SACRED HORIZONS

In an era of climate change and environmental degradation, the sacredness of nature holds deep significance, particularly in Hinduism, where nature conservation is deeply rooted in reverence for rivers, trees, and animals. These projects explore how sacredness can be honored and sustained through a lens of sacred ecology, re-imagining the relationship between spirituality, community, and the environment. Whether through revitalizing sacred gardens, re-imagining temple precincts, or preserving ecosystems, each initiative aims to foster harmonious spaces that nurture both human and non-human communities, encouraging collective responsibility for the land and its future.

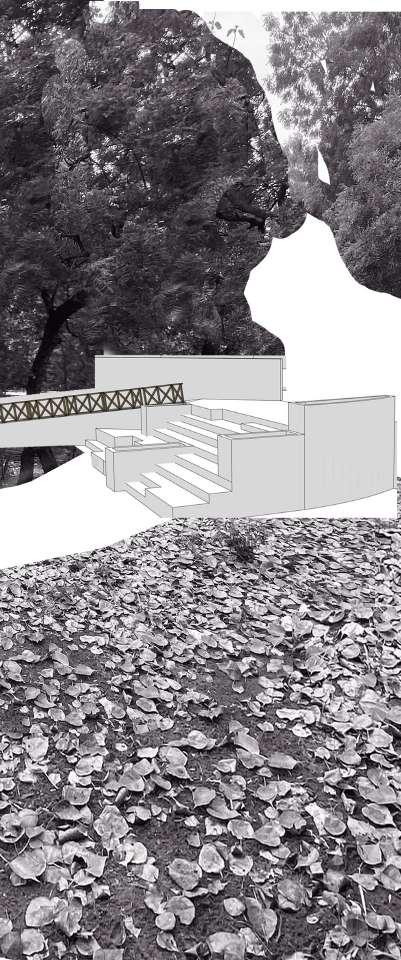

Harnessing the existing interest in the temples of the region, ATREE’s knowledge of ecology, and the widespread appreciation of the trees and plants of the region, this project aims to reposition and refocus Sacred Gardens to be a reservoir of resources for local communities now and in the future.

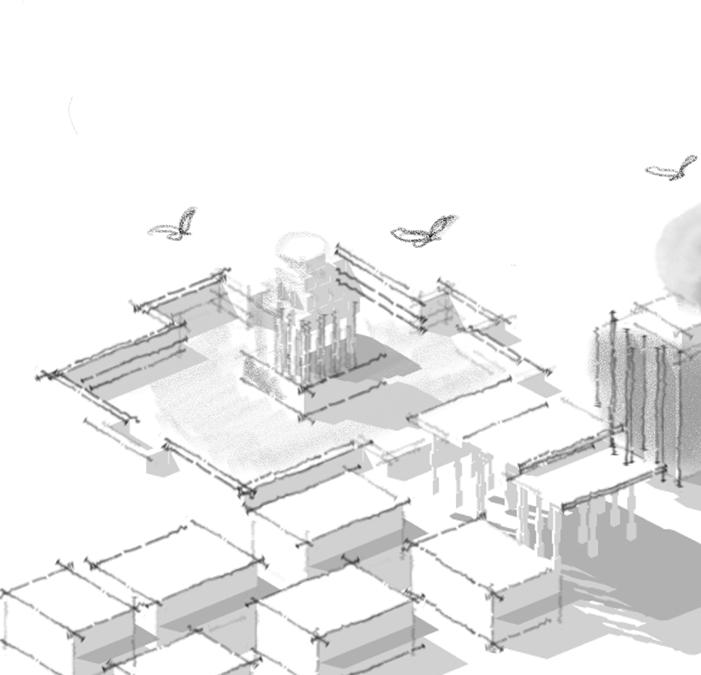

The project reinterprets the temple procession while integrating the surrounding community precinct. By preserving key elements and introducing unique typologies, this approach fosters a sense of shared responsibility and encourages community engagement, ultimately, creating a harmonious space where tradition and modernity coexist.

This project focuses on the reinterpretation of water’s sacredness through a speculative investigation of the potential futures of each region of the five landscapes that will bear witness to the accelerating climatic changes defining the current state we live in.

As someone who grew up in the U.S., I was struck by many things when I visited India for the first time this past year. But what stood out most to me was the relationship between the people and the waters, lands, animals, and temples of Tamil Nadu. There is a humility and understanding among the people that seems innate to the culture. The root cause of this understanding seems to lie in what is interpreted as sacred. Recognizing this as a profound force, this project examines and re-interprets the notion of the sacred with the aim of upholding and strengthening the ecological and social traditions that will be a stalwart against the rising tide of global warming and modernization.

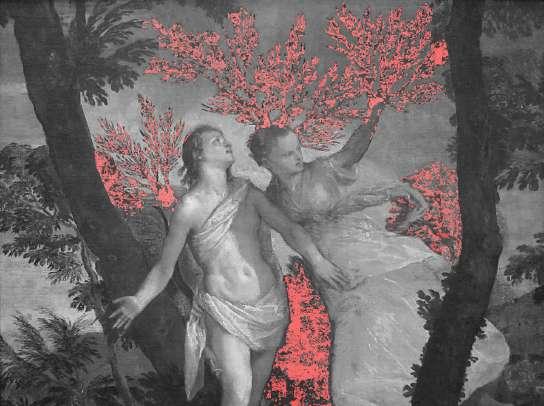

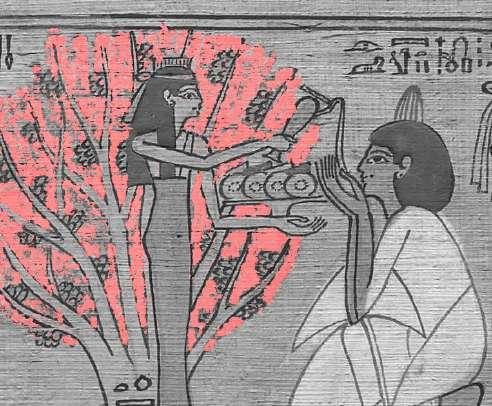

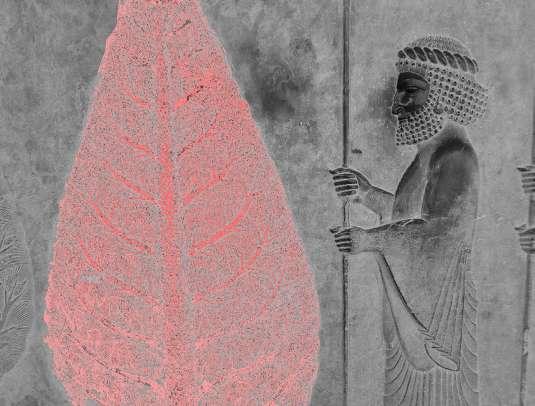

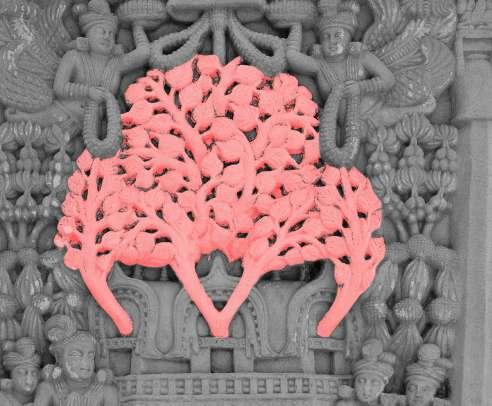

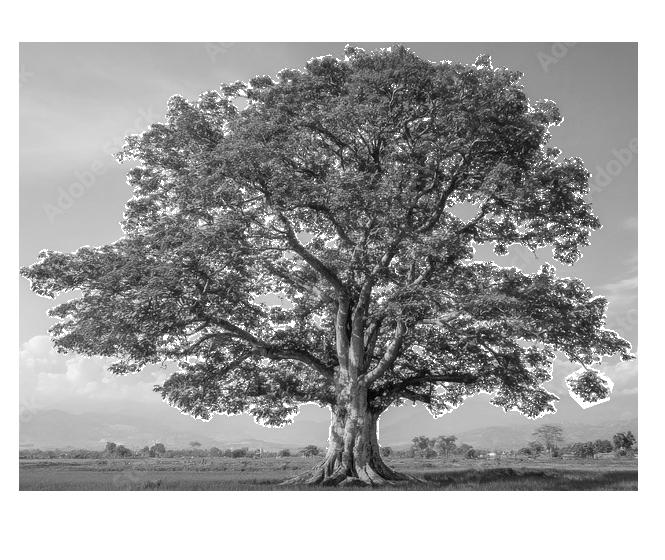

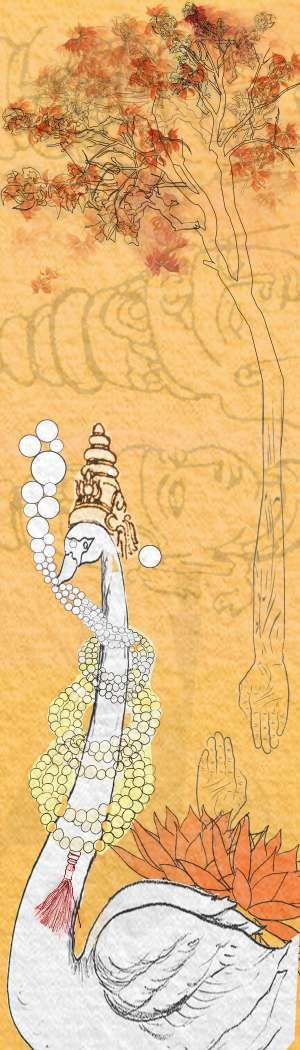

Throughout time, trees have held a unique place among cultures and civilizations. Whether through carving in stone, an association with a deity, a depiction in a temple, a painting, or through an elaborate sculpture, many cultures have showed a degree of reverence and appreciation for trees that elevate them above the rest of the natural world.

1. Indus Valley Civilization, 3300 BCE - 1300 BCE, Peepal tree shown in a Harrapan Seal dating to 2500 BCE.

2. Ancient Egypt, 3150 BCE - 300 BCE, Lady of the Sycamore granting nourishment and protection to Khonsu-mes, Papyrus dating to 1000 BCE.

3. Ancient Persia, 550 BCE - 300 BCE, bas-relief of cypress tree, representing beauty and strength, alongside a soldier in Persepolis, dated 559 BCE.

4. Ancient Greece, 1200 BCE - 600 CE, Apollo and Daphne, as she metamorphosizes into a Laurel tree, by Veronese, dated 1560 -1565 CE.

5. Bodhi Tree, 500 BCE - Present, Peepal tree, the sacred tree of enlightenment, depicted as a temple for the Buddha, Bodh Gaya, 1st century CE.

6. Kalpavrishka, 1500 BCE - Present, Kalpavrishka, a wish fulfilling divine tree in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, guarded by mythical creatures in an 8th century Pawon temple in Java, Indonesia.

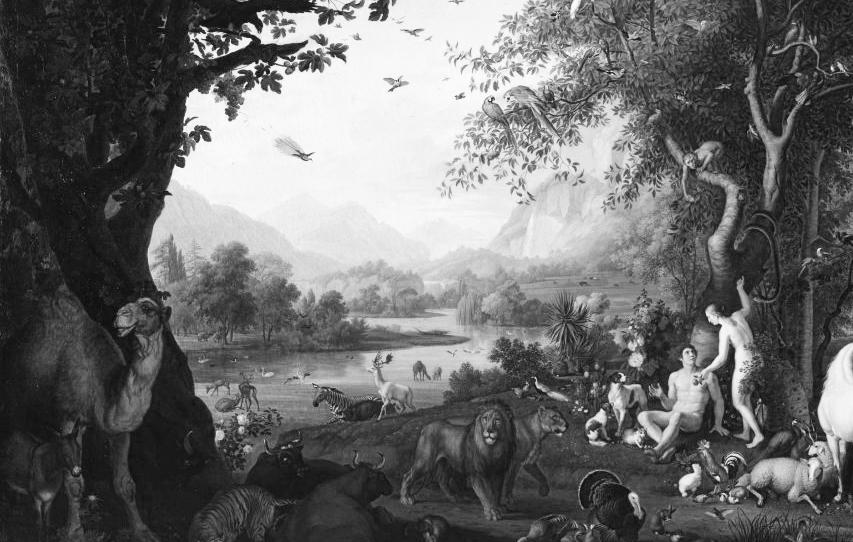

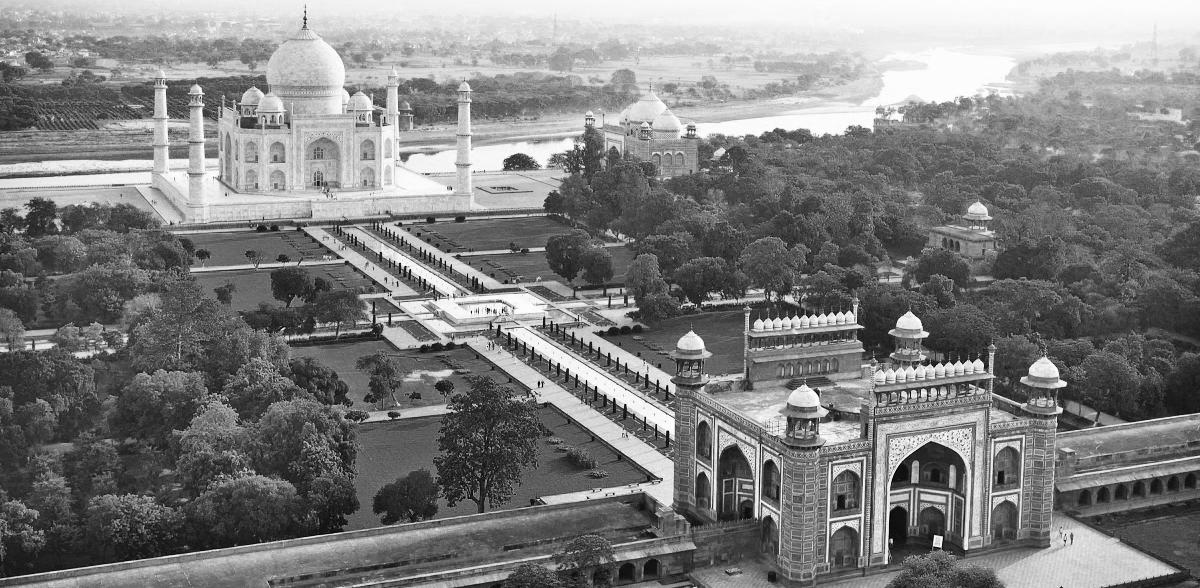

In the Hebrew Bible book of Genesis, an earthly paradise was inhabited by the first created man and woman, Adam and Eve. After eating the forbidden fruit, they were cast out of the garden, relegated to the accursed ground, and sentenced to toil and sweat for their subsistence. According to the Quran, ‘jannat’ (paradise) awaits the faithful. It is a place where springs burst forth from the earth, a place where there are shady groves, trees, and bushes, whose fruits are within easy reach and are just waiting to be enjoyed. These are two examples among many of the notion of a garden as an enclosed space where one could approach a semblance of perfection and balance, affording a measure of bliss, that might not be attainable outside the garden walls.

2.

3. Shinjuku Gyōen in Tokyo, Japan.

4. Garden at Versailles, Versailles, France.

Pontederia vaginalis

Colocasia esculenta

Saccharum spontaneum

Arundo donax

Heteropogon contortus

Cyperus corymbosus

Ficus hispida

Mallotus nudiflorus

Trema orientale

Mitragyna parvifolia

Colophyllum inophyllum

Terminalia arjuna

Madhuca longifolia

Syzygium cumini

Pongamia pinnata

Ficus benghalensis

Adina cordifolia

Mangifera indica

Ficus racemosa

Ficus religiosa

Borassus flabellifer

Azadirachta indica

Cordia dichotoma

J F M A M J J A S O N D

The Mahua tree, or Iliuppa as it is known locally, like many of the native plants and trees of the region, is valued not only for its role in the larger ecosystem, but also for the multitude of uses that humans have for its many elements. The leaves and bark are used for purposes ranging from ulcer treatments to the purification of a liquor made locally. The flowers are used to cure cough and swelling. Ripe fruit is eaten raw or converted into a sugar and mixed as a beverage. The seeds of the fruit produce an oil that is applied as a skin treatment, used a cooking oil, or in some rural communities, as soap. And for centuries, the oil of the seeds lighted the many temples throughout the region.

6.

Ancient temples are a fixture of Tamil Nadu. They are scattered along and among the regions many rivers. But before there were any temples, small shrines were built under trees. When construction evolved and allowed temples to be built, the trees that served as shrines to the deities were kept in place and preserved. Alongside these trees, other plants were introduced that provided the temples with many of their day to day needs. These places became known as Sacred Gardens or Nandavanams. This practice has mostly been forgotten, but ATREE began reviving it in 2021. With a temple located within close proximity to most small communities, this project seeks to re-establish Sacred Gardens at every suitable temple, allowing the knowledge and joy of caring for the native ecology and biodiversity to spread far and wide, ensuring its preservation.

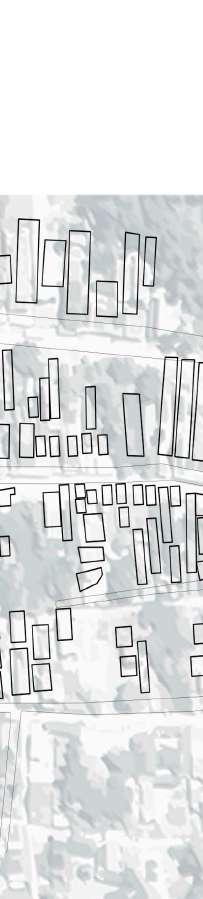

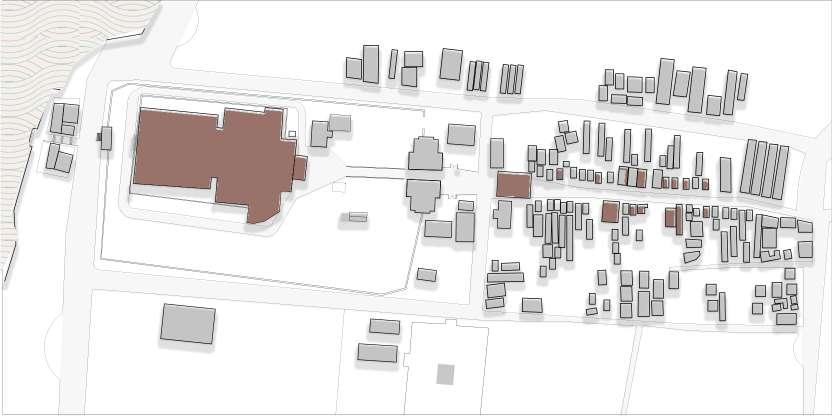

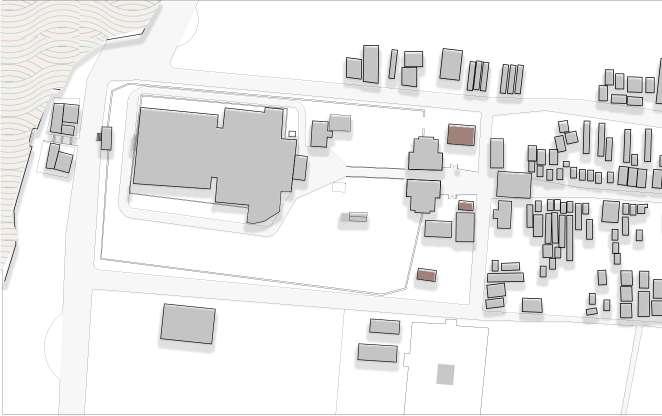

Temples without Sacred Gardens

Temples with Sacred Gardens

Thiruppadaimaruthur Bird Conservation Reserve Roads Water

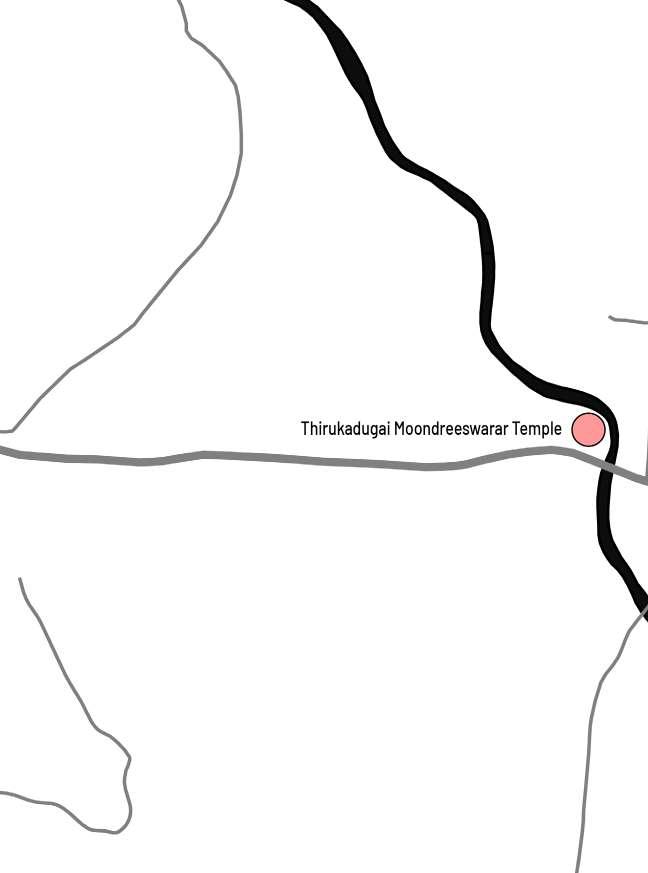

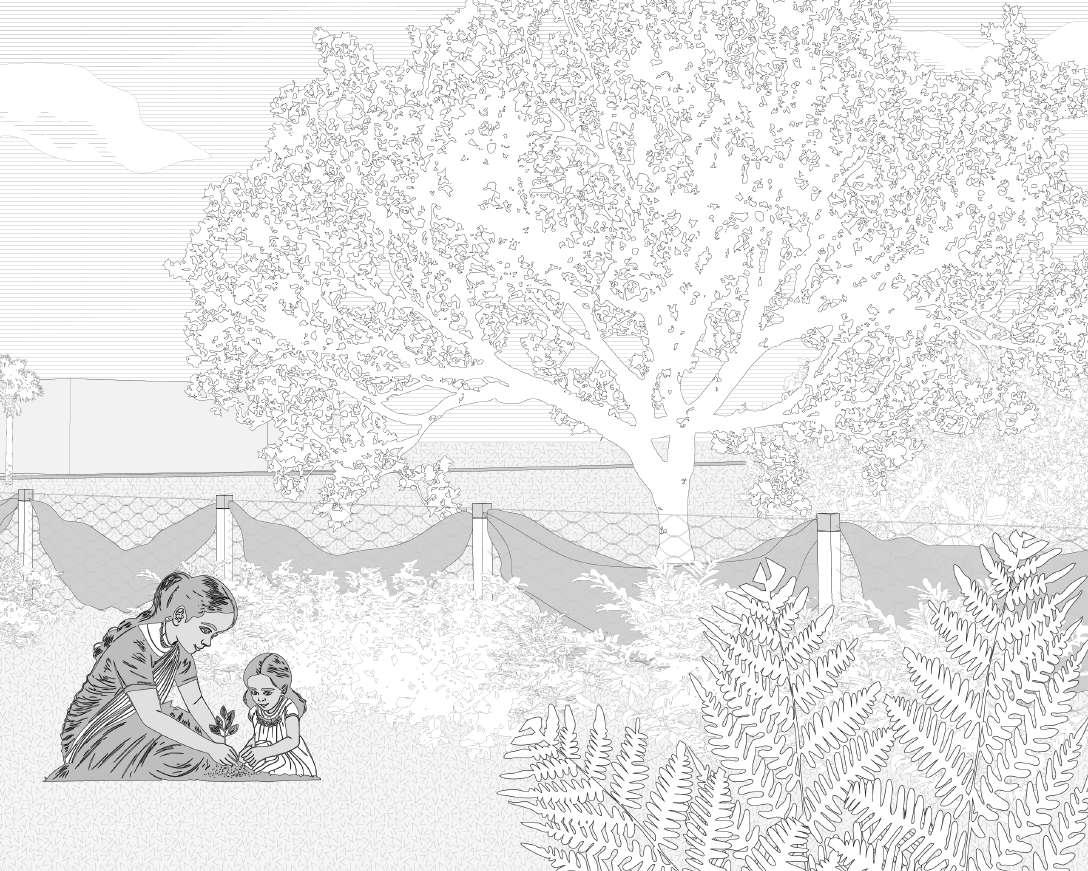

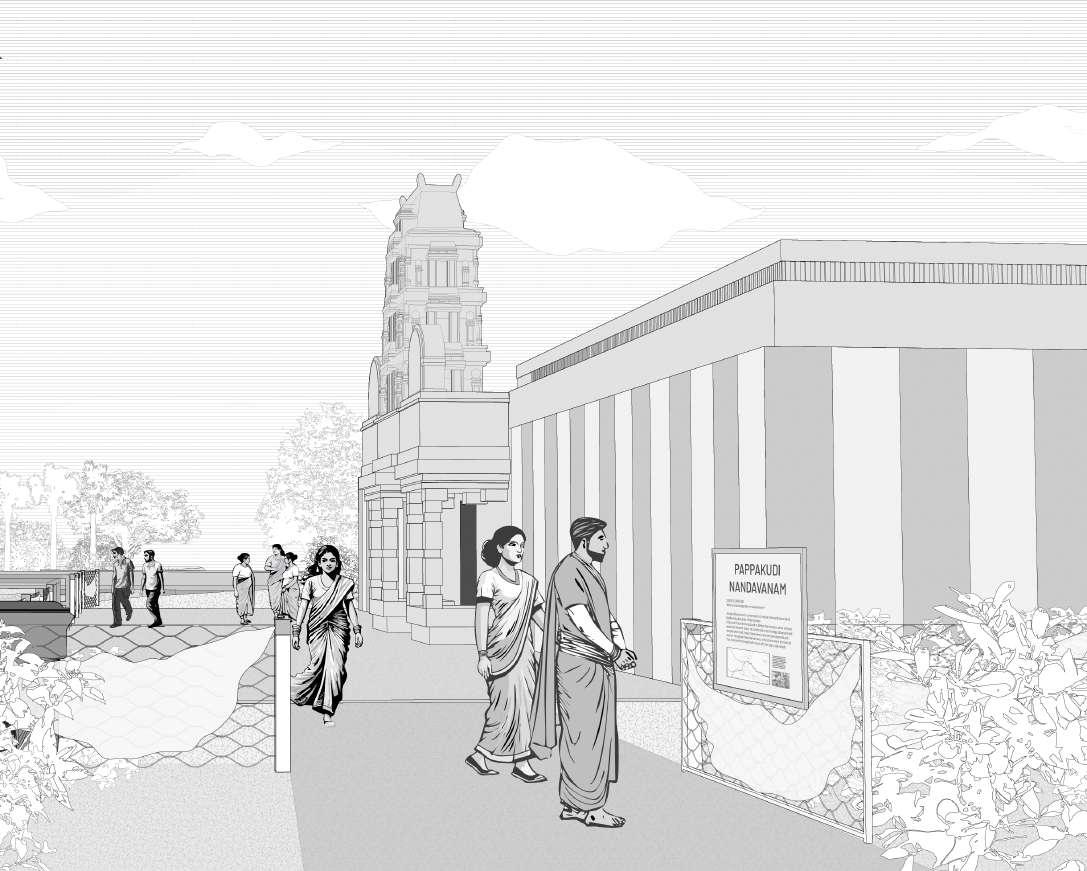

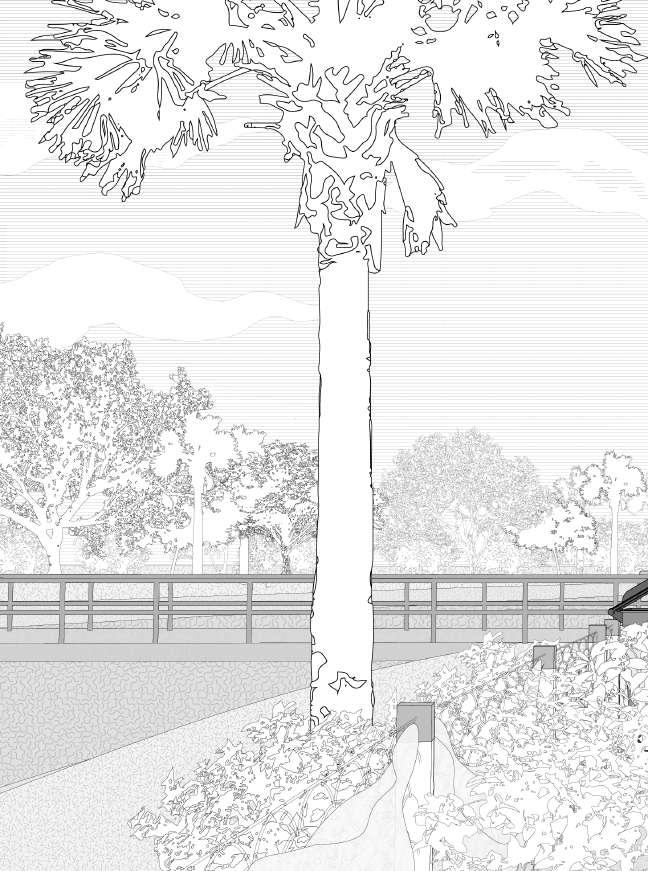

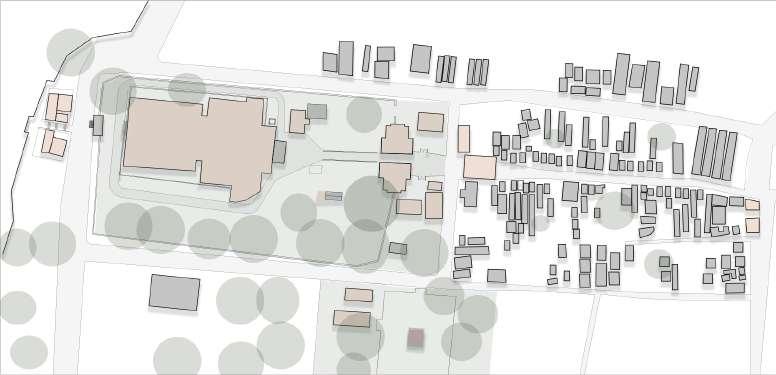

The Thirukadugai Moondreeswarar temple in the village of Pappakudi was the first sacred garden to be re-established by ATREE in 2021. Approximately one hundred trees and plants have since been planted. The planting is done with the intented proportion of 50% native trees, 20% medicinal plants, 10% flowering plants, and 10% commercial plants. A survey of the existing species, the concerns and needs of the local people, the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment Board, and ATREE’s knowledge are all considered and taken into account when deciding which species to plant. While the ecological aspects of these gardens are well understood, deliberate interventions, initiatives, and programs are needed to integrate these spaces into the local communities, allowing this knowledge of ecology and the practice of co-existence between humans, animals, and plants to grow and thrive now and in the future.

This proposal begins with the notion that Sacred Gardens are spaces that have the potential to become beautiful and bountiful and teaming with life and energy. Further, the aim of this proposal is to have these spaces utilized, managed, and enjoyed by the local communities. Utilizing ATREE’s knowledge, and harnessing the existing interest and usage of the temples, these spaces could become focal points at which the tradition of ecological stewardship are further developed, maintained, and promoted for future generations.

The extension of ATREE’s and the wider region’s knowledge and appreciation for the native plants and animals into the future relies on the stewardship of future generations. Utilizing this moment when ATREE is re-establishing Sacred Gardens to include young children in this process by physically involving them in the planting of new species, which they can then care for and nourish, would be a small investment in the present that could have profound effects in the longer term.

While the species being planted may be native to the region, they still need nourishment and protection. With regular watering and care, they will thrive, but their growth and maintenance is reliant upon a concerted and consistent effort from the local communities. And in return, the trees, as always, will do their part to protect the local environment by providing shelter and nourishment for other forms of life including those both seen and unseen.

Any investment in the Sacred Gardens now, with the inclusion of younger generations, is an investment that has the potential to become a selfreinforcing cycle. As these spaces become inclusive spaces of learning and collaboration and joy, not only among humans, but among the native plants and animals as well, future generations will undboutedly come to appreciate their use and utility and importance, not only in practical terms, but in spirit as well. And with this understanding, future generations will work to maintain the gardens just as their elders did before them.

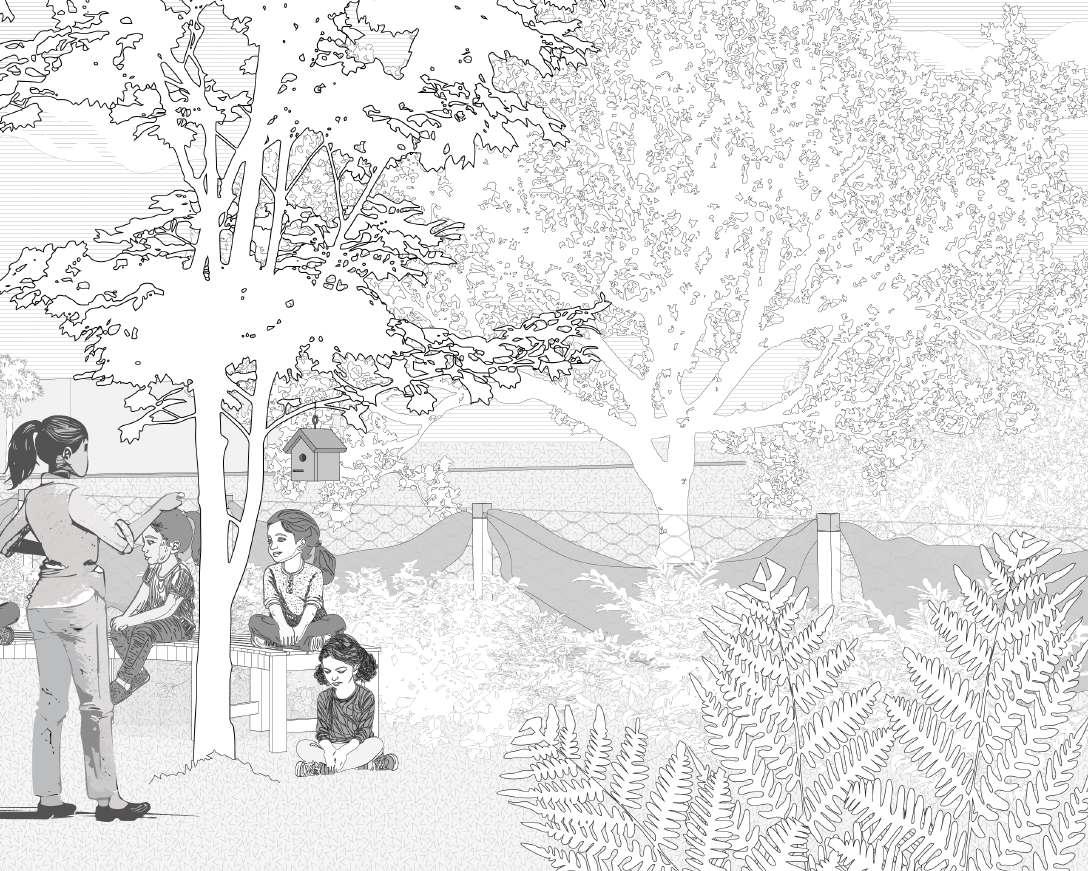

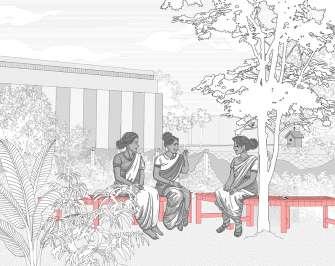

Above all else, the Sacred Gardens should be spaces of joy and delight for humans, plants, and animals alike. Under the shade of native trees, with flowering plants in bloom, butterflies percolating through the air, and birds singing softly to each other, the community can use these spaces in whatever manner they choose, even if thats just for a chat among friends. Likewise, with native plants and trees in abundance, native wildlife such as birds and pollinators will undoubtedly enjoy the shelter and sustenance the plants and trees will provide.

While the Sacred Gardens exist in an enclosed space, they are connected to the outside world in innumerable ways. Perhaps most importantly, they play a role in helping to support the local communities. As part of re-establishing Sacred Gardens throughout the region, there is an incentive to develop ponds in each garden. In these ponds, reed plants, such as the Cyperus corymbosus, or jointed flat grass, could grow and provide the raw materials for mat weaving and other textile industries.

The Sacred Gardens are positioned primarily toward humans, but with an abundance of trees and plants, they will inevitably attract other forms of wildlife. With small interventions such as bat houses and bird houses, and limiting human access to selected areas, non humans animals will enhance and balance the ecology systems within the gardens and the broader, local environment as a whole. In this way, the gardens will serve as one small example of a more reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationship between humans and non-human animals.

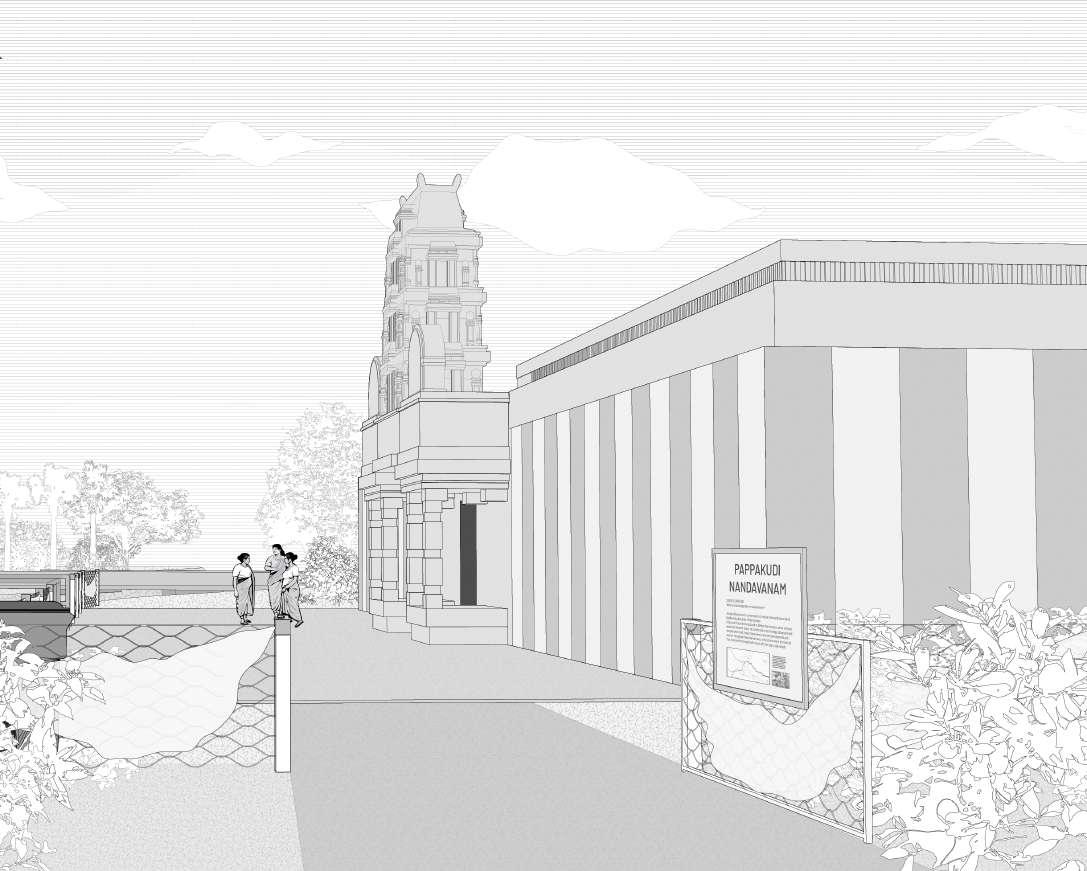

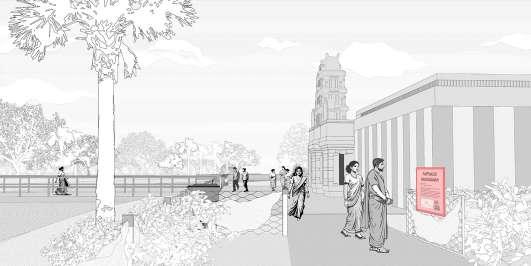

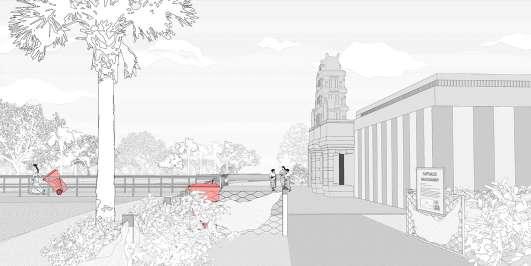

A key component of the Sacred Gardens is making them inclusive spaces where everyone is welcome. Integral to this endeavor is a methodical and measured approach to visual cues such as signage which will not only invite tourists and locals alike into the spaces, but will offer them information addressing the various ecological and social initiatives that ATREE and their partners are continuously pursuing, as well information concerning the adjacent temples, information which may not be presented in an accessible or easily understood manner to tourists and foreigners, or simply those persons not familiar with Hindu traditions.

Understanding that waste and it’s improper disposal is a persistent issue in the region, the Sacred Gardens will serve as advocates and practioners of better practices. Because Sacred Gardens are situated in close proximity to the temples of the region, they are in a unique position to tackle the issue of waste given that the visitors to the temples are often responsible for much of the waste produced. Waste bins situated outside the temples, adjacent to both the temples and the Sacred Gardens, are one example of a modest intervention that could be easily reproduced at any site, that if executed and maintained properly, could have significant cumulative effects.

Understanding that climate change is an ever pressing issue globally, and that management and proper disposal of waste is a seemingly intractable issue locally, Sacred Gardens can directly confront both of these issues simultaneously. By upholding the values of ecological stewardship and serving as a champion and haven of biodiversity, the gardens will address the larger issue of climate change through their dissemination and propogation of native species. And by actively confronting and managing the dispospal of waste within their vicinity, the gardens can be a bastion of better practices for their local communities.

All of these initiatives, programs, and ideas are nothing without the input, involvement, and support of the local communites. ATREE has a wealth of ecological knowledge. But in order to fully apply and capitlize on this knowledge the local communities are needed as active accomplices in these endeavors. As such, the interventions suggested are intentionally small in scale and flexible in execution so that they can be more easily reproduced at each distinct site. ATREE already has a flexible formula for the plant and tree species to be planted in each garden. These micro-interventions will likewise serve as flexible design interventions that could be implemented at each garden.

SIGNAGE

WASTE MANAGEMENT

The Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department (HRCE) and ATREE, alongside various philanthropies are the organizations that are most relevant to the execution of this project. The HRCE controls the temples and the adjacent grounds where the Sacred Gardens will be situated. ATREE has the knowledge and experience in regards to the native ecology and plant species. Various philanthropies, thus far, have been necessary for funding. But it is the people, in the form of activists and supporters, the local communities, and the younger generations that have the most influence in the execution and maintenance of this proposal. And of course, the plants and trees, the birds and animals and all the other forms of wildlife, alongside the ever flowing rivers and waters are the silent recipients of humanity’s footprint. Ever forgiving, ever evolving, they will silently abide our progress, whichever direction that may be.

ADVOCATES AND SUPPORTERS

AND ANIMALS ALL FORMS OF WILDLIFE

RIVERS AND WATER

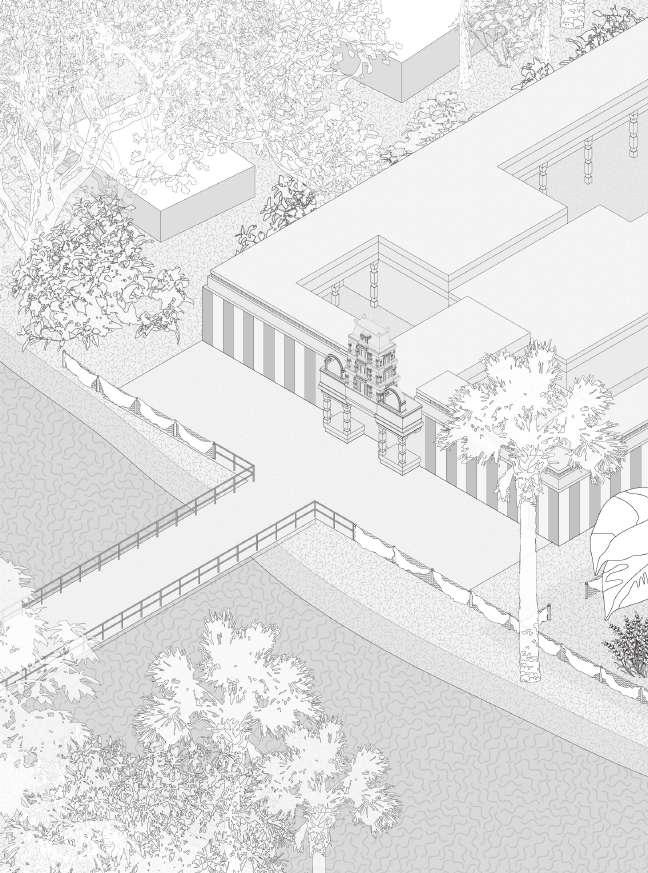

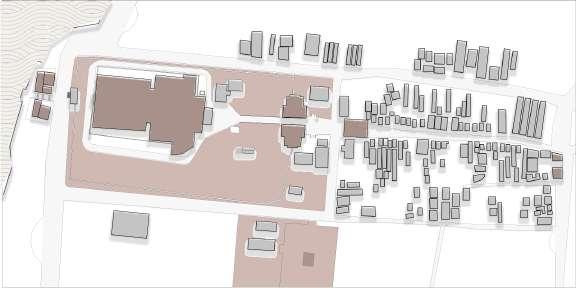

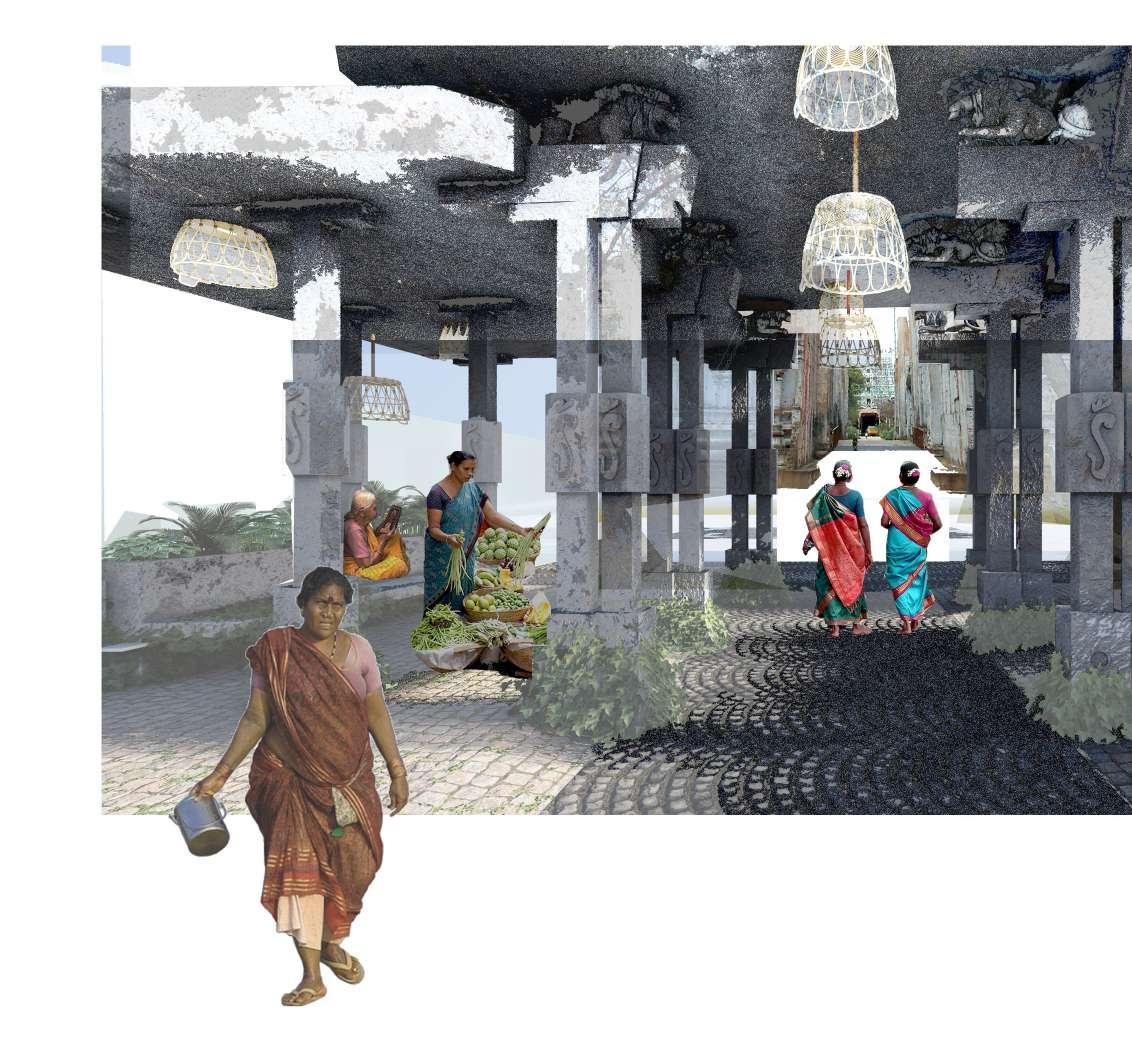

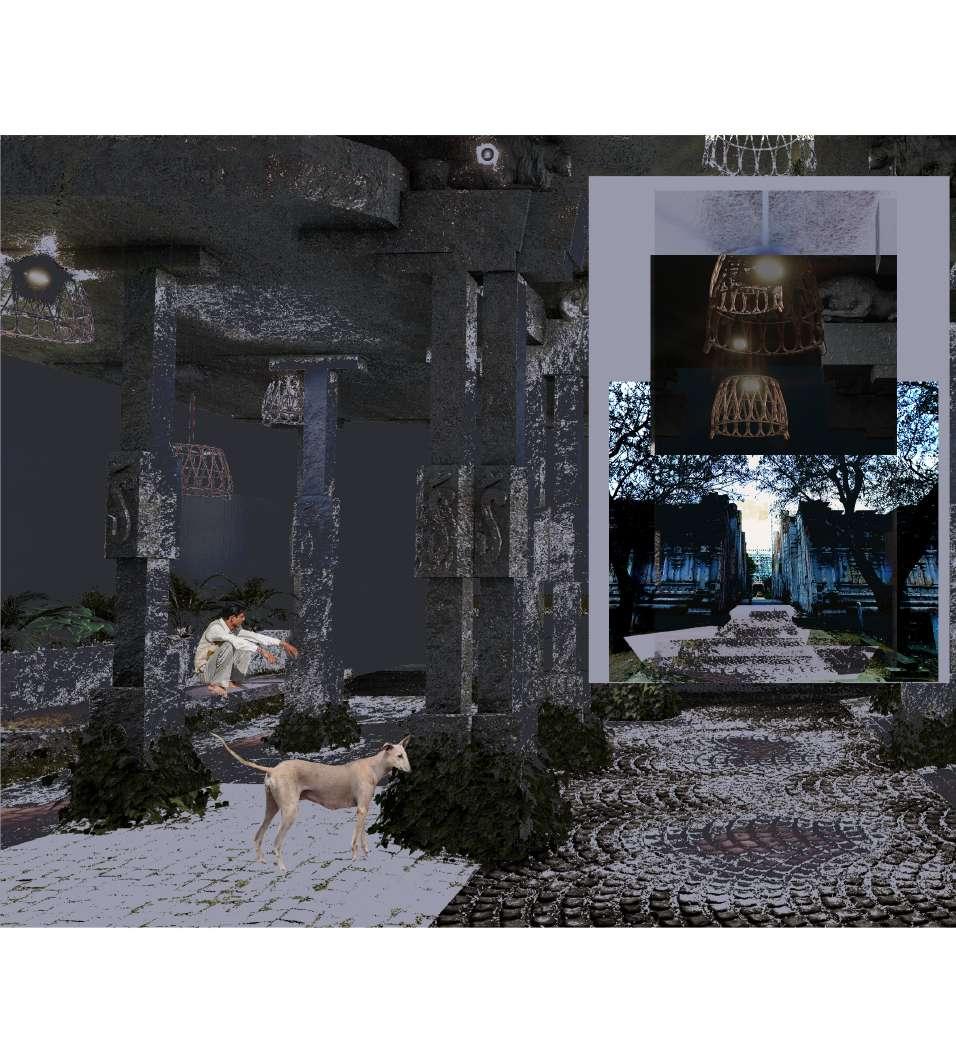

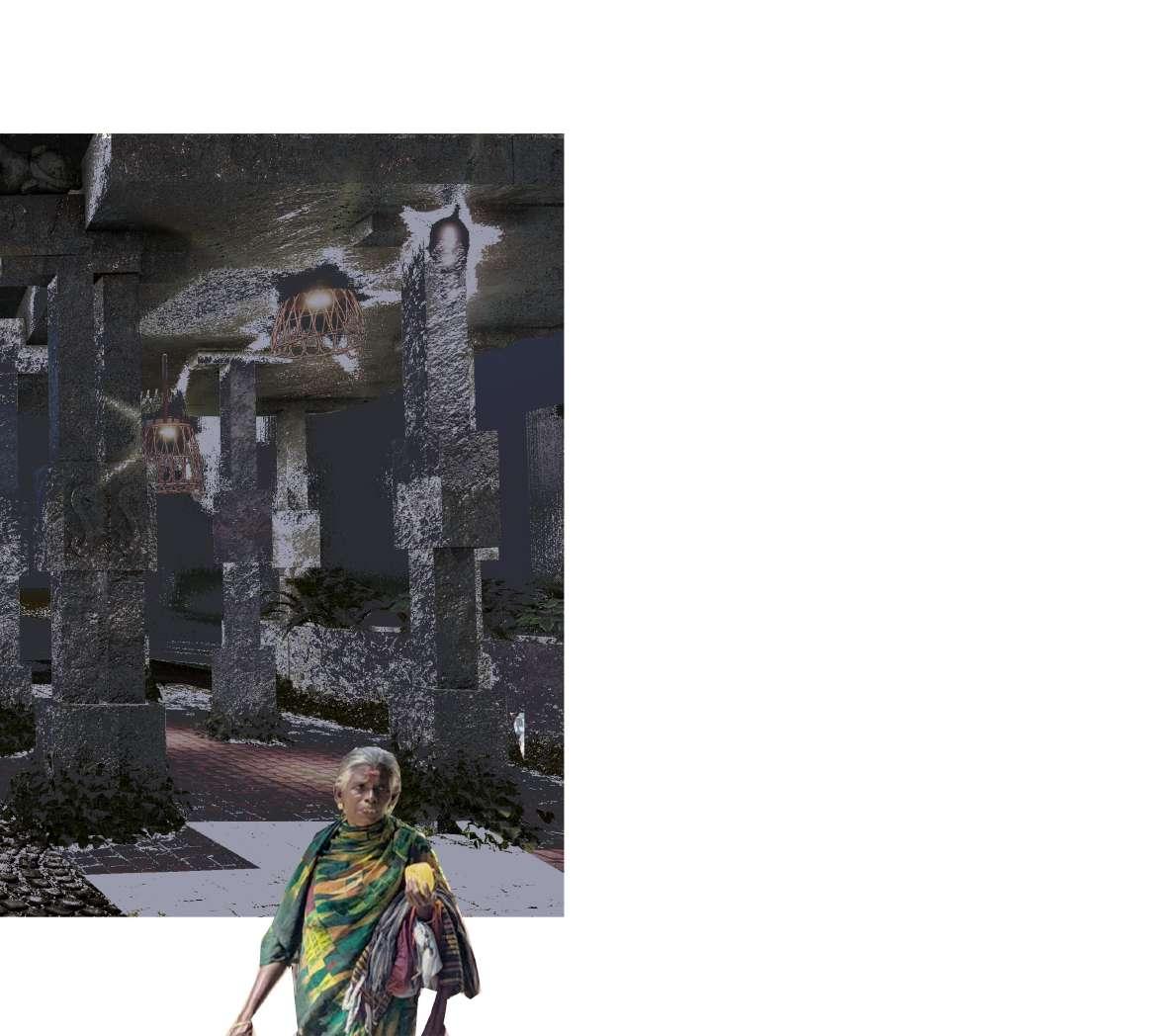

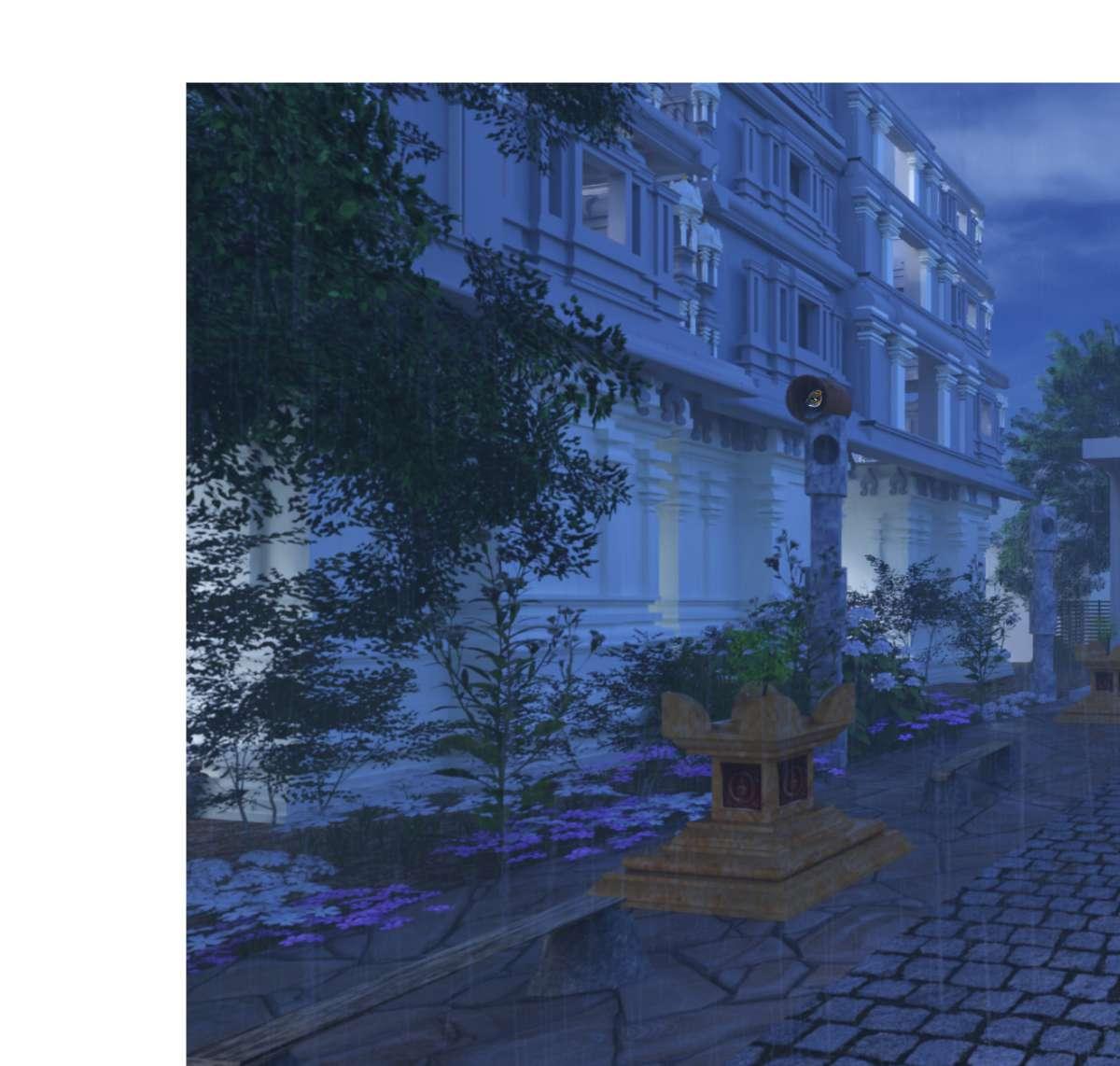

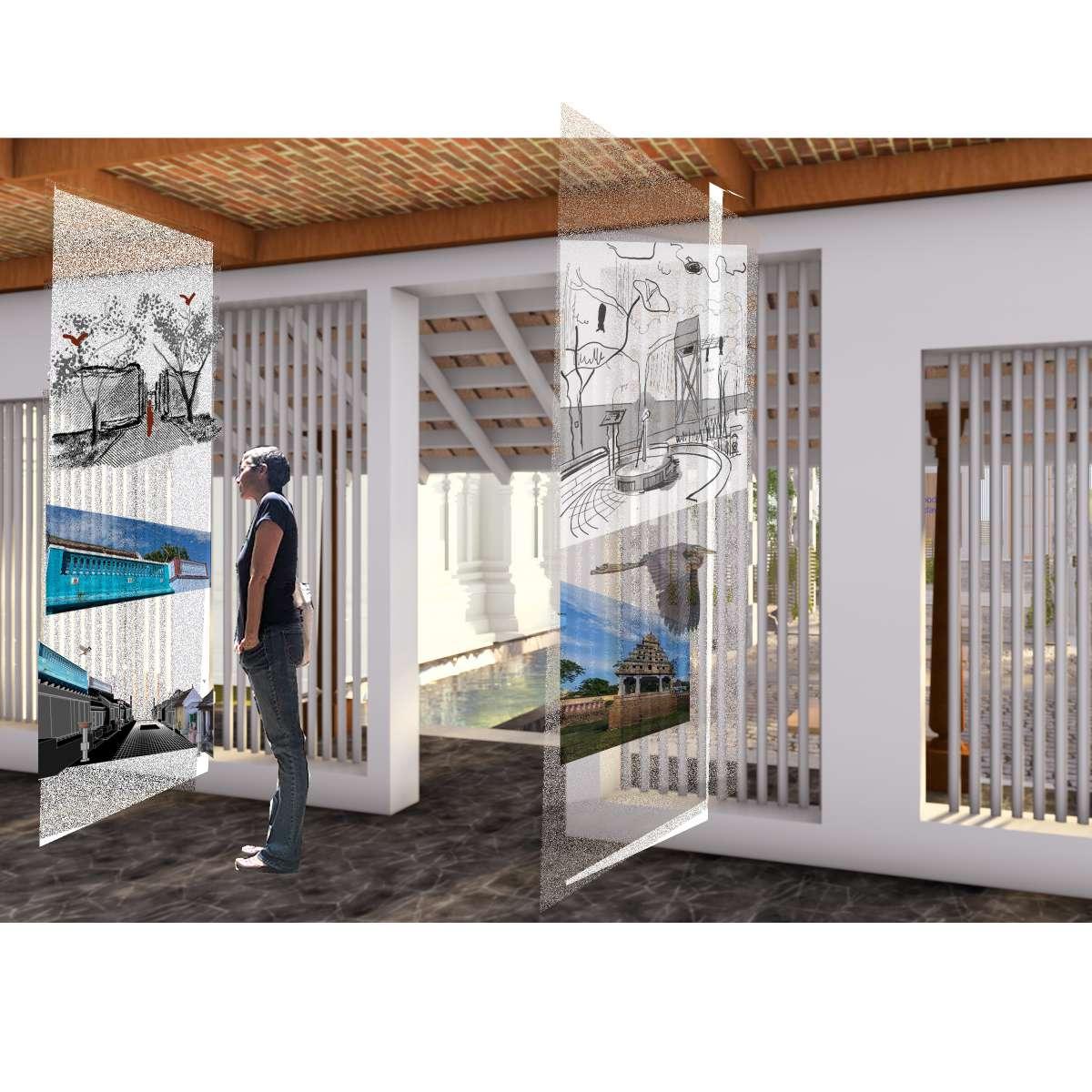

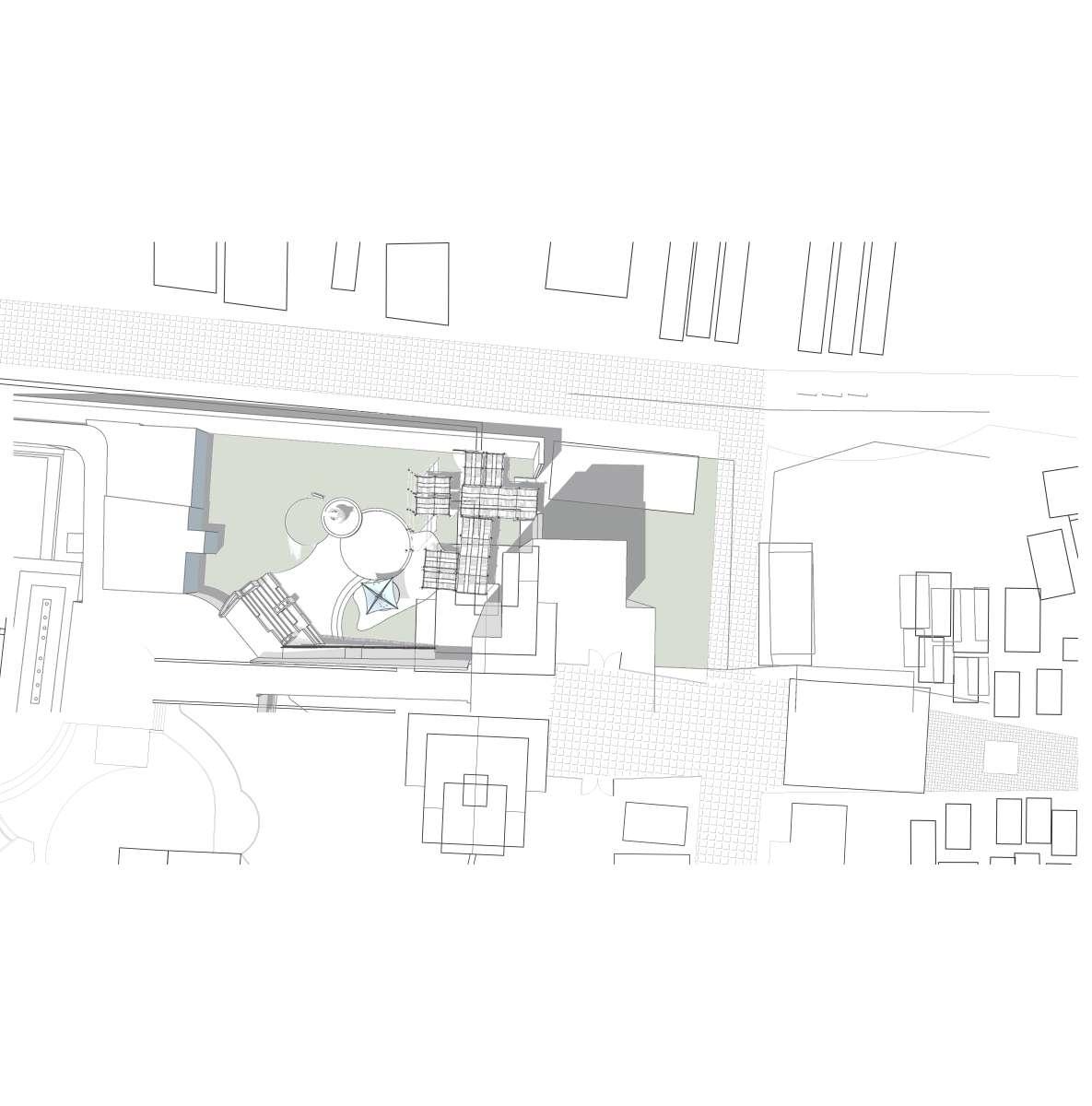

Kovil Chimes interprets the sacred nature of the temple procession while integrating a multiplicity of references to the ways in which human and nonhuman communities have coexisted over centuries. By extending the presence of temple elements to the main street, the project encourages the community to recognize the sacred in their everyday routines. The reinterpretation of key elements of the local housing typology in the surrounding community precinct honors the area’s cultural heritage and fosters a sense of shared responsibility in the protection of the site’s significance. This approach to heritage interpretation rekindles cultural identity and reestablishes connections to sacred roots.

(i) INTRODUCTION

SACRED NATURE PROCESSION

(ii)ANALYSIS

ISSUES

AREAS IDENTIFIED CONCLUSION

(iii) PROJECT

STRATERGIES ALONG THE PROCESSION

1.MOVEMENT AND CIRCULATION

2.KOVIL CHIMES PROCESSION-

ORAL HISTORIES STREET

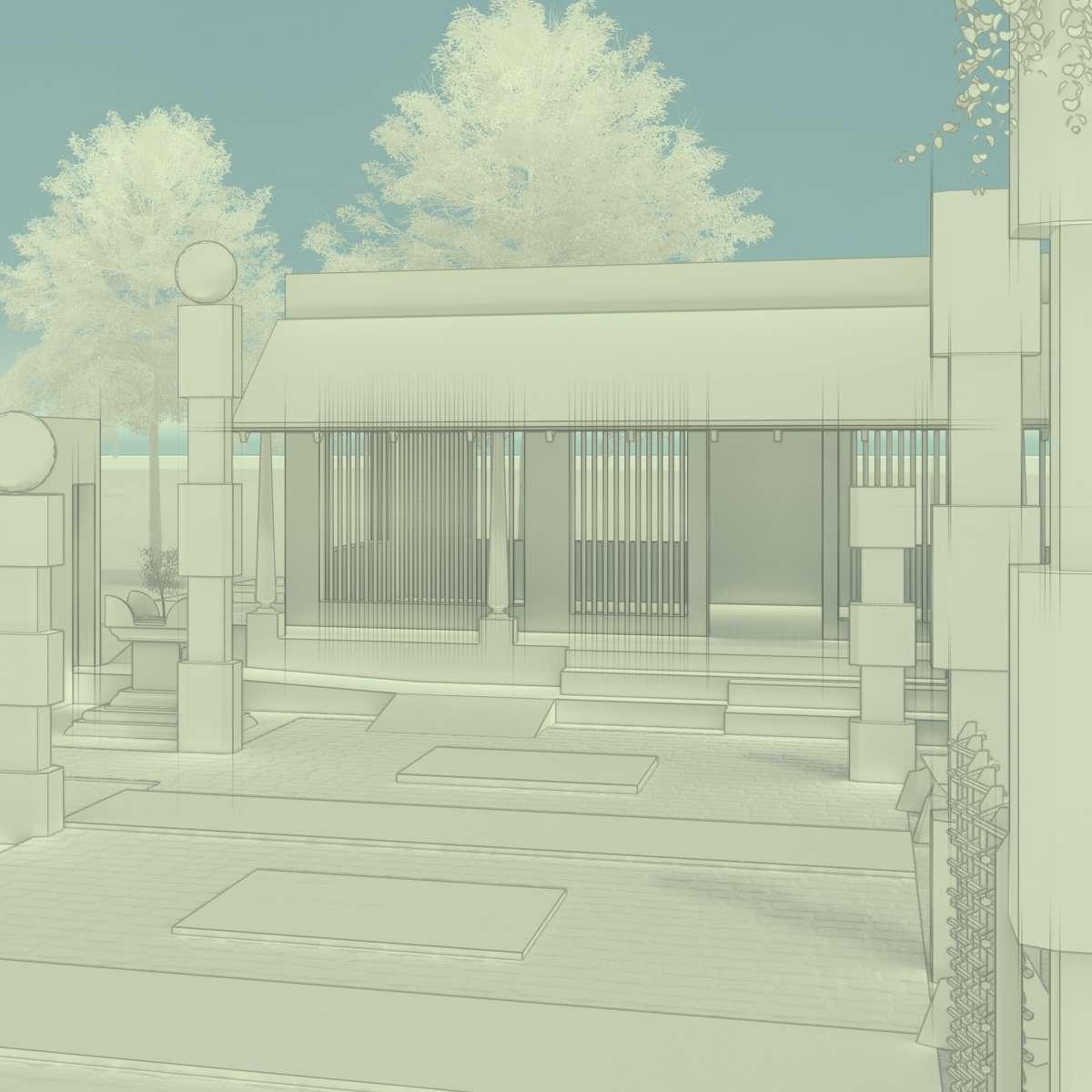

MUKHAMANTPA

THEERTHAM-RAIN PONDS

UYARNTA VAAYIRPADI

NANDAVANAM PORTAL

NANDA VALI

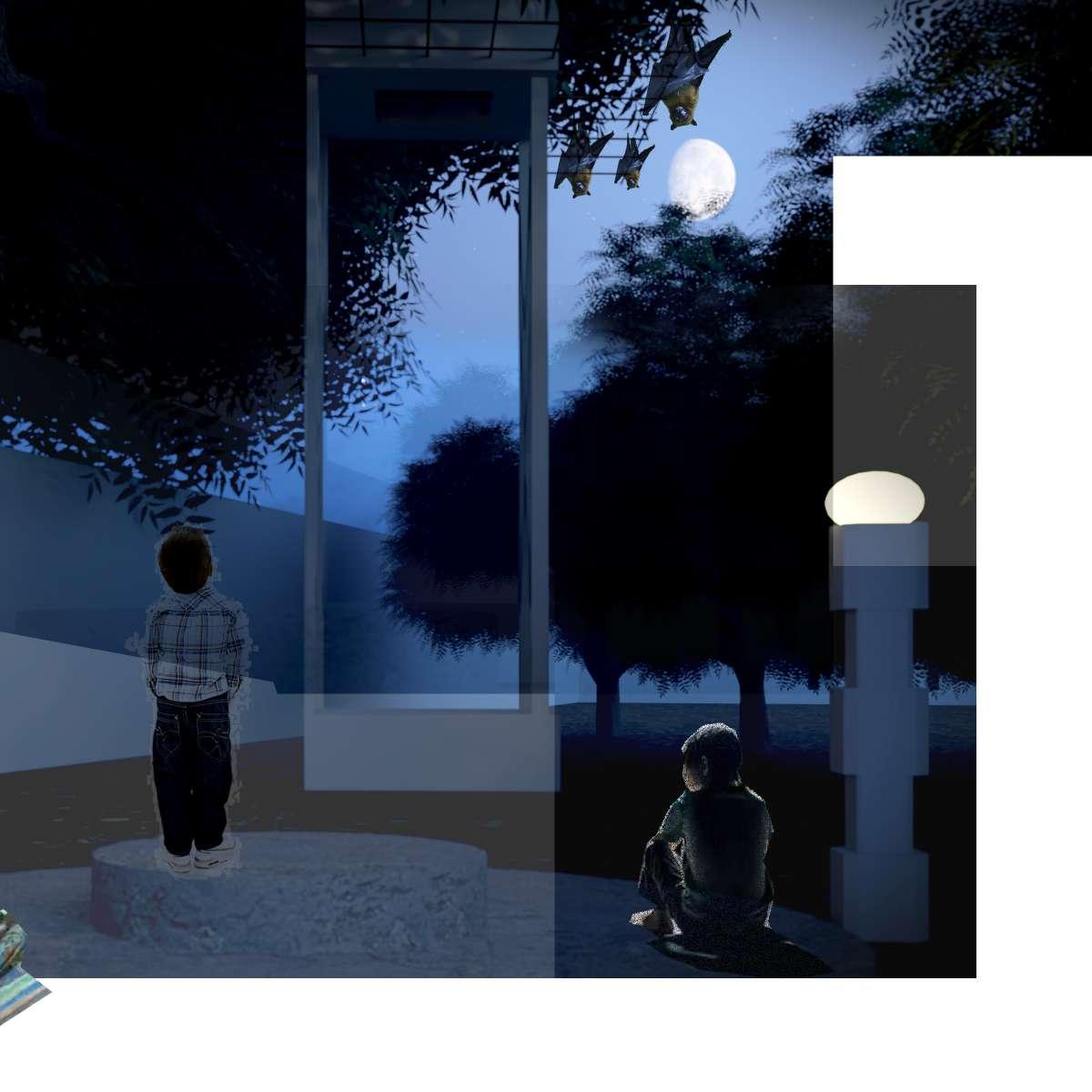

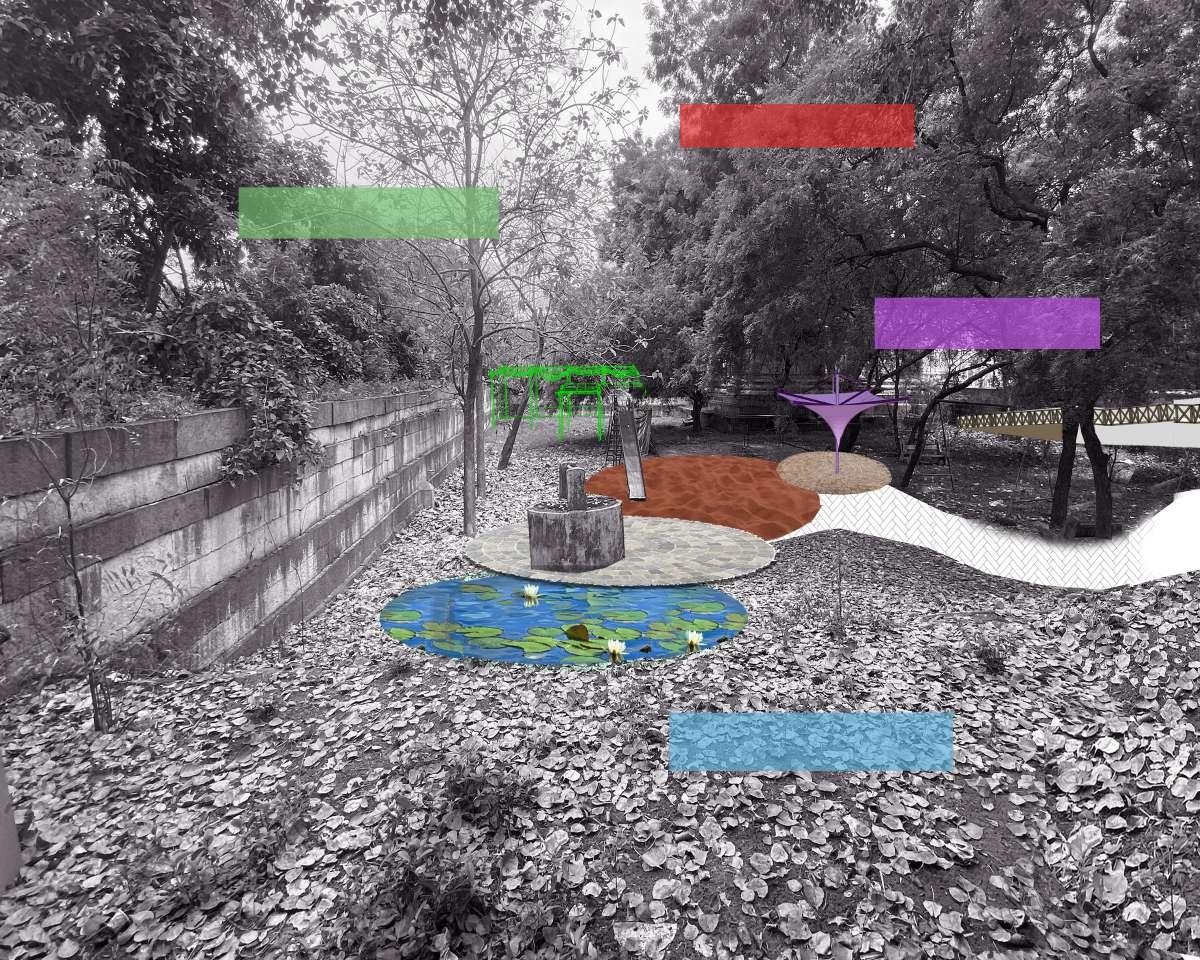

KUTTIVANAM

RIVER EDGE

In Hinduism, nature is deeply intertwined with spirituality and divinity, reflecting a profound respect for the Earth and all its living beings. The natural world is seen as a manifestation of the divine, with elements like rivers, mountains, trees, and animals revered as sacred. Gods and goddesses are often associated with natural forces; for example, Ganga, the goddess of the sacred river Ganges, symbolizes purity and the life-giving qualities of water, while Lord Shiva, depicted in harmony with the natural world, is often shown surrounded by mountains and forests. Hindu philosophy promotes the idea of ahimsa (non-violence) and Dharma (righteousness), which extend to all living beings, encouraging a sustainable and harmonious relationship with the environment. The interconnectedness of humanity with nature is a central theme in Hindu thought, guiding practices that prioritize ecological balance, respect for the Earth, and the belief that all life is sacred and interconnected.

6.SACRED GARDEN TEMPLE

Hinduism deeply reveres nature, and this temple features a shrine dedicated to the ritual worship of snakes. The surrounding gardens, known as Nandavanams (“Happiness Forests”), enhance the spiritual and natural harmony.

3.TANK TEMPLE

Temples always have an associated water body, in this case.

Dravidian style temples have a man made tank with its on temple here

7.RIVER EDGE

The worship and procession ends at the water the final threshold is the steps that blend into the water.

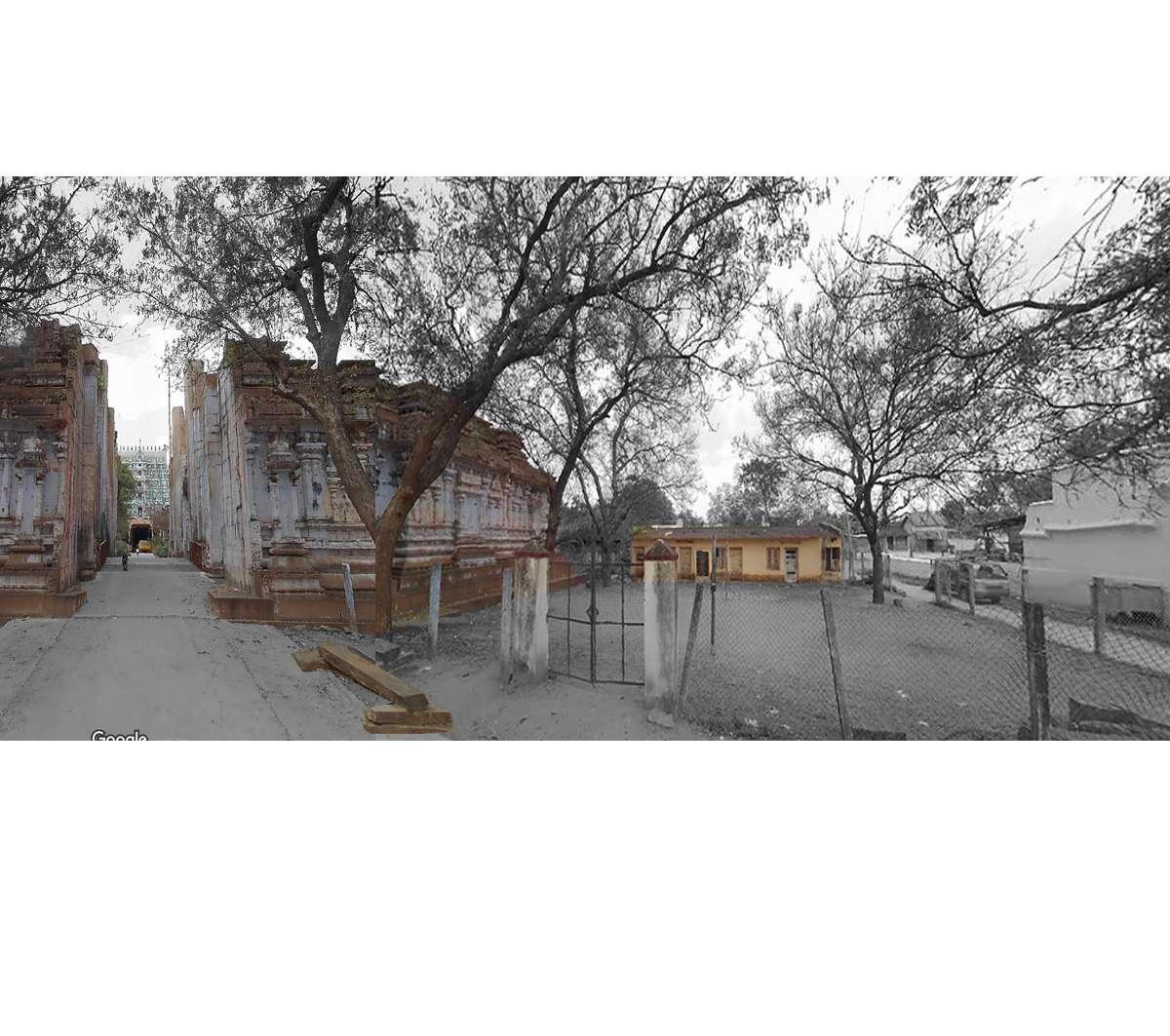

5.GOPURAM TEMPLE GATE

The gate to the interior of the temple is called Gopuram which takes one to meet the God’s idol and the pillared halls.

4.TEMPLE GROUND GATES

The Gate serves as a vista . It is a gate to the temple garden grounds that surround the temple.

2.MUKHA-MANTAPA

1. COMMUNITY PRECINCT

First temple relic is a pillared interstitial space often referred as Mukhamantapa for and from the community. It is used as a flexible space Historic houses stand as relics of the past and enduring symbols of a centuries-old community.

1.The temple replicates the ecology around it It also holds insectivorouss bats due to creating natural habitat for bats

Visnu tank temple carvings about marine wildlife and tortoise is also an incarnation of lord Vishnu

and Bat species

Contested land

Clashes between conservation priorities, local livelihoods, tourism interests, and developmental pressures from different organizations leading to disorganization and loss of agency

Manages the functioning, appointments, and governance of temples and related institutions.

Financial Oversight: Oversees donations, endowments, and properties to ensure proper utilization for religious and charitable purposes.

Safeguards the biodiversity of the reserve, including its flora, fauna, and ecological systems, by enforcing wildlife laws and monitoring human activities. Sustainable Management: Implements programs for sustainable use of forest resources, preventing deforestation, and promoting Eco-tourism that benefits local communities while preserving the ecosystem.

Preserving and restoring ancient temple structures and art to maintain cultural heritage.

Documentation: Recording historical and architectural details of temples for research and awareness.

Advocacy: Promoting awareness and campaigns to protect temple heritage and ensure sustainable practices.

A concrete pillar has been erected in place of a heritage column within the temple, highlighting a glaring neglect of architectural conservation. This act underscores the failure of two designated organizations tasked with preserving the site’s historical integrity.

Architectural details and intricately designed nooks are being neglected and repurposed as storage spaces for brooms, reflecting a lack of appreciation for the craftsmanship and historical value of the structure.

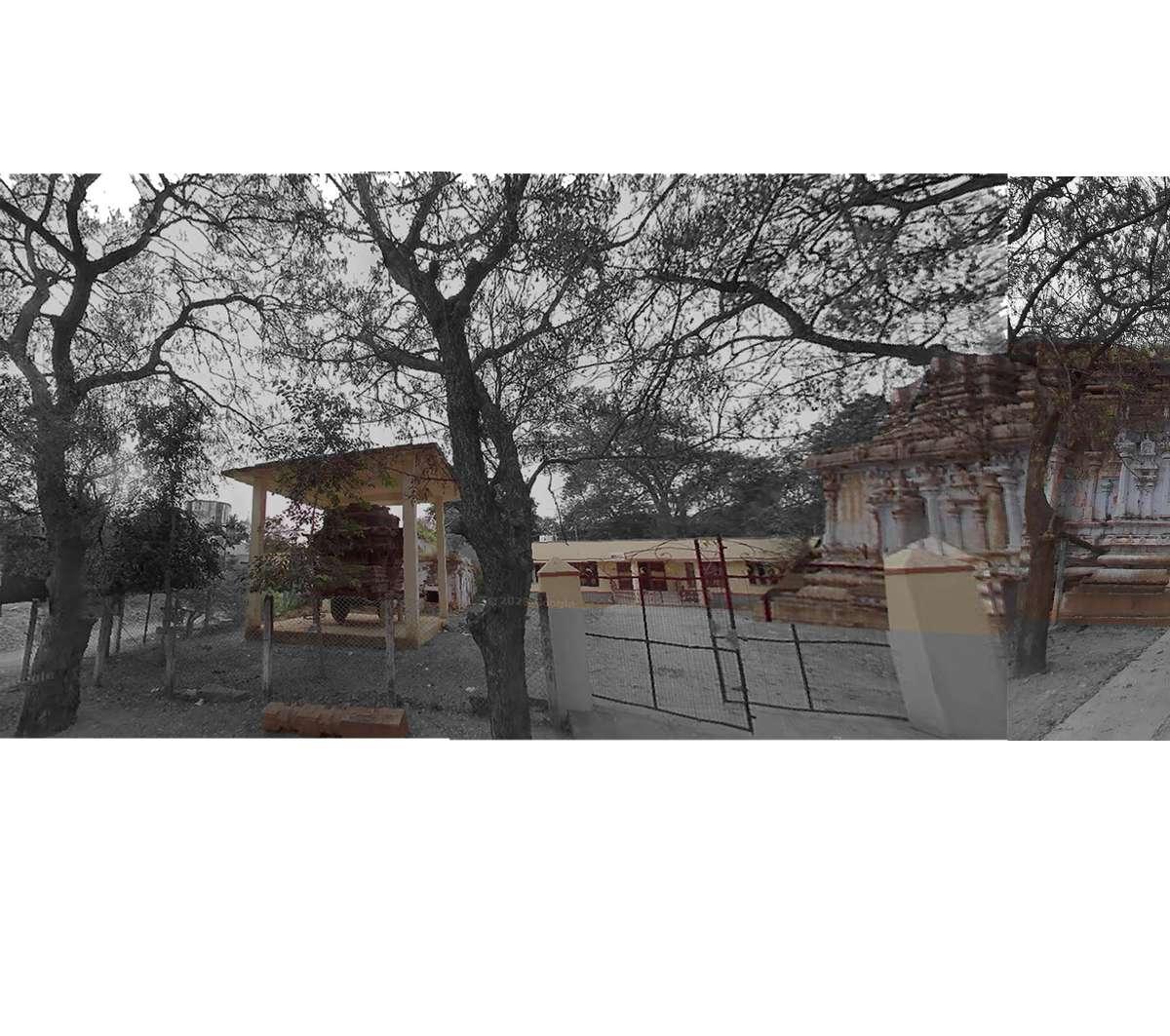

The threshold between the temple and the surrounding communities features a relic mukhamantapa, a space with potential for flexible use. However, it suffers from poor organization and general neglect, undermining its role as a cultural and communal interface.

The vernacular domestic buildings with semipublic openings that create a living street are rare remnants on this lane and urgently need preservation, yet remain neglected.

The existing bathroom infrastructure can be reestablished, a transforming the area into a visitor rest space.

The abandoned infrastructure, intended for temple use but mostly unused, holds potential for repurposing and could be revitalized for meaningful use

Given for merchandise sale to villagers, shops that sell temple merchandise, sacred offerings, garden produce and bird conservation information center

Ratham, a divine vehicle in Hindu mythology, lies neglected, with no signage and only a roof supported by pillars. The structure, now decapitated, urgently needs proper recognition, signage, and conservation.

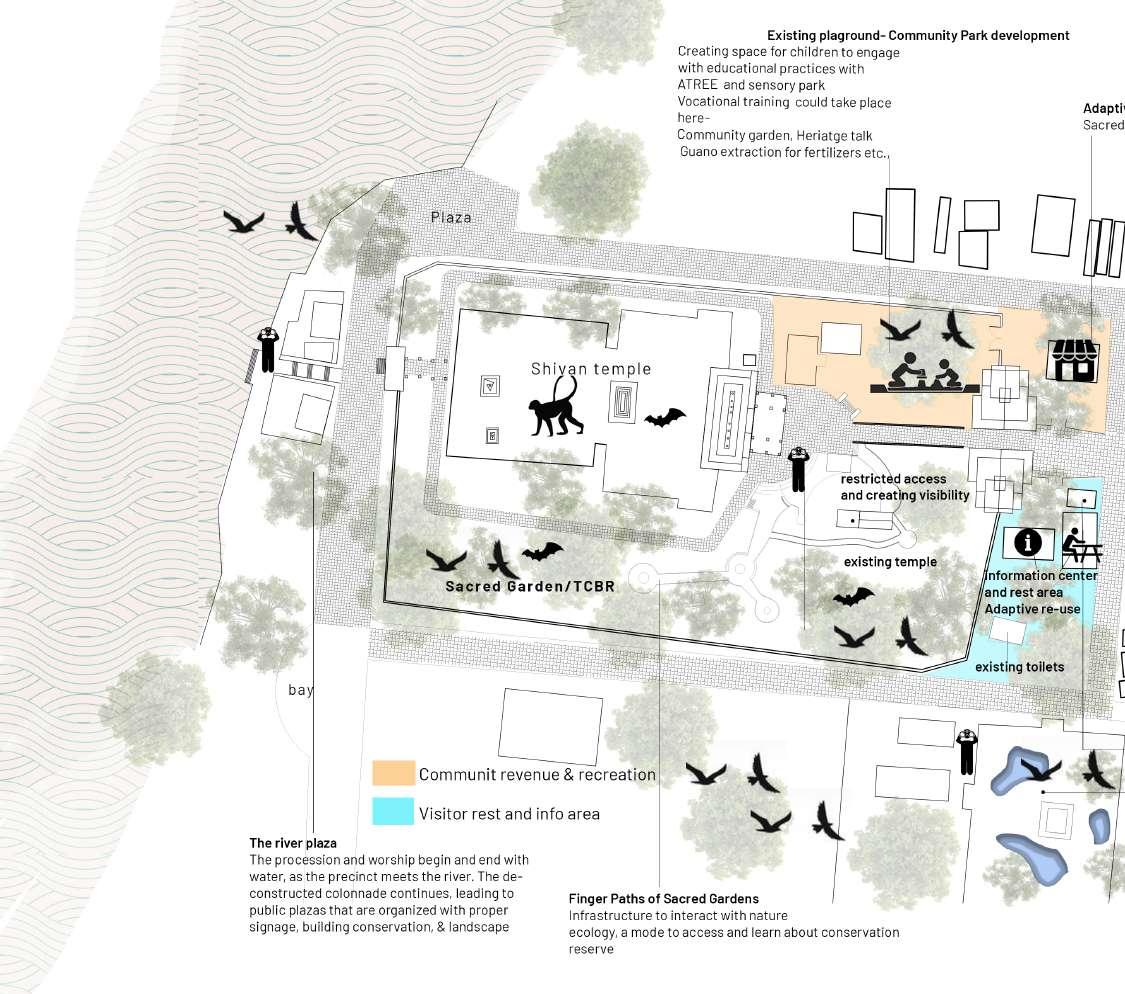

With this portion recognised and made a visitor hub for resting, repurposing infrastructure into information center about the bird reserve, archeology and cultural heritage.

The garden, situated low and hidden from view during processions, has become a littering pocket due to its lack of maintenance and visibility.

Monkeys consume human waste due to the neglected, unclean garden pockets.

The access to the shrine, located in the gardens, lacks a proper pathway or steps, making it difficult to reach, especially due to its lower location.

QR codes on trees posted b ATREE an NGO organization that puts effort for awareness of Ecology of this land

ATREE’s efforts and educational programs can be better recognized and accessed, with a dedicated portal connecting to the gardens and its heritage, thus informing,zoning and activating both wings of the sacred garden tactically.

The existing park infrastructure can be reactivated as a functional kids’ zone, teaching bird conservation, sacred garden ecology, and heritage. This entire portion can be revitalized by giving agency to the community, enhancing its care and functionality. It can further include proper access to the outside, along with a revitalized, adaptive reuse of the merchandise portion.

INTERPRETATION KOVIL CHIMES, RECOGNIZES EXISTING SACRED ELEMENTS, PROTECTS AND REINFORCES FRAGILE ECOLOGY AND ARCHITECTURE, AND EMPOWERS BOTH HUMAN AND NON-HUMAN COMMUNITIES THROUGH REUSE, REACTIVATION, AND STRATEGIC ZONING, WHILE BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN USERS AND ECOLOGY THROUGH EMPOWERMENT, OWNERSHIP, AGENCY, AND MUTUAL BENEFIT.

TCBR - Tiruvidaimarudur Conservation Reserve

While the heritage precinct declared in 2005 a bird conservation reserve, the site is extremely fragile. Strategies to restrict heavy motor movement and promote pedestrianization will also include underground wiring and rain permeable pavers.

pedestrian dominant temple buildings combined access vehicles allowed bird reserve

Areas around TCBR and the precinct procession will discourage vehicular access inviting instead bicycle and pedestrian flows.

Traffic during festivities is restricted to avoid disturbance on the precinct. Parking zones are allocated, drop off bas, round abouts and shaded foot-paths are created.

Roads discouraged from motor activity will be accesible, in case of flood or fire emergency, with good accesibility for modes of transport.

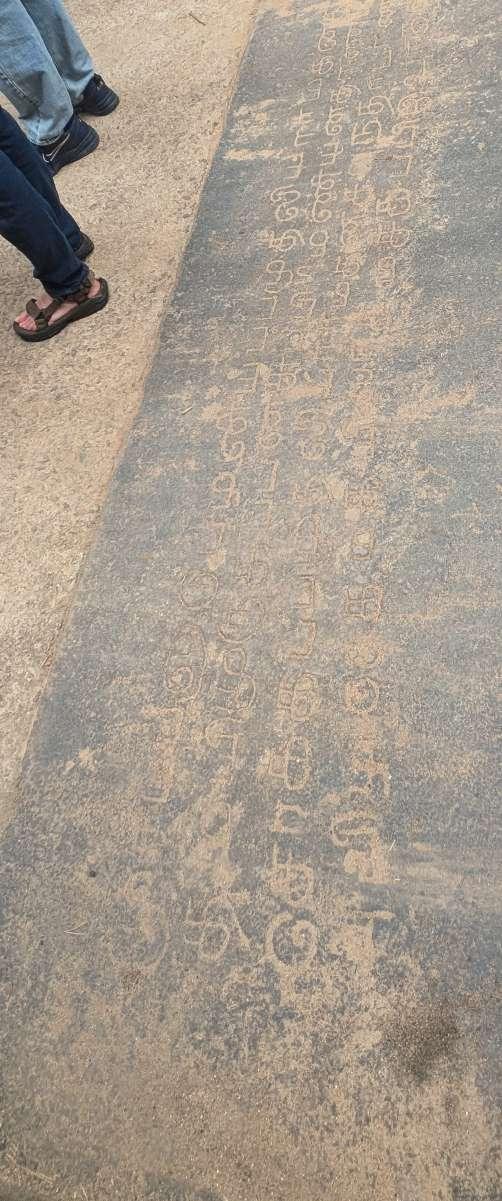

TACTILE FLOORING

USE OF TEXTURED ROCK CUT PAVERS FROM LOCALLY SOURCED MATERIALS LIKE GRANITE, TERRACOTTA TO CREATE TACTILE SURFACES NOT ONLY MAKES THE PROCESSION ENGAGING BUT ALSO ENCOURAGES PEDESTRIAN ACTIVIT AND DISCOURAGES VEHICULAR ACTIVITY, SOME OLD TECQUNIQUES OF PAVING NEAR RIVEREDGE CAN BE REVIVED RESTORING HERITAGE

Using tactile pavers creates engagement, discourages vehicles around TCBR and creates order.

Reviving traditional flooring techniques seen near temple this image is existing ancient paving near river edge

The intervention will get rid of impermeable concrete floor and enable rain water permeable roofing allowing water to be returned to soil. This is also a practice going on b conservation organizations in Indian temples to remove concrete paving bringing back heritage and restoring a lost era of vernacular pavers.

image of a bird sitting on wires near TCBR

Clearing overhead along pedestrianization will help avoid electrocution of urban ecology

PEDESTRIANIZING THE PRECINCT

Restricting vehicular activity b creating tactile paving. This also ensures electrical lines are underground and rainwater permeability

Creating space for children to engage with educational practices with ATREE and sensory park with metaphors and elements from 5 landscapes of Sangamm

Vocational training could take place hereCommunity garden, Heriatge talk Guano extraction for fertilizers etc.,

ADAPTIVE SHOPS

EXISTING TOILETS

RESTRICTED ACCESS

COMMUNITY OPERATED

VISITOR ZONE

The procession and worship begin and end with water, as the precinct meets the river. The deconstructed colonnade continues, leading to public plazas that are organized with proper signage, building conservation, & landscape

Infrastructure to interact with nature ecology, a mode to access and learn about Conservation Reserve. Restricted access to sacred ecology

ADAPTIVE REUSE COMMUNITY OPERATED

garden produce , sacred goods etc

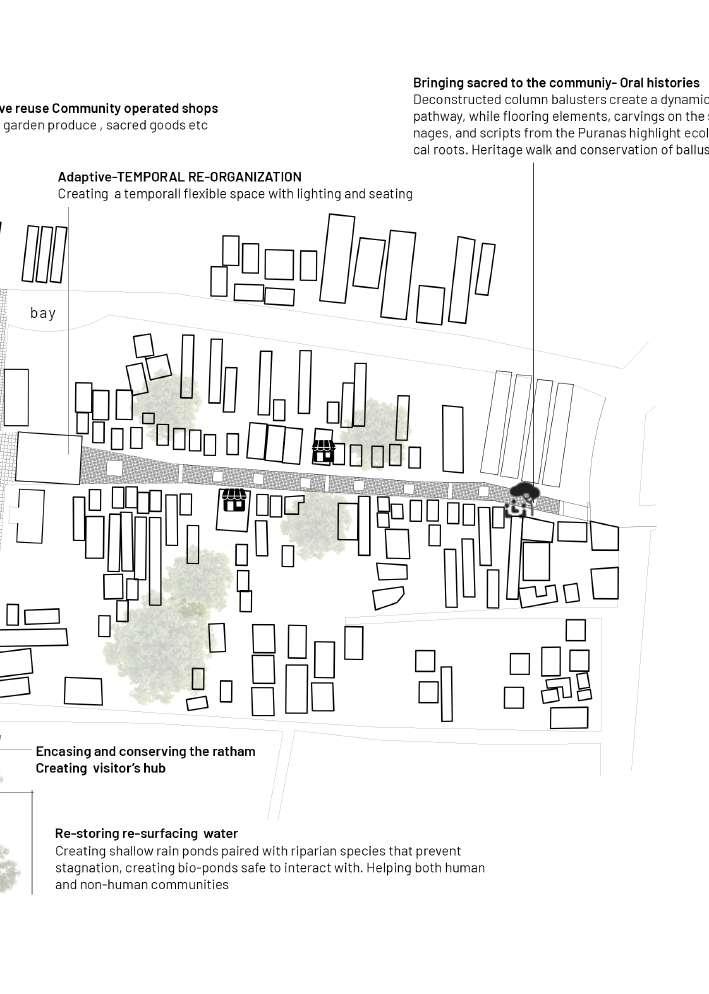

ADAPTIVE-TEMPORAL RE-ORGANIZATION

Creating a temporal flexible space with lighting and seating

The unique mixed use of housing topology of shops serve as stop points to grab a snack along the procession to temple

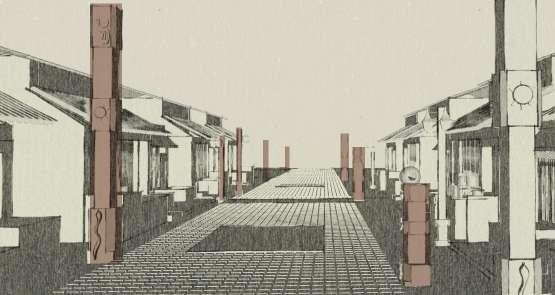

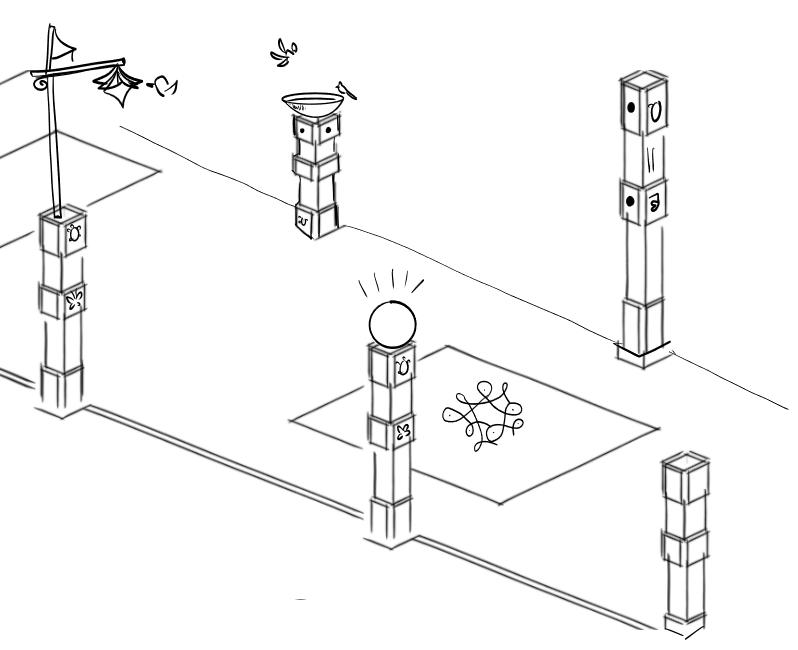

Deconstructed column balusters create a dynamic pathway, while flooring elements, carvings on the signage, and scripts from the Puranas highlight ecological roots. Heritage walk and conservation of balusters

RATHAM ANCIENT RELIC conserving the ratham

Creating visitor’s hub around this area

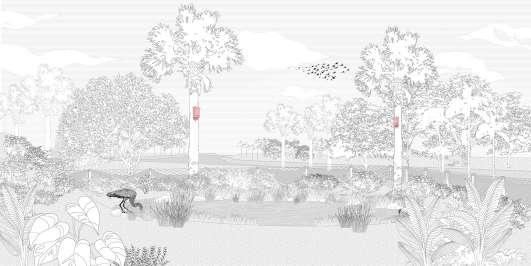

Creating shallow rain ponds paired with riparian species that prevent stagnation, creating bio-ponds safe to interact with. Helping both human and non-human communities

Restored heritage and natural environment, recognizing existing elements, reactivating and reorganizing spaces, zoning pedestrian areas for conservation, and fostering overall empowerment.

This process reinforces community identity through spatial recall and creates agency for the community to care for the land.

A deconstructed column design highlights Dravidian columns and intricate temple carvings, replicated along the street to create a dynamic pathway. Villagers can learn about the carvings’ cultural significance. Each column, varying in height, serves as a typology of street furniture, functioning as bird feeders, sparrow baths, lighting elements, signage, and streetlights.

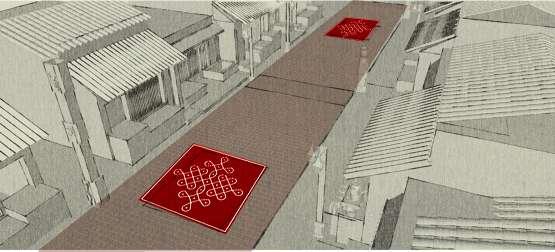

Pedestrianization here incorporates rain-permeable pavers, thoughtfully designed with additional features. Periodically, a stone slab is placed for communal practices by women, alternating with rectangular slabs inscribed with scriptures from Sangam literature, Puranas, or Vedas, emphasizing nature and its importance. These inscriptions are explained by the villagers, fostering cultural and ecological awareness.

Carvings inside the temple to take inspiration from and replicated for oral histories

Ancient scriptures at the temple gate are replicated along the Oral Histories Street, featuring texts from the Vedas and Sangam literature that emphasize the importance of the local flora, fauna, and natural resources. These inscriptions serve as educational tools for villagers, helping them reconnect with their heritage and reinforce their self-identity while also fostering awareness among visitors about the significance of protecting the cultural and ecological context.

THE TAMIL PURANANAURU (2.1 – 10) COMPARES THE CHERA KING TO THE PANCHA-MAHA-BHUTA, AS THE IDEAL OF PERFECTION: OH LORD OF GLORY! YOU POSSESS FORBIDANCE WITH ENEMIES, EXTENSIVE PLANNING SKILL AND VALIANT GLORIES, RESEMBLE THE PATIENCE OF THE EARTH (PRITHVI), DENSE WITH ITS PACKED DUST-PARTICLES AND OF THE EXPANSE OF THE SKY (AKASHA), HIGH OVER THE EARTH (PRITHVI), AND OF THE MIGHT OF THE WIND (VAYU) EMBRACING THE SKY AND OF THE DESTRUCTION OF FIRE (AGNI) JOINED WITH WIND AND BENEFICENCE OF WATER (AAPA) OPPOSED TO FIRE OH LORD OF THE GOOD LAND OF EVER FRESH RESOURCES, WHERE THE SUN, BORN ON YOUR SEA, AGAIN BATHES BY SETTING IN YOUR WESTERN SEA OF WHITE- CRESTED WAVES! GOD AND PRAKRITI ARE ONE AND THE SAME, FORMING A SINGLE NUCLEUS. DIFFERENT ELEMENTS ARE PERSONIFIED AS PARTS OF HIS BODY. HE GAVE BIRTH TO PURUSHA FROM A THOUSANDTH PART OF HIS BODY, A BIRTH WHICH WAS ACKNOWLEDGED BY THE RISHIS WHO CALLED THE NEWBORN MANASA PURUSHA, WHO IS ETERNAL, INFINITE, AGELESS AND IMMORTAL:

Excerpts from “Sacred Animals of India” and “Hinduism and Nature” by Nandita krishna

SARVEPI SUKHINAH SANTU , SARVESANTU MIRAMAYA, SARVE BHADRANI PASHYANTU, MA KAASCHIT DUKHAMAPNUYAT (MAY ALL BE HAPPY, MAY ALL BE FREE FROM FEAR; MAY ALL SEE ONLY GOOD; MAY NO ONE BE UNHAPPY) (BRIHADARANYAKA UPANISHAD, 1.4.14)

The concept of welfare of all creation has been beautifully described by Karan Singh: WELFARE IS DESCRIBED BOT IN LIMITED TERMS BUT AS ALL-EMBRACING, COVERING NOT ONLY THE HUMAN RACE BUT ALSO WHAT, IN OUR ARROGANCE WE CALL ‘LOWER’ BEINGS – ANIMALS AND BIRDS, INSECTS AND PLANTS, AS WELL AS ‘NATURAL’ FORMATIONS, SUCH AS MOUNTAINS AND OCEANS. IN ADDITION TO THE HORRORS THAT MANKIND HAS PERPETRATED UPON ITS OWN MEMBERS, WE HAVE ALSO INDULGED IN A RAPACIOUS AND RUTHLESS EXPLOITATION OF THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENT. THOUSANDS OF SPECIES HAVE BECOME EXTINCT, MILLIONS OF ACRES OF FOREST AND OTHER NATURAL HABITAT LAID WASTE, THE LAND AND THE AIR POISONED, THE GREAT OCEANS THEMSELVES, THE EARLIEST RESERVOIRS OF LIFE, POLLUTES BEYOND BELIEF. ALL THIS HAS HAPPENED BECAUSE OF A LIMITED CONCEPT OF WELFARE, AN INABILITY TO GRASP THE ESSENTIAL UNITY OF ALL THINGS, A STUBBORN REFUSAL TO ACCEPT THE EARTH NOT AS A SPIRITUAL ENTITY THAT HAS OVER BILLIONS OF YEARS NURTURED CONSCIOUSNESS UP FROM THE SLIME OF THE PRIMEVAL OCEAN TO WHERE WE ARE TODAY. SUCH AN INTERPRETATION OF WELFARE APPLICABLE TO THE WHOLE CREATION IS PERFECTLY CONSISTENT WITH THE VEDIC VIEW OF THE UNITY AND INTERRELATEDNESS OF ALL THAT IS – GOD SELF, THE NATURAL WORLD.

The Yajur veda (13.47) says that service to animals leads to heaven: ‘ NO PERSON SHOULD KILL ANIMALS HELPFUL TO ALL AND PERSONS SERVING THEM SHOULD OBTAIN HEAVEN.’

ACCORDING TO THE ATHARVA VEDA (12.1.15), THE EARTH WAS CREATED FOR THE ENJOYMENT OF NOT ONLY HUMAN BEINGS BUT ALSO FOR BIPEDS AND QUADRUPEDS, BIRDS, ANIMALS AND ALL OTHER CREATURES. THE EMERGENCE OF ALL LIFE FORMSFROM THE SUPREME BEING IS EXPRESSED IN THE MUNDAKOPANISHAD (2.1.7): FROM HIM, TOO, GODS ARE PRODUCED MANYFOLD, THE CELESTIALS, MEN, CATTLE, BIRDS, THESE IDEAS LED TO THE CONCEPT OF AHIMSA OR NON-VIOLANCE.

MUCH LATER, THE MANUSMRITI SAYS, ‘HE WHO INJURES INNOCENT BEINGS WITH A DESIRE TO GIVE HIMSELF PLEASURE NEVER FINDS HAPPINESS, NEITHER IN LIFE NOR IN DEATH.’ THE SHRIMAD BHAGAVATAM (1.7.38) SAYS THAT A CRUEL PERSON WHO KILLS OTHERS FOR HIS EXISTENCE DESERVES TO BE KILLED, AND CANNOT BE HAPPY, EITHER IN LIFE OR IN DEATH. SO LONG AS THE EARTH IS ABLE TO MAINTAIN MOUNTAINS, FORESTS AND TREES. UNTIL THEN THE HUMAN RACE AND ITS PRWOGENY WILL BE ABLE TO SURVIVE. - Durga Saptashati ‘ Devi Kavacham’

Excerpts from “Sacred Animals of India” and “Hinduism and Nature” by Nandita krishnaInspiration for scriptures on Sacred floor-scape carvings

A dynamic pathway, inspired by traditional temple architecture, features a deconstructed column design adorned with intricate carvings that echo ancient temple scriptures. The pavement, crafted from local vernacular stone, is rain-permeable, allowing for sustainable water flow and offering a tactile connection to the environment. As you walk along this living street, you are immersed in the community’s cultural narrative, with inscriptions from ancient literature guiding your journey. The electrical lines are cleared from vista, avoiding electrocution of urban wildlife, underground wiring is proposed in this area, eventually leads to Mukhamantappa the first relic of temple .

The revenue generated by these shops becomes a crucial part of sustaining the space and its surrounding area, offering economic support to local vendors and encouraging a thriving market atmosphere.

The surrounding architectural features, such as beautifully crafted balusters, enhance the space’s sacred and contemplative atmosphere. The design also integrates ecological principles, incorporating bird feeders, bird baths, and designated watering areas, creating a sanctuary for local wildlife. The use of terracotta elements and locally sourced stone reinforces the sense of connection to the land, promoting both sustainability and cultural preservation.

Organized through paving and seating elements Mukhamantappa serves as floral markets in the morning or a place for market use for sacred offerings during the time of festivals. Pedestrianization avoids random parking in this area freeing up the space encouraging community gathers and relaxation spot.

with created order lighting and landscaping this area becomes a cozy relaxation spot for villagers in the evening

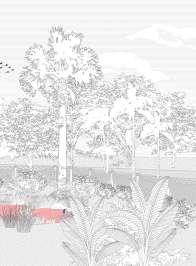

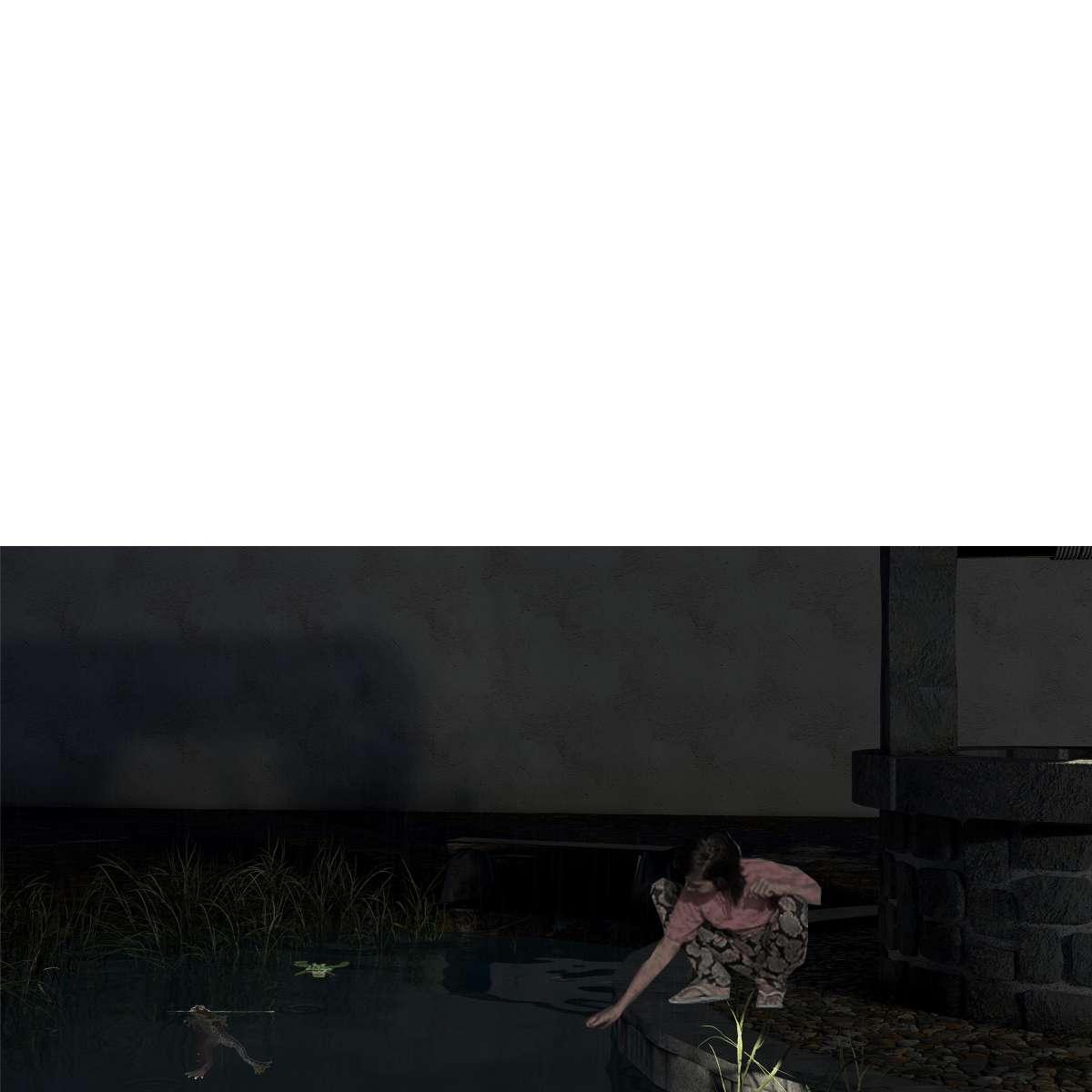

THE WORSHIP BEGINS WITH A DIP IN WATER MAN DRAVIDIAN TEMPLES HAVE A TANK ASSOCIATED WITH IT CALLED THEERTHAM, HERE DEDICATED TO LORD VISHNU WHO IS ASSOCIATED TO BE THE GOD OF WATER ECOLOGIES, THE TANK HAS ALSO BEEN DECLARED AS BIRD RESERVE. THE TANK WAS DRAINED DUE TO SAFETY REASONS WAS OF CULTURAL AND ECOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE THUS, LANDSCAPING TECHNIQUES OF RAIN WATER PONDS WILL BE APPLIED THAT CREATE SELF CLEANSING ECOLOGIES USING FILTERING PLANTS AND WATER SPECIES THUS RESURFACING WATER AND ENABLING SPECIES TO THRIVE AGAIN THAT FLOURISHED AROUND AND LIVED AROUND THIS TANK SINCE CENTURIES

Left side with ratham an age old relic and existing abandoned building and connection to existing bathrooms gives an opportunity to turn this side of temple entrance into a visitors hub

A vast space with an underused temple infrastructure can be converted into a flexible temple responsive market specific to the sacred ecologies and also enables marketing and propagation of native plants grown on site and sustainable goods for community and visitors as operated by community thus giving agency.

Flexible space to sell temple related goods for offerings , it can also be a space for make activity or festival fairs etc, here new traditions can be set around ecologies. Native species are sold for landscaping and it also is a museum of the aesthetic of native species.

SACRED ECOLOGIES TCBR- Abandoned structure is transformed into information center about the bird reserve, importance of protecting ecologies in Hindu culture will also be precisely propagated with respect to each species that visits TCBR and gardens and its presence in temple Murals and carvings, Making the Sacred values visible.

CULTURAL CENTER- Sacred stories around ecologies from murals and historians are well recorded and depicted in these areas , the areas also mention about native festivals , archaeological importance, culture and traditions of tiruppudaimaruthur

Native species pollinator garden as maintained b community show case the beauty and promote its aesthetic, enabling pollinator gardens

on-site plant nursery & space to sell merchandise related to interpretation of sacred ecologies -TCBR and temple with an outdoor selling area.

Adaptive re-use will enable a flexible space by integrating details from housing typology ensuring heritage is recognized serving a charming and peaceful place to learn about the Journey of interpretation of Tiruppudaimarudur’s Sacred Ecologies through the procession - Kovil Chimes.

CANE TRUSS LOW INTRUSION ECOLOGICAL INCLUSIVE ENCLOSURE THAT SERVES VISIBILITY TO SACRED GARDENS THE EXISTING PLATFORM BEING USED FLEXIBLY FURTHER-INTO AN AMPHITHEATER AND A PORTAL TO VIEW NATURE CO-EXISTING WITH HUMAN STRUCTURES JUST LIKE HOW TEMPLE WECOMES ECOLOGY.

THIS WILL ALSO SERVE AS AN ENTR POINT TO THE RESTRICTED PATHWAS TO SACRED GARDENS CALLED NANDAVALI.

Concept of Nandavali

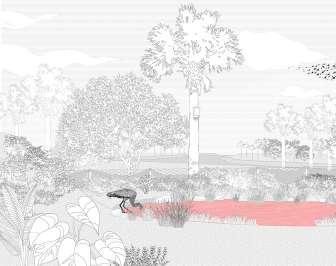

After identifying the presence of species and importance built from procession one proceeds to get intimate with garden ecologies with restricted access pathways that show case TCBR while also protecting ecology from being over accessed creating buffers and blocks using landscaping and living fences

Planters seats and signage help awareness, A Trees efforts are realized and visitor learns b engaging Herbs and native species and sacred (milk-weed other pollinator species) important to Hindu culture are planted along Nandavali and its planters. Herbs like Ajwain, mint, tulsi are planted that could be useful to villagers and priests, flowers for temple offerings can also be grown here around as a measure of softscaping.

Pathways that take you far enough to look at the bat-hoses developed by ATREE to enable safe transfer of bats inside the temple to reside in the gardens, ATREE also engages in fun non human designs like insect hotel etc which can be integrated to these Vali (pathways)

Low lighting and non intrusive access will be ensured to both experience the intimate ecology et also protect it

on site plant nursery

Analysis suggests from zoning, The proposal connects this zone as highlighted for community revenue, vocation and successful maintenance and operation of KOVIL CHIMES interpretation. Involving children in traditional practices through learn and play is identified as the first step to awareness protection and welfare of this region

FOREST- PLANT NURSERY

SAND DUNES - PLAY PIT

EXISTING WELL

WATER ECOLOGIES

MOTH WATCHING-PADDY

EASTERB GHATS-GRAND ENTRANCE

KUTTIVANAM IS REACTIVATION AND RE-DESIGN OF AN EXISTING PARK INFRASTRUCTURE, DESIGNED WITH SENSOR PLAY LOGIC OF ENGAGING WITH TACTILITY. THE ZONES WILL SERVE AS ECOLOGICAL LEARNINGS AND LANDSCAPE LEARNING WITH ATREE. THE PLANT NURSERY FOR FLAURA CONSERVATION AND NATIVE SPECIES THE MOTH WATCHING AND RECORDING,THE REPTILE WATCHING,THESE TECHNIQUES AND LOGICS WILL BE EXPOSED TO KIDS BY ATREE AND VILLAGERS WHO CAN BE FURTHER TRAINED ENGAGE CHILDREN HERE BOTH VISITOR AND RESIDENTIAL AT SOME POINT CHILDREN AT THE VILLAGE END UP TEACHING THEIR AREAS IMPORTANCE TO THE VISITOR CHILDREN...

Plant Nursery as run with ATREE by community can be connected to outside merchandise area for sale and enable landscaping for interventions on site as well as enaging students with sacred native species

Toddler play area around the existing slide making a soft ground with sand pit, relic sand from surround red sand dunes will be used so children are introduced to the landscape

BIO-POND enables water ecosystems as implemented by researchers at ATREE with community

Flexi-roof that lights up at night to teach kids about moth ecology as conducted by ATREE for children The children also learn about paddy ecology and important insects

Native Plant species that will be signaged QR coded b the scientists at ATREE as an introduction to their importance The production for landscaping happens on-site plant nursery

Paddy Ecologies and Moth watching zone is where children will engage in the importance of ecolgy of insects. The will learn about native species and sacred values of insects to their culture. The will learn about native species and invasive species of agriculture. The structure enables moth counting will light up and safely release the moths and insects after activities

BIO-POND that fosters frogs and other water ecologies will be created with ATREE’s collaboration and thus children can engage with researchers in identifing and tracking the frogs of this delicate area of tiruppudaimaruthur.

THE WORSHIP AND PROCESSION OF KOVIL CHIMES ENDS AT THE RIVER EDGE. THE FINAL STOP ENABLES THE VISITOR TO WITNESS THE ROOT TO THE ECO-REGION OF TIRRUPUDAIMARUDUR VILLAGE AND ECOLOGICAL VALUE, THE RIVER. AS ORAL HISTORIES COMMENCE WITH SCRIPTURES CONCLUDING ABOUT SACREDNESS OF RIVER AND HINTING USERS TO REFLECT AND RE-INSTILL THEIR CULTURAL VALUES BY SPATIAL RECALLS FROM TEMPLE , ANCIENT SCRIPTURES AND HERITAGE VALUES. A BIRD HOUSE TOWER IS INTRODUCED HONORING THE RIVER BIRDS ACTING AS A MONUMENT TO THE END OF WORSHIP AT TCBR WHERE WORSHIP IS BALANCE AND HARMONY OF ECOLOGY AND MANKIND

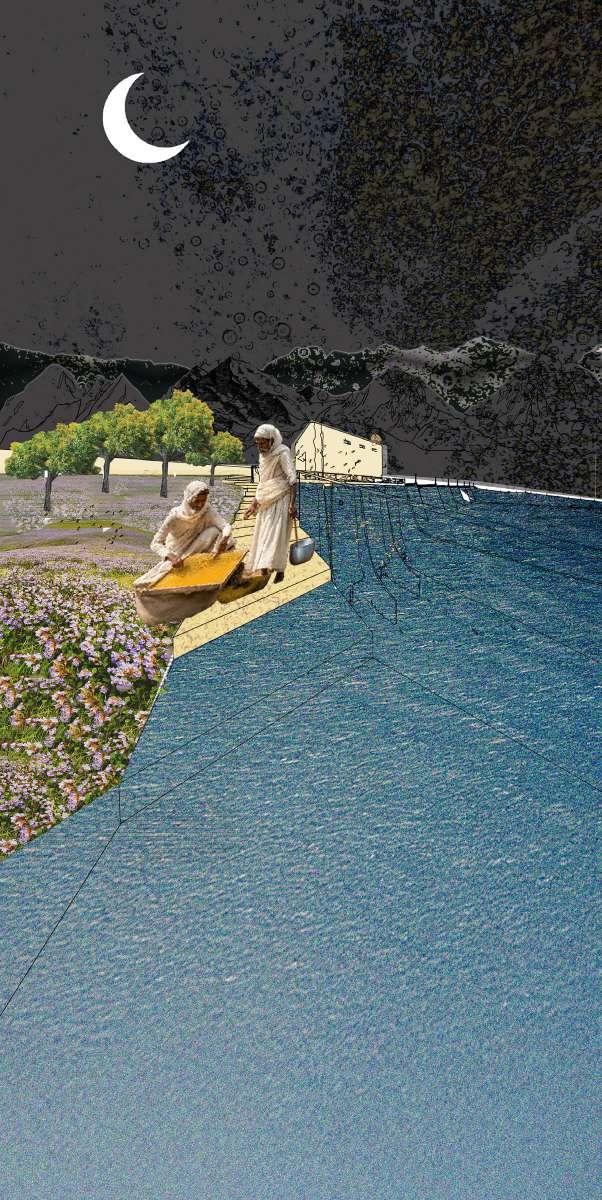

Facilitators of sacredness take various forms and can be seen through differing scales. Speculating the Sangam acts as more of a reworlding device that utilizes historic pieces of Tamil literature, contemporary notions of climatic changes, and a re-imagination of existing landscapes to truly comprehend and reinterpret sacredness with landscape, infrastructure, and time as the vessels.

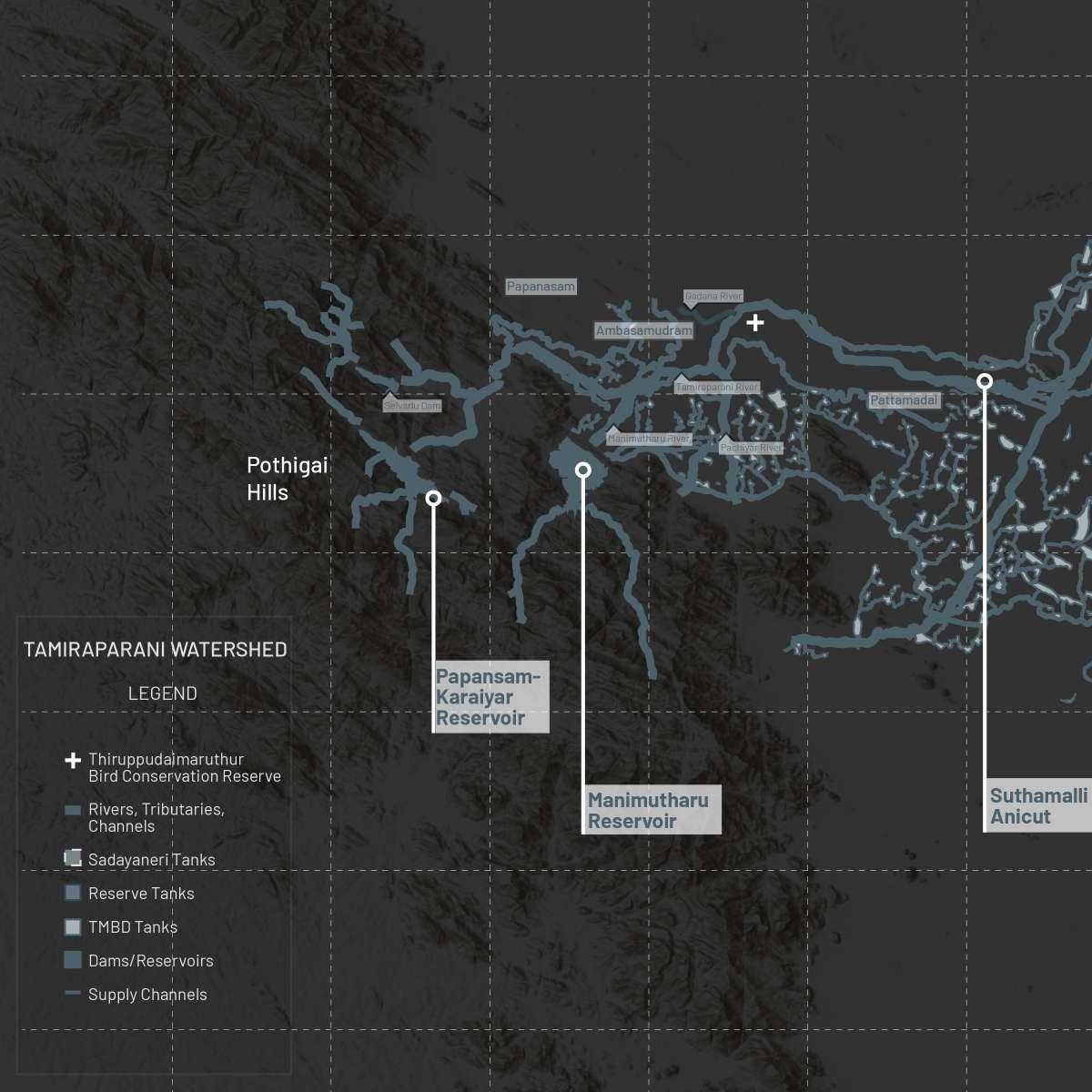

In knowing who our facilitator of sacredness is, we establish and fortify the core of humanity and civilization. To question who the facilitator of sacredness is, one must identify what is sacred. In this story, the Tamiraparani river is the sacredwith its streams, tributaries, and channels are the veins that run through the five regions of the landscape-the water is the sacred.

Throughout the course of time and development of society, there have been attempts to harness the sacred. We have examined these attempts in taking the form of infrastructure. Whether they are dams, tanks, wells, reservoirs, or canals, mankind has created these vessels as a means of manipulating the sacred for their own terms, whether its energy, irrigation, or agriculture.

Across the landscape we look at two scenarios that show how infrastructural interjection in facilitating water eventually leads to catastrophic events and a re-imagination to how sacredness continues to be pursued.

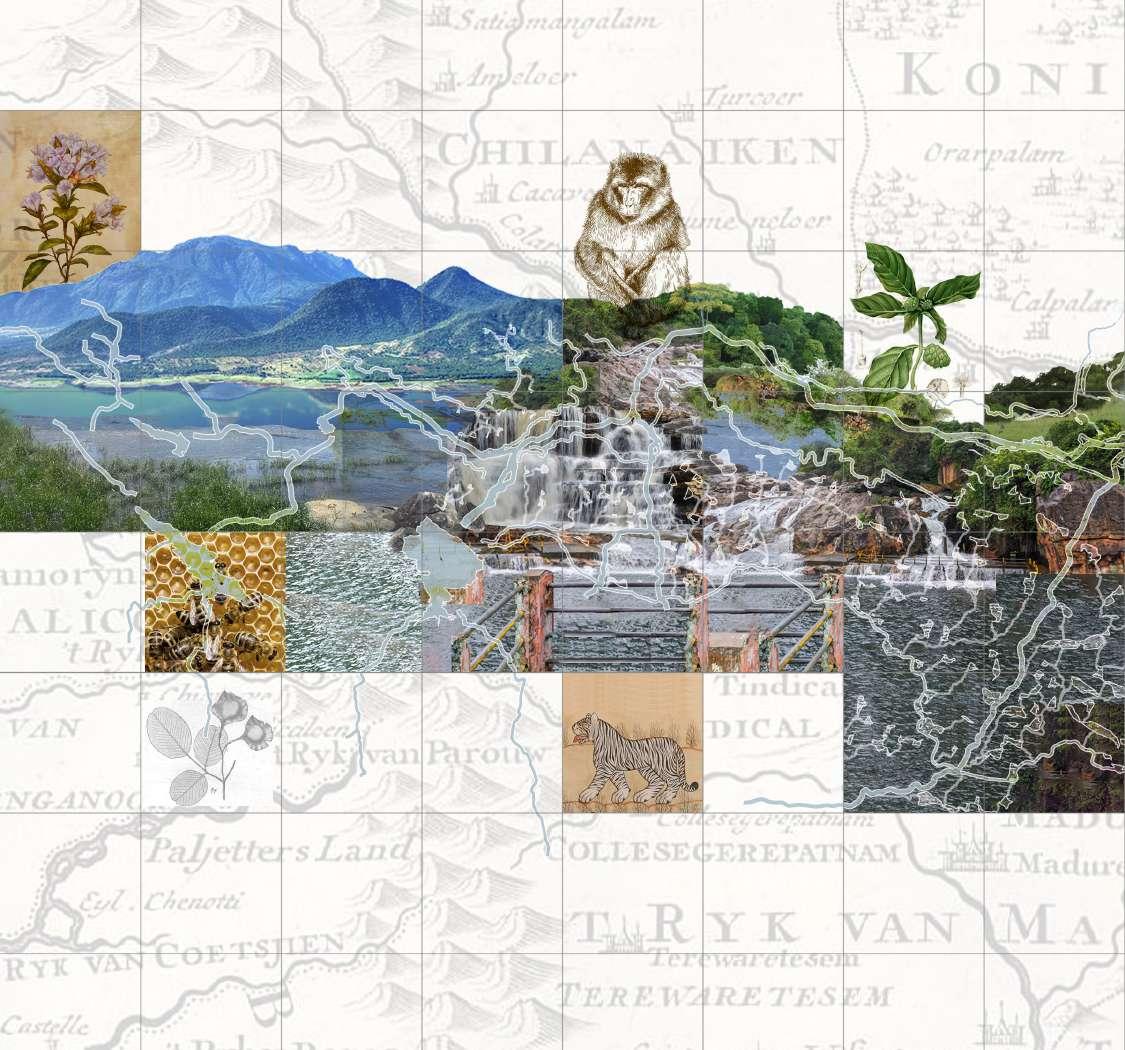

We start off in the Kurinji region, known for its mountainous terrain that is adorned by the kurinji flowers that bloom every 12 years alongside the native venkai, bamboo, and jack fruit trees just to name a few. In utilizing the Papansam-Karaiyar dam as the first site, the poem sets the scene for how the steady rise in water levels within the reservoir raises new alarms for local honey harvesters and millet cultivators the region is known for.

Bigger than the earth, certainly,

Higher than the sky, More unfathomable than the mysterious waters that continuously collect in what seem like an increasingly small reservoir, Is this love for this land

Of the mountain slopes

Where bees make rich honey

From the flowers of the kurinji

That has such black stalks to the macaques that patrol our temples

The land of love soon becomes the land of alarm Where must one go?

To the land of the forest

Speculating The Sangam

As we move onto the forest landscape known as Mullai, we start to see how the characteristics of this landscape get turned on its head when the very infrastructure meant to nourish these elements turn against the people, leading to the treacherous flooding that was similarly faced by the city of Tirunelveli in 2023. In the re-imagination of how to harness water on a grander, more unprecedented scale-a possibility that takes place is the inhabitation of the very banyan trees the region is known for that have been uprooted by the coursing waters and now serve the people as a means of crossing the deadly waters of below and the possible habitation of them.

The rumbling clouds winged with lightning

Poured amain big drops of rain and augured the rainy season; Buds with pointed tips have sprouted in the jasmine vines; The stags, their black and big horns like twisted iron

Rushed up along the the streets now streams But harnessing the power of 10,000 streams now that the dam has given out and released its vigorous might down upon us.

The wide expansive Earth is now free

From all the restrain this structure imposed. And the forest that looked exceedingly sweet is now in shambles as its remains accompany us as we trekk on.

Those with wings fly high and have found means of escape. Till we meet again feathered friends

On and up

Speculating The Sangam

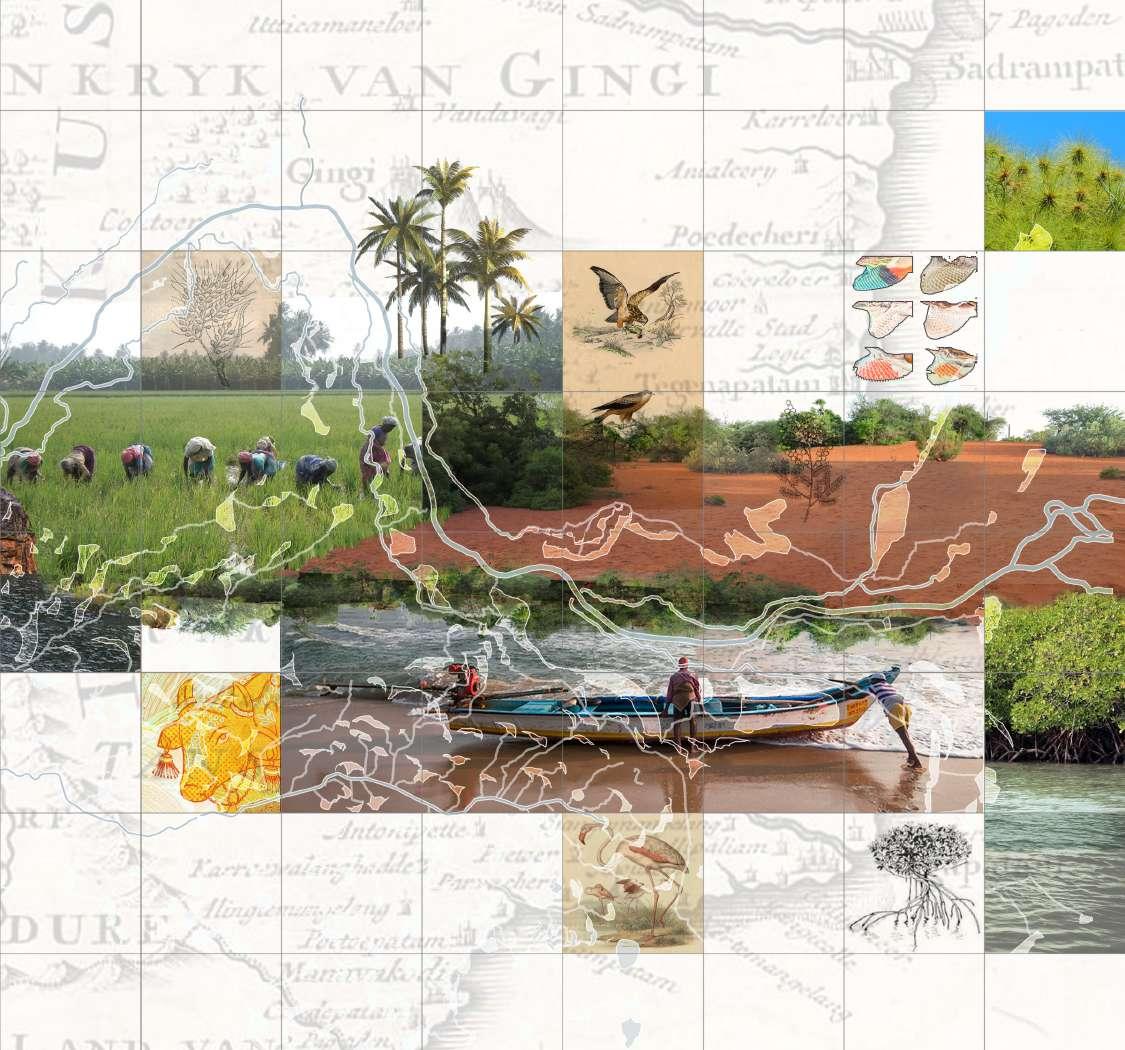

The next scenario taking place in the Marutham region, one known for being the traditional croplands that grows rice and banana in the monsoon season or cotton black gram in the off. This scene shows the extreme drought that could take place if our infrastructure could no longer hold the sacred, something that is very close to the conditions many farmers have experienced in the past. The Suthamalli anicut serves as a backdrop that demonstrates its abandonment and service that is left astray when the Tamiraparani River is all dried up.

Oh chief of a once fertile plain

In your domain, the tillers would take

Baskets full of seeds, to sow In the vast fields ploughed again

After a harvest, for raising a second crop; They return home, with the same baskets

Filled with many a kind of fishes. You must know, chief, Those times are far gone; Tillers would go to the fields to plant their seeds,

But with a scorching sun and absence of clouds

What can one plow when everything is further than dead?

It’ll pass over they said, wait till the next harvest

Until that happened ten times over;

The desperation for water becomes like no other

To the rivers, to the dams, To the coast and back,

When not a lick of spring can be found, where does one go? Down below.

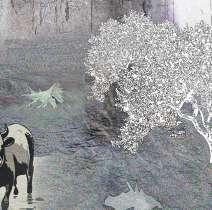

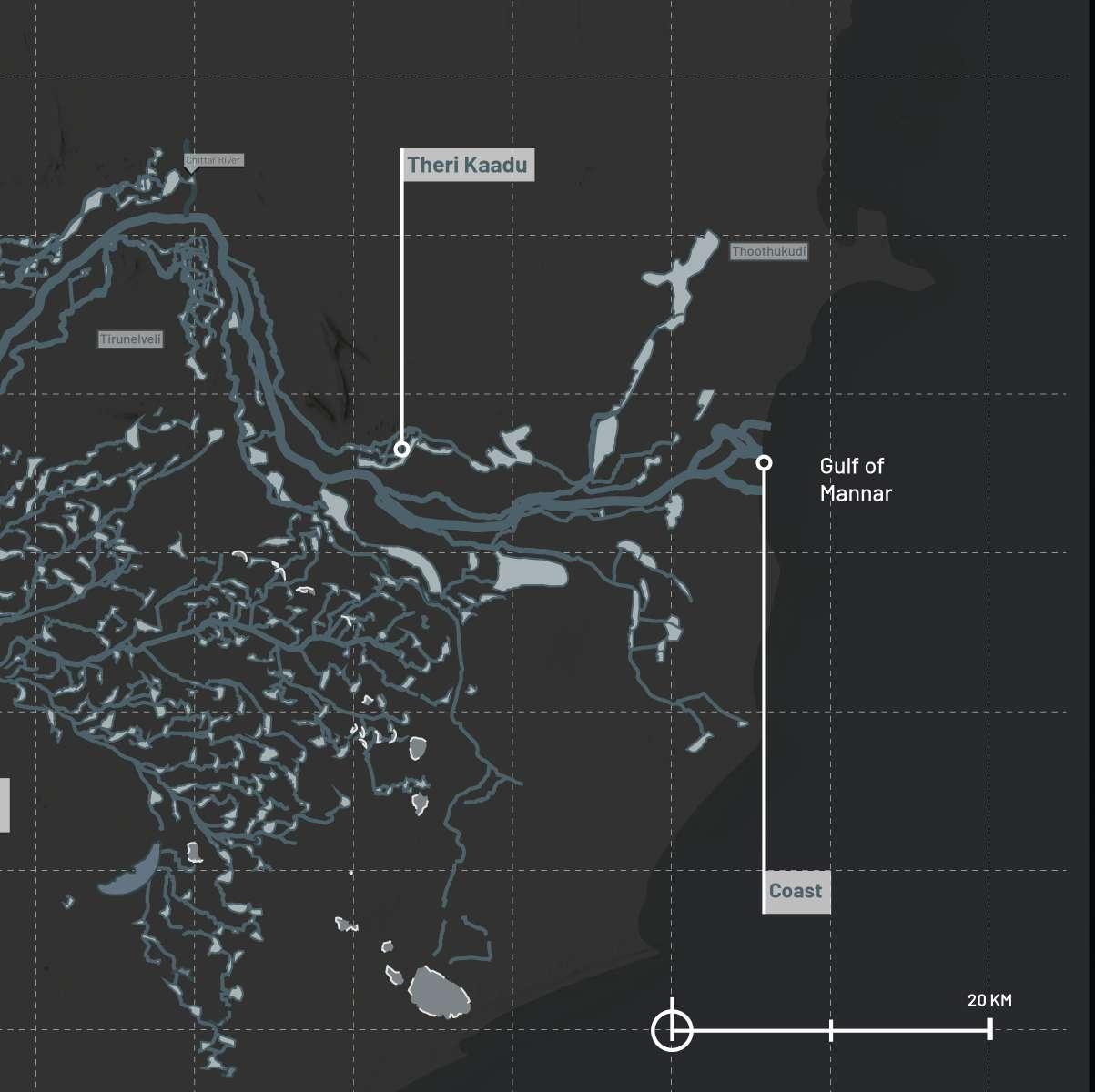

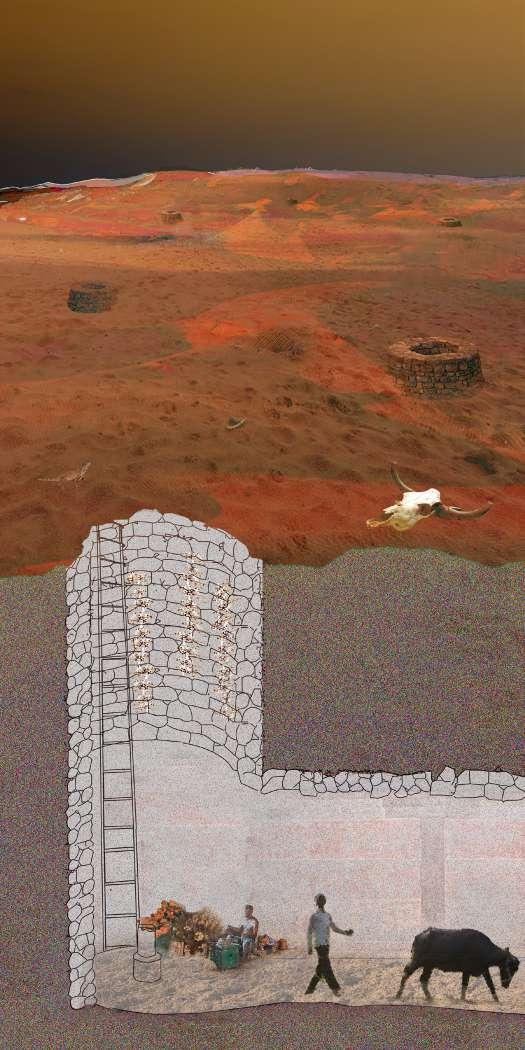

This imaginative scenario in the region of Palai entails the desertification of the land. Years of drought have gone on for so long with the sun’s aid of rising temperature to exploit what the Palai region is known for, the red sands of the Therikaduu desert, and expand its boundaries for miles and miles to come. With the river being all dried up in this scene and the further depths of the sand containing the last bits of moisture, the means of harnessing water obligates inhabitants to utilize traditional farmer wells so much so that it has led to an underground society to manifest itself to live alongside the only form of reaching water.

The borders of the new city with great fame are bordered by the cows and livestock that have followed us down under.

Legend has it that swift horses with lifted heads used to arrive on ships from abroad, with sacks of black pepper from inland by wagons, gold coming from northern mountains, sandalwood and akil wood coming from the western mountains, and materials coming from a strange place formerly known as the Tamiraparani.

When a river dries, the search for water becomes like no other.

For miles and miles all you can muster of the red sand are the wells that grant new entrance to the people’s homes. But we persist, forge on for our attainment of the sacred.

This leads us to our final region, Neithal-a prominent arrival to the coast. We come to a point where the river meets the sea. In this meetings of waters, we come to realize who is the true facilitator-the ecology itself. We meet the mangroves that acts as a natural filtration system and truly take care of what the people of the region see as sacred. But with how human interjection has been taking form, as present day shows the clearing of this system to allow room for future development. This is meant to present the question of how can one interpret the land and protect the sacred when its facilitators are put in harm’s way?

Like the monsoon season

When water scooped up by the clouds

Pours down the mountain And water from the mountain Flows back to the sea, I the water recount my journey and the multiplicity of lives I have encountered and experienced. My commitment for life persists, though has increasingly become mangled and manipulated in ways I wish never to return, But when I pass through the mangroves that cleanses me of my sins and takes me to the sea, I am at peace I am at home

To eventually return once again