Sustainable Packaging

A practical guide to understanding the technologies, terminologies, facts, and nuances of sustainable (responsible) packaging and consumers’ [mis]understanding of it.

A practical guide to understanding the technologies, terminologies, facts, and nuances of sustainable (responsible) packaging and consumers’ [mis]understanding of it.

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, April 2022

41% of US consumers believe companies should do more to recycle packaging than governments or themselves

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, April 2022

41% of US consumers believe companies should do more to recycle packaging than governments or themselves

37% of US consumers don’t trust companies to be honest about their environmental reporting

68% of US consumers believe their behavior can make a positive difference to the environment

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, April 2022

68% of US consumers believe their behavior can make a positive difference to the environment

74% of US consumers say they properly sort, wash, and recycle all the packaging in their home

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, April 2022

Let’s bring consumers and sustainability into focus

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2021, April 2022

26% of US consumers say they would pay 6% to 10% more for coffee if it were produced and packaged sustainably

26% of US consumers say they would pay 6% to 10% more for coffee if it were produced and packaged sustainably

79% of US consumers are overwhelmed by sustainability

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2021, April 2022

There is no single "most sustainable" package structure or material. Period. Every package format and every package material exhibits some positive attribute of environmental responsibility. Conversely, certain formats and materials may exhibit less positive attributes when compared to others.

More recently, the eight criteria were replaced by five guiding principles.

• Uses SMART* design

• Advances the use of recycled materials and/or sustainably-sourced, renewable feed stocks

Historically, there has been 8 specific criteria with the definition of sustainable packaging.

• Beneficial, safe, healthy throughout its lifecycle

• Uses renewable energy from sourcing to recycling

• Meets market criteria for performance and cost

• Optimizes renewable or recycled source materials

• Designed to optimize materials and energy

• Made with clean production and best practices

• Uses materials healthy throughout the life cycle

• Recovered and used in closed-loop cycles

• Is designed for reusability, recyclability, or composability, and labeled with appropriate endof-life instructions

• Engages with reuse and refill models

• Invests in the growth of recycling and composting infrastructure, collection, and access

*SMART: Systems approach

Material health

Accessibility

Reduction and elimination

Life-cycle Thinking

The terms "sustainable", "sustainability", and "sustainable packaging" have been universally used for more than two decades. Their over-use and exploitation during that time has caused them to become ill-defined and often misunderstood by consumers and industry alike. Further, they have lost relevance among consumers and have become largely non-actionable for them as well.

Mintel's expert packaging advisors prefer and routinely use the terms "responsible", "responsibility", and "responsible packaging" in lieu of "sustainable", "sustainability", and "sustainable packaging".

The latter terms reflect more easily understood terminology and impart a personal connection and ability to take action toward the greater issues, challenges, and solutions associated with our planet, its people, consumer products, and of course, packaging. In short, it is intuitive to understand what it means to be responsible, where the idea of being more sustainable is often obtuse and lacks context.

48% of US consumers are unsure of what “sustainably made” actually means

Base: 1,000 internet users age 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2022

Determine what is most important to you

Consider and then prioritize each individual criteria according to what reflects the goals of "this" project, product, package, or supply chain process. Consider how those goals mesh with a greater environmental strategy. Pick one criteria. Work toward it. Achieve it. Report it. Pick another. Work toward it, achieve it. Report it.

Don't think 'all or nothing'

It's cliché, but it's true...eco responsibility is a journey. Consider this analogy: breaking the sound barrier only came after decades of progress in aerodynamics and propulsion. It did not happen the day after the Wright Brothers' first flight. Every small step toward environmental responsibility counts toward the greater good.

Take credit, but exercise restraint

Promote and celebrate the positive steps toward environmental responsibility, even if more can be been done. By the same token, do not stretch the truth about accomplishments. Remember, there is no "most sustainable" package nor practice. There is always more to do.

Plastic: For better or worse

Sentiment about plastic trends toward consumers seeing it as a bad player and one not preferred, especially for food.

IN THE US

74% of consumers believe brands should limit their use of plastic for food packaging

IN THE UK

46% of consumers rank plastic pollution among their top three environmental concerns

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2022, April 2021; Kantar Profiles/Mintel Consulting Sustainability Barometer, April 2022

IN BRAZIL

60% of consumers equate paper/board food packaging with being the easiest to recycle

'Paper

Let's compare:

• 2,000 plastic retail bags weigh 30 pounds, while 2,000 paper grocery bags weigh 280 pounds. This extra weight adds to the greenhouse gas emissions during transportation

• There is a 7:1 ratio in plastics' favor in terms of trucks needed to deliver an equal number of paper vs plastic bags

• It takes more than four times as much energy to manufacture a paper bag as it does to manufacture a plastic bag

• The production of paper bags generates 70% more air and 50 times more water pollutants than plastic bags

• It takes 91% less energy to recycle a pound of plastic than it takes to recycle a pound of paper

• Plastic bags generate 80% less waste by volume than paper bags

• Paper bags must be reused three times to be as eco-responsible as plastic bags. And in case you were wondering, a reusable cotton bag must be used at least 131 times to be as overall responsible as a plastic bag

The bottom line: plastic bags float in the air, get caught in trees, clog waterways, and include the word "plastic" in their description. Right or wrong, plastic bags lose in the minds of consumers.

We should never want to live in a world without plastic. Plastic provides safety, convenience, freshness, and efficacy. We should want, and endeavor, to live in world that uses less plastic, and one where even that plastic is used responsibly. That means optimized, not eliminated.

Source: American Chemistry Council; taking account of deforestation, greenhouse gasses, chemicals and transportation; Denmark Ministry of the Environment;Allaboutbag; Northern Ireland Assembly

Commitments to produce and use 100% recycled content in packaging by 2025 or 2030 are admirable*. They are also a bit misleading for consumers to understand, and here's why.

48%

of US consumers did not know that just because a package includes recycled content does not mean it is automatically recyclable

Take, for instance, laminated flexible packaging for salty snacks. They often include 5 to 7 layers of materials, each performing a specific function: print receptivity, barrier to oxygen, puncture- or tear-resistance, tie layers that add additional barrier and layer bonding, and sealant layers.

Adding recycled content can reduce the amount of virgin material used. But because these layers still cannot be separated, the structure cannot be recycled, if it is even collected curbside. It still ends up in a landfill or at best, incinerated in a waste-to- energy program. Moreover, high-quality, high-value recycled content that could be recycled again and again becomes buried in a landfill, its value lost forever.

* According to the EMF, 2025 targets are expected to be missed

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2021

Recycle-ready

Recycle-ready packaging refers to that which the base material and all other materials and components are of a similar material, and which COULD be recycled IF municipalities collected them curbside, and IF a MRF can properly sort and recycle them vs. those which are marked for store take-back programs.

Recycled content

Just because a package is made with, or includes, recycled content does not automatically mean it is recyclable. Many packs made with recycled content, particularly flexible packaging, still end up in landfills or in waste to energy scenarios at best.

Degradable vs biodegradable

The Titanic is degradable, not biodegradable. It will eventually break apart but only into smaller and smaller pieces of steel. It will not biodegrade and return to carbon dioxide nor to an element marine life can consume as a nutrient.

Compostable

The reality is that most packs labeled as compostable will break down only under industrial compost conditions, not in backyard compost bins.

*Biodegradable packaging and compostable packaging are not the same.

*Biodegradable material can take an undetermined time to break down. In contrast, compostable materials will decompose into natural elements within a specific time frame

Ocean plastic’s future is exciting but limited. The reality is degradation due to UV exposure makes for poor quality material. The truth is that collecting ocean plastic is costly, inefficient, and neither a sustainable nor a financially profitable process. At best, it creates an opportunity to educate consumers on recycling.

A new genre of plastic waste has emerged that on the surface seems like a nextgeneration effort aimed at cleaning up our oceans and beaches. That new genre is "ocean-bound" plastic. But without a clear definition, it can be misleading to consumers.

Ocean-bound plastic is not plastic recovered from the ocean, or often, not even close to an ocean. It is plastic recovered from "at risk" zones. These are primarily, but not exclusively, third-world countries where plastic is "at risk" of potentially entering the ocean. An "at-risk" zone can be a coastal zone, but it also can be any area within 31 miles of the ocean, to include parking lots, road sides, or, shockingly, even recycling bins where plastic has been placed for proper disposal or recycling.

62% of consumers do not know that only a very small percentage of recovered ocean plastic can be included in new packaging

Base: US: 1,000 internet users age 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel Consulting Sustainability Barometer, April 2022

Become bio-savvy

Plastic packaging options should never be overlooked just because they are plastic. Though consumers expect brands to eliminate or reduce plastic, when it is used, an explanation of why it is the more appropriate material/format for this occasion, this region, or this point in time is paramount.

Understanding the nuances of biobased plastics is critical to using them wisely. Such factors as land/water use, total raw materials needed, recyclability, or other end-oflife/second-life scenarios are critical to ensuring they are the better choice in a given occasion, and that they also fit within your, or your client's budget.

Realize the future isn't what it used to be

There was a point a decade ago when recovered ocean plastic looked to be a panacea for plastics. Going forward, the future for plastics lies in a combination of curbside recyclability, mono-materials and bio-based hybrids, each of which brings new strategic, market share, and financial opportunities to the table.

Recycling efforts are…[exaggerated]

No case may be stronger for a once-in-a-generation overhaul of a package format than that of multi-laminate soft/flexible plastics and multi-laminate tubes.

Manufacturers of raw materials and converted bags, pouches, sachets, sticks and tubes are mid-stream in finding monomaterial structures that achieve parity of barrier and a future promise of curbside recyclability in lieu of the current, interim genre of "recycled-ready" or "technically" recyclable plastic materials – those that could be recycled right now if infrastructures existed.

Finding the right combination of like polymers that ensure freshness, efficacy and shelf-appeal, while not impacting recyclability or driving costs through the roof, remains the ultimate prize.

Base: US: 500 internet users aged 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, March 2021

56%

of US consumers say they have recycled packaging in the past 12 months

The How2Recycle label positioned beside the Recycle Ready message is misleading. The H2R group rescinded its approval for the brand to use the logo, as it believed it conveyed confusing claims to the consumer.

Feb. 8, 2024

Colgate-Palmolive faces lawsuit over ‘misleading’ recyclable toothpaste tube claims

A judge denied Colgate-Palmolive’s request to dismiss a lawsuit brought by consumers who say thecompany’s recyclability claims on certain types of toothpaste packagingis “false, deceptive, misleadingand/or unlawful.”

The lawsuit’s plaintiffs reported purchasingthetoothpaste thinkingthey could recycle thetubes curbside, and said they wouldn’t have purchased it or would have paid less if they hadknown their municipalrecycling programs in Californiadidn’t accept theproduct.

The lawsuit states only a “miniscule number of consumers” in California and across thecountry can recycle the HDPE tubes, because few facilities accept them.

Colgate acknowledged at the timethattube recycling success would requirea “critical mass of tubes on shelf thatmeet recycling standards.”

Consumers generally believe that a package marked as compostable can be freely disposed of in the environment or simply placed in a backyard compost heap, and it will "go away." This is not the case.

Home compost heaps/bins do not support the conditions necessary for the composting of packaging labeled as "compostable." This claim most often means a package is compostable under industrial conditions, even if the claim does not specify that.

IF compostable packaging provided the structure and barriers required for food preservation and IF they were compatible with beauty, personal care, and household products, and IF everyone lived where compostable packaging was collected curbside, and IF consumers understood the differences between home and industrial composting, then yes – all packaging should be compostable. That's not the case.

It should be noted that most compostable packaging materials lack barrier properties sufficient to ensure shelf-life and prevent food waste. While additives to achieve extended shelf-life can be included, they often negatively impact composability.

64%

of consumers didn't know most packaging marked as compostable can only be composted at an industrial facility, not in backyard bins

Base: 1,000 internet users age 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel. April 2022

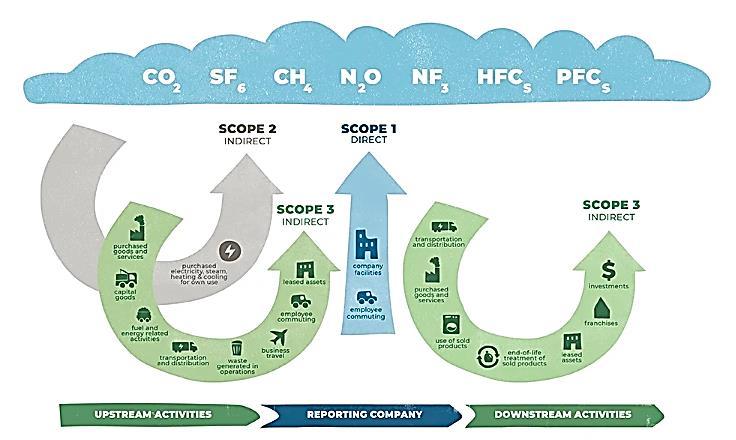

A carbon footprint is the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions caused directly and indirectly by a nation, an organization, an event, activity, a product, a package or even a person.

There are direct and indirect carbon emissions.

• Direct emissions are those produced by a company via heating/cooling, company-owned vehicles etc.

• Indirect emissions are those emissions embedded in a company’s supply chain, to include sourcing, manufacturing, transportation, use phase and end-of-life disposal.

The carbon footprint definition, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) is a measure of the impact activities have on the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) produced through the burning of fossil fuels and is expressed as a weight of CO2 emissions produced in tons.

Source: University of Michigan Center for Sustainable Systems

Mintel's Global New Products Database shows on-pack carbon neutral claims rose 438% between Jan. 2015 and Nov. 2022. Along with that proliferation of carbon claims comes confusion as to which are good, better, best or perhaps just less bad.

Mintel’s Global New Products Database has recorded the following on-pack claims related to carbon reporting:

• Carbon Neutral

• Carbon Balanced

• Carbon Positive

• Carbon Negative

• Carbon Free

• Carbon Responsible

• Carbon Offset

• Carbon Net Zero

Base: 1,000 internet users age 16+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel, April 2022

58% of US consumers would prefer companies to reduce their own carbon emissions rather than use "carbon offsetting" programs

• Corrugated/Paper: 2 lbs. CO2 per 2.2 lbs. of packaging

• Aluminum: 4.9 lbs. CO2 per 2.2 lbs. of packaging

• Plastic: 7.7 lbs. CO2 per 2.2 lbs. of packaging

For packaged food, the growing, harvesting, production, and distribution of the food itself accounts for more than 98% of the product’s carbon footprint. The packaging generally accounts for less 2%.

Halve the amount of virgin plastic use by 100,000 tons

DS Smith: 50,000 tons of CO2e per year

150,000 ton reduction in 2021

33% absolute reduction in CO2 by 2028

Carbon

grasp

1 ton of carbon emissions =

34%

Of US consumers say labeling that shows environmental impact (CO2 emitted) would encourage them to buy sustainable products

37%

Of US consumers say labeling that shows a score of how eco-friendly a product/package is would encourage them to purchase

Base: 1,000 internet users age 18+

Source: Kantar Profiles/Mintel April 2022

Just when you thought you had a handle on the shift from sustainability to responsibility and the introduction of carbon footprint reporting, carbon hand-printing is emerging.

Unlike a carbon footprint, which is the total amount of greenhouse gases (including carbon dioxide and methane) that are generated by such actions as farming, manufacturing, transportation or disposal, a carbon handprint is more personal.

In the same way that responsibility is an intuitive concept for consumers, carbon hand-printing is the "hyper-actionable" events an individual consumer can take to offset the footprint of the goods and services they buy or use.

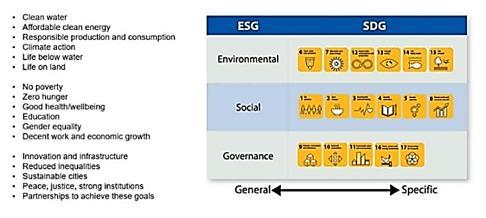

The expectations regarding the scope of what sustainability encompasses are shifting. No longer will it be sufficient to align environmental strategies with the now two-decades-old construct of corporate social responsibility (CSR) or even the more recent – but non-specific – guidelines allied with environmental, social and governance (ESG).

Mintel believes total carbon footprint, in context with the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (“as shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and planet”), will be the global standard by which packaged goods and packaging be inextricably aligned with social and environmental issues that consider, embrace, measure, and solve specific challenges

The bottom line

Keep an open mind

Glass, metal, paper or board; rigid or flexible plastic...fossil-fuel or biobased. Listen to all arguments. Give each option the fullest consideration. Make the most responsible choice based on what is most important to your brand or your business at this moment in time.

Never say never Don't rule out any package format or material (including plastic), or end-oflife scenario for future consideration simply because it may not appear to be the most popular choice today.

Continue to explore, continue to adapt, continue to keep an open mind.

Take the first step

Arming yourself and your organization with a more enlightened perspective may make it easier to keep an open mind and provide the ability to make an informed decision based on science rather the popular (and often misinformed) public opinion.

David Luttenberger, CPPL Global Packaging Director dluttenberger@mintel.com

David has 33 years of diverse packaging experience. He works across all end-use categories, all pack format, and all materials. He has 23 years’ experience in sustainable packaging, and holds a Certificate in Circular Economic and Sustainable Business Strategies from Cambridge University’s Judge Business School.