7 minute read

Hybrid PCTC order

WINGD RECEIVES 1ST ORDER FOR ELECTRIFICATION SOLUTION

The award of a fi rst contract for a WinGD battery-hybrid powerpack represents a next step on the engine designer’s journey into system integration and electrifi cation, Paul Gunton reports

Swiss-based engine and marine propulsion designer WinGD has secured its fi rst order for a battery-hybrid powerpack for deep-sea ships following a contract with Jinling Shipyard earlier this year. The contract will see the company’s system installed on four 7,000CEU PCTC vessels on order at China’s CSC Jinling Shipyard with deliveries due to start in 2023.

In an exclusive interview in early July with The Motorship, WinGD’s hybridisation programme manager Stefan Goranov said the order “is a good sign that we are [moving] in the right direction”. A formal announcement about this first order with more details will be issued soon.

The Motorship has followed WinGD’s development since September 2019, when we first reported that it was working on feasibility studies to quantify the benefits and the tradeoffs between a conventional and hybrid propulsion system for deep sea vessels.

A transient-capable full-system simulations and modular Hybrid Control System, backed up by a seamless workflow across all the stages of development and deployment, sets WinGD’s development apart from other providers, Goranov believes.

He indicated that the specifications for the energy management controller are continuously evolving, explaining that its approach to such projects is to prepare bespoke solutions, that are based on a customer’s specific requirements, rather than off-the-shelf options. These include such details as how the system shall behave in certain conditions and what information is to be displayed on board.

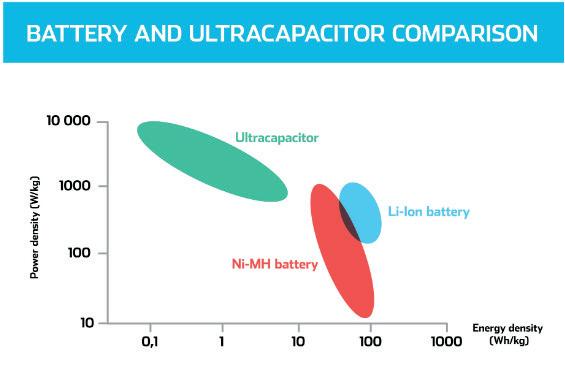

Other ship operators are also taking an interest in WinGD’s system. “We are now working on a few feeder container ships with some customers,” Goranov said, without mentioning names. He is also looking at the potential for adding similar systems – but using super capacitors rather than batteries – for example on LNG carriers, which are traditionally equipped with shaft generators only.

Main engine; main focus

Offering hybrid systems may seem an unusual departure for a traditional engine designer, but Goranov sees that as an advantage. “We are a component-agnostic system integrator; the only piece of equipment we are designing in this whole system is the main engine.” By contrast, system is the main engine.” By contrast, pure system integrators do not have pure system integrators do not have any in-house engine expertise and any in-house engine expertise and access to the latest engine-related access to the latest engine-related technologies which can be technologies which can be combined to further boost the combined to further boost the overall ships’ efficiency, he said. overall ships’ efficiency, he said. Since WinGD began developing Since WinGD began developing

8 Stefan Goranov,

WinGD's hybridisation programme manager

this programme in 2018, “our approach is to put the main engine in the centre we then match the rest of the components, and we actively control everything as one coordinated whole, with the main engine in the equation”, Goranov said. For example, if the goal is to shave peaks – taking engine power to charge batteries when other demands are reduced – that must be plannedto take into account all the inefficiencies in a system. As well as the main engine, that is coupled to a shaft generator, two converter stages and the battery itself, which could amount to 10% total losses. So there is a risk that although peak-shaving might result in an engine running more efficiently, because of losses elsewhere that it has to overcome, fuel consumption of the ship as a whole could actually increase.

To overcome this risk, WinGD has developed a hybrid control system that interfaces with the engine control system to allow peak-shaving “only when its optimisation functions show that, given all the constraints, we will be better off doing it,” he said.

To illustrate these points when a ship is at the design stage, WinGD has built a full-system simulation suite, which it also believes sets it apart from other system integrators. “We use the same main engine models that we use for designing those engines,” Goranov said, “and when we model the rest of the systems around it, we can input any operational profile and can see what behaviour and the fuel consumption would be, and derive figures on what the corresponding CO2-equivalent emissions are anticipated.”

8 Bunker vessels,

as well as smaller inland vessels, represent an interesting 4-stroke segment for WinGD's new electrifi cation off ering. Cruise vessels are an interesting market for electrifi cation solutions, but "generally fi t components from a single supplier", Goranov noted

Deepsea hybrid options

The Motorship suggested to him that, for ships on deepsea voyages, their machinery operates in a steady state for much of the time and some might be surprised that there are enough opportunities to benefit from a peak-shaving battery hybrid set-up.

That view is too simplistic, he suggested, as the peakshaving is not the only feature a hybrid system enables. He prefers to refer to ‘electrification’ rather than ‘hybrid’, since

the latter implies that there is a battery in the system. An appropriately sized and controlled battery would certainly avoid a power black-out, but “does it justify the business case?” he wondered.

Instead, “we maximise the use of the main engine... and any alternative energy resources in the hybrid setup, if there are any.” This might involve increasing efficiency by making use of the engine’s light-running margin for electrical production via a power take-off and – if there is a battery in the system – use electrical power to support propulsion.

Two-stroke engines, such as WinGD’s, produce less CO2emissions than four-stroke machines, he said, “so we maximise usage of a the two-stroke engine and minimise usage of the four stroke ones. And even if we need to use them, if we have a battery on board, we will load them optimally.” It is this optimisation of the auxiliary power production that makes system integration attractive, he confirmed.

During manoeuvring operations, for example, a ship with a bow thruster normally runs its auxiliaries at around 20-40% load, which is “very inefficient point of running those engines.” On ships with typical fixed-pitch propellers, the main engine will be running at low speed during manoeuvring, so the shaft generator cannot be used for electrical power but if a battery is installed, one solution would be to run less numbers of gensets at a more efficient load range while the battery handles the surplus or deficit of the produced power and provides the equivalent of a spinning reserve in case of a black-out.

Four-stroke benefits

Although WinGD’s focus for its system integration work is on its engine, with no preference for which supplier’s equipment is specified in support, as long as set of crucial requirements are met, it has not ruled out extending their offerings on vessels without WinGD two-stroke main engines.

“We don’t differentiate [between] engines”, Goranov said, revealing that it has received enquiries about integrated systems for small craft – such as bunker and river ships – with four stroke engines. Cruise ships might then be potential customers, The Motorship suggested, since their engine output varies considerably because of their frequent port calls.

“Hybridisation makes perfect sense there,” said Goranov, who was previously chief electrical engineer for a major cruise operator, but he indicated that this is not a market he is targeting since they generally fit components from a single supplier. WinGD’s value proposition for four-stroke systems is more appropriate for smaller vessels, in which a range of suppliers provide the engines, generators, switchboards pumps and other auxiliaries. “We can glue them all together in terms of control,” he said.

8 WinGD's value

proposition for four-stroke systems is more appropriate for smaller vessels where a range of suppliers provide the engines, generators, switchboards pumps and other auxiliaries

System integration gains momentum

WinGD’s electrification ideas form part of a plan to broaden its scope to include more system integration technologies into its current digital and hybrid programme.

With the shipping industry expected to increase the degree of electrification on board and on-shore facilities, in the coming years, “I see opportunity for us to help increasing the pace of adoption of such technologies”, Goranov told The Motorship. “I firmly believe that all ships will be more electrified in the near future.”

But he insisted that this does not indicate a drastic change in direction for WinGD; “we will still design the engines our customers need to operate their ships and fleets in the most sustainable way” so this new emphasis marks “a parallel direction that the company’s taking to even further enhance the environmental and financial performance of our customers’ operations,” he said. “Our goal is to help increasing the pace of electrification and smart system-level control in shipping, as we believe it is an enabler for boosting the efficiency of the ship as a whole,” Goranov said.