This thesis would not have been possible without the invaluable support of those who guided, encouraged, and believed in me throughout this journey.

First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude towards my thesis supervisor, Simon Withers, for his unwavering guidance, patience, and expertise. His insight and support were instrumental in shaping my research and pushing me to refine my ideas.

I am also grateful to the University of Greenwich, the Design School, for providing the academic resources and environment necessary for my studies. A special thanks to my studio tutors, John Bell and Simon Miller, whose unimaginable patience and continuous support have been a cornerstone of my master’s experience. Their dedication and encouragement have been truly inspiring.

A heartfelt thank you to my friends, offering me encouragement, fresh perspectives, and much needed distractions when needed. To the Baraitaru family, your unwavering encouragement, love and belief in me since the very beginning, even in my lowest moments, have meant more than words can express.

Lastly, I owe a profound debt of gratitude to my family, whose unconditional support and unshaken belief in me have been my greatest motivation. Their patience and emotional support have been invaluable throughout this process.

This work stands as a reflection of the collective support, patience, and inspiration I have received, and for that, I am profoundly grateful.

“We can not have a future without respecting our past.” - King Michael of Romania

Romania’s architectural identity has historically evolved through the reinterpretation of external influences, from Byzantine and Ottoman elements in the Brancovenesc style to the later Romanian Renaissance movement. Today, however, globalization, urbanization, and neglect threaten to erase this tradition, leaving many historic structures abandoned or altered beyond recognition.

This study explores photogrammetry as a method for preserving endangered architecture, digitally documenting multiple styled structures and objects. Through high-precision 3D scanning and modeling, the research provides an approach for accurate conservation, restoration, and adaptive reuse.

The findings emphasize that Romanian architecture must continue its legacy of adaptation while ensuring that modernization does not erase its identity. This research advocates for digital preservation and thoughtful design strategies that allow Romania’s built heritage to evolve without compromising its cultural essence.

For centuries, Romania’s architectural landscape has embodied the intersection of diverse cultural, political, and economic forces. Before the unification of Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania, each region developed distinct architectural identities shaped by their respective historical affiliations; Transylvania absorbed Saxon and Austro-Hungarian influences, while Wallachia and Moldavia reflected a fusion of Byzantine, Ottoman, and later French styles. This diversity, once a hallmark of Romania’s cultural adaptability, now faces an existential threat due to the pressures of globalization, political upheaval, and economic migration.

Despite enduring external influences, Romania retained a strong architectural identity through its vernacular traditions, where craftsmanship and locally sourced materials dictated construction methods. The early 20th-century Romanian Revival movement sought to unify these traditions into a distinct national style, incorporating wooden gates, arched porticos, and decorative facades. However, the continuity of this cultural identity was severely disrupted in the aftermath of World War II, when

the communist regime imposed a rigid architectural doctrine inspired by Soviet urbanism. Entire historical districts were razed, displacing communities and replacing traditional village homes, characterized by timber frames and adobe walls, with prefabricated concrete blocks. Alongside this physical erasure, long standing cultural practices, including Romani craftsmanship, religious celebrations, and folk architecture, were actively suppressed or discouraged, severing the link between built heritage and cultural identity.

The fall of communism in 1989 brought an abrupt but equally transformative shift. The rapid embrace of capitalism and Romania’s reintegration into the global economy facilitated a wave of foreign influences permeating

architecture, design, and urban planning. Mass migration to Western Europe contributed to the abandonment of rural settlements, while urban expansion prioritized efficiency over heritage preservation. In this period of transition, historic homes deteriorated due to neglect, while new developments favored standardized, globalized aesthetics that often disregarded Romania’s architectural heritage. Public spaces, once platforms for local customs, became increasingly dominated by Western commercial trends, leading to the marginalization of traditional cultural expressions.

A striking example of this cultural displacement, no only in the built environment, is the transformation of public festivities,

such as Craiova’s Christmas Market, which in recent years has become the second largest in Europe.

Despite its prominence, the market’s thematic focus has largely abandoned traditional Romanian celebrations in favor of Westernized, commercially driven spectacles.

can Romania’s architectural heritage thrive with the pressures of rapid cultural homogenization, or will its distinctive identity be consumed by a globally uniform aesthetic?

This study not only highlights the vulnerabilities of Romania’s cultural

Architecture is an essential element of cultural identity, reflecting the traditions, history, and environmental adaptations of a society. In Romania, vernacular architecture embodies centuries of local craftsmanship, regional influences, and foreign interactions. Before the political unification of Wallachia and Moldavia in 1859, each region (including Transylvania) had a distinctive architectural character shaped by its specific history and exposure to neighboring cultures (Munteanu, 2022). This diversity contributed to a rich and complex architectural landscape that balanced functionality with deeply ingrained symbolic and aesthetic values. However, as modernization, political shifts, and globalization took hold, many of these architectural traditions began to erode, replaced by standardized, industrialized, and increasingly Westernized forms.

Romanian vernacular architecture was never static; rather, it evolved as communities adapted to geographical, social, and economic

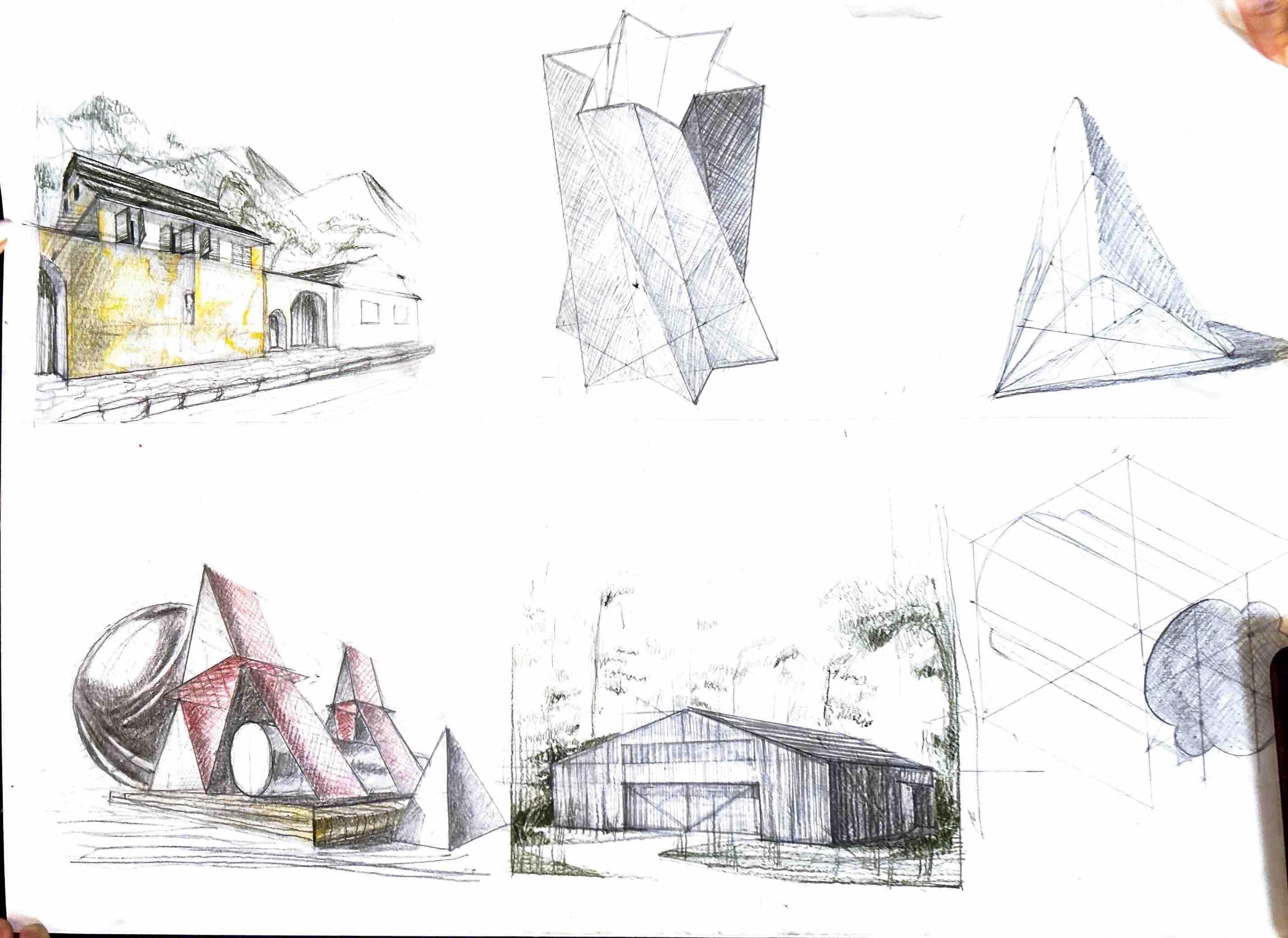

circumstances. In Transylvania, centuries of Austro-Hungarian rule influenced the development of fortified churches, compact stone villages, and steeply pitched roofs, designed to withstand the region’s harsh winters (Pascu & PătruStupariu, 2021). Saxon settlements in the region, which were primarily agricultural, showcased a coherence in design, material use, and construction techniques, reinforcing a distinct architectural identity deeply rooted in communal living.

The characteristic layout of Saxon villages, featuring parallel streets and a centrally located fortified church, points to a deliberate and coherent design approach; “The regular form of parallel streets, the layout of the fortified church in the center and the architecture of the houses were specific features of Saxon settlements..” (Pătru-Stupariu et al., 2019, p. 3)

In contrast, Wallachia and Moldavia, shaped by Byzantine and Ottoman traditions, featured open

courtyards, wooden porches, and rich decorative elements, which emphasized intricate wood carvings and a greater fluidity between indoor and outdoor spaces (Munteanu, 2022). These houses, constructed mainly from timber and adobe, reflected the influence of Ottoman domestic architecture while maintaining unique local craftsmanship. Along the Black Sea coast, Dobrogea’s architecture blended Greek and Turkish elements, characterized by flat roofs, wind-resistant structures, and adobe walls, adapting to the coastal climate and maritime economy (Munteanu, 2022). These regional variations underline the importance of local environmental and historical contexts in shaping

Despite this regional diversity, efforts to define a national architectural identity intensified in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the Romanian Revival style. This movement sought to synthesize vernacular traditions with national symbolism, distancing itself from both Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian influences (Sima, 2013). The Romanian Revival style incorporated Byzantine domes, medieval motifs, and folkloric ornamentation, creating an aesthetic that reflected both the past and aspirations for a distinct national culture. However, this style was primarily an elite-driven project, applied mainly to public buildings, urban mansions, and civic

industrialization and collectivization policies, demolished large portions of historic cities and replaced them with prefabricated apartment blocks (Sima, 2013) ( Marinescu 2022). Entire villages were forcibly relocated or destroyed, leading to the loss of traditional architectural forms and building techniques (Oltean et al., 2024). This period marked a significant rupture in the continuity of vernacular architecture, as centuries-old construction practices were abandoned in favor of mass-produced, utilitarian housing. The destruction of Bucharest’s historic districts to make way for the Palace of the Parliament stands as one of the most striking examples of architectural erasure driven by political ideology (Sima, 2013). These policies did not simply reshape urban centers— they also disrupted the cultural and social fabric of rural communities, where traditional agricultural and construction methods were either prohibited or deemed obsolete; “While in general, rural areas are known for their traditionalism, in Romania they have been greatly shaped and reshaped, in no longer than 70 years, through the profound changes generated by forced collectivization, industrialization and intense urbanization” (Zodian and Diaconeasa, 2018, p. 33).

While the communist era saw the suppression of traditional architectural forms, the postcommunist period presented a different challenge; the rapid shift to free-market capitalism and globalization. In the wake of economic privatization and mass migration, many rural heritage sites were abandoned, left to deteriorate as younger generations moved abroad or relocated to cities (Oltean et al., 2024). In urban areas, new developments prioritized Westerninspired architectural trends, leading to the rise of glass-andsteel office buildings, suburban commercial centers, and standardized housing developments, which often disregarded local architectural traditions (Sima, 2013). The struggle to balance heritage conservation with modernization remains a pressing issue in post-communist Romania, as the country navigates economic growth while grappling with the erosion of its built heritage.

Beyond Romania, other postcommunist countries have faced similar struggles in preserving their vernacular heritage. Zosim et al. (2024), in their study of Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction, highlight the importance of preserving national traditions in

architecture while acknowledging the complex interplay between preserving historical buildings and adapting to contemporary needs. Similarly, Pescaru (2018) highlights the tensions between maintaining authentic values and embracing modernization, particularly in societies where Western aesthetics are perceived as markers of economic progress (Pescaru, 2018). In Romania, this tension is evident in the way vernacular traditions have been either commodified for tourism or disregarded in favor of modernist designs. While heritage preservation efforts exist, they are often underfunded or secondary to commercial development (Pescaru, 2018).

As vernacular architecture continues to decline, the challenge of safeguarding cultural identity through built heritage becomes increasingly urgent. The erosion of traditional crafts, construction techniques, and community-driven architecture is more than a loss of aesthetic value—it represents a fundamental shift in the way Romanians relate to their past. Architectural heritage is not just about preserving old buildings; it is about maintaining a connection to cultural memory, historical identity, and regional diversity (Oltean et al., 2024).

This chapter establishes the historical trajectory of Romanian vernacular architecture, showing in the following subchapters how regional styles developed and political regimes reshaped the built environment.

The diversity of styles and recognising the craft’s origins

Transylvania: Saxon and AustroHungarian styles.

Transylvania’s architectural identity has been shaped by centuries of Saxon settlement and AustroHungarian rule, leading to a unique blend of fortified defensive structures, organized village layouts, Baroque civic buildings, and vernacular farmhouses. This combination of styles reflects both strategic necessity and cultural adaptation, reinforcing Transylvania’s role as a historical frontier between Central Europe and the Balkans. However, demographic shifts, economic transformation, and modernization continue to threaten this architectural legacy, as traditional Saxon and AustroHungarian buildings face neglect, abandonment, or inappropriate restorations (Pătru-Stupariu et al., 2019).

The Saxon settlers, a Germanic ethnic group invited by Hungarian rulers in the 12th century, played a crucial role in shaping Transylvania’s built environment. Their settlements were strategically designed to protect against frequent Ottoman and Tatar invasions, incorporating fortified

churches, structured town layouts, and enclosed homesteads. The fortified churches remain among the most defining features of Saxon architecture in Transylvania, with examples such as Biertan, Prejmer, Hărman, and Viscri now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites (Pascu and PătruStupariu, 2021).

The construction of these fortifications was essential for survival. According to, “The fortified churches in southern Transylvania, including those of the analyzed villages Prejmer, Hărman, Biertan, Mălăncrav, and Vulcan, are very well preserved, unlike the one in Sânpetru, which needs extensive restoration work.” (PătruStupariu et al., 2019, p. 12). These churches, enclosed by high stone walls, defensive towers, and bastions, functioned as both religious sites and emergency shelters for the local population during military conflicts. Beyond their military role, Saxon urban planning emphasized security and economic sustainability. “The Saxons left a significant mark in southern Transylvania in the built heritage, linked to a specific form of village planning” (Pătru-Stupariu et al., 2019, p. 3). Villages were structured around a central axis, with long, rectangular plots, ensuring that each household had direct access to both the village road

and agricultural fields (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021).

The fortified gates of Saxon homes serve as another key feature of their architecture. These large wooden and iron-reinforced gates, often adorned with intricate carvings and geometric motifs, provided both security and a symbol of wealth (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021); and sometimes, from folkloric tales, they simbolised protection from evil spirits. Despite their aesthetic appeal and historical value, many of these structures face deterioration due to population decline and changing property ownership (Pătru-Stupariu et al., 2019).

Following Transylvania’s integration into the Habsburg Monarchy in 1699, the region experienced a profound architectural transformation, particularly in its urban centers. The Habsburg administration sought to modernize and centralize Transylvanian

cities, introducing Baroque and later Secessionist (Art Nouveau) styles, which replaced the medieval fortified aesthetic with monumental civic and religious structures (Pascu and PătruStupariu, 2021).

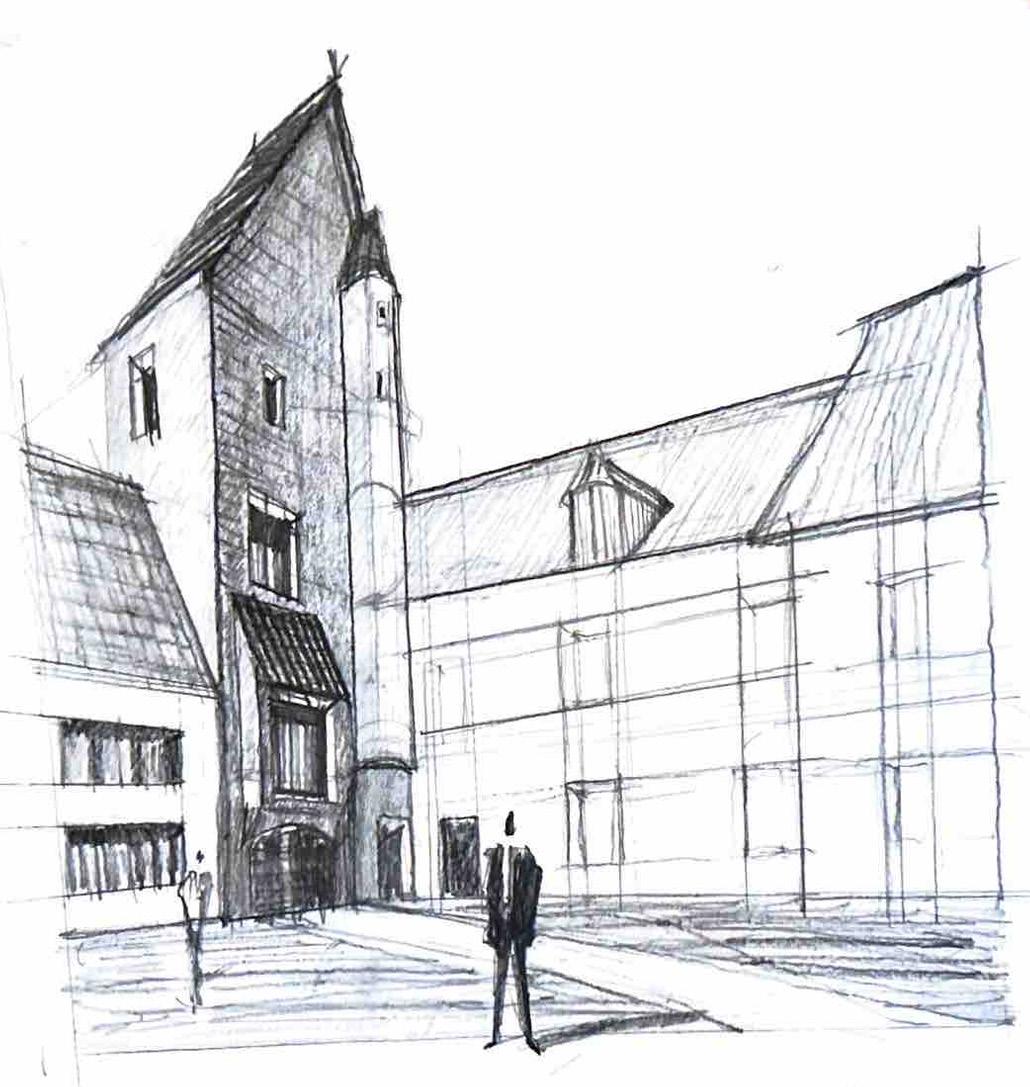

While Baroque architecture, flourishing in the 18th and early 19th centuries, is characterized by grandeur, symmetry, and elaborate decoration, its application in Romanian religious and urban architecture is a subject of ongoing debate. As Felipov notes, “The unique consideration of this decoration allowed to speak of a Brancovenian baroque, the appreciation being a hasty one if we take into account the structures of the edifices as belonging rather to classicism” (Felipov, 2019, p. 99). Key examples include the Bánffy Palace in Cluj-Napoca (Fig. 1), which reflects Viennese Baroque influences, and the Roman Catholic Cathedral in Alba Iulia, which serves as a testament to Habsburg religious dominance in the region.

centuries, Secessionist (Art Nouveau) architecture reshaped Transylvanian urban centers, introducing fluid, organic forms, curved facades, and floral motifs. Oradea became the focal point of this movement, with structures like the Black Eagle Palace and Moskovits Palace, which feature stained glass, wrought-iron balconies, and intricate mosaics (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021).

By the late 19th and early 20th

Challenges to the Preservation of Saxon and Austro-Hungarian Heritage.

Despite their historical significance, Saxon and AustroHungarian architectural sites face increasing threats from depopulation, economic shifts, and urbanization. “The vernacular architectural style is on the verge of disappearing in Transylvania because of the depopulation of the Saxon villages of German origin as a result of massive migration to Germany.” (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021, p. 3). The mass emigration of Saxon populations, particularly during the late 20th century, has resulted in abandoned villages and declining efforts to maintain traditional structures. The problem extends beyond mere abandonment. “The authenticity state of the Saxon buildings was not altered as a result of the financial shortages necessary for the preservation; on the contrary, the owners have invested a lot in performing inappropriate restoration works (for example, a wrought iron gate with opaque plastic mass background is much more expensive than a traditional wooden one)” (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021, p. 14) (fig. 2). Many historical buildings have been subjected to uncoordinated renovations, often using modern materials incompatible

with traditional construction techniques, leading to a loss of authenticity and structural integrity.

Efforts to preserve Saxon and Austro-Hungarian heritage are ongoing, particularly in regions with UNESCO recognition. “The enrolment of Harman cultural property on the UNESCO list provides an important contribution to the increase of the resilience of the Saxon material patrimony to the preservation of local culture and patrimony as a sustainability objective towards the preservation of cultural diversity.” (Pascu and Pătru-Stupariu, 2021, p. 4). However, without continued investment in heritage conservation and community engagement, the architectural legacy of Transylvania remains at risk.

The architectural identity of Transylvania remains one of the most distinctive in Romania, shaped by Saxon defensive planning and AustroHungarian artistic refinement. While fortified churches and structured Saxon villages reflect medieval resilience, the Baroque and Secessionist urban centers highlight imperial grandeur and modernization efforts. However, this architectural legacy faces ongoing challenges. “Long term persistence of the remaining tangible and intangible Saxon heritage relies on the Saxon people who remain in the area and are willing to maintain andrevitalize specific heritage features” (Pătru-Stupariu et al., 2019, p. 15). As urbanization and economic shifts transform Transylvania’s landscape, efforts must be made to balance modernization with the protection of historical sites.

Preserving Saxon and AustroHungarian architecture is not only about protecting old buildings but also about maintaining cultural identity and historical continuity. If sustained restoration projects, legal protections, and local engagement are not prioritized, Transylvania risks losing a critical part of its heritage. The legacy of Saxon and Austro-Hungarian styles must be actively safeguarded, ensuring that future generations continue to experience and appreciate Transylvania’s architectural past.

Wallachia and Moldavia: Byzantine, Ottoman Architectural Styles

The architectural heritage of Romania, particularly in Wallachia and Moldavia, presents a rich and complex and diverse threads of cultural influence and indigenous innovation. The narrative moves beyond a simple chronological progression, emphasizing the regional variations and the enduring interplay between indigenous traditions and external influences.

The early development of Romanian architecture from Wallachia and Moldavia was significantly shaped by the adoption and adaptation of Byzantine styles, as evidenced by the prevalence of religious structures reflecting “The first churches that were built in the region represent the influence of the byzantine architecture and iconographic representation, with the Greek alphabet and language used for writing” (Popovici & Moșoarcă, 2024, p. 2). However, this was not a monolithic adoption. The integration of Byzantine elements varied regionally, reflecting local traditions and the impact of other external influences. For example, in the southern regions, “The south Romanian expression of Christian

orthodox architecture is a mixture of the Romanic, Greek and Slavic styles of the period” (Popovici & Moșoarcă, 2024, p. 2). This blending of styles is further emphasized by the use of both the Greek and Cyrillic alphabets in inscriptions, reflecting the complex cultural landscape of the time.

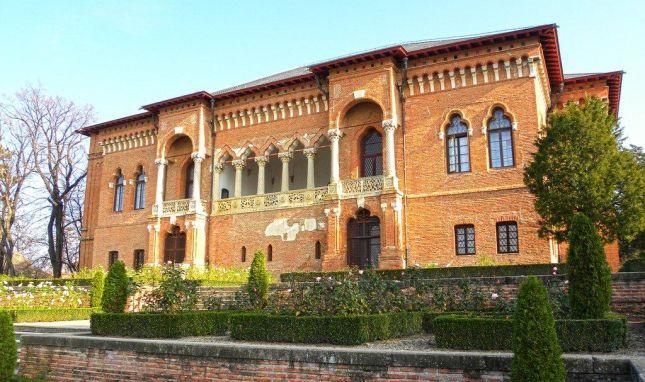

The arrival of Ottoman rule introduced new influences, yet local building traditions persisted and adapted. The Brâncovenesc style, flourishing in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, stands as a testament to this dynamic interplay. Felipov (2019) describes the Brâncovenesc style as a significant model for Romanian art, resulting from a balanced exploration between historical, stylistic, pictorial, and archaeological foundations. This style, while exhibiting a distinct aesthetic, also incorporated elements from both Eastern and Western traditions, reflecting the ongoing cultural exchange and adaptation. Felipov cites this fusion of cultures

Fig. 3

as “while the double-twisted rope is an old decorative motif of Caucasian origin, the heraldic shields come from the ornamental Wsphere of the West” (Felipov, 2019, p. 92).

The Byzantine Empire profoundly influenced the religious architecture of Wallachia and Moldavia. Churches from the 14th to 16th centuries often adhered to the triconch or cross-insquare plans, featuring central domes, richly frescoed interiors, and elaborate iconostases. The Curtea de Argeș Monastery (1517) exemplifies this influence with its tall drum domes and intricate decorative friezes.

Similarly, the Trei Ierarhi Church in Iași (1639) showcases alternating brick and stone masonry, a hallmark of Byzantine aesthetics in Romania.

Ottoman Influence: Integration of Courtyard Designs and Decorative Elements. Birth of Brancovenesc

The 16th and 17th centuries saw Wallachia and Moldavia under Ottoman suzerainty, leading to the incorporation of Ottoman architectural elements into local designs. This period introduced features such as open courtyards, wooden porches, and intricate interior decorations. Residences and public buildings

began to reflect Ottoman spatial arrangements, emphasizing central courtyards surrounded by arcaded verandas. The “Hanul lui Manuc” (1808) in Bucharest stands as a surviving example, showcasing a twostory wooden gallery and an interior courtyard, a very strong example of early bancovenesc architecture.

Romanian Renaissance and Brâncovenesc Style : Embracing tradition through reinterpretation

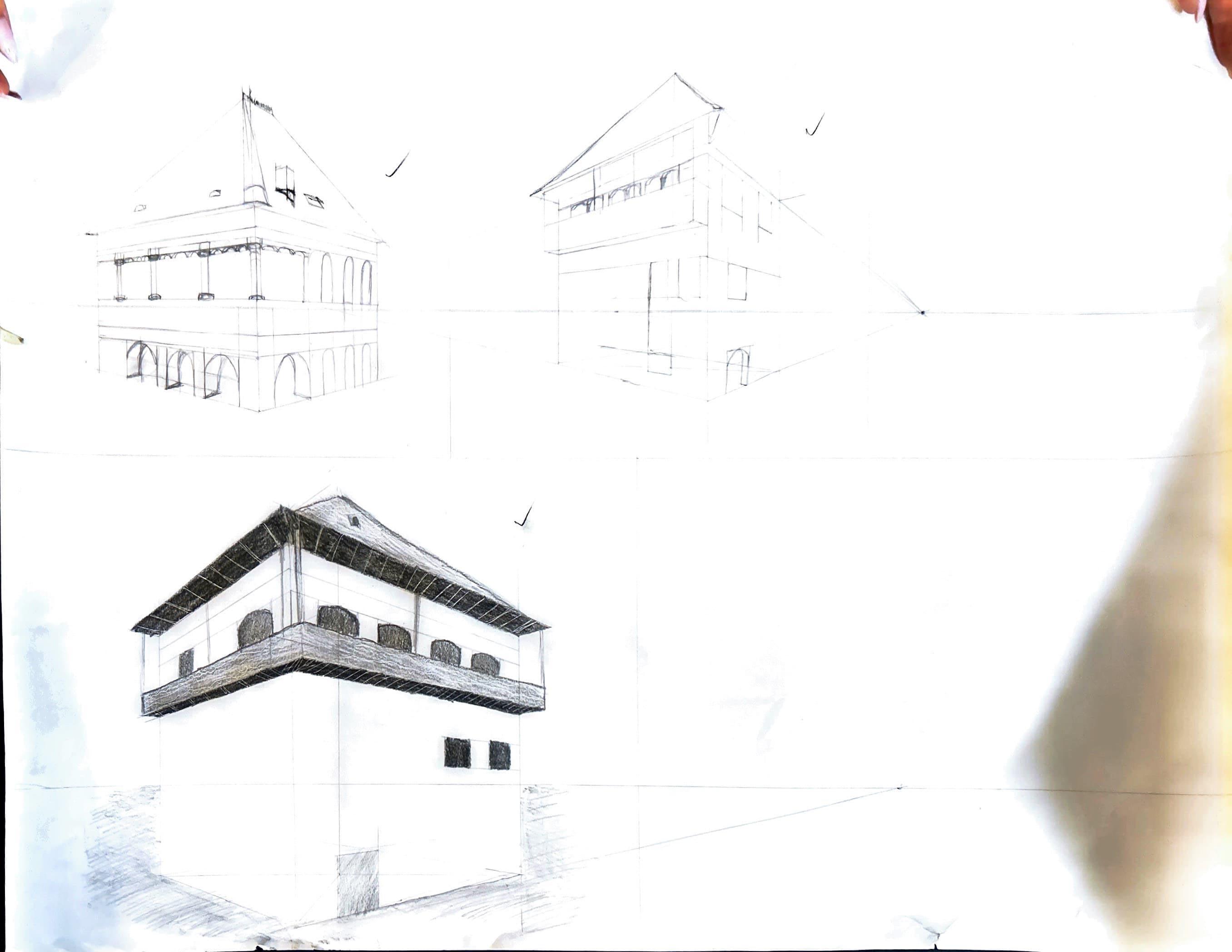

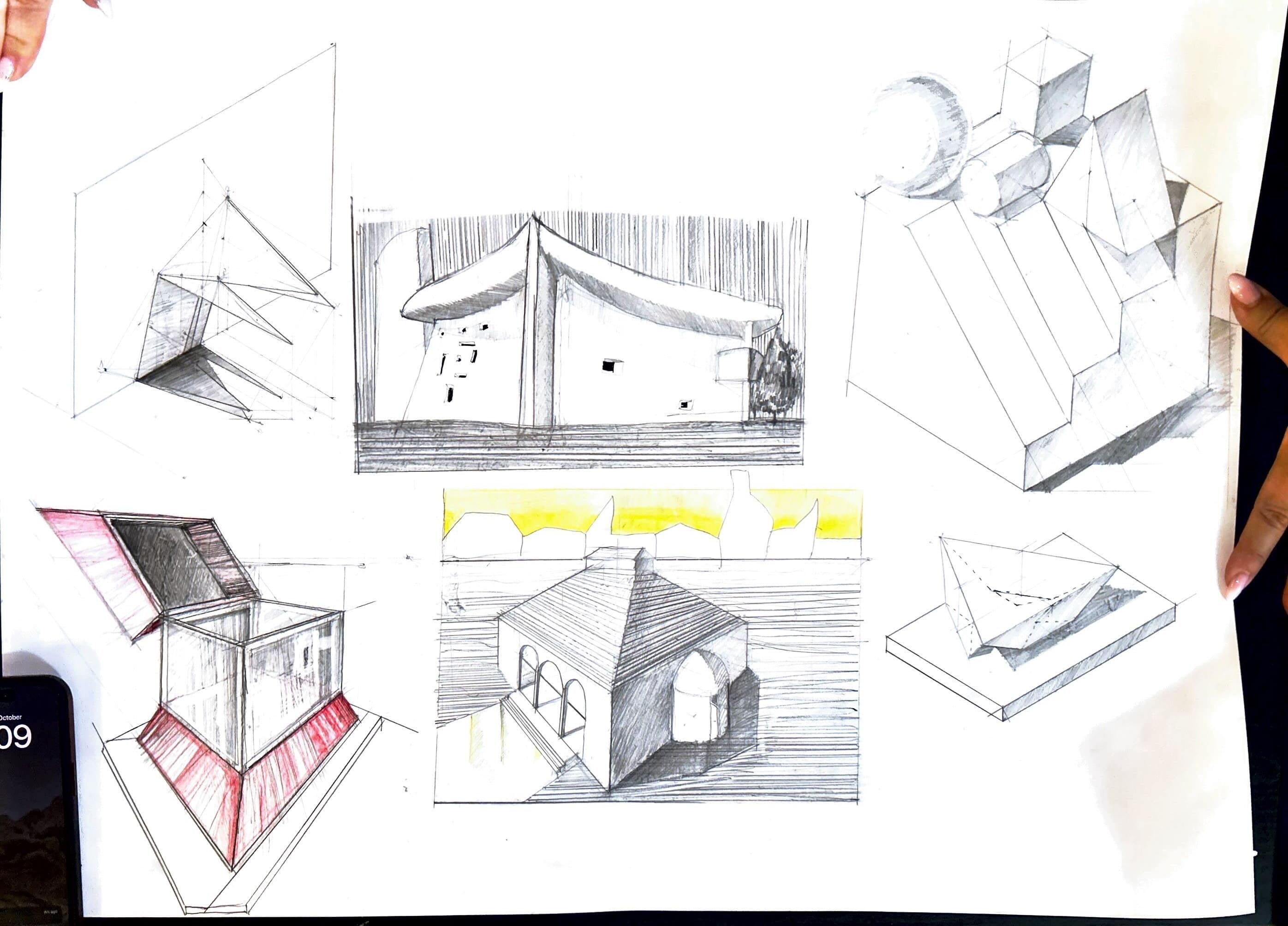

Neoromanian architecture, which developed in Romania between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, represents an intricate synthesis of national identity, historical heritage, and contemporary architectural movements. Rather than simply reviving past styles, this movement selectively reinterpreted traditional Romanian architectural elements, particularly those from the Brâncovenesc period, while incorporating modern building techniques and materials.

The Neoromanian style reflected the broader cultural and political aspirations of the time, seeking to establish a distinct national identity in architecture while engaging with European trends.

The Brâncovenesc style, trending in the 17th and early 18th centuries, during Prince Constantin Brâncoveanu’s rule (1688–1714), served as a primary source of inspiration for Neoromanian architects. As Felipov (2019) notes, “The 17th century religious architecture offers a great variety of remedies with a confusing rivalry between the new and the classical forms, and the decorative apparatus offers a huge range of combinations with frequent entanglements between the Western origins (Gothic, Renaissance, but also Baroque), on one hand, but also oriental (especially Persian and Ottoman)” (Felipov, 2019., p. 91). The key features of the Brâncovenesc

style, including the triconch church plan, open porches, elaborately carved wooden and stone details, and the use of white plaster to emphasize architectural ornamentation, became defining elements of the Neoromanian movement (Felipov, 2019). However, Neoromanian architects did not simply copy these elements; rather, they reinterpreted them within a modern framework, integrating them into secular buildings, civic structures, and urban villas.

Notable examples include: - Mogoșoaia Palace (Fig. 4): Showcases arched verandas and sculpted balustrades, blending Ottoman and Italian Renaissance influences -Stavropoleos Church (1724) in Bucharest: Features richly carved stone and wooden elements, reflecting both Byzantine and Ottoman traditions.

its development. His architectural approach combined Brâncovenesc and vernacular traditions with modern structural innovations, setting a precedent for the widespread adoption of this style in urban architecture (Minea, 2022). As Minea (2022) explains, “Mincu’s designs are diverse and vary from building to building, escaping established artistic categories and, more importantly, contradicting scholars who saw his creations as working towards defining a single unified style” (Minea, 2022, p.53). His works, such as the Central School for Girls in Bucharest (1890) and the Lahovari House, demonstrate this synthesis of old and new, incorporating trefoil arches, wooden balconies, and decorative ceramic friezes while utilizing modern materials such as reinforced concrete and steel.

The Lahovari House is particularly emblematic of Mincu’s approach, as it blends vernacular motifs with refined decorations reminiscent of Romanian Orthodox churches (Minea, 2022).

Minea notes that “ Mincu added to the

Ion Mincu is widely regarded as the founder of the Neoromanian style and played a crucial role in

simple construction a large, raised open balcony, with wooden pillars, trefoil arches, a decorative ceramic freeze and a wooden roof with a projecting cornice” (Minea, 2022, p. 70).

This selective appropriation of traditional elements within a modernist design framework became a hallmark of Neoromanian architecture and influenced generations of architects

behaviour, government and public were far more receptive to the idea of a ‘national style” (Kallestrup, 2002, p. 160). The exhibition featured numerous Neoromanian pavilions, civic buildings, and monuments, reinforcing the style’s position as a state-supported architectural movement.

However, the adoption of

the Neoromanian movement. While her early projects adhered to the principles established by Mincu, she later experimented with modernist influences, transitioning away from historicism toward functionalist design (Bostenaru Dan, 2013). One of her key works, the Tinerimea Română Palace, exemplifies the fusion of traditional Romanian motifs with contemporary construction

Virginia Haret’s architectural designs demonstrate a deep understanding of both Romanian traditions and the functional requirements of modern urban structures, resulting in a unique synthesis of old and new, “In the early years she had built in Neo-Romanian style, moving then to Modernism” (Bostenaru Dan, 2013, p.172).

Following World War I, the

Fig. 6

international and homogenizing trends of post-war architecture. The rise of Modernism, International Style, and later Postmodernism, presented alternative aesthetic paradigms that prioritized functionality, universality, and often, a rejection of historical styles. This shift in architectural thinking is reflected in the observation that “A distinctive trait that has become emblematic of contemporary architecture is the abandonment of localized designs in favor of a more cosmopolitan and less region-specific approach” (Zosim et al., 2024, p. 229).

The loss of Neo-Romanian traditional features, as evidenced by the alterations described by IdiceanuMathe and Carjan (2017, p. 2) in the reconstruction of Mărăști village, “The new architectural products were designed in the style that was already considered the Neo-Romania style in the 1910-1920 decade” (IdiceanuMathe & Carjan, 2017, p. 1) explain that the focus shifted to a standardized NeoRomanian style, sometimes neglecting

regional variations, which underscores a broader decline in the nuanced application of this architectural style. While the reconstruction aimed to celebrate Romania’s national identity, the process itself resulted in a homogenization of the style, potentially diminishing its regional diversity and authenticity. This homogenization, as seen in Mărăști, contrasts with the more varied and context-specific applications of NeoRomanian architecture in other projects. Further research is needed to fully quantify the extent of this loss across different regions and projects.

The inherent tensions within the Neoromanian style itself also played a role in its eventual decline. The style’s “oscillation between “traditional” and Western-derived styles” (Dinulescu, 2009, p. 29), reflecting the architects’ training in European schools and their engagement with contemporary architectural trends, created internal inconsistencies ”characterized by this “oscillation” between the different referential variants” (Dinulescu, 2009, p. 29). The shifting definitions of Romanian national identity, as seen in the 1906 Exhibition where “vernacular revivalism played a subsidiary role to the expression of Latin

identity on the one hand and the celebration of Orthodox forms on the other” (Kallestrup, 2002, p. 147), further contributed to the style’s eventual decline. While Neoromanian architecture remains a crucial part of Romania’s architectural heritage, its relevance diminished as new architectural paradigms took hold in the mid-20th century.

The decline of Neoromanian architecture in Romania was shaped by multiple factors that collectively led to its diminished presence in the built environment. While the growing dominance of Modernist and International styles in the mid-20th century played a role in diminishing interest in historicist revival styles, the more significant blow came from the Ceaușescu regime’s systematic destruction of historic structures. Beyond outright destruction, many Neoromanian buildings that remained standing suffered from prolonged neglect, poorly executed modifications, or restorations that failed to respect their original design (Pascu & Pătru-Stupariu, 2021).

Over time, these buildings lost many of their defining features, either through inappropriate interventions or through gradual deterioration. The Brancovenesc style had the same

fate, but compared to Neo-romanian decor, the most common physical alterations included the demolition of auxiliary structures such as summer kitchens and chimneys, the obstruction of cellar ventilation, and the introduction of stylistically unrelated elements. Additionally, changes such as “widening the windows or turning two into one, the shape of the traditional gate model was destroyed either by removing the masonry or by increasing the size of the gate or both, shrill colours of the façade and of the roof, and by removing the ridged roof shape with dull fronton and pinion” significantly impacted the architectural coherence of these buildings (Pascu & Pătru-Stupariu, 2021, p. 14). Even buildings designed by prominent architects such as Virginia Haret were not spared, with the extension to the Rosetti-Solești house being among those lost to demolition (Bostenaru Dan, 2013).

The decline of the Neoromanian style was also influenced by certain

inherent limitations within the movement itself. The architectural principles underpinning the style were strongly tied to a particular historical period and an elaborate, decorative approach that made largescale application difficult in the context of rapid urbanization and post-war reconstruction (Dinulescu, 2009). As Dinulescu previously mentions, the style’s “oscillation between “traditional” and Western-derived styles” (Dinulescu, 2009, p. 29) created contradictions in its development, particularly in efforts to adapt it to secular and functional architecture. Its reliance on historical motifs and handcrafted ornamentation further constrained its ability to evolve in line with modern construction techniques and planning principles. The difficulty in applying Neoromanian aesthetics beyond religious and civic buildings further hindered its potential for widespread adaptation (Dinulescu, 2009).

Despite its decline, Neoromanian architecture remains an important part of Romania’s cultural and architectural history. The surviving structures continue to be regarded as integral components of the nation’s heritage, recognized for their aesthetic and historical significance (Minea, 2022). However, their future depends on committed preservation efforts, scholarly research, and a renewed public appreciation for their role in shaping national identity (Minea, 2022). The loss of so many Neoromanian buildings under the Ceaușescu regime serves as a stark reminder of how political agendas can shape and even erase aspects of a nation’s architectural legacy. As Sima notes, the regime’s approach reflected a deliberate choice between “commercialising an unwanted past or ‘deleting’ its existence by modernising communist heritage to the point where it may no longer be recognised as such” (Sima, 2013, p. 65), with the latter being the dominant strategy for much of Romania’s architectural history during this period. Ensuring that the remaining Neoromanian buildings are preserved and understood in their proper historical context is essential for maintaining the architectural and cultural richness they represent.

Buildings from this era often feature:

- Domed cupolas with slender profiles, inspired by Byzantine and Baroque church designs.

- Elaborate facades adorned with classical pilasters, reflecting Italian Renaissance symmetry. - Grand staircases and open colonnades, combining Ottoman courtyard layouts with Western palace designs.

However, many of these historical structures face challenges due to neglect, improper restoration, and urbanization pressures. While efforts by organizations like UNESCO have aided in preserving landmarks such as the Horezu Monastery, numerous vernacular and Ottomaninfluenced buildings remain at risk. Future preservation initiatives must focus on maintaining the authenticity of these structures, ensuring that this rich architectural heritage endures for future generations.

during the interwar period

The Mediterranean architectural current in Romania during the interwar period represented a synthesis of various influences, particularly from Spanish, Italian Renaissance, and North African styles, which were adapted to local conditions and aesthetic preferences. This period was characterized by a growing appreciation for historicist and regionalist architectural trends, influenced by international developments, particularly those emerging from the United States and Western Europe.

The emergence of the Mediterranean style in Romania can be traced to the broader European and American fascination with historicist revivals, which gained prominence in the early 20th century. The influence of Andalusian and NeoMudejar architecture was particularly

manner that reflected local cultural “An important role was also played Neo-Mudejar style of the Hispanountil the end of the 1930’s” (Ghigeanu, 2022, p. 43). This adaptation process allowed architects to create a distinctive architectural language that resonated with both traditional Romanian elements and the broader Mediterranean aesthetic.

The architectural movement was reinforced by the cultural exchanges facilitated by Romania’s political and economic elite. Members of the Romanian aristocracy and bourgeoisie, particularly those with connections to the royal court, played a crucial role in popularizing the Mediterranean Revival. The influence of American architecture, particularly through cinema and illustrated magazines, further fueled this trend. It is documented that “In the interwar period, the influence of American culture - especially on the masses - less on the French-loving elitewas at its peak in Romania, being strongly supported by the tabloid

press - Realitatea llustrata, Romania llustrata, etc., but also by the cinema.” (Ghigeanu, 2022, p. 63). This exposure led to an increased demand for residences and public buildings that reflected a Mediterranean aesthetic, resulting in an influx of architectural designs featuring stucco facades, red clay-tiled roofs, and arched windows.

A pivotal figure in the Romanian adaptation of the Mediterranean style was Henrieta Delavrancea-Gibory, one of the leading architects of the interwar period. She successfully merged Mediterranean influences with the vernacular traditions of Dobrogea and the Romanian Black Sea coast. Her works, such as the Rasoviceanu House in Balcic (1934), illustrate a refined synthesis of “An important role was also played by the attachment to Andalusian architectural regionalism of the Neo-Mudejar style of the Hispano-Iberian style” (Ghigeanu, 2022) and local architectural traditions Delavrancea-Gibory, along with other prominent architects, demonstrated a keen ability to reinterpret Mediterranean architectural elements to suit the Romanian climate and cultural landscape.

One of the most notable aspects

of the Mediterranean architectural influence in Romania was its adaptation within the framework of national identity construction. The period saw a tension between the acceptance of foreign styles and the desire to maintain a distinct Romanian

received by the Romanian architects, in the years to follow”(Ghigeanu, p. 43, 2022).

Despite these controversies, the Mediterranean architectural current became firmly established in interwar Romania, with numerous villas, public buildings, and even royal residences adopting its stylistic elements. The Scroviștea Royal Palace, which was demolished in 1959 (Ghigeanu, 2022) and the Elisabeta Palace stand as prime examples of how Mediterranean aesthetics were embraced at the highest levels of Romanian society. The movement’s impact extended beyond architecture, influencing urban planning and landscape design, with many interwar neighborhoods in Bucharest and other cities displaying a cohesive Mediterranean-inspired aesthetic .

The Mediterranean architectural current in interwar Romania was not

merely an imported stylistic trend but a complex cultural phenomenon. It reflected Romania’s engagement with international architectural movements while also responding to local traditions and identity debates. The adaptation of Mediterranean influences within Romanian architecture highlights the dynamic nature of cultural exchange and the ways in which architectural styles are negotiated within broader sociopolitical and aesthetic frameworks.

The Ceaușescu Regime and the Systematic Destruction of Romanian Architectural Heritage

Nicolae Ceaușescu’s dictatorship in Romania (1965-1989) inflicted catastrophic damage on the nation’s architectural heritage, particularly targeting Neoromanian and Brâncovenesc styles. The destruction of these architectural forms was not an incidental consequence of modernization but a deliberate political strategy aimed at erasing Romania’s pre-communist identity and replacing it with a monumental socialist realist aesthetic that aligned with Ceaușescu’s vision of absolute control (Marinescu, 2022). His regime sought to reshape national identity through

architecture, eliminating structures that symbolized previous political regimes and reinforcing a new, authoritarian urban landscape dominated by state-approved monumentalism. Marinescu describes this effort as an attempt to ”erase the memory of these districts from the collective consciousness” (Marinescu, 2022, p. 18).

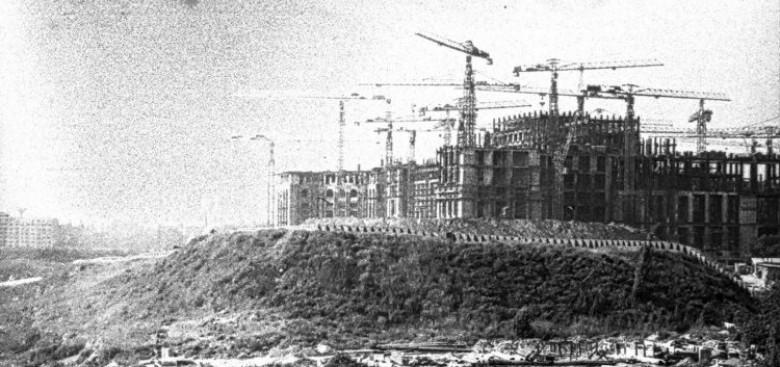

Nowhere was this transformation more visible than in Bucharest, where Ceaușescu’s large-scale urban redevelopment projects resulted in the loss of vast sections of the city’s historical core. The most infamous example of this is the construction of the Palace of the Parliament, initially conceived as the “House of the People.” This massive building project required the complete destruction of entire neighborhoods. Marinescu details the sheer scale of destruction, noting that ” Between 1982 and 1989, about 400 hectares – a quarter of the old centre of Bucharest – were razed to the ground for the project.” (Marinescu, 2022, p. 57). The loss was immeasurable, with ”thousands of houses and historical monuments,” including “centuries-old churches”, being demolished to clear space for the new structures (Marinescu,

2022, p. 57). The process was swift and often brutal, as residents were forcibly displaced with minimal notice. Many

The Neoromanian and Brâncovenesc architectural styles were primary targets of Ceaușescu’s demolition campaigns. These styles, associated with national identity and historical continuity, were in direct conflict with the regime’s efforts to impose a uniform architectural vision rooted in socialist realism. The demolition of historical districts was not merely an act of urban renewal but an erasure of cultural memory. The chaotic and rushed nature of the demolition process reflects the regime’s disregard for historical preservation, as entire neighborhoods were wiped from existence without proper documentation or consideration for their historical significance (Marinescu, 2022). The suppression of photography and the prohibition of filming in demolition sites further ensured that much of this destruction went unrecorded. Marinescu emphasizes this suppression, noting that ” there was limited historical information on the erased districts, due to indifference towards the subject and a general lack

Fig. 7

of archival culture” (Marinescu, 2022, p. 19) and that “archives remained difficult to access, whilst bureaucracy and indifference prevailed. This amnesia seemed to serve various interests” (Marinescu, 2022, p. 63). The Palace of the Parliament itself, now one of the most controversial symbols of Ceaușescu’s rule, stands as a physical manifestation of this erasure, overshadowing the historical fabric that was lost to its construction.

The replacement of historic neighborhoods with socialist realist architecture was not simply a functional necessity but a calculated choice to reinforce state ideology through the built environment. Socialist realism, characterized by monumental scale, symmetrical forms, and imposing structures, was intended to project an image of power, unity, and progress (Maxim, 2011). The regime carefully curated the way these projects were presented to the public, using photography and media to portray them as symbols of advancement. As Maxim points out, “the photographs, although documentary in appearance, nonetheless constituted powerful tools of visual propaganda” (Maxim, 2011, p. 2). This controlled representation not only glorified

the new architecture but also minimized public awareness of the destruction that preceded it. The regime systematically replaced diverse architectural styles with a uniform socialist aesthetic, stripping Romania of much of its architectural diversity. This ideological battle over architecture extended beyond Romania, as seen in discussions of cultural erasure in post-communist Eastern Europe. The choice between ‘deleting’ and ‘commercializing’ historical architecture has been a subject of debate, particularly regarding how nations choose to deal with the architectural remnants of previous regimes. In Romania, the choice was largely one of deletion, as evidenced by the wholesale destruction of historic districts in Bucharest (Sima, p. 69). Meanwhile, Marinescu explores similar phenomena in post-Soviet

states, stating that ”The lack of official recognition of the massive demolitions in the 1980s has had direct implications for Bucharest’s development, shaping both the political decisions behind some of the post-1989 urban proposals and the public attitude towards the built heritage” (Marinescu, 2022, p. 63). The fact that the Palace of the Parliament was ultimately preserved, despite its initial rejection by postcommunist society, underscores the complex relationship between political power and architectural heritage. As Marinescu observes, ”The lack of official recognition of the massive demolitions in the 1980s has had direct implications for Bucharest’s development, shaping both the political decisions behind some of the post1989 urban proposals and the public attitude towards the built heritage” (Marinescu 2022, p. 63), reflecting the fluid and evolving interpretations of

Beyond large-scale demolition, Neoromanian and Brâncovenesc architecture also suffered from neglect and inappropriate modifications. Many structures that survived the socialist period underwent unsympathetic alterations, with key architectural features being removed or degraded over time. Pascu & Pătru-Stupariu document the various ways in which traditional architectural elements were lost, stating that “the rooms belonging to the summer kitchen were demolished, the chimneys were demolished, the cellar ventilation was

obstructed, introducing elements not related to the style, widening the windows or turning two into one, the shape of the traditional gate model was destroyed either by removing the masonry or by increasing the size of the gate or both, shrill colours of the façade and of the roof, and by removing the ridged roof shape with dull fronton and pinion” (Pascu & Pătru-Stupariu, 2021 pp. 13-14). This deterioration was not limited to private residences; even historically significant buildings, such as the Rosetti-Solești house, were subject to neglect and eventual demolition (Bostenaru Dan, 2013).

The decline of Neoromanian architecture was further compounded by its internal contradictions. As an architectural style, it struggled to adapt to modern urban planning and large-scale reconstruction efforts. The balance between historicism and innovation was never fully resolved, making it difficult to integrate into mid-20th-century architectural practices (Dinulescu, 2009). The tension between traditional and Western influences also created inconsistencies in how the style was applied, particularly in secular architecture (Dinulescu, 2009).

The shift away from Neoromanian principles was not just a result of external pressures but also an internal struggle within the architectural movement itself.

Despite its decline, Neoromanian architecture remains an essential part of Romania’s built heritage. Surviving examples of the style continue to be regarded as significant cultural landmarks, and preservation efforts in recent decades have aimed to restore what remains (Minea, 2022). However, these efforts remain incomplete, as much of what was lost can never be fully reconstructed. As Sima notes, the regime’s actions forced Romania into a binary choice between “commercialising an unwanted past or ‘deleting’ its existence by modernising communist heritage to the point where it may no longer be recognised as such” (Sima, 2013, p. 65), with the latter being the dominant approach under Ceaușescu. The long-term effects of this erasure continue to shape Bucharest’s urban landscape, where entire sections of the historic city were replaced by socialist monuments.

The fate of Neoromanian architecture serves as a powerful reminder of how political ideology can shape, suppress, and in some cases, obliterate national architectural identity. Its survival now depends on continued preservation efforts, renewed public interest, and a recognition of the historical forces that shaped its decline.

Cultural Erosion and Commercialization in the Craiova Christmas Market

Craiova’s Christmas Market has gained significant international recognition in recent years, culminating in second place in the European Best Destinations competition in 2024. Spanning 280,000 square meters, it has become a key attraction for both Romanian and international visitors, contributing to Craiova’s growing reputation as a winter destination. The market is designed around multiple thematic zones, each offering a distinct experience:

Beauty and the Beast, Santa’s Village, Traditional Romanian Christmas, Galactic Christmas, and an Ice Skating Rink (RomaniaInsider, 2024). The event’s international appeal is evident in the over 80% of votes it received from outside Romania, reflecting its success in attracting foreign tourism (Romania-Insider, 2024). However, this very success has sparked a debate over cultural authenticity and the preservation of Romanian identity in public spaces.

Despite the presence of a Traditional Romanian Christmas zone which was represented by traditional street food stalls, much of the market is dominated by Western-inspired fantasy unlicensed Disney themes, such as Beauty and the Beast and Star Wars. These choices suggest a prioritization of commercial spectacle over cultural heritage, raising concerns about whether the event is truly representative of Romania’s winter traditions. This tension reflects broader issues of cultural identity in postcommunist Romania, where the struggle to define national heritage is often complicated by economic

pressures, globalization, and the need to appeal to international audiences.

The market is not an isolated phenomenon. Instead, it represents a microcosm of Romania’s ongoing negotiations with its cultural past and present, as analyzed by Sima (2013) in her study she mentions: “post-communist capital cities, transition was characterised by many changes in built environment, atmosphere and lifestyle... historic spaces and attractions, especially socialist heritage sites and objects, had to be given to reflect the city’s desire to be seen as dynamic and

cosmopolitan and free of their socialist past” (Sima, 2013, p. 15). This dynamic is clearly visible in Craiova, where cultural heritage is acknowledged, but only as part of a larger, commercially driven narrative. The dominance of Western fantasy aesthetics within the market suggests that economic gain and mass appeal have become more significant considerations than the preservation of local traditions.

Christmas Practices

Romanian Christmas celebrations have historically been deeply rooted in folklore, music, and ritualistic performances, particularly in rural areas where

such customs have been passed down for generations. Among the most important winter traditions are the Goat Dance (“Capra”) and the Bear Dance (“Ursul”), both of which have strong symbolic meanings related to fertility, renewal, and the cyclical passage of time. These performances, once central to village life, are increasingly being sidelined or even omitted in favor of imported, Westernized holiday aesthetics that cater to contemporary consumer expectations.

The Goat Dance (Capra) is performed by costumed individuals who mimic the lively movements of a goat, often wearing elaborate masks and vibrant decorations. It is traditionally believed to ward off

evil spirits and bring prosperity for the new year. Similarly, the Bear Dance (Ursul), which is particularly associated with Moldavian folklore, involves participants dressed in bear pelts, symbolizing the death and rebirth of nature as the seasons change. These rituals, while still practiced in certain regions, are increasingly absent from urban, tourist-oriented Christmas celebrations such as those in Craiova.

This marginalization of traditional customs reflects a larger pattern of cultural displacement that extends beyond Christmas. Purcaru (2019) highlights a similar dynamic in her analysis

of Romanian media portrayals of Valentine’s Day and Dragobete, showing how foreign traditions are frequently elevated at the expense of authentic Romanian celebrations, “reporting on the holiday of Saint Valentine in an antagonistic manner with the celebration of Dragobete and vice versa, trying to promote the second on an insufficiently documented national criterion does no justice to any of the events” ( Purcaru 2019, p. 59). The media, she argues, often frames Valentine’s Day as the dominant holiday, while Dragobete is presented as a secondary, “ethnic” alternative, leading to an artificial competition between cultural traditions (Purcaru, 2019). This phenomenon mirrors what is occurring in Craiova, where traditional Romanian customs are included as part of the event, but only as a minor attraction rather than the focal point of the celebration.

As globalization intensifies, Romanian traditions risk being further marginalized or selectively rebranded to fit a commercially viable narrative. The Craiova Christmas Market, while successful

in boosting local tourism and economy, contributes to this process by prioritizing themes that align with global trends rather than reinforcing local cultural identity.

The transformation of public spaces in Romania is deeply linked to the country’s post-communist transition, which reshaped how national identity is expressed in architecture, urban planning, and public celebrations. Pescaru (2017) explores this issue in the context of Romania’s struggle to reclaim cultural heritage after decades of ideological suppression, showing how the post-1989

shift to capitalism created an identity vacuum in which heritage preservation often clashed with economic imperatives (Pescaru, 2017).

This tension is clearly reflected in Romania’s architectural landscape, where the NeoRomanian style, once a symbol of national pride, has been largely abandoned in favor of modern, Western-inspired developments. In many cities, historic buildings have been demolished or altered beyond recognition to accommodate contemporary commercial needs. The Craiova Christmas Market follows a similar pattern, as its design and aesthetic choices prioritize universal, globally recognized themes rather than a consistent representation of

Romanian culture. “The question becomes why modify unwanted heritage or build new tourism spaces when in fact it is the mismatch and chaotic nature of the city that grants it originality.”

(Sima 2013, p. 70)

Sima (2013) further illustrates this issue in her discussion of Bucharest’s approach to tourism marketing, explaining how city branding strategies often prioritize a neutral international image over a nuanced representation of local history. “Often city marketing campaigns and travel literature use the city’s urban characteristics – the diverse architectural style of its buildings for example, to emphasize the attractiveness, uniqueness and originality of the place” (Sima, 2013, p. 70).

The Craiova Christmas Market exemplifies this tendency by blending Romanian elements with dominant Western narratives, ultimately diluting its cultural distinctiveness.

The case of Craiova’s Christmas market is part of a broader phenomenon of cultural homogenization, in which traditional practices are either erased or commodified to better fit a globalized marketplace. Similar trends have been observed in other parts of Europe, as explored in Spennemann’s (2024) study on

German Christmas markets, which examines how heritage elements are often reinterpreted to meet the expectations of international tourists (Spennemann, 2024, pp. 22-35). While such adaptations can enhance economic success, they also raise important concerns about authenticity and the long-term sustainability of cultural traditions.

Mustafa Koç’s article aligns with themes of cultural identity and globalization, which are evident across the country: “We now live… in an open space-time, in which there are no more identities, only transformations” (Koç, 2006, p. 1). This perspective resonates with what is happening in Craiova and throughout Romania, where traditional cultural practices and architectural styles are increasingly overshadowed by global influences.

The Craiova Christmas Market,

for example, represents this shift, prioritizing universal themes rather than authentic representations of Romanian culture. This trend can be seen as part of a larger phenomenon that impacts urban architectural choices, where the drive for modernization and alignment with Western aesthetics often leads to the erasure or commodification of local heritage. As communities navigate globalization, the transformations in their built environments reflect a struggle to maintain cultural identity amidst the pressures of a homogenized global marketplace. This dynamic affects not only the architectural landscape but also raises critical questions about the sustainability of cultural traditions in the face of rapid change.

Romania can learn from other European nations that have successfully integrated tradition into

modern tourism without sacrificing cultural integrity. Many German and Austrian Christmas markets, for example, maintain a strong emphasis on handcrafted decorations, regional folklore performances, and local artisanal products, rather than relying solely on mass-produced, commercially driven attractions (Spennemann, 2024) . The Craiova market could benefit from a similar approach by ensuring that Romanian craftsmanship, traditional performances, and historical narratives remain central to its identity.

Craiova’s market, despite its international acclaim, raises important questions about cultural representation and the role of public events in shaping national identity. While its success as a tourism attraction cannot be denied, the dominance of Westernized fantasy themes and commercial spectacle over traditional Romanian customs reflects a wider crisis of cultural identity in post-communist Romania. This issue extends beyond Christmas celebrations and is visible in Romanian media representations (Purcaru, 2019), urban development policies (Pescaru, 2017), and tourism

marketing strategies (Sima, 2013). If Romanian traditions continue to be treated as secondary to globalized aesthetics, there is a risk that they will gradually disappear from public consciousness.

Cultural preservation does not mean rejecting modernization, but rather integrating traditional heritage into contemporary frameworks in a meaningful way. The Craiova Christmas Market, and similar public events, should seek to balance economic success with cultural authenticity, ensuring that Romanian identity is actively celebrated rather than passively displayed. By doing so, Romania can position itself not just as a destination for international visitors, but as a country that takes pride in its own unique traditions.

structures, affecting traditional construction techniques, local craftsmanship, and intangible cultural heritage (Pascu & PătruStupariu, 2021, pp. 11–12).

that cultural heritage is not solely about material conservation but also involves safeguarding traditions, artisanal methods, and the sense of community that these spaces foster; as Pascu mentions in his paper the importance of

considering “The immaterial aspects belonging to culture have an identity and memorial value” (Pascu & Pătru-Stupariu, 2021 p. 3) and the interconnectedness of tangible and intangible heritage .

Similarly, Scott argues that the documentation of heritage structures before their potential disappearance is crucial, as many traditional buildings, despite being functionally obsolete, retain significant historical value. They stress that ”recording the intact built heritage...provides a rich data set” (Scott et al., p. 1). , which can be used for various purposes, including restoration and contemporary design applications

Photogrammetry capturing methods:

Photogrammetry offers an advanced method of digital preservation that enables the detailed recording of these structures, ensuring their survival in the form of highprecision 3D models. These models serve multiple purposes, ranging from academic study and restoration efforts to contemporary reinterpretations in architectural practice, “cultural heritage is facing irreversible changes” (Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev 2021, p. 1), making detailed documentation essential for condition assessments and conservation planning. Even if

Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev paper is subject to Central Asian heritage and not specifically romanian, his experience and findings should applicable in such scenario (Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev, 2021). They further highlight the role of photogrammetry in conservation, stating that ”3D models support the preparation of...conservation works by finding appropriate informed solutions” (Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev, 2021, p. 7). The high-resolution 3D models generated through photogrammetry allow for detailed analysis of materiality, construction techniques, and spatial configurations, providing insights that traditional documentation methods often fail to capture (Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev, 2021).

Scott emphasize the necessity of geometric accuracy and high detail levels in digital models, noting that ”a prerequisite for visualization and animation processes” (Scott et al., 2013, p. 89) is a precise and comprehensive dataset. The ability to capture fine details, such as carved ornamentation, material textures, and structural deformations, is crucial for mitigating risks of deterioration and loss (Scott et al., 2013). The integration of drone-based and DSLR scanning technologies enhances data acquisition, ensuring that both

aerial perspectives and close-up details are recorded with accuracy (Vileikis & Khabibullaeyev, 2021). By combining these imaging methods, researchers can produce models that preserve the structural and aesthetic integrity of heritage buildings, allowing for long-term comparative studies and future restoration efforts.

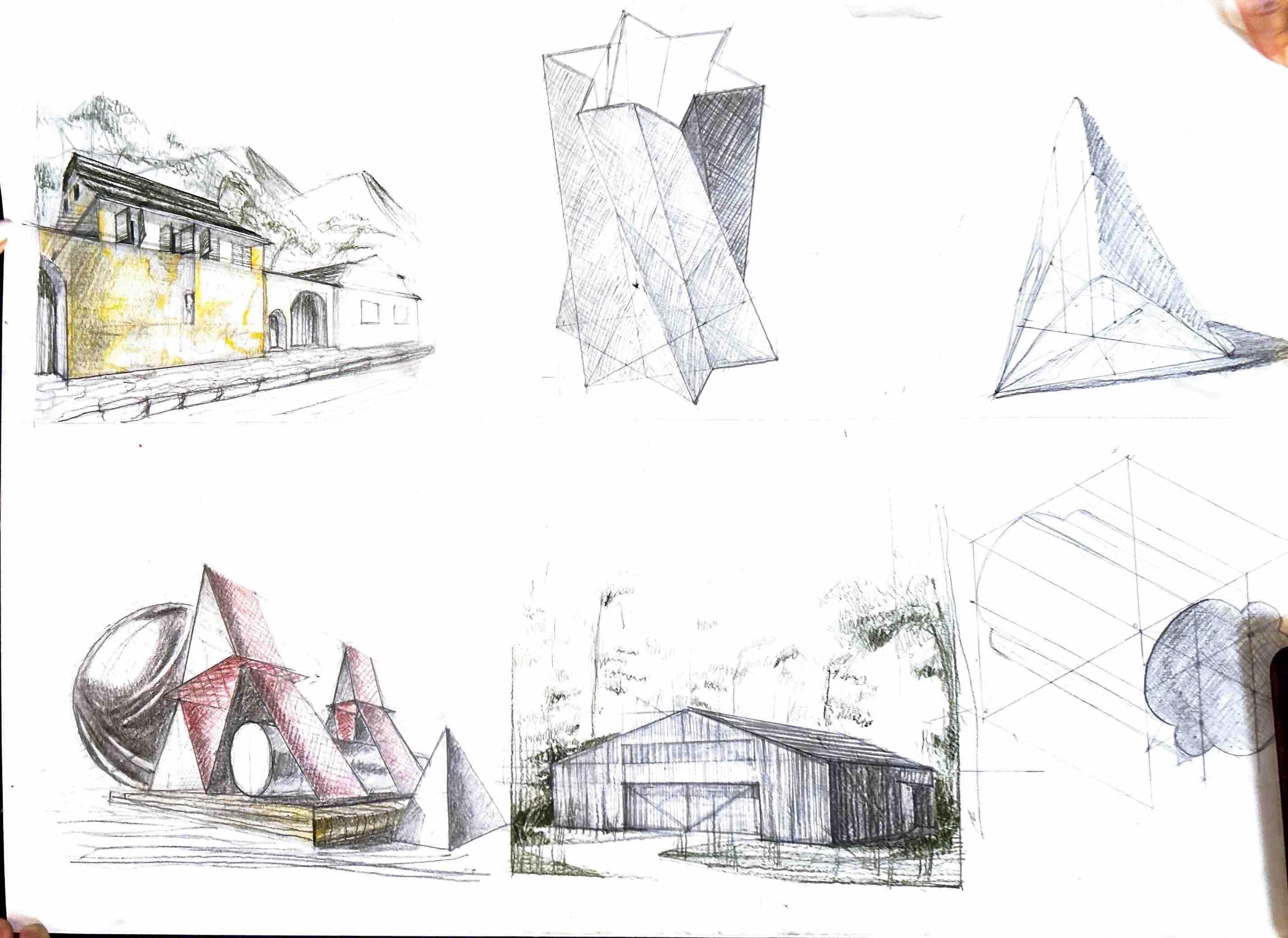

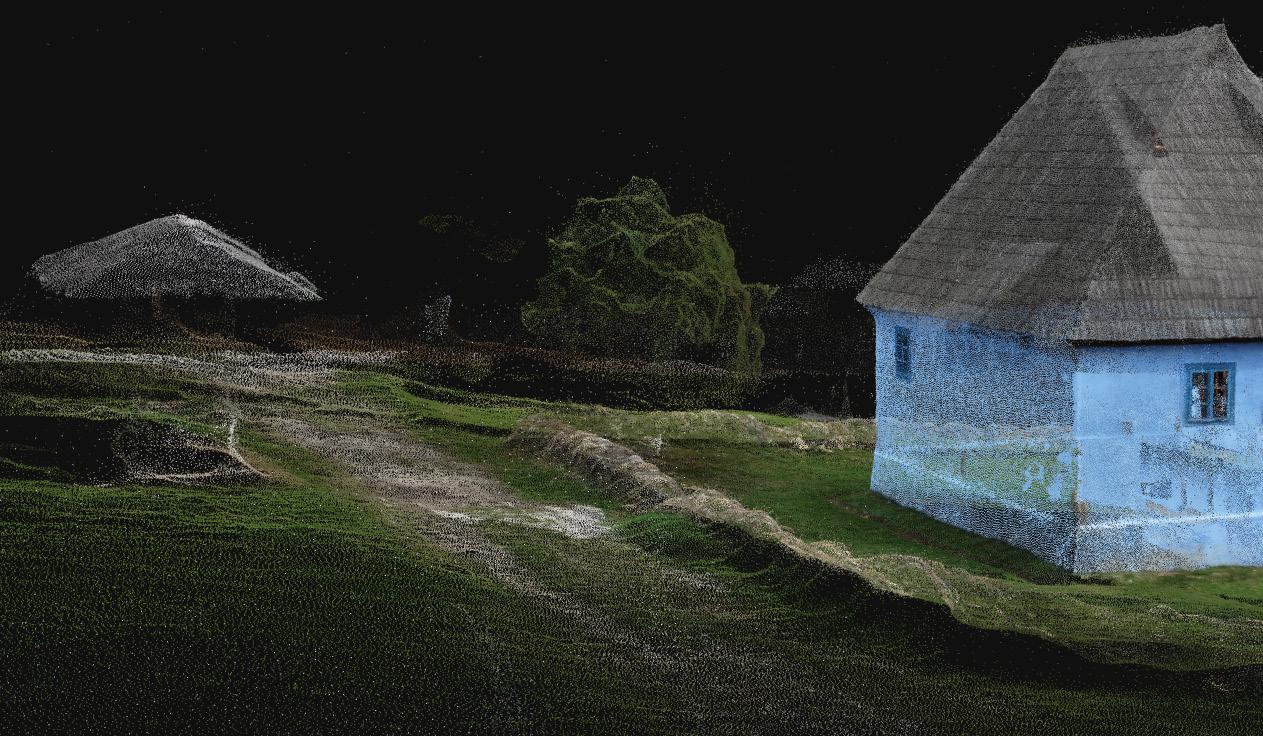

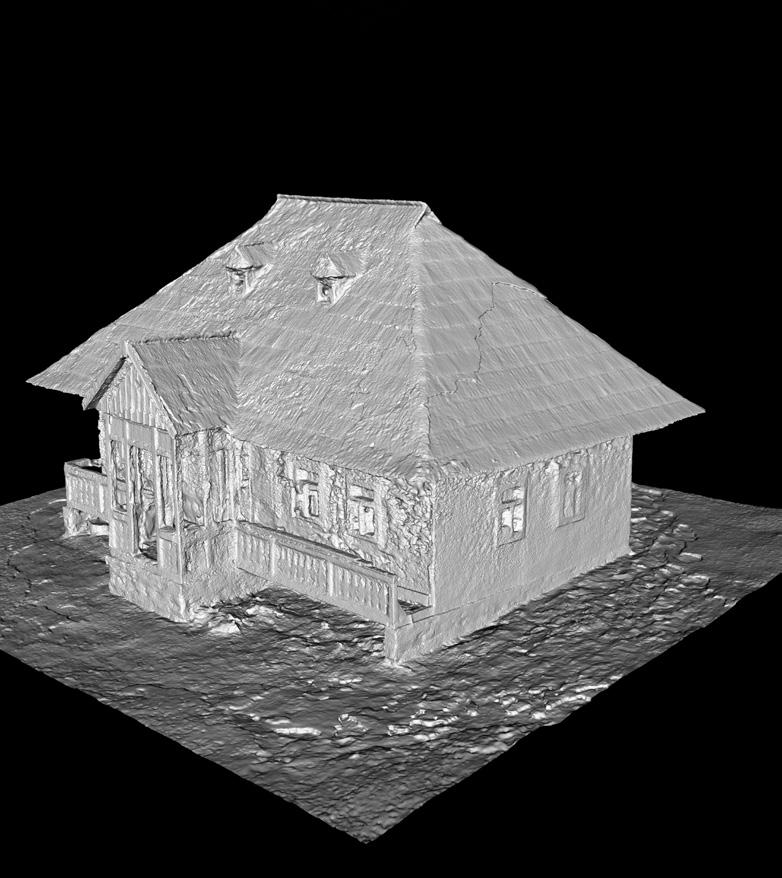

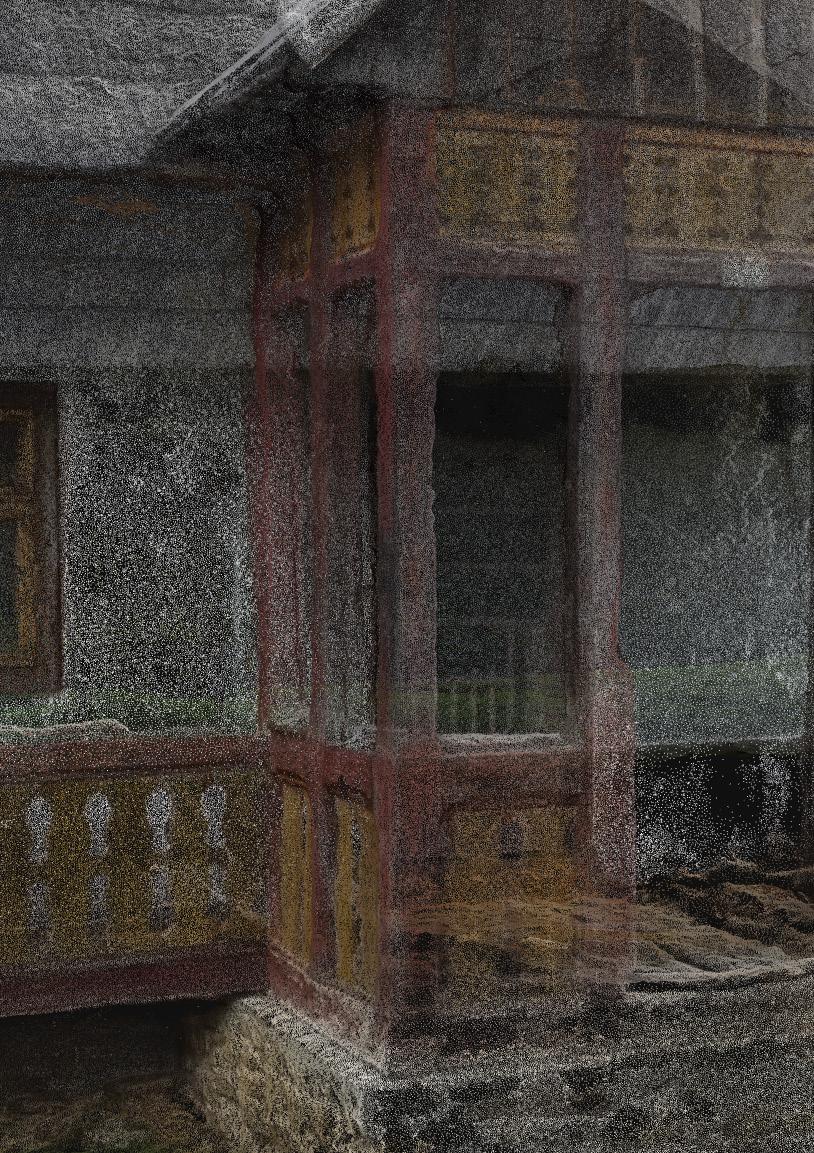

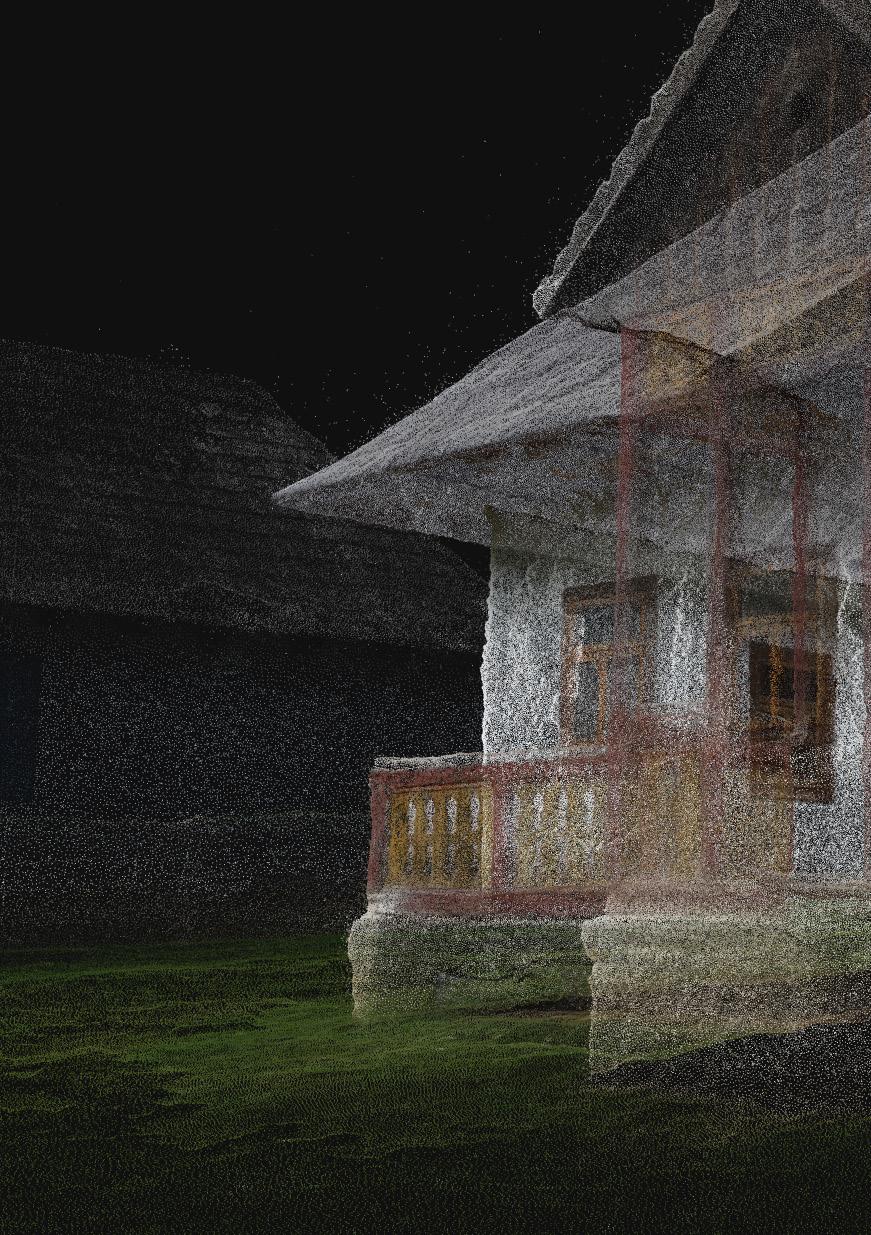

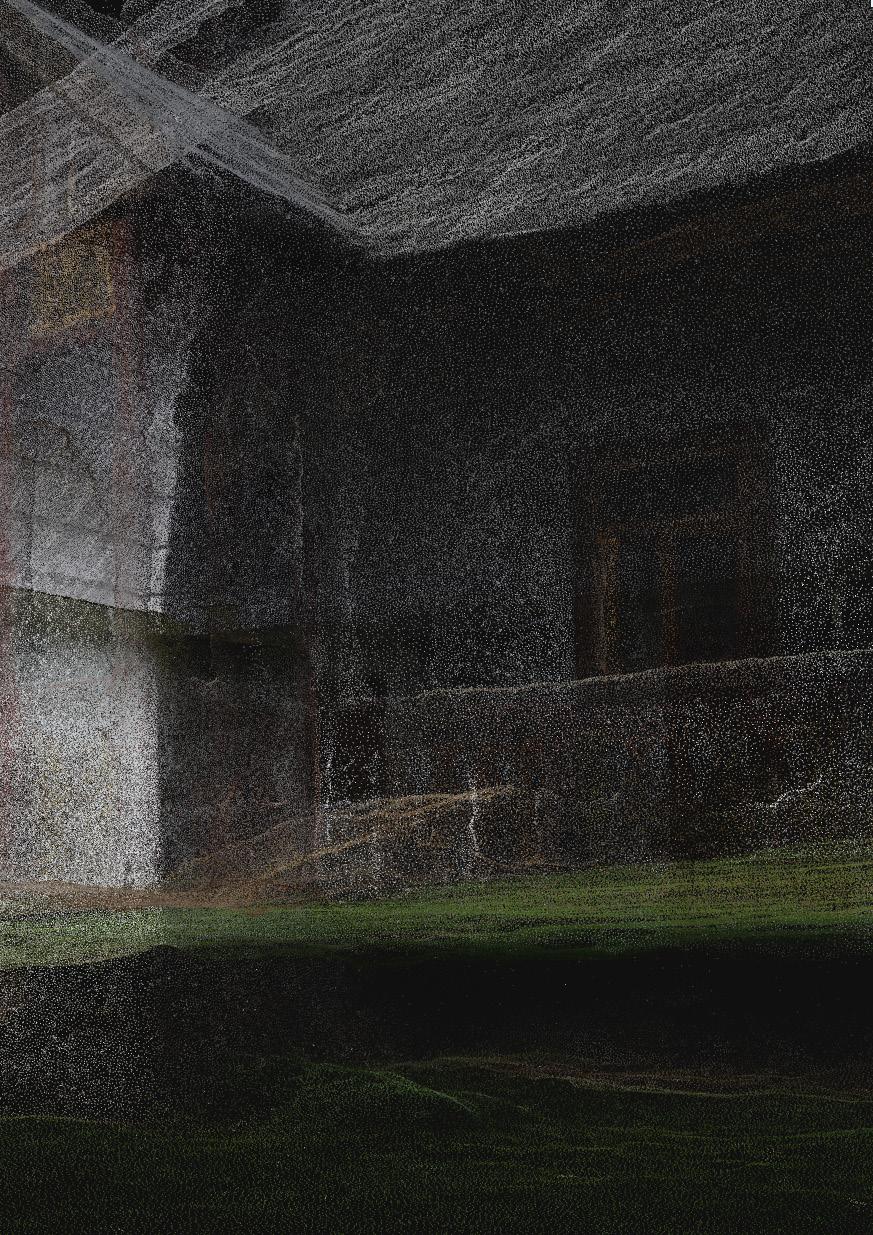

My photogrammetric process follows a rigorous methodology, beginning with data acquisition using a DJI mini 3 SE drone and a high-resolution DSLR MarkVI Cannon camera, followed by image processing in Photoshop and compiling them in RealityCapture.

This study focuses on a selection of vernacular structures from different Romanian regions, ensuring a representative crosssection of architectural styles and traditions. Included in the research are traditional wooden houses, fortified farmsteads, Romani carriages, and urban dwellings influenced by Romanian Renaissance aesthetics. Each of these structures represents a distinct architectural legacy that is currently at risk due to environmental degradation, neglect, and modern urban development pressures.

The precision of photogrammetric documentation ensures that visual, material, and structural characteristics are recorded accurately, laying the foundation for future conservation projects and comparative historical research.

According to Scott’s study, the 3D models produced through this process could as digital blueprints, which can be utilized in preservation planning, architectural analysis, and even contemporary design reinterpretations (Scott et al., 2013). The ability to interact with these digital reconstructions in virtual space makes them an invaluable tool for architectural education, heritage tourism, and urban planning, facilitating broader engagement with cultural heritage beyond physical site visits.

Furthermore, photogrammetry allows architectural heritage to be made widely accessible through virtual exhibitions, interactive databases, and augmented reality applications (Scott et al., 2014). These technologies ensure that even remote or endangered sites remain part of public awareness, bridging the gap between historical research and contemporary

digital engagement. The longterm preservation of Romania’s architectural heritage depends not only on documenting existing structures but also on developing sustainable conservation strategies that integrate digital tools with physical preservation efforts. By adopting photogrammetry as a core method in architectural conservation, researchers and preservationists can safeguard Romania’s vernacular and Neoromanian heritage while creating opportunities for future generations to engage with these structures in new and meaningful ways.

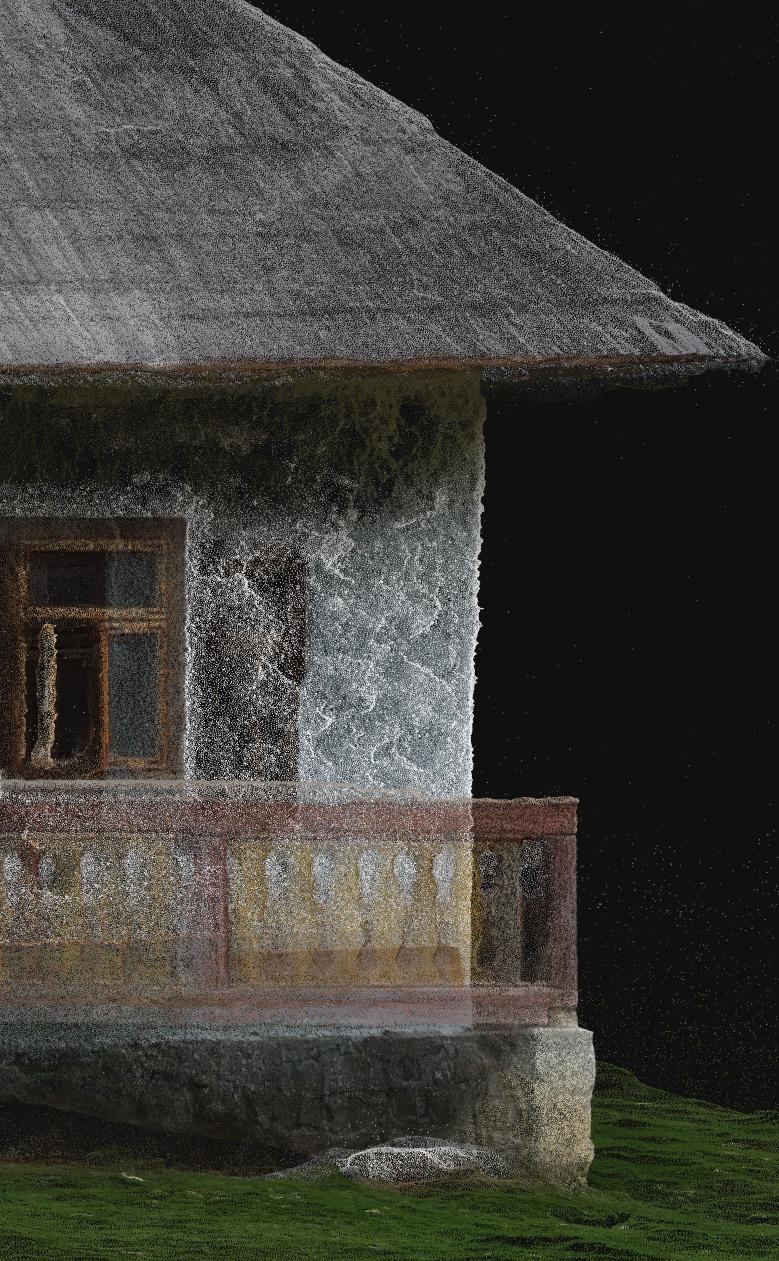

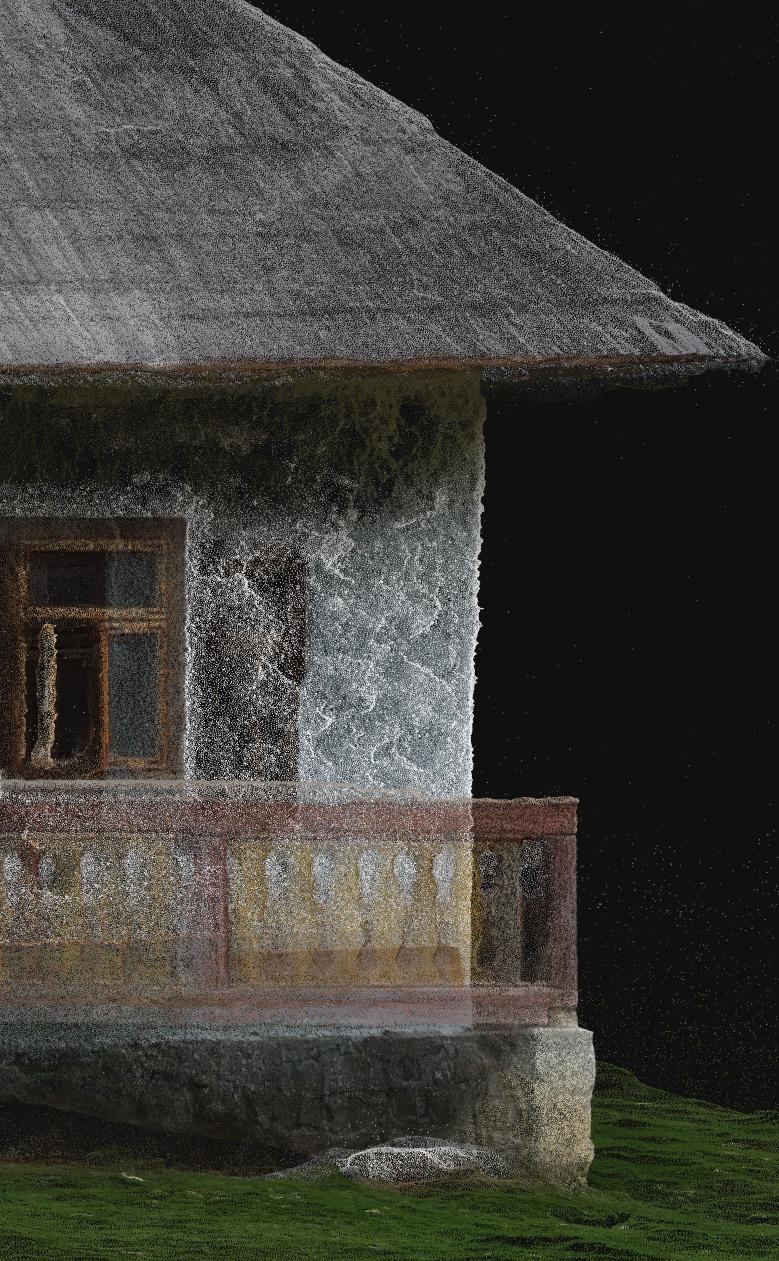

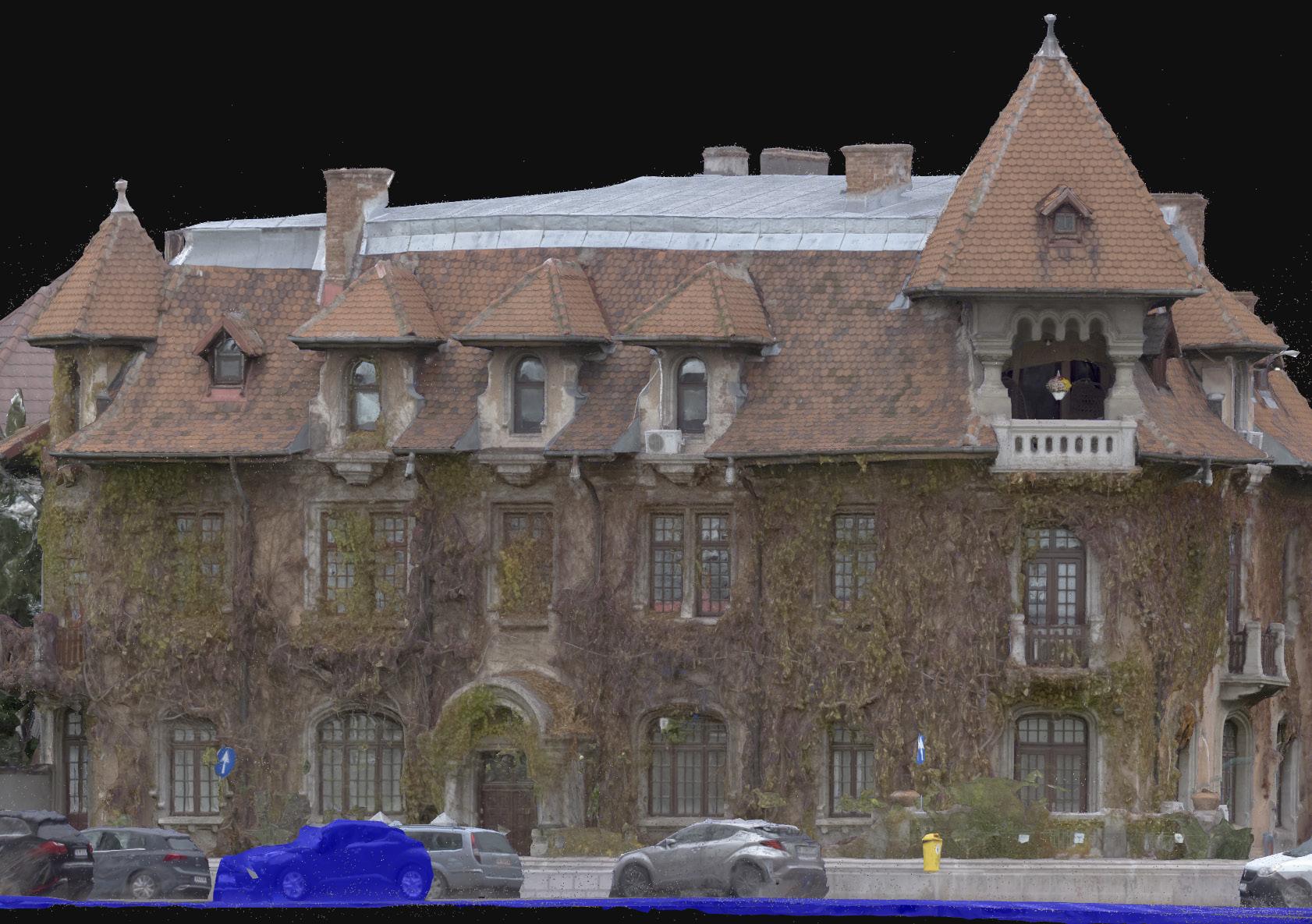

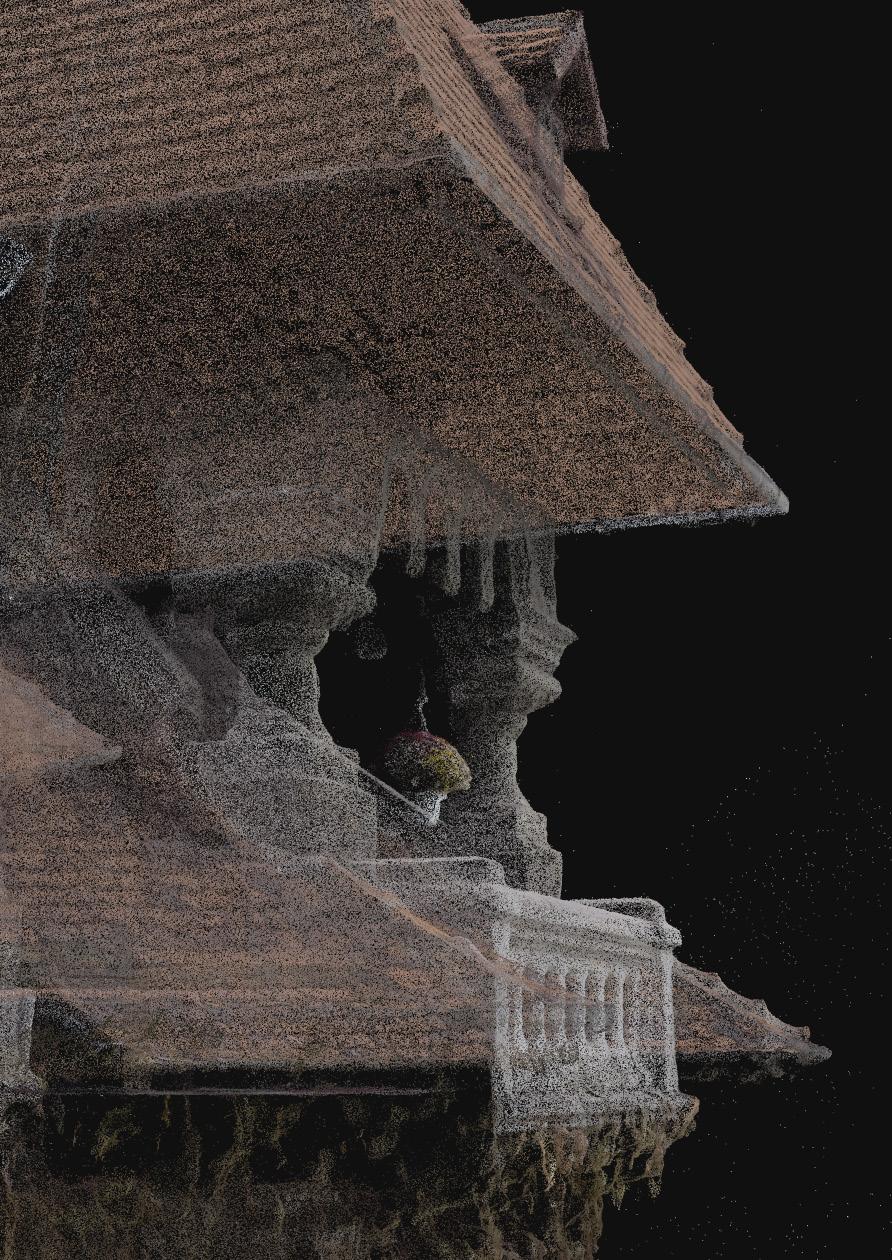

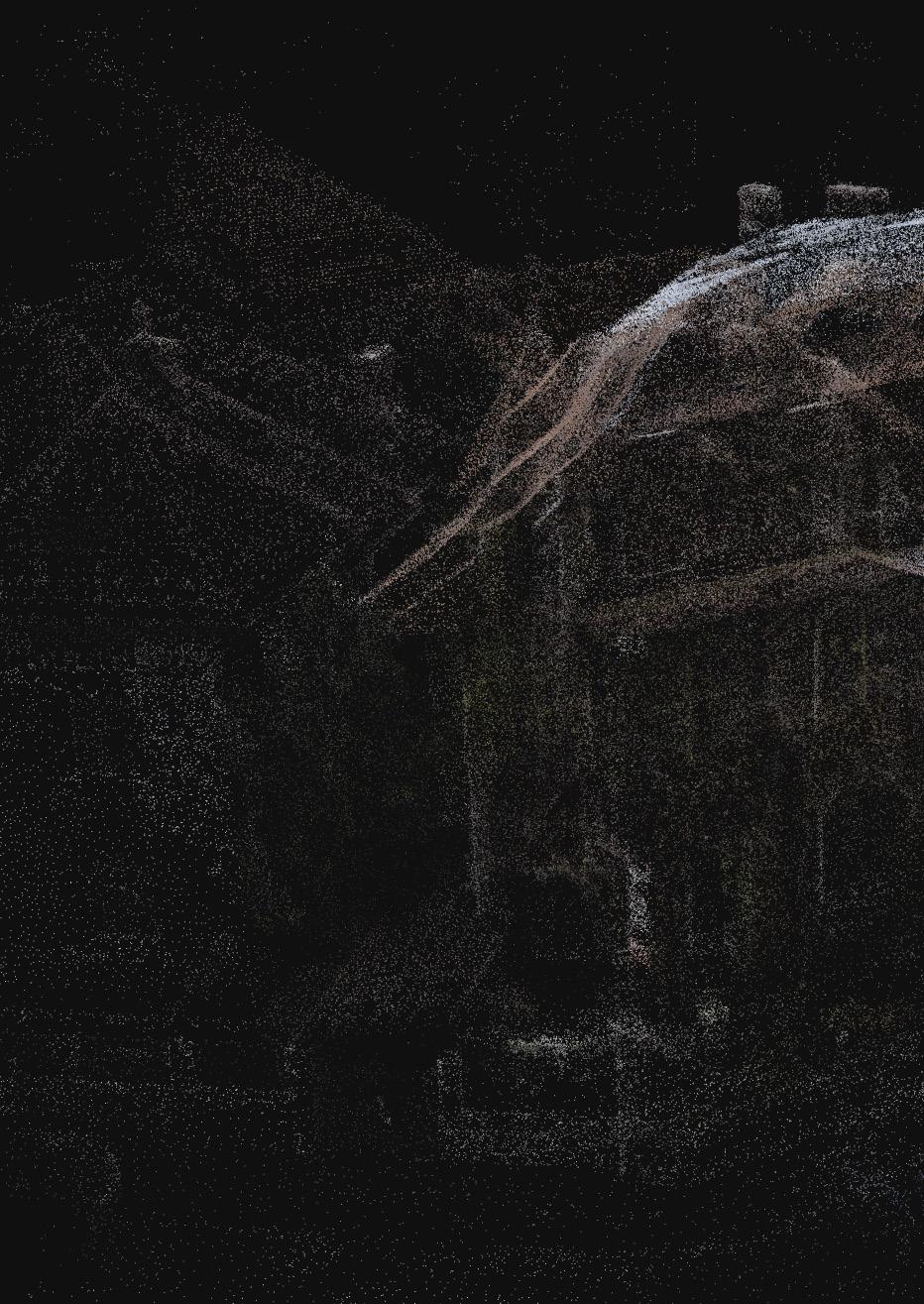

The Neo-Romanian style, emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sought to synthesize traditional Romanian architectural motifs with modern construction techniques. This particular building exemplifies the style with its steeply pitched roof, decorative wooden elements, sculpted window surrounds, and arched loggias. The overgrown vegetation cascading down the façade adds another layer of texture, reinforcing the organic relationship between built form and nature. The scan effectively captures these nuances, highlighting the intricate ornamentation and the distinct interplay of light and shadow.

From a methodological perspective, drone technology facilitated aerial data acquisition, enabling a comprehensive survey of the roof and upper levels, areas traditionally difficult to access. Meanwhile, the DSLR camera provided high-resolution imagery, crucial for refining textures and ensuring the fidelity of fine architectural details. However, challenges emerged in balancing exposure settings across different light conditions, particularly when capturing darker recesses and bright

sky-lit surfaces. Additionally, reflective and transparent materials introduced distortions in the point cloud, requiring post-processing adjustments to refine the accuracy of the reconstruction.

The ability to analyze the predominant color palette and texture distribution in a digital format extends beyond heritage documentation. Such data can serve as an asset in architectural conservation efforts, material studies, and even contemporary design interpretations inspired by historical forms. The process of digital preservation offers an opportunity to recontextualize these structures within new frameworks, ensuring that their architectural legacy remains accessible, regardless of the evolving urban landscape.

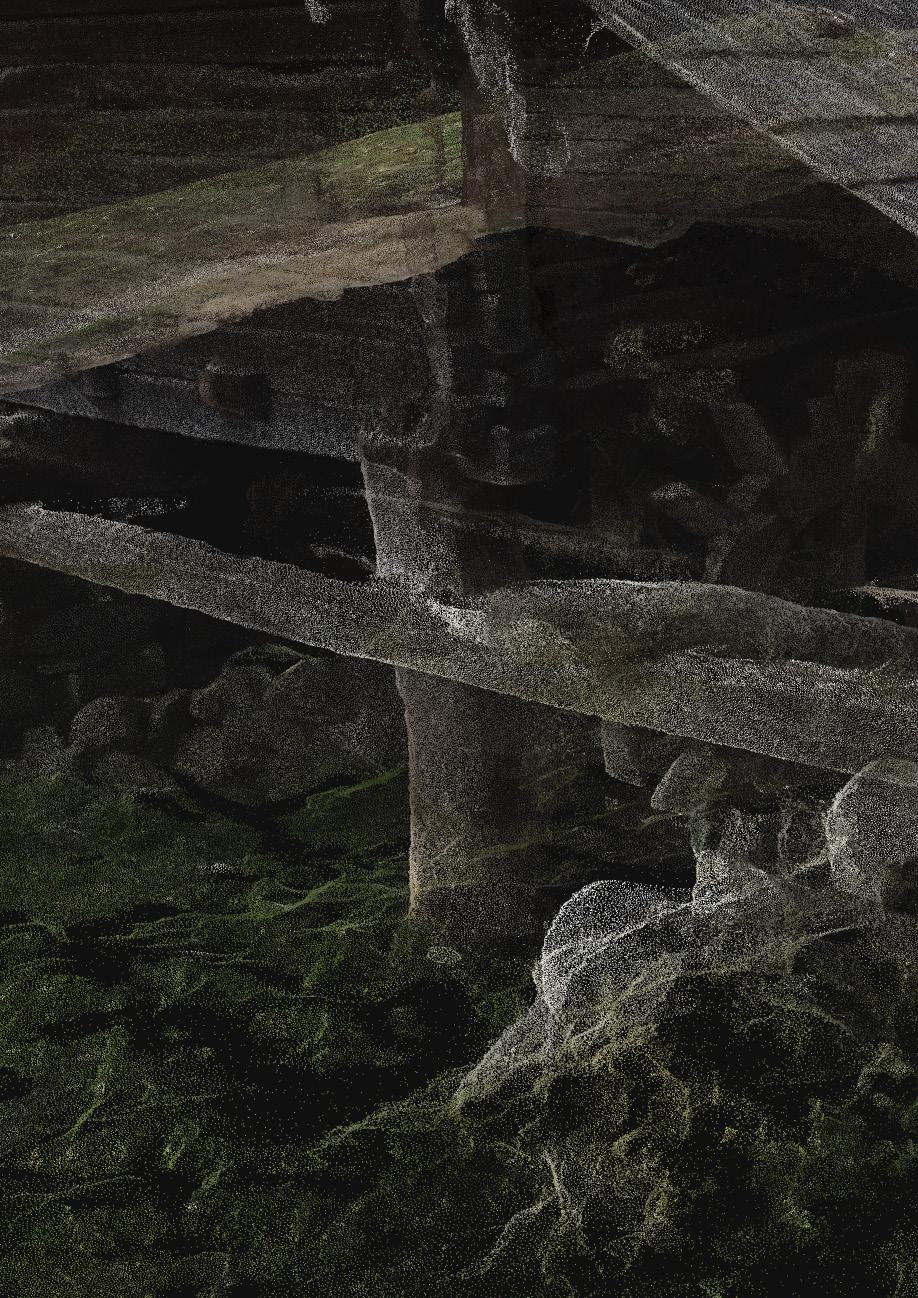

This scan captures a traditional 19thcentury Romani carriage, a significant artifact from a time when Romani communities had little to no legal rights and survived through skilled craftsmanship and trade. Many Romani artisans specialized in silversmithing, leatherwork, and shoemaking, exchanging their work for food, jewelry, and gold. The nomadic lifestyle, which was both a cultural choice and a necessity, was shaped by systemic discrimination, forced slavery, and the lack of governmental support. These carriages served as both transportation and mobile dwellings, allowing families to remain self-sufficient despite ongoing societal hardships.

This photogrammetric scan was an experimental attempt using an iPhone camera, testing the feasibility and limitations of phone photography. While the resolution remained relatively high, the field of view introduced challenges, resulting in inconsistencies and missing data. The process revealed noticeable gaps in the model, highlighting the difficulties

in maintaining consistent exposure, ISO settings, and depth accuracy with a mobile camera. Unlike DSLR or drone-based scanning, the limitations of an iPhone made it significantly harder to capture complex geometry and shadowed areas, particularly when dealing with larger objects or intricate structural details.

Despite these challenges, the scan provides valuable insight into the structural composition of Romani carriages, emphasizing their wooden framework, iron-rimmed wheels, and protective fabric covering. The imperfections in the model underscore the importance of using professional-grade photogrammetry equipment when working on highaccuracy architectural documentation, especially for historical artifacts requiring comprehensive conservation records. This test also suggests that while mobile photogrammetry offers accessibility, it may not be suitable for capturing large-scale heritage structures with intricate details.

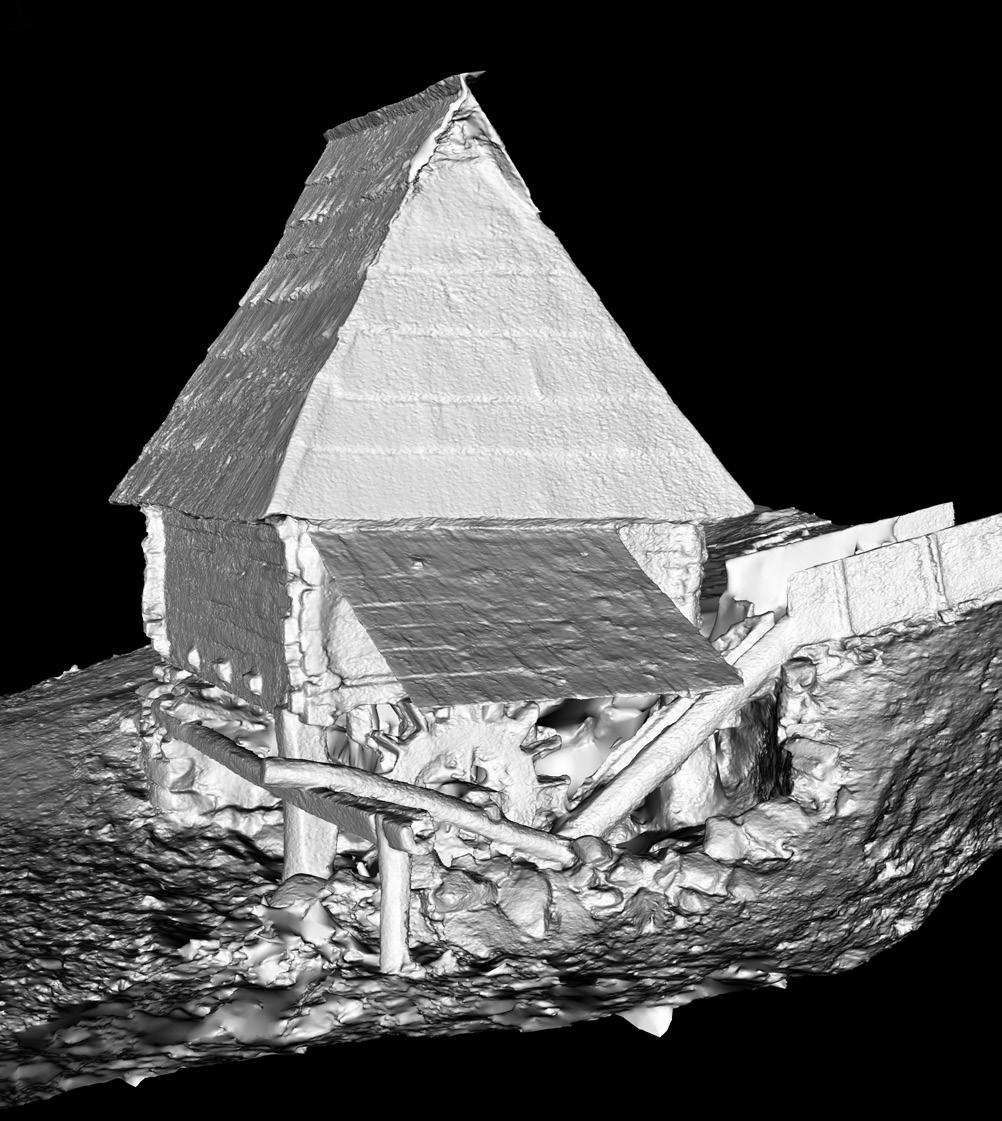

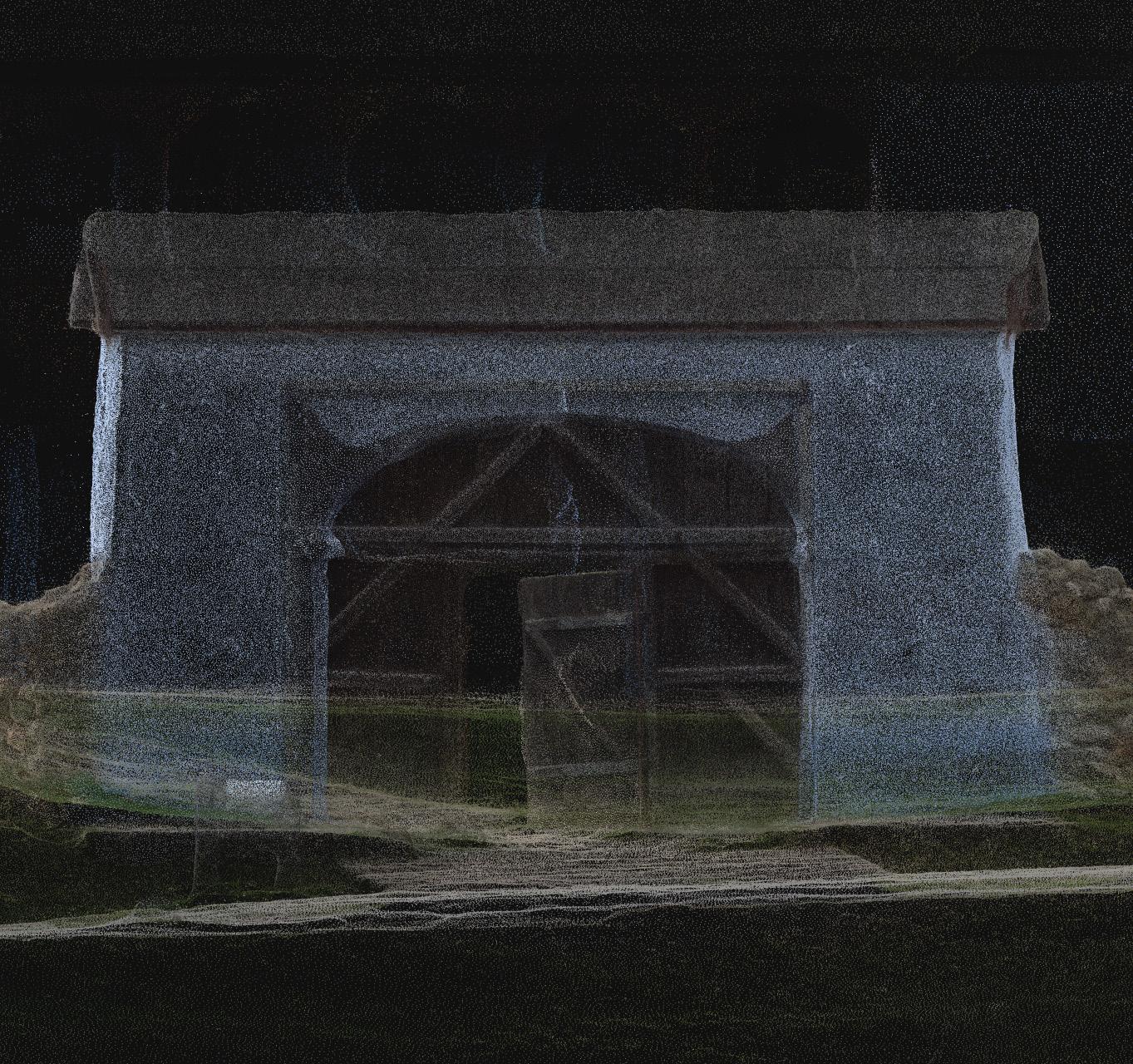

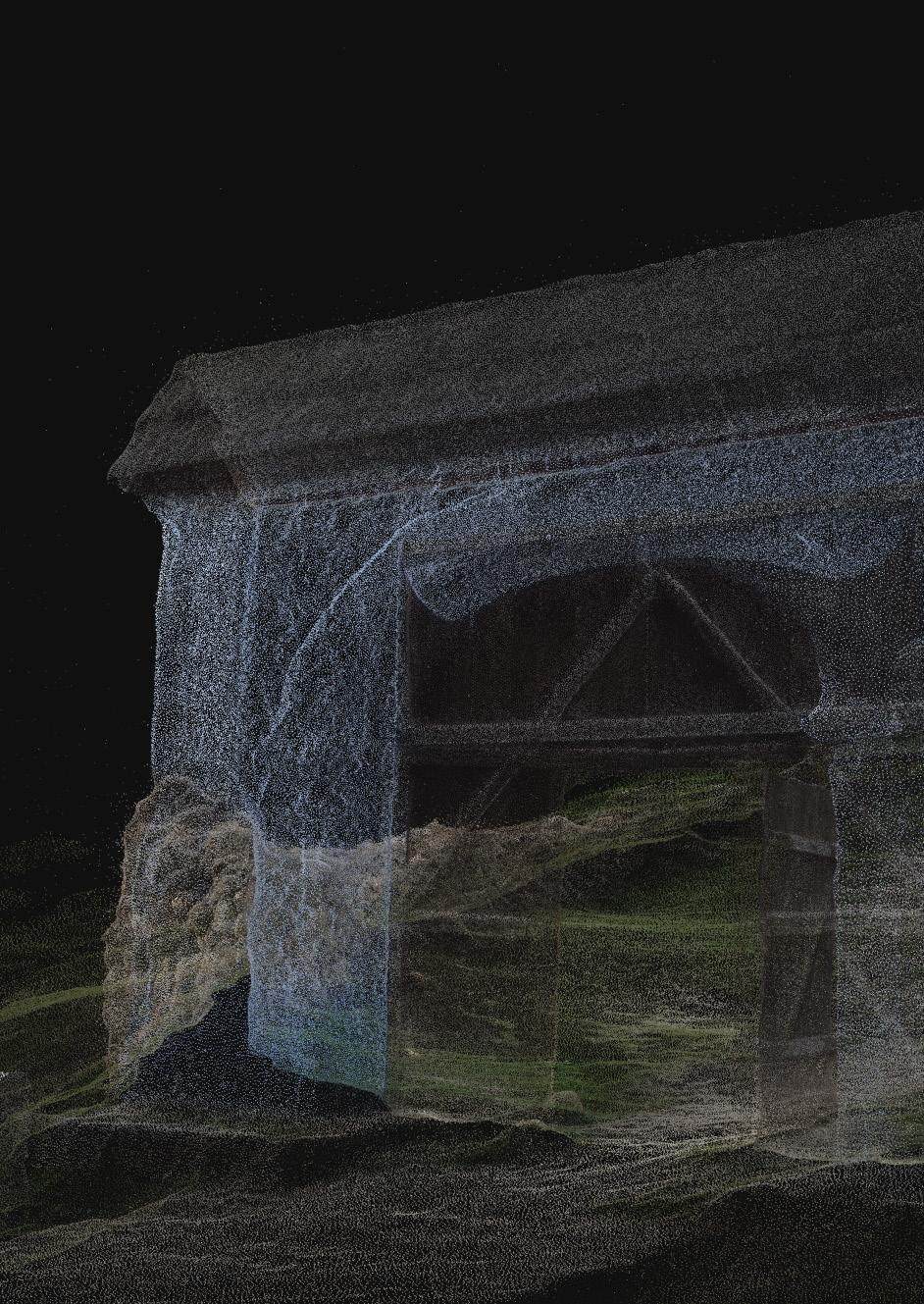

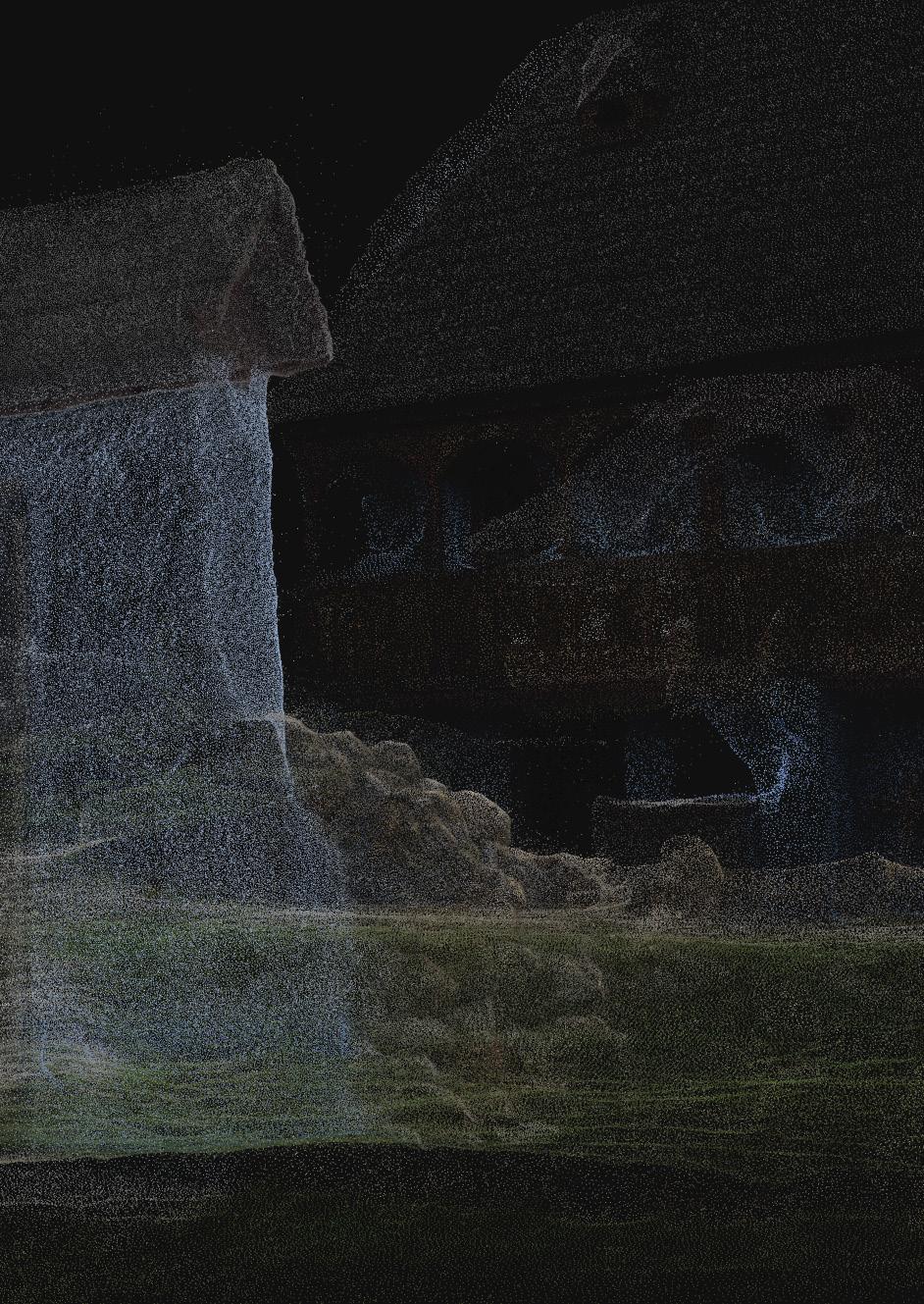

RIVER MILL

This 19th-century watermill exemplifies the ingenuity of vernacular architecture in Transylvania, where traditional knowledge and environmental adaptation shaped rural structures. Positioned near a river to harness the natural flow for grain milling, these mills played a crucial role in community subsistence. The steeply pitched wooden shingle roof, characteristic of mountain regions, reflects a pragmatic response to harsh climatic conditions, preventing excessive snow accumulation and ensuring durability.

The structure sits on a solid stone foundation, stabilizing it against moisture and ground shifts. The wooden beams and planks, carefully assembled using interlocking joinery, highlight traditional carpentry techniques that have endured for generations. The walls, built with hewn timber, exhibit a robust yet simple construction, ensuring longevity with minimal maintenance. The thatched overhang at the entrance provides

additional shelter, shielding the working mechanisms from excessive exposure to the elements.

The mill’s wheel and channeling system, partially preserved, reveal the craftsmanship involved in water-driven milling technology. The wooden paddles and support beams, though weathered, demonstrate the efficiency of the design, optimized to operate with minimal manual intervention. The use of local materials—stone, timber, and thatch— further emphasizes the sustainable building practices intrinsic to vernacular architecture.

This scan captures the texture and depth of the materials, preserving their tactile qualities in a digital format. However, certain areas suffer from incomplete data acquisition due to the complexity of overlapping wooden elements and shadowed recesses. Despite these challenges, the high-resolution model enables a thorough analysis of the structure’s integrity, which might offer valuable insights for future conservation efforts.

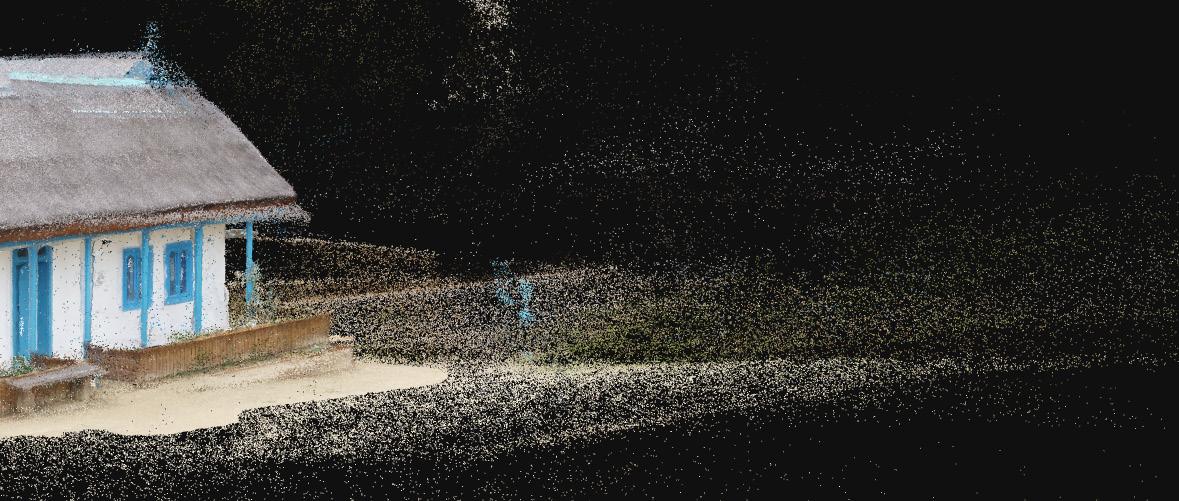

This 19th-century seaside village dwelling from Constanța is a prime example of Romania’s coastal vernacular architecture. The whitewashed walls and striking blue accents are characteristic of the region, with the use of blue likely influenced by the Phanariot period, a time when Greek culture left a notable imprint on architecture and decorative elements around Dobrogea region. This color choice, also seen in Greek coastal settlements, was both aesthetic and practical, helping to reflect sunlight and keep interiors cool.

The thatched roof provides natural insulation against the coastal climate, shielding the house from the heat of summer and the dampness of the Black Sea air. The elongated, linear structure was designed to accommodate large families, a common trait in rural dwellings of the time. A covered wooden porch runs along the facade, serving

as both a transitional space and a shaded outdoor area for daily life. Unlike many rural houses of the time, which often had separate cooking structures to reduce fire risks, this dwelling features a chimney, indicating the presence of an integrated kitchen within the home.

Compared to other scans in this study, this particular 3D reconstruction faced more challenges. Captured exclusively with a drone, the process was hindered by dense surrounding vegetation, which obstructed the field of view and introduced inaccuracies in the final model. Despite these setbacks, the scan still highlights the building’s key architectural features, preserving its place within the historical narrative of Romania’s coastal heritage.

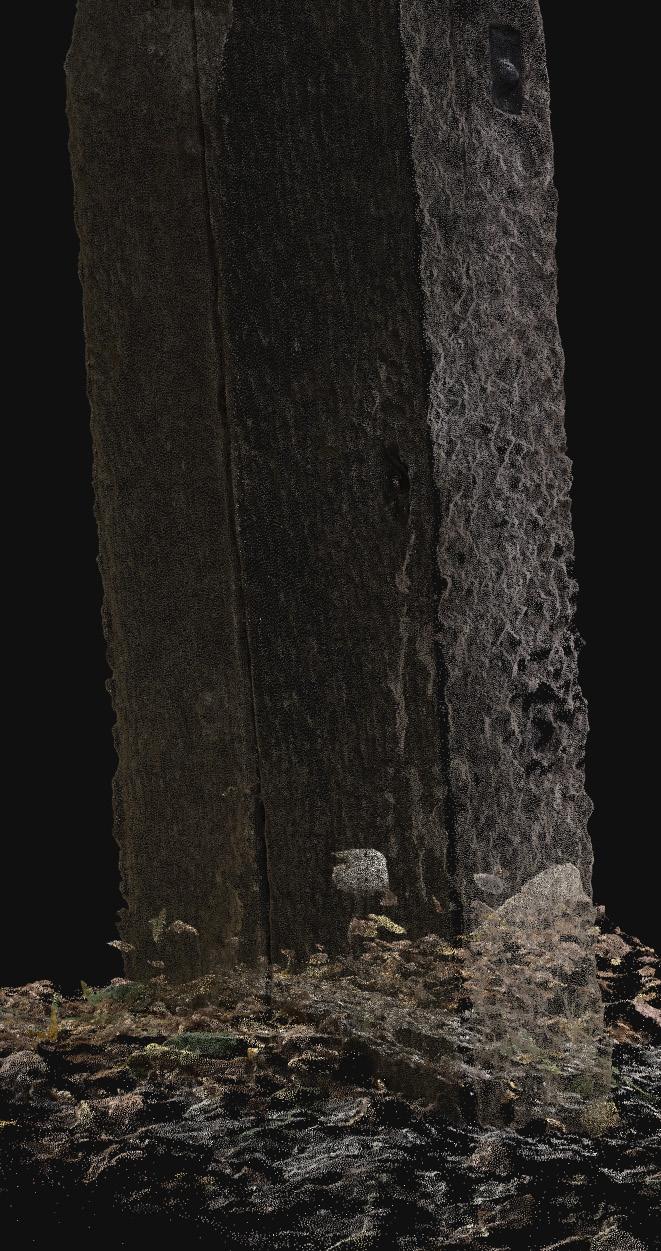

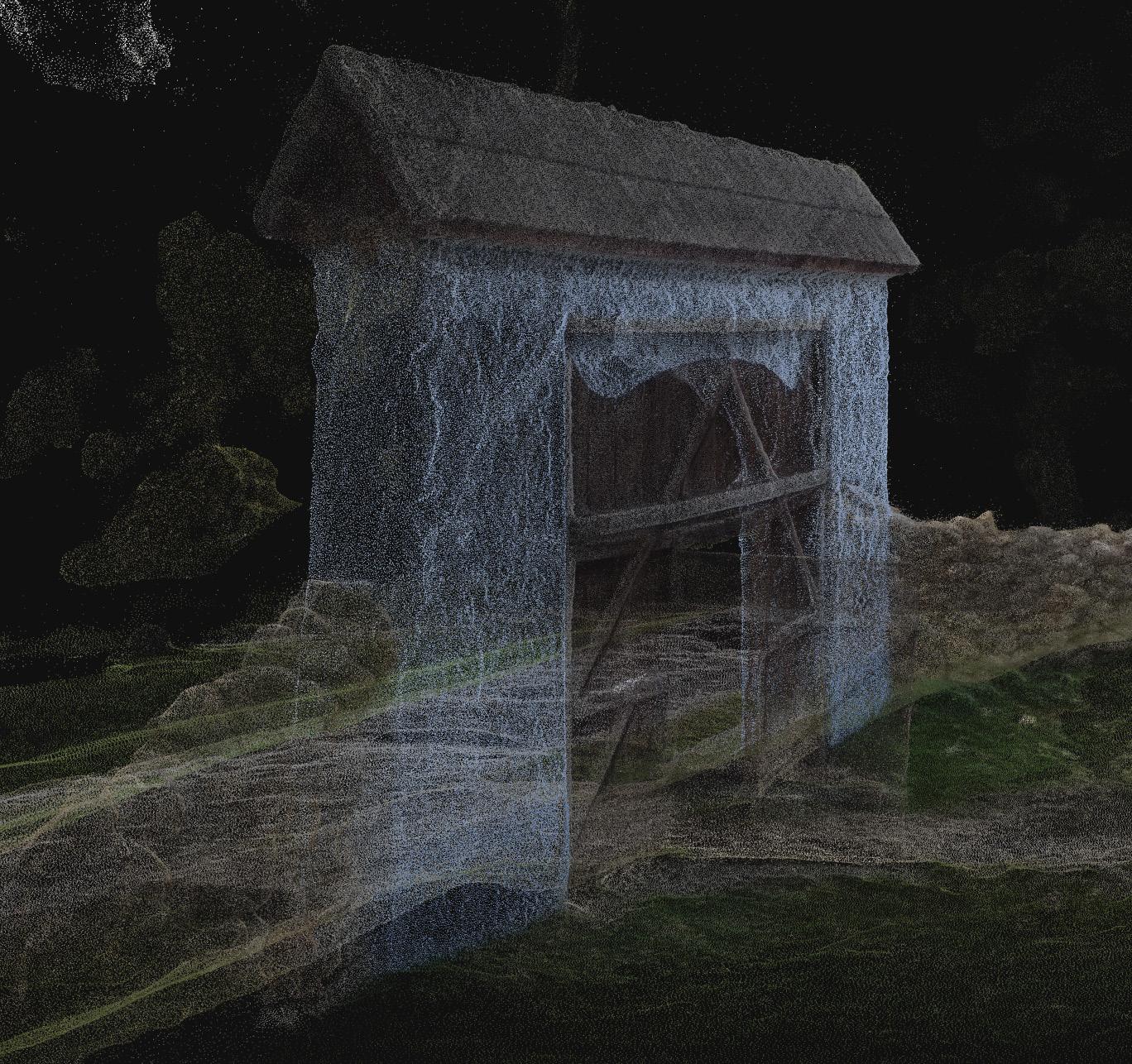

The entrance gate of the Goldsmith’s House in Alba County is a defining architectural element, reflecting both the functional and symbolic aspects of traditional Transylvanian rural architecture. With a robust double wooden door and a pitched roof, the gate provided protection against external threats while also marking the transition between public and private space. These gates were often built to secure homesteads from intruders, wild animals, and

harsh weather conditions, while their size accommodated carts and livestock.

Beyond its practical function, this type of entrance gate carried deep cultural significance, rooted in folkloric beliefs and regional identity. In many rural communities, a wellconstructed gate was thought to ward off misfortune and bad spirits, reinforcing the idea of a protected and sacred household space. The use of heavy timber and

whitewashed masonry reflects local craftsmanship traditions, ensuring durability and aesthetic harmony with the surrounding architecture.

The gate of the Goldsmith’s House follows the characteristic Transylvanian style, commonly found in fortified farmsteads, where security and self-sufficiency were essential. Its structure integrates seamlessly with the broader estate, which was designed for both residential and artisanal purposes, showcasing the architectural resilience of historic rural Romania.

Through photogrammetric scanning, this gate has been digitally preserved, allowing for further study of its materials and construction techniques. This documentation ensures that, even as physical structures age and degrade, their cultural and historical value remains accessible for future conservation efforts.

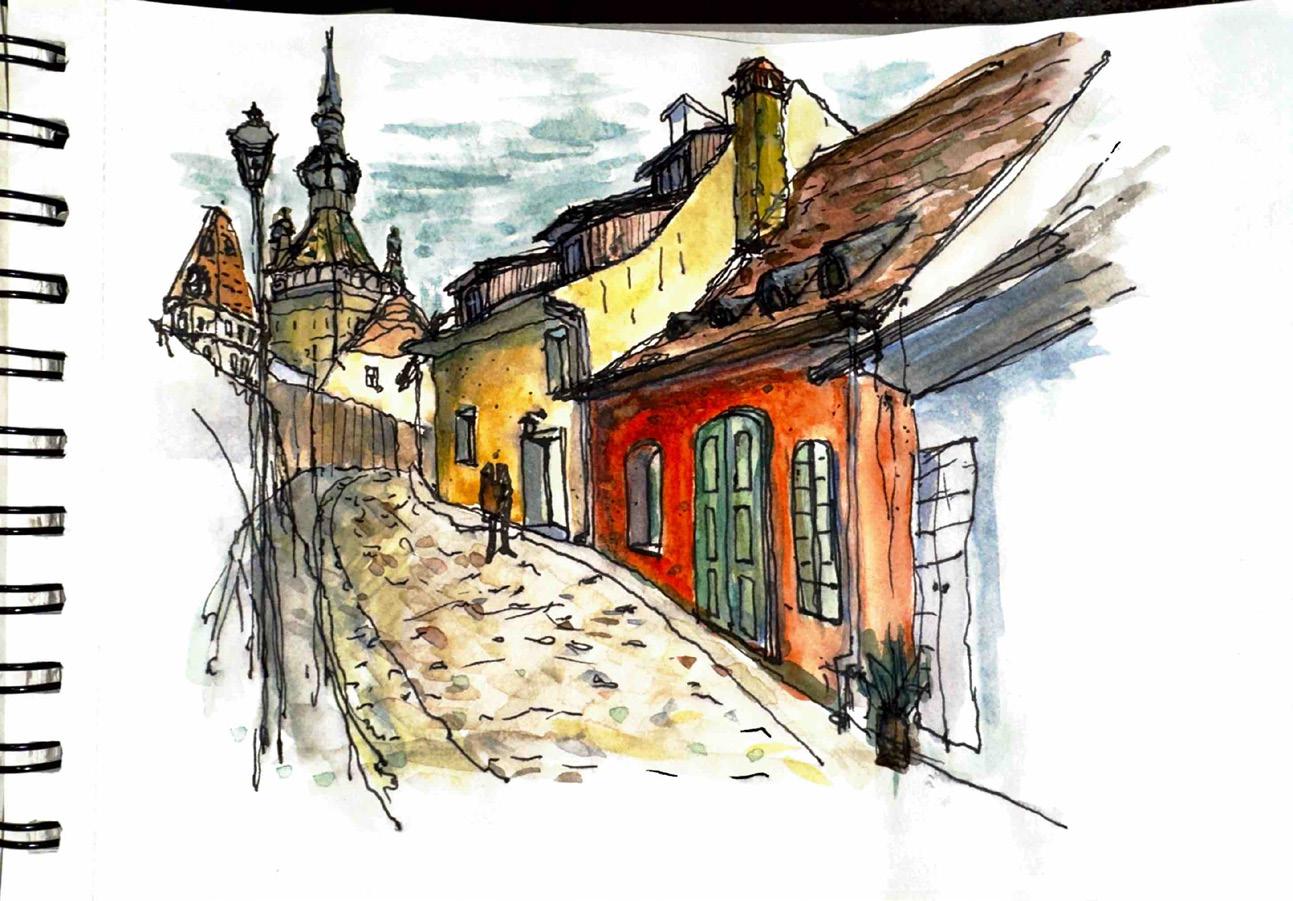

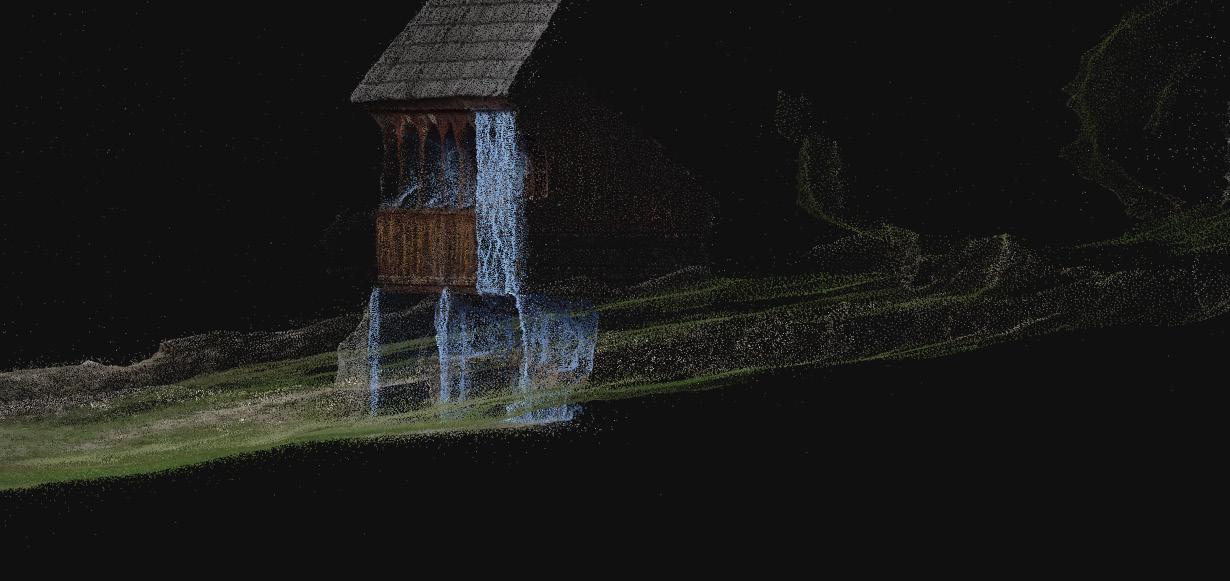

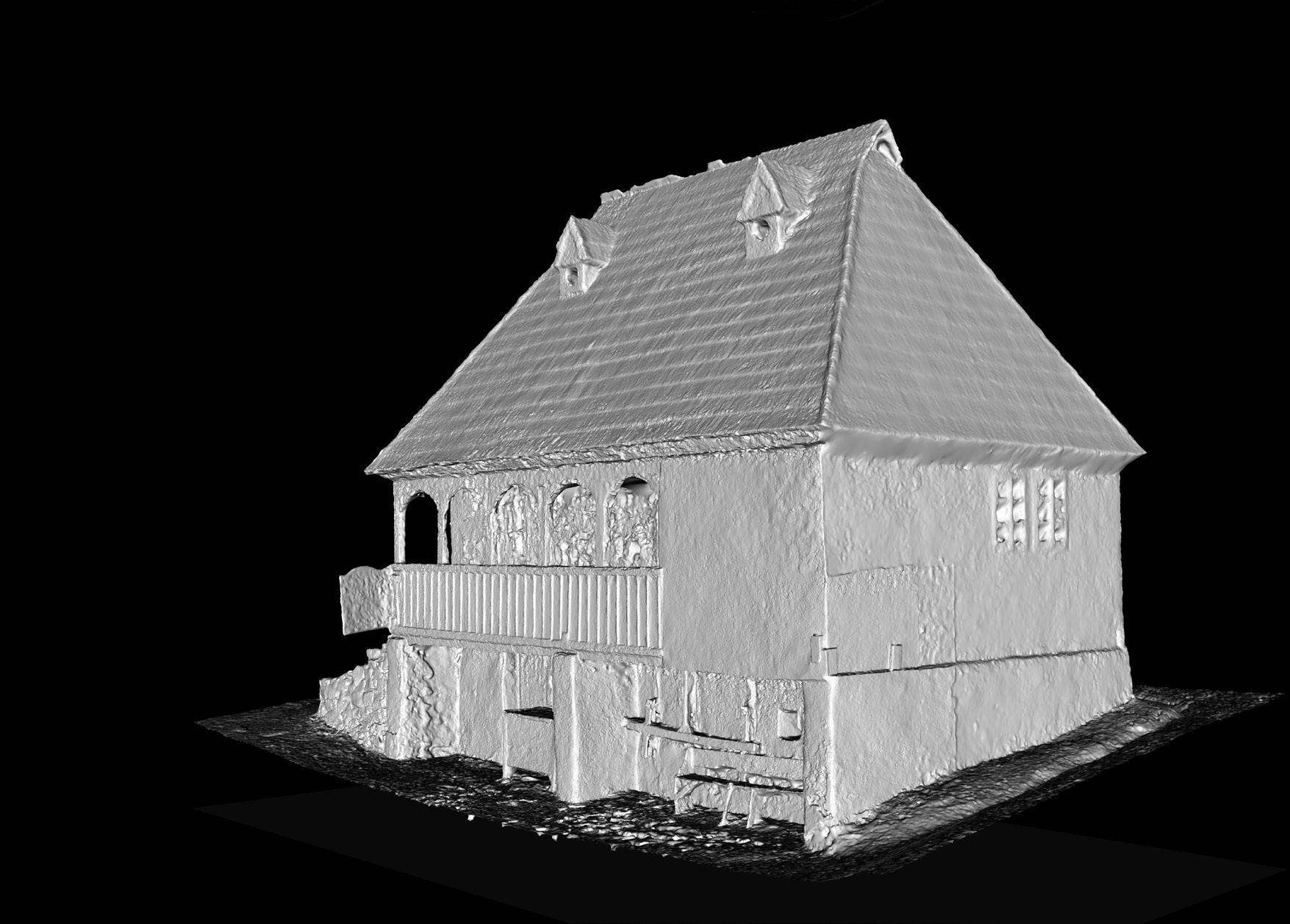

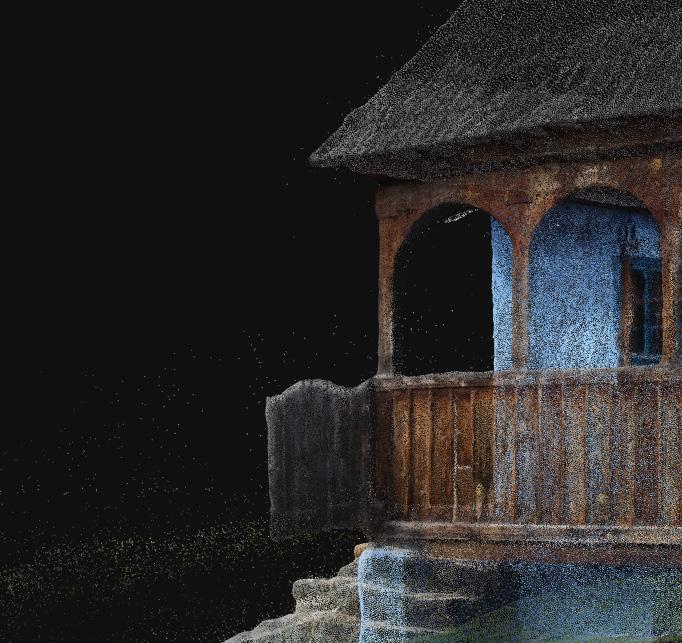

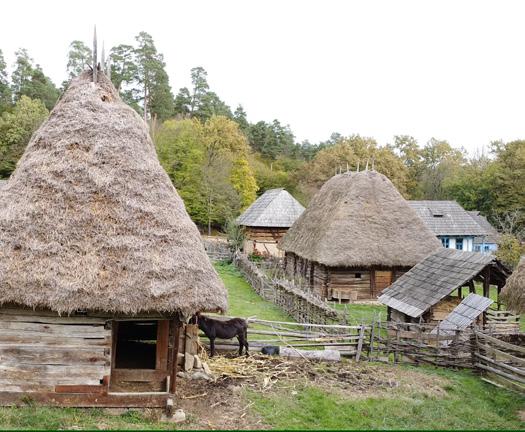

This dwelling is a remarkable example of vernacular Transylvanian architecture, preserved and restored as part of Astra Museum’s initiative to safeguard Romania’s ethnographic heritage. With a budget of 2.5 million euros, the restoration project aimed to maintain the authenticity of the structure . The project was completed in 2011, ensuring the house’s structural integrity while keeping its historical character intact.

This house represents a regional adaptation of Brâncovenesc influences (such as the terrace), though its primary identity aligns with local Transylvanian rural architecture of the early 19th century. The design follows the typical split-level layout, where the lower level served as storage for agricultural produce, benefiting from the thermal insulation of the stone foundation, while the upper level housed living quarters, featuring two bedrooms and a communal space. The steeply pitched shingled roof are defining features that reflect the adaptation to the harsh winters of the region.

The blue façade, a common characteristic in rural Transylvanian houses, was both an aesthetic choice and a practical one, as lime-based paint with blue pigment was believed to deter insects. Through photogrammetric documentation, this project captures the architectural and cultural significance of the Goldsmith Miner’s House, allowing for its precise digital preservation and future study. The use of highresolution 3D scanning provides an accurate representation of the house’s textural details, structural elements, and material composition, contributing to longterm conservation and heritage education efforts.

In Chapter 5, I am proposing an interpretation of retrofitting this house, exploring how a contemporary extension design could co-live, but contrast, the historic fabric, while respecting the existing architectural language. While the design will not be explored in full detail, just to serve as an example, the focus will be on maintaining authenticity while addressing contemporary functional needs, ensuring that such heritage structures remain adaptable and relevant in a modern context.

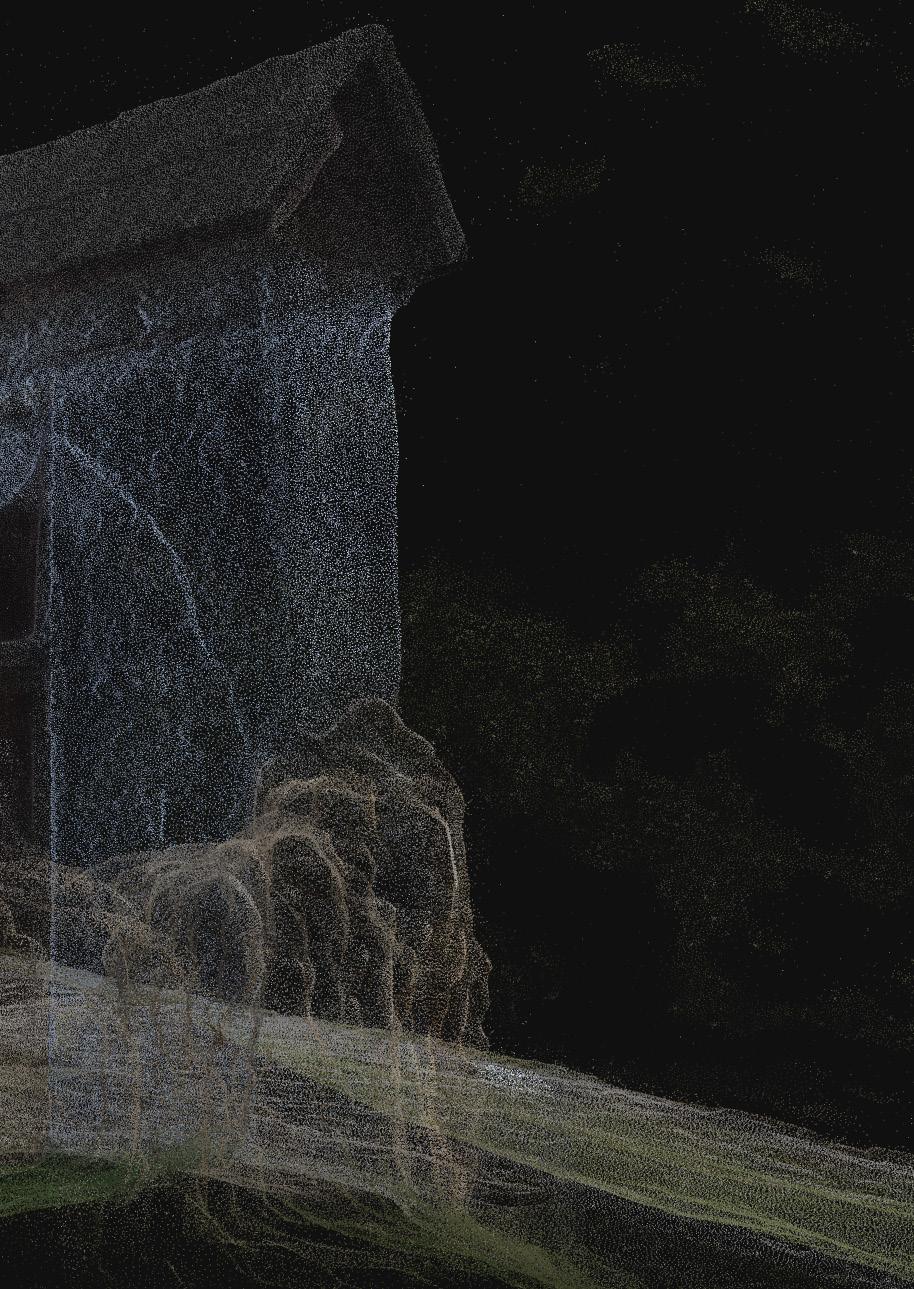

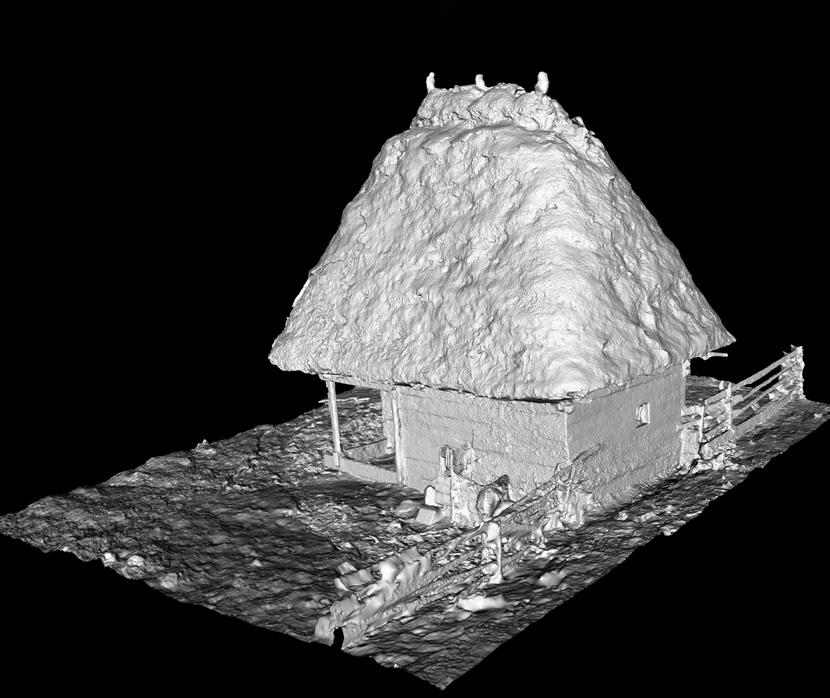

This traditional Transylvanian animal shelter stands around four meters tall, its steeply pitched thatched roof providing insulation against harsh winters while preventing snow buildup. Made from locally sourced timber and stacked wooden planks, its compact rectangular footprint minimizes heat loss, offering essential protection for livestock.

The photogrammetric scan captures the weathered textures of the timber and the densely packed thatch, highlighting the handcrafted nature of its construction. While highly detailed, minor depth inconsistencies reveal the challenges of scanning organic surfaces under variable lighting conditions.

This shelter is a prime example of vernacular architecture, demonstrating function-driven design that remains relevant for heritage conservation and sustainable building practices.

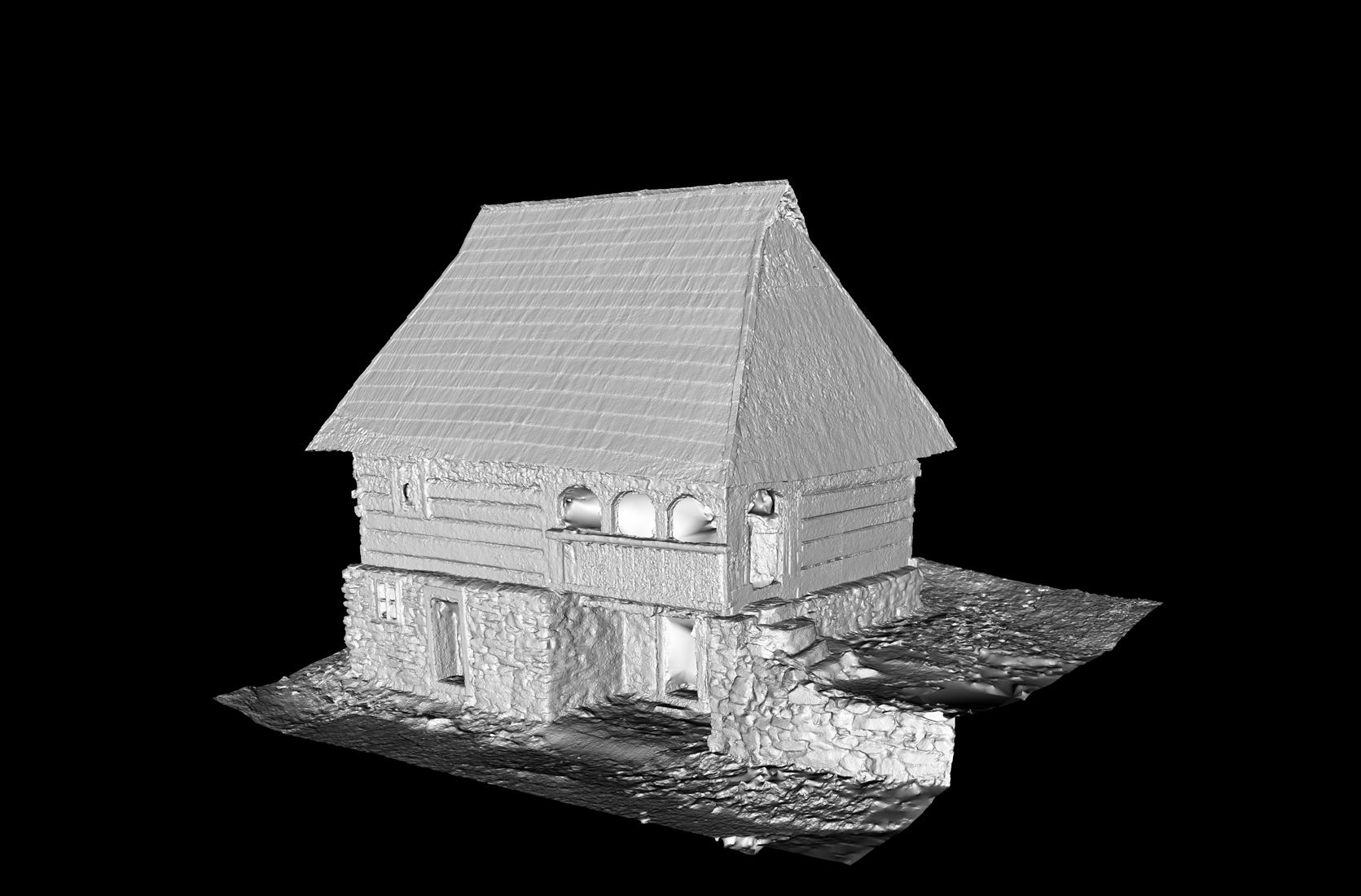

This 19th-century miner’s house from Transylvania is a testament to the region’s adaptation to the landscape and climate.

Constructed on sloped terrain, the stone-clad ground floor is partially embedded into the land, providing natural insulation and stability. The upper floor, framed in timber, is elevated and protected by a steeply pitched roof covered with charred timber slates, enhancing durability and weather resistance.

The solid stone walls of the lower floor create a well-insulated space, likely used for storage and preserving food supplies. The

upper level, accessible from the sloped side of the terrain, serves as the main living quarters.

A small balcony with arched openings adds both functional and aesthetic value, allowing ventilation while maintaining privacy.

This house embodies the resourceful craftsmanship of miners, using locally sourced materials to create a structure that balances functionality with vernacular architectural charm.