WATER MEMORIES

Water is sacred and serene, Water is part of our culture, Water is an economy, Water is the essence of life................

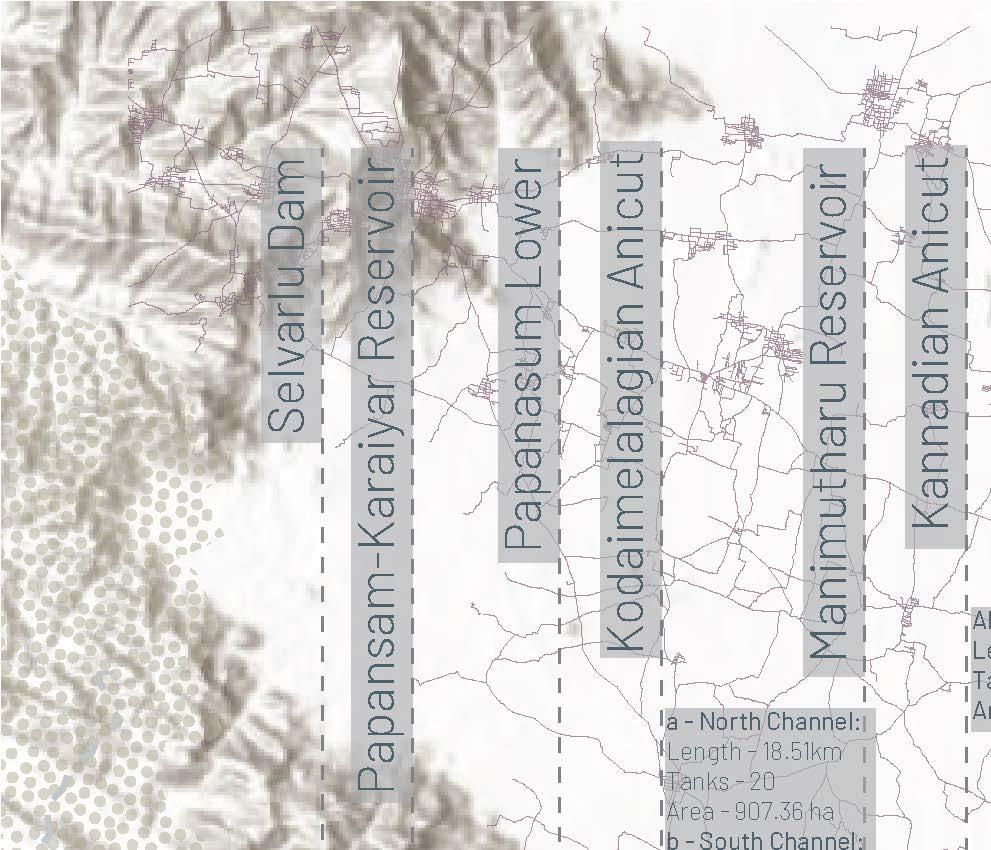

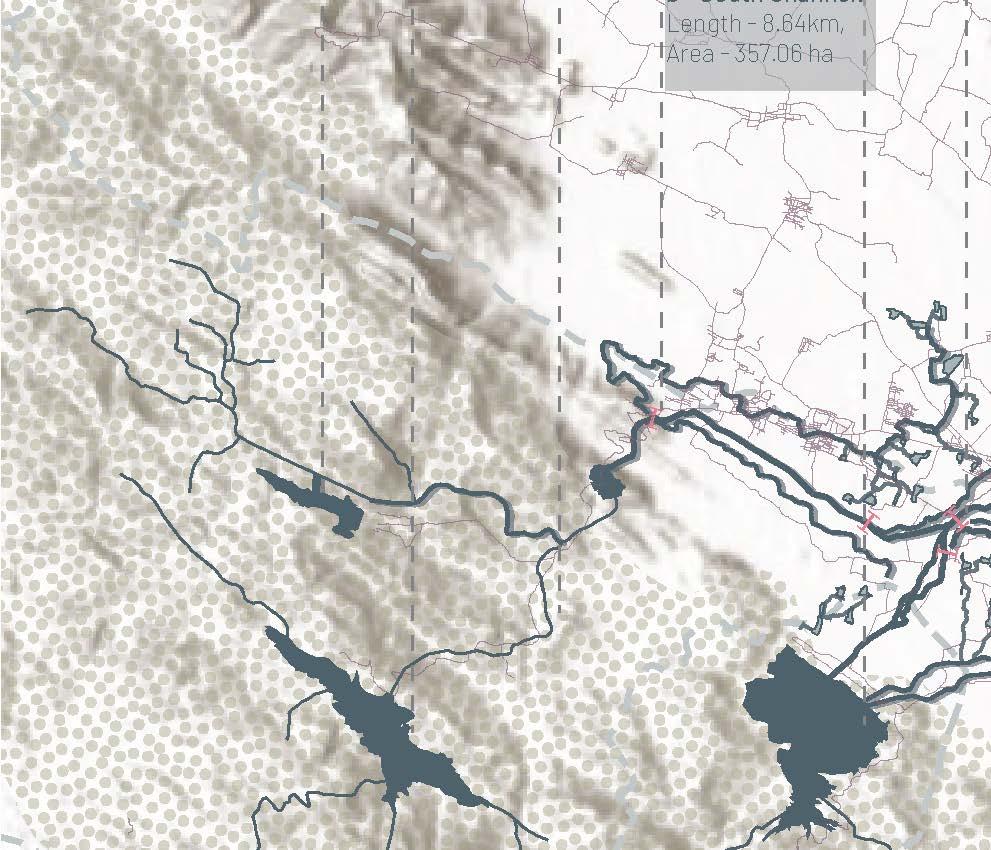

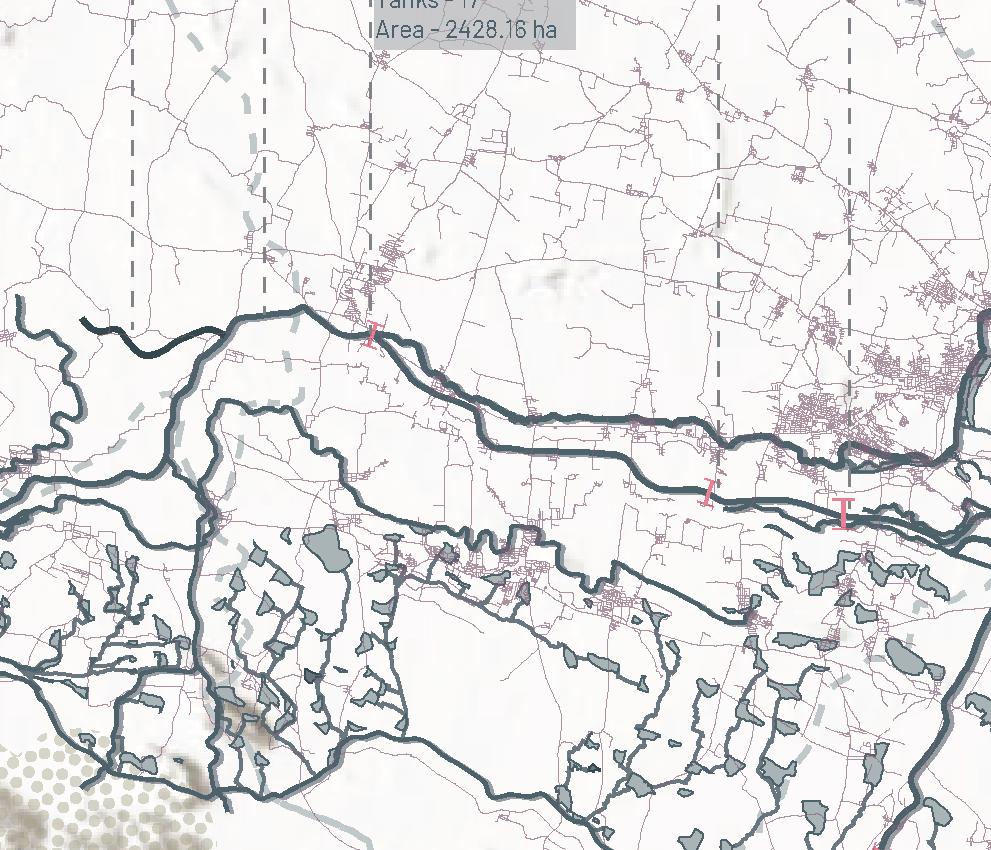

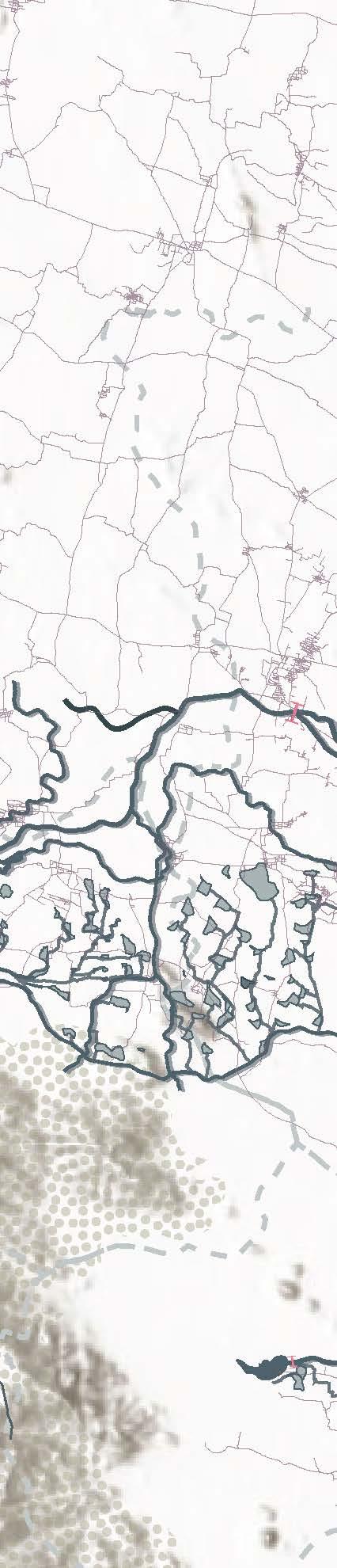

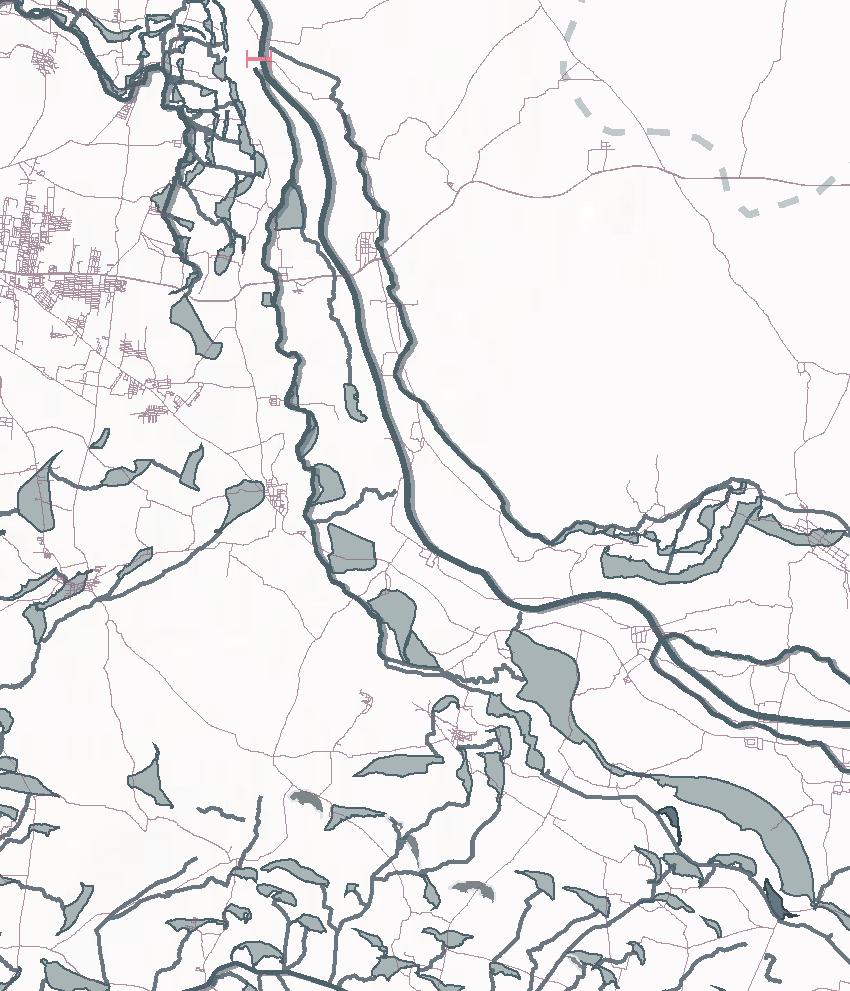

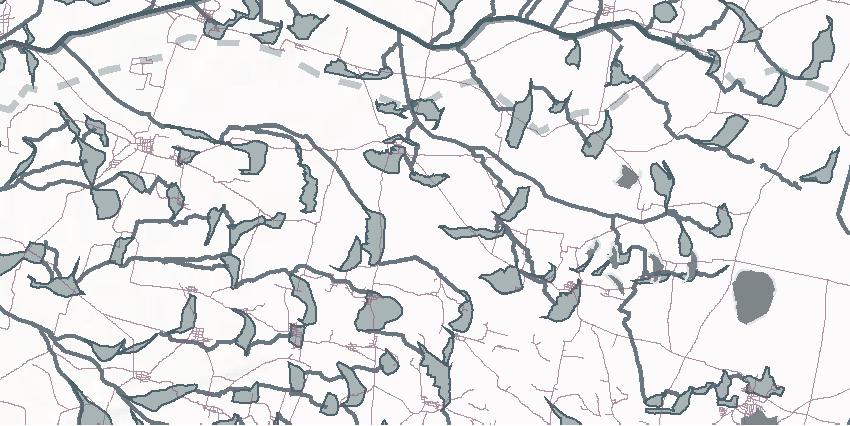

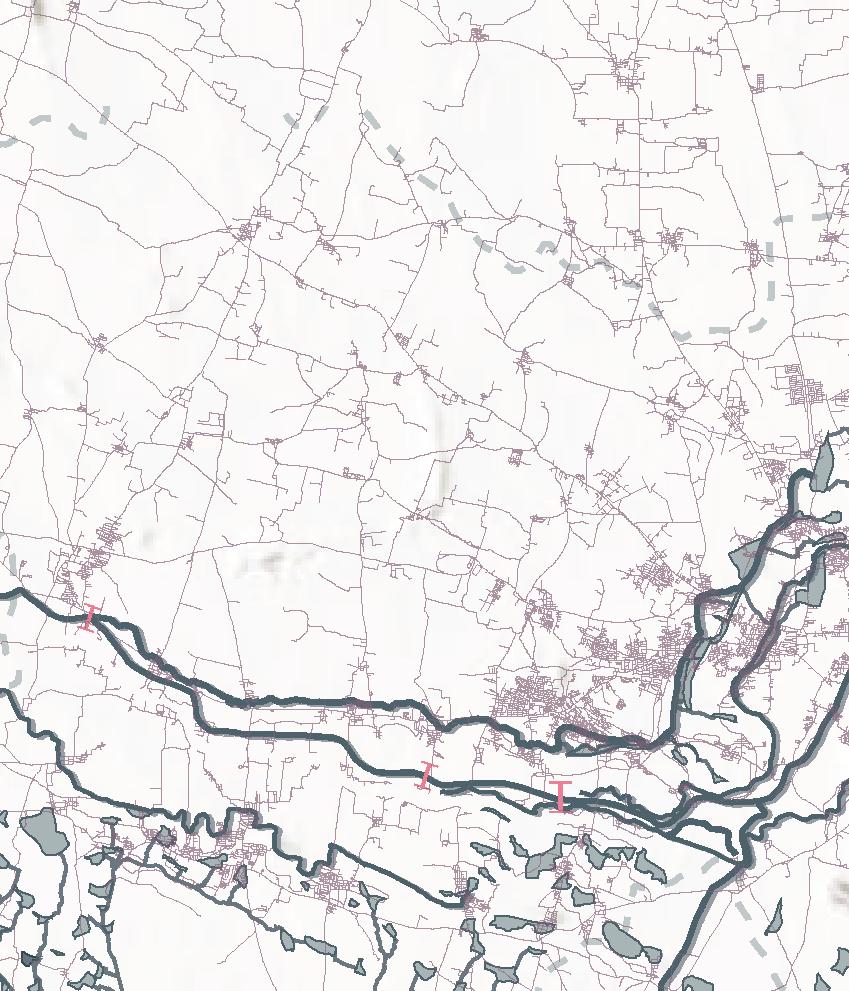

Water infrastructures, such as dams, reservoirs, canals, and irrigation tanks, play a crucial role in shaping the availability and management of water. These systems harness and distribute water to meet agricultural, domestic, and industrial needs, often transforming landscapes into thriving ecosystems and supporting human settlements. By regulating and storing water, they create an intricate network that ensures its availability even in arid or seasonal environments, giving the illusion of water abundance.

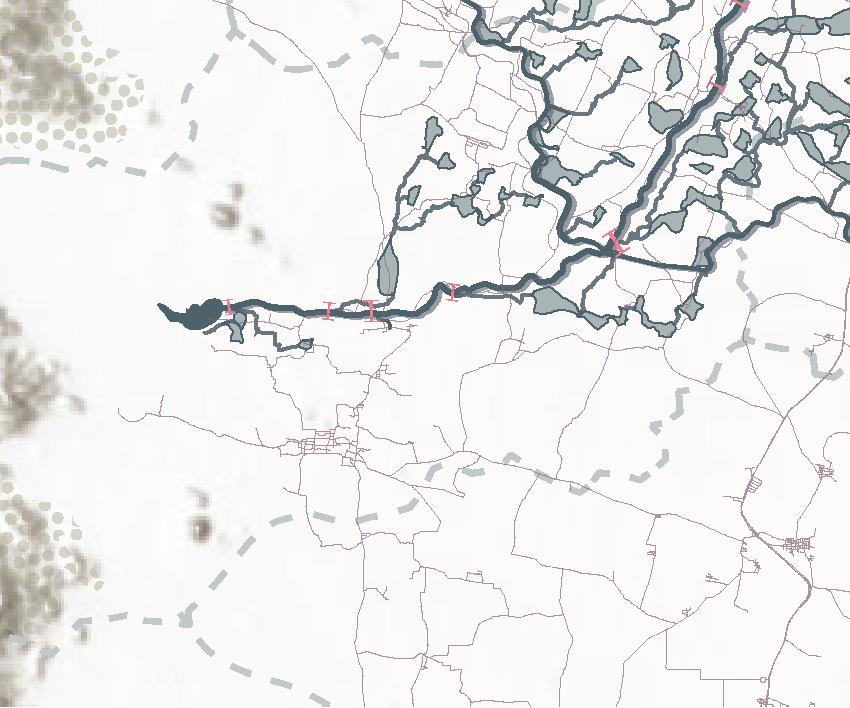

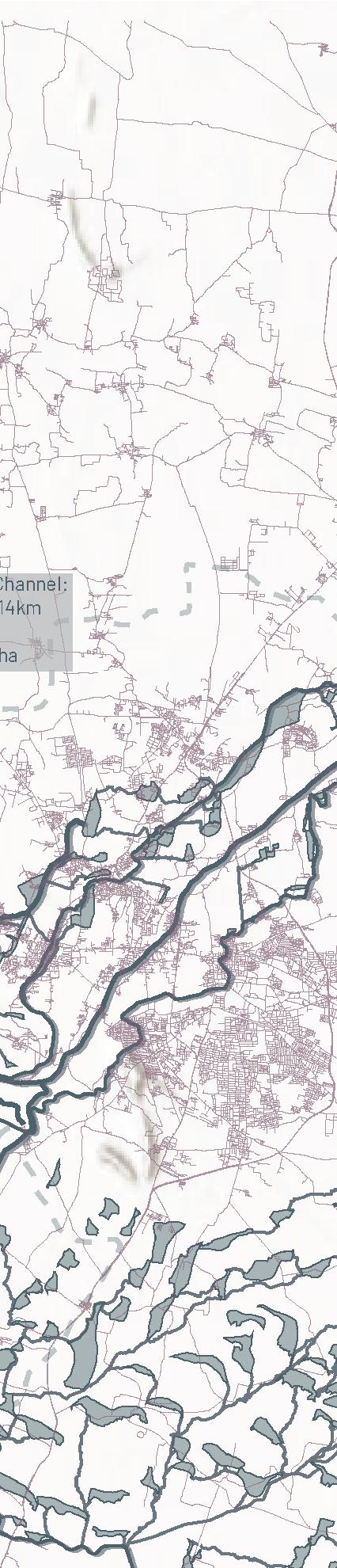

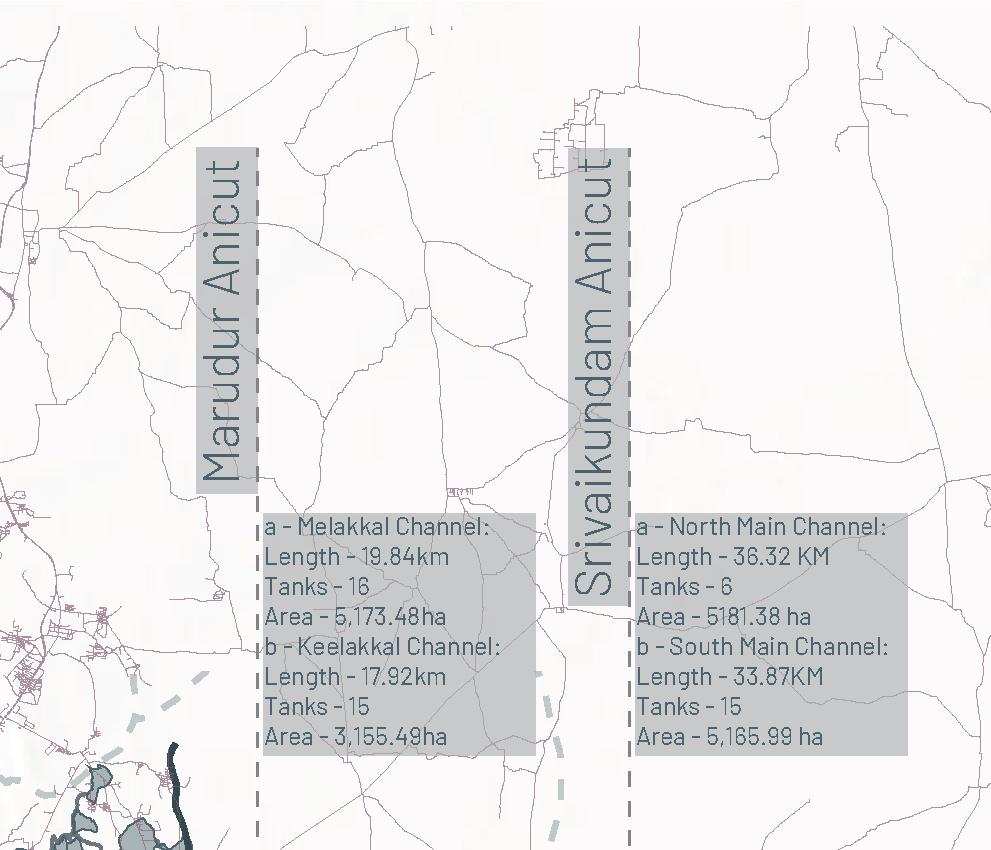

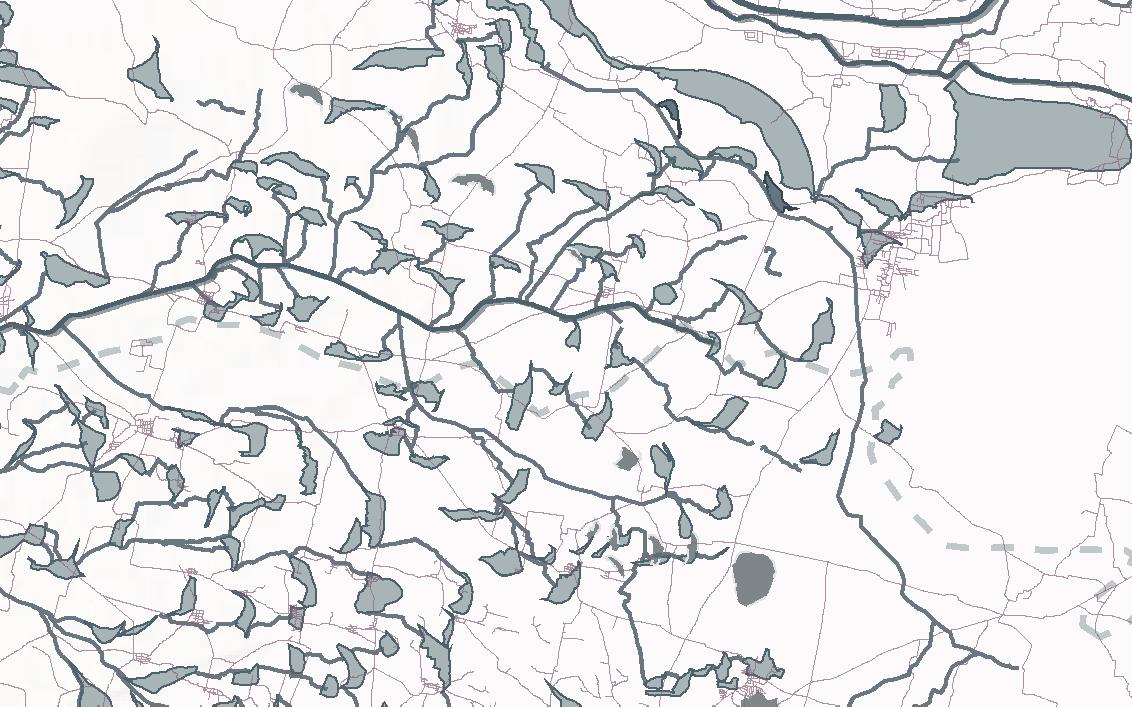

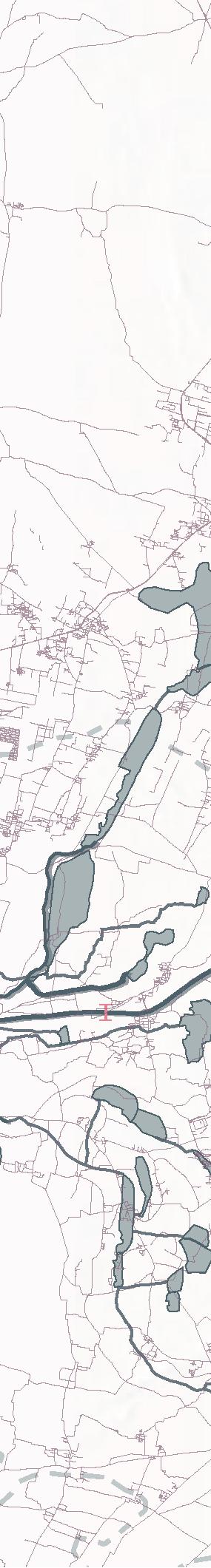

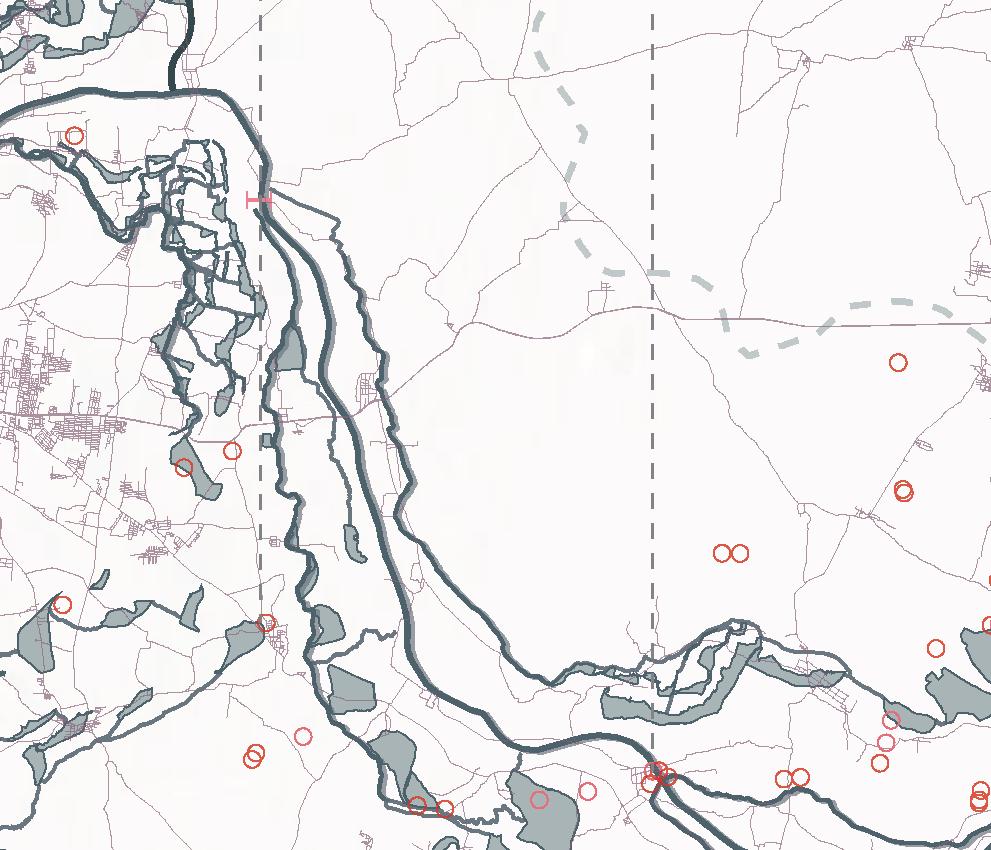

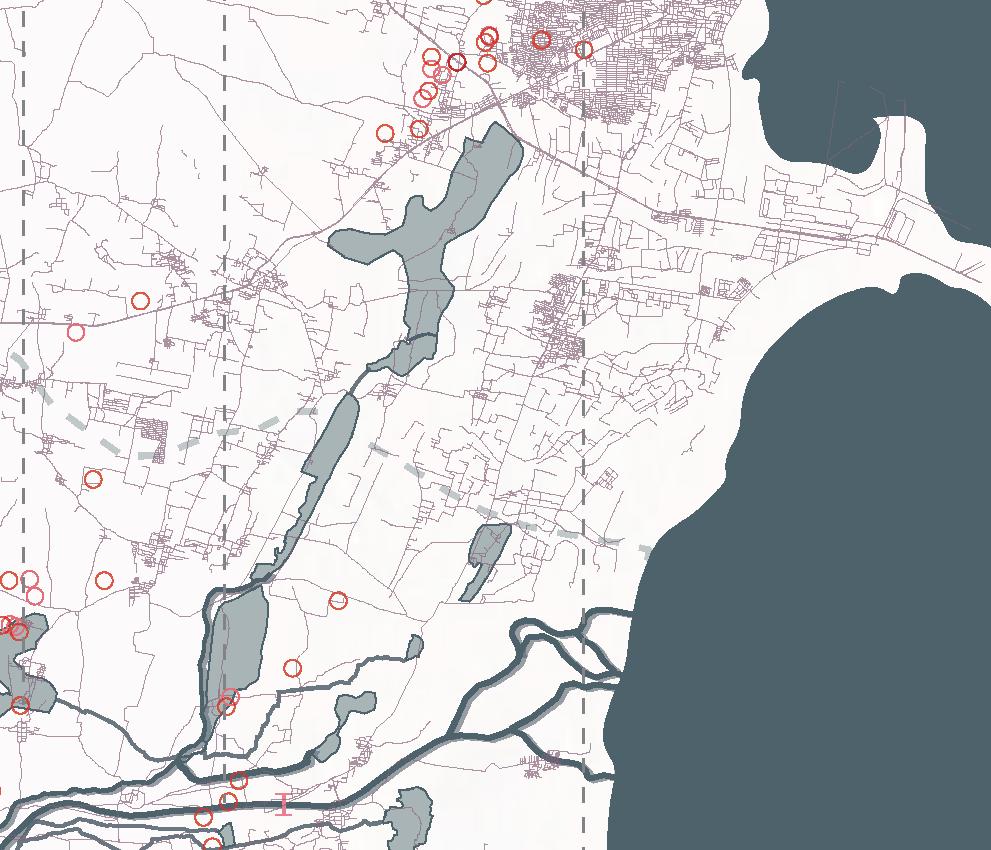

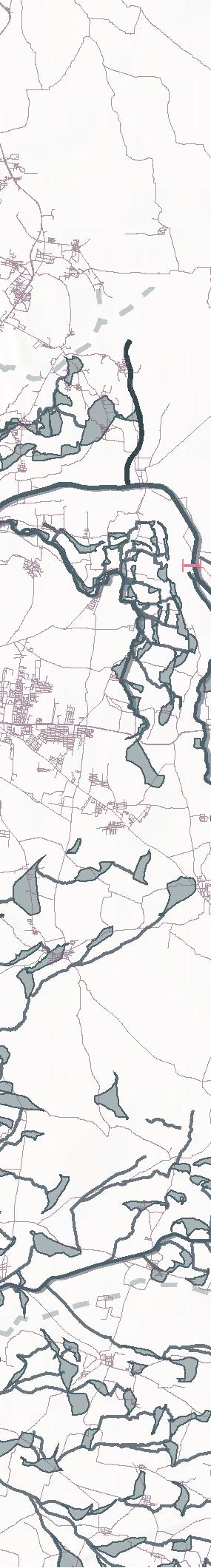

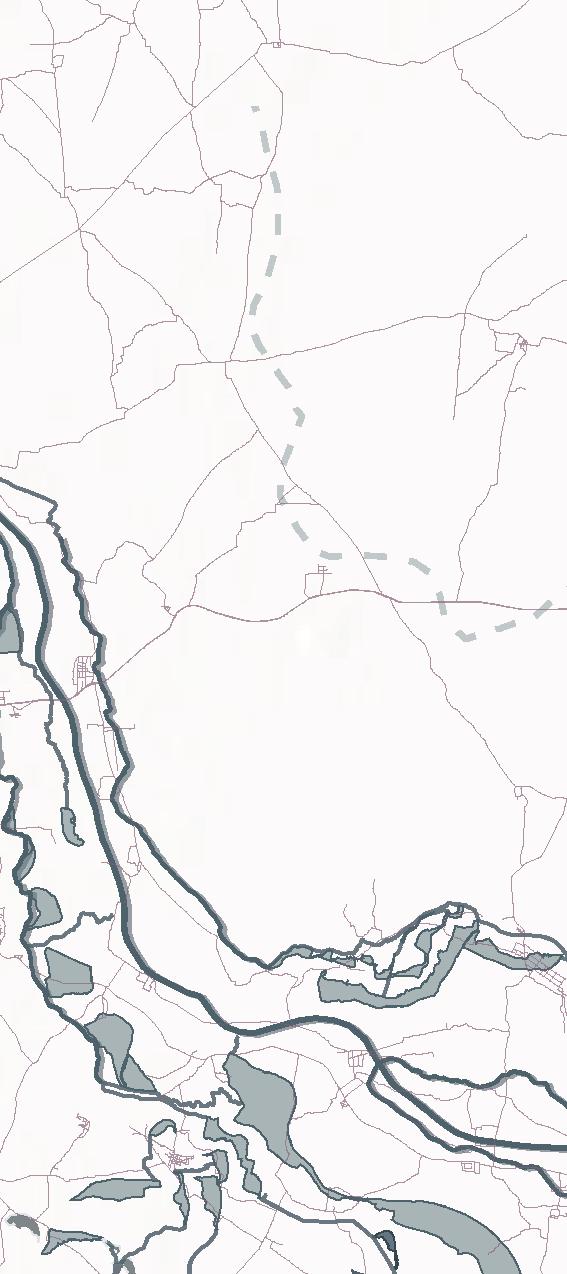

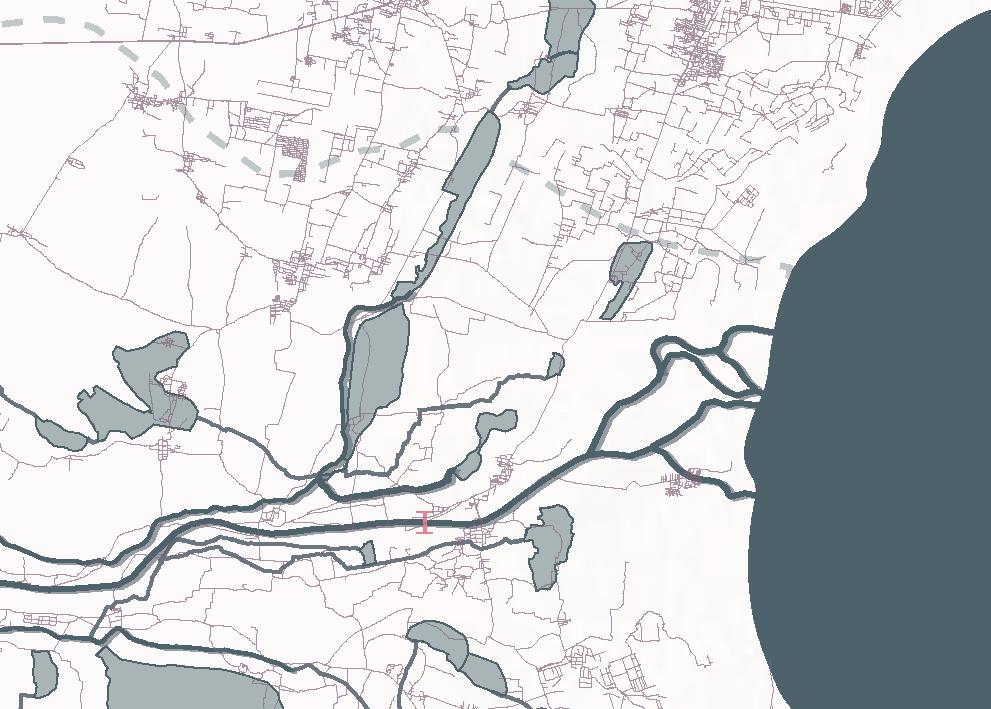

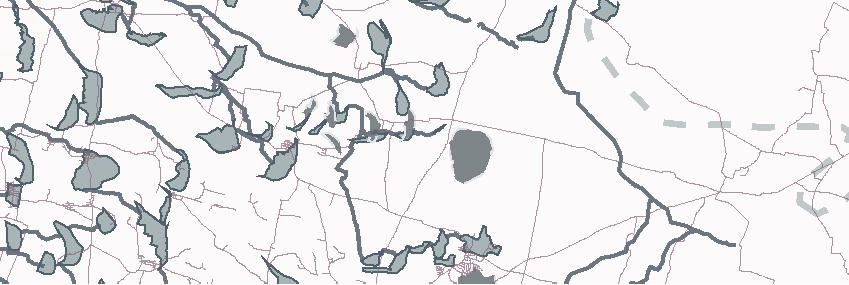

The water infrastructure on the Thamirabarani river is a testament to centuries of water management expertise. A well-planned network of canals from the river supports a thriving agricultural economy, particularly for paddy and banana cultivation. Thamirabarani’s water systems are designed to sustain the region’s wetlands, fostering biodiversity while addressing human needs.

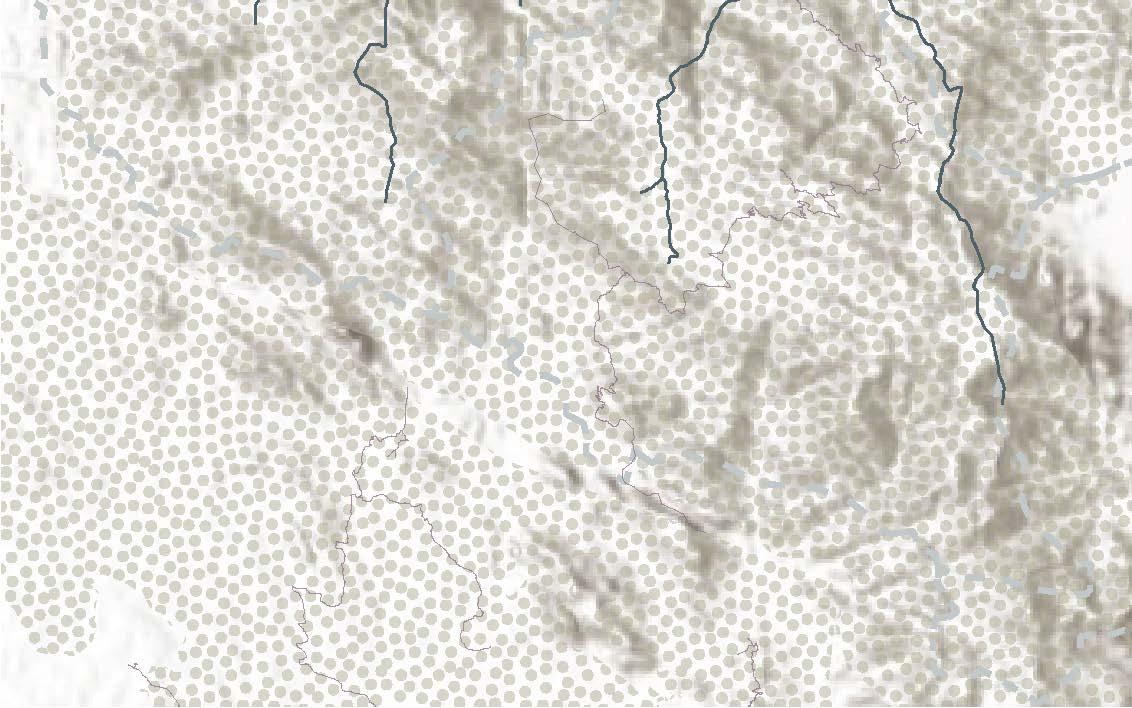

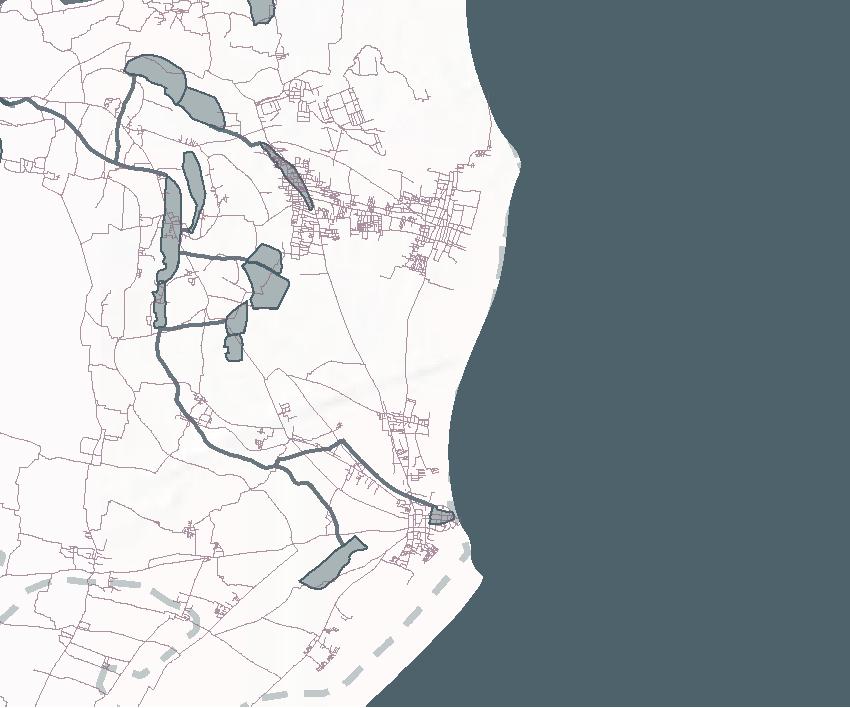

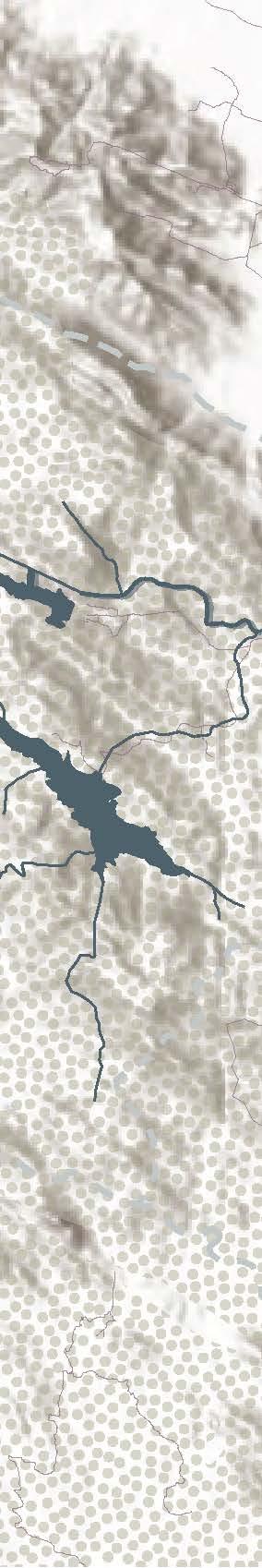

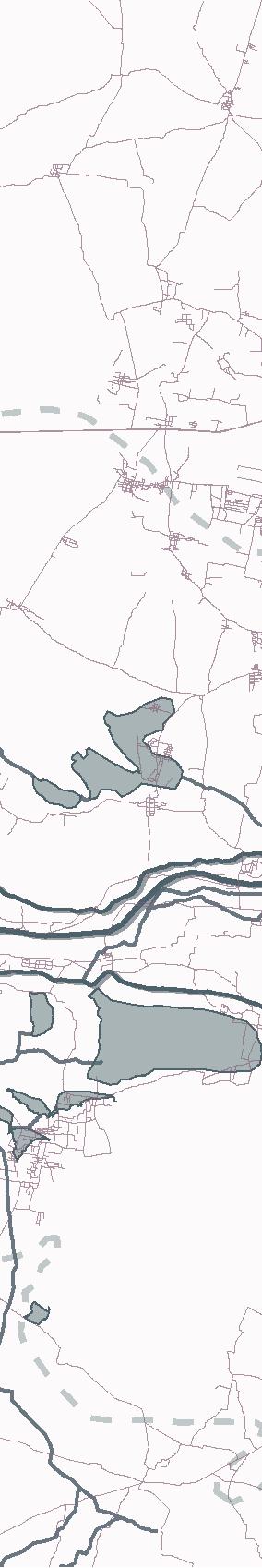

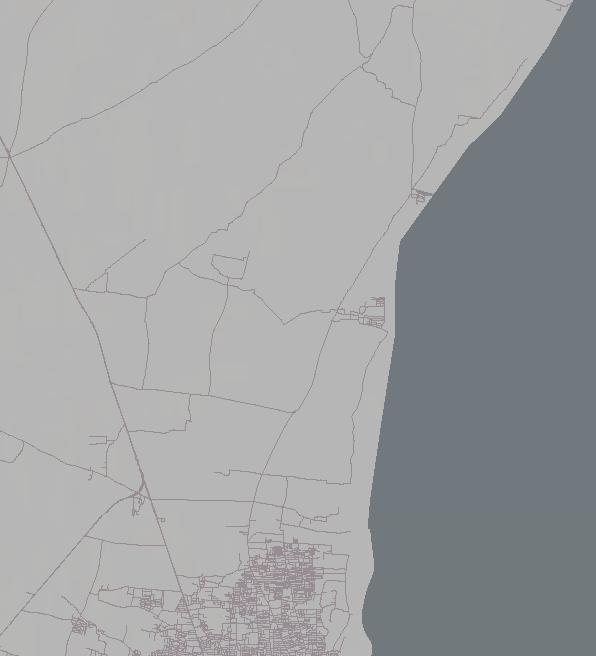

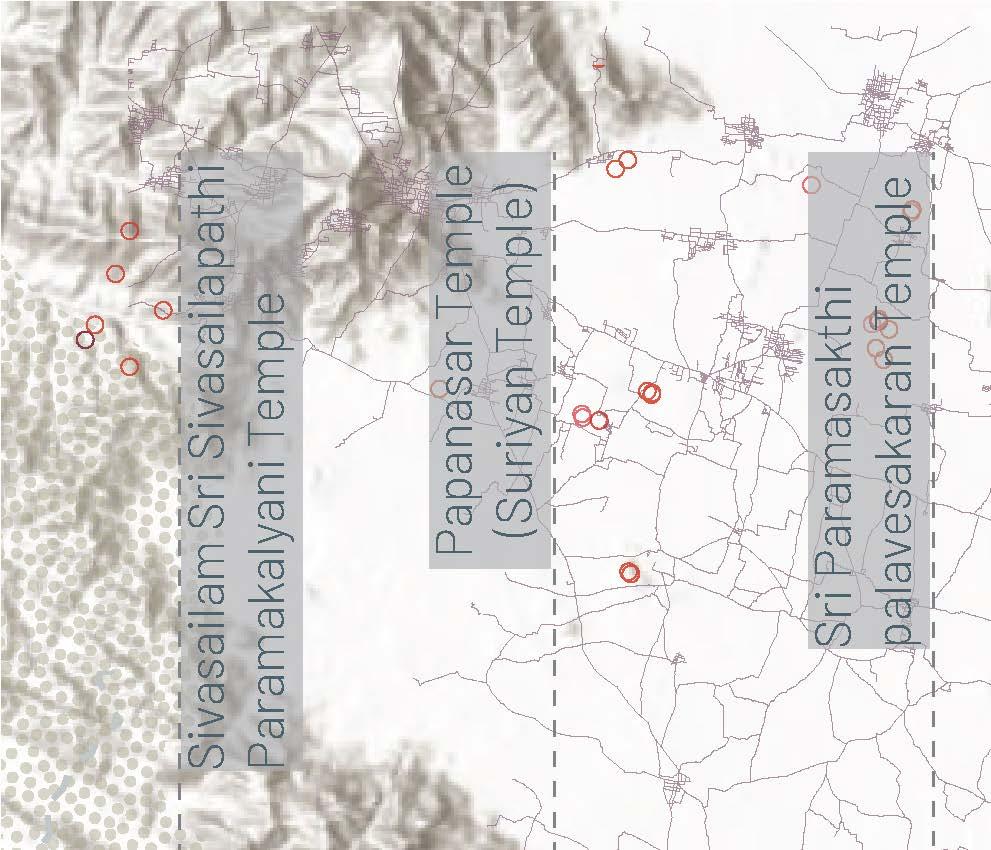

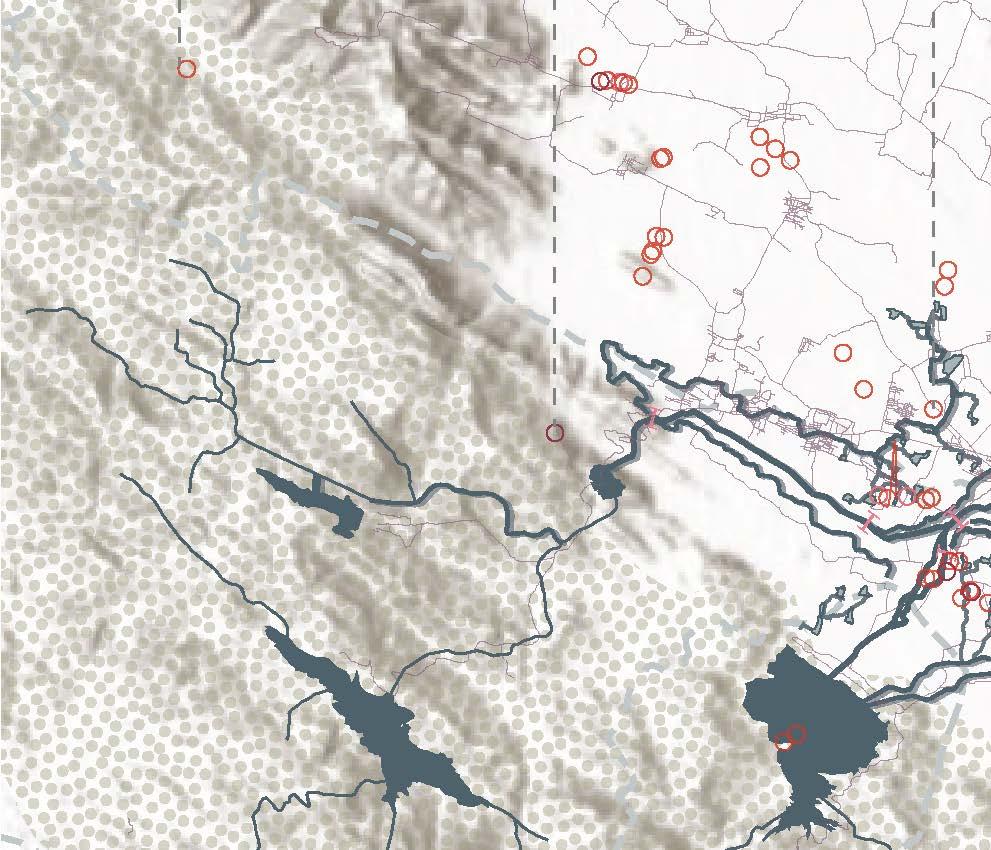

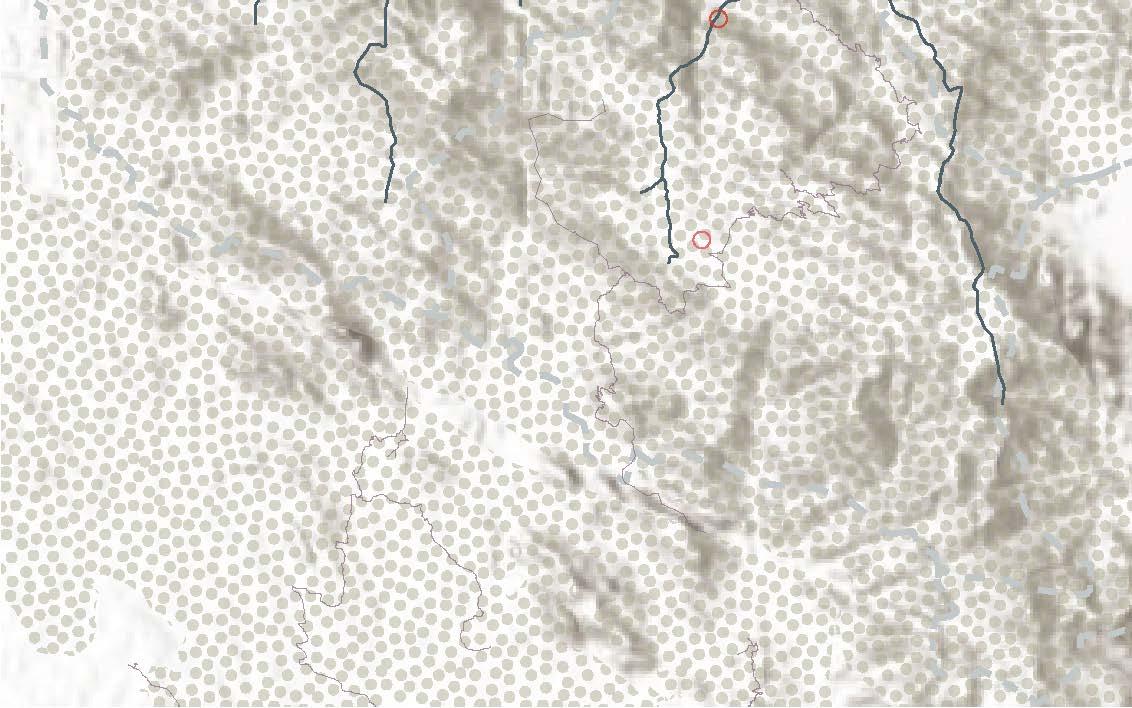

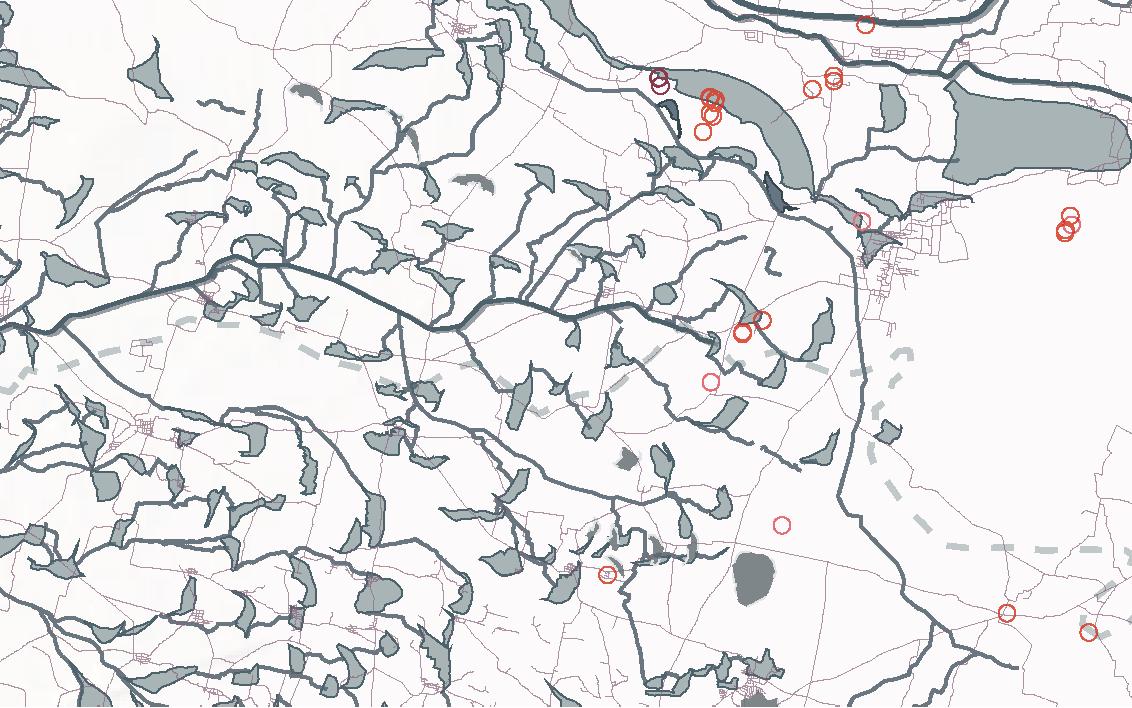

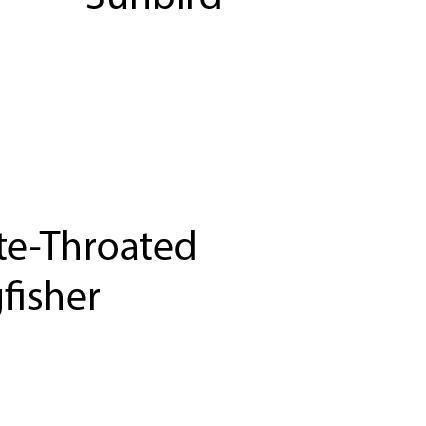

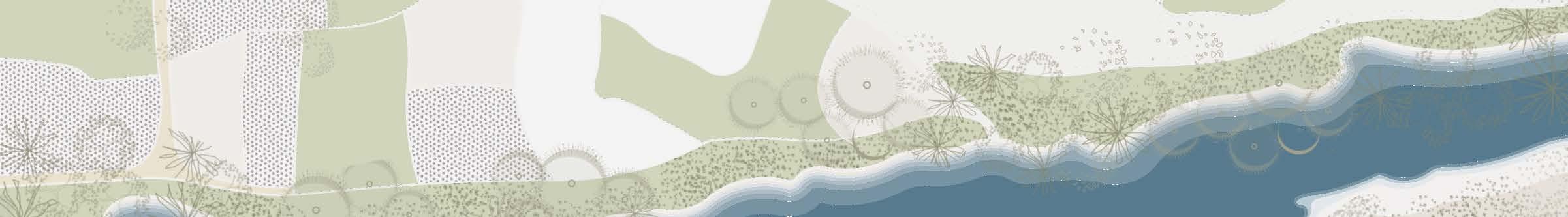

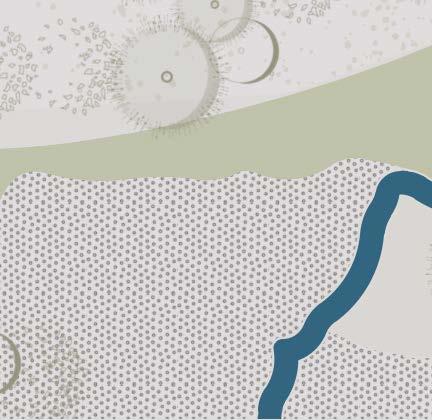

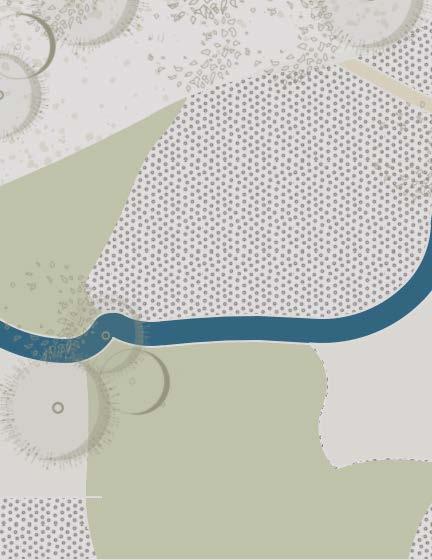

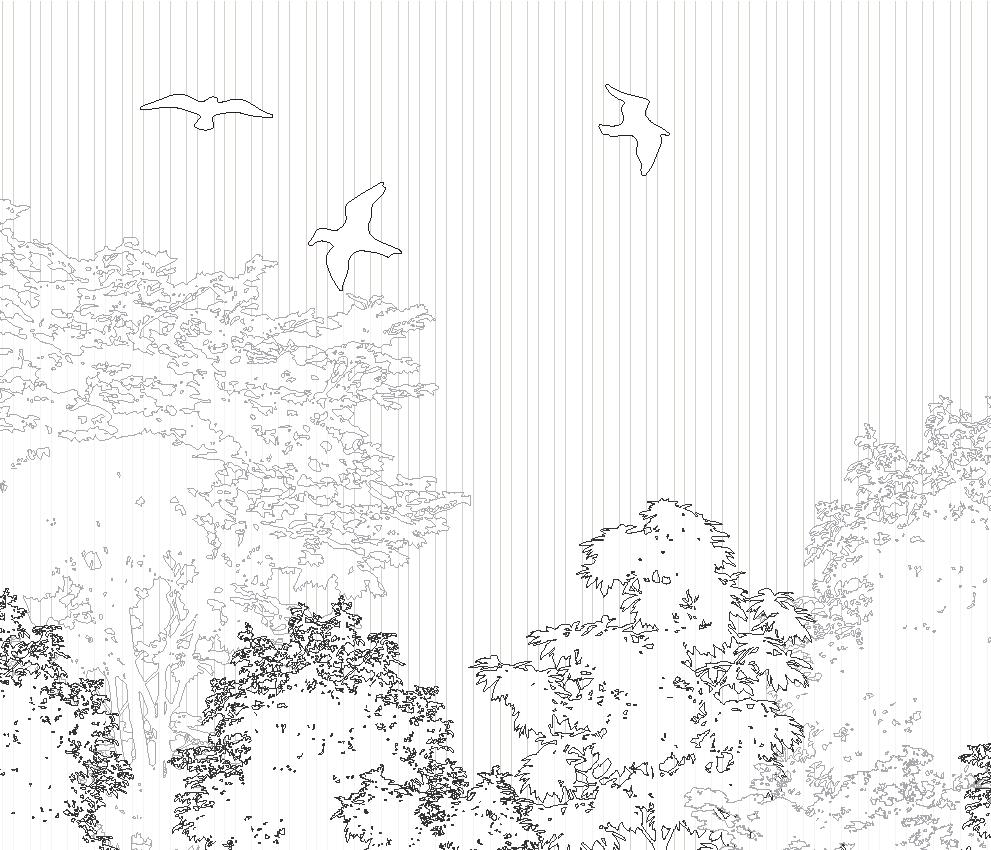

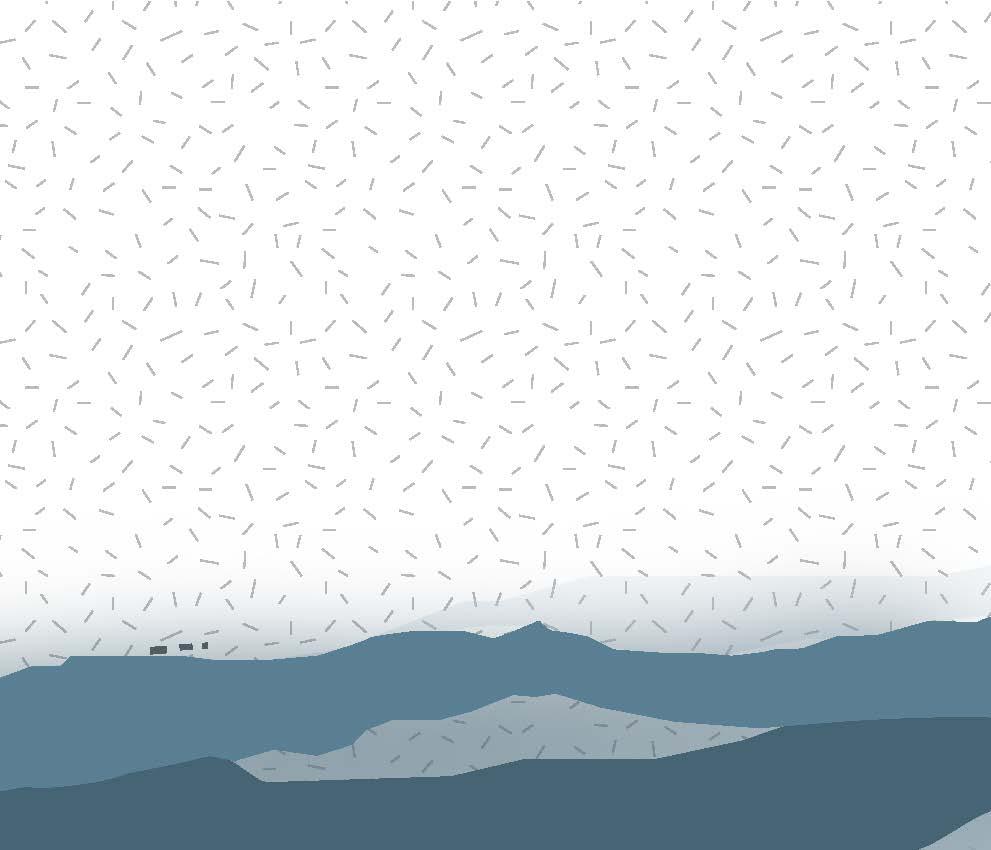

The Thamirabarani River flows through five distinct landscape types as it journeys from the mountainous west to the plains in the east, mirroring the five thinais described in Tamil Sangam literature. These thinais poetically connect the geography and ecology of Tamilagam with human emotions, often tied to romantic relationships.

The river begins in the lush, serene Kurinji (mountainous terrain), symbolizing love and union, and descends into the pastoral Mullai (forests), evoking patience and longing. It then nourishes the fertile Marutham (agricultural plains), representing harmony and domestic life, before transitioning to the coastal Neithal (riverine and estuarine landscapes), associated with yearning and separation. Along its course, stretches of arid Paalai (dry regions) reflect hardship and resilience. The river’s journey weaves together ecology, human experience, and literary tradition, showcasing the interconnectedness of nature and culture.

The mountainous region that sets the scene for a lover’s midnight union is best known for their hill slopes populated with the flower that gave it its name the strobilanthes kuringi.

The land of the forest-characterized by it’s waterfalls, ponds, and lakes that receives its name from the jasminum auriculatum flower commonly found in this territory.

The region, known for its croplands and the Marutham tree that gave the landscape its name, was the scene for triangular love plots. The inhabitants were known as ulavar, velanmadar, toluvar, and kadaiyar or kadasiyan, whose occupations involved tilling, ploughing, and farmworking.

A region of dry lands and, in Tamil prosody, seen as a wasteland that emerges from other landscapes withering under a burning sun, is named after the pala indigo plant, Wrightia.

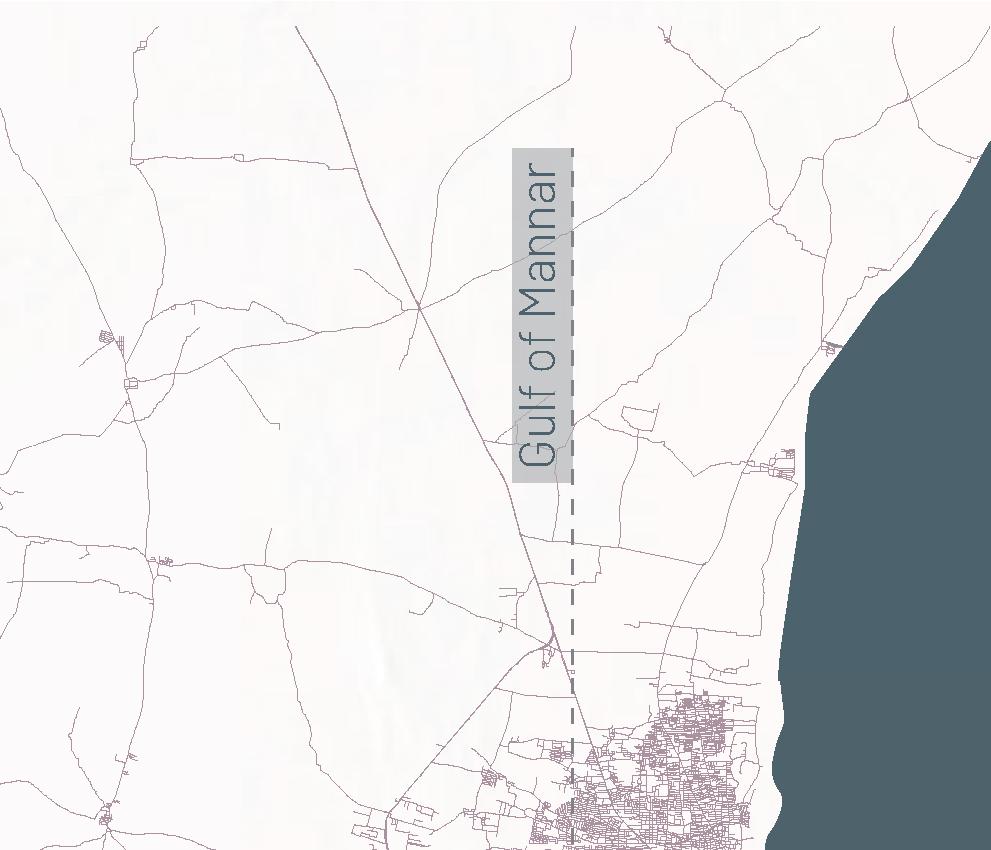

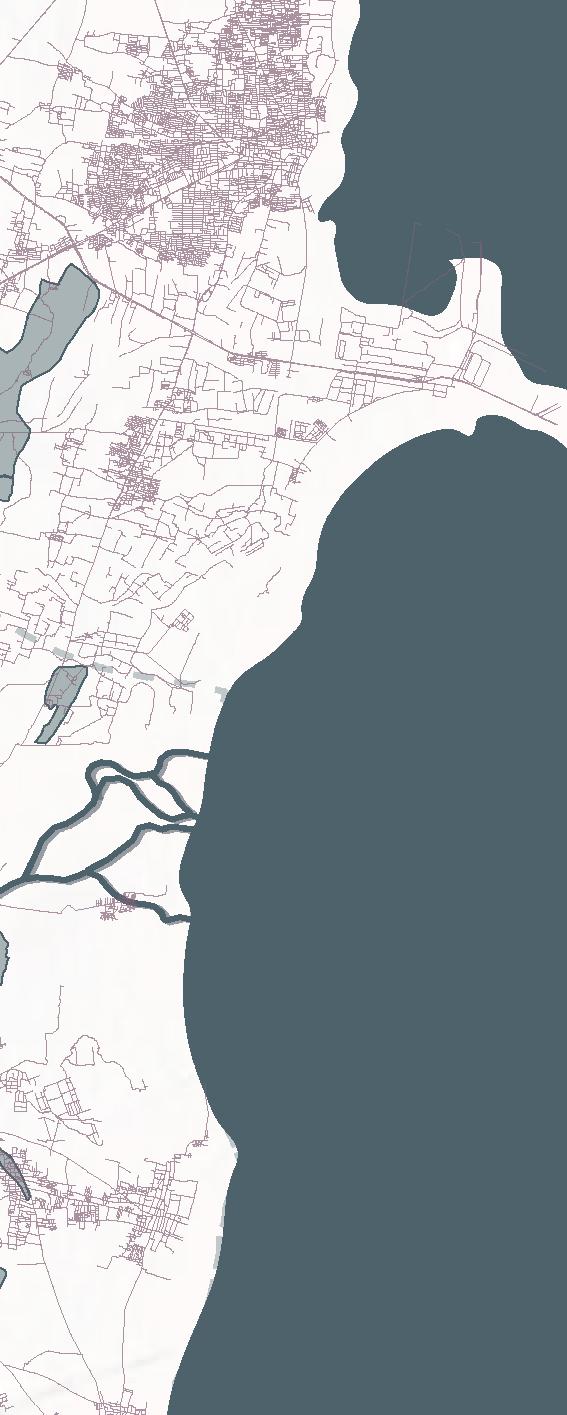

A region defined by seashore and beaches, and named after the common water lily found here, with inhabitants known as parathavar, nulaiyar and umanar being known for salt manufacturing, pearl diving, fishing, and coastal trade.

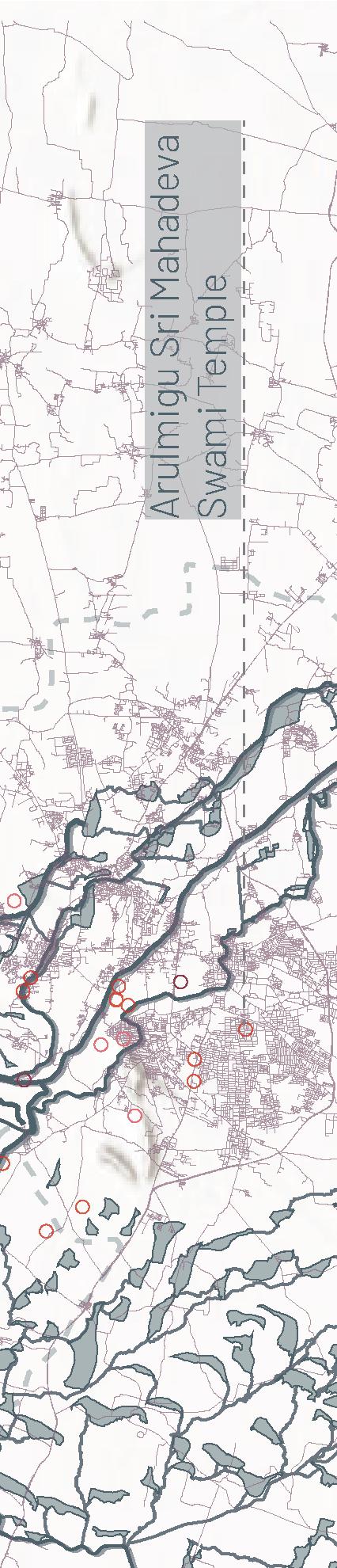

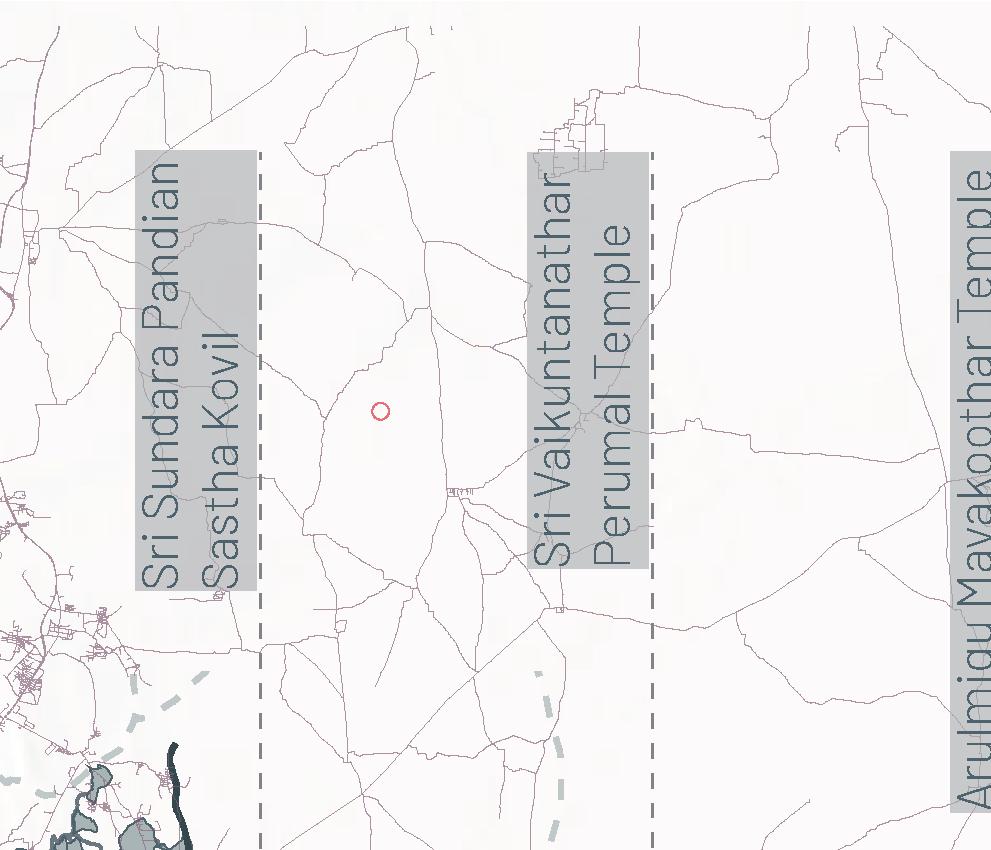

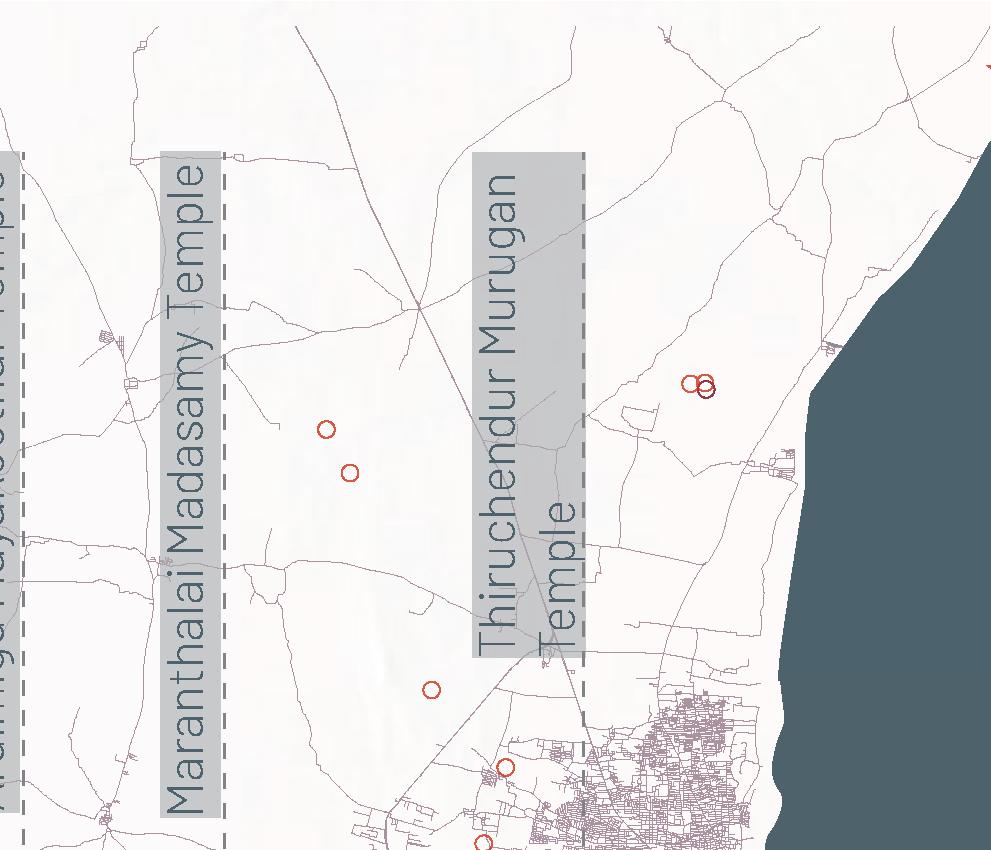

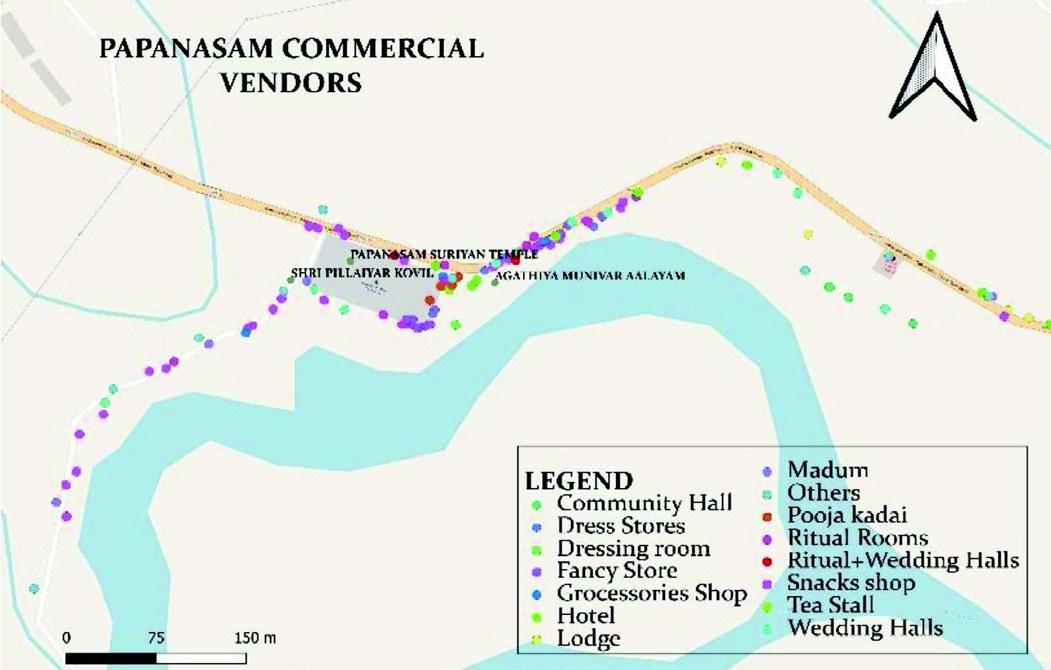

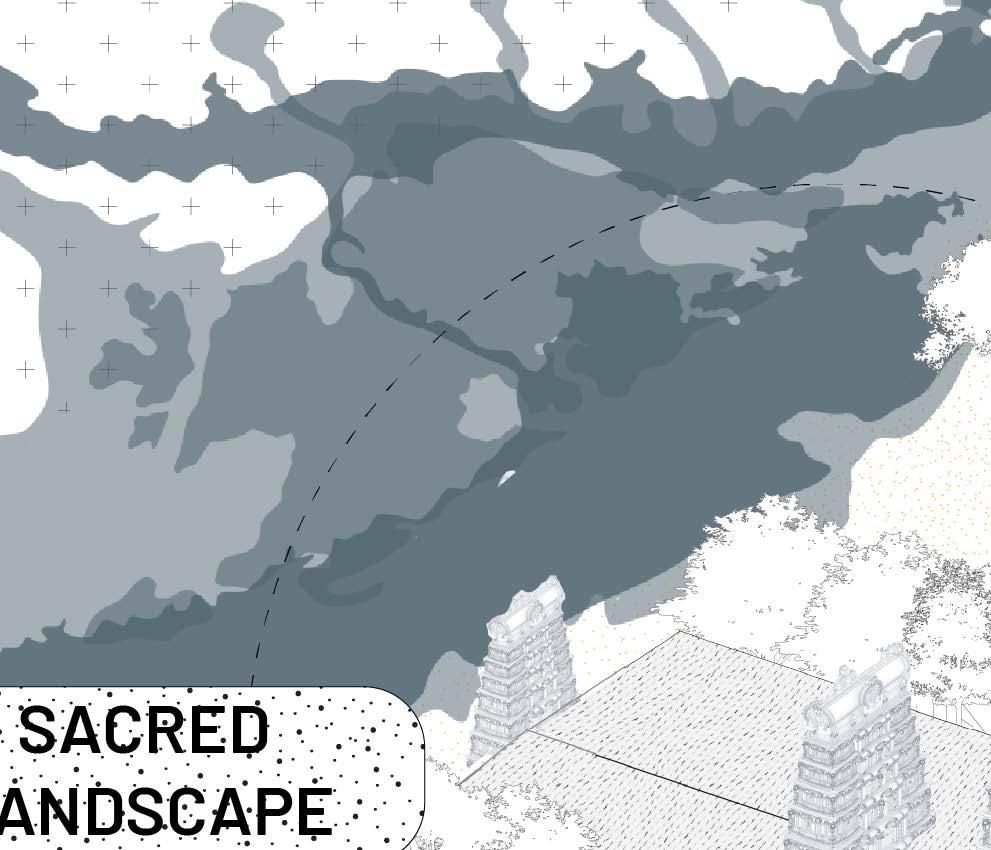

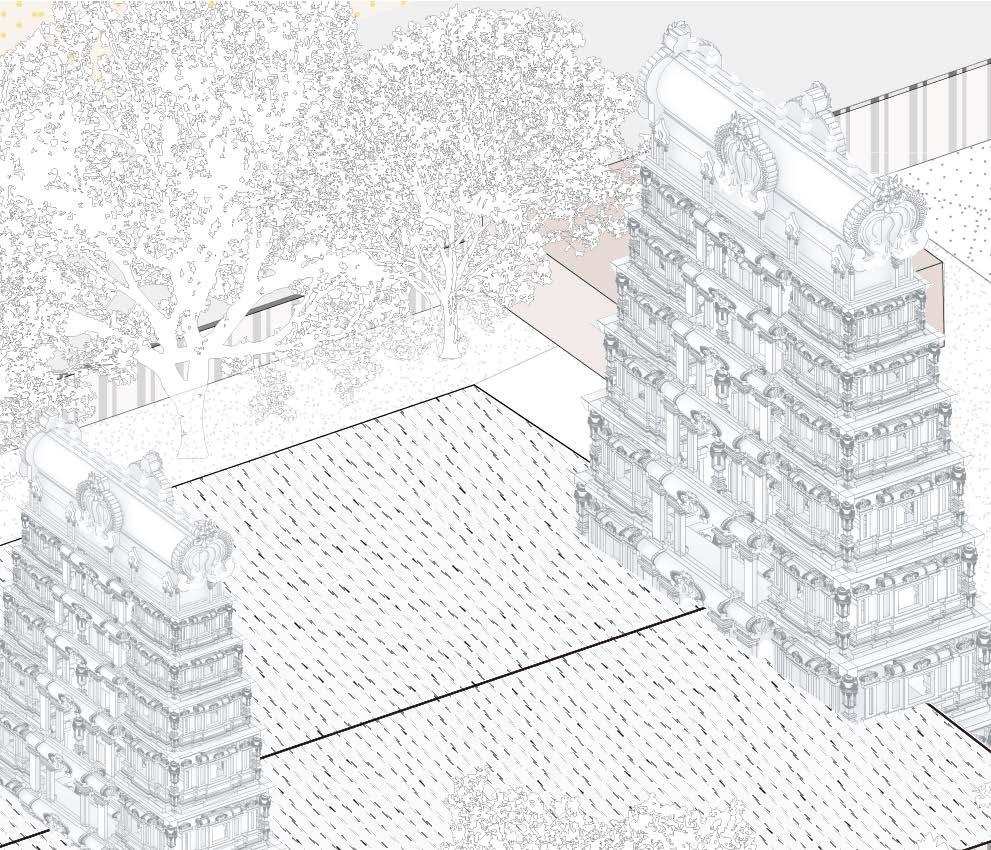

The Thamirabarani River holds a sacred and profound connection with the cultural and spiritual life of the region it nurtures. Revered as a holy river, its waters are believed to possess purifying and life-sustaining qualities. Along its course, numerous temples, such as the Srivaikuntam Temple and Agasthiyar Temple, are situated near its banks, symbolizing the river’s divine significance. The river is often associated with religious myths, including the sage Agastya, who is believed to have brought the river’s waters to the region.

During festivals like Thamirabarani Pushkaram, thousands of devotees gather along its banks to perform rituals, take holy dips, and offer prayers to ancestors. The Thamirabarani is more than a river; it is a sacred thread weaving together the spiritual, cultural, and practical lives of the communities it sustains, making it a cherished and life-giving force in Tamil Nadu.

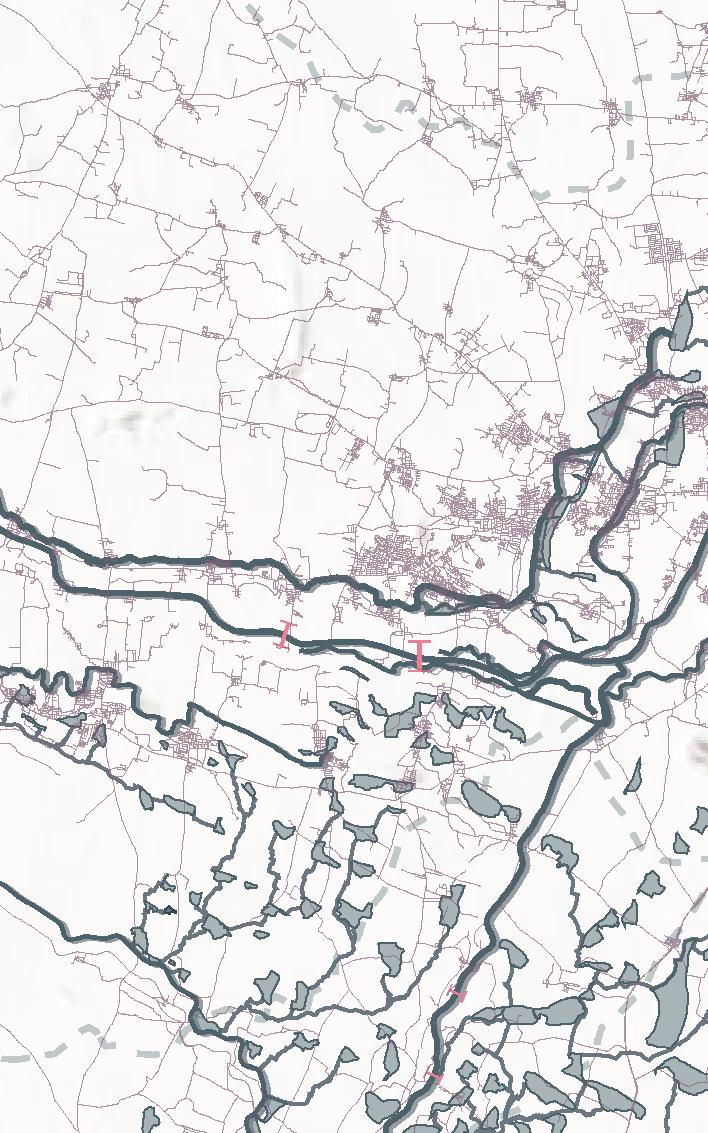

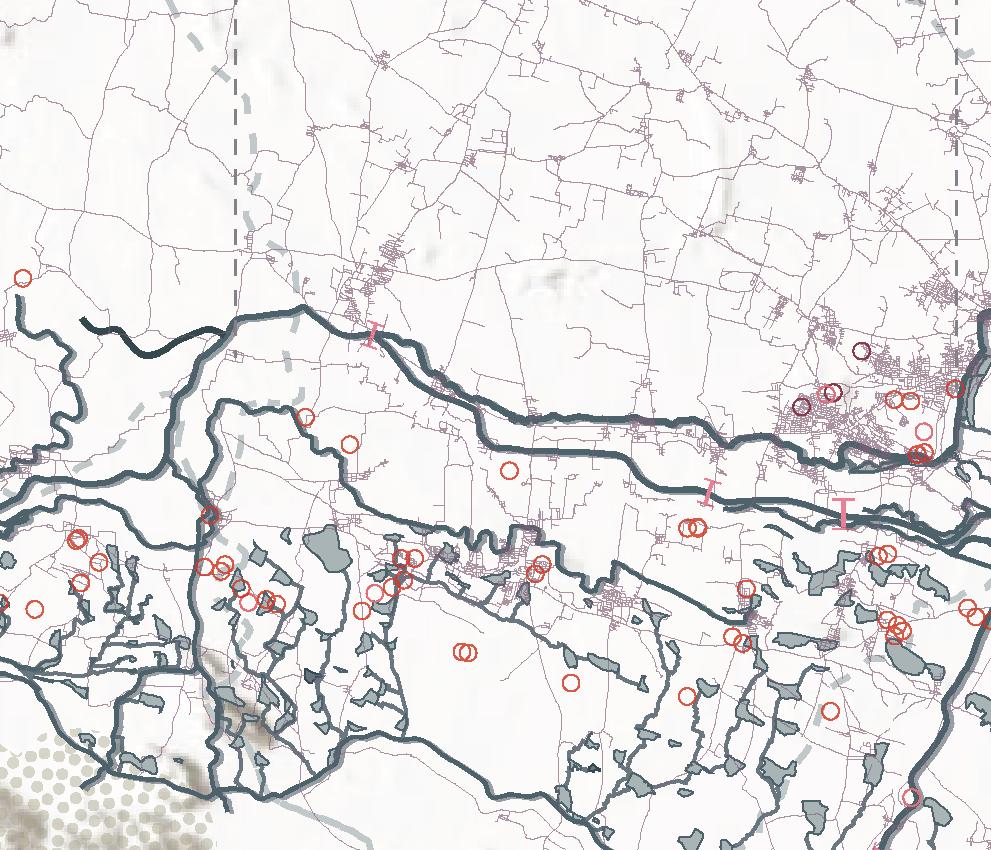

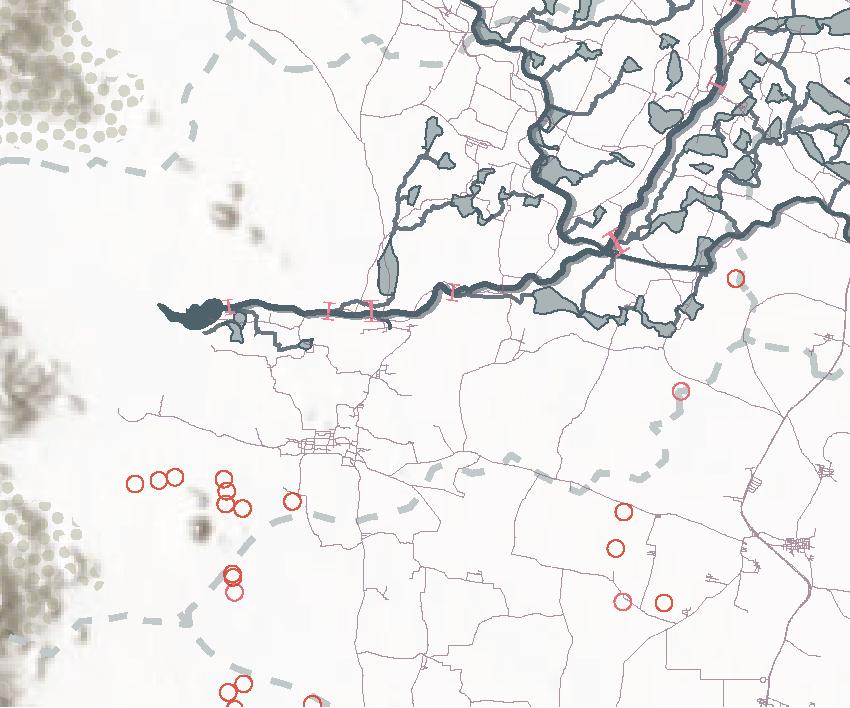

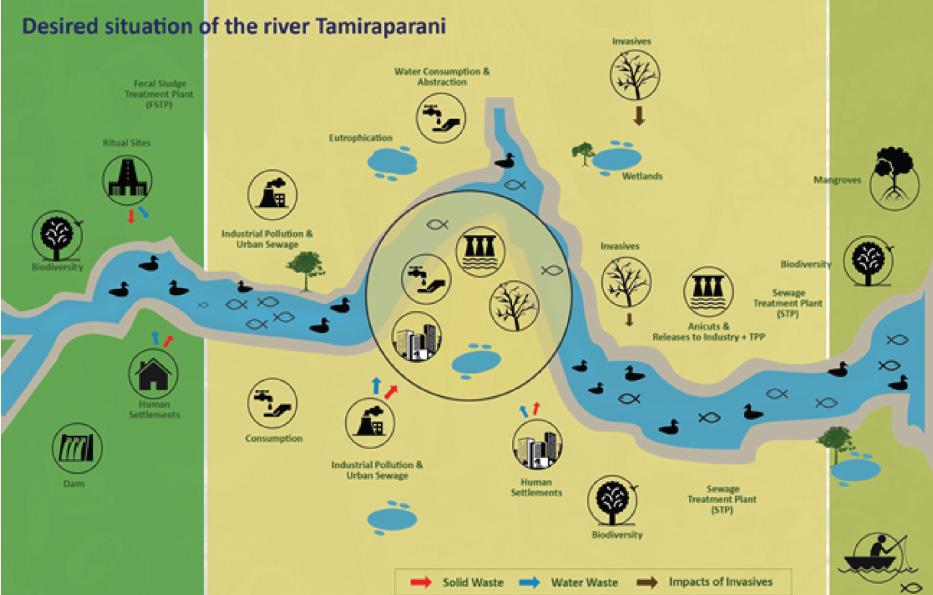

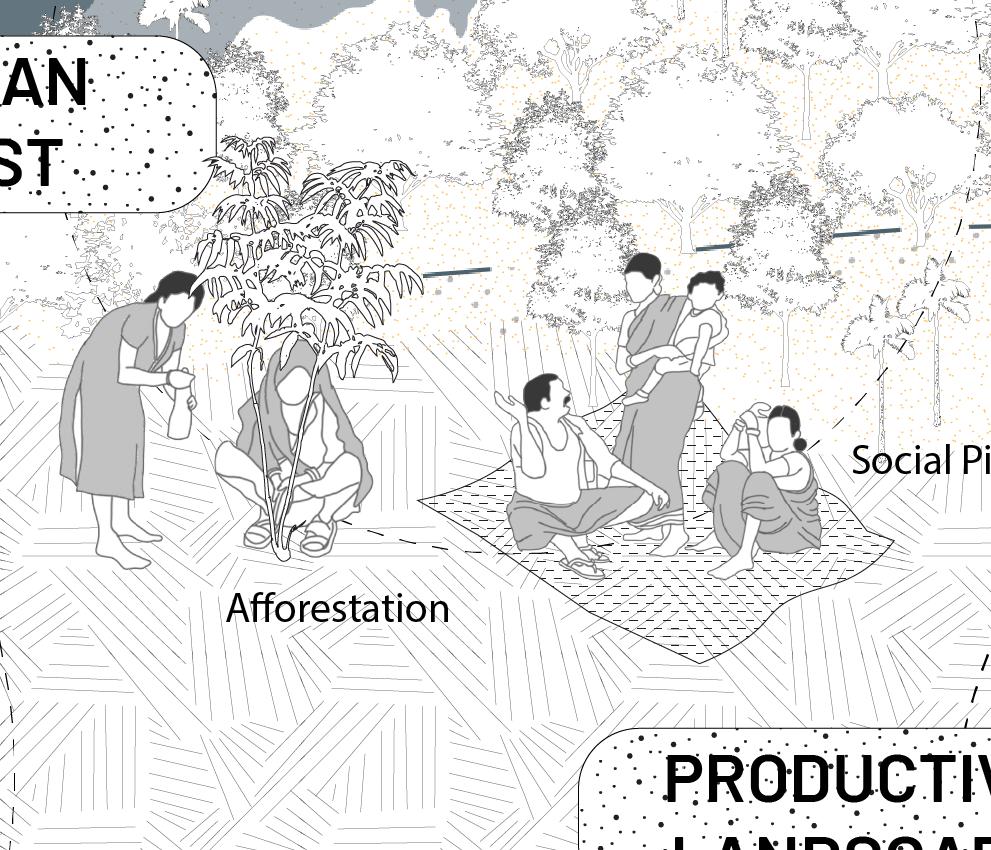

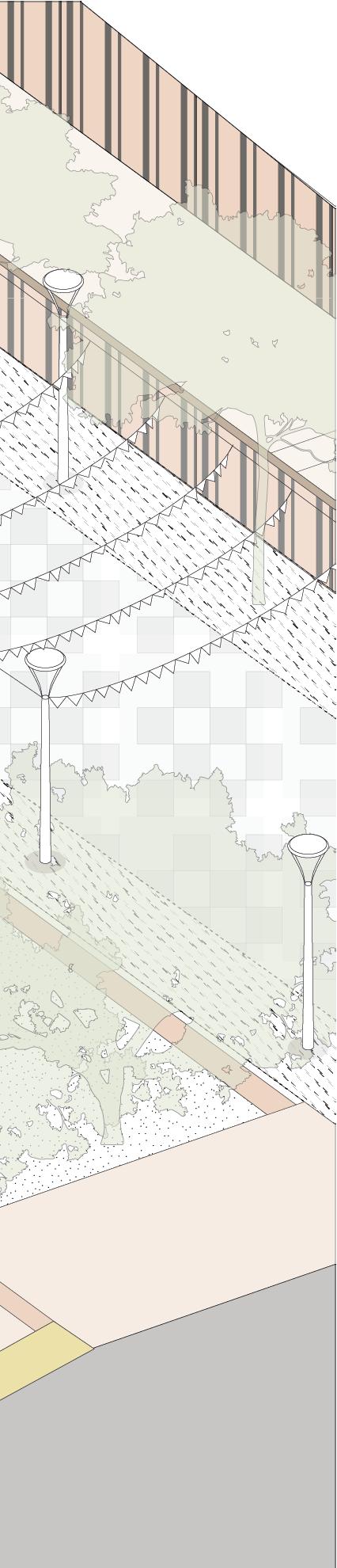

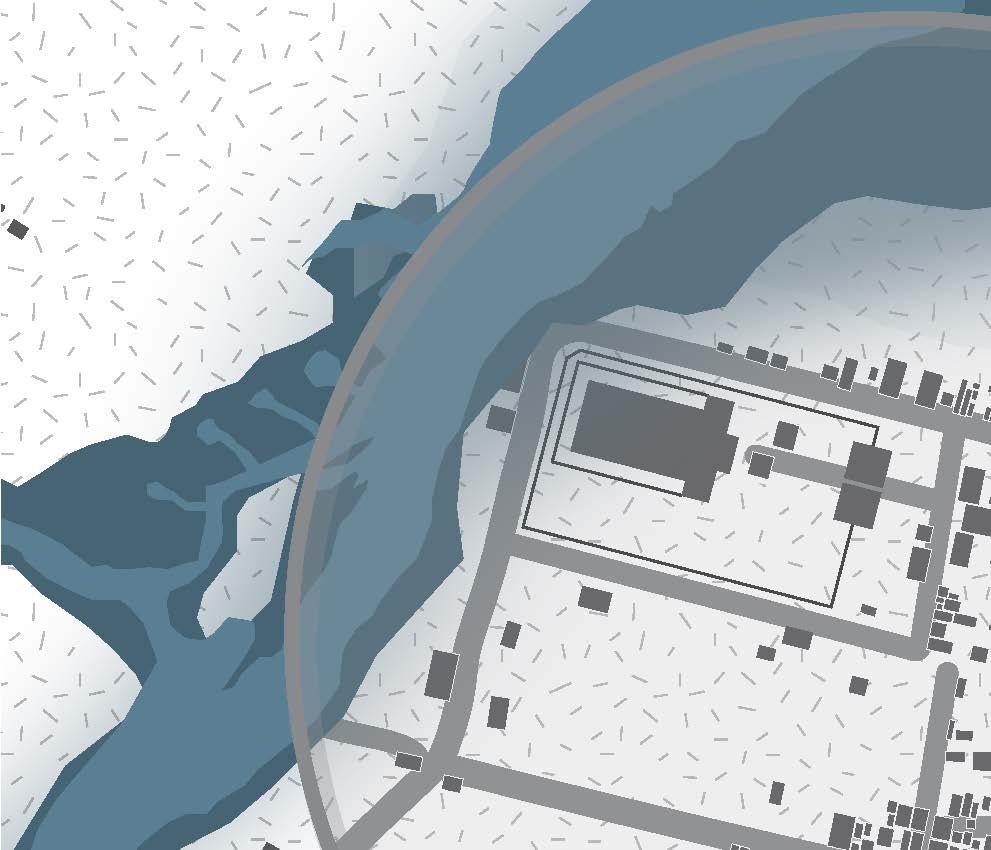

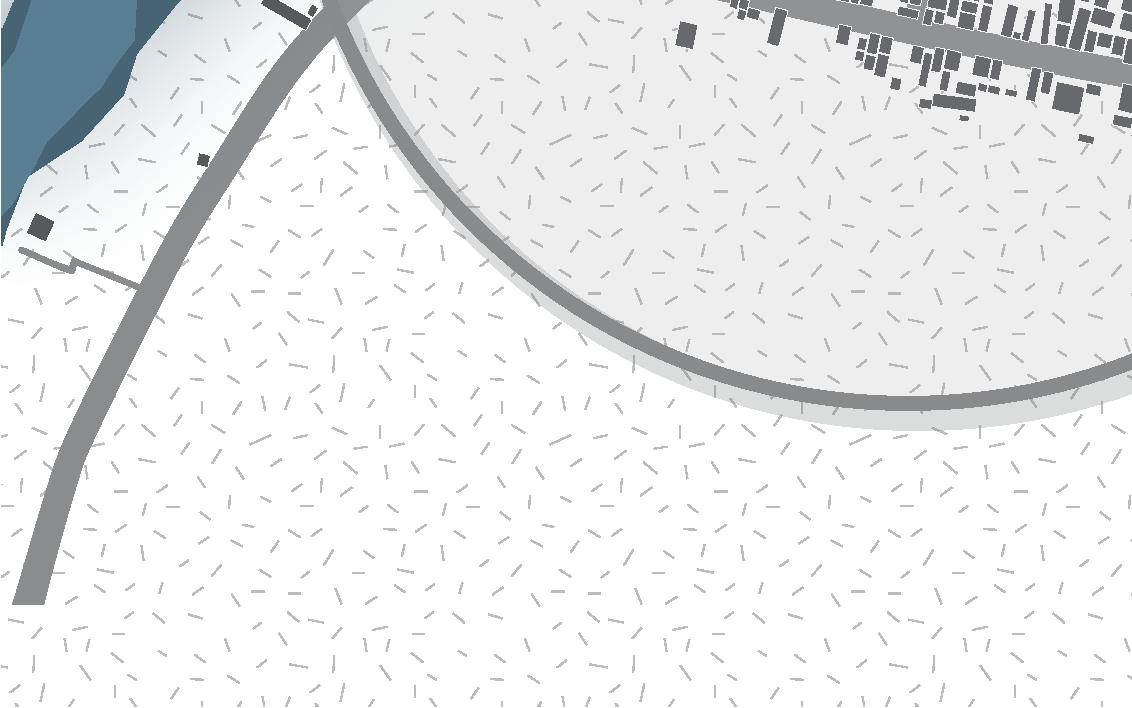

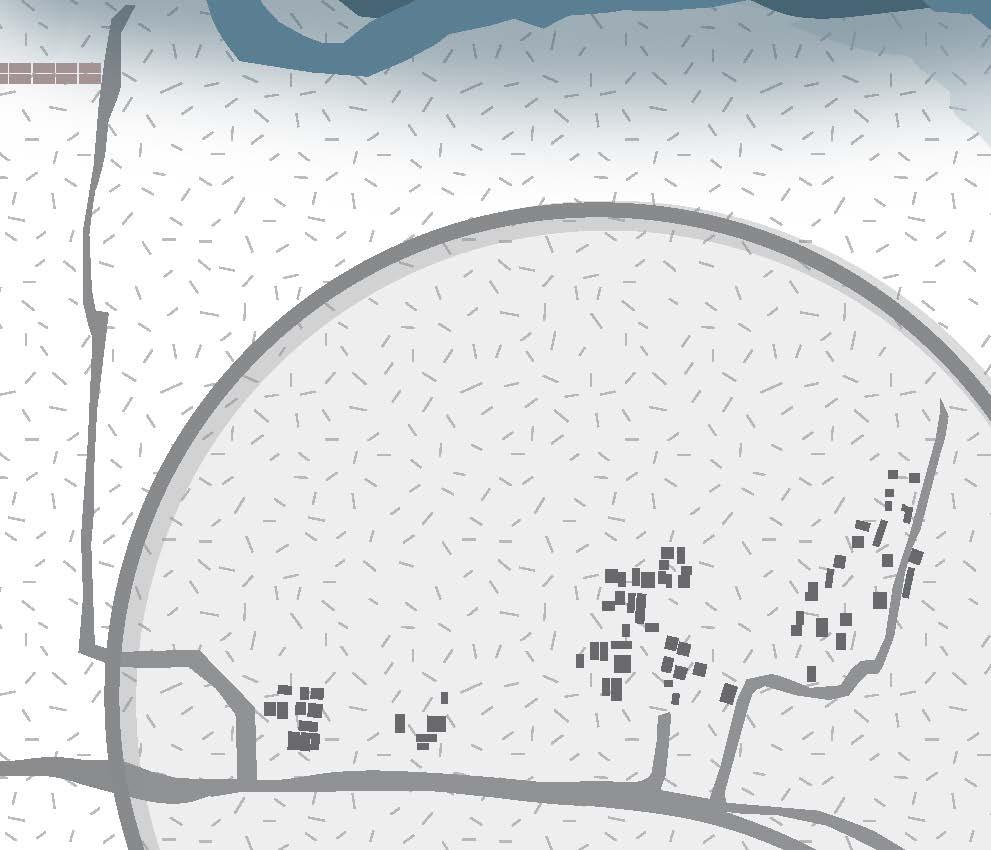

The restoration of the Thamirabarani river scape’s Social-Ecological Systems (SES) adopts a holistic approach, integrating ecological processes and social systems. The initiative, driven by scientific principles and community collaboration, identifies key hot spots for intervention in its first phase. Five pilot sites across municipalities and panchayats have been selected to establish Social-Ecological Observatories, focusing on hydrology, water chemistry, riparian vegetation, biodiversity, and human wellbeing.

The restoration plan emphasizes a bottomup, stakeholder-inclusive strategy, engaging communities, local institutions, selfhelp groups, district administration, and policymakers to co-develop solutions. This road map, presented on World Rivers Day 2022, aims to sustain ecosystem services and improve river health through continuous monitoring and collaborative efforts.

• Focus group discussions with Pandarams (Shaivite monks)

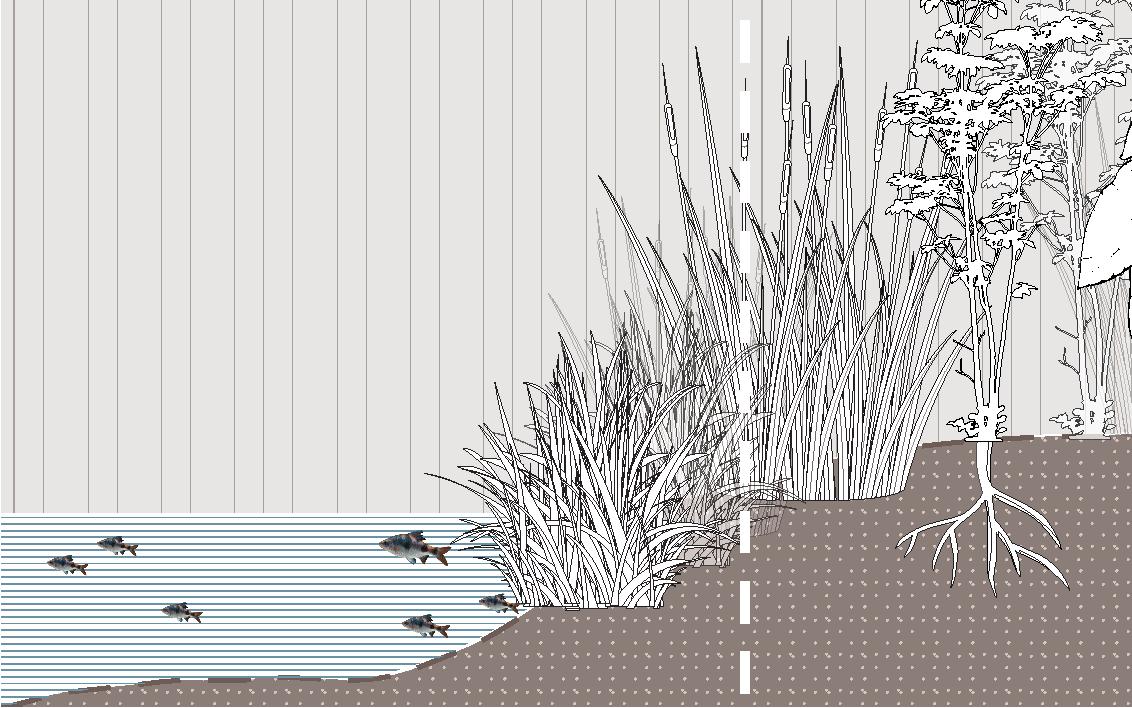

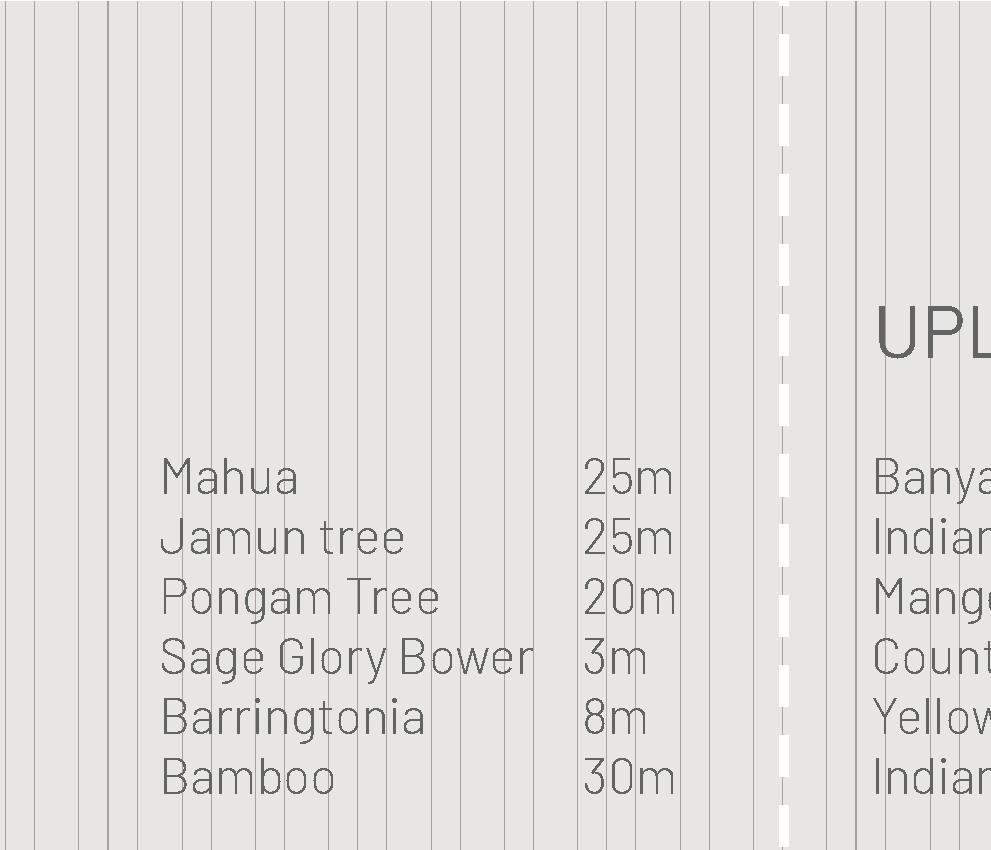

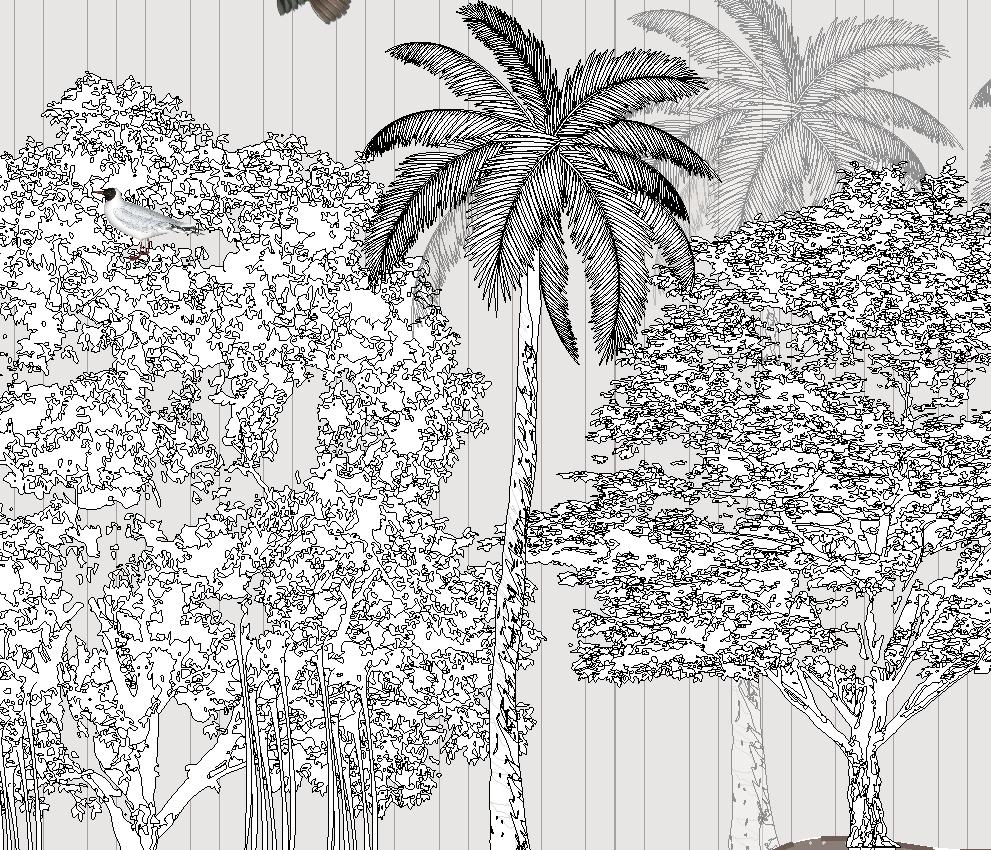

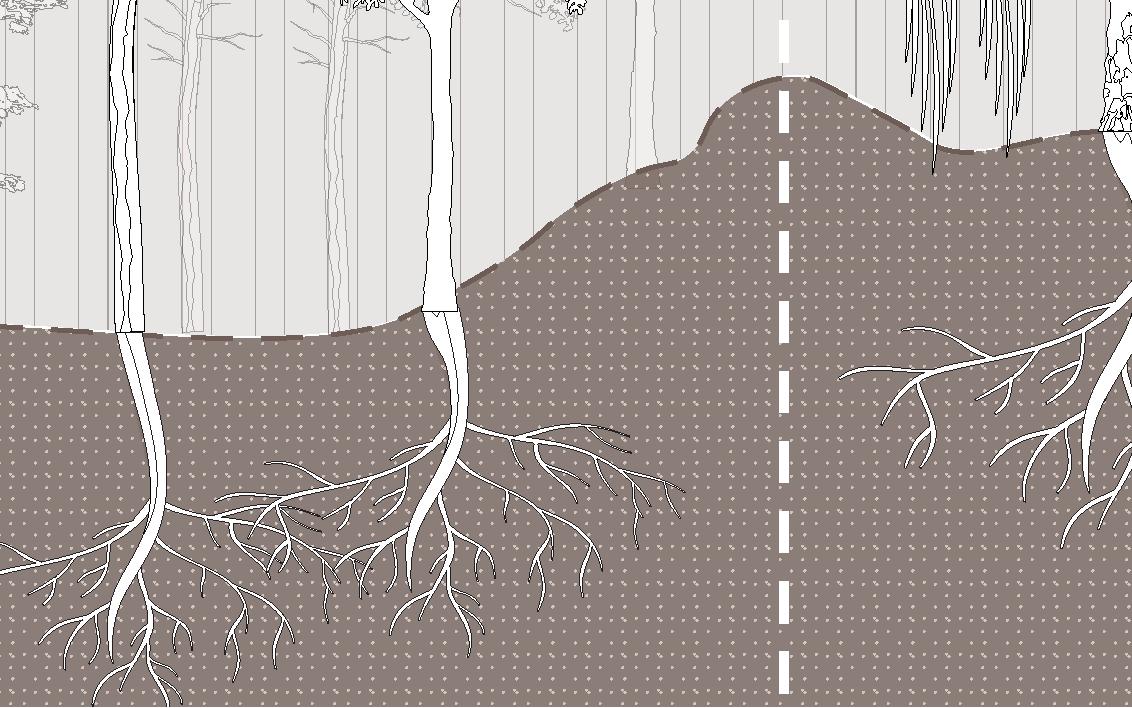

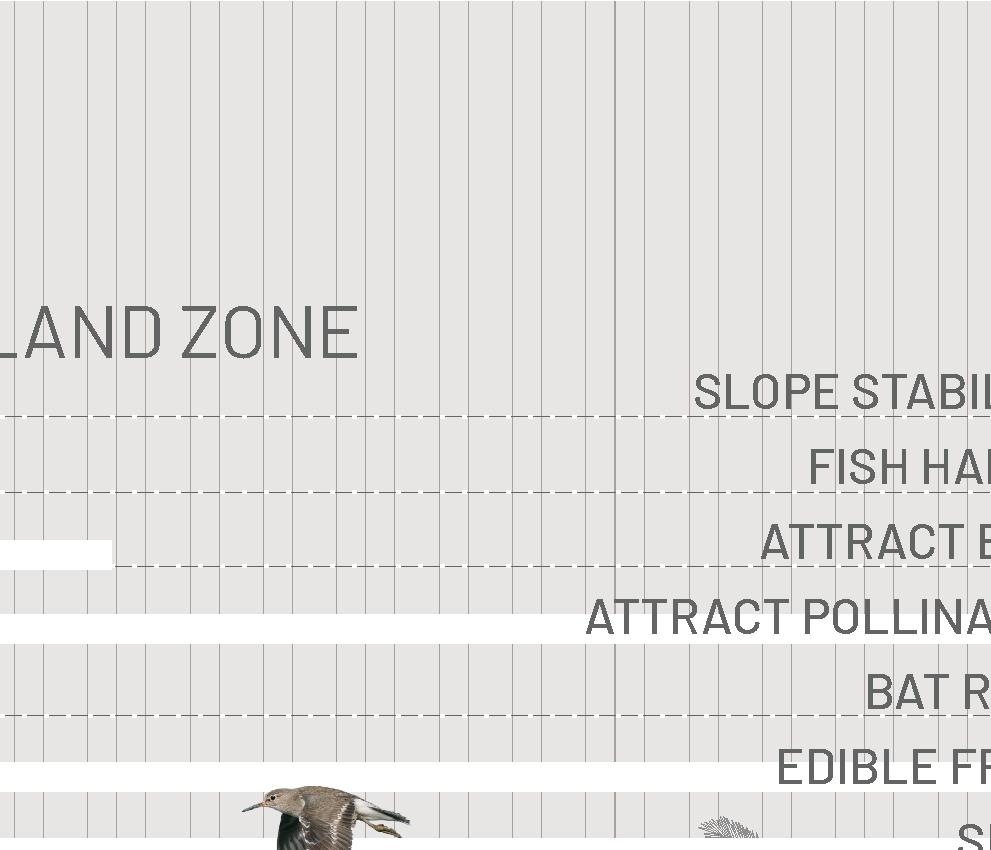

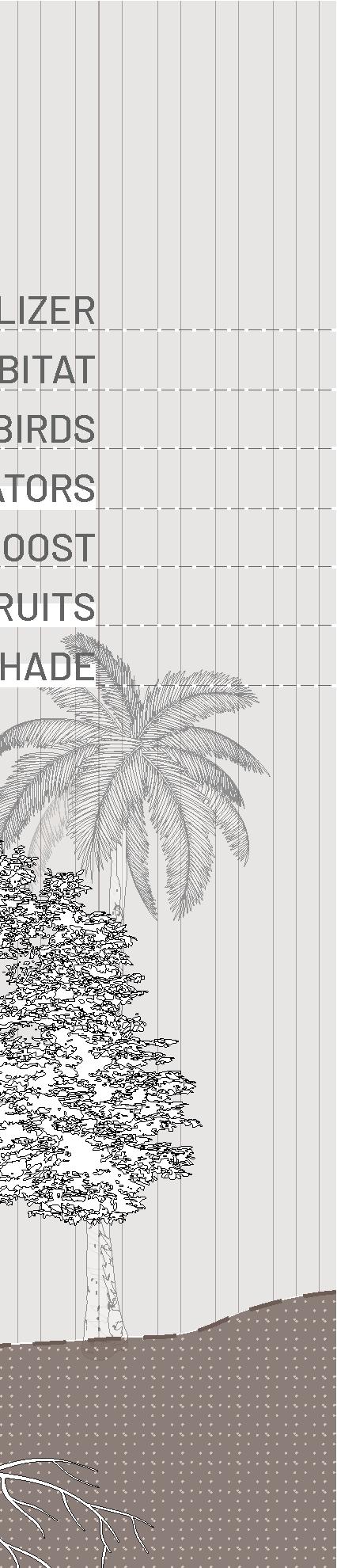

• Afforestation of the Riparian buffer: sample project supports an exceptionally high number of plant species

• Sampling efforts to observe water quality parameters

•Stakeholder engagement

•Placing more bins (near bathing ghats)

•Increasing the number of toilets (Paid)

•Create awareness about dumping clothes

• “Porunai Nadhi Paakanume” - A nature trail for educating about conservation around the river to highlight the importance of local biodiversity

•Scaling up the usage of bio fertilizers

•Proper solid-waste management

• Water and Sanitation Survey conducted to document river water use for their livelihood activities suggesting a strong co-dependency

•Pilot project: DEWATS sustainable sanitation solutions

• Planting sacred flowering trees

•Clearing of Invasive & restoring native vegetation

•Cleaning and Restoration of some kal mandapams(bathing ghats)

• Working towards Open-Defecation Free (ODF) village.

• Wetland Socio-ecological Observatories

• Strengthening disaster management measures and riparian restoration

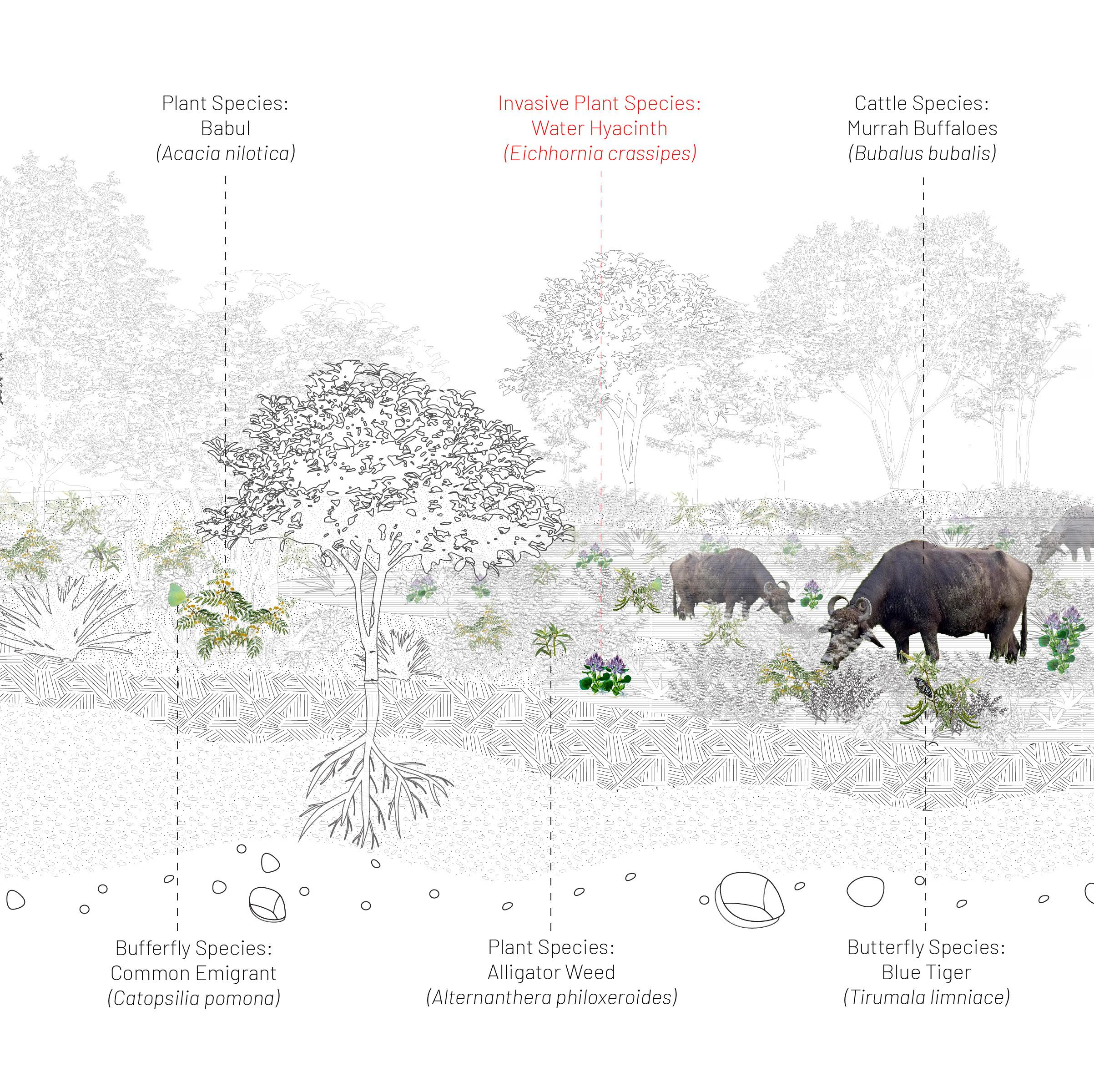

•Clearing of Water Hyacinths

• Capacity building using a sustainable method of harvesting medicinal plant

•Scaling up the usage of bio fertilizers

• Introducing cycling trail along with community support

• Clearing invasive species and introduction of native vegetation to restore the river bank

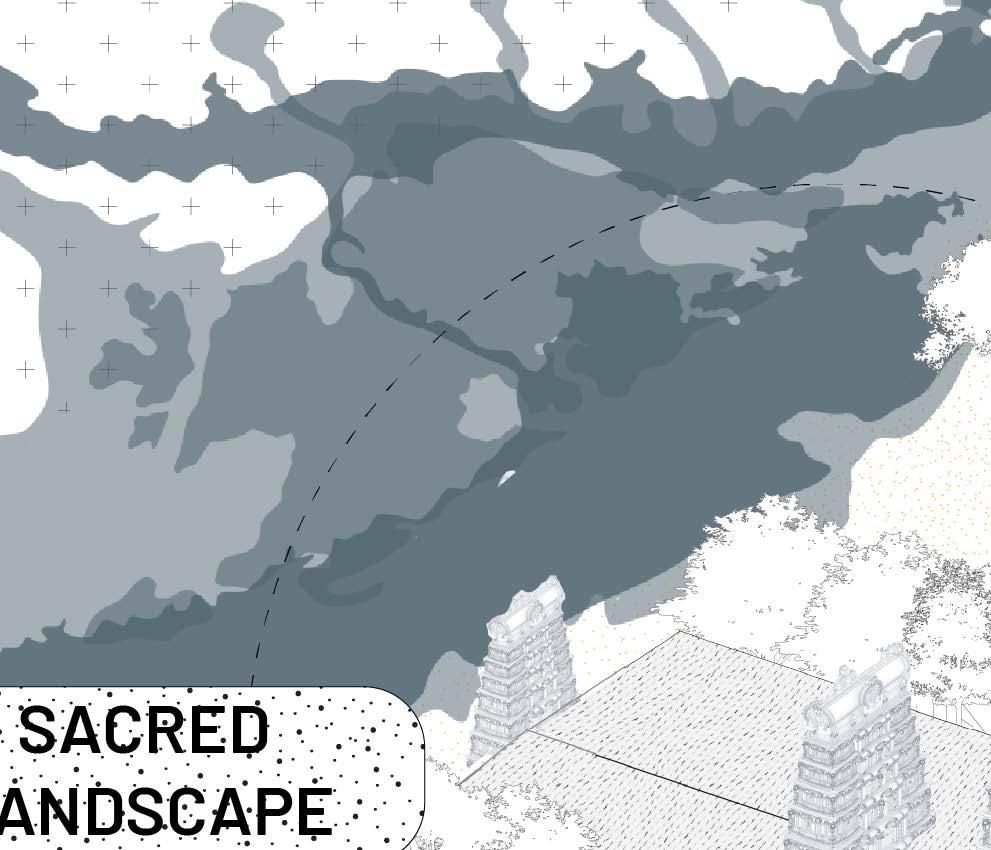

......and it’s connection to the social and ecological life mainly in the Marutham region, across three different landscapes.

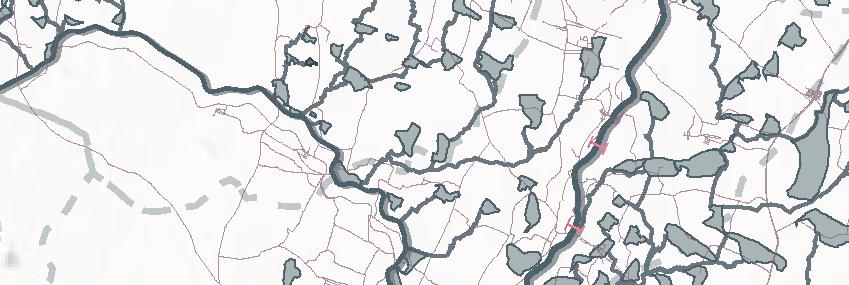

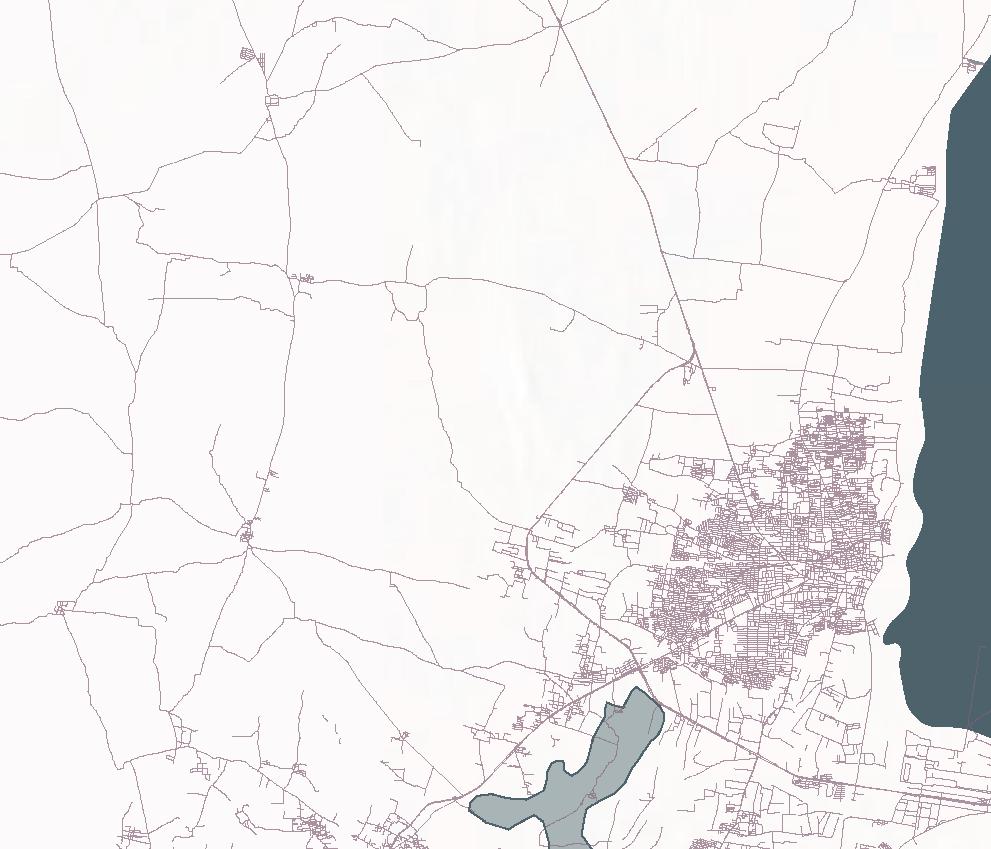

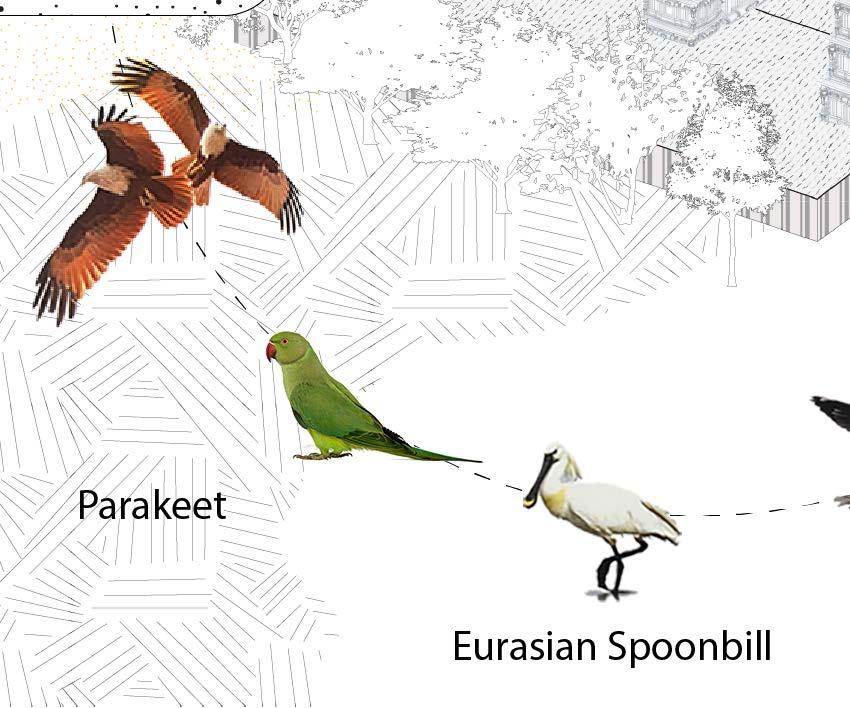

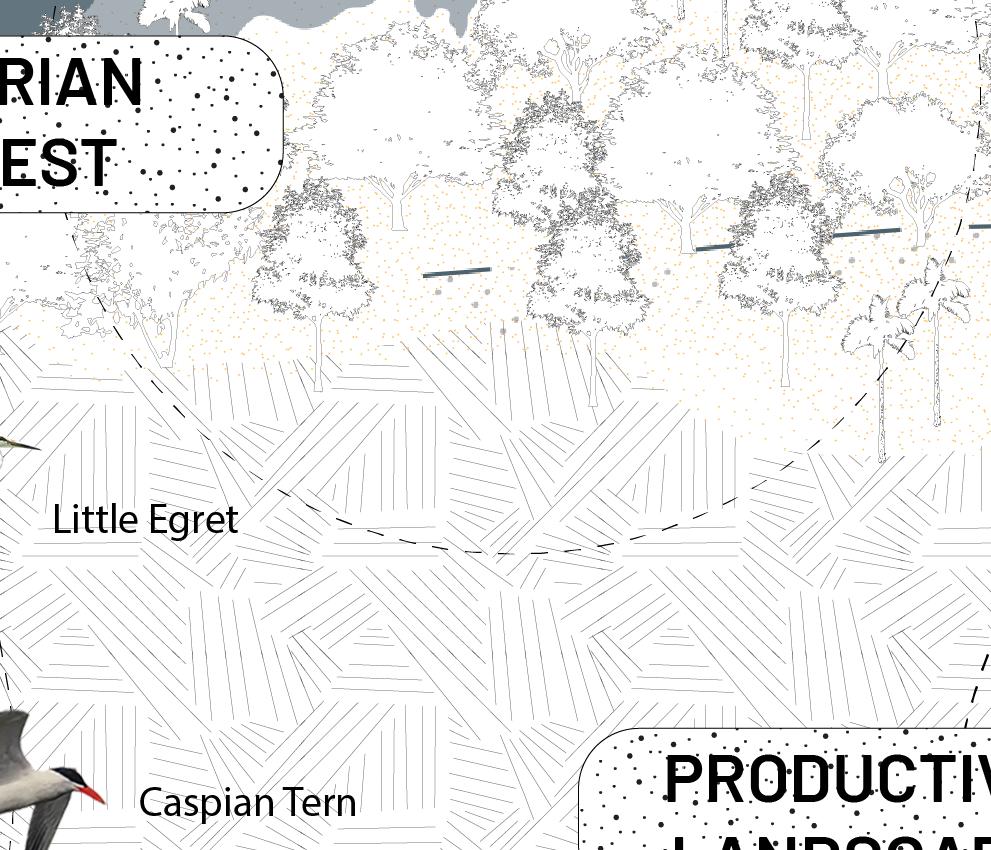

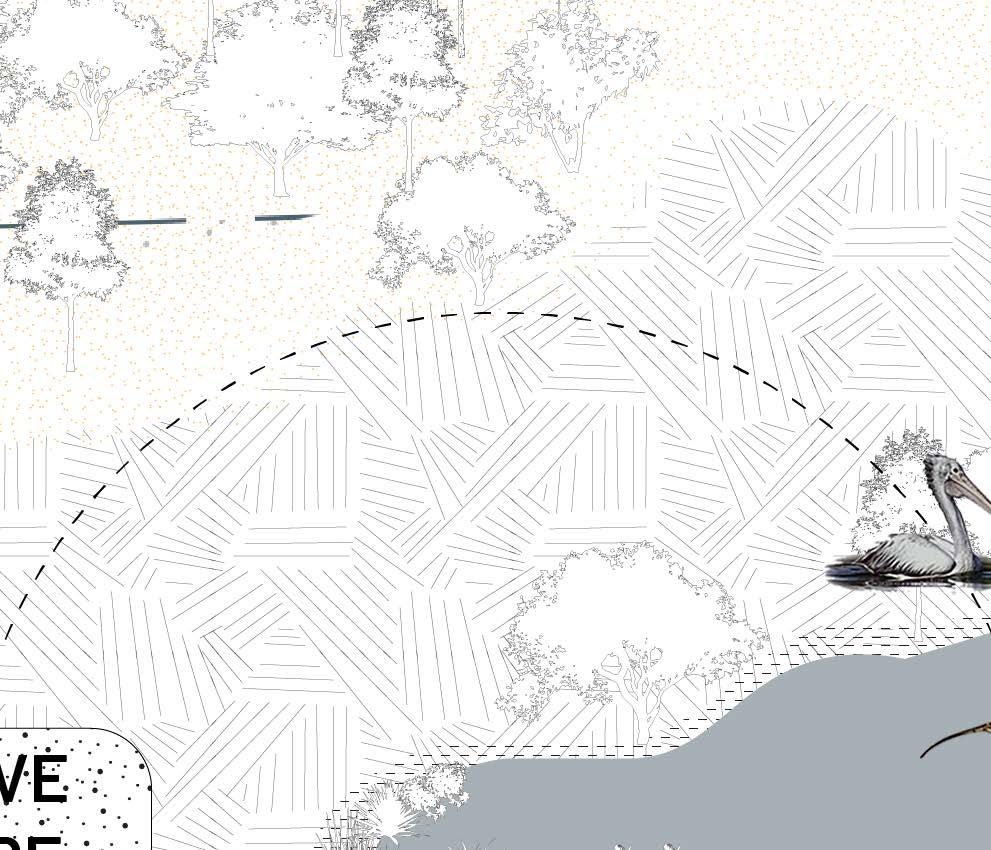

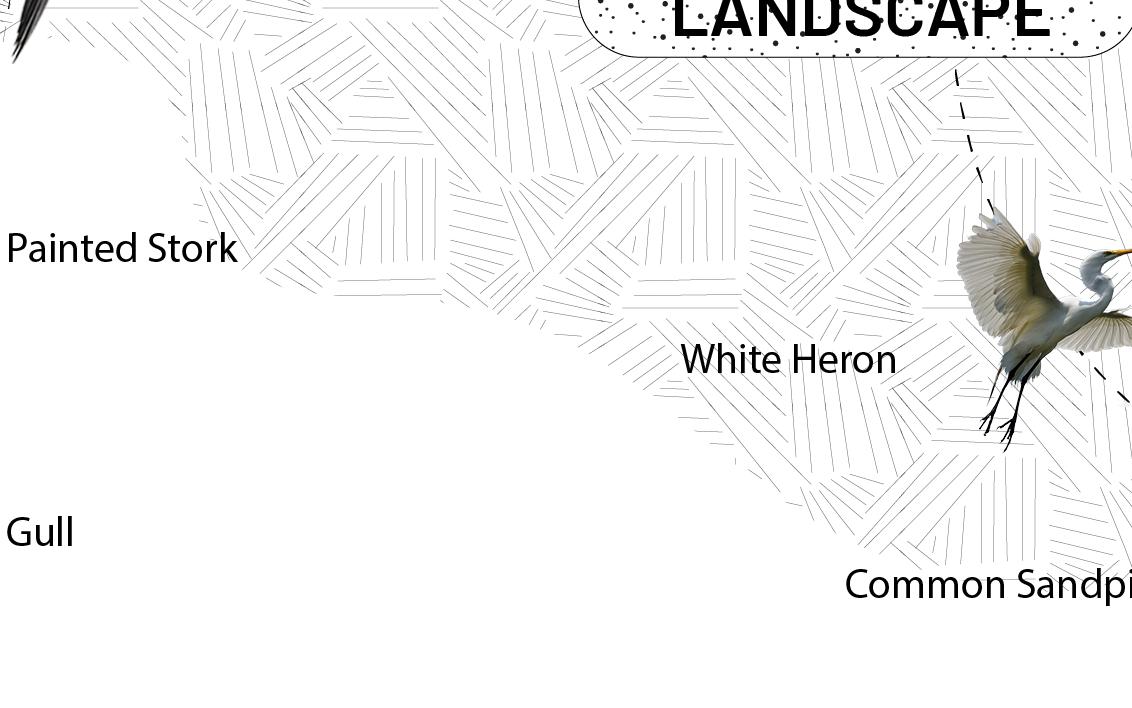

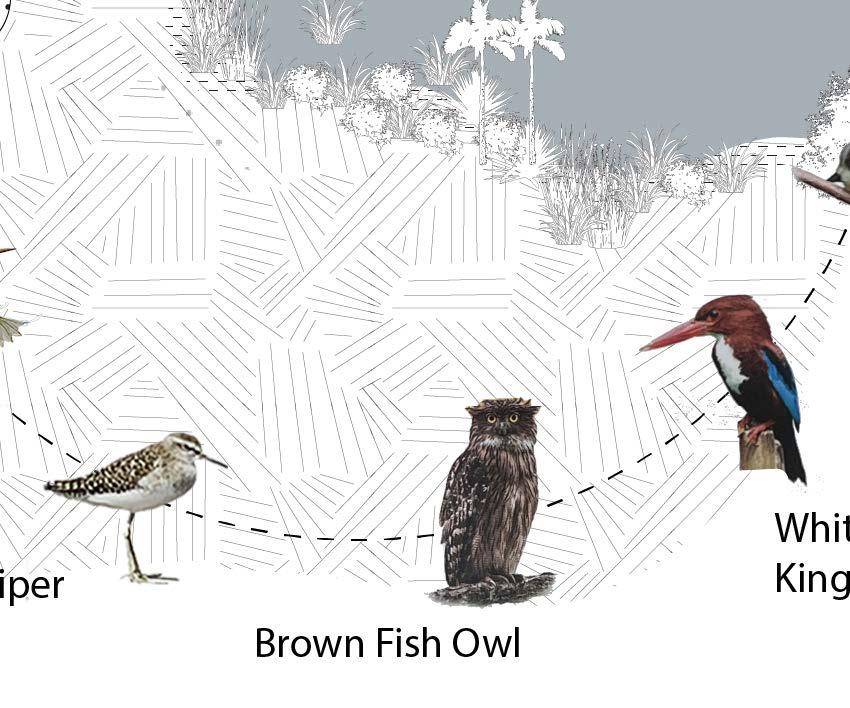

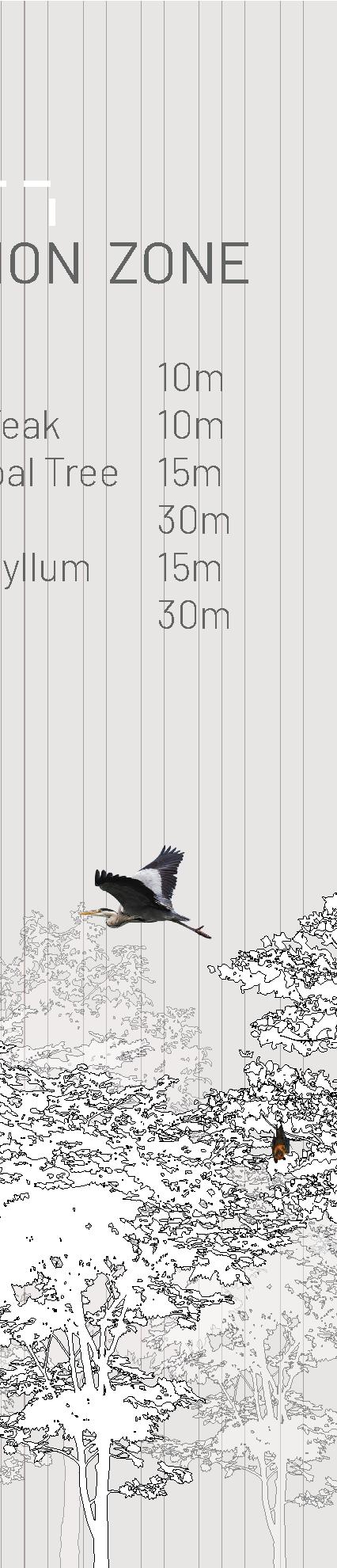

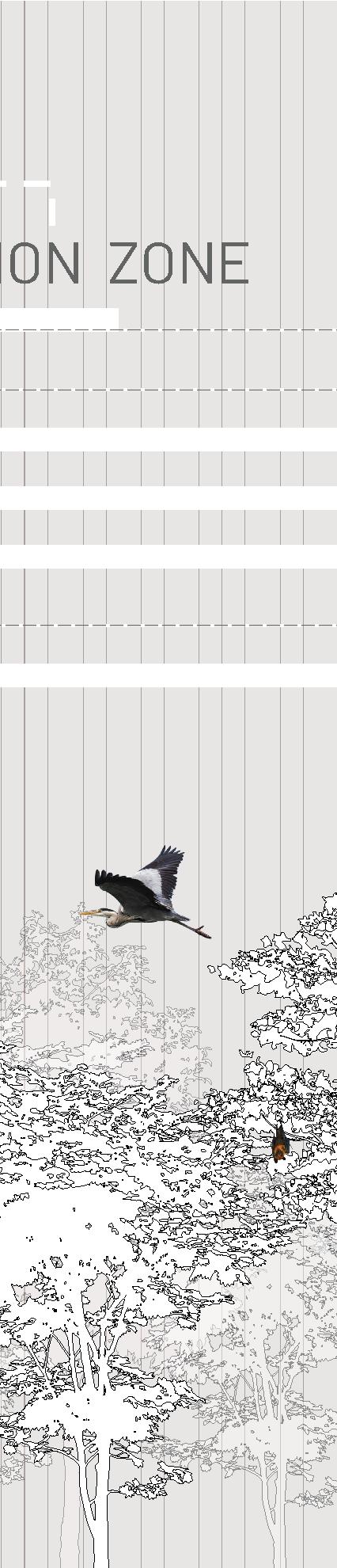

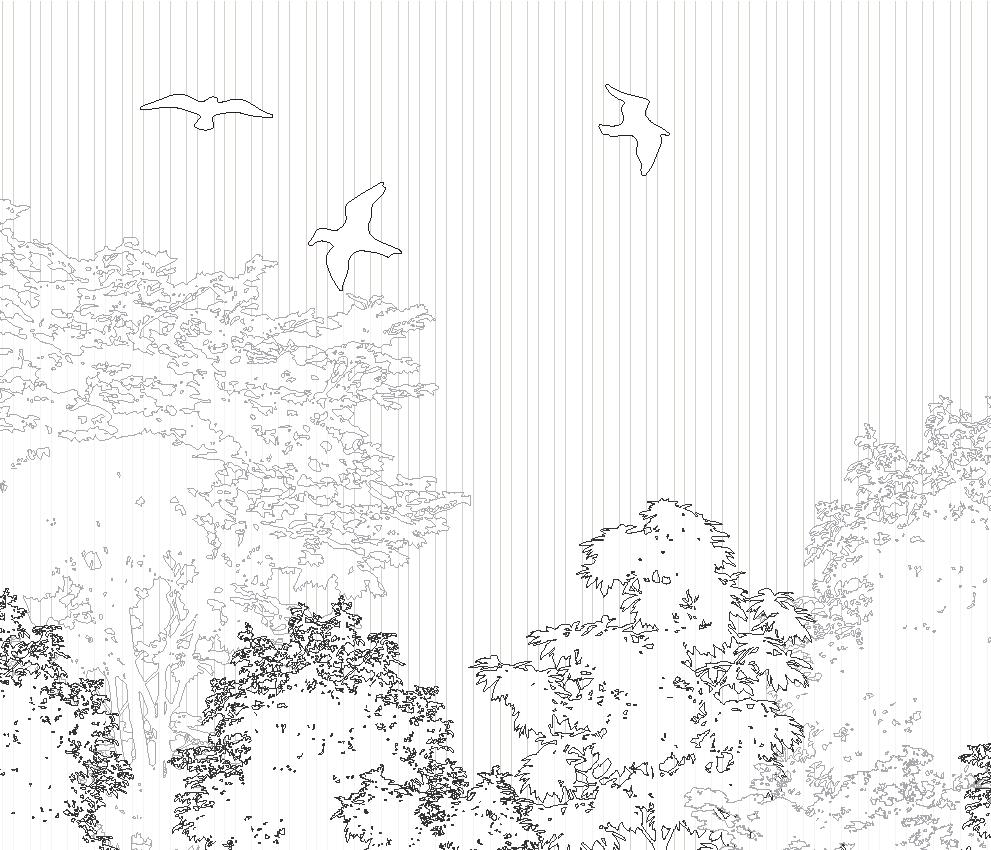

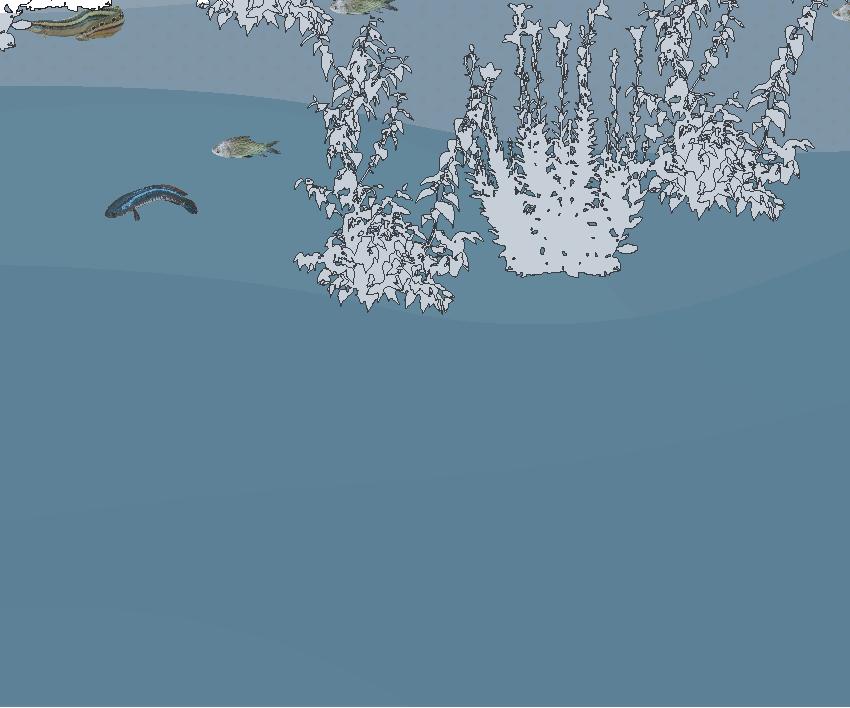

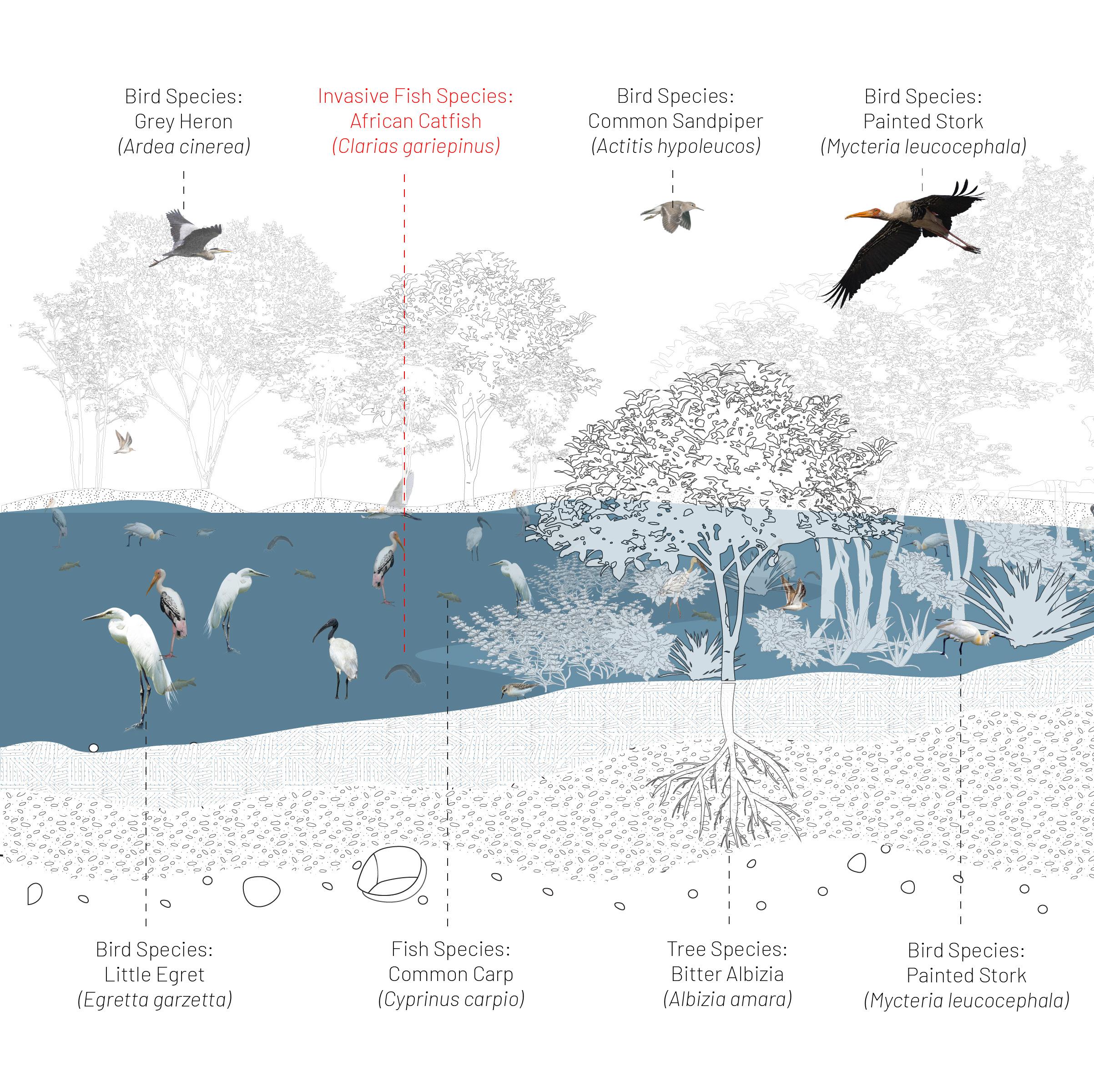

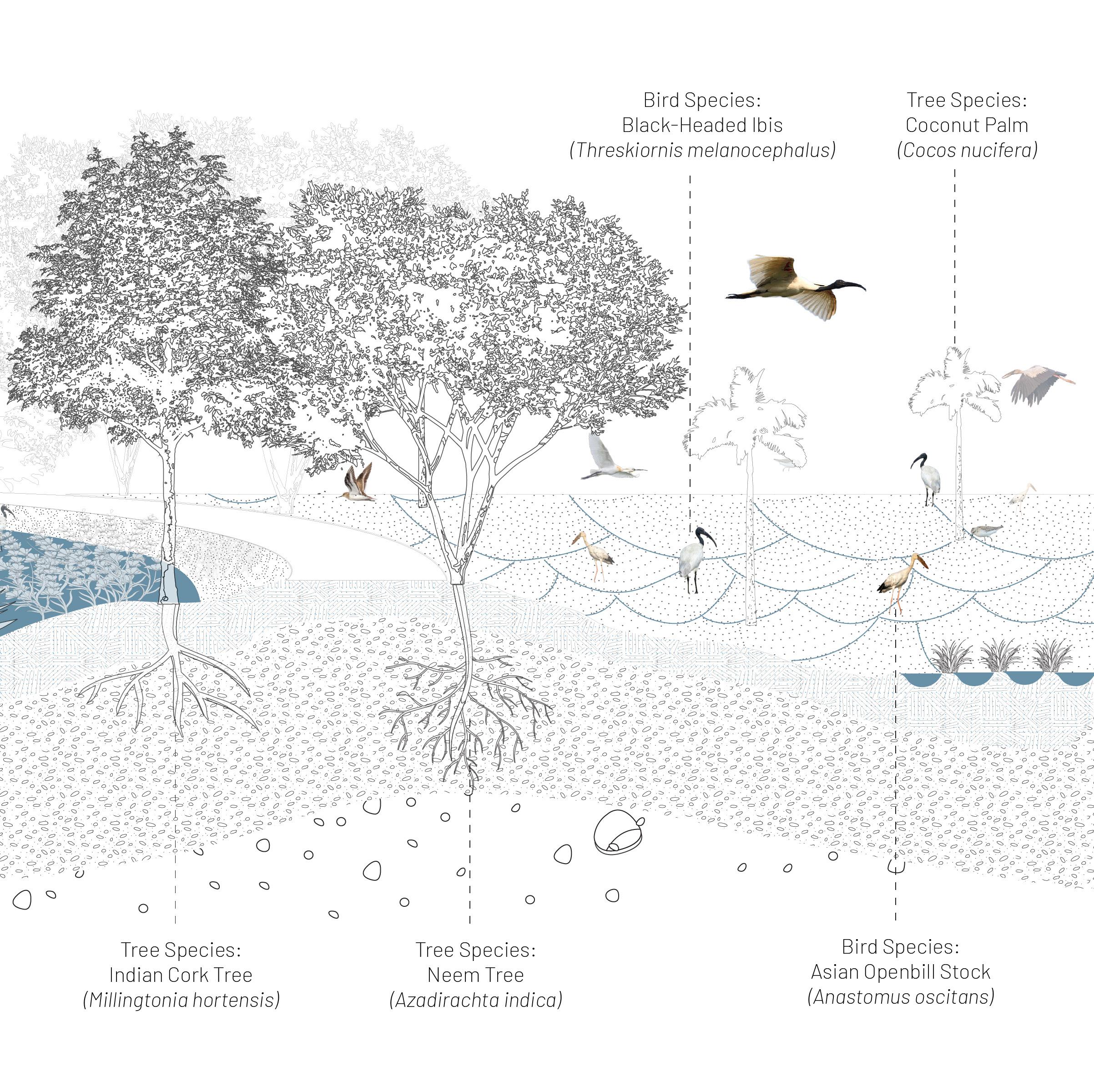

Tirunelveli district, holds vivid memories of a thriving ecological tapestry, where lush paddy fields and banana plantations flourish alongside the rhythmic flow of the Tamaraparani River. This agricultural village is not just a haven for farmers but also a sanctuary for a vibrant congregation of migratory and local aquatic birds. Painted Storks and White Ibises nest annually among the tall trees that shade the village and its temple, embodying a harmonious coexistence with the villagers. The river, teeming with life, supports over 60 species of fish, many endemic to its waters, reminding us of the delicate yet enduring balance of this ecosystem.

Three Landscapes are rooted in history and centered around the ancient temple dating back to 675 BC, reflects a tapestry of community life enriched by shared traditions and spiritual diversity. Here, people from various castes and communities coexist, worshiping a multitude of Gods and Goddesses in harmony. The villagers’ daily lives are intertwined with the rhythms of the river, which sustains their agricultural pursuits and cultural heritage. Rolling tendu leaves for beedi-making during spare hours adds a unique layer to their lifestyle, blending self-reliance with a deep connection to the land and its resources. This bond between the people, their traditions, and the river speaks of a harmonious balance that defines the spirit of the village.

1.

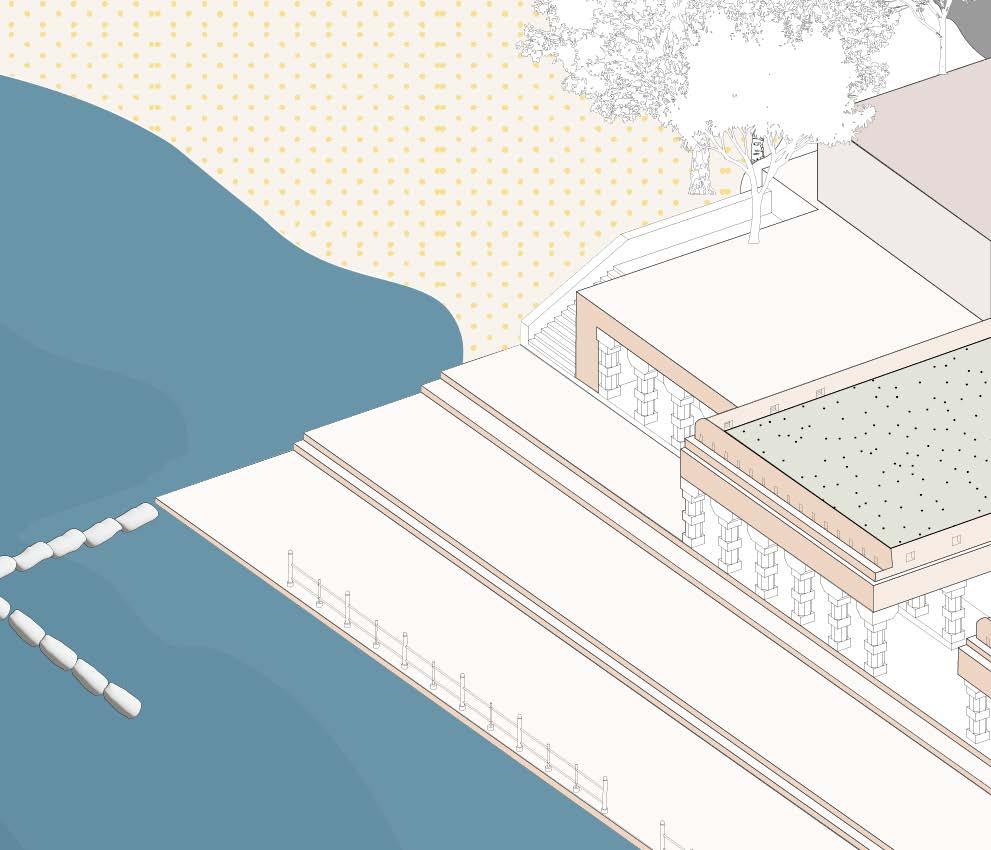

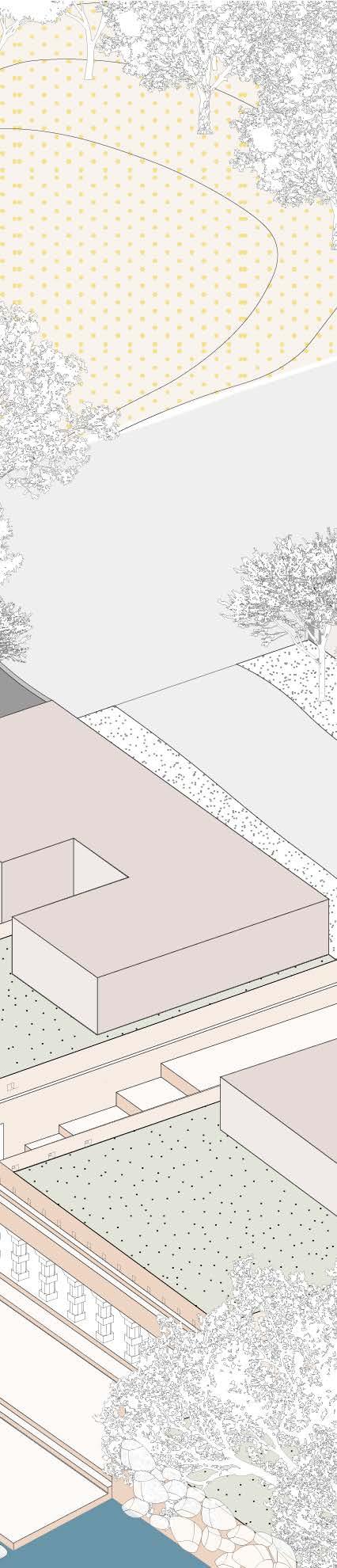

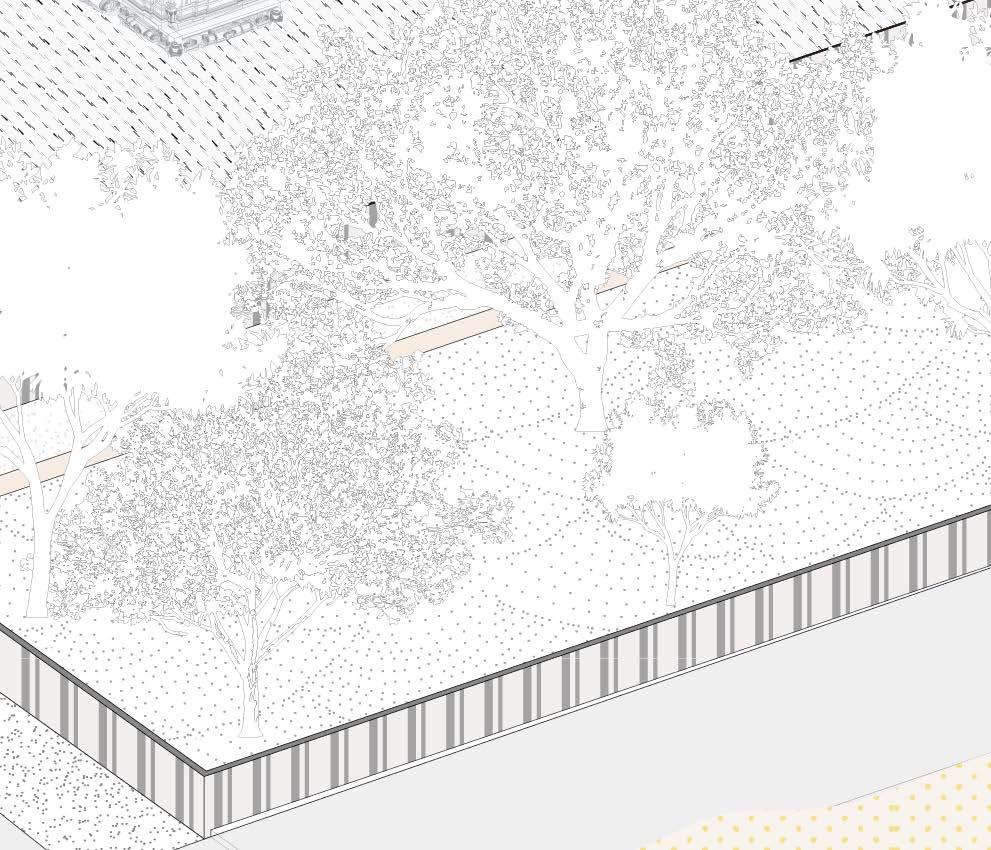

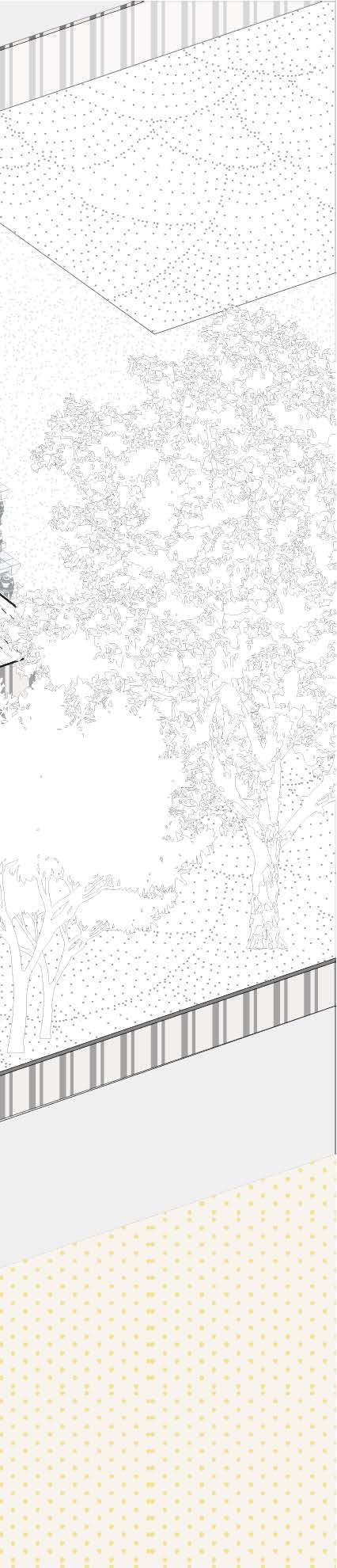

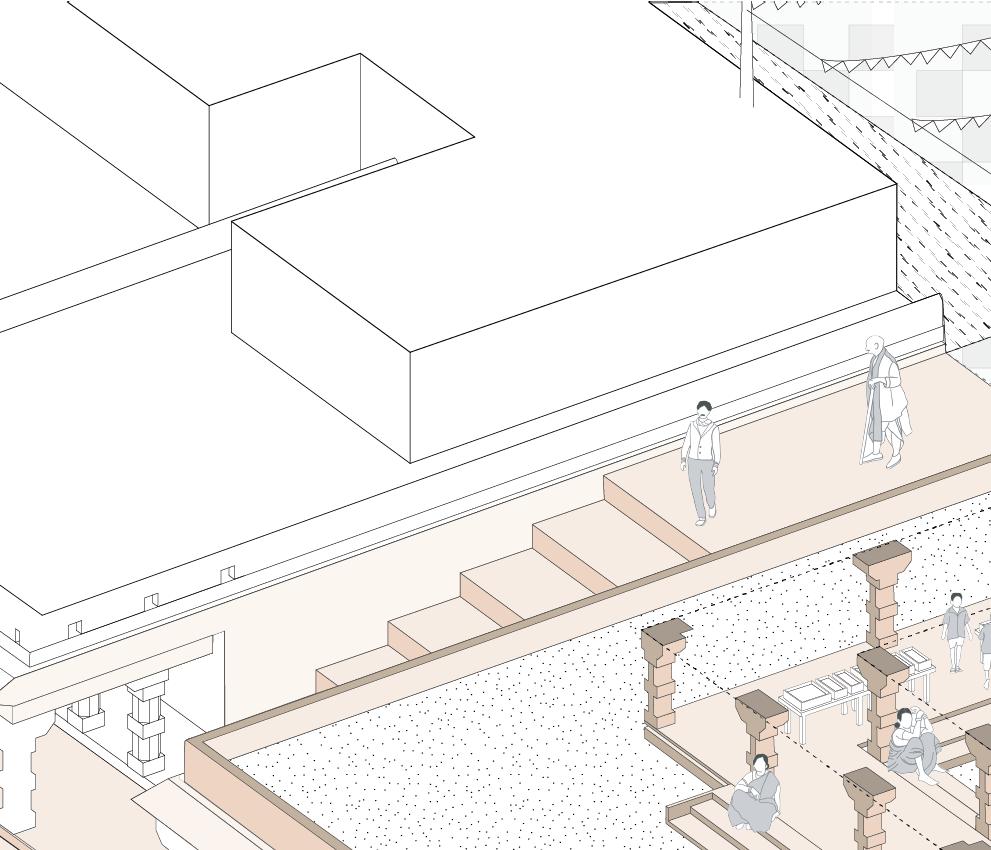

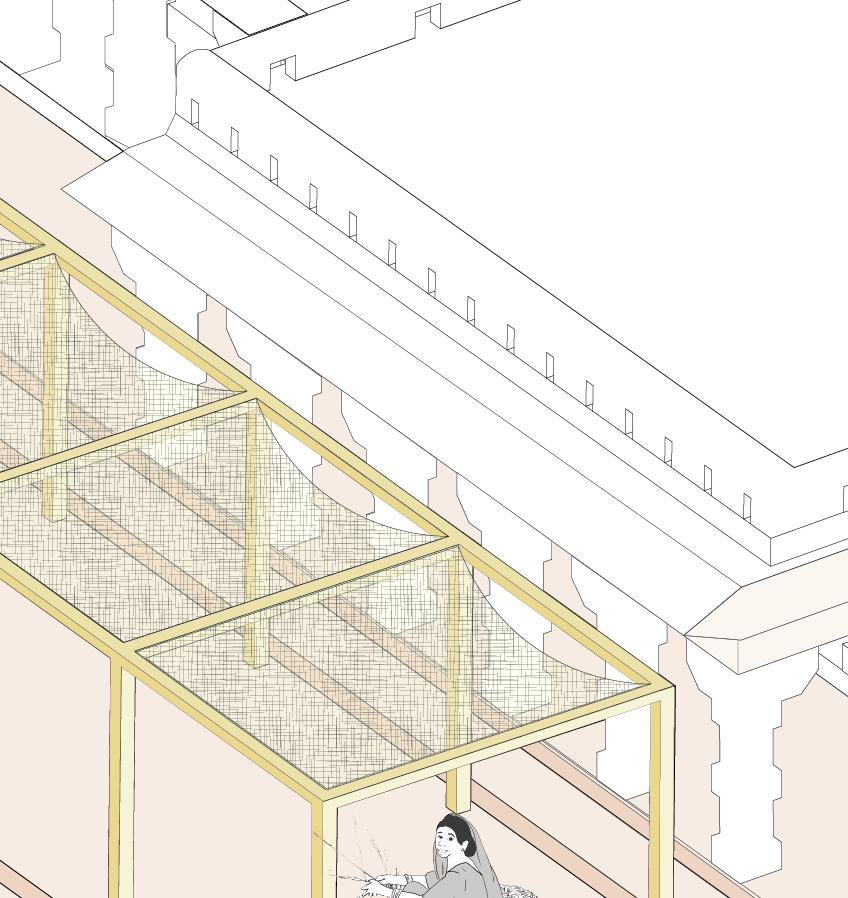

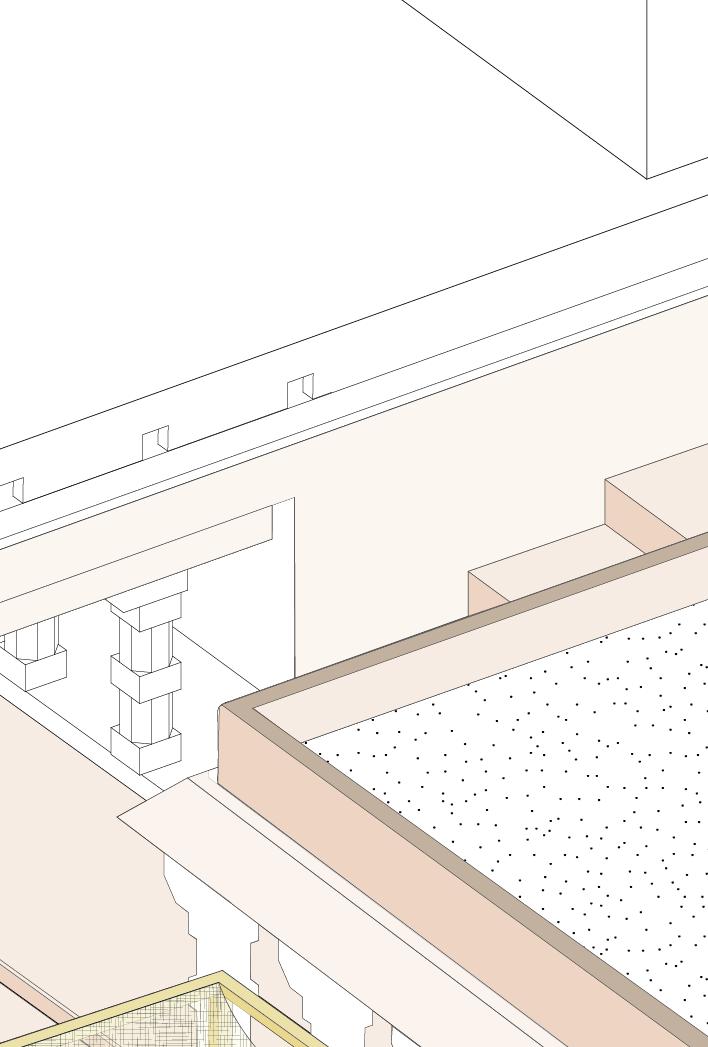

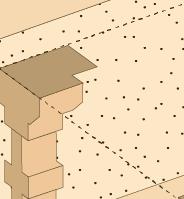

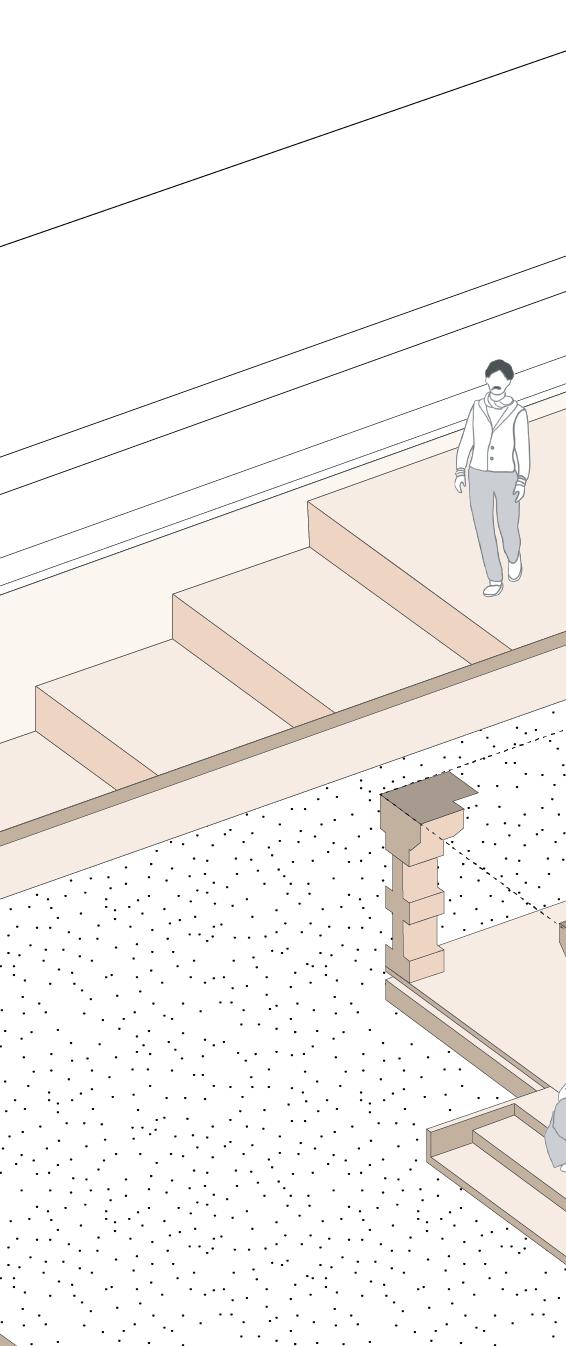

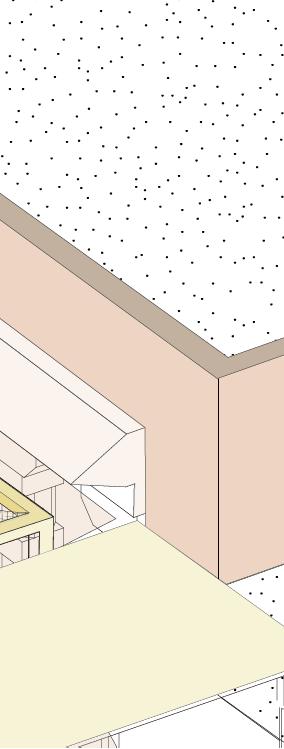

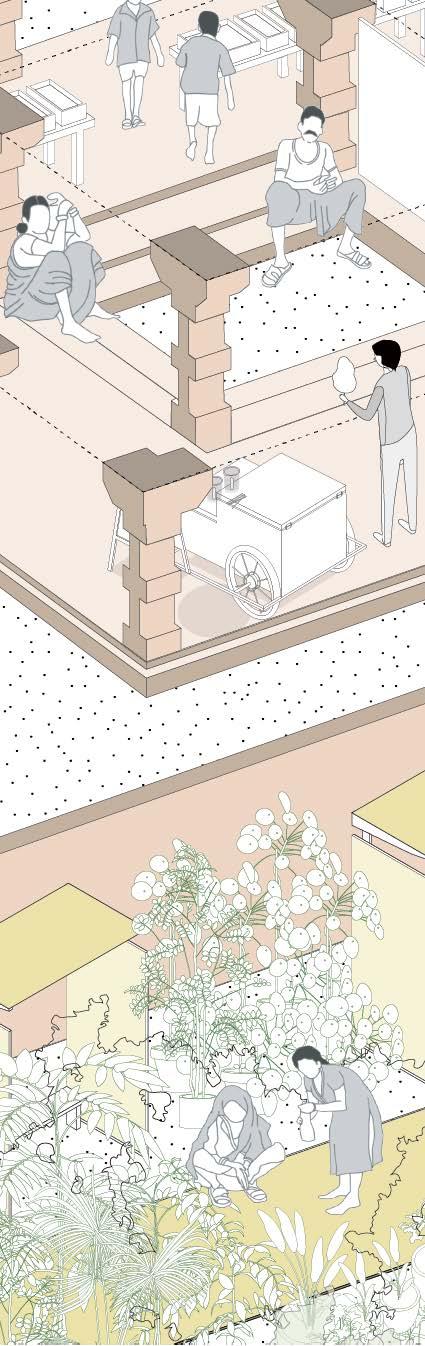

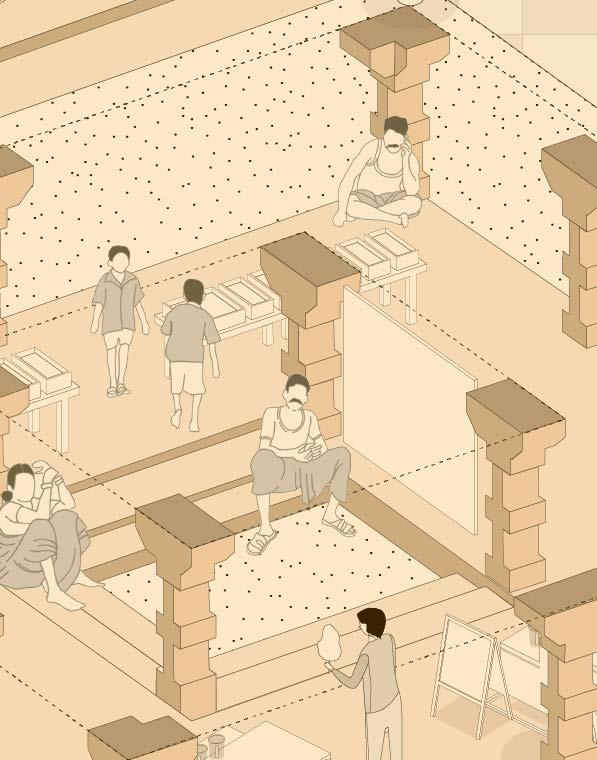

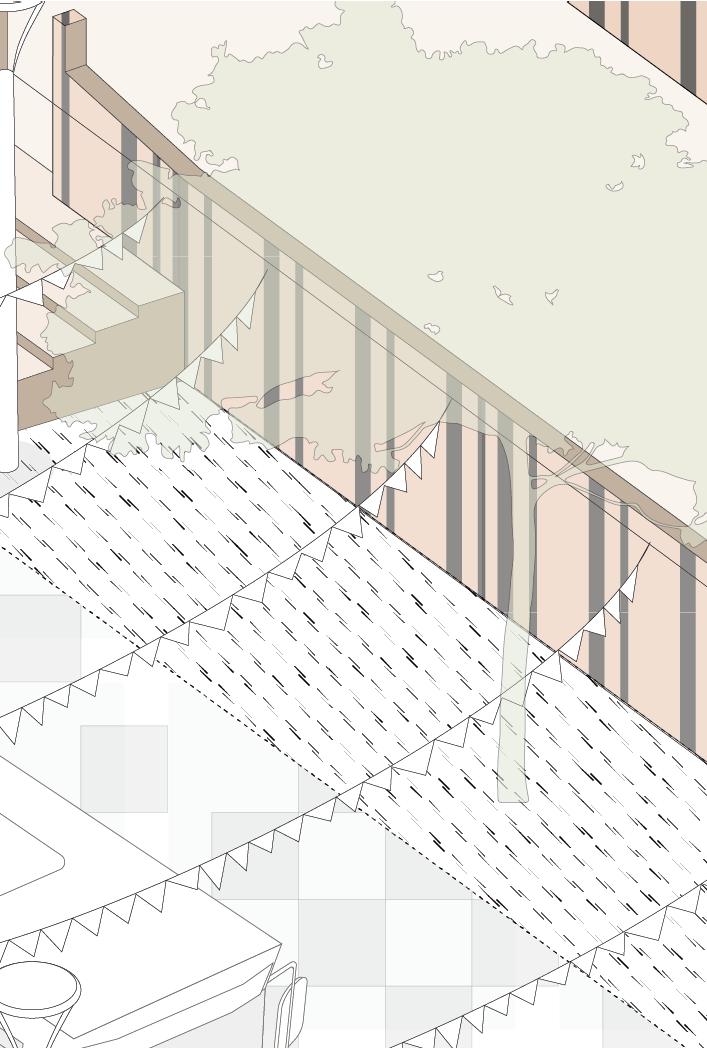

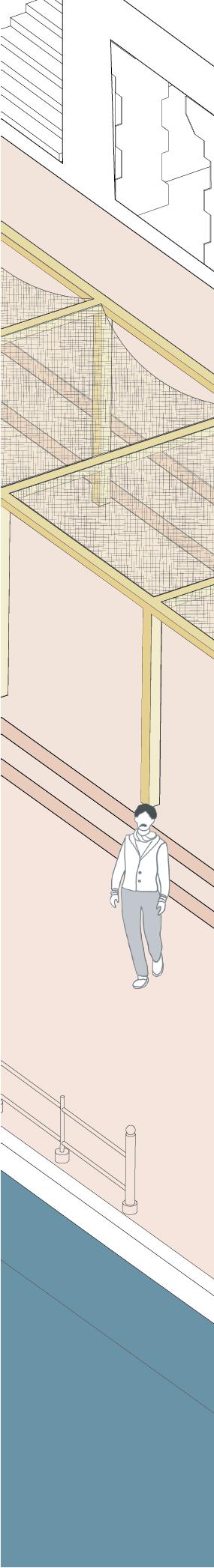

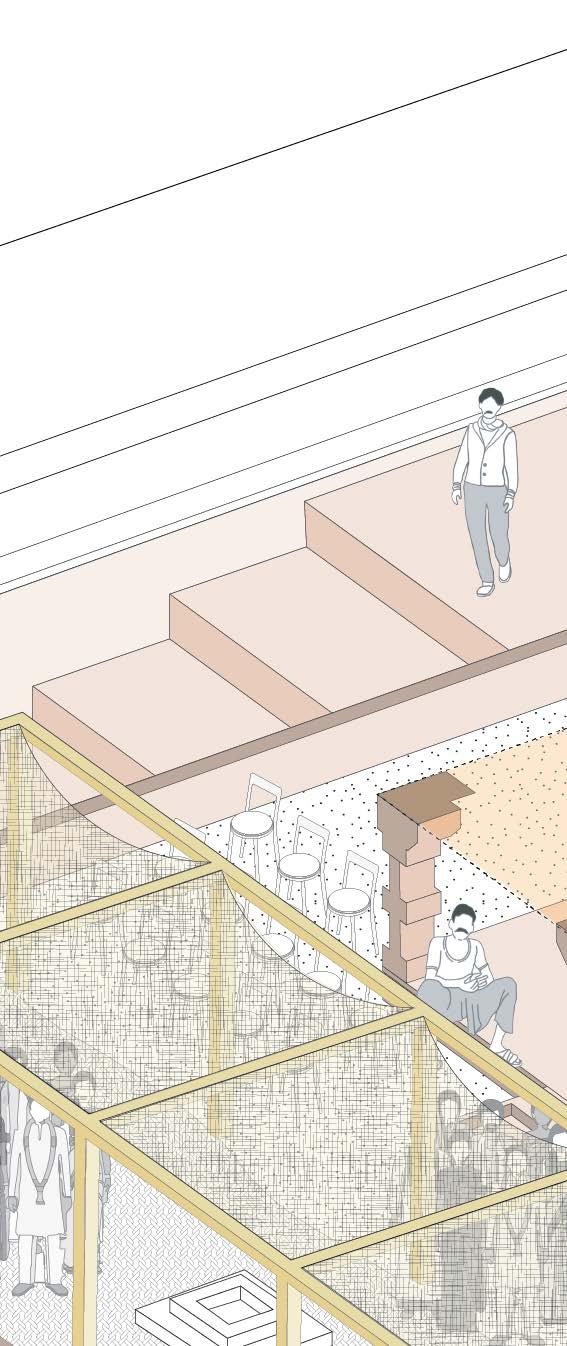

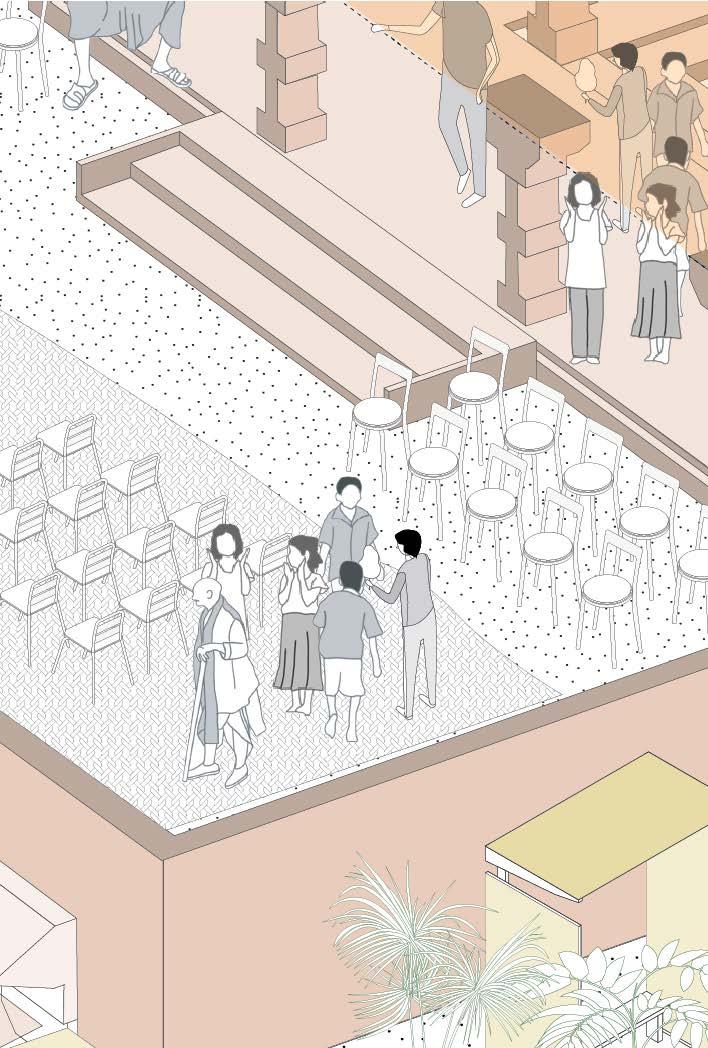

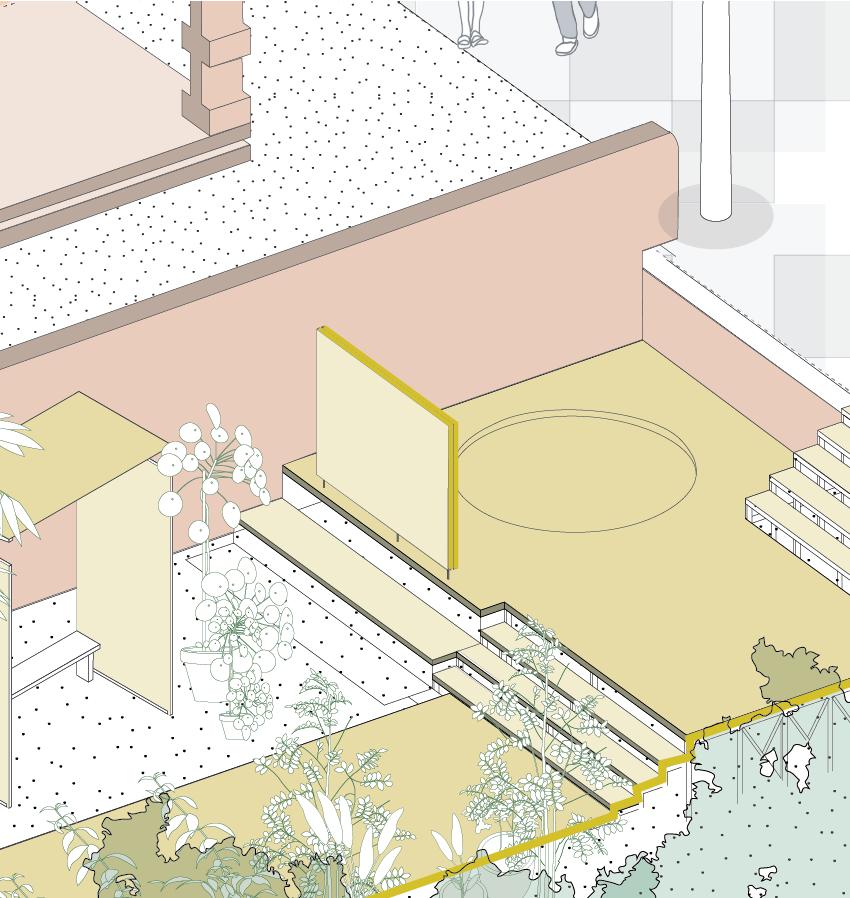

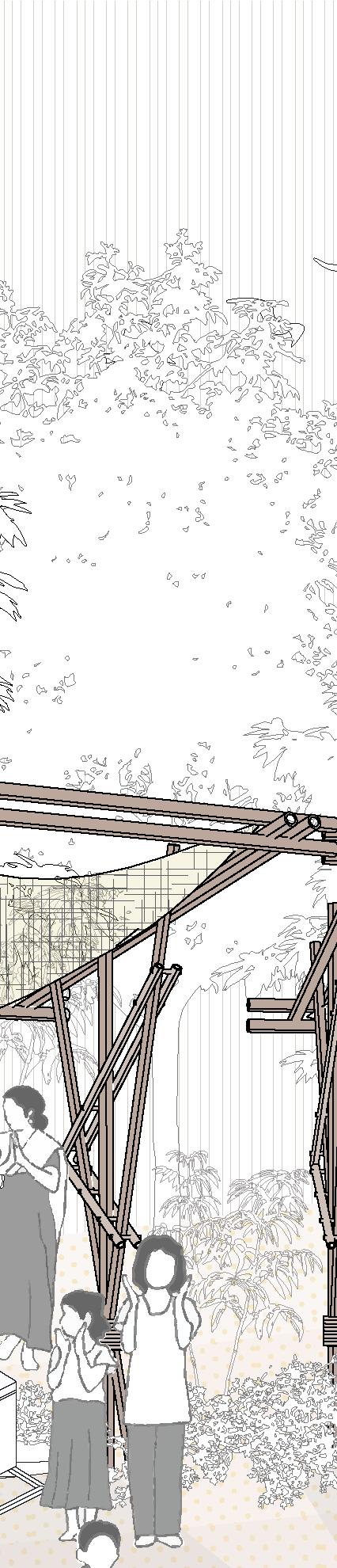

The Heritage Pavilion serves as a gathering place for the village, hosting daily rituals, festivals, and celebrations. It also offers women a moment of respite after their journey from the river, carrying water buckets. For visitors, the pavilion marks the beginning of a journey to explore the village, its river, and the surrounding ecology. A place of connection, rest, and learning, it bridges the village’s traditions with the broader natural and cultural landscape.

Columns 2.

The Heritage Pavilion, owned by the temple authority, serves as a versatile space that can be rented by villagers for personal events such as weddings and private celebrations.

Water as Sacred Landscape

Water as Sacred Landscape ...........

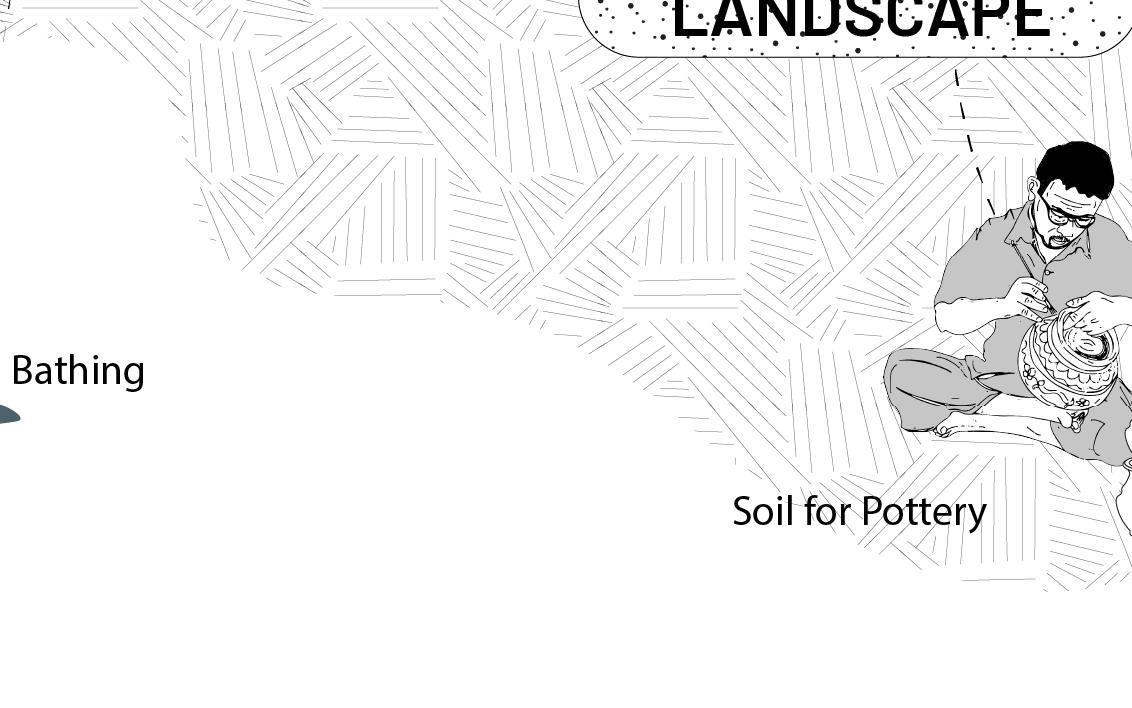

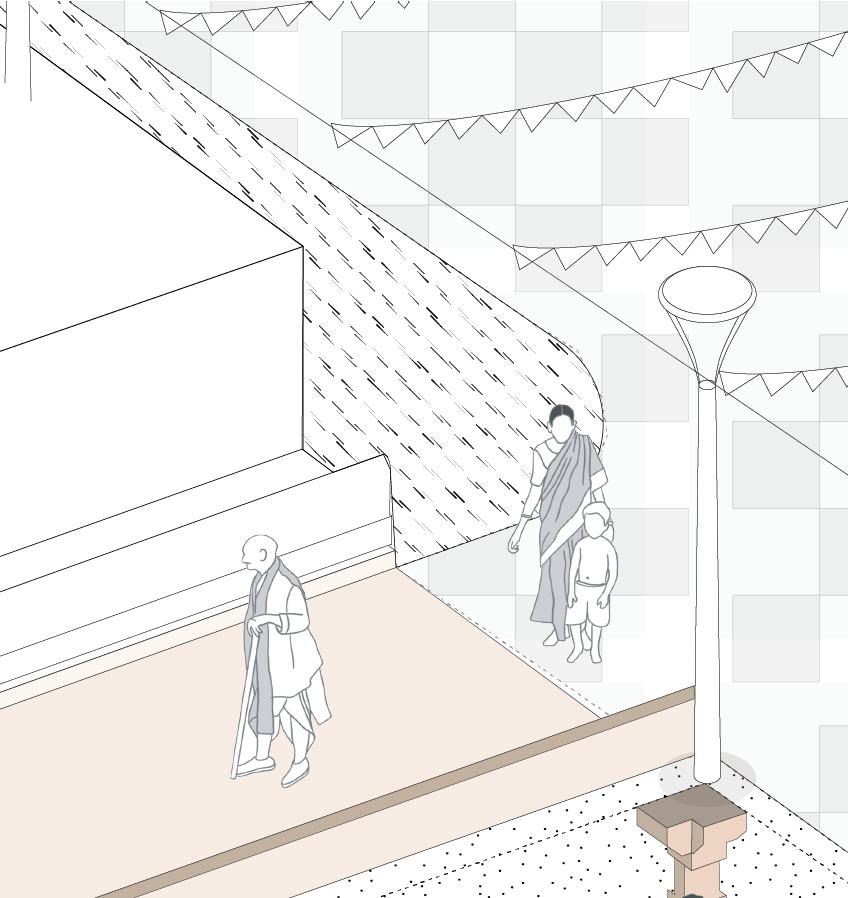

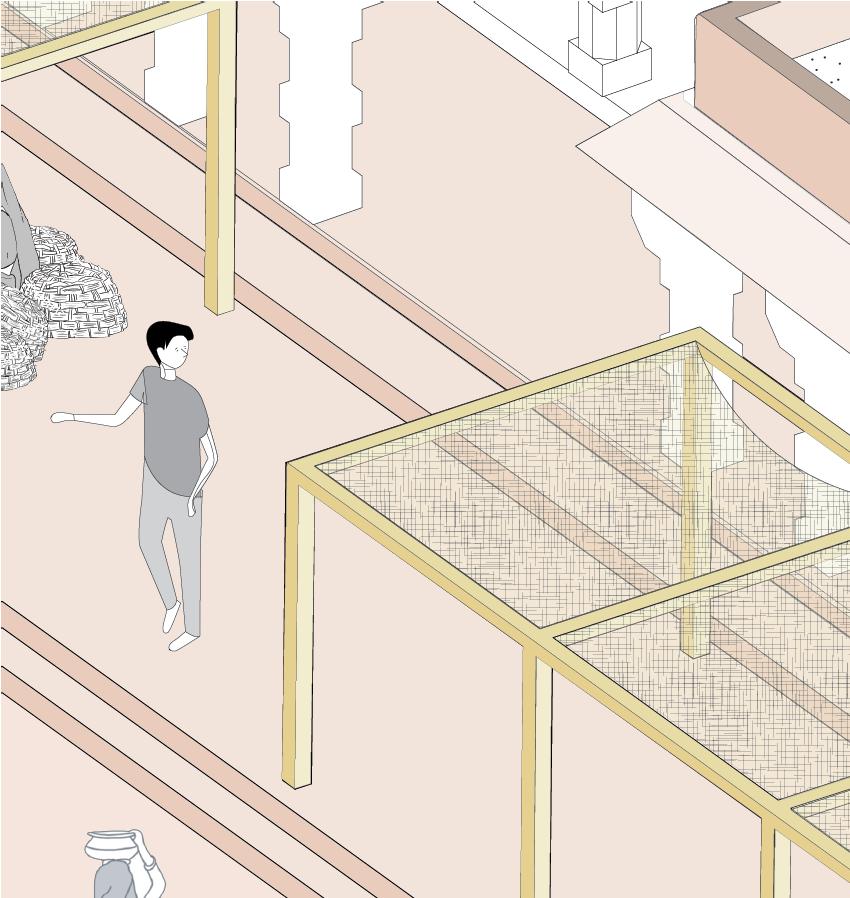

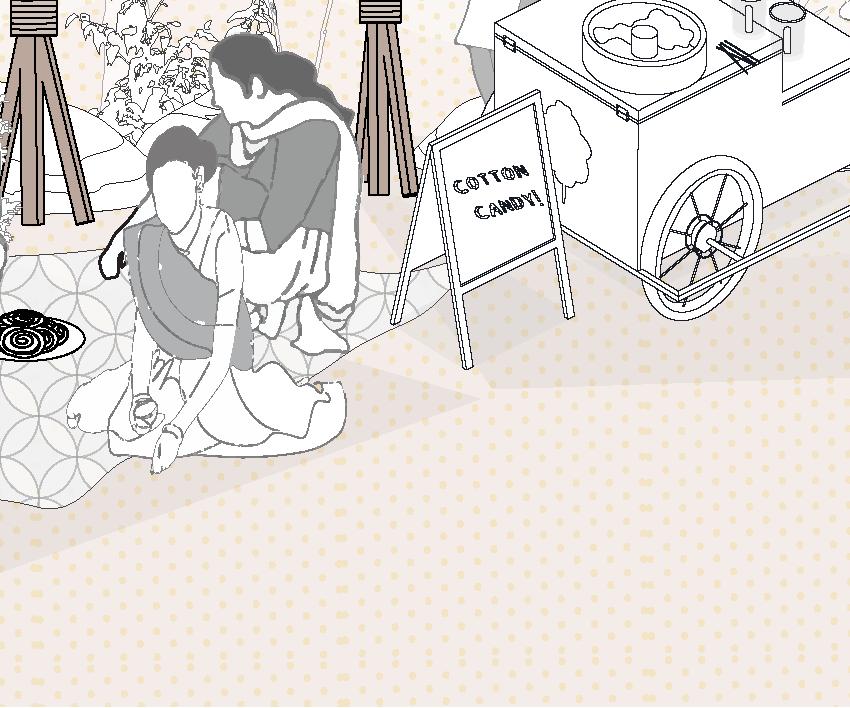

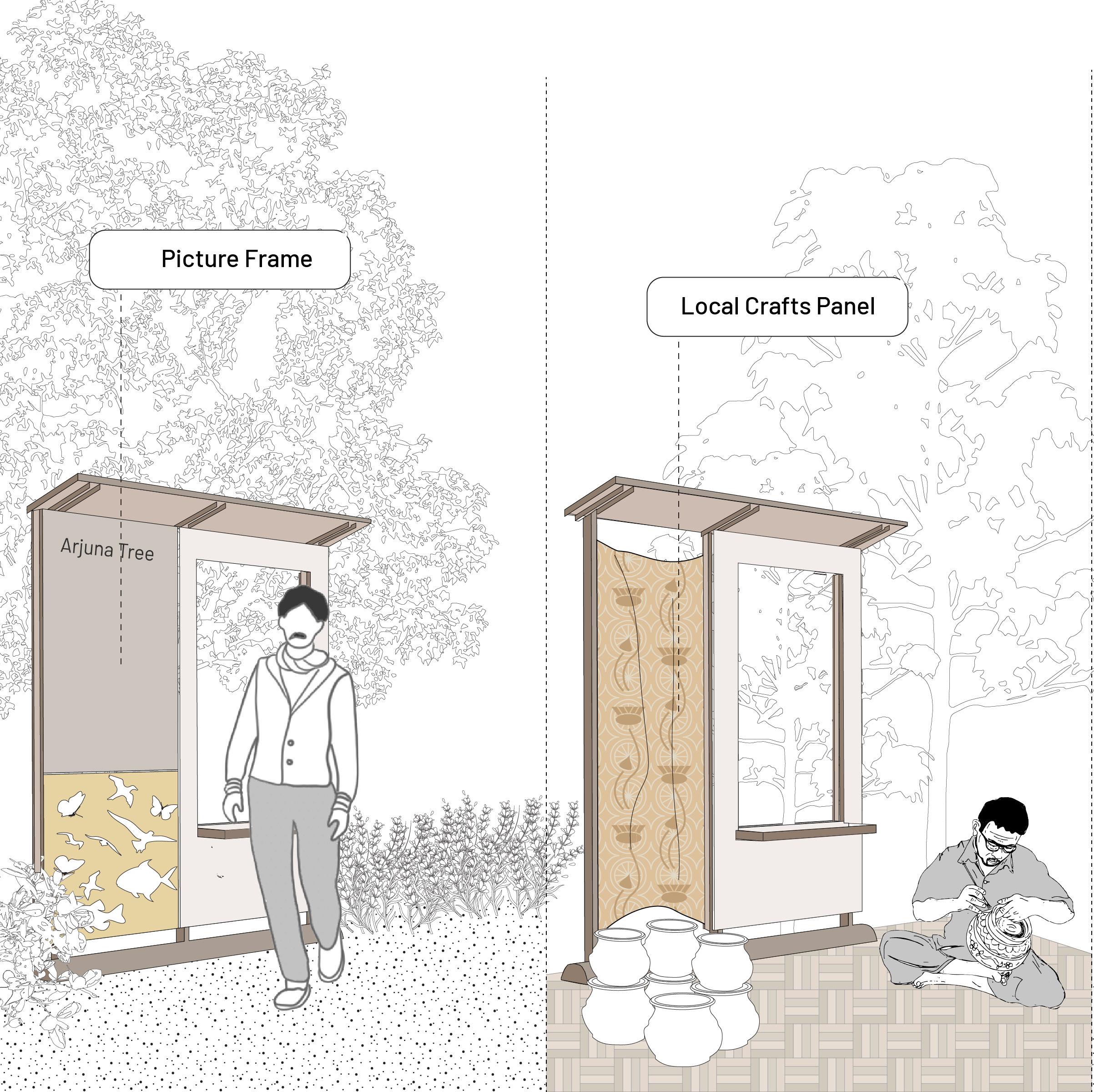

Before the festival, the riverbank bustles with villagers, local craftsmen, and visitors coming together to learn traditional crafts. Skilled artisans carve intricate wood patterns, while others shade fabric with delicate designs. Potters shape clay on spinning wheels, creating functional and decorative pieces. As the hot summer approaches, the community shares tips on staying cool and preparing for the season. This gathering embodies a spirit of learning, craftsmanship, and unity, where culture and tradition flourish along the river’s edge.

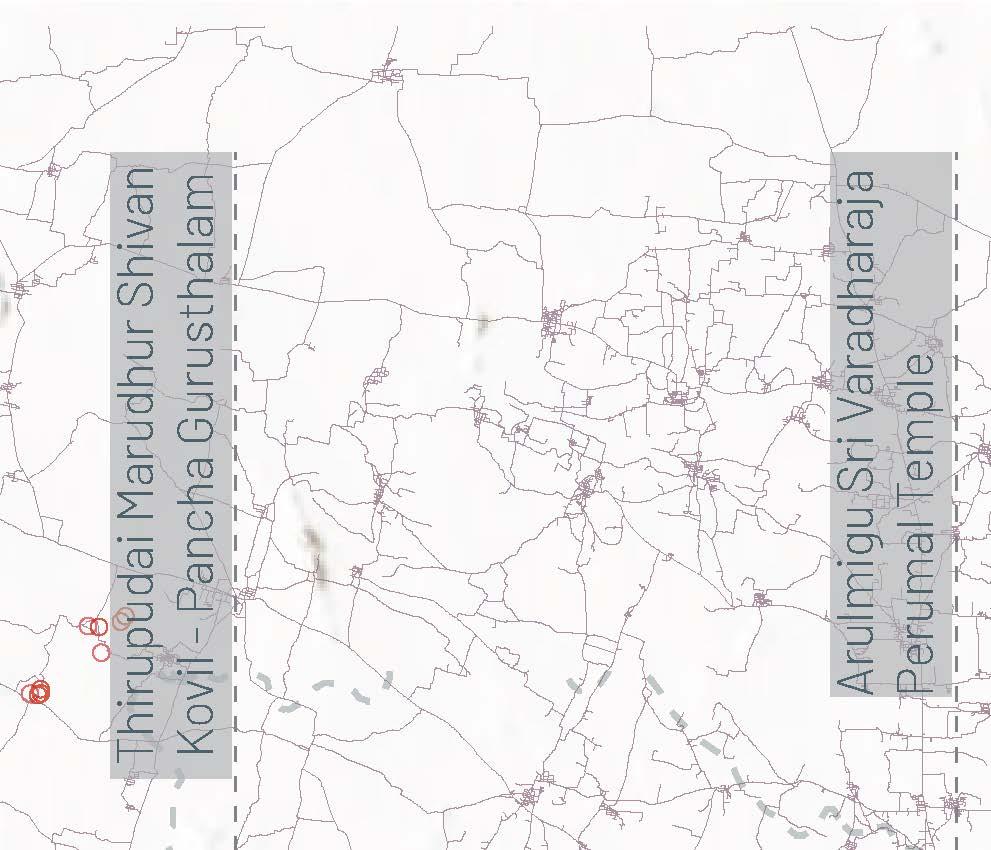

ThirupudaiMarudhurTemple

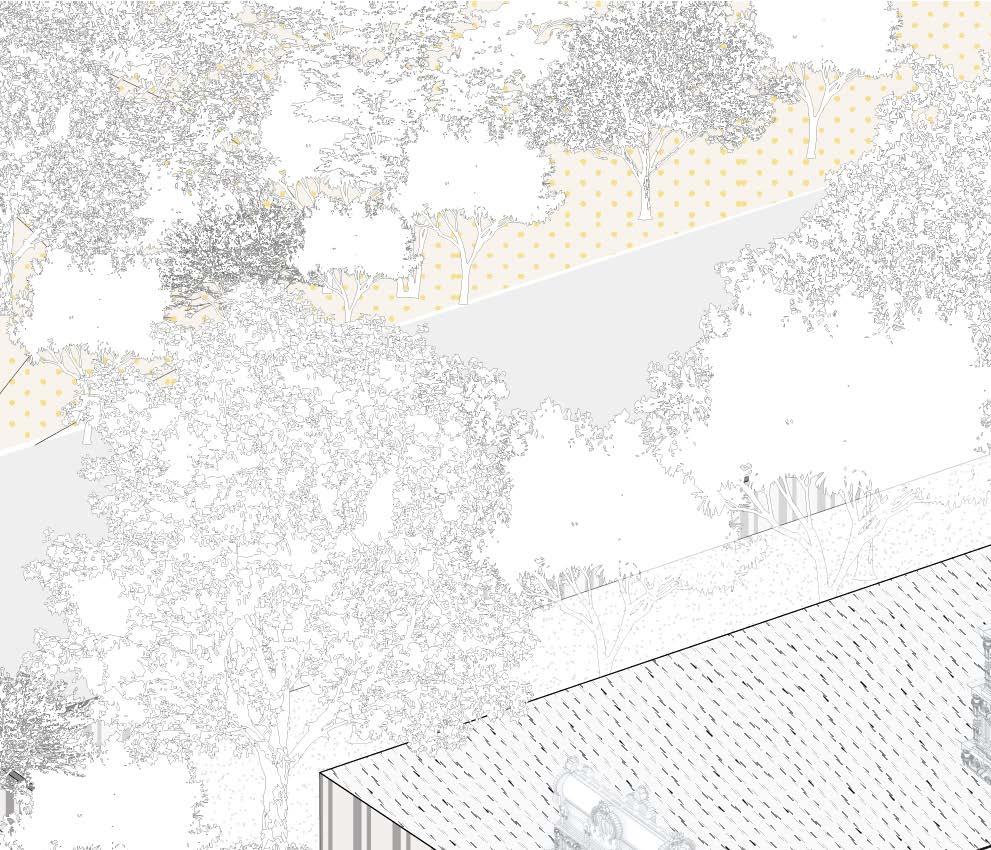

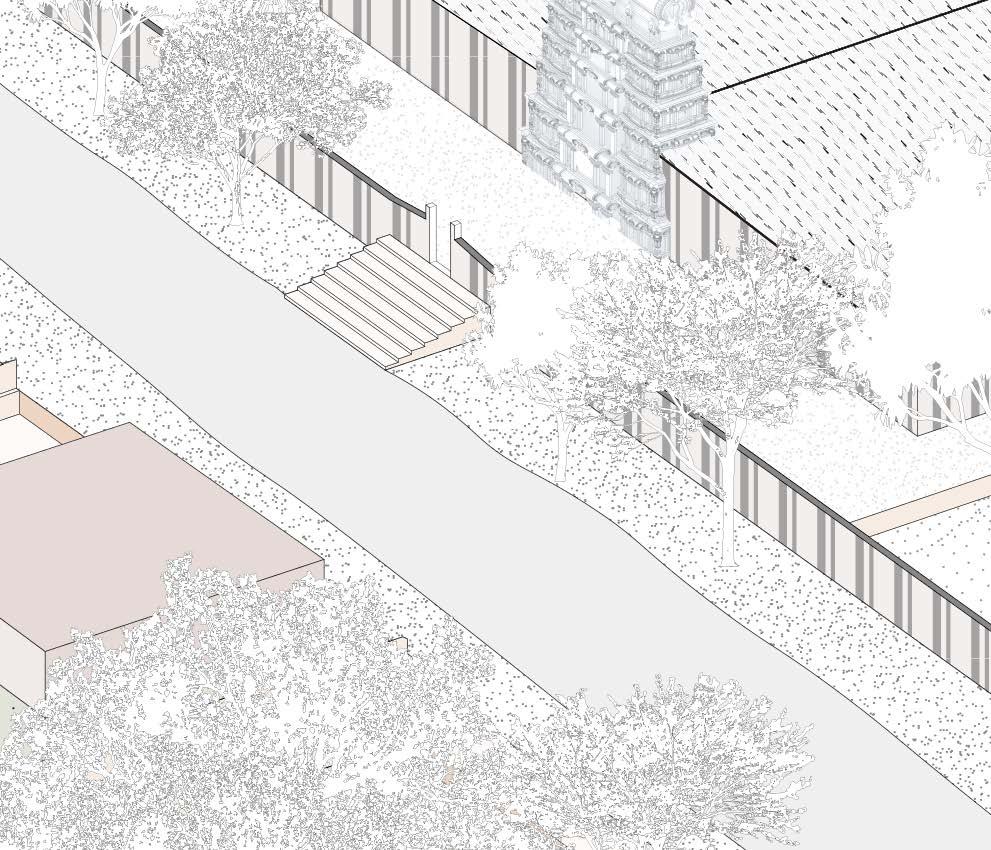

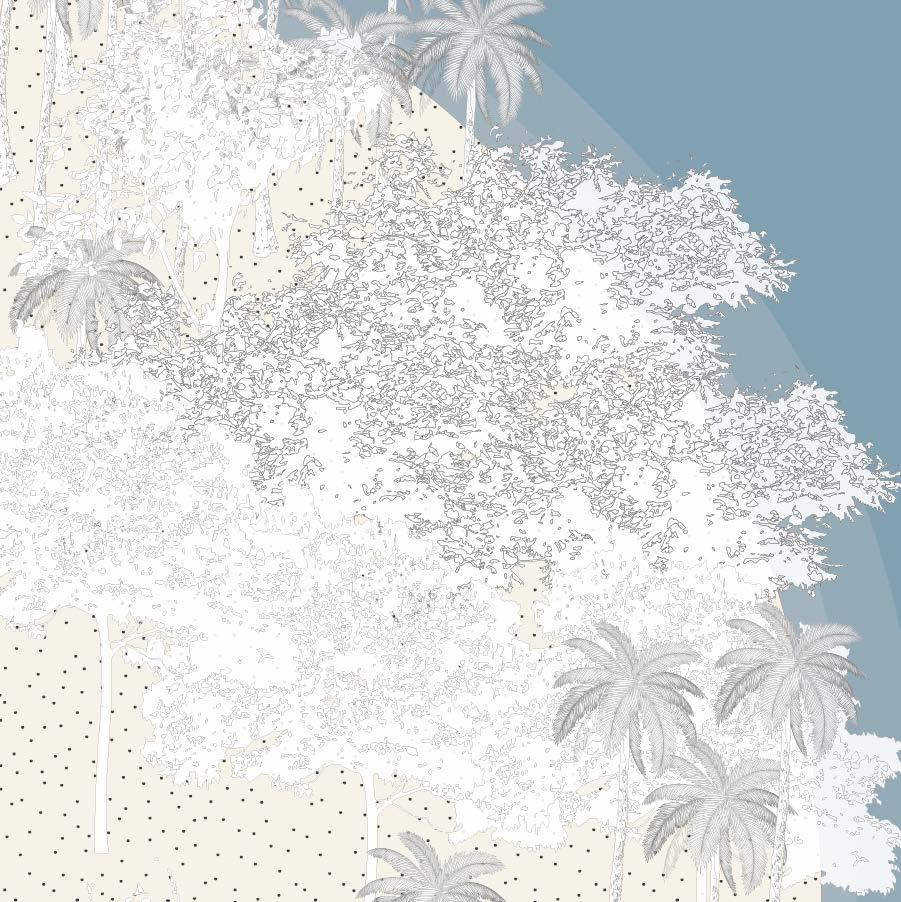

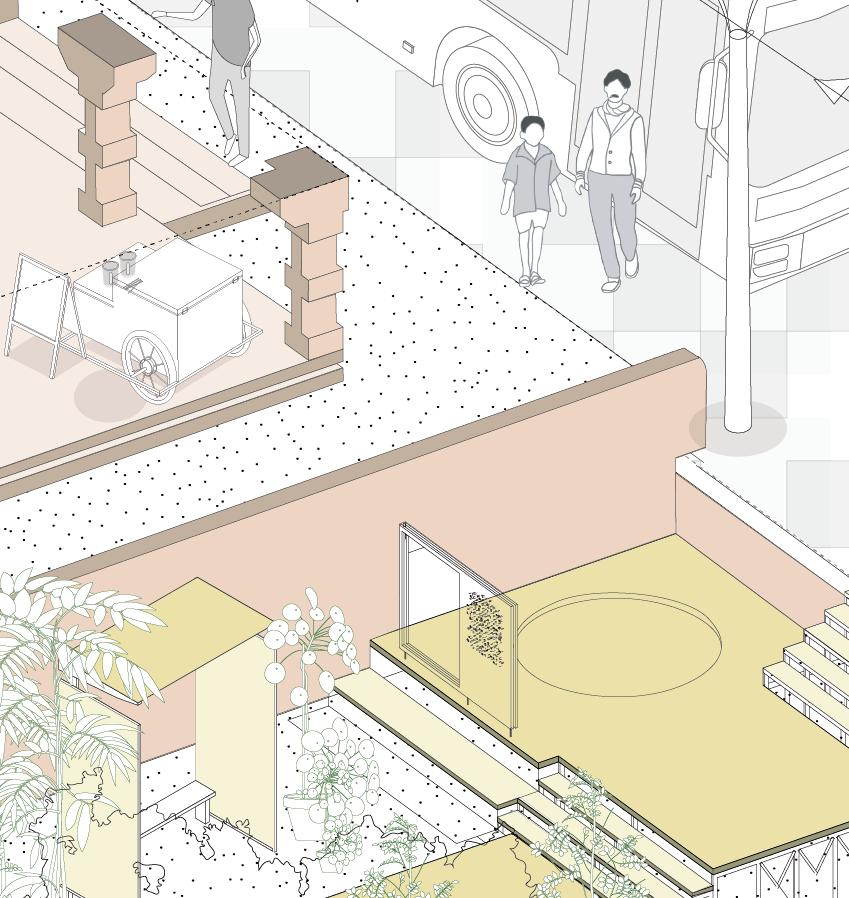

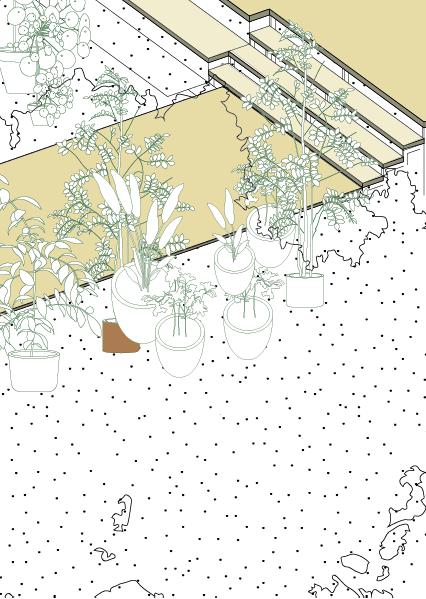

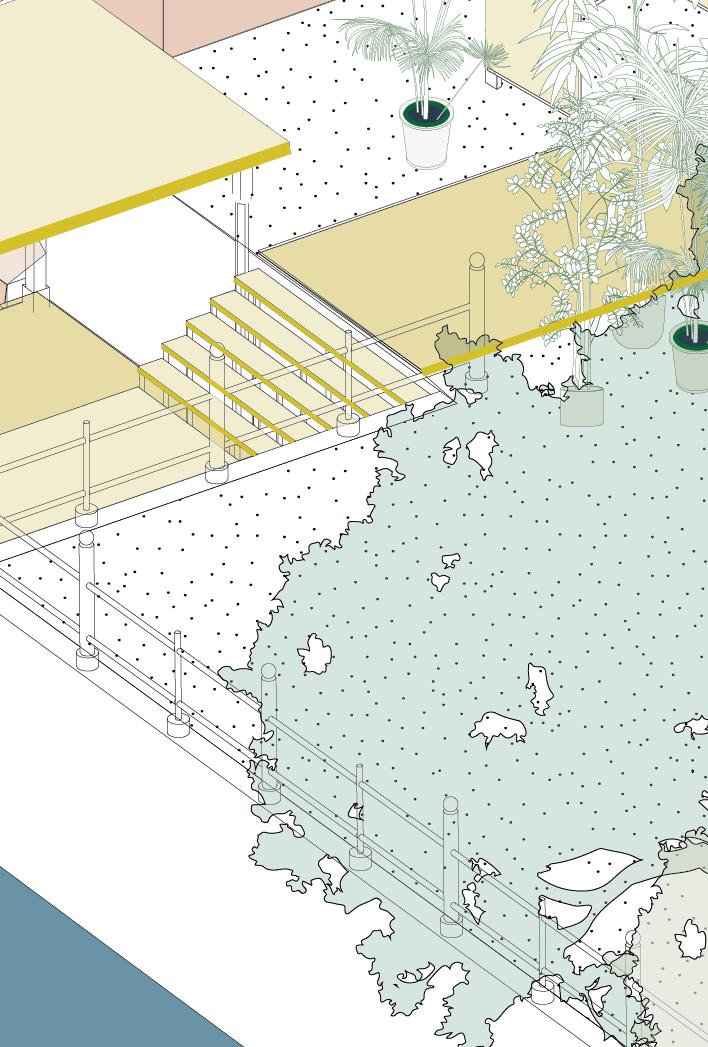

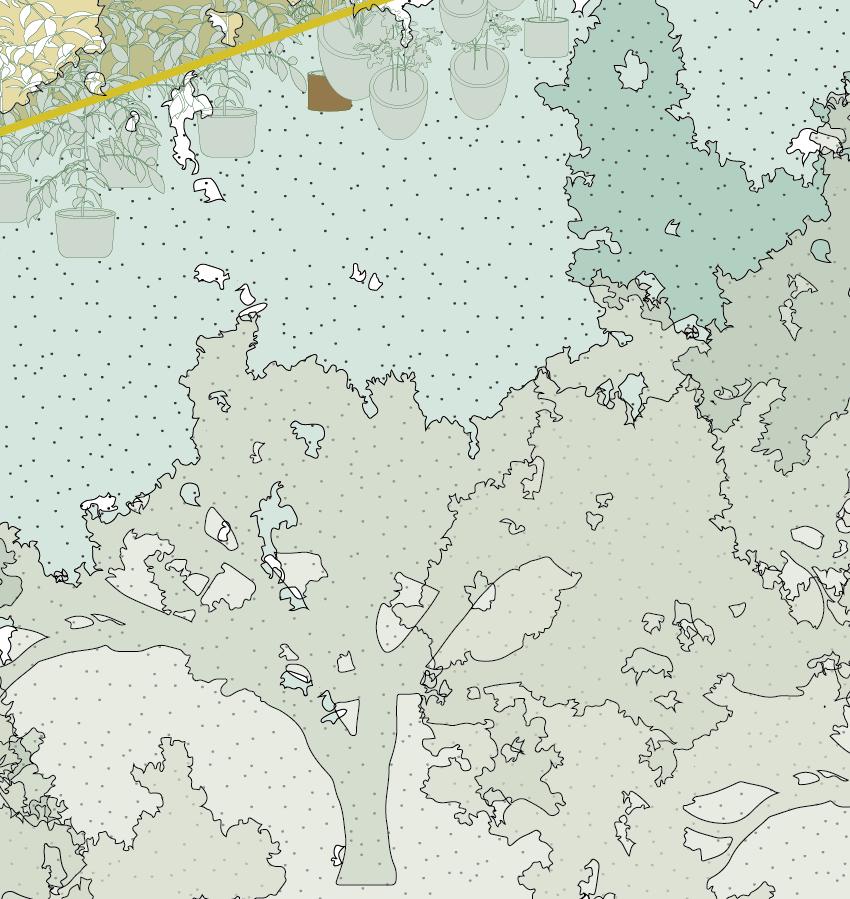

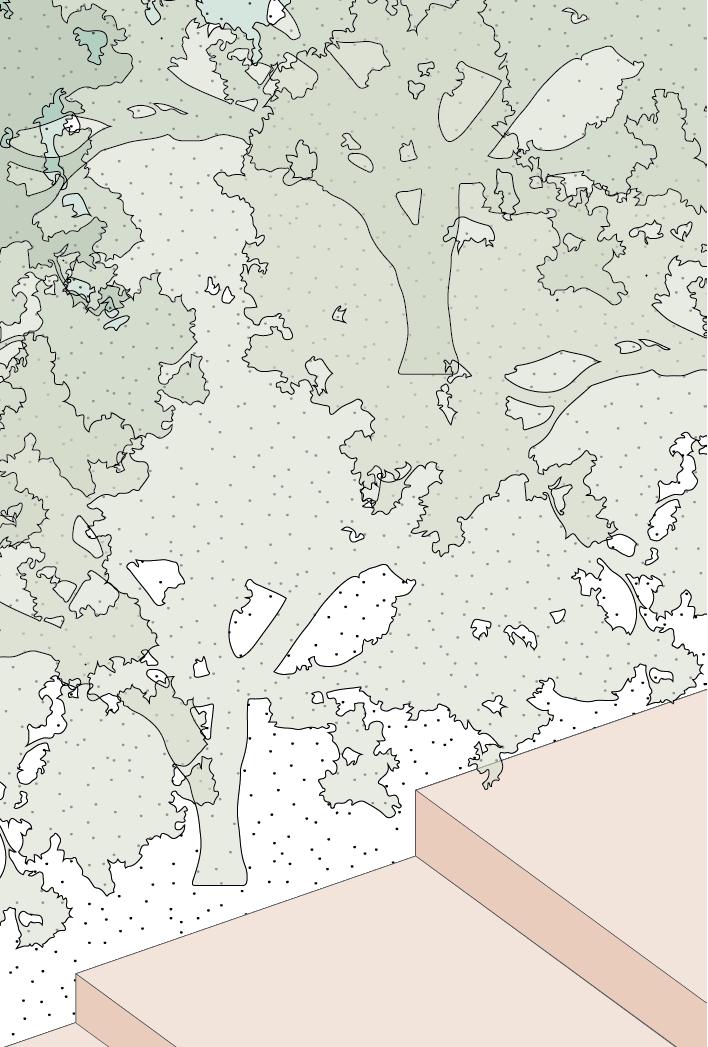

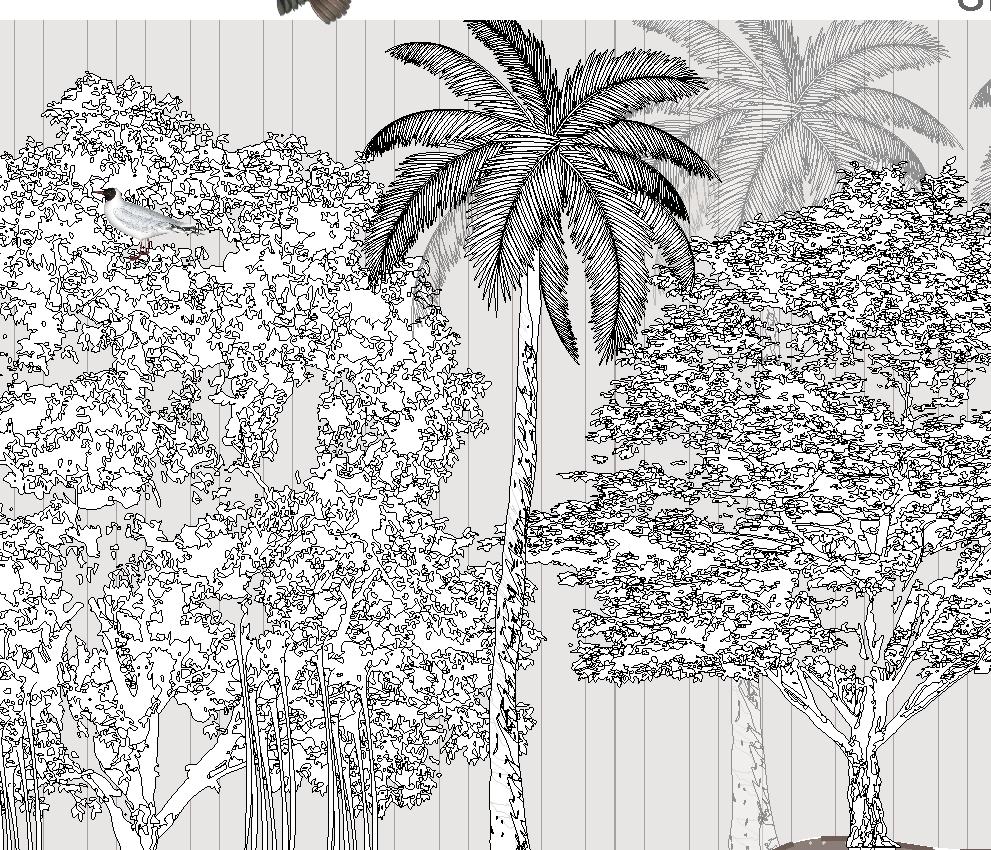

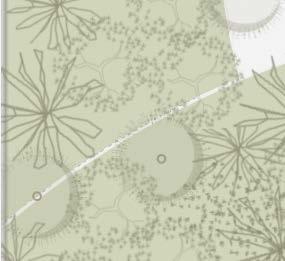

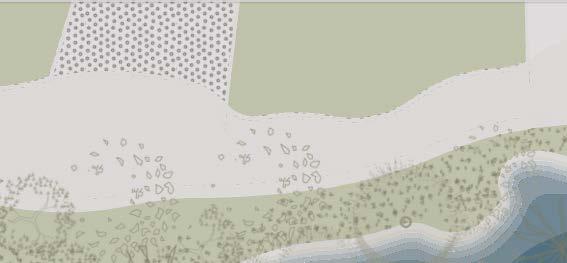

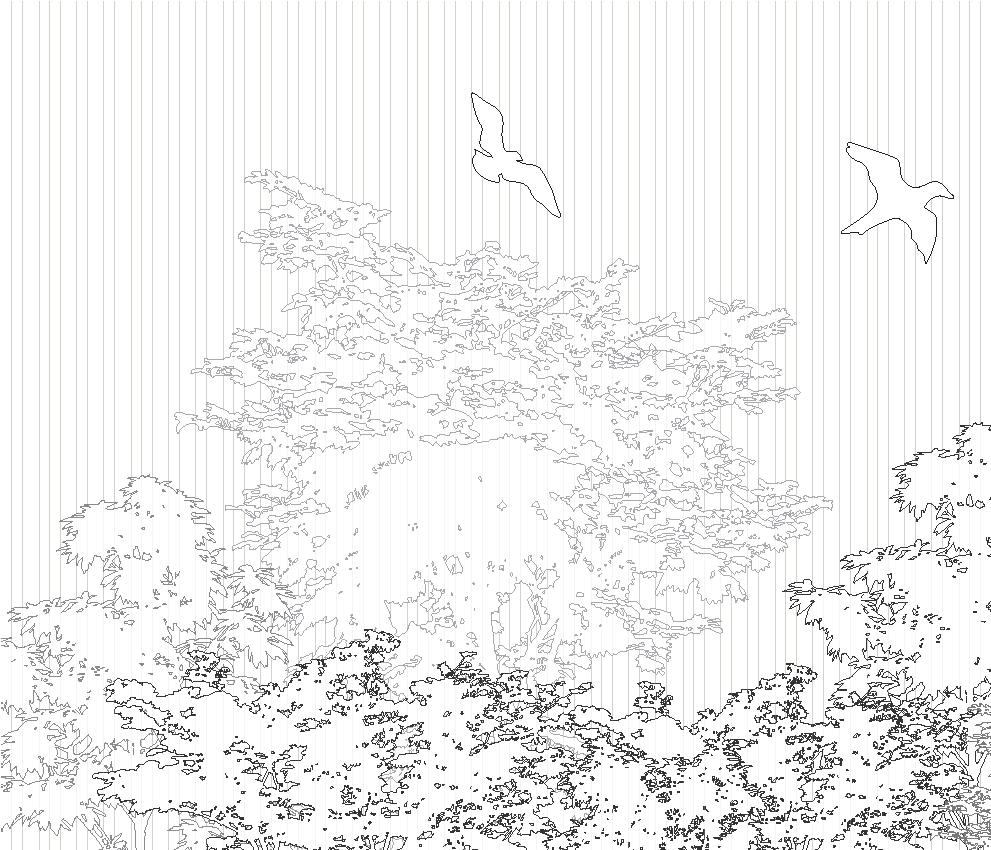

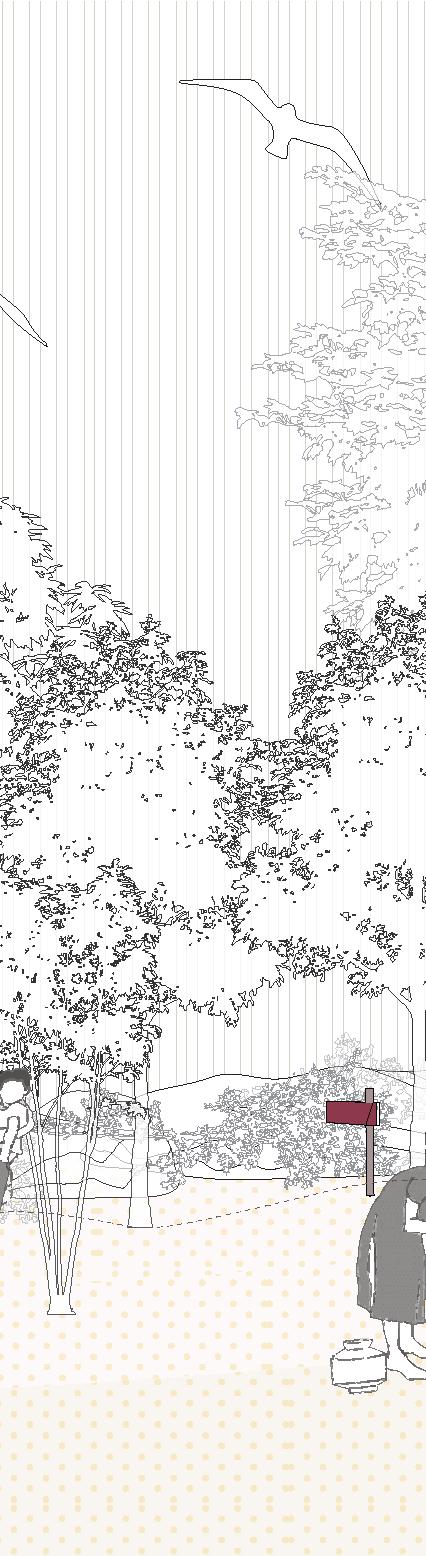

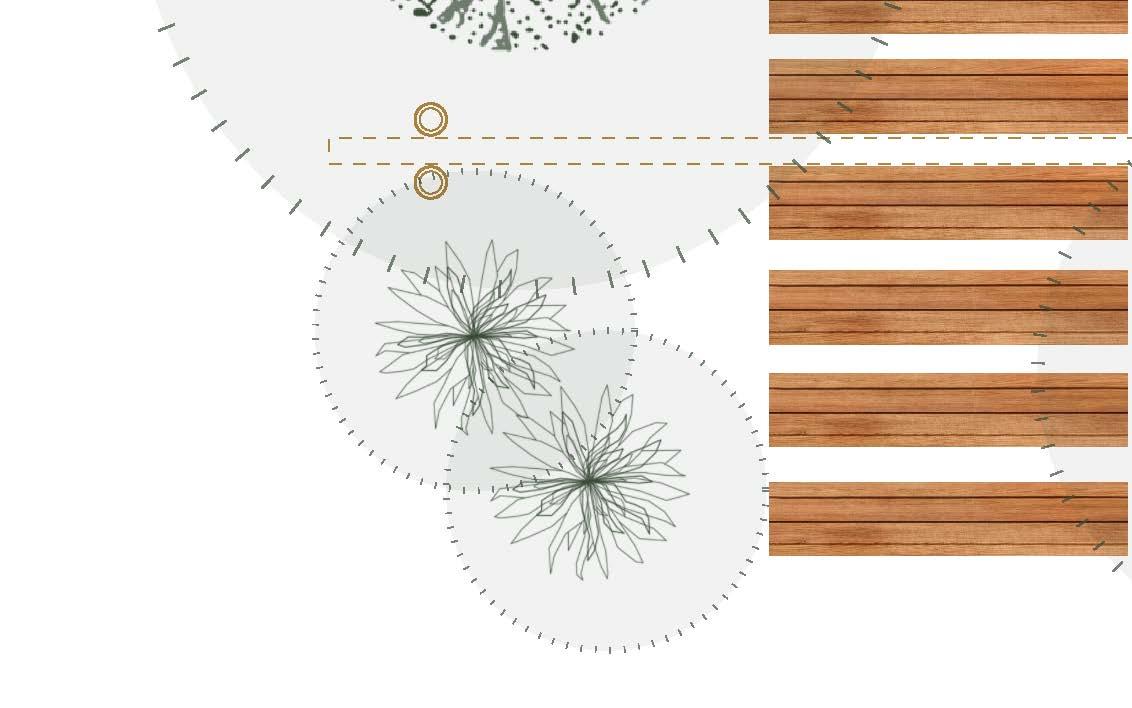

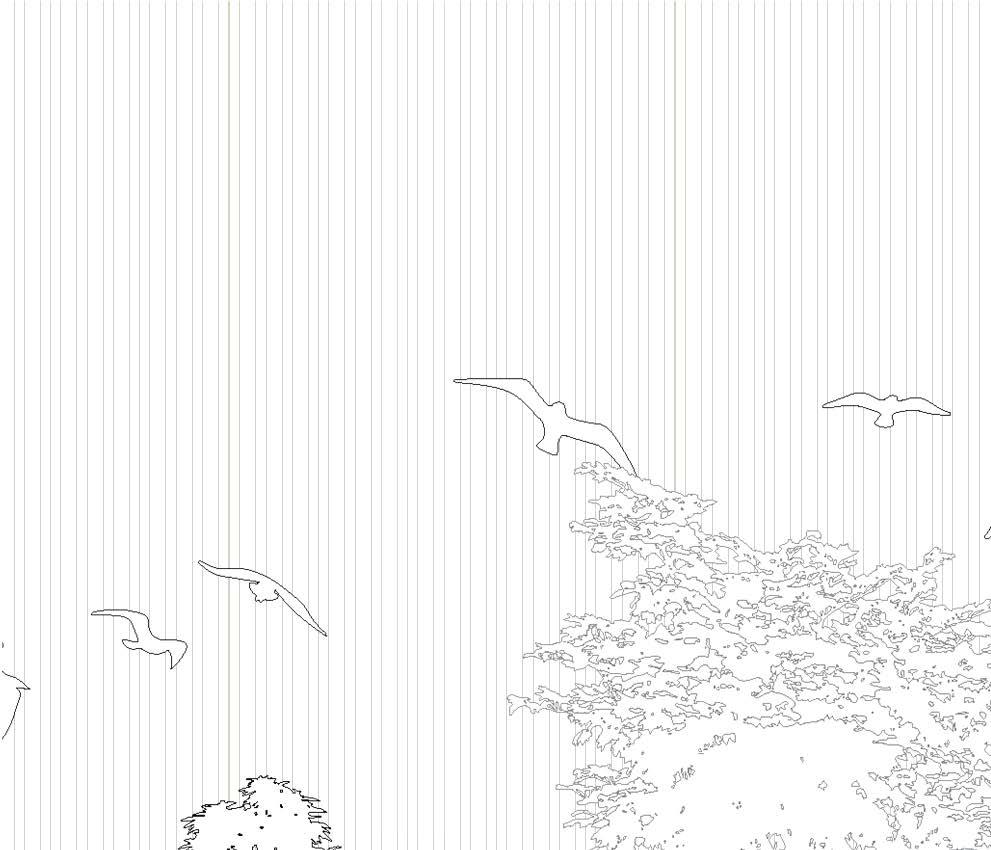

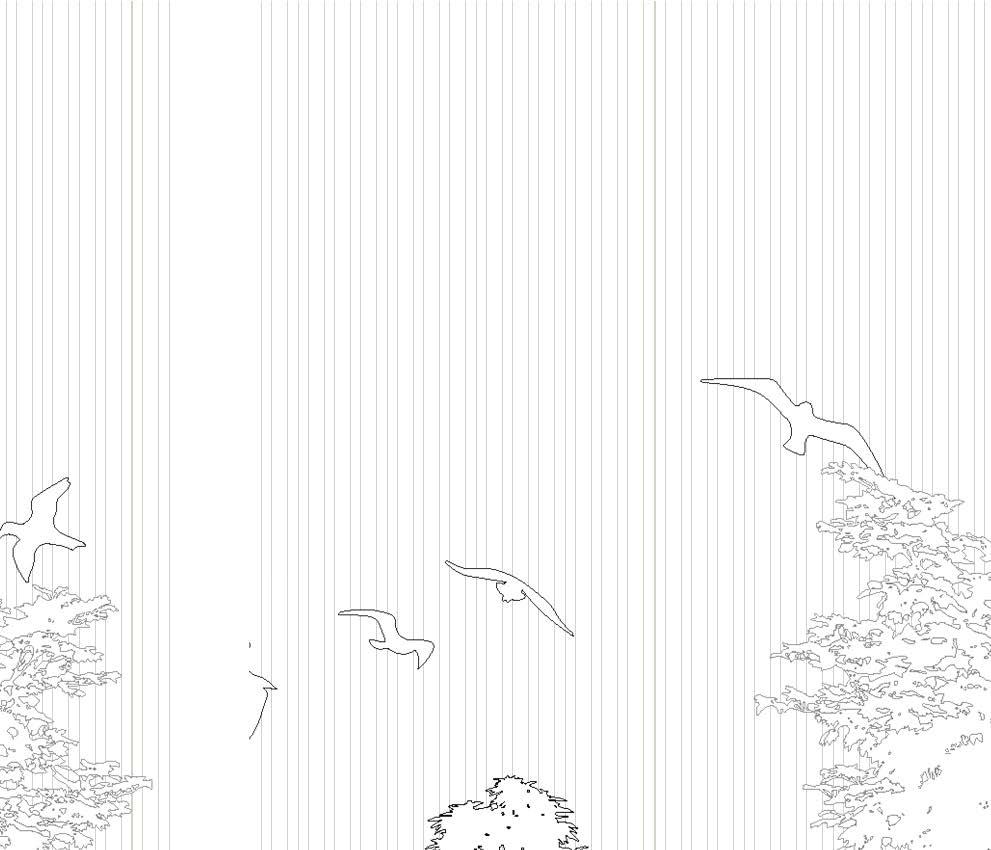

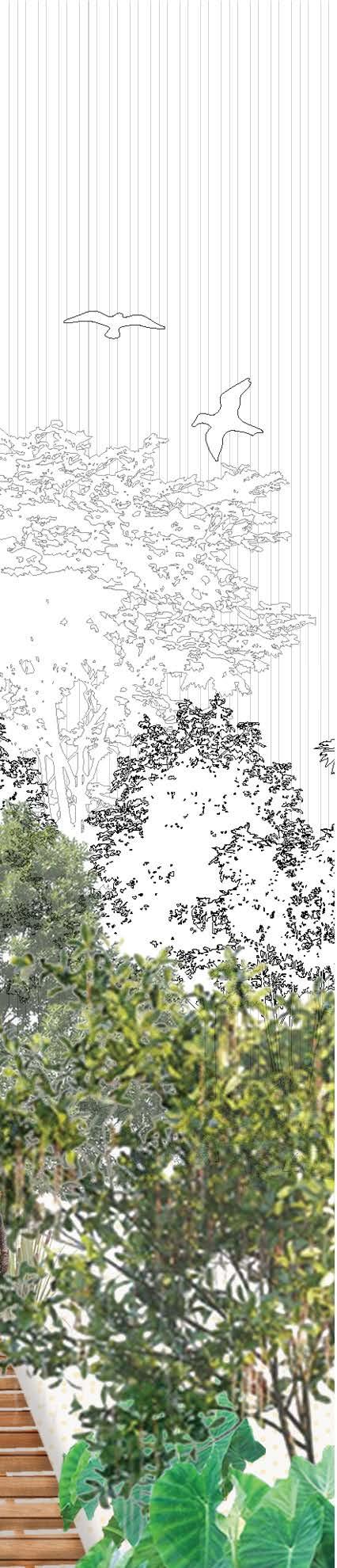

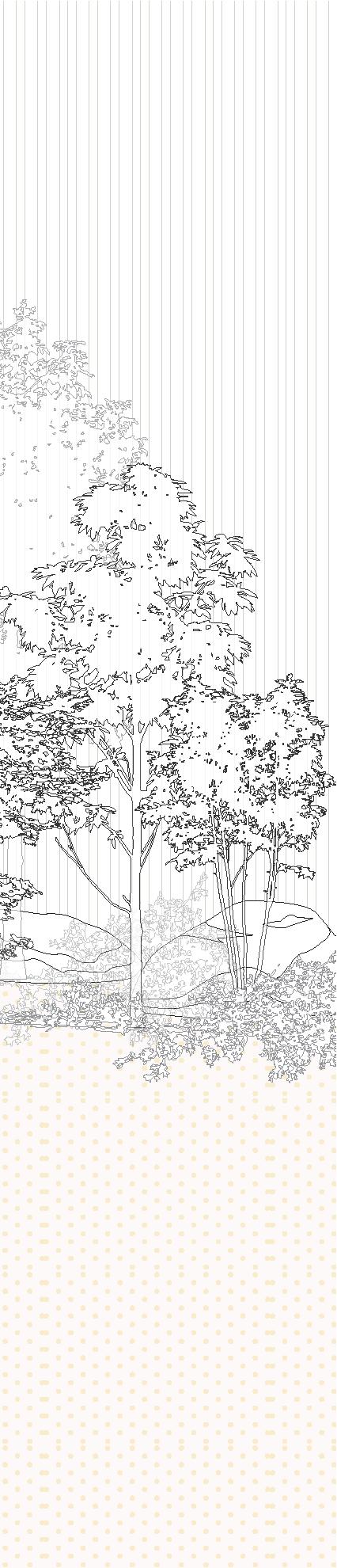

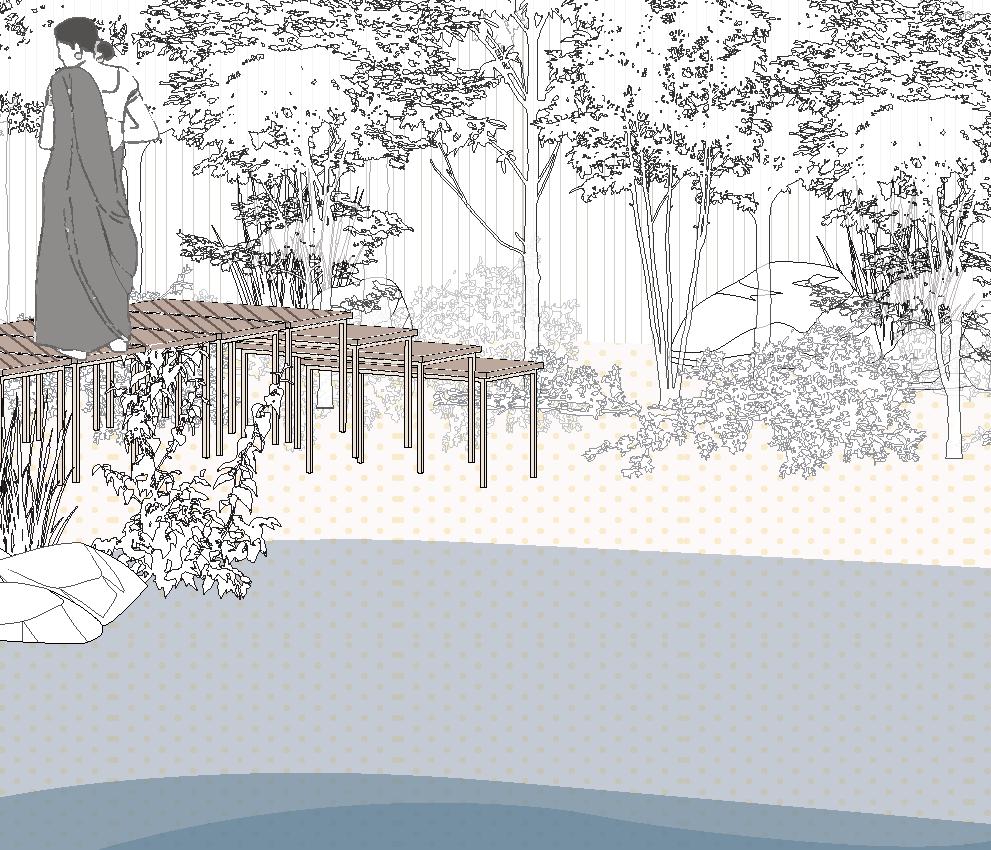

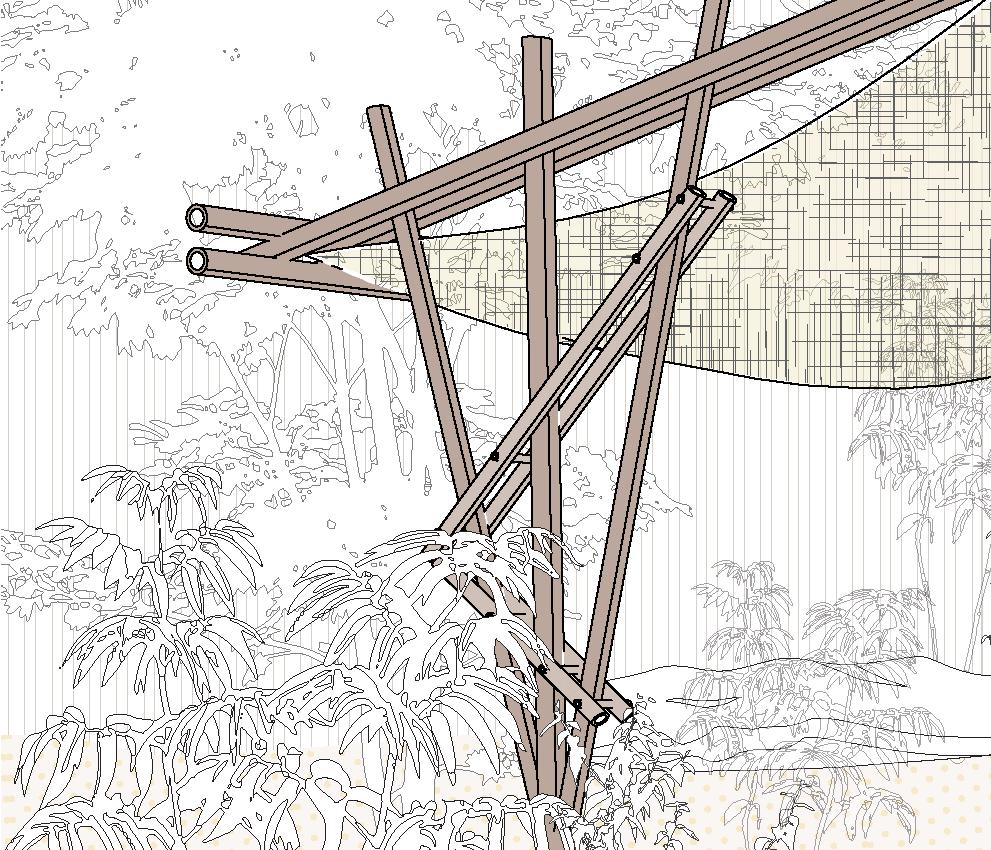

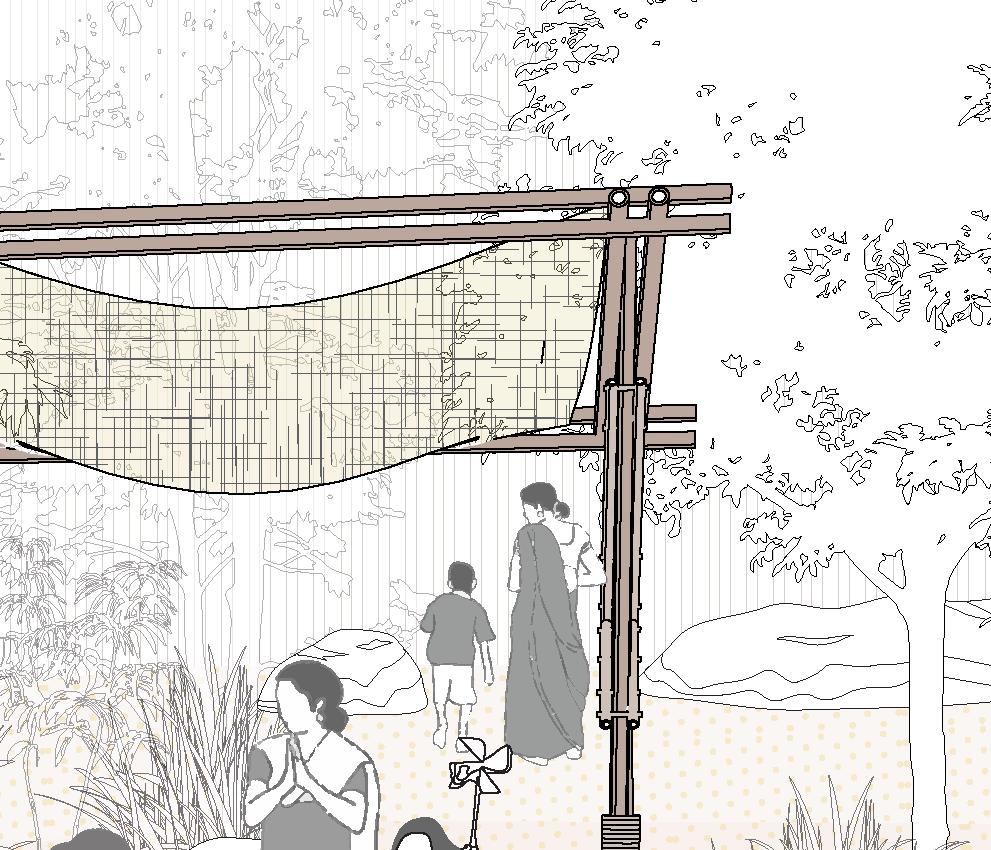

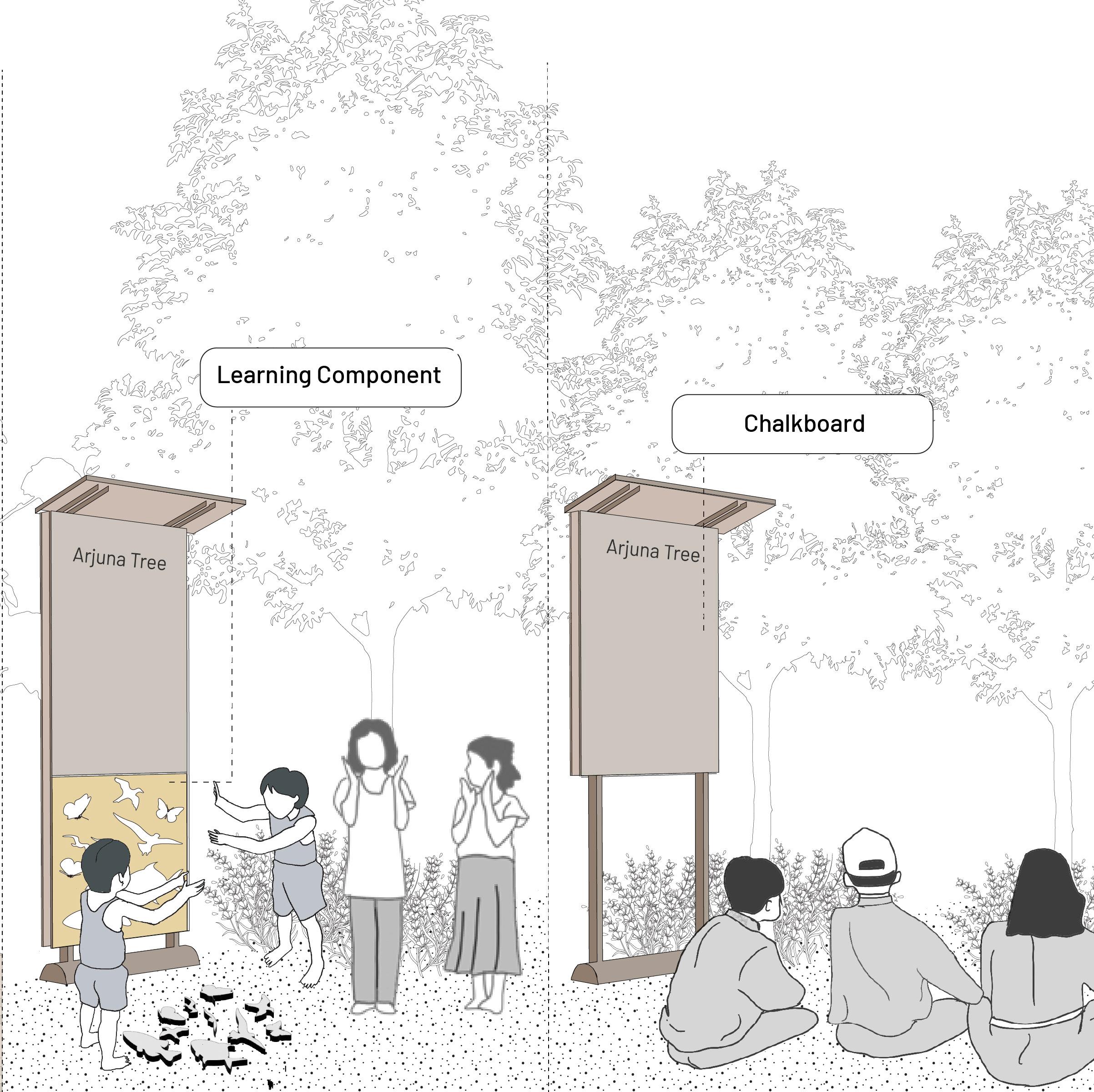

A hidden gem awaits visitors to the Thirupudai Maruthur Temple: the riparian landscape often overlooked. To unveil this natural treasure, a new trail guides explorers from the temple grounds to the riverbank. Additionally along this path, colorful signage with QR codes offers a more comprehensive understanding of the surrounding forest ecosystem.

The trail’s design embodies simplicity and sustainability, crafted from bamboo, wooden planks, and dry stems characterizing its temporary, flexible, and cost-effective construction. Envisioned as a community project, built by local villagers, this rustic walkway serves as a bridge between cultural heritage and natural beauty.

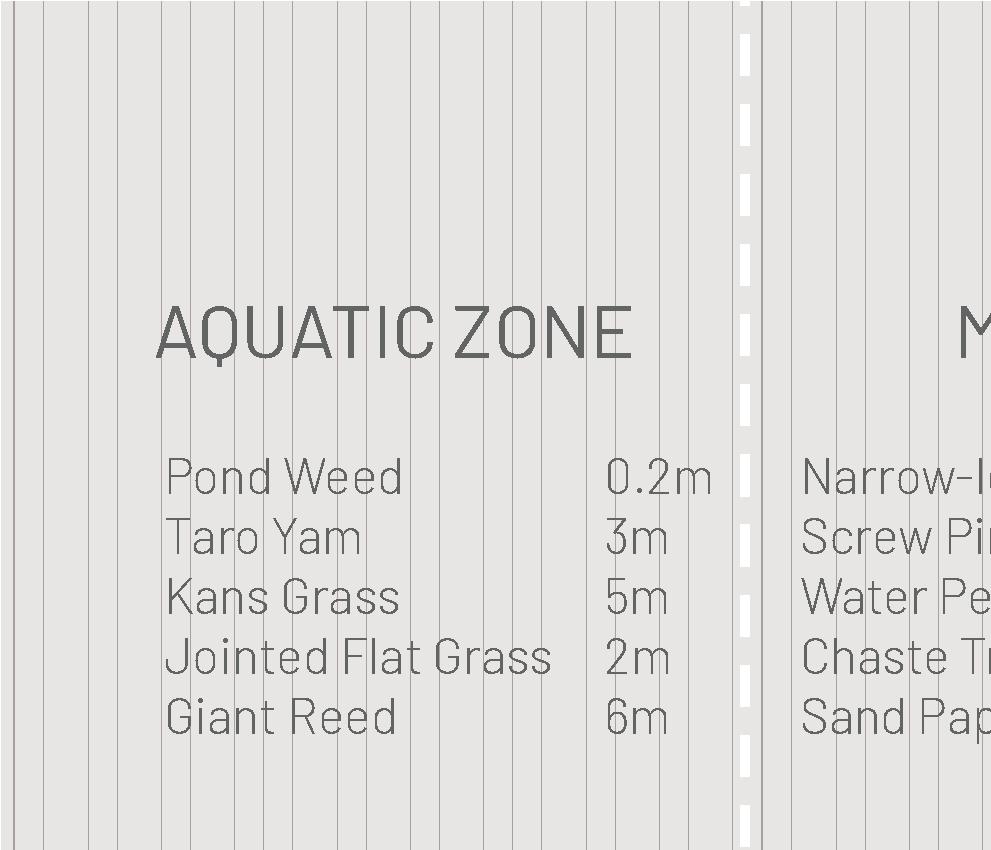

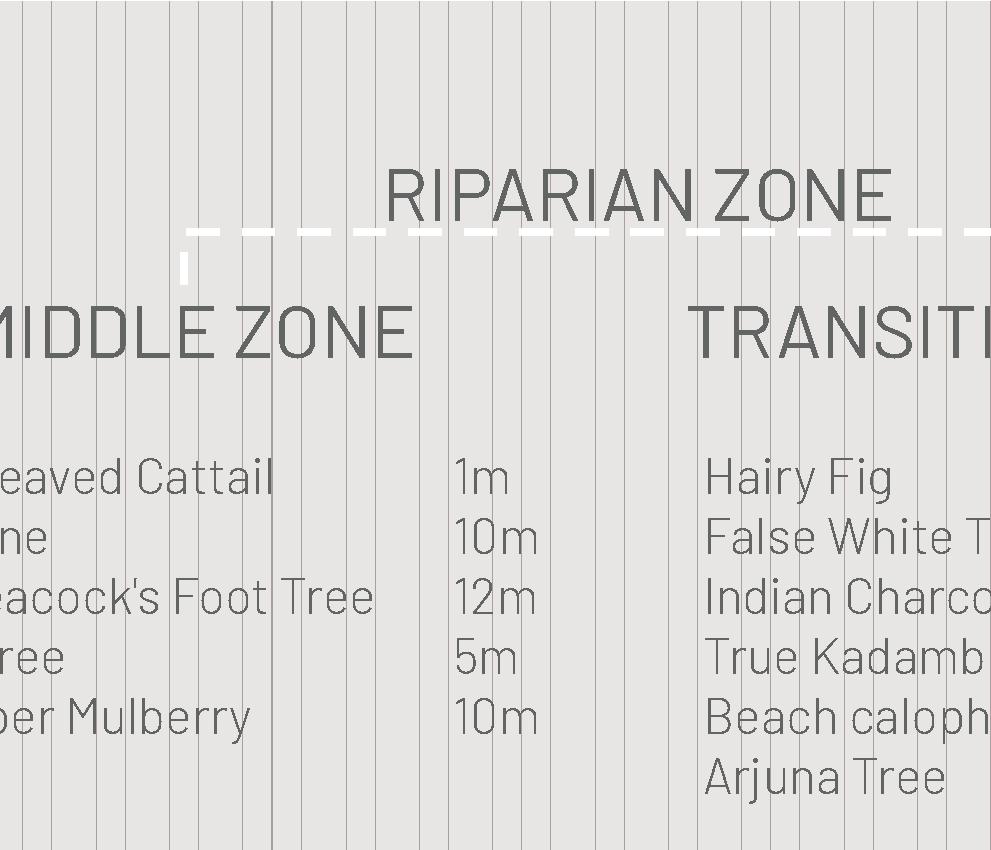

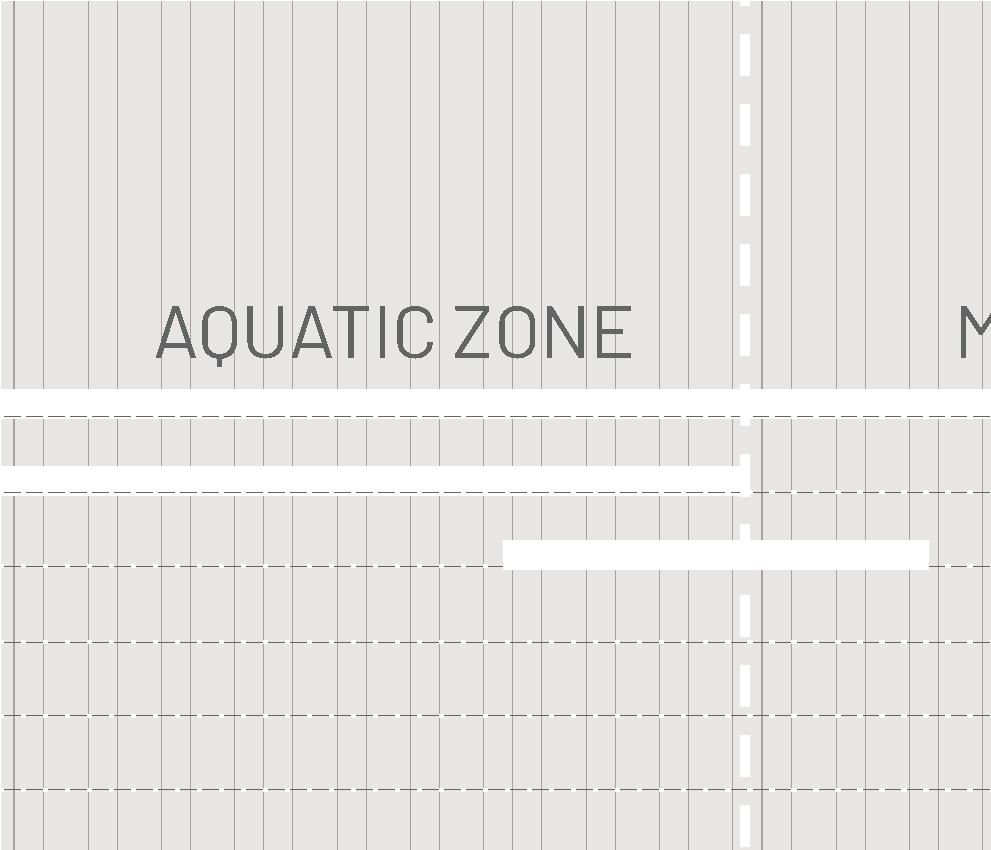

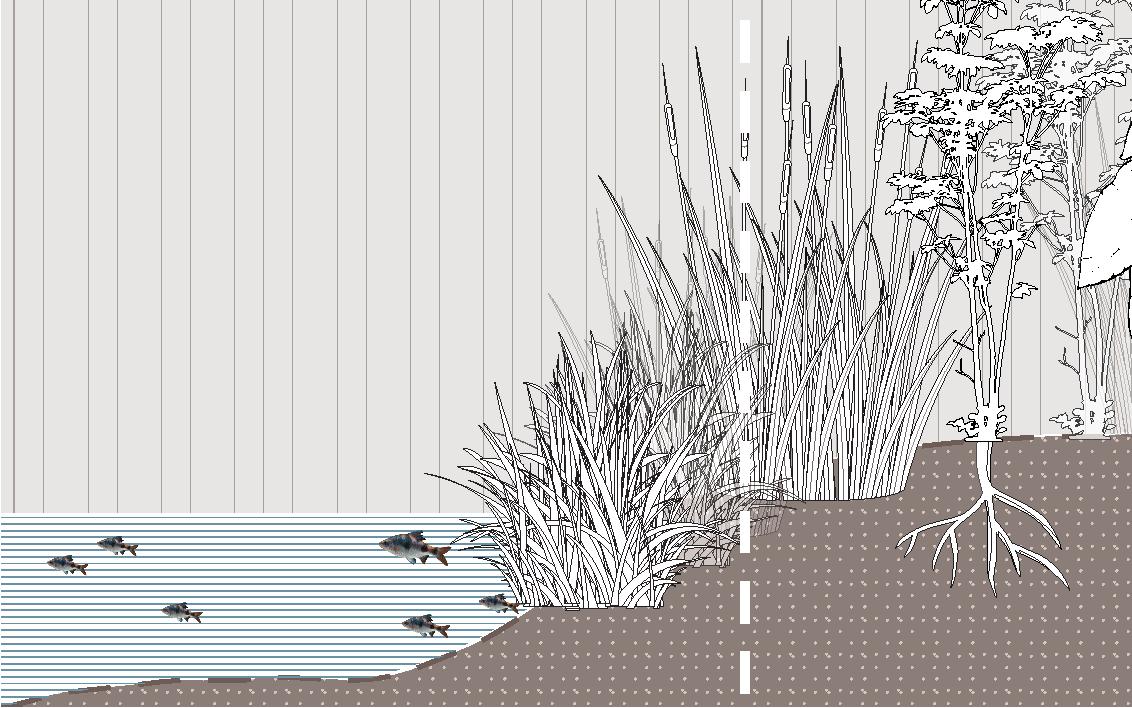

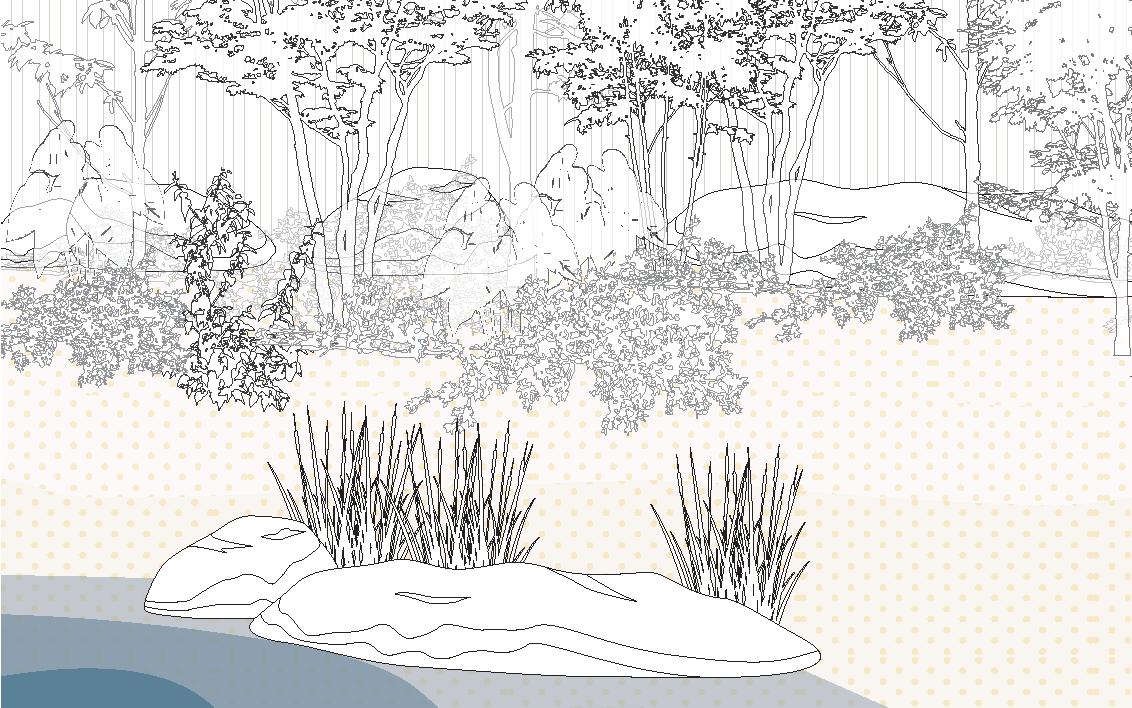

Narrow-leaved Cattail

Height: 1 m

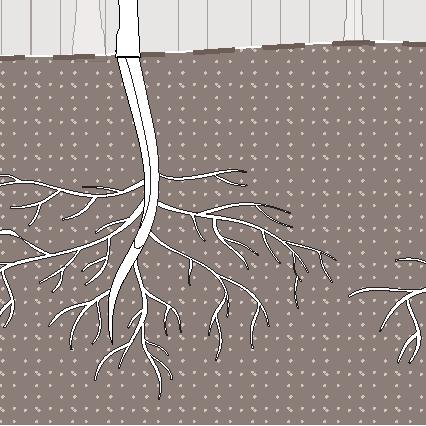

Terminalia arjuna

Height: 30 m

Colocasia esculenta

Height: 3 m

Chaste Tree

Height: 5 m

Colocasia esculenta

Height: 3 m

Terminalia arjuna Height: 30 m

Chaste Tree

Height: 5 m

Narrow-leaved Cattail

Height: 1 m

Water as Riparian Landscape ...........

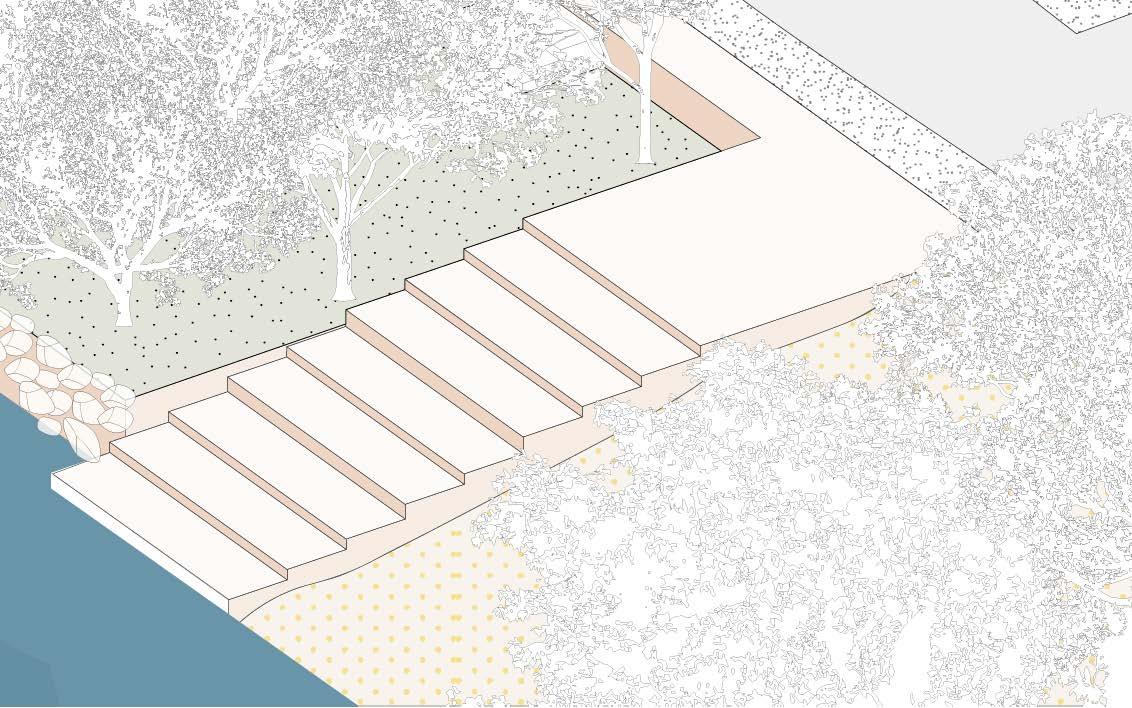

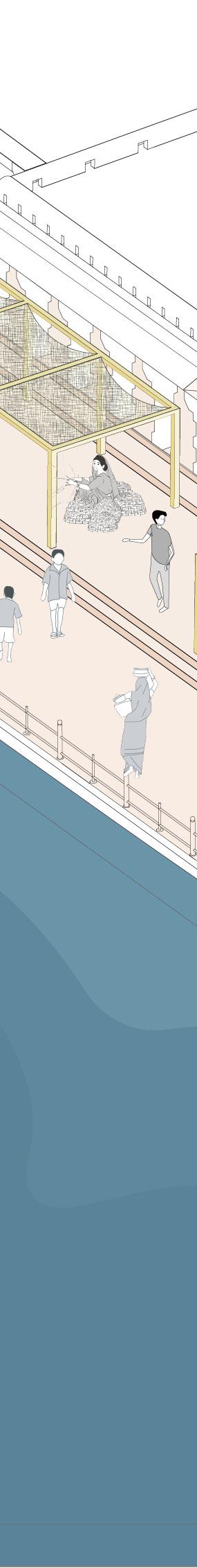

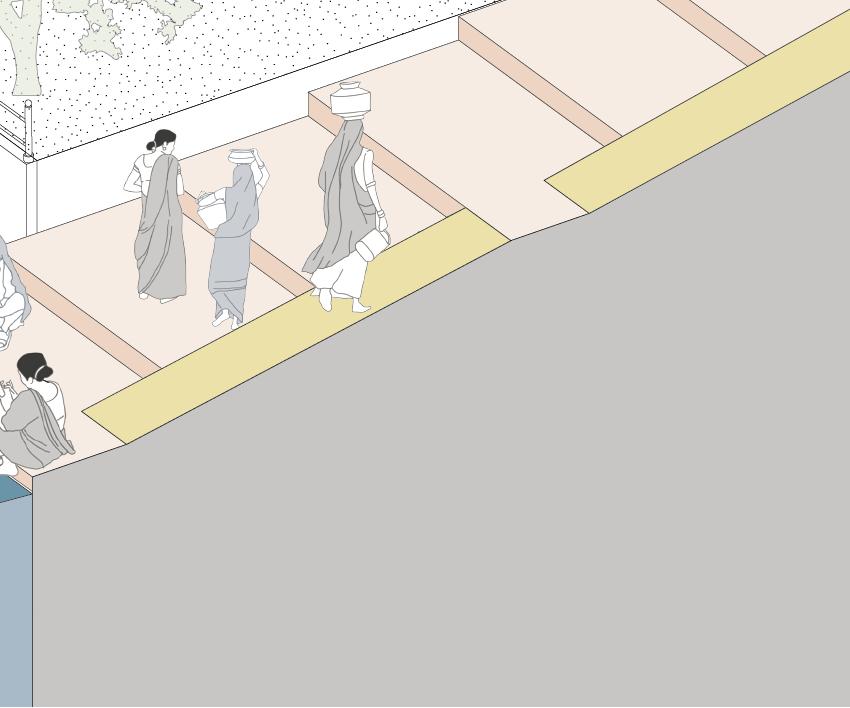

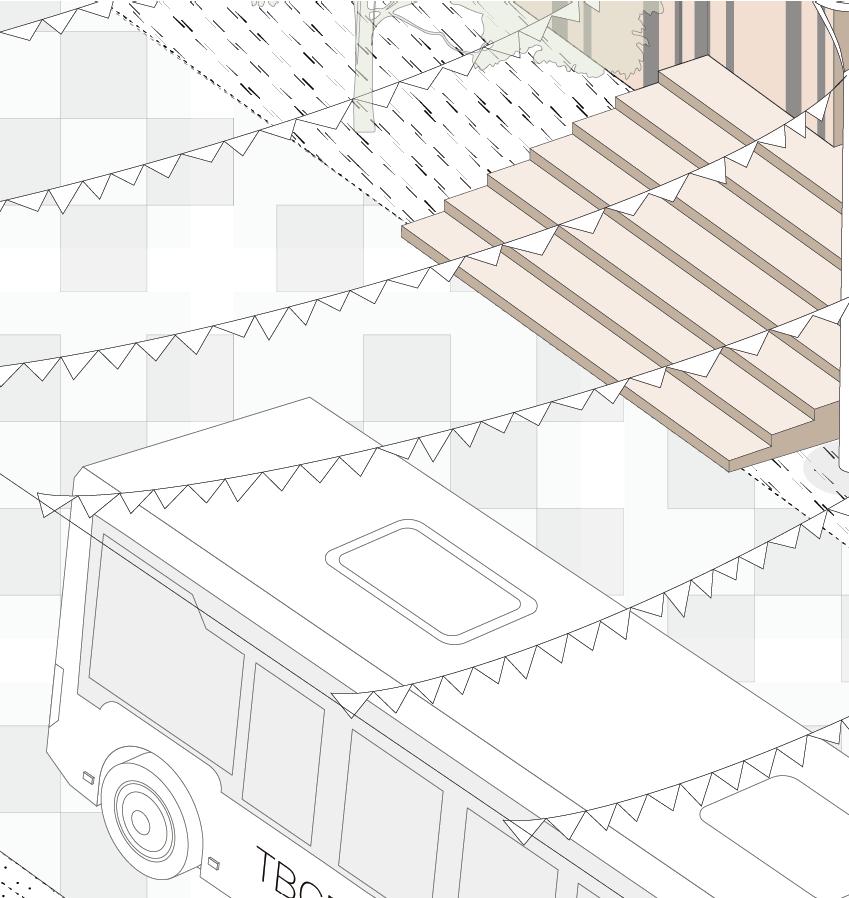

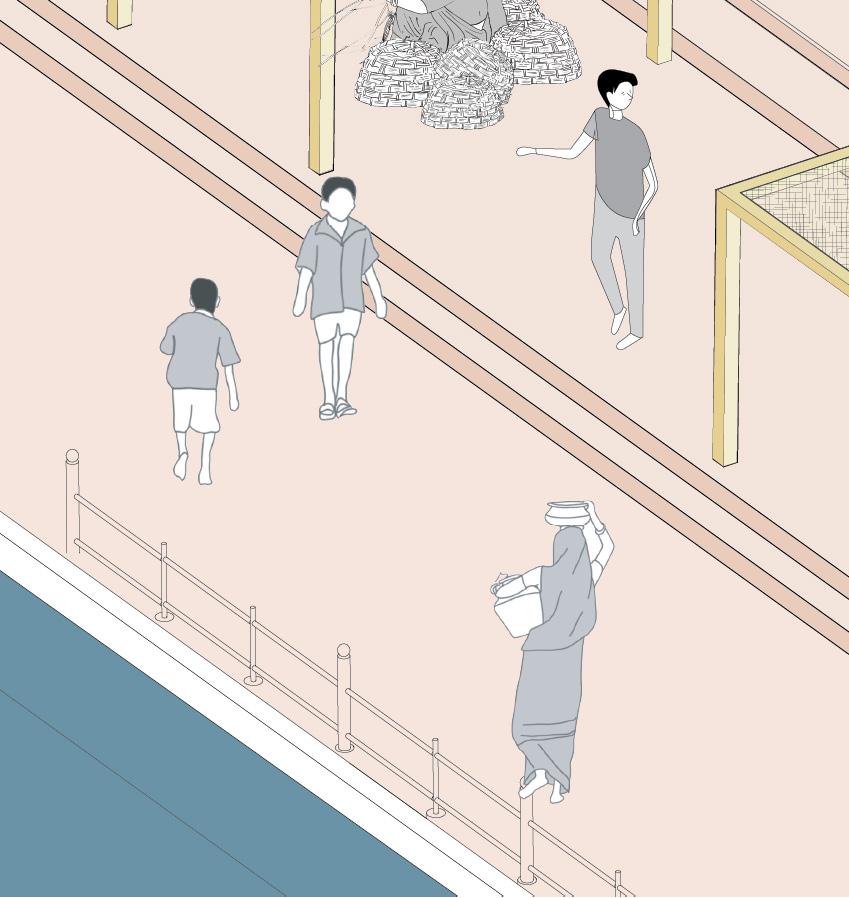

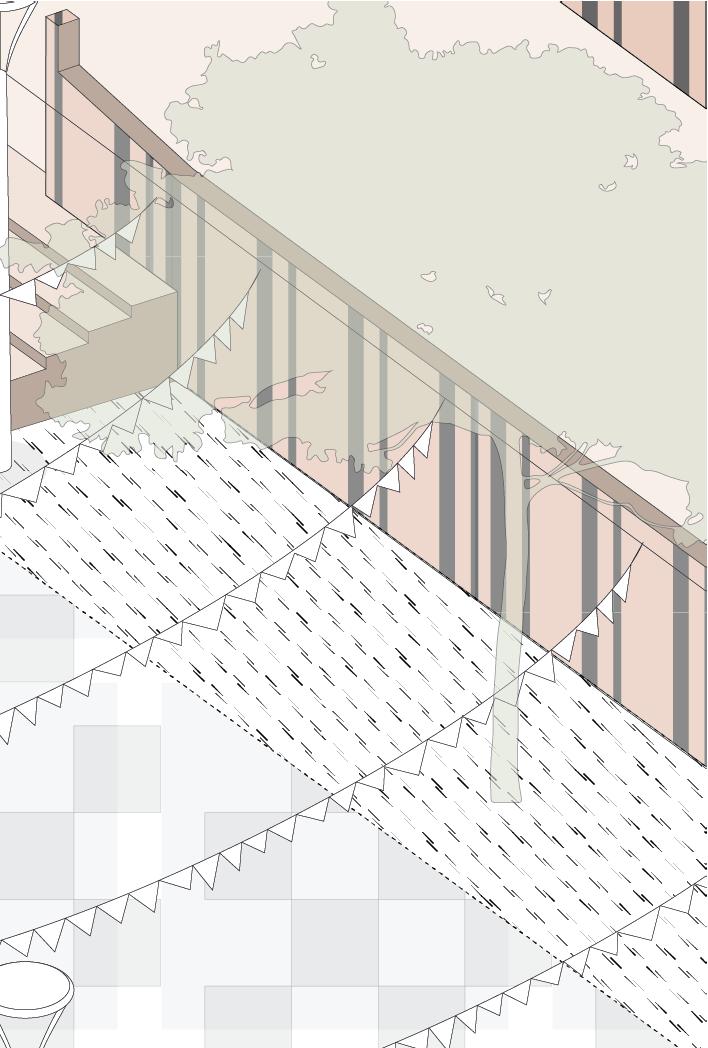

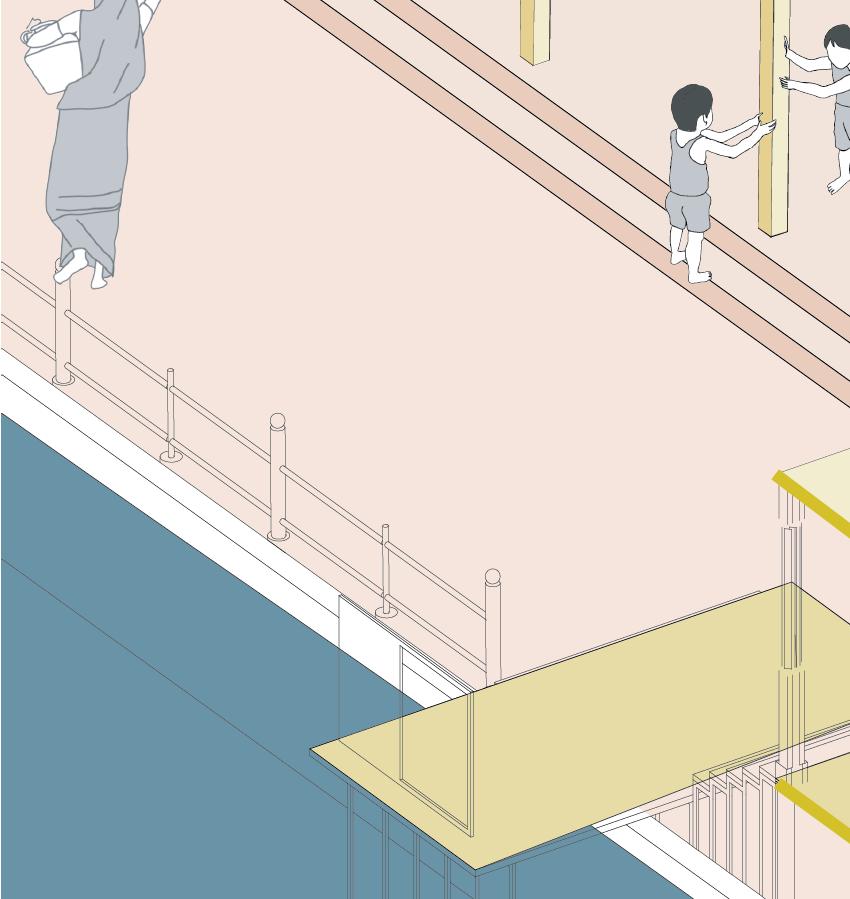

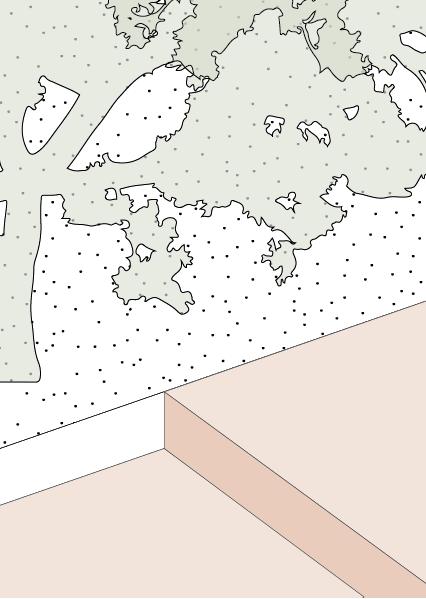

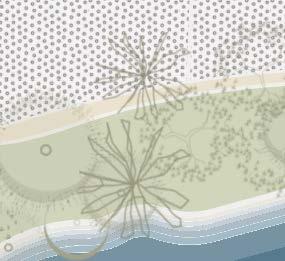

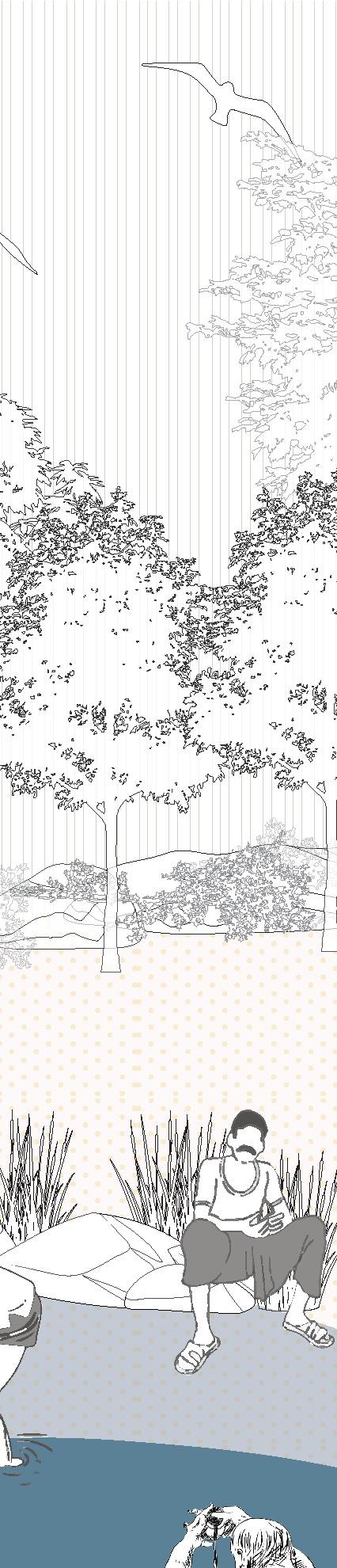

Direct access to river water, also facilitates for daily activities such as bathing and washing clothes. These flowing bodies of water are not merely functional; they are vibrant social spaces where villagers gather at the ghats, engaging in communal rituals that strengthen community bonds.

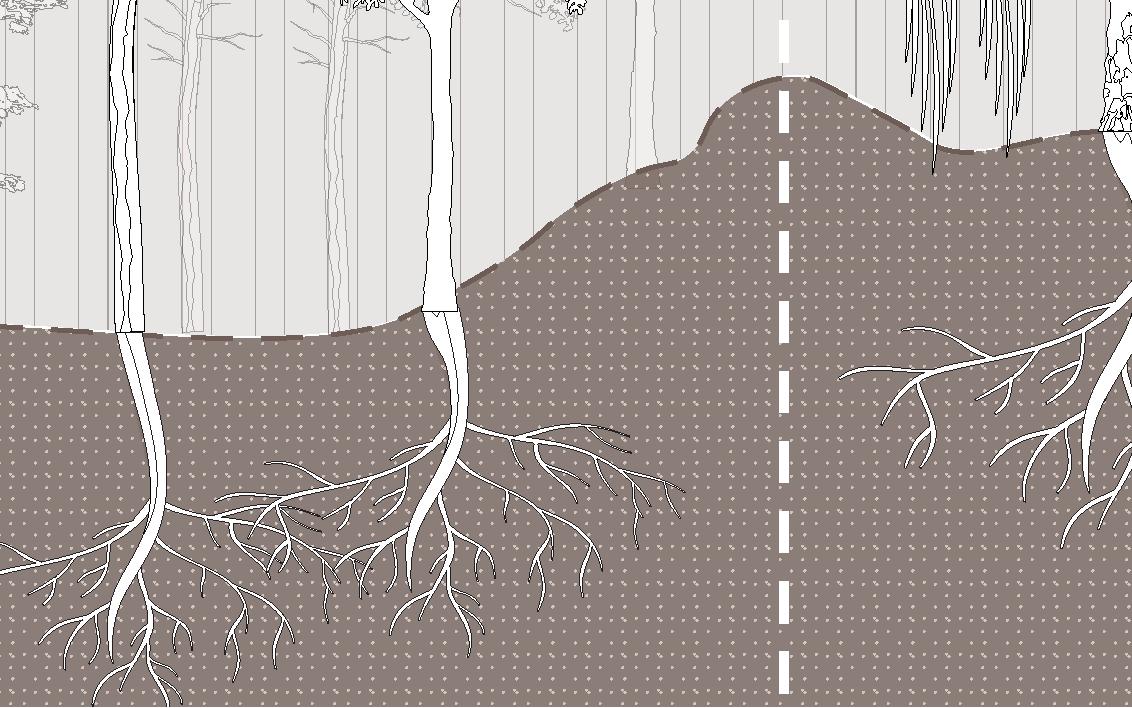

However, recent heavy rains and floods have made the riverbank increasingly unstable and hazardous in many circumstances.

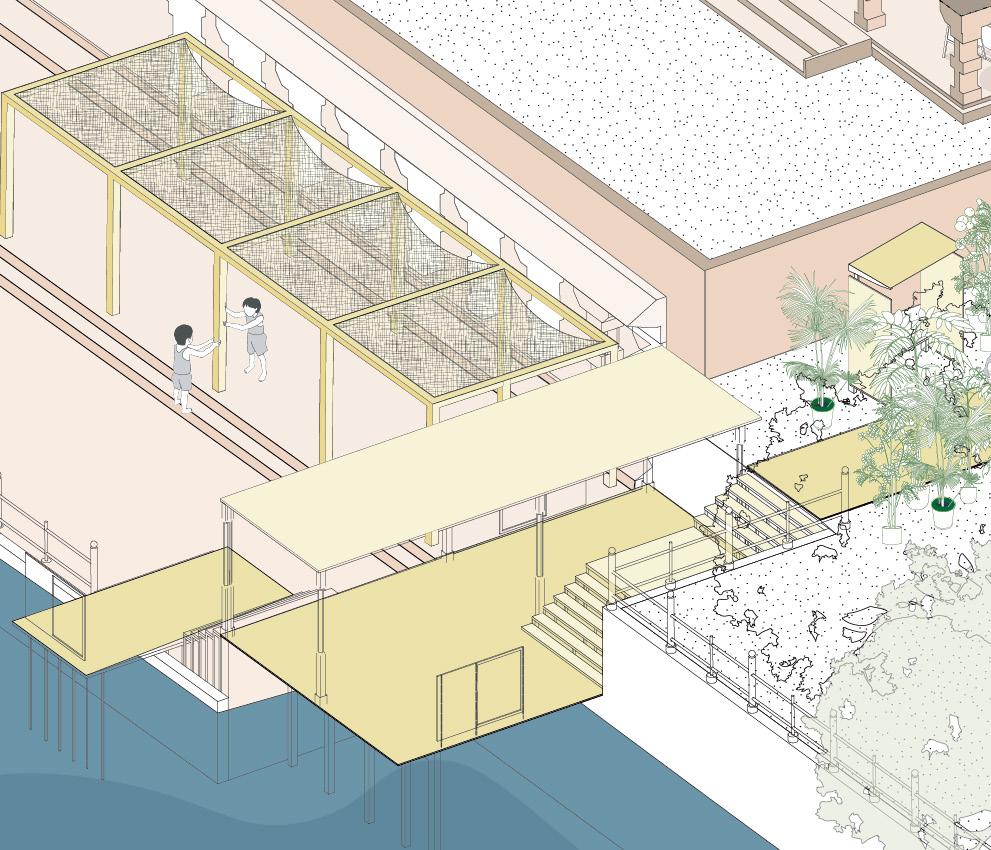

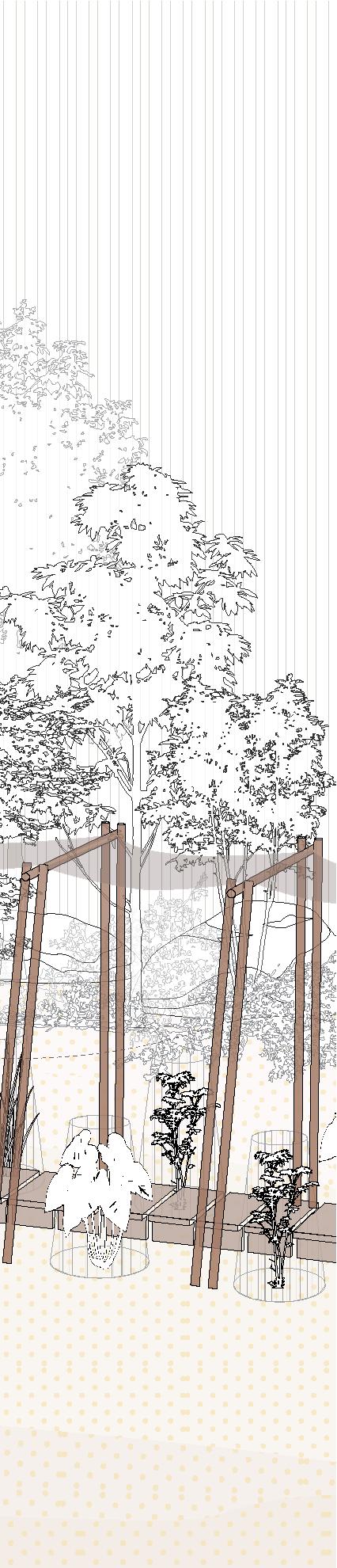

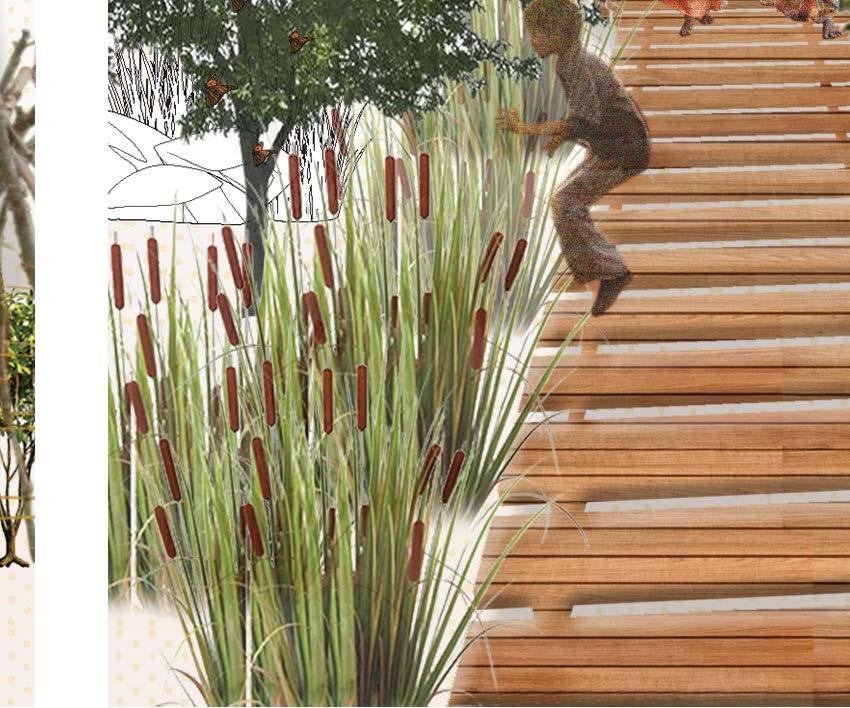

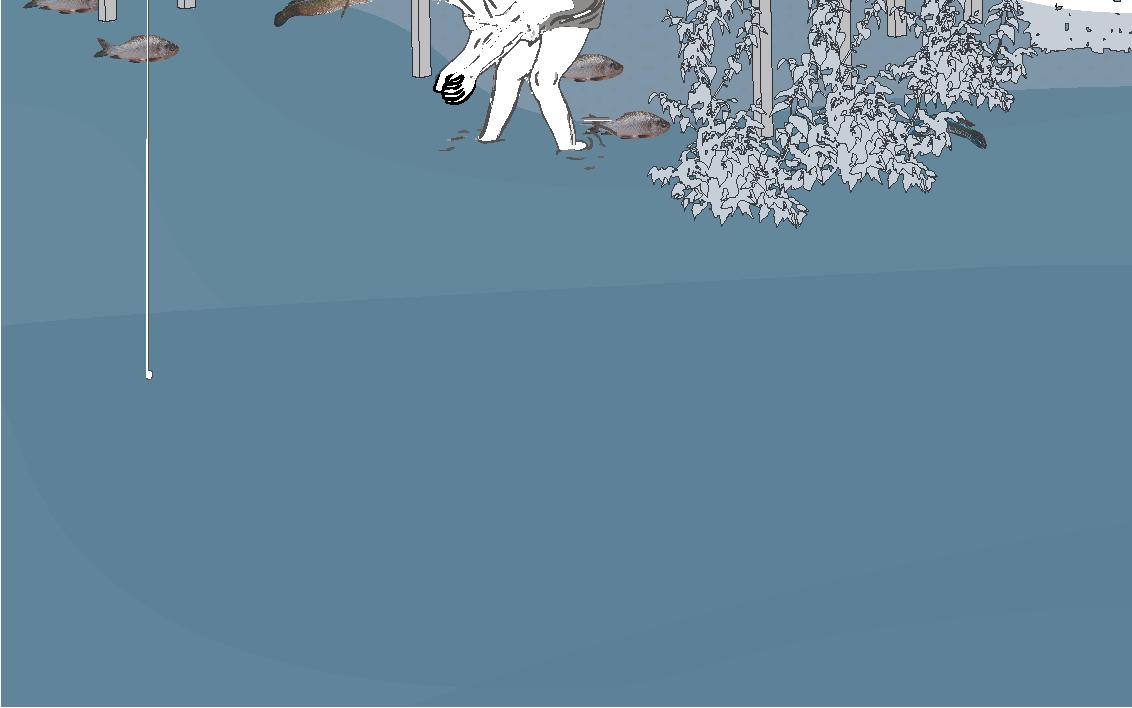

The deck is designed as a modular and flexible component, specifically created to provide safer access to water during periods of high water levels. Constructed with manageable dimensions and crafted from locally available materials, the deck can be easily assembled, disassembled, and stored in a compact space when not in use.

Women can now carry out their daily water-related chores such as washing clothes and fetching water more safely and conveniently, even during challenging conditions.

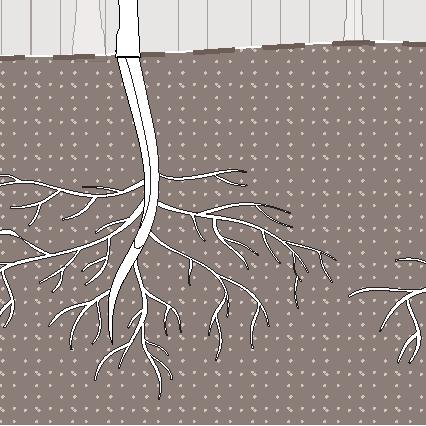

The aquatic zones of the riparian forest also create an ideal micro climate for native fish species to breed. During periods of high water, the deck also provides a provision to get a closer peek in the amazing marine world with any external disturbances.

The men of the village may also gather along the riverside, where they not only socialize but also partake in fishing as a recreational activity.

Currently, these decks are primarily planned for installation near the second and third hamlets, as these areas are particularly vulnerable to heavy rains and flooding. This initiative not only enhances safety but also fosters resilience within the community, allowing them to adapt to the challenges posed by seasonal changes.

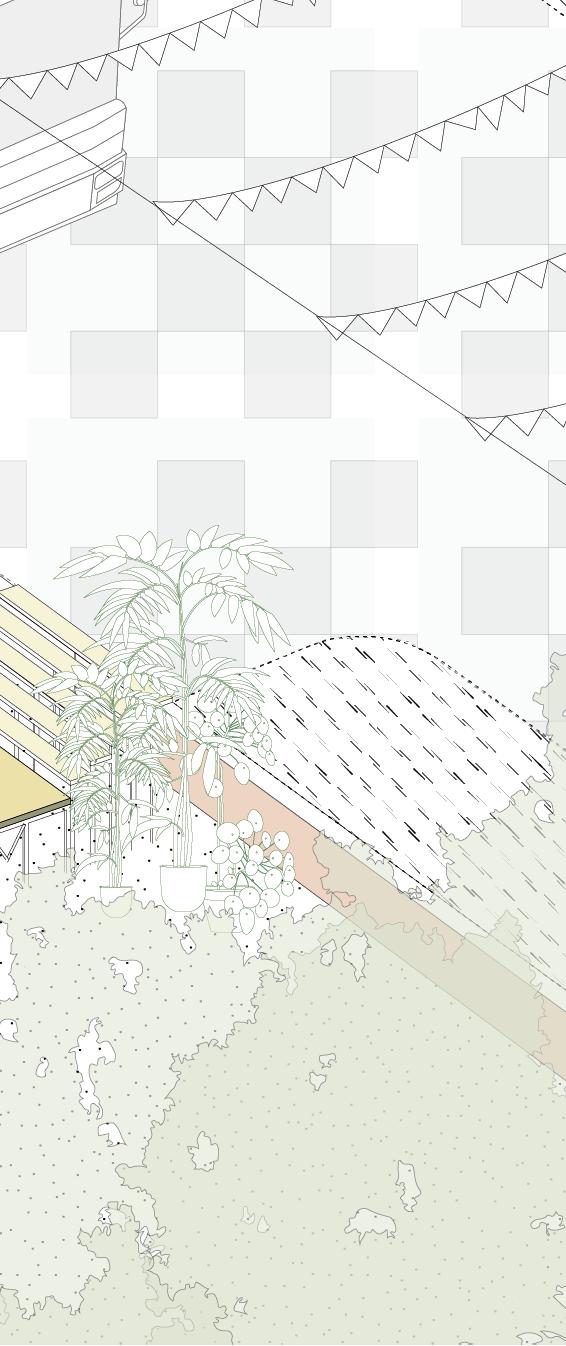

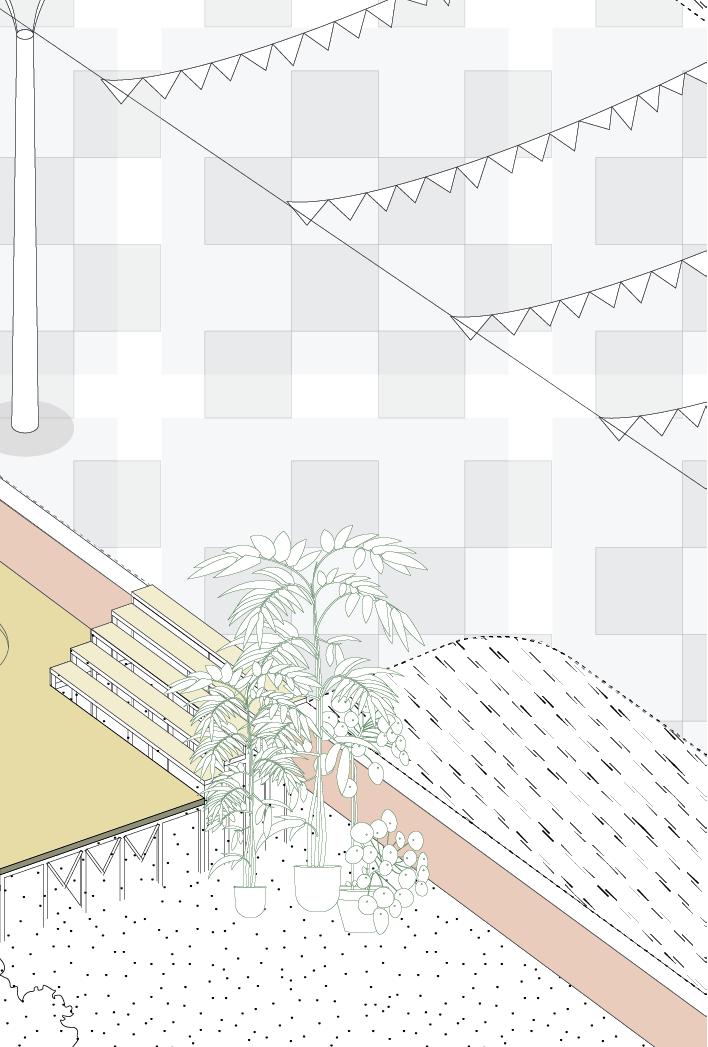

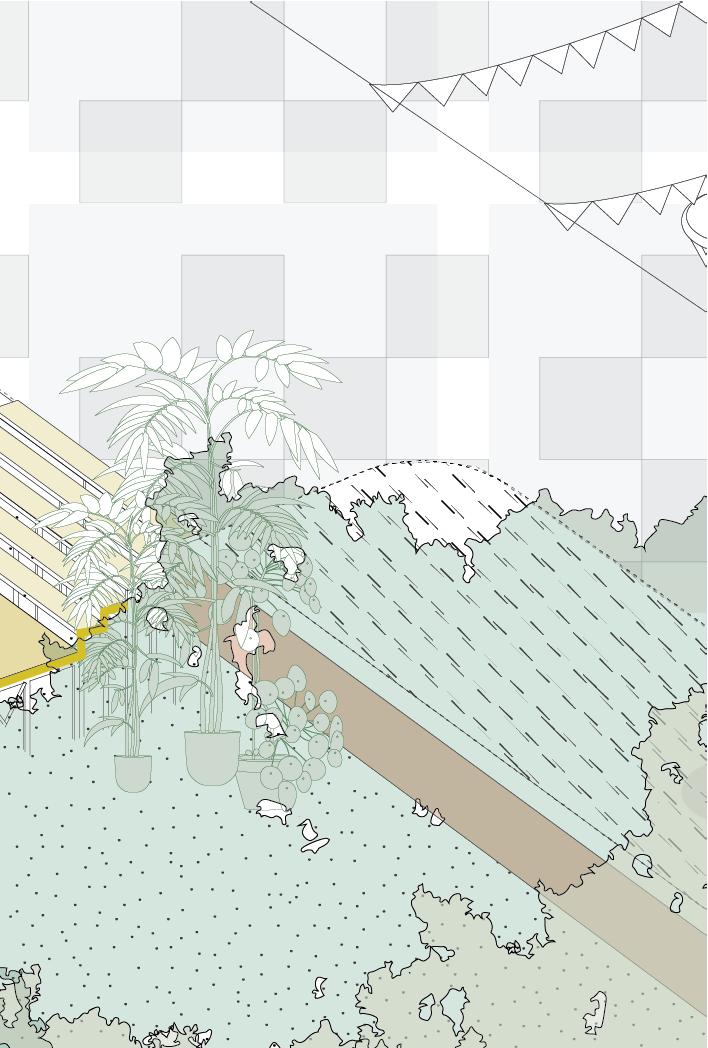

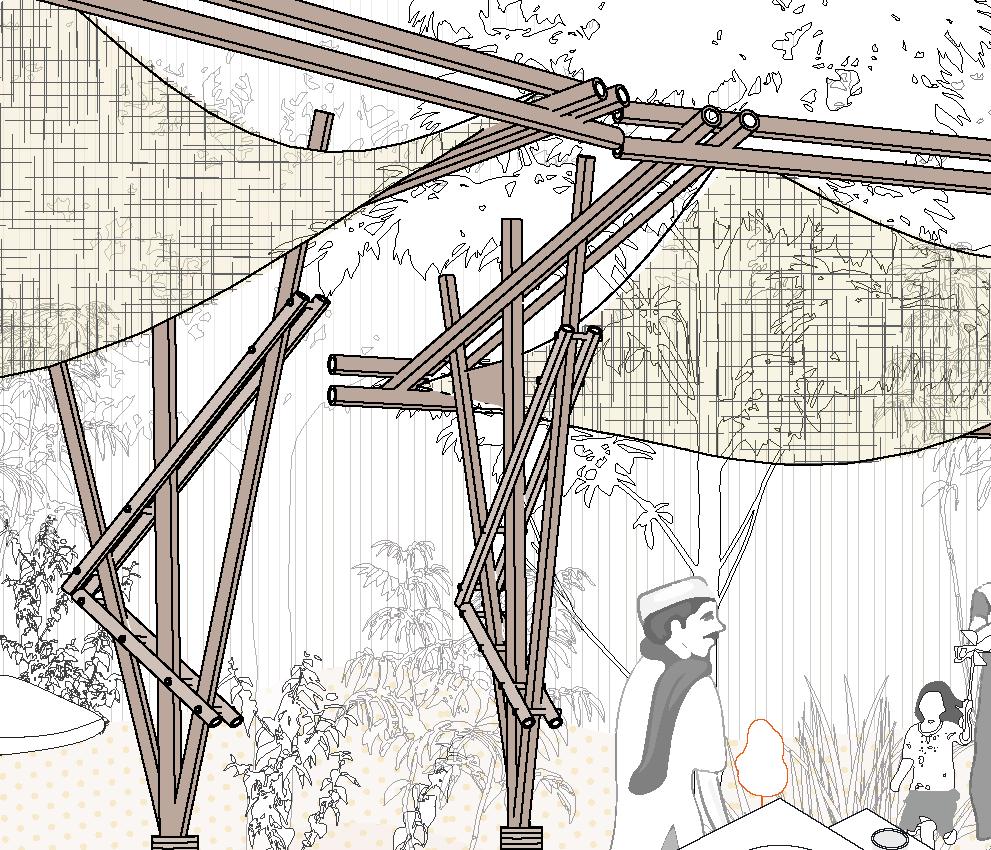

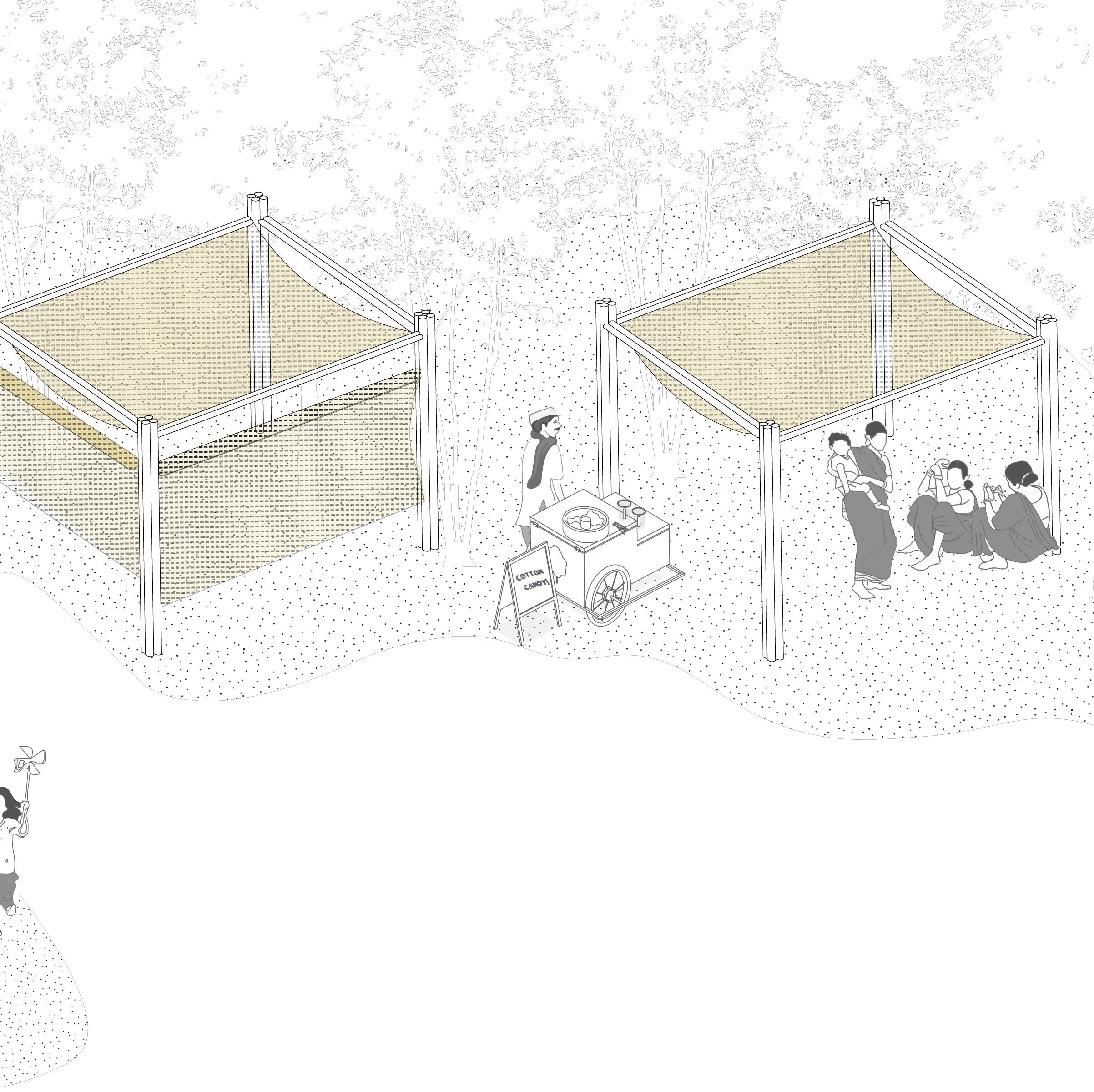

In areas near the village, a specially designed shading structure a testament to local ingenuity and sustainable design. Crafted from resilient bamboo and adorned with lightweight mats woven from dry grass, this structure serves as a multifunctional gathering space that seamlessly blends with its natural surroundings. During festive occasions, it transforms into a vibrant hub of celebration. Additionally, this space can also be a catalyst for environmental awareness. It serves as an informal classroom where knowledge about afforestation and ecological conservation is shared.

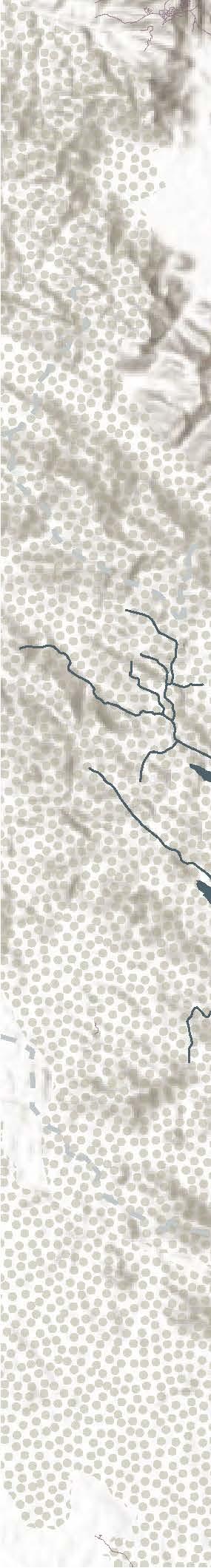

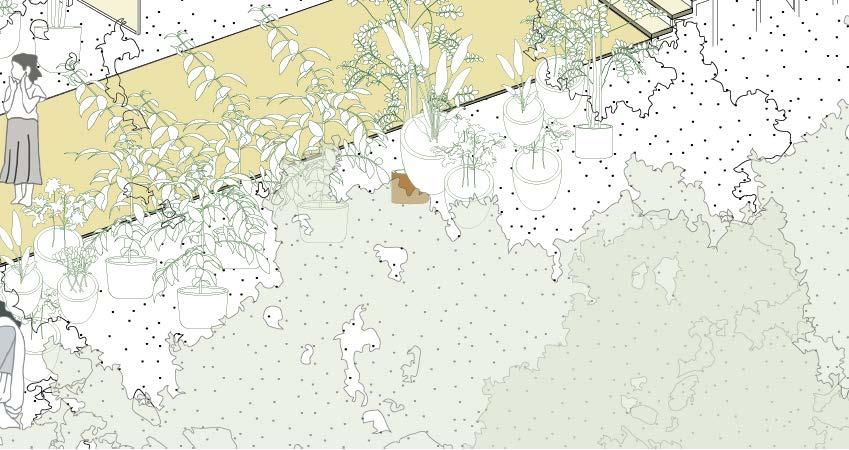

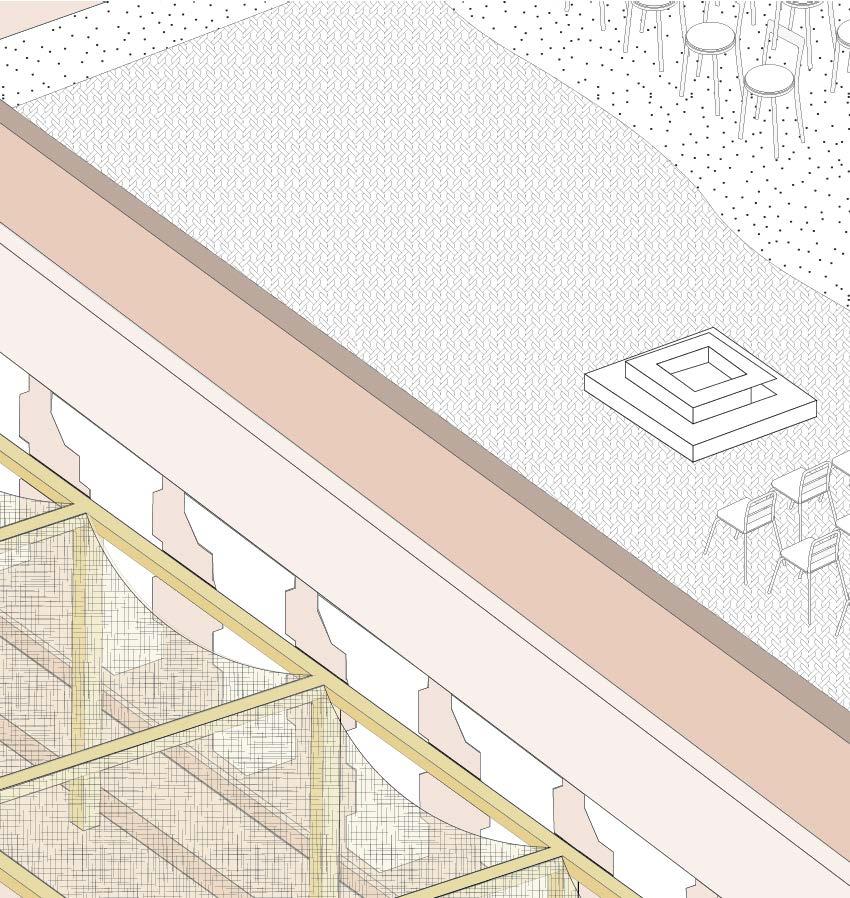

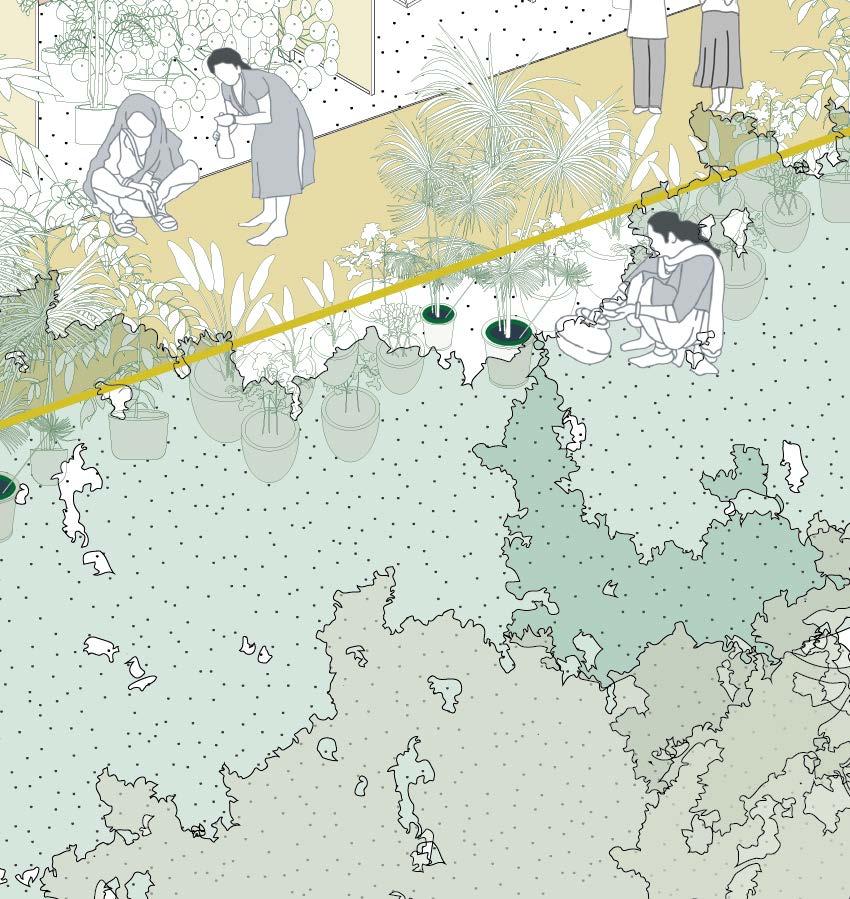

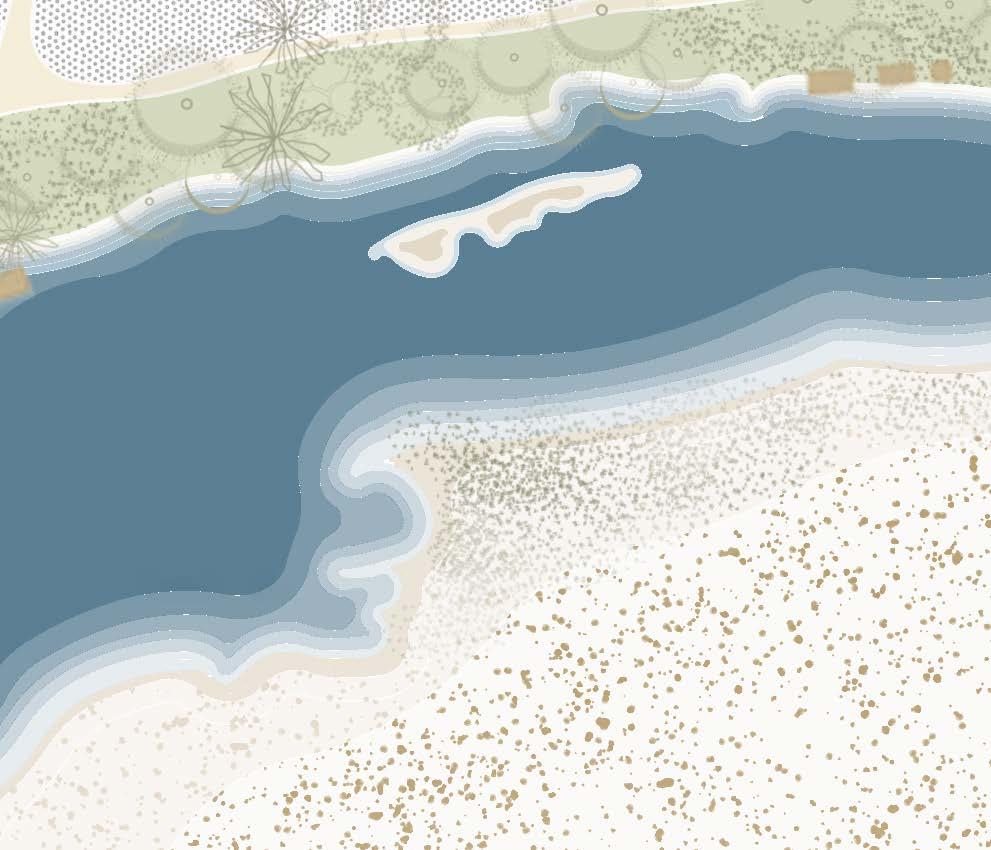

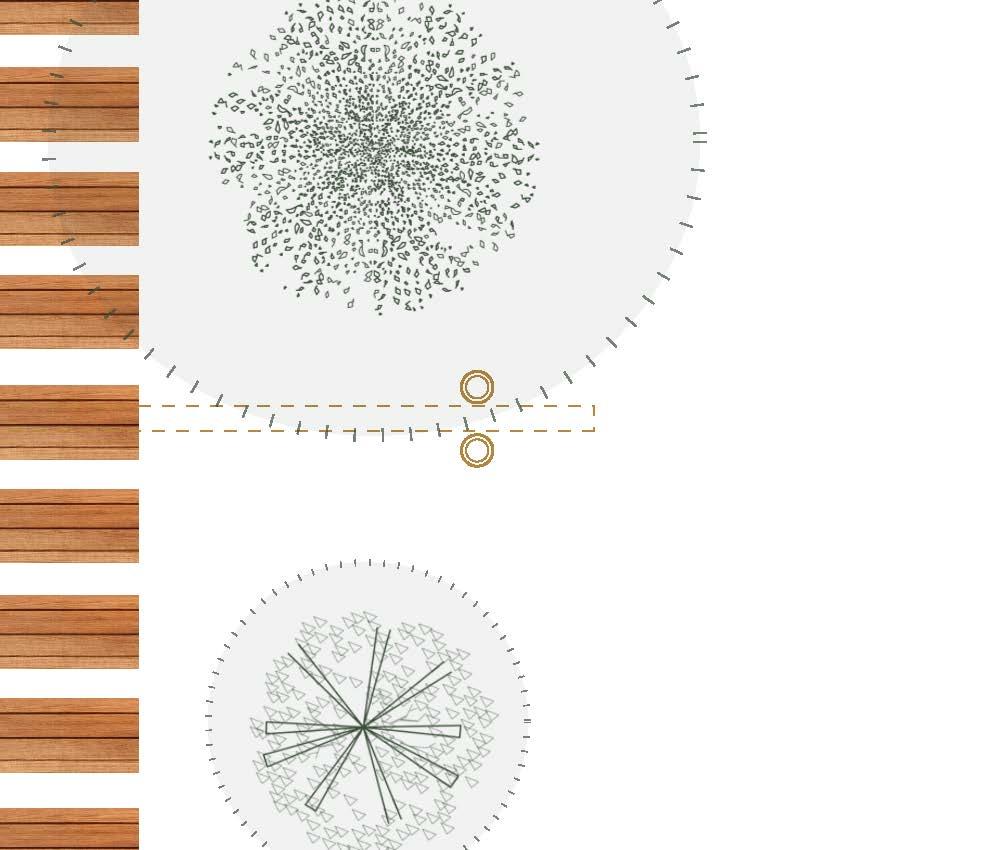

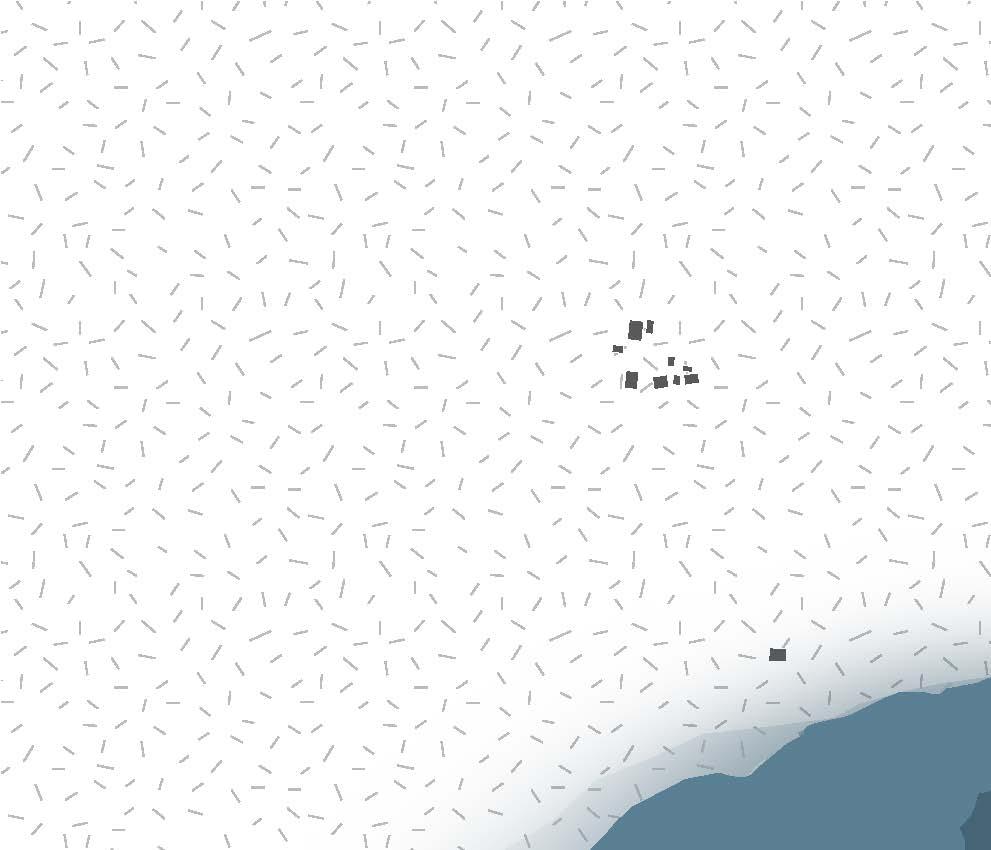

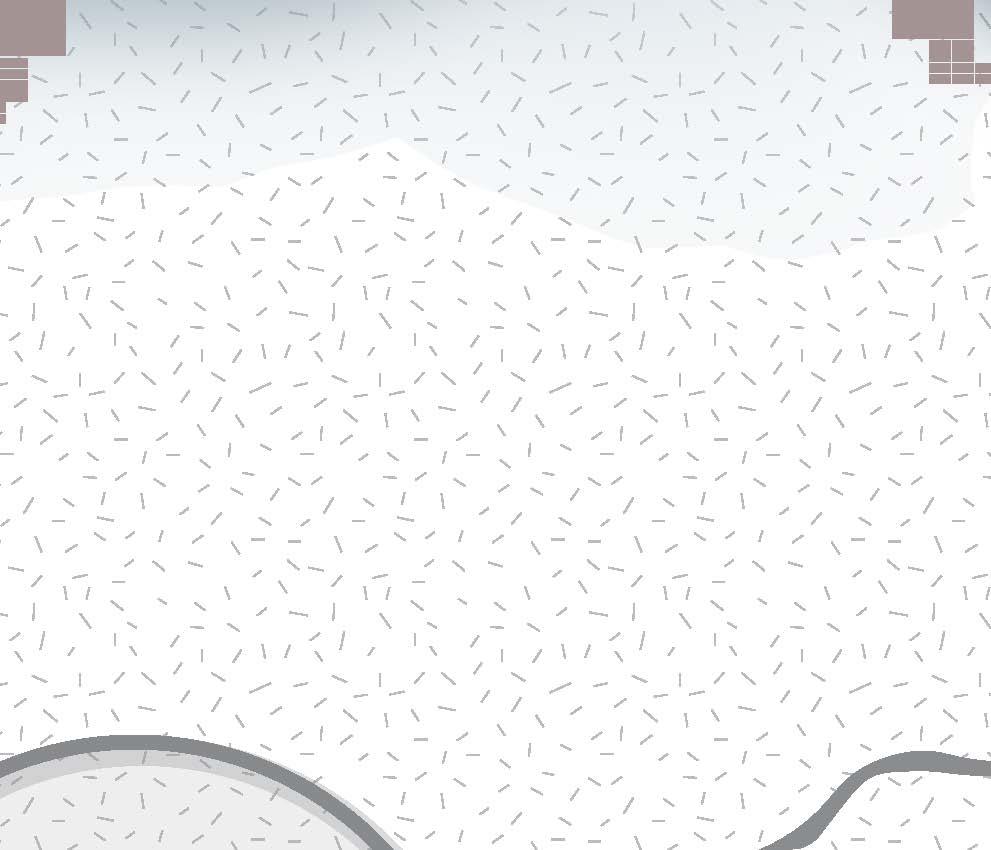

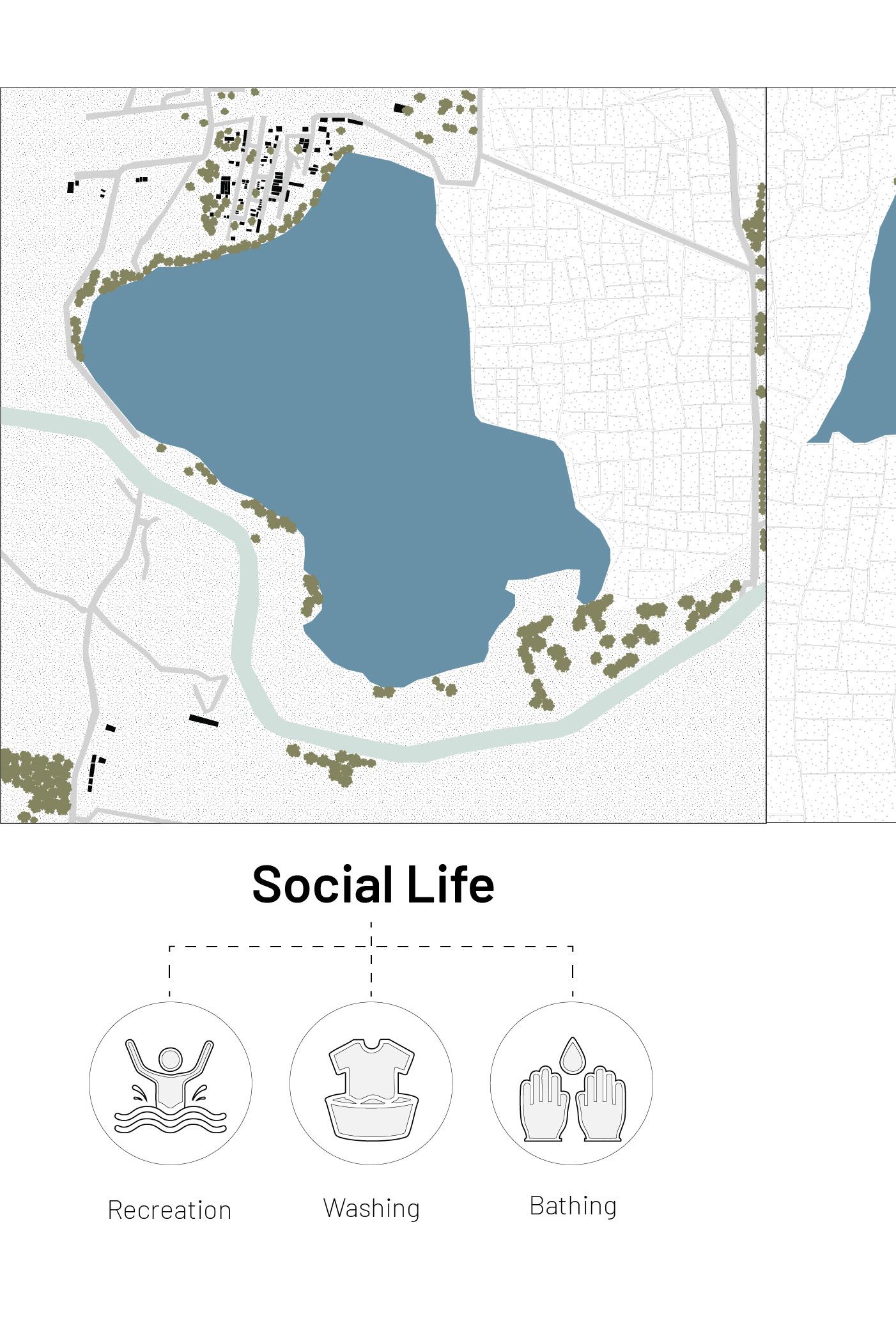

Wetlands are one of the most crucial elements of the water infrastructural system. They become an integral part of the social life of the villagers residing close by and are used for bathing, recreation and washing clothes.

Furthermore, it has also became the cornerstone for the livelihoods of the villagers from the distribution of water to the paddy fields, the soil as the fertilizing source for the corps, and also the use of the soil to make hand crafted-potteries and construction bricks.

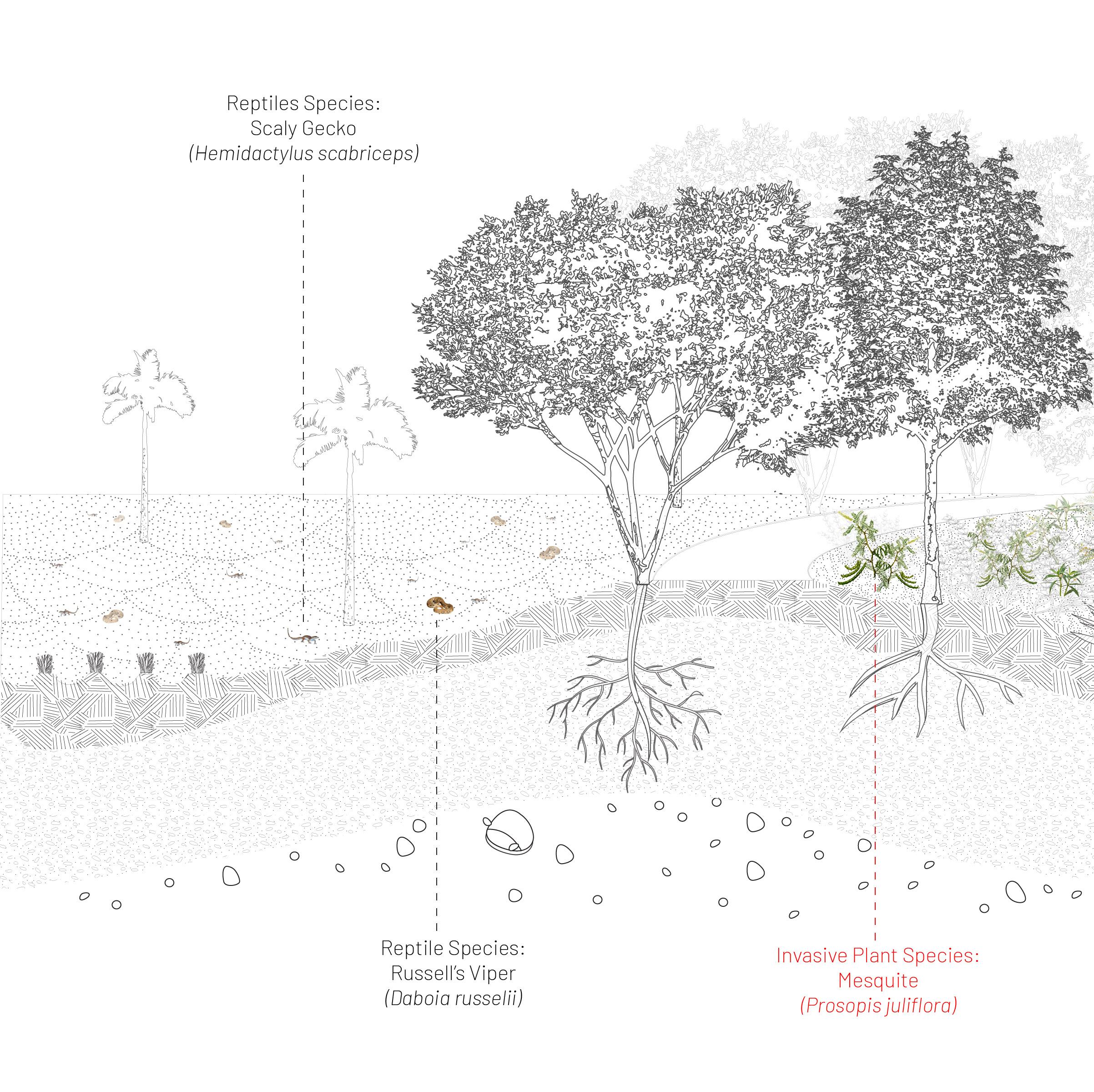

Lastly, the wetlands also supports and sustains the many ecological lives of the region. From mammals to reptiles to insects, not to the mention the different aquatic plants and tree species.

(June - October)

(November - May)

A pavilion of learning serves to invite a diverse range of people to learn about the rich ecological diversity and economic value of this landscape. The learning pavilion will be experienced differently in both wet and dry seasons. In the dry season, people are able to walk down to the wetland bund to learn about invasive plant species, uproot water hyacinth plants and use it for other purposes; but they are also be able to see artificial islands made for breeding and resting of migratory birds.

While in the wet season, people will be able to engage in bird-watching activities, and recreational activities within the wetlands, witnessing locals perform social activities along the landscape. The pavilion can also be converted to a ‘changing room’ for women to change their clothes before/after entering the wetland, using the rollable shades.

PILGRIMS

TOURISTS TO TBCR

STUDENTS / EDUCATORS

NON PROFIT ORGANIZATION

SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL ACTIVIST

PEOPLE OF THIRUPUDAI MARUTHUR

Our interpretation center thus aims to rejuvenate these distinct water landscapes. We envision our design components not only as solutions for these specific sites but also as adaptable prototypes that can be modified and implemented at various locations along the river.