Seeing the Effigy Mounds

Martyn Smith

Preface

This is a book about why it’s so difficult to see the effigy mounds of Wisconsin. That might seem a strange question to ask because these ancient mounds are present all around southern Wisconsin in state and city parks, so in one sense they are easy to see. But the mounds have become invisible to us. The conical and effigy mounds are by far the oldest human-built elements of the Wisconsin landscape, and they testify to a far older way of inhabiting this landscape. They are a reminder that there’s nothing inevitable about the way we use this land. Just as Native American peoples did a millennium or more in the past, we too express values and beliefs as we build up physical landscapes. Sustained consideration of the effigy mounds makes us more conscious of the choices we are making. But first we need to be able to see these mounds, and that’s the goal of this book: to show the mounds as they continue to exist in the midst of our modern landscapes. This book is a visual travel narrative. It comes out of years of thinking about (and teaching) the effigy mounds, but in the summer of 2020 during the Covid pandemic I felt a call to get in the car and visit these mound sites in succession. I realized it wasn’t just the mounds that were my story, but the context we have constructed around

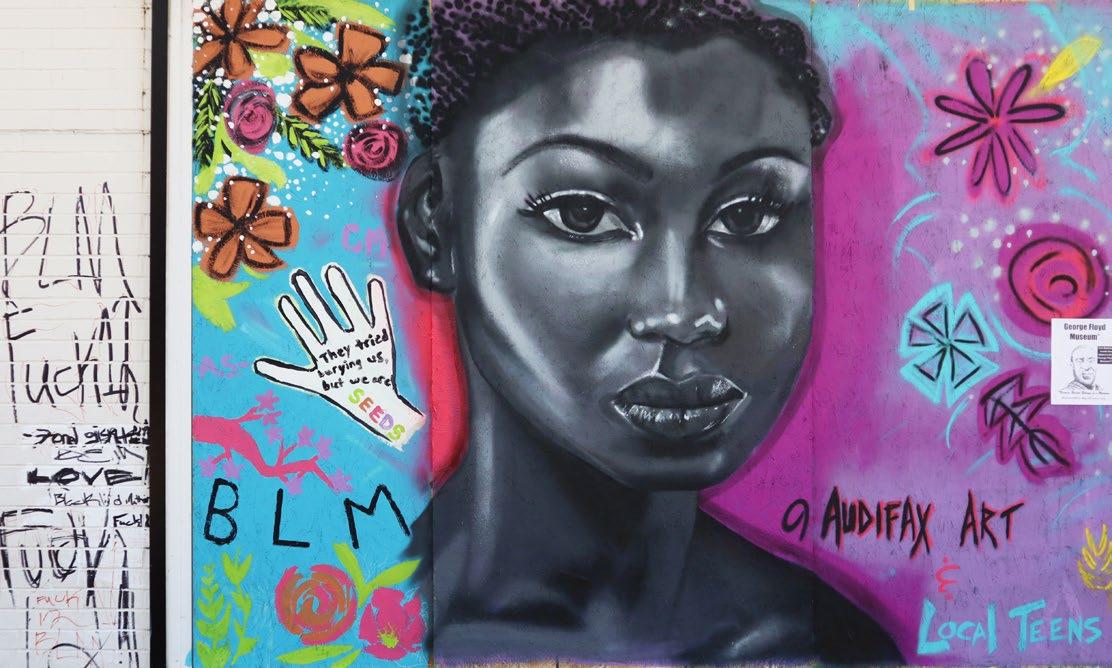

them, cloaking their presence. I took photos along the way to document the mounds and that context. This included signs and ephemera, along with residential or commercial developments. Along the way I stopped to see small town murals and baroque Veterans Memorials along state highways. At the end of it all I walked down a mostly deserted State Street in Madison and saw plywood covered shop windows bearing memorials for the recently murdered George Floyd. This trip turned out to be a documentary of an America that wasn’t able to find its footing in a time of social and environmental change.

I should say at the start that this book doesn’t offer a new archaeological interpretation of the effigy mounds. I follow the research and interpretations of scholars like Robert A. Birmingham and others mentioned in the text. This also isn’t an examination of the mounds as they function today in contemporary Native American cultures. I simply tried to see the mounds as they exist in our contemporary landscapes. Nobody has the perfect key to unlock the ancient meaning of the mounds, but that mystery is what makes them a challenge. Our most impressive buildings ask us to look up, but the effigy mounds always point our attention back to the land itself.

State Capitol

Arboretum

Lake Michigan Mississippi River

Lake Winnebago

Day 1

Day 2

Appleton

High Cliff State Park Fond Du Lac

Nitschke Mounds County Park

Fort Atkinson

Aztalan Lake Koshkonong Sites

Beloit

Janesville

Brodhead

Dickeyville

Nelson Dewey State Park

Effigy Mounds National Monument

Viroqua Cassville

Day 3

Richland Center Wisconsin River

Mendota Mental Health Institute Holy Wisdom Monastery

Governor Nelson State Park

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Milwaukee

Madison

Lake Michigan Mississippi River

Lake Winnebago

Day 1

Day 2

Appleton

High Cliff State Park Fond Du Lac

Nitschke Mounds County Park

Fort Atkinson

Aztalan Lake Koshkonong Sites

Beloit

Janesville

Brodhead

Dickeyville

Nelson Dewey State Park

Effigy Mounds National Monument

Viroqua Cassville

Day 3

Richland Center Wisconsin River

Mendota Mental Health Institute Holy Wisdom Monastery

Governor Nelson State Park

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Milwaukee

Madison

It’s rare for an ancient cultural system to fall neatly within modern political borders, but the effigy mounds are mostly encompassed by the borders of the state of Wisconsin. Some important mound sites bleed across the Mississippi River into Iowa as well as south across the border into Illinois, but the vast majority of the effigy mounds were constructed in the southern half of Wisconsin. Ancient Native American mounds are found in many places, but in Wisconsin the mounds were given distinct zoomorphic shapes like birds, panthers, turtles, and water spirits. For years I had been drawn to these mounds (my ideal bumper sticker would be one that reads “I break for effigy mounds”), but something

about the pandemic and our cultural moment pushed me to take a roadtrip to re-visit mound sites around Wisconsin. My goal wasn’t to get to the bottom of the deep history of the effigy mounds. That’s the goal of archaeologists. I wanted to see how these mounds functioned within contemporary American culture. The effigy mounds are some of the most unique archaeological remains in the US, and yet even Wisconsinites often know nothing about them. Why are they invisible to us? Answering this question would mean paying attention to the context of the mounds at the various sites, which included the signage that was often long overdue for replacement. At some sites the signs were newer and still in

good shape, but at others they were quite worn. I learned that there was no broadly accepted way to tell the story of the effigy mounds. I began my socially-distanced exploration of these mounds at the site closest to my home in Appleton.

South of Appleton is Lake Winnebago, a shallow but expansive inland lake. High Cliff State Park provides an overlook onto the lake, and out there on the horizon line—toward the right—it’s possible to make out the larger buildings in Appleton’s modest downtown. Today a scenic overlook like this is bound to be designated a state park, and include a campground and hiking trails. For Native Americans a millennium ago and longer these same natural features made it

a perfect site for a group of mounds, the earliest being conical mounds and then finally effigy mounds. The “high cliff” of High Cliff State Park was formed by an outcrop of the Niagara Escarpment. A tough cap of dolomitic limestone led to unequal erosion, and the result is what we recognize now as a cliff. Geological maps of the escarpment show a crescent that begins here in Wisconsin and then runs north into Ontario before curving back down to New York, at which point its cliffs form the famous Niagara Falls. This geological formation (especially with that cue provided by its name) prompts visitors to imagine themselves in the context of the North American continent. There’s a spatial resonance for us in that

word “Niagara.” This continent-wide vantage point wouldn’t have been available to the Native Americans who sited their burial mounds at the edge of these cliffs. The Antiquities of Wisconsin, published in 1855, was the first writing about the effigy mounds that can make a claim to continued historical validity. The author, Increase Lapham, included plates of his surveys of mound sites from around the state. He made it to Lake Winnebago and describes climbing this “formidable” ledge. It’s curious how the mounds Lapham depicts on top of the ledge don’t align well with what’s visible now at High Cliff State Park. For example, that bird mound in the center is nowhere to be seen, and the conical mounds

now present at the site aren’t represented on his survey. High Cliff State Park is easy to pull up on Google Maps. It’s possible to get directions or to browse from overhead the layout of the park. Near the center of the image is the marina and a grassy area running down to the shore. Above that is a forested area, and amidst the trees on the far right is the location of the effigy mounds. The effigy mounds are a bad match for Google’s search system. The mounds aren’t a business with a website. They aren’t a campsite that can be reserved on the Wisconsin State Parks website. They aren’t monumental in a way that makes them a popular landmark. The mounds are an example of features in the American

landscape that don’t play well with Google. Along the ledge of the Niagara Escarpment runs a trail. On a warm summer day lots of people come here for a short hike, often bringing their dog along. What draws people is the chance for outdoor exercise with occasional scenic views out over the lake. Along this popular route I came to a smaller trail promising effigy mounds, and immediately I came upon the low signs marking the mounds. The signs here haven’t been updated in a long time. They function as low key markers for sites that aren’t expected to get much attention. Only a subset of visitors will take the quick detour to look at the mounds, and an even smaller group will take any real interest

and linger at the site. Above is the actual mound marked by that “panther mound” sign. It’s not always easy to see the effigy mounds, but it’s possible here to just make out (maybe?) a long mound extending ahead and then two legs coming from that body (toward the forest). The mound area is covered with mowed grass in order to set it apart from the messy underbrush in the forest. Even with the grass cover the mound doesn’t exactly “pop” visually. These effigy mounds aren’t Instagram friendly since they can’t be seen from any single vantage point and used as a background for a selfie, but rather demand to be experienced from multiple angles or even imagined from above. A kind of slow looking is

required. The effigy mounds were built during the Late Woodland period, which covered a period from about 500–1200 AD. The effigy mounds represented a late flowering of this Late Woodland culture, constructed largely between 900–1200 AD. Then construction of these mounds abruptly ends. The effigy mounds signalled a new cultural development, but conical mounds had been present in the landscape for many centuries, back well into the Middle Woodland period (100 BC–500 AD). These simple conical mounds are present at High Cliff State Park as well, visible in this photo as a gentle bump in the grassy area. The effigy mound builders knew they were part of a far-reaching tradition of sacred

space, and continued this tradition that they inherited even as they innovated with mound design. So far as we know, all effigy mound groups served as burial sites, something like an ancient cemetery. We know this because as European settlers came to Wisconsin in the mid-19th century they dug into the effigy mounds and found human remains. That cavalier treatment of the ancient dead was deeply hurtful to Native Americans, some of whom understand themselves as descendants of the mound builders. The mounds are now protected by state law, as this sign at High Cliff points out. Though there’s much we don’t understand about who was buried in these mounds, and why specific effigy animals

were used, there’s broad agreement that their fundamental purpose was to bury the dead. Many effigy mound sites have now been made into parks. In the case of High Cliff that means a state park, but in other cases we’ll see that they are set in county or city parks. The most common feature to find at sites with effigy mounds is a bench set up to take in a grand view. It’s not the case that mounds on their own have generated park status, or that they inspired the creation of benches.

Rather, parks and benches are typical modern responses to the types of sites that Native Americans chose for sacred burial sites. This ought to remind us that parks aren’t afterthoughts in city design, but a contemporary way of responding

to that deeply human feeling of the sacred. In 1961, a few years after High Cliff became a state park, this larger than life statue of Chief Red Bird was set in place. Red Bird is labeled on the plaque as “Chief of the Winnebagos” (a tribe now known as the Ho-Chunk). The main events of Red Bird’s life took place out in eastern Wisconsin, but since this was “Lake

Winnebago” it seemed fitting to memorialize a leader from that tribe here. The statue is more interested in the image of heroic Native Americans than any historical event. The plaque fixed to the base of the statue of Chief Red Bird has nothing to say about his biography or the history of his tribe. It emphasizes the “authentic tribal costume of 1827.” The statue’s details in clothing were made possible by a published image of Red Bird, which depicted him in 1827 surrendering to federal authorities to avoid a broader war. He was dressed in white robes and he carried an elaborate peace pipe. That image was closely copied for this 1961 statue. It depicted Red Bird at a particular moment, but the statue snatches Red

Bird out of any specific time or place. He’s becomes instead an authentic “Wisconsin Indian.” Unlike the effigy mounds, Google Earth prominently labels the “Lime Kiln Ruins.” These ruins are reached via a short hike. There’s a picturesque quality to the ruins since they seem to emerge from the hillside. These structures were built by the Western Lime and Cement Company, in operation from 1856 to 1956 (at which time the land was taken over to become a park). The company quarried limestone from the escarpment and then crushed and baked the rock until it became quick lime. In many parts of the world it’d be hard to imagine a cement plant as a picturesque ruin, but in Wisconsin nothing is very

old (except for the effigy mounds further up the cliff!). Right down the way from High Cliff State Park is a series of housing developments now incorporated into the nearby town of Sherwood. It’s necessary to drive past these houses to reach High Cliff State Park and the mounds. These houses begin to answer the question as to why it’s so difficult to see the effigy mounds. The first answer to that question is that the mounds are dwarfed by contemporary development. Driving past the golf course I saw artificial mounds and sand traps on a golf course, all made highly visible by their placement upon a manicured lawn. Just that one bunker is far more visible than all the mounds up on top of High Cliff.

We hardly stop to consider the earth-moving energy that has transformed the modern American landscape. The houses near High Cliff State Park all looked the same. An American child’s drawing of a house will commonly feature a box with a triangle on top, and these houses seem designed to multiply that elemental triangle-over-box design. No other type of structure is so strongly associated with the triangle in the American imagination. These houses aren’t meant to stand out as unique, or as rooted in some particular place, but to be interchangeable so that one family can leave and another move in with a minimum of friction. The lawns and curving streets speak the language of the American suburban ideal,

totally distinct from the view of land expressed by the effigy mounds on the escarpment. One home owner had set up a flag toward the edge of an extended private lawn. Within a circular stone border stood a flagpole with an American flag waving at the top. The line of trees beyond the grass wasn’t the edge of some deep forest, but a simple border that visually isolated this residential development from a similar one on the other side. The houses divulged little about the owners, but they occasionally announced that the owners were “proud to be an American” through a flag. In the context of this essay on the effigy mounds, this serves as a reminder that humans have always used the earth for the display of

identity and values. After my visit to High Cliff State Park I was off on my longer journey around southern Wisconsin. I stopped in the town of Sherwood for gas, and with mounds on my mind I could now see the massive earth moving that had been necessary even for this average-sized gas station. That straight grassy berm would’ve demanded heavy machinery and energy. This bright Mobil station offered not just fuel but “Synergy,” and there were signs for smart phone apps that would reward repeat customers. Whatever the high-tech exterior shell, what this station sells is the energy to live in a rural area and commute to work, as well as energy to move earth and build. As I drove south along the

eastern side of Lake Winnebago I passed though an agricultural landscape. Some of the farm houses were decked out with Trump 2020 flags. I passed an extended range of windmills capturing energy. A ghostly sound surrounded me as I stood on the side of the road for this photo, and the idea occurred to me that this was an energy landscape. The fields were producing calories for human and animal consumption (and some of the corn from these fields would be mixed into fuel as ethanol). The windmills were another kind of energy harvest. The earth including its atmosphere was being brought steadily under the yoke of energy production, becoming a support for our modern lives. My next stop was at

Taylor Park in Fond du Lac, the city at the southern tip of Lake Winnebago. The park was a large square within an older neighborhood. It contained tennis courts, a swimming pool, and a pavilion. Three conical mounds sat right alongside the fenced-in tennis courts. The grass was mottled by the sun, and I had to search for the angle that would allow the gentle curve of a mound to appear in a photo. The diameter of the three mounds was about 40 feet, and they rose 2½ feet from the plain of the grass. These mounds are by far the oldest human structures in Fond du Lac, but they were mostly a footnote to activities in the park, which was a pattern at many mound sites. No one quite knows what to do with the

presence of mounds. The signage for mounds around Wisconsin is oddly diverse. The effigy mounds would feel more like a single story if a unified style were used for these signs around the state. This sign was no doubt created by the group that oversees the small Taylor Park, and it contains some errors. First, the mound builders of the Late Woodland period weren’t immigrants to the region. Conical mounds had been used for centuries, but between 900-1200 AD the Woodland peoples began to build these effigy mounds. This wasn’t a case of new arrivals but of cultural change. Second, these mounds weren’t so much located out in woodlands and prairies as on sites that overlook bodies of water or high

ground near natural springs. All mound signs ought to push visitors to ask a simple question: why were mounds built here? What was sacred about this particular space? This bird’s eye view of Fond du Lac was created in 1867. The city was only incorporated in 1852, so it was at this point going on just fifteen years of growth. The main street, heading straight toward Lake Winnebago, is visible along the top of the image. At the bottom center is an empty wooded square that would later become Taylor Park. It’s unique on the map for its overgrown look. It appears that this was a wetland at that time, and no doubt residents were aware of the mounds. The square was not yet a city park, but even now there was

something numinous about the space that kept it from development, and the fitting thing for space like this was evidently to make it a public park. According to the brief history put online by the Friends of Taylor Park, before his death in 1865

Jared Morey Taylor envisioned this piece of land as a city park. Then in 1893 the son sold the land to the city. In a plat book from 1910 the park appears as a standard issue city park, with a pond sitting in the center. This memorial plaque sets Taylor at the head of the relevant local history, but the striking glacial erratic that holds the plaque hints at a far deeper timeline for this land, one that involves ice age geology, miraculous springs, and the presence of Native American

burials. Today Taylor Park feels like a perfect neighborhood park. Old houses line each side of its perimeter. At its center is a community swimming pool. The presence of Native American mounds here seems like happenstance, but if we step back for a deeper broader we see that the park is near the west branch of the Fond du Lac River, which flows into Lake Winnebago. That swimming pool was the replacement for what was once a naturally forming pond. So at one time this was a spring-fed wetland whose water flowed into the nearby river. The mound builders were extraordinarily sensitive to sites of natural abundance. These connections are now hidden by the city layout, but thoughtful encounters with

ancient mounds would make us more conscious of the underlying flow and logic of a landscape. There’s a second historic structure in Taylor Park: the pavilion, built in 1907, and restored in the 2000s. A document prepared by the Fond du Lac Historic Preservation Committee calls the pavilion an example of Late Victorian style, with its gabled roofs and cupola. I have no argument against its preservation, but we should remember what the pavilion meant in context. We’ve seen that in its earliest stages Taylor Park was a wetland, and then it was transformed into neighborhood space. The water was step-by-step regularized into a pond and then a pool, paths were created, and this pavilion stood as a final

symbol for civic control over this natural space. From Taylor Park I headed south toward the first extensive mound group of this trip. It used to be that when I drove across a state I’d have the Rand McNally Road Atlas open on the empty seat beside me, or even on my lap. I’ve long enjoyed getting off Interstate Highways to drive on smaller state or county roads, and this required some facility with the road atlas. Now most of this navigation is done with a cell phone. I type in a destination on Google Maps, and a choice of routes shows up. In this case the shortest route was the one that got me off Highway 41. Then I set my cell phone down beside me and followed its regular advice. With this ease of direction

comes indifference to the physical landscape through which I am moving. Increase Lapham included a map of the state of Wisconsin in his study of Native American mounds, The Antiquities of Wisconsin. He used dots to indicate known mound groups, many of which no longer exist. From this map it’s possible to see the extent to which the mound groups followed water systems. These systems of flow served as both transportation routes and resource banks. When ancient Native Americans imagined this area they saw rivers and wetlands. Their point of view is impossible for us to recoup since the land is wholly overlaid with roads, the bodies of water standing more as obstacles to getting somewhere than

as vital routes. The Nitschke mound group is located just west of the expansive wetlands of the Horicon Marsh. This group is now maintained as a county park. This dense group contains 37 visible mounds. This isn’t a “complete” mound group since many mounds were lost due to agricultural use of the land. Thousands of mounds across the state were simply plowed over, and so lost to us. The Nitschke group was first described in 1892, and then in 1927 the remaining mounds were mapped and measured by W.C. McKern of the Milwaukee Public Museum. Since 2003 there’s been significant work clearing brush and creating new trails and signs that allow visitors to see the mounds more clearly.

McKern had found 37 mounds and several (in purple above) for which there were traces but which were no longer visible. A further look at the diagram and you might notice how in the north the mounds end abruptly at a property line.

That line represents the place where an agricultural field was cultivated year over year. The mounds that continued in that direction are lost. The Nitschke Mound Group offers a reminder of both how densely packed effigy mounds could be as well as clear evidence for the loss of likely more than half the effigy mounds that once existed. That serves as another answer as to why the mounds are invisible today: they have largely been erased from the landscape. Here and

elsewhere we have fragments. This printed metal sign was set up so that visitors would see it as they started the trail through the Nitschke mound group. The trail is dedicated to the memory of Don Gehrke, who volunteered labor to make these mounds a place people would want to visit. It’s remarkable to imagine this local man coming week after week to clear trails. I like reading that he enjoyed “contemplating

the mystery of the site.” It’s a gift to be so connected to a place. I walked around the Nitschke mounds on trails mowed into the grass. Contemporary Native Americans see the mounds as sacred, so people are discouraged from tramping around on top of the mounds. This mown grass makes clear a proper trail through the mounds and the unmown grass discourages groups or families from treating the actual mounds as a place for a picnic and games. This afternoon I was the only person here, and that turned out to be typical for mounds sites, which were largely off the beaten path of tourism. That’s also what continued to draw me to the mounds: they aren’t easy to assimilate into contemporary

American culture, which is another way of saying that they stand as a challenge to that culture. The signage at the Nitschke mounds was new. The metal plates were computer designed and printed so that they resembled nothing so much as PowerPoint slides with boxed images and text. This sign explained what was right in front of me: this low mound is a buffalo (or bear) shaped effigy mound. The location of the mound in the larger group is illustrated on the left, and its exact measurements given. In addition, since this mound was excavated back in 1927 (something no longer allowed), there’s information about the burial pits present within the mound. This information—even about the

shape—I took on trust, since what was in front of me was an indistinct swell. Above is a photo of what it looks like to stand inside the Nitschke mound group. The individual mounds have been mapped out, and they are so close that at times theis shapes overlap. As I followed the trail into the group, I was soon standing amidst a series of hummocky curving forms. Nothing in nature makes the ground look quite like this, so European settlers never questioned that the mounds were made by humans. But these effigy shapes don’t dominate this landscape either. I suspect the ancient mound builders had a mental map that made the landscape feel alive with living shapes. No doubt they were expert

readers of these mound groups. Grass is today the dominant way of presenting the effigy mounds, and this held true for the Nitschke group. The low cover of grass allows for the gentle curves of mounds to appear. But all this grass connects us to the contemporary norms of park grounds. The strange thing about this choice of grass is that ancient mound builders couldn’t possibly have imagined the mounds like this. Our idea of the grassy lawn developed in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and of course this thin lawn grass isn’t native to Wisconsin. A closer look at the grass revealed a dense mixture with red clover and dandelions, both invasive plants from Europe that have successfully colonized the

North American ground. Not all the mounds were contained within the open grass here at Nitschke. As I continued along the path, heading to the nearby spring, I entered an area of dense undergrowth. A sign absurdly presented me with information about a panther mound that was impossible to see. This demonstrates precisely why open grass is used for mounds: the alternative is to let them be swallowed up by woody shrubs. All this undergrowth consists mostly of buckthorn, an invasive shrubby tree that’s ubiquitous in Wisconsin. It takes over the understory of forested areas. It has been common in North America since the 1800s, but it was unknown to the ancient mound builders. The Nitschke

group was built on a swell of land near a wetland. This wetland is fed by a naturally occuring spring where water appeared to flow out of the rocky ground. I stopped and listened to the water flowing seemingly from nowhere, and the miraculous quality of a site like this dawned on me. We have an easier time understanding the mounds built to overlook grand views over lakes or rivers. These views get translated into modern parks. Since contemporary life is mostly alienated from ecological sources of life, we’ve lost the sense of awe that Native Americans felt at the site of a spring where water naturally flows. That question “why here?” is always worthwhile for the mounds, and never failed to bring me closer to

the actual landscape. Near the mounds I also came across this boulder. A rock like this is in the landscape of southern Wisconsin will usually be an erratic left behind by retreating glaciers. Contemporary parks often put such erratics on display, though here the boulder was left in place. Encircling weeds were held back by weed killing chemicals. This rock was visible in 1927 when the mounds were surveyed (as evidenced in photographs), and there’s no reason to think the mound builders weren’t also aware of its presence. A boulder like this also seems to come from nowhere, and although the glacial geology that fully explains it’s presence would’ve been unknown to the mound builders, it nevertheless had

a miraculous quality not so different from that nearby spring. My next stop was Aztalan, a site located roughly between the cities of Milwaukee and Madison. Its entrance is marked by three separate markers. The brown sign is a Wisconsin State Historical Marker, connecting Aztalan to almost 600 other such markers around the state. The metal plaque to its left goes back to 1927 and notes that the mounds were first described by N.F. Hyer in the Milwaukee Advertiser in 1837.

The name Aztalan came from an early story about the Aztecs having a homeland in the north, and early writers jumped to the conclusion that this was the Aztec homeland. The plaque on the right is from 1964 and notes that Aztalan has

been designated a National Historic Landmark. What makes Aztalan unique in Wisconsin is the fact that it was the site of a good-sized settlement. At its heart was this impressive temple mound. The mound is still easily visible, though its lines were sharper in the mid-19th century when Increase Lapham made his survey. The presence of a temple mound signals that this was a culture quite distinct from that of the effigy mound builders. This settlement of Aztalan flourished during the same years as the mounds were being built, but it represents a different way of occupying and imagining the landscape. A temple implies hierarchy and organized rituals. It also implies a degree of stability that we don’t see in the

effigy mounds. Aztalan represents another lifeway that coexisted with that of the effigy mound builders. The signage at Aztalan is better than at any of the effigy mound sites in Wisconsin. Aztalan is a National Historic Landmark and so has access to federal funding, but something else is at play: Aztalan is easier for us to imagine. It was the site for a permanent settlement, and artistic recreations of it (based on archaeological work) show small houses, each with a warm fire at its center. It’s a world that’s distant, but familiar too. The effigy mounds, in contrast, are symbols of a less settled lifeway built around the rhythms of the year, including semi-permanent small villages, seasonal gatherings at sacred sites, and

the pursuit of resources like deer. Like other mound sites around Wisconsin, Aztalan is given contemporary shape by paths of mown grass. I followed these paths around the site, and at intervals I came across illustrated signs that filled in some aspect of ancient Native American life in this settlement. The signs covered all aspects of their lives: agricultural practices, the reality of warfare, the remains of small houses, and more. These grounds function as an open air museum.

The choice to let the central plaza be taken over by prairie grass would not reflect historic Aztalan. These central areas were once important social and ceremonial grounds. This current prairie provides empty space that our modern

imaginations can populate with ancient life, aided by interpretive signs. The most notable feature of Aztalan State Park as it now stands are the stockade walls made of bare tree trunks. This stockade surrounded the entire settlement, and the space between the trunks was tightly filled in with branches and covered with a mixture of clay and grass. It clearly functioned as a solid defensive wall. Something of the imposing size of this wall is communicated by its full-scale recreation with these bare trunks. The wall tells us two things about the settlement: 1) the labor of building this wall proves the permanent nature of this settlement, and 2) it was highly important to keep some people out, and so we know this

settlement had enemies. The Crawfish River flows beside the Aztalan site. The Crawfish flows into the Rock River, which in turn flows into the Mississippi River down around the Quad Cities region of Illinois and Iowa. This river would’ve functioned as a highway reaching up from the south, where the stronghold of this Mississippian culture was located. In addition the river was a source for fish, caught in weirs and other traps. The protein from fish supplemented the corn and squash grown intensively on nearby land just outside the stockade. This deep reliance on agriculture and fish is another difference between the cultures of Aztalan and the effigy mound builders. Increase Lapham surveyed Aztalan

in 1850 and this gives us our earliest reliable image of its layout. It’s clear why it was a baffling site for 19th century visitors. The remains of the exterior stockade wall were clear. Lapham reports finding pieces of “hard reddish clay” that we now recognize as the covering material of the stockade wall. The question arises as to what kind of place Aztalan was, and Lapham believed that its small size meant it was never a city. He speculated that it might have been “a kind of Mecca, to which a periodical pilgrimage was prescribed...” Archaeologists today suggest it functioned like a later fur trading outpost, with a permanent but small population living and working here year round. Extending out to the west

of the enclosure was a line of conical mounds along a ridge. On the lower portion of the ridge was a second line of conical mounds. Archaeological excavations in the 20th century demonstrated that this main line of conical mounds weren’t the expected burial mounds, but rather mounds heaped over sites where tall wooden posts had stood. In some cases the lower portions of these posts was still in place. The presence of such a post indicates seasonal ceremonies, and alerts us again to the “foreignness” of Aztalan at this time. That smaller, second line of conical mounds, however, did contain burials, likely pre-dating Aztalan itself. So we can glimpse in this contrast of mounds an arriving culture taking

over an earlier site. An informational sign at Aztalan begins: “The stockade suggests on-going conflict during Aztalan’s occupation.” It seems pretty obvious that you don’t build a huge wall around a settlement unless you fear being overrun. A skull with an embedded arrow point serves as direct evidence of warfare, and that find is supplemented by numerous discarded human bones. It appears that Aztalan was a contested site, and the word “occupation” should be taken seriously. As opposed to the effigy mounds builders, who were indigenous to southern Wisconsin, the site of Aztalan speaks the language of a colonizing power, present on the land to extract resources. This also serves as a reminder that

there was no unified ancient Native American culture, but in fact competing groups with clashing societal values. Above is theh site of Aztalan as it looks from atop the large temple mound. The stockade on the far side gives a feel for the site’s dimensions. The smaller platform mound at the opposite corner was used for important burials. Aztalan was laid out according to a system, and when we look for the origin of this system we are drawn toward a larger North American story. The ultimate model for Aztalan is most clearly seen at Cahokia outside St. Louis, but smaller versions turn up around the interior of North America. The Mississippian mound sites range from Florida along the Gulf Coast up to

Georgia and Alabama, and then north into Missouri and Illinois. These sites represent a wide reaching ancient civilization. On a trip some years earlier I had visited Monks Mound at Cahokia, the city at the center of this civilization.

From Monks Mound it was possible to see St. Louis on the other side of the Mississippi River. There’s no surprise that this would be the setting of both an ancient and modern city since it’s just below the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. St. Louis’s famous Arch commemorates the pioneer spirit of America’s westward expansion. The Lewis and Clark expedition to explore the western United States began here at St. Louis. The north-south flow of the

Mississippi serves as a natural east-west division line for the continent. By some ironic twist the monument celebrating that forward movement sits within sight of Cahokia, the great earthen symbol calling us to consider a deeper past centered right here. A group of Trappist Monks came to Cahokia in the early 1900s, in hope of offering education for Native American youth. This Trappist community was for a while centered at Cahokia, and for this reason the central mound got the name “Monks Mound.” This large mound has the same base perimeter as the Great Pyramid in Egypt, but since it was constructed of earth it has proven far more difficult to maintain. Construction of the mound began

around 900 AD, and it continued to be enlarged through the centuries that Cahokia flourished as a city. Unlike the Egyptian pyramids, this was not a burial site but a platform for a temple or residence. The Cahokia Museum included this wall-sized portrait of the city in its time of flourishing. Residential structures surrounded the city, but its central area was defined by large mounds. Monuments express power by the implied labor that went into their construction. Millions of hours of labor were devoted to the construction of these platform mounds, and once completed they broadcast far and wide the presence of a ruling power that could coerce so many people. Such mounds require power over the bodies

of laborers, then they come to represent the presence of that power. Finally, they become sites for rituals that reenact and reaffirm that power. The Cahokia Museum also presented a graphic depicting what we know about the social hierarchy of ancient Mississippian society. Even in devising this image, the artist resorted to raised platforms in order to make relative status clear. Humans intuitively grasp the idea that elevation translates into status. The birdman imagery on a sandstone tablet found in an excavation hints at the mythical imagery that once

underwrote this social hierarchy. Cahokia’s population likely reached over 20,000 at its peak around 1100 AD. It was the central city among a widespread group of associated settlements (including Aztalan). We can be sure that Mississippian culture was rich in stories and traditions, though we have no written texts to serve as guides. We get clues about this culture from ceremonial structures like the “woodhenge,” discovered 850 meters west of Monks Mound. This model in the museum illustrates how on the morning of the winter solstice, those standing near the central pole would’ve seen the sun emerge from behind Monks Mound. This emphasis on sun and calendar points to Cahokia’s agricultural

economy and permanent settlements. We visited Cahokia during a trip to St. Louis, and others had similarly stopped and taken the time for a tour of the site. Cahokia will never compete with the St. Louis Arch when it comes to the number of visitors, but it attracted more people than I’ve seen at any effigy mound site in Wisconsin. These temple mound complexes are the easiest remains of the Native American past for modern Americans to appreciate. Agriculture makes a dense permanent city possible, and then that density of population produces a clear social hierarchy, religious ceremonies tied to the seasons, and even games. Cities have a lot in common with other cities, no matter the era or

culture. It seems clear that Aztalan was a smaller version of Cahokia since many elements are shared between the sites: central platform mounds that define a broad open space, location near a river, and an agricultural economy. The people at Aztalan were faithfully reproducing a lifeway that had its vibrant center elsewhere. This is helpful when considering the line of conical mounds extending to the west of the site. It’s still easy to see this gently rolling line of mounds, created at spots where tall wooden posts had once been erected. At Cahokia we saw evidence of ceremonies related to agriculture and the sun, and we can infer a parallel set of ceremonies here at Aztalan. The open area at the heart of Aztalan is

allowed to grow undisturbed. There’s no question of turning the site into some sort of living history museum where actors would demonstrate the life of this settlement since we know too little about ancient life here. Instead of trying to imagine Aztalan as it once was, the choice was made to let the prairie stand as an invitation to the imagination. With the help of interpretive signs visitors can imagine well-travelled paths, people busy at work, and children at play. But when I stared at the open prairie I noticed Queen Anne’s Lace and wild daisy growing thickly—both invasive. Even in space that’s meant to be open, we see signs of our contemporary global linkages and transformations. As I got back on the

road after Aztalan I was on the lookout for signs of large-scale earth moving. We don’t notice the effigy mounds because too many examples of earth moving litter our landscapes. We are so profligate when it comes to piling up earth that we have become numb to the mounds. I began noticing all the freeway overpasses that scoot over the smaller county roads. The berms that define the two sides of this overpass aren’t naturally formed, but machine created hills that allow traffic to flow without interruption. There’s no symbolic value built into these berms, as is the case with most things we classify as infrastructure. These elements of our landscape become hidden in plain site and we drive past them without thinking.

It’s easy also to drive right past rivers without thinking. A sign at a bridge will often give a name to the dark flowing body of water underneath, but that’s it. The river slides unobtrusively through the farming landscape, no one crowds their houses up to it, and no one appears to make any use of it. Every now and then the river flows through a road, and at such points it’s passed over with as little attention as possible. We navigate the landscape now indifferent to minor flowing rivers. When examined from above on Google Earth it’s notable how the rivers flow blankly through the landscape, without attracting any construction or symbolic note. There’s no such thing as “Google River View” for the twists and

turns of the river as it anonymously moves through the landscape. The above depression lies along the river road in Fort Atkinson. It’s not easy to see in the evenly mowed grass, but that depression is in the shape of a panther. When the water from nearby Rock River would overflow, the animal shape would stand out clearly against the ground. This is the last surviving example of a rare type of effigy mound, dug into the ground instead of formed by heaping dirt up onto the ground. When Increase Lapham made his survey of Wisconsin’s mounds in 1850, he found a handful of these intaglio mounds, and called them “excavations.” I like the word “intaglio” because it puts the earth shape into the context of gem

cutting and printmaking. The oldest historical signs for the mounds were like this one: a plaque set into a low cement curb. The marker gives basic information about the intaglio, but also informs us that it was the Fort Atkinson Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution that had preserved and marked the intaglio mound back in 1920. A more common brown Wisconsin state historical marker also stands at the roadside, explaining the rarity of this intaglio effigy to anyone who might stop (“only known intaglio effigy in the world”). Back in 1850 Fort Atkinson had not yet expanded along Rock River. About 15 mounds lined the river, and one of them was this unique negative version of the usual effigy.

In his survey of the area Increase Lapham showed that dirt had been heaped around the edges of “The Excavation” to make the depressed shape yet more distinct. The other mounds that were part of this group disappeared in following decades. We’re fortunate that the panther intaglio was preserved, but it’s misleading to experience it as some isolated and subtle ancient relic, as if this lone shape was inset just here with nothing else around it. Upon visiting mound sites, the scale of our loss of ancient landscapes becomes clear. The city of Fort Atkinson has a population now of a little over 12,000. The city is located here because in the 1830s this site along the Rock River was of strategic value, and the US

military even built a fort to control passage along the river. Today the Rock River is more of a nuisance for its occasional flooding than a benefit that offers economic advantage. A middle class neighborhood now sidles up to the river’s edge, though the effigy mound group was long gone by the time these houses were built. Today Fort Atkinson is a typical small Wisconsin city, but it has this one intaglio mound (its location marked above with a small yellow box) that serves as a reminder of past ways of being on this land. Small towns throughout Wisconsin organize themselves as if there were some one master plan for human thriving, but this lone intaglio can serve us as a sign for the possibility of other ways of

being. Standing at the panther intaglio I looked down the curving river road through a series of front lawns. Mailboxes were perched along the road so that the delivery person could drive through with no problem. One yard had a “mallard xing” sign to remind motorists that living creatures might make their way into the road from the river opposite. The yards were uniformly well kept, with trimmed bushes and ornamental plants. Since this was the summer of 2020 political positions were already being staked out, and two yards announced their support for Joe Biden. The grand showdown between Biden and Donald Trump was still months away, but preferences were becoming part of the landscape. In the

image above, with the intaglio in the foreground, I’m looking in the other direction down the river road. In this direction a small Trump sign sits near the road, setting the panther effigy in the middle of a contest. The large flag at the door and the failing yard fence set this house within another set of cultural symbols. This house served as the entrance for L&L Auto, and on Google Earth

I could see how that business extended back from the road like a gash in the

landscape. Lake Koshkonong was about 3½ miles from the panther intaglio along Rock River. As with so many lakes in southern Wisconsin, this lake had attracted the attention of the mound builders. A small park preserved a number of effigy mounds, but their direct connection to the lake is now obscured by a row of lakeside houses. The lake is down to the right of this road, but owners had worked hard to keep their piece of lake private. Since views of Lake Koshkonong have been ceded to property owners, the mounds on the other side of the road have come to feel like they are enclosed within an isolated forest. Anything that breaks the connection between mounds and nearby natural features of the

landscape creates a false impression, since the mounds are expressions of a location. They weren’t constructed as standalone symbols, but as complements to the landscape as a whole. This insistence on locking up bits of land for private use is another reason it’s hard for us to see the mounds. As a woodland mound group this park did succeed, making the mounds visible by a division between short mowed grass and longer unkempt grass. The result was a sense of curving low shapes rippling through the shaded forest. The forest was interrupted by clearings, and those clearings were defined by sinuous mounds. The signs were there to help visitors understand the overall shapes, which might

otherwise be difficult to guess. Indian Mounds Park at Lake Koshkonong also preserved a trail used historically by Native Americans. Archaeologist Charles E. Brown mapped such old trails back in 1930. The red lines on his Wisconsin map showed the major overland trails used by Native Americans. These have been entirely erased, but a small section of one old trail is preserved here, marked by a line running alongside the forest underbrush. Such trails once complemented

the rivers that served as the main transportation links. Parks can be more or less successful in presenting the effigy mounds. This county park was effective because the mound curves were clearly visible and yet the grass wasn’t overly manicured. The park brochure asked visitors “Imagine, as you walk, that you are an ancient Native American. You’ve traveled far along the trail to reach one of your villages that is tucked into the bank... The sacred mounds have great significance to you…” Once I read this, I realized why I liked this park so much: it was designed as an experience a visitor could enter into with empathy and imagination. That preserved trail became an aid to thinking about someone else’s

experience, someone living in the deep past, with a completely different set of cultural values. From the edge of Indian Mounds Park I looked out onto the Koshkonong Mounds Country Club. Looked at from above on Google Earth, the mounds park is easy to see as a densely wooded area. But that land opens up into the long grassy fairways that make up a golf course. We can be sure that the mound builders didn’t stop at the artificial lines of a later golf club, and we can expect that some mounds spilled over into the land of the country club. This led me to the country club itself, and introduced me to another type of institutional setting for the effigy mounds. A private club would have its own

motivations and goals for preserving and presenting these mounds. The Koshkonong Mounds Country Club hosts weddings on its open lawn that slopes toward the lake. This white arbor serves as the focal point, and the country club’s website provides a gallery of sample images of weddings that took place right here. The attraction of this site for those looking to get married is obvious, with that lake view in the background. I’ve already noted that effigy mound sites are the places Americans instinctively identify as perfect for a park, and a country club can be considered a private park. The land that Native Americans once identified as the perfect setting for effigy mounds now readily serves as a scenic

backdrop for the modern ritual of a wedding. This bird effigy sits on the edge of that same open lawn on which weddings are celebrated at the country club. The low mound becomes a part of the lawn, with almost no distinction between mound and the slope. An effigy mound like this functions as a sort of lawn ornament, adding history and distinction to a site. The whole concept of a lawn was unknown to ancient Native Americans, but this grassy setting allows the sweptback wings and body of the effigy bird to stand out. None of the wedding photos on the country club website show this bird (probably for the best), but it’s also likely that effigy mounds are difficult to incorporate into a contemporary cultural

form like a wedding. Such a mound doesn’t readily cooperate as a background to a group photo. The country club today sets the effigy mounds on the course margins, but manages to give them some visual distinction. The website sketches the history of the club: “In 1922, the initial golf course construction took place, utilizing many of the native effigy mounds as navigational hazards.” The course was not at first designed around the mounds, but used the mounds as course obstacles. It’s hard to believe the mounds here once served as ready-made golf challenges. More respectful treatment then becomes the rule: “We will always honor these hallowed grounds in which we walk. Enjoy the game!” The mounds

thus shift from a pragmatic to an emotional role, adding a touch of frisson to the experience of playing golf. Tracking the mounds at the country club sometimes meant nearly intruding on a friendly round of golf. The mounds along the course were well cared for, their shapes clear enough, but the whole environment of a country club wasn’t conducive to imaginative engagement. No one was golfing on top of the effigy mounds, but the mounds nevertheless blended into the look and feel of the course. Preservation shouldn’t be just about keeping mounds physically protected, but about presenting external cues and stations that allow for thoughtful engagement with them. As Americans we have trouble

seeing a landscape as a holder of memory rather than blank container for distinct private objects. The Koshkonong Mounds Country Club does its duty by the mounds. They are well preserved and those who are interested can get a brochure from the club with some explanation (though on this trip the office was closed due to Covid). But I started to think about what an ideal effigy mounds tour would look like. First, there should be a design unity that ties together mound sites across Wisconsin. The effect of the mounds is cumulative and visitors need to grasp that sites weren’t random islands in the landscape. Second, there should be an effort to point out the waterways and natural resources in

the nearby environment. A tour should connect us to the landscape. Leaving the country club I headed back to the main road and passed new housing developments. Some had already been completed, but in this case the work had just begun. A map of available lots was posted and the invitation was for people to design and build their dream house on one of these empty lots. This private and individualized use of land was in obvious contrast to the ethos shown in the effigy mound landscapes. On the Koshkonong Mounds

Road there were plenty of mounds, only they weren’t ancient or meaningful. These were careless piles of earth created as part of the construction process. It seemed as if work had ceased for a time, and so the piles had become covered with weeds. Such mounds would no doubt be erased as homes were finished and landscaped, but still there’s a kind of land carelessness fully on display. As we drive up and down roads like this without ceasing, the notion that a mound of earth could be a holder of meaning has become a strange concept. Our default read of human-made mounds is that they are construction leftovers. We don’t commonly ascribe meaning to such piles, nor do we see purpose beyond convenience.

Beloit College was founded in 1846, in the southern Wisconsin city of the same name. The New England founders felt a proper city needed a college, and so they acquired this land and built this structure, the oldest building on campus (which later acquired that Greek-style entrance). Beloit College was from the start situated among ancient mounds. The mounds are still easily visible on the well-maintained campus. The mound group occupied space at the edge of a bluff overlooking the Rock River—perfect land for a college! On the frontier the mounds also lent the land a sense of age and sacredness that could distinguish a young college. Increase Lapham included a survey of the ancient mounds at Beloit

College in the Antiquities of Wisconsin. He relied in this case on the survey work of Beloit professor S.P. Lathrop. This survey was completed six years after the founding of the college, and it’s obvious from the survey that the main college building is oriented toward the ancient mound group, thus defining itself through its relationship to these (then) mysterious mounds. Of the original 25 mounds encompassed by the campus, 20 mounds survive now. A college campus bestows protection that isn’t easy to find in commercial or residential settings. At the same time any sense of an ancient mound landscape is lost in the distinctive leafy setting of a classic college campus. A college campus is a landscape of

leisure and individual growth. Many colleges in the Midwest began with a single building, its rooms serving as dorms, classrooms, and library at the same time. Even the University of Wisconsin at Madison began with its modest North Hall set onto a hillside. At Beloit this earliest building is known as Middle College, and we’ve noted how it was oriented toward the nearby mounds. Its Doric Greek entrance was part of a renovation in 1938-39. Before that it had a decorative Victorian exterior. Throughout its history the architectural form of this building has laid claim to a Classical European past. If the mounds point to something inherently sacred about this land, the architecture asserts value based on what’s

been planted here from the outside. Like many institutions in this summer of Covid, Beloit College was closed. Promotional material from earlier in the year was still hanging on lampposts. In January the college had kicked off its “Be All In” fundraising campaign. The goal was to raise $50 million, much of which would be funneled back to students. The banners put a student photo right at the center. The college campus has become a site for self-discovery. Entering students take up the challenge of fashioning themselves amidst a host of possibilities. The language of education has shifted from acquiring connection to the past to gaining a personal skillset that promises success. Wherever mounds are

incorporated into a contemporary institution, they are changed. This is true even when the landscape in question is that of a college campus. The mounds are made to speak the language of individualism. First, they take their place as another form of public art, among many other examples around the campus. Second, they are fixtures on a campus lawn that symbolizes self-discovery. So finally the mounds become markers for the sacredness of the inner Self. Walking around a bit further on campus I came to a short

sidewalk on the campus of Beloit College. It served as an example of the casual creativity we expect at a modern liberal arts college. It’s meant as a celebration of Native American heritage, and it complemented the presence of the mounds.

It’s no surprise to learn that a student group is working to raise awareness about the mounds at Beloit. Learning to

respect and celebrate diverse identities is a key component of higher education, and the effigy mounds are readily drafted into this effort. The campus of Beloit College is easily visible from above in Google Earth. Its curving footpaths break up the grid layout of the surrounding neighborhood. The college occupies land on a slight hill east of the Rock River. If we ask a further question about why it was here that New England settlers founded a city, then we can look to that dam along the Rock River, built at a natural drop in the river. Even before industrial development, the presence of rapids made this a place to stop, and a French trader Joseph Thibault occupied a cabin here. The New England

businessmen liked Beloit because the fall in water level both here and at nearby Turtle Creek meant there’d be power for their industrial enterprises. In this postcard it’s possible to see Middle College peaking up behind the line of trees at the center. In the foreground is the Rock River dam and the old Blackrock Generating Station, a coal-powered plant constructed between 1908-47. The plant was decommissioned in 2010, and not long after that Beloit College began to imagine this power station as an extension of its campus. In 2020 the Beloit College “Powerhouse” opened, becoming a combination student center, gym, and field house. Structures that were part of the base of the US industrial economy

are everywhere getting a quirky supporting role in the information economy. Across the Rock River from Beloit College was once the Beloit Corporation, an industrial factory that goes back to 1858. For a time it was known as “Iron Works” and its primary product was machinery for paper making. The company filed for bankruptcy in 2000. Since then the factory has become the “Ironworks Campus” and houses a number of innovative business ventures. In the new economy the industrial past is recalled with equal parts nostalgia and patriotism. This US flag, pieced together from industrial equipment, points to a widespread belief that the industrial landscape is the true American landscape. Another part of

what used to be the Beloit Corporation has been turned into a luxury boutique hotel. It’s set right alongside the Rock River, which is no longer a driver of industry, but a site for recreation. Visitors to the Ironworks Hotel can go for a morning run or a take an evening stroll along the new river path. The river setting is now part of the attraction. The basic price for a room here is $189 per night, and the hotel website advertises a stay here as the ultimate date night. The website leads with images of a knife cutting into a tender steak, and the aesthetic is dark and serious. We get glimpses of the rooms, with wood paneling, a gas fireplace, and large central TV. Right beside the Ironworks Hotel, and along the

river trail is a statue of businessman Ken Hendricks. In a city like London, a visitor comes across statues of past noblemen and leaders of parliament, or of famous artists and poets. Ken Hendricks represents a more recent cultural ideal: the entrepreneur who rose from humble beginnings to achieve a net worth of $2.7 billion before his death in 2007. As with all American entrepreneurs, there appears to be nothing formal about his manner. He doesn’t dress in a suit. The summary of his career in Wikipedia is succinct: he dropped out of high school to begin in the roofing business. He founded the chain ABC Supply. And most important for this context, he had a vision for the redevelopment of the old

industrial properties in downtown Beloit. The plaque in front of the statue baffled me. There was no information about who this guy in a leather jacket was. There were no details about his career, though we should know that as an “entrepreneur and a dreamer” he was likely a successful businessman. The statue’s location suggested he had something to do with all this new development, but that was just an inference. Mostly the interest was in stating a specific cultural ideal. A person should be optimistic, believe in hard work and the American Dream, and “give back” to the community.

The statue ends with a ringing reminder that there is “greatness in all of us!” It sets up the businessman as the cultural

ideal to which everyone should aspire. Big box stores had existed for some time, but between 1999 and 2019 this type of development had become an insistent part of the American experience. Beloit lies about three miles off the north-south Interstate 90, and the road into town was a place for fast food restaurants and transport companies. But during these years Walmart opened a “Supercenter” and Menards a home improvement store. Along with such massive anchor stores came an ecosystem of smaller chains. In this case there would be no worry about this development covering Native American mounds, since these stores thrive most in the nowheres of the American landscape. The mounds

builders were alive to numinous places in the landscape, but the developers of roadside America are drawn to blankness and placelessness. A Walmart Supercenter averages 185,000 square feet and employs about 350 people. The exterior is marked by a neverending parking lot, perhaps only fully utilized in the days leading up to Christmas. The Supercenter makes no effort to be architecturally impressive, and the only thing that catches the eye is the logo on a blue background.

Besides that logo there are just markers directing shoppers to the best entrance for their purposes (“over here for the pharmacy”). There’s nothing historic or even notable in this horizontal stretch. Since there are more than 3,500

Supercenters in the US, this photo could have been taken almost anywhere. Above is one of an estimated 65,000 strip malls in the US. These are “strips” of shops under one roof and linked by an outdoor sidewalk. They are meant to be accessible by car. As with the Walmart Supercenter (directly behind this strip mall), there’s nothing architecturally notable to be seen here. Only the corporate logos even make an attempt to catch the eye. These stores in the strip mall are a kind of index as to what can survive as physical businesses in this age of Amazon (which went into overdrive with the arrival of Covid). We see coffee and sandwiches, discount eye care, nail care, cell phone service, and a place to cash

checks. These are all businesses that require some level of in-person service, and so can’t be swallowed up by the internet. This commercial area near Interstate 90 includes a large number of budget hotels. In central Beloit, near the Rock River, it’s possible to find upscale lodging (such as the Ironworks Hotel we just saw), but these hotels on the edge of the city have far more rooms. My Google search for a hotel in Beloit turned up lots of hits out here, ranging from $76-$98 per night. Tall signs identified the corporate brand of these nondescript

structures and sometimes they advertised an amenity like “indoor pool.” Among the box stores, the strip malls, the fast food restaurants, and the budget hotels, is a nondenominational church. For some reason it’s named “Central Christian Church,” though it’s far out on the margins of the city. (They must be thinking of it as “central” amid a group of regional cities linked by the freeway.) This is the church in the Beloit area that has the largest number of people in attendance on any Sunday. It’s important to see the church not as accidentally located here, but as a precise expression of the same economic and social trends that gave us these other placeless enterprises. The web page for the Central Christian

Church greets visitors with a highly produced video montage of scenes from its Sunday service. We see a large worship band, a pastor with an easygoing manner, and we even catch a glimpse of the socially distanced congregation. The church experience here is as homogenous as the products of any of the nearby corporate big box stores. In this case the look and feel isn’t generated by designers at a central office, rather it’s the result of a shared taste for this megachurch style. I tried to learn about the history of the church, but I was defeated because the website showed no interest in history. There are no notes about when this church began or where it was first located. The only interest is in repeating

a timeless Christian message. I had driven past Janesville on my way south to Beloit, but now at the end of my first day I doubled back to this city to stay the night at an Airbnb that promised a rigorous cleaning regimen. I knew of no effigy mound groups in the Janesville area, though historically this site along the Rock River had been home to several Native American villages. Their populations had been removed and forced onto reservations after 1830. What drew me to Janesville now was my curiosity to see this historic city that had suffered economic catastrophe in 2008 and 2009 as the old General Motors plant was closed. I wanted to see how this city presented itself after such a loss. The Rock River flows

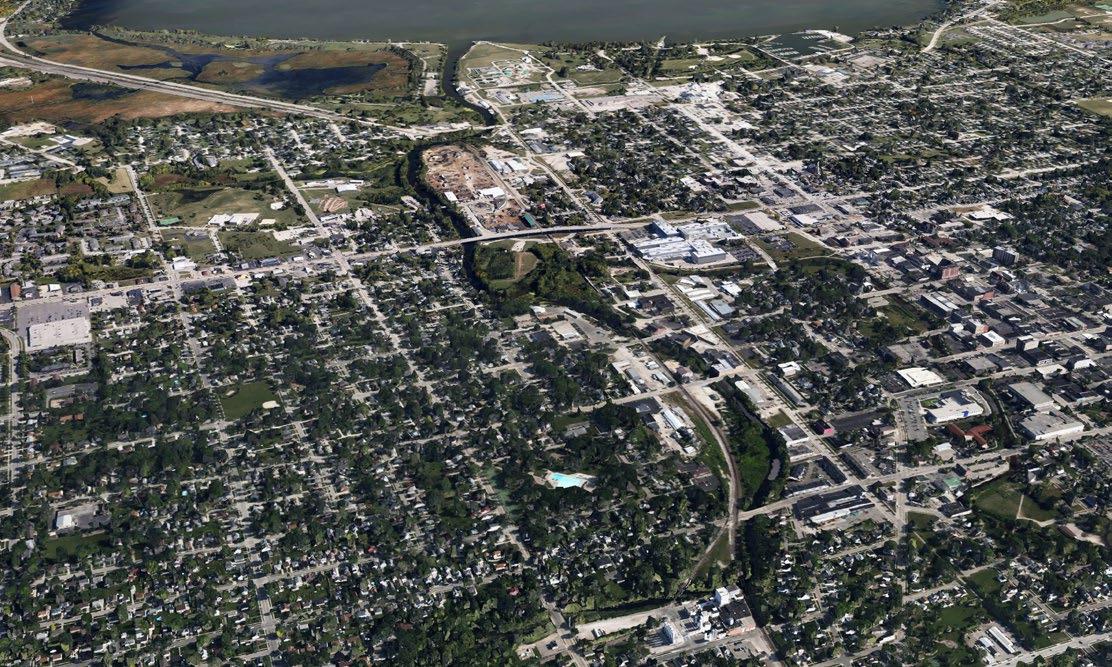

out of Lake Koshkonong and proceeds in a southerly direction, and in time it arrives at Janesville and then Beloit. This part of the Rock River is a corridor of past industrial development. On Google Earth

it’s possible to make out three main bulges along this corridor. At the top is Janesville, in the middle Beloit, and at the bottom Rockford, Illinois. The river represented to settlers power and industrial capability, plus connection to commerce on the Mississippi River. Today the river has a blank look as it flows through Janesville. What exactly is a river supposed to do nowadays? The Janesville Assembly

Plant was opened in 1919. It had an 89 year run before General Motors decommissioned it completely and for good in 2009. During the 1970s over 7,000 workers were employed in this sprawling complex. In a city of about 50,000 people at that time, a sizable percentage would have worked at this plant. Personal note: the first car I ever owned was a 1989 Chevrolet Cavalier, and it likely would’ve rolled out here on the Janesville plant assembly line. I find factories impossible to read from the outside. They are created and expanded with the internal logic of large-scale production that feels no need to explain itself or to educate those who are curious and looking on from the outside. Ten years after the Janesville

Assembly Plant was closed, it was completely torn down. By 2019 there was nothing left but pavement here and there, weeds growing in the gaps. Google Earth still shows that 3D view of the full plant from above, but once I moved into Street View that plant disappeared and I was left facing this vast empty space. As I went back and forth between the two views the industrial plant came to seem like a dream palace from the Arabian Nights. The effigy mound landscapes seem alien to an industrial scene like this, but perhaps both are united in their silent testimony to loss, and invitation to mourning. Our human landscapes refuse to stay put, and stable meanings slide away. The economic growth in older

cities has shifted to the margins where there’s space for those massive box stores. The traditional main streets, where growth was concentrated from the founding of these cities through much of the 20th century, have been left behind.

Throughout Wisconsin there’s an effort to support and promote older Main Streets. The playbook is now defined by four points:

1) Organize (get everyone from business owners to bankers involved),

2) Design (restore old buildings, use colorful banners),

3) Restructure the space (creatively re-use older retail space), and

4) Promote (use parades and events to generate excitement). The revitalization of Janesville is following this well-trodden path. The goal is to make

the river front a destination, and just a few months after my visit a pedestrian bridge was opened and public art unveiled.

During my time here banners were already drumming up excitement. It’s easy for me to root for downtowns against the large zones of faceless box stores on the outskirts, but I also see that this fighting back means building corresponding

generic spaces that will appeal to creative-class professionals. The running paths and unique restaurants are the markers of a different economic class. This marker along Main Street commemorates a speech given by Abraham Lincoln at the Young America Hall. That hall is long gone, and the space used now as a parking lot, but still it’s possible to imagine that Abraham Lincoln stood up to speak at some spatial point on this parking lot ground on October 1, 1859. That sign dutifully records that he spoke on slavery, free labor, and popular sovereignty. Lincoln then spent the night at the house of William Tallman on the other side of the Rock River. Janesville’s downtown is thus tied to the national story, and

sacred in that way. But looking at this marker I get the sense that this way of relating to space doesn’t get much traction nowadays. Looking up from the Lincoln marker, I saw this mural. I learned later it was a portrait of Black Hawk, the leader of the 1832 uprising named after him. This uprising spilled out of Illinois and into Wisconsin, and was an act of resistance against an earlier treaty that ceded a large tract of land east of the Mississippi to the United States. Black Hawk was defeated, but he gained a lasting cultural presence (think of that dark battle helicopter that bears his name). The mountainous landscape of the mural isn’t characteristic of the area in which Black Hawk’s life played out, and makes

the mural into an evocation of Native American experience in broad strokes, liberated of the specifics of place. At the center of Janesville is the Rock County Courthouse, this addition completed in 1999. It mostly ignores classical references for a style that at first seems more fitting for a performing arts center. In front stands a type of granite war

memorial common in cities that sent young men to fight and die in the Civil War. On the memorial that war isn’t remembered as the “Civil War” but as the “War of the Rebellion.” This 1901 memorial seems old, solitary, like it stands for a layer of history that has lost meaning. The center of Janesville, like the center of Beloit, felt like it was casting about for an identity. That church in the background is the First Congregational United Church of Christ, founded in 1845.

Abraham Lincoln worshipped in the church in 1859, though the present building wasn’t constructed until 1876. On the website I see that the church is progressive, welcoming to immigrants and the LGBT community. But whatever its

former prestige, on Sunday it will be empty in comparison with Evangelical churches on the edges of the city. It’s hard to believe, but in 1963 Janesville felt it was short of downtown parking, and so they built a parking lot over the river. There could be no better example of how rivers are seen as wasted space. Today a flourishing downtown must welcome young professionals, and so that parking lot has been removed and in its place is an artsy

pedestrian bridge and prominent outdoor fitness equipment. At the 2018 ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Fitness Court in Janesville, the city manager praised the public-private partnerships that made it possible. The subtext, as always, was to make sure listeners understood that taxpayer money hadn’t been used on this shared space. I took a closer look at the Fitness Court and could guess the underlying business model: this workout space would move people into the virtual space of an app as they tried to use the equipment, and that app would lead them to paid features like a virtual coach. It’s not uncommon now to see physical spaces that function as fancy lures that move us into a universal online world.

Starting off on the second day of this road trip, I headed west from Janesville along Wisconsin Highway 11. This two lane highway runs along the southern border of the state. My goal was to arrive at effigy mound sites along the Mississippi River, including Effigy Mound National Monument in Iowa. To get out there I needed to cover some ground. I knew I’d be traveling through small towns, and I decided to stop and see some of these along the way. Cities like New York and Chicago define the economic pulse of the US, and draw visitors to their cultural destinations, but the small towns along state and county highways better represent our patterns of inhabiting this land. When traveling I keep an eye out for

typical scenes. Unusual scenes are easy to spot, and they are often marked by something spectacular or strange. Unusual scenes do well on Instagram because they surprise the user and so stop the unending scroll. But a typical scene isn’t about the spectacular, it’s about the usual landscape looking the way it usually does. Anybody can take a picture of a typical scene, but for that reason many don’t bother. Southern Wisconsin is part of the corn belt, and fields of corn and soybeans stretch to the horizon. The land isn’t as flat and monotonous as it gets further south in Illinois, so there’s a gentle rolling feel to much of this Wisconsin landscape. It’s always easy to find something to say about unusual events

or places, and in fact the website Atlas Obscura has developed a business model out of spotlighting just such surprising places. But for me the true challenge is to see and write about the ordinary and typical. As I came into Brodhead this stand-alone coffee shack came into view along the roadside. I got a coffee and pulled over on this unpaved drive lined with cut-out forest animals roasting hotdogs. It was a genuine tableau of

small town Wisconsin: a whimsical aesthetic, a fat water tower broadcasting the city name, and a small town business standing alone and inartfully just outside the city. Across the highway from Bullwinkle’s Coffee was a self-storage business. Such businesses are so numerous that it’s easy to drive past them without a second thought. They’ve successfully become invisible and unremarkable. There are about 50,000 self-storage facilities in the US—thousands more than the combined number of Dollar Stores and McDonalds restaurants. They are representative of the unstructured crab-grass development of US rural landscapes. Since the storage structures are put up as cheaply as

possible they show total indifference to aesthetic value. Many small towns now put up a mural that encapsulates the town’s view of itself. These “identity” murals aren’t the work of one person, but reflect some serious consideration of the look the town wants to broadcast. In Brodhead it was clear that the golden age had drawn near in the 1950s. This could be a scene straight out of the film American Graffiti. The mural illustrates a cultural disconnect between the imagined ideal of American life and the economic realities that have hollowed out so many small towns. On the city website there’s talk of revitalization with the addition of “flower baskets, barrels, trees, bushes, bicycle racks, receptacles, flags,

and Tinkers Garden.” The mural includes a set of adults portrayed with obvious individuality. Next to the mural is a smaller sign that names these three men and records their accomplishments. Again it appears that the only thing worth celebrating is business success. Jack Pierce (on the left) co-founded Pierce Furniture in 1952. He spent a lifetime promoting quality furniture and leading civic institutions. Stan Knight (in the middle, with his wife) started Knight Manufacturing, a maker of farm equipment. Arnold Ayres (on the right) opened a car repair shop in 1935, so when these classic American cars in the mural came along in the 1950s, he was there ready to fix them. Brodhead is laid out in a