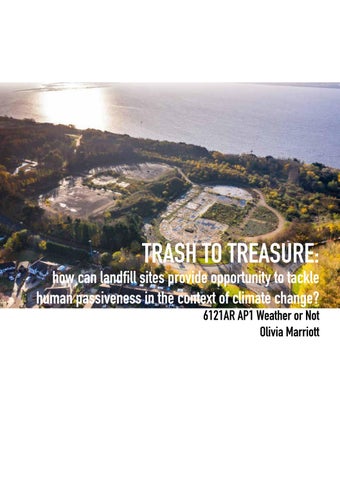

TRASH TO TREASURE: how can landfill sites provide opportunity to tackle human passiveness in the context of climate change? 6121AR AP1 Weather or Not Olivia Marriott

contents 3 introduction 4 how can we stop passiveness? 5 reclaiming methane 7 creating architecture for the future 8 conclusion 9 bibliography 10 image refrences

It is obvious that we need to find alternate energy solutions to prolong the impending effects of climate change. There are a variety of reasons to explain why we as humans act passively towards climate change. These reasons include distance and dissonance (Stoknes 2016), suggesting that part of the problem is that we aren’t connected to where our energy comes from and how global warming could po tentially affect our lives. With over 500 landfill sites in the UK, harnessing methane energy and making these areas an opportunity for people to see and understand where their energy is coming from could encourage people to be less passive about climate change, and the implications of using finite energy sources. A huge part of our problem is that we are exhausting our finite supply of non-renewable energy sources and are also stuck in a constant cycle of consuming and then disposing, as evidenced by the 14 million tonnes of waste that we put into landfill every year in the UK (DEFRA, 2019). A way to repurpose much of this waste is by harvesting the methane energy produced in the deterioration of this waste, rather than let it be released slowly as a greenhouse gas and contribute further to global warming. It is estimated that globally we could generate 75 million kW^3 of methane energy per year (we are currently only harvesting about 10% of this) (Themelis N J. and Ulloa P A.,2007) , enough to power 20,000 average UK household. Methane is dependent on waste going to landfill; however, it provides us a second chance to try and reclaim some energy from what would otherwise be released as a greenhouse gas. This is a unique element of methane energy and could help to address major problems associated with climate change, one of the more prominent being human passiveness.

introduction 3

how can we stop passiveness?

A problem we face with existing architectural solutions to climate change is that we are passive in our approach; often we use energy efficiency strategies to make a building ‘okay’ in its wider environ ment. This isn’t good enough when considering how urgently we need to change our approach to new architecture; architecture has a duty to be responsive and adaptive to climate change, not just fulfil a brief to make the building acceptable. There is a need for a balance in this kind of architecture: it can be believed that “low-tech ecological architecture is mostly embraced by those who are already seduced by this way of thinking” (Ryghaug, M 2002) . The alternative appears to be trying to follow a high-tech, modernist appearance and using design strategies such as triple glazing, using copious amounts of insulation, and perhaps taking advantage of one source of renewable energy such as solar energy. In most of these scenarios, these strategies are not part of a cohesive design plan that uses energy efficiency tactics to influence the building aesthetically, but more as things that will help the building meet sustainability and energy criteria and also be socially acceptable in case of any criticism. An example of architecture that not only has can be considered ‘green’ in its building strategies but in its façade and relationship with the pub lic is the KMC Nordhavn Centre in Copenhagen by Christensen & Co arkitekter. This project is a soil treating centre – where soil displaced from other projects around Copenhagen is sent and treated for future use. The building has implemented energy efficiency strategies such as being entirely reliant on reuseable energy sources, some generated on site. The site and surrounding areas use geothermal energy, and the building uses solar panels to generate more electric ity- taking full advantage of the orientation of the site. It is also highly insulated and airtight meaning that it doesn’t require a lot of energy to heat (ace, 2014) . The appearance of the building is reflective of these environmental considerations also; the weathered steel façade in an undulating shape makes the relationship between the building and the environment homogenous (archdaily, 2014) . This is also really important when considering the human experience of this space. Although the function of this building could have been rationalised as a small office building and large workshop, a choice has been made that the narrative of the building should be reflective of the building and its surroundings, thus encouraging any visitor or user of the site to perceive that a buildings relationship to the environment should be far greater than fulfilling any energy-efficiency certifica tions. The effectiveness of this building suggests that the aesthetic impact of a building in relationship to its environment is very important – even on a subconscious level, one can acknowledge that the appearance of the building is harmonious with its wider context.

4

Architecture that is reactive against climate change comes from taking measures to be more sustainable and ecological, and challenging our passive attitude to climate change (Weissman, 2012) . An oppor tunity to do this could be by utilising methane energy – particularly in the context of landfill sites. An example that reclaims what was previously a landfill site is the Valdemingomez Forest Park in Madrid, by Israel Alba Estudio. The purpose was to transform a 272-acre area into a parkland with a cultural and educational facility, while extracting and using the biogas from the site (methane and carbon dioxide). Interestingly, the formation of the landscape for public use has been curated in a ‘layering’ system, which correspond to the contours of the landscape (made through landfill), as well as the system to collect the methane and reuse it as a renewable energy source (Archdaily, 2013) . This site could almost be a blueprint as to how we continue to reclaim landfill sites for multiple reasons – the first being how the methane extraction system is obvious and approachable by visitors. This creates a direct impact on the visitor, and the way that the unit is situated in the park makes it an interesting feature of the landscape and could be considered an attraction. Secondly, the site is actually extremely beneficial to users as well as the environment; physically, it provides the visitor respite from bustling life in central Madrid, as well as the pollution. This is particularly relevant in this context, as Madrid has been six times over the limit of healthy Nitrogen dioxide levels in the air on multiple occasions (Sánchez, E. and Sevillano, E G., 2018). This is an example of a project that responds to environ mental changes- as the pollutants within the area have begun to have a greater effect on people’s lives, a park has been created to provide a space with improved air quality, no traffic and no noise pollution. However, it can be argued that it is not enough for a project to only be responsive, it has to be boldly reactive or even innovative, with the capacity to predict what we will need from it before significant changes to the environment have happened. This ideology is applicable to the Festival Garden site, as the methane stored within the landfill does pose a threat to the environment and subsequently the wellbeing of local people if it is not collected and released from the site naturally.

reclaiming methane

5

Similarly, Ukubutha by Nicole Moyo is an imagined settlement that is completely centred around the use of biogas. The project is a se ries of varying sized domes, serving as community spaces, shops and dwellings. This works on a smaller level as well as being the fundamental part of the whole scheme. In each individual dwelling or shop, methane can be collected through rubbish or from human waste. The largest dome in the epicentre of the settlement collects methane and other biogases from the ground below, and produces energy on a larger scale for the whole village. In this particular con text, this settlement is used to mobilise slum communities and pro vide them with shelter and also to aid a cycle of growing plants and using the community’s waste to fertilise them (Crook, 2019). Although this small-scale infrastructure is extremely valuable in the context of mobilising a slum community, there are some limitations to this project. The project has not been specifically set on a landfill site, and potentially the waste of one household would not produce enough methane energy for itself. This is appropriate in this proposed project as its primary purpose is to house a community and assist with their existing livelihoods, not to take advantage of an energy source. The relationship between using a renewable energy source and creating a space that is reactive against climate change needs to be consid ered carefully; if the entire purpose of the project is to pioneer a new type of architecture that has been created to combat passiveness and educate people on climate change, it could be perceived has hypocritical or even counterproductive if it was not self-sufficient in terms of energy production and use (Bokalders, V. and Block, M.,2004).

6

creating architecture for the future

From previous points, it could be deduced that many existing architectural projects are only reactionary against climate change. This is helpful in stopping human passiveness as it uses architecture as a link between the climate, and the effect it has on us. However, being ‘reactionary’ implies waiting for a cause to react to. In the context of global warming, this isn’t enough. We need to be proactive and design for changes that we are almost certain will happen, such as the exhaustion of non-renewable energy sources, rising sea levels, rising global temperatures and the extinction of many species amongst many other things. Although all of these factors can be viewed as a ‘looming disaster’(Stoknes, 2016) which can contrib ute to human passiveness, viewing the reality of what the long-term effects of climate change will do to Earth could spur us into action. We are looking at a 10% rise in rainfall in the UK by 2100 compared to 1985 – 2005 (CarbonBrief, 2014) , and it is estimated that by 2100 sea levels could rise by 80cm, which would displace approximately 414,000 people from their homes (CCP, n.d) . A physical manifestation of this shocking statistic could help reduce the distance element of human passiveness in the UK, which would suggest that on a wider level, proactive architecture is a very effective way of combating human passiveness. A project that uses this strategy is Oceanix City, by BIG. This is a conceptual project that could potentially be used as a prototype in the future. It is a floating city, compiled of small er ‘villages’ that can withstand up to category 5 hurricanes (Gibson, 2019) , and is a solution to rehoming the inhabitants of coastal cities that will be displaced after sea levels have risen. Upon first glance, this project appears to be a ‘utopia’ of urban living; Oceanix city has lush green public areas, the capacity to harvest its own food and spaces for entertainment and leisure as well as being affordable. However, as a final solution to climate change, the overall effect is somewhat dystopian. Although pleasant living conditions, the place seems unidentifiable and lacks the character that naturally comes with living in a city. As a concept, this definitely has the capacity to stop people acting passively towards climate change; seeing a pos sible result of what future life may look like, especially as it is so different from current city life, could provoke people to start thinking actively about climate change. Although the context of this essay is to harness methane as an energy source, the notion of using ‘climate prototype’ architecture can be taken from looking at Oceanix City and applied to all projects that are trying to address human passiveness.

7

conclusion

It is clear that we need to start being more proactive and focused in our response to climate change, and absolutely take advantage of any possible energy sources – such as methane. It is imperative that we utilise all appropriate landfill sites to utilise methane as an energy source to stop it being released back into the environment as a greenhouse gas, thus contributing further to global warming. This means we should approach these sites similarly to how we need to approach climate change as a whole: urgently, whilst also ensuring that we are promoting long term sustainability through successful architecture and education on climate change. These sites also provide a great opportunity to revitalising otherwise abandoned or ‘hopeless sites’, as seen in the turbulent relationship between the Liverpool Festival Gardens site and the wider public’s use of it. As well as taking advantage of any potential methane energy sources, it is imperative that we start using architecture and design as a tool to combat human passiveness. As mentioned in previous examples, fostering a link between the architecture and the impact it has on its local environment is very im portant when encouraging people to think actively about climate change. This could look like public parks, educational centres or even buildings that serve the environment, such as the KMC Nordhavn Building, The most important factor of all architecture that has the intent to help the plight against climate change, is that it must make the user think about the context of the building in the envi ronment, thus encouraging a wider sense of awareness and responsibility around climate change.

8

bibliography

podcasts

TEDGlobal (2019) How to Transform apocalypse fatigue into action on global warming [podcast], 2019

Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/per_espen_stoknes_how_ to_transform_apocalypse_fatigue_into_action_on_global_warm ing/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

reports

Themelis N J. and Ulloa P A. (2007) Methane generation in landfills [online] June 2007

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (2019) UK Statistics on Waste [online] 19/3/20 Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

essays

Ryghaug, M (2002) Towards A Sustainable Aesthetics: Architects Constructing Energy Efficient Buildings Ph.D. thesis, NTNU

Weissman, D. (2012) Landfill Urbanism: Opportunistic Ecologies, Wasted Landscapes [online] 23/2/12 Available at: https://issuu.com/daweissman/docs/lu_split [Accessed 12/10/20]

Bokalders, V. and Block, M. (2004) The Whole Building Handbook: How to Design Healthy, Efficient and Sustainable Buildings. UK: Earthscan pp.547-8

webpages

Archdaily (2014) Soil Centre Copenhagen / Christensen & Co [online]

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/469885/soil-centre-copenha gen-christensen-and-co [Accessed 12/10/20]

Archdaily (2013) Valdemingomez Forest Park/ Israel Alba Estudio [online]

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/795780/valdemingomez-forest-park-israel-alba-estudio [Accessed: 13/10/20]

Architect’s Council of Europe (2014) KMC Nordhavn [online] Available at: https://www.ace-cae.eu/ [Accessed 12/10/20]

CarbonBrief (2014) How Much flooding is in the UK’s future? A look at the IPPC report [online] Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org

Climate Change Post (n.d) Coastal Flood Risk in England [online] Available at: https://www.climatechangepost.com/united-kingdom/ coastal-floods/ [Accessed 15/10/20]

Crook, L. (2019) Nicole Moyo’s waste-to-energy system will “mobilise communities in informal settlements” [online] Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/04/01/nicole-moyo-ukubutha-waste-energy-infrastructure/ [Accessed 13/10/20]

Gibson, E. (2019) BIG unveils Oceanix City concept for floating villages that can withstand hurricanes [online]

Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/04/04/oceanix-city-float ing-big-mit-united-nations/ [Accessed 16/10/20]

1 million women (2016) Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Why We Don’t Care About Climate Change [online] 8/3/16 Available at: https://www.1millionwomen.com.au [Accessed 12/10/20]

9

image references

cover

Ant Clausen (n.d) ‘Festival Gardens’ [online image]

Available at: https://iondevelopments.co.uk/projects/festival-gardens/ Accessed 17/10/20

page 3 (all images)

Available at: http://www.strawberryfieldsart.com/story5.asp Accessed 17/10/20

page 4 (all images)

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/469885/soil-centre-copenhagen-christensen-and-co/52e06863e8e44e9f140001ea-soil-centrecopenhagen-christensen-and-co-photo?next_project=no Accessed 17/10/20

page 5 (all images)

Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/795780/valdemingomez-forest-park-israel-alba-estudio/57e3424ce58ecebef8000ab0-valdemingomez-forest-park-israel-alba-estudio-site-plan?next_project=no Accessed 17/10/20

page 6 (all images)

Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/04/01/nicole-moyo-uku butha-waste-energy-infrastructure/ Accessed 18/10/20

page 7 (all images)

Available at: https://big.dk/#projects-sfc Accessed 19/10/20

10