Carolyne Wright About the Building of “Bildungsgedicht”

Poets often get asked what influenced them to start writing, and what made them fall in love with poetry—of all things—since (as the unvoiced subtext to this question often goes) of all literary genres it is the most poorly remunerated. This poem evolved as my response to that question. It’s called “ Bildungsgedicht ,” which is a play on Bildungsroman (formation novel), the German term for a novel about the artist’s early education and development. Examples are Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel, and most of the books by Hermann Hesse. These are autobiographical novels about a gifted, but lonely and melancholy, misunderstood young man—in these novels it’s always a young man—who gradually finds himself, and becomes a brilliant and renowned writer through a series of transformative adventures and encounters in late adolescence and early manhood.

These life-changing encounters usually begin with a less talented but trusty and valiant pal or side-kick of his own age, who serves as foil and sounding board, until our hero moves on to his first romantic involvement, often with an unselfish older woman who serves as an early “muse” or (Jung’s term) “anima,” and who often—so unselfish of her!—initiates him sexually. After he learns what he needs from her, he moves on again (some would say he dumps her) to a connection with an older man who serves as teacher, mentor, spiritual guide, and—frequently—the first important contact in the wider world of publishing. This final encounter and interaction—with a powerful man—is really the key one, for which the others serve as mere preludes, since it launches our hero into the realm of his true identity and life’s work.

Until my graduate school days I didn’t much question the fact that all of the Bildungsromanen I was aware of were written by men, with male protagonists. But once I began to think about my own formation as a writer and poet, I grew skeptical of this male-centered literary paradigm. What about the writer who is female, I asked, and who writes poetry, of all poverty-inducing literary genres? How could I tell her story. . . my own story? It would have to be in poem form. So in good Germanic style, I invented (I thought) a compound word for “formation poem”: Bildungsgedicht . Several years later, glancing through a German-English dictionary, I discovered that the word already existed! Well, the wheel was no doubt invented independently by several different Neolithic geniuses on different continents during the same Ice Age.

In any case, Bildungsgedicht recounts how I first fell in love with poetry by falling into an infatuation, during the summer I turned sixteen, with a self-proclaimed poet—”Johnny Dee,” as he called himself—a Bob Dylan wannabe from the Boeingindustrial suburb of Renton who spent a lot of time “making the scene” at the Seattle Center. That was the same summer that Dylan “went electric” at the Newport festival, scandalizing the folk music elite, so Dylan was on every hip young person’s mind. I remember sitting in the downtown Seattle office of an acting studio where I was registering for a summer class, and hearing for the first time Dylan’s new song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” playing on a radio in one of the studio rooms. It was electrified— and electrifying.

I wondered, with all of Dylan’s sneering contempt for the woman he addresses in the lyrics, if I would be able to avoid becoming the subject of such competitive disdain if I got anywhere close to fame, or to famous people, or even to wannabe famous people. I had been through the Beatles craze phase, hearing them perform at the Seattle Coliseum the previous year–but I was not one of the screamers! I was fascinated by their work and their world, but also already skeptical. I could see, in the fast-paced, glamorous, and thoroughly macho culture of rock music, that there was no place for creative, independent women. The only role for cute young girls my age was as “chicks”—groupies, pieces of arm candy, and worse. Even at sixteen, I knew that I wanted to create art–whether in the theatre, graphic arts, or literature, I wasn’t yet clear–but I was certain that I did not want to be a chick: the fluffy poultry, and paltry, subordinate of some macho male artist.

Such as the Dylan rock star-wannabe Johnny Dee, who simply showed up one day in the Piccoli Theatre at the Seattle Center, where my summer acting class was rehearsing its final project, a full-length production of Kind Lady. He presented an immediate problem of emotional conflict—he had that bad-boy air so attractive to girls my age, the (no doubt carefully cultivated) Byronic-Dylanesque hero mystique of artistic talent, righteous indignation at social injustice, flirtations with the drug subculture and hard living, and the long-haired, slim good looks of the male ingenue Romeo. And he played in a band! I didn’t want to be any boy’s subordinate, competing with himself for his attention, but I was intrigued. I wanted to be with him, so that I could figure out how to be him—how to be what I thought he was: an independentminded creative artist. (Interestingly, the Piccoli Theatre stood where the Jimi Hendrix “Experience Music Project” complex now stands, a monument to a true rock star and brilliant blues musician.)

Johnny Dee actually wrote what I later realized was appalling drivel, when I came upon a few pages of his lyrics in one of my file boxes years later. But the mannerisms and pretensions of this Beatle-suited youth stirred my imagination, and I wrote a few bad Bob Dylan imitation lyrics in his honor. Once the Piccoli Theatre production of Kind Lady ended, I landed a small role in another community theatre’s production of The Tempest, so I was hearing, and reciting, some of the finest poetry in the English language in rehearsals every evening. The eminently speakable quality of Shakespeare’s poetry for the theatre impressed me, even more than reading it on the page. I was entranced with the way that poetry is truly an oral / aural medium, a performance medium. After Johnny Dee unceremoniously dumped me later that summer, as the poem recounts, I turned to more dependable literary sources for solace: to Shakespeare, the Romantics and Modernists, and to contemporary American poetry as I could discover it then. That’s when I first started to write poetry in a serious manner. I haven’t yet written poetry for the stage—plays and other performance pieces—but I do try to perform my poems when I give readings, incorporating Slam Poetry energy and performative qualities with complex and nuanced literary language.

The poem “Bildungsgedicht” started in the mid-1980s, when I was back in Seattle during the summer, between teaching and fellowship “gigs,” staying at my parents’ house. I was reading the latest Marilyn Hacker book: Assumptions, I think it was. With the brilliant melding of formal and narrative elements in her poetry, and a fastpaced, colloquial, and culturally allusive mixed diction, Hacker has been called the Lord Byron of our age. I found myself playing around with lines in a similar tone, and an early version of “Bildungsgedicht” emerged. But the poem felt awkward—I didn’t yet have the “chops” for poetic wit in form, and I was engrossed in writing two different series of poems in altogether different voices—so I put this poem away for years. In the winter of 2000-2001, leafing through a file of old drafts, I came upon that version, typed on my long-retired Smith Corona electronic word processor. Rereading it, I had one of those ah-ha moments: Hey, this is pretty good, I should work on it. It didn’t take long at that point to revise the poem to its current form. I began sending it to magazines and contests—it subsequently received an Honorable Mention in the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Awards competition sponsored by the Poetry Center at Passaic County Community College.

This poem became a “hit” of sorts at readings, and I have liked to conclude with it, because it ends the performance “where all poems start” (to paraphrase Yeats)—the beginning at the end—with the nascent poet writing her first poem. To read the poem aloud is like a brief return to the acting career that I put aside in favor of teaching (another profession calling for histrionic skills) and of writing / performing my own poetry. It has the comic parts I was too serious and too shy to play back in my teens. Now that I have lived long enough to take a humorous perspective on my own life, I can recreate with my grown-up voice the sixteen-year-old personae of Johnny Dee, his sidekick Don, and the poet-performer herself. I’ve discovered that listeners in their teens and early twenties enthusiastically identify with the adolescent younger self who speaks in the poem, and are gratified to hear this revelation of my own beginnings. They can glimpse, in the “successful, accomplished” poet’s early days, all the flaws and disappointments to which they themselves are susceptible. Grown-up listeners, especially fellow baby-boomer children of the Sixties, recall their own younger selves in the voices of adolescent aspiration, and pretension, in the poem. They recognize how the mature speaker both honors and pokes fun at her younger self in the process of retrospection: with affectionate exasperation at her youthful foolishness, and with nostalgia for the days when all her potential was wide open—not yet tested, not yet realized, and also not yet humbled by the awareness of its inevitable human limitation.

One presentation of this poem was a particular hit. I was more than halfway through an early evening reading at a Borders bookstore, among the literature and poetry shelves. Unbeknownst to my listeners, in the café across the store, I could see that a local rock ‘n’ roll group was setting up for a gig—clearly an overlapping performance that the store’s event organizers had not informed us about. I hastened to bring my reading to a close, and began reciting “Bildungsgedicht” just as the guitar and bass began tuning up and trading preliminary riffs. Talk about synchronicity! My listeners wondered for the first minute or so if I had not secretly arranged for this accompaniment, but then the group launched into their first number, and I had to declaim the last few stanzas at the top of my lungs as the cacophony of drums and guitars blasted through the building and ricocheted off the walls.

Another memorable reading of this poem was at the scene of the crime, as it were— at the Seattle Center for Bumbershoot. This was a Labor Day weekend, on the Starbucks Stage—only a few hundred yards from where Johnny Dee had eased into the Piccoli Theatre to check out the rehearsal, and where he and the chick who had been me had made the scene at the Food Circus, the fountain, and the boot-scuffed, cigarette butt-littered grassy knoll near the carnival rides with the infamous informal name, Hippy Hill. As I read the poem to the ideal audience, one who recognized every landmark and caught every allusion, I half-expected to see John Dee Roy (his real name) lurking at the edge of the crowd. Not as the mop-topped, Beatle-booted youth, but more likely—as I imagined him in late middle age—a balding, paunchy, laid-off fork-lift operator in cargo shorts and wife-beater tee shirt, with tattoos snaking up and down his arms and gaps in graying teeth, scowling in recognition of his younger self in the poem. If I had glimpsed him there, I might have waved and beckoned him to join me on the stage, to take a bow and share the applause.

continued overleaf...

Bildungsgedicht

At sixteen, I roamed Seattle Center with Johnny Dee, the wicked-thin, mop-topped rock singer who’d bopped into the Piccoli Theatre while we rehearsed Kind Lady, and straightaway asked me out. “Like, I dig your style,”

he drawled, lounging in a cracked plastic chair under the Food Circus awning. Slipping off his mirror shades, he talked of gigs and record deals, his band “the hottest, you dig?, in the whole South End.” So, would I be his chick?

Hours later, he put me on the city bus to View Ridge. “Ta, luv,” he grinned. So cool. So British. I waved to him through tinted windows till he vanished in a swirling plume of diesel. “Where have you been?” my mother fumed, stabbing a toothpick into her midnight slice of avocado. “Oh mother!” I rolled my eyes. “Chill out! It was a long rehearsal.” My senses tuned to night, I waited for the phone to ring. “Mom, do you like my hair like this?”

I poked at it in the mirror. “Hey Mom? You think I can sing?” A week slid by. He showed up at dress rehearsal, in a blue tailored Beatles suit, with his sidekick Don, who played drum and bass. “I dig your threads,”

he chuckled, tightening his arm around my gauzy black frock, on the park bench by the fountain. Don slouched, smoking, at the other end. “So foxy.” He kissed me, and took a cigarette from Don. “Hey, you’re gonna dig this song

I wrote for you.” His tenor was smoky and nasal like Dylan’s in A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall. “Well?” he looked me up and down. “Symbolical,” I breathed, not yet knowing the word cliché or bright moments of love’s throwaways.

All summer Johnny was prince of the penny arcade, arms around me on the tilt-a-whirl, mug-shot grins in the quarter photo booth, twanging his guitar for street kids on the hill who scored baggies of hashish and Panama Red

until security cameras zeroed in.

Johnny’s stoned effusions never let on the double-mortgaged double-wide in Renton, his father on the graveyard shift at Boeing, his mother scolding my mother on the phone—

his needle tracks my fault, his Dexedrine knocked back with coke, his hook-ups with “hookers, maybe faggots.” The day he brought blonde Suzee to the Food Court, I sobbed by the Orange Julius machine. “Stop it,” he snapped. “Your mascara’s smeared.”

continued overleaf...

I rode north alone to the next rehearsal: The Tempest. Iris, messenger of the gods, weaving the river spell through tears because the show goes on.

“Clear, concise, poetic,” wrote the reviewer of my part, before he panned the rest.

I went home, tore up Johnny’s song, wrote one and tore it up. If I couldn’t be with him I wouldn’t be him. I opened the Cambridge edition of Shakespeare, and told my mother the truth. I’m starting a poem.

Published in This Dream the World: New & Selected Poems (Lost Horse Press, 2017). Copyright ©2017 by Carolyne Wright.

Carolyne Wright, A Change of Maps (Lost Horse Press, 2006). http://losthorsepress.org/catalog/a-change-of-maps/

© Carolyne Wright

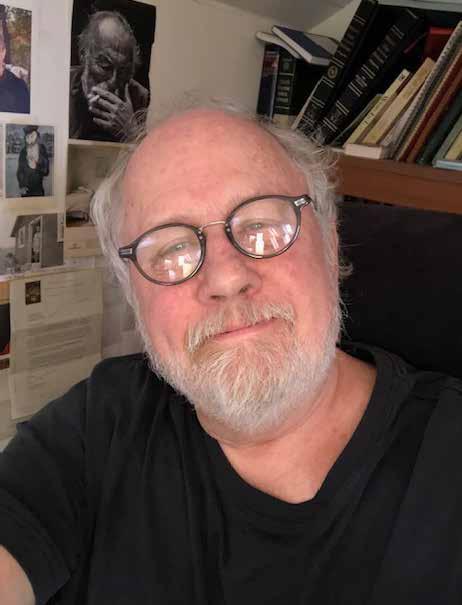

David Rigsbee

David Rigsbee is the recipient of many fellowships and awards, including two Fellowships in Literature from The National Endowment for the Arts, The National Endowment for the Humanities (for The American Academy in Rome), The Djerassi Foundation, The Jentel Foundation, and The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, as well as a Pushcart Prize, an Award from the Academy of American Poets, and others. In addition to his twelve collections of poems, he has published critical books on the poetry of Joseph Brodsky and Carolyn Kizer and coedited Invited Guest: An Anthology of Twentieth Century Southern Poetry. His work has appeared in Agni, The American Poetry Review, The Georgia Review, The Iowa Review, The New Yorker, The Southern Review, and many others. Main Street Rag published his collection of found poems, MAGA Sonnets of Donald Trump in 2021. His translation of Dante’s Paradiso was published by Salmon Poetry in 2023, and Watchman in the Knife Factory: New & Selected Poems was published by Black Lawrence Press in 2024.

In the Picture

When the dandelion has conquered all, or my deep suspicion as we sit to eat: I hear these things inside my head. What scenarios and tales--age and love and injury--trumping each other! A mockingbird’s feathered border climbs a limb. By the garbage patio are these same feathers forcibly separated from the body. If one were to perpetrate some fraud, pretending hatred, say, or boredom a whole life long, only to recant on one’s deathbed, which would be true: that or the truth (realizing how you leaned into the fraud, shaded the fraud with time)? If I awoke each morning to a mockingbird only to find it a woodpecker in age, wasn’t the mockingbird also— perhaps even more so—in the picture? Wouldn’t the fraud, suspending itself over the abyss of the truth, come to seem lovely there in the morning of an old man?

Door Frame

When the sun hits that same spot as it comes down out of a cloud, more attic-haunted kid than muscular Apollo, and burns the water like that, the seabird’s cry, the spreading city, the religious water, the duck’s yodel, all step forward to ease the difference between order and a thing not understood. They hang for a moment in hardness and happiness until the sun has slipped away like someone at a party. Where he was is now the door frame, where before were guests in conversation, animated, drinks in hand.

Mounted

Much I couldn’t get right: names of local trees, for instance, of a bird that perched on the skillet handle, kinds of rain on a day charged with the splendor. An old caravel unspools a white wake as it trudges up the shoreline. A maid boards a transport up into the hills where there is work. Smoke and sun rush on her face. “Stand on the stick,” the boy said looking up at me. It was a log between trees, trees whose names I didn’t know, but I did, and saddled up.

Bakery

A man kicked loose the rubber doorstop to a chilly bakery, his sandaled feet trim but blue. A man and woman bend their heads over coffee whose steam rises in the space between them. A crow discovers that to fly straight into the wind is to be hustled backwards. Several try like Ninjas that the Master orders against a supervillain. Each tries, peels off, and dives out of the screen. Bakery goods beckon from their trays like students on the first day of class positioned to see the new kid whose reputation preceded him just when he thought anonymity would at least get him through lunch. The wind accelerates and the limbs twist to see the pack of stock cars race past the grandstand, and in turning their eyes fall on others like themselves, not in the race but jumping in the same spot, inspired by the hot smell of gas and oil.

Reporting to the Martians

I watched the light line coming down the house plank by plank, until first the collared trumpets then the stems of the daffodils were at full illumination, and all were revealed with their shadows, like personal assistants, connected but standing off to the side. We must report to the Martians how it is with us. I was leaving the faculty club and the faces trying to make their way, eager, agreeable, or making a point, were as clueless as could be to the full glare on the rain pipe and the white that traced the window around, and that bush pruned to next to nothing, roses and camellias too.

Jordan Smith

Jordan Smith is the author of eight full-length books of poems, most recently Little Black Train, winner of the Three Mile Harbor Press Prize and Clare’s Empire, a fantasia on the life and work of John Clare from The Hydroelectric Press, as well as several chapbooks, including Cold Night, Long Dog from Ambidextrous Bloodhound Press. The recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim and Ingram Merrill foundations, he is the Edward Everett Hale Jr., Professor of English at Union College.

Notebook for David Rigsbee

Not the cheap, top-spiral-bound shirt-pocket one With the stubby miniature golf course pencil That he read somewhere Kerouac used,

And not the old blue-cloth-and-red-leather ledger He found in his father’s rolltop desk, tucked sideways In a hidden cabinet next to the pigeonholes for bills, Pale blue ruled lines on paler paper,

Nor any of the Moleskines, tossed in the lightship basket, Hardly used, like the fountain pen.

No, the one he chose Was a red calendar diary from sometime in the mid-70s Found in the open stacks in the college library, No name and no entries, and he picked it up, tried it out,

Put it away, forgotten, until fifty years later, unpacking, And the poems he found there dated His imagination more precisely than he cared to admit…

The notebook, tucked neatly in a carton between Blackburn and Cavafy and Bly, And nothing changed all that much, he thought As he wrote this on the next blank page.

Variations on a Song of William Byrd

My mind to me a kingdom is…

What I heard wrong was the tense, heard was for is And so I assumed a sort of self-elegy Or a practice, as of self-abnegation, which I thought was the past (not Nostalgia, not confessions, simply the distance at which memory is composed)

When the lyric is all present; my mind to me a kingdom is; I believed I heard an exile’s lament, a restlessness nearly silence, and so I turned the music down, Before I knew my error, before I recognized that kingdom was neither

What I’d thought nor what I’d thought to lose.

For the Poet Who Studied Composition

I remember the piano

In the basement studio of his suburban house, The evening, the picture window

Opening onto the dark lawn.

When someone read another heartbroken poem, He looked at me and winked.

If that was a lesson in irony, I hardly needed it.

If that was a lesson in candor, it barely scratched my solitude.

I was listening for the music I could almost hear. Nothing I wrote came close.

All long poems have their slow moments, He said when I finished reading mine.

If that was a lesson in composition, I might have paid more attention.

Somewhere upstairs, a door closed.

In the ebony gloss of the piano, he left hardly a trace. When I remember that room, I’m not sure he was even there.

If that was a lesson at all, it suited his voice better than mine

Evening Song, Late Summer

I must sing of what I do not want (Beatriz de Dia)

I do not want the light beyond the trees Which is a translation of the lament sung in a language No one speaks,

Out of longing, perhaps, or because the idiom seems too clumsy For any but the simplest losses.

I do not want to believe my own sorrows are greater Than the blue-gray mug shattered on the kitchen tile, Unmendable but trivial,

As I do not want to get by heart the lyric In my rendering or any other That keeps time by the passage of the horse’s hoof,

Since to admit there is a distance to be crossed Is to sing that her heart and mine are not the same, And I will not sing of what I do not want.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Terry McDonagh

Terry McDonagh, poet and dramatist, has worked in Europe, Asia and Australia. He’s taught creative writing at Hamburg University and was Drama Director at Hamburg International School. Published fifteen poetry collections, as well as letters, drama, prose and poetry for young people. In March 2022, he was poet in residence and Grand Marshal as part of the Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations in Brussels. His work has been translated into German, Indonesian and Arabic. His poem, ‘UCG by Degrees’ is included in the Galway Poetry Trail on Galway University campus. He’s been a voice and narrator on several RTE radio dramas (All Points West production) for young people. In 2020, Two Notes for Home – a two-part radio documentary, compiled and presented by Werner Lewon, on The Life and Work of Terry McDonagh, The Modern Bard of Cill Aodáin. His latest poetry collections: A) An eBook ‘Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Not Dead’ – Live Encounters Publishing. B) ‘I Write Because’ – Calendar Road Press. After more than thirty years in Hamburg, he returned to live in County Mayo in 2019.

Not from Here

They arrive from god knows where, some bombed out of babyhood, others on the run from hunger and crumbling dreams. To beat the foreign out of them we call them non-nationals, tribe-less-ones who come to us with odd names and languages but they learn so quickly we almost forget they are not native. They don’t forget but they don’t tell us. Some of them are brighter than our own. a teacher told a mother.

Conversation over Coffee

Why are we sitting here discussing dystopia and things we know little about

when we could be chanting football hymns or toasting a couple walking out of a lavender wood as a church bell calls to prayer – or with finger on chin, we could be dreaming of fireflies

and a gaggle of geese taking charge of crossroads. A figure in black and two policemen might turn up too,

and when the fireflies have had enough of blue and cackle, they will buzz off to light up hedgerows before sunrise

and then, in comical undertones, you rattles on about a relative who borrowed a hearse to transport a ladder with a strip of red lingerie hooked to the end poking out. Flat out he was. Foot to the floor – full tilt

exhaust fumes pluming to the skyline and all for a wilting wife and roof-tiles in tatters. It was urgent.

But if his spouse took a bad turn and mayhem broke out on rooftops, he’d be lost

having to fight a periodic fit of peeve while settling for a pizza and Stella as stopgaps.

Relationships can be tricky if literature is to be trusted. You say the fat lady sings this side of the far horizon but what if her song is nothing more than a moody moment in coffee breaks? The same again with nice spice please.

And above all else, let’s stay put and palavering with coffee and cake in convivial conversation.

I Am

I am the child in the adult that meanders.

I am the singer serenading in sunlight.

I am the cheerful rover by a great river.

I am the believer on a dream team.

I am the outsider taking to the hills.

I am the bicycle transporting the teacher.

I am the drover driving cattle to high ground.

I am the puzzled beast walking to its doom.

I am the donkey pulling above its weight.

I am the drifter drifting to and from the altar.

I am the teenager in and out of love.

I am the trader who wronged and was wronged.

I am the snake in the long grass.

I am the golden apple of the far-away moon.

I am the one who writes to make things right.

I am the Púca at the foot of a blackthorn.

I am the touched child that couldn’t be satisfied.

I am the one who turns his back on the light.

I am the trickster ducking about under cover.

I am the falling star lighting up a legend.

I am hope trying to stretch a single breath.

I am all things in hedgerows and in shadows.

I am Adam and Eve in an orchard.

I am wrong itself when I thought wrong was right.

I am in the dark – occasionally glimpsing the light.

I am a mystery but I am not divine.

I am.

An Ode to a Puma

Carty had always liked cars and as he stood under an umbrella in the corner of the carpark next to a hangdog Ford Puma with the rain dumbing-down, he wondered about Ford schemers that had the gall to imagine this offensive object moving with the grace and precision of a puma. It was too late to change misdeeds. This thing was no showpiece in a valley of precious metals, more like a sepulchre, mausoleum, henhouse or makeshift coffin that would see its owner out, only then to be scrapped, squashed, folded and flattened with writhing bits dumped in a ditch and with some parts remodelled as cutting-edge creatures.

No moral intended but – as ever Cartty would be talking cars and quizzing his wife at teatime on how, in the name of ancients, this ailing object could be a puma when anteater would be adequate. His wife wondered about weapons.

Derek Coyle

Derek Coyle’s Reading John Ashbery in Costa Coffee Carlow (2019) was shortlisted for the Shine Strong 2020 award for best first collection. Sipping Martinis under Mount Leinster (2024) is published in a dual language edition in Tranas, Sweden. His poems have appeared in The Irish Times, Irish Pages, The Stinging Fly, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Texas Literary Review, The Honest Ulsterman, Orbis, Skylight 47, Assaracus, The High Window and The Stony Thursday Book. He reviews books regularly, and he has written literary essays on the poetry of Seamus Heaney, John Montague, James Schuyler and Paula Meehan. He lectures in Carlow College/ St Patrick’s, Ireland.

Just Off the Old N7

(for Nathan Moran)

I guess you wanted to know where I started from when you asked me to share photographs from my childhood. I have none. At least not here in Carlow.

I cried when you shared yours, to a soundtrack of Kate Bush, Hounds of Love on freshly pressed vinyl.

You at about six or seven, coming in on the phone in a series of messages. Your fair hair, a mousey blonde, before you became the mild ginger I know.

Sometime in the nineties. You with your bowl haircut

continued overleaf...

I thought they’d banned after the seventies.

A happy boy, that cheery smile, in your Mickey Mouse belt, your arms above your head, wide open, the measure of those dumbbell piers in that medieval church arcade, a monk of sorts, the meditative type, tonsured for sure. But that boy is gone, like your recently lost Nanny, the reason the attic is being cleared up there in Castlepollard, this treasure trove found.

I’ll give you a portrait in words, what I was then, me dressing up in old cast-offs from Grandad Willie, he of the Allenwood side, my mother’s people.

A charcoal-grey dress-jacket and, perhaps, a daft zippy tie

borrowed from my father, pink paisley, the type of tie

you might wear with an Hawaiian shirt, if you can imagine that. When harmony was all out of kilter with the times, and zany was in. Some class of Paddy Cap, the type this granddad always wore.

What Scottish friends call a bunnet and the Welsh a Dai cap.

And then there’s this one. Me hiding out in the trees with my sister, lithe and lean, clambering through this tangled copse that bordered the road

leading up to our estate, long lost now to brick walls, mortar and concrete.

Sure they grant privacy to the houses, the type we enjoyed up in the branches, looking out at the world going by, spies, like those on TV. MI5 on the trail of some deadly Russian killer armed with poison and plans to take down the West in a nuclear haze.

And later, Ben Higgins and me in those battered World War I helmets his folks picked up in a sale.

He wanted the Tommy helmet, and, I have to admit,

I liked the style and shape of the German helmet I was given to wear. Something about its abstract contour and design

had its appeal even then. We are storming ‘Muck Hill’, a heap of builder’s clay and rubble in the still unfinished section of ‘The Gables’. Dublin was spilling out into North Kildare even then. But, how can I capture in a picture what it was I felt lying beside that smooth-skinned, silky-haired English lad I was friendly with?

That time we lay down between the gorse bushes up on Kill Hill. I wanted to see him naked, terrified of all that that meant, and yet, some new thing pulsed inside, some insatiable fire, a flame. We never touched. Zilch.

overleaf...

I don’t know what he felt as we talked and talked, the endless chat we were capable of then. All this lay before my blue eyes, that photo I remember of me with my bowl cut, in chocolate brown dungarees (the height of children’s fashion in the seventies), my canary yellow jumper, this photo I remember from my parents’ albums. I guess I won’t see it again until I have to climb up into their attic someday soon. But here, in this poem, I put my photo beside yours.

Two boys, wide-eyed innocents, indubitably so, with our bowl hair cuts and no idea of all that lies before us.

Richard W. Halperin. Photo credit: Joseph Woods.

Richard W. Halperin was born in Chicago, holds U.S.-Irish dual nationality and lives in Paris. His work is part of University College Dublin’s Irish Poetry Reading Archive. This year Salmon Poetry/Cliffs of Moher will bring out All the Tattered Stars: New and Selected Poems, Introduction by Joseph Woods, which draws upon four Salmon collections and sixteen shorter collections via Lapwing Publications/Belfast & Ballyhalbert. In 2024, Lapwing brought out two additional collections: The Painted Word and Three Red Hats.

Beauty from Ashes

After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline and Robert Kennedy were helped for years by reading Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way, for the deep strength it gave them. According to friends, Robert read from it daily until he himself was assassinated. I am helped by Isaiah 53, the Suffering Servant – ‘so disfigured did he look that he seemed no longer human’ –which most images of Jesus entirely ignore. My wife was helped by many things; when young, by Howards End. One can be helped by anything of beauty which has managed to survive: a picture, a book, a prayer, a conversation, a piece of music. Maugham, old, said he was helped by the last Act of Die Meistersinger. My father, at age 22, was asked by his fraternity brothers at University of Illinois, Urbana, to buy for the fraternity house a record, the kind we now call 78s. He bought John McCormack singing the Prize Song from Die Meistersinger. This poem is not really about any of this, but I must write it. It is about the Aegean Sea, very bright and very blue, very bright and very blue.

Far from the Ship The Nellie

‘. . . we knew, before the ebb began to run, that we were fated to hear about one of Marlowe’s inconclusive experiences.’ - Joseph Conrad, The Heart of Darkness

There follows one of the great explorations of the human soul. ‘Inconclusive.’ That does me good at the start of another heavy day, given the world news, its gratuitous wars, its maniacs and clowns, which I cannot separate myself off from, which seem to be part of the vast inconclusiveness of my own experiences. Except for some. Which are brilliant. Which are brilliance. Love. A shock extended over whatever time is – my marriage, for example, my parents, for example, and if there was guilt there – and there was; mine – even that was brilliant, all torn off and given me from wherever something different from experience comes from in the first place.

Saturday Morning

‘Purgation, illumination, and (if so privileged) union’ is part of Clifton Wolters’ preface to his modern translation of The Cloud of Unknowing. All the late plays and poems of T.S. Eliot dramatise these. Most of the late plays and poems of Yeats dramatise these. I live with all of them, recently, as evil – both radical and banal –lodge themselves in my natal land and in a few countries which I know a little.

Things will move on. Nothing ever goes away completely. Emersonian America never went away. The Gorbachevs never went away.

‘Purgation, illumination, and (if so privileged) union. I think these happen every second in each star, including our own sun. And between each second, what has to be purged.

A Small Blue Glass Stone

for Theresa Nicholas

The Chorus in T.S. Eliot’s 1939 verse play The Family Reunion says ‘And now it is time for the news We must listen to the weather report And the international catastrophes.’ This morning I listen to the news. My pen feels natural in my hand. Nothing else does.

Paper and scissors and a tube of glue, I think, feel natural in the hand of my friend Theresa in New York State as she works on one of her collages. I look at a recent one, which includes a small blue glass stone and a fragment of a small twig. The stillness of it. Would it have come out that way without bombs? There are bombs in ‘Lapis Lazuli.’ There are bombs –if one listens – in ‘Dover Beach.’

The Blue Rose of Forgetfulness

When young, I heard pings which later I knew were poetry: the shadow of the valley of death the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg the blue rose of forgetfulness.

The latter was from the film The Thief of Bagdad, as was ‘I want to be a sailor sailing out to sea.’

I am way out on that sea now. Alone, although for a while I was not alone.

Other sailors went sailing out to sea in their little matchbox boats. Milton, Larry Hart, so many. They help, these great ones.

They find the music in the heart of sorrow. The OK of having made so many mistakes. The ridiculousness of explanation. The ping of poetry.

‘Ecce Puer’

‘Ecce Puer.’ Sixteen fragile lines by Joyce. A hand up – a newborn’s. It makes me glad I did not throw in the towel all those desperate times. I did once, and was rescued.

‘Ecce Puer.’ Some things are so pure they are the smile without the moon or the pallor without the moon. A faceprint in the sky or crib which makes sky and crib seem pudgy and dowdy.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Alan Walowitz

Alan Walowitz is a Contributing Editor at Verse-Virtual, an Online Community Journal of Poetry. His chapbook Exactly Like Love comes from Osedax Press. The Story of the Milkman and Other Poems is available from Truth Serum Press. From Arroyo Seco Press: In the Muddle of the Night, written with poet Betsy Mars. The chapbook, The Poems of the Air, is from Red Wolf Editions, free for downloading from Red Wolf’s site.

Empirical

Based on what can be observed, that’s me reflected in the Forever Dollar Store window, freshly swabbed and squeegeed, as I walk the length of The Sunshine Indoor Mall. So much slower now than I remember in any old daydream of myself.

Then, that’s me again all wild and woolly in the fun-house mirror of the barber shop. the blue neon sign which flashes this message from the Universe: Couldn’t You Use a Cut and Blow?---19.50, tax included. Might even have made for a Norman Rockwell on the cover of a 50s magazine-a man exiting middle age and approaching the end ignoring all entreaties by loved ones, strangers, friends: How ‘bout it, Pops? Maybe there’s still time--

if only to see the handsome lady barber inside— the place she bought from the Italian guy who drank a little and sometimes closed his eyes as he wielded his razor; who changed the name from Baldi’s to No Embarrassment and shut off Fox News for good; who tossed out those hard worn Playboys nobody but a 12-year-old would ever touch.

I pause at the door and take a deep breath. Watch her scissors dance in concert with the comb, like the birds of Pinaud as they exit the steeple over Harvest Home, the senior center a proud guy like me will never go.

Sometimes, despite myself, the world will change for the good, might finally seem-even at this late date-a place I might actually choose to remain.

Good Company

What could have made her wake this ungodly hour and throw her things in the old valise she had fetched from beneath the bed-the vinyl, glued and re-glued to the pressboard with two brass clasps for fastening, though the hinges at the rear seemed ready to come apart? The faux-leather handle might serve to carry, or could lead her through a crowd at the station if she chose to swing it with the arc of an old scythe mowing memories--where she’d been and no longer wished to be.

But why so close to daylight. when the chill was biting hardest? Made me wonder in my sleepiness, perhaps she hadn’t slept at all, and was waiting for the coldest moment when I might accidentally come to. Though this performance required so much planning-the magic of her T-shirts flying into place, and her underwear finding the crannies among the jeans, which had been riffled from the closet like a trick deck of cards.

Though sleep is sometimes hard to come by my side of any story I prefer to tell, she smiled, and seemed to say, Sorry-apt for someone who always promised she would leave and seemed determined to keep her word. I ought to go back to sleep and dream of the inevitable-what we most fear coming true when we want it least.

I didn’t mean to yawn, but was so tired and what was required any odd moment always seemed to elude me. She sighed as if she understood everything about me and might have remained, maybe all night, if it weren’t for my utter predictability. It’s what some said made me good company, if only measurable in stays of a week, or the occasional cold month, like this, when any of us might prefer a little heat.

© Alan Walowitz

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Anne Fitzgerald

Anne Fitzgerald was raised in Sandycove, Co. Dublin, Ireland and educated at Loreto Abbey Dalkey, Trinity College, Dublin (Law); and Queen’s University, Belfast (MA in Creative Writing). Not to Scale (2024) is Anne’s fifth poetry collection. In 2006 Anne founded Forty Foot Press in addition to two Schools’ Publishing Houses. She is widely anthologised and has edited, produced and designed four anthologies of young adults’ poetry. She is a recipient of the Ireland Fund of Monaco Writer-in-Residence bursary at The Princess Grace Irish Library, Monaco. She has taught Creative Writing extensively across Ireland, Iceland and the United States of America. Anne lives in Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin, Ireland. For biography visit Forty Foot Press at https://www.fortyfootpress.ie/ anne-fitzgerald.html.

Hitler in the Shelbourne

Eighteen-year-old Bridget Dowling caught the eye of hotelier Alois, at the 1909 Dublin Horse Show.

Touring Europe he claims before eloping to Stanhope Liverpool. She bagged a bragger in Alois, former Shelbourne kitchen porter. Handy with his fists, he splits their marriage, fights for the Fatherland. Bridget sees out her days on Long Island, reinvented.

Her brother in-law, the failed artist, leaves us questioning if Yahweh really exists.

The Body Politic, 1982

after her shift at St. James’s, nurse Bridie Gargan heard July’s

birdsong and bees flit from daisy to clover until a bow-tied gentleman with a lump

hammer, Malcom MacArthur bludgeoned her to kingdom come, on the feast of St. Mary Magdalene.

Three days later following a small ad to Edenderry for Dónal Dunne’s farm shotgun, he emptied the twelve

bore into Dunne’s cavity chest wall. On the road back, a paper seller spots MacArthur at Blackrock,

days before Garda arrest him at the Attorney General’s Pilot View pad. Rumours abounded.

Still government does not fall, despite a Teflon Taoiseach’s GUBU remarks: Grotesque, Unbelievable, Bizarre, Unprecedented.

Mac Arthur pleaded guilty only, to nurse Gargan’s murder. The State entered a Nolle Prosequi plea for the life Dónal Dunne had lived. Ensuring no public trial ensued nothing came out in the wash.

Mac Arthur kept shtum. Yet rumours abounded. Government does not fall till, throwaway

phone-tapping talk, on television’s Nighthawks brought it down hook line and sinker, a decade later.

A released Mac Arthur still speaks silence. Yet, rumours run on.

Nolle Prosequi the normal effect of it is to leave matters as if charges had never been filed. It’s not an acquittal, which (through the principle of double jeopardy) prevents further proceedings against the defendant for the conduct in question.

This acronym GUBU (Grotesque, Unbelievable, Bizarre, Unprecedented) coined by Conor Cruise O’Brien, on foot of Taoiseach Charles J Haughey’s comment on this double murder, a phrase occasionally used in Irish political discourse to describe notorious scandals.

Nighthawks was an Irish television series (1988-1992), whose informal a late night café style content was current affairs and comedy.

The Little Club, Mayfair

The supreme mercy I can extend to them, is to give them and sustain in them, their dignity and death. The gentleness must remain.

— Albert Pierrepoint, 1977

By Easter Sunday 1955, Bournville had mastered uniform thickness of two halves of the chocolate egg. Little hands broke bits off before Basingstoke bedtimes.

Ruth Ellis tracked her racing car cad of a lover down. Waited till David Blakely left the Magdala Tavern.

Into the night Ruth stepped. Gifts Blakely four Smith & Wesson 38’s. Darkness fell. Flowed and pooled.

On Bastille eve, Ruth’s three Holloway months ended turning over; had Sandhurst taught him to excel at love triangles

or, had she not known stuff a plentyn ought not, would his fists have blackened her blue?

It was Albert Pierrepoint opened ground beneath this Welsh nightclub hostess’ feet, in the year of our Lord, 1955.

* Ruth Ellis, was the last woman hanged in England.

* plentyn, is the Welsh word for child.

* Albert Pierrepoint was an English hangman.

Michael Leach

Michael Leach lives and works on unceded Dja Dja Wurrung Country in his birthplace of Bendigo. Michael’s poems have appeared in journals such as Cordite Poetry Review, anthologies such as The Best Australian Science Writing 2024 (NewSouth Publishing, 2024), and his three poetry books: Chronicity (MPU, 2020), Natural Philosophies (RWP, 2022), and Rural Ecologies (ICOE Press, 2024). A fourth poetry book, Chords in the Soundscapes, is forthcoming from Ginninderra Press. Michael’s poems have been recognised in competitions: first place in the UniSA Mental Health and Wellbeing Poetry Competition 2015, commended in the Hippocrates Prize for Poetry and Medicine 2021, joint first place in the poetry category of the MSB Confidence Writing Competition 2022, longlisted for the poetry category of the MSB Confidence Writing Competition 2023, shortlisted for the poetry category of the Woollahra Digital Literary Award 2023, highly commended in and longlisted for the Liquid Amber Poetry Prize 2024, longlisted for the University of Canberra Health Poetry Prize 2024, and highly commended in the Hush Foundation Kindness in Healthcare Writing Prize 2024.

A Day Out in Suburbia

i. sunrise willie wagtails perched along tennis nets

ii. peak-hour traffic a hare makes it across the road

iii. a ‘no dogs’ sign at the reserve— dogs

iv. I drive down the road a roo hops down the footpath

v. moonlit boardwalk the same two seagulls as last night

Kaaren Kitchell

Kaaren Kitchell’s poems have appeared in numerous literary journals, including The Jung Journal Winter-Spring 2023, anthologies, and in a fine art manuscript at the Getty Museum. She received an MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University, LA. She and her late husband, Richard Beban, taught Living Mythically at the C.G. Jung Institute in L.A., at Esalen in Big Sur, and in private workshops, based on her 30-year vision quest. A collection of her essays and his photos can be found at www.parisplay.com. Her most recent book of poems is Ariadne’s Threads. She lives in Paris, France, and Berkeley, California. She can be reached at ariadnesweb@msn.com

Merle

Past Dante and Montaigne, there she is!— the sweetest dawn singer in Paris.

She’s black with a plump worm in her yellow beak facing the bower of pink roses around Ronsard whose lines I first read at nineteen in New York long before I’d pass him every day on rue des Écoles.

Epic poet, essayist, lyric poet, blackbird— four great singers—be with me as I write!

City Of Shadow And Light

(Report from Paris, after October 7, 2023)

Sorrow shows its face in strange oblique ways. Mother and child blaring as if through bullhorns in the small Chinese market on rue Monge.

The North African guard at the pharmacy knocking over a forklift that almost severed someone’s foot.

The clerk at the bio store who won’t meet anyone’s gaze. The neighbor hustling home with groceries in an anxious haze.

Muslim men scanning faces for judgment. Something hectic, disturbed in the clusters of students and friends in sidewalk cafés.

Mocking punks emboldened by the violence far away—a continent!— (so close).

Dreams of long ago grief in Barcelona, wrenched from the arms of my love by parents who sought to save my teenage purity,

rescue the Virgin from the Dragon, dragged me back to the desert, where I fell into darkness at home, leaden with shame.

A year later I bolted. What virgin? What dragon? Remnants of Christian faith—they weren’t even believers. I followed my blazing life north and inward, forged my own myth. How can the horrors exploding in the Holy Land be so interwoven with our lives here?

Centuries of religious madness. There is no space, no time, in this city of shadow and light.

Zeus Attack

When a swordfish leaps out of the sea near Indonesia and pierces a woman’s breast, a shapely glowing woman in red tank suit, a champion surfer, Giulia Manfrini,

I think, it’s probably Zeus, up to his old tricks, shapeshifting, disguising himself so he can savor a succulent morsel of female pulchritude.

She dies instantly. Or maybe she’s changed into something else—a Flying Fish who skims the waves?— to escape the King of the Gods, as Daphne did Apollo, freezing into the form of a laurel tree.

Daphne, fleeing from love, became the emblem of victory. Giulia, where are you now? What have you become?

Diamonds And Rust

I was Crane Dancing to Diamonds and Rust and her voice took me back to that tiny house in Phoenix they bought on the G.I. bill where my mother played records by Joan Baez long before Bob appeared on the scene. She, the Madonna with high clear voice sang of causes, kept her feelings to herself, except in this most vulnerable of songs that is all yearning, all truth of the heart, the snow falling all around them in Washington Square.

My mother was Joan the Madonna. I was vagabond Bob. We loved each other like diamonds. And then the years of rust.

Now?

Now there is only tenderness between us, and the ache of her loss.

Kate Maxwell

Kate Maxwell is a poet and writer living in Canberra. She has been published widely in journals such as Cordite, Meniscus, StylusLit, Rochford St Review and Books Ireland. She has work forthcoming in The Threepenny Review. Kate has published two collections of poetry, Never Good at Maths (2021) and Down the Rabbit Hole (2023). Her interests include film, wine, and sleeping.

Astral

Instead of too much wine and mediocre streaming, tonight I’m drinking in the sky searching for stars. Refused a screen-lit shrieking lounge-room bare arms offered to the breeze as I shiver in this unbricked evening. Hum of hidden frog or beetle small things scuttling in leaves, an argument at number five — Told you fifty times already — accompanied by groan and drip of loose-hinged drainpipe, leaking gutter. Dark is thick, unrelenting pushing back at city glare with matte black frown, reserving diamonds for another maybe one on mountaintop or wide grass plain who might marvel at the unencumbered heavens. Here, a stubborn star or two blinks

some small resistance fighting through suburban shroud, weight of way too many with a dull, wan flicker. Hunched upon cold concrete steps curving neck to sky, I leave the day, so long and loud and wish into the night.

Even Though the Revolution was Televised

With apologies to Gil Scott-Heron

It was the morning of the press conference when the body — offended once again, by three triple scotches, a glut of carbohydrates, and salt consumed the night before — decided to revolt.

All night, the gurgling of stomach acids, itch of night sweats, mutterings of schemes had robbed it of rest. After yet a few more after-breakfast shots the body’s outrage peaked. Ageing and weary, you could hardly blame

the body for insurrection. It was the vessel spewing out trash on a soulsapping loop of lies and spin. It must have been exhausted by the owner’s addiction to buzz and bluster. Credit should at least be given

for the body’s stamina. It had endured years of neglect, the humiliation of the comb-over years, and now: this. Debate still rages about the exact source and trigger for dissolution. An endocrine system, already compromised

must have reached threshold. Spill seemed inevitable. After an hour, standing in polished shoes without arch supports, bright lights blazing, saliva drying in the mouth, the sweat glands began the mutiny. Expunging body odours and fluids was simply not enough. A statement was needed. A visible signal to the world that the body had ceded and was releasing itself from the owner. A sovereign entity, so to speak. Dark rivulets streamed down sallow cheeks.

Hair dye — or maybe just mascara globs —began to melt from the temples like blood from an icon’s eyes. Hairdressers have since defensively claimed that hair dye won’t drip once the solution oxidises and colour adheres to the hair.

Damn fool must’ve applied too much mascara to his old white sideburns. However it began, and of course, hairdressers cannot stand accused the body obviously acted on its own. With no accomplice but its own internal furies, bubbling and hissing at such mistreatment, the body took protest. Yet, while the world watched and mocked, shame and contrition were emotions unfamiliar to the owner. A life led under flashing lights and self-promotion adapts to the sweat and grime of carnival ways. So, even though the revolution was televised, deniers claim a simple sleight of hand, a digital distortion of the truth, even when the screen reveals.

Kevin Cowdall

Kevin Cowdall was born in Liverpool, England, where he still lives and works. In all, over 300 of Kevin’s poems have been published in journals, magazines, and anthologies, and on web sites, in the UK and Ireland, across Europe, Australia, Japan, Indonesia, Hong Kong, India, Canada, and the USA, and broadcast on BBC Radio, RTÉ Radio, Ireland, and local radio stations across the UK. His 2016 retrospective collection, Assorted Bric-à-brac, brought together the best from three previous collections with a selection of newer poems. His 2019 collection, Natural Inclinations, features fifty poems with a common theme of the natural world. His most recent collection, 100 Haiku (2024), is a celebration of the traditional Japanese unrhymed poetic form, mostly on the theme of nature. His poem for children, The Land of Dreams, was published on the Letterpress Project website, wonderfully illustrated by Chris Riddell, and is available on YouTube.

The Twinkling Firefly

‘Bioluminescence.’

There’s a word for a scientist to explain:

The emission of light by living organisms, usually at night.

A poet would say: Flashing patterns of scattered lights glowing in the darkness.

A twinkling galaxy of dancing fireflies, weaving a moving tapestry of luminous stiches across Nature’s blank canvas.

The Towering Giraffe

At first glance, while they stand with necks extended still further to reach the topmost leaves of the acacia tree, one ponders at length, imaging such towering creatures to move with an ungainly stride.

But there is an innate elegance, almost majestic, in their gait; as they demonstrate of a sudden, moving off with a casual ease toward the nearby watering hole. Standing with forelegs wide spread, they stoop to lap at the surface, ever ready, all senses keen, alert for any potential danger.

Peacock (Tanka)

Strutting and preening, with tail feathers fully fanned, a peacock poses with a pomp and grand conceit. Peahens remain unimpressed.

Piet Nieuwland

Piet Nieuwland lives in Whangarei. His poems and flash fiction appear in print and online journals in Australia, USA, India, Aotearoa, Antarctica and elsewhere. His latest books, As light into water, and We enter the, are published by Cyberwit. He publishes Fast Fibres Poetry, an annual anthology of Te Tai Tokerau poetry and participates in collaborative visual art exhibitions. As co-ordinator of Intangential, a short poetry flash fiction music dance show for the local fringe festival, he also performs live poetry and is a book reviewer. He trained as a forester and once worked as a conservation strategist for Te Papa Atawhai. www.pietnieuwland.com

On the luxurious morning

At the bay of languages sashaying and swaggering flexing in the dark pandemonium of corporate hunger a syntax of nightmares of shudders and perforations of leaking hernias, a spectacle of bitter grimaces reading the symbols of birds / on the wrinkles of the marshland wet sheets of the monsoon / like a night on a dune swollen rivers and whirlwinds of pain / years of wind I see the shape I see the shorelines I see the white caps / I see the cliffs / the cliffs of the endlessly returning storm

Ideas break like fragments towards the portal renewing myself before all the things in the world flowers growing where they fell and rotted the vernal green of memory / memory the medium of experience over the endless hours of bloodstream / there are no more stories

The blinks of a billion eyes watch the horizon of planetary limits a solar system of flower-heads the smell of warm rain, the last shower slivers of time joined shared woven together peaches eaten with small caterpillars and toast with jam a flock of violins in Tchaikovsky concerto a kotare pair warming in the sun

Just this

In this inlet swept by tides of cloud and wind we celebrate the taste of rain a jeweled cascade of sutra like lightning at dusk

Hibiscus flowers fall in the night wind orchids light the dawn with no need for words just this, just this

Lily of a weightless shadow

In the echo of a twilight smile I want to know how to speak in the garden of glances and leave before the uncertain sky, its restless angry ocean ignites over Hauraki Pacific as it reaches the mathematical limit of temperature in the dark violet hour as we drink with our voices in the labyrinth of final forms when we touch with our eyes and I see you with my hands

Pearl indigo

With a soft scaffold of crushed gauze and foam on your chest you walk in step with Moana oceania your eyes blush with roses verbs of your presence caught in a white madness of wings the restless horizon shines like a quivering skin bells of the dawn toll an uncertain hour

Cloak of gathering

An exponential sequence of everything in transition the soil making of us / what it can / in the dark throat of sunset with questions of place / hanging over / like an elegant interval as the rain begins / thudding on the rippled surface of memory / calling in the shadows like the sound of sunlight falling / as cicada as aircraft landing / as fog clearing as molecular excitement / a lyric of flame an ultra-violet mirage / a blustering staggering neon dazzle a syrup of colloquial translations / the scent of sea salt while swimming a neighbor sharing tomatoes and tamure distant purple mountains, lime green lakes and apricot skies the g-side of another ten hundred thousand ten hundred ten jungle edge tipping over / an iceberg decomposing Pukenui Forest melting / in the sweaty river of clouds then evening sits over the city / like a jumble of syllables collisions / howls / skids / spins / sirens / screams of no no no / no consent and you wander / through the marshes of night amongst families of taraire and kohekohe a gathering of friends and colleagues, lovers and acquaintances a subtle mist of shower / humid / soaking like breath / hovers

Charlie Brice

Charlie Brice won the 2020 Field Guide Poetry Magazine Poetry Contest and placed third in the 2021 Allen Ginsberg Poetry Prize. His ninth full-length poetry collection is Tragedy in the Arugula Aisle (Arroyo Seco Press, 2025). His poetry has been nominated for the Best of Net Anthology and the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in Atlanta Review, The Honest Ulsterman, Ibbetson Street, Chiron Review, The MacGuffin, and elsewhere.

The Heat of the Son

My mother was in a UPS box atop a tiny stool near the altar, a priest-draped doily over the box. When it was my time to speak, I eulogized that mother owned a CB radio. Her handle: Mountain Momma. She once heard a trucker call a Smokie— Trucker: There’s a dog lying out here on I-80.

Smokie: Is he hurt? Trucker: I don’t know if he’s hurt, but he’s dead. My friend Jack Bower worked at mom’s restaurant supply store. When he put a carton of glasses on a shelf upside down, she picked up a 100-lb barrel of industrial dishwasher soap and threw it at him, then accused him of giving her a hernia!

When my father died her suppliers shipped everything COD. They assumed a women couldn’t manage a business alone in the early sixties. She finagled loans, saved the business, sent me to college. As a final goodbye, I read that beautiful song from Cymbeline: “Fear no more the heat o’ the sun.” Later in the service, the priest

said something about the Jews, something about their eventual conversion. When it came time for the kiss of peace, I grabbed my Jewish wife, bent her over, laid one on her. I kissed her, she kissed me, and we meant it. We didn’t hang around for conversion.

What They Did to Pat

He was the only one of us who talked back to the nuns. During algebra class he let out a yawn that was more like a howl.

Who did that?! Sister Joseph demanded. I did, Pat said. You have a detention, the nun intoned. No can do, Pat yawned again, I’ve got to work.

We laughed as Sister Joseph’s face turned Advent-purple with rage. She grabbed her rosary beads to anchor herself.

I’ll call your parents, Patrick. The number’s 632-1548, bellowed Pat. They know I gotta work.

We savored each insolent word out of Pat’s mouth.

More than anything Pat wanted to be a Marine, wanted to go to war in Vietnam. We tried to dissuade him, but he was adamant, enlisted right after graduation. In bootcamp the schizophrenia bivouacked in his brain commenced a sneak attack. He used a bayonet to cut his wrists. His DI thought he wanted to wash out.

No one wore the uniform more proudly than Pat.

The Marine Corps gave him an honorable discharge, shipped him back to Cheyenne in a catatonic state, lost his records. His parents fought for a medical discharge so the government would pay for his psychiatric treatment. I visited him in Bethesda Hospital in Denver. He showed me a sculpture he’d done in OT, a plaster bust of Satan—long black donkey ears on either side of the fire-red face, eyes wide and wild from watching the demons that patrolled his psyche.

So why write about this this sad, tragic life?

I still yearn to spend a little more time with Pat, remember the Coors quarts I drank with him, car-parked somewhere north of Cheyenne on a frozen prairie, eating pizza, arguing about the war—just a few extra moments loving this boy whose trouble was so special to all of us. At our 25th high school reunion he wrote that he hoped he’d be dead by our fiftieth.

He got his wish.

Robyn Rowland

Robyn Rowland has 15 books, 12 of poetry, including Under This Saffron Sun – Safran Güneşin Altında, Turkish translations, Mehmet Ali Çelikel, (Ireland, 2019). Her recent book Steep Curve is out with 5Islands Press, 2024. These poems encompass her two years caring for her father, who died at 102, and her decision to leave Ireland to do so. Her poetry appears in many national/international journals, over forty anthologies, and eight editions of Best Australian Poems. Her readings for National Irish Poetry Reading Archive, James Joyce Library, UCD, available on YouTube. https://robynrowland.com/

After the Carnage

Relaxed in Coole Park, we sit and listen to the Irishman weave his voice into Eric Bogle’s song All The Fine Young Men, and it saddens breath, a helpless kind of sorrow. We drink wine from allies in trade, Germany and France, in company with the bemused ghost of Lady Gregory’s airman son, Robert, who crashed spinning into dust, Italy, 1918.

And in the town of Çanakkale on the Dardanelles we buy bullet key-rings a boy sells on the boat to Gallipoli, and small wooden images of Mehmetçik, the Turkish soldier carrying his wounded ‘enemy’ Johnny Mehmetçik (Tommy, Digger), away from the sunlit slash of bayonet. Cash tills bulge in cafes through the villages of Ypres where my grandfather was shot in his right thigh, ferried through tent hospitals to Britain, then back to France. His body managed bullet, Spanish flu, appendicitis, damaged back from a fall in a trench, from a truck, on a ridge of bones. And he never spoke on any of it. And never marched to commemorate, unsure the purpose.

But he would love my Turkish sister-in-law as I do, and the blossoms that flower from our shared branches. Now that war is tourism – music, art, even my own poems –and the stain that ran in the fabric of those empires fades, I wonder, in the din of battle, in following orders to kill, to be killed, is this what they imagined, after – all those fine young men?

A Year Gone

Four we are in the boat, rocking through the mouth of our small harbour you loved, heading to where you fished over sixty years, and me a child with you then. Maybe an hour in, you’d return me.

Green-gills, white cheeks, I’d walk home, vomit at the corner of the church, whose steeple you repaired, reshaped, repainted with Desi Cox –remains slightly squew-whiff you’d grin, winking.

Never impatient with fishing, though not so with cards, you’d watch me heading up along the slipway, then curve round, back out to the reef, bringing schnapper home for tea.

This last ritual I now create, modern times being bereft of such things. We’re ready, a yellow rose each, Sue with lemon verbena from Dunsters’ farm,

me with a knotted inch cut from my hair to keep you from being alone out there. Two boatmen we tried for the task, and the surf club, but everywhere, rules.

Then Tony found your man, Ivor. Unknown to us he’d worked with you at Tallawarra, would take nothing for the petrol, for taking a good man out to sea.

He says there are dolphin pods everywhere today, and wide schools of overfat fish. He says, I’ll steer along the stretch and you find the place when you’re ready.

Tears are rippling the edges of my eyes: his kindness, the salt spray, the momentary ridge of dolphin fins chasing down shawls. We can see boats out past the dark water.

They’re marlin-hopping, and on the rocks inshore at Bass Point people are hoping for bream. They line up like an avenue of saluting rods, honour guards, both horizons.

And now that sense of urgency that signals yes, here. We laugh at how hard it is to open this box of your ‘excess ashes’. But I’m sure, doing what I’ve wanted all along.

Casting them overboard, flower heads bloom into the mirrored sky. With slight tremble I spill you out, expecting you’ll float about a bit, crinkle down onto the ocean floor, settle.

But a startling swirl of the petals, a whorl threading a constellation of golden flecks into the salt, and you’re off, shooting along with a comet’s tail. So fast you go,

sweeping away like a young lad glad to be free. Ah, says Ivor, he’s going south with the Eastern Current. Good choice Norm, raising his hand; mine, suddenly empty. And you are gone.

Fear Works

It’s a small Irish town, not the Türkiye I’ve travelled hurriedly from, where bombs were shocking Ankara apart, children marching for peace, blown to shreds of bright wind. In this school poetry circle, writing madly students are quiet finally, giggling stopped, interest piqued, Jack and Liam split up. Just the heating is going crazy, interior fan beating the air about behind a boxed-wall with gilded lattice like an old Ottoman harem grill. It had intruded on speech, my throat scratchy for water.

A boom-like explosion – suddenly – Crack Crack! Paul’s head jerks up toward the library door. I tread carefully towards it, beginning to shake.

BANG – BANG POP POP-POP My bare neck feels the brush of its speed. So, it has come. The moment is here, to be riddled, shot apart, left for a news-bite, quickly covered by newsprint waiting for ambulance, police, terror squad.

And because they are here with me, teenagers I’ve come to know intensely, fiercely I force myself calm, breath held, jaw tight, shoulders braced like a primed maternal shield. Knees slightly bent, shoulder cocked to bar any entrance, I wait for the next shot. I wait. The handle is steel-cold in my palm gripping it wet.

Ready at the glass window in the door, I peer towards clarity, feeling suddenly Ridiculous.

It’s only a girl in the corridor, long uniform hanging, exasperated, fed up, slapping down heavy folders onto the shiny flat concrete floor outside, one by one. For a moment I’m lost, confused, caught into cross-fired realities, tense in a world now full of dark surprises –but no – yes – this is a small safe Irish town, isn’t it?

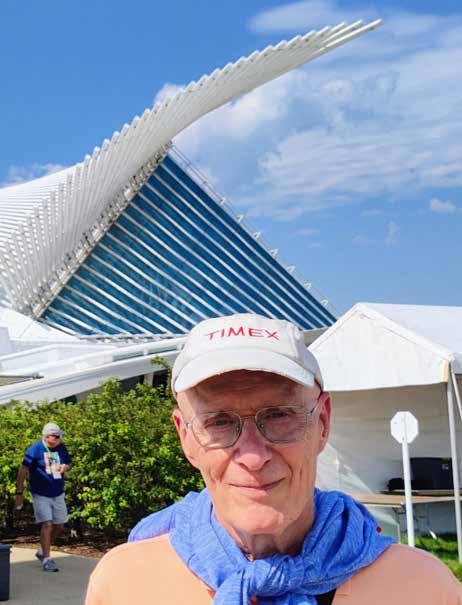

DeWitt Clinton

DeWitt Clinton taught English, Creative Writing, and World of Ideas courses for over 30 years at the University of Wisconsin— Whitewater. Recent book collections include At the End of the War (Kelsay Books, 2018), By A Lake Near A Moon: Fishing with the Chinese Masters (Is A Rose Press, 2020), and Hello There (Word Poetry, 2021) which was awarded the 2022 Edna Meudt Poetry Book Award from the Council for Wisconsin Writers. He has a new collection of poems coming out this fall. His poems and essays have appeared in a variety of national and international journals and anthologies.

Bees

Exactly, or for those who like a bit of charm, exactamente, but that’s what we’re all so terribly nervous about, that something is going on, and we don’t know why, but suddenly, it’s as if we know we’re going to be okay, at least for the night, well, perhaps just a few more hours, as who knows who will scatter our home with such rapid fire that the sofa actually is on fire, and how in the world could that happen, but we’re all wondering about that which is what some will say is the buzzing bee syndrome, first witnessed from a tearful couple who didn’t even know how the flying bees even found a way into the old blue VW van so long ago, but it’s repeated over and over, don’t you know this, first the small child gets a sharp poke in the neck, back side, and then screams her head almost off, much to the consternation of the parents in front, trying their best to keep the steering wheel from disengaging from whatever a steering wheel disengages from, for the couple up front weren’t thinking about bees, but in fact, something more pleasant and totally risqué that we can’t even talk about it, now, so long ago, but then the new bride is smacked silly with another bee stinger, and now we have two wailing and whimpering, and the only one left

set up for a sting, is the driver, who, by the way is delirious knowing somewhere in the tiny van a bee is scouting out where to post his life and let die a poker into the driver who will if that happens most likely swerve off of the highway into some totally perilous off highway disaster, and that, dear ones, you’re still dear, right, that is what continues to this hour, knowing something much more frightening will happen just like that sofa, a nice one even, will just set fire and two are already bleeding out, and the one left is quite unable to dial anybody but something like this is happening all over, in malls, in schools, in holy places where the unsuspected are just starting into a long prayer about something, and just like that, in comes an AK-47 or something even more rapid as it’s no longer Vietnam, but now, to just make a short aside, why is everyone loading up, leaving last messages, as if the entire world is going to be a shootout in old Dodge City though that was the day when one bullet left the chamber one at a time, and the deadly cowboy had to use his other palm just to make the bees fly out faster, and why is that, why is that the answer as that’s the only answer anymore, anywhere, everywhere.

Peppermint

Really, like who would have thought of this, or thought this up, as it’s too wonderful to believe but yes, I’ve never ever tried it, but now I know it would work as the kindly looking fellow staring out from my screen (how’d he get there?) spoke with such confidence, such candor, so truly convincing, that I don’t ever want to even question what he’s discovered, but yes, tell me again, he’s just an actor, not a real scientist, and the director said to the actor, with feeling, say it with feeling, and so many of us have no idea how to even begin to start with feeling as we all want facts, even if they’re not facts, as it really doesn’t matter anymore as there are now more facts that are not even close to facts as there are truly believable facts, but that’s another problem here, the notion that something is believable which is questionable as just who says it’s believable as, and here’s the part that really gets me, I may not, or heck, I don’t believe what you said is believable for that’s all in the head of the believer, yes, and so don’t try to push that hooey over on me, or anyone around me, as it’s probably A, not, as so many beliefs are just some someone pontificating about something they’re only reading a script from, and who can’t read a script and sound so, yes, so convincing especially if they’ve signed a contract to sound, exactly, to sound as if all this who-haw I’m pontificating over truly is a miracle and why wouldn’t anyone believe in a miracle as so many miracles have come by us long since those Books were sealed so no one could write about anymore miracles but it’s so true, what we heard could be a miracle especially if we believe whatever anyone tries to pull something

over on us which, as you very well know, happens quite often, I’d say probably more often than that as in not quite, but very often, as who, really, who has the time to go out there and discover if the miracle is believable or not believable as most, as you know, are not believable but so many have no idea what’s really going on that they assume if someone does say it’s believable, and they sound so entirely, well, so believable that all of us are pretty skeptical about putting up a challenge and saying something nervy like how do you know this, where’s the proof, where’s the beef? and if we bring beef into all of this, well, then we’ll be at each other’s throats for such a long time for we know someone has planted a terrible idea in all of us, that soy might actually be more believable than beef, and then, O god, or O GOD, all hell breaks through in this civilized gathering and nice people, very nice people who we once thought were very nice, now they are actually throwing raw patties at us and some just are so flabbergasted with a patty pasted on their face so they, and this is documented, so they actually start to nibble a bit at what’s on their face, and they rather like the slightly warm but not charred raw patty and pretty soon, patties are flying back and forth creating a kind of ruckus no one has seen around here for such a long time

and all of this, all of this unbelievable patty flying is the result of one nice spokesperson who knows nothing, says, with conviction and aplomb, try peppermint plants, or peppermint spray and you won’t ever again be bothered by those impossible to kill in any way nice mice who keep returning no matter how many electrical or cheesy trap devices you’ve planted throughout the house, so believe it dear friends, this is a miracle, the miracle and you know all about miracles now, so send your credit card numbers right away, and you, too, will never ever see your mice scattering across your floors, just set down your plants, or spray, and wait for the peppermint to send all off scurrying so soon that you’ll soon wonder, what other wonders are out there that you haven’t believed in for so long, so please, please believe what you can’t believe with your first payment of, yes, peppermint patties.

Patricia Sykes

Patricia Sykes is a poet and librettist. Her poems and collections have received various awards, including the Newcastle Poetry Prize, John Shaw Neilson award and the Tom Howard Poetry Prize. She has read her work widely and it has featured on ABC radio programs Poetica and The Spirit of Things. Her collaborations with composer Liza Lim have been performed in Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney, Paris, Germany, Russia, New York and the UK. She was Asialink Writer in Residence, Malaysia, 2006. A selection of her poems was published in an English/Chinese edition by Flying Island Books in 2017. A song cycle composed by Andrew Aronowicz, based on her collection The Abbotsford Mysteries, premiered at The Abbotsford Convent Melbourne — now an arts precinct — in 2019. A podcast of this work is available on various platforms.

Ritual Doorway

When I lay my head on my tired pillow this winter solstice I will think as I do each year of the multitudes sinking likewise into the softs of peace or the hards of duress the trials born into the ones chosen the ones inflicted

Today winter’s media is at full capacity loud with an announcement of death, the end of a friend’s disabling blindness, deafness, her latest fall the killer who broke her ribs and punctured her lung, no surgery she said, her son weeping in my arms as he told of her final “I love you”, her gift his forever pillow.

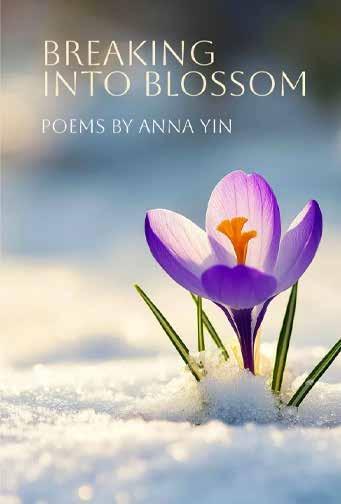

Yuan Fan

Yuan Fan: poet, poetry activist, and pioneer of poetic expression through sound and visual art. Member of the Chinese Poetry Society, partner of Reading Poetry for You, and former vice president of the Jiangsu Province Recitation Association. A global traveler and explorer of life’s poetic essence.

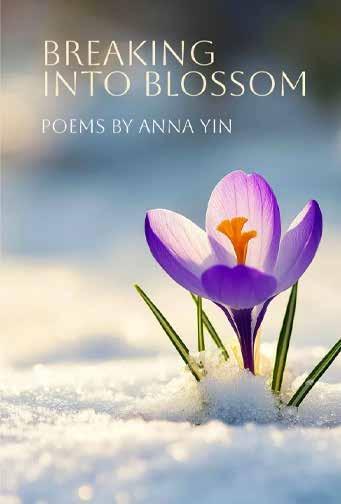

Two poems translated from Chinese to English by

Anna Yin

Fiction

A few pages quivering in the dusk, time begins to wrinkle where Ink stains A comma lingering at the end of a sentence an unfinished sigh

Beneath a table, the yellowed Novel Monthly lies — Stories stretch; vines grow tendrils from memory’s cracks invented rain drips from the eaves of reality, I lower my head, take my leave…

We once sought our own shadows in others’ plots until closing the book, we discovered we were the more beautiful chapter yet unwritten…

小说

几页纸在黄昏里轻轻颤动,墨迹 经过的地方,时间开始褶皱 一个逗号在句末徘徊 像未完成的叹息

桌下发黄的小说月报,故事在生长 记忆开裂处,藤蔓伸出次生根 虚构的雨水淌下现实的屋檐,我 低下头,然后出走……

我们曾在别人的情节里 寻找自己的影子 直到合上书页,才发现 自己原来是更好看的 未写出的章回……

Ordinary

When young, I feared being ordinary, feared a life like an ant’s, like a pendulum’s listless swing, like a fallen leaf, silent and unseen, like rivers clouded with silt.

Halfway through life, I’ve come to understand— ordinary is not so bad.

Ordinary enough to kiss her forehead or lips without hesitation.

Ordinary enough to savor the quiet joy of cooking a good meal for each other.

Ordinary enough to find delight in a bargain well-struck, to take pride in holding my ground, yielding nothing of true worth.