Just over an hour from the Research Triangle, the Yadkin Valley offers foothill beauty, celebrated wines, outdoor adventure, and a slower rhythm that feels worlds away from city life.

“ History settles into the soil here the way mist settles into the foothills. ”

Long before tasting rooms, hiking trails, or river access points appeared on maps, the Yadkin Valley was home to Indigenous peoples who lived, hunted, farmed, and fished along the winding river. Siouan-speaking tribes — including the Tutelo, Cheraw, Saponi, Saura, Catawba, and Cherokee — named the waterway Yattkin, meaning “place of big trees.” Trader Abraham Wood recorded the word in 1674, offering the earliest written glimpse into the region’s identity.

By the mid-1700s, Europeans began arriving in steady numbers. Fertile soil and abundant water drew German, Scotch-Irish, and English families westward from the coast and Piedmont. Among these early settlers were the Bryans, whose granddaughter Rebecca would marry Daniel Boone. The young Boone spent his formative years in the Yadkin Valley, where he learned frontier skills, raised a family, and developed the self-reliance that later made him a legend. He left the region in 1769 to explore the lands beyond the mountains, but the valley shaped the man who shaped the myth.

Following the Revolutionary War, the Yadkin Valley became one of the most populated areas in North Carolina. Communities clustered around the river, powering iron forges, grist mills, and burgeoning textile operations. When attempts to make the river navigable proved impractical, railroads arrived in the late 1800s, linking rural towns and spurring commercial growth. The region stepped into the modern era with the construction of Idol’s Dam in 1898 — the state’s first hydroelectric power plant — which energized Winston-Salem’s expansion and propelled new industries forward.

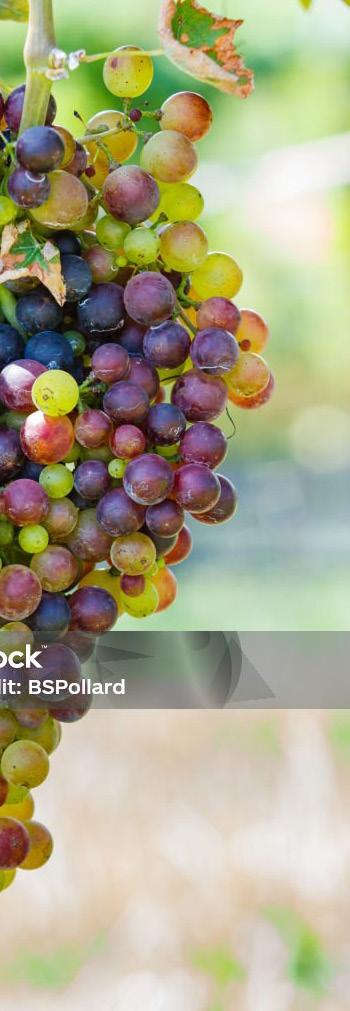

As the twentieth century progressed, the valley adapted again. When tobacco declined, the land itself offered a new direction. Sharing climate similarities with Bordeaux and soils akin to northern Italy, the Yadkin Valley revealed its potential for growing European-style grapes. Farmers and entrepreneurs planted the first modern vineyards in the late 20th century, and by the early 2000s, the region became North Carolina’s first federally recognized American Viticultural Area.

Today, the Yadkin Valley’s story remains one of resilience, reinvention, and a deep connection to the land — qualities that shape everything visitors experience here.

As the Yadkin Valley moved into the late twentieth century, another chapter began to unfold—one that would reshape the region’s identity and draw visitors from across the country. Long after mills quieted and railroad whistles faded, farmers looked again to the earth beneath their feet for possibility. They knew its strengths intimately: soil that had nourished families for generations, foothill slopes warmed by sunlight and cooled by mountain breezes, and a river that had sustained life for thousands of years.

What they didn’t yet know was that this land could also grow some of the most promising grapes on the East Coast.

When the Shelton brothers bought a foreclosed dairy farm at auction, their vision was bold, almost improbable. But they sensed that the same landscape once relied upon for tobacco, grain, and cattle held the potential for something new. With a climate echoing Bordeaux and soils reminiscent of northern Italy, the Yadkin Valley proved not just suitable for European-style grapes—it excelled at them.

That single decision rippled across the region. Vine by vine, ridge by ridge, the valley transformed. Today, more than 45 wineries rise from former fields, their tasting rooms overlooking hillsides where sunrise catches the silver-green shimmer of leaves after early morning dew.

Visitors see the quiet beauty—rosebushes marking each row, willow trees bowing toward reflective ponds, oak barrels stacked in cool cellars. But the reality is far more demanding, and far more interesting. At the Shelton-Badgett NC Center for Viticulture & Enology, students train in everything from microscopic vine diseases to the chemistry of fermentation. They learn that grape growing here is equal parts art and endurance: fending off Japanese beetles, managing humidity, preventing erosion, and pruning with the precision of a sculptor.

Inside the teaching winery, beakers clink, stainless-steel tanks hum, and young winemakers sharpen their craft. Their Surry Cellars label represents the valley’s forward momentum—a place where tradition and experimentation work hand in hand.

Sip a Chambourcin, and you taste warm foothill nights. Enjoy a Traminette, and you catch the crisp edge of mountain air.

Savor a Viognier, and you sense the same sunlight that once fell on ancient forests.

The valley didn’t try to replicate Napa or France. Instead, it let the land speak. And they listened.

With wine shaping one of the valley’s most vibrant modern chapters, visitors soon discover that its beauty doesn’t end at the vineyard fence.

Just beyond the tasting rooms lie trails that climb granite domes, rivers that curl past orchards and farms, and small towns where history is never more than a short walk away. The Yadkin Valley invites travelers to savor its wines, but also to wander, climb, taste, hike, and discover the many stories waiting beyond the glass.

You see Pilot Mountain before anything else—an unmistakable quartzite knob rising above the patchwork of farms and forests. Indigenous peoples once used it as a landmark, a guidepost on seasonal journeys. Early settlers knew it as a beacon when crossing the foothills.

Today, hikers approach it with the same sense of recognition. Trails wind around its flanks, each turn revealing a sweeping view of the valley floor. Peregrine falcons circle the cliffs; breezes carry the scent of pine and sun-warmed rock. From its overlooks, the vastness of the Yadkin Valley spreads out like an open book—every ridge and river a line of its story.

Step onto the Mountains-toSea Trail here, and you’re literally walking across North Carolina, one step at a time. Pilot Mountain is not just a destination; it’s a beginning.

If Pilot Mountain is the valley’s exclamation point, Hanging Rock State Park is its poetry. The moment you enter, the air feels different—cooler, greener, alive with the sound of falling water. More than 20 miles of trails twist through shaded forests and rocky ledges, leading explorers to five waterfalls whose names alone—Lower Cascades, Indian Creek, Tory’s Den—sound like chapters in a mountain tale.

The summit trail rewards you with a panorama that stretches for miles: layers of blue ridges fading into the horizon, with stone outcrops jutting into the sky like ancient sentinels. At sunset, the rock glows rose-gold, and the valley below softens into shadow.

Families wander the easier paths. Solo hikers seek out solitude. Adventurers push toward the cliffs. There’s a place in this park for everyone—and always one more hidden corner to discover.

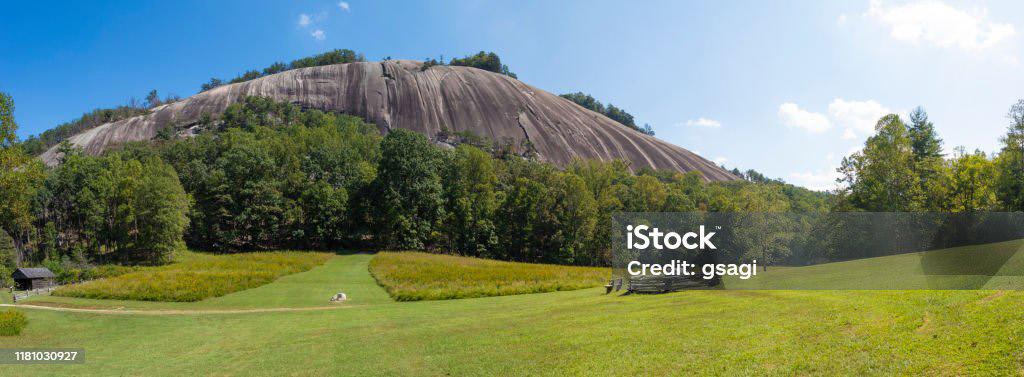

Then there is Stone Mountain, a giant granite dome that rises unexpectedly from the forest, as if the earth itself decided to surface for a better view. Approaching it feels almost cinematic—the trees suddenly part, and there it is, vast and silver, catching light in a way no photograph ever fully captures.

The loop trail takes you up, around, and beside this monolith. Along the way you’ll hear the rush of trout streams, clear and cold even in summer. Experienced anglers wade into the East Prong of the Roaring River, their lines flicking through the air, the forest muffling all sound except the water.

Here, a person can disappear into the quiet for hours. The granite dome watches over everything, patient and unchanging.

The Yadkin River curls through the valley like a long, winding sentence—shaping farms, carving banks, and gathering stories from every community it touches. On the 125-mile Yadkin River State Trail, paddlers drift past steep bluffs, waving grasses, and quiet coves where turtles slip off logs into the water.

Some stretches feel timeless, as if the river remembers the feet that once walked its banks long before kayaks and canoes. Early morning brings mist that hovers just above the surface; afternoons sparkle as sunlight glints off the water. It is peace in motion.

The Yadkin Valley is a haven for anglers. This is not by accident, but because its waters are as varied as its landscapes. The Yadkin River holds bass, catfish, and sunfish in its calm pools. High Rock Lake, a favorite among tournament anglers, reliably produces trophy-sized largemouth bass.

Cold, clear creeks like the Mitchell, Ararat, and Big Elkin slice through the foothills, ideal for trout who thrive in untouched, oxygen-rich waters.

In the Yadkin Valley, every trail, river bend, and mountain edge carries a stoy. Some storiez are centuries old, some just beginning, many waiting to be discovered by the next traveler who steps off the highway and follows curiosity into the foothills.

This is a landscape that invites exploration.

A place where the wild and the peaceful live side by side.

A valley that never stops revealing itself, no matter how many times you return.

While hikers and paddlers follow the valley’s more dramatic landscapes, cyclists experience its heartbeat. Rolling roads dip into hollows and rise to gentle ridgelines. Farmland stretches out in quilt-like patches.

Old barns lean gracefully with age. Wind moves through meadow grasses. And the quiet—interrupted only by the rhythmic hum of tires, reminds riders why the Yadkin Valley feels like home even on a first visit.

may be known for its vineyards and mountain views, but its soul lives in its small towns, in the places where sidewalks still feel like gathering spots, porches double as welcome mats, and traditions are carried forward with quiet pride.

Whether you wander through Elkin, Dobson, or Mount Airy, each town offers its own rhythm, shaped by generations who learned to live from the land and from one another.

Strolling along Mount Airy’s main street feels like stepping into a story you already know. It is lined with references to Andy Griffith. It is a city filled with friendly waves, familiar architecture, and a pace that invites you to linger. Murals brighten tucked-away alleys, and the sound of conversation drifts out of doorways as though the town itself is happy to see you.

Dobson moves to a steadier, agricultural rhythms. The sounds of farms, vineyards, and open fields marking the landscape. In home kitchens, the stories run deep. Sonker recipes are passed down like heirlooms, each with its own subtle variations: more fruit here, a thinner batter there, the occasional swirl of spice known only to one family.

Elkin is a trail town at heart. It is a place where river, footpaths, and historic streets all meet. It’s impossible to miss the sense of welcome here. The tradition of sonker feels especially alive, woven into gatherings, celebrations, and moments that call for something warm on the table.

Each region and city boasts its own Sonker ... A Sonker is the dessert that defies strict definition. It is part cobbler, part baked pudding, wholly its own. Some believe the fruit “sinks” into the batter, giving rise to the name. Others point to the region’s Scots-Irish roots. Truthfully, no one knows for sure, and no one minds.

A sonker is always shared. It’s a dish that carries stories with it.

Stories of family tables, seasonal fruit, and the simple pleasure of warm dessert on a cool evening.

A Simple Surry County Sonker Recipe

Ingredients

4 cups sliced peaches, berries, or thinly sliced sweet potatoes

1 cup sugar (adjust to taste)

1 cup all-purpose flour

1 cup milk

½ cup melted butter

1 tsp vanilla extract

Pinch of salt

For the Dip

1 cup whole milk

½ cup sugar

1 tsp vanilla

Instructions

Preheat oven to 350°F.

Toss fruit with half the sugar.

Whisk flour, remaining sugar, milk, butter, vanilla, and salt until smooth.

Pour batter into a deep baking dish; spoon fruit over top (don’t stir).

Bake 50–60 minutes until golden and bubbling.

Warm the dip ingredients on the stove until sugar dissolves.

Serve warm sonker with a spoonful of dip.

Rustic. Homey. Impossible to resist.

Here, history lingers in river bends and in the shadow of ancient trees. Artists and vintners continue traditions of craft. Bakers pass down recipes that connect generations. And visitors from the Triangle find themselves returning again and again, each drawn by the valley’s peaceful rhythm and the way it makes the world feel a little lighter.

Whether you come for an afternoon or for a weekend, the Yadkin Valley welcomes you with stories as deep as its river and beauty that stays with you long after the drive home.