6ideas

Six projects illustrate a series of strategies aiming to rediscover the Cuyahoga River on its course though Cleveland. The proposals reclaim land, pause time, frame view, draw institutions, and seed new occupations.

The projects could operate simultaneously or in an incremental manner. They learn from the cues found in place and look at the future with optimism.

Each project includes a series of precedent studies to offer lessons learned from other cities in the journey of recovery and reimagination of the urban waters.

Fall 2019 - Arch 509 Emerging Urbanisms

University of Michigan Taubman College

Instructor: Maria Arquero de Alarcon Thanks

Cuyahoga River Valley Authority

by

Jacob Hite

Common Thread Cleveland

by Christine Darragh

“Terrain Vague”

by Yunsong Liu

Interface by Lei Nie

Bridging the City

by Liyah M. George, Salvador Lindquist, Abbie Prost

Cultivating Wilderness

Cuyahoga River Valley Authority

Introduction

This proposal of a new governance model for the Cuyahoga River Valley in Cleveland frames the need to guide a new chapter of history to preserve the Cuyahoga riverfront development as a resource for the city and its residents.

The river valley has served as Cleveland’s main productive hub since the City’s founding, and today is undergoing a rapid transformation. For over a century the river had facilitated the transport and production of steel, cement, and petroleum, as well as the shipping of minerals and other raw materials. Industry is still an important part of the city and its economic health, employing hundreds, but sections of the riverfront are increasing open to other opportunities.

The legacy of heavy pollution still hangs over the Cuyahoga, but communities once adjacent to factories and gravel piles now have the possibility to experience the river in new ways. The interaction between the calm nature of the river and massive infrastructure of the city embues the valley almost magical properties, a sense of place that is increasingly rare. But this balance is tenuous. Developers have begun to propose large residential and commercial projects in the newly empty lots, drawn by beautiful views, a proximity to downtown, and waterfront access. While development in the valley might be desirable, there is a risk of losing an asset vital to the City’s past, present, and future.

An independent quasi-governmental non-profit consisting of representatives of the various levels of governments, citizens, and local organizations should be established to steward development with the valley and preserve public access to the river. The creation of the Cuyahoga River Valley Authority would ensure the protection of the unique features on the Cuyahoga, promote coordination between new and existing uses, and create an advocate for local residents.

Objectives

The Cuyahoga River Valley Authority should strive for the improvement and preservation of the river valley for all residents. The organization’s objectives reflect its commitment to accessibility, equality, and sustainability for the common good.

Ensure public access to river and riverfront

Encourage harmony between new and existing uses along the river

Establish continuity along the river by coordinating design of new developments

Preserve the river’s function as a working waterway while facilitating new users

Promote a healthy environment through the reintroduction of natural processes

Create and upgrade infrastructure to serve local communities and industries

Cultivate opportunities for the citizens to directly shape the future of the river valley

Who Will Be Involved?

Because of the complex claims of ownership of the river valley, both cultural and physical, the Cuyahoga River Valley Authority will need to collaborate with, lead, and empower a broad coalition of stakeholders to ensure its success. Utilizing Cleveland’s existing institutional infrastructure increases the operational capacity of the organization and creates opportunities to build on other’s efforts.

Engagement

Community Meetings

Community engagement is crucial to the success of the Cuyahoga River Valley Authority. Public involvement throughout the process of revitalization can steer development toward more equitable outcomes while promoting community support for future projects. From the beginning, the CRVA should continuously collect citizen input to build a collective vision for the future of the river valley. After extensive community workshops and educational meetings, this vision should be crafted into a Master Plan to guide the organization’s actions as it moves forward with redevelopment.

Public Workshops

In order to give residents a direct opportunity to shape the riverfront, a participatory budgeting process could be established. This way, a portion of the organization’s budget is dedicated to publicly elected projects. This process can be implemented in a number of ways. Participants can vote which projects to implement to approve or rank those they believe the organization should prioritize. This form of direct local democracy builds stronger communities and promotes a more equitable distribution of public resources.

Master Plan Community Meetings

Operational Nexus Objectives

PRESERVE THE RIVER’S FUNCTION AS A WORKING WATERWAY WHILE FACILITATING NEW USERS

CREATE AND UPGRADE INFRASTRUCTURE TO SERVE LOCAL COMMUNITIES AND INDUSTRIES

ESTABLISH CONTINUITY ALONG THE RIVER BY COORDINATING DESIGN OF NEW DEVELOPMENTS

ENCOURAGE HARMONY BETWEEN NEW AND EXISTING USES ALONG THE RIVER

PROMOTE A HEALTHY ENVIRONMENT THROUGH THE REINTRODUCTION OF NATURAL PROCESSES

ENSURE PUBLIC ACCESS TO RIVER AND RIVERFRONT

CULTIVATE OPPORTUNITIES FOR CITIZENS TO DIRECTLY SHAPE THE FUTURE OF THE RIVER VALLEY

Organizational powers will be bestowed by the government and used to accomplish the Authority’ objectives. Funding can come from a number of sources both public and private, with opportunities to build independent revenue streams. Due to the complexity of the Cuyahoga River Valley Authority’s mission, it will be crucial to coordinate actions with intent.

wers Funding

wnership

y Leasing

e Programming

Remediation

LAND SALES

RENT FROM LEASES

PHILANTHROPIC GRANTS AND DONATIONS

FEDERAL AND STATE GRANTS

e Development

ent Financing

Review

Development

CITY AND COUNTY FUNDING

Case Studies

New York City, New York

Battery Park City Authority

Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) is a public benefit corporation created by New York State in 1963 to oversee the redevelopment of part of the Port of New York. The organization managed the creation of 92 acres of land on the Hudson River and established a plan for future development. The area is now a residential and commercial community. The BPCA owns and leases land, issues bonds, and manages large scale projects. One of BPCA’s most notable projects is the preservation of 36 acres of public open space.

Washington DC Anacostia Waterfront Corporation

The Anacostia Waterfront Corporation (AWC) was a government-owned corporation established in 2004 to head the environmental rehabilitation of the Anacostia River and revitalization of the surrounding neighborhoods. Working off a plan made by the city, the organization set the ground for the development of the DC stadium district. It also established programs for environmental clean-up and workforce training. The AWC faced criticism due to lack of communication with city agencies and was ultimately dissolved.

Wilmington, Delaware

Riverfront Development Corporation of Delaware

Created by a Governor’s Task Force, the Riverfront Development Corporation of Delaware (RDC) redeveloped former shipping yards along the Brandywine and Christina Rivers into an major employment center and tourist destination. Funded by the State government, the organization has made major investments into the public realm, including environmental remediation. Today the RDC strives for complete ownership of the riverfront through acquisition, long-term leases or in participation with private developers.

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Waterfront Toronto

Waterfront Toronto is organizational partnership between 3 levels of government that aims to revitalize the Toronto waterfront along Lake Ontario, promoting the environmental, social, and economic health of the citizens. This collaboration between the City, the Providence, and the Federal Government was created to encourage corroboration while utilizing the collective resources of the various agencies within each government. The organization oversees all aspects of the planning and development of 1,977 acres of land.

Copenhagen, Denmark

City & Port Development Corporation

Co-owned by the city of Copenhagen and the Danish national state, the City & Port Development Corporation utilizes the value gained from rezoned public land to finance major infrastructure improvements, with the largest portion of developable land being the federally owned port. This investment in infrastructure has created a vibrant, multi-purpose waterfront, major extensions of the City’s transit system and thousands of housing units built for market and social purposes.

Brussels, Belgium

Brussels Productive City and The Canal Plan

Brussels Productive City is an initiative by various regional planning agencies including the Master Architect of Brussels to preserve the industrial economy within the city, particularly along Brussel’s canal. The Canal Plan is a vision that guides the actions needed to ensure the continuation of the city’s industrial zones. In addition to traditional land use controls such as zoning, the Master Architect conducts formal design reviews for new developments and organizes design competitions for city projects to further the region’s goals.

Waterfront Development Corporation

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY (1999–ONGOING)

Louisville Waterfront Park is a 85 acre linear park along the Ohio Riverfront just east of downtown Louisville, Kentucky. The park is stewarded by the Waterfront Development Corporation, which is responsible for park maintenance, planning, and programming. The Louisville Waterfront consists of primarily open green space with a mix of passive and active recreational areas, all linked by paved walking trails. Within the space there are distinct areas such as Entry Plaza, Great Lawn, and Festival Plaza which attract a variety of uses.

Precedent Study

Image Source: Waterfront Development Corporation

More than 150 events are held on the Louisville Waterfront every year. Programming is an important aspect of the park with thousands attending concerts, festivals, and craft fairs held on the grounds. The park also contains 2 marinas and a community boathouse, offering access for rowers and motorboats. The Big Four pedestrian bridge spans the Ohio River to Indiana, providing an unique connection to the neighboring city.

Waterfront Development Corporation

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY (1999–ONGOING)

Louisville’s waterfront had been claimed almost entirely by industrial uses throughout the 20th century. Rail lines and an elevated freeway separate the land where the park now sits from the urban fabric of downtown Louisville. Louisville Waterfront Park shows the potential of what many would consider troubled spaces. What was once primarily scrapyards and sandpits has been transformed into the heart of the city, with the park attracting more than a million visitors every year. The park and the surrounding district has attracted an estimated $1.3 billion in investment since its creation, including residential apartments and condominiums, Louisville Slugger Field, and the Yum! Center sports and concert arena.

The park sits on public land, owned by the Metroparks Agency, and is ran by the Waterfront Development Corporation. The park was financed by funds from the local, county, and state government, as well as donations from local corporations, foundations and individuals. The current iteration of the park was constructed over three phases of development that spanned over 2 decades; the most recent completed in 2014. The total cost of development for these phases and related infrastructure was $112,870,000. A fourth phase will add another 22 acres to the existing park. Continued operations are funded by the metro and state governments and park-generated revenue including event fees and rents from concessions.

THE WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION

The Waterfront Development Corporation is a quasi-independent, non-governmental entity established to lead the redevelopment of the Downtown Louisville riverfront. The organization was formed in 1986 as a government partnership by the City of Louisville, Jefferson County, and the State of Kentucky, with each level of government providing equal funding and holding the same number of seats on the board. The initial WDC responsibilities did not include creation of a park, but the waterfront revitalization.

For the first 5 years, the WDC hosted a series of public forums to find out community needs. It was the strong expression of interest in green space that led to construct a park. Following the initial forums, and for a number of years, WDC staff averaged more than 85 public presentations per year to keep the community updated on construction and they currently average 30 to 40 per year.

In 2001, the Waterfront Development Corporation became a corporate entity. State and city officials still make up most, if not all, the organization’s board. It’s relationship with the various levels of government has been credited as one of the reasons for its continued success, as well as held as an example of inter-government corporation. At the same time, its non-governmental structure allows independence and ability to focus on its responsibilities free of political interference.

Waterfront Development Corporation

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY (1999–ONGOING)

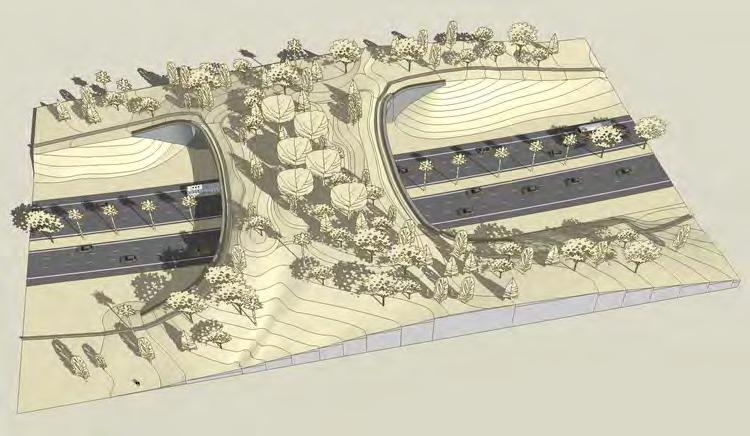

DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

The park was master planned by Hargreaves Associates (now Hargreaves Jones) after five years of community engagement by the Waterfront Development Corporation determined that city residents valued open space and access to the river. The landscape architecture firm focused on the parks relationship to the river, allowing the river and its natural ecology to be enjoyed with minimal obstruction through greens paces.

The main iteration of the park was built in 3 phases, with construction on the space continuous from 1994 through 2012. Phase I opened in stages from 1996 t0 1999 starting with the Wharf and finishing with the Great Lawn, Harbor Lawn and Harbor. This was largest section of the park that serves as the gateway between the waterfront and downtown. Phase II on the eastern end of the park included passive and active recreation spaces as well as natural areas such as meadows and groves. Phase III added some of the parks largest features such as the Big Four pedestrian bridge and the Big Four Lawn, one of the main gathering spaces in the park.

1997 2006

Phase IV of the Louisville Waterfront Park has been announced with plans provided by MKSK. This new development is focused on the waterfront west of downtown, connected to the rest of the park by a riverwalk. Plans include an experiential learning area and observation pier to create a destination spot distinct from the rest of the park. Connections between the new phase of the park and surrounding neighborhoods are prioritized with riverwalk improvements and dedicated pedestrian and cycling paths.

Waterfront Development Corporation

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY (1999–ONGOING)

WATERFRONT OVERLAY DISTRICT

In addition to their responsibilities within Louisville Waterfront Park, the Waterfront Development Corporation also has design review authority for the Waterfront Overlay District. The district encompasses both the riverfront park that WDC designs, maintains, and programs, as well as large areas of land that border the park and the riverfront. This includes active industrial areas to the east, large portions of downtown commercial, swaths of neighborhood residential, and areas of former industrial land and open space.

A design board at the Louisville Waterfront Corporation reviews plans for development within the overlay district before they can apply for permits and approvals from the city. As part of this special zoning regulation, the WDC review board does not scrutinize the appropriateness of the use, but rather the design of the development and its context to surrounding uses and the river, prioritizing creation of pedestrian access and preservation of visual corridors.

The specific design criteria that the review board looks for differs based on the development goals in the area and the type of development proposed, but there are overarching goals that the Waterfront Development Corporation hopes to achieve with the review process. This includes unity between public spaces and private development, coordinating space systems and pedestrian flows between parcels and the river. Public access ability is prioritized for most of the riverfront, particularly near downtown and residential districts. Views are also considered, with both the visual experience traveling through the outer edges of the district and the slight lines to the parks and the river part of the review criteria.

The Waterfront Overlay District is divided into six separate sections, each with their own design intent that the Board uses in their review of new developments along the river:

Area A-1: Downtown (CBD) waterfront area aims a high degree of public use with parks, hotels, public assembly areas, high density residential areas, and river theme retail commercial uses. The character envisioned is an urban district with hard-edged landscape and streetscape treatment, especially pedestrian oriented for day and night use with continuous public access to the water’s edge.

Area A-2: This area provides the potential to expand the downtown waterfront oriented businesses and public uses. Protection of the established character of historic structures and the extension of the established Main Street scale are important. The transition and connection from the CBD to the river for the public, and especially pedestrian movement and vehicular linkages north and south across River Road, are key concepts.

Area A-3: This area encompasses Waterfront Park Phase IV and the transition into the surrounding neighborhoods. The transition of current industrial operations to commercial and residential mixed uses is encouraged. Strong visual and pedestrian connections to the park are emphasized, with a focus on walkability and multi-modal connectivity.

Area B: This area contains community active and passive recreation infrastructure, including large community gathering spaces. It serves as a transition buffer from the urbanizing waterfront to the west to the industrial waterfront to the east and encourages the extension of the public assembly and gathering facilities and river’s edge accessibility.

Area C-1: Providing river-oriented industry a location for operation, public access to the river’s edge is preferred, but it is understood that safety, security or other business needs may make river edge access impractical. The key design issues for the area include the visual relationships of proposed development to the Ohio River and preservation of the view shed from the interstates to the Ohio River. Industrial developments receive a decreased level of review focused on primarily exterior design.

Area C-2: This area is expected to have open space and recreational uses on the eastern end an the potential for private and public uses on the western side. Development intensity is expected to diminish from the medium density to the open space character present at the eastern edge of the Review District. The design issues focus on the corridors, where it is desirable for these to continue to serve as scenic, landscaped approaches to Louisville’s CBD from the east.

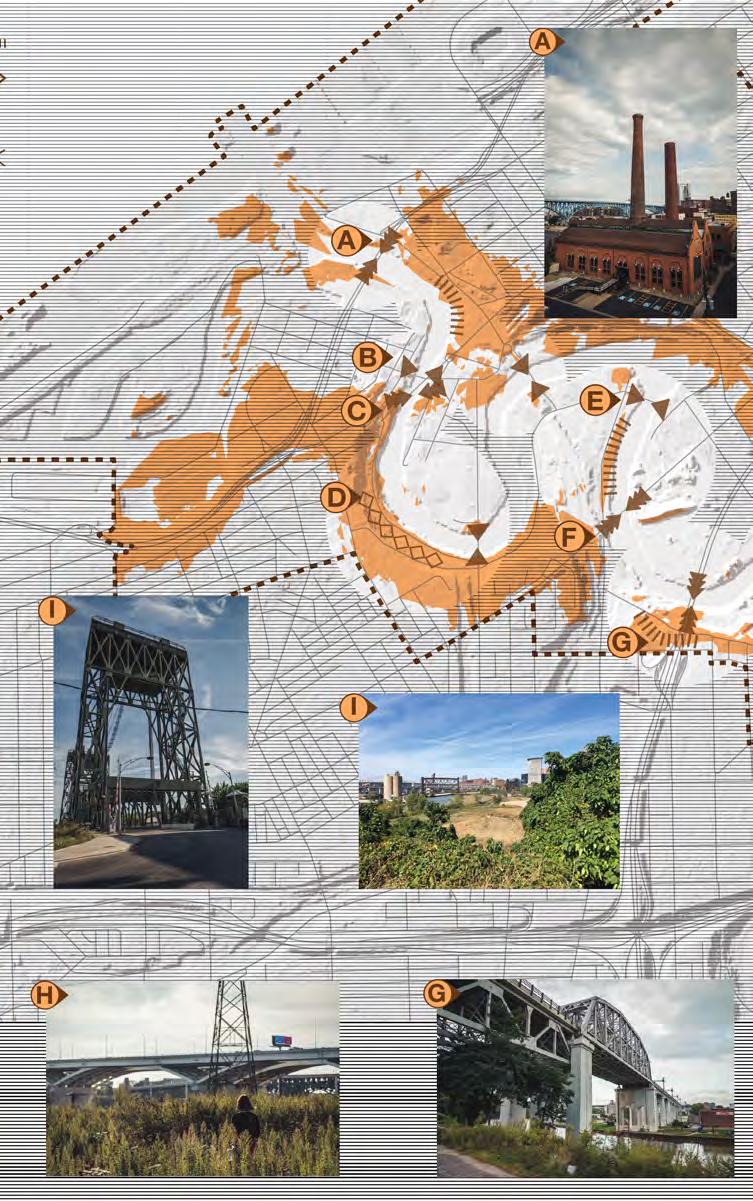

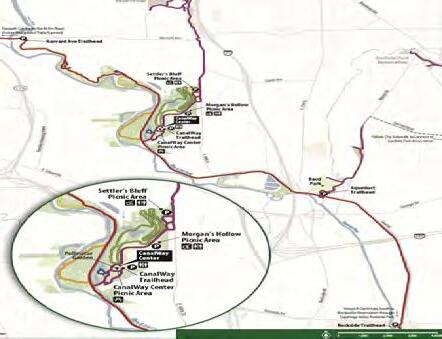

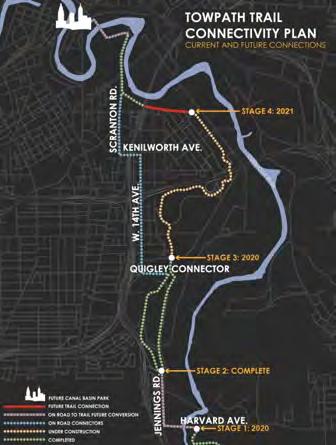

CONNECTIVITY, RIVERFRONT ACCESS IN CLEVELAND AND ALONG THE CUYAHOGA RIVER VALLEY

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

WHAT:

This project aims to establish a framework for a bi-annual (or multi-annual) design competition which would engage the public from viewpoints within the city of Cleveland in order to begin a comprehensive and open conversation about the future and health of the Cuyahoga River Valley.

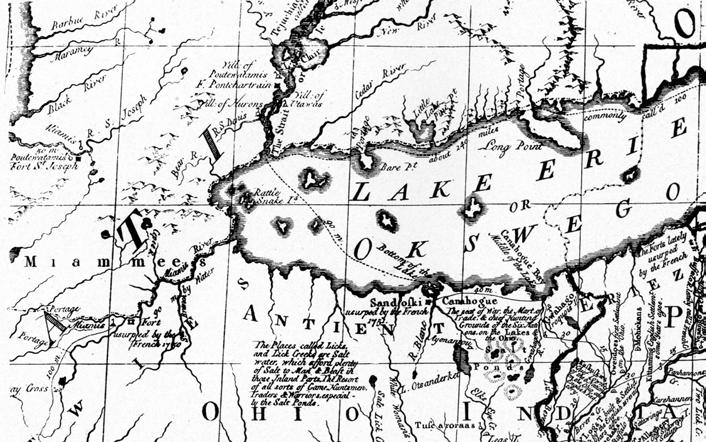

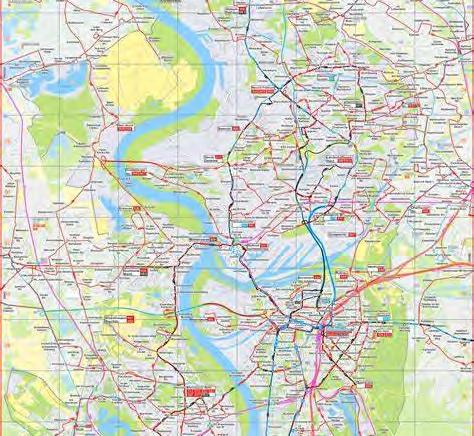

CONTEXT:

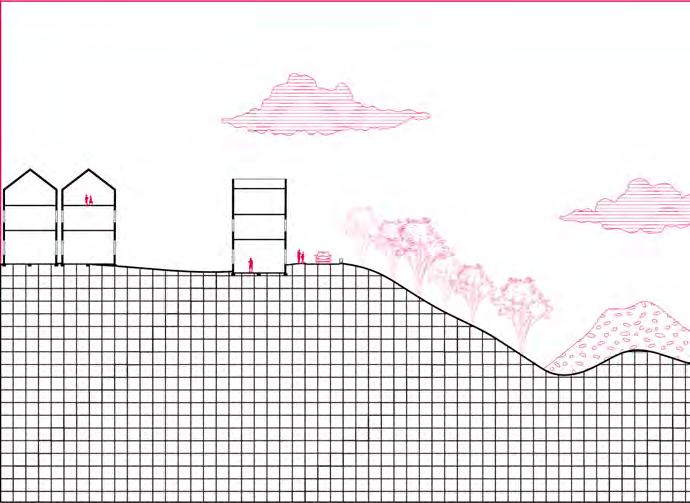

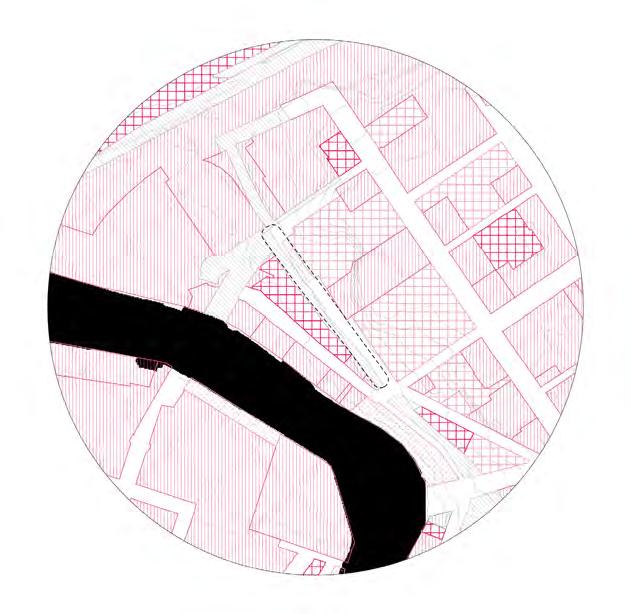

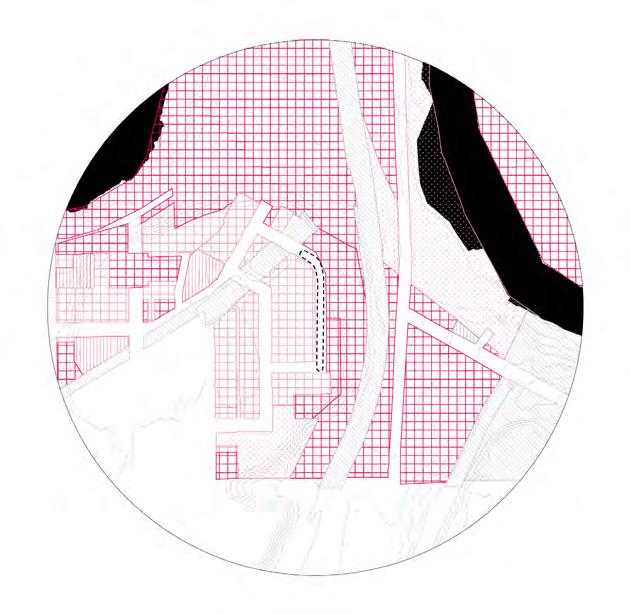

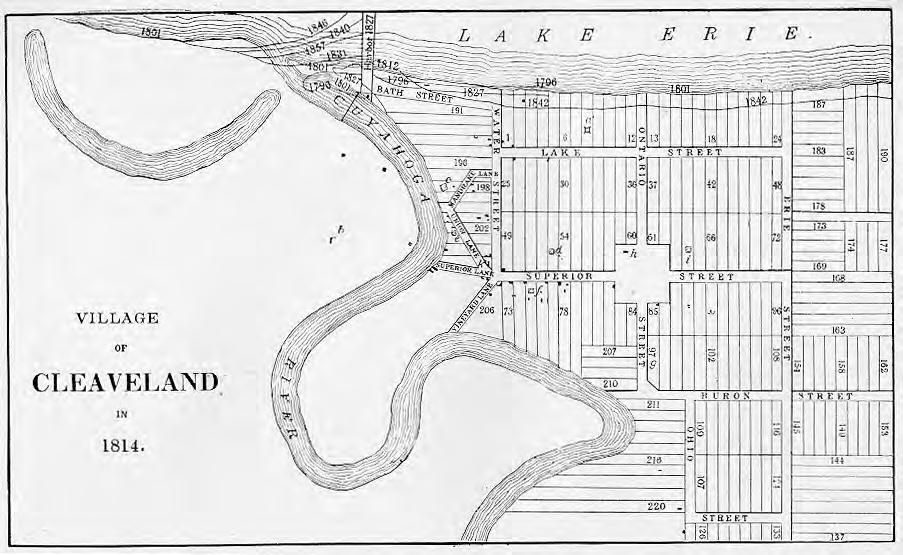

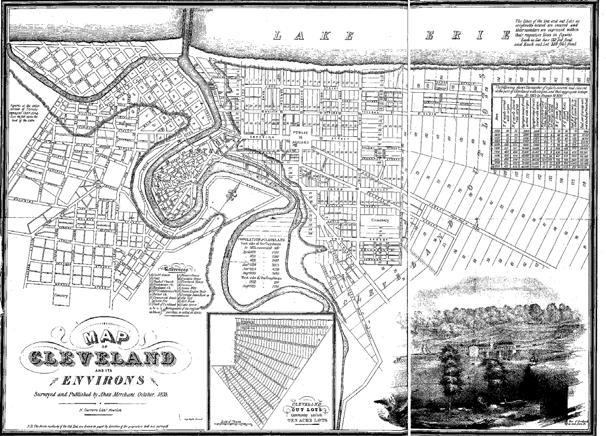

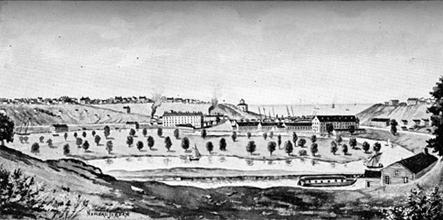

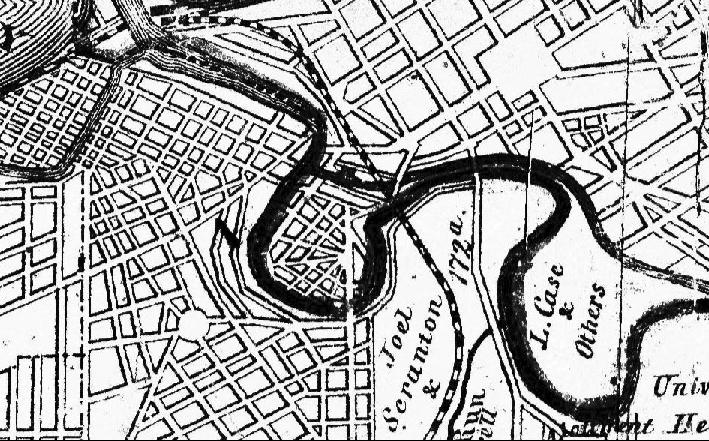

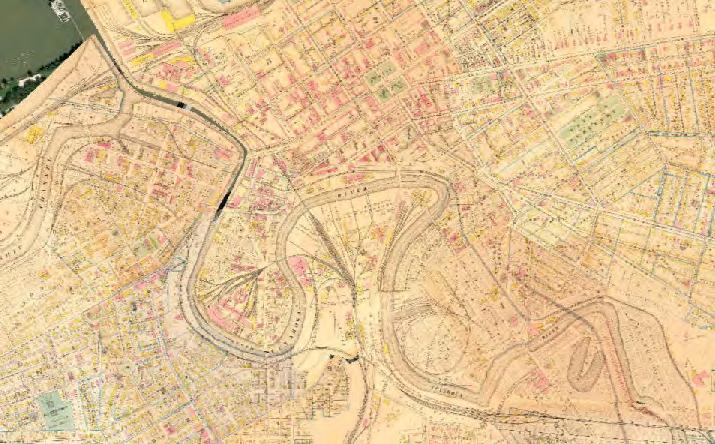

The Cuyahoga River is a central component to the geography of Cleveland. It winds its way through the center of the city, creating peninsulas from a series of ox-bows which twist back on themselves. Early plans of the city show a grid system (in gray above) struggling to respond to the irregular river winding through its middle.

HISTORY:

Cleveland was founded as a network city, a node in a supply chain which shipped raw materials through the mid-west to the east coast. Over time, manufacturing companies used those raw materials to create component parts to ship over the world. Cleveland eventually grew to become the 5th largest city in the world.

In a deindustrializing landscape facing limited resources and a shrinking population, the city and the river must open itself to new definitions in order to maintain a vital, intertwined identity. The goal is the collective reimagination of the future Cuyahoga as a common thread connecting the diverse ecologies from the National Park in the south to Lake Erie in the north; connecting communities across the geographical breadth of the valley.

1Q: 1VIEW

A B C D E

BRIEF:

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND is a bi-annual series of installations staged across the city by artists, designers and architects whose proposals respond to themes of accessibility for the river front. Provocations are required to respond to both the site context and the question posed by that location.

1Q:1VIEW

Poses a relevant question at each site of access along the river. The sites are chosen for their visual access to the river, a point of dissonance which sheds light on the lack of physical access to the river through the city. The corresponding questions address the thematic concerns of the group tasked with envisioning the future of the Cuyahoga River Valley.

BACKGROUND

Cleveland is transitioning away from its industrial roots. Reimagining the city means new uses for the river, which is centrally located, but blocked by private properties and inaccessible industrial sites. Retaining its historic character as a port city is important to the future identity of Cleveland. But, accessibility means finding ways to open up paths along the river and across the city.

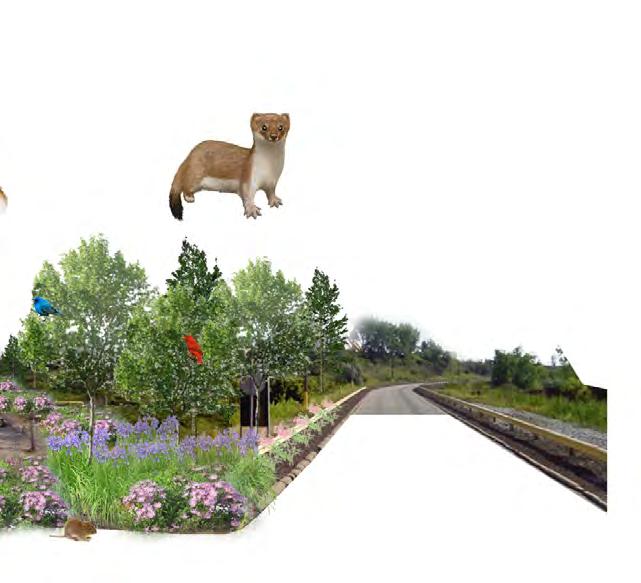

THE Q (Question)

What would it look like, if “wild places” were protected as safe spaces for individuality?

THE VIEW

Third Spaces are places with a sense of mystique and unfamiliarity; a place where others feel welcome.

These places are often physically isolated and remain inclusive by resisting traditional programs or assigned uses. They are rarely maintained and by the very nature of being “forgotten”, they nurture safe spaces for animals and humans who don’t conform to common norms. Even these left-over spaces are valuable. How can you design for “third spaces” in the contemporary city, while embracing their very spirit? Yet here it is. This particular site is located along a forgotten railroad bed. It is overgrown from lack of use and maintenance. Located down an embankment from well-used railroad tracks, and next to the river, this is a space of wonder.

HOW TO APPROACH THIS BRIEF

Your project should imagine what accessibility to and along the Cuyahoga River means. Proposed narratives should be bold, take a clear position, engage the public, and offer an educational component. Different and previously unconsidered perspectives are encouraged. Projects thoughtfully engage both the view as well as the question will be the most successful.

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

1

Build public engagement toward a connected and accessible waterfront through interventions designed to spark discourse.

2

Build public interest in an organizational body tasked with stewarding the Cuyahoga River and its interests in the city of Cleveland.

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

1The city employment demographic is changing. Industry is no longer the lead economic driver of the city. Primary sources of income come from the medical sector--the city is home to an internationally known hospital--the Cleveland Clinic. The service industry is growing as well. A transformation of the workforce is also a transformation of the businesses present in the city. Dwindling reliance on manufacturing and industry means that in some cases, the centrality and power of the manufacturing sector in Cleveland is also ebbing. This provides an opportunity to act strategically in regards to properties which are and were formerly occupied by large industrial sites. In many cases, these properties are located on or along the river. Creating on how to address future vacancies and properties for sale along the river gives the City leveraging power as future developers express interest in land along the river front.

2

Historically, developers have a strong voice in the city of Cleveland. Starting with Shaker Heights, one of the first developer-owned and maintained municipalities, developers have been an integral part of the city’s growth. However, if the city’s interests are to provide access to the public along a connected waterfront, a representative for the riverfront and the Cuyahoga River Valley must be present from the early negotiation stages to assure that the future of the river is cared for adequately.

OCCUPATION

Cleveland for Context

OCCUPATION

Percent of Employed

Less than 5%

5% to 20%

20% to 35%

35% to 50%

Over 50%

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

Cleveland is rich with views. In fact, views, especially from bridges, are the most available form of access to the Cuyahoga River. This project seeks to exploit the dissonance between physical and visual access in the city to stage interventions at these viewpoints in order to provoke conversation and public interest.

Building upon the interests of this group, each visual access point will have a question mapped onto it. The project brief requires applicants to propose a project which responds to both the context of the view as well as the question posed.

The questions broadly address the following areas of interest: Appropriation of Bridges

Cultivation of Wilderness within the City Celebration of Third Space

Industrial & Domestic Legacy

1Q: 1VIEW

WHAT IF...

... if bridges spanned more than just sides of the river? ... if the Forest City were a sea of green and blue?

... if “wild places” were protected as safe spaces for individuality?

... if what’s unfamiliar wasn’t scary, and hidden spaces didn’t need finding?

Photo Credit Salvador Lindquist

... if Cleveland’s bridges connected us to the future?

... to imagine a hybrid habitat where humans and nature coexist?

... if Industrial Zones didn’t block access to the river?

... if Humans Invited Nature (back) into their Cities?

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

“FLOW” CHART

Cuyahoga River Valley Authority

Biennial Sub-committee

9 Total Members, 3 Members representing each interest area, with at least one each currently serving on Cuyahoga River Valley Authority.

NEIGHBORHOOD REPRESENTATIVES

Detroit Shoreway

Historic Gateway

Ohio City

Tremont West

Burten Bell Carr

Campus District

Metro West

Historic Warehouse

Old Brooklyn Flats Forward

CULTURAL REPRESENTATIVES

LAND Studio

Ohio Arts Council

Cuyahoga Arts and Culture Arts Cleveland

CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

Entertainment Districts

Commercial Business

TASKS:

Execute the timeline of the Common Thread Cleveland Biennial, Choose and advise independent jury.

Manage corporate sponsorship, grants and other fundraising mechanisms.

Objectives

This project fulfills the following two objectives laid out in the Charter of the Cuyahoga River Valley Authority:

1

2

ENSURE PUBLIC ACCESS TO THE RIVER AND RIVERFRONT

CULTIVATE OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE CITIZENS TO DIRECTLY SHAPE THE FUTURE OF THE RIVER VALLEY

JURY

2 Individuals

Chosen from among members and leaders of the neighborhood, business, and non-profit community

GUEST JURY

2 Individuals

Well-known architects and artists, and celebrities with ties to the Cleveland Area.

LOCAL ARTISTS

2 Individuals

Chosen from among the local artist, architecture community.

TASKS:

Review proposal submissions, choose a proposal for each site.

Issue semi-finalist list and finalist list according to deadlines laid out in the proposed timeline

After the biennial, award a juried prize and confer a public input prize.

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

TIMELINE

18 MONTHS

•Common Thread Cleveland Biennial Committee is Convened

•Jury Chosen

•Grant writing Solicited

15 MONTHS

•View locations identified, Questions determined

1 YEAR

•Corporate Sponsorships Solicited

•Call for Proposal issued

10 MONTHS

•Deadline for Submissions

9 MONTHS

•Semi-finalists announced

6 MONTHS

•Finalists Chosen

5 MONTHS

•Call for Volunteers

3 MONTHS

•Volunteers gathered and trained to assist with site specific weekly promotional events.

2 MONTHS

•Weekend events scheduled, promoted in local calendars. 4 WEEKS

•Construction begins at each site

2 WEEKS

•Local businesses receive map of the project locations, questions & directions for crowd voting.

1 WEEK

•Signage in place to educate and promote circulation of crowds.

WEEK 1

•Kick-off Gala

WEEK 2

•Weekend Events: Ecological Awareness Educational Theme

WEEK 3

•Weekend Event: Ride the River Biking Event

WEEK 4

•Meet the Designer

•Sponsorship Fundraiser, Designers in Attendance

WEEK 5

•Weekend Event: Run the River 5k Footrace Event

WEEK 6

•Entertainment or musical event staged WEEK 7

•Community events sponsored by adjacent community groups.

WEEK 8

•Closing ceremonies

•Awards Issued: Jury Prize and Community Engagement

•Next Celebrity Jurors Announced

AFTER

•Community Engagement aimed at soliciting community feedback into Biennial process.

•Business community debrief.

•Public Solicitation of Places and Questions.

COMMON THREAD CLEVELAND

FUNDING PROPOSAL

CORPORATE FUNDING

Corporate sponsors and community stakeholder organizations sponsor a particular site

Material companies (glass, lumber) sponsor building and assembly materials for the proposal installations

Community Groups, Activist Organizations sponsor weekly activities at the sites as a way to educate the public, raise awareness, and promote agendas of riverfront connectivity, community and

Match grants offered by the public allow companies to match funds raised through community support campaigns.

GRANT WRITING

Grant writing campaign can assist in funding of expanded site support, particular activities

COMMUNITY SUPPORT

By becoming individual sponsors, members of the community are given special access to artists, designers and activists, private “sneak peek events” and thematic “swag”.

ed Funding:

SWAG

Items available for purchase both assist in marketing and awareness of the bi-annual event, but also raise money at a level.

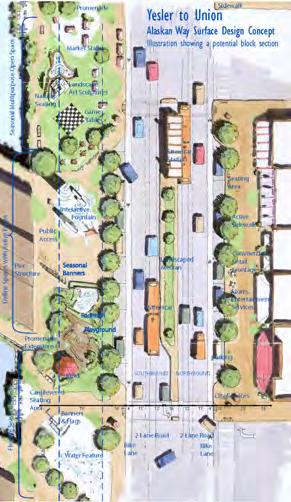

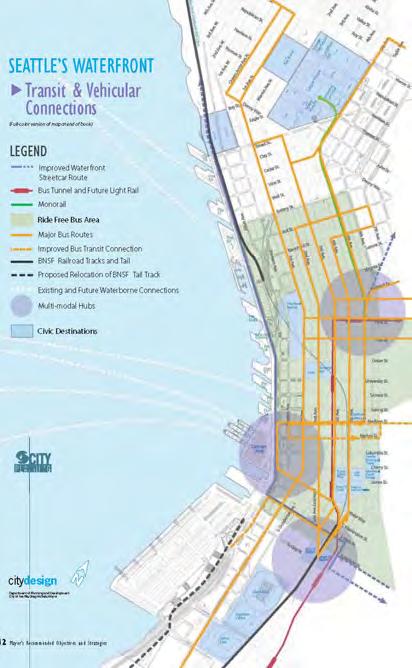

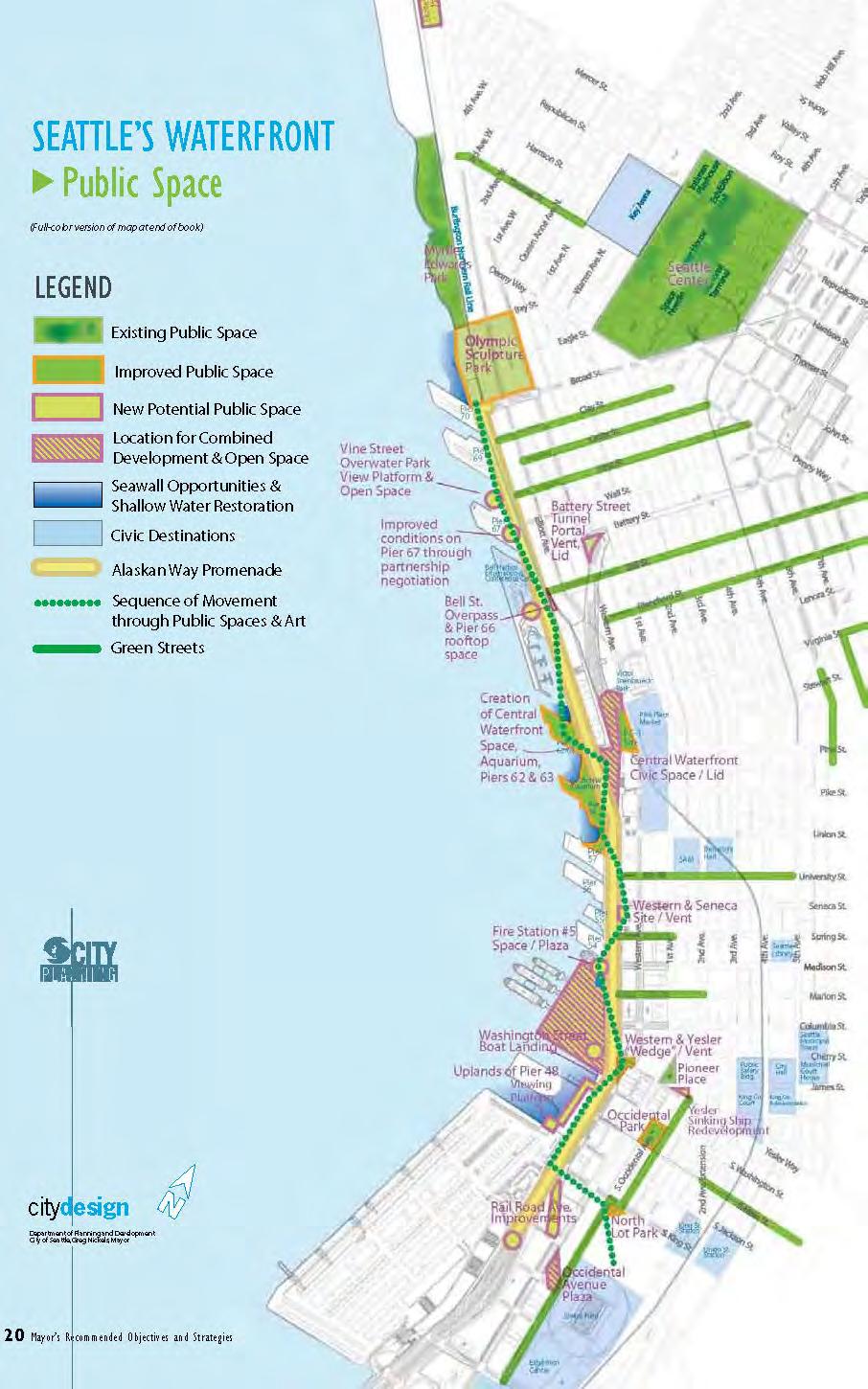

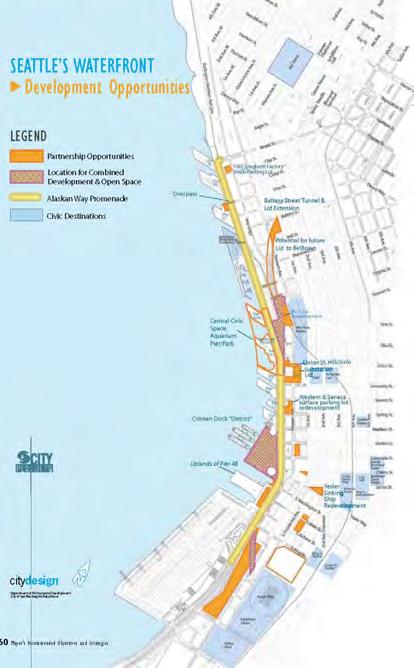

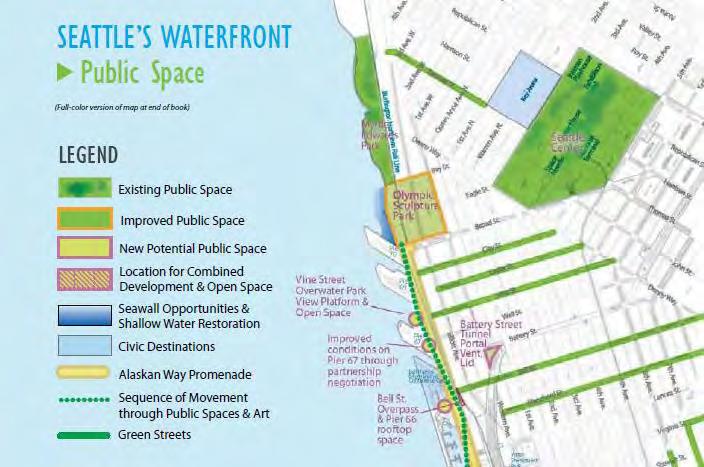

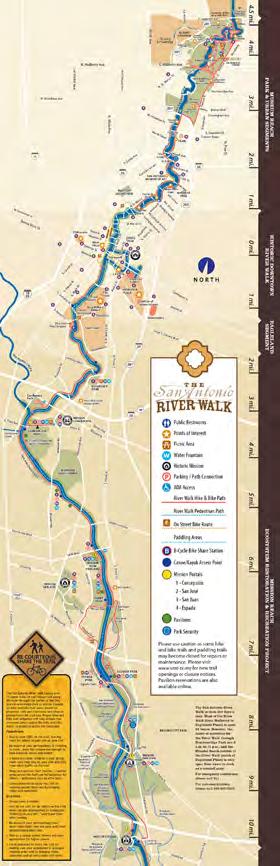

Seattle’s Central Waterfront Plan

SEATTLE, WA (2006-ONGOING)

START WITH A CLEAR VISION

A simple and inspiring paragraph describing a future where all the proposed and imagined changes have taken place. The vision is a common agreement on a preferred future and helps both define and direct the work to generate momentum.

Seattle’s is simple but practical, mentioning the necessary replacement of the viaduct, and the reclamation of the waterfront. It makes clear its intentions of using the waterfront to unite the city, to welcome diversity, recognize the heritage of the place, but establish a framework for future growth which will make Seattle a standard for other aspiring cities.

The act of envisioning an accessible waterfront connecting Cuyahoga National Park with the Lake Erie shoreline is an opportunity to establish agency in the future of Cleveland.

ROOT IN THE PRESENT

For Seattle, the present is a place in flux. A location pivoting from one type of space to another. Change can be unsettling for people and places which perceive the new as a threat to their livelihood or existence. Simple acknowledgment can ease the growing pains.

HONOR THE PAST

Seattle takes a moment to recognize it’s history as a port and maritime center. It recognizes the pre-western history of its native population. Seattle establishes these stories as a part of it’s origins in order to root the city in a geographic location, to instill it with a sense of place, and to lay the foundations of the forward looking language which will honor but not be nostalgic for a past which has brought Seattle to the place it is today. A past which thrusts upon it a need to conceive of a new future.

Cleveland’s history instills in a sense of place, gives identity, which differentiates it from all other cities. Remembering the past, lays the foundation for a way forward into the future.

LOOK TO THE FUTURE

Idealistic and somewhat utopian, the future has a blankness about it which allows individuals and municipalities to write their hoped-for plans of diversity and inclusion, care for the ecology of place. But the documentation of what’s hoped for can be realized through goals, prioritization and consensus. For Seattle, or Cleveland, or any municipality, statements about the

Precedent Study

future allow a place to have agency. By establishing a forward-looking plan, a city is less likely to be responsive to the whims of developers who also have an ideal future (and profit margin) which may or may not include the hopes laid out by the city. Documented, these become a conversation to establish common aims between competing interests within a city.

Seattle’s Central Waterfront Plan

SEATTLE, WA (2006-ONGOING)

ADVOCATE FOR URBAN NATURE

Seattle appointed a team to study the waterfront local ecologies. Why? In order to be good stewards of the water and waterfront as part of Seattle’s unique identity. It is a thread of history, a foundation upon which to build a way forward. Seattle’s ecology team identified ways that the waterfront ought to be protected for aquatic species and those residing in the intertidal zone. Knowing that development would threaten or conflict with the priorities laid out by this team of ecology advocates, the plan includes suggestions for how to build in a less impactful way, and what interventions could sit more lightly at the waters’ edge.

For Cleveland, also a city with a rich maritime past, identifying ways to reestablish, grow and protect the river’s edge ecology can help create a link between the upstream waters at the National Park and the Lake Erie shoreline.

SEATTLE’S WATERFRONT LEGEND

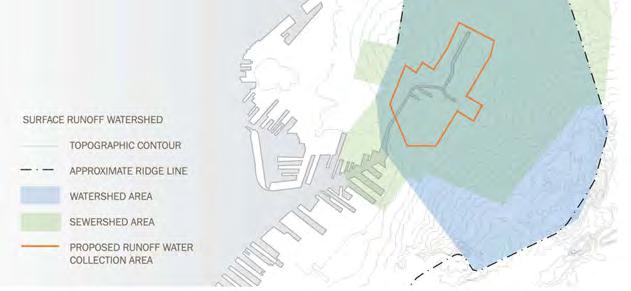

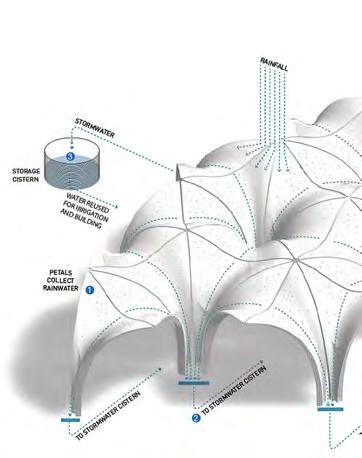

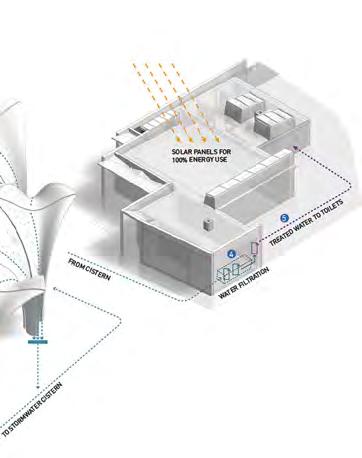

RAINWATER MANAGEMENT

In this plan, Seattle recognizes the need to manage the rain water volume which can cause sewage outfalls. These overflows damage water quality and occur when the volume of water flowing through the sewers is too great for the system to handle. Adding rain water management to the waterfront project allows Seattle to build a delay time between when it rains, and when some of the rainwater enters the sewers.

Clean water is a matter of public health. For Cleveland, similar issues of point source pollution exist. And, managing outfalls is a necessary component of any future including the river as a central figure.

Seattle’s Central Waterfront Plan

SEATTLE, WA (2006-ONGOING)

PEDESTRIAN FRIENDLY

Through zoning or incentives, encourage retail spaces along pedestrian zones.

Reorient adjacent building facades to face toward these zones. Encourage housing and mixed-use development in areas near to pedestrian zones.

WATER’S EDGE

Access to the edge of the water is a right of the public. Ownership along the water’s edge is now stipulated to allow access for public passage on and through the space.

Reflecting a statement made in the Chicago Plan of 1919, making water access a matter of public right, allows the city to manage future development with linear connections in mind.

PARKING

Protect access to the waterfront by locating parking away from the water or connecting it off-site through direct lanes of public transit.

VIEW PROTECTION

Through zoning initiatives, Seattle protects the “view corridors,” places with visual access to the sound are unique or Mount Hood. These two geographical elements of Seattle’s identity, and establish a sense of place. They also act as orienting marks.

A system of air rights transfers maintains view corridors and insures that the cityline does not obstruct the sigh lines of its most singular pieces of identity, and creates democratic access to these. This way, views are not reserved for those who can purchase the highest window in the city.

WATERFRONT ZONE

Seattle created a special development area with additional expectations for building and developing land within that waterfront. These add to the already existing zoning provisions, but provide for the special concerns associated with building on or near the water front.

SEATTLE’S WATERFRONT

Zoning&RegulatoryChanges

LEGEND

Designated Green Streets

Proposed Green Streets

View Corridors

View Corridors with Upper Level Setbacks Required

Shoreline Regulation Zone

A Battery Street View Point & View Corridor

B Historic Piers

C Area Zoned DMC

D Colman Dock

E Current Industrial Zones

Seattle’s Central Waterfront Plan

SEATTLE, WA (2006-ONGOING)

AREAS OF RESPONSIBILITY: PARTNERSHIPS

Included in this vision is a clear table stating all entities with a stake or a responsibility for the proposed projects. The plan specifically identified areas where interventions would be beneficial to the city. It outlined those properties, buildings and areas and described them and the city’s intentions for those individual spaces. This difference makes Seattle an active partner in development. By maintaining an oversight and defining what development looks like, Seattle exercises its municipal authority to establish a future city within the guidelines it has laid out in its vision.

IMPLEMENTATION

BE STRATEGIC

Prioritize a public realm plan.

Establish guidelines for private development. Champion rights of way and open spaces.

PHASE IMPLEMENTATION + PRIORITIES

Develop clear priorities, have a plan for public access and education during the construction process.

PUBLIC REALM STRATEGY

Establish location and design of major public spaces, allow change to occur around spaces according to guidelines established in the public realm plan. Include regulatory incentives.

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

Find innovative ways to involved the public efficiently and meaningfully.

OVERSIGHT/COORDINATING ENTITY

Create one or more coordinating entities, with oversight to manage the redevelopment of waterfront in diff phases of project: quasi-public development agency for financing, construction management or a non-profit for programming and maintenance. Functions could include fundraising, construction, planning, assembling land, planning/ design new open spaces, and right of way improvements, ensuring integration of projects by jurisdictions other than the city of Seattle, coordinating construction schedules, maintaining programming and new/existing open spaces.

IDENTIFY THE ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

of agencies and non-profit organizations who have a stake or sense of responsibility in this area… make a table of areas cross referenced by what agency/group has oversight.

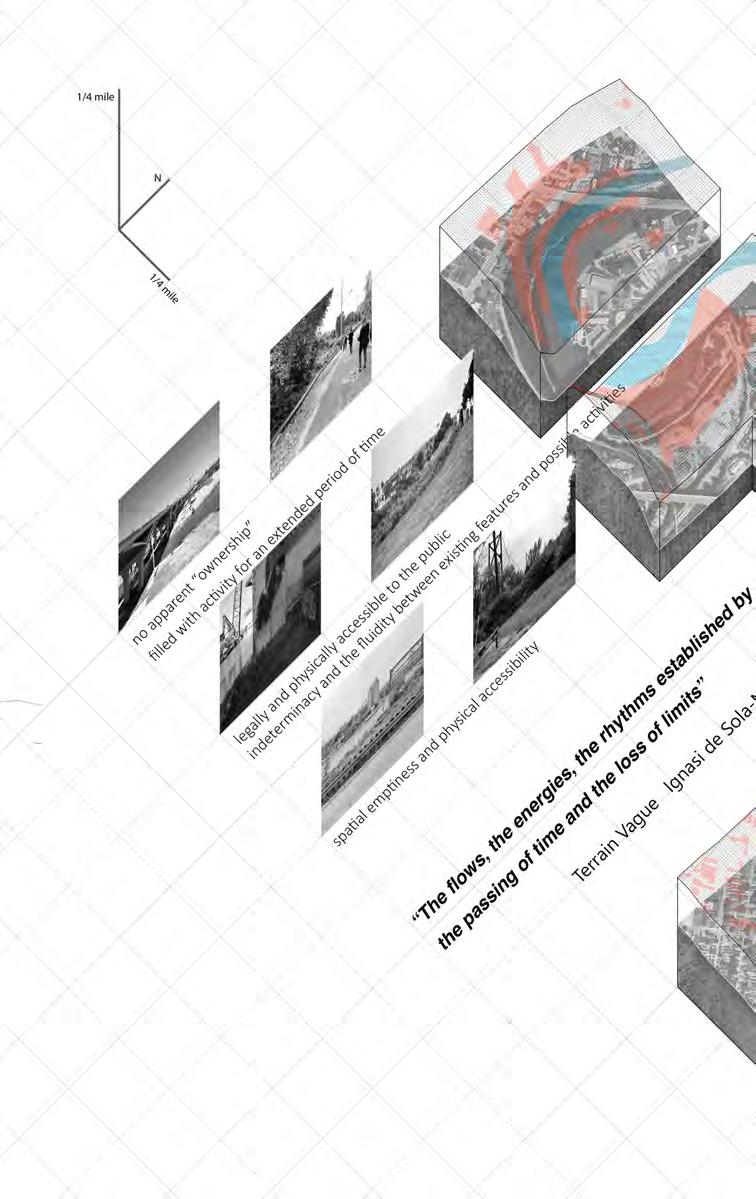

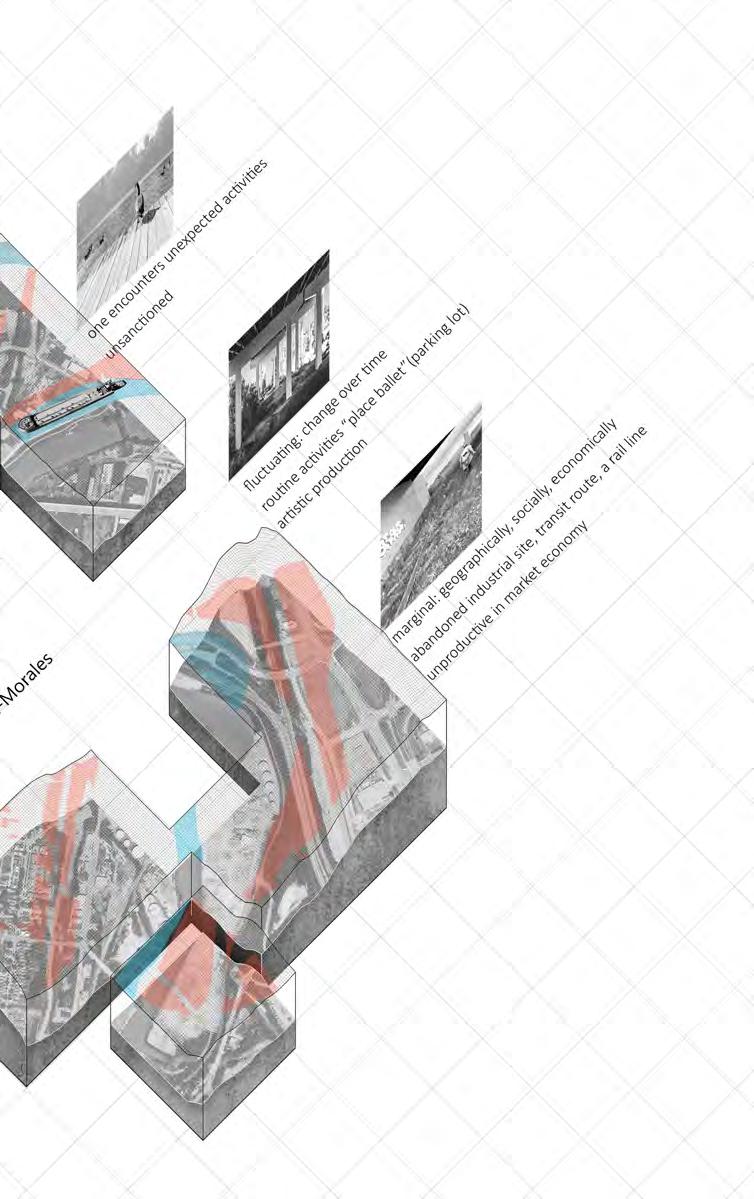

“an illusory inertia”

Terrain Vague in the Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River Valley

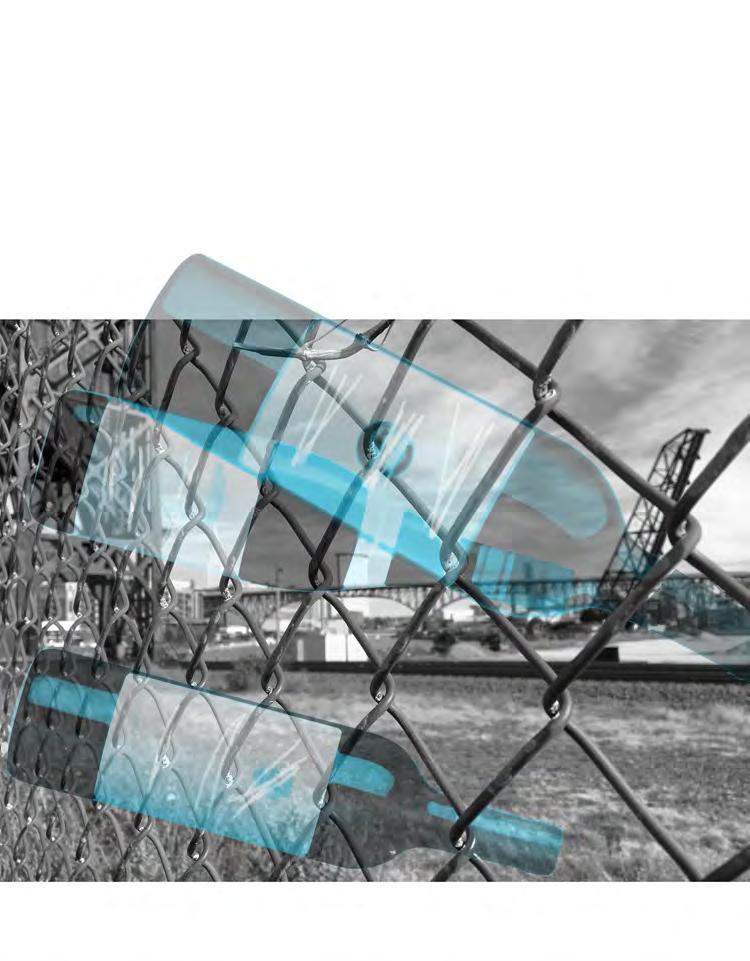

Terrain Vague are everyday areas that expose the stratified or palimpsest nature of all places, especially those with the appearance of codified stability where there exists. As Michel de Certeau puts it, a sense of “immobility” and “an illusory inertia”. Terrain Vague are what the architect-and-artist collective stalker calls, in its manifesto, “space of confrontation and contamination between the organic and the inorganic, between nature and artifice” that “constitute the built city’s negative, the interstitial and the marginal, spaces abandoned or in process of transformation.”

Spatial emptiness and physical accessibility, along with various smaller-scale physical features, generate many possibilities that people recognize and pursue with creativity and determination.

the terrain vague in Cleveland is silently inspiring and simultaneously inspiringly silent it has the capacity to narrate as well as the patience to listen stagnant in the process of urban development it is constantly open to interpretation it is the voice into the valley also registered as echoes from the previous always conflated with multiple moments in time and devoided of any. well categorized by the qualities of the unpromising yet resisting definition.

in searching . . .

“of time and the river”

“the meaning of the river flowing is not that all things are changing so that we cannot encounter them twice, but that some things stay the same only by changing.”

LAND COVER

The “terrain vague” encounters various configurations of land features, giving each and every one of them a unique character and potential for exploration.

SEEING SEWS THE CITY

First Flats Rail Bridge

Main Avenue Viaduct

Center Street Bridge

Detroit-Superior Bridge

Columbus Rd Bridge

Quigley-Rockefeller rail draw bridge

West 3rd Street Bridge

rail draw bridge

r e s i d e n t i a l n e i g h b o r h o o d

r e s i d e n t i a l n e i g h b o r h o o d

RECREATION RECLAIMS THE CITY

stay hungry and hungrier

This map documents both the formal and informal ways of recreation, meaning some of them were designed with a purpose of entertaining and some are unexpectedly explored with happy moods through everyday interaction.

Terrain vagues share the feature of unattended and differ from each other in terms of other characters, for instance, the views that refine its sophistication, the land covers that sharpen its definition etc...

TERRAIN VAGUE ID

reference: Mariani, Manuela, and Patrick Barron, eds.

“Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale,”

What can the designer propose... ... to appreciate the existing, to discover the imperfect place that captures the lazy gaze, where unsolicited programs welcome all...?

un on the unromantic

in terms of property

what is your take on the “make-no-sense”s how you read the

unreadables?

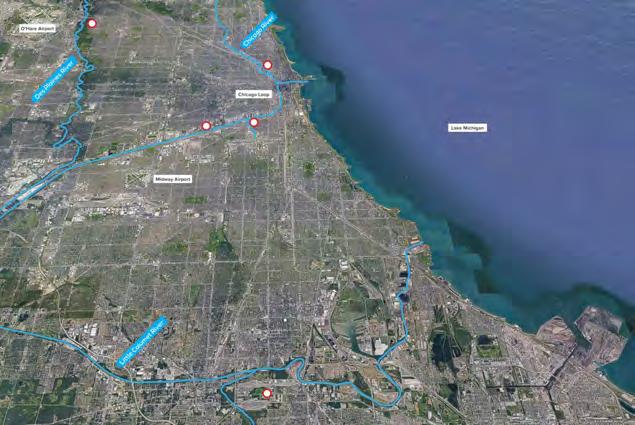

Great Rivers Chicago Vision Plan

CHICAGO, IL (2016-ONGOING)

BACKGROUND

The existence of the city of Chicago is attributed to the rivers in the region. Native Americans and settlers saw that the slow flow into Lake Michigan provided an important transport route to the Mississippi River. The potential of this trade route quickly attracted settlers in the Chicago area. In just a few decades, as the city grew up almost overnight, the Chicagoans quickly and dramatically changed the river and the surrounding wetlands.

The river not only acted as a sewer, it provided sewage for more and more residents and emerging industries such as slaughterhouses, livestock farms, tanneries and steel mills. As time went by, the natural path of the river was deepened and straightened in many places to guide the flow of water, adapt to barge traffic and facilitate transportation.

The Chicago Land has experienced two centuries of settlement, industry, commerce and urban development. The city’s establishment and success over centuries has defied nature to change the curse of its rivers to suit the needs of the growing metropolis.

https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/misc/chicagoriver/pdf/pamphlet.pdf

Precedent Study

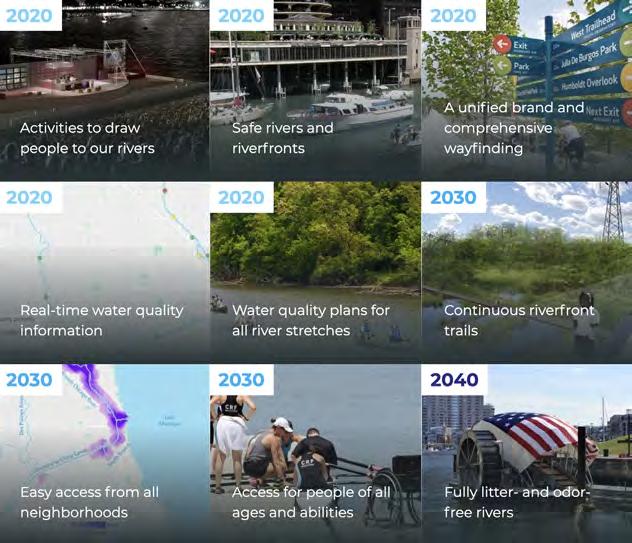

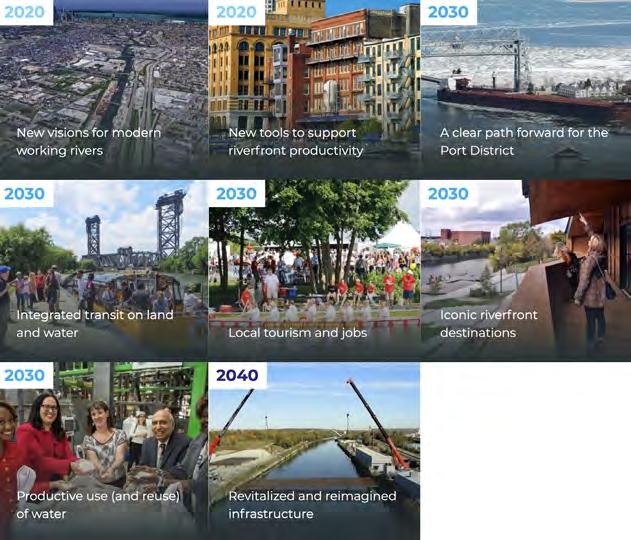

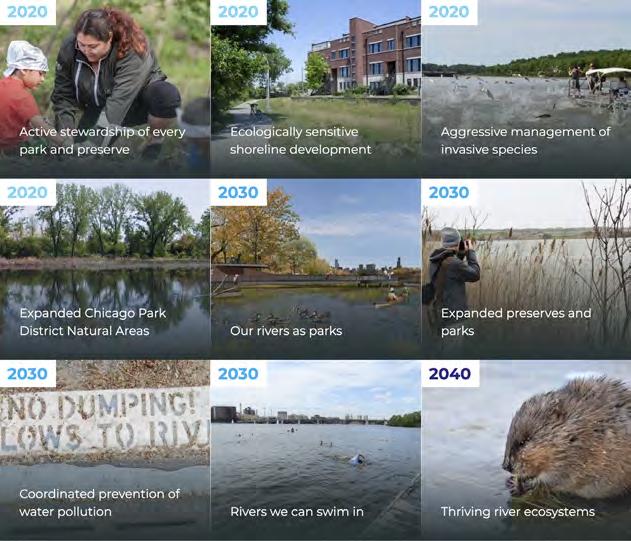

GOALS

“Our rivers will be inviting: enhancements to infrastructure, information and programming will make our rivers more intuitive, meaningful and exciting places to be, drawing more people for recreation, work and relaxation.”

Inviting:

Cleanliness, safety and improved community connections will create more pleasant rivers and riversides. Better pathfinding and interpretive signage ensure that the system will be easy to navigate. The partnership with the city of Chicago, communities and civic leaders will advance further interventions like adding new access points, amenities, entertainment venues and events for residents and visitors of all ages and abilities. Programming activities will attract people to the rivers and et the foundation for the incremental reclamation of the riverfronts for citizens’ use.

http://greatriverschicago.com/goals/index.html

Great Rivers Chicago Vision Plan

GOALS

“Our rivers will be productive: they have historically been and will continue to be working rivers that are transportation arteries, commercial corridors and tourism generators.”

Productive:

The project harnesses the economic value of the river and retains the water integrity. Modern working rivers generate more job opportunities and business attractions, for example, river’s transportation infrastructure to accommodate barges, tour boats, water taxis and recreational watercraft. Business, community, government and civic leaders will work together for innovative riverside development projects that coordinate people, businesses and nature.

http://greatriverschicago.com/goals/index.html

GOALS

“Our rivers will be living: from riverbeds to shorelines, plants, animals and people will co-exist in vibrant, healthy ecosystems.”

Living:

Apart from life and human wellbeing, the project’s vision also focuses on the biological diversity including the preservation of wildlife and habitat. The process involves a series of studies on management of invasive species, reducing pollution by releasing of policies, and retrieving a balanced river ecosystem.

http://greatriverschicago.com/goals/index.html

Great Rivers Chicago Vision Plan

CHICAGO, IL (2016-ONGOING)

STRATEGIES

Great Rivers Chicago is a vision to unlock the potential of the Chicago, Calumet, and Des Plaines rivers and riverfronts. The goal: to create inviting, productive, and living rivers that will make citizens proud, and connect communities. By reinterpreting the relationship to water, Great Rivers Chicago focuses on five place-based examinations that manifest new dimensions and perceptions.

• The suburban context--as connection between office park, transportation, and forest preserve is knit together by a riverfront trail.

• Post-industrial canal--a relationship between river, production, and commerce.

• Goose island--opportunity for a wetland park and recreation paradise for a booming tech-innovation community.

• The contaminated collateral channel--a natural ecosystem to filter river water.

• The plan includes outlining more riverfront activities and a unified system of wayfinding, a continuous system of riverfront trails that connects neighborhoods, and the relocation of certain industries that do not relay on river transportation.

http://www.r-barc.com/projects/great-rivers-chicago-vision-plan/

APPLICATION TO THE CUYAHOGA RIVER

The Cuyahoga River takes on different physical and environmental conditions as it runs through Cleveland to Lake Erie: from a National Park, industrial sites, residential areas, and downtown. More activities and programming near the riverfront could vary accordingly to better utilize the existing resources and attract users.

industrial site downtown

residential

mapping of surrounding urban conditions

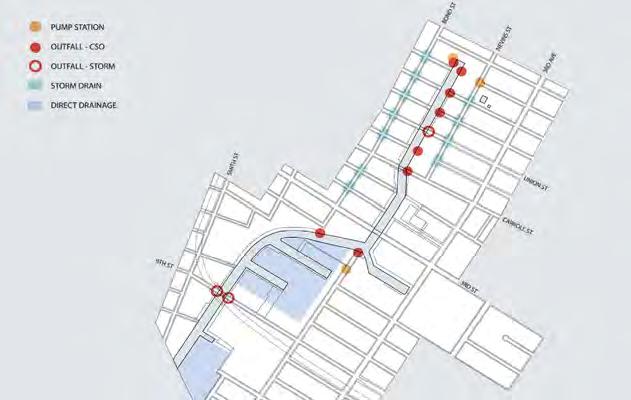

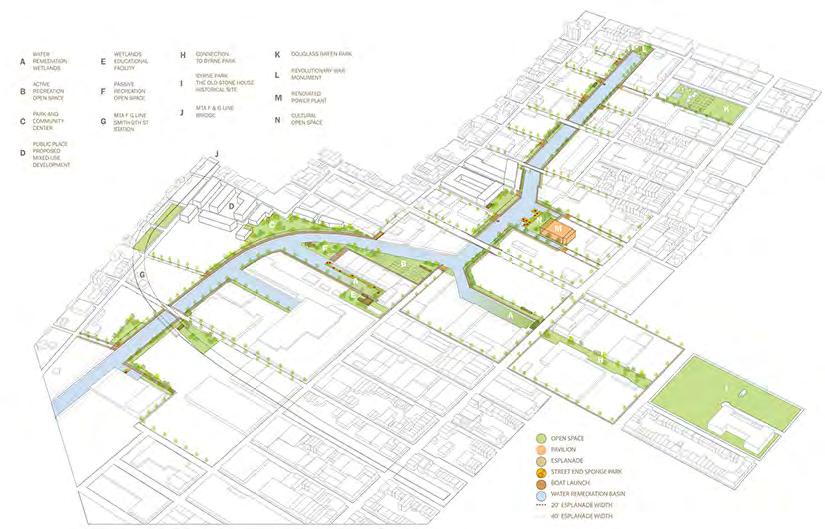

Gowanus Canal Sponge Park™

BROOKLYN, NY (PILOT 2016)

BACKGROUND:

The Gowanus Canal (aka Gowanus Creek) is a 1.8-Mile (2.9-Kilometer) canal in Brooklyn, New York City, in the westernmost tip of Long Island. Since the middle of the 20th century, the canal was an important cargo transportation hub but in recent decades its use is decreasing. Although domestic water transport has also decreased, it is still used for occasional cargo transportation as well as daily sailing of boats, tugs and barges.

By the end of the 19th century, the massive use of industry had led to a large amount of large wastewater discharge into the Gowanus pipeline. Even most of it was recognized as one of the most polluted waters in the United States by 1990. Although generally considered incompatible with marine organisms due to the high proportion of fecal coliforms, low mortality caused by pathogenic bacteria and low oxygen concentrations. Various attempts to remove pollution or water from the canal have failed.

SIMILARITIES:

Both the Gowanus Canal and the Cuyahoga River have been used as major transportation and sewage for industries along the water bank. The historic contamination caused the US Environmental Protection Agency to target the Gowanus Canal, while the Cuyahoga River fire of 1969 raised the public’s attention of environmental consequences caused by industrial use of the river. Both two sites are now in need of reshaping the water’s value in terms of environmental economic and civic engagement.

https://gowanuscanalconservancy.org/history/ http://nymag.com/news/intelligencer/topic/57886/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gowanus_Canal_Map.jpg

GOAL :

The Gowanus Canal is surrounded by a layer of industrial buildings and another layer of residential neighborhoods. Both the bank and the water are polluted by the industrial waste and New York’s combined sewer system regular discharges.

The accessibility of the water edge is limited. The Sponge Park™ masterplan by dlandstudio was created to address the need generated by several private development projects that open to the water.

In order to keep a safe and healthy place for public engagement, the sponge park is designed for surface water runoff management and absorption.

https://dlandstudio.com/Gowanus-Canal-Sponge-Park-Pilot

Gowanus Canal Sponge Park™

BROOKLYN, NY (PILOT 2016)

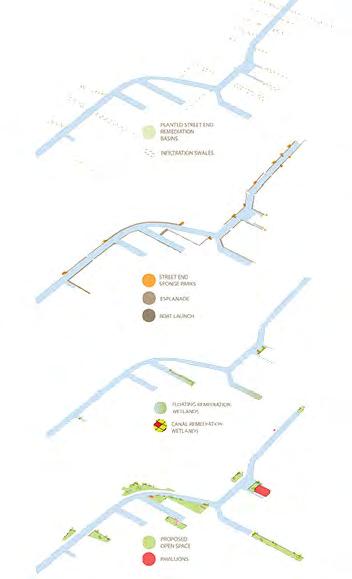

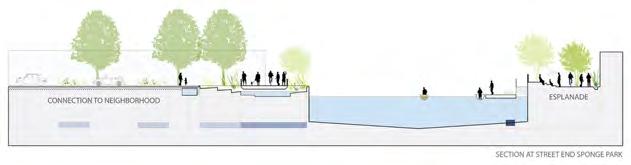

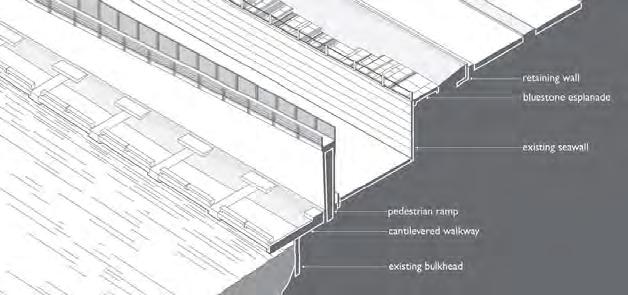

SITE CONDITION STRATEGIES:

The Masterplan proposes a strategy of urban stitching, connecting the public and private lands adjacent to the canal to create a continuous esplanade with recreational spaces running the length of the canal. Existing street-ends would serve as entry-parks providing access to the esplanade and the water. These parks provide for community oriented programs such as dog runs, community gardens, public exhibition spaces and temporary markets. The park is a working landscape: it improves the canal environment while supporting active public engagement.

https://dlandstudio.com/Gowanus-Canal-Sponge-Park-Masterplan

PLACE_BASED PROGRAMMING

Holistically sporadic plan:

More than just a park, the project consists of a system of infrastructural, public engagement components, for instance, street end park, infiltration swales, esplanade, boat launch, open space, and wetland... This system covers both the accessibility, playfulness, and the functional parts of the project.

Community engagement:

To better promote neighborhood’s engagement in the park’s use, the programming process invites the nearby residents into envisioning the uses of the parks. So instead of just having one “perfect” park in the whole area, the gowanus canal sponge park ends up having many place-based parks suitable for nearby residents.

https://dlandstudio.com/Gowanus-Canal-Sponge-Park-Pilot

Gowanus Canal Sponge Park™

BROOKLYN, NY (PILOT 2016)

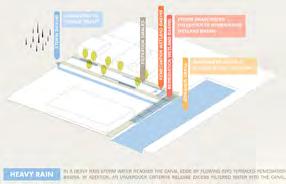

The water runoff collectors deal with different levels of water volume.

MECHANISMS

Planting

To maximize the parks’ environmental protection value, the plants chosen are based on their ability to absorb heavy metals and biological toxins.

“In a light rain storm water is captured by filtration swales.”

“In a medium rain storm water flows to filtration remediation wetland basins.”

“In a heavy rain storm water reaches the canal edge by flowing into terraced remediation basins. In addition, cisterns release excess filtered water into the canal.”

http://www.r-barc.com/projects/great-rivers-chicago-vision-plan/

APPLICATION

The notion of urban stitching offers an insight for designing the riverfront accesses in Cleveland, as can be seen in previous mapping of “terrain vague”. The river front is accessible to nearby residential neighborhoods, downtown buildings and industrial factories through dead-end roads and river walk trails. Small intervention seems more practical due to the scarcity of funding available.

Moreover, the solution for water leaking in a controlled manner is a way to address current problems. Especially the three-level-control with water runoff could be promising in the Cuyahoga River banks in Cleveland where the sinking land and running water combined may lead to serious natural issues. Metal absorbing plants for detoxifying the water and riverfront might need a second thought for they could be invasive species that cause further problems.

http://www.r-barc.com/projects/great-rivers-chicago-vision-plan/

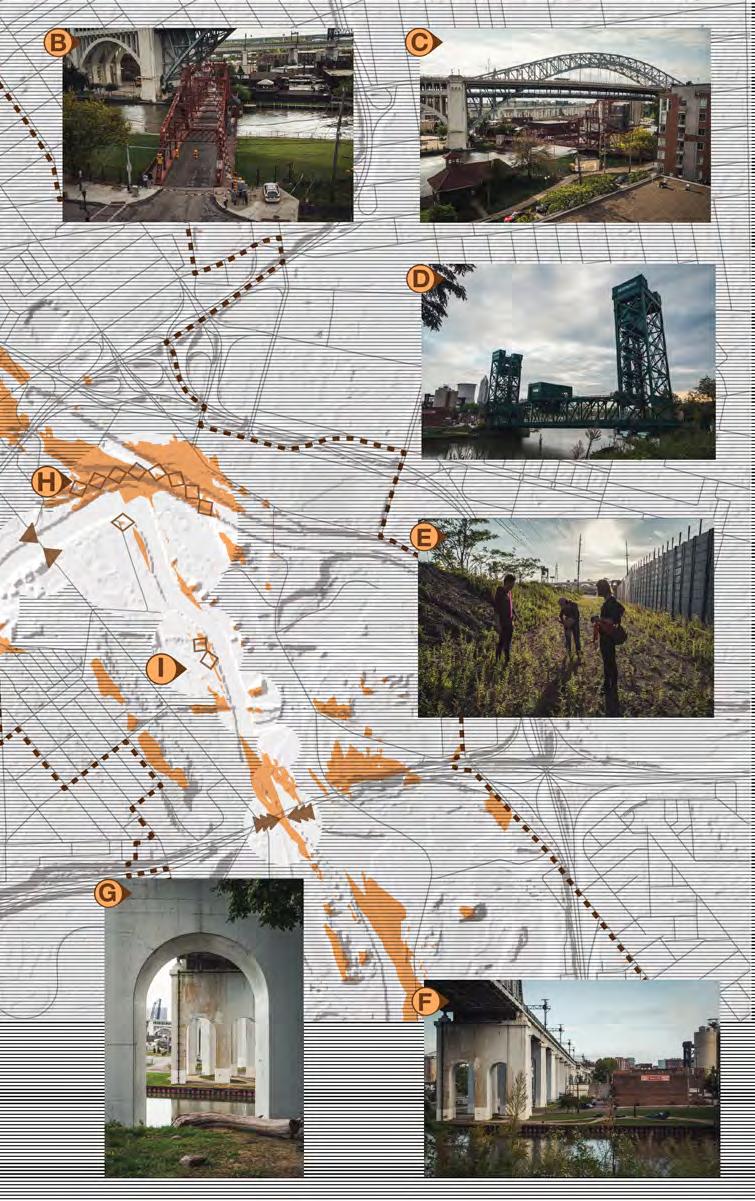

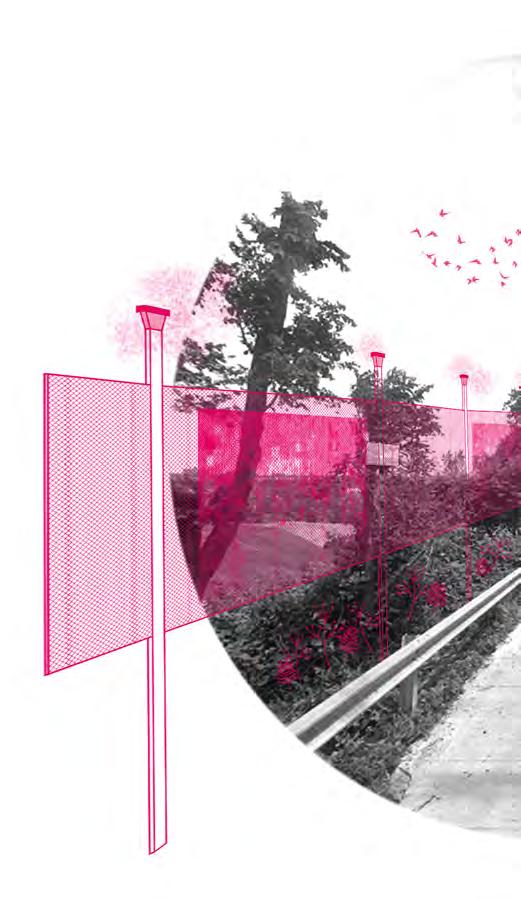

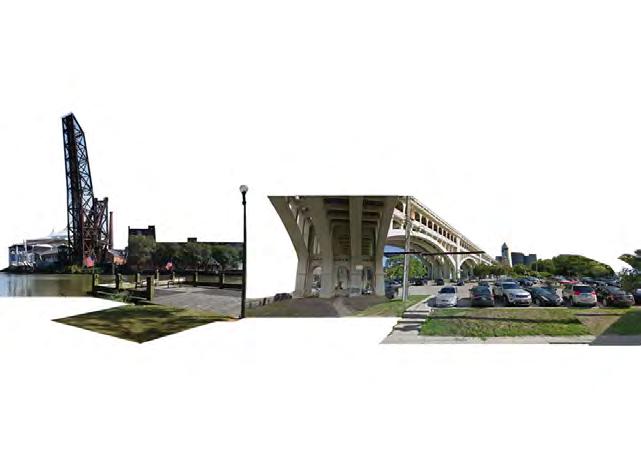

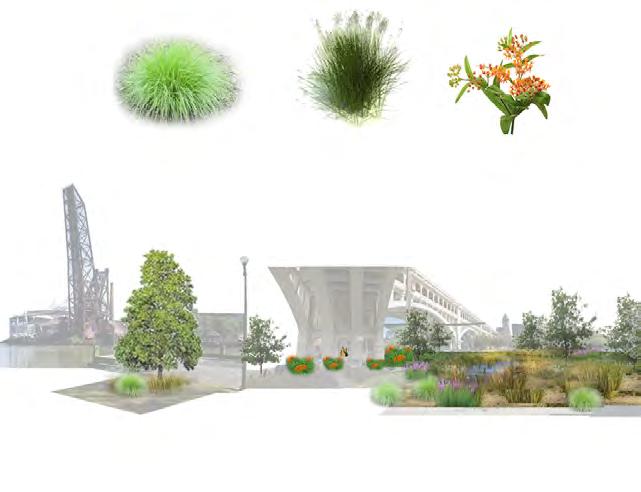

INTERFACE

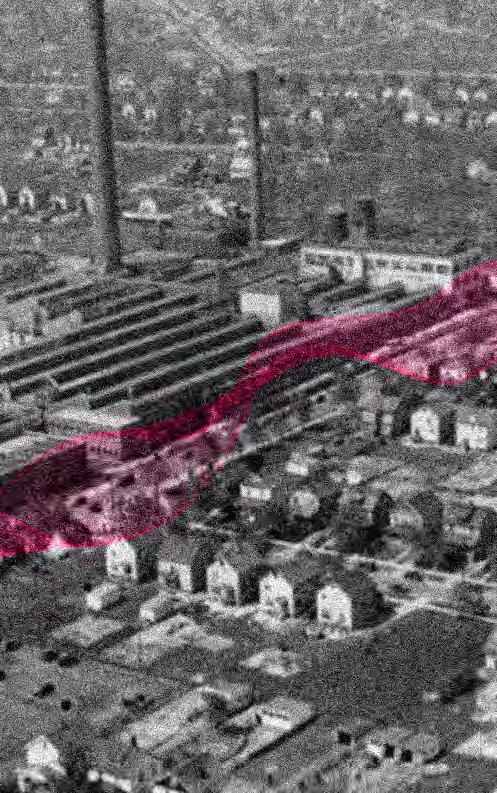

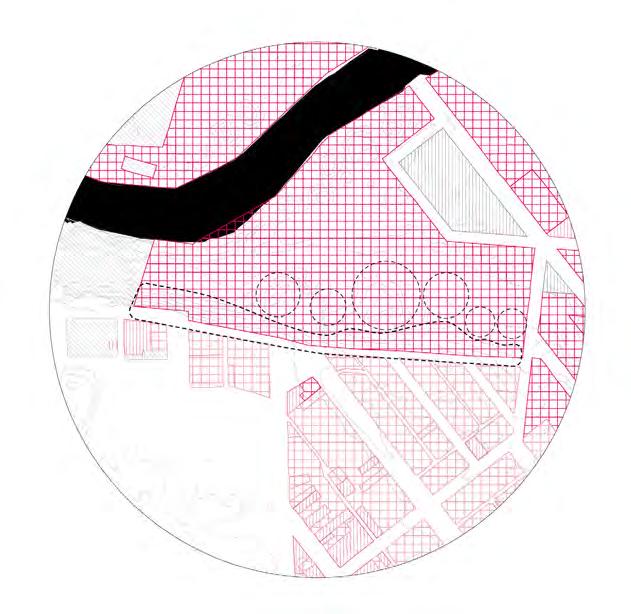

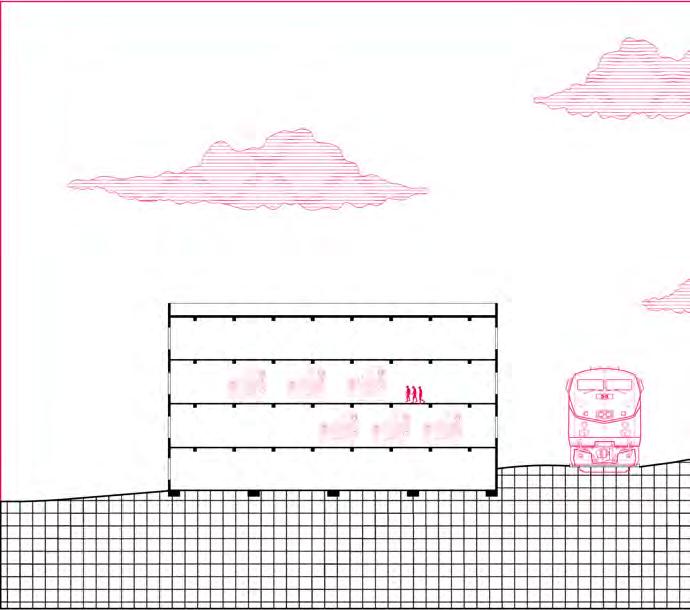

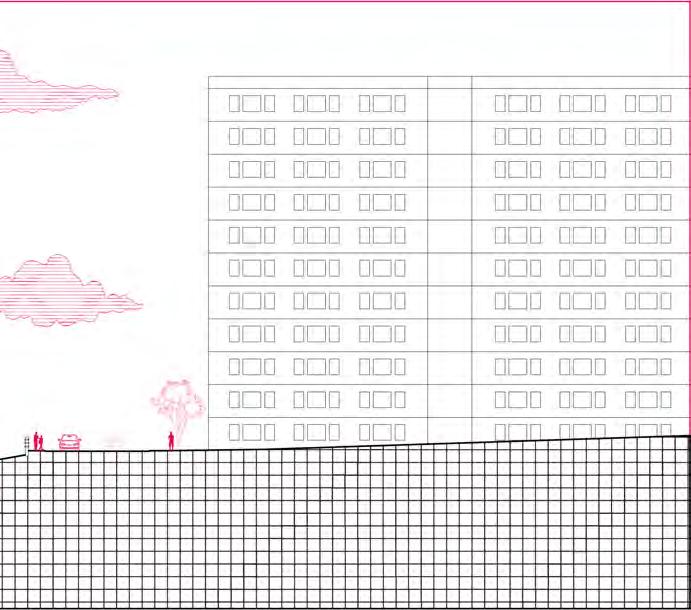

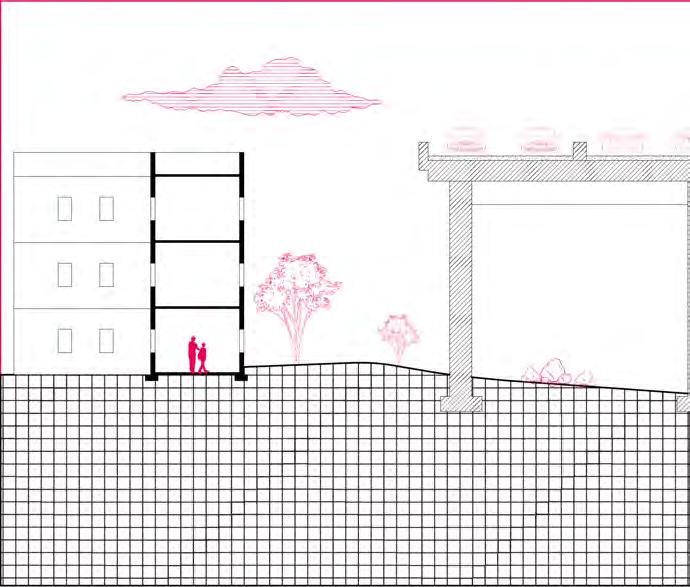

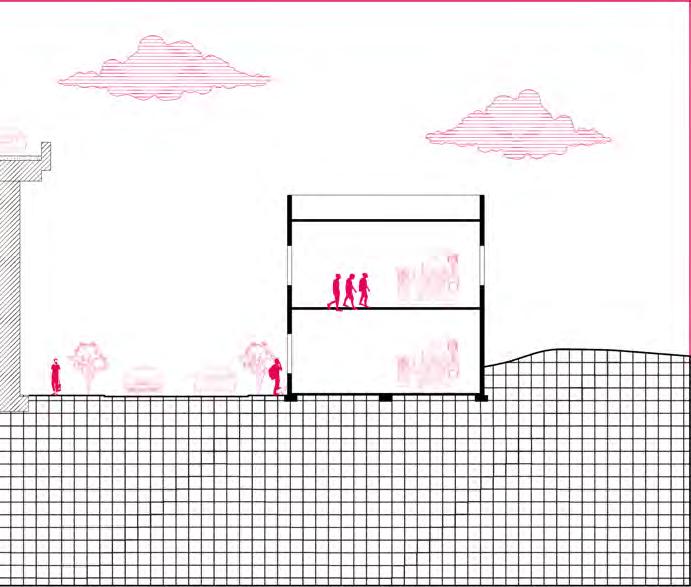

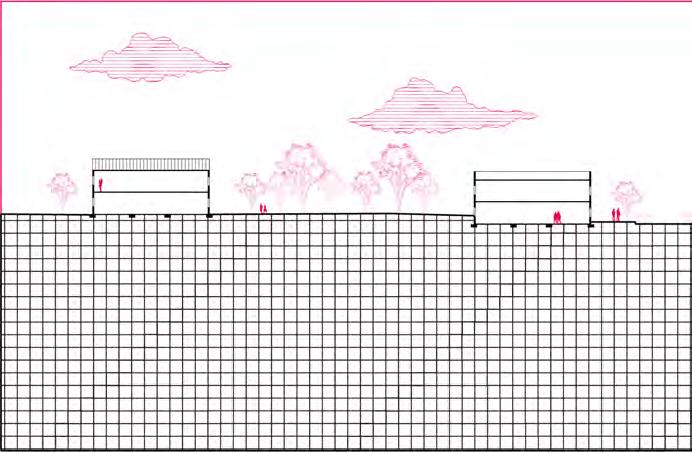

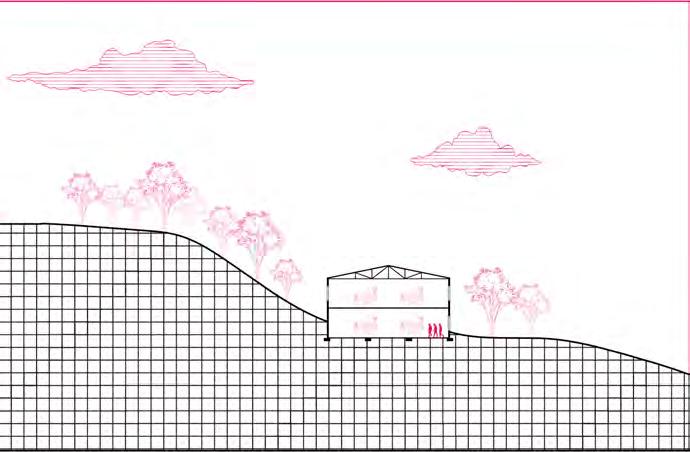

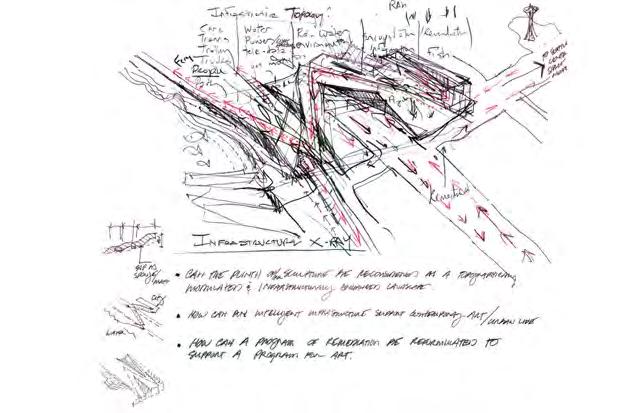

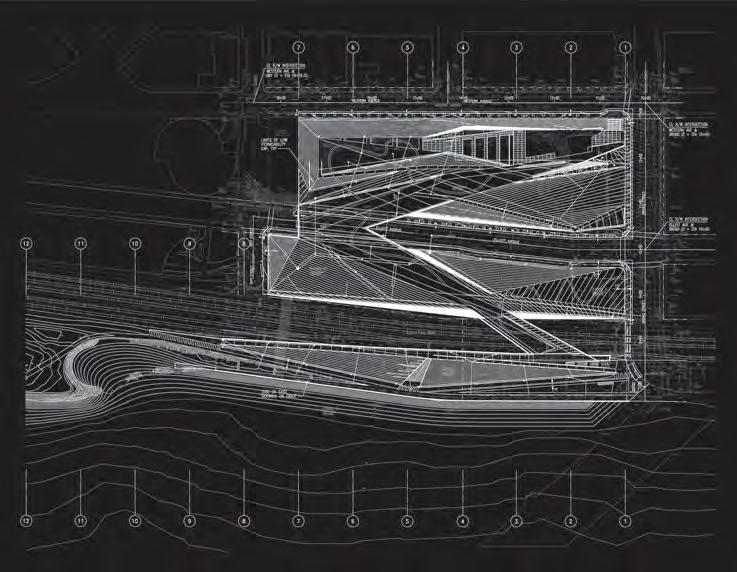

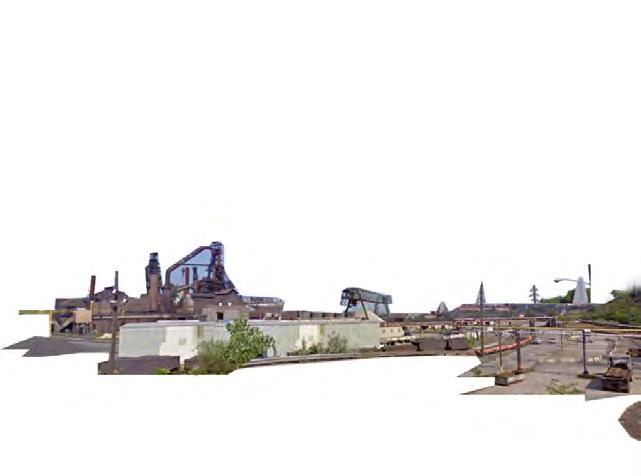

In Cleveland, industry claimed most of the lands along the Cuyahoga River in order to take advantage of its strong carrying capacity for the transportation of goods. This resulted in the decreased accessibility to the river for other uses than the industrial ones. And close to the industrial plants, a sea of working housing with no gap or protection for the residents. The thin interfaces between the two land uses, industry and dwelling, shaped the geographies of Cleveland. Indeed, the smell, dirt, and noise from the industry side have negative impacts on the neighborhoods. However, the magnificent scenes of the Cuyahoga Industrial Valley remain intensively captivating.

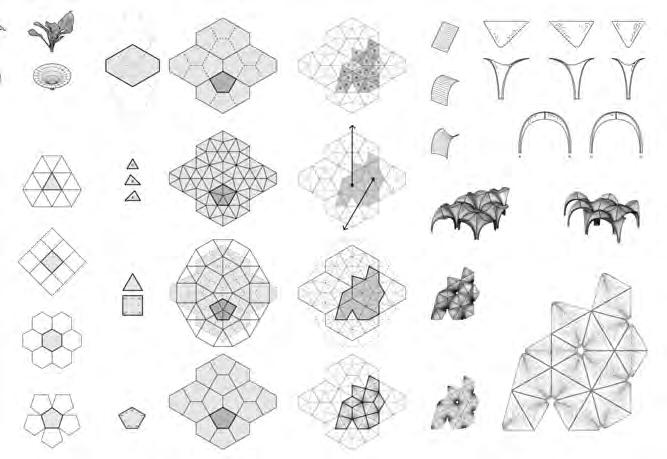

This project established an inventory of the typologies of the interfaces and proposes different interventions to create more diversified human oriented microenvironments. Since most of the industrial sites are still in use and contribute to the local economy, the interventions aim to give visibility to this situation through tactical components. Humble interventions to the existing interfaces help both sides get along with each other in a better way. Improvement of these micro-environment qualities makes the interfaces softer and more appropriate.

Typologies, Sites & Implementation Mechanisms

Erie

Site C

41°29’35.95” N

81°42’30.15” W

Block Group

Residential Building

Industry Building

Dump

Interface Type A: Gravel Pile

Interface Type B: Rail Track

Interface Type C: Viaduct

Interface Type D: Alley

Towpath Trail

Selected Sites

Phasing: different proposals will be implemented based on how polluted the sites are. Sites with higher level of pollution have greater priority and will be implemented firstly.

Funding: EPA, addressing industrial pollution issues; philanthropies, to increase public environmental quality; funding can be also from local-resident donation so as to make their homeland a better one.

The dust is blowing all the time!

The industry looks magnificent!

The green buffer helps!

It is noisy!

There is not enough trees!

The rail track looks cool tho!

A little bit smelly!

The viaduct is nice!

I don’t like the wastes!

Land Use and Ownership of Site C

I like the sunshine and the green!

I wanna sit around the alley and enjoy!

Olympic Sculpture Park

SEATTLE, WA (2001-2007)

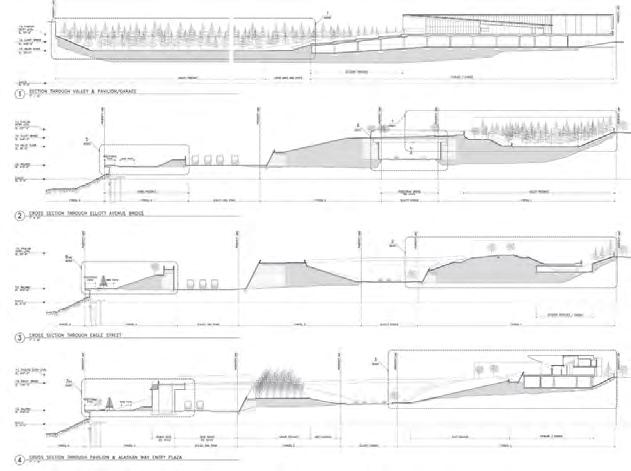

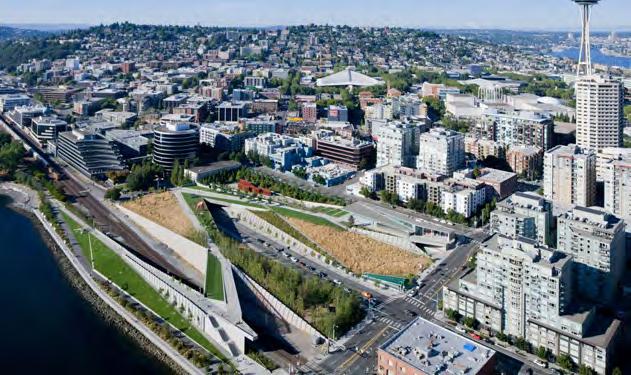

The Olympic Sculpture park, designed by Weiss/Manfredi Architecture/Landscape/ Urbanism, is located in Seattle. It is planned as an improved public space according to the Seattle’s Central Waterfront Concept Plan which aims to reconnect the urban core to the water front. The park is located on a former industrial brownfield site, which was separated from the city context by an arterial road and several train tracks. The z-shaped

Image Source: Seattle’s Central Water Front Concept Plan

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Precedent Study

configuration is used to connect the fragmented parts into a whole. In other words, it is a continuous landscape which starts from the city to the shoreline. What really shocking is its manipulation of the topography of the site, specifically, it is descending almost 40 feet from the top to the bottom. It is a brand-new pedestrian amenity for people to enjoy not only masterpieces of sculpture but also the spectacular river scene.

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Olympic Sculpture Park

SEATTLE, WA (2001-2007)

Image Source: http://www. weissmanfredi.com/project/ seattle-art-museum-olympicsculpture-park

Image Source: http://www. weissmanfredi.com/project/ seattle-art-museum-olympicsculpture-park

Image Source: http://www. weissmanfredi.com/project/ seattle-art-museum-olympicsculpture-park

The starting point of this proposal is the PACCAR Pavilion of 18,000 square feet. The site transitioned from a brownfield to a construction site and then to the final sculpture park. It is like a magnet that can attract people coming from the urban core to visit this place. A z-shaped green platform welcomes the visitors and initiate the promenade crossing an arterial road, and gaining views to the Olympic Mountains. The main sculpture collections are located in this section: Calder’s Eagle, Mark Dion’s Neukom Vivarium, Roxy Paine’s Split, etc.

The second part crosses several train tracks, and people can have a look at the city scene, the port, as well as the magnificent industrial train tracks. The last part of it offer people the views of a newly built beach as well as the gorgeous shoreline. It is a creative intervention which really focuses on how to reuse former industrial sites, how to make riverfront accessible, and how to deal with contaminated brownfield. However, a little critique here is that the space under the bridge crossing the train tracks and the arterial road looks a little bit monotonous. Indeed, design is important, however, the forces behind it might deserve more attention from us. The initial force for this park is a $25 million dollars donated by the former Microsoft president Jon Shirley and his wife Mary Shirley.

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Olympic Sculpture Park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park SEATTLE, WA (2001-2007)

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Olympic Sculpture Park

SEATTLE, WA (2001-2007)

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

This donation gave eternal free access to the public. The Shirley family also bought the very first piece of the series of sculptures, which is Calder’s Eagle. The total donation of the park is around $85 million dollars. According to the Seattle Time, 25 % of it comes

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

from public sources, such as the City of Seattle, King County, Fish and Wild Life Service, Department of Housing and Urban Development, etc. What interesting here is some of the donation come from hundreds of thousands of ordinary people. The range is from

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Olympic Sculpture Park

SEATTLE, WA (2001-2007)

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

$50 dollars to $500,000 dollars. Diversified donation sources imply the Olympic Sculpture Park is truly a park which belongs to the citizens and the public. High-level participation should be appreciated for sure. Even though the site condition is complicated, the team

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

is willing to face the challenge and bold enough to create this fantastic and gorgeous proposal.

Image Source: http://www.weissmanfredi.com/project/seattle-art-museum-olympic-sculpture-park

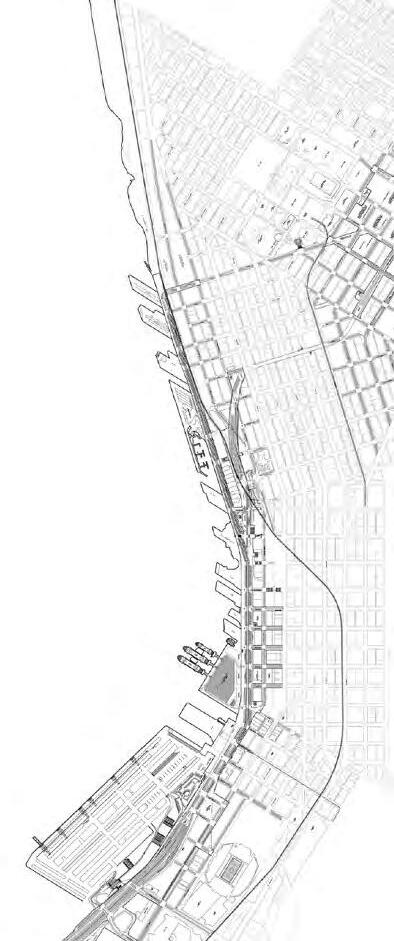

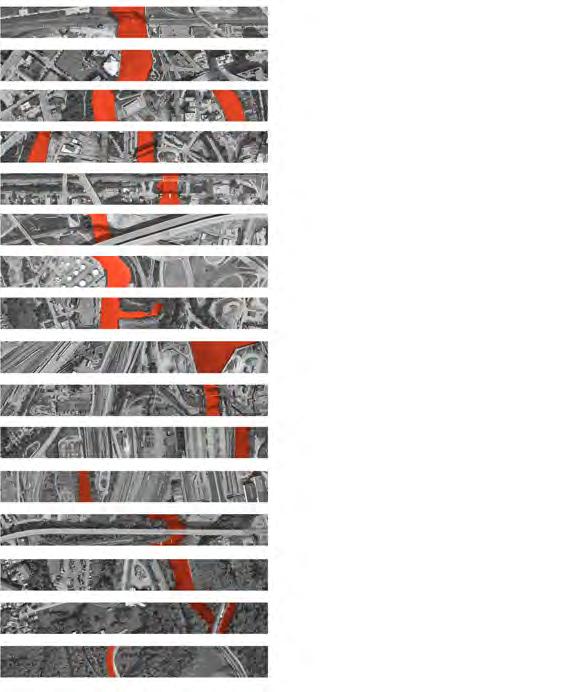

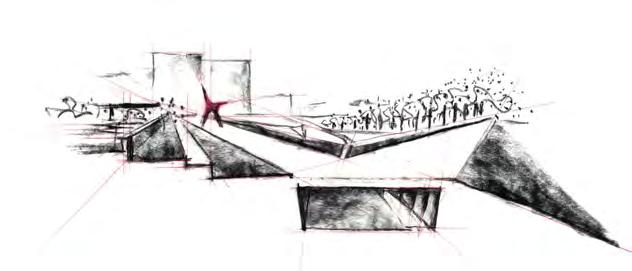

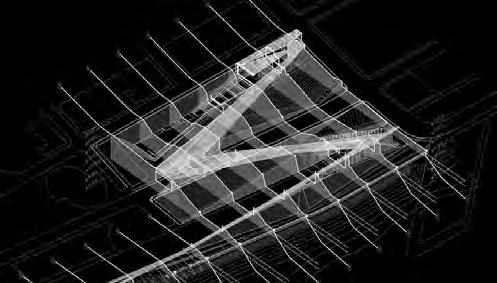

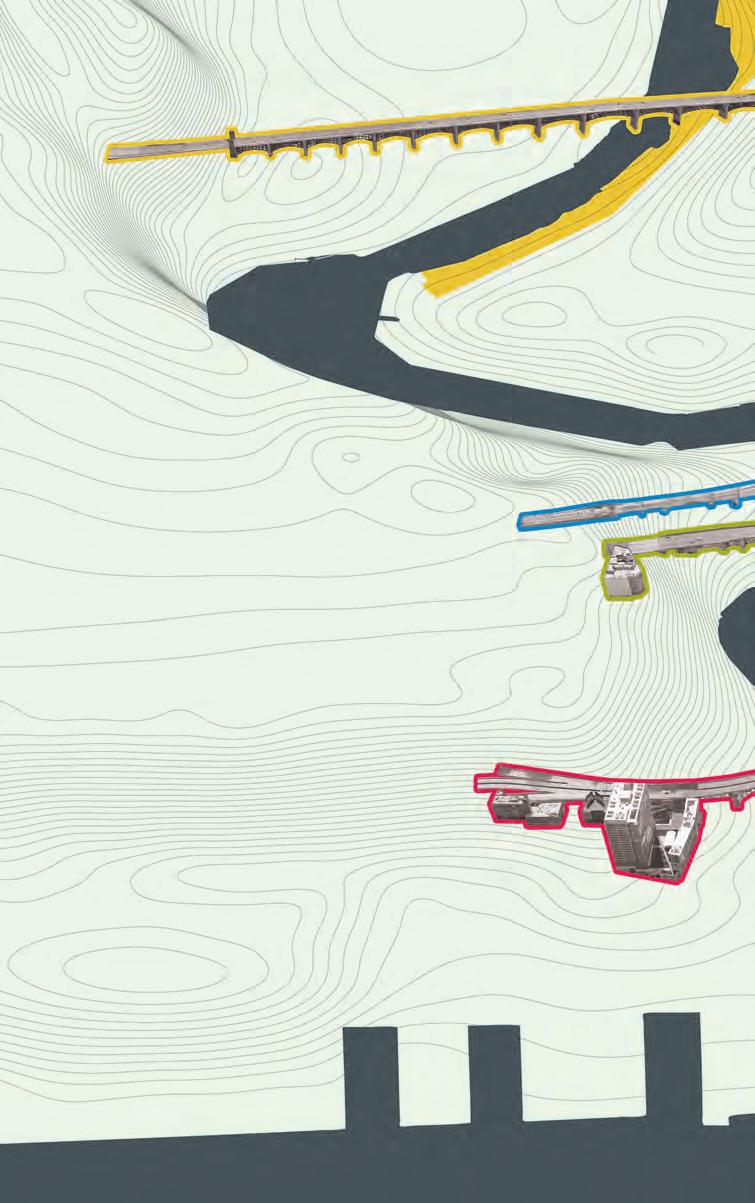

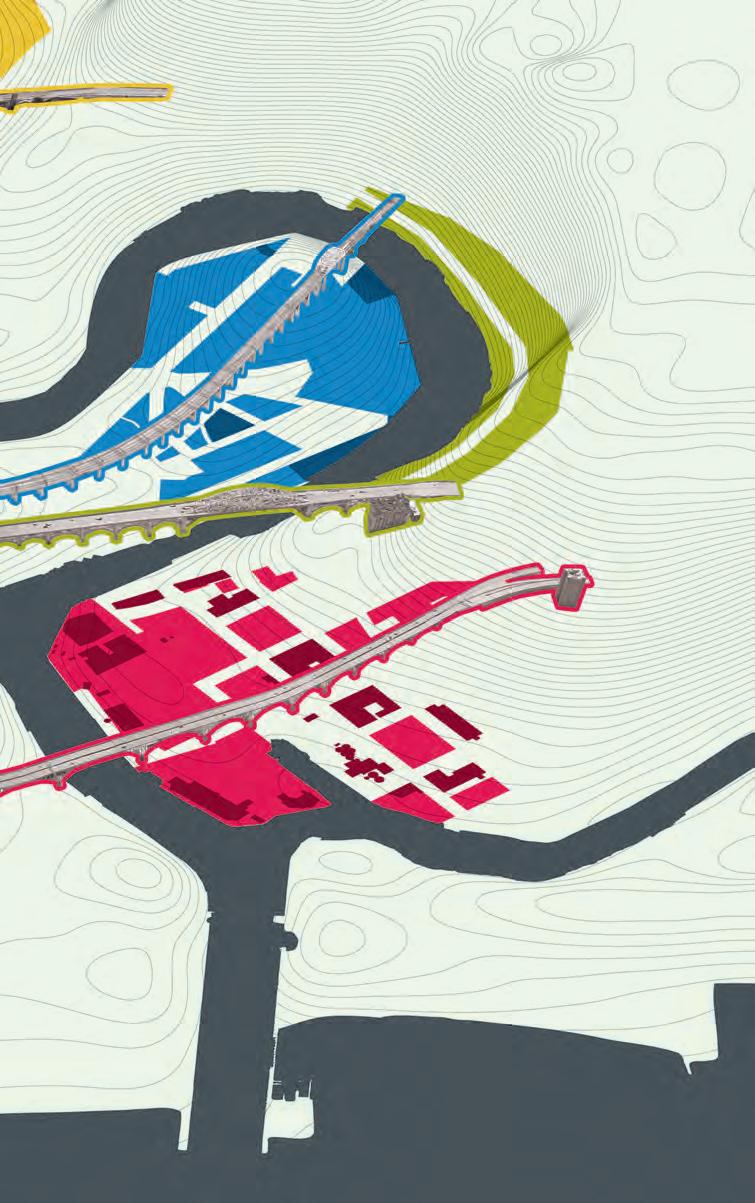

BRIDGING THE CITY

The meandering Cuyahoga River runs through the city of Cleveland on its way to Lake Erie, carving spectacular views for those crossing one of the many bridges that stitch east and west. Connecting both sides of the river, down in the valley or up in the higher city grounds, the constellation of bridges shape the historical identity of the industrial valley. This project aims to amplify the opportunities for interaction between the city and the Cuyahoga valley activating the bridges as social infrastructures and places of encounter. The high-level transit bridges and elevated rail perform as architectural icons for the city dweller and celebrate the working river as a spine of industrial transportation. The low level movable bridges, drawbridge, swing bridge vertical swing bridge) is an architectural performance.

Identifying these spaces and pedestrian corridors throughout the city, the project activates these infrastructural landmarks through a series of tactical moves driving new occupations, opportunities economic activity, and engagement zones.

Movable Bridges

Abandoned Bridges

Indexing Cleveland’s bridges foregrounds the iconicity of transportation infrastructure along the Cuyahoga River Valley. By examining the various typologies of the bridges intersecting the river, we instigate new opportunities for appropriation of these infrastructures and their grounds to connect the city and the river.

Through the compilation of the Cuyahoga River Bridge Index, we identified four high-span bridges as having excellent opportunity for proposing contextual design interventions. The four bridges diagram identifies the infrastructures and places them in relationship to their characteristic context. In addition, each intervention addresses the unique structural and aesthetic value of the bridges, all holding significant monumental value to the Cuyahoga Valley. In considering both the aesthetic and contextual characteristics of the individual bridges, we propose four conceptual approaches to amplify the recreational, programmatic, and aesthetic qualities of the valley that celebrates infrastructure, industry, and the grit embedded within Cleveland’s cultural fabric.

THE INDEX

SITE

The Site map indicates the location of the bride in relation to the Cuyahoga river valley.

The adjacency diagram contextualizes the bridge with its adjacent urban space.

Industrial Land use

Green Spaces

Residential / Commercial

Riverfront Potential Activity zone

The aerial image indicates the terrain and occupancy of the adjacent landscape.

The spaces below the bridge which extends into the riverscape create interesting views of these structural landmarks. The images highlight potential nodes or spaces of activity.

MAIN AVENUE BRIDGE

DETROIT SUPERIOR BRIDGE

HOPE MEMORIAL BRIDGE

CLEVELAND UNION TERMINAL VIADUCT

DETROIT SUPERIOR BRIDGE

MAIN AVENUE BRIDGE

HOPE MEMORIAL BRIDGE

HOPE MEMORIAL BRIDGE

The Hope Memorial Bridge, originally the Lorain-Carnegie Bridge, was opened in 1932, the second of the major highlevel spans in downtown Cleveland.

CLEVELAND UNION TERMINAL VIADUCT

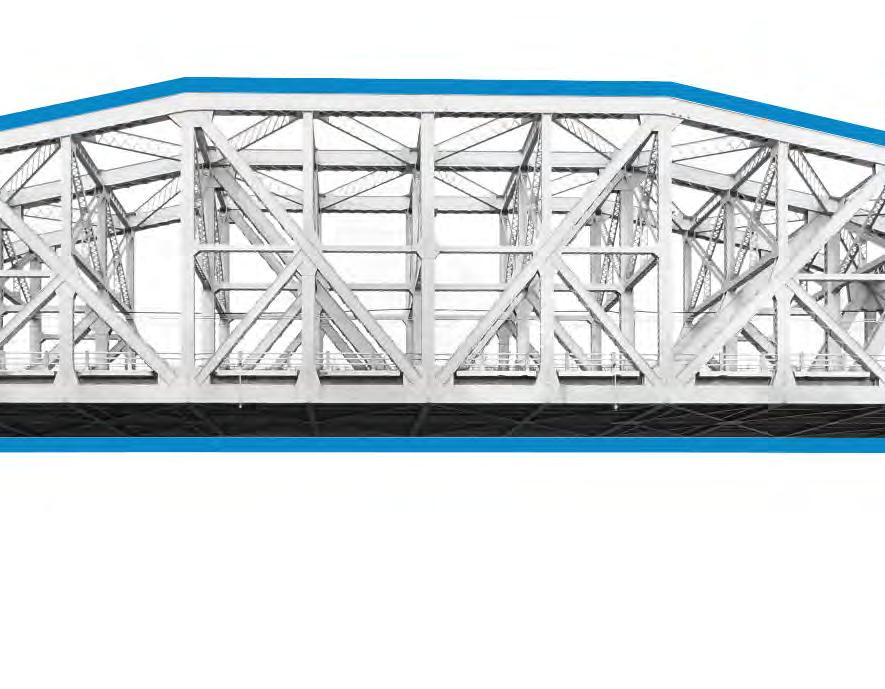

This bridge is a Pennsylvania through truss bridge owned by the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority opened in 1935.

DETROIT SUPERIOR BRIDGE

This bridge was opened in 1917 as the city’s first high-level bridge over the Cuyahoga River. It was built to relieve pressure from the old Superior Viaduct.

MAIN AVENUE BRIDGE

Also known as the Harold H. Burton Memorial Bridge, this bridge is a cantilever truss bridge competed in 1939 and is over 8,000 feet in length, the longest elevated structure in Ohio until 2007.

BRIDGE

Through the Cleveland Bridge index, four bridges emerged as having high iconicity and presented high opportunities for elevating their inherent characteristics. Aside from their monumental value, these four bridges have the potential to capitalize on their adjacent land use. The Hope Memorial Bridge spans over the Tow Path Trail and Scranton Flats, the Irishtown Bridge spans large tracts of vacant and industrial land, the Detroit Superior Bridge has a connection to the Irishtown Bend ecological patch, and the Cleveland Memorial Shoreway Bridge is directly adjacent to major commercial hubs like the Greater Cleveland Aquarium and Jacobs Pavilion at Nautica.

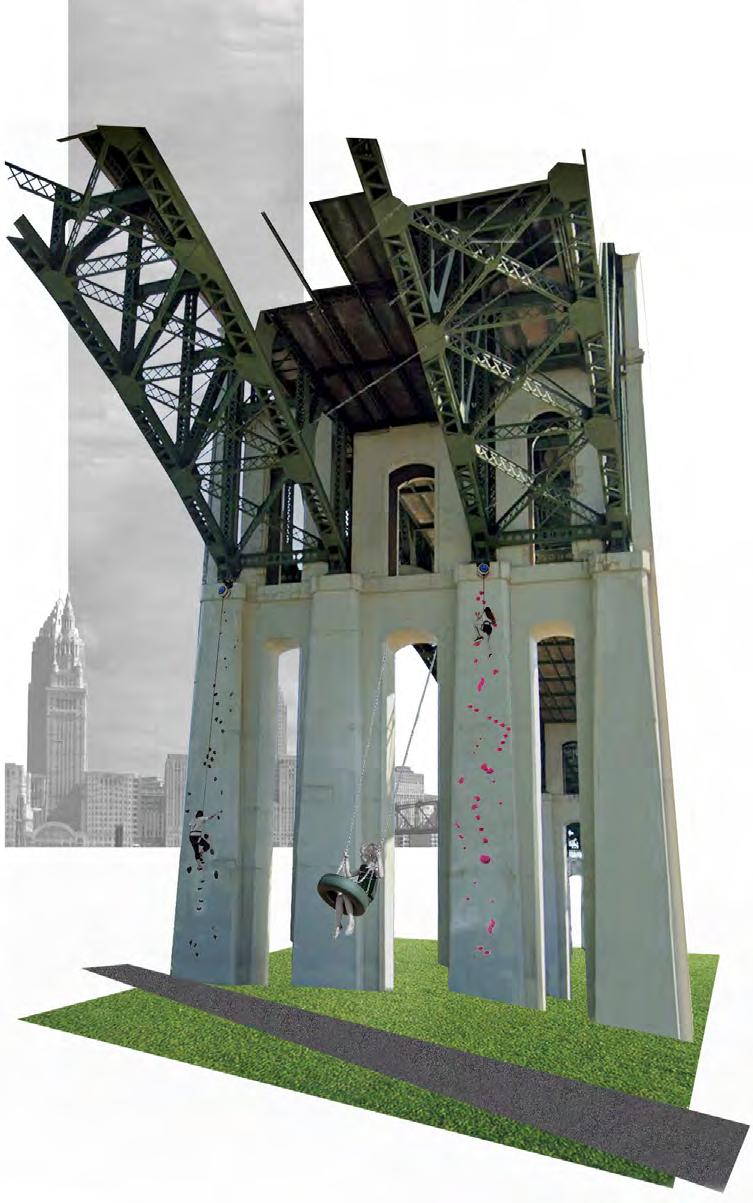

GIANT SWING

ROCK CLIMBING THE COLUMNS

TRUSS-SLIDE

TRUSS-TRUSS ZIPLINE

OTHER SUCH THRILLS

SUSPENSE SUSPENDED

Hope Memorial Bridge

Suspense Suspended expands upon the notion of suspense and thrill by utilizing the truss structure of the Hope Memorial Bridge to suspend various types of play equipment. Giant swings, slides, rock climbing, and more build off of the recreational capacities of the Scranton Flats and the Tow Path Trail to infuse a bit more adventure along the Cuyahoga River.

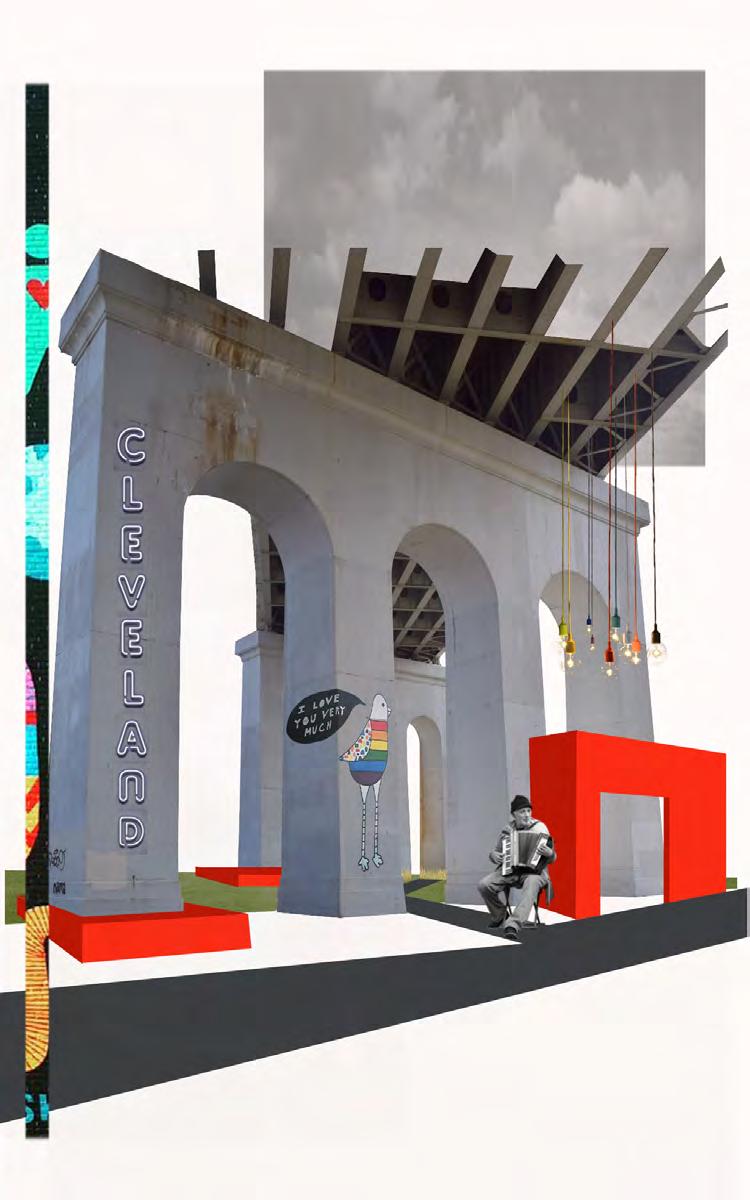

NEON SIGNAGE

ARCH SCULPTURES

ARCH MURALS

ARCH LIGHTING

MUSICAL PROGRAMMING

ARCH

ARCHITECTURE

ARCHWAY

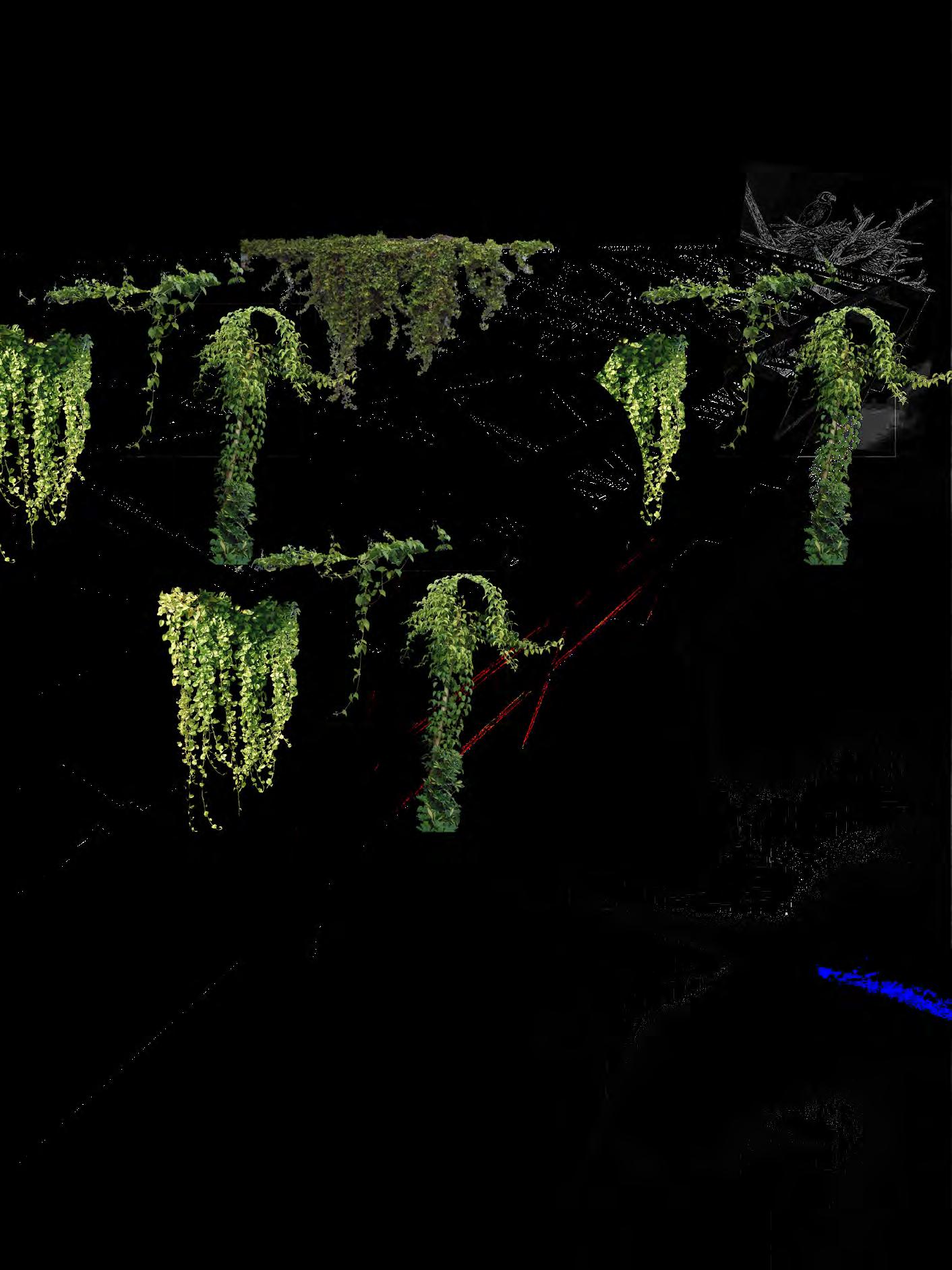

Cleveland Union Terminal Viaduct

The Archway builds upon the repetition of arches the frame views beneath the bridge and across the Cuyahoga by occupying the structure through art, architecture, sculpture, light, and signage. The aesthetic of this intervention has the potential to playfully celebrate its unconventional adjacencies to vacant land, industry, infrastructure, and strip clubs.

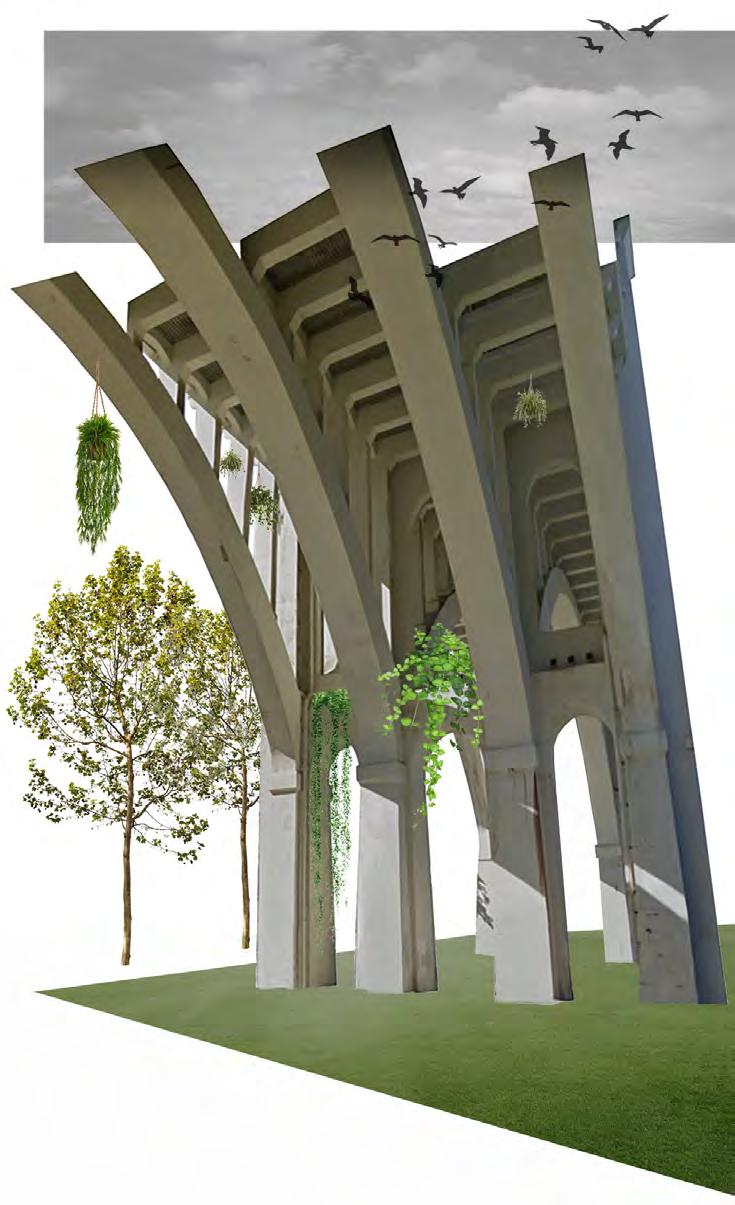

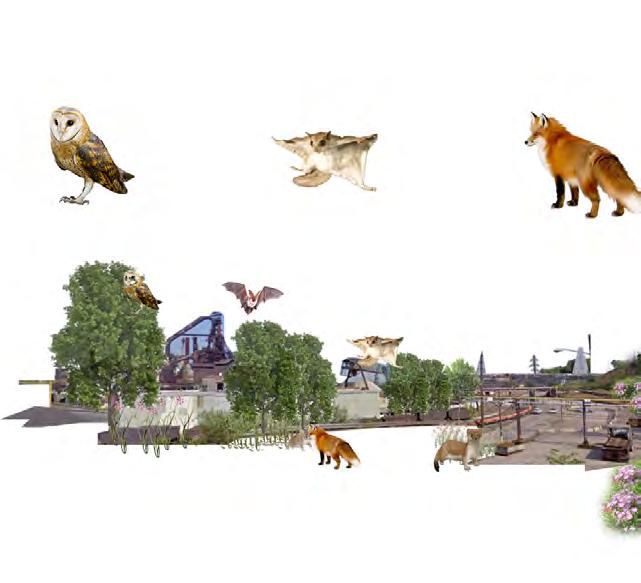

VINES + OTHER HANGING VEGETATION

SCULPTURAL BIRD HOUSES

INVERTED BAT TOWERS

SUSPENDED PLANTERS

SUPERIOR WILD

Detroit Superior Bridge

Directly adjacent to one of the largest patches of continuous riparian habitat at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River. Superior Wild celebrates habitat creation by introducing new urban sculptural habitats beneath the Detroit Superior Bridge. Inverted bat towers, suspended vegetation, oversized bird houses, and more reintroduce the “wild” back into downtown Cleveland.

PAINTED TRUSS GEOMETRY PROJECTION

TRUSS PROJECT

Main Avenue Bridge

The Truss Project recognizes the iconicity of the cantilever deck truss structure of the Main Avenue Bridge by projecting an abstraction of the structural geometries onto the ground plane. The projection is relentless and envelopes everything in its path, drawing a relationship to the verticality of the bridge and its relative proportion to the ground.

PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION

The individual bridge proposals are intended to provoke an imagination for Cleveland that foregrounds infrastructure as one of its most defining characteristics. But the question remains, who stands to gain from this redefinition? And who gets to refine it? Our hope is that the transformation of the bridges along the Cuyahoga River leverages a transdisciplinary approach and engages many different stakeholders throughout the process.

The residential communities adjacent to the bridges benefit from recreational spaces integrated within the fabric of the city and organizations like Cleveland Metro Housing Authority have the potential to capitalize on the transformation from vacant land to public space.

Cleveland Metro Housing Authority (Institution)

Cleveland Foundation (Non-profit/Foundation/Organization)

Metro West Community Development (Non-profit/Foundation/Organization)

Tremont West Development Corporation (Non-profit/Foundation/Organization)

Cleveland Foundation (Non-profit/Foundation/Organization)

Neighborhood development organizations

Cleveland City Council (Municipal)

The Cleveland Foundation (Non-profit/Foundation/Organization)

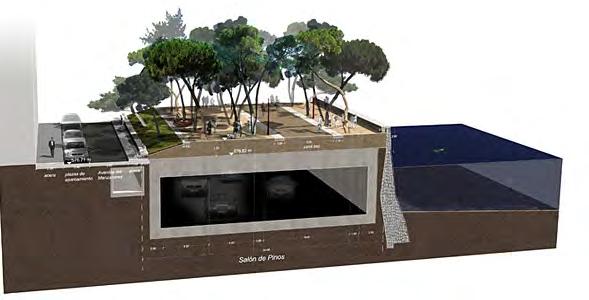

Madrid Rio

MADRID, SPAIN (2006-2011)

Madrid Rio is a project that began with the reconfiguration of transportation infrastructure, where five miles of roads that previously segmented the River Manzanares from the city were routed through tunnels. This project was perhaps one of the most ambitious projects ever undertaken in Madrid, costing nearly $5 billion to implement. The design aspirations for Madrid Rio emerged out of a design competition conducted in 2006 which was won by an interdisciplinary team of local and international practices including the likes of Burgos & Garrido, Porras La Casta, Rubio & Álvarez-Sala, and West 8.

This project was intended to be a holistic plan for the River Manzanares as it intersects with the city. Mobility, flood protection, bridge infrastructure, and public park space were just a few of the considerations this project had to grapple with. The complexity of an urban project at this scale is further compounded by contending political interests,. Mayor Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón was fortunately able to build consensus between political parties.

Precedent Study

The Madrid Rio project cost was officially estimated at 4.1 million euros. Only 10% is attributed to the above ground interventions, and 90% is attributed to the underlying infrastructural costs. In order to facilitate the construction, maintenance, and financial operations, the autonomous company, Madrid Calle 30, was established. Madrid Calle 30 receives its funding from 80% public and 20% private participation.

Where the river used to be a dividing element of the city, the park is now considered as a link between two previously disparate locations. Subterraneously shifting transportation infrastructure was just the first step to catalyzing this much improved connection, but was only one such intervention that contributed to this notion of a connected city. The intermingling of public, landscape, and bridge infrastructure not only provided the means of access, but also served as a new public commons. The following images illustrate how Madrid Rio improves accessibility by studying the various typologies of the public commons, landscapes, and bridges. This case study looks specifically at how the bridge infrastructure was utilized to improve the connectivity and iconicity of the riverfront.

Madrid Rio

MADRID, SPAIN (2006-2011)

SITE PLAN

The extent of the infrastructural upgrades undertaken by the city expanded some 26 miles, about 4 of which occupied the banks of the River Manzanares. West 8 and a group of renowned architects from Madrid established a team, MRIO arquitectos, to develop the master plan for Madrid Rio. The team was selected because of their proposal to address the urban complexities through the means of landscape as their primary medium.

The design addressed issues of temporality by dividing the 80 hectare urban development into a series of seed projects that would establish the framework and foundation for other future projects. There has since been a total of 47 subprojects that have since been realized. Some of the more notable projects include: the Avenida de Portugal, Huerta de la Partida, Jardines de Puente de Segovia, Jardines de Puente de Toledo, Jardines de la Virgen del Puerto, Parque de la Arganzuela and the Salón de Pinos.

Larger park spaces weren’t the only major improvements, the Madrid Rio project also introduced 6 hectares of public and social spaces like sports facilities, artistic amenities, an urban beach, and kids play areas; the restoration of the river’s hydraulic heritage, and the construction of 12 new pedestrian bridges.

These bridges help to redefine the River Manzanares not as a divisive geographic feature, but key moments in which two previously disparate sides are stitched together.

Madrid Rio

Puente de la Reina Victoria MADRID, SPAIN (2006-2011)

Pasarela Aniceto Marinas

Infrastructure x Bridge

Pedestrian x Bridge

Landscape x Bridge

Statement x Bridge

Monument x Bridge

Conduit x Bridge

Puente del Rey

Puente de Segovia

Puente Oblicuo

Salón de Pinos

Pasarela y Puente de San Isidro Puente de Toledo

Puente de Argenzuela

Zona de Niños y Playas

Public Spaces + Bridges

Madrid Rio

MADRID, SPAIN (2006-2011)

40°23'20.92"N 3°41'53.41"W

40°23'14.93"N 3°41'46.54"W

40°23'18.18"N 3°41'50.28"W

40°23'53.46"N 3°42'45.02"W

Conduit x Bridge

40°23'42.35"N 3°42'17.05"W

40°23'59.78"N 3°43'2.31"W

Hydrology x Bridge

40°23'44.76"N 3°42'25.36"W

40°23'59.62"N 3°43'4.55"W

Pedestrian x Bridge

40°23'28.39"N 3°42'0.65"W

40°23'54.42"N 3°42'46.25"W

40°23'35.56"N 3°42'7.25"W

40°23'59.90"N 3°42'59.67"W

40°24'13.63"N 3°43'21.18"W

40°23'59.62"N 3°43'4.55"W

40°23'46.88"N 3°42'32.10"W

40°25'18.21"N 3°43'23.65"W

Types

40°23'58.76"N 3°42'53.75"W

Landscape x Bridge

40°24'39.63"N 3°43'20.57"W

Monument x Bridge

40°24'50.47"N 3°43'22.46"W

Statement x Bridge

40°23'53.28"N 3°42'40.75"W

40°25'8.00"N 3°43'19.13"W

40°24'18.60"N 3°43'22.03"W

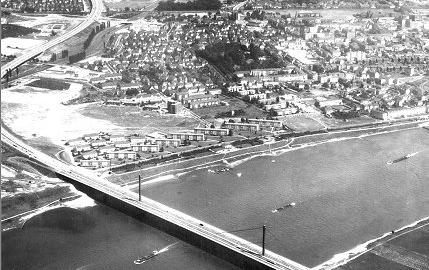

Leverkusen,Neuland Park

RHEINALLEE, GERMANY (COMPLETION 2005)

The Rhine forms both the geographical center of the Cologne/Bonn region as well as the focus of its people’s emotional attachment to their homeland. This stretch of river –between the Rhine Bad Honnef in the south and Leverkusen with its huge chemical plants in the north – is the linking element and showcase for the region’s variety and riches. But for a long time, the cities on the Rhine neglected their relationship with the river to which they owed their existence in the first place. Still an enormous potential for design lies untapped along the 142-kilometer stretch of riverbank. Mighty industries, roads and railroad tracks, single architectural highlights but also nondescript settlements with their backs to the river bank define the waterfront. Green banks and landscape areas are clearly second to the urbanised areas. But within the last decade the Rhine has been rediscovered in the Cologne/Bonn region.

Regionale 2010 projects along the Rhine show the current efforts to change the built image of the region along its river and to reconnect the people with the river at different scales. Projects like the Cologne ´Rheinauhafen` (Rheinau Harbor) with ‘crane houses’, the reconfigured trade fair halls on the right bank in Cologne, the ‘re-coding’ of the Bonn cement factory (‘Bonn Visio’) in terms of content and architecture, and the ‘Neuland-Park’ on a former chemical dump site in Leverkusen all signify a changing attitude to this stretch of the river.

The Neuland Park is a combination of landscape and industrial park, a green area of retreat in this industrial sector. The park was created by filling in, sealing and planting a former waste dump has afforded direct access to the Rhine from the city center of Leverkusen, which was previously publicly inaccessible. The Chemiepark Leverkusen Park to the south, the Dhunnaune Mitte waste dump to the north and the main feeder roads had barred public access to the Rhine. The former waste dump was sealed and in-filled with topsoil, and seeded with grass. The park design plays with landscape park section and Rhine embankment park with vast lawns on one hand and natural areas on the floodplain areas. Signaling a new quality of life and work in the city, the park has opened a unique view of the impressive skyline of the chemical plants while offering recreational areas with opportunities for leisure and sports.

PROJECT RELEVANCE

The Rhine was the easiest transport connection as well as freshwater source in the Cologne-Bonn region. Not unlike the Cuyahoga Valley, industrial landscapes dominated the riverscape as factories established at riverside locations. This project exemplifies the reconstruction of green connection corridors from the city center to the river and creation of spaces of recreation by embracing the existing industrial landscape. The intervention secures the riverfront and rediscovers spatial vistas once blocked off, for the public.

Leverkusen,Neuland Park

RHEINALLEE, GERMANY (COMPLETION 2005)

STRATEGIC LOCATION

The Chemiepark Leverkusen to the south, the Dhunnaune Mitte waste dump to the north and the many motorway feeder roads had barred public access to the Rhine. Plans to extend the motorway A59, parallel to the Rhine between the Bayer plant and the city, to connect to the A1 further isolated the site. As a result, the urban periphery on the river were neglected by urban planners for a long time.