LEARNING FR OM INTERPRETATION

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF TREES, BIRDS, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

THE RIVER WHISPERS: OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

Propositions Studio Arch 672/UD732 | Fall 2024

Client Partners:

Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE)

Agasthyamalai Community Conservation Centre (ACCC)

Mathivanan M.

Maria Antony P.

Dr. Thanigaivel A.

Saravanan A.

Thalavaipandi S.

Sanmadi K.R.

Teresa Scholastica Thomas Santhanamari

Anish A.

Karthika

Graduate Students (MArch and MUD):

Zannatun Alim

Deepa Bansal

Virginia Bassily

Jaydipkumar Bharatbhai Nakrani

Jordan Biniker

Haley Cope

Stephanie Dutan

Max Freyberger

Akshita Mandhyan

Nahj Marium

Srinjayee Saha

Yi Min Tan

Studio Instructor:

Maria Arquero de Alarcon

Associate Professor in Architecture + Urban Planning

Sponsor:

A.Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning - Travel Fund

University of Michigan

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION

SUNGEI BULOH WETLAND RESERVE

MAPUNGUBWE INTERPRETATION CENTRE

TENEMENT MUSEUM

CONFLICTORIUM

NORTHEAST BAMBOO PAVILION

ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM AND PARK KALKRIESE

INTRODUCTION

WATER MEMORIES

Deepa Bansal, Jaydipkumar Bharatbhai Nakrani, & Yi Min Tan

VILLAGE SECRETS

Max Freyberger, Srinjayee Saha, & Zannatun Alim

SACRED HORIZONS

Jordan Biniker, Nahj Marium, & Stephanie Dutan

MISSING MOBILE

Akshita Mandhyan, Haley Cope, & Virginia Bassily

INTRODUCTION

ARCHITECTURE, URBANISM AND CONSERVATION

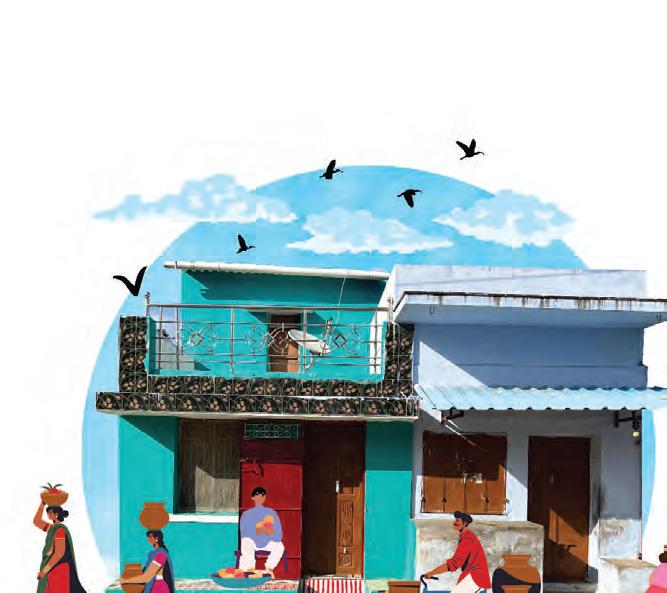

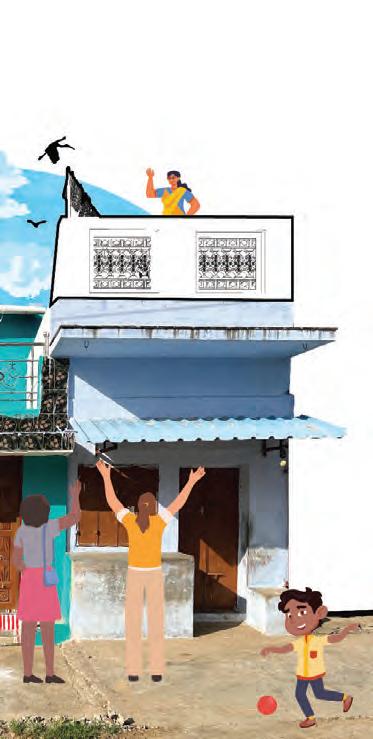

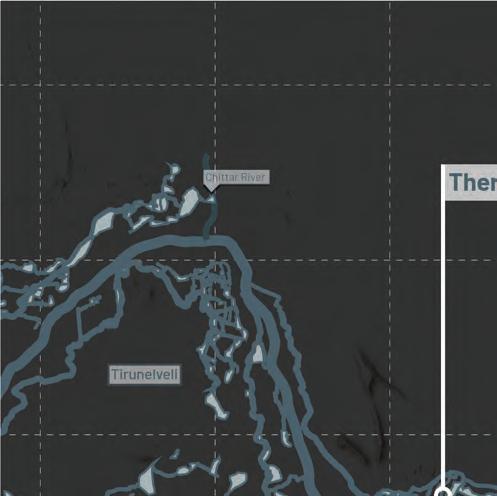

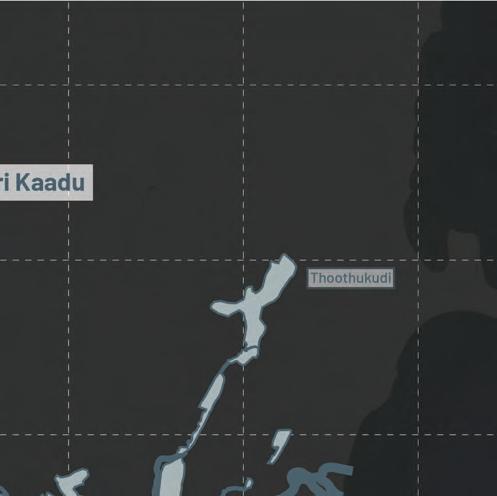

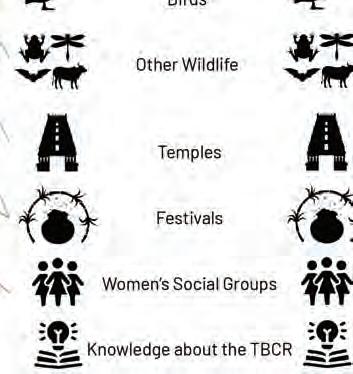

The River Whispers: of Birds, Trees, Temples, and Their People explores the unique socioecological and cultural landscape values of the Thiruppudaimaruthur Bird Conservation Reserve (TBCR). Designated as the first of its kind in India in 2005, this year marks an important milestone for the Reserve and an opportunity to take stock on what has been achieved and the challenges and opportunities ahead. Located on the banks of the perennial Tamarapirani River, the TBCR sits at the heart of the Village of Thiruppudaimaruthur and includes the grounds of the Thiruppudaimaruthur Temple. Every year, thousands of birds transverse the region and dwell on the magical tree canopies that dot the riverine village in the District of Tirunaveli, Tamil Nadu, India. In partnership with Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), this interdisciplinary graduate studio investigated the mechanisms for landscape interpretation of TBCR. ATREE provided the extensive knowledge about socio-ecological process in the region by their team based at ACCC . Specificaly, ATREE is leading a participatory action research project to assess the viability of an eco-tourism initiative to further advance local economic opportunities for the villagers while preserving the cultural, ecological, and social integrity. This studio invited the students to co-imagine, with the knowlegdge and expertise of ATREE, an interpretation centre for the Thirruppudaimaruthur Bird Conservation Reserve as part of this larger eco-tourism project.

Architecture and urban design students took on the challenge to support ATREE’s initiative with a series of studies and design propositions that imagine new ways of interpreting place and centering local’s lived experiences and expertise in their take on what an interpretation center could be. Rather than thinking on architecture and urban design as fixed schemes and permanent markers to attract the visitors’ imagination, students explored a range of design concepts that seek instead to participate of everyday life and ensure interpretation happens with residents and for the residents first.

INTERPRETATION AND IMAGINATION

What does it mean to interpret a landscape? How can architecture and urban design enable access to place and people’s memories, stories, and their everyday life? How can architecture become a medium for listening, storytelling, conservation and transformation all at the same time?

The semester was structured in four stages. Imagination introduced the notion of interpretation through presonal experience, ideas of play and speculative thinking. Investigation focused on research and analysis through the making of an atlas, interpretation case studies, and a game called Habitat Hustle, and engaging with the work of ATREE in the region. Observation involved mapping and reflecting on fieldwork conducted in India. The final stage, Interpretation, asked students to synthesize their knowledge into design proposals that engage with the site and its many layers. This volume records a constellation of the ideas, conversations, and sources of inspiration that inform the final project. This Introduction recounts early semester phases through personal Imaginations, the maps and the game help us situate the larger context, and last, the Interpretation phase of the studio discusses four design projects created by students. These projects represent diverse responses to the landscape, ecology, history, and people of Thiruppudaimaruthur, and the projects take many forms. Some are structured as dispersed networks. Others are ecological interventions, ritual spaces, or sensory pathways. All share a commitment to attentive observation and thoughtful storytelling. They are interpretive acts that seek to amplify what already exists. Each project aims to make visible, legible, and shareable the intricate relationships between birds, trees, temples, and their people.

Together, the four projects explore interpretation as both a design method and a practice. They remind us that architecture and urban design, when practiced with humility and care, can become an instrument for listening and a framework for retelling the layered stories of a living landscape.

ASHOKA TRUST FOR RESEARCH IN ECOLOGY AND

THE ENVIRONMENT

LOCAL PARTNERS + SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL EXPERTISE

Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) is a non-profit organization focused on environmental conservation and sustainable, socially just development. Founded in 1996, they work to generate and disseminate rigorous interdisciplinary knowledge that informs and is informed by the needs of grassroots communities, policymakers, and the wider public.

The core of ATREE’s work pertains to biodiversity conservation and restoration, water security, sustainable resource use, livelihoods and human well-being, and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Their ecological initiatives and research include long term planning, conservation planning, and bio resource management. Their educational programs include graduate programs, educational programs for children, and local engagement and awareness.

ATREE’s research is anchored in its Community Conservation Centres (CCCs) located in different parts of India. These Centres cover a broad spectrum of research areas, with each Centre emphasizing a unique focus. With the belief that conservation efforts in human-dominated landscapes require active grassroots participation from communities, ATREE’s CCCs facilitate a flow of knowledge between local stakeholders and researchers. As part of our field experience, we stayed at the Agasthyamalai CCC, an educational campus that ATREE runs in Tamil Nadu.

ATREE has been researching a number of areas that align with our project including a detailed study on the restoration of the socio-ecological systems of the Tamiraparani riverscape, a study of the wetlands of Kulam, and the re-introduction and expansion of the age-old practice of temple nadavanams or sacred gardens. They’ve produced their research in a form of pamphlets and brochures geared towards children and the wider public.

ATREE

RESEARCH AND EDUCATION INITIATIVES

LONG TERM PLANNING

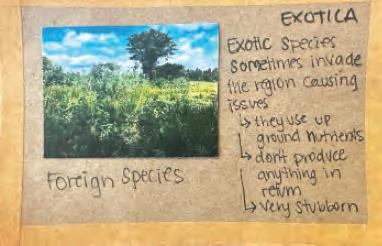

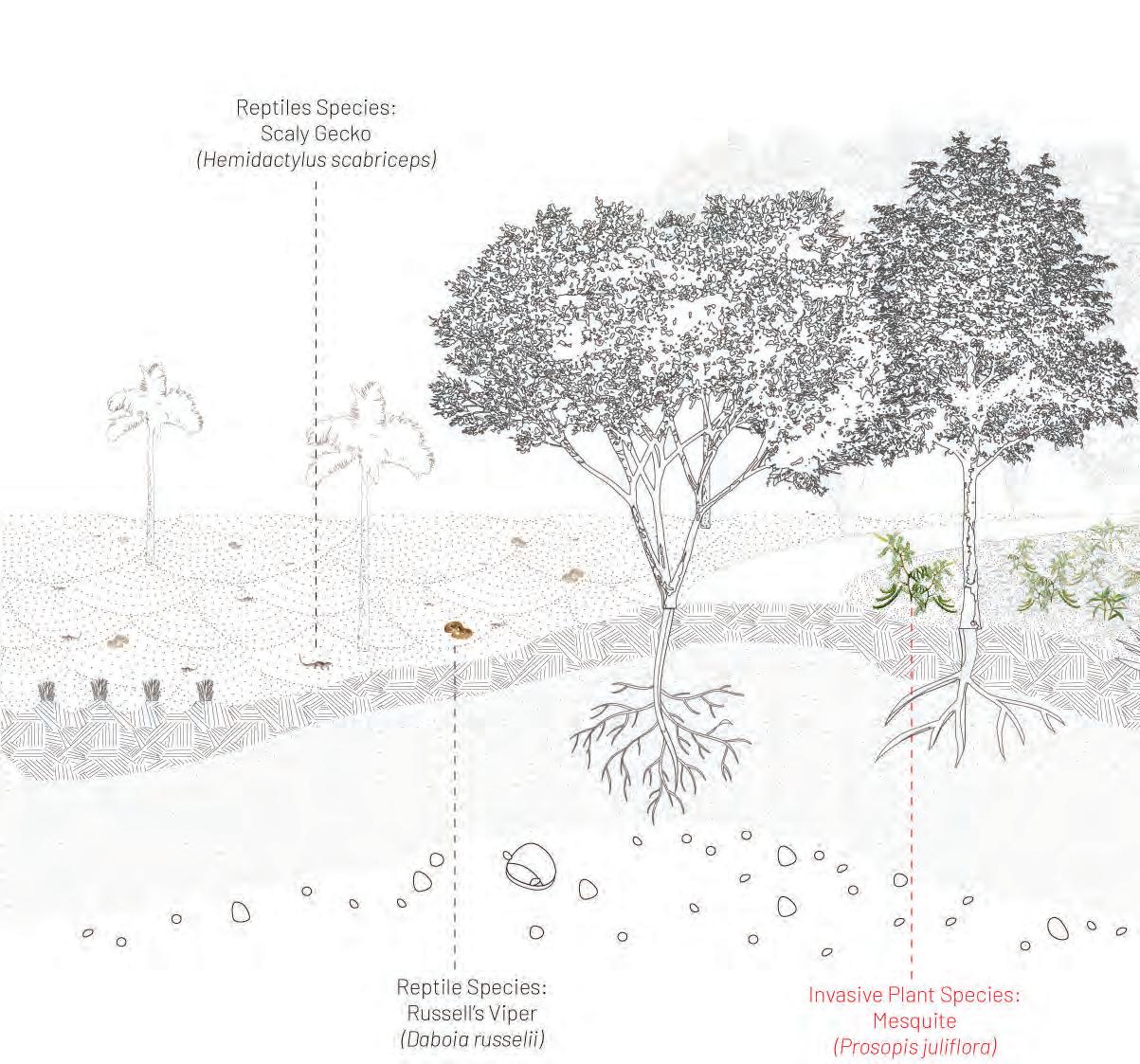

ATREE works in long term monitoring efforts that include studying the regeneration, growth, and reproduction of trees in the Western Ghats, the long term impacts of invasive plant species, and lastly, the studying of the impact of grassland loss on raptors roosts, populations, and migration patterns.

CONSERVATION PLANNING

ATREE engages in conservation planning by collecting landscape data around protected areas to inform conservation efforts, studying distribution, population dynamics and behaviors of species, and analyzing the dynamics of habitat use and species adaptations to better understand interactions between humans and wildlife.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

BIO RESERVE

ATREE studies the potential of insects as bioresources, strategies to promote comanagement and sustainable harvest of forest resources, conservation of highly traded and threatened medicinal plants, and chronicling the use of wild edible plant species.

GRADUATE PROGRAMS

The Academy for Conservation Science and Sustainability

Studies at ATREE offers a PhD Programme, a Master of Science course, and Certificate courses that enable researchers to develop interdisciplinary skills and gain experience in sustainable development and biodiversity conservation.

CHILDREN’S EDUCATION

Engagements with schools include direct interventions with government and private schools in the vicinity of the Community Conservation Centres. The curriculum educates students about the various ecosystems that each particular landscape is endowed with.

ENGAGEMENT/AWARENESS

ATREE facilitates citizen science initiatives and regularly hosts nature walks, in addition to organizing various outreach events to promote community conservation in the space of lake restoration, waste management, water quality testing, school kitchen gardens and more.

ATREE

RESEARCH AND DISSEMINATION

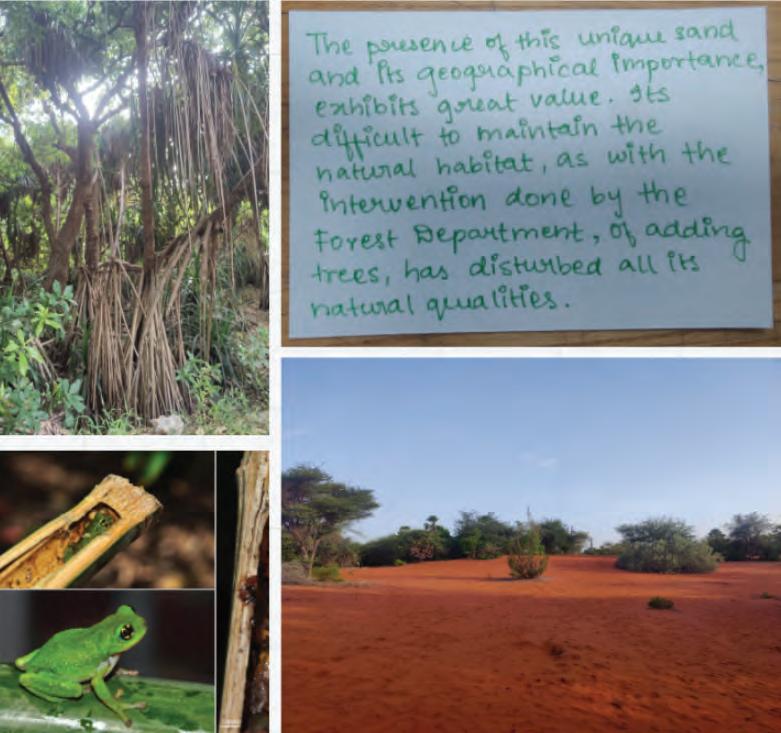

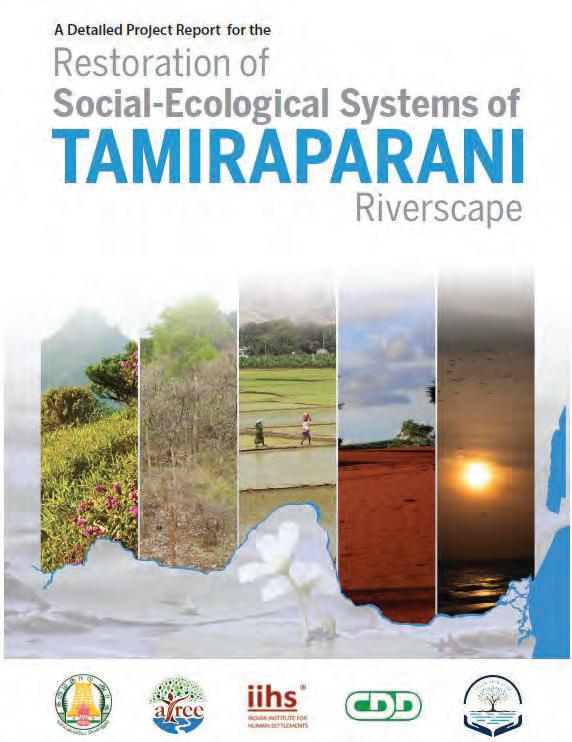

“A Detailed Report for the Restoration of Social-Ecological Systems of Tamiraparani Riverscape” presents the complex Tamiraparani riverscape social-ecological systems (SES) to develop a roadmap for restoration. Resource restoration and conservation are continuous process identifying problems, drivers, and building local scalable and sustainable restoration models. Phase-I identified concerns based on the ground survey, local engagement and support of the ULBs including village and town panchayats, and the district administration. The models proposed are bottom-up, employing scientific methods, and inclusive of key stakeholders ranging from the public and private sector including policy makers, practitioners, scientists and non-government organizations, as well as citizens groups potentially impacted.

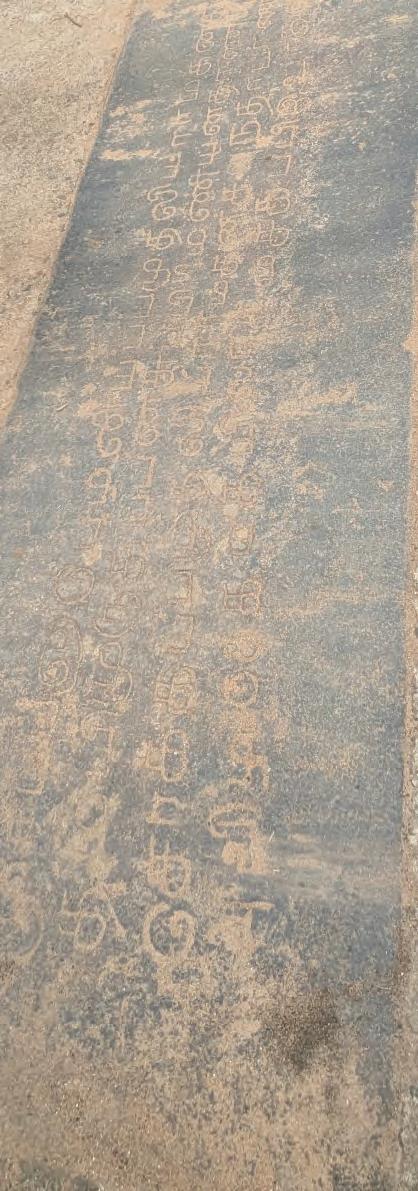

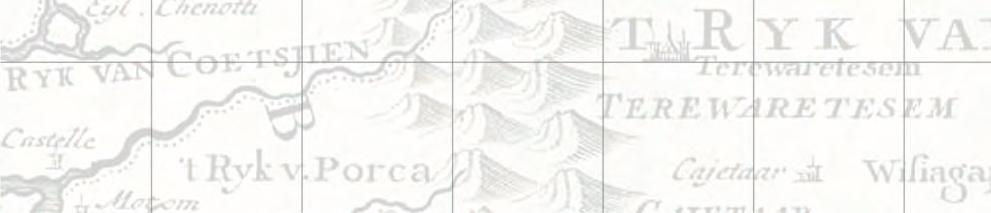

“Trails of Tamiraparani” is an attempt to capture the myriad hues of the landscape, the travails of the past, its glorious heritage, and the prosperity of the region. The river Tamiraparani, the only perennial river in Tamil Nadu. It originates in the Pothigai Hills in Tirunelveli District. The book comprises four chapters—Ainthinai, Panpadu, Varalaru, and Vazhviyal as enshrined in the ancient Tamil Sangam literature. Ainthinai (landscapes), captures the five vivid landscapes of Tirunelveli from the mountains to the shores, while Panpadu (culture) reminisces the symbols of past glory. Varalaru (history) offers a glimpse into the transition from Tinnevelly to Tirunelveli and Vazhviyal is a colorful narrative of people, culture, and livelihoods.

Restoration of Social-Ecological Systems of

ATREE

ENVIRONMENTAL

EDUCATION

Based at the Agasthyamalai Community Conservation Centre (ACCC), ATREE conducts several environmental education programmes for children and youth in the Agasthyamalai landscape and beyond. The ACCC works with over 20 government and private schools across five districts –Tirunelveli, Tenkasi, Thoothukudi, Virudhunagar, and Kanyakumari of Tamil Nadu. It has designed a specific activity based, ‘Ainthinai Arivom’ curriculum about various ecosystems that the landscape is endowed with – mountains, wetlands, forests, grasslands and coastal lands.

The Conservation Connect course by ATREE ACCC helps participants explore biodiversity and ecosystems, learn about the flora and fauna, understand ecological significance and threats, and plan and lead immersive nature-based education. This certificate course on biodiversity and climate literacy that “ trains the trainers” to empower educators connect children to nature. This course aims to inspire the next generation of environmental stewards with hands-on activities, nature walks, and outdoor experiences!

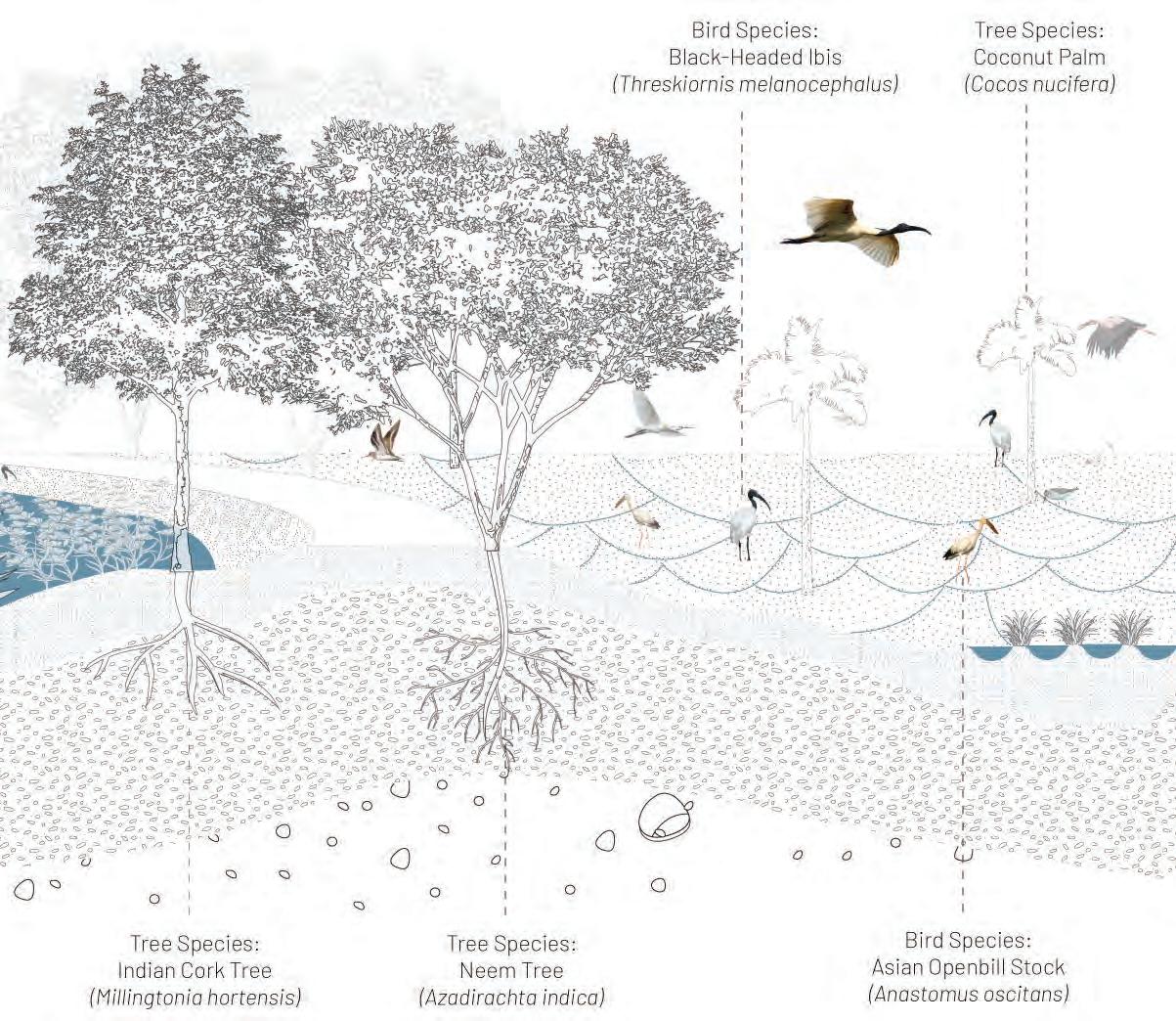

SACRED GARDENS ATREE

ATREE works to revive the tradition of sacred gardens around temples, recognizing them as important refuges of biodiversity. By studying temple gardens as living sanctuaries, ATREE documented the diversity of birds, butterflies, small mammals, and native flora that thrive under community protection. Their research highlights how factors such as tree density, species richness, and canopy height are directly linked to greater faunal diversity. This understanding helps inform garden management practices that not only enhance ecological services locally but also sustain the cultural and spiritual values embedded in these landscapes.

Opportunities for Wilding

ABOUT ATREE

INITIATIVE - WETLAND RESTORATION

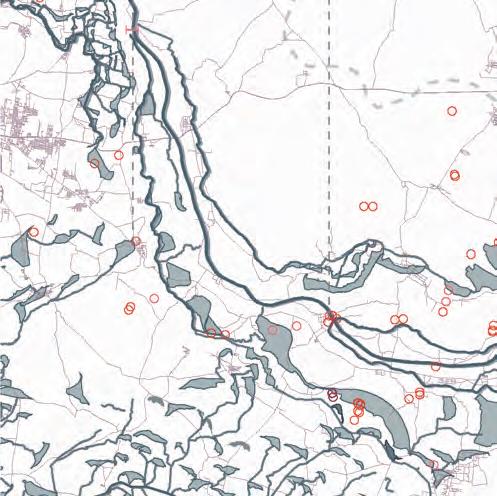

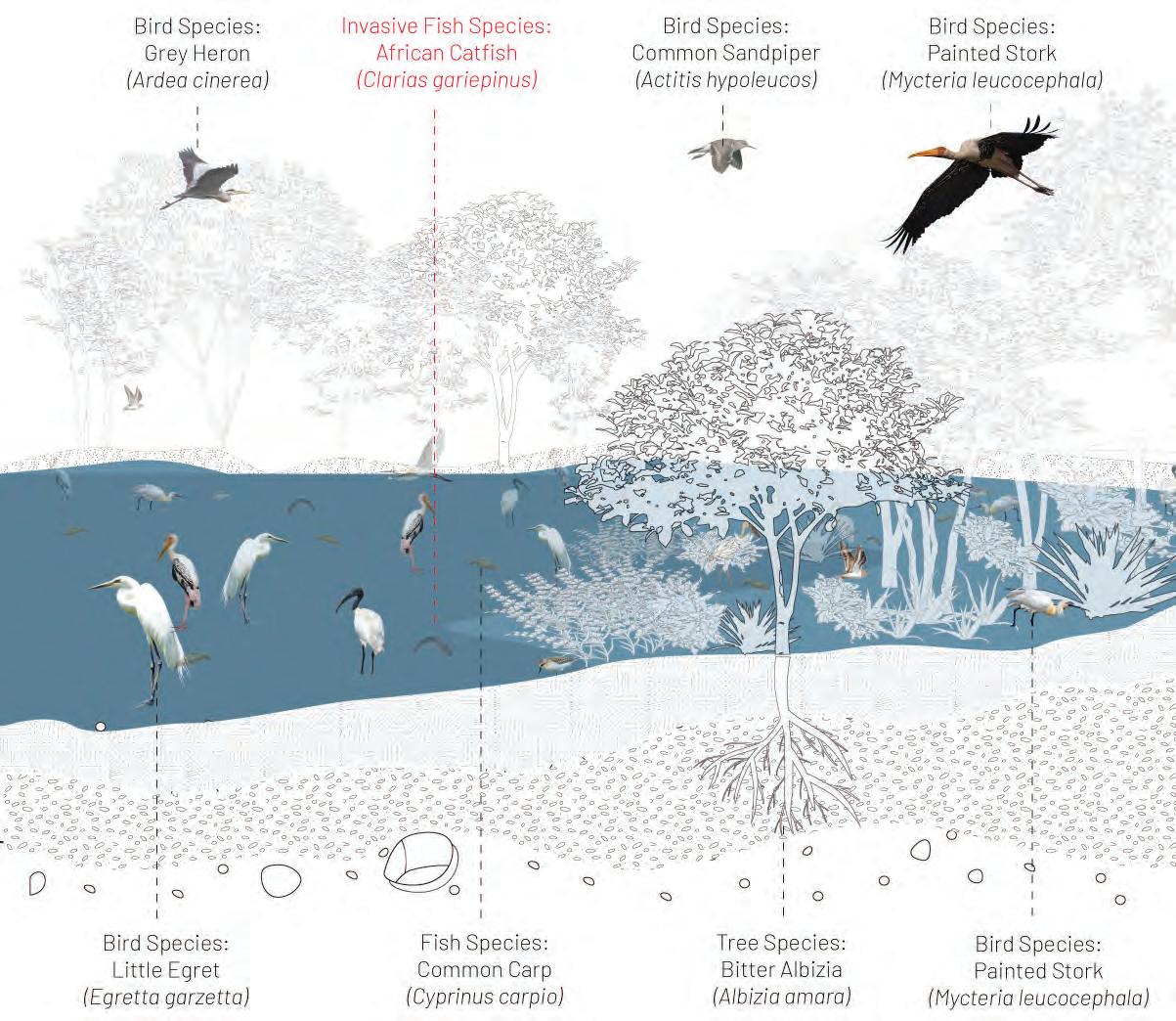

ATREE is at the forefront of understanding and conserving wetlands in South India. Through long term monitoring of 133 irrigation tanks in the Tamiraparani river basin, ATREE and its network of volunteers have generated rare landscape scale data on waterbird diversity and abundance. Their research not only reveals subtle but concerning declines in several resident and migratory species, but also pioneers methods to identify priority tanks for conservation. By focusing on these ancient man made wetlands, integral to both ecological and agrarian systems, ATREE emphasizes the need to safeguard them as critical habitats in the face of global wetland loss.

Prepared by

ATREE

AGASTHYAMALI

COMMUNITY CONSERVATION CENTRE

ATREE’s research is anchored in its Community Conservation Centres (CCCs) located in different parts of India. These Centres cover a broad spectrum of research areas, with each Centre emphasizing a unique focus. With the belief that conservation efforts in human-dominated landscapes require active grassroots participation from communities, ATREE’s CCCs facilitate a flow of knowledge between local stakeholders and researchers. As part of our field experience, we stayed at the Agasthyamalai CCC, an educational campus that ATREE runs in Tamil Nadu.

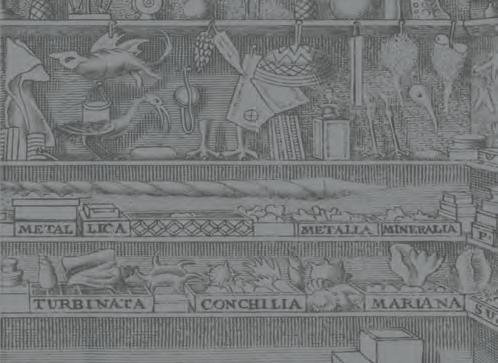

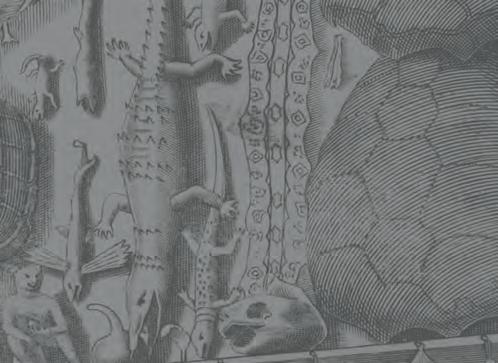

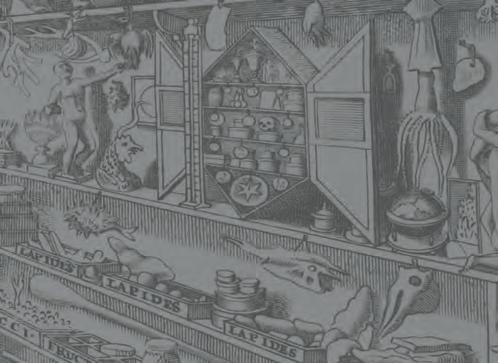

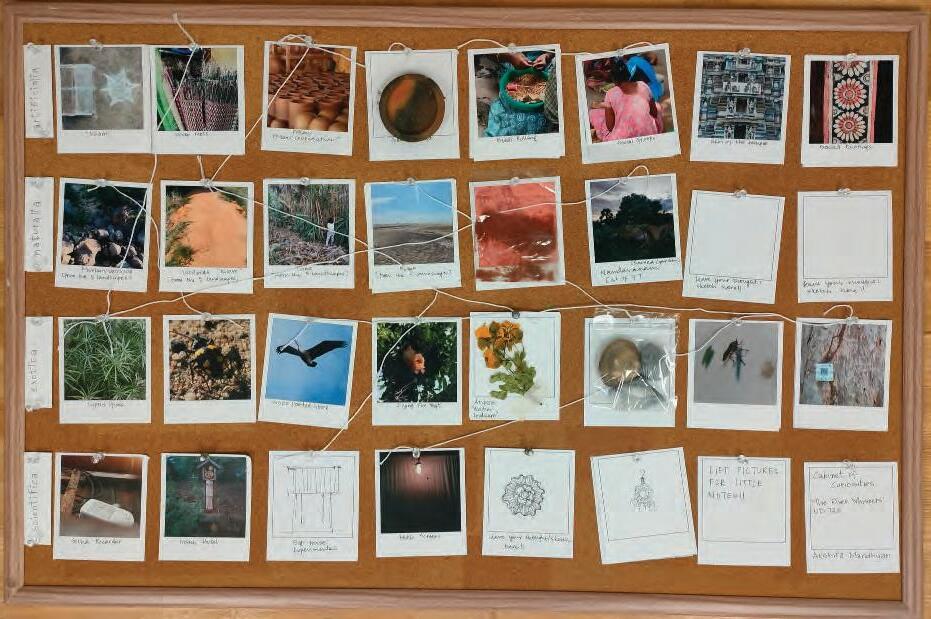

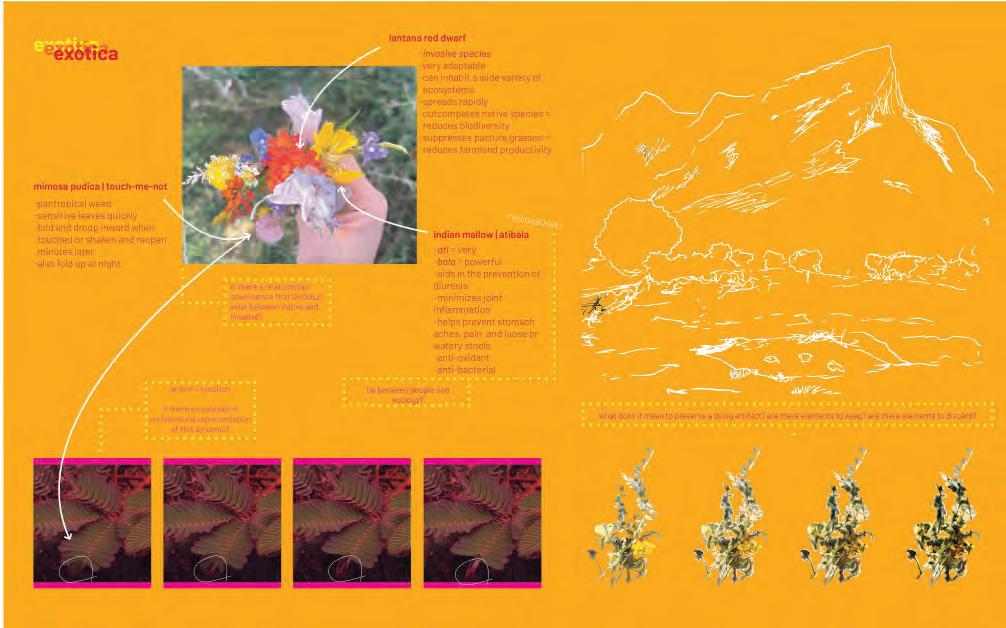

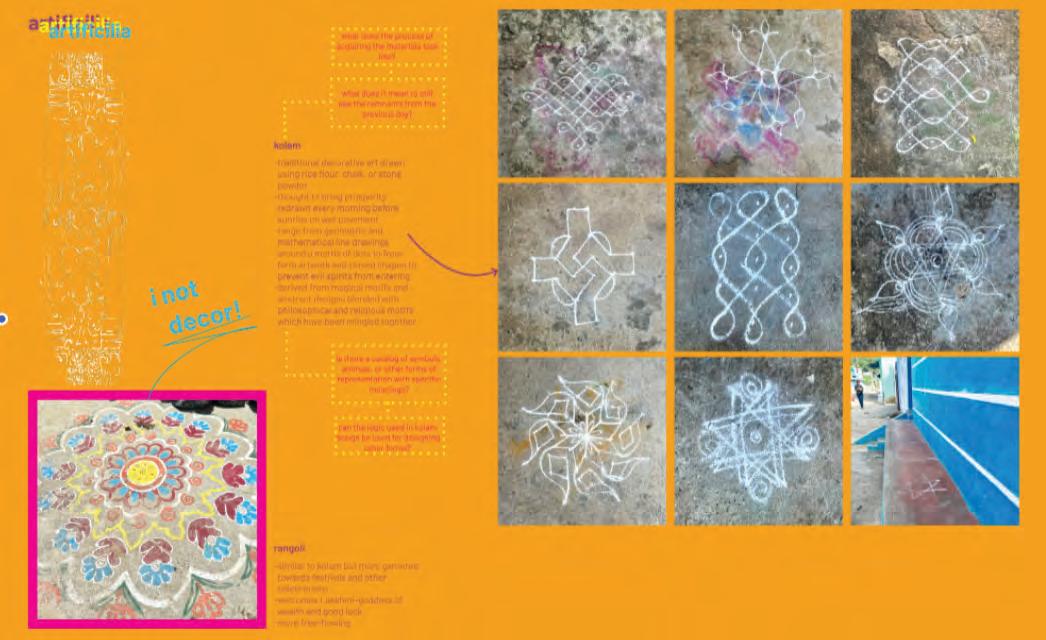

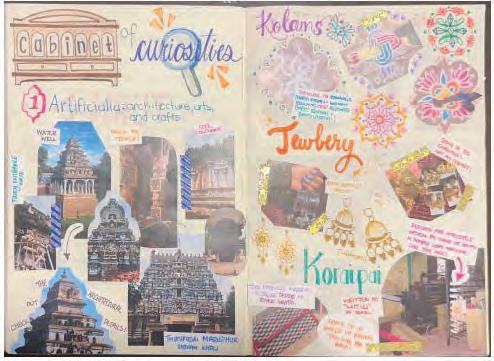

CABINETS OF CURIOSITIES

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

LANDSCAPE IMMERSION

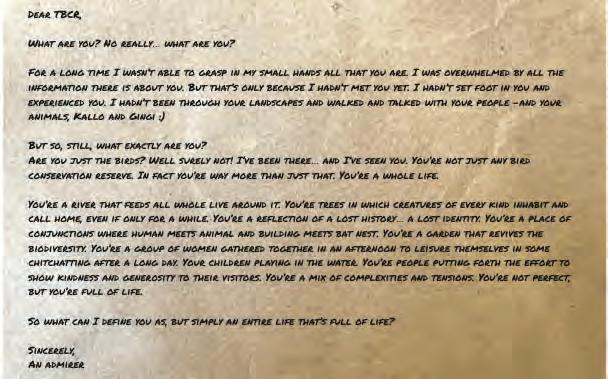

A Cabinet of Curiosities, or Wunderkammer, is inspired by the practice of meticulously collecting and archiving relics from travel that are arranged as microcosms reflecting the entwined worlds of nature, science, culture, and art, combining scientific exploration with subjective interpretation. The field experience at the ACCC brought us into direct contact with the intangible and material worlds we had studied from afar. During our visit, we actively engaged in observing and understanding, hearing and listening, collecting and documenting, and critically examining the world around us. After returning home, it was essential to recollect, classify, and reflect on our individual notes and discoveries. For our Cabinet of Curiosities, each one of us chose a different medium, from narrations, soundscapes, and vlogging to pinboarding. If the site visits invited us to engage with the region with all five senses and be able to understand the many knowledges embedded in place, this exercise ushered us to take stock, to connect the dots between experience and research, personal interests, and documentation. This way, this assignment marks a pivotal transition from the initial stages of the semester to the synthesis and articulation of design proposals focused on the concept of an interpretation center. This exercise ultimately prepared us to articulate design proposals that are not only informed by our observations but are also deeply empathetic and interdisciplinary. By weaving together the tangible and intangible, the subjective and the scientific, we have laid the foundation for creating meaningful interpretations of the region that resonate across scales and disciplines.

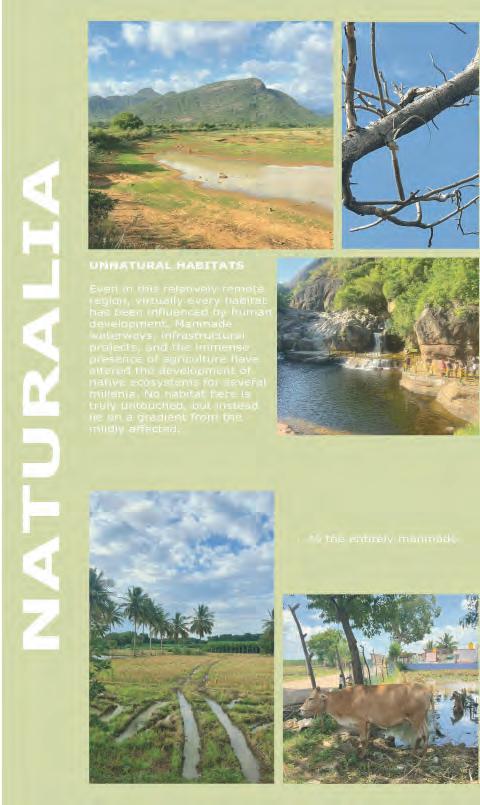

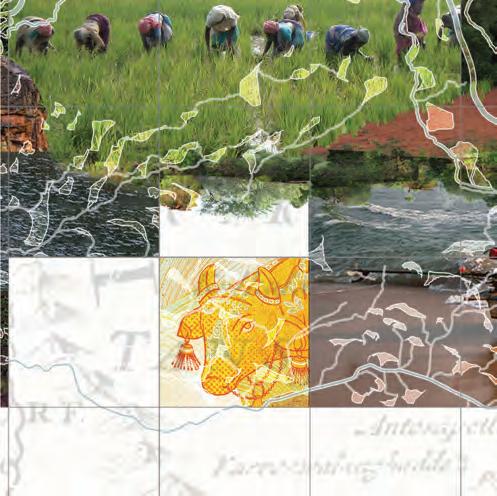

Max Freyberger

The TBCR is an infinitely complex microcosm of the ecological productivity, historical heritage, and social dynamics of life in Tamil Nadu. It is a compelling site, where the landscape is defined by the millenia-old conflict between a region rich in native biodiversity and the endless reshaping of the environment by an ancient human culture. To understand the TBCR is to understand a condition replicated endlessly along the banks of the Tamirabarani. The secret worlds of its species, interactions, practices, and structures provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the broader region of the Tamirabarani watershed. From the droves of bats that dwell in its cavernous temple to the hordes of ibis scouring flooded paddy fields, the TBCR presents an amalgamation of unique biological interactions where humans play a pivotal role.

Max Freyberger

The landscape of Thiruppudaimaruthur is a reminder of our inextricable relationship with the natural world, and the closeness with which the villagers live to the earth vividly illustrates both our dependence and our influence on the environments we inhabit. It is furthermore a landscape in constant flux - endless, cyclical change drives this space and those that inhabit it. The monsoon rains come and go, the floodwaters rise and fall, and the diurnal rhythms reveal a different collection of species and village activities with every passing hour.

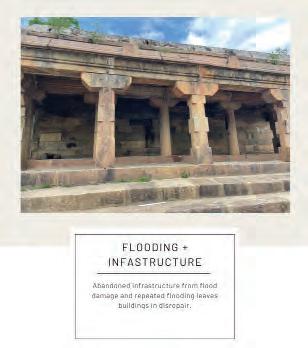

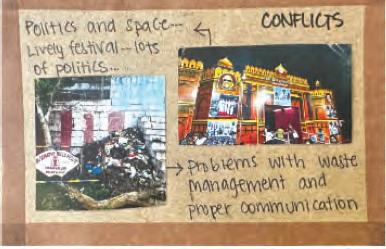

The TBCR is not an idyllic paradise. On the contrary, this delicate ecosystem - of which humans are an integral component - is under constant threat from a variety of sources. The flood of 2023 and its devastating effects on local infrastructure highlights the precariousness of this riverside settlement. The blight of human waste, found abundant even in the sacred forests surrounding the temple, presents a complicated socioecological issue that must be addressed if the TBCR is to flourish. While these challenges are pressing, they nonetheless provide an opportunity for further understanding and rewriting the complex relationships found within the reserve.

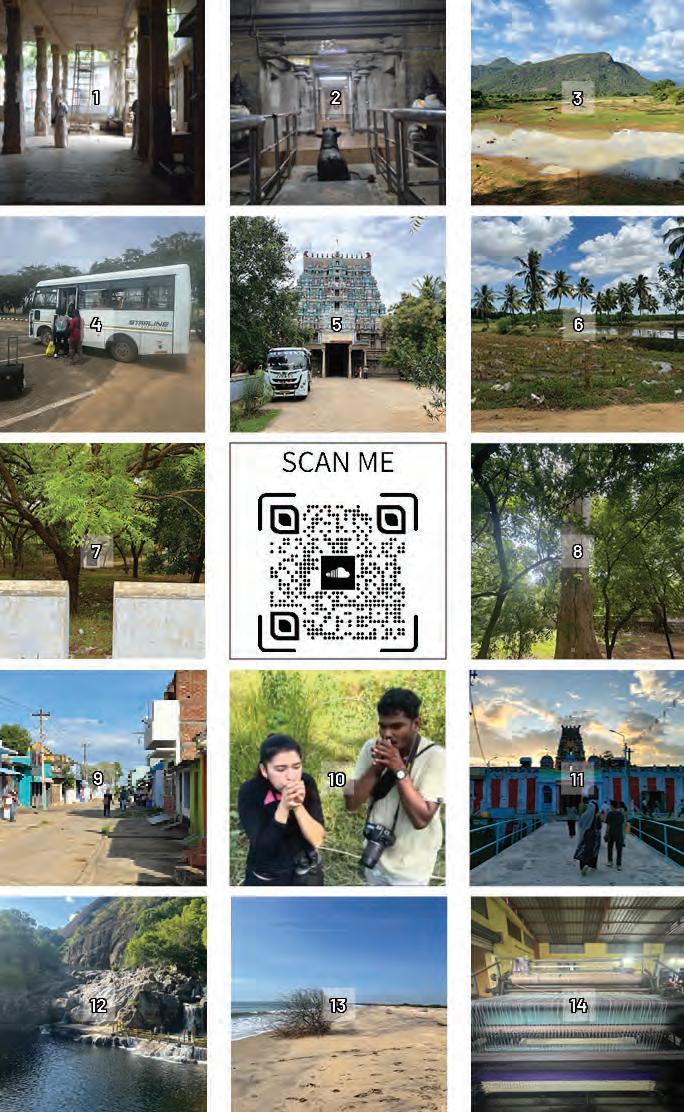

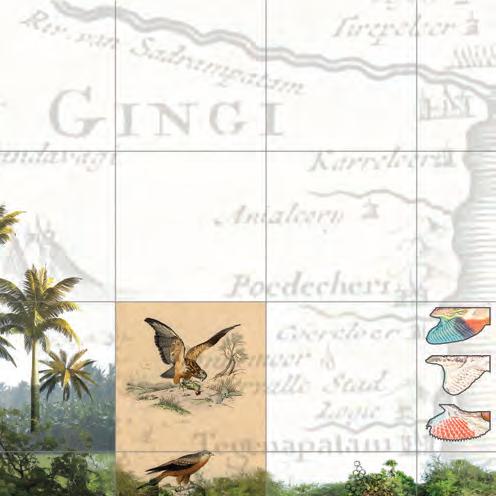

Yi Min Tan

The Sounds of the Tamiraparani & Beyond is deeply inspired by the rich and varied landscapes shaped by the Tamiraparani River as it winds its way through the region. This project seeks to explore and celebrate the profound ways in which these diverse environments interact with and influence the human senses, offering unique sensory experiences that are deeply rooted in the natural and cultural fabric of the area. By focusing on the intricate relationship between sound and space, it aspires to serve as a vital and immersive part of the journey, inviting participants to engage more fully with the essence of these landscapes through a carefully curated auditory lens that complements their visual and spatial qualities.

The photographs featured in this collection are personally captured, and the accompanying audio recordings are meticulously gathered on-site, ensuring an authentic and intimate representation of each location. This approach is intended to offer those who engage with this “cabinet of curiosity” a deeply personal connection to the experience. By immersing themselves in these carefully curated sights and sounds, viewers are invited to share in the emotions and sensations I encountered during my time at each unique place, fostering a more meaningful and heartfelt engagement with the landscapes and their stories.

A QR code linked to a specially curated playlist of sounds associated with the photograph of a particular location provides a simple yet innovative way to immerse oneself in the essence of various places and landscapes. This feature allows individuals to access and experience the unique auditory elements of these environments at their convenience, enabling a deeply engaging sensory journey that can be enjoyed anytime and anywhere, seamlessly blending soundscapes with visual memories.

Akshita Mandhyan

Nested in the Tamiraparani Riverscapes, TBRC is reflective of the constant tensions between various elements that make it. On the one hand, the human beings have held onto the sacredness of the space with the presence of temples, history, bird species, religious practices, the perennial waters but on the other hand, the dichotomy lies in how their behavior continues to exploit and pollute the very landscapes they consider sacred. The presence of casteism is almost a system of apartheid that no longer holds any relevance. Somehow we have even managed to create castes within the lower castes to further create divisions instead of uniting - this is reflective in the presence of three hamlets with varying levels of access to infrastructure, opportunities, and facilities. There are aspirations of co-existence between human beings and nature but the challenges of coexistence are also very real as in the case of the birds claiming a whole school and driving children away. This particular example also makes me wonder how this is exactly what us humans have been doing since the beginning of our time on earth, claiming space and territories and pushing other species away, or treating them differently and sometimes, even certain groups of our own species based on caste, gender, color, religion, and various beliefs.

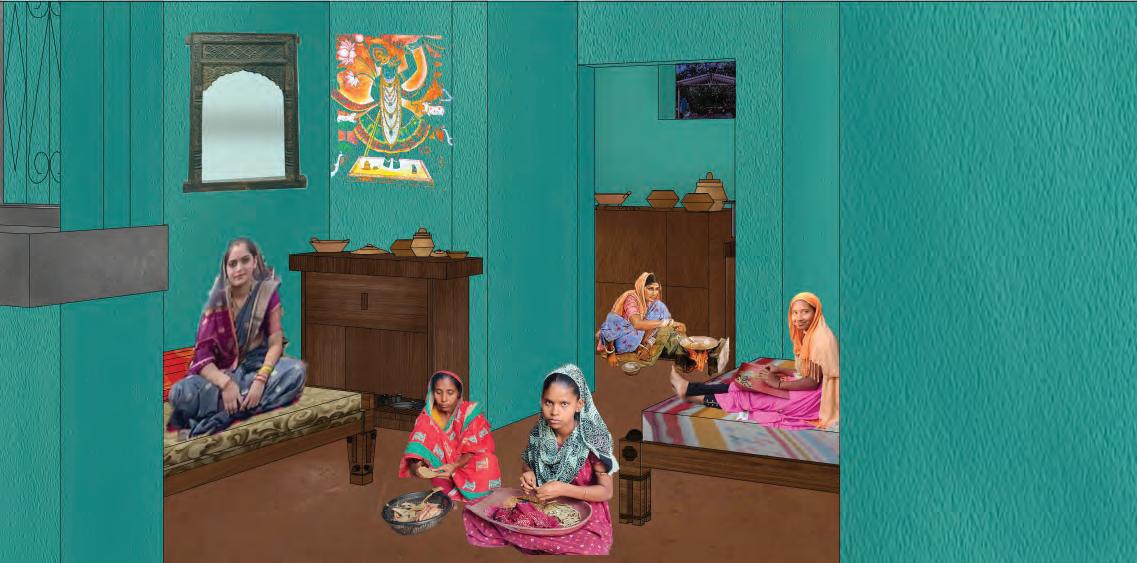

And, almost like an oxymoron, there is the existence of enormous joy and laughter and companionship within the social groups of women united by the hazardous profession of beedi rolling. And so, I interpret TBCR as a representation of conflicts of existence and behaviors and interactions between interspecies and interspecies.

Stephanie Dutan

After visiting the TBCR and the adjacent landscapes that have found themselves rooted into the ebbs and flows of the Tamiraparani River, to interpret means to understand the interconnectivity and relationships built upon each of the coexisting systems within the smaller scale of Thirruppudaimaruthur up to the regional of Tamil Nadu. In doing so, reading the landscape as one story aids to the cohesiveness and interdependency various elements unknowingly reach and take a part in. To do so, one needs to establish the actors at play, the various scenes that have found relevance to the plot, and characterize their roles to somehow formalize an interconnected network that soon reveals opportunities to further their story.

Stephanie Dutan

The actors range from the living to nonliving, human and nonhuman, with the protagonist shifting from which story is being told. Principle leads include the birds of the conservation reserve, the temple groundskeepers (whether that be the monkeys, goats, or the humans facilitating the temple’s opening and closing times), the neighboring residents within the three clusters (this ranges from the beedi rollers, waste management workers, paddy field workers, tea shop owners, and those classified as all the above), and the children who get to learn about all five landscapes in which this is all set in. The river itself could be seen as both actor and site with its dynamic nature being enough to characterize itself and yet also be a grounding point for others and their means/purposes. Besides the river, the temple, the paddy fields, sacred gardens, and the connecting road can be utilized as speculative sites to further conversation.

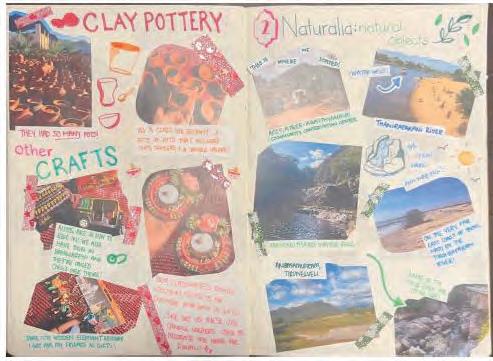

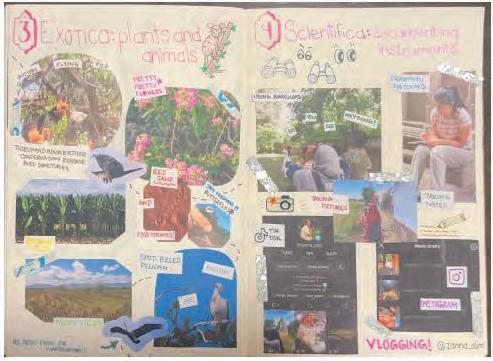

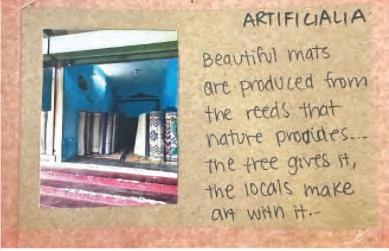

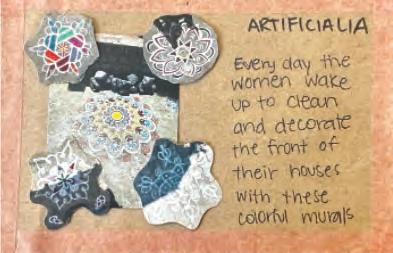

Zannatun Alim

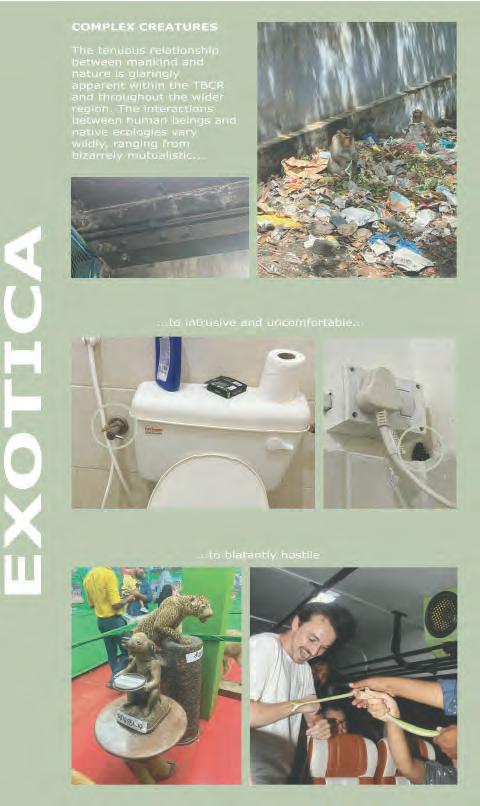

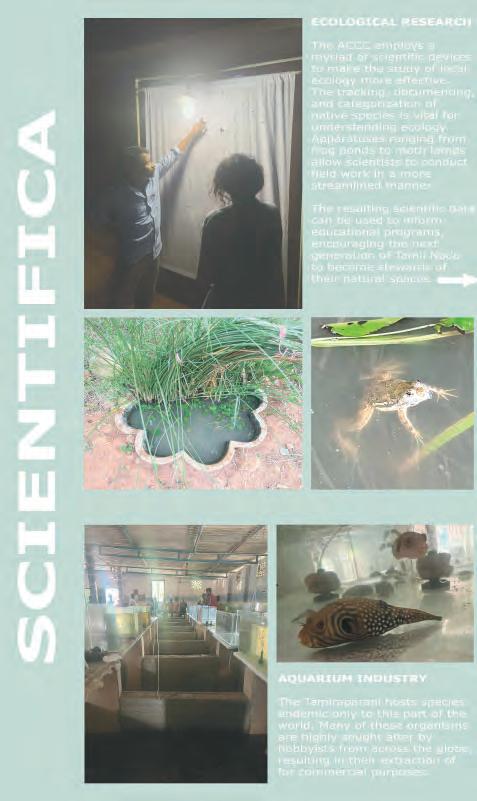

My Cabinet of Curiosities is a scrapbook to showcase the four categories— artificialia, naturalia, exotica, and scientifica—and my personal interpretations. By combining a variety of media, including photographs, sketches, and even some physical artifacts, I sought to create an immersive and artful presentation. Each page reflects my findings and intertwines my interests, personality, and creative perspective.

As the project evolved, I incorporated a modern twist on scientific documentation. Inspired by the growing popularity of digital storytelling, I decided to experiment with vlogging as a contemporary method of recording and sharing discoveries. Towards the end, I created a series of brief, one-minute vlogs, featuring short clips of our activities and adventures during our trip to India. These videos capture the essence of our journey, blending raw exploration with a touch of personal storytelling. Dive into my scrapbook and vlogs to join us on this vibrant and memorable adventure!

I’ve provided a QR code for you to explore the travel vlogs I created and shared on my personal and private Instagram Reels and TikTok accounts. For your convenience, I’ve combined all the clips into one seamless, chronological video, making it easy and enjoyable to relive the journey from start to finish.

Deepa Bansal

“The birds sing tales of lives entwined, where faith and nature gently bind. In temple halls and fields of green, a timeless harmony can be seen.”

In the quiet dawn of Thirruppudaimaruthur, I found myself standing by the Tamiraparani River, its waters whispering stories as old as the earth itself. This place felt alive—not just with the hum of insects or the rustling of riparian forests, but with a pulse that connected every element to the sacredness of the land. I wandered along the trails, where each step unlocked a fragment of history. By the end of the day, as the sun dipped into the horizon and the air grew heavy with the aroma of paddy fields, I realized this journey was more than an exploration. It was a conversation between me and the land, its waters drawing me into its rhythm, its stories etching themselves into my soul. My Cabinet of Curiosities is not just a collection of artifacts; it’s a living memory of these encounters, a place where every element carries the weight of its interconnected beauty and fragility. Every item within it whispers of a life intertwined with devotion, nature, and history. There are earthen pots shaped from the soil of irrigation tanks, their texture carrying the memories of the hands that sculpted them. Mats woven from dried grass hold the scent of sun-kissed fields, while delicate wooden toys, tied with silent prayers, embody the hopes of families yearning for blessings. And then, there is the temple chariot—majestic and timeless—an emblem of faith rolling through the village as a bridge between the divine and the human.

To step into the cabinet is to feel the rhythm of this place, where belief flows like the Tamiraparani, sustaining and connecting every life. It is a harmony not just heard but felt, where even the birds’ songs seem to carry the stories of people, fields, and forests. Here, life sings a melody that transcends time—a song of coexistence, resilience, and beauty.

EXOTICA

SCIENTIFICA

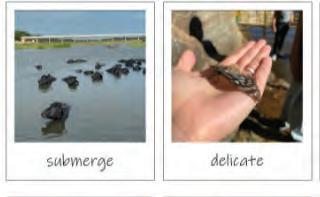

Srinjayee Saha

For my cabinet of curiosities, I sought to capture elements that sparked my curiosity and imagination. Each photograph is accompanied by a single word—a feeling, an idea, or a concept—that resonated with me when I looked at it. Rather than naming the object or subject directly, I chose words that evoke its essence as I perceive it. This invites viewers to reflect on what the image means to them rather than relying on my interpretation. This approach allows the collection to remain open-ended, encouraging personal connections and unique perspectives.

Jordan Biniker

The TBRC is a microcosm of Tamil Nadu and a significant aspect of India as a whole. That aspect is the application of the concept of the word ‘sacred’. Where I come from, the word is rarely used outside of places of worship. It is a word that evokes images of religion and religious iconography. However, in India, the term is also applied to the natural world: rivers, trees, plants, and animals. And so the TBRC, nested in the Tamiraparani riverscape, encompasses all that is sacred in India.

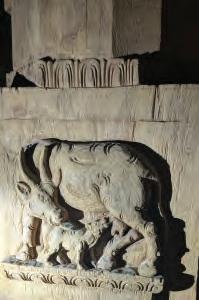

First, there is the Hindu temple, dating back to the 15th or 16th century, whose age underscores how long humans have inhabited the region. Of equal importance is the river, almost touching and feeding the temple and its trees. Arjun trees thrive in a riparian environment. Mahua trees, whose utilitarian purposes ranged from using the oil from their seeds for lamps, bug repellent, and many medicinal uses, were allowed to grow unimpeded. Trees, provided for humans and more than humans alike. Since the temple was sacred, so were its grounds. Left untouched, they produced a natural bounty that served all forms of life.

Learning from this legacy, the space for interpretation may add meaning and impact to this relationship and the evolving Tamil Nadu culture. Reinterpreting and reconsidering what is sacred, and how to protect it, we can harness the widespread appreciation of Hindu temples throughout Tamil Nadu.

Nahj Marium

From what once was… Interpreting TCBR in the context of Thirruppudaimaruthur village and the Tamiraparani riverscapes involves understanding the relationship between humans and their environment. Nestled within the Western Ghats, the village reflects a long-standing human presence rooted in nature. From hunter-gatherer civilizations to agricultural settlers, the community relied on the rich resources of forests and riverbanks. The shift from tribal life to Sangam literature, religious traditions, and dynastic rule highlights its growth alongside the landscape.

What entailed… As the village expanded, forests and scrublands gave way to temples, housing, and farmland. The Tamiraparani River was increasingly harnessed through embankments and dams to support agriculture and domestic use. Yet the original flora and fauna long predated human intervention. While some species adapted, others perished. The resilience of birds and other wildlife, which still inhabit the region, shows the ongoing interplay between humans and nature.

Towards balance… Today, the village’s bird reserve exemplifies controlled growth and degrowth, preserving biodiversity while fostering harmony. This initiative sustains ecological balance and reconnects the community with traditional practices of stewardship. Interpreting TBCR thus means maintaining sustainable models that promote socio-economic and ecological resilience, ensuring future growth respects both cultural heritage and natural surroundings.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

FOUR INTERPRETATIO FOR THIRUPPUD BIRD CONSERVA

ONS DAIMARUTHUR ATION RESERVE

WATER MEMORIES

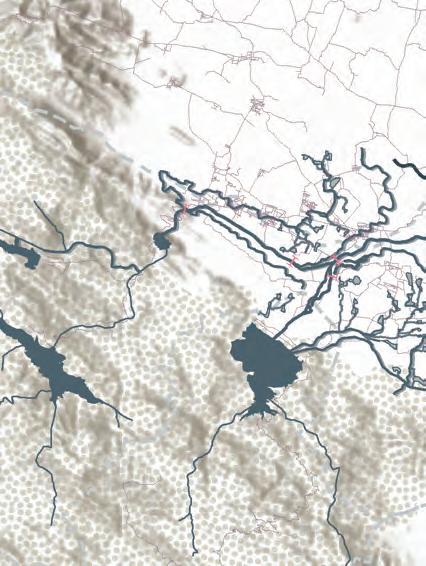

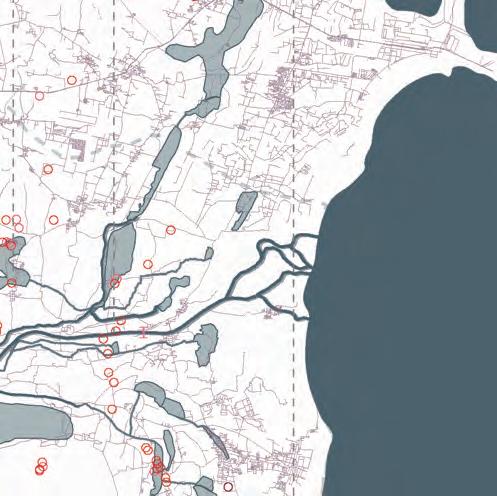

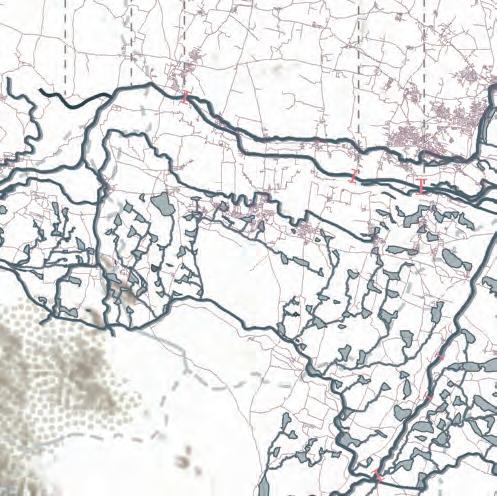

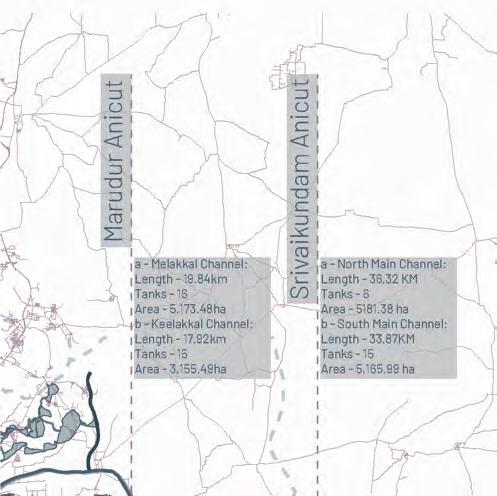

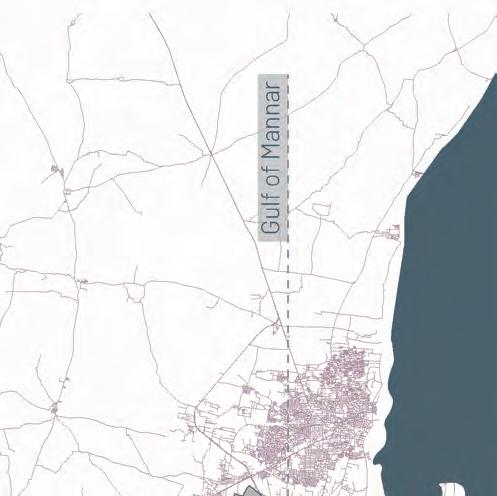

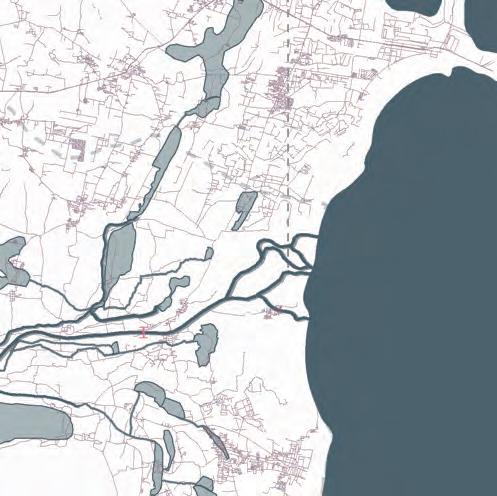

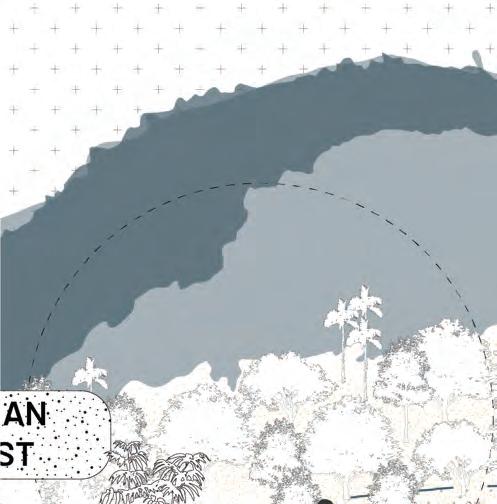

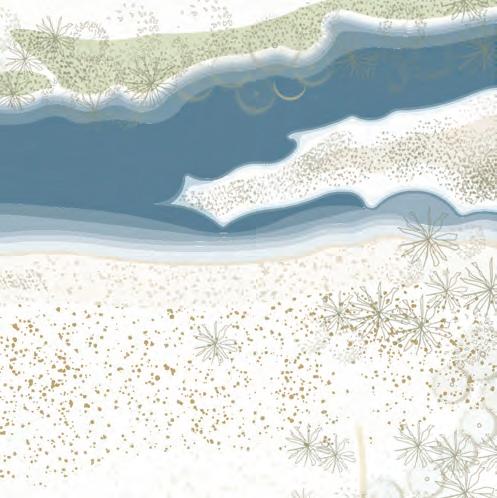

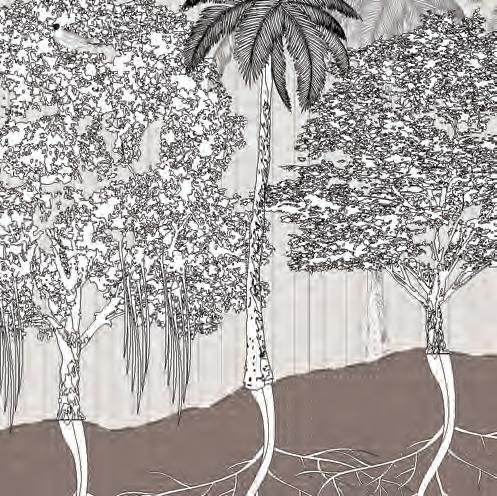

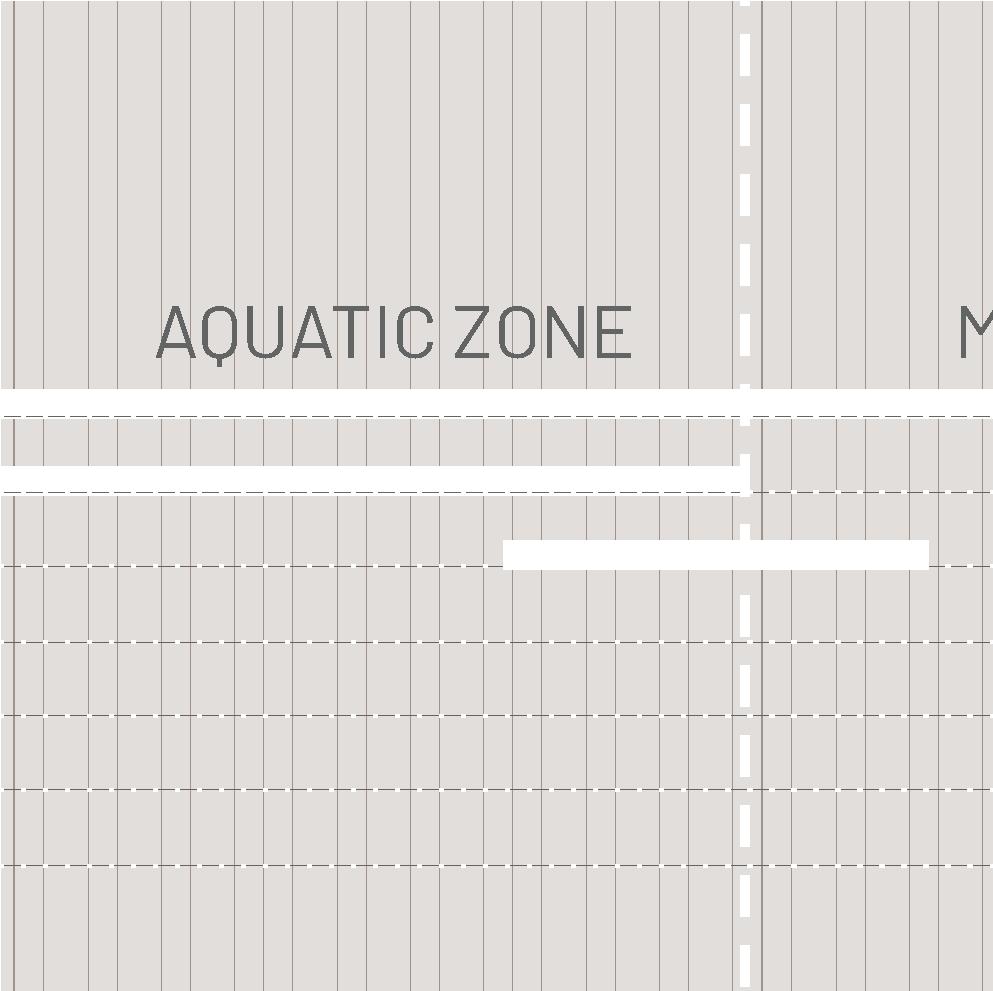

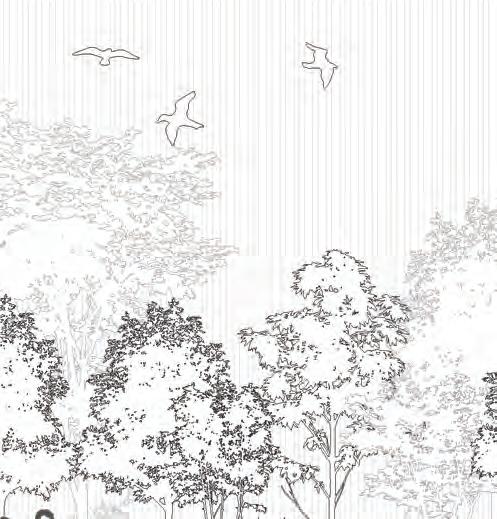

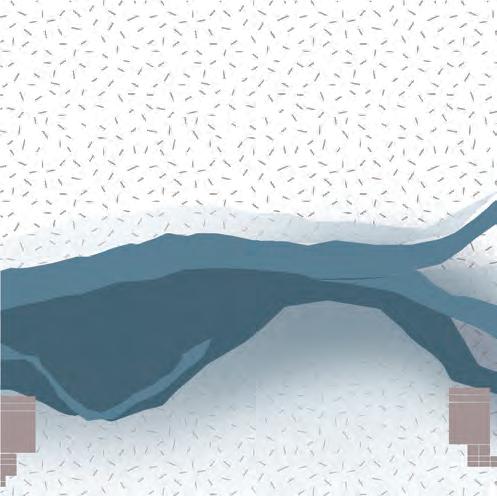

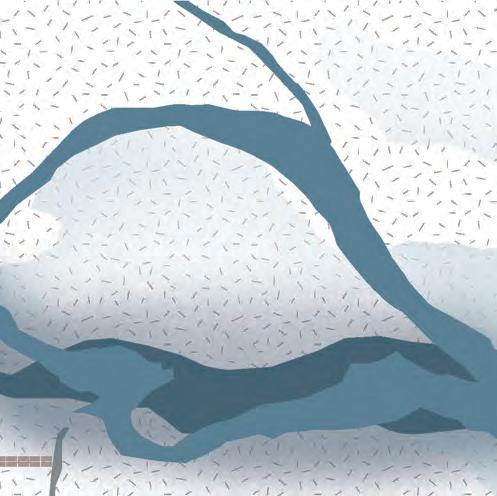

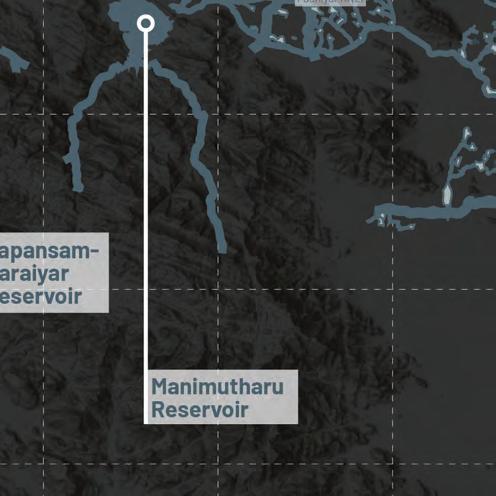

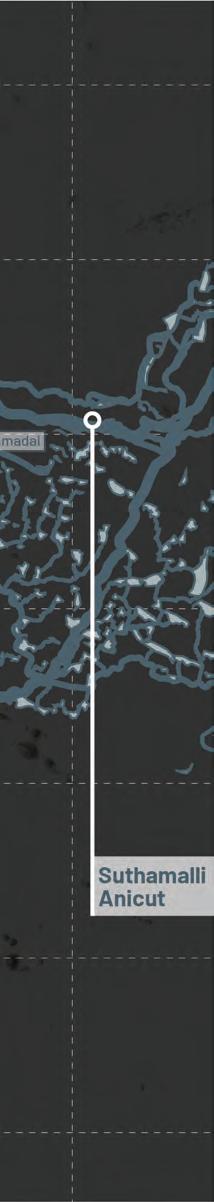

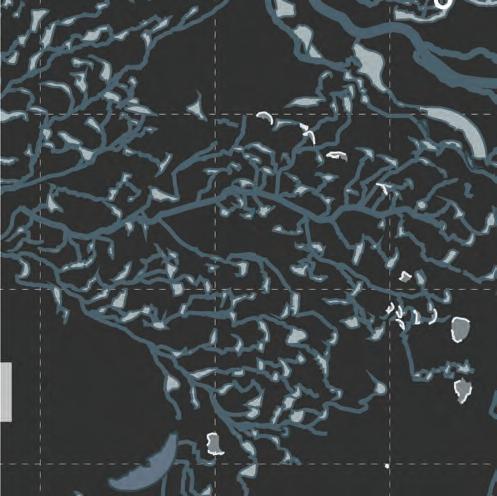

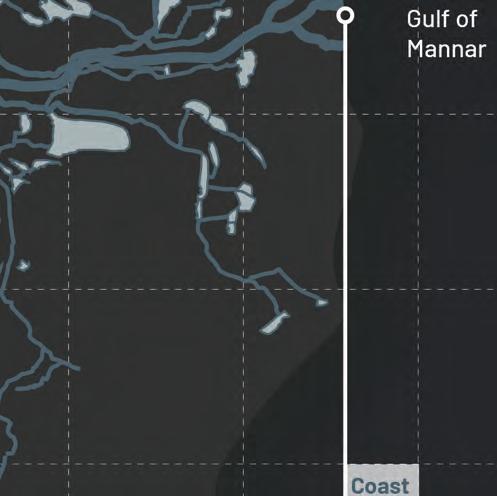

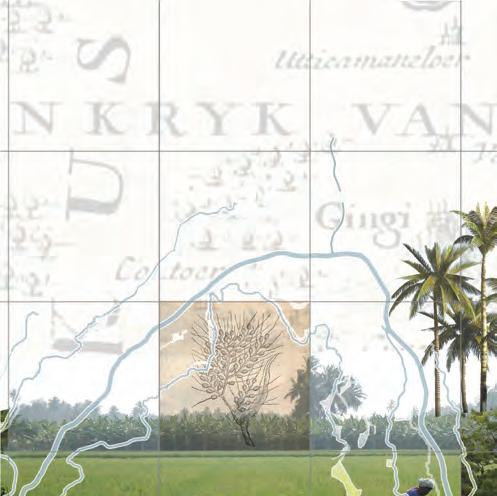

Located along the banks of the Tamiraparani River, the Village of Thirupuddaimaruthur is home to a bird conservation reserve (TBCR) and waterscapes of great cultural and spiritual significance, deeply rooted in Hindu mythology. Shaping diverse landscapes on its course—wetlands, paddy fields, irrigation tanks, riparian forests, tiger reserves, and the Gulf of Mannar—, the river sustain many life forms of flora and fauna, extending beyond human life to nurture the broader ecosystem.

The perennial Tamiraparani River is too the lifeline for the many agricultural communities that populate the district. Ancient irrigation systems like canals, tanks, and reservoirs reflect the ingenuity of early civilizations, who developed a deep understanding of the water regimes and their sustainable stewardship.

Interpreting these watery landscapes in their many forms and states requires careful observation of the interconnectedness between culture and nature. The curation of a series of itineraries across this constellation of waterscapes invites locals and visitors alike to experience wetness, history, and ecology. Small-scale interventions involving local communities encourage conservation practices in the region, disseminating local knowledge and stories, while other components connect with the practices of domesticity, religion, and ecotourism across seasons. Our interpretation strategy includes design components that are adaptable prototypes that can be implemented at various locations along the river.

WATER EVERYWHERE IS

NATURE, ESSENCE OF LIFE SACRED

CULTURE AND TRADITION ECONOMIC LIFELINE

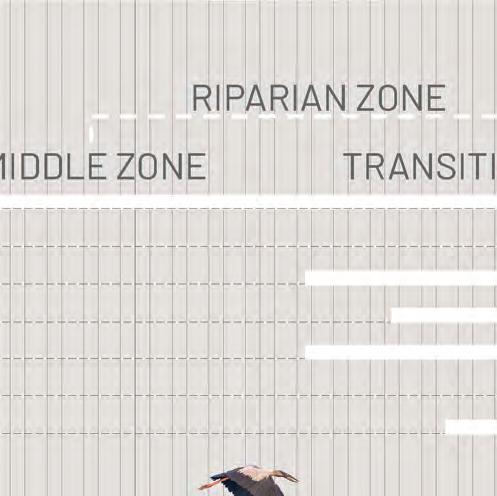

RIVER LANDSCAPES

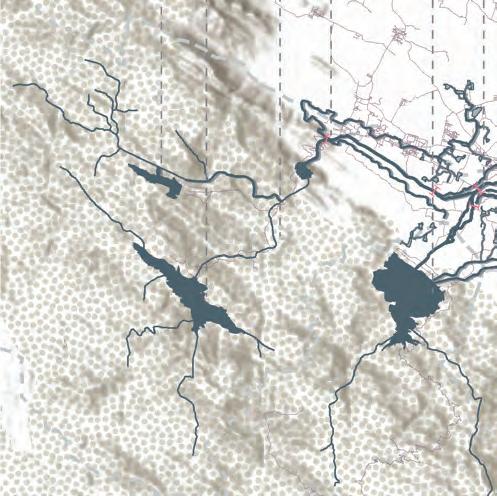

The Tamiraparini River flows through five distinct landscape types as it journeys from the mountainous west to the plains in the east, mirroring the five thinais described in Tamil Sangam literature. These thinais poetically connect the geography and ecology of Tamilagam with human emotions, often tied to romantic relationships. The river begins in the lush, serene Kurinji (mountainous terrain), symbolizing love and union, and descends into the pastoral Mullai (forests), evoking patience and longing. It then nourishes the fertile Marutham (agricultural plains), representing harmony and domestic life, before transitioning to the coastal Neithal (riverine and estuarine landscapes), associated with yearning and separation. Along its course, stretches of arid Paalai (dry regions) reflect hardship and resilience. The river’s journey weaves together ecology, human experience, and tradition, showcasing the interconnectedness of nature and culture.

RIVER LANDSCAPES

KURINJIMULLAIMARUTHAM

The mountainous region that sets the scene for a lover’s midnight union is best known for their hill slopes populated with the flower that gave it its name the strobilanthes kuringi.

The land of the forestcharacterized by it’s waterfalls, ponds, and lakes that receives its name from the jasminum auriculatum flower commonly found in this territory.

The region, known for its croplands and the Marutham tree that gave the landscape its name, was the scene for triangular love plots. The inhabitants were known as ulavar, velanmadar, toluvar, and kadaiyar or kadasiyan, whose occupations involved tilling, ploughing, and farmworking.

PALAINEITHAL

A region of dry lands and, in Tamil prosody, seen as a wasteland that emerges from other landscapes withering under a burning sun, is named after the pala indigo plant, Wrightia.

A region defined by seashore and beaches, and named after the common water lily found here, with inhabitants known as parathavar, nulaiyar and umanar being known for salt manufacturing, pearl diving, fishing, and coastal trade.

SACRED LANDS

The Thamirabarani River holds a sacred and profound connection with the cultural and spiritual life of the region. Revered as a holy river, its waters are believed to possess purifying and life-sustaining qualities. Along its course, numerous sacred places, such as the Srivaikuntam Temple and Agasthiyar Temple, are situated near its banks, symbolizing the river’s divine significance. The river is often associated with religious myths, including the sage Agastya, who is believed to have brought the river’s waters to the region.

During festivals like Thamirabarani Pushkaram, thousands of devotees gather along the riverbanks to perform rituals, take holy dips, and offer prayers to ancestors. The Thamirabarani is a sacred thread weaving together the spiritual, cultural, and practical lives of the communities it sustains, making it a cherished and life-giving force in Tamil Nadu.

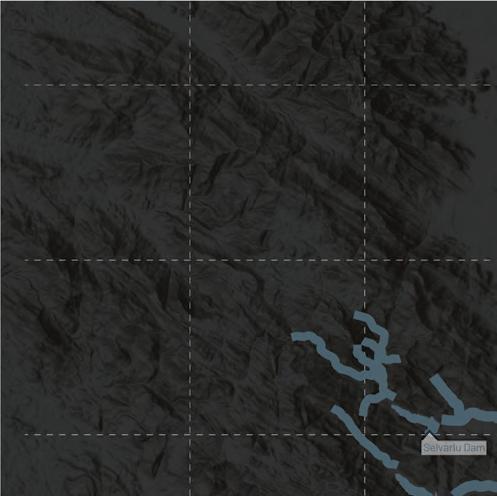

WATER INFRASTRUCTURE

River infrastructures, such as dams, reservoirs, canals, and irrigation tanks, play a crucial role in managing water. These systems harness and distribute water to meet agricultural, domestic, and industrial needs, transforming landscapes to support human needs. By regulating and storing water, they create an intricate network that ensures availability in environments, giving the illusion of water abundance.

The river infrastructures on the Thamirabarani watershed are a testament to centuries of water management expertise. A well-planned network of canals from the river supports a thriving agricultural economy, particularly for paddy and banana cultivation.

RESTORATION PLAN

ATREE’s work on the restoration of the Thamirabarani Riverscape’s SocialEcological Systems (SES) adopts a holistic approach. The initiative, driven by scientific principles and community collaboration, identifies key hot spots for intervention in its first phase. Five pilot sites across municipalities and panchayats have been selected to establish SocialEcological Observatories, focusing on hydrology, water chemistry, riparian vegetation, biodiversity, and human well-being.

The restoration plan emphasizes a bottom-up, stakeholder-inclusive strategy, engaging communities, local institutions, self-help groups, district administration, and policymakers to co-develop solutions. This road map aims to sustain ecosystem services and improve river health through continuous monitoring and collaborative efforts.

RESTORATION PLAN

Focus group discussions with Pandarams (Shaivite monks)

Riparian Buffer Afforestation project

Efforts to observe water quality

Stakeholder engagement

Additional bins and tolilets near ghats

Awareness raising on dumping clothes

THIRUPPUDAIMARUTHUR

(Z III)

“Porunai Nadhi Paakanume” - A nature trail to educate about river conservation and the importance of local biodiversity

Scaling up bio fertilizers use

Proper solid-waste management

Working towards OpenDefecation Free (ODF) village.

Socio-Ecological Observatories

Strengthening disaster management measures and riparian restoration

Clearing Water Hyacinths

KALLIDAIKURICHI BATHING GHATS (Z II)

Condusting Water and Sanitation Survey to document river water use for livelihood activities suggesting a strong co-dependency

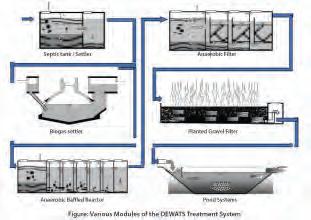

Pilot DEWATS sustainable sanitation solutions

Planting sacred flowering trees

Clearing of Invasive & restoring native vegetation

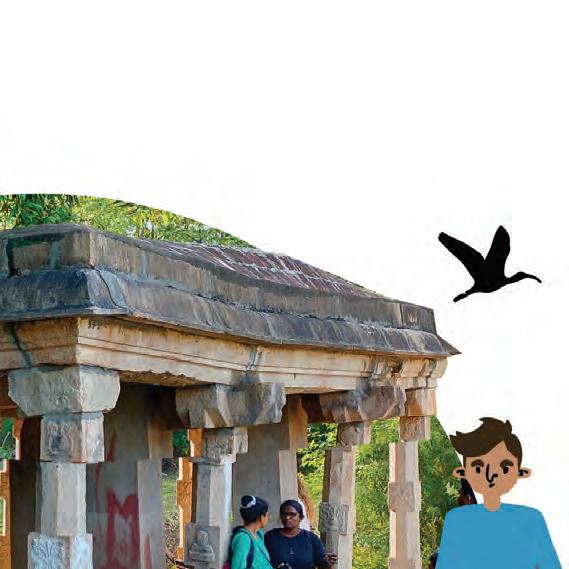

Cleaning and Restoring kal mandapams (bathing ghats)

GOPALASAMUDRAM (Z IV)

Capacity building using a sustainable method of harvesting medicinal plant

Scaling up the usage of bio fertilizers

Introducing cycling trail with community support

Clearing invasive species and introducing native vegetation to restore the river banks

INTERPRETING WATER

The Tirunelveli District holds a thriving ecological tapestry, where lush paddy fields and banana plantations flourish alongside the rhythmic flow of the Tamaraparani River. The agricultural village of Thiruppudaimaruthur is not just a haven for farmers but also a sanctuary for a vibrant congregation of migratory and local aquatic birds. Painted Storks and White Ibises nest annually among the tall trees that shade the village and its temple, embodying a harmonious coexistence with the villagers. The river, teeming with life, supports over 60 species of fish, many endemic to its waters, reminding us of the delicate yet enduring balance of this ecosystem.

INTERPRETING WATER

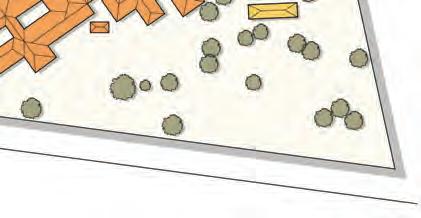

A series of Memory Landscapes connect the ecological and social everyday life across around the ancient temple dating back to 675 BC in the Marutham region. They reflect a tapestry of community life enriched by shared traditions and spiritual diversity. Here, people from various castes and communities coexist, worshiping a multitude of Gods and Goddesses in harmony.

INTERPRETING WATER

The villagers’ everyday practices are intertwined with the rhythms of the river, which sustains their agricultural pursuits and cultural heritage. Local lifestyles blend selfreliance with a deep connection to the land and its resources. This bond between the people, traditions, and the river speaks of a harmonious balance that defines the spirit of the village.

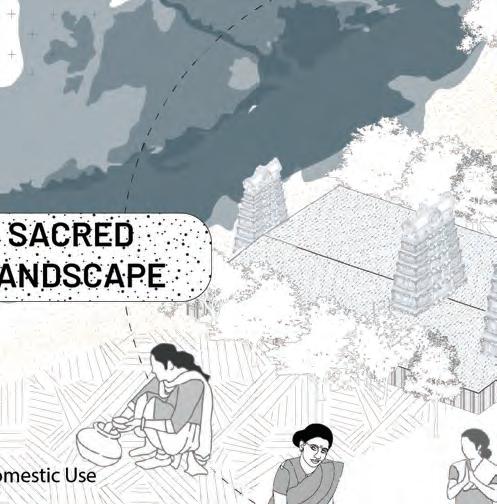

A SACRED LANDSCAPE WATER AS

L A N D S C A P E

A P R O D U C T I V E L A N D S C A P E

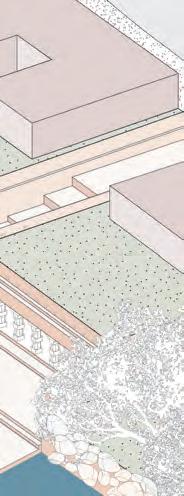

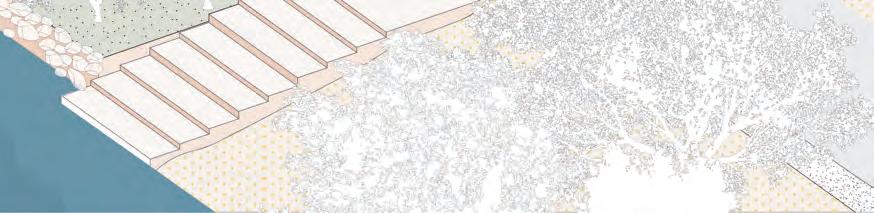

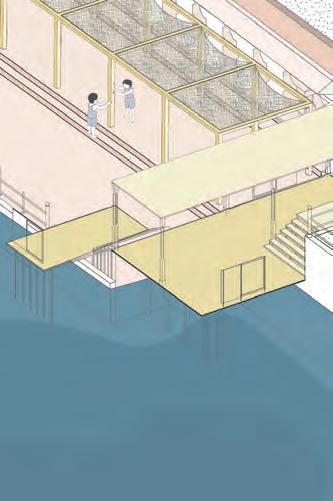

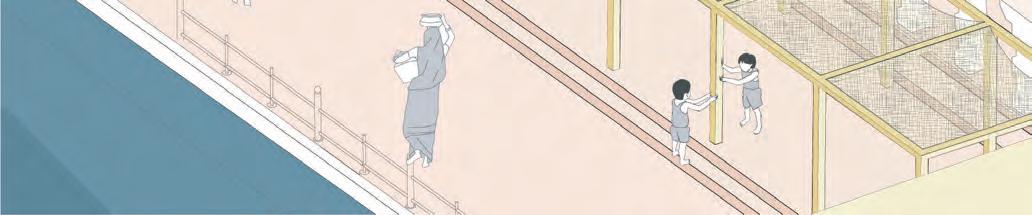

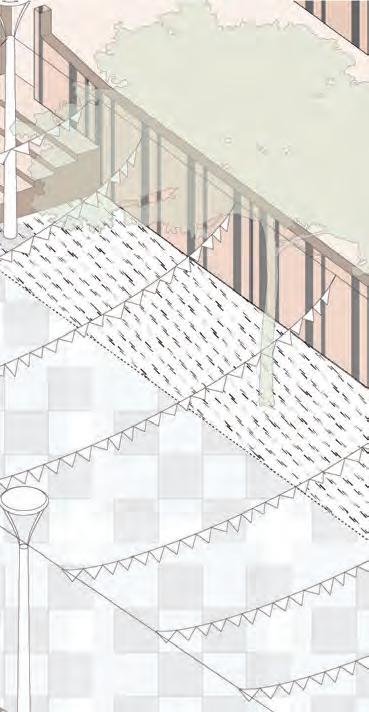

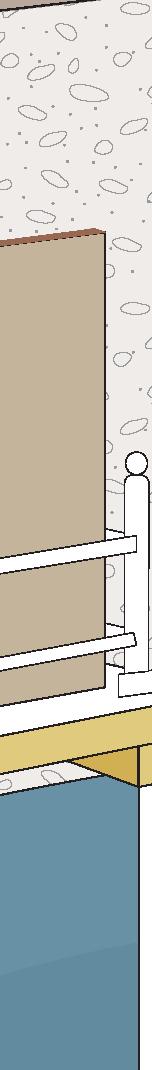

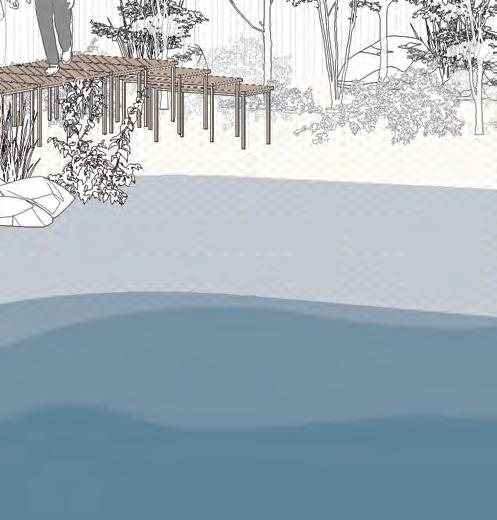

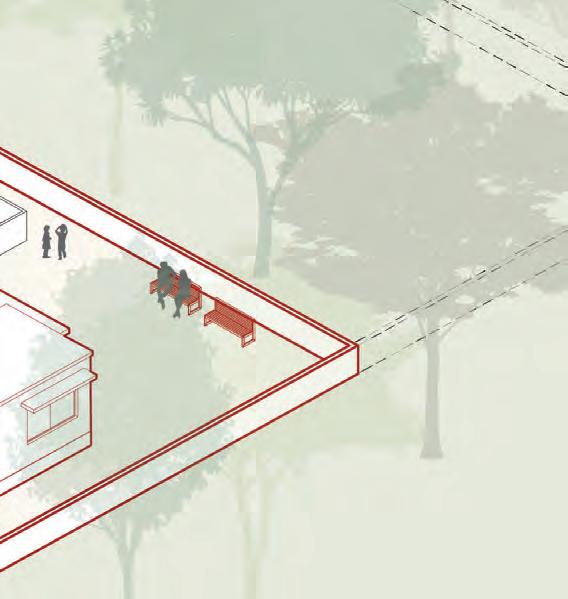

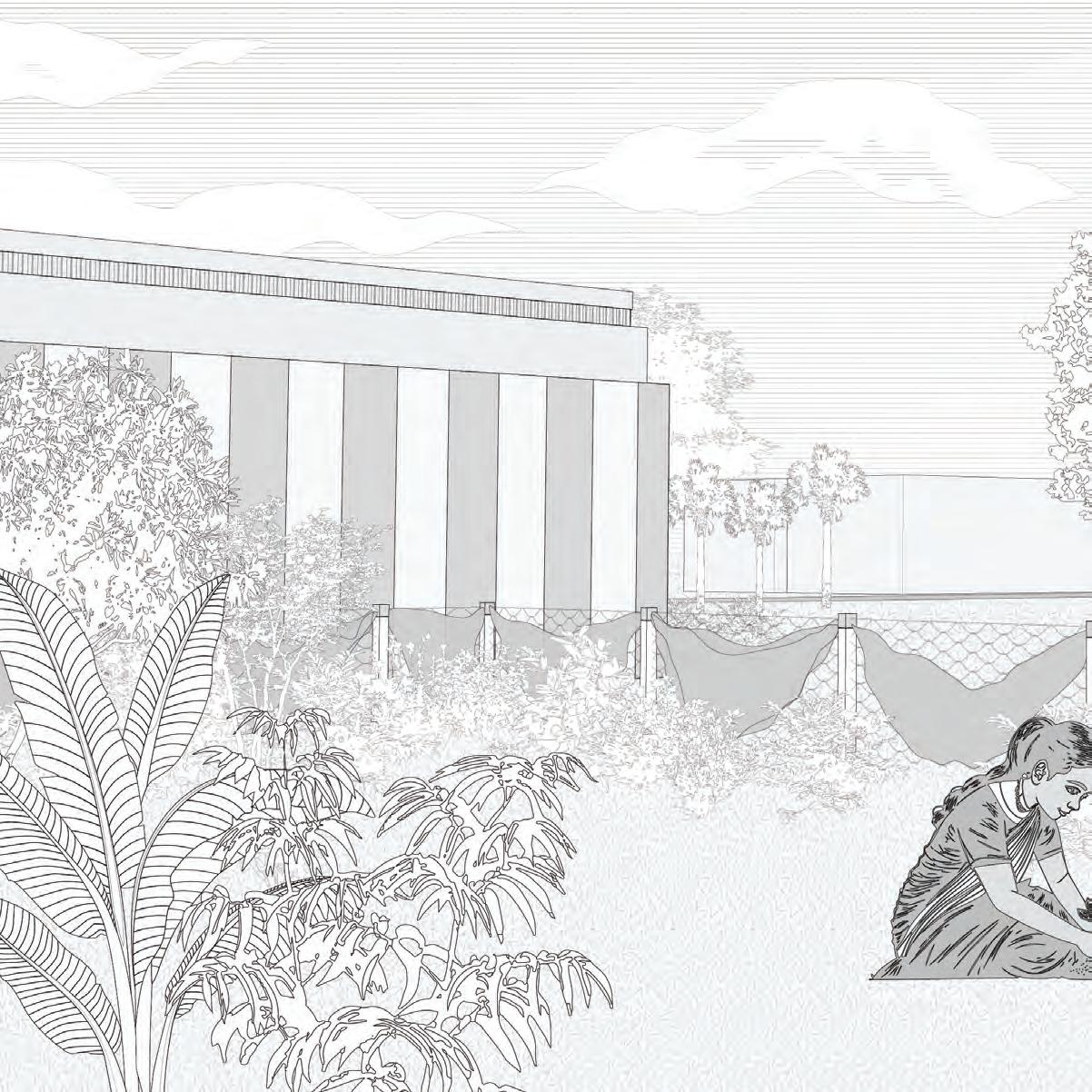

RIVERSIDE SANCTUM

Part of the procession that leads from the temple to the riverbanks through a gentle descending precession, a small compound of publicly accessible buildings and platforms bring the pilgrims in contact with the Tamarapirani.

SACRED CONFLUENCE

It is at this confluence of the sacred itinerary with water that pilgrims can perform additional functions.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

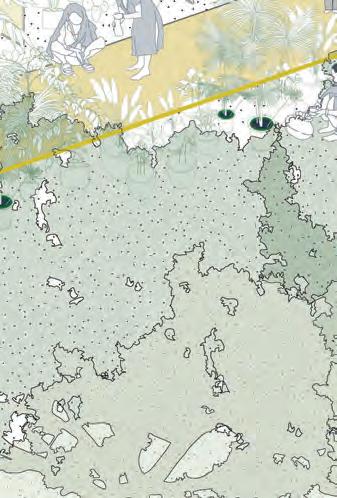

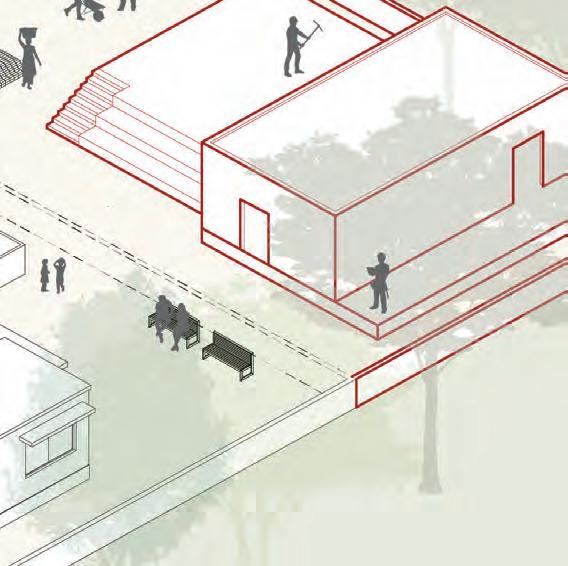

HERITAGE PAVILION

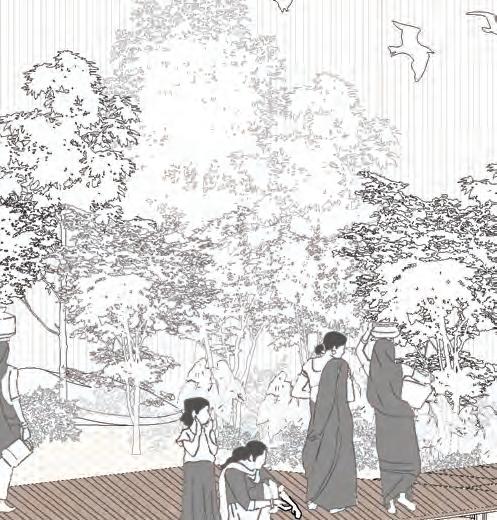

A gathering place for the village, hosting daily rituals, festivals, and celebrations. It offers women a moment of respite after their journey from the river, carrying water buckets. For visitors, the pavilion marks the beginning of a journey to explore the village, its river, and the surrounding ecology. A place of connection, rest, and learning, it bridges the village’s traditions with the broader natural and cultural landscape.

HERITAGE PAVILION

The Heritage Pavilion, owned by the temple authority, serves as a versatile space that can be rented by villagers for personal events such as weddings and private celebrations.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

CONTEMPLATION GARDEN

At the river’s edge, the small forested patch offers shade and respite, a small playground and additional opportunities for meditation and contemplation.

CELEBRATING WATER

Before the festival, the riverbank bustles with villagers, local craftsmen, and visitors coming together to learn traditional crafts. Skilled artisans carve intricate wood patterns, while others shade fabric with delicate designs. Potters shape clay on spinning wheels, creating functional and decorative pieces. As the hot summer approaches, the community shares tips on staying cool and preparing for the season. This gathering embodies a spirit of learning, craftsmanship, and unity, where culture and tradition flourish along the river’s edge.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

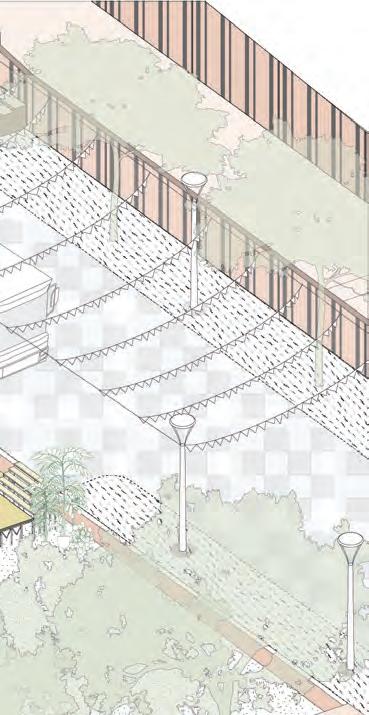

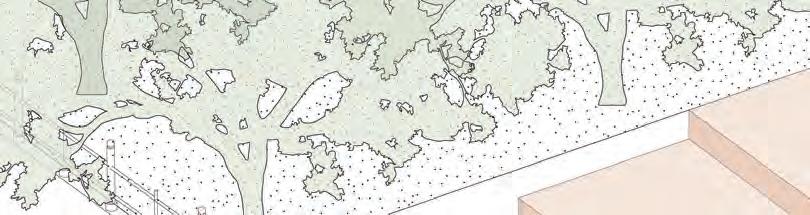

A hidden gem awaits visitors to the Thirupuddaimaruthur Temple: an often overlooked riparian landscape. To unveil this natural treasure, a series of soft infrastructures enable the connection from the temple grounds to the riverbank.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

RIVER THRESHOLD

RIVER THRESHOLD

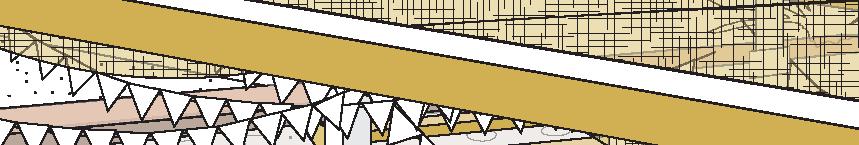

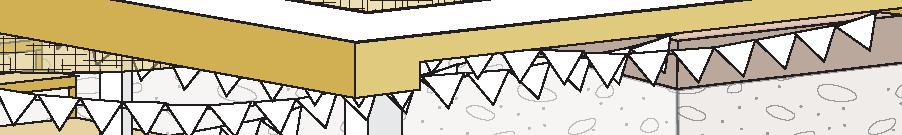

Additionally along this path, colorful signage with QR codes offers a more comprehensive understanding of the surrounding forest ecosystem. The trail’s design embodies simplicity and sustainability, crafted from bamboo, wooden planks, and dry stems characterizing its temporary, flexible, and cost-effective construction. Envisioned as a community project, built by local villagers, this rustic walkway serves as a bridge between cultural heritage and natural beauty.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

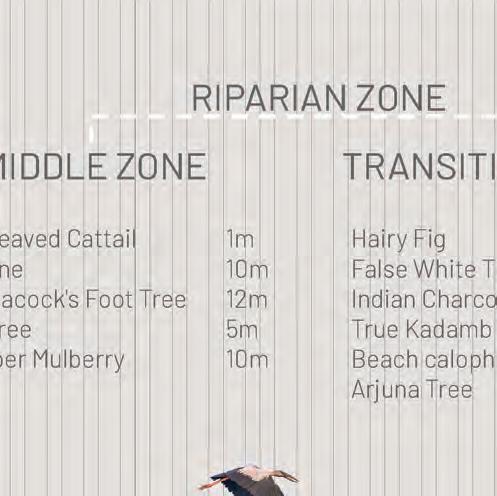

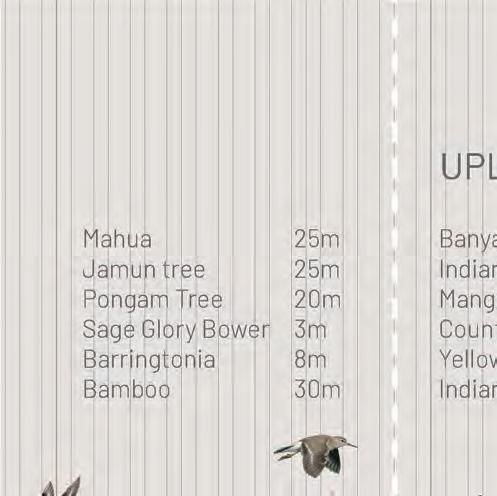

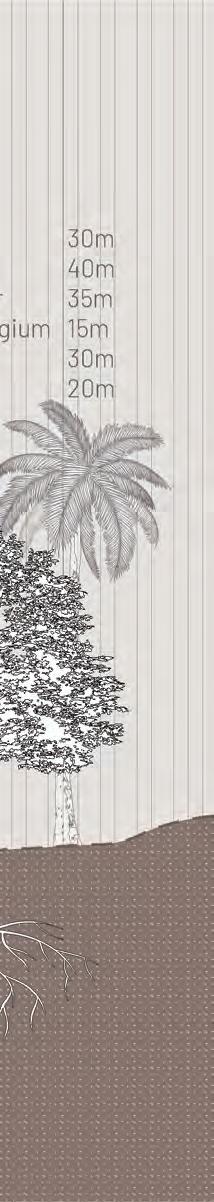

Narrow-leaved Cattail

Height: 1 m

Terminalia arjuna

Height: 30 m

Colocasia esculenta

Height: 3 m

Chaste Tree

Height: 5 m

Colocasia esculenta

Height: 3 m

Terminalia arjuna

Height: 30 m

Chaste Tree

Height: 5 m

Narrow-leaved Cattail

Height: 1 m

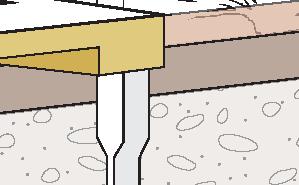

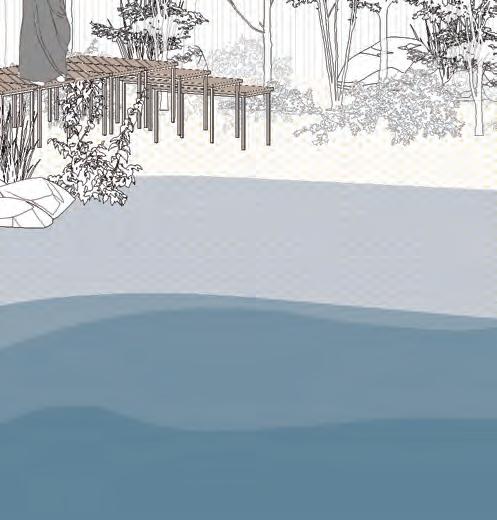

RIVER THRESHOLD

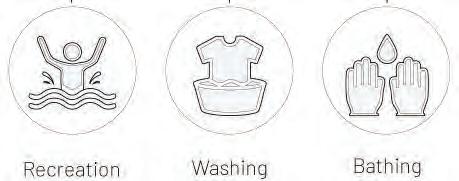

Direct access to the river facilitates daily activities such as bathing and washing clothes. The riverbanks are vibrant social spaces where villagers gather at the ghats, engaging in communal rituals that strengthen community bonds. Heavy rains and natural floods compromise continued access to these dynamic riverbanks.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

The deck is modular and flexible, specifically created to provide safer access to the river during periods of high water levels. Crafted with locally available materials, the deck can be easily assembled, disassembled, and stored when not in use. Women can now carry out their daily chores such as washing clothes and fetching water safely and conveniently.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

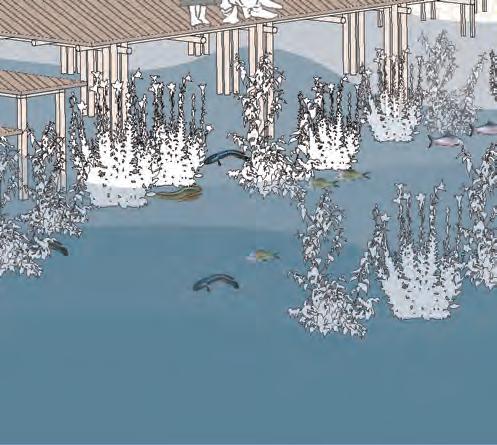

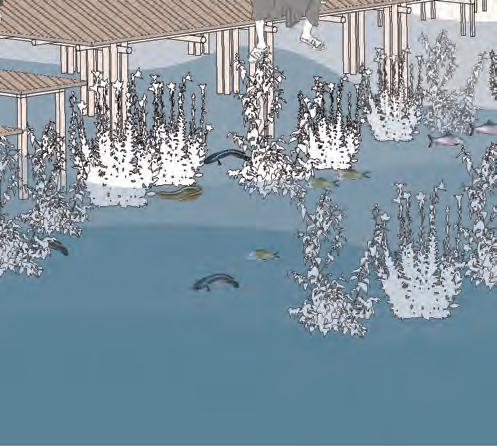

The aquatic zones of the riparian forest also create an ideal micro climate for native fish species to breed. During periods of high water, the deck provides a platform for fishing and socialization, enable research support to study water quality and fish species.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER THRESHOLD

The decks are planned for Hamlets II and III, as these areas are particularly vulnerable to heavy rains and flooding. This initiative enhances safety and fosters community resilience, allowing to adapt to seasonal changes.

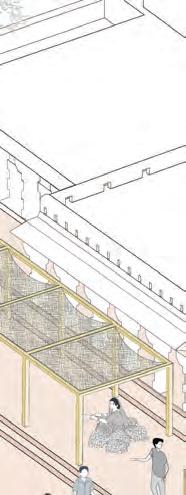

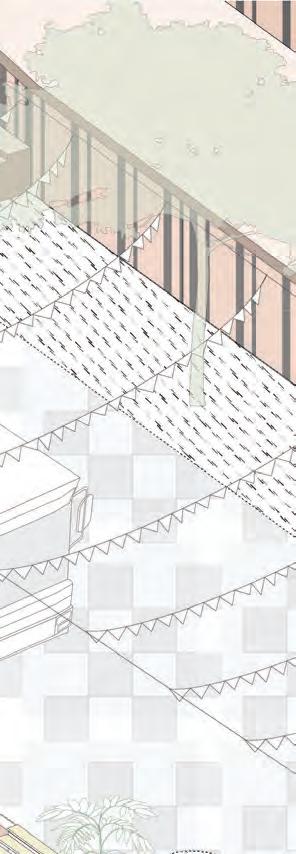

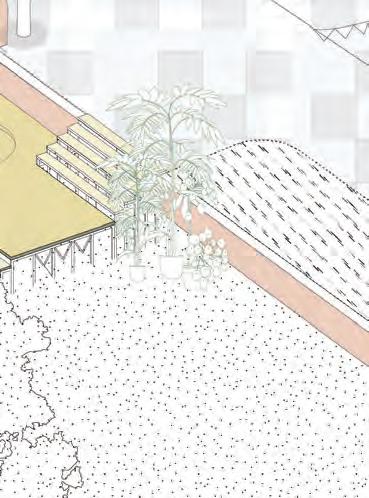

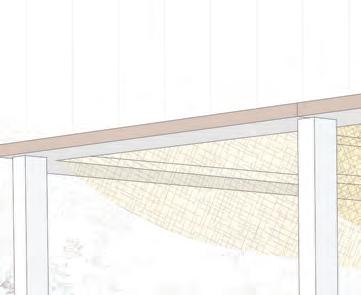

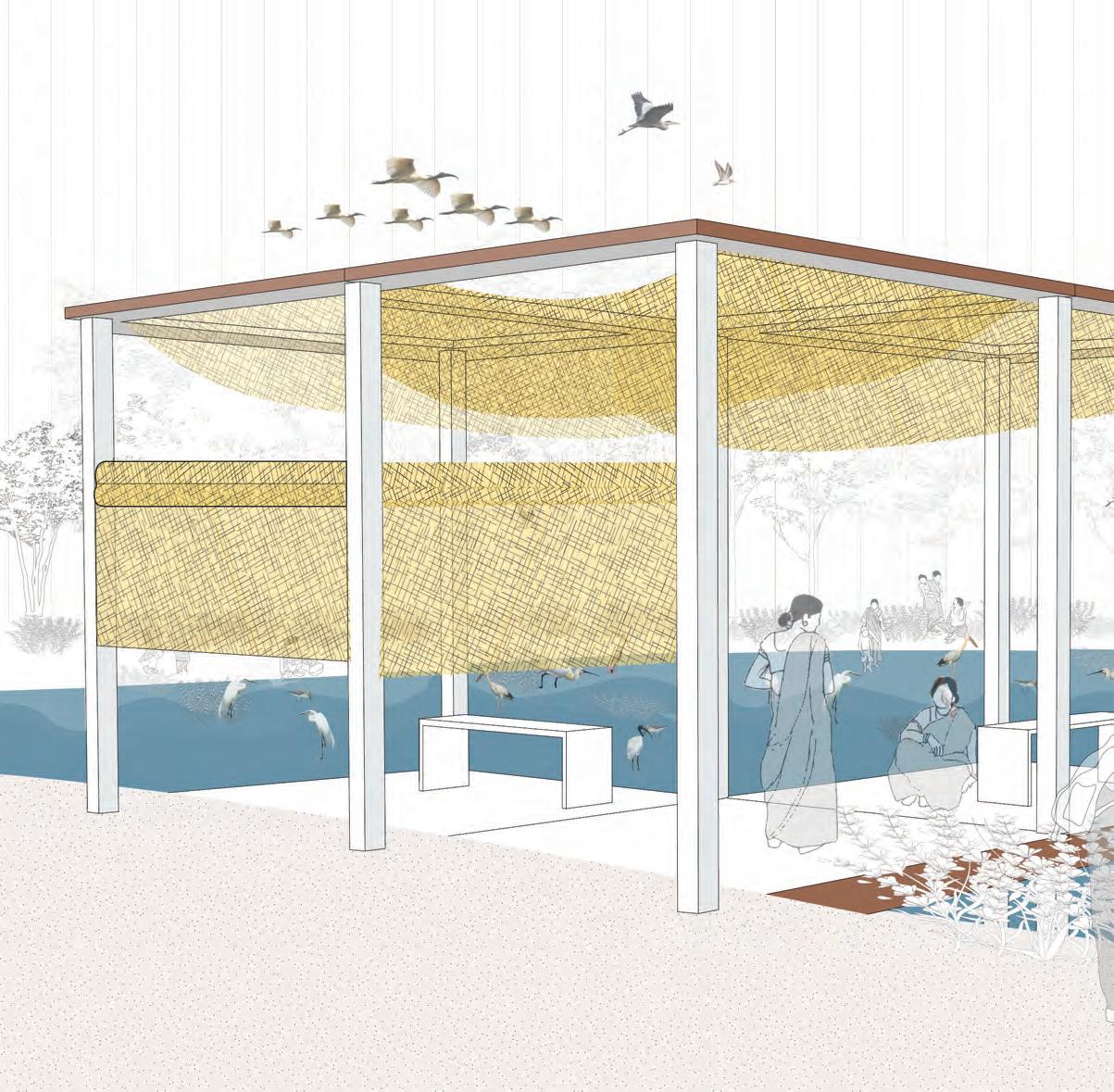

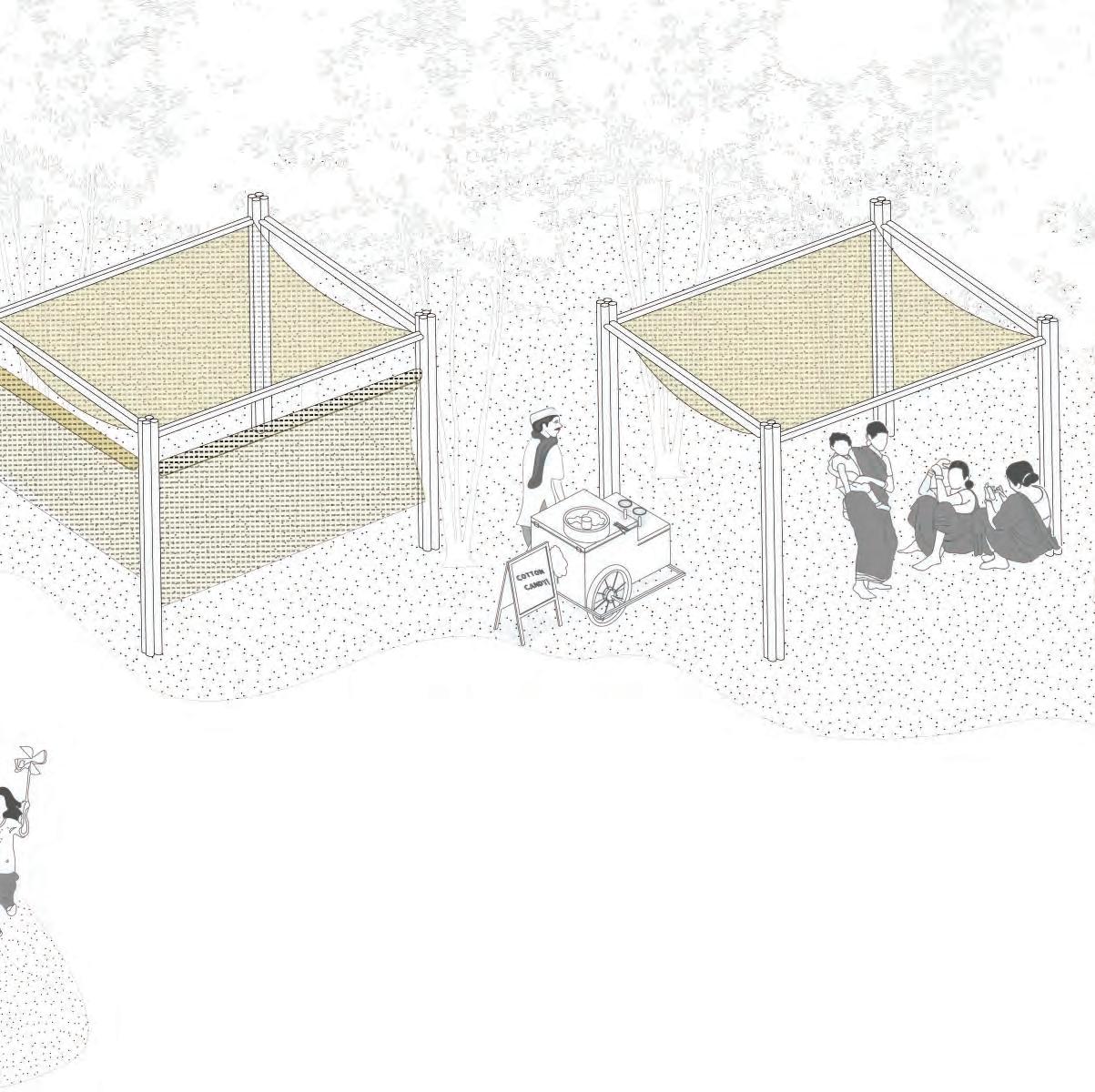

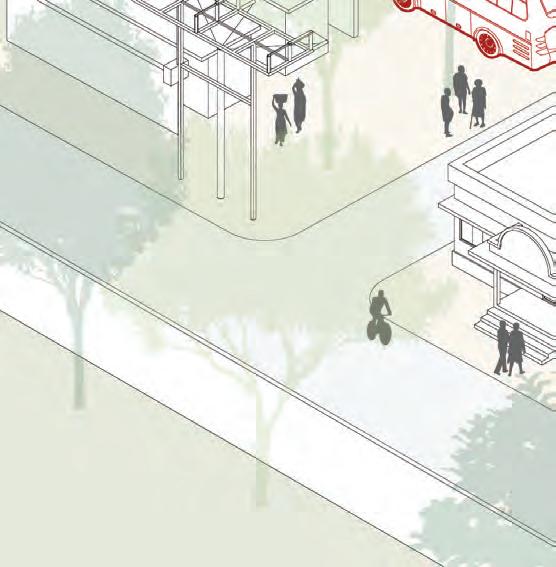

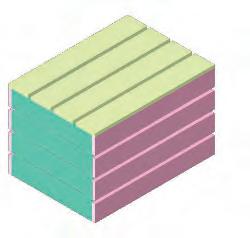

ECO SHADES

Crafted from resilient bamboo and lightweight mats woven from dry grass, the multi-functional shading infrastructure creates a gathering space that blends with its natural surroundings. It serves as a hub of celebration during festivals and classroom to work on afforestation and ecological conservation.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

A PRODUCTIVE LANDSCAPE WATER AS

IRRIGATION TANKS AND WETLANDS

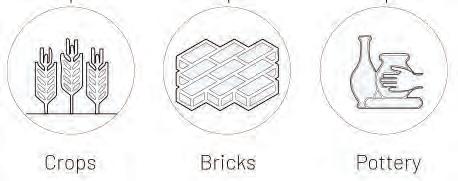

Wetlands and irrigation tanks are critical water infrastructures and an integral part of the social life for the villagers, who use them for bathing, recreation and washing clothes. Wetlands provide for their livelihoods, providing water to the paddy fields, nutrients as fertilizing source for the crops, and matter for hand crafted-potteries and construction bricks. Lastly, wetlands support and sustain the many ecological lives of the region. From mammals, reptiles, insects, aquatic plants and tree species.

ECONOMY

SOCIAL LIFE

ECOLOGY

WETLANDS IN DRY SEASON

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

WETLANDS IN WET SEASON

(NOVEMBERMAY)

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

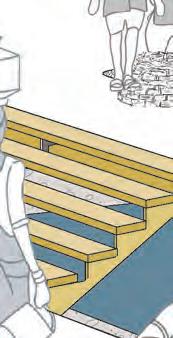

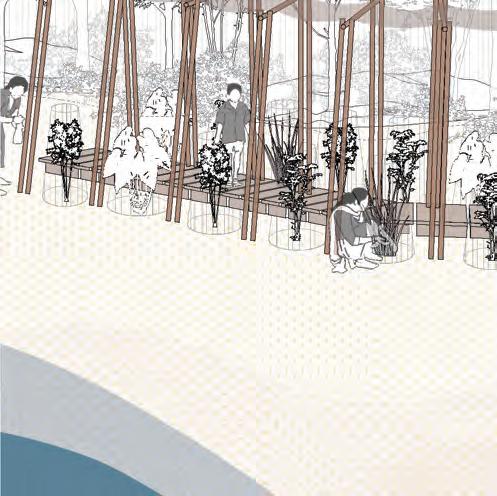

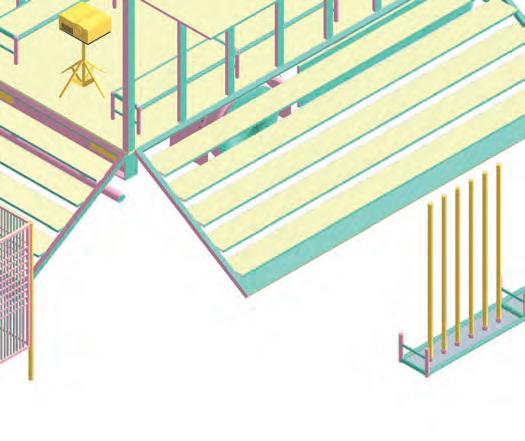

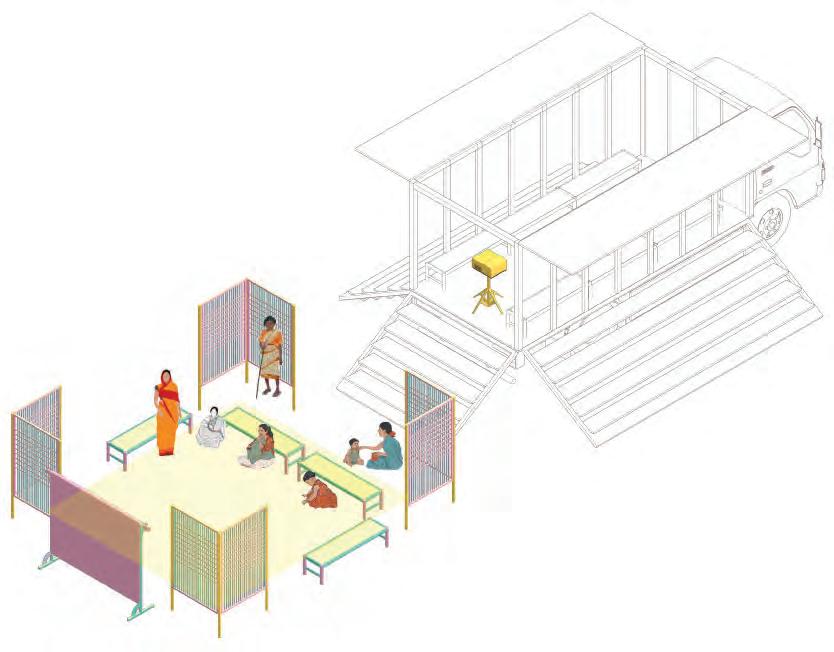

LEARNING PAVILION

The pavilion invites visitors to learn about the rich landscape ecological diversity and economic values. The experience changes in wet and dry seasons. In the dry season, people walk down to the wetland bund to learn about invasive plant species, uproot water hyacinth plants and see artificial islands made for breeding and resting of migratory birds.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

LEARNING PAVILION

During the wet season, it can be used for bird-watching and other recreational uses; it can also can be converted to a ‘changing room’ for women before/after entering the wetland, using the rollable shades.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

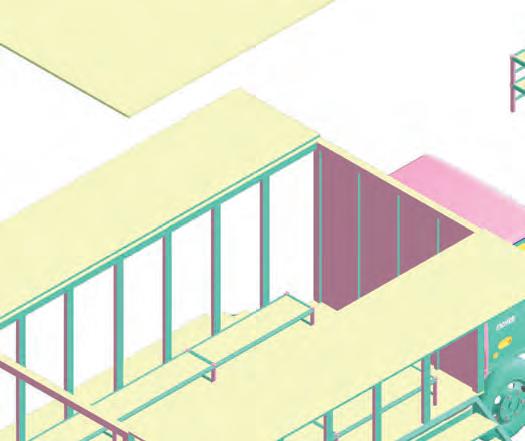

ADAPTIVE COMPONENTS

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

ADAPTIVE COMPONENTS

SOCIAL SHED

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

CHANGING UNIT

FLEXIBLE MARKET

RECREATIONAL

COLLECTIVE STEWARDSHIP

PILGRIMS

TOURISTS TO TBCR

STUDENTS / EDUCATORS

NON PROFIT ORGANIZATION

SOCIO-ECOLOGICAL ACTIVIST

PEOPLE OF THIRUPUDAI MARUTHUR

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

CONSORTIUM FOR DEWATS DISSEMINATION

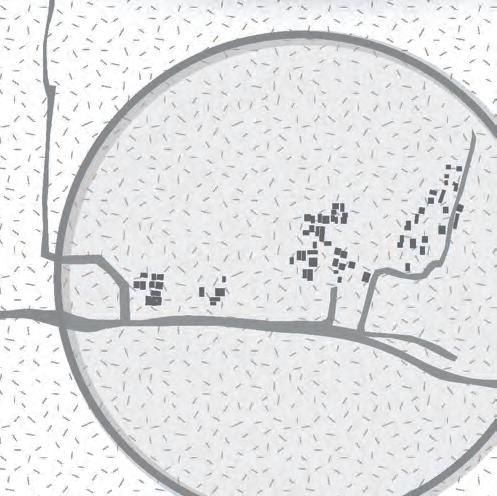

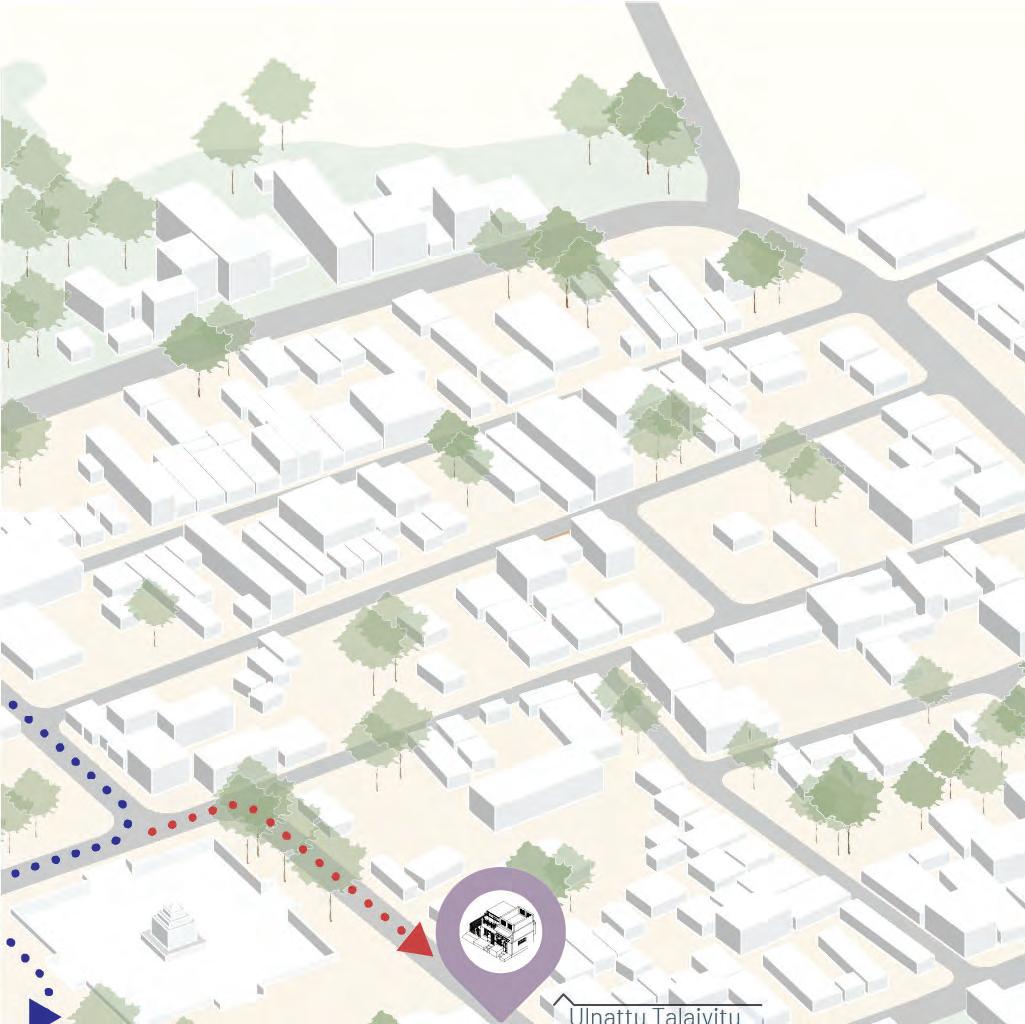

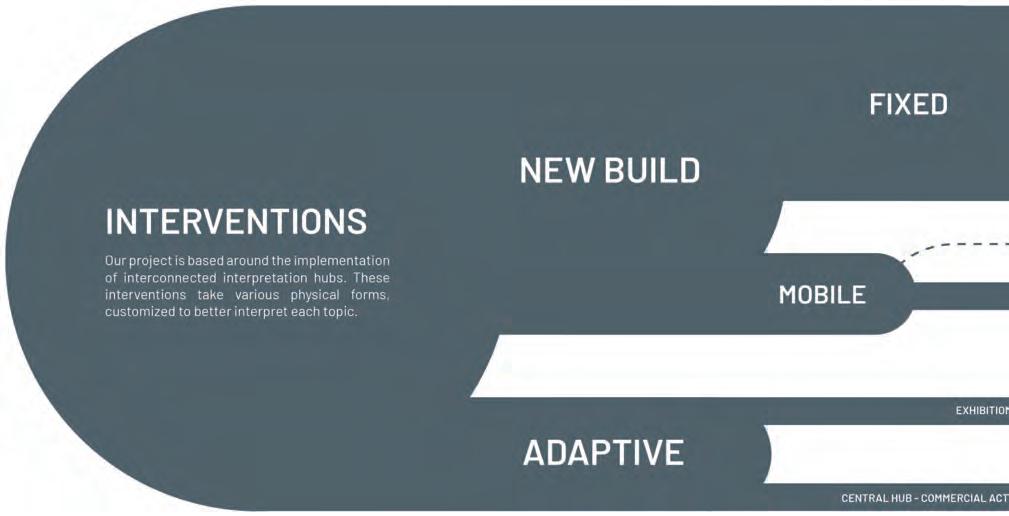

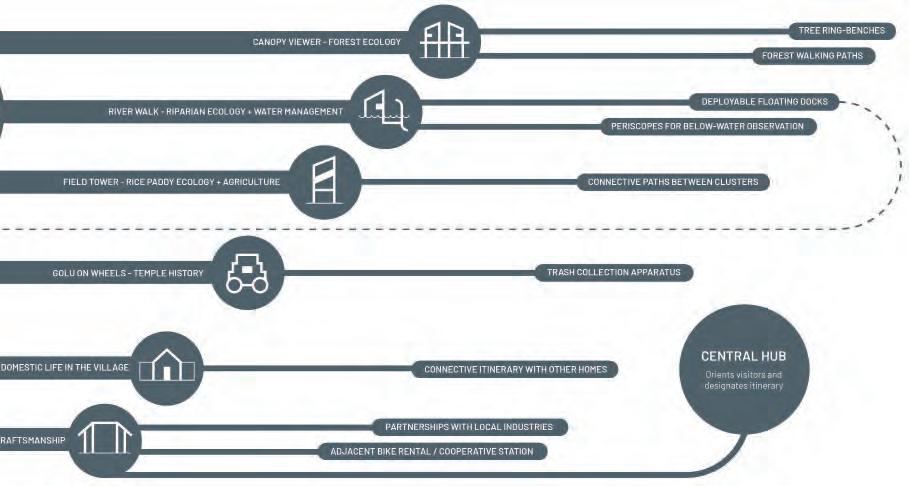

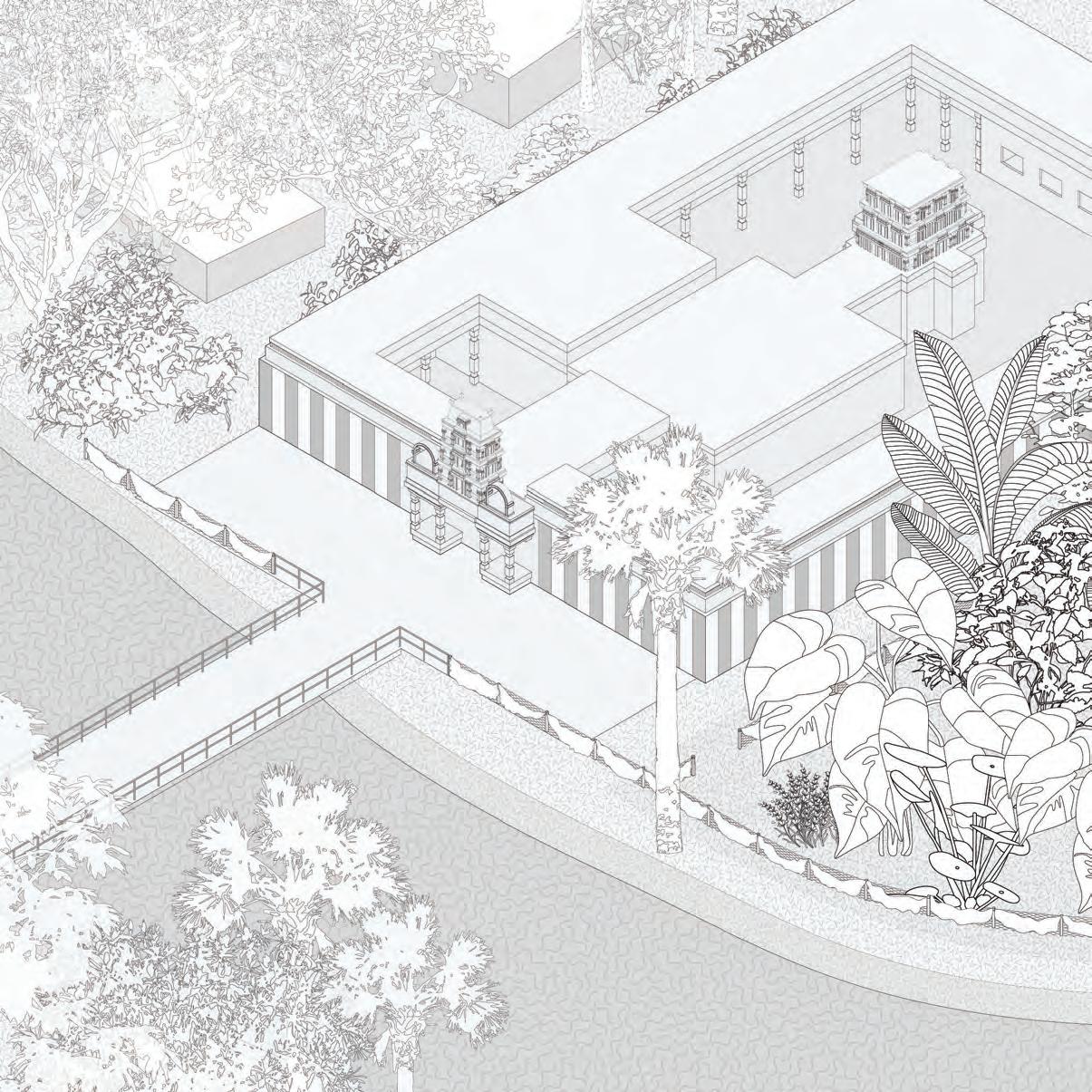

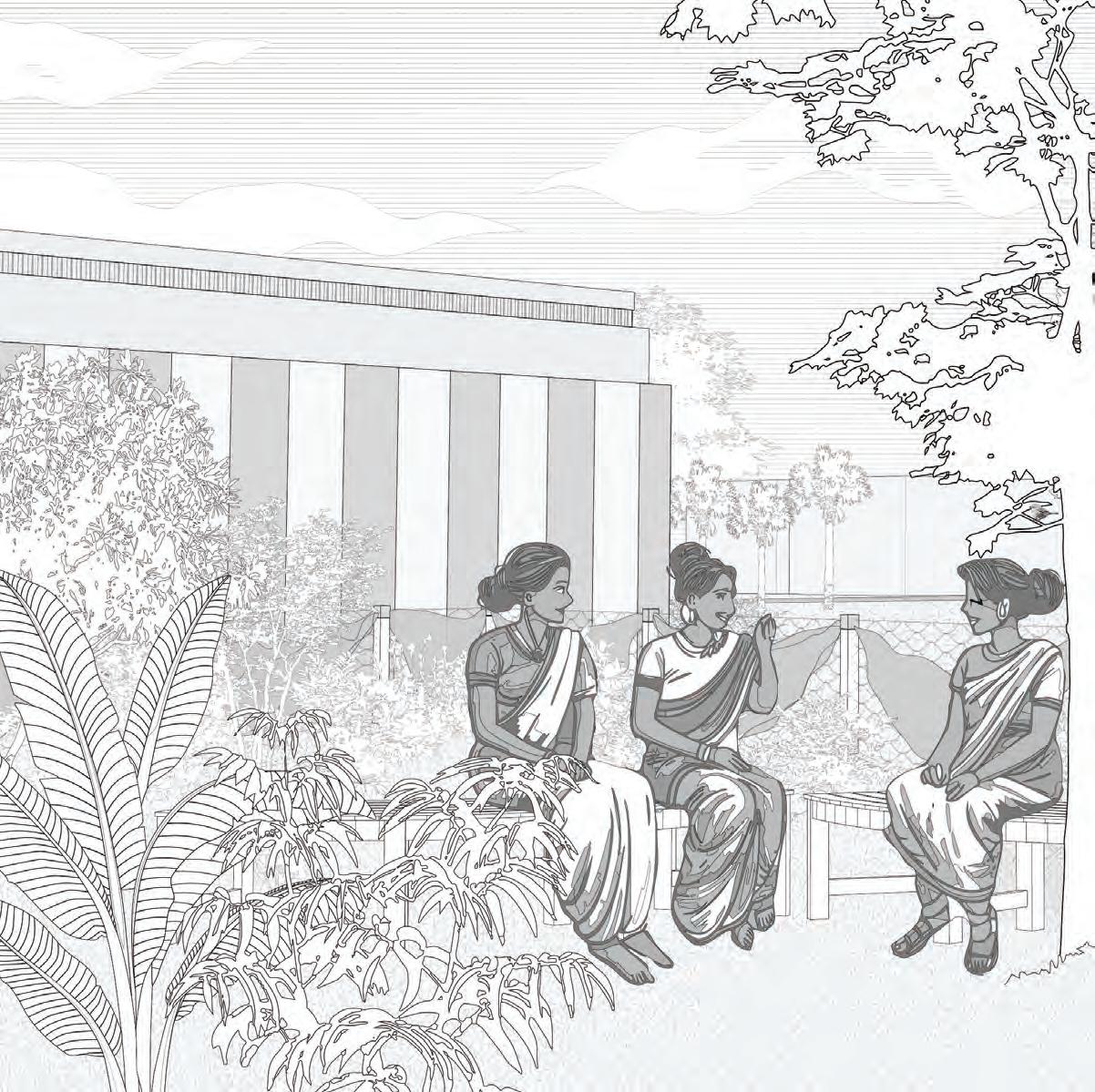

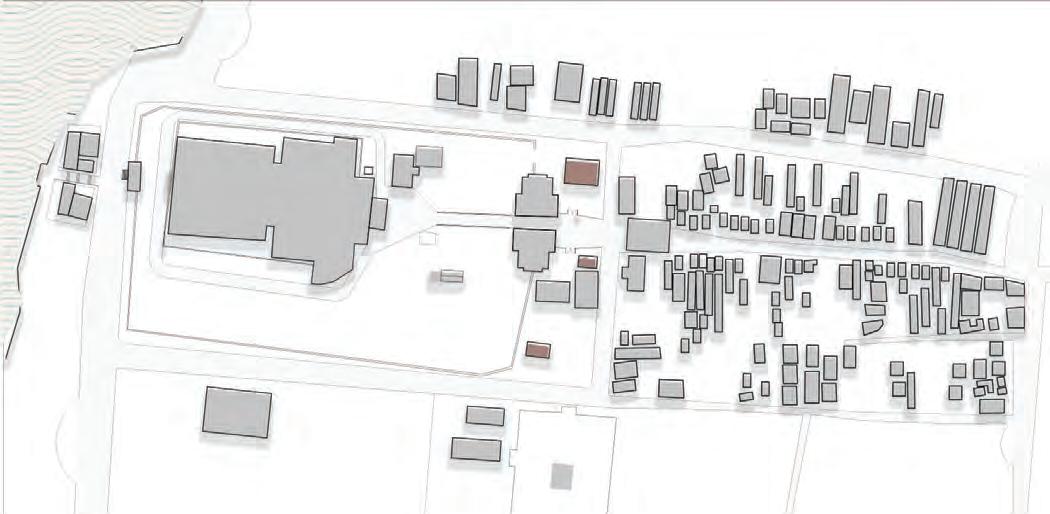

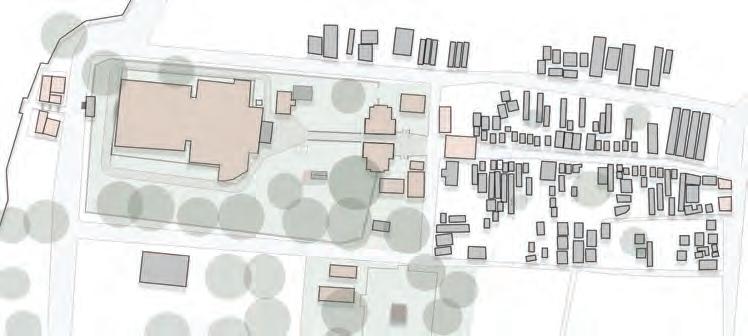

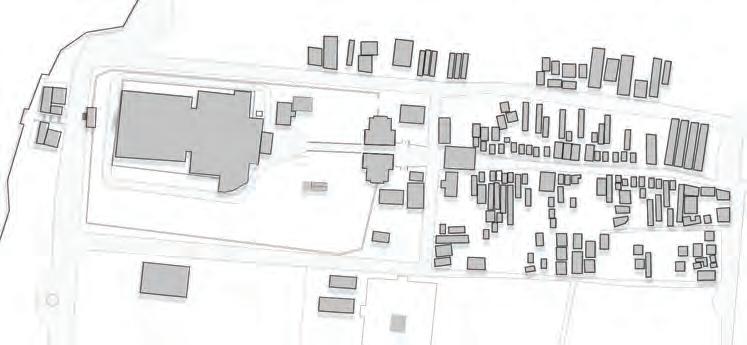

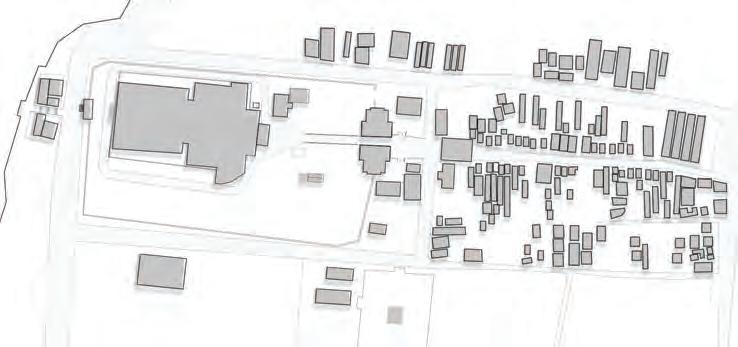

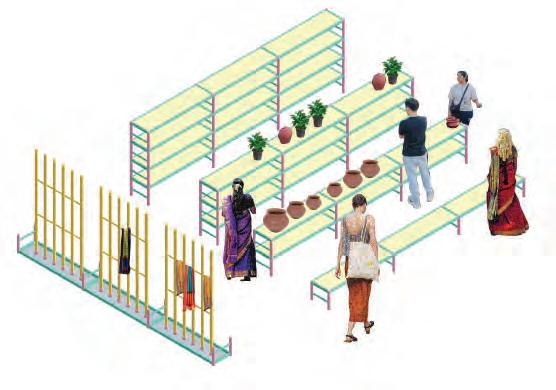

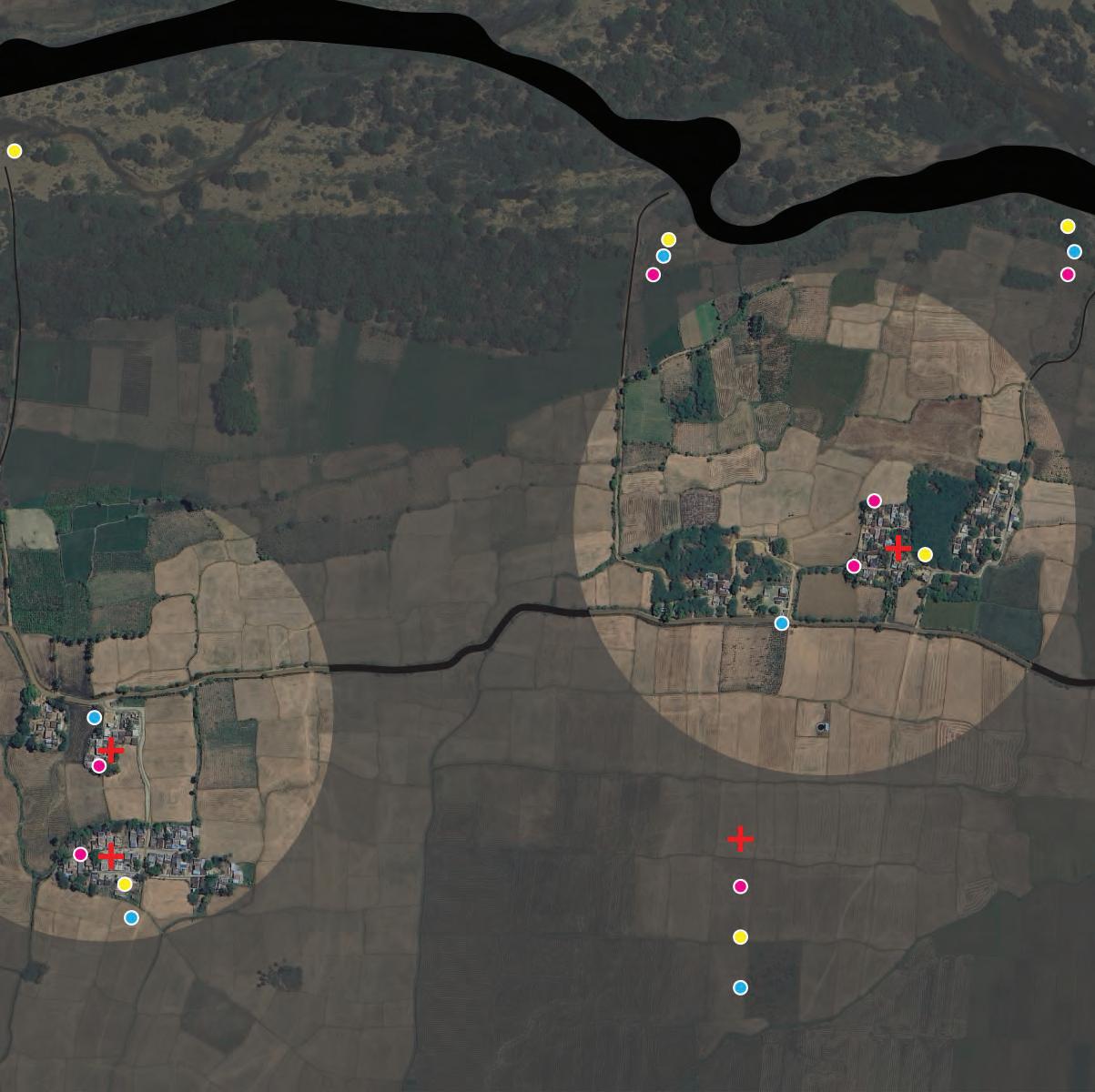

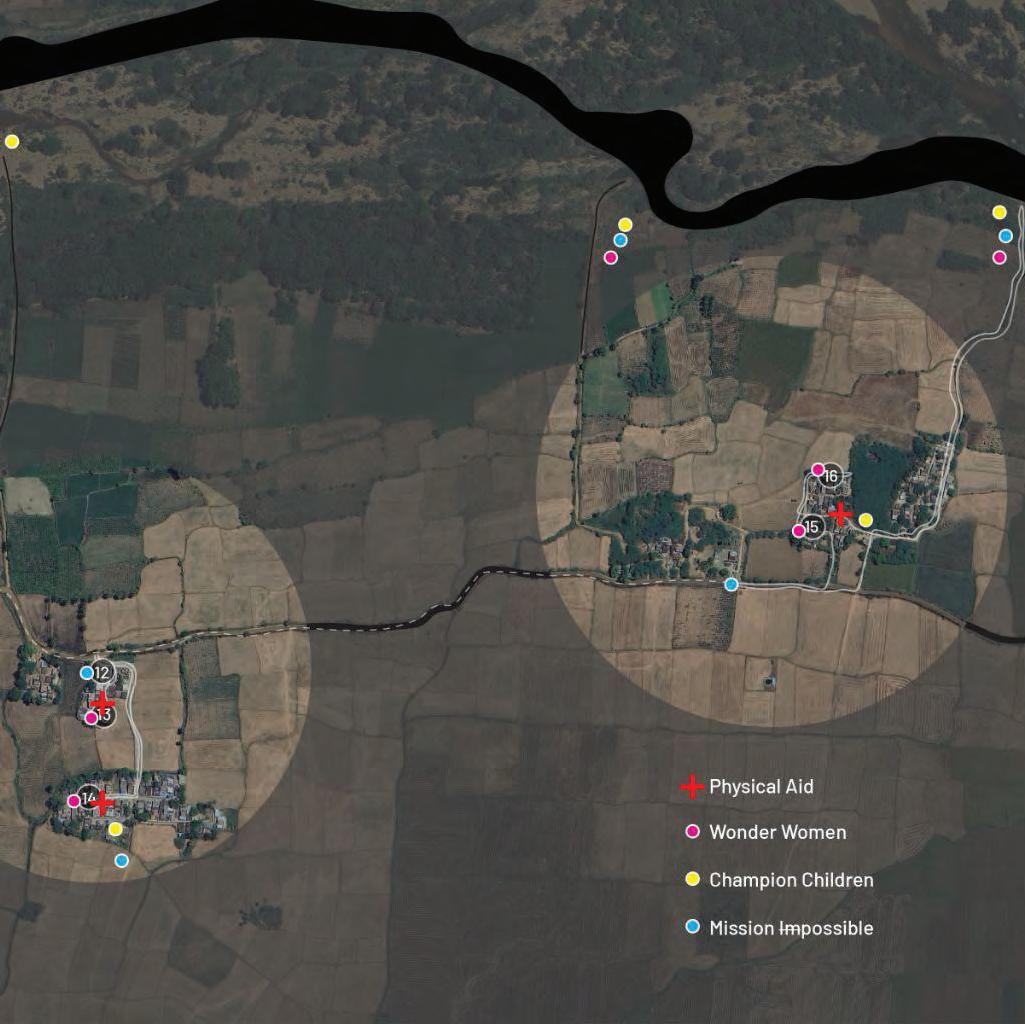

VILLAGE SECRETS

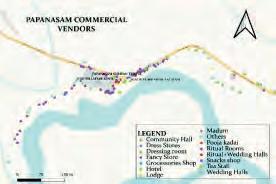

The Interpretation Center exposes the cultural and ecological richness embedded within the village of Thirupudaimaruthur, offering visitors an immersive experience that uncovers its unique heritage. From the villagers personal stories to the diverse species thriving within the temple grounds, the center aims to guide visitors toward a deeper appreciation of the phenomena they might otherwise overlook. In addition to enriching the visitor experience, the proposed physical interventions are designed to provide meaningful benefits for the local community. Addressing key issues identified by our partners at ATREE, these interventions focus on improving infrastructure, promoting sustainable practices, and enhancing the village’s livability. At the core of the project lies interconnectivity, creating a seamless web of connections between shelters, pathways, and experiences. This network, comprising walkways, itineraries, and biking routes, ensures a cohesive journey through the village’s landscape, encouraging engagement with its stories, traditions, and biodiversity.

The overarching goals of the interpretation center are to celebrate the intrinsic bond between the people and their land, to weave together the past and present in a way that respects and honors the village’s identity, and to foster a direct connection between the community and the project, ensuring its shared success and sustainability. Much like an effective tour guide, the networked interventions steer the senses to discover and steward the village’s hidden treasures.

DAKSHINACHITRA PRECEDENT LEARNING FROM

Dakshinachitra, a heritage craft village located along Chennai’s scenic East Coast Road, is a living example of how vernacular South Indian culture can be conserved and celebrated. This interactive outdoor museum offers visitors an immersive experience that showcases the regional lifestyles, art, craft, and architecture. Through its reconstructed heritage homes from Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, Dakshinachitra invites visitors to step into a cultural journey, walking through spaces that tell the stories of the people who once lived there. By combining traditional practices, architectural authenticity, and interactive experiences, DakshinaChitra demonstrates how to honor a region’s identity while fostering a deeper connection with visitors. Integrating cultural conservation and community engagement, this precedent study serves as a guiding principle for our interventions.

DAKSHINACHITRA PRECEDENT LEARNING FROM

Unlike a static museum, it functions as a vibrant, living heritage site where visitors can explore at their own pace, meandering through an itinerary-like path that connects one experience to the next. What makes Dakshinachitra especially compelling is its focus on hands-on engagement and community involvement. Visitors are encouraged to actively participate in traditional activities like pottery, weaving, and puppet-making, ensuring that the crafts are not only preserved but also understood and appreciated. The space comes alive through the work of local artisans, performers, and storytellers, creating both authentic cultural experiences and economic opportunities for the communities involved. Its adaptability as a space for festivals, workshops, and cultural programs ensures its continued relevance, fostering deeper connections to the heritage it celebrates.

INTERPRETING HOME

COEXISTENCE

AND RECIPROCITY

Learning from the initial findings from the Participatory Action Research project in Thirupudaimaruthur led by our partners at ATREE, our intervention addresses the challenges the village is currently facing. At the heart of our strategy are notions of coexistence and reciprocity, so every physical and programmatic intervention for landscape interpretation provides direct benefits bolstering the strength of the community and local ecologies.

Some of the key challenges highlighted by our partners include waste management, dilapidated public facilities, and a lack of social spaces for women. While these are complex issues that need systemic and multilayered approaches, our designs provide a set of resources to help the community to address them head-on.

SANITATION + WASTE MANAGEMENT

TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE

MISSING SOCIAL SPACES FOR WOMENSAFETY AROUND THE RIVER

LACK OF LOCAL FAMILIARITY WITH TOURISM

LACK OF ALTERNATIVE WORK OPPORTUNITIES

INTERPRETING HOME

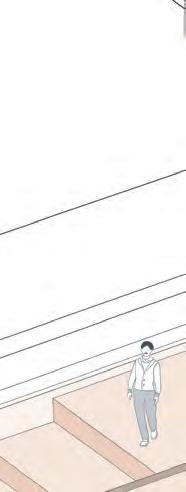

A seamless network of paths, viewing shelters to observe wildlife, repurposed homes and facilities to educate and interpret on local traditions, guide visitors through the cultural and ecological richness of Thirupudaimaruthur while fostering meaningful connections between village, people, and wildlife.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

NETWORKED INTERPRETATION

COMPONENTS

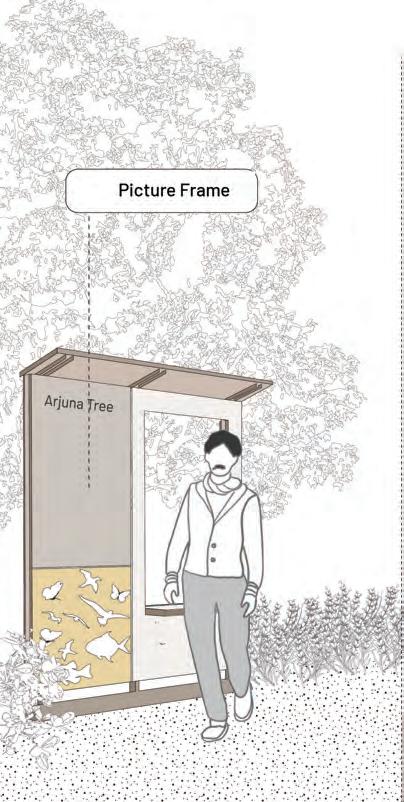

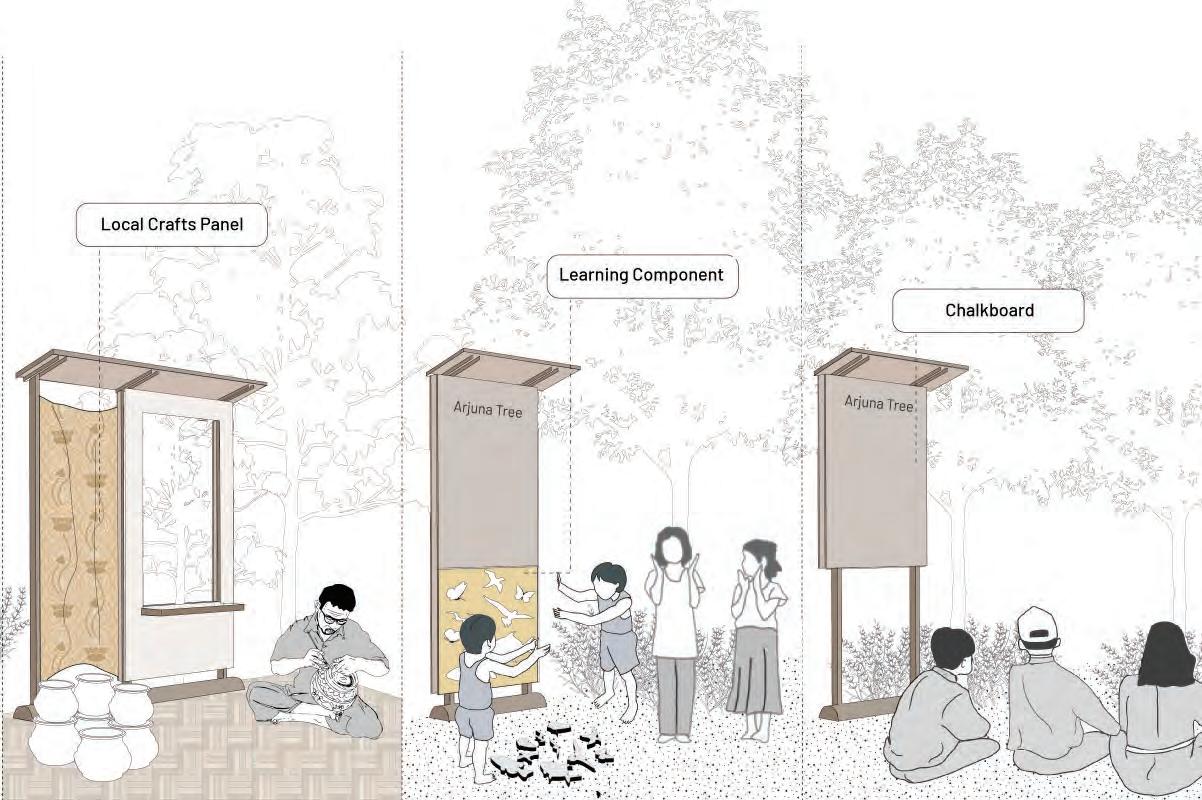

The six design components function cohesively, interpreting local socio-ecological phenomena, enhancing the visitor experience, and providing concrete opportunities for the local community’s involvement.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU DOMESTIC INTERVENTIONS

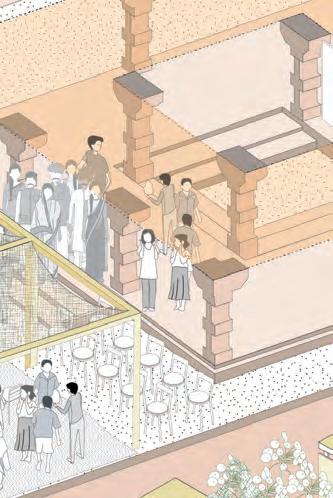

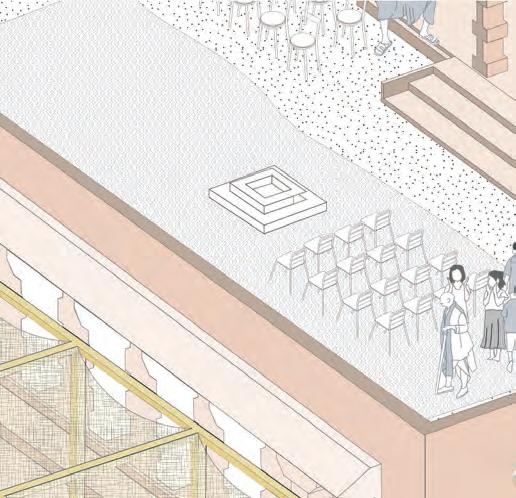

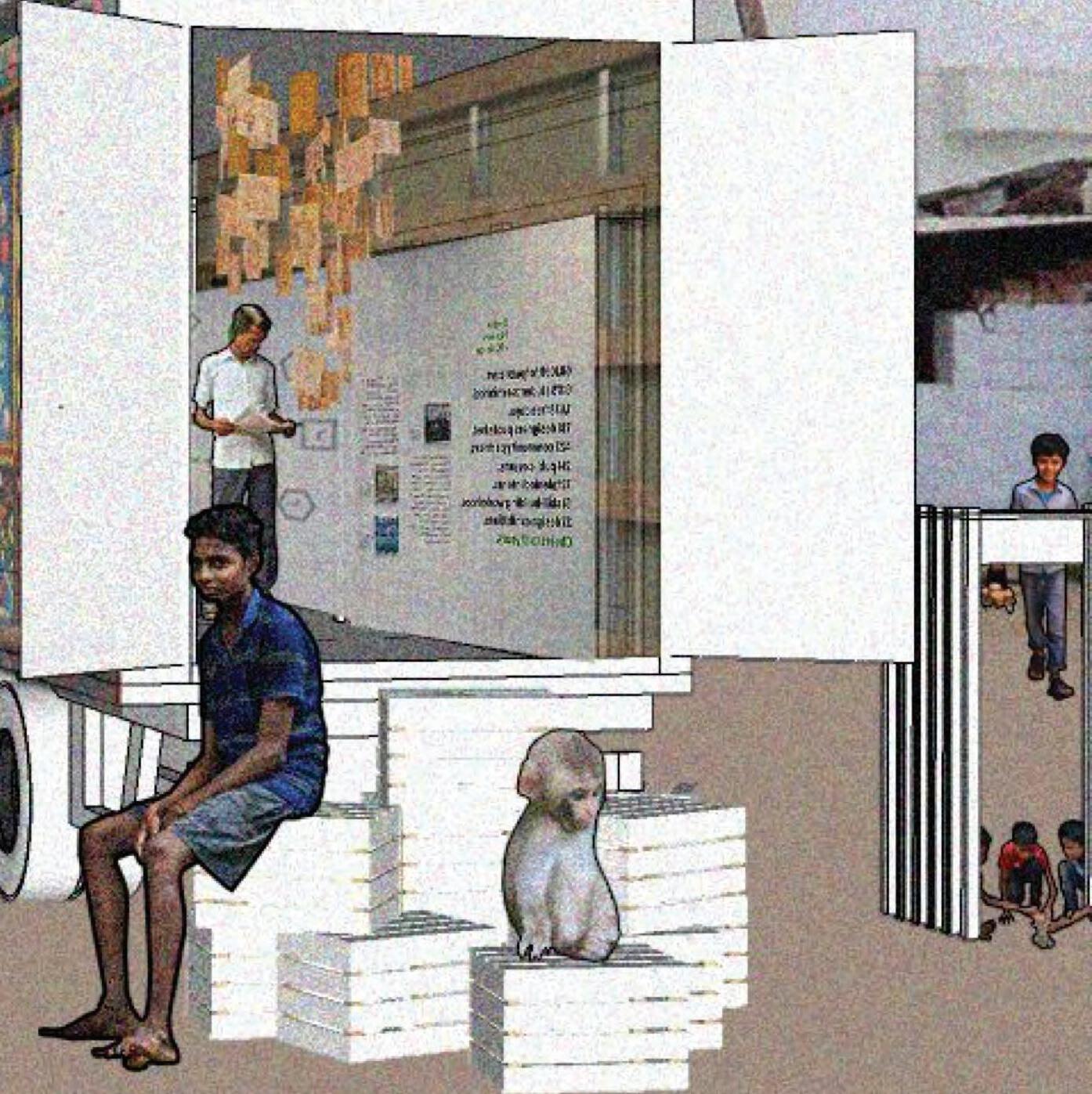

MADHYA MANDAPAM

The Madhya Mandapam is a vibrant space created within existing infrastructure, the library and community center, to benefit both visitors and villagers alike. By revitalizing these underused structures, the development aims to enhance their functionality, ensuring they remain integral to the community while also serving as a welcoming starting point for visitors. This is not just a place for tourists—it is a shared space that retains its purpose for the villagers, preserving the existing activities in place and enhancing the facilities.

Visitors will begin their visit to the village here, connecting with villagers, hearing their stories, and receiving maps and guidance to navigate the curated paths through the village. Given the scale and complexity of this intervention, we are adopting a phased approach.

MADHYA MANDAPAM

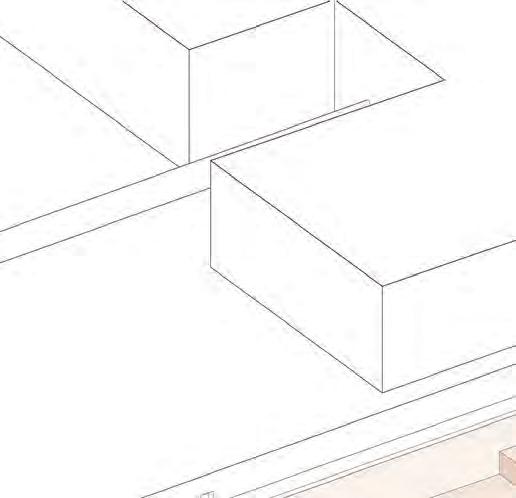

PHASE I: REVITALIZE

The redevelopment of existing structures address immediate needs and support future growth. A dilapidated building is transformed into a reception and ticket counter, creating a functional and welcoming entry point. New washrooms with bathing areas will address needs for villagers bathing in the river due to lack of home services and provide a safer, hygienic alternative. A water tank will support these facilities and future developments. The perimeter wall includes a drainage system as the site is in the floodplain. A gateway will signal the reactivation of the Madhya Mandapam as the starting point of a broader development, establishing it as a key hub for the site’s growth.

3 4

MADHYA MANDAPAM

PHASE II: GROW

The site expansion incorporates a paved road to improve access and support future construction. A transportation system brings visitors to the site, benefiting villagers if schedules align. All construction will be carried out by local villagers, providing them with employment opportunities and allowing them to develop new skills. This phase includes a new perimeter wall and extensive drainage, initial construction of a kitchen and craft center, while temporary shaded structures on the roof will serve as versatile spaces for exhibitions, textile sales, and community events, creating opportunities for both visitors and the local community.

MADHYA MANDAPAM

PHASE III: ANCHOR

Commercial spaces will enhance the visitor experience while supporting the local economy. Visitors can enjoy live demonstrations of traditional crafts like pottery and purchase handmade items directly from artisans. A nursery will offer plants encountered along the trail, allowing visitors to take home a piece of the landscape. The food and beverage section will provide authentic local cuisine, offering a taste of the region’s rich flavors. At the end of the day, visitors can climb up to the amphitheater to enjoy a breathtaking sunset, creating a serene and memorable conclusion to their journey.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

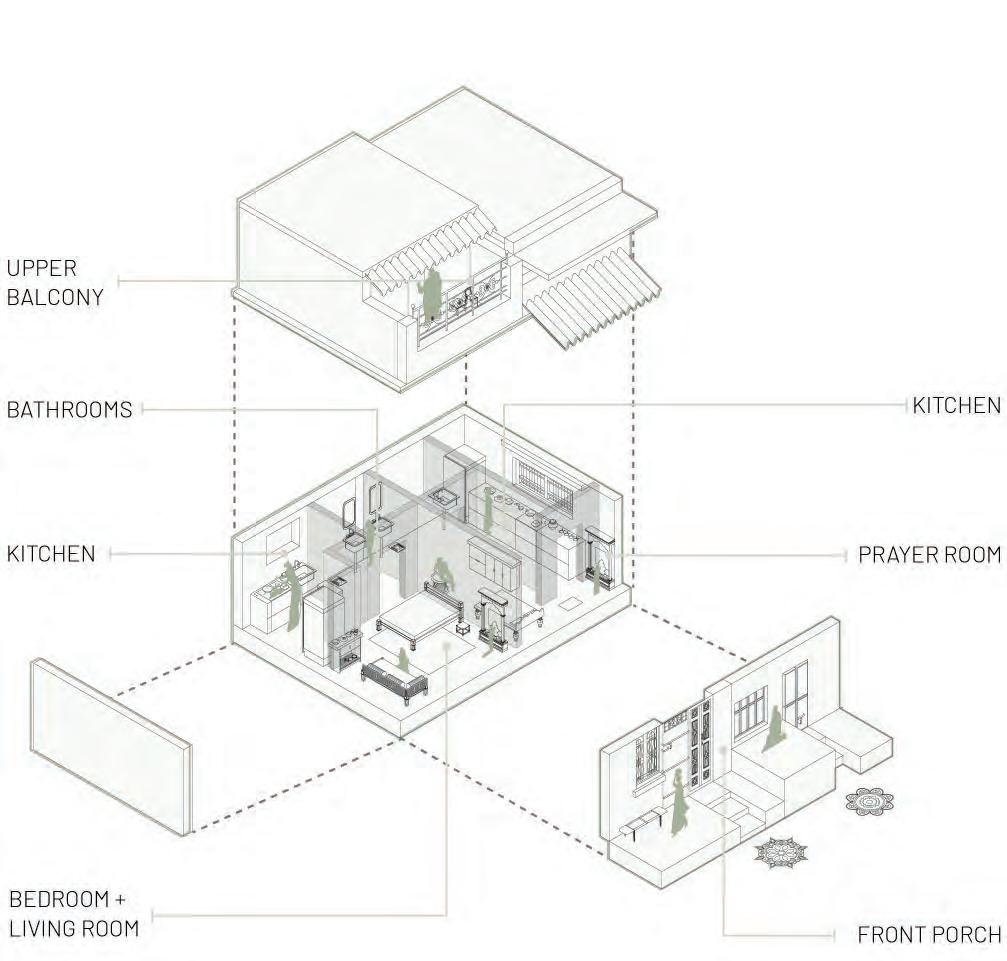

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

DOMESTIC INTERVENTIONS

To explore and celebrate the village domestic life, the project proposes repurposing an existing home within the village as a platform for learning and immersive experiences. Selecting one of the abandoned homes under decay, the transformation will include an exhibition space, managed and maintained by local residents already partnered with the initiative, ensuring authenticity and community involvement in its operation.

The question of ownership and operation of these renovated homes is an important one. The homes can become part of a village trust that ensure maintenance and operation by employing locals. Regional NGOs can help initiate the process and the government can incentivize the process through micro-grants and other incentives.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

REHABILITATION OF DOMESTIC SPACES

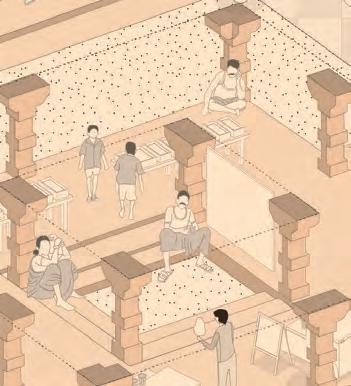

In a typical South Indian village home, the spaces of welcome begin with the outside porch. These porches are adorned with colorful floral designs called kolams, which are drawn on the ground. Upon entering the home, visitors are greeted by a shrine or prayer room where family members perform their daily rituals, offering flowers and lighting candles to honor their deities. Venturing deeper into the home, one encounters furniture that showcases the villagers’ traditional craftsmanship. For example, seating made from a wicker-like material called sedge (also known as river grass) is common. The layout of these homes typically includes: a common area serving as a living and dining room, one or more bedrooms, a bathroom, and a kitchen. Each of these spaces plays a crucial role in the daily life and cultural practices of the village inhabitants.

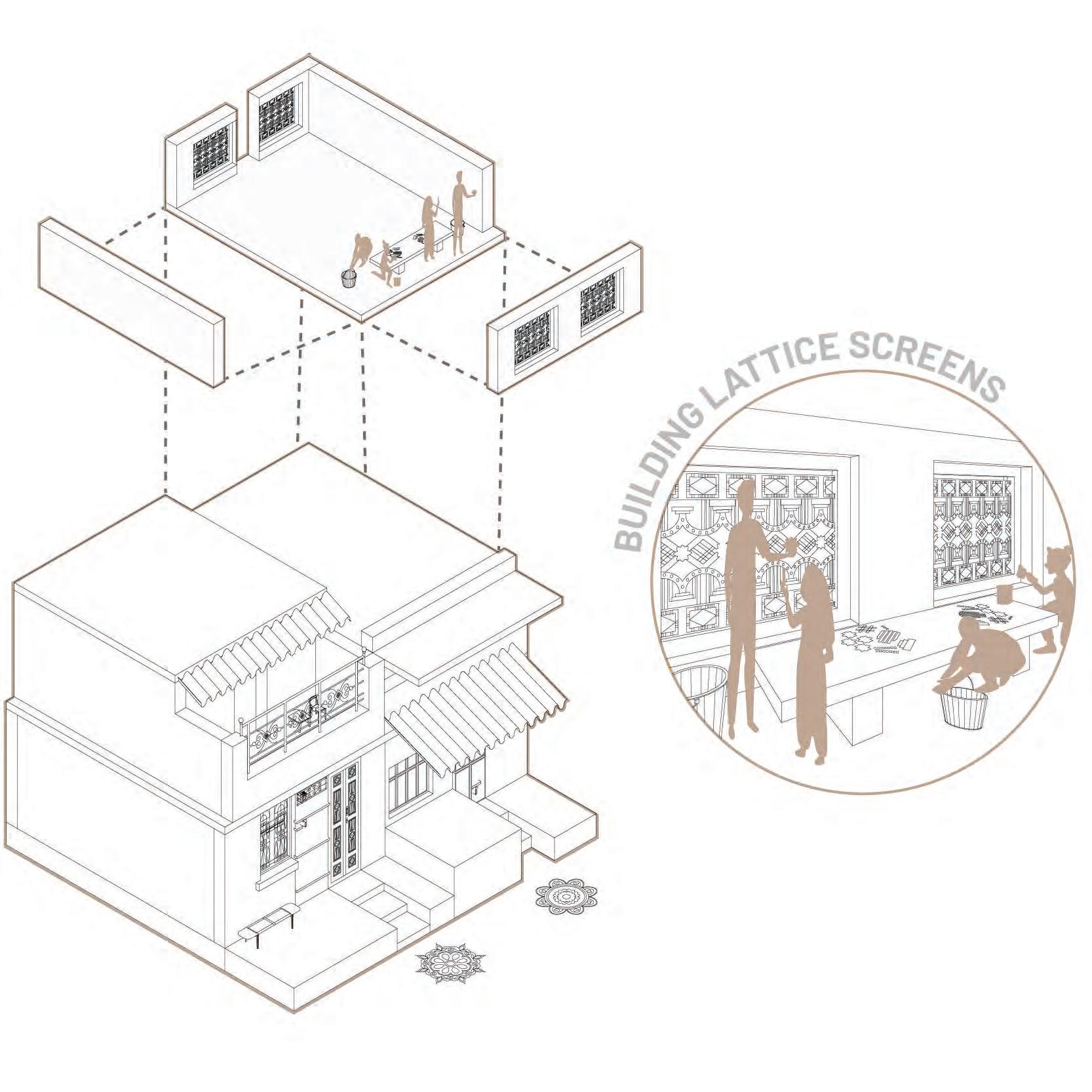

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

EXPANDING VERNACULAR EXPERTISE

One way to showcase the vernacular methods, artistry, and expertise of local residents is by expanding upon an existing house. This approach not only fosters greater opportunities for communal engagement but also allows visitors to experience these practices firsthand. Additionally, it creates educational opportunities for both visitors and locals, encouraging the exchange of knowledge. This shared learning experience can inspire the adaptation and application of these methods to other domestic spaces across the village.

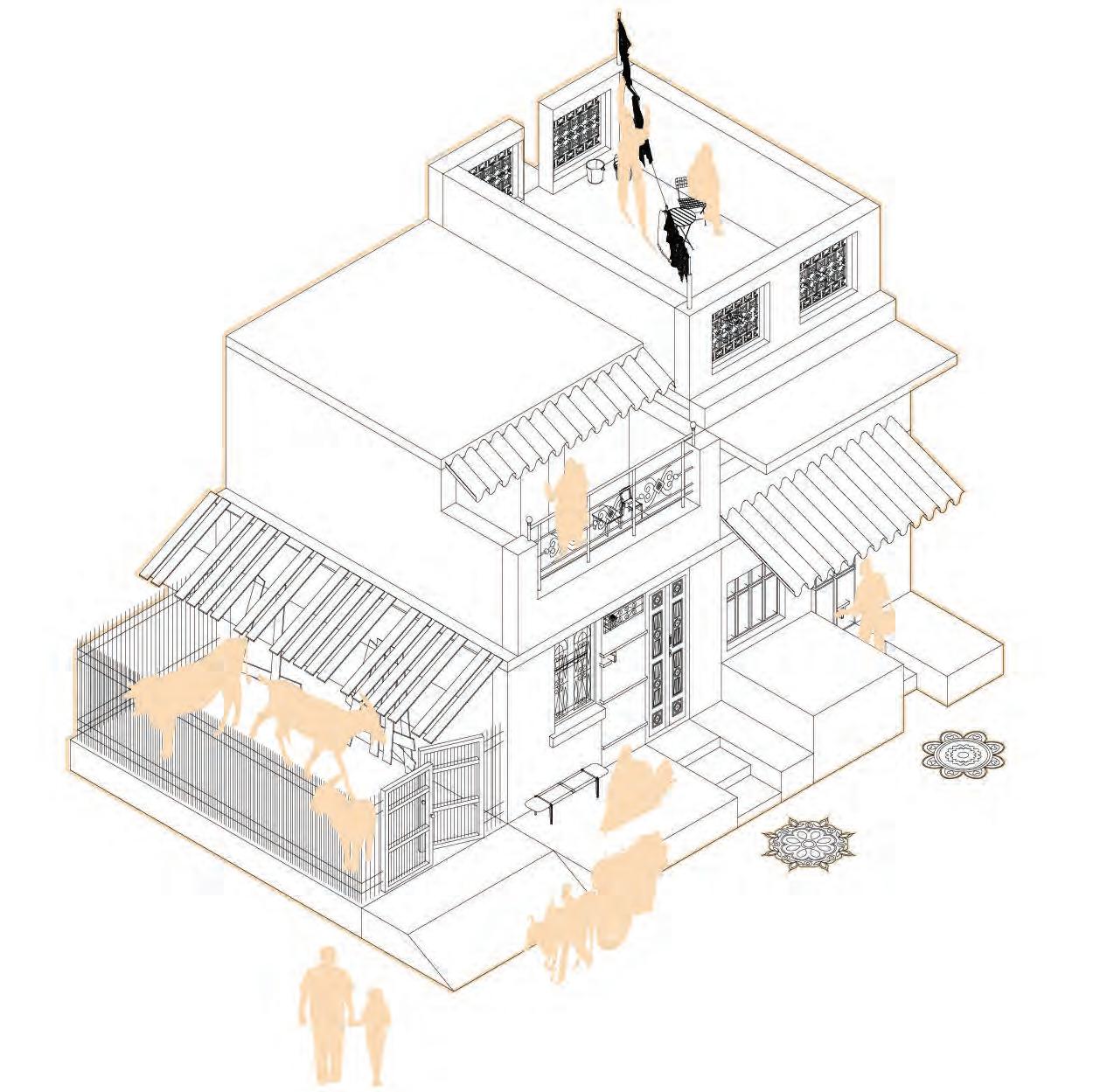

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

LIVESTOCK

IN DOMESTIC LIFE

A key component of village life is raising livestock, which is deeply integrated into the daily routines of many households. Common practices include constructing vernacular-style sheds or enclosures, often built adjacent to homes, to house animals like cows, goats, and sheep, as well as ducks and birds. These structures are essential for accommodating livestock in a practical yet culturally authentic way.

This initiative also offers a way for visitors to better understand and adapt to these everyday practices, fostering appreciation for the rhythms of village life. By experiencing the coexistence of livestock and people—such as cattle freely roaming the streets, which is a common sight—visitors can immerse themselves more naturally into the local environment without feeling surprised or out of place.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

LIVING HERITAGE

This component provides an immersive experience of the village domestic life through exhibition spaces. This concept can be implemented as an adaptable model across all three village clusters, with a focus on repurposing old and unused buildings in early process of decay. Each domestic intervention will be customized to reflect the typical house layout specific to its cluster so visitors can explore different and unique perspectives of rural living across the region. By tailoring the exhibitions to local architectural styles and cultural nuances, we offer a more authentic and diverse representation of village life. Through these carefully curated spaces, visitors can gain insights into the daily routines, traditions, and living conditions of villagers, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of rural culture.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

CULTURAL EXCHANGE AND EVERYDAY LIFE

These spaces are designed to host demonstrations, inviting visitors to experience various aspects of domestic village life. Activities may include cooking authentic cuisines and showcasing traditional craftsmanship such as pottery and wicker weaving. The offer an environment where visitors can engage directly with locals, fostering meaningful interactions. This setting encourages open, comfortable, and heartfelt exchanges, allowing locals to share and express their culture in a more intimate and authentic way.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

DUAL-PURPOSE COMMUNITY SPACES

These spaces are designed to serve a dual purpose, operating not only during visiting hours but also as a resource and safe haven for the local community. In the evenings, after visitors have left, the spaces transform into open homes where villagers can gather and benefit from the facilities. For example, local women, many of whom are beedi rollers, can use the space as a safe and supportive environment to carry out their work while socializing with others in their community. Additionally, the kitchen can be utilized for meal preparation, either for their families or for the next day’s demonstrations, offering a practical resource and a space for communal bonding.

ULNATTU TALAIYITU

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

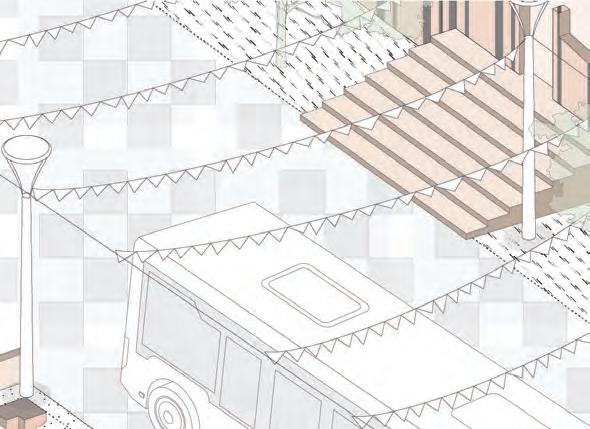

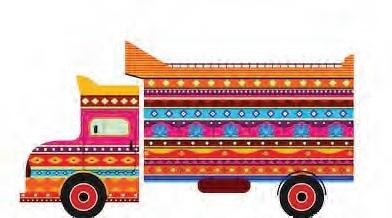

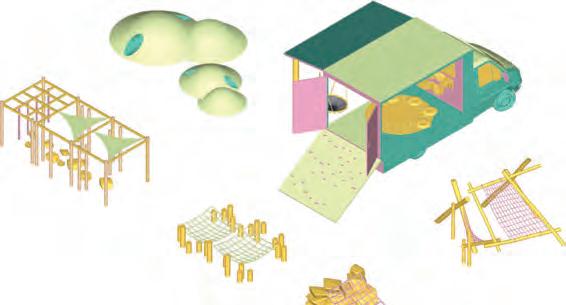

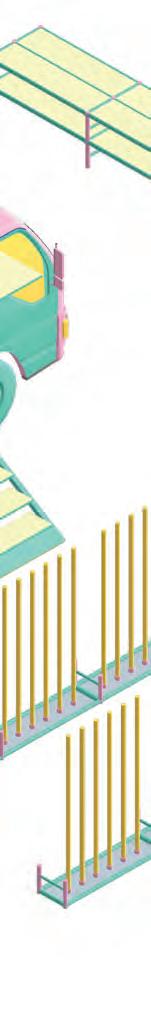

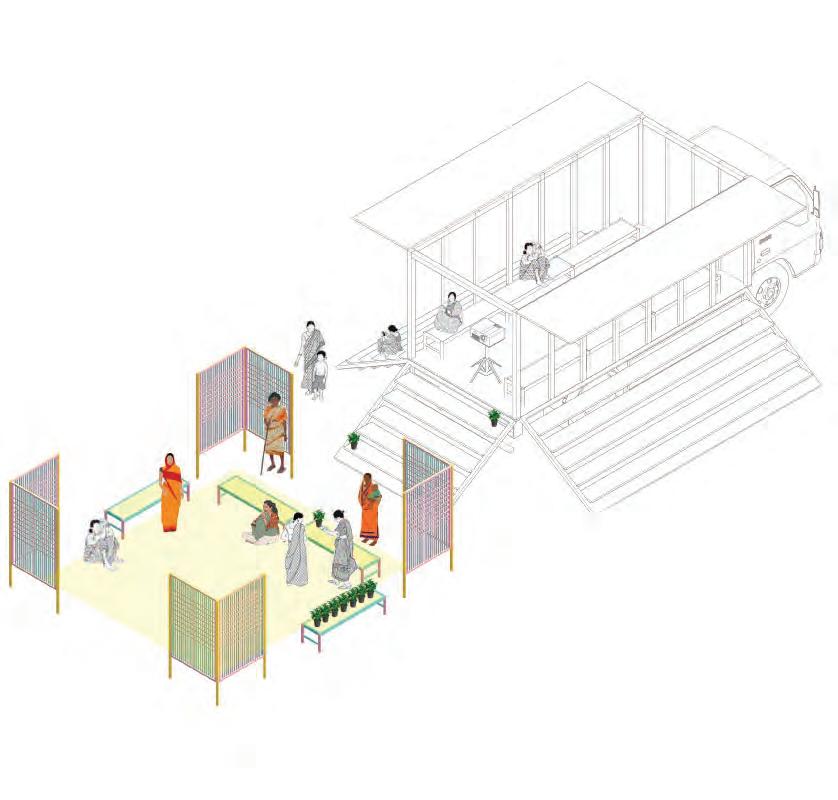

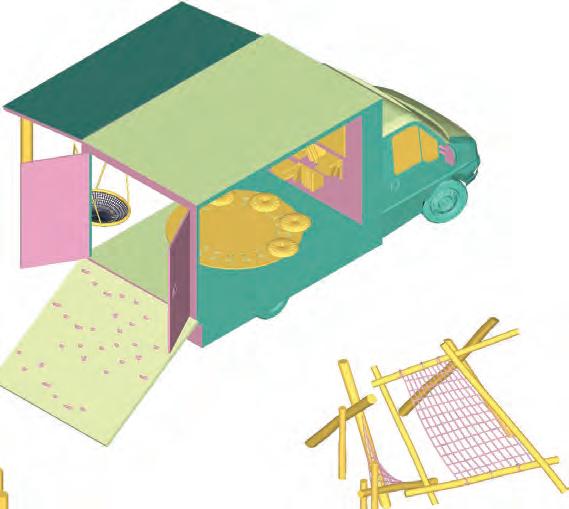

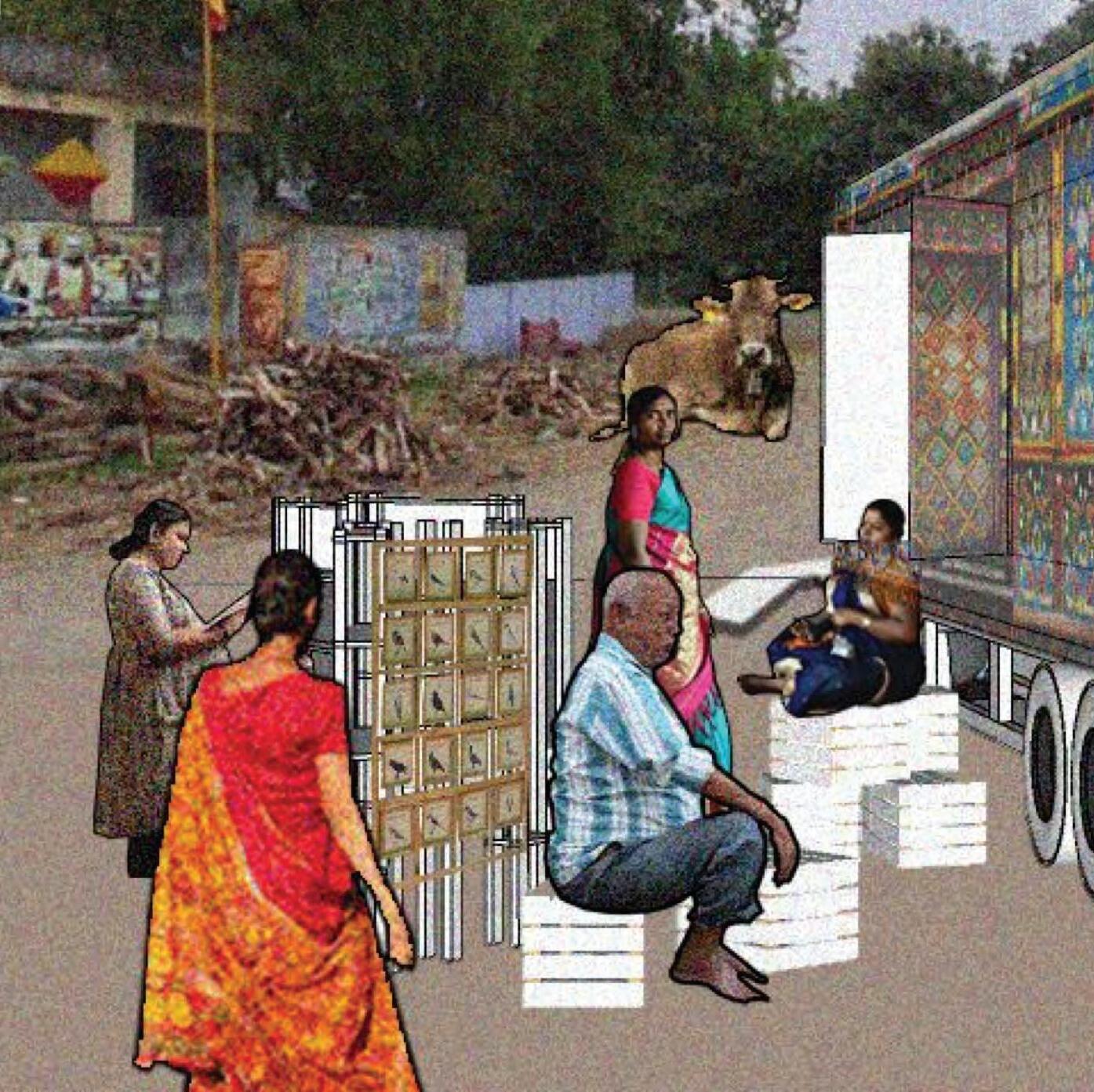

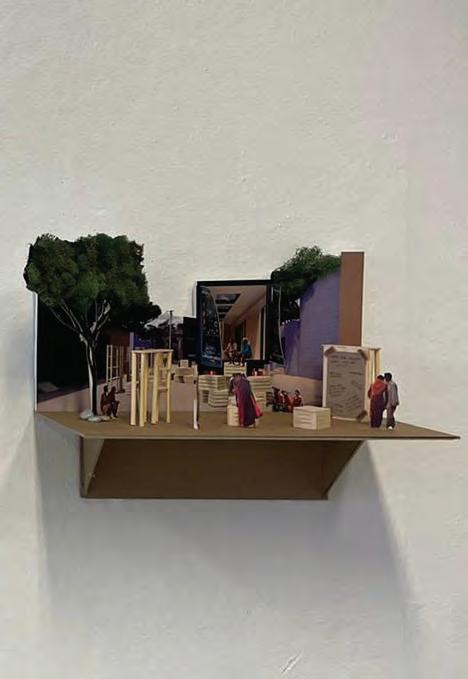

GOLU A MOBILE WAGON

The mobile Golu works in tandem with our ecological interventions, primarily collecting trash throughout the village and depositing it into designated spaces to be properly sorted out and disposed of. While organic waste can be transformed into fresh fertilizer and compost, providing nutrient-rich soil for local agriculture, plastic and other nonorganic waste permanently impacts human and wildlife.

Additionally, this process offers an educational opportunity by allowing people to witness firsthand the cycle of waste collection, composting, and farming. This hands-on experience invites both visitors and locals to observe the farming process up close, learn about the importance of sustainable agriculture and waste management, and participate in these eco-friendly practices. Through this initiative, we aim to foster a deeper understanding of ecological processes and encourage active engagement in sustainable practices within the village communities.

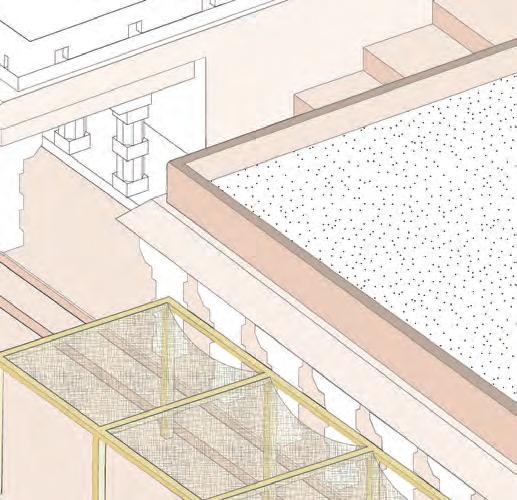

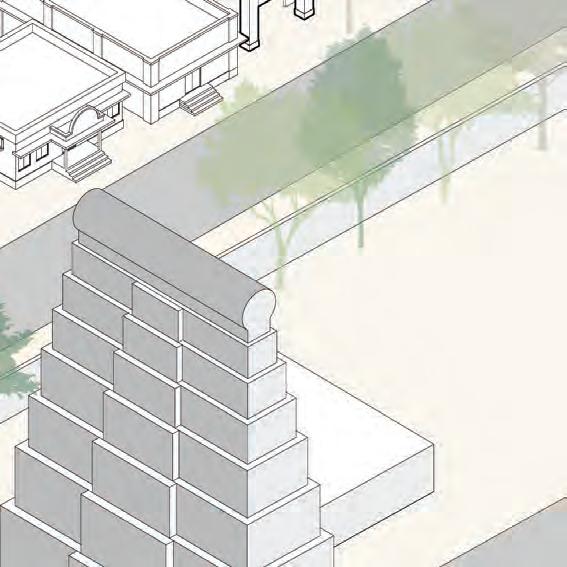

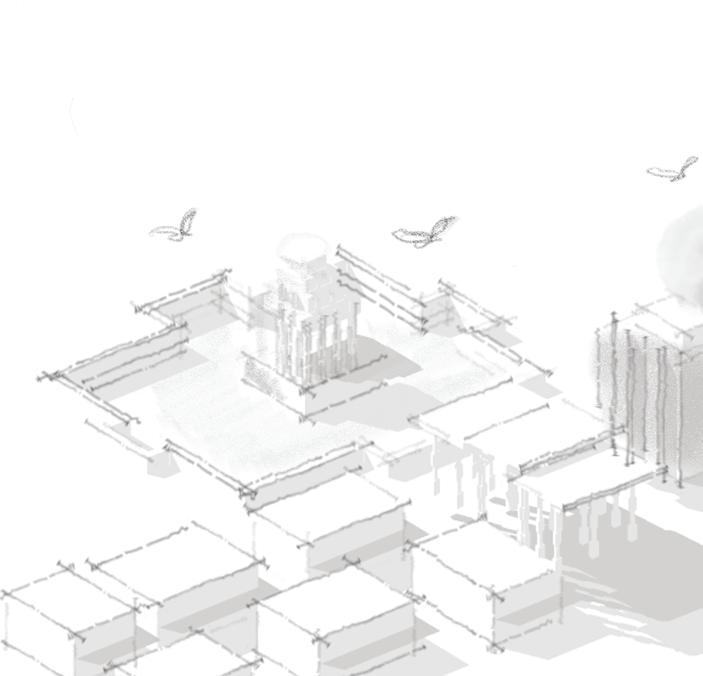

GOLU

TEMPLE ON WHEELS

A mobile prototype serves as an educational and functional tool to bring the stories of the Thirupudai Marudhur Shivan Koli temple to the community. This mobile golu features a miniature replica of the original temple, adorned with the murals and emphasizing the storytelling and cultural heritage. The mobile also addresses the pressing issue of waste management in the village. It includes a trash collection area beneath the structure, symbolizing the behind-the-scenes efforts required to maintain cleanliness around the temple. This dual-purpose prototype not only raises awareness about the temple’s history and stories but also promotes sustainable practices within the community.

GOLU

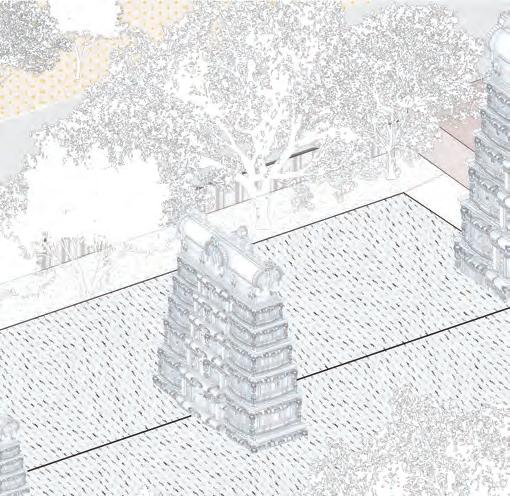

MOBILE STORYTELLING:

FROM TEMPLE TO COMMUNITY

Daily rituals and offerings from locals and visitors signify the importance of the temple. Less accessible tough are the stunning murals within the temple upper levels depicting various aspects of Hindu mythology, and the stories of the deity Shiva and his consort Parvati. These intricate artworks serve as both spiritual and artistic expressions, illustrating narratives from the Shiva Purana, Mahabharata, and Ramayana. These murals are largely inaccessible to the public due to their delicate nature and difficult access via narrow, unlit staircases. In the other, regularly accessible areas in the main floor, visitors bring offerings to the shrines and idols that punctuate the temple grounds, these offerings are often discarded outside the temple, contributing to waste accumulation in the area.

The mobile golu makes the temple stories and murals replicas accessible while addressing waste management concerns. It will be managed by our knowledgeable partners, who can lead discussions and share insights about the murals, ensuring the storytelling aspect is preserved and shared with a wider audience.

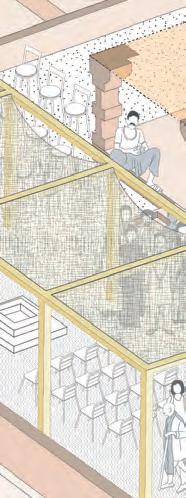

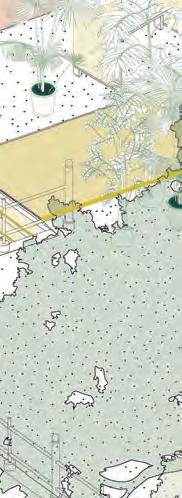

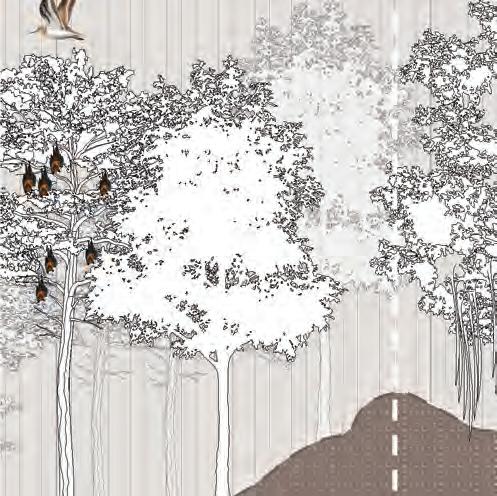

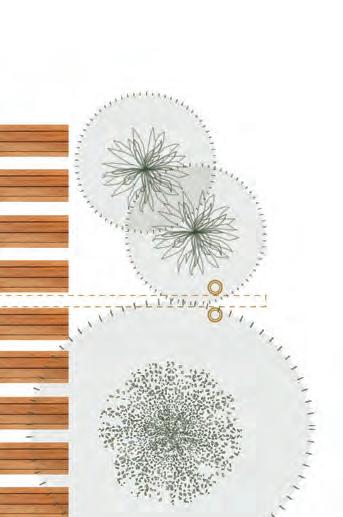

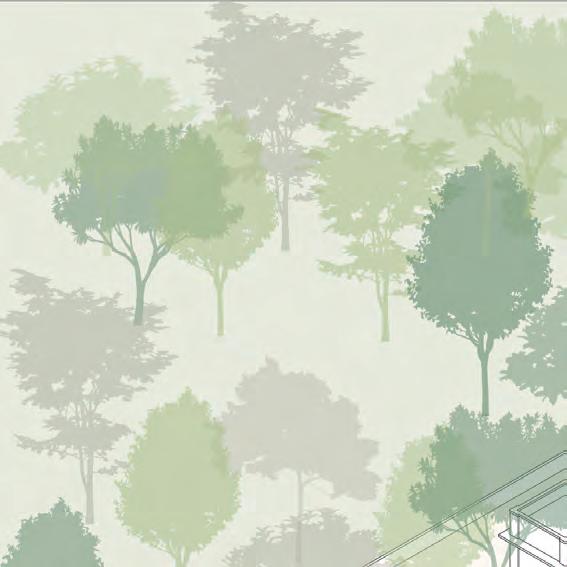

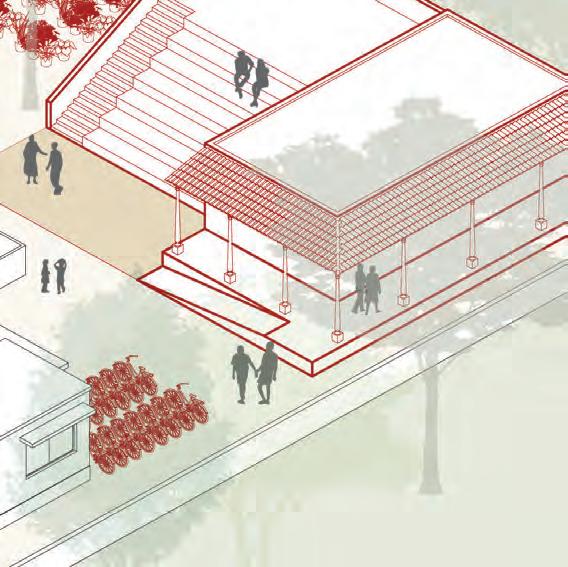

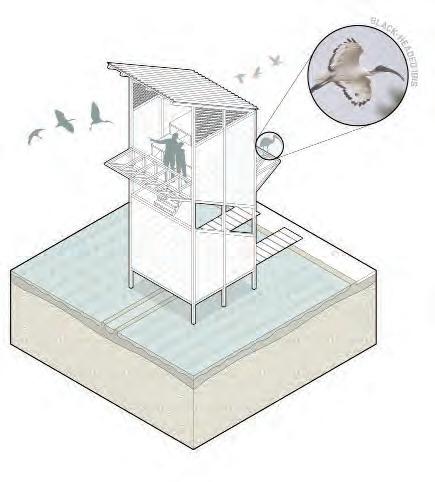

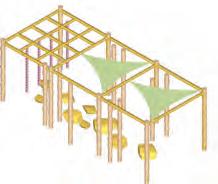

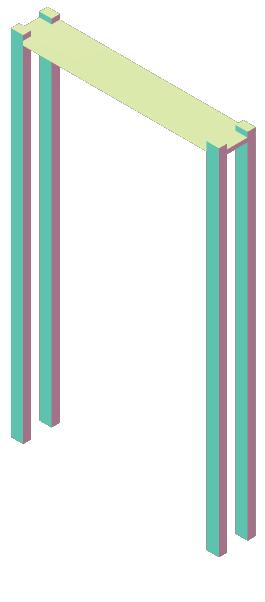

VANA VIDHAANAM CANOPY

VIEWER

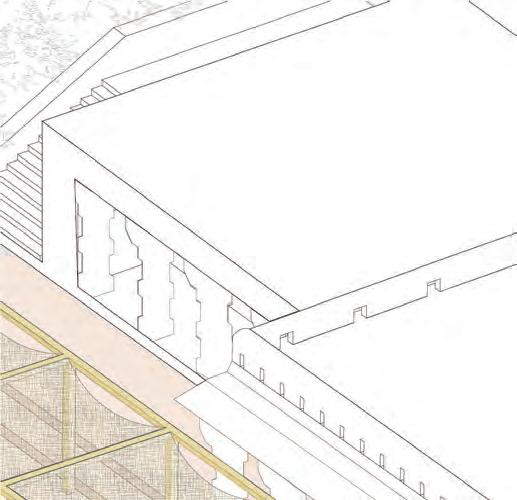

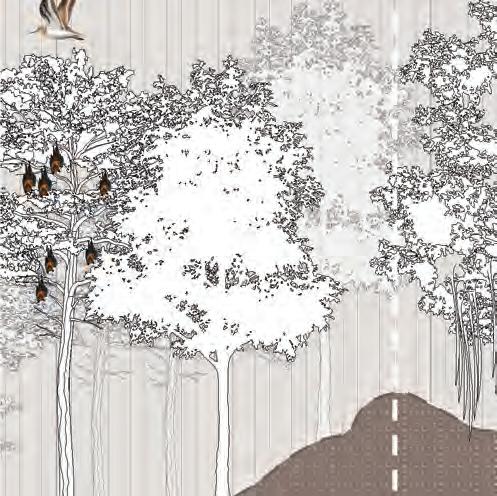

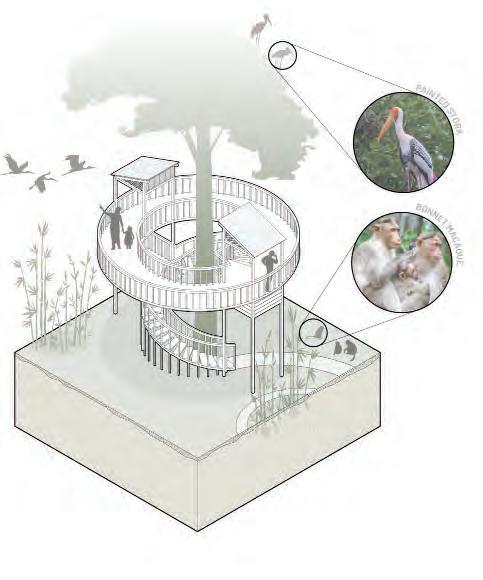

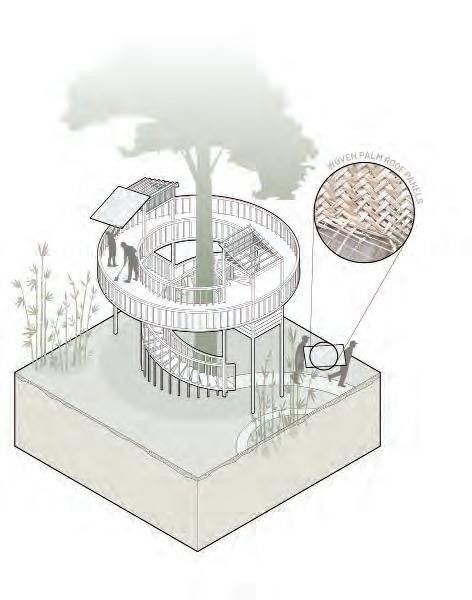

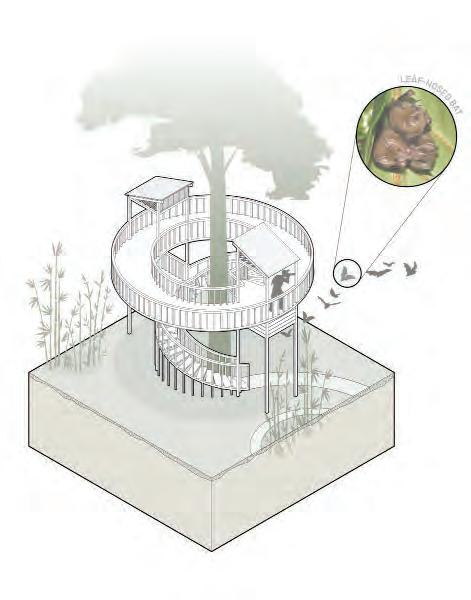

This component brings people as close as possible to the wonders of the TBCR’s forest canopy, and stewards a garden that encourages a flourishing habitat directly around the new viewing station. By day, these platforms provide a shaded shelter for observing common species like monkeys and the many forest-dwelling birds. By night, the shelter transforms and attracts the nocturnal secrets of the forest to life for visitors.

The shelter draws inspiration from the ATREE’s ecologists who rediscovered a species of frog thought to be extinct in the area. This frog has a unique life cycle; it lays its eggs within a nursery of bamboo stalks, which parent frogs will guard ferociously. This shelter will provide scientists with a functional research station for the observation and protection of such unique organisms. It includes certain elements like the bamboo groves and built in bat houses to aid ATREE’s ongoing conservation projects. Elements like the roof panels are made of biodegradable local materials like woven palm, allowing them to be easily dismantled and replaced when they are inevitably saturated in waste produced by nesting bird species.

VANA VIDHAANAM

DIURNAL VIEWING

NOCTURNAL VIEWING

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

SEASONAL MAINTENANCE

ECOLOGICAL RESEARCH

VANA VIDHAANAM

This intervention will work in partnership with the mobile golu to mitigate the ritual waste produced by the temple. An ecologically productive garden space could be fed by the organic composted offerings of the temple, allowing these sacred gifts to serve a purpose beyond their expiration. The garden will in turn attract additional wildlife species, amplifying the role of the viewing shelter as a magnifying telescope of local biodiversity.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

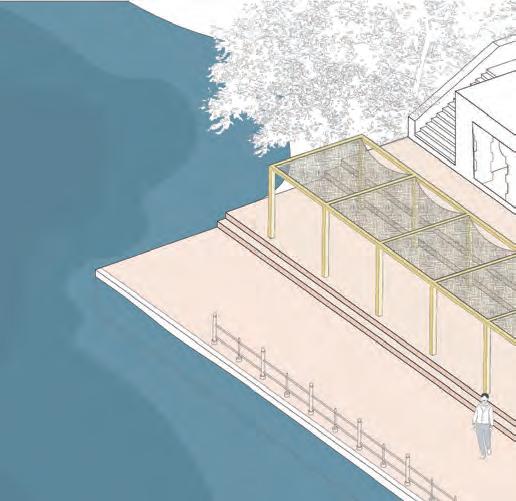

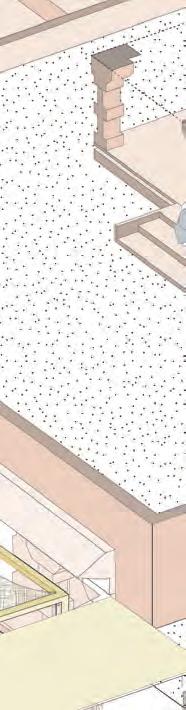

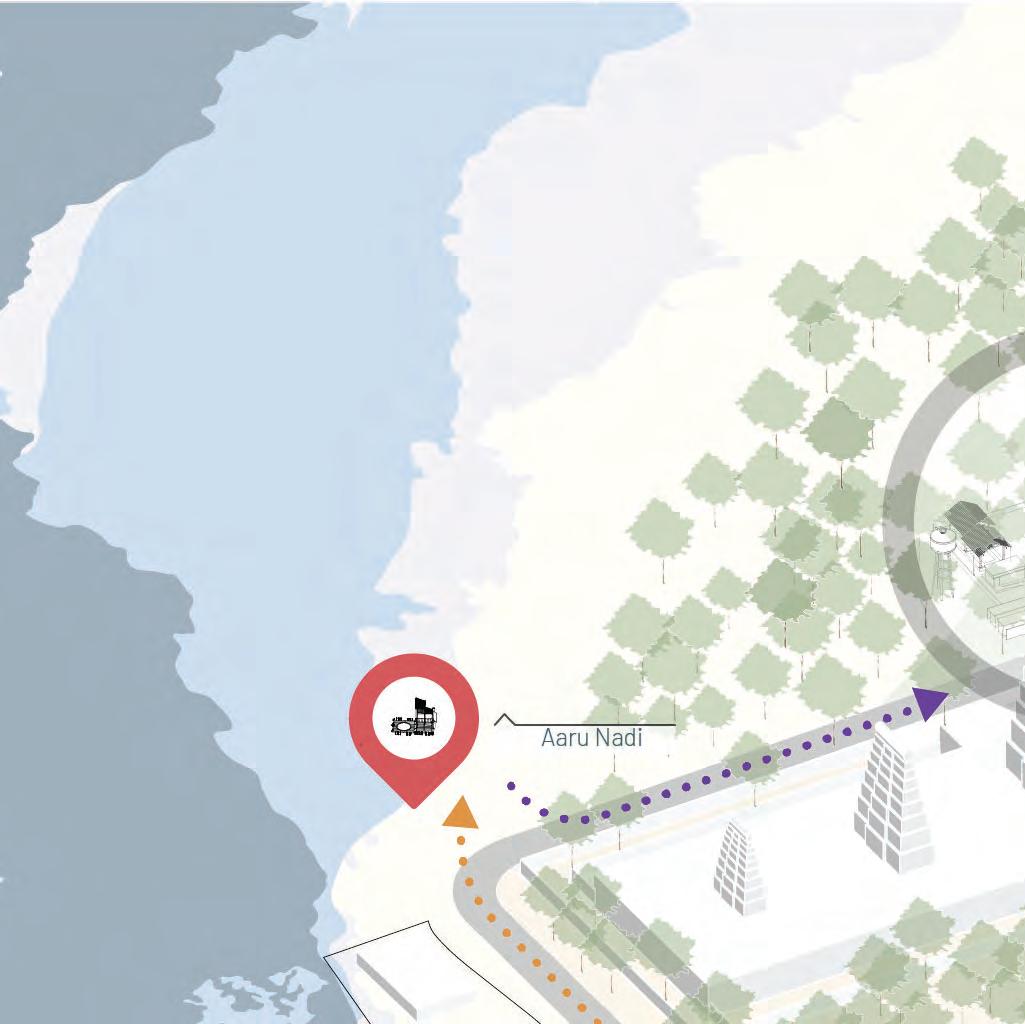

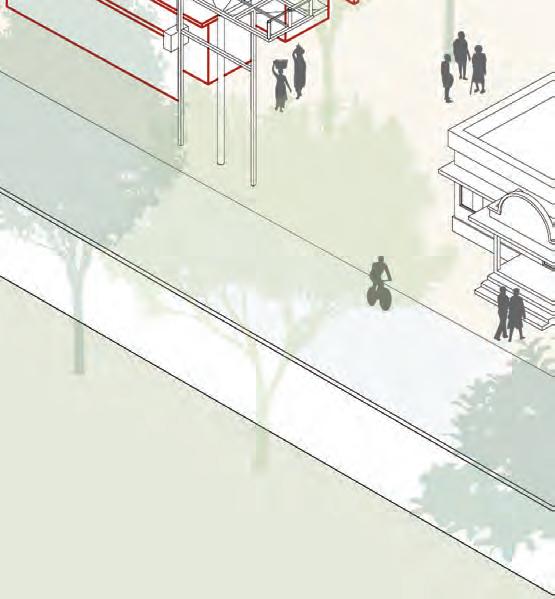

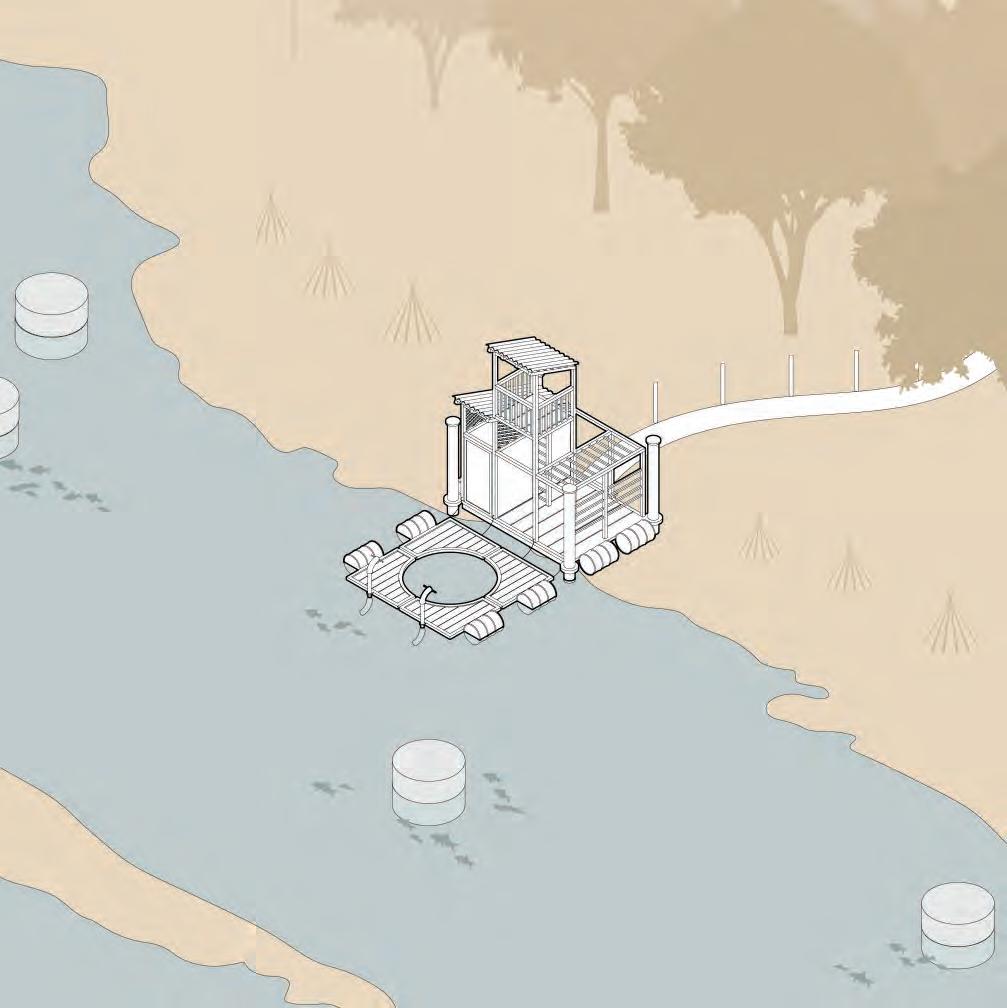

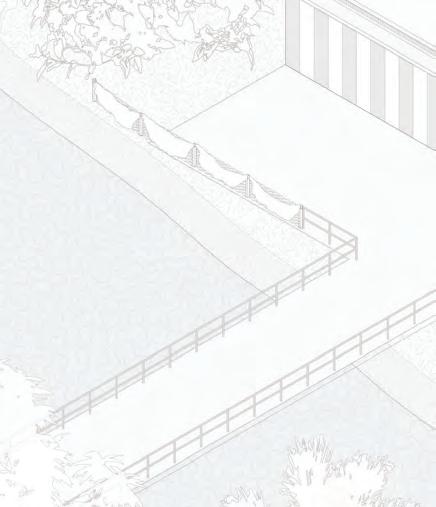

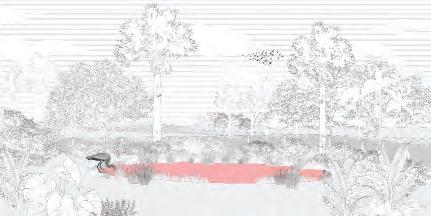

AARU NADI RIVER WALK

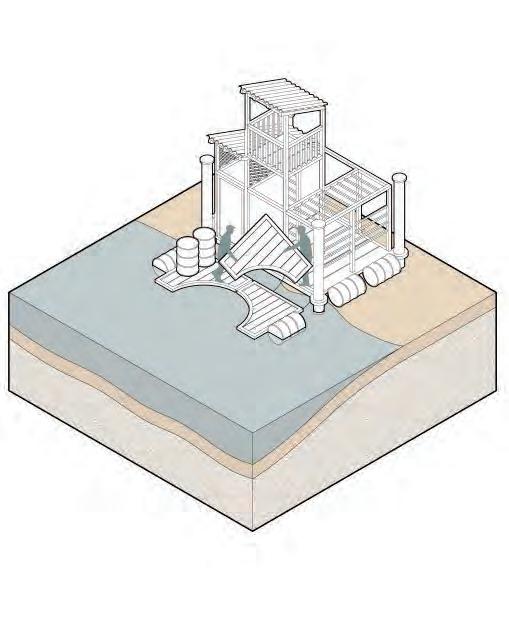

The “River Walk”provides a safe and engaging way for people to interact with the Tamiraparani. Floating platforms allow guests to walk out onto the water, and crude periscopes let them observe aquatic wildlife, such as theTamiraparani barb found only in here. Structures built alongside the river rarely last due to the cyclical flood waters, and to address this, the intervention can be packed away in a floating “amphibious” shed structure.

To the locals, however, the river is far more than a wildlife sanctuary. In addition to providing freshwater for consumption and irrigation, people utilize this waterway for bathing and washing clothing. During religious festivals and times of heavy pilgrimage, new challenges arise along the river with safety concerns due to occasional drownings and issues with quick sand. The River Walk elevated platform may provide a way to monitor crowds and ensure the safety of visitors and villagers alike.

AARU NADI

RAFT DEPLOYMENT AQUATIC OBSERVATION

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

RIVER SAFETY MONITORING MONSOON ADAPTION

AARU NADI

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

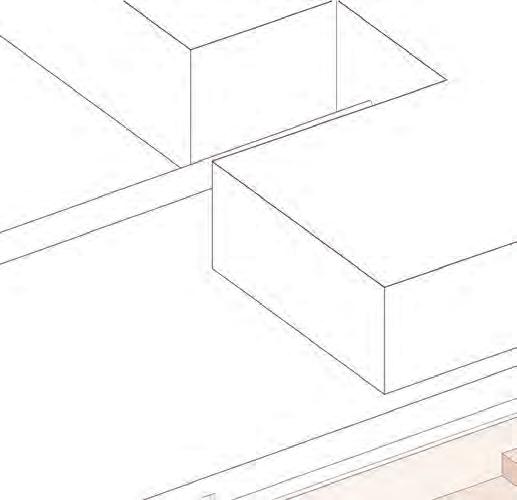

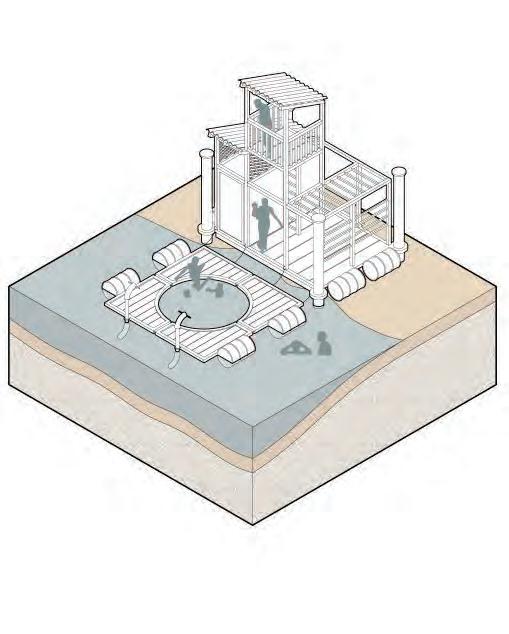

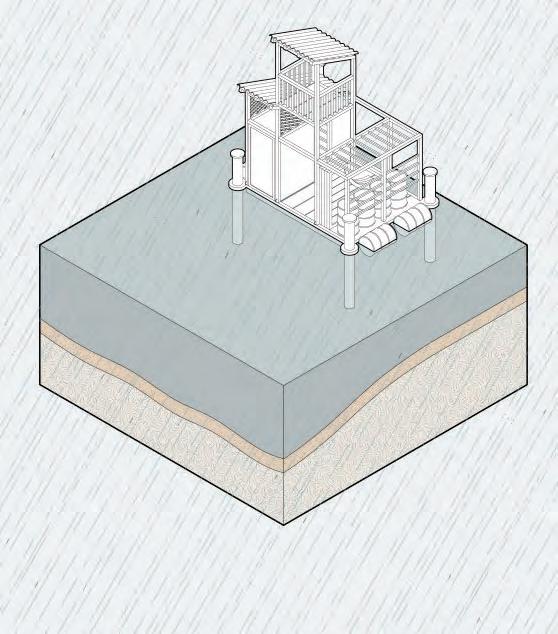

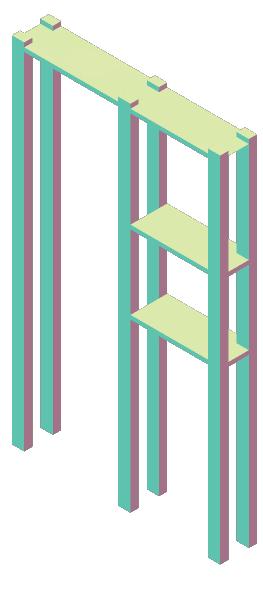

KATCHI THALAM

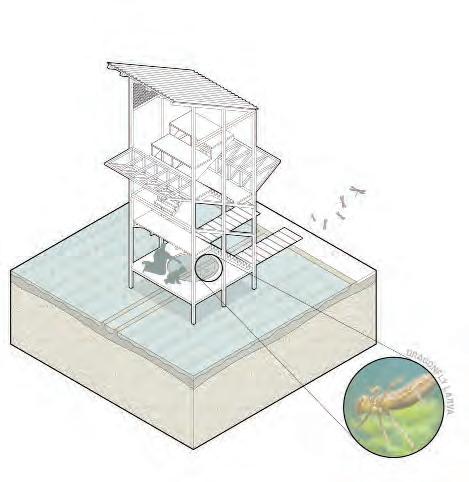

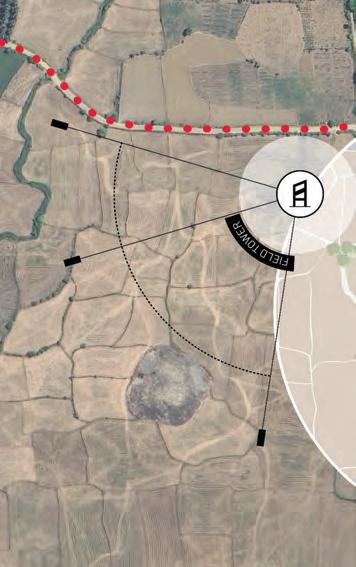

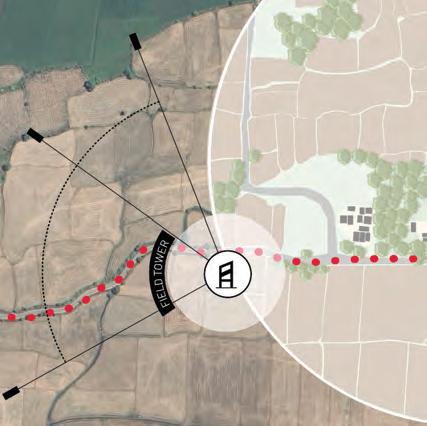

FIELD TOWER

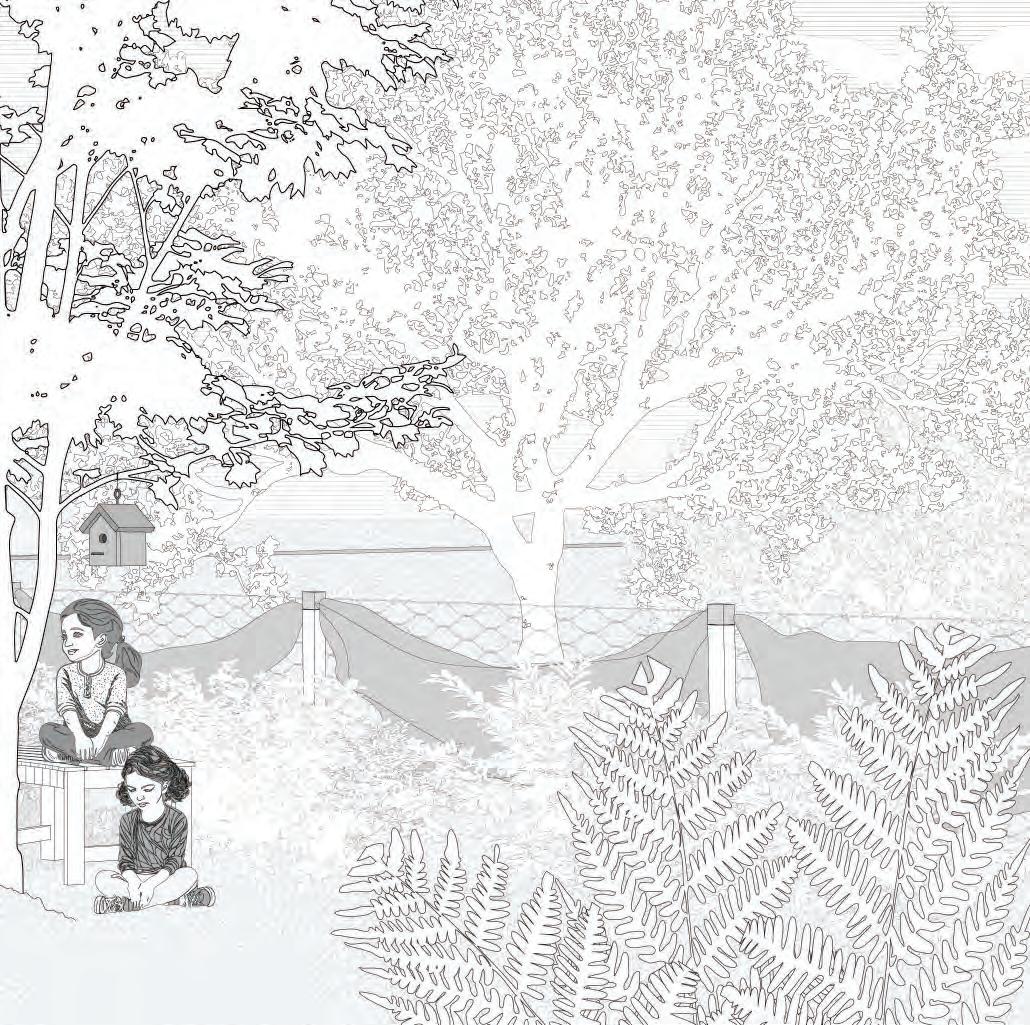

The village is almost entirely surrounded by rice paddies, and this man made landscape host an incredibly productive habitat alongside human activity. The skies above paddies are an “avian battlefield” where countless birds and insects are constantly on the move, and the irrigation pits that run through the paddies host a variety of wetland species.

Learning from ATREE’s program bringing school children to these channels to learn about the insect larvae that inhabit them, the “Field Tower” provides a platform for landscape interpretation. On its lowest level, visitors can observe the fascinating wildlife of the irrigation channels up close, while the upper levels provide scenic views of the endless paddies, as well as nesting roosts that bring local bird species closer to guests.

KATCHI THALAM

WILDLIFE VIEWING YOUTH EDUCATION

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

INTERCONNECTION SHADE AND RESPITE

KATCHI THALAM

The ecotourism initiative benefits all villagers, including those in clusters 2 and 3, which are separated from the preserve by a long road amongst the paddies. These towers serve different purposes: as a visual connection between the clusters to encourage people to explore beyond the boundaries of the central village, and as a respite from the intense heat of the South Indian sun for farmers in the fields, villagers traversing the long road between clusters, and visitors wishing to explore.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

ACROSS CLUSTERS

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

Over time, these prototypes will reach all clusters, refining the approach based on lessons learned, community feedback, and visitor engagement. Whether through field towers fostering interconnectivity or revitalizing select domestic houses, the goal is to create a cohesive network across all clusters.

PARTNERSHIPS AND STEWARDSHIP

The success of this intervention relies on leveraging local resources with organizational and governmental support to ensure the interpretation center offers a sustainable model that balances eco-tourism investment with the stewardship of local assets to serve the needs of local residents.

Partnerships can support research capacities informing storytelling components seamlessly weaving the cultural and ecological significance of the area. Supporting the organizations already present on site through government grants will ensure the sustainability of the project.

Last, our project recognizes that local expertise and leadership are essential to co-producing a strategy of interpretation grounded on the uniqueness of Thirupudaimaruthur. Prioritizing strategies for engagement and involvement will be key to the project success.

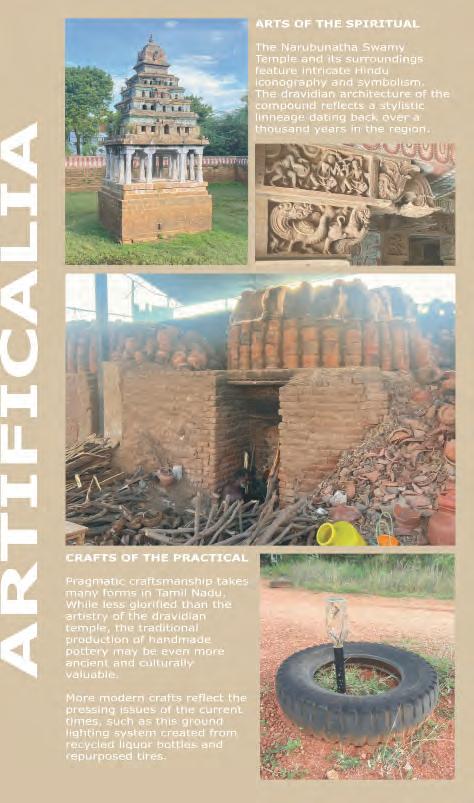

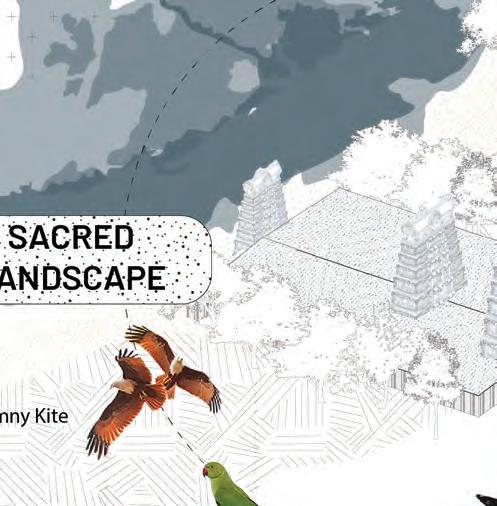

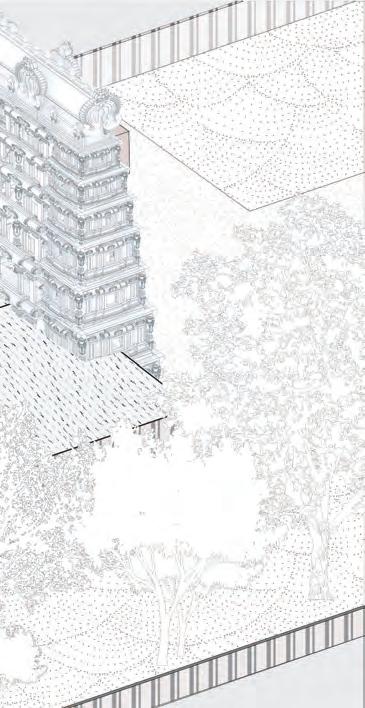

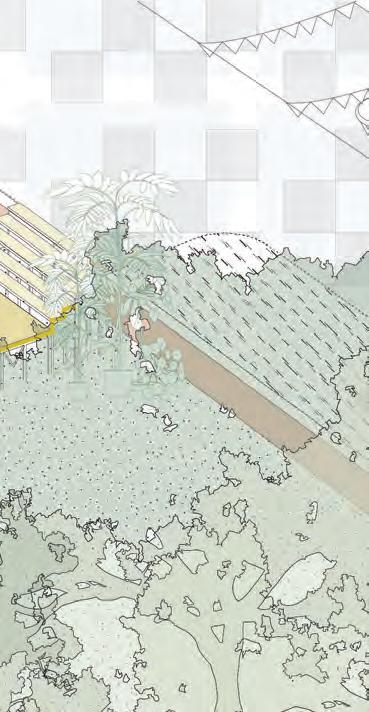

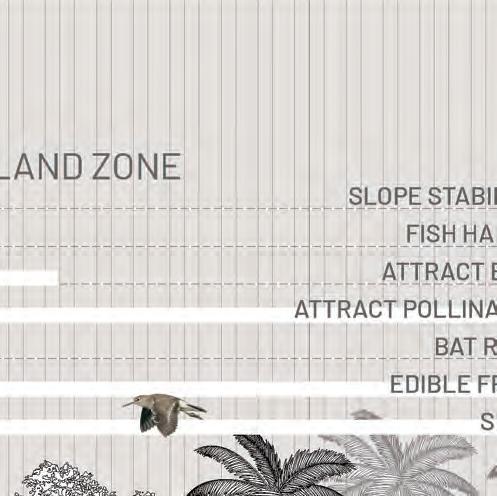

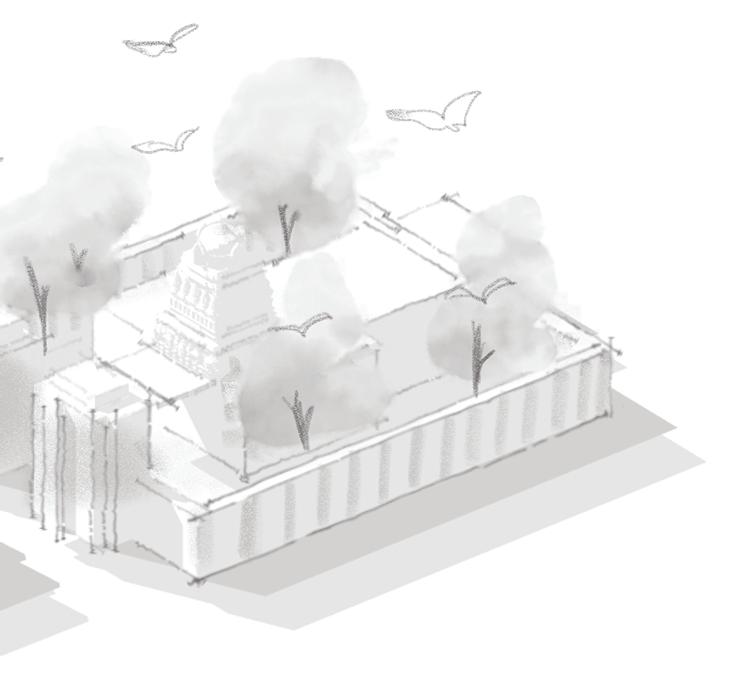

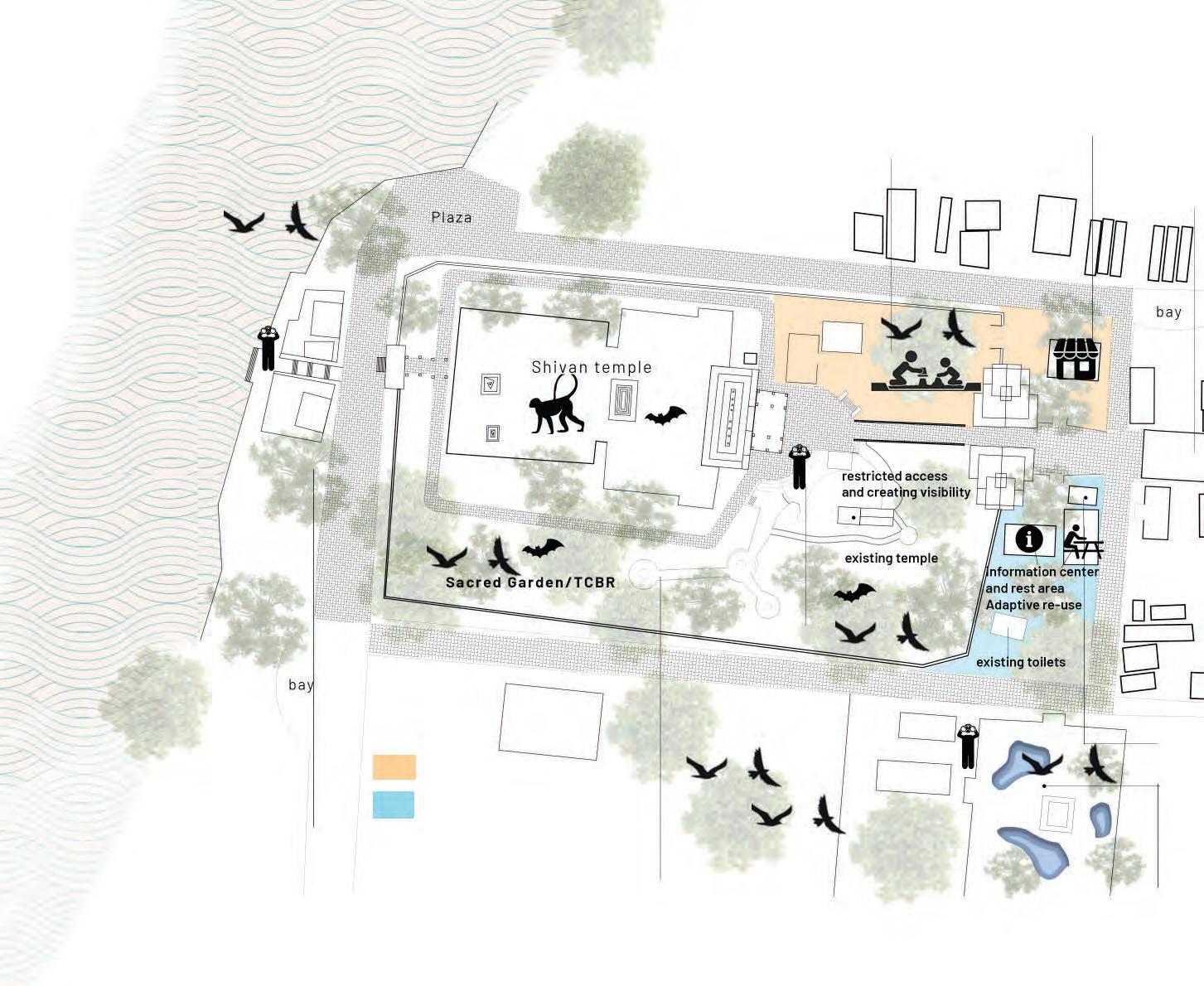

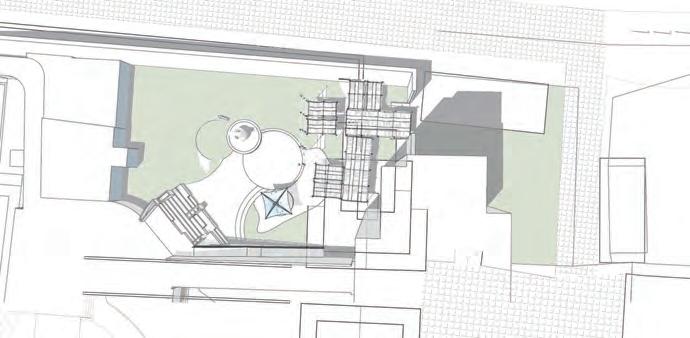

SACRED HORIZONS

In an era of climate change and environmental degradation, the sacredness of nature holds deep significance, particularly in Hinduism, where nature conservation is deeply rooted in reverence for rivers, trees, and animals. This project is not one, but three projects that explore how sacredness can be honored and sustained through a lens of sacred ecology, re-imagining the relationship between spirituality, community, and the environment. Whether through revitalizing sacred gardens, re-imagining temple precincts, or preserving ecosystems, each initiative aims to foster harmonious spaces that nurture both human and non-human communities, encouraging collective responsibility for the land and its future.

THE SACRED

IN THE GARDEN

Harnessing the existing interest in the temples of the region, ATREE’s knowledge of ecology, and the widespread appreciation of the trees and plants of the region, this project aims to reposition and refocus Sacred Gardens to be a reservoir of resources for local communities now and in the future.

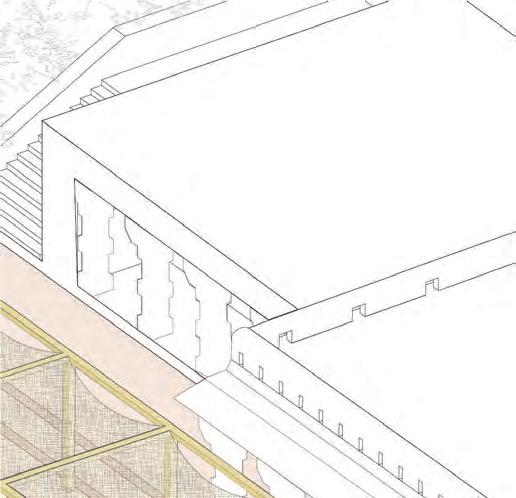

KOVIL CHIMES

The project reinterprets the temple procession while integrating the surrounding community precinct. By preserving key elements and introducing unique typologies, this approach fosters a sense of shared responsibility and encourages community engagement, ultimately, creating a harmonious space where tradition and modernity coexist.

SPECULATING THE SANGAM

This project focuses on the reinterpretation of water’s sacredness through a speculative investigation of the potential futures of each region of the five landscapes that will bear witness to the accelerating climatic changes defining the current state we live in.

IN THE GARDEN

As someone who grew up in the U.S., I was struck by many things when I visited India for the first time this past year. But what stood out most to me was the relationship between the people and the waters, lands, animals, and temples of Tamil Nadu. There is a humility and understanding among the people that seems innate to the culture. The root cause of this understanding seems to lie in what is interpreted as sacred. Recognizing this as a profound force, this project examines and re-interprets the notion of the sacred with the aim of upholding and strengthening the ecological and social traditions that will be a stalwart against the rising tide of global warming and modernization.

IN TIME

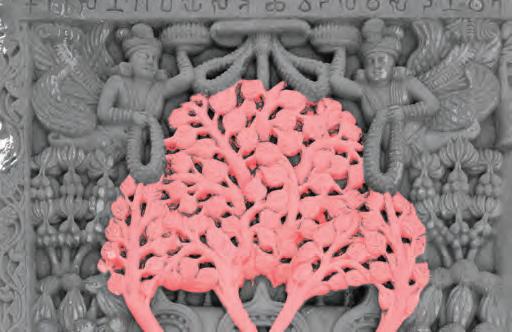

Throughout time, trees have held a unique place among cultures and civilizations. Whether through carving in stone, an association with a deity, a depiction in a temple, a painting, or through an elaborate sculpture, many cultures have showed a degree of reverence and appreciation for trees that elevate them above the rest of the natural world.

1. Indus Valley Civilization, 3300 BCE - 1300 BCE, Peepal tree shown in a Harrapan Seal dating to 2500 BCE.

2. Ancient Egypt, 3150 BCE - 300 BCE, Lady of the Sycamore granting nourishment and protection to Khonsu-mes, Papyrus dating to 1000 BCE.

3. Ancient Persia, 550 BCE - 300 BCE, bas-relief of cypress tree, representing beauty and strength, alongside a soldier in Persepolis, dated 559 BCE.

4. Ancient Greece, 1200 BCE - 600 CE, Apollo and Daphne, as she metamorphosizes into a Laurel tree, by Veronese, dated 1560 -1565 CE.

5. Bodhi Tree, 500 BCE - Present, Peepal tree, the sacred tree of enlightenment, depicted as a temple for the Buddha, Bodh Gaya, 1st century CE.

6. Kalpavrishka, 1500 BCE - Present, Kalpavrishka, a wish fulfilling divine tree in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, guarded by mythical creatures in an 8th C. Pawon temple in Java, Indonesia.

THE GARDEN

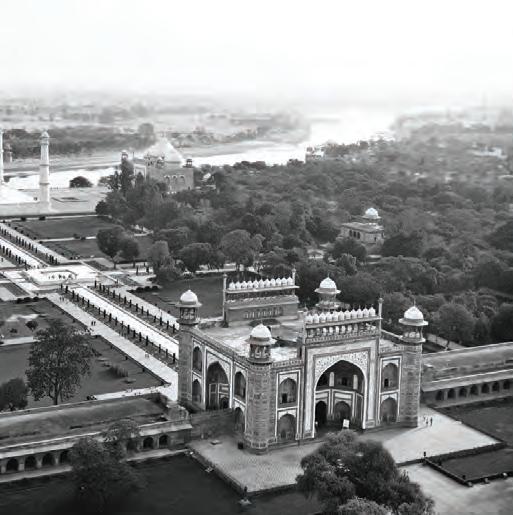

In the Hebrew Bible book of Genesis, an earthly paradise was inhabited by the first created man and woman, Adam and Eve. After eating the forbidden fruit, they were cast out of the garden, relegated to the accursed ground, and sentenced to toil and sweat for their subsistence. According to the Quran, ‘jannat’ (paradise) awaits the faithful. It is a place where springs burst forth from the earth, a place where there are shady groves, trees, and bushes, whose fruits are within easy reach and are just waiting to be enjoyed. These are two examples among many of the notion of a garden as an enclosed space where one could approach a semblance of perfection and balance, affording a measure of bliss, that might not be attainable outside the garden walls.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

1. Garden of Eden, Wenzel Peter, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, oil on canvas.

2. Paradise Garden, Taj Mahal, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India.

3. Shinjuku Gyōen in Tokyo, Japan.

4. Garden at Versailles, Versailles, France.

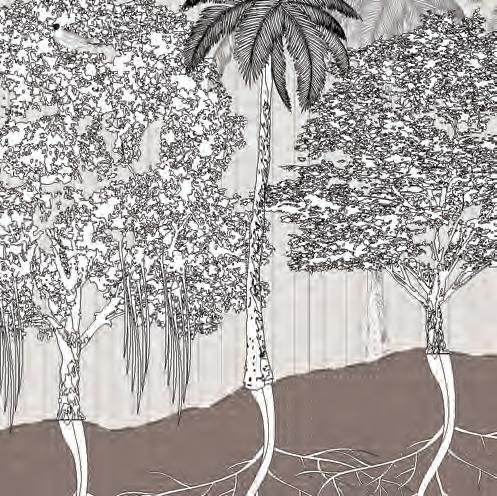

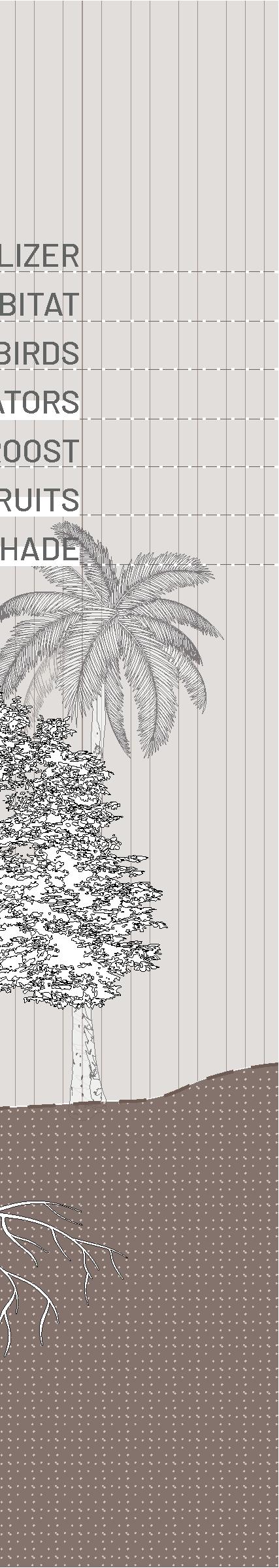

THE GARDEN

LOWER BANK ZONE J F M A M J J A S O N D POLLINATORS

Pontederia vaginalis

Colocasia esculenta

Saccharum spontaneum

Arundo donax

Heteropogon contortus

Cyperus corymbosus

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

Vitex negundo

Vitex leucoxylon

THE GARDEN

Ficus hispida

Mallotus nudiflorus

Trema orientale

Mitragyna parvifolia

Colophyllum inophyllum

Terminalia arjuna

Madhuca longifolia

Syzygium cumini

Pongamia pinnata

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

Ficus benghalensis

Adina cordifolia

Mangifera indica

Ficus religiosa

Borassus flabellifer

Azadirachta indica

Cordia dichotoma

MAHUA

The Mahua tree, or Iliuppa as it is known locally, like many of the native plants and trees of the region, is valued not only for its role in the larger ecosystem, but also for the multitude of uses that humans have for its many elements. The leaves and bark are used for purposes ranging from ulcer treatments to the purification of a liquor made locally. The flowers are used to cure cough and swelling. Ripe fruit is eaten raw or converted into a sugar and mixed as a beverage. The seeds of the fruit produce an oil that is applied as a skin treatment, used a cooking oil, or in some rural communities, as soap. And for centuries, the oil of the seeds lighted the many temples throughout the region.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

1. Leaves of Mahua

2. Bark of Mahua

3. Latex being harvested from Mahua

4. Flower of Mahua in bloom

5. Ripe fruit of Mahua

6. Seeds of Mahua

THE REGION

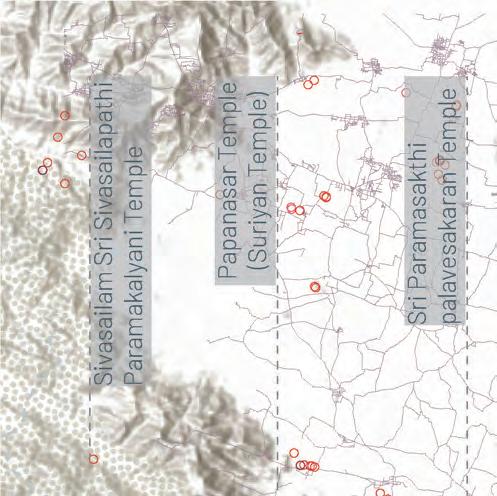

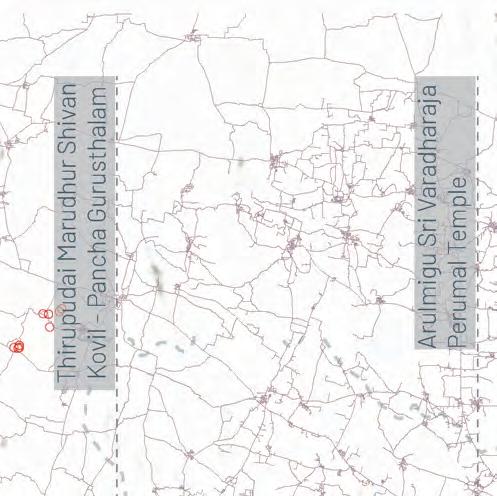

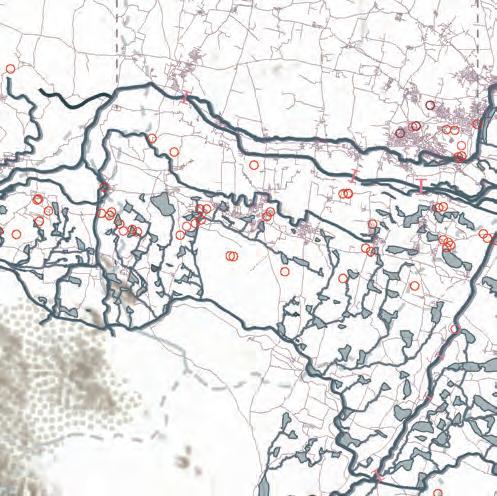

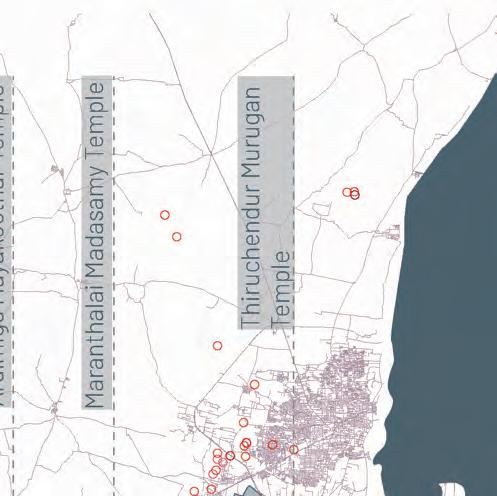

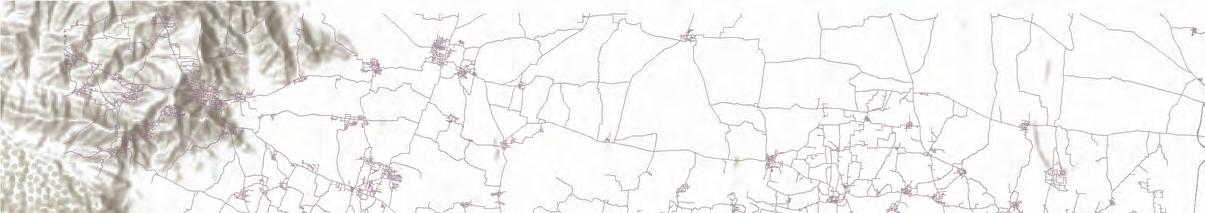

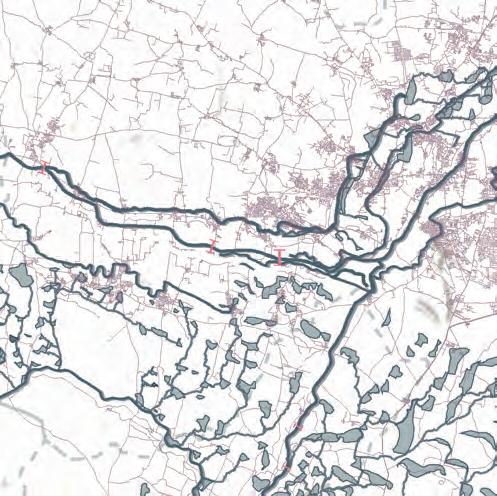

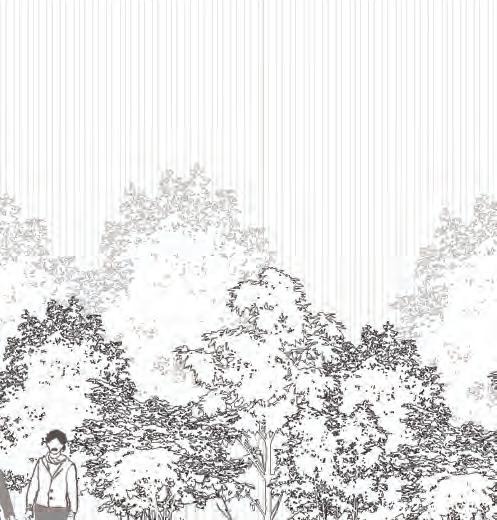

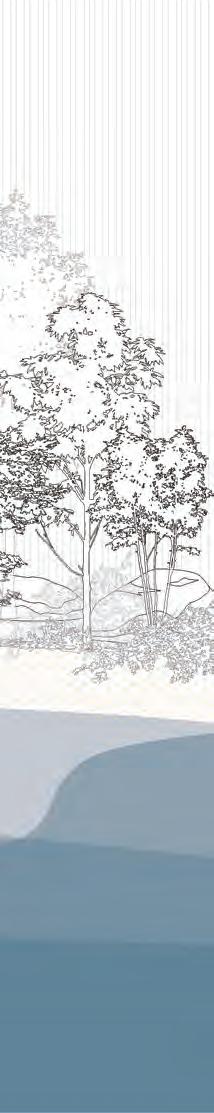

Ancient temples are a fixture of Tamil Nadu. They are scattered along xture They and among the regions many rivers. But before there were any temples, there any small shrines were built under trees. When construction evolved and allowed temples to be built, the trees that served as shrines to the served deities were kept in place and preserved. Alongside these trees, other Alongside plants were introduced that provided the temples with many of their that provided day to day needs. These places became known as Sacred Gardens or day needs. places Nandavanams. This practice has mostly been forgotten, but ATREE mostly began reviving it in 2021. With a temple located within close proximity to most small communities, this project seeks to re-establish Sacred Gardens at every suitable temple, allowing the knowledge and joy of at caring for the native ecology and biodiversity to spread far and wide, ensuring its preservation.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

Temples without Sacred Gardens

Temples with Sacred Gardens

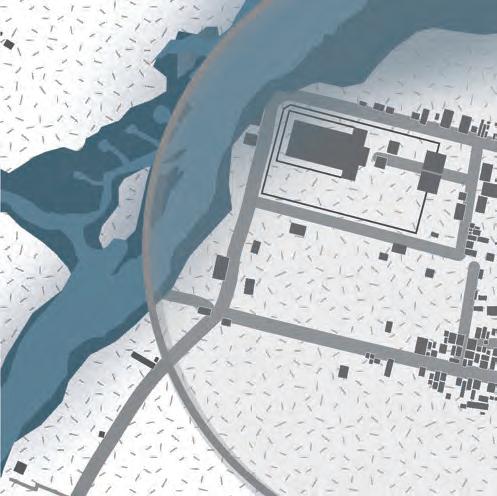

Thiruppadaimaruthur Bird Conservation Reserve Roads Water

nservation Reserve

PAPPAKUDI

The Thirukadugai Moondreeswarar temple in the village of Pappakudi was the first sacred garden to be re-established by ATREE in 2021. Approximately one hundred trees and plants have since been planted. The planting is done with the intented proportion of 50% native trees, 20% medicinal plants, 10% flowering plants, and 10% commercial plants. A survey of the existing species, the concerns and needs of the local people, the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment Board, and ATREE’s knowledge are all considered and taken into account when deciding which species to plant. While the ecological aspects of these gardens are well understood, deliberate interventions, initiatives, and programs are needed to integrate these spaces into the local communities, allowing this knowledge of ecology and the practice of co-existence between humans, animals, and plants to grow and thrive now and in the future.

BOUNTY

This proposal begins with the notion that Sacred Gardens are spaces that have the potential to become beautiful and bountiful and teaming with life and energy. Further, the aim of this proposal is to have these spaces utilized, managed, and enjoyed by the local communities. Utilizing ATREE’s knowledge, and harnessing the existing interest and usage of the temples, these spaces could become focal points at which the tradition of ecological stewardship are further developed, maintained, and promoted for future generations.

THE RIVER WHISPERS OF BIRDS, TREES, TEMPLES, AND THEIR PEOPLE

SEED