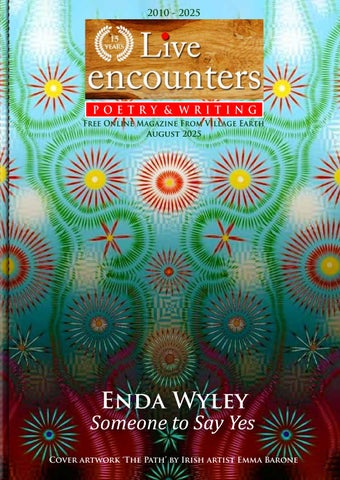

Someone to Say Yes Enda Wyley

Cover artwork ‘The Path’ by Irish artist Emma Barone

Mushroom season. Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

August 2025

Support Live Encounters.

Donate Now and Keep the Magazine Live in 2025

Live Encounters is a not-for-profit free online magazine that was founded in 2009 in Bali, Indonesia. It showcases some of the best writing from around the world. Poets, writers, academics, civil & human/animal rights activists, academics, environmentalists, social workers, photographers and more have contributed their time and knowledge for the benefit of the readers of:

Live Encounters Magazine (2010), Live Encounters Poetry & Writing (2016), Live Encounters Young Poets & Writers (2019) and now, Live Encounters Books (August 2020).

We are appealing for donations to pay for the administrative and technical aspects of the publication. Please help by donating any amount for this just cause as events are threatening the very future of Live Encounters.

Om Shanti Shanti Shanti Om

Mark Ulyseas Publisher/Editor

All articles and photographs are the copyright of www.liveencounters.net and its contributors. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the explicit written permission of www.liveencounters.net. Offenders will be criminally prosecuted to the full extent of the law prevailing in their home country and/or elsewhere.

Contributors

August 2025

Enda Wyley – guest editorial

Geraldine Mills

Trevor M Landers

Richard W Halperin

Sharon Fagan McDermott

John Philip Drury

Jonathan Cant

Paul Williamson

Jena Woodhouse

Michael Minassian

Kate McNamara

Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal

Alicia Viguer-Espert

Linda Goin

Joe Kidd

Neil Brosnan

Enda Wyley

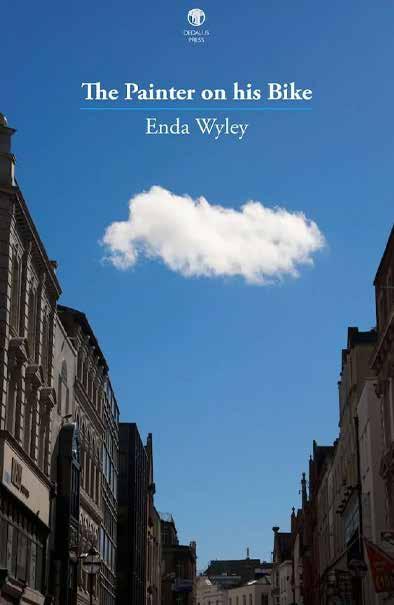

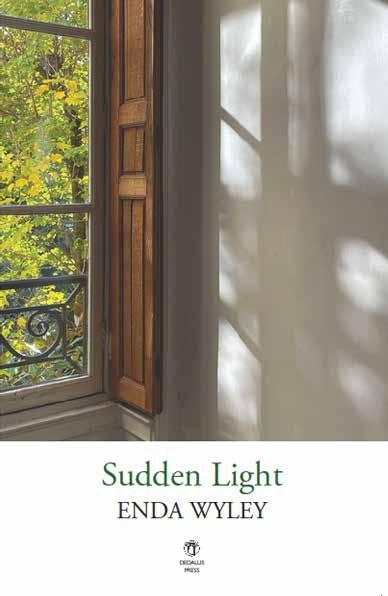

Enda Wyley’s six poetry collections are Sudden Light (due October 2025), The Painter on his Bike (2019), To Wake to This (2009), Poems for Breakfast ( 2004 ), Socrates in the Garden (1998 ) and Eating Baby Jesus (1993). She has also published Borrowed Space: New and Selected Poems (2014), all from Dedalus Press. Awards include the Vincent Buckley Poetry Prize, Melbourne University and a Reading Association of Ireland Award. Enda has been widely translated and anthologised. including in The Harvard Anthology of Modern Irish Poetry, Lines of Vision, The National Gallery of Ireland and If Ever You Go, One City, One Book. Enda’s work has also been broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1. She is an experienced teacher of poetry, co-hosts the popular podcast Books for Breakfast and is a member of Aosdána. ‘Enda Wyley is a true poet,’ The Irish Times.

Enda Wyley

Someone to Say Yes

The child is delirious with fever, shouting about lions. The next day in the garden, in a state of weak recovery, he makes a sundial from stones. The woman observes the boy closely. She is his concerned and watchful mother – but also, although she doesn’t realise it just yet, a poet in the making. As he creates the makeshift sundial, she reaches for a pen and begins her own work, vividly detailing the intimacy of her son’s illness and his slow recovery. She sees him crouch, ‘slightly / trembling with fever, calculating / the mathematics of sunshine.’ She comes to understand how ‘the wave of fever taught silence / and immobility for the first time.’ The poem fills the page, builds with emotional intensity, and reaches an eight-line crescendo:

Here, in his enforced rest, he found deliberation and the slow finger of light, quieter than night lions, more worthy of his concentration. All day he told the time to me. All day he felt and watched the sun caged in its white diurnal heat, pointing at us with his black stick.

She stops writing, crumples the page, and throws it in the bin. It isn’t good enough. Who could possibly want to read about a sick boy building a sundial? But her husband at the time rescues the poem from the wastepaper basket. He flattens it out, carefully reads it, irons it, an idea coming to him. He will post it off to the magazine Poetry Wales. The poem is immediately accepted, and it becomes the title poem of her first collection, The Sundial, published by the Welsh publishing house Gwasg Gomer in 1978.

Gillian Clarke tells me all this as we sit on the edge of her bed in a Dublin hotel. It is autumn 1999, and I have come to interview the acclaimed Welsh poet for Poetry Ireland Review. The lobby had been too noisy, so she invited me to her room. It was an unorthodox interview setting, but an unforgettable one. There, with my pencil flying across my notebook and my small tape recorder pressed to play, I listened. ‘In those days,’ she tells me, ‘it was very difficult to get a book published and, until The Sundial came out, the TLS had never reviewed a book of poems by a Welsh poet.’ She was lucky, she says. Her journey as a published poet began because of the inspired action of someone who believed in her poem, sent it off to an editor who instantly recognised it as what it was, and still remains: a real poem. ‘We all need someone to say yes to us,’ she concludes.

Writing this editorial now, I think back to that afternoon in the late nineties and how her story resonated with me, the younger Irish poet, so intensely listening. Back then, I was starting off as a poet, having published two collections, Eating Baby Jesus (1993) and Socrates in the Garden (1998). But my real beginnings went back even further, to when I was ten years old and wrote my first attempt at a poem. Like Gillian Clarke, I threw it away, only for it to be found by my mother who, like Clarke’s husband, took an iron to it and posted it off from Dublin to a poetry competition in Cork, where she was from. To my surprise, I won. My prize? A volume of Literary Life: Prose and Poems by Canon Sheehan, presented to me by Professor John A. Murphy from U.C.C. at the North Cork Literature Festival in Doneraile. A peculiar award for a young child –but not even that dour, dark-covered book could dampen my enthusiasm for words. What mattered most to me wasn’t the prize. It was that someone had said yes to my fledgling poem. Because of this, I set off in my own way, filling notebooks, playing with words, and being rewarded with a feeling of intense joy and possibility that has never left me, most especially when, even now, I reach for a pen and feel the rush of a new poem claiming the page.

Other writers, too, have been buoyed by that vital early encouragement. Dennis O’Driscoll, for instance, was famous for sending handwritten postcards to fellow poets – simple affirmations that validated and inspired. His writing was distinctive – dark ink curls that poets in Ireland were always chuffed to receive. As though a new poem or collection wasn’t fully complete without the O’Driscoll stamp of approval. The flap of a card falling onto a hall floor. Words to goad you on to new poems, better ways of writing. Dennis, after all, was well skilled in writing postcards.

He had written to Enid Blyton when he was a child, and she had replied, praising his handwriting! He’d also written to W.H. Auden, Samuel Beckett, Stevie Smith, and Brian Patten – and received responses from them, too. No wonder, then, that he wrote to us Irish poets. Yes, you can do it. Yes, you are doing it, his messages seemed to say. Keep going.

David Marcus, too – Ireland’s most influential literary editor of the twentieth century –offered his ‘yes’ through his editorship of the New Irish Writing page in The Irish Press. Between 1968 and 1986, he showcased emerging voices like Claire Keegan, Colum McCann, and Kevin Barry. As a teenager still in school, I was thrilled to see my poems appear alongside Paul Durcan’s. Marcus sent me feedback that sharpened my craft, and his publication of my early work remains one of my most cherished memories.

These encouragements matter. Think of Elizabeth Bishop, whose fateful first meeting with Marianne Moore – on a bench outside the main reading room of the New York Public Library in March 1934 – sparked a decades-long friendship, with poetry as its central force. Bishop wrote in her essay on Moore, Efforts of Affection, “It seems to me that Marianne talked to me steadily for the next thirty-five years… her talk, like her poetry, was quite different from anyone else’s in the world.”

Moore became Bishop’s earliest advocate, championing her work, nurturing a talent that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. Nearly all of Bishop’s early poems were published in magazines thanks to Moore. She also wrote an introduction for Bishop’s poetry in an anthology of work by younger poets, where she praised her for her “methodically oblique, intent way of working,” while also recognising the inspiration Bishop drew from earlier poets: “One notices the deferences and vigilances in Miss Bishop’s writing, and the debt to Donne and to Gerard Hopkins.”

When they first met that day in the library, Bishop reportedly asked Moore if she’d like to go to the circus — not realising that Moore never missed a single one. Their second meeting was, in fact, at the circus, where Moore arrived with brown bread to feed the elephants, instructing Bishop to distract the enormous creatures with the bread while she tried to snip elephant hair from their heads. It was to be used for a bracelet she had, a special gift from her brother, made from elephant hair that needed mending. Shortly after this encounter, Bishop wrote to a friend, ‘I’ve seen her only twice and I think I have enough anecdotes to meditate on for years.’ Elephants and the circus aside, it was poetry that was to always remain central to their friendship.

Not every writer or poet, however, has had someone to say yes to them. Many remained relatively unknown in their lifetimes. Emily Dickinson wrote nearly 1,800 poems, yet just a handful were published while she was alive. Only after her death in 1886 were her complete works published, leading to her recognition as one of America’s greatest poets. Similarly, John Keats, too, struggled for recognition in his short life, publishing only a few poems. Yet after his death in 1821, he became one of the most celebrated of the Romantic poets. But whether championed or ignored, poets and writers have always shared one trait: a fierce creative resilience. That resilience is the mark of the writer. And always, it is sustained by reading.

Elizabeth Bishop may have been lucky to meet Marianne Moore at the New York Public Library. But with or without that encounter, she would still have made her daily visits there in the years after she moved to the city, finding guidance and inspiration in the books she discovered on its shelves. There, she read Charles Darwin, George Herbert, John Donne, and Sigmund Freud. There, she read herself into becoming a poet.

Reading, in its own mysterious way, reminds us of what is possible. As the poet Mark Strand said: “When I read poetry, I want to feel myself suddenly larger … in touch with— or at least close to—what I deem magical, astonishing. I want to experience a kind of wonderment. And when you report back to your own daily world after experiencing the strangeness of a world sort of recombined and reordered in the depths of a poet’s soul, the world looks fresher somehow. Your daily world has been taken out of context. It has the voice of the poet written all over it, for one thing, but it also seems suddenly more alive …” (The Art of Poetry No. 77, 1998).

I value the poems I have read and carried with me over the years. What would I have done without Philip Larkin’s wise words? His poem, ‘The Mower,’ hangs over my desk, encourages me to keep going, says, ‘we should be careful/ of each other, we should be kind/ while there is still time.’ Then there’s Miroslav Holub’s poem, ‘The Door,’ that always puts a spring in my step; ‘go and open the door./At least/ there’ll be/a draught.’ There’s Thomas Hardy’s woman calling, Edward Thomas on a train that stops at Adlestrop, Louis Mac Neice peeling an orange while snow outside falls, Sylvia Plath’s morning song of motherhood, Maxine Kumin rummaging in the coat pocket of her dead friend Anne Sexton, Eavan Boland on a bridge over the Iowa river remembering the early intense years of her marriage, W.S. Graham laying a poem at the ear of his love before she wakes, Heaney’s tinsmith’s scoop of love in Mossbawn.

Enda Wyley, The Painter on his Bike (2019).

Order https://www.amazon.com/Painter-his-Bike-Enda-Wyley/dp/1910251631

These are just some of the powerful poems and vivid poetic scenes that I return to over and over, to be renewed by them.

Reading is a journey that knows no end, surprises and inspires. Just this morning, for instance, my day came suddenly alive when I read the opening poem ‘Monet in Árann,’ from Moya Cannon’s new book, Bunting’s Honey, Carcanet Press, 2025. How wonderful to be ‘ambushed by the sway/ and scent of a July meadow.’ This is the joy of reading – to be caught, ‘in the blurry, summery sway of it.’

So, we all need someone to say yes to us – a mentor, a reader, a kindred spirit, a gifted editor who sees something worth saving in our writing. But even more, we need books and poems – read and reread – until the world gleams again, strange and new. And sometimes, if we’re very lucky, someone who might even reach into that waste paper basket.

A poem is ironed, the sundial is complete.

Enda Wyley, Sudden Light (23 October, 2025).

Pre-order https://www.amazon.co.uk/Sudden-Light-Enda-Wyley/dp/1915629454

Geraldine Mills

Geraldine Mills is a poet and fiction writer from the west of Ireland. She has published six collections of poetry, three of short stories and two children’s novels. Her fourth short story collection, Survival Games, will be published by Arlen House in the autumn.

Best Eaten Cold

When you came back, the sky was the same colour as the mackerel I served you on that old copper plate.

The dog slept in its paws by the fire, didn’t lift its head.

So long since we had sat and eaten like this, you licking the fish juice off the plate with your scarred finger, telling me that since you left that day,

you had been losing little pieces of yourself, not knowing where they had gone or how to bring them back.

You cried because you could no longer hear the night fall, years since you saw the wind, or tasted the dazzle of stars.

In a Fifties Photograph

The old black and white photo jogs no memory until digitised to colour. Suddenly there we all are: dressed up for the races in our Sunday going-to-mass clothes, our father in his brown suit, our mother in her best costume, my younger sisters in fancy plaid rigouts sent over in a parcel from the Bronx.

But it’s my own dress that flames with the past: peach and blue tea roses swirling around the bodice, the standy-out skirt, the one mother made for me when she cycled against the wind into Galway and bought that length of fabric in Brennan’s shop, fire-damaged stock sold off for a pittance.

She cleared the kitchen table of breakfast things and with our only scissors (wiped clean of chicken feathers) cut out the pattern already drawn in her head. With a whole world threaded through the eye of her needle, she matched flower to flower along each sleeve, shaped the neckline, scalloped the collar, singing away the telltale whiff of smoke, the singed edges. Singing.

Background floral image from https://couture-moda.com/ Compsite graphic by Mark Ulyseas.

Trevor M Landers

Trevor M Landers is a graduate of the renown Masters of Creative Writing at Auckland University of Technology, where he was fortunate to be tutored by Siobhan Harvey, Mike Johnson and James George. He is widely published in his native New Zealand and in 2024 worked on a major sub-regional anthology (424 pages) in his home province of Taranaki with Dr Vaughan Rapatahana and Ngauru Rawiri entitled Ngā Purehu Kapahou (The spinning turbine blades) (2024). A larger companion volume with renown Te reo Māori kairangi reo Tipene Hoskins will be released early in 2026. It is called Ngā Tāngata Tūturu: (the truly impressive people): a paean to the people and places of the rohe of Ngāti Maruwharanui (forthcoming 2026, 600+ pages). He currently lives and works in Brussels, Belgium.

Uprooting (Littoral: Kaupokonui Beach)

The anguished heart lends itself paradoxically to uprooting, after rain, the nodes and nodules freed from the matted imbroglio of loamy soils Tug on me and it all comes out too easily: ryegrass, fescue, oioi, kowhangatara, toetoe upoku-tangata botanical specimens seem to leap out decay in speckled brown bundled bunches relinquishments at the slightest touch of saltine squall this precarious fragility is a leitmotif, so too equiponderations we tread wearily within our constraints serendipity, fortune and dedication play a part longevity, imparts temperance and patience that which heals slowly is luxated, expunged, offered as atonement to the ingurgitive sands or the profligate gifts of a flurry of mercurial breezes which heals so slowly it may as well be uprooted, salvaged as humus and mulch, haven for huhu beetles in driftwood wassail for opportunistic pūwereriki, morsels for saprophytic sand scarabs social housing for swarming māwhitiwhiti a lone pepeke kaukiore blown inland, propitiously: a puddle of phloem among these casual deracinations, our own uprootings after rain. the promise of unwithered, verdant vigours proliferations after the storm.

* Kowhangatara is more commonly known as Spinifex. Oioi, is jointed wire rush, most often found around marshes and swamps, or in sand dune hollows around the coast. Pūwereriki is a generic term for the family of mites. Māwhitiwhiti is the common New Zealand grasshopper. Te pepeke kaukiore is the common backswimmer.

Departure snows

Vinod mistakes lenticular cloud for rain, ‘snow tonight’ I proffer laconically, answering an unarticulated question ‘Make sure Radhna is wrapped up warm’, skipping to 34.

This morning, the glacial plates of home lost their moorings, adrift in a sea of connubial possibilities, boat unroped from a wharf the mounga cream-iced fathoms deep, an auspicious farewell, Koro. Cristina’s fire roars with primal satisfaction, each incinerated log whistling a ecstatic sing of immolation.

At Vintage Industries, bagel, toastie, smoothie disappear to sounds of laughter, picaresque takes of feral cattle in the Kaupokonui Sandhills, the necessity of someone else’s rifle, Tony and Lesley guffawing, a coterie of neighbours, including Ngāti Tu, unimpressed by regular i incursions, cattle wilded far beyond tameable animal husbandry norms yet owner gleefully shooting, then butchering, friable chevrons of peripatetic neglect.

Still the mounga, luminous and wearing another chimeric face, the same comforting constancy of Kāhui Maunga providence. The ancient people of Mimi Maunganui and the old kainga of Karakatonga, High in the Waiwhakaiho Valley, powdered deep like the ancient refuges like Te Ana Tahatiti, the sacred urupā, the wellspring of Hangatahua awa, near Ahukawakawa swamp, cascading like a promise guaranteed over Te Rere a Tahurangi with a pirouette of time.[1] It alone shall remain.

The chill wind exalting hearts, nirvana for skiers at Manganui, fresh frosting for slalom and moguls, near perfect denouément, a last snatched kiss from the metamorphosis of Pukehaupapa.

Thence Pukeonaki, renamed by tūpuna Ruataranaki, Maruwhakatare, and Tahurangi, guided by Te Taipairu o Rauhotu

to the present spot. Here he stands magisterially, this exultant whakatauki in my head:

Tū kē Tongariro

Motu kē a Taranaki

He riri kia Pihanga Waiho i muri nei

Te Uri ko au ee![2]

[1] Also known as Bells’s Falls

[2] My translation: Tongariro is standing/Taranaki is an island, after a fight with Pihanga, leave it behind, his descendents are him (Taranaki)!

Ornamental Gorse No.2 Wharehuia

after Chris Orsman[1]

Yes, there is ornamentality I grant you, This veritable noxious exotic weed. It might be obsequious and buttery & dispersed widely into fecund soils

however, as ornaments hedging the aesthetic there is none more bellicose when it run rife. Sharp, shiny swords pierce lush paddocks and the breast of venerable Papatūānuku.

Yellowing it might haze the forgotten histories of occupation, reprisal & muru raupatu these crown of thorns are not a garland for pitiful countrymen, but blots & blemishes

To colossal arrogance & gracelessness of forethought Not reluctant, but an ubiquitous sign of the error, Xanthous conquest, another emblem of ‘unforeseen’, consequence: encroachment in the land of Maruwharanui

A leitmotif of turbulent histories looks pleasant superficially, the yellowness soon turns to prickliness. The best that can be said; it binds eroding cliff-faces; Why these hills are eroding takes us back to the source.[2]

[1] Chris Orsman, ‘Ormental Gorse’, in James Brown (Ed.,)

The Nature of Things: Poems from the New Zealand Landscape, Craig Potton Publishing, Nelson, (2005),p.34.

[2] Te Taru Kōwhai Ae, he tāku whakapaipai, ka hoatu ki a koe/ Ko tēnei taru kino rawa atu. He mokemoke me te pata & ka marara whãnui ki roto i ngā oneone pai/Heoi anō, hei whakapaipai i te āhua ataahua/kua kore he riri i te wā e rere ana/Ko ngā hoari koi, kanapa, ka werohia ngā papā puihi me te uma o Papatūānuku/Ko te kowhai, ka paopao pea i nga hītori kua warewarehia o te mahi, te whakawhiu, me muru raupatu/ehara ēnēi karauna tataramoa i te whakapaipai/mō ngā tangata whenua pouri, engari he para me te koha. Ki te whakahihi nui me te kore whakaaro o mua/ehara i te whakaroa, engari he tohu puta noa mo te he/Ko te raupatu kōwhai, tetahi atu tohu o te ‘kaore i kitea’, te mutunga: te pokanoa ki te whenua o Maruwharanui/Ko te kaupapa o ngā hītori ohooho, he ataahua te āhua, ka huri te kōwhai ki te koikoi/Ko te pai ka taea te kōrero; ka herea e ia ngā mata pari kua horo; He aha ēnei puke e horo ana ka hoki anō tātou ki te puna.

Richard W. Halperin. Photo credit: Bertrand A.

Richard W. Halperin is a U.S./Irish dual national living in Paris. His poetry is published by Salmon (four collections) and by Lapwing (eighteen smaller collections.). In Autumn 2025, Salmon will bring out All the Tattered Stars: New and Selected Poems, Introduction by Joseph Woods.

Further

If I were forced to name, at this moment, the greatest poet who ever lived, Homer and Sappho included, I would say Wilfred Owen. Further, I would say the twenty-three poems which Siegfried Sassoon selected and sequenced for the first published collection of Wilfred Owen’s poetry. Sassoon’s Introduction shames me by its brevity and by its absolute rightness.

‘At this moment’ because: look at our world. This is what (again) we have done with peace.

Why write at all, when writing changes nothing? And it has changed nothing: look at our world. But sometimes writing does change something. Wilfred Owen’s poetry changes me. I know more than ever, thanks to him, that I am ashamed.

Einstein writes, in his book on relativity, that he rejects a formula put forth by one of his great predecessors, because it lacks charm. The universe must have charm. I think that Einstein might say that his own formula acknowledges charm, and that it also acknowledges the strong possibility of being used shamefully.

A friend just wrote me, ‘The holes in reality may reveal spaces for mercy.’ I hope so.

Chance

Two gratuitous wars are going on at the moment. I do not understand any of it. I only understand that those who start a war are responsible for every single subsequent death and maiming, because a war, once started, is uncontrollable. It takes on a madness of its own. In Thomas Mann’s Dr Faustus, which is chaos portrayed without respite for six hundred pages, a Mephistophelian being to whom Dr Faustus wants to sell his soul says to him, That you can only see me because you are mad, does not mean that I do not really exist.

It is not given to me to understand Caesar and the things that are Caesar’s.

I think of 1991, Vienna. My wife and I met by chance the composer Gottfried von Einem and his wife the playwright Lotte Ingrisch who owned a flat we were about to rent. They invited us to the Stüberl which Schubert had frequented. Schubert’s booth there had become ‘Gottfried’s booth.’ Gottfried showed us the scratches, some of them musical, which Schubert had made on the wood. Schubert who, like all the artists I have ever met, had been very happy and very unhappy.

This I understand. This, I am glad to understand.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Sharon Fagan McDermott

Sharon Fagan McDermott is a poet, essayist, and teacher who lives with her dog Beowulf in Pittsburgh, PA. She has published four collections of poetry, most recently Life Without Furniture (Jacar Press, 2018). Her first collection of essays, Millions of Suns: On Writing and Life, co-written with M.C. Benner Dixon was published in 2023 by the University of Michigan Press. “Poets and Writers Magazine” named this collection of essays and writing prompts one of its “Best Books for Writers.”

Patti Smith Speaks of Dylan Thomas

and of the fisherman in his poem with the “long-legged heart,” and of tonight’s Flower Moon that blooms like my peonies, petaled wide and white as sails on a windy sea, and I suddenly want to dance in my night yard like the woman in Dylan Thomas’ poem whom he calls “mad as birds,” so now I add to my list of goals—yes!—let me be “mad as birds,” because right now I hear a Tennessee Warbler calling from my neighbor’s pine. His notes cut through the noisy Pittsburgh morning and make it whole and full as a Thursday moon. And my hero, Patti Smith, is mad in love with poetry. She reads from Dylan’ Thomas book with its threadbare binding with such delight. And though I was sure I was ready for sleep, this magic coalesces in my ear, and I rise up—now a bird singing in a copse of shadowed pines, waking the dear warblers who are migrating through—with the moon, a steadfast bloom, in my hand.

Starlings

1.

Starlings love to hang in flocks. Opera singers of the canopy, they stop me in my tracks with their pure, high, fluted notes. My relationship with them is mixed. This late spring, I love to watch the mothers with their fledglings because it’s always such a loud and lively conversation. But starlings leave no seed unturned and crowd the yard and so the other hungry ones: wrens, sparrows, robins, cardinals—get short shrift when starlings come to dine.

2.

Mozart’s beloved pet starling mimicked his melodies and sang them back to him with variations and embellishments enough to inspire and push the composer further. His bird became a muse on loop, the bond between them thrived, lasting three years. And when the starling died, Mozart threw the bird a lavish funeral with mourners, hymns, and poems. As he inscribed his grief upon the starling’s tiny gravestone.

3.

Tonight, before the Strawberry Moon begins its rise, I watch a starling posed and poised upon my planter of zinnia’s and wish that The Night Queen’s aria from Mozart’s “Magic Flute” might spill from its bright yellow beak like gold coins rained down into fountains--

4.

--or that the flock of starlings nattering dusk into being—from my maple tree might take to sky all at once—swooping, diving and form a murmuration so voluble as to write new songs for our angry, battered world. To teach us, once again, how to look up and learn the black notes of the winged wild: their score against the waning light.

John Philip Drury. Photo credit: Tess Despres Weinberg.

John Philip Drury is the author of six poetry collections: The Stray Ghost (a chapbook-length sequence), The Disappearing Town, Burning the Aspern Papers, The Refugee Camp, Sea Level Rising, and most recently The Teller’s Cage (Able Muse Press, 2024). His first book of narrative nonfiction, Bobby and Carolyn: A Memoir of My Two Mothers, was published by Finishing Line Press in August 2024. After teaching at the University of Cincinnati for 37 years, he is now an emeritus professor and lives with his wife, fellow poet LaWanda Walters, in a hundred-year-old house on the edge of a wooded ravine.

Elegy in a Room of Windows

for Dana and Mary

Beyond the open French doors to the sunroom, my son slept on a blanket, rotating on the floor, like a boat around its anchor. I knelt and listened for the swell and lull of his breathing. Sometimes it was hard to tell in faint street light that seeped between the shades. I eased my hand upon his puny chest and always thought about your first child, Michael. In my son’s room of windows, his angel was a boy he’d never meet, the thought of whom jostled me awake to drop on my knees, there in the half-dark, as the heat flicked on.

The Dead Man Visits in a Dream

1. About the Dead Man Giving Me Advice

I was browsing in a backwoods convenience store, with coolers of fishing bait by the counter.

Around a corner, there were coin-operated washers and dryers. Then Marvin Bell showed up, although he had just died of cancer. He was wearing a slicker and a cold-weather cap with flaps. But I recognized the grin behind his beard and the twinkly investigating eyes.

He said something, but it flutters just beyond memory in daylight. It might have been advice, maybe “Don’t forget to dress for the weather.”

Maybe “Be sure to get the right kind of bait—but anything could be the right kind.”

Something Delphic, some Yiddish koan.

He was always generous with double-edged suggestions. In class one afternoon, I read aloud “The Flooded Quarry.” At the bottom of the quarry lurked a catfish “big as a circus strongman.”

I was thinking of rumors that they grew to six feet in length. I was thinking of the muscle-bound show-off’s handlebar mustache like the barbels curling from the fish’s snout.

After I finished, he grinned and quipped, “That sounds like Charlie the Tuna.”

So the draft descended to the limbo of a file folder in a basement drawer.

He gauged what level of criticism a student could take. I was happy he thought I could take his ribbing.

2. More about the Dead Man Giving Me Advice

He haunted me while still alive.

In my own classes, I quoted his maxims and passed along his advice. Don’t “enjamb out of anxiety.”

Make sure there’s a “payoff” at the start of the next line.

Now, when I look through his kaleidoscope, I see duck farms at the Moriches.

That’s the watery region where he grew up, a half-line in my thesis, and we talked about it on a winter afternoon in his office.

I drive through his Long Island, beside his Atlantic and the hole he found in the ocean.

I watch him playing his cornet at an X-rated reading in the English Department lounge.

I glimpse his mother, Belle Bell, and hear the Yiddish proverbs he may have learned from her.

I want to “sleep faster,” to relinquish those pillows they needed, so I give up tea and learn to drink coffee, my amphetamine in the morning.

It jolts me, makes me hum, and shifts my teaching into higher gears, a swirl of music in poetry.

I learn to be less and less embarrassed about more and more, after he tells me that’s what “maturity means.”

He questions the models I’ve drifted toward but acknowledges that’s my prerogative.

He doesn’t say Write like me, exactly, but he’s hinting Write like me inexactly.

I keep on looking for that bait—to take or to use—which could be anything.

Jonathan Cant

Jonathan Cant is a writer, poet, and musician. His work was shortlisted in the 2025 Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize; won the 2023 Banjo Paterson Writing Awards for Contemporary Poetry; was longlisted for the 2023 Fish Poetry Prize; and commended in the W. B. Yeats Poetry Prize. Jonathan’s poems have appeared in Cordite, Island, Verandah, fourW, Meuse Press, and Otoliths.

Little Stingrays

Hoop Pine, how your branches cheered us on—waving those green pom poms in the wind. Your flat seeds floated down and around us like tickertape.

On sun-rayed, childhood holidays, through your hostile burs of winged spurs, we’d run barefoot. Those small hooks, barbed and sharp, fishing for soft soles and finding them. Our pain followed us home—the stinging worse than bindieye. We’d try to out-Aussie each other with brave stupidity.

Note: “bindi-eye” (or “lawnweed”) is an introduced plant species with tiny seed spikes that sting when stepped on. The girl’s name “Bindi” is Aboriginal in origin and means “little spear; or a stick on which a coat is hung”.

Lifeseeker

after Howl by Allen Ginsberg

Bobstar: “Otis”: Lifeseeker! Spontaneous, potential hipster and presiding Dylan disciple spirited in a town of blind fear, who strolled suburban night-streets in quiet contemplation, who drove reckless along forest ridges in souped-up Leyland bushcars spoke with esoteric passengers on all manner of worldly matters, who, with drunken awareness, nodded, exchanging lyrics & lingo, accents & everything with those wise enough to listen, who scatted endless Blues at the water’s edge under steely girders’ railroad rattle, who sought the elusive riff, who hollered thru East Memphis juke-joint jams with tall, slow-talkin’ Texas guitar cowboys then took Chevy south to hometown Muddy Waters ate Cajun-fried chicken en route before venturing into voodoo swamps of hot-ass Loos-ee-Anna! who starved at Frisco airport, footloose & content, having spent final greenbacks on Rolling Stone magazine, who returned home to a cultural vacuum, went walking among Raskols in steamy mudslide night,

who conspired with others wanting to flee to ol’ Mehico for cerveza, chili-hot senoritas, myths & scenery, to follow Jack down Pan-Am path in search of drowsy afternoons, who conquered mountains in the morning reached the highest plain and saw his own reflection in the stream and more signposts pointing upward forever onward. Move! Go! You, who dared to Break on Through, who Lived while others merely existed.

Celestial Bodies

Look! A distant light source brightens—high out of the ink of Sydney’s southern sky.

Each night before eleven, new stars are born and die like Mercury or Mars.

They form a strict and steady cavalcade comprised of metal objects, all man-made— populated with our likeness, too. And, from the darkness, more join the queue.

Observe how their transit trusts the chart. Obeying orbits helps keep them apart.

They turn to port: their pulsing, flashing signs of brilliance caught—like Sirius shines.

Then dimming downwards, finding Earth quite naturally. Although weary, it’s worth the wait for faces pressed upon the glass, so thrilled to see their kin arrive at last.

This time tomorrow, other worlds will show, appearing there from thin air. And, though they move in similar circles and merge in close proximity, their paths will soon diverge.

The lightships land from far away. Fly in, fly out, fly over Kamay Botany Bay.

Paul Williamson

Paul Williamson lives in Canberra. He has published poems on a range of topics in Australia, NZ, the US, UK, Canada and Japan. His collections include A Hint of Eden, Along the Forest Corridor, and Edge of Southern Bright, published by Ginninderra Press. His background is in Earth Sciences.

Fearing for the Forests

The great log in the park at Ross is there to celebrate wood cutters who took boisterous breaks in the town; but the log was one of thousands so it mourns the felling of native giants for farming or timber.

Huon pine, Tasmanian oak, myrtle and blackwood fell.

The Central Highlands road before the lakes is like a cemetery trail through strewn and bleached remains of trees some blackened by later bushfire. Now logging is more controlled. Much is from plantations.

We spend a night beside the working port of Burnie in a rented apartment amid nonstop industrial rumblings while woodchip from logging trucks on highways heaps and loads and people fear for the breathing forests.

Hovering Together

After months of nesting the two kestrels fly together to hunt in glimmering sunlight in the early autumn morning. The hen and smaller male ride the southerly breeze hover close on honey wings drift apart then drop in stages to check for prey in long grass perhaps to feed last fledglings of the giving season or just to share each other’s company in the peaceful quiet.

Those Questions

Through duty and adventure between joy and jokes the surgery of time wields crude blades on minds and bodies that rouse and carry on.

We heal or not in growth that after youthful surges seems mostly in the mind. As one stage fades the wounds from its struggles move forward with us part of training.

Half heard words whisper behind daily noise reemerge in calmer days. The questions that recur need answers. Sometimes the answer is ‘Yes I have done what was needed’. Sometimes ‘That still waits’.

Jena Woodhouse has twelve book and chapbook publications spanning several genres, including seven poetry titles. A traveller and speaker of several European languages, she lived and worked for a decade in Greece, where her unpublished poetry collection, Tidings from the Pelagos: a Polyphony, was shortlisted in the Greek-based Eyelands International Book Awards 2024. A recipient of writing residencies and retreats in Scotland, Ireland, France and Greece, she has also been shortlisted three times for the Montreal International Poetry Prize and awarded other honours, including invitations to give poetry readings in France, Germany and Greece.

Adieu to Polynesia

...not to wake by the shining sea, the limpid eye of the sky in me...

Linked in coralline tiaras, sagas the seafarers made, looped in leis and pearly chains the fragrant islands floated then to grace sublime meridians, dream-wreaths with mesmerising names romancing the intensity of bleu-marine and emerald; a melded, deliquescent glaze defining the horizon’s rim in azure, sapphire, tourmaline and jade.

Wide and starry were the night skies there, and limitless the sea, that shows its gleaming tides and mirrors nevermore to me—

Whales and the Moon

Cetacean Odyssey

Present at the birth of whales are midwives of the deep, who thrust the newborn up to where the lungs meet air in quantum leap.

Forged from the Icelandic tongue, “hvalr” becomes English “whale”, pursued for oil and ambergris in barbarous days of steam and sail.

The moon that governs water, the element of mystery, is sacred to cetaceans and dictates their history.

Skin that withers in the sun is offered to the moon, whose image in callosites recalls a Nordic rune.

It is for the silver-faced Selene that the humpbacks sing— protector of pelagic nomads in their voyaging.

It is the moon that shepherds whales through sea-lanes fraught with hidden threat, where bones of ancestors recount how ambush dealt a brutal death.

When calves are born their mothers transmute blood to warm galactic streams; their love unlocks the universe, where moon meets whales in cosmic dreams.

From argonauts to cosmonauts, from fabled Colchis to Selene, whale migrations re-enact the archetypal epic journey.

The young inherit timeless lore as sagas, ocean lullabies, to guide them on their odyssey in quest of paradise.

A Lore unto Themselves*

Awed by their immense reserves of stamina and eloquence, belatedly we strive to save those gentle giants, the planet’s whales, working with colossal brains and memories to right old wrong, yearning for safe passage on their marathon endurance trials— singers in the wilderness whose hearts are audible for miles, evoking journeys that arouse our sublimated consciousness— nomadic spirits of the great abyss, whom we regard as brave, imagining our forebears of the steppe, the heirs to freedom’s song—

* from the series, The Epic Voyages of Whales

Michael Minassian

Michael Minassian is a Contributing Editor for Verse-Virtual, an online poetry journal. His poetry collections Time is Not a River, Morning Calm, and A Matter of Timing as well as a chapbook, Jack Pays a Visit, are all available on Amazon. For more information: https://michaelminassian.com

Unwinding the Past

This afternoon, the sky turned a deep shock of blue like a swath of canvas in a Renaissance painting with gold clad angels and women with braided hair.

Overhead, crows fly in erratic circles defying gravity and math then disappear behind a cloud shaped like a mermaid’s tail.

Across the street a few kids kick a mishappen soccer ball— it lands at my feet like the head of a saint separated from its neck, a kind of delirium when the past opens its mouth to speak.

Mailing Postcards To Myself

I send post cards to myself, preferring the tactile experience of pen on paper to text messages and email, Instagram and Facebook.

On the back of the cards, I scribble nonsense phrases beginning with the word love and ending with the word postscript, misspelled seventeen times.

I wait for the mail to be delivered, not sure what to think about cards that arrive.

My own handwriting covers both sides like a confession I forgot to burn.

When Gravity Isn’t Enough

I wonder when I became the cartographer of catastrophe.

The moonlit sky cold, my hands white with love’s snow

I wonder if I could chase the shadow of sleep or if touching the shadow will bring the sleeper close.

To touch her voluptuous cheek or see myself reflected in her eccentric eyes, fixed to the spot, anchored to earth.

Kate McNamara

Kate McNamara is a poet, playwright and critical theorist. She also works as an editor. Her plays have been performed internationally and she was invited to deliver the opening address to the 4th International Conference of Women Playwrights in Galway. She has recently returned to her first love: poetry. Her works have been published in a range of formats. A founding member of the Canberra Surrealist movement, Aktion Surreal, she lives in Ainslie with her sons, cats and a menagerie of wild birds.

Horses

Beyond the final province we could ride out to the place of autumn one day riding away from fantasies from those safe roads we travelled once now no longer certain for the unwary no careful notes of those journeys will help not now they are of no use out behind the steppe plains where the great Khan once kept a court in the kingdom of long grasses with his shaman in that sky. If wishes were horses we could ride away from the cold country where spring is not a season but a caution of blizzards where the air is ice peeling our flesh back to bone galloping past that old cemetery where the dead never sleep to that country of wind where storms are born constantly blowing our nights away. On those desolate plains nothing is concealable but for the moon the omens the sound of wild horses riding away if wishes were horses we could ride with them into the night and the river of stars.

The Snow Leopard

It is a red day blood day I cannot write it down for fear it might unravel me even now the platinum light is blinding my head is like an overripe mango waiting for an implosion until the world goes grey and the words fall out of my mouth like gauzy moths unable to cluster my throat opens they fall the medic is coming I have hidden all the evidence the hypodermic comes down like a hammer an anvil on a stone.

Under the feral moon harvest moon last night we wept and screamed and danced we could not stop for hours it was all Hieronymus Bosch all night then the morning light came it was ethereal pearly like a satin oyster colored dress knowing how we would pay and pay I fled into the garden the sun was being pulled up into the sky by currawongs and mynah birds I ran into the grotto sacred with plants and old seeds where parrots and fairy wrens came to feed lavender and thyme grow there statues can move.

It is where the wild lives unmastered by time and schedules of wards and rules arbitrated only by power I escape from the relentless protocols that rule the wards the units the doctors the containment of our days working tirelessly to bringing us back to mindless conformity. I was sprawling on the earth hiding I was watching blue banded bees in the roses the hive the peppercorn gums the little pool O solitude it does relieve me then turning

I see you

I am as quiet as the cat I was named for chameleon to the core but I know the White Goddess it was already too late somehow in that singular moment I cut myself on you you got into my blood like an infection a virus there is no cure Bach’s Fugue in G Minor there was nothing I could do.

You were all mauled so damaged you had been hunted too long blue-eyed blazing with rage you were seeking a crevice a shape change you needed a transfusion of energy you were already scoping the compound you were computing the possibilities of escape noting the exits potential weakness in the structure are the hinges well oiled?

Yeah you scanned it like a machine your eyes were like metallic chip reflecting nothing I always know a master strategist I am one there only three moves here: advance attack retreat but you O you should have been executed on arrival this a dangerous war there are no flesh wounds here it is all inside in the bones that play beneath the skin the wounded walk they shuffle forward all day bruised by the chemical cosh fried by electrification or pacing like a snow leopard in a fetid zoo.

O let him go free I cannot bear that image pacing the endless cage pacing the furry smell the golden eyes that see all and admit to nothing how his shoulders are coiled with muscle always ready to spring upward here he is another needless death in custody.

There is now no mountain lair waiting in the high clear air so clean the purity of rocks no camouflage left not now.

He is a statistical probability. He is just the data of possible extinction.

Then I break I shatter like a pane of glass And you hold me as I sob and cry and plead. I told you later that I would be good for anything my flaws are all in the end game then I can fold like water. Love: it’s always a killer here and you my ancient ragged love you must leave you are my absolute necessity.

And I must stay a sentinel at the gateway my strident voice unfailing roiling the last lost priestess of the Delphic oracle:

An enemy of God.

Photograph by Mark Ulyseas.

©Mark Ulyseas

Kate McNamara

Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal

Born in Mexico, Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal lives in California and works in Los Angeles. He is the author of Raw Materials (Pygmy Forest Press), Make the Water Laugh (Rogue Wolf Press), and Peering into the Sun (Poet’s Democracy). His recent poetry has been featured in Blue Collar Review, Live Encounters, Mad Swirl, Oddball Magazine, and Unlikely Stories

Evening Strolls Outside

Sitting at home as evening strolls outside. Wildflowers plays. A girl is on my mind as evening stops to smell the roses. Outside in the sky there is a row of birds.

Sitting silent, sleeping wide awake, while evening strolls in my dreams one snore at a time. The birds sing a song in the distance. The skies darken. A girl is on my mind.

Stubborn

Because I am stubborn I fail to see the signs. I only see what I want to see when someone smiles.

The days grow too long. I am bothered by time. I do not smell the roses. But I tear up the petals.

Each syllable I speak is rough and hoarse. I speak an inexhaustible language of made-up words.

Like a Circle

Round like a circle. I am restless inside. That is my nightmare. The land is round. I stand on my hands. I found I am trapped. I take my last breath. Is this poetry? Is this madness? I give birth to death. I search for freedom. I walk and walk Until I walk out of The circle all around.

Alicia Viguer-Espert

Alicia Viguer-Espert, born and raised in Valencia, Spain is a three-times Pushcart nominee. Winner of the San Gabriel Valley Poetry Festival (2017) with her chapbook “Holding a Hummingbird.” Two chapbooks, “Out of the Blue Womb of the Sea” (2020) and “Four in 1” (2022) are published by Four Feather Press. She has published at Panoply, Amethyst Review, Lummox, Altadena Poetry Review, Odyssey, Sin Cesar, Live Encounters, Galway Review, and Thimble among others. Panelist for “Writing from Our Immigrant Hearts,” presented at: LifeFest in the Dena Pasadena (2023), Avenue 50 Studio, Los Angeles (2023), San Diego Writers Festival, San Diego (2024), Burbank Buena Vista Library, Burbank (2024), Eagle Rock Library, Los Angeles (2024)

Planting

I listen to crows when I walk under the chestnut trees, repeating my name like an incantation.

Sometimes, we make eye contact, share clouds, - our sacred chuppah,meditate on our experiences in the planet.

Breeze braids their voices with pine needles, songs of colorful more musical birds, and a sky clear like a champagne flute.

April arrived, enigmatic perfum from orange blossoms reach my heart like fever. By the open-door light embraces every nook.

In silence, the earth hums loudly, my chest expands to the yonder horizon, a whole universe arranges inside my chest.

I want to gather my noblest sentiments group them into batches, like rice, plant them in the flooded soil, and whisper to them: “grow!”

Power

I follow the turning coppery brown of its back, golden on the wings’ underside, claws landing next to me on the railing.

Too close for comfort. Those nail-like eyes fixed on me, bent neck to better listen to my pounding heart.

The majestic chest of a king imposing silence, death to small creatures, I’m too awe to move.

I breathe slowly to befriend something, not a companion but a reminder

of the power of effortless union with everything on the sky and the hawk’s s ability to achieve stillness.

I Ask for Quiet

Give me the space birds take for granted even on broken branches.

The olive tree withstands wind loudly scrapping branches with bullet-train-speed.

Down the road, sitting on a rock I dream of holding opposite universes in both hands, create a pathway for the mind to heal shattered hearts.

It’s tempting to stop combing my hair, abandon disentangling errors for later, forget about opposite universes, oceanic depths where, some say, pearls hide.

Scent from roses misdirects my steeps, a dove, witness of eternity, ponders about human struggles, leaning on the sill of a mind filled with karmic debris.

Astral doors open in invitation, I listen to its music, get distracted on purpose I write my indecision on sand more luminous than gold.

I’m determined to hear bells, ignore flaming birds of seduction, dismiss calling shouts from the dance. It’s time to open my hands to gather the silent rain calling my name.

Linda Goin

Linda Goin is an award-winning writer and artist from the United States. Her poetry has been featured in Mojave River Review, Sundress Publications, Verse-Virtual, and Nightingale & Sparrow, among other publications and anthologies. She is the author of two chapbooks, She-Oak and Fearless Morning. Linda’s poetry explores themes of relationships, trauma, healing, and surrealism—often infused with a sharp, unexpected sense of humor.

The Length of Ritual

Arctic terns fly three months without sleep as they follow the sun to breed and back again every year, many miles. Constant daylight casts uniform memory between frozen poles.

Sunday morning, on land, the arms of a man spread out and around two young sons. He carries them safely through a sermon, a score on Paul and his critics. Four more brothers shape

this tight family formation. They indicate a sure flock, secure in their inherited map, nature’s internal rhythm. Wife and mother sits sentinel at the end of the pew, gray braids brace her for private storms.

She envisions other waves, hands entwined. A silhouette flutters against snow white walls, a man shadow leaves, no farewell. How these rituals carry us, every week, every year.

Writing Around Life’s Edges

I’m interested in writing images that illustrate how my ass was similar to my mother’s as we bent side by side to pick weeds from her deer-ravaged garden.

When I write laments about her death, my words appear white on white, like the blocks that cement bodies to the hill behind the church.

Loss is a cliché. My hands, darker than a grave digger’s grip, leave me with nothing to write about the internal shift.

My mother once offered to lend two boxes of shoes I didn’t need. She said, never mind. I’ll leave them to you after I’m gone.

Words that describe change conjure soil eroding around life’s edges. Everything disintegrates over time, except those thresholds. I want to capture the pith and pivot, the nitty gritty bright digs that bring roots to light.

A woman who holds a pen is not a grave digger. A woman who holds a pen is not a savior.

Night

Night is a prime example of reckless, when excess dares caution and wins, tossing remnants to attorneys.

Night is impulsive. It pilfers affection from the cashier’s rack when she turns her back, hoarding her warmth.

Night is bodies burning, heatwaves rising to ride unbridled horses, wild eyes straddling constellations.

Night falls fast. When it hits the horizon it explodes into a million misconducts. The light’s too dim to sing.

Night is not an ensemble. so don’t worry about cellos or halos, but you might remember your dreams.

Night is a prime example of impossible wings, when old legs feel ready and young legs run from reverence.

Joe Kidd

Joe Kidd is a working poet/songwriter/artist. He has been awarded by the Michigan Governor’s Office and the United States House of Representatives for his efforts to promote social justice, cultural diversity, and world peace. Joe was appointed Beat Poet Laureate State of Michigan 2022-2024. Joe Kidd has received numerous awards including: Songwriter of the Year, 2024 Platinum Eagle Award, Champion of Diversity Award from Images & Perceptions Organization. He is a Pushcart Prize nominee 2025. He has toured 9 countries in Western Europe. Also Canada, Mexico, Jamaica, Greece, and 33 states in America. Joe is a member of National & International Beat Poetry Foundation, 100 Thousand Poets For Change, Society of Classical Poets, International Singer Songwriter Association, Michigan Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Joe Kidd has published 2 full length books. In 2020, published The Invisible Waterhole, a collection of spiritual and sensual verse. In 2024, published a short auto biograpy titled ‘Digging Underground - Portrait of a Beat Poet Laureate’. Joe Kidd & Sheila Burke released their first album titled Everybody Has A Purpose in 2015. They have also been featured in compilation albums titled Songs For Standing Rock, and Music For Japan. Since then, they have periodically released a number of recordings including their latest release in January 2025, titled Liberation! Which have received international recognition and a variety of awards.

Mother Said “Do Your Homework”

today we celebrate what the old men died for pledge allegiance to a flag sing our songs of patriotism and thank the soldiers for their service

we did our homework when we were children we passed through school like invisible ghosts they taught us history, they taught us English they taught us to be quiet, they taught us well

“you’ll need to know this when you grow up you’ll need to follow the golden rule you could be the next president you could live the American dream you could make your parents proud”

but parents get old and fade to glory memories disappear before our eyes their vision of happiness follows behind

enlist in the forces the world needs heroes save the city, the country, and the world they will feed you democracy tell you what to do when and how to do it salute the officers at the rear

but this is not a video game if you miss this shot it is going to hurt if you make the wrong turn somebody is killed the wrong decision and boom, you’re gone

traffic is backed up for 15 miles a car on fire upside down 110 miles per hour motorcycle, helmet, ambulance

we were all babies at least born free had no idea of what could be they gave us everything we ever wanted turned us into cannibals the zombies are real, walking in the street pointing and hollering at something they see but it’s not there and neither are they

the hospital is full of people like us who eat the apples and drink the wine broken bodies, demented minds

we are told to call on the government that line is busy, disconnected out till Tuesday, you’ll be dead by then what the agents of insurance have calculated played and lied to, our entire life stopped in the middle of a crooked road free to be hungry beasts of burden a talking machine, an indulgent facade deflected, disposed of, a slow surrender we let them in, we gave them the right they stole the power in the middle of the night the asteroid hit and left a crater deep in the heart of a living planet but the corpse kept walking, covered with dirt a whale on the beach and a fallen leaf

“we bought you and sold you auctioned off your soul the contract is signed, no clause for escape” so said the river rat in the city of capital

“down on your knees and give me 100 how fast can you run with an ape on your back” and that river keeps rising and swallowing the dream

now jump on that pony, painted with blood over the mountain of buried bones your paleontology exposes your heritage this body was alive at the time of death

so be not afraid, the lord is with you as you walk through the valley of snipers and mines these friends and these enemies, identical masks want to feast on the brains and the thoughts and the remains of the treasure left behind when we can no longer bleed

this is no secret and no surprise that when we look back on what was not done that the space once occupied in the universe expanding is larger than the life ever possible to live

she told us all that, and everything else did you cast a ballot, were you so brave did you make history on that fateful day did you hear what mother had to say did you do your homework, emancipate the slave within

Neil Brosnan

From Listowel, Ireland, Neil Brosnan’s stories appear in print and digital anthologies and magazines in Ireland, Britain, Europe, Australia, India, USA, Latin America, and Canada. A multiple Pushcart nominee, he has won The Bryan MacMahon, The Maurice Walsh, and Ireland’s Own short story awards, and has published two short story collections.

Same Time Tomorrow

My parents – whose home this was – could never have imagined how their bedroom would be just as warm on a January midnight as on a July afternoon. Although Dad was familiar with electricity from his workplace, Mam was highly suspicious of its arrival in her kitchen, a modern falderal that could kill you just as soon as it would boil an egg for your breakfast. With time, she became accepting of light bulbs: the fragile glass orbs could be lit or quenched at a safe distance by simply flicking an apparently innocuous switch on the wall. Grudgingly, she soon conceded that the new kettle could be safely filled and emptied once it had been unplugged, while the volume and waveband of the radio could be adjusted without having to remove the plug from the socket. The cooker, however, was a different matter, and remained the subject of extreme suspicion to the end of her days. In spite of Dad’s frequent reassurances, Mam steadfastly refused to turn her back on the appliance until whatever she was baking, boiling, frying or roasting was removed to the safety of the kitchen table, and then only after the big red switch on the wall was clicked to off.

As a pre-teen I thought her fear irrational; now, more than a half-century later, I can fully empathise: her dread of electricity was no different to my present day technophobia. While I regularly use a basic desktop computer for email and Internet, I am highly suspicious of any device with an inbuilt camera. I view smart phones, laptops, and tablets with deep misgiving; likewise, camera doorbells and CCTV systems, and the mere mention of this Alexa contraption sends a shiver scurrying up my spine. Recently, I find that I’m being increasingly discommoded by technology. Even a shopping trip to my old workplace can become a cause of utter frustration when my checkout queue is stalled by some gormless shopper’s failed attempt to effect a cashless payment with a smartphone store app. With my correct change coins pulsating in my clammy palm, I stifle an oath while the balls of my toes burrow into the insoles of my shoes. Perhaps I will mellow in time, as Mam did when embracing the magical immersion heater after Dad added the new kitchen and bathroom to their two-storey terraced home.

continued overleaf...

I now accept that it’s a generational thing. Undoubtedly, Mam’s parents would have gaped in awe at early horseless carriages, while their parents would have endured the horrors of the Irish Famine of the eighteen-forties. I have no doubt that today’s teenagers will one day be viewed with amused disbelief when they attempt to describe the Covid-19 pandemic to their descendants. Coronavirus will be to their grandchildren what tuberculosis and polio are to them, what Spanish ‘flu is to my generation, and what the Irish Famine was to our parents: just another old granny tale; and we all know that granny tales should always be taken with a pinch of salt.

All grannies are liars; they’ve been lying ever since they first became mothers – if not before – and their lies continue to make liars of subsequent generations. I became a liar at the age of five. It was the end of my first Christmas holidays; the Sunday when the priest announced the reopening of the parish’s schools. I returned from mass with Mam to find Gran drinking tea in the kitchen with her friend Mrs Lane.

“He loves it,” Gran instantly replied when Mrs Lane asked me if I liked school.

“Loves it…” Mam echoed, much to my annoyance. While I didn’t actually hate school, I can’t recall having ever claimed to like it – never mind love it!

“Aren’t you the great little scholar?” Mrs Lane smiled, handing me a red lollipop. In solidarity with Mam and Gran, I nodded, fully aware that not only was I accepting the reward under false pretences, but I had also added myself to a lengthening line of family liars – and all before my sixth birthday. Ever since, I’ve found myself questioning everything and everyone – even people whose reputations were universally accepted as being beyond reproach. Once the first seed of doubt had been sown, I found myself viewing everything from Christmas stockings and Easter eggs, to heads of cabbage and the tooth fairy through an increasingly jaundiced eye.

Whatever about the Famine and horseless carriages, the spectre of Spanish ‘flu had cast a long shadow over Gran’s life. Gran was widowed at the age of twenty-seven, when her husband succumbed to the pandemic within weeks of Mam’s birth, leaving her not only with a newborn but with seven other children under the age of ten.

I can only imagine what those children’s bedtime stories were like in an era before radio and TV, at a time when books of any kind were scarce, and children’s books were as rare as hens’ teeth. If indeed there were bedtime stories, they would have been whispered through the foreboding gloom of a flickering candle, where every shadow, nook and cranny sheltered a myriad of unimaginable monsters lying in wait to wreak their havoc under the pitch-black cover of night. I wonder if those children had toys, even the familiar comfort of a grubby rag doll to cling to after the candle had been blown out. They certainly hadn’t lain awake – crammed together between flour-sack sheets, on mattresses of straw, beneath old army greatcoats – whinging and whining about cancelled playdates, forbidden smart phones, postponed First Communion parties, and deferred trips to Disneyland.

It would be many years before such words would enter the vocabulary of our street, but there were no restrictions on hugging in those days. I didn’t have to wait fifteen months to hug my granny; I could have hugged her every day – if I’d wanted to – because she lived with us. She was Mam’s mam, and when she came to live with us, Dad’s dad – whose house it actually was – had to share my bedroom. Granddad was born in the house and had attended the primary school just up the road; at the age of thirteen, joined his dad working in the tannery at the end of the street. Two further generations would find employment at that same address, albeit in vastly different occupations. After the tannery closed, the site became a preparation and storage depot for the poles required for the Electricity Supply Board’s rural electrification scheme, where Dad worked before becoming an electricity meter reader in his later years. Meanwhile, I was climbing the ranks within the supermarket chain I had joined on completing secondary school, ultimately attaining the position of assistant manager when the chain opened an outlet on the old tannery site. I’d initially intended my move back to my childhood home as an interim measure, but as Dad’s only child I felt duty-bound to remain with him after Mam’s sudden death soon after my appointment at the store.

That was when I really got to know Dad, and to like him all over again. I was surprised at how much we had in common and as I began to appreciate his wisdom, he increasingly became my main sounding board whenever a work-related issue would follow me home.

continued overleaf...

I could see why some far-sighted project manager decided to promote him from tarring and creosoting seasoned poles to negotiating with landowners regarding the optimum placement of those very poles throughout the countryside.

With rural electrification finally up and running, the pole depot was shut down but instead of the dreaded form P45 received by many of his colleagues, Dad was given a ledger, a ballpoint pen, and a torch, and commenced his new career as an electricity meter reader. While the new job was cleaner and less demanding than its predecessors, it soon became clear that Dad was missing the camaraderie of his old gang. He was never been much of a pubgoer, but when I suggested he should drop into the local beside the former pole yard on a Friday evening, he readily agreed. It proved a success beyond my greatest expectations: not only was he meeting up with his old buddies but he was interacting with contemporaries from other walks of life, with a variety of interests and diverse points of view.

By the time he retired, Dad was established in a whole new social circle. It seemed that each outing brought new names and interests to our suppertime chats: a game of pitch and putt with Tom could lead to a day’s fishing with Dick or a trip to a race meeting with Harry. He was making full use of his free public travel pass, and despite my concerns for his safety, I accepted his reluctance to keep me abreast of his movements. After all, he was finally free having been in full-time employment from the age of sixteen until his retirement at sixty-six. For him, there were no gap years or travelling; for him, annual leave meant a fortnight working in his cousin’s bog to save enough turf to keep our household warm through another winter.

It wasn’t until I retired that I began to fully understand how he must have felt after he’d finally hung up his meter-reading torch. Already deprived of his daily consultations with pole-hosting landowners, the banter with his pole yard colleagues, and the sense of inclusion he had enjoyed ever since his schooldays, retirement also cost him the dignity of employment – so highly prized by his peer group. I’m sure retirement was as painful to Dad as it is pleasing to me.

I see my former colleagues whenever I need a pint of milk or a loaf of bread, an avenue that was closed to Dad once the revamped electric company began to use outside contractors for network maintenance. Let sleeping dogs lie, was my motto, choosing to interpret his periods of silence as contentment, while I continued to enjoy the benefits of a live-in companion, cook and counsel.

After some years I began to notice that almost all of Dad’s social outings revolved around funerals and anniversaries. At about the same time he suggested moving into my box bedroom, allowing me to occupy the big back room where he had continued to sleep after Mam’s death. I thought it odd at the time, thinking that he might be more comfortable in the downstairs bedroom – originally the parlour – convenient to both kitchen and bathroom; thankfully, I kept my thoughts to myself. A year or two later, as the stairs became increasingly challenging, I did broach the subject of the spare room but he quickly put me in my place by telling me that he had no desire to spend his final days looking out at a weed-infested backyard.

The mention of his final days brought a smile, but the smile died one morning soon afterwards when he asked if he could accompany me to mass. I pointed out that it was Friday, that I was going to work, and then watched in horror as confusion clouded his steel-grey eyes.

“But, Daddy,” he whimpered, “your Sunday suit will get dirty at the tannery; what will Mammy say?”

At his wake, I was surprised to hear about his regular morning vigil at his box room window; the spot from where he’d seen his father walk to work, and later watched me follow the very path he himself had trodden, to both school and work, for almost seventy years, and I finally understood why he had chosen the only bedroom with a street-facing window. Most mornings, I sit here for a while after breakfast, returning the waves of giggling schoolchildren, the dutiful nods of former colleagues, and the bemused glances of passing strangers. I suppose I’ll sit here again at the same time tomorrow.

Cover artwork ‘The Path’ by Irish artist Emma Barone