By Jacob Hoffman Express correspondent

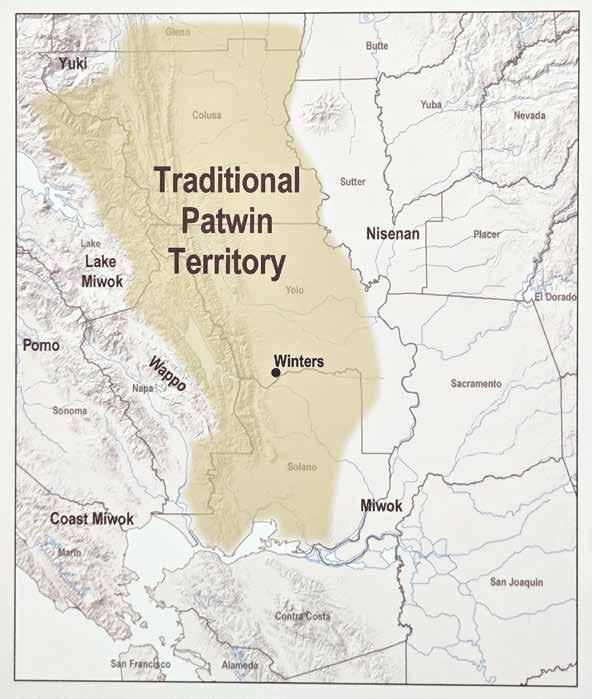

Long before the founding of Winters, the land along Putah Creek was home to the Patwin people, a part of the Southern Wintun Native American tribe.

For more than a thousand years, the Patwin lived, thrived, and built a community in this region — drawing sustenance from the creek, shaping the land with care, and establishing deep roots that long predate modern settlement.

According to Joann Leach Larkey and the Yolo County Historical Society’s book “Winters: A Heritage of Horticulture, A Harmony of Purpose,” the Patwin arrived in the area where Winters, Vacaville and Putah Creek are now around 1,200 years ago. In these areas, a number of villages thrived, with Sherburne Friend Cook suggesting in his comprehensive 1976 study on Native Californian populations that the Patwin may have numbered around 5,000 prior to the mission system.

Living from the land

Larkey describes how Patwin villages were organized around families living in dome-like homes and communal dwellings constructed with poles and thatches of tules or packed earth. She continues that these villages were typically led by, “a chief, a council of elders and one or more shamans, who had curative powers.” These authorities directed the village’s economic and religious activities. Households were made up of a husband and wife, their unmarried children, and their married daughters and their families.

“These family groups contributed to the welfare of the entire community by specializing in hereditary functions,” Larkey wrote,

“These family groups contributed to the welfare of the entire community by specializing in hereditary functions.”

Joann Leach Larkey, Yolo County historian

“such as fishing, tool-making, basket weaving or healing. Grass, flower and seed tracts were privately owned by families, while oak groves and hunting areas were communally owned by the village or tribelet.”

The Patwin were deft at utilizing the many resources of their surroundings to provide for themselves and their communities. Larkey describes how, “few edible plants, fish, fowl, animals or insects were not eaten or processed for later use,” as the Patwin made use of everything they could. “Both plant materials and animal skins were used to make functional items or protective and ceremonial clothing,” she continued, noting that in particular, “acorns, gathered in the fall from the black, valley and blue oak trees, were the staple of the Patwin diet.”

The UC Davis Natural Reserves Handbook, describing life in Quail Ridge where the Patwin’s territory extended to, also noted the importance of acorns in the diet of the Patwin, especially from acorn-producing oaks.

“Acorns are highly nutritious,” the explained, “relatively easy to prepare, and have good flavor…moreover, the yield per acre is very high (up to 2,722

kilograms per acre (6,000 pounds per acre), with a mature oak tree producing 227–454 kilograms (500–1,000 pounds) annually.” When acorns were difficult to procure, Patwin would also eat buckeye nuts, as well as supplement these staple foods with pine nuts from sugar and gray pines, blackberries, juniper berries, elderberries, wild grape, and manzanita berries, and even certain roots and bulbs, “such as Indian

potatoes (“pela” in Patwin), sweet potatoes (“tusu”) and onions (“buswai”).”

Hunting also played a major role in the Patwin diet and in their society as a whole. Larkey wrote that river animals like salmon and turtles, birds like ducks and geese, and game like deer and elk were often eaten by the Patwin, who prepared these foods in particular ways to preserve them for later use and improve their flavor.

These animals had many uses outside of food as well. The Natural Reserves handbook describes how animal bones were made into harpoons and nets for catching fish, and that furs from mammals, including deer, elk, antelope, black bears and rarely grizzly bears, mountain lions, bobcats, foxes, wolves, beavers and young skunks, were an

Reprinted from the May 22, 1975, Centennial Edition published by the Winters Express

Winters Express

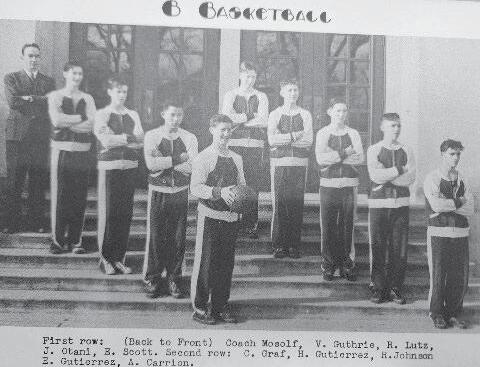

Japanese first came into the Winters area about 1890 as agricultural laborers. An account in the Express in 1890 reported that 15 Japanese men came to work in fruit orchards in Pleasants Valley.

The story noted that Chinese laborers in the area were unhappy about the influx of Japanese because “they work too cheap.”

Chinese, originally imported to work on building the Pacific end of the transcontinental railroad, drifted into agriculture in this area.

Mojiro “Charlie” Hamakawa, of Sacramento, who operated the Horai Company here from 1910 until 1942, said that the number of Japanese increased in this area in the 1890s, with the Horai store opening between 1898 and 1900. The building, located near Putah Creek and east of the railroad tracks, had previously housed a Chinese store.

North of the Horai Company was a Buddhist Church, then two Chinese restaurants and a Chinese store. Behind the two restaurants was a boarding house for Chinese. Hamakawa said that the restaurants, during a part of the time he operated his store, were just fronts for gambling houses, with various Chinese games played.

Hamakawa lived in a house behind his store

important resource for utility and trade.

“The Hill Patwin traded shells, skins, red woodpecker scalp belts, flicker quill bands, and dried salmon, among other valued items, with the neighboring Wappo, Pomo, and Lake Miwok,” the handbook continues, “whose lands to the north and west included the headwaters of Putah Creek, and with the River Patwin, Maidu, and Eastern Miwok to the south and east.”

Disruption, displacement

However, this way of life would be forever changed with the arrival of European colonists in the early 1800s, beginning a succession of arrivals from Spanish, Mexican and American settlers. The initial arrival of Spanish and Mexican colonists from 1808 on disrupted the existing demographic equilibrium of the area, as the Patwin and other natives soon found their land taken, the resources they’d previously re-

and there was another house there housing a Chinese family.

This cluster of buildings, known by people in Winters as “Jap Town,” remained until the late 1940s when Fred Smith, former Express publisher, sold the paper in 1947 and bought the buildings, razing them.

The Horai Company served not only the Japanese community, but did a big business with migrant fruit workers. Hamakawa frequently supplied families with food when they arrived in the spring to thin apricots or to pick apricots or peaches. These families would make sure that all bills were paid when they went to other communities as they wanted their credit to be good when they returned the following year. Before World War II about 40 families or about 175 people made up the Japanese community. The Japanese school, now owned by Mr. and Mrs. John Martin and Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Montosa, was built in 1930 by the late Art Gale. The school was used as a community meeting place and was also a school where their children could learn to read and write the Japanese language and learn something of their culture. Classes were conducted one day a week, usually on Saturday. The children attended public schools. Buddhist services were conducted in the church

See JAPANESE, Page 5

lied on increasingly scarce, and their people forced into missions that sought to eliminate their native cultures.

“The extension of Spanish and Mexican authority into the western Sacramento Valley, inter-tribal rivalries that subjugated Patwin villages to the Suisun Chief Francisco de Solano, and the subsequent intrusion of British and American trapping parties had devastating effects upon Patwin villages in the Putah Creek area,” according to Larkey.

This depopulation from warfare and disease combined with efforts by the mission system to see the Patwin people in the areas around Winters mostly killed or forced to give up their native culture and history.

Cook noted in 1976 that, “one element which has almost nullified the efforts of ethnographers is the fact that the Southern Patwin were swept into the missions as early as 1810, long before the memory of modern informants,” making even oral sources from this time

Reprinted from the May 22, 1975, Centennial Edition published by the Winters Express

By Rob Giddings Special to the Express

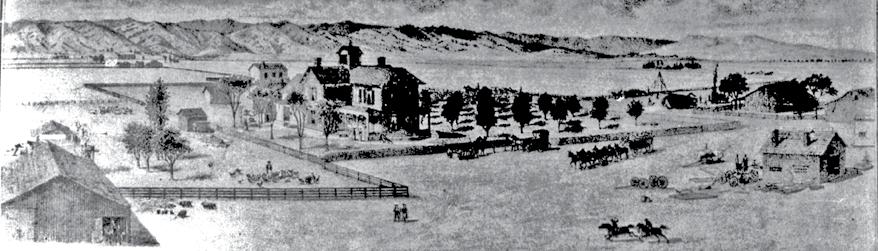

Located about 6 miles north of Winters there once thrived a small, and little-known community called Buckeye. Named after the wild bushes which grace the banks of the dry channel termed Buckeye Creek, the town of Buckeye became a calling point for numerous early California settlers hoping to establish themselves as farmers on the rich lands which characterize Yolo County. From its founding to the time of its disappearance in 1875, Buckeye represented the place of origin for several early and popular Winters residents. However, the coming of the railroad in 1875 terminated any prospects of future growth for Buckeye; losing its prosperity to the railroad community of Winters and thereby linking Yolo County with the commerce of the state, and hence the nation. 1856 marked the arrival of Buckeye’s first residents. During its first year Buckeye boasted a post office headed by J. P. Charles and one home, that of J. O. Maxwell, which he built in April of that year. Maxwell’s home was situated on the site of Benjamin Ely’s

period extremely difficult to come by.

Because of this, Larkey argued that “the practice of inducing or coercing the native people into relocating effectively removed the native population from the Winters area at an early date.”

“This occurred even before raging epidemics of malaria, introduced by the hunters and trappers in the early 1830s, and smallpox in 1837 and 1838 further reduced the Patwin population,” Larkey wrote.

Even well into the 20th century, the Patwin who survived faced discrimination and challenges to their way of life. Patwin man Bill Wright told NPR in 2008 about his experience at the Stewart Indian School in Nevada in 1945 when he was 6 years old. Wright described how he was bathed in kerosene, his head was shaved, and he and his fellow students were “forbidden to express their culture — everything from wearing long hair to speaking even a single Indian … word. Wright said he lost not only his

ranch, the ranch which eventually developed into the nucleus of the community. In 1857 Buckeye received its first general store. T. J. Maxwell, the father of J. O. Maxwell, erected the store and started to sell general merchandise. At the same time Postmaster Charles moved, having served but one year, and the post office was moved to Maxwell’s store with T. J. Maxwell assuming the responsibilities of Postmaster.

T. J. Maxwell served as post-master for Buckeye township for three years, then in 1860 he sold his store and goods to one Charles Zimmermaker.

Upon the Maxwells’ departure from the area Robert C. Briggs, a prominent rancher and grain raiser in the area, became the postmaster for Buckeye with Mr. Zimmermaker running his store, operated by Jacobson and Cramer, and the blacksmith’s services of one John Ford entered the Buckeye community. In the fall of the same year the Good Templars organized at Buckeye. By 1864 the town of Buckeye consisted of two stores, a blacksmith shop, a saloon and a post office.

In the Spring of 1865 one John Troutman started a business in Buckeye only to sell out to York and Harling

language, but also his American Indian name.”

Endurance, revival

Despite these centuries of adversity, the Patwin/Wintun people and their language have survived to this day, with three federally recognized tribes existing in California, the Cachil DeHe Band of Wintun Indians of the Colusa Indian Community of the Colusa Rancheria, the Kletsel Dehe Band of Wintun Indians and the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation.

The Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, located in Yolo County, writes on its website about its long history, as well as its determination to maintain its

the following year. George Tandy Jr. brought his harness-making skills to Buckeye from Ireland in 1867 and continued there until 1875, when he moved his shop to Madison. By 1869 Buckeye sported a new hotel run by the Hunt Bros., a shoemaking business under the proprietorship of one P. J. Dorney, and a Masonic Lodge. Three years later, in 1872 an additional blacksmith shop opened services on the property of J. H. Moody and the next year J. D. Gregory started a drug store within the town’s limits. Buckeye now appeared to be growing at a steady and healthy rate, becoming a community of importance in the county. But in 1875 the great “octopus,” or rather, the railroad came to the Buckeye area; establishing its town at what is now known as Winters, drawing the area’s commerce and residents there and forcing Buckeye into obscurity.

Though the town of Buckeye disappeared, its residents continued on in the Yolo area. To sum up this history of Buckeye some brief biographical sketches of her more prominent citizens follows in an effort to illustrate how and per- haps why they came to Buckeye and the effect the railroad played upon their interests and lifestyles.

culture and cultivate a proud community for themselves and future generations.

“Our Patwin ancestors lived in villages spread across a large territory that spans from Sonoma Valley in the west to the Sacramento River in the east, and from just south of Clear Lake in the north to San Pablo Bay in the south.”

“For us the meaning of success is not just a thriving community and prosperous enterprises; it is also the recovery and revitalization of our language and traditions, as well as the protection of cultural and burial sites from disturbance and desecration. The mission of the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation

Cultural Resources Department is to identify, preserve and protect the Patwin language, culture and sacred sites.”

This article draws from foundational research including “Winters: A Heritage of Horticulture, A Harmony of Purpose” by Joann Leach Larkey, published by the Yolo County Historical Society in 1991, which offers detailed insight into Patwin village life, leadership structures, and resource use. It also incorporates demographic analysis from Sherburne Friend Cook’s seminal 1976 study, “The Population of the California Indians, 1769–1970,” which provides historical population estimates and examines the profound impacts of colonization on Native communities.

Reprinted from the May 22, 2024 edition of the Winters Express

By Amelia Biscardi Winters Express

Thanks to a May shower, the Winters Community Center was full with limited standing room as the community, descendants of local Japanese families and beyond gathered for the Japantown Monument Dedication on Saturday, May 4. The community center was transformed for the celebration with the deep drums of the Taiko Drums, paper cranes, Koinobori (carp streamers), and floral arrangements.

With multiple books in tow Flloyd Shimomura detailed some of the history of Winters’ Japantown. He shared some of the history explaining that after the Pearl Harbor bombing, those of Japanese descent were forced into internment camps in Arizona and Colorado and most did not return afterwards. With Putah Creek serving as the diving line between Yolo and Solano Counties, families were sent to one of the two camps based on which side of the creek they lived on. Shimomura said that most didn’t re-

next to the Horai store, with a priest coming up from Vacaville, but social events were held in the Japanese school.

World War II

Following the outbreak of hostilities between Japan and the United States in December 1941, feelings against Japanese in California ran high, and all people of Japanese descent were ordered evacuated from the coast in March 1942.

Winters was tense that spring, with the city council and the local American Legion post demanding that they be evacuated. Prior to the evacuation, the FBI swooped into Winters and seized six men — their only crime being that they had visited Japan within the past few years.

When the local Japanese were rounded up, those living south of Putah Creek were sent to Arizona and those north of the creek were sent to Colorado, splitting up the Japanese community.

The Japanese had just a few days to prepare for evacuation into the hastily set up camps. A number of families stored their belongings in barns on ranches where they had been living, but practically all of these possessions were stolen or vandalized during the war years.

Hamakawa sold all of his merchandise to Vasey Brothers, who stored all of the Horai store fixtures in the old Opera House above their store.

Bitterness

Feelings towards the Japanese ran high here during the war.

A local chapter was formed of an anti-Japanese society pledged to work to keep these families from returning.

turn to Winters due to backlash from some of the community. This all culminated in a fire of “unknown origin” that burnt down most of Japantown.

For those who returned, they didn’t face an easy road back.

Vasey Coman, Winters resident shared an essay she wrote when she was 16 about a story of her great-grandfather Jack Vasey. Comas said that a Japanese woman and her child had made their way into town only to have the mob chase them. Jack Vasey protected them in his store and got them help.

Yolo County Supervisor Lucas Frerichs noted the importance of the government acknowledging past mistakes.

“And I think it’s so important to recognize a number of these really tragic mistakes of the past,” Frerichs said. “Especially considering that some of the same themes that were occurring in the 1940s again occurring today. There is definitely an increasing amount of ‘othering’ going on in our society.”

In February, Winters city council member Jesse Loren was invited to help the committee. Loren felt honored to take over

Petitions were circulated throughout the ranches in the area getting pledges not to hire Japanese or permit them to reside on their property.

A few of the ranchers, notably the Pleasants families, refused to sign such petitions.

During the latter part of the war, Mr. and Mrs. Hamakawa were transferred from Colorado to Sharp Park and while there, Jack Vasey and the late Clarence Wyatt were able to contact authorities and have the Hamakawa’s released.

Because of the intense feelings in Winters, they located in Sacramento where they lived two years until Mrs. A. P. Pleasants asked Noble Nishida, who also lived in Sacramento, if he wanted to come back to the Pleasants ranch. Nishida mentioned the offer to the Hamakawas and they jumped at the chance to return to Winters.

Ugly episode

Shortly after the end of the war, the first Japanese family returned to the Winters area, and a mother and her small child came into town to do some shopping.

A mob was hastily organized to run them out of town and they chased the woman and her child down Main Street, up Railroad Avenue where they dashed down the alley.

Jack Vasey, who was outside the rear door of his store, motioned the fleeing pair to come into the store, then locked the back door to keep the howling mob out and went through the store, locking the front door to protect the woman and child.

The mob grew larger and more threatening, calling on the Vasey brothers to turn the woman and child over to them. Local law officers couldn’t be reached, so Jack Va-

and write the proclamation that was read at the city council meeting on April 16 rescinding a 1942 resolution that urged the “removal of all Japanese from California” and demanded that “immediate steps be taken by the constituted authorities to see that all such enemy aliens be placed in concentration camps and that the land and/ or property owned or operated by such aliens be placed under government supervision for the duration of the war.”

Both Shimomura and Loren pointed out that when looking at the monument, you are viewing the area where the photo was taken where Japantown and its business district originally stood.

Winters resident Howard Kato explained to the crowd the importance of educating oneself on this matter and not just ignoring this part of Winters and American history.

“The monument is an educational tool that teaches a part of US history that most Americans do not know about,” Kato said. “The monument is even educational for my generation, the

Page 6

sey called Yolo County

Sheriff Forrest Monroe.

Sheriff Monroe drove up to the store, went in and got the woman and her child, loaded them in his car, told the mob to act like American citizens, and took the pair back to the ranch where they were living. Gradually, more Japanese families began returning to the area, but only a fraction of the number that were here before the war.

During the war, the city council took over the Japanese school, but that was returned to the Japanese in 1947. It was used for social events and also for Buddhist services until sold in 1973.

Japanese picnics

Bitterness engendered during the war years was gradually forgotten as the new generation didn’t share the prejudices of the older generation.

One factor that greatly improved the relations was the Japanese Picnic, held each spring at the Roth Hills west of Winters. The community had never seen such well-run picnics, complete with races, games, contests of all kinds, along with a wide selection of Japanese foods. Invitations were highly prized and eagerly hoped for.

Young are leaving

In another generation, there probably will be few Americans of Japanese descent living in the community. Those who have graduated from high school have gone on to college and entered the professions and are attorneys, dentists, teachers, or have entered the business or engineering fields. At the present time, there are no students with Japanese surnames attending Winters High School.

Reprinted from the May 22, 1975, Centennial Edition published by the Winters Express

By Susanne Rockwell Winters Express

Today the Spanish in Winters are mostly first or second-generation Americans who can only remember tales of the way times were hard enough in the old country to push their fathers out into a new world to find their living.

But, from 1907 to 1920 when Spain was wallowing in economic stagnation and hurt pride from her defeat in the 1898 Spanish-American War, the first substantial flow of Spanish immigrants began arriving in this area.

The first traceable Spanish immigrants coming to the Vacaville-Winters area are remembered by older residents as being single men from the rocky southern coast of Almeria on the Mediterranean Sea. They began arriving sometime near 1906 or 1907.

One of these immigrant adventurers was John Invernon, who left his wife and the first of his offspring back in Spain to find work in America. He crossed the ocean to New York in 1907 and then traveled out to the

orchard lands in California. The Winters-Vacaville area held a special attraction for John and his fellow countrymen — there were jobs to be had in orchard agriculture which was work they were used to in Spain. Two centuries before, it was the Spanish missionaries from Southern Spain who had transferred the nut trees and fruit agriculture from their native land to their missions in California where the trees had flourished.

The newcomers, who spoke little English, became fruit workers migrating from apricots to peaches to nuts in the northern valleys of California such as the Santa Clara, the Suisun, Pleasants and Vaca Valleys. Many of the men would spend more than 15 years crossing back and forth over the Atlantic. They would visit their families for a year or so and then return to their jobs in California. Invernon returned to Spain in 1913 for a visit and again in 1920 when he finally had saved up enough passage to bring his wife and children to California.

Other Almerian men such as John R. Martinez came to the States single and then

the rich history that has shaped our schools, our families, and our shared future As we look ahead we remain committed to educating and empowering the next 150 years of Winters residents.

later returned home to marry only to leave their wives in Spain to wait for another few years while they continued to work in California, saving enough money to buy passage for their families and, eventually to purchase their dream ranches.

Although a few Spanish came to the U. S. with enough capital to travel all the way to California, others had to start working in the mills and mines of the east before they heard about the Far West fruit basket or could afford the trip. John Fernandez was one such man. John left Spain in 1918 for the United States via Cuba, although he later realized he could have traveled directly to New York. He explains that the crooked ticket seller was trying to make extra money by convincing the emigrants they had to sail to Cuba first to enter the U.S.

From New York, Fernandez began looking for jobs. His first work was in the coal mines of West Virginia and Pennsylvania. Later he found work in the steel mills of Canton, Ohio with other Spanish immigrants, who, he says, were always

See SPANISH, Page 12

from Page 5

Sansei (third-generation Japanese Americans), because our parents hardly or never talked about what happened.”

Resolutions from US Congressman Mike Thompson and Assembly Majority Leader Cecilia Aguiar-Curry were on display alongside resolutions from the Winters City Council and the Yolo County Board of Supervisors acknowledging the importance and valuable contributions the Japanese community brought to the Winters area.

The dedication program ended with a benediction from Rev. Matt Hamasaki of the Sacramento Buddhist Church. A Buddhist service was scheduled earlier that morning at the Winters Cemetery near where many of the Japanese families were buried. Afterwards, the monument was unveiled showcasing a picture of around 150 people at the Nishida funeral in 1930. Floyd Shimomura invited his 98-year-old

aunt Harumi March, who was featured in the photograph in the arms of her mother at 3 years old and is the last person in the photo who is still alive today, to take the cover off of the monument with the assistance of some of the family’s children in the crowd.

Many descendants and different generations were able to make the event and families of three and four generations took pictures next to the monument.

“It’s very gratifying and I’m really pleased and satisfied that so many descendants came,” Shimomura said. “Because right now they’re probably only about five Japanese Americans that live in Winters.”

The journey of the Historical Society of Winters from creating the “Lost Japanese Community of Winters” exhibit to having the monument created and placed was a long process. According to Gloria Lopez, a Historical Society volunteer, they began discussing an exhibit just before the COVID-19 pandemic. As the committee started asking

for stories or photos, they didn’t get anything at first.

“Then one person finally said, I have this photo,” Lopez said. “The floodgates open and they just really contributed, you know, the members of the Japanese community just started contributing all these photos and stories and — so we had the exhibit.”

And the flow of mementos and photos continues as Lopez said she just printed out a story last week.

“This is one of the most beautiful events I’ve ever experienced in Winters,” Loren said. “It has been a manifold event of a deep connection and sorrow and a painful past and bringing people together and acknowledging the great sacrifice of the Japanese in regard to our own people, our residents.”

Editor’s Note: The Winters Museum hosts a condensed version of the “Lost Japanese Community of Winters” for the public. View it during the museum’s public hours Thursday through Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m.

Tucked between farmland and foothills, the city of Winters holds a charm that is both deeply rooted in tradition and full of potential. Though not the smallest community in Yolo County, Winters is still considered rural — a characteristic that brings with it both beauty and barriers. For many residents, accessing county services located in Woodland or Davis presents a challenge, whether due to lack of transportation, language barriers, or simply the distance itself. But where official infrastructure struggles to reach, local nonprofit organizations step in — and their impact is immeasurable.

In Winters, nonprofits are more than service providers — they are lifelines. They bridge the gap between need and access, between aspiration and opportunity. Whether it’s through health and wellness programs, youth sports, arts education, environmental initiatives, or cultural enrichment, these organizations offer something beyond programming — they offer hope.

From its earliest beginnings, members of the Winters community have gathered in groups to offer services, champion causes, and foster social connection among residents. This culture of civic engagement is woven into the town’s identity. Two of the oldest community organizations still active today — the Winters Fortnightly Club

and the Rotary Club of Winters — reflect this long-standing spirit. Their continued presence is a testament to the town’s enduring values of service, leadership, and collaboration, and they’ve paved the way for many of the nonprofit efforts thriving in Winters today. There’s something magical about small towns, especially those like Winters where generations have stayed or returned to raise families of their own. In this kind of place, nonprofits don’t operate in silos. Instead, they collaborate, leaning on each other’s strengths to create programs that reflect the true spirit of community. When these organizations join forces, they multiply their impact — and the residents of Winters reap the benefits. A shining example of this collaboration is how Winters nonprofits have approached the Big Day of Giving. In 2019, a few local groups banded together to jointly market the annual regional fundraising event. By pooling resources and sharing outreach efforts, they lowered costs and sent a unified message to the community: they weren’t competing — they were working together. That spirit of unity struck a chord. Since then, the number of participating Winters nonprofits has grown to 14, and their coordinated marketing efforts have only flourished, serving as a model of rural collaboration and community-cen-

tered fundraising.

As Winters grows and welcomes back those who once left for college or careers, there’s a unique opportunity to blend tradition with innovation. The community holds fast to its roots — local festivals, historic buildings, and beloved customs — while also embracing new ideas and challenges.

Nonprofits are often the first to navigate that balance. They bring fresh energy to longstanding traditions and create spaces where new voices can be heard. In doing so, they ensure that Winters remains not only a place where history lives, but where the future is being actively shaped.

Of course, like all nonprofits, the ones in Winters face challenges. A top one among them is finding volunteers and board members who can help carry out their missions. Recognizing this, local leaders launched the Winters Volunteer Fair, a now-annual event that connects residents to causes they care about. It’s also a chance for organizations to network, share resources, and explore ways to work together more effectively.

This is especially crucial in a rural community, where the same passionate people are often called on to do more with less. Collaboration isn’t just a feel-good idea — it’s a necessity.

This special edition is just a small sampling of the work being done every day in Winters.

Continued from Page 9

including the Winters Express. Meanwhile, shop class students are crafting custom wooden plaques for parade winners and honorees — a tangible display of skill and school pride. These hands-on projects showcase not only student talent but also the power of collaboration and mentorship.

A downtown homecoming

One of the most significant changes this year was the relocation of the post-parade festival to Rotary Park in downtown Winters. The goal to breathe new life into Youth Day while strengthening ties between the event and local businesses, attempting to tie all of the Youth Day events together across more space, and try something new.

Despite logistical challenges, the committee views this year’s event as a learning opportunity and is already planning improvements for next

year. Among the bright spots — the return of student-run booths and carnival games, a tradition the committee hopes to expand with even more activities for children and families.

Reimagining royalty

The Youth Day Royal Court — a tradition dating back to the event’s origins — has undergone reflection and change in recent years. Once a coveted role, recent events have seen a decline in student participation, prompting discussions about its relevance.

Rather than retire the tradition, the committee is reimagining it. This year, the Royal Court took a break and became an opportunity for student-led marketing and outreach, with middle schoolers helping to brainstorm how royalty roles can contribute to the promotion and spirit of the event.

While the concept is still taking shape, the hope is to transform what was once a symbolic title into a meaningful role with

purpose and impact — especially for students who may not otherwise engage with Youth Day activities.

Looking ahead

As Winters Youth Day approaches its 100th anniversary in a little over a decade, the committee remains focused on honoring tradition while evolving to meet the needs and interests of new generations.

For many, the day holds personal meaning. Youth Day is not only a celebration of the community but it’s a legacy — one that connects past, present and future. Children who participate in the parade or remember waving to those in it, are now adults who are taking part in it. With continued collaboration between city leaders, educators, students, and families, Winters Youth Day is not just surviving — it’s thriving. And in doing so, it remains what it has always been — a powerful testament to what’s possible when a community comes together to lift up its youth.

By Crystal Apilado Winters Express

In Winters, elders are not just respected — they are celebrated, supported and embraced. As the city’s older adult population continues to grow, so too has the community’s commitment to empowering seniors, ensuring that they age with dignity, connection and purpose.

While the disbanding of the Winters Senior Commission on Aging marks the end of one chapter, it also signals the beginning of a broader movement that places senior well-being at the heart of community development.

A community-driven shift

Formed in 2019, the Winters Senior Commission on Aging was tasked with advocating for local elders and serving as a bridge between residents and City Hall. But dwindling participation and unavoidable health-related resignations led to the recent loss of quorum — the minimum number of members needed to function. Without enough commissioners, the city council chose to dissolve the group.

Still, the city isn’t stepping away from senior support. Instead, it is

pivoting. There was talk to create a new parks and recreation-style commission that incorporates senior issues into a broader community agenda — although some community members are still waiting to see if there is action to do so.

Filling the gap

Long before the commission’s closure, the Winters Senior Foundation had already stepped up to fill the void. Founded in 2014, WSF is a powerhouse of compassion and programming, built by and for the community.

“As a community organization, our goal is to help older adults get out of the isolation of living alone,” said WSF President Jerry Lowden. “We’re here to provide social opportunities, creative outlets, and support that many seniors otherwise wouldn’t have.”

Among its many initiatives is the Santa Bag program, a grassroots effort that ensures elders in need receive essential supplies — from toiletries to cleaning products — during the holiday season and beyond. Volunteers work directly with senior apartment managers to identify those most in need, delivering more than just goods: they

See ELDERS, Page 13

By Angela Underwood Winters Express

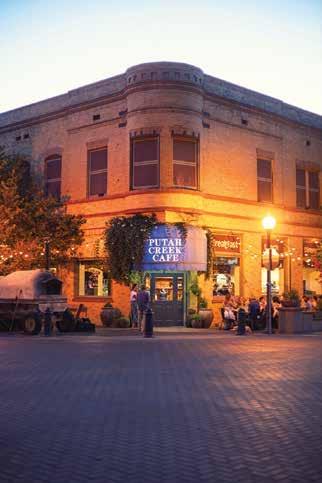

Putah Creek’s history runs as long as the miles it flows along, with Winters claiming a serious section.

The Putah Creek Council executive director says the same.

“Winters seems to have an unusually large population of nature lovers relative to its size,” Executive Director Phil Stevens said of the community culture surrounding the waterway.

“We don’t know whether that love was inspired by experiencing the creek, or if experiences of nature elsewhere have translated into affection for the creek or some combination of both.”

That affection helped save the inlet long before the celebratory annual Salmon festivals in Winters that began nearly a decade

Continued from Page 11

deliver dignity and care.

WSF also offers weekly yoga classes, guest speakers, field trips, arts and crafts, and the beloved Senior Social Activities day every Thursday afternoon. Held after the Café Yolo community meal, these events give Winters elders a consistent opportunity to connect, move, and engage.

To learn more, visit www. wintersseniorfoundation.

org Café Yolo returns

A critical partner in this ecosystem of support is Meals on Wheels Yolo County, which not only delivers meals to homebound seniors but has also revived in-person communal dining through Café Yolo.

After nearly five years of pandemic-related pause, Café Yolo Social Dining

ago. Rewind to 1957, when Putah Creek suffered dire droughts, creating a catalyst for change.

“Among the biggest milestones were the completion of Monticello Dam in 1957, which permanently changed the character of

made its triumphant return to the Winters Community Center on March 6. Every Thursday from 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., elders aged 60 and up are treated to a free, nourishing meal in the company of their peers. Reservations are required, but the experience is open-hearted and welcoming.

“Café Yolo isn’t just about food,” said one volunteer. “It’s about fellowship. It brings people together.”

The lunch seamlessly flows into WSF’s Thursday programming, turning one meal into an afternoon of enrichment.

To reserve a spot at the Café Yolo lunch, visit mowyolo.org/nutrition-access or call 530-662-7035. Honoring the legacies of elders

Not all support comes in the form of meals or services — sometimes, it’s about recognition. Since

the creek, and the drought years of 1989 and 1990, when the creek went dry,” Stevens said.

The drought greatly affected the waterway, specifically the 23-mile stretch between Solano Diversion Dam and the Putah Creek

2017, Winters Elder Day has been a beacon of respect and celebration, honoring residents 90 years and older.

Each year, the Elder Day Council hosts a free public celebration that highlights the lives of Winters’ oldest citizens, many of whom have helped shape the city itself. The day is filled with storytelling, laughter, and heartfelt connection.

“Our elders are the living roots of our community,” said Wally Pearce of the Elder Day Council. “Honoring them helps younger generations understand the importance of history, service, and connection.”

Volunteers are always welcome to support this intergenerational celebration — from setting up chairs to simply listening to stories. Call 707-249-7975 to learn more about how you can lend a hand in planning or the day of.

Sinks in the bypass. Hence, in 1988, the Putah Creek Council was formed with great purpose.

“Putah Creek Council’s mission is to inspire love of Putah Creek, its wildlife and natural habitats, and promote their protection and restoration through advocacy, education, and community-based stewardship,” Stevens said. That inspiration fueled years of legal battles. In 1996, the Sacramento Superior Court ordered 50 percent more water for Putah, but failed to address the wildlife, specifically Chinook salmon and steelhead trout.

The Putah Creek Council refused to settle for less and joined with the University of Davis and the city of Davis, which led to a 10-year legal battle that resulted in the Putah Creek Accord of 2000.

The accord is founded on six elements: resident native fish flows, anadromous fish flows, scheduled extended droughts, a new forum for management, restoration and monitoring funds, and landowner water rights.

The decree also secured a streamkeeper position. Reflecting on the creek’s history, Streamkeeper Max Stevenson ties the past to the future.

“This year we’ll be celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Putah Creek Accord at the Salmon Festival on Nov. 1,” Stevenson said. The stream keeper rewound to 1920, when the federal government and the Army Corps of Engineers strengthened their policy of creating navigable rivers “free and clear of logjams.”

See CREEK, Page 14

ahead

Though the formal Senior Commission may be no more, Winters has proven that elder advocacy is not confined to government — it lives and breathes in the actions of its residents, nonprofits and volunteers.

From the personal touch of a Santa Bag delivery to

the shared joy of a Thursday meal, Winters is building a model of aging that is rooted in community, not isolation. As the community continues to advocate for a senior center space and wait for a new commission to take shape, they do so on the strong foundation laid by those who have spent their lives giving to others.

As the city of Winters celebrates its 150th anniversary, The Winters Express is proud to honor the legacy we've shared with this community since 1884. For over 140 years, we've been Winters’ trusted local newspaper — reporting on city government, schools, sports, and the stories that shape our town. From milestones and memories to challenges and triumphs, we’ve stood as a watchdog, a voice, and a record keeper for generations. Here’s to 150 years of community — and to continuing the story, together.

• Local News • Sports • City Hall

• Schools • Events • Organizations • Editorials • And More!

By Jerry Lowden

Compared to other community groups the Winters Senior Foundation is 11 years young.

Currently, we are the only group established with the specific goal of providing activities for seniors.

The WSF was built upon a concept developed by Joe Aguilar and friends and was formalized in 2014 with Wally Pearce as President guiding the organization through 2017.

In 2018, Karen May accepted the position of President and she continued the development of social and educational activities

through 2019. I became President in January 2020, one minute before the COVID-19 lockdown took effect.

The WSF continues to grow and add activities such as our Chair Yoga program and our partnership with Meals on Wheels as we manage the weekly lunch at Winters Cafe Yolo each Thursday.

The WSF continues holding its speaker program, ice cream social, amateur artist event and its December Santa Bag program. Contact us at 530-795-6607, email info@wintersseniorfoundation.org by mail to: Winters Senior Foundations, PO Box 392, Winters, CA 95694.

The WSF continues to provide activities all of which are aimed at getting seniors up & out. We partner with MOW to provide lunch each Thursday via Cafe Yolo. It is an opportunity to meet your friends, make new friends, & enjoy a free lunch. To continue our support for Cafe Yolo and our other programs which include Chair Yoga, Thursday social gatherings, amateur art program, Santa Bag event, outings in the area, ice cream social, & community wide information meetings we ask for your donation during the Big Day of Giving May 1st.

Continued from Page 13

“They wanted boat traffic to get through, which is very important, but now we have an aesthetic of free-flowing streams with no logjams,” Stevenson said. “But those logjams are good and necessary for the baby salmon to make it out to the ocean.”

Stevenson said that before the dam was built in 1957, the creek would overflow its banks, partially flood winters and other areas, and dry up in some summers.

The stream keeper explained how the Putah Creek Accord helped restore the channel’s natural shape after it had been widened and deepened over the years due to gravel mining, flood control plans, excavations for sewage ponds, and even recreational bulldozing.

“In 2014, hundreds

of salmon started showing up, and after that, hundreds or even thousands of salmon show up in Putah Creek each year,” Stevenson said, crediting the Solano County Water Agency, local landowners, and the city of Winters. “Everybody working together created this.”

Now protected during their swim downstream, the salmon are a local staple, becoming a cause for an annual celebration. The other 364 days of the year, history continues to be made by the next generation.

“Kids of all ages participate in our weekly stewardship workdays, during which they tend the natural areas along Putah Creek, with special emphasis on Winters Nature Park,” Stevens said, adding that older adolescents and young adults participate in the council’s OneCreek internship program.

“They learn the

basics of habitat restoration by working with partner agencies throughout the lower watershed,” Stevens said. “Winters Middle School students join PCC’s Putah Creek Club, where they carry out various stewardship activities such as planting native plants.”

Regarding the local creek, nature and nurture collaborate rather than compete.

“We recognize that the creek can thrive only if enough people love it enough to care for and protect it,” Stevens said.

After all the bureaucracy and legal battles, Mother Nature resumes her natural habitat here in Winters. Now, greater winter and spring flows secure a place for native fish to flow freely, truly a fantastical feat.

“It’s quite a cool and interesting story,” Stevenson said. “And they’re still coming back today, and we’re still working on it.”

By Logan Chrisp Winters Express

The Winters community boasts a deep, vibrant sports legacy — there’s no one more knowledgeable about that legacy than Tom Crisp.

A retired math teacher and former athletics director, Crisp has turned into a passionate historian dedicated to local history. He’s devoted countless hours to researching and preserving the history of athletics in Winters.

Crisp’s efforts led to a sports history exhibit at the Winters Museum in collaboration with the Historical Society of Winters, has authored around a dozen books and has uncovered a treasure trove of discoveries about local athletics legends. There is no other

way to describe Crisp than a dedicated historian. Whether it’s combing historical newspapers from decades ago, like the Express, or traveling all the way to Quincy to find a single game score to complete a standings list for his research.

I like finding things,” Crisp said. Finding money would be a heck of a lot more productive than finding a junior varsity football score, but I’ll do it.”

His work spans centuries, which is appropriate given Winters is soon to celebrate its 150th anniversary. Crisp has tracked down countless game scores, player stats, and given context to where greats like Frank Demaree got their start.

Damaree, a 1927

Winters High School graduate, played in the 1932 World Series with the Chicago Cubs, the same series where Babe Ruth famously made his “called shot.”

“He wasn’t in the game, but he was on the bench,” Crisp said. “He might have been one of those guys razzing Ruth.”

Demaree played 12 seasons in Major League Baseball, participating in 1,155 games, earning a .299 career batting average, becoming a twotime All-Star, and placing seventh in MVP voting in 1936.

He also shined in the Pacific Coast League, where he was named Player of the Year in 1934, leading the league in home runs, batting average, and RBIs.

Yet, despite his

impressive career, Demaree was nearly forgotten. After pass ing away in 1958, he was buried in Winters Cemetery with only a simple concrete headstone marking his grave — hardly a tribute befitting a lo cal sports hero. Through his re search, Crisp tracked down surviving mem bers of the Demaree family. After reassur ing them of his purely historical intentions — unlike others who had sought memora bilia — he was able to gather vital informa tion about the former athlete. Unfortunately, most of Demaree’s personal memorabilia was lost in a house fire during the 1960s. However,

See SPORTS, Page 16