Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Dubai International Airport Dubai Frame

Jebel Ali Port

Burj Khalifa & Dubai Mall

Ain Dubai

Palm Jumeirah

Dubai Marina

Burj al-Arab

The World

Dubai International Airport Dubai Frame

Jebel Ali Port

Burj Khalifa & Dubai Mall

Ain Dubai

Palm Jumeirah

Dubai Marina

Burj al-Arab

The World

We entered Dubai, really, as my son and I stepped aboard the Emirates airplane waiting at a gate in the international terminal of Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. Soon we’d fly thirteen hours non-stop to Dubai (or DXB per our checked bags). The Emirates planes advertised the event that had drawn us to this trip: Expo 2020. The year was now 2021, but the signage remained “Expo 2020” since the event had been postponed for a year because of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Expo had struck me as a chance to gauge the viability of the “global” in our era of cascading climate challenges. My questions had only sharpened after watching the social strains brought on by the pandemic. The moment called for global unity, but in fact events had strengthened the

1

hand of ultra-nationalists. It was early evening as we entered the plane, and the interior lights were subdued as passengers arrived to their seats. Here in the economy section each traveler sat down in front of a bright screen loaded with entertainment and information about the flight and Dubai. Staring at a story playing out on a screen is now by far and away the preferred way to pass time. I’d brought a book with me, but since the overhead light in my row wasn’t well aligned with my seat, I gave up on reading and spent my time watching a movie or aimlessly browsing the offerings on the screen. Looking back on the trip as a whole, I realize now that screens are a big part of my memory of Dubai. No matter where we went, reality was augmented by

2

screens. One default screen on the Emirates flight was a series of maps showing the global reach of the airline. The connections reached out from Dubai to multiple points in Asia. Subsequent images showed red lines connected to points in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. In Dubai and the Expo we’d see many versions of this map of global connections. When we use the word “global” we mean the notion of interconnected human culture that plays out on the surface of the planet. The global in this usage pertains to what humans have built, and to express it most clearly we draw lines of connection between points on the globe. The tendency of such global line drawing is to ignore the deep planetary systems that underlie life on Earth. We are

3

blinded to the planet by our fascination with what humans have built on its surface. Upon our arrival in Dubai we walked down the usual airport halls. We descended a tall escalator that delivered us to the security area where visitors lined up to get their passports stamped. The United Arab Emirates charges no fee for a tourist visa for visitors from many countries. Dubai depends on foreign visitors so intense scrutiny isn’t their game. The arrival hall shone with a kind of metallic sheen, especially those silver columns. Nowhere in Dubai did we see much effort to turn down the shine or temper grandiosity. The baggage claim carousels are visible right behind the passport control barrier, so an illusion is created that this space is easily permeable by all

4

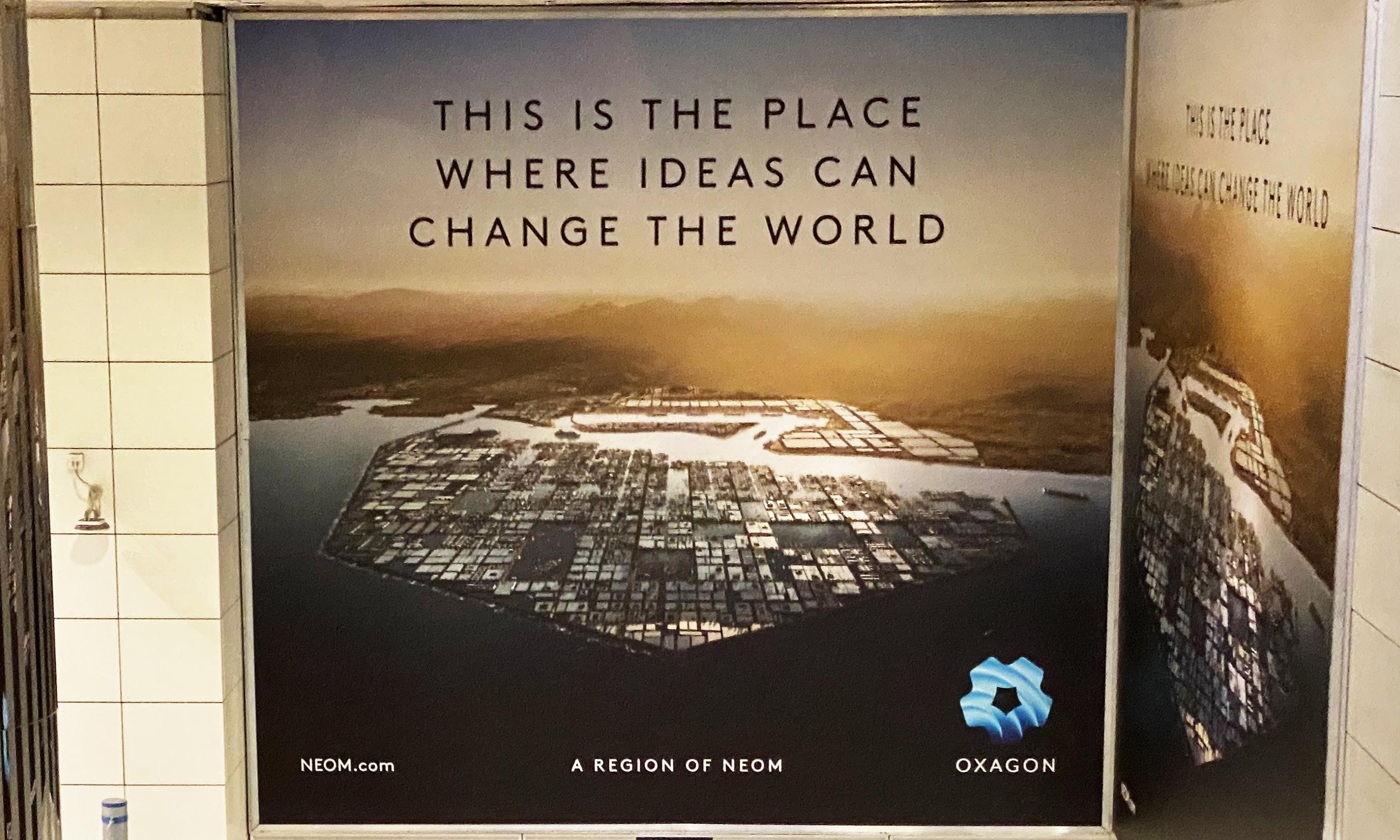

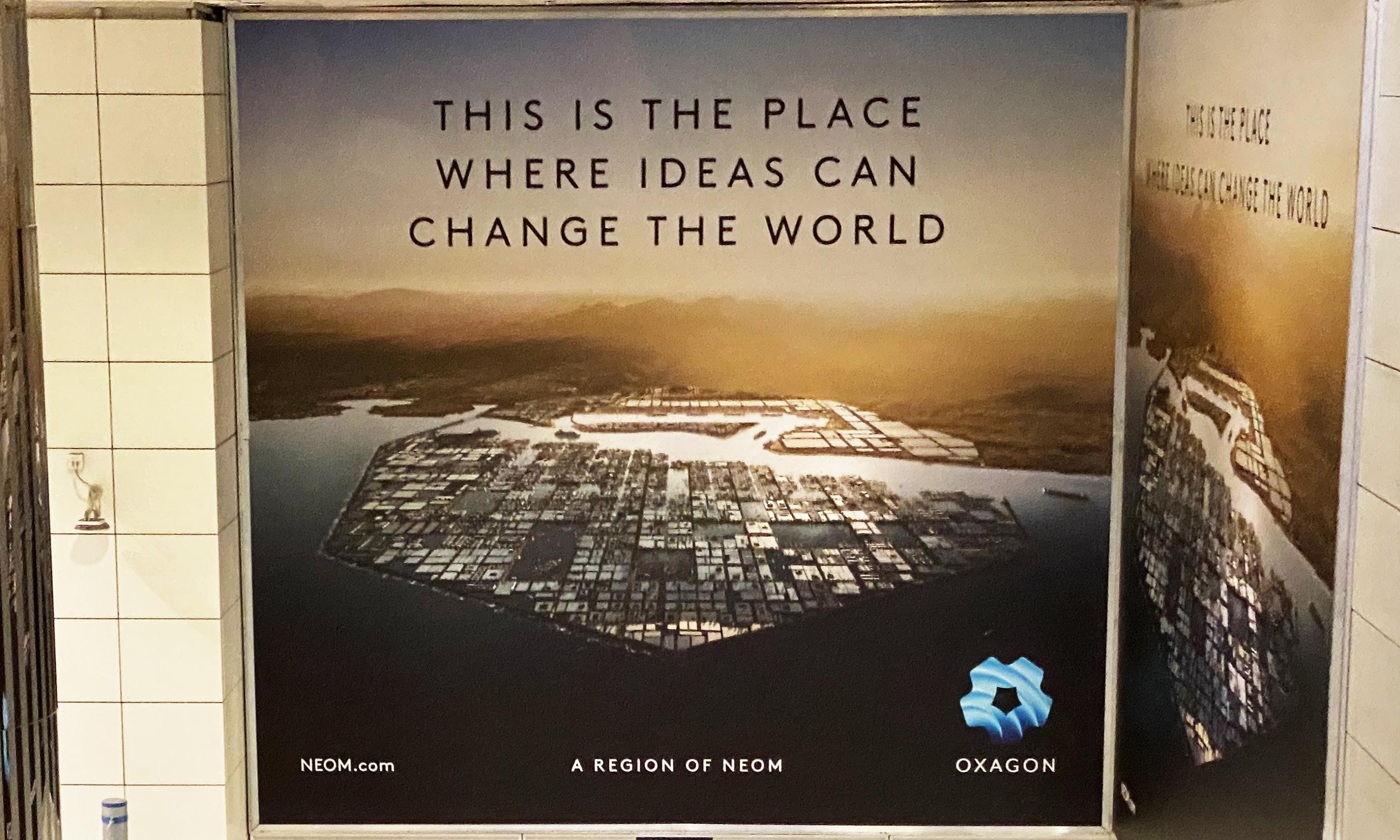

nationalities, though this isn’t the case. Throughout Dubai it was impossible to miss the advertisements for Neom, a massive city-project slated for construction by Saudi Arabia. This advertising for Neom began in the airport. A large sign portrayed the industrial area Oxagon, a floating port and data center. The hope is that this manufacturing center and the city of Neom will rearrange the flow of global trade and draw the smartest people from around the world. The advertised image was only a rendering, but it succeeded in showing the area miraculously arising like a crystallizing mineral in a barren desert. Since the context for this ad campaign is Dubai, where residents have witnessed a miraculous city bloom out of seemingly nothing, there

5

could well be a willingness among those who know this city to believe that other miracle cities might appear. Most of our time in Dubai we stayed at an Airbnb on the 33rd floor of a residential building that overlooked the marina. This short inlet of the Arabian Gulf is entirely artificial. A lot of digging and voilà!, a beautiful area is ready for residential construction. It’s a kind of sleight of hand that’s accomplished over and over in Dubai. Nothing becomes something; worthless land gains astounding value. The evening view was stunning, with all the varied high-rises lit up and the waterway outlined with deep purple. This could all be mistaken for the city itself, but in Dubai it’s just one of many urban islands. The marina was our main view, but if I

6

looked to the left, between two residential buildings, I could see the great outer circle of the Palm Jumeirah development. I’d looked many times at this development on Google Earth, and noted the artificial palm extending into the gulf. Now I realized that the palm and other famous sites were perceptible in the oblique ways of real things. They were no longer perfect images on a screen, but structures present in surprising ways from a distance. One goal in Dubai would be to note how structures formerly existing as ideal objects on the internet established their meaning in an actual landscape. I’d be pursuing the sidelong glance and trying to leave behind the idealized internet viewpoint of this city. The most attractive feature of the Dubai Marina

7

was the way it offered open public space. A bifurcated path wended its way around the marina. The inner tan-colored section was for walkers, the pink-colored section was for bikes and scooters. I’ve lived in Egypt and traveled to various Arabic-speaking countries, but I’d never encountered in those countries such comfortable public space. There were even benches spaced evenly along the path. It was a fine place for a morning run. The lazy curves of the marina could easily become micro-harbors for trash, but in the morning (from above) I watched a boat whose job it was to collect discarded plastic or wrappers floating on top of the water. The overwhelming visual impression of the Dubai Marina was of high-rise residential buildings (with hotels mixed

8

in). It was always possible to look up at stacks of balconies. At some inlets there was space for docking private boats and yachts, reminders of the wealth in residence in these buildings. Along the path I saw constant effort at place building through public art or words. Here the hashtag symbol functioned as an implicit request to post images onto social media. So much of Dubai has been built in the era of social media that we can think of it as a social media native city. This space was created to be represented on social media, and its social media presence in turn builds actual value into this space. I’ve praised this public marina space, but the deeper question is for whom was it all built? Many obvious tourists made their way around the path,

9

since (like us) they were staying in a nearby hotel or Airbnb. But many were actual residents of Dubai. Something like 3% of people in the UAE are from Western Europe or North America, but here in the Dubai Marina that percentage is far larger. Everyone walking around here, whatever their country of origin (excepting the service workers), show themselves to be comfortable participants in global culture. The marina isn’t a British or American colony, as might’ve been true in the colonial past, but a global district that harbors a group of international workers who have more in common with each other than with the mass of people in their home countries. Just north of the marina is the Dubai Internet City. This Internet City is what Dubai

10

labels a “free economic zone” where foreign corporations are allowed full ownership of work spaces and enjoy hands-off economic policies. The area is dotted with low-rise office buildings, many with a prominent corporate logo at the top. Above is the building for the computer and software maker HP. Nearby it was possible to see buildings for Google, Microsoft, Samsung, Oracle, Huawei, and others. These offices employ knowledge workers from around the world (already 10,000+), and the Dubai Marina is the obvious residential space for the educated and well-connected workers of this Internet City. Global knowledge workers thus get to live in space that has been constructed with their taste and predilections in mind. From the Dubai Marina

11

it took just a few minutes to walk to the nearest Metro station (an aboveground tube-like structure, visible on the left). The Metro runs alongside the central road of Dubai, Sheikh Zayed Road. This modern highway has seven lanes running in each direction, and connects the individual emirates that make up the United Arab Emirates. Each emirate functions like a citystate, and so this road does what highways do best: connects a series of cities for travel by car. In the city of Dubai the Metro covers most of the length of Sheikh Zayed Road, which runs parallel to the coast. This road and the Metro are the transportation backbone of Dubai that visitors to Dubai get to know well. Metro maps simplify the physical and social geographies of a place.

12

No better example of this exists than the stylized map of the London Tube. In Dubai the Metro map is dominated by a central Red Line, defining what we might call the “mainline” experience of Dubai. The Red Line serves tourists and residents who move around to the standard tourist sites and work zones. The map adds images for popular buildings around the city. What’s missing from this map is a guide to the two sides of this line: a private world of luxury exists along the coast while the crammed neighborhoods for workers living in shared dorm spaces extends inland from the mainline. There exists a coastal, luxury Dubai as well as a faceless, sandy Dubai of unimpressive worker accommodations. Upon arriving in Dubai there’s little that feels

13

strange. This is by design: the city is meant to be impressive, or even marvelous, but never strange. Its leaders aim to deliver the grandest versions of things for which modern tourists already feel a high level of comfort. Something similar could be said about the transportation. The city is designed for private cars, but acknowledges the benefit of an easy-to-use Metro. The things that have worked well in other global cities are in place here. Since really nothing in Dubai is older than 50 years, and few things older than 25 years, the entirety of the city has been designed to the expectations of the most modern places around the world. Nothing has to be retrofitted. Consequently, the Dubai Metro is an easy experience. A person buys a re-usable silver card at the

14

ticket kiosk, then uses that card to enter and exit from each ride. The cost of the ride and the total held by the card shows up on a little window at the turnstile. The Metro has the above ground ease of the more recent extensions of the London Underground, like the line to Canary Wharf. It’s no surprise to learn that the Dubai Metro is operated by the British service corporation Serco. This turns out to be true about many things in Dubai. They aren’t the product of regional know-how (“this worked well in Riyadh...”), but designed by corporations with global reach (“we’ll make this just like the one we built in London”). As a traveler in Dubai I often felt that somehow things should be more difficult. The Burj al-Arab is a global icon, and there’s a good chance

15

you’ve seen this luxury hotel pop up on social media accounts. Construction began in 1994 and it was finished in 1999. It accomplished its primary goal of putting Dubai (and the Arab world) on the map of contemporary architecture. As opposed to a building like the Sydney Opera House or the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, this dazzling structure is impossible to interpret as serving the public. It’s resolutely private and exclusive. It can be seen from Sheikh Zayed Road (or the Metro, as with this photo) and from this mainline vantage it symbolizes an elite and luxurious world along the coast. Long before I visited Dubai I knew about the Burj al-Arab and had appreciated its sail-like design. A model of the hotel is set within a glass display

16

in the lobby of the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. The label notes that Roger Federer and Andre Agassi played a friendly tennis match on the helipad near its top. Why would this building be put on display on the other side of the world? The “Tower of the Arabs” was built as an icon for the Arab world, and so a distant museum celebrating Arab identity took

17

pride in this architectural gem. Sheikh Zayed Road passes a series of luxury car dealerships. High end sports cars could be glimpsed through the windows of this Lamborghini dealership. The Urus, a sport SUV, costs somewhat over $200,000. The ultra sleek Aventador comes in at more than $400,000. The global website for Lamborghini describes the Aventador as “created to anticipate the future, as demonstrated by the use of innovative technology...” Those words fits nicely with the entire ethos of Dubai: future, innovation, and technology. The Burj al-Arab (visible in back) didn’t offer any sort of contrast, but complements Lamborghini’s luxury appeal. Everywhere in Dubai visitors come across construction zones. We were in no doubt that if we

18

returned in the near future, the city would be substantially changed. Projects will be completed; Vistas transformed. This level of transformation isn’t some passing state for Dubai, but the city appears based on the idea that it will always be a place of becoming. The future of Dubai rests on the idea that it will continue to be a construction zone. Even along the Metro from Dubai Marina to the downtown there are numerous examples of buildings under construction, whether in the distance or close up, like this photo of the Safa Park Residential Towers near the inlet for the Business Bay water course. Sheikh Zayed Road, as it passed through Dubai, presented a neverending series of billboards. These were aimed at drivers, but it was

19

impossible to miss them from the Metro. The billboards were mostly advertising products from well-known corporate brands (with a smattering of local delivery services). In this case Apple sets out its iPhone 13. The Arabic says: “We present to you,” and then the corporate logo and English take over. That new iPhone was a return to the straight edges of earlier models, but the design is still sleek and shiny. The subjects on these billboards never stand in contrast to the design ethos that reigns in Dubai, which likewise speaks with this same monotone of modern design. The background to the above billboard image is worth examining more closely. It has a typicality that I find valuable when thinking about cities. In back on the left is a common cell

20

phone tower, an example of the infrastructure (on which every iPhone depends). It’s easy to spot the construction crane, pretty much a universal feature of Dubai vistas no matter where I turned my camera. Nothing’s ever finished here; something’s always going up. Two minarets are visible in the background too. Dubai (as part of the UAE) is a Muslim country, and though it’s not pushy when it comes to religion, it insists on the role of Islam as the one public religion. In most neighborhoods or residential developments it’s possible to spot a mosque somehwere nearby. No other religious traditions besides Islam are visibly present in the city. The minarets are the markers for this official religious commitment. We’d come to Dubai to see Expo 2020. Since the

21

Expo was ongoing, advertising for it was everywhere, such as this billboard along Sheikh Zayed Road. A kind of Disney’s Magic Kingdom feel pervades this and other advertisements for the Expo. I half expected Tinker Bell to appear from that dome. Yet deeper cultural points were being made in advertising such as this. I see an argument here that Islam is fully compatible with global values. A woman wearing a traditional abaya gazes at the Expo dome with her son. The design of that central dome draws on the abstraction characteristic of the Islamic tradition, but reflects the wonder aesthetic of contemporary architecture at the same time. There should be no cause for anxiety on the part of Muslims when it comes to interacting with the global

22

world. Saudi Arabia is right next door to the UAE. In both geographic size and population (of actual citizens) the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia dwarfs the smaller UAE. But the Saudis evidently see something they want in the Dubai model. Saudi Arabia is a culturally conservative state, built on a specific fundamentalist reading of Islam. This billboard sets all that history aside for an emphasis on pastel spirituality and outdoor adventure. On the left a Western woman meditates in the desert; on the right a man leans forward to snap a photo of some fancy chef-created dish. At the center is the call to “Celebrate Every Moment,” a nugget of wisdom for an era that craves adventure and experiences that look good on Instagram. The Saudis saw the Expo as

23

their chance to introduce themselves to travelers. We’d gotten on the Metro in order to visit the Burj Khalifa. This needle-like skyscraper is well-known as the world’s tallest building. At the Burj Khalifa’s foot was the Dubai Mall, at this time the world’s second largest mall. For a while it looked as if the Burj Khalifa might become the second tallest skyscraper, once the Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia was completed. But since construction on that Saudi tower has halted, its place appears secure for the time being. It was a lengthy walk from the Metro station to the mall and tower. Along the way we got glimpses of the tower through the glass of the walkway. Below was the “Fashion Avenue” mall entrance. Before visiting I hadn’t realized that the

24

experience of the skyscraper is inextricably linked to the mall. Visitors arrive at the entrance to the Burj Khalifa by walking through the Dubai Mall. In effect the tower becomes another high end store, this one offering the experience of being “At the Top,” and then selling souvenirs so that visitors can prove it back home. Even with tickets in hand, there’s no quick way to the elevator. Before going up the Burj Khalifa must be framed as a tremendously serious enterprise. An illuminated model gave us a view of the tower as a whole, and we browsed images of the tower from first sketch on through its final construction. What’s obscured is that the Burj Khalifa is the definition of a vanity project. It was built as a marvel to insert Dubai into our collective

25

mental map. The Burj Khalifa cost around $1.5 billion, all of which went toward making a simple point. This point is set onto a wall that all visitors must pass. The tower should be experienced as “a shining symbol of what Dubai strives for and what we can accomplish.” It was meant to prove the grand future of possibility embodied in Dubai. The Arabic header is different than the English, reading “from the sand to the clouds” instead of “from the earth to the sky.” That Arabic phrasing ties in better with the foundational story of Dubai, that it went from barren desert to global skyscrapers in mere decades. Where Israel claims to have made the desert bloom, Dubai speaks of real estate that reaches up to the clouds. The image of one person comes up repeatedly

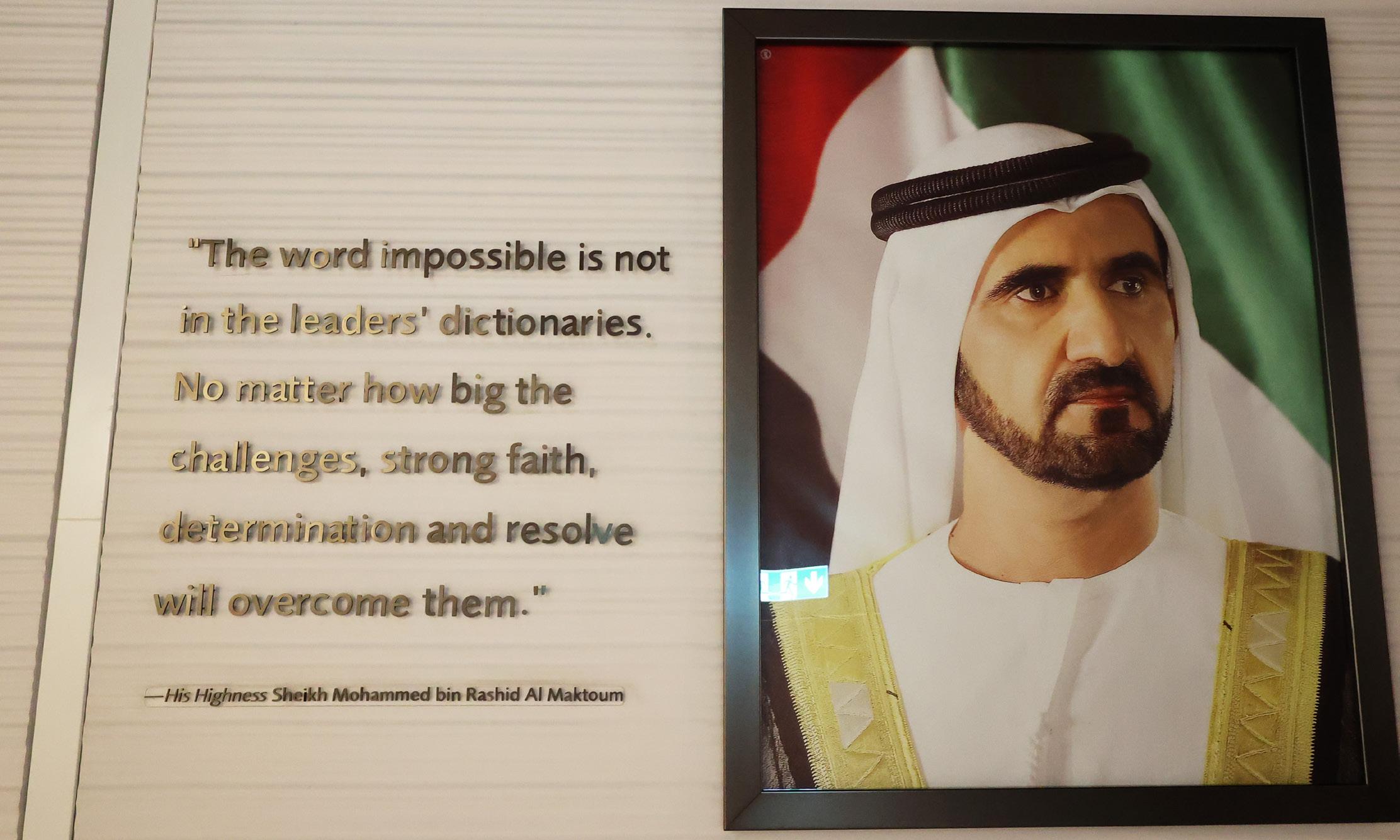

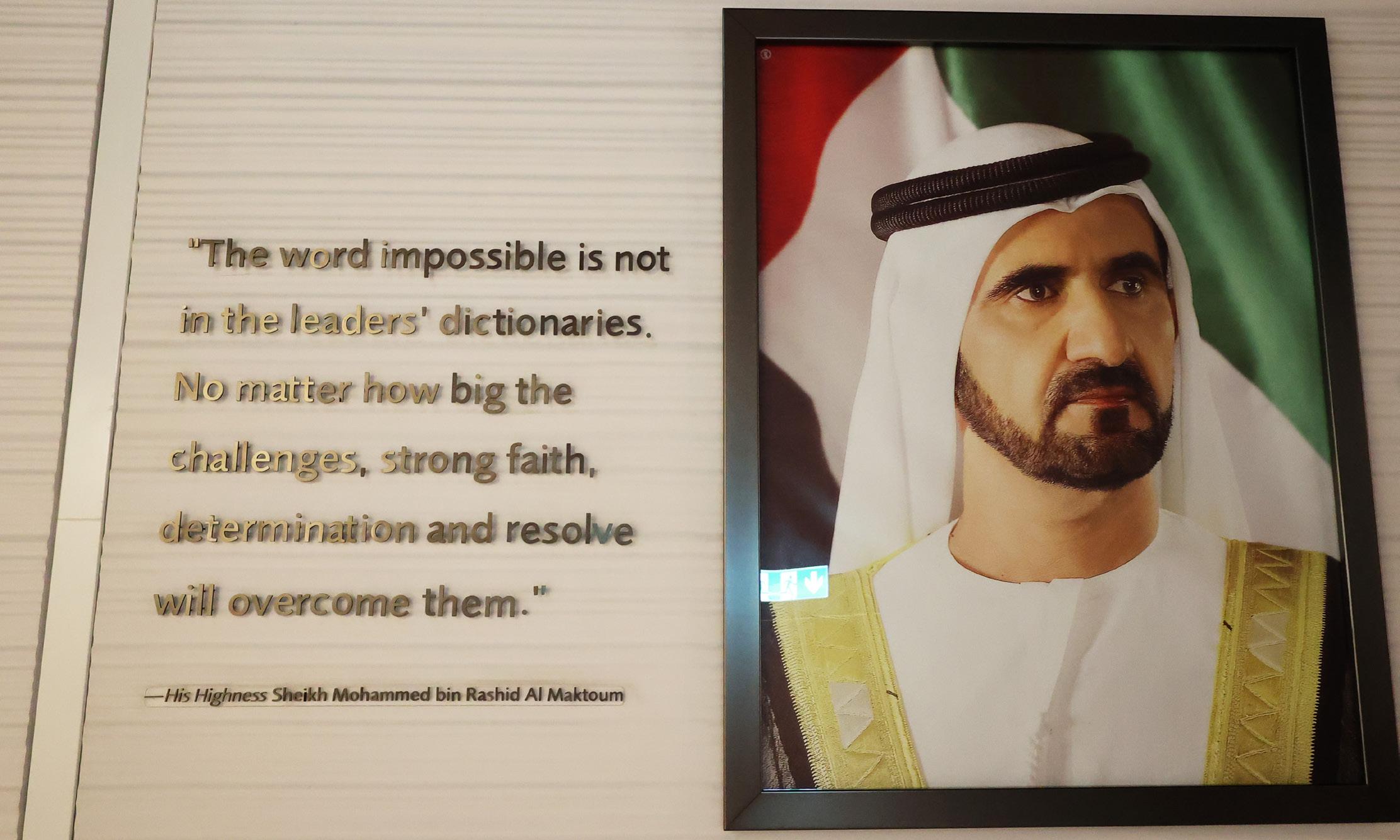

26

around Dubai. He is not present in the same way as royalty in other Arabic speaking countries, such as Mohamed VI in Morocco or Abdullah II in Jordan. Those leaders are present everywhere in their respective countries as reminders of power. There’s something of that same power in these images of Sheikh Mohammed, but these images also came with a short sermon about innovation. At times they are a bromide, like here: “The word impossible is not in the leaders’ dictionaries.” Given the placement of these words, the Burj Khalifa is transformed into a symbol for the overcoming of challenges by faith and resolve on the part of a great leader. Legitimacy is created in the UAE not by democratic approval, but by the Sheikh’s similarity to a tech CEO. It

27

took only one minute for the elevator to go from the ground floor to the observation deck on the 124th floor of the Burj Khalifa. Even the elevator had to be presented as a marvel: “one of the fastest in the world.” The elevator had screens for walls and ceiling, and as the ascent continues, we watched a computer simulation of the tower going up. It was a strange choice to present not the view from the tower, but a view of the tower while enclosed in that same tower’s elevator. On one wall we saw a lineup comparison of the world’s tallest buildings, emphasizing the extent to which the Burj Khalifa towers over its nearest competitors, and meanwhile the tower simulation was still adding floor on floor. Toward the end of the elevator lift to the

28

observation deck we left behind the screen view of the cityscape. The clouds on the walls and ceiling thin and suddenly we were in space, and a satellite was projected above us. Perhaps the speed of the elevator suggested to designers the idea of a rocket, and the obvious destination then becomes space. As designers thought more about this, they realized that the Burj Khalifa was a kind of down payment for even loftier goals. There’s a science fiction feel to Dubai now, and a space extension to this real estate dream could bring the Sheikh closer to the realm occupied by his great exemplars like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. This tower isn’t the end of city-building, but a stepping stone. As the elevator doors opened onto the observation deck, we

29

walked out into selfie land. Everyone was required to wear a Covid mask, but when taking a selfie it was OK to take the mask off. The Burj Khalifa was a high-level wonder of the Instagram world, and everyone wanted an image “at the top” (though there were floors that ascended still higher). Construction began on the Burj Khalifa in 2004 (the same year as the founding of Facebook) and it was finished in 2010 (the same year Instagram appeared). This is another example of how Dubai should be considered a social media native city—meaning, a city that’s been imagined and built with the digital ecosystem already firmly in place. Its success with the modern photo-snapping tourist crowd is no accident, but a built in feature. The people who come

30

to Dubai as international tourists knew exactly how to consume and present these angel wings. I find it unlikely that the millions of service workers in Dubai from South Asia and the Phillipines would imagine themselves as angels in disguise. For international tourists there’s no more alluring contemporary myth than the idea that deep inside they are rising angels, meant to be in this privileged space. The angel wings convert the Burj Khalifa observation deck into a metaphor for their own uniqueness, forgetting that the surrounding crowds of people prove that it’s not so unusual to be here. For a moment, in front of these wings, a visitor feels unique, and that’s how it’ll look on Instagram. We could say that the success of the Burj Khalifa

31

stems from the perch it provides for the modern Self. From the observation deck we could more fully consider the Burj Khalifa. It was designed by the Chicago firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which has a lengthy skyscraper resume. The John Hancock Building and Willis Tower in Chicago are two examples of their work. So when it comes to the Burj Khalifa, it’s no accident that visitors might feel instantly familiar with this space. The International Style reigns, with repeating panels of reflective glass and stainless steel vertical fins. There’s nothing burnished or toned-down about the exterior, which had a shiny aluminum look that surprised me. I recalled that it was built in years when Apple made such effective use of flat aluminum in iPhones and

32

computers. The observation deck is hardly the most exclusive space generated by the Burj Khalifa. Going up to the observation deck allows for the experience of a “wonder of the world” on the part of tourists, but the building is far more valuable for the way it generates views of itself. This is easy to see if you browse sales pitches for apartment residences in downtown Dubai. The ads for these luxury spaces inevitably feature a window view of the stand-alone tower. The real profit in building the Burj Khalifa isn’t in the actual use of the building (which doesn’t have all that much floor space), but in developing the open space around the tower and leveraging the view of this architectural marvel for profit. In my classes I’ve often used Dubai as a

33

counterpoint to traditional Islamic cities like Cairo or Damascus. Those cities are steeped in centuries of history and layers of physical change, while Dubai is the opposite. It takes effort to find a structure here older than 50 years. I’ve looked at Dubai through the lens of Google Earth, and with its help zoomed in on various buildings. But this visit to Dubai demonstrated how impossible it is to know a city without being present as a body. I was quickly learning how Dubai is composed of separate islands of development. Below is the downtown and financial sector, then out on the far horizon is Sharjah, another emirate. None of this is close to being on a walking scale. We lingered here on the observation deck, supplementing our experience with

34

a latte from the cafe. The sun began to sink in the Gulf, and the southern half of Dubai was thrown into hazy color. The Palm Jumeirah development appeared now from yet another angle. The luxury icon Burj al-Arab stood in front of the Palm, on the coast. Off to the left was the Dubai Marina, where we were staying (soon we’d be taking the Metro back to that island of tall buildings). In between was a flat and stable sea of villas and retail stores. What seemed to be largely missing even now—early in our trip—were factories and offices. It was always hard to imagine what exactly people did in Dubai. Tourism can be thought of as a form of pilgrimage for participants in global culture. It’s a form of pilgrimage disconnected from traditional religions,

35

and based instead on the sacredness of the individual Self. Because YOLO, the Self proves its value through the accumulation of experiences. The world is thus converted into something like a smorgasbord of possible experiences, a choose-your-ownadventure text. Sites that contribute to this underlying Self-creation narrative offer souvenirs in a gift shop. These expensive Burj Khalifa models represented for some visitors a point in the story of the Self, and so they’ll take their place in a distant home or office as witness to Self expansion. It’s not that the tower is itself sacred, but it contributes to the sacred becoming of the Self. There was no end to stuff with the image of the Burj Khalifa. These change purses carried an artistic rendering of the tower

36

reminiscent of the starry night painting by Van Gogh. The Burj Khalifa rises here amidst some latter day Garden of Eden, with only a vague Metro line to suggest further urban context. What is it about Van Gogh that makes him useful in souvenirs like this around the world? His paintings suggest the presence of creative vision, as unique as an individual fingerprint. And since his paintings are now valued at millions of dollars and displayed in the best museums they suggest that such outlandish creativity can be monetized and integrated into global Capitalism. Through no fault or intention of his own, Van Gogh became the artist whose work best expresses the modern understanding of the becoming Self. The souvenirs in the Burj Khalifa included a rack

37

of books written by or about Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid al Maktoum. These books placed him outside the usual frame of political dictators (though he is absolute ruler in the emirate of Dubai). He appears in these books as a teacher of happiness and positivity, and most importantly as the “Sheikh CEO” dispensing lessons in leadership. With these books it becomes clear that the Sheikh sees himself as on a different plain than normal dictators. We’re led to see Dubai as the type of creative product we’d get from Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk if they held actual territory rather than headed up transnational corporations. And maybe they are right, if Elon Musk ruled a state it might well look and feel a lot like Dubai! At the base of the Burj Khalifa is this

38

mixed group of structures. On the left is the curved edge of the Dubai Mall. That mall front meets the blue of an artificial lake, containing a massive fountain. All around the lake are multi-residence villas and high rises, a substantial portion of whose value stems from reversing this view (that is, the ability to look up at the Burj Khalifa). Many of the structures bear the name Emaar at their top, a development company closely aligned with the interests of the state. The Burj Khalifa doesn’t make economic sense as a standalone structure (it could never justify its cost), but only as the centerpiece of a huge project built by the same corporation. The Dubai Mall is massive, and it would take more than a day to explore. In 2019 more than 80 million

39

people visited the mall. An internationally famous museum like the Louvre in Paris gets 10 million annual visitors. Central Park in New York City gets 40 million visitors. Hartsfield-Jackson Airport in Atlanta, as a national hub, oversaw visits from 107 million passengers in 2018. From these numbers it would appear that the Dubai Mall is closer to being an airport than a globally famous museum. That size demands signage reminiscent of what’s found in an airport. The main goal becomes the frictionless movement of people around this huge space. But that makes the space feel like an airport, or a huge convention center. It loses any sense of intimacy that comes from small scale. Such grand space attracts global brands that have established expectations

40

in the minds of customers. What is there even to say about stores in a mall? Pottery Barn is a global chain owned by WilliamsSonoma. It’s headquartered in San Francisco, but Pottery Barns are found around the world. This mall image could be from dozens of locations. There’s nothing place-specific in the display. It’s December so the Christmas theme is prominent, but that gives no clue about whether this scene is in China or Brazil. Christmas is broadly a global token for acceptance of global commerce. Some sections of the mall featured highly exclusive designer brands, but even they are still ultimately chains with a global ambition. Of course Apple is here. Its store has a prime location overlooking the grand fountain. The Apple aesthetic is

41

in full force: glass is everywhere, and parallel rows of wooden tables display the latest products. We had to wait in line to get in, and upon entering we were accompanied by a young female employee. In its insistent sameness to Apple stores everywhere I thought about what Steve Jobs recalled from his trip to Istanbul: “They were all drinking what every other kid in the world drinks, and they were wearing clothes that... were bought at the Gap, and they were all using cell phones... It hit me that, for young people, the whole world is the same...” Corporations like Apple certainly act like the world is the same, and create stores that are interchangeable with their other stores around the world. In 2021 the Italian corporation De’Longhi named American

42

actor Brad Pitt the global ambassador for its high end coffee maker. Photos of Brad Pitt drinking coffee were present on billboards along Sheikh Zayed Road and on banners like these in the Dubai Mall. The visual presence of Brad Pitt added another layer of familiarity to the mall. On the one hand many stores and brands were immediately recognizable. And then these banners featured a global celebrity whose image was well known. The charisma that might have traditionally resided in the person of saints or other religious figures has come to reside in global celebrities, whose films visitors could well have viewed during the plane ride to Dubai. Store fronts in the Dubai Mall offer few clues about geographic location. It’s far more

43

telling to look at the actual people walking around. A large number of people in the Dubai Mall were walking around in the regional dress of the Gulf region. For females this includes the abaya and headscarf. For men the dress style is a loose white robe known as a thobe, along with a patterned scarf known as a keffiyeh. This clothing is marked in the West as “Islamic,” and the Gulf region is indeed overwhelmingly Muslim, but one of the useful things about visiting a mall is the growing obviousness that the shared concerns of global life are more pressing and visible than religious expression. Settled into the context of a mall it becomes clear that religion is of secondary concern in comparison to the shared global culture. Dubai is in the process of

44

constructing itself as a meeting place for people from around the world. One part of this is its openness to global brands, but another part is its special welcome to business ideas from around the Islamic world. Hafiz Mustafa 1864 is a popular Turkish confectionary maker with branches in Istanbul. It’s been building up an online venture through which international customers can order Turkish Delight, Baklava, and other sweets and have them delivered to their home. To support that online effort it was useful to have a prominent store in the Dubai Mall, where millions of people will walk by and stop to look in the window.

It’s hard to believe that internet advertising could entice future online purchases more than this delicious window display.

45

Brands live in the digital world, but they find actuality and presence in high end malls. The Dubai Mall is an overwhelming visual experience. There are signs in English and Arabic that direct the airport-level crowds, but within the individual stores the emphasis is on screens and display. The Nike store led off at the entrance with a high energy video split onto a series of tall thin screens. Mannequins modelled an ideal sport physique and showed off Nike branded clothes starting at the shoe and moving up to the hat. The mannequins were ethnically and religiously blank, offering zero cultural friction for any customers. This body look and clothing style is American in origin, but by erasing specificity Nike has transformed this into a global body, in

46

much the same way that Apple has done with its sleek products. Entering the Dubai Mall after a lengthy walk from the Metro station, a huge bookstore materialized. That giant sign directed visitors to the food court and mall attractions, but for anyone interested a million books are right there for browsing. The store is Kinokuniya, a Japanese chain with stores in major Asian cities (Singapore, Jakarta, Bangkok) as well as some US cities (Chicago, New York). The experience of Dubai was definitely not marked by the omnipresence of books. Sure, those books about the Sheikh CEO were present in gift shops, but there was no sense that books were an important key to the experience. London is a city of novels, Dubai a city of Instagram. I had to move

47

some way into Kinokuniya to find the Arabic books. English was the assumed spoken language in Dubai, and the assumed book-buyer seemed to prefer English books. As I browsed I could feel an American taste radiated back. The autobiographies of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama were there, matching the broad cultural alignment of Dubai, which was at least superficially in step with America and its global values. I was surprised to see a whole shelf dedicated to the works of Israeli intellectural Yuval Noah Harari. His books Sapiens and Homo Deus are popular in Silicon Valley, and so they fit this city where the leader has 100% bought into the innovation ideology. It took some searching to find the Arabic section, but it was easier to find the

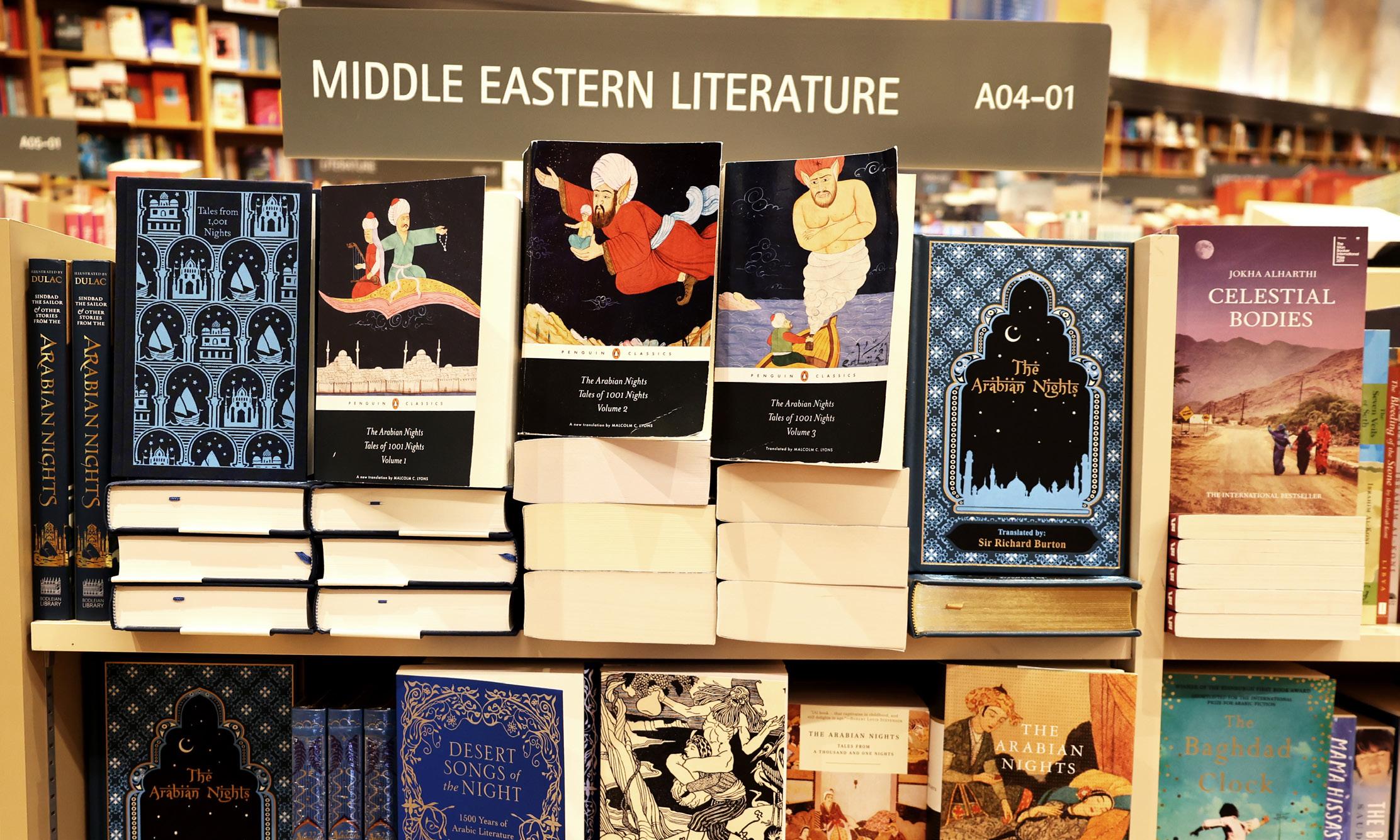

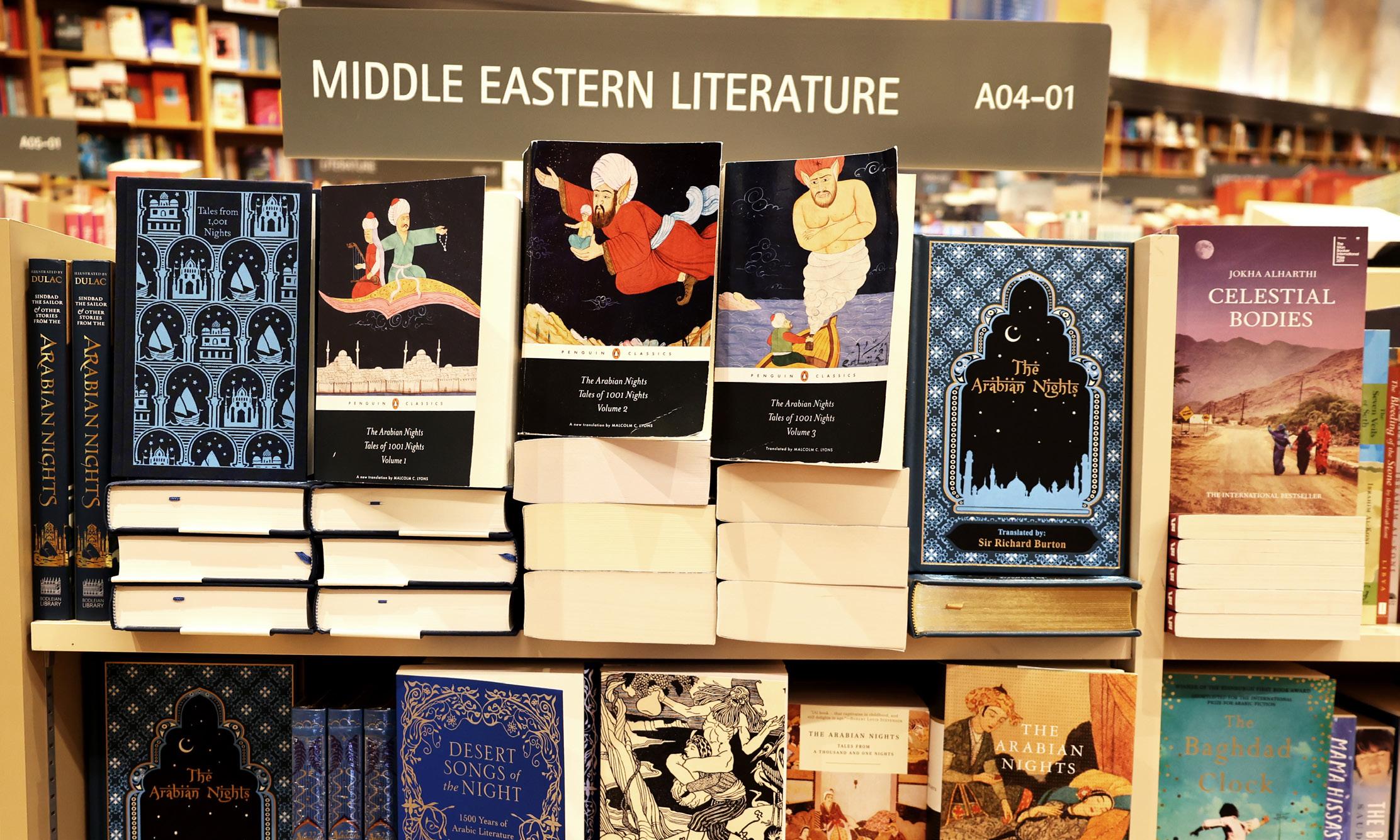

48

English translations of “Middle Eastern Literature.” These included the English works of Kahlil Gibran and the novels of Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk. So “Middle Eastern” was quite a broad category. Most in evidence were translations and take-offs of the Arabian Nights along with English novels that had Arabian Nights themes. Writers from the Golden Age of Islamic civilization would’ve been shocked to learn that their era would someday be represented in popular memory by this ribald collection of tales. There’s no competitor to this story collection when it comes to a contribution to World Literature from the Middle East.

Many of the Arabian Nights translations in the bookstore were in my own library back home (and well read). The stories of the

49

Arabian Nights add up to a sprawling reference work for the medieval imagination. They avoid religious questions and cast their winding plots back into the reign of Harun al-Rashid, caliph of Baghdad. Since the setting of these stories is often Cairo or Damascus, it’s strange that they aquired the title “Arabian Nights.” The Arabian peninsula and its empty desert landscape have nothing to do with these urban tales, but looking around Dubai and its miraculous landscape on the edge of the Arabian landmass, it’s tempting to understand this title as a prophecy about the future. Dubai is busy putting the “Arabian” into the Arabian Nights. Shiny lamps are some of the most common items for sale in Dubai’s souvenir shops. The implicit reference

50

with these lamps is to the story “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp.” This story has no Arabic original, having been more or less invented for inclusion in the first French translation of the Arabian Nights at the start of the 18th century. “Aladdin” has the flavor of a European fairy tale, but it can be interpreted as the source story for the fantasy development of Dubai. Its central plot point is the acquisition of a lamp by the young ‘Ala al-Din. When he rubs the lamp a genie appears, who asks: “What do you wish? Here I am, ready to obey.” Whatever ‘Ala al-Din asks for, no matter how outlandish, is fulfilled. “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” can be read as a real estate fantasy. Once Aladdin witnesses the great beauty of Princess Badr al-Budur he sets his mind

51

to winning her by strategem and through the stunning creations he demands of the genie in the lamp. Rich parades and great riches materialize from nowhere. Having won the right to marry the princess, he asks the demon to create a splendid palace right next to that of the king: “I expect you to build at the top of the palace a large hall with a dome and four equal sides made entirely of alternate layers of heavy gold and silver... in a way the like of which has never been seen anywhere in the world.”

When the king, the father of the princess, awakened the next morning he was astonished to see a newly completed palace nearby. The vizier tried to convince him that this could only have been done through enchantment, but after many previous

52

marvels the king understood the new palace as a true product of unlimited riches. “Aladdin,” starting as a European dream about the Islamic world, can be read as an allegory for the creation of Dubai. In world-historic terms Dubai has been created overnight, through stratagem and the vast resources of global finance. Where “Aladdin” was a fantasy, Dubai is the realization of that dream of extravagant dream of constant creation. Both the story and the city make a claim for Arab origins, but at the same time represent a deflected or mirrored imagination of the Middle East. A form borrowed from the West (fairy tale or skyscraper) is repurposed to represent a supposed magical exuberance in the Middle East. From outside the Dubai Mall we

53

gazed up at the impossibly tall Burj Khalifa. Up close it doesn’t rise like a tapering needle, but rather through a series of cutaways that create terraces at various levels. Near the top these begin to look like a spiral, and according to reports the tower was meant to resemble the spiral minaret of the Abbasid era Great Mosque of Samarra from the 9th century. The architectural language and engineering practices of skyscraper construction are international, but in every region designers add superficial visual twists that give the illusion that a global object is at home in some local place. Thus the skyscraper moved out of New York City and found a home in Singapore, Shanghai, Dubai, London, and other cities looking to signal an embrace of the global. There’s

54

no end to the marvels of Dubai. After ascending the world’s tallest building, some visitors will continue to Dubai’s downtown along Sheikh Zayed Road, and if they happen to look out the car window, they’ll see one of the most unique structures in the city: the Museum of the Future. It was supposed to open in 2021, but as of December of that year it still hadn’t. The museum is dedicated to the future, and its website carries this invitation: “Explore a museum where history is made rather than displayed— where instead of absorbing the past, you help the future to emerge.” The museum’s novel architecture underscores the goal of leaving behind any sort of tradition. Not far from the Museum of the Future (the next offramp) was a sign featuring Sheikh

55

Mohammed al-Maktoum. Still more construction was in the background, and next to his image was an Arabic statement with English translation underneath: “The future belongs to those who can imagine it, design it, and execute it. It isn’t something you await, but rather create.” It’s hard to imagine a point of view more distant from traditional Islam, where God disposes and humans acknowledge limits, and where “innovation” (bid‘ah) is the actual word for heresy. In Dubai there’s a steady thrum about orienting life toward the future, which humans are able to shape. Again, I see no daylight between this and the ideology of Silicon Valley technologists, who also see the future as theirs to master through innovation. If there’s anything salient about

56

our great religious traditions, it’s the manner in which they teach human beings to accept limitation. The Museum of the Future is covered with Arabic calligraphy. This Arabic is a key design feature of traditional Islamic architecture. A band of Arabic around a medieval mosque will pretty much always be a passage from the Quran. My assumption about this museum had been that while the building is hyper-modern in its material and computer-dependent design, the Arabic represented a tie with tradition. Perhaps this was some quotation from the Quran? No, it turned out that the Arabic is future-oriented “poetry” by Sheikh Mohammed al-Maktoum. The Arabic script is a surface-level tie to the past, but every deep connection to tradition has

57

been jettisoned. And this brings us to another “wonder” building: the Dubai Frame. It’s a challenge to find an angle that showcases the true height of this structure. At 50 storeys it’s a step smaller than the St. Louis Arch (492 ft vs. 630 ft). Like the St. Louis Arch it has an observation area at the top. Promotional materials call it the largest picture frame in the world, but that’s ridiculous. It’s a novelty building in the shape of a frame, but not actually a frame. Yet a frame is a suggestive shape in our Instagram era. It hints that the city as a whole is here to be photographed and shared on social media. I tried to imagine what would happen to this structure in a future post-Instagram era. What happens after the next and the next novelty structure in

58

Dubai draws away tourist attention? Designers never shied away from gleaming exteriors in Dubai. That shine is an essential part of these structures. The Dubai Frame goes a step further than most with its gold-colored stainless steel exterior. It has a wavy pattern embedded in the plates so that they don’t make a golden reflection. The spectacular novelty of the structure already communicates luxury, and the gold of the exterior reinforces that message. For now the Frame has a “brand new” feel, but the gleam spurred me to imagine what would happen when that newness fades, and the wind and sand dull this shine. The sheen covers over the lack of cultural significance invested in this structure. From below it’s possible to make out the observation

59

windows of the horizontal connector that bridges the frame at its top. Shiny gold trim ran around the inside of the frame while the outward facing sides carried an abstract pattern of interlocking gold circles that was inspired by the symbol for Expo 2020.

Designers thus hoped to preserve the memory of the Expo event into the future. The Frame needs a bottom, since it must look like a fully completed rectangle from a distance if it’s to be counted as a frame. As a result there’s no real open space around the base. Visitors queued at the base for entrance, and while waiting I took this photo of the strange rectangle reaching overhead.

My mind wandered to a similar view I had once of the St. Louis Arch, also from below. The St. Louis Arch bent into the sky,

60

hardly an arch from this angle, but some parabolic figure of advanced math. When I looked up at the Dubai Frame I was reminded of this view, and I started to think about the similarities and differences between these two structures and their settings. The Arch is taller than the Frame, and it comes from a different generation of design (completed in 1965). It’s just possible in this photo to see the small porthole windows of the narrow observation floor at the top. The Arch consists of a smooth curve that rises from the ground, covered with stainless steel. The exterior has a shine, but there’s no suggestion of precious metal, rather a dash of space-age technology. But it was the shape and form of the Arch that dominated my attention

61

up close, rather than the material. The visitor center worked to set the Arch in a broader perspective. St. Louis is the “Gateway to the West” since it was from here that the Lewis and Clark Expedition got its start in 1803, ascending the Missouri River and exploring the West. So the Arch commemorates a specific continental story told by the United States. No surprise that the Arch is now a National Park. A wall in the visitor center drew comparisons with other US monuments in regards to size and theme.

The St. Louis Arch is ambitiously large, but the wall reminds us that the United States abounds in outsized natural symbols. The shape of the Arch picks up on the natural arches that are a feature of Arches National Park in Utah. From atop the St. Louis Arch

62

visitors look down on the city of St. Louis on one side and the Mississippi River on the other. The river wasn’t an incidental feature of St. Louis, but the reason for its existence. The city was situated at the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. It got its name because from French fur traders who recognized its importance in the 18th century. We can go back even further and point to the nearby remains of the Native American city of Cahokia. The function of the Arch wasn’t to create meaning in the midst of empty space, but to provide a vantage point for seeing the meaning that had been invested in this landscape by others. That muddy river means something to Americans. Democratic spaces are marked by the ability of

63

individuals or groups to wander as they will. In their openness they become physical expressions of “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” They allow for the open display of affection toward people one chooses to love. Visitors mingle as equal citizens, and the signage and boundaries make no distinctions between them. Finally, these spaces can be messy. Manicured

64

spaces are controlled spaces. From the moment we bought entrance tickets to the Dubai Frame we were directed along clear paths to reach the entrance. There were no secondary goals. The path was lined with banners reminding us to visit the Expo 2020. (Yes, we’ll get there before long!) Through the trees we could look up and see a corner of the looming Frame. Before long the path turned into the queue for entering the Frame itself, and in that entrance space was an open area where visitors could step back and take a photo. A fountain curved around the front of the Frame, but like the trees it was here to enhance the visual quality of the golden structure, not for direct physical contact by visitors. Once we’d entered the Frame, we proceeded through

65

a hall of displays on the history of Dubai. The official story of Dubai (and the UAE as a whole) starts with sand. The fact that within the lifetimes of some visitors the ultra-developed sites in Dubai were nothing more than sand and scrub trees is no fact to be hidden under a bushel, but is the lead point in official displays of history. Out of sand came all this! It’s a real estate miracle narrative. For the environmentalist in me there’s a strange wistfulness I feel looking at this desert scene. What’s so bad about mere sand? Why can’t humans live within the constraints of the natural world? But Dubai is precisely a story of overcoming sand. After the sand we walked through a re-creation of Old Dubai. Rustic goods like a drum or water jar were used

66

as relics of this lost world. Behind the windows were illluminated black and white photos showing men and women going about their simple lives. What were we to make of the water jar on the right? It was held in place by pieces of wood stitched together with rope. We were meant to feel its simplicity and sturdy workmanship. And we were reminded of the age-old dependence on water for all life. What’s strangely missing throughout the displays was reference to Islam. It would seem that with its elemental concerns there was no deep need for religion in old Dubai. At any rate the designers chose not to emphasize the role of religion in this recreation of the region’s history. The only reason to enter the Frame is to get to the top bridge.

67

Anyone with memories of the St. Louis Arch recalls a cramped space with tiny windows. The frame is the opposite. It offers a spacious walkway that moves from the up elevator on one side to the down elevator on the other. The aesthetic is what we might label “Global Islamic.” It embraces abstract design reminiscent of the regional past (note the shadows and the pastel tiling above), but does so in a way that creates a pleasant and modern “wow” effect. The common visitor response is to take out a smary phone and begin snapping photos. This whole experience is overseen by deluxe framed portraits of the sheikhs who led the UAE to this extravagant future. What is a frame for? That seems like a trick question. It’s obvious what you’re supposed

68

to do with a frame (put a photo inside it). But what if you were to find yourself inside a frame? By transference it still seems that photography is the proper thing. Truly nothing was on offer in the Dubai Frame except the opportunity to take photos. If a person had brought no camera of any sort, and was completely uninterested in photography, I’m not sure what that person would do in the Frame. There were no tables for an expensive dinner or seats for a cafe. There are multiple places in Dubai that offer a vantage point on the city, so why come here? The Frame was designed for the production of images, and observing the other visitors, it didn’t look like any other activity was going on. The top of the Frame offered a view of downtown Dubai. The

69

Burj Khalifa stood most proudly among the downtown buildings, but nearby a curious structure was going up, this one with a striking horizontal bar. I later learned this was the One Za’abeel building, which would include the world’s longest cantilever.

(What is this need for everything to be a world record!) That horizontal stucture would be 226 meters long and heavier than the Eiffel Tower. The two vertical towers will include luxury residences and about 500 hotel rooms. That horizontal bar will house restaurants and shops, and an infinity pool so that leisure will be fully integrated with the skyline itself. In effect it will be a cantilevered multi-use mall. One side of the frame points visitors to this changing modern skyline, but the other looks back

70

toward Old Dubai. I’m not talking about that line of skyscrapers out there in the background (part of modern Sharjah, another emirate city). In the middle of this photo is a think blue line that is the Dubai Creek. Some of the oldest development in Dubai was along that tiny waterway (traditional dhows are still anchored there). None of these low buildings are notable in terms of modern architecture. The Frame is positioned as both a look backward and look forward. But something’s hollow with the Frame. It doesn’t connect visitors to a story about the nation of Dubai (as the St. Louis Arch did for the US), but implies that development and growth is the only story worth telling: “from that bareness came these marvels.” Running along the floor of

71

the Frame’s bridge was a line of windows enabling visitors to look down at the bottom of the gold Frame and the landscaped grounds around it. Most visitors I observed were taking selfies of themselves standing on this glass. I don’t begrudge anyone the fun of seeming to walk on air, but I still felt like something was amiss. The Frame was the monument of the moment in Dubai, but how will this one fare after the next is built? There’s a reason large cities have a single “ornamental building” that offers a view of the skyline (the Space Needle in Seattle, the CN Tower in Toronto). Dubai seems to believe that buildings with no purpose except to be eye-catching and to offer a skyline view can be endlessly multiplied, as if Seattle would keep building

72

new Space Needles. Looking down from the Frame it was impossible to miss the sheikh set into the circle of an exit along Sheikh Zayed Road. It was an image of the same Sheikh Zayed for whom the road was named. He’s considered the Founding Father of the UAE. Without his leadership over the course of his long life (1918-2004) the UAE would never be what it is today. A relatively small number of sheikhs form the backbone of the nation’s visual symbolism (in addition to the flag). Despite all the money poured into the building of luxury properties by state-owned companies, there’s no landmark civic building that translates state values into monumental architectural form. The state is present in these portraits and some waving flags.

73

Visitors from other Arab states are a core audience for Dubai. For me (and those who share my sensibility) the message of Dubai is runaway Global Capitalism. But what is the message for a man from Saudi Arabia? Or Iraq? Or another small Gulf state? In the 2010s the world witnessed the surprising appeal of the Islamic State (commonly referred to as ISIS), which spread an ideology of religious nihilism and total destruction. The goal of ISIS was to create a throwback Islamic polity that rejected Western values. Dubai could be experienced as a counter argument to ISIS. What would it feel like for someone who felt the pull of ISIS to come across this in the Dubai Frame: “The worthy man... is the one who works for the advancement and the

74

future of his country...” This message encourages connection to global institutions (states, markets) and dampens the desire to burn it all down. We took an elevator back down to the base of the Frame and exited onto a panoramic screen of the future. The scenes included an image of a futuristic city with drones moving in an ordered line through the sky. We saw medical advances coming fast and furious. Finally a rocket is shown high above the earth with the flag of the UAE painted on its side. On the earth below we see Europe outlined by the light of its cities. This is the vision for a Sheikh CEO like Mohammed al-Maktoum, who sees himself as a peer of the great tech innovators. It conveys to all the message that Dubai will be a partner in the global

75

capitalist process of mastering the Earth and its planetary systems. Since we’re now discussing Dubai’s marvels, we’ll head back to the Dubai Marina south of downtown and visit the Ain Dubai, which had only recently opened. Since “Ain” is the Arabic word for “Eye,” this Ferris wheel is an obvious reference to the London Eye. But this Eye is fully twice the size of the London Eye! This attraction has been set at the end of an artificial island that includes a walkway with retail outlets and restaurants. Those eye-catching “super trees” resemble similar structures in Singapore, but there the trees are part of an expansive green space and have plants growing vertically. Here these super trees function as fancy sun blocks. There is no end

76

to the amount of space devoted to retail and leisure in Dubai. This walkway in the shadow of the Ain Dubai is just one of many such spaces. There was simply no way to explore all the retail developments, where one space after another beckons visitors to spend money. It staggers belief that there are (or will be) enough people to spend the money to keep all these malls and walkways open (and perhaps that won’t, in the long run, be the case). Currently the Ain Dubai is new, and it’s an easy walk here from the the marina. A reinforcing cycle comes back into view: eccentric structures gain value by being seen and circulated on social media, and the presence of those attractive views makes retail spaces feel desirable and exclusive. Since we are so used

77

to the scale of a carnival Ferris wheel, it’s hard to imagine one that is 250 meters (820 ft) tall. The Ain Dubai is taller than many skyscrapers, and upon completion it became the largest Ferris wheel in the world by a wide margin. We decided not to buy a ticket to go up the Ain Dubai because it struck us as yet another structure charging money to get a view of Dubai. How many overlook experiences does one city need? Landmarks are useful for giving a destination to visitors and providing canonical points of view on a city. But with too many landmarks the opposite effect is achieved: a watering down of the public landscape. Various types of experience can’t be scaled up indefinitely without loss, and I’d argue that a Ferris wheel is an example of this.

78

The ideal Ferris wheel gives delight by its steady revolution around a wide circle. Ferris wheels are included on carnival grounds because they are still considered an amusement ride, albeit one that provides a view and not just a thrill. With its gigantism the Ain Dubai has left behind the proper delight of a Ferris wheel. Appoaching the wheel it looms as a space age attraction. It draws visitors by virtue of its abstract status as “the world’s largest,” but what’s the point of gaining a record if you lose the soul of the experience? The changes that occur to an experience as the scale is multiplied is not a concern or worry for the design masters who proceed inexorably with their abstract design plans for this city. In the immediate vicinity of the Ain Dubai is a towering

79

curved front for retail stores. The front was draped with flags to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the UAE. This retail front is inexplicably large. I’d label this fascist retail design except it doesn’t seem intended for any mass audience, just disconnected people milling about and spending money. The bigger story clicked once I realized that the Caesar’s Palace Dubai resort is just behind this front. This space really is meant to feel neo-Roman (and so vaguely Fascist) in design. What feels like public space becomes exclusive and private as one moves past this front and into the private resort behind it. The Ain Dubai and the resort are located on Bluewaters Island, which features elements that are repeated over and over in Dubai. With its straight lines and

80

smooth curves this is clearly an artificial island. The Ferris wheel landmark is used to attract wide attention. This landmark becomes the anchor for intense residential development or (in this case) a luxury resort. Public access is allowed (see the walkway on the top right giving pedestrian access from the Marina), but the public is kept penned up within limited sections of the island (retail stores, restaurants, Ain Dubai). This public access to the island allows for more expansive shopping and restaurants, and for resort-goers that limited public area enhances the retreat to the privacy of all those pools and the large artificial beach. Privilege in this context can be defined as the ability to move between domains. Every sign in Dubai carries

81

Google Earth image

both Arabic and English. Arabic is the native language for Emiratis, but the assumed language is always English. This is partly because a high percentage of service workers (in taxis, stores, restaurants, etc.) are from South Asia or the Phillipines. There’s also an evident desire to give a frictionless (that is, non-foreign) experience to visitors. Arabic has become not just a seldom used second language, but even a parallel version of English. So, for example, the retail area near the Ain Dubai is called “The Wharf.” The accompanying Arabic doesn’t say “the wharf,” but simply transliterates the English title. The article “the” is sounded out into Arabic as “the.” And “Wharf” is sounded out as “wharf.” From the moment we stepped off the plane in Dubai we’d seen

82

familiar corporate signage. Along the retail walkway along the beach of the Marina there was always a sense of familiarity, of having been here before, of knowing what to expect. Dubai was wide open to the opening of these transnational corporations.

The Sheikh CEOs have realized the profit to be made by having an open door policy to these familiar brands that allow people from anywhere to enjoy this space. And this wasn’t just any old Starbucks, but the more upscale flagship version of the cafe (Starbucks Reserve) found in major international destinations. In The Image of the City from 1960 Kevin Lynch breaks the building blocks of urban experience into paths, edges, nodes, districts, and landmarks. The “edge” is the most difficult of those

83

to understand. An edge functions as a boundary between two areas of a city. By way of example Lynch pointed to the shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago. He argued that most Chicagoans would begin a city map with that shore, and the city presents itself to viewers magnificently along that edge. Dubai in its Marina has learned from Chicago, and its artificial islands serve as canonical edge viewpoints for the skyline. Even the distant Burj Khalifa can be glimpsed out there on the far left. Lynch believed such vistas give cities the quality of “imageability.” We can define this as meaning that a city’s overall design should be graspable by its citizens. They should hold in their minds a basic outline of the city’s form. Lynch noted that cities have so far accomplished

84

imageability only on the scale of a few square miles, and what he saw arising (in 1960!) was the challenge of designing metropolitan regions with this same coherence. Dubai represents an attempt at this large-scale design project, its landmarks speaking to each other back and forth over great distances. From the Burj Khalifa visitors see the iconic Burj al-Arab and even further out the circle of the Ain Dubai is just visible. Such landmarks enable a large area to get stitched together in the mind of observers. The problem, though, remains one of meaning. Having the most world-record holding structures isn’t meaningful.

History and ideas create meaning, and that’s where Dubai is lacking. Walking back to the Marina from the Ain Dubai (still

85

taking in that spectacular skyline view) we passed glass-enclosed offices like this one. For real estate companies there is no better time to talk condo-buying than in such moments when enraptured by the pleasure of the skyline. Small screens broadcast to pedestrians on the walkway the luxurious glories of apartments in Dubai. The whole enterprise of this city depends on hooking people and getting them to think: “Yes, I could see myself coming back here regularly.” Construction is a huge part of the economy, and everything is predicated on the idea that more and more people will want to spend time here, for work or leisure. Some real estate offices put building models on display. These decontextualized models gave prospective buyers a

86

sense of the design and made sure to highlight private swimming pools and other amenities. Always an attractive young woman was present in the office, ready to hand out full-color flyers. What exactly is the appeal of living in Dubai? There’s no grand ambition to create or be a part of a community on offer. In fact, coming to Dubai means dropping the search for such a participative

87

community. The souvenir shops were endless. In this image models of the palm real estate island crowd the windows; outlines of the Burj al-Arab and the Burj Khalifa are visible through the front door. On the left is a display of “My Vision” books by Sheikh Mohammed al-Maktoum. Common souvenirs included magnets with Dubai’s buildings, and all manner of t-shirts and hats with “Dubai” across the front. Small models of all the most famous buildings were available for tourists to buy. True sacred space draws visitors by its own story. A battlefield or religious site just needs open ground and a few signs. Land with no story has to create reasons to visit out of whole cloth, and so “wow” becomes the architectural order. After the pedestrian walk with

88

its restaurants, souvenir shops, and real estate kiosks, we headed back to our Airbnb overlooking the Marina. This meant navigating sidewalks along busy streets. At this junction we were prompted to go up onto a footbridge to get over to the opposite corner. I appreciated the footbridge (so I didn’t have to cross this street), but I couldn’t shake the feeling that Dubai’s walkways were designed by people who don’t walk much. The tendency was to build large scale solutions for walkers, which isn’t at all the same as being pedestrian friendly. Walking was organized by district, so within certain sections of Dubai it was possible to walk around with no problem, but then at defined edges the paths simply ended, and I understood: OK, no more walking.

89

90

Transition: The Margins of Dubai

91

After some days getting to know the central areas of Dubai, we headed to Expo 2020, which was the reason we’d come. It was an easy Metro ride to the Expo grounds from the Marina (still visible above). The trip to the Expo meant leaving the showy areas of the city and going through land devoted to the power grid and other industrial uses. Dubai demanded massive infrastructure to deliver power and water to all those skyscrapers, resorts, and malls. Most of that infrastructure was kept out of sight for anyone passing time at the eye-catching sites, but on the Metro ride we caught glimpses of all that necessary stuff. We started to understand that parts of Dubai were meant to be passed by without comment (and without photos). On a later trip south

92

along Sheikh Zayed Road we got a better view of the industrial backbone of Dubai. This wasn’t where things were being made (as we might imagine with older industrial cities in the US), but rather these were sites where energy was being produced and then distributed. Those red smoke stacks in the distance mark one of several power stations along this road. Since the UAE has almost 100 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, and lots of gas reserves, it’s no surprise that almost 100% of its power comes from burning fossil fuels. The UAE hopes that a nuclear plant and solar energy will diversify its energy production, but for now this is a system based on turning a small percentage of its fossil fuel holdings into power, and then selling a larger amount of

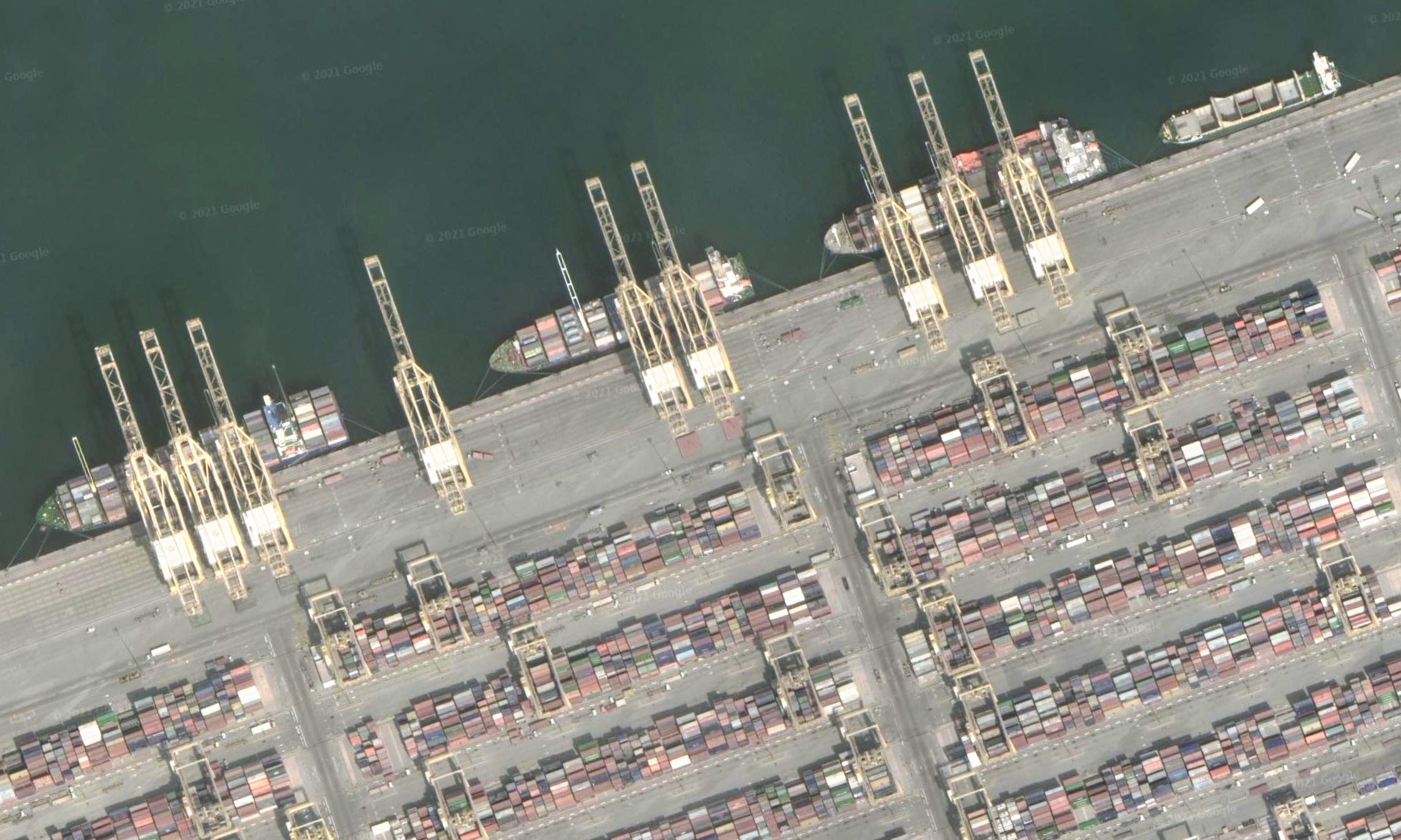

93

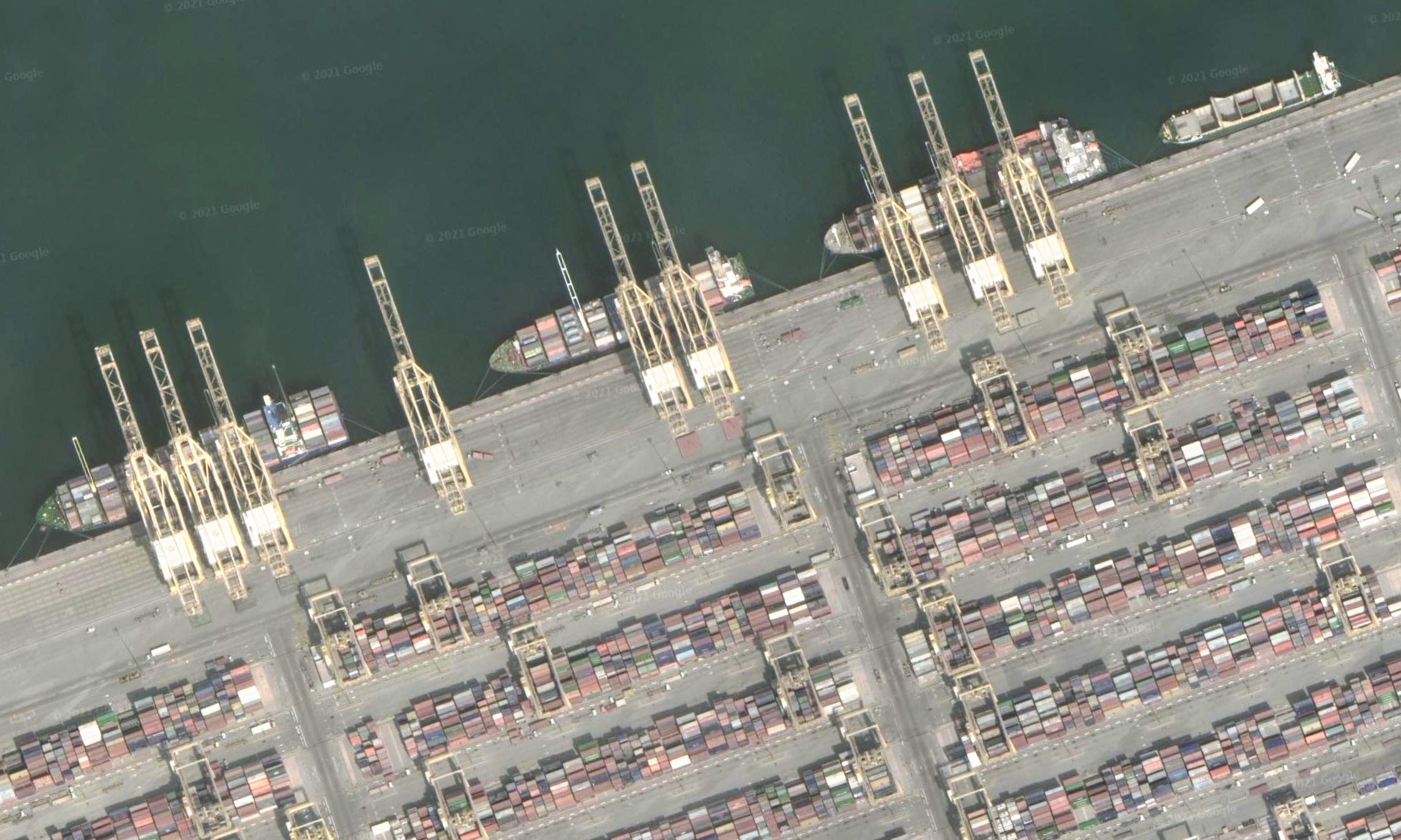

those reserves to other nations for outright profit. The world’s largest man-made harbor is located south of the Dubai Marina and the power stations. Right beside the Jebel Ali port is the still empty Jebel Ali palm (not to be confused with the luxurious Palm Jumeirah just up the coast). Jebel Ali is currently the 11th busiest port in the world, handling well over 13 million container units (with even more capacity coming online soon). This port was a visionary business investment for Dubai, long before all the eye-catching structures that now draw tourists. Sheikh Rashid al-Maktoum (father of Sheikh Mohammed) built the port in order to position Dubai in the middle of global trade. It worked, and tourism followed on this initial embrace of trade

94

Google Earth image

infrastructure. Although the Jebel Ali Port is as much an engineering marvel as any world record structure in Dubai, it’s closed for visits or tours. The infrastructure of Dubai is hidden, separated from the visible world of tourism. In the absence of inperson tours I thought it might still be possible to visit the port virtually. I often supplement my travel by poking around on Google Street View. But although much of Dubai is covered by Google (meaning it’s little cars with a camera on top have driven around most of its neighborhoods), Street View doesn’t get close to the Jebel Ali Port. The blue lines in this image show the very limited degree to which I could glimpse this essential infrastracture on Street View. I could get right up to the entrance gates of

95

Google Earth image

the port facility, but no further. This is the closest approach to the Jebel Ali Port on Street View. At the end of the road is a turnabout, and a low barrier prevents exploration. From here the container cranes at the far edge of terminal 2 stand out over the scrubby trees. I understand this is a huge operation, I don’t expect tourists to wander freely around the port. But why not build a small tower to the north where visitors could listen to a talk about the port? Or a roadside cutaway providing a clear view? But Dubai is being constructed as a magician’s trick, or as a jinn-conjured landscape. Integration between the working and the tourist versions of Dubai would threaten to break up that illusion, and so it’s avoided. Still on Street View, I followed

96

Google Street View image

another road approaching the port, I made it to an entry gate. Beyond I could make out a sign specifying directions within the vast port (offices, gates, free trade zone). The port is a city in itself, with thousands of employees (impossible to get a precise number). Dubai Ports International was founded in 1999, and it began its international reach by constructing ports in Saudi Arabia and Djibouti. Since then this corporation has become DP World, and it operates ports around the globe. A remarkable 10% of global container traffic is handled by DP World infrastructure. The company has assets north of $25 billion and is headed up by Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, who has close ties to Dubai’s ruling Maktoum family. The massive container ships

97

Google Street View image

that transport goods around the globe are manned by just 20-30 people. The vast majority of visitors to Dubai arrive at the international airport (DXB), but a trickle of workers arrive by sea at the Jebel Ali Port. Since so many fragments of global experience are hosted on YouTube, I looked there to see if someone had posted a sea arrival to Dubai. The video I found had been sped up, making it seem like the ship was speeding along. The royalty free sounds of a happy orchestra gave the video clip a buoyant touch. The Dubai that takes shape on the horizon isn’t one of spectacular skyscrapers, but a landscape of container cranes, ordered and waiting. There’s something amazing—even beautiful—about the sight of a massive container ship awaiting

98

YouTube Video posted by Raikar Films

"Cargo ship arrival at Jebel Ali Port | Dubai Port"

attention from those yellow cranes. This process is all controlled from a room lined with computer screens. An amount of work that in past eras would’ve necessitated an army of laborers is accomplished now by automated processes. This YouTube video makes no attempt to convey a critical view of this port or working conditions. There’s rather a feeling of awe at the immensity of all this and how it proceeds on its own with hardly a person in sight. The YouTube clip, more than novels or film has become the best entry point for thinking about global infrastructure and the experience at its heart. I want to return to the idea that a city would choose to hide its infrastructure. Working ports don’t have to be kept separate from the cityscape. When I visit

99

YouTube Video posted by Raikar Films "Cargo ship arrival at Jebel Ali Port | Dubai Port"

Seattle I usually find myself at Kerry Park on Queen Anne Hill, known for its postcard view of the Space Needle and downtown. On my last visit I shifted my camera to the right for a photo of the Port of Seattle in the distance. Democratic space doesn’t hide its make up, but reveals its parts to itself. A port that brings money and jobs isn’t something to be hidden away. The busy port doesn’t in any way sully a slender architectural icon like the Space Needle. The Port of Seattle has published a document online explaining where visitors can go to get a view of the work going on at the port, and this document goes even further and explains the different types of cranes and trucks that an observer might notice. The malls of Dubai make visible the fact that

100

goods (and workers) are moving around the world. But the mechanisms underneath this process are kept hidden, as if invisible genies right out of the Arabian Nights were transporting merchandise at night. Stores in the Dubai Mall competed to present miraculous windows of perfect goods for visitors. The layout of Dubai makes clear which districts are meant to be seen. Tourist districts are marked by grand structures connected to each other by direct lines of sight. Outside of that tourist region is the realm of infrastructure, which can’t be easily observed by visitors. You can almost hear the question from the designers of Dubai: “Why would anyone want to see a port?” As a result the workings of global trade are only visible to those who sleuth for

101

Google Street View image

shared images or videos online. Dubai isn’t an especially religious place. Billboards, posters, and monuments combine to tell the story of heroic innovation led by the ruling CEO sheikhs. But mosques are nevertheless everywhere, and this is easy to forget. The Al-Rahim Mosque overlooks the curving pedestrian path of the Dubai Marina. It was constructed in 2013 on the recommendation of a powerful sheikh and it allows for the public presence of Islam even in the Marina development that caters to expatriate workers. The presence of a mosque in this and other developments defines Islam as the state religion, though it’s consigned to a scenic presence rather than being a message of spiritual conviction. With all the foreign workers

102

comes inevitable pressure to have diverse places of worship. Christians from different parts of the world will want their own form of church. Hindu and Sikh workers inevitably seek a temple for their own faiths. Dubai solves this problem by dedicating a plot of land to accommodate these faiths. In one location just outside a suburban-style housing development a passel of worship structures stand right next to each other (even sharing the parking lots!). This land is in the infrastructure zone near the power stations and port (away from tourist sites), so their presence isn’t part of the “real” Dubai nor do they challenge the public role of Islam. The Pact of Umar was a set of restrictions that applied to Christians and Jews in Islamic lands. The agreement

103

Google Street View image

was attributed to Umar, the second Caliph after Muhammad, but it was likely codified a century or two later. Christians were allowed to continue their worship, but limits were placed on building new churches and on public display of the cross. Churches couldn’t be taller than any mosque in the same city. The pact has only been patchily enforced by states, but some version has been applied in Dubai. The Coptic Church in the foreground and the Sikh Temple to its right are low, nondescript structures. They are built well outside the visual lines of tourist Dubai. These places of worship on the outskirts of Dubai never come up on “must see” lists for Dubai. They aren’t built to draw outsider attention. They should rather be considered more like necessary

104

Google Street View image

gurpal_singh_waraich

kuldeepsidhu949

teenchandandave

infrastructure. I searched on Instagram for images of the Sikh Temple, and I found dozens of posts with individuals or groups posing for a photo right outside the temple. Enough of the exterior is shown to allow clear identification of the temple, and the posts were tagged for location (enabling my search). Taken as a group these Instagram photos demonstrate the symbolic value of the temple for Sikhs living in Dubai. Wherever all these people were employed in the business world of Dubai, they found in this temple a way to touch base with home. I was fascinated by the way they all managed the trick of making the temple appear to stand alone, not surrounded by other places of worship. On our first Friday morning in Dubai we attended Gateway Church,

105

which met in the second floor ballroom of the Grand Millennium Hotel in Dubai’s Business Bay. The man who gave the sermon was from Zimbabwe, and we later learned that he worked as an accountant at a shipping corporation. It was a Pentecostal service, which meant that the music was rousing (if repetitive) and in transitional moments we could hear worshippers speaking in tongues. This church might be presented by some as evidence of religious freedom in Dubai, but its temporary housing in a hotel ballroom makes it a better example of the marginal location of all religions except Islam. However, the Gateway Church did give the feeling that Jesus’ Great Commission hadn’t been in vain. The Gospel had gone out from Jerusalem