MEGALITH

I.

Alexi Kenney, violin

The Spin Fivers; James Baker, conductor

Michael Nicolas, cello

Mikko Luoma, accordion

Jacqueline

Executive Producers: Fred Sherry and Carol Archer

Tracks 1-4 Orchestra Contracted by Fred Sherry

Tracks 1-5, 9 Produced and Engineered by Ryan Streber

Tracks 1-5, 9 Edited by Ryan Streber and Charles Mueller

Track 6 Engineered by Shae Brossard

Track 7 Engineered by Jeremy Tressler

Track 8 Engineered by Cameron Wiley

Album Mastered by Ryan Streber

Music Published by C.F. Peters

SPIN 5 (2006)

Alexi Kenney, solo violin

Barry Crawford, flute

Stephen Taylor, oboe

Alan R. Kay, clarinet

Rebekah Heller, bassoon

Zohar Schondorf, horn

David Byrd-Marrow, horn

Brandon Ridenour, trumpet

Marshall Gilkes, trombone

Dan Peck, tuba

Mike Truesdell, marimba/bass drum

Sae Hashimoto, vibraphone/guiro

June Han, harp

Steven Beck, piano

Dov Scheindlin, viola

Caeli Smith, viola

Eric Bartlett, cello

Sophie Shao, cello

Greg Chudzik, contrabass

James Baker, conductor

BUTTONS AND BOWS (2001)

Michael Nicolas, cello

Mikko Luoma, accordion IRIDULE (2006)

Jacqueline Leclair, solo oboe

Natalina Scarsellone, flute/piccolo

Charlotte Layec, bass clarinet

Sofia Yatsyuk, violin

McKinley James, cello

Charles Chiovato Rambaldo, mallets

Mai Miyagaki, piano

Mark Powell, conductor

ZOE (2012)

Christopher Otto, violin

Ari Streisfeld, violin

John Pickford Richards, viola

Kevin McFarland, cello

Miranda Cuckson, viola

Jay Campbell, cello MEGALITH (2014)

Peter Serkin, piano

Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra

Matthias Pintscher, conductor

SCHERZO (2007)

Tengku Irfan, piano

Spin 5 recorded at The DiMenna Center for Classical Music, New York, NY, Oct 4, 2023

Buttons and Bows recorded at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY, April 25, 2022

Iridule recorded at Studio Pierre Marchand, Montreal Canada, December 11, 2023

Zoe recorded live at Italian Academy-Columbia University, New York, NY, October 30, 2014

Megalith recorded live at Ordway Concert Hall, St. Paul, MN, April 11, 2015

Audio of "Megalith" from YourClassical®, a service of Minnesota Public Radio®.

(c) 2015 Minnesota Public Radio®. Used with permission. All rights reserved Scherzo recorded at Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, NY, May 9, 2022

Spin 5, Buttons and Bows, Iridule, Zoe, and Megalith are world premiere recordings

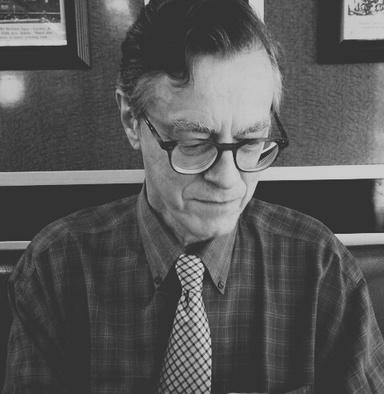

Charles Wuorinen (1938-2020), who until the age of 6 was not sure whether he wanted to be an astrophysicist or a composer, amassed a catalog of nearly 300 works in every genre. He wrote the operas Haroun and the Sea of Stories with James Fenton, and Brokeback Mountain with Annie Proulx. In 1970, at 32, Charles was the youngest composer ever to win a Pulitzer Prize for his groundbreaking and timeless fulllength purely electronic work, Time’s Encomium. He later became one of the first composers to win a MacArthur, the “genius award” - and Charles was, as a matter of fact, a genius.

The son of John Wuorinen, chairman of the Columbia University history department, and Alfhild Kalijarvi, a biologist, young Charles was accepted at Harvard, Princeton and Yale, but his parents were against his leaving New York, and he received his MA from Columbia in 1963.

With Harvey Sollberger, he founded the Group for Contemporary Music in 1962. It was the first contemporary music ensemble based at a university and run by composers. “The Group” as it was known, commissioned and premiered hundreds of works and cultivated a new generation of performers. It consisted of the finest musicians in New York, many of whom became his longtime friends, including cellist, Fred Sherry; percussionist, Raymond DesRoches; pianist; Robert Miller; and oboist Josef Marx. Together they worked with major composers such as Boulez, Babbitt, Cage, Carter, Copland, Davidovsky, Feldman, Takemitsu, Varèse, and Wolpe.

Wuorinen went on to be championed by Peter Serkin, Ursula Oppens, Oliver Knussen, James Levine, Michael Tilson Thomas and Peter Martins, who commissioned Charles for seven ballets for the New York City Ballet.

As a conductor and pianist, he appeared with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, New York Philharmonic, L.A. Philharmonic and the San Francisco Symphony.

I first met Charles at the scandalous premiere of his Concerto for Amplified Violin and Orchestra performed by Paul Zukofsky and the Boston Symphony at Tanglewood in the summer of 1972. I was 18, and I thought - through this electric and electrifying music - I was experiencing the very voice of God. Charles became my teacher and mentor that fall. Selflessly, he literally taught me how to compose and showed me what it meant to be a composer. In his book Simple Composition, Charles gave advice to young composers:

I would caution the beginning composer against resisting the necessary and healthful discipline that must always precede the acquisition of real skill and understanding…after some decades… an artist may truly discard all method, ‘learn to unlearn his learning,’ and function fully in the direct interplay between his own intuition and the nature of the world at large… [The] seductive notion of self-expression, merchandized to those who have as yet no self to express, is the most dangerous and destructive idea to corrupt a young composer. Remember always that freedom can be had only if it is earned…freedom means nothing unless there are co-ordinates, fixed and clear, whose very immobility allows the one who is free to measure the unfetteredness of his flight. His work was everything to him. The only time I ever saw Charles take a day off was some time in 1973 when he was simply too hung over to work because the night before was spent at Igor Stravinsky’s apartment drinking with Robert Craft and Stravinsky’s widow, Vera who gave Charles the master’s deathbed sketches and asked him to make something out of them. These became the basis of his orchestral work “A Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky.”

Charles Wuorinen was a titan whose music will stand the test of time. It is utterly original and uncompromising. It is a generous music that keeps giving - more and more upon repeated hearings.

—Tobias Picker

Perhaps I am not the most likely composer to write in memory of Charles Wuorinen but, as different as we are, it is impossible for me not to admire his compositional virtuosity, mercurial orchestration and sheer productivity. We met now and then through Howard Stokar, my friend and personal representative and Charles’ companion of many years. Charles struck me as a man of lucid intelligence and firm convictions. I just listened for the first time to his “A Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky.” The last movement, Coda, ends with an F major triad in the harp, piano and winds, leading to G doubled in 5 octaves from Contra Bass to piccolo with one D - G fourth in the chimes. This cadence, reminiscent of late medieval music, after 5 movements of extremely complex serial music came as a shock. It struck me as the work of a composer in a basically non-tonal language willing to make an emphatic, unexpected ending. Bravo, Charles.

—Steve Reich

Charles was always inspiring and invigorating, most of all through his challenging but also delightful music. In 1970 he encouraged a group of rag-tag musicians to form their own group with no official sponsorship and so Speculum Musicae was born. Not only did he encourage the group, he supported me as a musician and as an incoming member of the previously all-male Century Association.

Charles was a composer who wrote notes on paper, but when I asked him about electronic music, he answered that he liked the variability in the human interpretation of his notation. His music is endlessly fascinating, and a source of joy and wonder to me every day.

—Ursula Oppens

The music world had trouble keeping up with Charles Wuorinen. He started out as “the angry young man ” and continued moving up the ladder to “ an unequaled creator.” His music always triggered a powerful response, be it booing or standing ovations.

In the spring of 1967, when I was 18 years old, Jack Glick, a violist and a good friend, got me a job playing with The Group for Contemporary Music. Showing up early to the first rehearsal I encountered a person with a cigarette holder clamped between his teeth, warming up with Hanon exercises at the piano. He rushed the tempo until he gave up and executed a forearm smashed cluster which was followed by another Hanon exercise. That was Charles Wuorinen.

In the over fifty years I continued performing with Charles, that image remained. At the piano or the podium Charles got what he wanted: fast and brilliant performances of his work.

Many of the outstanding musicians featured on this album worked with Wuorinen, and their authentic and energetic interpretations lead the listener to an appreciation of the composer ’ s mastery.

—Fred Sherry

Special thanks to Caroline Cronson of Works & Process at the Guggenheim for her personal advocacy and generous support. The recording of Spin 5 was made possible by a grant from the Ann & Gordon Getty Foundation and the assistance of William Anderson at the Roger Shapiro Fund for New Music. Gene Caprioglio, who looked after Wuorinen's music so thoughtfully at C.F. Peters, was always responsive and helpful. The brilliant producer Ryan Streber and Jessica Slaven at Oktaven Audio saw this album through with Wuorinen's champion, cellist Fred Sherry.

—Carol Archer

In memory of Charles Wuorinen (1938–2020)

Peter Serkin (1947–2020)