maine farms

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2020

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2020

The future is present.

Approaching the year 2020 felt expectant: a new decade, Maine’s bicentennial, but also a sharp reminder that what once felt like the far off future is now the present. For so long, the year 2020 represented a distant, brighter, and better moment in time—a turning point, a deadline, a distant star to strive for. In 2020—we imagined from our short-sighted perspectives in 1980, 2000, and even 2010—things would be different. We’d have so much figured out.

Yet, here we are. In the midst of what was the future, the world around us feels more uncertain and more turbulent than ever. So many of the systems we’ve chosen to rely on have been exposed as broken and vulnerable, and past due for change. The concurrent exposure of our country’s systemic failures makes it startlingly clear how interconnected and interdependent we all are, and that every one of us has a role to play in taking care of each other and our communities. And while there is so much that, as individuals, we can’t control, when we work together our collective action can make real difference.

This spring, we found hope in the interdependence of our local farms and communities, and in the potential for a brighter future for a vibrant local food system. It has been amazing to see how the food and farm community has come together to continue to feed Maine, through farm stands, delivery services, pop-up markets, CSAs and other responsive and creative means. In turn, eaters have a renewed appreciation for the farmers who feed them, and are more aware of why knowing where your food comes from matters, and who is at the table. We have been pushed to examine what it means to work towards a truly just and equitable food system, and reckon with our complicity in reinforcing the many inequities that persist. Honestly, we have a lot of growing to do. The vulnerabilities and failings of our current food system offer us an urgent opportunity to grow a new one—one that harnesses the energy and awareness of this time and honors the land, honors all farmers, and can nourish every one of us. Stories of resilience and connectivity remind us that a new way forward is possible and necessary. While the stories in this issue were captured before 2020 began, salient threads run throughout. A story about the power of healthy soils shows us that when we steward the earth, we create resilience for ourselves, too. A photo essay about flint corn demonstrates how something as small as a seed can connect people across generations and cultures. A piece about how farms are experiencing climate change reminds us of our vulnerability, and that we can change our trajectory.

Taken all together, the stories in this issue point to the abundance of farming in Maine. However we recognize that there are many stories missing from these pages, and to truly represent the breadth and depth of Maine farms, we need to do more. Going forward we will use this journal to better amplify the voices of Maine’s diverse and abundant farm landscape, and uplift Black, Indigenous and farmers of color through these pages. I hope the stories in this issue and in future issues help us all imagine what a new future might look like, and step towards it, together. Let’s stay connected,

maine farms

3 field

Snippets from the farming landscape

4 poem

“Tide Mill Farm Seedling Sale”

VALERIE LAWSON

5 art

Singing to garlic: Maine's farmer musicians

CARRIE BRAMAN & MOLLY HALEY

13 future

Observations on climate change from Maine farms

KATE OLSON & GRETA RYBUS

23 business

Farmers find creative ways to diversify their production

BRIDGET M. BURNS & RUSSELL FRENCH

27 food

On growing, eating, and restoring flint corn to Maine

KELSEY KOBIK

41 travel

Community snapshot: Dover-Foxcroft

KATY KELLEHER & YOON S. BYUN

51 land

Greater than dirt: cultivating healthy soil systems

LAURA POPPICK & ERIKA MELHUS

editors

Ellen Sabina

Katy Kelleher

design

Might & Main

writing

Albie Barden

Carrie Braman

Bridget M. Burns

Katy Kelleher

Kelsey Kobik

Valerie Lawson

Kate Olson

Laura Poppick

photography

Yoon S. Byun

Russell French

Molly Haley

Kelsey Kobik

Greta Rybus

illustration

Erika Melhus

publisher

Maine Farmland Trust

97 Main Street, Belfast, Maine 04915 (207) 338-6575 mainefarmlandtrust.org info@mainefarmlandtrust.org

Printed on 80# Finch Opaque Bright

White Smooth by J.S. McCarthy Printers, Augusta, Maine

All material © 2020 Maine Farmland Trust

The Maine Farms journal is a publication of Maine Farmland Trust, a statewide nonprofit that protects farmland, supports farmers and advances the future of farming.

Ellen Sabina, Outreach and Communications Director, Maine Farmland Trust

Ellen Sabina, Outreach and Communications Director, Maine Farmland Trust

the field

snippets from the farming landscape

farm camp

Around the state, farm-based camps and educational programs are helping to cultivate the next generation of growers and stewards.

chill out Popsicles for locavores

crowdsourced

The Maine Bicentennial Community Cookbook

Compiled by author Margaret Hathaway, photographer Karl Schatz, and historian Don Lindgren, the Maine Bicentennial Community Cookbook aims to bring together stories, recipes, and images from families across the state. Recipes range from the basic to the obscure, and feature locally prized ingredients like smelts, fiddleheads, lobsters, and maple syrup.

Tide Mill Farm Seedling Sale

by Valerie Lawson

Hart to Hart Farm, Albion

Offering winter, spring, and summer sessions, kids can spend a week (or more) learning about land stewardship and interacting with animals on a family-owned organic dairy farm.

Broadturn Farm Summer Camp, Scarborough

Following a morning yoga session, kids and teens help feed and water animals, check up on chickens, and do some light chores around the farm. Other activities include baking, daily story time, and trips down to the frog-filled riverbeds.

Farm to Table Kids, North Yarmouth

Each session at the Summer Farm Camp has a different theme, where kids aged five to twelve learn (through hands-on lessons) about topics like pollinators, happy harvesting, forest farming, and earth science.

Morris Farm Camp, Wiscasset

With February, April, and summer sessions, the Morris Farm Camp provides children time to roam a 50-acre midcoast farm and gain valuable skills in planting, cooking, and crafts.

Paleta Guy

If you’re attending an event around Portland during the warmer months, you might run across Korik Vargas’s colorful cart. The mobile vendor (and biologist) infuses a certain tropical sensibility into his frozen fruit treats. “It’s hard to choose a favorite one,” he says, “but I love roasted peach. Maine peaches remind me of the peaches from my hometown in Colombia.”

Pasture Pops

This one-woman operation is run by Katie Gualtieri, who uses in-season produce and local organic dairy to make creative creamy popsicles out of Fork Food Lab in downtown Portland. This summer, she hopes to steep peach leaves in cream to add another unique flavor to her lineup (it tastes, she says, “similar to toasted almond”). Other regular offerings include dark chocolate sea salt, buttermilk rhubarb, and blueberry muffin.

Wicked Maine Pops

Made by Abby Freethy of Northwoods Gourmet Girl, these chilly treats can be found at farmers markets from Monson to Boothbay to Bangor, and at catered events. “There is virtually a pop for everyone, no matter your diet restrictions,” Freethy says. Flavors change frequently, but standbys include Maine wild blueberry cheesecake, raspberry jam, and strawberry goat cheese.

“It was humbling to be the recipients of people's personal stories, photos, and family histories,” says Hathaway. “It is remarkable how food connects us to memories, places and people, and that is what this book is about more than anything.” She hopes that the book will inspire more Mainers to eat and cook together at home—and to share their food traditions with friends and neighbors. Published by Islandport Press, a portion of proceeds from the Community Cookbook will go to fight hunger in Maine.

Hay-Time Switchel

“Etta Pratt McIntire always served the ‘men folk’ this drink when they were haying at Sweet Hill Farm. A look at its history says that it originated in the West Indies. By the 1800s, it had become a tradition to serve it to thirsty farmers at the hay harvest time, thus it acquired the alternate name of ‘Haymakers Punch.’ There was always a lot of this on hand during haying season. It kept the workers hydrated and tasted very good.”

The woman in the green apron combs unruly curly onion with her fingers, reels off Latin names and common varieties, tells the stories of natives and invasives.

The Brandywine tomatoes have a 50/50 chance of bearing fruit. Cherished heritage seed planted in winter’s darkest hour just another roll of the dice. That’s life in zone 5. You trust Nova Scotias, but little else.

Don’t let them tell you lavender doesn’t grow here, whispers a summer voice from away to the south. Roots come from many sources. Tough stock can appear from surprising places.

From sawhorse and plywood tables we choose, artemisia, geranium, campanula, campion, tomatoes, peppers, beans, squash, familiar plants or ones we know nothing about.

Who knows what will make it this year.

In the midst of our gathering, a man calls out, All plants are now half-price!

1 cup light brown sugar

1 quart cold water

1 cup apple cider vinegar

1 tablespoon ground ginger

1/2 cup light molasses

The sale nearly over, the growing season short. We need to go now, get these in the ground before winter comes.

Valerie Lawson is an

4 5

award-winning poet whose work has been published in Main Street Rag, BigCityLit, About Place Journal, The Catch, Ibbetson Street, and others. Lawson's first book, Dog Watch from Ragged Sky Press, was released in 2007. A chapbook, As Far Away was released in 2015. She lives in Robinson, Maine.

all ingredients and stir well. Ingredients

Caryl Edwards · Harrison, Cumberland County

Combine

singing to garlic:

MAINE ’S FARMER

MUSICIANS

BY CARRIE BRAMAN

PHOTOGRAPHS BY MOLLY HALEY

7 ART

When I arrive at Songbird Farm in the gray midmorning rain, the power is out. Johanna Davis and Adam Nordell are tending to their son, Caleb, who roams the rug in the living room while the trees sway outside. It’s November, the time of year when the demands of farm work are starting to slow down a bit—the grain has been harvested, the mornings are frosty, the days are shorter. Usually, this is when the couple would be thinking about a tour, playing at contradance festivals in Ottawa or Florida or Alaska, visiting Adam’s family in Montana, focusing on music while snow blankets their fields in Maine. The two have been farming for ten years, and pretty much every winter they get out of dodge for a while to play traditional fiddle tunes as Sassafras Stomp. That’s not to say they don’t make music in Maine, even during the busiest months. “We try to plan for at least a few gigs a month during the summer,” Johanna says, “though that’s when we’re not really practicing much.” But the winter has historically been a time where music rises to the forefront, and when the

couple can take a break from the relentless pace of the farm to do some traveling and adventuring. This year, though, things are different. “Driving cross-country with a one-and-a-half-year-old just doesn’t sound fun to me,” Johanna says. “And now that we’re parents, we’re asking ourselves how much we want to be doing all the things we were doing.” They’re anticipating making music, both together as Sassafras Stomp and separately as solo artists, that feels more rooted to their relationships in state. “We do contradances every fifth Friday here in Freedom at the Grange Hall,” Adam says. “That’s something that feels really nice—to make local music and build local community, see people, catch up. Before people caught up with each other’s farms on Instagram, they would see each other in person.” It’s easy to forget that these kinds of gatherings at the Grange Hall were crucial to surviving a Maine winter in the old days. Adam and Johanna are invested in reviving that tradition. Of a similar mind is Bennett Konesni, a work song archivist, musician, educator, and farmer, who grew

8 9

Opening Spread Musicians and farmers Adam Nordell and Johanna Davis in their cornfield. The two grow heritage and heirloom grains and organic vegetables together. They also play fiddle tunes. Left Adam and Johanna at home on their farm in Freedom. “The farming feeds the music,” Johanna says. Below Life on the farm provides imagery for the songs that Adam writes. It also grounds the couple in the same rural traditions that their music celebrates.

up raking blueberries near his childhood home in Appleton. Later, as a crewmember on a schooner in Penobscot Bay, he learned traditional sea shanties, discovering the rich history of the work songs that would become his life’s passion. It’s a passion that has stayed with Bennett for over 20 years, taking him far from those blueberry fields—he’s traveled to Africa, Asia, Europe, and across the United States, learning the music people sing while laboring, songs that are in danger of being forgotten. The universality of the tradition struck Bennett, and so did its effectiveness. Wherever he went, he found farmers using music to find a shared rhythm, to enliven the drudgery of daily tasks, and to connect with one another. “In work songs we see a tradition of invention, just like we see in tool development,” he explains. “The music becomes a tool for being more productive, efficient, and present.” He collected these songs on his travels, eventually bringing them back to Maine. He now teaches workshops all over the country; performs solo and with several bands including Drive Train, The Gawler Family Band, and the Maine Coast Worksongers; writes songs inspired by the farm work he does; and leads a

community chorus where people work while singing.

“The intention is to bring the culture back to agriculture,” Bennett says. Doing so begins in his own backyard, where he uses the tool of song to add value to his garlic farm in Belfast. “Not only are songs a tool for enhancing teamwork, they are an under-utilized resource for bringing community and audiences to farms. There’s a synergy between the two that feeds the financial end of farming.” He stresses the value of having customers feel an emotional attachment to the farm. “People love to hear that their garlic has been sung to,” he says. Finding a way to make music and grow food requires that a person straddle two ways of being in the world that can seem at odds. Farming is all consuming. It’s hard to leave, and carving out time for travel and practice is often a tricky proposition. Except that the combination has real benefit—bringing in income, generating community excitement for a farm’s projects and a band’s music, and allowing relief, as Adam says, “from the aspects of rural life that can be isolating.”

There are places in Maine where old traditions of sharing music still hold strong. “In Washington

County, we’re behind the times in a really great way,” says Rachel Bell. Rachel is an eighth-generation dairy farmer from Edmunds and the lead singer for two bands, the Milk and Honey Rebellion and Bare Back Rider. “We still remember how to be a community. When my band is playing out at the local bar, I feel this incredible sense of appreciation.”

At a recent gig at the Tattooed Dad in Brooks, Bare Back Rider performed moody originals and atmospheric covers in an alt-country vein. Kids ran around in a scrim of woods at the brewery’s edge and the older crowd warmed their hands by a bonfire, nodding along appreciatively. Rachel danced on a makeshift stage, her arms undulating with balletic grace, her voice carrying across the field. Friends stopped by, waving to the musicians on stage, and strangers drinking beers at shared picnic tables struck up conversations.

Rachel is deeply interested in place. “I became a farmer so I could participate in and observe the cycle of the seasons,” she says. “The inspiration for my art is often grounded in that world.” But for someone so rooted, it’s been a tough year. Facing grim financial realities, she recently decided to stop milking her

goats. Production of her nationally-recognized cheeses has slid to a halt, and it’s a loss that Rachel grieves. Increasingly, she’s turning to music for the kind of groundedness and solace she found in farm work. Music, and songwriting in particular, helps her make sense of the challenges. It also funnels the creative energy she has dedicated to cheese making into something less burdensome but equally fulfilling. That’s a sentiment that Sara Trunzo understands. For years she ran an organization called Veggies for All in Unity, where she grew and distributed crops to food pantries while managing the administrative aspects of the non-profit. Sara was passionate about feeding her neighbors—and without question, it was a job she loved—but she began to doubt how much impact she was having on the larger issues that contributed to food scarcity. And, she says, “I’d forgotten the role that joy plays in effectiveness, in feeling present.”

In 2015, after a period of personal turmoil that led to a re-examination of her priorities, Sara enrolled in a workshop with Darrell Scott, a country songwriter she’d long admired. She returned to Maine invigorated and full of ideas for her own work. Still, it took her another six months to realize how fully the

10 11

Members of Bennett Konesni’s community chorus at his farm in Belfast.

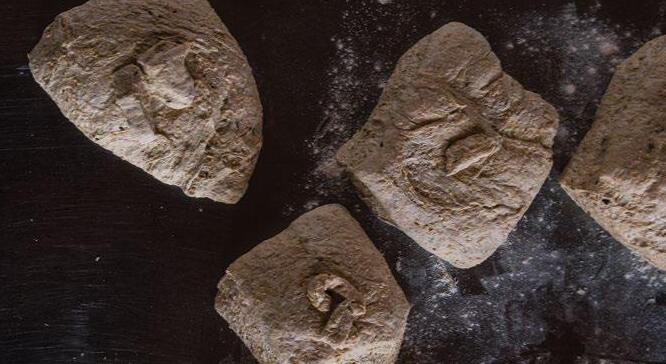

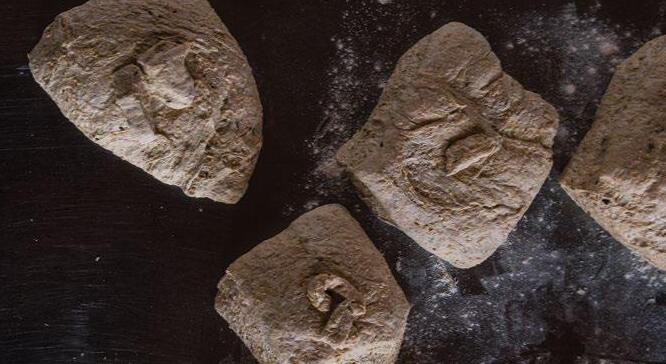

Left Bennett leads a song in the garlic field. Right Garlic ready to be planted by the work crew, who sing while they get their hands dirty.

experience had changed her. Eventually, it became clear that she needed to re-channel the energy she’d dedicated to farming and social justice toward music. Now, Sara lives part of the year in Nashville, where she writes country songs with a Mainer-y slant. “Socalled ‘rural music’ isn’t often representative of the real experience of rural people,” she says. “Poverty, for example, doesn’t really show up, or if it does, it’s romanticized.” She’s working to change that. In songs like “Food and Medicine” from her 2019 album Dirigo Attitude, Sara tells stories about the people she feels she can meaningfully represent, rural New Englanders facing real life struggles, the kind of people she got to know well at Veggies for All. She sings: It’s the last week of the month again and I’m choosing between food and medicine medicine and heat heat and doing something with my girlfriends I suppose the choice is easy 'Cause I refuse to let the pipes freeze let a bunch of ice bust up the best thing that I own…

Perhaps because of the lived experience that shines through it, the song rose to number three on the folk charts. Its success hints that there may be room for more authentic voices in commercial music, just like there has been a shift toward less industrial approaches to agriculture. “One of the things that gives me hope,” Sara says, “is that the old systems in both music and farming are corroding. Now the producer can be in direct contact with the consumer.” In food and in songs, we’re seeing a return to regional identity and pride of place. She points out another parallel, too. “Both deal in magic.”

13

Left Sara Trunzo takes a walk during her residency at MFT’s Fiore Art Center in October. Right After years of farming and social justice work, Sara went all in with songwriting, saying to herself, “If I’m going to do this instead of feeding people, I need to really do it.” Opposite page A happy crew. “Singing is a productivity tool across cultures,” Bennett says. “But the good news is, it also makes work way more fun.”

carrie braman is the co-owner of Frontier Maple Sugarworks with her husband, a banjo player. She has an MFA from the University of Montana and lives in Jackman and Northport.

FORCED

TO PAY

ATTENTION

OBSERVATIONS ON CLIMATE CHANGE FROM MAINE FARMERS

BY KATE OLSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

BY KATE OLSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

FUTURE

Tom Drew thought he had seen it all. A dairy farmer of 30 years in Woodland, Drew has weathered an awful lot of change. On an overcast, chilly day last fall, Tom and I rest in his milking parlor. As he leans his large frame on the metal table, he tells me about the history of the farm, and the old jack pines out front, how the two sisters who raised his grandfather were so attached to them. We discuss the dairy industry, how difficult it has been to remain profitable through so many changes, and how uncertain every day as a dairy farmer feels.

Even so, he was not prepared for the drought of 2018. Tom watched as his pasture withered. He waited for rain that never came. Finally, he had to buy hay to feed his cows, a substantial extra cost that he only managed to pay off more than a year later. “You live through something horrible like last year [drought of 2018], which is something I’ve never seen in my lifetime…I mean I think I’ve seen an extreme. Could you survive two of those [droughts] in a row here? No, I don’t believe you could.”

Between the weather, pests, and markets, farming has always made for an unpredictable life. But that unpredictability has gotten worse, farmers say. “Last year there was no way to control a thing about what was going on around you, you were caught in the middle of something that you could not have imagined would continue.” Tom pauses, weaving his fingers together. He gazes around the white walls of the milking parlor, then looks me straight in the eye. “You say well, I didn’t get a good first cuttin’ [of hay], it’ll rain, I’ll get a second cutting. Then all of a sudden the second cutting didn’t come cuz the rain didn’t come. So you eventually see yourself having lived the extremes you couldn’t have imagined…I was forced to pay attention.”

The last three years have brought challenging drought conditions to Maine. In a state where abundant rainfall was once considered a given, farmers have had to rethink their strategies. These drought conditions fit into a larger pattern of shifting weather trends attributed to climate change. According to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, the Northeast is experiencing longer, drier summers punctuated by more intense precipitation events. In addition, winter has become less reliably cold and snowy, and the onset of spring temperatures less predictable. Spring of 2019, for example, set records for coldest temperatures reached in May as well as rainfall amounts. Many farmers, with the prior year’s drought still lingering in their minds, found their fields overwhelmed with precipitation, so soggy they could not plant where they needed to. As Jill Agnew, of Willow Pond Farm says, “You don’t have any idea what’s coming. It’s hugely variable—way more than it used to be.”

On a chilly day in March, I meet up with Rob Johanson on a typically busy day at Goranson Farm in Dresden. Rob has a very quiet presence and seems surprised (and perhaps a bit disappointed) that we want to take his picture. He shows us around

Opening spread Some years are soggy, others are dry. This has always been true, but farmers have been noticing increasingly dramatic shifts in weather due to climate change. Many fear it will wreak havoc on their land and livelihoods. Left Tom Drew has been farming his entire life in Woodland, Maine. He has “never seen anything like” the drought of 2018. Above Rob Johanson crumbles soggy soil in spring of 2019. Erratic weather and wet fields have affected the crop rotations at Goranson Farm.

Goranson Farm’s new barn and washing station, then we drive up the road to check out some fields. Normally, Goranson Farm likes to do a four-year crop rotation to build organic matter into their soils. But the fields were so wet this spring—it’s been the wettest April in 40 years—they were forced to plant into fields they wanted to be resting, as those were the only viable ones. Rob shows us some fields they would like to be using, across the street, and grabs a handful of soil to demonstrate how soggy it is. As he squeezes it into a ball in his hand, water seeps out around it. They want to get their machines in to plant, he explains, but the soil is just too moist. “Could we hand transplant? Yes. Does it make economic sense? No. So we wait.” Surrounded by soggy fields, we switch gears and talk about how hot the summers have been. Rob jokes that he spends his summer vacation irrigating. “We’ve had to invest a lot in being able to get water to plants, it’s been an expense, an increasing expense every year for us, to buy pumps, more pipe, and more time to move irrigation around the farm.” Farmers are used to being thrifty, but the changing weather

17

•••

conditions are requiring them to invest in more equipment. In addition to the money, there is the additional labor involved in setting out irrigation infrastructure, or building new storage facilities. The changes keep piling up, as do the costs.

At King Hill Farm in Penobscot, Amanda Provencher remembers when they started eleven years ago, they might have to irrigate once in August or September, or not at all. But lately there has been a steady progression in the other direction. “One year it’s so dry and we’re like…we’re setting up irrigation in July? And the next year it was June. And the last two or three years we have irrigated in April and May and that used to be the heaviest rainfall.” Like Tom Drew, they have had to feed their cows hay in the summer when it hasn’t rained. That solves the problem for the short term, but doesn’t address the bigger picture of increasing water scarcity. “I feel like I can handle anything else,” says Amanda, “but it’s the lack of water that really stresses me out.”

King Hill is known for their sweet winter carrots, which have always been harvested in the fall and stored in the root cellar in the old barn. But Amanda explains that the root cellar is no longer enough. “When we first started we could fill our root cellar with root crops and they’d stay there all winter and they’d stay good for our deliveries all fall, winter, into the spring. And three years ago we had to convert parts of the barn into coolers because the root cellar wasn’t getting cold enough and stuff was either rotting or getting soft.” In ten years they have found that by the end of October, when they would normally be putting up carrots, the root cellar was not reliably cold enough to take them. While it may not seem like a big deal to put in cool storage or add some irrigation, both changes represent additional expenses that farmers cannot necessarily pass on to consumers. Beyond the more noticeable changes like drought, there are other, more subtle shifts occurring in the fields and forests. Throughout Maine, maple sugaring season is a time to celebrate winter’s thaw, collecting buckets and boiling sap around the clock. The timing of maple sugaring season, though, has been steadily creeping earlier. Rob Johanson has been making maple syrup for nearly 40 years. He recalls worrying about getting the buckets out in March, but now he’s thinking about it in early February, or sooner. Indeed, according to the USDA, in 2001, the earliest sap flow in Maine was in mid-March. In 2018, it was February 1st. “Though there have been many changes on the farm over the years,” he says, “this is the most recognizable shift.”

19

Above Irrigation pipes ready to be set up at King Hill Farm. Below Amanda Provencher calls herself a perpetual optimist but can’t help but worry about heat, water, and the ability to farm in the future. Opposite Page Lettuces bolt early due to increasing summer heat.

Maple syrup is one of Maine’s sweetest treats, and wild blueberries are another one. Blueberry farmers, too, are experiencing change. Although the extended fall season Maine is experiencing can be beneficial in terms of an extended fall season, it also has implications for pests. The blueberry industry has been facing a tough new one, the spotted winged drosophila, which is thriving in part due to a less predictable deep freeze in the winter. Beyond that, the warmer falls mean that even native plants are growing longer, seeding more, and offering up competition for blueberries. At Blue Hill Berry Company in Blue Hill, Nicolas Lindholm cultivates 100 acres of organic blueberries. He finds that insects and diseases are becoming more visible, but also that the shifting seasons are helping some native species thrive for a longer period of time.

“The longer seasons we’re generally having with the last frost in the spring getting earlier and the first frost in the fall getting later means that a lot of plants, even native plants like goldenrod, can keep going and going,” says Nicolas. He explains that these plants have been able to “produce more seed, or get more

photosynthesis and feed their roots, so even with the native wild plants, there is more competition with the blueberries.” I had noticed the goldenrod driving up to Nicolas’ house earlier that day. The yellow spires looked glorious poking up above the berry bushes. Now I understand that their strong growth puts extra pressure on the berries. This requires more time weeding, to clear out space for the blueberries, at busy times when hands are needed on other tasks. In addition to the goldenrod, Nicolas and his wife, Maryann, have also noticed some other “odd activity” in the fall. Some plants seem to be reacting to false winters and putting on blossoms. For the last few years, he says, buds have been waking up following a long, warm fall, a cold snap in late October, and a warm stretch in November. “They think they’ve been through winter,” Nicolas explains. “Then of course they get frosted by real winter in December, and the buds are destroyed and the plants lose a lot of energy.” So far, Nicolas has only noticed this in one particular species of wild blueberry, but it gives him a funny feeling. The extended seasons, he says, “are throwing strange wrenches.”

21 20

Opposite Page Nicolas Lindholm of Blue Hill Berry Company sees resilience in the genetic diversity of wild blueberries. But he worries about the impacts of erratic weather. Left Crops don’t know how to react to “odd activity.” Warm falls, cold snaps, spring droughts, and mild winters can all trick a plant into using too much energy too soon. Right Even native Maine plants can be fooled.

I find myself thinking about change, and how to cope with it, when I drop by Willow Pond Farm in Sabattus. The sky is thick with clouds. It is one of those May days that feels closer to winter than to spring. Two employees are picking kale and spinach in an unheated greenhouse near the farmstand, and point out back when I ask about where I can find Jill Agnew.

I find Jill walking out from her back field, where she is fixing up deer fencing. Jill started Willow Pond Farm more than 30 years ago, and was the first farm in the state to try out the CSA model. She is a slight woman, still wearing her winter flannel because it’s been such a chilly spring. As we walk through the orchard, our feet sink into the wet earth. We talk about how both of our oregano plants, which usually winter well, died this year. Following fluctuating fall temperatures, Jill’s raspberries also took a major hit. We talk about how things are always shifting on the farm. “That’s why we like farming. You have to pay attention,” she says. “You have to learn and adapt every single year. But the changes are coming so fast, and the fact is its becoming hugely economic too.”

Like so many others, she’s had to invest in hoop houses, switch around her planting schedule, and adapt. Indeed, as the Northeast is projected to warm more than any other region in the contiguous United States by 2035, Maine farmers may have to adapt more than they could ever have imagined. That’s certainly a tall order in a profession that is already pretty risky in the best of years.

The good news is that Maine farmers are already doing things that make them more resilient. Things like rotating their crops, managing irrigation differently, and minimizing tillage. As Jill says, “farmers— that’s what we do—we adapt to changes. We have to. We don’t analyze them, we don’t say no, no, no. There’s nothing we can do about it except go with the flow.” I ask her how she’s been holding up this spring, with the wet weather. She looks around then points down. “We work hard to get a lot of organic matter into our soil, and I think that helps in these wet years. I’m feeling pretty resilient right now, pretty okay.” We turn and slowly walk up toward the barn. The gray of the day remains, but the rows of white apple blossoms, stark against the dark tree trunks, lead us on.

kate olson is a writer, scholar, and activist who lives in Maine. Learn more about her multimedia project documenting lived experiences of climate change in Maine. | livingchange.blog @livingchangeme

23 •••

Above Employees at Willow Pond Farm harvest early spinach.

Below Jill Agnew of Willow Pond Farm in Sabattus worries about the economic costs due to unpredictable weather. Opposite Page Gus Schultz digs in the carrot patch at King Hill Farm.

Going Wholesale

BY BRIDGET M. BURNS | PHOTOGRAPH BY RUSSELL FRENCH

For Nicolas Lindholm and Ruth Fiske of Penobscot’s Blue Hill Berry Co., producing wild blueberry powder was not a calculated business move, nor part of their long-range projections. It was a shrewd solution to meet new customer demand.

The couple had been growing organic blueberries for almost twenty years when Anthony William, a self-described “Medical Medium” known for his role as the originator of the celery juice movement, listed wild Maine blueberries as one of his recommended life changing foods. (According to his website, wild blueberries can heal illness thanks to their “ancient and sacred survival information from the heavens.”)

Summer visitors to Maine had long asked Lindholm and Fiske if they could ship frozen berries, but the farmers felt it would be costprohibitive. After William’s endorsement, the inquiries increased. Several scientific studies affirm the berries’ antioxidant—if not biblical—properties, so the couple decided to make them available for mail-order. Still, the cost kept many would-be customers from completing their purchase. The solution? Shelf-stable wild blueberry powder ground from dehydrated, whole fruit.

“Blueberries are really in vogue, and not because people suddenly love making pancakes and muffins,” Lindholm says. “Wild blueberries are mostly now used in smoothies or yogurt, that sort of thing.”

When it comes to more health conscious recipes, the powder is a worthy substitute to whole, frozen berries. Perhaps unsurprisingly, most of Lindholm’s orders come from the Southwest and the West coast.

Lindholm and Fiske don’t worry too much about promoting the website, instead considering the powder as a secondary revenue stream to their existing success. “We just throw it out there,” Lindholm says. “And you know, people find it.”

It’s an opportunity of which Taja Dockendorf, owner of Portland’s Pulp & Wire marketing agency, thinks more farmers should be taking advantage. “In the natural and organic set, people want quality products,” she says. “We get tired of all the mass produced products that are out there. On the internet, you can get anything from anywhere. Why not offer people a delightful product from Maine?”

Jed Beach, owner of Midcoast’s 3 Bug Farm and CFO for hire through his business, FarmSmart Maine, agrees that diversification through value-added products or branded wholesale can be an effective way for smaller farms to reach new customers while simultaneously increasing margins.

“Value added products are taking over market share in just about every category of retail food right now,” says Beach, who explains that customers are really looking for convenience. “Taking something that is a raw product, and moving it further along the line of being ready to eat—it's an exciting space for local producers to move into. The price markup is really high.”

The added value could be as simple as turning raw kale into a chopped product, or in the case of Copper Tail Farm in Waldoboro, turning goat’s milk into cajeta, a shelf-stable caramel sauce originally from Mexico. “A lot of people don't know what it is and they're really interested and intrigued by it,” explains owner and producer, Christelle Mckee.

25

In search of sales, farmers find creative ways to diversify their production

BUSINESS

Cajeta is available for order on the Copper Tail Farm website, along with Mckee’s goat’s milk soap, but a larger portion of the farm’s value-added business is achieved through wholesale accounts for these products, plus kefir, cheese, and goat’s milk yogurt. Mckee says that when she and her husband Jon were deciding where to start their business, they were attracted to all of the programs and support available to new farmers in Maine. This included Maine Farmland Trust’s Farming for Wholesale program, which helped the couple expand their reach beyond their local farmer’s markets. “We now have over 20 accounts from Portland to Bar Harbor,” Mckee says.

Alex Fouliard, who manages the Farming for Wholesale program, explains that it started simultaneous to the Maine Food Strategy releasing its framework, and the University of Maine System announcing its pledge to source 20% of its food locally by 2020. UMS now sources 23% of food purchases locally and has announced a new pledge to source 25% locally by 2025.

This pledge, Fouliard says, “evolved at a time where there was a lot of excitement around scaling up local food. There was all this energy, and we were hearing from farmers that they really needed some support.”

Fouliard believes that in order for Maine’s agricultural sector to continue to thrive, farms at all scales need to be profitable, whether that comes through introducing new products, diversifying customer base, or both. What launched in 2015 as a series of pilot workshops is now a robust business planning program with the opportunity to apply for a cash infusion by way of an Implementation Grant.

One farmer to benefit is Katheryn Langelier, founder and formulator of Union-based Herbal Revolution Farm and Apothecary. The Implementation Grant served as a down payment for the building Langelier’s business is based in, with a portion also helping to renovate her production kitchen, where she makes preventative products like Elderberry Tonics (to aid immune health) and gentle sleep aids like Goodnight Moon Tea (packed with chamomile, catnip, and lemon balm). “It was an incredibly huge deal for us to receive that and it has brought us to that next level that we were needing to go,” Langelier says.

That next level includes a variety of herbal products like tonics, elixirs, shrubs, and teas, now available nationwide, with 75% sold through wholesale markets, including big industry players like Whole Foods. Still, Langelier fully believes in the importance of knowing your farmer, and works hard to keep her brand transparent and accessible. She also continues to manage production, with a staff of three female farmers and clinical herbalists.

“I think it is important to see where your medicine, just like your food, is coming from,” Langelier says. “There's just so many plants that support us in a preventative way.”

Ben Rooney of Benton’s Wild Folk Farm is another farmer who believes in the power of plants and like Langelier, he has grown that belief into a wholesale business. Rooney was pre-med during his undergraduate studies; he had considered transitioning Wild Folk Farm from vegetables to herbs as a way of getting back to his interest in healing. But as a no-till, human powered farm,

he realized he would not be able to do so on a large enough scale to be competitive. At the same time, he had been reading success stories from hemp growers out West. After a little research— and realizing that growing hemp had recently become legal in Maine—his idea was born.

CBD, or cannabidiol, is a phytocannabinoid that accounts for about 40% of a cannabis plant’s extract. It has gained popularity in recent years due to preliminary studies connecting it with relief of both anxiety and pain.

“I was excited about doing something different,” Rooney says. “CBD was already on the shelves in Maine when our first harvest came in a few years ago, but none of it was local. None of it was organic, and most of it was very low quality.”

Wild Folk Farm CBD products include tinctures, salves, and even honey, all produced absent of THC and its psychoactive properties. Thanks to consumer testimonials and sales data from early adopters, Wild Folk Farm has built a wholesale business spanning 50 retailers since Rooney received his license to grow hemp in 2017. A farm’s value-added products may not always be their own. For Jenn Legnini, chef and owner of Turtle Rock Farm craft cannery in Brunswick, co-packing for other area farms has proven to be an efficient and mutually beneficial way to generate additional income. “The more newer farmers I met, the more I had the conversation of, how can we make a value added product if kitchens are so hard to find?” Legnini says.”I fully experienced that. It was so hard to find a kitchen for the first couple of years. I guess I saw an opportunity.”

Turtle Rock Farm currently produces their

own line of relishes, pickles, and spreadable fruit, while also supporting ten co-packing clients. Legnini primarily works with smaller, organic farms for whom obtaining commercial kitchen space is not currently viable. Even when clients are in the startup stage, Legnini sees an opportunity.

“As you're establishing your fresh markets, you have so much incredible food,” she says.

“It's about how to get it past the two day shelf life and not put all that pressure on your first years of growing and establishing. With canning you can use the hours in a more opportune way. You can scale up quicker.”

Still, Pulp & Wire’s Dockendorf warns against scaling up without first doing your research. “What I tell brands who are just starting up is, own your backyard. Saturate as much as you can locally because you can be there in person,” she says. “By focusing on local and owning that positioning, you can learn so much about your products and your target audience before branching out. There's so many learnings to be had locally. That first step is the key to making sure you're not going to lose money making too big of a push, too soon.”

Or to paraphrase, if you want to think global, it pays to act local.

bridget M. burns lives in the remaining barn of Kennebunkport's historic Freedom Farm, where she balances freelance writing with life as a stay-athome mom.

26 27

On the internet, you can get anything from anywhere...

Why not offer people a delightful product from Maine?

heritage grain on growing, eating, and restoring flint corn to Maine

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELSEY KOBIK

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELSEY KOBIK

INTERVIEWS BY KATY KELLEHER

INTERVIEWS BY KATY KELLEHER

Left Harvesting flint corn at the annual Harvest Party at Songbird Farm in Thorndike. Top An ear of Byron corn dries in the fields at South Paw Farm in Freedom. Bottom Ears of harvested Byron flint corn are dried thoroughly before storage.

albie barden

Corn started in Mexico. It took about a thousand years for it to cross the country, hand to hand, farmer to farmer, mouth to mouth.

As it crossed the country, every time it moved from one community to another, it was adapted by the indigenous farmer to meet the needs of the climate. It was being selected by the farmers. And guess who they were? They were women. Women were the biologists, the scientists, the farmers, who were watching every stalk of corn.

As it moved across the country, the variety that developed, the type that was developed, was called flint corn. It had eight rows. Tall, narrow ears. They would mature more easily and dry out more easily.

The reason I am involved is that I believe we are up against the wall for our survival. The only grain that is truly North American is corn. The corn belonged to

the Native people; as their cultures were broken and stolen, as their territory was taken, their tradition of growing corn was taken.

Pockets of corn survived. Those ancient varieties of flint corn, some of it has survived in vaults in agricultural vaults. Some survived in a shoebox with two or three ears of corn in it in a shoebox in an attic. Ten years ago, I started to pick up interest in this corn stuff. I was drawn to it not because it was easy, but because it was critical.

We can grow that corn again. We are growing it now. If you have a five-gallon bucket and a back yard, I can give you five seeds of flint corn. And you can begin to redevelop the sacred relationship to the corn and the earth.

30 31

FARMER, NORRIDGEWOCK

Above A field of Roy's Calais/Abenaki flint corn. Opposite Page Albie Barden at his home in Norridgewock.

Songbird Farm grows a variety of other grains in rotation, including wheat, rye, and oats. These photos are from a day harvesting their Red Fife wheat. Clockwise from top left: 1. Chaff falls from the combine after being separated from the grain.

2. Farmer Adam Nordell keeps an eye on the combine as he drives through the field of wheat. 3. Johanna Davis adjusts a belt on the combine. 4. Weed seeds fall into the bin to be discarded after passing through the separator. 5. Johanna, Caleb, and Adam peer into the combine.

33

dan towle

BAKER AT VESPER BREAD, SCARBOROUGH

I can't remember exactly when I first tasted flint corn, but I do recall hearing more about it after the Somerset Grist Mill opened up in Skowhegan. I was baking at Scratch in South Portland at the time and we had started using it in some of our doughs.

I immediately noticed how different it was from the yellow cornmeal we had been using. The smell, the texture, the color; it was obvious to me right off the bat we were working with a superior product. It wasn't until this past year that I began baking on my own and I was able to choose my ingredients and formulate my own recipes. The decision to use and highlight the Abenaki flint (grown by Songbird Farm) was a no-brainer. I usually toast or soak the cornmeal before adding it to a bread dough and I'm always amazed at the rich, wholesome, nutty aroma and creamy texture it imparts to the final loaf. You can't

find that sort of flavor and texture anywhere else. More importantly though, I use flint corn because I feel it helps connect us to the land we live on, our past and the people who lived here before us.

I prefer baking with locally grown, organic grains because it helps build community among farmers, millers, bakers and anyone who chooses to participate. All are welcome and we are stronger together.

I'm very proud and very privileged to be able to say that I know, personally, the people who grow most of the food I eat. How incredible is that? And I'm really psyched to see the variety of local, heritage grains increasing in availability.

I've heard it said that in any endeavor we have two choices: to go with nature or to go against nature. And that's why it's such a no-brainer for me.

35 34

Opposite Page Dan measures toasted cornmeal in the kitchen at Frith Farm in Scarborough. Above A version of Dan's formula for “Abenaki Rosemary” bread.

36

Baking Abenaki Rosemary bread with Mainegrown grains including flint corn. Clockwise from top left: 1. Mixing in the cornmeal. 2. Divided dough. 3. A loaf of the bread, hot out of the oven. 4. First mix. 5. Shaping the loaf.

kelsey kobik

I grew up visiting my grandparents in Wilton, and although no one in my family owned any land, I always felt deeply connected to the lake and mountains, the muddy trails and mossy rocks. One thing my Grampa Joe always insisted on was having “the good corn” for supper—no grocery store corn for us. We'd ride in his Buick almost out to Weld, pull over between an old house and a big barn, and wait for the man to appear out of the garden. “Hi Joe, how many?” We'd wait by the car while he picked it for us. “Same day, that’s the only way to eat corn,” my Grampa would say. He had grown up working on farms with his family all around Franklin County. But that was sweet corn. When I drove up to Norridgewock last spring for the first Cornference, I was going to learn about flint corn. I had worked on a vegetable farm and knew all about that, but didn't know the first thing about grain farming. This gathering was about our native grain and its history, which is also the history of our land. There on a floodplain of the Kennebec River, where Norridgewock people once cultivated more than

1,000 acres of flint corn to ship through their massive trade network, at an address on the road bearing the same name as the 1724 massacre by the English that destroyed their community, we sat in a room and listened and cried and laughed about the power of seeds. When I looked across the room and recognized the face of Conrad Heeschen, the sweet corn farmer from Wilton Intervale, I was overwhelmed. When his partner, Pam Prodan, told the story of Byron corn seeds finding their way to her via Will Bonsall and ultimately a shoebox under a neighbor's mother's bed, and the realization those seeds had initially been selected and bred on the same land she was farming, some 150 years back, I cried. I had never even touched a corn seed, and yet it had the power to bring me back, hard, to memories of my late grandfather and the land. Understanding what has happened before us and what will happen after us in the place where we are is a big part of what it means to be alive. Real food from the land where you live brings all time to the present and puts it on your plate, to nourish you in that moment.

39

Opposite Page A few wheat berries have made their way into the discard bin of weed seeds. Above Cousins helping at the Corn Harvest Party.

PHOTOGRAPHER AND FARMER, PORTLAND

41

Clockwise from top left: 1. Nate Gorlin-Crenshaw hauls a full bag of Roy's Calais flint corn to the truck. 2. Harvesting the wheat. 3. Neighbors Rainna, Ben, and Hadley help with the corn harvest. 4. A mature head of red fife wheat. 5. Nate and Ursa Beckford have a full truckload of corn.

COMMUNITY SNAPSHOT

A vibrant food and farm scene grows in Dover-Foxcroft

BY KATY KELLEHER | PHOTOGRAPHS BY YOON S. BYUN

BY KATY KELLEHER | PHOTOGRAPHS BY YOON S. BYUN

TRAVEL

Central Maine was once the breadbasket of New England. Two hundred years ago, this is where Boston sourced their bread, where New Yorkers got their wheat. It was grown in the fertile area between the coast and the White Mountains, where rivers were abundant and land was cheap. It still is, if you know where to look. Piscataquis County isn’t quite as well known as Aroostook (“The County”) or as well-trod as the jagged little counties that march up the coast. But here, fresh food thrives and farming has established a strong foothold. In 2009, when Gene and Mary Margaret Ripley were looking for a place to settle down and buy some farmland, they looked first towards the Dover-Foxcroft, Farmington, and Skowhegan areas. “We wanted to be somewhere with good farmland,” says Ripley,

“and this area has really good farmland.” The soil is easy to work, he explains, a silt-loam that both drains well (thanks to a loose upper layer) and retains enough moisture to get them through a dry spell (credit here goes to the dense lower layers). Originally from Washington County, Ripley wanted to be near a population center (like Dover-Foxcroft) and he wanted to find land he could afford, dirt he could pay for, a community he could join.

The half-cleared plot in Dover-Foxcroft proved to be “the right property at the right time,” he says. They started with less than an acre of fields, thinking that would be enough for them to handle. But a decade later, Gene and Mary Margaret are still there, still digging and harvesting and farming on their five acres of MOFGA-certified land. Other things have changed, too. Now, they’re raising a family on the farm, just

45

Opening Page The scene at Spruce Mill Farm and Kitchen in Dover-Foxcroft. Located in mid-Maine, this is an area that was once known as the breadbasket of New England, where farmland is cheap, plentiful, and fruitful, and where many new growers are setting up shop. Opposite Page An aerial view of Ripley Farm surrounded by fall foliage. Left Gene and Mary Margaret Ripley take a break from a day of work to be photographed in a lush field. Together, they run Ripley Farms, a successful organic farm that is supported almost entirely through CSAs. Right Gene Ripley harvests a purple top turnip in early October.

like they’ve always dreamed. “We live in the poorest county in Maine,” he says, but he doesn’t sound resigned or particularly sad as he states the fact. Because here, both the Ripley Farm and the Ripley family has thrived. The organic farm has so much demand for their Community Supported Agriculture program that they no longer need to load trucks for farmers markets and spend their weekend days hawking veggies in Bangor. “Pretty much 100 percent of our produce is already sold when we plant it,” he says. One thing that makes this area so special is the value its residents place on good, fresh, healthy food. People are aware that these towns were built on farming, and they care about supporting their local farms, says Steve Grammont, founder of Piscataquis Regional Food Center “I can’t see how our area relates to other places in the country or even in Maine, but

it appears to me what we have here is quite special,” he says. In the past two decades, Grammont has observed a shift in awareness around locally farmed produce. “As manufacturing jobs have gone away for good and people have started to re-appreciate real food, the opportunities for the reestablishment of smaller farms seems to have found its way back,” he says. “Especially in the past 10 years.” In the national media, “buying local” is often presented as a niche interest, a fad or a trend—something that urban hipsters and suburban yuppies do. It’s ironic, considering how important small farms are to both rural communities and smaller cities like Dover-Foxcroft. Organic produce, too, is often represented as a luxury item, but that tells us more about what popular media values than it does about what regular Americans want. “We have quite a number

46

Left Squash for sale in the farm stand area of Stutzman’s Farm Stand & Brick Oven Cafe in Sangerville. Right Further bounty for sale at Stutzman’s, plus evidence of their popular brick-oven pizzas, which you can eat on-site or grab take-out. Stutzman’s also offers Sunday brunch. Opposite Page Gene Ripley strolls through a field of turnips. “Personally, for my family, healthy food from local farms is a top priority in terms of our home and personal budget,” he says of the choice to eat and grow organic. “We’d cut other places before we cut there.”

of customers who fall into the category of people who would be generally considered unable to afford organic food,” says Ripley. “But they value it very strongly, and they find ways to afford it. Personally, for my family, healthy food from local farms is a top priority in terms of our home and personal budget. We’d cut other places before we cut there.”

Jason Kafka of Checkerberry Farm has long believed in the power of produce. He settled in Parkman, a town sixteen miles west of Dover, in the 1980s. “Back then, people mostly worked in the mills or in the shoe shop,” Kafka remembers. “It was a producing region, a wood region. A lot of people made their living cutting wood.” At first, Kafka’s farm was an outlier. People saw Kafka and his wife, Barbara, as a “couple of hippies. But we wove ourselves into the community, and over time, the word organic came into the vernac-

ular.” Now, Kafka says, “Holy moly, it’s come all the way around. There are all these young folks coming to farm and I’m the old timer. How did that happen?”

Kafka calls the shift “gratifying.” It’s made it easier for him to eat the way he wants to eat, live the way he wants to live. He can have pork chops raised locally from Spruce Mill Farm and Kitchen in Dover-Foxcroft, paired with root cellar veggies grown right out back. “Over the years,” he says, “you make your place fit you.” In addition to eating off the land, Kafka also donates to the Mainers Feeding Mainers program, so all his neighbors can do the same.

“While it could be said that we don’t have any single thing that can’t be found elsewhere, and sometimes measurably better, I suspect we have more going for us in total than most other places,” says Grammont. He points out that Cumberland County

49

Opposite Page Beyond tomatoes, a view of fall fields. Left Sabrina Beck of Monmouth sorts vegetables that will be picked up and taken to Dover-Foxcroft from Ripley Farm. Right Sid and Rainie Stutzman stand in the parking lot overlooking their Sangerville farm and restaurant.

has better access to urban markets, but do they have better access to affordable land? “Yeah, right,” he scoffs. “More agriculturally friendly land use regulations? Forget about it. And sure our weather up here is a bit colder, but farmers can grow things other than oranges and iceberg lettuce.” (For example, carrots. “People say we have the best carrots they’ve ever tasted,” says Ripley. “I credit the soil for that.”)

When speaking with farmers from Dover-Foxcroft, it’s hard to miss the emphasis on affordability. It’s a place where land is cheap and abundant, where would-be farmers can get a foot in the door, start a new life. There aren’t that many younger farmers yet, but Grammont, Ripley, and Kafka all expect to see more people settling down in the rural region to take advantage of the rich soil, the welcoming community, the resource-full grange. “The

folks living here have been exposed to real food over the past ten years, and I don’t think they’re going to go back,” says Grammont. “It’s kind of like the explosion of craft brewing in Maine—once people get a taste, there’s no going back.”

“I love being a carrot snob, a tomato snob,” adds Kafka. “Work isn’t a four-letter word for me. Aren’t I a lucky guy?”

katy kelleher is the managing editor of Maine Farms . She lives in Buxton with her two dogs, one husband, and one daughter.

LOCAL RESOURCES FOR GROWERS & EATERS

Checkerberry Farm

530 Wellington Road, Parkman 207.277.3114

East Sangerville Grange East Sangerville Road, Sangerville eastsangervillegrange.org

Marr Pond Farm

471 Flanders Hill Road, Sangerville 207.659.3519 marrpondfarm.com

Piscataquis Regional Food Center

76 North Street, Dover-Foxcroft 207.343.0171 prfoodcenter.org

Ripley Farm

62 Merrills Mills Road, Dover-Foxcroft 207.564.0563 ripleyorganicfarm.com

Spruce Mill Farm & Kitchen 920 West Main Street, Dover-Foxcroft 207.564.0300 sprucemillfarm.com

Stutzman’s Farm & Bakery 891 Pine Street, Sangerville 207.564.8596

Turning Page Farm Brewery

842 North Guilford Road, Monson 207.876.6360 turningpagefarm.com

50 51

Left Rainie Stutzman prepares a raisin, walnut, olive oil, spinach and feta pizza in a wood-fired oven at Stutzman's Farm & Bakery in Sangerville, Maine. Right Gene Ripley examines a head of cauliflower. Opposite Page Top Fresh baked bread at Spruce Mill Farm and Kitchen. Bottom Natasha Colbry, co-owner of Spruce Mill Farm and Kitchen, stands outside in front of the shop, where their motto is “loyal to our soil.”

GREATER THAN DIRT

BY LAURA POPPICK | ILLUSTRATION BY ERIKA MELHUS

On a grey afternoon in late August, I sit around a large wooden table at Frith Farm, waiting out a storm. I’m with owner Daniel Mays and four of his crew members, discussing what makes this farm in Scarborough different from others they’ve worked on.

Through rain-streaked windows, we can see neatly arranged fields with colorful perennial blossoms, lush herbs, and brilliant greens that exude health even beyond the veil of wet glass. Though the abundance is striking, our conversation lingers not on the crops themselves but on what underlies the emerald greens, deep blues, and fuchsias brimming with life: soil.

With the mind of an engineer (he was one in a previous life), Mays has designed every nook and cranny of his three-acre farm to support his soils. The immaculate rows of crops look like bar graphs charting years of care and intention directed below ground. He plants beets beside tomatoes because their roots target different soil zones; sows parsley beside kale to fuel helpful fungal growth that kale can’t generate on its own; and fosters many other beneficial underground relationships, year after year, by never tilling his fields.

The results are what set this farm apart from others, says Ana Solis, an apprentice who last worked on a small livestock farm in Florida. “There’s a lot more life, there’s a lot more vibrance,” she says.

Mays goes to great and relatively uncommon lengths to boost his soil’s health, with tasks that require many hours of manual wheelbarrow labor rather than tractor work. But these methods are becoming more commonplace across the state as farmers increasingly recognize the vast benefits of healthy soils. Amongst their multitudinous powers, healthy soils retain more water, contain more nutrients, and increase productivity. They support communities of beneficial insects that prey on harmful pests, and offer plants the strength they need to combat disease. Because healthy soils can store carbon underground and out of the atmosphere, they also help slow climate change. From larger-scale dairy farmers to smaller diversified vegetable farmers, Maine growers are increasingly boosting their soils in ways that produce greater productivity, larger profits, a healthier environment—and, as Solis notes, “a lot more beauty.”

“There are lots of reasons why farmers are implementing these practices,” says Bill Toomey, Maine Farmland Trust’s executive director. Toomey has a Master’s in soil science and a habit of reminding people to “stop treating soil like dirt.” He’s working to ramp up MFT’s efforts to educate Maine farmers about how they might improve their soil health with practices that are not technically challenging or overly expensive. In the end, any initial investment of time and resources required to shift to

52 53 LAND

Healthy soils that teem with life offer countless benefits on the farm—and beyond.

more soil-friendly practices should reap long-term rewards. “If we give it what it needs,” he says of soil (not dirt!), “it’s going to give us what we need.”

When the storm clears, Mays and his crew tour me around the farm. Just under an inch of rain has fallen, and puddles have gathered on the grassy path between the fields. “This ground is compacted from the tractor and foot traffic,” says Mays, toeing a puddle. But just a stone’s throw away, the bed of tomatoes and beets remains puddle-free. “This,” he says, pointing with pride, “is such a sponge.”

The fields are able to retain their sponginess because they haven’t been compacted by heavy machinery through tillage. The more delicate manual methods Mays has adopted (including broad forking and hand weeding) keep the soils looser and richer, and allow them to drain during storms so that topsoil and nutrients don’t get washed away. The lighter-touch approach also keeps an expansive network of underground microbes intact—and that proves critical to overall soil health. A key player in this subsurface microbiome is mycorrhizal fungi, a group of fungi that grows thin white threads called hyphae that pierce plant roots and snake outward into the soil horizon, sometimes expanding for meters. “They almost look like roots themselves,” says Sue Erich, a soil scientist at the University of Maine who studies plant-soil interactions. The fungi offer plants nutrients that they (the plants) can’t make on their own; in return, plants offer fungi energy in the form of carbon that they brew during photosynthesis. These fungal connections increase root contact with soil by up to 100 times, giving plants access to a far greater spread of water and nutrients than they would have on their own—so long as they keep pumping carbon to feed this symbiotic relationship, Mays says.

Some of this carbon eventually gets released back into the atmosphere when the fungi die. But a portion can become bound to tiny subsurface minerals and stored for years on end, Erich notes. This is how healthy, carbon-rich soils also help slow climate change. “The more carbon that we can keep stored and stabilized in soil, the better,” she says. Aside from not tilling—which breaks up soil aggregates and can cause mineral-bound carbon to escape back into the atmosphere—rotationally grazing pastures also helps keep carbon underground as well. Katia Holmes, owner of Misty Brook Farm in Albion, adopted this practice when she opened the 600-acre farm in 2005. Amongst the many benefits she has noticed since then, she finds that her soils

have become more resilient to extreme weather shifts, staying cooler in hot weather and warmer in cold weather. “It helps balance things out,” she says.

The pasture grass itself is healthier, too. The animals only eat the top third of the long grasses, and they tromp down the rest. This feeds the earthworms and microbes down below, Katia says, “which in turn then feed the plants.”

“You are basically cultivating an ecosystem below ground,” says Boudreau, owner of Winslow Farm in Falmouth who has adopted low- and no-till practices on his diversified vegetable fields over the past several years thanks, in part, to inspiration from Frith Farm.

I’ve worked with Boudreau as a work-share helper for the past five seasons, and have witnessed the transformation of some of his fields within that timeframe. What were once pale, compacted clayey rows that were difficult to penetrate with fingers or shovels are now dark, fluffy beds that produce rockstar crops. “The quality of the veggies is superior, for sure,” Boudreau says as we eye the field that produced hundreds of delicious peppers and eggplants last season, with barely any need for weeding. A few afternoons of pitchforking mulch had shaded out weed growth and helped the fields retain rainwater, producing crops that burst with moisture and flavor.

I tell Mays that his practices inspired Boudreau to care for his soil in these ways. He tells me that other small-scale farmers—some from Maine and others from around the world—have reached out to him seeking advice for ways to implement no-till practices on their own farms as well. “In the last few years, it’s really taken off,” he says.

As we continue on our farm tour, the sky clears up and birds swoop across the fields between jousting grasshoppers. Solis reiterates how their attention to soils nourishes all life on the farm—not just the crops, but the beneficial microbes, burrowing worms and insects, and aboveground pollinators. “It allows everything to shine,” she says.

laura poppick is a freelance environmental journalist based in Portland, Maine who's favorite garden snacks are strawberries and sugar snap peas. She contributes to Scientific American, Audubon Magazine and elsewhere.

erika melhus is an illustrator in Western Maine who creates botanical-inspired work highlighting the complexities of the natural world.

54 55

Let's invest in a resilient local food system.

2020 underscores the urgent need to work together to grow a vibrant, local food system that honors the land, the farmers, farmworkers, and nourishes ALL of us.

The future of our farms and our communities depends on all of us, together. Dig in at mainefarmlandtrust.org

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2020

JOURNAL OF MAINE FARMLAND TRUST • 2020

Ellen Sabina, Outreach and Communications Director, Maine Farmland Trust

Ellen Sabina, Outreach and Communications Director, Maine Farmland Trust

BY KATE OLSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

BY KATE OLSON | PHOTOGRAPHS BY GRETA RYBUS

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELSEY KOBIK

PHOTOGRAPHS BY KELSEY KOBIK

INTERVIEWS BY KATY KELLEHER

INTERVIEWS BY KATY KELLEHER

BY KATY KELLEHER | PHOTOGRAPHS BY YOON S. BYUN

BY KATY KELLEHER | PHOTOGRAPHS BY YOON S. BYUN