Palm Jumeirah, Dubai

Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque

Louvre Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi

Dukes: The Palm

The View

Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque

Louvre Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi

Dukes: The Palm

The View

It was one thing to be in Dubai and vist the Expo and see tourist sights, but we would miss something important if we didn’t get a sense of the luxury Dubai that was then filling my Instagram page. So the Lux Life (as it’s termed by some popular social media accounts) is the subject of this third visual essay on Dubai. The city’s leadership has positioned Dubai as a global meetup place for the ultra wealthy. So while it was possible to experience the malls and spectacular buildings of Dubai as mid-level tourists, we ended our time here with three days at a high-end hotel on the artificial sand palm that extended into the Gulf. For many visitors this kind of experience is Dubai. The English-themed hotel, Dukes: The Palm, wasn’t even close to the tippy top

1

of luxury (which we couldn’t touch), but it brought a limited view of the luxury life. Dukes: The Palm had opened in 2017. It was patterned after a luxury hotel of the same name in London’s Mayfair (near Hyde Park and Buckingham Palace). On the driveway up to the hotel entrance we saw this statue group of a foxhunter with dogs. Foxhunting is a controversial part of English culture, so much so that is was actually banned in 2005! But banned or not this “sport” retained its value as an instant symbol for a certain lifestyle. The hotel featured a British-themed restaurant and pub (of course), along with other touches of obvious Englishness. To the side of this entrance was also a sign encouraging visitors to use the hashtag “royal hideaway.” The implication

2

was that by staying at this luxury hotel we were participants in the British royal life, though that was nonsense and just a ploy dreamed up in some blank-walled modern office. Dubai trades in fantasy every bit as much as Las Vegas. The two sides of the lobby (near the check-in desk) were decorated with portraits, one side fictional, the other quite real. On one side was a suggestion of stuffy English royalty—the type of person who would thoroughly approve of this hotel! Since this hotel is owned by an international corporation based in Spain (Barceló Group), this Englishman a figment of the imagination. On the other side were portraits of the ruling sheikhs. Only by their permission does anything get built in Dubai, so this is the standard

3

acknowledgment by corporate owners of the power authorizing every business endeavor. For many people travel represents mainly a chance to unplug from anxiety and work. The basic idea is water and a place to lounge in the sun—fruity alcoholic drinks are a plus. Dukes delivered all this with its hideaway beach and lounge area. The Dukes hotel is the central structure back there, and then two wings of lookalike private condos surround the swimming area, which faced out onto the beach. It was impossible to know where all these lounging people were from. It sounded like a mix of European origins, but language didn’t matter, since everyone shared the same global vacation ideal. This space is off limits to curiosity, and cameras weren’t

4

allowed, but no one bans iPhone photos. Dubai has a population of about 3.3 million, but only 10-15% of that number is a citizen of the UAE. As a result, the workers at hotels and restaurants are never citizens. The jobs are filled by laborers drawn from South Asia and the Philippines. The workers cleaning things up and manning lifeguard stations at Dukes were all from South Asia. We can distinguish two global populations in Dubai: first, laborers from the Global South, drawn here for work, and second, the tourists and businessmen who are the global elite. Globalization is visibly composed of these two classes, those crossing borders for subsistence and those who do so for pleasure and immense profit. After some months looking at Instagram

5

photos tagged #Dubai it was insightful to witness the actual production of these images. As I stood on the edge of the pool to get an iPhone photo of the skyline, I noticed this amateur photo session in progress, whose end result could probably be entitled “cheeks with brilliant cityscape.” On Instagram these photos take on an impossible veneer, but the process is ridiculous. What’s erased isn’t just the onlookers, but the sheer boredom of the process. These two had lounged silently in chairs through the afternoon, until the golden hour approached, when they suddenly felt the call of the water. The guy worked to position his girlfriend’s body with an envy-generating cityscape as the perfect background. As I’ve mentioned, cameras weren’t allowed in

6

the Dukes beach area. There was a South Asian guy handing out towels at the entrance, and his job was also to look out for cameras. Why no cameras? Privacy is part of the definition of global wealth. These luxury spaces are remarkably quiet, and also unseen except by paying participants. Personal iPhones will capture the outward vista of water and cityscape, but the experience itself is hidden. These spaces of wealth work to erase history and context. With no interest outside the immediate moment of enjoyment, there’s no reason for photos or videos except invidious spying. But we must get better practice at turning our cameras on the luxury life that demands the right not to be seen, and so speak about this emptiness. Modern architecture relies

7

heavily on glass exteriors. The beauty of the resultant structures depends on reflection and light. The glass makes pleasant distortions out of structural lines, and the shadows and colors of the sun throughout each day are neverending—so why work too hard on ornamentation? Another motif of this architecture is the contrast of organic forms with the rectangles, straight lines, and circles of these structures. Any structure set on an artificial island doesn’t start out with much: no history; no nearby structures. There’s only the reality of that beach, and so builders pack in the saleable units and create buildings that strive to do nothing but reflect their setting. It turned out that one reason our room at Dukes was affordable was because it opened onto an

8

active construction zone. This isn’t unusual. Whatever the ideal look of the glossy advertising, the experience of Dubai will include a construction zone within sight or ear shot. It turned out to be the Seven Palm Hotel and Residences that was going up (studios start at $175k). I watched the workers go about their work sanding and leveling the concrete slabs that’d become tennis courts. Like the poolside, the workers down there were South Asian. Strange how within a stone’s throw of so much aimless leisure this continuous dusty work would go on all day. The temporary screens that hid them from vacationers showed off the good life (biking, family playing on the sand, sunset) toward which they could barely aspire. It was as if the screens were

9

taunting them. Any number of times we saw luxury sports cars pull up to the Dukes entrance. I didn’t find it easy to start taking photos of the people in these cars, though they deserve to be treated like freaks. Maybe a part of me wanted to play it cool and be seen as the type of person who wouldn’t ooh and ahh at luxury? I was determined to get a photo of these cars, and on our last evening we saw this bright red Lamborghini. Likely this car was just being rented for a few days, but this luxury experience is what Dubai offers: “Live like a millionaire!” Since it’s a security state with little or no criminal threat to property, wealth is brought into open view like few places in the world. After getting a photo of that red Lamborghini we walked down the hotel

10

drive and stumbled upon the mode of transportation at the other end of Dubai’s spectrum: a bus for laborers. The workers at the construction site next door were getting aboard the Airolink bus at the end of their day, and no doubt they’d be returned to some crowded dormitory well inland from any luxury hotels along the beach. These men are most often not working for themselves, but for their families back home in Pakistan or Bangladesh. The nice condos at this construction site will start at only $175k because of the absurdly low cost of the sweat and bodily risk taken on by these workers. They live invisibly here and won’t be missed when they return home. Dukes hotel was on the Palm Jumeirah archipelago, a vast artificial extension of

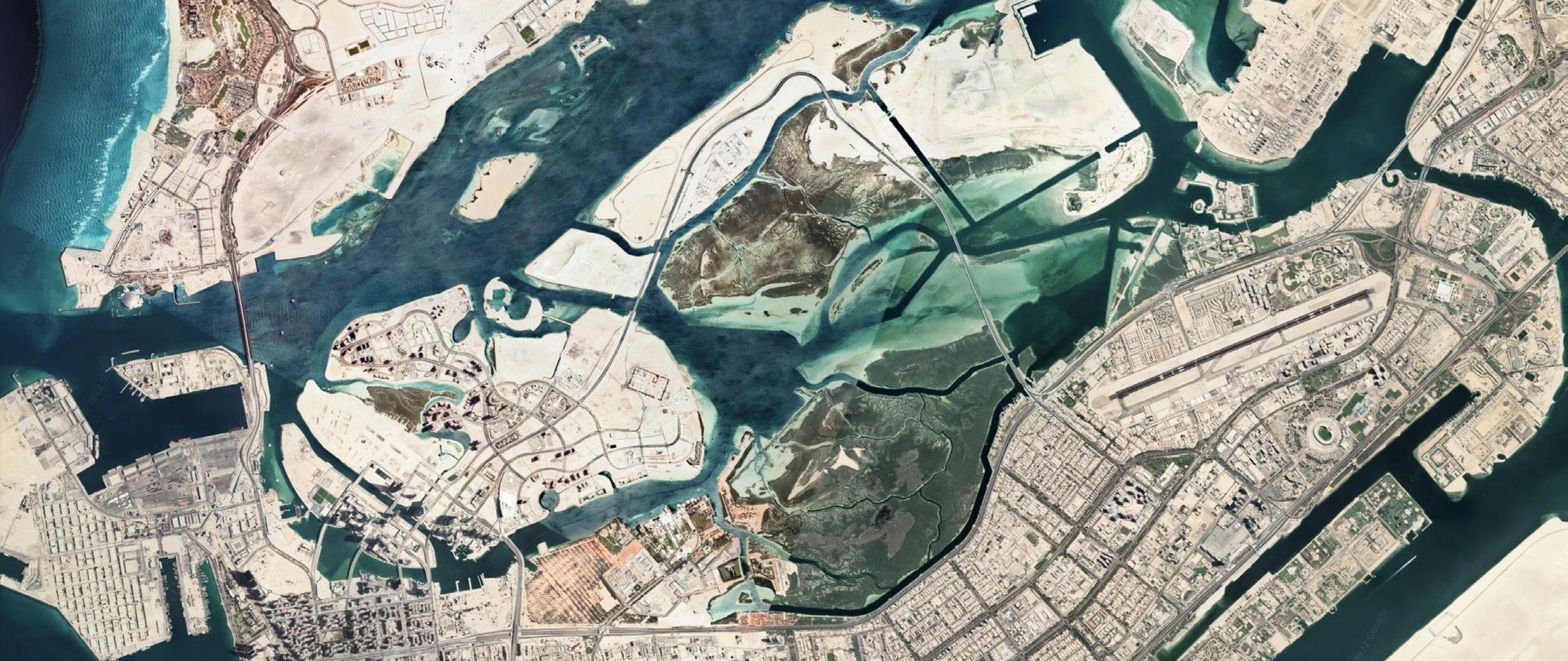

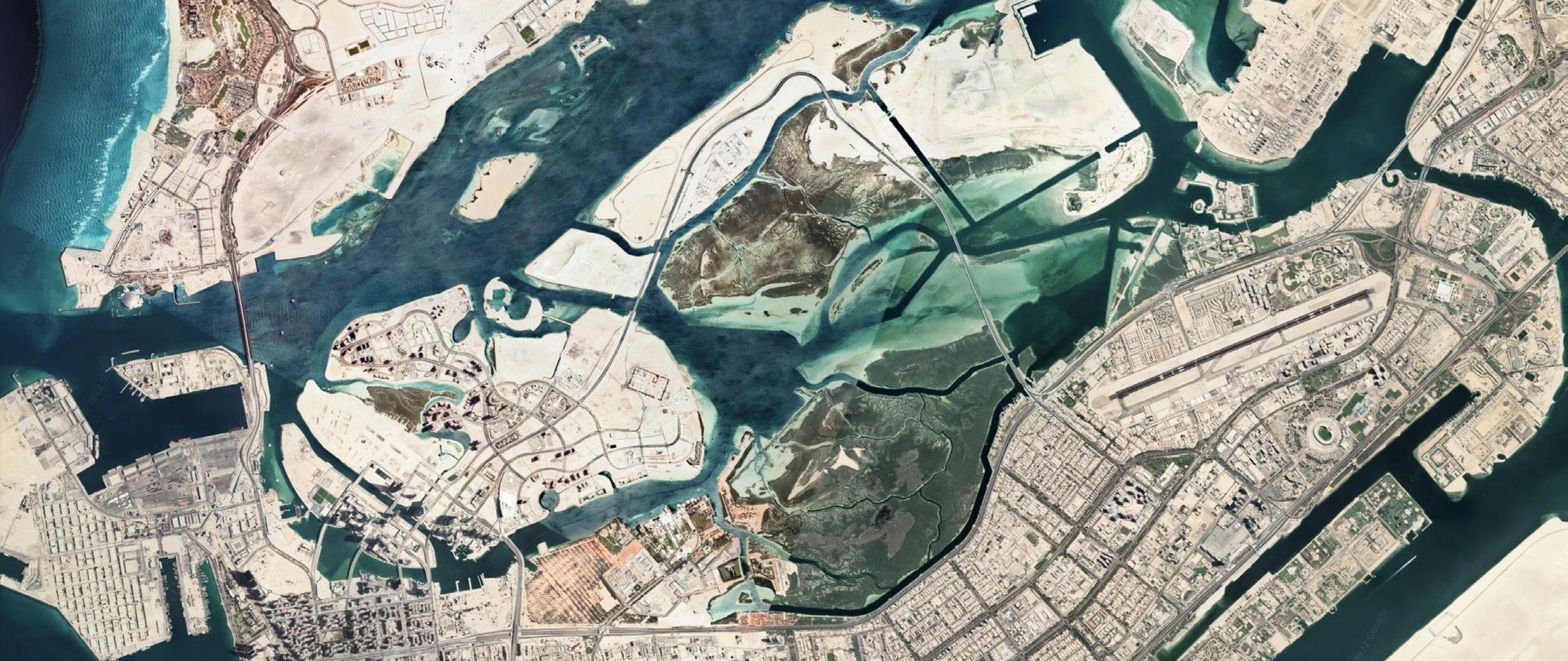

11

Dubai (as is the “World” a short ways off). I’ve written in the past about large scale geo-projects such as the effigy mounds of Wisconsin and the Nazca lines in Peru. Large scale re-configurations of a landscape always yield insights about the deepest values of a society. For years I’d looked at Dubai from above, with Google Earth, and thought about the meaning of these islands. In my teaching I’ve used Dubai as an example of the changing nature cities in the Middle East. Dubai began construction of the Palm in 2001, the same year that Google Earth was released. So I like to start by noting that the project makes immediate sense as an object of internet browsing. Dukes hotel was on that “trunk” of the palm archipelago. Across from the entrance was

12

Google Earth image

the Nakheel Mall, and rising from the center of the mall was this building (not quite a skyscraper by Dubai’s standards). A visit to the top of this structure had been strongly recommended since it offered the best view (at least in real life!) of the Palm. The Nakheel Mall opened in 2014, but The View observation deck at the top of the tower only opened in 2019. Every ambitious human

13

construction generates a demand for a way to look back at it. Although the Nakheel Mall was just across the main road of the Palm, it wasn’t easy to get here. We had to be shown to a door that led to an underground concrete walkway that ended in a parking garage and then we followed bright lights to the mall entrance. Once inside we were reassured by its bland mallness. Now there would be no surprises. The amazing thing about Dubai is that so many malls manage to stay in business, but then the malls are themselves a major attraction for tourists, so that makes it more understandable. One gambit for mall design in Dubai is to anchor the mall with an architectural wonder, and the Nakheel Mall touted its great overlooks onto the Palm to

14

attract outside visitors who have no end of mall choices. The Nakheel Mall included this kiosk where an attendant was handing out a full-color pamphlet on the residential units for sale in the tower. A scale model gave a sense of its size and the nearby amenities, which included a stop for the monorail on roof of the mall. Residents here would find it easy to travel further down the Palm, or to go the other way and link up with the main transit line heading downtown. The pamphlet sang the praises of the residential units in corporate speak: “Every detail of the apartments at The Palm Tower Residences has been meticulously selected to exude glamour and elegance. The neutral color palette is complemented by luxury flooring...” OK, Sign me up! Like

15

a lot of visitors to Dubai, I’d traveled a long way to get here. But despite that, not much in Dubai presented a conceptual challenge for understanding, and this was especially true of the Nakheel Mall. It was even a bit dispiriting to see the storefronts of all these tired brands, with blank ceilings and cheap lighting (and always security cameras). The Beverly Hills Polo Club brand was founded in 1982, an unashamed mashup of the high-end reputation of California’s Beverly Hills and the upper-crust “sport” of polo. The chance to associate the self with those words is exactly what’s on sale. The shirts contain that regal but unreal image of a man on horseback swinging a polo mallet. Only on the Palm did it feel like we’d fully merged with global

16

space. We were no longer standing in a nation or region of the world, but a more abstract type of space. The stores in the Nakheel Mall were were all global brands. Only the names transliterated into Arabic and the prices listed in AED gave away our setting in Dubai. Signs within these store were in English, which remained the language of global exchange. If Dubai as a whole functioned as a kind of getaway from the strictures of other Middle Eastern countries, then the Palm was a getaway from even Dubai. The Palm is well known for its nightclubs and rooftop parties. Its condos and villas—and luxury hotels—function like a country of their own, and the Nakheel Mall let itself speak only in global signifiers. After wandering through the mall we arrived

17

at the entrance to The View. Some marketing company had decided that “wonder” was going to be the key word for this experience. The promise of that feeling was going to prod us (yet again!) to pull out a credit card and pay to get a view of the place we were visiting. If ever there were a thoroughly monetized skyline, it’s here. But I’m stuck on this concept of “wonder.”

We feel wonder in response to the world, and it enlarges the Self with elation but at the same time reminds the Self of its final limitations. We feel wonder at the sight of the Grand Canyon, or a whale breaching in the ocean. How would the Palm inspire this “wonder”? If some vast amount of money and effort has been expended to build a structure, then Dubai feels visitors need

18

a full introduction regarding the the stunning proportions of the accomplishment and the Sheikh’s visionary qualities. So there we were, waiting to take an elevator up to The View and survey the Palm, but first we had to watch a program that lit up the floor. The group instinctively backed up so that we could all see the Palm unfold. I still wasn’t sure that wonder was the right emotion. It was jaw-dropping how much sand was dumped on the Gulf to create this land, but ultimately that was a brute force effort. Rich people and their stuff don’t fill me with anything properly called wonder. The program didn’t just light up the floor, but also the screens curving around us. It’s a godlike power to create dry land in the midst of water, taking us back to Genesis. But

19

when we imagine God gathering the waters so that dry ground could appear, we don’t picture a scene like this. It’s hard to see anything miraculous in this sand spewing process. Dubai has plenty of rock and sand in its desert landscapes, and by taking that valueless stuff from there and dumping it here extraordinary value was created. Out of nothing comes a coveted site to build luxury hotels and villas. But it’s not Genesis so much as Jesus’ parable about building on shifting sand that lodged in my mind as I watched this scene. Is this Palm really built on a firm foundation to withstand the planetary and social changes we face in coming decades? Mark me down as a doubter. Finally I could look down on this Palm I’ve seen so many times on Google

20

Earth. More than any aesthetic quality the palm tree represented the best possible design for multiplying beachfront property. Its elegance served to hide the fact that this was the work of a cynical world creator who wanted nothing but to multiply lots with beach access. The Palm’s fronds are lined with pricey villas, and this is a popular area for celebrities like football star David Beckham and fashion designer Giorgio Armani. Those are celebrities with faces, but the most important class of owners here are the faceless global elite, who find in Dubai a stable and luxurious escape. They know that their privacy will be defended above any conception of the public good. Standing at The View we located Dukes, our hotel for some nights. The structure in

21

the middle was the hotel proper, and then it’s possible to see how two wings extended behind, each containing luxury residences. The wings opened outwards so that they could contain that secluded pool where we had already spent some time.

As can be seen, there’s zero interest in public walkways or beaches. Value could be captured only by privacy, and as I scanned the layout of Dubai from this vantage, the pattern of screens and limitation kept repeating itself, whether at the level of the private home or the luxury hotel. Dubai offers golden visas to the wealthy and business entrepreneurs who choose to live here, but it refuses to offer actual citizenship, which is to say a full stake in the success of this place or a voice in its future. For some

22

reason I had long imagined it would be fun to take a long walk on the Palm. The experience of being here convinced me otherwise. This is a view of the trunk of the Palm, heading toward the mainland. There’s nothing scenic because the trunk just feels like one big highway. From the ground the beach is invisible behind unending screens of luxury residential developments. The special Palm monorail line runs right down the middle (see that station ahead). Beside the monorail are two red-colored paths for walking or running, but even these paths dead end at the Nakheel Mall. It’s impossible to walk along those main roads or the beach, or to explore on foot any of the Palm’s fronds lined with private villas. There was no mystery about how to consume

23

The View. Everywhere I looked the smart phones were out and people were taking photos to post on social media. Those palm fronds, lined with orderly villas then interlaced with turquoise inlets, made for a recognizable background. That languid point from the woman on the left perhaps directs attention to the place where she is staying. For me it was difficult not to feel bored on the Palm. What I value about travel is the encounter with difference, but I had to put that aside and ponder for a moment the perfect flatness of this global space. What other distant place could I visit and experience so few genuine surprises? There was nothing but surface here, composed of private spaces where immediate bodily comfort was the only point. In his book on

24

city design, Kevin Lynch wrote about the “imageable” city, by which he meant a city that “would seem well formed, distinct, remarkable; it would invite the eye and ear to greater attention and participation.” He broke down the image of a city into five elements: paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks. All of those elements are in play for Dubai. The close visual alignment between landmarks like the Palm, Burj al-Arab, and Burj Khalifa is of course intentional. (I noted this alignment of structures in my first visual essay as I looked out on Dubai from the Burj Khalifa skyscraper). City planning in Dubai takes place on a scale that’s difficult to imagine in other locations, where growth has proceeded over time on a more organic basis (or with no

25

planning at all). The 18th century paintings of Venice by Canaletto (on display in the National Gallery in London) show the extent to which one city can serve as a paradigm for city design. In this painting (starting on the far left) Canaletto painted the Column of St. Mark, the Doge’s Palace, and the busy waterfront of St. Mark’s Basin. This was successful city design, but its imageability exists on a very small scale. This architectural wonder is contained within a tiny space (in comparison to modern sprawling cities). Kevin Lynch pointed out near the end of his book that imageability has been achieved on the scale of the traditional city, but the modern challenge is to achieve that distinction over a much larger space. Lynch speculated about

26

building imageability into a modern metropolis, and expressed his ideas in Democratic values: “...the form of a metropolis... will not exhibit some gigantic, stratified order... It must invite its viewers to explore the world.” One thing to note in Canaletto’s paintings of Venice is the emphasis on large public events and the presence of different classes of people in his foregrounds. These are never cityscapes empty of a true public, with different social classes mixing and participating together. Venice represented city design on a human scale, and if Dubai has successfully built grand city vistas, it has failed when it comes to creating space for open social participation. There is nothing messy or heterogenous about the Palm. At the end of the Palm is

27

Atlantis, a hotel that goes full-on Arabian Nights in its design. The pointed keyhole arch in the center is more typical of Islamic architecture in the Maghreb, or far west of the Islamic world, but the point is to evoke a fantasy, and to give a near miraculous view of that blue Gulf beyond. It’s possible to stay at the Atlantis for about $500 per night, and the Aquaventure Waterpark makes this a family friendly destination. That monorail line moves forward to the Atlantis and its waterpark, as does the access road, but forget about moving on foot through this upper section of the Palm. The villa-lined palm fronds are accessible only for paying visitors arriving in a car. To my disappointment there was no way to casually stroll down the frond “neighborhoods.”

28

For one of our nights on the Palm we took the monorail all the way to the Atlantis. It let us off at a mall (of course!), but we tried to walk to the far side of the Atlantis. We were stopped right here by a kindly security guard who understood our desire to get a view (and so offered to take a photo of us with the hotel in the background). But he couldn’t let us approach the lobby. It was December so the palm trees were wrapped in Christmas lights. I was perfectly satisfied with this view of the arch. The name Atlantis evoked the mythical lost continent sketched by Plato, but at water’s edge, and sitting on piled sand, perhaps that name was tempting fate? It wasn’t so hard to imagine this Atlantis as a climate ruin a century hence. The Atlantis was connected to a

29

mall. These stores appealed to people with real money to spend. Typical mall stores strive for a seamless transition between the semi-public mall space and the private space of a store, but here stores like Rodeo Drive, Vilebrequin, and Hamac found various ways to project exclusivity even within the mall setting. Some stores used windows to emphasize limited entry (and so exclusivity). Clothing racks weren’t stocked with every possible size, just a few versions of each piece of clothing. The expectation was that a person with a recognized body type for the global elite would walk into this space and drop hundreds of dollars on almost nothing. The Pointe sits right across the lagoon from the Atlantis. A dozen or more restaurants line this area, offering

30

visitors a place to sit and gaze over at that keyhole arch. A huge fountain (visible even on Google Earth) sits in the lagoon. This fountain is the holder of a “Guinness Certificate” for the world’s largest musical fountain. (I have no idea about the competition when it comes to jumbo-sized fountains.) Unlike any notion of a traditional fountain, the idea here wasn’t to propel a continuous jet of water into the air. Instead hundreds of spouts were choreographed to popular songs. We watched “Jingle Bell Rock” get the full treatment of dancing jets and bright Christmas colors. Along with the luxury mall, the international cuisine, and spoken English, it was as if we’d wandered through a looking glass into a place where culture and nation had lost any and all meaning.

31

The View kept bringing up the idea of wonder. From the lookout it was impossible to miss the preferred social media hashtag #inspirewonder. But that word “wonder” didn’t sit right with me. I understand that I’m looking out at a masterpiece of real estate branding. I can see the tremendous wealth that was dumped into creating the palm and then the further wealth invested in luxury hotels and villas. But I reserve the word “wonder” for things that aren’t, at heart, boring. What was unexpexted about all the elements in this view? Rich people were getting exactly what they wanted: private pleasure grounds with just enough visibility to be an object of envy. But the design ethos was obvious and ultimately dull. Beyond the outer ring of the Palm was a

32

further group of islands. From The View it looked like a mess of low sand bars, but from Google Earth we knew that from above all those sand bars would resolve into a Mercator projection of the world. Unlike the Palm, those islands won’t be reachable by car, but will demand water transport. But anyone building out there won’t blink at a private yacht. To my eye it didn’t look like much had been developed, but the report for years has been that Madonna owns a luxury house in the World Islands. Those islands were the perfect metaphor for the hubris of Dubai: it sees itself as offering the world, but it delivers only the vacuity of global wealth and celebrity. “The World” isn’t the messy and diverse reality of our globe, but a set of private islands visitable

33

only by those with private water transportation. On one of our last days in Dubai we drove to Abu Dhabi to see a bit of this other famous city of the UAE. We got an Uber to cover the hour and a half ride along the coast. Our driver was from Pakistan, living in Dubai to earn money to send home to his wife and children. We negotiated for his time after the Uber ride, and so he stayed with us the whole day, waiting at the various stops. Abu Dhabi is the most oil-rich of the Emirates, and it doesn’t feel the same need as Dubai to create architectural marvels for the global tourist crowd. There’s not such an overt attempt to capture eyeballs and attention, but the need to display massive wealth still explains much that we encountered here. On a side note, someone

34

should write a history of freeways signs. I don’t think any nation has tried to reinvent this signage, they’ve all just borrowed from systems already in place. The United States built the first national highway system back in the 1950s, so it’s there I’d look for the origin of this system of signage. The sign colors are instantly communicative. Standard highway directions get that turquoise-leaning green, with arrows marking out freeway lanes. Serious cultural sites get a brown sign, while deep blue points to civic sites or districts. This is all instantly readable, but it’s a system that was invented and then grew so successful we hardly think of it as having an origin. Because of this system-borrowing, we travel around the world and find ourselves in the midst of

35

a system that makes intuitive sense. Our first visit in Abu Dhabi was to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. This ornate mosque was completed in 2007, at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars. I took this photo through the window of our Uber car as we made our way to the parking garage. Up close it’d prove impossible to get a full view, and so this vantage was my only chance to take in the mosque as a whole. The bulbous domes bestowed a dream-like quality to the structure since that wasn’t anchored in the architecture of the Middle East, but a borrowing from Mughal India. The multiplication of domes took over the appearance, making it seem a set of dream bubbles about to burst into the empty desert air. That evening after a day in Abu

36

Dhabi we began our return to Dubai. As with any trip through the UAE, we traveled on the multilane Sheikh Zayed Road. Early on we looked over and watched the purple-lit Sheikh Zayed Mosque slip silently by. It’s no accident that both highway and mosque share the same name. Sheikh Zayed was a founding father of the UAE, and he served as president from 1971 until his death in 2004. His image and name are everywhere in the UAE, but especially concentrated in Abu Dhabi. The confluence of the name of the highway and mosque made me consider the vantage from which this mosque was meant to be seen. It’s oriented toward Mecca, sure, but it was sited here to enable this common highway view. No matter the splendor of a site, we’ve

37

grown used to the necessity of underground parking. Nobody bothers to make these hidden lots a luxury experience since they serve solely as a place to deposit a vehicle. The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque was no exception with its underground parking lot. The mosque holds more than 40,000 worshippers, and isn’t surrounded by urban residences, so everyone must arrive by car or bus. Underground parking allows developers to avoid devoting a staggering amount of surface space to parking (and so undermining any big visual impression). Someday underground parking lots will be seen as the key infrastructure that made possible most modern architectural marvels. But somehow we erase them from our memories of the marvels. This underground

38

parking lot opened onto a mall with a Starbucks, Bath & Body Works, and various fast food options. This was all underground (but with skylights above), so it was as separate from the mosque experience as the underground parking. But it was still jarring to come to a mosque and find ourselves within yet another mall. The design vocabulary here was easy—100% global mall. Arabic was more prevalent in signage than had been the case in Dubai, but there was no real need for language. We were among familiar brands and images of frozen yogurt. We didn’t yet feel like browsing the souvenir shops, so we kept moving toward the grand mosque. From the mall we headed down a lengthy corridor, made easier by a moving walkway of the type we

39

know from airports. That similarity should set off alarm bells. Do we really want places of worship to be so large that they demand airport-level transportation devices to be workable? I’d say no: size will inevitably erode purpose. Of course we hadn’t arrived at the Grand Mosque alone. There were several medium-sized tour groups arriving at the same time as us, and we moved toward the mosque destination within this stream of people. The moving walkway took us past images of the mosque’s construction, and we got the usual UAE vision boasts, like “From Dream to Reality.” The mosque was of course an inherently religious structure, but in its presentation and framing it was no different than the architectural marvels of Dubai. Finally we

40

were heading from the mall level up to the surface. We could glimpse through the skylight ahead a minaret and the white walls of the Grand Mosque. We were still behind the same group of tourists, who looked to be from Europe. The women had put on the basic head scarves required for entrance. I’ve known people whose main goal in travel is to get away from these tourist crowds and the places that everyone sees, but if the goal is to study global space then there’s no avoiding these crowds. Their presence is one marker of global space. Global sites are well represented on Instagram and travel websites, but always from well-worn vantage points. The meaning of the experience goes entirely unwritten. Up close the Grand Mosque recedes, being

41

too large and sprawling to fit into the camera lens. The domes and minarets compete for attention. The insistence on a brilliant white exterior eliminated any contrast of materials, and made it feel like a shimmering mirage in the direct sunlight. I wished I had brought sunglasses with me. No doubt the UAE had much to consider about the style of its mosque, whose construction started in 1994. Would they follow the austere neo-Mamluk appearance of the great Saudi mosques, or adopt some other national style? In the event the Grand Mosque would be an amalgamation of styles stretching from Morocco to India. By combining all these regional styles it staked a claim as a global mosque. Nothing about the Grand Mosque speaks of a private

42

sphere of religiosity. It cost over half a billion dollars to construct. The tour groups coming through aren’t simply a concession to demand, but the intended audience for the mosque. The message that can be read on every gleaming floor and every wall is that this is a state with money to burn. There are no choices here that speak of pragmatism or cost-saving. The material and workmanship are impeccable. All this expenditure also embodies a claim to leadership. The Saudis control the sacred sites of Islam. To the north Iran preserves a distinct Shi’a counter tradition. This mosque sets the UAE as a new cultural capital of the Islamic world. Its architectural diversity offers a summative vision of Islam as a global religion, and its luxury signals mastery

43

of the economic forces of globalization. Every purpose-built mosque reflects a commitment to a version of Islam. Sometimes this means national origin, but sometimes an attempt to sidestep national origins. In this case the UAE began with no native tradition of monumental mosques, and instead of inventing a tradition they borrowed freely. I’ve already mentioned the bulbous domes from India. The large screen at the entrance resembles an iwan from the great Persian mosques, but its floral design is corrected from colorful tiling to white on white design. The horseshoe arches facing into the court are drawn from the Islamic west. Meanwhile the minarets on the sides were inspired by Egyptian design. Dubai and Abu Dhabi are the first digital

44

native cities. A glance at the Grand Mosque in Google Earth shows that its design makes the most sense from this overhead internet vantage point. The green foliage that precisely creeps along the ground isn’t legible by an in-person visitor. The mosque is surrounded by small rectangles of blue, which are pools of water. Up close these don’t work as reflective pools, and even in my photos they are hard to notice. There isn’t enough distance to achieve striking reflections of the mosque. But those pools look great from above! Most spectacularly the mosque courtyard is covered by a marble floral mosaic, so extensive that it’s easily seen from above. This has all the symmetry we expect from a French garden. Dubai is addicted to constructions that can

45

make a claim to being the “world’s largest” of this or that. The Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi continues in this path of grandiosity. The floor of the courtyard is claimed as the world’s largest marble mosaic. Those flowing images that can be seen on Google Earth aren’t some great painting on the floor of the mosque, but inlays made of colored marble. Close up it can be seen that the floor was made by means of large pre-finished squares that were set into place on the floor. So it’s not like we should imagine craftsmen on their hands and knees setting mosaic pieces (the type of work that went into a medieval Byzantine mosaic).

Largeness of this sort can only be achieved by the adoption of an industrial process. This photo gives a sense of the floor as a

46

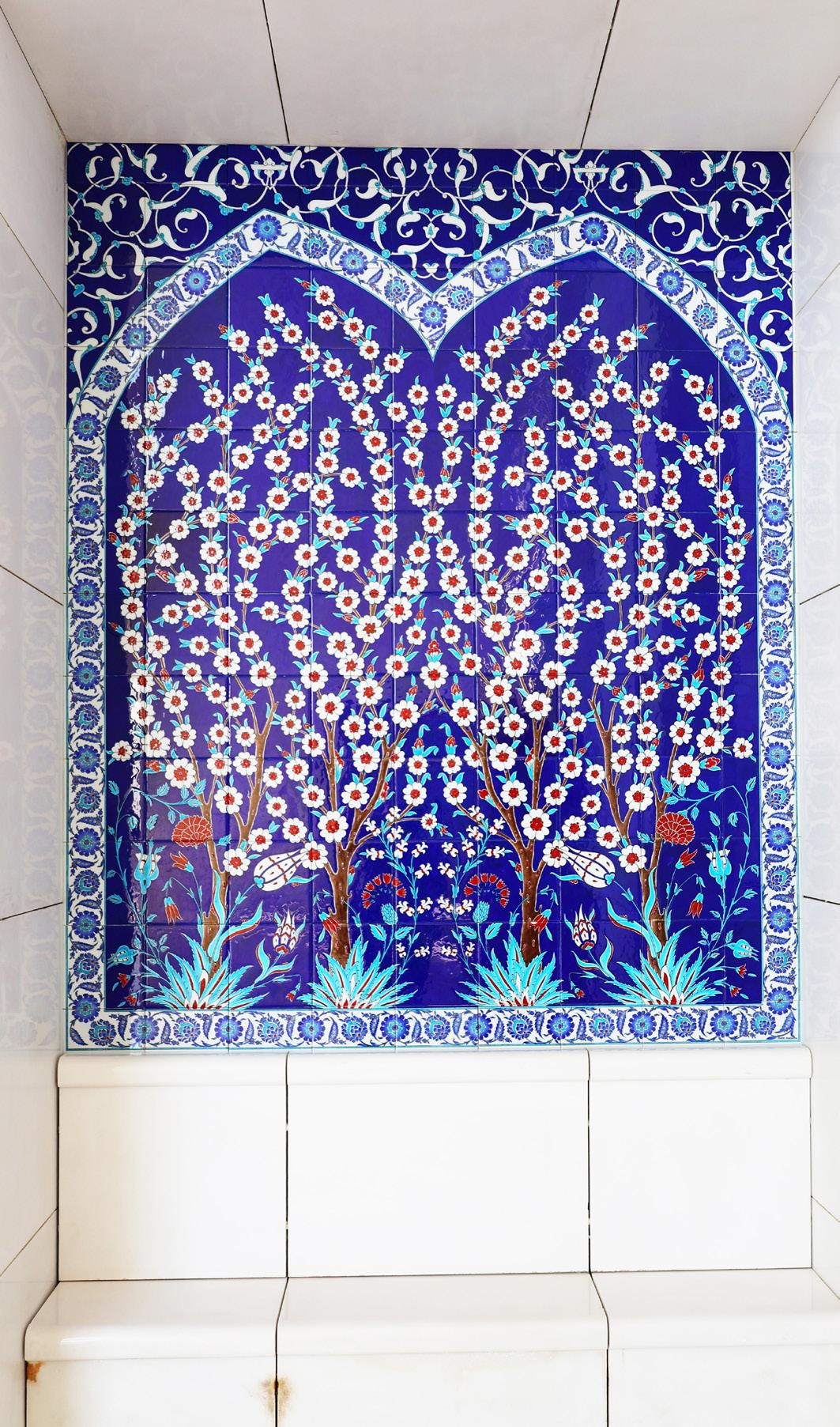

mosaic. The background to the flowers is composed of square or rectangular pieces of white marble. Those pieces were fit into place around the irregular shape of the flower, and they continued to the edges of the preformatted square. The flower is composed of what seems to be natural marble. (I see on the internet that marbles of these bright hues exist, and no doubt Abu Dhabi had money to acquire them!) The marble workmanship is fine, but a giant pattern like this is dependent on computer modeling—as much as any postmodern building by Frank Gehry. The finished large squares were set into the floor and the design came to life. The process seems worlds away from any traditional notion of “mosaic.” Colorful tile designs were set into

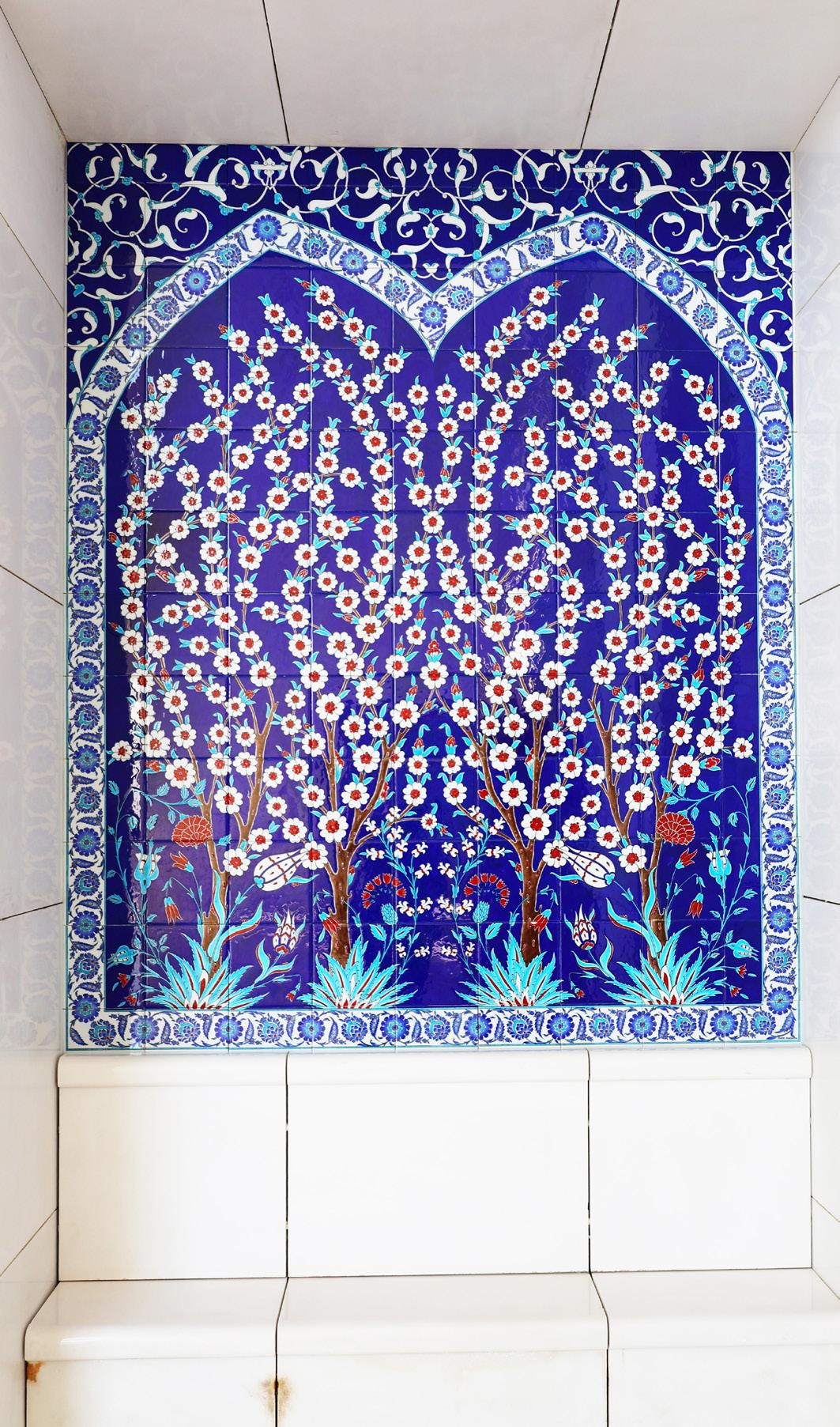

47

small alcoves around the Grand Mosque. These tiles don’t just recall but actively mimic the Ottoman Iznik tiles (named after the city where they were made). The impression one gets in this mosque is that someone laid out a bunch of favorite design elements drawn from the central Islamic lands, and then found a way to mix and match them into a single large structure. Where

48

these individual elements had once pointed to a regional tradition, here they become part of a bricolage. In a classic Ottoman mosque, like the Rüstem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul from the 16th century, the Iznik tiles aren’t “one more decoration”

but the leading design feature. This image from the entrance has similarities to the last image, but it’s more complex. The imitation

49

Iznik in the Grand Mosque is a computer generated version, with telltale simplifications that reveal its makers were playing at design. Though many of the Grand Mosque’s details were lifted from earlier structures, these palm capitals stand out as unique.

Efforts to design a palm capital are ancient, going all the way back to ancient Egypt, but this design is more realistic and novel. The palm serves as a natural symbol for Dubai, given its dry climate. With the construction of the luxury geo-glyph of the Palm Islands, palms have become still more closely associated with the UAE. The gleaming gold coloring of these capitals makes them stand out against the bright white exterior of the mosque. This one detail points to the UAE, and the gold color emphasizes

50

the wealth of the builders. Ours is an era of giant mosques. The mosque as a structure is being pulled and bothered into becoming an expression of national identity, and its size has grown to reflect that state-level ambition. The downside to this expansion is that the primary purpose of a mosque as a place for daily worship is undermined. A national mosque such as this is a place where visitors could get lost, and so the signage appropriate to a convention center or a mall is imported to help people find their way around. The mosque is laid out in a fashion that’s more convenient for viewing than use, and since such views lead to widely-viewed social media posts, it achieves its primary goal of building national identity. At the entrance to the

51

main prayer hall the flowering vines that had run along the floor or up onto the columns suddenly expanded onto the walls. Even the golden patterns of the door worked to suggested the organic form of a flower. The designers strove to make the mosque feel like a living thing, but to what end? What does it mean for a state that lives off of exporting oil and gas to make a claim for organic exuberance through its national mosque? The flowers and vines make an implicit claim for human flourishing, whether in this life or the next, but with such heightened formal control (including video surveillance placed onto the wall!) there’s no impression of human freedom. It’s a difficult question: how should design respond to the fact of climate change? We

52

judge design, in part, for the way it responds to the currents of its time. A surface reading of these floral walls is that they display some sensitivity to nature. This makes the mosque the equivalent of a green-washing TV ad from a big oil corporation. But there’s only surface here. It doesn’t appear that mosque designers grappled at all with climate change or the realities of this economy. Extreme wealth is used to claim global religious leadership (yes, the flowers and vines are made of natural stone), but the intellectual struggle to find real meaning has been side-stepped. One counter argument to what I’ve been writing is that mosques have always been like this. They become places for the display of a ruler’s wealth and they use contemporary art styles

53

to achieve that end. The Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, pictured here in the summer of 2004, was completed in 711 AD. It was constructed on the site of what had been a pagan temple, and then a Christian church. As a mosque it reincorporated classical columns, and used Christian Byzantine craftsmen to create vegetal mosaics appropriate to Islam along the walls. The

54

best preserved early mosaics are located under protective eaves along the courtyard. Like the near contemporary mosaics on the interior of the Dome of the Rock, this imagery testifies to a tradition still under construction. Islam was the true religion, supplanting Christianity, but how should it look in our world? That’s the basic design question: how should this identity or concept really look? Byzantine mosaics were glorious, so that didn’t need to be reinvented, but images of Jesus and emperors would need to go, not to mention crosses. Someone saw the opportunity to let vegetal design, suggesting paradise with hints of a city, take the center. Those grand trees still hold our attention. When I lived in Damascus for the summer of 2004, I used to

55

come to this mosque and sit in the courtyard and try to take it all in, to burn it into my memory. The experience of historic mosques like this one has shaped my perception of the success or failure of modern structures. This mosque has a complex history (gutted by fire in the 19th century, followed by a heavy-handed restoration), but I’ll make two quick comparisons. First, there was no way to get lost in the Umayyad Mosque, and so no need for large people-moving signage. The mosque was built on a human scale. Second, the mosque served the city in a clear way, and the courtyard felt like an open park more than a museum. The Umayyad Mosque was never free from commercial association. Most visitors arrive at the mosque entrance by

56

walking through the long covered Hamidiyah Suq (market). Suq and Mosque were two central institutions of the traditional Islamic city, and they were often bound together, with proceeds from the market paying directly for the upkeep of the mosque.

This is different from a mall in Dubai, where global brands dominate, profits go into corporate pockets, and goods are priced

57

for the global elite, not the public. Returning now to the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, we stepped into the interior. This chandelier is the centerpiece, hanging from the central dome, and supposedly represents an “upturned” palm tree. At the time of its installation it was the world’s largest chandelier, incorporating over 15,000 LED lights. It was made by Faustig, a German corporation that claims not to make “faceless, massproduced items,” and no one would use those words for this centerpiece crystal chandelier. This is the perfect object in a mosque for which cost was no object. Here at the central section of the mosque, at the mihrab (the niche that marks the direction of prayer) is a glowing reminder not of spiritual values, but of wealth. Under

58

the chandelier is the wall with the mihrab. Since it’s set into the wall that everyone faces at the time of prayer, a mihrab is often richly decorated. This mihrab becomes a golden accent on the rich wall, flanked by Arabic words that appear to bloom from a flowering vine. These Arabic words are some of the 99 names of God, most derived from the Quran, each calling attention to a divine attribute. I see in this photo of the words near the mihrab al-Hakim (the Wise) and al-’Afu (the Forgiver). The recitation of the 99 names is a longstanding and popular devotional practice in Islam, often done with the aid of prayer beads. But the 99 names is a bland choice for a grand mosque, avoiding any Quranic text that might narrow the mosque’s appeal. I can’t leave

59

the interior of the Grand Mosque without mentioning its Guiness World Record holding carpet. It’s the world’s largest handwoven carpet, covering 5,400 square meters. Cutouts were made for the columns, but it was stitched as a connected whole by 1,200 craftsmen in northern Iran. Its green color provides a pleasant contrast to the cream interior, but more importantly green was supposedly the favorite color of its patron, Sheikh Zayed. During our visit the Grand Mosque was empty, and I imagine its casual use would feel forbidding. Sure, it’s possible to find online videos of the mosque crowded for Ramadan, but it’s for tourist viewing more than real daily use. As I walked around the Grand Mosque I kept trying to decide if this should even be

60

considered a religious site. It’s a mosque, and so the structure relates itself to the practice of Islam, but as I examine the details of the mosque, the motivation time and again was wealth display. No doubt there’s an attempt to capture our attention, but where is spiritual feeling? The builders imagined the mosque as an expression of global Islam and their leadership, but as with any ecumenical structure, the design choices that make a place of worship unobjectionable also make it boring. More people consume the mosque through taking photos than actually praying in the great hall. By the end I didn’t think the Grand Mosque functioned as a sacred site so much as a national shrine to global success. Returning on the moving walkway, I paid more

61

attention now to the images framed along the wall. I was taken by this one of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip getting a tour of the Grand Mosque. Looking this up later on the internet, I saw that this was in 2010, just three years after the mosque’s completion. This mosque was meant for such visits. The show-offy buildings that Dubai loves so much (the world’s tallest skyscraper, the biggest frame, the biggest Ferris wheel) are, when you think about it, gauche. Those aren’t places to take someone of the stature of the Queen of England. A luxurious state mosque, on the other hand, is perfect for such an official occasion. It has the necessary gravity. Along the same walkway I came across a photo of Pope Francis visiting the Grand Mosque

62

in 2019. The bottom of the mosque’s great chandelier can be glimpsed behind him. The Pope is flanked by Vatican officials, but to the far right is the chief Muslim cleric who welcomed the Pope, the Grand Imam of Egypt’s al-Azhar Mosque, Ahmed elTayeb. It’s telling, to my mind, that a religious leader from a historic center of Islamic learning must be imported to the UAE for this religious dialogue. The UAE can spend its way to a luxurious meeting space, and underwrite a grand event, but they can’t simply acquire spiritual leadership, or buy legitimacy within global Islam. That will be a project that takes much more time than the construction of a billion dollar mosque. We were now free to spend time looking around the mall that served as

63

entrance and exit for the Grand Mosque. We passed some high end souvenir shops, but saw no religious bookstores or even a presentation about Islam. This went right along with my growing sense that the mosque had little to do with religion beyond a surface level definition. The mall was a site for global consumerism, though most the goods on sale in souvenir shops like this one would have been most tempting for Gulf visitors, with the emphasis on pricey abayas, prayer carpets that served as wall hangings, and golden statues of running horses. It occurred to me that the religion of Islam was getting fixed onto the global success of the UAE and the Gulf broadly. The message here is that God is blessing this region, and so it’s right and good to

64

participate in this material overflow. No need to think to hard about participating in the luxury life. Another store had smaller souvenirs, such as this plate with an image of the Grand Mosque. The mosque shimmered in the store light, and the central domes again took on the appearance of bubbles ready to burst into the empty blue. We also saw framed images of the mosque, one in the midst of a dramatic lightning storm. Large photo books allowed the mosque and its world-record attributes to be set out for perusal in some public space. Its image was there on refrigerator magnets too. The point of the Grand Mosque is precisely this image. It’s hard to imagine a structure more reliant on the “wow” of an impression and the jaw-dropping expense of its built

65

details. Here in the entrance mall I again came across the souvenir lamps whose only point of reference is the Arabian Nights. Medieval Muslim clerics were never comfortable with the popular tales in this collection and they would’ve been stunned to learn that these stories would someday become the chief cultural remnant of their age. The tales of the Arabian Nights match the spirit of the fantasy structures of Dubai, and their presence even here at the Grand Mosque points to the takeover of Gulf Islam by a similar spirit of fantasy. The sobriety and seriousness of traditional Islam has been undermined by the decades-long bonanza of the global energy market, which appeared like a genie rising out of a bottle to the 20th century leaders of oil rich

66

lands. Our next stop was the Louvre Abu Dhabi, sited on the edge of the Arabian Gulf. On the approach to the museum, the turquoise water could be seen lapping against the modern building. The design feature that most captured the eye was the vast metal dome covering the museum, which acted as a contrast to the verticality in the region. Abu Dhabi had in effect rented the name “Louvre” until 2037, aiming to create a world class museum in the Islamic world. I arrived to this point skeptical. Wouldn’t the Louvre function as yet another showcase for the wealth of the ruling sheikhs? They’d probably be most interested in making a show of their ability to buy or rent world masterpieces. From the outside the Louvre’s dome had appeared to be an orderly

67

design drawing from the Islamic tradition of abstraction. On the inside, the dome dissolved into something more complex. My impression was that multiple patterns had been laid one on top of the other, and in fact, eight unique design layers were used to construct this dome, and those layers could be grouped into a stainless steel exterior shell and then an aluminum interior shell. Looking up, these design layers fit with each other in changing, even random ways. The dome had shifted from an impression of control on the outside to an interior view where control was hidden, though even now I searched for moments of pattern in the lattice. The Louvre Abu Dhabi was designed by renowned French architect Jean Nouvel. So we aren’t exactly

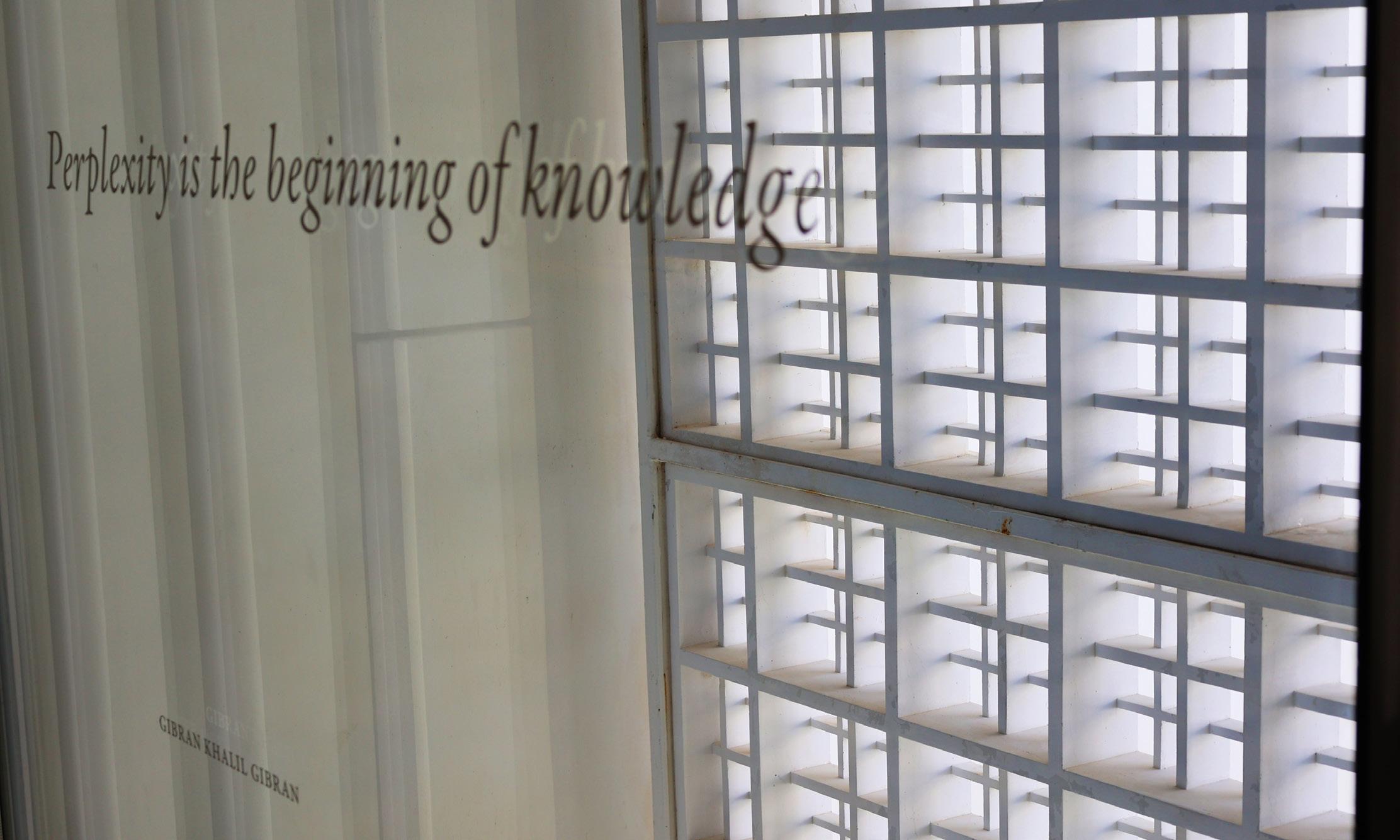

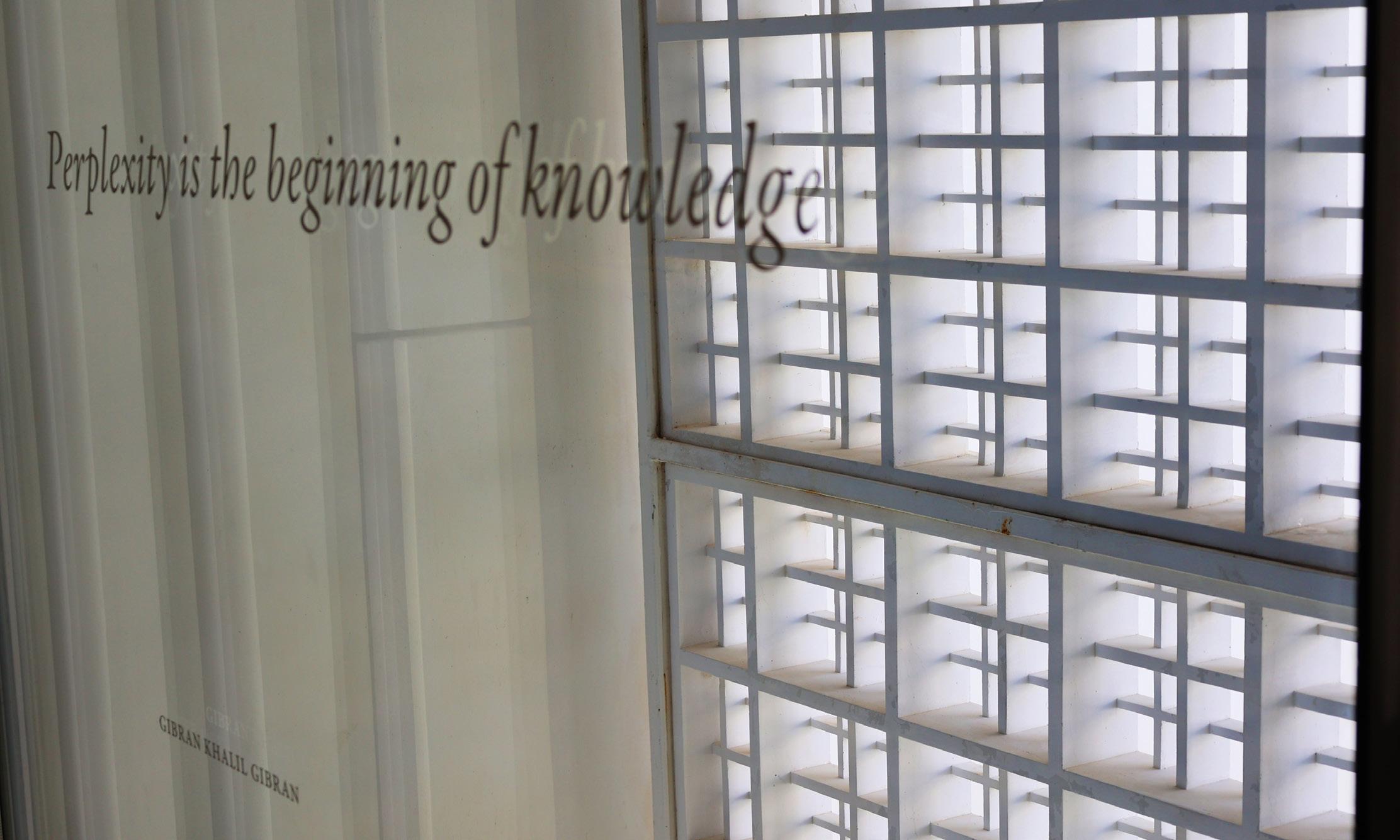

68

surprised that this new museum is housed in an elegant structure that mediates between traditional and modernist design. I was suprised to find that the art and messages of the museum (including quotations on the walls) worked together to help visitors interpret the intentions behind the museum’s design. This window-inscribed line from Lebanese-American writer Kahlil Gibran sets up a reason for the perplexity induced by the lattice dome: The experience of perplexity is the start of true thinking. This can be understood as an alternative to the epistemological authority of other times. Here as elsewhere the Louvre Abu Dhabi was more than a vanity project, but acted something like a secular sermon. One marker for contemporary art is a

69

drive to foster moments of beauty. The building (or painting, or sculpture) doesn’t demand a standard point of view, but accepts the smaller works of art that light and weather create. The modern work of art becomes a canvas for its environment.

In this photo that perplexing dome has scattered a spray of sun motes onto the facing wall, while the Gulf water contributes by reflecting its undulating lines onto the same wall. If we could package all this up it’d be an abstract work worthy of a museum wall. Then right around the corner is a white wall that absorbed and reflected the blue of facing sky and water. And yet... someone at another time of day or year will see something else, or notice another wall. The Louvre Abu Dhabi wasn’t constructed

70

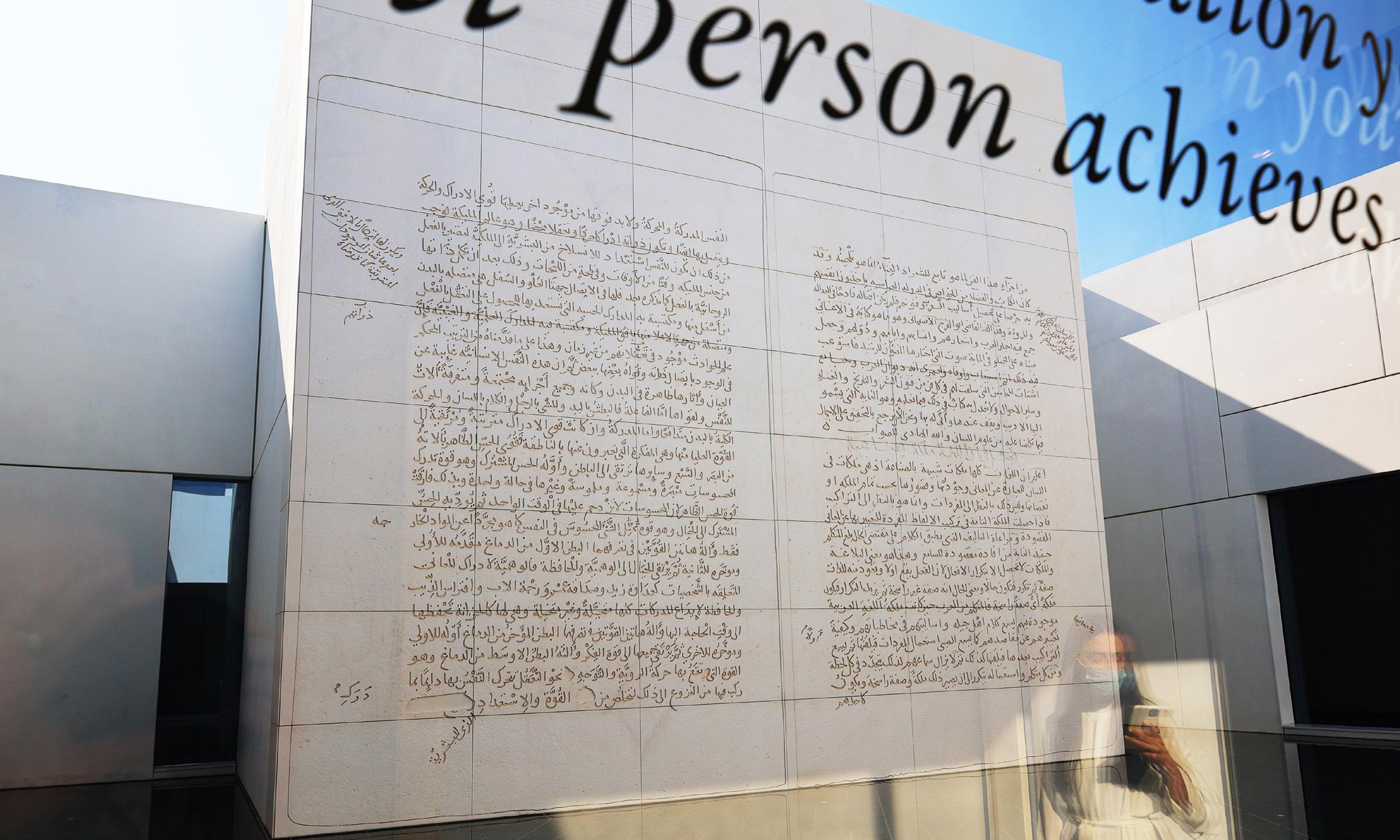

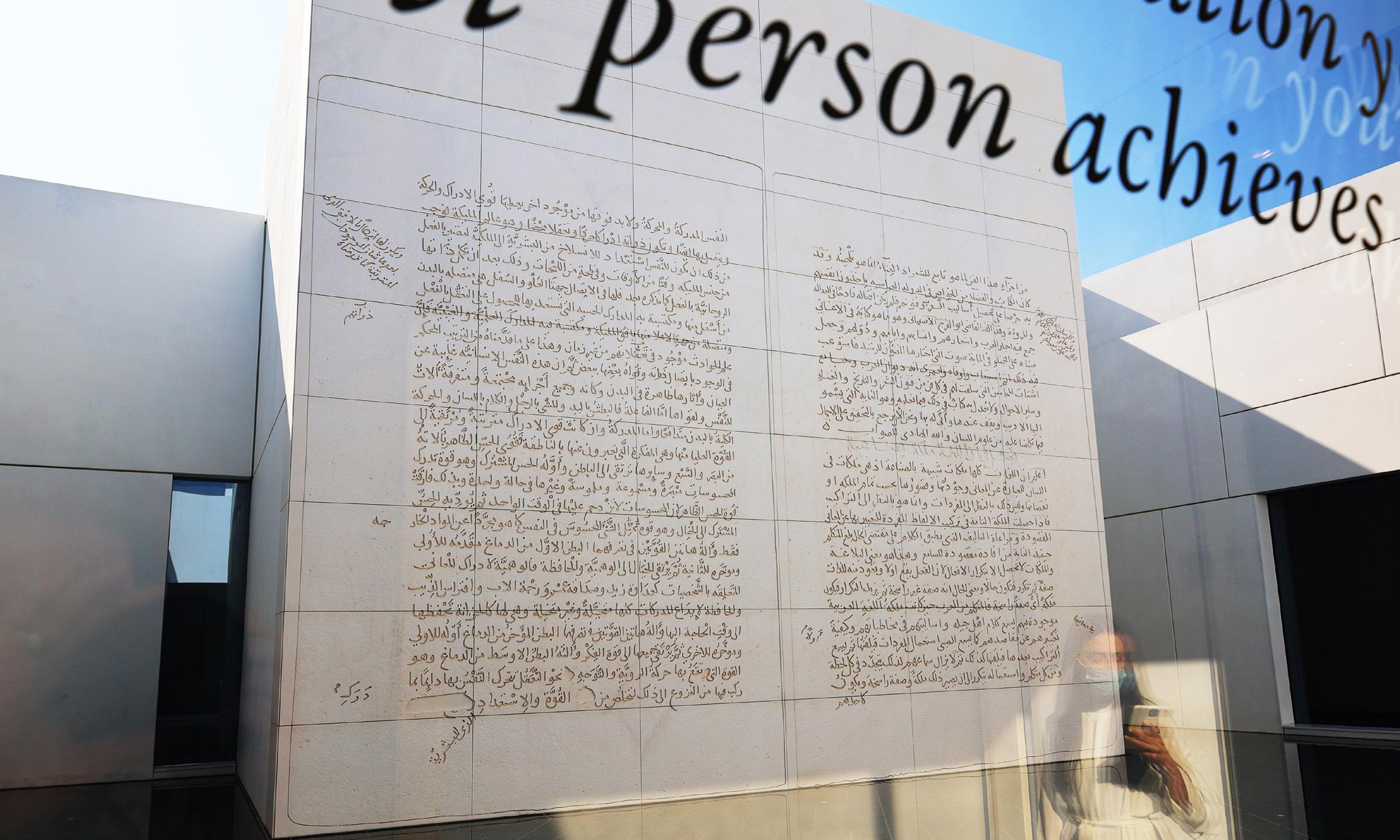

as a single large building, but as a village of box-like structures. Some of the boxes spilt out from under that dome into the open light of the sun. Moving through the museum we looked out at nearby boxes, and saw walls transformed into limestone likenesses of writing. One wall contained a a reproduction of an ancient cuneiform tablet that contained a creation myth, reminding visitors of the physical origin even of book culture. Other walls reproduced pages from actual books, including the above limestone relief of two facing Arabic pages from the Muqaddimah of medieval historian Ibn Khaldun. The presence of even marginal notes on these relief pages helped make the point that words too are things, even as all of culture appears to

71

dissolve into swipable images on our smart phones. The first room featured this juxtoposition of a series of paintings with a metal sculpture composed of Arabic calligraphy. The paintings were by 16th century artist Jacob de Backer and depicted the five liberal arts and three theological virtues. I’m not sure any other museum would open its entire collection with these paintings. The point appeared to be that this museum will take a directly educational role. The museum wasn’t about a pleasant outing in Abu Dhabi, but about learning to see the world in new ways. That contemporary sculpture is present perhaps to demonstrate that Arab culture and tradition has the inherent capability of embracing this universal modernity. We weren’t

72

limited to guessing the museum goals through its choice of art to display. At points its goals were stated directly, in English, Arabic, and French. This idea of the “universal” wasn’t a claim to the comprehensive nature of the collection. The museum doesn’t house a terribly large collection. It’s not one of those museums most profitably experienced over several long days. The Louvre Abu Dhabi was more like a three hour educational lecture. Its main points are represented by rooms that move forward in history or present a theme. The argument is that human experience through time is best understood as a unity, but this unity is expressed through varied cultural particulars. The rooms of the universal museum framed broad comparisons. This medieval

73

statue of Mary and Jesus sits next to exquisite tile calligraphy of the Quran. These two modes, figurative and textual, achieved similar aims: beautifying a place of worship and providing a point for meditation. Elsewhere a statue of a Roman emperor was set near one of the Buddha. Most cagey of all was perhaps the display of hand axes knacked by ancient humans, one from France, one from Algeria, and the last from Saudi Arabia. The museum doesn’t have the quantity of art to fill vast rooms, but uses its holdings to help visitors see cultures together and mark common human goals. At every turn we came across art given fresh resonance by its placement next to works from a different era or region. I was impressed with both the intelligence and

74

the cultural sensitivity of the unknown curator. I was relieved that the Louvre Abu Dhabi wasn’t another blunt display of wealth. Take for example this final room of the museum. Along the wall were a series of abstract paintings by American artist Cy Twombly. The label explained how these paintings were inspired by the idea of an oasis in Oman. Out front are the far more ancient rock carvings from the deserts of Arabia. Those rock-inscribed images appear both at home in the imagined oasis and like participants with the far later abstractions. Abu Dhabi in effect rented the word “Louvre” until 2037 at the price of €400 million. If we add in other costs like loans of art works and special exhibits, the total will approach €1 billion, making the Louvre

75

Abu Dhabi an expensive lecture on universal culture. The price only makes sense because of the global prestige of the actual Louvre. Yet the experience of these two museums couldn’t be more different. This view of the vast Napoleon Courtyard reveals what a monster the Paris Louvre is. Its immense and historic periphery was accented by I.M. Pei’s modernist glass pyramid. This is space that demands days of exploration and offers a fractal point of view on human history. The Louvre is so vast that it would be difficult to offer many clear lessons on humanity after going through its holdings. It could be argued that this vast museum is more about France than a universal vision of humanity. One famous work of art in the Paris Louvre is the Winged

76

Nike, standing on the prow of a ship. Its remains were discovered in 1863 during archaeological work on the island of Samothrace in the Aegean. Statue and prow date from the 2nd century BC, making it a rare Greek original. It’s been on prominent display since 1884, set at the top of this grand staircase, where it remains even now. The quality of this statue is such that there’s no desire to enrich the experience by a contrasting work from another time or place. That’s true about the Louvre broadly: it spends far more effort framing single great achievements than presenting juxtapositions that expand our notions about people and places. When unique works aren’t set within an isolating frame, they are grouped together in large rooms. This is a look

77

down the hall of Classical sculpture, at the Louvre. With far too many statues to take in, visitors must brush past the vast majority of works, though stopping in front of one or two that catch their interest. Since there are more than enough statues to fill this hall (and the room beyond), curators have no reason to mix in statues of ancient Egyptian kings or of the Buddha. Those statues will have their own grand sections in the museum. So the very riches of the Louvre make it harder to generate the surprises that are possible for a museum that makes due with fewer works (and ones of lesser importance). I made a start on the Paris Louvre’s Islamic Art collection, but I wasn’t able to devote another hour or two to seeing this final room crowded with

78

works of art. (Family plans limited my time.) Before I left I took this photo of the room I was passing up. It’s possible at the back to see deep blue samples of Iznik tiling from the Ottomans, and large Persian rugs on display on the right. After visiting the Abu Dhabi Louvre, I came to believe that this overflow of objects would have a greater impact if spread between a series of small global museums, where single objects would be magnified and the creativity of a curator could bring out deep connections. The point in this room was quantity and coverage, and visitors could leave feeling confident they’d surveyed some of the best art from the lands of Islam. The danger was that none of this would truly stick in the mind after moving on to another section,

79

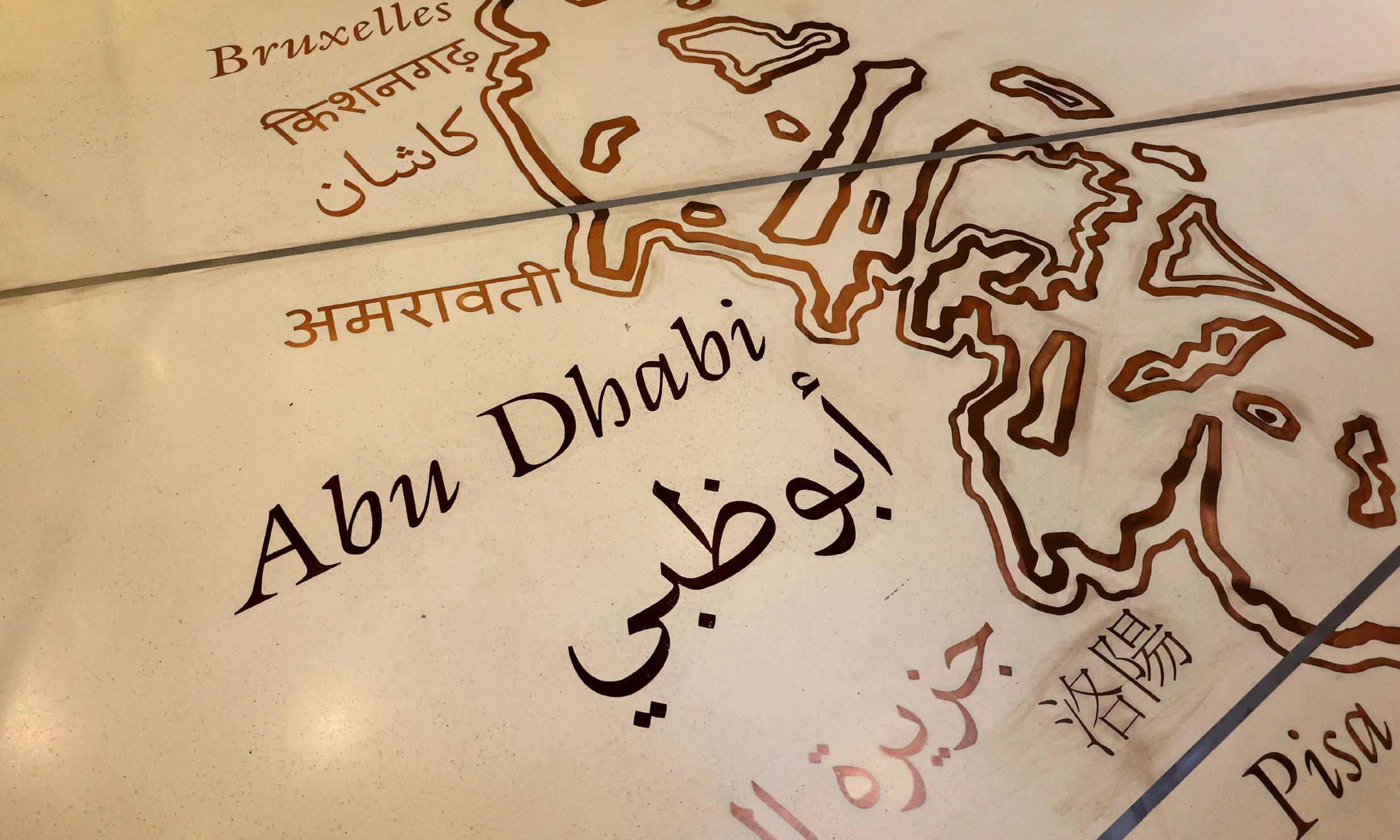

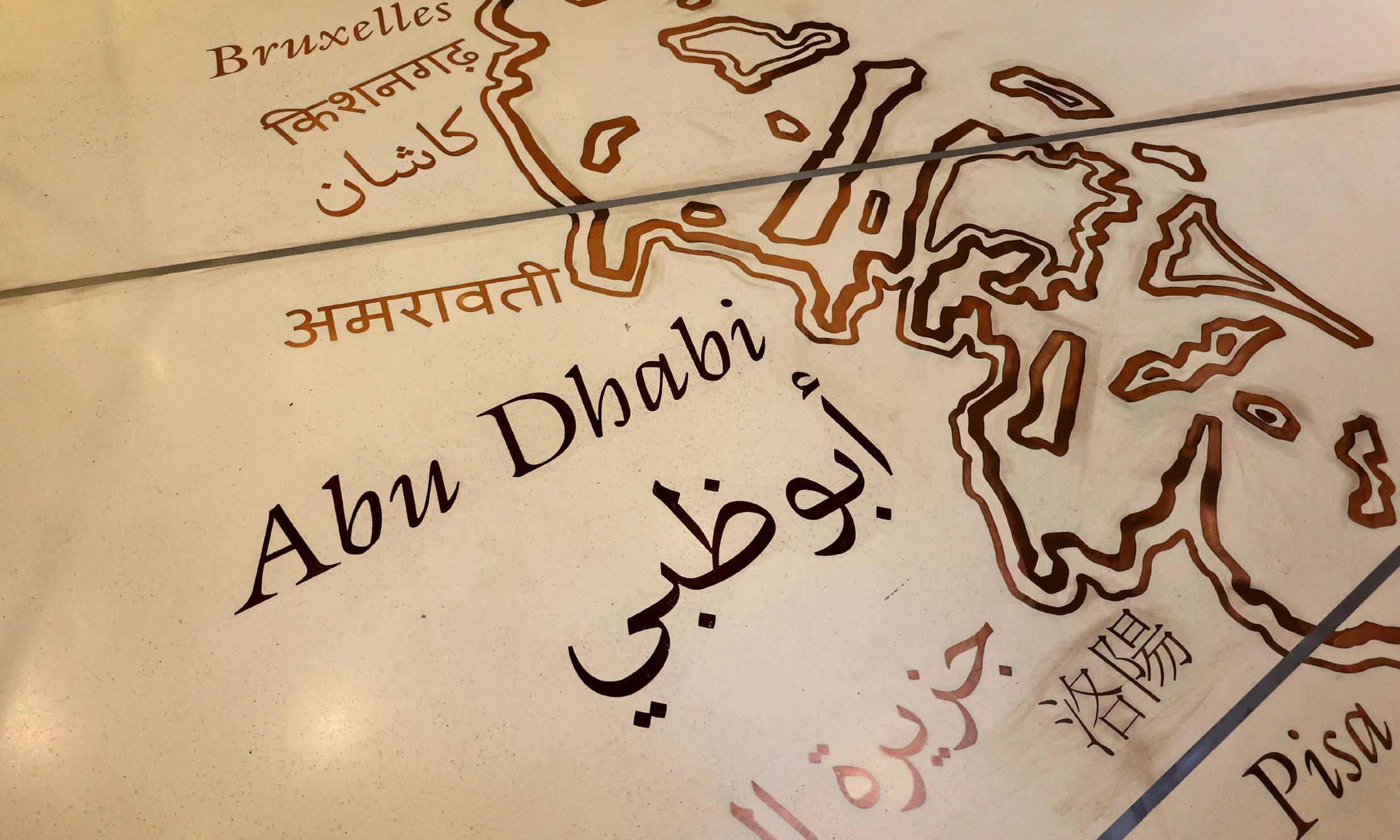

another culture. An opening room of the Louvre Abu Dhabi included an extended floor map, which took the Arabian coastline of the UAE and other states and set onto it the names of great artistic and commercial cities throughout history. These city names were written in the dominant script of their people. I walked this unfamiliar coastline and came to Abu Dhabi. The rest of the world had joined it along the coast. This was no longer the Trucial Coast, named by 19th century British colonial powers for the truces drawn up with leading sheikhs. It steps forward as a global coast, set along this line of great cities. The presence of an institution like the Louvre here underlines the implicit argument in this imagined map. It’s not just the Louvre that’s been

80

imported. Other cultural institutions such as New York University have arrived here as well through the construction of a “portal campus” in Abu Dhabi. This model of outpost building is hugely profitable to home institutions. For Abu Dhabi they represent a short-cut to cultural respectability. One outcome of the NYU/Abu Dhabi pairing is this Library of Arabic Literature, a series that publishes a critical Arabic text for works plus the English translation on the facing page. I try to buy the new volumes as they come out, and now the books span more than a shelf in my office. This publication project is underwritten by Abu Dhabi, whose place is marked by that fine gazelle sitting just above the symbol for NYU Press. Whatever the claim to a

81

Google Earth image

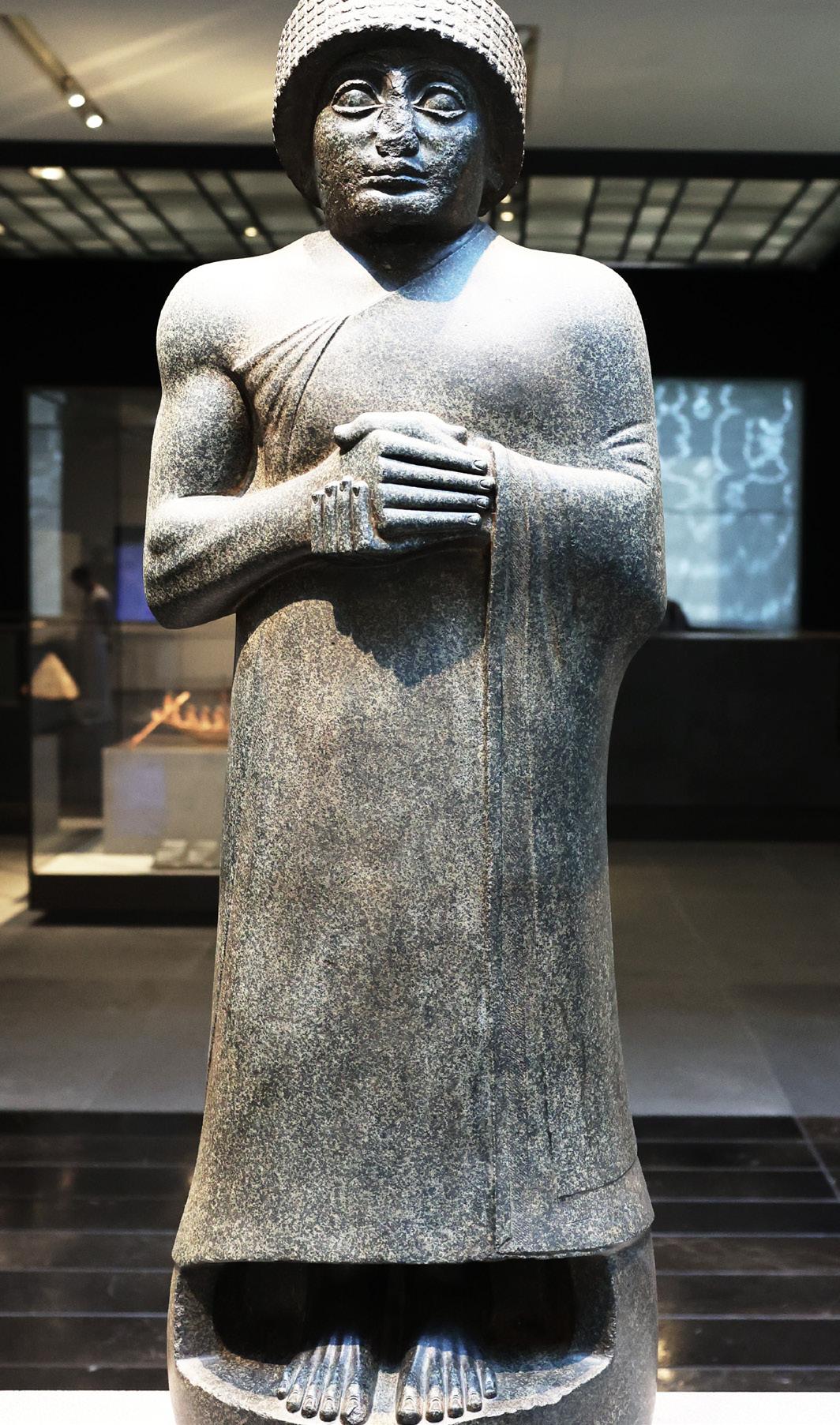

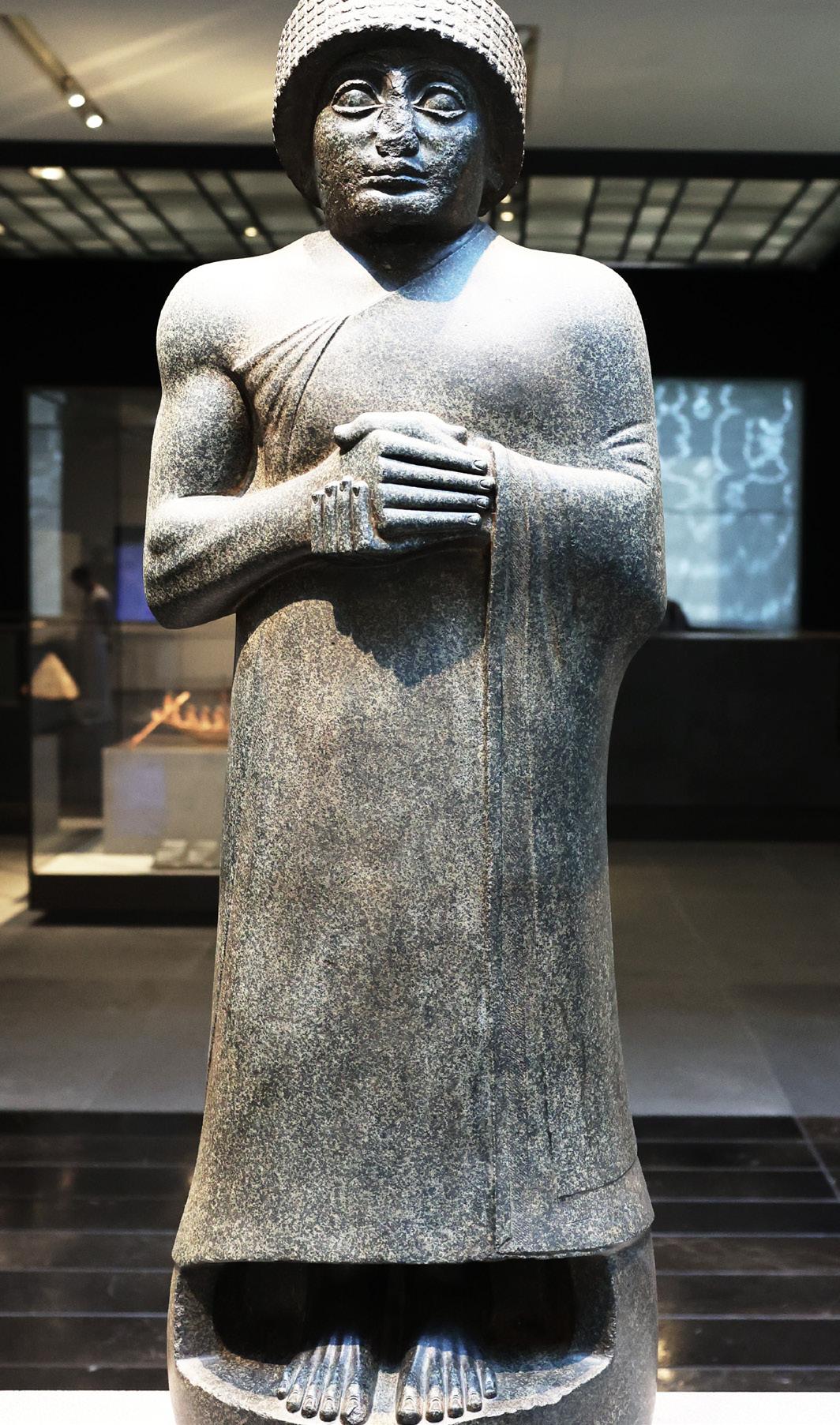

universal story, the objects in the Louvre Abu Dhabi were working to tell a more specific one too, pushing visitors to view the UAE (and its broader region) in a new light. For example, this statue of Gudea, Prince of Lagash around 2100 BC comes from southern Iraq (easily reached by continuing on to the end of the Arabian Gulf, then pushing further on the Tigris or Euphrates

82

Rivers.) Gudea had statues such as this carved from black diorite acquired from the land of Oman, neighbor of the UAE. Those eyes and clasped hands still project power and control. I had recently visited the UAE exhibit at Expo 2020, a self-presentation that included the nation’s space ambitions. It was no surprise to discover at this flagship museum finely crafted astrolabes. This one was the work of al-Zarkali, who lived in Andalusia in the 13th century. The Arabic on its face identifies the religious community out of which this tool was developed. Astrolabes already existed, but this later and more advanced version enabled the universal projection of the sky from any latitude. The precise mechanics of this tool were beyond the knowledge of visitors,

83

but it was readable by all as a symbol of scientific excellence. That’s a heritage the UAE wants to claim. It’s likely there were others walking through this museum right after having toured the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. Perhaps they had also been turned off by the non-stop display of wealth in the mosque. Anyone walking through this museum was reminded of the role of massive wealth in the production of museum quality objects. This table was created by the Medici family of Renaissance Florence. The label noted how the Medicis collected precious stones through their trading network, and used the stones to create “works rich in symbolism.” How is this so different from what we see in the UAE? The luxury life has produced some of

84

humanity’s greatest works of art—argue with the table if you don’t like that! The museum included much more than European art in its galleries. This Japanese painted screen from around 1625 pictures Portuguese traders arriving and off-loading goods from their ship. Curators had much Japanese art to choose from, including works from two and a half centuries of the Tokugawa Shogunate, when Japan was largely cut off from foreign trade and isolated from the world. Beginning in 1635 foreign ships were no longer welcome at Japanese ports. But the UAE wanted to project a positive view of global trade, and so this image of connection became the choice. Visitors are shown nothing that would color global connection as inauthentic, rather we see it

85

as the shared practice of powerful states throughout world history. This Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington from 1822 was bought by the UAE prior to the museum’s opening. So it wasn’t a passive loan of an artwork, but an acquisition they’d sought out. It was strange to run into this singular American face in Abu Dhabi. How should I process it in an environment where I was nonstop seeing portraits of the UAE’s founders? Does this image here historicize (and thus discount) the American project? Does the ideal of Democracy hold up for visitors? The rainbow on the left promises the world a new start, but that gilded frame and the painting’s presence here reminded that even this ideal American image is up for sale on the global market.

86

In the final galleries we came to examples of modern art, such as this Impressionist painting by Claude Monet, on loan from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Monet painted at least 19 versions of the Houses of Parliament in London, so visitors might well know another version. I’ve seen a bluer one at the Art Institute of Chicago (and used that painting to make a point in my visual essay on Dubai’s Expo 2020). Monet’s true interest is the ever-changing atmosphere, but always back there is a subject solid as the British state. It was painted by the artist in temporary exile because of war. This idea of creative work carried out in a foreign city is another theme embraced by the UAE, which sees itself as a global destination for the right kind of creative workers. It was

87

fitting that the museum presented (behind glass) this working globe, created in Venice in 1697. One could argue that this was the era when the globe came to be a fixed thing in the imagination of many. Yes, the globe still had blank spots, but its human expanse could be literally felt and traced out on a globe like this. All big cities are, by one definition, “global” since people and ideas from diverse places interact with each other in cities as far apart as Tokyo and Lagos. But Dubai and Abu Dhabi are global in another way. They consciously fashion themselves, whether by a World Expo pavilion or a new Louvre museum, as cities that epitomize and express a growing global culture. A closer look at this globe allowed for a view of the area now home to the

88

UAE. The Arabian Gulf was named here the “Gulf of Basra,” pointing to the importance of that city in southern Iraq that gave river access to Baghdad. This north coast of Arabia was once the sleepiest of global places. If the Louvre Abu Dhabi was presenting a universal story, it also wanted to sound out a regional sermon. The resentment that fueled 9/11 bomber Muhammad Atta (famously a hater of modern skyscrapers) is nowhere. The museum sermonizes about past power in this region and future thriving through active participation in global connections. It could be argued that this message is doing more to lessen extremism in this region than any recent military actions. I’m not claiming that every work of art in the Louvre

89

Abu Dhabi falls into one of a handful of categories, but the work of ingenius curators is clear at every turn. Their choices take visitors around the globe to see a common humanity, but succeed too in explaining why Abu Dhabi might be a valuable vantage from which to view this globe. We should notesome blind spots too. There is no prophetic questioning here of extreme wealth or dependence on the global oil economy. That might have been too much for the ruling sheikhs to accept: spending billions for a message that actually undermines their power. The setting of the Louvre and its museum cafe is another instance of its embrace of the current global reality. The wealthy sit quietly and scroll on their phones, while massive cruise ships dock

90

across the Gulf inlet. This Louvre takes all of this and gently frames it within a larger story. Back in Dubai, after our time in Abu Dhabi, we tried to see how close we could get to the Burj al-Arab without paying a ton of money. This photo shows the short answer: the guard station at the entrance lane. We got no further. The $2000+ nightly rate at this luxury hotel was steep, but less expensive options were possible. We could’ve gotten afternoon tea. We could’ve made a reservation for a meal at one of the restaurants. But by this time we’d been up in so many vista points and city frames that it felt extraneous. Other people apparently felt the same, and stopped at the guarded entrance to get a quick photo of themselves with the iconic hotel in back. We made

91

another approach to the Burj al-Arab, this time along the Jumeirah Public Beach. It felt somewhat novel to be in an area labeled as “public.” I wasn’t sure that word was in use here in Dubai. An Expo 2020 sign advertised that ongoing event. The public beach ended at the expansive construction site between us and the Burj al-Arab. Closer up the signage promised that this would become a “stunning luxury hotel” (designed to resemble a huge yacht at dock). A cordon of private luxury hotels is getting shaped all around the Burj al-Arab, not so tall that they distract from the iconic hotel from a distance, but amplifying its value by creating rooms with a view of the hotel and that exclusive private realm. The hotel would be named Jumeirah Marsa

92

(that last word means “harbor”). Near the construction zone I saw images of what it’d look like when finished. Those elegant curves turned out to be perfect for a line of infinity pools, giving the illusion of private, open space, no one above, no one below. Sky above, Arabian Gulf stretching out in front. The computer generated view included the famous Burj al-Arab to the side, but we get no look back at the public beach. Private yachts are shown out there in the water, and Jumeirah Marsa will have facilities for docking such yachts. If the global elite were to close their eyes and imagine some heavenly afterlife, they’d fashion a vision that looks something like this. If there was a Bible or Quran for the global elite, its English words would paint this picture.

93

Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque

Louvre Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi

Dukes: The Palm

The View

Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque

Louvre Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi

Dukes: The Palm

The View