Art can be considered as a product or a response of its context, and thus interpreted as a reflection of society and culture at any given time, and more specifically how art has been consumed and perceived by the masses. The journey towards ‘modern’ art, particularly post World War Two is greatly valuable in expressing how public attitude towards art has changed, and how this can be considered indicative of society at any given point. In the 19th century, art remained on a pedestal for the poorer classes, and was not easily accessible. The National Gallery was created as a concept in 1824, but was not open to the public until 1838, and it was built with the idea that it would be accessible by all in the heart of London, whether you arrived by carriage or foot (The National Gallery, N.D). However, the National Gallery appears to be an exception in the Victorian era, many other galleries and artistic spaces were classist, as art had a direct correlation with wealth; this meant that the profit made from making exhibition spaces exclusively for the middle and upper classes was not deemed as important as allowing art to be accessible by all (Helmreich,2017). Furthermore, the renowned Victorian art movement ‘romanticism’ further dismissed many from the art world. This movement glorified simple, working class lifestyles yet completely ignored the reality of 70-80% of the population (Steinbach, 2019) who did not have the luxury to take up painting as a hobby or the ability to go and view these artworks in an establishment. Impressionism and Post-impressionism as artistic movements focused more on capturing fleeting moments of serenity, enjoyment and reflection yet still focuses on ‘everyday’ situations and scenery. This is exemplar of pre-war society in Britain; art at this point is not a medium for the masses to convey their emotions and express their feelings towards society. Despite the obvious aesthetic progression from roman ticism and realism movements, impressionism and post impressionism are still very consumable and desirable for the elite few who can afford to collect art. The commencement of two world wars in Britain saw a monumental shift in art styles and the emotions behind them, which is perhaps a reflection of the turmoil Britain itself was feeling. War had obvious consequences on society physically, emotionally and financially, and this upheaval seen in the country was reflected in new art movements such as Expressionism, Cubism, Constructivism and Surrealism. These move ments are far bolder, experimental, and aggressive in style, reflecting upheaval both morally and societally caused by war. However, public engagement with art peaked with the influence of American culture post war. Suddenly, capitalism, consumerism and propaganda were the driving forces behind much art, with Pop Art as an example, all of which had a direct relationship with everyday life. The drive for the “American Dream” became symbiotic with monotony and sameness and led to huge cultural backlash, in movements such as deconstructivism, punk and fem inism, which in turn caused huge waves in the art world. Moving into the present day, all predispositions towards art and the parameters in which it should exist have mainly disappeared. There is a general consensus that art should be accessible by all, with more galleries and museums offering free entry and exhibitions than ever before, art and design as part of the national curriculum, and with interactive projects such as Antony Gormley’s Field, and schemes such as the National Saturday Club (art and design). Despite this, along with new-found creative freedom for everyone, comes polarising response. The series of movements for art and design post war has led to an eclec tic idea of what actually constitutes art, and people are not afraid to be vocal about what doesn’t fit their template of what art can be, especially within the realms of contemporary art. This leads to a new phenomenon where the process behind a project and the response it initiates become just as valuable as the finished item on display in a gallery space. This progression from public perception of art as being something inaccessible and unreflective of everyday life pre-World War One, to the overwhelming influence of American culture post-World War Two, lead ing to a diaspora in artistic and cultural movements, thus changing how people have consumed and perceived art.

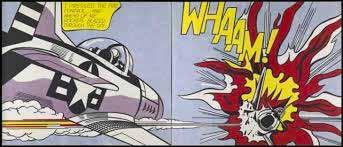

America hugely influenced art post-World War Two. First, it is important to under stand America’s thriving economy and cultural priorities after the war. Similar to the British art scene at the time, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and other Abstract Ex pressionists became immensely popular, as they portrayed a completely new type of imagery. Bold, reflective and impactful, with no rules as to geometry, shape or style (Britannica, 1998), this movement can be considered reflection of the trauma faced as a nation in the war, as well as foreshadowing the ambiguity of American status in an emerging Cold War. The freedom of shape and colour indicates that this is an emo tional release and is reflective of the uncertainty and trauma experienced as a nation. This movement can definitely be seen to be a human response to World War Two, but due to the limited accessibility of the art world at the time, it isn’t necessarily an ac curate indicator of public response to post-war art as a whole. There is no doubt that Abstract Expressionism was very impactful and popular globally, but the sphere remained fairly insular at this time, due to its centralisation around New York , and the general inaccessibility to art by the working-class person at this time. However, the economic success of America post-war massively increased public consumption in art, in a less obvious way. By 1949, America had 7% of the world’s population but 42% of its income (Willette, 2012). Factories that had been producing ammunition and other resources for the war effort, turned their efforts into creating consumer goods, which initiated a new type of buying culture. With servicemen returning home and starting their own families, consumerism rocketed. This led to what is now recog nised as the ‘American Dream’- a feeling of prosperity and the notion that a nice, new car, a suburban home and a kitchen fully equipped with all modern conveniences was achievable for all (white) Americans. Despite this positive impact on working class people, it is important to note that this cultural shift is underpinned entirely by materialism and patriarchy. This consumer boom and egotism led to the movement known as Pop Art. Key artists of this hugely influential movement were Andy Warhol and Ed Ruscha. This art movement captures the rise of consumerism and dominance America had in the world at this time, through powerful imagery of commonplace items and prevalent things in many peoples lives, infamously including gas stations, Campbell’s soup cans, and even imagery related to politics at the time. The direct relationship between Pop Art, consumerism and advertisement in America and Britain in the 1950’s and 60’s shows that public consumption of art is really changing; whether intentional or not, the public have far more access to a certain art and design movement, reinforcing the link between societal affairs, the type of art produced as a result, and in turn public consumption. It is important to note that there were dis crepancies between the Pop Art movements in the US and Britain. Britain recognised the significance of Pop Art in ‘manipulating people’s lifestyles’ (Tate, N.D) with regard to consumerism and politics and employed ‘irony and parody’ in its own recreation of the American movement, focusing more on the bold imagery and contemporary approach to colour and graphics, rather than using it as a form of propaganda (Tate, N.D). Unsurprisingly, the overwhelming ‘push’ of the American dream led to fierce backlash. People resented the monotony of this lifestyle, and the lack of identity and predictability caused by consumer culture. This is evidenced by the surge of cultural movements such as feminism – Betty Friedan’s ‘The Feminine Mystique’ (1963) highlighted how advertisement and a new culture of buying was negatively impacting the lives of housewives (Sanders, 2018). Postmodernism emerged as new art movements in the 1970’s and can be seen to be a direct reaction against utopian ideals of Pop Art, and as an embrace of multiple counter-movements. This shows that public consumption and perception of art underwent a massive shift between 195080 (Tate, N.D); modernism signified the explicit impact on society to art and design, whereas post modernism created a platform where any creative response to culture and society was acceptable, unbound by typical conventions of what art ‘should’ be.

Another factor which is insightful in explaining how and why our consumption and perception of art has changed over time, is the discovery of creativity as a neces sary part of human life. As previously mentioned, mainstream art movements are a response to society and culture at any given time, but on an individual level, the ability to create and express our emotions artistically can also be an indicator of how we are able to consume and perceive art. Most art movements follow a certain line of progression; a cause is identified (often reactionary from other art movements), individual artists become pioneers of the movement, this is then imitated by admir ers and hence the movement may grow exponentially, this creates a platform for a reaction and thus influences another ‘cause’ and subsequently the creation of other movements (Tate, N.D). In a traditional sense, art has been deemed ‘successful’ by either its monetary value, or how influential it has been. However, moving towards the present day, the definition of ‘successful’ art has become far more difficult. A WIRED article analyses the psychology behind how we make these distinctions by using neuroscience to assess the brain’s response when presented with a real Rembrandt painting and an imitation. The conclusion of this experiment was that creating judgements on the aesthetics of a piece alone is complicated, subconsciously “our response to [his] art is conditioned by all sorts of variables that have nothing to do with oil paint… these variables are capable of distorting our perceptions”(Lehrer, 2011). This shows that the greater context of any given piece of art can predetermine our response. These factors may include where we see it, if we are familiar with the artist, and what is being displayed alongside it. Later I will discuss how the specific typology of a space can influence our intake of art, but as an example, traditional galleries such as the National Gallery are very grand and almost imposing, therefore without even viewing the art inside, one may already believe it is very valuable and of a certain calibre. This could be problematic when one compares this to their own creative worth; the artists in display in these spaces are highly celebrated and often renowned for their impact on the art world, either for their talent or maybe for the pioneering of new movements, but this can alter how comfortable one feels in evaluating a piece of work based on their own judgement. This museumification of art has relaxed slightly as we have approached the present day, as we have a greater understanding of the importance of interaction with art, rather than just observing. As we have progressed and understood art and creativity to be necessary for hu man productiveness, this has naturally changed how we are able to consume and perceive art. As previously mentioned, the slide in art genres from modernism to post-modernism saw evolution in public response to art, suggesting art had become more perceptible for the masses. The recognition of “space and time” as a “cultural reference” by O’Dogherty revolutionises and amplifies the importance of the specta tor; “As we move around that space, looking at the walls, avoiding things on the floor, we become aware that the gallery also contains a wandering phantom frequently mentioned in avant-garde dispatches – the Spectator.”(O’Dogherty, 1976) The appre ciation that the observer is as important as the gallery itself is immeasurably valua ble – the notion that art is not just a showcase of an artist but is there to be interacted with and responded to is absolutely symbolic of post-modernism, and thus demon strative of how public perception and consumption of art has changed post war.

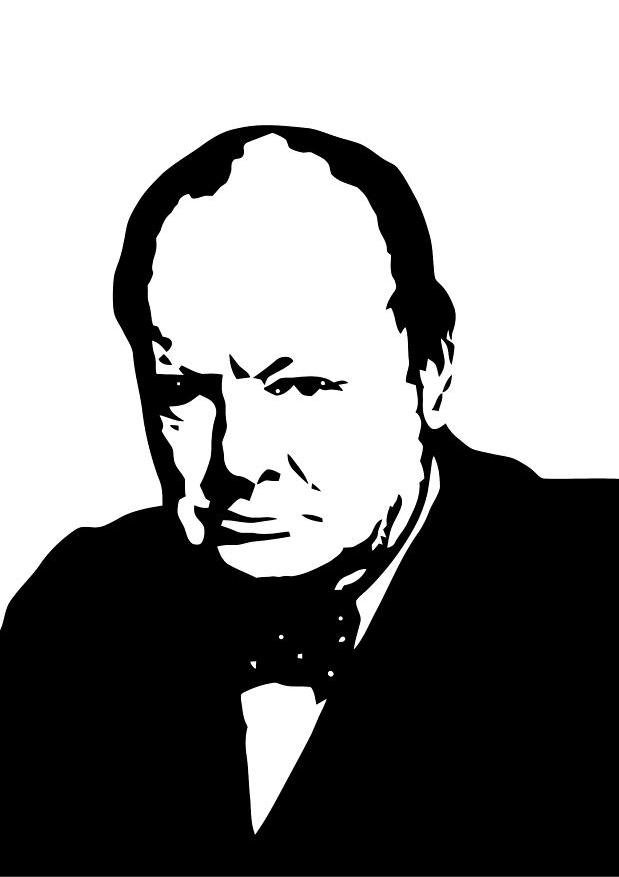

Outside of gallery spaces, our consumption of art is multifarious. We are now en gaged more than ever, and encouraged to interact on larger scale projects, at community and national levels. Art has become a celebration of culture and could be considered a service to the public; Liverpool Biennial is a key example of this, and it shows some interesting differences to the Festival of Britain in 1951. Although on different scales, the intention of both of these events are similar, but have huge differences in how they connect to the public. Liverpool Biennial brings artists from all over the world together through a particular narrative, the 2021 title being ‘The Stomach and the Port’(Culture Liverpool, 2020). Artists are encouraged to respond to the title creatively and inclusively, and the end result is an exhibition that is placed all around Liverpool, and encourages locals and people from further afield to connect with the city, the artists, and the art. This shows that Liverpool Biennial could also be considered a ‘service’ or a ‘gift’ to the people of Liverpool. The Festival of Britain in 1951 was also created to engage people; in the context of post-war Britain it was im portant to showcase the ‘Best of British’ and show advancements in technology, art and science to the rest of the world (Johnson, N.D). However, the amount of contro versy this project caused could suggest that the motivation behind it was entirely dif ferent to that seen in the ongoing Liverpool Biennial. It was condemned as a waste of money by much of the public and to some politicians of the time, who felt that the £12 billion (Johnson, N.D) spent on the fair could have been more beneficial elsewhere, especially as the country was still recovering from the war. The incoming Prime Minister at the time Winston Churchill apparently believed that the Festival of Britain was just entirely socialist propaganda and a celebration of achievements of the Labour party (Johnson, N.D). There is evidence to prove this, considering the majority of the festival site was demolished in the following six years, and only one building remains on the Southwark site. Although Churchill’s beliefs were rooted in political bias, it is likely that the Festival was a not a ‘gift’ to the public in the way that Liverpool Biennial is; it is an experience they can enjoy but ultimately is about showcasing British success and a subtle attempt at reinforcing British status on a national and international playground post-World War Two. This variation between the two events signifies how big projects are ‘given’ to the public, thus explaining further how our perception and consumption of art has changed post war. Overlooking the scale of the events, it is clear that Liverpool Biennial is far more focused on connecting individuals and communities through various projects, rather than purely representing Liverpool as a ‘successful’ city. This shows how public engagement has changed – people have gone from only observing art and design at large scales to becoming involved. The idea that art and design is ‘given’ to the public is a theme perpetuated in contemporary art and is an idea that had evolved massively in recent years.

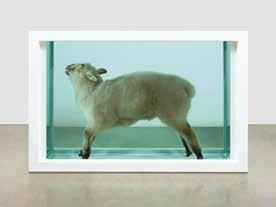

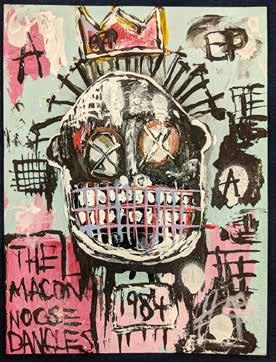

The infamous street artist Banksy is another key example of this. Under the guise of an onymity, he uses street art to comment on societal issues, including poverty, the effect of warfare, terrorism and homelessness. His crude and obvious dissatisfaction with society is represented directly in his work, which shows that his art is his way of expressing his grievances. The fact that he does this without revealing his identity show that his motiva tions are based on social commentary, causing a stir and spreading awareness rather than personal gratification. This shows that public perception of art has changed: it is accessible to all regardless of status – you can be an acclaimed artist even with no identity, as the con tent and reactive element of the art becomes more valuable than accreditation of the artists, whereas throughout other art ‘movements’, particularly modernist movements, a few key artists became the forefront of the movement. This could mean that personal agendas such as fame or profit could detract from the sincerity of the art produced as merely a ‘comment on society’ or a personal expression. Modern art movements provided a way to comment in society, as evidenced by the consumerist undertones of Pop Art and the subtle notions of confusion and uncertainty of Expressionism in a post-war world, but in the present day, art comments on society in a far more obvious and explicit way, as evidenced by Banksy. His medium, graffiti is also very telling on how attitudes towards art have changed. Graffiti is a form of responsive art – it often provokes strong opinions, as some see it as vandalism and a nuisance, whereas others see it as a valid art medium. Jean-Michel Basquiat was another artist who used street art as a way of commenting on society in New York in the late 1970’s. His work also highlighted capitalism and racism as massive social issues, which are themes still enormously relevant in today’s society. Interestingly, Basquiat did have close links with renowned pop artist Andy Warhol – suggesting that status was still extremely important as an artist, particularly when being a black artist and commenting on controversial topics (Mosny, 2008). This shows how public perception of art has developed with regard to street art. Bold, garish, but immeasurably valuable, the works of both Banksy and Basquiat pro vide a truthful account of society and culture relevant to their times, but Banksy benefits from the mystery surrounding his work and despite his anonymity his work is impactful, whereas Basquiat had to work harder to become involved in the modernist art scene at the time, evidenced in his closeness to the Pop Art Movement (Mosny, 2008). This shows that art was less accessible to the masses as status was still important, Basquiat was actively commenting on the negative impact of race and capitalism, even though Pop Art could be con sidered an extension of the ‘American Dream’ which perpetuated these issues to an extent.

As previously mentioned, the typology of a space can hugely influence our perception and consumption of art. Gallery spaces traditionally elude to the museumification of art, and the subject almost becomes out of reach for the observer. There are arguments for and against this approach to sharing art with the community; on one hand it ensures preservation and means we can admire pieces that we would not have been able to if it wasn’t for the curation of galleries or museums. On the other hand, the art is automatically on a pedestal that means the observer doesn’t feel like they can relate or connect to the piece with the same effect as the artist intended. Gallery spaces can become archaic over time, and the works in them reduced to mere artifacts if the user does not have the opportunity to engage with them. The Guggenheim Museum, New York and the Tate Modern, London, are both expres sive of how public consumption and perception of art has changed post war, from the completion of the Guggenheim in 1959 to the opening of the Tate modern in 2001. Frank Lloyd Wright was commissioned to build a gallery to accommodate Solomon R. Guggenheim’s extensive modern art collection in 1939, in the midst of modernist art movements. The Guggenheim was Wright’s final major building and could also be considered a fundamental part of his legacy. Guggenheims collection was centred mostly around American and European Abstract art (Guggenheim, N.D), and this is definitely reflected in the overall impact of the building, most obviously the dominating, spiralling atrium. The most compelling part of this project is how the user travels throughout the space – the idea is to start at either the top or bottom, and then descend or ascend in a spiralling motion around the rotunda. This makes the process of being a spectator directly linked to the journey through the space. Movement through the space becomes quite sociable, as at every point you can look across the atrium and see other people progressing on their journey. The Guggenheim is completely unique, and houses a multitude of notorious artworks, from the likes of Picasso, Kandinsky and Malevich. This space is so far removed from any suggestion of ‘stuffiness’ that might typically be associated with a traditional gallery or museum, and is so bright and airy inside that one does not approach the gallery with trepidation or bated breath like is common in a more austere gallery. This shows how, at the time of building, attitudes regarding pub lic consumption of art; the Guggenheim’s most beguiling feature is the ramp circulating the rotunda, which highlights the playfulness and interactivity of the space. People can freely enjoy the space and with such an attraction at the heart of it feel inspired to do so.

The Tate modern has a slightly different effect as to how people perceive and consume art in the space. Again, this museum is primarily dedicated to modern art, but its content leans more towards the contemporary than The Guggenheim. It has even been home to some extremely controversial post-modernist pieces, such as Lightning with Stag in its Glare by Joseph Beuys, and Behold by Sheela Gowda. The Tate Modern resides in what was Bankside power station, overlooking the Thames. What is remarkable about this gallery, is the sheer volume of the space, it is a sure companion of contemporary art; the space means that the observer has the freedom to move around and approach pieces from different angles, and each installation has the opportunity to be observed individually without the association of another project. The typology of the building provides a new and modern way for the public to consume and perceive art. Bankside power station was chosen despite its daunting scale, and its dominating presence on the Thames (Tate, 2012) made it an ideal opportunity to bring modern art to the masses. Herzog & de Meuron’s approach to the conversion was centred entirely around how users will apprehend the space both internally and externally; as previously mentioned, the sentiment of giving art as a ‘gift’ to the public is something that has evolved as we approach the present day, but the birth of the Tate Modern was definitely in keeping with this. A driving force behind its creation was that it should serve the Bankside and revitalise a disused building for the celebration of modern art and giving people the opportunity to look at this freely. This is evident in projects such as Michael Craig-Martin’s ‘Swiss Light’, which was intended to symbolise “the birth of the gallery and the reincarnation of Bankside”(Tate, 2012). Throughout the interior spaces, light and views are an integral part of the user’s journey; showing that it is important for any observer to make connections between the art inside, to the view outside, and perhaps even their relationship with London. The importance of ‘user-orientated’ design as seen in the Tate Modern really highlights how the typology of gallery spaces has grown in accordance with public perception and consumption of art; the user is now recognised as the most important component in a gallery, and it is realised that the internal experience should prioritise their movement and engagement with the art , rather than be a place merely for the ob servation of artworks, which can often leave visitors feeling intimidated or disillusioned.

A final reason as to how public perception and consumption of art has changed post-war, is how we value creativity in the present day. As previously discussed, gallery spaces are there to host finished artworks. What we can acquire from looking at finished pieces is really valuable, as a piece in a gallery is ultimately a summation of a journey an artist has been on. However, by displaying only ‘whole’ pieces, the artist and curator of the gallery space reduces a creative expedition to one final output, which minimises how deeply a viewer can connect to a piece without knowing its full context. There is evidence to suggest that the creative journey from start to finish is actually the most valuable part of art, and by doing this encourages creative thinking and increases accessibility to art, as people can see failures as well as the triumphs of artists and perhaps relate this to their own creative explorations. Bruce Mau’s ‘Incomplete Manifesto for Growth’ further perpetuates this rhetoric by encouraging people to “forget about good” and realise “process is more important than outcome”(Mau, 2004). This realisation that process is an integral part of how we perceive art and design encourages people to become more involved, a key example of this is Antony Gormley, particularly in his piece ‘Field’. The process becomes the destination in this cir cumstance; the finished product relies entirely on the public creating the individual figures, which will later become the whole piece (Tate, N.D). Not only is this a way of celebrating the creative journey, but also a valuable way of incorporating art into people’s lives where there might have not been an opportunity before. Participatory projects and community-based art, as seen in Gormley’s work, appear to have had a poignant impact on how we consume art in the present day. Obviously, art has been recognised as an integral part of human development, evidenced from cave drawings being the earliest form of communication, to now, where art and design is a key part of the national curriculum. Although somewhat removed from traditional forms of fine art, community-based projects mean that people are invited into a world that might not have been accessible to them otherwise. The importance we place on this in the present day goes to show how public attitudes towards art really have evolved post war; people are able to consume art more availably which is progressive; but also how we perceive art as not just being something we can look at and understand, but as something one can become involved with and participate in creatively, is a transformation.

In conclusion, how the public perceive and consume art has changed radically post war. As a society, we now have more platforms than ever before to express our discontentment with the world, and also to express ourselves crea tively. America should not be diminished as a huge influencing factor in post-war art; without the rise and fall of the ‘American Dream’, Pop Art and its many counter movements would not have existed. An ongoing factor in the creation of art is that more often than not it is reactive – disillusion with consumerism and the monotony of life in America post war can be seen as the fundamental element of most Postmodernist movements, which consequently leads to contemporary art as we know it. The idea that art is a reactive force has changed how we consume art because it invites us to form our own personal opinions and perpetuate the cycle of creating and reacting on a smaller scale. On a larger scale, the idea that art is given to the public as a gift is a positive advancement in society post war. As previously mentioned, this was seen as early as 1951 in the Festival of Britain, but there is evidence that its motives were more aimed at reinstating Britain on the global playground post war, rather than as an exercise to encourage the public to become more engaged with art and design. However, the successful introduction of Liverpool Biennial in 1999 indicates that now art is given to the public without ulterior motives, it can be used as a tool to celebrate culture and bring together communities as well as encouraging individuals to be creative. Furthermore, our new found approach to the creative process is a huge indicator how public perception and consumption has changed. Art is physically more available than ever to our society, but changing the way we perceive it is the most radical transformation that has happened; the de-museumification of art has happened through making art seem relatable and approachable to the public. This has been realised though ‘user-led’ gallery spaces such as the Tate Modern, the rise in popularity of community based projects and other interactive art schemes, and the rising understanding that the creative process is actually immeasurably valuable. Looking to the future, creating a away of combining both a successful gallery typology with an artistic focus on the whole creative journey could be the most successful way to increase consumption and perception of art even further, to reiterate to the public that art is a tool for everyone.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (1998) Abstract Expressionism Britannica [online] July 1998 Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/Abstract-Expressionism [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Culture Liverpool (2019) Liverpool Biennial Launches Programme for the 11th edition in Spring Culture Liverpool [online] 2019 Available at: https://www.cultureliverpool.co.uk [Accessed: 5th January 2021]

Johnson, Ben (date unknown) The Festival of Britain 1951 Historic UK [online] Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-Festival-of-Britain-1951/ [Accessed: 5th January 2021]

Guggenheim (date unknown) The Frank Lloyd Wright Building Timeline Guggenheim [online] Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/the-frank-lloyd-wright-building/timeline [Accessed: 6th January 2021]

Lehrer, Jonah (2011) How Does the Brain Perceive Art? Wired [online] December 2011 Available at: https://www.wired.com/2011/12/how-does-the-brain-perceive-art/ [Accessed: 5th January 2021]

Mau, Bruce (2004) The Incomplete Manifesto For Growth Massive Change Network [online] Available at: https://www.massivechangenetwork.com/bruce-mau-manifesto [Accesses: 7th January 2021]

Steinback, Susie (2019) Victorian era Britannica [online], October 2019 Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Victorian-era [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Tate (date unknowm) Antony Gormley: Field Tate [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/antony-gormley-field [Accessed: 8th January 2021]

Tate (date unknown) How to start a movement Tate [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/how-to-start-a-movement [Accessed: 5th January 2021]

Tate (date unknown) Postmodernism Tate [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/postmodernism [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Tate (date unknown) Pop Art Tate [online] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pop-art [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

The National Gallery (date unknown) About the Building: A gallery for all The National Gallery [online] Available at: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Willette, Jeanne (2012) Post-War Culture in America art history unstuffed [online] January 2012 Available at: https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/post-war-culture-in-america/ [Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Helmreich, Anne (2017) The Art Market and the Spaces of Sociability in Victorian London [online]

Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.2979/victorianstudies

[Accessed: 4th January 2021]

Books

Macleod, Suzanne (2005) Reshaping Museum Space: architecture, design, exhibitions. Oxon: Routledge

O’Doherty, Brian (1976) Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. London: University of California Press

Sanders, Vivienne (2018) The American Dream: Reality and Illusion. London: Hodder Education

Tate (2012) Tate Modern: The Building. London: Tate Publishing

Theses

Young Mosny, Alaina (2008) The Reconsideration of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work from the hybrid cultural perspective Master’s Thesis University of Richmond

image references

1 unknown author, The National Gallery [online image]

Available at: https://artuk.org/visit/venues/the-national-gallery-london-2030 [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

2 Claude Monet, Waterlilies (1916) [online image]

Available at: https://www.claude-monet.com/waterlilies.jsp [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

3 Jackson Pollock, Mural (1943) [online image]

Available at: https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/jackson-pollock-mural-berlin-372689 [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

4 unknown author, The American Dream [online image]

Available at: https://www.ultraswank.net/kitsch/american-dream-1940s-1950s/ [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

5 Campbell’s Soup Can (1964) Andy Warhol [online image]

Available at: https://collections.lacma.org/node/207423 [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

6 Wham!! (1963) Roy Lichenstein [online image]

Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/roy-lichtenstein-1508 [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

7 Away From the Flock (1994) Damien Hirst [online image]

Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hirst-away-from-the-flock-ar00499 [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

8 unknown author, inside view of the National Gallery [online image]

Available at: https://worldtravelfamily.com/london-national-gallery-art-kids/ [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

9 Francesco Machetti (no date ) a man spectating [online image]

Available at: http://www.fmarchettiphotography.com/works/museum/ [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

10 Cenotaph (2018) Holly Henly [online image]

Available at: https://biennial.com/news/liverpool-biennial-touring-programme-across-north-of-england-announced [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

11 unknown author (no date) photograph of the skylon [online image]

Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-Festival-of-Britain-1951/ [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

12 Flower Thrower (2005) Banksy [online image]

Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/banksy-loses-flower-thrower-trademark-case-calling-his-anonymity-into-question [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

13 Man with a Crown (year unknown) Jean-Michel Basquiat [online image]

Available at: https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/jean-michel-basquiat-artwork-depicting-a-man-with-40-c-eff43298ec [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

14 + 15 unknown author (no date) Guggenheim [online image]

Available at: https://www.guggenheim.org/exhibitions [Accessed: 10th January 2021]

16 unknown author (no date) Tate Modern [online image]

Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/mar/16/danish-superflex-tate-modern-turbine-hall-london

[Accessed: 10th January 2021]

17 unknown author (no date) Tate Modern [online image]

Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/news/the-tate-modern-and-tate-britain-reopen-in-london-today-072720

[Accessed: 10th January 2021]

18 Field (1993) Antony Gormley [online image]

Available at: https://www.antonygormley.com/projects/item-view/id/245

[Accessed: 10th January 2021]