BETTER FROST DECISIONS

Knowledge to inform grower and adviser decisions for pre-season planning, in-season management and post-frost event responses

IN THIS ISSUE

Making better risky decisions about frost

In-season strategies to manage frost

June podcast

Frost Economic scenario calculator

Manipulating the flowering window to avoid frost

MAKING BETTER RISKY DECISIONS ABOUT FROST WELCOME

PeterHayman,SARDI

Makingbetterdecisionsaboutfrostisanongoingchallengefor graingrowers.Zoningpaddocksthatarefrostproneandliningup salvageoptionssuchashayorgrazingareconsideredbest practicefrostmanagement.Bestpracticeisasetofrulesthat growersadapttotheirenterpriseandlargelyfolloweachyear. Anotherbestpracticeruleistosowcropvarietiesinthe recommendedsowingwindow.Sometimesthereisanearly sowingopportunityandgrowersinfrostproneareashaveto decidewhethertodeviatefrombestpracticeandtaketheriskof sowingaspringwheatabitearlierthanrecommended.

Sowingdecisionsinfrostproneregionscanbetricky.Ideally,the cropshouldflowerafterthelastdamagingfrostandbeforethe onsetofheatandwaterstress.Gettingthecropinearlyand floweringbeforespringbecomestoodryandhothasprovento begoodagronomy.Somegrowershavesaidtheydon’tmind seeingveryminorfrostdamageasthisindicatesthattheywere pushingupagainstjusttherightamountoffrostriskforthatyear

Theproblemisthatthedateoflightfrostdamageinoneyearcan bemajorfrostdamageinotheryears.Aswedon’thaveacrystal ballandtherearen’t100%frosttolerantvarieties(yet),allfrost decisionshavesomedegreeofrisk.Themostprofitablechoices willonlybeknownaftertheseason.

Our first issue for 2023 starts with conditions that have been generally dry across the region and talk of an El Niño.

Seeding has progressed albeit slowly for some. So what can we expect with frost this year?

In this issue, we continue our regular catch-up with Dr. Peter Hayman to chat about the season and the decisions made on farm when it comes to frosthow can we make these decision less risky?

And if you're still on the tractor seeding, spraying, spreading or rolling tune in to the Better Frost Decisions Podcast where we chat to Peter Hayman, Max Bloomfield from FAR Australian and CSIRO's Bonnie Flohr.

Next issue August 2023.

ISSUE 7 | JUNE 2023

Continued

The upcoming GRDC National Risk Management Initiative will work with growers, advisers and researchers to explore how to make better decisions about risk – for frost and other farm decisions.

Making better decisions is a process

When asked to list some good decisions, most of us list decisions that ended well. When asked to list bad decisions, we list decisions that ended badly. In other words, we focus on the outcomes of the decision rather than the process of making decision. This ‘outcome bias’ is a natural and necessary mental shortcut everyone takes, and recognising it is important when making big or risky decisions.

A good decision:

considers the process that led to the decision itself, not just the outcome considers multiple scenarios before making the final decision, and

uses the best available information at the time, such as understanding which paddocks are more frost-prone, optimum flowering window for crops, options available to the farming enterprise to salvage frosted crops such as hay and/or grazing, the impact of a frost on total farm cash flow and in some cases, the forecast for the coming season

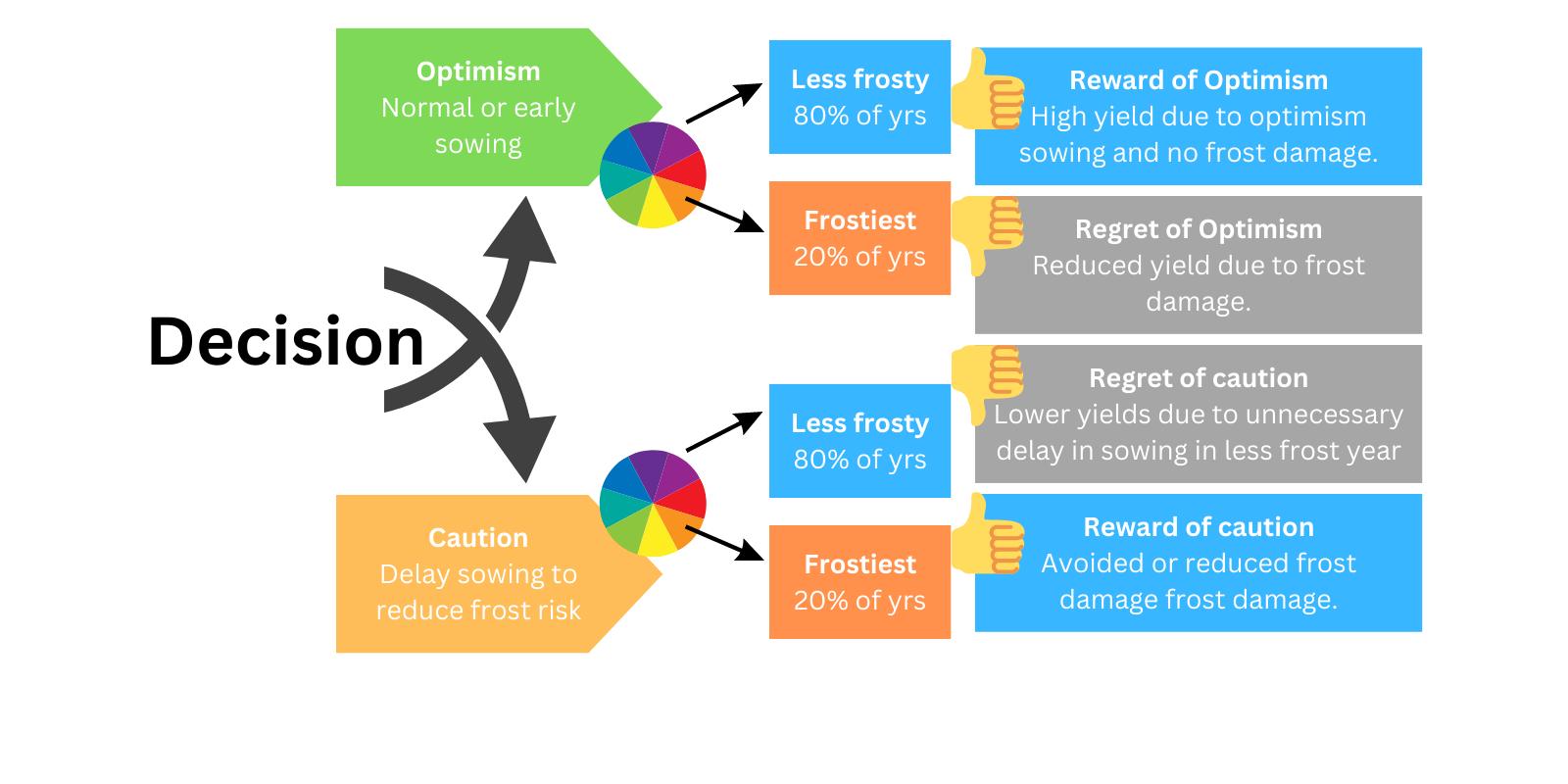

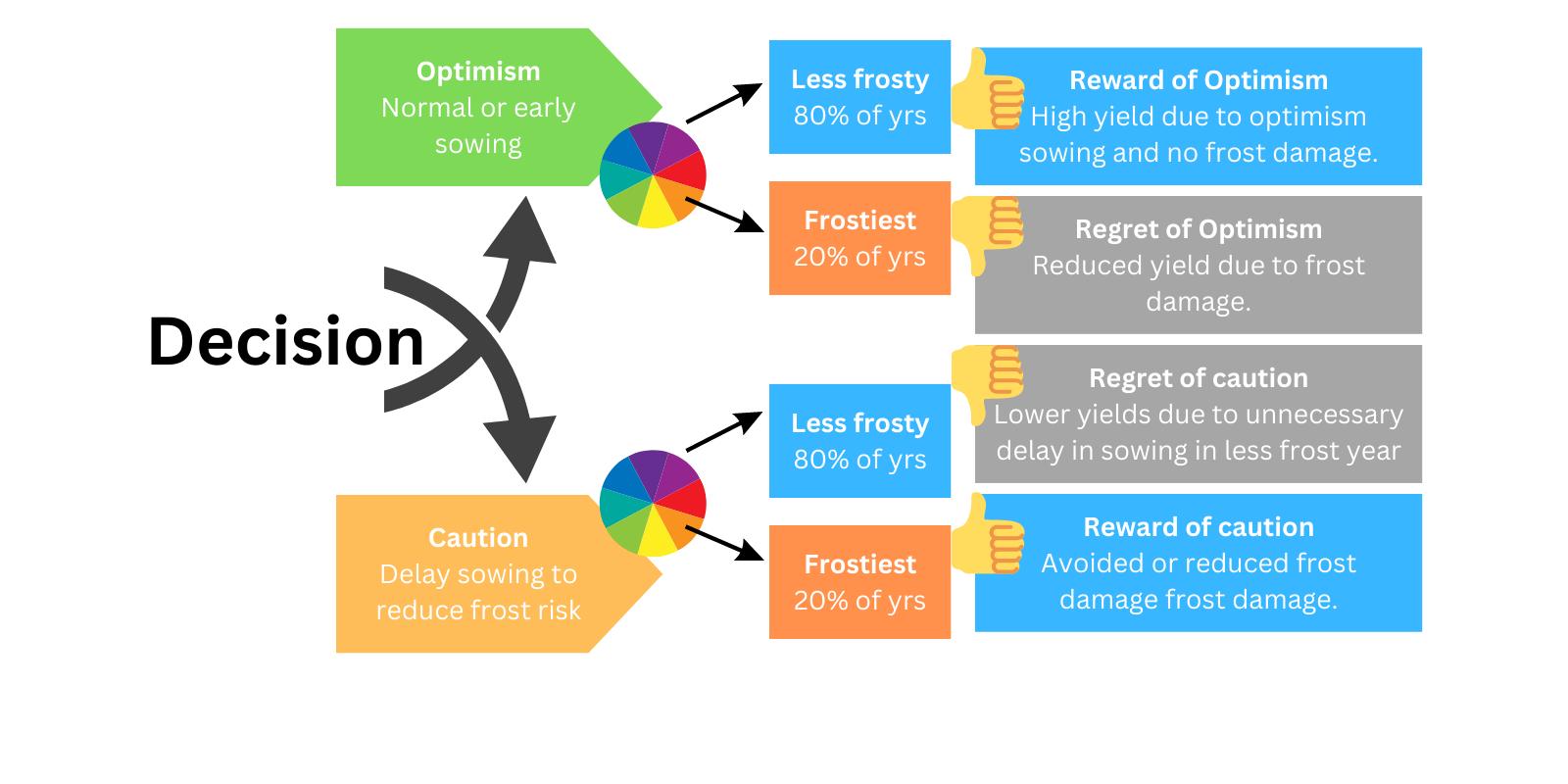

For example, Figure 1 maps out the decision to sow at the normal time or to delay sowing on a paddock in the SA Mallee that experiences frost damage in some years but escapes frost in most years.

A more optimistic approach is to sow during the recommended sowing window to flower in the optimal flowering window for that region. Because this paddock is not badly frosted in most years, the optimistic approach will lead to higher yields and avoid moisture and heat stress by flowering earlier in spring There are good rewards for optimism, but in some years the crop will be frosted and the grower might have wished they were more cautious.

Continued

Figure 1 Mapping the decision to either sow at the normal time or delay sowing, with four outcomes depending on the season

Making frost decisions considering El Niño

After three years of La Niña, this year many growers will be aware that there is an increased chance of El Niño. El Niño means less cloud cover with warmer days and colder nights.

Theoretically this means more chance of frost, but the relationship between frost and El Niño is complicated.

If you had to choose which of the last ten years had the most frosts, more of these would be El Niño years. However, if you had to guess which 10 years had the latest frosts, the results are more random. Late frosts can happen in any year, such as the severe frosts in 2021 (a La Niña year)

Unfortunately, in cropping, the date of the late frosts is more important than the total number of frosts. Additionally, we do know that El Niño means more heat and less moisture later in the season. With this El Niño arm wrestle, we're more confident about an increase in heat and water stress in an El Niño year than we are about frost.

IN-SEASON STRATEGIES TO MANAGE FROST

Year two is now underway with a series of trials exploring agronomic options in those areas more prone to frost events. Historically, a lot of frost work has focused on finding genetic tolerance to frost. This Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) investment Enhancing frost tolerance and/or avoidance in wheat, barley and canola crops through in-season agronomic manipulation, led by FAR Australia (FAR2203001RTX), aims to explore ways to improve frost tolerance by manipulating crop phenology and improving frost resilience using novel agronomic practices

There is no easy answer, and a frost that causes 90% damage in one year is hard to weigh against 10 to 15% damage from heat and water stress in most years Preliminary APSIM runs that consider frost, heat and water stress suggest that in an El Niño year, the better outcomes are from crops that flower before the heat and water stress. Paradoxically, this means taking on slightly more frost risk in an El Nino year and hence reinforces the need to have salvage plans for dealing with a frosted crops

In summary, the ‘right’ frost decisions depend on the farm and grower. A grower still has to weigh up the reward and regret of optimism against the reward and regret of caution Decisions are improved by knowing frost risk across the landscape, knowing about flowering windows and having options to soften the regret through hay and/or grazing.

The three main strategies are:

Using mechanical defoliation or grazing to delay flowering. This project is pushing the limits by cutting the crops back to 5-10 cm above the ground and defoliating later than normal to remove or impede the developing apex (Z31 in cereals, bud visible in canola). Applying plant growth regulators at early stem elongation to slow crop development Applying cryoprotectants and bactericides to manage the frost damage caused by ice nucleating bacteria.

All strategies are being tested on fast developing wheat, barley and canola.

1 2. 3.

Continued

CSIRO are modeling crop development after defoliating wheat crops established at different times, with the aim of defining the optimum defoliation intensity and timing across different cropping regions.

Many aspects of the trials are exploratory as there has been little work done with these interventions and products with regards to frost. Some products used in the trials are already commercially available for other uses, though not yet registered for use on wheat, barley or canola crops.

More flexibility to hit the flowering period

These options would also give growers more flexibility with variety choice and sowing time to hit the optimal flowering period. The project is assessing how these agronomic interventions can delay development into avoid frost risk and still flower in the optimal flowering period before heat and drought stress

Bonnie Flohr (CSIRO) says, “grain yield is more sensitive to stress during flowering, so the whole idea of the optimal flowering period is to target the lowest risk of heat, drought and frost. Hitting the optimal flowering period means aligning the time of sowing with cultivar development ”

But what if an early sowing opportunity arises?

The ideal choice is to sow a slower developing variety that can still hit the optimal flowering period. If a slower developing variety isn’t available, a grower could potentially use these agronomic options to slow development and still hit the optimal flowering period. A win-win of sorts

If these interventions prove useful, growers could be more tactical in their cultivar choice, for example, “You could sow a fast cultivar early, then delay flowering using the strategies so that it acts like a winter wheat,” says Bonnie.

The project is experimenting on fast developing wheat, barley and canola but are growing slower developing cultivars alongside them that will not be sprayed or defoliated. This is to compare how the agronomic interventions delay development compared to slower developing varieties.

Next steps

With a late project start and mild season, 2022 was largely based on pilot trials and controlled environment research. This year the project is ramping up, with full-scale trials continuing until the end of 2024

Max says, “This year there are more field experiments going in across the country, with a range of sowing times from early sowing to late sowing. Some of the plant growth regulators, bioprotectants and bactericides that were tested in lab conditions in 2022 are going into the field this year.”

And while no one wishes a frost upon a farmer, a few frosts this year would help put these strategies to the test.

Wheat defoliation field trial at Gnarwarre, south west Victoria, on 29 June 2022. Photo source: Aaron Vague, FAR Australia.

NEW PODCAST RELEASEBETTER FROST DECISIONS PODCAST OUT NOW!

This month we chat to:

Our regular Dr Peter Hayman, SARDI Climate Applications is back to discuss risky decision making and the chance of El Nino.

Max Bloomfield, FAR Australia talks about manipulating flowering time with agronomic strategies and we catch up with Bonnie Flohr, CSIRO to understand optimal flowering window in different regions.

FROST ECONOMIC SCENARIO CALCULATOR

In December 2021 issue of Better Frost Decisions, we introduced the Frost Economic Scenario calculator Now available online, the calculator is a way to test out different frost scenarios and management options to see the impact they have on the farm’s bottom line.

The calculator gives users a broad idea of how gross margins change with management decisions, such as cutting a certain amount for hay or growing different crops. Users can compare up to five scenarios to help choose which management strategies might work best for them this season

Information needed to use the calculator

The calculator uses zones to classify frost risk:

Green: areas with no frost risk

Amber: sometimes frosted and if not frosted has production capability like the red zone Red: areas frequently or severely damaged by frost

As such, using the calculator requires a decent understanding of frost risk and impacts across the farm i.e. which areas get severely damaged, areas that are only sometimes damaged, and how yields are affected by varying levels of frost. Printing off a map of the farm and mark out green, amber and red zones, can help gauge the area of each.

Users also need to know and have considered:

the unfrosted yield/ha for each enterprise on-farm price for each enterprise ($/ha) what salvage options you could choose and when you would choose them, e.g. if a certain amount of the wheat crop is damaged by frost, cut for hay variable costs ($/ha) such as fertiliser, weed control, cutting, baling, etc. for both normal operations and salvage operations.

The calculator is best used as a guide and is only as good as the data entered. It does not account for capital costs such as buying new machinery.

Testing scenarios

To get the most out of the calculator, think through how the farm operates normally and what management options are available in various frost situations, ranging from no frost up to the worst frost. Test different scenarios, such as a different crop, more or less area of certain crops, and different salvage options, to compare the impact on the overall gross margin. The calculator will show if various decisions, such as salvaging frosted wheat for hay, are viable options

The calculator is very flexible, letting users specify their crop choices, frost management options, and trigger points for when to implement a salvage option.

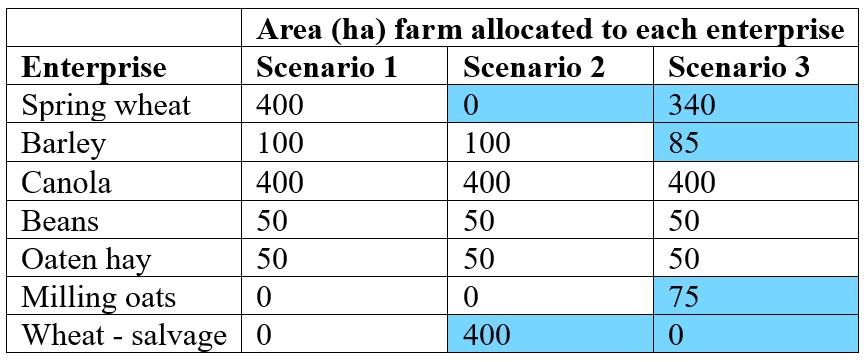

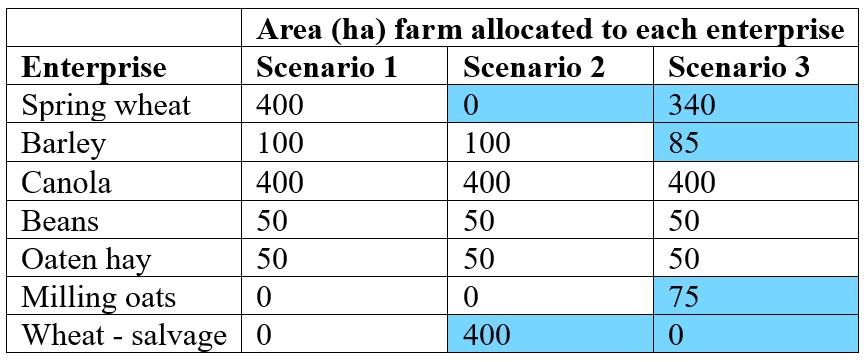

For example, three scenarios were set up in the calculator (Table 1). Scenario 1 is the baseline farming system, used to compare changes. In scenario 2, the grower will cut up to 200 ha of wheat for hay if it is more than 50% damaged (these parameters are set up in the calculator).

In scenario 3, the grower plants milling oats instead of cereals on 75 ha of country that is the most frost prone (red zone).

(

Table 1. Hectares allocated to each enterprise in three scenarios.

Continued

Note: blue shading indicates different management strategies chosen compared to scenario 1.)

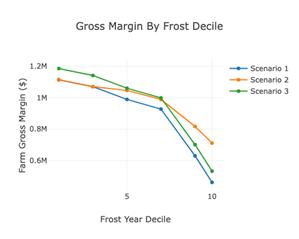

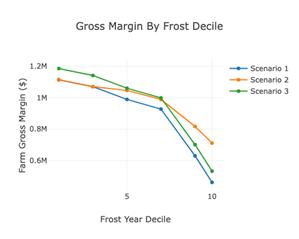

During less frosty years, allocating 75ha to milling oats rather than cereals in the worst frost areas (scenario 3) had the highest gross margin while there was little difference in scenarios 1 and 2. In more severe frosts, cutting frosted wheat for hay (scenario 2) outperforms scenarios 1 and 3 (Figure 1 left).

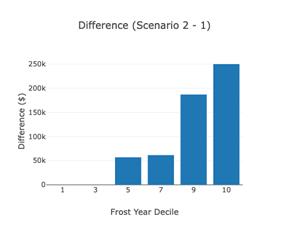

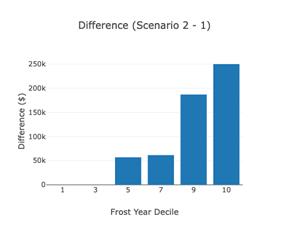

The ‘Difference’ column graphs (Figure 1 right) compares the difference in gross margin between the scenarios This example shows that cutting frosted wheat for hay generated a profit of $50 – 60,000 each year in the lower frost deciles, and $250,000 in the highest frost decile, compared to not cutting for hay (scenario 1).

A planning tool

The calculator is a planning tool, best used at the start of the season. The creators envisage growers and agronomists going through the plans for the season, past experiences, predictions for this season, and running through a few scenarios to work out the ideal way to manage frost this season.

Users can download the data file ( json) to reimport next year and tweak, rather than having to fill it out again. Agronomists can save files for each client.

Try it out

Try it online at: https://sfs.org.au/frost-calculator

Help videos are underway to walk users through each section

The calculator has been designed by Michael Moodie, Frontier Farming Systems and further developed by Southern Farming Systems through investment from GRDC and the Better Frost Decisions Project.

Figure 1 Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right)

Figure 1 Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right)

MANIPULATING THE FLOWERING WINDOW TO AVOID FROST

Matthew Tucker and Phil Brewer (University of Adelaide) and Brendan Kupke (SARDI)

Crop varieties with different flowering windows are one tool growers can use to hedge against frost. But as we can’t predict when frosts will hit when planting, or how bad they will be, changing when the crop flowers in-season could be a way to avoid the worst of it.

Exploratory research at the University of Adelaide and SARDI, as part of a GRDC investment led by Field Applied Research (FAR) Australia, is assessing management options to speed up or slow down crop development to potentially avoid frost. This includes a combination of defoliation and in-season treatments by plant growth regulators.

Defoliation

Growers already use grazing to defoliate dualpurpose crops, but whether this can be used as a practical solution to change flowering time, avoid frost and retain yield has remained unclear. A previous GRDC investment showed that mechanical defoliation can delay the flowering window in wheat and barley by at least 1 week, but the impact of defoliation intensity was not determined. As part of a new GRDC investment, trials are going harder - cutting away all biomass aboveground and then applying spray treatments of growth regulators

“The concept might sound outrageous, but the reality is we need to consider multiple strategies to better manage frost,” says Associate Professor Matthew Tucker, project lead from the University of Adelaide.

To test how well barley bounces back from what is effectively mowing, the crop was cut back both below and above the apex at growth stage 31, when the first node is visible Researchers are tracking growth to see how well the crop recovers, how long flowering is delayed, and the overall impact on yield.

Plant Growth Regulators

Plant growth regulators are commonly used in mid to high rainfall zones to defend against lodging and head-loss, especially in barley. Registered products typically interfere with the plant hormone gibberellin, leading to reduced height and stronger stems, thereby protecting yield. Strigolactones are another family of hormones that are made by the plant to control a variety of growth processes, such as branching, and stress responses Although first discovered in the mid-1960s, research into this family of hormones only began in earnest around 2010

Because there is very little research available on strigolactone and frost in cereals, this project is exploratory.

“It’s a case of spray the plant in a controlled environment and see what happens before moving to the field,” says Matthew. “However, we know enough to think that strigolactone could have two benefits for crops in frost-prone areas – increased tolerance to stress and altering the flowering window.”

Continued

Figure 1: Mechanical defoliation in barley (right) can lead to significant changes in flowering time. Source: Adapted with permission from Marzec et al., 2020, Plant Cell and Environment.

Better stress tolerance

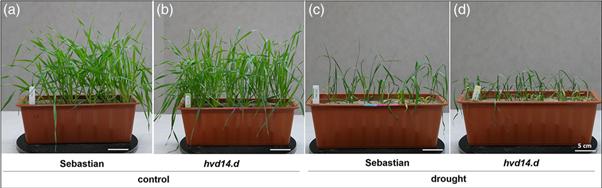

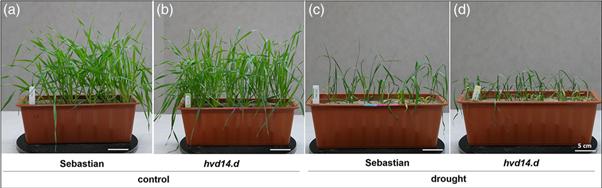

Plants respond better to stress when they can produce and respond to strigolactone. For example, barley plants that can’t sense strigolactone (see hvd14.d in Figure 2) do not cope as well with drought stress as those that can (cv. Sebastian in Figure 2). A recent study showed that under optimal growth conditions there was not much difference in early growth between hvd14 d and its parental line Sebastian (Figure 2a and b), but under stress the Sebastian barley fared better.

Importantly for the current project, recent studies in tomato indicate that strigolactone is also involved in in promoting acclimatisation to cold. Could strigolactone sprays be used to prepare crops for frost before the frost hits?

Researchers are now spraying crops with strigolactone and anti-strigolactone (a chemical that stops the crops from producing strigolactone) to see how they affect growth and development.

We need to see what strigolactone does when applied to a crop,” says Matthew, “whether we can stimulate more tillers after defoliation, or slow flowering a bit more, or stimulate resilience against stress ”

It’s also important to determine whether there are any unexpected effects on grain yield and quality.”

Figure 2 Sebastian barley vs hvd14 d, a variety that cannot sense strigolactone Under normal conditions, Sebastian and hvd14 d show similar growth However, under stressful conditions, hvd14 d performs poorly because it is missing the strigolactone response Source: Marzec et al , 2020; Plant Cell and Environment

Changing plant growth

Applying plant growth regulators such as gibberellin or auxin can also delay or speed up flowering. A recent study at SARDI and the University of Adelaide suggested in season application of plant growth regulators by spraying can change the flowering window by around 12 days.

Preliminary results indicate that strigolactone can change flowering time in barley, but more work is needed to understand by how much It is also important to understand the impact of dose, since in the future this will dictate whether products are registered and of economic value to growers. Strigolactones are non-toxic and do not persist in the environment They also work at very low doses, which makes them highly useful for use in crops destined for food or beverage production.

Next steps

Research so far has been in controlled environment growth cabinets. Now researchers will decide which aspects of the project to test in the field.

This research is part of the GRDC project UCS2301-002RTX ‘Enhancing frost tolerance and/or avoidance in wheat, barley and canola crops through in season agronomic manipulation.’

Team: FAR Australia, University of Adelaide, SARDI etc

Contact: A/Prof Matthew Tucker, University of Adelaide. Dr Phil Brewer, University of Adelaide.

References Kupke B M, Tucker M R, Able J A, Porker K D Manipulation of Barley Development and Flowering Time by Exogenous Application of Plant Growth Regulators Frontiers in Plant Science 2022; 12 DOI=10 3389/fpls 2021 694424 Marzec, M, Daszkowska-Golec, A, Collin, A, Melzer, M, Eggert, K, Szarejko, I Barley strigolactone signalling mutant hvd14 d reveals the role of strigolactones in abscisic acid-dependent response to drought Plant Cell Environ 2020; 43: 2239– 2253 https://doi org/10 1111/pce 13815

Figure 1 Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right)

Figure 1 Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right)