Case Study: Addressing the Rhinoceros in the Room

Tyler Linnehan Emerging Professional

Rhino 3D – now well into its eighth iteration – is a remarkably versatile design software which offers its users unmatched control over geometry, composition, and design complexity. Its propensity towards precision through splines and “non-uniform rational b-splines” (NURBS) geometry has placed it – in my opinion – at the zenith of 3D design software. Before, in its sixth iteration, users with a proclivity for the bulbous and blobby might have been better off looking to “Blender” to achieve their globular design dreams. But across its last two generations, Rhino’s newest design tool, SUB-D Modeling, has allowed it to regain its competitive edge as one of the world’s most flexible design tools.

SUB-D Modeling is a deeply complex, algorithmic interpolation process. From the user’s perspective, however, it appears as one of the simplest and most freeform methods of modeling; simply extrude your curves into surfaces (or polysurfaces) and then massage them into the desired location. The smoothed SUB-D objects bend and blend effortlessly into place. Substantial alterations are never more than a few clicks and drags away. The entire process evokes a nostalgic sense of childlike play and creativity. It goes without saying that these imprecise, non-Revit forms exist far from most of the work that we do as architects at LS3P. However, I recently found myself in a rare position in which these exact techniques were not only useful, but essential, to the creation of a small architectural intervention on a large project. This case study revolves around that ongoing experiment.

The Problem

Kelly Gilreath, the Design Leader of the Charleston Office’s Interiors Team and a crossdisciplinary mentor, asked me to assist in a large interior renovation project. My sole purpose on this project was to design a new architectural intervention which would sit in the large open atrium/lounge in the center of the office plan. This would be a series of extremely “designed” forms which would wrap and enclose – at key moments –a new employee’s café, kitchen, lounge, interior garden, and gathering space. The entire atrium/lounge was approximately 100’ x 38’. In the center of this area was an approximately 31 ½’ x 28’ subspace, which was to hold the largest, central component of our design.

Through inspiration from a series of bold precedents as well as in continuity with the aesthetic language that the interiors team had established in the adjacent spaces, we arrived quickly at our concept, and I began sculpting the forms.

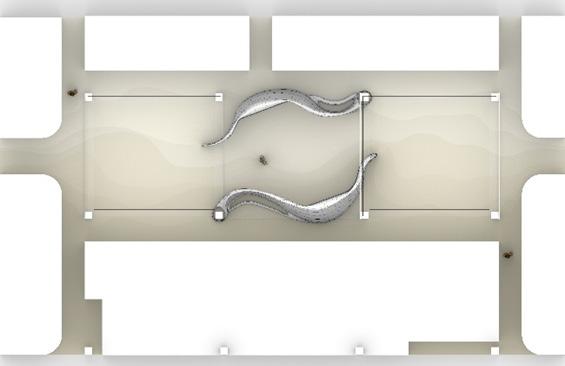

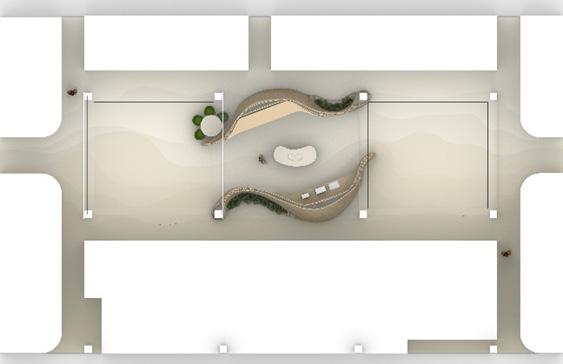

Floor Plan: Lounge (Left Under Skylight), Atrium (Center), Interior Garden (Right Under Skylight)

8

The Solution

The team and I met to sketch up the general shape of the forms. We conceived two semi-mirrored, smooth bracket shapes which would enclose the bulk of the necessary café, kitchen, and food storage elements, with a central – similarly designed – island. We started affectionately referring to this form as “The Amoeba.”

This architectural object was conceived as a series of stacked, evenly spaced, lighthued wood slats. Here, Rhino’s SUB-D modeling allowed me to rapidly produce a series of iterations on these forms. Through some simple contouring, extruding, and offsetting of surfaces, we then produced our slats as projections around the form’s “isographies.”The nature of these slats being polysurfaces meant that we could then find key moments in which their profiles could wrap and bend around tertiary design elements such as floor planters and pop-out benches. Simultaneously, this afforded us a basic understanding of the challenges that we will need to address during manufacturing (a process that is only just beginning).

Iteration

of the Amoeba form which wraps around the adjacent columns and peels out for planters at the floor

The central Amoeba form, with its café, kitchen, and food storage program blocked in, with its wood slat materiality

In the two adjacent spaces, this same design language was used to two varying degrees. On the garden side of the atrium, a smattering of more cloud-like versions of this object creates spaces for larger plants and trees which vie towards the skylights above. These elements also act as seating and, at certain times, hug and accentuate more traditional furniture schemes. Across the room, a more rational and (respectively) traditional layout of furniture exists as a space for employees to gather. However, the wood slat design still wraps itself around the outer columns and provides for some smaller planters.

The Payoff

While this project is still in development - even the design of the architectural element is still undergoing some small changes - it has already been an immensely rewarding experiment in computational design and advanced software use at LS3P. I have spent the bulk of both my academic and occupational career working specifically in Rhino. While Revit is the fundamental design software used in our work here, there are specific design challenges that it is ill-equipped to tackle.

Conceptualizing a complex and unique architectural design like the Amoeba, and then, being able to draw up, 3D model, refine, and iterate upon it rapidly, were inextricably linked to the computational affordances of Rhino 8.

Alongside this, the entire experience, thus far, has been an immensely rewarding experience for someone who has a deep affinity for the software and its creative capabilities.

Top: The current Amoeba iteration and its “Amoebites” in both adjacent rooms, in plan

Bottom: The current Amoeba iteration and its “Amoebites” in both adjacent rooms, in isometric

The Opportunities

As stated, Rhino can never truly be a replacement for our standardized, buildinginformation-sensitive, and collaborative software like Revit. But it can act as an unrivaled conceptual tool for explorations in creative, complex, and standout design on large building projects and as a spectacular design tool for small or manufacturing-dependent projects. I would love to see Rhino increase in ubiquity at LS3P and for its immense capabilities for design excellence, creativity, and innovation in architectural form and space to become more widely recognized.

Tyler Linnehan is an Emerging Professional in LS3P’s Charleston office, bringing a strong foundation in architectural design and a forward-thinking approach to practice. He holds a Master of Architecture from Cornell University and a Bachelor of Architecture from Ball State University, and has been recognized with multiple student design awards. Tyler’s prior experience includes civic and multifamily projects with firms in New York City and Phoenix, AZ. His expertise in computational design, advanced 3D modeling, rendering, and Adobe Creative Suite enhances his ability to contribute innovative, visually compelling solutions that support the firm’s design excellence.

The Amoeba graveyard; some of the iterations that were explored in the process of arriving at our design