10 minute read

food

Why not offer people a delightful product from Maine?

he realized he would not be able to do so on a large enough scale to be competitive. At the same time, he had been reading success stories from hemp growers out West. After a little research— and realizing that growing hemp had recently become legal in Maine—his idea was born.

Advertisement

CBD, or cannabidiol, is a phytocannabinoid that accounts for about 40% of a cannabis plant’s extract. It has gained popularity in recent years due to preliminary studies connecting it with relief of both anxiety and pain.

“I was excited about doing something different,” Rooney says. “CBD was already on the shelves in Maine when our first harvest came in a few years ago, but none of it was local. None of it was organic, and most of it was very low quality.” Wild Folk Farm CBD products include tinctures, salves, and even honey, all produced absent of THC and its psychoactive properties. Thanks to consumer testimonials and sales data from early adopters, Wild Folk Farm has built a wholesale business spanning 50 retailers since Rooney received his license to grow hemp in 2017.

A farm’s value-added products may not always be their own. For Jenn Legnini, chef and owner of Turtle Rock Farm craft cannery in Brunswick, co-packing for other area farms has proven to be an efficient and mutually beneficial way to generate additional income. “The more newer farmers I met, the more I had the conversation of, how can we make a value added product if kitchens are so hard to find?” Legnini says.”I fully experienced that. It was so hard to find a kitchen for the first couple of years. I guess I saw an opportunity.”

Turtle Rock Farm currently produces their own line of relishes, pickles, and spreadable fruit, while also supporting ten co-packing clients. Legnini primarily works with smaller, organic farms for whom obtaining commercial kitchen space is not currently viable. Even when clients are in the startup stage, Legnini sees an opportunity.

“As you're establishing your fresh markets, you have so much incredible food,” she says. “It's about how to get it past the two day shelf life and not put all that pressure on your first years of growing and establishing. With canning you can use the hours in a more opportune way. You can scale up quicker.”

Still, Pulp & Wire’s Dockendorf warns against scaling up without first doing your research. “What I tell brands who are just starting up is, own your backyard. Saturate as much as you can locally because you can be there in person,” she says. “By focusing on local and owning that positioning, you can learn so much about your products and your target audience before branching out. There's so many learnings to be had locally. That first step is the key to making sure you're not going to lose money making too big of a push, too soon.”

Or to paraphrase, if you want to think global, it pays to act local. bridget M. burns lives in the remaining barn of Kennebunkport's historic Freedom Farm, where she balances freelance writing with life as a stay-athome mom.

27

Left Harvesting flint corn at the annual Harvest Party at Songbird Farm in Thorndike. Top An ear of Byron corn dries in the fields at South Paw Farm in Freedom. Bottom Ears of harvested Byron flint corn are dried thoroughly before storage.

Above A field of Roy's Calais/Abenaki flint corn. Opposite Page Albie Barden at his home in Norridgewock.

albie barden

FARMER, NORRIDGEWOCK

Corn started in Mexico. It took about a thousand years for it to cross the country, hand to hand, farmer to farmer, mouth to mouth.

As it crossed the country, every time it moved from one community to another, it was adapted by the indigenous farmer to meet the needs of the climate. It was being selected by the farmers. And guess who they were? They were women. Women were the biologists, the scientists, the farmers, who were watching every stalk of corn.

As it moved across the country, the variety that developed, the type that was developed, was called flint corn. It had eight rows. Tall, narrow ears. They would mature more easily and dry out more easily.

The reason I am involved is that I believe we are up against the wall for our survival. The only grain that is truly North American is corn. The corn belonged to the Native people; as their cultures were broken and stolen, as their territory was taken, their tradition of growing corn was taken.

Pockets of corn survived. Those ancient varieties of flint corn, some of it has survived in vaults in agricultural vaults. Some survived in a shoebox with two or three ears of corn in it in a shoebox in an attic. Ten years ago, I started to pick up interest in this corn stuff. I was drawn to it not because it was easy, but because it was critical.

We can grow that corn again. We are growing it now. If you have a five-gallon bucket and a back yard, I can give you five seeds of flint corn. And you can begin to redevelop the sacred relationship to the corn and the earth.

30

31

32

Songbird Farm grows a variety of other grains in rotation, including wheat, rye, and oats. These photos are from a day harvesting their Red Fife wheat. Clockwise from top left:1. Chaff falls from the combine after being separated from the grain. 2. Farmer Adam Nordell keeps an eye on the combine as he drives through the field of wheat. 3. Johanna Davis adjusts a belt on the combine. 4. Weed seeds fall into the bin to be discarded after passing through the separator. 5. Johanna, Caleb, and Adam peer into the combine.

33

34

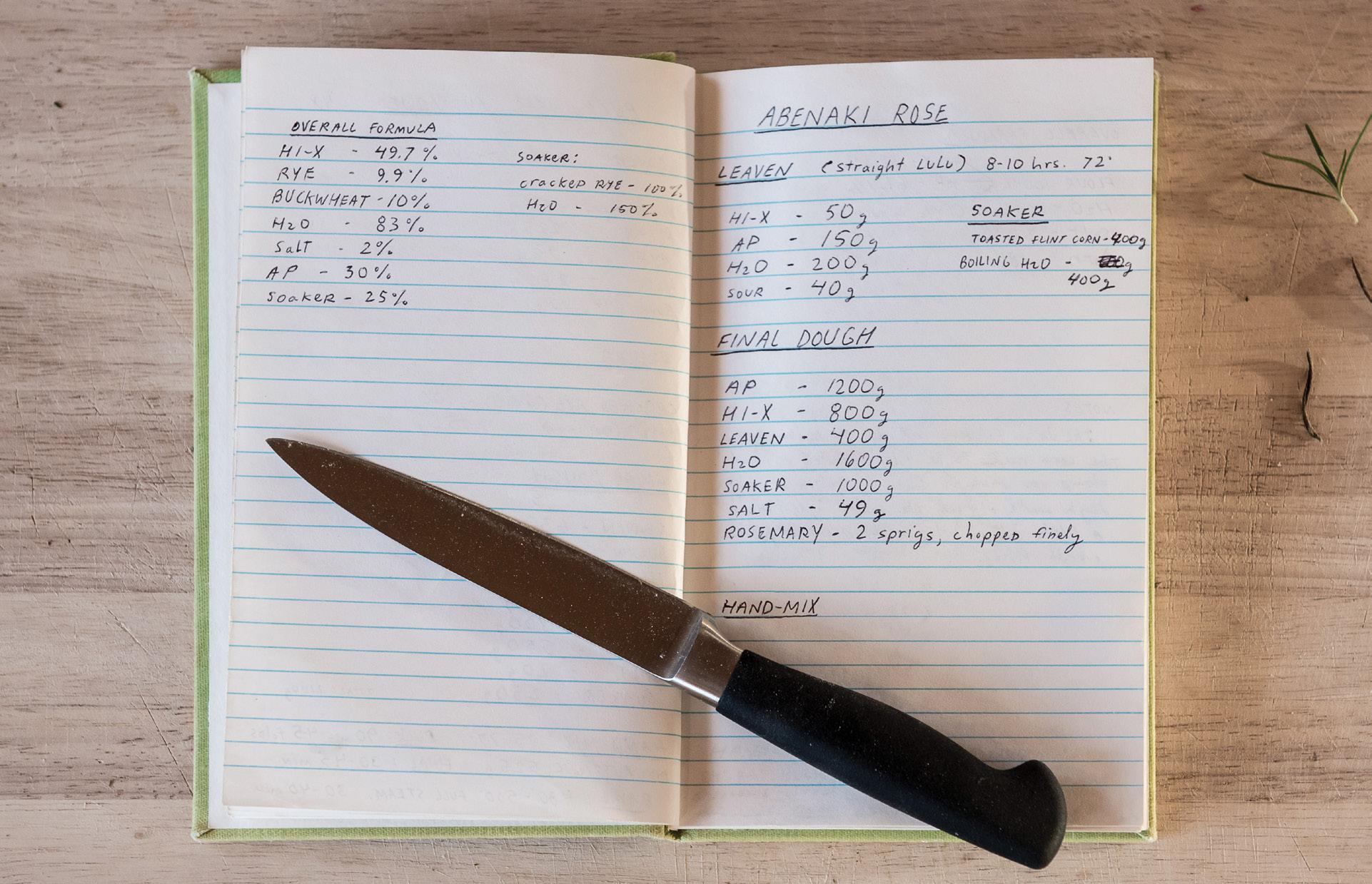

Opposite Page Dan measures toasted cornmeal in the kitchen at Frith Farm in Scarborough. Above A version of Dan's formula for “Abenaki Rosemary” bread.

dan towle

BAKER AT VESPER BREAD, SCARBOROUGH

I can't remember exactly when I first tasted flint corn, but I do recall hearing more about it after the Somerset Grist Mill opened up in Skowhegan. I was baking at Scratch in South Portland at the time and we had started using it in some of our doughs.

I immediately noticed how different it was from the yellow cornmeal we had been using. The smell, the texture, the color; it was obvious to me right off the bat we were working with a superior product.

It wasn't until this past year that I began baking on my own and I was able to choose my ingredients and formulate my own recipes. The decision to use and highlight the Abenaki flint (grown by Songbird Farm) was a no-brainer. I usually toast or soak the cornmeal before adding it to a bread dough and I'm always amazed at the rich, wholesome, nutty aroma and creamy texture it imparts to the final loaf. You can't find that sort of flavor and texture anywhere else.

More importantly though, I use flint corn because I feel it helps connect us to the land we live on, our past and the people who lived here before us.

I prefer baking with locally grown, organic grains because it helps build community among farmers, millers, bakers and anyone who chooses to participate. All are welcome and we are stronger together.

I'm very proud and very privileged to be able to say that I know, personally, the people who grow most of the food I eat. How incredible is that? And I'm really psyched to see the variety of local, heritage grains increasing in availability.

I've heard it said that in any endeavor we have two choices: to go with nature or to go against nature. And that's why it's such a no-brainer for me.

35

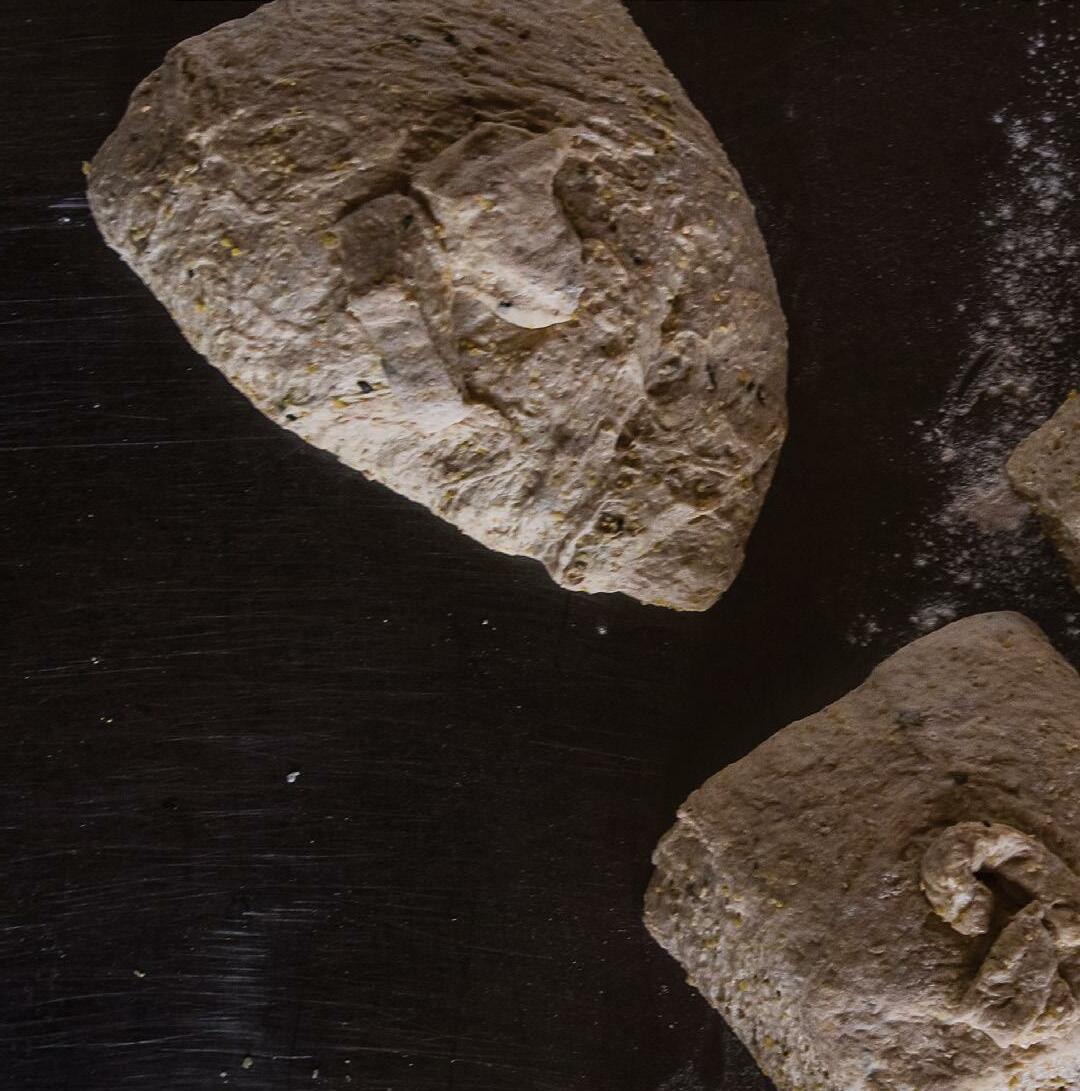

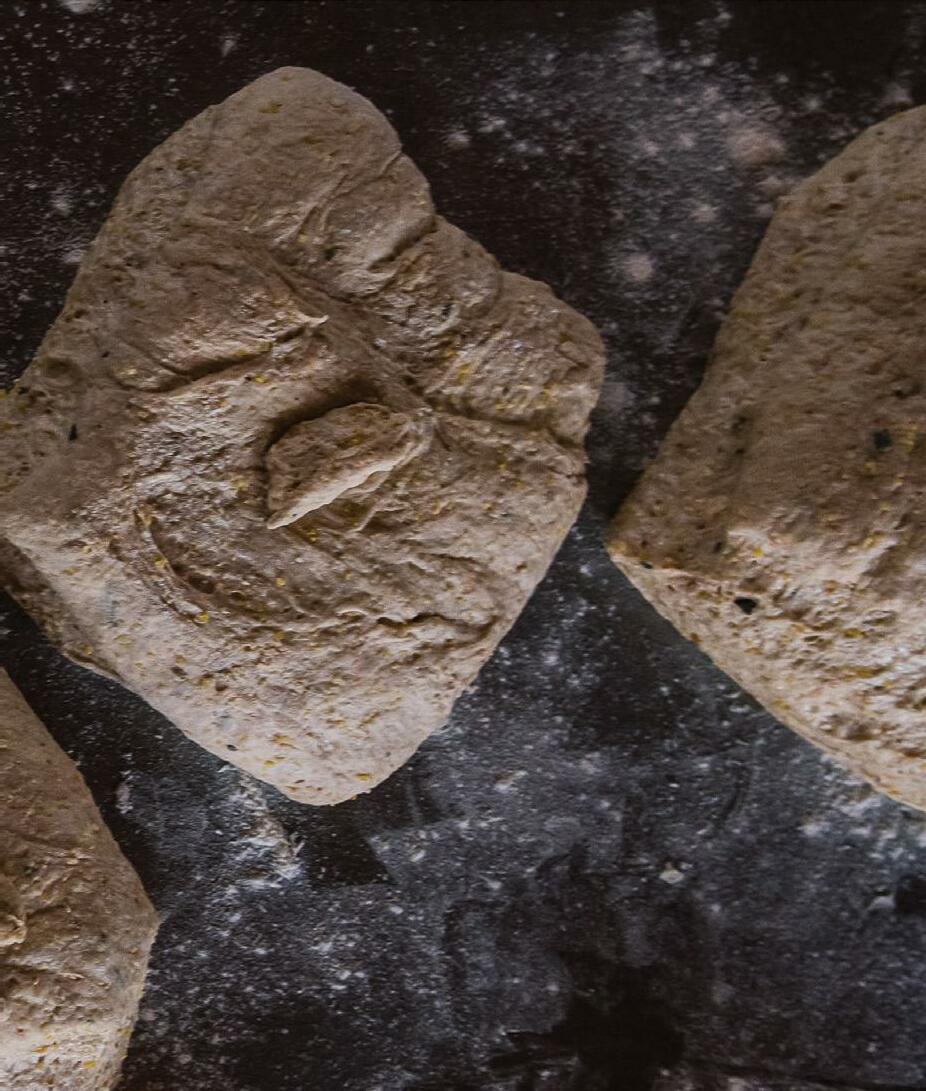

Baking Abenaki Rosemary bread with Mainegrown grains including flint corn. Clockwise from top left: 1. Mixing in the cornmeal. 2. Divided dough. 3. A loaf of the bread, hot out of the oven. 4. First mix. 5. Shaping the loaf.

36

37

38

Opposite Page A few wheat berries have made their way into the discard bin of weed seeds. Above Cousins helping at the Corn Harvest Party.

kelsey kobik

PHOTOGRAPHER AND FARMER, PORTLAND

I grew up visiting my grandparents in Wilton, and although no one in my family owned any land, I always felt deeply connected to the lake and mountains, the muddy trails and mossy rocks. One thing my Grampa Joe always insisted on was having “the good corn” for supper—no grocery store corn for us. We'd ride in his Buick almost out to Weld, pull over between an old house and a big barn, and wait for the man to appear out of the garden. “Hi Joe, how many?” We'd wait by the car while he picked it for us. “Same day, that’s the only way to eat corn,” my Grampa would say. He had grown up working on farms with his family all around Franklin County.

But that was sweet corn. When I drove up to Norridgewock last spring for the first Cornference, I was going to learn about flint corn. I had worked on a vegetable farm and knew all about that, but didn't know the first thing about grain farming.

This gathering was about our native grain and its history, which is also the history of our land. There on a floodplain of the Kennebec River, where Norridgewock people once cultivated more than 1,000 acres of flint corn to ship through their massive trade network, at an address on the road bearing the same name as the 1724 massacre by the English that destroyed their community, we sat in a room and listened and cried and laughed about the power of seeds.

When I looked across the room and recognized the face of Conrad Heeschen, the sweet corn farmer from Wilton Intervale, I was overwhelmed. When his partner, Pam Prodan, told the story of Byron corn seeds finding their way to her via Will Bonsall and ultimately a shoebox under a neighbor's mother's bed, and the realization those seeds had initially been selected and bred on the same land she was farming, some 150 years back, I cried. I had never even touched a corn seed, and yet it had the power to bring me back, hard, to memories of my late grandfather and the land.

Understanding what has happened before us and what will happen after us in the place where we are is a big part of what it means to be alive. Real food from the land where you live brings all time to the present and puts it on your plate, to nourish you in that moment.

39

40