A CENTER TO BE YOUR AUTHENTIC SELF

CULTURAL HUB SHOWCASES

AFRICAN AMERICAN ART A PLACE TO FIND A POSITIVE PATHWAY

A CENTER TO BE YOUR AUTHENTIC SELF

CULTURAL HUB SHOWCASES

AFRICAN AMERICAN ART A PLACE TO FIND A POSITIVE PATHWAY

Americans overcome barriers to engage in civic life.

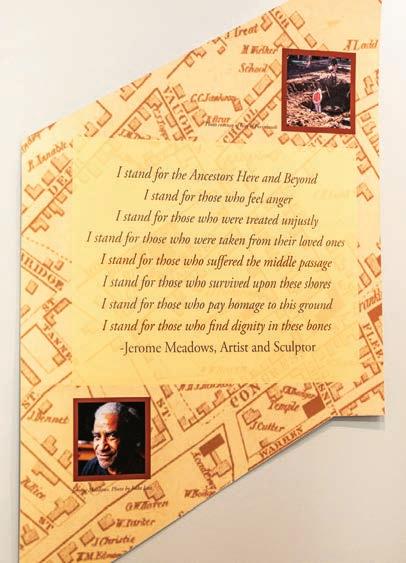

As the nation nears the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire sheds light on the often overlooked history of Black resilience, brilliance, and courage.

Join us on the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, where monuments, guided tours, and public programs reveal stories of a people who chose freedom first.

BHTNH MISSION

The Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire promotes awareness and appreciation of African American history and life in order to build more welcoming and inclusive communities today.

We moved around a lot when I was a kid. Over that time, I developed an enthusiasm for the new, the unexpected and the far flung. I loved exploring new cities and struggling to be understood in new languages.

That urge to leap into the unknown became part of my identity. Only later did I realize how much it was made possible by something deeply grounding: a fundamental sense of place and belonging. That’s the theme at the heart of this issue of 603 Diversity.

I was born in Vermont but lived the first year of my life in Lima, Peru, with my mother, who was from Vermont, and father, who was Indigenous Peruvian. My mother and I came back to New England when I was a year old. We lived with her parents, next door to my greatgrandmother. From the time my memory begins, I was raised by my mother, grandmother and great-grandmother in the house my grandparents had built next door to the old farmhouse my greatgrandmother had occupied her whole life.

Those three women created an extraordinary sense of place for me growing up. Even when I didn’t exactly fit in at school because of how I looked or how my name sounded, I grew up knowing I was from this place, learning to fish in those rivers, walking those roads, picking blackberries with my mother on the mountain where my grandfather used to hunt and his ashes were scattered.

Those three women told stories, about the history of the place we lived, but also about us in this place. And why we

belonged. They stitched my identity to a landscape with beautiful words. I knew how to find my way, and somewhere deep in my intuition, I trusted I always would, no matter how far or frightening the journey.

This issue’s stories underscore the fierce importance of belonging and having a sense of place as armature for your stories, history and identity.

The essays in the back of the book, including James McKim’s exploration of how crucial belonging is to human life (pg. 34) and Tina Kim Philibotte’s exploration of what it’s like to be a transracial Korean adoptee raised by French-Canadian parents (pg. 36), are powerful. The feature stories: becoming new Americans (pg. 12), creating safe, welcoming gathering places for LGBTQ+ people in Manchester (pg. 16), MY TURN (pg. 20) and the Seacoast African American Cultural Center (pg. 24), all starkly illustrate the importance of belonging and place, and equally crucial, the diverse ways it can be created.

The impact of a sense of belonging on the human psyche is immense. As McKim points out, it’s right there in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, directly above core physiological and safety needs. Conceptually, each of the needs lower on the hierarchy must be met to move toward the higher most effectively.

This means that the work that institutions such as MY TURN or the Manchester True Center is not just a “feel good” gesture but essential; for individuals, for communities and for our culture. 603

To illustrate the mission of 603 Diversity, Seacoast artist Richard Haynes has provided one of his recent designs to accompany our motto “Live Free and Rise.”

We are selling T-shirts and other merchandise featuring Haynes’ design, or a design created by art student Chloe Paradis, to benefit the Manchester Chapter of the NAACP.

The 603 Diversity underwriters provide a significant financial foundation for our mission, enabling us to provide representation to diverse communities and for diverse writers and photographers, ensuring the quality of journalistic storytelling and underwriting BIPOC-owned and other diverse business advertising in the publication at a fraction of the typical cost. We’re grateful for our underwriters’ commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion in this magazine, their businesses and their communities.

THANKS TO THE UNDERWRITER OF THIS ISSUE FOR THEIR SUPPORT:

Contributing Writers

Rony Camille

Amara Phelps

Yasmin Sarfarzadeh

Trisha Nail

Emily Reily

Suzanne Laurent

Tina Philibotte

James McKim

Contributing Photographers

Robert Ortiz

Contributing Artist

Richard Haynes

Editor/Publisher

Ernesto Burden x5117 ernestob@yankeepub.com

Managing Editor Mike Cote x5141 editors@603diversity.com

Managing Editor, Custom Publishing

Sarah Pearson x5128 sarahekp@yankeepub.com

Creative Services Director Jodie Hall x5122 jodieh@yankeepub.com

Graphic Designer Christian Seyster x5126 christians@yankeepub.com

Senior Production Artist Nicole Huot x5116 nicoleh@yankeepub.com

Sales Executive John Ryan x5120 johnr@yankeepub.com

Operations Manager Ren Chase x5114 renc@yankeepub.com

Digital Operations and Marketing Manager Morgen Connor x5149 morgenc@yankeepub.com

Information Manager

Gail Bleakley x113 gailb@yankeepub.com

250 Commercial Street, Suite 4014 Manchester, NH 03101 (603) 624-1442

Email: editors@603diversity.com

Advertising: sales@603diversity.com

Raised in a diverse community in Boston, Massachusetts, Suzanne Laurent worked as a registered nurse for the Boston Head Start Program. She moved to Toronto, Ontario, in 1982, and unable to work as a nurse, Laurent pursued a career in photojournalism. She has been a resident of New Hampshire since 1987. She has an extensive awardwinning background in journalism. She is also a juried photography member of the New Hampshire Art Association and a published poet.

Tina Kim Philibotte is an education justice advocate committed to nurturing liberating spaces for youth and community. Tina resigned from the Manchester School District in the fall of 2024 as the district’s first chief equity officer. She previously spent over 15 years teaching English and dance at the high school and university levels. Tina recently received the NAACP Manchester’s Excellence in Education award as well as the NH MLK Coalition’s Social Justice Warrior award. She was a 2019 NH State Teacher of the Year finalist and a two-time National Writing Project Fellow. Tina received both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education from Plymouth State University and is currently a doctoral candidate in Boston University’s Educational Leadership & Policy Studies program.

Trisha Nail is an experienced business reporter who has worked for The NH Business Review and The Keene Sentinel based in the Monadnock Region. She completed four years of undergraduate journalism studies and community reporting in her native Alabama. She holds a bachelor of arts degree in journalism from Auburn University. Trisha resides in Concord, New Hampshire.

Primary photographer for 603 Diversity is Robert Ortiz of Robert Ortiz Photography. Ortiz began his photographic career at 15, and has chronicled everything from local weddings and events to the lives of the native peoples of the Peruvian Amazon. He lives in Rochester with his wife and son and 15-yearold daughter, Isabella, who is currently in training as his photo assistant.

A regular 603 Diversity contributor is Rony Camille, a freelance journalist and a native of Canada. He became a U.S. citizen in 2019 after being a U.S. permanent resident for nearly 25 years. Camille is currently the media program director for the Town of Tyngsborough, Massachusetts.

Musician and community organizer Amara Phelps loves to engage with her city of Manchester in more ways than one: fronting her popular local rock band Cozy Throne, teaching and sharing art in southern New Hampshire, and promoting community events and efforts for local publications, including Manchester Ink Link.

James McKim, who was involved in the original planning of 603 Diversity and has written essays for past issues, serves as managing partner of Organizational Ignition. He is driven by an intense need to help organizations achieve their peak performance through the alignment of people, business processes and technology. He is recognized as a thought leader in organizational performance, the uses of neuroscience and program management.

Emily Reily, an assistant editor at Yankee Publishing, contributes to 603 Diversity, New Hampshire Magazine and NH Business Review. Prior to joining YPI, she worked as a newspaper photojournalist, copy editor and freelance writer. Her work has appeared in the New Hampshire Union Leader, NH Home Magazine, New York Times for Kids and Washington Post Magazine.

Sarah Pearson is managing editor of custom publications for Yankee Publishing, which produces 603 Diversity and many other titles. She is an award-winning editor and journalist who previously worked for a newspaper. She is a lifelong New Hampshire resident and mother of two.

Advocate, coordinator and educator Yasamin Safarzadeh, a native Angelino and current resident of Manchester, compiled our calendar and wrote the feature on Jezmina von Thiele. Safarzadeh hopes to secure a future for a more diverse young adult population in New Hampshire to ensure a more prosperous and effective future for all. DM her at phat_riot on Instagram.

As publisher of New Hampshire Magazine and the NH Business Review, Ernesto oversees their publication and that of 603 Diversity, NH Bride, Run NH and many more. He’s also a writer who’s published a couple of novels, a bunch of short stories and a livelihood of non-fiction pieces. Outside the office, you might spot him running around Manchester and at the 2025 Boston Marathon, or playing guitar and singing at one of southern New Hampshire’s bars and restaurants.

Jezmina von Thiele is an advocate and placemaker in New Hampshire, enhancing the health and well-being of communities here in the Granite State. Von Thiele is a beacon of light and resilience, not only championing the arts and culture of the Romani people, but also a trailblazer for the needs of individuals with disabilities, herself included. These people belong to our communities and deserve to express themselves unapologetically and authentically.

The Romani people have a rich history, and it is as varied and space-based as any other kingdom or empire. The Romani are documented to have originated from India and began their migration more than 1,000 years ago. The Romani people are estimated as 14 million globally, with 12 million in Europe.

This migration was followed by 500 years of slavery in Romania. During the 1930s and 1940s, the Romani populations in Austria and Germany were decimated by up to 90%. This minority group was significantly impacted by the atrocities committed in Nazi-era Germany, a fact often overlooked in school curricula when covering European and global histories.

Romani people are more commonly referred to by the racial slur, “Gypsies,” which conjures harmful stereotypes normalized in Western and American cultures. Some Roma reclaim the word Gypsy, which is their right, but unless you are Romani or a related group, instead use the correct terms, like Roma or Romani.

In the 1970s, delegations of Roma people from all over the world came together in India and solicited the government to sponsor their recognition as a distinct nationality.

With this context in mind, here is my conversation with von Thiele, edited lightly for clarity.

Q:The influence of the Romani people on the arts and culture is vast. What do you think about when someone mentions Roma and the arts?

Von Thiele: Our culture has influenced everything from Flamenco in Spain to contemporary Hollywood movies. There was an incredible painter, an anarchist communist writer named Helios Gómez Rodríguez. He left a great legacy and persevered through much of the fascism corroding Europe during the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

Johann Trollmann was also an incredible figure in Nazi resistance; a boxer who continued to stand and fight, reclaiming humanity in the face of Nazi propaganda regarding biological inferiority of minorities in Europe. We have this vitality and an unconquerable spirit.

Often, in film, we are represented as evil or as witches and warlocks. I like to think of it as the greatness of our historic presence creating fear around our culture, and so we are often turned villainous. Often, our

spiritual practices are commodified and exploited. There are many aspects of our personhood, which have been appropriated into inaccurate portrayals of curses and witchcraft in the media.

Q: You will be conducting a curse soon. Does it have a history or an intention that goes beyond the caricatures Hollywood has rendered?

Von Thiele: Historically, magical practices like cursing are often about communal intention setting. Our spiritual practices are centered on spiritual and physical cleanliness, an easing of the mind. But we have cursed fascists in times of great tumult as spiritual defense, and sometimes we will idiomatically or poetically curse ourselves to keep ourselves honest or emphasize our earnestness — like “may my eyes fall out if I’m lying to you right now.” Sometimes, they are things you say to yourself. Sometimes these curse rituals embody the rage of the oppressed, and are performed privately in community, or theatrically in public to protect and empower the vulnerable, and take down the energy of the oppressors.

I will be performing this very thing in Salem, Mass., on Aug. 21 at 1 p.m.

Q:Though most of the Roma population lives in Europe, they still face much displacement. Recently, France had conducted mass deportations of the Romani people under the guise of reducing crime. Is the United States a more favorable home to your community?

Von Thiele: In some ways, it’s easier to blend in here, and not as many people even understand who Roma are, but there is still discrimination, documented for the first time in a 2020 study entitled “Roma Realities in the United States” through the Harvard FXB Center led by Margareta Matache. Sometimes American culture celebrates some aspects of that wild independence which we cherish, but often in a way that whitewashes our persecution and appropriates our culture. This is a huge issue considering the centuries of violence, slavery and multiple genocides. Some of us even ended up here as a result of the slave trade, for instance, the Romani population in the American South, especially Louisiana, as well as the Caribbean, and South and Central Americas. My own grandmother came from Germany in the 1950s after the Holocaust to escape continued persecution and the threat of death.

Q: You and a friend of yours, Paulina Stevens, have co-authored a book together, “Secrets of Romani Fortune-Telling:

Diving with Tarot, Palmistry, Tea Leaves and More,” as well as co-created the podcast “Romanistan.” There is much which is covered in your podcast from art shows throughout the country, alternative healing practices and debunking much of the racist colorations on the Roma peoples. What are some of the hardships that arise from more traditional Romani communities?

Von Thiele: There are some traditional communities that do not want to assimilate, which is totally reasonable, but insularity can further marginalize Romani women and LGBTQ+ folks, and make it harder to find help and support through experiences like domestic abuse, arranged teen marriage, lack of access to education, etc.

Paulina Stevens, my partner in crime, was exiled from her community for resisting traditional gender norms, mainly leaving her arranged marriage, fighting for custody of her children, and dating outside of her culture. Her story is told in the LA Times podcast “Foretold,” as well as our own podcast, “Romanistan.”

I, on the other hand, am mixed and grew up fairly assimilated, but even assimilated Roma can suffer the harms of insularity and the pressure of keeping their identity a secret, like I did as a kid. But I did not grow up with any expectation of an arranged marriage, and I was encouraged to attend school as long as I wanted. I was pressured to marry early by my Romani mother, but I could marry whoever I wanted.

Paulina and I like to clarify that any abuse we have experienced is a result of intergenerational trauma and oppression, not a result of our culture, which is beautiful and diverse.

Q: I assume like any other cultural practices, within the Romani people there are approaches to healing, which are integrated?

Von Thiele: Absolutely. Many Roma see Western doctors and so do I. There are, of course, religious fundamentalists within the Romani community, as well as many other communities, who may

reject modern medical practices. Many Roma look to both Western and traditional medicine these days. Often, Roma adopt the dominant religion of wherever they settle or travel, which can sometimes influence us away from our folk practices, but sometimes they live side by side in a kind of syncretism. My family is ostensibly Catholic, but I never went to church and my spiritual upbringing, especially my family trade of fortune telling, is far more rooted in folk beliefs.

We have our own folk medicine and herbalism, much of which is rooted in Ayurvedic practices that incorporate the balance of body and mind as integral components of whole health and well-being. Ayurveda is of Indian origins, and the Romani have adapted these practices over a thousand years of diaspora to reflect which herbs and medicines were locally available, and we have influenced the cultural, linguistic and healing practices of all the places we’ve traveled. I needed to connect with these traditional means of medicine as a result of chronic illness, as well as the spiritual traditions my grandmother taught me. These practices have brought me peace where Western medicine cannot.

Q:I want to know more about the patriarchal practices within Romani clans.

Von Thiele: We are mostly a patriarchal culture, but that might not reflect everyone’s experiences because we aren’t a monolith. There is an argument among some academics that due to the Romani experience of exile, displacement and genocide, patriarchy is prevalent because of the assimilation of different cultures, dependent on where we could resettle.

Feminism, gender liberationism and queerness is an important movement in our communities today, however, and are integral aspects of my personhood as a queer, nonbinary person, and survivor of CSA, SA, and DV. Paulina and I use “Romanistan” as a platform to challenge traditions that no longer serve us, rid ourselves of shame, and celebrate the evolution and progression of Romani culture.

trianglecu.org (603) 889-2470

Q:Through some of the work I have done with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Mashpee Confederacy, I can draw parallels to the amorphous nature of each clans’ essence, that each tribe will have different stories and variations in cultural practices. How does it work for systems of justice?

Von Thiele: Because we are not federally recognized, we fall under the established court system in this country. But Romani courts, called Kris, exist in larger, traditional communities, and they are the only law for them. It is rare for Roma in these communities to use American courts or call the police.

When Paulina used the American court system to fight for custody of her children, this was a grave offense, and part of the reason she was exiled, even though she was advocating for the well-being of her children, since the Kris in her community would rule that she would have to leave her children if she left her marriage. This is not the kind of experience I had growing up, nor is it the experience of every other Romani person. However, since my grandmother came to the U.S. alone, I had a more fragmented relationship to culture and community.

Q:In much of the racist lore aimed at Romani people, often in movies, individuals are characterized by colorful garb, jewels and headwear. What is your relation to your personal aesthetic?

Von Thiele: To contradict some of the misunderstandings of our culture, we did not have access to intergenerational wealth. Roma women traditionally wear big skirts for modesty, and sometimes a head covering called a dikhlo. The bright colors are for spiritual protection, or they just reflect the aesthetics of your vitsa (your clan or tribe), and there is much pride in looking nice and being decked out.

Men traditionally wear vests and hats. We wear our wealth (the jewelry) because banks, historically, would not let us put our money within them, and sometimes still don’t, and it is a quicker way to trade for goods and services.

There are many laws aimed at our type of work — healing, fortune telling, especially — creating more barriers in order to make money legitimately. Often, people think there is much theft and scamming, but those aspects are more associated with anyone experiencing extreme poverty than with Romani people in general.

Q:I assume you face aspects of bigotry in today’s environment.

Von Thiele: I was 10 the first time I had a bad encounter with the law. I was wearing a head covering, my grandmother’s dikhlo, and the police picked me up for “looking like a runaway,” code for looking like a Gypsy.

When I tried to explain that my father was just a block away, I was surrounded by five cop cars and detained in a police car and questioned, and it took half an hour to convince the police to take me to my father instead of the police station.

Today, I face the usual racism online and sometimes in person. More recently, I was accused of faking my disability for money and sympathy, a common racist and ableist trope of the “crippled Gypsy beggar.” Can you get more crude than that?

Q:How can people get access to your services?

Von Thiele: People can visit my website jezminavonthiele.com. I conduct tarot, palm, and tea leaf readings and workshops at shops around the Seacoast, and I like to travel to give readings and to speak about Romani arts, spirituality and culture at colleges, libraries and more. I also offer readings and workshops online and on my Patreon, and I have a monthly Tarot column in Bustle. In addition to my fortune-telling work, I’m a writer, storyteller, artist and performer, and all of these disciplines influence and inform each other.

People can also follow our podcast “Romanistan” for interviews with Roma from all walks of life, on Apple, Spotify, Audible, Sticker and more. You can visit romanistanpodcast.com to listen, too, and to use our cultural resources page. Paulina and I offer

cultural sensitivity editing and consulting for creators and the media, and our book “Secrets of Romani Fortune Telling” (Weiser Books, 2024) is available everywhere.

I want to end this interview by saying that I care about trauma and spiritually informed aid as a community healing. Roma has practiced fortune telling for others and ourselves as our first community care. We use this belief system to uplift ourselves and individuals who access our resources. My work is rooted in grounded, non-judgmental, solution-oriented advice for anyone seeking direction from a spiritual source.

You write your own story, and I can help you find the narrative. I think of myself as a salve between the cracks. People need to seek medical professionals, but also people need to feel safe and held in other ways. This is where we show up. 603

“Beyond the “Roma Issue”: Holistically Combatting the Marginalization of Roma Populations” jstor.org/stable/43746163

“Historical Amnesia: The Romani Holocaust” jstor.org/stable/4418585

“Screen Gypsies” jstor.org/stable/41552366

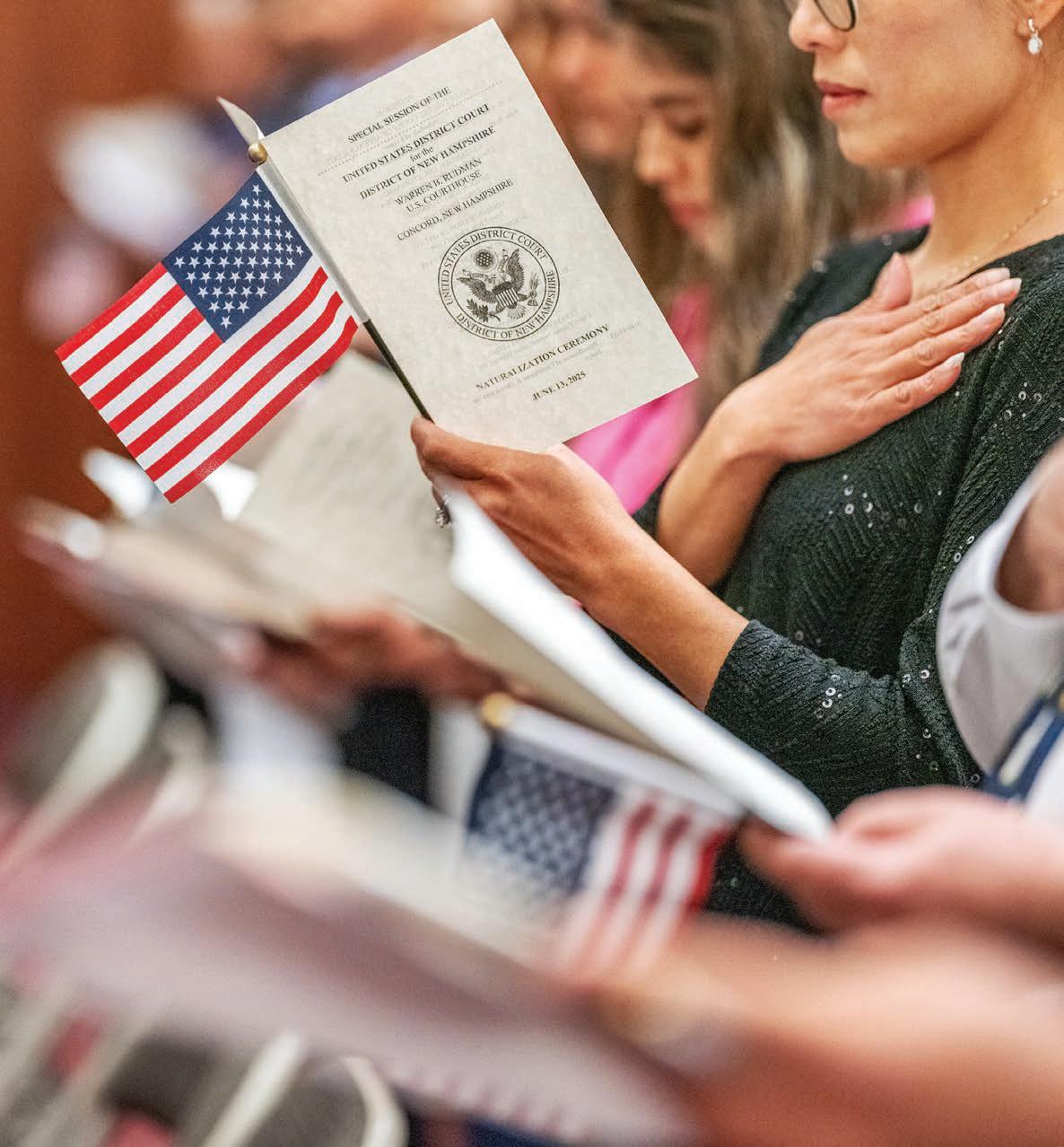

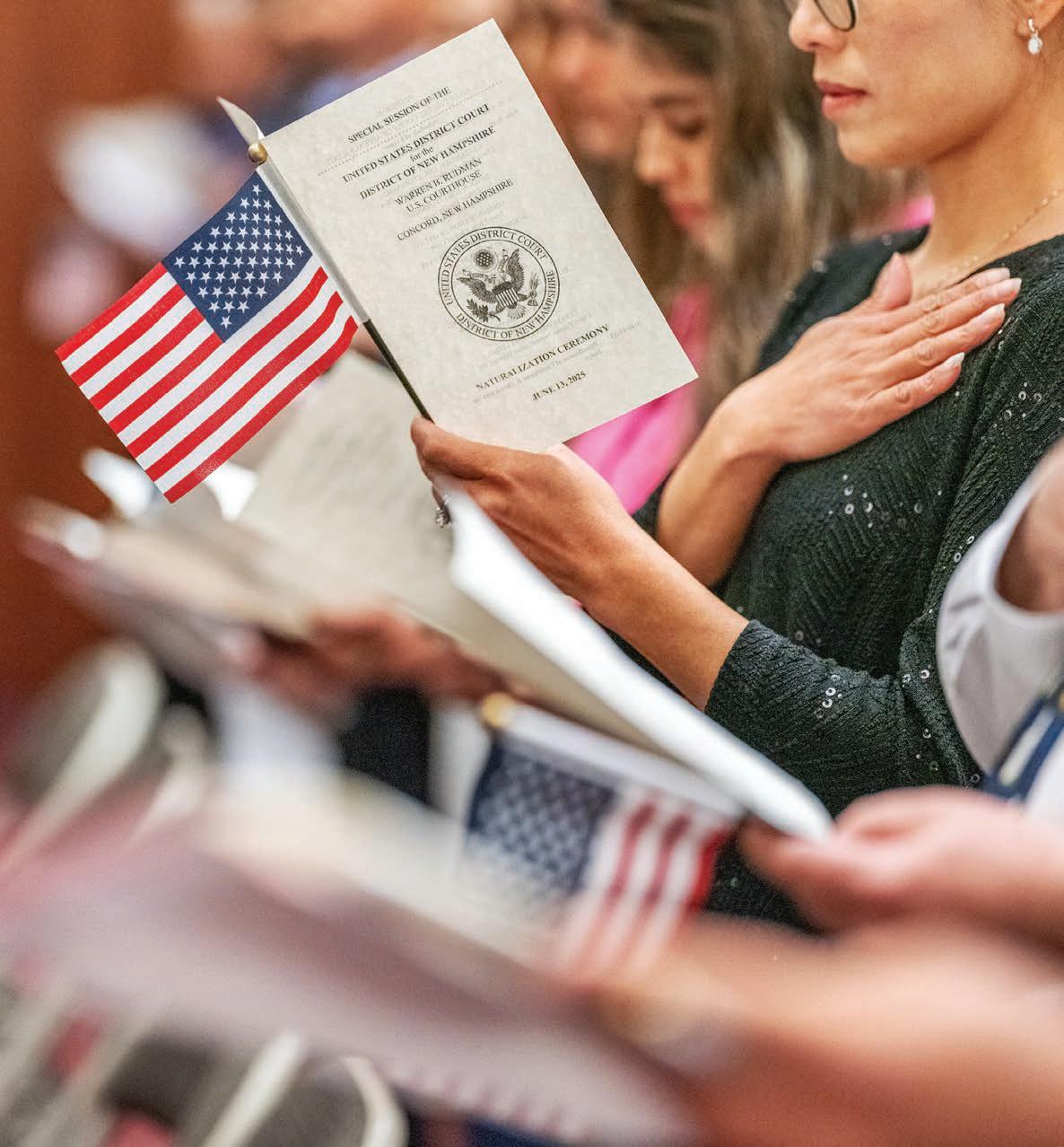

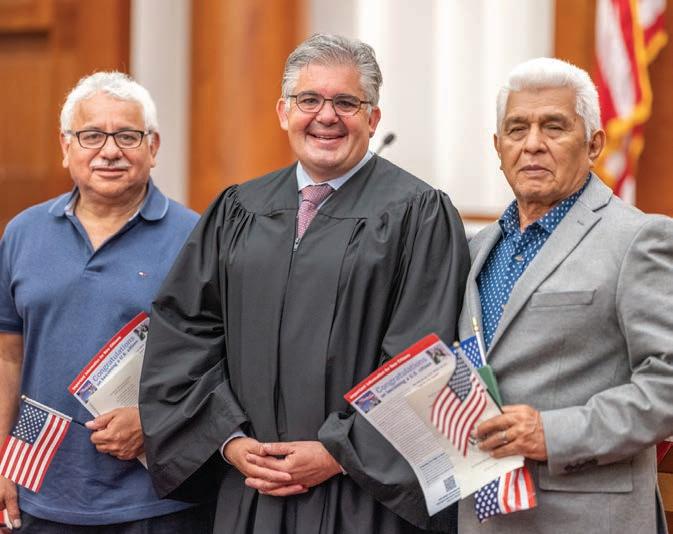

BY RONY CAMILLE / PHOTOS BY ROBERT ORTIZ

New Americans overcome legal forms, language barriers and personal sacrifices for the obligation to engage in civic life.

On a cool and crisp June morning in Concord, the skies outside were gray and overcast. But inside the federal U.S. District Courthouse, the mood was joyous and warm. More than 70 Granite Staters from across the world, different languages, cultures and walks of life gathered to complete a journey that was years in the making.

In unison, they stood, raised their right hands, and took the Oath of Allegiance in front of their family and friends.

And in that moment, they became American citizens.

The ceremony was fittingly held on Flag Day, and U.S. First Circuit Judge Seth Aframe warmly addressed the courtroom with solemnity and clarity.

“We’re not just celebrating the country,” he said. “We’re celebrating you.” Drawing on history, civic philosophy and his own family’s immigration story, Aframe reminded those assembled that American identity isn’t forged by bloodline or birthplace, but by commitment.

“This country is never in decline,” he said, “because of people like you with new hopes, new ideas and new dreams.” He also reminded the new citizens of what the oath symbolized. Not just loyalty to a new country, but full participation in a shared democratic life.

“It is now your obligation to work to preserve this Constitution, which guarantees equal protection of the law and due

process of the law, and empowers us all with the freedom of speech,” Aframe said.

“It is your duty to use that power to speak freely, to call out injustice when you see it, to work for positive change, to convince your fellow citizens of the path to justice, to run for office if you can, and, of course and always, to vote.”

Naturalization ceremonies like this one occur monthly across the state, at the U.S. Courthouse, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) field offices in Bedford, and occasionally at Strawbery Banke in Portsmouth, one of New Hampshire’s oldest neighborhoods, which eventually grew into a multicultural neighborhood of newcomers.

While each event is a celebration, behind every raised hand is a story of paperwork, perseverance, language barriers, long waits, and, for many, the tireless support of local nonprofits.

“We meet them where they are,” said Vijay Bhujel, deputy director of Building Community in New Hampshire (BCNH), a Manchester-based nonprofit that provides ESOL classes, citizenship preparation, and one-on-one case management. “Some of the people we work with have never been to school. They don’t read or write English. And the system doesn’t make it easy.”

Bhujel described one case involving an elderly woman from Haiti who couldn’t read or speak English. “There’s a medical waiver called a Form N-648 for people with conditions like dementia who can’t complete the civics test. But even that is treated with suspicion. A USCIS officer asked her if she had paid off her doctor. It was humiliating.”

Legal hurdles, changing immigration policies and bureaucratic delays add to the stress. That’s where organizations like BCNH and the International Institute of New England (IINE) step in. With offices

in Manchester, Lowell and Boston, IINE provides resettlement services, legal support, and job placement for immigrants and refugees.

“We are always educating our clients about their rights,” said Jeff Thielman, president and CEO of IINE.

“We tell people: If you’re a refugee, you have legal status. You have a pathway to citizenship. But delays, costs and fear, especially around deportation, are real concerns.”

Thielman points to recent changes requiring in-person interviews for green card applicants. It was a step that was previously waived due to extensive background checks before refugees arrived in the U.S. “It’s slowing down the process and adding unnecessary stress,” he said.

Despite the obstacles, Thielman says, the reward is undeniable. “I’ve been to naturalization ceremonies, and it’s one of the most moving parts of this work. When a former client becomes a citizen, you know they’ve made it. They’re protected. They belong,”

That sense of belonging was palpable for Margarita Cáceres, a Manchester resident who became a U.S. citizen at the June

THE NATURALIZATION

A Step-by-Step Overview (Source: USCIS)

Applicants must typically be lawful permanent residents (green card holders) for at least five years (or three if married to a U.S. citizen), be 18 or older, and demonstrate good moral character, continuous residence, and the ability to speak, read, and write basic English.

2. Prepare Form N-400

The Application for Naturalization (Form N-400) can be completed online or on paper. As of 2025, the filing fee is $640, plus an $85 biometric services fee (fee waivers are available for eligible applicants).

3. Attend Biometrics Appointment

Applicants are scheduled for a fingerprinting appointment to conduct background checks.

4. Complete the Naturalization Interview and Tests

At the interview, applicants must answer questions about their application and take English and civics tests. Exceptions exist for older applicants and those with medical conditions.

5. Receive a Decision

USCIS will approve, continue (ask for more information), or deny the application. If approved, the applicant proceeds to the final step.

6. Take the Oath of Allegiance

Applicants are scheduled for a naturalization ceremony, where they take the Oath of Allegiance and receive a Certificate of Naturalization, officially becoming U.S. citizens.

ceremony. Originally from El Salvador, she moved to New Hampshire in 2011 in search of a better life.

“Everything is very hard right now with immigration,” she said. “As soon as I had my years in (as a permanent resident), I said, I want to be a citizen.”

Cáceres said she studied diligently, passing her civics and English tests on the first try despite her nerves. “The officer said, ‘Can you please relax?’ But I couldn’t. I cared too much,” she said, laughing.

Her husband, Juan, and their 6-year-old daughter, Allison, a U.S. citizen by birth, were there to witness her milestone. Her next dream? Homeownership. “I want to own my own house. That’s what I’m working toward now,” she said.

As Judge Aframe reminded the room, it’s not just about arriving. It’s about engaging, knowing your neighbors, joining a PTA, starting a book club, or running for office. It’s about living the American story while never forgetting your own.

“You are a hero,” he told the new citizens. “Your children, and your children’s children, will one day look back and thank you for your courage.”

William Louisdor, 28, Nashua

For William Louisdor, the journey to citizenship was long and at times frus-

trating. The 28-year-old systems engineer immigrated from the Delmas neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as a child and had spent most of his life in the U.S. before deciding to formalize it all in 2025.

“I mean, I’ve been here most of my life… basically a citizen,” he said. “But I had no official paperwork. I wanted to get it done so that if anything were to happen, I wouldn’t get deported to my country.”

William filed for naturalization in 2022 and attempted to navigate the process alone. That decision led to delays and reviews, including some court-related issues. “It was difficult because I did it on my own,” he said. “I missed a couple of things, and that prolonged the process.”

Three years later, standing inside the Concord federal courthouse, he finally reached the finish line. “It feels amazing. Like a new man,” he said with a smile. First on his to-do list? “Update my license, my Social Security card, and my passport.”

His advice for others? Don’t go it alone. “Definitely consult a lawyer and work with someone. The process is difficult,” he said.

Anjeli Santos, 24, Nashua (with Zunilda Tavares and Mari Anjel Santos) When Anjeli Santos raised her hand

to take the Oath of Allegiance, her voice trembled with emotion. Her mother, Zunilda Tavares, stood beside her, hand raised, eyes glistening, while her younger sister, Mari Anjel, just 17, watched quietly from the gallery. Though Mari became a citizen too, her age meant she didn’t take part in the formal ceremony.

Still, for this family, the moment marked the end of a long journey and the beginning of a new chapter. Anjeli, now 24 and living in Nashua, did most of the talking on Concord’s Main Street that day.

As the family translator, she not only interpreted words but also bore the weight of their shared story. The family moved to New Hampshire from the Dominican Republic five years ago, seeking better economic opportunities and stability. Zunilda had married an American, which allowed her and her daughters to emigrate legally. But the road wasn’t easy.

“I didn’t understand the sacrifice at first,” she said. “I was 18, I’d just graduated high school, and all I wanted was to stay with my friends and enjoy my life back home.” But the promise of something more, a life where dreams like owning a car, going to college or becoming a homeowner felt possible, gradually took root.

Learning English was one of the first hurdles. Anjeli remembers stumbling at first, struggling to understand even basic conversations. “Now, I speak fluently,” she said proudly. “I have a good job. I’ve built something here that would’ve taken me so much longer back in the Dominican Republic if it was even possible at all.”

Still, that transition wasn’t without fear. “I was really anxious when we started the citizenship process,” Santos said. “Especially for my mom, because she doesn’t speak English. I worried … what if she got pulled aside during the interview? What if they didn’t believe her? Even though we were here legally, the fear was real.”

That anxiety speaks to a deeper truth for many immigrants in America: That legality doesn’t shield you from vulnerability. “Even now, as citizens, we still look Latino. That doesn’t change how people might treat us. But I’ve been lucky. At work, I’ve always been welcomed by white colleagues, by Latinos, by everyone. That’s made a difference,” she said.

The family found community in unexpected places. An early job at Forever 21 connected Anjeli with a Cuban co-worker who helped her feel at home. Since then, she’s seen New Hampshire grow more diverse than it once was.

“We were worried we wouldn’t see people who looked like us,” she said. “But that’s changing. There’s a big Dominican community now.”

Becoming a citizen, Anjeli said, isn’t just about papers. “It’s about having a voice. It means you can vote. It means you have the right to speak up about the laws that affect your life. People who live here without citizenship are still part of this community. They go to school, they pay taxes, they raise families, but they don’t have that same power.”

She spoke candidly about the challenges others face in trying to “do it the right way,” a phrase often used by critics of undocumented immigrants.

“There is no ‘right way,’” Santos said plainly. “This is stolen land. People who

were born here were just lucky. They don’t always understand the sacrifice it takes to come here.”

She knows people who are undocumented, college-educated, tax-paying, law-abiding, and yet unable to live freely. “It breaks my heart,” she said. “Because they’re doing everything a citizen does, but without the rights or recognition.”

What’s next for the Santos-Tavares family? They’re registering to vote. They’re updating their licenses, Social Security records and applying for passports. And they’re holding onto the gratitude that anchors their American story, one built not just on paperwork and policy, but on persistence, courage and love.

“It’s a privilege to be here,” Santos said. “And now, we get to help tell the story of what being American really means.”

For many, this journey is years in the making. But with the help of local nonprofits, dedicated volunteers and personal grit, the path, while complex, remains one worth walking. 603

Building Community in New Hampshire (BCNH)

Manchester

Provides ESOL classes, naturalization test prep, and assistance with USCIS paperwork. Staff support immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, especially those facing barriers due to age, language, or disability. bcinnh.org

Catholic Charities of New Hampshire

Statewide

Offers Department of Justice-accredited legal assistance for citizenship applications, green card renewals, and DACA cases. cc-nh.org

International Institute of New England (IINE — Manchester Office)

Manchester

Supports refugees and immigrants with legal help for naturalization, work permits, and green card applications, as well as ESOL and workforce readiness. iine.org

New Hampshire Alliance of Immigrants and Refugees (NHAIR)

Statewide via Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition

Promotes civic engagement, immigrant leadership, and inclusive policy through

organizing and advocacy. While not a direct legal provider, NHAIR connects residents with citizenship resources and training. miracoalition.org

Granite United Way — Project United Statewide

Facilitates referrals to partner agencies offering naturalization workshops and legal clinics. Supports community-based access to immigrant resources. graniteuw.org.

Ascentria Care Alliance — Services for New Americans

Various NH locations

Provides refugee resettlement, English instruction, and social services. May refer clients for legal help related to citizenship and immigration. ascentria.org

Overcomers Refugee Services

Concord

Led by former refugees, this organization offers culturally grounded support, including ESOL classes, citizenship preparation, and assistance with USCIS forms. Also focuses on refugee resettlement and integration. overcomersnh.org

BY TRISHA NAIL

PHOTOS BY MILA PAVEK AND ROBERT ORTIZ

When Matt Bohannon thinks about where he can find tolerance and safety as a gay man in his travels, he seeks out rainbow pride flags on doors and windows almost as a beacon.

“I go in because I know they’re supportive, and I love to give back to community members who aren’t afraid to support our community,” he said.

However, Bohannon says, those places are often businesses where people are encouraged or required to spend money to stay around. When he looked toward his home in Manchester, he wished for a third space — a communal place that is separate from one’s home or workplace, like a public library or park, that doesn’t always require a financial contribution to visit.

The team at the Queen City’s LGBTQ+ pride organization, Manchester True Collaborative (MTC), felt the same. After Bohannon joined on as communications director in December, the launch of an LGBTQ+ center was one of the nonprofit’s priorities.

MTC was formed in 2022 to manage the city’s annual Pride events in June, succeeding previous organizers. It gained nonprofit status in September 2024, according to president and co-founder Scott Cloutier, who stated that the organization then received an unexpected windfall.

“In the last year, we got a nice anonymous donation … (with) nothing attached on how we had to use the funds,” Cloutier said. “It was how best we believed we should use them, and that’s why we set half of that aside and said, ‘We’re going to put it to use on actually renting space.’”

The organization’s board gathered together, and over a few months, worked to establish the Manchester True Center, which opened in April at 72 Concord St. with an event that welcomed more than 300 visitors, Bohannon recalled.

At the center, LGBTQ+ community members of all ages gather for activities where they can find comfort in mingling with people who share their identities and values, as well as access resources MTC has built up and learn about goings-on in the city.

“In May, we had about 22 events, and in June, we probably had somewhere between 20 and 30 events,” Cloutier said.

“Those are all scheduled at specific times, and they’ve been very well attended. I think we’ve probably gotten somewhere upwards of 700 different people who have been coming in and doing stuff.”

Among the resources is Chloe’s Closet, a small room named for a founding member of MTC and transgender community

Members of New Hampshire’s LGBTQ+ community and its supporters attended the grand opening celebration of Manchester True’s community center at the YWCA in Manchester in April. This “third space” is a welcoming gathering place that also offers resources including a free clothing closet.

advocate, filled with donated clothes that are free for gender-diverse individuals in need to take. And next to the closet is the Rainbow Book Nook, a reading corner featuring books that promote inclusion, contributed by visitors.

Social opportunities at the True Center include clubs focused on books, movies and sewing, weekly mindfulness meditation meetups and identity-based support groups.

Though MTC itself organizes some, many are member-hosted. Manchester resident Zach, 25, started a group for transgender men like himself at the center in late June, citing his personal difficulties finding people he could relate to. At its first meeting, he said that about eight people attended, which he described as a promising start.

“It was a really diverse group who showed up, who were all different ages and at different stages of their transitions, who all had different life experiences,” Zach said. “It was really inspiring to see that, not only were there so many of us, but we’re all in different walks of life.”

For Zach, the center is more than a gathering place; it’s a lifeline. The group leader moved to New Hampshire last summer from his birth state of Florida to join a childhood friend who had already made the same journey some time earlier.

After coming out as a trans man in 2020, Zach said he experienced increasing prejudice each year and state-imposed laws

challenging, then restricting, his abilities to be his identity.

Florida legislation began impacting Zach directly in 2023, cutting off his access to hormone medications as gender-affirming care.

“I woke up one day and suddenly couldn’t get my hormones anymore; my prescription wasn’t valid,” he said. “I was getting them through Planned Parenthood, so I called, and their hands were tied — they were trying to figure out a way to get around it, and they couldn’t. It was very distressing to have such an abrupt change.”

Later that year, he was working to have the sex listed on his identification legally changed, with a signed letter from a physician who confirmed the change as evidence.

“Just a couple of days after I had finally gotten that paperwork, the Florida Department of Transportation released a statement saying they were no longer permitting legal changes, and that if somebody attempted to do so, it could be considered identity fraud.”

This crossed a threshold for Zach, who moved to the Granite State as soon as possible. After the move, he found greater ease in updating his documents to reflect his name and gender.

Zach noted that New Hampshire lawmakers are also presenting some legal challenges to the state’s trans community as a whole, indirectly referencing recent legislation like House Bill 148, which awaits Gov. Kelly Ayotte’s signature and would allow people’s use of restroom facilities to be classified based on their sex at birth.

Still, he feels “very, very happy” here, despite those hurdles, thanks in part to the True Center, which is already serving an important role as he continues to adjust to his new life.

“I think now more than ever, it’s important to find that community and see that we all live here and that we all exist,” Zach said. “We can offer each other support and strengths, and in difficult times like this, we can be there for each other. … Because there is so much negativity out there (toward LGBTQ+ people), we need to be able to see each other succeed and be strong.”

Donna, a volunteer with MTC who also moved to Manchester from Florida several years ago, seconded that notion. She first visited the center for a Trans Day of Awareness event held there just ahead of the grand opening later that week, and says she’s found kinship with others in the community by attending meetups for Dungeons & Dragons and board games.

“Being able to see a community around yourself to show you’re not just alone in the world is so valuable,” Donna said. “Because you see the news with anti-trans and anti-queer stuff

going on, it’s so easy to get into the ‘doom’ mindset. Having events and people around you to remind you it’s not all doom and gloom helps.”

That rationale is driving Cloutier, Bohannon and the MTC team to endeavor to create “open hours” where the True Center is free to visit for a window of time on days without people needing to participate in a specified event, based on volunteer availability.

“Now that it’s the summertime, we’ve got a set of about 20 to 30 volunteers that are going to take some time and do different open hours, because our ultimate goal is to have this place open all the time,” Cloutier said.

He believes it’s not entirely out of the realm of possibility. The center occupies a space that MTC has rented long-term from YWCA New Hampshire, which owns the building and also leases an office there to Queerlective, an LGBTQ+ arts collective.

Additional grant funding could help MTC build its True Center into something greater, he says.

“This building has a lot of opportunity in it,” Cloutier said. “The YWCA is super flexible on how we’re using the space. … Even if there are any bumps in the road, by next year, I have a feeling we’ll either potentially have a full-time employee or a couple of part-time folks consistently keeping things open.” 603

MY TURN is known to community members in gateway cities as a launch point where people unleash their potential and strive for personal successes and new heights.

Tucked quietly away on the threshold to Manchester’s West Side, with additional services offered in Nashua, Rochester and Franklin, MY TURN is a nonprofit sector stronghold that evades a single definition.

Executive Director Allison Joseph, the heart of the organization, even struggles to pin it down.

“In a nutshell version, we’re an anti-poverty agency. We help people gain financial stability, through primarily education and employment training opportunities,” she says. “But we do so much work on the front end to make sure that the people who come through

our doors know they are worthy of the opportunities in front of them. When you’re having the worst day of your life, we’re where you come.”

While primarily servicing youth in grades 6-12 plus young adults, MY TURN’s helping hand, community care and programming are available to just about anyone in need. Their offerings are varied and myriad: They offer assistance with High School Equivalency Diploma (HiSET) education and individualized services for students in high school, job placement and career guidance, and financial assistance to complete job training courses or obtaining higher education.

Based within the communities they care for, MY TURN also strives to reduce violence in Manchester through Project Connect, a drop-in center targeting youth from high-crime neighborhoods, which offers incredible structured events like their highly attended basketball tournaments and a free third space for youth to commune, engage, inquire about services or even play Playstation. Other services range from giving away almost 400 backpacks of brandnew school supplies last year to an all-occasions closet of clothes by its boardroom for anyone in need. MY TURN staff are even known to turn up in the stands of students’ school sports games as a cheering face of support.

Former clients, now MY TURN employees, Reda Shehabeldin and Sethe Shea

know that the organization has changed the course of their lives. For them, MY TURN unlocked potential and pathways each man could never have dreamed of. Shehabeldin “had been referred to us when Manchester Police had a grant called Project Safe Neighborhoods,” Joseph says. “It was a multitiered project that tested various data-driven approaches to crime reduction; they did a social network analysis to identify the 13 young adults in the city of Manchester most connected to violent crimes (which includes victims, perpetrators, witnesses and anyone else mentioned in reports of incidents) and he was No. 1.”

Shehabeldin and Shea each had a history of street-based violence dating back into their teenage years and had recently completed criminal sentences when they first met with MY TURN. They had turned to MY TURN for assistance with reintegration after incarceration on the gracious word of friends and neighborhood connections who honored and verified their trusted reputation. Both young men still remained a bit skeptical upon their first meetings with Joseph and the staff.

Joseph was determined to win them over and implemented self-described “sneaky” tactics. She friend-requested both guys and all of their peers on Facebook all at once.

“We were like ‘who is this person that keeps adding all of us?’” Shehabeldin says.

“In a nutshell version, we’re an anti-poverty agency. We help people gain financial stability, through primarily education and employment training opportunities.”

— Allison Joseph

Shea remembers the panic that rippled through their circle. “It was really suspect to be honest,” he says with a laugh. “When she did that, I blocked her at first.”

Over time, each of the young men found themselves drawn back to the organization again and again. Each enjoyed the laid-back, approachable energy put forth by what they found there, and noted that MY TURN proved to be different than any other program

or space they’d engaged. Joseph’s heart and solid presence won them over.

“She’s miles beyond everything and anything here,” Shea says. “If Allie wasn’t here, I’m not gonna lie to you, me and him would be having this convo from behind the walls in jail, somewhere. Or I would be dead. For a fact.”

Shehabeldin echoes the sentiment.

Shea finds that his success and career with MY TURN have continually surprised him, both in his incredibly

transformational personal growth and his trepidation towards establishing trust in others.

“I never expected to work here,” Shea says. “I didn’t know what this was, who these people were, but my friend was like, ‘Just come mess with these people.’” He reminisces on his mindset and goals as they compare to now. “I was expecting to go out to do the same stuff I was doing before, to be honest. She kind of stopped me in my tracks. She

kind of forced my hand to be honest; I’m glad she did. I had a lot of shenanigans in mind.”

Shea says the spirit of the organization makes a big impact on clients through small acts of showing up.

“I don’t ask for much. When I first came here, I realized they can help with this or help with that,” he says. “I asked them to get my birth certificate, and they did it mad quick. I think I only asked them one time, and they did it. It’s not like a big deal to regular people, but in my head, I asked one time, and they did it. … It was just something little.”

The breadth of MY TURN’s personalized, wraparound services is found peppered through the testimonies of those they’ve served.

“Before, I couldn’t be in the same room as someone I don’t like,” Shehabeldin says. Now, he’s a role model for others. “I didn’t know I could be part of the community in a positive way. It was always negative, you know? Here it’s

positive. I didn’t think in my whole life I was gonna do that.”

MY TURN has also shaped Shehabeldin into a working young professional.

“I never really had a job before this, to be honest with you. Being here taught me how to be an adult,” Shehabeldin says. “I didn’t even know how to send emails or any of that stuff. I didn’t know how to print papers!”

He’s proud of his company email, his own laptop and an unofficial title as the wizard of fixing the office printer. Joseph says Shehabeldin even rubs elbows in board meetings and presentations, where his moving words and friendly nature scored the group $50,000 in funding for adult education programming.

Many individuals leave incarceration set back to square one, without documentation, employment or even a roof over their head. Offering completely legitimate help free from preconceptions, MY TURN has established lasting, meaningful connections with

clients that last a lifetime. Its approach meets clients directly at their personal point of entry and is there as a guiding hand with whatever questions, struggles or roadblocks individuals may face along the journey they choose for themselves, at their own preferred pace.

“They let me be me. They don’t judge me. They give me room to mess up,” Shea says. “Not too many people do that.”

In many ways, MY TURN offers a network of connections to everything one could need help with at their most difficult junctures, from social programming and job placements to housing, health care, and even mentors and social links within communities, steps into place within clients lives to provide the structure, care and assistance typically brought by one’s own families or parents.

For clients like Shehabeldin and Shea, who expressed that their upbringings and influences left little space for positive impact or support, these relationships are crucial.

“They let me be me. They don’t judge me. They give me room to mess up. Not too many people do that.”

— Sethe Shea

“The people here, when you want to help, and you’re not doing it for something, it’s different,” Shehabeldin says. “Everybody here cares, you know? To do this line of work, you have to care.”

Shea knows what gives MY TURN the magic touch.

“No program does it like this,” Shea says. “If I had this when I was first jumping off the porch, when I was in like sixth, seventh grade … I probably wouldn’t be here. I just want the younger kids in the city to utilize it like I utilized it.”

To their clients, MY TURN’s staff and community are unsung heroes, showing up and standing in support, in often thankless situations. MY TURN’s impact and efficacy within the lives of the people they serve come from the sincerity of all they do. The staff show up for clients, even when they may not want the attention, with dependability, understanding and real-world advice. 603

“I didn’t know I could be part of the community in a positive way. It was always negative, you know? Here it’s positive.”

— Reda Shehabeldin

Present day SAACC president Sandi Clark Kaddy standing next to African figures found at the organization.

BY SUZANNE LAURENT

PHOTOS BY ROBERT ORTIZ

ucked into the left of the entrance of the Portsmouth Historical Society on Middle Street is a wealth of history of the culture of the lives and achievements of Black people, with an emphasis on the unique story of African Americans in the Seacoast region.

It all began with a dream of one woman, Vernis Jackson, who founded the Seacoast African American Cultural Center (SAACC) in 2000 with other members of Kwanza Inc., a community service organization.

Jackson came to Portsmouth in 1963 with her husband, Emerald Jackson, and two daughters when Emerald was assigned to Pease Air Force Base in Newington after several relocations since they married in Savannah, Georgia.

She was a longtime elementary school teacher in Portsmouth, and after she retired in June 2000, she turned her full attention to getting SAACC off the ground. In August of that year, Jackson formed a committee that represented nine African American organizations in Portsmouth.

These included the African American Resource Center, the Blue Bank Collective, Kwanza Inc., the Seacoast National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the New Hope Baptist Church, the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail Inc., the Seacoast Martin Luther King Jr. Coalition, the Seacoast Men’s Friendship Group and the Triple 8 Traveler’s Lodge 32.

“We approached the town manager, and we were given a little room at City Hall for meetings,” Jackson recalled.

Shortly afterward, a room at the old Connie Bean Center on Daniel Street became available.

“We also acquired a storage room after the meter maids moved out,” Jackson told the Portsmouth Herald in 2016. “Our beginnings make me emotional.”

SAACC held its first exhibition at this location in 2001, “Quilts: The Underground Railroad Connections,” a community-engaged exhibition about African American quilting traditions as coded, fugitive artwork that enabled enslaved people to escape to freedom.

SAACC moved to its current location on Middle Street in 2010. Along with Jackson, other founding members include Kelvin Edwards, who was also a former board president, and Geraldine (Jeri) Palmer.

Jackson died on Feb. 13, 2025, at the age of 92. But her legacy carries on in the work of present board president Sandi Clark Kaddy, the board and the volunteer network.

On the main floor of SAACC’s space is a painting of Jackson titled, “Mrs. Vernis Jackson, The Divine,” by artist Demarcus McGaughey. It is a visual homage to Jackson and her invaluable contributions to Black ancestry, celebrating resilience, faith and cultural strength. The painting was commissioned by Harold Steward on behalf of the New England Foundation for the Arts and dedicated to the Seacoast African American Cultural Center on June 4, 2025.

SAACC has held numerous exhibits over the years that are described online at saaccnh.org.

In 2018, SAACC partnered with Dr. Casey Golomski, an assistant professor of anthropology at UNH, who helped catalogue and curate an exhibit, “Guinea to Great Bay: Afro-Atlantic Lives, Cultures and History,” with 50 of 267 African artifacts donated by an archaeology professor’s estate. Golomski continues to work with SAACC, creating an internship program for UNH students to do some curatorial and outreach programming with SAACC.

Since its founding, SAACC has distinguished itself as a Black arts and culture center, showcasing original and visiting exhibitions within its gallery space and hosting events, clubs and performances both there and in the wider community. Art students from Portsmouth Middle School often hold exhibits at the center.

Its board and members regularly collaborate with other area African American organizations like Black Lives Matter Seacoast, NAACP, Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire, Theater for the People, and others committed to celebrating our legacy and future through public cultural education.

“We are all volunteers,” Kaddy said. “We raise money through programming donations and are hoping to raise $25,000 for our 25th anniversary.”

Kaddy said she especially enjoys winter holiday time at the center.

“We have Black dolls, Black Pride, Black Santas and Black Angels,” she said. “And the ‘Holidays Around the World’ exhibit is very special.”

One current exhibit, “Crown,” celebrates the beauty, legacy and joy of Black hair, featuring the works of three renowned photographers – Robert Sipho Bellinger, Jordan Naheesi and Najee Brown – whose artistry highlights the depth and diversity of Black hair across generations, cultures and styles.

And in further celebration of SAACC’s 25th year, a second space, the Rowland Gallery at Strawbery Banke Museum, reflects on its role as New Hampshire’s first Black arts and cultural center.

There was an opening reception on June 19 (Juneteenth) to celebrate the exhibit that runs through Oct. 26.

“We’re honored to help celebrate SAACC’s 25 years of powerful storytelling, advocacy and cultural leadership,” said

Linnea Grim, president and CEO of Strawbery Banke Museum.

“As part of this partnership, we’re also proud to honor the legacy of Geraldine ‘Jeri’ Cousins Palmer, one of SAACC’s founders. Her family’s story will be featured in the Penhallow-Cousins House when it opens next spring, and we look forward to sharing that history with all who visit.”

Eleanor and Kenneth Cousins moved into the house in 1937 with their daughter, Geraldine (Jeri) Cousins Palmer, who was just 8 years old at the time. After five years, the family moved to Massachusetts.

After Palmer’s divorce, she and her daughter, Judith Baumann, returned to Portsmouth in 1970, where Palmer was a founding member of the Seacoast African

American Cultural Center and a deacon of the Middle Street Baptist Church. She died in June 2020 at the age of 90.

Kaddy said one future exhibit proposed to SAACC was to display goods that featured Black people and the stories behind them, such as Aunt Jemima (syrup), Uncle Ben (rice), Mrs. Butterworth (pancake and syrup) and Cream of Wheat. She said she likes this idea.

“Our board, members and volunteers are hoping to attract some younger people to SAACC,” Kaddy said. “One of the avenues we’re looking at is for Casey (Golomski) to get the UNH students more involved.”

Kaddy ended on a positive and fun note, saying each of the three floors of SAACC was named after its founders.

“We have the Palmer Room on the lower level where Jeri spent most of her time,” she said. “The Jackson Room is the main floor, and the top floor is named for Kel (Edwards).” 603

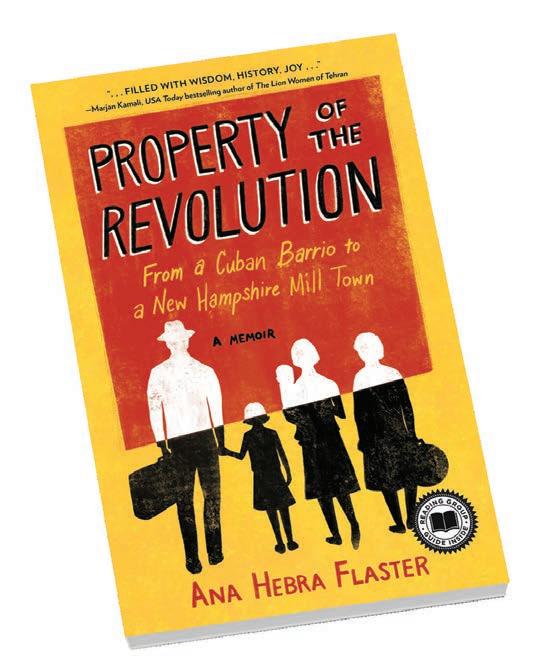

As a 5-year-old in November 1967, Ana Hebra Flaster lived in a “lemon yellow house on the corner,” in Juanelo, a neighborhood outside Havana, Cuba. Back then, Ana was constantly surrounded by four generations of her loving family — aunts, uncles, brothers, cousins and grandparents — in a tight-knit, vibrant community.

Although a typical day for Ana included “chasing skinny hens in Abuela Cuca’s yard,” she also started noticing something else: Her friends would be there one day and vanish the next, the front doors of their empty homes emblazoned with an ominous message.

In her new memoir, “Property of the

Revolution: From a Cuban Barrio to a New Hampshire Mill Town,” Flaster remembers “that last normal afternoon in the barrio,” when the family itself hastily uprooted from all they knew and became immigrants, arriving in the U.S. as political refugees from post-revolutionary Cuba.

Landing in New Hampshire, they were forced to rely on the kindness of strangers. They were part of the mass exodus of Cubans escaping Fidel Castro’s regime, which had overthrown Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship on Jan. 1, 1959.

Through stories that were told and retold over the decades, Flaster unpacks the trauma of being a child immigrant and shares narratives of love, heroism and strength.

Q:Why is now the right time for you to write a memoir?

Hebra Flaster: I’ve been collecting material for this story all my life, having listened to five adults in the household describe the revolution, its promises and betrayals, the tipping points they reached and what triggered them, what it was like to start from nothing in a climate and culture so foreign to them. Of course, my own childhood memories supplied a lot of the material for the book. But I think the spark for the serious writing came from the growing anti-immigrant sentiment over the last decade or so. It wasn’t happening in just our country. Europe, Latin America, countries bordering war zones were all affected by the record-breaking numbers of displaced persons and the pushback from native populations.

Q:What does the phrase “Property of the Revolution” mean to you?

Hebra Flaster: Two things. First, it was the slogan printed on the banner the guard used to seal our front door when he kicked us out of our home. It was years before I learned what the banner said, but it stuck with me. It was the emblem of a life-changing moment, not just in my life and in my family’s lives, but in the lives of the loved ones we left behind and never saw again.

Second, as much as I hated to admit it, the revolution still marks me and my family, and I think anyone who lost home, country and culture to it ... it’s a bittersweet title, like the experience of forced exile itself.

Q:Why did you write the book from your perspective as a child?

Hebra Flaster: I wanted to explore the child refugee experience. Being kicked out of your house and losing your family and never seeing people again, suddenly being uprooted and being thrown into a new culture and what it did to my family — fundamentally, it changed everybody. So in a way, I’ve been in that same moment

all my life. It’s a moment that changed me forever. So I really wanted to capture the confusion and the emotional toll it takes on a child. I also wanted to make sure to pay attention to the impact on elders. I feel like, in the story of immigrants and refugees, usually it’s the people in their prime and family that are leading the way and solving the problems. And then there are these two forgotten bookend generations that kind of roll along with everything, don’t have much of a voice, and often don’t even understand what’s happening.

“I’ve been collecting material for this story all my life, having listened to five adults in the household describe the revolution, its promises and betrayals, the tipping points they reached and what triggered them.”

— Ana Hebra Flaster

Q:Your departure from Cuba in an airplane, as you describe watching your homeland just disappear, is a powerful moment in the book.

Hebra Flaster: Just hearing you say that, I can see exactly what I saw through that little window, but I didn’t know that it was going away forever, which was a challenge actually, when I was writing the book. It’s told from a child’s point of view, but it’s shaped by an adult decades later, looking back at that and interpreting it. The Ana in that moment didn’t know it was the end of that world. She was just

looking at something new, ridiculously beautiful and new in the turquoise of that water. But the woman writing it knows what it meant.

Q:

In Chapter 4, “Receive From Me a Warrior’s Heart,” your dad, who you call “Papi,” and the other men in the family had found a newspaper listing about a farmhouse for rent at 62 Amherst St. in Nashua, a month after leaving Cuba. Why did you include this excerpt?

Hebra Flaster: It was the moment my father hit the most important home run of his life. He’d left us in New York, hoping to find a better home for us in Nashua, where another Cuban family had settled. Ray Flanders, the owner of the rental Papi found in the Nashua Telegraph listings, liked Papi from the start, and Cubans, too — lucky for us. He not only offered to rent the house to Papi without a deposit, he also offered any adults of working age jobs at the factory where he was a foreman. Just like that, we met our future. Thank you, Ray!

Q:What were some comforts to you when you first got to Nashua?

Hebra Flaster: The love in our home, and especially the central place of us as children in the home. Above all, the love in our multigenerational family. We may have been shattered in some ways, but we were unshatterable in the most important way. That’s one of the things I loved about writing the book, is that over and over I kept thinking about how great New Hampshire had been for our family as a place to grow up and land, and it was just a wonderful, wonderful place to have grown up. The way my parents’ co-workers at the factories took us all under their wing (also made us feel welcome). They probably never understood the impact of their kindness to a family trying to find a home.

Q:As so many of your family members lived together in one house, did others in the community welcome that new dynamic?

Hebra Flaster: A lot of our friends liked to hang out at the house, and I think it

was weird to them but fascinating. And of course, my grandmother always made them food.

Q:Some of your family members wanted to live in other Cuban neighborhoods in America rather than New Hampshire. Did you feel like you were missing out on some parts of your culture?

Hebra Flaster: I’m really glad my parents didn’t settle in a heavily populated community of Cubans, because I think we were able to shape what it meant to be Cuban completely, because we created our own little island of Cuban-ness.

Were you able to find peace in going back and processing all that happened?

Hebra Flaster: In general, therapy hasn’t really worked for me, but writing has. It was a key to recovering a lot of the memories that I had buried as I began to write. These elders who did the unthinkable and split apart from their family in order to save the younger family and let them live in liberty … they’ve always been heroes to us, but writing about it, I appreciated it in a whole new way.

Q: Can you give a few examples about how the women in your family were such strong role models for you?

Hebra Flaster: My mother and my aunt were really different people, but they both had a very strong moral foundation. They were wise.

As an example: I wanted to be an American girl and go away to college like my friends were. My father was horrified because I wasn’t married. How could he have let me outside of the home as an unmarried young woman? My mother, aunt and grandmother, for a couple of years, worked on him and worked on him until he finally agreed, and then I went out to Smith College. But he wanted me to go to the local Catholic college and come home every night.

Let’s see ... strength: A lot of the stories of their strengths and belief in

“I’m really glad my parents didn’t settle in a heavily populated community of Cubans, because I think we were able to shape what it meant to be Cuban completely, because we created our own little island of Cuban-ness.”

— Ana Hebra Flaster

themselves come from the stories of how they handled the post-revolution. My mother stood up for people many times and got in a lot of trouble. She had been a supporter of the revolution.

Here’s an example: Right when the rebels came into Havana in January of 1959, there was a lot of violence because people wanted to settle scores with people who had been in the dictatorship, the soldiers, police. There was a police officer in our neighborhood who saved her, possibly her life. And he was somebody that everybody knew and respected, a good man. When the rebels rolled them in, they were targeting anybody in a uniform, and a crowd of friends from the neighborhood came running and said ‘they’re going to hang Manso’ — his last name was Manso — and (saying) ‘you have to help.’ And she and her uncle ran off and the neighbors joined them, and when they got to Manso’s house, there was a gang inside his house with a rope, a big, long rope coiled around one of the guys’ arms, and they had guns, and Manso, in his uniform, was sitting on the couch next to his wife. And there was a tension in that room. It was incredible, and my mother talked them down and saved Manso.

Q:You describe the sacrifices and risks your family took to ensure they could survive, and thrive, in New Hampshire. You don’t want it revealed here, but in the book, your aunt found an ingenious way to smuggle her diploma out of Cuba, which allowed her to have a teaching career in the U.S.

Hebra Flaster: My aunt was a strong woman, in a different way. Once she decided what was right, there was nobody who was going to stop her. For example, she was once a big fan of the revolution at the beginning. She had been a revolutionary, and something happened, and that’s in the book, too.

My aunt decided that the revolution wasn’t honest, it wasn’t fair. So she decided she was going to get her two boys out of the country. But the problem was that they were changing the age of military duty — lowering it — and once a boy reached that age, he wouldn’t be allowed to leave. So she convinced her husband to officially separate from her, even though they loved each other.

When you left, (everything) you owned (went) to the government. No bank accounts, no money, and you couldn’t give it to a relative. You couldn’t sell anything you owned. Everything (would) just go right into the revolution’s coffers, and you couldn’t take anything of value, including diplomas. But my aunt had a doctorate in pedagogy. She wanted to teach in the United States, and knew that she would need the diploma, right?

But how could she take it out? My mother and she fought over this decision. My mother said, ‘You’re risking everything. If they catch you, they’ll throw you in jail. What will happen to the kids?’

Once (my aunt) decided, she was like a horse with blinders: Bam. That’s what she was gonna do, and that’s what she did. Thank God she did, because (she taught) Spanish at Nashua High for over 30 years. I thought of her as a hero. 603

Ana

Hebra Flaster is a freelance writer who’s known for her @CubaCurious blog on Substack.

Excerpted with permission

from “Property of the Revolution” (She Writes Press)

by Ana Hebra Flaster

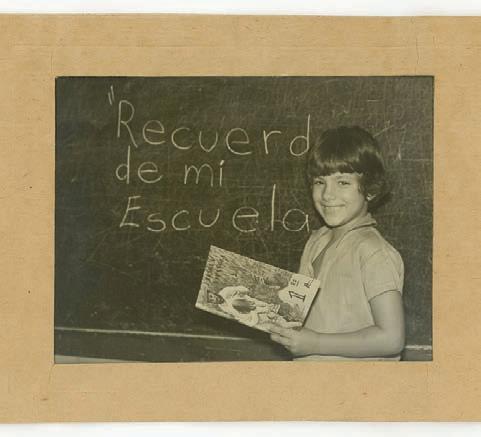

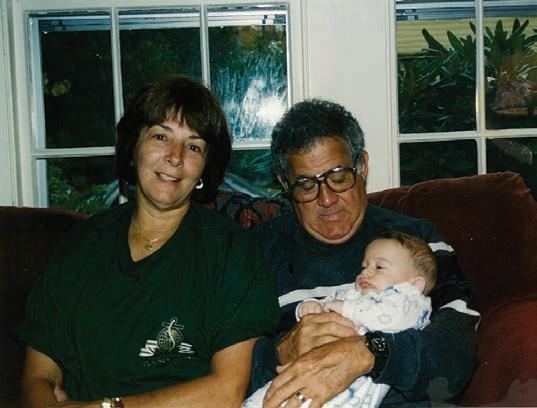

Top: Hebra Flaster’s parents at their wedding, flanked by her grandparents.

Center: Don Manuel.

Below: Ana in first grade in Juanelo, a neighborhood outside Havana, Cuba.

Nashua, New Hampshire, December 1967

Ray Flanders liked Cubans, thank God. Papi didn’t know that when he first stood in front of him, another tall American with big teeth, but it turned out to be a bit of luck that broke our way.

Papi had been hopeful on the journey north with the Cernudas, even though the roads were iced over and the trip took more than six hours instead of the expected four. The next morning, the men searched the Nashua Telegraph and found a promising house for rent. It was on a busy street, Armando warned, but it was directly across from an elementary school and a baseball field, which at the moment served as a community ice-skating rink. The farmhouse, with its dirt-floor basement, steam radiators, and old-fashioned wallpaper everywhere, dated back to the late 1800s, but Papi said it felt more like something from medieval times. It smelled like that, at least.

Ray, the owner, took a liking to Papi immediately, recalling how a Cuban classmate of his had disarmed a crazed, knife-wielding intruder in their dorm when he was in college. Ray said the Cuban student had known his way around machetes—he’d grown up on a sugar plantation—so a knife had been no problem.

“Thank God the guy with the knife wasn’t the Cuban guy,” Papi said to Armando as they drove away. “We’d still be looking for a house.”

Papi felt triumphant. He didn’t know if Tío would ever join us—and as the only man present, he felt responsible for both families. That day, he’d not only found a new home for us but had also gotten jobs for himself, my mother, and my aunt at Hampshire Manufacturing, the rubber boot factory where Ray was a foreman.

“Hold off on the first month’s rent,” Ray told Papi. “You can pay me after you get your first paychecks.”

The eight of us moved into the rickety farmhouse at 62 Amherst Street—or “Amehr Estreet,” as the viejos pronounced it—soon afterward, although Tía dragged her feet in protest. She thought a city would be better than a quiet town so far north. Why couldn’t we live in Union City or Newark like all the other Cubans?

When Tía lobbied hard for us to move again, Mami pointed to New Hampshire’s apt state motto and tried to convince her. “Live Free or Die” on all those license plates looked like a good omen to everyone. And the adults all agreed that if the United States fell to communism, we’d be grateful that the Canadian border lay just a few hours north. From now on, they’d always have an exit plan. With all the anti-war demonstrations, pot-smoking hippies, and race riots of the late ’60s, a revolution here seemed plausible. But they saw the upside of all that turmoil and held on to it for dear life. They were in a country that allowed its citizens to shout in sults at their president without throwing them in jail. Maybe that was a country worth freezing for.

And freezing we were. The week we moved in, a blizzard dumped eighteen inches of snow and ice on us. Frost covered the windows.Three-foot icicles hung from the eaves. I studied the warped worlds inside the icicles that crashed to the ground. There was magic in that house. I pressed my hands against the drafty windows and watched the handprints that appeared and disappeared there. When the loud steam radiators hissed and spat, I stood in awe, marveling at yet another American contraption.

And we all fit. Abuela, Sergito, and I in one room, Tía in another, my parents in their own on the ground floor. Angel and Alberto got the best one: a large closet in the living room. The viejos found a bunk bed somewhere and squeezed it into that long, windowless space, creating a cozy, mysterious hideout for my overjoyed cousins.

Those first weeks in New Hampshire, my parents and aunt dug deep into the Cuban tradition of facing difficulty with great bluster, denial, and a smile. “A mal tiempo, buena cara” was Tía’s favorite Spanish saying. For Tía, especially, “To a bad time, a good face” allowed her to live with the possibility that Tío might never join us. The viejos distracted themselves by telling funny barrio stories, remembering the past as if it was theirs to recreate at will. They kept the barrio and our lost family right there, just under the happy present they were trying to create. 603

BY JAMES MCKIM

Let’s start with a definition — because here in New Hampshire, we like things to be clear and orderly (not to mention I was a philosophy major in college, focusing on metaphysics and language, as I was attracted to understanding meaning). “Belonging” isn’t just a fuzzy, warm feeling like sipping maple syrup by a woodstove. Belonging means being accepted and included as your full self. It means being:

• Recognized for your contributions.

• Respected regardless of where you’re from or what accent you carry.

• Included in decision-making.

• Safe from bias, discrimination and invisibility.

• Needed, not just tolerated.