02 NEWS

Students’ Union to host Annual General Meeting on November 27

Aaron Calpito News Editor

The UTMSU’s AGM is an opportunity for students to voice their concerns to their elected representatives.

The University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) Students’ Union (UTMSU) is set to host their Annual General Meeting (AGM) on Thursday, November 27 at 6 p.m. At the time of writing, the UTMSU has yet to determine a venue.

The union announced the AGM via their email newsletter on November 6, in which they billed the event as “the most important decision-making event of the year.” Also in the announcement, the Union explained that the AGM is an opportunity for undergraduates to “give input on student life, approve financial statements, and weigh in on Constitution and By-Law changes.”

According to UTMSU Bylaw III, AGMs include “receiving the financial statements and the auditor’s report,” “appointing auditors for the ensuing year,” “amendments, if any, to the Bylaws unless previously approved,” and “other items on the Agenda.” The union should provide the agenda to meeting registrants by November 17.

Students can RSVP for the AGM via Microsoft Form, available on the UTMSU’s website and Linktree. To submit a motion for the agenda, students should con-

tact President Andrew Park via email at president@ utmsu.ca. Those who wish to attend but are unable can request that up to 10 proxies vote at the meeting on

Careers in Teaching Alumni Panel invites students to explore education pathways

Rocio Escalante Contributor

UTM held its second annual Careers in Teaching Alumni Panel, inviting students to explore the many pathways within education.

OnOctober 22, the Careers in Teaching Alumni Panel welcomed back University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) alumni from various educational career streams to inform students that there is no single path into teaching. The Career Centre and Literature is Alive! hosted the event in room MN3230 of the Maanjiwe nendamowinan building, with support from the Departments of Language Studies and English & Drama.

Attendees gathered in a relaxed, round-table format as faculty and panelists shared their personal career journeys, discussed the realities of working in education, and offered advice to students considering the field. A networking session followed, allowing students to connect directly with professionals and learn from their experiences.

Fourth-year student Neha Dhillon, an English and sociology major and member of Literature is Alive!, co-moderated the evening. She explained that the event’s purpose was not only to showcase career options, but also to remind students about the various career paths within education.

“Sometimes it gets overwhelming trying to figure out where you want to go,” Dhillon said. “Having real examples of people in those fields shows that there isn’t one linear path to teaching—there are teachers of all kinds.”

The panel featured five UTM alumni working in diverse areas of education. Among them was Garth Ngo, a firstgeneration graduate who now teaches second grade with the Peel District School Board, and Nancy Del Col, an ed-

their behalf, via email to Vice President Internal Rui (Owen) Zhang at internal@utmsu.ca.

ucation specialist at World Vision Canada who supports educational programming across multiple countries.

Another panelist, Laura McKinley, the universal design for learning and accessible pedagogy coordinator at the Robert Gillespie Academic Skills Centre, spoke about the importance of connecting academic learning with realworld application. “There’s often a missing piece between what you do in the classroom and what you end up doing afterward,” said McKinley. “Events like this act as a bridge—they help you take what you’re learning at university and move it forward into a career.”

Several faculty members in attendance echoed the impor-

tance of these opportunities for students. Leigh-Anne Ingram, a professor in the Education Studies program who supported the event, reflected on how such experiences weren’t always available when she was a student.

“When I was in undergrad, I didn’t have many events like this to help connect me to potential future career pathways,” said Ingram. “I wish I had chances like this on campus where I could have learned the nitty gritty of some jobs and meet people from different organizations and learn more about their work.”

The event attracted about 70 students, a turnout that reflected a growing interest in education-related careers. For some, the evening helped clarify their professional goals, including Jasneet Mundae, a fourth-year biology and psychology double major who recently decided to pursue teaching.

“I’ve gone through a huge change myself—I did a 180 into

teaching,” Mundae said. “I wanted to know how people get into teaching and what different experiences look like. The diversity of the panel stood out—there was something for everybody.”

Throughout the evening, organizers encouraged students to scan QR codes that linked to information sheets about each panelist detailing their credentials, fields of study, and professional experience. This feature helped attendees identify which speakers to connect with during the networking session, where conversations between students, professors, and alumni centred around shared academic and career interests.

The networking session ran later than planned, but organizers said the extended discussions were a sign of success.

For Assistant Professor Julia Boyd of the Department of English & Drama, the event’s lead organizer, seeing those exchanges take shape was the most rewarding part of the

evening. “For me as a professor, one of the greatest joys of being able to help organize an event like this is to see those connections form and see all of this amazing work that’s happening on campus,” she shared.

By the end of the night, students and faculty alike agreed that events like this are essential in allowing students an inside peek into real-world career expectations, which are vital for guiding them and providing the tools they need to make well-informed decisions about career paths.

That shared message carried through the evening, as nearly everyone involved—whether hosting, moderating, or attending—encouraged students to take advantage of such opportunities.

“For any students who are reading this… take the step to go to one of these events,” said Boyd. “You’ll be surprised by the amazing connections you’ll make and the sense of community that you’ll be able to build.”

Students gather in celebration of the Fall Harvest with the IEC and the Office of Indigenous Initiatives

Natalie Ramadan

On November 6, amid National Indigenous Education Month, the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM)’s International Education Centre (IEC) partnered with the Office of Indigenous Initiatives (OII) to host a dinner for meaningful dialogue centred on the fall harvest. Hosted in the Student Centre Presentation Room from 5 to 7 p.m., the sold-out event attracted over 40 students and featured a listening session on Indigenous fall harvest traditions, storytelling, and a shared meal.

The dinner was “inspired by the Indigenous tradition of the Fall Harvest,” according to an Instagram post by the IEC and OII. The organizers intended the dinner to provide a welcoming space for students to “celebrate the season of gratitude and togetherness through cultural sharing, storytelling, and community connections.”

Attendees seated themselves throughout the venue at tables decorated in autumn decor while lo-fi music played in the background. There was also a buffet featuring a traditional Thanksgiving feast, including turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, gravy, cranberry sauce, and mixed vegetables.

Jordan Jamieson, an Indigenous knowledge keeper from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, led the event by sharing what it means to give thanks to the land and its resources. Jamieson is an Indigenous student support specialist for the OII. He works alongside Faith Desmoun, the coordinator of Indigenous programming at the OII, to bring Anishinaabemowin speakers to teach classes at UTM. This integration of Indigenous language began recently, in September of the 2025-26 academic year.

Jamieson acknowledged the presence of Indigenous spaces on campus, such as the Maanjiwe nendamowinan (MN) building, and spread knowledge on the maple, birch, pine and cedar trees, which provided for the Indigenous peoples

during their time of harvest.

Common around the UTM campus, the pine tree features heavily in traditional teas in the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee cultures. It also contains vitamin C, and during the time the pilgrims came, it was used to help cure scurvy and continues to be used as a salve.

The maple tree helped provide for the Ojibwe and Anishinabek people when they had food shortages towards the end of winter. As Indigenous people are nomadic, constantly moving throughout the seasons, they know to stop collecting syrup in the fall when the tree leaves change from green to yellow.

Cedar trees can also be found on campus near the MN building and the Principal’s House, and cedar bushes are located near the MiWay bus stop in front of the Kaneff Centre. Indigenous people use cedar trees in their medicine, and when taken from the trees, usually dried tobacco is given back to the land as a way of giving thanks.

Birch bark trees are also used by Anishinabek people, such as to make paper or scrolls, baskets, and canoes.

Along with the trees, there are three main feast foods the Indigenous nations include during fall harvest celebrations and winter preparations, including wild rice, maple syrup, and wild berries. Wild rice is interconnected with the creation story and migration for the Anishinabek people, and maple syrup has deep ties with sustaining Indigenous nations during food shortages.

Jamieson explained the process of collecting wild rice, describing taking canoes out on rivers, knocking the rice grain into canoes using poles, and using birch bark baskets to toss the grains into the air, which separates the rice from the surrounding husks, a process called winnowing. The process also includes a traditional song shared by Jamieson called the Bowam, which is sung while dancing over the wild rice as it is cooking.

The future for Dinner and Dialogues

Some attendees expressed that they haven’t celebrated Fall Harvest before, while others expressed that last year’s Dinner and Dialogues was the first time they celebrated the fall harvest.

In an interview with The Medium following the event, Samuel Kamalendran, the programming team lead for the IEC, discussed the importance and uniqueness of hosting Dinner and Dialogues. “The event is unique in how it has a very considerable budget, allowing us to cater food to participants—our events are the largest in the department. [We use] that vehicle to promote intercultural discussion about cultures celebrated at UTM.”

As this is only the second year of Dinner and Dialogues and the first time the IEC collaborated with the OII for the series, the IEC hopes to continue this event for future students. Kamalendran shared his personal experience working alongside the OII, stating, “I enjoyed being able to share knowledge directly from someone Indigenous—that’s a first for us and something I want to continue.”

In an interview with The Medium, Jamieson expressed that the event is “a chance for students to connect with Indigenous presence and spaces.” As a new support staff for Indigenous students at UTM, he intends to use “different Indigenous pedagogies like land-based, intergenerational, relational ways of learning.”

He also pointed out that the OII will host its next event during International Education Week. Information on events happening during the Education Week can be found on the OII website.

To attend future IEC Dinner and Dialogues, check out the IEC website or Instagram page. The upcoming event will be the Christmas dinner.

UTM community donates to support those affected by Hurricane Melissa

Natalie Ramadan Contributor

In the wake of the strongest recorded hurricane in Jamaica’s history, Caribbean Connections and the Students’ Union held a week-long relief drive.

On the week of November 3, the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) Students’ Union (UTMSU) and Caribbean Connections UTM brought the UTM community together to support relief efforts following the recent devastation of Hurricane Melissa in Jamaica

According to The Guardian, Hurricane Melissa was the most severe storm Jamaica has experienced on record, with some experts stating that it was “on the edge of what is physically possible in the Atlantic Ocean.” Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness reported that the hurricane caused damages equivalent to around 30% of last year’s total gross domestic product, or between US$6 billion and US$7 billion, according to Reuters. At least 75 are reported dead at the time of writing.

As leaders and community groups around the world unite in vital humanitarian efforts, the UTM community, too, contributed toiletries, food, and other essentials as well as monetary donations raised at a multi-day patties and coco bread charity sale in the Student Centre.

Caribbean Connections Vice President External Chanelle Blair has personal connections to the cause. In an interview with The Medium, Blair described how playing a role in organizing these initiatives was deeply meaningful, as it allowed her to “give back to [her] community despite not being physically present.”

Vice President Community Outreach and Engagement Giovanni Ustany shared similar insights, adding the powerful reminder that despite the distance, the effects are felt right here at UTM. “[We are] doing our best to give back to the community.”

The team acted quickly, organizing the catering logistics and working with the Jamaica Canadian Association (JCA). Working with this organization guaranteed that all of the donations, whether physical or monetary, would reach the affected communities.

Participants were enthusiastic to donate and support the cause, as reported by the teams. This positive impact does not need to end here, however. Following the initiative, Blair described the numerous ways UTM community members can still make an impact: they can donate monetarily through the official Jamaican government channel and community relief drives, volunteer in the execution of these initiatives, and spread awareness on social media

The organizers also stressed that those who weren’t able to participate in the drive can still support relief efforts. Ustany described that organizations like the JCA have the logistical means and connections to quickly provide direct support, adding that “it’s all about working together in this time.”

The Medium also interviewed UTMSU Vice President Equity Miatah McCallum. After describing the importance of supporting Jamaican families amid the disastrous after-

math, she explained, “I think it’s really important that students come together in these times… when we are doing the dropbox and the fundraiser, we want to see all demographics of students come out for that because we are only stronger as a collective…. We can’t be free until all of us are free.”

For students who are looking to get involved in organizing such initiatives, McCallum highlighted how the Students’ Union values and encourages any ideas. The initiative for Jamaica and other initiatives reflect how the UTMSU wants “to make sure that students feel that [we] see them and recognize these struggles and that we are supporting them as much as we can.”

The hurricane has been disastrous and communities are suffering in Jamaica and beyond. Together, however, supporting relief efforts—whether through spreading awareness, donating, or planning such initiatives—is not only a responsibility, but can also be an empowering and deeply impactful experience. As concluded by The Caribbean Connections team, “we empathize with the Jamaican community and we know that they will come back and come back stronger.”

Students elect new UTMSU representatives in fall by-elections

Prekshaa

Fresh

Every fall, the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) Students’ Union (UTMSU) holds by-elections to fill vacant positions within the student government. The process allows students to nominate themselves for open positions. All full-time and part-time undergraduate students are eligible to run, although certain roles have specific eligibility criteria.

This year, students voted in two first-year representatives for Division I: Mekayel Omier and Maryam Kashif Zeeshan. A part-time representative seat for Division III was also available, although no candidate ran for it.

Other Division I candidates included Victoria (Shuran Kou), Oliver (XinChun) Wang, and Syed Shayan Husain. Husain was disqualified from the race after receiving too many demerit points for two counts of “unauthorized and unapproved campaign materials,” according to the UTMSU’s Virtual Wall of Transparency.

By-election rundown

UTMSU President Andrew Park clarified the election process in an email to The Medium. Candidates had to be enrolled in the constituency they wished to represent and remain members in good standing throughout the election period. To qualify, they submitted a nomination package outlining their goals and plans for the upcoming year and commitment to student representation.

First-year representative candidates had to obtain a

minimum of 25 nominations from their constituency, each comprising all full-time and part-time fee-paying students, according to UTMSU Bylaw I. Candidates then submitted and verified their nomination packages with the Chief Returning Officer (CRO) and attended a mandatory All-Candidates Meeting, where the CRO reviewed the election rules. Nominations opened in late September, followed by a short silent period before campaigning began.

The official voting period was from October 14 to 16. The voting had to be done physically at polling stations across campus, which operated between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. each day. Students presented their T-Card and used a pen or pencil to cast their vote.

While the by-elections open the door for new leaders, student participation remains a persistent challenge. This fall, only a small fraction of UTM’s undergraduate students cast their votes, a pattern consistent with previous years. Many students cited limited awareness or uncertainty about what the UTMSU actually does as reasons for not voting. Around eight per cent of eligible students cast their ballot in this year’s by-election, compared to the five per cent turnout last year. For comparison, the UTMSU’s 2025 spring general elections had a turnout of nearly 20 per cent.

Once elected, representatives attend board meetings, vote on budget allocations, and advocate for student priorities such as affordability, accessibility, and cam-

Interviews with the winners

For newly elected Board of Directors members Omier and Zeeshan, joining the UTMSU is about more than holding a title—it’s about amplifying student voices and driving change on campus. Both first-year political science students entered the byelections hoping to make advocacy more accessible and representation more visible.

“I really enjoyed orientation,” said Omier, an aspiring criminology and political science double major with a background from the UAE and Pakistan. “I met so many first-years going through the same things. I want to continue that sense of connection through the student union.” Encouraged by friends, he decided to join a team already “putting real effort into helping students” and wanted to contribute to that mission.

Omier’s campaign centred on Instagram, where he created a separate account and conducted digital surveys to learn about students’ concerns. His top goals include expanding bidet access across campus, partnering with the Muslim Students’ Association, and advocating for discounted food during exam season.

He also hopes to involve more first-years in UTMSU activities through volunteer and job opportuni-

ties. “They often don’t know anyone or how to get started,” he explained. “I want to change that.”

Zeeshan, planning to major in political science and double minor in forensic science and business, shared a similar commitment to community. “To see change and be a part of it is really rewarding,” she said. “Being on the board means having input on policies—whether supporting or challenging them—and that’s powerful.”

Zeeshan focused on accessibility and outreach. “There are so many resources students don’t know about,” she said. Using Instagram reels and in-person outreach—from chatting with students in busy buildings to offering sweet treats—she prioritized connection. Her goals include installing bidets and musallah spaces in more buildings, working with the U of T Bidet Club, and boosting engagement through inclusive events. “I want to listen, hear concerns, and advocate for what students actually want,” she said.

The representatives’ shared focus on accessibility, representation, and student engagement highlights the evolving priorities of UTM’s student community. Whether through social media, advocacy, or on-the-ground connection, they hope to make UTMSU more approachable and transparent.

OPINION

EDITORIAL

Editor | Yasmine Benabderrahmane opinion@themedium.ca

Indige nous presence beyond land acknowledgements

May Alsaigh Copy Editor

Music, academia and food are important parts of our everyday lives, so why don’t we ensure Indigenous voices are present and celebrated in all of them?

Last year, I wrote an editorial arguing that land acknowledgements were performative and empty gestures. I still stand by that statement today and continue to reflect on how we can better uplift and spotlight Indigenous voices. We must continue to hold Canada accountable for its years of exploitation and ongoing neglect of Indigenous communities today, but this should not be our sole focus.

While land acknowledgements are important, they do not do enough to create meaningful change, and are often treated as a checklist to be completed rather than a commitment to action. Here, I will highlight how we can create more opportunities for Indigenous presence in the everyday spaces that influence our culture, education, and communities.

Indigenous voices to the main stage

I love music. It’s there when I drive, fold laundry, or wash the dishes. Even when I’m not looking for it, it finds me at the mall, the grocery store, and through TikTok and Instagram Reels. Music is a huge part of our world, and we see lots of representation from different cultures and ethnicities across the industry. But the representation for Indigenous voices in the music industry is still lacking.

Many artists are discovered through other artists and music figures who invite them on tours as openers or feature them in a song or album. Last month, I saw a video clip of Shawn Mendes, the Canadian singer we all know and love, inviting Cree and Salish singer Tia Wood to his Vancouver concert on October 12. Wood incorporated Indigenous vocals and beats into the song’s tune while Mendes played his guitar.

I also recall going to a Coldplay concert this year in July, and one of the first things that caught my eye was the band inviting youth from the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation in Ontario to perform a prayer in the Ojibway language as well as a traditional welcome and song. I was beyond happy seeing Indigenous representation alongside famous names like Shawn Mendes and Coldplay, for it signalled an important step in acknowledging Indigenous talent and presence in the music world.

Artists inviting Indigenous artists or Indigenous communities to their stage is a powerful gesture that shows inclusion can manifest in many ways, even within the music industry. Other artists should follow along in these footsteps to ensure Indigenous voices are amplified and present, especially when performing on occupied land.

Indigenous thought in academia

I took a course about critical Indigenous and decolonial thought in my Master’s program.

This is not the first time I have taken a course in this field. I entered the course expecting to know most of the curriculum, as I have studied colonialism and the mistreatment of Indigenous communities during my undergraduate degree, but I was wrong.

In the course, I was not only learning about things I did not know before, but I was also

engaging in important and thought-provoking discussions with my peers about critical issues, from the lack of clean water in Indigenous reserves to the lack of Indigenous scholars in academia. One of the issues that stuck with me was one my classmates brought up: we never truly learned about Indigenous colonialism in high school, or before.

Before taking these courses, I never truly understood or paid much attention to Indigenous issues. I became more passionate and more conscious once I entered my undergraduate studies, but why did I not feel this way before? Why are Indigenous histories and voices treated as optional lessons rather than essential parts of our education? Shouldn’t we learn about the land and territory we’re occupying? If we are not learning this in school, when will we?

We must learn about topics like Indigenous self-determination and the historical and ongoing oppression of Indigenous communities in our education, so we can be aware of Canada’s history, address these issues, and work toward meaningful change. Universi-

ties and academic institutions should also provide scholarships and grants for Indigenous students and scholars to increase Indigenous presence in the academic field, so we can truly learn about these issues, not just from scholars, but through the lived experiences and insights of Indigenous peoples themselves. Indigenous cuisine

Living in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), I have tried many cuisines, from Lebanese, Greek, Nigerian, Thai, Indian, and so much more. Finding food from a culture is not hard in this area, especially if you visit the infamous Ridgeway Plaza. Not to mention, Toronto is where you find Little Italy and Little Jamaica to try some of the tastiest cultural and traditional foods. Many of us are immigrants, and when we miss a taste of our home, it is not hard for us to find it through the array of restaurants in the GTA. But why can’t Indigenous communities access the taste of their home in their own home? We have several restaurants featuring countless cultures across the world, yet Indigenous cuisines remain invisible.

The absence is not just about food, but a reflection of how Indigenous culture is overlooked even in places where it belongs. Food is another huge part of our lives, and we need to increase Indigenous presence through food to celebrate their rich history and provide them with spaces to connect to their land that has been theirs before we called it our own.

Music, academia, and food are three huge aspects of our lives, and Indigenous presence in each of these spaces matters deeply. Representation is not just about visibility, it’s about respect, inclusion and giving Indigenous communities control over the spaces they belong in. If we are serious about acknowledging history and highlighting Indigenous communities, we must create opportunities for their voices to be heard and do more than limit our efforts to just land acknowledgements and performative gestures that give the appearance of action without creating real change.

I am my mother’s reflection

Jia Bawa Contributor

Where our mothers end and where we begin

If mother-daughter relationships could be summed up in one word, it would be complicated. Is that the most cliché thing I could have written? Yes. Am I wrong? No.

Let’s look at what popular media has to say on this topic. Usually, mother-daughter relationships on our screens tend to be saddled into one of two extremes.

Exhibit A: We are best friends for life, totally inseparable, and the only conflict we will ever have may endure a maximum of two episodes, but other than that, it’s rainbows and sunshine. (Example: Gilmore Girls).

Exhibit B: My mum and I hate each other; we never get along. Breathing in the same space as her makes it feel like I am being poisoned; I can’t wait to get out of here. Help me! (Example: Lady Bird)

Reality, on the other hand, cannot be contained in neat little boxes. There’s a lot of spillage. It bleeds into identity, gender, and emotional inheritance. Somewhere in the vast area between admiration and rebellion lies reflection.

Mothers often see their daughters as mirrors: living and breathing reminders of what they once were, or who they could’ve been. They can be reflections of who they are if they weren’t bound by the shackles of a society that terminates a woman’s life when she becomes a mother and reduces her to the identity of motherhood.

Writer Rebecca Solnit in The Faraway Nearby, describes this situation eloquently, claiming, “mothers are divided by daughters.” A daughter doesn’t simply reflect her mother, she signifies the sacrifice that women survived for motherhood. Perhaps that is why pride and pressure often exist alongside each other. When a daughter succeeds, it can feel like restoration; when she chooses differently, it can feel like a deep betrayal. Some mothers lose a piece of themselves when their daughters stray away from the path they envision..

I wouldn’t call this dynamic a competition, but rather continuity. Solnit also writes about “the mother who gave herself away to everyone or someone, and tried to get herself back from a daughter.” This is a sentiment that many of the women I know hold true. Oftentimes, mothers project not just dreams, but fragments of the selves they never got to really become. And daughters, in turn, spend perhaps the entirety of their lives trying to step out of that idealised reflection; out of a desire to be loved not for what they restore, but who they are.

The result: an emotional tug of war between recognition and independence. You want to honour where you came from, but ultimately, this is your life. It’s not appalling to want to build something of your own, that is representative of your realest and most authentic self. And that is the paradox of this bond: it’s an inheritance of love and expectation, passed down like a family heirloom, whether we ask for it or not.

Maybe that’s where the soul-crushing weight of being a daughter stems from, not solely from the mother, but from everything that shaped her before you. The expectations she learned about what it means to be a “good woman, good daughter, good wife” don’t disappear overnight. They trickle down, slowly seeping into every “life lesson” you ever receive. For a multitude of mothers, especially those raised in cultures that hold modesty and sacrifice to a higher standard, control often masquerades as care. “Be polite. Don’t talk back. Keep your voice down. Focus on your family.” Mothers of these backgrounds think they are passing on advice that will protect daughters from the world. But what they seem to forget is that these insipid rules were suffocating and endlessly aggravating when they were young, and they continue to be so, even now.

I think of how easily love turns into supervision: how daughters are told to smile, help, and hold everything together. It is grilled into women that silence signifies strength, that being a caregiver should be instinctual, rather than something you learn. In so many families, that lesson extends across generations: mothers carry the emotional load, and daughters are forced to honour it.

In Indian culture, that weight is often called by a different name: izzat, meaning honour or respect. Daughters are seen as the family’s reputation, embodied in flesh. Every little detail about her—the way she dresses, speaks or behaves—is subject to ridicule, and becomes a public reflection of how well she was raised. Respectability becomes a shared project between a mother and a daughter: one upholds it, while the other inherits it. On the surface, this kind of love looks like protection, but it feels like you’re locked up in a dingy cell with your executioner watching over you 24/7. When you are the representation of your family, you can’t step a toe out of line or even take a breath for longer than you’re supposed to, lest you sully your family’s good name.

In immigrant or racialised households, this pressure is tenfold. Daughters become the cultural glue, the translators, the emotional interpreters for their parents. They are a bridge between two worlds that may not necessarily mesh together all that well. There is labour in this sort of love. The kind that rarely gets acknowledged, let alone shared.

Being away from my mother now, I find myself wondering who takes care of the women in my life. The ones who teach everyone else how to endure. Mothers spend their lives caring: first for their parents, then for their husbands, and then

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editor-in-Chief

Aya Yafaoui editor@themedium.ca

Managing Editor Samuel Kamalendran managing@themedium.ca

News

Aaron Calpito news@themedium.ca

Opinion

Yasmine Benabderrahmane opinion@themedium.ca

Features

Gisele Tang features@themedium.ca

A&E

Yusuf Larizza-Ali arts@themedium.ca

Sports

Joseph Falzata sports@themedium.ca

Photo

Melody Zhou photos@themedium.ca

Design

Sehajleen Wander design@themedium.ca

Podcast

Jia Bawa

Social Media

Jannine Uy

Outreach

Mashiyat Ahmed

Copy May Alsaigh may@themedium.ca

Anaam Khan anaam@themedium.ca

TO CONTRIBUTE & CONNECT: themedium.ca/contact @themediumUTM @themediumUTM @themessageUTM social@themedium.ca outreach@themedium.ca

for their children. By the time someone finally asks them what they want, it seems like they have forgotten how to answer such a question. It’s the strangest thing: they’re like a shell of who they were once before marriage.

Daughters learn by watching. As children, our mothers are our role models. We pick up on these things. We see the quiet exhaustion behind our mothers’ composure, the swallowed screams, words that never made it past her tongue, and smiles that barely reach their eyes. And somewhere, between all that watching and observing, we inherit that too.

That is not to say that we don’t try to resist. Trust me, we try our hardest. But somehow, the pattern repeats. We are always the ones checking in, picking up the phone first, remembering every single birthday, and refilling everyone’s prescriptions. Caretaking becomes a reflex. So, it would surprise no one if I said that motherdaughter relationships are built on an economy of care that leaves both parties exhausted. Each one is pouring from an empty cup, hoping the other won’t notice the

cracks.

The idea that mothers and daughters are destined to compete is one of patriarchy’s oldest and most adored party tricks. It tells women that there can only be one of you at a time—go battle it out in the arena, best one wins. Youth threatens age, ambition threatens tradition. This is a myth that thrives on scarcity: the belief that womanhood is a zero-sum game. Real life does not imitate whatever brainwashing has occurred through generations of patriarchal individuals. Through my own eyes, in my family and in others, I’ve seen this to be not a competition, but an inheritance—of care, of pressure, of love so complicated that it’s untranslatable.

What the media calls rivalry may just be two women trying to rewrite the same story differently. My mom grew up in a world that asked her to be small so she could survive. I grew up in one that encouraged me to take up space, but not too much. When those worlds collide, a mess is expected. But again, mess does not equal failure, but rather, evolution.

Is renaming enough?

Rebecca Christopher Contributor

While we commemorate Indigenous cultures, we must also alert our attention to Indigenous causes.

Being introduced to Canadian history eventually introduced me to the many roads, buildings, and town squares that have been renamed from colonial to Indigenous names. An act that honours rich languages and commemorates Indigenous history, bringing about decolonization and reconciliation.

I would like to note that as a non-Indigenous writer and new member to Canadian society, my perspective has been limited to the online resources of Indigenous perspectives. Yet, it remains an honour being able to access resources on a voice that has been silenced, shamed, and stripped of dignity throughout history by the colonial regime.

Renaming spaces with Indigenous names is part of an initiative by Canadian governments and institutes to honour the Indigenous nations that claimed this land before the illegal occupation of their homes by European settlers. While, European settlers undermined the Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty over their land through genocide and forced assimilation, they were still revered by the government. Many buildings and statues were constructed to remember these colonial European figures such as Adolphus Egerton Ryerson, Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir William Cornwallis. Hence, many renaming initiatives have been assumed to remove their influence. For instance, we have

Contemporary feminist literature reminds us that these relationships don’t have to be perfect or peaceful to be powerful. Solnit was right: mothers and daughters divide each other, but in doing so, they also multiply—new ways of thinking, living, and being. Every argument, every misunderstanding, every quiet reconciliation is just part of that multiplication.

Perhaps our relationship being complicated or undefinable isn’t necessarily a problem, but proof. Proof that something very real is happening between two women shaped by different versions of the same world. Maybe we aren’t meant to perfect this relationship, but to keep on revising it, learning how to care without control, how to love without stripping ourselves of the essence of our being.

The point isn’t to escape the mirror, but to stand beside it: to recognise where our mothers end and where we begin, and to quietly thank them for teaching us both.

the Anaquod road in Regina, Saskatchewan named after Glen Anaquod, an Elder, member of Muscowpetung First Nation, and a residential school survivor. Another instance would be the renaming of the “Langevin Block” on Parliament Hill to the “Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council” in June 2017 due to Sir Hector-Louis Langevin’s involvement in the residential school system.

Removing the settlers’ influence also includes light to the rich and diverse Indigenous languages to rename these places and buildings. The Maanjiwe Nendamowinan building at UTM is an instance that we, students, see everyday. The name translates to gathering of minds in Anishinaabemowin. The city of Regina, Saskatchewan also named their new recreation centre the Mitaukuyé Owâs’ā Centre, with videos made to teach non-Indigenous people on the pronunciation and meaning of the name. According to Natural Resources Canada, as of 2025, “close to 30,000 official place names are of Indigenous origin, and efforts are ongoing to restore traditional names to reflect Indigenous cultures.”

Whilst honouring Indigenous heritages seems like a simple way to explain the reasons for these initiatives, a Metis writer and professor, Brenda Macdougall, claims that renaming forms people’s memories and sense of belonging instead of just solely a historical legacy.

Christina Gray, a Ts’msyen and Dene lawyer, explains that renaming places from colonial names revitalizes rich Indigenous languages and that is more than just a symbolic gesture; it reflects on Indigenous histories and connections to the land. The Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. builds upon this by reminding us of the value of the place names and how they are mnemonic devices that serve a historical, geographical and spiritual purpose.

One fascinating part about the renaming initiative is that it aims specifically at educating others about the history of Turtle Island that doesn’t rely within the boundaries of colonization. It teaches newcomers, like me, about the Indigenous cultures of the land. It is also a counter to the assimilation of the residential school system that forced Indigenous children away from their nations, lands and cultures, to internalize European ideals, resulting in mass cultural genocide and generation trauma.

However, I think that it’s important to remember that the issues surrounding Indigenous people go beyond just naming spaces. This is an issue laced in current struggles with European-instituted bureaucracies and the survival of the colonial regime. For example, Indigenous children are overrepresented in the foster care system and in prison inmate population, making up 53.8% of children in foster care and 42.8% of the prison population on average. Indigenous populations have also been subjected to greater rates of poverty and homelessness.

We must address the fact that Indigenous peoples are still displaced in their own lands, since their sovereignty has been revoked and restored only to a partial extent. In cases like these, resourcing the renaming of buildings and places turns a blind eye to the present plight that requires just as much funding, attention, and support. In fact, renaming buildings without aiding those struggling to live within their lands may become ostentatious since there is no value to commemorating Indigenous cultures when Indigenous communities are still condemned to the colonial systems and abuses of the Canadian government.

08 FEATURES

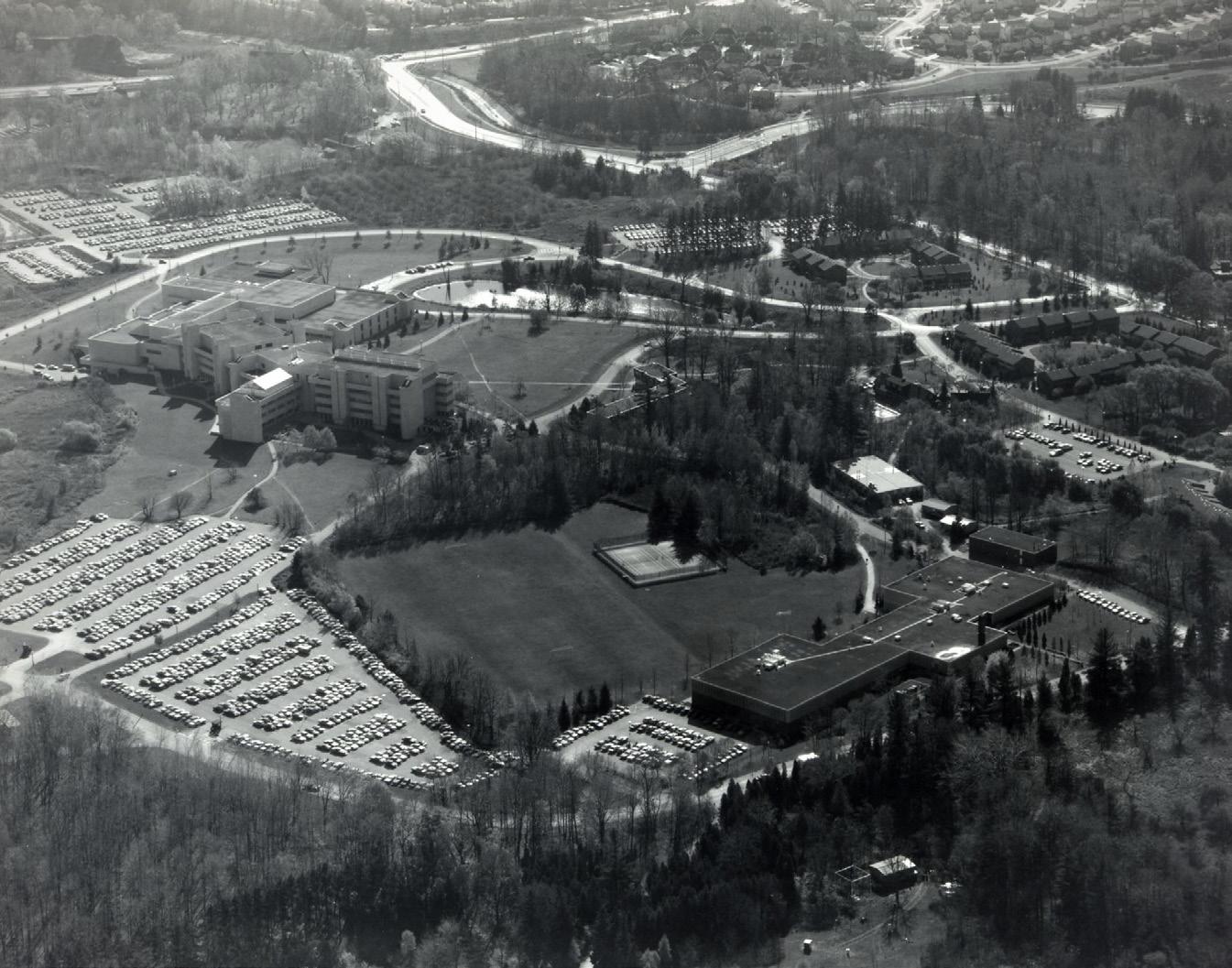

Honouring UTM’s original caretaker

Editor | Gisele Tang features@themedium.ca

Long before the University of Toronto Mississauga, the land on which our campus is situated was home to the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

The grounds of the University of Toronto Mississauga (UTM) were not always built with lecture halls or laboratories. These lands were home to generations of people. Long before the concrete paths were laid, this land belonged to the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation is part of one of the largest Aboriginal Nations in North America—the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) Nation. The Mississaugas speak Anishinaabemowin, which means “language,” and is made up of three main dialects: Ojibway, Pottawatomi, and Odawa. Mississauga comes from the Anishinaabe Misi-zaagiin, translating to “those at the great river-mouth.”

The Mississaugas saw themselves as caretakers across a wide stretch of territory — around 3.9 million acres in southern Ontario, which includes forests, rivers, and natural supplies.

Their territory stretched from the Rouge River Valley in the east, westward to the headwaters of the Thames River, down to Long Point on Lake Erie, and followed the shores of Lake Erie, the Niagara River, and Lake Ontario before returning to the Rouge River Valley.

The community moved with the seasons instead of against them. They would hunt when needed, fish where streams met lakes, collect herbs and healing roots, then paddle through waterways in bark canoes. The Mississaugas understood rivers, creeks and lakes not just as supplies, but as breathing parts tied to how they viewed the world.

The Mississaugas held a deep relationship with the Earth, rooted in interconnectedness and respect. They viewed the land, waters, plants, and animals as parts of one living system, each element essential to the balance of life. As Heritage Mississauga describes, the Mississaugas “lived lightly on the land,” following a lifestyle that left little trace of their presence.

The Mississaugas once lived in areas surrounding the Credit River, Etobicoke Creek, and Burlington Bay. Toward the late 1700s and early 1800s, the British Crown negotiated a series of land agreements through which the Mississaugas surrendered large portions of their traditional territory. Today, the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation live on a reserve near Hagersville, Ontario, which covers approximately 6,100 acres.

Honouring traditions and respecting sacred land

Being part of campus life means seeing the grounds, parks, waterways and critters not just as perks to use, but as networks that require our care and respect—and there are various ways to do so.

Land acknowledgements hold great significance. Whenever an event is held on the grounds our campus stands on, we should start by recognizing we are gathering on ancestral grounds tied to the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, alongside oth-

er Indigenous communities. This practice is not a mere procedure, but a reminder that we should pay gratitude and respect to our land and to honour Indigenous communities that took care of it.

Also, learning about native traditions, such as digging into the actual communities tied to the area, can help us learn more about Indigenous communities. This can provide us with a truly comprehensive understanding of history. Activities like exploring gatherings hosted by locals, reading books or articles written by Indigenous voices and appreciating displays featured through initiatives like Mississauga’s heritage projects are also ways to respect and honour the Indigenous community.

Amplifying Indigenous voices is also another practical way to ensure native perspectives are accurately shared. Through channels like the UTM radio, Instagram accounts, or lectures, we can spotlight Indigenous writers, creators and thinkers.

Respecting the history behind UTM grounds

Understanding the history of the land we stand on is important because it fosters a deeper sense of connection. Instead of seeing UTM as a place shaped only by recent hands, picture it growing from old rivers, shifting soil, and generations who lived and cared for this scratch of earth. This can teach us the harmony that Indigenous communities have always shared with nature.

Our individual knowledge does make a difference. If we look past Indigenous stories, they fade away. But when we pay attention, we create a community that values what came before, what lives now, and what shapes tomorrow.

Being a UTM student is a privilege, as we study and live on land that has been cared for by generations long before us. Our campus has the potential to be a living reflection of the admirable spirit embodied by the Mississaugas. Through care and intention in what we do here, we can express our respect in ways that words alone cannot.

AI, Ethics and the Earth: Professor Stephen Scharper on Technology’s Spiritual Reckoning

Audrey Thilloy Contributor

In an interview with The Medium, Professor Scharper shares his insights on AI’s ethical dilemmas, environmental consequences, and what they mean for humanity.

In an era of climate anxiety and technological advancement, the conversation surrounding artificial intelligence (AI) frequently centers on productivity, effectiveness, and innovation. But for Professor Scharper at the University of Toronto (U of T) Mississauga (UTM), the most urgent question is not what AI can do, but what it is doing to us— to our planet, our sense of morality and our relationship

with the sacred.

As an anthropology professor at UTM jointly appointed to the School of the Environment, Professor Scharper’s career has been dedicated to the intersection of religion, ecology, and ethics. Yet today, his concerns have turned to a new frontier—AI. As technology rapidly evolves, a new question emerges: What happens when humanity entrusts machines?

Professor Scharper begins the conversation with reference to sacred stories, including the Hebrew prophets, Latin American liberation theologians, and the Catholic priest Thomas Berry, who called himself a “geologian.” Professor Scharper explains that Berry viewed the universe itself as a revelation. Berry noted that while so much attention has been given to scripture, people often overlook the first book of Revelation: the Universe.

From theology to ecology: integrating disciplines

Professor Scharper’s work blends social justice, religion, and ecology. Inspired by figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Gustavo Gutiérrez, and Thomas Berry, he has long explored how ethical reflection and care for the Earth intersect. His PhD at McGill extended this dialogue, connecting human liberation with ecological responsibility, a focus that continues in his teaching at U of T. Today, he asks what it means to be human in a world increasingly shaped by algorithms and AI.

In practice, Professor Scharper encourages students to engage directly with the natural world. Each week, students spend half an hour at a designated “sit-spot,” observing without screens or earbuds and linking the experience to class readings and discussion. Initially skeptical, students often report that by the third or fourth week,

the practice restores focus, sparks curiosity, and offers a sense of hope.

Professor Scharper frames this as a remedy for what Richard Louv calls “nature deficit disorder.” By helping students reconnect with the natural world, it helps them to see technology for what it truly is, rather than what it is disguised as.

The ecological cost of AI

AI has the potential to serve the planet as well as strain it. Professor Scharper points out that machine learning systems can help with environmental monitoring, such as quickly detecting contaminants in water or scanning large datasets to detect climate and ecological insights.

AI’s environmental footprint is substantial. Professor Scharper cites Karen Hao’s Empire of AI, which examines how the expansion of data infrastructure often mirrors colonial patterns. He noted, “Two-thirds of the data centers in the world now are being placed in areas of water scarcity.” Such practice effectively exploits resources in the Global South to power AI.

For Professor Scharper, this is more than an environmental issue—it is also a spiritual and ethical crisis. “Pope Francis calls it ‘integral ecology’,” he says, referencing the 2015 encyclical Laudato si’. This concept emphasizes that we must hear the cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor as one, where the ecological crisis and the social crisis are two sides of the same coin.

Risk of over-reliance on AI: meaning, critical thinking, humanity

Professor Scharper reflected on the growing dependence on AI and its impact on how we think and relate to the

world. He warned that as we delegate tasks to machines, we risk losing our grounded relationships with nature and with one another.

“There is this belief that AI, as an apex reality with superior intelligence, is going to tell us our proper role of who we are,” said Professor Scharper. We risk losing our capacity to ask good questions, to sit in nature, to listen deeply to the more-than-human world. When machines provide ready answers, humans become “passive consumers,” dulling curiosity, problem-solving, and moral discernment.

What worries Professor Scharpermost is how easily humans surrender moral authority to machines. “We’re turning to computers to be our spiritual mentors,” he noted, referencing a tragic case of a man who died by suicide after a long exchange with an AI chatbot. This reflects a broader trend of seeking guidance from “corporately driven, sycophantic voices” rather than the “energies of the Earth,” compassionate counsellors, or wise elders.

Technology without a moral compass

Professor Scharper situates today’s AI moment within a long history of technological critique, citing Marshall McLuhan’s warnings about media power and Ursula Franklin’s reflections on the colonial nature of technology.

“The computer… is not a value-neutral tool. It imposes, by its very power, a kind of cultural frame. It stands next to the typewriter and says that old technology is completely bereft. It’s obsolete,” shared Professor Scharper, citing the insight of Canadian philosopher George Grant. He argues that AI has placed humanity at a crossroads. Borrowing from Thomas Berry, Professor Scharper con-

trasts two futures: the “Technozoic Era,” defined by technological dependence, waste, and spiritual emptiness, and the “Ecozoic Era,” where technologies work with, rather than against, Earth’s systems.

Much of today’s technology prioritizes profit and engagement over truth, with algorithms fostering addiction and blurring reality. Professor Scharper points to U.S. efforts to suppress independent research at universities like Harvard, Brown, and Columbia, and the fusion of corporate and governmental power, including examples like Trump advancing personal interests through office. He likens this trend to the movie WALL-E, where corporate and state dominance commodifies ecological and social systems.

Transitioning to an Ecozoic future requires moral action from governments, educators, and citizens. With AI intertwined with corporate, governmental, and military interests, self-regulation is insufficient, and societal safeguards, oversight, and reflective engagement are required.

The power is in your hands

Professor Scharper offered several practical pointers for students and young people trying to find balance in an age of rapid technological change. He first emphasized the importance of agency and the belief that individuals can still shape their world. “This is not just some huge tsunami that we’re powerless to control,” said Professor Scharper. “You have a right to a flourishing life.”

He encourages students to reclaim agency and reconnect with nature. He also stresses the importance of choosing sources carefully, relying on peer-reviewed research and trusted journalism, and engaging with communities and values, instead of solely relying on technologies.

Professor Scharper reminds students that small acts matter. “Anything you do on behalf of the earth or love, integrity and protection of animals is worthwhile.” Everyday choices reflect our attention, values and contribution to meaningful changes.

A call to action

Professor Scharper cautions against what he calls “corporate doomism,” which is the belief that individuals are powerless against global systems that are designed to make them feel small. He emphasizes that people still “have a right to make a difference” and “a right to a democratic freedom of expression,” even amid uncertainty.

Professor Scharper suggests that what the world needs most is more wisdom, instead of more information or research. Recalling the words of former UTM principal Deep Saini, Professor Scharper notes that “the real purpose of the university is to help you find your place in the cosmos.”

Looking ahead, Professor Scharper is considering a course on the ethics, culture, and emergence of AI, focusing on ecological perspectives. He and Professor Simon Apolloni are exploring “eco-anxiety,” which reflects deeper cultural and imaginative pressures. Professor Scharper’s message is clear: remember what it means to be human and the role we play in shaping the future.

“We have a choice. The Earth is calling. Let us not respond by becoming mere processors of data, but by becoming curious, compassionate, present, and relational with all life.”

ARTS Indigenous Literature Celebrated at UTM

Emma Catarino Staff Writer

UTM offers many courses and texts on Indigenous literature and appreciating these works, while recognizing implicit bias, is one step towards reconciliation.

Our UTM campus, located on the historical Indigenous lands of the Secena, Huron-Wendat, and Mississaugas of the Credit, has a history of honoring Indigenous culture on campus. In 2018, one of UTM’s newest buildings was opened. MN, or Maanjiwe Nendamowinan, means “gathering of minds” in Anishinaabemowin, and was named in consultation with the Mississaugas of the First Credit Nation. In 2023, the Office of Indigenous Initiatives recruited volunteers to help erect a Tipi and wooden lodge just off Principal Road. The structures have since been used for ceremonies, events, and the lodge even hosts classes. The Indigenous community on campus also holds powwows every year, which is a celebration of Indigenous culture.

UTM provides many courses surrounding Indigenous culture, with some centered on Indigenous literature specifically. One such course, ENG274 Indigenous Literature and Storytelling, focuses on the idea that reconciliation starts with acknowledging the past, and working to make the future better. The course looks at different texts with themes like cultural genocide, growing up in residential schools/ on reservations, different forms of assault, suicide, etc. But they also tell tales of resilience, determination, and the unfaltering community that Indigenous people have created for themselves over centuries.

ENG274 goes through multiple texts that have Indigenous themes/ stories, or were written by Indigenous peoples. One of these novels is The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline, a Metis author. It is a fictional dystopian novel where Indigenous people were hunted for their bone marrow, which had magical powers that others wanted to take away so they could possess those powers themselves. This is, of course, a metaphor for the cultural genocide that Indigenous people faced for centuries in residential schools, where children were forcibly stripped of their identities,

language, religion, and families.

Editor | Yusuf Larizza-Ali arts@themedium.ca

Indian Horse was written by an Ojibway author, Richard Wagamese. It follows a young First Nations boy, Saul Indian Horse, who endures years of trauma at residential schools. He tries to escape multiple times and watches his siblings die after their attempts. However the book also demonstrates Saul’s resilience, as he learns to play hockey while in his residential school and quickly becomes talented. Unfortunately, the more famous Saul became, the more racial prejudice he faced, which led him to leave the game and confront the trauma that he’s carried throughout his life.

Professor Daniela Janes teaches literature courses like ENG274. When teaching this course, Professor Janes thinks, “It’s important for students to understand the way implicit bias can shape their reading practices and to understand that literary criticism (the way we read and write about texts) can work to re-entrench existing inequalities or to challenge them. By centering Indigenous scholarship, the course helps students to understand Indigenous

ship, the course helps students to understand Indigenous ways of thinking about place, language, and relationality.”

Understanding and appreciating the struggles that Indigenous peoples have to face daily, even in the twenty-first century, is just one step towards reconciliation. Reading novels and texts like these, written about the Indigenous experience, are a great way to start working towards that goal.

Indigenous Filmmaker Recommendations

Yusuf Larizza-Ali Arts Editor

An overview of Jeff Barnaby and Zacharias Kunuk, two contemporary Indigenous filmmakers who have helped give Indigenous cinema greater attention.

Many Indigenous forms of artwork are receiving a greater amount of attention today. The contributions to Canadian culture made by Indigenous people is getting more recognition and recognized as part of Canadian artwork. One example of these is cinema in which several Indigenous films focus on themes of colonization and particularly how it impacts individual communities within Canada’s political landscape. The course CIN205H5 Canadian Auteurs discusses contemporary filmmakers in Canada in a comparative study. Several key Auteurs looked at in the course are Indigenous and their contributions to Canadian cinema.

One Indigenous filmmaker is Jeff Barnaby the director of the films Blood Quantum (2019) and Rhymes For Young Ghouls (2013). Barnaby was a Mi’kmaq an Indigenous group of people who are native to areas in Canada’s Atlantic provinces. He started his career by directing short films and his debut short titled From Cherry English (2004) an allegory for the threats posed on Indigenous identity told through the hallucinogenic journey the protagonist embarks on. The short earned two Golden Sheaf Awards for “Best Aboriginal” and “Best Videography” in that year’s Yorkton Film Festival.

Later he directed another short film titled File Under Miscellaneous (2010) a dystopian science fiction film about a Mi’kmaq man who undergoes intense surgery to become white as a response to being victimized by antiFirst Nations racism. The film received a Genie Award for “Best Live Action Short Drama.” The full extent of Barnaby’s authorial style can be seen in his debut film Rhymes For Young Ghouls (2013). The premise of this film is that a teenager named Aila is plotting revenge against the Canadian residential school system. The

film is based on the documented history of abuse First nations people experienced in this system. For his work on the film the Vancouver Film Critics Circle named Barnaby “Best Director of a Canadian Film.”

Then, in 2019, he directed a horror film titled Blood Quantum (2019) which takes place on the Red Crow Indian Reservation in Quebec and is about an infection turning people into zombies. The film uses the horror genre to depict new ideas on colonialism and de civilization. The film features a role reversal between Indigenous people and Europeans as the Indigenous people are immune to the plague while the white refugees on the land aren’t. Through this storytelling Barnaby is depicting the broader societal norms and audience expectations since the Indigenous’s people immunity reinforces their connection to the land. Sadly Barnaby died on October 13, 2022 after battling cancer, however his influence on Indigenous filmmaking remains intact to this day.

Another Indigenous filmmaker who discusses similar things to Barnaby is Zacharias Kunuk. Kunuk was born in 1957 in Nunavut (then part of the Northwest Territories) and attended school in Igloolik in 1966. He began practicing filmmaking from a young age as he purchased cameras and photographed Inuit hunting scenes before purchasing his own video camera to make movies. He started off his career with Nunavut Our Land (1995) a docudrama series covering the formation of the territory of Nunavut. He then served as a co-writer and codirector for the film The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006) about Inuit spiritual beliefs documented by the Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen across the Canadian arctic. The film was a nominee for the “Rogers Best Canadian Film Award” at the Toronto Film Critics Association Awards 2006.

Another film by Kunuk is One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019) about a real life Inuk hunter by the same name who was encouraged to give up their Inuk lifestyle and assimilate into a modern settlement by a Canadian government agent. The film has a unique approach to cinema as it is mostly scenes of Noah sitting

Art To Voice What Was Lost

Indigenous artwork encompasses native spirituality, myths, nature, and anything that embraces a love of the land. But it’s also a token of memory—of reclaiming the values and traditions of a group who witnessed their culture nearly dissolve before them.

I recently visited the McMichael Art Gallery in Kleinburg, Ontario. It features Canadian art and history, with a wide collection of work from the famous Group of Seven at the forefront. The gallery also highlights the heritage of Indigenous Peoples native to Canada. From cultural masks and paintings, to beaded belts and totem poles, the gallery is a haven for Indigenous art and cultural mementos.

From now until March of 2026, the art gallery has an exhibition called Early Days: Indigenous Art at the McMichael, featuring artwork from the late-twentieth century, and historical pieces from early native history.

The exhibit honed in on the artwork of Norval Morrisseau, a Canadian-born Indigenous artist. Emerging during the 1960s, Morrisseau was a pioneer of the contemporary Indigenous art style which bled into pop culture. His acrylic paintings dazzled audiences: they portrayed Indigenous figures, blending colour and geometric shapes to create a story of native land in a way that “popped,” and inspired an

in silence, in many of these he consumes large amounts of sugar to emphasize the psychological impact of colonization. This unique cinematic style causes the viewing experience to stick with the viewer and helps them process the impact of the struggles Noah and other Indigenous people faced. The film received the award for “Best Canadian Film” at the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Overall both Jeff Barnaby and Zachiaras Kunuk are prime examples of contemporary Indigenous filmmakers who have impacted cinema.

almost avant-garde movement among his contemporaries. Morrisseau’s paintings at McMichael incorporated Indigenous peoples’ symbolic elements and myths. In his “Merman—Ruler of Water” (1969), there’s a gliding half-man, half-fish. It reflects how the earth and the land are integral parts of Indigenous culture.

The McMichael gallery even featured some work of Emily Carr, a Canadian and contemporary artist of the Group of Seven era. Her art was denoted for showcasing native people, specifically those of the Indigenous Northwest Coast.

An eerie piece from the gallery was the “Indian Residential School, Leaving the Shallow Graves and Going Home” (2022) by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, a residential school survivor. Spirits of totem poles and a colourful skeleton walked in a procession to something unknown on a dark, rocky terrain. The acrylic painting commemorates the unmarked graves of Indigenous children discovered in British Columbia the previous year. These unmarked graves evoked the atrocities of the residential school system. The painting gives voices to those long-forgotten Indigenous children.

Totem pole carvings guarded the rooms in certain corners

of the gallery’s exhibit; carvings of Indigenous creatures, possibly from their folklore, animals (birds), and celebratory masks. A mini stone carving by Billy Gauthier, an Inuit, was of swimming loons in webs of what appear to be kelp. He carved the loons from muskox horn, while carving the intertwining kelp out of a moose antler. Symbolically, Indigenous peoples hunted their food, but after gathering their meat, never wasting the animal, they used the materials that remained to create art.

One of the most incredible art pieces I observed was the “Scar Paintings” (2006) by Nadia Myre, an Indigenous to

Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, Algonquin. On canvases of pastel pink and yellow, red, brown, and orange, Myre depicted different skin tones and the wounds of human flesh, by slitting each canvas and physically stitching them back up. Her art draws from personal experience, hinting at the violence endured by her own people and the scars left upon their lineages.

Indigenous communities utilize beads in various ways, whether as accessories or artwork. One example I saw at McMichael was a wampum belt, circa 1770, made of whelk-shell beads and clamshells, woven into several rows

SPORTS & HEALTH

on thin leather string.

You can see the appreciation of Indigenous art at our campus as well in the MN building. This past year, the stairs from the main floor ascending to the second level showcased an array of Indigenous paintings: colourful art displays of nature and lands they once inhabited, and the storytellings of their people.

To learn more about the McMichael gallery and its Indigenous pieces, visit mcmichael.com.

Editor | Joseph Falzata sports@themedium.ca

Tri-campus soccer semi-finals recap

Tyler Medeiros Associate Sports & Health Editor

Recapping the semi-final upsets that sent the men’s and women’s tri-campus soccer teams to the finals for back-to-back years

For the second season in a row, our men’s team will take on their eternal rivals University of St. George (UTSG) Red, in the outdoor finals. The women’s side also secured a spot in the final against University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC) at Valley Fields with an exceptional penalty shootout win against UTSG Blue last Sunday.

A six-goal thriller downtown

The men knew that it was a do-or-die match against UTSG Blue at Varsity Field. The Eagles came out firing, and Aiden Gideon scored the first goal of the match with his wand of a right foot, squeezing the ball between the keeper and the post. The Eagles imposed themselves on the opposition, but a mental mistake from UTM’s back line with just a minute left in the first half helped UTSG Blue equalize with a chip from just outside the box.

The match went from bad to worse in the second 45 when Captain Pietro Arrigoni went down with an injury. The coaching staff, players, and fans began to fear the worst as doubts over Arrigoni’s availability for the final came into question.

The Eagles couldn’t let Arrigoni’s availability for the final distract them. UTM finally settled into the second half of the match with 15 minutes left to play. After a good passing sequence between Paul Doherty and Krish Chaven, Ethan Swan found himself 1v1 on the wing. Swan cut in and whipped a left-footed shot to the far post and into the net. Swan and Gideon both added to their tallies and picked up a brace each. With the final score 4-2 in favour of UTM, the only thing left to think about before the final was the injury to Arrigoni.

The captain provided a statement of encouragement days before the final. “Mentally, I’m feeling fantastic, and physically, I feel better every day, as I nurse my ankle back to full

health. I will for sure play in the final.”

Flawless penalty shootout send the Eagles to the final

The women’s team also picked up a critical win in what could have been their last game of the season. The game finished 1-1 in normal time with a penalty shootout to break the tie. The Eagles scored all of 4 of their penalty shots taking home the win and a place in the finals against UTSC.

“Coach Krista Pantin reminded us that this was the most important game of the season,” Amal Rashid, forward for the UTM women’s team. “Every single one of our penalties were scored, despite not preparing to go into penalty kicks. We are super excited to be playing this weekend and look forward to carrying the same energy that we had the previous game.”

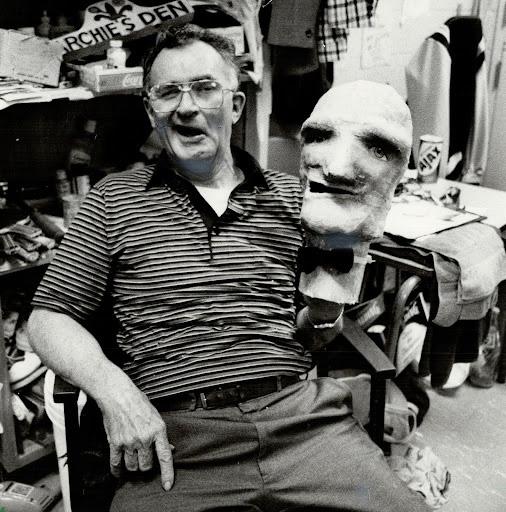

UTM History: Archie French

Laila Alkelani Contributor

A look back at Ronald “Archie” French, the beloved trainer and mentor who shaped student life in Erindale College in the 1970s

Few figures in early Erindale College history are remembered as vividly as Ronald “Archie” French— umpire, trainer, and mentor. Students knew him for his sharp humour, loud music, and crooked smile, and while a tragic accident changed the trajectory of his life, it didn’t stop him from becoming one of the most iconic faces in UTM history.

Archie French was born in Toronto on the 26th of October, 1929. In 1935, at the age of 6, Archie was vacationing in West Hill, a cottage community in Toronto, with his family. He was riding on the back of a local grocer’s truck when he forgot to duck and was hit on the head by an overhanging branch. Archie survived, though only just, with a skull fracture and left facial paralysis. He underwent five surgeries over the 30 months that followed, which only slightly improved his facial muscles. “Ron was in [the hospital] more times than I can remember,” said his brother Stan.

Every day after the accident, in a fruitless attempt to teach his face to move again, Archie stood before a mirror, making funny faces. Often, he took the Gerrard streetcar from his east-end home to Toronto General Hospital to receive shock treatments on his face. He never took the TTC again; the memories of those hospital trips were too dreadful. A noted physician of the time performed surgery on his brain via the ear, damaging his hearing on one side. His injury had also left one side of his face paralyzed, which he would later refer to as “the kisser.”

Matty Eckler, ballplayer and one of the first staff members of the Pape Playground (now known as the Matty Eckler Community Centre), encouraged Archie to pursue umpiring. Archie went on to win a scholarship to a Florida umpire school in 1951. There he met legendary umpire Al Sommers, who one day pulled Archie aside and told him, “Kid, you’ve got the goods, but with a kisser like yours, the players will ride you out of the league.” Archie loved Eckler for his honesty.

Though he didn’t make the big leagues, Archie was admired in the minors across Pape Playground, Leaside