diverse conversations

SEEKING FAIRNESS THROUGH FOOD JUSTICE Alabamians Address the Injustices and Shortfalls of Mainstream Environmentalism

grinchh/Adobestock.com

by Meredith Montgomery

Marian Mwenja’s passion for fairness began at a young age: “My mom tells me that as a child, even when I was the one getting the good end of the deal, I would get upset if something wasn’t fair for everyone.” The Birmingham native participated in social justice initiatives as a high schooler and discovered a deep connection to environmental justice at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, when a professor argued that social justice issues can almost always be connected to land issues. “This concept of environmental justice really made my soul light up—I can do something to protect this beautiful Earth that I love so dearly while also tending to this ache I have for all the harm and violence that is happening to people all the time,” says Mwenja. Believing that environmental destruction is rooted in the control and oppression of certain groups of people, Mwenja can’t fathom talking about climate crisis without talking about anti-Blackness and colonialism. 20

THE CULTURAL COST OF ENVIRONMENTALISM Indigenous people see themselves as a part of the natural world, acknowledging that when the land suffers, they suffer. When colonization occurred and native people were stripped from their connection with the land—a connection that fostered the health of people and the planet—the mentality shifted to one that separates humans from their natural world. Instead of a mutual relationship with nature, humans see themselves more as having power and control over all that surrounds them. “Indigenous genocide and the enslavement of Africans laid the framework and continue to fuel the environmental crisis we are currently facing. Any work around ecological protection or regeneration that does not also include the protection and restoration and regeneration of people and cultures connected to that land, is violent and ineffective because you’re not actually looking at the entire problem,” Mwenja explains.

Gulf Coast Alabama/Mississippi Edition

HealthyLivingHealthyPlanet.com

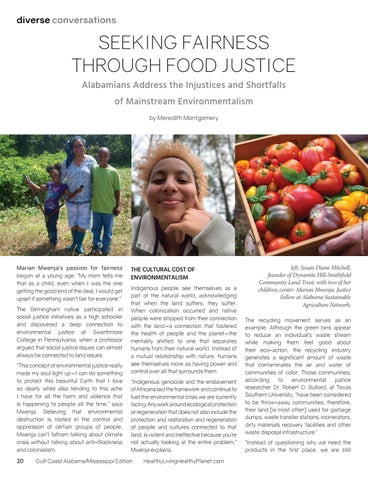

left: Susan Diane Mitchell, founder of Dynamite Hill-Smithfield Community Land Trust, with two of her children; center: Marian Mwenja, Justice Fellow at Alabama Sustainable Agriculture Network; The recycling movement serves as an example. Although the green bins appear to reduce an individual’s waste stream while making them feel good about their eco-action, the recycling industry generates a significant amount of waste that contaminates the air and water of communities of color. Those communities, according to environmental justice researcher Dr. Robert D. Bullard, at Texas Southern University, “have been considered to be throw-away communities; therefore, their land [is most often] used for garbage dumps, waste transfer stations, incinerators, dirty materials recovery facilities and other waste disposal infrastructure.” “Instead of questioning why we need the products in the first place, we are still