Just over an hour from the Research Triangle, the Yadkin Valley offers foothill beauty, celebrated wines, outdoor adventure, and a slower rhythm that feels worlds away from city life.

“ History settles into the soil here the way mist settles into the foothills. ”

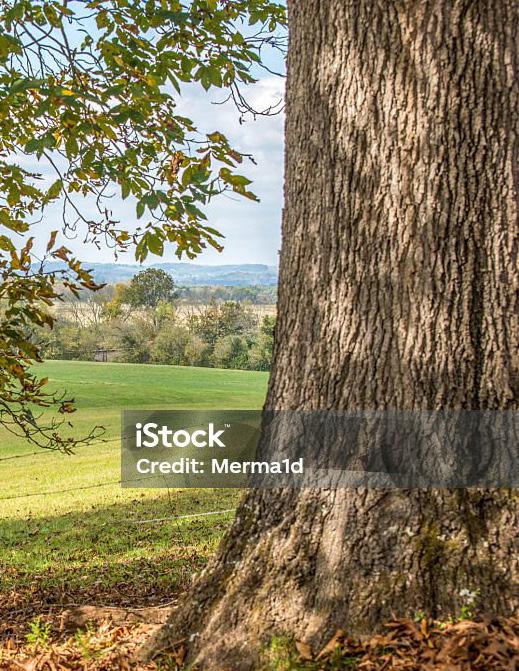

Long before tasting rooms, hiking trails, or river access points appeared on maps, the Yadkin Valley was home to Indigenous peoples who lived, hunted, farmed, and fished along the winding river. Siouan-speaking tribes — including the Tutelo, Cheraw, Saponi, Saura, Catawba, and Cherokee — named the waterway Yattkin, meaning “place of big trees.” Trader Abraham Wood recorded the word in 1674, offering the earliest written glimpse into the region’s identity.

By the mid-1700s, Europeans began arriving in steady numbers. Fertile soil and abundant water drew German, Scotch-Irish, and English families westward from the coast and Piedmont. Among these early settlers were the Bryans, whose granddaughter Rebecca would marry Daniel Boone. The young Boone spent his formative years in the Yadkin Valley, where he learned frontier skills, raised a family, and developed the self-reliance that later made him a legend. He left the region in 1769 to explore the lands beyond the mountains, but the valley shaped the man who shaped the myth.

Following the Revolutionary War, the Yadkin Valley became one of the most populated areas in North Carolina. Communities clustered around the river, powering iron forges, grist mills, and burgeoning textile operations. When attempts to make the river navigable proved impractical, railroads arrived in the late 1800s, linking rural towns and spurring commercial growth. The region stepped into the modern era with the construction of Idol’s Dam in 1898 — the state’s first hydroelectric power plant — which energized Winston-Salem’s expansion and propelled new industries forward.

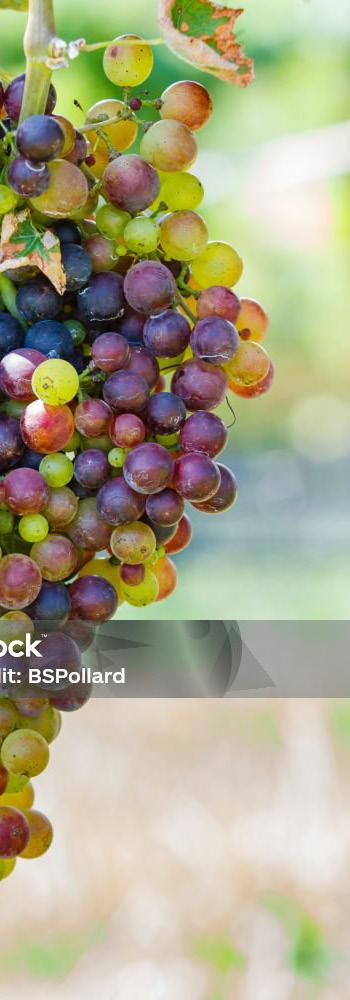

As the twentieth century progressed, the valley adapted again. When tobacco declined, the land itself offered a new direction. Sharing climate similarities with Bordeaux and soils akin to northern Italy, the Yadkin Valley revealed its potential for growing European-style grapes. Farmers and entrepreneurs planted the first modern vineyards in the late 20th century, and by the early 2000s, the region became North Carolina’s first federally recognized American Viticultural Area.

Today, the Yadkin Valley’s story remains one of resilience, reinvention, and a deep connection to the land — qualities that shape everything visitors experience here.

As the Yadkin Valley moved into the late twentieth century, another chapter began to unfold—one that would reshape the region’s identity and draw visitors from across the country. Long after mills quieted and railroad whistles faded, farmers looked again to the earth beneath their feet for possibility. They knew its strengths intimately: soil that had nourished families for generations, foothill slopes warmed by sunlight and cooled by mountain breezes, and a river that had sustained life for thousands of years.

What they didn’t yet know was that this land could also grow some of the most promising grapes on the East Coast.

When the Shelton brothers bought a foreclosed dairy farm at auction, their vision was bold, almost improbable. But they sensed that the same landscape once relied upon for tobacco, grain, and cattle held the potential for something new. With a climate echoing Bordeaux and soils reminiscent of northern Italy, the Yadkin Valley proved not just suitable for European-style grapes—it excelled at them.

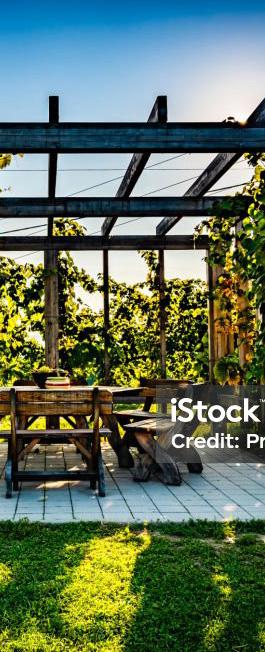

That single decision rippled across the region. Vine by vine, ridge by ridge, the valley transformed. Today, more than 45 wineries rise from former fields, their tasting rooms overlooking hillsides where sunrise catches the silver-green shimmer of leaves after early morning dew.

Visitors see the quiet beauty—rosebushes marking each row, willow trees bowing toward reflective ponds, oak barrels stacked in cool cellars. But the reality is far more demanding, and far more interesting. At the Shelton-Badgett NC Center for Viticulture & Enology, students train in everything from microscopic vine diseases to the chemistry of fermentation. They learn that grape growing here is equal parts art and endurance: fending off Japanese beetles, managing humidity, preventing erosion, and pruning with the precision of a sculptor.

Inside the teaching winery, beakers clink, stainless-steel tanks hum, and young winemakers sharpen their craft. Their Surry Cellars label represents the valley’s forward momentum—a place where tradition and experimentation work hand in hand.

Sip a Chambourcin, and you taste warm foothill nights. Enjoy a Traminette, and you catch the crisp edge of mountain air.

Savor a Viognier, and you sense the same sunlight that once fell on ancient forests.

The valley didn’t try to replicate Napa or France. Instead, it let the land speak. And they listened.