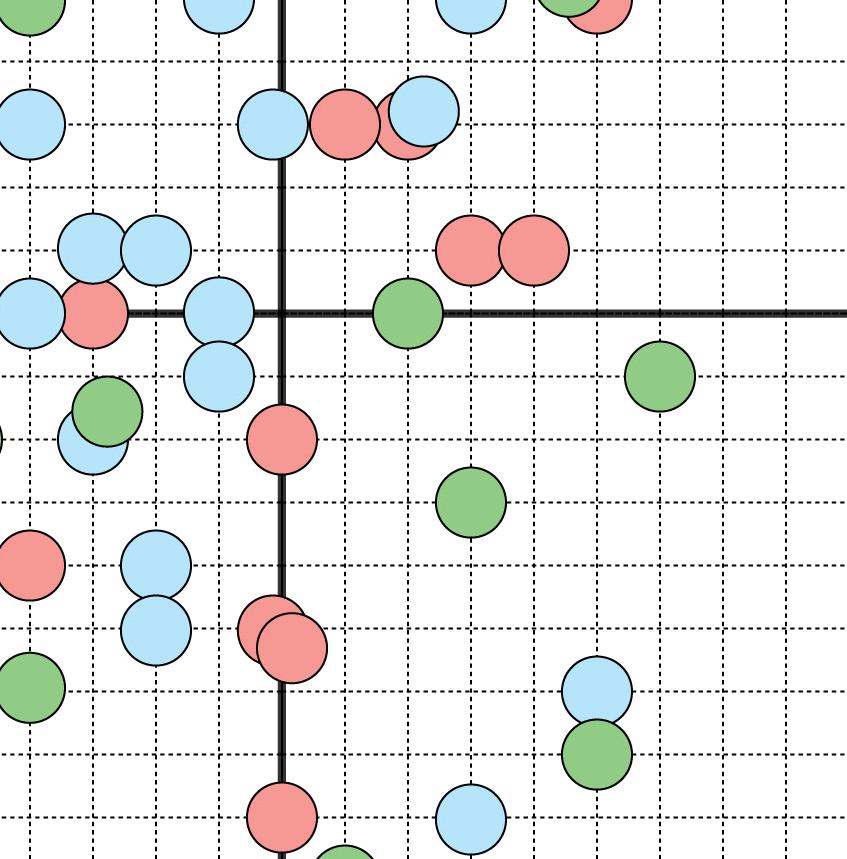

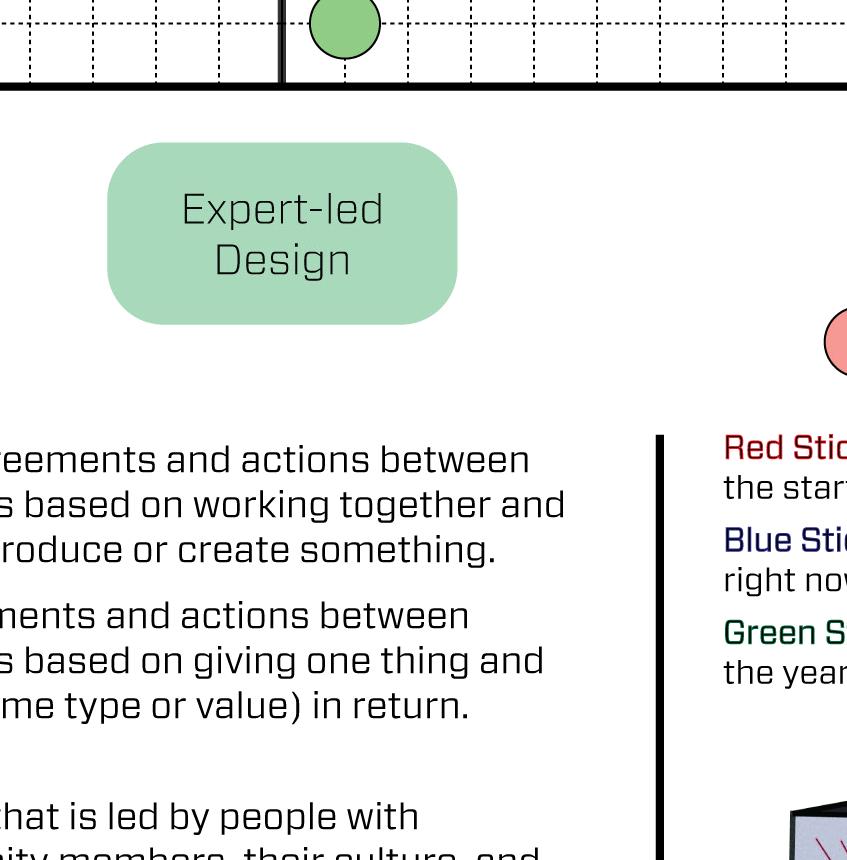

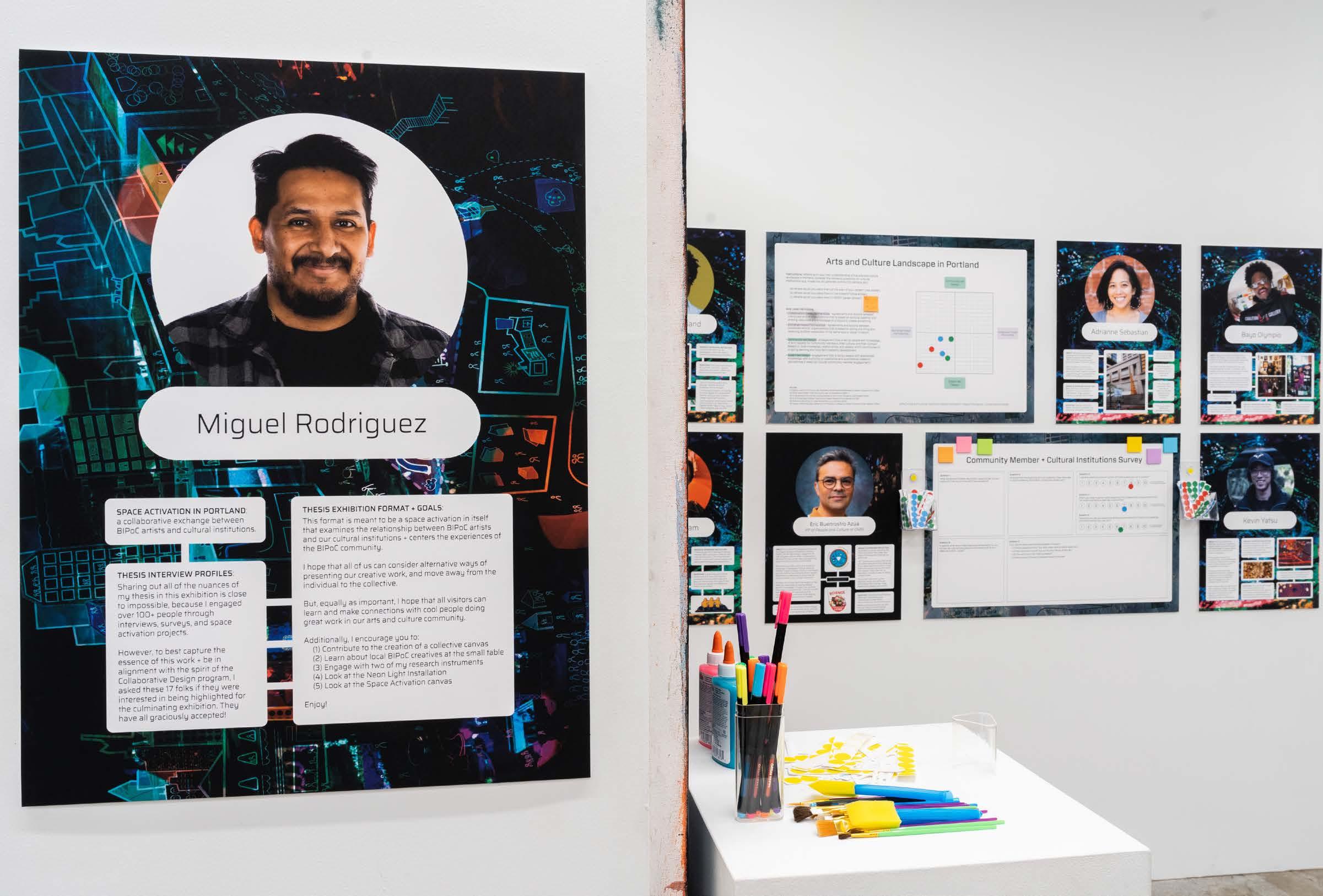

Space Activation: a collaborative exchange between BIPoC artists and cultural institutions

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MASTERS OF FINE ARTS DEGREE

Collaborative Design MFA Program

Miguel Rodriguez May 25, 2023

APPROVED BY

Karim Hassanein

MFA Thesis Mentor

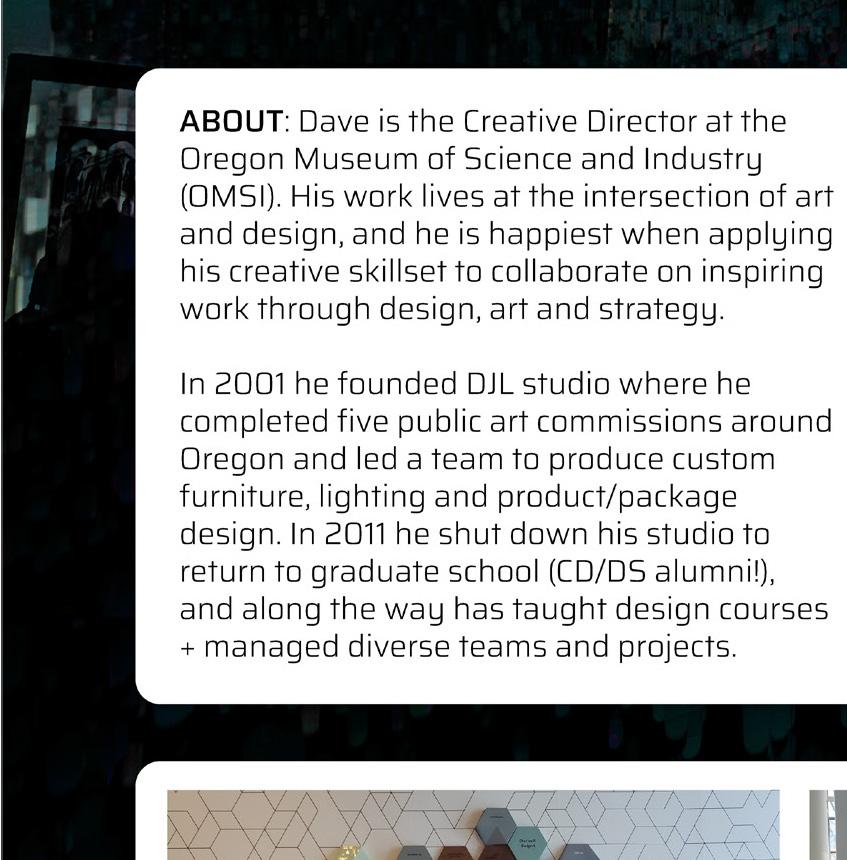

Dave Laubenthal

MFA Thesis Mentor

Skye Morét

Chair of Collaborative Design & Design Systems

Shawna Lipton Academic Director of HFSGS

Cultural institutions have been at the nexus of many conversations about their role in appropriation and extraction. They serve as a perpetual reminder of the lasting effects of colonialism, racism, and capitalism when BIPoC community members engage with institutional content, experiences, and are gate-kept from accessing or creating in these spaces. However, they have also been described as conduits for cultural exchange, preservation, and educational incubators that spark conversation, inspire calls for action, and provide artists with platforms for creativity and expression.

These contradictions briefly highlight the complicated history and relationship between BIPoC community members and our cultural institutions, but it also provides an opportunity for both groups to examine, intervene, and dismantle the underlying causes of these systems of oppression within cultural institution contexts.

My thesis specifically explores how space activation can encourage and foster stronger and healthier collaborations between BIPoC artists and cultural institutions in Portland, and what it can look like through design justice and participatory frameworks. The space activation projects I engaged my stakeholders in helped with the development of new coalitions, increased the number of meaningful, fun, and inspiring artistic collaborations across multiple institutions, and contributed to a more nuanced understanding of how designers and cultural institutions can approach multi-scalable and strategic interventions and solutions with a systems and people-centered approach.

Despite some of the challenges I faced while conducting my research, I remain steadfast in the belief that cultural institutions can and have an obligation to dismantle these oppressive systems and structures, and as a result contribute to a shifting arts and cultural landscape that centers the wellbeing of communities of color.

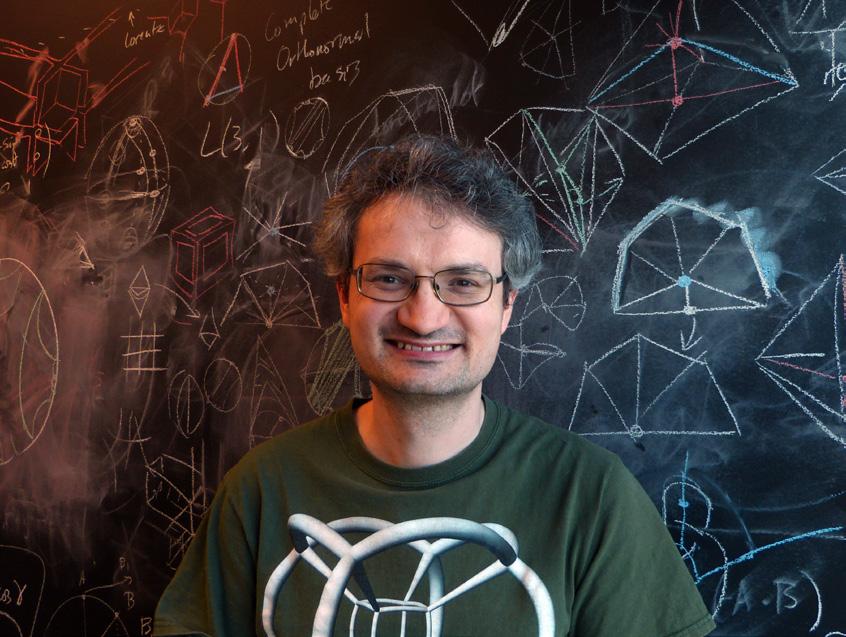

Hello there, and welcome! For those that don’t know me, my name is Miguel Rodriguez (aka Mike Firm), and I’m a Portland-based creative with a focus on multimedia, storytelling, and community building. During the past 10+ years I’ve worked in secondary and higher education, as well as the museum and nonprofit sectors.

And, as of recently, I have also assumed the label of artist/designer; because of this program, this label has felt truer, and it has deeply impacted my work, community organizing efforts, relationships, and more.

As you explore my thesis, I invite you to tap into this same energy and examine your own relationship to art and design. Maybe it’s the educator in me, but I want you to consider the following while reading:

1.You’re an artist/designer: we all have an inner child that encourages us to be curious, seeks to understand the inherent and hidden complexities of our world, and desires to be creative (minus the label). Follow the thread of a new idea, and see where it takes you without worrying about being right or wrong.

2. Reflect on and dissect the contradictions, but don’t let cynicism consume you: I hope that you experience moments of awe and anger, joy and concern, and imagination and frustration. This should make you uncomfortable in some form or another, especially as it relates to issues and conversations about race and other identity markers.

3.It’s all about context: what might work for me, might not work for you. Think of this as a smorgasbord of information, inspiration, examples, and a call-to-action based on my experiences, research, and process. However, you will need to make it relevant to you, your communities, and your goals.

4.Practice collaboration more frequently: none of this was possible without my communities, loved ones, and colleagues supporting my education, and we never create or design without influence from someone or something else. This requires consistency, intentionality, and constant interrogation of our practices and processes as artists/designers or as members or representatives of a cultural institution.

The last two years have been a whirlwind of a ride... In between juggling full-time grad school, full-time work, and the countless side projects that I probably should've not taken on (just kidding, I love it), I couldn't have done it without the support, collaboration, and insights of my amazing family and friends, colleagues, peers, professors, mentors, and my newfound and growing artist and designer community.

I will probably forget to mention some people, but I want to provide a special shout out to the following people for keeping me sane throughout this program and for believing in the kid. I couldn't have done it without ya'll:

•Adrianne S.

•Aineias E.

•Amy B.

•Andrew N.

•Angie M.

•Anne A.

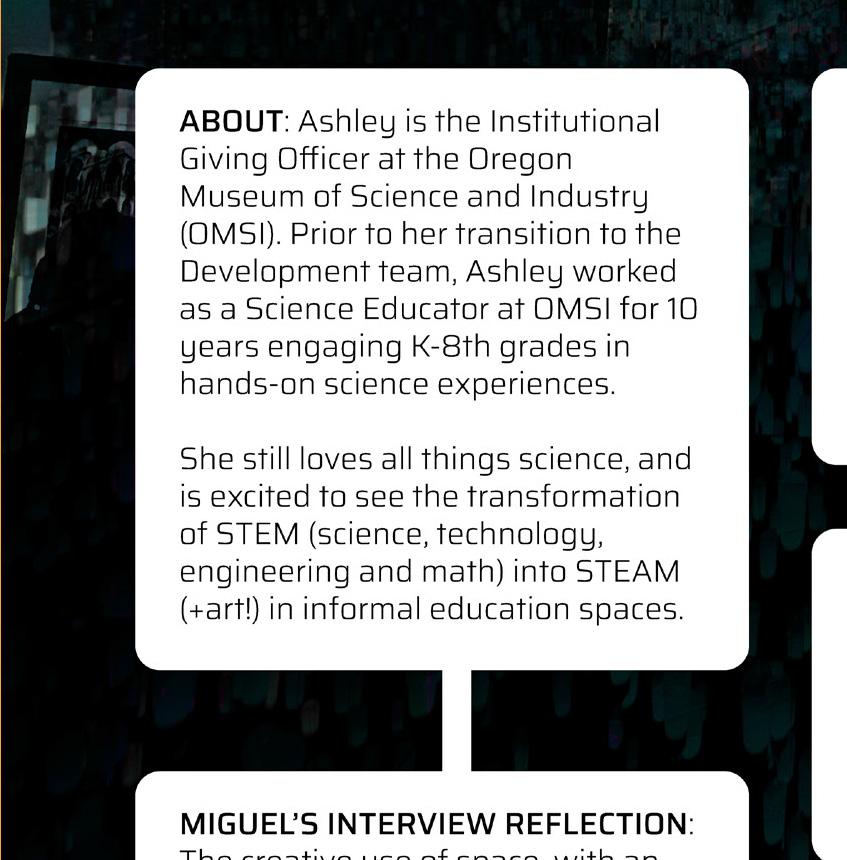

•Ashley J.

•Bayo O.

•Bevin M.

•Brendy H.

•Cindy RV.

•Daelyn D.

•Daniela E.

•Dave L.

•Edgar H.

•Eric BA.

•Erin D.

•Erin F.

•Erin G.

•Estefania Z.

•Hafsa A.

•Herman D.

•Holly H.

•Jackie I.

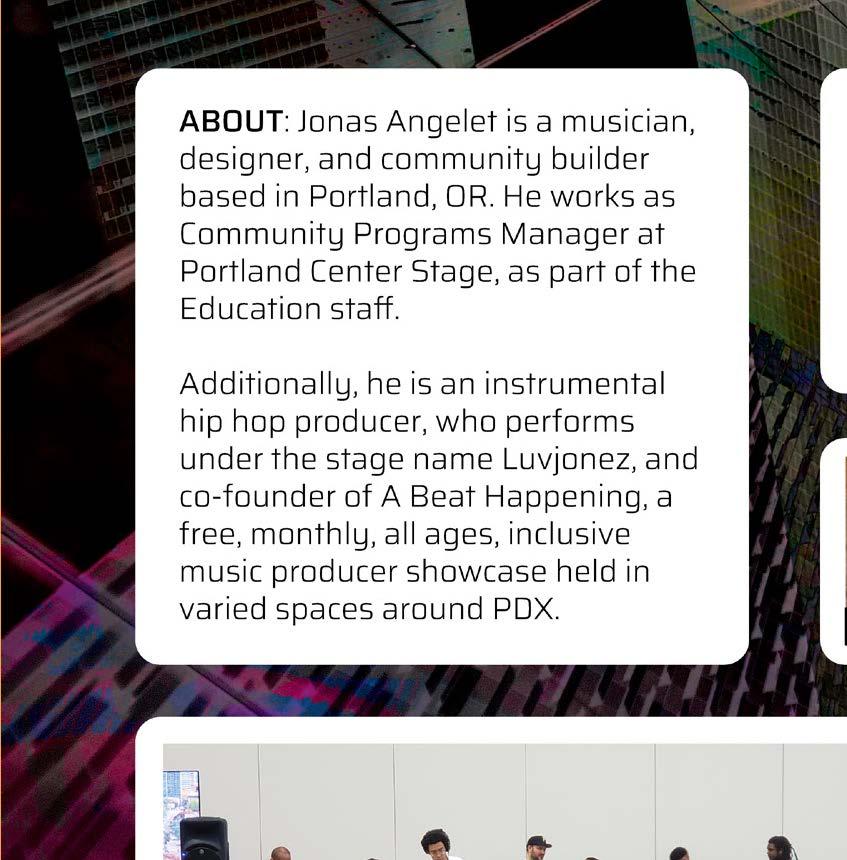

•Jonas A.

•Jooyoung O.

•Joy D.

•Joyce C.

•Karim H.

•Kate M.

•Katie F.

•Katie V.

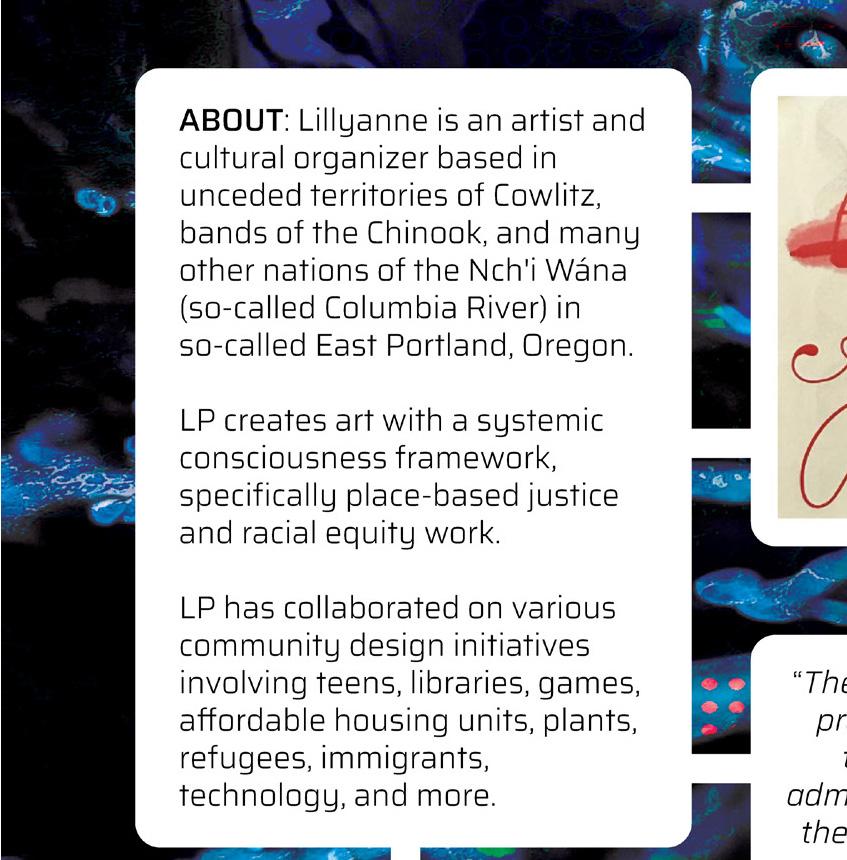

•Lillyanne P.

•Marissa S.

•Mary S.

•Megan M.

•Meghan D.

•Meghann G.

With all of that out of the way, I want to preemptively thank you for taking the time to read and support my thesis work. My lifelong dream of being an art kid going to an art school doing art stuff is finally realized, and it means the world to me that I could connect with and design with people across disciplines, professions, and backgrounds for my MFA thesis.

Make sure to follow and support all of the amazing people, organizations, and cultural institutions highlighted within, doing great work in our communities and beyond here in Portland, nationally, and internationally.

Enjoy!

•Mireaya M.

•Mom

•Omar RV.

•Paola C.

•Raquel B.

•Rebecca B.

•Riza L.

•Savana S.

•Sharita T.

•Shauna CF.

•Shohei K.

•Skye M.

•Sophia XA

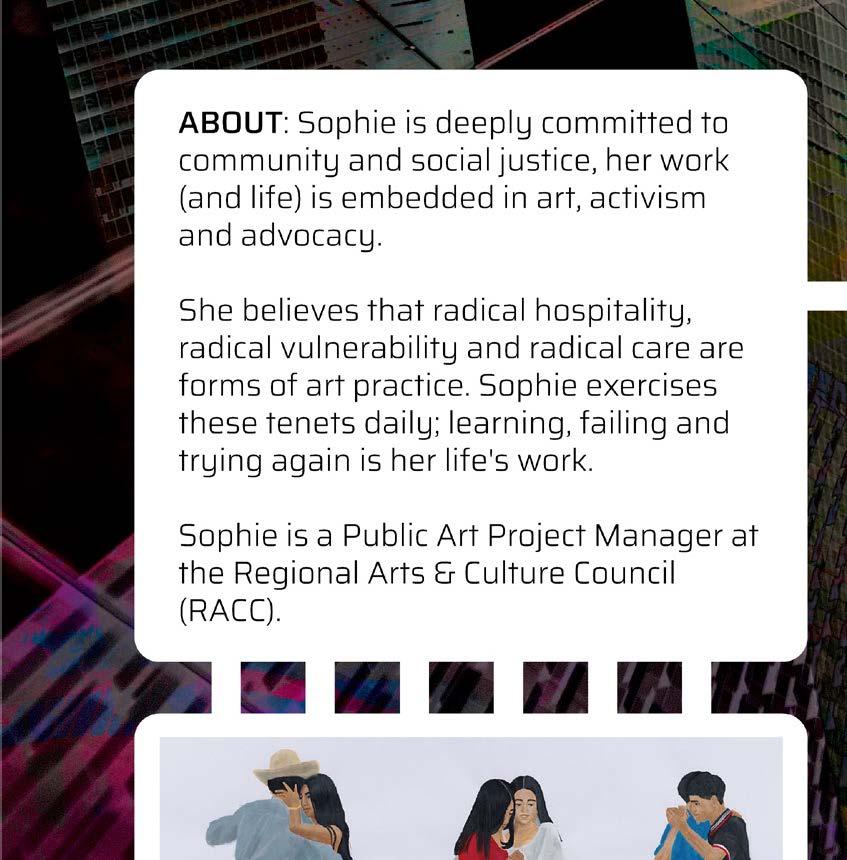

•Sophie H.

•Spencer G.

•Suzanne C.

•Todd U.

•Tyrel O.

•Vale E.

As a young kid living in southern California during the early 2000s, I was usually mesmerized by the sprawl of Los Angeles and its surrounding counties. The built environment was a living organism in of itself, and there was always something new to discover down the countless streets, alleys, and freeways stretching across its populous, unique, and skyscraperladened landscape.

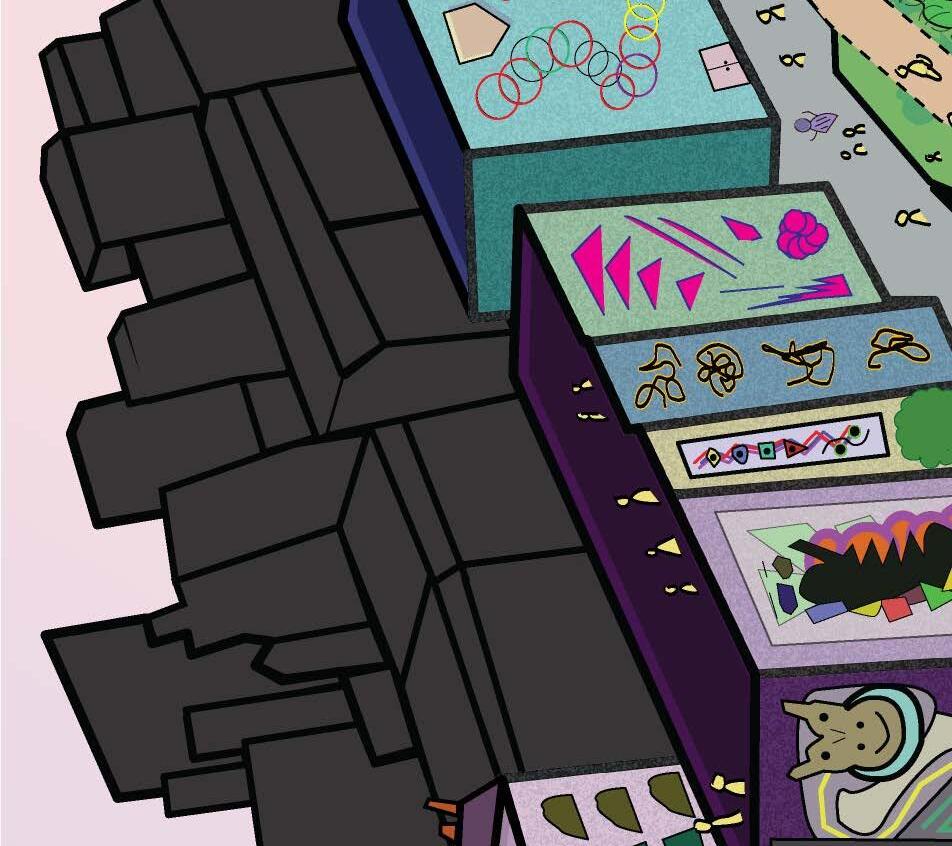

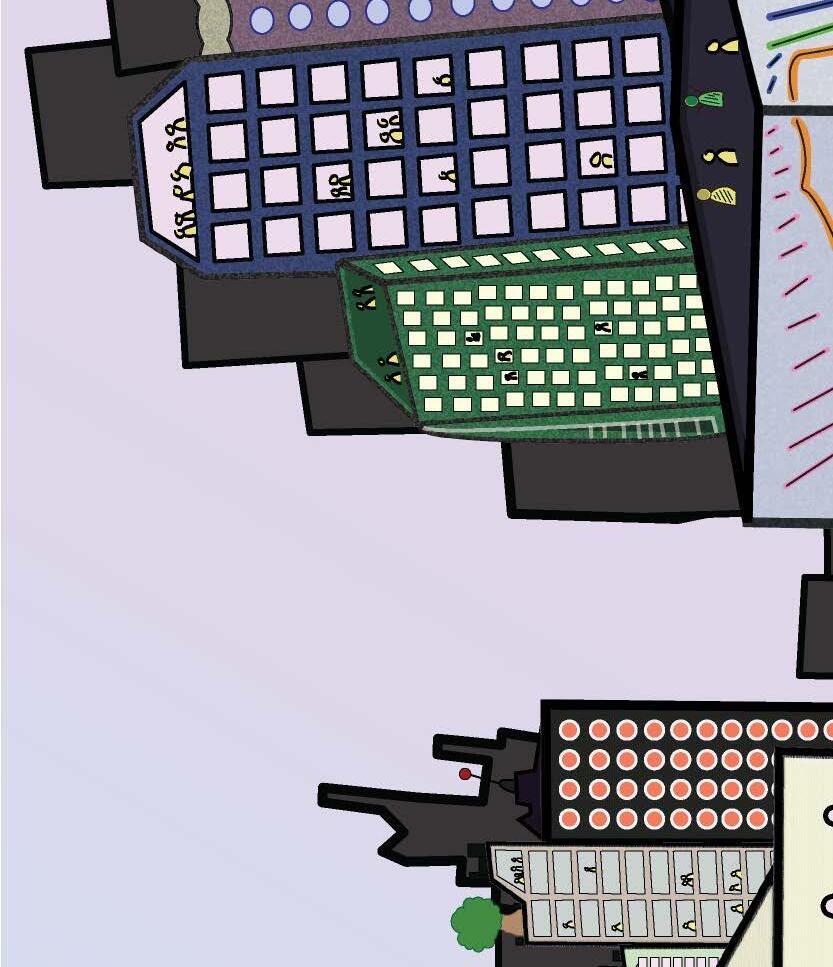

Travel became synonymous with discovery and daydreaming, and I actively sought opportunities to imagine, create, and immerse myself in the development of new worlds of my own making. However, it was my affinity for video games that encouraged me to tap into this creativity more intentionally; the blend of games like Command and Conquer, SimCity 4, Army Men: Toys in Space, and Fallout 3 fostered a significant appreciation and skill for building, exploring, and imagining, including a knack for testing the boundaries and mechanisms at work.

These video games were foundational for the development of my own strategy, design, and resource management skills—at a young age I was already thinking like a designer, with all of the nuances, affordances, and considerations necessary for a successful player. Additionally, these worlds would translate into the fake cities I would build out of Hot Wheels and Legos, trying to turn the digital into the physical.

After some time, the accumulation of these interests coalesced into an interest in architecture / urban design as a career path. In particular, I found the idea of designing buildings and spaces that would serve peoples’ needs to be exhilarating; this excitement translated to some key architecture and AutoCad drawing classes throughout high school.

Now, while this path didn’t materialize as a child and young adult, I am fond of recent experiences that have slowly drawn me back into the realm of architecture and urban design. In particular, I am invested in the subfield of space activation and placemaking, and how this framework and process can support communities’ connection to spaces that they want to live, play, and connect within.

The concept of space activation and placemaking speaks to me because of the interdisciplinary and community-led approach it requires, and how it’s basically an amalgamation of my countless interests and values as a designer. As described by the Project for Public Spaces and Max Musicant of the space activation firm The Musicant Group, this framework and process emphasizes the need and importance of using a people-centered approach for designing spaces with people, as well as a focus on reenvisioning our current built spaces, whether they are physical or digital, temporary or permanent, and public or private.1

Without knowing it, I had already been practicing this framework and process, and I just needed some new knowledge and experiences to better understand my affinity with our built environments. For context, in my professional and community organizing career to date, there have been three key experiences that have shaped my current trajectory into space activation and placemaking. These include my time with the non-profit College Possible, the grassroots collective that I lead and cofounded Portland Through a Latinx Lens, and my current role as a Talent Development & Inclusion Strategist at the Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (OMSI).

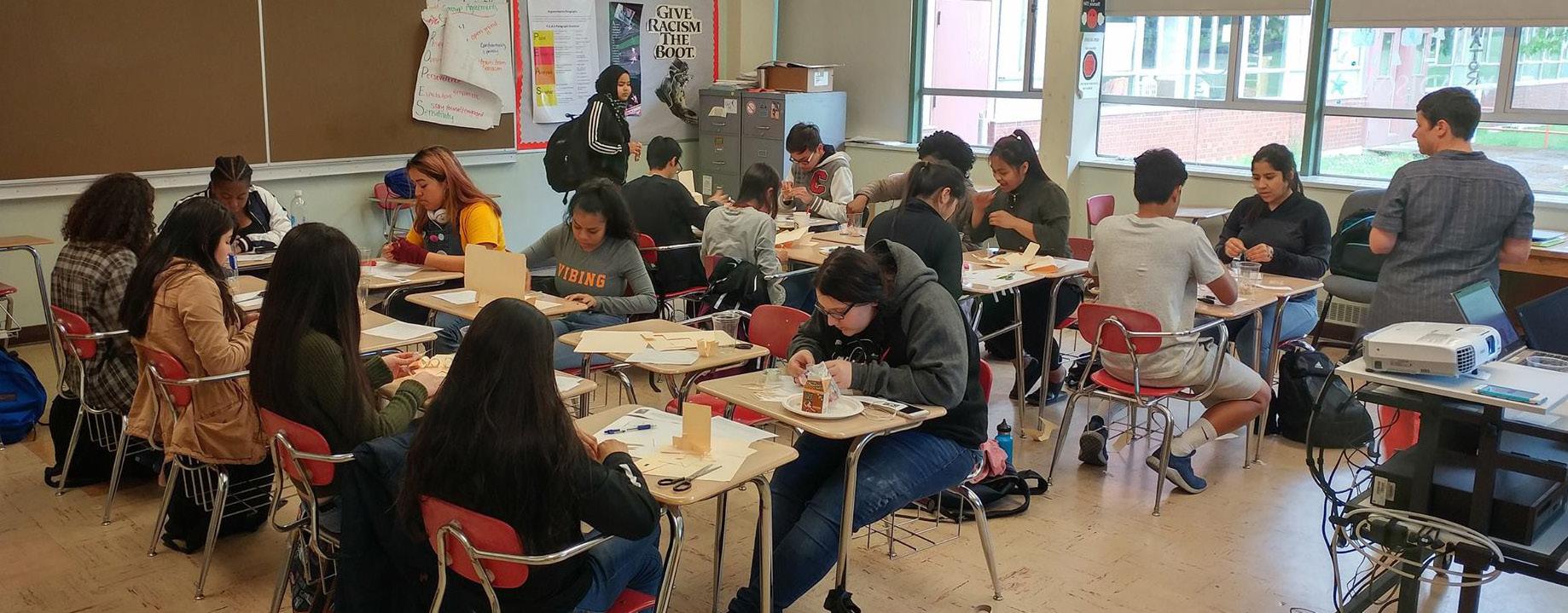

My time working at College Possible was complicated, emotionally taxing, and arduous, but it has been a defining moment in my professional career. Over the span of two years, my caseload revolved around supporting 40+ youth in a college access capacity. While I could probably write an entire novel about the difficulties happening on a day-to-day basis, the lessons learned (both positive, negative, and in between), and the breadth of pervasive systems of oppression operating at McDaniel High School, all of it was worth it because of the relationships, community, and trust that my students, their families and caregivers, and I built together.

Whether we knew it or not, we had been practicing space activation and placemaking in the health classroom and computer labs where we spent most of our days. Whether we knew it or not, my students kept coming back because the physical space we were building together was inviting, safe, and fun (except for the dreaded ACT test practice days or when crunch time was in full effect).

Now, as the 5 year anniversary of their high school graduation approaches in June 2023, some have graduated from college, others are fully embedded in the workforce, and others are still in the process of completing their degrees. While we don’t keep in touch as we used to, I’m confident in all of my students’ skills and abilities to be successful as they navigate systems and spaces that were not built for BIPoC communities to thrive in, partially because of the two years we spent together in our shared, community-focused space.

But, that's not okay or enough. They deserve better than just surviving and navigating these systems. They deserve access to multiple spaces where they can be unapologetic with their forms of expression and create alternative spaces for their communities to thrive in.

Before we move on to the next experience that has influenced my thesis work, I want to leave y'all with a story for reflection. During my final year with College Possible, I was working with a student who wanted to share her story and thoughts for the grassroots collective I’m a part of, Portland Through a Latinx Lens. Ann’s contribution focused on the nuances of her being the “first” in a variety of contexts, specifically as a Latina woman navigating family, societal, and cultural norms in Portland. But, it was her focus on the future that was the most illuminating and impactful for her peers, mentors, and I to hear out loud:

For our future, I feel that we have a lot of work to do. Hopefully we are embraced more. However, why don’t we have cultural centers centered around our culture? With that in mind, I want to build and help communities; I wish there were places where kids wanted to go to receive the help they need. Not just school. But life therapists, mentors, tutors so that they have places where they can feel supported… we have community places, but not community centers for our people and run by us… Portland needs to have more work done for the Latino community; places like Portland Mercado are great, but there needs to be more.2

Ann’s journal contribution has had a long-lasting and resonating effect on me as an educator, professional, and designer. Her words highlight the curiosity, ambition, and thoughtfulness that many youth take into consideration when reflecting about the larger context of their worlds, despite the various systems of oppression that they face in their daily lives on a consistent basis. Even more, her words are a constant reminder of the types of spaces that need to exist in Portland, and the types of outcomes we need to strive for with space activation and placemaking.

2 Caballero-Pateyro, Ann, "I am First Generation," Portland Through a Latinx Lens, 2018. https://pdxlatinx.org/#/anncaballeropateyro/

As a result, this experience spawned a question that I have continuously asked myself during moments of doubt, confusion, or when I needed reorientation; seeing myself in Ann and my other students of color, this question draws from similar reflections in my own adolescence. It is a question that I now pose to you, the reader: what are we all going to do about the lack of these types of spaces? However, reflecting further on my current context as a systems-orientated designer, the question has since evolved to be more detailed, multi-faceted, and accountable:

1.How will WE make sure these spaces materialize?

2. What do these culturally-specific spaces look and feel like?

3.What do these spaces look like for youth?

When I arrived in Portland in 2014, it was overwhelming. Not because of my recent transition from a rural community, but because I felt isolated and confused. More explicitly, I was hoping to see more Black and brown people in Portland, at school, and at work, and this—alongside other complicated issues I was navigating at the time—heavily impacted my mental health and school progress. Partially attributable to my assumption that big cities meant more diversity, I was slightly shocked but felt strong disappointment to realize that Portland was not excluded from its shared history with the rest of Oregon: it was predominantly white, and it had a complicated and pervasive history with racism.3

I was expecting the city to be a space where I could more easily connect with folks of diverse backgrounds based on my Los Angeles days. However, it would take nearly five years for me to find and create a meaningful space with others who shared similar backgrounds, values, and goals with me in the whitest city in America.

3 Alana Semuels, “The Racist History of Portland, the Whitest City in America,” The Atlantic, July 22, 2016. https://www. theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/07/racist-history-portland/492035/

In late 2017, I joined AVANZA: Programa de Liderazgo para Jóvenes Adultos Latinos4 with Edúcate Ya per the suggestion of one of my College Possible colleagues. Over the span of eight weeks, I met with 15 other Latin identifying folks in a culturally-affirming space that expanded my thoughts, skills, and knowledge of leadership.

Despite having different lived experiences in Portland, our shared cultural background united and encouraged us to explore possibilities that we hadn’t thought were possible; we all knew that living in Portland as BIPoC people was difficult, but we knew it could be easier if we stuck together. Our new community was a mechanism for times when we needed to share, cope, strategize, or just have fun amidst the overwhelming feelings of isolation in our day-to-day lives caused by the whiteness of the city.

https://www.educateya.org/avanza.html

Moving forward to early 2018, I was contracted by the executive director to be the program’s next coordinator, and that’s where I met some of my closest friends and collaborators with Portland Through a Latinx Lens. The idea of sharing our stories of being Latinx in Portland emerged from the culminating project, and the groundwork was set: social media, and the digital ecosystem, became our preferred form of space activation.

Since then, our programming evolved to include community workshops, zines, a digital archive/website of our stories, and pop-up art galleries. We actively relied on the support of our various communities and community organizations to elevate these experiences through grant funding, free rental spaces, volunteer hours, and more. While the pandemic and our busy lives impacted our trajectory and slowed down future plans for the collective, the five of us are incredibly proud of the work we’ve done. The spaces we activated, while temporary, brought many BIPoC and white community members together to learn more about Latin culture and how to support our community, which has far surpassed our initial ambitions and expectations.

Our next steps are a bit uncertain, but the idea of having our own physical space has crossed our minds multiple times; speaking for myself, I believe that such a decision would be a tangible step towards realizing my student Ann’s dream (and that of many other students, youth, creatives, designers, and cultural workers I’m in community with) of culturally-specific places for the Latin community and other communities of color.

A physical could take on many forms, but fundamentally it would have to adhere to our mission, values, and vision, as well as the Design Justice Network Principles5 (please visit the methodology section for more details). Bearing in mind these principles, a physical space that is malleable, inclusive, and education-focused would round it out.

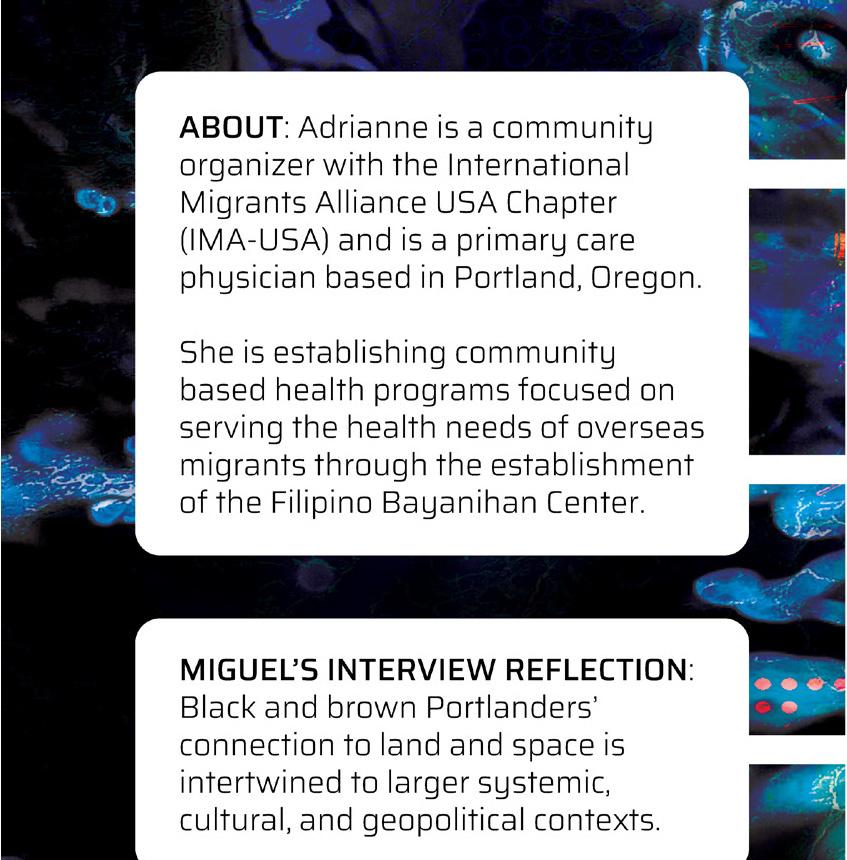

Looking through some local spaces, Portland’s BIPoC community has been exploring these types of spaces already. Examples include Portland State University's Cultural Resource Centers,6 the Filipino Bayanihan Center,7 Marrow PDX,8 or the forthcoming Creative Homies9 and La Plaza Esperanza spaces.10

All of these spaces have their own affordances and consideration, but they serve as a foundation and inspiration for a more permanent location for our collective: a permanent space activation that emphasizes a communal environment based on shared cultural heritage, cross-cultural pollination, safety, and creativity and expression.

5 “Design Justice Network Principles,” Design Justice Network, n.d. https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles

6 “Cultural Resource Centers,” Postland State University, n.d. https://www.pdx.edu/cultural-resource-centers/

7 Filipino Bayanihan Center, n.d. https://www.bayanihanoregon.org/

8 Marrow PDX, Instagram, n.d. https://www.instagram.com/marrowpdx/

9 Creative Homies, n.d. https://www.creativehomies.com/

10 "La Plaza Esperanza," Latino Network, n.d. https://www.latnet.org/la-plaza-esperanza

Transitioning from McDaniel High School was one of the toughest decisions I’ve had to make in my professional career, but it was a necessary step towards delving into more systemic work that could impact the lives of more students, their families, and the larger community.

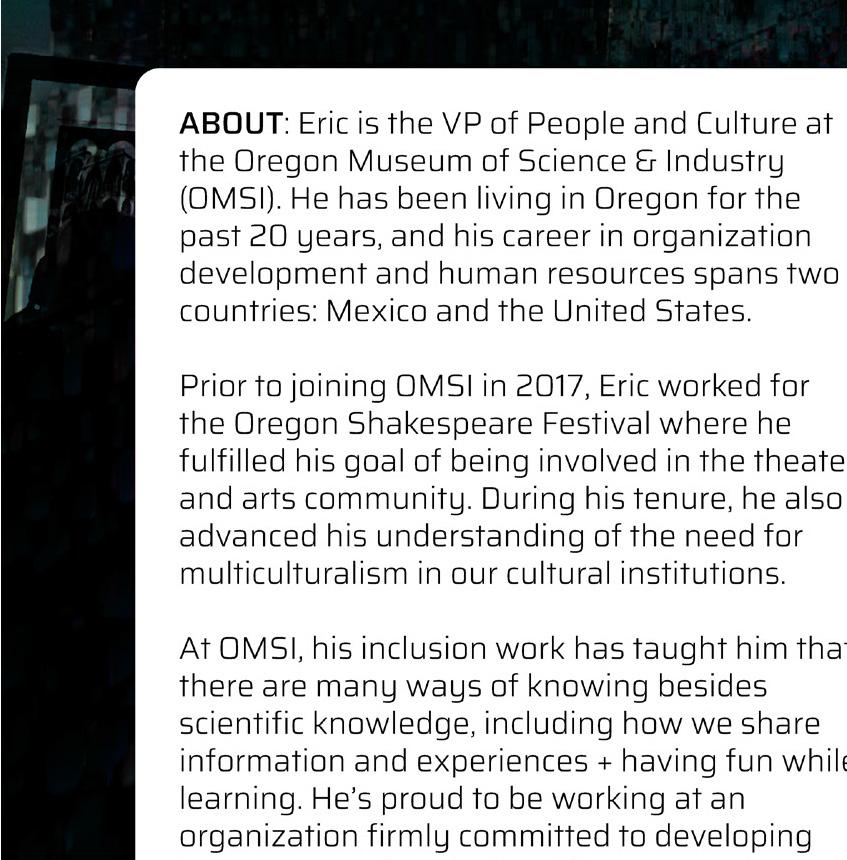

After a lengthy search and interview process with multiple non-profit organizations, I became the first Talent Development & Inclusion Strategist at the Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (OMSI). I was excited to assume this position because of its unique emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in a science-based museum. Furthermore, the ability to mold the position to the needs of BIPoC communities, who have been traditionally excluded from these spaces, was an opportunity I could not shy away from.

Throughout my adolescence, I saw the influence and power that cultural institutions—e.g. museums, art galleries, libraries, community centers, etc.— have in shaping the zeitgeist of our societies’ norms and values, as well as how they maintain the status quo and perpetuate various systems of oppression within.

For example, when I moved to Oregon, many people would consistently talk about the role OMSI played in shaping their STEAM identity and affinity. But at the same time, I would hear from many communities of color that it was a predominantly white space, which did not take a nuanced approach in its offerings, representation of its staff, and other experiences that made it an unwelcoming and sometimes hostile space for them to visit.

Nevertheless, once I was set to transition to my new role, many friends, colleagues, and students of color were excited and interested to see how I would fare in navigating this role and environment.

While the past three years have been a whirlwind because of the pandemic and shifting societal norms and values, the work that my team and I have been doing at OMSI has set the foundation for a stronger and more inclusive environment for BIPoC communities.

We’ve had a solid amount of wins that keep us pushing, but also a string of losses that have felt demoralizing. Yet, despite these conditions and challenges, I still have hope. Tackling systems of oppression in these types of spaces is unique, multifaceted, and intersectional.

The symptoms of white supremacy values in a cultural institution cannot be changed just by an individual or solely at an interpersonal level; it requires a multitude of strategies, changing mindsets,11 and design to disrupt and intervene systems so as to not replicate the same results.

The work never ends, and there will always be another struggle, disappointment, or setback in our journey for more inclusive BIPoC spaces, but it's important to note that this is also temporary and that better days are to come as well.

I wholeheartedly believe that cultural institutions like OMSI can and have an obligation to dismantle these systems and structures that prevent BIPoC communities from wholly participating and accessing the resources these spaces hold.

11 FrameWorks Institute, “Mindset Shifts: What Are They? Why Do They Matter? How Do They Happen?” June 2020. https:// www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/FRAJ8064-Mindset-Shifts-200612-WEB.pdf

My role as a designer, cultural worker, and educational professional working within one of these institutions is to not only highlight the underlying issues, but to also take actionable steps towards facilitating stronger and healthier relationships between these two groups. In particular, this requires me to have an interdisciplinary, collaborative, and people-centered approach to design, trial, and materialize alternative models and frameworks with my communities.

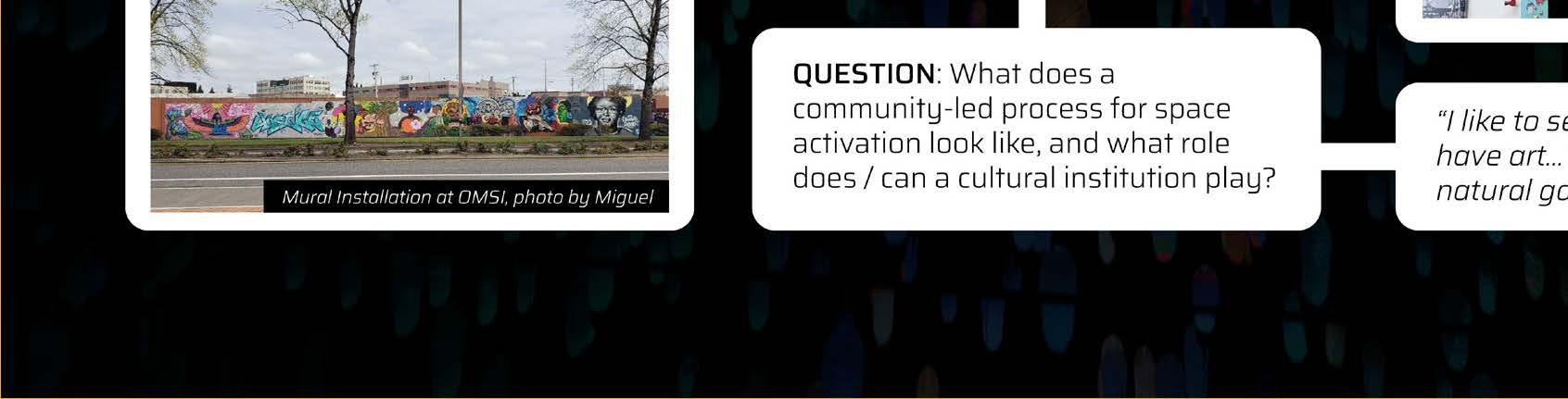

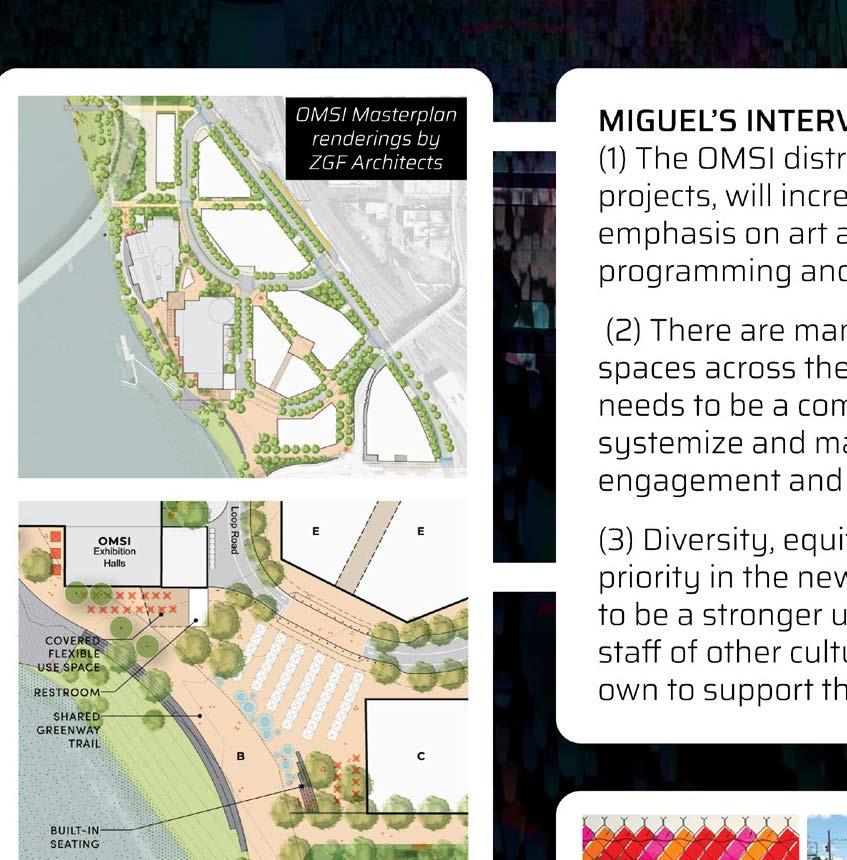

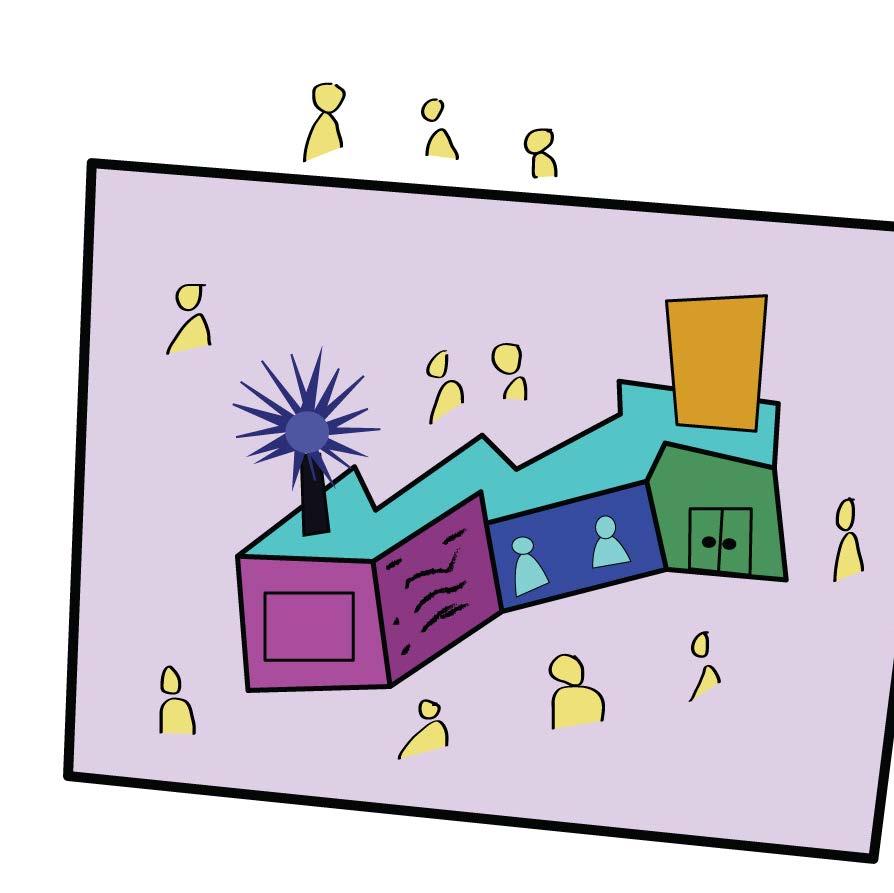

My unique position provides me the opportunity and responsibility to advance this important work, and model this type of engagement and processes to other community members and cultural institutions interested in community-led space activation. Recent examples include our series of culturally-specific Community Science Nights, the OMSI-specific projects within the space activation section of my thesis, and the upcoming Waterfront Education Park, Center for Tribal Nations, and OMSI district.12

Figure 13: Imagining the OMSI District, a mixed-use development (residential, commercial, cultural, institutional, and entertainment) space in inner SE Portland. Rendering by ZGF Architects.

12 “Visioning a Center for Tribal Nations and Waterfront Education Park in the OMSI District,” Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (OMSI), 2022. https://omsi.edu/articles/visioning-a-center-for-tribal-nations-and-waterfront-education-park-in-the-omsidistrict/

Before we can delve into the local, nuanced relationship between BIPoC artists and cultural institutions, and how space activation can encourage and foster stronger and healthier collaborations between both groups, we need to understand the larger arts and culture landscape in both cultural and national contexts.

At a cultural level, the importance and prominence of the arts is far reaching, interdisciplinary, and impacts every person. This is best summarized in the introduction of Cultural Times — The First Global Map of Cultural and Creative Industries 2015 report, commissioned by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC) and EY (formerly Ernst & Young), with support from The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and many other international arts and cultural organizations:

The world has a shared history and a rich, diverse cultural heritage. This heritage is cherished globally as an asset that belongs to us all, yet gives our societies their identity and binds them together, nurturing a rich cultural and creative present and future. That is why stakeholders of the creative and cultural world must do everything in their power to preserve this heritage and the diversity of actual cultural content, amid a political and economic climate that is subject to major upheavals.13

While the report’s content leans towards the economic impacts of the arts and cultural industries, the inclusion of country and artist profiles rounds out and emphasizes the essence of the human condition in relation to culture, as experienced and amplified through the arts: necessary, valuable, and a method for preserving our collective histories.

On the national stage, CISAC and EY’s study findings easily translate to this context. However, the frameworks and efforts of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) are of particular significance because of its status and reputation as one of the most influential arts and cultural institutions in the United States.

In particular, the NEA “fosters and sustains an environment in which the arts benefit everyone in the United States”14 through a variety of tactics and methods, including funding opportunities, honorifics, partnerships and initiatives, research publications, and more. The impact of the NEA in shaping the arts and cultural landscapes across the U.S. is severely understated. I encourage everyone to peruse their annual reports, timeline of highlights, and milestone videos for a more comprehensive picture of the government's approach in "...advancing equitable opportunities for arts participation and practice."14

Besides the NEA, the magnitude and scope of arts and cultural institutions across the country is outstanding,15 and every single one— no matter its size or scope—has impacted the ever evolving zeitgeist of American culture (and globally, for that matter). As of recently, however, they have come under scrutiny because of the need for their systems and processes to change, which would advance a multitude of social causes in their institutions.

13 “Cultural Times — The First Global Map of Cultural and Creative Industries,” International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers and EY, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, 2015. https://en.unesco.org/creativity/files/ culturaltimesthefirstglobalmapofculturalandcreativeindustriespdf

Figure 17: The NEA was established in 1965 by Congress as an independent federal agency that is the largest funder of the arts and arts education in the United States.

14 “What Is the NEA?” National Endowment for the Arts, n.d. https://www.arts.gov/about/what-is-the-nea

15 “United States of Culture,” Google Arts & Culture, n.d. https://artsandculture.google.com/project/american-wonders

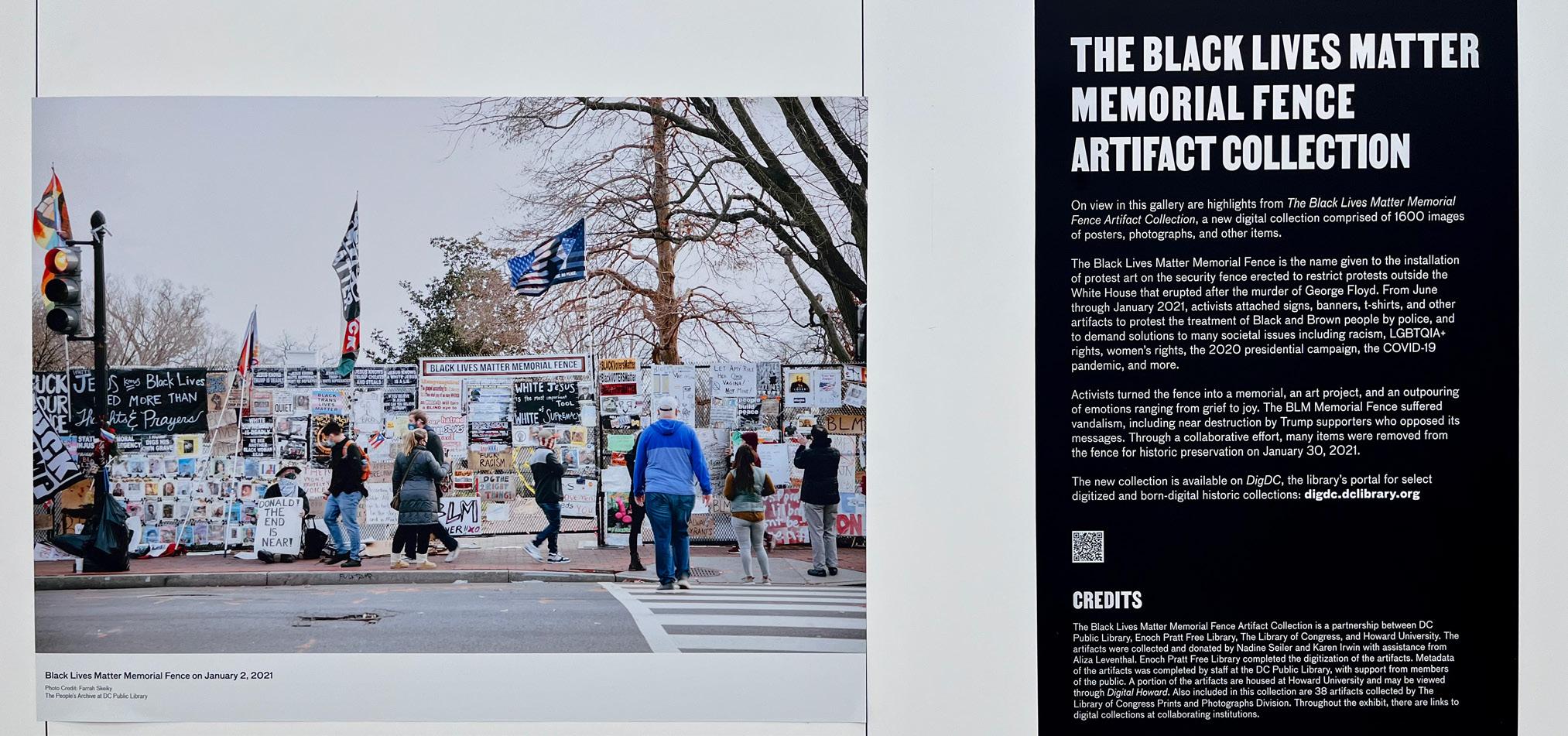

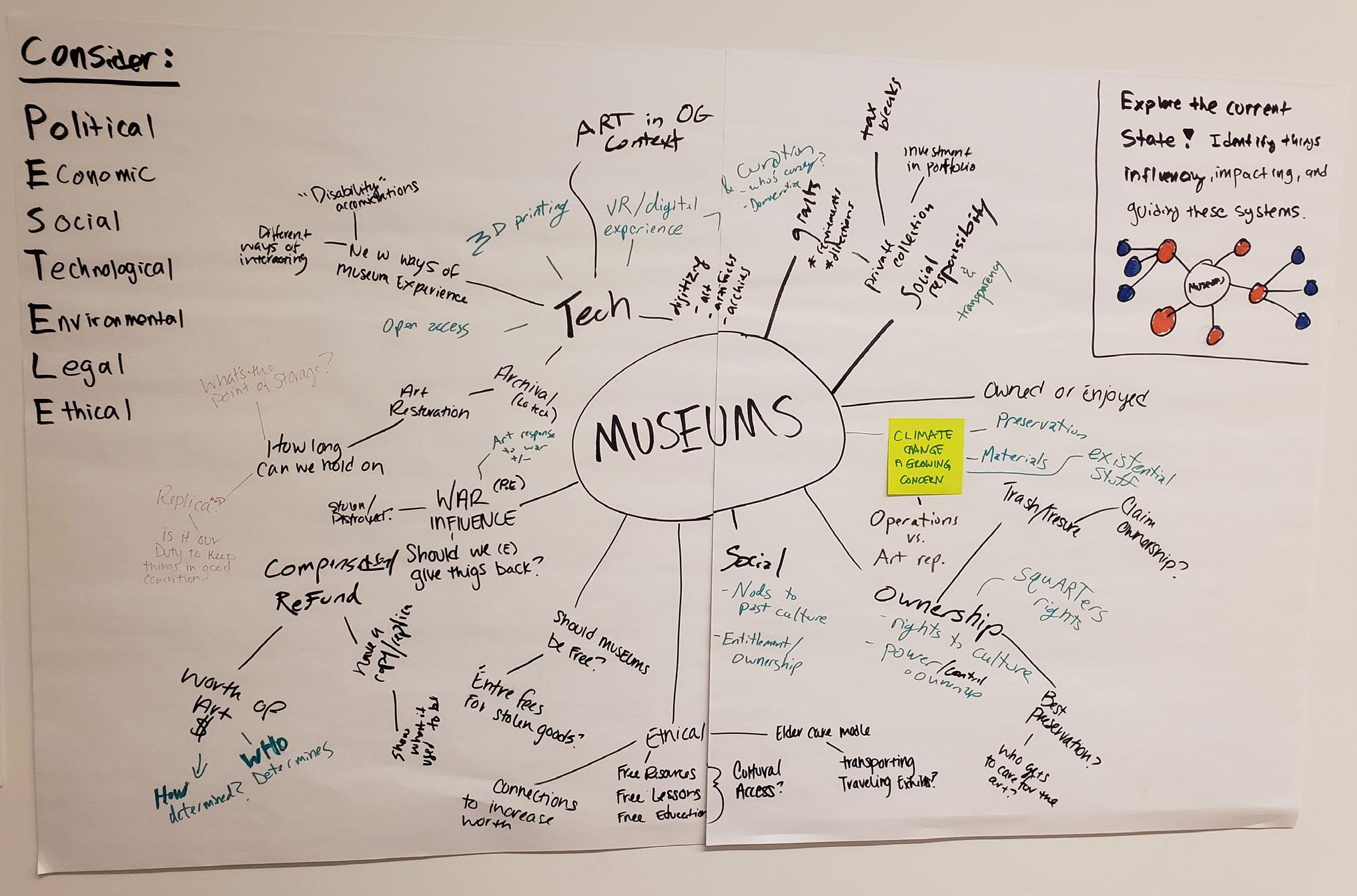

From a social issues perspective, the arts landscape in the U.S. has not been free of the effects of systemic racism, capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy, and more. All of this was amplified by the murder of George Floyd (and many other Black folks) during the spring of 2020 and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as the uncertainty and collective trauma caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.16

Through these combined experiences, there were calls for systemic change and racial justice spanning various systems and institutions (i.e., educational, healthcare, political, environmental, and cultural), albeit with varied success.17 Even more, the pervasiveness of systemic racism and its many forms within our cultural institutions were also called out by museum workers and BIPoC communities,18 especially due to their role in shaping cultural and social norms.

For example, museums were explicitly highlighted because of their role and complicity in perpetuating white supremacist norms and values through a lack of representation in collections, lack of diversity in artists, staff, and leadership, issues of microaggressions and gatekeeping, and remnants of archaic policies and practices that maintain the status quo.19

To learn more about these issues, consider checking out the following:

1.Ithaka S+R's "Art Museum Director Survey 2022: Documenting Change in Museum Strategy and Operations" (link).

2.Hyperallergic's "Artists in 18 Major U.S. Museums are 85% White and 87% Male, Study Says" (link).

3.HBO's "Museums: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver" (link).

4.Museum Next's "How Have Museums Responded to the Black Lives Matter Protests?" (link).

5.Museums Association's "Black Lives Matter: One Year On" (link).

6.New York Time's "Museums Are Finally Taking a Stand. But Can They Find Their Footing?" (link).

7.Vox's "If Museums Want to Diversify, They’ll Have to Change. A lot." (link).

8.northjersey.com's "Systemic Racism is Shaping our Access to Art. How East Coast Art Institutions Strive for Change" (link).

16 Taylor, Yamahtta, “Did Last Summer's Black Lives Matter Protests Change Anything?” The New Yorker, 2021. https://www. newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/did-last-summers-protests-change-anything

17 Cox, Kiana, and Khadijah Edwards, “Black Americans' Views of Racial Inequality, Racism, Reparations and Systemic Change,” Pew Research Center, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2022/08/30/black-americans-have-a-clear-vision-forreducing-racism-but-little-hope-it-will-happen/

18 Lieu, Clara, Jordan McCracken-Foster, and Alex Rowe, “Racism in the Art World & Art School,” Art Prof: Create & Critique, 2021. https://artprof.org/pro-development/racism-in-the-art-world/

19 Kenney, Nancy, “Exclusive Survey: What Progress have US Museums Made on Diversity, After a Year of Racial Reckoning?” The Art Newspaper, 2021. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/05/25/exclusive-survey-what-progress-have-us-museumsmade-on-diversity-after-a-year-of-racial-reckoning

Lastly, before we transition into the local context, it is pivotal to know that many cities across the United States have vibrant arts communities. In a 2022 study conducted by SMU DataArts, they provided a summary of the Top 40 Arts-Vibrant Communities, a cross examination of small, medium, and large cities based on the number of art providers, movement of arts dollars, and the types of government support (including funds) received, as well as an interactive map.20

Key art cities recognized include New York, Miami, Seattle, San Francisco, Santa Fe (NM), and Boulder (CO); and, it’s also exciting to see that Portland ranked twenty-second in the nation amongst these other major cities. Concurrently, while the tone of this report is mainly positive, it also describes how many arts communities were severely impacted by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, arts and cultural institutions, artists, and audiences had to adapt and pivot to the situation, including the closing of physical spaces, an uptick in virtual/digital experiences, and loss of revenue for all groups.21

As of recently, there has been a slight sense of relief amongst these institutions towards the future, but these factors continue to be pressing and stressing them to evolve to the times and cultural and national contexts. While we could dig even further by taking a look at the political and economic factors, some of this is best understood at the local context. Let’s see how this plays out in Portland.

20 “The Top 40 Most Arts-Vibrant Communities of 2022," SMU DataArts, 2022. https://culturaldata.org/what-we-do/artsvibrancy-index/

21 Wolff, Benjaim, “New NEA Report Reveals How Bad Covid Was For The Arts — With A Silver Lining,” Forbes, 2022. https:// https://www.forbes.com/sites/benjaminwolff/2022/03/21/new-nea-report-reveals-how-bad-covid-was-for-the-arts---with-a-silverlining

Trigger Warning:

While brief, the next two pages mention the origins and ongoing systemic marginalization and opression of Oregon and Portland's Black and brown residents through racist policies, hate crimes, and institutionalized white supremacy. I do not like writing about these things, but I find it necessary to contextualize how these factors and legacies impact the arts and cultural landscape of Portland.

Since their inceptions, Oregon and the city of Portland have never truly been welcoming spaces for Black and brown communities. The historical, political, and cultural context of both have roots in white supremacy that permeate across every sector and industry in the city. Three significant manifestations include:

1.Oregon originally being envisioned as a whites-only state (e.g. Black exclusionary laws written in the constitution, cases of sundown towns, and more).22

2.Portland systemizing many displacement policies and initiatives that disproportionately affect and continue to impact communities of color (redlining practices, gentrification, hostile architecture, and the Legacy Emanuel Medical Center + I-5 Corridor + Moda Center “urban renewal” processes).23

3.Portland experiencing a myriad of systematic and individual acts of violence against communities of color, in the past and to this date (e.g. Vanport Flooding, anti-Chinese sentiments and violence, the murder of Mulugeta Seraw, MAX stabbings, and more).24

22 Camhi, Tiffany, “A Racist History Shows Why Oregon is Still so White,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2020. https://www.opb. org/news/article/oregon-white-history-racist-foundations-black-exclusion-laws/

23 Albina Vision Trust, n.d. https://albinavision.org/arts-and-culture/ Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS), “Historical Context of Racist Planning: A History of How Planning Segregated Portland,” City of Portland, 2019. https://www.portland.gov/bps/ documents/historical-context-racist-planning/download Burkett, Red, "Racialized Space: Historical, Economic, and Social Factors Contributing to the Gentrification of North & Northeast Portland’s Albina Neighborhoods," University Honors Theses, 2021. Paper 1123. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.1154 Jaquiss, Nigel, “The City of Portland Tried to Undo Gentrification. Black Portlanders Are Conflicted About the Results,” Willamette Week, 2022. https://www.wweek.com/news/2022/05/25/the-city-of-portland-tried-toundo-gentrification-black-portlanders-are-conflicted-about-the-results/

24 Law, Steve, “Unburying History: Portland's Shameful Anti-Chinese Violence,” Portland Tribune, 2020. https://www. portlandtribune.com/opinion/unburying-history-portlands-shameful-anti-chinese-violence/article_4f1d5d16-1f25-5737-a9660f582640eade.html; Frost, Allison, “Celebrating The Life Of And Justice For Mulugeta Seraw,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2018. https://www.opb.org/radio/programs/think-out-loud/article/mulugeta-seraw-portland-ethiopia-africa-white-supremacist-murder/ Powell, Meerah, “Portland MAX Stabbing Victims Call Out Racist System During Sentencing Hearing,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, 2020. https://www.opb.org/news/article/jeremy-christian-sentencing-hearing-victim-impact-statements-portland-oregon/

While some may consider these manifestations as separate from the framework and process of space activation and placemaking, I argue that they’re not. They are intimately intertwined. They inform each other and establish the cultural conditions many designers, architects, urban planners, creatives, cultural institutions, industries, and sectors operate in and reinforce.25 As a result, this creates disproportionate effects on communities of color, including how people use and access space.26

In essence, the state and city of Portland have been key actors in creating spaces that allow white people to thrive and prosper in the built environment at the expense of communities of color. In turn, many Black and brown Portlanders have been unable to create spaces that allow their respective communities to do the same.

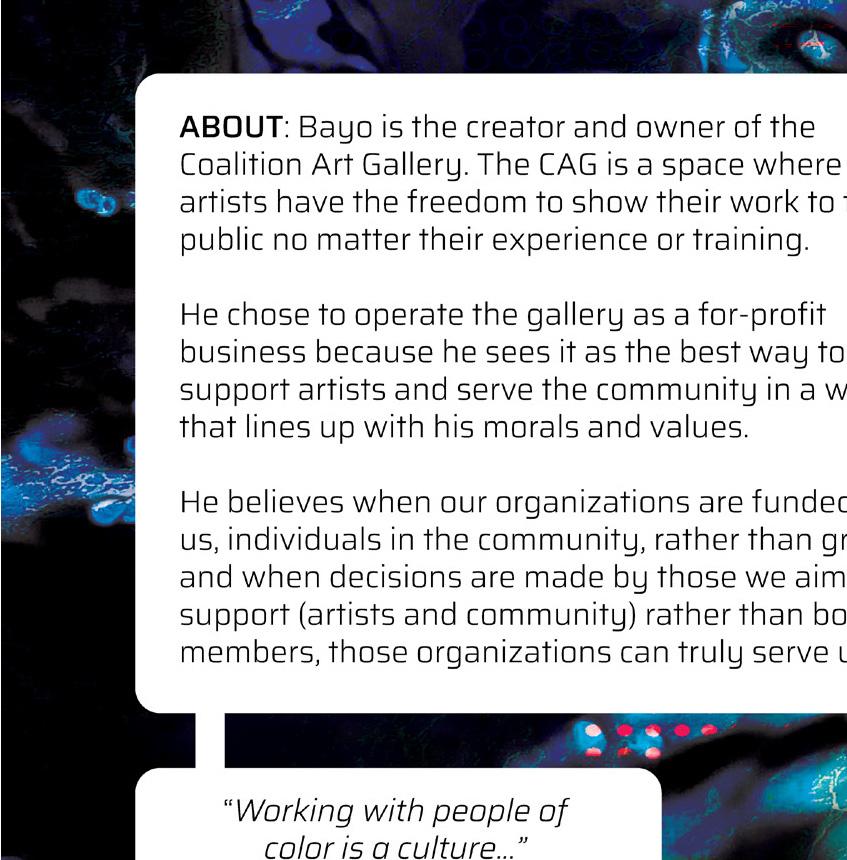

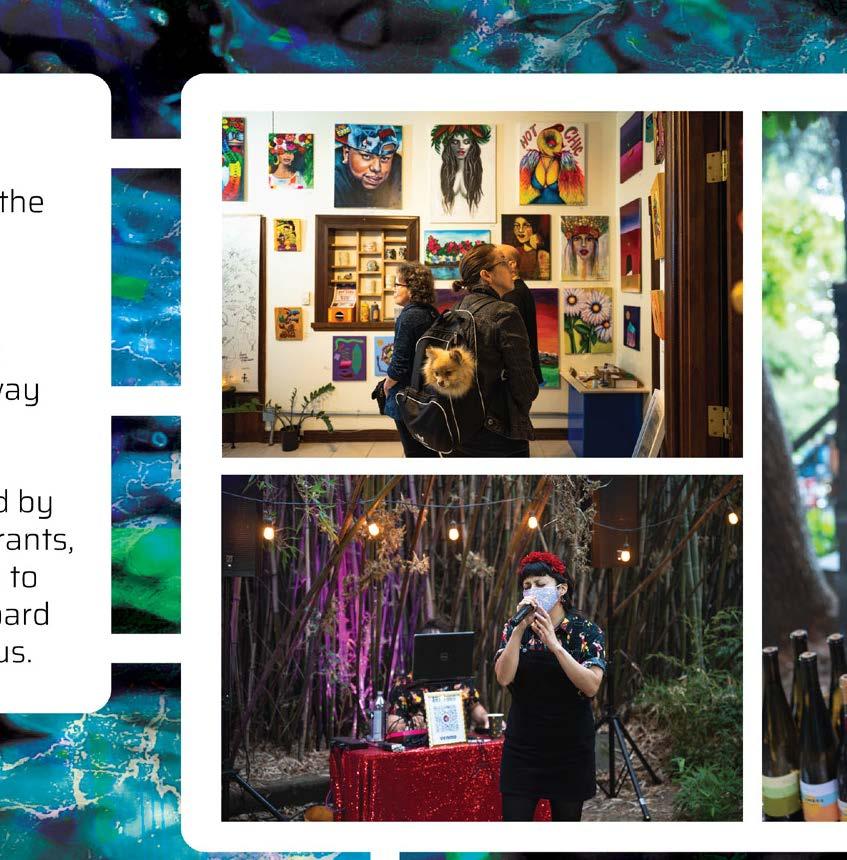

Yes, there are examples and cases of BIPoC communities developing these spaces (e.g. ORI Art Gallery,27 Portland Mercado,28 and the Coalition Art Gallery29), but they are few and far between and more often than not are simultaneously combatting institutionalized white supremacist systems and processes while trying to keep their culturally-specific spaces alive. This includes trying to secure and maintain ongoing funding, having access to affordable physical spaces, and having the appropriate support mechanisms to sustain their efforts.

25 Curry-Stevens, Ann, Amanda Cross-Hemmer, and Coalition of Communities of Color, “Communities of Color in Multnomah County: An Unsettling Profile,” Portland State University, 2010. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1091&context=socwork_fac

26 Breon, Autumn (@autumnbreon), “Be a part of my new artwork and share where your leisure lives,” Instagram, 2023. https:// www.instagram.com/p/CofdLuIpJqU/

27 Vivas, Maya, and Leila Haile. “About — Ori Gallery,” Ori Gallery, n.d. https://oriartgallery.org/about-ori

28 Hacienda CDC, “About Us — Portland Mercado,” n.d. https://www.portlandmercado.org/about-us

29 Olympio, Bayo, “About Us - Coalition Art Gallery,” n.d. https://coalitionartgallery.com/about/

While Oregon and Portland’s complicated racial history impacts every facet of the city’s ecosystem, cultural institutions play a significant role in the normalization of white supremacy through the creation, curation, and access of culture.

Recently, as previously mentioned in the national and cultural landscape section, many cultural institutions have been tasked with examining and re-envisioning their systems and processes. As a result, there’s work being done to change the status quo at many cultural institutions across the U.S.

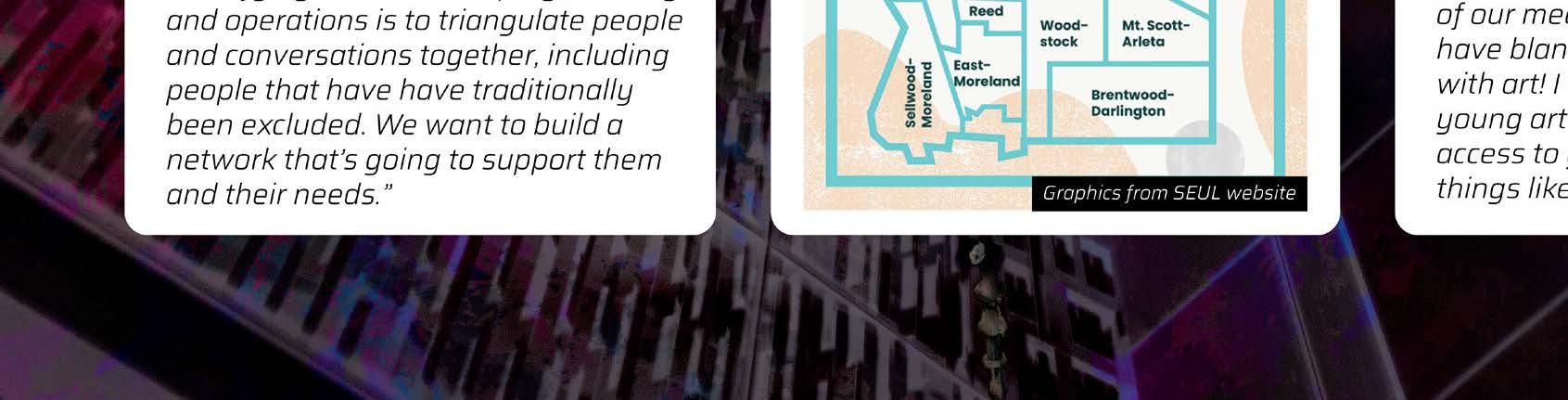

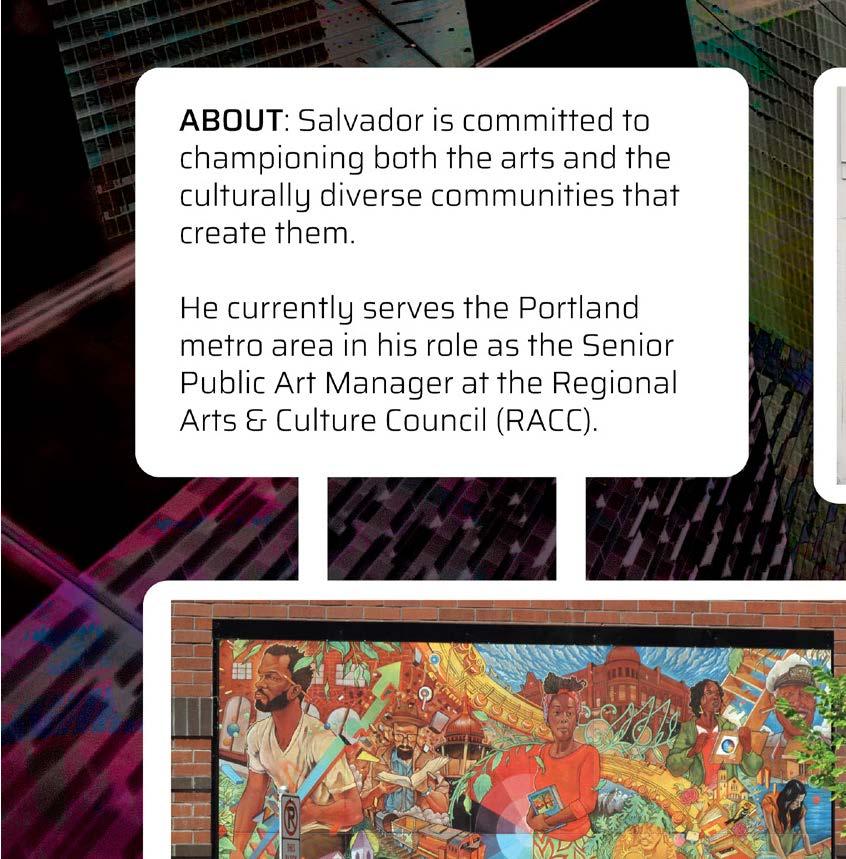

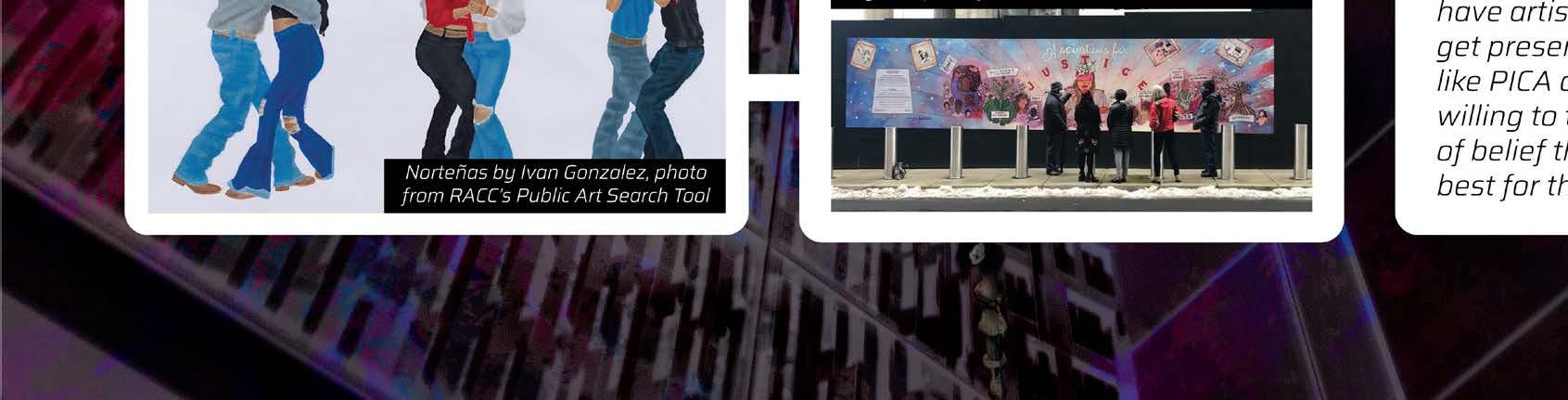

Here in Portland, the collaboration between the city and the Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC) has fostered some incredible work that aims to address these concerns (even though there’s more that needs to be done), whose intertwined histories span over 50 years and includes a variety of master arts plans and reports aimed at moving the arts and cultural landscape forward in the Portland metro area, which includes the Multnomah, Clackamas, Clark, and Washington counties:30

• Arts Plan 2000+, published on February 1992 by the City of Portland’s Metropolitan Arts Commision (predecessor to RACC before a restructure).31

• Act for Art, published on April 2009 by RACC.32

•The Portland Plan, commissioned on April 2012 by the City of Portland’s Bureau Planning and Sustainability Commission (the arts and culture sections of the drafts and background reports, leading up to the final document, are highlighted).33

• A Plan for Preserving and Expanding Affordable Arts Spaces in Portland, published on January 2018 by the Art Council of Portland.34

30 Hull Caballero, Mary, Kari Guy, Jenny Scott, and Martha Prinz, “Regional Arts and Culture Council: Clear City Goals Aligned with Strong Arts Council Strategy will Improve Arts and Culture Services,” Portland City Auditor: Audit Services, 2018. https://www. portlandoregon.gov/fish/article/685075 29 Hull Caballero, Mary, Kari Guy, Jenny Scott, and Martha Prinz, “Regional Arts and Culture Council: Clear City Goals Aligned with Strong Arts Council Strategy will Improve Arts and Culture Services,” Portland City Auditor: Audit Services, 2018. https://www.portlandoregon.gov/fish/article/685075

31 Metropolitan Arts Commission, “Arts Plan: Animating Our Community,” Regional Arts and Culture Council, 1992. https://racc. org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Arts-Plan_Animating-our-Community-1992_Summary.pdf

32 Curtis Cosgrove, Kathleen, Jeff Hawthorne, Regional Arts & Culture Council, and Creative Advocacy Network, “Act for Art: The Creative Action Plan for the Portland Metropolitan Region,” Regional Arts and Culture Council, 2009. https://racc.org/wp-content/ uploads/2016/02/Act4Art_FINAL-1.pdf

33 City of Portland’s Bureau Planning and Sustainability Commission, “The Portland Plan: Arts & Culture.” Portland Online, 2011. https://www.portlandonline.com/portlandplan/index.cfm?c=51427&a=373231 City of Portland's Bureau of Planning and Sustainability Commission, “Portland Plan: Background Report Overviews,” Portland Online, 2009. https://www.portlandonline.com/ portlandplan/index.cfm?c=51427&a=279502

34 Art Council of Portland, “A Plan for Preserving and Expanding Affordable Arts Spaces in Portland,” Portland.gov, 2018. https:// www.portlandoregon.gov/fish/article/667747

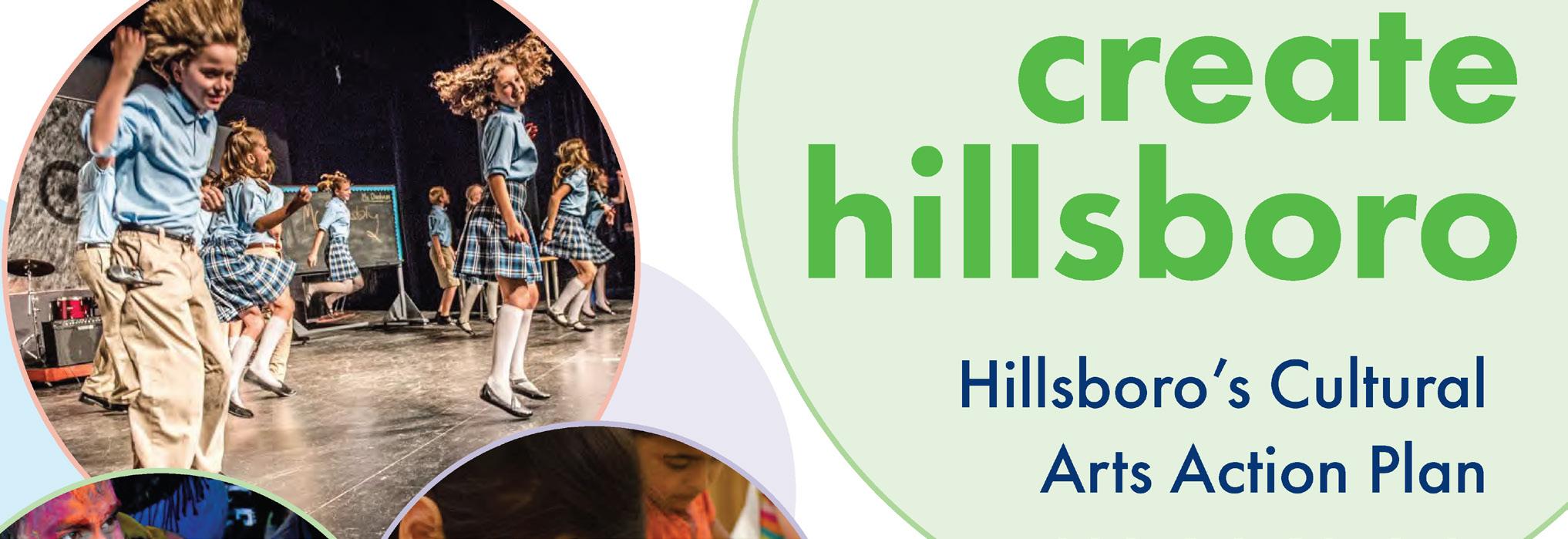

Figure 23: Front covers of the mentioned arts and culture-related reports from RACC and the City of Portland.

•Regional Arts and Culture Council: Clear City Goals Aligned with Strong Arts Council Strategy will Improve Arts and Culture Services, published on May 2018 by the Audit Services Division of Portland.35

•Our Creative Future, a recent initiative to create a new arts and cultural plan for the Portland metro region and Clackamas, Multnomah, and Washington Counties. This effort is being led by staff from Portland’s City Arts Program, the aforementioned counties, the cities of Hillsboro and Beaverton, the Metro regional government, and RACC.36

35 “Regional Arts and Culture Council: Clear City Goals Aligned with Strong Arts Council Strategy will Improve Arts and Culture Services,” Portland City Auditor: Audit Services.

36 “About – Our Creative Future,” Our Creative Future, 2023. https://ourcreativefuture.org/about/

While these reports and initiatives have consistently highlighted the desire for a comprehensive arts and cultural plan for the region, the Audit Division of Portland describes—with some cynicism—a pressing and overarching issue present within the older reports. They emphasize a common thread and need for more nuanced collaborative processes and collective action between many of the city’s institutions spearheading or contributing to the arts and cultural landscape: While proactive, these efforts do not address Portland’s entire arts ecology and do not articulate either a vision or goals for what the City wants to do in terms of arts and culture generally, and how they intend to get there through the work of the Arts Council and City bureaus.37

In sum, Portland’s art and culture landscape struggles with actionable steps, which is the key step towards systemizing, normalizing, and enabling the city’s creatives to thrive, especially for its Black and brown creatives. For example, some of Portland’s most significant and recognizable cultural institutions need to continue investing and implementing genuine diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives across all of their operations, personnel, and systems to deliver on the countless statements and promises shared in response to the social unrest culminating from the murder of George Floyd—and many other Black folks—alongside the impacts of COVID-19 in our communities.

Lastly, it’s pivotal to know that museums in Portland—a major subset of cultural institutions—are strategically posed to contribute more meaningfully than their counterparts (e.g. art galleries, community centers, etc.) to the arts and culture landscape. The role of museums in advancing these efforts is best described by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM): Museums are a vital part of how we tell the stories of who we are, who we’ve been, and how we will live together. They maintain our cultural heritage and teach us about all the ways we are different and the same. Reflecting the diversity of that heritage is a critical part of museums’ work. We cannot claim to be truly essential to society if we are not accessible to all… we believe that equity is our goal, inclusion is how we move toward that goal, and diversity describes the breadth of our experiences and perspectives.38

In the context of my experience working in the museum industry as a Talent Development & Inclusion Strategist at the Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (OMSI), I’ve noticed that museums tend to have more capacity, influence, and power to implement and systemize the space activation and placemaking framework and process if combined effectively with their DEI initiatives, goals, and policies. However, this is easier said than done; this type of pivot requires commitment, intention, accountability, and action to realize.

As mentioned in the cultural and national context section, in 2020 museums were called out and pressured to analyze, confront, and address their current and inadequate systems and processes, which normalize and perpetuate white supremacist culture. While some of the key target initiatives included DEI trainings, increased diversity of staff and senior leadership, and more diverse representation in museum collections, there was also a notable emphasis on diversifying and strengthening programming, opportunities, and resources in order to increase the sense of belonging and community of BIPoC communities, which have historically been excluded from these spaces.39

38 “Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion,” American Alliance of Museums, 2020. https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ diversity-equity-accessibility-and-inclusion/

39 Lawson-Tancred, Jo, “Two Years Ago, Museums Across the U.S. Promised to Address Diversity and Equity. Here's Exactly What They Have Done So Far,” Artnet News, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/museum-dei-plans-2022-2161690

While prioritizing a framework and process like space activation and placemaking in a museum can never fully address the problematic historical, political, and cultural contexts of these institutions, it has the potential to tackle them by creating, revising, or dismantling policies, funding models, and processes that center Black and brown creatives and their communities.

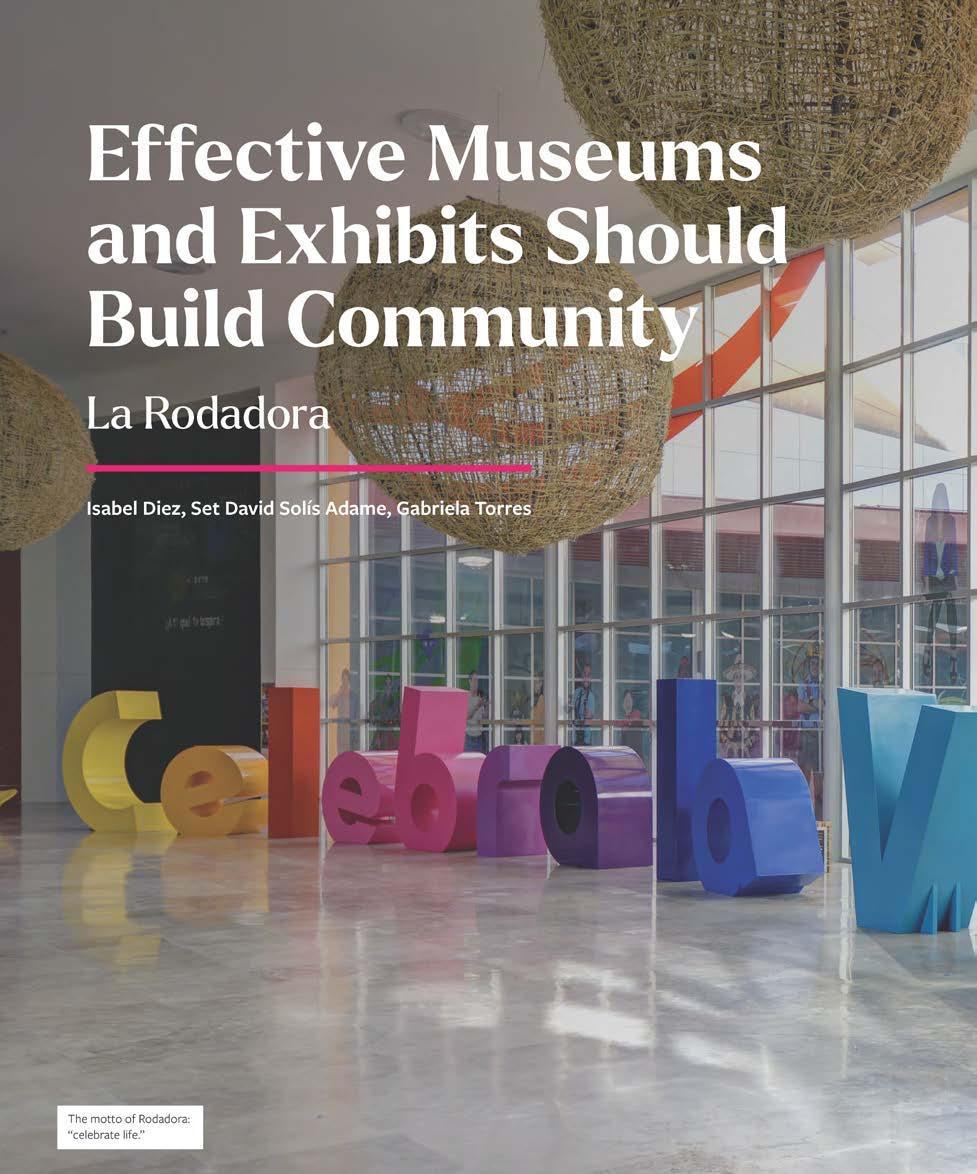

For nuanced and beautiful examples of museums engaged in culturallyspecific space activation and placemaking, please take a look at AAM’s Effective Museums and Exhibits Should Build Community: La Rodadora and Public Spaces and Potential Places 40

40 Diez, Isabel, David Solís, and Gabriela Torres. 2022. “Effective Museums and Exhibits Should Build Community: La Rodadora.” American Alliance of Museums. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58fa260a725e25c4f30020f3/t/ 635a8bf5d89bad67e70daae5/1666878454018/07_Exhibition_22FA_EffectiveMuseumsShouldBuildCommunity.pdf

Campbell, Eileen, and Shawn Lani, “Public Spaces and Potential Places,” American Alliance of Museums, 2022. https://static1. squarespace.com/static/58fa260a725e25c4f30020f3/t/616f30f83e0225214a21b252/1634676997066/09_Exhibition_21FA_ PublicSpacesPotentialPlaces.pdf

In wrapping up this section, I want to share the following list which highlights what I believe are some of Portland’s key cultural institutions (with half of the list being comprised of museums);41 it’s important to be privy of their areas of strength, areas for improvement, their past, present, and future, and how they are centering and being held accountable by BIPoC communities (or whether they are not, for that matter) because many have shared their own versions of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals and initiatives, equity statements, or some combination of the two.

I encourage ya’ll to read their statements and explore the types of space activation projects they host and contribute to. There is a breadth of examples, ranging from window exhibits about local history, outside exhibits and interactives, murals, projections, performances, cultural districts, and more.

41 Maia, Gaby, “Top 15 Best Art And Cultural Attractions In Portland,” Global Grasshopper, 2022. https://globalgrasshopper. com/destinations/north-america/best-art-and-cultural-attractions-in-portland/ “Arts and Culture.” Portland Relocation Guide n.d. https://portlandreloguide.com/museums-theaters-galleries-music-and-more/ “Arts | The Official Guide to Portland,” Travel Portland, n.d. https://www.travelportland.com/culture/arts/ “THE 10 BEST Museums You'll Want to Visit in Portland,” TripAdvisor, n.d. https:// www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g52024-Activities-c49-Portland_Oregon.html; State of Oregon, “Blue Book - Oregon's Major Arts Organizations,” Oregon Secretary of State, n.d. https://sos.oregon.gov/blue-book/Pages/cultural/arts-major.aspx

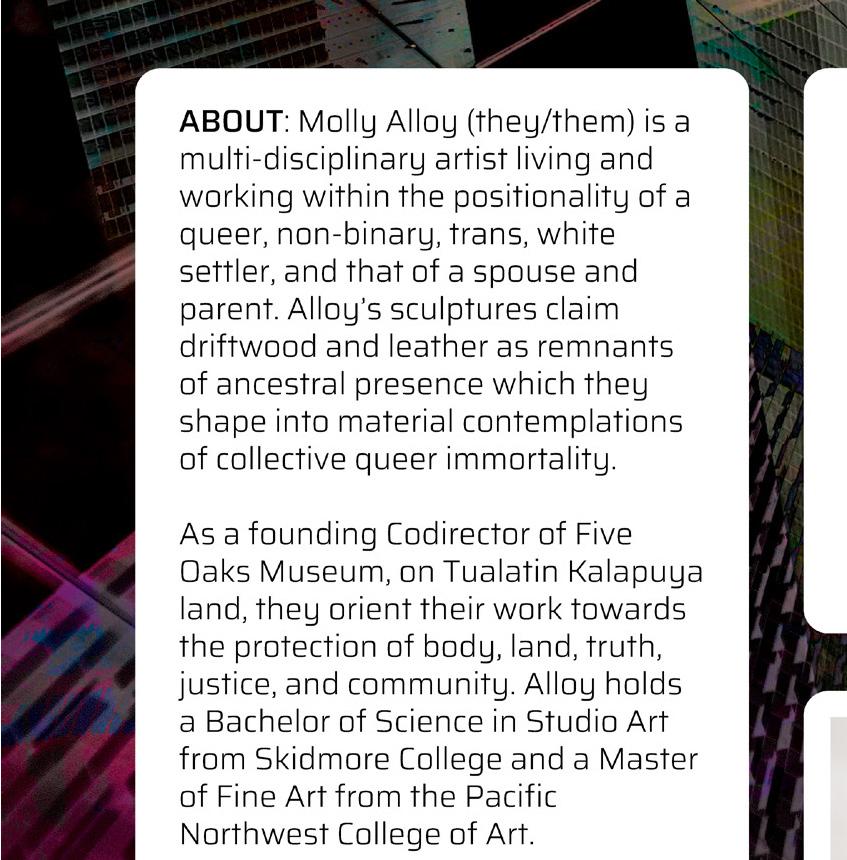

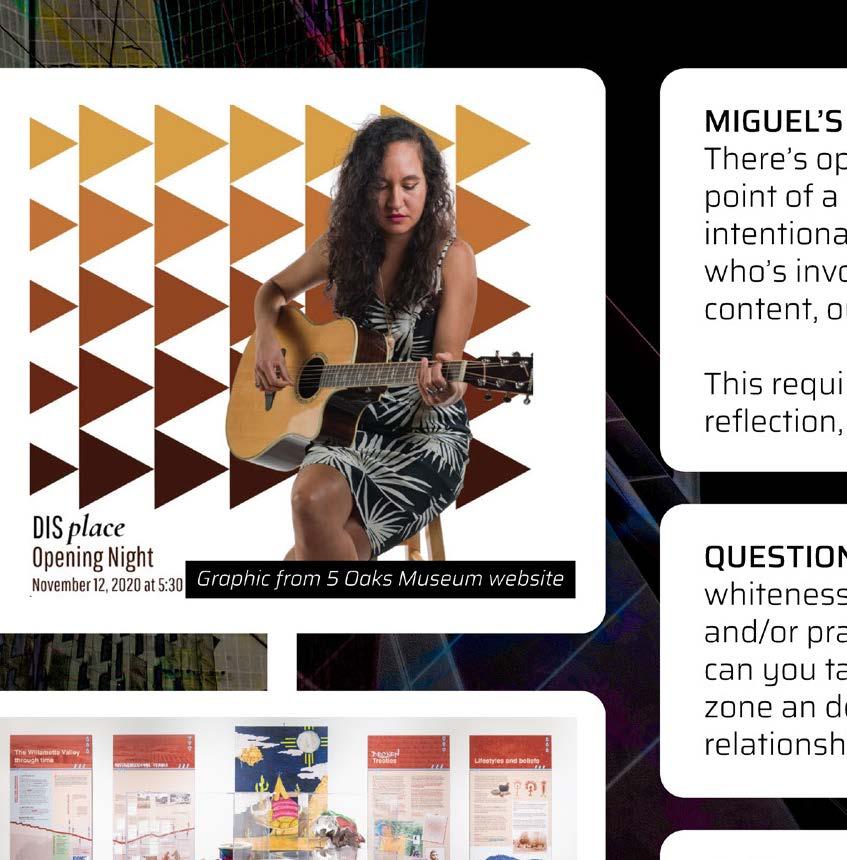

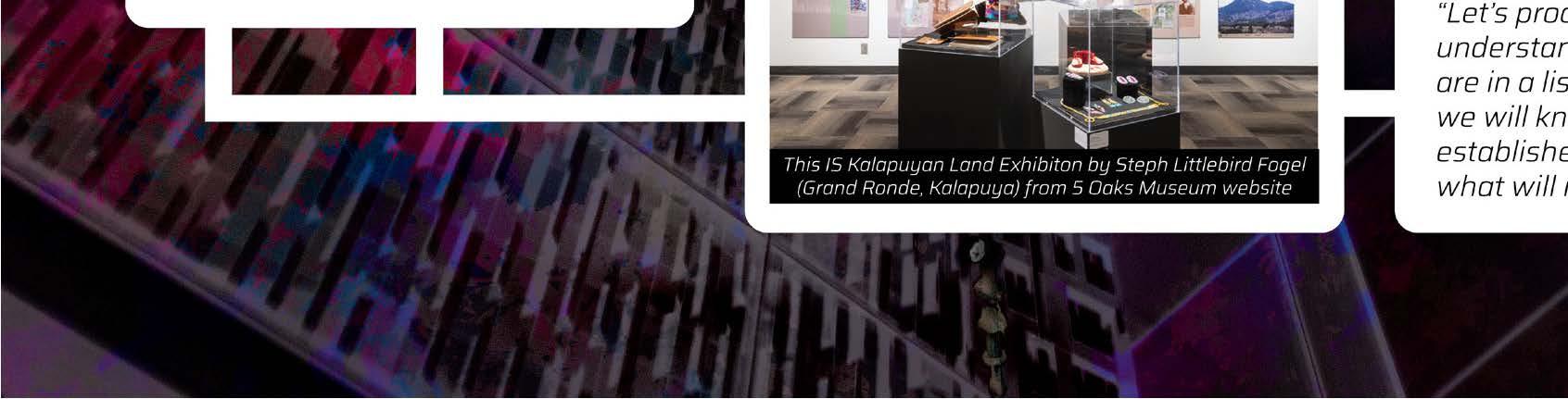

•Five Oaks Museum (formerly the Washington County Museum).

•Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at Portland State University.

•Lan Su Chinese Garden.

•Oregon Center for Contemporary Art.

•Oregon Historical Society.

•Oregon Jewish Museum and Center For Holocaust Education.

•Oregon Museum of Science & Industry (OMSI).

•Oregon Symphony.

•Portland Art Museum.

•Portland Children’s Museum (closed due to the pandemic).

•Portland Chinatown Museum.

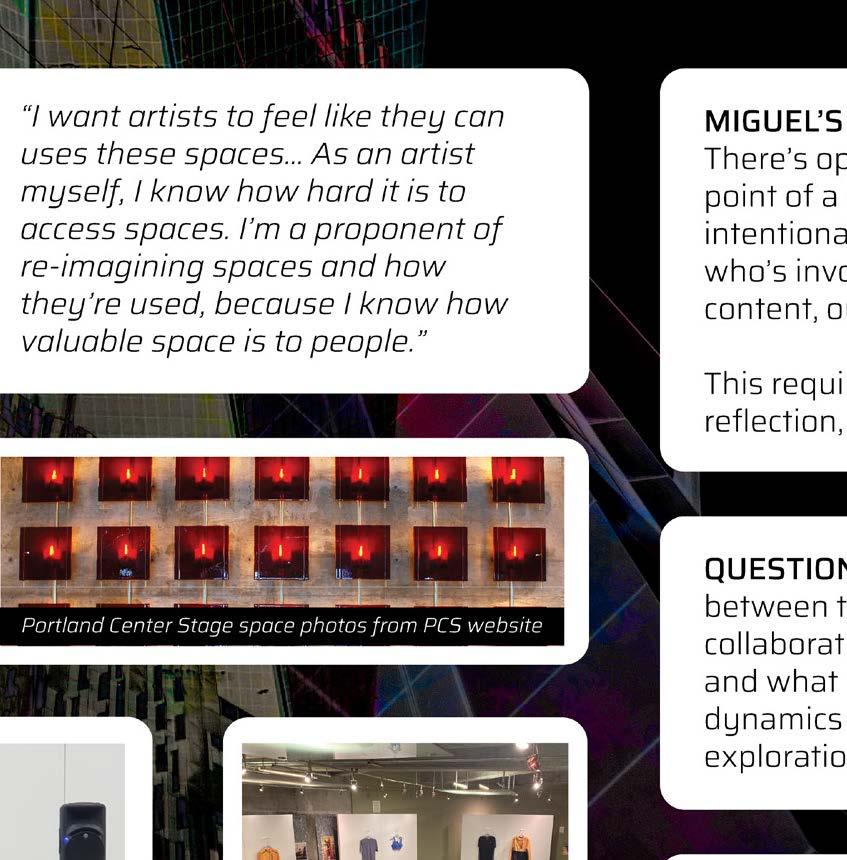

•Portland Center Stage (PCS).

•Portland'5 Centers for the Arts.

•Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA).

•Portland Japanese Garden.

•Portland Playhouse.

•Portland Opera.

•Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC).

•World Forestry Center - Discovery Museum.

•Yale Union (closed and transferred building and land rights to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation [NACF]).

Please note this is not a comprehensive list; on top of these cultural institutions, there are many local art galleries, festivals, and events across the city that contribute to Portland’s arts and culture landscape + actively practice space activation and placemaking. Additionally, I curated this list based on my own—subjective—understanding of each cultural institutions’ brand recognition, size, and cultural impact potential on Portland’s populace and art and cultural landscape.

As mentioned in previous sections, space activation and placemaking emphasizes the need and importance of using a people-centered approach for designing spaces with people, as well as a focus on re-envisioning our current built spaces, whether they are physical or digital, temporary or permanent, and public or private.42 But this framework and process is part of a larger philosophical question of the human condition: how do humans define space and place, and what effects does it have on people in cultural, societal, spiritual, and social contexts?

Tim Cresswell’s book, Place: An Introduction, explores these questions and highlights a breadth of theories, considerations, and examples while simultaneously making significant connections to both historical and contemporary contexts:

•For some, space and place is about a physical location i.e. a pin on the map, a landmark to visit, or a city to travel to.

•For some, it’s a method for connecting with others i.e. a gathering spot for the community to gather, socialize, and interact with each other.

•For some, it’s a political space that symbolizes power and cultural heritage e.g. The 2011 Egyptian Revolution at Tahrir Square in 2011.

•For some, spaces aren’t always stationary. Both permanent and mobile spaces can encourage a sense of place and affinity i.e., a building (permanent) and a ship (mobile) can both achieve this.

•And many more. The list goes on…43

42 Arnold, “Podcast: What is Space Activation and Placemaking?” Authentic Form & Function; “The Placemaking Process.” Project for Public Spaces, 2018.

43 Cresswell, Tim, Place: An Introduction (Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2015), 1-18.

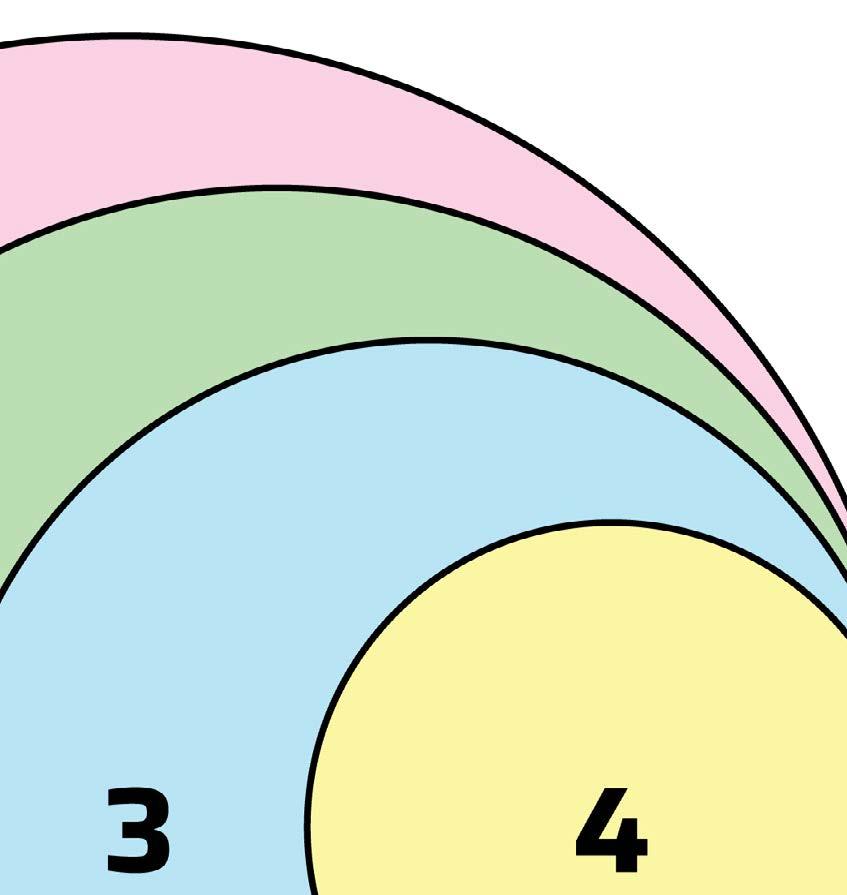

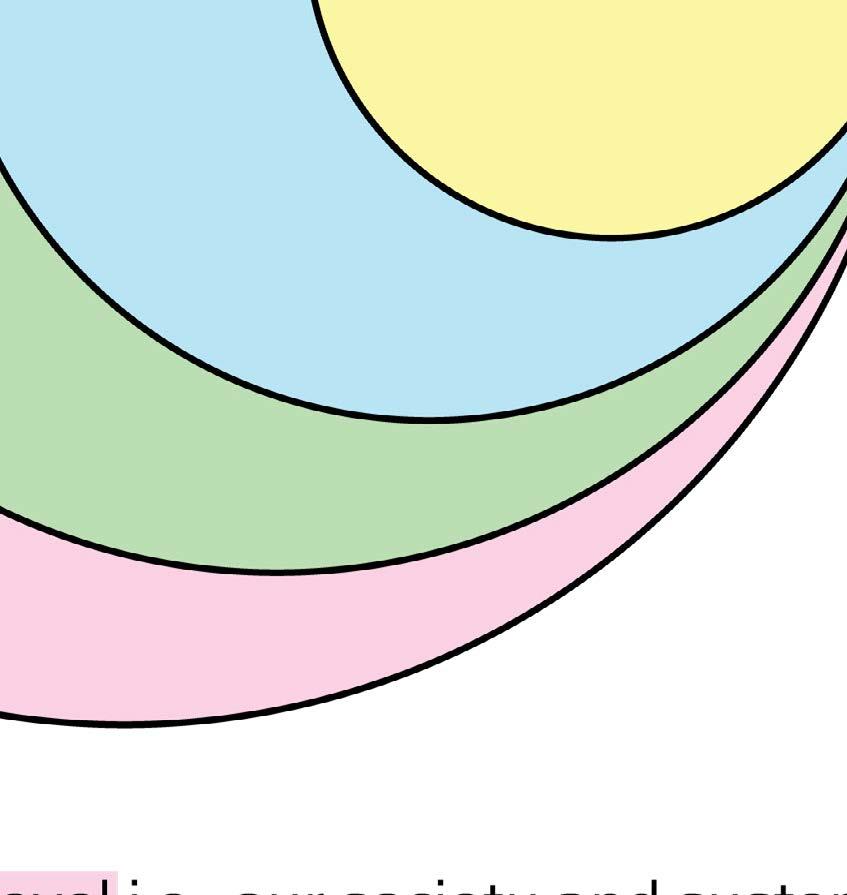

But, it’s Creswell’s attribution to political geographer John Agnew’s definition of place that best summarizes my own understanding of space and place. Agnew states that every place has three inherent qualities: location, locale, and sense of place.44

The first—location—is about knowing where a place is, akin to the pin on a map metaphor or the use of GPS coordinates to triangulate a place. The second—locale—is about the physical shape and social network of a place, akin to the walls, the buildings, the streetlights, the wildlife, and interconnectivity at a place. The third—sense of place—is about the emotions and meaning that people attach to a place, akin to a feeling, a memory, or a cultural history within a place.

All three are important to understand and consider when using the framework and process of space activation and placemaking, but a sense of place is of most significance because of the connection it facilitates between people and their built environments.

For me, however, a sense of place requires additional factors to round out the foundations and principles with which we are leading space activation and placemaking design processes; in particular, we must prioritize the concepts of memory, time, and culture.

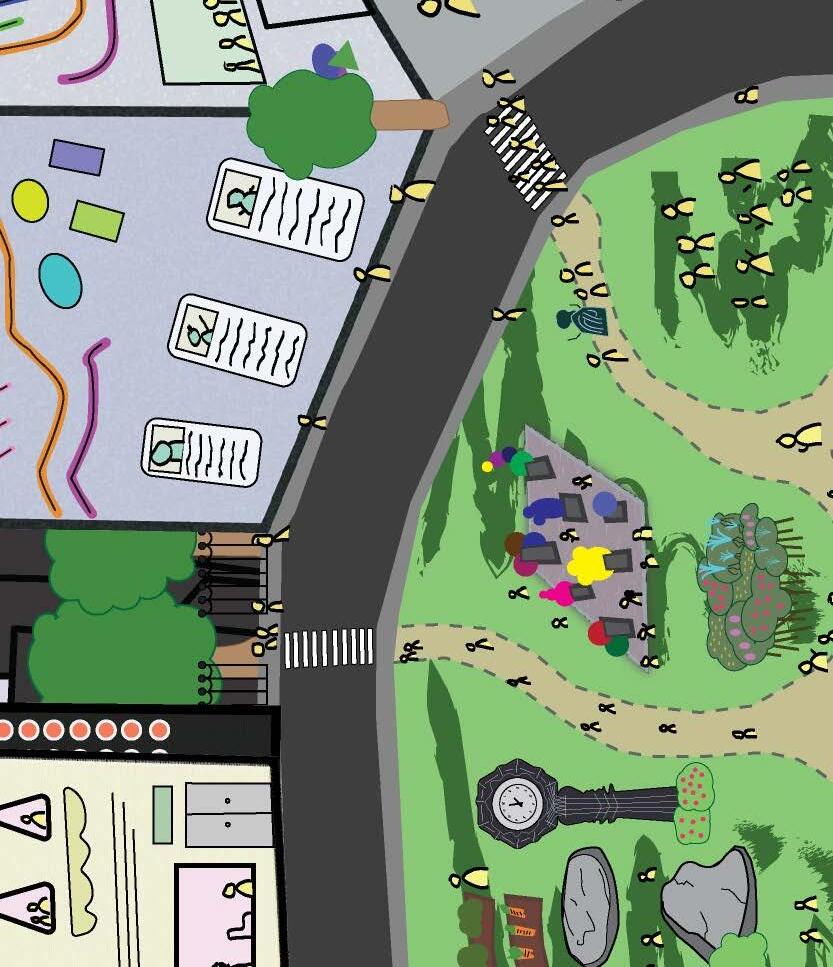

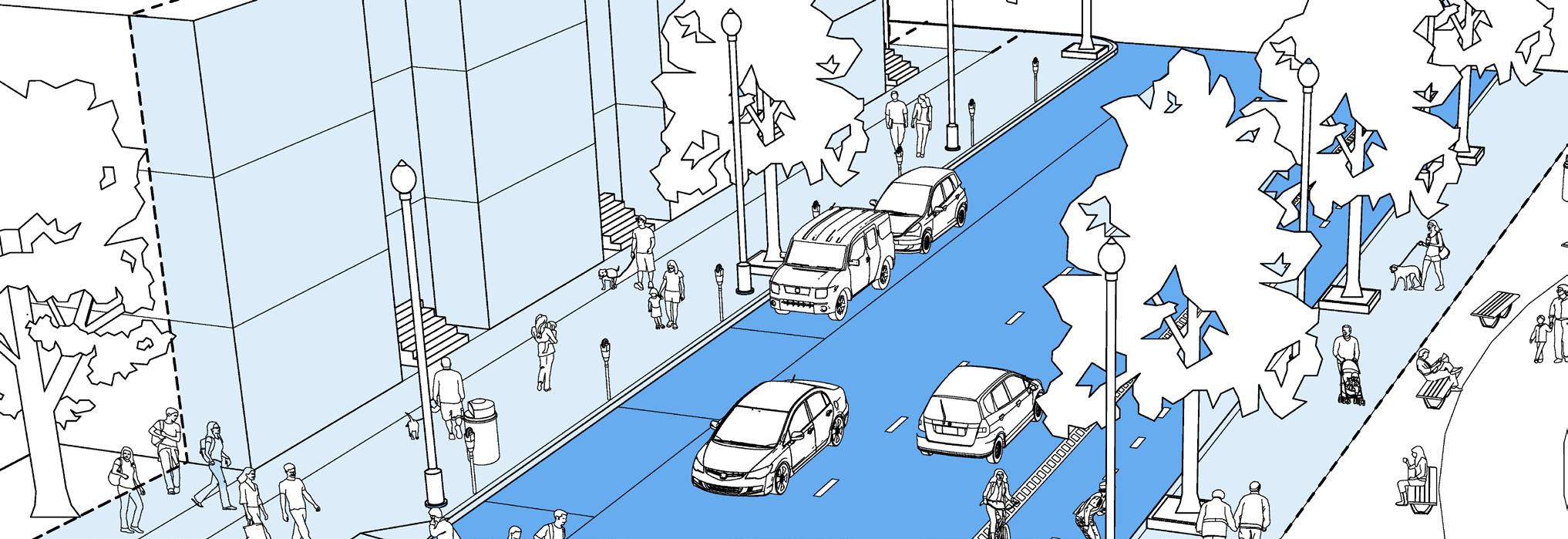

Figure 36: Public Street Plaza (bottom) [SE Ankeny Street / SE 28th Ave]. Photo by author.

44 Agnew, John A, Place and Politics: The Geographical Mediation of State and Society (Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin 1987), 5; “Changing Places,” University of Plymouth, n.d. https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/19/19721/ Geography_Changing_Places_Poster.pdf

Delving into the three additional factors more closely—memory, time, and culture—Creswell states that “place and memory are, it seems, inevitably intertwined… monuments, museums, the preservation of particular buildings (and not others), plaques, inscriptions, and the promotion of whole urban neighborhoods as ‘heritage zones’ are all examples of the placing of memory,” which highlights the process of attributing a space as valuable, culturally significant, and worth preserving (time and memory).

Further on, Creswell also mentions the concept of genius loci, or the the prevailing character, atmosphere, or ‘spirit’ of a place, as an example of architects and urban planners being tasked with balancing the pre-existing sense of place alongside the needs of its users45, which emphasizes a process instead of just a snapshot and/or state of being (culture).

If conversations and engagement with community members and stakeholders do not prioritize these attributes of sense of place throughout the design process, confusion, frustration, and skepticism can occur. These potential emotions and outcomes parallel renowned humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s own reflections about the introduction of improvements to our built environments, and the subsequent loss of context if not stewarded (time): “wheelchair ramps in public spaces are an example… [they] were built at great expense. They are an emblem of civilization, yet who now see them with a sense of civic pride?”46

46

45 Cresswell, Tim, Place: An Introduction 119-120, 128-129.

Thompson Pub 2012).

In essence, if mechanisms aren’t in place to protect, document, and systemize the space activation and placemaking process, the new benchmark is the standard by which the community is held accountable to. This absence does not always honor or represent the individual and collective efforts of all groups involved, in turn allowing history to be forgotten, which can be detrimental to a community’s understanding and commitment to the process and/or project.

Therefore—in order to honor a sense of place in relation to memory, time, and culture—practicing effective community-led preservation is critical to a project’s long-term success and sustainability. Moving towards the practical applications of this framework and process, let’s make sure to keep these factors in mind and consistently reference them: before, during, and after.

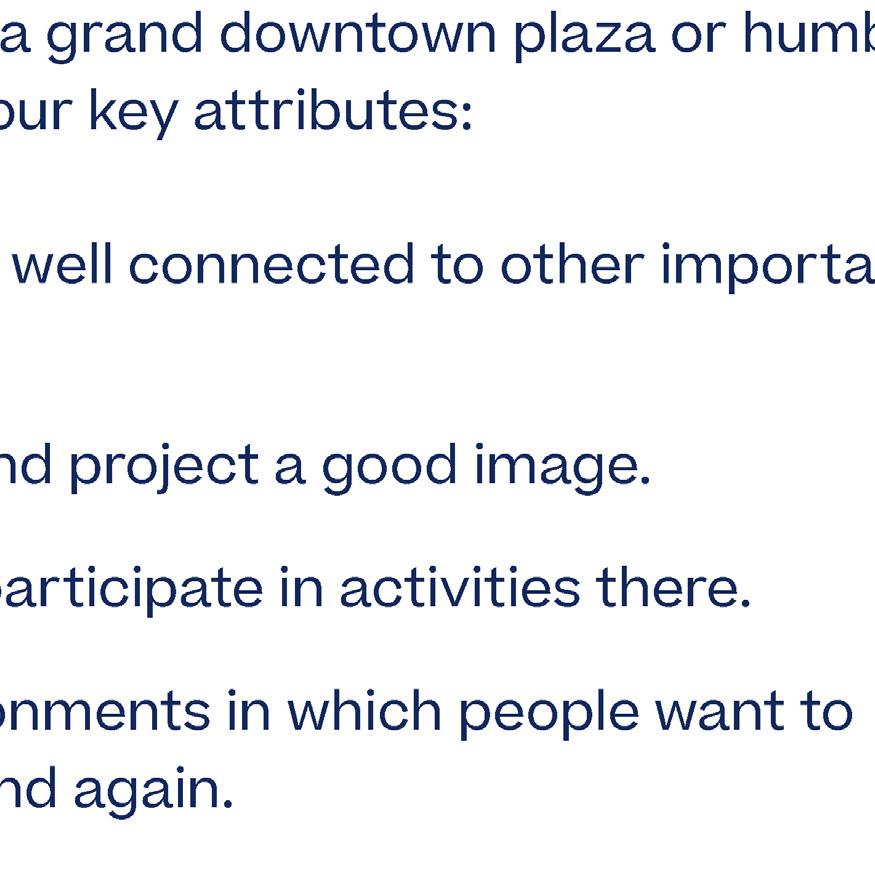

Before we move on to actual space activation and placemaking examples, there’s a pressing question we must ask ourselves: what makes a great space? Taking it further, what makes a great space activation and placemaking process and project? A foundational primer to consider is Project for Public Spaces' Placemaking: What If We Built Our Cities Around Places? which highlights four key attributes for a great place:47

1.They are accessible and well connected to other important places in the area.

2.They are comfortable and project a good image.

3.They attract people to participate in activities there.

4.They are sociable environments in which people want to gather and visit again and again.

47 “Placemaking: What If We Built Our Cities Around Places?” Project for Public Spaces, 2022, 5-6. https://assets-global.websitefiles.com/581110f944272e4a11871c01/638a1fe260f36b92be75784f_2022%20placemaking%20booklet.pdf

Project for Public Spaces' full report provides more details, information, and questions for designers engaged in space activation and placemaking. However, I want to add some additional considerations that I believe the report is lacking; in particular, there’s a glaring and minimal consideration of how race and ethnic background impacts the use, access, and design of spaces for communities of color.

In order to address this issue—and on a local level—I want to center the work that Imagine Black (formerly known as PAALF Action Fund) conducted through its 2017 report, The People’s Plan, as well as the work that the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization (IRCO) conducted through its 2022 Community Needs Assessment report.48

Both of these reports highlight the need for resources and spaces that are culturally relevant for communities of color, especially given the historical marginalization that manifests as various social issues (e.g. food insecurity, hate crimes, environmental racism). In sum, both reports emphasize how the built environment, social, and community contexts that communities navigate are rooted in racist systems that actively contribute to the loss of culture and mental health issues.

As a designer, if you are not actively considering and tackling these racist structures and symptoms of white supremacy during a space activation and placemaking process or project, you are unable to make a great place. If the experiences, culture, and expertise of Black and brown communities are not being centered and prioritized, there’s no great place.

48 “The People's Plan,” Imagine Black, 2017. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c1ad1377106994934ad2548/t/616cd794 ede41951358def30/1634523053052/_PAALF+Peoples+Plan_2017_final.pdf; “2022 Community Needs Assessment,” Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization (IRCO), 2022. https://irco.org/who-we-are/reports/

Space activation and placemaking projects can take on a variety of forms, and an exhaustive list is not possible. Nevertheless, the following pages showcase examples that regularly come up; please note that there will always be emerging and/or remixed projects because of the evolving nature of this framework and process.

Furthermore, as previously mentioned, cultural, societal, spiritual, and social contexts alongside communities’ local, state, and national landscapes will inform the manner in which these manifest e.g. the affordances between U.S. cities such as Portland, San Francisco, New York, Seattle, and Miami have some similarities, but they are uniquely different based on their individual and respective policies, histories, and populations.

For us to practice effective space activation and placemaking, we must remain knowledgeable of other practitioners and examples throughout every step of the design process. If we intentionally practice and keep these things in mind, we are able to make meaningful progress towards creating meaningful spaces that people and communities want to be in; when we center folks that are traditionally excluded from the design process, we are able to make progress towards improving our collective conditions.

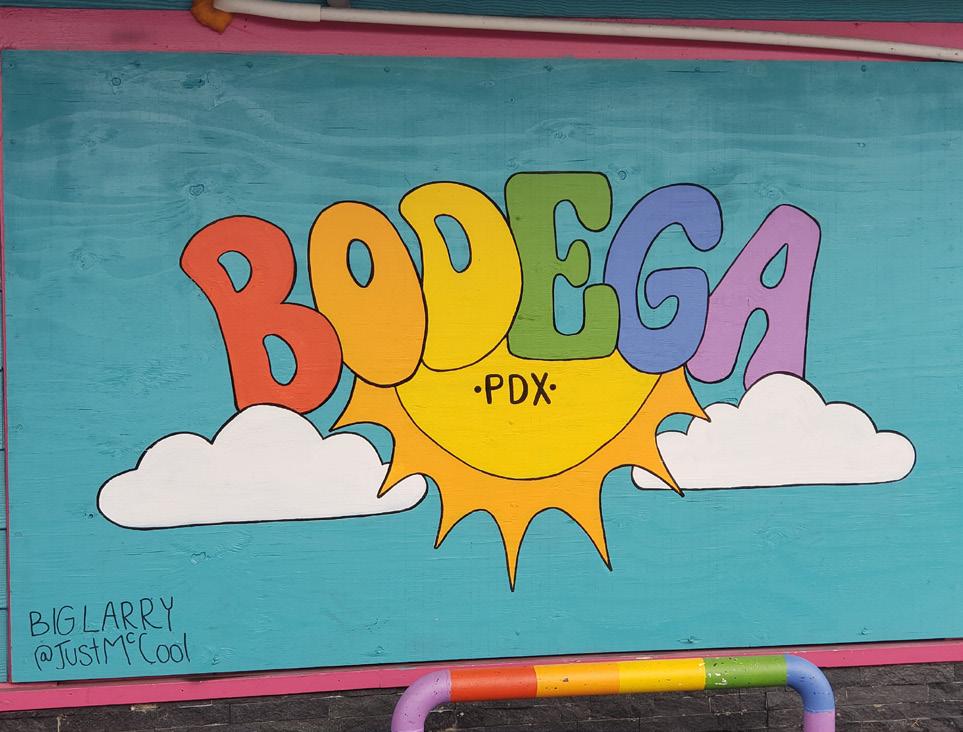

On a personal and individual level, consider exploring your own neighborhoods and cities for space activation and placemaking examples and projects; for example, the images used throughout are a combination of images I took while exploring Portland, photographs sourced from my fellow CD/DS peers, and from a variety of reports, articles, artists, photographers, and websites.

And lastly, the resources and links across the following pages span space activation and placemaking projects at local, national, and international contexts. As you explore, what ideas do they spark for you?

Common Space Activation and Placemaking Examples:

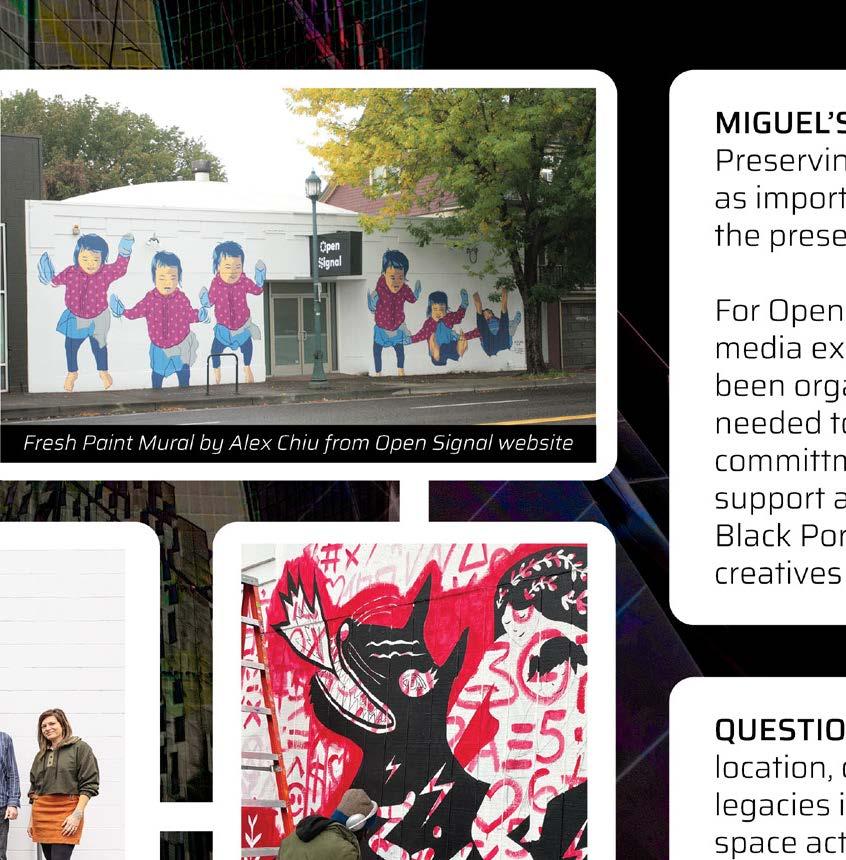

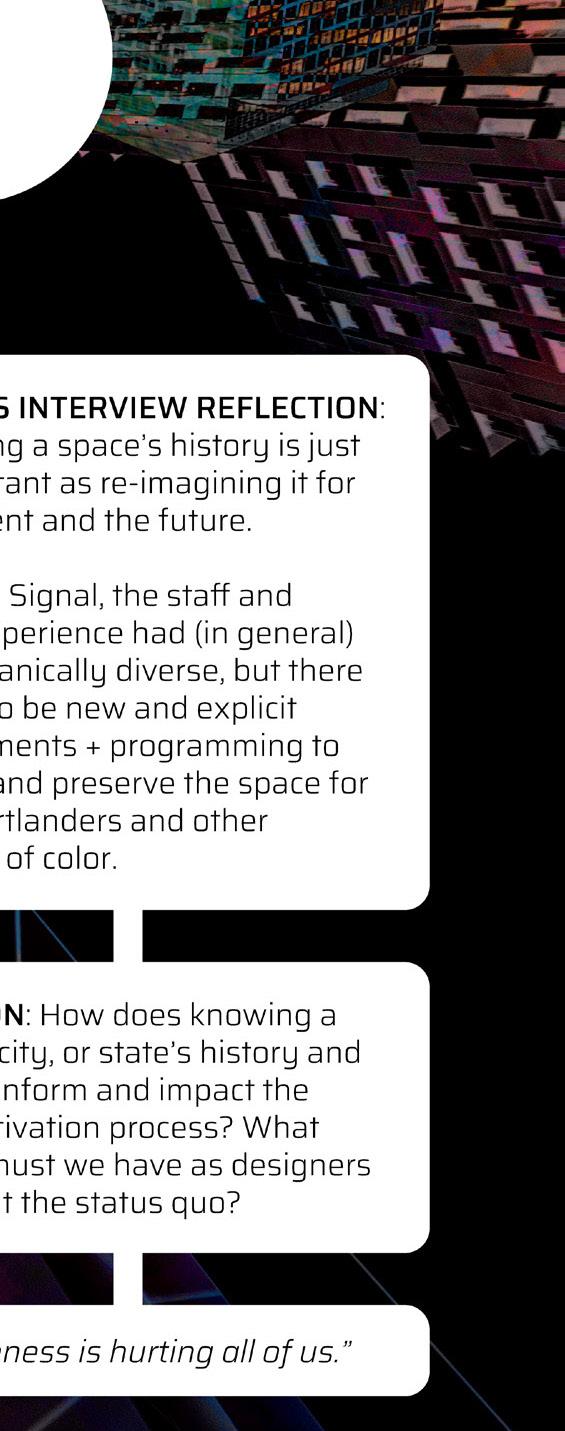

•Murals

•Community Centers

•Interactive Exhibits / Installations

•Gathering Places / Plazas

•Pop-ups / Markets

•Events and Festivals

•Classes, Workshops, and Performances

Arts East: A Plan for Increasing Arts Equity, Access, and Resources in East Portland, Oregon

Regional Arts and Culture Council and Portland’s City Council (link)

Center for Native Arts and Culture

Native Arts and Cultures Foundation (link)

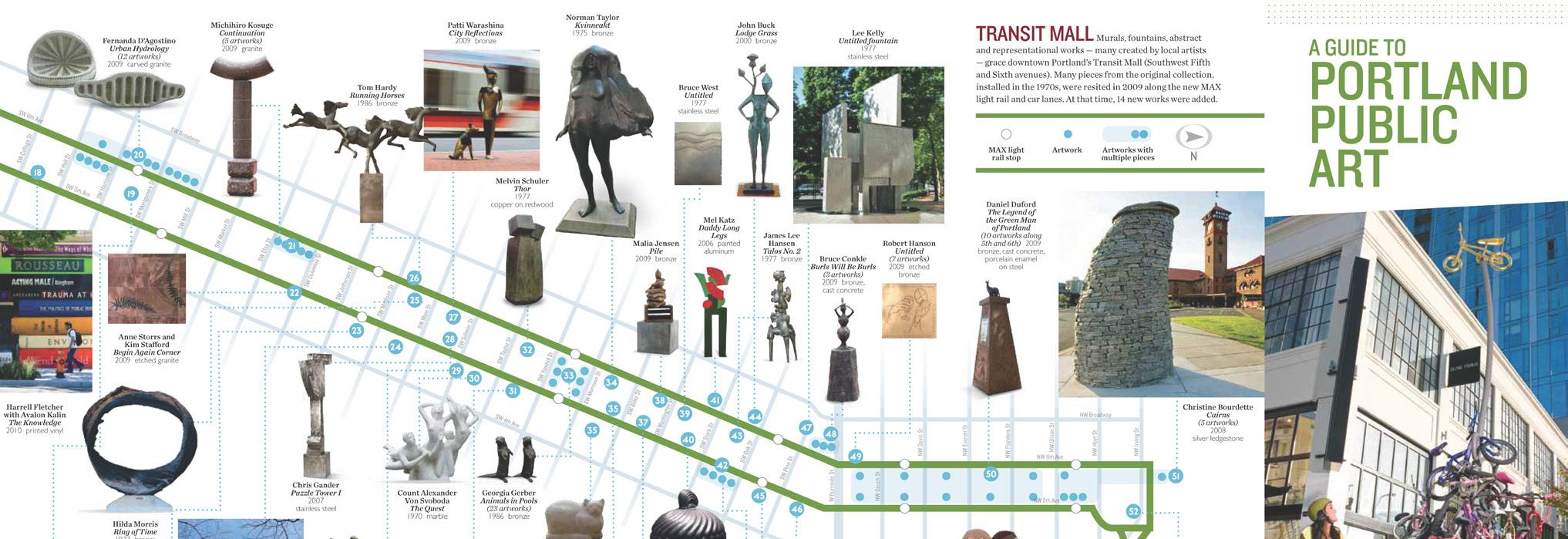

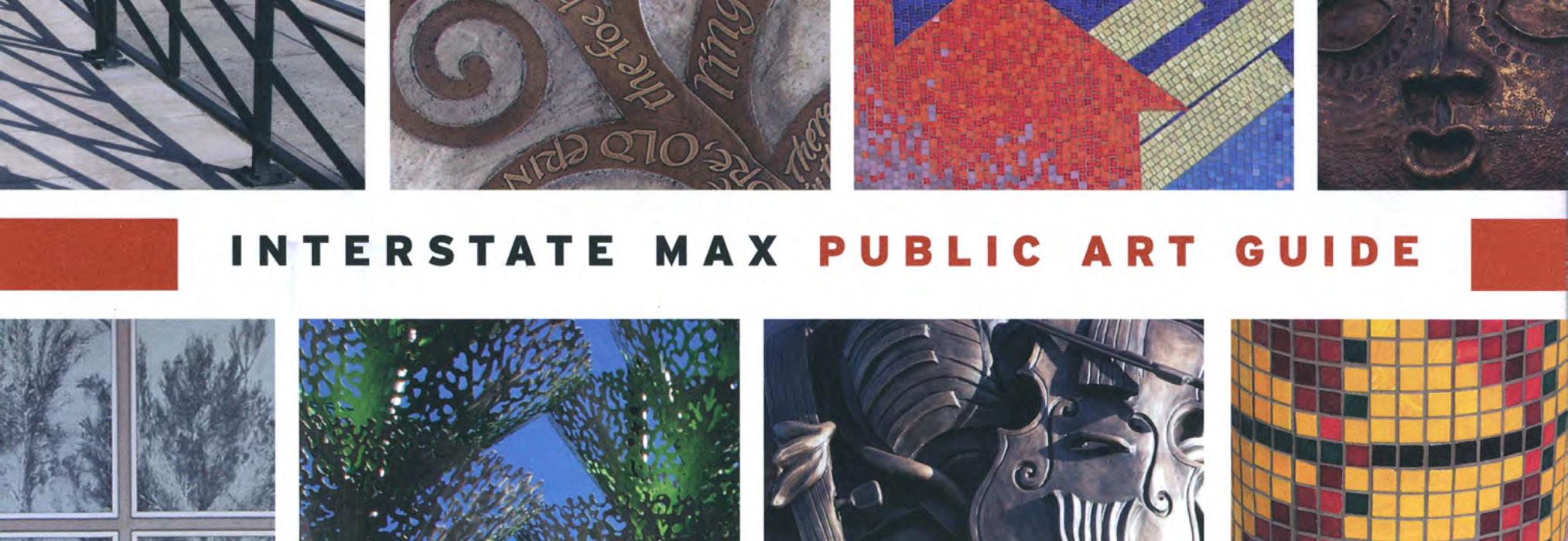

Interstate MAX Public Art Guide

TriMet (link)

PDX Sidewalk Joy Map

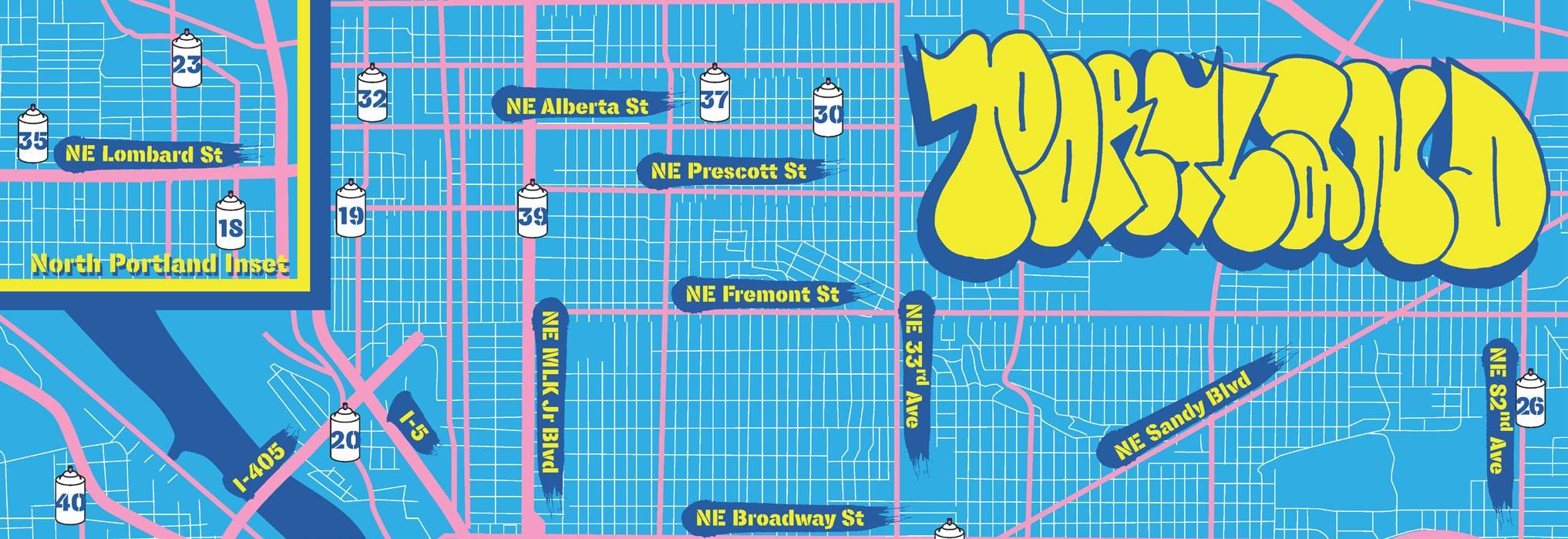

PDX Dinorama and the growing list of folks who have curated galleries, exchanges, and displays in curb gardens, front yards, or sides of buildings (link)

Street Art in PDX

Project P.A.I.N.T. (link)

Street Roots New Headquarters

Street Roots and Holst Architecture (link)

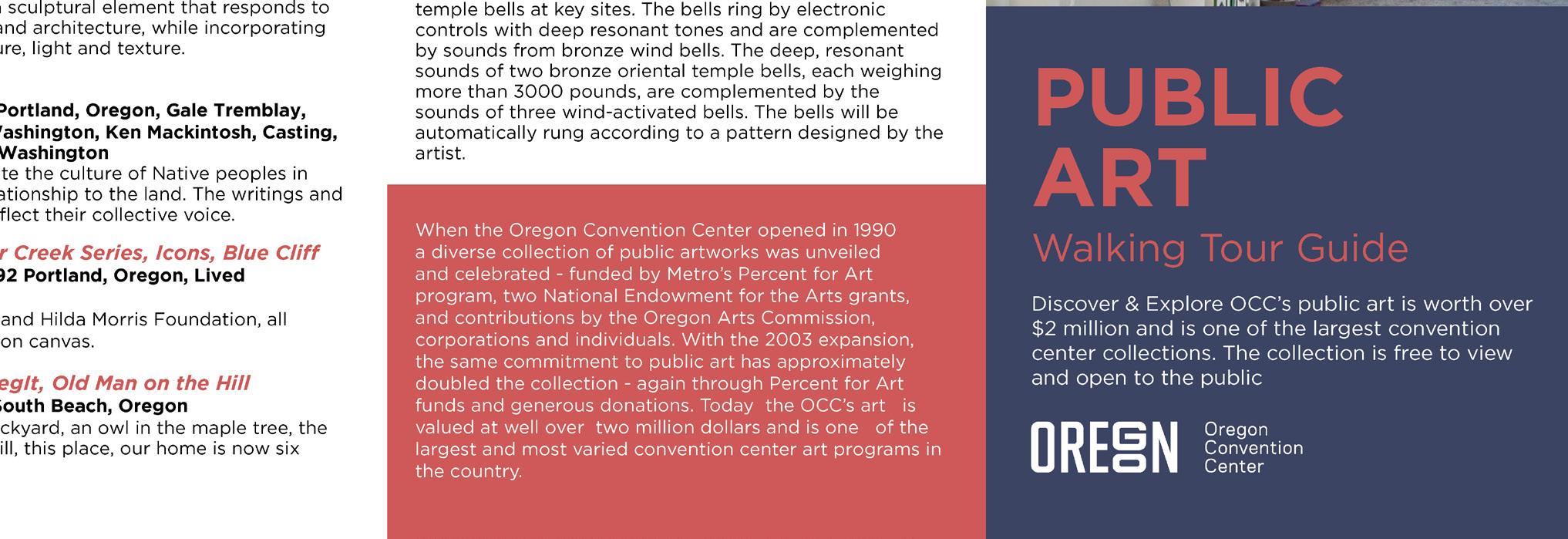

Public Art Walking Tour Guide

Oregon Convention Center (link)

The Summer Series at Madison Plaza on SW Park Ave and SW Madison Street

The Numberz FM, Portland Art Museum, and the Portland Bureau of Transportation [PBOT] (link)

A Voice at the Table: An Exploration Around Affirmative Space for Black Womxn in Roxbury, MA

Sasaki in Boston, MA (link)

Activating Austin's Downtown Alleys as Public Spaces

City of Austin's Downtown Commission Alley Activation Workgroup in Austin, TX (link)

Envisioning an Art-driven Economy with Little Africa's Creative Placemaking

African Economic Development Solutions (AEDS) in St. Paul, MN (link)

National Space Activation Examples

Exploring our Town

National Endowment for the Arts across the United States (link)

Parks & Public Spaces

Downtown Seattle Association in Seattle, WA (link)

Public-Space Activation Fund (PAF)

Department of Cultural Affairs in Los Angeles, CA (link)

Public Space Activation & Stewardship Guide

District of Columbia Office of Planning in Washington D.C. (link)

Safe Places and Active Spaces

Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice in New York City, NY (link)

Space Activation Artist in Residence Program

Intersection for the Arts in San Francisco, CA (link)

A New Placemaking Agenda for African Cities

Our Future Cities across the African continent (link)

Creative Placemaking in Denmark

Urban Land Institute in the country of Denmark (link)

The Politics of Solidarity and Erasure in South Asia (HaP)

Heritage as Placemaking (HaP) in the countries of India and Nepal (link)

How to Make a Great Place: Placemaking Stories in Singapore from Communities and Designers

Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in the country of Singapore (link)

NSW Guides to Public Space Activation

New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment in the country of Australia (link)

The Toolbox

Placemaking Europe across the European continent (link)

Space Activation Examples

Shaping the Future of African Cities

Futures Cities Africa across the African continent (link)

Stories, Insights, and Work

8 80 Cities in the country of Canada (link)

Human(e)

The Centre on African Public Spaces in the country of South Africa (link)

The Eye of Mexico

Massiv Art in the country of Mexico (link)

The Journal of Public Space

City Space Architecture and the UN-Habitat in the countries of Italy and Kenya (link)

This Must be the Place: Learning by Doing in Mexico City

Project for Public Spaces in the country of Mexico (link)

Written by B. Cannon Ivers, with examples spanning the world (link)

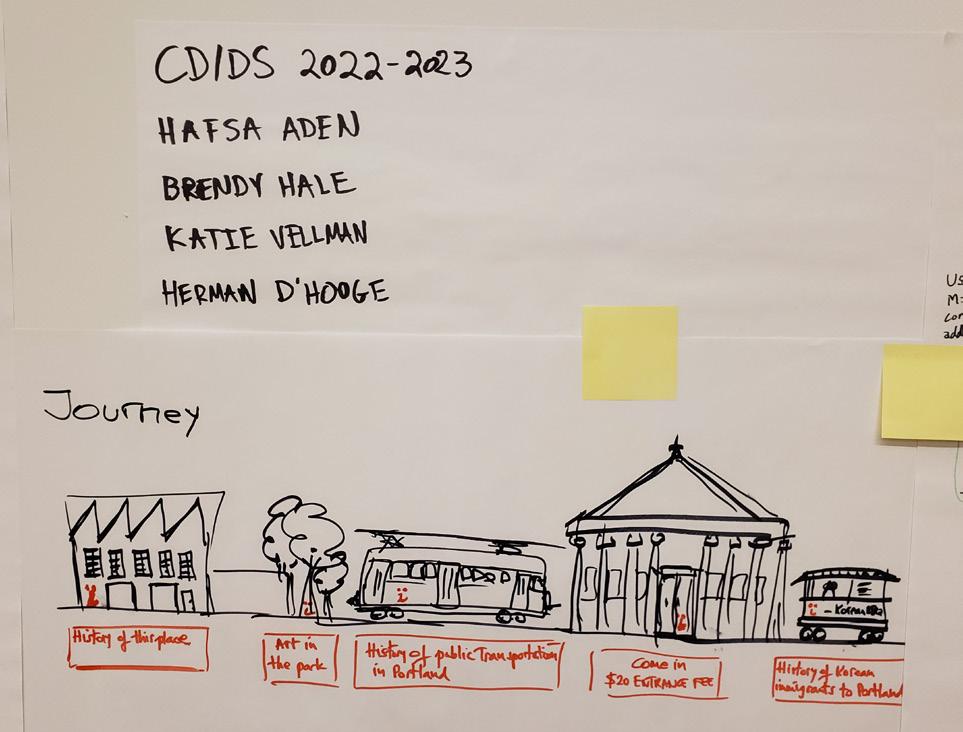

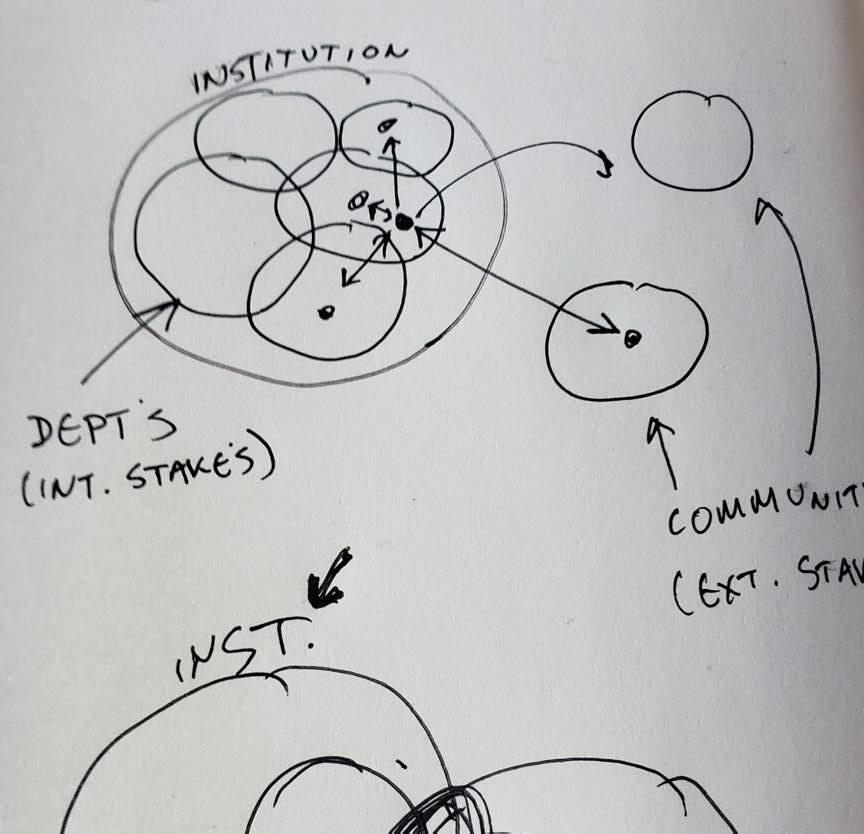

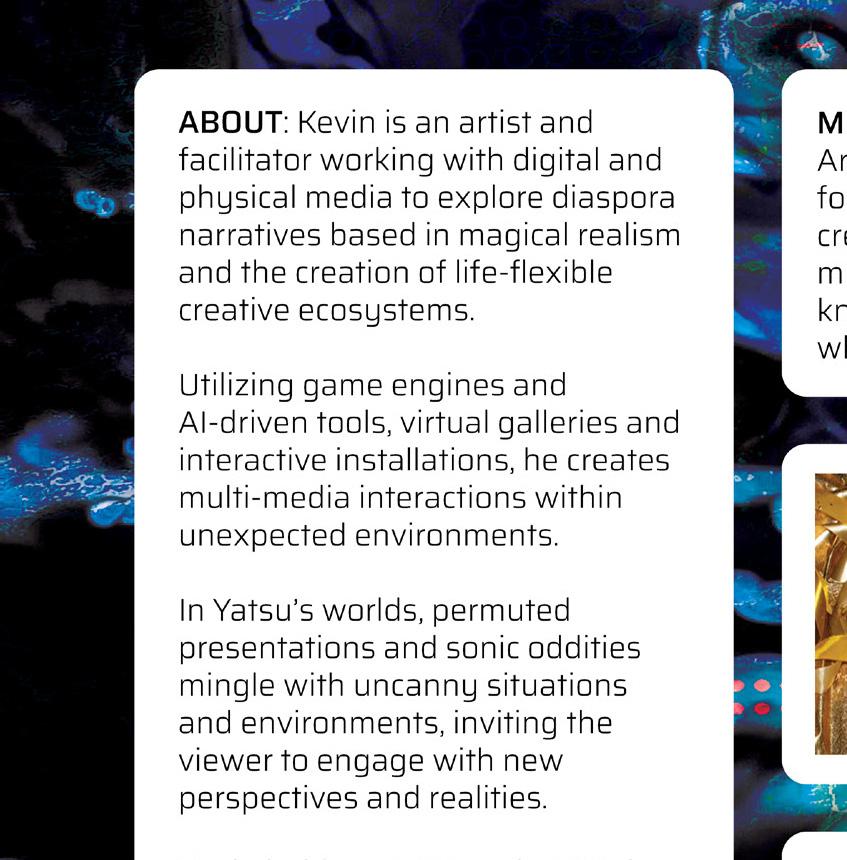

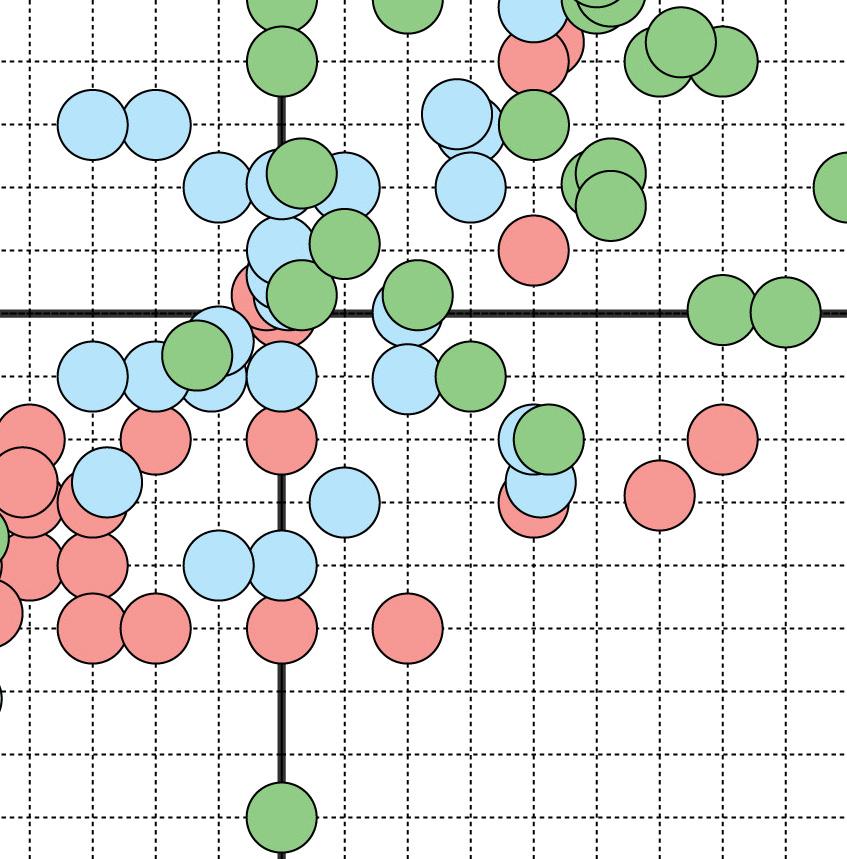

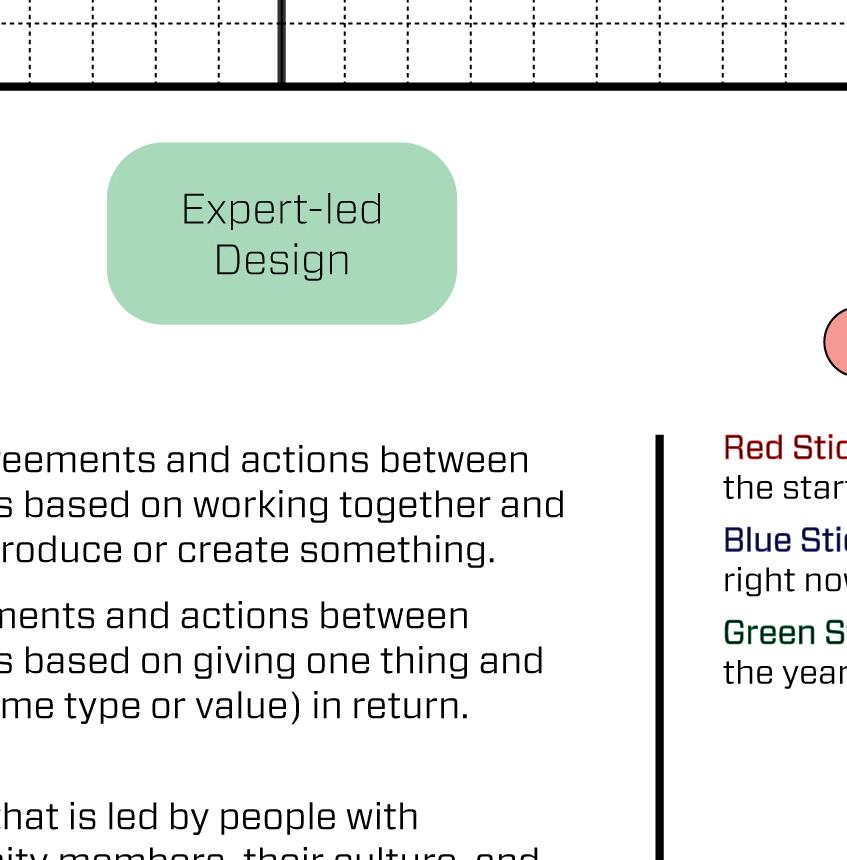

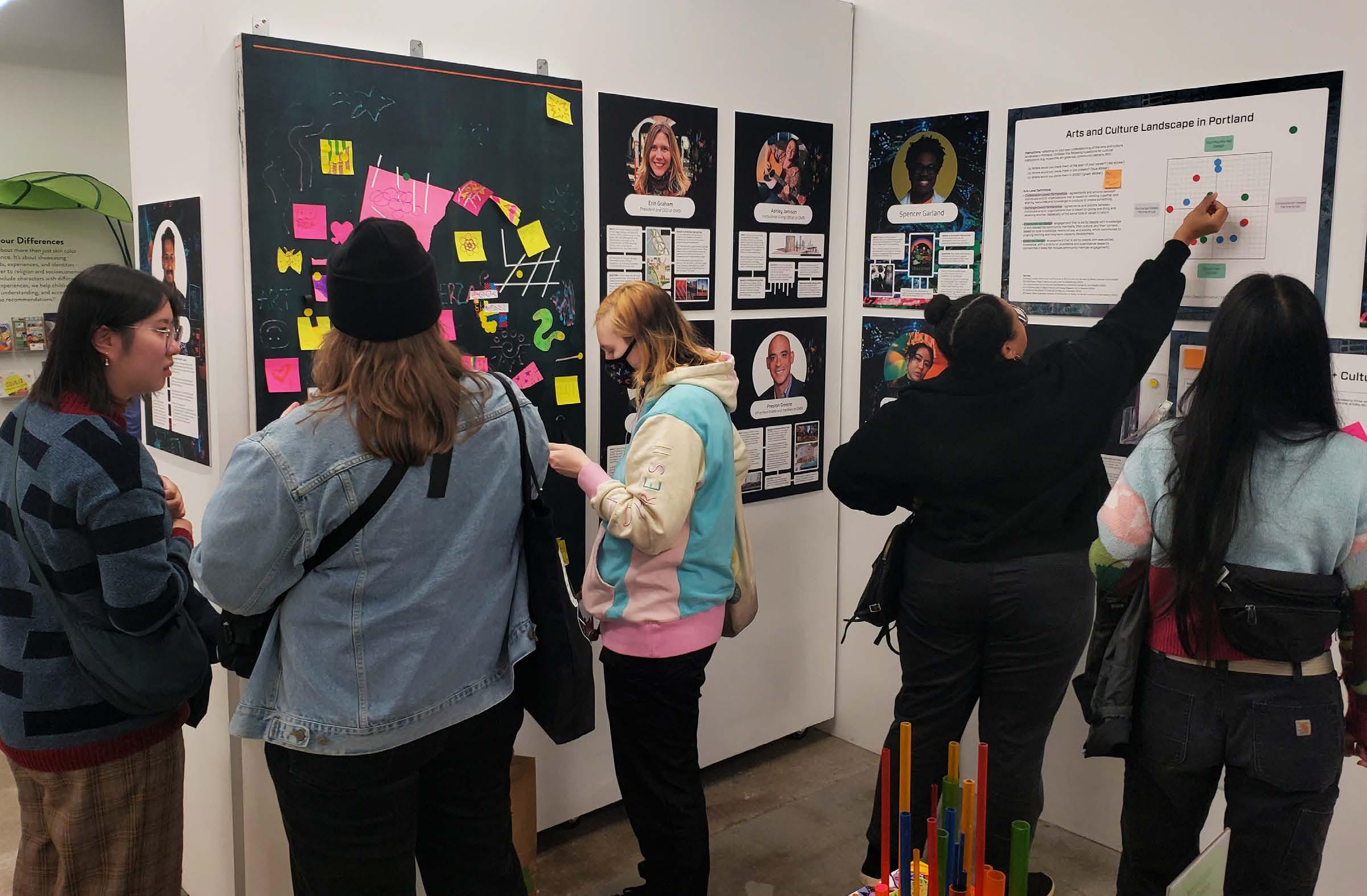

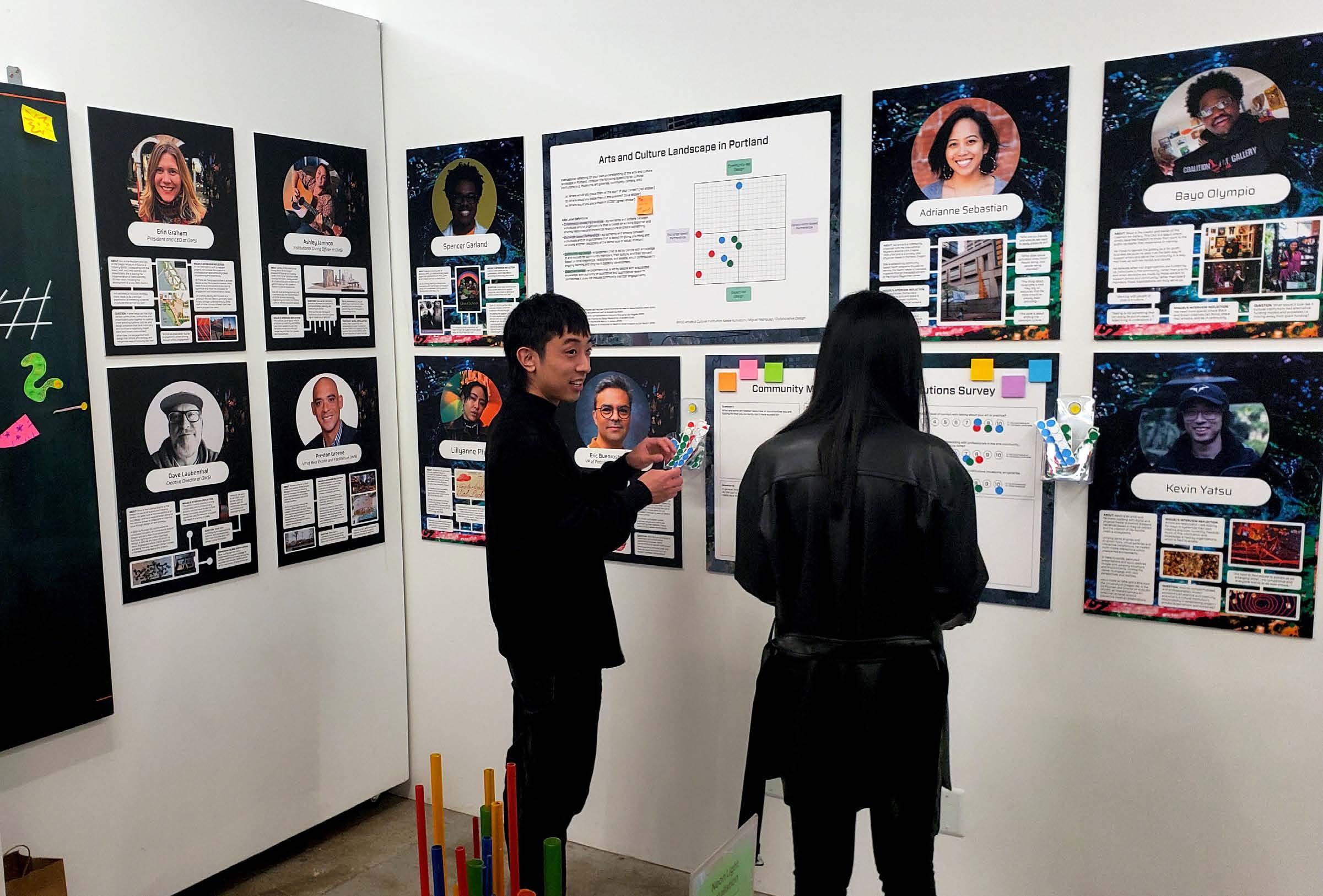

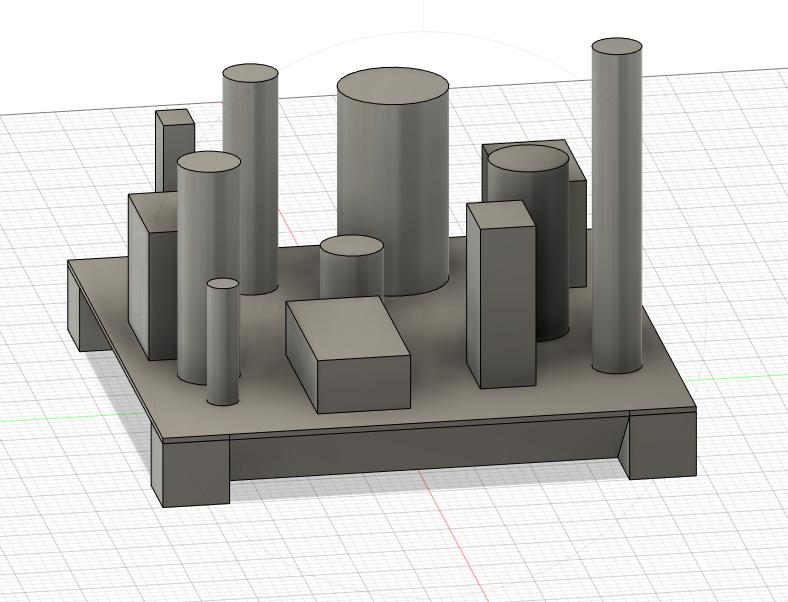

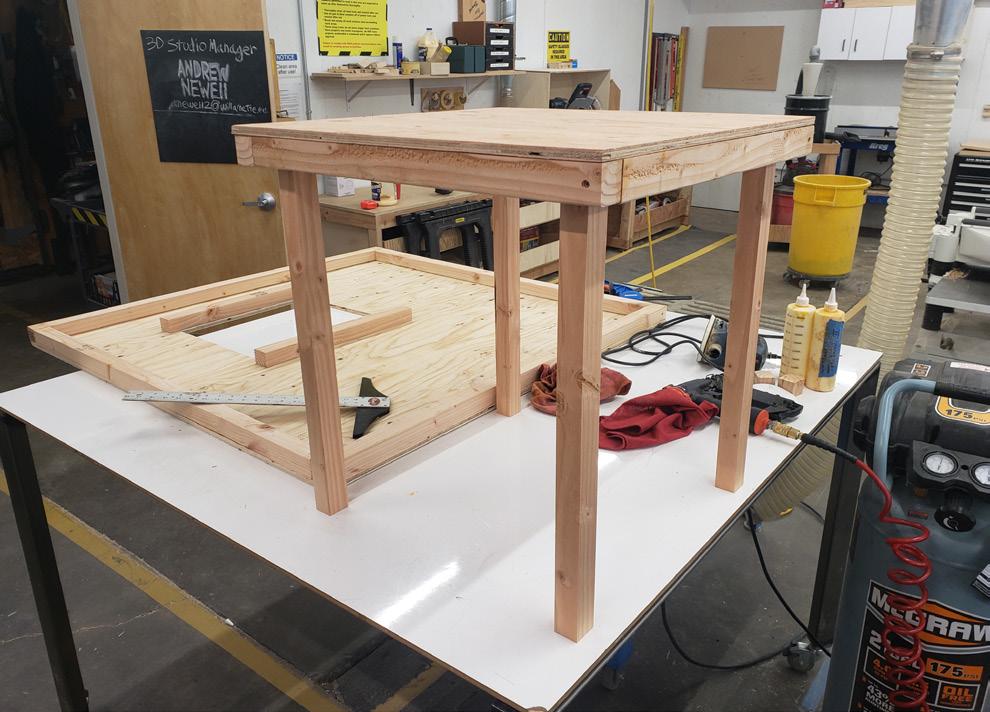

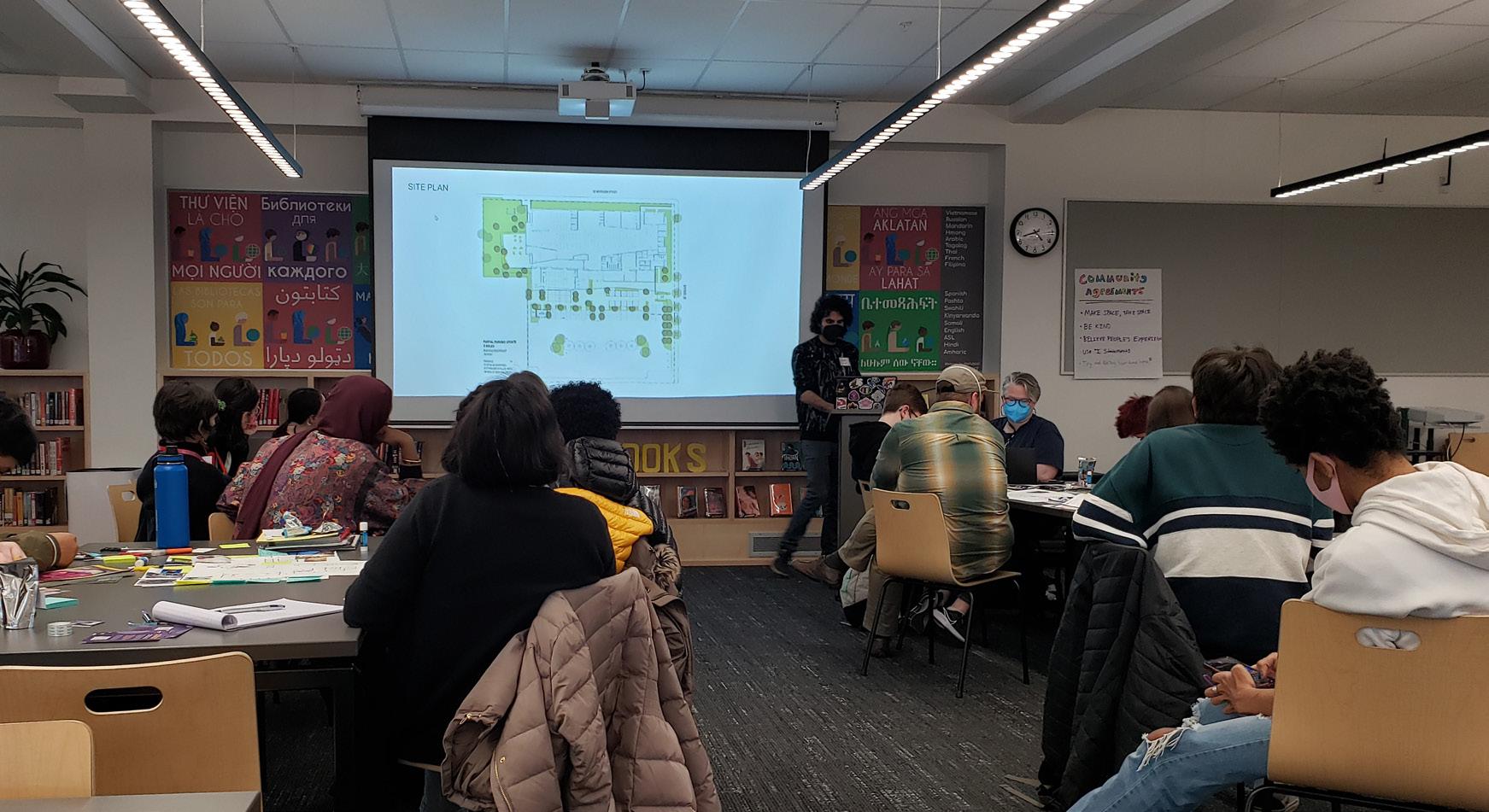

With the majority of my secondary research of the arts and culture landscape completed, I embarked on eight months of rigorous, fun, creative, community-centered, and coalition-building engagements. This included conducting a series of interviews, surveys, and space activation and placemaking engagements with key stakeholders (I focused on four priority groups):

1.BIPoC artists / designers / cultural workers

2.Cultural institutions and community organizations

3. Staff from the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI)

4.Mathematicians / creative math artists

The overarching goal of my engagement was to better understand the affordances of space activation and placemaking:

1.In our local context.

2. By identifying commonalities and differences amongst the groups, and what influences them.

3.By understanding the systems and processes that prevent strong and healthy collaborations between these groups.

While ambitious in scope, I envisioned my collaborative design process requiring a significant number of stakeholders because of the complexity, nuance, and interconnectedness of my thesis topic.

For example, the needs of an individual artist are different from that of another artist, a cultural institution’s strategies and approaches do not necessarily translate 1-to-1 to another institution, the systems and process impacting people are based on their individual/collective and localized contexts, and so forth.

While this process was not free of challenges, I’m incredibly proud of the collaborative design approach I was able to research, develop, and iterate on, which led to many lessons learned, strengthened my practice as a designer, and provided collaborative opportunities for all parties involved.

As you read on, please note that my approach is not a template, but a guide; my hope is that elements of my experience can be replicated, but informed by your own individual context.

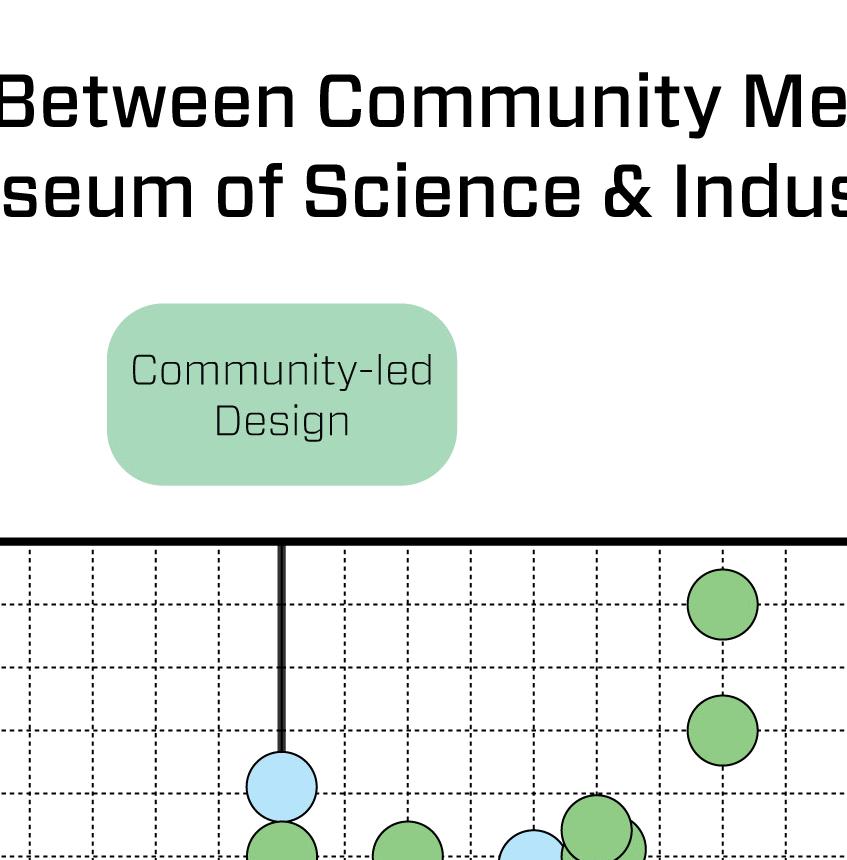

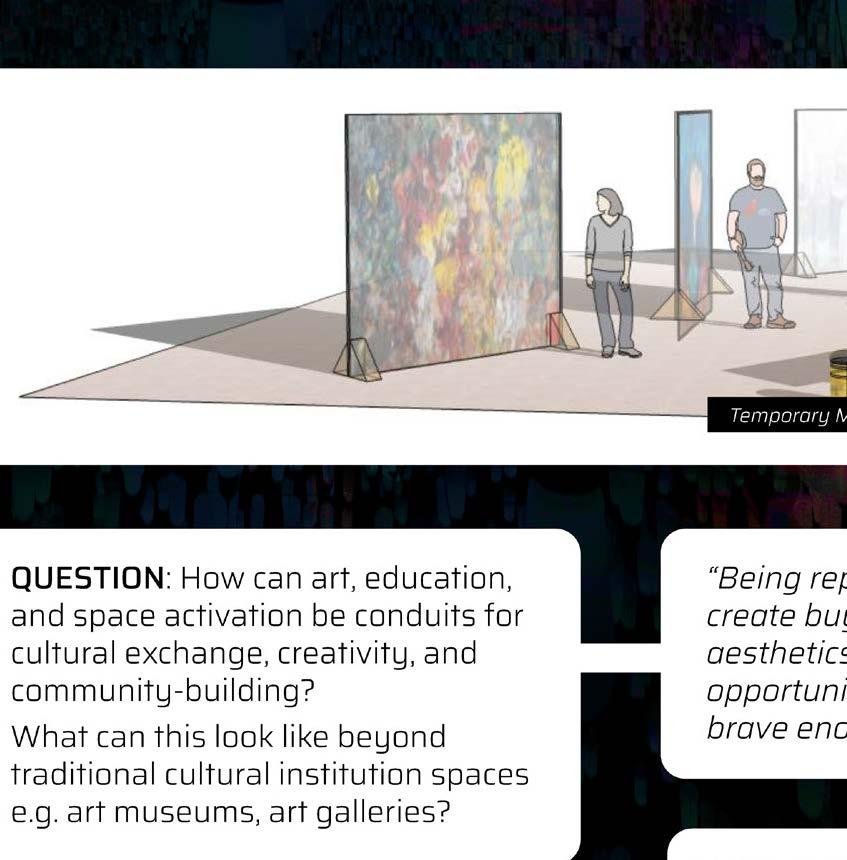

How can space activation encourage and foster stronger and healthier collaborations between BIPoC artists and cultural institutions in Portland, and what can it look like through design justice and participatory frameworks?

As described in previous sections, because cultural institutions have traditionally and systematically excluded BIPoC communities from using and accessing their spaces and resources, I wanted my design and research requirements to center and emphasize their experiences and needs through meaningful, collaborative, and community-centered frameworks, practices, and principles.

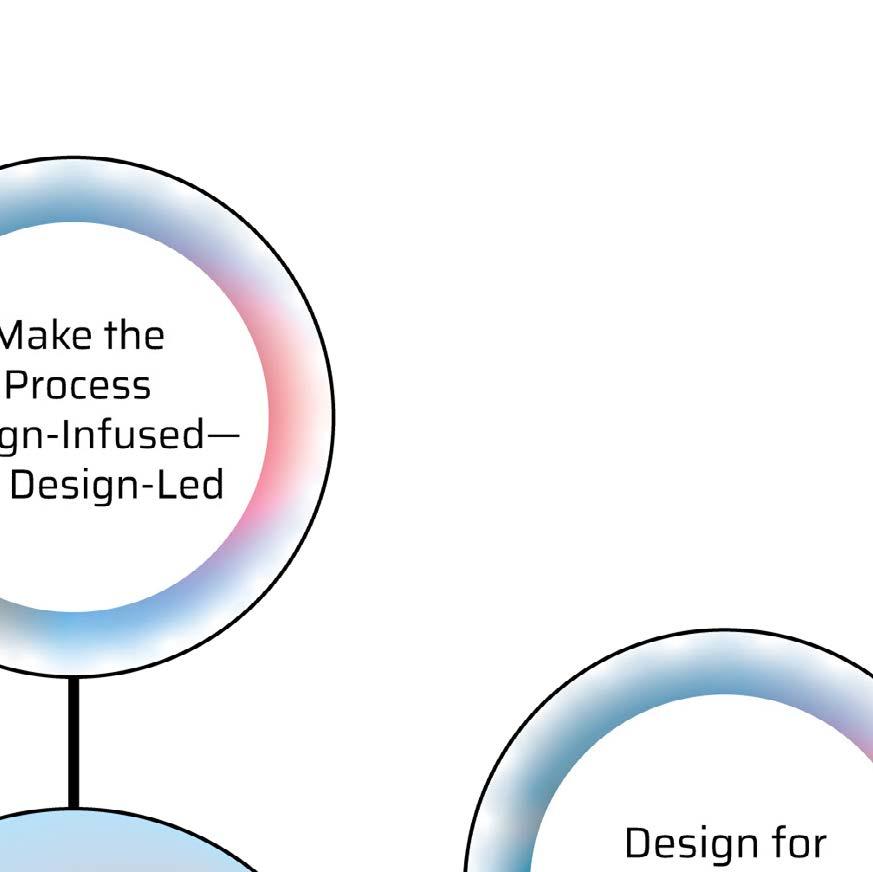

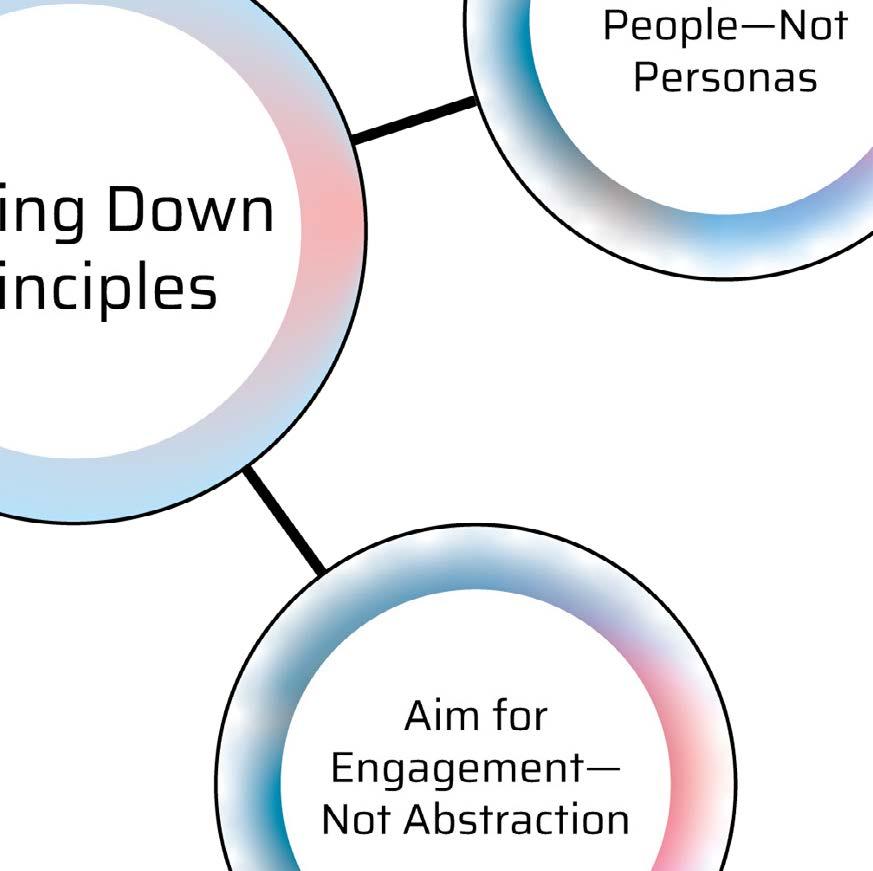

Because of my secondary research, I was able to learn about, create, or revisit the following throughout my primary research and space activation and placemaking engagements:

1.The Design Justice Principles by the Design Justice Network.49

2.What Makes a Great Place + The 11 Principles for Creating Great Community Places by the Project for Public Spaces.50

3.Scaling Down Principles by Jeremy Myerson, which are rooted in community-led design and participatory action research.51

4.Principles of play to guide my engagement, research, and creation processes.52

5. My own guiding pillars, which are influenced by my own individual context and spheres of influence as a designer.

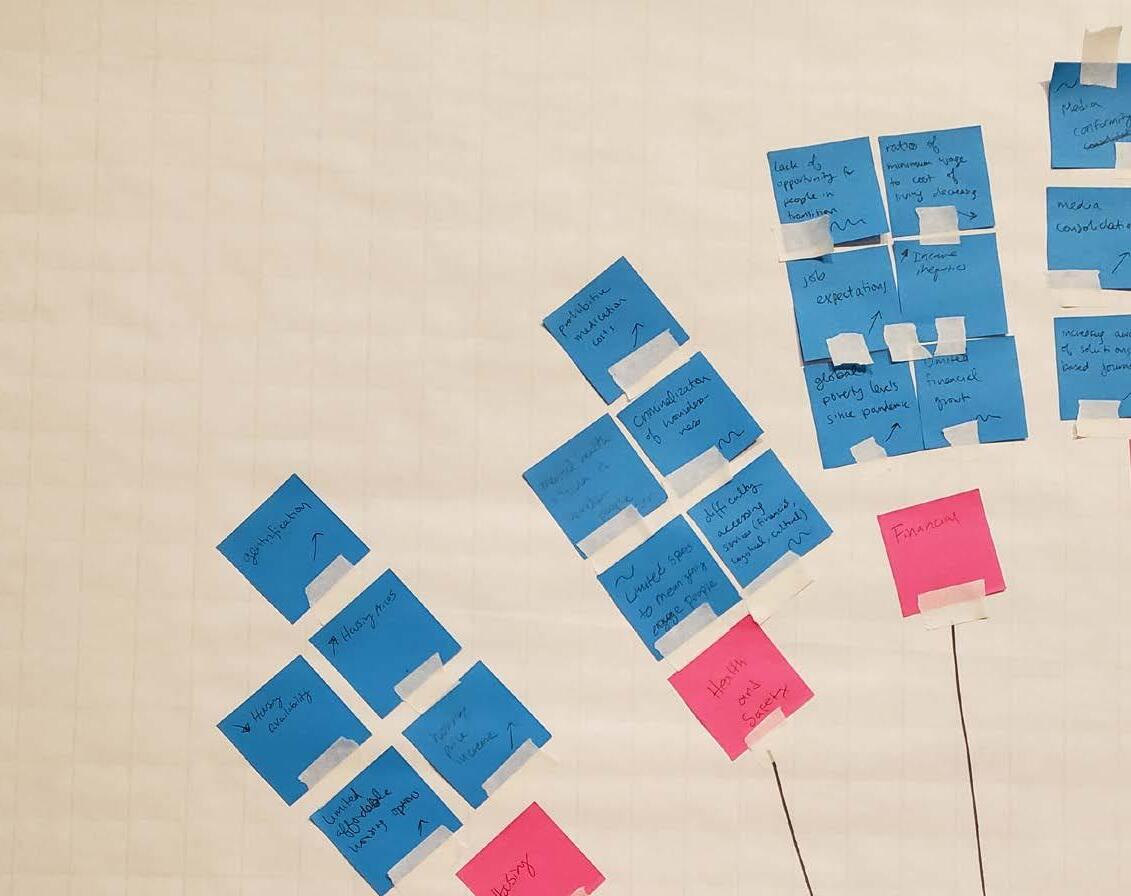

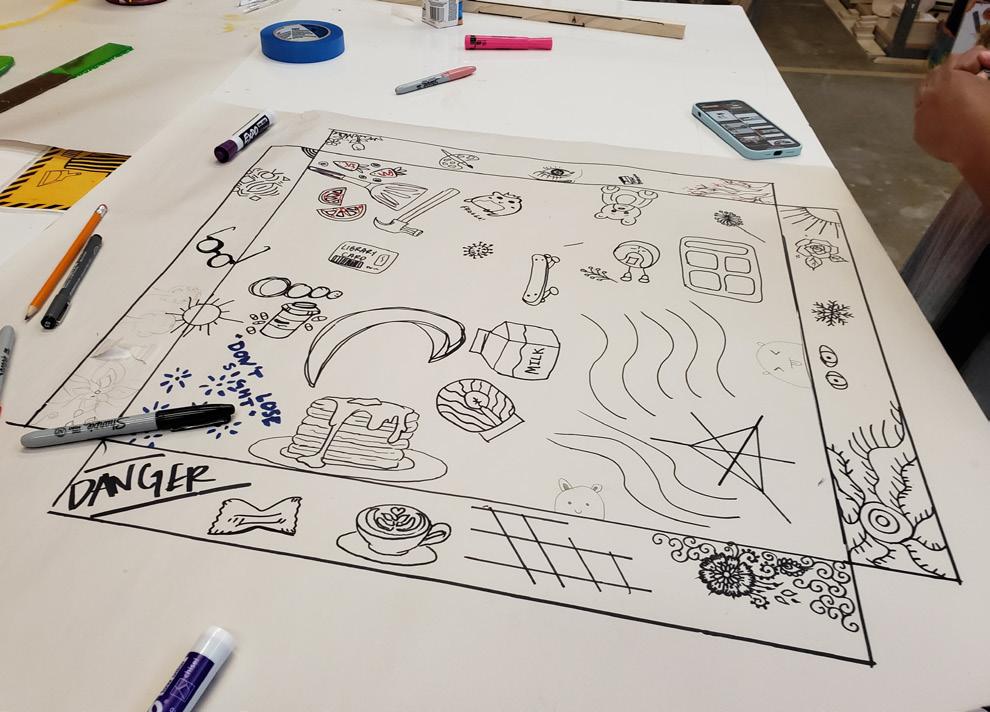

Consequently, these five informed how I designed a suite of interactive and partipicant-focused survey instruments (i.e., Interest Form, MURAL Survey, and Mapping Activities) for my engagements.

49 “Read the Principles,” Design Justice Network, 2018. https://designjustice.org/read-the-principles

50 “Placemaking: What If We Built Our Cities Around Places?” Project for Public Spaces, 5-6.

51 Myerson, Jeremy, “Scaling Down: Why Designers Need to Reverse Their Thinking,” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2, no. 4 (September 2017): 288-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sheji.2017.06.001 Blake Stevenson, WBA Creative Architecture, and Scottish Government, “Evaluation of Community-led Design Initiatives: Impacts and Outcomes of the Charrettes and Making Place Funds: People, Communities, and Places,” 2019. https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/ publications/research-and-analysis/2019/10/evaluation-community-led-design-initiatives-impacts-outcomes-charrettes-makingplaces-funds/documents/people-communities-places-evaluation-community-led-desi Baum, Fran, Colin MacDougal, and Danielle Smith, “Participatory Action Research.” National Library of Medicine: National center for Biotechnology Medicine, 2006. https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2566051/

52 “Principles of Play,” Institute for Self Active Education, n.d. https://isaeplay.org/the-power-of-play/principles-of-play/

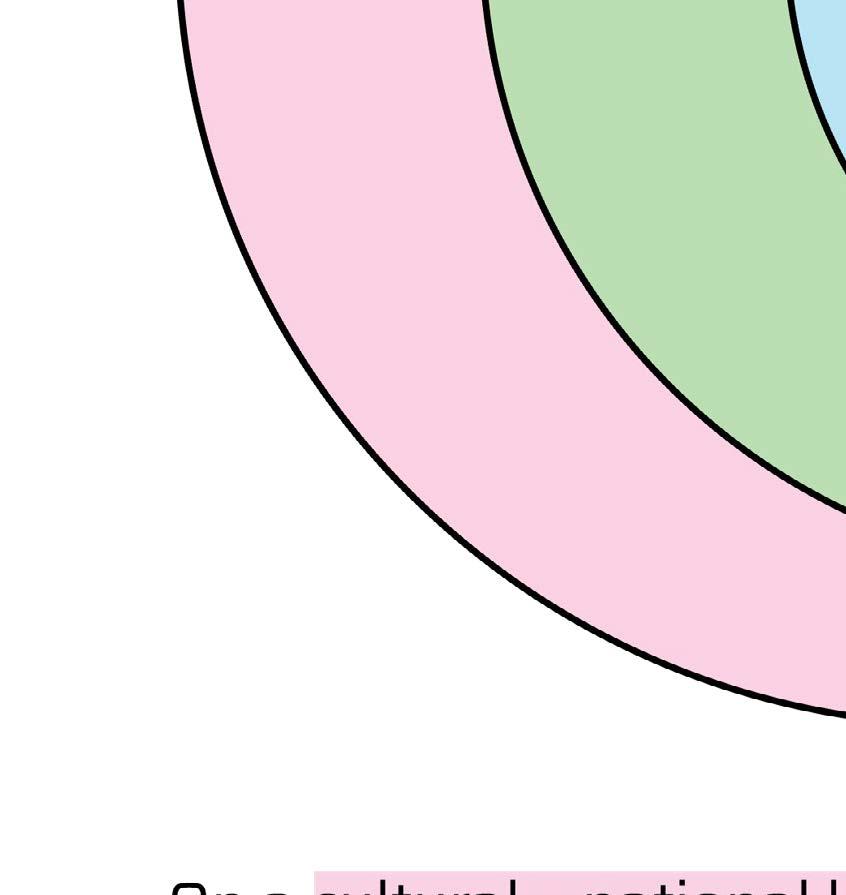

Center BIPoC Communities

Center STEAM education

Center fun and creativity

Center trial and error

Prioritize Design Justice Frameworks

Prioritize Participatory Action Research

Prioritize Community-led Practices

Prioritize collaboration

Understand cultural institution landscapes

Understand design processes

Understand systems + processes

Understand trends

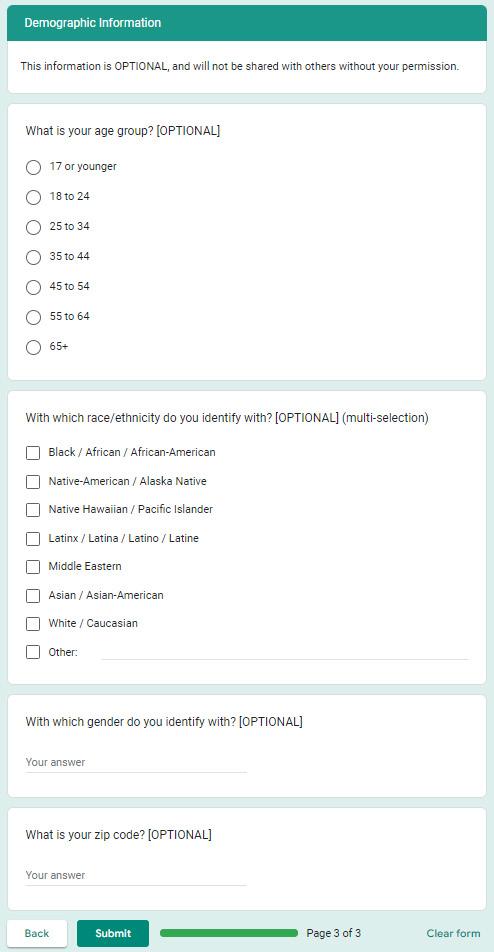

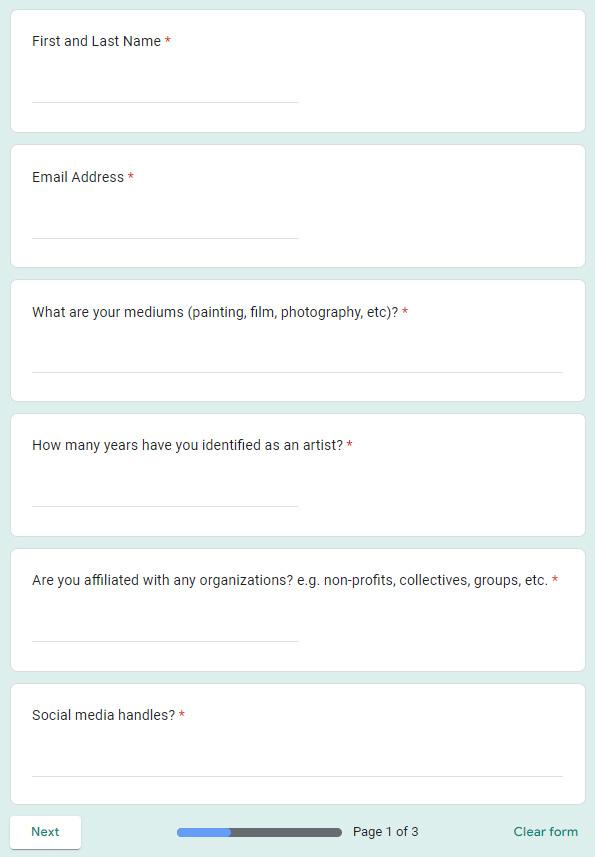

This interest form was part of my initial engagement with BIPoC community stakeholders. I had forty respondents, which eventually resulted in a subset of twenty folks for the interview, survey, or space activation project engagements.

• FOCUS: In order to respect people’s time, energy, and expertise for my primary research, I developed a short <5 min form to gauge initial interest for the more intensive engagement parts of my research i.e. 1-on-1 interviews, focus groups, and/or surveys.

• PROCESS: I collaborated with the chair of the CD/DS program, my CD/DS peers, and my thesis mentor Karim Hassanein to trial, test, and design this form.

• DESIGN: The structure and intent of the form is in alignment with Design Justice Principles, which emphasizes and centers relationship building, the needs and desires of the community, and accountability and transparency in the research process.

• CHOICE: This form provided respondents with the power to identify the engagement opportunities they were most interested in and specify the compensation/experience they were looking to receive for their time and expertises.

• DATA COLLECTION: General information collected included contact details, their art/design/cultural work mediums, years as an artist, organization affiliations, and their social media handles.

• SAMPLE REPRESENTATION: To make sure that I had a diverse representation of people, I asked respondents to share optional demographic information about their age, race/ethnicity, gender, and zip code.

• OUTREACH METHODS: I reached out to folks by sharing the form through word of mouth, asking for referrals, email blasts, and social media posts.

Hello there,

Welcome to my Space Activation Research (Interest Form)!

Introduction: My name is Miguel Rodriguez, and I'm currently studying Collaborative Design at the Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA). For my thesis, I'm exploring the concept of space activation between BIPoC artists, designers, and cultural workers in Portland and cultural institutions (museums, art galleries, community centers, pop-ups, etc.), and I would love to interview artists, designers, cultural workers, and more of varying disciplines and experiences!

Purpose of Research This research is incredibly important to me because I have both seen and experienced the effects of gatekeeping that cultural institutions engage in and how difficult it can be for BIPoC artists, designers, and cultural workers to work with them, and I hope that my research helps both groups better understand:

•What systems, processes, and politics are at play;

•Identifying opportunities for collaboration and alternative processes for space activation;

•Exploring what meaningful and authentic collaborations can look like.

Wrapping Up: By completing this short interest form (<5 mins), I can make sure that I'm respecting Design Justice principles, and that I also have a diverse representation of people (with an emphasis on BIPoC artists, designers, and cultural workers) for my research.

If you have any questions, please feel free to email me at [email]. Super excited to meet new people and reconnect with others as we explore space activation in Portland! -Miguel

How many years have you identified as an artist?* [text answer]

Are you affiliated with any organizations? e.g. non-profits, collectives, groups, etc.* [text answer]

Question 1

Which of the following engagements are ideal for you?* [multiple choice checkbox]

•1-on-1 Zoom Interview

•1-on-1 In-Person Interview

•Focus Group (Zoom)

•Focus Group (In-Person)

•Online Survey

•Space Activation Exploration

•Not interested at the moment, but I would like to follow your research!

•Other:

Question 2

What type of compensation/experience are you interested in for your time and expertise?* [multiple choice checkbox]

•Financial

• Coffee / share a meal

•Opportunity to meet other BIPoC creatives

•Networking opportunities

•Donation to an org

•Sharing your work / collaborating

•Game of chess

•None

•Other:

This information is OPTIONAL, and will not be shared with others without your permission.

Question 1

What is your age group? [single choice]

•17 or younger

•18 to 24

•25 to 34

•35 to 44

•45 to 54

•55 to 64

•65+

Question 2

With which race/ethnicity do you identify with? [multiple choice checkbox]

•Black / African / African-American

•Native-American / Alaska Native

• Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander

•Latinx / Latina / Latino / Latine

•Middle Eastern

•Asian / Asian-American

•White / Caucasian

•Other:

Question 3

With which gender do you identify with? [text answer]

Question 4

What is your zip code? [text answer]

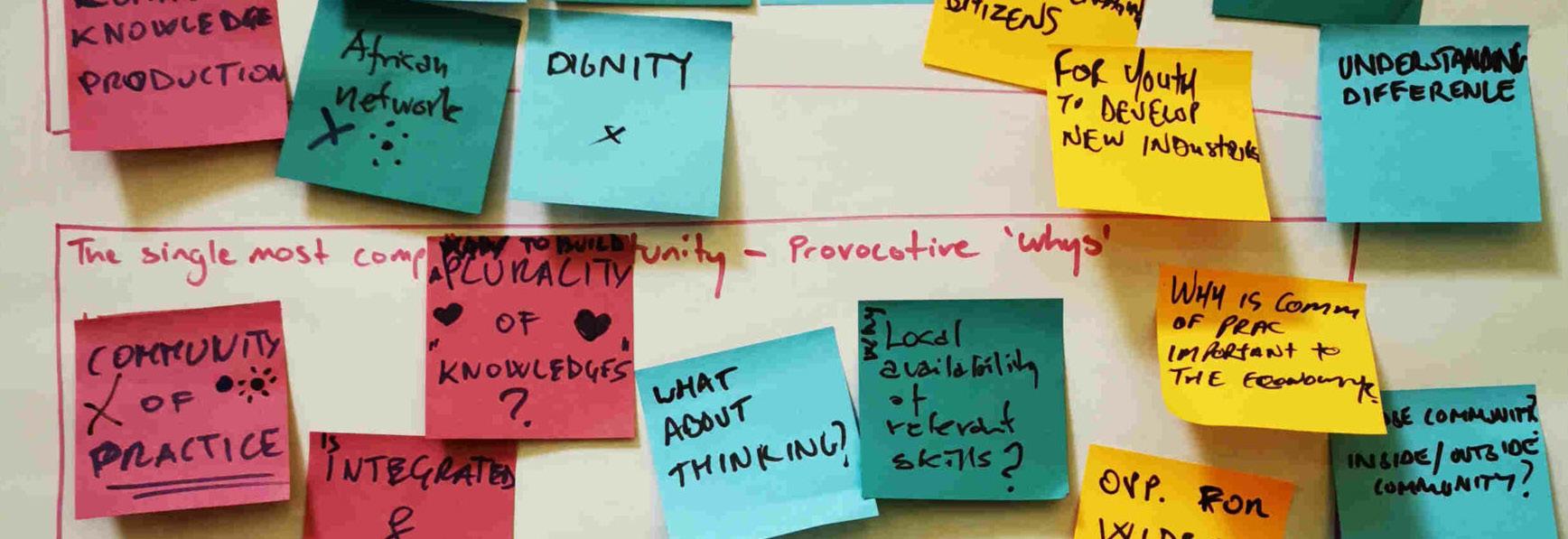

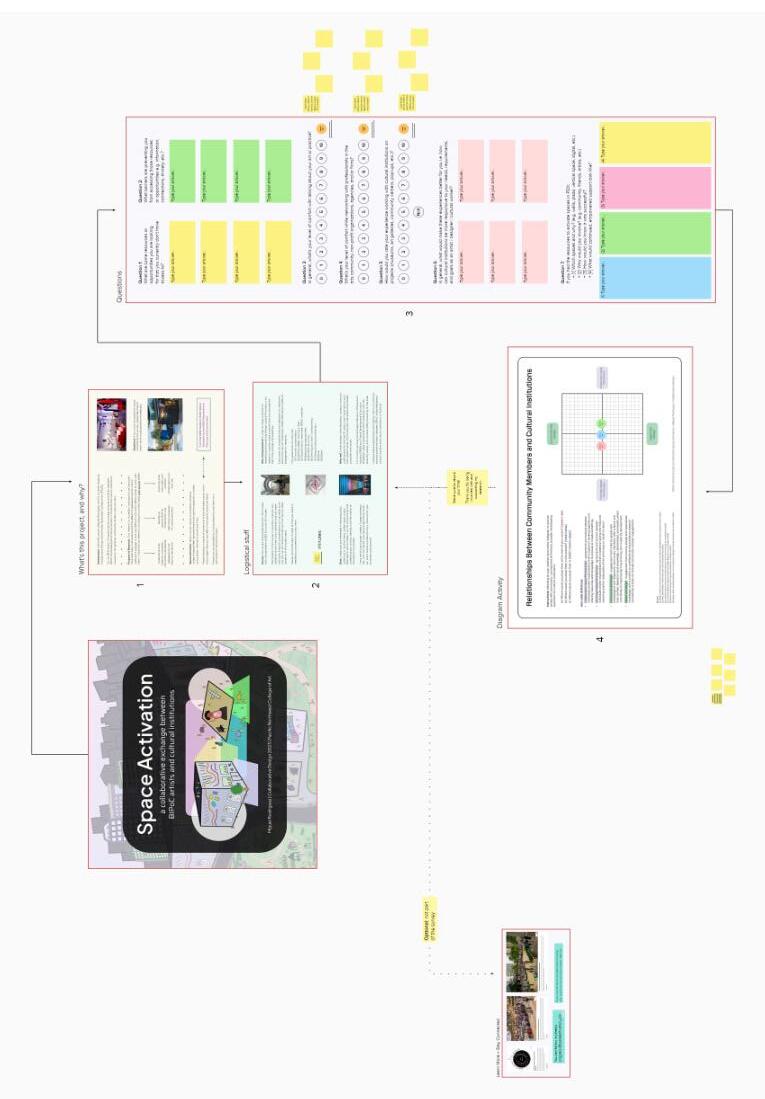

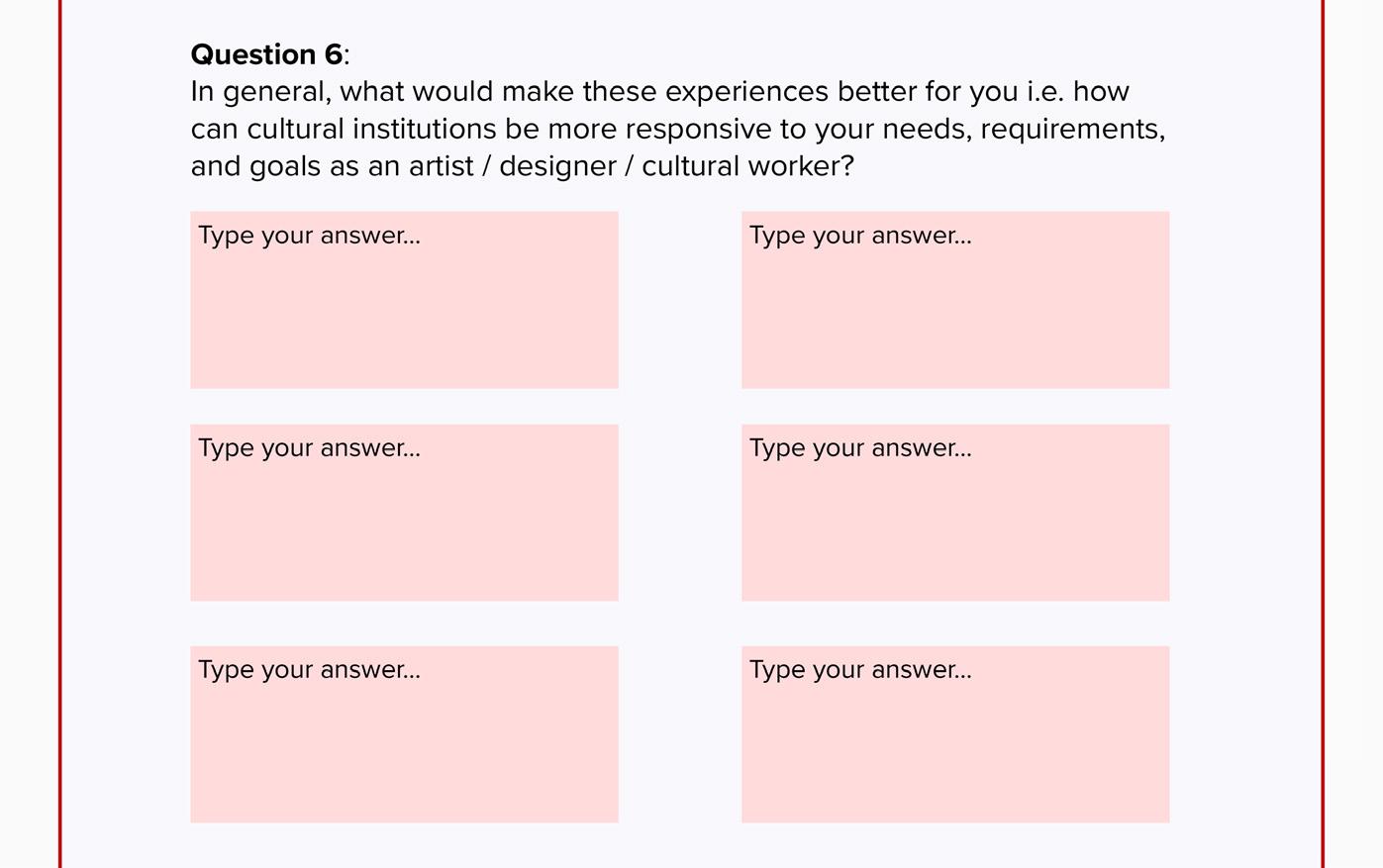

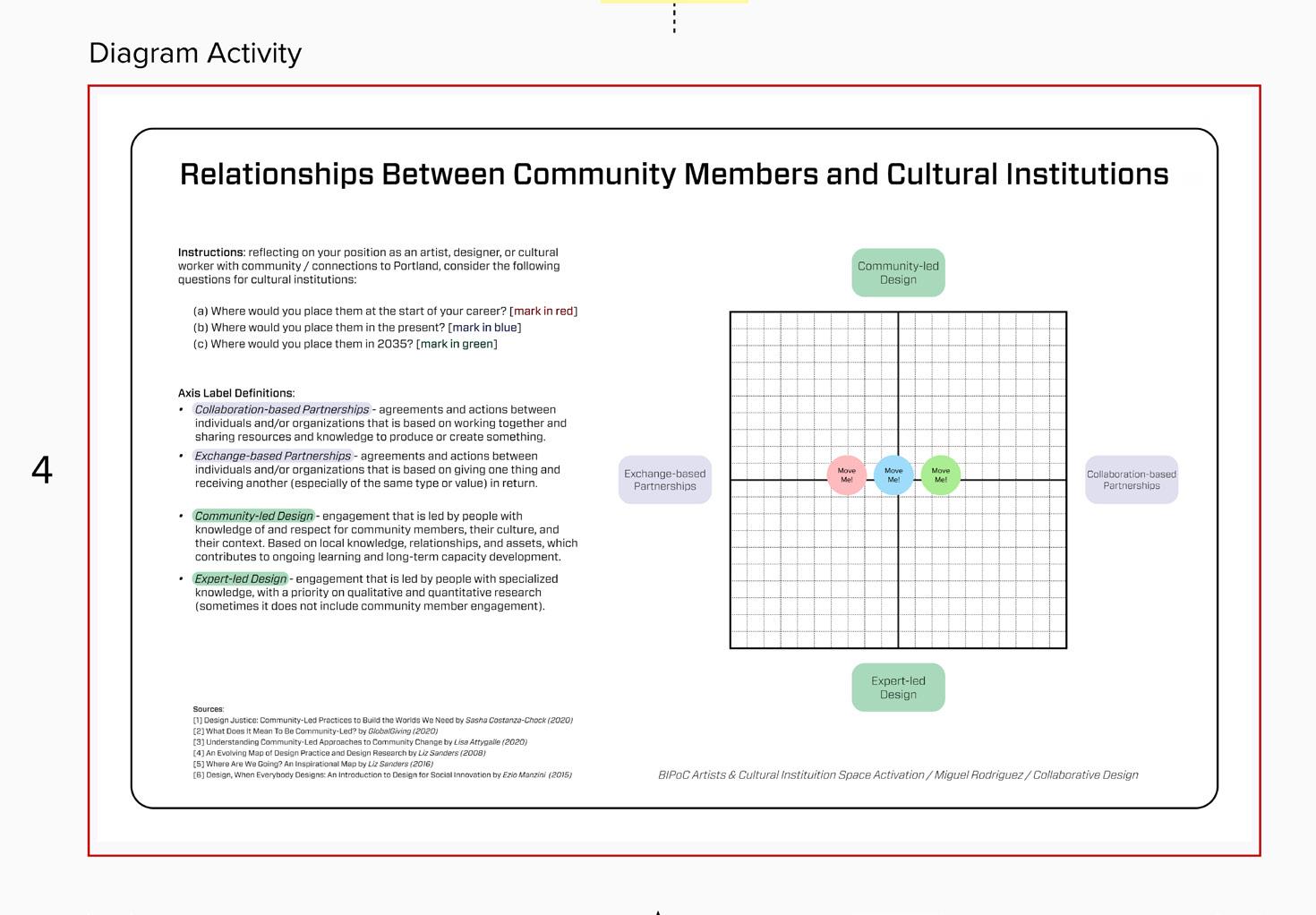

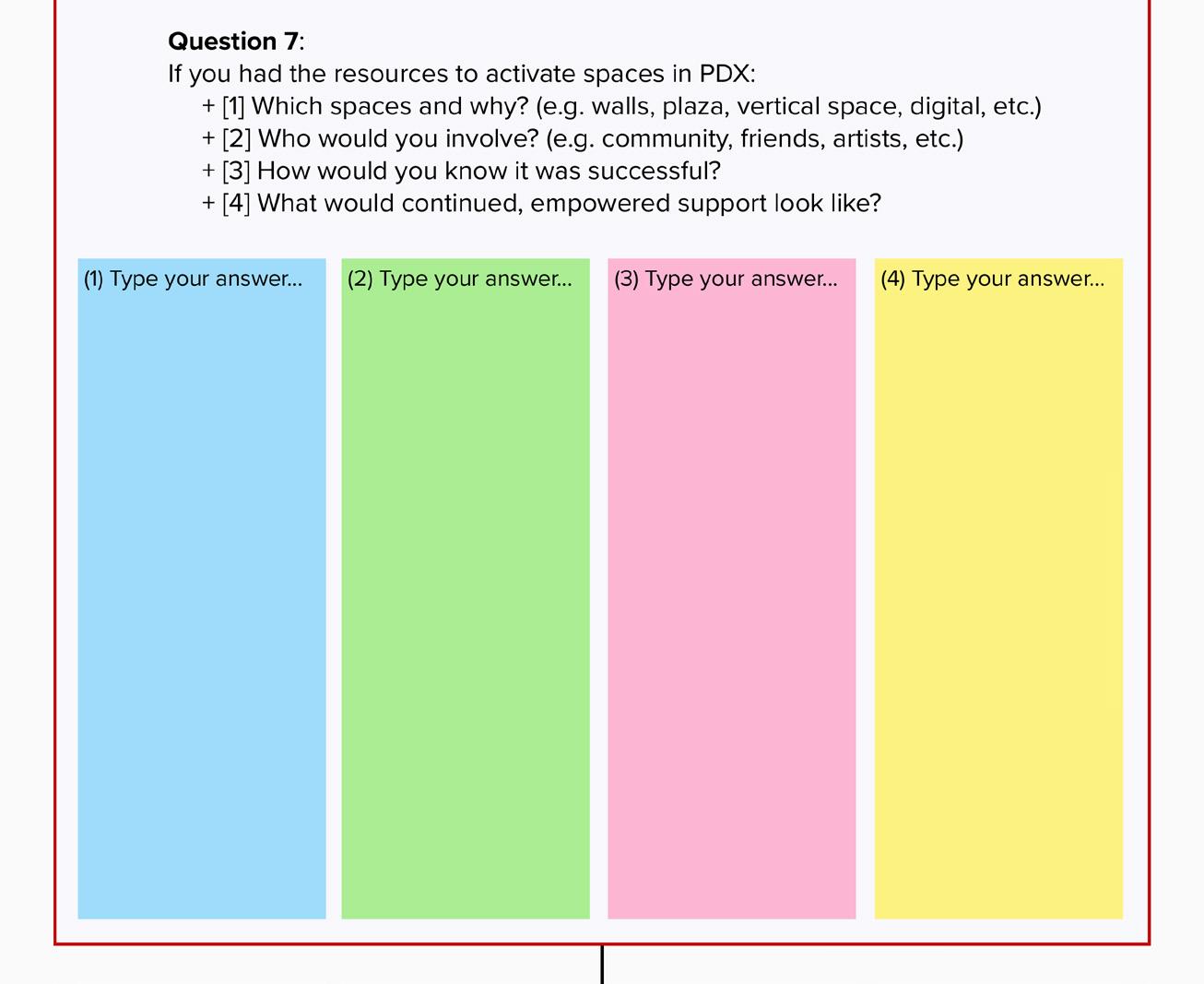

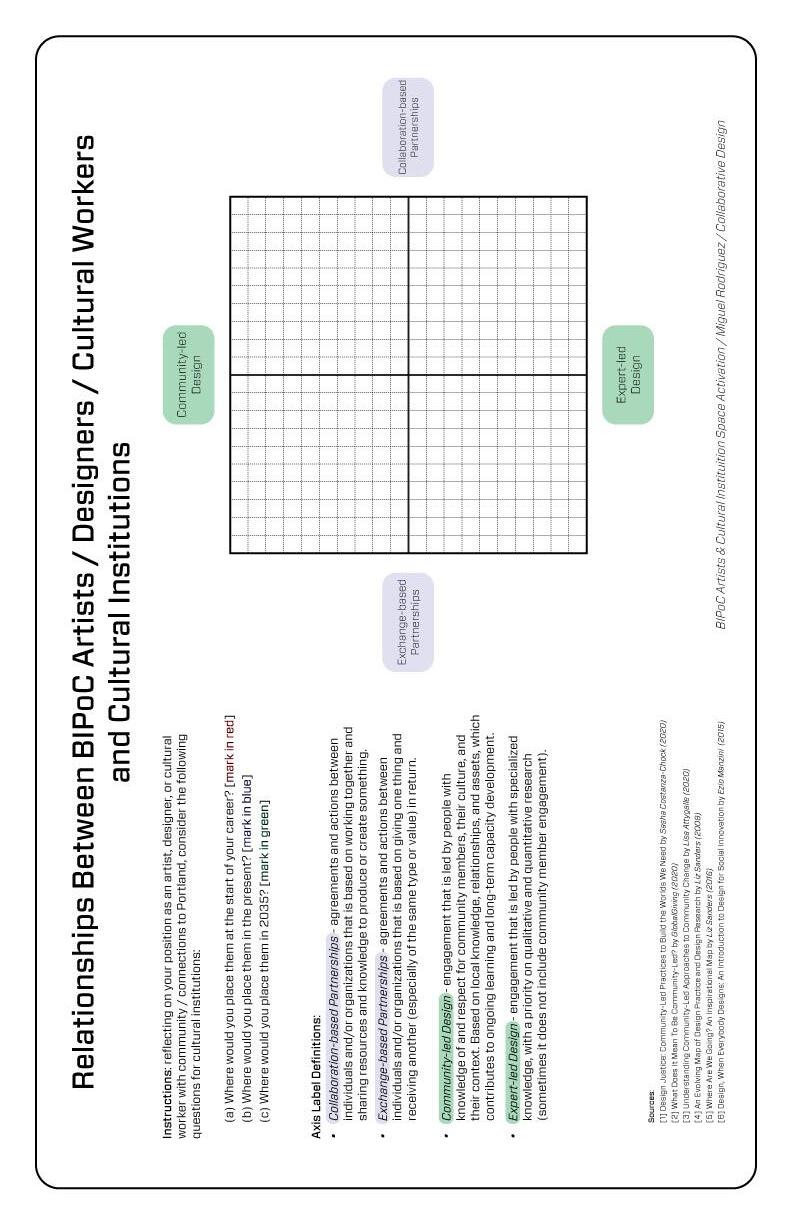

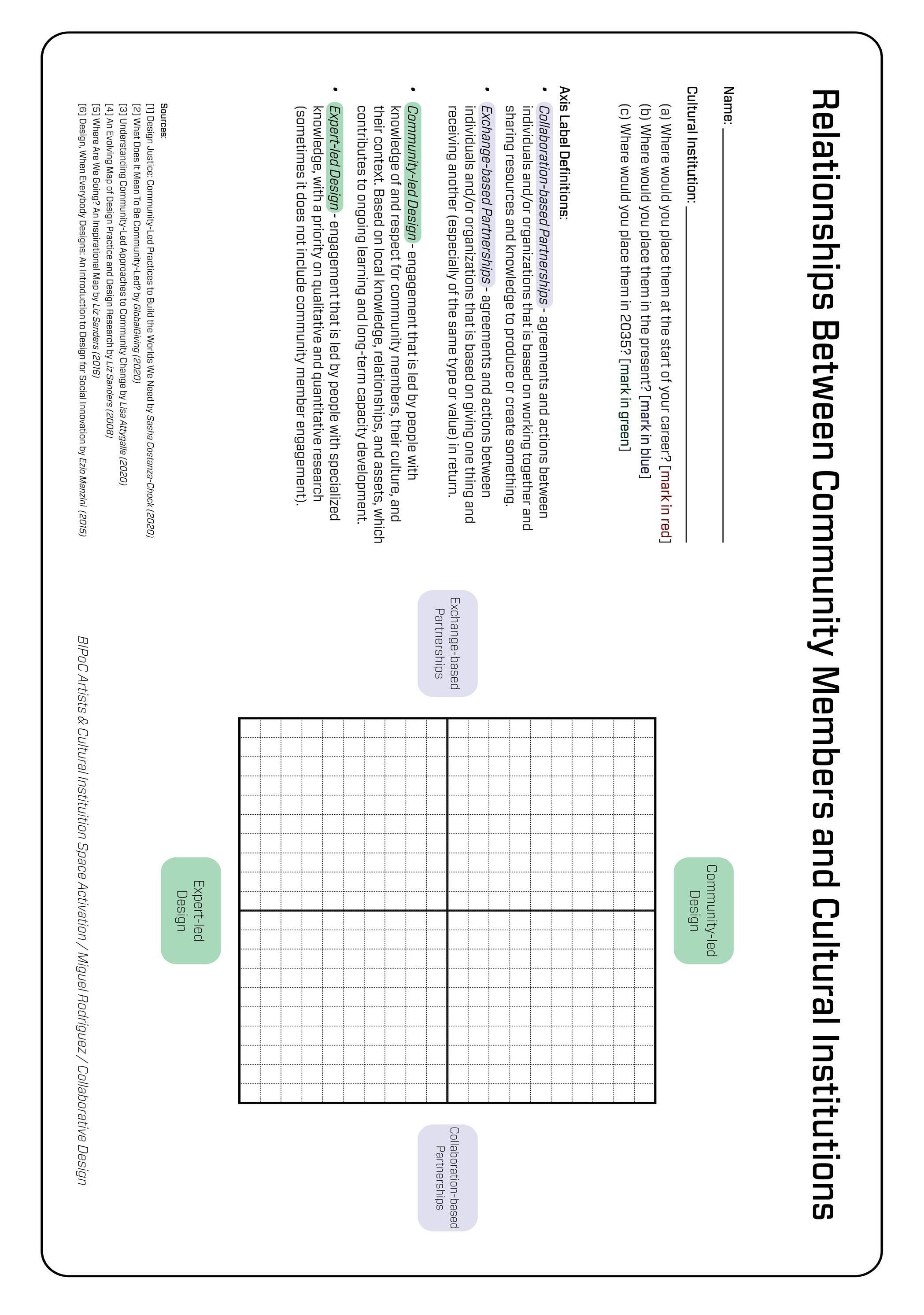

I had twenty BIPoC respondents that were interested in the survey aspect of my thesis work. This online survey helped facilitate a unique, interactive, and alternative method for data collection, with a focus on encouraging a positive experience for my respondents.

• FOCUS: the survey was designed to engage BIPoC community members in a digital format, with the survey ideally being completed ~20 to 45 minutes.

• PROCESS: I collaborated with the chair of the CD/DS program and my CD/DS peers to trial, test, and design this approach.

• DESIGN: because traditional research surveys have the potential of feeling less dynamic and engaging, I developed a survey through MURAL (an online tool used mainly in project management, design sprints, and other contexts) to encourage a different experience for my respondents.

• CHOICE: in general, the surveys were self-led; however, I did meet with some respondents in a 1-on-1 context to support them through the process.

• COMPENSATION / EXPERIENCE: in alignment with Design Justice Principles, I provided respondents with multiple options to choose (as well as write-in) for their time and expertise, including financial and non-financial options.

• SURVEY GOALS: the questions aimed to understand:

→ Their positionality within the arts and cultural landscape.

→ Needs and desires as artists / designers / cultural workers.

→ Comfort talking about their practice.

→ Comfort networking and working with institutions.

→ Exploring ideal experiences with institutions.

→ The types of space activations meaningful to them, including type, stakeholders, measurements of success, and how to sustain space activation projects in the long-term.

What’s this project, and why?

Introduction: Hello! My name is Miguel Rodriguez, and I'm currently studying Collaborative Design at the Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA).

For my MFA thesis, I'm exploring the concept of space activation between BIPoC artists/ designers/cultural workers in Portland and cultural institutions (museums, art galleries, community centers, pop-ups, etc.).

Purpose of Research: This research is incredibly important to me because I have both seen and experienced the effects of gatekeeping that cultural institutions engage in and how difficult it can be for BIPoC artists to work with them. I hope that my research (including this survey) helps both groups better:

1.Understand what systems, processes, and politics perpetuate gatekeeping and require intervention.

2.Identifying opportunities for collaboration and alternative processes for space activation.

3.Exploring what meaningful and authentic collaborations can look like.

Space Activation: When a public space is activated, a diverse range of people feel welcome there and use the space for a variety of purposes, making it vibrant and lively.

People develop a sense of ownership of the activated space, which encourages them to look after it and spend more time there.

Places can be activated by inviting people to use them on a permanent or temporary basis (definition from the NSW Guide to Public Space Activation by the NSW Department of Planning and Environment).

Questions: If you have any questions about completing this survey, please feel free to email me at [email].