BETTER FROST DECISIONS

Knowledge to inform grower and adviser decisions for pre-season planning, in-season management and post-frost event responses.

CAN CLIMATE INFORMATION HELP WITH RISK MANAGEMENT?

PeterHaymanandBronyaCooper,SARDIClimateApplications

Grainfarmingisriskybusiness.Growersinvestincropsthat maybelosttodrought,frost,heat,diseaseoruntimelyrainat harvest.Notonlyisproductionrisky,butgrowersfaceprice risk,costrisk,financerisk,especiallywithhigherinterestrates, andriskstotheirownsafetyandthesafetyofstaff.Inrecent consultationsthatGRDCheldwithgraingrowersandadvisers, theincreasedriskinessofgrainfarmingisoneoftheissuesthat hasbeenraised.Inresponse,theGRDCdevelopedthe NationalRiskManagementInitiativewhichisnowcalled RiskWi$e.ThisprojectisledbyCSIRO(RickLlewellynbasedin AdelaideandLindsayBellbasedinToowoomba).

ThedefinitionforriskusedinRiskWi$eis“uncertaintyof outcomesthatmatter”;adefinitionthatappliestotherainfall andfrostinessofthecomingseason.Anyreliableinformation thatreducesthisuncertaintyispotentiallyofvaluetograin growers.ThisarticleaddresseshowclimatedriverssuchasEl NinoandLaNinaandtheIndianOceanDipoleinfluence rainfall,heatandfrostoverthegrowingseason.Acloseto perfectforecastthatreducedtheuncertaintywouldmake decisionseasyandsubstantiallyreducetherisk Seasonal forecastsarefarfromperfect,andwewillalwayshaveashift inprobabilities. Itisfrustratingwhentheoutlookiscloseto 50%chancewetterthanaverageand50%chanceofbeing drier.Whatthismeansisthatweneedtousethelong-term recordsforplanningandassumethateachdecileisequally likely.

IN THIS ISSUE

Can climate information help with risk management? Join the BFD Facebook Group May BFD podcast out now!! In-season agronomic interventions to avoid frost The Hay Harvest Decision: Frost Management Strategies on South Australian Farms. Using crop phenology to help mitigate frost risk Frost Economic Scenario Calculator

WELCOME

Welcome to the May edition of the Better Frost Decisions newsletter! This month, we explore the intricacies of climate drivers, phenology, and the hay/frost decision making process.

As we eagerly anticipate the rain to inaugurate the 2024 season and witness tractors bustling in the paddocks amidst cooler mornings, we invite you to uncover insights and strategies for the journey ahead.

We wish you a successful 2024 growing season

ISSUE 10 | MAY 2024

Where to find information on climate drivers

Most grain growers and advisers are aware of climate drivers such as El Nino, La Nina and the Indian Ocean Dipole. For a refresher, it is worth visiting the excellent material from the Bureau of Meteorology and the award winning videos on the climate dogs developed by Agriculture Victoria and a general description of climate and weather forecasting. The ABC has an explainer about what’s been driving Australia’s climate recently . The Bureau of Meteorology encourages users to use forecasts from their climate model rather than paying too much attention to climate drivers. This is a reasonable request as the climate model takes into account a vast amount of information from the oceans and atmosphere when generating the forecast. However, many grain growers and advisers find it helpful to follow the climate drivers for interest but also understanding and confidence in the forecast.

What is the influence of climate drivers on growing season rainfall in the southern grains industry?

The Local Climate Tool was designed to examine the impact of ENSO and IOD on southern Australian rainfall Local Climate Tool (forecasts4profit.com.au) . The screen grabs (Figure 1) show the change in odds for growing season rainfall at Mildura. With no forecast and just randomly sampling the historical record, there is a 33% chance of drier than 136mm (red slice), a 33% chance of wetter than 207mm (blue slice) and 33% chance of the rainfall being between 136 and 207mm. In the 28 El Nino years since 1900 the chance of being in the driest third increases to over 50% and the chance and in a La Nina the chance of being in the wettest third increases to 48%. In Mildura, like much of the southern grains region, the swing in the odds of growing season rainfall are even greater for the two phases of the Indian Ocean Dipole

These pie charts show that there is a swing in probabilities, but even the strongest swing of a negative IOD only shifts the chance of less than 136mm from 33% (1 in 3) to about 20% (1 in 5). This shows that it would be a mistake to assume that a negative IOD eliminates the chance of a dry season.

The Local Climate Tool can be used for a range of locations as shown in the maps in Figure 2. The important message from Figure 2 is that the swings in probabilities across the region are broadly the same. When we developed this tool as a part of a consortium of SARDI Climate Applications, Federation University and Agriculture Victoria in an earlier GRDC project, we were quite surprised at how consistent the swing in probabilities was across the region.

Figure 1 Screen grabs showing pie charts of chance of growing season rainfall for Mildura under phases of ENSO and IOD Local Climate Tool (forecasts4profit com au)

What is the influence on temperature compared to rainfall?

Table 1 shows the difference in April to October rainfall, minimum and maximum temperature and frost sum and heat sum for a range of towns in the SA and Victorian Mallee. El Nino and positive IOD are drier, with colder minimum temperature and warmer maximum temperature and a higher accumulated frost sum and heat sum. The most likely reason is that El Nino and positive IOD years have less cloud cover hence colder nights and warmer days.

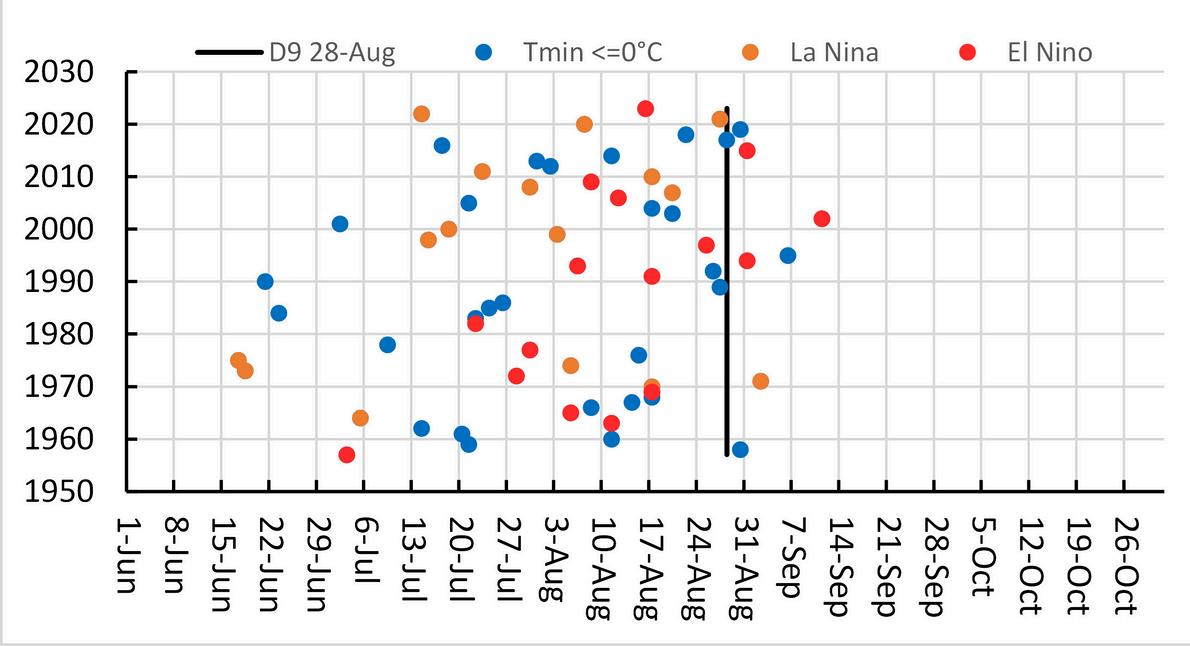

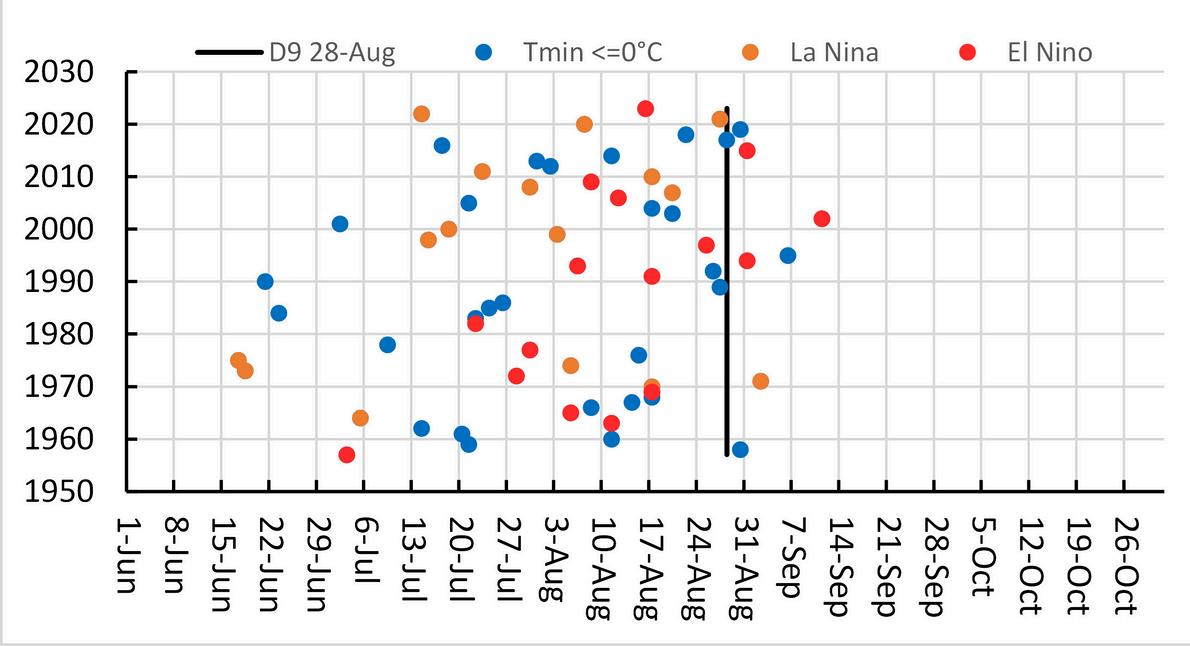

The shifts in rainfall are greater than the shifts in temperature. A grain grower is not so much concerned with the number of cold nights, but the chance of the late frosts. Figure 3 that shows the date of the last night in each year since 1957 that the temperature was equal to or below zero degrees Celsius. Although the latest year (2002) was an El Nino year, of the other six years in the 10% latest cold night, two were El Nino, one La Nina and three neutral years

(forecasts4profit.com.au)

Table 1 Climate indices averaged over all years (1957-2023), along with the difference from the average during years with specific climate drivers of El Nino (EN), La Nina (LN), Indian Ocean Dipole positive (IOD +) and negative (IOD -). Climate indices include Apr-Oct Minimum Temperature, Maximum Temperature and Rainfall, plus Cold Sum and Heat Sum accumulated between 1-Aug and 31-Oct. Values less than the average are shaded.

Figure 2. Screen grabs showing maps of pie charts of chance of growing season rainfall under phases of ENSO and IOD Local Climate Tool

April to October rainfall during El Nino April to October rainfall during La Nina

April to October rainfall during -ve IOD

April to October rainfall during +ve IOD

Figure 3. Date of last night for each year when the temperature is colder than or equal to zero degrees Celsius at Mildura.

The date of chance of a late cold night that might lead to frost damage will only ever be predicted by short term weather forecasts. The Frost Potential maps show forecast low temperature thresholds for various locations across Australian weather station locations. While climate drivers provide a shift in the odds for rainfall cold nights, they are less reliable for cold nights. Furthermore a grain grower is likely to require a major shift in the probabilities to change frost related decisions

An uncertain outlook for 2024

Updates on climate drivers are available from the BoM (updated twice a month) Climate Driver Update (bom.gov.au) and for Victoria by Dale Grey with the Break. The BoM have a YouTube channel and the May Grains Climate Outlook - SA, VIC & Tas can be accessed here.

Figure 4 shows the three La Nina events in 2020, 21 and 22 ending with an El Nino in 2023 In addition to the events (dark blue and dark red) the figure also shows the Bureau’s ENSO outlook status as a watch, an alert and inactive The El Nino watch in March 2023 generated interest which was followed by media discussion as to why the Australian Bureau of Meteorology took longer than the US NOAA to declare an El Nino

As a summary, the El Nino that developed late in 2023 has dissipated with interesting possible developments in both the Indian and Pacific Ocean In the Pacific Ocean, some international models are predicting the development of a La Nina later this year. Although this has received press coverage, it is still early to make the prediction. It is important to note that other international models are favouring neutral conditions but none are pointing to El Nino. Recent values of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) are above the positive IOD threshold (+0.40 °C). If a positive IOD develops, it would be earlier in the calendar year than is typical historically The early development of a positive IOD is not the only surprise, it is unusual (but not unprecedented) for there to be a positive IOD (associated with dryer springs in Australia and a La Nina (associated with wetter springs). It is more common for a positive IOD to be associated with El Nino and a negative IOD to be associated with La Nina.

Graeme Anderson (Vic DPI) has the useful football analogy for climate drivers. Early in the season there is a lot of talk about how different teams will go but by July and August we have a lot more information. Climate scientists urge caution about over interpreting talks of climate drivers this early in the season, so it is more a case of what to look out for. The current forecast from the Bureau of Meteorology is increased chance of dry for the month of May but returning to a neutral to wetter odds later in the season.

support to identify frost damage info to assess your options for frosted crops planning for next season an opportunity to reflect and review on frost events and your response.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ 1120487535225571

Join here!

A public group providing frost updates

frost response information, including:

and

JOIN OUR BETTER

GROUP!

FROST DECISIONS FACEBOOK

OUT NOW!!

IN-SEASON AGRONOMIC INTERVENTIONS

TO AVOID FROST

A national GRDC investment ‘Enhancing Frost Tolerance and/or Avoidance in Wheat, Barley and Canola Crops Through In-Season Agronomic Manipulation (FAR2204-001RTX)’ led by Field Applied Research (FAR) Australia aims to provide growers with novel ways to avoid frost in early emerging quick developing wheat, barley and canola cultivars. Early emergence of quick developing cultivars may result from an unexpected early rainfall break germinating an early dry sown crop, a desire to get “something in the ground” when an early break opportunity arises but seed of a slower developing cultivar is not on hand, or a sowing error where the wrong cultivar may have been sown These crops are at higher risk of frost damage because they will flower early at a time when frost risk is higher

As part of this multi-year national project, field experiments are testing crop defoliation as a way to delay crop development and move flowering time out of the early and higher frost risk windows. While the concept of defoliation is not new (eg grazing crops with livestock), this project is defoliating crops much later than the typical window in order to remove the developing spikes during early stem elongation (Zadoks stage Z31)

Defoliation treatments are being tested at different intensities on early sown, quick developing cultivars to measure the biomass removed at the time of defoliation, crop recovery, change in flowering time, and grain yield and quality. They are also being compared to undefoliated control cultivars of a range of phenology classes (quick to slow spring types and quick to mid winter types) across three sowing times (early: 5-15 April; on time: 25 April to 5 May; late: 15 May or later).

One of the core cereal sites managed by Frontier Farming Systems is located near Loxton in the SA Mallee, with trials completed in 2023 and repeating again in 2024.

The trials in 2023 involved three times of sowing –early (13 April), on time (1 May), and late (16 May) –of six wheat and three barley cultivars selected for their diversity in phenology (development rate) Quick wheat Vixen, quick-mid wheat Scepter, very quick barley Spartacus CL, and quick barley RGT Planet were defoliated at early stem elongation (Z31) in time of sowing (TOS) 1, and Vixen and Spartacus CL in TOS2 at medium defoliation (4-8 cm of crop remaining) and light defoliation (8-12 cm of crop remaining) intensities. There were no defoliation treatments in TOS3

Heading/floweringdate

Time to heading (wheat) and awn peep (barley) were measured as a surrogate to flowering. The wheat controls all reached 50% heading in order of their phenology classifications across all three TOS, although there was only 1 day difference between Vixen and Scepter, and Rockstar and Denison in TOS3 (Table 1). In barley, Minotaur was the slowest to awn peep in TOS1, but was quicker than RGT Planet in TOS2 and both Spartacus and RGT Planet in TOS3.

Defoliations delayed heading by 0-22 days across all treatments The biggest delays were in Vixen in TOS1, with medium and light defoliations delaying heading by 22 and 12 days, respectively In TOS1 delays were 18 (medium) and 6 days (light) in Scepter, 14 (medium) and 4 days (light) in Spartacus CL, and 6 (medium) and 0 days (light) in RGT Planet. In TOS2 heading was delayed by 12 (medium) and 7 days (light) days in Vixen, and 3 (medium) and 0 days (light) days in Spartacus CL.

Medium defoliation in TOS1 Vixen and Scepter delayed heading to be 5-6 days later than slow Denison, while light defoliation delayed them 2-3 days later than mid-slow Rockstar. In TOS2 medium defoliated Vixen fell between Scepter (quick-mid) and Rockstar (mid-slow) and light defoliated Vixen was 3 days quicker than Scepter.

Medium defoliation in TOS1 Spartacus CL and RGT Planet delayed awn peep to 1-2 days quicker than Minotaur (mid) Light defoliation delayed awn peep in Spartacus CL to between Spartacus CL and RGT Planet controls, but had no effect on RGT Planet. In TOS2 light defoliated Spartacus CL was not delayed, while medium defoliated Spartacus CL aligned with RGT Planet.

Grainyield

Minotaur and Illabo were the highest yielding control cultivars in TOS1, while Minotaur was also the highest yielding cultivar in TOS2 and TOS3 (Figure 1). Both defoliation treatments in Spartacus CL and the medium defoliation in RGT Planet significantly increased yields to be statistically similar to Minotaur and Illabo The small yield increases in light and medium defoliated Vixen and Scepter, and light defoliated RGT Planet were not significantly more than their respective controls.

Both defoliations in TOS2 Vixen significantly reduced yield, however the reductions in Spartacus CL were not significant

TOS1 defoliations in barley proved beneficial but could not match TOS2 Minotaur yield. Time of sowing and cultivar selection was a better strategy in wheat, with Illabo being the highest yielding TOS1 wheat cultivar There were no significant differences between the spring wheat yields in TOS2 and TOS3, but the winter types yielded significantly less in the later sowing times.

Frostoccurrences

Temperatures recorded on the experimental site indicated a number of days had mild to severe frost inducing temperatures through July to September in 2023 (Figure 2). Sixteen days had frost temperatures that were considered mild (2 to 0°C), eight considered moderate (0 to -2°C), and four considered severe (< -2°C) Medium defoliations on the four quick cultivars delayed heading/awn peep to occur between 18-20 August, which was after the consistent period of frost events that occurred from 6 to 17 August and resulted in higher yields in Spartacus CL and RGT Planet compared to the controls. Highest yielding TOS1 cultivars Minotaur and Illabo also reached heading/awn peep after this time

Table 1. 50% heading date of undefoliated controls, and medium and heavy defoliated quick and quick-mid wheat and very quick and quick barley cultivars across three times of sowing (TOS) in 2023. Assessment was not replicated so no statistical comparison is provided.

Table 1. 50% heading date of undefoliated controls, and medium and heavy defoliated quick and quick-mid wheat and very quick and quick barley cultivars across three times of sowing (TOS) in 2023. Assessment was not replicated so no statistical comparison is provided.

Figure 1 Grain yields (t/ha) of undefoliated controls (yellow) and light and medium (green) defoliated quick and quick-mid wheat and very quick and quick barley cultivars across three (1, 2, 3) times of sowing Letters indicate significance level within each time of sowing P < 0 001 for the interaction between TOS and treatment

Figure 2. Daily temperature ranges recorded at 15 min intervals at experimental site in Loxton from 1 July to 30 September 2023. Light blue and blue dashed lines indicate the ranges for frost severity (mild frost: 2 to 0°C; moderate frost: 0 to -2°C; severe frost: < -2°C).

Futurework

Another season of field data will be collected in 2024 with some slight modifications to defoliation protocols. Project collaborators CSIRO and SARDI are using APSIM modelling to simulate time of sowing by defoliation strategies with long-term climate data which will be validated from the field experiment data.

The project is research-focussed and does not have an extension component However, if the defoliation concepts tested continue to prove successful then the project team intend to create a decision treestyle guide with risk and reward analyses based on economic and long-term climate data for different agroecological zones.

CONTACTDETAILS

Max Bloomfield | Field Applied Research (FAR) Australia Max.Bloomfield@faraustralia.com.au | 0477 786 441

PROJECT PARTNERS

We gratefully acknowledge the investment support of growers through the GRDC (project code FAR2204-001RTX) in order to generate this research. We also thank host farm Bulla Burra for providing the site and Frontier Farming Systems for trial management throughout the season and project collaboration

THE HAY HARVEST DECISION: FROST MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES ON SOUTH AUSTRALIAN FARMS.

Donald Downing farms with his brother Peter and son Jordan in the mid north of South Australia. They farm their own land at Belalie North, lease land at Belalie East and recently they have started leasing land at Gladstone.

All properties are affected by frost to some degree. In 2023, the Gladstone property was hit with early frosts, while Belalie North was subjected to later frosts.

As frost is an issue on all properties, Donald spreads the risk by assigning roughly onequarter of the farms to vetch, wheat, barley and hay He is also prepared to cut a portion of the wheat and barley for hay if the frost damage is severe enough.

How and when Donald decides to cut for hay is a balance between the severity of the frost damage, storage availability, price of grain vs hay, and the logistics of hay production, including cutting, baling, and storage. Cutting frosted grain crops for hays is as much of, if not more, of a business decision than an agronomic one.

“We have a very small window to work that [whether to cut for hay] out because we've got a programme that's a bit hectic that time of year,” says Donald.

Frost damage

In 2023, the Downing’s cut about one-third of the wheat at Gladstone for hay, but the extent of frost damage wasn’t obvious until harvest.

“Gladstone was almost a write-off in patches. We knew the barley had some issues, but was very surprised the barley was as bad as it was The barley looked good with nice big plump grains, so part of the damage may have been lack of moisture as well. In hindsight, when we cut the wheat, we should have been cutting the barley too,” Donald says.

However, this would have meant adding more hay to an already rather full shed.

Hay logistics and storage

Even if cutting for hay makes economic sense, Donald still has to cut, bale and store the hay, then sell it

Donald notes that in 2023, cutting all the wheat and barley that was frosted worse than he thought would have been a better financial decision, but then he would have had to store and sell the hay. Hay can remain unsold for extended periods while he waits for favourable market conditions. Donald is still holding hay from 2021, which due to the wet weather means there hasn’t been the demand or good enough prices to warrant selling it. If the crop has been sprayed with Lontrel™, the market is restricted even further.

Agronomist advice

Donald says it is important to have an agronomist who often inspects and can spot the early signs of frost damage, which can assist with making the decision to go for grain or hay. His agronomist had seen suspect frost issues and had them monitor the lower areas. This early warning helped Donald start planning the hay cutting operation.

Cash flow

Ultimately, Donald wants to harvest as much of the cereal crop each year as possible as grain often fetches a higher price and is easier to cash Donald says, ‘We want the grain if we can as we already have one-quarter of the farm to hay, and it takes time to cut and bale the export hay, when you have harvest starting soon after.”

To this end, he takes out the worst of the frosted crop (under 2 tonne per ha of grain but has a mass of 4-5 tonnes per ha of hay) Wheat area harvested averaged 2.8 tonnes,

Frost barley crop at Gladstone 2023 Photo credit: L Smallacombe

Frost barley crop at Gladstone 2023 Photo credit: L Smallacombe

Deciding where to cut

Practically, Donald draws straight lines in the paddock to make cutting/baling easier. This does mean a small amount of frosted grain ends up being harvested, and some better grain gets cut for hay, but trying to work to complicated boundaries will cause damage running over cut rows.

Selling the hay

For Donald, having strong relationships with hay processors and having contracts are essential to sell the hay, particularly for access to export markets, which don’t always offer a higher price but can offer more stable demand. “I wouldn't do as many acres if I was relying solely on the domestic market, domestic hay sells easy in a drought," he said.

Even then, Donald is still somewhat at the mercy of domestic markets. “We thought the perfect time to sell that [vetch hay from 2021] would be in 2023 and into 2024 because the weather forecast we were going to have an El Niño but it’s done nothing but rain in New South Wales, Queensland and parts of Victoria where they probably would have been buying it. That will stay in the shed for how many years? I'm not sure, so it's not always easy.”

Not a silver bullet

Hay is now an integral part of the Downing’s farming operation, but Donald says it’s not always easy and requires a lot of time and equipment.

“Producing hay cost a lot of money and effort. We bought a baler, we bought a rake and we bought a mower conditioner. Then you need another shed and then you get a bigger baler and on it goes. We started off doing 300 acres of hay and did that for a few years, then went to 1000 and now we might do 1300 or 1400,” Donald said.

What to think about before cutting for hay

From Donald’s experience, cutting frosted crops for hay can form part of the farm business if the farm has the equipment and access to markets, but is not a magic solution to a frost problem. The key elements to think about if deciding to cut for hay are:

1. Can you store the hay, potentially for years?

Equipment to cut and bail the hay. If not, can you access a contractor in a timely manner?

2. Market access. Do you have access to a market to sell the hay? Strong relationships with hay producers make it easier to sell than someone who doesn’t

3. Cash flow. Can you store the hay so that you're not compelled to have to sell it to the market if it's already saturated?

5.

4. How will it affect your bottom line?

The Frost Economic Scenario Calculator (https://sfs.org.au/tool/frost-economic-scenariocalculator) allows you to work through scenarios on the farm, such as cutting a certain amount for hay or growing different crops, and calculate the impact frost has on the farm business bottom line

A Harvested barley stubble post frost, B Reshot plants in frosted areas, C Wheat head damaged by frost

Photo credit: D Downing

A B C

USINGCROPPHENOLOGYTOHELP MITIGATEFROSTRISK

KEY POINTS

Understand your frost zones (red, amber, green) before deciding to implement frost management strategies.

Phenology is a tactic to mitigate frost. Select varieties with suitable developmental drivers such as temperature sensitivity, photoperiod sensitivity, and vernalisation requirement for the desired sowing time.

Consider varietal mixtures and a spread of sowing dates to further mitigate frost risk

Deciding when to sow is an annual decision for growers. For frost management, the primary goal is to synchronise the crop's most sensitive development stages with periods less likely to experience stresses. Sowing early if late frosts are projected is considered an avoidance strategy that works in environments where a grower is confident of the ending of the major frost window. In some environments, avoiding the frost window is not possible.

Understanding plant phenology – the timing of the plant’s lifecycle events – and what drives them, helps target flowering when abiotic stresses like frost are less likely. Using phenology well requires first understanding your frost risk.

ZONE FIRST

Zoning is the cornerstone of frost management as different frost risk zones need different management strategies. Divide the farm into red (frost is severe, frequent or both), amber (sometimes frosted, sometimes not) and green zones (no frost risk).

“Zoning is the first step to frost management because a lot of the tactics that can be done in red or in frost prone areas of your farm can often reduce profitability on the non-frost prone areas,” says Ben Smith from Agrilink Agricultural Consultants in Penwortham, South Australia.

This includes phenological choices to mitigate frost risk. Ben has been working at the Frost Learning Centre near Farrell Flat in SA, a cerealfocussed trial site, on a range of frost intervention, prevention and mitigation strategies.

Ben recommends reviewing frost data over multiple years gives a long-term perspective on the frequency and severity of frost events historically and in recent years.

CONSIDER PHENOLOGICAL TRAITS

The three key cereal developmental drivers to consider to help mitigate frost risk are temperature sensitivity, photoperiod and vernalization requirement

Temperature Sensitivity is a trait where certain varieties progress rapidly through their growth stages as temperatures rise. Calibre wheat and Vixen are examples. Crops with a high temperature sensitivity may be grown when sowing is delayed in frost-prone areas which may prevent the crop from reaching vulnerable stages during potential frost events. Early sowing in frost-prone areas means their quick development could coincide with the frost window.

Photoperiod Sensitivity is a response to day length, with varieties ranging from comparatively weaker photoperiod (e.g., Cutlass wheat) to strong photoperiod sensitivity (e.g., LongReach Bale). Varieties with a strong sensitivity need longer daylight hours to progress through developmental stages meaning crops won’t flower until day length is long enough, ideally missing the worst of the frosts.

Careful sowing time planning is required to leverage this trait effectively “You need to be careful with photoperiod varieties and the time of seeding interaction, because if the weaker photoperiod varieties are sown too early they can actually achieve their photoperiod requirement at the start of the season, as opposed to the end of the season. Which then means that you won't get that frost avoidance or delayed maturity that you were aiming for,” says Ben.

DEVELOPMENTAL DRIVERS TO CONSIDER IF SOWING EARLY

For growers wanting to sow early in red or amber zones, the developmental drivers to consider are:

High photoperiod sensitivity to delay flowering until the frost risk has decreased.

High vernalisation requirement to delay flowering until the frost risk has decreased

Ben says, “If you're going to sow early, look at using varieties with some sort of developmental driver, whether it be photoperiod or vernalisation that just holds the maturity back so that you're flowering at a time when the frost risk isn’t too great.”

Varieties with a low photoperiod sensitivity and vernalisation requirement, or are temperature sensitive aren’t suited to sowing early in red zones because they are exposed to too much frost risk

OTHER FROST RISK MITIGATION STRATEGIES

Ben’s further suggestions to reduce frost risk include using a spread of sowing dates across varieties and using varietal mixtures.

Employing a spread of sowing dates distributes the risk of frost damage. If a frost event occurs, it may only affect part of the crop that is at a sensitive development stage, while other parts that were sown later or earlier may escape damage. Sowing earlier to avoid late season frost events can be successful but is highly risky if there are many frosts early in the season.

Mixing varieties with different maturation times serves as a hedge against unpredictable frosts. Later-maturing varieties should avoid early frosts, while early maturing varieties can do well if there are no frosts. "If you don't know when the frosts are going to occur, then having a mixture of a faster maturing variety and a slower maturing variety may be a fit," says Ben

Frosts are unpredictable and at the Frost Learning Centre near Farrell Flat, an area known for heavy frosts, the later frosts in 2023 were more severe meaning the earlier sown varieties did better.

Ben says, “Generally the thought with phenology is to try and delay the development of the crop so that you avoid the frost window, or at least get exposed to fewer frost events. But in the case of the 2023 trial, we actually found that earlier maturing varieties were better yielding in time of seeding one (germinating late may) The later time of seeding (germinating mid June, had the opposite affect where earlier maturing varieties had higher levels of frost damage (observed through lower grain yields) and the later maturing variety DS Bennett had the highest grain yield. All time of seeding two grain yields were poor for the season in this region. While there were frost events earlier in spring, they weren't severe…but then we had a severe frost at the end of the season on October 26.”

Mixing varieties doesn’t tend to overly affect yield. “We’ve tested yields by growing the range of varieties of sole species, then combined to make a mixture. We generally find that the mixture's yield is in between the yield of the two varieties,” says Ben.

Ben’s final suggestions for frost mitigation include:

Sowing frost tolerant crop types such as oats for grain hay or faba beans Looking at preparing paddocks for salvage hay cut operations if this is an option In red zones, carefully consider inputs and expenditure in season.

FROST ECONOMIC SCENARIO CALCULATOR

The Frost Economic Scenario Calculator is a way to test out different frost scenarios and management options to see the impact they have on the farm’s bottom line.

The calculator gives users a broad idea of how gross margins change with management decisions, such as cutting a certain amount for hay or growing different crops. Users can compare up to five scenarios to help choose which management strategies might work best for them this season.

Information needed to use the calculator

The calculator uses zones to classify frost risk: Green: areas with no frost risk Amber: sometimes frosted and if not frosted has production capability like the red zone Red: areas frequently or severely damaged by frost.

As such, using the calculator requires a decent understanding of frost risk and impacts across the farm i.e. which areas get severely damaged, areas that are only sometimes damaged, and how yields are affected by varying levels of frost. Printing off a map of the farm and mark out green, amber and red zones, can help gauge the area of each

Users also need to know and have considered: the unfrosted yield/ha for each enterprise on-farm price for each enterprise ($/ha) what salvage options you could choose and when you would choose them, e.g. if a certain amount of the wheat crop is damaged by frost, cut for hay variable costs ($/ha) such as fertiliser, weed control, cutting, baling, etc. for both normal operations and salvage operations.

The calculator is best used as a guide and is only as good as the data entered. It does not account for capital costs such as buying new machinery.

Testing scenarios

To get the most out of the calculator, think through how the farm operates normally and what management options are available in various frost situations, ranging from no frost up to the worst frost. Test different scenarios, such as a different crop, more or less area of certain crops, and different salvage options, to compare the impact on the overall gross margin. The calculator will show if various decisions, such as salvaging frosted wheat for hay, are viable options.

The calculator is very flexible, letting users specify their crop choices, frost management options, and trigger points for when to implement a salvage option

For example, three scenarios were set up in the calculator (Table 1). Scenario 1 is the baseline farming system, used to compare changes. In scenario 2, the grower will cut up to 200 ha of wheat for hay if it is more than 50% damaged (these parameters are set up in the calculator).

In scenario 3, the grower plants milling oats instead of cereals on 75 ha of country that is the most frost prone (red zone)

Table 1. Hectares allocated to each enterprise in three scenarios.

(Note: blue shading indicates different management strategies chosen compared to scenario 1.)

During less frosty years, allocating 75ha to milling oats rather than cereals in the worst frost areas (scenario 3) had the highest gross margin while there was little difference in scenarios 1 and 2 In more severe frosts, cutting frosted wheat for hay (scenario 2) outperforms scenarios 1 and 3 (Figure 1 left).

The ‘Difference’ column graphs (Figure 1 right) compares the difference in gross margin between the scenarios. This example shows that cutting frosted wheat for hay generated a profit of $50 – 60,000 each year in the lower frost deciles, and $250,000 in the highest frost decile, compared to not cutting for hay (scenario 1).

A planning tool

The calculator is a planning tool, best used at the start of the season. The creators envisage growers and agronomists going through the plans for the season, past experiences, predictions for this season, and running through a few scenarios to work out the ideal way to manage frost this season.

Users can download the data file (.json) to reimport next year and tweak, rather than having to fill it out again. Agronomists can save files for each client

Try it out

Try it online at: https://sfs.org.au/tool/frosteconomic-scenario-calculator

A link to the instructional video is on the calculator landing page.

The calculator has been designed by Michael Moodie, Frontier Farming Systems and further developed by Southern Farming Systems through investment from GRDC and the Better Frost Decisions Project.

Figure 1. Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right).

Figure 1. Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right).

Table 1. 50% heading date of undefoliated controls, and medium and heavy defoliated quick and quick-mid wheat and very quick and quick barley cultivars across three times of sowing (TOS) in 2023. Assessment was not replicated so no statistical comparison is provided.

Table 1. 50% heading date of undefoliated controls, and medium and heavy defoliated quick and quick-mid wheat and very quick and quick barley cultivars across three times of sowing (TOS) in 2023. Assessment was not replicated so no statistical comparison is provided.

Frost barley crop at Gladstone 2023 Photo credit: L Smallacombe

Frost barley crop at Gladstone 2023 Photo credit: L Smallacombe

Figure 1. Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right).

Figure 1. Line graph comparing gross margins at different frost deciles between the three scenarios (left); column graph showing the difference in gross margin between scenarios 1 and 2 for various frost deciles (right).